Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1808/239. The contractual start date was in June 2009. The final report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in August 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Harvey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

In this introduction we present the policy context within which the research was set, and outline its aims and objectives. The literature which informed the analytical framework for the study is presented in Chapter 2 .

In 2008 when the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) Programme Management Practice call was announced, the Griffiths report into management in the NHS1 was over 25 years old. Although Griffiths (p. 1)1 focused on general managers who ultimately would be accountable for the performance of NHS organisations,2 middle managers in health care have subsequently been identified as key strategic actors. Hence, predictably, in many organisations the number and variety of their roles steadily increased. 3,4 The NIHR SDO Programme call seemed to reflect the need for organisation and management researchers to more directly address the concerns and challenges facing management5 and to realise the potential of research evidence to improve managerial practice and decision-making. 6 It also mirrored the more general emphasis on evidence-based practice that now predominates in health care.

During the development phase of the present research, the role and responsibilities of the NHS manager were being expressed in various ways. For example, they have been described as enablers within the framework of ‘system management, regulation and decision-making that guarantees safety, quality, equity and value for money’ (p. 71). 7 The NHS was deemed to be ‘rapidly becoming a rules-based system’ (p. 5)8 where managers are expected to ‘build capacity, to manage choice and competition’, and hold the organisation to account ‘through assurance mechanisms’ (p. 71)7 and transparent performance metrics. 9,10 In 2010 when the fieldwork commenced, the then new coalition government had announced a 45% reduction in management costs (to be implemented over the next 4 years). This was classed as the ‘largest reduction in administrative costs in NHS history’ (p. 43). 11 Thus, NHS managers and their work is a subject of enduring concern. In recent years in particular this has been set alongside the increasing involvement of clinical staff in management.

NHS management came increasingly into the media spotlight and to the fore of government concern during the period of data collection for this study (which took place during 2010–12; see Chapter 3 , Introduction). Thus, the King’s Fund report on leadership and management in the NHS, published in 2011 (p. 8),12 highlighted the ‘spectacular management failures of NHS management and leadership’ revealed by enquiries into the Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust and the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. The juncture between the drafting of this report and the preparation of the present final version, saw the publication of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Enquiry (Francis Report). 13 The report identifies catastrophic failures of care associated with the trust’s ‘ingrained culture of tolerance of poor standards’ (p. 43). 13 The trust board and senior leaders are held accountable for undue attention to financial issues and for paying ‘insufficient attention to the risks in relation to the quality of service this entailed’ (p. 45). 13 The subsequent government response, Patients First and Foremost: The Initial Government Response to the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry 14 signals measures to reduce ‘paperwork, box ticking and duplicating regulation and information burdens by at least one third’ and to set up a barring list for unfit managers, based on the barring scheme for teachers. The NHS Leadership Academy’s programmes are identified as a key arena for the harnessing of leadership skills to the provision of high-quality care. One part of this has been renewed attention to the challenges of the clinical manager role, i.e. those staff whose work combines the management/leadership of others with clinical work. For example, Patients First and Foremost14 identifies ward managers (termed nursing supervisory ward managers) as key to the delivery of safe, high-quality care to patients.

These recent calls are part of a longstanding agenda to reform clinical work and to improve efficiency and quality by forging more effective working relationships between clinicians and management in the NHS. 15,16 The most recent Labour government10 and the current Coalition government11 alike have emphasised the need to empower clinicians and promote clinical leadership. The White Paper Equality and Excellence: Liberating the NHS,11 which presaged the Health and Social Care Act of 2012,17 puts a strong emphasis on empowering front-line health care professionals and the incorporation of managerial and leaderships skills at all levels of clinical engagement (concerning not only doctors, but also other clinical staff). This seems to echo Griffiths’1 decades-earlier belief that clinicians are natural managers whose talents need to be encouraged and enabled. This expectation sits alongside the intent to reduce management costs by at least 45% between 2010 and 2014 and to remove layers of management in the NHS with the introduction of Clinical Commissioning Groups.

The NHS Modernisation Agenda and measures in its wake are premised on well-functioning relationships between doctors and managers18 and other clinical staff. Yet from the perspective of clinicians [by which we mean the spectrum of practitioners to include doctors, nurses, midwives and allied health professionals (AHPs)], the role of general middle managers has shifted over the last 20 or so years from that of administrators, who ‘provided an environment for clinical work to be done’ to controllers and implementers of top-down government policy. 19,20 Clinicians themselves have been increasingly recruited into roles which involve management as well as clinical duties. Hospital clinical directors were the vanguard of this phenomenon. It was noted early on21,22 that being a clinical director or the equivalent is a potential threat to the professional identity of the individual concerned as well as to collegiality and the autonomy of the professional group. Whether or not the long-standing tension between clinical professionals and general managers, and the particular challenges of the ‘hybrid’ clinical–manager role, are diminishing16,22 remains open to empirical investigation, especially as it is likely to be quite variable according to specialism and span of responsibility and control within an organisation.

When this research was at planning stage, the NHS Employers deputy director had stressed that ‘managers must look at what they can do to create a sense of identity among staff’ within their organisations, particularly in the midst of merger and restructuring activity in the NHS. 23 Yet relatively little consideration had then, or has since, been given to the identity of managers themselves within the health sector generally or in hospitals specifically, and even less to how this may influence how they go about their work. This especially has been the case at ranks below the top management or executive team level and particularly at the level of junior, or ‘front-line’, clinical and non-clinical managers.

An extensive and longstanding literature exists on the ethnography of management. 24,25 However, much of it focuses on private rather than on public sector organisations, such as the NHS. Hence the aim of this research was to undertake ethnographic research within the hospital sector to explore the identities of clinical and non-clinical middle and junior health-care managers and to chart the kind of work they do, including the mobilisation of their identities within the distinctive organisational context of the NHS. As part of this we wanted to investigate whether or not managers with different clinical and non-clinical backgrounds, and at middle and junior levels, have different sources of identification, leading to different identities, which, in turn, might shape their interpretations of their roles and the ways in which they carry them out.

Definitions

Middle and junior managers

Chapter 2 describes how the academic literature has sought to define junior and middle managers. It is somewhat vague and inconsistent. In general, definitions of middle managers are broad in conception and typically see them as below executive level, and above managers who oversee ‘front-line’ operations. Junior managers, by contrast, are generally defined as ‘front-line’ or ‘first-line’ managers, concerned with operational rather than strategic management and with a supervisory component; in fact, they are referred to as ‘supervisors’ in some contexts. The NIHR SDO Programme call did not define junior or middle managers. For the purposes of this research, we define middle managers as those in a management role below executive board level but above the level of ‘front-line’ operational management, whom we take to be junior managers. Within the pay grade structure this equates to those on Agenda for Change (AfC) bands 4–7 being classed as junior managers and those on band 8 and above (but not full members of the executive board) as middle managers. Even so, as discussed in Chapter 3 , actually distinguishing middle and junior managers (especially from job titles) and, to a lesser extent, clinical and non-clinical managers was problematic.

Identity

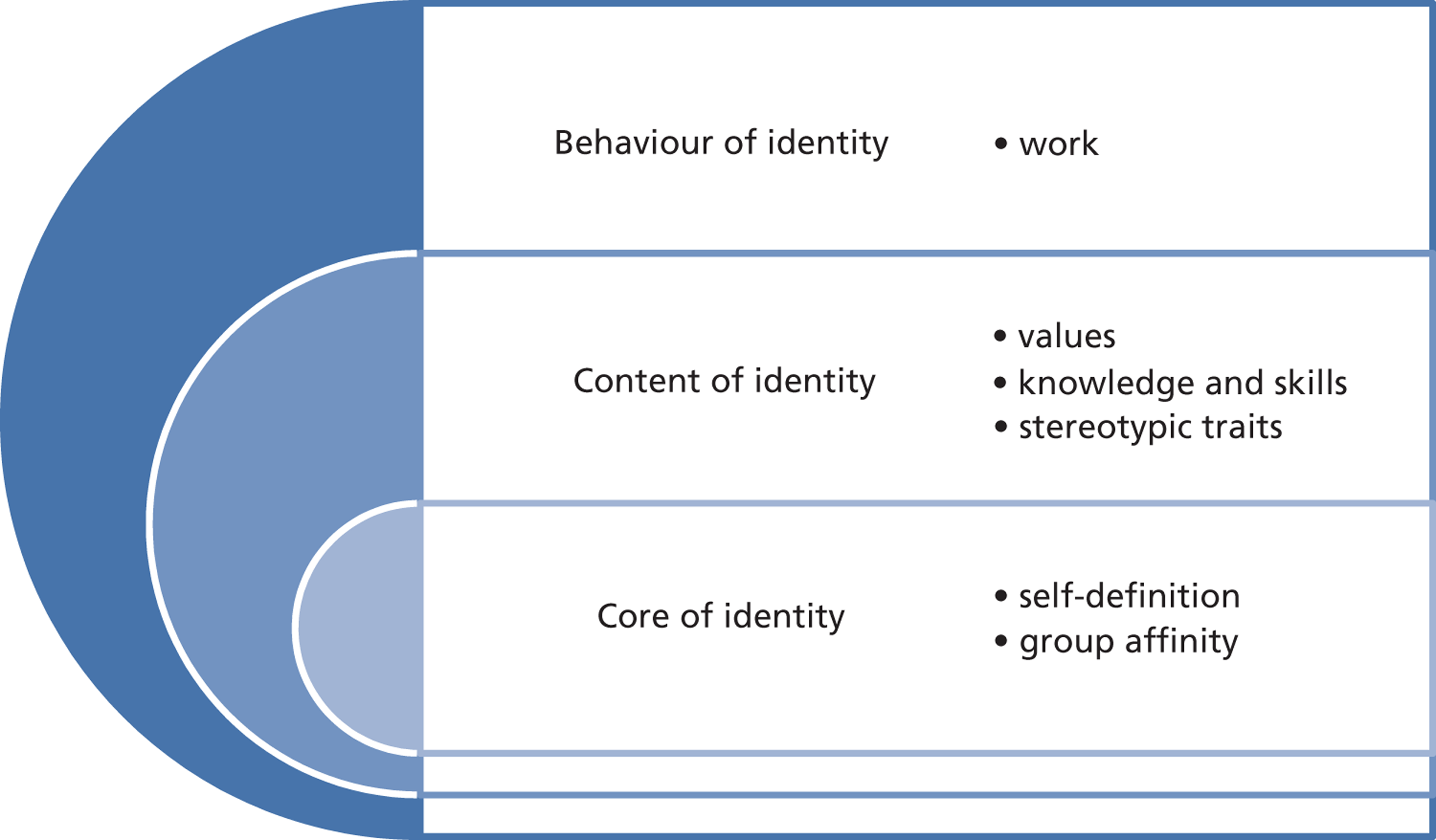

Once the research commenced we elected to adapt the model of social identity proposed by Ashforth et al. (pp. 328–31). 26 Here social identity is placed on a continuum from (i) the ‘core’ of identity (such as ‘I am’ a nurse, a manager), (ii) the ‘content of identity’ (e.g. values, motivations, beliefs, stereotypical personal traits), to (iii) the ‘behaviour of identity’ (i.e. the work that they do). As a composite we refer to elements of an identity, such as self-definition, values and work, as ‘facets of identity’.

Identities may conflict, converge and combine,26,27 thus we considered middle and junior managers as carriers of multiple identities. 13,27 This approach has an affinity with the recently published (after the completion of our research) Foresight report28 on future identities in the UK, which emphasises that contemporary identities are ‘multiple, culturally contingent and contextual’ (p. 1). 13 Managers’ identities may be seen as inherently in flux, as an organisation comprises ‘a series of influential discourses, often competing against each other, which create the possibilities of conflicting identities’ (pp. 212–13). 29 In this context, managers have been identified as ‘boundary spanners’,30 ‘translators’ and ‘integrators’,31,32 with a key role in mediating and facilitating between ‘tribes’, while not really coalescing into a ‘tribe’ themselves.

Wider research on the mobilising potential of identity has tended to focus on how shared identities, such as those associated, for example, with ethnicity, age or gender, or on how identification with a particular issue, such as racism, ageism or sexism, are collectively organised to effect change (e.g. social movements research). We are aware of no existing research which looks, as we do here, at how individual managers mobilise their identities in organisational contexts. We focus on the ‘mobilising capacity’ of those facets of their identities that strengthen and weaken their ability to influence others and the enactment of this capacity in the context of their work with others, which we call their ‘mobilising strategies’ (these concepts were derived inductively from the data).

Effectiveness

It has been argued that ‘the way that professionals view their role identity is central in how they interpret and act in work situations’ (p. 1515)33 and hence, comprehending managers’ identities seems essential to understanding their work performance and the performance of their team, unit or organisation. However, as has long been recognised34 linking facets of identity to managerial performance is particularly problematic. Our focus is on managers’ own self-reported effectiveness and what influences this in their assessments. We adopted a general definition of effectiveness as a multidimensional concept concerned with the attainment of desired outcomes. 24,35

Research aims and objectives

As advised by Mintzberg24 more than 40 years ago now, we sought to locate managerial work in the context of organisational structures and processes. Through this we hoped to discover whether or not managers with clinical and non-clinical responsibilities and at middle and junior levels have different sources of identification, leading to different identities, which might shape their interpretations of their roles and the ways in which they carried them out.

The primary typology of managers was based on the two dimensions of management level (middle or junior managers) and clinical engagement (whether the manager is counted as clinical or non-clinical staff). This generated four primary groups: junior clinical (JC), junior non-clinical (JNC), middle clinical (MC) and middle non-clinical (MNC). We also employ a more fine-grained categorisation according of ‘work groups’ (which maps back onto the four ‘primary groups’) for some aspects of the analysis which follows.

In summary, the aims and objectives of the research were:

-

to chart the work of middle and junior health-care managers, including identity work, and to produce an ethnography of the lived experience of middle and junior management within the specific context of the NHS

-

to explore the identities of managers (goals, values, motivations, beliefs and interaction styles) and how these are constructed, and further, how the performance of managers’ roles is shaped by these identities

-

to capture how middle and junior health-care managers leverage their identities to create success, establish trust and broker alliances to exert influence in different and various spheres and to determine how they interpret and take forward their ‘project’ to achieve organisational, group and personal goals within the framework of the NHS

-

to determine the influence of managerial identities on organisational processes and outcomes.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 provides an outline of the key bodies of research relevant to the research and outlines the analytical framework that guided the conduct of the study and data analysis. Chapter 3 details the research methodology and Chapter 4 provides an overview of the two research sites (two acute hospital trusts). Chapters 5–8 set out the research findings. Specifically, Chapter 5 explores the ‘facets of identity’ of the four main categories of manager. Chapter 6 analyses what managers do in their work, based on the more fine-grained work groups. In Chapter 7 we consider the managers’ self-reported accounts of how effective they are as managers and what facilitates and what inhibits their effectiveness. Finally, in Chapter 8 , we report on how managers seek to mobilise their identities to exert influence in the various and different spheres in which they operate. Chapter 9 summarises the main findings and outlines the recommendations for practice and for future research. Although of necessity the chapters build on and relate to each other, the report has been written in such a way that readers interested in particular findings can also read each chapter as a stand alone.

Chapter 2 Analytical framework

This chapter presents the analytical framework for our study. The first part (see Identity, Professions, and Junior and middle managers) offers a brief overview of research in three topic areas relevant to our investigation. The aim of the overview is not to provide a comprehensive survey of the literature, but rather to establish the key reference points germane to our conceptualisation of identity and its mobilisation in the context of managerial work in the NHS. The second part of the chapter (see Analytical framework) lays out our analytical framework.

Identity

Identity is defined as ‘a self-referential description that provides contextually appropriate answers to the question “Who am I?”’ (p. 327). 26 Identity as a concept helps to ‘capture the essence of who people are’ and ‘to explain why people think about their environments the way they do and why people do what they do in these environments’ (p. 334). 26

Identification is ‘the process by which people come to define themselves, communicate that definition to others and use that definition to navigate their lives’ (p. 334). 26

An individual’s self-concept consists of (a) personal identity, or ‘a person’s unique sense of self’ (p. 260)36 and encompasses their idiosyncratic characteristics, such as bodily attributes, psychological traits and interests, and (b) social identity, or ‘a person’s sense of belonging to some human aggregate’ (from a small group to a nation) (p. 21). 37 The focus of our project is on social identities.

Research on identity is prominent in anthropology, organisation science, philosophy, psychology and sociology. Of these, the research in sociology and organisation science is most relevant to the project topic.

In sociology, research on identity consists of two distinct strands (1) a (sociological) social psychology strand, which focuses on individual agency, and (2) a collective identity strand, which focuses on group agency.

The social psychology strand focuses on the identities of individuals and encompasses two inter-related research traditions. The first (e.g. identity theory38) emphasises ‘internalized role-identity meanings’ and examines ‘how the social positions that people occupy become stable, internalized aspects of their self-concepts’. The second (e.g. social identity theory39) emphasises ‘culture and situational context’ and investigates how ‘cultural meanings associated with identities are imported by actors into local interactions and how situational environments shape the localized meanings of the situationally relevant identities’ (pp. 480–4). 40

The collective identity strand focuses on the identities of groups, or collective identities, and examines how collective identities are constructed and influence mobilising joint action. The collective identities examined in this strand are primarily associated with the ‘holy trinity’ of social categories: gender/sexuality, race/ethnicity and class (p. 1). 41 A notable example of research in this strand is the studies of social movements. 40,42

In organisation science, research on identity traces its roots to the works of Simon43 and March and Simon,44 but has gained strength from the late 1980s following the publications by Albert and Whetten45 and Ashforth and Mael. 37 Recently, research on identity has been deemed ‘one of the fastest growing, most fertile, and . . . most contested’ research areas in organisation science46 impacting nearly all research domains in the field. 26 Identity and identification are considered as ‘root constructs in organizational phenomena’ because ‘they speak to the very definition of an entity – an organization, a group, a person’ and because they ‘situate the organization, group, person’, which is essential for interaction between the entities (p. 13). 47,48

Research shows that identity and identification are essential for the well-being of both individuals and collectives (groups and organisations).

For individuals, the two basic motives for – and the outcomes of – social identification are (1) self-enhancement and (2) uncertainty reduction. Self-enhancement (or self-esteem) underpins the striving for positive intergroup distinctiveness: ‘a belief that “we” are better than “them”‘. Uncertainty reduction is associated with social categorisation: ‘People . . . like to know who they are and how to behave and who others are and how they might behave’ (p. 120). 48 An additional motive/outcome, specific to work context, is employee strengthening, or a process of increasing individual capacity to endure stress and take on new challenges. Employee strengthening is associated with a particular type of social identity, dubbed ‘positive identity’, variously interpreted as ‘infused with virtuous qualities’, entailing ‘subjective feelings of self-regard’, or keeping ‘the multiple facets of the identity . . . in a balanced . . . relationship’. Positive identity leads to employee strengthening, because it helps to build social resources, i.e. ‘the number, breadth, diversity, and quality of relationships employees have at work’ (pp. 268–73). 46

With regard to collective outcomes, research has mainly focused on organisational identification, showing that such identification job satisfaction, intrinsic motivation, task performance, employee turnover, co-operation, teamwork, information sharing, organisational citizenship, creative and helping behaviours, customer orientation, improved organisational control, and positive evaluation of the organisation (though this list may be misleading) (pp. 336–7). 26

Despite the wealth of research on identity, considerable gaps remain in our understanding of this phenomenon, especially with regard to work-related identities.

Thus, the research on work-related identities has focused largely on the identification with the organisation as a whole (‘organisational identity’), whereas other loci of identification, namely work groups, organisational units and occupations, have received little attention (p. 348). 26 In particular, research on occupational and professional identification has been ‘sporadic’, though more frequent recently33,49,50 and the topic of managerial identity has been particularly neglected (for notable exceptions). 50,51 Hence, researchers have primarily concentrated on how managers manage the identities of other groups (e.g. medical professionals; see Covaleski et al. 52) and of the organisation as a whole, but largely disregarded the identities of the managers themselves. Within the research on the identities of managers, the identity of junior and middle managers has received much less attention than the identity of senior management; and the identities of those working in public service contexts have received far less attention than those working in the private sector (p. 5). 53

Our project addresses these gaps, contributing both to better understanding of management in the NHS and to the broader research on identity.

We also note that research on mobilising identities has been mainly confined to identity mobilisation in the context of social movements, with particular reference to social category identities, such as gender, race and class. We were unable to find any research on identity mobilisation in the organisational context and with reference to occupational/professional work.

Professions

The changing role of the professional worker in the 21st century has been identified as of critical sociological importance. 54

Early accounts of professions were based primarily on studies of the liberal professions (especially medicine) and focused on their distinctiveness from other occupations, cataloguing their traits and documenting their (successful) quest for power and autonomy. 55–57 These accounts clearly differentiated between professionals and managers. 58 The latter were described as depending for their power on their position within, and knowledge, of a particular organisation, whereas that of the former stemmed from abstract knowledge and was independent from organisations.

More recently, however, the emphasis has shifted to reflect new realities as the privileged position of traditional professions has been threatened by globalisation, technological change, neo-liberal ideologies,59 the encroachment of managerialism60 and the spread of ‘new professions’ (such as ‘knowledge workers’). 61,62 The boundary between managers and professionals has also been blurred by the increasing professionalisation of management and the co-optation of professionals into managerial jobs. Yet, although some have argued that the rise of new forms of professionalism advances co-operation and reduces barriers between occupational groups, others have observed the persistence of the classic patterns of professionalism, based on status hierarchy and exclusion. 63

Particularly germane to this research is the literature on the relationships between managers and (other) professionals in health care. For expediency, in what follows we present a stylised composite picture of this literature.

Most has focused on clinicians – as managers and vis-à-vis managers. Clinical and managerial logic are usually portrayed as incompatible and hence conflicting. Yet, with the advent of New Public Management (NPM), clinicians have been drawn into management processes, both indirectly, by having to contend with the increasing organisational constraints (e.g. leaner budgets, closer control of performance), and directly, by assuming managerial roles64,65 and moving into ‘hybrid’ (clinical and managerial) organisational positions. 66 As Kirkpatrick et al. (p. 121)67 relate with reference to physicians, extending clinical leadership in the hospital sector has become an ‘international fashion’ though how it is enacted and the level of engagement varies considerably and depends very much on local conditions. Research frequently has found that clinicians are reluctant to engage in managerial work,68 but are also uncomfortable with the idea of non-medics taking decisions that affect patient care69 and may be motivated to enter management by the desire to influence the direction of change. 66 Nurses see management as a step up the nursing career ladder, whereas medics see it as a step away from what really matters. 70 Most clinicians, on entering management, strive to maintain their clinical responsibilities and are keen to disassociate themselves from the term ‘management’. 71 This has led some to conclude that the boundaries between medicine and management are no longer sustainable. 72 As Kuhlmann et al. relate, organisations, such as hospitals, are ‘“switchboards” of clinical practice, where “medicine meets management” and control is made and remade’ (p. 723). 72

In post, many clinical managers see themselves as performing a critical boundary role, translating between different groups,33 and nurses in particular come to espouse managerial definitions of professional work. 73 At the same time, many feel isolated from other clinicians (the feeling exacerbated by hostility from their former colleagues)66 and ‘caught in the middle’ between the expectations of subordinates (to represent clinical interests) and the demands of senior management (to run efficient and effective services). 74 Qualitative research by Spehar et al. 75 in Norway on nurses’ and physicians’ journeys into management found that most had not anticipated a career in management but were persuaded into it. Most were thrown into the position unprepared for the challenges, which they had to learn to deal with ‘on the fly’ (i.e. with insufficient training).

Getting into management does not necessarily mean subjugating a clinical agenda to a managerial one. Indeed, as a detailed analysis of one US manager reveals, it can mean finding oneself on the boundaries of several discourses, such as the profession-specific discourse of medicine; the resource-efficiency and systematisation discourse of management; and the ‘inter-personalising discourse devoted to hedging and mitigating contradictions’ (p. 15). 76 In the UK, clinical directors have been shown to subvert market discourse by making rhetorical appeals to ‘service quality’ and to ‘market demand’ in order to bargain for extra resources, defend the status quo,77 and to counter managerialism by asserting their capacity to be ‘close to the customer’ in a way that management cannot. 78

Nor do the differences between clinical and managerial logics necessarily lead to a conflict. As Reay and Hinings79 demonstrated, based on their research on health care in Canada, a rivalry between these logics may be managed by a collaboration that allows the collaborators to maintain their independence (e.g. differentiating medical decisions from managerial decisions, seeking informal input from medics as part of decision-making processes, and working together against the Government). Similarly, drawing on ethnographic case studies of Dutch health-care organisations, Stoopendaal80 suggests that rather than provoking conflict between different interest groups, the position of non-clinical managers as ‘outsiders’, can allow managers to serve as a tie connecting these groups.

Clinicians may also become ‘managerialised’ without entering the ranks of management. As Waring and Currie81 argue, medics may draw managerial expertise into their professional practice in order to stave off managerial encroachment by taking responsibility away from managers (‘co-optation’), adapting existing professional systems to better reflect the aspirations of policy (‘adaptation’) or circumventing management systems (‘circumvention’) by emphasising the superiority of their own systems.

Yet, however blurred, boundaries between clinicians and managers persist, even when clinicians become managers. Thus, Hoque et al. 82 showed a clear divide between consultant managers and non-consultant managers in how they perceived each other and their own roles: whereas non-clinical managers spoke of being an interface between management and medical staff, promoting a quality service, fulfilling the daily needs of clinicians and patients, and improving the environment in terms of training, recruitment and personnel; clinicians alternatively talked about having a blueprint for the NHS and delivering it. Consultant managers, who retained a ‘strong identification with their profession’ were also left feeling unduly constrained, whereas non-consultant managers saw themselves as agents of government and their role as delivering targets and centrally derived objectives.

Junior and middle managers

The literature on managers mirrors management hierarchy, with senior managers attracting the most attention and junior managers the least. Furthermore, whereas the research on middle managers generally and in the NHS in particular, has burgeoned in the past two decades, the research on junior managers peaked between the 1940s and 1970s, and then petered out recently, with a paucity of studies in the health-care context.

Junior managers

The delineation of junior management has been a contentious issue. Some authors have used terms such as ‘junior manager’, ‘front-line manager’, ‘shop-floor manager’, ‘team leader’ and ‘supervisor’ interchangeably,83,84 whereas others have distinguished between supervisors, who engage with workers directly and only implement decisions at an operational level, and front-line managers, who deal with workers through the supervisor and possess delegated authority. 85 We follow Hales86 in treating supervisors and ‘first-’ or ‘front-line’ managers as parts of one entity, in which various functions of ‘management’ and ‘supervision’ are distributed in different ways among different positions, and refer to them jointly as junior managers.

Traditionally, the role of junior managers (as depicted, for example, in the research on industrial supervisors and foremen that proliferated from the 1940s to the 1980s87,88) was fairly clearly and consistently defined as encompassing planning, scheduling and allocating work, monitoring output and conduct of work, checking equipment, ensuring safety and cleanliness, dealing with unforeseen staffing, equipment and production problems, maintaining discipline, handling disputes, training, counselling and record keeping. 89,90

More recently, in his review and survey of 135 organisations in the south of England, Hales86 relates that organisational changes, such as the spread of team-working, flattening of organisational hierarchies and devolution of budgetary responsibilities from middle to junior management, have engendered a shift in the junior manager’s role. Though some have suggested that these changes entail the decline of supervisory responsibilities, Hales86 asserts that they have strengthened the supervisory core of junior manager’s responsibility (especially in the light of increasing external regulations), while adding a panoply of managerial responsibilities, relating to stewardship, translating strategy into operations and business management.

Given this intensification of core supervisory duties with additional devolved managerial responsibilities, Hales (p. 174)91 suggests that junior managers construct a ‘precarious coping identity’, which may have potentially negative consequences for their work performance.

The literature highlights the importance of junior managers, who ‘direct as much as two-thirds of the workforce and are responsible for the part of the organisation that typically defines the customer experience’ (p. 2). 92 Yet, it also acknowledges that junior managers are primarily seen as ‘cogs in the system’ and have limited flexibility in decision-making. They have considerable power over operational matters, some power over the people management, little or no power over resources, and a limited capacity to influence upwards in the organisation. 93

Overall, however, our review indicates that, in the past two decades, there has been insufficient research on junior management, particularly in professional organisations and the health-care sector. Our project, therefore, fills a gap in the literature.

Middle managers

Similar to junior management, the delineation of middle management has been a thorny issue: the boundaries of the ‘middle’ are contingent on organisational structure and so the ‘middle’ may extend across several levels of management. 51 Generally, however, ‘middle management’ refers to the managers situated ‘below the top managers and above first-level supervision’ (p. 1192). 94

Also similar to junior management, there have been considerable debates about the impact of organisational changes on the role and responsibilities of middle managers (for an overview, see Thomas and Linstead51). Some believe that changes such as developments in information technology (IT) have significantly limited the role and undermined the position of middle managers,95 whereas others hold a more optimistic view, suggesting that ‘a slimmer middle management in a time of rapid change has a more important role to play than in the past’ (p. 43). 3 In the context of NPM, the position of middle managers has been equally equivocal: strengthened by the emphasis on management96 but threatened by the focus on cost-improvements.

There is a burgeoning literature that argues that organisational performance is heavily influenced by what happens in the middle of the organisation, rather than at the top (for overviews, see Dopson and Fitzgerald3 and Wooldridge et al. 94), and that middle managers are key strategic actors. Middle managers are a linking-pin between the strategic apex of the organisation and the operating core (p. 70). 97 They ‘mediate, negotiate and interpret connections between organisations’ institutional (strategic) and technical (operational) levels’ (p. 6). 98 Nurse managers appear to be particularly well suited for linking operational and strategic management71 and managing relationships between various categories of staff (particularly doctors and nurses). 3 Middle managers are seen to perform the critical roles of interpreting and framing strategic objectives for front-line staff, ‘selling’ strategic ideas to executive management and elaborating on the detailed content of strategic change99,100 and boundary-spanning. 101 Their work also frequently goes beyond their job description (which generally concerns standard general management roles, such as staff management, representation, monitoring performance standards) to embrace the management of major organisational changes (e.g. the relocation or expansion of a service to a new site, the adoption of new technology; the reconfiguration of staff skills to provide more effective use of resources). (See Fitzgerald66 for clinical directors.)

Yet, similar to clinical managers, middle managers also feel ‘caught in the middle’, being required to be both team players and executioners. 101,102 Further, at least in the NHS, middle managers’ potential strategic contribution is constrained by ‘a powerful professional cadre of core employees’ (i.e. medics) and by ‘the changing priorities of government policy’ (p. 1326). 103 Although frequently portrayed as instruments of Government in the public sector in respect of cost control and targets,104 middle managers tend to resist changes that they see as politically imposed and unnecessary or inimical to public services. ‘Hybrid’ managers, drawn from the clinical ranks, have an additional challenge of experiencing the conflict between their professional and managerial roles. 4,64,70

A new twist on junior and middle management has been introduced by a recent shift of emphasis by policy-makers from management to leadership. 99,100,105 Leadership has been advocated as means of reinvigorating public services (p. 770)106 and viewed as an ‘identity’ that should be utilised across organisations, not just by those at the top. In particular, in the NHS, various grades of staff (from matrons to operating assistants) have been given the designation ‘leader’. 107 This move might have been particularly welcomed by clinical managers that have been traditionally reluctant to identify themselves as managers. However, although there is much talk about the shift to leadership, there is little detail about how it is exercised in practice. Thus, Martin and Waring107 note that the effectiveness of newly designated leaders is limited, they can be effective only as long as what they do is consistent with the existing organisational arrangements and power structures.

Analytical framework

We use the term ‘analytical framework’ to signal that we consider our work as exploratory rather than aimed at testing or refining particular theories.

This analytical framework consists of a set of ‘sensitising’ concepts108 and ideas that guided our empirical investigation.

Identity

In order to examine the process and outcomes of mobilising identities, we needed first to map the social identities of the junior and middle managers in the NHS and establish what was characteristic of their identities. Although we acknowledge that social category identities (such as gender) and non-work-related identities (e.g. parent) might be important, our project focused on occupational/professional identities.

To describe the managers’ identities we adapted the model of social identity proposed by Ashforth et al. (pp. 328–31). 26 Their original model portrays social identity as a continuum that encompasses (moving from the narrow to the broad formulation): (1) core of identity, including self-definition (‘I am “A”’), importance (‘I value “A”’), and affect (‘I feel about “A”’); (2) content of identity (i.e. values, goals and beliefs, stereotypic traits, knowledge, skills and abilities); and (3) behaviour of identity. Our adapted version of their model is presented in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

A model of identity.

We refer to particular elements of an identity, such as self-definition, values and work, as the facets of identity.

An individual’s identities may:

-

conflict – when there is ‘an inconsistency between the contents of two or more identities, such as a clash of values, goals, or norms’

-

converge – so that different identities become aligned and reinforce each other, and/or

-

combine – so that different identities are compartmentalised (pp. 354–9). 26

Social identities are ‘relational and comparative’ (p. 16)39 because individuals develop the self-definition and the evaluative component of identity by contrasting the group with which they identify with a salient other group.

An individual’s identity is further ‘verified or falsified by experiences provided by interactions with similar others’ and by the ways one is described by others (p. 208). 109

Identities evolve, fluctuate and change. Individuals learn identities through the processes of identity enactment and sense-making (reflecting on the reactions to the identity enactment). ‘Much if not all activity involves active identity work: people are continuously engaged in forming, repairing, maintaining, and strengthening or revising’ (p. 626). 110

Effectiveness

Within the framework of NPM it is usual to connect effectiveness with quality, safety and financial targets. 111,112 This ties effectiveness to objective ‘performance indicators’ which in turn are associated with the attitudes, actions and achievements of individuals. Accordingly, we expected that these ‘hard’, evidential forms of effectiveness would be vital for most managers.

However, we also anticipated that managers would imbue the notion of effectiveness with a wider meaning, because in the health-care environment the achievement of effectiveness occurs in the ongoing interaction between people. Thus effectiveness is also ‘softer’, diffuse, processual and difficult to tie to hard outcome measures.

Mobilising identity

As noted above, the extant literature provides little, if any, guidance on identity mobilisation in organisational context and on the mobilisation of occupational/professional identities. Perhaps, even more importantly, it only discusses identity mobilisation as a group phenomenon that contributes to collective action. In contrast, this research does not deal with group or collective action (indeed, one would be hard pressed to conceive of the grounds for and the forms of such action in our empirical context). Hence, we had to navigate the uncharted waters and develop our own conceptual structure to explore how junior and middle managers mobilised their identities.

The dearth of existing research on the mobilisation of individual identities means that we need to anticipate some of our results not yet presented in order to explicate our analytical framework. As discussed in Chapter 8 , we found that identity mobilisation was an individual rather than a group project, even though the individuals mobilised their social identities as members of particular professional groups. This identity mobilisation mainly took the form of individual action and was directed at the members of other groups within the organisation: the junior and middle managers’ subordinates, superiors and peers (colleagues at the same ‘lateral’ level of organisational hierarchy). The goal of this mobilisation was to influence these others to act in the way that would enable them to achieve their own effectiveness (variously defined, as above). To influence others, the managers drew on the specific facets of their identities that strengthened their ability to influence others. We termed these facets mobilisation capacity. The enactment of the mobilisation capacity in the context of a relationship between the manager and others we termed mobilisation strategy.

Chapter 3 Methods

Introduction

We ascertained that the best way to capture the lived experience of middle and junior, clinical and non-clinical, managers was to situate their work within its organisational context. This follows from our theoretical approach. Identities are recognised to be highly contextual. In other words, they are formed in interaction with others and can alter in their emphasis according to the interaction context in which the individual is engaged. 13 Thus workplace organisational contexts – which in the case of hospital trusts are likely to be wide in scope for some managers (see Chapter 6 , General parameters of managers’ work) – are important to capture empirically because they facilitate the formation and enactment of identities.

Two large hospital trusts in the same region with similar organisational structures (at the start of the fieldwork) were selected for study (see Chapter 4 ). To recap, we endeavoured to collect rich, ethnographic data to enable us to provide an account of the every-day work of these categories of manager, and to capture any associations between their sense of identity, how they mobilised their identities in the course of their work, and how this contributed or detracted from their self-reported effectiveness.

The main data collection method was one-to-one, in-depth, semistructured interviews, including a reflection on respondent-generated schematic work diaries. This was supplemented by shadowing of a number of respondents and the observation of meetings. The fieldwork took place consecutively in the two hospital trusts over approximately 24 months between 2010 and 2012. The research was approved by the Regional Research Ethics Committee in December 2009 (i.e. before the harmonised edition of the Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committees,113 which excludes research on NHS staff by virtue of their professional role from the National Research Ethics Committee, came into effect).

The two research sites

Case studies are an appropriate method to use when posing ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions, when the researcher has little control over events, and when the ‘focus is on a contemporary phenomenon in a real-life context’ (p. 2). 114 Case studies are generalisable to theoretical propositions, not to populations or universes. 114

The case study hospital trusts were both multisite organisations which had not yet achieved foundation trust status: we refer to them as Metropolitan Hospital Trust (Metropolitan; case study 1) and Cityscape Hospital Trust (Cityscape; case study 2). As discussed further in Chapter 4 , at the design, inception and negotiation of access for the study (via senior board-level individuals in each trust), the two trusts were virtually identical in size and structure. Our initial expectation was that using very similar organisations would enable us to identify whether or not the association between identity and work activity was common for managers in both trusts following Yin’s114 concept of multiple-case design using literal replication with embedded units of analysis [i.e. the four groups generated from the primary typology based on the two dimensions of management level (middle or junior managers) and clinical engagement (clinical or non-clinical staff)].

However, this was impeded by organisational restructuring at Cityscape following changes in key members of their executive team. Even though Metropolitan was not undergoing the same degree of organisational change, it was not static either. In fact, the dynamics that the two trusts faced such as multisite working, year-on-year efficiency savings and cost improvement programmes, and mergers of services are mirrored by trusts across the country.

Once the full phase of data analysis began (see Data analysis), it became apparent that the organisational factors affecting the work of the middle and junior managers were of a similar order across the two trusts. A further factor inhibiting comparison was the distribution of respondents (see Sampling method). For example, all scientist managers were located at Metropolitan and the majority of nurse middle managers at Cityscape.

We, therefore, did not seek to compare the two trusts but rather combined the two sets of data for analysis to generate cross-case theoretical generalisations, drawing out specific references to any organisational differences where they mattered for aspects of the managers’ work where appropriate.

Sampling method

The intention was to recruit 24 middle managers (12 clinical and 12 non-clinical) and 24 junior managers (12 clinical and 12 non-clinical) at each site, constituting a total sample of 96. We chose these numbers as they were deemed large enough to capture internal variation within each of the four categories for what we anticipated to be a diversity of jobs and sufficient for any differences across categories – such as between middle and junior managers, and between clinical and non-clinical managers – to emerge.

Respondents were purposively sampled and drawn in consultation with human resources (HR) staff in the two trusts with the aim of maximising variance across the organisation (i.e. managers were chosen from a wide range of directorates/divisions and specialities/departments occupying a variety of comparable roles across the two trusts). Prospective participants were contacted by HR staff by letter and those opting into the research then contacted the research team directly (see Appendices 1–3 ).

As shown in Table 1 , slightly more respondents were recruited from Metropolitan (52%) than from Cityscape (48%), and there is slightly more clinical (53%) than non-clinical staff (47%) in the overall sample.

| Category | Metropolitan | Cityscape | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Junior | Clinical | 11 | 12% | 10 | 11% | 21 | 23% |

| Non-clinical | 9 | 10% | 6 | 7% | 15 | 16% | |

| Middle | Clinical | 12 | 13% | 15 | 16% | 27 | 30% |

| Non-clinical | 15 | 16% | 13 | 14% | 28 | 31% | |

| Total | 47 | 52% | 44 | 48% | 91 | 100% | |

The achieved sample reflects difficulties in recruiting certain types of staff, predominantly non-clinical staff, notably JNC managers at Cityscape. Also, within the MC category, we experienced particular difficulties recruiting doctors (nurses, midwives and scientists are the major work category for MC managers, Table 2 ). This may reflect the more general observation within the two trusts of generating the involvement, participation and presence of medical doctors. For example, our observations showed that both trusts (but Cityscape in particular) experienced difficulties in getting medical doctors to attend meetings in sufficient numbers. It may also be the case that doctors were less likely to opt into the study, as they are less likely to think of themselves as ‘managers’.

| Work group | Metropolitan | Cityscape | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | MNC | JC | JNC | MC | MNC | JC | JNC | ||

| 1. Consultant managers | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||||||

| 2. Nurse and midwife managers | |||||||||

| (a) Middle | 4 | 10 | 14 | ||||||

| (b) Junior | 5 | 8 | 13 | ||||||

| 3. Scientist managers | |||||||||

| (a) Middle | 5 | 5 | |||||||

| (b) Junior | 4 | 4 | |||||||

| 4. AHPs | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||||||

| 5. Managers of clinical units | |||||||||

| (a) Middle | 10 | 2 | 9 | 21 | |||||

| (b) Junior | 5 | 3 | 8 | ||||||

| 6. Managers of corporate units | |||||||||

| (a) Middle | 5 | 4 | 9 | ||||||

| (b) Junior | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||||||

| Total | 12 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 6 | 91 |

The slight shortfall in the overall number of interviews (n = 91) against the target (n = 96) is not significant as it was still possible to reach analytical saturation when analysing the data for the four primary categories.

The sample is predominantly (75%) female. The only subcategory in which males exceed females is the MC managers at Metropolitan.

Table 2 illustrates the job titles of managers in each of the four overarching categories of managers. The NHS grading and pay system AfC115 allocates posts to one of nine pay bands based on the knowledge, responsibilities, skill and effort needed for the job. Band was not available for the whole sample. However, for those providing this information, all of the middle managers (both clinical and non-clinical) were within bands 8a–d, with one respondent in band 9. The JC managers were mainly band 7, with some band 6. JNC managers ranged mostly from band 5 to band 7, though one was band 4. Generally speaking, those classed as middle managers had larger ‘spans of responsibility’ than junior managers. ‘Span of control’ (defined as the number of the manager’s direct reports) often was larger for junior managers than for middle managers, though, again, there was variation within this (see Chapter 6 ).

Blurred boundaries

As already discussed, the terms middle and junior manager are contested terms. Grouping respondents into the four primary categories was not always straightforward. This is well illustrated by the following scientist manager:

Well, whether I’m classed as a middle or junior manager, or am I healthcare professional? Actually, I’m probably all of them.

MC 21

The boundaries of the middle extend across various levels of management and depend on specific organisational structures. 51 Unsurprisingly, therefore, some of those we classified as ‘middle’, self-identified as ‘senior’. The term ‘junior manager’ was particularly unfamiliar to most respondents. For example, when asked if the terms junior manager and middle manager were familiar, one respondent commented:

Not really, no, which is why I signed up in the first place, because I thought well, as far as I know, I was a middle manager because I manage some things in quite a lot of detail and I don’t manage others and there are people above me and there are people below, so I am probably in the middle then so . . .

MC 14

The line between clinical and non-clinical staff was not straightforward either. Some managers whose roles were non-clinical, and are classified as such here, were clinically qualified (e.g. in nursing or the allied health professions). The following radiography services manager was on AfC band 8a as a result of her clinical qualifications, but the scope of her activity was more similar to JNC managers on band 7. Highlighting the complexity, but also connectedness, she mused,

You know, you can’t think of yourself as . . . it’s hard to know whether you’re a middle manager, senior manager, or clinical person because you can one minute find yourself doing something which you regard as fairly low level, and the next minute you can be doing something that you think is very strategic and you feel it’s a higher level. But the whole thing goes together and so it’s hard to know, you know, you work as a team and the whole team working at all these different levels is about what you want to do.

MNC 45

Work categories

In some of the analysis – mainly Chapter 6 , which provides a textured account of ‘what managers do’ – we further subdivided the sample into what we call ‘work groups’ as follows:

-

group 1: consultant managers

-

group 2: nurse and midwife managers

-

– middle (e.g. matron),

-

– junior (e.g. ward sister)

-

-

group 3: scientist managers

-

– middle (e.g. consultant scientist)

-

– junior (e.g. team leader)

-

-

group 4: AHPs

-

group 5: managers of clinical units

-

– middle (e.g. division general manager, service manager)

-

– junior (e.g. administrative manager)

-

-

group 6: managers of corporate units

-

– middle (e.g. chief accountant, head of contracts and commissioning)

-

– junior (e.g. booking centre manager, business change manager).

-

Data collection

Interview questions

The flexible schedule of questions for the semistructured interviews was devised based on issues raised in the literature review (see Chapter 2 ) and the related concerns of the research proposal. Questions were grouped under six headings: current role; professional background; day-to-day work; management work; effectiveness/accountability; and mobilising identities. The content of the questions varied slightly to reflect what was anticipated to be the different work of clinical and non-clinical managers and of middle and junior managers (see Appendices 4 and 5 ).

Pilot interviews

The questionnaires were piloted with four managers at Metropolitan (two JNC managers, one MC manager and one MNC manager). As we judged the questions to appropriately capture the issues of interest, these interviews were included in the final sample of 91 respondents.

Diaries

Part of the interview involved using the diary-interview method. 116 The intention was that managers would keep a simple, brief, schematic diary for up to 3 working days prior to the interview (see Appendix 6 ). This was intended to generate the outline of a ‘concrete’ description of how they had spent the proceeding days (rather than a potentially idealised appraisal of their work) to be explored and fleshed-out during the interview (thus the diaries were a tool to generate interview data rather than data for analysis in their own right). This was modified during the course of data collection as it was found that some respondents routinely kept their own electronic diaries that could be used to the same end, and this was viewed by the team as preferable to duplicating effort by asking the respondent to replicate this process. Where a respondent had neither a paper nor an electronic version of the diary they were asked to choose a recent day to talk through.

The interview process

All of the interviews took place at the manager’s workplace, usually in their office or, if this was shared and a colleague was present, elsewhere in the work area. The length of interviews was on average 1 hour, although when the interviewee chose to extend them they were longer. The large majority of the managers spoke expansively about their work, generating a rich and detailed corpus of data for analysis (see Data analysis).

All consented for their interview to be audio-recorded. These were then professionally transcribed in full. Equipment failure meant that three interviews were not transcribed or transcribed only in part. In these instances the interviewer wrote up as much as they could capture immediately on its conclusion.

Shadowing

The weight of the analysis in this report rests on the interview data. However, we also wished to consider practices and discourses as they occurred in vivo and in situ117 [i.e. not only to explore what managers say they do (in interview) but what they actually do in ‘real-time’]. Shadowing involves observation and also asking questions which prompt a running commentary which helps to clarify and reveal purpose from the person shadowed. 118

In total, 16 managers were shadowed: four middle managers (two clinical and two non-clinical) and four junior managers (two clinical and two non-clinical) from each trust. Those shadowed were selected, post-interview, from the interview sample to represent a range of professional background characteristics, operating at a range of levels within the organisations.

The original intention was for shadowing to take place over 2 days, but, in practice, we had to negotiate what the managers felt to be ‘realistic’ and this was generally 1 day only. In view of restrictions of the Ethical Approval, we were required to withdraw during shadowing from situations which directly involved patient contact (on grounds of confidentiality). Hence, if shadowing took place in a ward or clinic, for example, we retired to a position some distance from the patient–staff interactions, such as the nursing station. Field notes were written immediately after the shadowing sessions.

Observations

Observation of meetings took place at both case study sites (12 observations per case study, n = 24) where middle and junior managers (including those who had been interviewed and, in some cases, shadowed) were present. These were varied. At Metropolitan, meetings observed included six operations group meetings, three directors group meetings and three directorate-level meetings. At Cityscape, a much wider range were observed, such as a review of services meeting, waiting-list meetings, divisional meetings, a project group meeting, a reconfiguration group meeting, a quality and performance meeting and an executive board meeting. The more dispersed spread of meetings at Cityscape to some extent reflects the more diffuse and project management working that characterises this trust.

We had hoped direct observation of interaction between different categories of managers at different levels of the hierarchy would enable us to see how, for example, those attending emphasised or de-emphasised certain aspects of their identities when interacting with colleagues (e.g. as clinician, as manager, as long-standing member of staff, etc.), thereby providing contextual information for the analysis of the interview data. However, many of the meetings observed – and, significantly, this seems to be a feature of key hospital acute trust meetings – had large numbers of people present (often between 15 and 25, or sometimes more) which made it very difficult to know the background of all present. In addition, some, such as operations group meetings at Metropolitan, appeared to be largely briefing meetings and, consequently, dialogues between those present was limited. That said, field notes from meetings furnished us with some useful background information about contextual factors and the ‘burning’ issues within the trusts which aided in the interpretation of the interview data.

Data analysis

The project generated a large volume of qualitative data in the form of interviews and field notes. As is common in qualitative research, the analysis ran alongside data collection. Thus the work to generate an initial coding frame began while the fieldwork was taking place at Metropolitan, the first research site. This was fleshed out and finalised while it proceeded there and began at Cityscape. The process of developing a coding frame is itself part of the analytical process, providing the researcher with an initial template against which to assess the data still being collected.

Data coding (interviews)

To promote reliability and validity we put in place a coding agreement process, which involved double-coding subsets of early interview transcripts and field notes from Metropolitan (site 1). Research team meetings were held to:

-

develop initial codes, check and re-check them against the interview data and to generate an agreed on coding frame

-

all of the interviews were then coded by two of the team members using NVivo [initially NVivo7 (QSR International, Southport, UK), then imported into NVivo9]

-

tree nodes were organised under six main categories: how work is experienced; identity; mobilising identity; the organisation; what work they do; and who (the latter covering such matters as educational and work background, prior experience and training). This was supplemented by the use of free nodes as the analysis progressed.

(See coding frame in Appendix 7. )

Rather than generating a coding frame for the shadowing data we drew on field notes to illustrate some of the issues which arose in interviews in relation to the mobilising of identities (reported in Chapter 8 ).

The analytical process

The data were analysed using qualitative and quantitative methods.

The qualitative analysis was based on the constant comparative method. 119,120 First, transcripts were read to ensure familiarisation with the data. The second step consisted of developing the coding frame, as already described. The third step involved the coding process, and the fourth step was the analysis of the NVivo nodes to explore associations and any possible patterns between key matters of interest such as identity, the work managers do, their self-reported effectiveness, and how they might mobilise their identities to achieve their goals. Themes of interest were highly interwoven with each other and embedded in the narrative accounts of personal experience making the analytical process particularly challenging.

The quantitative analysis methods were chosen depending on the objectives of the analysis and the type of data. As noted under The two research sites, case study research is concerned mainly with ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions rather than enumerating ‘who does what’. 114 However, quantitative analysis can be instrumental both for summarising ‘who does what’ and for examining the ‘how and why’.

Thus in Chapter 6 , in line with the objective to chart the work of MC and JC and MNC and JNC managers, we have summarised the more quantifiable aspects of the content of work (what managers do) and the form of work (how they do it) by providing numerical comparisons between the four primary manager groups and also between the nine work groups. Some of the data for these comparisons were quantitative in nature, such as the number of staff managers are responsible for and the average number of work hours per week. These were captured in descriptive statistics per group. Other data, such as cross-site working and responsibilities outside the trust, were partly translated into binaries (e.g. whether a manager worked across two sites or more) and presented as the numbers of respondents in each group who did cross-site work and had external responsibilities.

In Chapter 5 , in line with the objective to explore the identities of MC and JC and MNC and JNC managers, we undertook more extensive quantitative analysis. Following the theoretical model presented in Chapter 2 , which depicts identity as a continuum of facets, from the core of identity (self-definition and group affinity) to the content of identity (values, stereotypical traits, knowledge and skills) to the behaviour of identity, we sought to uncover the potential patterns of association (a) between the core and content facets of identity and the managerial groups, and (b) between the self-definition and other core and content facets of identity. Our initial intuition, which was derived from both the theory and the qualitative analysis of the data, was that the functional differences between clinical and non-clinical managers and the positional differences between junior and middle managers may relate to the differences in the facets of identity. Our other intuition was that the self-definition may be congruent with other facets of identity. To facilitate pattern recognition, we used the method of ‘quantitising’ or ‘the numerical translation, transformation, or conversion of qualitative data’ (p. 208). 121 Quantitative treatment of qualitative data is commonly undertaken ‘to form qualitative data in ways that will allow analysts to discern and to show regularities or peculiarities in qualitative data they might not otherwise see or be able to communicate, or to determine that a pattern or idiosyncrasy they thought was there is not’ (p. 210). 121

Thus, we extracted from the interview transcripts the responses pertaining to specific facets of identity, namely, self-definition as a manager, group affinity, values, and knowledge and skills (covering general educational qualifications, management qualifications, training, job tenure and work experience outside of the NHS) and grouped them into categories. Some data, such as the information on a person’s general educational qualifications, yielded themselves more easily to categorisation. (For example, for general educational qualifications, we mapped the highest reported level of education onto the Framework for Higher Education Qualifications (FHEQ)104 and then coded it into Level 5 or below, Level 6, Level 7, or Level 8.) For other data, we had to devise the categories based on our reading of the data and the extant theoretical constructs. (For example, for values, we distinguished between the responses reflective of a public service ethos and responses indicative of a performance ethos.) Then we coded the individual responses into these categories and constructed the contingency tables, cross-tabulating (a) a particular facet of identity with managerial groups and (b) self-definition with another facet of identity.

Here it should be noted that where data are listed as ‘missing’, this should not be interpreted as missing in the conventional sense employed in, for example, survey research. Rather it reflects the flexibility of qualitative interviews where not all questions are asked of all respondents.

We constructed contingency tables for all core and content facets of identity, with the exception of job tenure. (As job tenure was reported in years or months, we have provided descriptive statistics by managerial group and self-definition category and conducted Kruskal–Wallis and Mann–Whitney tests to establish whether or not the differences between groups or categories are significant). We then analysed these data using the Fisher’s exact probability test or chi-squared test, as appropriate, to establish whether or not there was a significant association between particular facets of identity and managerial groups or between self-definition and other facets of identity. Where the tests showed a significant association, we followed these with analysis of the strength of association, using Cramer’s V, and the analysis of the reduction in the error of predicting (a) a particular facet of identity from the managerial group (or vice versa) and (b) self-definition from another facet of identity (or vice versa), using Goodman–Kruskal’s λ. The results of these analyses are presented in the text and tables. In both chapters we also provide the qualitative analysis that supplemented the quantitative analysis.

Anonymity and confidentiality

We assured anonymity and confidentiality to our respondents. To preserve this, where respondents held quite distinctive roles, these have been made deliberately vague. Equally, where respondents talk about particular work areas or kinds of patient-related work these have been made as non-specific as possible to avoid identification. We have also avoided giving too much specific detail on the organisational structures of the two trusts in Chapter 4 . In Chapters 5 – 8 we use abbreviations (JC, MC, JNC and MNC) to describe manager level. The accompanying numbers are those allocated to the interviewee from 1 to 91. Where the number is preceded by P (e.g. P4) this indicates that this was a pilot interview.

Chapter 4 Research setting: case study sites

This chapter presents the background information on the two case study sites and provides the context for our analysis. It describes the activities, structure and performance of the two trusts and the recent organisational changes and management development initiatives within them.

As noted in Chapter 3 , the two sites were chosen because of their geographical proximity and organisational similarities (e.g. both being large acute trusts). The description in this chapter highlights further similarities and differences between the sites.

The data for the chapter were obtained from various sources, including:

-

publicly available documents produced by the trusts themselves (e.g. annual reports, websites)

-

independent publications/websites [e.g. Healthcare Commission; Care Quality Commission (CQC); internal documents, such as organisational charts and quality accounts, field notes from observations of meetings (see Chapter 3 ); and policy documents].

We have not referenced any of these sources either in this chapter or in the References section of the report in order to preserve the anonymity of the participating organisations.

Much of the information reported in this chapter comes from the financial year 2010–11, which provided a near complete overlap with the timing of the fieldwork undertaken.

The two hospital trusts

It should be noted that the research took place before the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act of 201217 which has established different commissioning arrangements to those described below and elsewhere in the report.

Both trusts are based in medium-sized cities in England and, at the time of the research, belonged to the same strategic health authority regions.

Metropolitan, which was formed in the late 2000s, comprises two hospital sites and liaised with two primary care trusts (PCTs) in its area. Formed in the early 2000s, Cityscape consists of three hospital sites and liaised with three PCTs.

Each trust employs over 10,000 staff and provides services for 2–3 million people in their city, surrounding areas, and nationally for specialist services. Metropolitan has approximately 1700 beds and Cityscape 1900 beds. Both trusts claim in their annual reports that they are among the largest teaching trusts in England and have among the country’s busiest emergency departments (each with over 160,000 accident and emergency patients treated annually). They also have high aspirations. Thus, at the time of the fieldwork Metropolitan was aiming to be the country’s best acute teaching hospital, whereas Cityscape wished to be the number one provider of emergency and specialist services in England.

When the research began (June 2009), based on the Healthcare Commission Annual Health Check for the 2008–9 financial year, both trusts were rated ‘good’ for use of resources (the effectiveness of resource utilisation). For quality of services (covering a range of areas such as patient safety, cleanliness and waiting times), Metropolitan was rated as ‘fair’ and Cityscape was rated as ‘good’.

At the start of the research period, both trusts were in the process of applying for foundation trust status and were seeking to achieve it by the end of our 3-year project, but neither did.

Both trusts were engaged in organisational change programmes (see Organisational change and management development initiatives within the trusts).

Financial performance

In 2010/11 Metropolitan achieved a surplus of £5M despite making cost savings of over £24M. Given changes to funding formulas, commissioners’ budgets, etc., the trust was aiming to achieve a surplus of £3M in 2011/12 despite having to make cost savings of over £30M. The XYZ Change programme (see below) was considered the key mechanism for achieving cost savings.

Cityscape achieved a surplus of £1M with cost savings of £31M in 2010/11, and was seeking to make further savings of nearly £40M in 2011/12.

Clinical performance indicators

Metropolitan achieved the 18-week referral target with a figure of 95%, Cityscape also achieved the target. Metropolitan’s emergency department dealt with 97% of patients within 4 hours, whereas Cityscape’s dealt with 94%. At Metropolitan 87% of cancer patients were cared for within 62 days of urgent referral against the national target of 85%, and 97% of cancer patients were cared for within 31 days of diagnosis against the national target of 96%. Cityscape also achieved both national cancer targets.

The larger of the two hospitals within Metropolitan was inspected by the CQC mid-way through 2010/11 and was assessed as meeting all essential standards of quality and safety. All three hospitals at Cityscape were assessed during the same period and were found to be compliant with all 16 outcome requirements.

Organisational structures

At the time when research access to the trusts was initially negotiated, they had similar organisational structures.

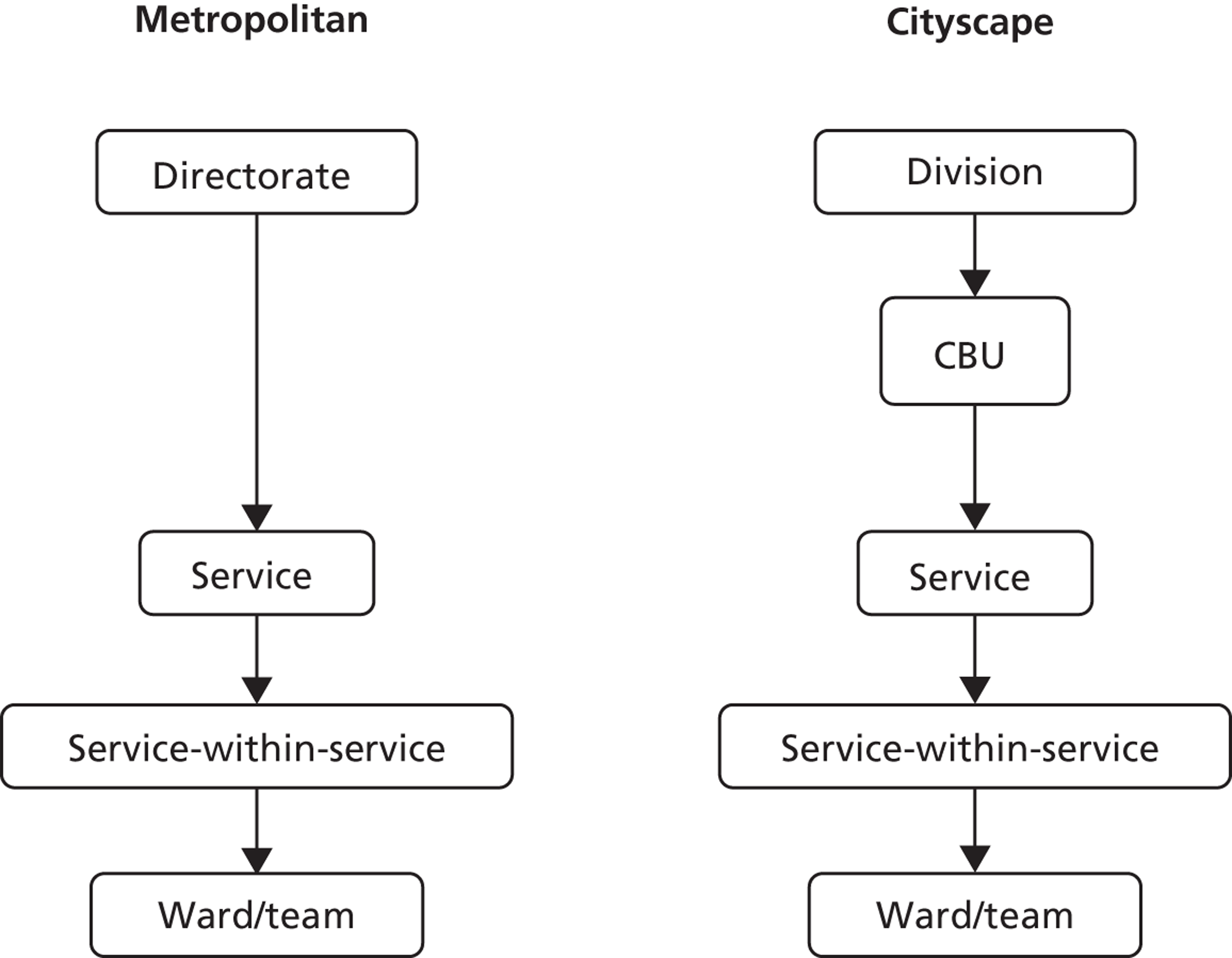

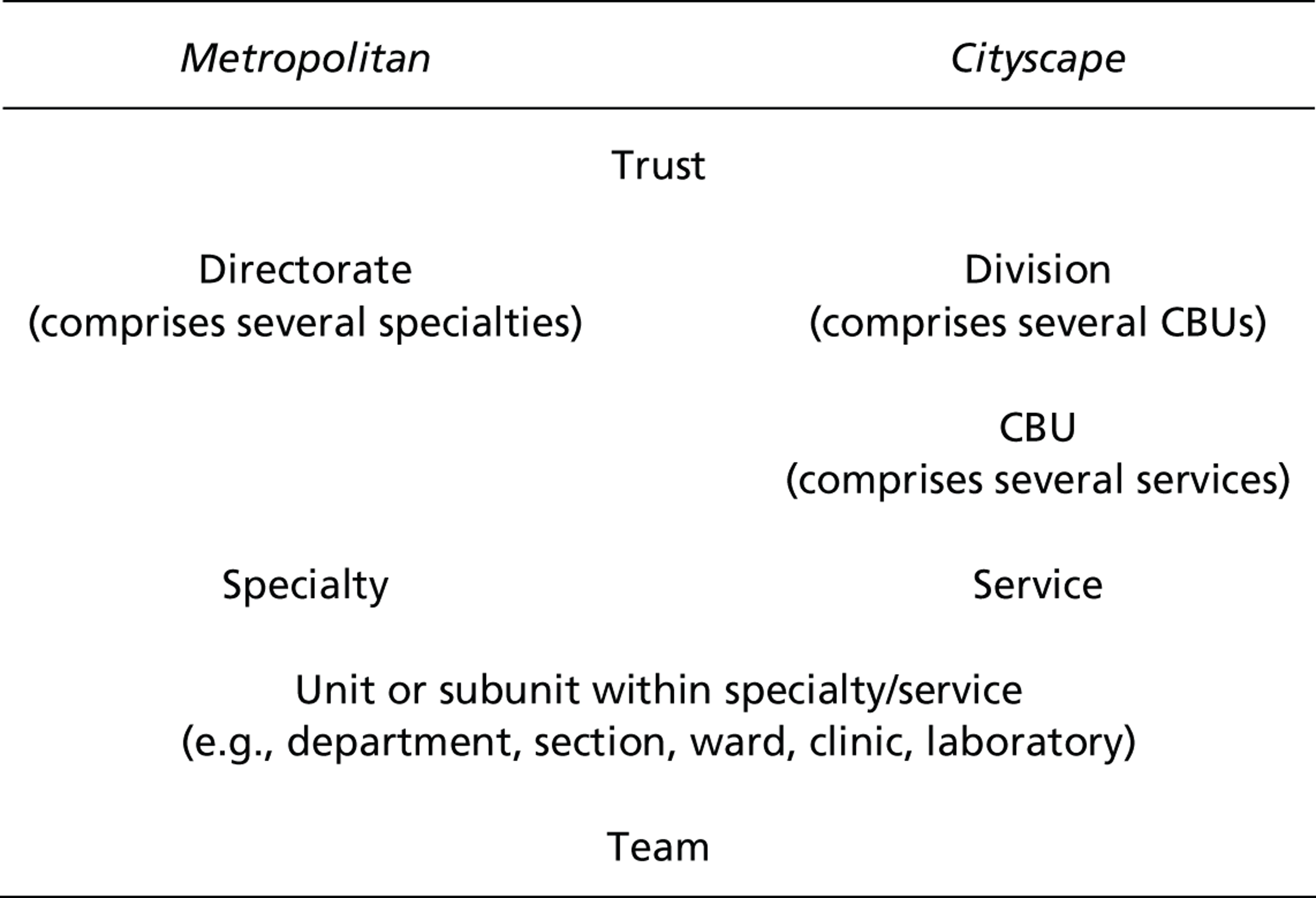

Metropolitan consisted of several clinical and corporate directorates each led by a clinical director, a general manager and a clinical lead, and was supported by heads of service and matrons that led each of the 50 or more service areas within the directorates. Each corporate directorate was led by an executive and a deputy.

Cityscape comprised a series of clinical and corporate directorates. Each clinical directorate was headed by a clinical director and a general manager and each corporate directorate by an executive or associate director. However, in 2010 a new structure was introduced, and the trust was organised into clinical divisions, with each division containing a number of clinical business units (CBUs) containing a number of services (a structure adopted by several other hospital trusts in England in recent years).

Therefore, the overall structure of both trusts consists of two blocks: (1) corporate and (2) clinical.

Corporate block

The corporate block consists of corporate directorates and is similar across the two trusts.

Thus, both trusts have eight corporate directorates, each led by a director who is a member of the board. In both trusts, four of these directors are executive directors and the other four are associate directors/advisors to the board.

The four executive directors’ directorates are nearly identical in name/function in both trusts and include (1) nursing, (2) medical, (3) finance and procurement and (4) HR.

The other four directorates somewhat differ in name and function and include:

-

in Metropolitan: (1) ‘trust secretary’ (e.g. governance, policies and procedures), (2) estates and facilities, (3) information and communication technology (ICT), and (4) operations

-

in Cityscape: (1) strategy, (2) research and development (R&D), (3) corporate and legal affairs, and (4) communications and external relations.

Clinical block

The clinical blocks are also similar across the two trusts, but there is a difference in the degree of aggregation and number of levels, owing to the corporate restructuring in Cityscape.