Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1007/47. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David Roberts has declared a competing interest. Capsticks LLP acts on behalf of, and so has a financial relationship with, a number of organisations who participated in this research.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Birks et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

. . . there are no easy answers when it comes to making mistakes. That needs to be said outright lest someone, especially someone in training who is less experienced, think that admitting a mistake stops at quality control or sharing responsibility, and that there is then some way around the difficult task of actually taking responsibility for the mistake. Within the culture of medicine and even more broadly in modern society there seems to be a drive for finding the easy way out. In this case there is none, and it needs to be made very clear that this is a defining moment in the life of a physician with regard to integrity and professionalism

Reproduced from Medical Errors and Medical Culture. There is no Easy Way Around Taking Responsibility for Mistakes, Lyckholm L, Vol. 323, p. 570, 20011 with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.

Estimates suggest that approximately 1 in 10 patients admitted to hospital will experience some sort of unintended harm; approximately half of these cases are thought to be preventable. 2,3 In a recent review of prevalence studies, between 3% and 16% of hospitalised patients were found to have suffered harm from medical care. 4 This represents a significant proportion of patients, and the Department of Health in the UK has identified quality and safety of care as a major concern. 5 The recent publication of the Francis report has brought this into even sharper focus. 6 Internationally, other agencies are dedicated to co-ordinating improvement efforts [e.g. the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) and The Joint Commission (TJC) – formerly the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) – in the USA, and the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare (ACSQH)]. A central component of a just patient safety culture is thought to include the disclosure of serious medical incidents to patients who have been affected or their families, often termed open disclosure. 7 The concept of openly disclosing the details of medical incidents has been adopted by several organisations, including ones in Canada,8 New Zealand,9 the UK,10,11 the USA12 and Australia,13 which implemented a national open disclosure policy in 2003. However, it is estimated that as few as 30% of harmful errors may currently be disclosed to patients. 14

Historically, the disclosure of adverse events to patients was neglected. Prior to the 1970s there was a general acceptance of medical expertise; medical notes were rarely seen by patients or families and, if required, often had to be obtained through a legal process. Discussions recognising this as problematic appear to have emerged during the 1970s and early 1980s, when it was identified that patients suffering from ‘medical mishap’ were often unable to find out who was responsible for an error or whether or not anyone had been at fault. 15 The importance of transparency in relation to improving quality and safety in health care became increasingly discussed in the wake of seminal documents such as To Err is Human 16 in the USA and An Organisation With a Memory 17 in the UK. Standards that promote open communication with patients following events where errors have occurred are rapidly emerging in both the UK and a wider international setting. 4,17–19 Advocates of open disclosure propose that failing to communicate effectively with patients following errors could reduce patient trust in health services, perhaps with negative consequences for future care, and may increase the likelihood of litigation. Patient trust may be diminished if they consider that their health service provider has not honoured their commitment to care for patients by apologising. There is some evidence, mainly emerging from the USA, to support such concerns. 20,21

In the UK, the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) relaunched its Being Open framework in November 2009. 11 The framework describes Being Open as being about the way in which health-care organisations and their staff communicate with patients and/or their carers following a patient safety incident, and sets out 10 key principles that underpin the successful facilitation of this process. These include providing a genuine and timely apology for what has happened, keeping patients and/or their carers informed about the progress made with the incident investigation, reassuring patients and/or carers that the incident is being taken seriously and ensuring that measures are taken to prevent the incident from happening again.

An apology is described as different from an admission of liability, and though an apology may be referred to in legal proceedings, the NHS Litigation Authority (NHSLA) stresses that this should in no way deter those involved from providing explanations and apologies following adverse events. 22 Being Open suggests that good communication and trust are fundamental to the relationship between health-care professionals and patients, but also that it is the ethical course of action. The Being Open framework was part of a broader NPSA initiative in the UK to create an open and fair culture in the NHS. The NPSA stressed that open disclosure should be explicitly linked to systems of incident reporting and analysis in health-care organisations. 23 Reorganisation within the NHS meant that on 1 June 2012 the key functions and expertise for patient safety developed by the NPSA transferred to the NHS Commissioning Board. It was anticipated that this would ensure that patient safety remains at the heart of the NHS and builds on the learning and expertise developed by the NPSA in driving patient safety improvement. The Board will continue to use the National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) to identify important patient safety issues at their root cause. Health-care organisations are expected to report patient safety incidents to the NRLS as previously. The approach to monitoring safety within UK NHS trusts is therefore unchanged, and the stance that disclosure should be part of safer patient care remains.

Despite limited empirical work assessing the effectiveness of implementing open disclosure policies (largely undertaken in the USA, Australia and New Zealand), a review of the available literature in 2008 revealed increasing recognition of open disclosure as an important issue for both organisations and patients. 24 The review also highlighted key debates around the ethical principles of ‘being open’ versus the legal liability and economic risk involved. The absence of investigation into non-hypothetical scenarios and individuals’ actual experiences of open disclosure was also noted. With growing acknowledgement of the challenges associated with open disclosure, the literature in this field has rapidly expanded, and there is now a need to update the synthesis undertaken in 2008 to identify a point from which to move forward, particularly in relation to the UK. Further work undertaken by Iedema et al. includes the assessment of open disclosure in terms of the impact on patients and health-care staff in Australia. 25–27 Qualitative analysis of interviews with 131 clinical staff and 23 patients/family members indicated that, despite some uncertainty surrounding the use and consequences of open disclosure, the system was strongly supported. 24 Further work has examined 119 patients’ and family members’ responses to questions about whether or not, and how, they experienced disclosure. 27

Complementary work by Gallagher et al. has conducted an investigation into patients’ and doctors’ attitudes towards the disclosure of medical errors, which highlighted the need for doctors to meet patients’ expectations of an apology following medical errors and also to provide information about the error. 28 Further work by Gallagher et al. ,29 in line with findings from other studies,30,31 has discussed the increasing need and desire for open disclosure of medical errors.

Although the ethical arguments for the open disclosure of adverse events to patients are strong, there are many stakeholders (e.g. patients and clinicians, hospital managers, health policy-makers, unions, equipment companies, insurers, legal advisers and indemnifying organisations) involved in the delivery of such a framework at a variety of levels. (Future reference to stakeholders will include the aforementioned groups, although this is not intended as an exhaustive list.) The complexities of the differing perspectives of all of these stakeholders means that implementation of any initiative is challenging. Embedding incident disclosure into national and local culture within the NHS is a substantial challenge for NHS managers, as well as for the individuals involved in direct patient care. It has been suggested that this is due to a culture that favours risk aversion over patient-centred disclosure, despite the suggestion that the latter produces better financial and relational outcomes. 32 Current barriers to disclosure, such as fear of litigation or damaged reputation, can obstruct clinicians in maintaining good relationships with patients and becoming more open to learning from error or mistakes. If such barriers are not recognised, challenged and addressed appropriately and overtly, they may cause significant problems for the implementation of a more open safety culture.

There appears to be a small but significant literature within the area of patient safety which looks at the open disclosure of adverse events, including the important area of the impact of open disclosure on the health professionals involved in the error and the link between disclosure and systems improvement. 33 However, this research is almost exclusively grounded in contexts outside of the UK, and much of the empirical work is based on training scenarios rather than in situ practice. We know little about how the policy of open disclosure is being, or might be, implemented and applied locally or nationally in the UK and how it is, or will be, aligned with current incident reporting and analysis systems in health-care organisations. As is the case with many patient safety outcomes, there is also a lack of knowledge around how open disclosure might best be evaluated and improved. In addition to examining the current breadth and quality of the literature in the area of open disclosure to date, this research will provide information about the implementation and current stakeholder perceptions of open disclosure within the UK.

Aim

The overall aim of this project was to critically evaluate and extend both the evidence base and practice in relation to the implementation of a policy of open disclosure of adverse events to patients within the UK.

Objectives

-

To extend a previous literature review of open disclosure conducted by one of the applicants in 2008.

-

To identify the strategies which have been considered or used to encourage an open disclosure culture, and to assess the evidence of effectiveness of such strategies.

-

To identify and critique the various ways in which open disclosure has been conceptualised and measured.

-

To determine the understanding of, views on and interpretation of a policy of open disclosure of adverse events among a variety of UK stakeholders.

-

To identify specific situations and ways in which the various stakeholders have been involved in the disclosure of adverse events in the UK, and their experiences of this.

-

To explore how open disclosure can be linked effectively into safety and quality management systems at all levels.

-

To explore the extent to which disclosure activity is actually linked in practice to safety and quality management.

-

To develop a summary of evidence-based guidance for managers to facilitate the implementation of open disclosure in individual trusts.

The objectives were addressed in three main phases, each of which built on the previous work. The first phase comprised a focused literature review, summarising current knowledge on different stakeholder roles, current interventions and proposed interventions, underpinning theory and the ways in which current strategies feed into established reporting systems. The second phase involved individual interviews, with the objective of generating new knowledge about UK-based stakeholders’ views on their roles in and experiences of open disclosure of safety incidents in health-care settings. The third phase involved the development of a set of short pragmatic suggestions aimed at NHS trust executives and managers, to facilitate the implementation and evaluation of open disclosure in UK NHS trusts.

The main product of this research was intended to be new information which can be used to:

-

identify areas where current evidence and knowledge remain sparse

-

supplement the current guidance on implementing open disclosure

-

inform training and support for organisations and individuals in this area

-

identify continuing barriers to the implementation of open disclosure

-

identify well-developed models for open disclosure.

We also aimed to produce a series of short and pragmatic guidelines for NHS trust managers to facilitate the implementation and evaluation of open disclosure initiatives.

Chapter 2 Methods

This study addressed the objectives via three main phases of work. A review phase and a qualitative phase directly contributed to a synthesis of the information, to address specific issues in relation to delivery of the Being Open guidance in the UK in the final phase of the study.

Phase 1: reviews

The reviews were conducted to capture data from a diversity of sources, in a systematic way, to identify how open disclosure (an openness with patients about avoidable potentially harmful incidents) has been conceptualised, the key ethical and legal debates associated with the process, the roles of the different stakeholder groups and the outcomes that have been used to assess its impact.

A more focused review of the effectiveness of open disclosure interventions to date was carried out to sit within this broader conceptual synthesis.

Two previous reviews have been conducted, both of which involved one of the current project team (RI). The authors of these reviews planned to search five electronic databases using terms related to open disclosure, as well as the websites of health and government regulatory bodies in a number of countries. 34,35 Although both of these reviews are seminal pieces of work and comprehensive, the authors adopted a less standard systematic search strategy than the strategy presented in this work. In the previous work, searching was stopped after three databases had been searched as it was considered they had ‘reached saturation’ (the same articles began to appear), whereas all literature identified will be considered in this work. This makes the current work the most comprehensive exploration of previous literature to date.

Objectives

Review 1: scoping review

The aim of this review was to identify and critique the literature around open disclosure, including (i) the ways in which it has been conceptualised and discussed within current systems of quality and safety, (ii) the wider debates around legal and ethical issues in open disclosure, (iii) the outcomes used to explore its impact, (iv) the roles of stakeholder groups, (v) the relationship between open disclosure policy and systems of reporting and monitoring adverse events worldwide and (vi) the extent to which open disclosure policies appear to have been informed by research evidence.

Review 2: effectiveness review

This review was carried out to identify, assess and summarise the effectiveness of open disclosure and strategies/interventions that have been explicitly used with the intention of promoting and supporting open disclosure of patient safety incidents in a health-care context.

Definitions

Patient safety incident

The term patient safety incident refers to any unintended or unexpected incident which could have, or did, lead to harm for one or more patients. 23

Open disclosure

There is no agreed international definition of open disclosure, but its underlying principle involves clinicians informing patients and/or family members when a safety incident has occurred. Many policies describe the use of an honest and consistent approach to communication which should happen as soon as possible following the incident (e.g. Canadian Patient Safety Institute,8 New Zealand Health and Disability Commissioner,9 NPSA,10,11 Joint Commission Resources Inc.,12 ACSQH13). Elements of such policies, including that of the UK, commonly include saying sorry for what has happened; keeping patients and/or their carers informed about the progress of the incident investigation; reassuring patients and/or carers that the incident is being taken seriously; and ensuring measures are taken to prevent the incident from happening again. 11

Search strategy

The aim of the search was to systematically identify literature on the open disclosure of adverse events in health care to inform both systematic reviews. A broad search strategy was initially developed on MEDLINE (Ovid SP) using the two main concepts of open disclosure and adverse events. A range of text words, synonyms and subject headings for each of the two concepts were identified by scanning key papers identified at the beginning of the project, and through discussion with the review team and collaborators, and the use of database thesauri. The terms for open disclosure were combined with those for adverse events using the AND Boolean operator (see Appendix 2 for the full search strategy). The MEDLINE strategy was adapted for use in each database. These searches are considerably more detailed than those adopted in the previous literature reviews. 34,35

Retrieval of studies was restricted to those published after 1980 as little literature appears before this date. The early reports which reinvigorated the drive for higher-quality and safer patient care began to appear from the early 1990s, and a period of 10 years prior to this was felt reasonable to capture the vast majority of the literature. No language restrictions were applied to the search strategy, to ensure that non-English-language papers were retrieved. Study design filters were not applied to the search strategy, so that any literature – including papers about the effectiveness of specific open disclosure interventions, reviews, opinion pieces, policy documents and discussion articles – was identified by the search.

A wide range of electronic resources were searched, including databases, research registers, trials registers and other internet resources, to retrieve both published and unpublished literature, grey literature and ongoing research. The resources searched covered literature from the medical, health, nursing, social science and legal fields. The full list of searched databases can be seen in Appendix 3 .

The above searches were supplemented by searching key patient safety organisation websites and government agency websites to identify reports, policy documents and grey literature not indexed in the electronic databases. Further references were identified by scanning the reference lists of key papers and reports identified during the searching process, from the personal collections of the review team and consultations with key personnel from patient safety organisations, and by hand-searching the reference lists of key seminal papers.

Records were managed within an EndNote library (EndNote version X3; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). After deduplication, 10,527 records in total were identified.

The literature search was designed and carried out by an information specialist from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, with input from the review team. Peer review of the search strategy was undertaken by a second information specialist at the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Searching of the legal databases was carried out by an information specialist from Capsticks (a specialist health and social care law firm), using a search strategy adapted from the initial MEDLINE strategy.

Inclusion criteria

Review 1: scoping review

Types of literature included

-

Available in English.

-

Produced after 1980 following the rise of patient safety/medical error research.

This could be any of the following:

-

policy documents

-

opinion pieces

-

research that has investigated

-

– perceptions or experiences of open disclosure

-

– ethical or legal issues in open disclosure

-

– the process or outcomes of open disclosure

-

– the role of any stakeholder in open disclosure

-

-

accounts of stakeholders’ experiences of open disclosure, including those of patients, patient support groups, health professionals, health-care managers and litigation services

-

literature developed to guide patients, health-care providers or litigation services about open disclosure

-

grey literature reporting activities/initiatives/research that focuses on open disclosure.

Types of participants included

Participants could be stakeholders in open disclosure from any health-care context in any location, including:

-

health service users who may have been affected by safety incidents (patients, relatives, carers)

-

potential health service users

-

representatives or members of support groups for health service users

-

health-care professionals

-

health-care managers

-

representatives or members of medical litigation services

-

professional/regulatory bodies such as the General Medical Council (GMC) or Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC).

Nature of content

The content of the literature could be any of the following:

-

conceptualisation of open disclosure

-

discussion of the principles or implementation of open disclosure

-

discussion of the ethics of open disclosure

-

discussion of legal issues relating to open disclosure

-

reporting or describing criteria for assessing quality and/or consequences of open disclosure

-

reporting the implications of open disclosure for health services

-

discussion of the roles of any of the stakeholders in the open disclosure process

-

discussion or development of open disclosure policies or experiences of its use

-

professional expectations from bodies/regulatory bodies.

Exclusion criteria

Documents were excluded if they:

-

did not include stakeholders in open disclosure from a health-care context, i.e. none of the types of participants described above

-

described/discussed/reported disclosure relating to deliberate acts of harm

-

were not available in English

-

were produced before 1980.

Additional criteria for the effectiveness review

Population

These could be stakeholders in open disclosure from any health-care context in any location, including health service users, potential health service users, representatives or members of support groups for health service users, health-care professionals, health-care managers and representatives or members of medical litigation services.

Intervention

We included open disclosure as an intervention. Interventions that were explicitly intended to promote, enhance or support open disclosure were also included.

The following comparisons were included:

-

Open disclosure versus against non-disclosure. Any intervention which involved an act of informing a patient and/or family member or representative that a patient safety incident had occurred. Characteristics of open disclosure interventions were likely to differ, however seemed likely to include elements commonly identified in open disclosure policy (see definition above).

-

Interventions to promote or support open disclosure in combination with open disclosure versus against open disclosure alone.

Any intervention that was explicitly intended to promote, enhance or support open disclosure of patient safety incidents in a health-care context was included. It was anticipated that candidate interventions would be, for example, training or education in communication techniques and peer support groups.

Studies of interventions using actual events (real cases) or hypothetical scenarios were included. Studies where the intervention aimed to promote or improve communication of illness (‘bad or sad news’), such as diagnosis of cancer or terminal illness, were excluded. Studies of interventions relating to deliberate acts of harm were also excluded.

Outcomes

Outcomes included (but were not restricted to):

-

patients’ and/or health professionals’ attitudes relating to the intervention

-

rates and patterns of uptake of the intervention (among patients and/or health professionals) and of any behaviours/practices it was designed to promote

-

other behaviours relating to health service delivery or use

-

patients’ assessments/evaluations of health-care quality, including their perceptions of involvement, of the quality of their interactions with health-care professionals, and of their safety

-

patients’ health status and sense of well-being

-

psychological effects on staff.

Study design

The following study designs were included:

-

Randomised controlled trials (including cross-over trials and cluster trials). Investigators allocated participants to groups using randomisation.

-

Quasi-experimental studies (non-randomised controlled studies, before-and-after studies and interrupted time series). Investigators allocated participants to groups using a non-random method.

It was not anticipated that many studies of these designs would be available. Therefore, observational data were included if there was a comparison group, as in the following studies:

-

Cohort studies A defined group of participants is followed over time and a comparison is made between those who did and those who did not receive the intervention.

-

Case–control studies Groups from the same population, with (cases) and without (controls) a specific outcome of interest, are compared to evaluate the association between exposure to an intervention and the outcome.

Case series and case reports were excluded.

Study selection

Four reviewers screened citations of the title and abstract for potential relevance, with all citations being viewed by two reviewers. Full papers were obtained for citations judged potentially relevant. On receipt of the full paper, one reviewer applied the inclusion criteria for all papers to identify material of relevance. A second reviewer screened a random subset (10%) of the sample to ensure that no potentially relevant papers were missed and that the inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied consistently. Where decisions were unresolved, the two reviewers discussed the decision, and a third party was consulted if agreement could not be reached.

Information extraction

Review 1

Given the complexity and variety of literature explored, we specified that data extraction would be based on the study objectives to ensure that the review had a clear and consistent focus and was carried out in a systematic way.

Given the ultimate aim of developing current guidance on open disclosure in the NHS, we extracted data from the reviewed papers that related to any of the 10 principles of open disclosure described in the Being Open framework. These were:

-

acknowledgement

-

apology

-

truthfulness, timeliness and clarity

-

professional support

-

recognise patient and caregiver expectations

-

risk management and systems improvement

-

individual/multidisciplinary team responsibility

-

clinical governance

-

continuity of care

-

confidentiality.

It was anticipated that this would provide an idea of those aspects of the framework for which there was currently supporting literature and those that had been implemented in health care, and the extent to which implementation had been perceived as successful. It would also highlight the areas of the framework for which there was less evidence or support, that were less clearly defined or enacted or that had been less successfully implemented to date. Both intended and unintended outcomes were documented during this process.

On this basis we extracted:

-

author/investigator

-

date

-

location

-

type of literature

-

population

-

study design (if applicable)

-

outcomes/arguments/guidance, which were summarised in relation to

-

– acknowledgement

-

– truthfulness, timeliness and clarity of communication

-

– apology

-

– recognising patient and carer expectations

-

– professional support

-

– risk management and systems improvement

-

– multidisciplinary responsibility

-

– clinical governance

-

– confidentiality

-

– continuity of care.

-

There were two stages of information extraction: in the first stage, a basic extraction that provided an outline of the paper, and in the second, a more detailed extraction in which particular aspects of the work were drawn out, depending on the type of material and its salience to the review objectives and domains outlined in the Being Open guidance.

Review 2

The following data were extracted from included studies (where available):

-

general information (author, article title, type of publication, country of origin, source of funding)

-

study characteristics (aims and objectives, study design, inclusion/exclusion criteria, recruitment procedures, unit of allocation)

-

participant characteristics (of both health-care workers/managers and patients, including age, gender, ethnicity, profession/position of health-care worker, disease or condition/adverse event details of patient)

-

intervention and setting (setting where the intervention was delivered, description of the intervention and comparator)

-

outcome data (for intervention and comparator groups the following were reported: number enrolled, number included in analysis, number lost to follow-up, withdrawals and exclusions. For each reported outcome the following were extracted: definition of outcome, measurement tool used, length of follow-up, results of study analysis).

Data collection and analysis

In the larger primary review (review 1), each included paper was summarised to provide an overview of research, discussion and policy or guidance documents relating to open disclosure of error.

In the smaller systematic review of interventions (review 2), no formal pooling of data was appropriate owing to a lack of studies with a comparator group and uncontrolled before-and-after designs. Findings were grouped into two sections:

-

studies where disclosure was the intervention

-

studies where interventions were intended to promote or support disclosure.

In each of these sections the included studies were described in terms of their setting, participants, methods, intervention, outcomes, outcome measures and reported findings, and linked to tabulated descriptions of studies.

Phase 2: interviews

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this phase of the project was obtained from the Bradford NHS Research Ethics Committee (ref. 10/1007/47). Research governance approval was obtained from the relevant NHS trusts (see Appendix 4 ).

In-depth individual interviews were used to describe, explore and explain stakeholders’ views and experiences of open disclosure in health care. The rationale for selecting a qualitative approach was threefold. Firstly, little research has been conducted in the UK in this area to date; qualitative methods are ideally suited to reveal the range of views or practices and key issues that might be missed through the use of more structured data collection instruments. Secondly, in-depth interviews are the most effective and valid way of exploring people’s experiences, beliefs and meanings, from the perspective of the respondent, in order to provide a ‘rich’ data set which is grounded in the experiences of the interviewees themselves. Thirdly, one of the strengths of qualitative research is that it can identify the complex ways in which particular beliefs or experiences are likely to influence behaviour.

Perspectives were likely to vary according to stakeholder, health-care setting and participant demographics; therefore, we employed sampling strategies and data collection techniques that allowed for an inductive, hypothesis-generating approach to interpretation of the data.

Populations studied

In order to explore the views of a range of stakeholders who might contribute to open disclosure, with diverse clinical backgrounds and differing degrees of patient contact in a variety of health-care contexts, study participants were strategically selected from four different groups:

-

Policy-makers Individuals with a current or previous position of responsibility for developing health policy, and in particular the Being Open guidance.

-

Professional organisations Individuals from professional organisations that represent or regulate the health professions.

-

NHS managers and health professionals Health-care managers included members of the senior management team, some of whom had dual clinical and management roles. Health professionals were staff who carried out work on the ‘shop floor’, from matron and consultant level to junior doctors and nurses (from band 5 up).

-

Patients and patient organisations Participants were approached through national patient groups. Participants could include patient advocates and those with experiences of disclosure or a lack of disclosure.

Details of the original sampling framework and the planned participant numbers in each group are shown in Appendix 1 .

Recruitment and consent

Recruitment procedures were tailored according to the stakeholder groups. Policy-makers, leaders of professional and patient organisations and senior managers were contacted in the first instance by a targeted letter from the research team. All other participants were contacted, in the first instance, by an appropriate member of the identified organisation. In all cases, potential participants were sent information about the study and asked to return a short slip (or contact the research team by e-mail or telephone if preferred) to discuss participation.

A member of the research team then contacted respondents to explain the nature and purpose of the study. In the case of patient participants, we emphasised that the research would not directly help them to seek a remedy or redress for any problems they may have experienced related to the disclosure of adverse events. Where people expressed willingness to participate, the researcher made arrangements to hold an individual interview at a time and place convenient for the respondent. A small number of interviews were conducted over the telephone if specifically requested by the participant.

Prior to the commencement of interviews, the researcher reminded participants of the purpose of the research; asked respondents if they had any further questions; checked that they were still happy to take part; and reminded them that they could stop the interview or withdraw from the study at any time.

Data collection

The aim of the interviews was to explore:

-

stakeholders’ general awareness and understanding of open disclosure

-

their personal experiences and perceptions of both the principle of openness in relation to disclosure of adverse incidents and the Being Open guidance, in the context of their own position in relation to health care

-

their views on the contribution that they might make to promote and enhance open disclosure

-

their thoughts about the Being Open guidance.

Although all interviews shared these aims, the emphasis in the interviews varied by stakeholder group. Interviews with policy-makers focused on the development of the Being Open guidance and perceptions of its current use. With professional organisations, the translation of national and local guidance into practice was emphasised, along with the perceived contribution that such organisations can make to support health professionals in delivering open disclosure. Interviews with NHS managers and staff explored experiences of open disclosure and of implementing the Being Open guidance specifically. We also explored the challenges of discussing adverse events with patients. Representatives from patient organisations were asked about their perceptions of open disclosure in the policy context and from a broader patient perspective, and patients were asked to share their individual experiences and beliefs.

A core topic guide (see Appendix 5 ) covering these investigative areas was developed and piloted. This was refined before interviews commenced with the target populations. Interviews opened with questions exploring respondents’ broad understanding of the term ‘open disclosure’, the reasons for implementing open disclosure, experiences or beliefs about the Being Open guidance and, finally, where the challenges lie. Modified versions of the topic guide were developed for use with each stakeholder group. After initial interviews, some minor alterations were made to the wording of the guide to be used with NHS managers, to make it more sensitive to exploring the experiences of this group.

Data analysis

Interviews were audiotaped and fully transcribed. Transcripts were analysed using framework analysis. 36 This approach was selected for several reasons. Firstly, it is especially well suited to applied qualitative research, in which the objectives of the investigation are typically set a priori, and shaped by the information requirements of the funding body, rather than wholly emerging from a reflexive research process. Secondly, framework analysis provides a visible method which can be scrutinised, carried out, and discussed and operated by individuals in a team. Lastly, the approach lends itself to reconsidering and reworking ideas because the analysis follows a well-defined procedure, which can be documented and accessed by several members of a research team.

Framework analysis comprised the following steps:

-

Familiarisation with the data, sometimes referred to as ‘immersion’.

-

Thematic analysis, carried out in order to develop a coding scheme.

-

Systematic coding of the data.

-

Charting of data using a Microsoft Excel 2010 spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Charts contained summaries of data (supported by references to data points in the original transcripts), so the research team was able to build a matrix to see across cases and the range of data under themes.

-

Mapping and interpretation of the data in order to explore relationships between the codes.

Each of the three researchers (YB, RH, KB) most involved in fieldwork took a sample of interviews, and initial data were open coded. The coding framework emerged from a focus on the questions posed by the research document, but at initial stages was also open to emergent codes. The coding framework was further developed through discussions with members of the wider research team with extensive qualitative (VE) and clinical (IW) experience, to discuss emerging codes and categories, the interpretation of key texts and potential new lines of enquiry. The coding framework is included in Appendix 6 .

Data sampling

Sampling decisions always fluctuate between the aims of covering as wide a field as possible and conducting analyses which are as deep as possible. 37 A strategic decision was made to aim for depth in analysing the qualitative interview data, as we sought to present findings which were ‘rich’ in relevant information. All interviews were coded, and 33 interview transcripts were selected for in-depth analysis, to represent diversity in the total data set of 86 interviews. The interviews were selected strategically from the complete data set using maximum variation sampling;38 that is to say, they included ‘typical’ cases (reflecting the views of the majority of respondents), ‘deviant’ cases (extreme cases of the phenomena under investigation) and ‘critical’ cases (those that appeared to be especially information rich and thus particularly illuminating). These 33 interviews related to 33 participants (four policy-makers, four professional organisations, 10 health-care managers, 12 health professionals and three patients/family members who had experienced error). Although these transcripts formed the basis of the analysis, data from across the whole sample contributed to the analysis. The selected transcripts included interviews with males and females, who had wide-ranging views and experiences of open disclosure (see Appendix 7 for a detailed participant breakdown).

Rigour and transparency in the analytic process

Analytic rigour and accurate interpretation of data were promoted and enhanced in a number of ways. The three team members most closely involved in fieldwork (YB, RH, KB) met frequently to discuss data collection and analysis. At regular intervals, meetings were held with members of the wider research team with extensive qualitative (VE) and clinical (IW) experience, to discuss emerging codes and categories, the interpretation of key texts and potential new lines of enquiry. In this way, the combined insights of those ‘handling’ the data closely and members of the team with a wider perspective of methodological and open disclosure issues could be incorporated into the coding framework to be used for all data analysis (see Appendix 6 ). In addition, a small subsample of transcripts coded using this agreed framework (n = 5) were examined by a member of the wider research team (VE) as an independent check on the assignment of codes to data.

The framework approach to data analysis allowed data to be compared within cases, facilitating the exploration of contextual meaning; comparing cases across the data set facilitated the search for regularities (key themes) and exceptions (negative cases). The use of memos during initial stages of analysis provided a visible ‘audit trail’ as the analysis moved from ‘raw’ data, through interpretation to the production of findings. A reflexive approach has been taken throughout the entire research process, from the initial development of the research questions, through data collection and analysis (for a full statement on reflexivity see Appendix 8 ).

Chapter 3 Results

Phase 1: review 1

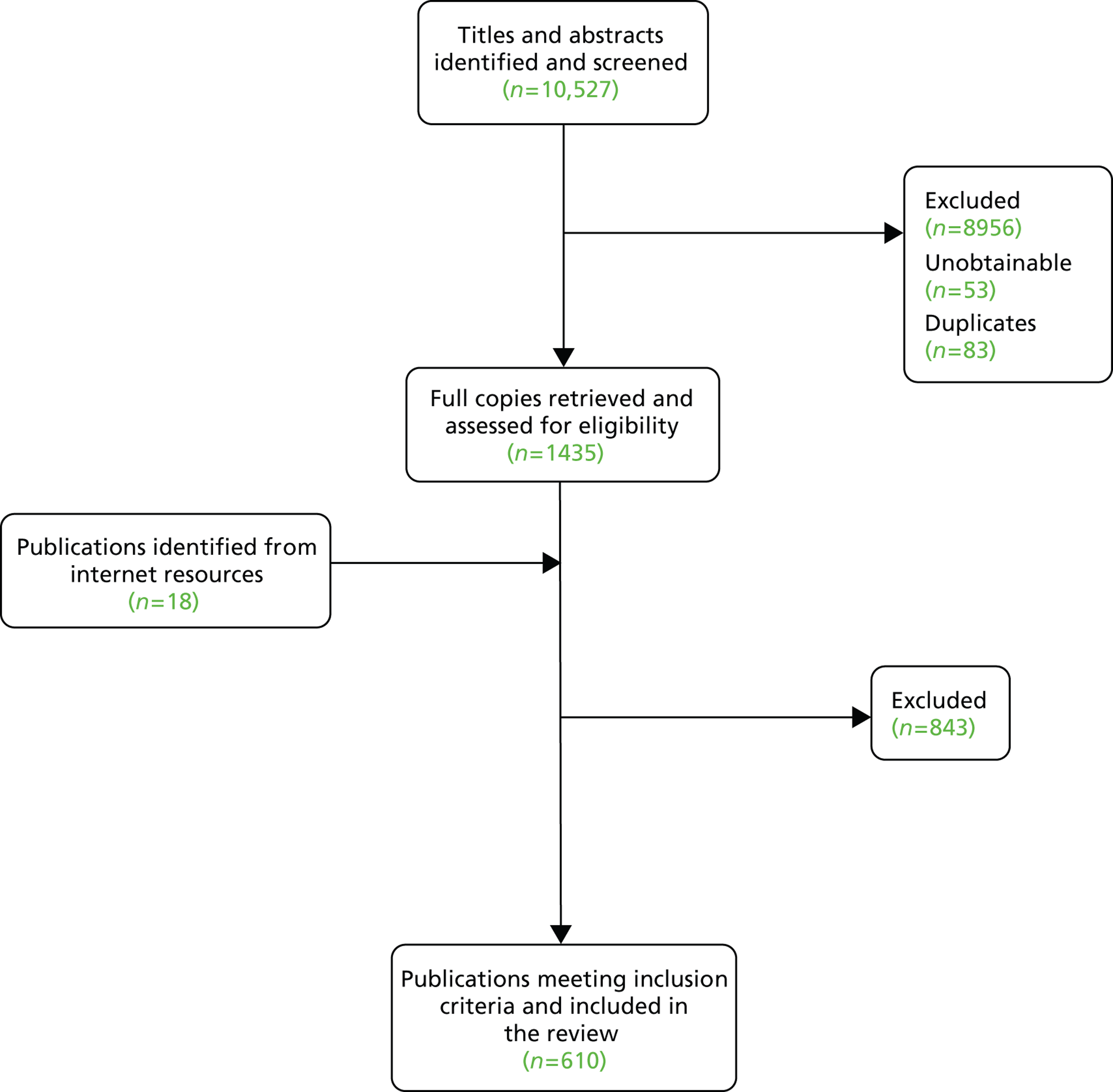

The searches identified over 10,000 pieces of literature. Of these, 1435 full copies were retrieved and 610 pieces of literature were included in the final review. Full details of the literature selection process are illustrated in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

Selection of literature.

A broad description of the literature

Literature published over a 22-year period was examined, with the majority of papers published from 2001 onwards. A broad description of the literature is presented below. We were interested in capturing the volume and type of literature and the pattern of publications over time, which has been little discussed in previous reviews.

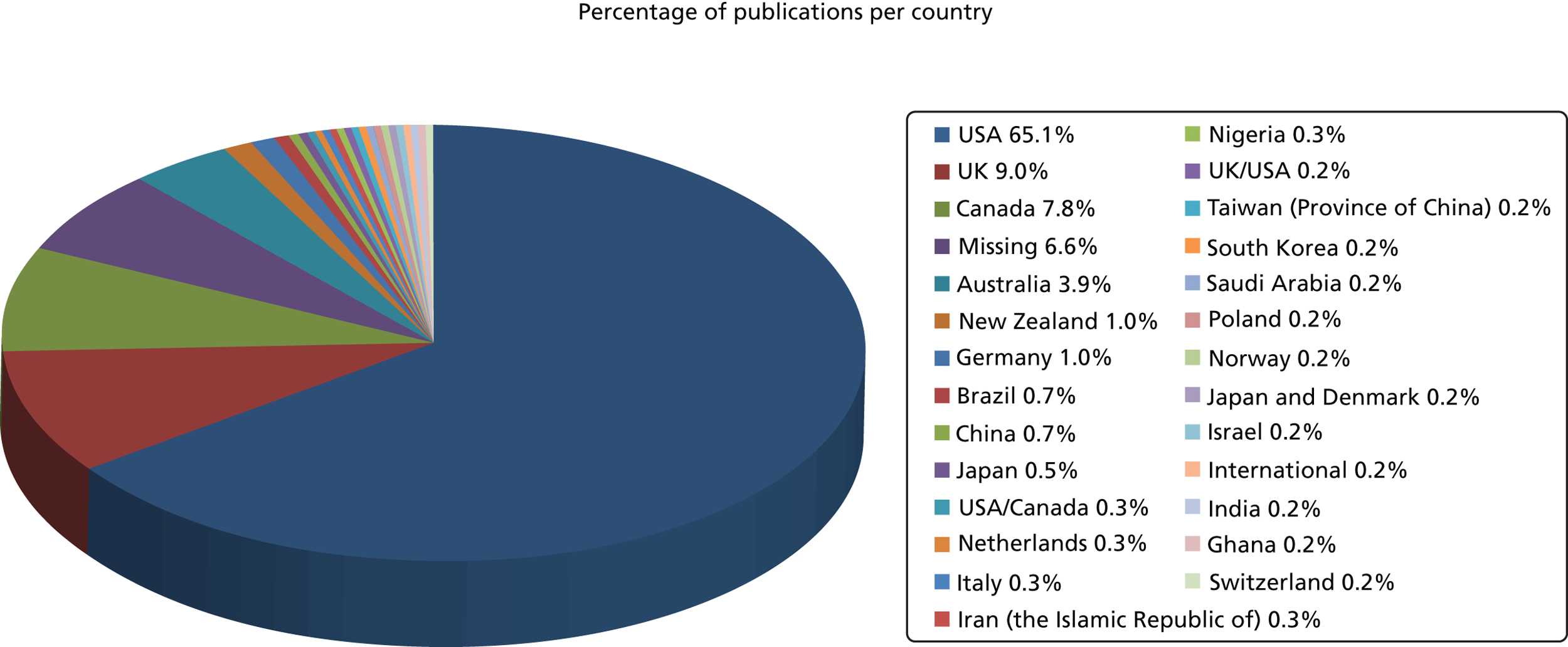

The majority of literature discussing open disclosure is from the USA (65.1%). A further 20% is from Canada, the UK and Australia. The remainder consists primarily of single publications from a range of countries, and in just under 7% of papers the country of origin was not clear. Further details are shown in Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2.

Countries of origin of the literature.

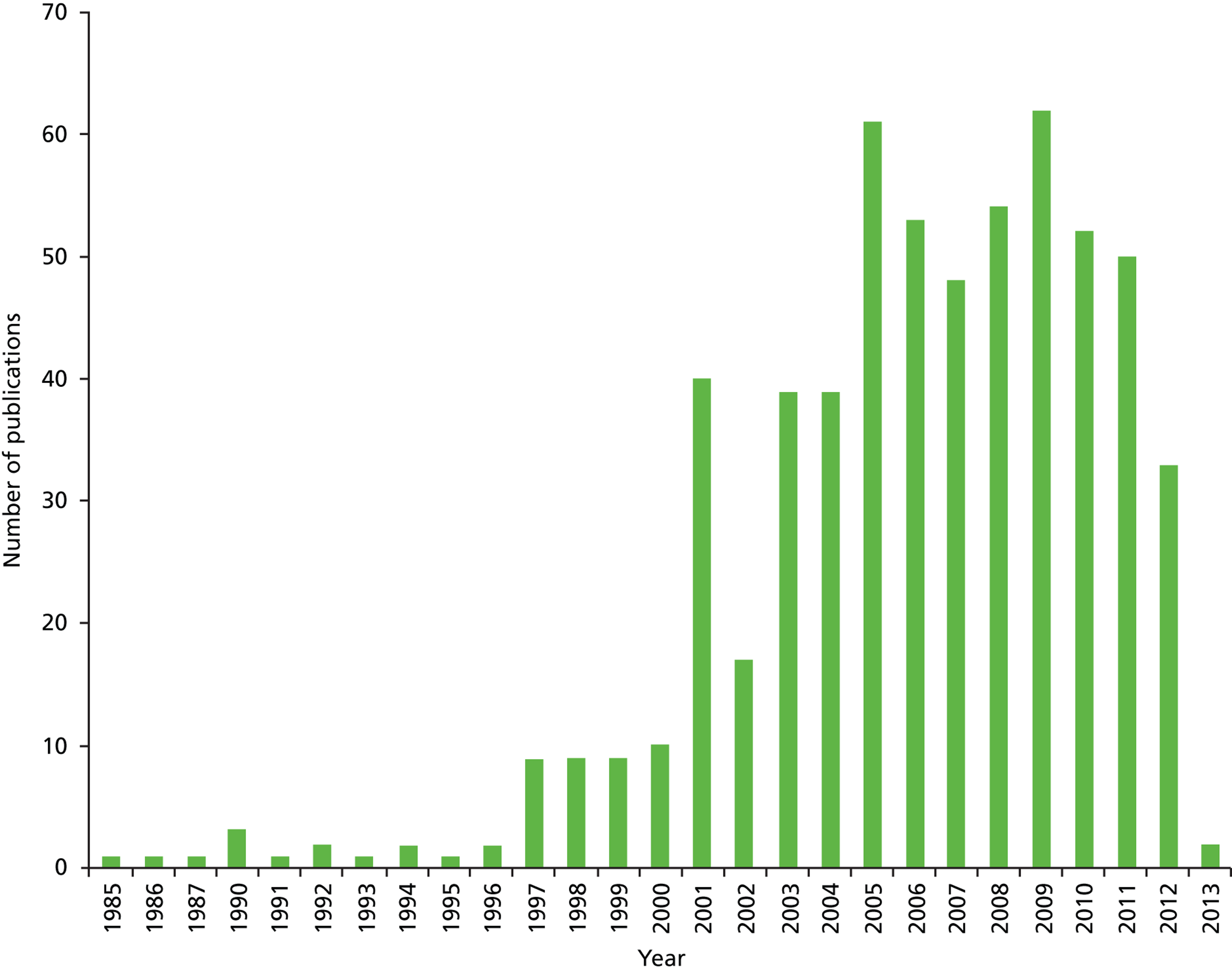

The literature search was restricted to 1980 onwards as previous work had demonstrated a surge in safety literature in the 1990s,39 and this was felt to be an appropriately sensitive time frame in which to capture the main body of literature. Figure 3 demonstrates that until 2000 there were few publications per year relating to open disclosure. From 2001, the number of publications suddenly increased to an approximate average of 50 publications per year. The rise in publications is likely to reflect the increased awareness of patient safety issues and the publication of articles now regarded as seminal pieces in the safety literature, such as To Err is Human in 1999;16 this article drew attention to the consequences and cost of medical error in the US health system and other health systems worldwide.

FIGURE 3.

Number of publications per year.

The majority (just over two-thirds) of the literature comprised opinion or ‘think’ pieces, journalistic-type articles and a variety of articles containing reports of other (previously published) publications and guidelines. Thirty-five per cent consisted of either primary research or papers which were judged to be of seminal importance to the topic, largely based on authorship by well-published or well-cited figures in the open disclosure field. There were small pockets of literature emerging from Europe, Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, as well as the better-known literature from North America and Australia, where discussion of the area of disclosure of adverse events is well established. Largely, this consists of descriptive literature outlining what clinicians feel about disclosing error and harm and what they report that they do in relation to disclosure, as well as descriptions of patient preferences and experiences in the context of open disclosure. There is little primary research and referencing back to early publications is common, with key messages largely unchanged. Clinicians, in principle, and for the most part, agree that patients should be informed of errors in their care that cause harm but are challenged by mixed messages from their institutions about what they perceive to be their legal status in this context. This is further exacerbated by concerns about their skills in disclosing error, due to a lack of specific training or exposure to this kind of communication. Additionally, the literature includes inconsistent terminology and ideas about which events should be disclosed, which adds further confusion.

Patients unequivocally report that they want disclosure of all unanticipated events and errors that occur during care. In some literature, the barriers to disclosure are explored more deeply and there are some in-depth critiques of what ‘telling the truth’ means. Although a good understanding of the concepts that underpin openness is valuable, such theoretical accounts may have limited application in changing the current culture in health care or persuading the NHS to fully implement the policy of open disclosure rigorously and consistently. However, these accounts have been included alongside more practical accounts and primary research to fully illustrate the types of literature available to inform each principle.

Main findings

Given the challenges which open disclosure appears to present for some individuals and health-care organisations, it is surprising how little attention the topic has received in the UK. There is good reason to think that open disclosure may be different in different contexts. 40 In the limited evidence available, UK doctors were more likely than US doctors to agree that significant medical errors should always be disclosed to patients, and more US doctors reported that they had not disclosed an error to a patient because they were afraid of litigation. 40 The context of care may influence both how professional values are expressed and the extent to which behaviours are in line with stated values. Lessons may be learned from the largely US and other literature about the implementation of a policy of open disclosure, but the clinical negligence contexts in each country may have implications for how open disclosure is perceived locally. A large and growing body of literature exists in relation to open disclosure. Much of this is in practice journals and summarises a small number of frequently cited pieces of original research in the area. Thus, although there appears to be a great deal of activity in this field, there is limited underpinning primary research to substantiate conclusions; received truth is perpetuated from past references often based on small before-and-after studies or single cases.

Following detailed data extraction and appraisal of the literature, the results were synthesised under the specific principles of Being Open. Although there are vigorous and ongoing debates within the literature related to open disclosure, the nature of the UK health-care context, and in particular the NHS, means that some of these debates have less relevance than in other countries. This is reflected in the attention afforded to some of the areas presented in this review and we did not seek to capture the very valid but less applicable areas within State and Federal statute in other international contexts. The large volume of literature on this topic has been surprising, but the aim of this project was to examine open disclosure specifically in a UK context. The legal frameworks and statutory requirements differ in various contexts and therefore some of the literature is less applicable to the UK. The review will address the international literature but focus on its applicability to a UK context, concentrating on lessons which can be learned to specifically address the implementation of open disclosure policy and duty of candour in relation to unanticipated outcomes in the UK.

A complete list of included literature sources is included in Appendix 9 .

Acknowledgement

The Being Open guidance10 states that all patient safety incidents should be acknowledged and reported as soon as they are identified. In cases where the patient, or his or her family and carers, inform health-care staff that something untoward has happened, this must be taken seriously from the outset. Any concerns should be treated with compassion and understanding by all health-care professionals. However, the literature suggests that defining the events that warrant disclosure presents a fundamental challenge for organisations, managers and clinicians. Although a number of definitions of what constitutes an error or an adverse event exist, there is much less clarity about what should be disclosed. Often the need to disclose has been associated with whether or not an event is classed as an error or constitutes harm. This is further complicated by an abundance of diverse error definitions in the literature. The terminology used to describe and categorise errors is also complex and includes an array of synonyms such as ‘bad outcome’, ‘sentinel event’, ‘adverse event’, ‘mishap’, ‘mistake’, and ‘untoward incident’. All are used as synonyms or (partial) explanations of the word ‘error’. 41 Additionally, errors can occur through acts of commission or omission; that is, not only as a result of what is done, but also as a result of what is not done. 41 The guidance suggests that ‘error’ refers to ‘any unintended or unexpected incident that could have or did lead to harm for one or more patients receiving NHS-funded healthcare’. 10 ‘Error’ seems to be problematic in its definition, and although harm, certainly in a biomedical context, may be easier to define, it does not address issues of culpability. Although this appears to be a well-defined principle, the discussions in the literature reflect continued ambiguity about the events that individuals feel are covered by any principle of openness.

Definitions of error or harm

Patients and clinicians appear to define error differently. 42 From the patient perspective, the distinctions between the terms ‘error’, ‘adverse event’ and ‘unexpected outcome’ seem relatively unimportant. Such definitions are largely constructed from the systems perspective and may be at odds with the way in which patients interpret harm. In the patient experience, harm is perceived, and regardless of how members of the health-care community and legal profession wish to classify this harm, patients who perceive that they have suffered as a result of their treatment feel that they deserve a timely, supportive and informative conversation about their concerns. In 2003, the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario recognised this with the publication of its policy on disclosure of harm. 43 This describes a definition of harm as a concept which is not always preventable nor necessarily an indicator of substandard care. According to this definition, harm refers to any unintended outcome arising during the course of treatment, which may be reasonably expected to negatively affect a patient’s health and/or quality of life. Such outcomes may occur as a result of individual or systemic acts or omissions, and include adverse events related to the care and/or services provided to the patient rather than to the patient’s underlying medical condition. This is a considerably broader definition than many and has the potential to address the broader nature of patient concerns which are often raised but not addressed.

What should be disclosed?

The definitions of which events should be disclosed have subtle differences but there are common recommended elements of disclosure including ‘an expression of sympathy or regret’,10 as well as the provision of practical and emotional support for the patient. Most guidance is keen to stress that disclosure discussions should ensure that no speculation, opinion or attribution of blame occurs and that an apology to patients by health-care providers is not taken as an admission of liability. The Canadian Patient Safety Institute44 has non-binding disclosure guidelines for adverse events which state that all harm must be communicated to patients, irrespective of the reason for the harm. There does not appear to be any consensus about the obligation to disclose adverse events with minor consequences,16,20,21,28,45–48 despite the fact that most patients express the desire to be informed of these types of errors. It is proposed that the need for disclosure is proportionate and increases as the harm or risk of harm to the patient increases. 49 Others have proposed the ‘view from below’, putting oneself in the patient’s position to determine how he or she would want the situation to be handled. 50 Disclosure should be the norm, with practitioners expected to justify why there should be any exception to this rule. The 2008 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) directive, Disclosure of Adverse Events to Patients,51 is one of the few policies which has been explicit about its stance on serious and minor errors and events, stating that even when a near miss occurs, disclosure of such ‘close calls’ is recommended if the patient may have become aware that something strange had occurred. 52,53 One account describes the useful role lay members can play in informing decisions with regard to disclosure. Even in well-motivated organisations which try to implement openness, it can be useful to have lay members as part of a review board to ensure decisions remain patient centred. 54

Truthfulness, timeliness and clarity of communication

Being Open guidance10 stresses the three principles of truthfulness, timeliness and clarity, mentioning specifically an ‘appropriately nominated person’, a step-by-step explanation which is timely and based on fact and that patients and families should be kept up to date with the progress of any investigation. Additionally, communication should be clear and unambiguous with a single point of contact.

Why is truthfulness important?

There are a number of involved critiques of why disclosure should occur, which refer to philosophical underpinnings. The most powerful argument in favour of disclosure is deontological in nature. This deontological perspective, which is the perspective of duty-based ethics, is largely attributed to German philosopher Immanuel Kant and suggests that, in principle, all errors must be disclosed. 55,56 In this argument, truth-telling is not mandated by the specific detail of the situation. Therefore, factors such as whether or not an error is serious, or does or does not cause harm, or indeed whether or not an institution or practitioner is liable for harm, are not relevant. The duty is simply one of honesty. The same ethical principles insist that any proposed ethical rule must be universally applicable; it must bind everybody in all situations or else individuals are unable to know if they are bound by it or not. An in-depth but accessible critique of this perspective as it applies to disclosure is presented by Scheirton. 41 In this critique, the reader is asked to imagine that we propose a rule that therapists, nurses, pharmacists and physicians should generally tell the truth but that sometimes it may be acceptable to hide the truth or even lie (for example, in the case of an error). The outcome for patients in this scenario, as soon as they learn about this rule for health-care practitioners, is likely to be suspicion. One family member’s account of non-disclosure refers to the fact that they ‘know of no other industry where honesty is optional’. 57 A practitioner may be telling the truth, but the patient knows this may not be the case, as the practitioner is ethically allowed not to tell the truth sometimes. Therefore, in this paradigm the practitioner’s moral duty to tell the truth cannot logically accommodate exceptions for errors.

Scheirton also describes patient rights as the other side of a similar argument, as the flip side of duties. 41 Laws, professional bodies and institutions agree that patients have a right to be informed about their own medical situation and health care. This right is not conditional upon the individual qualities of the patient or their condition. It is argued that any information is the patient’s and it does not matter whether the particular condition or intervention is the result of an error or some other cause. The patient’s right is to be informed, and this should be honoured by the health-care practitioners who have entered into a therapeutic relationship with the patient.

The picture of disclosure and non-disclosure

A recent paper looking at error and disclosure in emergency care in the USA has outlined the scale of non-disclosure,58 at least in one context. A large number of medication errors (13,932) from 496 emergency departments were analysed. Physicians were responsible for 24% of errors, nurses for 54% and most occurred in the administration (36%). Although 3% of the errors resulted in harm, in only 2.7% of these cases were patients or family members notified. Other work59 indicates that willingness to disclose was related to the severity of the error, with the majority of near misses not even reported to the head of department or the hospital error committees. Such studies indicate that health professionals still hesitate in their reports of many errors or adverse events unless serious harm occurs. A small number of papers have looked at the kinds of factors which may affect whether or not a patient or his or her family experiences disclosure. 60–63 These tend to be conducted in survey work directed at either clinicians or patients. One study60 conducted with patients who had experienced error suggests that patients were less likely to report that disclosure had occurred if they were older than 50 years, did not generally report good health, experienced preventable events, or were still affected by the event at the time of the interview. Disclosure seems to have been more likely to occur when events required additional treatment and among patients who reported good health. 60 This suggests that disclosure occurs when individuals and organisations feel compelled to do so because the error is more visible. 61 Although there is little work directly addressing attitudes to and rates of disclosure in Britain, one paper looking at trainee anaesthetists as recently as 2009 reported that, although 57% had made an error which caused harm, only 68% of these had informed the patient. In the 32% of cases where the patient had not been told, a number of reasons, including negligible perception of patient harm, fear of litigation, fear of organisational or professional reprisal, and the patient having moved, died or remained unconscious were cited as reasons for non-disclosure. 62 This highlights the need for further training among this group of clinicians in relation to both current duty of candour and also medico-legal aspects of care. Other work in the UK63 has demonstrated norms of selective disclosure in medical trainees whereby errors were disclosed informally to colleagues, particularly when teams were seen as supportive, but formal reports and disclosures to patients were rare.

The disclosure gap

There is an increasing literature stressing the importance of disclosing health-care errors, but the available, largely USA-based evidence suggests that this enthusiasm for what is seen by many as the moral imperative may not be reflected in practice. 60,64–66 Disclosure still remains an elusive concept for some and the evidence from a number of surveys points to a marked difference between what patients want from their health-care provider, in terms of honest conversations about mistakes and errors, and what clinicians (doctors in particular) say they would provide. 67,68 This term has been referred to as the ‘disclosure gap’. 69 Several sources give a number of well-cited reasons to explain this mismatch between patient expectations and health-care provider practice, which are discussed at length in a wide variety of outputs from academic papers to short journalistic pieces. However, they seem to fall into four main areas. 69

-

Truthfulness requires an admission of a mistake. For clinicians, admitting that they have harmed a patient is psychologically difficult. As well-trained and compassionate individuals they have a professional and often personal commitment to helping patients. The challenge to this identity posed by unanticipated outcomes and errors in particular is uncomfortable. Many physicians are upset by an allegation that they have been negligent, even if this turns out not to be the case. 70 This is further complicated by a culture of self-regulation and one where the belief is that health-care professionals heal rather than harm.

-

Health-care professionals undergo extensive training, both initially and as part of continuing professional development. However, this rarely extends to conducting the challenging conversations that are required by disclosures of errors or mistakes. 71,72 US work by Gallagher revealed that only 9% of physicians reported receiving any training in disclosing medical errors. 71 Where work has used standardised patients to explore skills in error disclosure, current evidence suggests that doctors are relatively lacking in such skills. 73,74 There is no literature to support training input in the UK.

-

It seems likely that health-care organisations and the individuals who work within them may not fully appreciate how important full disclosure is to their patients, and thus make interpretations about what it is important to disclose. In fact, many examples are given where individuals argue that they are protecting patients from difficult information. A number of studies show that physicians are less likely to tell patients about errors if the error is not obvious to the patient. 67,71

-

In the extensive literature from the USA, one of the arguments is that the biggest barrier to full disclosure is fear of litigation. 75 Risks and costs associated with malpractice are high, and physicians and institutions are worried that admitting an error will increase the likelihood that patients will sue them. The emphasis on this has changed with a number of reforms in state law and in the policy adopted by a number of large insurers, but physicians remain sceptical about the power of such ‘apology clauses’ to protect them in practice. Additionally, most clinicians do not understand the law or update themselves, as they are too busy with clinical decision-making and practising medicine. 70

Delaying disclosure or non-disclosure

Common objections to open disclosure policies suggest that disclosures may not always be in the best interest of the patient. Some work suggests that even if many physicians are perceived to prefer to limit disclosure for their own rather than patients’ interests, or that as a society we believe paternalism is no longer acceptable, there may still be good reasons not to inform a patient of an error, or at least not to disclose immediately. 41 The idea that information conveys power to the patient is sometimes questioned in relation to whether or not such information may also harm them. Does the patient’s right to information always trump emotional well-being? It has been suggested that if an error has no consequences for the patient’s well-being and disclosure does not empower the patient, but is more likely to cause distress or reduce the patient’s trust, then non-disclosure for the sake of sustaining the therapeutic relationship may be the ethical course. 76 However, this rule of therapeutic exception means that the burden of proof is on the one who wishes to use the exception. 41 At this point, proving that full disclosure will create an unreasonable risk of serious harm to the patient before the patient has the information is impossible. Unless research could demonstrate that patients would like clinicians to judge whether or not information relating to an error would be more distressing than non-disclosure, this reasoning ultimately fails. Largely, the limited literature suggests that the opposite appears to be the case, as patients have indicated when surveyed that they would prefer to be told about errors. 28 However, a patient can only judge how distressing the conversation might be after the event, and often such surveys are conducted in patients who have not experienced error and, as such, lack ecological validity. Even bearing this in mind, the best argument for non-disclosure of errors may be difficult to navigate with conviction. Aside from the well-intentioned motive of protecting the patient from what might be judged to be additional distress, the decision not to disclose for whatever reason may backfire. Another member of the team may (inadvertently) disclose the error, the patient may request copies of his or her records, or the error may be discovered during another procedure or even at post-mortem.

The literature here highlights the consistent findings in relation to the disclosure gap. This work comes largely from the USA, but some UK evidence also exists which indicates that disclosure policy is at best inconsistently applied. 28,41,76 There remain considerable challenges for and barriers to the principles and enactment of any policy of open disclosure, which range from a well-intentioned but paternalistic view of protecting patients and families from additional distress to a self-preserving strategy based on fear of reprisals from a legal or professional perspective.

Apologies

Being Open guidance10 stresses that patients and families should receive a sincere apology and this may include expressions of regret for the harm. The wording of the apology should be agreed as early as possible and a decision about who should apologise and how would be based on local circumstances. Characteristics of the person to apologise may include judgements of seniority, relationship to the patient, and experience and expertise in the type of patient safety incident that has occurred. The role of both verbal and written apology is stressed and the time frame suggested is ‘as soon as possible’. The purpose of the verbal apology is stated as allowing face-to-face contact between the patient/family and the health-care team. It is stressed that an apology should not be withheld on the basis of setting up a more formal enquiry, organisational apprehension or staff availability. The guidance also relates evidence from focus groups that families are more likely to seek legal advice if apologies are not forthcoming.

The issue of an apology is related to, but distinct from, openness. The decision about whether or not and when to give an apology, and about what an apology is, seems to be complicated in the literature by the open disclosure process. Individuals often feel they are unable to apologise as this may be construed as an admission of fault or negligence, or that a full investigation has to have been completed before an apology can occur; that is, that an apology can only occur once fault has been determined. A key recommendation of the various global policies on medical error disclosure is to apologise to the patient, which is thought to reduce anger and increase trust. 77 Apologies are recommended elements and processes of all disclosure policies, which generally include who, when, where and what to disclose, as well as how disclosure should be conducted. In a number of descriptive accounts from patients, the concept of an appropriate and sincere apology is often raised as a key element of the perception of an adequate or inadequate disclosure. There are often repeated and strong claims for the power of disclosure and apologies in a number of contexts. Allan suggests that apologies are powerful factors in the healing of harmed patients. 78 This may or may not be the case, but there appears to be little evidence to support this belief. Although a lack of openness, accompanied by little information and no apology, often causes a prolonged and distressing period for patients or their families, we know very little about what ‘good’ disclosure conversations might look like from the patient perspective beyond some common-sense recommendations. The fact that an apology is made does not necessarily make a situation better for the patient who has been harmed and there is little to substantiate this claim. It has been articulated that some feel that the ability of current laws to protect against use of apologies in legal proceedings is perceived as inadequate in the US and Australian contexts. 79

What is an apology?

An apology refers to an encounter between two parties in which one party, the offender, acknowledges responsibility for a harm or grievance and expresses regret or remorse to the aggrieved party. 80 Building on this core definition, Lazare, who has published extensively on the concept of apology,80 outlines the vital components of an apology to include:

-

acknowledging offence

-

providing an explanation for committing the offence

-

expressing remorse

-

offering reparation.

However, it is thought that an apology may have a number of functions. For patients an apology can restore self-respect and dignity, facilitate forgiveness and provide the basis for a reconciliation with an individual health-care professional or institution; for the physician, it is thought to moderate feelings of guilt, shame and fear of retaliation. For both parties, it may strengthen a previously satisfactory relationship, or restore one that has been damaged. 80 However, reassuring though these statements are, there is currently little empirical evidence which can support these claims beyond expert opinion.

What do apologies achieve?

Zammit81 suggests that although people often fear giving an apology as it implies an admission of guilt, the reality may be that the courts have a certain respect for apologies; apologies may actually be viewed favourably. However, this work also suggests that there is little evidence that apologies reduce malpractice claims, as the studies cited in support of this claim are often based on scenarios and have little ecological validity. Additionally, the dangers of unskilled apologies, or weak and insincere apologies made by clinicians who are unsure whether an apology may be protected or not, may actually inflame rather than calm an angry patient or family. This point relates specifically to training in open disclosure conversations, which will be followed up in a section addressing training (see Professional support).

Recognising patient and caregiver expectations

Being Open recognises the need to fully inform patients and families and to attempt to ensure that the process of disclosure meets their expectations. Although there are some practical suggestions for an appropriate attitude from the health-care organisation reflecting sympathy and respect, addressing additional support needs and informing the family of any appropriate support networks is less well reported; we know relatively little about the patient experience of disclosure.

What do patients and families say they want?

Since 1996 there has been some evidence that patients report a wish for an acknowledgement of even minor errors, that they may wish to be referred to another doctor if other treatment is required and that they are more likely to litigate if they have not had an error disclosed. 21 Since this paper, there has been a limited amount of work exploring how patients feel after an error and exploring their responses to disclosure. In survey work the majority of patients clearly indicate that they would want full disclosure of medical error and wish to be informed of error immediately upon its detection. 82 Patients also clearly support reporting of errors to government agencies, state medical boards and hospital committees focused on patient safety. Patients also indicate that they support teaching health-care professionals error disclosure techniques, with honesty and compassion endorsed as a priority for educators who teach clinicians about error management. 83 Patients are clear that, as the person who has experienced harm, they are important, and if apologies are perceived to be driven by regulatory standards and institutional policies alone, and are felt to be insincere and purely managing risk to the organisation, then this may well carry its own risks in terms of the subsequent patient or family response to any apology. One study which explored how patients had experienced disclosure and error described patients reporting that the actual error was less concerning than the continued relationship with their health-care provider. 84 These individuals described being treated not as experts in their own experience of care, but as outsiders. The authors described this as patients feeling like a foreigner in a strange land experiencing a different culture and language, and highlight how poor communication suggests a conflict between a model of person-centred care, with the patient–provider relationship at its heart, and the business or corporate model of health care. A number of other studies have suggested that when poor communication occurs, it can be perceived as medical error by the patient. 28,85

Patients are known to value apologies and expressions of remorse, empathy and caring. They indicate that what they want from disclosure is an explanation of any potential harm and an acknowledgement of responsibility, and they need to see efforts to prevent recurrences; however, these are often reported as missing elements in the disclosure process. 82,83 For many patients, actions and evidence of learning were most important. Current reports of patients’ accounts of apology and disclosure suggest that clinicians’ and organisational responses continue to fall short of expectations. 86