Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1809/232. The contractual start date was in December 2008. The final report began editorial review in October 2012 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors:

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Hanratty et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background, context and scope

Introduction

As life expectancy increases, older adults are living and dying with multiple conditions. Their health-care needs are complex, and may involve a range of professionals working in different settings. Ensuring that the patients experience co-ordinated and coherent care, and that moves occur because of individual needs rather than system imperatives, is crucial to patients’ well-being. Such patient-focused care has attracted much attention in recent years in an effort to improve individual outcomes1 and promote cost-containment and efficient use of resources.

At the end of life, a move into or out of hospital, a care home or a hospice is potentially one of the most disruptive events for older adults and their carers, with consequences for their mental, physical and emotional well-being. Older adults are particularly sensitive to the consequences of inadvertent alterations to their care, for example existing medication regimes failing to be maintained or follow-up blood tests not being performed. Patients’ experiences of moving between places of care offer an opportunity to explore the extent of integration at the interfaces between different professional roles, services and approaches to care. Understanding the challenges of providing high-quality care at transitions between care settings for older adults is a crucial step towards improving patients’ and families’ experiences of care in the final months, weeks and days of life.

Background

More people are living into old age across the world. There are currently 650 million people aged over 60 years, and expected to reach 2 billion by 2050. 2 In England, almost two-thirds of the half a million people who die each year are aged over 75 years. 3 While some deaths may be unexpected, most deaths follow a period of chronic illness requiring ongoing management, often in different care settings.

Definition and importance of transitions

A transition occurs between two locations or settings of care, for example moving from hospital to a care home. It may also represent a shift in the nature of care, such as the decision not to continue with curative treatments. For some older adults with chronic progressive conditions, the realisation or acknowledgement that the aim of treatment is to control symptoms, and no longer to prolong life, may come late in the illness. In a number of common conditions, such as heart failure, the course of an illness may be unpredictable. In such cases, clinical considerations and the wishes of patients and family have to be weighed and discussed to judge the appropriate time to move towards palliative care. Therapies that improve symptoms may also lengthen survival and the possibility of a change of gear from curative to palliative care may never arise. The nature and location of care are interdependent and changing one may naturally influence the other; a move to a hospice or a return to primary care, for example, may offer an opportunity to broach sensitive subjects that are overlooked in the faster-paced world of acute medicine. Hence, although this study has focused on transition as a change in setting, it will have relevance to the relationship between active and palliative care.

For many older adults, the majority of transitions will take place in the 12 months before death. The proportion of people admitted to hospital in their last year of life rises with age. People over the age of 85 years are less likely to be admitted to hospital in their last year, but, when they are, they remain in hospital for longer periods than younger adults. 4 Although improved detection and treatment of disease means that some older adults are surviving with multiple comorbidities and complex health-care needs, recent decades have seen reductions in morbidity and functional decline among older adults. 5–7 Increasing survival has not invariably led to more years of sickness and disability, and the total time spent in hospital at older ages has not increased, though the last year of life remains a time of high health service utilisation. 8–10 Patterns of hospital and other service utilisation suggest that rapid increases in the costs of end-of-life care are unlikely to be realised. Nevertheless, the large number of older decedents will mean that costs are still considerable. Findings from time-to-death cost analyses are not entirely consistent across different health systems and study methodologies. Approaching death is associated with increased health service expenditures, and costs of care for decedents in the year before death are greater than for comparable survivors. 11–16 In some countries, this effect is diminished in extreme old age because of substitution of care in other settings (such as care homes) for hospital admission. 17,18 The overall effect of increased survival appears to be to delay the years of high spending to the end of life, with some shift away from acute care costs. Transitions, therefore, are likely to be a major contributor to overall health-care costs. Ensuring that they are necessary and that they enhance health outcomes and experiences should, therefore, be a priority.

Terminology

There are many different, overlapping, concepts, processes and labels applied to the organisation of care that is provided by multiple players. Many of them originate from work in the US health-care market, and have meanings specific to their original context. Transitional care, for example, is focused on processes and defined as a set of actions to ensure co-ordination and continuity of health care as patients transfer between different locations or levels of care within the same location. 19 This is similar to the more broadly defined ‘integrated care’ – a process of reducing fragmentation, improving connections between the different components of health and social services and delivering continuity of care. 20,21 Case management is a tool that is well established within the US-managed care system,22 which aims to integrate services around the needs of people with complex long-term conditions. 23 Case management encompasses case-finding, assessment, care planning, and care co-ordination.

Amid some definitional and conceptual confusion, it is possible to observe common components of initiatives to improve care across settings. Multidisciplinary teams have been identified as a means of providing integrated care, though moves to achieve this have not focused specifically on transitions between settings. Many initiatives to integrate care rely on having a dedicated worker, often a nurse, who co-ordinates, and may also provide care. The evidence for such approaches to management preventing readmissions to hospital or improving quality of care at the end of life is limited, as studies have focused on highly selected patient groups, often excluding people who are known to be terminally ill, or living in the community. 24,25 In some circumstances, case management has been able to improve the experience of patients and carers and reduce use of hospital services,23 and there is some evidence to support the adoption of disease-specific strategies to improve transitions between care settings for older adults. Cameron and Gignac26 recommended that recognising the changing needs of relatives caring for stroke survivors who moved from hospital to home would assist professionals in providing more timely and appropriate support. For heart failure patients, a nurse-directed, multidisciplinary intervention was found to improve the quality of life and reduce hospital use for elderly patients. 27 Continuity of care is a common thread across almost all of this work, either as a core component or as an outcome of any intervention.

Care across transitions and continuity of care

In the last decade, Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) has funded a range of work on the concept, measurement and promotion of continuity of care. 28 Freeman et al. 29 originally defined continuity as the experience of a co-ordinated and smooth progression of care from the patient’s point of view. He went on to propose a six-dimension model of continuity, that was later refined to three: (1) informational continuity relates to the use of past information to ensure that current care is appropriate; (2) relationship continuity refers to a therapeutic relationship with a health professional; (3) management continuity is concerned with a consistent and coherent approach to the management of a health condition across boundaries, which is responsive to changing needs. 30 Continuity is thus framed as an individual, relational concept, experienced by patients and carers and dependent on their preferences, priorities and perceptions. The SDO-funded projects that followed took a broad and sometimes divergent approach to defining continuity. As a group, they developed a more complex, fragmented concept that emphasised the quality and strength of partnerships. Continuity of care was understood to be a process, an outcome, or some combination of the two by different research teams.

The individual research projects concerned specific disease or patient groups, and the work with cancer patients is most relevant to the subject of our study. Nevertheless, there are three findings from the overall body of work on continuity that are relevant to this study of transitions. First, certain groups were identified as disadvantaged by an inability or reluctance to negotiate continuity: for example, patients who were too ill, or facing socioeconomic or cultural barriers. Such people were under-represented in the empirical work, and were highlighted, along with people with multiple comorbidities, as a group requiring future research. Older adults in the last year of life could be expected to fall into this category. Second, in most projects, transitions between care settings was an issue that emerged as important to service users. This was synthesised by researchers into their understanding of continuity, but it was not the focus of study for any of the projects. Finally, the synthesis and conceptual analysis of the overall SDO programme on continuity identified a number of implications for research that are likely to be pertinent to any study of transitions. The gaps in our understanding included carers’ views and experiences of continuity for themselves and those they support; if and how health professionals see themselves, patients and carers in partnership and what would facilitate this; how patients and carers see themselves as being in partnership; and how leadership and culture can encourage continuity of care.

Areas of enquiry that are relevant to the study of transitions between care settings

There are multiple ways of looking at health-care utilisation, and there are separate bodies of literature, beyond end-of-life care, that may provide important context for any enquiry into transitions between settings. The next section briefly considers readmissions to hospital, delayed discharges and care-home transfers.

Readmissions to hospital

Readmissions to hospital shortly after discharge are among the most common and potentially distressing transitions for individuals. They are monitored as a marker of quality of care, and a potentially avoidable cost. 31 Although analyses of hospital admissions and discharges are rarely specific to the last year of life, they are relevant to end-of-life care because of high utilisation rates in the period before death. Data from different countries across the world provide a common picture of frequent transfers for older people following an acute hospital admission.

In England, in 2007–8, over 1 million (1,130,271) people aged 75 years or older were discharged from hospital and almost 160,000 (159,134) older adults were readmitted within 28 days. This equates to 14.2% of older adults being readmitted to hospital within 28 days of discharge. 32 Readmission rates within 28 days have risen considerably in recent years, from 10% in 1998 to 13.9% in 2008 for older adults aged 75 years or older. 33 Overall in England, between 1998–99 and 2007–8, the number of emergency readmissions in England rose by 52%, from 359,719 to 546,354. Financial penalties for hospitals in England and Wales were introduced in 2011 as part of the Payment by Results initiative. 34 Local commissioners are no longer paying for emergency readmissions within 30 days of discharge following a planned stay. The Department of Health also expected commissioners to deliver a 25% reduction in readmissions following a non-elective admission.

The picture is similar in the USA. Medicare provides health coverage for all people who are aged over 65 years and some people under that age who live with a disability. Analysis of claims data showed that around one in five of the approximately 12 million Medicare recipients who were discharged from hospital in 2003–4 were readmitted within 30 days, and more than one in three were readmitted within 90 days of discharge. Over the age of 70 years, readmission became more likely with increasing age, up to the age of 89. 35 In the month after leaving hospital, a significant proportion of Medicare recipients aged over 65 years are transferred multiple times between different places of care. Analysis of data from 1997–8 showed that 18% of older adults moved twice, while up to 25% had complex patterns of care in a range of different settings. Overall, 46 distinct patterns of care were described, but the majority (61.2%) of people underwent only one transfer; 18% had two transfers and 4% more than four transitions in the 30 days after discharge from hospital. Eight per cent of this older patient population died within 1 month of leaving hospital. 1 Information on how the method of payment for care influences movements after hospital discharge is limited, but appears to suggest that patients whose health care is provided on a fee-for-service (FFS) basis rather than as managed care will experience more frequent transfers. In a study of 1055 older adults who passed through acute-care units, two-thirds of managed-care patients and three-quarters of those receiving FFS health care had two or three transitions, and a slightly higher proportion of FFS were transferred four to six times, all in the 3 months after discharge (14.6% vs. 13.8%).

A wide range of interventions to reduce emergency or unplanned readmissions have been tried, most with limited success. 33,36 However, discharge planning,37 self-management and multidisciplinary interventions with heart failure patients38–40 have had some success.

Transitions for care-home residents

Patterns of hospital utilisation by care-home residents have been studied extensively in the USA, through analysis of large, nationally representative survey data. 41 Data from the national Long Term Care Survey in 1992–94 showed that 18% of over-65-year-olds in long-term care (around 5 million people) were admitted to hospital in a 2-year period and almost one-quarter (22.4%) of these people moved again. 42 Commentators have questioned the appropriateness of transitions of nursing home residents to hospital, particularly at the end of life. 43,44 Estimates of the proportion of emergency department attendances or admissions that were not in the patients’ best interests are as high as 36–40%. In the UK, there is a perception that residents of nursing homes are still sent into acute hospitals to die,45 and the probability of readmission to hospital within a short period of discharge is considerably higher for nursing home residents. 46–48 Analysis of data from the Cambridge City Over-75s Cohort Study49 found that 15% of deaths in acute hospitals were from (predominantly residential) care homes. The more recent introduction of initiatives to improve end-of-life care in the care-home sector may lead to future changes. 45 For residents in care homes who are not close to death, specialist in-reach nursing teams in the UK have been employed to try to avert hospital admissions. 50 An evaluation of the impact of the nursing team in four residential homes included the convening of an expert panel, who judged that 197 admissions were avoided for 131 residents. However, the cost savings from the intervention were only modest, which may limit its wider adoption.

Delayed discharges

Frequent transitions are generally held to be undesirable for individuals and care systems, but delayed transfers may also be a source of great distress to older adults and their families. Older people are more likely than those in other age groups to remain in hospital when their care might be more appropriately provided elsewhere. People with multiple comorbidities and a need for high levels of support are most often affected and there is a range of service-related factors, such as the availability of community support, or internal hospital processes, that may contribute to delays. Research into the reasons why the discharge of patients from hospital may be delayed is suggestive of a complex set of influences, which means that simple solutions are unlikely to be successful. However, recent reviews have found the literature to be of poor quality, with a tendency to neglect patient and family perspectives. 51,52 The provision of rehabilitation services and residential care places, internal hospital processes, and co-ordination and communication with social care service processes and staff are all common causes of delay. This can be exacerbated by discharge planning being delayed until the patient is ready for hospital discharge. Aside from the additional costs of delayed hospital discharge, qualitative interviews indicate that uncertainty in having their hospital discharge delayed and guilt about being identified as a ‘bed blocker’ can cause considerable anxiety and stress to patients at the end of life. 53,54 When provision for support outside hospital is in place, arranging timely and appropriate transport can cause further delays. 55

Care pathways

Care pathways have been developed for a range of conditions, often involving professionals working together with a focus on continuity of care. 56 In end-of-life care, the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) extends good practice, based on hospice care, to other settings. 57 However, while the LCP takes a patient-focused approach that maximises quality of life and involves and supports carers, it is concerned with the last days before death. Greater attention to communication and work across settings is found in the Gold Standards Framework (GSF) for patients in the last months of life. 58 This aims to support generalist professionals to work together to provide high-quality care regardless of the setting. The GSF proposes a three-stage approach to care: identify, assess and plan. Anticipating needs through advance planning and enabling death in the place of choice are at the heart of the GSF, but it does not specifically address transitions or their management. All of these structured approaches to care could be incorporated into the planning and management of transitions, but this would be contingent on close communication and joint working across settings. In the UK, at least, there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that both continue to be a problem.

Researching end-of-life transitions

Three contrasting approaches to the study of transitions between care settings at the end of life can be identified in the research literature. All are likely to produce complementary yet different perspectives on experiences of transitions.

The first involves quantitatively analysing patterns of service utilisation. For example, a population-based study in the Netherlands identified an increase in service utilisation of formal care in the last 3 months of life, with half of community-dwelling older people experiencing transitions to institutional care, in most cases to hospitals. 59 Two separate studies based on surveys of GPs in Belgium and the Netherlands found that, among non-sudden deaths, the majority of patients were transferred between settings. 60,61 In the Belgian study, 37% of patients were transferred once in their final 3 months, 16% were transferred twice and 10% were transferred three times or more. Figures reported in the Dutch study were similar: 38%, 21% and 8%, respectively. In both studies, more than 70% of those living at home had at least one transfer; care home residents in the Netherlands were, however, much more likely than their Belgian equivalents to have moved at least once (92% and 36%, respectively).

A second method used to study end-of-life transitions is sequential analysis of changes in health and symptom control for individual patients across different settings. Trask et al. ’s62 mortality follow-back study is typical of this approach, using telephone-administered questionnaires to collect nationally representative data from bereaved relatives in the USA. They studied relatives’ perceptions of distressing pain in cancer patients in their last care settings and found that transitions were not necessarily associated with improvement in symptom control. Similarly, in a comparison of hospice and hospital care for cancer patients in the last 3 months of life in the UK, the transition from one setting to the other appeared to make little difference in the experience of pain and breathlessness, although participants rated pain control by the hospice as more effective. 63

The third approach to the study of transitions at the end of life has been to explore people’s perceptions using qualitative methods. Many studies of this type have collected bereaved family carers’ retrospective accounts or professionals’ perspectives, rather than those of older adults themselves. For example, Harrison and Verhoef64 interviewed 33 carers to explore their perceptions of co-ordination of care. Levine65 conducted six focus groups with 56 carers in New York, in a well-recognised study of carers’ journeys through the health-care system. Many more studies, including some of those funded under the SDO continuity stream, will have collected data on experiences of transitions when exploring other issues.

Summary

The preceding background has emphasised the importance of transitions to patients, families and health systems. Older adults with complex health-care needs are likely to be more vulnerable than other sections of the population to the effects of moving from one place of care to another. To minimise the impact on patients’ and carers’ well-being, care should be co-ordinated and consistent across settings. To achieve this, we need to draw on and combine the strengths of the different settings and approaches in health and social care provision.

Quality improvement initiatives in health services have been criticised for missing the obvious in patient care – the need for caring – and focusing on technical aspects of health services. 66 Many of the recent initiatives in integrated or guided care and care pathways are aimed at quality improvement, but share similarities with the hospice approach. The hospice movement has traditionally been interested in holistic care, with continuity across time and settings, rather than efficiency and cost-effectiveness. A focus on bridging the gap between these approaches may be a particularly effective way of addressing any shortcomings in current experiences of care. The following study aims to combine perspectives from health services research and end-of-life care, to this end.

To improve patients’ and carers’ experiences of end-of-life transitions, we need to appreciate the complexity of their journey. Current knowledge of transition experiences in health systems outside the USA is limited, as is the application of components of managed or integrated care in other health systems. Financial incentives are in their infancy in the UK and elsewhere, and their consequences for transitions are as yet unknown. For older adults’ transitions between care settings to be better understood, we need to gauge the frequency and nature of transitions in the last year of life; deepen our understanding of the consequences of transitions for carers; and understand how decisions are made and what the constraints are for professionals who commission and provide care.

The major part of the following study adopts the third approach to the study of transitions described above, and uses qualitative methods to explore patient, carer and professional experiences. However, we also analyse quantitative data on service utilisation and a structured questionnaire to capture carers’ proxy views of patient experiences in different settings.

Theoretical framework

We sought an appropriate theoretical framework within which to site our study from the previously funded SDO work on continuity. Freeman et al. ’s29 three-dimensional construct of continuity (informational, relationship and management) was used to inform our work. Continuity was considered as both a part of the process of transitions and an outcome of good care across transitions. Throughout this project, Donabedian’s approach to quality, examining structure, process and outcome, provided an underlying framework for our thinking. 67,68

To understand end-of-life transitions, we wished to explore patient, family and staff experiences and explore how these were influenced by wider factors in both their surrounding social networks and the wider health and social care system. Our choice of methodology allowed us to gain insight into how ‘end-of-life care’ was constructed through the relations between the different categories of participants. It also enabled us to begin to understand the diverse and dispersed nature of ‘palliative care’ within systems of health and social care, and wider policy frameworks.

We took a mixed-methods approach in this study. Mixed-methods research involves the collection and analysis of data, and integration of findings, using both qualitative and quantitative approaches. Such approaches are especially suitable for understanding complexity and for enabling understanding of both the experiential and ‘systems’ factors surrounding any given phenomena. 69,70 In this report, we present findings that have been combined at the analysis stage, based on the ‘following a thread’ technique. 69,71

The majority of our work in this project was qualitative, and we approached the analysis of our qualitative data with a broadly social interactionist lens. We were interested in how patients, families and staff interact and attribute meaning to others’ behaviours, in order to understand how transitions were experienced. This approach allowed us to consider carers’ and patients’ negotiation of their roles, the social construction of patient and professional behaviours, and how all of these link to service structures. We aimed to gain an in-depth understanding of transitions, set within social and organisational contexts.

Chapter 2 Objectives

The aim of this study was to understand the patterns, potential causes and consequences of transitions between settings and their association with older people’s experiences at the end of life. The three conditions under study, heart failure, stroke and lung cancer, will provide information on care provided across contrasting disease trajectories. Whereas cancer patients commonly undergo a steady progression with a clear terminal phase, gradual decline in people with heart failure is characterised by episodes of acute deterioration and some recovery, with a more sudden and seemingly unexpected death. 72 Older stroke patients, meanwhile, have a trajectory marked by episodes of sharp decline.

Objectives

-

To explore the effect of transitions towards the end of life on health status, quality of life, symptom control and satisfaction with care.

-

To understand the factors that influence decisions about transitions in the nature and location of care.

-

To elicit patient and provider views on the appropriateness of different transition patterns and the factors that constrain or shape decisions.

-

To describe transitions in and out of hospital at the end of life for older people with selected conditions in England.

-

To identify individual- and service-level factors associated with frequency of transitions.

The major part of this project used qualitative interviews to address objectives 1 to 5. A structured questionnaire was administered to bereaved carers to inform objective 1, while quantitative data were analysed to complete objective 4.

Rationale: interviews with patients

The aim of this section of the study was to explore older adults’ own experiences of moving between care settings in their last year of life. Previous research into end-of-life care has rarely sought out care recipients’ perspectives, relying instead upon carers as a proxy voice for people who have died73 or are too unwell to be interviewed. Our aim, in interviewing patients themselves, was to understand how relationships with carers and professionals affect older adults’ experience of transitions at the end of life. We anticipated that patients’ accounts of how their care was delivered and experienced, and how they interpreted their interactions with professionals and carers, would provide new and valuable insights into older people’s experiences of end-of-life care. In order to provide representation of the settings and services involved in transitions at the end of life, we interviewed people identified by secondary care and specialist nurse teams.

Rationale: interviews with bereaved family carers

Bereaved family carers were interviewed to provide a proxy view of patients’ experiences and explore their own perspectives on the transitions experienced by the decedent. The interviews explored the reasons underlying any moves, the experiences and consequences for decedent and family, and perceptions of care across settings. Carers were able to provide a different and often complementary perspective to the patients’ reports of experiences in their last months. In addition, the carers had insights into the time around the death and beyond, which is often the subject of great scrutiny.

Rationale: interviews with professionals

Professionals were interviewed with the aim of understanding their perspectives on decision-making concerning transitions, and the organisation and management of transitions between care settings for older adults at the end of life. Participants were made aware that the study team was particularly interested in care for older adults who die with lung cancer, heart failure or stroke. However, many of the professionals had a broader remit focused on older people, palliative or end-of-life care. This is reflected in their interview data, which are not solely concerned with these conditions.

Senior professionals responsible for providing or commissioning health or social care services for older people, and with some insights into transitions between care settings, were the target participants. Senior staff were considered more likely to have an overview of the way services are provided, interfaces with other settings and services, and views and insights about the reasons why services are organised as they are, including alternative models of care, and piloting and developing new services. Insights from both providers and commissioners were sought as a means of gaining insights into different stages and levels of the structure, organisation, planning and delivery of care.

The sampling frame covered medical and nursing staff in different settings, with representation of ambulance, paramedic and out-of-hours services, as well as a range of commissioners. Most senior social care interviewees were commissioners rather than providers of services, although some had direct contact with patients and their relatives in making assessments and commissioning care for individuals.

Chapter 3 Methods

Issues, problems and responses

Research ethics and research governance approvals

To conduct this study, which included interviews with 191 individuals, approval from research ethics committees (RECs) and NHS and social care research governance approvals were obtained. Standard application procedures to NHS RECs were followed for all components of the project, except for the research with professionals, where a fast-track process for low-risk studies was followed (proportionate ethical review) and permission granted within 2 weeks. Ensuring that appropriate research governance approvals were in place was a far more time-consuming process, as procedures were locally derived and frequently opaque. Changes to the information technology (IT) supporting the central application process for research governance approvals (Integrated Research Application System or IRAS) produced a 4-month delay in the processing of our application for professional interviews, and we were obliged to send all the application paperwork to each trust in addition to making a centralised online application.

Two primary care trusts (PCTs) refused permission to interview carers in their area. One gave no reasons; the other was critical of the study design, stating that GPs would be unlikely to be able to identify carers. A resubmission of the application to this PCT was also unsuccessful. Seeking permission for professional interviews was complicated by variation between organisations in interpretation of the national guidance. We sought permission to conduct telephone interviews with staff members, unless they preferred to meet the researcher. Some organisations considered themselves to be participant identification centres, while others argued that they were research sites. This was not resolved with intervention from the lead PCT and, consequently, the time taken to approve the study ranged from a few days to more than 3 months. Both researchers were in possession of NHS research passports, but almost all trusts also insisted on additional local approval procedures for individual researchers. In total, across the project we applied for NHS research governance approval 86 times.

Staffing

Recruitment and retention of staff, along with contractual difficulties, were responsible for delays to the start of the project in the south. An extension to the end of the project within original resources was granted to enable the work to be completed.

Qualitative interviews

Recruitment and data collection from patients

We sought a purposive sample of older adults aged over 75 years who had moved at least once between care settings in the 3 months leading up to the interview, and for whom specialist health professionals answered ‘no’ to the question ‘would you be surprised if this patient was to die in the next 12 months?’. This ‘surprise’ question is commonly used to identify individuals nearing the end of life,74,75 in particular where prognosis is complex, as is the case with heart or renal failure, for example. 76 Along with the criteria listed above, participants had to be aware of their heart failure, stroke or lung cancer diagnosis. Our initial aim was to interview 10 patients for each of these three conditions.

Potential participants were identified and invited by their specialist health professionals to contact the research team. On receipt of an expression of interest, a researcher telephoned the patient to explain the study and, if appropriate, send further information by post. All of the interviews were arranged and conducted by one member of the research team between June 2009 and July 2010. They took place at the participants’ place of residence and lasted an average of 1 hour.

Interviews followed a flexible person-centred topic guide that covered interviewees’ social background, family circumstances and their experiences as a patient. Participants were asked about their illness, the health and social care they received, their experiences of the transitions that they had experienced, and how they felt about these moves between care settings. People were encouraged to talk about issues which were important to them, and to share their perspectives on the quality of the care received in different settings as well as on the impact of transfers between places of care. A comprehensive list of prompts for the interviewer ensured consistency across interviews. All interviews were audiotaped with permission, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber and anonymised by the research team.

Recruitment and data collection from bereaved caregivers

Family carer interviewees were identified in a two-stage process. Primary care research networks (PCRNs) in three NHS regions of England first advertised the study to GP practices enrolled with their Primary Care Incentive Scheme for research participation. Comprehensive local research networks facilitated the involvement of general practices by funding service support costs.

Support from primary care research networks

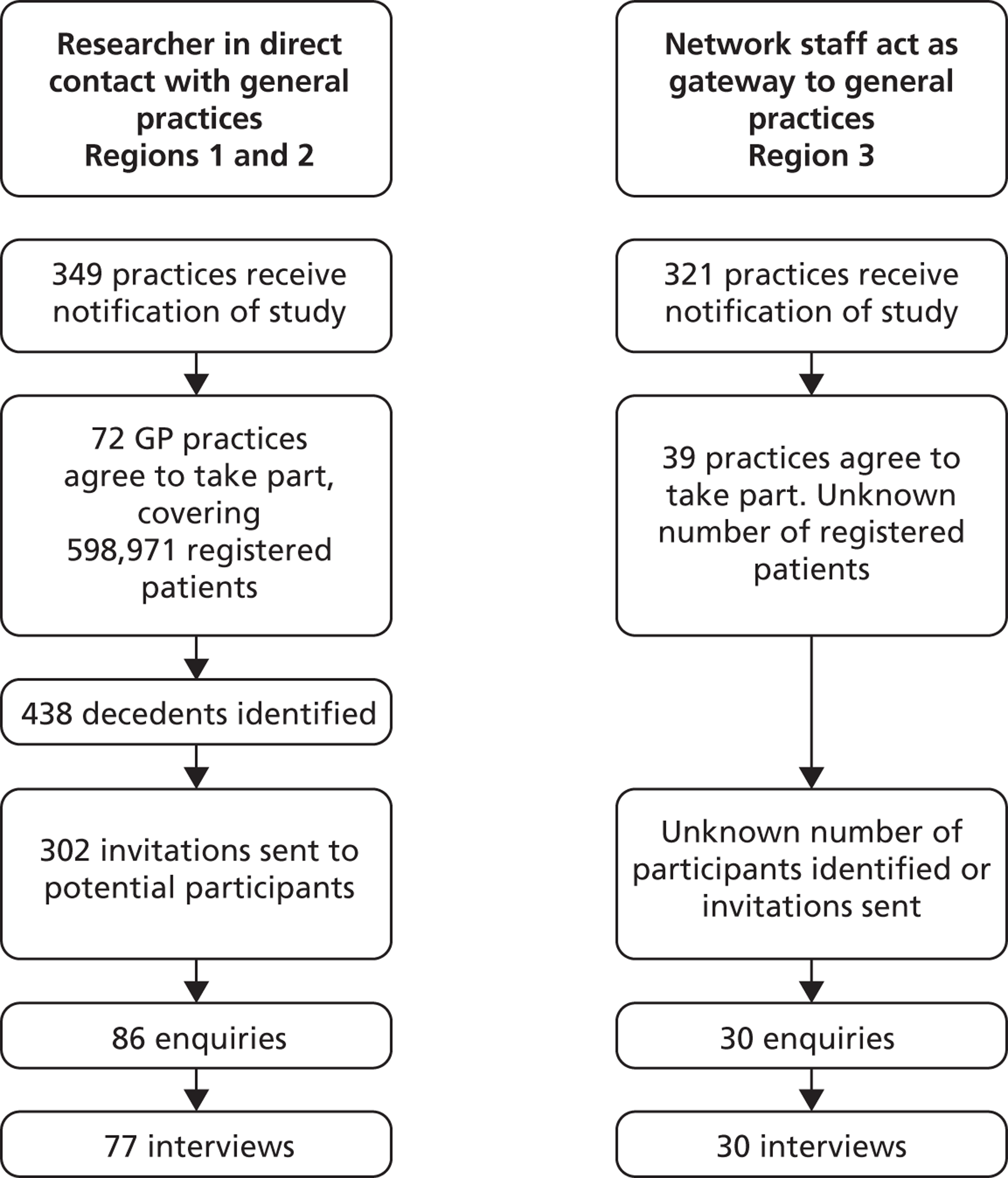

Two approaches to recruitment were adopted once GP practices were recruited to the study (Figure 1). 77 In the north-west region, the Merseyside and Cheshire PCRN and the North Lancashire PCRN worked directly with GP practices. PCRN staff visited each practice assisted with database searches and distribution of recruitment materials to eligible individuals and collected some data about practice involvement in the study. In other areas [South Central Strategic Health Authority (SHA) (Portsmouth, Southampton, Hampshire, Isle of Wight PCTs), parts of the South West SHA that were encompassed by the same primary care research network (Devon, Plymouth, Torbay, Somerset, Bath and North Somerset, Bristol, Swindon, Wiltshire, Dorset, Bournemouth and Poole, Greater Manchester)], PCRN staff dealt with initial enquiries from practices and passed on formal expressions of interest as they arose to the research team, who then supported practices through their involvement. In all regions, participating practices were provided with the recruitment materials: invitation letters, participant information sheets, reply slips and stamped envelopes.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment of family carers by general practices.

General practices were asked to identify people who had died within the last 3–9 months aged 75 years or older with lung cancer or heart failure or following a stroke. Most were able to scrutinise a list of patients who had died, though appropriate read codes were made available for searching electronic databases if required. The list of eligible decedents was restricted to individuals who had experienced more than one transition between care settings in the last 3 months of their lives.

Identification of carers

The primary care team identified carers for each decedent in cases where the team knew the carer as a result of providing care to the patient. The GP took responsibility for inviting carers into the study. Most were family members or friends. A small number of care-home professionals who had known the decedent well and were able to talk about transitions and end-of-life experiences were also included.

Interviews were conducted between 3 and 9 months following the death. Within end-of-life care research, 3 months after bereavement is acknowledged as an appropriate minimum threshold for inviting bereaved people to participate in research. This is because, by 3 months, memories are sufficiently fresh for a person to provide details about the experience, but enough time will have passed for most individuals to feel able to speak with a research interviewer about their experiences without feeling too upset to do so. Care was taken to avoid holding any interviews around the first anniversary of the death.

Interviews were conducted at a time and a place chosen by each participant. For the majority, this was a face-to-face interview in their own home. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and interviews were conducted by a research team member experienced in working with vulnerable adults and older people. One family carer living in Scotland and one care-home professional were interviewed by telephone, while two participants chose to be interviewed in the researcher’s office and one at their own place of work. Another care-home owner chose to be interviewed face to face at the care home where she lived.

Some carer participants chose to be interviewed with a relative or friend present. In some cases, this was prearranged, but, in others, the person was present when the interviewer arrived. Informed consent was received from and documented with all individuals. Additional participants were almost always female: one widow and two widowers were accompanied by their daughters; another widow had a female friend with her; five sons and one daughter had their spouses present.

Most interviews opened with a question to prompt an overview about the transitions experienced in the last year of life. This approach was used in order to tailor the subsequent questions. Where it was difficult to obtain this overview, interviewees provided detailed accounts of each setting and transition. The interviewers then probed for details about the final transition, and asked a series of structured questions. If interviewees were reticent after probing, structured questions were introduced sooner. If interviewees had an account they wanted to provide about later transitions, this was explored before the introduction of structured questions.

Administration of questionnaire

The previously validated VOICES survey78 was used in this study with minor modifications. We added a small number of open questions after separate blocks of questions to invite the participants to give examples to clarify their answers (e.g. if a participant’s answer indicated that the nurses had treated the patient with dignity and respect, we asked the participant to offer an example of such behaviour). Responses to open questions were coded if appropriate and reported with the VOICES data. In addition, we inserted two questions that have been used elsewhere, to ask about co-ordination of care. VOICES is available elsewhere;78 additional questions are available from the author on request. The questionnaire was administered face to face as part of the interview, and responses were entered into a touchscreen computer by choosing responses from drop-down menus of options. The interviewers were also able to type short open answers using the onscreen keyboard. The structured questions were followed in sections appropriate to the interviewee’s circumstances, and not all were applicable to every interviewee. The questions on places of care were completed first, followed by medications, GP care, out-of-hours services, and the circumstances of the death, finishing with questions that required the respondent to take an overview of the care transitions. A small number of participants expressed discomfort about the specificity of the structured VOICES questions and, to avoid distress in these cases, open questions were substituted for the same themes.

All of the interviews were audio recorded with permission and transcribed in full. With the exception of one telephone interview (two separate conversations 2 weeks apart), each interview was conducted on a single day, sometimes with short breaks. The recorded interview duration was 90 minutes on average, but varied between 45 and 180 minutes.

Recruitment and data collection from professionals

After research governance approval had been granted, some organisations provided assistance with recruitment and in other organisations the researcher sent invitations directly to individuals. Five individuals already known to the study team (three of whom had expressed interest in earlier phases of the study) participated after direct invitation. Four organisations granted permission to recruit on the grounds that they would nominate potential participants to be sent invitations. One of these organisations (social care) sent the invitations to potential participants and the researcher was asked to wait for a direct response before making any contact with the potential participants. Six organisations circulated information to a large number of potential participants, but there were no restrictions on the research team to also make contact. Other invitations were sent on the basis of organisation structures and contacts, recommendations from other professionals, and the results of telephone calls to establish the most appropriate people to invite. All of the social care organisations provided assistance with recruitment.

Telephone interviews

The majority (37) of interviews were conducted on the telephone, but six were face to face in a private room at the participant’s place of work. Four of the professionals interviewed by telephone were at home for the interview, and the other 33 were at work. The interviews were 36–90 minutes in length.

Interviews followed a topic guide. Professionals were asked to talk about what their role involved and how this fitted within their service or organisation. They were then asked to discuss challenges associated with transitions at the end of life for older people, and to provide information about good practice and any pilot initiatives. Some had identified key issues in advance which they wanted to mention. Each individual was asked if they would like to explore commissioning or provision (the opposite of their own role); how care was organised for individuals without readily accessible family carers; which pieces of strategy or guidance they work within; and what impact they saw the (at that stage planned) changes within NHS structures having on the care of older adults at transitions between care settings. Short summaries of particular experiences of care derived from the interviews with bereaved carers were sent to participants in advance. These scenarios were identified from an initial analysis of the first 60 interviews with carers. They were chosen to reflect themes and issues that were frequently occurring, or that reflected particularly challenging circumstances for the service providers. Each scenario was a composite of data from a number of different interviews, with important demographic data modified to ensure that the individuals involved remained anonymous. The scenarios were carefully selected to ensure that individuals were not able to recognise or asked to respond to patient care in which they were directly involved. The interviewees were invited to share their perceptions of the events, with prompts about whether or not such things could occur in their area and what provision was or could be implemented to minimise the chances of poor care.

Interviews were audio recorded with permission. Assurances were given about the study team’s commitment to confidentiality for the participants, including not publishing job titles that would identify an individual and restricting information available data on any participant’s location. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants. For participants interviewed by telephone, the consent form was sent in advance by e-mail or post. Verbal consent was obtained at the time of the interview and forms were signed by the participant and interviewer and exchanged after the interview. Audio recordings were transcribed in full by a professional transcriber.

Qualitative data analysis

A common approach was taken to data analysis across all three sets of interviews. For the patient and carer interviews, three researchers familiarised themselves with the data by reading and rereading the transcripts and identified key issues, concepts and themes. These served as a basis for developing a coding framework of initial categories and themes, which was tested on a 10% sample of transcripts before being used to code all transcripts line by line. Two researchers coded the same 20 transcripts, and a third researcher coded a further 10. Any discrepancies were discussed and, if agreed, the minor modifications were made to the coding framework.

Each major theme was allocated to a chart in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), with a row for every case and a column for each category. Data were entered into the relevant cells and summaries were prepared at the base of every column. The data were compared within and across cases, searching for commonalities and differences. This enabled the research team to identify patterns and main issues arising from the interviews. The original transcripts and field notes were referred to in order to ensure that analysis took the context of interviews into account.

In the case of the professional interviews, the thematic framework brought together key themes emerging from those transcripts with a priori issues and questions derived from the aims and objectives of the study and concepts raised by respondents in the first two phases. One researcher, in discussion with two others, tested and adapted the framework on the basis of a 25% sample of interviews transcribed. All transcripts were subsequently coded line by line by one researcher, using NVivo software (version 9.2, QSR International, Warrington, UK) to manage the data. A second researcher double coded five transcripts to check the validity of the framework. The NVivo programme’s framework matrix function was used to allocate each theme to a chart, with a row for every source and a column for each category. Data were mapped and interpreted by searching for associations between themes and identifying the commonalities and differences in interviewees’ attitudes.

The researchers involved discussed and refined their analysis throughout the process, drawing on their different backgrounds (medicine and public health, nursing, psychology, sociology and social policy) and their different relationships with the data (study design, interviewers or data analysts) to reach agreement. Findings were discussed with an external group of research partners, comprising people who had themselves provided care for older adults and were keen to ensure relevance to patients’ needs.

Chapter 4 Analysis of linked Hospital Episode Statistics and mortality data

The aim of this section of the project was to analyse data on care received by older adult patients with specific causes of death, in the year before death. Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) records details of each episode of inpatient care provided by a consultant. Total length of each admission (made up of all consultant episodes), dates of admission and discharge, destinations, procedures undertaken and specialty of treatment are recorded.

Linked HES and mortality data were obtained for patients aged ≥ 75 years who had been admitted to hospital with a diagnosis of heart failure or lung cancer in the 12 months before their death. At the time of the study, it was not possible to select a group of individuals using mortality data and then extract HES data relating to their hospital use. The study data set was, therefore, defined by diagnoses recorded by HES and not by cause of death. Hence, patients who had received hospital treatment for specified conditions but did not have any of these recorded as a cause of death would still be included in the study. As the starting point for the study data set was hospital admissions, the data provide a reflection of resource use, but are liable to inaccuracies within HES. Deficiencies in the quality of HES data are well recognised, including many mistakes of coding and omission. 79,80 People who died without any inpatient episodes in the 12 months before death would not be included in this study. However, we know that 78% of all deaths recorded by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) are associated with one admission in the last year of life; the same is true for 88% of all age cancer deaths and 66% of deaths from cardiovascular disease. 81

Pseudonymised HES containing records of admitted patient care in England, linked to ONS mortality data, were selected for years 2000–1 to 2010–11. The data were restricted to people aged > 74 years with diagnoses of either lung cancer or heart failure [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes I50–I50.9, I11.0. I42.0, I25.5, I42.9, C33.0–34.9]. HES data variables were selected relating to diagnosis, length of stay and discharge destination. No variables that would identify geographical locations for patients or institutions or dates of birth were used in this analysis. The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) was provided with the data, calculated from the postcode of residence provided on hospital admission. Mortality data were obtained only for patients who had been in hospital in the year before their death and, therefore, had a record in the HES. Cause of death and whether this took place at home or in a communal establishment were extracted. Data were reported to be cleaned prior to being released for analysis.

Data management

The data were provided in a .ZIP file, copied from the encrypted hard disk onto a non-networked computer, and then expanded. PASW Statistics version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used to import the delimited files into a statistical and data management environment. Loading syntax kept the variable names from the HES data set.

Plan for analysis

There are 20 diagnosis fields within the HES data set. The study data set was then defined by searching for the diagnostic codes. Heart failure admissions were restricted to the primary diagnosis, in line with the approach taken in the national audit of heart failure care. 82 A broader definition was used for lung cancer admissions, using positions 1–10. The data set was ordered according to patient ID and increasing date of discharge. Using the date of admission, spells were identified if they had occurred in the 12 months preceding the date of death. The total number of bed-days within the 12 months before death was calculated from the sum of the spell durations. The ONS file was expanded and imported into PASW. The ‘merge files add variable’ command was used to join the ONS fields to the HES records using the common ID. Deaths were allocated to the final spell for each case in the data set.

The rank of the IMD was recoded into quintiles (with the recode into different variable command), using publicly available data from the Communities and Local Government website83 to provide cut off ranks for each quintile. Patients who died in hospital on their last admission were identified using the discharge method and discharge destination variables. For all other cases, the time in days between last admission and death was calculated using the ‘date wizard’ function. For deaths within each patient group, the number of admissions, bed-days in year before death and the time between the last admission and death were calculated.

Chapter 5 Findings

Participant characteristics

Patients: participant characteristics

Thirty people were interviewed (Table 1). Thirteen of the 20 people with heart failure who were sent information about the study agreed to be interviewed (four female and nine male). Thirty-five older adults with lung cancer expressed interest, but only 14 were interviewed (three male and 11 female). One of the patients died before the interview date and 20 others were too unwell to participate at the time. We interviewed three stroke patients. Other planned interviews were cancelled because of deterioration in the patient’s condition, or death. Lung cancer patients were aged 73–89 years, heart failure patients were aged 69–88 years and stroke patients were aged 81–93 years. Four of the interviewees (three heart failure patients and one person with lung cancer) were interviewed despite being younger than the inclusion criteria minimum age of 75 years, as they had been invited by their responsible clinicians to take part in the study. We monitored the sociodemographic composition of the sample, based on IMD, derived from the participants’ postcodes, and used the last reported occupation to allocate the participant to one of the five categories in the National Statistics Socioeconomic Classification. 84 Our aim was to make sure that people from disadvantaged areas were represented, and this was the case, without intervention.

| Characteristics | Heart failure | Lung cancer | Stroke | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years (median, range) | 77 (69–88) | 80 (73–89) | 85 (81–93) | |

| Male | 9 | 3 | 2 | |

| Female | 4 | 11 | 1 | |

| Social classificationa | ||||

| 1 and 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | |

| 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 4 and 5 | 6 | 10 | 0 | |

| IMD | ||||

| Quintile 1 | 16 (53%) | |||

| Quintile 2 | 3 (10%) | |||

| Quintile 3 | 8 (27%) | |||

| Quintile 4 | 1 (3%) | |||

| Quintile 5 | 0 (0%) | |||

| Living circumstances | ||||

| Home, alone | 3 | 5 | 1 | |

| Home, with others | 9 | 7 | 1 | |

| Institution | 1 | 2 | 1 | |

| Totals | 13 | 14 | 3 | |

Carers: participant characteristics

One hundred and eighteen carers were interviewed (77 from 302 invitations from GPs in the south, 30 from an unknown number of GP invitations in the north-west and 11 recruited via other means) (Table 2). They ranged in age from 38 to 87 years (median 66 years). The majority (75%) were female; around half (47%) had been the spouse or partner of the patient. More carers were recruited from the southern regions (73%) and a disproportionate number were from less disadvantaged areas. The participants’ postcodes were used to allocate an IMD score to the carer, which was then placed into quintiles based on the scores for England. This provided a measure of relative disadvantage across our sample.

| Characteristics | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age, years (median, range) | 65.5 (38–87) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 30 (25.4) |

| Female | 88 (74.6) |

| Marital status | |

| Married or cohabiting | 42 (35.6) |

| Widowed | 59 (50) |

| Single | 12 (10.2) |

| Divorced or separated | 1 (< 1) |

| N/A | 4 (3.4) |

| Relationship to the decedent | |

| Spouse or partner | 56 (47.5) |

| Child | 53 (44.9) |

| Other relative | 6 (5.1) |

| Friend | 1 (< 1) |

| Professional | 2 (1.2) |

| Decedent resident in | |

| North-west | 32 (27) |

| South-central or south-west | 86 (73) |

The patients whose care was the subject of the interviews had a median age of 84 years (range 66–97 years) and half of them were female (Table 3). Treatment had been received for at least one of the three main study conditions (heart failure, lung cancer or stroke) by 82 (77%) of the decedents. The sample was supplemented by carers of people who had had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (18.6%), colorectal cancer (7.6%) and breast cancer (2.5%). The vast majority of decedents had lived at home (84%) or in a care home (9%), and hospital was the most usual place of death (58%). Thirty-two per cent of patients had died in their own or a relative’s home (n = 17) or in a care home (n = 19). Reported levels of comorbidities were low.

| Characteristics | n (%)a |

|---|---|

| Age, years (median, range) | 84 (66–97) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 62 (52.5) |

| Female | 56 (47.5) |

| Main condition | |

| Heart failure | 40 (33.9) |

| Stroke | 27 (22.9) |

| Lung cancer | 16 (13.6) |

| COPD | 22 (18.6) |

| Colorectal cancer | 9 (7.6) |

| Breast cancer | 3 (2.5) |

| Cancer unknown primary | 1 (< 1) |

| Reported comorbiditiesb | |

| COPD | 4 (3.4) |

| Colorectal cancer | 3 (2.5) |

| Breast cancer | 2 (1.7) |

| Heart failure | 1 (0.8) |

| Stroke | 1 (0.8) |

| Place of residence 3 months before death | |

| Own home | 99 (83.9) |

| Relative’s home | 4 (3.4) |

| Care home | 11 (9.3) |

| Hospital | 3 (2.5) |

| Other | 1 (< 1) |

| Place of death | |

| Hospital | 68 (57.6) |

| Care home | 19 (16.1) |

| Own home | 17 (14.4) |

| Relative’s home | 2 (1.7) |

| Hospice | 11 (9.3) |

| Ambulance/A&E | 1 (< 1) |

| Transitions in the last year of life | |

| One or more in last 12 months | 118 (100) |

| One or more in last 6 months | 114 (96.6) |

| One or more in last 3 months | 110 (93.2) |

The carer and patient interviewees had different socioeconomic profiles, with a disproportionate number of patients drawn from the most disadvantaged areas (Table 4). Carers from the south were predominantly resident in more advantaged areas. However, it is important to note that not all of the carers were co-resident with the person receiving care. When the IMD is examined by decedent diagnosis, there is a significant gradient only for COPD, where fewer carers were found in the least disadvantaged quintiles (Table 5).

| IMD quintiles | Number (%) of interviewees, north-west | Number (%) of interviewees, southern regions | Totals, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1 (most deprived) | 4 (12.5) | 1 (1.2) | 5 (4.3) |

| Quintile 2 | 9 (28.1) | 3 (3.5) | 12 (10.3) |

| Quintile 3 | 8 (25.0) | 17 (20.0) | 25 (21.4) |

| Quintile 4 | 6 (18.8) | 29 (34.1) | 35 (29.9) |

| Quintile 5 (least deprived) | 5 (15.6) | 35 (41.2) | 40 (34.2) |

| Totals | 32 (100) | 85 (100) | 117a (100) |

| IMD quintiles | All cancers, n (%) | Heart failure, n (%) | Stroke, n (%) | COPD, n (%) | Totals, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintiles 1, 2 and 3 | 10 (35.7) | 14 (35) | 8 (28.6) | 11 (50) | 43 (36.4) |

| Quintile 4 | 8 (28.6) | 11 (27.5) | 9 (32.1) | 7 (31.8) | 35 (29.7) |

| Quintile 5 | 10 (35.7) | 15 (37.5) | 11 (39.3) | 4 (18.2) | 40 (33.9) |

| Totals | 28 (100) | 40 (100) | 28 (100) | 22 (100) | 118 (100) |

Professionals: participant characteristics

Forty-three professionals were interviewed from 10 PCTs, four PCT provider arms, four acute hospital trusts, two ambulance trusts, five social care organisations and five hospices. Interviewees were drawn from the north-west (n = 20) and south-central and south-west NHS regions (n = 23), but no staff participated from any of the 11 care trusts in England. The roles of the interviewed staff are shown below (Table 6).

| Roles | North-west, n | South-central and south-west, n | Totals, N |

|---|---|---|---|

| Social care commissioner | 6 | 1 | 7 |

| Social care operational | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Health commissioner | 1 | 6 | 7 |

| Community matron | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| GP | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Hospital doctor | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Hospice senior staff | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Senior/specialist acute nursing staff | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Urgent/out-of-hours service | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ambulance service | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Totals | 20 | 23 | 43 |

Questionnaire findings: carers’ views of end-of-life care transitions

Overview of care

A minority of respondents reported that care from health and social services had been well co-ordinated (42%) or flexible to the needs of the patient (47%) (Table 7). Half of the participants were aware of a main contact person for the decedent at their general practice, hospital or elsewhere in their last 3 months. Most often, that contact person had been the GP, either alone or in combination with nurse, consultant or care-home colleagues. Only 26 (22%) of all respondents judged that any of the transitions in the final 3 months of life could have been avoided. Ratings of both the amount and the nature of help and support were not high; 42% received as much help and support as needed (Table 8).

| Care from health and social services | Responses, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don’t know | N/A or no response | |

| Well co-ordinated | 50 (42.4) | 36 (30.5) | 12 (10.2) | 20 (16.9) |

| Consistent | 60 (50.8) | 31 (26.3) | 7 (5.9) | 20 (16.9) |

| Flexible to decedent’s needs | 55 (46.6) | 30 (25.4) | – | 33 (28) |

| Everyone involved had enough information about decedent’s needs | 61 (51.7) | 26 (22) | 11 (9.3) | 20 (16.9) |

| Decedent had a main contact person at hospital, general practice or elsewhere over last 3 months | 59 (50) | 27 (22.9) | 7 (5.9) | 25 (21.2) |

| Could any of the transitions in last 3 months have been avoided? | 26 (22) | 54 (45.8) | 5 (4.2) | 33 (28) |

| Questions | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Who was main contact person in last 3 months? | |

| GP, alone or in combination with nurse, consultant, care home | 33 (28.0) |

| District or specialist nurse | 3 (2.5) |

| Social worker | 4 (3.4) |

| Care home | 5 (4.2) |

| Hospital consultant or ward staff | 7 (5.9) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 66 (55.9) |

| Do you feel your family got as much help and support as you needed when caring for the decedent? | |

| Yes, as much as needed | 50 (42.4) |

| Yes, some support but not as much as needed | 10 (8.5) |

| No, although we tried to get more help | 10 (8.5) |

| No, but we did not ask for more help | 15 (12.7) |

| We did not need any help | 6 (5.1) |

| No recorded response | 27 (22.9) |

Care from general practitioners and out-of-hours care

Almost all of the decedents had seen their GP in the last 3 months of life, and the respondents gave high ratings to all aspects of the care provided. A minority received no home visits and a number were seen at home at a frequency equivalent to more than twice each week. Out-of-hours care was sought by around 30% of people in their final months. Only one used NHS Direct and most telephoned the out-of-hours service or their own GP, which resulted in a home visit. Advice to go straight to hospital was uncommon (4%). Table 9 presents carers’ views of GP care and Table 10 presents carers’ views of out-of-hours care.

| Questions | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Did the decedent have any contact with his or her GP in last 3 months of life? | |

| Yes | 103 (87.3) |

| No | 9 (7.6) |

| Don’t know | 1 (< 1) |

| No response | 5 (4.2) |

| In your opinion, did the GP know enough about their condition or treatment? | |

| Yes | 85 (72) |

| No | 10 (8.5) |

| Don’t know | 9 (7.6) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 14 (11.9) |

| Did you have confidence and trust in the GPs who were caring for them? | |

| Yes, in all of them | 84 (71.2) |

| Yes, in some of them | 10 (8.5) |

| No, not in any of them | 9 (7.6) |

| Don’t know | 0 |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 15 (12.7) |

| Do you feel that the GPs had time to listen and discuss things? | |

| Yes, definitely | 81 (68.6) |

| Yes, to some extent | 11 (9.3) |

| No | 4 (3.4) |

| Don’t know | 2 (1.7) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 20 (16.9) |

| Were you able to discuss with the GP any worries or fears that you may have had about his or her condition, treatment or tests? | |

| Yes, I discussed them as much as I wanted | 71 (60.2) |

| Yes, I discussed them, but not as much as I wanted | 4 (3.4) |

| No, although I tried to discuss them | 5 (4.2) |

| No, but I did not try to discuss them | 6 (5.1) |

| Don’t know | 0 |

| I had no worries or fears to discuss | 9 (7.6) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 23 (19.5) |

| How much of the time were you treated with respect and dignity by the GP? | |

| Always | 91 (77.1) |

| Most of the time | 8 (6.8) |

| Some of the time | 1 (< 1) |

| Never | 2 (1.7) |

| Don’t know | 0 |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 16 (13.6) |

| How often did the GP visit at home during the last 3 months of life? | |

| Once | 11 (9.3) |

| Two to five times | 50 (42.4) |

| Six to 10 times | 10 (8.5) |

| Eleven to 15 times | 5 (4.2) |

| Sixteen to 20 times | 1 (< 1) |

| More than 21 times | 3 (2.5) |

| Did not visit, no visits were needed | 15 (12.7) |

| Did not visit, but wanted the GP to visit | 1 (< 1) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 22 (18.6) |

| Questions | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| In the last 3 months, did the decedent ever need to contact a doctor for something urgent in the evening or at a weekend? | |

| Not at all | 47 (39.8) |

| Once or twice | 26 (22) |

| Three to four times | 6 (5.1) |

| Five or more times | 3 (2.5) |

| Don’t know | 7 (5.9) |

| No recorded response | 29 (24.6) |

| For the 35 decedents who reported using OOH services, who did the decedent contact (last time this happened)? | |

| Own GP or OOH number | 25 (71.4) |

| NHS Direct | 1 (2.8) |

| District nurses | 3 (8.6) |

| No recorded response | 6 (17.1) |

| What happened as a result of making contact in the evening or weekend | |

| Advised to call 999 | 3 (8.6) |

| Advised to go to A&E | 1 (2.8) |

| The OOH service called an ambulance | 1 (2.8) |

| They were visited by their own GP at home | 2 (5.7) |

| They were visited by another GP at home | 13 (37.1) |

| Advice was given over the phone, no visit | 1 (2.8) |

| No recorded response | 14 (40.0) |

| Was this the right thing for them to do or not? | |

| Yes | 26 (74.3) |

| No | 3 (8.6) |

| Don’t know | 3 (8.6) |

| No recorded response | 3 (8.6) |

Medication

Deficiencies in the information relating to medication, or choice of medication, were reported by few respondents, with misunderstandings or errors recalled by 14 carers (12%) (Table 11).

| Questions | Responses, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don’t know | N/A or non-response | |

| Was the decendent or carer given enough information about the medications that the decendent was taking? | 42 (35.6) | 19 (16.1) | 2 (1.7) | 55 (46.6) |

| Was the decedent or carer given enough choice about the medications that the decendent was taking? | 21 (17.8) | 14 (11.9) | 8 (6.8) | 75 (63.6) |

| Were there any incidents when there was a misunderstanding or error regarding mediations? | 14 (11.9) | 61 (51.7) | 4 (3.4) | 39 (33.3) |

| Throughout the last 3 months, did all the professionals know enough about the decedent’s medication? | 53 (44.9) | 7 (5.9) | 9 (7.6) | 49 (41.5) |

Death and bereavement

Carers of two-thirds of decedents believed that their relative or friend was aware that they were about to die, though a substantial proportion of decedents (40%) had not been told by a health professional or family member. Fewer than one-third had expressed a preference for place of death but, for almost all of these, the preferred place was home. Most respondents felt that the choice over place of death was sufficient, and around one-quarter said that it was important to have choices. In retrospect, 85 (72%) participants felt that the decedent died in the right place (Table 12).

| Questions | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Did the decedent know they were likely to die? | |

| Yes | 78 (66.1) |

| No | 20 (16.9) |

| Not sure | 3 (11) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 9 (7.6) |

| Who had told them they were likely to die? | |

| Hospital doctor | 19 (16.1) |

| GP | 2 (1.7) |

| Family member | 3 (2.5) |

| No one | 47 (39.8) |

| Don’t know | 7 (5.9) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 40 (33.9) |

| Did the decedent ever say where they would like to die? | |

| Yes | 34 (28.8) |

| No | 64 (54.2) |

| Not sure | 2 (1.7) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 18 (15.3) |

| Where did they say they would like to die? | |

| Home | 32 (27.1) |

| Hospice | 2 (1.7) |

| Hospital | 1 (< 1) |

| Care home | 1 (< 1) |

| Somewhere else | 1 (< 1) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 81 (68.6) |

| Did you have enough choice about where the decedent died? | |

| Yes | 25 (21.2) |

| No | 13 (11) |

| Don’t know | 10 (8.5) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 70 (59.3) |

| How important to the carer/decedent was it to have choices? | |

| Very important | 23 (19.5) |

| Fairly important | 10 (8.5) |

| Not important | 3 (2.5) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 82 (69.5) |

| On balance, did the decedent die in the right place? | |

| Yes | 85 (72) |

| No | 9 (7.6) |

| Not sure | 7 (5.9) |

| Don’t know | 6 (5.1) |

| No recorded response | 11 (9.3) |

Care homes

Ten decedents were living in a care home for most of the last 3 months of life, but 19 died in a care home. Seven people moved into a home within 1 month of their death. Care needs that could not be met at home were the most frequently cited reason for admission (Table 13).

| Questions | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| During the last 3 months, was the decedent admitted to a care home at all? | |

| Yes | 19 (16.1) |

| All other responses | 99 (83.9) |

| During the last 3 months, did the decedent live for most of the time in a care home? | |

| Yes | 10 (8.5) |

| All other responses | 108 (91.5) |

| Where was the decedent living when they were admitted to a care home? | |

| Own home | 8 (6.8) |

| With friends or relatives | 1 (< 1) |

| Other care home | 2 (1.7) |

| Hospice | 1 (< 1) |

| Other | 12 (10.2) |

| Not applicable or no response | 94 (79.7) |

| How long did they spend in a care home on the last admission? | |

| One week or less | 2 (1.6) |

| One to 4 weeks | 5 (4.2) |

| More than 4 weeks | 2 (1.6) |

| Not applicable or no response | 109 (92.4) |

| Why was the decedent admitted to a care home? | |

| Care needs | 11 (9.3) |

| Respite | 4 (3.4) |

| Rehabilitation | 2 (1.7) |

| Not applicable or no response | 101 (85.6) |

Care at home

Most decedents had spent time at home in the last 3 months of life. Relatively small proportions of carers recalled care from specialist nurses, but social carers were a commonly reported component of end-of-life care. Informal carers were the most frequently cited additional sources of care. Twenty-seven patients (23%) were known to have had their care needs assessed on at least one occasion. This led to observed changes in the care received for 15 patients. All of the health and social services involved in the care worked well together (definitely or to some extent) for 20 (17%) respondents. Six carers reported that the services did not work well together. Help to meet personal care needs was reported as sufficient for 42 decedents (45%).

In the last 3 months of life, 45 (38%) of carers reported that the decedent had experienced pain. Forty of these had treatment for the pain; 21 had their pain relieved some or all of the time. Thirty-three carers (32%) felt that all or most of the community staff knew enough about the decedent’s condition or treatment.

Care in hospital

Forty-five (38%) of the decedents experienced pain during their hospital stay, the majority of whom received treatment for the pain (Table 14). The question of whether or not the treatment relieved their pain was answered by a low proportion of respondents. More than half of carers felt that the hospital staff treated their relative with respect and dignity most or all of the time, and a similar proportion had sufficient opportunities to talk privately with their relative or friend while they were an inpatient.

| Questions | Responses, n (%) |

|---|---|

| During this hospital stay, did they experience any pain? | |

| Yes | 45 (38) |

| No | 36 (30.5) |

| Don’t know | 9 (7.6) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 28 (23.7) |

| Did they have any treatment of their pain? | |

| Yes | 40 (33.9) |

| No | 6 (5) |

| Don’t know | 3 (2.5) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 69 (58.5) |

| Did the treatment relieve their pain? | |

| Completely, all of the time | 12 (10.2) |

| Some of the time | 11 (9.3) |

| Partially | 2 (1.7) |

| Not at all | 2 (1.7) |

| Don’t know | 8 (6.8) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 83 (70.3) |

| Did you have confidence and trust in the staff who were caring for them? | |

| Yes, in all of them | 48 (40.7) |

| Yes, in some of them | 26 (22) |

| No, not in any of them | 10 (8.5) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0.8) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 33 (28) |

| Do you feel that the staff had time to listen and discuss things? | |

| Yes, definitely | 31 (26.3) |

| Yes, to some extent | 31 (26.3) |

| No | 16 (13.6) |

| Don’t know | 1 (0.8) |

| Not applicable or no recorded response | 39 (33.1) |

| Were you able to discuss with the any worries or fears that you may have had about his/her condition, treatment or tests? | |

| Yes, I discussed them as much as I wanted | 25 (21.2) |