Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1008/35 The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by McCourt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Aims and objectives

The aims of this study were to investigate how care is organised and provided in alongside midwifery units (AMUs), commonly called birth centres. We use the term ‘alongside midwifery unit’ to distinguish hospital-based birth centres from free-standing midwifery units (FMUs) (or free-standing birth centres) and to highlight that these are both midwifery-led services. AMUs provide midwife-led care for women who are deemed ‘low risk’ according to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) intrapartum guidelines at the start of labour care on a hospital site that has a consultant-led obstetric unit (OU), either within the same building or in close proximity.

The need for this study arose out of questions emerging from the Birthplace in England study1,2 about the rationale for AMUs’ development. A number of factors may affect effective working within the units, including appropriate staffing models and their stability, training and preparation for midwife-led care, and interprofessional relationships and cultural and communication issues, particularly when escalation or transfer of care is required within a single site. The number of such services had risen rapidly, from 0% in 1995/6 to 7% of NHS trusts in 2005/6. 3 The Birthplace Mapping Study noted an increase in the percentage of NHS trusts with an AMU from 13.2% in 2007 to 25.7% in 2010. There has also been an increase in trusts with both an AMU and a FMU, from 3.3% to 8.8%. 4 Their development has aimed to enhance maternal choice and satisfaction and facilitate opportunities for ‘normal’ birth for women of low obstetric risk by providing a homely environment with a low-intervention philosophy. In addition, it was hoped to improve midwife job satisfaction and retention.

The primary research questions for this study were:

-

How are AMUs organised, staffed and managed in order to seek to provide safe and high-quality care on a sustainable basis?

-

What are the professional and service user perceptions and experiences of care in AMUs?

Objectives:

-

Exploration and analysis of potential unanticipated as well as intended consequences of AMU development, including system effects.

-

Analysis of models of organisation and staffing that addresses such aims and challenges and contributes to staff satisfaction and retention.

-

Analysis of how AMU development can respond to current policy directions, including provision of choice for service users, and safe effective and equitable care.

Background and literature

Current policy on place of birth in England

Over the last 10 years, there has been a clear policy direction on the importance of offering women choice in childbearing, and particularly on giving healthy women the choice of where they give birth. The National Service Framework (NSF) emphasised the importance of choice, continuity and control for women in maternity care and advocated more targeted approaches to ensure a safe and high-quality service. 5 The maternity standard of the NSF specified that service providers and trusts should ensure that ‘. . . options for midwife-led care will include midwife-led units in the community or on a hospital site.’ Care is to be provided in a ‘. . . framework which enables easy and early transfer of women and babies who unexpectedly require specialist care’ (© Crown copyright 2004, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0). 5 The related guidance Maternity Matters6 identified that all women should have a choice of place of birth by 2009, including birth in a local facility, including a hospital or under the care of a midwife. 6 Current NICE intrapartum care guidelines for healthy women provide information for women, health professionals and managers to inform decision-making on choice of place of birth. 7

Overarching NHS objectives inform the commissioning of maternity services. 8 Maternity services are specifically highlighted within the 2012/13 Operating Framework for the NHS9 with expectations that services will deliver improved continuity of care, choice, access and productivity:

Continuity in all aspects of maternity care is vital, from antenatal care through to support at home. Mothers and their families should feel supported and experience well-coordinated and integrated care.

Para 2.39, © Crown copyright 2011, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.09

Choice is critical to giving patients more power in our systems. PCT [primary care trust] clusters should drive forward improvements in patient choice so there is a presumption of choice for most services from 2013/14. During 2012/13 this means continuing the implementation of choice about maternity care.

Para 3.22, © Crown copyright 2011, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.09

In addition, the Outcomes Framework for the NHS 2012/1310 sets the high level nationally required outcome measures that commissioners should use to judge the quality and effectiveness of their services, including maternity services, as reflected in Table 1.

| Domain | Aim | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Domain 1 | Preventing people from dying prematurely | Perinatal mortality rates |

| Domain 4 | Ensuring that people have a positive experience of care | Patient-reported outcome measures using nationally determined survey questions to users |

| Did you get enough information from a midwife or doctor to help you decide where to have your baby? | ||

| Thinking about your antenatal care, were you involved enough in decisions about your care? | ||

| Were you (and/or your partner or companion) left alone by midwives or doctors at a time when it worried you? | ||

| Thinking about the care you received in hospital after the birth of your baby, were you treated with kindness and understanding? Did you feel that midwives and other carers gave you active support and encouragement? | ||

| Did you feel that midwives and other carers gave you active support and encouragement? | ||

| Domain 5 | Treating and caring for people in a safe environment and protecting them from harm | Percentage of term babies admitted to neonatal intensive care |

Finally, the Government’s mandate to the NHS Commissioning Board for the period April 2013 to March 201511 advised work with partner organisations to ensure that the NHS:

-

offers women the greatest possible choice of providers

-

ensures that every woman has a named midwife who is responsible for ensuring she has personalised, one-to-one care throughout pregnancy, childbirth and during the postnatal period, including additional support for those who have a mental health problem.

The Board is legally required to pursue the objectives in the mandate, and the way in which services are organised is an important factor in meeting these policy objectives to improve services. There is considerable variation within and between regions regarding what services are provided and inequalities in provision. Options for place of birth have improved since 2007,12 but almost half of women did not have a full range of choice in 2010. Currently 13% of women give birth outside an OU, in midwife-led units (AMUs or FMUs) or at home. 13

Maternity services offer a range of models of care, aimed at improving continuity14 and organisational configuration reflecting local needs, which include offering services in midwife-led settings of AMUs, FMUs and home. The number of AMUs has increased since 2007 compared with FMUs,4 and they are, therefore, increasingly relevant to the configuration of maternity services currently under consideration in England. They have the potential to deliver responsive and effective high-quality care, but there remains a paucity of evidence to inform these processes, and the ways in which AMUs operate requires greater scrutiny. AMUs are more likely to be developed than FMUs because of the political and financial climate, in which funds for rebuilds are scarce, and also because of concerns about transfer times and distances. 15

Additionally, changes to medical training, the European Working Time Directive,16 maternity staffing standards and neonatal service reconfigurations are all altering the configuration of maternity units, professional practice boundaries, skill mix and relationships. 17

Development of birth centres

Midwife-led birth centres have been developed in an effort to provide a better birth environment for women and their families and to tackle rising intervention rates, but they also aim to address the problem of midwife retention within the NHS. The most comprehensive survey to date on why midwives leave the profession found that, aside from retirement, the most common reason was because they were ‘unwilling to practise the kind of midwifery demanded of them by the NHS, despite their desire to continue working as midwives’. 18 Furthermore, the evidence suggests that this tension between how midwives would like to practise and how they are required to practise is a significant source of emotional difficulty for them. 19 Birth centres were developed in part as an attempt to resolve some of the discrepancy between the ideals of midwifery and the perceived reality of work within the NHS, by creating a separate space within which midwives could practise with a social model of care. 20

Environment and ‘home-like’ spaces

Midwifery scholars and social scientists have both addressed issues of space and place in birth. To date this interest has mainly been incidental to other concerns, such as women’s choice of place of birth21 or the development of midwife-led services outside OUs. 22–26 Other work in this area has focused on midwives rather than women and explored the effects on midwives of working in the community19,27 or in midwife-led units28–30 rather than in consultant-led units. In addition, much of the wider work in health care that has explored problems of space and place has done so while focusing on workplace relationships, for example health-care professionals’ relationships with managers31 and midwives’ relationships with junior doctors32 and support staff. 33,34

Shaw and Kitzinger35 and Davis-Floyd and Davis36 are among scholars who have suggested that women feel more in control of their birth at home or in home-like settings such as free-standing birth centres. One reason given for this feeling of control is that the woman has the higher status of ‘resident’ at home and the midwife is constructed as a ‘visitor’, whereas in hospital these roles are reversed. 37 Following this, Gilmour38 argued that transforming hospital spaces so they are more home-like challenges the dominance of biomedical values, a claim disputed by Fannin,39 who argued that it is presumptive to assume that making a hospital space more like a home will in itself fend off the controlling influence of biomedicine. Others have also been critical of the assumptions that underlie the discourses of pro-home birth academics and activists. The discourse of home equals control assumes that women have agency in their own homes, which is not always the case: ‘home does not signify autonomy and bodily control for all women, nor is domestic space always the safest place for women’. 40

The discipline of geography has put space and place more firmly into the social science agenda. There is little literature by geographers on maternity care, but the literature on geographies of nursing, like that of health and medicine, is growing rapidly. Andrews41–43 and Andrews and Shaw44 have written a number of introductory ‘manifestos’ for the geography of nursing, which explore the role of space in health-care organisations.

Hospital developers, fuelled by the drive to build new hospitals though private finance initiatives,45 have sought to design hospital environments that promote the healing and well-being of patients. Aside from the architecture of the hospital building itself, the introduction of visual art into hospitals (see Lankston et al. 46 for an evaluation of its benefits) is one example of the way in which designers have attempted to make hospitals into therapeutic landscapes. These interior designs have particularly focused on integrating ‘nature’47 and ‘home’38 into the institutional space because they are two arenas strongly imbued with the qualities of a ‘therapeutic landscape’. 48 Contemporary interest in the design of hospitals has applied the principle that a therapeutic landscape is not only one that is outside, but may also be brought into an institution and that ‘the hospital, rather than being a place of scientific inquiry removed from everyday life, is conceptualised as the home place for its inhabitants’. 38

This trend towards designing hospital wards as what are considered to be ‘home-like’ spaces assumes (problematically) that the home is a therapeutic landscape for all women, while also allowing them to birth within a hospital environment that is specifically away from the home, where those tools that are culturally assumed to improve safety, such as medicines, doctors and monitors, are readily available. This ‘hybrid space’38 is a manifestation of a wider cultural conception of childbirth as both a normal life event49 and inherently risky and in need of medical assistance (see Hausman50 for a discussion of the discourse of obstetric risk).

Efficacy and effectiveness

The evidence regarding efficacy and effectiveness with respect to birth settings is also increasing. A Cochrane review of AMUs compared with conventional hospital labour wards (or OUs) found increased likelihood of spontaneous vaginal birth, labour and birth without analgesia or anaesthesia, breastfeeding at 6–8 weeks post partum and satisfaction with care and decreased likelihood of oxytocin augmentation, assisted vaginal birth, caesarean birth and episiotomy. 24 Although no difference occurred in infant outcomes, substantial numbers of women were transferred to standard care, either before or during labour, because of maternal request, such as for epidural pain relief or because they no longer met eligibility criteria for the midwifery unit setting. 51 A similar pattern has been found with planned home birth for ‘low-risk’ healthy women.

The Birthplace in England study assessed outcomes by intended place of birth at the start of care in labour for women at low risk in AMUs, FMUs and home, compared with women planning birth in OUs. 1 For all women, the incidence of major interventions including intrapartum caesarean section was significantly lower and normal birth increased in all settings outside the OU. The overall incidence of adverse perinatal outcomes was low in all birth settings. For multiparae, no significant differences were reported in adverse perinatal outcomes between any settings. For nulliparae, no significant differences were reported in adverse outcomes between AMU or FMU and OU care. However, the risk of a composite adverse perinatal outcome was significantly higher for nulliparae who planned to give birth at home than for those who planned to give birth in an OU.

For all women, planning birth in any of the settings outside the OU significantly lowered the incidence of major interventions, including intrapartum caesarean section, and increased the rate of normal birth, relative to the OU (Table 2).

| Maternal outcome | OU (%) | AMU (%) | FMU (%) | Home (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrapartum caesarean section | 11.1 | 4.4 | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| Forceps | 6.8 | 4.7 | 2.9 | 2.1 |

| Use of oxytocin | 23.5 | 10.3 | 7.1 | 5.4 |

| Normal birthb | 57.6 | 76.0 | 83.3 | 87.9 |

| Immersion in water | 9.1 | 30.2 | 45.7 | 33.3 |

The study also found that the cost to the NHS of intrapartum and related postnatal care, including costs associated with transfers and clinical complications and admission to higher-level care, was lower for birth planned at home, in a FMU or in an AMU than for planned birth in an OU. 53

Women’s choice, information, access and experience of alongside midwifery units

Unlike women who plan to give birth at home or in FMUs, women who planned to give birth in AMUs were reasonably similar in demographics to women who planned to give birth in OUs in the Birthplace in England study. 1 Research into how women and their families make decisions about where to give birth has tended to focus on home and OUs, with the following factors being consistently important to women: finding a balance between safety and a satisfactory birth experience, the influence of friends, family and doctors, social class and cultural values,54,55 and the model of care on offer. 56 More recent work has found that women value birth centre care, particularly the environment, personal attention, calm ambience and close to obstetric support if needed,51,57–59 in essence what is often perceived as ‘the best of both worlds’. 58

Longworth et al. 60 found that women who chose a home birth valued continuity of care, a homely environment and the ability to make their own decisions regarding interventions. In contrast, hospital birth respondents placed a relatively high value on access to an epidural for pain relief and not needing to be transferred to another location during labour if a problem arose. 60

Transfers from midwifery units

Transfer from midwifery units to OUs both during and after labour is common, especially for first-time mothers and more common from AMUs than free-standing ones. In the Birthplace in England study, the overall intrapartum transfer rate ranged from 21% to 26% for all women, but was higher for nulliparae (36–45%).

The overall intrapartum transfer rate ranged from 21% to 26% for all women but was higher for nulliparae (36–45%), as shown in Table 3.

| Parity | OU (%)a | AMU (%) | FMU (%) | Home (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primiparous | 1 | 40.2 | 36.3 | 45.0 |

| Multiparous | 0.4 | 12.5 | 9.4 | 12.0 |

| All | 0.7 | 26.4 | 21.9 | 21.0 |

In AMUs, the primary reason for transfer was failure to progress in labour, followed by request for an epidural. In FMUs or home birth cases, the primary reason was also failure to progress in labour, followed in this case by meconium staining. In both types of midwifery unit, compared with multiparous women aged 25–29 years, nulliparous women aged < 20 years had higher odds of transfer [FMU-adjusted odds ratio (OR) 4.5, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.10 to 6.57; AMU-adjusted OR 2.6, 95% CI 2.18 to 2.06] and the odds of transfer increased with increasing age. Nulliparous women aged ≥ 35 years in FMUs had 7.4 times the odds of transfer (95% CI 5.43 to 10.10) and, in AMUs, six times the odds of transfer (95% CI 4.81 to 7.41). Starting labour care after 40 weeks of gestation and the presence of complicating conditions at the start of labour care were also independently associated with a higher risk of transfer. 61

A qualitative study drawn from the same cohort found that most women hoped for, or expected, a natural birth and so did not expect to be transferred. Transfer was disappointing for many, but sensitive and supportive care and preparation for the need for transfer helped women to adjust to their changing circumstances. A small number of women, often in the context of prolonged labour, described transfer as a relief. For women transferred from FMUs, the ambulance journey could be described as a limbo period. Women who were worried or fearful felt as though they were being transported rather than cared for. For many, this was a direct contrast with the care they experienced in the midwifery unit. After transfer, most women appreciated the opportunity to talk about their experience to make sense of what happened and help them plan for future pregnancies, but they did not necessarily seek this out if it was not offered. 62 Sensitive care and preparation can help women adjust to changing circumstances, as some apparently straightforward changes to practice have the potential to make an important difference to women’s experience of ambulance transfer and transfer or escalation of care. 2

Organisation of care

Previous research that has focused on AMUs has uncovered a number of questions about their function, particularly in the long term. The Health Care Commission review63 and the Birthplace Mapping Study4 highlighted the ad-hoc nature of the development of AMUs, challenges in developing usable data systems and lack of agreed definitions, eligibility, staffing or operational criteria.

Following on from its previous inquiry into the safety of maternity services, The King’s Fund commissioned further research to answer a fundamental question: can the safety of maternity services be improved by more effectively deploying existing staffing resources? The report Staffing in Maternity Units: Getting the Right People in the Right Place at the Right Time concluded that the key to improving maternity care is using midwives and other maternity staff more effectively. 17 The report considered the available evidence about the relationship between staffing levels and deployment practices and safety of care for mothers and babies, focusing specifically on labour and birth. It reviewed evidence particularly on the relationship between staffing levels and outcomes, the potential for shifting tasks between various health professionals and making use of new and extended roles, the effectiveness of different models of care and the impact of these on use of resources. 17

There is very little published evidence on how midwife units should be organised and staffed. While midwives are present at all births and are the main providers of antenatal and postnatal care, it has been difficult in the past to prescribe appropriate staffing levels because patterns of care vary between maternity services. Staffing needs in both hospital and community settings depend on service design, buildings and facilities, local geography and demographic factors, as well as models of care and the capacity and skills of individual midwives. Other significant variables with an impact on staffing levels include women’s choice and risk status. As maternity services develop different models of service delivery, such as home birth, caseload midwifery practices and FMUs, their staffing requirements may alter, particularly in the service development phase. The ratios of midwives to births recommended by the Royal College of Midwives (RCM)64 are designed to deliver a safe, high-quality maternity service, as described in the Maternity Matters report. 6

The Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists’ review entitled Safer Childbirth recommended staffing levels in recovery, theatre and high-dependency units. 65 The NHS Litigation Authority66 has published risk management standards for NHS organisations providing labour ward services. 67 The standards require staffing levels for all obstetric midwifery, nursing and support staff for each care setting, which should be calculated using the figures identified in Safer Childbirth. 65 The ratio recommended by Safer Childbirth, based on the expected national birth rate, is 28 births to one whole-time equivalent (WTE) midwife for hospital births and 35 : 1 for home births. Further specific recommendations are as follows:

-

Birth centres/midwifery-led units: the normal recommended ratio is 35 : 1 to reflect the generally low dependency of women accessing these services. However, separate assessment is needed when providing intrapartum care for women requiring transfer to hospital care, or providing ante- or postnatal care on an inpatient basis.

-

Obstetric units: the number of midwives allocated to each shift must enable a minimum of 1–1.4 midwives for each woman in established labour, depending on case mix.

Research on the development, implementation and sustainability of AMUs has found that wider institutional support and senior leadership are crucial. 68 There has been little research carried out to date on the organisation of midwifery units in the UK, both free-standing69 and alongside. 70,71 The Birthplace in England Organisational Case Studies2 also included three sites with AMUs and two with FMUs. There is evidence that such settings provide a space for the development of specialist midwifery skill and expertise in physiological birth and improved midwife job satisfaction and retention. 72 However, while midwifery units have provided midwives with a space that allows them some congruence between ideals and practice, an unintended consequence is that the philosophy and practice of the midwifery unit and their local OU, labour ward or delivery suite can become polarised. This can have a negative effect on the relationships between the midwives in the two clinical areas. 70

While few studies have been conducted of AMUs, enquiries into safety problems in FMUs and in OUs have indicated that even when formal systems, such as staffing levels and mix, appear well functioning, problems in the informal operation of those systems may arise. These may be as a result of factors such as poor inter-professional teamworking, management and training limitations, and failure to consistently implement agreed guidelines or the effect of economic and political concerns on clinical decision-making. These all lead to quality and safety concerns. 73,74 Additionally, little is known about the effect on the OU or on women with higher or intermediate levels of clinical risk factors of developing separate places with different philosophies of care.

There is a need for research that analyses not only the everyday function of midwifery units, but also their role within the rest of the maternity system and their effects, both intended and unintended, on the function of the OU. Although substantive literature on AMUs is very limited to date, the wider sources and the theoretical literature points to the importance of structural and systemic features of health-care systems, and organisational culture as well as formal organisation. They suggest that power play and local cultures may strongly affect risk and safety within health-care institutions and that interpersonal or professional issues may influence behaviour and decision-making amongst health-care professionals. 70,75,76 Vaughan’s study of health-care organisation, for example, posited ‘structural secrecy’77 – inherent barriers or resistance to communication – as an important source of danger in complex systems. Vaughan proposed that social organisation in itself (rather than merely the actions or omissions of individuals, or technical systems in isolation from social systems) forms a source of safety or danger. 77 The theoretical and substantive literature points to the need to examine the environment and processes of care, looking at different areas of activity and different professional groups as part of a complex system, rather than in isolation. 75

The factors that may influence effective transfer are of particular interest since the Birthplace Cohort Study found that 21% (95% CI 19.2% to 23.2%) of women were transferred from AMUs to OUs during or shortly after labour. Overall, local transfer guidelines were of poor quality. 26 Few studies of transfer have focused on the management of transfers within hospital sites, but a study of home birth transfers in two cultures indicated that organisational and attitudinal factors were a primary cause for concern, rather than the more technical transport issues. 78 This was also found in a Scottish audit of outcomes of community maternity units (FMUs). 79

A case study of an AMU, conducted as part of a wider study of implementation of protocol-based care, indicated that while benefits were observed in terms of satisfaction and midwifery teamworking within the birth centre, there were also unintended consequences – specifically, more negative relationships with obstetric and other midwifery colleagues – which could have an impact on overall quality of care. 80 This study also highlighted, but did not investigate, the key role of managers and management approaches in such developments.

However, a small-scale study by Huber and Sandall81 of intrapartum referral and transfer in an AMU identified a number of organisational issues to be addressed in further research. Rather than promoting safe and effective coworking and transfer, the physical proximity of the units appeared to engender competition around physical and human resources, confusion and conflict around responsibility. Clashes of philosophy, rather than shared understandings or protocols, also formed barriers to teamworking and effective communication. This study indicated the need to explore approaches to staff deployment, management and training, clear guidelines and interprofessional communication that can avoid such problems arising. It echoed findings of the few earlier studies of transfer indicating that organisational and staffing as well as cultural issues may be of major importance to quality and safety.

Questions from the Birthplace in England Research Programme

The Birthplace in England Cohort Study raised a number of questions with particular relevance for AMUs. Although AMUs had lower intervention rates for low-risk women than for those planning to give birth in OUs, the rates were higher than for women planning to give birth in FMUs. 1 This raised questions about the possible reasons for these differences. Apart from differences in the nature and background of women planning to give birth in these settings, are any features of organisation or professional practice contributing to this? The Birthplace Organisational Case Studies2 found that more attention is given to the training and support needs of midwives in FMUs than to the needs of community midwives and those working in AMUs. Are the approaches different between types of midwifery unit and what might the reasons for or implications of this be? The case studies also highlighted a major issue of proximity of the AMUs leading to blurring of spatial and professional boundaries, with potential implications for safety. Differences in equity of information and access were also found. 2 Given that the profile of women in England planning birth in AMUs is more like that of women planning birth in OUs than that of those planning home births or birth in FMUs, do the AMUs offer access to midwife-led care in labour to a more diverse range of women and what might this be based on?

The trend towards provision of AMUs raises important questions. What factors may adversely (or positively) affect the safety of care and experience for women and babies in such units? There is a need to explore the specific function of those midwifery units that are situated close to – usually in the same building, or at least on the same campus as – an OU.

Many of the everyday tensions described by NHS midwives stem from the conflicting demands of different metrics and measures. Therefore, there is value in a study such as this that explores the key performance indicators, financial constraints and local commissioning priorities that filter down to the birth centres and the rest of their local maternity service.

These policy initiatives and previous research findings from the Birthplace Organisational Case Studies raised a number of questions about the organisation and function of AMUs in order to inform service planners and managers developing and operating AMUs in the future. Therefore, this study aimed to clarify the experiences of existing AMUs that impact on their functioning through addressing two key research questions: (1) how are AMUs organised, staffed and managed in order to seek to provide safe and high-quality care on a sustainable basis? (2) What are the professional and service user perceptions and experiences of care in AMUs?

Design and methodology

Design and conceptual/theoretical framework

The study used an organisational ethnography approach. 82–84 Since there is very little prior research on this topic, small-scale but in-depth qualitative case studies are most appropriate and will also inform future larger scale development and research. The ethnographic approach is particularly suited to more exploratory phases of research. It can provide a rich description and analysis of service models, which can inform service managers, commissioners and practitioners about how to develop and provide care effectively in such settings. This approach includes a range of data collection methods.

Sampling

Our selection of case study sites involved a maximum variation sampling approach, with purposive selection. The purposive criteria were based on key research aims and questions that built on the emerging findings of the Birthplace Programme and questions that were raised by the work. Our key criteria were size of unit, geographical/regional location, age of unit, staffing model and deployment, management approach and leadership (formal arrangements and style). The site description table (see Table 4) shows how these criteria were operationalised to select an optimal mix of participating sites.

Methods of data collection

Documentary analysis: service delivery and configuration

Key documents relevant to the study were obtained and analysed, prior to site visits and interviews when possible, to provide:

-

an initial description of the background, configuration and organisation of the service

-

key questions and queries for discussion during site visits.

Key documents included service planning, consultation and reconfiguration documents, eligibility criteria for AMU care, any formal care pathways, algorithms or transfer protocols in use, and any safety and risk management tools in use.

Interviews with key stakeholders

Interviews (see Appendix 1 for details) were conducted with key stakeholders such as service managers, commissioners and user representatives, using a semistructured approach. These interviews were also used to collect key data on the background and history, as well as the current configuration of the service and its rationale and aims.

Questions and topics included:

-

service configuration history, including consultations, service reconfigurations or developments and reasons for these

-

details of current service configuration and organisation, including workforce arrangements, skill mix, models of care and escalation/transfer services and protocols

-

any plans for change or development and reasons for these.

Observation of key decision making points in the service

Observation of selected aspects of the service was conducted at key locations and times, including staff handover meetings, audit and risk meetings and everyday life of the AMU. The observations were mainly conducted before interviews with staff and service users took place and used to inform the interview questions. The observation data were audio-recorded in note form, transcribed and added to the NVivo database (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Interviews with professionals

Interviews were conducted with a purposive sample of service providers in each case study, including midwives working in different settings, maternity care assistants (MCAs)/support workers, obstetricians and nurses.

The interviews were, in most cases, individual, but for certain staff groups it was more appropriate to arrange discussion meetings with a group of staff. The interviews used a semistructured approach, seeking unelicited views as well as responses to more focused questions developed through the earlier phases of the study and during the Birthplace study. The interview questions were also guided by the observations conducted by the researchers. In all sites (as appropriate to each interviewee), their views were sought on:

-

recent history of service configuration, including consultations, service reconfigurations or developments and reasons for these

-

service organisation, including workforce arrangements, skill mix, models of care and escalation/transfer services and protocols

-

facilitators and barriers to choice of place of birth in different settings for low-risk women

-

facilitators and barriers for professionals working in different birth settings

-

training provision and needs for staff working in different birth settings

-

management and staff support and development arrangements

-

any local, contextual or organisational factors impacting on quality of care and staff or user satisfaction.

All interviews were audio-recorded, with permission, and were transcribed in full, except in a few cases when recording was not practicable. In such cases, detailed notes were taken. Interviews were conducted in the venue chosen by the participant.

The team originally planned to use visual images within the staff interview process. Midwives were invited to take photographs of spaces and places and to bring these to the interview to trigger discussion of what matters to the staff and what different spaces and images mean to them. However, we found that this was not effective in practice as the busyness and unpredictability of current maternity service staffing meant that most midwives asked to be interviewed on the spot while they had quiet periods in the day (which were not predictable), or proved not to be available when the researcher returned on their next site visit. Additionally, we did not pursue this method following initial experience because the resulting narratives focused largely on the environment and less on other aspects of care and service organisation which were also of interest to the study.

Interviews with service users and their birth partners

Women’s experiences and pathways through care were explored using individual semistructured interviews with women and (when appropriate and available) their partners. Women were encouraged to tell the story of their maternity experience. However, to ensure that key study questions were addressed, an interview topic guide and prompts was used including:

-

pathways through care, including choices offered and made and any change of plans or referrals

-

experience of maternity care, with particular focus on the birth setting

-

experiences of birth complications and escalation or transfer of care.

Obtaining women’s, and their partners’, views and experiences is important to an understanding of the meanings of the choices available and taken, experiences of service provision, what works in practice and what they themselves define as important. The aim in this study was to understand how women came to access different types of care setting for birth and how these settings affected women’s perceptions and experience of care in labour and birth. Specifically, do AMUs succeed in providing women with the sense of autonomy, control, respect and privacy that research studies have suggested they value?85–88

Qualitative interviews were conducted with a range of women and, when possible, their birth partners, including those recruited from community centres in lower-income areas, with an emphasis on women who intended to give birth in AMUs at the onset of labour, or women who were offered the option of AMU care. The number of interviews was based on the theoretical sampling approach, using the principle of data saturation employed in grounded theory. The analysis of this sample built on the interviews conducted with women planning care in a range of settings conducted as part of the Birthplace programme, including women who required transfer or escalation of care during labour.

Data analysis

Qualitative and structural analytical approaches were employed according to data type and in order to facilitate exploration of process and structural as well as experiential aspects of the systems of care. Data were analysed using a framework approach. 89 A coding framework was developed based on the analysis and emerging questions from the Birthplace study and amended in the light of initial readings and discussion of the data collected and potentially emerging themes. This was done in a series of core study team, co-investigator and advisory group meetings, during the continuing data collection phase. This initial analysis was also used to guide further sampling and data collection decisions. In a framework approach, the prior coding frame is applied and tested by informing study questions and by mapping against the data, but a thematic approach is then incorporated using open coding to identify and explore newly developing themes and progressing to both axial and selective coding to identify key themes and categories. NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to facilitate systematic and rigorous analysis. Box 1 provides an illustration of this process, showing the nodes and codes used within the parent node referring to user experience.

-

Who uses AMUs?

-

Why and how women choose or end up birthing in AMUs.

-

Antenatal information.

-

Staff influence on choice of birthplace.

-

-

Users’ expectations for the AMU.

-

Opt-in and opt-out models.

-

-

Women’s and partners’ experiences of the AMU.

-

Features of care liked/not liked by users.

-

Features of environment liked/not liked by users.

-

Inclusion of partners and relatives.

-

Critical birth experiences.

-

-

Pain management.

-

Women’s perception of what is safe and risky.

-

Continuity of care and carer

-

Women’s observations about staff skills.

-

Negotiation of admission and being/not being sent home.

-

Women’s perceptions of staff relationships.

-

-

Transfers out of the AMU.

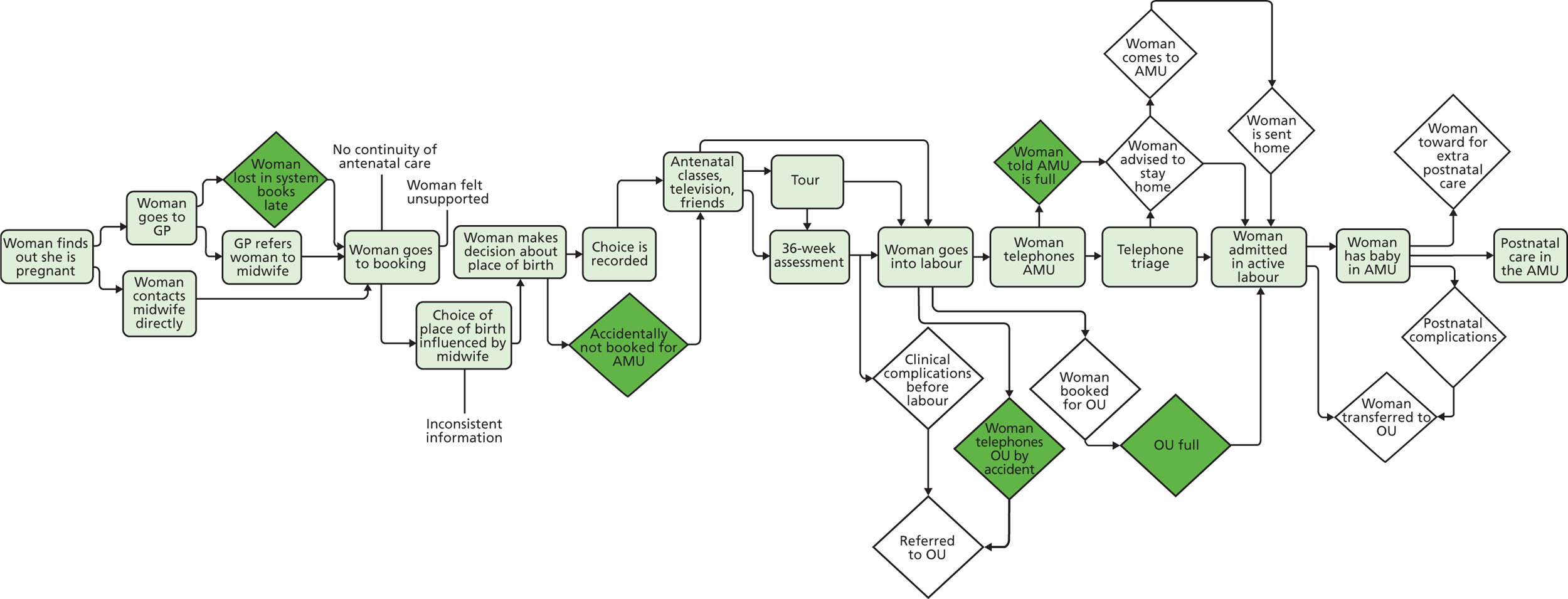

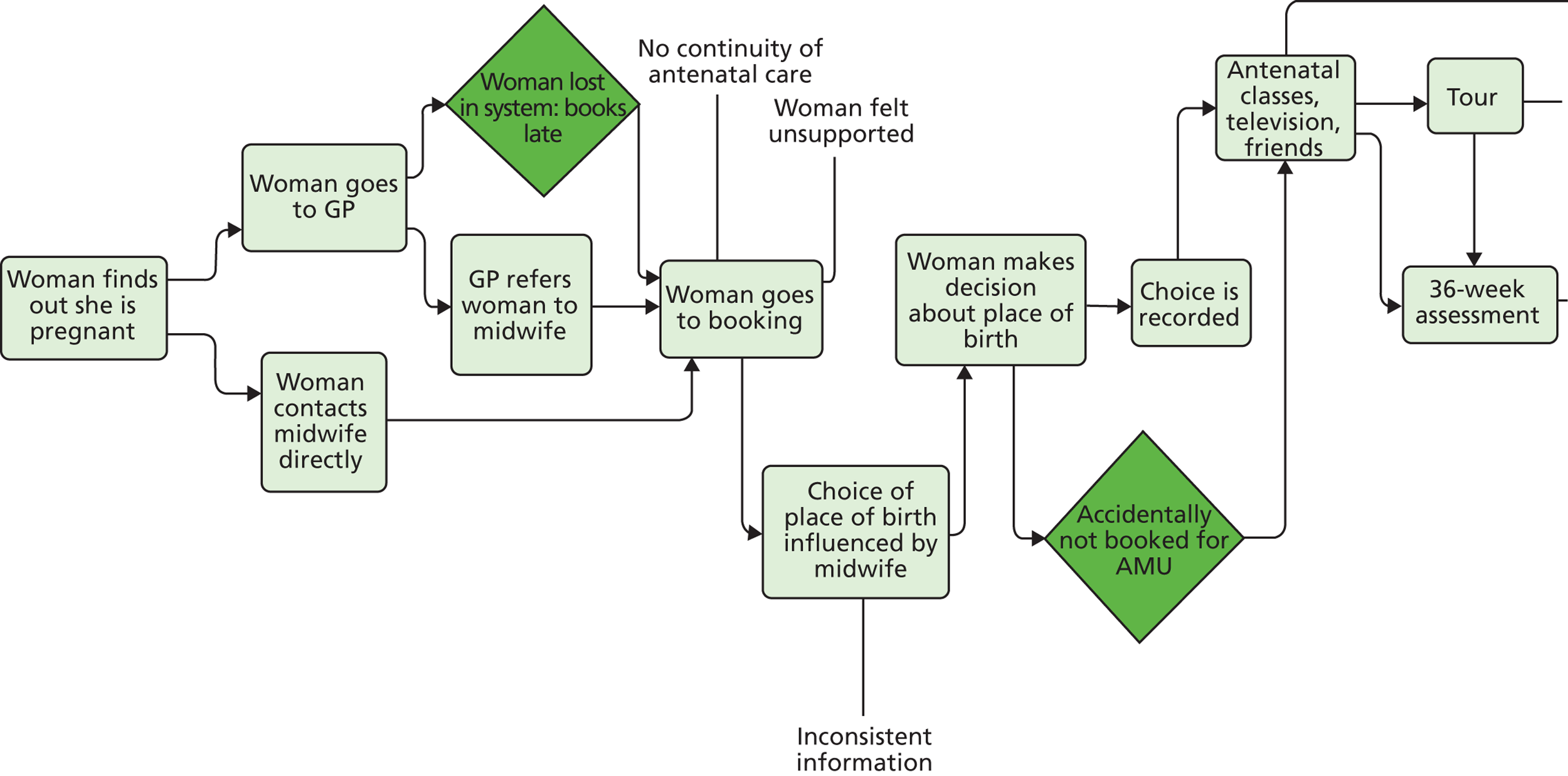

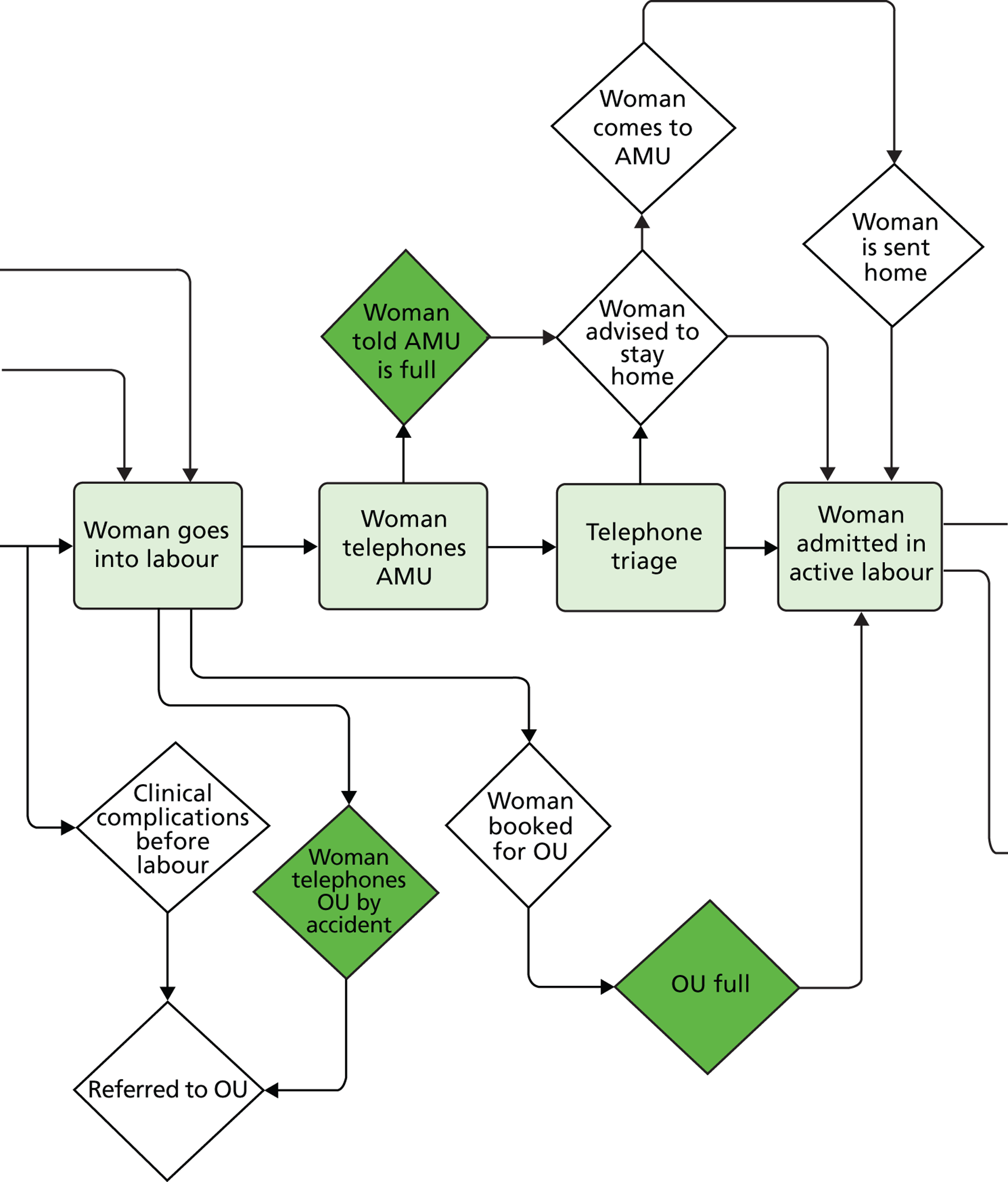

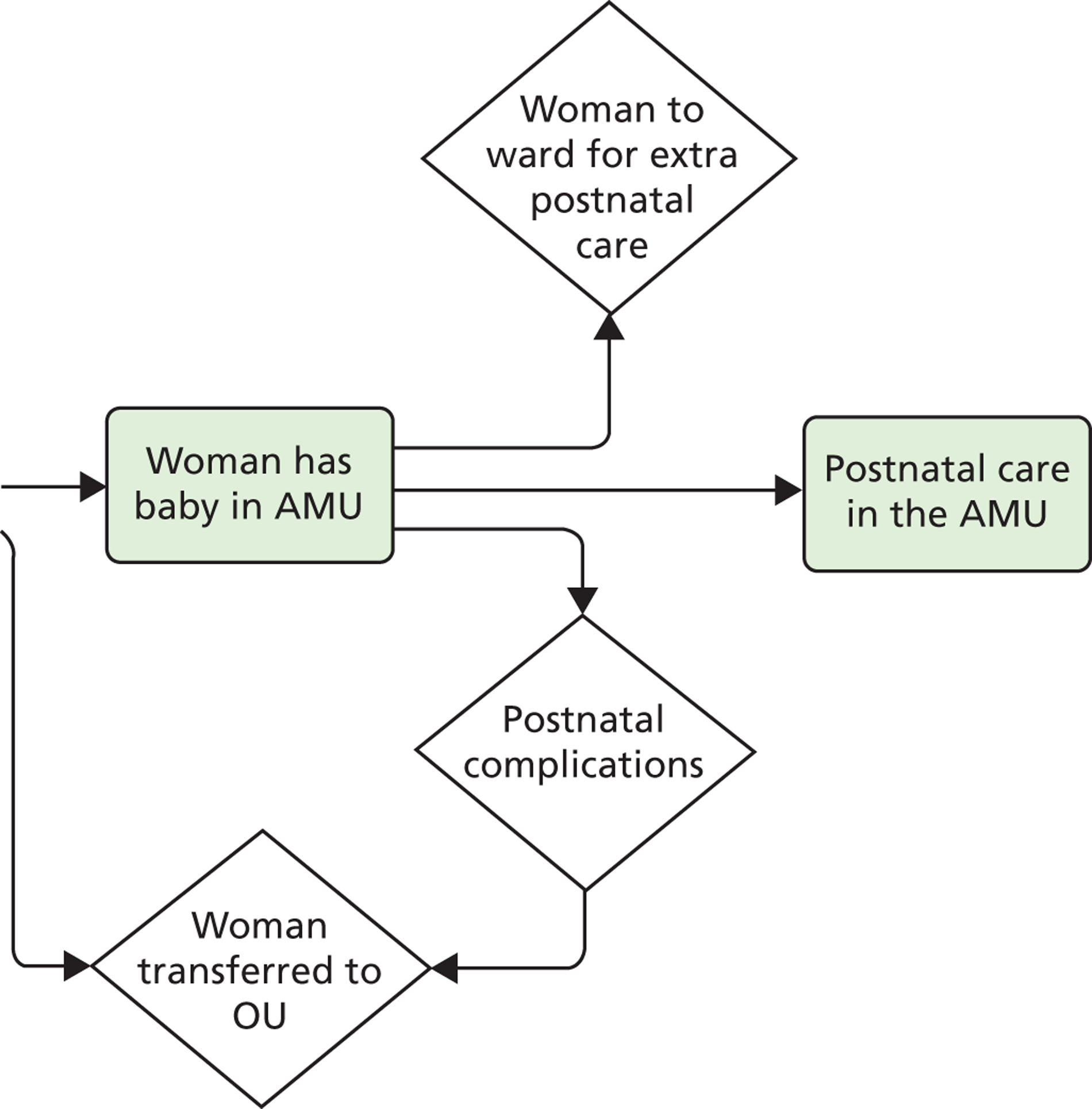

Structural approaches were also utilised to help explore the data. Process maps were used to focus particularly on mapping care pathways, transfer processes, staffing configuration and interprofessional teamworking and communication. While individual site descriptions were drawn up (see Case study site descriptions) subsequent analysis was largely on a cross-site basis. Strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT)-type summaries for which respondents’ perceptions of advantages or drawbacks, opportunities or threats relating to AMUs were mapped onto tables.

In order to ensure that the process was both valid and trustworthy, preliminary coding and data analyses were commenced as early as possible. Feedback was given at regular intervals to co-investigator and advisory group meetings and discussed fully. The members of the advisory group in particular were asked to comment on whether or not the emerging findings rang true for them, whether or not anything particularly surprised them and whether or not any important issues appeared to be missing or overlooked. A participative meeting approach was used to discuss emerging issues in small groups, to identify and prioritise them and to highlight additional questions or queries. Analysis was primarily conducted by the four core team members (CM, JS, JR and SR) but co-investigators also independently read, coded and discussed the data in selected areas in which they had particular knowledge and interest. Although initially planned for sharing findings, further validation also took place during a series of regional practice-based workshops during the report drafting, in which participants discussed the issues in relation to their own service.

Ethical Issues

Ethical permission to conduct the study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service Proportionate Review Committee (ref 11/LO/1028). Researchers were especially mindful of the need for continually negotiated consent when observing practice areas to ensure that staff and patients could exercise their right not to be included, and of the need to guard confidentiality when conducting research with small samples. Advisory group members were asked to read a draft of the report with particular reference to inclusion of any material that may lead to an inadvertent breach of confidentiality. Pseudonyms have been used for all people and places and some site details that may identify precise locations have been excluded. Professional and stakeholder respondents have been categorised very broadly to avoid identifying individuals with less common positions or work roles.

Chapter 2 Study findings

Case study site descriptions

In this section, we provide a summary description of the four case study sites to situate the findings and analyses. We focus on their history and organisational context, their locality and features of their formal organisation and practice. The experiences of staff and service users and the quality and safety of their care were shaped by the context in which this care took place. Table 4 presents some basic data on each of the sites. To maintain anonymity, pseudonyms have been adopted for these services and some figures have been rounded.

| Site (pseudonyms)/features | Westhaven | Northdale | Midburn | Southcity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geography | Urban/suburban | Suburban/rural | Urban | Urban |

| Total number of births 2011/12 in trust (rounded) (including AMU) | 6200 | 6000 | 5700 | 5300 |

| Of which, AMU total | 620 | 830 | 800 | 700 |

| Service configuration, % of total births 2011/12 (rounded). Home includes BBAs | OU: 87% | OU: 73% | OU: 77% | OU: 86% |

| AMU: 10% | AMU: 14% | AMU: 14% | AMU: 13% | |

| FMU: 11% | FMU: 7% | |||

| Home: 3% | Home: 3% | Home: 2% | Home: 1% | |

| Year AMU opened (in current location) | 2005 | 2008 | 2010 | 2001 |

| Location to the OU | Adjacent | Different floor | Different floor | Different floor |

| Number of birthing rooms in AMU | 4 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| Parity: primiparous/multiparous (rounded) | Data not available | Data not usable | ||

| Trust | 32%/68% | Data missing | ||

| AMU | 32%/68% | 46%/54% | ||

| Proportion of women transferred to OU in labour and immediate postnatal period | 32% | Data not usable | 27.5% | 26.5% |

| Top three reasons for transfer | 1. FTP | Data not usable | 1. Epidural | 1. FTP (first stage) |

| 2. Epidural | 2. Meconium | 2. Fetal distress | ||

| 3. Meconium | 3. FTP (first stage) | 3. Epidural | ||

| Trust normal birth ratea | 59% | 70% | 67% | 30%b |

| Instrumental delivery rate for trust | 14% | 9% | 9% | 18% |

| Caesarean section rate for trust | 27% | 21% | 23% | 29% |

| Epidural rate for trust | Data missing | 16% | Data missing | 56% |

| Level of multiple deprivation by PCT 2010 | Moderate | Moderate | Severe | Moderate |

| Ethnicity: trust/AMU (rounded) | Data missing | AMU only: white/mixed British 26%; Asian 39%; African/West Indian 20%; European 16% | ||

| White | 77%/83% | 56%/62% | ||

| BME | 23%/17% | 44%/38% |

We experienced difficulty in obtaining some figures for the services overall and for the AMUs. In addition, some data were not usable because of lack of clarity, obvious errors or inconsistencies in definitions. For example, in one case, there was apparent duplication of admission counting. Women sent home in early labour were counted twice, meaning that it was not possible to estimate transfer rates. For future research and audit purposes, an agreed, clearly defined and easily accessible dataset would be valuable.

Westhaven

Model of care

Westhaven AMU is located in city suburbs with varied levels of deprivation and affluence. The unit was opened in 2005 and since that time has continued to host, as planned, 10% of the trust’s births. This proportion has been maintained despite the increase from 5000 to over 6000 deliveries in the trust, with AMU births rising from 500 in 2005 to over 600 in 2011–12. In 2011/12, the AMU had a little over 900 admissions in labour with a total transfer rate of around 32%. The unit is situated on the same corridor as the OU delivery suite. It is run using an opt-in model, meaning that the OU is the default option and women have to make a specific choice and booking to attend the AMU. The AMU has a core staff of 9 (8.36 WTE): one band 7 midwife (0.6 WTE) and eight band 6 midwives. Support workers are not used on the AMU. The unit has four delivery rooms, all with birthing mats rather than beds, and one has a plumbed-in pool. There is a transitional room used by the AMU and delivery suite for women with some complications but who may not need transferred to the delivery suite. The trust has recently opened a midwifery unit a few miles away.

Alongside midwifery unit history and funding

The AMU was opened in 2005 in response to a public campaign and a trend that had seen a number of trusts opening birth centres at the time. It was funded with a bid won from a government competition. The work was delayed for 2 years by the trust’s financial difficulties, but the money was eventually used to undertake small renovations at one end of the delivery suite and to pay for some furnishing, mats and interior decoration.

Staffing model

While the delivery suite manager has overall responsibility for the AMU as well as the labour ward, the AMU has a designated part-time (band 7) manager who was appointed to lead and promote the unit. Individual shifts are co-ordinated across both areas by the on-duty delivery suite co-ordinator, but in practice the AMU and delivery suite remain quite distinct, with separate off-duties and a core group of midwives who work on the AMU. The AMU is staffed by one midwife per shift during the day and two at night, working 12-hour shifts. There has been a move to have two midwives on the AMU at all times, but this has not yet been implemented. The trust has introduced bespoke in-house training for maternity support workers (MSWs) on the delivery suite with protected study time. The trust plans to use these MSWs to support midwives on the delivery suite to release midwifery time.

Funding and future plans

There are plans to increase the number of midwives employed on the AMU and to increase the numbers of women using the service by making it the default birthplace for all low-risk women (i.e. an opt-out model) unless they request a birth at home, in the FMU or on the delivery suite. AMU staff expressed some concern that increasing their numbers would also increase the likelihood of them being ‘pulled’ (Southcity manager 2) to cover the delivery suite. The AMU is considered by the trust to be functioning well and there is no current threat to its future. This is in part because it is in high demand from women and in part because it is helping the trust achieve its Commissioning for QUality and Innovation targets to increase the normal birth rate by 1%. The trust is recruiting a senior midwife to manage the new FMU and to lead on normal birth across the trust.

Northdale

Model of care

Northdale is a town with moderate levels of deprivation. In 2011/12, the maternity service cared for a population of women consisting of 77% white and 23% BME. The population of women using the AMU was slightly different as 83% who used the AMU were white and 17% were BME. There were around 6000 births in the trust in 2011/12, with the AMU accommodating 14% of these and the local FMU 10%. Managers reported the transfer rate from AMU to OU in labour as approximately 16%, which is comparable to national averages. The AMU was opened in 2008 as part of a reconfiguration that included the merging of two local trusts. The two delivery suites were centralised at Northdale and the other delivery suite was converted into a FMU. The AMU is located two floors below the delivery suite and has seven en-suite delivery rooms. It is run on an opt-out model, meaning that the AMU is the default option for all women in the area who meet low-risk criteria, unless they request otherwise. The AMU has a core staff of 10.2 WTE midwives (1.2 at band 7 and nine at band 6), with two midwives and one MSW covering each shift. Additionally, on-call community midwives are encouraged to come in to attend births on the unit.

Alongside midwifery unit history and funding

The AMU commenced as a GP (general practitioner) unit in the 1970s, run by community midwives, with two labour rooms and around 250 births a year, which made up 10% of the total births in the trust’s maternity service. It remained a GP unit until the mid-1990s, when the service introduced midwife-led care following the Changing Childbirth91 report In 2001, Northdale Trust merged with another local trust and the obstetric services were centralised at Northdale. The old GP unit became a midwife-led unit next door to delivery suite in a newly built hospital. The head of midwifery drove a redevelopment of the AMU, and in 2008 the AMU opened in its current form. The old midwifery unit was moved to another floor in the hospital and increased in size from four to seven birth rooms, to cater for the increased birth rate.

Staffing model

The AMU has a full-time manager, who is responsible for its day-to-day running. The head of midwifery recently instigated some meetings to improve communication and teamwork between midwives on the AMU and the delivery suite. In the last year, the AMU has developed a core midwifery team headed by a new manager. There are two midwives and a midwifery assistant on duty for each shift and an on-call community midwife can be called in if needed. The AMU midwives are frequently also asked to cover shortages on the delivery suite.

There have been proposals to reintroduce the rotation of staff to improve working relationships between clinical areas. The trust has been using the Lean process ‘Visual Hospital’ to rationalise use of beds and staff92 (see Managing staff resources). This system is intended to facilitate placing midwives where they are most needed between the OU wards, the AMU and FMU.

Funding and future plans

Plans for the AMU are centred on the deployment of staff. Using Visual Hospital is seen by managers as helping them to deploy midwives where they are most needed although alternative plans for rotation or further integration of community midwives were also under consideration (see Managing staff resources). As with all the case study sites, Northdale is struggling with restricted spending and cost-saving measures, so managers aim to reduce the costs of bank staff by using their existing personnel more efficiently.

Midburn

Model of care

Midburn AMU opened in 2010 as part of the merging of two OUs that centralised at Midburn hospital, in an area of severe multiple deprivation. It is within the same building but on a different floor from the delivery suite. It hosts around 700 births a year, approximately 11% of the total births at the trust. Approximately 27.5% (2010–11) of the women are transferred during or shortly after labour, which is slightly below the national average. The AMU is organised on an opt-out model so that all women who meet low-risk criteria are booked for the AMU by default, unless they choose to birth at home, in the local FMU or in the OU.

The AMU received significant capital investment and a lot of attention was put into making it a comfortable, home-like space. There are six en-suite birthing rooms: two have plumbed pools, and inflatable birth pools are available for the other rooms. The unit has a kitchen that is shared between staff and patients, an aromatherapy room, a patient sitting room and staff room as well as the usual clinical stores and sluice.

Alongside midwifery unit history and funding

The AMU was conceived as part of a strategy to increase the capacity of Midburn maternity services following centralisation. It was proposed with the dual aim of improving facilities for women and attracting midwives to work at the trust, where recruitment had diminished in response to service quality problems that had been publicly observed. The AMU was developed quickly, with full support from the trust executives and an assigned budget to cover the development costs. The money was spent on adapting a ward, with a focus on interior design and decoration of the space.

The project was led by the consultant midwife who provided the brief, oversaw the building work and recruited the core staff team of midwives committed to working in a ‘low-tech’ birthing space that would promote normal birth. A FMU has since been opened nearby.

Staffing model

Midburn AMU has a dedicated manager who is responsible for the day-to-day running of the unit. She is supported by the consultant midwife, who continues to take a close interest in the unit and acts as its advocate both within the trust and by promoting it externally. The AMU midwives are core to that area, although they are frequently asked to cover for staffing shortages on the OU delivery suite. All community midwives are required to do one shift a month on the AMU to maintain their intrapartum skills. At each shift, there are three core AMU midwives, one on-call community midwife and a MSW. The three core midwives are on call for the FMU, which is opened on demand. Currently community midwives are not expected to work at the FMU.

Funding and future plans

A FMU was recently opened near the hospital and an effort is being made to increase the numbers of women using this service. A new manager has recently been appointed to oversee the AMU.

Southcity

Model of care

The AMU at Southcity was opened in 2001 and had approximately 750 births in 2011–12, which is around 13% of the total births at the hospital. There are plans to increase this to 1000 births a year (a level achieved in previous years), although some managers consider this to be unsustainable at current staffing levels. The unit has six delivery rooms that have delivery mats rather than beds. Approximately 20% of women admitted to the AMU are transferred to the OU delivery suite during or shortly after labour, which reflects the national average. Until recently, the AMU also cared for a proportion of postnatal women from the delivery suite, but this postnatal bay has now been closed. The trust has opened a triage centre to improve management of admissions in early labour and to divert more eligible women to the AMU, which is part of an on-going plan to increase the numbers of AMU births by changing from an opt-in to an opt-out model (AMU as default option for low-risk women unless they choose otherwise).

Alongside midwifery unit history and funding

The unit was opened to increase the capacity of the trust’s maternity services. Although there was some opposition from the trust’s obstetricians at the time, the AMU is now well established. Locally, the trust is known particularly for its obstetric care of higher-risk women. The trust recently merged with a neighbouring hospital, and this has brought challenges in finding consistent practices and guidelines across units with different histories and organisational cultures and a number of changes in management arrangements.

Staffing model

The AMU has two band 7 lead midwives who co-ordinate the everyday running of the unit. It is currently staffed by a core team of midwives but there are proposals for 6-monthly rotations for most midwives, which started to be introduced during the fieldwork period. The plans include keeping a core team on the AMU to ensure that midwives continue to practise according to its ethos of promoting normal birth. With a view to sustainability, the maternity service recently recruited a number of midwives at senior management level and the consultant midwife’s remit has been expanded to include the Southcity AMU.

Funding and future plans

The recent merger presented a number of difficulties for managers striving to create consistent working practices across both sites. The consultant midwife has implemented a number of changes to the AMU including closing the postnatal bay and adjusting AMU eligibility criteria to ensure that they are consistent with the trust’s AMU on its other site.

Summary

Although the case study sites were selected for maximum variation, each shared some key features. The AMUs catered for between 10% and 14% of births in their services, representing about one-third of the women eligible for such care. Although two operated an opt-in and two an opt-out booking system, there were no apparent differences in numbers or proportion of women using the AMU on this basis, although numbers overall were reported to be limited by staffing and room capacity and the basis for comparison is small. Despite having been open for different lengths of time, all AMUs had originated through some form of service reconfiguration that had provided an opportunity to develop the unit. The figures included in the summary data table indicate that these services were similar to the national picture for AMUs as reflected in the Birthplace study. 1 All four services were operating a core staffing model for the AMU, in three cases supported by MSWs. Two were in the process of integrating community midwifery teams and a third had operated with caseload midwifery group practices coming in to the AMU to attend births for women on their own caseloads. All were considering introduction of some form of midwifery staff rotation across areas in the future, and two were in a process of integrating community midwifery teams with the midwifery unit provision.

All the AMUs were said to be fully established within their service. They enabled midwife-led birth care for low-risk women within their trusts, and in two trusts the AMUs were considered to have helped enable the service to open a FMU. However, no plans were apparent for expanding the provision of the AMU itself to cater for a larger proportion of low-risk women in the four services. The numbers of women giving birth in the units had been maintained, on the whole, rather than increased over time.

Despite differing opportunities and funds for design or refurbishment of the unit, all had been designed to provide a low-intervention, homely and comfortable environment for women and their birth partners, in order to better facilitate normal, physiological birth. The rooms were mostly designed without birthing beds, to promote mobility and active birth, and all had birth pools plumbed in, or accessible, as well as various active birth aids. Beds were mostly intended for postnatal use and typically were either designed to pull down after birth or were hidden behind curtains. Attitudes towards the environment and use of beds are discussed in Chapters 4 and 5.

Two of the AMUs had a band 7 lead midwife (Westhaven and Southcity) while one (Northdale) had more senior leadership, with a consultant midwife as designated lead for the AMU or for normal birth care within the service. Across the units, there were between one and four midwives on each shift, and three of the AMUs also used some level of MSW. Westhaven had the lowest number of midwives on shift and did not use MSWs on the AMU, which, in addition to its small size, limited the numbers of births that could be catered for. However, Midburn, the newest unit, appeared to have more generous staffing, as we will discuss in Chapter 3, and these midwives also provided cover for the recently opened FMU from the AMU base.

Three of the AMUs were on different floors of the hospital from the OU delivery suite, while Westhaven was adjacent, having been converted from one end of the labour ward. As we will discuss, although preference was generally for a high degree of separation, we did not find clear evidence of differences between this and the other AMUs. However, this was a limited sample. On all four sites, midwives were ‘pulled’ to the OU delivery suite. In Westhaven, which was the adjacent unit and had only one midwife on shift during the day and two at night, midwives were reluctant to attend handover or transfer with women for fear of closing the AMU. This issue will be discussed in Chapter 4. Chapter 3 looks at management and stakeholder perspectives on the AMU and its place within its service, while Chapter 4 looks at staff perspectives and Chapter 5 looks at service user perspectives. Each section touches on the issue of relationships between service areas and professionals working them, in different ways.

Chapter 3 Organisation and management of the alongside midwifery units

This section addresses the first study aim: to explore how AMUs are organised, staffed and managed in the attempt to provide high-quality and safe care, on a sustainable basis. Here we discuss issues relating to provision of AMU care primarily from a management perspective, while following sections explore the perspectives of maternity care professionals, service users and families.

Our 136 interviewees (see Appendix 1) comprised 47 postnatal women and partners, 54 clinical staff members (midwives, obstetricians and support workers) and 35 managers and stakeholders (including midwifery and obstetric consultants with management roles, commissioners and user representatives). As there was not a clear line in practice between professionals in more senior roles and managers, this section draws on the perspectives of both. To conserve confidentiality, we do not give specific details of management roles. This section draws mainly on our interviews with managers and stakeholders such as commissioners.

The analysis in this section suggests that a number of key issues affect the capacity of services to provide high-quality and safe care across the range of birth settings, including lack of midwifery staffing resources and tensions around models or philosophies of care, which are often expressed in terms of place of care, and around professional skills, decision-making, teamwork and relationships. Providing choice of care settings creates new boundaries within the service that require careful management. Previous studies of quality and safety in health systems indicate that boundaries and discontinuities between different areas and professional groups in a service can present particular quality and safety challenges. 2,93 Our analysis in the Birthplace organisational case studies also indicated that the proximate nature of an AMU and the OU delivery suite to which it links can create particular tensions, with implications for quality and safety of care. 2 In this section, the development of AMUs is shown to present important opportunities to think differently in terms of service models and to provide a sustainable model of care, in a way that provides choice of birth setting for women and facilitates a more clinically appropriate level of birth interventions. However, a number of management and leadership challenges to maintaining safe and high-quality care in this distributed maternity care system are highlighted.

Drivers for service development and change

Pragmatic drivers

Key drivers for managers in respect of midwife units were economic and pragmatic, but also included a quality and safety aspect. Examining the history of these services revealed that the origins of their AMUs were predominantly pragmatic rather than ideological or philosophical, although practical considerations were embraced as opportunities to bring about desired service improvements, with anticipated benefits for service users and providers. In two services, Southcity and Northdale, creating the AMU had been part of a reconfiguration strategy to close a neighbouring OU and centralise services on one hospital site; in another, Midburn, it was a key element of a strategy to turn around what a senior manager described as a ‘failing’ service (Midburn manager 3). Westhaven was created by refurbishing rooms on an existing delivery suite, achieved opportunistically through a government fund for improving hospital environments. In Northdale, a GP unit that was run by community midwives had already been in existence on this hospital site, so that the reconfiguration enabled both continuity and renewal, in terms of offering midwife-led normal birth care.

In the Birthplace Organisational Case Studies, the view commonly expressed by managers, commissioners and many professionals was that midwife units were a luxury and an unaffordable drain on the overall service. 2 Therefore, we were interested to note that in the services included in the current study, finance had formed a key driver for the creation of these units. This was not only linked to reconfiguration of obstetric services towards a more centralised model. In Midburn, managers and senior professionals emphasised that the introduction of the AMU enabled them to provide more appropriate levels of care to women, thus using their resources more effectively to improve quality and safety:

[Before this change] There was no concept of low-risk care, higher-risk care, everybody was just managed poorly in the same way, whatever their risk

Midburn, manager 3

In Southcity, the AMU had been created to resolve an impending bed shortage with the merger of two OUs. When the new build of the maternity hospital proved insufficient, the AMU was designed through refurbishment of a disused ward in the adjoining older hospital building, to provide an additional 1000-birth capacity. Despite its pragmatic origins and support from a number of obstetricians, some saw the unit as a drain on resources in a service hard pressed by financial problems and insufficient midwifery staffing and as taking away from the low-risk birth experience of midwives on the labour ward:

Yeah, it does have an impact and this was a problem to us. It meant that you were sucking out very low risk deliveries from the labour ward and sending them off to a separate unit . . . And I come back to my point: if I were to design a unit I wouldn’t split my shop in two different places on the high street. It just doesn’t make sense to me. If you have everybody all in one place you don’t have those problems. You’ve got greater monitoring of everything that’s going on; you’ve got greater use of your resources, [it’s] more efficient

Southcity, consultant obstetrician 3

In contrast, some professionals – both obstetricians and midwives – talked of the removal of some low-risk women as lightening the workload of the OU:

We’ve got less [laugh] low-risk patients to be fair um [pause] (. . .) It’s made a positive impact that that they have . . . that it has lightened the load on us.

Midburn OU, midwife 8

While some concerns and anxieties were expressed regarding the levels and sensitivity of new tariffs to be shadowed in maternity services in the coming year, the shift from payment by results (measured in terms of interventions) to one based more on risk levels of those booking for care was seen as an opportunity to consolidate recent developments in midwife-led provision. Some obstetricians and managers in Southcity, in particular, commented on normal birth as being a ‘loss-making activity’ (Southcity manager 5) under the current commissioning system, and service managers and obstetric consultants in all services expressed concerns about service funding and midwife staffing levels:

. . . we are looking at, um, the bottom line, service line reporting of all of our services and looking at what makes a loss, what breaks even and what we can do at profit, and maternity, because of CNST [Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts], because of the costs of obstetricians and the costs of midwives against the current tariff is unquestionably loss-making. So it’s really difficult. With midwifery-led births, because the tariff is lower, you’ve got more costs to cover within a lower amount of income, so it’s cheaper to do but less profitable. Or rather, more loss-making.

. . . yes you have to make the risk argument, yes you have to make the safety argument, yes all of that has to be there, but you also need to think about how you are going to answer the questions about, well this is going to represent an increased spend on workforce, this, you’re not going to meet the cost reduction targets

Southcity, manager 6

The paradox here was that, although managers recognised that high intervention rates were expensive, leading midwife units to be more cost-effective than OUs,53 payment systems had not been not well matched to this and services in constrained financial situations received greater income for more interventionist approaches to care.

Commissioners explained the degree to which the tariff system had worked through targets and drivers, but despite introduction of specific targets to increase normal birth rates or reduce caesarean section rates, the general tariff system with differential rewards for normal or operative births had not facilitated this:

So you can use the, you know, the contractual levers and use performance as a good starting point really for looking at making the best use of resources. Sometimes it’s about service redesign, there’s not going to be more money so they’ve got to do things differently.

Southcity, commissioners 1 and 2

Midwifery units were seen as a key element in strategies to reduce unnecessary intervention, to contain costs as well as to improve health outcomes, while also enhancing the recruitment and retention of midwives, as reflected in this comment by one Southcity manager:

You know, we’re having to reduce Caesarean section rates, and it’s sad but since, you know, we’re having to save all this money finally even the most sort of, um . . . even the consultants that weren’t so supportive of the birth centre are realising that actually our normal birth rate here is double what it is upstairs [OU], so you know, we are a money-saving, um . . . entity.

Southcity, manager 2

The accounts of managers and obstetricians indicated that the development of a stable AMU service also increased confidence in the abilities of midwives to provide more autonomous care, to ensure escalation and transfer when needed, and in the likely cost-effectiveness of the service. Although each service experienced challenges in inter- and intraprofessional relationships relating to these issues, which will be described in Chapter 4, once embedded and accepted within a maternity service, the AMU appeared to increase confidence in midwifery-led and normal, physiological labour care. Although this was not, in any case, an easy process, it was reflected in decisions to develop FMUs. These had recently been opened in Northdale and Midburn, and one was being developed in Westhaven. These developments were also utilising opportunities created by wider service reconfigurations. A further key consideration was the need to recruit and retain a well-motivated midwifery workforce.

Philosophical drivers

Although the development of AMUs was generally achieved through pragmatic circumstances, managers on all sites had a clear view of the aims and philosophy of the unit to provide a more homely birth environment that would be woman and family centred and facilitate normal birth practices and midwife-led care for low-risk women:

If people are relaxed and in a relaxed environment their hormones and their body can work better than if they’re tense and they feel that they’re being imposed on in here. You know, we say to women as they come in, ‘Make yourself at home, go where you like, move things around, whatever you want to do,’ and it’s their area to do what they want in. And it’s been shown to improve outcomes and . . . I would say, I can’t say shorten labours but not prolong them by that fear aspect of changing, you know, if you’ve been at home and you’ve been relaxed and calm and then you come in and all of a sudden contractions go off, and that’s what we’re trying to avoid really. So they can relax and (pause) get on with their business.

Northdale, manager 2

Managers commented that, although it would be ideal to promote such care in all areas, this had not been achieved in practice previously and lack of progress in creating an environment to support normal birth and to establish midwife-led care on their labour ward had been a key motivator for creating a separate unit:

Part of what was very obvious at that stage, I kind of touched about midwifery performance, um, in the context of midwifery-led care it was virtually non-existent. Um . . . [name] was one of our consultant midwives, had been slaving away here for a few years and had tried to make inroads into providing low-risk/midwifery-led care, and at that point she had succeeded in having a couple of rooms assigned to that within the labour ward on [first hospital]: there was no such, I don’t think there was any such practical arrangement at [the other hospital] at the time. Um, but despite her best intentions it hadn’t really got anywhere because of the culture of the practice both by obstetricians and midwives . . . um . . . aligned to the performance issues that I’ve mentioned.

Midburn, manager 3