Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1008/17. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The final report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Kessler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and overview

Support workers: policy agendas and building upon previous research

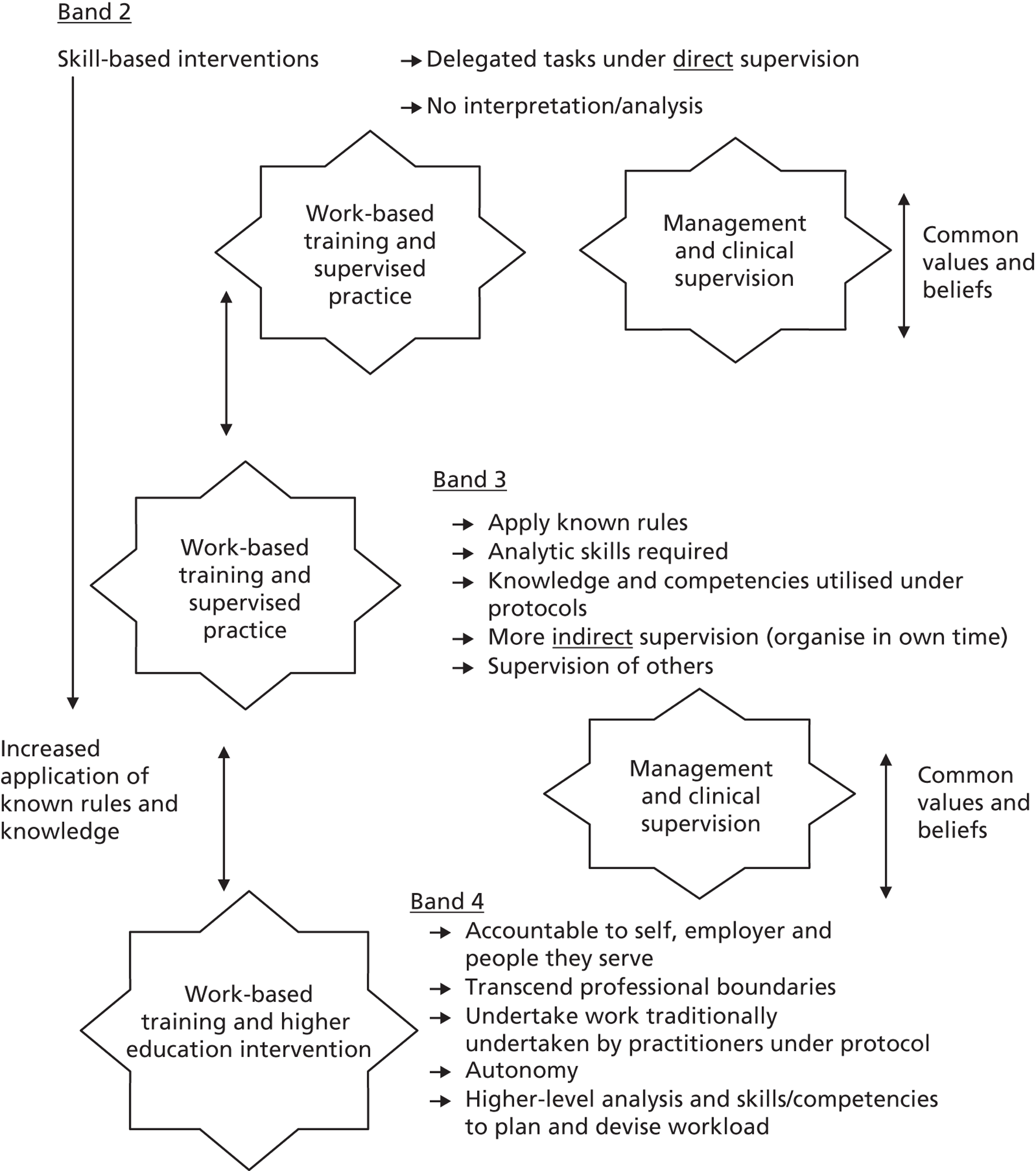

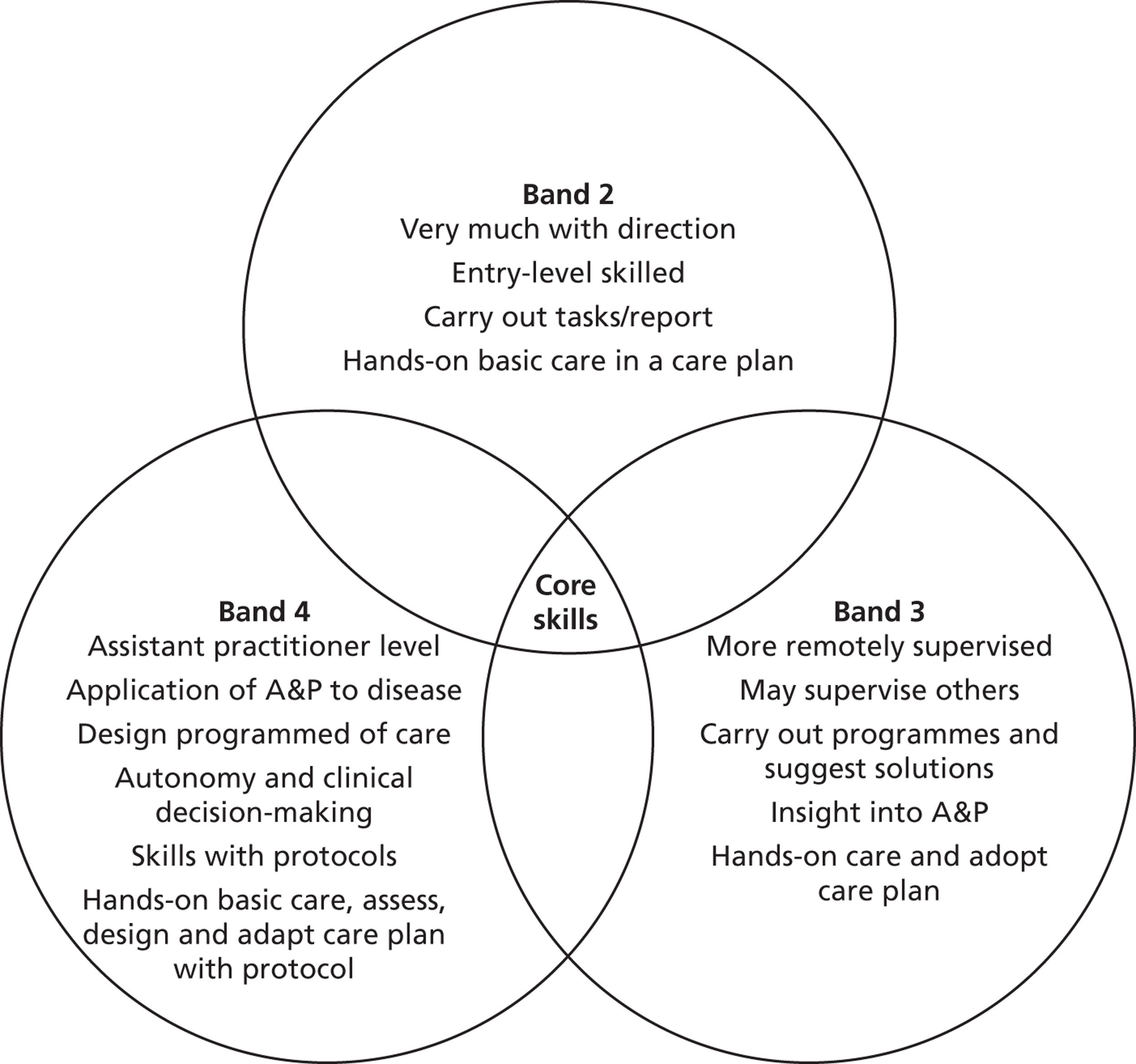

Over recent years, health-care support workers – employees working alongside and typically assisting the registered nurse (RN) – have become an increasingly important part of the nursing workforce in the acute care sector. This is reflected not only in the growing number of such workers, but also in their development as the main bedside presence and principal provider of the fundamentals of care. 1 Thus, the number of full-time equivalent workers ‘supporting doctors and nurses’ in the English NHS rose from 93,000 in 1995 to some 117,000 in 2010, a rise of around 26%. 2 This importance has, however, generated dilemmas and tensions for policy-makers and practitioners at different levels of the NHS. Comprising unregistered employees, positioned in Agenda for Change (AfC) pay bands 2 to 4, the health-care support workforce has often been presented as a ‘flexible’, low-cost source of labour, yet in the absence of regulation this same workforce has also been viewed as generating potential risks and uncertainties. For example, the absence of minimum entry and training requirements has prompted concerns about this workforce’s capability and capacity to deliver safe care. 3

Against such a backdrop, this report presents the findings from a 2-year study examining and contributing to organisational initiatives designed to help develop a high-performance nurse support workforce in acute health-care settings. Such support workers have variously been labelled as health-care assistants (HCAs), nursing assistants, nursing auxiliaries, assistant practitioners (APs) and clinical or health-care support workers. These various job titles are not without significance. In part, they point to the long-standing contribution made by support workers to the provision of health care in England; a support role has been a feature of the country’s modern nursing workforce since its inception in the mid-nineteenth century, and the various titles often equate to their use in different historical periods. 4

Moreover, these differing job titles sometimes denote contrasting signals sent by trusts to various stakeholders on the character and contribution of the nurse support role; for example, the terms ‘auxiliary’ and ‘assistant’ have somewhat different connotations in terms of how the support role is to be viewed, not least in relation to the RN. In the main, however, the different titles are no longer indicative of meaningful substantive difference. Indeed, in general, trusts refer to support workers at pay bands 2 and 3 as ‘HCAs’ and those at pay band 4 as ‘APs’. Where the report refers to support workers at these different levels, it uses these terms. Where these workers are referred to more generically, across the different pay bands, the term ‘nurse support worker’ is used.

In exploring the nurse support worker’s role in acute health care, this study is designed to develop and strengthen the evidence base on the deployment and management of such workers. In so doing, it seeks to draw lessons and provide guidance to policy-makers, and more especially practitioners, in addressing the dilemmas and tensions faced, as well as the opportunities presented, in the increasing use of this group of employees. In pursuing these objectives, the study builds upon research into the nurse support workforce previously undertaken by the investigators. Between 2008 and 2010, in parallel projects funded by the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), Kessler et al. 1 at the University of Oxford explored the nature and consequences of the HCA role at AfC pay bands 2 and 3, while Spilsbury et al. 5 at the University of York concentrated on the development of AP roles, typically positioned at AfC pay band 4. The current study, undertaken between 2011 and 2013, brought together these researchers to focus on the nurse support workforce across AfC pay bands 2 to 4.

The 2008–10 Oxford and York studies1,5 were prompted by the patchy evidence base on the nurse support workforce – its shape, management and consequences for various stakeholders. This patchiness arguably reflected a limited research interest in a low-status role, traditionally performing ‘mundane’, auxiliary tasks. 6 Indeed, while the role is a long-standing feature of the modern nursing workforce,4 there was a general reluctance on the part of policy-makers and practitioners at different levels of the NHS to develop and perhaps fully acknowledge the nurse support workers’ contribution to the delivery of care. Thus, Thornley7 referred to the HCA as an ‘invisible worker’, while the general orientation of the nursing establishment to the role was captured by the regulatory body for nursing at the time, the UK Central Council for Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting,8 when it noted its preference for registered professionals to deliver all care.

In important respects, this picture has significantly changed, with the nurse support worker assuming increased importance in the delivery of bedside care. In the late 1980s, Project 2000 not only removed an intermediate level of nursing, the state enrolled nurse (SEN), but, perhaps more significantly, placed nurse education within higher education establishments and led to the award of a nursing diploma. The government’s acceptance of Project 2000 reforms depended on the introduction of a new category of support worker, the HCA, to support RNs and make up for the loss of student numbers from the ward due to the supernumerary status awarded to student nurses. The introduction of the HCA grade was also accompanied by the government’s plans for formal training of this group of workers through vocational qualifications,9 but this was not fully realised in practice. 10 The recent move of nurse education to an all-graduate profession by 201311 further substantiates the future role of the HCA in supporting a smaller, highly skilled, registered nursing workforce. Simultaneously, the roles of RNs have been developed to take on a wider range of tasks. Indeed, the need for nurses to address and service new NHS performance regimes, based on the achievement of targets and the application of more robust systems of audit, has impacted upon their engagement in the fundamentals of care.

As nurses were withdrawn from the bedside, the HCA appeared to step in to fill this space. Indeed, national policy-makers explicitly presented HCAs as a key resource in these terms. Taking on more ‘routine’ bedside tasks, HCAs were viewed as relieving RNs of ‘burdens’, allowing them to deepen their specialist and advanced skills. As the Department of Health noted:12

As existing staff develop into new roles . . . so the time of more highly skilled staff can be used more effectively. For instance suitably skilled support workers could carry out some of the current tasks of registered nurses, freeing up these nurses to contribute more fully with their skills.

p. 1312 © Crown Copyright. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. URL: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/open-government-licence.htm

The enhanced use of HCAs was also presented by policy-makers as an end in its own right, making a distinctive and positive contribution to care quality. In the late 1990s, the then health minister, John Denham, stressed that:13

Health care assistants are an invaluable and important part of the NHS . . . they make an important contribution to the direct care of patients as well as supporting a range of health professionals in a wide variety of ways [emphasis added].

Moreover, the HCA was seen as a way of addressing supply-side difficulties in the recruitment of RNs through a ‘grow your own approach’. 14 Indeed, providing career opportunities for HCAs connected to the government’s broader agenda on widening participation and improving access to the professions. 15 The NHS Skills Escalator and a new career framework sought to establish the organisational infrastructure for new and clearer career pathways for nurse support workers (and other work groups in the NHS). 16 As the Department of Health noted:17

We want to open up opportunities for people who join NHS organisations at relatively low skill levels to progress their skills through investment in their training and development to professional levels and beyond.

p. 1717 © Crown Copyright. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. URL: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/open-government-licence.htm

In the context of these developments, the evidence base on the nature of the nurse support workforce and its consequences for various stakeholders remained limited and uneven. Indeed, there were relatively few attempts to draw upon established analytical and theoretical frameworks to enhance understanding of the health-care support role: its development, form and impact. In the case of the AP role, an unregistered band 4 role analogous to the old SEN, this was perhaps unsurprising. It was relatively new, being introduced under the AfC agreement, signed by the government and NHS unions in late 2004. 18 More surprising was the underdeveloped nature of the research literature on the standard and long-standing nurse auxiliary role. Certainly, research was emerging which provided greater insight into various features of the broader nurse support workforce. Surveys were building up a picture of the personal characteristics of the HCAs, revealed as principally made up of middle-aged and experienced women. 19 However, with some notable exceptions,7,10,20 these data were not framed by, and failed to feed into, debates on the gendered nature of the care workforce and the consequences of this gendering for various associated processes and outcomes.

Studies were also highlighting nurse and nurse manager perspectives on the HCA contribution to service delivery,21 albeit against the backdrop of ongoing uncertainty about variability in its use. 22–26 Yet again, however, these data were seldom connected to well-developed debates on interoccupational relations, and the contested nature of the division of labour. This was despite the attention drawn to the fluidity of occupational boundaries in health and other sectors,27,28 and to the nature of power-driven professionalisation projects seeking occupational closure. 29 Nurse professionalisation figured prominently in this literature, but with a focus mainly on the nursing–doctor rather than the nurse–support worker relationship. 30

The most developed research stream on the use and management of nurse support workers had developed in relation to skill mix: the ratio of registered to non-registered nursing staff on any given shift. In part, this stream was framed by a narrow, largely technical prescriptive debate on the appropriate algorithms for such a ratio: whether it should be, for example, linked to ward size and or patient acuity. 31 More generally, however, this stream was associated with a research literature on skill-mix dilution, the depletion of RN numbers relative to HCAs. For some commentators, HCAs as a ‘cheap’ resource had opportunistically been used by health-care managers to substitute for nurses as a means of controlling or reducing costs in periods of financial strain, a process predicated on the devaluation and under-rewarding of the HCAs’ skills. 10,31,32

Notwithstanding these debates and material, the research literature on health-care support workers remained partial in substantive terms, methodologically eclectic and significantly undertheorised, encouraging a more structured and systematic approach to the study of the nurse support workforce. The 2008–10 Oxford and York projects1,5 sought to develop such an approach. While designed as separate studies, with somewhat different methodologies, they shared an interest in mapping the incidence, use, management and impact of the component parts of the nurse support workforce, respectively at pay bands 2 and 3 and pay band 4. Indicative of shifting occupational jurisdictions, the studies confirmed the growing but uneven deployment and contribution made by nurse support workers to the delivery of bedside care, while at the same time highlighting ongoing ambiguities among stakeholders about such roles. The HCA post-holders themselves were revealed as typically satisfied with their working lives but retained concerns about being (over) used by nurses to undertake ‘dirty work’. In the main, RNs emerged as welcoming and valuing the support provided by HCAs, but with residual doubts about their own accountability for the performance of these workers and some uncertainty about how the HCA role impacted on their professionalisation project. Patients appeared to form closer emotional relationships with HCAs than nurses, while often being unable to distinguish between registered and unregistered staff and displaying some confusion about the relative contribution of the respective work groups to their care.

Yet the most striking findings from these earlier Oxford and York studies1,5 related to organisational or trust approaches to the management of the nurse support workforce: such approaches emerged as fragmented, ad hoc and possibly disordered. In general, this might be traced to the relatively weak institutionalisation of the nurse support role, as reflected in its unregistered status. Thus, in contrast to the RN and other strongly institutionalised NHS professions and allied professions, there were no standard regulations to guide trusts on the recruitment, training and development of HCAs. The result was a patchwork of different practices between trusts and underdeveloped systems to manage HCAs. The lack of order was particularly reflected in the degraded relationship between pay banding, training and the nature of the role performed; most HCAs were to be found at pay band 2, but performing very different sets of tasks with different levels of qualification.

A new public policy context

In providing baseline data on the nature and consequences of nurse support roles in acute health-care settings, the Oxford and York studies1,5 were able to formulate a research agenda for follow-up work on this part of the nursing workforce. Such an agenda provided the foundation for the current study. It was an agenda given added weight by the continued and indeed deepening public policy interest in nurse support workers. This deepening of interest in HCAs reflected an important shift of emphasis in debate among NHS policy-makers and practitioners on the role, closely associated with high-profile cases of failure in the delivery of health and social care. Such failures ranged from broad concern about the absence of dignity and compassion in the provision of care to older people to more specific instances of institutional failure, most obviously apparent at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust and Winterbourne View. The causes of these failures have been presented as complex and varied. 32 However, the increasing use of the unregulated HCA in the provision of frontline care inevitably encouraged a focus on and consideration of the role’s contribution to such failures. If the Oxford and York 2008–10 studies1,5 were rooted in policy assumptions about the value of HCAs in improving care quality, the current study was framed by concerns about the risks associated with the use of such workers.

These concerns were not new. A decade ago, McKenna et al. warned that ‘the increasing reliance on HCAs raises serious quality and safety questions’ (p. 457),33 while a survey of chief executives in health and social organisations found that over half (52%) felt there was ‘considerable’ or ‘moderate’ risk from the use of support workers. 34 More recently, however, such concerns have come to the fore, reflected not least in terms of a sharper debate on whether or not support workers should be registered. The General Secretary of the Royal College of Nursing (RCN)35 has criticised the level of quality of training received by health-care assistants. In a considered review of the evidence on the use of HCAs, Griffiths and Robinson36 concluded that the use of health-care support workers might well constitute a risk to public safety.

The present study

Focus and debates

This new public policy backdrop added particular significance and urgency to the present study. It encouraged a continuation of attempts to strengthen the evidence base on the nature and consequences of nurse support roles, and more particularly to focus on key issues highlighted in the earlier Oxford and York studies. 1,5 More specifically, this follow-up project centred on three related but distinct themes associated with the use and management of HCAs, each theme, in turn, concentrating on the pursuit of a particular objective:

-

innovation: to identify and facilitate the development of innovative and sustainable management and working practice as it relates to support worker roles in an acute health-care setting

-

evaluation: to evaluate various acute trust policies and practices designed to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of stakeholder interaction with support worker roles

-

engagement: to secure the engagement of various stakeholders in sharing knowledge, practice and learning on support worker roles.

Clearly, these themes cover a defuse range of issues, precluding the development of a strong central narrative and reducing our capacity to draw upon a single, unifying theoretical or analytical framework. This diffusion of interest might be related to the ‘follow-on’ status of the project. Building on previous, more tightly focused research, the current study was, in a sense, ‘mopping up’ and digging deeper into often loosely connected aspects of health-care support worker roles and their consequences. The central themes – innovation, evaluation and engagement – were an important organising device, but they were typically dealing with different sorts of issues: respectively, the incidence and development of new practices, the outcome of initiatives and the sharing of ideas and approaches. The current study, therefore, remains somewhat fragmented and might, by analogy, in part be viewed as a collection of self-contained ‘short stories’ rather than an integrated ‘novel’.

This is not, however, to detract from important cross-cutting issues and shared lessons emerging from the project or from our capacity to link the study to broader theoretical debates. The project’s predominant theme related to workforce change in the NHS, and in particular the challenges and difficulties faced in bringing about and sustaining such change. This was self-evidently the case in considering innovation, with its focus on the introduction of new ways of using and managing nurse support workers. Indeed, while centring on outcomes, the evaluation theme was still exploring initiatives which changed approaches to health-care delivery, particularly in terms of the new contribution made by the support worker. Moreover, although our engagement theme sought to encourage the sharing of views, and practices, this sharing principally related to changes in approaches to the use and management of nurse support workers.

A focus on workforce change, concentrating on the use and management of nurse support workers, encouraged a connection between the current study and a number of closely related theoretical debates. The first such debate related to organisational architecture, and, more specifically, to those organisational features that might facilitate or inhibit workforce change. An extensive literature provides a variety of organisational change models,37,38 rooted in differing assumptions about the drivers, nature and outcome of change. In crude terms, a distinction is often made between rational, often top-down, strategic change and normative, typically bottom-up, incremental or organic change, with very different prescriptive implications. Taking an inductive approach, the current study did not adopt a particular model of change. It was, however, sensitive to these different models and sought to explore which more usefully characterised and explained change in the management and use of nurse support workers.

The second debate linked to the literature on interoccupational relations,27,28 and, more particularly, role boundaries and jurisdictions, which, as noted, had previously devoted only limited attention to the positioning of the nurse support role. An acknowledgement that job territories are often contested, especially by occupations seeking to professionalise, encouraged an interest in how the development of the nurse support role was viewed by adjacent groups, most obviously RNs: whether changes to the nature of the nurse support role and its contribution to health care were welcomed or resisted.

The third and closely related debate touched on by the project was associated with the institutionalisation of new ways of using and managing nurse support workers. For (neo) institutional theorists, change had traditionally been problematic and not easily accommodated; after all, institutions are viewed by such theorists as enduring and constraining. 39 More recently, however, there has been a growing emphasis within this literature on agency, reflected in the figure of the institutional entrepreneur (IE),40 well placed and motivated to pursue institutional change, and the notion of institutional work, routine activity designed to ‘create, maintain and disrupt’ institutions. 41 This interest in institutional change at the workplace has increasingly been used by institutional theorists to examine the emergence of new work roles and practices, not least in health care,42–44 but again with little inclination to embrace the development of the nurse support role. The current project provided an opportunity to explore whether or not and how new ways of using and managing nurse support workers had become legitimised and taken for granted: in other words, institutionalised.

Approach

The research on the three themes – innovation, evaluation and engagement – was overseen by an advisory group comprising national and regional employer and employee representatives, plus academics with an expertise and interest in the nursing workforce (see Appendix 1 for list of members) and key actors from the project’s case study trusts (see Chapter 3, Focus and methods and Chapter 4, Introduction). Patient representatives were also members of the advisory group (see Appendix 2 for a more detailed statement on patient/public involvement in the project). The advisory group was a virtual network for the duration of the study. It was kept informed of project developments as well as being asked to comment on draft research instruments and papers. It was also sent research findings as they emerged. The group met once, on 19 April 2012, halfway through the project, with 20 members and senior case study representatives attending. This meeting reviewed and discussed available findings from the project and commented on the plans for future work.

The project also maintained a dedicated and openly available website for the posting of project documents and findings. 45 The material on this site complemented that produced by the previous Oxford and York studies,1,5 coming to constitute a significant and accessible repository for research data on nurse support workers. Indeed, indicative of the value of this site, there have been almost 3000 visits (according to Google Analytics website data) since the project began in 2011, with recent monthly averages of almost 50 hits per month from search engines, implying that the traffic is not simply generated from our own project mailings.

The NIHR-approved research protocol was granted full NHS ethical approval (11/LO/0770). Trust research and development approval was successfully sought prior to carrying out the fieldwork in all innovation case (IC) studies and evaluation case (EC) studies. The project fulfilled all university requirements for the ethical conduct of research.

The main body of the report is structured around the three main themes: Chapters 2 and 3 focus on the innovation theme, the former considering the scoping and survey work on this theme and the latter on the related case study work; Chapter 4 concentrates on the evaluation theme; and Chapter 5 examines the engagement theme. In each of these chapters, we present the context for the work undertaken, the methods used and the findings. A final chapter provides an overview and discussion.

Chapter 2 Innovation: scoping and survey

Innovation in the public services, and particularly in the NHS, has attracted increasing attention among policy-makers and practitioners over recent years as a means of both meeting pressures on, and improving the quality of, service provisions. 46 The NHS Modernisation Agency, established in 2001, was focused on innovation as the development and testing of new ideas, a role taken on by the National Institute for Innovation and Improvement in 2005. Indeed, the current NHS chief executive has stressed that:47

We need to do things differently. We need to radically transform the way we deliver services. Innovation is the way – the only way – we can meet [new] challenges. Innovation must become core business for the NHS.

Innovation Health and Wealth: Accelerating Adoption and Diffusion in the NHS. 47 © Crown Copyright. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0. URL: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130107105354/http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/open-government-licence.htm

This interest connects to an extensive and well-developed research literature, which has debated the nature of innovation: its definition, incidence and diffusion. In general, innovation has been seen to relate to ‘change’ and ‘difference’, with a particular emphasis on the ‘new’ as applied to ‘products’ as well as to ‘processes’. 48 This ‘newness’ might, in turn, be seen to refer to the completely original, or as Van de Ven49 has suggested, to something novel to those involved. As these authors note:49

As long as the idea is perceived as new to the people involved, it is ‘innovation’ even though it may appear to others to be an imitation of something that exist elsewhere.

p. 491

As a ‘process innovation’, new approaches to the use and management of the workforce have been a key feature in the NHS change agenda over recent years; for example, the Modernisation Agency had a changing workforce programme and, indeed, new ways of working have consistently informed contemporary developments in policy and practice in the NHS. The Oxford and York studies1,5 revealed examples of innovative practice in the use and management of HCAs. These examples were, however, unevenly distributed within and between trusts, raising three primary questions considered in the current study:

-

What form does innovation in the management and use of nurse support workers take?

-

As a means of characterising and categorising innovation in relation to nurse support roles, the current study distinguished various dimensions of innovative practice:

-

A new way of working within an established role, centred on the range and nature of the tasks performed. The extension of a nurse support role to take on new tasks might be seen as indicative of this form of innovation.

-

A new role, bundling tasks and responsibilities in a distinctive way. The development of a distinctive, specialist nurse support role by a trust might be viewed as illustrative of this type of innovation.

-

A new way of managing, associated with the systems used by trusts to manage HCAs in terms of their recruitment, retention, development and performance.

-

-

-

How is innovation distributed?

-

The different dimensions provided the basis for exploring patterns in the distribution of innovation both between and within trusts. This was essentially a mapping exercise, indicating the incidence of innovation and its location.

-

-

What explains patterns of innovation?

-

The uneven distribution of innovative practice encourages consideration of why some organisations or clinical areas are able to innovate, while others, delivering broadly similar services, are not. It suggests that there might be drivers, systems and styles which stimulate, support and sustain innovative practice.

-

The three questions were examined in a number of related but distinct phases:

-

scoping: a series of scoping interviews with senior trust managers as a means of both highlighting examples of innovation and providing context for the design of a survey

-

surveying: a national survey of directors of nursing and senior human resource managers at all English acute trusts

-

case study work: six case studies selected to reflect different forms of innovation:

-

management: values-based recruitment at York Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

management: a HCA development nurse role at University College London Hospitals (UCLH) NHS Foundation Trust

-

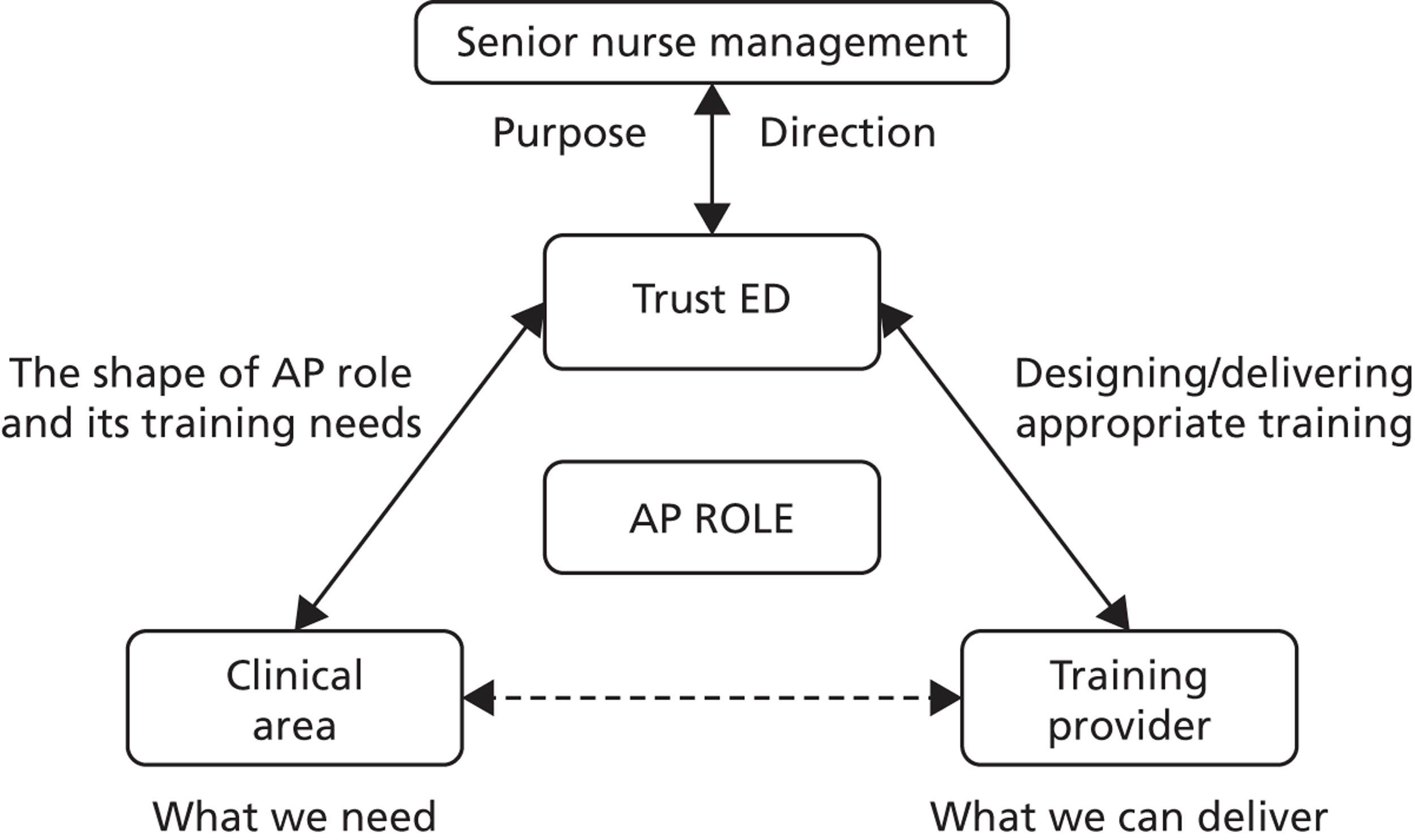

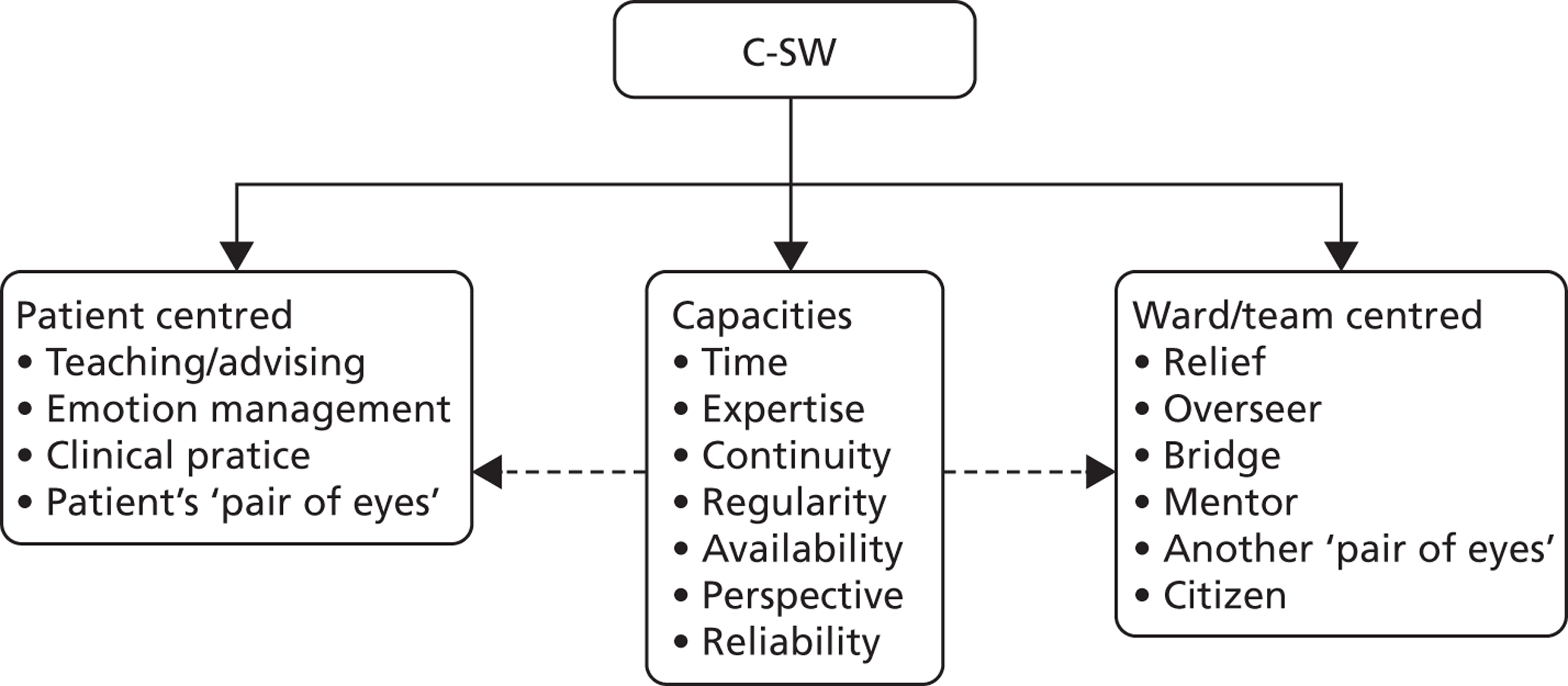

new role: a colorectal support worker (C-SW) at Hillingdon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

-

new role: a dermatology support worker at Oxford University Hospitals (OUH) NHS Trust

-

new role: a band 4 educator role with responsibility for training clinical support workers (CSWs) at OUH

-

new way of working: AP specialists at South Devon Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust.

-

This chapter concentrates on the scoping and surveying phases of the innovation theme and the next chapter focuses on the case study phase.

Scoping

Focus and methods

The scoping phase, conducted during the summer and autumn of 2011, aimed at developing an appreciation of the range and nature of innovative practices emerging within trusts across England. The findings from this phase were valuable in their own right, identifying practices, examples and debates on the management and use of nurse support workers. However, they were also used to inform the design of the national survey (see National survey, below). It was crucial to build a picture of the types of innovative practices being considered and implemented by trusts as a means of exploring their take-up and use in a more structured and systematic way through a survey. Moreover, without prejudging the outcome of the survey, these scoping meetings were used to explore the possibility of case study and evaluation work with trusts.

Conducted during 2011, the scoping phase comprised face-to-face interviews and meetings with key actors at different levels of the NHS – national, regional and local. A total of 116 actors were covered during this phase including:

-

national employee (RCN and UNISON) and employer representatives (NHS Employers)

-

regional workforce leads (in the east of England, the south-west, the north-west, Yorkshire and Humberside, London, Scotland and Wales)

-

directors and assistant directors of nursing, HR directors, education leads and practice development nurses (PDNs) from trusts

-

representatives from a miscellaneous range of organisations including higher education institutions (HEIs) and the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC).

This total included 12 one-to-one interviews; eight meetings involving two to three participants; four meetings covering five to six participants; and two more significant events involving trust support worker education leads in different regions of the country, one covering 15 and the other covering 35 participants. As a scoping or exploratory phase, these interviews and meetings were conducted in a flexible way, using open questions encouraging participants to highlight examples of innovative practice in the use and management of nurse support workers, why and how such practices were introduced and with what perceived impact on various outcomes. In the main, full notes were taken of the interviews and meetings. These examples were then classified and coded according to the three dimensions of innovation highlighted earlier to reveal the incidence and patterns of such innovation. Participants were also asked to raise more general issues: prevailing practice, emerging developments, and areas of debate or contention. The responses to these issues were processed to establish patterns and trends. For example, the prevailing practices and emergent trends raised by the respondents were again coded against our three forms of innovation. Similarly, areas of debate or contention were coded according to the substantive issue at stake to distinguish a spectrum of concerns.

Findings

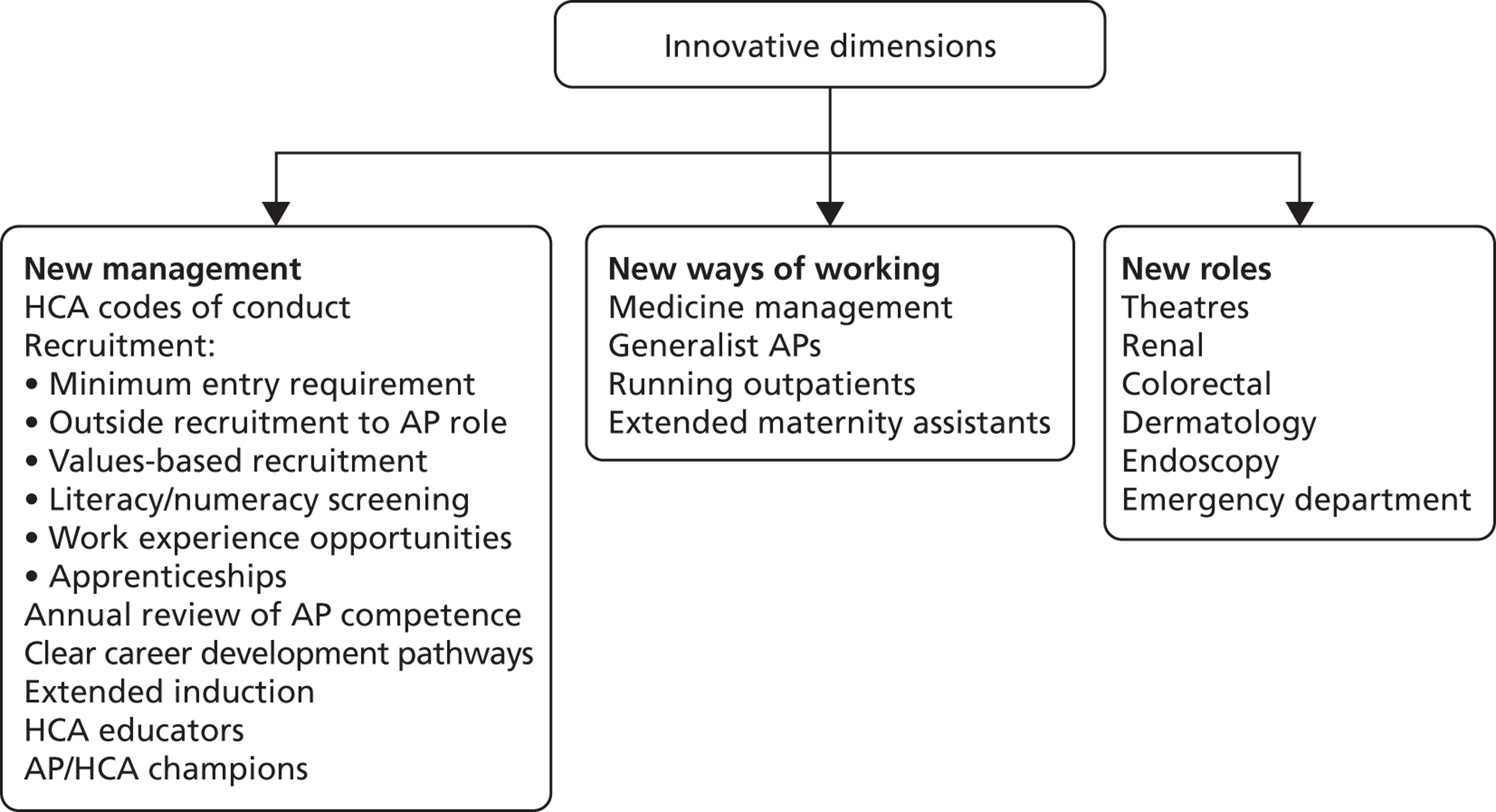

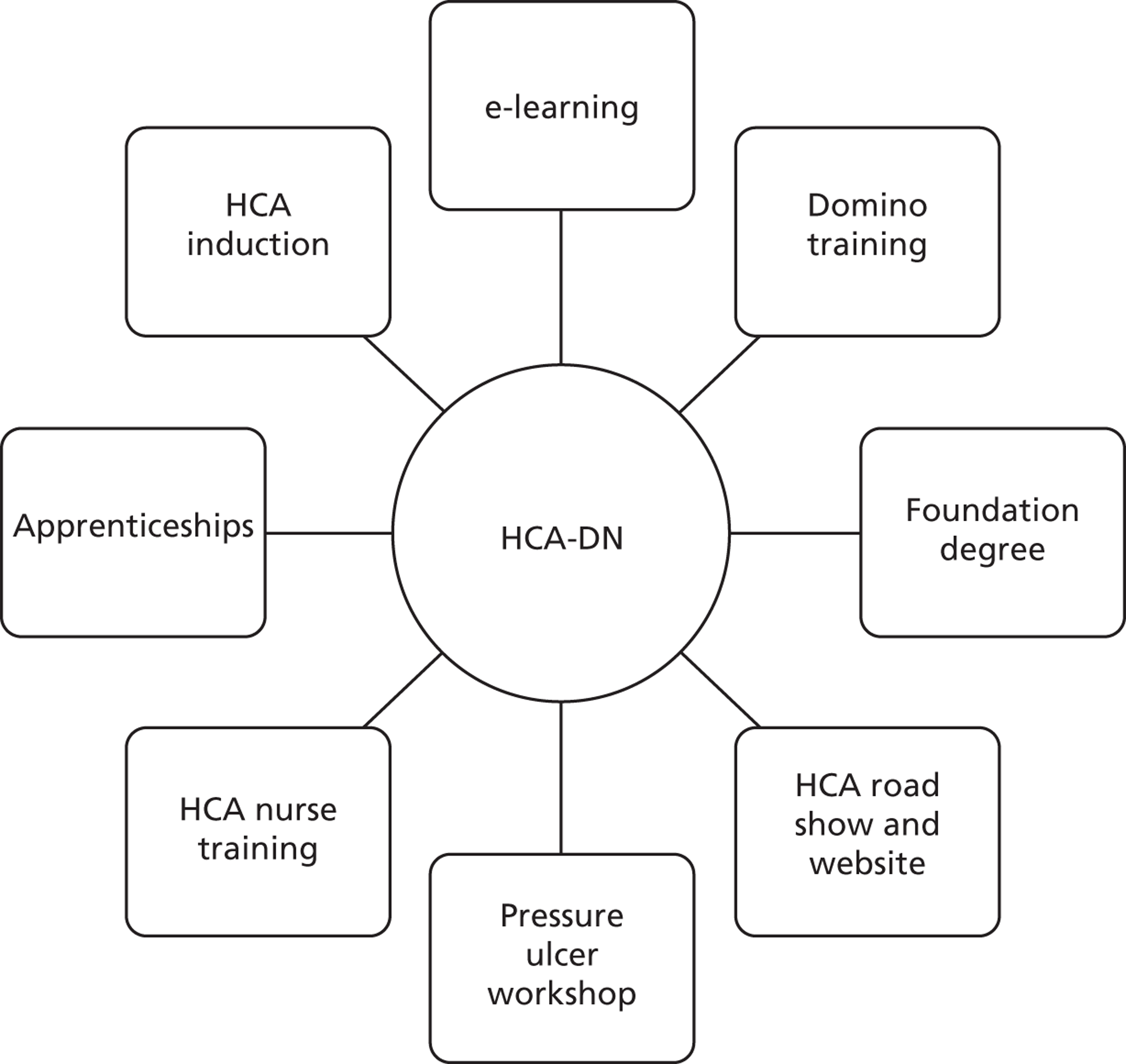

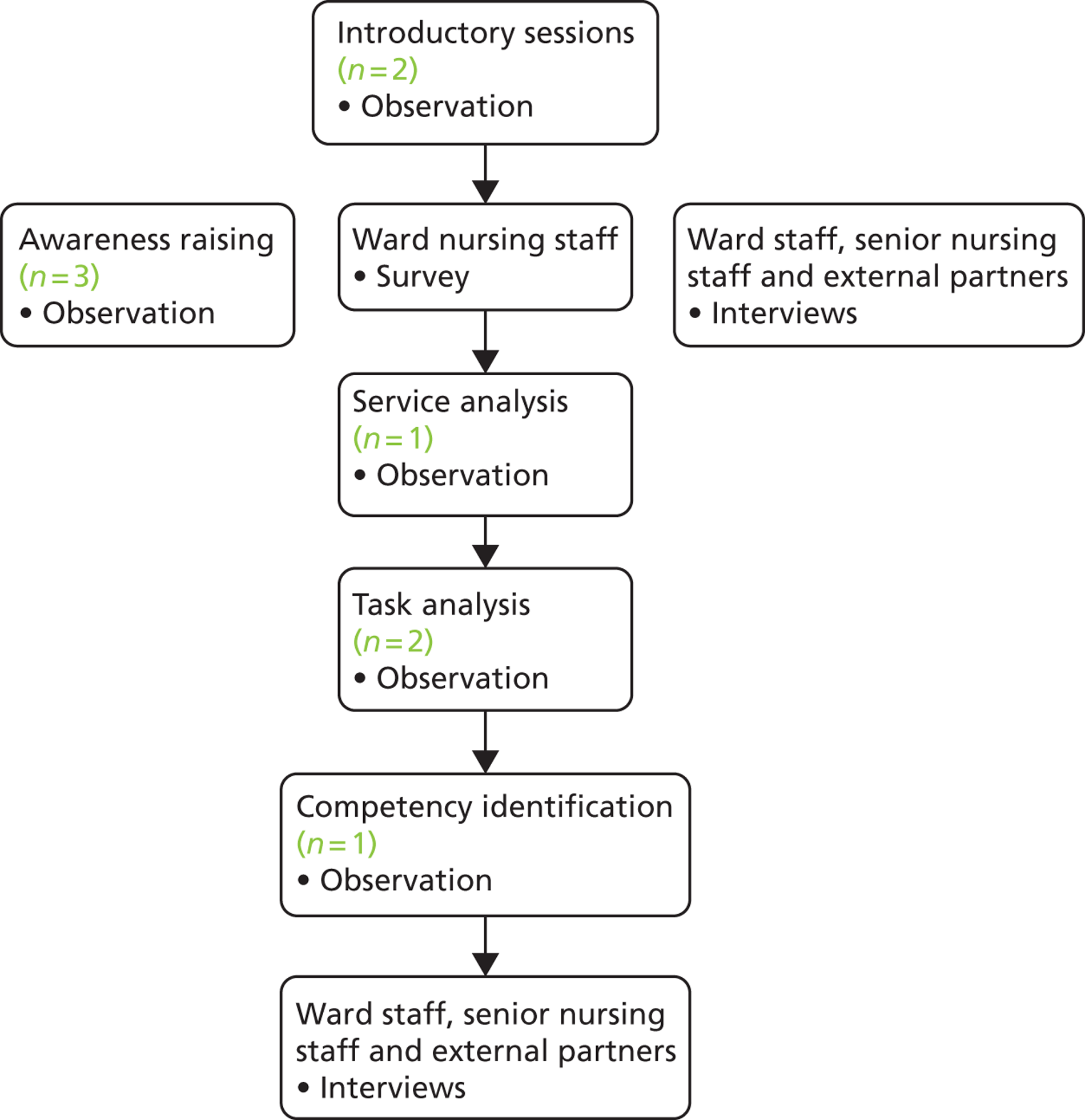

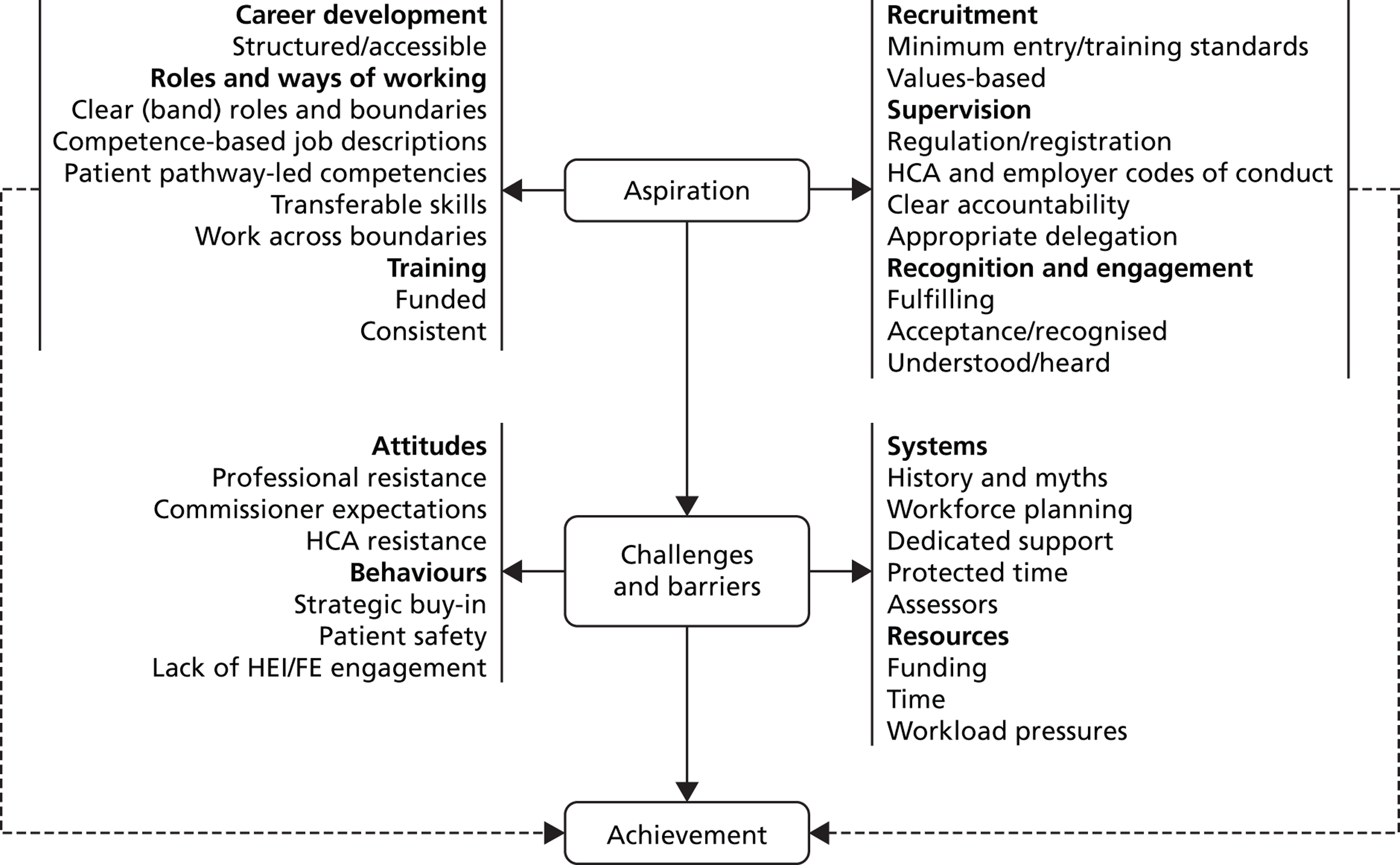

Figure 1 sets out innovative practice as it relates to the use and management of support workers along the three dimensions distinguished: new ways of working, new roles and new management practices. It is clear that most of the innovation has taken place along the new management dimension. Thus, there have been instances of trusts drafting their own codes of conduct for HCAs, establishing clearer career pathways for their HCAs, and creating champions for the role and dedicated corporate educators. Most striking, however, is the concentration of new management practice associated with the recruitment of HCAs and preparation for performing the role. In the absence of minimum entry requirements and with trusts recruiting from low-paid, low-status jobs from across the labour market,1 these new practices suggested that trusts have been seeking to develop and ensure the capabilities of starter HCAs.

FIGURE 1.

Innovative practice.

New recruitment practices have included the strengthening of entry requirements. In some cases this has been by stipulating a requisite qualification, typically National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) level 2, and in others it has been by recruiting straight on to an apprenticeship scheme. The new practices have also been apparent in numeracy and literacy tests, designed to filter out applicants deficient in these basic capabilities. Perhaps the most novel development relates to the use of values-based recruitment, which moves selection beyond capability to focus on the attitudes and beliefs of applicants: whether or not these are appropriate for care work and aligned with those of the trust. Finally, the introduction of extended induction programmes arguably reflects attempts to better prepare individuals for the HCA role, particularly before they join the ward team and begin delivering direct patient care.

The scoping phase revealed far fewer examples of new roles or ways of working, perhaps a reflection of the clinical governance issues generated by such change. New ways of working were highlighted, in particular the extension of AP roles to take on drugs administration and the greater use of maternity care support workers to perform more direct care duties. New specialist roles were being developed in clinical areas – theatres, emergency departments, endoscopy and dermatology – typically graded at pay band 4. However, changes involving the performance of new tasks, whether within an existing or in a new role, often had important implications for clinical practice, requiring revisions to trust policy and mechanisms to ensure patient safety and minimise risk. Dealing with such issues could be time-consuming, procedurally complex and sometimes contentious.

These difficulties informed broader debates among NHS policy-makers and practitioners on the management and use of nurse support roles in acute care settings. These debates were indicative of differences in approach to these roles and signalled continuing uncertainty as to how to deploy and deal with them. The debates often revolved around dilemmas or competing views along five dimensions, set out and discussed below:

-

Careers ←→ Costs

-

Developing career pathways for nurse support workers provided new opportunities, seen as a way of retaining this valued part of the workforce. However, career progression also incurred pay bill costs as employees were upgraded, not easily met in times of financial pressure.

-

-

Sweating ←→ Elevating

-

New roles and ways of working could be developed at pay band 4, but an alternative, perhaps cheaper and less difficult option was to ‘sweat’ those in band 2, in other words find ways of generating more work and effort from those in the lower band. This dilemma was deepened by the fact that trusts were sometimes uncertain about the tasks performed by their band 2s, particularly relative to those undertaken by band 3 HCAs. Such uncertainty was encouraging particular trusts to clarify and ‘sort out’ the tasks respectively undertaken by band 2 and 3 HCAs before considering the development of new roles at band 4.

-

-

Trained ←→ Registered

-

Traditionally, skill-mix ratios are based upon a distinction between unregistered and registered nursing staff. However, as AP training has developed and intensified, this distinction has become increasingly problematic, especially where trusts have been seeking to replace a band 5 RN with an AP. If APs continue to be counted as unregistered, their increased use inevitably dilutes skill mix and in so doing raises trust concerns about how such dilution might be perceived.

-

-

Assistant practitioners ←→ Registered nurses

-

Partly related, there is a debate on the relative worth of using band 4 APs or band 5 RNs. Some trusts question the value for the money of the former: the cost difference between the two is not great, and nurses as registered professionals are seen as a more cost-effective option.

-

-

‘Growing your own’ ←→ In-role development

-

The development of career pathways allows trusts to ‘grow their own’ nurses, but this might well be in tension with a trust’s interest in retaining those experienced staff in nurse support roles who might otherwise seek to move into RN roles. Nurse training takes support workers away from the trust, depleting workforce experience and stability.

-

National survey

Focus and methods

Findings from the scoping phase provided the basis for a more structured and systematic mapping of innovative practice in the management and use of nurse support workers by surveying directors of nursing and human resources (HR) in English acute trusts. A draft of the survey was developed and refined in response both to comments from the study’s advisory panel and to a pilot conducted among a national network for support worker co-ordinators.

The mapping of innovative practice comprised a number of elements, reflected in the final survey design. The first provided an overview of employment trends, with the aim of highlighting changes in the structure of the nursing workforce over the last 2 years. To this end, respondents were asked whether they had ‘increased’ or ‘decreased’ (or ‘not changed’) nursing staff at each of the pay bands from 2 to 6 inclusive. The second element centred on those factors driving trusts to innovate in the use and management of nurse support workers. The survey included a range of possible drivers such as efficiency gains and service delivery pressures, asking whether or not these had been influential, as well as directing respondents to specify ‘the most’ influential driver. The third element focused on organisational infrastructure. It had become clear during scoping that workforce innovation depended on the development of a supportive infrastructure: systems to facilitate, nurture and sustain innovation. Respondents were asked whether or not systems that constituted such an infrastructure were in place (‘yes’ or ‘no’); for example, a HCA champion at trust level or a HCA working group.

The centrepiece of the survey was three dimensions of innovation: management, new roles and new ways of working. Selectively drawing upon some of the innovations highlighted during the scoping phase, respondents were asked whether or not they had introduced a given number of such practices along each of these dimensions (‘yes’ or ‘no’), and, indeed, whether they had been introduced in ‘most’ or only ‘part of the trust’. Respondents were provided with an opportunity at the end of the questionnaire to provide additional comments on any of the issues covered in the survey (see Appendix 4 for questionnaire).

The survey was conducted online and invitations to participate were sent to the directors of nursing and of HR at all acute trusts in England during November 2011. To ensure that as many trusts as possible were covered, the final reminder sent in December asked those who had yet to complete the survey to forward it to the most appropriate person in their organisation. The survey was closed in January 2012 and the response details are available in Table 1. In total, 94 trusts took part in the survey, representing a response rate of 57%. The respondent in 90% of the trusts was the most senior nursing or HR director. This represents a very good response rate for a voluntary and independent survey among senior managers in the NHS. The original decision to cover both directors from any given trust was driven by an appreciation that the respective directorates were likely to be involved in innovations related to the nursing workforce. It was also informed by an interest in whether or not the views of the respective functional professionals on nurse support roles were aligned. It was disappointing that the response rate among HR directors was considerably lower than that among nursing directors, despite the promotion of the survey by the Healthcare People Management Association (HPMA). This limited the intended comparison of views between the two groups, although there were glimpses of how perspectives on the nurse support role might vary by function (see Miscellaneous, below).

| Position | Opted out | Returned | Multiple returns | Respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head of nursing | 13 | 69 | 3 | 66 |

| Head of HR | 5 | 28 | 9 | 19 |

| Other nursing/HR manager | 4 | 16 | 7 | 9 |

| Total | 22 | 113 | 19 | 94 |

| Response rate | 56.97%a | |||

Using data from the Department of Health, Monitor and the Audit Commission non-response analysis was carried out to ascertain if there was any bias in the type of trust that chose to respond to the survey. The analysis revealed that there was no significant difference between those trusts that responded and those that did not on background variables such as foundation trust status, regional location, trust type, nursing workforce size or financial well-being. We can, therefore, be confident that the results of the survey are likely to be representative of the wider population of English NHS acute trusts.

The survey findings are presented under the following headings:

-

the workforce trends for pay bands 2 to 6 during the last 2 years

-

common drivers of nurse support worker development

-

managerial infrastructure for nurse support workers

-

innovative practices to manage nurse support workers

-

innovative nurse support worker roles or ways of working

-

miscellaneous.

Where respondents provided comments on particular questions, they are referred to in the appropriate section.

Findings

The workforce trends for pay bands 2 to 6 during the last 2 years

The workforce trends highlighted in Table 2 need to be treated with some care, being based on the impressions of respondents rather than on hard data. As a means of ensuring a high response rate, the survey was deliberately designed to ask for views rather than hard data on changes in employment level between bands. We felt that if respondents had to seek out harder, more precise data on staff numbers, usually from other staff and departments in the trust, they would have been less likely to complete the survey. However, these trends do suggest considerable dynamism and change in the nature of the workforce over the last 2 years. Interpreting the picture presented is far from straightforward. In a period of financial pressure and broader resource constraint, it is clear that trusts are not simply decreasing numbers in the nursing workforce. Rather, it appears that they are increasing and decreasing numbers of nursing staff, with important differences in the net flow between pay bands. In part, these patterns might reflect broader organisational changes; for example, one respondent noted that the trust had mainly increased the size of its nursing workforce on taking over community care services from the primary care trust. Staff flows also appeared sensitive to regional or local labour market factors. As another respondent suggested:

We find band 6 nurses extremely difficult to recruit and so have converted some posts to band 5 to enable us to fill vacancies and grow our own. There is some evidence that this is a London phenomenon due to the cost of living at a time when people are embarking on life commitments such as starting a family.

Trust_42

| Pay band | Increased | Decreased | No change | Count (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse support workers at pay band 2 | 59.5 | 8.3 | 32.1 | 84 |

| Nurse support workers at pay band 3 | 44.6 | 21.7 | 33.7 | 83 |

| Nurse support workers at pay band 4 | 54.7 | 8.0 | 37.3 | 75a |

| RNs at pay band 5 | 56.8 | 21.0 | 22.2 | 81 |

| RNs at pay band 6 | 35.0 | 23.8 | 41.3 | 80 |

More generally, these data suggest three trends in employment centred on different pay bands:

-

Stability: the first is concentrated on RNs at band 6, with employment relatively stable: almost half of the respondents (41%) indicate no change in the employment of nurse in this pay band.

-

Churn: the second covers band 5 nurses and band 3 HCAs and displays considerable churn. A significant proportion of trusts, around half, are increasing the numbers employed in these bands, while at the same time, close to one-quarter are decreasing numbers employed at these levels. The band 3 HCA role is not used extensively by trusts, limiting the weight that can be placed on volatility of employment at this level. As the entry grade for RNs, the churn at pay band 5 is noteworthy and might well be related to trust variation in approaches to the band 4 AP role. Thus, the increased use of band 4 APs is often traded off against band 5 posts, perhaps accounting for the noteworthy minority of trusts decreasing employment at this level. Yet it is equally apparent that many trusts, well over a half (57%), are increasing their number of band 5 nurses, perhaps reflecting grade dilution with the employment of fewer band 6 nurses.

-

Expansion: the third pattern is characterised by increasing employment, with little sign of any decrease in numbers. This would seem to relate to those parts of the nursing workforce which trusts appear to be most keen on using and developing. More specifically, this pattern embraces band 2 HCAs and band 4 APs. In the case of both groups, well over half of trusts have increased levels of employment at these levels, with only 8% decreasing employment. The increase in band 2 HCAs lends some credence to the suggestion that trusts are seeking to ‘sweat’ the role in financially difficult times, employing more staff at the ‘low-cost’ end of the nursing workforce. Where APs replace band 5 nurses, it might similarly reflect a dilution of skill mix. As one of the respondents commented, ‘As we develop band 4’s they will replace some band 5’s’.

It also suggests a shift from the tardiness displayed by trusts in developing and using the AP role,5 along with a greater appreciation and understanding of the contribution to be made by such a role in the restructuring of their nursing workforce. Certainly, the AP role continues to be a source of some contention and debate with trusts. As one respondent stressed:

I have considered introducing the band 4 AP, but the lack of registration and ability to administer drugs does not appear to offer any efficiency savings.

Trust_91

Moreover, in an echo of the concerns raised in the scoping phase about the value for money of a band 4 AP, another argued that:

There needs to be a full cost–benefit analysis of band 4 roles on general wards to show whether there is an added value to the role. I personally believe that bands 2 and 3 already provide competent basic care and competency based clinical skills to patients and so am unclear what the added value of a band 4 is. There needs to be a clear steer on the administration of medications by any group of clinical support workers at 2, 3 or 4 and if there is a national push for unregistered staff to provide medications then there should be some form of registration or regulation with an appropriate body.

Trust_23

However, the balance of comments suggested that more trusts were seeking to develop AP roles for the first time. Nine respondents commented that this was the case, including those noting:

We are currently developing band 4 roles and a strategy for associate/assistant practitioners.

Trust_89

We are working to develop the band 4 AP workforce.

Trust_57

Common drivers of nurse support worker development

Table 3 indicates that trusts have been driven to address their nurse support workforce by a combination of factors. However, the primary drivers are service redesign (79%) and attempts to improve patient experience (73%). Other notable drivers are efficiency gains (65%) and service delivery pressures (49%).

| Driver | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Service redesign | 78.7 (70) |

| Improving patient experience | 73.0 (65) |

| Efficiency gains | 65.2 (58) |

| Service delivery pressures | 49.4 (44) |

| Financial pressures | 38.2 (34) |

| National and/or regional policy initiatives | 31.5 (28) |

| Trust restructuring | 29.2 (26) |

| Difficulties in recruiting and/or retaining RNs | 21.3 (19) |

| Other (e.g. patient safety, patient complexity, turnover of support workers, providing a career framework) | 7.9 (7) |

| No significant nurse support worker developments | 4.5 (4) |

When respondents were asked to choose between the drivers and specify the single most important one (Table 4), patient experience emerged as the principal driver, highlighted by well over one-third of respondents (39%), compared with service redesign (19%). At the same time, the table suggests that some trusts are being driven by more immediate pressures. A crude distinction can be made between drivers that suggest a proactive or strategic approach to the nurse support workforce, such as service redesign and improvements in the patient experience, and a more ad hoc and reactive approach reflected in the importance of efficiency gains, financial pressures, service pressures and recruitment and retention difficulties among nurses. In total, these more ad hoc and opportunistic pressures are driving nurse support workforce developments in well over one-third of trusts (39%).

| Most important driver | % (n) |

|---|---|

| Improving patient experience | 38.6 (32) |

| Service redesign | 19.3 (16) |

| Efficiency gains | 18.1 (15) |

| Financial pressures | 8.4 (7) |

| Service delivery pressures | 7.2 (6) |

| Difficulties in recruiting and/or retaining RNs | 4.8 (4) |

| Trust restructuring | 2.4 (2) |

| National and/or regional policy initiatives | 1.2 (1) |

Managerial infrastructure for nurse support workers

The three questions on managerial infrastructure were indicative of the kind of system which might stimulate and support innovation in the management and use of nurse support workers. The findings presented in Table 5 cast some doubts on whether or not such systems are in place. Certainly, around half of trusts had a designated nurse support worker champion at senior levels (48%), but given that many trusts have a senior (nurse) manager responsible for the development of the nursing workforce, it is perhaps surprising that more were unable to respond positively to this question. Indeed, suggestions that the lack of a champion reflects the absence of a supportive infrastructure for innovation finds some confirmation in the fact that only a minority of trusts have a strategy group (30%) and a written strategy covering this group (29%). A number of respondents in their open comments indicated that support workers were covered by more broadly based nursing strategies and associated working groups. Indeed, seven nursing directors volunteered this comment in the survey. However, in combination, responses to these questions still cast some doubt on the strength of the infrastructure to develop nurse support workers in innovative ways.

| Infrastructure | Yes | No | n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Designated nurse support worker champion at divisional or trust management level | 48.3 | 51.7 | 89 |

| Established support worker strategy group | 30.2 | 69.8 | 86 |

| A written nurse support workforce strategy | 28.9 | 71.1 | 83 |

Innovative practices to manage nurse support workers

A significant proportion of trusts have adopted new management practices designed to more tightly regulate entry into HCA roles within the trusts. Thus, Table 6 indicates that over two-thirds of trusts are using numeracy and literacy tests to screen band 2 candidates across most of their organisations, while a similar proportion have extended induction programmes for this group of workers (69%).

| Practice | Most of the trust | Some of the trust | No | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candidates at pay band 2 are screened for numeracy and literacy | 68.2 | 12.5 | 19.3 | 88 |

| All new pay band 2 staff recruited to an apprenticeship programme | 7.8 | 23.3 | 68.9 | 90 |

| An off-ward induction programme for new pay band 2 staff lasting 3 or more days | 69.2 | 12.1 | 18.7 | 91 |

| New pay band 2 recruits must achieve training targets to be confirmed in post | 39.3 | 16.9 | 43.8 | 89 |

| Guaranteed pay band 4 role to APs on completion of training | 27.1 | 17.1 | 55.7 | 70 |

| Forum/support group at division or trust level attended by nurse support workers | 20.5 | 25.3 | 54.2 | 83 |

However, other practices which might be seen to strengthen and regulate nurse support work preparation and engagement have been unevenly taken up. Only a small proportion of trusts recruit all band 2s onto an apprenticeship programme across most of the trust (8%), and barely more than one-third require band 2s to achieve training targets before they are confirmed in post (39%).

Guarantees for APs to receive a band 4 role on completion of training is not a comprehensive practice, with over half of trusts suggesting that the AP post is not confirmed in these circumstances (56%). Similarly, the direct nurse support worker voice remains fairly weak, with over half of trusts indicating that they have no dedicated forum anywhere in the trust above ward level for them (54%). Certainly, some trusts had explicitly engaged nurse support workers in more broadly based forums, thereby ensuring a fuller integration within the nursing workforce. As one respondent noted:

We have made a conscious effort to include support workers in other forums e.g. as infection control champions; tissue viability links; in addition to staff nurses completing these roles. Hence we involve HCAs in trust forums but not always in groups of only HCAs.

Trust_77

However, the absence of a dedicated HCA space raises issues about the effectiveness of the nurse support worker voice, with previous research suggesting that their view can be lost when combined with others. 1

Innovative nurse support worker roles or ways of working

Table 7 indicates that trusts are beginning to develop new nurse support roles. This is particularly marked in the case of maternity support workers, where the overwhelming majority of trusts have a support role delivering direct care; only 1 in 10 trusts reported this not to be the case (9%). A support role that works across professional boundaries is also a common feature in trusts (72%), although it is less established, with 50% of trusts reporting the role as occurring in only some parts of the organisation. Likewise, a critical care support role features in over half of the trusts (55%), but the majority of that occurrence is only in some parts of the organisation (30%).

| New role | Most of the trust | Some of the trust | No | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Critical care support worker role with patient care duties | 25.6 | 29.5 | 44.9 | 78 |

| Health-care support worker role that works across different professional boundaries | 22.0 | 50.0 | 28.0 | 82 |

| Maternity support worker role with direct care duties | 43.8 | 47.5 | 8.8 | 80 |

In terms of new ways of working, some trusts are seeking to clarify and sharpen responsibility for the performance of tasks. Table 8 points to a clear majority of trusts revising job descriptions for bands 2 and 3 (74%) in most or some parts of the trust. The issuing of guidelines for the delegation of tasks to nurse support workers also appears to be fairly prevalent (63%), although it is perhaps noteworthy that over one-third of trusts (37%) have no such guidelines anywhere in the trust. While the only substantive change in ways of working included in this section of survey, the administration of medicine, has not been widely taken up, it is still striking that nurse support workers undertake this activity in at least some parts of the organisation in almost one-fifth of trusts (18%).

| New way of working | Most of the trust | Some of the trust | No | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revised job descriptions for pay bands 2 or 3 in the last 2 years | 32.2 | 41.4 | 26.4 | 87 |

| Code of conduct for nurse support workers | 31.8 | 6.8 | 61.4 | 88 |

| Nurse support worker role that includes the administration of medicine | 4.9 | 13.4 | 81.7 | 82 |

| Guidelines for the delegation of tasks to nurse support workers | 40.5 | 22.8 | 36.7 | 79 |

In concentrating on the development and use of AP roles as a new of way working, Table 9 reveals the relatively high incidence of a preceptorship programme for newly qualified workers in these roles in at least some part of their organisation: well over half of trusts have such programmes (59%). In contrast, formal evaluation of the role and revalidation of AP competence are considerably less common.

| Most of the trust | Some of the trust | No | n | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual revalidation of AP competence | 10.0 | 15.0 | 75.0 | 60 |

| Formal evaluation of AP roles | 28.1 | 23.4 | 48.4 | 64 |

| A preceptorship programme for newly qualified APs | 46.0 | 12.7 | 41.3 | 63 |

Miscellaneous

A number of additional findings emerged from the survey, based on further statistical analysis and on the open comments made by respondents. First, as a means of seeking to categorise trusts by innovative approach in the use and management of nurse support workers, cluster analysis was undertaken. This drew upon data from the survey which related to new management practices, new roles and ways of working, including new approaches to the AP role, and trust infrastructure. The findings suggest five different types of trust summarised in Table 31, which can be found in Appendix 5.

The surveyed trusts are fairly evenly distributed across these five types, suggesting a variability of approach and perhaps an uncertainty as to how to approach and deal with the nurse support role. These five types can be labelled and briefly summarised as follows.

-

The non-innovator: a low take-up of any form of any innovation, alongside poorly developed infrastructure to support such developments. It is noteworthy that this type comprises the smallest number of trusts, just eight, suggesting that a significant majority of trusts are seeking to innovate in certain ways.

-

The regulatory innovator: mainly innovating in terms of the management of nurse support roles, in particular regulating entry into the role. These trusts have introduced numerical/literacy screening, extended induction programmes and revised job descriptions. However, they show few signs of more ambitiously innovating in relation to roles and or ways of working.

-

The grounded innovator: grounded in terms of both establishing infrastructure for the development of nurse support roles and concentrating their innovation mainly on AP rather than on band 2 HCA roles. This is the most common type of trust, covering 13 organisations, providing some support for the suggestion that trusts are now moving forward with the development of band 4 roles.

-

The focused innovator: centred on developing new roles rather than any other form of innovation and in the absence of developed infrastructure.

-

The full innovator: innovating along all three dimensions – roles, management and ways of working – and underpinned by a strong infrastructure. Clearly, these are the most innovative trusts, but just as there are few non-innovators trusts, there are relatively few (nine) full innovator trusts.

A second miscellaneous finding emerges as a glimpse of the divergence of perspective between nurse and HR directors on innovation associated with the nurse support workforce. While most innovative developments affecting nurse support workers are driven by the nursing directorate, the HR function plays a part, with a general interest in workforce planning and a more direct role in certain initiatives, especially those linked to the recruitment and selection of nurse support workers. A divergence of view is brought into sharp focus by survey comments from a HR director and nurse director at the same trust, the former suggesting that there is considerable scope to further extend the support worker role and the latter arguing quite the reverse:

This is an area in which I am particularly interested. We are not doing enough, in my view, to develop the nurse support workforce particularly at assistant practitioner band 4 level. There is a divergence of views within the organisation, those that are very keen and those that are not.

Trust_29_director of human resources

We have looked at the workload of the nursing staff in the clinical area, and I personally believe that use of non-clinical support workers for tasks like admin, housekeeping support, and decontamination, to allow trained nurses more time to care for patients, is a better use of untrained clinical support workers to provide direct patient care.

Trust_29_director of nursing

This was one of the few trusts which provided a response from both the nursing and the HR directors, although in hinting at a divergence of view between the two functional professionals, this finding encourages more focused work on this issue.

Third, a number of respondents highlighted the significance of a competency framework or model as the basis for innovating around nurse support roles. The survey did ask a few questions about competencies, but the open comments suggest that they are being used to confirm HCA appointments, develop AP roles, review capabilities and distinguish roles, and establish career pathways and performance manage, as follows.

-

Confirm HCA appointments:

-

‘We have a centralised recruitment for trainee HCAs with a nine day skills training programme then completion of portfolio and clinical competencies over six months before they become qualified HCAs.’ [Trust_114 (emphasis added)]

-

-

Develop AP roles:

-

‘As we develop band 4s we will utilise competencies and training in administration of medicines in a controlled way to benefit patient care.’ [Trust_18 (emphasis added)]

-

-

Review capabilities and distinguish roles:

-

‘We have introduced a full week’s refresher training for nursing assistants to ensure competence and clarity of roles.’ [Trust_40 (emphasis added)]

-

-

Establish carer pathways and performance manage:

-

‘Our support worker programme is undergoing many changes and developments to ensure that quality patient care is delivered at all levels, and to provide a robust career pathway linked to education and competency attainment. We are just beginning the implementation of this work, with a CSW framework from recruitment, cadets and apprentices, through to AP levels.’ [Trust_119 (emphasis added)]

-

Finally, comments suggested that many trust were on the cusp of developing new approaches to the management and use of nurse support workers. The survey was, arguably, conducted in a period of uncertainty with the trusts awaiting a more detailed report on Mid Staffordshire by Robert Francis, and the government’s response, before addressing the issue of unregistered nursing staff. Some trusts were more explicit about their forthcoming intention to develop this part of the nursing workforce:

We are working towards implementing our 3-year workforce strategy that aims to improve productivity by maximising benefits of new roles i.e. APs and reduce reliance upon temp staff along with many other goals.

Trust_1

Overview: discussion and lessons

Process and product innovation has assumed increasing importance to NHS policy-makers and practitioners as a means of delivering cost-efficient and effective care services. As a process innovation, new developments in the structure of the nursing workforce – in particular the distribution of tasks and responsibilities – have figured prominently on this agenda. There have, however, been few attempts to map innovative practice in the management and use of nurse support workers: in other words to explore what form innovation has taken, how it has been distributed by trust and clinical area and what has driven it. Distinguishing between innovations associated with the management of nurse support workers, their ways of working and their roles, the scoping phase of the research, based on consultation with over 100 policy-makers and practitioners at different levels of the NHS, has presented a picture of patchy, uneven and uncertain developments. Innovation had been most evident in the management of nurse support workers, particularly during recruitment and preparation for the role; this form of innovation might be more straightforward than in relation to new roles or ways of working where issues of clinical governance add a layer of complexity to the process. Indeed, these complexities seemed to generate a number of dilemmas and competing views within trusts on the use and management of the nurse support workforce.

Of value in their own right, the findings from the scoping phase also fed into the design of a national survey, which provided a more detailed, structured and systematic picture of innovation. In important respects, the survey findings reinforced those presented in the scoping phase. The increasing employment of band 2 and 4 nurse support workers suggested that trusts were concentrating their efforts at these levels. Driven by an interest in improving patient experience and service redesign, the infrastructure to support innovation remained fragile, although some innovative practice had become relatively widespread. Again, these practices relate mainly to the management of nurse support workers: numeracy and literacy tests and extended induction. The adoption of codes of practice and guidelines for the delegation of tasks suggests that systems were being put in place to develop new ways of working, and new roles were being developed, particularly in maternity care. However, the cluster analysis revealed the tentativeness of trust approaches to innovation. Certainly, this analysis suggested that there were few non-innovative trusts; in other words, most trusts were innovating in some way. However, there were also few fully innovating trusts, and the fairly even distribution of the trusts across the five types pointed to the diversity of approaches being adopted.

Such diversity encourages consideration of why and how certain trusts were able to innovate, and in the next chapter, attention turns to the case study phase of the innovation theme, which sought to address these questions.

A number of lessons can be drawn from the scoping and survey phases of the innovation stream:

-

Given the relatively high incidence of new ways of managing, this approach to innovation appears to be more viable and lower risk than one based upon new roles or ways of working. New ways of managing generate far fewer clinical governance issues than other forms of innovation, and are less likely to be contested by various stakeholders from within trusts.

-

While dilemmas remain about how to use and manage support workers, if trusts are to make progress on the innovative deployment of this group of workers, these dilemmas need to be systematically worked through, with any uncertainties and tensions directly addressed.

-

Certainly, the dilemmas or trade-offs highlighted are not easily reconciled. However, any resolution might usefully be related to local trust circumstances and needs: the state of the local labour market for the nurse support workers; the capacity to recruit and retain RNs; and or the financial well-being of the trust. Thus, the decision to employ APs, or to develop nurse support workers as a means of ‘growing your own nurses’, might be linked to a trust’s ability to attract nurses. Difficulties in this respect are likely to encourage the search for alternative sources of nursing labour. Similarly, the development of career pathways for support workers might be associated with the ‘tightness’ of the local labour market for ‘low-paid, low-skilled’ jobs. Career pathways are a useful way of retaining nurse support workers, who might otherwise seek alternative job opportunities, providing the trust with value for money.

-

Despite the limited incidence of new roles and ways of working, there were examples of such practices in these areas, suggesting scope for the sharing of ideas and approaches. It was not, however, immediately apparent what institutional spaces or network at national, regional or indeed trust level might provide the opportunity to share such ideas and approaches. There were laudable examples of attempts to engage, for example a national network of trust AP education leads, but greater consideration should be given to the development and resourcing of such spaces and networks.

-

Many trusts need a more robust infrastructure for developing the support worker role, for example in the form of a support worker champion at senior management levels and or nursing strategies sensitive to the contribution of such workers.

-

If support workers are to be used and managed more innovatively, there needs to be a closer alignment between functional views and approaches, particularly in the case of the nursing and HR management teams.

Chapter 3 Innovation: case studies

Focus and methods

The primary aim of the IC studies was to develop an understanding of the development of a new role or practice in a given trust, examining the details of how and why it emerged and evolved within a specific organisational context. If the scoping and survey phases were designed to map the form taken by, and the distribution of, innovation, the case study phase sought to explain innovative management and the use of nurse support workers in particular trusts. More specifically, why were some trusts able to innovate in these respects, while others, providing similar health-care services, were not?

Table 10 sets out the six IC studies. The cases were purposefully selected to fall within three dimensions of innovation. Two cases focused on new approaches to management: values-based recruitment and the introduction of a HCA development nurse. Three cases examined new roles: a C-SW; a surgical assistant practitioner; and a band 4 educator role with responsibility for training CSWs. Finally, one case study looked at new ways of working: APs in specialist clinical areas. In all cases, the role or practice was new to the trust, although not necessarily unique to the NHS. The six trusts explicitly agreed to attach their names to the presentation of the material in this report. The cases were, after all, examples of ‘good practice’, and in general the trusts were proud of their achievement in ‘successfully’ introducing them.

| Trust | Innovation | Fieldwork dates | Level of staff interviewed | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trust managers | Service managers | Ward staff | ||||

| York | Values-based recruitment | December 2011–March 2012 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 18 |

| South Devon | APs as flexible resource | August 2012 | 7 | 2 | 8 | 17 |

| Hillingdon | Stoma care support worker | June–November 2012 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 11 |

| UCLH | HCA development nurse | July 2012 | 4 | 0 | 14 | 18 |

| OUH | Surgical assistant practitioner | January 2013 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 4 |

| OUH | CSW trainer at band 4 | December 2012–May 2013 | 8 | 0 | 3 | 11 |

| 30 | 12 | 37 | 79 | |||

Carried out between the winter of 2011 and the early summer of 2013, the cases were mainly based upon interviews with a vertical slice of trust actors who had a stake in the innovation under consideration. Table 10 sets out those interviewed in the respective cases. In total, there were 79 interviews carried out. These interviews were typically supplemented by relevant documentary material, for example trust policies, job descriptions and training programmes.

In general, the interviewees were asked fairly open questions about:

-

the context for the innovation, including trust structure, culture and history

-

the nature and aims of the innovation

-

the design and implementation of the innovation

-

the impact of the innovation on various stakeholders and outcomes

-

the broader lessons.

All interviews were recorded and transcribed. The transcriptions were read through on a number of occasions with a view to establishing whether or not there was an agreed narrative from the stakeholders on the development of the innovation, its aims, design features and consequences, and, if not, where differences of view lay. A draft case report was fed back to the respective trusts, providing the opportunity for inaccuracies and misinterpretation to be picked up.

This section presents an overview of the findings from the respective cases. A final section provides a summary and discussion. To protect the identity of those we interviewed, and to provide consistency between the case study reports, the quotes within the text use the identifier IC plus attributions related to three broad job areas: trust manager, which may include senior and executive managers, personnel within HR, the education and learning teams and external managers; service manager, which can include matrons, divisional managers and senior nurses not working on wards; and ward staff, which can include ward or clinic managers, medical staff, nurses, HCAs and APs. Where an interviewee could be easily identified owing to their specific role, they were contacted to give their approval prior to the case study report being made public. Approval was given in all instances.

Values-based recruitment

Context

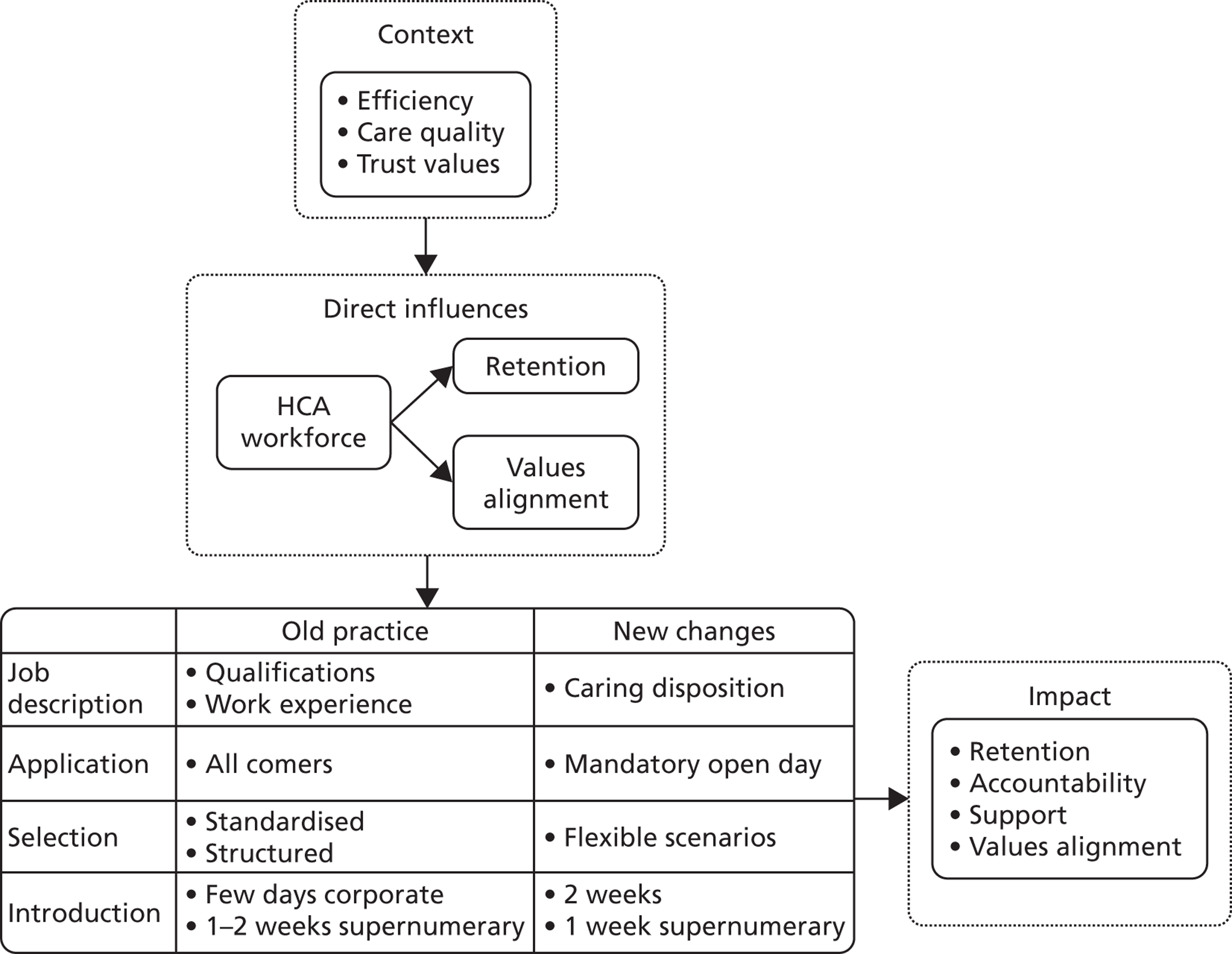

This case study deals with a new values-based approach to the recruitment and retention of HCAs introduced by York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust in 2010. The innovative character of this initiative was reflected in the fact that it had won the 2011 HPMA award for innovation in HR and a similar Health Service Journal (HSJ) award in 2012. The trust’s interest in such an approach was underpinned by two broad considerations. The first related to a high turnover among its 500-or-so HCAs, particularly in the first 6 months of employment, which the trust found to be associated with recruits not being fully aware of the nature of the HCA job:

So many people just came and didn’t have a clue really what they were going to be doing . . . They come and think, ‘oh I thought I was only making tea’. And you think, ‘gosh no, there’s a whole host of things, and tea isn’t one of them’.

IC1_ward staff_1

The second consideration was values based, and reflected York’s interest in aligning its values, revolving around ‘caring and ‘compassion’, with those of new HCAs:

We wanted to be able create the opportunity for the individual to demonstrate their caring disposition.

IC1_trust manager_1

The new recruitment model

York’s new approach to HCA recruitment comprised a number of elements:

-