Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1002/38. The contractual start date was in November 2010. The final report began editorial review in November 2012 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Kyratsis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The emergence and increasing popularity of evidence-based medicine (EBM) since the 1990s1 has provided support for ideas advocating the use of research evidence to improve managerial practice and decision-making in health care. 2,3 It is argued that health policy and management, although admittedly different from clinical practice in significant ways, are lagging behind clinical practice in addressing the problems of ‘overuse, underuse and misuse’ of evidence related to management practice and that this has a significant impact on the quality of care and patient outcomes. 2 Under this perspective, health service delivery and organisation, as well as decision-making, could be improved by applying robust and relevant research findings and other forms of knowledge relating to good practice. More recently, discourse espousing the principles of evidence-based management (EBMgt) and the idea of using research evidence to support managerial decisions also emerged in mainstream management and organisation studies literature. 4,5

Following a similar strand of argument, policy-making circles in the UK have been increasingly advocating the merits of using research evidence to inform clinical and managerial practice. This policy discourse has particularly emphasised the need to spread ‘best practices’ and implement innovations within the NHS to help enhance health-care quality and productivity. 6 In recent years, the Department of Health has issued a number of policy reports and has set up agencies with the aim of promoting evidence-based practice and innovation.

The Cooksey report on UK health research funding7 identified a ‘gap’ in translating innovative ideas and products into practice. The Report of the High Level Group on Clinical Effectiveness, established by the Chief Medical Officer, reviewed areas of significant variation in implementing evidence-based practice. Among a number of recommendations on enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of clinical care, the report emphasised the need for increased understanding of the mechanisms that encourage the adoption of new interventions. 8 The Report of the Clinical Effectiveness Research Agenda Group highlighted the need to develop the capacity of NHS staff to use implementation (and clinical) research in daily practice and the need for greater understanding of the processes by which managers and others access and apply implementation and clinical research when making decisions. 9

A number of agencies were also created, with the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement and the NHS Technology Adoption Centre being prime examples. Following the Cooksey report,7 Academic Health Sciences Centres (AHSCs) and Biomedical Research Centres and Units (BRCs and BRUs) were established to facilitate the translation of research knowledge into clinical practice. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) was set up, and in recent years it has become involved in health technology evaluations. With the publication of the latest report, Innovation, Health and Wealth,10 further organisational changes are being envisaged as the NHS seeks to provide more effective support for innovation and adoption.

However, the adoption of new ideas and technologies is regarded as a challenging issue. On the one hand, there is a need to ensure that, once identified, effective new technologies are adopted and disseminated across the NHS, as the policy goals above suggest. The assumption is that relevant and robust evidence of efficacy and cost-effectiveness produced centrally (i.e. via the NICE or the NHS Technology Adoption Centre) will facilitate such dissemination efforts. On the other hand, much recent research suggests that the way in which evidence comes into play during the adoption and system-wide diffusion is a far more situated and context-mediated process. 11,12 Understanding of the actual practice of how evidence is used in organisational decisions within the multiprofessional setting of NHS is limited. We know even less when this process involves non-clinical decisions. This is where our study aims to make a significant contribution to the NHS and to patient benefit.

We empirically focus on infection prevention and control (IPC) in NHS acute care. In this field, relevant NHS policy reports6,13 and legislation14 have highlighted that countermeasures of known effectiveness have not been universally implemented. In addition, the NHS has commissioned large projects in recent years to identify new technologies and products which work best. One example in the field of health-care-associated infections (HCAIs) is the Department of Health’s ‘Showcase Hospitals’ programme, which aimed to evaluate technologies ‘in use’ across a number of NHS hospitals in England and diffuse such learning among health-care practitioners.

Targets for HCAIs are high on the UK Government’s agenda with performance being monitored carefully by regulatory agencies, such as the Care Quality Commission (CQC), with powers to issue warnings and penalty notices to public and private providers. High media attention combined with high public and patient interest in recent years has demanded transparency of investment and resultant benefit to patients and the NHS. This accountability to the public is facilitated by formal channels, such as the patient environment action teams, who assist inspections of NHS sites, as well as the third sector. The complexity of interorganisational contextual influences and the multiprofessional, cross-cutting nature of IPC make our selected empirical setting an information-rich case for investigating the adoption of innovative technologies and the use of evidence in this process.

In summary, despite the interest in EBM in recent decades, which has led to considerable empirical research on the use of clinical evidence by health professionals, there has so far been limited empirical work in health care in relation to the use (or non-use) of management research or other forms of knowledge in decision-making and the adoption of innovations.

Aims and research questions

The main aim of the project is to investigate the use of research-based knowledge in health-care management decisions. A key objective is to explore the construction of what is regarded as evidence by health-care managers when they make organisational decisions. We include general managers (non-clinical staff) and ‘clinical hybrid managers’ (clinicians in a managerial role) to investigate how health-care managers draw upon and make sense of different types and sources of evidence when they make decisions about innovations. Emphasis is also placed on the facilitating or constraining influences of contextual factors on health-care managers’ decision-making processes. The research is empirically set within the context of management decisions relating to HCAIs. In particular, we explored how health-care managers adopt, and implement, innovative technologies to combat HCAIs in NHS acute trusts.

The study design incorporates multiple levels of analysis: (1) it explores the influences of wider ‘macro’-level contextual dynamics on managers’ decision-making, (2) it explores decision-making processes at the ‘meso’ organisational level, and (3) it analyses at a ‘micro’ level the processes by which health-care managers construct meaning of available evidence and how they might use such evidence when deciding on the adoption or rejection of innovations.

The study aimed to address the following key research questions:

-

How do managers (non-clinical and clinical hybrid managers) make sense of evidence?

-

What role does evidence play in management decision-making when adopting and implementing innovations in health care?

-

How do wider contextual conditions and intraorganisational capacity influence research use and application by health-care managers?

Structure of the report

The report is organised as follows. In Chapter 2 we outline a summary of the relevant literature and the research context linked to the aims of this study. Chapter 3 presents our methodology, including the study’s research design and methods.

Overall, Chapters 4 to 9 outline our empirical findings and centre on our research questions, namely:

-

How do managers (with clinical and non-clinical backgrounds) make sense of evidence?

-

What role does evidence play in management decision-making when adopting and implementing innovations in health care?

Chapter 4 presents findings and emergent themes on the challenges to making sense of evidence reported by health-care managers (including both non-clinical and clinical hybrid managers). The chapter sketches out the background for the more detailed exploration of empirical processes presented in later chapters and draws on qualitative interview data from phase 1. Chapters 4 and 5 (drawing mainly on phase 1 data) reflect on what decision-makers ‘say they usually do’ and Chapter 8 (drawing primarily on phase 2 data) investigates in detail ‘what they actually did’ in specific empirical cases of innovation adoption and implementation, thus addressing:

-

How do wider contextual conditions and intraorganisational capacity influence research use and application by health-care managers?

Chapter 5 explores the sensemaking process for individual professionals in context (organisational and macro), using data from the interviews and the structured questionnaires. In this part of the report we review how decision-makers at different levels of the hierarchy within the organisation report on access and use of various sources and types of evidence related to innovation decisions. We also outline key contextual influences at organisational and macro levels with a focus on IPC and the NHS.

Chapters 6 to 8 look at ‘evidence in action’ (how evidence played out in specific empirical cases). In detail, Chapters 6 and 7 set the background for the in-depth exploration of the innovation products’ journeys. Chapter 6 draws principally on secondary data sources to present an overview of the eight ‘macrocases’ (the acute-care NHS trusts included in phase 2). Important characteristics of the trusts, such as size, performance, crises and critical events during the period of the study, the research and innovation activity, communication and espoused values, are presented in a comparative fashion. The aim is to sensitise subsequent analysis and inform the reader of the potential impact of local and historical contexts on the social and organisational processes investigated. Chapter 7 outlines the 27 adoption and implementation journeys of the technology products, as selected by the trusts (microcases), using interview data from phase 2 and complementary secondary data on supporting evidence for efficacy and cost. In this chapter we also provide a typology of the 27 technologies, distinguishing among three important dimensions: (1) the strength of the evidence on efficacy, (2) perceived impact on practice, and (3) expected impact on budget.

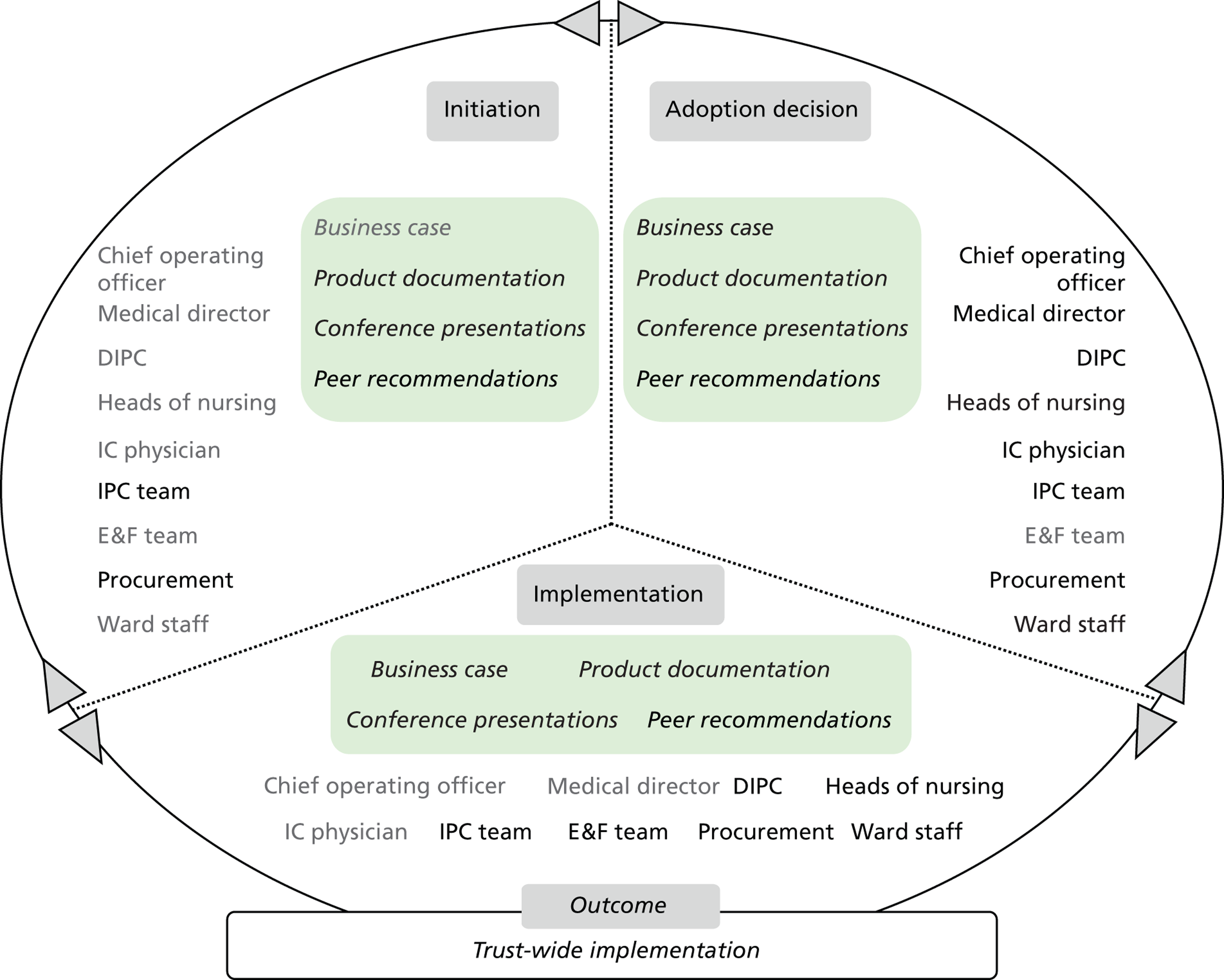

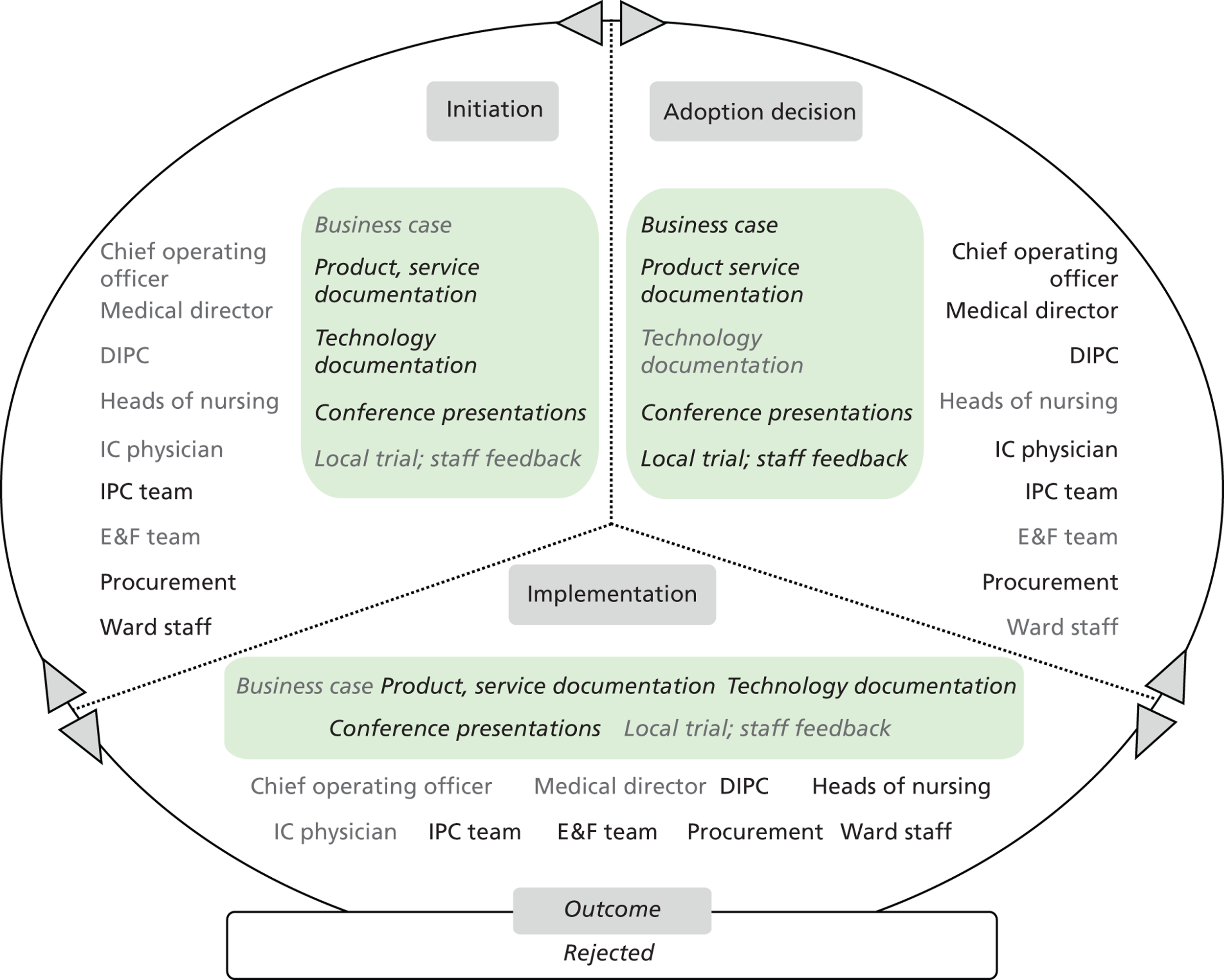

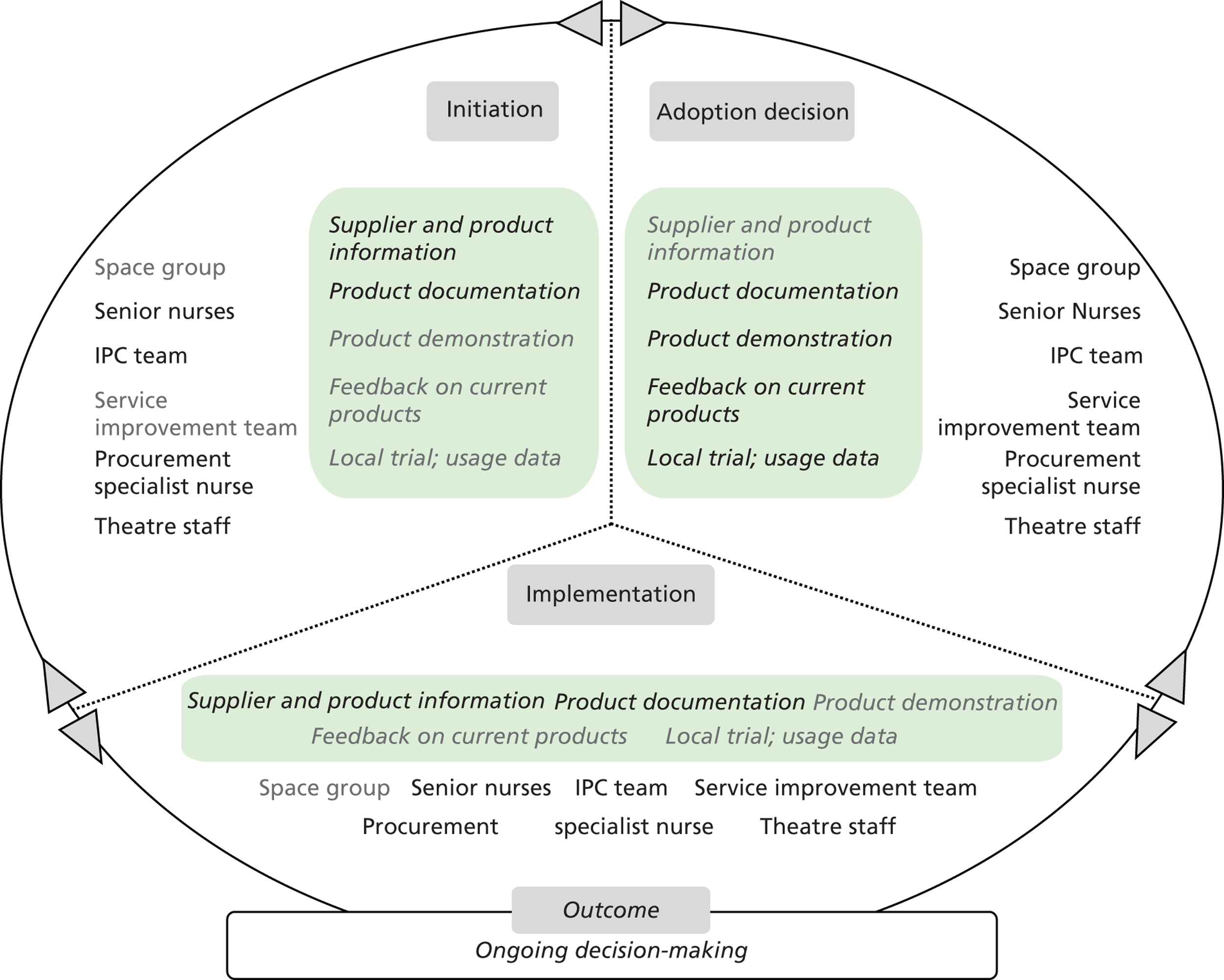

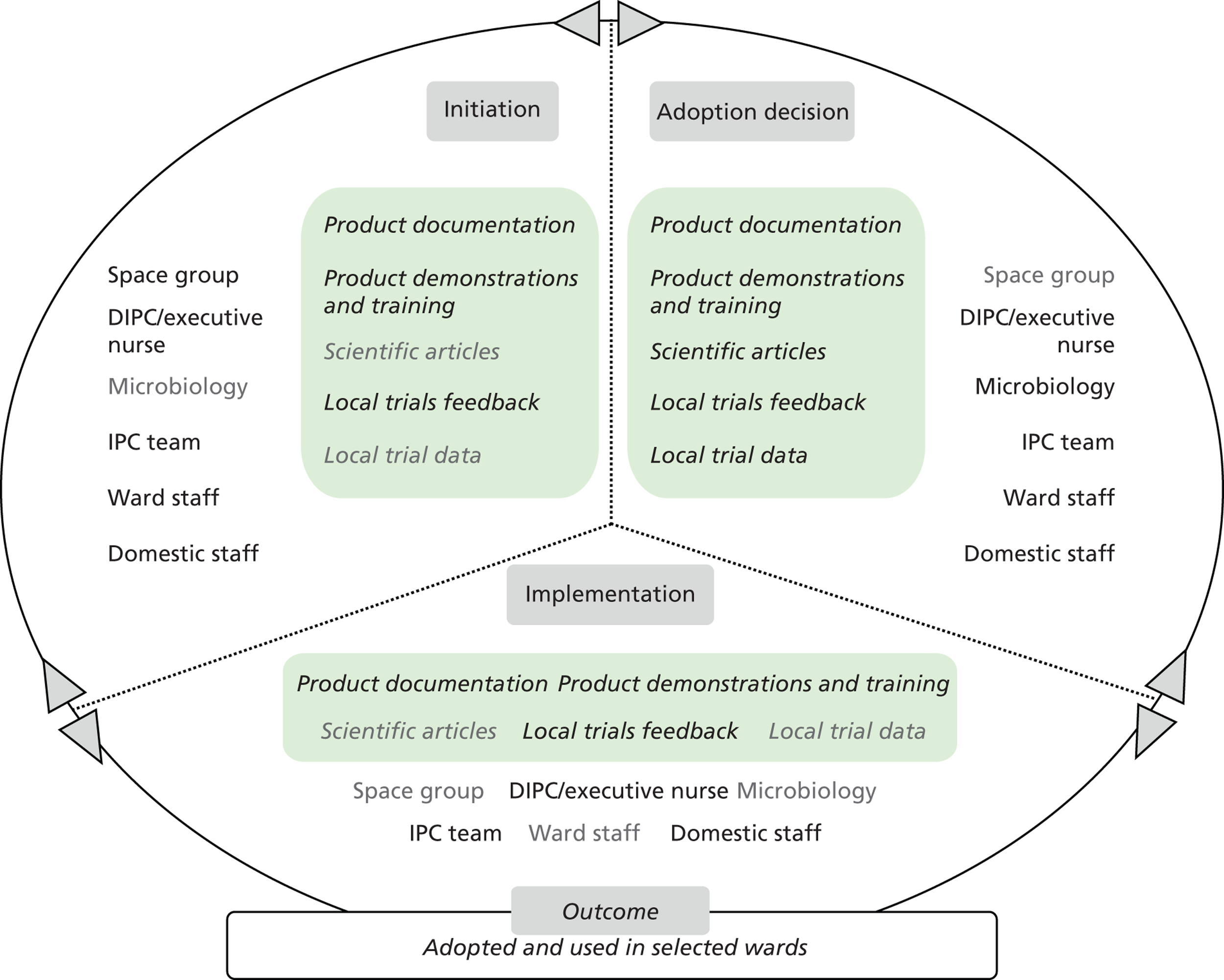

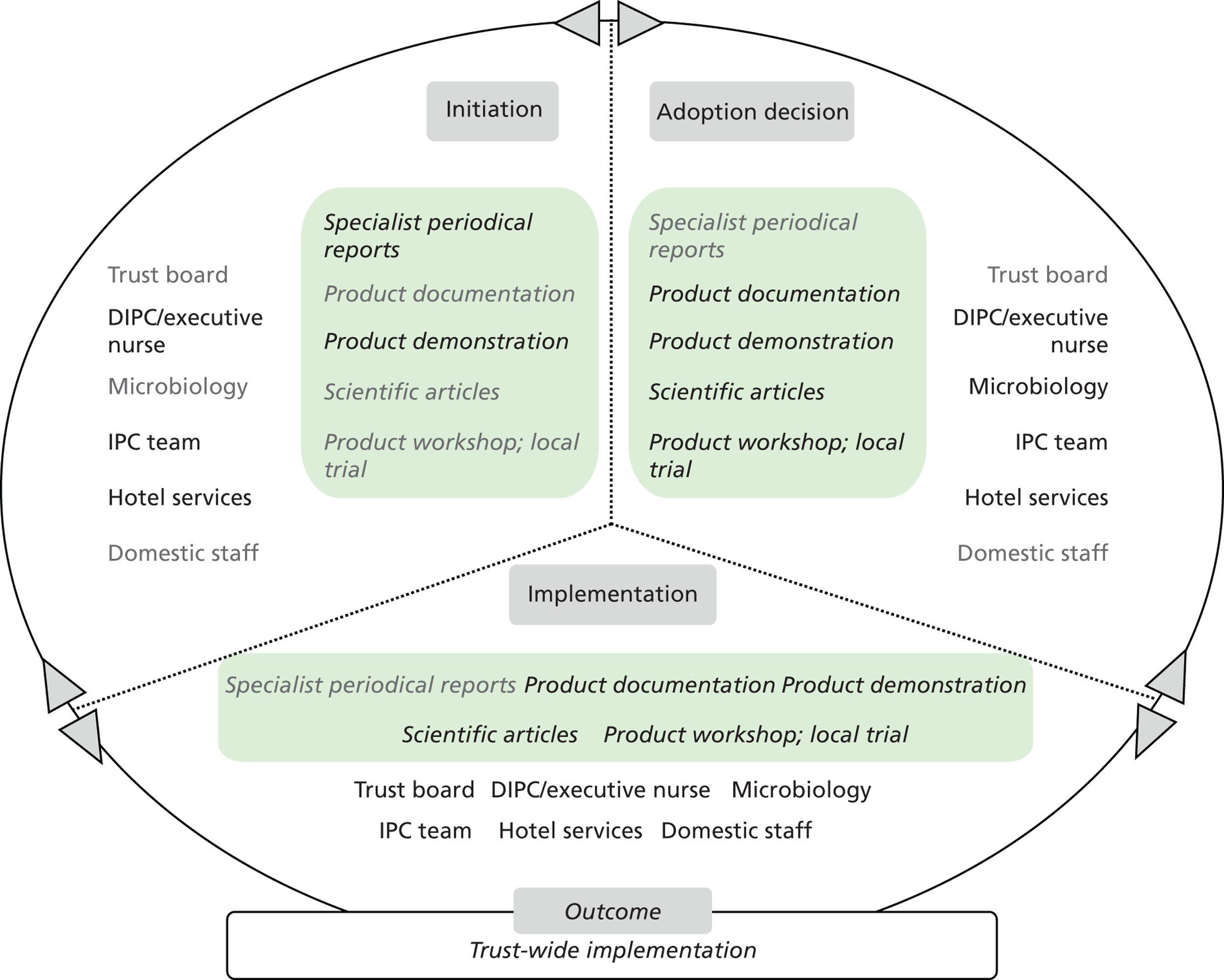

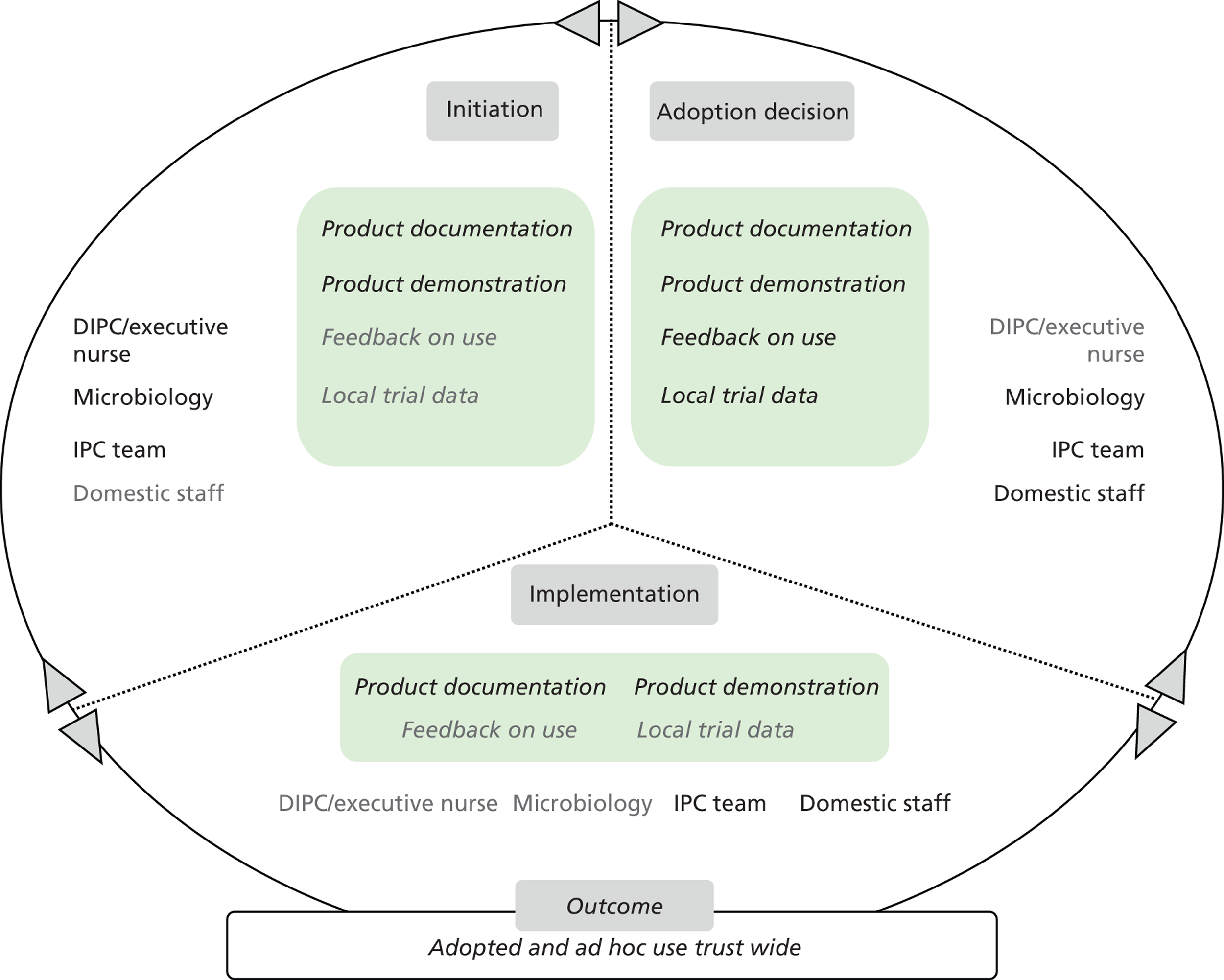

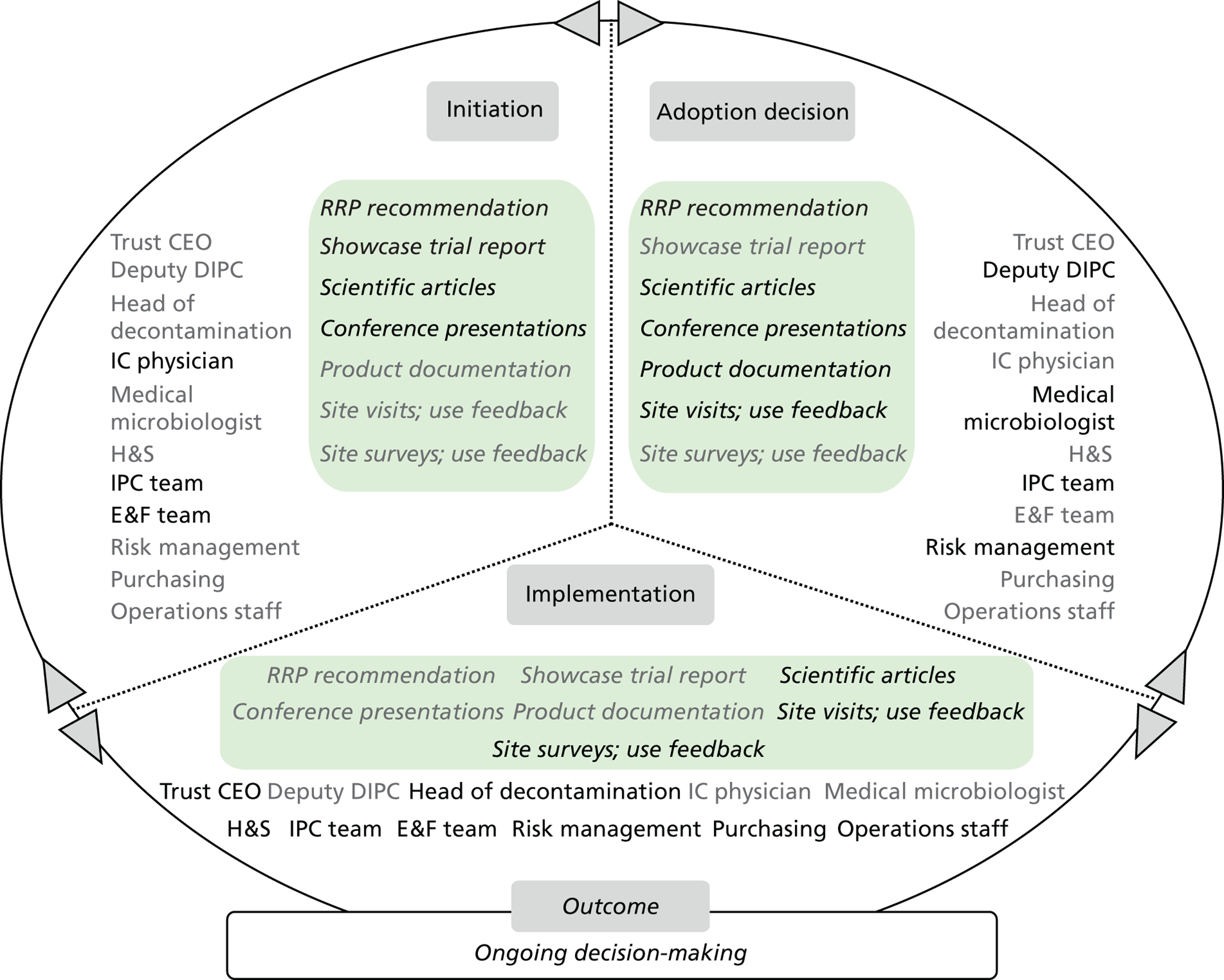

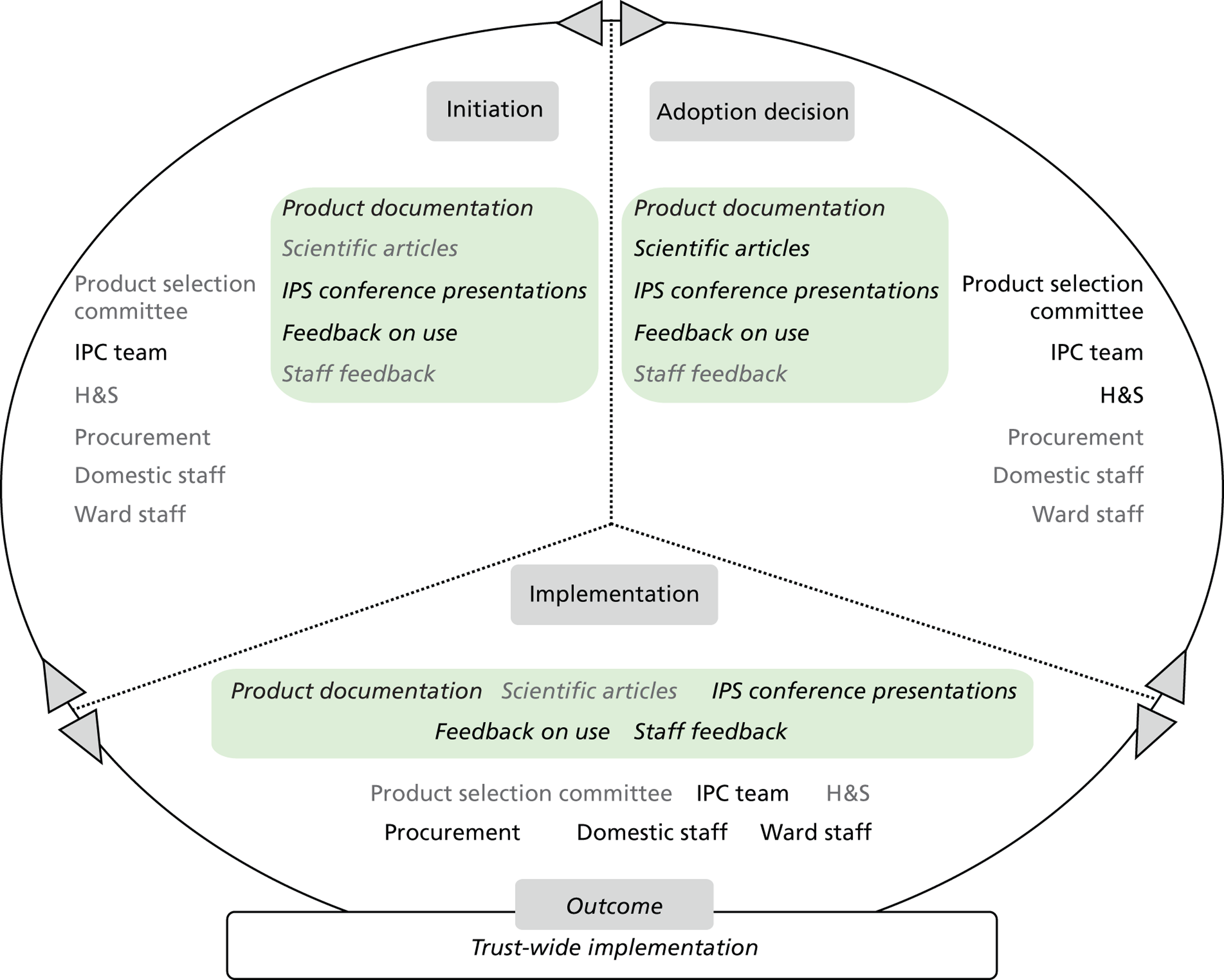

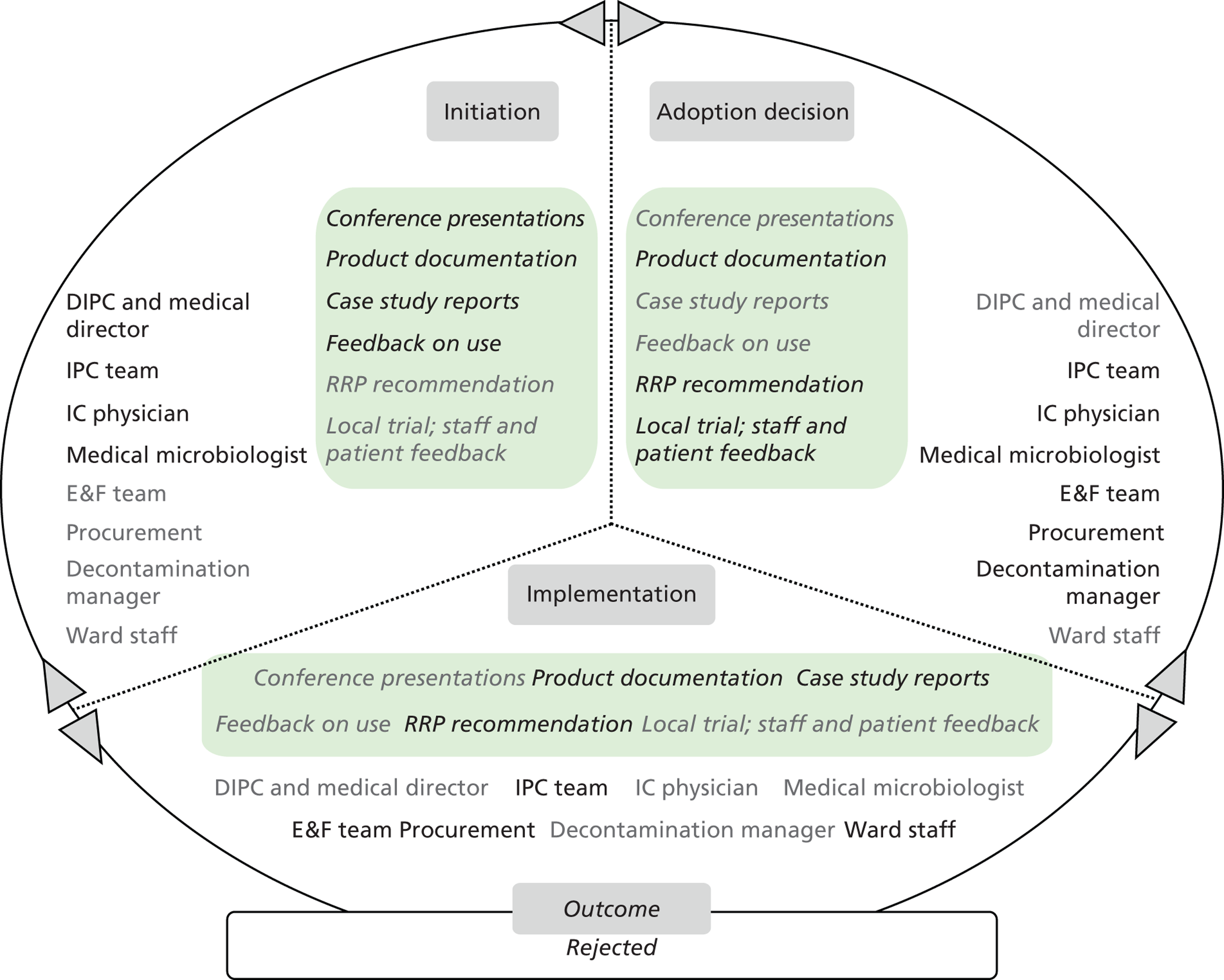

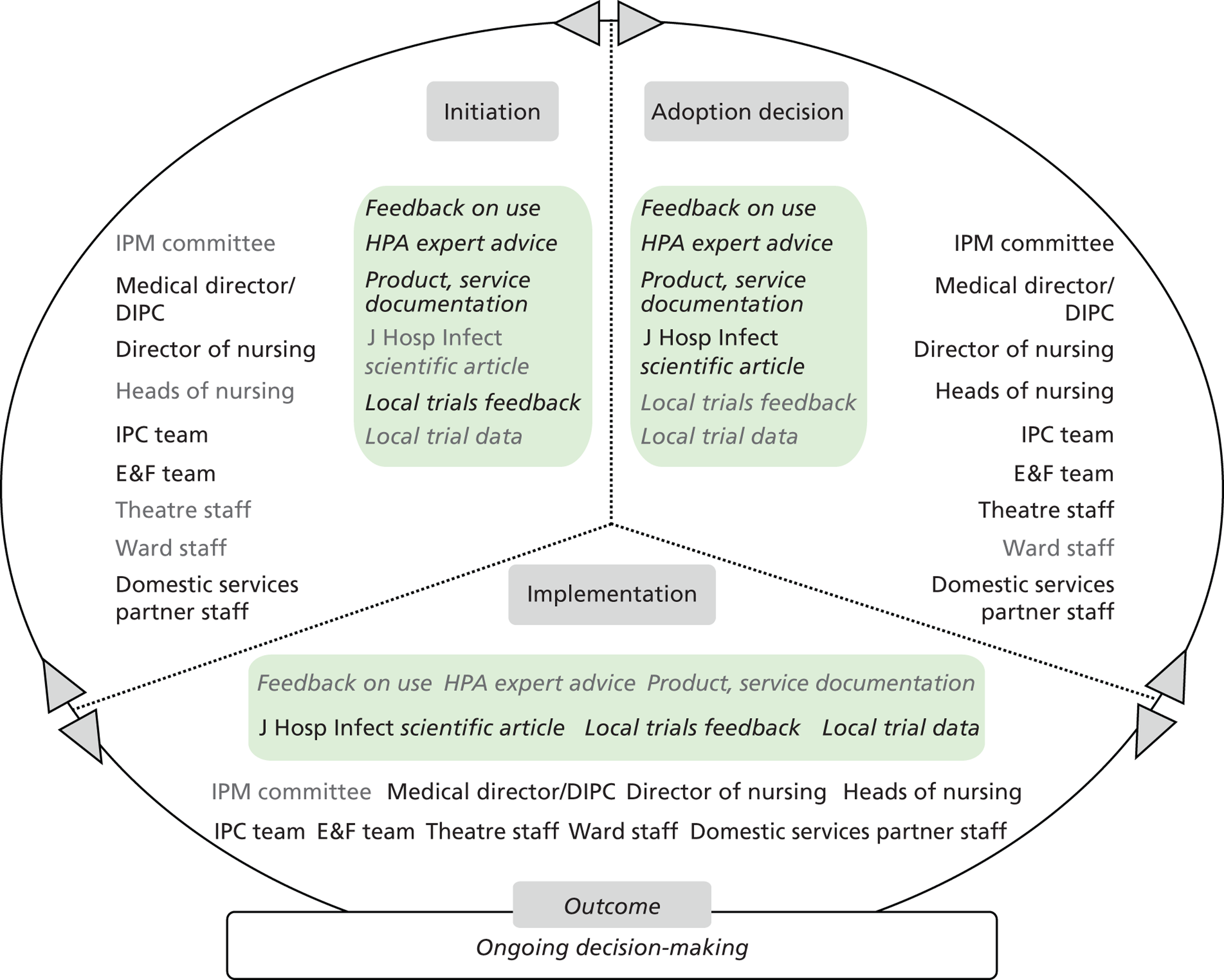

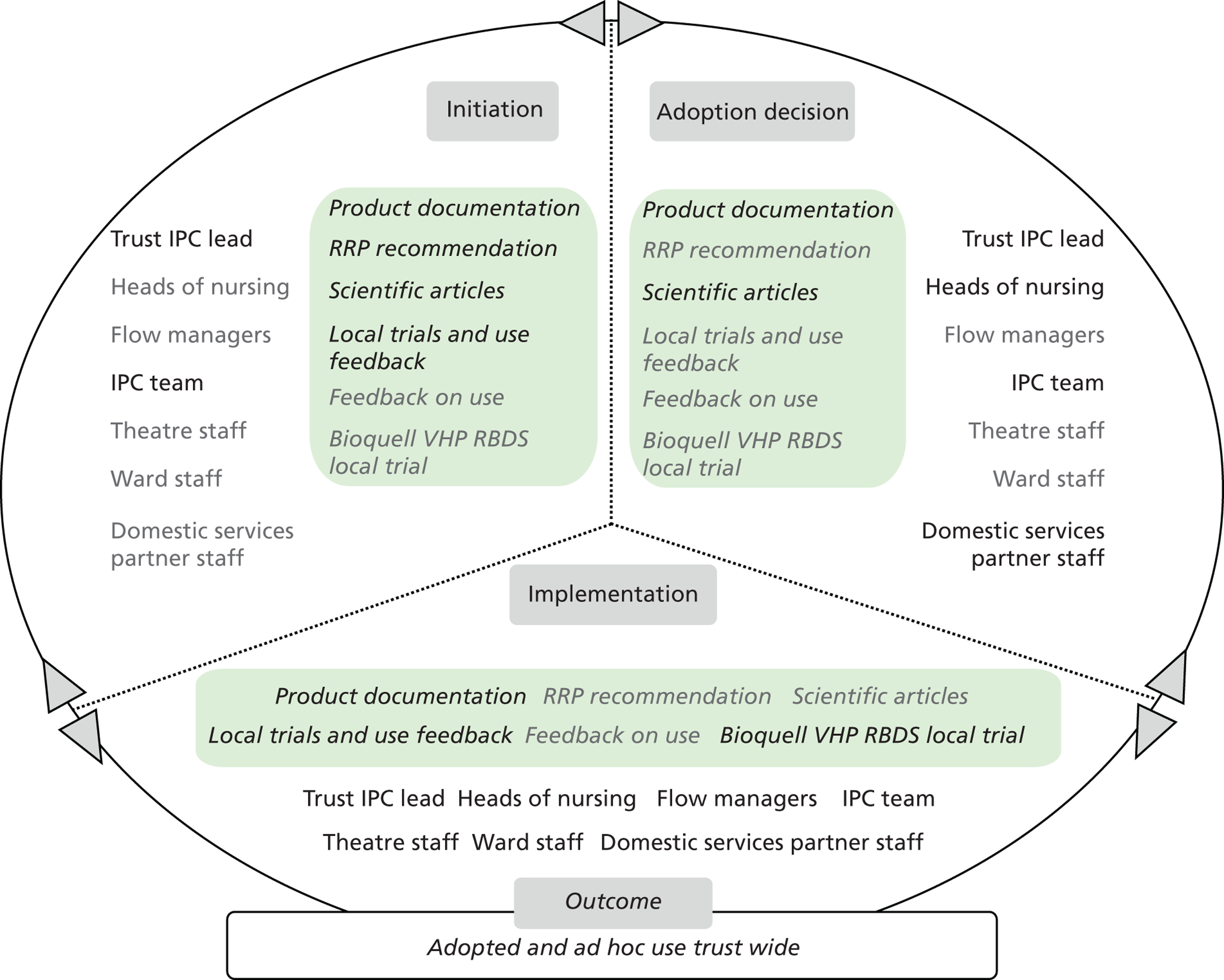

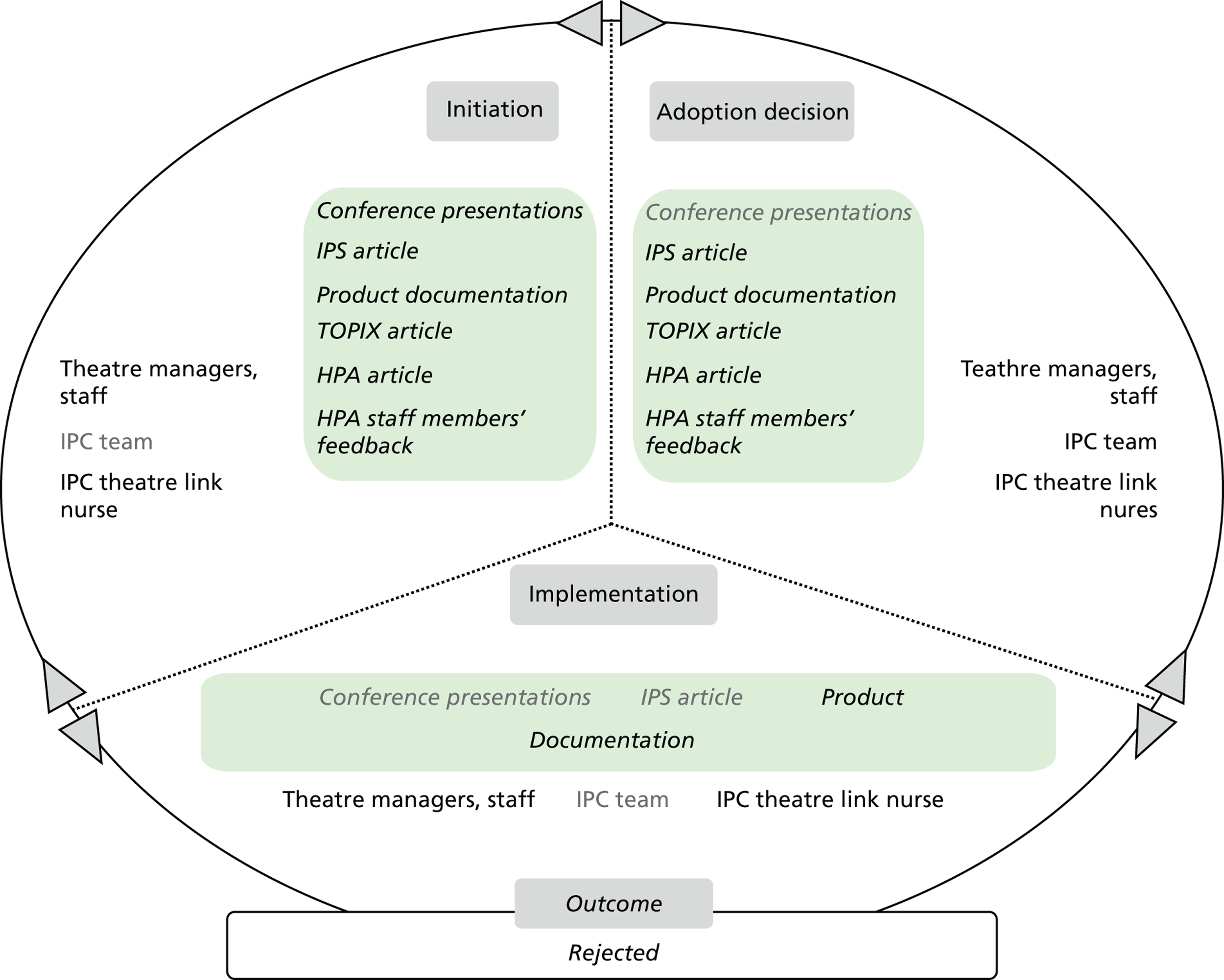

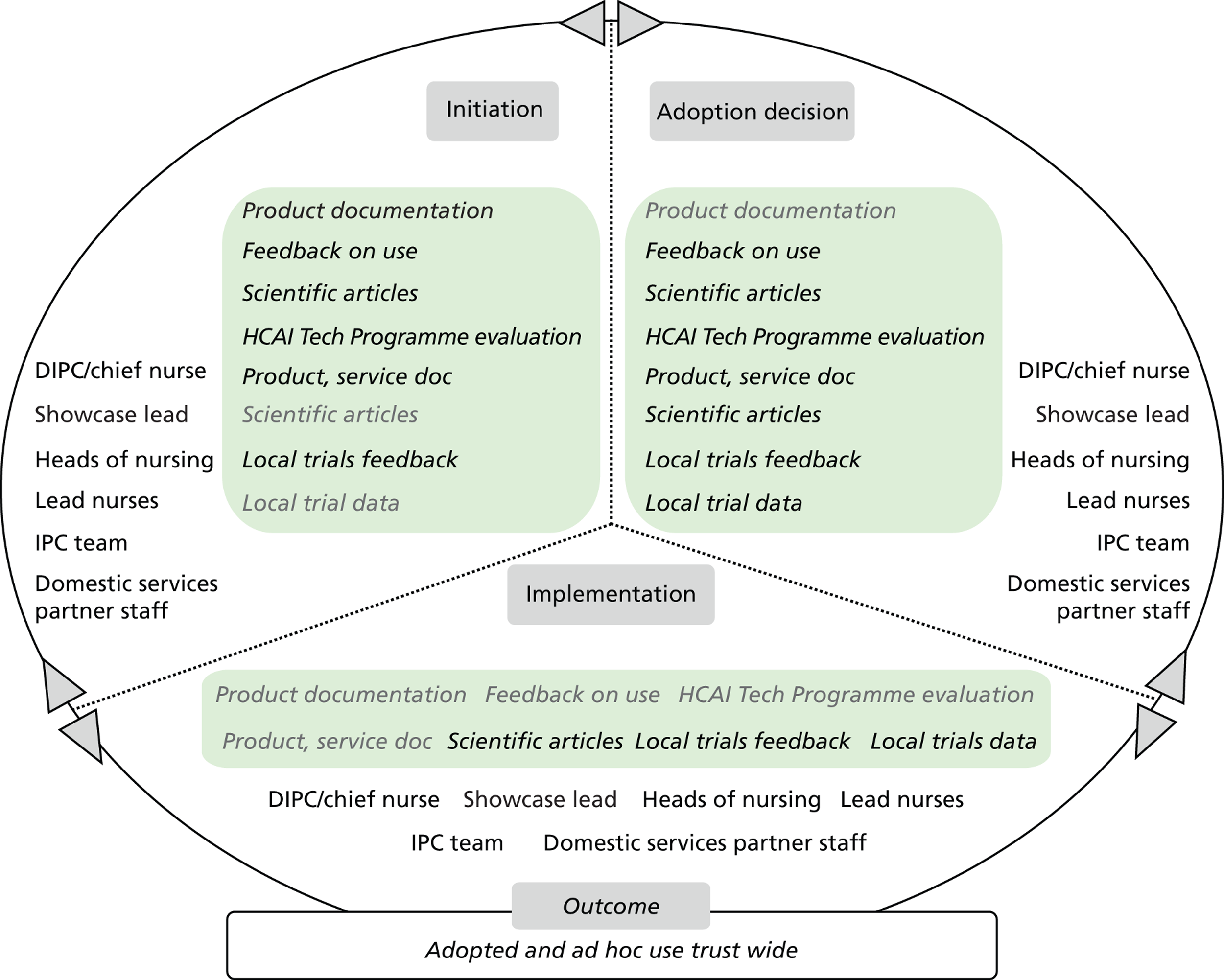

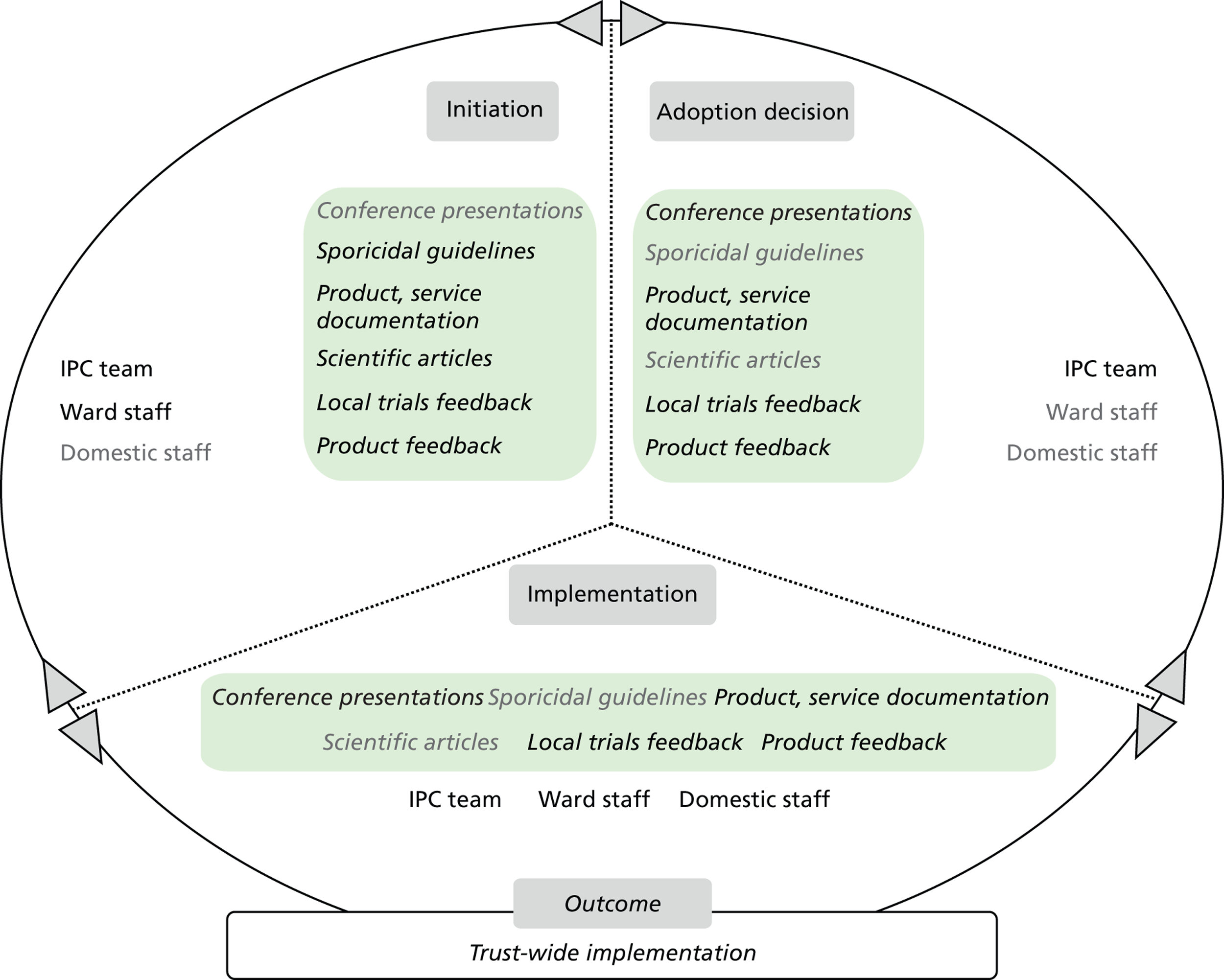

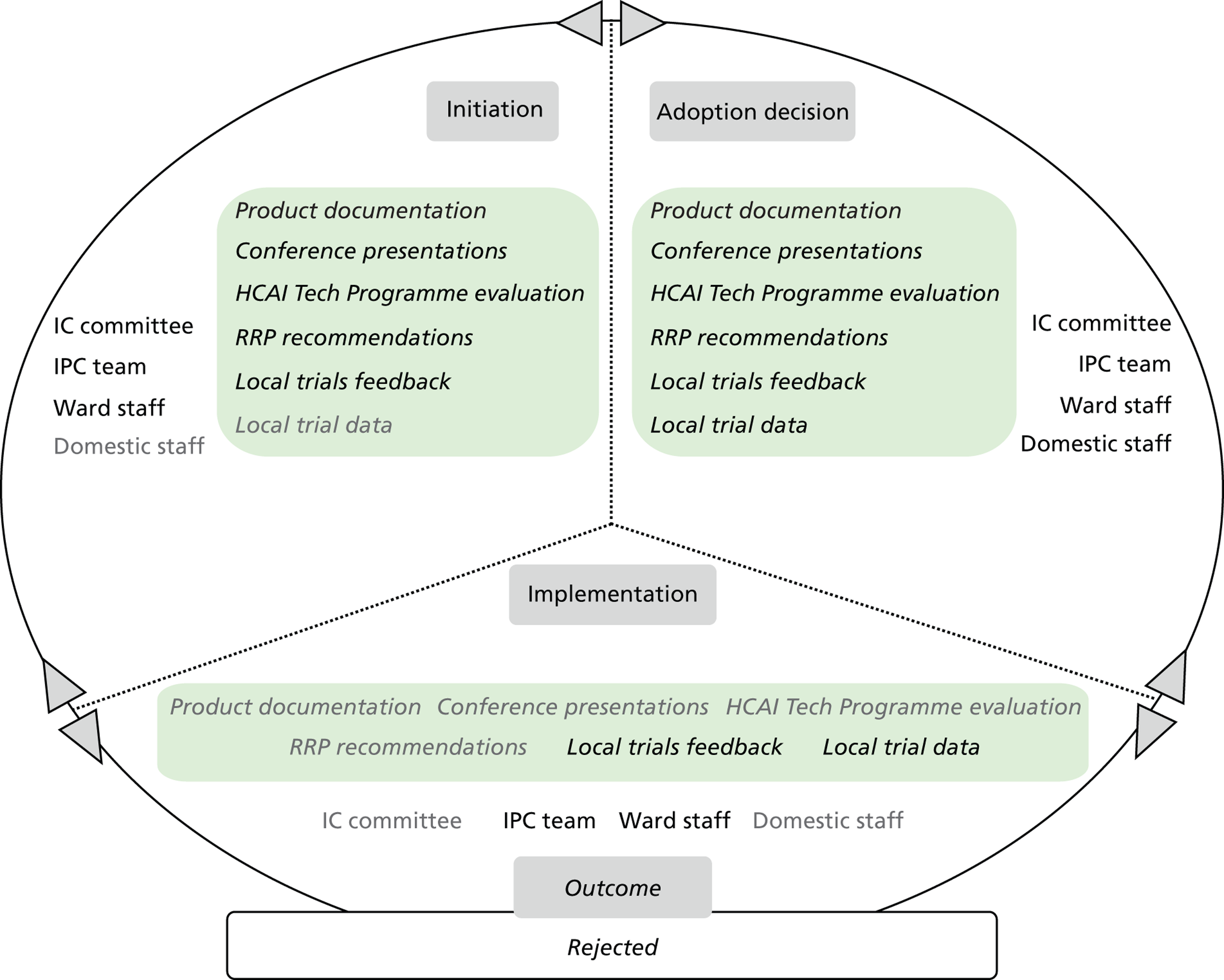

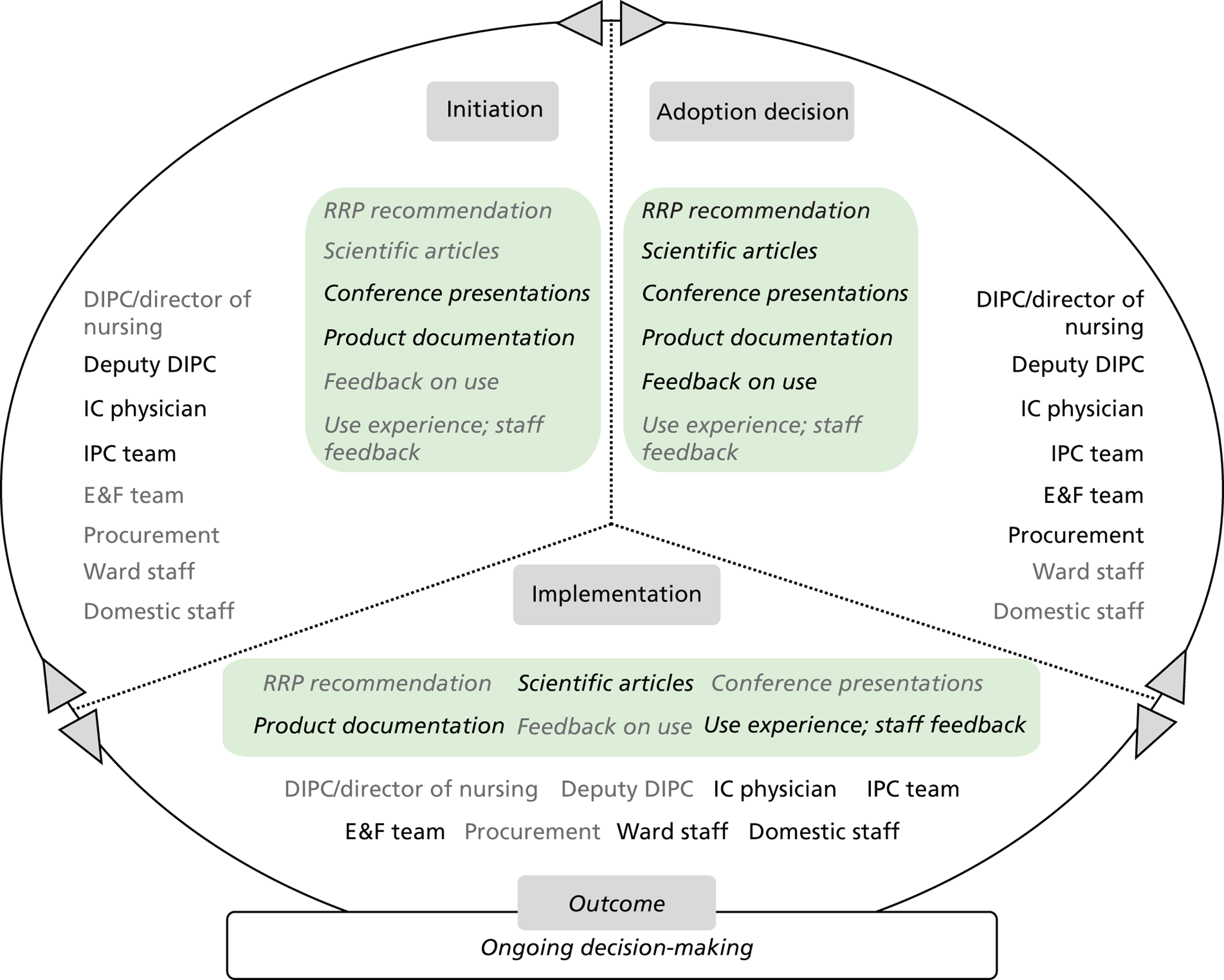

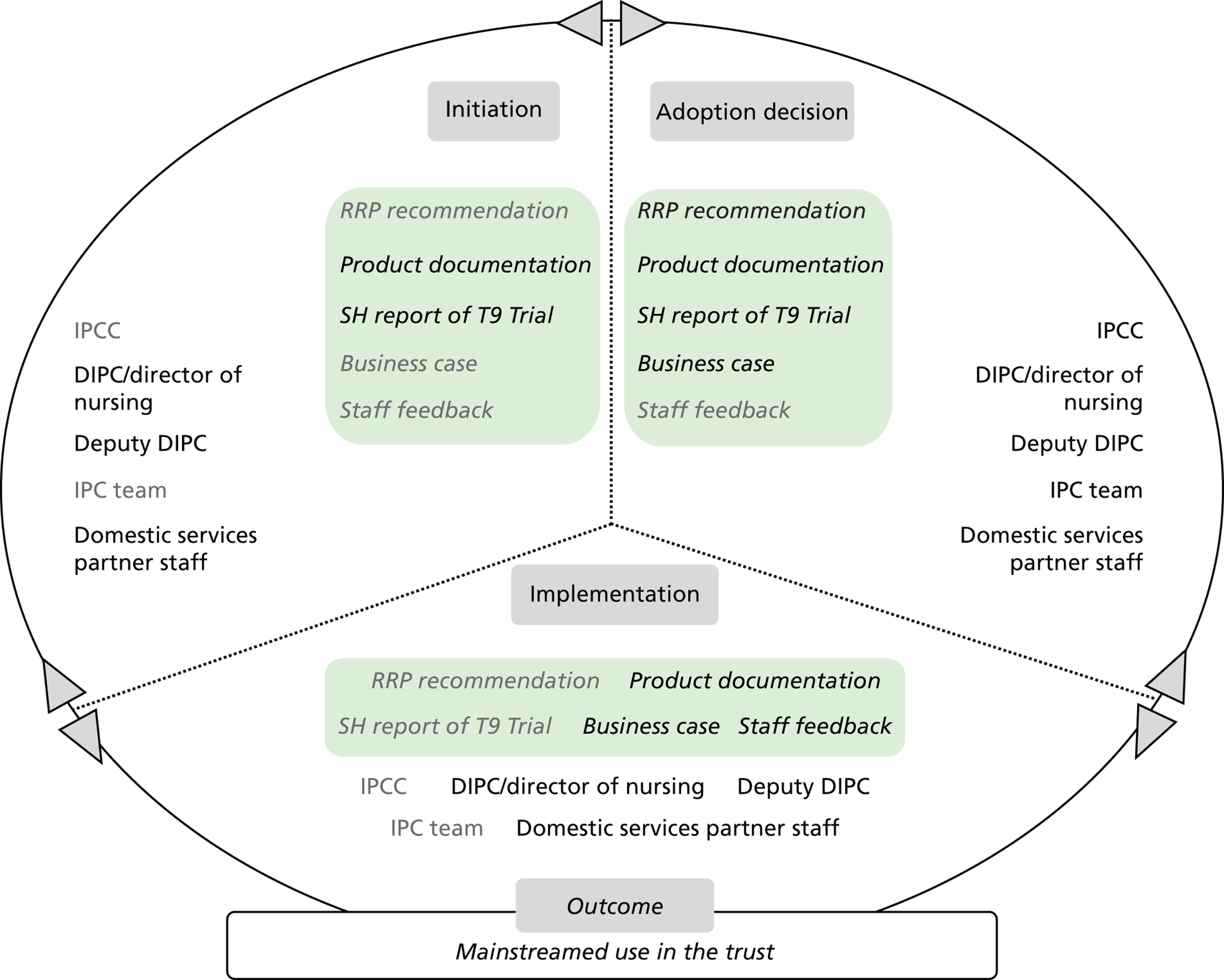

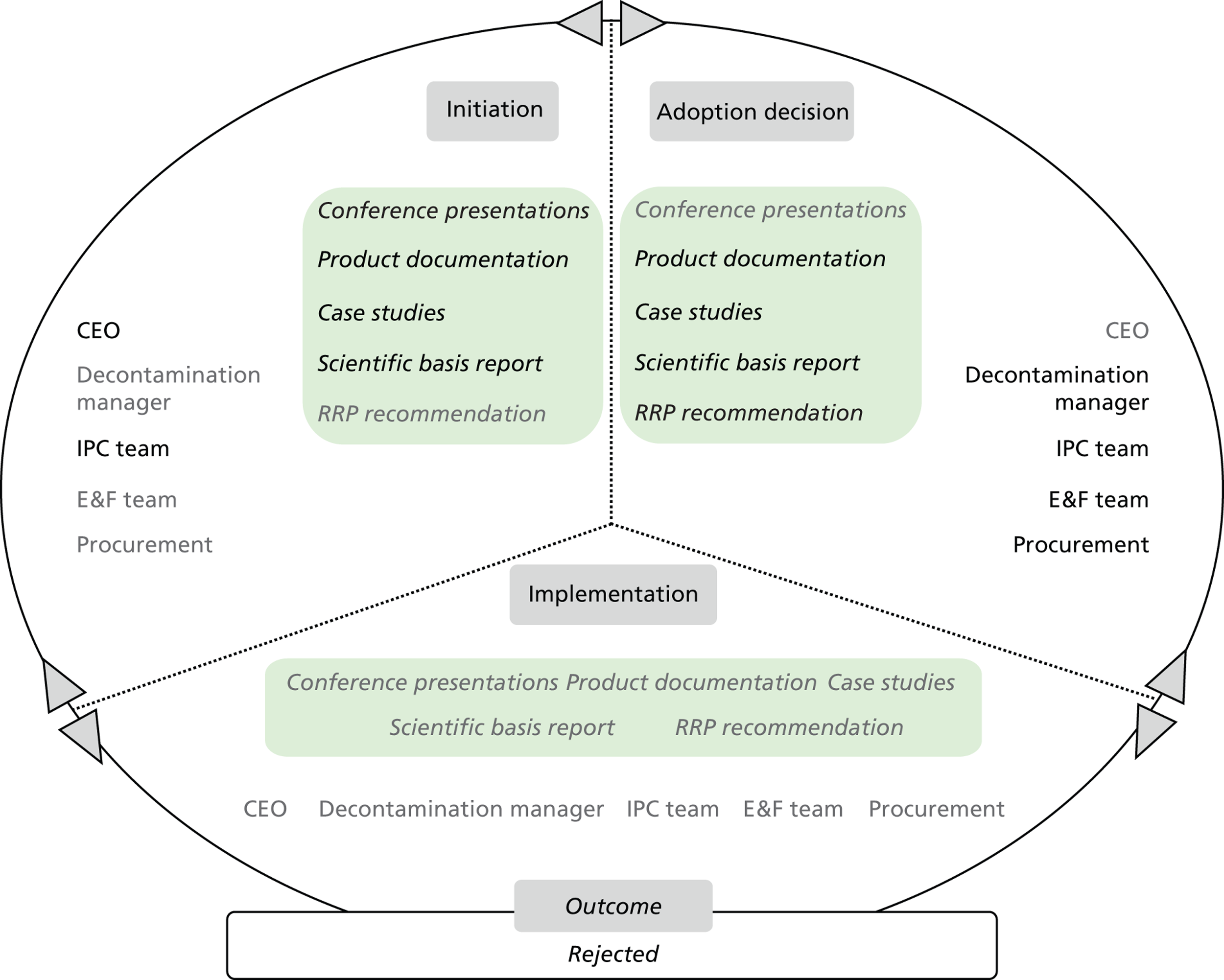

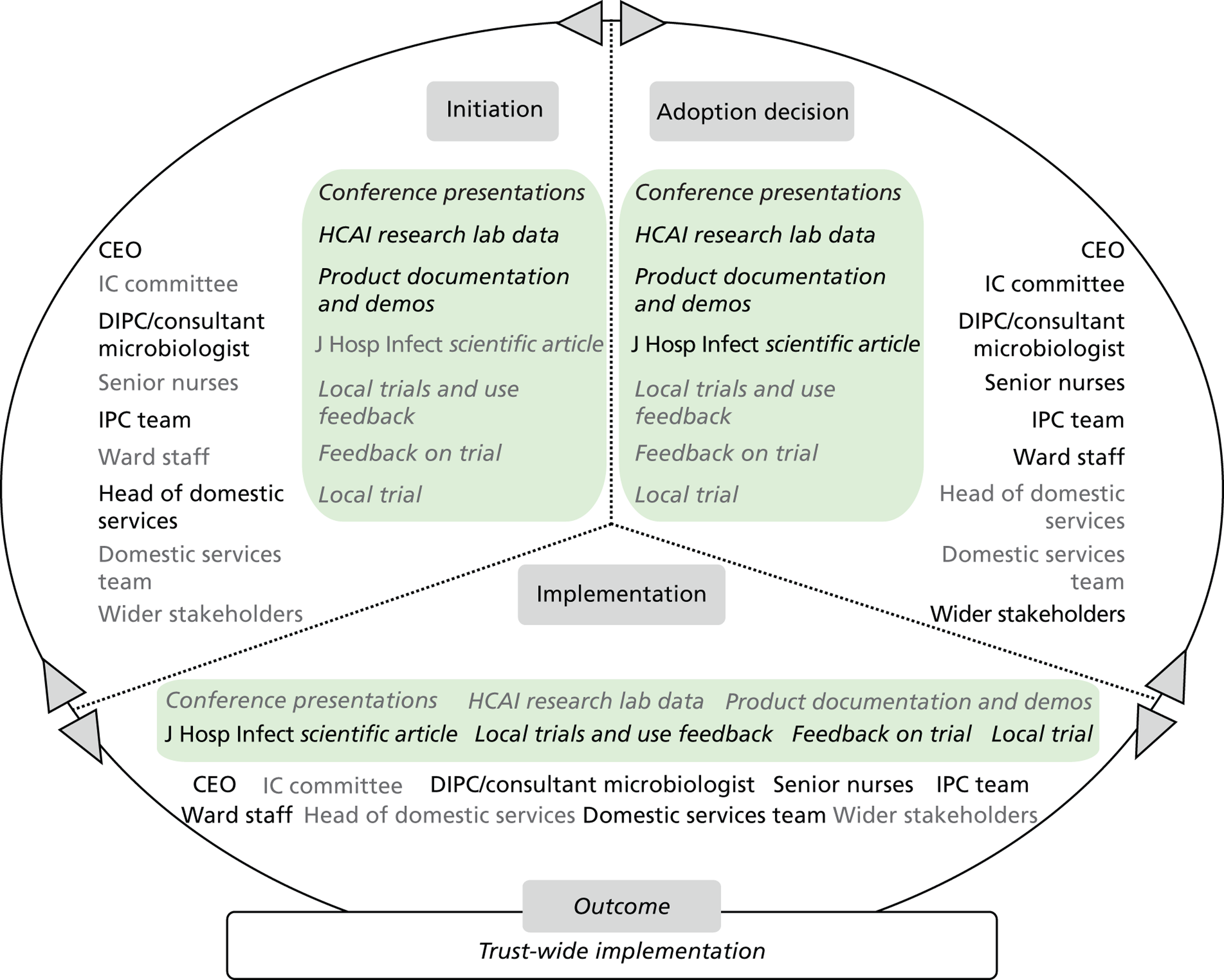

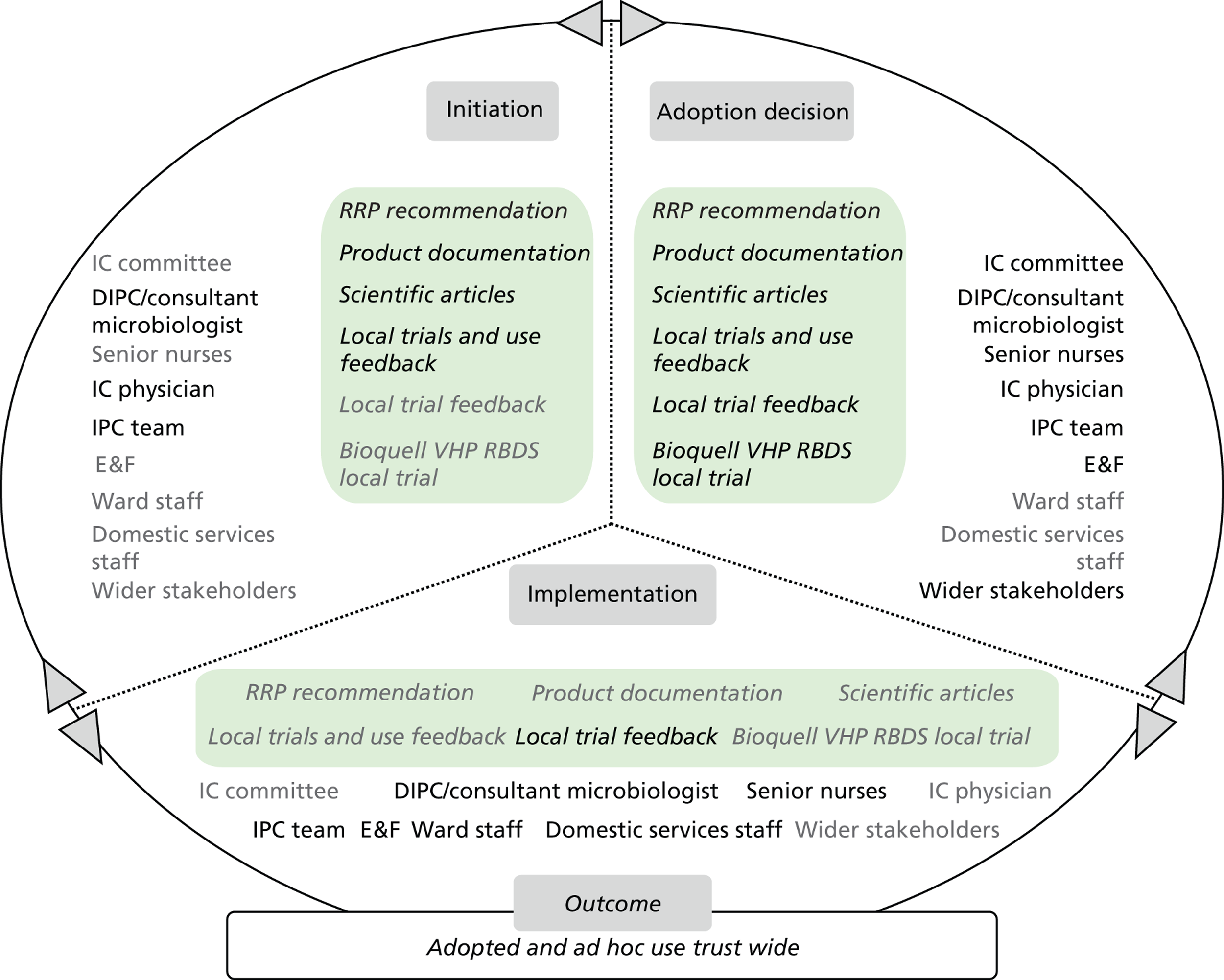

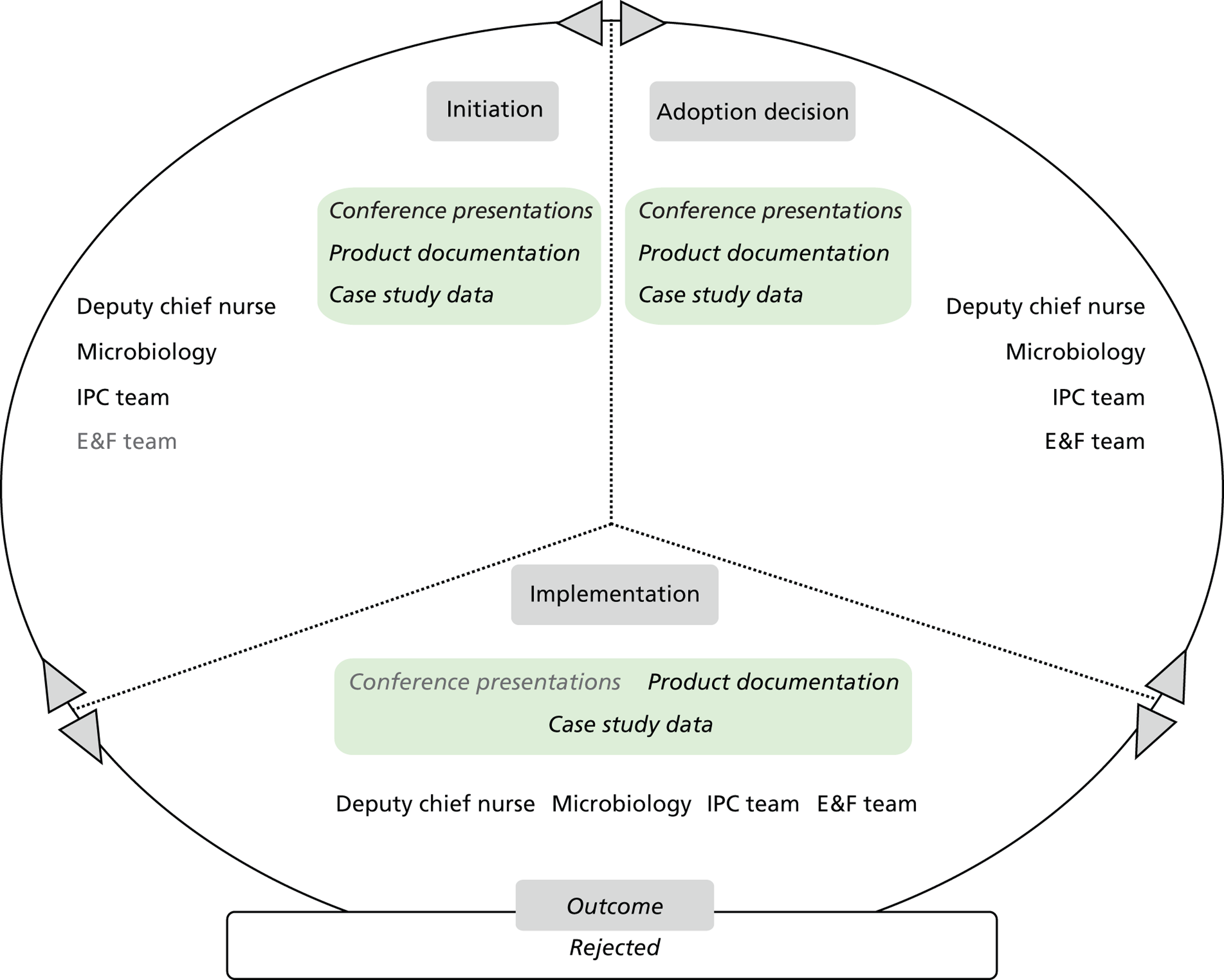

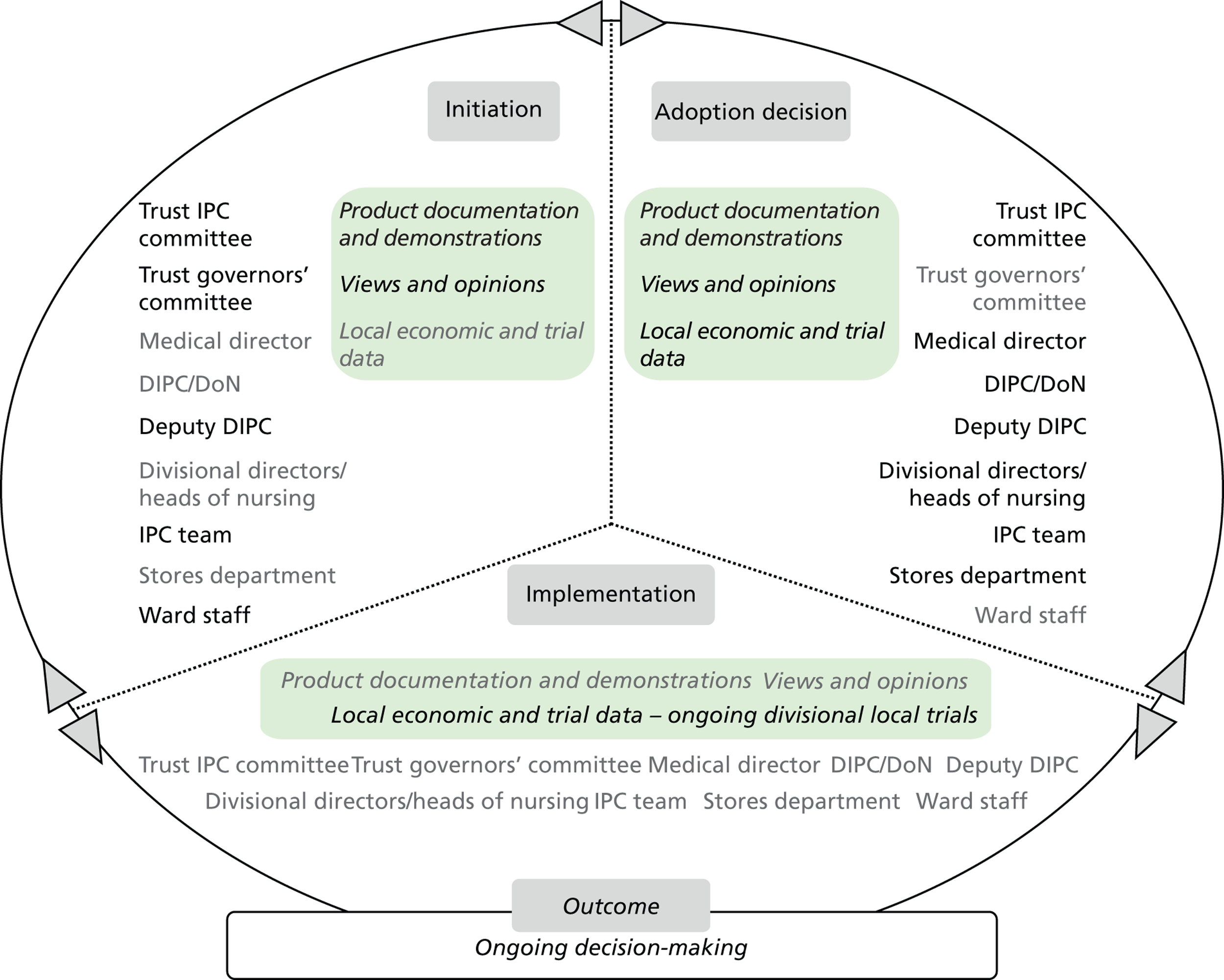

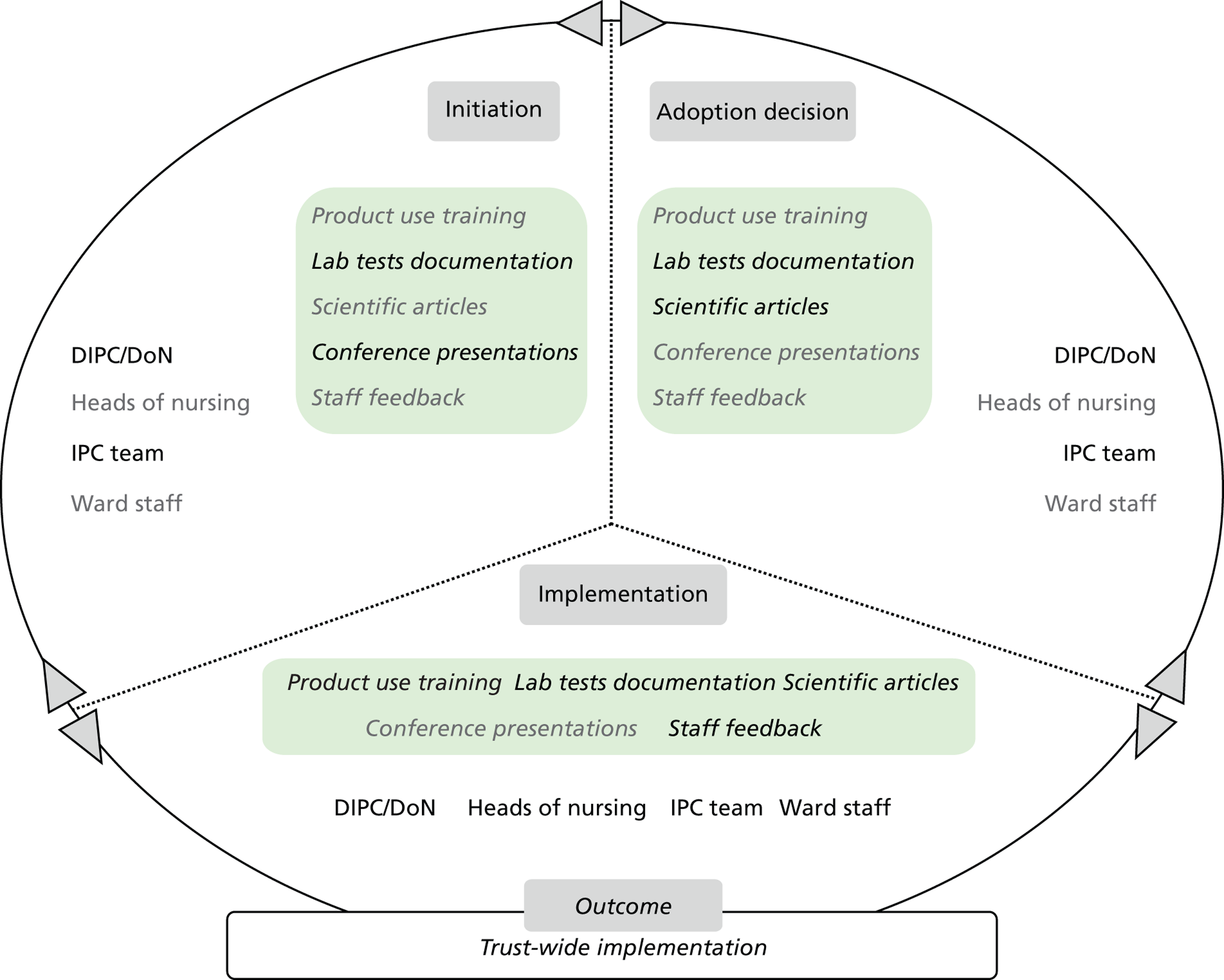

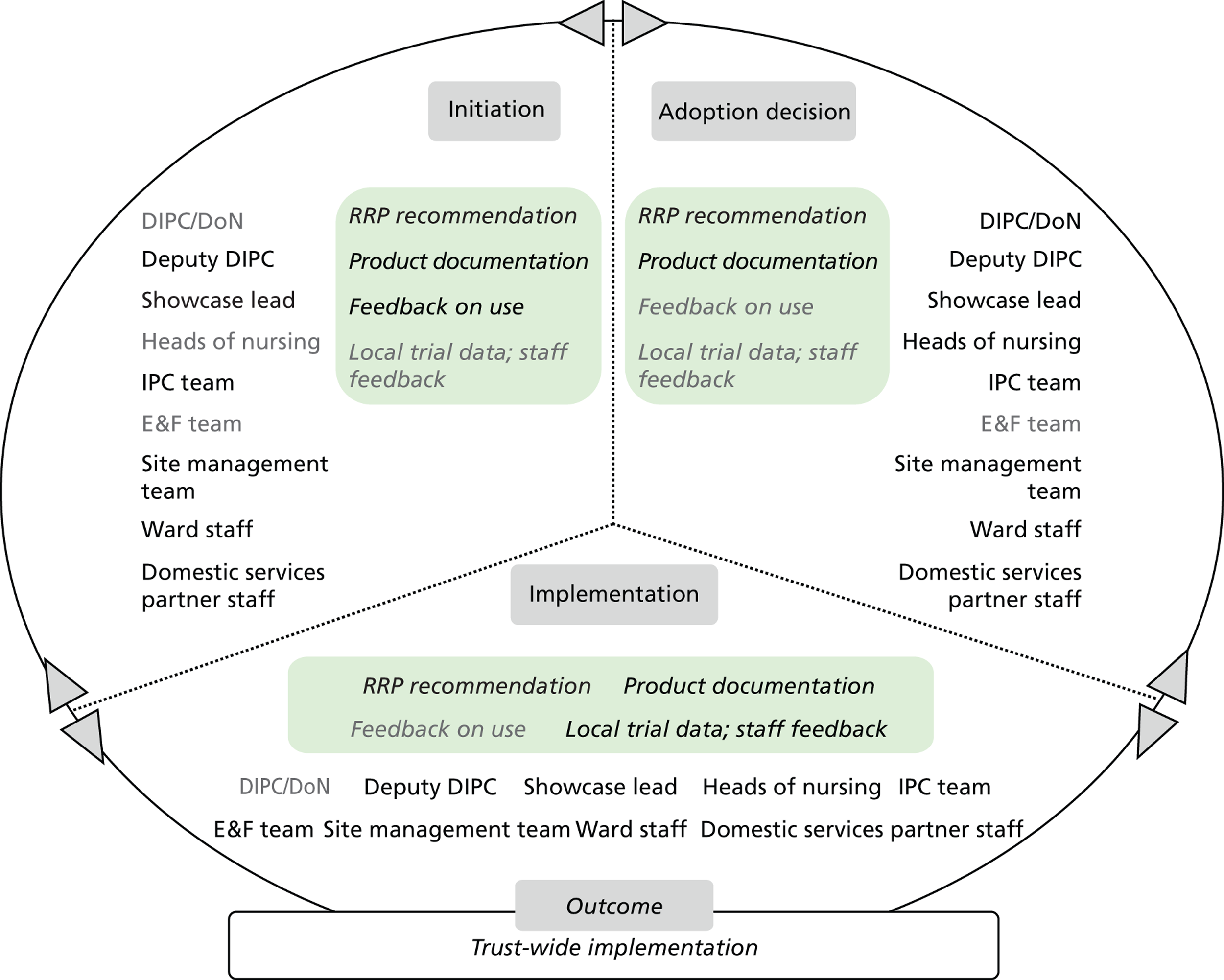

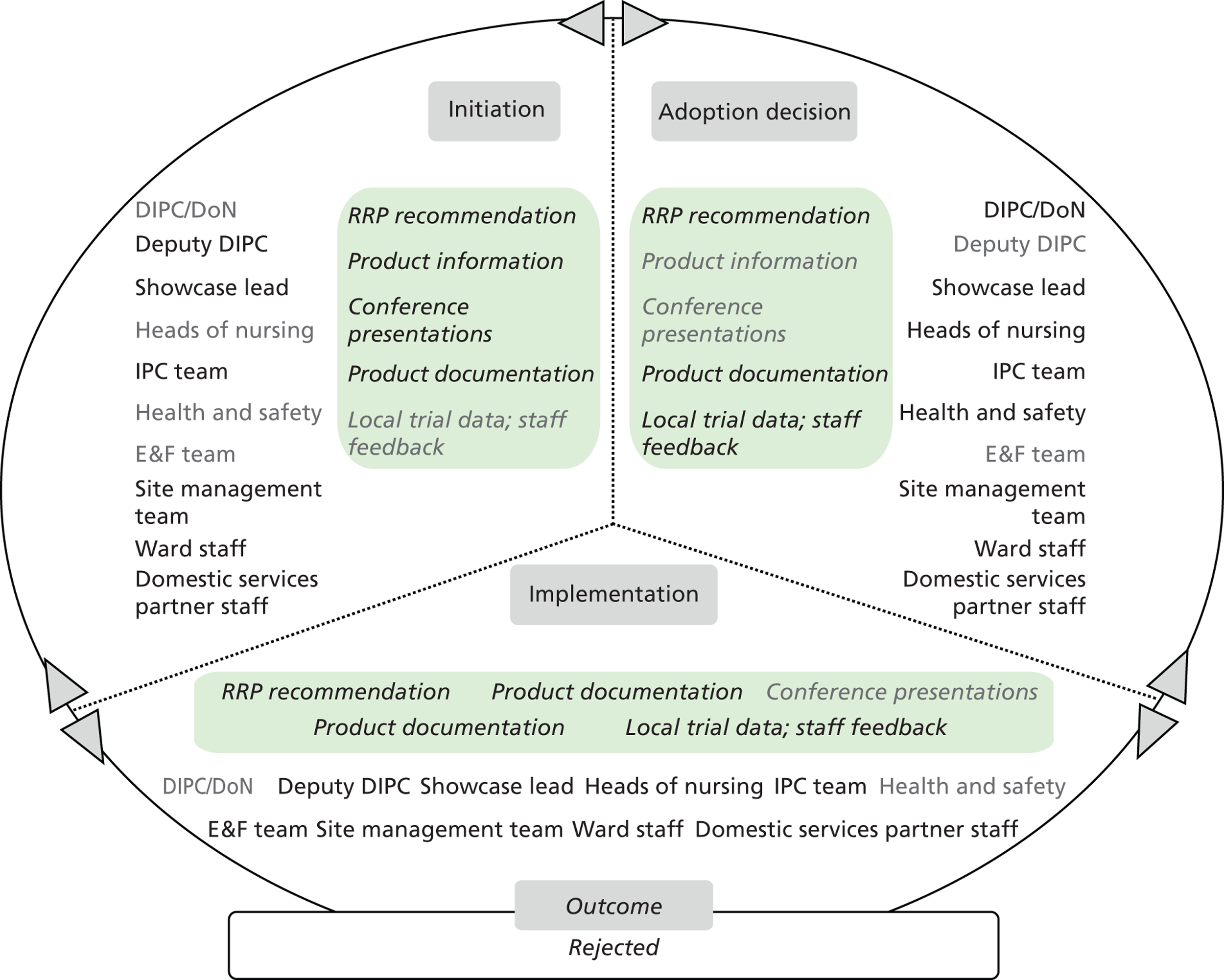

Chapter 8 reports on the 27 microcases in depth. We look at each technology product journey in detail along the three key stages of the innovation process, namely initiation, adoption decision and implementation. We present the interplay among stakeholders involved at each stage, associated evidence types and sources, and how these were linked to organisational adoption and implementation outcomes. This is the longest chapter of the report, and the chapter in which the 27 microcases are presented in detail. We purposely followed the same format across cases to facilitate analysis. The detailed evidence presented in this chapter enables the reader to verify the validity of the inferences made in the following chapters. Chapter 9 outlines key themes from the cross-case analysis (looking at relevant patterns across the macrocases – eight trusts – and microcases – 27 technology product journeys). In Chapters 10 and 11 we reflect on what we have learnt and synthesise the relevant findings as to how the collective sensemaking process took place within the multiprofessional empirical setting of our investigation. The report concludes with a discussion on potential implications for policy and practice and suggestions for future research.

Chapter 2 Relevant literature and the research context

Evidence-based medicine and the spread of innovations

The spread and adoption of innovations re-emerged as an important theme in health care with the rise of the EBM movement in the 1990s. 1,15 A central argument in this literature is that clinical practice should be based on rigorous and systematic evidence rather than individual opinion. The EBM movement is evident in a number of health systems, especially in Canada, in the USA and in the UK NHS, with explicit interest in understanding the diffusion of evidence-based innovations. 16–18 One of the central questions in organisational innovation diffusion literature that aligns with the aims of this study is as follows: ‘Why do innovations not readily spread, even if backed by strong (scientifically generated) evidence?’

There has now emerged considerable empirical evidence that argues that the adoption of health technologies and innovations, even if supported by sound research evidence on effectiveness, is a far more dynamic and complex process than previously suggested. 19–22 The classic innovation diffusion model of change, which has been particularly influential in UK health policy, suggests that the adoption of innovative ideas, practices or products is conditioned by the interaction among the attributes of the innovation, the characteristics of the adopter and the environment. 23 However, this early innovation diffusion work was criticised for adopting a simplistic rational view of change that ignores the complexities of the change process: also focusing on individuals rather than organisations. Later work by Rogers24 partly addressed the criticism by explicitly considering the adoption process within organisations.

Recent studies have departed from the linear model of innovation diffusion23 to offer more dynamic and interactive conceptualisations25,26 and respond to a need for context-sensitive, contingent approaches. 19,27 Building on this latter literature stream, it is suggested that innovation adoption is a process which is highly dependent on the interactions among the innovation, local actors and contextual factors. 11,27–31 These factors include the interaction among the attributes of the innovation, the organisational context and leadership;32 an organisational culture encouraging involvement, experimentation and learning; micropolitical factors; support by peer and expert opinion leadership;23,30,33 social networks;23,34 structural organisational characteristics;35 organisational capacity for absorbing new knowledge;36 and the existence of a ‘receptive context for change’. 37

Organisational innovation process and the use of evidence

The innovation process in organisations is complex and involves several stages. Damanpour and Schneider38 suggest that the process can be divided into three broad phases of ‘pre adoption’, ‘adoption decision’ and ‘post adoption’, also referred to in the literature as ‘initiation’, ‘adoption (decision)’ and ‘implementation’. 24 In this report, we use the latter terminology, which is also more commonly applied in the literature. Different concerns are central at the different phases, from an initial focus on innovation awareness and information seeking, through innovation use and application to manage a task or solve a problem, to consequences, and issues of sustainability. Adoption is often viewed as a process in which organisational members examine the potential benefits and costs or potential negative consequences of an innovation on the basis of relevant knowledge. 24 Potential adopters move from ‘ignorance’, through awareness, attitude formation, evaluation, and on to adoption: ‘the decision to make full use of the innovation as the best course of action available’. However, organisations should not be thought of as merely rational decision-making entities and innovation as an ordered sequential process. Rather, the adoption process should be recognised as complex, iterative and organic. 19,26

A key element in the organisational decision-making process that underpins innovation and technology adoption is the availability of supporting evidence of effectiveness. Despite the challenges above, there has been impetus for the development of EBMgt in health care to improve managerial decision-making through the use of the ‘best available scientific evidence’. 2,39 The integration of EBMgt with EBM is advocated to enhance the performance of health-care organisations. 3

However, within a health-care setting the evaluation of a technology can take a number of forms and include technical, economic and social assessments. Adoption decisions involve a number of stakeholders and thus it is important that the evidence used to support adoption is not just sufficient but also relevant and addresses the concerns of all parties. The earlier innovation evaluation stages are concerned with technical assessments of efficiency40 – as well as efficacy and safety in health-care interventions41 – whereas the focus in the later stages includes considerations of ease of use and social acceptance. 42 It, thus, marks a move away from scientific assessment to consideration of the complete value system for technology factors relating to types of evidence supporting adoption and contextual factors that might help or hinder implementation.

Implementation includes local trials and evaluation. The approach taken to implementation needs to vary according to the type and scale of the technology being adopted and the level and type of consequential changes it brings about. 43 For example, some technologies can be procured and put into service, whereas others require strategies such as pilots and phased roll outs. Implementation is linked to trialling and experimentation. For more complex technologies, and for those that require or lead to wider changes, such as changes in practice of health-care staff and changes to a process involving several stakeholders or cutting across departments, or even organisations, or need to be rolled out across many locations, implementation may be more challenging. 27 The end point for successful implementation will normally be the point at which the technology has become integrated into everyday practice.

A different insight on innovation adoption is available in a recent scoping review by Ferlie et al. 44 and Crilly et al. ,45 which conceptually synthesised issues of knowledge mobilisation in the NHS and, in particular, the perceived gaps in the process of translating knowledge from ‘bench to bedside’. The change towards EBMgt raises key questions such as ‘what evidence is considered as credible (and by whom)?’. And what is regarded as a legitimate epistemological basis for validating evidence (what is viewed as legitimate knowledge)? For example, should the evidence base for implementing an innovation into a specific context be exclusively focused on scientific reproducibility? Or alternatively, should the basis of innovation evidence take into account broader forms of evidence and wider concepts of what constitutes relevant and acceptable forms of knowledge?

Sensemaking in organisations

When making decisions, managers need to justify these to themselves and to organisational members. The sensemaking lens allows these two processes to be examined in context. 46,47 Sensemaking theory is a social psychological approach that emphasises cognitions. Sensemaking is about ‘reality’ as ‘an ongoing accomplishment that emerges from efforts to create order and make retrospective sense of what occurs’ (p. 635). 48 According to this perspective, values, beliefs, culture and language are important concepts. Central to this approach is enactment: the important role that people play in creating the environments that impose on them. The implications of a sensemaking lens in the evaluation of critical events is the difference between action as an ‘individual making bad choices’ and action as a result of an individual in a set of circumstances at a given time. 49 The event is therefore reframed ‘where context and individual action overlap’ (p. 410). 47 Thus, this perspective provides an analytical lens that helps understand actions in context.

The sensemaking perspective asks: how does a manager define his or her role? How is this shaped by the organisational culture, by peers, by professionals, by patients? Does his or her educational and professional background draw him or her to a particular paradigm of what constitutes evidence? This perspective is also interested in drawing out differences according to who the decision-maker is, and how individuals influence the sensemaking of others.

The sensemaking lens has been useful because of the nature of health care, with multiprofessional work in complex settings where organisational learning is important. 50 As Fitzgerald and Dopson51 observe, a clinical team is one example of an enactment of negotiated order, in which team members learn to work with each other through repeated interpersonal encounters around joint tasks. Those members with a higher degree of power are able to influence ways in which work roles are enacted. 51 This interplay between professionals is described well through nurses’ accounts in the management of hospitalised babies. 47 The nurse makes her case to the attendant physician that a baby requires immediate attention: ‘the first nurse translates her concerns for the second more powerful nurse, who then rearticulates the case using terms relevant to the Attending [physician]’ (p. 413). 47

Weick and Sutcliffe,52 in their reanalysis of the inquiry into deaths at the Bristol Royal Infirmary in the UK, found an environment in which they could further demonstrate how small actions can enact a social structure that keeps the organisation ‘entrapped in cycles of behavior that preclude improvement’ (p. 74);52 that is, easy explanations of an unusual situation should be challenged – this did not happen in Bristol. In the study of patient safety, sensemaking provides a powerful lens, as ‘the most fundamental level of data about patient safety is in the lived experience of staff as they struggle to function within an imperfect system’ (p. 1556). 53 Greenhalgh and coresearchers54 suggest collective sensemaking (developing shared meaning) as one narrative approach to understanding issues of organisational innovation processes. For proposed changes to be accepted and assimilated by providers and service users, the change ‘must make sense in a way that relates to previous understanding and experience’ (p. 447). 55

Our research questions aimed to explore ‘sensemaking’ in the local and wider contexts; that is, the health-care organisation and the NHS environment. 56 In addition, we explicitly set out to explore how individual and collective sensemaking plays out – which is particularly pertinent when making decisions about innovation adoption and implementation. This lens allows one to focus on an individual’s sensemaking processes and how these iteratively ‘update’ ways of approaching decision-making and use of evidence. This also allows reflection on how this process differs in ‘everyday’, more passive situations compared with those of heightened activity owing to the need for decision-making, either because of funding deadlines or because of external influences relevant to the empirical setting (in this case, infection outbreaks or poor performance in the infection rates). In the latter, sensemaking is usefully applied along Weick’s seven dimensions (grounded in identity construction; retrospective; enactive of sensible environments; social; ongoing; focused on and extracted by cues; driven by plausibility rather than accuracy), and emergent from this framework an appreciation of how ‘sense for self’ and ‘sense for others’ plays out.

Here the concept of ‘making sense for others’ or ‘sensegiving’ is useful. Sensegiving ‘is concerned with the process of attempting to influence the sensemaking and meaning construction of others towards a preferred organisational reality’ (p. 442). 57 The concept first emerged as an explanatory concept in the study of strategic change at an American university. 57 In this ethnographic study, the researchers observed the chief executive officer (CEO) adopt a ‘sensegiving mode’ whereby his actions and cues were used to ‘make sense for others [organisational members]’. This concept relates to previous literature in the study of organisational member behaviour, namely ‘impression management’58,59 and ‘self-monitoring’. 60 (The theory of self-monitoring60 proposes that individuals regulate their own behaviour in order to convey alignment with a preferred behaviour in any given context or situation. High self-monitors monitor and modify their behaviour to fit different situations; low self-monitors are more consistent in behaviour across situations.) Sensegiving describes the more purposeful and explicit action rather than implicit cues. The sense-giver will also make sense of organisational member behaviour and in turn modify sensegiving.

The social production of reality for oneself is a very tacit process which shapes decision-making and influences non-deliberate decisions. Sensemaking as justification to self and the resulting decision is influenced by other factors such as legitimacy and plausibility to others, that is, the publicly accountable decision. This lens pays particular attention to the social construction and coproduction of evidence through the interaction of a range of diverse professional and managerial groups. We engage with this body of literature summarised above, which has been useful in explaining organisational response to critical events in the health-care setting,47,52 as well as to strategic change. 61,62

Gaps in innovation, evidence-based health care and organisational sensemaking literatures

In summary, we note four key gaps in the relevant literature streams on innovation, evidence use and sensemaking in organisations which triggered our empirical exploration in this study.

First, with this study we address a significant gap in evidence-based health-care implementation literature. Namely, we respond to the call for more sustained interpretive work that explores the role and motives of actors and the influence of the organisational context and the social construction of evidence. 63

Second, despite the progress that has been achieved in our understanding of innovation diffusion and adoption processes, a consistent issue raised in high-quality reviews of general innovation diffusion literature26,64–66 and a review of related literature in health care19 is that empirical research has generally been limited to a single level of analysis – individual, organisational or interorganisational – thus failing to provide a holistic explanation of the influence of inter-related factors on innovation adoption and diffusion. Our study aimed to address the aforementioned criticism by exploring the innovation adoption process and by reflecting on influences at various embedded levels of analysis: namely, micro (individual), meso (organisational) and macro (interorganisational) levels.

Third, there are few empirical cases exploring issues of health management decision-making that focus on non-clinical decisions and particularly innovation, which is characterised by inherently high uncertainty and ambiguity. Moreover, little primary research exists that links the use of evidence to adoption decision-making and implementation within service organisations. We currently have a limited understanding of how pluralist evidence bases (and the associated diverse epistemological bases) might be reconciled or not in practice. The construction of shared meanings, or collective sensemaking,46 is key for understanding how new types of evidence may be successfully embedded in certain contexts, or even be rejected under conditions of innovation uncertainty and ambiguity.

Fourth, in sensemaking theory there is less emphasis on empirical studies that deal with the day-to-day processes of sensemaking, rather than crises and critical events, and on the sensemaking that occurs among many and diverse organisational stakeholders as they address a range of issues. 46,62 By applying this theoretical lens to the investigation of managerial decision-making on the adoption and implementation of innovative technologies, we aim to empirically contribute to the field.

Chapter 3 Study design and methods

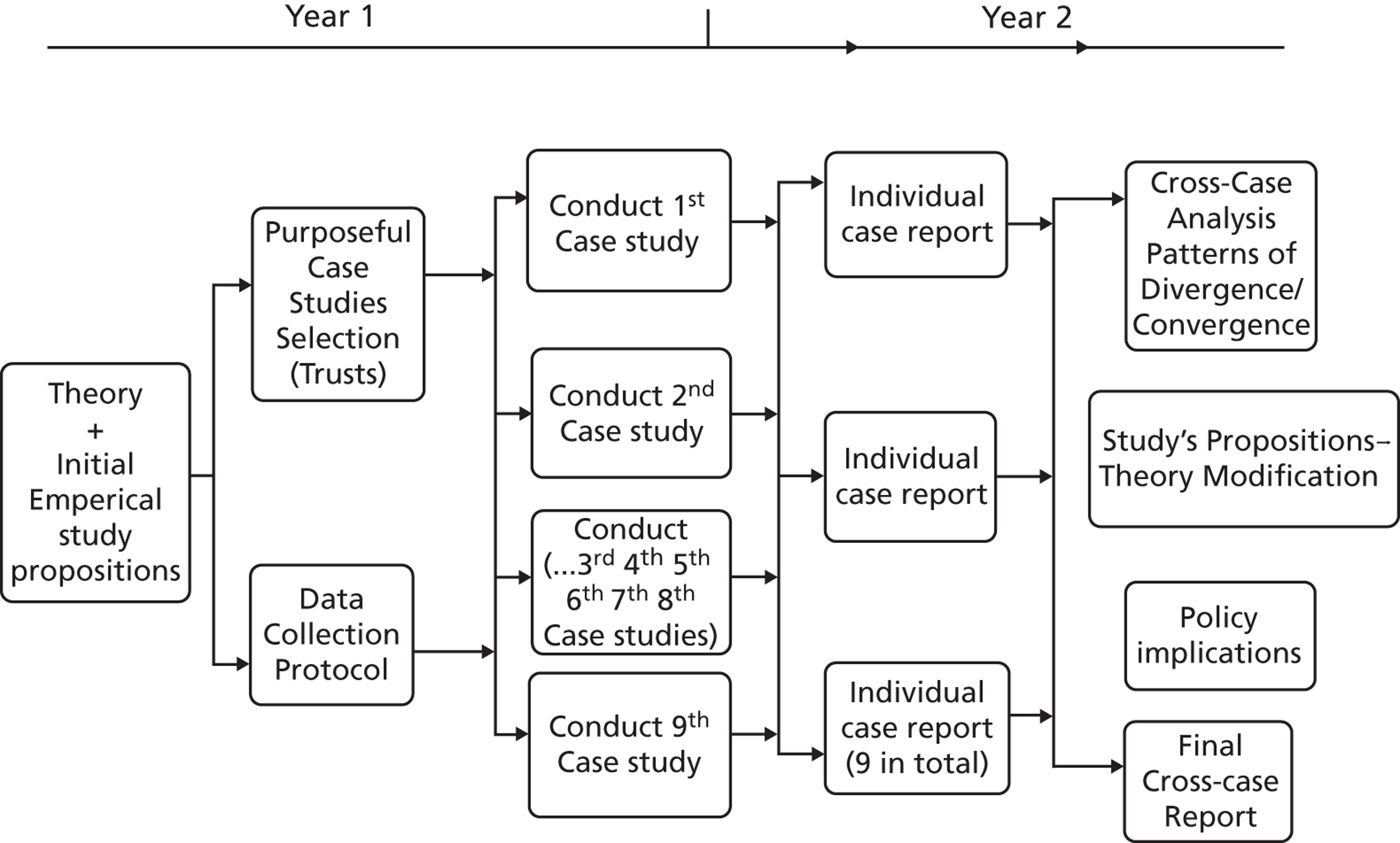

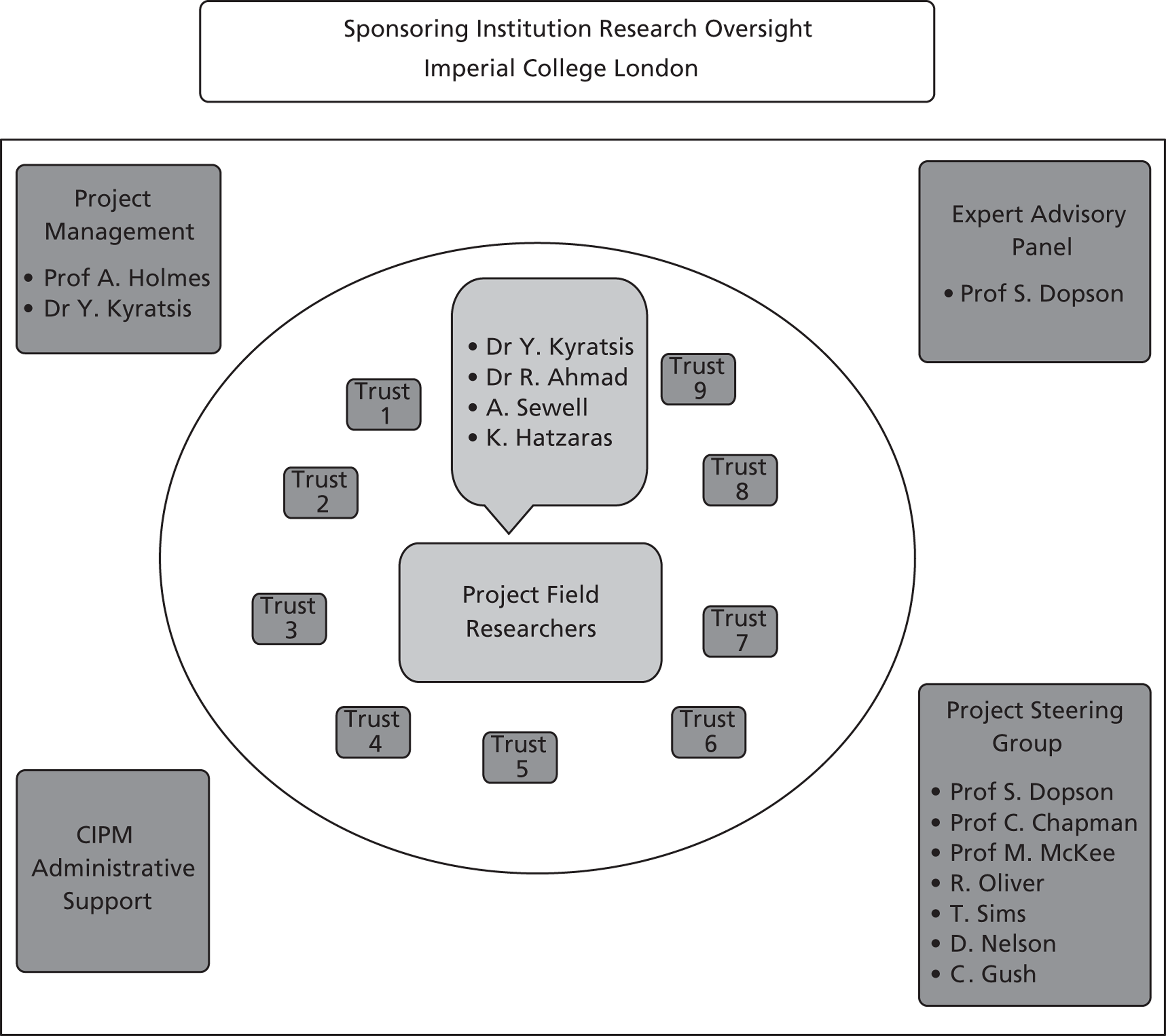

This study uses a comparative and processual case study design, that is, the study of organisational processes over time in multiple cases. Specifically, the research focuses on nine case sites purposely selected for comprising diverse organisational types, each with a potentially dissimilar level of engagement with research organisations and internal capacity for knowledge production and utilisation. The research also comprises 27 embedded microcases of specific technology products used to investigate the innovation processes over time and the use of evidence in these processes. This chapter provides the rationale for this research design and then considers the operational methods applied.

Study design

We employed a comparative case study approach with mixed methods. The employed study design aimed to develop theory inductively from multiple in-depth case studies combining an inductive search for emerging themes with deductive reason. 67,68 Comparative case studies offer the opportunity for a deeper insight to generate new conceptual and theoretical propositions or extend existing knowledge through comparing, linking and integrating different cases. The main aim of this study has been to produce new understanding of the access and use of research-based and other forms of knowledge by health-care managers in organisational decisions. This can be achieved through detailed descriptions and a rich understanding of contexts across the empirical sites. As our study objectives concerned interpretive ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, our overarching design drew primarily on qualitative methodology. 68 To retain the richness of unique cases and enhance the generalisability and applicability of findings, individual case studies were followed by cross-case analysis. Our study comprised nine ‘macrocases’ of acute-care organisations, and, for eight of them, we further investigated 27 embedded ‘microcases’ of technology product journeys, which we followed across the stages of the innovation process.

The selection of cases involved theoretical, rather than random, sampling. 69 Nine acute NHS trusts were selected across three broad geographic regions in England: (1) London, (2) northern and central England, and (3) southern England. The nine research case studies were conducted concurrently. By focusing across different localities, we sampled for diversity and aimed to explore the influence of any local network effects if present, for instance, by comparing London-based institutions to non-London-based institutions, bearing in mind the fact that London is a major cosmopolitan city which has many health-care institutions, universities and research centres and in which a plethora of social and professional events take place on a regular basis. We anticipated that this potential ‘regional effect’ might exert influence on the behaviour and perceptions of academics, health professionals and managers.

In our sample of cases, we sampled for diverse organisational types, including examples of research-engaged health-care organisations, such as AHSCs, university/teaching hospitals and ‘ordinary’ health-care service providers, such as district general hospitals ( Table 1 ). To better delineate the impact of contextual factors in research use and the application of various forms of evidence by health-care managers on the same innovation, we included multiple ‘showcase hospitals’ – as selected by the Department of Health – to evaluate the in-use value of HCAI technologies.

| Trust | PFI | Foundation | AHSC | UH/TH | SH | BRC 2007–12 | BRC 2012–17 | BRU 2008–12 | BRU 2012–17 | DGH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | ✗ | In the process | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| T2 | ✓ | In the process | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| T3 | ✓ | In the process | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| T4 | ✓ | In the process | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| T5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| T6 | ✓ | In the process | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| T7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| T9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

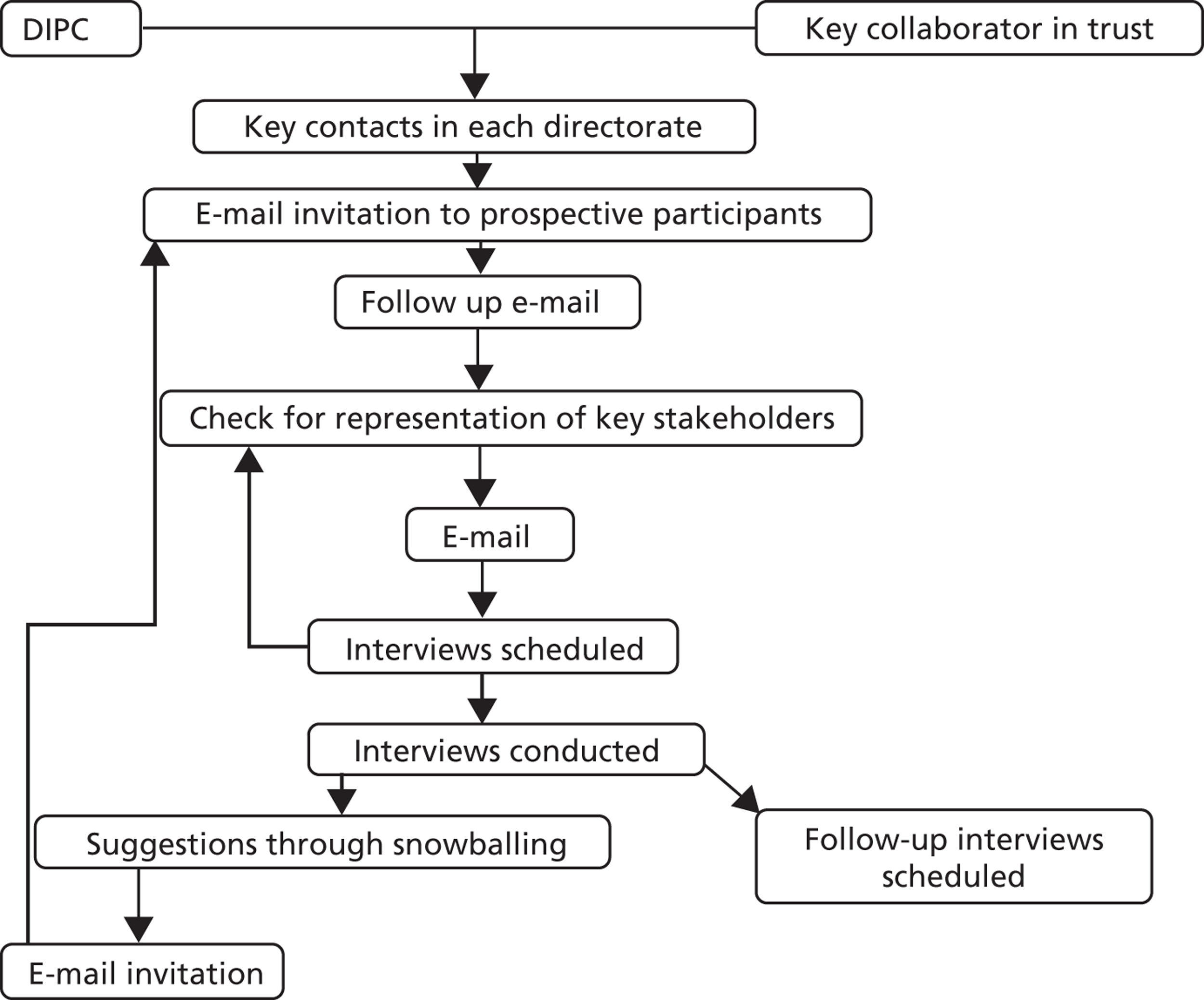

The study was conducted in two phases, looking in detail at processes in context. In phase 1 we first systematically examined espoused use of evidence by potential decision-makers in the studied organisations; then, in phase 2 we systematically analysed the use of evidence in practice at the point of decisions in relation to specific technology products. Phase 1 explored perceptions of senior and operational managers and health professionals of different backgrounds in managerial roles across each trust and, specifically, in IPC. Phase 2 explored those organisational members involved in the adoption decisions and implementation of particular technologies in IPC. Eight of the nine trusts in our initial sample participated in phase 2; trust 8 decided to withdraw from the study. This was a result of challenges faced by the trust in service delivery during the study period. Two infection outbreaks impacted significantly on the availability of staff to participate in our study.

A robust, systematic and participatory options appraisal (see Appendix 1 ) was carried out to inform the sampling strategy of phase 2. This involved input from steering group members, expert advice by Professor Sue Dopson, and input from peers within the research team and from NHS colleagues working in IPC. One particular IPC priority area, namely ‘environmental hygiene/cleaning/disinfection’, was finally selected. Other IPC areas considered but not sampled included ‘hand hygiene’, ‘diagnostics’, ‘antibiotic prescribing’, ‘catheter-related care’, ‘training and education’, ‘medical devices/equipment hygiene’, ‘information technology surveillance systems’ and ‘patient hygiene’. Interview respondents at each trust during phase 1 were asked to select three environmental hygiene innovations/technologies considered by the trust from 2007 onwards (2007–12) as follows:

-

A technology that has been selected but not implemented yet.

-

A technology that has been selected and successfully implemented.

-

A technology that has been rejected.

The initial selection of a technology may finally lead to adoption or rejection of organisational decisions. Following earlier work,22,41 by ‘successful adoption’ we refer to the organisational executive decision to introduce and make full use of a technology, which results in procurement. By ‘successful implementation’ we refer to the actual introduction of the new technology in the organisation, meaning that the technology is put into use and operationalised; the extensiveness of implementation may vary from trust-wide use to use in selected wards. The rationale for the selection of environmental hygiene as the IPC area of focus for our empirical investigation in phase 2 and the defined time period of 2007–12 are detailed below.

First, the selected time frame (dimension A in Appendix 1 ) captures the period when major policy initiatives in IPC were implemented or already in place, for example, The Health Act 2006: Code of Practice for the Prevention and Control of Healthcare Associated Infections (known as the ‘hygiene code’);70 the introduction of the evidence-based EPIC-2 guidelines;71 the mandatory reporting of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia and Clostridium difficile infections (April 2001 and January 2004, respectively); the Saving Lives programme 2007;72 and the Clean Safe Care programme launched in 2008. 6 We selected ‘environmental hygiene’ technologies because they represented 50% of selection decisions according to a recent study of innovation adoption in IPC in England. 43,73 In addition, environmental hygiene is a cross-cutting intervention for various HCAIs. Such interventions range from an inexpensive poster and basic cleaning products to expensive cutting-edge technologies including hydrogen peroxide robots. This is a growing area in industry and has gathered particular attention in recent years through regulations, such as the Department of Health’s Deep Clean Programme. More importantly, a wide range of stakeholders could be involved to debate the evidence in this area in contrast to a highly specialised or technical field, such as diagnostics.

Conceptual framework

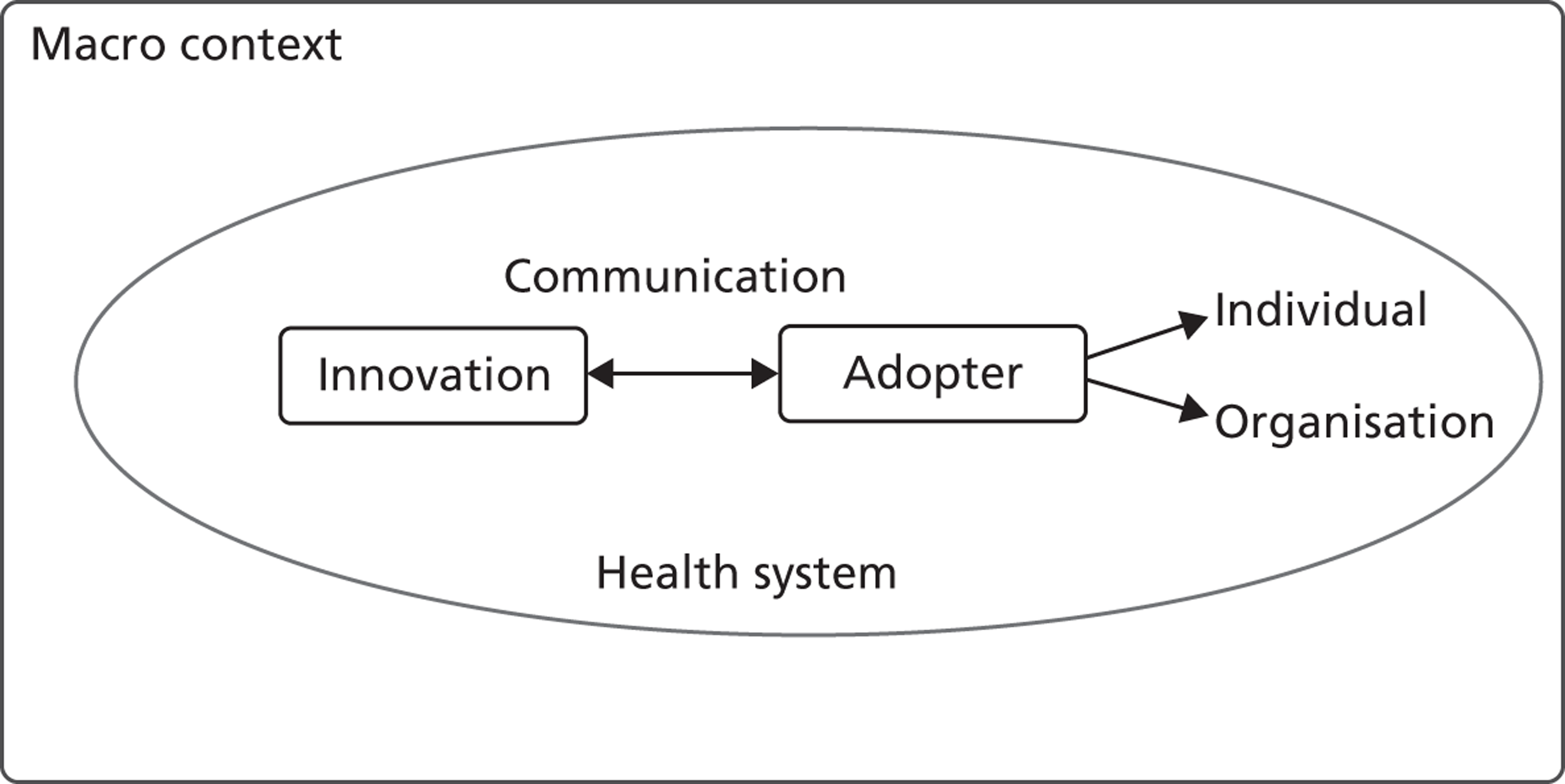

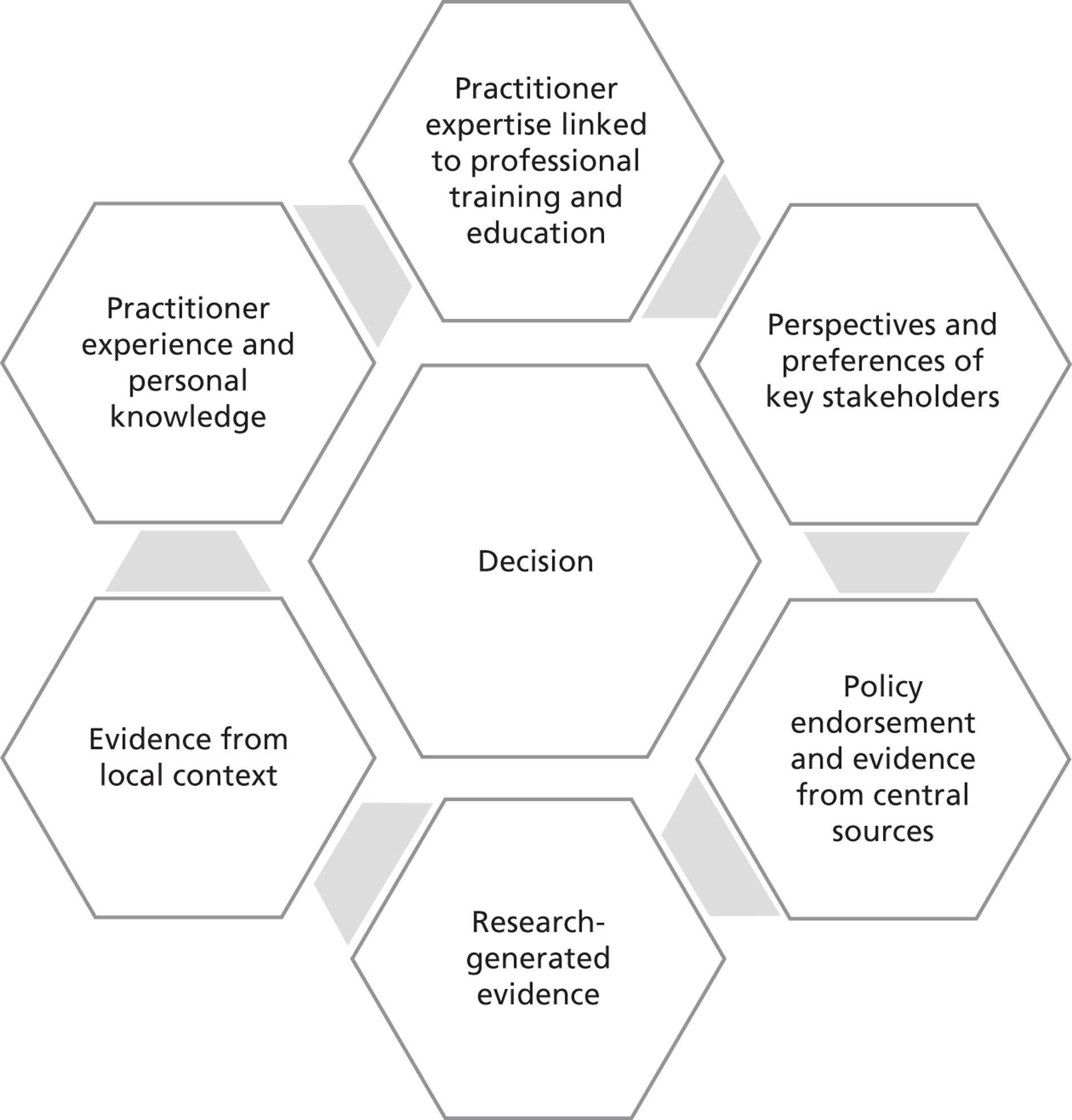

Our approach draws primarily on innovation diffusion theory of change. 24 We specifically focus on four factors ( Figure 1 ) that health-care researchers11,21,22,27,31 broadly agree influence the adoption decision and subsequent implementation of health innovations: (1) the perceived attributes of the innovative technologies, (2) the characteristics of adopters, including both individual health-care managers and their organisations, (3) contextual factors that include the relevant sector (NHS) and wider societal, political, economic and institutional (symbolic, ideational and material) environments, and (4) the communication process.

FIGURE 1.

A conceptual framework for the adoption of complex health innovations.

Data collection strategy and methods

We employed a two-phased approach to the field work. Phase 1 focused upon senior (director level, including trust directors of medicine and nursing), middle-level and operational managers involved in organisational decision-making. We focused on a specific type of organisational decision, the adoption of innovative interventions, which entails uncertainty and the risk of newness, and thus offers great potential for sourcing evidence from the decision-makers. Technology products for phase 2 research were then sampled, which examined in detail the stakeholders involved in specific cases of evidence use in practice.

Primary data

In phase 1 the unit of analysis was the individual manager (non-clinical and clinical hybrid managers) and the level of analysis was each of the nine trusts (macrocases). For phase 1 we used a combination of semistructured interviews with structured questionnaires embedded in the interview schedules (see Appendix 4 ). We employed a multilevel sample of key informants. Informants included senior, middle and operational managers and representatives from different professional groups, including doctors, infection control specialists, clinical microbiologists, nurses, pharmacists, allied health professionals and non-clinical managers with diverse professional backgrounds (i.e. in engineering, science, accounting or finance). The categories of evidence used in these questionnaires were informed by a previous study on HCAI technology adoption funded by the Department of Health which involved 121 interviews with NHS staff from 12 NHS trusts across England. 22,43 The categories were further refined and validated following expert advice from policy-makers in the Health Protection Agency (HPA) and the Department of Health, as well as health professionals in IPC with non-clinical, nursing and medical backgrounds. We further validated and finalised the categories in consultation with the members of our project steering group.

The primary focus of phase 2 was the mobilisation and use of evidence in the decision-making for specific technology products ‘in context’ and in relation to the task of solving an identified problem in IPC. The unit of analysis was the group of stakeholders involved through the innovation journey for each of the selected technology products and the level of analysis was each of the eight trusts that participated in phase 2 (macrocases) and each of the 27 embedded technology journeys (microcases).

The longitudinal, real-time design of the study was intended to give a better understanding than short-term and ‘snap-shot’ methods. As well as these measures of methodological rigour through the study design and methods of analysis, we used measures of acceptability and relevance of the research as defined by key stakeholders, namely professional, managerial and patient groups (e.g. patient environment action teams, the two patient advisors who were members of the project’s steering group).

For both phases we also looked at the wider context through the systematic collection of secondary data (discussed in more detailed below). For example, we considered for each macrocase the profile of the population, the institutional conditions (e.g. legislation and regulatory frameworks, the influence of professional associations, social norms), intraorganisational factors, including practices and organisational culture, and trusts’ history and tradition. For the microcases we additionally considered the capacity and previous experience relating to the technology under consideration and similar innovations.

The research was conducted over a period of 2 years, between November 2010 and October 2012. After ethical approvals were obtained, field work and data collection began in April 2011, and was completed in July 2012. The recruitment of respondents followed closely the plan outlined in Appendix 3 , the study protocol. YK or KH invited potential participants via e-mail to take part in the study and these e-mails were accompanied by a participant information sheet (see Appendix 2 ). Our predefined roles detailed in the study protocol, suggestions by local study leads and snowballing shaped the actual respondents’ sample. In addition, for phase 2 the final sample of respondents was determined by participation of staff in the adoption and/or implementation of the selected technology products studied in each of the eight trusts. Very high respondent recruitment was achieved (> 90% acceptance of invitations with the exception of T8, as outlined above). We used semistructured interview schedules for both phases of the research (see Appendices 4 and 5 ).

Prior to the field visits, interviewers familiarised themselves with contextual information on each trust and information about IPC-related innovations. This enhanced their knowledge on local contexts and enabled them to ask relevant questions to explore areas of further interest. On average, each interview lasted 60–90 minutes. Face- to-face interviews were conducted at trust sites, and we obtained prior consent to audio record interviews (see Appendix 3 ). The total number of interviews was 191, including 126 for phase 1 (with all 126 informants also having completed the embedded structured questionnaires) and 65 semistructured interviews for phase 2. The detailed breakdown per trust and professional background of informant is summarised in Tables 2 (phase 1) and 3 (phase 2).

| Type of informant | Number of respondents per trust | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T8 | T9 | ||

| Doctor | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 24 |

| Nurse | 10 | 9 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 61 |

| Non-clinical manager | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 25 |

| Allied health professional | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Pharmacist | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 20 | 16 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 3 | 13 | 126 |

| Type of informant | Number of respondents per trust | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | T6 | T7 | T9 | ||

| Doctor | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Nurse | 7 | 4 | 5 | 3 (6) | 7 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 44 (47) |

| Non-clinical manager | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | – | 1 | 1 | 2 | 15 |

| Allied health professional | – | – | – | 1 | – | – | – | – | 1 |

| Pharmacist | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 10 | 8 | 8 | 5 (8) | 7 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 62 (65) |

Secondary data

We systematically collected data from secondary sources (both trust specific and global) for each case study site to obtain a detailed contextual description for each trust. The trust-specific sources included the following: trusts’ annual reports and financial accounts (2007/08; 2008/09; 2009/10; 2010/11; 2011/12 where available and applicable), trusts’ quality accounts (2009/10; 2010/11; 2011/12), reports by the director of IPC (DIPC) (where available), trust board meeting minutes (where available), staff magazines, and newsletters and/or bulletins that were published up to spring 2011. We also collected publications from governmental or regulatory agencies, including the CQC (previously the Healthcare Commission), the Audit Commission, the Monitor and the Network of Public Health Observatories, to highlight wider contextual factors that might influence the innovation decision-making processes at the trusts. We systematically reviewed a total of > 800 documents derived from the aforementioned sources. The trust-specific secondary data sources supplemented and/or triangulated other data sources, including global secondary data sources and our primary data originating from interviews with trust managers.

Data analysis

Data analysis comprised six interlinked and, to some extent, overlapping stages: (1) transcribing of qualitative data; (2) initial open coding of interview data focusing around the research questions; (3) systematic coding of interview data; (4) cleaning, error checking, creation of descriptive summaries and tabulation of the questionnaire data; (5) individual case study analyses; and (6) cross-case analysis.

Soon after the completion of interviews, the content of audio recordings was verbatim transcribed by professional transcribers – an independent professional and an agency. The linguistic accuracy of texts was checked by the interviewers themselves, and, whenever transcribers felt unsure, the researchers who conducted the interviews confirmed the accuracy of the text and revised it accordingly by paying close attention to the raw interview data. Interviewees validated most transcripts (the option was offered to obtain a copy their transcribed interview).

Upon completion of transcription, three researchers thoroughly read through the full transcribed texts several times to enable understanding of the meaning of the data in their entirety. 74 The reviewing of data prior to coding helped us identify emergent themes without losing the connections between concepts and the context associated with these concepts. The qualitative data analysis computer software package NVivo 9 (QSR International, Cambridge, MA) was used to systematically code the collected data and assist analysis. In line with recommendations by qualitative methodologists, we used multiple coders (MI, RA, KH, YK) to enhance inter-rater reliability of the qualitative study. 74,75

Our qualitative analysis followed an integrated approach. 76 We employed an inductive approach to open up new lines of enquiry and then agreed a framework for data analysis based on these findings together with our conceptual framework (delineating factors that influence the adoption process of complex health innovations, see also Figure 1 ).

The development of the code structure was finalised when the point of theoretical saturation was reached in each of the empirical cases. 69,77 Secondary data were used as complementary to the preliminary interpretation (based on interview data) of each case study and for triangulation, through cross-checking the validity of claims in interview accounts. Field notes taken by the interviewers during the visits to the trusts were shared with the other members of the research team during analysis of the interview and documentary data. The field notes provided a ‘feeling’ for each trust, allowed for a better understanding of the trust context and included explanatory information about the ‘technologies in use’. In particular, the field notes helped sensitise and ‘acclimatise’ the researchers not familiar with the microcases.

Analysis within cases was followed by a cross-case analysis of emergent themes. The cross-case analysis commenced with a systematic examination of the data based on our research questions. We compared the data on these questions across the macrocases and across the microcases (technology product journeys). Individual case study reports with common formats were produced for each of the eight trusts that participated in phase 2. Summary tables were used to simultaneously compare several categories and dimensions of the content and context of change implied by the adoption and implementation of the innovative technologies across the nine trusts. The above strategies helped us to reduce the volume of primary data. The final interpretation was conducted through comparison and integration of seemingly common or contradictory themes, categories, patterns and cases.

Learning from project challenges

The context of the NHS poses challenges to access to participants. In the field of IPC, this is further exacerbated because critical events can pose high demands on IPC teams and senior management within trusts. We employed a multifaceted approach to gaining access, building on our previous relationship with five of the trusts in the first instance. We found that the nature of the research questions prompted genuine interest and, therefore, engagement in the research. We were able to access a higher than initially anticipated number of respondents. Nonetheless, these very pressures resulted in incomplete participation in the study for one of the trusts, T8.

The initial delays in gaining ethics approval and then local access did make data collection challenging. Internal contingency and a highly flexible approach by the research team was employed to maximise interview opportunities at each research site visit.

We found that the guidance from our expert steering committee and, notably, our patient advisors helped with every stage of the research process, enhancing the quality of the research. Perspectives from health policy, quantitative methods and accounting, organisational management, service users, and IPC and service managers were present and debated. The multidisciplinary make up of this group reflected well the stakeholders we were studying and allowed a reflexive approach to data analysis and will inform dissemination activities beyond the project.

Chapter 4 Challenges in making sense of evidence

In this chapter we summarise some key themes from the qualitative study, which drew on primary data collected through interviews in phase 1. These themes were deemed helpful in providing a conceptual understanding of the main ‘challenges to making sense of evidence’ reported by the informants. The emergent issues discussed in this chapter help place individual sensemaking of evidence by health-care managers in the context of the hospital and wider NHS environment.

Ongoing sensemaking: keeping up with the evolving evidence

The very nature of evidence as emergent, iterative and changing featured in the majority of interviews with respondents, particularly as the context of this research was innovation. The accuracy of evidence therefore had a temporal dimension, irrespective of the source of the evidence, or the audience making sense of the evidence. The need for ‘up-to-date’ evidence, which sometimes needed to be generated locally, was an important theme in respondents’ accounts:

Well-written trials that have been peer reviewed and written up in trusted journals. But I am also now old enough to see that some of the things that we took as facts, 10 years ago, have already been proved incorrect.

T5M4 – doctor

This evolving landscape of evidence posed a challenge, therefore, for individuals and groups when making decisions about adoption and methods of implementation. Further challenges to making sense of evidence reported by the respondents ranged from the individual’s internal capacity to process the scientific data presented to external factors, such as the lack of evidence in the specific areas of innovation and IPC. The lack of ‘high-quality’ evidence was reported by the majority of respondents, although this definition of quality varied across the professional groups and is discussed later when we look at the importance attributed to various sources and types of evidence (see Chapter 5 ):

As a doctor I go to the medical literature, didn’t find a lot. So my nurses came back with a lot of nursing literature evidence. Which I felt was of poorer quality evidence, but there was a large volume of it, so it was put into the mix somewhere.

T3M3 – doctor

In terms of the individual’s internal capacity, respondents across the professional groups cited difficulties in understanding the evidence presented in published papers and reports. Specifically, 75% of medical hybrid managers and 77% of nursing hybrid managers said that they sometimes found ‘the content of presented evidence difficult to understand’. Similarly, the majority in each of these groups found it ‘difficult to relate evidence to practice’: 63% of doctors and 72% of nurses. The non-clinical managers reported a different experience – 60% stated that they sometimes found the content of presented evidence difficult to understand, but only 40% had difficulty in relating this to practice.

There was consistency among the groups in agreeing that different professional groups have access to different sources of evidence because of different needs for evidence. This access and need for different types of evidence was deemed to have direct implications for practice:

If everybody isn’t looking at the same piece of information it can affect how you make the decision because we can all be coming at it from different points of view. I can say generally speaking within this organisation when we are looking to do anything we get the relevant people round the table. It’s not that IPC would make a decision that would impact on the provider without involving, they would involve our actual service provider and we will be involved as well. And I do think we do that well really.

T2M2 – non-clinical manager

Missing research evidence

Looking in greater detail at the gap in evidence or ‘missing evidence’ as identified by the respondents, there is more consensus than variation on this issue across professional groups and across the trusts. Challenges arising from the lack of relevant evidence as well as incomplete evidence were mentioned by the majority of respondents. For example, a laboratory-based/microbiology study may be available for a given product but no studies relating to cost. Implementation studies may be available, but may only report a ward-based small study, which may not be relevant to the hospital-wide context. A lack of product trials was described, the products being either untested in the ‘real-world’ setting or untested in the locally relevant setting. Particularly among doctors, basing decisions within the context of incomplete evidence was reported as not just a challenge but undesirable:

There’s damn all evidence most of the time. So we’re very used to doing what seems sensible from first principles, which may not actually be, so often we do things without a formal level of evidence basically.

T9M2 – doctor

It’s difficult because some of the things we do I must admit they are based on very little evidence.

T1M17 – doctor

It [personalised care plans for renal patients] was a good idea but it wasn’t trialled anywhere, there was no sort of pilot study to demonstrate how much time it was going to take to fill these things out, whether they would actually be useful, did the patients think they were useful, did the doctors think it was useful.

T5M5 – doctor

These findings have an important implication as to what managers currently perceive as ‘incomplete evidence’ in research when making decisions on innovation adoption, and what future research should focus on to meet such local needs.

Types or topics of research studies perceived as missing by the respondents did vary across the respondents and across the trusts, but views converged for three types of research study, which were identified as missing in the following order: behavioural studies, implementation research and organisational studies or management research.

Approximately one-third of respondents in trusts T1, T3, T6 and T9 felt a need for behavioural studies to assist decision-making, implementation and evaluation. Specifically, interest in behavioural studies was driven by the need to overcome ‘non-compliant’ behaviour; insights into bringing about change in the way people work; learning from training and development mechanisms; and better communication. More importantly, the respondents identified a need for better understanding of decision-making across the different levels of hospital staff, from senior management to front-line staff:

I think that there is quite a lot of management research that is missing. Partly because managers don’t tend to do a great deal of research in this organisation. Then again all the behavioural work that is done is linked to nursing or medical, I think this is the first research that I have seen that is linked to managers as well. I would like to see a lot more research based around behaviours and how managers and clinical staff could work much better together, to deliver a health service, because I see models out there where they work so well and yet somehow the NHS cannot get it right across the whole trust.

T1M1 – non-clinical manager

Yeah not enough is done around the whole decision architecture and influencing behaviours in the clinical areas. How do we improve behaviours? Not just in the clinical areas, managerial areas, but how do we improve the way we work which is not around new technologies but how can we stop wasting huge amounts of time repeating the same things over and over again.

T1M10 – doctor

The ‘missing evidence’ highlighted by respondents is interlinked and demonstrated a need by the hospital managers not only for applied, meaningful evidence use in adoption decision-making itself, but also more operational and managerial research. This ranged from effective management to psycho-social research about behaviour change and receptive organisational culture. The following respondent highlighted a shift in evidence needs – highlighting what is most useful to managers:

My research brain has gone exponential in the last year or two. I think there needs to be far more focus on the behavioural and cultural aspects of innovation spread as well as just the subject matter. Because the understanding ‘how’ to challenge the behaviours and ‘how’ to develop the people who are involved in the organisations is far more important than the actual evidence that drives it. Increasingly I’m convinced more and more.

T3M4 – doctor

[. . .] where we’ve got the catheter project, the CAUTI project we’re doing, where we’ve got John who’s our clinical academic, we’re looking at doing some sort of research around people’s decision making as to why they’re putting catheters in. [. . .] Why do people make those decisions to do that or why do people make decisions to move away from the guideline that’s there [. . .] There’s a lot, from an infection prevention point of view there’s a lot of scientific type stuff we could do but that is quite difficult already because we don’t want to inject people with, but [. . .] I find that behaviour really interesting as to why people do make the decisions they do.

T9M1 – nurse

I work with a public health doctor and he was really interested in implementing change, change methodology. And I think as much importance of thinking about that as thinking about the evidence. If the evidence stacks up, or evidence doesn’t stack up particularly well. You could have good evidence and poor implementation and no effect. Poor evidence not even particularly good but with really good implementation will make it improve but almost, I think there is something there. What I would say [is] that even if I’d like to assimilate stuff, actually it’s not what other people want to do, you don’t have the time to do it. Lots of people who are over-committed and busy and sometime go, I’m sure there is something better unless you tell me what you want to do.

T9M8 – doctor

This type of management literature was not accessible to the respondents largely because of the sources used by these professionals, and also because of the time constraints faced by these professionals, who were not able to branch out to wider literature streams.

Of the professionals groups, pharmacists appeared to be more aware of the discrepancy between recommended practice (through national or local guidelines and protocols) and ‘non-adherence’ or ‘deviation’ of behaviour than the other professionals in our study sample. Approximately two-thirds of respondents, despite the small sample size, commented on the importance of behavioural studies and the lack of such studies. One-quarter of nurses and non-clinical managers identified the importance of studies to address ‘non-adherence’ to guidelines, whereas this view was less prevalent in accounts from medical managers and missing in accounts from managers with an allied health professional background. Medical managers were the ‘outliers’ in terms of being less concerned about understanding behavioural change in greater depth.

Making sense of evidence for self and others

Sourcing practice-based evidence was mentioned as being important across professional groups. The practice of learning from other trusts and peers featured across respondents’ accounts. This was because of the locally relevant information in practice-based evidence but also because of the exchange of information which is possible through such means:

A microbiologist in another hospital or someone who has used something in practice and any research or studies they have done, that is usually the most useful. I guess because you are talking to them you can ask questions and get feedback straight away, so you know where you are with it. So that’s a really good source.

T7M3 – doctor

Upon direct questioning, respondents reported a hierarchy of evidence, but this was articulated more as processual rather than as an objective vertical hierarchy, or means to exclude certain forms of evidence. Although the first port of call may be scientific randomised controlled trials (when available), this was assessed in tandem with experiential evidence:

We used that, literature searches for that [Gentamicin (antibiotic) as first line for the treatment of urinary tract infections]. But we also used experience of other hospitals, our own experiences, we drew on that. So actually it was probably a decision which was much more of a pragmatic decision rather than a pure academic-based decision.

T3M17 – pharmacist

The approach described by the majority of respondents was an iterative process of ‘triangulating’ different types of evidence. There were few reports of an evidence dichotomy within professional groups, but rather a more complex picture of synthesis across the professional groups. Paradoxically, many respondents did view other professional groups as having a more dichotomous approach to evidence, as illustrated by this view of non-clinical managers:

[. . .] if they’re an accountant it will be purely based on cost effectiveness without looking at the wider picture of your added value this technique may bring.

T1M19 – doctor

This view was reciprocated by non-clinical managers:

Partly because people spend more time critiquing the research paper than looking at how we can implement it, or not implement it or how we can try it ourselves. That’s how we get stuck sometimes, people spending too much time focusing on their research, was it true was it evidence-based, did it have flaws?

T1M1 – non-clinical manager

A contested ground emerged, with each professional group claiming a more rounded view of evidence and perceiving other groups as taking a one-dimensional approach.

The quest for evidence of doctors was driven primarily by plausibility and accuracy to self. The evidence sought was largely of a biomedical nature. Doctors appreciated that the cost-effectiveness of interventions was important but, as shown above, described non-clinical managers’ approach as too focused on the business case.

Although both the nursing group and the non-clinical managers group reported a relatively balanced multidimensional view to evidence, the motivation for sourcing a diverse evidence base was different for these two groups. Non-clinical managers took a multidimensional view to satisfy the major objective in their organisational role, that is, to improve performance and outcomes. Nurses were driven primarily by the need to ‘make the case’ for others and appreciated that different professionals had different evidence needs:

Most of things I do are evidence-based. I would be looking for things such as standard of construction, standard of validation with processing that sort of thing. I can’t honestly say that I can think of an instance that I did something where I didn’t actually have the evidence.

T2M12 – non-clinical manager

Non-clinical managers were similar to doctors in that the way they made sense of evidence was driven primarily by ‘plausibility and accuracy to self’, although their sensemaking was based on different views of evidence. That is, what came to count as evidence for doctors and non-clinical managers was different, but what counted most was that they themselves were satisfied with the evidence. The nursing group differed markedly in this respect from the doctors and non-clinical managers. The nursing hybrid managers focused on the pursuit of evidence for ‘plausibility and accuracy for self and others’. For the nurses, what counted as evidence to others mattered equally and sometimes more than their own satisfaction with evidence. This shaped the types and sources of evidence used by nurses.

In the nursing group, we found there was a high awareness of different types of evidence being relevant to different organisational members. They appreciated the evidence needs of those working both at the front-line and at more strategic levels, and the needs across professional groups. Nurses were also the only group to make explicit reference to the perceptions of patients. Plausibility to others thus featured highly in accounts by nurses. Nurses made purposeful attempts to frame evidence using language which was meaningful and tailored to the audience. Nurses also were aware of their own professional role and identity and how they were perceived by others – that is, being reflective on their own ‘credibility’ as sources of evidence. This non-clinical manager articulated this varying credibility of the presenter of evidence:

Although it galls me to say it but I think the medical colleagues within the team are better at accessing [evidence] and they may come to a meeting and say I have had a look at the evidence. I don’t think it could necessarily have been a systematic review of the evidence. Stating quite confidently a particular position and that could be quite influential so that is something they are more likely to do than nursing members of the team.

T7M13 – non-clinical manager

Nurses therefore approached sourcing evidence in a systematic and comprehensive way in order to find evidence that was meaningful and accurate for themselves as well as for significant others. There was a convergence towards synthesising diverse forms of evidence, but, ultimately, evidence synthesis was grounded in the biomedical paradigm. This was partly a result of their own training but also reflected a need to resonate with doctors, who were consistently identified as influential stakeholders in organisational decision-making:

You will see it in very specialist nurses that they will do scoping exercises around what the evidence is, systematic review around evidence of implementing a certain thing and clinical evidence to support it. I think the reason why nurses do that is because they know that the doctors, that are going to try and influence [the decision], will ask them for that evidence, so they already do it.

T1M2 – nurse

I think it is the availability of good quality evidence and research something that will convince the senior members and the medical staff that this is a good quality piece of research, peer reviewed etc.

T6M5 – senior nurse

I can remember quite clearly presenting to our anaesthetist body, some 200 odd anaesthetists on one of the clinical audit days, on a topic, [. . .] around line care, and the changes we had made in the organisation. And there was one consultant, a specific consultant who’d been a problem all the way through, he’d not engaged well. We gave the presentation, we demonstrated what we’d achieved in the organisation since we’d introduced our changes in practice, and he actually turned round in front of the other 200, and he said ‘I change my opinion’, he says, ‘I accept what you’ve been championing’. And to be honest that was one of the most powerful moments in my career, to get that individual to, in front of 200 of his colleagues, to turn round and say ‘I’ve seen the light.’ [. . .] And sort of do, do the St Paul’s Damascus moment, it was just, it was tremendous, [. . .] It was strongly presented with good, we used, took an epidemiological approach to demonstrate that the changes we had made had had a significant impact.

T8M1 – nurse

Nurses were aware of the use of evidence for different agendas, but overall perceived that evidence was used primarily for the benefit of patients in the context of financial constraints. This, in turn, led to the need for combining different types of evidence (i.e. clinical effectiveness, cost, usability) to satisfy the perceptions and priorities of key organisational stakeholders – from doctors to managers.

Doctors and non-clinical managers were both mindful of issues of cost-effectiveness, particularly given that our sample in phase 1 comprises senior managers.

The findings from the qualitative interviews are validated by quantitative analysis. The quantitative analysis shows that nurses were aware of, and utilise more widely, the full range of centrally available evidence sources when compared with the other professional groups (see Chapter 5 ). In addition, nurses were more formally engaged across the phases of the innovation process, whereas doctors were more formally involved in the later phases of technology adoption decisions and post-implementation evaluation. The nursing group was, across the trusts, more formally tasked with ‘making the case’ to diverse groups.

Across respondent groups, plausibility to self was closely linked with perceived ‘accuracy’ of the evidence. This was influenced by social and personal identities situated within a wider organisational context. For example, financial considerations were evident in the sensemaking of the majority of respondents. The influences of the local and macro context of financial parsimony added to the challenges of making sense of evidence:

Financial viability [. . .] that has rapidly changed, we have to justify everything that is new in terms of spending.

T1M2 – nurse

Reflection on this chapter

In summary, all respondents reported that they experienced challenges in making sense of evidence. Key issues that contributed to this were reported as a lack of capacity or skills to process presented evidence, a lack of time to thoroughly search for and review the evidence base, unawareness of appropriate literature on management and implementation research and poor perceived quality of available evidence. Professional background and training coupled with differential access to different evidence reinforced some of the divergence in the type of evidence accessed. Pursuit of evidence to satisfy oneself or others was found to guide action and explained some of the complexity in the process of decision-making. Looking across the professional groups, what counted as evidence for doctors and non-clinical managers was different, but what counted most was that they themselves (doctors and non-clinical managers) were satisfied with the evidence. For the nurses, what counted as evidence to others mattered equally and sometimes more than their own satisfaction with evidence. This shaped the types and sources of evidence used by nurses.

As regards perceived missing evidence, three research study types were identified by respondents: behavioural studies, implementation research, and organisational and management research. Pharmacists were particularly mindful of the need to understand behavioural change within organisations, particularly in relation to non-compliance with guidelines.

Chapter 5 Making sense of evidence in the health-care organisational and macro context

In this chapter we summarise findings on how non-clinical and clinical hybrid managers from various professional backgrounds reported on how they make sense of evidence within the health-care context. We review how they access and use different sources and types of evidence related to innovation decisions and outline key contextual influences at organisational and macro levels within IPC and the NHS. This chapter draws on data from, first, the structured questionnaires embedded in the phase 1 interview schedule and, subsequently, from the semistructured interviews themselves.

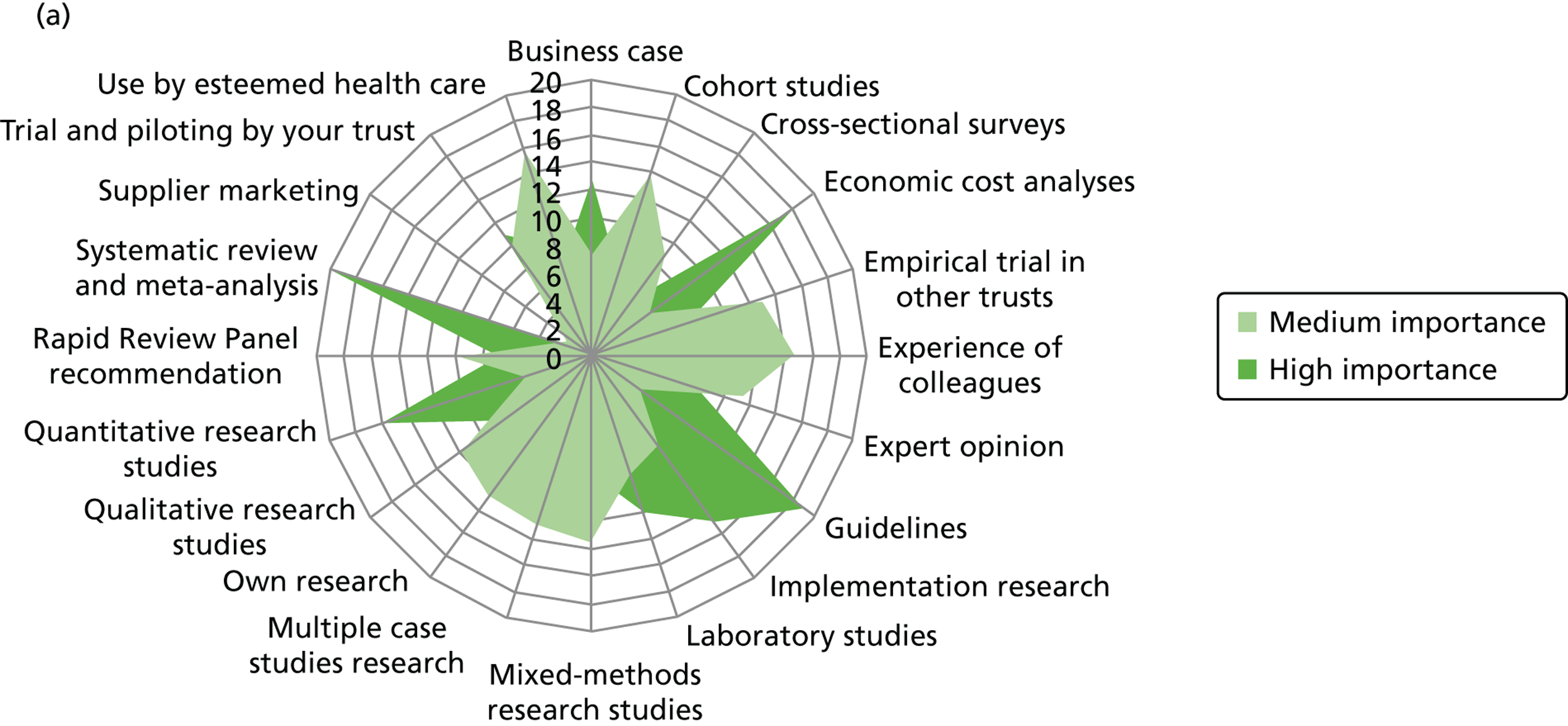

We outline the espoused use of evidence by the decision-makers. First, we look at the reported use of more general sources of evidence (such as peer-reviewed journals, professional networks, peers, the industry) to inform the decision-making of different professionals. Second, we outline the reported awareness and use of central evidence sources including sources directly linked to IPC. Third, we outline responses on the use of different types of evidence (such as systematic reviews, guidelines, economic cost analyses and expert opinion). In the final sections, we delineate important influences on the use of evidence by health-care decision-makers from the organisational context (main level of analysis) and the wider context.

In the proceeding chapters we find out how this espoused use is actioned.

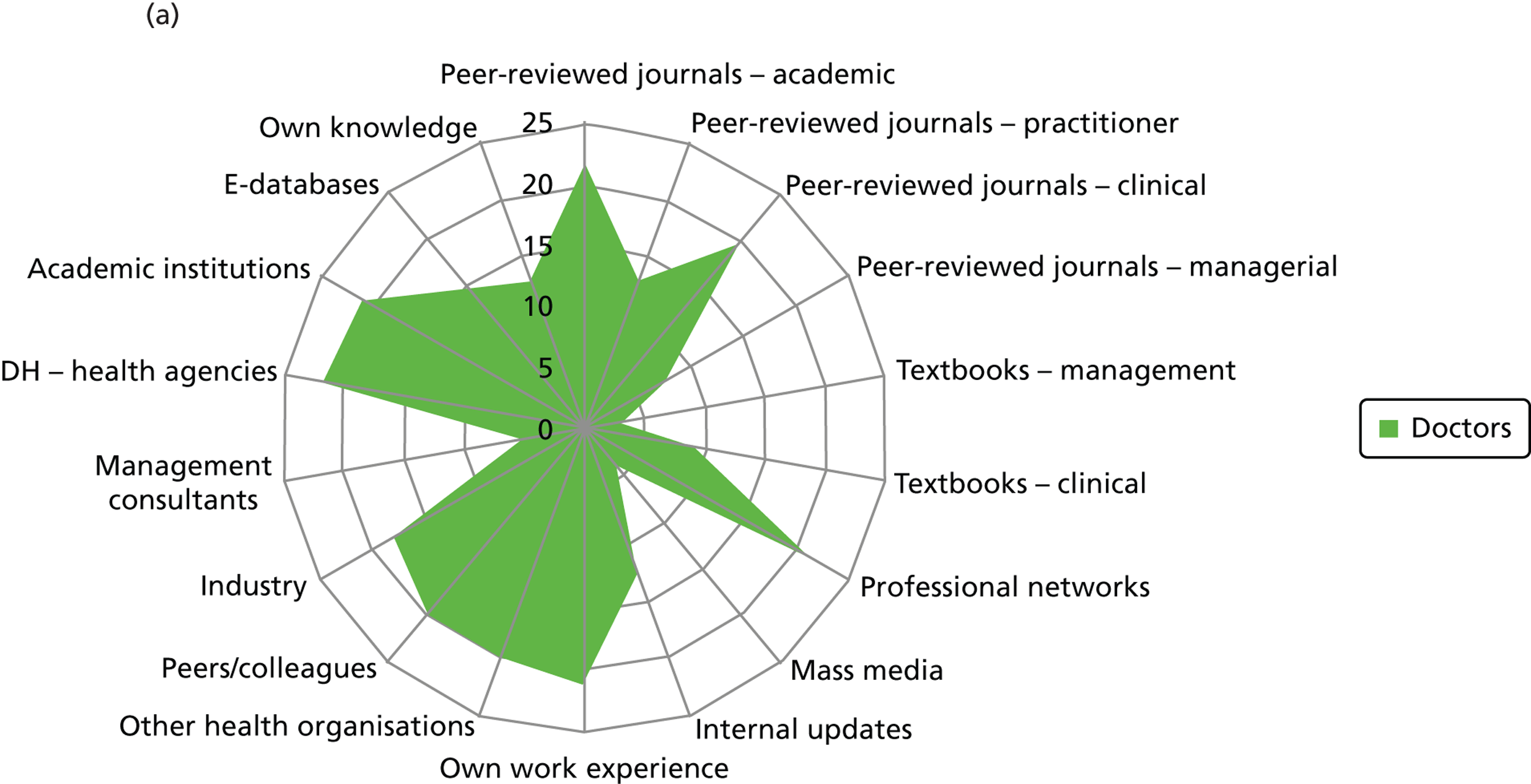

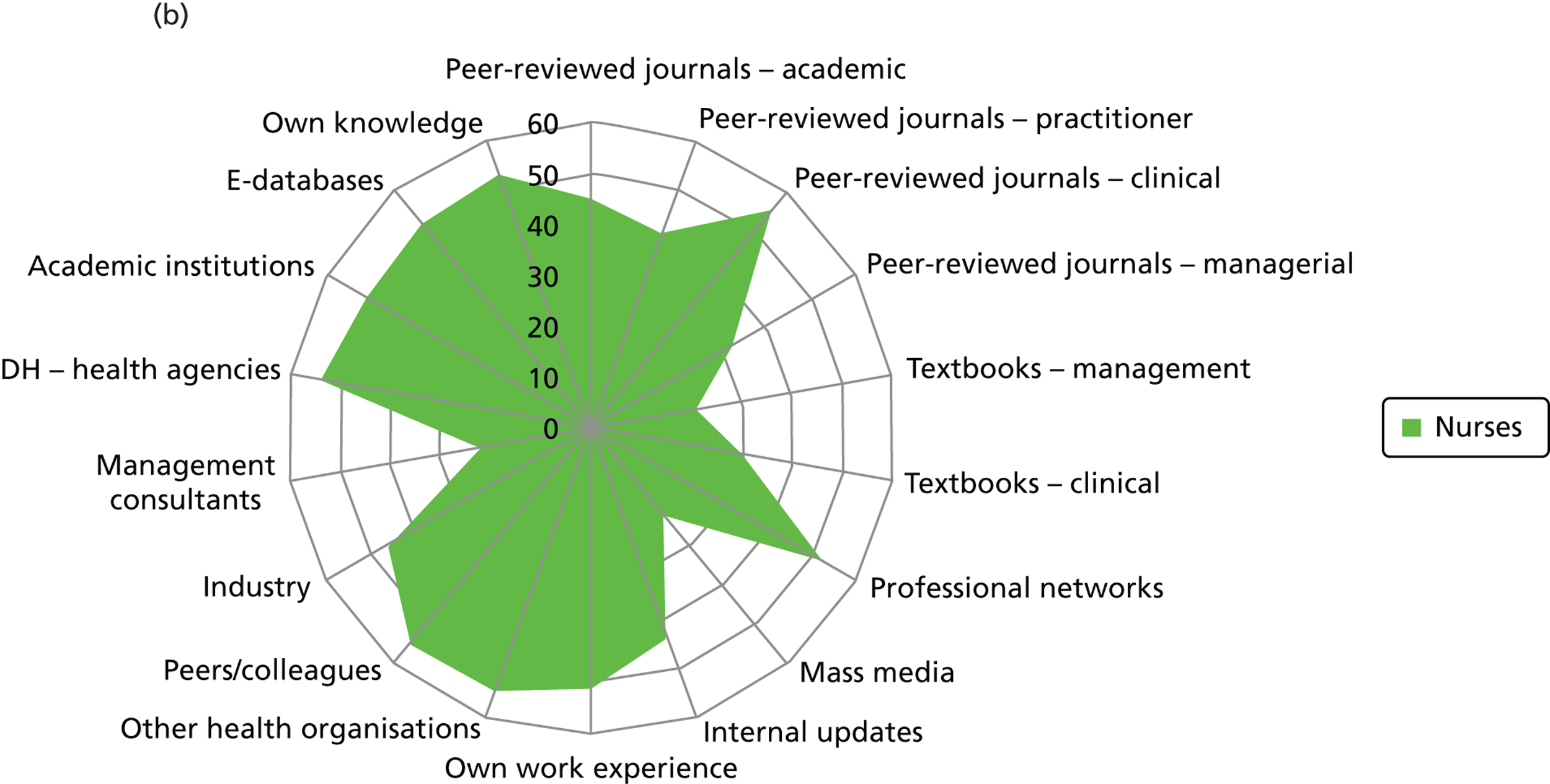

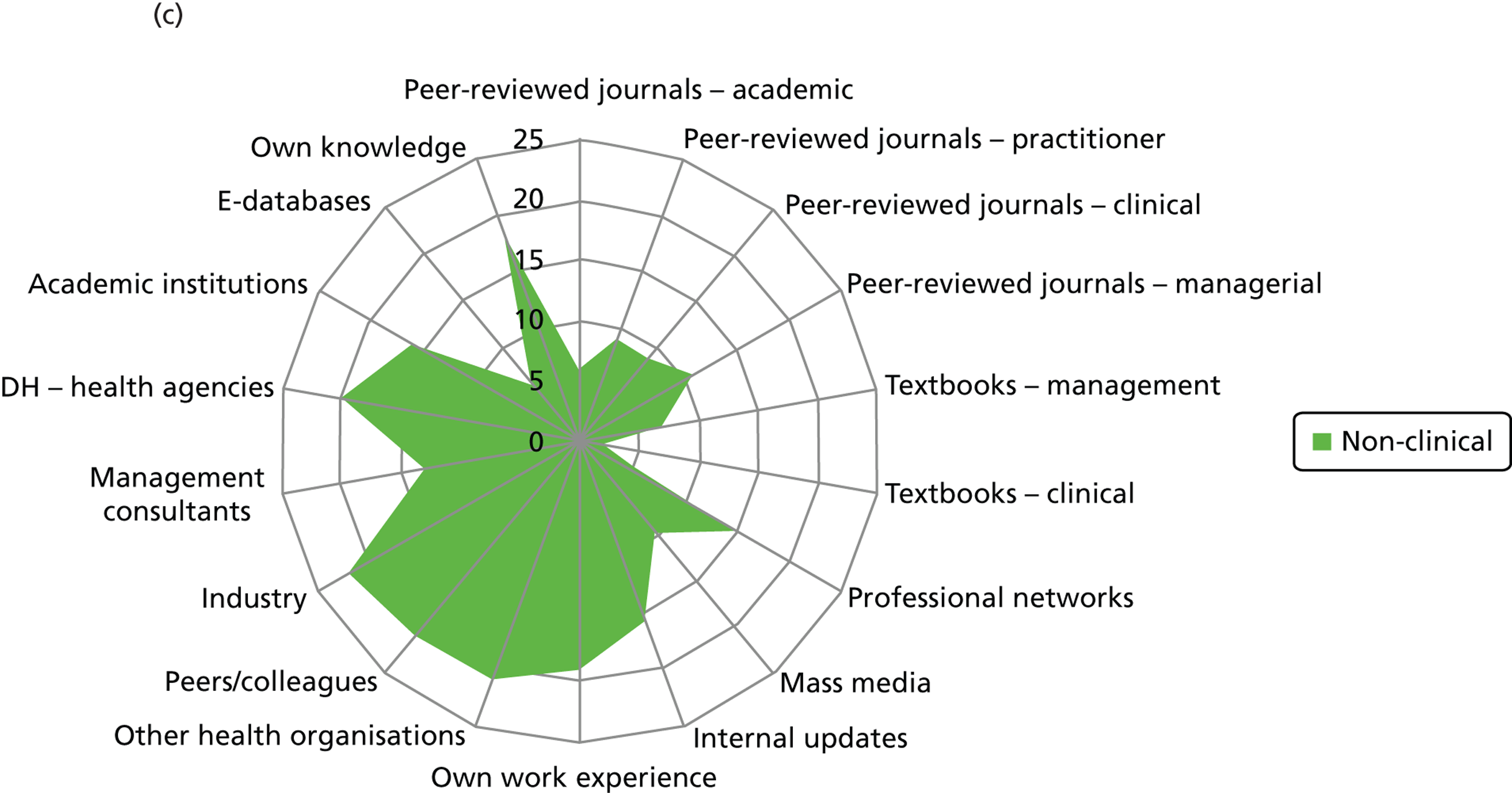

Innovation decisions: evidence sources

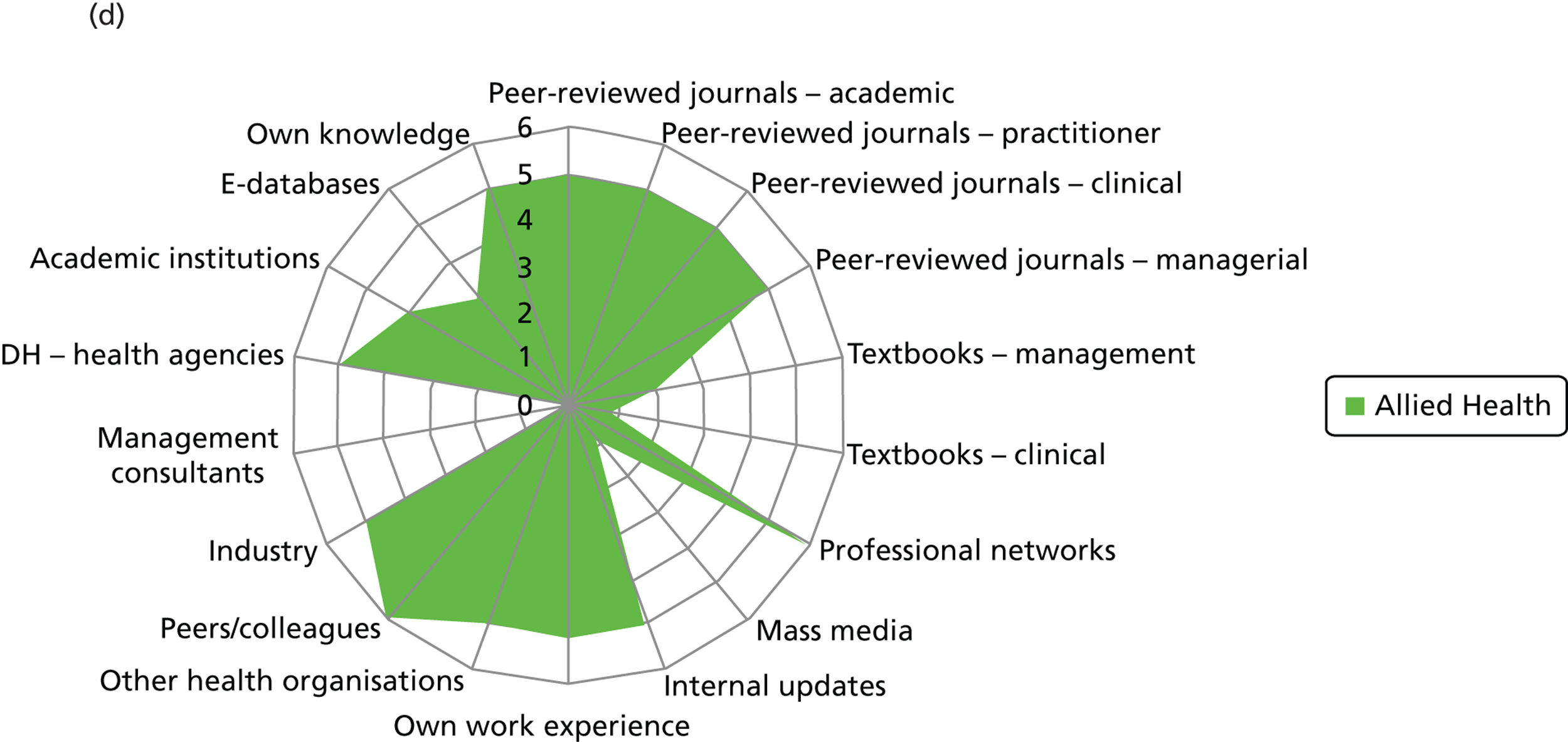

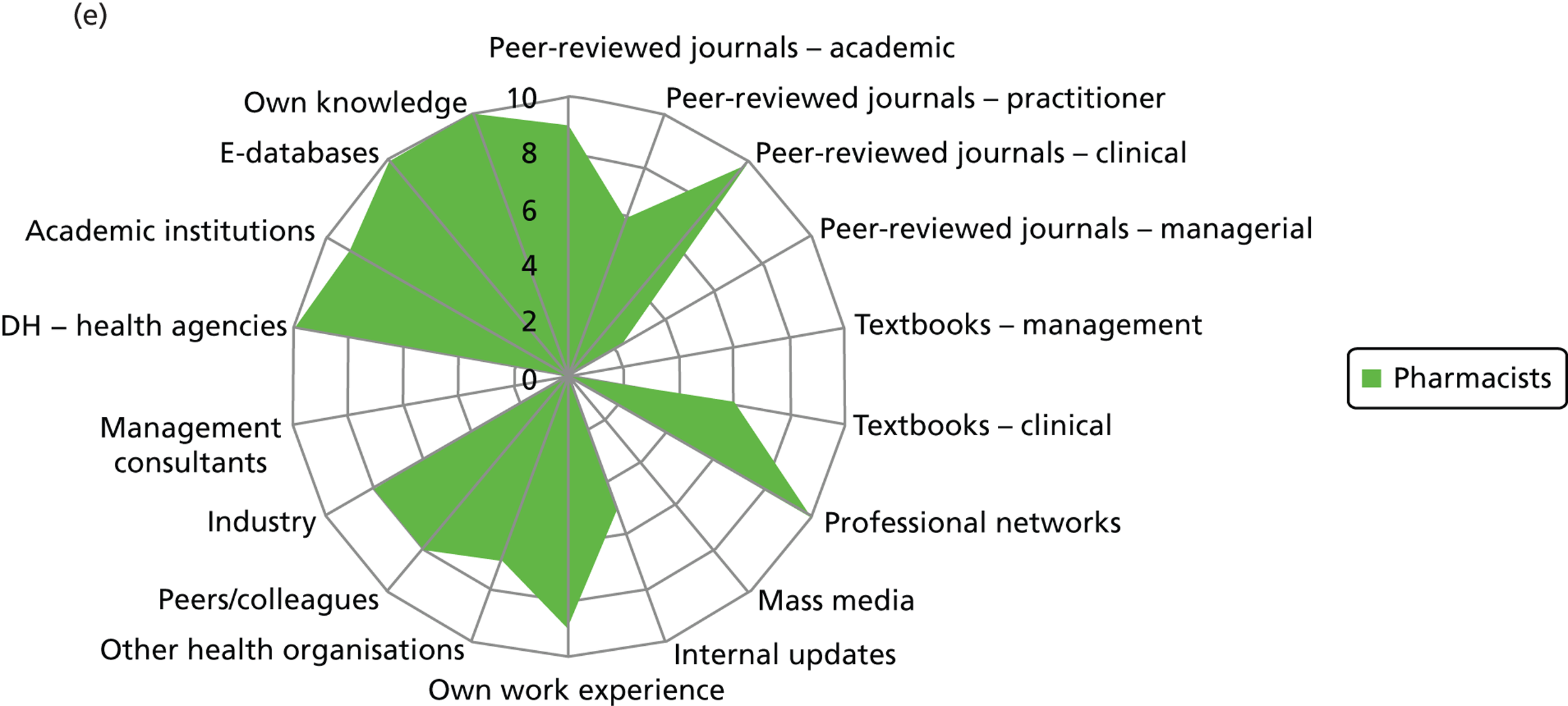

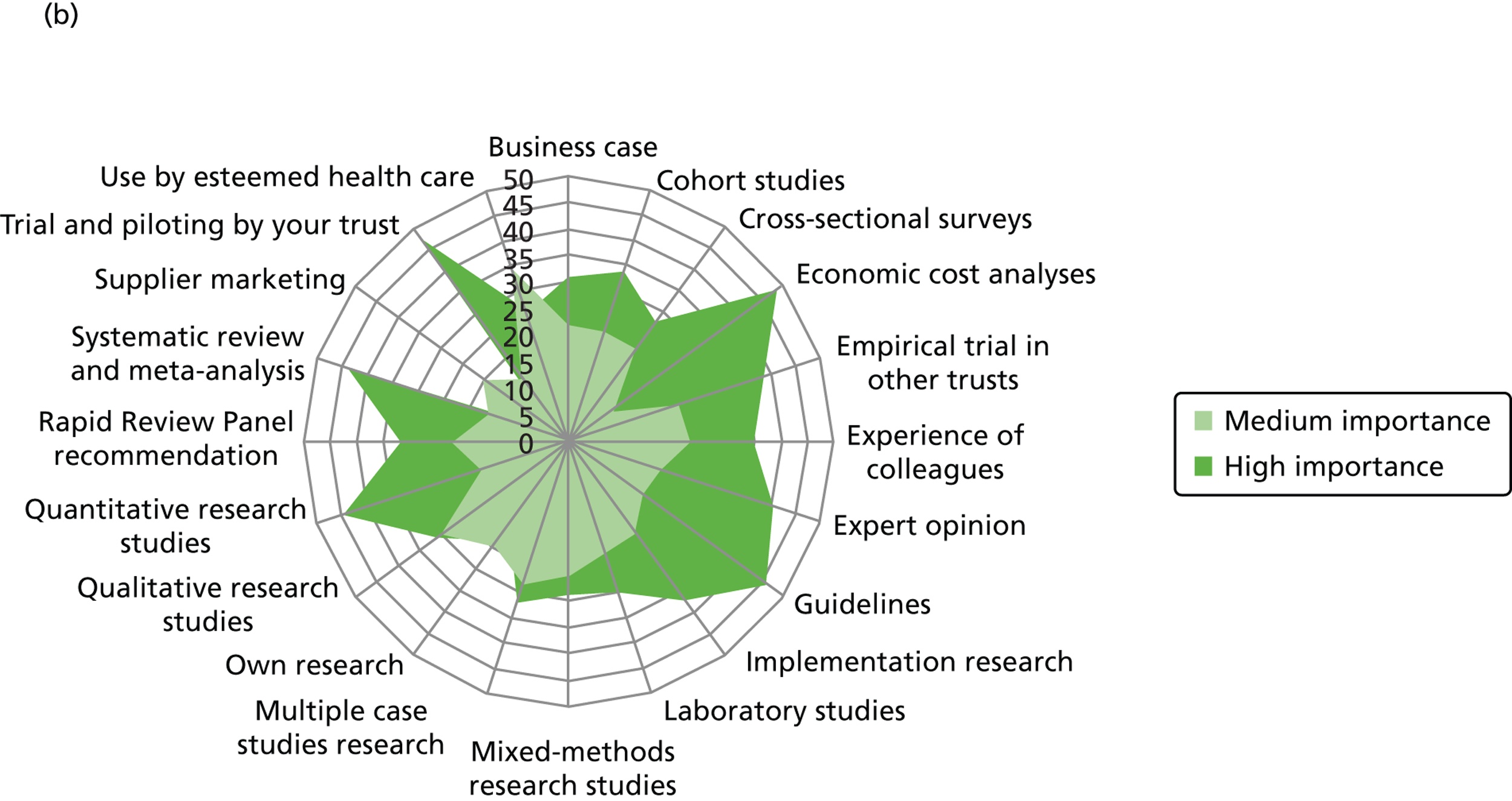

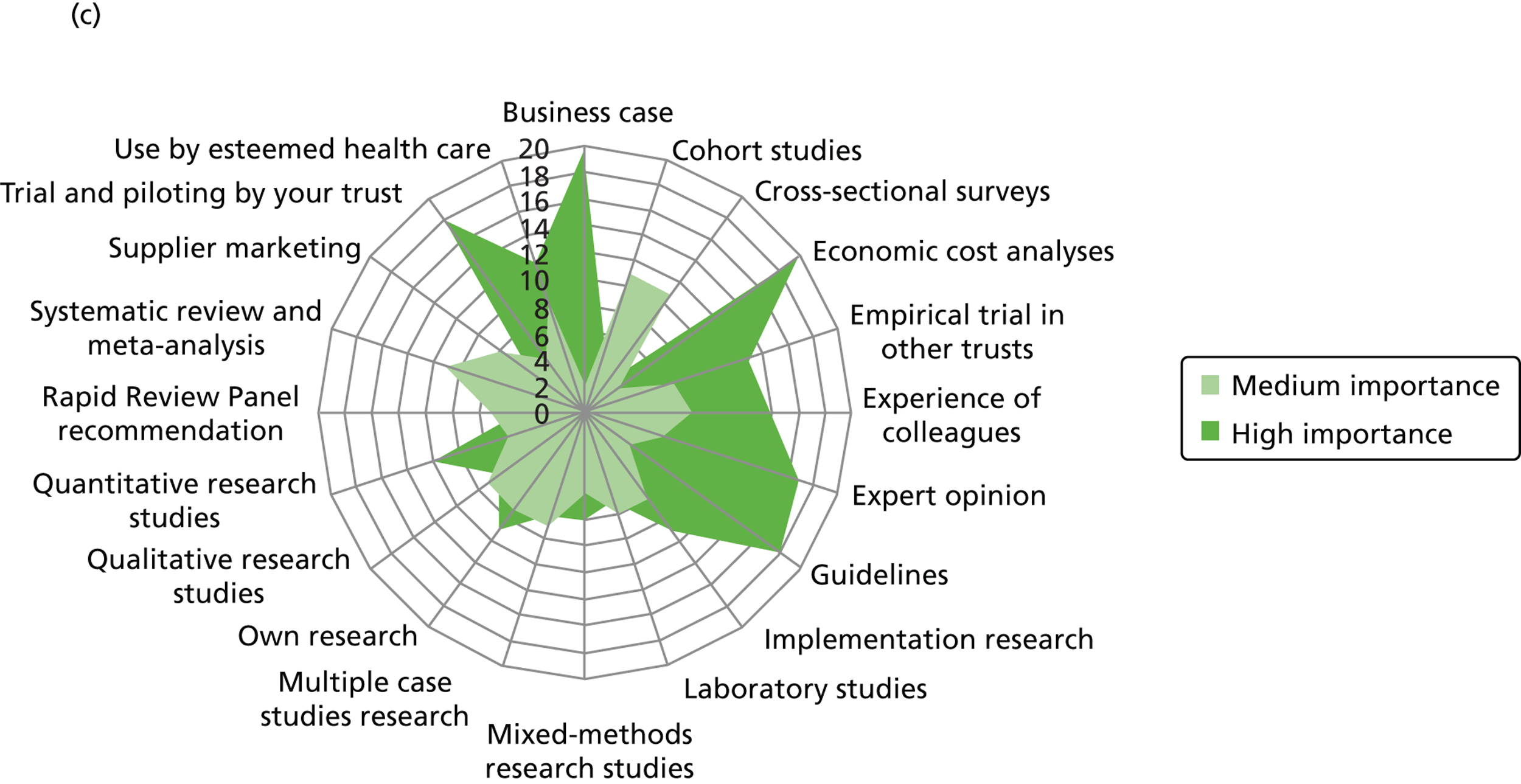

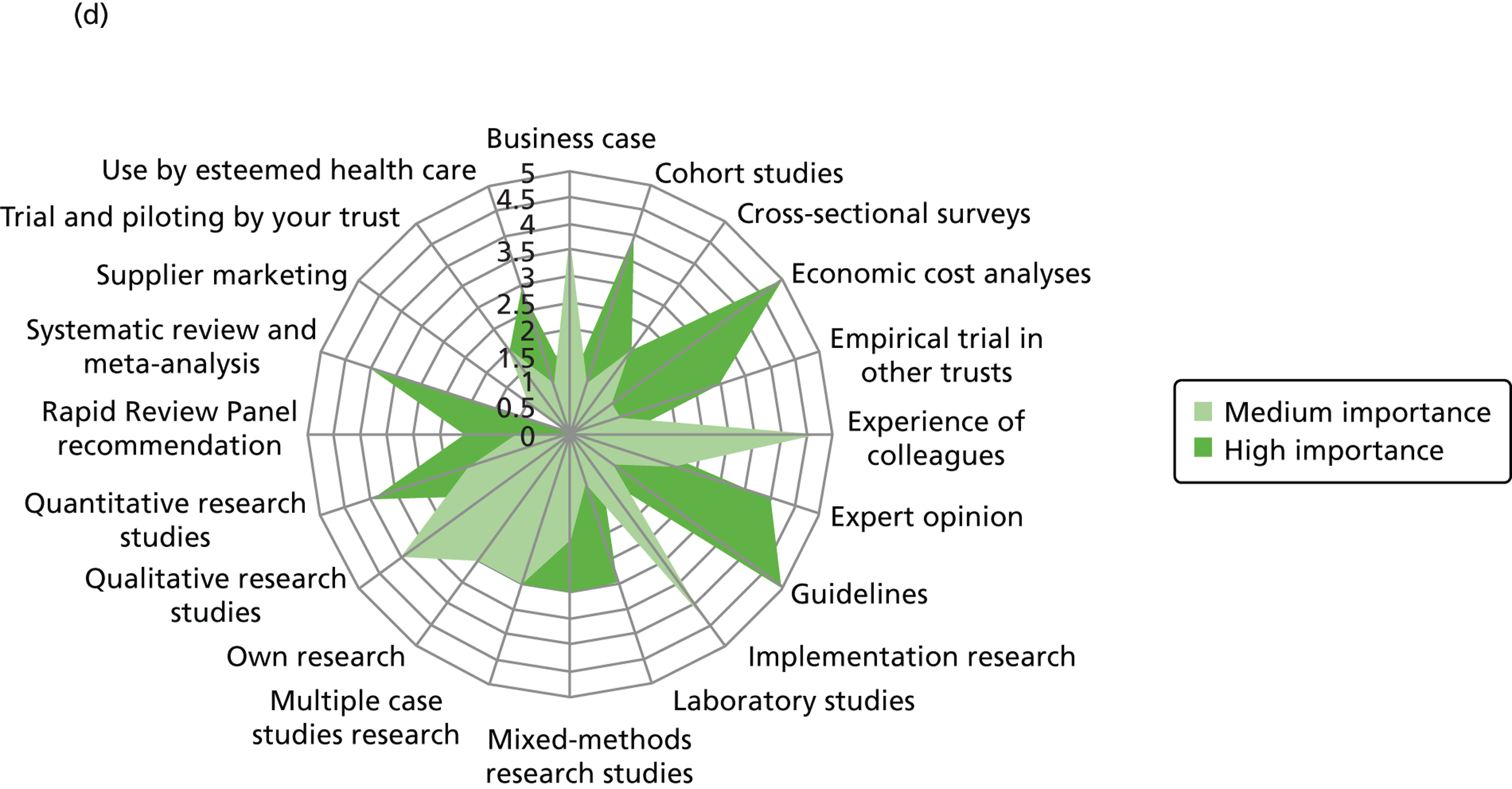

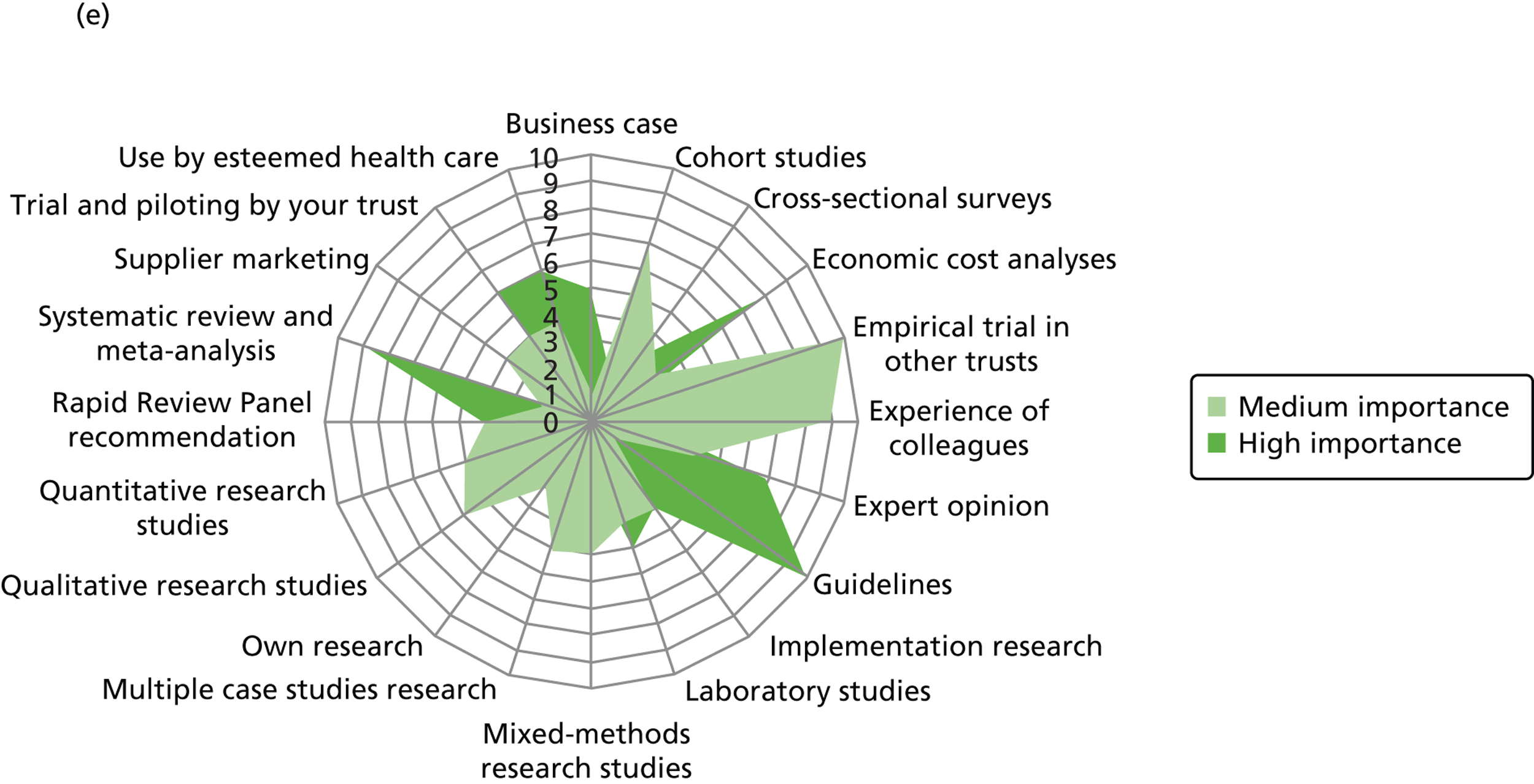

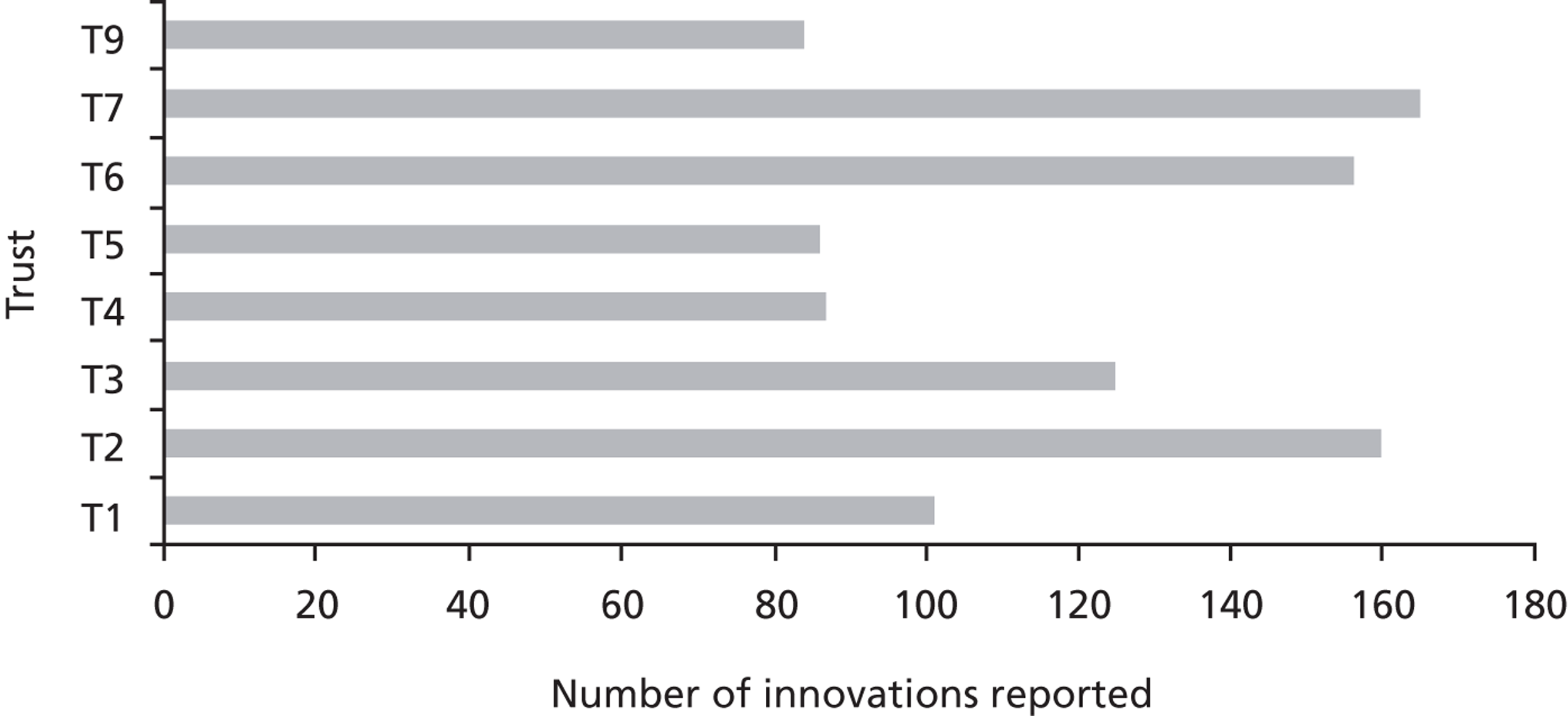

Figure 2 presents the use of more general sources of evidence, such as peer-reviewed journals, professional networks, peers and the industry, in decision-making by different professionals.

FIGURE 2.

Evidence sources – breakdown by professional group (a) Doctors; (b) nurses; (c) non-clinical managers; (d) allied health professionals; and (e) pharmacists. DH, Department of Health.

Few non-clinical managers sourced peer-reviewed journals, either management or clinical. This group clearly veered towards centralised and standardised sources of evidence (Department of Health agencies), internal updates and also locally derived evidence from other health-care organisations. They were the only group to source management consultants. These sources align well with the organisational role of non-clinical managers as well as the diversity in professional background of this group. Non-clinical managers were reported to show the least preference (15/25) for accessing evidence through their professional networks out of the different professional groups: doctors (22/24), nurses (53/61), pharmacists (10/10) and allied health professionals (6/6).

Nurses reported a uniform and consensus view within this group, reporting use of a wide range of sources. Doctors, allied health professionals and pharmacists displayed very similar patterns of reported evidence use with a strong preference for professional networks and most making use of academic institutions.

Across the professional groups, and not surprisingly given the context of the interviews was innovation, text books were not reported as an evidence source. Mass media was evident as a source for only a few nurses and non-clinical managers. Peer-reviewed management journals were mentioned as a source by only a few of the allied health professionals.

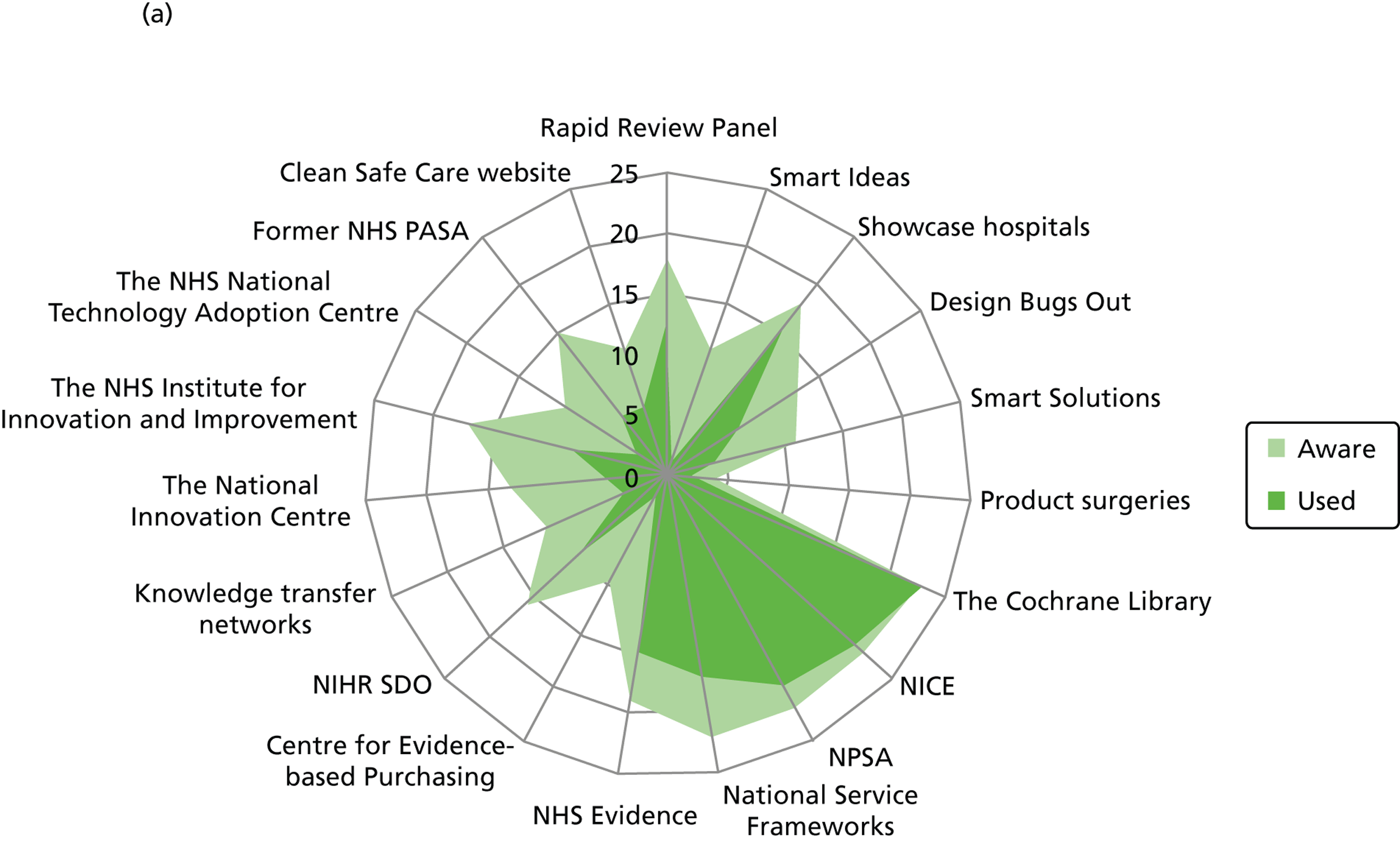

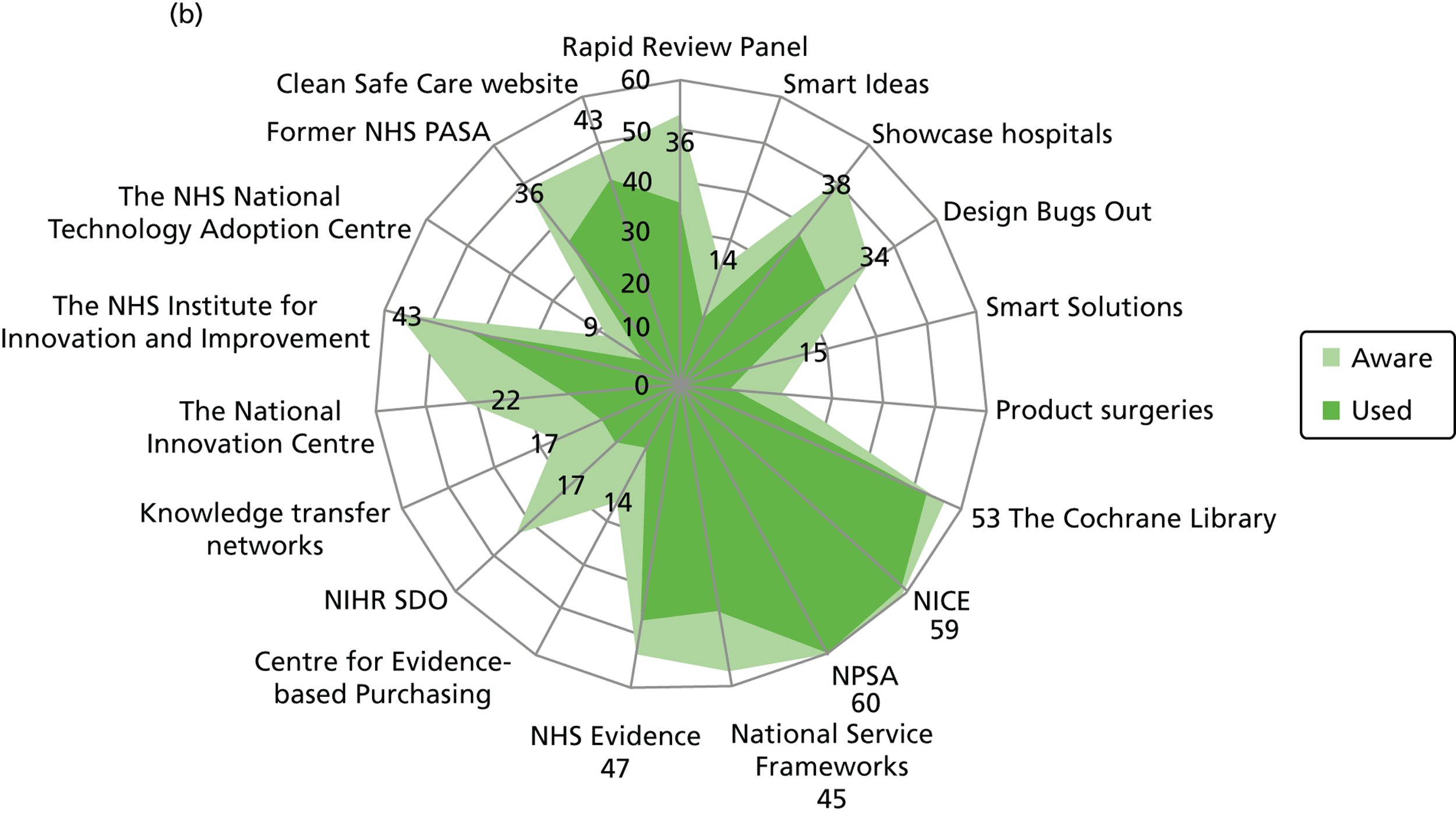

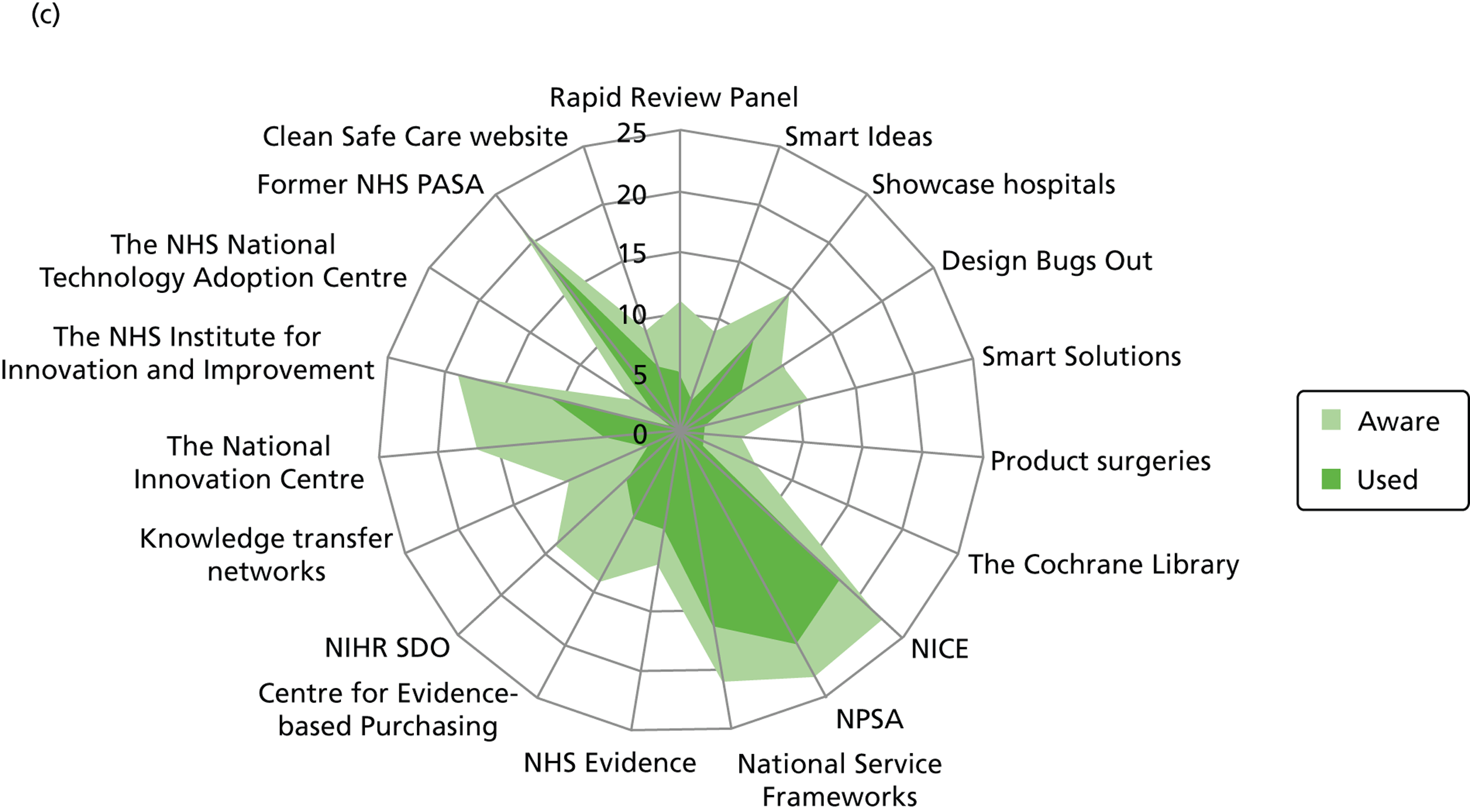

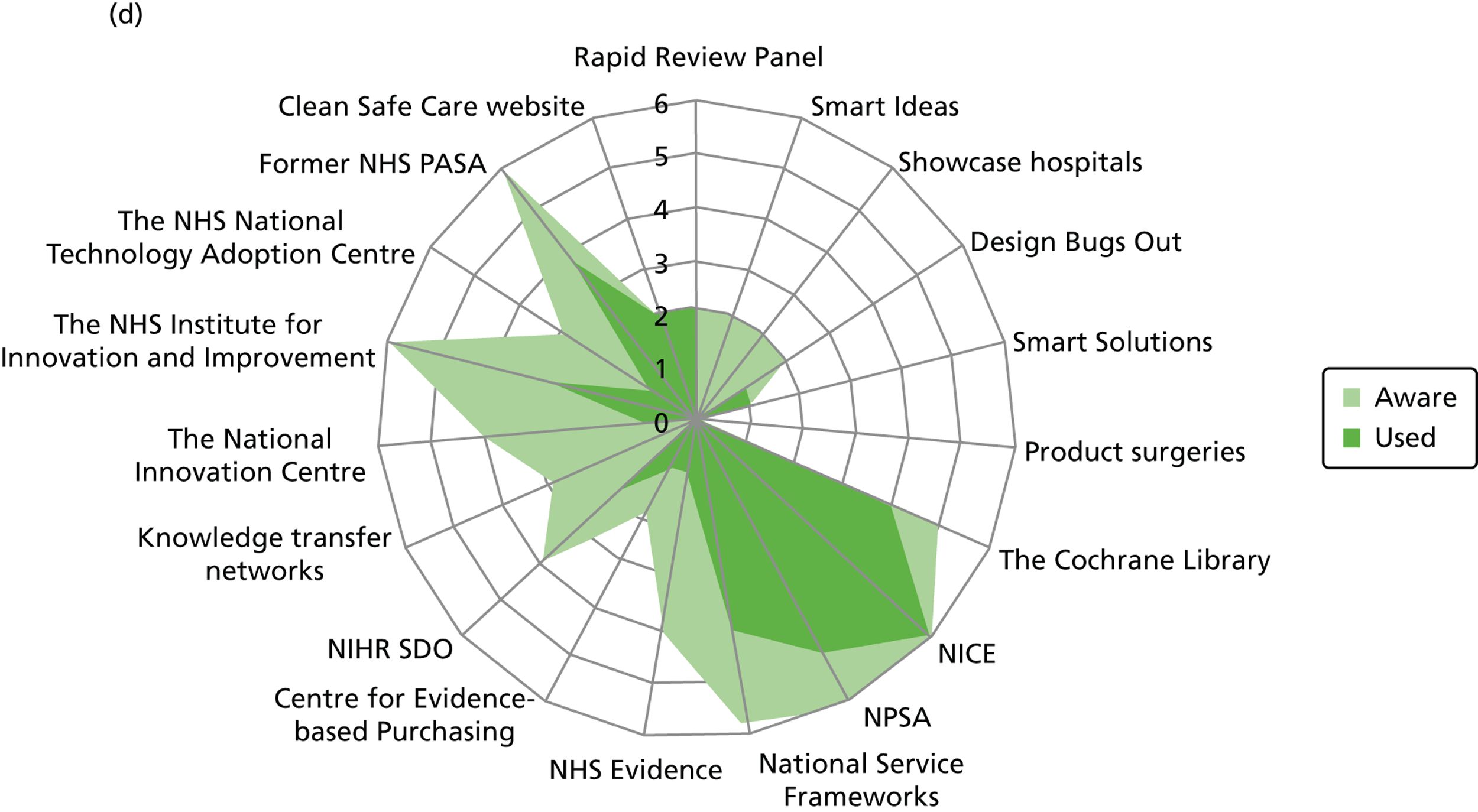

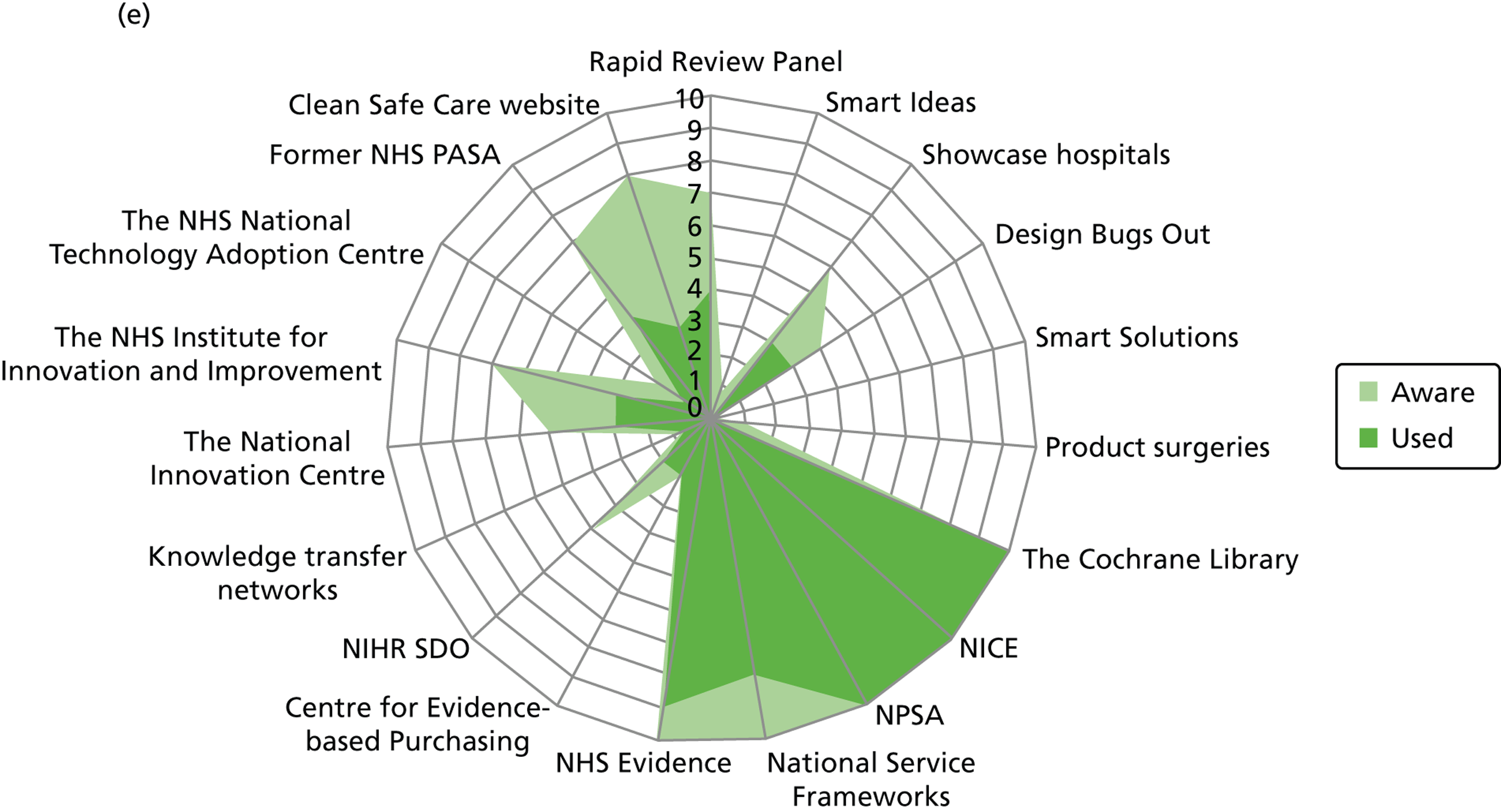

Innovation decisions: awareness and use of central evidence sources including sources concerning infection prevention and control

Figure 3 details the reported awareness and use of central evidence sources, including sources directly linked to IPC. Central here refers to those sources available across professional groups, generated by the Department of Health or one of the Department of Health’s arm’s length bodies.

FIGURE 3.