Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/2002/16. The contractual start date was in February 2012. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Morris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Epidemiology

Estimates of the prevalence of childhood disability in the UK vary from 5% to 18%, depending on the definition or indicator of disability. 1 Most commonly, an estimate of 1 in 20 children is cited. 2 Based on the Family Resource Survey (2004–5), there are an estimated 952,741 ‘disabled’ children in the UK, which is 7.3% of the population of children aged 0–18 years (8.8% boys and 5.8% girls). 3,4 However, the survey used a definition that broadly comprises any long-term health conditions, including neurodisability, but also, for instance, health conditions such as diabetes, arthritis and asthma.

Neurodisability is an umbrella term for conditions associated with impairment of the nervous system and includes conditions such as cerebral palsy, autism and epilepsy; it is not uncommon for neurological impairments to co-occur. Aside from asthma, neurodisability probably represents the largest proportion of significant childhood disability. 5 Individually, many conditions that result in a neurodisability are rare, whereas, grouped together, they are relatively common.

Neurodisability is a UK term; there is a subspecialty of paediatric training within the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health devoted to this group of children. However, the term neurodisability is not defined, and there is no universally recognised agreement as to which conditions are included. The term has arisen as a way of describing a group of conditions which give rise to similar problems, health and educational needs, and which are commonly managed by the multidisciplinary teams skilled in multisystem health conditions.

Without a clear and agreed definition, it is not possible to derive consistent and reliable estimates of the prevalence of neurodisability to inform needs assessment and appropriate resource planning. The lack of a definition of neurodisability, and lack of clarity about which conditions are included, also hinders effective communication, especially when considering health outcomes and the planning and evaluating of health services, multiprofessional teams and care pathways.

In other English-speaking countries, the term neurodevelopmental disorders is used to describe similar conditions in children. For instance, we found a definition of neurodevelopmental disorders as ‘disorders where motor, cognitive, behavioural, and/or language functioning are affected by central nervous system impairments, resulting in a variety of challenges associated with ambulation, information processing, self-regulation and communication’. 6 To our knowledge, no definition is widely agreed on.

Health services for neurodisability

Although neurodisability comprises a heterogeneous group of conditions, these conditions have much in common in terms of resulting health-care needs. Children and young people affected by neurodisability have a range of impairments; some of these are relatively minor, but many give rise to complex health-care needs. As a consequence, they are among the most frequent and intensive users of the NHS, requiring care and support from health services across primary and community care, hospital services and specialist centres.

Although largely unable to cure the neurological impairments, health services aim to optimise functioning and to maintain/improve the health and well-being of these children, most of whom can be expected to survive into adulthood. 7 Funding and provision of health services for disabled children are recognised to be highly variable. 8 A report by Sir Ian Kennedy into improving health services for children and young people acknowledged that children ‘do not always get the attention and care from health care services that they need’. 9 He also recommended the need to identify a ‘common vision’ between families and professionals for what services are seeking to achieve (p. 54). 9 A further level of complexity is that NHS care for children is often integrated with education and social care services.

Disabled children are known to face health and social disadvantage. Thus, over recent years, a range of initiatives have sought to improve health and social care provision, for example the National Service Framework for Children, Aiming High for Disabled Children, and the Centre for Excellence and Outcomes in Children and Young People’s Services. The Every Child Matters outcome framework has provided a useful means to develop indicators assessing educational and social care outcomes for children and, with adjustments, is proposed to be appropriate and meaningful for disabled children. 10

Nevertheless, it has been difficult to assess the impact of NHS care on disabled children, as there is no overall measure of their health outcomes. Hence, identifying outcome measures of how the NHS is impacting on the health of children with neurodisability would be extremely useful, particularly if the measurement was grounded in the perspectives and priorities of children, young people and their parents. Identifying an agreed set of health outcomes between families and professionals would also provide a focus for the combined efforts of the NHS. In fact, such outcomes could constitute the ‘shared vision’ of what health services are trying to achieve for disabled children, as recommended by Sir Ian Kennedy.

Health outcomes

Outcomes of a health condition or injury can be considered within the bio-psychosocial framework expressed through the World Health Organization’s (WHOs) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). 11 The WHO ICF classifies components of health and functioning as ‘body structures and functions’ and ‘activities and participation’. Thus, a disease or injury may lead to impairments of body structure or function, limitation in activities and/or restriction in participation. These impairments, limitations and restrictions are collectively referred to as disability, and the relationships between these components are mediated by environmental and personal factors. Key environmental factors are health-care services, systems and policies, and social interventions.

In the context of neurodisability, it is often difficult for health services to make changes in chronic impairments of ‘body functions and structures’. Consequently, there may be a greater likelihood of health and social interventions maintaining or improving ‘activities’ and/or the ‘participation’. Clearly, the constructs assessed using outcome measures should be those most appropriate to assessing likely impacts of health care, and must be credible to patients, in this instance children and young people affected by neurodisability, and their parents. 12,13

Patient-reported outcome measures

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) assess the quality of care delivered to NHS patients from the patient perspective. PROMs measure a patient’s health at a single point in time, and are collected through short, self-completed questionnaires. PROMs aim to assess components of health, which are largely the components of the ICF under the rubric of health status or health-related quality of life (HRQoL). A wide range of generic and condition-specific PROMs has been developed for children and young people. 14 Identifying PROMs for neurodisability requires, first, identification of the precise constructs to be measured and, then, the gathering of evidence of psychometric performance of available measures. 12

Language and cultural issues can affect how people interpret and/or respond to questions; hence, one cannot simply assume that PROMs perform consistently across languages and cultures. 15 Therefore, for example, the Food and Drug Administration guidance on PROMs recommends that evidence be provided of the process used to test measurement properties across different language and cultures. 15

Structured reviews have identified generic and condition-specific PROMs that can be used with children. 14 Others have discussed conceptual issues pertaining to what such instruments measure for children and young people affected by neurodisability. 16–18 However, no systematic reviews have comprehensively appraised published research about the psychometric performance of generic PROMs when used with children and young people affected by neurodisability.

Children and young people have the right to report on their own health. 12 Although there has been wide recognition that children’s voices should be heard in research and service design, this is often not the case19 and, in particular, the voices of disabled children are frequently overlooked. Chronological age is not a clear criterion for judging when children are capable to self-report their health by completing a questionnaire, although children aged ≥ 8 years are widely believed to be competent. 12 Parent and carer proxy reports are the only way to assess outcomes for children cognitively unable to self-report, but these do represent a different perspective to the child’s own view. However, as it is parents who typically seek health care on their child’s behalf, they need to be offered an opportunity to report their perspective. Ideally, both children’s and parents’ reports should be collected so that both perspectives are represented independently. 12

NHS Outcomes Framework

The NHS Outcomes Framework is part of a strategy that aims to deliver ‘the outcomes that matter most to people’. 20 Domain 2 of this framework will detail indicators of the ‘quality of life of people with long-term conditions’. Much of the detail is still being determined and will evolve over the coming years. 20

Proposed indicators include PROMs. There continues to be a substantive programme of methodological, applied and policy research about PROMs funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Medical Research Council and the Department of Health. Much of the work has focused on adults and less on children. There is a clear direction of travel whereby PROMs look set to be one of the key performance indicators in the UK and other health systems. 13

As part of consultations on the initial proposal for the NHS Outcomes Framework , the Royal College of Paediatrics & Child Health proposed, pragmatically, that there should be a single PROM ‘for a basket of conditions’ rather than aiming to have one for every diagnosis. 21

The identification of suitable outcome measures will improve the evaluation of integrated NHS care for the large number of children affected by neurodisability, and has the potential to encourage the provision of more appropriate and effective health care. This research sought to contribute to positively improving children’s health outcomes by providing a high-quality means for measuring them. Identifying a common purpose for NHS services will improve health outcomes for children and young people affected by neurodisability. 9 Establishing appropriate outcome measures will help to ensure that NHS resources are deployed effectively and in an efficient manner.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

This research aimed to determine (a) which outcomes of NHS care should be assessed for children and young people affected by neurodisability and (b) the extent to which they can be measured by existing PROMs.

To address this aim, the study had the following objectives:

-

to identify key health-care outcomes, beyond measures of morbidity and mortality, that are regarded as important by children with neurodisability and parents

-

to ascertain what outcomes of services health professionals think are important for this group and to assess the extent to which they agree with families’ views

-

to seek consensus between families and professionals on what health outcomes are important and assess the usefulness of candidate generic PROMs for routine use in the NHS

-

to identify generic PROMs which have been evaluated using English-language questionnaires, and identify which best map onto outcomes identified as most important by families and professionals

-

to appraise evidence of the psychometric performance of these PROMs when evaluated with general population samples and/or children with neurodisability

-

to make recommendations about the use of generic PROMs to measure health-care outcomes for children with neurodisability.

As part of this research, the serendipitous opportunity arose to develop and determine agreement on a definition of ‘neurodisability’, in terms of the types of conditions it includes. Hence, the following objective was in addition to those specified in the protocol:

-

vii. to develop and test agreement with a definition of neurodisability that would be acceptable and meaningful to both families and health professionals.

The research design comprised three main work streams to address these aims and objectives:

-

a systematic review of the psychometric properties of generic PROMs used to measure the health of children and young people

-

qualitative research involving focus groups and interviews with children and young people affected by neurodisability, and separately with parents

-

an online Delphi survey with health professionals working with children and young people affected by neurodisability.

Finally, a consensus meeting with a small group of young people, parents and professionals was convened to seek agreement on a core set of more important aspects of health that could represent key health outcomes for neurodisability.

The report

The approach taken for each work stream, and findings from each approach, are described separately in the report. We begin by describing the public and patient involvement (PPI) in the research (see Chapter 3 ). Then, we describe the systematic review (see Chapter 4 ), the qualitative research (see Chapter 5 ) and online Delphi survey (see Chapter 6 ). In practice, these activities were carried out in parallel. In Chapter 7 we describe the consensus meeting. These sections are followed by a narrative synthesis (see Chapter 8 ), where the findings of each component of the research are brought together, conclusions are drawn, and relevant implications for health policy and research are considered.

Chapter 3 Public and patient involvement

We define PPI using the NIHR INVOLVE terminology as ‘where members of the public are actively involved in research projects and in research organisations’, as distinct from being research participants. 22 In this research, the members of the public involved were parents of children and young people. This chapter describes how parents of children affected by neurodisability were involved as part of the research team, and discusses the impacts that parent involvement had on the research, parents and the researchers. This chapter is intended to describe the PPI activities and provide reflections rather than be a rigorous appraisal of the involvement. The report takes in to account the recommendations for complete and transparent reporting of PPI in health services research. 23

Peninsula Cerebra Research Unit and public and patient involvement

Involving stakeholders and members of the public in research is believed to improve the utility of applied health service research. 22 The Peninsula Cerebra Research Unit (PenCRU) at University of Exeter Medical School is committed to involving families of disabled children in all aspects of the research process. PenCRU achieves this involvement through recruiting and retaining a ‘Family Faculty’. Our rationale for involving families of disabled children in research embraces the philosophical as well as pragmatic advantages and policy-relevant advantages. 24

The PenCRU Family Faculty is currently a cadre of several hundred parents of disabled children, mostly resident in Devon, who have indicated a willingness to be involved in research. We have learned to be flexible in our approaches to PPI in the context of childhood disability research. We understand that being involved in research is not a top priority for these parents and, therefore, provide opportunities for them to be involved in research at a level that suits their situation and the time they have available. Therefore, while our overall approach and ethos is to seek to work in partnership with families, in practice our methods for PPI vary from being wholly collaborative to, in other instances, being relatively consultative.

Methods

The chief investigator (CM) conceived the idea for the research based on policy relevance and personal interests, skills and experience; we do not believe that parents in the Family Faculty would have suggested the topic. However, the proposal was discussed and endorsed by the PenCRU advisory group prior to applying for funding. One parent participated as a co-applicant on the application, although their contribution to the protocol was consultative regarding the salience of the research rather than methodological.

Subsequent to funding being approved by NIHR, the opportunity to be involved in the research was advertised to the Family Faculty by e-mail. Including the parent who was a co-applicant, five parents volunteered to become involved. Four of these parents participated alongside members of the research team in the first co-investigator meeting held in Exeter, UK, in November 2012, and three participated in the co-investigator meeting held towards the end of the project, in April 2013.

Parents participated in several meetings during the research to help develop and review appropriate topic guides for the qualitative research (described in more detail in Chapter 5 ), to hear progress and ask questions about the systematic review, contribute to and refine the definition of neurodisability, and to reflect on the outcomes suggested by professionals in the Delphi survey (see Chapter 6 ). Parents also communicated and contributed by e-mail, particularly in relation to developing the definition. The time that parents contributed to the research was acknowledged financially, and their expenses were reimbursed.

The Research Fellow (AJ) convened involvement activities with support from the PenCRU Family Involvement Co-ordinator (CMc) and chief investigator (CM). Meetings were held generally during the school day (10 a.m. to 1 p.m.) and, although they were structured with an agenda, the meetings were informal and discursive, and followed by a sociable lunch.

Parents were provided opportunities to comment on the final report and conclusions and recommendations, and helped to write the plain English summary. They will help to produce plain language summaries for subsequent academic papers produced from the research, and help in implementing the dissemination strategy for the findings.

Measuring the impact of the PPI was not a formal element in the protocol. Nevertheless, we sought the views of the parents who had been involved using a feedback questionnaire. We asked parents how they had been involved in the research; their general experience of being involved; what were positive or good things about being involved; whether there were any parts of the experience of being involved that were not so good or could have perhaps been better; whether or not they felt that they had an impact on the way the research was done; whether or not being involved had any particular impacts on them; and whether or not they felt part of the research team. Members of the whole research team were offered the opportunity to comment by e-mail on whether they felt parents having been involved had an impact on the research or on them personally.

Parent feedback

Parents who gave feedback generally described their involvement as having been part of a ‘group of parents’ involved with the research team. They recalled the co-investigator meetings, other meetings, being sent documents and commenting on these by e-mail. They described their experience generally as interesting and educational, and appeared to have enjoyed meeting other members of the team and adding their own perspectives to those expressed by others in the team. There were indications that they felt that any impact they might have had on the research was as a group, rather than by them as individual parents. Their impression was that their greatest impact on the research was their contributions to the definition of neurodisability.

While they did feel involved in the research, they did not feel that they were necessarily integral to the research team, and one expressed that they felt in some ways the research could have been carried out without them. One parent indicated that they would have liked greater involvement in the interviews and analysis for the qualitative research but also appreciated that parents are busy and they may not have been able to be more involved, even if the opportunity had been offered. One indicated that they wished that they could have been more help to the team, which was expressed as a slightly negative reflection.

Researcher perceptions

Members of the research team in Exeter felt that parents made significant and valuable contributions both at co-investigator meetings and through their other contributions. In the first co-investigator meeting, parents were noted to have made important contributions in the small group discussion planning the qualitative research. At the second co-investigator meeting, parents were felt to have provided important perspectives to the general discussions interpreting the findings of the three research streams, and in particular the discussion on how to approach and conduct the consensus meeting. Involving parents at these meetings meant that documents and presentations had to be prepared in accessible formats, which may have taken a little more time. The feeling generally among researchers appeared to be that parents’ input positively influenced the dynamics of discussion.

The researchers involved in the Delphi survey that developed the definition of neurodisability felt that the contributions of parents made by e-mail and at meetings were invaluable. The two meetings the Exeter team had with parents to develop the topic guides for the qualitative research were felt to have been crucial to developing an appropriate format for these events. Researchers carrying out the systematic review found it difficult to find ways to involve parents meaningfully and usefully in that aspect of the research due the technicalities of psychometric evaluation, and the tasks associated with systematic reviews generally.

Feedback from members of the research team based elsewhere in the UK was that the approach taken to PPI in this research was laudable, and went beyond the ‘tick-box’ approach that they had observed previously with some other projects. One researcher who was less familiar with childhood disability felt educated to the demands of parenting disabled children by meeting and talking with the parents, and remarked profound admiration for their contributions to the research given the demands of their daily lives.

Discussion

There was a general feeling that this project presented a number of challenges for enabling the full collaborative involvement of parents, especially given the technical nature of the systematic review. There are several opportunities for PPI when conducting systematic reviews: suggestion of the topic and development of specific research questions; in the development of the protocol and determining the appropriate inclusion and exclusion criteria; and in the conduct of the review by helping to draft or review the report. 25 For this project, the opportunity to involve parents in each of these activities was somewhat compromised due to the topic and research questions having been predetermined, and the technical understanding required for appraising the psychometric aspects of PROMs.

There were greater opportunities for involving parents as part of the research team in planning the qualitative research and Delphi survey with professionals. Pragmatically, there were few opportunities to involve parents in the analysis of qualitative data, as members of the research team (AA and AF) who led this aspect of the analysis were based in London. Planning more substantive involvement of parents throughout the qualitative analysis may well have provided enhanced insight and depth of analysis; nevertheless, it would also have taken more time, and would have needed to be factored into the overall project management.

We have learned from this project that full collaborative involvement of families in designing and managing the project would have provided greater scope for impacting on the research from the start, and also may have enabled us to plan greater opportunities for involvement throughout. Developing a more detailed plan for involvement activities as part of the protocol may have been beneficial. In addition, producing a plain language summary of the protocol would have been helpful to assist parents to understand the context and purpose of the study; the plain language summary would have aided advertising of the opportunity for being involved. Time and interest of parents permitting, providing a package of introductory training for parents about PROMs and appraising measurement properties would have been ideal.

In terms of evaluating the impact of involving parents in childhood disability research generally, it may be useful to record the preconceived notions and plans that researchers take into meetings with parents, and recording afterwards what, if anything, has changed by the end of the meeting. Involving disabled children and young people more fully as partners in research requires resources to identify interested young people and to support them throughout their involvement. There remains scope for methodological research to learn more about appropriate approaches to PPI in the childhood disability research context.

Summary

There was a strong commitment to involving parents of children and young people affected by neurodisability in this research. In practice, a number of challenges were identified. In particular, the topic and technical methodology presented opportunities for more innovative involvement activities, such as a plain language summary of the protocol, or providing training. On balance, involvement of parents was perceived positively by those parents involved and by the researchers.

Chapter 4 Systematic review of patient-reported outcomes for children and young people

Aims and objectives

The aims of the review were to identify generic PROMs used to measure the health of children and young people and to appraise psychometric evidence of the performance when evaluated using English-language questionnaires.

The objectives for the systematic review were:

-

to identify eligible candidate generic PROMs for measuring the health of children and young people

-

to identify peer-reviewed publications of studies in which the psychometric performance of candidate PROMs had been evaluated in general populations

-

to identify peer-reviewed publications of studies in which the psychometric properties of candidate PROMs had been evaluated specifically in a population of children and young people affected by neurodisability

-

to appraise the methodological quality of the identified studies that evaluated psychometric properties of candidate PROMs

-

to appraise the evidence for the psychometric properties of candidate PROMs both in general populations and with children and young people affected by neurodisability.

Methods

The systematic review was designed in two stages. In stage 1, we sought to identify all generic PROMs used to measure the health of children and young people < 18 years of age. In stage 2, we identified and critically appraised peer-reviewed publications of studies in which the psychometric performance of identified candidate PROMs had been evaluated with children and young people. In stage 2, studies were categorised depending on whether they evaluated PROMs in (i) a general population of children or (ii) children and young people affected by neurodisability.

The systematic review was conducted following the general principles published by the NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 26 The systematic review team developed a detailed protocol for the review from the original proposal (www.netscc.ac.uk/hsdr/files/project/HSR_PRO_10–2002–16_V01.pdf). We applied to publish the full protocol with PROSPERO in February 2012; however, we were informed that, as a methodology review, our systematic review did not meet their inclusion criteria at the time. However, the protocol was published on the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for the South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC) website (http://clahrc-peninsula.nihr.ac.uk/patient-reported-outcome-measures-in-children-with-neurodisability.php). The protocol was updated to take account of methodological decisions that were required as the review progressed.

Stage 1: identification of patient-reported outcome measures

Search strategy

The search strategy was designed by an information specialist (MR) following consultation with the systematic review team, and with reference to the methodological filters published by the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) group27 and the construct filters developed by the Oxford PROMs group. 28 The strategy used a combination of medical subject headings (MeSH) and free-text terms. Search terms were grouped as follows:

-

group 1: general names for measures (e.g. questionnaires, instruments or tools)

-

group 2: multidimensional health construct terms (e.g. quality of life or health status)

-

group 3: terms to describe children and young people (e.g. children, teenagers or adolescents).

The terms within each group were combined with a Boolean OR command and were searched in combination using a Boolean AND command. Piloting this search strategy produced a total of 38,893 citations. Systematic screening of this number of citations was judged to be too burdensome within the confines of the resources allocated to the project. A fourth set of terms was therefore added to increase the specificity of the search:

-

group 4: terms relevant to psychometric performance (e.g. validity or reliability).

As this project was conceived to inform the NHS Outcomes Framework in the UK, we were interested only in PROM questionnaires that were available and evaluated in English; hence, the search was limited to English language. The search was also limited by date to publications from 1992, as the team agreed that it was unlikely that PROMs had been developed before this date.

The search strategy was designed for MEDLINE (via OvidSP) and modified for EMBASE and PsycINFO (via OvidSP) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost). The searches were run on 20 and 21 March 2012. Separate searches were carried out on the Oxford PROM bibliographic database and Patient-Reported Outcome and Quality of Life Instruments Database. Reference lists of systematic reviews were also checked. 14,29–32 The search strategy (for MEDLINE/OvidSP) is shown in Appendix 1 . All search results were exported to reference manager software (EndNote X6, Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and deduplicated. EndNote was used to manage the citation database throughout the project.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The aim of this stage of the review was to identify potential candidate PROMs. Eligibility criteria were developed to guide selection ( Table 1 ).

| Inclusion criteria | Specification |

|---|---|

| Population | Children and young people < 18 years old |

| Instruments | Generic PROMs used in the English language; child self-report and/or parent (primary carer) reported |

| Evidence | Indication of testing/reporting of psychometric performance, such as aspects of validity or reliability |

| Study design | Any type of study design |

| Date | 1992 to March 2012 |

| Language | English language |

| Exclusion criteria | Specification |

| Instrument not used in a population of children (< 18 years) | |

| Condition-specific PROMs | |

| Instruments administered by an interviewer | |

| Any instrument where the proxy respondent is not a parent or primary carer (e.g. clinicians or teachers) | |

| English-language version not used |

Study selection

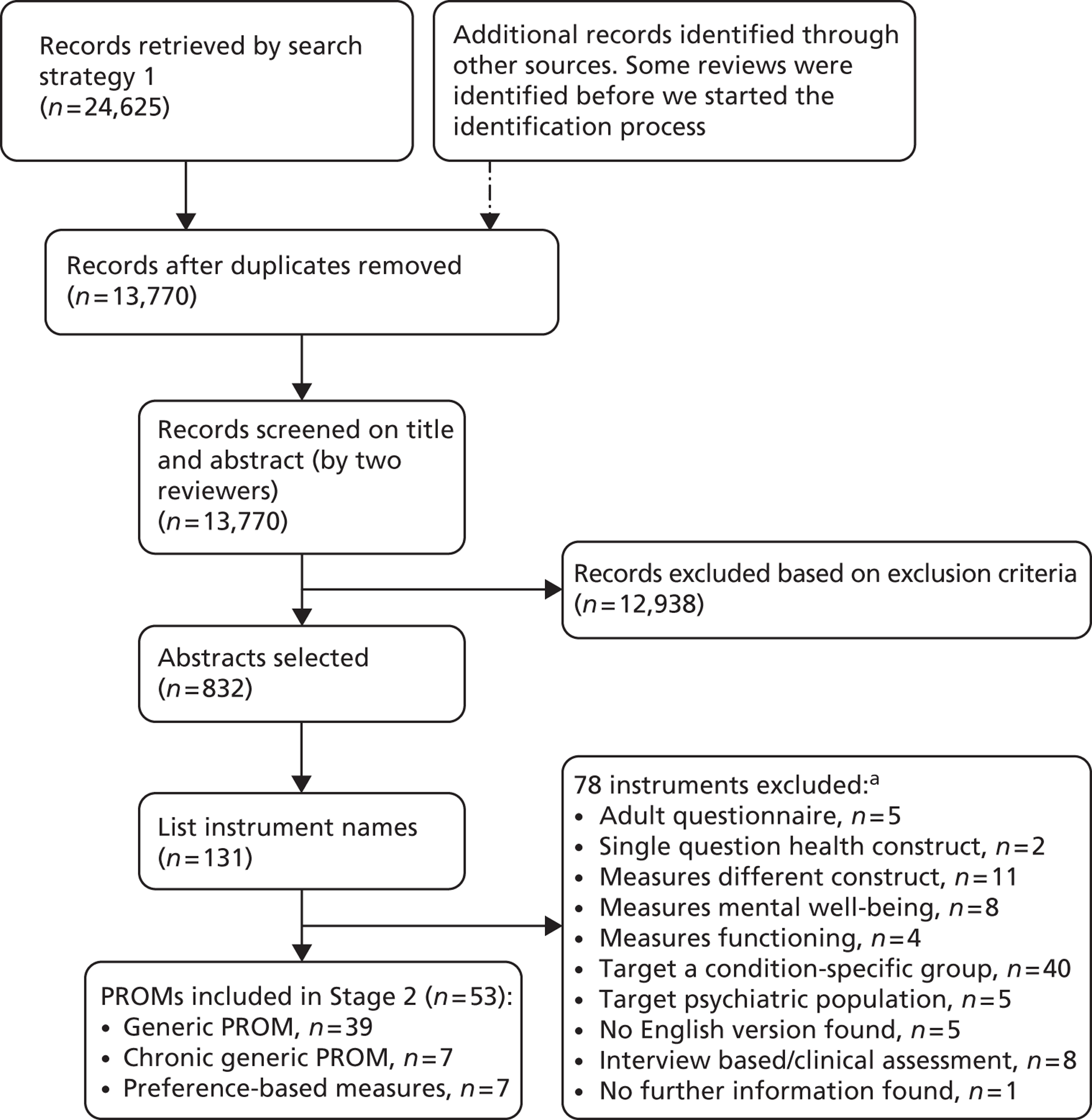

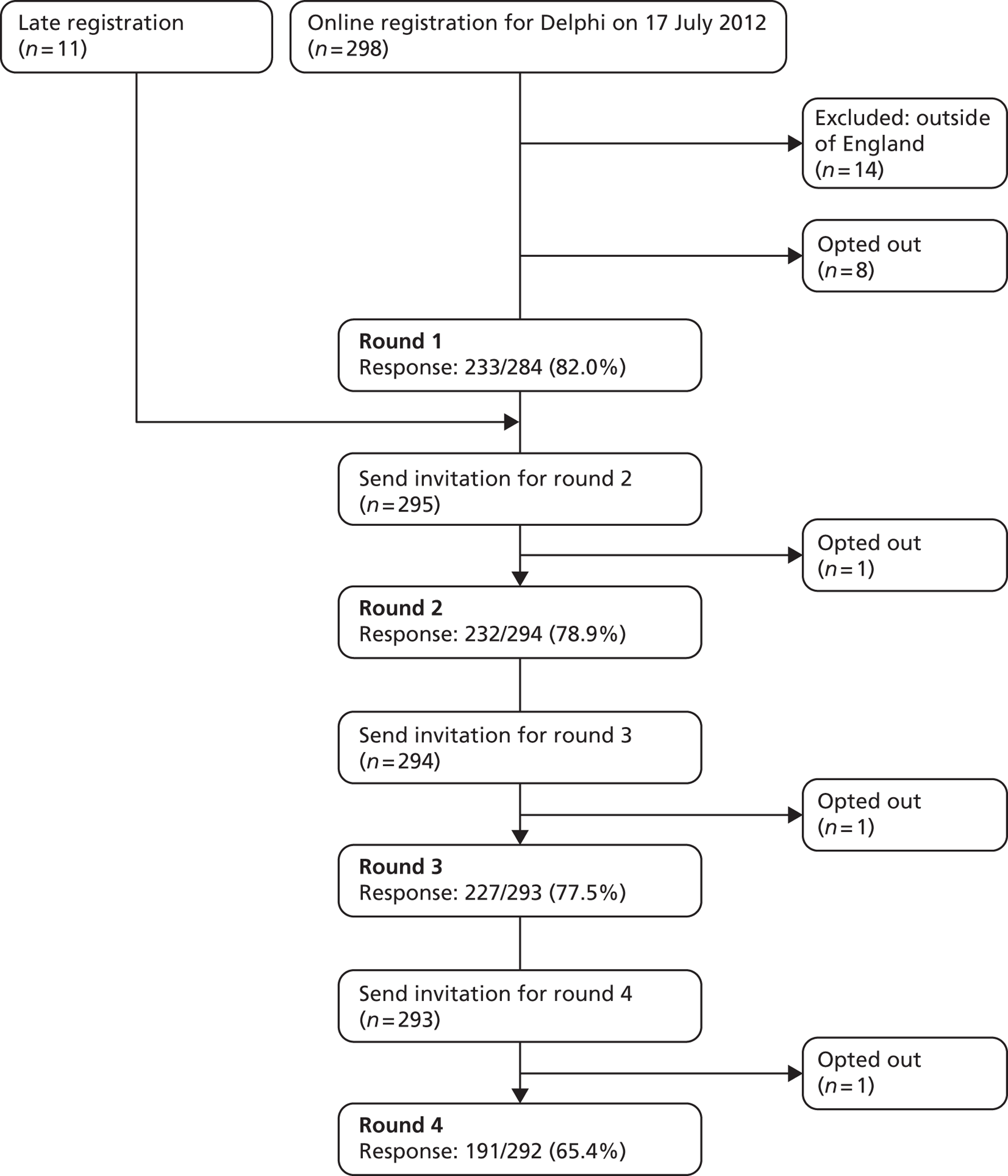

Two groups of reviewers (group 1: AJ, VS, SB; group 2: CM, JTC, MR, DM, RW, RA) independently screened all titles and abstracts to locate papers in which potential candidate PROMs were cited. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved with the arbitration of a third reviewer (either CM or AJ), where necessary. A flow chart describing the process of identifying relevant literature for this stage of the review can be found in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing identification and selection of potentially eligible candidate PROMs. a, Some instruments were excluded for more than one reason.

Data extraction

The result of this stage of the search was a list of potentially eligible candidate PROMs. Names and acronyms of all PROMs cited were extracted by one reviewer (AJ) who applied the eligibility criteria. Where there was insufficient detail provided in the paper to address all eligibility criteria, additional information was sought by internet searching.

Stage 2: identification of studies evaluating psychometric performance of patient-reported outcome measures

Search strategy

The search for the second stage of the review was designed using the names, alternative names and standard acronyms of the candidate PROMs identified in stage 1. For each candidate PROM, an individual search strategy was created to identify studies where the PROM had been used and evaluated in general populations (search 2.1). Three groups of search terms were used:

-

group 1: name(s) of the PROM

-

group 2: terms to describe children and young people

-

group 3: psychometric terms (e.g. validity or reliability).

The electronic search was designed for MEDLINE (via OvidSP) and modified for EMBASE and PsycINFO (via OvidSP). No language or date limits were applied to the search. The search used in MEDLINE (OvidSP) can be found in Appendix 2 . In total, 51 searches were run on each of the three databases between 18 July and 5 September 2012.

A further search strategy was designed to identify studies where candidate PROMs might have been used specifically with neurodisability (search 2.2). Three groups of search terms were used:

-

group 1: name(s) of the PROM

-

group 2: terms to describe children and young people

-

group 3: neurodisability terms, including key exemplar conditions.

The terms used included MeSH terms, and variations of the three exemplar conditions set out in our original proposal, namely cerebral palsy, autism and epilepsy. The search was designed in MEDLINE (OvidSP) and modified for EMBASE, PsycINFO and the Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (via OvidSP), CINAHL (via EBSCOhost) and NHS Database of Economic Evaluations. Searches were run between 12 and 25 September 2012. The strategy used for MEDLINE/OvidSP can be found in Appendix 3 .

Backwards citation chasing (one generation) was carried out using all reference lists from papers included in this stage of the review. Forward citation chasing was carried out between 28 January and 6 February 2013 using Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index (via Web of Knowledge) for included studies. Search results were exported into separate EndNote libraries created for each PROM.

We sought to locate a copy of each questionnaire; if a copy was not readily available, authors and/or developers of the PROMs were contacted to request a copy. We also contacted the authors or developers of all PROMs for which no evidence of the psychometric performance in an English-speaking population was found.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The aim of this stage of the review was to identify evidence for the performance of candidate PROMs when evaluated with children and young people. Criteria to guide inclusion and exclusion are shown in Table 2 .

| Inclusion criteria | Specification |

|---|---|

| Population | English speaking children and young people < 18 years old |

| General and/or neurodisability populations | |

| Instruments | Generic PROMs as listed as a result of stage 1; child self-report and parent (primary carer) reported measures are eligible |

| English version of the instrument administered | |

| Evidence | Reporting of any aspects of psychometric performance, including reliability, validity, responsiveness, precision, interpretability, acceptability and feasibility |

| Study design | Studies specifically designed to evaluate psychometric properties. Cross-cultural studies were included if referencing an English-language version of the instrument |

| Date | Inception of databases to September 2012 |

| Forward citation chasing until February 2013 | |

| Language | English version of the PROM administered |

| Paper written in English | |

| Exclusion criteria | Specification |

| Instrument/study design | Adult PROMs |

| PROM was used only as a ‘gold standard’ to test other instrument | |

| Incidental mention of psychometric evidence in studies designed not designed to evaluate those properties, e.g. trials of interventions | |

| Studies addressing ‘preference weighting or scaling’ issues for preference-based measures | |

| Population | Fewer than 10% of the sample were < 18 years |

| Data presentation | Data regarding neurodisability not reported separately in mixed samples of chronic conditions |

Study selection

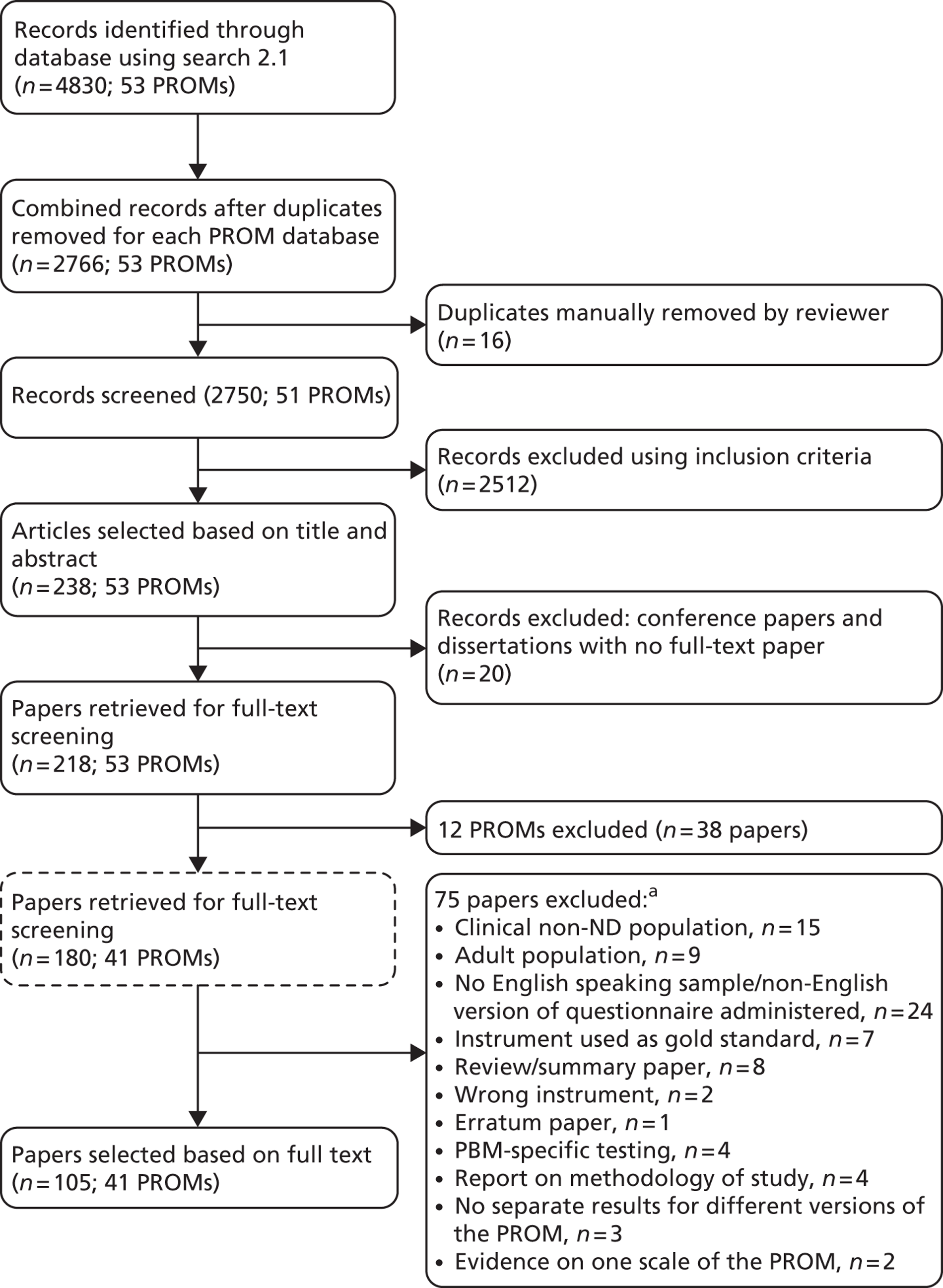

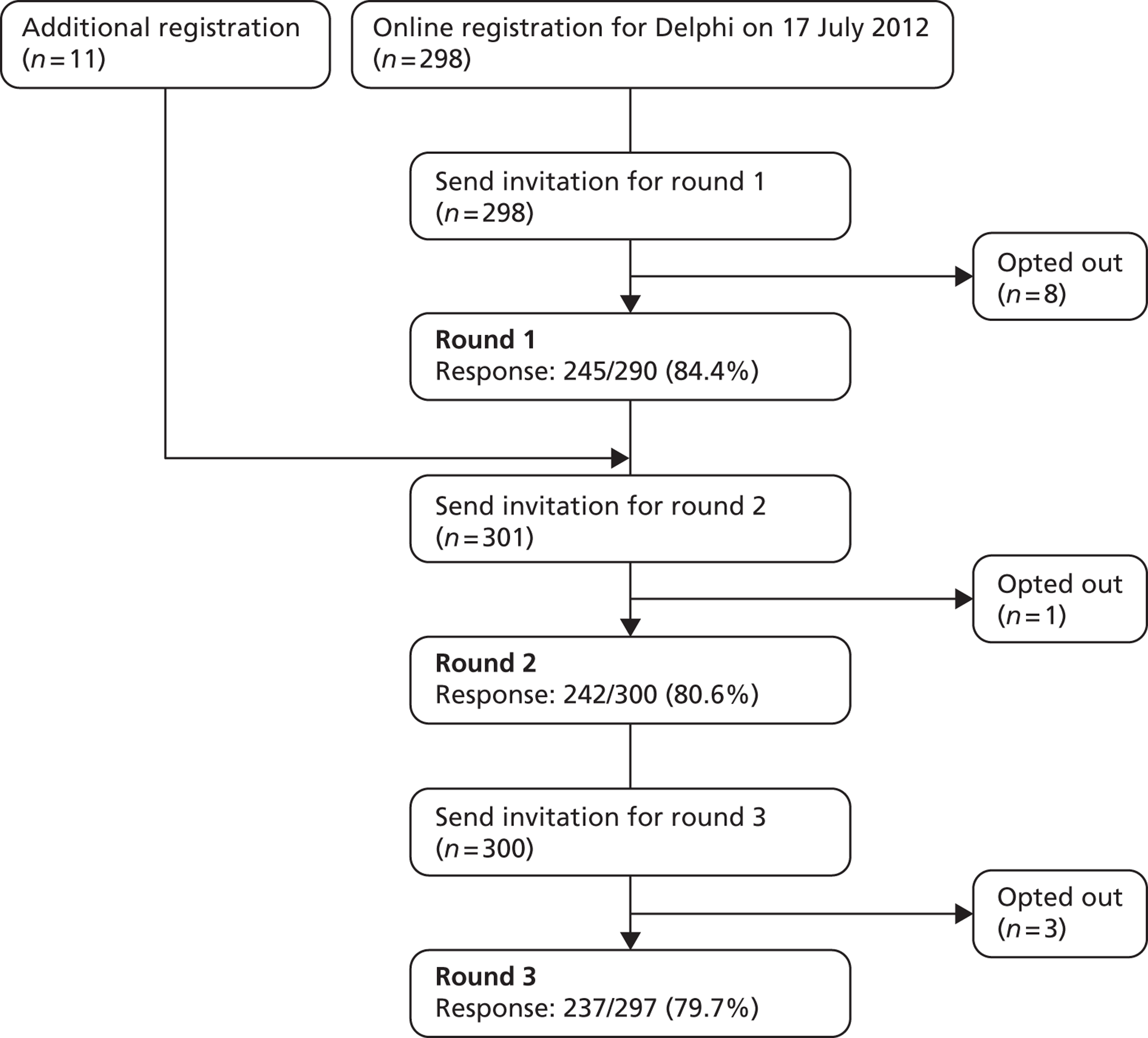

Titles and abstracts of all unique citations were screened against the eligibility criteria by one reviewer (AJ) and a sample of 10% of decisions was checked by a second reviewer, (CM) with disagreements resolved by discussion with a third (CJ) where necessary. The full text of any potentially relevant article was retrieved and screened using the same procedure. A flow chart describing the process of study selection for this stage of the review can be found later in this chapter ( Figure 2 ).

Data extraction

Data were extracted using standardised, piloted data extraction forms. For each included candidate PROM, the following were extracted: name of PROM and acronym, purpose of measurement, number of items, the responder, completion time, age range, recall period, response options, key reference paper, and types of domains/dimensions assessed.

We determined that there were three types of eligible candidate generic PROMs: (i) generic PROMs, designed for use across all people; (ii) chronic-generic PROMs, intended for use across people with chronic conditions; and (iii) preference-based measures (PBMs). Scores from generic and chronic-generic PROMs are typically determined directly from responses to items in the questionnaires. PBMs have two components; the responses to patient questionnaires are transformed using a weighting system, based on valuation of health states by a reference population, to produce a single index score between 1 and 0 (or less), where 1 equates to full health and 0 is dead. 33,34

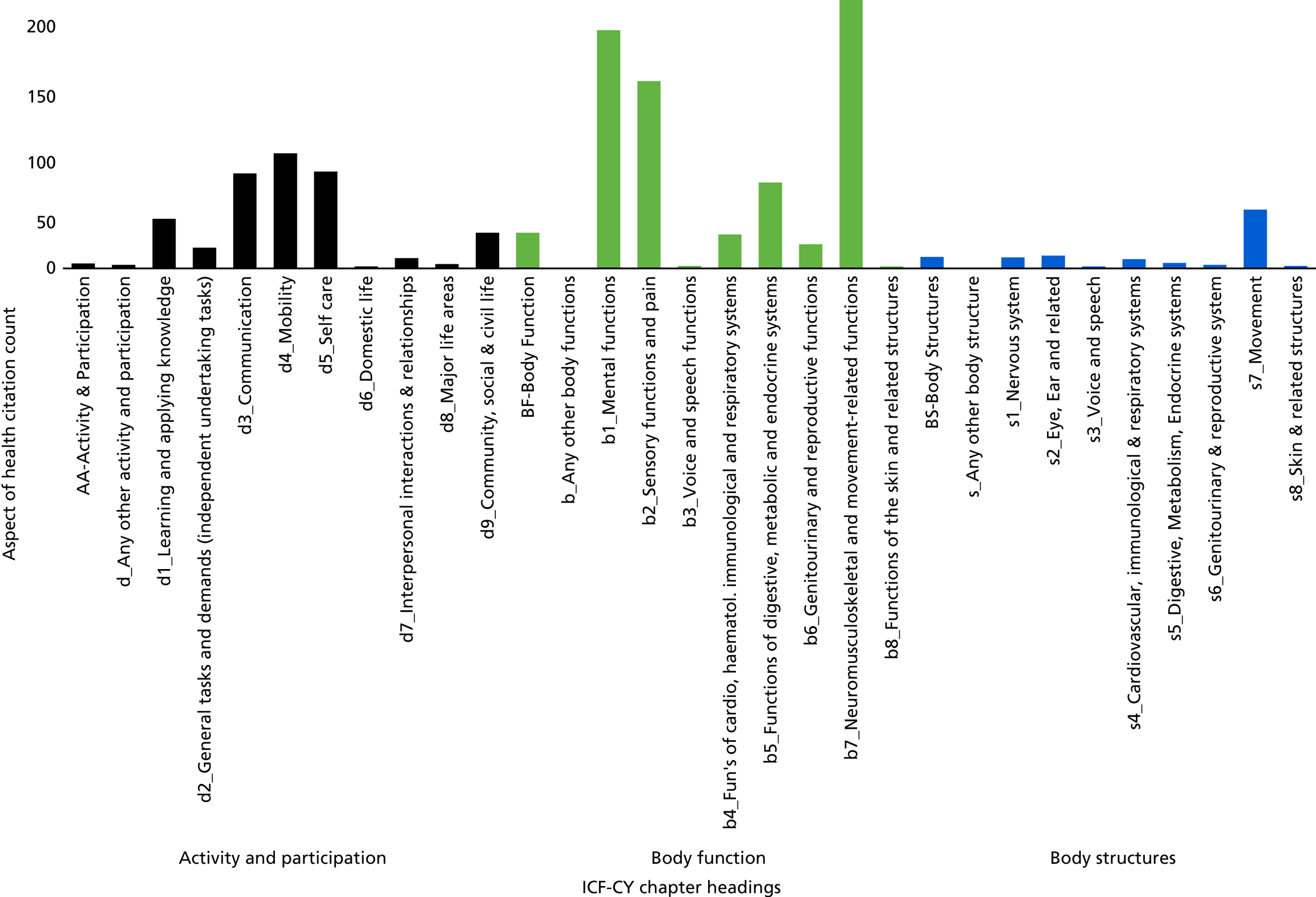

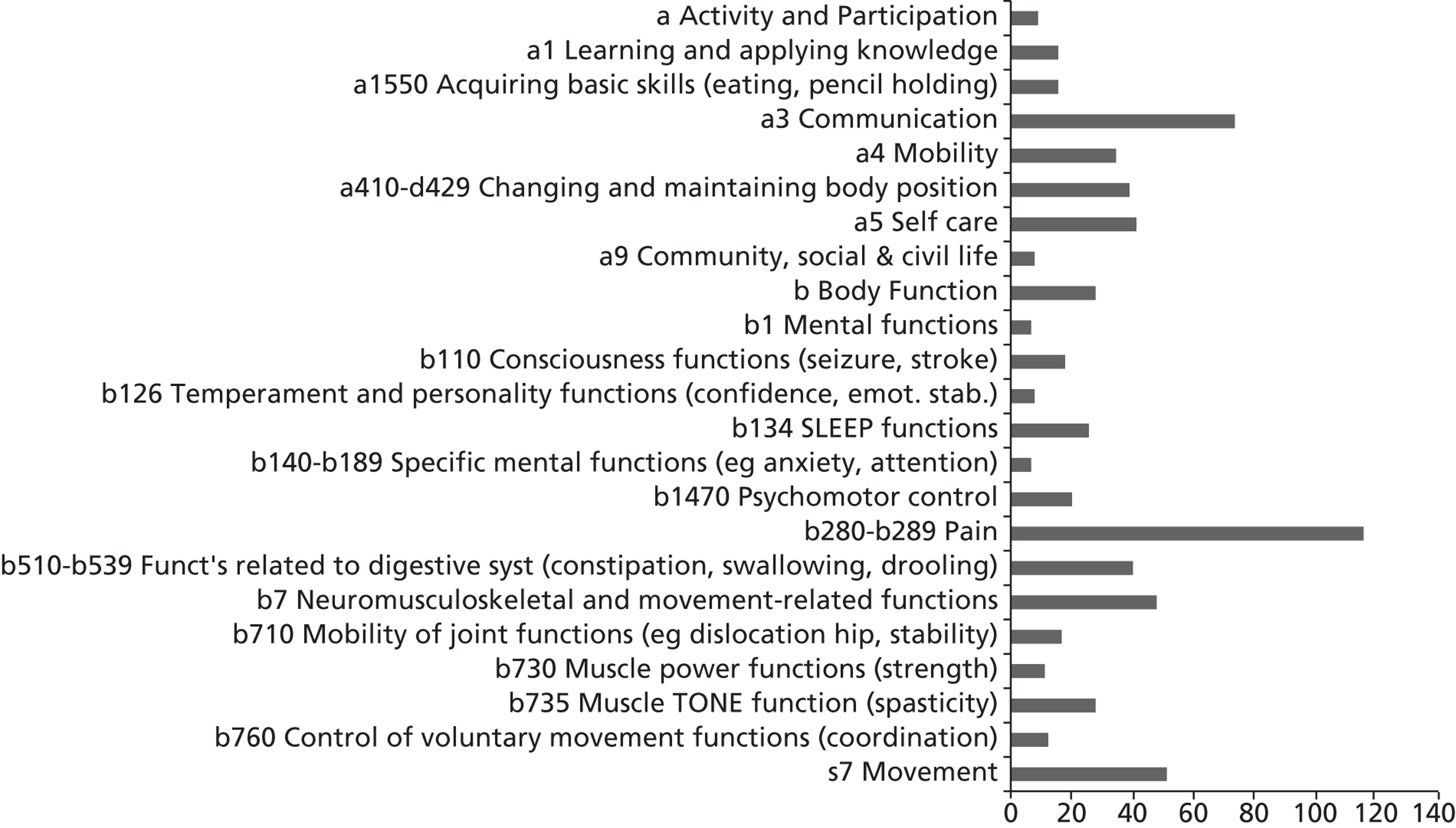

The domain scales and items of each candidate PROM were inspected with reference to the WHO’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Children and Youth Version (ICF-CY)11,35 to provide an indication of the constructs each instrument was measuring. It was not our aim to allocate every item from candidate PROM questionnaires to a precise ICF code using proposed linking rules. 36 Instead, our mapping sought to use the ICF-CY to describe what the scales of each candidate PROM proposed to measure. We coded at the higher levels of the ICF-CY, and also identified separately constructs not represented in the ICF-CY.

For each paper describing a study evaluating the psychometric performance of an eligible candidate PROM, the following descriptive data were extracted: instrument version, first author name, publication year, study aim, study population, number of participants, age range, mean age [standard deviation (SD)], and setting/country where the study was conducted. Data were extracted by one reviewer (KA/AJ) and checked by a second reviewer (AJ/KA), with disagreements resolved by discussion with a third (CM) where necessary.

For each included paper, the methodological quality of the study and the completeness of the report were assessed using the COSMIN checklist. 37 The COSMIN checklist assesses the methods and reporting of internal consistency, reliability, measurement error, content validity, structural validity, hypothesis testing, cross-cultural validity, criterion validity and responsiveness. Cross-cultural validity is not reported as we only included studies using an English version of the eligible PROMs. The checklist was administered by one reviewer (CM) and a 10% sample was rated by a second (AJ). Studies that used Rasch analysis were also assessed by one of the team with expertise in these techniques (AT). The COSMIN checklist uses a ‘worst score counts’ rating for methods used to test psychometric properties, producing a quality assessment of excellent, good, fair or poor. 37 Any discrepancies were resolved by discussion, or with the involvement of a third reviewer (CJ), where necessary.

Then, any data on evidence of the psychometric properties or performance of instruments were extracted including content validity (theoretical framework and/or qualitative research), construct validity (structural validity and hypothesis testing), internal consistency, test–retest reliability, proxy reliability, precision, responsiveness, acceptability and feasibility. Data were extracted by one reviewer (KA/AJ) and checked by a second reviewer (AJ/KA), with disagreements resolved by discussion with a third (CM) where necessary.

Appraisal of evidence for psychometric performance

Our original proposal focused on evidence of psychometric properties when evaluated with children and young people affected by neurodisability. However, we were mindful that some emerging PROMs may have only been tested with general populations, and it would be advantageous to be aware of the state of the evidence of the psychometric performance of such PROMs. Therefore, the evidence of psychometric performance for each instrument was organised by whether the sample in the study was (i) a general population of children and young people, (ii) children and young people with mixed chronic conditions that included neurodisability, or (iii) specifically, children and young people affected by neurodisability.

Evidence for each of these populations was studied separately for the three groups of PROMs: generic PROMs, chronic-generic PROMs, and PBMs.

Appraisal criteria

Standardised criteria and thresholds were used to judge the evidence of psychometric performance of each candidate PROM. 38,39 The criteria used to assess and select patient-completed instruments included their appropriateness for measuring the health of children and young people affected by neurodisability, and an appraisal of their validity, reliability, responsiveness, precision, interpretability, acceptability and feasibility. 38 A summary of the criteria and indices used to judge psychometric properties is provided in Table 3 .

| Psychometric property | Indicative criteria |

|---|---|

| Content validity | Clear conceptual framework consistent with stated purpose of measurement |

| Qualitative research with potential respondents | |

| Construct validity | Structural validity from factor analysis |

| Post-hoc tests of unidimensionality by Rasch analysis | |

| Hypothesis testing, with a priori hypotheses about direction and magnitude of expected effect sizes | |

| Tests for differential item and scale functioning between sex, age groups and different diagnoses | |

| Reproducibility | Test–retest reliability ICC > 0.7 adequate, > 0.9 excellent |

| Child- and parent-reported reliability ICC > 0.7 | |

| Internal consistency | Cronbach’s alpha coefficient: α > 0.7 and < 0.9 |

| Responsiveness | Longitudinal data about change in scores with reference to hypotheses, measurement error, minimal important difference |

| Precision | Assessment of measurement error; floor or ceiling effects < 15%; evidence provided by Rasch analysis and/or interval level scaling |

| Acceptability | Non-participation or non-response to surveys |

| Proportion of missing data | |

| Appropriateness | Content pertinent to children and young people affected by neurodisability |

| Excellent psychometric performance when evaluated with children and young people affected by neurodisability |

To demonstrate content validity, PROM developers should describe a clear conceptual framework underpinning the instrument, and incorporate qualitative research with potential respondents to inform development of the items in the questionnaire. This is also likely to ensure that the questionnaire has face validity to future potential respondents.

Construct validity concerns whether or not a scale is measuring what is stated as the purpose of measurement. Construct validity can be seen as comprising two aspects, internal and external. Internal construct validity is concerned with the valid structure of the scale, and is often examined through factor analysis. 40,41 Item response theory approaches also can apply an initial factor analysis, as they assume unidimensionality,42 but Rasch analysis often implements a post-hoc test of unidimensionality based upon analysis of the residuals. 43 External construct validity can take several forms; for example, hypothesis testing examines evidence of whether scales correlate well with other scales measuring a similar construct (convergent validity) or correlate poorly with instruments that are measured something unrelated (divergent validity). Correlations are considered low if r < 0.3, moderate if r lies between 0.30 and 0.49 and high if r < 0.5. 44 Hypotheses should be stated a priori, including the postulated direction and magnitude of correlation. 37 Discriminative validity describes whether or not an instrument detects ‘known differences’ between respondents.

Internal consistency is the extent to which all items in a scale are measuring the construct of interest and is assessed by Cronbach’s alpha statistic (α). Scales with an α statistic between 0.7 and 0.9 are considered to be composed of items that adequately measure a uniform construct. 45 The statistic assumes unidimensionality. If the assumption of local independence is violated, or there are simply a large number of items, Cronbach’s alpha may be inflated and/or an unreliable indicator. 45

All scores from PROMs include some level of measurement error, which can be estimated using calculations such as standard error of measurement;45 Rasch analysis estimates the measurement error for individual items (and persons) rather than the average of the scale level. 46

The reliability of instruments is determined by repeating administration on different occasions when respondents have not changed with respect to the construct being measured (test–retest). The level of agreement is also reported where child and parent responses are typically compared (inter-rater reliability). 38 Reliability coefficients are directly related to the variability in the population in which they are used;45 however, intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) exceeding 0.7 are generally regarded to indicate reliability for population-based research and ICCs exceeding 0.9 are considered to indicate reliability for use clinically with individuals. 45

Responsiveness describes the ability of instruments to detect important change when it has occurred. 47 Methods for evaluating responsiveness are either distribution based [effect size, minimal detectable change (MDC)] or anchor based [minimal important difference (MID)]. The effect size is a standardised measure of the magnitude of change, calculated by dividing the amount of change by the SD of the baseline score. 44 MDC is an indication of the amount of change required to have confidence that it is change beyond measurement error; a common standard is to use a 90% confidence level (MDC90). 48 The MID is the mean change in score reported by the respondents who indicate that they had noticed some small change. 49

Precision is concerned with the number and accuracy of distinctions made by an instrument. 50 Indices include how well the possible responses to each item are distributed over a true range. Use of Rasch analysis in scale development has suggested that scale scores vary in their precision (standard error) across the spectrum of the scale, with greater precision at the centre of the scale. Interval-level scales, such as those derived in the weighting of PBMs, inherently offer greater precision. A further aspect of precision is to examine whether there is any evidence of floor or ceiling effects, typically judged to occur when more than 15% of respondents’ scores aggregate at one end of the scale. 38

Acceptability to respondents is influenced by the design of a questionnaire, the number of items and the time necessary to complete the questionnaire. 51 Cognitive interviewing is a process to investigate how potential respondents understand PROM questions.

Appropriateness in this context is also dependent on evidence of excellent psychometric properties of candidate PROMs when evaluated with children and young people affected by neurodisability. Given that the purpose of the review is to identify and recommend a generic PROM for children < 18 years, and with different diagnoses under the umbrella of neurodisability conditions, we looked particularly for evidence of group invariance across age groups and different conditions. This would indicate that valid comparisons could be made across age and diagnostic groups.

Two practical issues considered were interpretability and feasibility. Interpretability is concerned with how meaningful the scores are produced by an instrument; indicators of interpretability are their face validity to those using the scores from PROMs. 51 Feasibility is also concerned with the researchers’ perspectives, and assesses whether or not the instrument is easy to administer and process, in terms of managing data and the calculation of scores. 52

Summarising evidence of psychometric performance

Several similar systems have evolved for summarising evidence to support psychometric properties of PROMs in systematic reviews. In our original protocol, we proposed using the system of the Oxford PROMs group: 0 for not reported; – for no evidence in favour; + for some evidence in favour; ++ for some good evidence in favour; and +++ for good evidence in favour. 28 The COSMIN group later proposed something similar: + positive rating; ? for an indeterminate rating; – negative rating; and 0 for no information available. 53 On balance, we elected to use a combination of these systems to summarise available evidence ( Table 4 ).

| Rating | Definition |

|---|---|

| 0 | Not reported |

| ? | Not clearly determined (poor study) |

| – | Evidence not in favour |

| +/– | Conflicting evidence |

| + | Some evidence in favour |

| ++ | Some good evidence in favour |

| +++ | Good evidence in favour (multiple studies) |

Summary ratings of evidence of psychometric performance were made using data extracted from included studies, with reference to whether or not standard criteria33,34 were met. When making the ratings, we also took account of the methodological quality of studies, number of studies, and giving further weight to any apparently independent studies that appeared not to have been conducted by the original developers. 54 We made an overall judgement separately for evidence emerging from studies conducted with (a) samples from general populations and (b) samples of young people with neurodisability.

Results

Search results stage 1: identification of patient-reported outcome measures

The first search, to identify potentially eligible PROMs, resulted in 13,770 records after duplicates were removed. Following screening of the records by two independent reviewers, 832 abstracts were reviewed for names and/or acronyms of potentially eligible PROMs. This resulted in a list of 131 PROMs (see Appendix 4 ), of which 78 were excluded based on the exclusion criteria. The flow chart in Figure 1 illustrates the different steps in the selection process.

In total, stage 1 identified the names of 53 potentially eligible candidate PROMs, including 39 generic PROMs, seven chronic-generic PROMs and seven PBMs.

Search results stage 2: identification of studies evaluating psychometric performance of candidate patient-reported outcome measures

Search for eligible studies in general population samples (search 2.1)

The combination of the searches for each of the 53 individual PROMs in general populations resulted in 4830 records. Screening the deduplicated file of 2750 records resulted in 238 records that were selected for full-text screening. In total, we retrieved 218 full-text papers. We excluded 12 further PROMs (and their corresponding 38 papers), as they did not match our inclusion criteria. These were instruments that were developed for adults or were dimension-specific to mental health, assessed health-related behaviours, or were screening tools.

This reduced the number of eligible papers to 180, which described 41 PROMs. Another 75 records were excluded on closer examination of the full text; most papers were excluded because they had not administered an English version of the PROM (n = 24) or because a clinical but non-neurodisability group of children and young people had been studied (n = 15). The flow chart in Figure 2 shows the different steps in the process and details on the different exclusion criteria and number of papers excluded. This search process resulted in the selection of 105 papers reporting on psychometric evidence on one of the 41 eligible candidate PROMs.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart showing identification and selection of studies evaluating psychometric performance of PROMs in general populations (search 2.1). ND, neurodisability. a, Some papers were excluded for more than one reason.

Search for eligible studies in neurodisability samples (search 2.2)

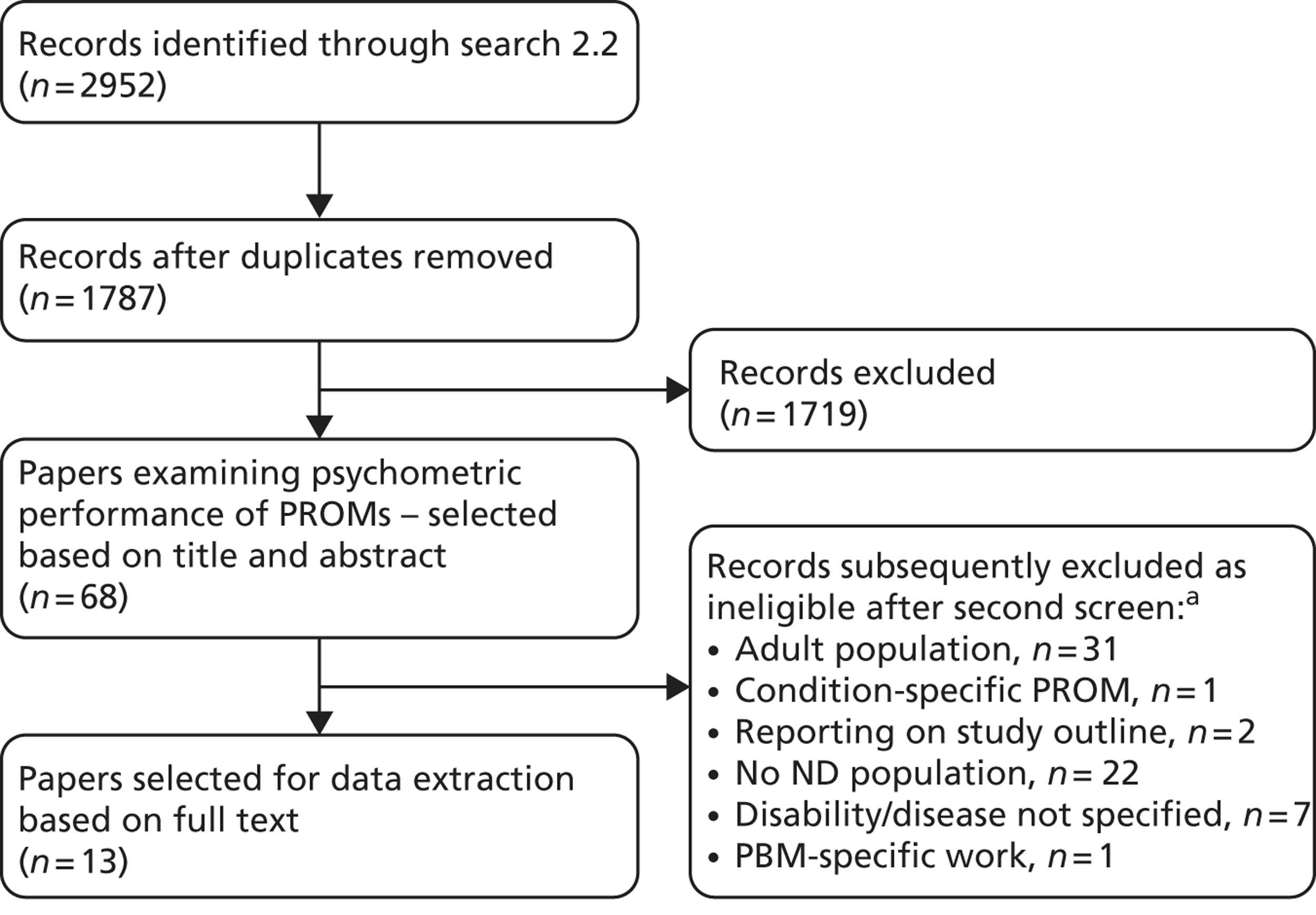

The combination of searches for the 53 individual PROMs used with neurodisability resulted in 2952 records. A total of 68 papers studying psychometric properties were selected based on title and abstract. After full-text screening, 13 papers were identified as eligible: nine were duplicates from search 2.1 and four new papers were selected for data extraction. Figure 3 gives an overview of the selection process.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart showing identification and selection of studies evaluating psychometric performance of PROMs in neurodisability (search 2.2). ND, neurodisability. a, Some papers were excluded for more than one reason.

Citation chasing

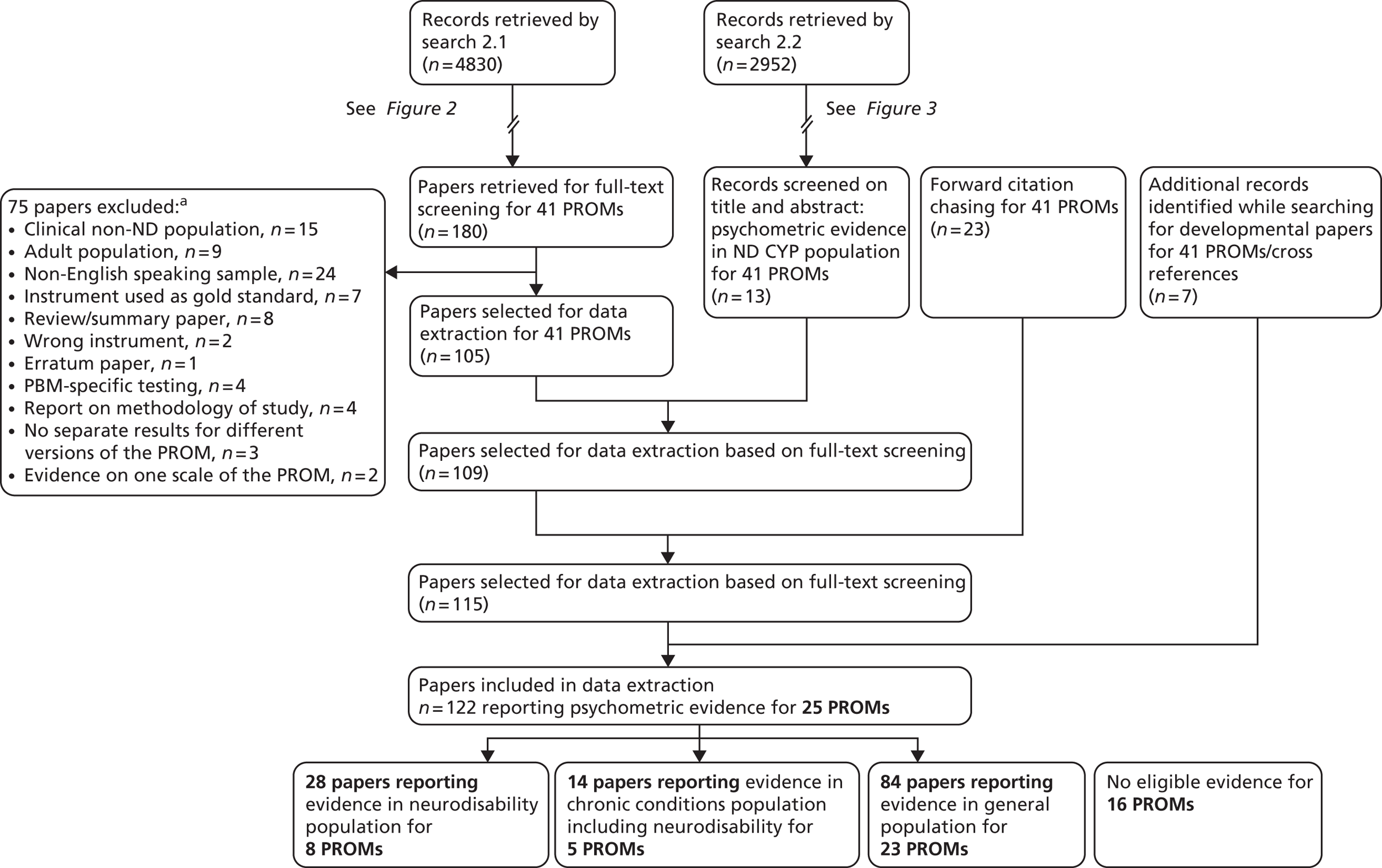

The forward citation chasing used 80 references; this resulted in 7858 records (5654 after deduplication). Filtering the EndNote file to only select records that mentioned validity (and derivatives, e.g. validation) or reliability (and derivatives) reduced the number of records to 235. Screening the titles and abstracts of these 235 records revealed 23 papers reporting on studies examining psychometric properties of a selected PROM in a population of children and young people with neurodisability. This strategy highlighted four papers not otherwise identified, which were included in data extraction. A further 10 papers were identified while searching for the key reference paper and were also included for data extraction.

Search results summary

In total, 126 papers were selected for data extraction. These papers report evidence from evaluations of the psychometric performance of 25 PROMs (notwithstanding that some PROMs have more than one version) evaluated in an English-language questionnaire. No evidence was found for 16 other PROMs.

Eligible evidence was found for:

-

19 generic PROMs

-

two chronic-generic PROMs

-

four PMBs.

The evidence is grouped according to the study population:

-

Eighty-four papers report results collected in a general population.

-

Fourteen papers report evidence for a PROM administered in a group of children with various chronic conditions including neurodisability; the results are not presented separately for each individual chronic condition.

-

Twenty-eight papers present results gathered in a neurodisability population.

The flow chart in Figure 4 illustrates the process of the selection of papers for data extraction.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of selection of papers for data extraction. CYP, children and young people; ND, neurodisability. a, Some papers have been excluded for more than one reason.

Data presentation

The results are presented within each category of PROM:

-

generic measures

-

chronic-generic measures

-

preference-based measures.

The following data are presented for each type of PROM:

-

Descriptive characteristics of all versions of the candidate PROMs.

-

There are substantively different versions of some PROMs, either with different target age groups, varying items, domains or dimensions assessed, or responder, short and long versions, or revised versions. Each variation has been catalogued.

-

-

Content assessed by the PROMs coded using the WHO ICF-CY.

-

The items of the questionnaires were mapped, as far as possible, to the chapter levels and domains of the WHO ICF-CY version.

-

-

Evidence of psychometric performance for candidate PROMs.

The data were further categorised by the sample with which the evaluation was conducted:

-

general population

-

mixed chronic conditions population including neurodisability

-

neurodisability population.

The evidence in each of the study populations is presented as follows:

-

a description of the study reported in the selected paper: instrument version, author, publication year, aim or purpose, study population, number of participants, age range, mean age (SD) and setting/country

-

the methodological quality of the paper rated following the COSMIN checklist

-

a summary of evidence of the psychometric performance of the PROM with reference to whether or not the study population was a sample of the general population or neurodisability.

Generic patient-reported outcome measures

Initially, in stage 1, 30 generic PROMs were identified. For 11 PROMs, no evidence was found from eligible studies meeting our inclusion criteria: Pictured Child’s Quality of Life Self Questionnaire [Autoquestionnaire de Qualité de Vie Enfant Image (AUQUEI): QUALIN,55 AUQUEI Soleil,56 AUQUEI Ours,57 OK.ado Questionnaire58], the Child’s Health Assessed by Self-Ladder (CHASL),59 the Duke Health Profile – Adolescent version (DHP-A),60 Health And Life Functioning Scale (HALFS),61 How Are You? (HAY),62,63 the Illness Perception Questionnaire (IPQ, IPQ Revised, Brief IPQ),64 Infant Toddler Quality of Life (ITQoL long and short versions),65,66 Nordic Quality of Life (QoL) Questionnaire,67,68 Quality of Life Questionnaire for Children (QLQC),69 the Quality of My Life (QoML)70 and the Dutch Organization for Applied Science Research – University Medical Centre Leiden [Toegepast Natuurwetenschappelijk Onderzoek – Academisch Ziekenhuis Leiden (TNO-AZL)] questionnaires [TNO-AZL Questionnaire for Preschool Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life (TAPQOL),71 TNO-AZL Questionnaire for Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life (TACQOL)72 and TNO-AZL Questionnaire for Adult Health-Related Quality of Life (TAAQOL)73].

The authors and or developers of these PROMs were contacted to verify that we had identified all available peer-reviewed papers. We received responses from the authors of the AUQUEI, the CHASL, the HALFS, the Nordic Quality of Life and the QLQC who sent us a full-text version of the PROM; no additional eligible papers were received. The characteristics of these PROMs can be found in Appendix 5 .

Generic PROMs with evidence from studies using an English-language questionnaire that have more than one version include:

-

Child Health and Illness Profile (CHIP) – age groups and short/long (four versions)74

-

Child Health Questionnaire (CHQ) – child/parent and short/long (three versions)75–77

-

Functional Status II Revised (FSIIR) – age group and short/long (six versions)78

-

KINDL – age group (three versions)82

-

Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) – age group and short/long (10 versions)83–85

-

Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI) – revised and age groups (three versions)86

-

Student Life Satisfaction Scale (SLSS)87/Multidimensional SLSS (MSLSS) – revised and short/long (three versions)88–90

-

Youth Quality of Life instrument (YQoL) – short/long (two versions). 91

Generic patient-reported outcome measures: general characteristics

Table 5 contains descriptive characteristics for all identified versions of the 19 candidate generic PROMs, including the purpose of the instrument, number of items, age range, responder (self or proxy), response options, completion time (as mentioned in the key reference paper or manual), recall period, and the domains or dimensions assessed.

| Acronym | Author | Purpose | n of items | Age range | Responder | Response options | Completion time | Recall period | Domains/dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHAQ | Singh 199492 | To measure functional status (functional ability in daily living activities) | 30 Four disability related and two VAS |

0–18 years | Proxy | Four-level difficulty scale + VAS for pain and overall well-being | < 10 minutes | Past week | Dressing and grooming, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and activities + (VAS) pain, overall well-being |

| CHIP-CE CRF | Riley 199874 | To broadly describe the health of children so that infrequent but important differences in health could be identified | 45 | 6–11 years | Self | Five graduated circle responses (frequency) with cartoons at beginning/end | 20 minutes | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction, comfort, resilience, risk avoidance, achievement |

| CHIP-CE PRF (45) | Riley 199874 | To broadly describe the health of children so that infrequent but important differences in health could be identified | 45 | 6–11 years | Proxy | Five-option frequency scale (never–always) | 15 minutes | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction, comfort, resilience, risk avoidance, achievement |

| CHIP-CE PRF (76) | Riley 199874 | To broadly describe the health of children so that infrequent but important differences in health could be identified | 76 | 6–11 years | Proxy | Five-option frequency scale (never–always) | 20 minutes | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction (health, self), comfort (physical and emotional, restricted activity), resilience (family involvement, physical activity, social problem-solving), risk avoidance, achievement (academic performance, peer relations) |

| CHIP-AE | Riley 199874 | To broadly describe the health of adolescents so that infrequent but important differences in health can be identified | 138 | 1–17 years | Self | Mostly five-option frequency scale (no days–15 to 28 days) | 30 minutes | Past 4 weeks | Satisfaction, discomfort, resilience, risks, achievement |

| Healthy Pathways | Bevans 201093 | To broadly describe the health of youth in transition from childhood to adolescence and identify differences in health | 88 | 9–11 years | Self and proxy | Five-point Likert scale | 20 minutes | Past 4 weeks | Comfort, energy, resilience, risk avoidance, subjective well-being, achievement |

| CHQ-PF28 | Kurtin 199475 | To measure the physical and psychosocial well-being of CYP | 28 | 5–18 years | Proxy | Response options vary from four to six levels | 5–10 minutes | Past 4 weeks; global health items: in general; global change items: as compared with 1 year ago | General health, change in health, physical functioning, bodily pain, limitations in school work and activities with friends, behaviour, mental health, self-esteem, time and emotional impact on the parent, limitations in family activities and family cohesion |

| CHQ-PF50 | Landgraf 199876 | To measure the physical and psychosocial well-being of CYP | 50 | 5–18 years | Proxy | Response options vary from four to six levels | 10–15 minutes | Past 4 weeks; global health items: in general; global change items: as compared with 1 year ago | General health, change in health, physical functioning, bodily pain, limitations in school work and activities with friends, behaviour, mental health, self-esteem, time and emotional impact on the parent, limitations in family activities and family cohesion |

| CHQ-87 | Landgraf 199777 | To measure the physical and psychosocial well-being of CYP | 87 | ≥ 10 years | Self | Response options vary from four to six levels | 16–25 minutes | Past 4 weeks; global health items: in general; global change items: as compared with 1 year ago | General health, change in health, physical functioning, bodily pain, limitations in school work and activities with friends, behaviour, mental health, self-esteem, time and emotional impact on the parent, limitations in family activities and family cohesion |

| CHRS-PF | Maylath 199094 | To assess a child’s perception of general health | 17 | 9–12 years | Proxy | Five-point response scale rating agreement | 5 minutes | Today or ‘in general’ | No information |

| CHSCS | Hester 198495 | To measure a child’s perceptions of his or her health and health-related behaviours | 45 | 7–13 years | Self | Four-point Likert scale: more positive health perception, to more negative health perception | 20–30 minutes | No information | Activity exercise, personal grooming, physical, nutrition, behaviour, emotional, dental health, sleep, friends, substance use, general health, and family |

| COOP/WONCA | Nelson 198796 | To assess adolescents’ health and social problems (using a single-item picture-and-words chart) | 6 | Adolescent | Self | Five-point Likert-type scale with descriptors and cartoons | 4–5 minutes | During the past month | Physical fitness, emotional feelings, school work, social support, family communications, health habits |

| CQoL | Graham 199797 | To measure the child’s function, together with their own upset and satisfaction for each of the domains measured | 15 | 9–15 years | Self and proxy | Seven-point Likert scale rating of function, upset and satisfaction | 10–15 minutes | Over the past month | Activities, appearance, communication, continence, depression, discomfort, eating, family, friends, mobility, school, sight, self-care, sleep, worry, overall |

| ExQoL | Eiser 200098 | Computer-based assessment of quality of life as a result of perceived discrepancies between a child’s actual and ideal selves | 12 | 6–12 years | Self | VAS: not like me–exactly like me | 20 minutes | Not used | Symptoms (sleep, aches, food allergies, sickness), social well-being, school achievements, physical activity, worry, and family relationships |

| FSIIR long version, infants | Stein 199078 | Describes children’s functional status in the previous 2 weeks | 22 | Up to 1 year | Proxy | Three-point Likert scales: (1) difficulty; (2) extent this is due to illness | 20 minutes | Last 2 weeks | General health, responsiveness |

| FSIIR long version, toddlers | Stein 199078 | See above | 30 | 1–2 years | Proxy | See above | 5–30 minutes | Last 2 weeks | General health, responsiveness |

| FSIIR long version, preschoolers | Stein 199078 | See above | 40 | 2–4 years | Proxy | See above | 15–30 minutes | Last 2 weeks | General health, activity |

| FSIIR long version, school-age children | Stein 199078 | See above | 40 | 4 years and older | Proxy | See above | 15–30 minutes | Last 2 weeks | General health, interpersonal functioning |

| FSIIR-7 | Stein 199078 | See above | 7 | 0–16 years | Proxy | See above | 10 minutes | Last 2 weeks | General health |

| FSIIR-14 | Stein 199078 | See above | 14 | 0–16 years | Proxy | See above | 10 minutes | Last 2 weeks | General health |

| GCQ | Collier 199799 | To assess discrepancy between a child’s perception of their actual and desired lives | 25 | 6–14 years | Self | Five-point Likert scale: (1) child most like you; (2) child you would like to be | 15 minutes | Today | Perceived and preferred quality of life |

| KIDSCREEN-52 | Ravens-Sieberer 200579 | To assess children’s health and well-being; can be used as a screening, monitoring and evaluation tool | 52 | 8–18 years | Self and proxy | Five-point Likert scale assessing frequency or intensity | 15–20 minutes | Last week | Physical well-being, psychological well-being, moods and emotions, self-perception, autonomy, parent relations and home life, social support and peers, school environment, social acceptance (bullying), financial resources |

| KIDSCREEN-27 | Ravens-Sieberer 200780 | See above | 27 | 8–18 years | Self and proxy | Five-point Likert scale assessing frequency or intensity | 10–15 minutes | Last week | Physical well-being, psychological well-being, autonomy and parents, peers and social support, and school environment |

| KIDSCREEN-10 | Ravens-Sieberer 201081 | See above | 10 | 8–18 years | Self and proxy | Five-point Likert scale assessing frequency or intensity | 5 minutes | Last week | Physical activity, depressive moods and emotions, social and leisure time, relationship with parents and peers, cognitive capacities and school performance |

| KINDL: Kiddy-KINDLR | Bullinger 199482 | To assess the physical, mental and social well-being of children and adolescents using age-appropriate versions | 12 | 4–7 years | Self by interview | Three-point Likert scale assessing frequency | 15 minutes | Last week | Physical health, general health, family functioning, self-esteem, social functioning, school functioning |

| KINDL: Kid-KINDLR | Bullinger 199482 | To assess the physical, mental and social well-being of children and adolescents using age-appropriate versions | 24 | 8–12 years | Self and proxy | Five-point Likert-scale assessing frequency | 5–10 minutes | Last week | Physical health, general health, family functioning, self-esteem, social functioning, school functioning |

| KINDL: Kiddo-KINDLR | Bullinger 199482 | To assess the physical, mental and social well-being of children and adolescents using age-appropriate versions | 24 | 13–16 years | Self and proxy | Five-point Likert-scale assessing frequency | 5–10 minutes | Last week | Physical health, general health, family functioning, self-esteem, social functioning, school functioning |

| PedsQL Infant Scales | Varni 201183 | To assess the core dimensions of health according to the WHO as well as school functioning using age-appropriate versions | 36 45 |

1–12 months 13–24 months |

Proxy | Five-point Likert scale rating frequency | < 4 minutes | Past month | Physical functioning, physical symptoms, emotional functioning, social functioning, cognitive functioning |

| PedsQL Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory Trade Mark 4.0 Generic Core Scales | Varni 199984 | 21 23 |

2–4 years 5–7 years 8–12 years 3–18 years |

Self and proxy (proxy only age 2–4 years) | Physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, school functioning | ||||

| PedsQL Short Form 15 Generic Core Scales | Chan 200585 | 2–4 years 5–7 years 8–12 years 13–18 years |

Self and proxy (proxy only age 2–4 years) | Physical functioning, emotional functioning, social functioning, school functioning | |||||

| ComQOL-S5 | Cummins 1997100 | To describe current health status and perceived importance and satisfaction with selected life domains | 21 | 11–18 years | Self | Mostly five-point Likert scale rating frequency, importance and satisfaction | 15–20 minutes | Stated for each items | Material well-being, health, productivity, intimacy, safety, place in community, emotional well-being |

| PWI-PS | Cummins 200586 | To assess degree of satisfaction with seven life domains | 7 | Up to 5 years | Proxy | Eleven-point happiness scale | 10–20 minutes | Not stated (today) | Standard of living, health, life achievement, personal relationships, personal safety, community connectedness, future security |

| PWI-SC | Cummins 200586 | To assess degree of satisfaction with seven life domains | 7 | 5–18 years | Self | Ten-point scale from very sad to very happy | 10–20 minutes | Not stated (today) | Standard of living, health, life achievement, personal relationships, personal safety, community connectedness, future security |

| QoLP-AV | Raphael 1996101 | To assess quality of life in three broad domains of adolescent functioning: being, belonging and becoming | 54 | 14–20 years | Self | Five-point Likert scale rating importance, satisfaction, control and opportunities | 40 minutes | Not stated (today) | Being: physical, psychological, spiritual Belonging: physical, social, community Becoming: practical, leisure, growth |

| SLSS | Huebner 199187 | To assess satisfaction with life as a whole | 7 | 7–14 years | Self | Six-point Likert scale rating agreement | < 5 minutes | Not stated | Family, friends, school, living environment, self |

| MSLSS | Huebner 199488 | To assess satisfaction with life as a whole and specific life domains | 40 | 8–18 years | Self | Six-point Likert scale rating agreement | 10 minutes | Not stated | Family, friends, school, living environment, self |

| BMSLSS | Seligson 200389 | To assess satisfaction with life as a whole and specific life domains | 6 | 8–18 years | Self | Seven-point Likert scale rating satisfaction | Less than 5 minutes | Past several weeks | Family, friends, school, living environment, self |

| MSLSS-A | Gilligan 200790 | 53 | Six-point Likert scale rating agreement | Past several weeks | Family, same-sex friends, school, opposite-sex friends, living environment, and self | ||||

| WCHMP | Spencer 1996102 | To assess parent-reported health and morbidity in infancy and childhood | 10 | Up to 5 years | Proxy | Four response options and free text | 10 minutes | Not stated | General health status, acute minor illness, behavioural, accident, acute significant illness, hospital admission, immunisation, chronic illness, functional health, HRQoL |

| YQoL-S | Edwards 200291 | To assess adolescents’ perceived quality of life in a broad sense | 13 | 11–18 years | Self | Five-point Likert scales with anchors for each point; 11-point rating scales with anchors each side of the scale | 5–10 minutes | In general or during the past month | Relation parents, future aspirations, loneliness, confidence, joy/happiness, satisfaction, lust for life, overall quality of life |

| YQoL-R | Edwards 200291 | To assess adolescents’ perceived quality of life in a broad sense | 56 | 11–18 years | Self | Five-point Likert scale with anchors for each point; 11-point rating scales with anchors each side of the scale | 15–20 minutes | In general or during the past month | Sense of self, social relationships, culture and community, and general quality of life |

After contacting the authors or developers of the PROMs, we received a free copy of the questionnaires and manuals for the CHIP, and paid for the Quality of Life Profile – Adolescent Version (QoLP-AV)101 and FSIIR. 78 For the Healthy Pathways,93 the Child Health Ratings Scale (CHRS)94 and the Exeter Quality of Life Measure (ExQoL),98 we located a copy of the items but had no instructions. The Comprehensive Health Status Classification System (CHSCS) has 45 items; the development paper provides instructions, details of the first eight items, and broadly describes the topics covered by the other items. 95 The Child Quality of Life Questionnaire (CQoL) has 15 items; instructions, an exemplar item, and domains covered by the remaining items are reported in the developmental paper. 97 Data for the CHQ were obtained from the website www.healthactchq.com; exemplar items and general information are provided.

Three PROMs provide different versions according to age group for self-report:

-

CHIP (two versions; youngest: 6 years old)74

-

KINDL (three versions; youngest: 4 years old)82

-

PedsQL (three versions of short and longer forms; youngest: 5 years old). 83–85

Instruments providing only a self-report version were:

-

Healthy Pathways (9–11 years)93

-

CHSCS (7–13 years)95

-