Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1002/29. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The final report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in September 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Bresnen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background to the research

Understanding how managers in the NHS access and use management knowledge to help improve organisational processes and so promote better service delivery is of pressing importance in health-care research. 1–3 Given the expectations we have of managers in the NHS to improve performance in the face of constant pressures for change, and the grave consequences of poor management,4 it is important to know that managers are at the leading edge of thinking in management theory and research. For this, it is key to understand how managers access ideas that can improve health-care delivery and are able to translate these effectively into a health-care setting.

Yet, despite a good deal of research that has begun to look in-depth at how managers in the NHS perform their roles, we have only limited understanding of how managers access management knowledge, how they interpret it and how they adapt and apply it in their own health-care settings. 5 There is also very little research that has tried to understand how the use of management knowledge relates to managers’ individual learning and development, how this ties in with their own development as ‘professional’ managers among different communities across the NHS. 6,7 Similarly, we know relatively little about how the organisational setting itself influences the ways in which managers access, make sense of, select, adapt and apply relevant management knowledge. 8

This research sets out to fill these gaps by exploring how middle managers in the NHS access knowledge and learning from various sources to apply, develop and improve management practice. In doing so, it recognises that there are different groups within management that have their own needs and perspectives and that draw upon different types of management knowledge (e.g. operational, financial), that management knowledge itself is often the subject of considerable debate (particularly when transferred from different contexts, such as manufacturing industry) and that managers are part of wider communities and networks of practice (NoPs) within the NHS and beyond that influence approaches to professional training and development.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the research is to investigate how NHS middle managers encounter and apply management knowledge and to examine the factors [particularly organisational context, career background and NoPs/communities of practice (CoPs)] that facilitate or impede the acceptance of new management knowledge and its integration with practice in health-care settings. Following on from this are three specific objectives:

-

to establish how occupational background and career influence knowledge receptivity, knowledge sharing and learning among health-care managers

-

to examine how relevant CoPs enable or obstruct knowledge sharing and learning

-

to ascertain which mechanisms are effective in supporting knowledge receptivity, knowledge sharing and learning/unlearning within and across such communities.

The research therefore emphasises the importance of understanding flows of management knowledge and learning as heavily influenced by the social and organisational context within which managers and their work are embedded. 8,9 These contextual influences – namely, their background and career development, the organisational settings in which managers operate, and the networks and communities to which they belong – are expected to have an important effect on the ways in which managers access and use management knowledge and how they apply it to their management practices.

Research context

Managerial capacity development is considered integral to the UK government’s strategy for implementing programmatic change connected to public service modernisation,10 particularly within the modern NHS. Reform in the NHS has closely reflected some broader trends in the private economy as market-based and performance management incentives have been introduced and competition has increased. 11 The emergence of new public management in public sector restructuring has led to changing demands on the managerial workforce. 6,7,12,13 Findings from such studies have been echoed in recent NHS research that has reported huge growth in the complexity of managers’ work owing to increased outsourcing and the need to deal with outside organisations, privatised hotel and cleaning services, private hospitals and private finance initiative companies. 14–16 At the same time, the devolution of authority and the flattening of hierarchies has given managers wider spans of control and broader responsibilities. 17–19

Coping with, and excelling within, these conditions requires the capacity of health-care managers to engage with, interpret, adapt and support the implementation of innovations and other advances in research. 20,21 Improving this capacity relies then on a clear understanding of the dynamics of knowledge flow at an individual and collective level and the social, political and professional landscape within which knowledge flows associated with management learning take place.

There has been, in the last decade, a renewed interest in how health-care organisations manage or mobilise knowledge, reflected in active debates on evidence-based medicine and evidence-based management. 1,22 This research has been given some impetus by studies such as the Cooksey review of publicly funded research into health care in 2006, which identified substantial ‘cultural, institutional and financial barriers to translating research into practice’ (p. 4, © Crown copyright 2006, A Review of UK Health Research Funding). 2 While a significant amount of research has been conducted into policy-makers and their relationship with new clinical and medical innovations,3,21 there is a pressing need for more research into the uptake of management research and innovative practice by NHS health-care managers and how this relates to their professional development as managers. 4 Moreover, there is a need to understand better how managers access and use knowledge in the context of wider NoPs and CoPs that operate at a more meso level and which are associated with the existence of relevant professional and personal networks. These not only provide access to different sources and types of knowledge and learning, but also help shape how managers make sense of and apply that knowledge and learning to the health-care context. 23,24

Locating health-care management

To identify these knowledge and learning processes accurately, there is a need to unpack further the notion of middle management. This is particularly so in the health-care sector, given the diversity of operational and functional groups and roles found within the NHS as well as the diversity of routes into NHS management.

Middle managers are traditionally a difficult cadre to define, as boundaries between levels of hierarchy in contemporary organisations are frequently unclear and demarcation is often ambiguous. 19,25,26 For the purposes of this study, middle managers were defined inductively as ‘people identified as such within the organisation, provided that they were part of a clear chain of management and involved in the delivery of an end service, being responsible for at least two subordinate levels within the hierarchy, and with at least one superior between them and the organisational executive.’ (p. 639). 25 This approach allows for a more contextualised understanding of the exact location and nature of middle management in the organisations studied, in contrast with an alternative approach that may tend to impose a more abstract definition on the data from the outset.

This definition also enabled us to attempt to encapsulate a broad range of health-care managers, with diverse professional, clinical and/or managerial experience and training, different career trajectories and varied managerial roles and responsibilities. It also enabled us to explore the distributed nature of management in health care27 as well as focus in on the levels at which conceptions of management and leadership may intertwine. 28 While it is important to somehow capture systematically such diversity, at the same time it is important to be able to pragmatically differentiate between distinct managerial cohorts for study. As will be explored in Chapter 2 , to do this we developed an initial taxonomy of management cohorts within the NHS that provided us with a framework for capturing and categorising the diversity of NHS middle managers that we could then refine more inductively as we moved into the empirical stages of the research.

Given the diversity within middle management, there is a need to understand not only the distinct perspectives on knowledge and practice that these differences may give rise to, but also the ways in which contextual factors and practices at an organisational level may combine to impact on orientations towards management knowledge within the managerial cadre.

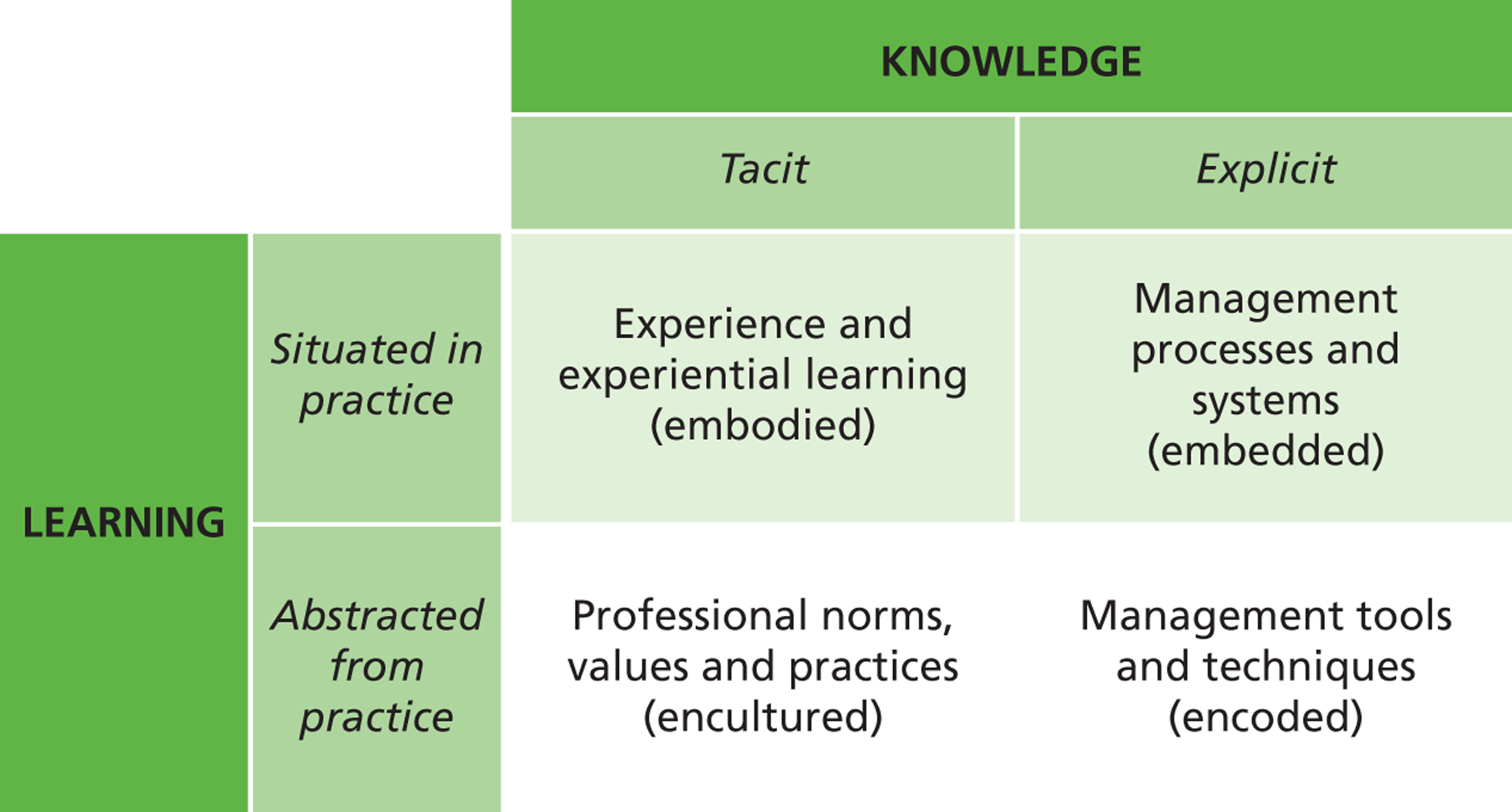

To understand the flow, translation and utilisation of managerial knowledge into practice in the NHS, we adopted an approach that was sensitive not only to the complexities (and contested nature) of that managerial knowledge base itself, but also to the socially constituted and situated nature of knowledge and learning. That is, the research approach paid particular attention to the ways in which the translation of managerial knowledge into practice is strongly influenced by that particular context. 29–31

For example, while the provision of bespoke management training through the nationally provided NHS Graduate Management Training Scheme (GMTS) provides some collective socialisation for NHS managers, previous educational and employment history, foundational professional affiliations and function-specific training programmes promote quite substantial differences in the orientation towards knowledge of NHS managers. 21,32 Furthermore, such differences in interest and perspective highlight the potential importance of power relations as they relate to flows of knowledge and learning occurring within and between managerial groups. 33–35 As the managerial knowledge base is continually contested and debated,4,36 it becomes important to recognise that the acquisition and use of such knowledge to effect change is not necessarily neutral in its effect.

Knowledge, networks, community and identity

Research into flows of knowledge and learning through and between groups has evolved significantly in recent years from earlier, more mechanistic models that tended to stress knowledge codification37 and that treated knowledge (including management knowledge) as an object or commodity that could readily be transferred from one setting to another. 38 Advances in this area draw inspiration instead from understandings of knowledge flows as socially constructed processes,39 which are inevitably shaped by social and power relations within organisations and across wider communities. 40,41

Of particular value here are the insights generated from the CoPs literature. 42–44 CoPs link individuals and groups with shared interests and professions and provide the networks of social and professional relationships within which information and experiences are shared and, through which, learning and professional identity develop. Lave and Wenger42 refer to the socialisation processes involved in becoming part of a CoP as legitimate peripheral participation and make strong connections between the situated learning that occurs as individuals engage in joint practice and the development of professional identity. Importantly, therefore, CoPs can extend within and/or beyond organisational/functional boundaries to encompass the wider networks of professional relationships within which individuals are embedded. 9 In some cases, of course, these can become formalised and institutionalised in what we would recognise as clearly demarcated professions which are able to achieve occupational closure providing accreditation based on a distinct and accepted body of knowledge. 45

Consequently, understanding how CoPs – whether institutionalised or not – promote knowledge sharing and learning prompts one to seek to understand not only the barriers and enablers of knowledge sharing which reside in organisational cultures and subcultures,35 but also how processes of knowledge sharing, knowledge diffusion and learning occur within wider networks of knowledge and practice and how these processes, in turn, relate to the ongoing development and transformation of managerial and professional practice and identity. 9,46,47

Within the NHS, flows of management knowledge into practice are also inevitably affected by the socialisation associated with induction into, and progression within, the various communities that constitute the managerial cadre. Although a number of researchers have applied practice-based perspectives to explore these distinct epistemic communities in health-care management and their impact on the development or implementation of cross-cutting initiatives,48–50 so far there has been little attempt made to focus on the reproduction of knowledge and transmission of learning through and between the various CoPs found within NHS middle management. Divisions within health-care management that mirror political and epistemic differences between policy makers and various professional communities have been well recorded. 23,32 Yet comparatively little attention has been directed towards exploring how such differences influence processes of knowledge and learning associated with the translation of management knowledge into practice, via distinct patterns of socialisation and learning associated with the immersion of managers in differentiated managerial and professional activity.

The various (cross-cutting) NoPs within which managers are embedded are likely to affect, in complex ways, their knowledge sharing and learning and, through these, their managerial identity and orientations. So, for example, research on the constant interaction between NHS managers and colleagues in various clinical domains frequently highlights significant differences in perspective on the nature of knowledge or evidence informing practice. 1,22 These professional/occupational boundaries, in which two or more professional groups are engaged in joint practice, and the mechanisms used to translate knowledge at such boundaries, have a significant effect on the knowledge base of managers and their ability to influence practice across the organisation, and more widely. 35,46,48,49 Therefore, they constitute important knowledge and learning processes that can only be properly understood by inductively tracing the effects of such cross–cutting NoPs and CoPs on the accessing, appropriation, mobilisation, translation and use of managerial knowledge and how this shapes, and is shaped by, the development of managerial identity. 42,51

Research approach

An emphasis on understanding the effects of context requires an approach that can capture the subtleties of how different groups of managers go about accessing and using management knowledge in their everyday work. Not only does this suggest a very qualitative approach to data collection and analysis (examined further in Chapter 2 ), it also points to the value of a comparative case study approach that allows for the in-depth examination of important similarities and differences between, and within, cases and managerial communities. 52–54

The study examined middle managers within and across three types of NHS trust (located in England). Three trusts were selected to provide quite distinct cases with regard to the diversity of services provided and, consequently, the knowledge requirements faced by managers and the networks likely to be available to them.

To capture differences across managerial groups in each trust, a selection framework was developed in the early stages of the project that was refined as the project developed and which allowed us to differentiate between cohorts of managers that could be selected in each trust on the basis of their managerial and clinical orientation. This framework was used as the basis for the selection of managerial respondents in the main empirical part of the study. The derivation, refinement and application of the model are explained fully in Chapter 2 .

Patient and Public Involvement was not a feature of this study as it concerned and required only interviews and interaction with health-care managers concerning their management responsibilities.

Report structure

The rest of this report is structured as follows.

In Chapter 2 we explain the methodology of the research, outlining the epistemological basis of our approach, the logic behind the choice of case studies and managerial groups for our study and the detailed qualitative research methods that we used to collect, code and analyse the data from interviews and observations.

Chapter 3 sets the scene for the analysis of the data by examining the institutional and organisational context for the research, exploring management within the sector as a whole in a changing institutional context. After that, we drill down into an outline description of each of the three trusts and an assessment of the organisational contexts affecting management, knowledge and learning at each of them.

Chapters 4–6 then constitute the main set of findings, which are ordered according to three main themes: management, knowledge and networks. An explanation of the derivation and use of this schematic is presented at the end of Chapter 3 . In each chapter, we present the data from the interviews and observations to surface and analyse the key themes and issues identified by different groups of managers across, and within, the three trusts.

Chapter 7 discusses the main findings of the research. Despite a great deal of (sometimes unexpected) similarity in the themes identified and accounts given across the trusts and groups of managers, our analysis also allows us to identify some important differences (both obvious and more nuanced) between the trusts and managerial groups. This leads to a short final concluding Chapter 8 in which we present our conclusions and recommendations.

Chapter 2 Research methodology

General approach to the research

In this chapter, we outline and explain the methodology used to conduct the research. The chapter is developed in four parts that consider the general approach to the research and underpinning epistemology, the design of the study (including the selection of cases and identification of managerial cohorts), the research process and schedule of activities, and the methods of data collection and analysis used.

As noted in Chapter 1 , this research project aimed to investigate how NHS managers encounter and apply new management knowledge, examining the organisational and extra-organisational factors that facilitate or impede the acceptance of new management knowledge and its integration with practice in health-care settings. As such, there were three specific questions addressed in the course of our research:

-

How do occupational background and careers influence knowledge receptivity, knowledge sharing and learning among health-care managers?

-

How do relevant CoPs enable/obstruct knowledge sharing and learning?

-

What mechanisms are effective in supporting knowledge receptivity, knowledge sharing and learning/unlearning within and across such communities?

Before we outline and explain the design of the study and the detailed methods used to gather data to address these questions, it is important to say something about the general approach to the research and its underpinning epistemology as the research reported here departs significantly from approaches to research that rely on orthodox quantitative analysis based on statistical generalisation or experimental design.

Research philosophy and methodological choices

This study takes up an interpretivist qualitative methodology, underscored by a broadly constructivist epistemology, which contends that realities are socially constructed, the product of individual interpretations and meanings, intersubjective relations and the affordances and limitations of particular social and historical conditions. Accordingly, research that seeks to understand particular realities, such as the knowledge mobilisation of middle managers in the NHS, begins with the assumption that terms such as middle manager and knowledge are socially defined. Therefore, our research attempts to explore a range of interpretations of specific phenomena on the part of individuals, the relations in which they are embedded and the social forces that shape, and are shaped by, these interpretations and relations.

Research of this kind therefore attempts to place individuals at the centre of the analysis and explores the relations, connections and broader social forces within which individuals are embedded. The overall aim is to produce an analysis that is meaningful to individuals within these types of situations, while also remaining sensitive to changing social and political forces. This last point is particularly relevant to the context of the current study. The launch of the government white paper directed at ‘Liberating the NHS’55 (© Crown Copyright 2010, Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS) appeared at the time of our investigation, contributing to a highly salient political climate for health care and its management. This was a context in which, in Burrell and Morgan’s terms,56 conditions could arguably be characterised as much by ‘change, conflict, disintegration and coercion’ (p. 13) as by ‘stability, integration, coordination and consensus’ (p.16). The sociological context therefore reflects forces of ‘radical change’ rather more than ‘regulation’ (p. 16). 56

Our adoption of the comparative case study method in this study reflects this broad epistemological perspective of phenomenology. Following Silverman,57 this contends that sociology should be concerned with the phenomenological understanding, rather than positivist measurement of behaviour, as it is the meanings ascribed to phenomena that define social reality rather than social reality being self-evident through inspection. Social reality does not somehow reside outside of people’s perceptions, but instead is constituted intersubjectively. The inference is that people can adjust and even change meanings through social interaction. Explanations of social action therefore need to take account of the meanings that those participating attach to actions. For Silverman,57 social researchers should build their theories on foundations that view reality as being socially constructed, sustained and changed. In the study of organisations, he argued that the social actor should be at the centre of the analytical stage, for it is crucial that researchers understand subjective and intersubjective meanings if they are to understand the significance of organisational actions. This puts an emphasis on a view of the social world as processual, in which organisational actors interpret the situation in which they find themselves and act in ways that are meaningful to them. It also requires interpretive, qualitative methods that can tap into action at the level of meaning.

The comparative case study method54 adopted here draws on interpretive ethnography, which is a qualitative approach and set of methods directed at understanding cultural phenomena that, in turn, reflect the system of meanings guiding the actions of a social group – in our case, health-care managers. This method also contends that research participants’ perceptions of social reality are themselves theoretical constructs. While participants’ constructs are more directly connected with lived experience58 than the researchers’, they remain, nevertheless, subjective constructions of social reality.

In remaining cognisant of the changing political context experienced by managers in this study, we understand that participants’ reconstructions are embedded within particular policy narratives, which, in turn, are embedded within a particular social order. Implicit in the understanding of management as a socially constructed phenomenon is the understanding that particular constructions of management promote the reproduction of particular social and economic relations. Therefore, the attempt made through fieldwork is to present an integrated perspective of context, arguing that external factors are a fundamental part of the internal composition of the local domain and should be recognised as such – even at the most micro level of interaction.

Design of the study

In developing such research, it can be argued that our attempt to understand the effects of differences in organisational and community context on how managers use managerial knowledge requires a research strategy that allows depth of analysis as well as breadth of application. This suggests the need for a comparative case study approach that is able to examine, using in-depth qualitative methods, the practices of managers – but in a way that is also sensitive to important differences in context (both organisational and institutional).

A comparative case study approach has proven to be a powerful methodology, particularly for allowing the direct application of research findings to their practical context and also for helping understand the issues involved in complex organisational settings. 53 It is particularly important when, as the previous discussion suggests, it is difficult to separate out analysis of the phenomenon of interest from its context. 52 Research into health-care organisations has, of course, made particular use of the case study method to explore complex network-based interactions amongst managers and clinicians. 48,54

Sample of organisations

A comparative case study approach was adopted by focusing attention on studying middle managers within and across three very different types of NHS trust. These three trusts were selected to provide quite distinct cases with regard to the diversity of services provided and, consequently, the knowledge requirements faced by managers and the networks likely to be available to them. The three trusts studied were all based in the north-west of England and consisted of a foundation acute trust, a foundation care trust (mental health and community services) and a foundation tertiary/specialist trust.

Our expectation on commencing the research was that each trust context would be distinct with regard to the knowledge requirements faced by managers and the networks likely to be available to them. Our assumption was that this would be reflected in several characteristics that differentiate these types of trust, including their geographical spread, the number of locations from which services are provided, the diversity of services provided and the number of organisations purchasing services from them. More specifically:

-

Acute trust, which offers a wide range of acute services centralised mainly in one location and covering a fairly limited (local) geographical area. Service contracts are likely to originate largely with one commissioner. Knowledge networks are likely to be available to managers according to specialism.

-

Care trust, which delivers a diverse range of mental health and community services with operations distributed in many locations over a large (regional) geographical area. Multiple purchasers are likely from both health and social care. Knowledge networks are likely to reflect a more limited range of specialisms.

-

Specialist trust, which offers a limited range of specialist services mainly from one central location to patients spread across a very wide (regional and national) geographical area. The trust has to contract with multiple purchasers. Knowledge networks are more likely to be focused on the particular specialism.

A summary of these characteristics can be seen in Table 1 .

| Type of trust | Diversity of services | Area coverage | Number of purchasers | Number of locations | Nature of patient contact | Managerial knowledge networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | High | Low | Low | Low | Mixed | Varied according to specialism |

| Care | High | High | Medium | High | Cyclic | Limited specialisms |

| Specialist | Low | High | High | Low | Episodic | Focused specialism |

The categorisation of each trust in this table is necessarily very broad, highlighting factors which were relatively objective and identifiable and which may be expected to have an impact on issues of relevance to the study. However, this categorisation was also largely a priori, inferred and set out in the research project design in advance of detailed empirical work in each trust (the exceptions were the two bold areas for which original expectations that the care trust would rate medium were revised to high ratings following initial investigations). A key priority in the research was to establish empirically which aspects of context, both historical and immediate, impacted most directly on operations and activity in each trust. This is the focus of Chapter 3 , in which we provide a more fine-grained analysis of the salient aspects of the organisational context in each trust and also indicate the most pressing current concerns for managers at each organisation, drawing directly upon the perceptions of our interviewees.

Identifying managerial cohorts

As was noted in Chapter 1 , management in the NHS is highly complex, consisting of groups with very distinctive professional orientations and knowledge bases. 59 The dependence on management and markets to drive health care reform has meant that a range of hybrid managerial roles have emerged that require combinations of clinical expertise, public administration and business acumen. 60 Furthermore, there is little standardisation of role titles between and even within trusts, and few people with managerial responsibility actually carry the formal title of manager. 61 As a consequence, the identification of distinct cohorts of managers is a difficult problem in a setting as complex as the NHS.

We set out to include middle managers across the three types of trust, to be selected on the basis of important expected differences in the community of middle managers who work in these organisations and in the managerial activities and challenges that they face. Our intention was to understand the effects of differences amongst communities of NHS managers (in terms of sources of managerial knowledge, knowledge utilisation and learning processes). Therefore, it was important to be able to develop a systematic framework for the identification and selection of managers.

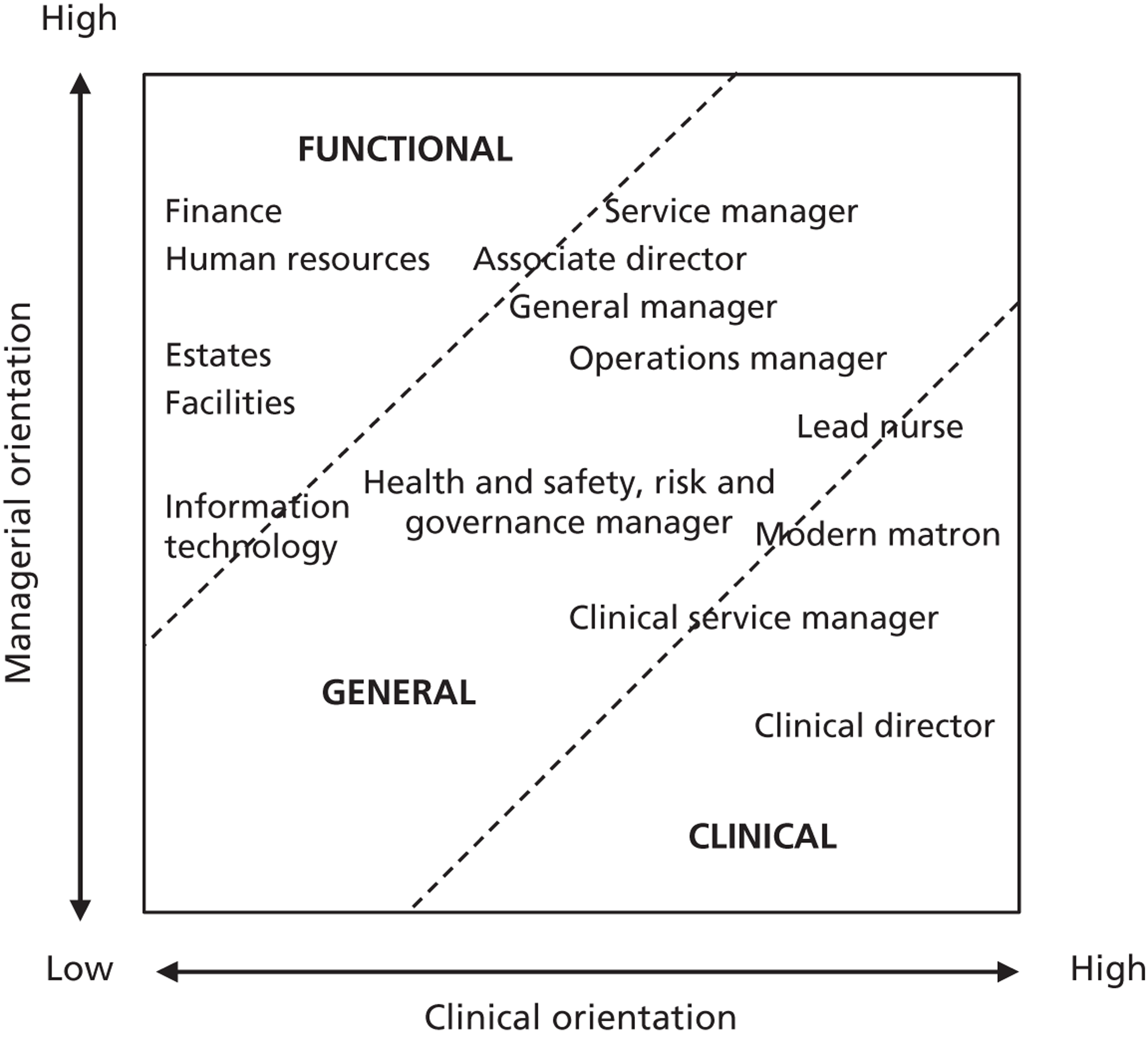

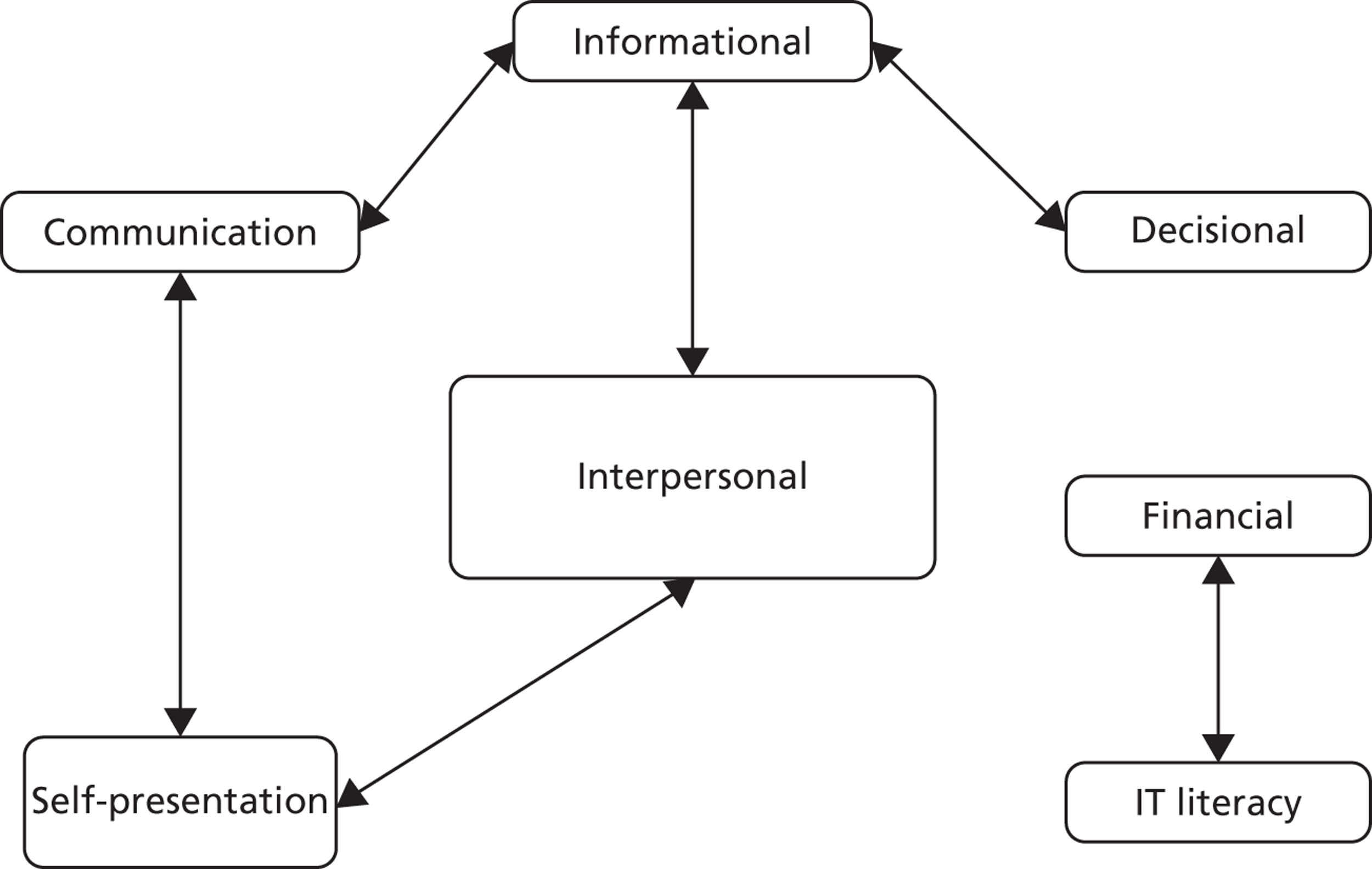

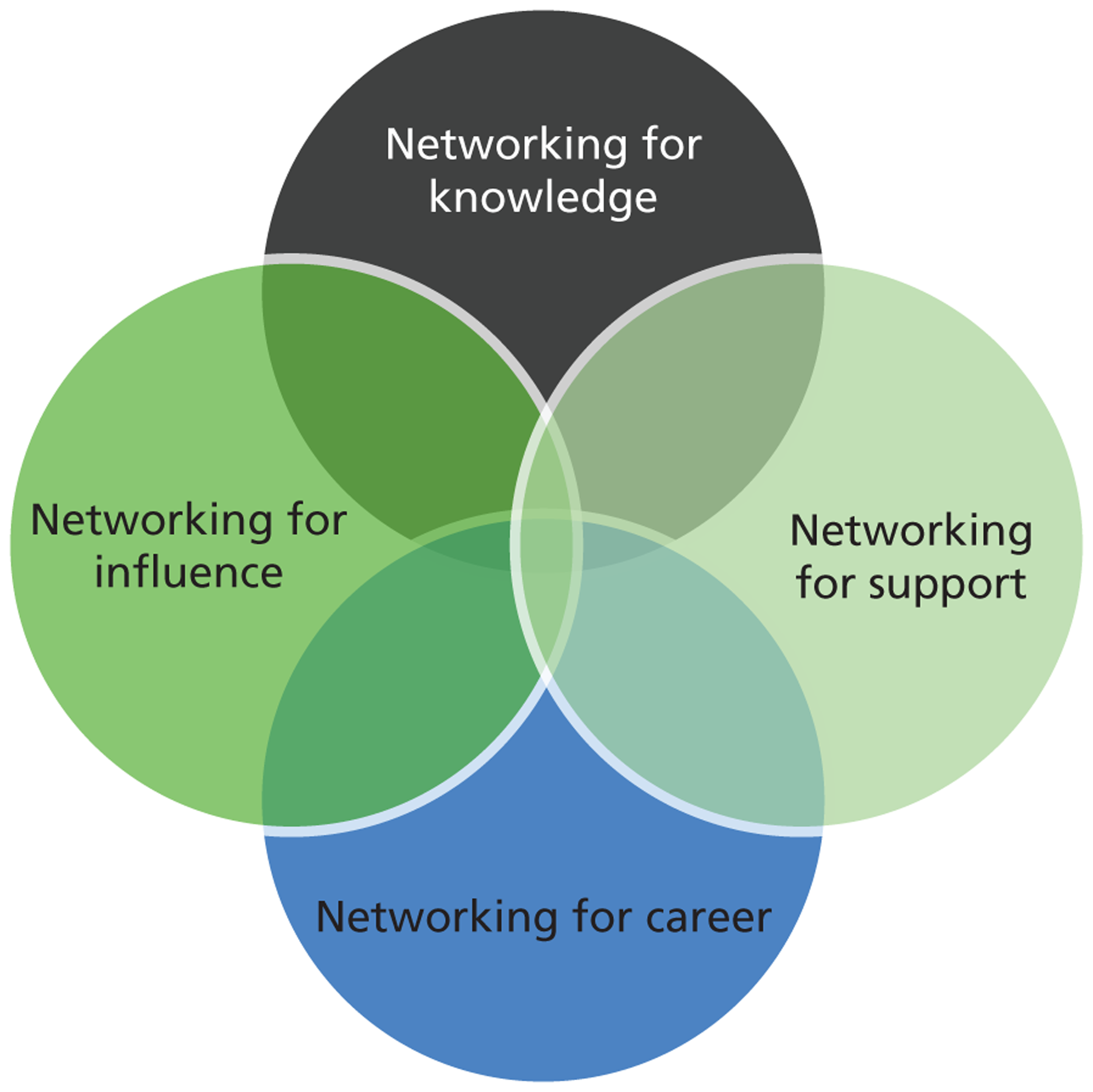

Our NHS Management Model, which broadly differentiates between three general categories of manager – functional, general and clinical – and which includes within it more precise indications of the locations of particular managerial roles, is presented in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

NHS Management Model (final version).

This model was the result of the development and refinement of an initial framework that had attempted to differentiate between managerial groups on the basis of their qualifications and experience. It was arrived at through interviews and meetings with advisory group members and other key informants from across the sector in the early phase of the research. The model goes further than the original framework in recognising the interconnectedness of managerial and clinical orientations (especially among some general managers), as well as the often blurred boundaries between managerial groups.

Using this framework, it was possible, in principle, to locate particular managerial roles in terms of the expected combination of clinical and managerial orientation, which may of course reflect and represent very different patterns of managerial and clinical training/experience. Pragmatically, this would also enable us to construct a sample of interviewees in each organisation that we were confident covered the diversity of middle management in each trust in a balanced manner and which we hoped and expected would be clearly recognisable to potential participants in the study. Of course, our interviewees were not types or categories but real individuals, hence the precise combination of background, experience, training and inclination of each particular interviewee was likely to vary significantly, as might be expected. The focus of the empirical analysis was to explore this in some considerable detail.

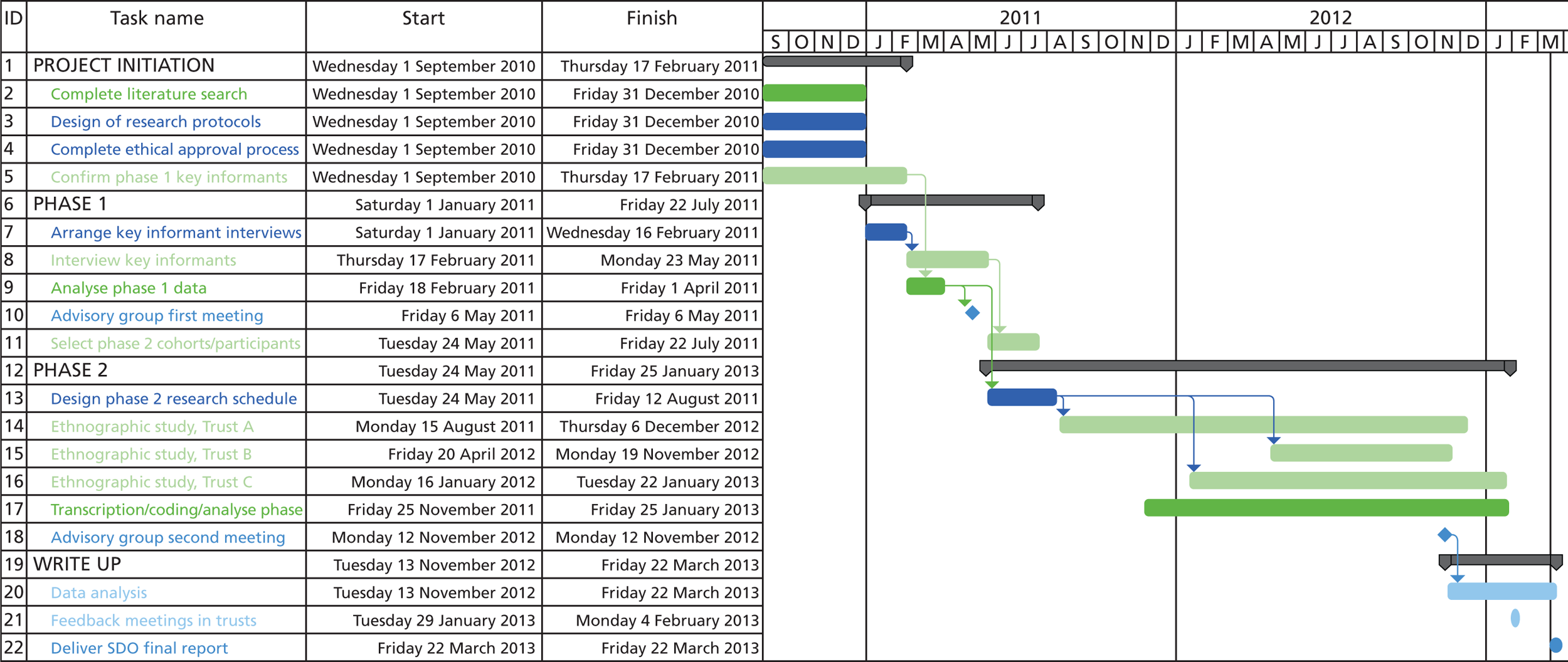

Research process and schedule of activities

The research project was scheduled to last 28 months and our original plan of investigation saw the research organised into four main stages or phases: project initiation, phase 1 empirical work, phase 2 empirical work and write-up. These phases are captured in the project flow chart in Appendix 1 and are summarised below.

Project initiation

This phase lasted 5 months and involved the appointment of the research associate and establishment of an advisory group, an extensive literature search, identification and contact with key informants for interview, detailed design of research protocols and the securing of ethical approval.

Phase 1: key informant interviews

The first empirical phase of the study (months 6–12) involved face-to-face or telephone interviews with a variety of key informants, selected to provide overviews of the key challenges and problems facing managers at a local, regional and national level in locating, interpreting and applying knowledge and learning.

The advisory group included six external members (including the lead collaborator or their representative from each trust) who were among the key informants who were interviewed. Interviewees during this stage also included a number of figures of national and regional prominence, including those associated with:

-

NHS employers

-

NHS Confederation

-

The King’s Fund

-

regional strategic health authority (SHA)

-

regional leadership academies

-

participating trusts.

These interviews generally lasted approximately an hour and were structured around a set of broad questions (see Appendix 2 ) regarding:

-

NHS trust contexts (appropriateness of choices and categorisations)

-

framework for selection of managerial cohorts (validity, suitability)

-

encounters/events (to observe management knowledge processes in action)

-

current changes and possible effects

-

management knowledge and learning

-

human resources (HR) practices

-

organisation, systems and practices.

Interviews were conducted by at least two members of the research team, they were recorded and transcribed and notes were also taken.

They allowed a detailed picture to be built up of the background, capabilities and orientation towards management knowledge of diverse groups of managers, as well as providing further background sources on the policy/practitioner context of the research. As already suggested, they also represented the first stages in the coproduction62 of the research framework and research instruments, by contributing significantly to the validation/refinement of the framework for trust and participant selection.

During this phase, the first advisory group meeting was also held in order to help steer the design of the study (by further validating the frameworks being developed) and to assist with the identification of appropriate managerial cohorts. Advisory group members were also prompted to identify and discuss with the research team appropriate managers for interview and key events to observe. Trust participants on the advisory group were also able to identify common interests and concerns across each trust as well as important differences in the use and exploitation of managerial knowledge.

Phase 2: ethnographic study via interviews and non-participant observation

Phase 2 represented the main empirical component of the research (months 9–24) and combined semistructured interviews with selected cohorts of managers with ethnographic observation methods. Data collection was phased over a rolling programme of research over a period of about a year at each trust. Details of interviewing and observation methods and processes, as well as the coding and analysis of the data, are explained in greater detail in Methods of data collection and analysis.

Write-up

The final stage of the research (months 24–28) involved further analysis of the empirical material and activity leading to the production of this final report. During this phase, a second advisory group meeting was held, at which emergent findings were presented and discussed. Following this, separate research symposia were held at each of the three trusts where the results of the research were presented and discussed with managers who had participated in the research. This enabled the results to be further validated and also fed directly back into practice.

Selection of phase 2 interviewees

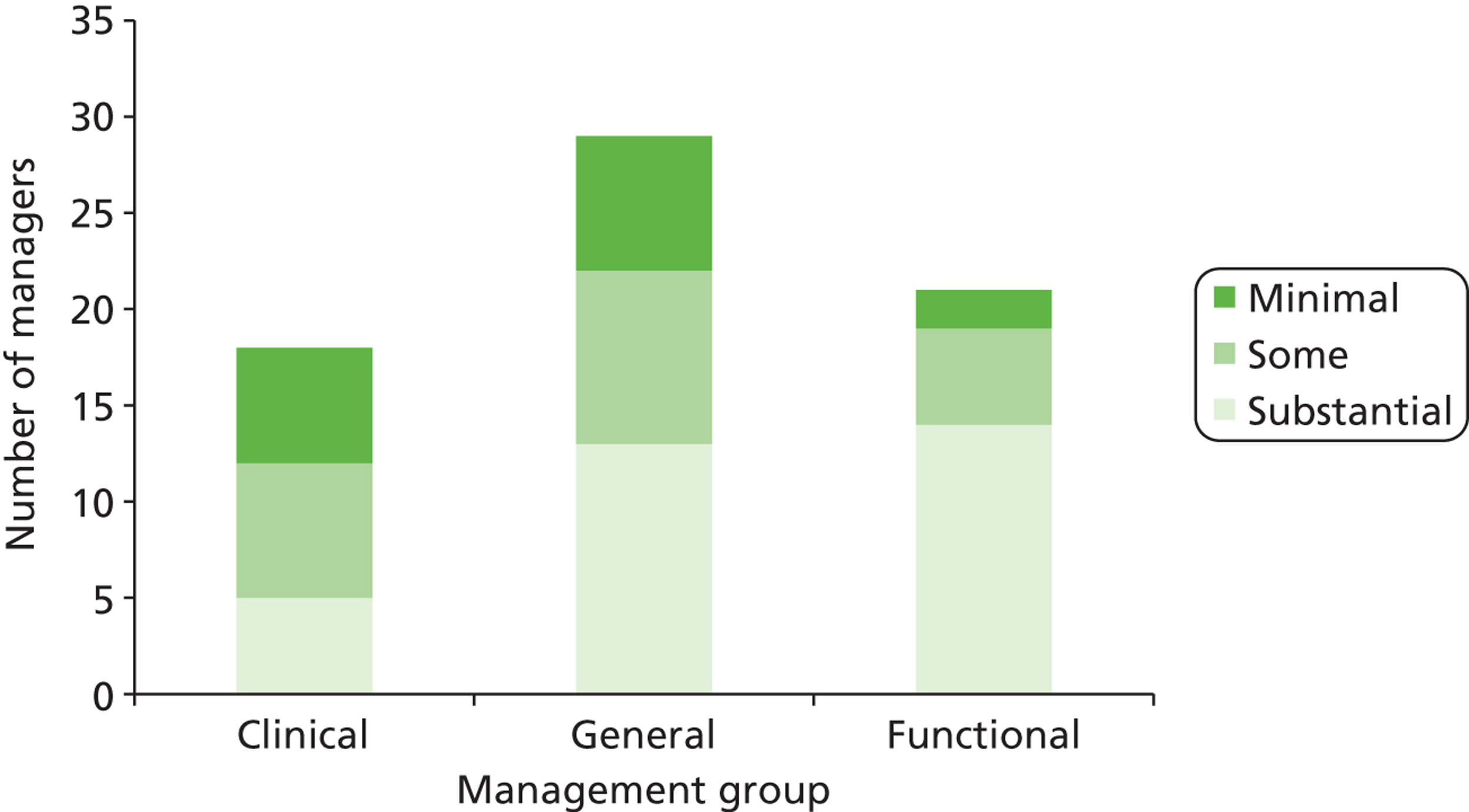

The second phase of the study required the selection of a limited number of participants from identifiable groups of managers – clinical, general and functional – who could exemplify the range in each group. By selecting individuals from each group or cohort, it would then be possible to explore important sources of similarity and difference both within and between each trust. To capture this qualitative variation, a purposive, non-random sample of approximately eight managers was identified for each of the three cohorts of managers in each of the three participating trusts, yielding a total target sample size of around 72 managers across the three trusts who would be interviewed during the main fieldwork phase (in the event, 68 were actually interviewed).

Access to potential participants was arranged through each trust’s lead collaborator and HR department. In the early stages of research, the research team worked with lead collaborators to identify potential interviewees among the managers. Selections were made on the basis of meeting the need to generate sufficient numbers of interviews in each broad group (clinical, general and functional) while allowing some variation in their work position and context (e.g. different clinical/functional specialism or service operations). It also became clear that managerial grade was a useful proxy indicator of middle management status. In the event, most of those managers interviewed had salaries that were in grades 8a–8d (the exceptions were one grade 7 manager, four grade 9 managers and five who were on the consultants scale).

Once potential candidates for interview were identified, they were contacted by e-mail via the trust’s HR department and asked if they would be willing to be contacted by a member of the research team to establish their willingness to participate. The initial e-mail contact had been drafted by the researchers and included outline details of the research. Contact details of managers who agreed were then passed on from the HR department and they were contacted directly and provided with full information about the research, including an invitation letter, participant information sheet, project summary document and consent form (see Appendices 3–6 ). As part of the process of obtaining consent, managers were guaranteed that any information they gave would be kept confidential. There was also a guarantee of anonymity in the use of any examples and quotes from interviews. Consequently, the interview data presented in this report have been anonymised and pseudonyms are used to protect the identity of respondents. Managers were given time to confirm whether or not they wanted to participate and, if there was agreement, interviews were arranged in situ at the manager’s convenience, at which time consent forms were signed.

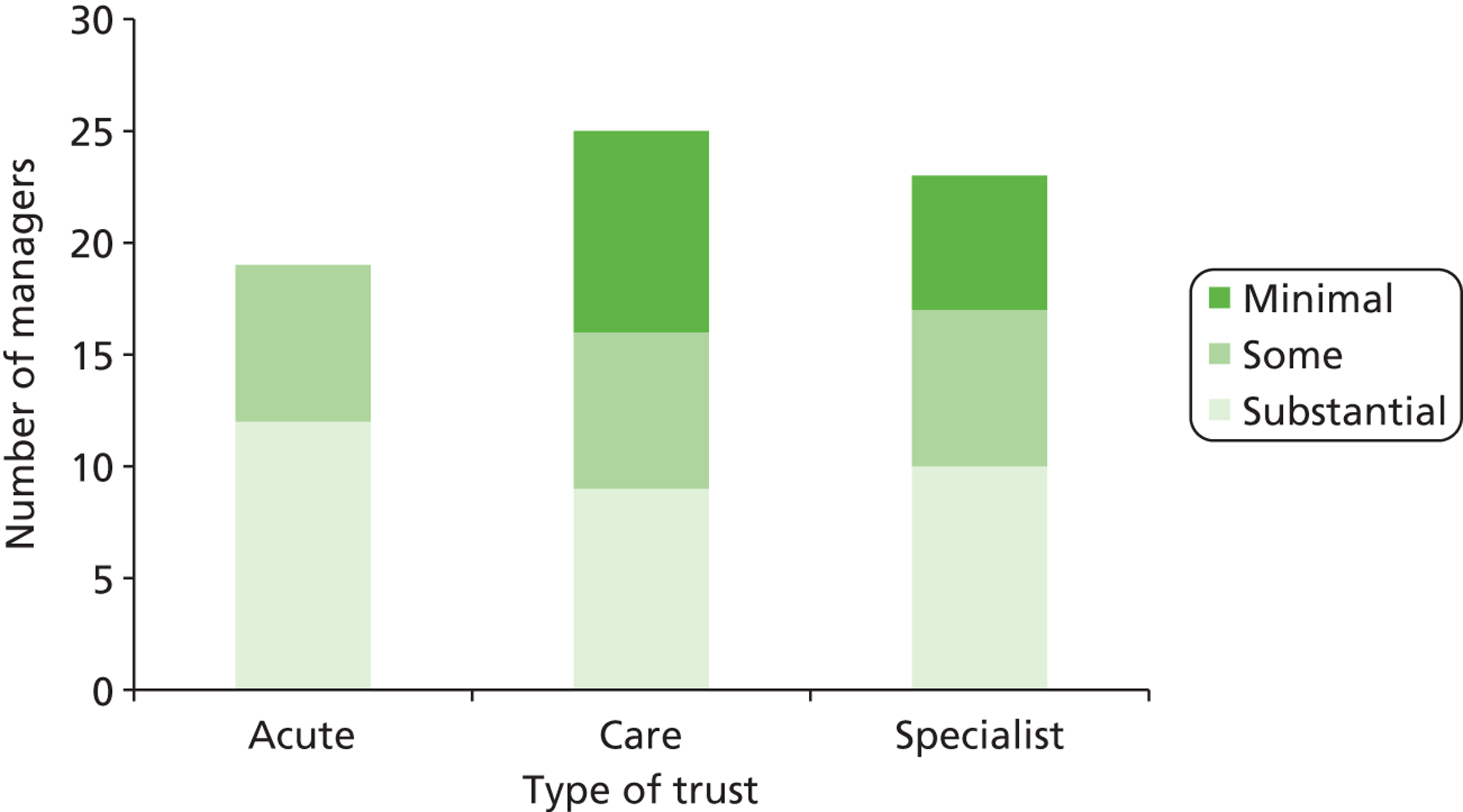

The final sample consisted of a total of 68 interviewees across the three trusts. Details of the sample of managers, including information about their distribution and response rates with regard to numbers willing to participate, are presented in Table 2.

| Trust | Clinical managers | Functional managers | General managers | Declined/did not respond | Total participantsa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | 5 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 20 |

| Care | 7 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 25 |

| Specialist | 6 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 23 |

| Total | 18 | 21 | 29 | 24 | 68 |

Character of phase 2 sample

The gender and age distribution of the 68 managers interviewed are summarised and compared by trust and managerial group in Table 3 .

| Trust | Clinical | Functional | General |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | 3 male, 2 female | 4 male, 3 female | 3 male, 5 female |

| Care | 3 male, 4 female | 3 male, 3 female | 3 male, 9 female |

| Specialist | 2 male, 4 female | 3 male, 5 female | 4 male, 5 female |

| Total | 18 | 21 | 29 |

There was a relatively even gender spread, apart from a concentration of female general managers in the care trust. The distribution of managers by age was also relatively even across the trusts, although the age profile of managers in the care trust was a little higher and of those in the specialist trust a little lower ( Table 4 ).

| Trust | 18–30 years | 30–40 years | 40–50 years | 50–60 years | 60 + years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | 2 | 4 | 10 | 4 | – |

| Care | 1 | 4 | 13 | 7 | – |

| Specialist | 2 | 9 | 9 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 5 | 17 | 32 | 13 | 1 |

Most of those interviewed (64, 94%) were white British, with the remaining four (6%) being Asian British and male (two in the care trust and one in each of the other trusts).

Table 5 shows the average time that managers had spent in their current post, their current organisation, in the NHS more generally and also outside the sector.

| Trust | In post | In organisation | In NHS | Outside NHS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute | 2.30 | 4.86 | 17.25 | 4.83 |

| Care | 3.87 | 11.71 | 22.34 | 3.03 |

| Specialist | 3.02 | 9.09 | 14.41 | 6.70 |

The greatest longevity of employment in both the organisation and NHS was found amongst managers interviewed in the care trust (where many had worked for long periods prior to trust status and reorganisation). Those with considerable experience outside the sector were found mainly in functional management roles and also amongst clinical and general management staff who had worked in private health care. Other distinctive and quantifiable features of experience, including educational qualifications and training received, will be explored in Chapter 5 .

Methods of data collection and analysis

The methodological strategy was that the research would make use of a qualitative mixed-method approach that combined a primary emphasis on semistructured interviews with ethnographic observation methods, so as to get as complete as possible a picture of the engagement of cohorts of managers with their networks and communities.

Qualitative methods such as these are well suited to exploring the workings of CoPs, both within and outside organisations, and have been used effectively to illuminate the dynamics of organisational relationships between managers and staff63 as well as between staff and patients. 64

Interviews at each trust were carried out by two members of the research team – one of the principal investigators (who focused on that particular trust and who took the lead in questioning) and the research associate (who covered interviews at all three trusts to ensure consistency and comparability).

The interview followed a semistructured format based on a set of questions and detailed prompts that ranged across seven key thematic areas (see Appendix 7 ):

-

Background information: including age, gender, managerial role and grade, educational and professional qualifications, professional background and length of experience in the NHS, the trust and the role.

-

Occupation/career: including current position and role, educational background and career path and entry into the organisation/role.

-

Leadership/management: including current responsibilities, conceptions of management and leadership and views on the occupational/professional status of management groups.

-

Knowledge: including managerial skills needed, formal and informal sources of knowledge and learning, and organisational mechanisms in support of knowledge and learning.

-

Networks: including internal and external networks, their nature, purpose, scope and mode of operation and individual networking activity.

-

Organisational context: including factors enabling/hindering knowledge work and barriers and enablers of communication (e.g. structural and spatial aspects of work organisation, technology, HR policies and practices).

-

Change: including sector/organisational changes affecting knowledge and learning processes, the personal impact of change and future career aspirations.

Interviews lasted between 1 and 2 hours (the majority lasting around 1.5 hours) and all were recorded and transcribed. Including interviews from phase 1, the result was a primary data set that consisted of a 139 hours of recording and over 924,000 words!

Phase 2 non-participant observations

When possible and appropriate, meetings and other forms of event or encounter at each trust were also observed when these managers were involved and knowledge processes would be expected to be most critical (this was with the explicit agreement of those managers and others present). The aim was to underpin the analysis by supplementing interview-based accounts of knowledge processes with observation of the reality of how management knowledge was accessed, used and shared in practice. It would also allow the research team to gather more in-depth understanding of how management knowledge and management processes were related and allow the follow-up of key themes and issues identified in interviews. It therefore also allowed the introduction of a more longitudinal element to the research.

A number of events were observed, including management meetings and training events and these are listed in Appendix 8 , along with the thematic guide used for the ethnographic encounters (see Appendix 9 ).

Standard note-taking by those members of the research team present, structured broadly by the thematic guide to ensure consistency, formed the main means of capturing action in these events and management meetings and these were transferred to electronic format. In addition, observational elements were included through field note summaries produced by each member of the research team before and after the interviews that aimed to capture general observations and impressions. Table 6 provides an overall summary of data collection across the two phases of research, including the time spent in observations.

| Data source | Interviews (formal recorded) | Interviews (informal) | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Key informants | 13 | 0 | 3 hours over 3 days |

| Acute trust | 20 | 0 | 18 hours over 6 days |

| Care trust | 25 | 13 | 22 hours over 9 days |

| Specialist trust | 23 | 6 | 11 hours over 2 days |

| Totals | 81 | 19 | 54 hours over 20 days |

The rich detail obtained from the observations did not lend itself to coding or presentation in the same way as the interview data did, and this detailed background information was used instead to help contextualise the interview data and/or to provide confirmatory information for points raised or claims made in interviews (e.g. about decision-making or management training processes – see illustrative examples in Chapter 7 ). Consequently, the observation data were used more implicitly and/or illustratively to support the analysis and were not subject to the same coding or analytical techniques as the interview data.

Data coding and analysis

All the data collected were transcribed, collated and stored centrally for coding and analysis using NVivo 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative data analysis software. The development of the coding framework for the semistructured interviews that made up the greater part of the data set relied on a schema combining open and axial coding methods, which aimed to combine inductive and deductive logics in line with the construction of grounded theory. 65

Following the completion of the first set of semistructured interviews, three interview transcripts were chosen and were independently coded by each member of the research team. The research team then met in order to compare the coded transcripts so as to construct a basic list of coding categories. These categories were then structured into broad themes (management/leadership, knowledge, networks, organisation and personal), reflecting the research questions, the structure of the interviews and extant relevant classificatory schemas from the management literature. This resulted in the creation of an axial framework against which transcripts could then be coded.

The coding for each case was undertaken by the members of the research team responsible for data collection in that site, which capitalised on the tacit understandings each had gained through data collection. A smaller selection of transcripts were analysed by another member of the group in order to check interpretation and to improve inter-rater reliability. Additionally, regular meetings of the research team were held to discuss the emerging analysis, explore contradictions and disagreements and develop consensus. Throughout analysis, the coding framework remained open to the inclusion of additional categories or deletion/combination of nodes.

Once coding was complete, each team member selected one theme to explore the findings in more detail, drawing out comparisons and distinctions between the three trusts and the three management groups. The thematic analysis and interpretation of the data proceeded largely inductively, with each theme being explored using the structure provided by the coding framework (and being informed by observations in the field) while, at the same time, being shaped by the overarching research questions concerned with management knowledge and learning processes. Although individual team members were responsible for developing the thematic analysis, the process was an iterative one, with regular team meetings, presentations and comments on drafts being used to ensure accuracy and consistency of interpretation.

Themes, rather than cases, were used to organise further analysis and data presentation, as preliminary analysis of the emerging findings at each case through the later fieldwork and early coding stages clearly indicated that there was a good deal of consistency in responses across the interviews regarding the central themes of management, knowledge and networking. At the same time, however, it was clear that there were important differences between the cases that had effects on management activities and knowledge and learning processes (e.g. in the experiences of formal management training and development and the extent of networking activity). Consequently, while the preliminary analysis was case based (coinciding with the phased ending of fieldwork at each case), this gave way to further analysis which was more thematically driven.

However, comparative case analysis was also still important and this was retained through case narratives that described the context for the main findings and through the examination of significant differences (sometimes very obvious, but often quite subtle and nuanced) that were explored within each theme. The steps taken here to strike a balance between thematic analysis and rich case narrative are consistent with those normally expected in, and recommended for, qualitative case study research. 53 Preliminary results of this secondary analysis were also shared with the Advisory Group and then further developed through the feedback sessions held at each participating trust. Each team member then took responsibility for the final write-up of his or her theme, which culminated in the writing of this final report.

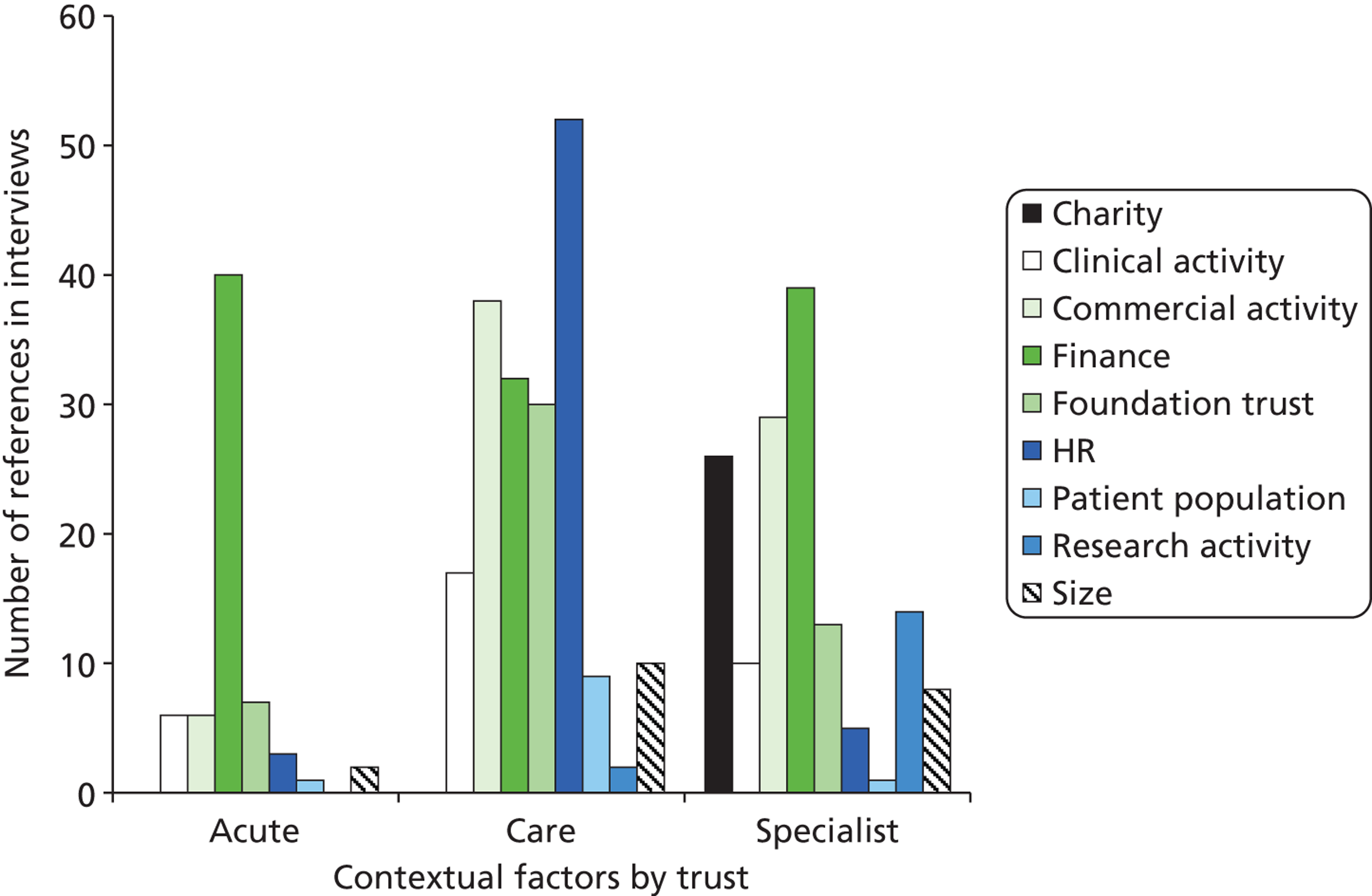

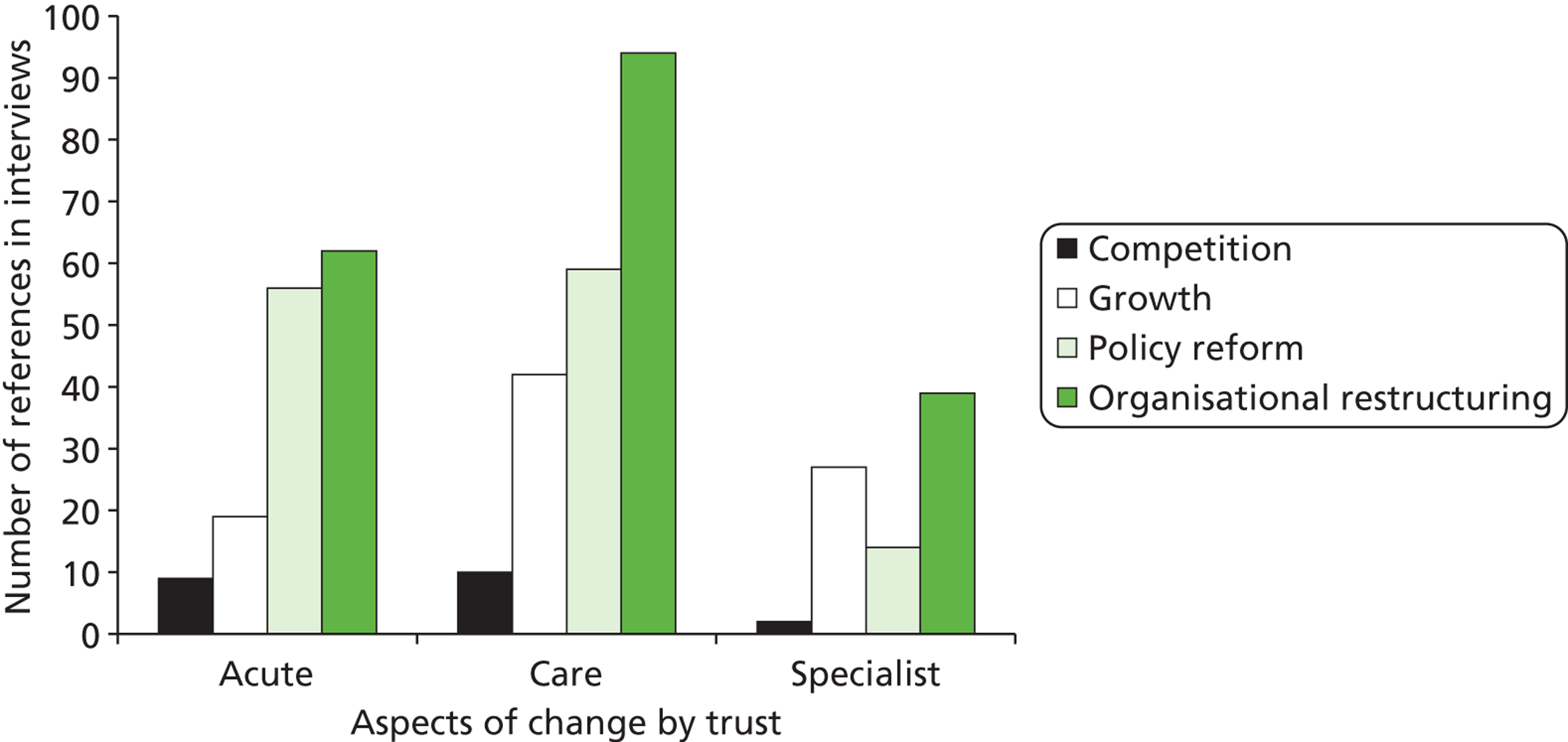

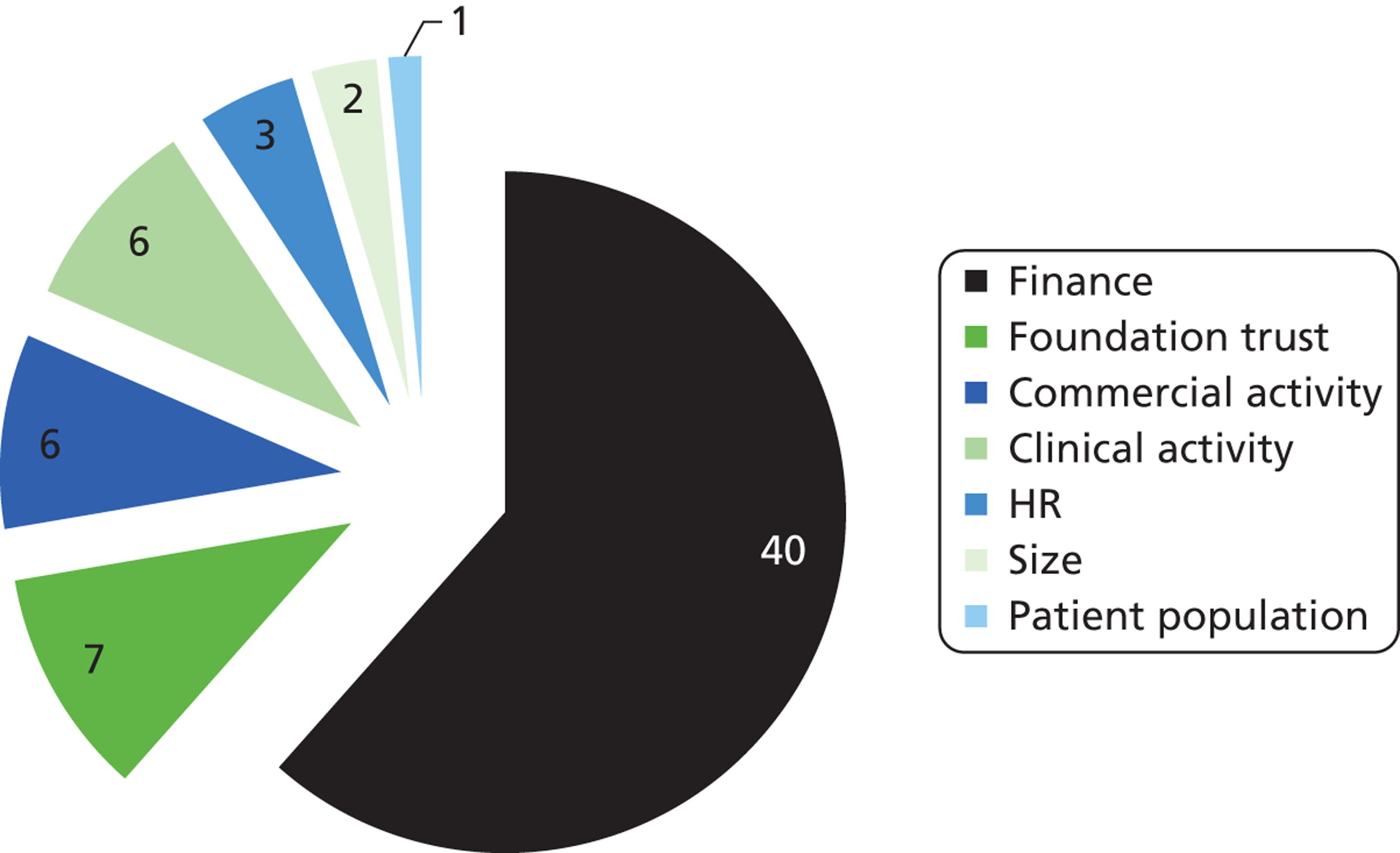

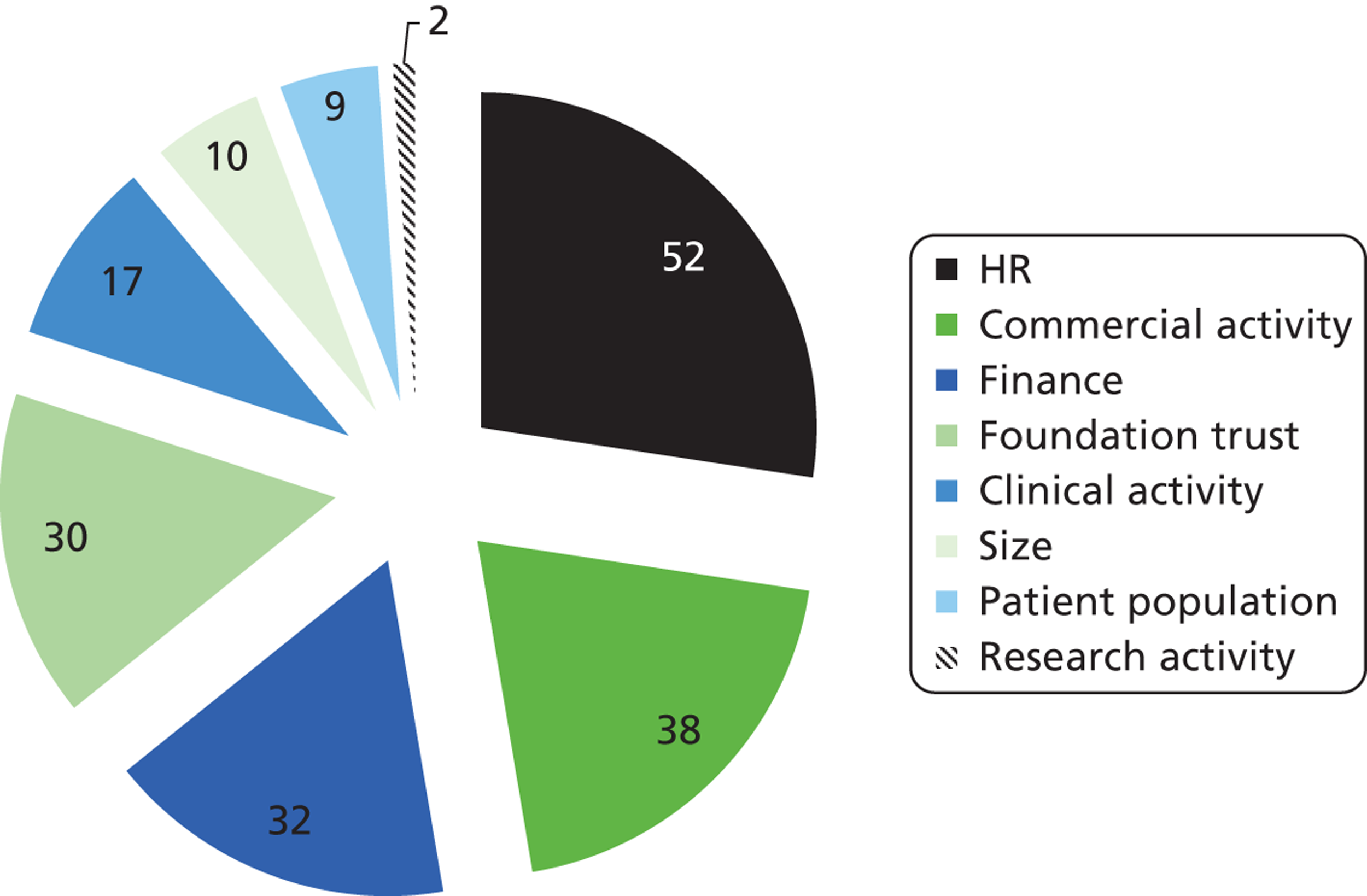

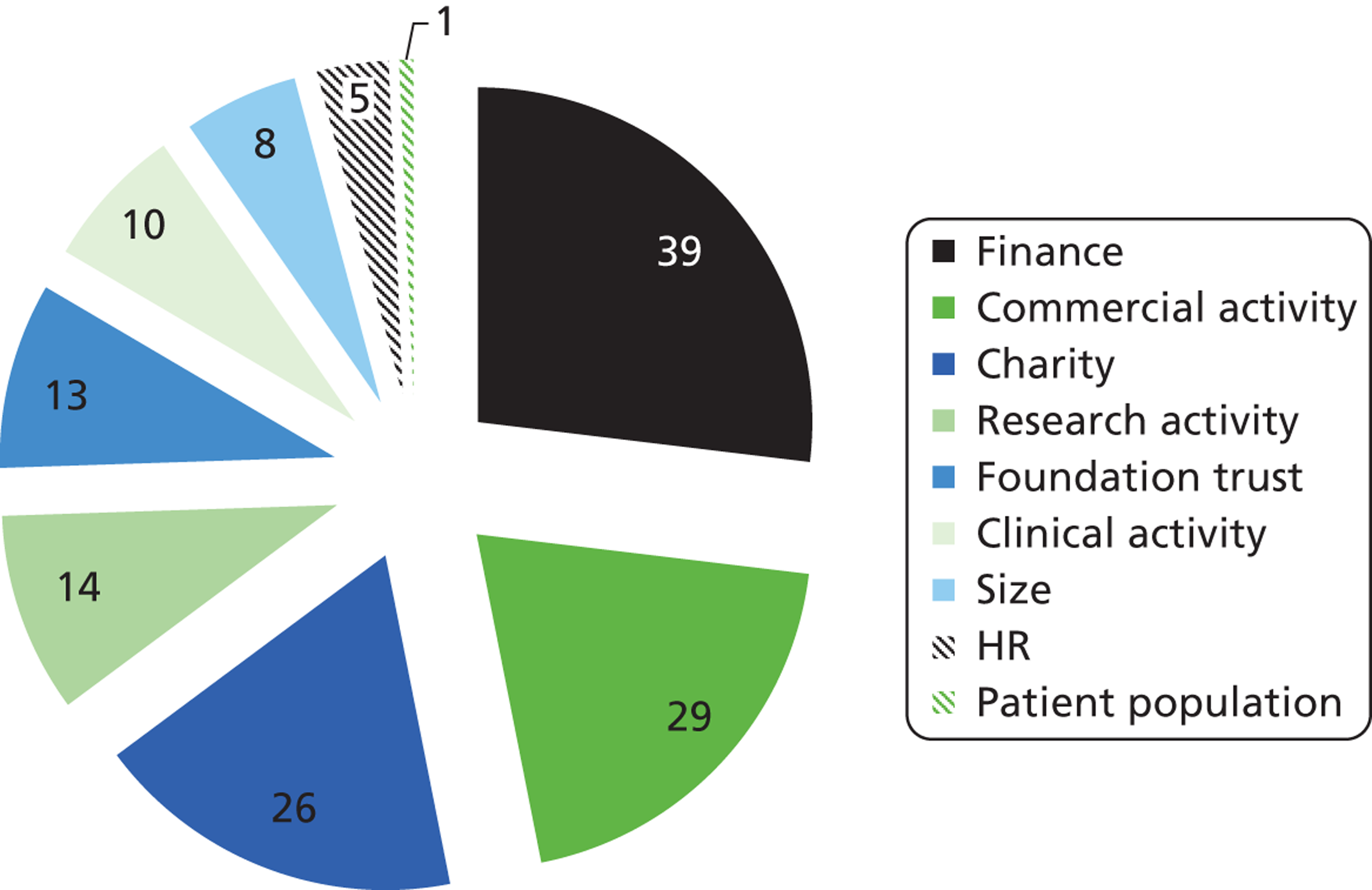

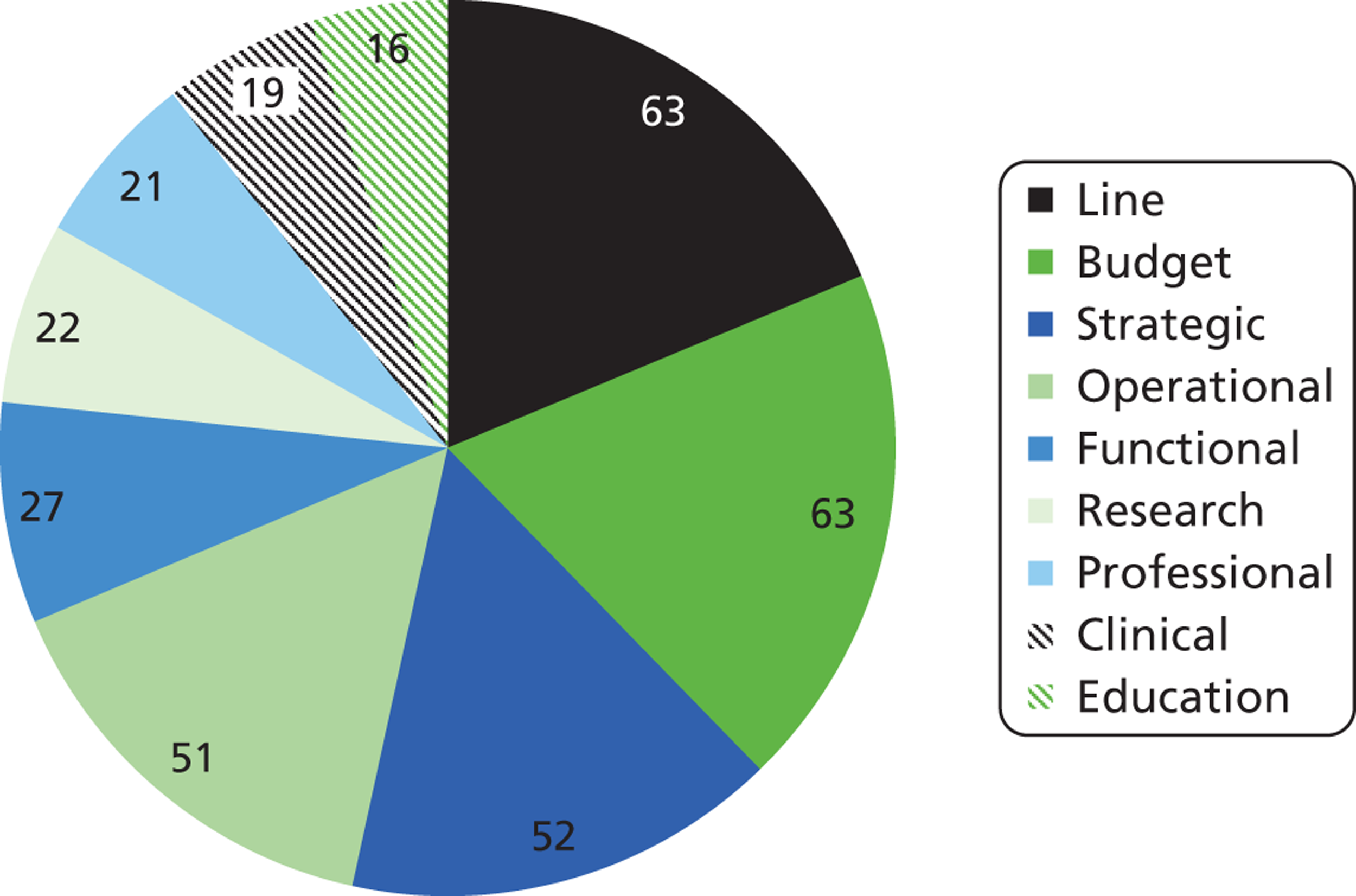

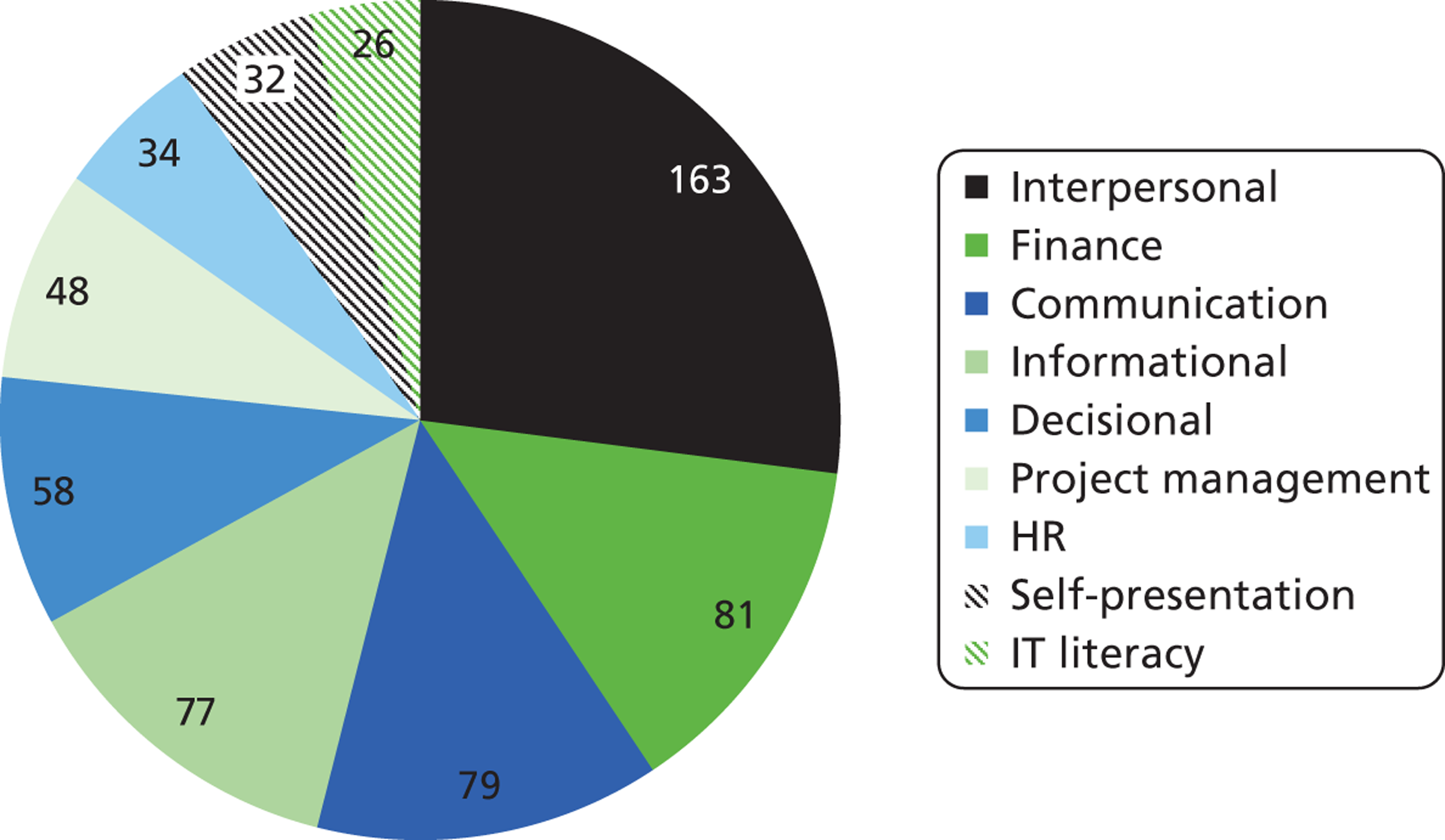

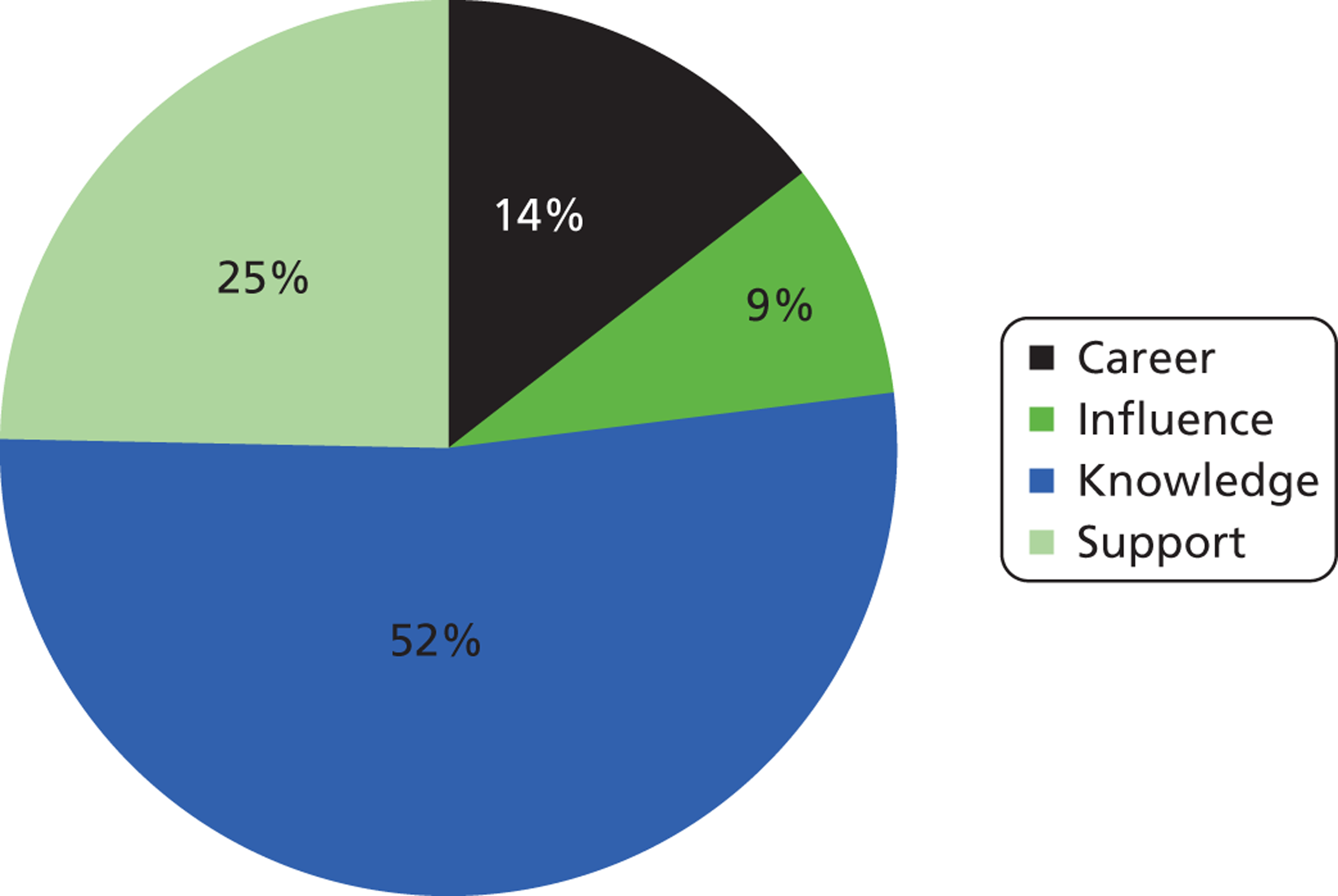

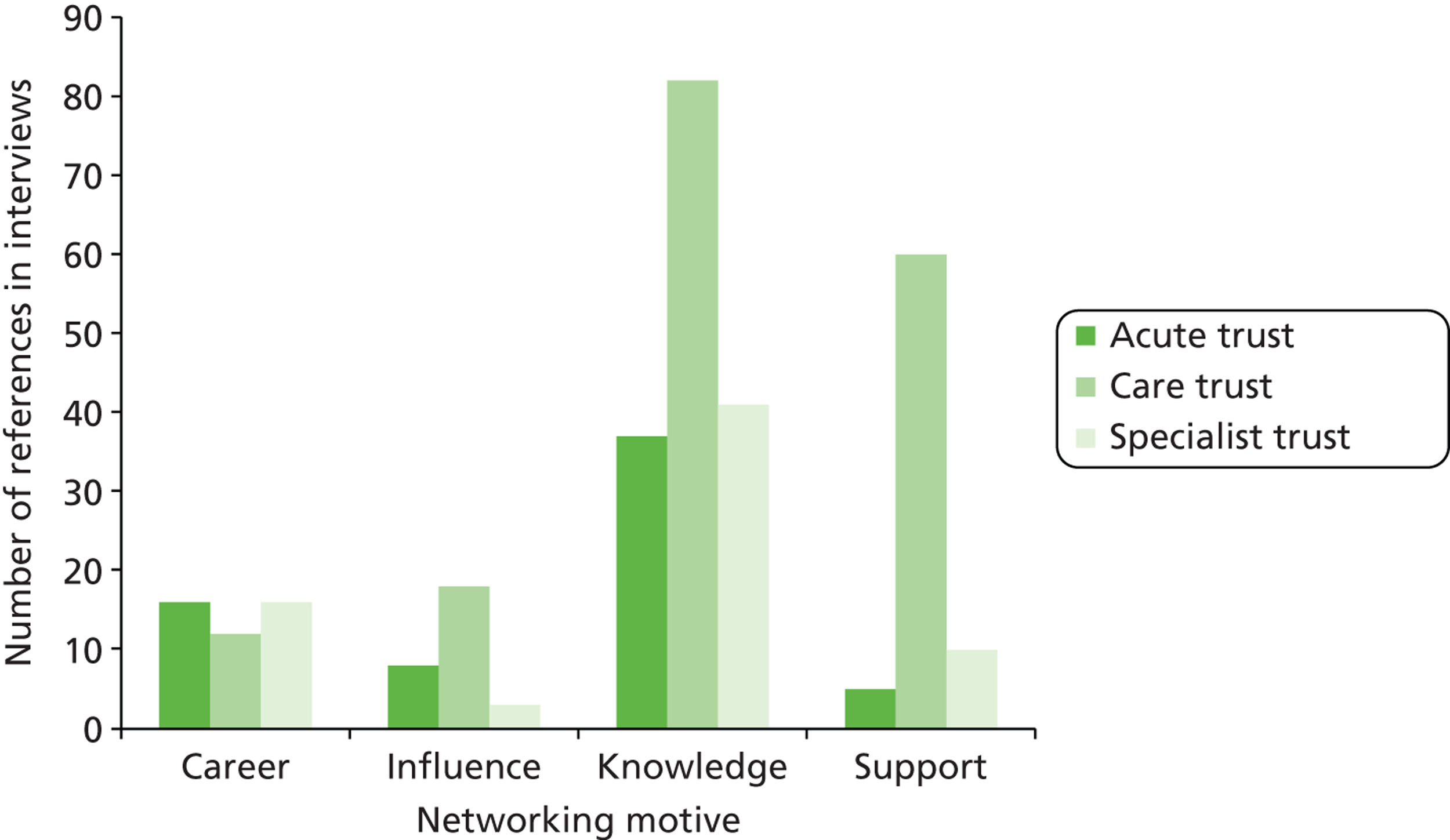

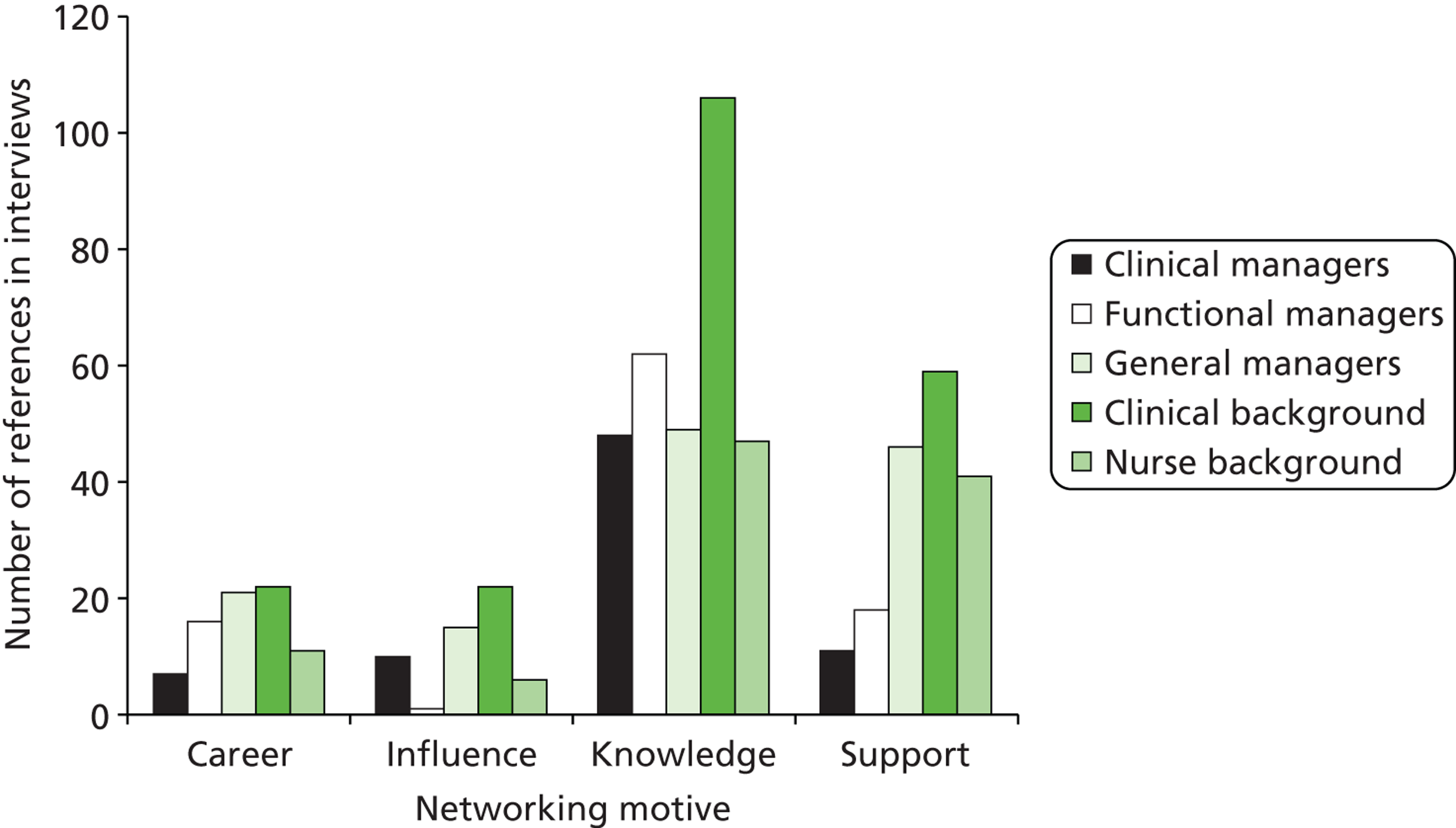

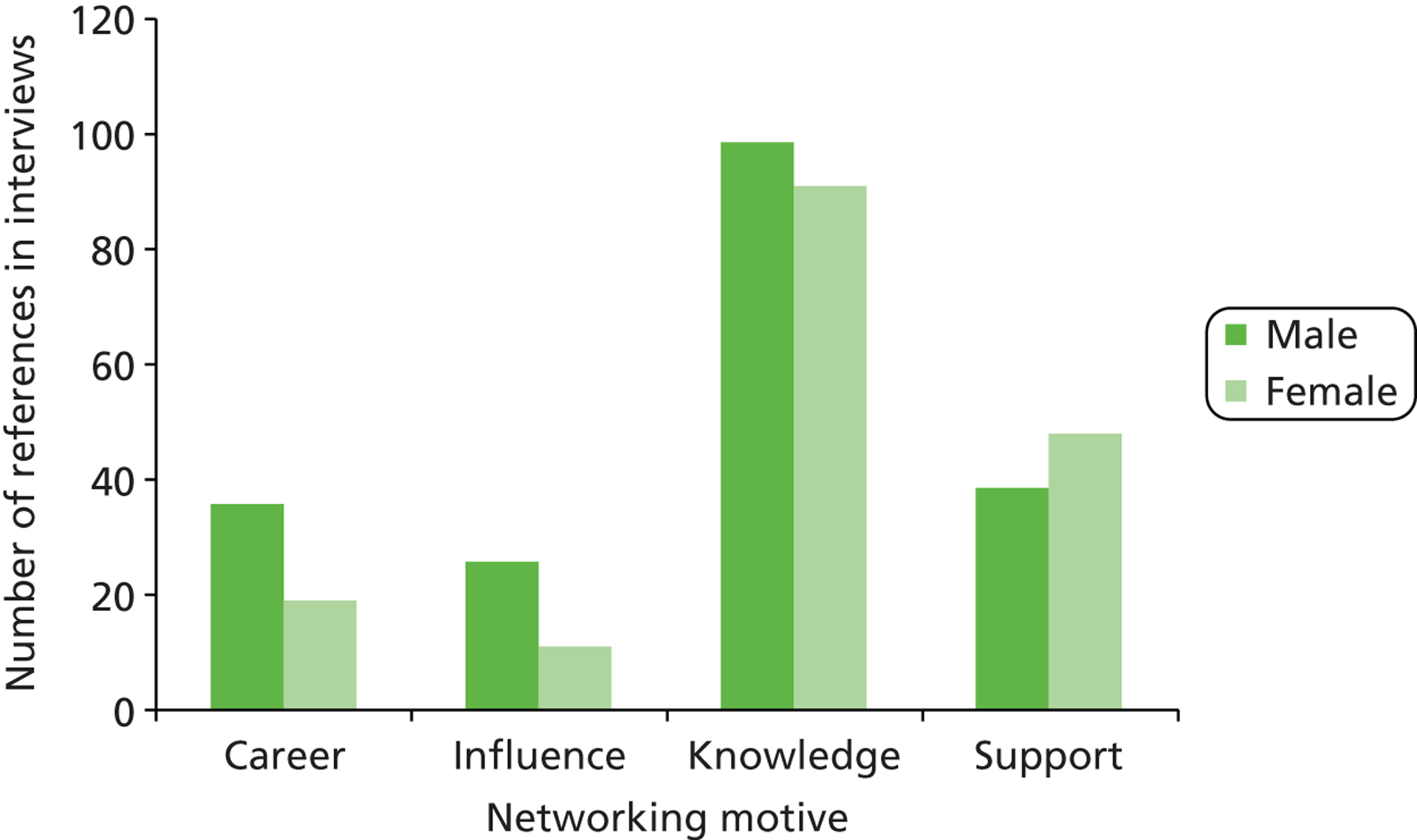

An important point to note is that some of the data presented in the next four chapters make use of the technical capabilities of NVivo to create quantitative summaries of each qualitatively coded data (represented in bar charts and pie charts). Unless otherwise indicated, the numbers given along the x-axis of each of the bar charts (and in segments of the pie charts) are frequency counts, indicating the number of times a specific theme or category was referred to by respondents in interviews. Although this proved to be a very useful way of identifying starting points for the preliminary and further analysis of the data, it is important to note that the frequency with which particular themes and issues were discussed by a particular group, or within a particular trust, does not necessarily correspond to the frequency with which managers engaged in or experienced this behaviour, or to particular outcomes. So, for example, frequent discussion of training might signify many different things, including its value, its absence or its inadequacy. Nevertheless, it does provide a useful entrée into the thematic analysis, flag up some basic but interesting points about presence or absence of a discourse and, perhaps, reflect to some extent managerial norms and key features of their cultural, organisational and professional environment. However, understanding these in detail requires us to look beyond these basic quantitative signifiers into the qualitative analysis that forms the bulk of each chapter.

Presentation of empirical data

Having explained the methodology and detailed research methods involved in our study, Chapter 3 turns to an exploration of the wider context in which the managers we interviewed were operating. This is partly informed by our wider literature search, but also by early findings and observations from phase 1 interviews and discussions with the Advisory Group, trust representatives and other academics and practitioners in the field.

The aim of Chapter 3 is to give an overview of the organisational context of management/leadership within the NHS, before drilling down into a summary full description of each of the three trusts and then into presenting summary data about the particular managerial cohorts and individual managers involved in their study.

The three chapters that follow then address, in turn, each of the three major themes of the research that emerged from the coding and analysis of the data, namely management/leadership (see Chapter 4 ), knowledge (see Chapter 5 ) and networks (see Chapter 6 ). After that, in Chapter 7 , we revisit what the data have to say about the research questions set out at the start of this chapter.

Chapter 3 The institutional and organisational context for National Health Service management

Introduction

Middle managers play a vital role in large organisations, co-ordinating activity between the upper and lower organisational reaches and across various departments, translating broader policy/strategy into operational outcomes and frequently serving as a key repository of organisational memory. 66,67 However, middle managers also represent one of the least contentious targets of restructuring, particularly reductions in headcount which attempt to avoid impacting the front-line of operations. 17,19 In this context, it is unsurprising that management represents an identity few find desirable, and that even those with the responsibility of managing repudiate the management part of their role68 – with, we argue, significant repercussions for managerial work.

It may be argued that these wider tensions impinge even more acutely on middle managers in the NHS. 25,30,69 Reforms introduced by the coalition government in 2010 to increase efficiency emphasise the importance of removing around half of management costs in the NHS. 55 Although many aspects of the reforms have been subject to intense debate, there has been remarkably little negative reaction to the proposed cuts in management costs. This lack of public outcry can be accounted for as resulting from negative characterisations of NHS middle managers, casting them as petty bureaucrats, and descriptions of the NHS as a whole as burdened by a growing, unproductive and even obstructive management cadre. 69,70,71 To understand the nature of management in the current NHS, it is essential to situate NHS management as an activity and a formal role in some historical context.

The aim of this chapter is to outline the context in which the study took place and we do this in four parts. First, we provide an overview of the institutional context for management in the NHS, in terms of broad policy and more specifically in terms of impact on NHS management. Second, we complement this overview with a brief exploration of the training and development of managers and leaders within this context, taking into account the impact of contemporary changes within the sector. Third, having selected out case studies, we examine the specific organisational context of the three participating organisations in detail, again in light of these ongoing changes, in order to elaborate key organisational characteristics and to examine points of difference and similarity to inform the research analysis. Fourth, having developed our management selection framework in the previous chapter, we outline characteristics of the sample of managers selected for in-depth interview and compare and contrast their demographic characteristics.

The institutional context of the study

The NHS has been undergoing regular and radical reform over the last 40 years. These reforms have involved structural changes, reorganisation and adjustments to management arrangements. There have been general moves towards marketisation and business-like functioning. These changes have had striking effects on management practice, professional values and service organisation and delivery in the NHS as a whole and in the English context in particular, which is the focus of this research. This section provides an overview of government policy as it affects NHS management; for fuller accounts of NHS policy see Harrison and McDonald72 and Klein. 73

Changing policy and management context

Table 7 indicates several periods of change mapped against major policy initiatives. Administrative arrangements for the NHS remained relatively stable in the period between nationalisation and the introduction of general management following the Griffiths Report. 74 The 1980s and 1990s saw government health policy that emphasised the importance of specific managerial roles to improve efficiencies as part of a number of NHS reorganisations. The NHS Management Inquiry by Roy Griffiths, Chairman of Sainsbury’s supermarket, effectively abolished consensus management in favour of general management and provided the structural arrangement for a rational management system. 80 As a result of Griffiths’ recommendations, the following management reforms took place: appointment of general managers, introduction of management budgets, value for money reforms and management training and education. General managers from inside and outside the NHS were to be in place in hospitals and health authorities by the end of 1985. Management budgets were to be introduced alongside greater financial controls. Savings arising from these reforms were to be returned to improving services for patients and the NHS Training Authority was established in order to extend management training, especially for doctors. 74 Doctors were to become more closely involved in financial matters and budgeting.

| Period | Major change(s) | Policy initiative |

|---|---|---|

| 1948–82 | Public administration | Nationalisation of health |

| 1974 NHS reorganisation | ||

| 1983–97 | General management | Griffiths Report (1983)74 |

| Quasi-markets | NHS and Community Care Act (1990)75 | |

| 1997–2007 | Business management | New NHS: Modern, Dependable (1997)76 |

| Reform | NHS Plan (2000)77 | |

| Foundation trusts | Community Health and Standards (2004)78 | |

| 2008–13 | Leadership | Darzi Review (2008)79 |

| Structural reform | Liberating the NHS (2010)55 |

The 1989 white paper ‘Working for Patients’81 passed into law as the NHS and Community Care Act in 1990. 75 This act introduced an (internal) quasi-market for health care by encouraging services to split along purchaser [health authority and some general practitioners (GPs)] and provider (acute, mental health, ambulance and community) lines. Purchasers were given budgets to buy health care from providers. Providers became NHS trusts (independent organisations with their own management teams), and it was envisaged that these trusts would then compete with each other to provide services to the purchasers. Between 1991 and 1995, all providers became NHS trusts and GPs could hold budgets (GP fund holding) to purchase care for their patients from the NHS or private providers. Some GP fund-holders were able to accelerate care for their patients, leading to accusations of an emerging two-tier health system. 73 As well as attempting to increase managerial control of services, these changes were also designed to introduce competition and a business culture.

Although these quasi-market institutions were originally abandoned by the New Labour government of 1997, these early experiences may have paved the way for market-orientated changes in the coming years. This period saw unprecedented change involving the formation and dissolution and rearrangement of structures and responsibilities of NHS authorities and trusts. The white paper ‘The New NHS: Modern, Dependable’76 saw the abolition of the internal market and dismantling of GP fund holding. This was an era of centralised management of the NHS as one organisation. It involved target setting intended to reduce waiting times and improve access to services and the introduction of a star rating system for NHS organisations. Organisations were rated by the newly established Commission for Health Improvement (CHI). Although national targets were subsequently abandoned, along with the star rating system, priorities continued to be indicated through the annual Operating Framework for the NHS that was published each year. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) was created to make decisions on the adoption of treatments. These two institutions (CHI and NICE) took control of areas previously controlled by the medical profession. Decisions about suitable treatments were now being made by NICE and clinical governance was being carried out by the CHI.

The NHS Plan77 in 2000 described a 10-year plan for the NHS and National Service Frameworks described service standards for areas such as mental health and cardiac care. Decades of under-spending on health care meant that England had notably poor health outcomes compared with other developed nations. In 2000, Tony Blair promised to increase health spending to European levels. This meant a rise from 6.6% (1999/2000) to 9% of gross domestic product (2005/6). 77 Although the targets and associated penalties were initially successful in reducing waiting times, increasingly disturbing behaviours linked to intense centralised control preceded a radical change in direction towards decentralisation and the readoption of market-based reforms. These included the promotion of patient choice and competition between providers as well as allowing for organisations based on not-for-profit structures – NHS foundation trusts (FTs).

The first wave of FTs came into being in 2004. At the same time, the previous system of block contracts to service providers was replaced by a new funding system called Payment by Results. This system was aimed at reducing waiting times by targeting payments towards specific treatments and, thus, providing a powerful incentive for trusts to direct activity towards areas of greatest need. In addition, it allowed for private providers to claim payments for services provided in independent treatment centres. GP incentives to provide additional services outside of hospital were provided for through the Quality Outcomes Framework. The 2008 review entitled High Quality Care for All (NHS Next Stage Review Final Report)79 set out the second 10-year plan for the NHS, although it was rapidly displaced by the unfolding financial crisis and the change of government in 2010. The review laid out plans to increase patient choice, to improve public health provision and to extend the role of doctors as managerial leaders.

This frequent and substantial institutional change over recent decades has continued through the course of the project to have striking effects on management practice, professional values and service organisation and delivery in the NHS as a whole. Moves towards the decentralised control of NHS organisations, with increasing numbers of hospitals becoming FTs, and efforts to increase patient choice and competition between health provider organisations, have relied on NHS management for delivery. Managers have thus been given increasing responsibility for implementing health service reforms,55 providing the links between those planning and organising services and those providing services to patients while at the same time bearing the brunt of the efficiencies implied by the reforms.

Consequences for managers and management

Between 2000 and 2009, amid these changes, the NHS workforce grew by around 30%. Across this period, figures for the number of managers and senior managers rose from 2.7% (full-time equivalent) in 2000 (n = 24,253) to 3.4% in 2009 (n = 40,094),82 remaining broadly in line with figures for most other developed countries. 83 Since 2010, employment in the NHS has been falling, and recent reductions in NHS staffing numbers generally have been more than matched by reductions in the total numbers of managers. Figures from 2012 show the proportion of managers at 3.2%, suggesting that policy reforms targeted at reducing management costs might be beginning to bite. 84 In all likelihood, managerial numbers will continue to decrease in subsequent years as middle managers are targeted in health reforms aimed at reducing management costs. This comes at a time when effective organisational co-ordination will be central to maintaining safety during a period of reduced investment.

As well as the increased demands for management resulting from higher staffing levels, other recent institutional changes that have generated additional management workloads include:

-

moving to service line management

-

applying for FT status

-

achieving national performance standards

-

payment by results, changing to tariffs, fines

-

the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention agenda

-

creation of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs)

-

changing regulatory, auditing and accreditation regimes

-

making £20B savings by 2015. 69

The new coalition government of 2010 brought health policy full circle by proposing the removal of management layers to improve efficiency. The white paper ‘Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS’55 proposed to deliver the 45% reduction in management costs by delayering the NHS, abolishing 151 primary care trusts (PCTs) and 10 SHAs. The Health and Social Care Act85 in 2012 took the changes further by reducing the emphasis on GPs as commissioners and providing for private sector commissioning. The impact of this across the NHS is still emerging, but through the period of study the immediate consequences were widespread uncertainty, exacerbated by the ongoing and substantial pressures to reduce costs significantly, year on year, while at the same time maintaining service quality. Achieving this with often reduced staff numbers, particularly reduced number of managers, as attempts were made to avoid reductions in ‘front-line’ staffing levels (i.e. doctors and nurses) led to a widespread experience of severe work intensification among NHS managers, described elsewhere as ‘normalised intensity’. 86

In this section, we have charted political change, influential government policies and consequent institutional and cultural changes involving management of the NHS from its inception to date. Since the start of this research project, the landscape has continued to change substantially. There have been three notable landmarks, acute financial pressures (the so-called ‘Nicholson Challenge’ to make savings of £20B over 5 years), major structural reforms (Health and Social Care Act, 2012)85 and expected changes to professional/managerial configurations emerging from the Francis Report. 4 In Management and leadership development in the NHS, we explore the professional development challenges facing managers in the sector and the initiatives taken to develop managerial and leadership capabilities.

Management and leadership development in the NHS

Since the first intake of the NHS Management Training Scheme in September 1956, the content, location and impact of management and later leadership development in the NHS has undergone regular transformation ( Table 8 ). Although terminology has changed, the core aim of these programmes remains consistent: in 1955, the aim was to provide the NHS with ‘well-trained administrators who would be competent to fill senior administrative posts in years to come’87 (p. 37, © Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012, Talent Management in the NHS Managerial Workforce). In 2012, the newly formed NHS Leadership Academy set out as its aim to equip managers from across the different professional backgrounds in health care with the skills needed for leading and improving their organisations in ways that were still consistent with the values of the NHS. 88

| Year of commencement | Key management training programme | Agency responsible |

|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Management Training Scheme | Regional Staffing Officers (RSO) |

| National Staff Committee for Administrative and Clerical Staff (NSCA&C) | ||

| Standing Committee on Management Education and Training (SCMET) | ||

| 1983 | National Management Training Scheme | NHS Training Authority |

| 1986 | GMTS | |

| 1993 | National Management Training Scheme | NHS Training Directorate |

| National management development programme | ||

| 2002 | GMTS | NHS Leadership Centre |

| Breaking Through | ||

| Gateway to Leadership | ||

| 2009 | Top Leaders | NHS Leadership Council |

| Emerging Leaders | ||

| Inclusion | ||

| Clinical Leadership | ||

| Board Development | ||

| 2012 | Foundation programme (award: post-graduate diploma) | NHS Leadership Academy |

| Mid-career programme (award: masters degree) | ||

| Executive/senior leadership programme (peer assessed) |

In the intervening period, the responsibility for producing these administrators, managers and, latterly, leaders has oscillated between the regions and more central NHS bodies. There has also been a notable shift in the basis of professionalisation of NHS managers represented by the shift in terminology from administration, to management and then to leadership. 28,89 Before exploring these very different orientations in greater depth in Chapter 4 , it is useful to note briefly this shifting emphasis in management training and development initiatives.

The NHS Management Graduate Training Scheme (MGTS) broadly retains the structure set up in 1986, combining formal education [leading to a Master of Science (MSc)] with a rotaring series of placements and internships in NHS organisations that give prospective managers direct experience of a range of health-care management situations together with formalised education and training. Other than the MGTS, most of the important current management/leadership development programmes were established as part of the Modernisation Agenda in the early 2000s, including initiatives promoting diversity in management, including Breaking Through (for black and minority ethnic employees), Gateway to Leadership (to develop senior managers from outside the NHS) and the Athena Programme for Executive Women. Such initiatives were underpinned by the creation of the Leadership Qualities Framework (LQF) in 2004 by the NHS Leadership Centre. Details of these programmes are summarised in Appendix 10 .

In 2009, the Department of Health published Inspiring Leaders. 90 Reflecting the strategy set out in The Operating Framework for the NHS in England 2008/09,91 the Inspiring Leaders report explicitly devolved responsibility for leadership development to regional employers, requiring SHAs to produce talent and leadership plans by the end of July 2009. In line with the principle of subsidiarity, these plans were to be cascaded down to the local and individual level, guided by the overarching activities of the newly formed NHS Leadership Council.

Any potential impact of this was, however, curtailed by the change of government and the Health and Social Care Act of 2012,85 which set in train the abolition of the bodies charged with overseeing leadership development. 92 The new arrangement to ensure continuity in this area took the form of the replacement of the short-lived NHS Leadership Council followed by a new NHS Leadership Academy (formed in April 2012). The principle of subsidiarity, whereby responsibility for leadership development would be cascaded down to regional and local organisations, was rejected. Instead, the NHS Leadership Academy was formed (1) to ensure a more centralised strategy, reducing duplication, fragmentation and discontinuity by providing a single national structure for leadership development and (2) to set in place a more bottom-up approach to development by giving employers ‘greater autonomy and accountability for planning and developing the workforce’55 (p. 40, © Crown Copyright 2010, Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS). The intention was to ensure that an integrated national approach was established that made better use of resources by rationalising and standardising what had previously been very localised and fragmented training for leadership. 88

The NHS Leadership Academy sets as one of its primary tasks the need to professionalise leadership in health care. Associated with this would be greater expectations of health-care managers to be more proactive in taking responsibility for performance. 88 Citing recent research reports,93 wider academic research and widely cited instances from the private sector (e.g. General Electric), the NHS Leadership Academy briefing makes strong claims regarding the ability of leadership to make a significant difference to the performance and outcomes of organisations. Although still at an early stage of development, the Leadership Academy has set out three core programmes that are to be established:

-

The foundation-level programme is aimed at aspiring leaders with some experience of managing people and leads to a postgraduate certificate.

-

The mid-career programme is aimed at those who manage team leaders, for example, and who seek a broader leadership role. This programme leads to a Masters degree.

-

The senior leadership programme is preparation for an executive, national or other senior leadership role. There is no formal qualification; instead, individualised, bespoke programmes will include academic support, coaching, peer review, self-management and self-direction.

If we also consider the managerial framework developed in Chapter 2 , it is clear that, quite apart from these general initiatives, managers face a considerable variety of forms of formal education, training and development associated with their distinct career pathways into management. 80,94 A well-established pathway of clinical training and development is likely to underpin not only medical staff who move into management positions (and medical science staff), but also nurses and allied health professionals (AHPs), whose development into management roles is likely to take a more experiential learning route. 95–97 Similarly, many functional experts are likely to follow quite distinct paths of professionalisation (e.g. in finance, HR, marketing, law) that may or may not coincide exactly with health service experience or with progression into health-care management roles. 31,32 General managers in health care are, of course, expected to be a more diverse group in terms of their background, training and experience. 98 The question becomes, ‘How do different types of manager in different types of trust access and develop their management knowledge base in order to help them become effective managers?’.

The case study trusts: organisational context