Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1002/36. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Powell is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment editorial board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Nicolini et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

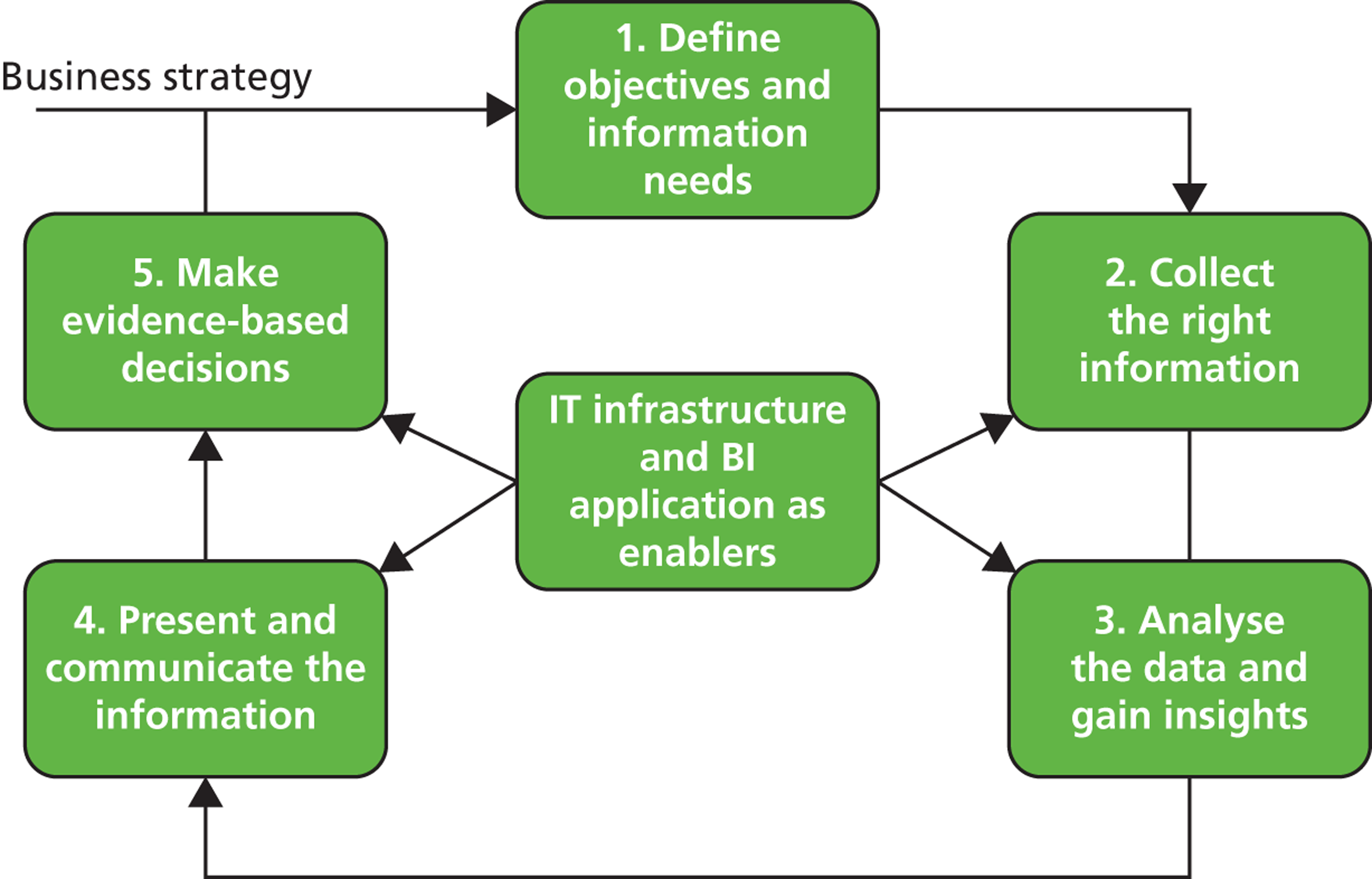

Evidence-based decision-making and evidence-based practice (EBP) have permeated professional life, establishing themselves as powerful norms. The phenomenon has come to have particular purchase in the context of the UK NHS, where it has become an imperative not only for clinicians, but increasingly also for managers. 1,2 As Rousseau3 explained, the resulting movement of ‘evidence-based management’ is premised on the presumed positive consequences of ensuring that ‘practicing managers develop into experts who make organisational decisions informed by social science and organisational research’, as a counterweight to the negative status quo of ‘continu[ing] to rely largely on personal experience’. Yet, while the normative argument for evidence-based management has been repeatedly, and increasingly prominently made,3,4 the practical realities of everyday knowledge- and ‘evidence’-work by managers more generally, and health-care managers in particular, still remain to a significant extent an empirical black box. In other words, we remain relatively unsure of the extent to which ‘evidence-based management’ is being done at all and, perhaps more importantly, how it is done. That being said, there is considerable scholarly research suggesting that organisational realities seldom unproblematically map onto their idealised ‘evidence-based’ representations. 5,6 As Gabbay and Le May7 noted with some concern, there is a ‘persistent mismatch between the rational, linear, scientistic approach that the EBP movement demands and the pragmatic, workable approach demanded by the messy world of practice’. Equally, the very concept of ‘evidence’ itself remains ripe for empirical unpicking in this context:8 what do we mean by evidence, what does evidence mean in practice, what practically counts or does not count as evidence, when might evidence be needed (and when might it not)? Seeking answers to these questions about EBP and evidence in health-care management is important, as the decisions of senior NHS managers in the UK have a direct impact on the quality, finances and delivery of patient services as a crucial public good.

Such questions are also intimately tied to the related issue of knowledge mobilisation, which we define here as the general effort of ‘moving knowledge into active service for the broadest possible common good’. 9 In the context of the present research, knowledge mobilisation refers to the process whereby relevant knowledge is sourced, evaluated and utilised by decision-makers, in this case NHS trust chief executive officers (CEOs), in their processes of decision-making. Traditionally, the issue of knowledge mobilisation was conceived as a largely utilitarian problem of efficient assimilation and use of ‘best information’, underpinned by the same assumptions of rationality and linearity bemoaned by Gabbay and Le May. 7 This traditional, linear approach to knowledge mobilisation was gradually replaced by what we will call the social approach, which highlights the relational ways in which knowledge is made sense of and acted upon in a given context. Dopson and her co-authors,10 for instance, argued that:

Utilising and adopting knowledge depends on a set of social processes which would include: sensing and interpreting new evidence; integrating it with existing evidence, including tacit evidence; its reinforcement or marginalisation by professional networks and communities of practice; relating the new evidence to the needs of the local context; discussing the evidence with local stakeholders; taking joint decisions about its enactment and finally changing practice.

As Swan and colleagues8 noted, the term ‘knowledge mobilisation’ in its ‘social’ conceptualisation implies a closer attention to the processes of transfer and transformation (instead of simply translation) of knowledge, as well as a question of the extent to which knowledge is in demand in particular settings, for particular audiences. Crucially however, as we outline in the literature section, this social view has been meaningfully extended in recent decades via the practice view of knowing (and of knowledge mobilisation), informed by the practice-based community of organisational scholars. 11–14 Complimentary to the social approach, the practice view encourages empirical engagements that recognise knowledge mobilisation as an ongoing relational accomplishment, which is emergent, embodied, embedded and material. 15 Taking such an approach would therefore imply attending to the everyday interactions, objects and people through and with which NHS CEOs make sense of information and knowledge, agree on its appropriateness and bring it to bear in given situational contexts.

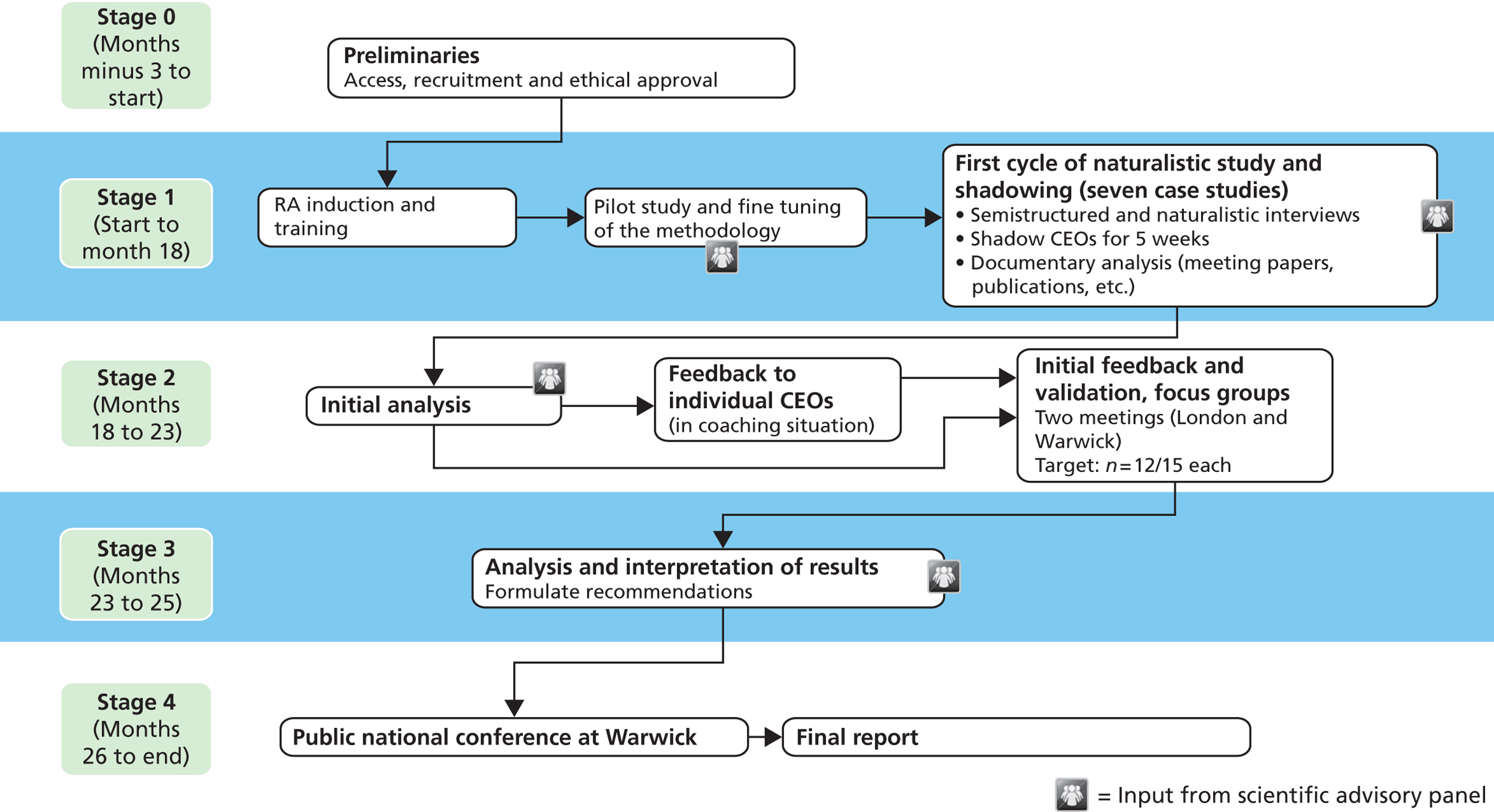

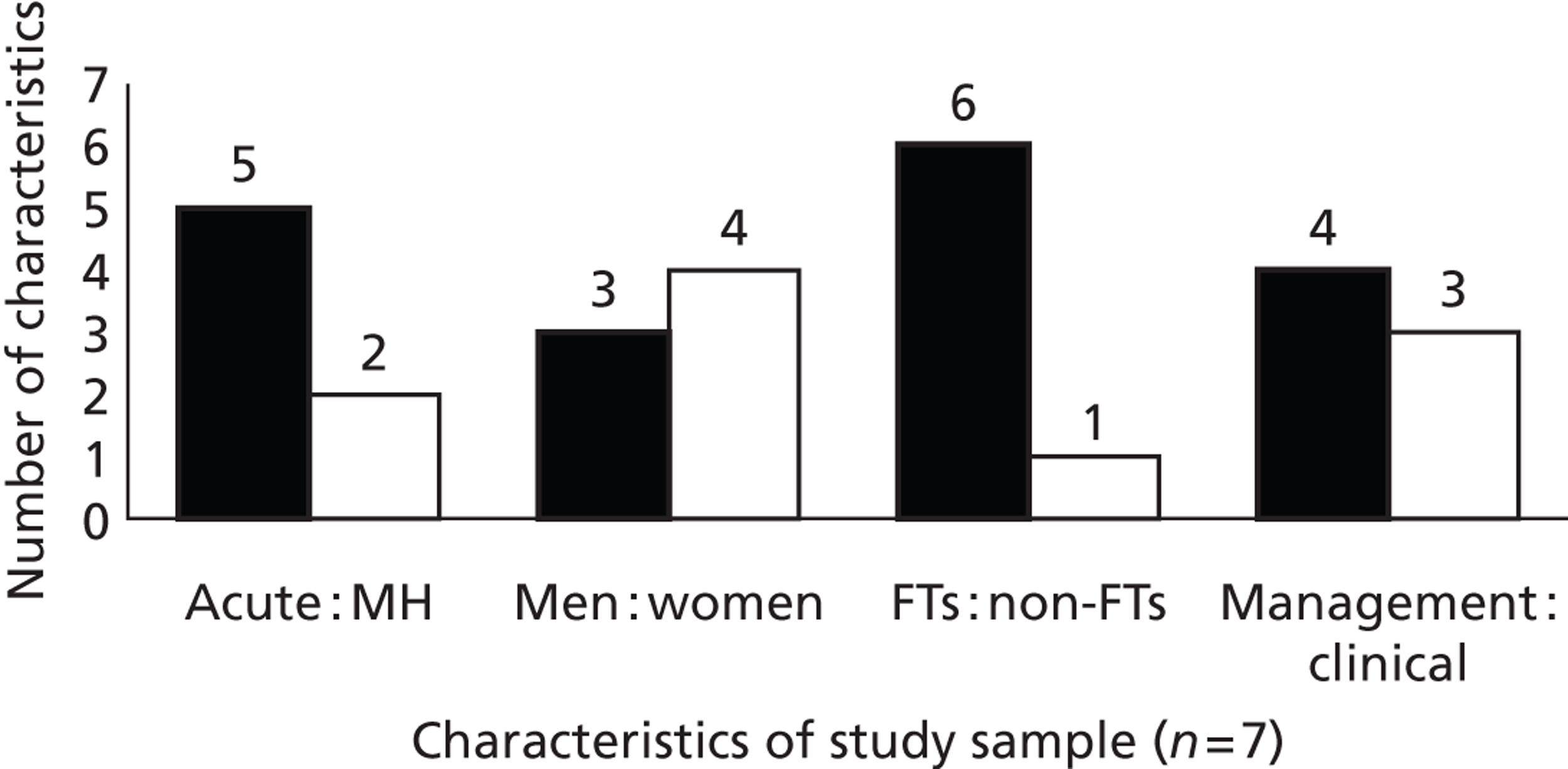

In this report, we outline the findings of a 2-year National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR)-funded project into the routine information, knowledge and ‘evidence’ work of seven NHS acute and mental health trust CEOs. In particular, by conducting an in-depth, shadowing and observation-based study of everyday CEO doings over a period of approximately 5 weeks each, we sought to answer the following key research questions:

-

How is knowledge mobilisation understood, performed, and enacted in the everyday working practice of NHS CEOs?

-

What are the material practices and organisational arrangements through which NHS trust CEOs source and use existing knowledge and ‘evidence’?

-

How are different types of ‘evidence’ used (or brought to bear) in their daily activities?

-

Do the source, the content and the format in which such ‘evidence’ (but also information and knowledge more widely conceived) is presented make a practical difference in terms of patterns of mobilisation?

-

Are there specific organisational arrangements that support or hinder the process of knowledge mobilisation by top managers (i.e. what is the practical influence of context on this process)?

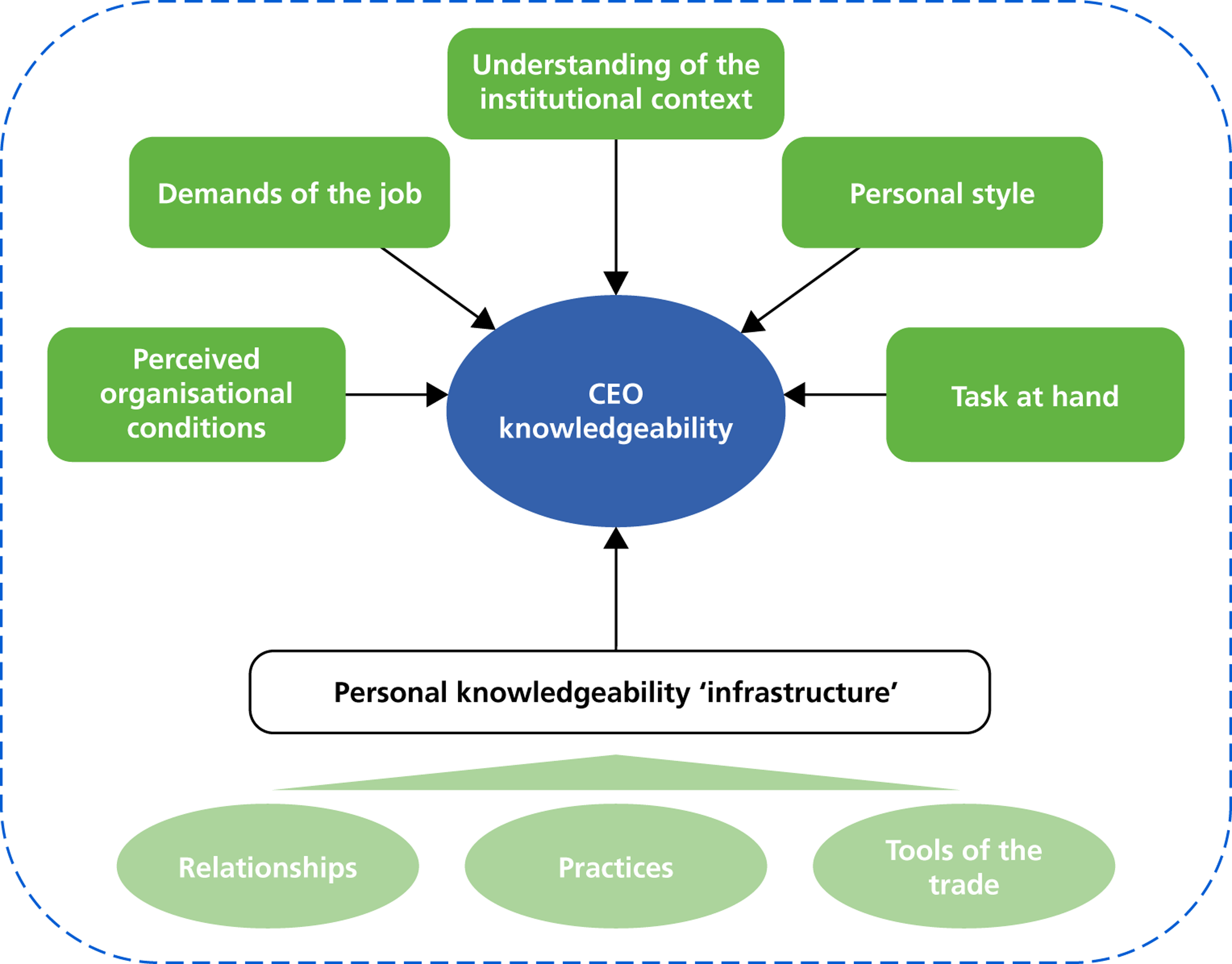

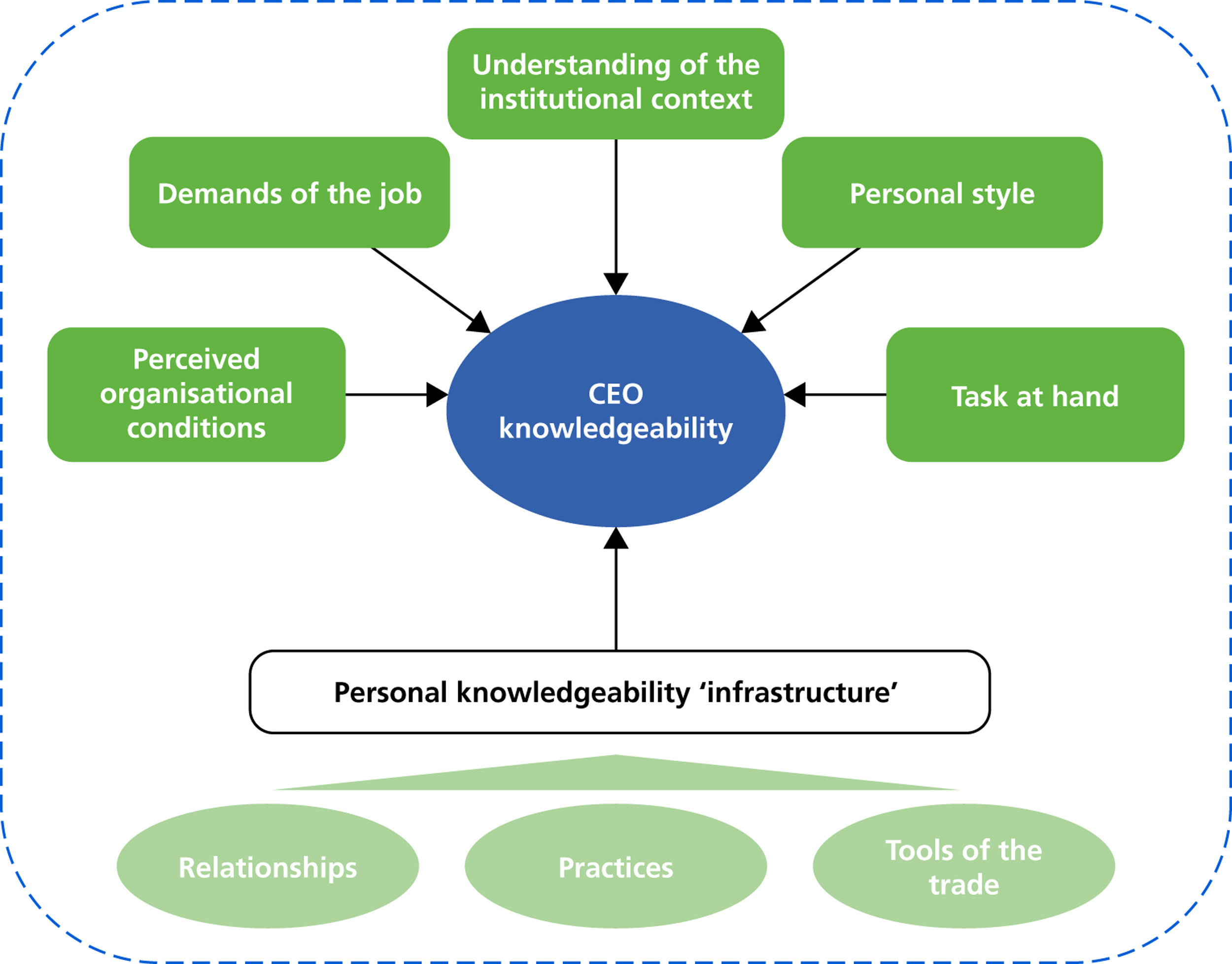

Building on our comprehensive analysis across the seven empirical cases, and informed by the emerging practice view briefly outlined above, we argue that, in order to understand how CEOs make decisions and mobilise particular knowledge and ‘evidence’ towards that goal (but also others), we must take a comprehensive approach to understanding their everyday knowledge work in/as mundane practice. In other words, paying attention solely to the ‘usual suspects’ of knowledge mobilisation, such as externally produced and research-underpinned ‘hard’-information-as-objects and ‘best evidence’, such as evidence-based guidelines, and the question of how these are mobilised towards particular instrumental goals, would have as its inevitable result an impoverished picture of the multiple, messy, non-linear everyday practices making up CEO knowledge work. Consequently, in this report we suggest that the question of how CEOs acquire, process and act on certain information and knowledge is better served by empirically attending to the matter of CEO knowledgeability, that is to the wider question of how CEOs build, maintain and enact their own practices of being knowledgeable as part of their daily work in situ (this echoes Gabbay and Le May’s7 characterisation of professional knowledge as ‘knowledge-in-practice-in-context’).

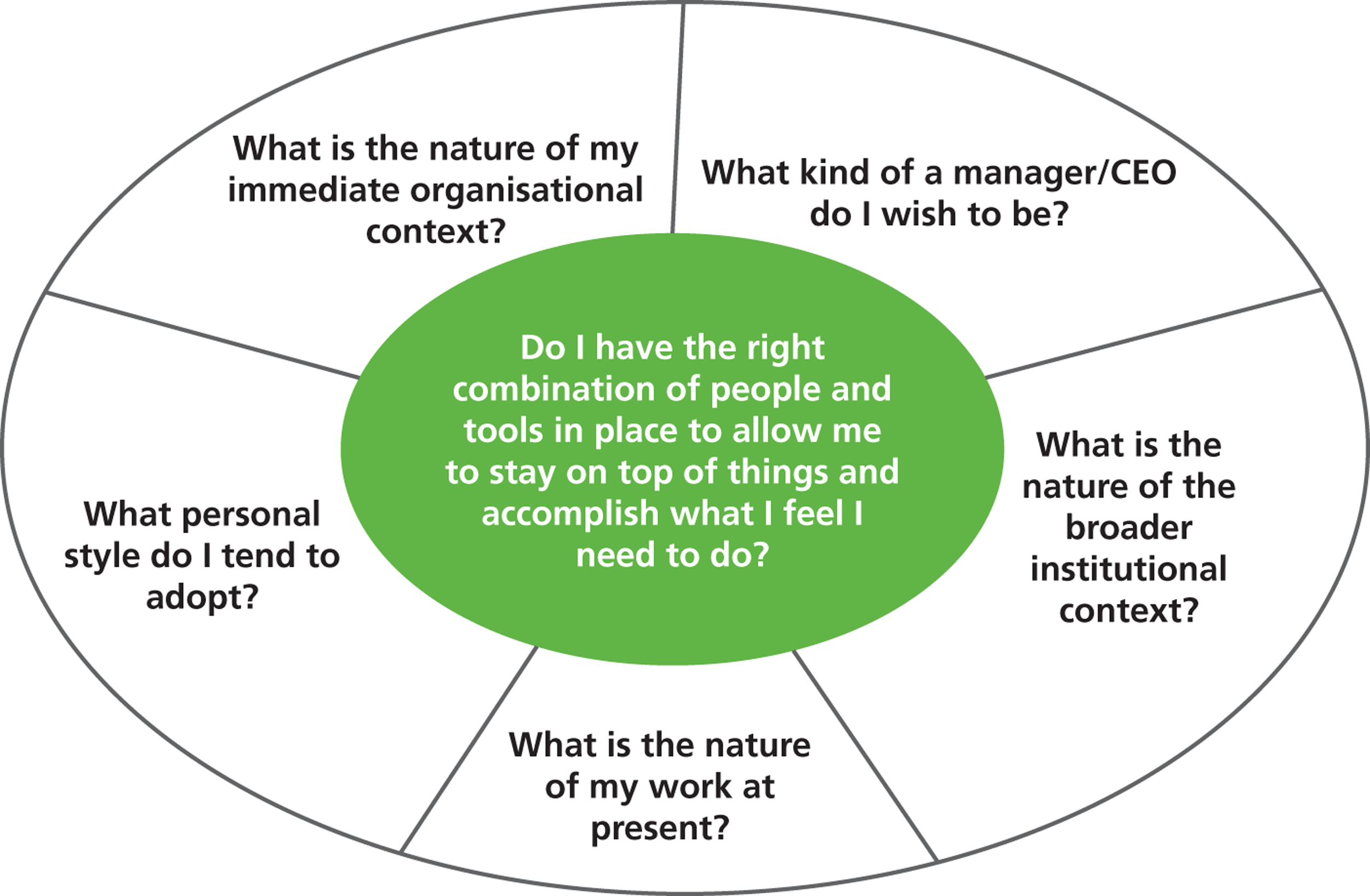

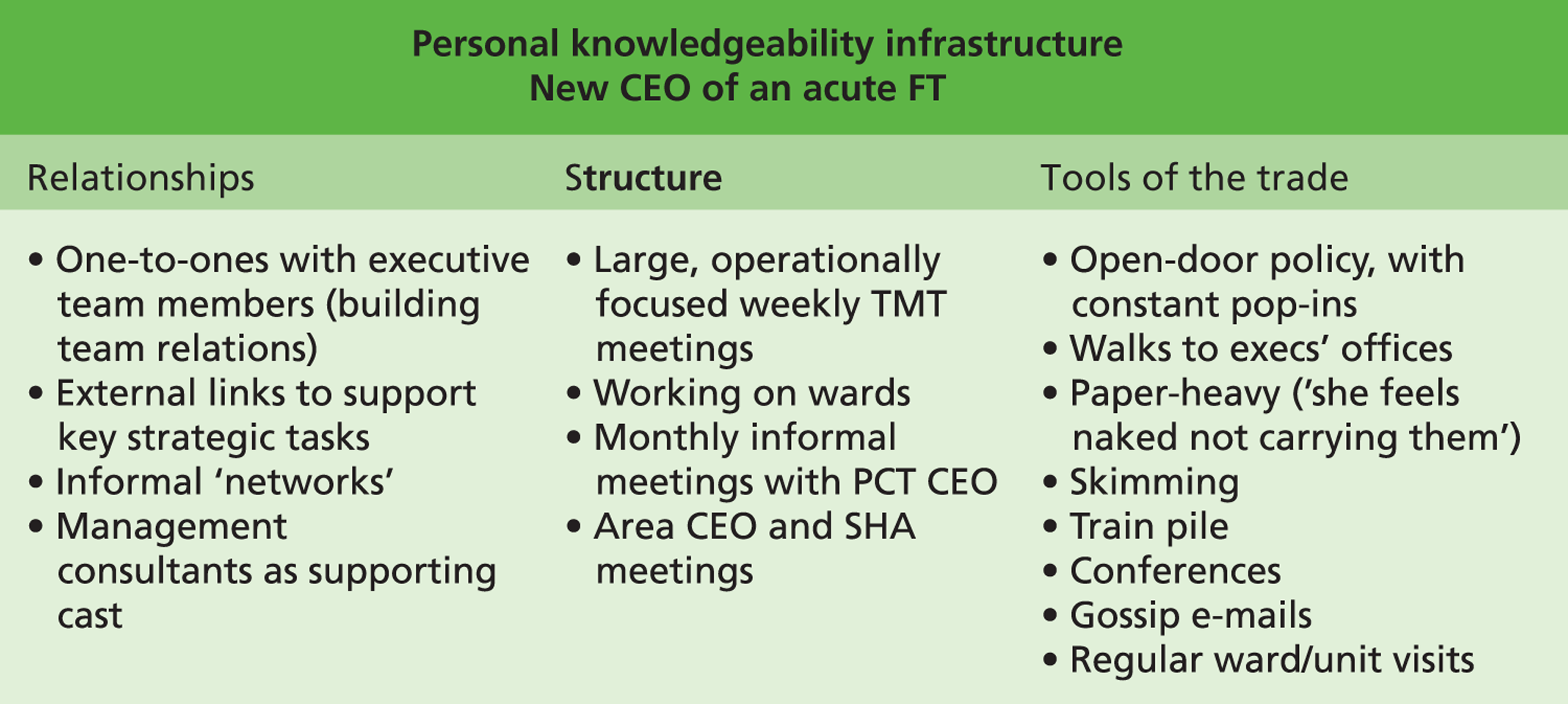

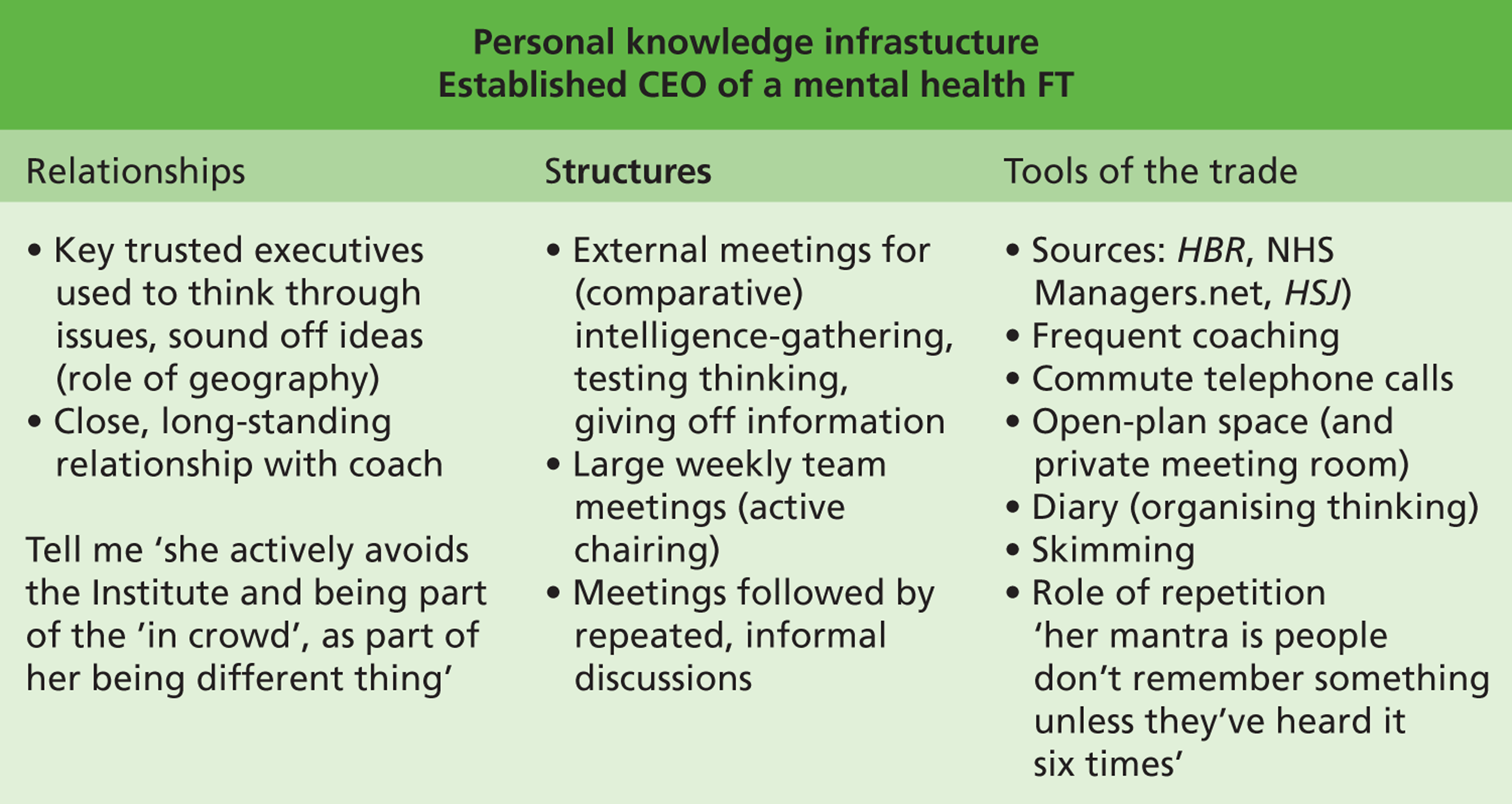

In particular, we consider the many ways in which CEO knowledgeability manifests itself in practice, how CEOs go about continually maintaining their knowledge infrastructures for the different tasks at hand, and how knowledge circulates in what we refer to as the local ecology of knowing, that is the specific contexts of knowledge work CEOs find themselves in, in relation to certain mundane objects and events, such as conversations, meetings and documents. We suggest that CEO knowledge mobilisation-in-practice can be mundane, occasioned or intentional, and that its nature as accomplished stands at the intersection of context, personal style and the CEO’s nature of work. Furthermore, we argue that CEO knowledgeability or everyday knowledge mobilisation-as-practice can be understood as a situated, continually evolving configuration of certain ‘tools of the trade’, that is objects, such as information technology (IT) systems but also publications, and trusted individuals, that they bring to bear in maintaining their practised knowledgeability. These subsequently represent their knowledge infrastructures mentioned above. Finally, we introduce the metaphor of CEOs as weavers, continually weaving together insights, information, experiential knowledge, emergent evidence and contextual needs in the effort of building narratives and ‘connecting the dots’, as a key part of not just what being knowledgeable, but also what being a CEO means in practice. Throughout, we highlight what Gabbay and Le May7 referred to as the ‘social life’ of knowledge, that is ‘the intricate, convoluted and confusing pathways by which people in an organisation negotiate, adapt and transform new knowledge that is often far from factual’.

We do not negate the value of ‘evidence’ as research-informed ‘best practice’ directed at enabling the making of optimal decisions, be they clinical or managerial, or deny that it is used and brought to bear in CEO work as we observed (albeit in specific and relatively rare instances). Instead, what we wish to suggest is that, based on our observations and the work of others,6,7 ‘evidence’ as traditionally conceived makes up one part, not the whole, of what the everyday practice of CEO knowledge mobilisation is about. As we shall see, CEOs themselves, as well as their organisations, are not passive adopters of externally produced ‘evidence’. Instead, we witnessed both systematic and informal ‘construction work’ by CEOs in their effort to create equally legitimate forms of evidential information, which they then brought to bear in their practices of decision-making. These had to do both with creating structures of ‘their’ evidence, but also with relational, negotiation-based creation of certain insights as equally valid forms of ‘evidence that counts’ in the context of particular decisions. Rousseau3 refers to this distinction as the difference between ‘Big E evidence’, or generalisable, cause–effect knowledge, and ‘little e evidence’, or situated, organisationally specific knowledge gathered systematically for the purposes of informing local decisions. As we shall see, however, this distinction still retains the presumption of linearity and formality to the process, which is in conflict with the emergent, often messy and largely informal processes of everyday practice that we observed.

Furthermore, it suggests that the latter have little legitimacy, which, if we take actual observed practice, rather than idealised depictions of it, as our analytical and scholarly guides, makes little pragmatic sense. As Rousseau3 herself acknowledged, the very nature of managerial work (e.g. contradictory pressures; a great many interactions, making the pin-pointing of an actual decision difficult; an absence of a common professional body of knowledge), means that managers often, and quite necessarily, rely on other sources, such as experience, when making decisions. Indeed, in her own words, ‘evidence-based practice is not one-size-fits-all; it’s the best current evidence coupled with informed expert judgement’.

This report begins with a comprehensive overview of the existing literature relevant to the question of knowledge mobilisation of managers and senior executives. In particular, we address in detail two distinct literatures, one on knowledge utilisation and the other on information behaviour, which, though they evolved largely independently of each other, nevertheless had a similar arc of development, from the linear to the social to the practice approach. Next we address the methods and research design, and introduce the sample of the seven trust CEOs and their organisational settings as the key arenas for our empirical research. We then turn to the section on how CEO knowledgeability manifests itself in practice, attending to the main CEO tasks and concerns as observed, and how CEOs make themselves knowledgeable in relation to those. This is followed by a section on information work, which covers the question of how relevant sources that feed CEO knowledgeability are accessed, how knowledge is created and processed in everyday interactions, and how these processes differ across different CEOs observed. This section is followed by a discussion of how CEOs create, use and maintain their knowledge infrastructures as particular mixes of ‘tools of the trade’ in practice, and how knowledge circulates in the local ecology of knowing in relation to certain objects, conversations, and structures. This part of the report is brought to a close with a detailed introduction of the metaphor of CEOs as weavers, via an overview of the work of evidence-in-practice in relation to specific observed CEO decisions and tasks. We then turn to the discussion, where we outline the emerging insights from the research, and in particular introduce the contingent approach to understanding knowledge mobilisation as mundane practice. We conclude with a discussion of emerging implications for research and practice.

Chapter 2 Literature review

This chapter reviews the literature on how managers mobilise knowledge in their effort to ensure the smooth running of the organisations they direct. We were particularly interested in identifying concepts and categories that could help us understand how knowledge (understood as a wide category that includes, but is not limited to, scientifically validated evidence) can be mobilised in, has an impact on and becomes relevant for the practice of executive-level managers.

Our review is specifically focussed on managerial work, which constitutes the topic of the present research. Accordingly, we refrained from an in-depth analysis of the vast corpus of research on the supply and take-up of clinical evidence by front-line clinical staff. 1,2,16–21 While we do not ignore this body of work, we limit ourselves to considering studies and concepts that can be fruitfully translated from the study of clinicians to that of managers. 7 In our review, we also intentionally pay limited attention to the evidence-based management literature. 3,4 This is for two main reasons. First, the debate on evidence-based management has been conducted mainly at a general level, and there is a dearth of in-depth studies of the processes through which managers integrate individual expertise with the best available external evidence from systematic management research. 22 Accordingly, the evidence-based management literature is of scarce use if one is to go and study this phenomenon empirically. Second, the topic has been recently discussed in depth in other work commissioned by the NIHR. 23 Instead, we focus on two bodies of literature that are potentially highly relevant for the topic under consideration, although they mainly lie outside the specific domain of health-care studies. These are the literature on knowledge utilisation and how policy-makers utilise evidence; and the literature on information-seeking behaviour and practices. The latter offers valuable insights on the processes whereby managers seek and utilise information and knowledge, although it is little known in health care or among health-care management scholars.

Given the scarcity of studies of executive managers of health-care organisations in general, and the almost total absence of studies of their knowledge and information practices, our narrative review was conducted using the snowball sampling exploratory method used by Contandriopoulos et al. 24 Accordingly, we relied on a non-keyword search strategy aimed at identifying papers that made a core conceptual or empirical contribution on the topic of managerial knowledge mobilisation and information behaviour. After establishing a few key references in the field, we used the ISI Web of Knowledge Science Citation Index to map the existing literature both retrospectively (i.e. targeting key references in seminal papers, as well as other references cited in later articles) and prospectively (i.e. targeting papers published after the selected seminal paper, using forward citation searching). Articles were clustered according to common underlying assumptions, and adherence to the same broad paradigm and/or the same intellectual tradition. The review, which was conducted at the beginning of the data collection phase and updated after the data analysis, was intentionally theoretically sensitive, rather than comprehensive in character. Our aim was to identify a set of sensitising concepts that could guide us in the conduct of our empirical work and analysis, rather than attempting to provide a systematic overview of all previous work.

Knowledge utilisation and mobilisation by managers and policy-makers

Most of the research on the issue of knowledge mobilisation by policy-makers, managers and decision-makers in general has been conducted under the heading of knowledge utilisation, which includes subfields such as research utilisation and EBP. Knowledge utilisation examines the use of knowledge generated through research for policy and practice decisions. 25 According to Backer,26 ‘knowledge utilisation includes research, scholarly and programmatic intervention activities aimed at increasing the use of knowledge to solve human problems’. Questions typical of this field of interest include:

-

To what specific uses is information put in decision-making?

-

What types of information enter into the decision-making process? Are there some types which are selectively passed over or ignored?

-

Do research findings advance the decision-making process?

-

To what extent do decision-makers take research into account in their work?

-

To what extent do research findings confirm or legitimate decisions which are already taken or about to be taken?25

The analysis of knowledge utilisation has been traditionally framed as an attempt to close the research–practice gap, and closing the ‘great divide’27 between the culture of science and the culture of government. Until recently, most studies adopted a product or process view of knowledge utilisation.

The product view tries to associate specific knowledge products with particular decisions that ‘would not have been made otherwise’. 28,29 Three forms of utilisation are usually considered. Instrumental utilisation captures instances when there is a clear correspondence between an identifiable piece from the corpus of research and specific decisions/interventions. Conceptual utilisation refers to ‘where knowledge of a single study provides new ideas, new theories, and new hypotheses leading to new interpretations about the issues and the facts surrounding the decision-making contexts without inducing changes in decisions’. 28 Symbolic utilisation involves the use of research as a persuasive or political tool to legitimise a position or practice. 30

Weiss31 suggested that knowledge utilisation can be conceptualised according to several different models:

-

The knowledge-driven (or science push) model, which suggests that researchers are producers of knowledge, which needs to be transferred and consumed by practitioners.

-

The problem-solving (or demand pull) model, which explains utilisation on the basis of need. According to this model, when practitioners lack critical information/evidence, they commission appropriate research and information, which is then transferred from researchers to the policy arenas. The relationship between the researcher and policy-maker is conceptualised in terms of producer–consumer.

-

The interactive model, which assumes that research evidence interacts with other sources of information and hence it constitutes only one kind of information to be utilised by practitioners. According to this model, the utilisation process is not linear, but a disorderly set of interconnections and back-and-forthness that defies neat diagrams. Diverse groups of people become involved in a decision-making process and bring their own talents, beliefs and understandings in an effort to make sense of problems.

-

The political model, which suggests that research is often used as political ammunition to support a pre-established position.

-

The tactical model. According to this model, research evidence is used for purposes that have little relation to the substance of the research. What is invoked is the sheer fact that research is being done. Research thus becomes a way to deflect any criticism.

-

The Enlightenment model, according to which social science research is utilised in the sense that it transforms the way people think about social matters, as a backdrop of ideas and orientations.

-

Research as part of the intellectual enterprise of society; that is, research is not utilised per se, rather it responds to the currents of thought and fads of a historical period.

While these models vary in the way they explain the reasons for putting knowledge to work, they all subscribe to an input–output model. The basic idea behind almost all the models listed above is that knowledge utilisation can be conceptualised as an input in the decision-making process. According to Rich25,32 and Rich and Oh33 however, this approach is necessarily limited in that:

-

It builds on a rationalist, simplified and linear view of decision-making, whereby information is first transmitted, then picked up and processed, and finally applied. 25 While the model is not false, it is an abstract description that captures only partly how decision-making unfolds in practice.

-

It ignores the fact that ‘decisions generally do not represent a single event [and they] must be viewed longitudinally’. 25 Accordingly, it is almost impossible to predict when and where a specific knowledge input is likely to have an effect on a particular policy or decision. The same piece of knowledge can also have multiple effects.

-

It underestimates that utilisation is not always tied to a particular action.

-

It does not consider that information is collected for a variety of reasons and not necessarily for purposes of use. 32

-

It ignores that the utilisation of knowledge can have negative and unintended consequences, and that it may be fully rational to ignore available information or actively reject it. 33

Rich32 suggests that, in order to make progress in the study of research utilisation, we need to abandon some of the assumptions of the input–output model and adopt the following wider view. First, knowledge utilisation needs to be reconceptualised as a process that ‘may or may not lead to a specific action by a particular actor at a given point in time’. 32 Second, more types of knowledge need to be taken into consideration and treated differently. For example, mundane types of information must be considered, as they are part of the spectrum of sources available to decision-makers. Third, the information needs of the user need to be taken into consideration. Fourth, types and levels of utilisation can vary over time. Fifth, utilisation is affected by the area in which information is applied, as well as its source. Legitimacy is therefore a fundamental factor. In summary, the rational linear input–output model should be abandoned, or at least its ‘steps’ (transmission, pick-up, processing and application) considered only as loosely coupled, and to be examined each in their own right.

From knowledge utilisation to knowledge mobilisation

A different way to summarise Rich’s32 criticism is to note that most of the study of knowledge mobilisation conducted in the 1980s and early 1990s is underpinned by a very specific view of knowledge (and information), which Cook and Brown34 described as the epistemology of possession. This view tends to conceive knowledge as a type of substance, resource or asset that can be accumulated, transmitted, diffused and utilised. The approach privileges explicit over tacit knowledge, and knowledge possessed by individuals over that possessed by groups. In so doing, it offers a view of knowledge that is severely undersocialised. This is in spite of the fact the knowledge utilisation research has consistently found that the most common facilitator of research use is personal contact between researcher and policy-maker. 35

The increasing attention to the role of social factors in influencing the use of scientific research by policy-makers is captured in the introduction of the concept of ‘knowledge mobilisation’. Knowledge mobilisation was defined by the Canadian Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC)9 as:

moving knowledge into active service for the broadest possible common good. Here knowledge is understood to mean any or all of (1) findings from specific social sciences and humanities research, (2) the accumulated knowledge and experience of social sciences and humanities researchers, and (3) the accumulated knowledge and experience of stakeholders concerned with social, cultural, economic and related issues.

The use of the word ‘mobilisation’ underscores the interactive, social and interpretive nature of the process, whereby individuals and teams acquire knowledge, absorb it and put it to work. According to Levin,36 mobilisation is preferred to utilisation because it emphasises the multi-dimensional, longer-term and often political nature of the work in comparison to earlier terms that seem to imply a ‘one directional and linear move from research to practice’. In contrast to the engineering, linear or ‘pipeline’ models described above as input–output, a socio-organisational view of knowledge mobilisation suggests that:

-

Knowledge is socially constructed and its use takes multiple forms that can be more or less direct and more or less rapid, with slower and less direct impacts being more common. Given this broad view, there is much more use of research and evidence in practice than is generally thought.

-

Knowledge takes shape and has effect in a wide variety of ways, but is always mediated through various social and political processes.

-

Knowledge by itself is not enough to change practice, since practices are social and therefore reinforced by many elements such as norms, cultures and habits. Simply telling people about evidence and urging them to change what they do is clearly ineffective. 36

-

The relationship between knowledge and use runs in both directions; practice affects research, just as research affects practice. Rather than knowledge transfer or mobilisation, we should conceive the process in terms of knowledge interaction. 37

-

Personal contact and interaction remains the most powerful vehicle for moving evidence into practice.

-

Third party organisations of all kinds – sometimes called mediators or brokers – play a critical role in the spread and impact of research. 36

In sum, the knowledge mobilisation approach suggests that the circulation and take-up of knowledge is heavily dependent on existing social relations and processes, and that these need to be brought to the centre of attention. A typically and often quoted example of this approach in health care is the work of Gabbay and Le May. 5 The scholars conducted an observational study of knowledge utilisation in primary care. Contrary to the precepts of knowledge utilisation, they found that explicit evidence was rarely used by doctors in their daily clinical decision-making. Rather clinicians used tacit ‘mind-lines’, which they defined as ‘collectively reinforced, internalised tacit guidelines’. 5 While mind-lines built on the doctor’s early training and experience, and while they were at times informed by short readings, they largely resulted from interactions with other clinicians and stakeholders (opinion leaders, patients, pharmaceutical representatives and other sources). The clinicians, in general, would ‘refine their mind-lines by acquiring tacit knowledge from trusted sources, mainly their colleagues, in ways that were mediated by the organisational features of the practice’. 5 The notion of mind-lines resonates with other concepts, such as ‘community of practice’38 and ‘network of practice’,39 which equally reject linear models of explicit knowledge take-up in favour of interactive models that put social relations and collective sense-making at centre stage. These theories are not discussed here, as they have been the subject of a recent extensive review of the literature funded by the NIHR. 21

What is notable here is that the adoption of a social understanding of knowledge mobilisation shifts the focus of empirical research towards an appreciation that:

-

Knowledge is social in character: it resides in communities of practice, networks of practice and other types of collectives that sustain it, legitimise it and preside over its transmission to the next generation of practitioners via socialisation.

-

Social networks, both informal and formal (e.g. professional associations), constitute at the same time the carriers and the conduits of knowledge and innovation. The nature and structure of networks matter to the circulation and take-up of knowledge. Brokers and boundary spanners acquire fundamental importance.

-

Political considerations, peer pressure, social emulation and interests play a central role in knowledge mobilisation. The social position and social capital of the source and recipient constitute major factors in determining the diffusion and use of research for decision-making.

-

Knowledge does not travel untouched through social interactions, but is necessarily modified in the process. Knowledge mobilisation is therefore necessarily a process of translation. The process allows for the same content to be utilised in different social and cultural contexts.

What is this knowledge that we seek to mobilise? Knowing as practice

As noted by Nicolini,14 while the social approach undermines naive instrumental views of knowledge in organisations, it is still ambivalent in terms of the meaning and status of the knowledge that needs to be mobilised. The social approach is in fact still compatible with the idea that knowledge is a substance that circulates through social ‘plumbing’, and that, once delivered at the right time and place, it can be used as a resource for action. For Greenhalgh and Wieringa,40 claiming that knowledge is created through social interaction and travels through social channels is not enough, as this view still assumes that knowledge equates to impersonal research findings; that knowledge and practice can be cleanly separated both empirically and analytically; and that practice consists of a series of rational decisions.

What is needed instead is recognition that knowing is always manifested in practice and through practice. Knowing is always knowledge-in-action, a form of social expertise and collective knowledgeability situated in the historical, social and cultural context from which it arises. While ways of knowing can be mediated through discourse, narratives, disciplined bodies, symbols and artefacts, knowing is always a practical accomplishment, and practice is where knowledgeability manifests itself and agency becomes possible. Practice, understood as the mediated performance of an activity where such performance has a history and a constituency, constitutes the figure of discourse that enables reconnecting knowing with working, and is the empirical grounds where such a relationship can be investigated. 14,40

Adopting a practice-based view thus completes the shifts initiated by the proponents of the social and contextual understanding of knowledge utilisation or knowledge mobilisation. It does so by indicating that to understand these phenomena one has to start by observing the practice itself, and asking what are the conditions and processes that underpin the individual and collective knowledgeability that enable the local accomplishment of the activity. The knowledge utilised in a decision-making process is in fact often personal, narrative and dialogical in nature. 40 In management, just as in clinical work or policy decision-making, knowledge is necessarily ‘knowledge-in-practice in context’. 7 Researchers should thus avoid approaching knowledge processes as if they were separate activities. Rather, their effort should be that of becoming sensitive to the knowledge dimension of mundane day-to-day work. This includes becoming sensitive to the local criteria of plausibility (what counts as rational, see Greenhalgh and Wieringa40); understanding the nature of the job and the rules of the game that govern it; observing the sociomaterial arrangements within which actors operate; and attending to the contextual constraints and power relations that are performed and sustained by different types of knowing (see, for example, Stevens41 for discussion of the role of power in the use of evidence in policy decision-making in the UK).

As we shall see in the next section, similar conclusions have been arrived at in the discussion of information-seeking behaviour. This research tradition, which stems from library and information studies, has traditionally investigated how people search for and utilise information. Here too there is an emerging sense that, to understand how individuals interact with information systems of all kinds, one has to focus on the mundane everyday activities of actors, asking how they deal with information as part of the conduct of their life and work tasks.

Information behaviour: how managers seek, utilise and interact with information

A number of useful insights on the practice of knowledge mobilisation by top managers can be derived from the field of ‘information behaviour’. The term describes a broad field of study that focuses on the many ways in which human beings interact with information in general, and the ways in which people seek and utilise information in particular.

According to Bates,42 this area of study emerged at the intersection of several disciplinary fields, from library and information science to social informatics and management, in response to a variety of practical and theoretical questions:

Librarians wanted to understand library users better, government agencies wanted to understand how scientists and engineers used technical information in order to promote more rapid uptake of new research results, and social scientists generally were interested in the social uses of information in a variety of senses.

Bates MJ42

For the last several decades, this area of study has generated a number of models and categories to study and analyse the ways in which people seek and utilise information for work-related purposes and in their everyday lives. Many of these models and categories are relevant to our investigation and will be summarised in the next section. The review will adopt a historical perspective. This is because a number of authors42–46 have described a clear paradigm shift in the field that mirrors the debate in the contiguous area of knowledge mobilisation. This evolutionary shift entailed an initial system/resource approach, focused on the sources of information themselves, which was substituted by a cognitive orientation that was more user-centred and focused on the needs and motivations of information-seekers. The approach was further enriched in the 1990s, when attention to contextual and social factors became predominant. In recent times, scholars within the social approach, which has run in parallel with the cognitive and individualistic orientation that remains active, started to converge towards the idea that information-seeking cannot be conceived as a separate activity. This led to the suggestion that information behaviour should be understood and analysed as a type of work that people carry out as part of their everyday or mundane activities. Information work should thus be studied as a form of practice, using naturalistic methods, as we do here.

What counts as information in information behaviour studies

The shift in theoretical sensibilities guiding the research into human information-seeking and use was mirrored in the change and expansion of the core object of its study: ‘information’ itself. Summarising a complex debate that unfolded over several decades,42,47 we can note that information has been academically considered in an increasingly comprehensive way. Initially defined as what is transmitted between a source and a receiver, information is now more broadly understood as ‘a difference that makes a difference’. 48 In particular, the term is assumed ‘to cover all instances where people interact with their environment in any such way that leaves some impression on them – that is, adds or changes their knowledge store’. 42 Impressions can be emotional (as when we react to a piece of news), and the encounter with information can be negative or have no effect, as information can be ignored, denied or rejected. The shift is relevant, as it marks a move away from the idea that information constitutes a substance (the ‘message’), towards a more dynamic view that conceives of information as a process.

This development is, for example, visible in the work of Michael Buckland,49 who developed a widely cited typology that suggested that information can be understood in three different ways. The first is information-as-process. This view refers to the act of informing, or communication of information, and how a person’s state of knowledge is changed. The second takes information to be synonymous with (or similar to) knowledge. This usage denotes the content of what is transmitted or shared or processed (i.e. the knowledge communicated). Finally, information can also be considered as a thing; in this case, the reference is to information objects or products, such as data and documents. These are referred to as ‘information’ because they are regarded as being informative. 42,44 This and other similar typologies, for example McCreadie and Rice’s50 distinction between information as a resource, information as data in the environment (including sounds, smells and objects), information as a representation of knowledge and information as meanings that are created as people go about their lives and try to make sense of their world, are important for at least three reasons.

First, they suggest that a broad and inclusive understanding of information is critical if we want to cast our net widely enough to capture the different aspects of this complex phenomenon. Case,44 for example, suggests that any conceptualisation of information needs to be broad enough so that it:

-

allows for common-sense notions of information used in everyday discourse

-

allows for unintentional origins of information (e.g. observations of the natural world), as well as for purposeful communication among people

-

allows for internally generated information (e.g. memories, constructions), as well as externally generated information (e.g. reading a text)

-

allows for types of information beyond that needed for ‘solving a problem’ or ‘making a decision’

-

admits the importance of informal sources (e.g. friends), as well as formal sources (e.g. data or documents)

-

involves the human mind in the creation, perception or interpretation of information; to leave out such a requirement is to effectively declare that anything is information, which would leave us with no focus in our investigations. 44

Second, the above-listed, inclusive categorisations of information underline the need to examine information behaviour as a process and an activity, rather than a substance. Finally, they indicate that information and knowledge (and data) need to be kept provisionally (and analytically) separated. That is to say, whether the three are overlapping or different is an empirical, not a theoretical question: while sometimes information and knowledge coincide, at other times a variety of social and cognitive processes are necessary so that information can become knowledge.

Information user studies as the departure point: the system-oriented view

The systematic investigation of information-seeking and information retrieval dates back several decades. Until the 1970s, however, the interest of the analysts was limited to the study of the sources, artefacts and venues of information-seeking, and of their use in the context of information retrieval activities. The questions investigated in these studies, which Vakkari51 described as ‘system oriented’, were centred around information needs of a distinct segment of the population, and the capacity of formal systems (universities, libraries, professional conferences, media, schools, etc.) to satisfy them. In short, the main question asked in these studies was ‘how often is a system used and by whom?’

For example, in 1948 Urquhart52 suggested that the study of information-seeking was:

an effort to discover, by means of a questionnaire addressed to readers of publications borrowed from the Science Museum Library, some information on such questions as how references to publications are obtained, what the expected information is required for, and whether, in fact, the publications contain the desired information.

Library studies were accompanied by surveys of specific groups (for example scientists), in the effort to map what their reading habits were, where they got their information from and how they used catalogues. The main strategy for determining what information had actually been used was citation analysis; user satisfaction analysis was utilised, but was relatively rare. The results were often a list of sources, rankings of preferences and maps of resources. These were often used to produce recommendations on how to develop information systems and services. Indeed, many of these studies were promoted or sponsored by the administrators of academic and public institutions.

From information-seeking to information behaviour

Starting in the 1970s, a number of scholars started to recognise the limitations of the ‘system orientation’. This was because the system-oriented studies ignored the attributes of the individuals, and omitted to consider ‘how an individual will apply his or her model or view of the world to the process of needing, seeking, giving, and using information’. 43

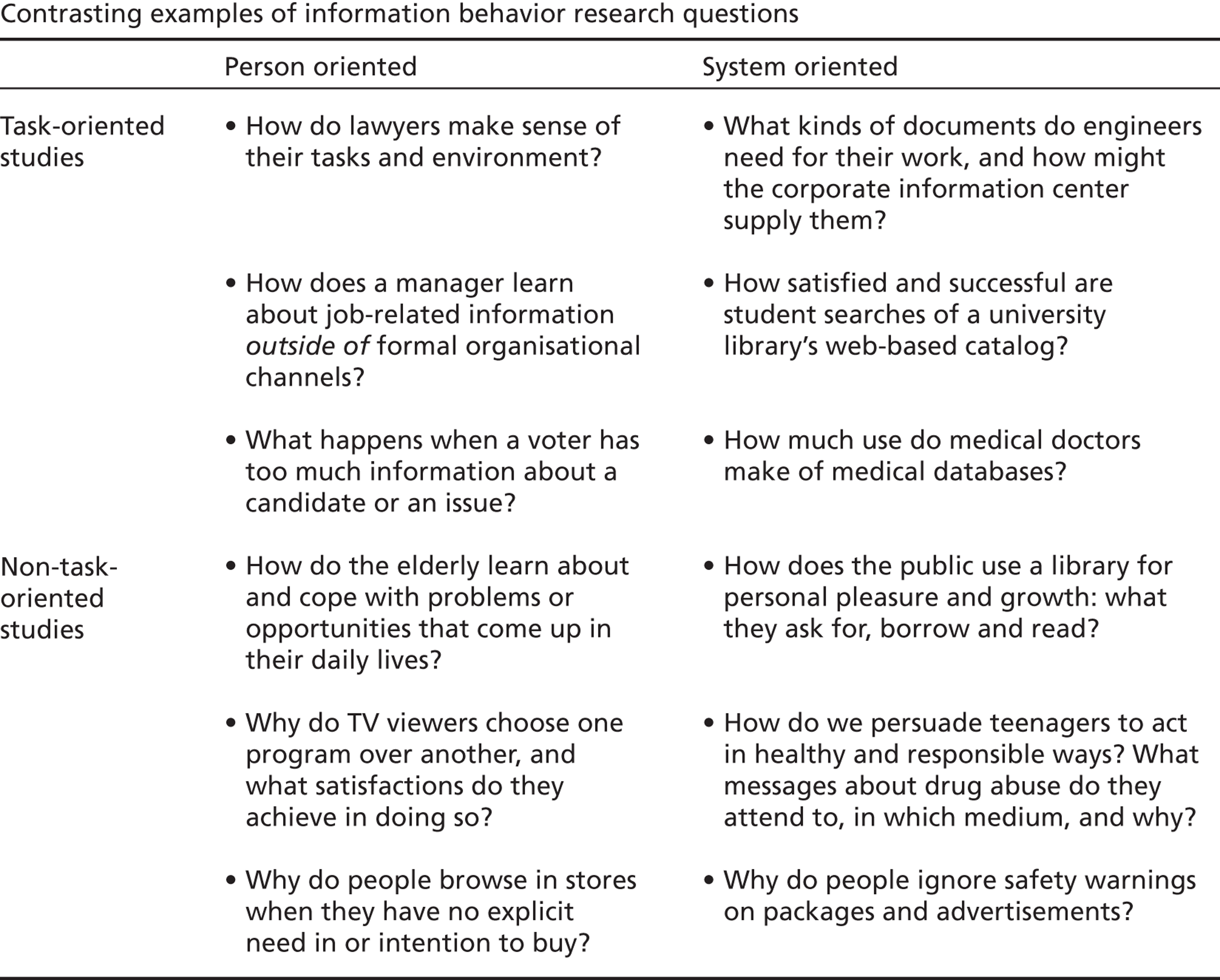

The move towards a person-oriented approach to the study of information retrieval and use was initiated more or less independently by researchers such as Belkin,53 Dervin55–57 and Wilson. 54,58 Their work introduced a strong personal and cognitive dimension to the study of information-seeking, suggesting the need to explore both the cognitive state of information users (considered a variable dependent upon the context of the situation of information-seeking) and their cognitive style and individual personal characteristics. According to Belkin,59 ‘the essence of the cognitive viewpoint is that it explicitly considers that the states of knowledge, beliefs and so on of human beings (or information-processing devices) mediate (or interact with) that which they receive/perceive or produce’. 59 This means that for the study of information behaviour one needs to take into consideration ‘the phenomena and situations of relevance in terms of representations (usually mental) of knowledge, intentions, beliefs, texts and so on’. 59 The attention thus shifts from the institutional and ‘systemic’ conditions to the information, in order to identify the conditions, characteristics and recurrent patterns in information-seeking and retrieval. As the attention moves from externally observable behaviours to personal, cognitive and affective processes, this also requires the adoption of qualitative methods of inquiry, which represents a clear departure from the predominantly quantitative system approach. The differences between the system-oriented and the person-oriented/cognitive approach are summarised in Figure 1. 44

FIGURE 1.

Examples of differences between the system- and the person-oriented/cognitive approaches to information-seeking. Reproduced with permission from Case DO. Looking for Information: A Survey of Research on Information Seeking, Needs and Behaviour. 2nd edn. London: Academic Press; 2007. 44

The person-oriented/cognitive approach thus shifts the focus from the nature, availability and usability of information sources to the nature and determinants of the behaviour of information-seekers. The approach rotates around three conceptual poles:

-

needs/motivations of the information-seeker

-

personal knowledge structures

-

actions.

Overall, the information behaviour approach thus proposes that information-seeking and other types of information behaviour constitute the response to a perceived state of need, or more generally an imbalance in the knowledge structures of individuals. This incompleteness, gap or deficiency, which can be experienced in either cognitive or affective terms, activates repair strategies conditioned by a combination of personal preferences and contextual factors.

Wilson,58 for example, argues that information behaviour arises as a consequence of:

A need perceived by an information user, who, in order to satisfy that need, makes demands upon formal or informal information sources or services, which result in success or failure to find relevant information. If successful, the individual then makes use of the information found and may either fully or partially satisfy the perceived need – or, indeed, fail to satisfy the need and have to reiterate the search process.

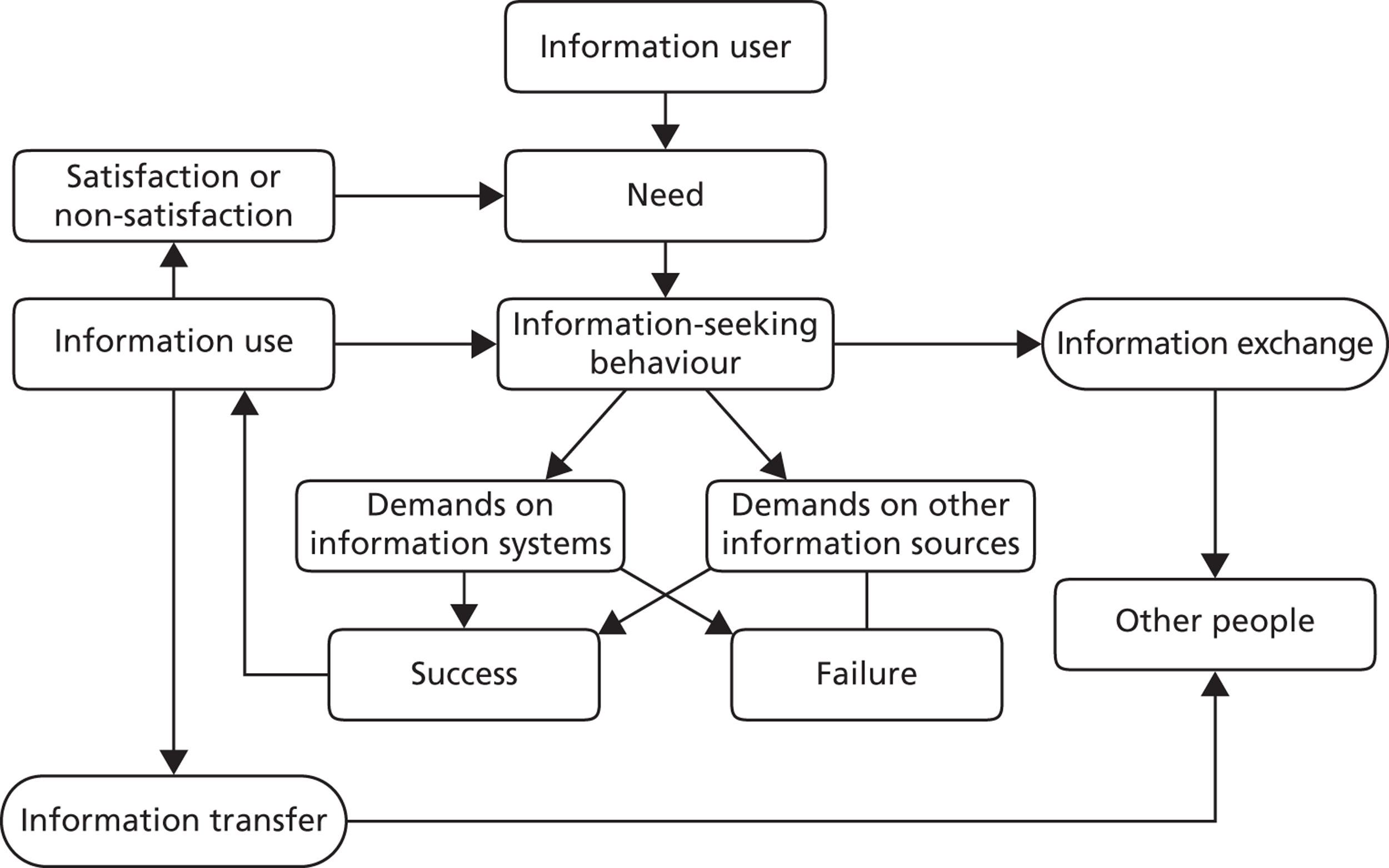

In his updated 1999 model of information behaviour,60 summarised in Figure 2, Wilson suggests that other people may be involved in the process. They can act both as sources (information can be exchanged among humans) and as recipients (information perceived as useful may be passed to other people).

FIGURE 2.

Wilson’s 1999 model of information behaviour. Reproduced with permission from Wilson TD. Models in information behaviour research. J Doc 1999;55:251. 60

As suggested by Figure 2, information needs and motivations are at the core of this approach. For example, Taylor61 suggests that information-seeking starts with an uneasiness or sense of dissatisfaction or curiosity that is often perceived in a very visceral way. In order for information behaviour to be activated, this uneasiness has to go through a number of steps, which aids the need in becoming first conscious and then rational (in the sense of being articulated and qualified). Only at this point does the individual take action in view of the constraints that the contextual conditions impose upon him or her. The final stage of the information-seeking process is thus necessarily a compromise between the information needs and the material opportunities offered by the environment – the implication being that the process may follow a satisficing, rather than completeness model (we stop when we are satisfied, rather than when we fulfil all our needs or obtain all the possible information; see Prabha et al. 62 for a discussion).

Kuhlthau63 found that the stages of the information search process followed by individuals are associated with specific feelings, so that information-seeking has to do with thoughts, actions and affect. The fundamental proposition is that:

the feelings of uncertainty associated with the need to search for information give rise to feelings of doubt, confusion and frustration and that, as the search process proceeds and is increasingly successful, those feelings change: as relevant material is collected confidence increases and is associated with feelings of relief, satisfaction and a sense of direction.

Wilson TD60

For example, the initiation of the search is associated with uncertainty; the selection of potentially relevant items with optimism; the exploration for further material with confusion, frustration and doubt; the formulation of a clear strategy with clarity; the collection of further material with sense of direction and confidence. Finally, the presentation of the results is associated with satisfaction or disappointment. 44,60,62

In partial disagreement with the previous authors, Dervin56,64 suggests that what triggers different types of information behaviour is not so much the immediate need to re-equilibrate our cognitive structures, but rather a more general tension to maintain and restore sense-making. The author consequently focused her attention on people as actors who strive to make sense of their daily world: ‘the individual, in her time and place, needs to make sense . . . She needs to inform herself constantly. Her head is filled with questions. These questions can be seen as her “information needs” ’. 64 The aim of information behaviour scholars is thus to explore the ways in which people face problematic situations and try to make sense of them by posing questions and seeking answers from various sources. Dervin’s approach, which builds on Dewey’s notion of inquiry, has the historical merit of questioning the idea that information is a substance that can be freely transferred without compromise. Information is, rather, created in specific circumstances by one or more humans. The implication is that, to understand information behaviour, one has to employ naturalistic methods, which can help us appreciate the contextual condition within which humans deal with information and turn information into meaning.

According to Dervin,56 such sense-making involves four constituent elements:63

-

a situation in time and space (which defines the context in which information problems arise)

-

a gap (which identifies the difference between the contextual situation and the desired situation, e.g. uncertainty)

-

an outcome (that is the consequences of the sense-making process)

-

a bridge (that is some means of closing the gap between situation and outcome).

Making sense thus implies filling a gap: ‘what is suggested is a gap that can be filled by something that the needing person calls “information” ’. 64 However, as noted by Case,44 for Dervin, ‘looking for “information” is only one response to a “gap” ’. Other responses could include ‘seeking reassurance, expressing feelings, connecting with another human being, and so forth’. 64 In addition, Dervin conceives situation, gap/bridge and outcome as mutually related (in some of her writings, she depicts them as corners of a triangle). 64

While the idea that information-seeking is triggered by a need to know or to reduce uncertainty and anxiety is appealing and largely intuitive, it presents several theoretical and empirical issues. First, needs are not observable. Therefore, whether needs ‘cause’ the search for information is debatable. Although, when asked, people may suggest that needs provide the reason for searching for information, the causal link is impossible to establish empirically. 58 Second, the idea that people seek information only when they need something flies in the face of the evidence that we very often obtain information unintentionally. Information behaviour is thus necessarily a more comprehensive category than information-seeking. Third, to bridge the determination of need and the initiation of action to satisfy the need, there must be an activating mechanism, such as those suggested by risk/reward theory65 or the concept of self-efficacy. Finally, what counts as ‘satisfaction’ of needs varies according to social and historical conditions.

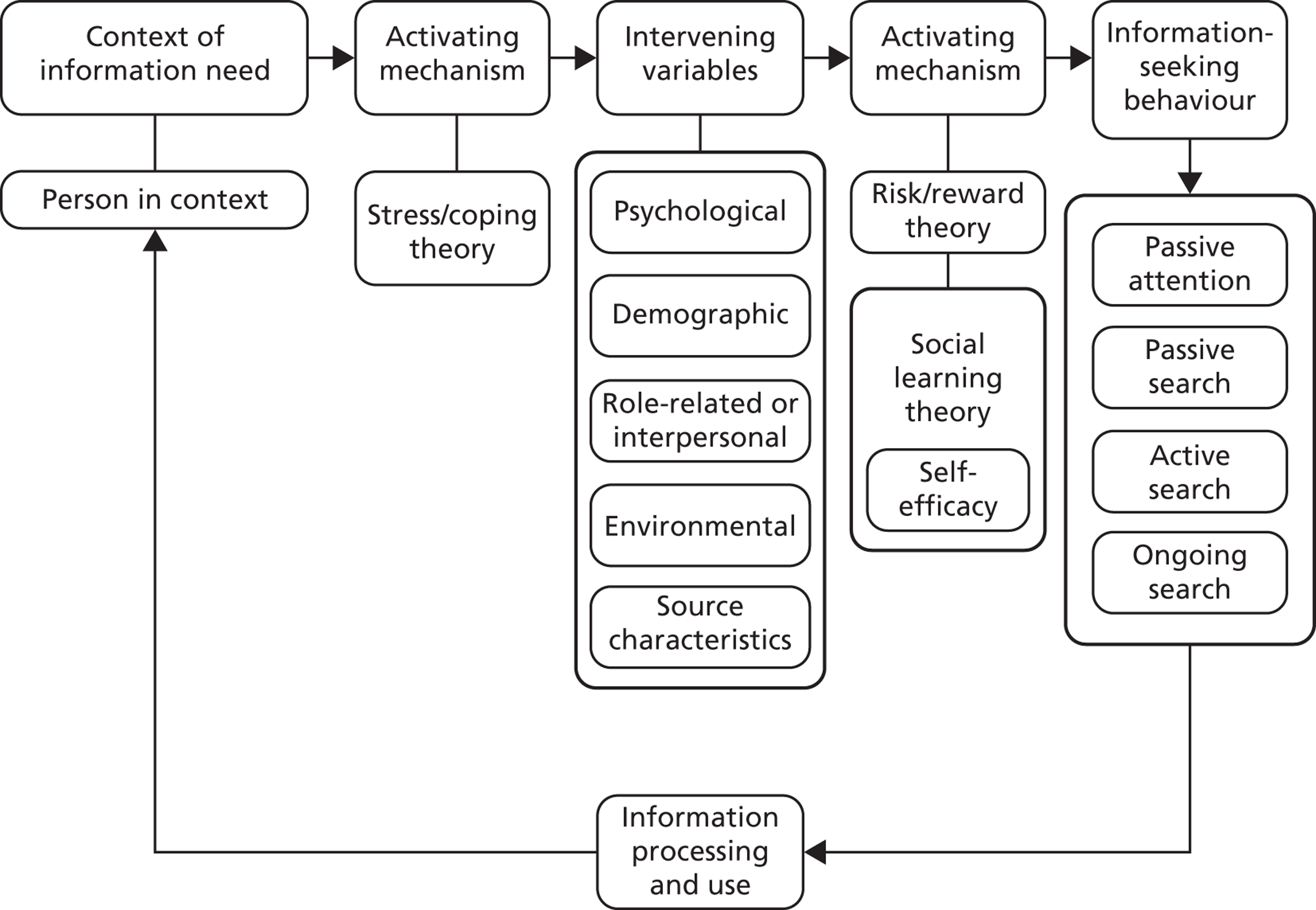

Wilson60,66 tried to address these issues by broadening the idea of information behaviour to incorporate a variety of situations and elements. The author therefore conceived of information behaviour largely as a process of problem-solving that unfolds in stepwise fashion through four stages: problem recognition, problem definition, resolution, and resolution statement. 66 He proposed that information behaviour follows his 1996 model summarised in Figure 3. The model suggests that the needs for problem-specific information arise from the situations in which seekers find themselves; that is, any need for help or information is situationally based and dependent on a particular context. People also tend to look for the information that is most accessible, which is sometimes referred to as the principle of the least effort. Several barriers can prevent people from obtaining the necessary information so that the need can remain unsatisfied. The model also suggests, among other points, that information-searching and information-seeking are two (nested) categories of a broader class of (information) behaviours.

FIGURE 3.

Wilson’s model of information behaviour. Reproduced with permission from Wilson TD. Models in information behaviour research. J Doc 1999;55:257. 60 © Emerald Group Publishing Limited all rights reserved.

In Wilson’s own words:66

information behaviour is the totality of human behaviour in relation to sources and channels of information, including both active and passive information seeking, and information use. Thus, it includes face-to-face communication with others, as well as the passive reception of information, such as, for example, watching TV advertisements, without any intention to act on the information given. Information seeking behaviour is the purposive seeking for information as a consequence of a need to satisfy some goal. Information searching behaviour is the ‘micro-level’ of behaviour employed by the searcher in interacting with information systems of all kinds. It consists of all the interactions with the system, whether at the level of human–computer interaction (for example, use of the computer mouse and clicking on links), or at the intellectual level (for example, adopting a Boolean search strategy or determining the criteria for deciding which of two books selected from adjacent places on a library shelf is most useful), which will also involve mental acts, such as judging the relevance of data or information retrieved. Information use behaviour consists of the physical and mental acts involved in incorporating the information found into the person’s existing knowledge base. It may involve, therefore, physical acts, such as marking sections in a text to note their importance or significance, as well as mental acts that involve, for example, comparison of new information with existing knowledge.

The social perspective on information behaviour

While Wilson’s integrative model discussed at the end of the previous section goes some way towards recognising that information behaviour can be unintentional and context-dependent, it remains necessarily anchored to the principle that, to understand information behaviour and knowledge mobilisation, one has to focus ‘on the individual and on understanding the ways in which each person thinks or behaves in response to information needs’. 43

This assumption was questioned, however, in the 1990s by a group of scholars, who suggested that one of the main deficiencies of the cognitive approach is that it ignores the fact that dealing with knowledge is fundamentally a social process. As Cornelius put it:67

My claim is that information is properly seen not as an objective independent entity as part of a ‘real world’, but that it is a human artefact, constructed and reconstructed within social situations. As in law, every bit of information is only information when understood within its own cultural packaging which allows us to interpret it.

Accordingly, a number of scholars started to utilise social science theory to understand ‘the impact of interpersonal relationships and dynamics of the information flow and on how information sharing is part of human communication’. 43 This resulted in a number of concepts that tried to respond in social terms to some of the critical questions posed by information behaviour scholars: What prompts the search for information? Why do some needs prompt information-seeking more than others? Why are some sources of information used more than others? Why may, or may not, people pursue a goal successfully? What prevents them? And what is the role of social processes and interaction in all of this?

A first way to redefine the issue of information behaviour in social terms is to acknowledge that the social context within which this activity takes place strongly influences both our preferences and choice criteria, and the way we go about mobilising and dealing with information and knowledge. Moreover, the nature of sociomaterial context presides not only over the modes of transmission and circulation of information, but also over how such information will be assimilated and interpreted. Contexts are thus conceived interpretively and holistically as both carriers of relevance and ‘carriers of meaning’. 43

Studying the circulation of information among workers, Chatman68,69 suggested that the way in which people seek, use and communicate information is strongly influenced and largely organised according to the small worlds people inhabit. Small worlds are defined as ‘the social environments where individuals live and work, bonded together by shared interests, expectations and information behaviour and often economic status and geographic proximity as well’. 70 Small worlds are thus settings of everyday life where ‘people have little contact with people outside their immediate social milieu and are only interested in the information that is perceived as useful, that which has a footing in everyday reality, and responds to some practical concern’. 68 According to Savolainen71 small worlds stand for local and often small-scale communities in which activities are routine and fairly predictable. Because small worlds are underpinned by a specific world view and regulated by a shared system of typification (i.e. the roles individuals play are a function of the ways in which they are typed by other members), everyday information-seeking and -sharing is oriented by generally recognised norms, based on beliefs shared by community members. From this, it follows that information behaviour cannot be studied in isolation from the social conditions in which it takes place: in social settings such as small worlds, information behaviour takes a wide range of forms beyond the standardised, stepwise process described by traditional cognitive-oriented information behaviour research. This ranges ‘from the informal exchange of information among friends, to the posting of fliers, to the active avoidance of information that is for some reason deemed inappropriate or dangerous’. 72

The idea of small worlds is strictly related to the notion of information poverty put forward by the same author. According to Chatman,68 some people live in informationally impoverished small worlds, where individuals know that they could and should access useful information but high social costs associated with acquiring this information prevent them from doing so. In order to give others (and themselves) the impression of coping well with their situation, these individuals engage in self-protective conducts (i.e. they find suitable excuses), which seal the boundaries of their small impoverished world, contributing to its perpetuation. In other words, information poverty is a self-perpetuating mechanism. Importantly, the avoidance of information may or may not have anything to do with the actual value or potential usefulness of the information itself. For example:

In a given community, information about different cooking techniques may be actively and enthusiastically passed from person to person, while information about avoiding sexually transmitted diseases may be rejected outright or distributed only with great care, because it is considered to be socially unacceptable.

Chatman EA68

The idea that the way in which people access, exchange and interpret information is strictly related to the social conditions in which this takes place resonates with the results of the study of information-seeking from a social network analysis perspective. For instance, using social network analysis, Borgatti and Cross73 found that the probability of seeking information from another person is a function of knowing what that person knows, valuing what that person knows and being able to gain timely access to that person’s thinking. What the information system behaviour literature adds to the tenets of social network analysis, however, is the identification of specific forms of networking, which helps to explain not only the transfer of information, but also its interpretation and use.

A focus on the social dimension of information-seeking behaviour also underlines that the process whereby information is given meaning and put to work is itself social and discursive in nature. Consequently, information-seeking should be examined as a dialogical and discursive achievement; something that people do together, in communication with each other. The use of information is therefore seen as part of the communicative actions of an individual in context. 74

Information practices and information work

The increased scholarly attention to the role that contextual factors play in orienting people’s information-seeking (as distinct from the individualist approaches characteristic of the assumptions underpinning ‘information behaviour’) has led several authors to reconceptualise information behaviours in terms of practice. The turn to practice makes the argument that traditional studies, developed from an individualistic, cognitive and decontextualised viewpoint, miss the social and collaborative aspects of information acquisition and use. The traditional viewpoint also downplays the fact that information practices are and should be conceived as mundane activities that are implicated in constituting the context of members’ daily work. Information practices are thus always embedded in practical projects, either task-oriented (as in work situations), or as part of broader ways of life. 75

Talja and Hansen,76 for example, emphasise this embeddedness of information practices in work and other social practices, as well as their drawing on the social practice of a community of practitioners, a sociotechnical infrastructure and a common language. According to these authors:

information seeking and retrieval are dimensions of social practices and that they are instances and dimensions of our participation in the social world in diverse roles, and in diverse communities of sharing. Receiving, interpreting, and indexing information . . . are part of the routine accomplishment of work tasks and everyday life.

Talja S and Hansen P76

The social practice approach thus focuses on the joint accomplishment of work through the organisation of social interaction, and the use of supporting technologies and artefacts as an integral part of this interactive process. The approach mandates empirical research efforts that concentrate on actual organisational environments, and on routine and everyday ways of performing situated interactions with and through social and technical resources needed for their accomplishment. 77 Such studies would first seek to form a grassroots-level understanding of epistemic communities and work practices, and then work to base information-seeking and knowledge-sharing processes upon those understandings.

For example, Pettigrew78 studied social settings in which people share everyday information while attending to a focal activity. She suggested that certain social situations and spaces, such as doctors’ offices, hair salons and cafes (or water coolers), can become information grounds, defined as ‘synergistic environment(s) temporarily created when people come together for a singular purpose but from whose behaviour emerges a social atmosphere that fosters the spontaneous and serendipitous sharing of information’. 78 Information grounds are thus socially constructed on the combined perception of place, people and information. Certain locales become information grounds only thanks to the existence of shared projects and goals that descend from the condition of being involved in the same activity (going to the doctor, dealing with your hair or doing the same job).

The approach also allows us to redefine the notion of information literacy in terms of a combination of practices, rather than an individual’s single skills. Information literacy thus emerges as the result of information work, information-sharing and coupling, or ‘the capacity to bring together the explicit knowledge with experiential and relationally based knowledge to produce a way of knowing within the site that is intersubjectively understood’. 79 Information literacy is therefore enacted within a social site and ‘reflects the social, historical, political and economic ways of knowing the shape and characteristics of a specific site’. 79

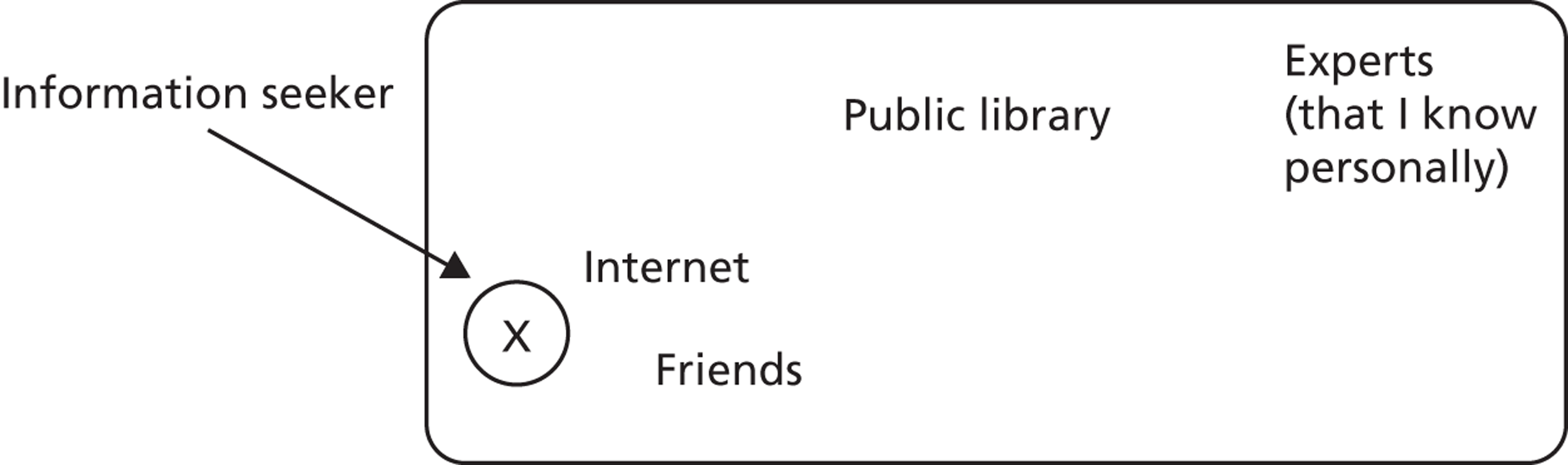

Practices can also be mobilised to explain the preference for (and relevance of) certain sources of information and how such preferences become habitualised and are incorporated in the practices of the information-seekers. Savolainen80 investigated the information horizon of environmental activists, asking what kind of information sources they included in their information source horizons, in the context of seeking problem-specific information; according to what criteria they chose information sources in the above context; and what kind of information pathways they used? He found that human and internet sources were at the top of the list, with people often starting out by searching information on the internet, only to contact a relevant human person soon after. Most importantly, his study suggested that the individuals he interviewed operated within a set information source horizon, which both specifies what individuals consider to be the accessible sources of information and establishes a set of preferences. This is critical, as research suggests that individuals tend to select their sources of information on the basis of their accessibility and perceived reliability or, in case of the humans, social capital. 43 Information source horizons are thus important, as they explain both source preference and relevance.

Information source horizons are in turn created within the broader context of a perceived information environment, defined as ‘a set of information sources of which the actor is aware and of which he or she may have obtained use experiences over years’. 80 When construing an information source horizon, the actor judges the relevance of information sources available in the information environment and selects a set of sources, for example to clarify a problematic issue at hand. A graphic representation of a pathway is provided in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Graphical representation of the information horizon. Reproduced from Savolainen R. Source preferences in the context of seeking problem-specific information. Inf Process Manag 2008;44:274–9380 with permission from Elsevier.

Perceived information environments are deeply rooted in an individual’s habits and tend to change quite slowly. Individuals thus develop information pathways, a notion that describes the sequences in which people use, intend to use or have actually used information sources placed in the information source horizon. Information pathways silently structure the perceived information horizon according to differential orders of relevance, so that certain sources (both human and non-human) are consistently considered as central or marginal. Information pathways and information horizons thus both structure and select (i.e. limit) our information horizon, creating intrinsic and invisible pragmatic biases in our ways of dealing with information.

Overall, the practice approach is underpinned by an increased attention to information work. Information work is firmly contextualised in mundane activities and is a necessary component of ‘the work of living’. 81 It is conceptualised as ‘something essential, dynamic, on-going and social that intermixes with, complements, supports and is supported by other kinds of work’ or ‘everyday life work’. 81 Studying information behaviour as information work therefore requires a focus on the ‘actual labour – the time, effort, resources and outcomes necessary in finding and using information’. 81 One critical implication is that information work is carried out together with, and as part of, other forms of work, and it should not be conceptualised as a separate activity.

What traditional studies have called information-seeking behaviour can thus be respecified in terms of ‘orders of monitoring’. 82 The idea suggests that information sources are monitored daily as a matter of habit; however, which sources are monitored is tightly bound to the routines of day-to-day life. The idea also suggests that information-seeking should be thought of as a stratified affair, progressing from the less to the more intentional. Quoting Erdelez,83 McKenzie84 consequently observed that the label ‘information-seeking behaviour’ ‘is a misnomer because passive and opportunistic information acquisition such as some types of browsing, environmental scanning or information encountering more resembles “gathering” than “hunting”, the active pursuit suggested in the term seeking’. In fact, empirically observed information practices include activities as different as identification of helpful sources, serendipitous encounters, being given information without active seeking, and planned encounters with sources (which can succeed or fail). 84 The author thus suggests that information practices should be ordered along a continuum from the more to the less intentional:

-

active seeking

-

active scanning

-

non-directed monitoring

-

by proxy.

This in turn implies that when addressing content (which together with availability and accessibility is the best predictor of the source of information preferred by seekers; see Savolainen80) we should distinguish between orienting and pragmatic information. While orienting information concerns current events and feeds our need for making sense of the world, pragmatic information derives from actively seeking practical information, which serves as the solution to specific problems. The two coexist, but are very different in nature. The former is fundamentally episodic and often results from some form of inquiry. The latter is regulated by both habit and chance. On the one hand, we all develop practices that feed our existential ‘infoscape’ [e.g. we read the newspaper, check Twitter (Twitter Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) or chat to get the latest office gossip]; on the other hand, we may derive orienting information from encounters that were not intended for this purpose and are partially fortuitous. In this sense, information-seeking is less an active conduct and more an openness to information.

In sum, in the practice approach the emphasis is thus placed on ‘social practices, the concrete and situated activities of interacting people, reproduced in routine social contexts across time and space’. 45 In this sense, the recent developments of the study of information behaviour converge with the debate on knowledge mobilisation discussed in the previous section. Both research traditions suggest in fact that much is to be gained if we focus on everyday practices, as the context within and process through which knowledge is mobilised and information is acquired and dealt with. Mundane activities, knowledgeability and information work should thus be conceived as sides of the same coin (assuming a metaphorical three-sided coin exists). In this sense, while the concept of information practice and information work have been mainly applied to the study of information activities in everyday life, as opposed to professionally connoted situations, it is our tenet that their central assumptions can be meaningfully extended to the study of managerial practices, to shed light on the knowledge mobilisation activities of NHS CEOs.

Information behaviour and managerial practice at chief executive level

The information practice and information behaviour of managers in general, and top managers in particular, have been seldom studied in the literature. As we saw, most of the work on information behaviour has been in fact historically conducted in the field of library and information studies, scientific work and, more recently, in the context of everyday life (for example the information behaviour associated with health-care issues or the pursuit of a serious hobby; see Savolainen45). Notably, information work is widely recognised as a critical aspect in bringing together different managerial roles. Mintzberg,85 for example, suggests that ‘it is the informational roles that tie all managerial work together’. Because of the unique access to external information, and an all-embracing access to internal information, managers, and especially top managers, function as an ‘information-processing system’ that receives information, directs its flow and takes action based on information assimilated. However, the topic has also received scarce attention in the managerial literature. For instance, over 20 years ago, Auster and Choo86 lamented that, in spite of the unequivocal importance of information in managerial work, there is a dearth of knowledge in the literature on information science about how managers acquire and use information in their work. Two decades later, the situation is only marginally improved. More importantly, many of the available studies fail to take into account the most recent development in the field of information behaviour, which we discussed above.

Early studies of managerial information behaviour were conducted by authors such as Aguilar,87 Keegan,88 Fahey et al. 89 and Daft et al. 90 Most of these found that very little systematic scanning was done, and that the focus was often on internal rather than external matters. Things, however, started to change after the radical changes in industry in the 1980s. Daft et al. ,90 for example, found that sectors differed widely in the amount of strategic uncertainty created for CEOs and that ‘customer, economic and competition sectors had greater strategic uncertainty than technological, regulatory and sociocultural sectors’. Chief executives used multiple sources to make sense of their environments, complementing information derived from personal interactions with written sources (so that, when one weak signal was detected using one type of source, other sources were used to expand and clarify its meaning – the study was conducted before the wide diffusion of the internet). Importantly, Daft and his colleagues also found that ‘chief executive scanning in higher-performing firms was characterized by more frequent scanning and by careful tailoring of scanning to perceived strategic uncertainty compared to chief executives in lower-performing firms’. 90 Chief executive officers defined as high-performing thus scanned more often, and cast their net wider than their less well-performing peers.

Auster and Choo86,91,92 replicated the Daft et al. study in Canada. Like Daft et al. they found that the level of scanning increased with perceived uncertainty, and that Canadian CEOs combined internal and external, human and non-human sources to satisfy their information needs. Unlike previous studies in other sectors, they found that source quality (rather than accessibility) was the most important factor in explaining source use in scanning. Their explanation was that, given the inherent difficulty and high level of uncertainty in which modern managers operate, the effort is focused on operating with the best possible available data on the environment; thus quality is more important than accessibility (although things may have changed with the advent of the internet).