Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1816/1004. The contractual start date was in April 2010. The final report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in September 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Aspinal et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This research, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (formerly Service Delivery and Organisation), built on previous research undertaken at the Social Policy Research Unit (SPRU) around integrated service provision and neurological conditions1 and outcomes. 2,3 It aimed to describe systems in which innovative models of integrated care for people with long-term neurological conditions (LTNCs) exist, identify the range of outcomes that people with LTNCs want to achieve and to consider how to assess these outcomes in integrated practice.

We undertook in-depth case study work in four primary care trusts (PCTs) in England, each with at least one community-based neurorehabilitation team (NRT), between 2010 and 2012. Data collection included reviewing local documentary evidence and interviewing different levels of staff to explore the context within which these teams worked; interviewing people with LTNCs to ascertain what types of outcomes they wanted to achieve; working with the teams to develop these service-user derived outcomes into an outcomes checklist (OC) that could be used in assessments; and evaluating the use of the OC in practice.

This document reports the methods, findings and conclusions of the research.

Background

Problems securing integration across health and social care boundaries for frail older people and those with long-term conditions have been evident since the early 1950s. 4 Similarly, concern about integration within service systems has been a consistent feature of evaluative research in both health and social care. This has become more so as increased specialisation, technological advances, and shifts in the place of care have accelerated. 5

There have been repeated attempts since the inception of the NHS to resolve these issues by changing policy and directing practice,4 and policy documents return continuously to the need to deliver ‘seamless’ care. Policy developments at the start of this research promoted integrated care provision ‘to enable partners to join together to design and deliver services around the needs of users rather than worrying about the boundaries of their organisations’. 6 It was assumed that these arrangements would help remove unnecessary gaps and duplication between services. 6

This emphasis on services rather than organisational structures was an important change, but left unresolved problems that impeded earlier attempts to encourage integrated provision. 7 Further, it takes for granted that we know that integrated care does make a difference, when the research literature is, at best, equivocal about this.

Our previous project on integrated care for people with LTNCs8 suggests three main reasons for this lack of clear evidence about outcomes of integration. The first relates to defining what integration means, the second to agreeing what integration should achieve, and the third to how we should measure the effects of integration.

What is integration? The literature contains examples of three main types of intervention described as ‘integration of health and social care’. 9 At the structural (macro) level, for example, ‘integration’ might be about bringing health and social care provision and/or commissioning into a single organisation. The second type of structural intervention relates to relationship issues (meso level); for example, facilitating joint planning, the exchange of information or budget sharing. Thirdly, the intervention may be about co-ordinating care at the level of the service user (micro level), for example via care/case management, single assessment processes or multidisciplinary teams.

What is integration for? Here, the literature shows that the aims of integrating health and social care can vary from enabling the closure of long-stay hospitals,10 through the reduction of acute hospital beds or nursing home use,11–13 to promoting user-directed services and empowerment,14,15 and most points between. In many cases, making better use of existing resources underpins these varied aims.

How should we measure the effects of integration? With little consistency in the literature (and indeed in policy) about the definition and aims of integration, it is perhaps not surprising that evidence about its impact for service users is limited. There is a substantial literature about organisational and professional issues involved in both structural integration and integration at the service level. 16–19 There is also some evidence about impact on process measures such as access, user satisfaction, and assessment. 20 However, evidence about effectiveness for service users and their families or carers – and, in particular, outcomes that are important to them, not just to service managers and professionals – is largely absent. 19–22

Our previous project underlined this lack of evidence about impact. The systematic review of integrated models of care (such as multidisciplinary teams, specialist nurses, integrated care pathways, and other services described as ‘integrated’) found little evidence of impact on physical function, health-related quality of life measures, clinical outcomes, mental health, and other outcomes reported in randomised controlled trials and controlled before-and-after studies. Other researchers, reviewing the wider literature on integration of health and social services for older people, have come to broadly similar conclusions about impact on these ‘conventional’ outcomes. 20–22

Yet people with LTNCs and their organisations argue that the experience of integrated provision is an important contributor to their quality of life. 23 The overwhelming view of people with LTNCs in our previous project who used integrated models of care was positive, particularly when compared with less integrated models. 1 However, the issues that concern them are rarely the outcomes about integrated provision reported in the research literature. For example, of the 50 studies included in the review, only 21 reported use of or contact with to services overall and 18 reported the users’ views of the model of care, both issues that service users themselves consider important. 24 Just three studies mentioned social outcomes such as housing, income, education or employment. Further, our evidence shows that issues such as a sense of empowerment or self-worth and the ability to make sense of one’s health condition can be very important to service users. However, these types of outcomes were totally absent from the evaluative literature we reviewed in that earlier project.

Integration and outcomes in national policy

Improving the integration of services across boundaries in order to deliver improved outcomes for service users, especially those with long-term conditions, has been a major concern of policy and system planning for some years.

Policy under the Labour government 1997–2010

Joint working and partnerships were central to the Labour administration’s reforms for public services. The Health Act 199925 removed some of the obstacles that had historically hindered joint working and these were formalised and consolidated in section 75 of the NHS Act 2006,26 providing mechanisms of pooled budgets and joint commissioning which might deliver integrated services more easily. The ‘NHS Plan’ in 200027 and the Health and Social Care Act 200128 explicitly encouraged structural integration of organisations providing health and social care services.

The importance of supporting people with long-term conditions was outlined in the NHS Improvement Plan,29 launched in June 2004. The subsequent Department of Health publication in 2005, ‘Supporting People with Long Term Conditions’30 set out the NHS and social care model for long-term conditions. In the same year, the National Service Framework (NSF) for LTNCs31 specifically addressed the needs of people with LTNCs. The need for an integrated approach to service provision was made clear, explicitly or implicitly, in all 11 quality requirements of the NSF.

Increasing interest in evidence-based policy and practice meant that monitoring service performance was increasingly important to commissioners and also focused attention on outcomes for users of services rather than just for the organisations delivering them. At the same time, the joint health and social care White Paper, Our Health, Our Care, Our Say: a new direction for community services, set a new strategic direction for community services. 32 It aimed to realign care in settings closer to home and introduce an outcomes-focused framework for commissioning health and well-being. Integration of services and support for people with long-term or complex needs, with a shift of resources away from secondary care to prevention, primary and community services, were the explicit aims. The Local Government and Public Involvement in Health Act33 and the Commissioning Framework for Health and Well-being34 went on to create a duty to design and deliver local area agreements and produce joint strategic needs assessments of the health and social care needs of local populations that would help inform and deliver a sustainable communities strategy.

The Integrated Care Pilot programme, introduced in the NHS Next Stage Review,6 focused on horizontal integration (i.e. between health and social care) and represented a ‘bottom-up’ approach to integrated care that was designed to explore the different ways health and social care could respond in an integrated way to address a particular local need. The national strategy ‘Transforming Community Services’35 helped to clarify relationships within community services and required a clear separation between commissioning and providing functions.

Despite such government initiatives, achieving effective integrated care remained elusive, or at best, patchy. Examples of joint financing across health and social care failed to be representative of a wider pattern. 36,37 In 2010, a report from the King’s Fund noted that there had been little significant shift in resources from acute care to the support of those with long-term conditions in the community. 38 The introduction of care trusts generally failed to result in comprehensively integrated structures39,40 and the evaluation of integrated care pilots highlighted specific problems in implementing large-scale organisational change. 41 Similarly, an evaluation of the NSF for LTNCs demonstrated how a policy can be overtaken by competing priorities when implemented with no new money and no firm targets in a culture of performance management. Despite the NSF, people with LTNCs struggled to access models of good practice for integrated care. 1,42 Moreover, the focus on outcomes had so far been framed primarily around organisational processes and performance management, with a lack of evidence around outcomes for individuals. 43

Policy under the coalition government since 2010

The persistent barriers to realising change were illustrated in the Nuffield Trust’s contribution to discussions about the possible direction of health reform under the incoming coalition government44. One concern that quickly arose was whether or not the interest in integrated care would continue despite a perceived greater emphasis being placed on choice and competition. 39,43,45 The new government’s health reforms were set out in the White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS46 and the initial draft of the Health and Social Care Bill focused on mechanisms to promote development of a competitive health-care market, with a key role in promoting competition for Monitor, the new economic regulator. However, the interim listening exercise before the Health and Social Care Act 201247 was passed, identifying integration as a neglected priority. 48

The NHS Future Forum reported a widespread concern and their ‘integration’ workstream report set out key recommendations to endorse and encourage integration ‘around the patient, not the system’. 48 The Health and Social Care Act, as it reached statute, placed new duties on the economic regulator Monitor, the new central NHS Commissioning Board, local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and health and well-being boards to promote integration between health and social care. 47 To facilitate key changes, the NHS Commissioning Board was to host four new strategic clinical networks for up to 5 years from April 2013. 49 At the end of 2012, it was announced that one of the networks would specifically cover neurological conditions, dementia and mental health.

Concerns have been raised that in the major structural upheavals, existing partnerships are being dismantled and established collaborative networks and relationships threatened or lost. 43,50 Moreover, the ability of general practitioner (GP)-led commissioning groups to champion the sorts of services that work across boundaries in a more holistic way is unproven. 51 The emphasis given to performance management through national targets has been largely abolished, and the focus shifted to outcomes as the main mechanism by which government sets objectives and levels of performance for health and social care. At a clinical level, patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), to assess the quality of care delivered to NHS patients from a patient perspective, currently covers four elective surgical procedures and have been collected by all providers of NHS-funded care since 2009. 52 PROMs for six long-term conditions – asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes, epilepsy, heart failure and stroke – are currently being piloted. 53 Three separate but inter-related outcome frameworks for the NHS, Adult Social Care and Public Health have been established. 54–56 The three frameworks are being increasingly aligned;57 shared and complementary indicators aim to reflect areas of joint responsibility and help provide a focus for joint-working and shared priorities.

Integration is likely to continue to be a significant policy theme. The Care and Support White Paper58 and accompanying draft bill59 affirmed the ambition that ‘everyone who uses health, care and support [will] experience joined-up services that meet their needs and goals’. 58 Aligning processes at an individual level via personal budgets (for social care) and the appointment of care co-ordinators to assist in navigating care systems are central proposals. However, a recent critique of social and health care integration views this more prominent role for care co-ordinators as accepting inherent fragmentation within services, without addressing the fundamental causes and, therefore, not necessarily enhancing integration. 60 Similarly, personal budgets could be viewed as a micro-level initiative that do not require change at a system level, at least until the results of pilots of health budgets are available and the feasibility of joint personal budgets for health and social care is established. Financial support for integration was pledged by enabling the transfer of £859M in 2013–14 from the NHS to local authorities via local agreements to support adult social care services that also have a health benefit.

The NHS Operating Framework 2012–13 illustrates the priority given to integrated care61 and supports a range of system levers to promote it. The management of long-term conditions remains a focus through the long-term conditions strategy: a cross-government initiative led by the Department of Health set up to look at how services such as health, social care, education, housing and others can work together to improve life chances and outcomes for people living with long-term conditions. 62 The Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) programme, designed to achieve productivity savings within the NHS of £20B by 2015, includes a long-term conditions QIPP workstream, in which joint working is seen as an important strategy in tackling financial constraint. 63 More specifically, it describes a ‘Year of Care’ funding model that focuses providers on jointly delivering a ‘year of care’ based on a risk-adjusted capitation budget, and away from episodic, activity-driven funding. 64 There was a renewed focus on LTNCs in particular, in the concerns raised by the Public Accounts Committee. They drew attention to the failures so far to improve services and the need for better information about resource use, services and outcomes around LTNCs. 65

Assessing progress

Despite health and social care policy continuing to embrace integration and an outcomes approach, a mid-term assessment of health policy under the coalition government called for more to be done in evaluating innovative approaches to integrated care and the way long-term conditions are managed. 66 The impact of a parallel policy emphasising increased competition in health care on collaborative working has also yet to be felt and evaluated. Attributing outcomes to policy interventions demands a sound evidence base and an appreciation of the complexity of cause-and-effect reasoning. 67 Furthermore, government acknowledges the inherent difficulties in developing outcomes that measure service users’ experience of integration. 68 A recent review in 2012 called for an urgent need to improve the evidence base by developing studies that could not only provide an analysis of cost-effectiveness, but also assess the process of joint and integrated working from the perspective of service users and carers. 69 The Neurological Alliance recently emphasised the need for the current NHS Outcomes Framework to develop better measures, including disaggregated measures relevant to neurological conditions, that can deliver improved services for people with LTNCs, specifically, and those with long-term conditions, generally. Identifying the outcomes that matter most to people with LTNCs is seen as central to this aim. 70

Outcomes

As described earlier in this chapter, the policy around outcomes tends to focus on the outcomes of interventions by different care sectors, as witnessed in the assessment criteria included in the National Outcomes Frameworks (NOFs). 54–56 While these are likely to be of relevance to people using health and social care services, these measures are essentially defined in line with professional, service, sector and policy-makers’ priorities.

Our research does not focus on the outcomes of service provision per se but, rather, aims to discover what outcomes people using ‘integrated’ services want to achieve and whether or not these services are able to assess these outcomes in practice.

Social Policy Research Unit’s outcomes research

A substantial programme of research at York, using this conception of outcomes, explored conceptual issues and measurement challenges of assessing outcomes when needs are complex and changing and deterioration is more likely than recovery,2,71 and identified how these could be used to influence practice in social care services. 3

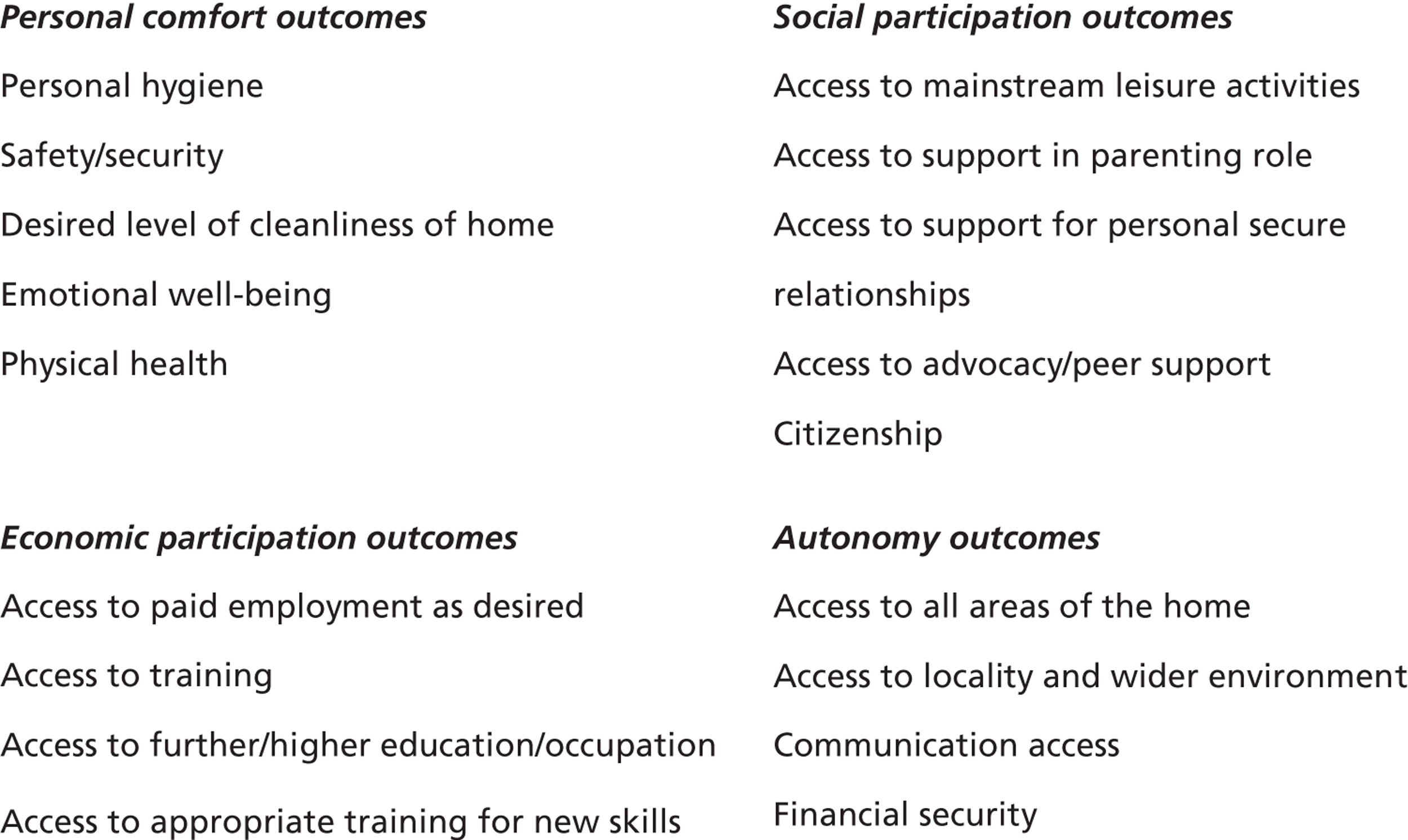

The work by Harris et al. 3 collated Qureshi’s2 findings into categories consistent with the social model of disability, which asserts that an individual’s impairment does not constitute disability but rather that society disables people with impairments through, for example, structural, ideological and material barriers. 72 It listed four main groups of outcomes: autonomy outcomes, personal comfort outcomes, economic participation outcomes and social participation outcomes. However, this work did not explain how these categories were determined, nor did it define their parameters, making it difficult to understand the origin and meaning attached to them. In addition, the research highlighted difficulties practitioners experienced in adopting a more ‘outcomes’ focused approach to assessment and service provision.

Our project built on this previous theoretical and empirical work. We wanted to understand what outcomes people with LTNCs wanted to achieve and, based on the views of people with a LTNC, to clarify the parameters of each of the outcomes outlined by Harris et al. 3 This approach to identifying outcomes follows a social model of disability that acknowledges that service users may view outcomes and outcome achievement differently from practitioners, commissioners and policy-makers. We also wanted to understand whether or not an outcomes-based approach to assessment could be implemented in practice and how this might influence practice in ‘integrated’ teams.

The need for research

At the time this research was commissioned, it was acknowledged that there was little evidence about how integrated care models are developed and implemented and about the effectiveness of integrated models of service delivery. 73 It would be easy to assume that the failure to demonstrate impact on conventional outcomes means that there is no impact to measure. However, it seems more likely to us that research has failed so far to measure the outcomes that might sensibly result from integrated health and social care and that actually matter to people with complex long-term conditions.

Our research aimed to improve understanding of the structures and mechanisms that allow integrated care delivery to work and the part that commissioning plays in enabling integration. This research was not intended to evaluate outcomes of integrated services or to result in a finished tool to assess the outcome of integrated care, but rather to address the need to develop ways of assessing outcomes that are important to people with LTNCs and that can be facilitated by integrated service provision. This research thus begins to fill the gap in evidence by exploring how user-desired outcomes can be incorporated in assessment processes in different micro-level models of integration, embedded within different meso- and macro-level structures.

Research questions and study aims

To address the gaps summarised above, we outlined four specific research questions:

-

What facilitates or impedes the development of innovative approaches to health and social care integration?

-

What outcomes do people with long-term conditions want from integrated health and social care?

-

Can these outcomes be assessed in everyday service delivery?

-

How can different models of integrated health and social care affect outcomes?

Associated with these were four main aims:

-

To describe innovative models of micro-level integrated care for people with LTNCs and the macro- and meso-level structures within which they are delivered.

-

To explore the relationship between models of care co-ordination and different structural approaches to health and social care integration. The focus was on what facilitates or impedes the delivery of integrated care, from the perspectives of service users, their families or carers, professionals who deliver care, and service managers and planners.

-

To work with those who use and those who provide innovative models of integrated care to develop and test ways of assessing outcomes that are meaningful to both.

-

To begin to understand if and how outcome assessment influences practice in integrated care, and whether or not this varies between different models, within different structures.

Long-term neurological conditions

We focused the research on adults with LTNCs because these clients pose complex challenges for effective health and social care integration. For example, with the exception of those who have Parkinson’s disease (PD), adults with LTNCs are younger than most long-term users of health and social care services. As a result, their roles as partners, parents, and economically active adults should be considered as part of their overall needs. The ‘boundaries’ that are important thus go beyond the conventional ones of health and even of social care, making the task of co-ordination potentially more complex.

Many LTNCs involve relative stability over long periods, interspersed with exacerbations that need rapid access to acute medical care or complex, community-based intervention. Unless people live close to specialist centres, their health needs during these periods are likely to be met via generalist services. Access to specialist advice, so that generalists can provide appropriate care for the specific LTNC, is a key boundary issue.

Some people with the same LTNC find that their condition changes slowly, while others experience rapid change and still others can experience both slow and rapid change at different stages. Responding to these differing trajectories and their unpredictability requires sophisticated management across boundaries within health care and between health and social care systems.

While innovations such as individual budgets can enable adults with health and social care needs to act as their own care co-ordinators,74 some people with LTNCs experience periods when their ability to do this will be seriously compromised. User-directed methods of integration thus introduce the potential of new boundaries to be negotiated from time to time.

For these and other reasons, we might expect that methods or mechanisms for integration that ‘get it right’ for people with LTNCs would also get it right for other adults with complex, long-term conditions. Using LTNCs as an exemplar thus generates knowledge that is transferable to other long-term conditions.

The research process

The research took place in four PCTs in England between 2010 and 2012. The evidence was collected using an in-depth case study approach, and included reviewing local documentary evidence and interviewing different levels of staff, people with LTNCs and their carers; developing an OC; and evaluating the use of the OC in practice. The research was undertaken in three stages.

Stage 1 – understanding the context and identifying outcomes

-

Documentary evidence was analysed and interviews were held with staff (e.g. PCT commissioners and senior managers, service-level managers and front-line staff) to help understand the context in which integrated teams were based.

-

Interviews were held with carers of people with LTNCs to help understand how they were included in integrated service provision.

-

Interviews were conducted with service users to identify outcomes.

Stage 2 – developing and implementing an outcomes checklist for use in practice

-

Service-user interview data were analysed to identify the outcomes that they wanted to achieve.

-

A summary list of outcomes was developed.

-

Working with the teams in each case site, the list of outcomes was developed into a checklist that they could use in practice.

-

Teams implemented the OC as part of their usual assessment processes.

-

Teams’ use of the checklist was monitored.

Stage 3 – evaluating the use of the checklist

-

Staff were interviewed about their views on the checklist and its utility in practice.

-

Service users were interviewed about their experience of the checklist being used in their assessment and about the items included on the checklist.

Service users, carers, representatives from voluntary sector organisations who sat on the project advisory group and the SPRU Adult Consultation Group (see Appendix 8, note a) advised on the research process for this study. Presentations and progress updates were given in meetings held regularly throughout the research and, as well as giving general advice throughout the period of research, they gave specific advice on documentation, recruitment, analysis and interpretation of findings. Between meetings, members of the project advisory group were also sent project newsletters to update them on progress and ask for advice on specific issues.

Ethical review

The research, and all associated documentation, was reviewed and approved by the University of York’s Humanities and Social Science Committee and was then reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (REC) for Wales in 2010 (see Appendix 8, note b). The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services also approved the research. PCTs and local authorities granted research governance approval prior to starting data collection.

Structure of the report

Chapter 1 has introduced the research. It has presented an overview of the study area and explained why this research is important. The introduction outlined the research context, research questions and the methods used for data collection.

Chapter 2 will present the case study methods. It will explain how the case study sites and participants were selected and recruited, and describe the methods used to collect data for each of the three stages of the research.

Chapter 3 will present case-by-case analysis of local demographics, commissioning arrangements and organisational and team profiles, providing a contextual backdrop for the rest of the findings. Team processes will be compared and service user and carer views about how processes could affect achievement of outcome will be reported.

Chapter 4 will report findings from staff, service users and carers about integration, how different elements of the organisation affect integration and how stakeholders are included. Cross-case comparisons, drawing together this evidence from across the four case sites, allowed us to identify some of the factors that might promote or inhibit integration at organisational and team level and help to answer the first research question: What facilitates or impedes the development of innovative approaches to health and social care integration? (See Appendix 8, note c for our working definition of ‘innovation’.)

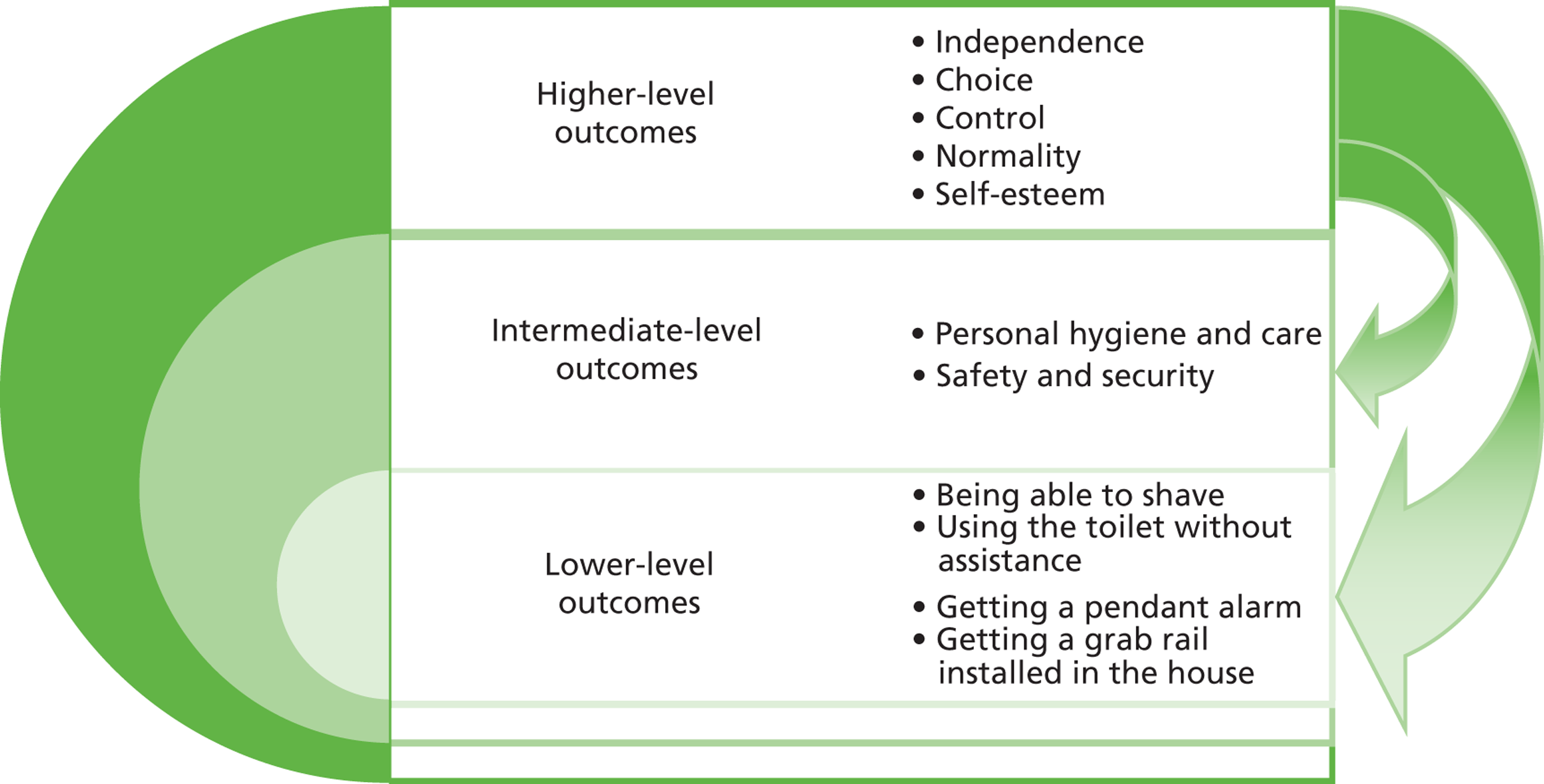

Chapter 5 will draw service user data from across the four case sites together in order to answer the second research question: What outcomes do people with long-term conditions want from integrated health and social care? We will explain the key issues that people with LTNCs discussed, provide a comprehensive list of outcomes based on service user views, and the different levels of outcomes people with LTNCs will be discussed.

Chapter 6 will describe how, working with the teams in each case site, we developed the list of outcomes into a checklist. The way that the teams implemented the OC into their usual assessment processes will be reported and teams’ experiences of using the checklist in practice will be explored. Service users’ experience of the checklist being used with them, and their opinions about the topics included on the OC, will also be reported. This chapter, therefore, will answer the third research question: Can these outcomes be assessed in everyday service delivery?

Chapter 7 will draw together the findings from each stage of the research and from across the case sites to answer the final research question: How can different models of integrated health and social care affect outcomes? It will present an assessment of the strengths and limitations of the research and the implications of this research for policy and practice. The report will conclude with recommendations for future research in this topic area and plans for dissemination.

Chapter 2 Methods

In this chapter, we set out the methodological approach taken in this project, outline how we identified our case study sites and our samples, and describe the methods we used to collect data across the four case studies. We have summarised the rationale for the choice of methods, data collection techniques and adaptations that we needed to make. We will also describe the sample we achieved in each case site.

Reporting of the methods is organised around the three stages of the research, as outlined in the introduction: understanding the context and identifying outcomes; developing and implementing an OC for use in practice; and evaluating the use of the checklist in practice. Participation rates are discussed in the relevant findings chapters (see Chapters 4 to 6).

Justification for methods

The first section describes the different approaches to data collection that were adopted for this research and explains how we overcame some of the general limitations of the methods.

Case studies

The case study approach ‘focuses on the circumstances, dynamics and complexity of a single case or a small number of cases’. 75 A case is a single unit in a study and can be, for example, a person, a profession or an organisation. The case study approach is distinguished from other approaches, in that it does not attempt to control or exclude variables. Rather, it is a holistic approach that enables the complex nature of an issue to be explored. 76

As Yin notes, a case study is particularly useful when the study aims to investigate ‘a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident’;76 for example, in circumstances where the relationship between organisational structure, approaches to practice or policy, and outcomes for people using those services, are unclear. The case study approach, therefore, is particularly suited to this research where the ability of people with LTNCs to achieve the outcomes they want may be determined by several factors. For example, having to deal with and navigate multiple services that are governed by many different policy directives might have as much impact as their level of ‘impairment’ or personal approaches to self-management.

Using a case study approach does not preclude any particular method of data collection, but for the purposes of this research, only qualitative methods were used. These comprised in-depth interviews with different stakeholders at the different stages of the research, group interviews, documentary analysis and field-note analysis.

Qualitative interviews

Qualitative interviews were used in two stages of the research: stages 1 and 3. They can be used to look below superficial and readily observable phenomena, allowing deep exploration of the study topic. 75 Interviews can provide information that is able to inform understanding of, for example, people’s opinions and preferences and also why they hold them. They allow for relationships between people, organisations and events to be explored and understood. 75,77

An ‘in-depth semistructured’ approach78 to interviews was used which allowed in-depth exploration of issues. During these types of interviews, the participant is allowed to talk through, or provide a narrative about, the issue being studied. This is important for this research, where we wanted to understand the things that were important to people with LTNCs, to explore reasons for their importance, and how they linked together. Furthermore, in using this method, we were able to explore the variety of factors that affect integration, service provision and outcomes.

Interviews were guided by a topic guide (all topic guides are included in Appendix 1), rather than by pre-set questions, which acted as an aide memoire for the researcher to ensure that relevant topics were addressed while a conversational style was maintained. Additional topics emerged from the dialogue during the interview. All topic guides were reviewed by our advisory group comprising commissioners, front-line professionals, service users and service user/carer representatives.

To counter the limitations of subject bias that can be associated with this method, we aimed to recruit a range of participants in each sample for each stage of the research. For views about the organisation and service structure, for example, we interviewed front-line professionals, commissioners and service managers across health and social care organisations and for views about outcomes people with LTNCs wanted to achieve, we aimed to hear the views of people representing different LTNCs, different condition trajectories and different points in that trajectory.

To counter interviewer bias, three researchers undertook interviews and reviewed each other’s interview transcripts at different points of the research. We also undertook some joint interviews so that feedback could be given on process and technique.

Focus groups

Focus groups use group discussion to generate qualitative data around a focused set of topics79 and, as with the in-depth interviews described above, they can be used not only to hear people’s opinions but also to understand why people hold these opinions. 75 Although focus groups can be used to explore dynamics of the group,80 for the purposes of this research we were only interested in understanding the views people had. Focus groups were thus used to gather views of staff who had used the checklist as part of their practice.

In stage 3, we offered staff in the NRTs the opportunity to take part in an individual interview or in a focus group with their colleagues. The topics covered in the individual interviews and focus group interviews were similar, but focus group interviews gave staff the opportunity to discuss issues as a team. We offered these choices for several reasons. First, focus groups would improve efficiency, reducing the time needed overall for staff to take part in interviews (i.e. 2 hours in all, rather than several interviews of approximately 1 hour each). Second, as this research addresses the feasibility of using the checklist in practice, a focus group provided the opportunity for staff to share experiences and learn from each other’s experiences. However, we also offered a choice of individual interviews so that NRT staff could express divergent views away from colleagues, if this is what they preferred.

One of the methodological concerns associated with focus group interviews is that divergent voices may not be heard in group discussion. To address this, the groups were facilitated by two experienced researchers who directed questions to participants who had not spoken, so that they were drawn into the discussion, and positively promoted discussion about views that were divergent from that expressed by the majority of participants.

Field notes

Field notes, an accepted approach in qualitative research to provide additional information to aid understanding of participants’ views, were made after interviews and focus groups, where appropriate, to record contextual information. For example, a person may express concern about leaving their home. For example, when a participant expressed concern about the safety of going out of their home, the researcher might make field notes about the participant's neighbourhood. Notes were also taken during meetings held with teams throughout the research process. Though these data have not been used to direct analysis, the information was used to provide contextual information and prompts for future interviews.

Documentary analysis

Analysis of documents is widely used in social research81 and also in health research75 and can draw on many documentary forms, including official demographic statistics and government department documents. 74 In this research, we wanted to learn about the local structures and processes for integrated service provision, the wider context in which these were based and to understand approaches to outcome assessment in services for people with LTNCs. Documentary analysis was thus well suited to this study.

Documentary accounts can be useful data sources, but as all documents are based on social constructions and judgements, it is important to be alert for inaccuracies and biases throughout the research process. 75 Documents from a variety of sources were triangulated to limit this and these were then triangulated, where appropriate, with staff interview data.

Non-participant observation of strategy meetings

Non-participant observation is a classic method that has been used extensively and is particularly useful for organisational analysis and evaluation. 75 It comprises observation of behaviour, actions, activities and interactions to inform understanding of complex situations and interactions. 75 As indicated above, the complexity of the systems being researched for this study made this approach potentially useful. Furthermore, non-participant observation is, by its nature, context specific. 77 Given that we were interested in understanding how local decisions were made around integration/co-ordination of services as well as who was involved in this decision-making, non-participant observation of meetings that focussed on integrating/co-ordinating services for people with LTNCs could provide interesting insight into how decisions about these issues were addressed.

Approach to analysis

We used the framework approach to data management and analysis. This is typically used in applied policy research where there are specific objectives or information needs. As such, frameworks can be data driven or led by a priori issues, or a mix of both. The approach also facilitates systematic data management and allows audit trails of the data management process.

Qualitative data are managed in a theme-by-case matrix, known as an ‘analytical framework’. 82 There are four stages of data management. First, researchers familiarise themselves with the data, and identify themes and key issues. Based on the identified themes and any other a priori issues, an index of themes is constructed, resulting in the analytical framework. Visually, this looks like a matrix or chart, with cases as rows and themes as columns. Data are then indexed according to which theme(s) in the framework they relate to. Finally, the indexed data from each case (e.g. participant, focus group) is summarised onto the chart under the relevant theme(s) (known as ‘charting’).

Where appropriate, we triangulated different sources of data. For example, in stage 1, we used both interview and documentary evidence to help understand organisational and wider contextual issues. When we took interview field notes, we also used these to help inform analysis of data from that interview.

Methods: in practice

Yin76 argues that carrying out multiple case studies increases generalisability of research data to other situations and contexts. We therefore undertook in-depth case studies in four PCT areas, including their associated local authorities.

We decided on four case studies because this research involved long-term in-depth work with the teams in each of the case sites. Having four cases would ensure we had enough time to manage each of the case studies, to develop and maintain relationships with the teams and to foster their interest and commitment throughout.

Ethical and research governance review

Before we undertook data collection, the research methods and all documentation were reviewed and approved by the appropriate ethical and research governance committees as outlined in Chapter 1.

Identifying and recruiting case sites

We invited PCTs to participate if they had a NRT that was based in a community setting. When we were planning the research, four PCTs, with whom we had worked in a previous study agreed, in principle, to take part in this study. These case sites reflected different approaches to integration at a strategic and/or commissioning level, different population profiles and different levels of rurality/urbanisation.

However, when the research was funded, one PCT was no longer able to take part because staff in the NRT did not have the capacity to be involved in long-term, in-depth research. In this site, health and social care was integrated at an organisational level, had a younger than average population with high deprivation and was classed as urban. To replace this case site, we wanted to include a site with similar characteristics, but the integrated structure of the PCT was our primary concern.

We identified several PCTs which had a NRT and integrated structural arrangements from benchmarking data that we had collected as part of a previous research study around LTNCS and integration. 50 We approached all of the sites with these characteristics (n = 11) and one of these agreed to participate in the research. Details of the four participating case sites are reported in Table 1.

| Organisation and population characteristics | Case site A | Case site B | Case site C | Case site D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisation integration arrangements (at start of research) | Standing joint commissioning board | Some joint commissioning posts | Standing joint commissioning unit | Integrated health and social care at operational level |

| Some joint commissioning posts | ||||

| Local authority type | Metropolitan | Borough | County | County |

| Urban/rural dataa | Major-urban | Major-urban | Significantly rural | Rural 50 |

| Populationb | 700,000 | 200,000 | 500,000 | 400,000 |

| Ethnic diversity | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Deprivationc | Average | Very high | Low | Very low |

As Table 1 shows, we chose sites that had different population profiles, different organisational arrangements and different levels of rurality, so that we had possible factors on which to base comparisons. Further information about the case sites and associated structures are presented in Chapter 3.

Identifying and recruiting neurorehabilitation teams

As described earlier, we recruited PCTs with a NRT. This is because in previous research we had identified NRTs as one of the ‘gold standard’ models of integrated service provision for people with LTNCs. 85

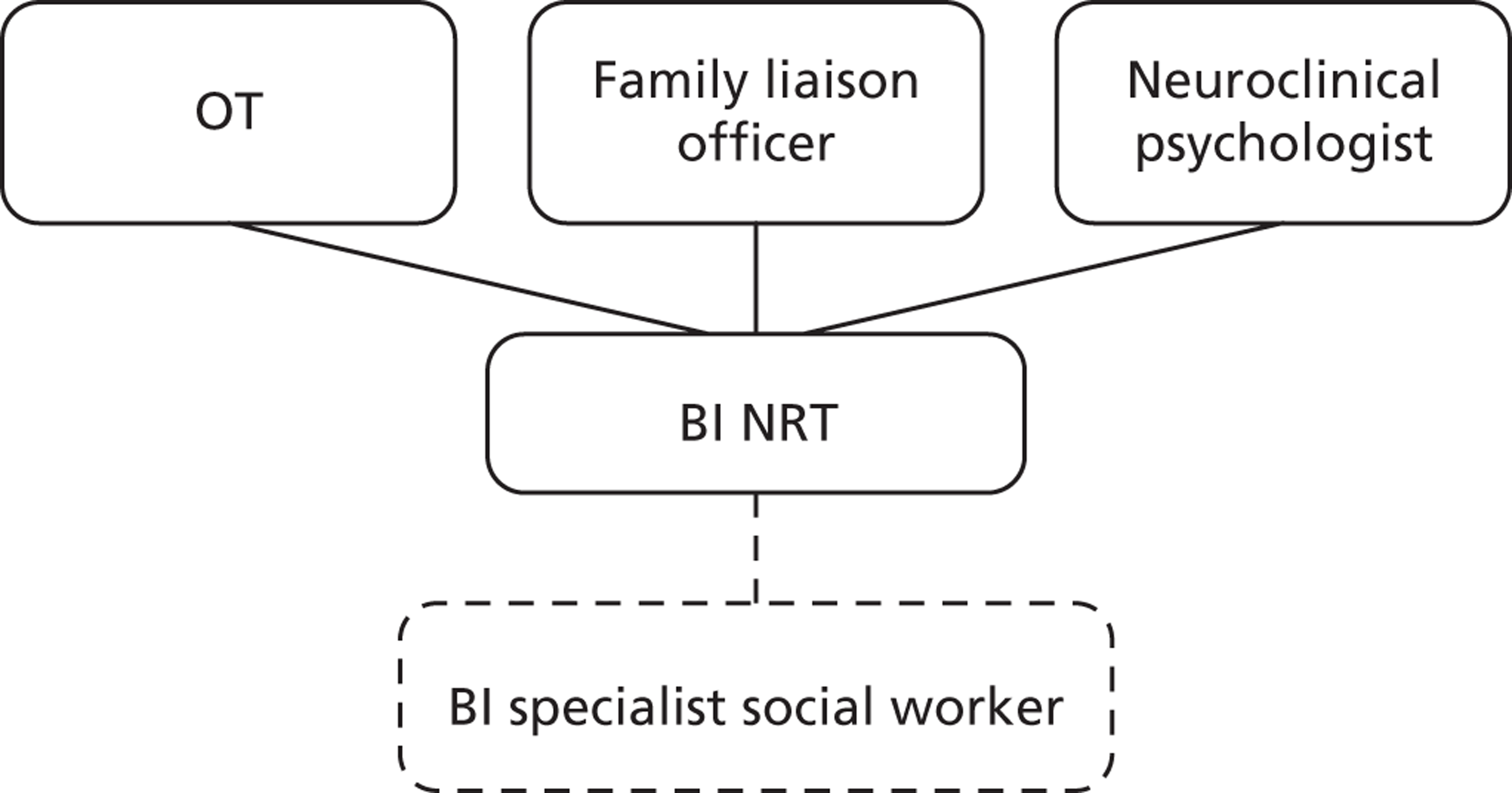

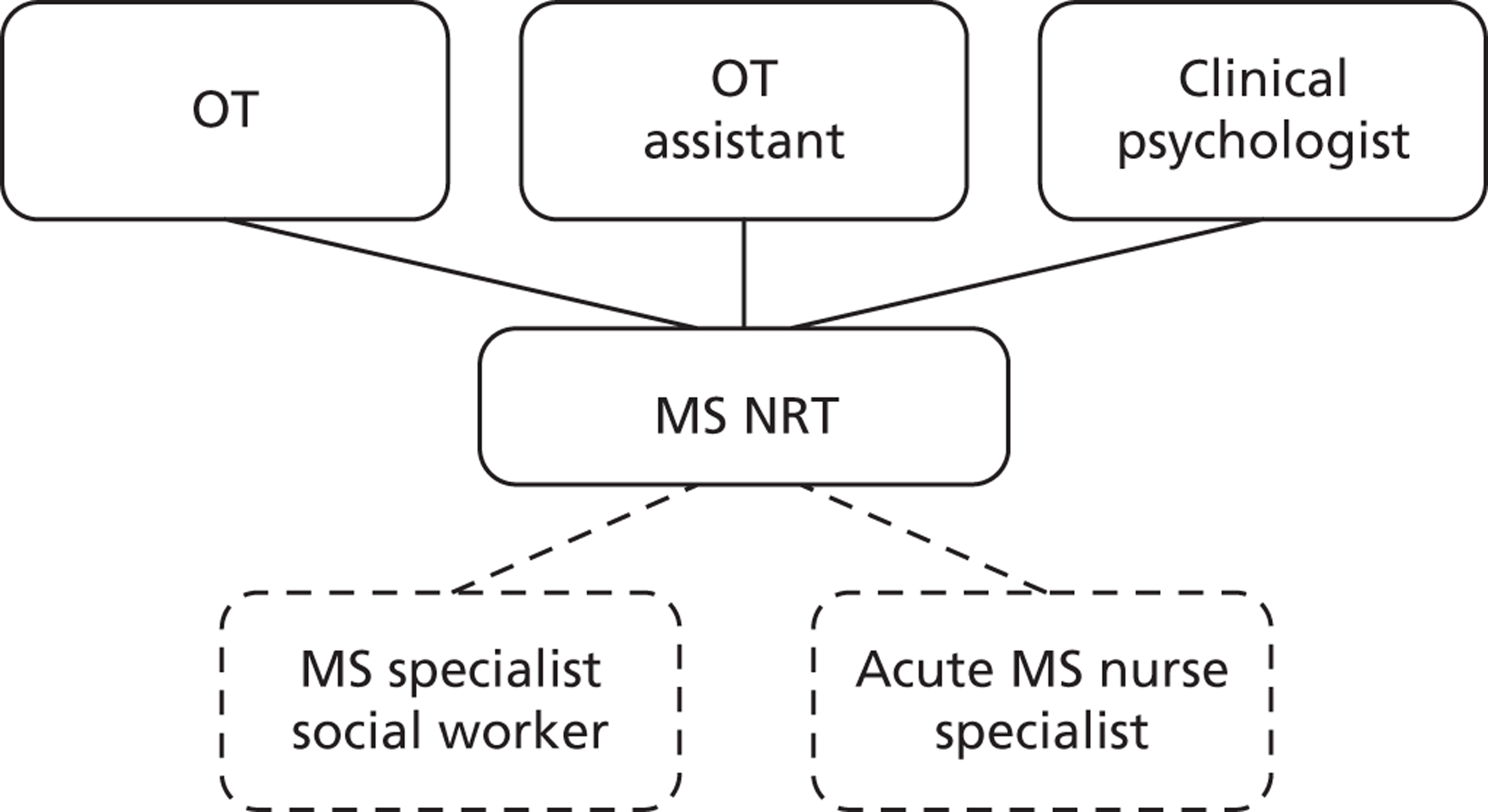

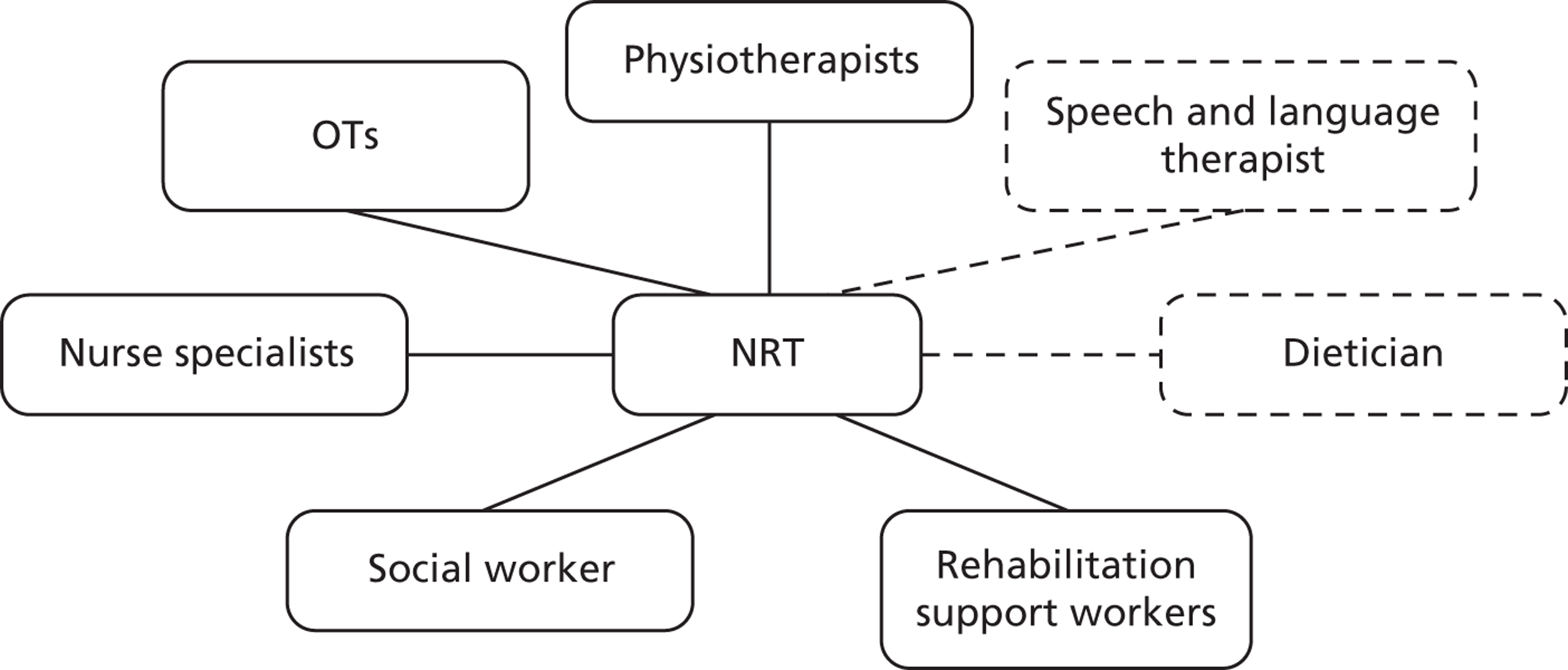

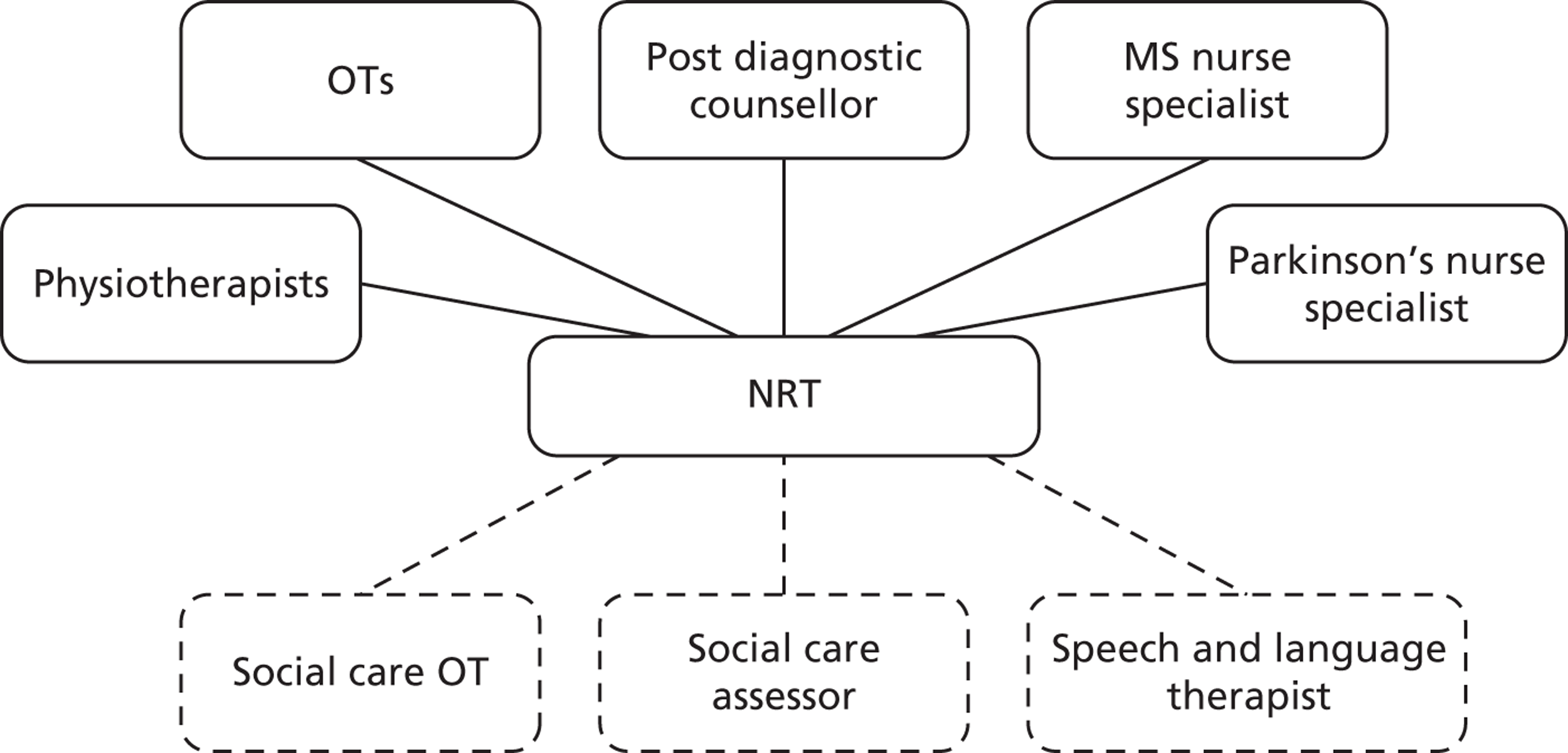

In one case site, we involved two condition-specific services provided by the same NHS trust, one for people with multiple sclerosis (MS) and one for people who had experienced a brain injury (BI). This was because the local service manager felt that a single team would not be able to produce the maximum sample size of clients we hoped to achieve for the OC implementation and evaluation (stages 2 and 3). In addition, the two teams were expected to merge during the research period and the service manager wanted both teams to be using the same paperwork.

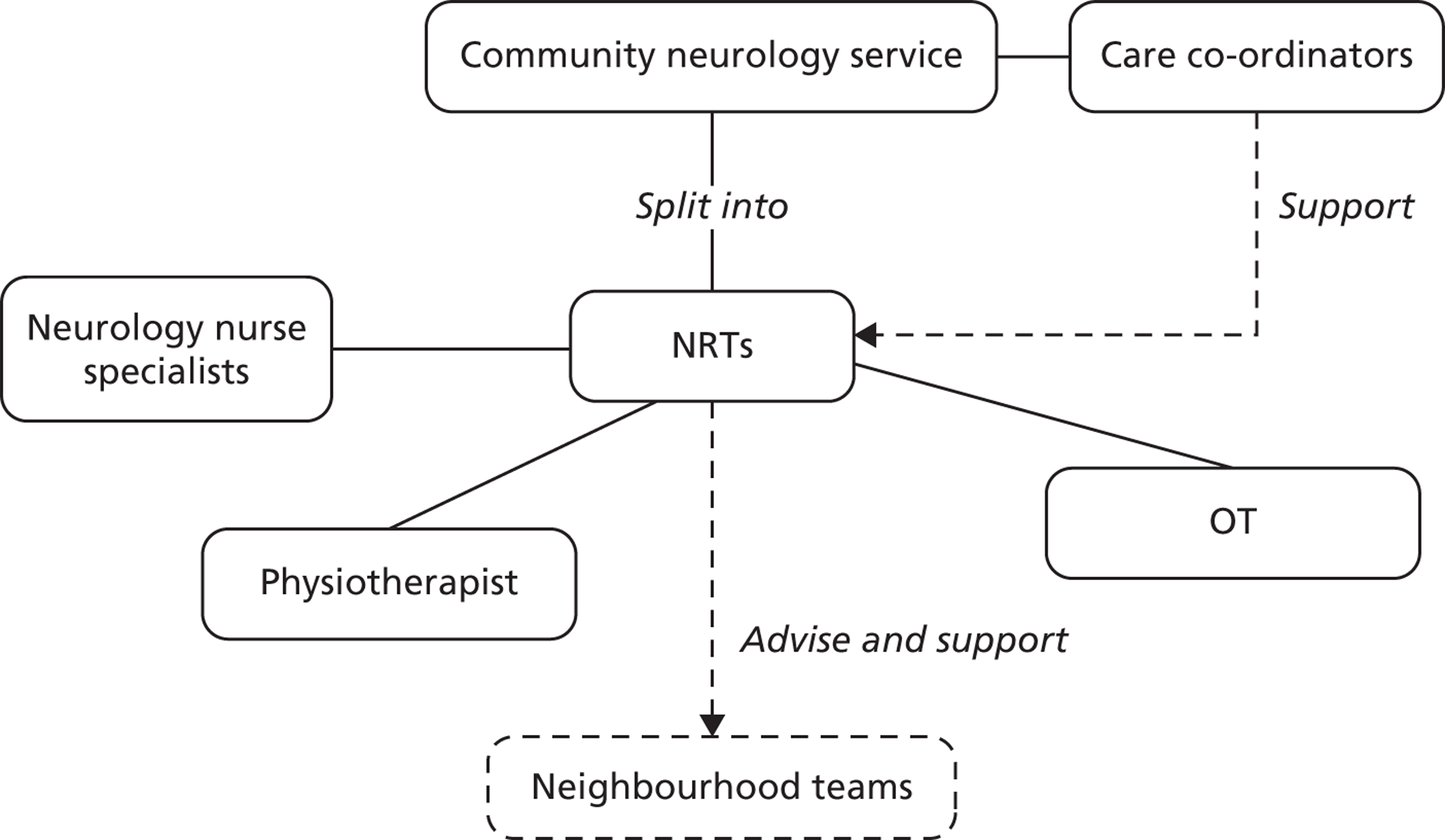

Our five NRTs, within our four case sites, represented different models of provision. For example, one of the teams was a joint health and social care team, three were based in the PCT but had semi-formal links with social care and one team had no links with social care. In this latter case site, the local authority (LA) declined to be involved with the research. The teams also differed in their relationships with acute services and how they involved service users and carers into their work. A detailed account of each of the teams is provided in Chapter 3.

Stages of research

The research took place in three stages and these are reported in turn.

Stage 1: understanding the service context and identifying outcomes

In this stage we had three aims:

-

to understand the models of integration for adults with LTNCs in each case site

-

to understand the relationship between NRTs and carers

-

to explore and identify the outcomes important to adults with LTNCs.

We used two forms of data collection for this stage of the research: documentary evidence and in-depth, semistructured interviews. We had also planned to collect data via observation of strategic meetings. Data collection for this stage took place between August 2010 and June 2011.

Documentary evidence

We collected three main documentary sources: national policy and population resources, local policy and strategy documents, and service-based assessment documents. Throughout the fieldwork period, new and additional documentary evidence was collected as we learnt about it.

National resources were used to identify official demographic statistics and national policy directives, providing a wider context to the research. Local documentary evidence included publications about local policies, services and strategies, such as PCT and public health annual reports and board discussion papers. These data were largely descriptive and were used to help develop a profile of integration and services for people with LTNCs within each of the case sites. We collected local documentary evidence via interview participants, key commissioning contacts and the NRTs and also accessed publicly available documents via local organisational websites. Where appropriate, we analysed these documentary data alongside interview data so that we could triangulate these in our analysis. This involved charting relevant documentary information into the analytical framework (as a separate ‘case’). We also used information in the documents for contextual purposes in describing the case sites. In addition, we collected examples of the ‘outcome’ and other assessment tools each of the NRTs used. This was to aid our understanding of the team’s general approach to assessment and to provide an insight into their current practice around ‘outcome assessment’.

Non-participant observation of meetings

As outlined earlier, we had intended to observe strategic meetings focusing on integrating/co-ordinating services for people with LTNCs. We were unable to do this in any of the case sites because there were no relevant meetings available for us to observe. Strategic teams including, for example, local implementation teams (LITs) that had developed in response to the NSF for LTNCs31 either had been disbanded or were suspended for the duration of the research. Further information about lack of strategic meetings is provided in Chapter 4.

In-depth semistructured interviews

We undertook interviews with commissioning and strategic staff, staff in the NRTs, people with LTNCs using the teams and carers of the people with LTNCs.

Interviews with organisational staff

To understand the structural integration arrangements of the organisations in the case sites, we conducted interviews with NHS and LA staff involved in commissioning and development of services for adults with LTNCs (hereafter referred to as ‘organisational staff’).

An initial interview was undertaken first with our key contact in each case study site. This person was typically a senior manager involved in service development. We then used a snowball approach to sampling,75 whereby our key contact identified other staff members involved in developing and/or commissioning services for adults with LTNCs. All subsequent interviewees were asked to identify any relevant individuals to approach. All of the relevant organisational staff identified were invited to participate in an interview. We assumed that all staff would be over 18 years old, be cognitively able to give informed consent and understand English well enough to take part in an in-depth interview.

All those invited to an interview were sent an invitation pack, either by e-mail or by post depending on the contact details we had for them. The pack contained a covering letter/e-mail, an information sheet, and a response form (see Appendix 1). Organisational staff were asked to return the response form directly to the research team, indicating whether or not they were willing to participate. Those who did not wish to be involved were given the opportunity to provide a reason, but were advised that this was entirely voluntary. Any reasons for not taking part were recorded. By using the response form, we were able to avoid recontacting people who did not wish to participate. Reminder packs were sent 3 weeks after the first invitation. If no response was received to this invitation, the person was not contacted again.

If a response was received indicating that a member of staff wanted to participate, they were contacted to clarify any issues, answer any questions and arrange a time for an interview. The interviews were conducted by telephone or in person, depending on the participant’s preference. Before telephone interviews were conducted, participants were sent a consent form to complete and return. The researcher signed the consent form, took a copy and sent it to the participant for their records. The original was stored securely by the research team. When conducting interviews in person, the consent from was completed in duplicate prior to the interview commencing and a copy given to the participant for their records. All participants were advised that they could ask questions, raise concerns or withdraw from the study at any point in the process.

Interviews focused on current structural arrangements, integration at different levels of the organisation, the factors that influenced integration, and future directions. Participants were also asked to provide, or direct us to, any documentation that might be relevant to the research. Participants were given the choice of a face-to-face or a telephone interview. Where participants consented, interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were given the option to view their transcript. All organisational staff agreed to allow audio recording and none asked to see their transcript. Interviews lasted between 30 minutes and 1 hour.

We were unable to set a target sample size for organisational staff interviews because the case sites had very different structures. It might be sufficient to interview one or two staff members in one case site, for example, while in another site we might need to interview several people to gather the same level of information. Thus, we intended to recruit and collect data until we achieved data saturation (see Appendix 8, note d) or, for stage 1 service information, until we had a map of local LTNC services and an understanding of how these worked together. A total of 15 organisational staff were recruited across our case sites. Table 2 summarises the number of organisational staff we approached for participation, and the number who agreed to participate, by case site. Further details of the sample are reported in Chapter 3.

| Site | NHS organisational staff | Social care organisational staff | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invited | Interviewed | Invited | Interviewed | |

| A | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| B | 6 | 3 | 4 | 1 |

| C | 6 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| D | 6 | 4 | Social care in this site declined involvement in the research | |

| Total | 21 | 11 | 8 | 4 |

As Table 2 indicates, 14 staff who were invited did not take part. Six of these did not respond even after a reminder letter and the remaining eight people declined. Reasons for declining to take part were that they were too busy (n = 4), the interview was about issues outside their remit (n = 2) and that they were retiring (n = 1). One person did not provide a reason.

We struggled to recruit NHS commissioners, particularly in sites A and B. We continued to try to recruit organisational staff throughout the first 18 months of the research to get this information, without success. This thus creates a gap in our understanding of the NHS and/or joint commissioning arrangements in these sites. In site D, social care declined participation in the study and, as such, our understanding of organisational integration arrangements in this site relies upon documentary evidence and the accounts of NHS staff.

Interviews with neurorehabilitation team staff

To understand each NRT’s model of practice and their approach to general and outcome assessment, we conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with NRT staff and other NHS and LA staff who worked closely with them. The process for recruitment, consenting and data collection followed that outlined above for organisational staff.

We asked NRT staff who we interviewed to identify professionals outside the team with whom they were ‘integrated’ and these staff were also invited to participate. For four of the teams, we invited all NRT staff to take part to ascertain different professional perspectives, but as the fifth team was large we invited a range of staff to represent the different professions within that team.

Interviews focused on the NRT’s structure and processes, including those around integration, relationships between the NRT and PCT, and factors affecting integration at practice level. Participants were also asked to provide examples of both their general and outcome assessment documentation. Using the same process as with organisational staff, interviews took place either in person or via telephone, were audio recorded and transcribed, and lasted approximately 1 hour.

We recruited staff in the team and practitioners who worked with the team. The size of NRTs differed across the case sites and this is reflected in the number of staff we could invite, and who agreed, to participate. Twenty-eight practitioners (team and non-team staff) were recruited across the four case sites. Table 3 summarises the number of team and non-team practitioners we approached and who were interviewed. Further details of the sample are reported in Chapter 3.

| Site | NRT staff | Non-NRT staff | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invited | Interviewed | Invited | Interviewed | |

| A | 5 | 5 | 2 | 2 |

| B | 9 | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| C | 7 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| D | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 25 | 23 | 5 | 5 |

As Table 3 indicates, one team member in site C and one in site D who were invited did not take part. The person in site C had agreed to take part but had to withdraw due to work commitments and we did not receive a response from the person in site D.

Interviews with people with long-term neurological conditions

To explore and identify the outcomes important to adults with LTNCs, we conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with clients using the NRTs in each case site. We ‘piloted’ interviews with four people with neurological conditions and their carers and adapted topic guides accordingly.

We aimed to recruit clients representing the range of conditions and different service needs that the NRTs covered. They were eligible if they had a LTNC, were existing clients or had been clients of the NRT within the previous 6 months, were aged 18 years or over, and were cognitively able to give informed consent and participate in an interview (as judged by the team using their usual cognitive assessment processes).

The NRTs identified clients who fulfilled these eligibility criteria and distributed invitation packs. We agreed to reimburse the cost of an independent advocacy agency to assist clients who required assistance to read the invitation documents and complete the response form but no client took this up. Packs contained an introductory letter and information sheet explaining the research and what taking part would entail, as well as response sheet, a demographic form and a freepost envelope (see Appendix 1). Clients were asked to complete and return the demographic form and the response form, indicating whether or not they were interested in taking part, directly to the research team.

Each pack was given a unique code and the NRTs kept a record of who received them. We contacted the teams regularly to find out which packs had been sent, and if we had not received a response with that code, we asked the NRT to send a reminder pack. Through this approach, the research team did not know the personal details of the NRT’s clients except those who agreed to take part and the NRT were not aware of clients’ decisions about participating, only that they had responded. Before interviews began we took consent following the procedures outlined for organisational staff interviews above.

The interviews focused on issues and outcomes that were important to the participant (using Harris et al. ’s3 outcomes framework to guide the discussion) and also whether or not, and how, the NRTs helped them to deal with their main concerns and to achieve the outcomes that were important to them. We also asked if they had a carer who we could invite to take part in a separate interview. People with LTNCs were given information about support organisations at the end of the interview.

As with the other types of participants, people with LTNCs were also offered the choice of in-person or telephone interviews. Interviews were audio recorded with the participant’s consent and transcribed. All service user participants chose to be interviewed in person and all agreed to audio recording of their interview; none requested to see their transcription. Interviews lasted between 30 minutes and 1.5 hours.

We intended to recruit a maximum of 10 people with LTNCs per site. This decision was based on experience in previous SPRU studies around LTNCs and around outcomes that indicated that this sample size would achieve data saturation across the dataset. A total of 35 people with LTNCs were interviewed across the four case sites. Table 4 gives details of the number of service users invited and that participated, by site. Further details of the participants are reported in Chapter 3.

| Site | Invited | Interviewed |

|---|---|---|

| A | 18 | 8 |

| B | 25 | 12 |

| C | 25 | 13 |

| D | 3 | 2 |

| Total | 71 | 35 |

As Table 4 indicates, approximately half of those invited agreed to take part. Of the other 36 people who were invited, one agreed to take part but had to withdraw due to an exacerbation of their condition, 26 did not respond despite being sent reminders and nine people declined to participate. Three people provided reasons for declining, all of which related to their neurological condition.

There were several occasions when we offered to contact participants’ NRTs about particular issues discussed during interviews but most declined, saying that they would discuss it with the team at the next visit. Even though we explained that doing so would mean that her involvement in the research would be disclosed, one participant asked that the researchers raise her issue with her NRT. A letter explaining the client’s concern was sent to the relevant NRT and a copy sent to the participant.

Interviews with carers

To explore integrated care from a carer perspective, we conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with informal carers or family members that service users identified as providing them with significant support. Not all the service users we interviewed had a carer or wanted to nominate a carer.

The process for recruitment, consent and data collection with carers followed those outlined earlier. The aim of interviews with unpaid carers or family members (informal carers) was to explore their experience of integrated care and to relate these experiences to the different service models in the case study sites. All carers chose to be interviewed in person and all agreed that the interview could be audio recorded and transcribed. As with the other participants, none requested to see their transcription. Interview length ranged from 30 minutes to 1 hour. Carers were given information about support organisations at the end of the interview.

We intended to recruit a maximum of 10 carers per site (one carer per client), though we recognised that not all service users would have, or would want to nominate, a carer for us to contact. A total of 13 carers were interviewed across the four case sites. Table 5 gives details of the number of carers sent recruitment packs, and the number interviewed.

| Site | Invited | Interviewed |

|---|---|---|

| A | 7 | 0 |

| B | 10 | 6 |

| C | 6 | 5 |

| D | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 25 | 13 |

As Table 5 indicates, 12 of the carers we invited to take part in an interview did not do so. Of these, eight did not respond despite a reminder being sent, one agreed but then withdrew before the interview without providing a reason, and three others declined to participate, only one of whom provided a reason, citing that they did ‘not like interviews’.

Analysis of stage 1 data

Data collected from in-depth, semistructured interviews were managed and analysed using the framework approach. 82 Analytical frameworks were developed based both on the issues addressed in the topic guide and on key themes emerging in the data (see Appendix 2 for frameworks for each data set). Data from transcripts were charted onto the framework and the research team discussed entries throughout this process to ensure consistency and accuracy and to review the ‘fit’ of the data. Data within the framework were analysed thematically.

The service user framework underwent several iterations. To do this, an initial, a priori analytical framework was developed based on Harris et al. ’s3 outcomes, which had also formed the basis of discussion for data collection. This framework did not adequately reflect the nuances of the issues discussed by people with LTNCs and although some of the issues discussed were similar to those in Harris et al. ’s3 framework, the people we interviewed discussed them in different ways. We met several times to adapt the framework to better reflect the data and data were recharted accordingly. This reflective/recharting process continued until we arrived at a framework of outcomes that most accurately reflected the data. Each outcome identified in the final iteration of the framework constituted a framework ‘theme’. Data for each outcome were analysed thematically in the first instance, and diversity within themes was explored. Relationships and overlap between outcomes were then explored. This analysis assessed whether or not the outcomes were important and provided a description of the parameters of each outcome. Data from service users about the outcomes were analysed as one data set across the four case sites.

Stage 2: developing and implementing an outcomes checklist for use in practice

Between June 2011 and October 2011, we developed an OC based on stage 1 service user data. In stage 2, the NRTs used this OC as part of their usual assessment procedures.

Developing the outcomes checklist in partnership with the neurorehabilitation teams

We worked in partnership with the NRTs in each case site to develop the outcomes into a checklist that would work for them in practice. The outcomes included on the checklist were standard across the case sites. However, to complement local documentation and approaches to assessment and service provision, NRTs were able to determine the format of their checklist and the way it was to be used.

Meetings were arranged with each case study site to discuss their preferences. A standard list of discussion points was used and included preference for paper or electronic checklists and the need for action planning to be recorded on the checklist (see Appendix 3). A draft checklist was prepared for each NRT and a process of feedback and changes continued until we were able to finalise a checklist each NRT was satisfied with. However, the OC continued to be developed throughout the implementation phase. We contacted NRTs monthly to monitor their progress with the checklist, to see how many people they had used it with and to give staff an opportunity to discuss any difficulties or benefits they were experiencing. We also met with each of the NRTs on several occasions to discuss ways to maximise its use and user-friendliness in practice. We made field notes at these visits.

Implementing the outcomes checklist in practice

Electronic and hard copies of the checklist were given to each team, along with guidance for use, including the parameters of each outcome (see Appendix 4). We asked the NRTs to implement the checklist with new and re-referred clients as part of routine practice for an initial period of 6 months (October 2011 to April 2012).

We were not prescriptive about how the checklist should be used. Rather, we encouraged teams to use it in whatever way suited them, as long as it was with new and re-referred clients. To monitor how the checklist was working in practice, in addition to the regular contacts and meetings we outlined above we also conducted an audit of clients’ care records held by the NRT.

Care record audit

When the OC was used with a client, NRT staff gave the client an invitation pack if they fulfilled the eligibility criteria for the study; that is, they had a neurological condition, were aged 18 years or over, were new or re-referred clients, and were cognitively able to understand the research and give informed consent to participate. Using the same process as that outlined above for service user interviews in stage 1, NRTs recorded who received invitation packs alongside the unique number on the pack so that reminder packs could be distributed as necessary. Researchers contacted the team on a monthly basis to ascertain the number of assessments undertaken using the OC and the number of invitation packs passed to clients. (As reported in the previous section, we also asked about their experiences of using the OC in practice at these monthly contacts.) The number of these might differ, because NRTs could use the checklist with any of their clients, while we only wanted to invite people who fulfilled our eligibility criteria to ‘take part’ in the care record audit (CRA).

The invitation pack included a letter and two information sheets (one brief and one in more detail) explaining the research and what being involved would entail, a demographic form, a decline form, a consent form and a freepost envelope. The consent form asked clients to indicate their agreement to the CRA and to indicate their willingness to be contacted for an interview at a later stage. Because of this complexity, we included a short information sheet. This gave NRT clients a chance to quickly make a decision about not taking part without having to read all the information. The brief information sheet advised those considering agreeing to the CRA to read the full information sheet, and contact the research team if they had any questions or concerns, before they made their final decision (see Appendix 1 for examples of these documents).

Clients were asked to respond, with their consent or decline forms, directly to the research team. The decline forms gave clients the opportunity to provide a reason for not participating. When consent forms were received, the researcher contacted the NRTs and arranged to visit to access that client’s care records. As we did not want to see information about any clients who had not given consent, one of the NRT staff was advised which notes to prepare for our visit. As such, clients’ participation was not confidential from the NRTs and clients were informed of this on the information sheet.

When we visited the NRT offices to complete the CRA, we used a proforma (see Appendix 5) to guide the information we recorded. We recorded information about, for example, members of staff completing the checklist, level of detail recorded and recording of actions.

We hoped to recruit a maximum of 25 clients per case site but all sites had difficulties in achieving this number despite, as described earlier, teams’ reassurances that this was feasible. In an effort to increase checklist use and recruitment, and after approval from relevant ethical and research governance bodies, we revised eligibility for the CRA to include review clients (as well as new/re-referred clients). However, only two teams (those in sites C and D) used the checklist during reviews. We also asked the NRTs to extend the implementation period. Two of the teams agreed to this, and the implementation period for these two sites was 10 months (i.e. from October 2011 until August 2012). In addition, we clarified with NRTs that they could use the OC as part of their assessment with any and all clients. This was so NRTs had experience of using the OC as part of practice and would be able to contribute to the evaluation stage of the research.

Invitation packs were given to 45 eligible clients, meaning that an OC was used with at least 45 clients. We know from telephone contacts and the evaluation phase of the research that at least another seven OCs were used (four in site C, two in site D and one in site A). Twenty-four clients agreed that we could monitor the use of the checklist in their care records. Table 6 summarises the figures by site.

| Site | Invited | Consented to CRA |

|---|---|---|

| A | 7 | 3 |

| B | 19 | 9 |

| C | 16 | 10 |

| D | 3 | 2 |

| Total | 45 | 24 |

As Table 6 indicates, just over half of those invited agreed to the CRA. Of the 21 clients who did not take part, 18 did not respond despite being sent a reminder and three declined to take part, none of whom provided a reason.

We monitored the use of the OC throughout the implementation phase, we amended the methods in response to recruitment difficulties and we amended the format of the checklist in some sites following staff suggestions. The findings are reported in Chapter 5 alongside the evaluation data from stage 3.

Stage 3: evaluating the use of the outcomes checklist in practice

In stage 3 we evaluated the use of the checklist to assess its use in practice, and whether or not and how it affected practice. We also wanted to seek feedback from service users with whom the checklist had been used in order to assess its face validity and ascertain whether or not any changes had resulted from the checklist’s use.

Neurorehabilitation team interviews/focus groups

We offered NRT staff the choice of taking part in an in-depth, semistructured interview or a focus group to discuss their experiences of using the OC in practice.

We sent NRT staff an invitation pack including similar documents and following the procedures outlined in stage 1. The invitation packs for this stage, however, included two information sheets: one informing staff about an individual interview and what this would entail and one doing the same for focus groups (see Appendix 8, note e). For four of the teams we invited all NRT staff to take part so that we would be sure to include different professional perspectives and to hear views from those who had not managed to use the checklist in practice. In the fifth team, which was large, we invited a range of staff to represent the different professions within the team, as well as staff who had and had not used the checklist. NRT staff in sites B, C and D chose to have a focus group and staff from both teams in site A chose to be interviewed separately.

Interviews and focus groups explored how the checklist was used, views of the checklist, and its perceived impact. The analysis of the CRA data highlighted additional ‘prompts’ to cover if they did not arise as part of the discussion, such as perceived similarities between outcomes. Interviews were conducted in person or via telephone, depending on what suited the participant. They were audio recorded and transcribed in all but one case. They lasted approximately 40 minutes. Focus groups were held in the NRT’s office, were audio-recorded with all participants’ consent and were transcribed verbatim. They lasted around 1.5 hours. For the person who did not want the interview audio-recorded we took extensive field notes and analysed these data alongside transcripts. In addition, we invited social care colleagues who worked closely with the teams in sites A, B and C to give their views (via interview or in writing/e-mail) on the content of the OC and how it might relate to their practice.

To provide different perspectives on the checklist, we intended to recruit all those who had used the checklist as well as members of the team who had not. Again, as team structures and the number of staff per team differed (see Chapter 3), no sample size was set. A total of 21 NRT staff were recruited across the four case sites. Table 7 gives a breakdown of recruitment by case site.

| Site | NRT Staff | Non-NRT Staff | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Invited | Participated | Invited | Participated | |

| A | 6 | 2a | 2 | 1 |

| B | 10 | 10 | 1 | 0 |

| C | 8 | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| D | 2 | 2 | Social care were not involved at this site | |

| Total | 26 | 20 | 5 | 1 |

Of the NRT staff who did not take part, two were ill on the day of focus group (C) and one in site A had agreed to take part in an interview but then withdrew due to scheduling conflicts. Of the three NRT members in site A who did not take part, one declined due to sickness and we did not receive a response from two people despite reminder packs being sent. The non-NRT staff invited were all social care practitioners who worked closely with the NRTs. (These relationships are explored in more detail in Chapter 3.) We received no response from three of them, despite reminders, and one declined because they had changed roles.

Evaluation interviews with people with long-term neurological conditions

We wanted to hear about service users’ experiences of having the checklist used as part of their assessment/review with the NRT, to hear about any resulting actions and to hear their views about the outcomes on the checklist.