Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/2001/19. The contractual start date was in September 2010. The final report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

During the MIA project, Monica Lakhanpaul was appointed as a National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Fellow, member of the NHS Evidence advisory board, the Health Technology Assessment advisory panel and the Drugs and Therapeutics Bulletin editorial panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Lakhanpaul et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Overview and background of the Management and Interventions for Asthma project

The Management and Interventions for Asthma (MIA) project, carried out in a largely urban area in and around Leicester, UK, aimed to work with families from Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnic backgrounds and healthcare professionals (HCPs) to collaboratively design interventions to improve management of childhood asthma in South Asian children. The MIA project consisted of three principal phases of work. The first phase consisted of a review of literature separately funded by Asthma UK, on barriers and facilitators to optimal management of asthma in South Asian families. In phase 2, exploration of community, family and HCPs’ perceptions of asthma and the asthma management pathway in South Asian families followed. This in turn led to the development of an asthma management intervention-planning framework and then a tailored focused, multifaceted, integrated programme to address one exemplar key issue identified. This chapter provides an overview of the background, aims and objectives of the integrated phases for the MIA project.

Introduction

The Management and Interventions for Asthma project

There is unacceptable variation across the country in the quality of care for children, e.g. in the treatment of long-term conditions such as asthma and diabetes. We want the NHS to do even more to improve care for children and young people. 1

While the burden of chronic illness (e.g. asthma and diabetes) continues to increase, the NHS is undergoing financial constraints. In children, it is noted that the outcomes for those with chronic disease are one of the worst in Europe, with death rates for illnesses that rely heavily on primary care services such as asthma being higher in the UK than in other countries. 2,3 The report also indicates that 75% of hospital admissions for children with asthma could have been prevented with better primary care. 2 Asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions in childhood, with inequalities existing in some ethnic minority groups. Children in South Asian communities, a group traditionally considered to be ‘hard to reach’, are known to suffer from under-recognition of symptoms/disease severity and increased attendance to the emergency department. The British Thoracic Society (BTS) guideline4 recommends that HCPs have a heightened awareness of the complex needs of minority ethnic groups among other named vulnerable groups. This is due to the recognition that care in minority ethnic groups is suboptimal and that there is a variation in the health care that they receive.

The Government White Paper5 recognises the importance of contextual factors and their contribution to maintaining good health, not only to the importance of employment and socioeconomic status (SES) but also to the environment and family relationships. An individual’s culture, beliefs and attitudes and those of their community also have an influence on behaviour towards their own health and their interaction with the health system. The Children’s Outcome forum report2 and Healthy Lives, Healthy People5 have not only recommended stronger partnerships between individuals, health, local authority and the voluntary sector to develop an integrated approach to health to tackle some of these issues, but have also delivered a strong recommendation to ensure that the voices of children, young people and their families are heard so that they can contribute to the improvements in services they will be accessing. Consequently, NHS HCPs, commissioners and policy makers are working more collaboratively with their communities so that services can be tailored to their needs. Tailoring, although recommended by a Cochrane review of 26 studies6 as an approach to intervention development, is, however, supported by little evidence on how the actual transition from evidence and theory to the design of the practical interventions should be made. Michie7 recommended that intervention developments use available evidence to inform and support the intervention. Michie7 noted that suggestions for intervention design tended to be evidence inspired rather than evidence based and that there is a need for studies of techniques, methods of delivery and implementation and use in a variety of target populations to identify the techniques and combinations that are needed to result in effective interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration ‘Equity’ group8,9 also noted that the evidence base for interventions to address inequalities is fundamentally flawed and recommended further research to inform intervention development.

The MIA project, therefore, chose asthma as an exemplar to demonstrate the processes aimed to enable collaboration between South Asian children, families, communities and HCPs to produce a multifaceted health intervention framework for asthma management tailored to the needs of South Asian children of primary school age, using a participatory, theory-based approach with an aim that the process could be transferrable to other chronic conditions and communities.

This introductory chapter explains, in more detail, why the MIA study focused on South Asian children with asthma and why the project adopted a participatory approach towards the development of the intervention framework.

Asthma

Asthma affects individuals of all ages. It is a disease characterised by recurrent attacks of breathlessness and wheezing, which vary in severity and frequency from person to person. In an individual, they may occur from hour to hour and day to day. 10

World Health Organization

Asthma produces a significant workload for general practice, hospital outpatient clinics and inpatient admissions. Asthma is responsible for 4 million general practitioner (GP) consultations, 70,000 hospital admissions and over 1000 deaths per year in the UK,11,12 and 1.1 million children are currently receiving treatment for asthma in the UK. 11 The total cost to the UK economy, including the use of primary and secondary care services, emergency services, medications and lost productivity from days off work/school, is estimated to be over £2.3B per year. 12 It is clear that much of this morbidity relates to poor management, particularly the underuse of preventative medicine. 4 While the patient with severe asthma is easy to recognise, patients with mild asthma merge imperceptibly with well people, with fluctuation between normal and asthmatic states. 13

Asthma and children

Childhood asthma is one of the most common chronic conditions of childhood. In the UK, current prevalence estimates suggest that 1.1 million children, or 1 in 11 children, will experience asthma at some point in their childhood. 11 Every year, 44,000 children are admitted to hospital, with between 40 and 50 children dying as a result of asthma. 11 In children under the age of 5 years, it is very difficult to differentiate, with any degree of certainty, wheezing attacks due to asthma from viral infections. Measurements of respiratory function is also known to be difficult, with very young children responding differently to many of the available drugs. 13 As a consequence, asthma places a substantial burden of care on families, communities and the health services. 11

Evidence suggests that UK children’s health services provide inferior care compared with equivalent European countries. 14 Wolfe et al. 14 acknowledged that, while there are pockets of good practice, there are also poor outcomes with services planned around the needs of organisations and providers rather than the children, young people and families. This ultimately means that services fail to recognise children and young people’s specific requirements, or acknowledge important recommendations for children’s health care. 15 Key recommendations from the Marmot Review16 indicate that investments in children’s services should be carefully planned and fit for purpose in order to improve care and reduce inequality while improving overall efficiency. The challenge for researchers, clinicians and policy makers is to understand what and why variations in care exist and to explore how these variations could be addressed.

Asthma management and control in children

Asthma management encompasses the whole pathway from awareness of asthma itself, recognition of symptoms, diagnostic, pharmacological, educational, clinical and preventative elements which reflect the diverse impact of asthma on a child’s life. This therefore includes both modifiable and non-modifiable factors, such as parental knowledge and compliance with medication (modifiable) and genetic variations in asthma phenotypes (non-modifiable). The asthma management pathway for the purposes of the MIA study has been defined by the research team as ‘stages of ideal care required to recognise, diagnose, treat and optimally manage asthma’.

In order to intervene in any condition, the issues present in its management must first be understood. The National Service Framework (NSF) for Children Asthma Exemplar17 highlights the many aspects of management along a patient journey from the onset of symptoms through to achieving asthma control and, while the mortality associated with asthma may be limited to acute asthma attacks, the morbidity associated with asthma is widespread. As a result, over the last 15 years HCPs have moved from a focus on treating acute asthma attacks to achieving overall asthma control. The US National Asthma Education and Prevention Programme (NAEPP) guideline defines control as ‘the degree to which the manifestations of asthma (symptoms, functional impairments, and risks of untoward events) are minimised and the goals of therapy are met’ (p. 36). 18 In contrast, the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA), acknowledges that control can be defined in different ways and suggests that assessment of asthma control should include ‘control of the clinical manifestations (symptoms, night waking, reliever use, activity limitation, lung function), but also control of the expected future risk to the patient such as exacerbations, accelerated decline in lung function and side effects of treatment’ (p. 23). 19 The British Guidelines on the Management of Asthma state that the aim of asthma management is control. Complete control of asthma is defined as ‘no day time symptoms, no night-time awakening due to asthma, no need for rescue medication, no exacerbations, no limitations on activity including exercise, normal lung function and minimal side effects from medication’ (p. 37). 4 It also means that a child’s asthma will not interfere with his or her daily life including exercise and going to school, in addition to having normal breathing tests, for example peak flow and spirometry. 4 Having good asthma control therefore reduces the risk of children having asthma attacks. 4

Minority ethnic health and the UK

Minority ethnic groups often experience higher morbidity and mortality than majority populations for a range of chronic diseases. 20 Erickson et al. 21 indicated that minority ethnic groups frequently have poor outcomes for long-term conditions. Finding effective interventions to address these health inequalities is, therefore, important. The need to reduce inequalities in health outcomes between majority and minority groups is widely recognised by governments22,23 and physician groups. 24 There is a considerable body of evidence that indicates that some minority ethnic groups in the UK experience disproportionate levels of morbidity and mortality compared with the majority White European-origin population. 25 However, while there are significant differences in health outcomes between ethnic groups, it is important to note that there are also differences in health outcomes within minority ethnic groups. 26 Even where inequalities in health status are not present, there is evidence of inequity in access to health care and preventive services with worse patient experience. 27

The Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report28 highlighted both ethnic and class-related inequalities in health and recommended that minority ethnic groups be specifically considered in needs assessment, resource allocation, healthcare planning and provision. The 2010 White Paper Equity and Excellence focused on the need to address ethnicity and inequalities in health,29 with the Marmot Review16 identifying numerous influences on health inequalities and the urgent need to address them. While restructuring of NHS and Department of Health management has continued, a commitment to adhere to the equality and diversity objectives and the ‘Public Sector Equality Duty’ laid out in the Equality Act 2010 remains in Government policy and NHS pronouncements.

Asthma and South Asian children

In the UK, people of South Asian origin with asthma experience excess morbidity, with hospitalisation rates three times those of the majority White population. 30 There is evidence to suggest a disproportionate impact of asthma on minority ethnic children, with calls to urgently redress this imbalance. 31,32 A 13-trial meta-analysis30 reported lower prevalence of wheeze and asthma in South Asian children than in White British children, but the same prevalence of exercise-induced bronchospasm on objective testing. These findings suggested an underdiagnosis of asthma in South Asian children. The meta-analysis additionally reported that, once diagnosed with asthma, South Asian children were less likely to receive prescriptions for reliever and preventer medications than their White British counterparts.

Additionally, further UK data indicate that South Asian children with asthma are more likely to suffer uncontrolled symptoms and be admitted to hospital with acute asthma than White British children, with no evidence to suggest that South Asian children have more severe asthma. 30,31,33 There are numerous risk factors associated with asthma, some of which have been specifically highlighted in relation to South Asian children. Several reports identify being UK born (compared with being of the same ethnic origin but non-UK born) as a risk factor for developing asthma. 34,35 Gilthorpe et al. 36 and Rona et al. 37 both indicated that sex may be relevant. Furthermore, Gilthorpe et al. 36 reported that Pakistani and Indian boys tended to use emergency department (ED) services more than other groups or sexes, with Rona et al. 37 identifying that the male sex is a risk factor for developing asthma.

Socioeconomic status is an important determinant of asthma control for both South Asian and majority populations,31,36 as low SES is associated with poor access to primary health care and higher hospitalisation. However, even with adjustment for SES, there is still a correlation between South Asian ethnicity and poorer health outcomes for asthma. 36,38 Potential explanations include ethnicity-specific health beliefs and explanatory models of asthma,39–43 which in turn influence concordance and adherence to management plans. 44 In Leicester, the hospital admission rate for South Asian children is 4.6 times higher than for White British children. 33 Given the high number of families of Asian descent living in the UK, with the three largest groups being of South Asian origin (Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi),45 the inequalities experienced by South Asian children are of significant concern.

Barriers and facilitators to asthma management in South Asian children

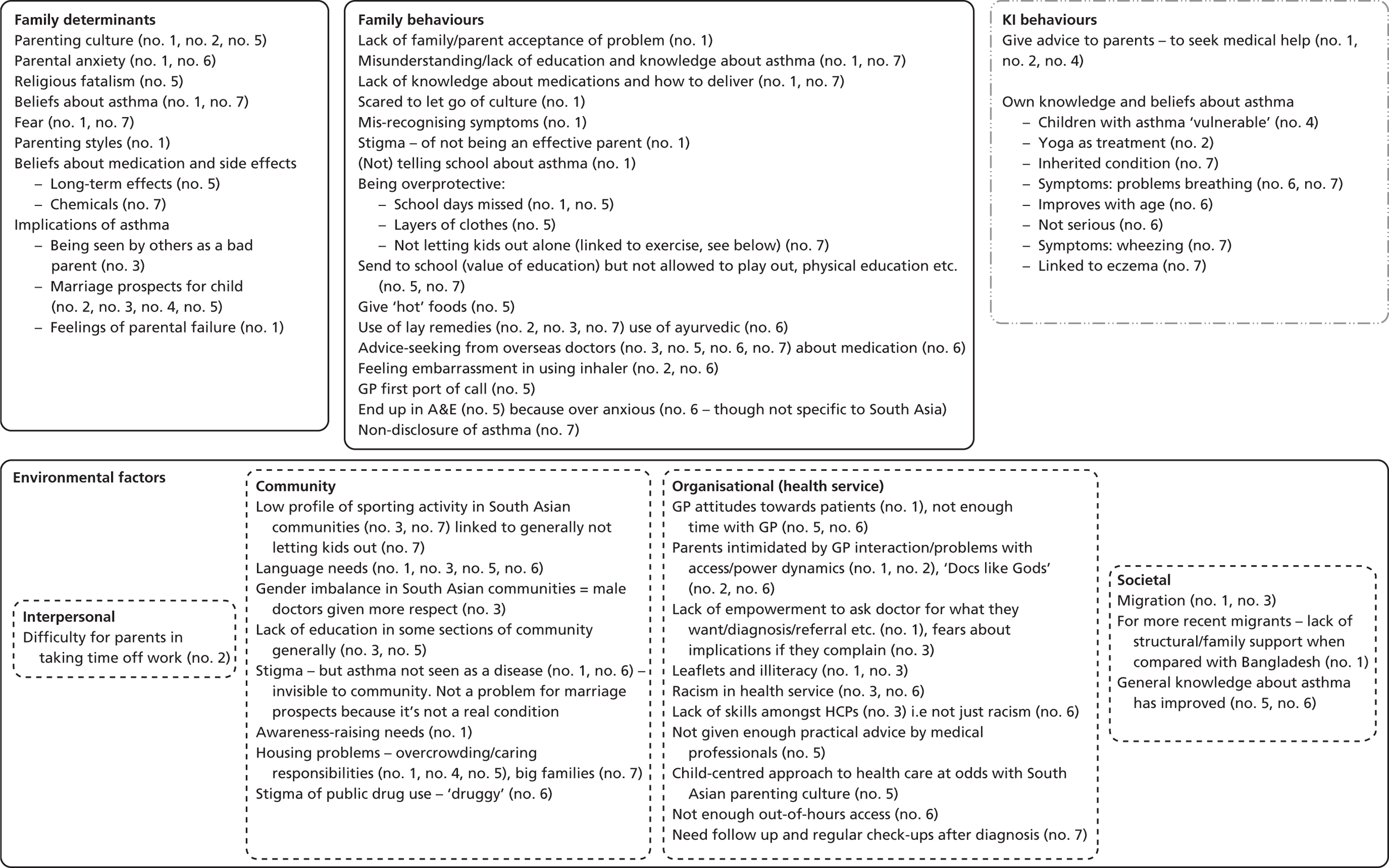

An Asthma UK-funded review on the barriers and facilitators to asthma management in South Asian children was carried out by members of the MIA research team (see Appendix 1). 46 The review identified barriers including knowledge gaps and erroneous beliefs regarding the nature of asthma, underuse of preventer medications (due to underprescription and fears of overuse), non-acceptance and denial of asthma, reliance on EDs in preference to primary care, difficulties in perception of symptom severity, language barriers and use of complementary therapies.

The review highlighted the importance of not only establishing what a barrier might be, but also exploring why that barrier exists. For each barrier identified, there were various documented and theorised explanations; however, the majority of studies did not identify clear associations between a barrier, its explanations and management behaviour. Several key issues were identified as likely to be ethnic-specific in relation to South Asian families: the impact of parental and professional knowledge and beliefs; access to health services and preventer medication utilisation patterns; dietary modifications; and the presence and impact of prejudice and stigmatisation.

Given the large number of potential barriers and explanations that may impact upon asthma management, it is understandable that clinicians may be daunted by the prospect of attempting to address these barriers in everyday practice. Nonetheless, these findings highlight the importance of cultural and community beliefs. For example, there is minimal evidence to support the theory that dietary restrictions are an appropriate method for asthma management. As a consequence, they are often not considered a key factor in asthma management according to the BTS guidelines, used by the majority of British practitioners. 47 However, it was identified that beliefs and practices concerning food and asthma are prevalent among minority families in the UK. Thus, there is a need for clear and clinically applicable interventions that have considered the various barriers and explanatory factors, including the impact of cultural and community beliefs. While identifying ethnicity-specific barriers is important in developing ethnically tailored intervention programmes, academics and clinicians must guard against assuming too great a role for ethnicity. In exploring cultural difference, it is important not to ignore the commonalities in experience between ethnic groups. 48 The focus of research, therefore, needs to shift towards clearly linking ethnic-specific beliefs, barriers and management practices to development of interventions and improving clinical outcomes. A shift also needs to be made from a focus on deficit models of culture in minority ethnic groups as an explanation for health inequalities towards an approach which recognises the responsibility of healthcare systems to develop services which are sensitive and appropriate to the needs of their communities.

Interventions in asthma management

Asthma management and morbidity can be improved by effective interventions including increasing awareness of trigger factors, new ways of monitoring of symptoms, or the usage of newer medications and written self-management plans. 49 The BTS guideline for asthma4 and an Asthma UK systematic evidence synthesis carried out by the MIA research team (www.asthma.org.uk)46 regarded education as an important step in asthma management. A Cochrane review50 found that education-based strategies for improving self-management in children can reduce school absences and emergency visits. For primary school-aged children, a variety of educational interventions and techniques, including group or individual sessions at home, clinic or school, use of didactic teaching, written materials, role plays/problem-solving, artistic activities, games and puzzles, were all used to educate children, their families, their teachers and their doctors about asthma. 50 However, a subsequent systematic review51 concluded that information-only education resulted in very little improvement in any clinical outcome measure.

There have been several successful reported interventions with reference to children and asthma that focus on issues other than education. These have included a community-based programme to identify and address environmental triggers,52 a school nurse initiative to ensure correct use of inhalers through supervised monitoring,53 child-centred, psychology-based training to enhance self-belief and management,54 a web-based intervention using an online diary, interactive symptom manager and reminder system55 and a nurse-led outreach programme for practical advice, support and education. 56 However, while these and many other programmes report success in improving various aspects of asthma management, they either excluded minority ethnic groups, or were significantly less effective or successful in minority ethnic groups. This may, consequently, increase inequality. Even when language-appropriate educational materials are provided, educational interventions still provide better outcomes for White patients than for South Asian patients. 57 The development of cost-effective interventions to reduce morbidity in minority populations with asthma must, therefore, remain a high priority,58 with evidence suggesting that, while most interventions are focused on one particular domain, an effective asthma management needs to be multifaceted. The MIA project was based on the recognition that, when trying to understand health behaviour, it is important to explore not just the beliefs and attitudes of individual patients, but also the wider socioeconomic, cultural and environmental context. These must be integrated to develop multifaceted interventions which can support individuals across the whole pathway of care and wider health system.

Intervention design

A 2004 literature review regarding the design of interventions to change health behaviours7 concluded that many intervention evaluations were inconclusive due to research design limitations and, as a consequence, represented a waste of resources, time and effort. It has been suggested that health interventions are often developed without sufficient consideration given to their evidential or theoretical base, their fundamental design or appropriateness to the target population. 59

Tailored interventions

One important issue in intervention design thus concerns the need to tailor interventions to specific populations. The Medical Research Council (MRC)60 guidance on the design of complex interventions suggests that, rather than assume that standardised interventions designed for generic groups are applicable to all groups, interventions should be tailored to the needs of ethnic minority groups as these are more likely to succeed than generic approaches. The MRC argue that complex interventions may work best if tailored to local circumstances such as ethnicity or SES, rather than being completely standardised. 60 Three systematic reviews have addressed the question of whether or not culturally sensitive education programmes are more effective than generic ones;61–64 all three concluded that, while the reviews were limited by the small number of available trials for inclusion, culturally sensitive programmes were more effective with further study warranted.

A Cochrane review of interventions for improving asthma management in children demonstrated that interventions specifically tailored to address the needs of ethnic minority groups were more successful than those focusing on the generic population. 61 A further Cochrane review explored whether or not culture-specific asthma programmes, in comparison with generic asthma education programmes or care, improved asthma-related outcomes in children and adults with asthma who belonged to minority groups. 65 Interventions included individual asthma educational sessions focusing on relational and collaborative asthma management among children, parents, families, physicians and mental health specialists; and others on the optimisation of treatment and improving knowledge about disease severity and medication. The report noted that the use of culturally specific asthma education programmes for children from minority groups was effective at improving overall asthma-knowledge scores for children. However, it failed to note significant improvements in the number of participants with asthma exacerbations or its frequency, including ED visits. While the report noted a benefit of tailoring interventions to be culture-specific with regard to asthma knowledge in children, the evidence base was lacking and, as a result, these findings could not be confirmed.

Adaptation and tailoring

There remains some controversy over the relative merits of ‘adaptation’ and ‘tailoring’ and the difference between these. Based on a systematic review of the literature, a recent Health Technology Assessment review66 discussed this at great length in relation to minority ethnic groups. It noted that some intervention studies reported were based on generic interventions already operating for mainstream populations, which had been altered to meet the characteristics of the ethnic population that it was (intended to be) serving, as opposed to those that were designed from first principle for ethnic minority populations (e.g. using a community participatory-based approach). In strict terms, adaptation would refer to the former type of interventions; however, on reviewing the literature, there were no interventions demonstrated that were not in some way based on a generic intervention or principle (e.g. a smoking cessation intervention may be designed through a community participatory-based approach to target an ethnic minority population but still remained based on nicotine replacement therapy or counselling). We have, therefore, used this previous evidence to ensure that the intervention would incorporate both ‘tailoring’, based on community beliefs and preferences, and ‘adaptation’ of general principles. 67

There also remains some concern over the appropriateness of targeting investment in interventions on specific minority or high-risk groups, rather than focusing on a more ‘equitable’ distribution of resources through tailoring generic services. It appears that, while there is little strong evidence, there is a consensus suggesting that interventions that specifically target high-risk groups and seek, thereby, to reduce inequalities are relatively cost-effective, and may be more clinically effective than seeking to ensure that broader interventions also ensure inclusion of those most at risk. The arguments for reducing health inequality by targeted action, therefore, serve more than a political or a moral agenda: they can be justified on the basis that this type of action reduces the costs overall for society, and produces a higher return on investment in terms of improved health, than otherwise. 68–70 Targeted action without tailoring the intervention for the group being targeted, however, is unlikely to have any benefits.

User involvement in service design and improvement

Recent White Papers and other policy documents have emphasised the need to strengthen local communities by empowering people to influence the decisions that affect them. 71 It is argued that involving patients, clients and other service users directly in working alongside professionals to create and deliver services will have a more positive effect on people’s health and well-being than merely informing, advising or consulting them. 72 The Darzi report ‘High Quality Care for All’ stated that interventions should be effectively designed around the needs of children and families,73 indicating that their involvement in the design of interventions would be beneficial. In contrast, the Marmot Review16 recommended stronger engagement with minority ethnic groups in service design and improvement. The review suggested that there needed to be a more systematic approach to engaging communities, moving beyond often routine, brief consultations to effective participation in which individuals and communities define the problem and develop community solutions. It is argued that without such participation and a shift of power towards individuals and communities it will be difficult to achieve the penetration of interventions needed to impact effectively on health inequalities. That said, specific issues and complexities in incorporating the views of minority ethnic groups in this process remained, which the MIA project was specifically designed to address. 66

Intervention design approaches

Creating a Patient-led NHS74 highlighted the ambition of the government to create a NHS that moves away from doing things ‘to’ and ‘for’ patients, towards a NHS that works ‘with’ patients. However, there is little consensus on how this should be operationalised. Neither traditional deficit models of service development (where health professionals identify a deficit in service provision and develop/identify services to fill them) nor newer patient-led models of service development (where patients identify their needs and either they or service providers provide/adapt services for them) entirely address the needs of the NHS. 75 An exclusive focus on either the healthcare provider or the patient is, therefore, unlikely to be effective in the long term. It is argued by Bovaid76 that partnerships developed between health professionals/systems, patients, and the public will be the key to success in creating a new, more effective NHS. 76 Several approaches to intervention design are suggested. Evidence suggests that multifaceted interventions are more effective in improving clinical outcomes than those which take a single approach. 50,51,77,78 Research suggests that the more strategies are combined in one intervention, the more likely an improvement in clinical outcome will be found. 79 Equally, it remains true that the more complex an intervention, the harder it is to evaluate and to identify which elements are the most critical. 80

Participatory research

Working with individuals and communities to define problems and develop solutions is one of the fundamental principles of participatory research (PR). PR does not replace other forms of research, but instead defines how the research process is carried out. Green et al. 81 defined PR as systematic inquiry, with the collaboration of those affected by the issue being studied for purposes of education and taking action or effecting social change (p. 1927). PR is a way of addressing health issues in their social context, rather than in the traditional medical model where health issues are addressed in their clinical context. 82 PR is based upon effective information exchange and shared decision-making to respond to service users’ needs. 83

Community-based participatory research

Community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a collaborative approach to research. CBPR involves all partners in the research process equally and recognises the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with identifying a research topic of importance to the community with the aim of combining knowledge and action for social change to improve community health and eliminate health disparities. 84 CBPR is, therefore, a collaborative research approach designed to ensure and establish structures for participation by communities affected by the issue being studied, representatives of organisations, and researchers in all aspects of the research process; the aim is to improve health and well-being through taking action, including social change, which has been widely recognised internationally as a core principle of equal participation. 85 It is an orientation to research that focuses on relationships between academic and community partners, with principles of co-learning, mutual benefit and long-term commitment, while incorporating community theories, participation and practices into research efforts. 84

Engaging minority ethnic communities in health research

People from minority ethnic groups are under-represented in UK research. This problem is particularly prevalent in the field of asthma. 30 This under-representation may be a result of a range of factors, including difficulties encountered by researchers or the deliberate exclusion of minority ethnic communities from clinical trials. 86 The involvement of people from minority ethnic backgrounds should therefore be considered at the outset of the research process. 87 Effective inclusive research can be argued to require specific forms of community engagement, consent and data collection methods,16,88,89 provision of interpreters,16 engagement with community leaders to build trust,87,90,91 utilisation of community facilitators (CFs)/lay researchers and dissemination of results to participants and communities. 87,92

Engaging children in research

Just as minority ethnic groups have been under-represented in research, children have similarly been excluded from research,93,94 yet engaging both children and parents in research is vital for the success of interventions and the production of interventions with positive outcomes. 95 Paediatric research has traditionally utilised parents and carers as the primary information source, based on the belief that children do not possess the necessary communication and recall skills to express themselves,96 or that adult carers ‘know best’. 93,97,98 However, there is an increasing view that the best source of information about a child’s experience is the child himself,99–101 with reports suggesting that children from age 3 years can give graphic but accurate descriptions and demonstrate good recall for experiences related to illness. 100,102–104

Ethical constraints have also often prevented children’s engagement in research. Adults have power over children and, as a consequence, children are vulnerable to exploitation, including from adult researchers; engaging with adult carers is, therefore, a way of protecting children from harm. 105 Practical considerations have also hampered children’s research participation. Children have their own language, concepts and understandings that are distinct from adult versions and can be difficult for adults to access and interpret. 97 As a consequence, engaging adult carers is seen as a practical measure to gain interpretable data. 97 Children’s participation in research has also been influenced by documentation of children’s rights, such as Article 12 of the United Nations (UN) convention on the Rights of the Child106 which recognises a child’s right to participate in making decisions that affect their lives. Glauser107 indicated that ‘it is inappropriate that international organisations, policy makers, social institutions and individuals who feel entitled to intervene in the lives of children with problems, do so on the basis of obviously unclear and arbitrary knowledge about the reality of these children’s lives’. Thus, there is an urgent need to improve children’s engagement with research, particularly in the field of intervention design and research. There are many potential benefits of including children in participatory research, in terms of both improving the relevance of the research and personal benefits for children. However, it must be noted that there are also potential risks in including children in PR, including raising unrealistic expectations and placing an unreasonable burden on them. 108

A child is defined by the UN as person under the age of 18 years;106 however, childhood is more complex than a simple number. Definitions, understandings and expectations of children and childhood vary between cultures and societies. 109,110 These differences affect the expectations of a child’s developmental level at a given age, and the perceived appropriateness of a child’s participation in various activities, including research. When working with someone under 18 years, not only is their ‘child’ status considered, but their race, ethnicity, social class, religion and various other influences need to be evaluated in parallel. It has been suggested that the complexity of taking all of these factors into consideration when developing research projects may be a factor in why the voices of minority ethnic children are often missing from research. 110

Use of the socio-ecological model in intervention design

Commitment to participatory research was one of the guiding principles of the MIA project. This was complemented by the use of a socio-ecological model of health and intervention design. Over the past 20 years there has been a shift from examination of determinants and interventions to address individual behaviour change towards broader, multilevel behaviour and social change models, not least because even the most effective individual interventions cannot address larger population-based health goals. 111 With the introduction of co-production and the necessary partnerships between service users and service providers, behaviour change models that link health planning with public health organisations, community and environmental organisations, policy makers and clinicians are rising in prominence and relevance. These are known as ecological models. 111

A basic tenet of the socio-ecological model is that any behaviour has multiple levels of influence, including biological, psychological, social, cultural, organisational, community, physical, environmental and policy. 111 Ecological models provide comprehensive frameworks for understanding multiple and interacting determinants of health behaviours and can be used to develop comprehensive intervention approaches that systematically target each level of influence. 112 In particular, in contrast to interventions that reach only individuals who choose to participate, ecological interventions can affect large populations. 113

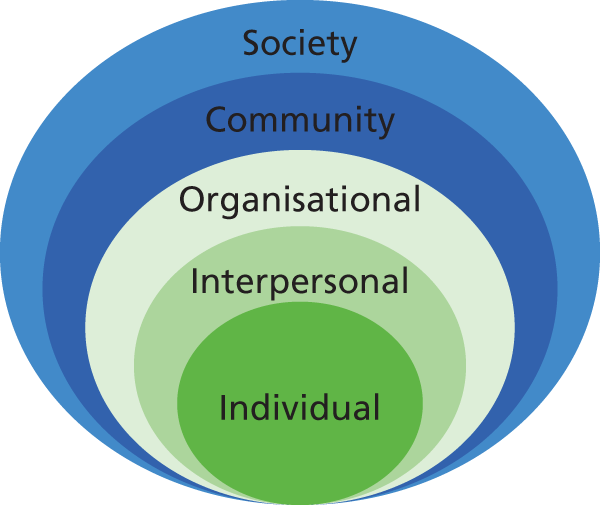

The socio-ecological model (Figure 1) is a theoretical framework that considers the complex interplay between several factors, with particular focus on the influence of the social/community environment. 114 This model has been used successfully for the development of interventions in other conditions, such as obesity. 112 The model proposes that individual perspectives and opinions, with those of family, community and healthcare providers, integrate to form a healthcare system, such that all aspects must be addressed to bring about change. 115,116 It is argued that research that focuses on only one factor will underestimate the importance of the other levels. 115,116 The socio-ecological model provides a holistic approach for interventions as it ensures that structural, individual and interpersonal factors are considered.

FIGURE 1.

Socio-ecological model.

In view of the dominance of cultural influences and community perspectives in health behaviours in South Asian communities,117 it was decided that interventions should draw upon a socio-ecological perspective and be informed by relevant inputs through a process of co-production.

Intervention mapping as a structured process for intervention design

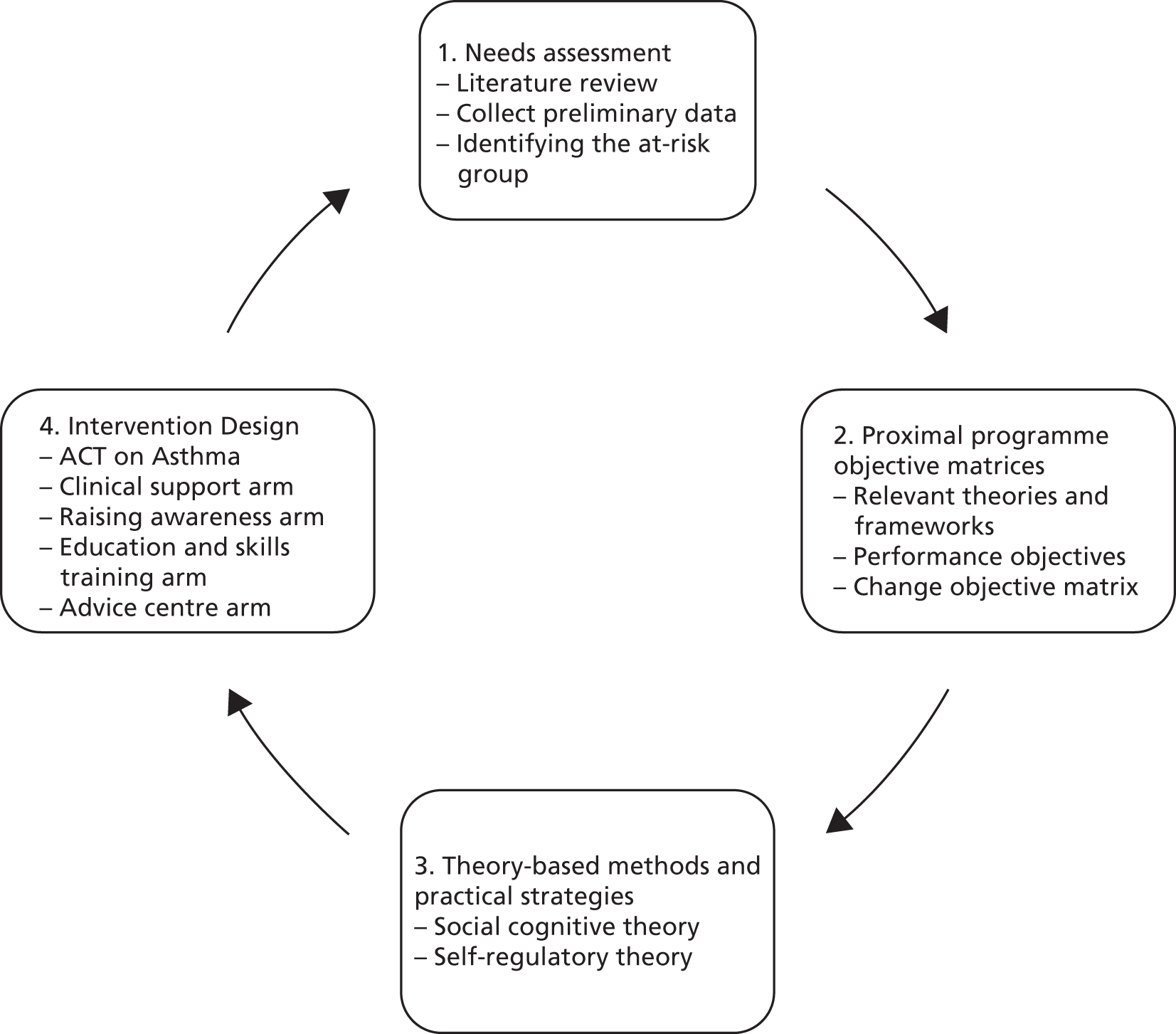

The socio-ecological model requires an intervention development programme which can address multiple levels of influence on behaviour. The MIA project used some of the principles of an approach to intervention design and evaluation known as intervention mapping (IM). 118,119 This approach insisted on the importance of programmes being guided by theories of health behaviour and behaviour change.

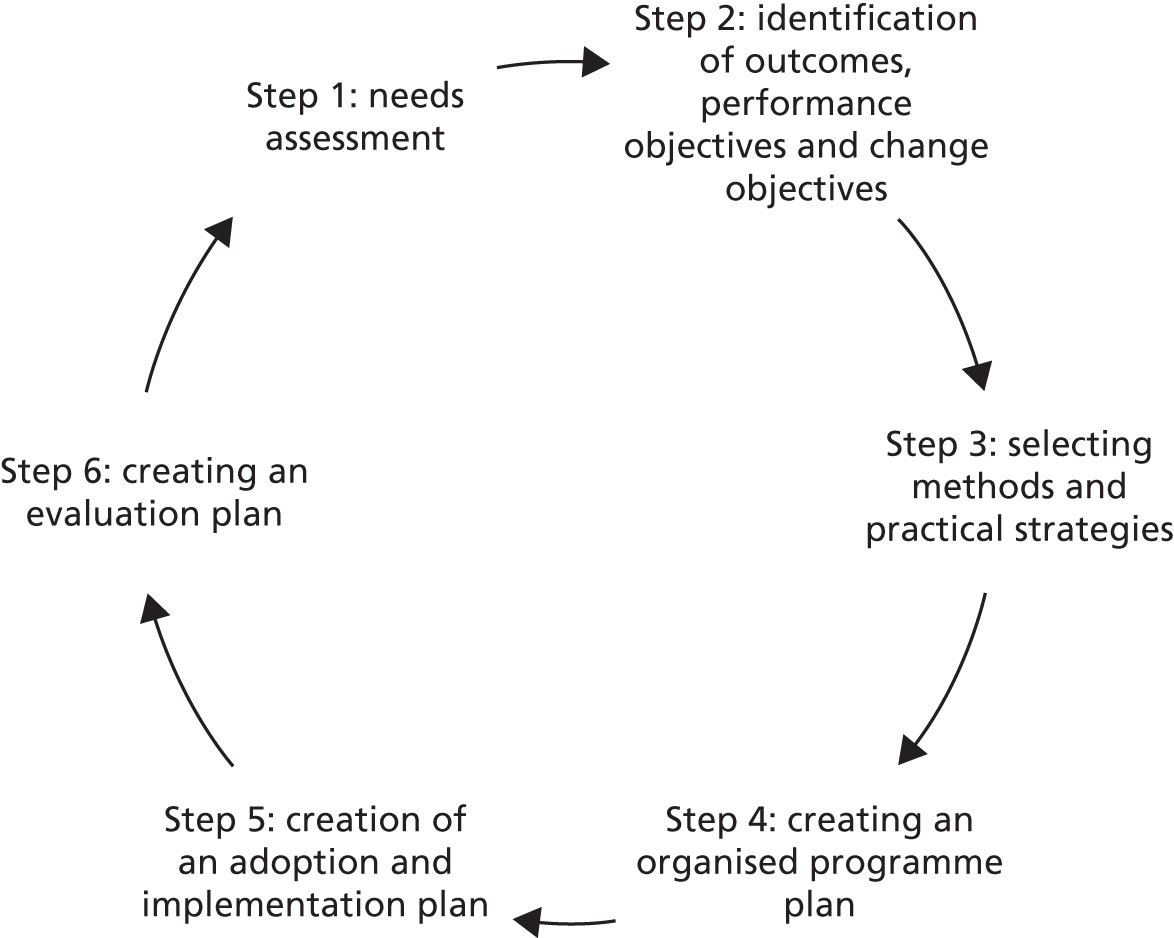

Intervention mapping is a stepwise, structured approach moving through an iterative process of assessing the current health and behavioural change needs, identifying health limiting behaviours and their determinants, identifying change objectives and programme outcomes, utilising psychological theories to identify the best means of delivering the programme to achieve these outcomes, implementing and subsequently evaluating the programme. 118,119 IM acknowledges the numerous levels implicit in healthcare delivery, their interwoven nature and the broader social and cultural context in which they exist: a fundamental requirement for successful knowledge translation. 120

Intervention mapping typically follows six iterative steps (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Intervention mapping steps.

Intervention mapping has been used successfully to develop interventions for asthma, obesity, sexual health, mental health and healthy-eating programmes;121–124 however, it has been applied only a limited number of times to healthcare design in the UK124 for the development of a workplace physical activity promotion programme. Results concluded that, while IM was successful at generating a tailored intervention programme due to its structured, evidenced and needs-based iterative approach, it was resource and time intensive, in addition to being challenging to apply. The MIA team made a proactive decision to use a modified form of IM, adopting the principles of a structured, stepwise approach and the consideration of theory, but recognising that the framework could not be easily applied to our broad set of research questions. This application is described in Chapter 5. Using the principles of IM, the MIA study intended to enable collaboration between patients, carers, community members and health professionals to plan and design an intervention planning framework and then a tailored exemplar programme. It is an example of collaboration in health services research starting at the earliest stage. Though it is beyond the life of this particular project, it is anticipated that participation will continue as the intervention programme is commissioned, managed, delivered, monitored and evaluated.

The MIA study was based in Leicester, UK. Leicester has a diverse population consisting of a high proportion (35.8%) of the population categorised as South Asian (including Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani and other Asian). 125 South Asian, for the purposes of this project, refers to a person with ancestry in countries of the Indian subcontinent, including India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka. The MIA study, therefore, used purposive sampling to ensure proportionate representation from the four largest South Asian religious/ethnic groups (Indian Sikh, Indian Hindu, Pakistani Muslim and Bangladeshi Muslim) and from four of the linguistic/ethnic groups (Bengali, Urdu, Gujarati and Punjabi). Participants were asked to self-assign their ethnicity. A comparator group of White British families and children were included in the study to identify commonalities and differences across groups in addition to generic recommendations.

The MIA project recruited primary school-aged children and their families, as the children were largely dependent on their parents for asthma management. As adolescents are encouraged to take a leading role in their management, an intervention targeted to adolescents would require a different approach. As a consequence, a proactive team decision was therefore made not to include them in this study. 17 Purposive sampling was used to identify children with a wide range of asthma severity within each ethnic group. Severity was defined by the BTS guidelines’ ‘stepwise approach to management’, which places a child’s asthma control in one of five steps or categories of asthma. 49

An examination of the literature on asthma and its management in South Asian children, consideration of approaches to participatory intervention design, and discussions with South Asian families and HCPs responsible for delivering asthma services in Leicester led to the following research aims and objectives.

Aims and objectives

Study aim

-

To use a collaborative method of designing healthcare interventions to develop an intervention programme for South Asian children with asthma.

Study objectives

The MIA project sought to explore and answer four key questions:

-

to test a participatory model of healthcare intervention development;

-

to provide an evidenced-based understanding of asthma and its management in South Asian children;

-

to provide a comparative analysis of understandings of asthma and its management in White British and South Asian children to account for geographical and sociocultural context; and

-

to produce a realistic and achievable intervention planning framework for asthma management.

Research questions

There were four key research questions that the MIA project sought to explore and answer:

-

What are the lay understandings and perceptions of asthma in South Asian communities?

-

How do health professionals perceive asthma and its management in South Asian children?

-

What is the knowledge and awareness of asthma, its triggers, and control among South Asian families and children with asthma and, correspondingly, what are the facilitators and barriers to good asthma management?

-

What interventions to optimise asthma management are effective, acceptable and feasible for children and parents from South Asian communities?

The following chapter discusses the methodological approach of the MIA project in more detail.

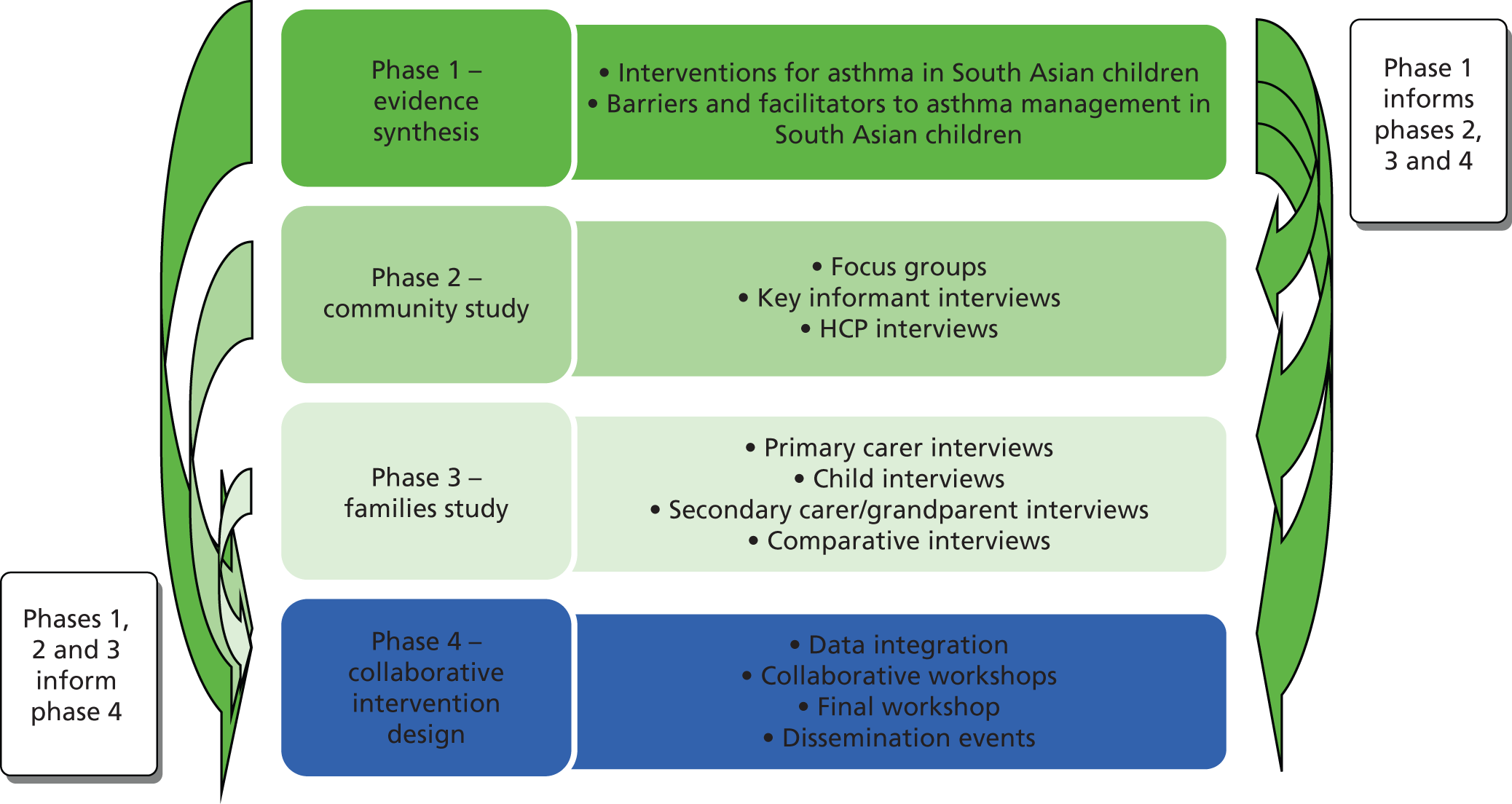

Chapter 2 Overview of project design, collaborative approach and methods

This chapter presents a brief overview of the project design as well as the collaborative approach taken to researching asthma within South Asian communities. The project was a community-based study designed with four main phases (see Figure 3) and utilised a participatory approach throughout. The design was informed by the socioecological model of health (see Figure 1) and drew on principles of qualitative inquiry and methods of IM (see Figure 2). Given the methodological complexity of the study, a more detailed description of the methods and the sampling that relate to each particular phase of the study is provided at the beginning of the appropriate chapters.

Overview of design and methods

The phased project structure was designed to enable the research team to build iteratively on findings from each stage and to use this to guide subsequent stages of the research. Iterative working requires flexibility and, thus, despite the apparently linear structure, there was a degree of overlap between the stages (Figure 3). A brief overview of the stages is described below.

FIGURE 3.

The stages of the MIA project.

Phase 1: systematic evidence synthesis

Phase 1 was a systematic evidence synthesis of the barriers and facilitators to asthma management in South Asian children, funded by Asthma UK and conducted prior to the MIA project. While this review was an important prestudy activity which contextualised the subsequent phases, it was not funded as part of the MIA study and is therefore not discussed at length in the rest of this report. An overview can be found in Appendix 1 with a copy of the report available online (www.asthma.org.uk) later in 2013. 46

Phase 2: community study

Phase 2 of the MIA study was a study of community perceptions designed to explore lay understandings of asthma and its management in children. The objectives of phase 2 were to understand the South Asian community perceptions of asthma and to gain an understanding of the ways in which families of children with asthma are perceived and treated by the wider community. Community focus groups and key informant interviews were used to explore lay perceptions among a range of individuals and groups and to take into account the wider cultural, religious and socioenvironmental context of a potential intervention targeted at asthma. The research team, in partnership with CFs, developed interviews and focus group question schedules built on the findings from the review in phase 1.

Phase 3: families and healthcare professionals study

Phase 3 aimed to explore the perceptions and experiences of families living with childhood asthma (South Asian and White British) and experiences of healthcare providers who had supported or treated South Asian children living with asthma, with a particular focus in barriers and facilitators to its management. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with South Asian children and their parents or carers to discuss and explore perceptions and experiences of living with asthma. A subsample of White British families were also interviewed in order to further clarify the role of ethnicity in determining barriers to management by assessing the perceptions of the ‘majority’ White British population (see Chapter 4). Semi-structured interviews were carried out with HCPs involved in the management of children with asthma. As the primary aim of the study was to develop tailored interventions for South Asian children, HCPs were asked only to comment on their experiences and work with South Asian children and their families (see Chapter 4). No attempt was made, therefore, to ask HCPs about perceptions regarding the care of White British children. Interview schedules were developed in partnership between the research team and CFs in response to the initial findings from phases 1 and 2.

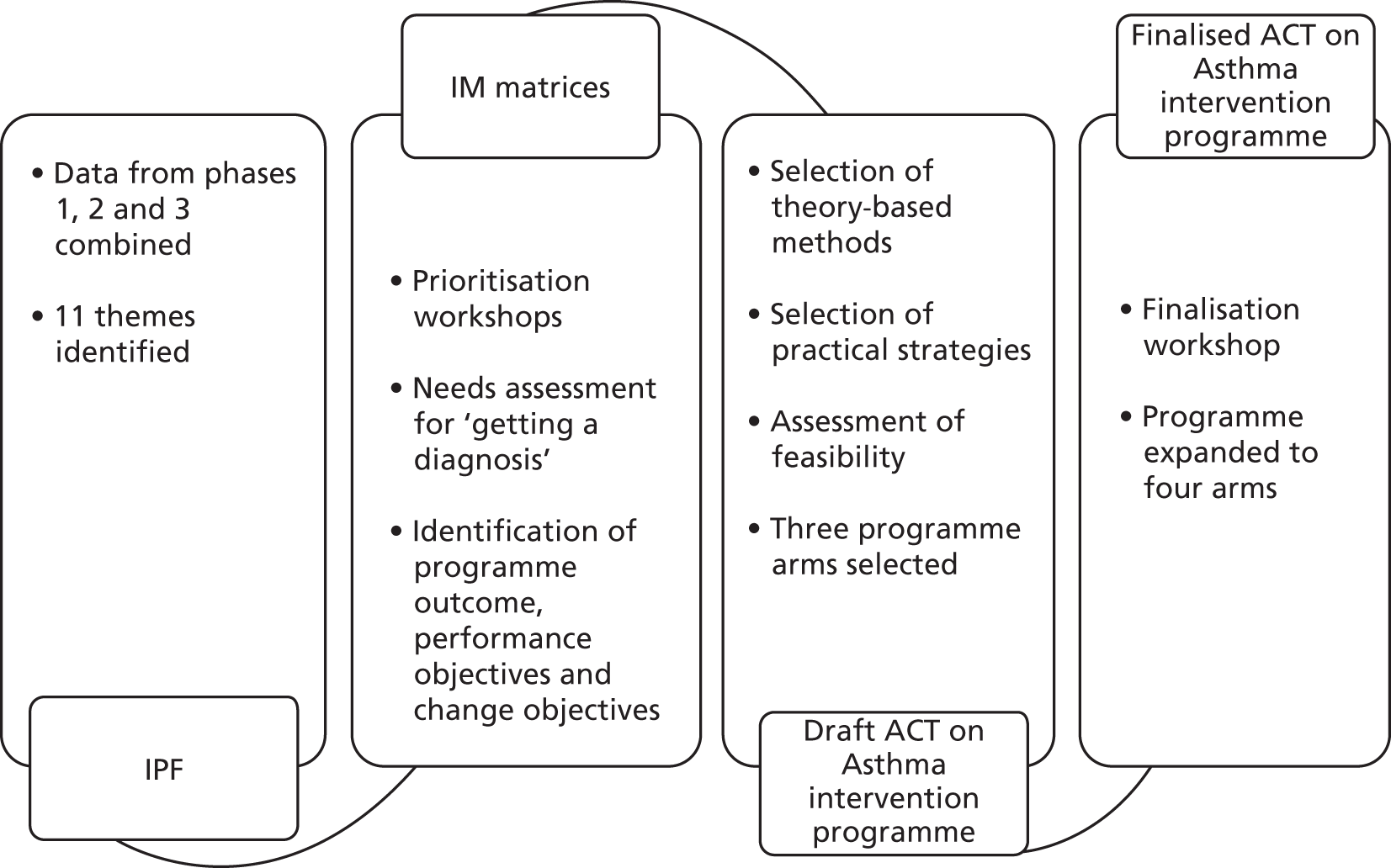

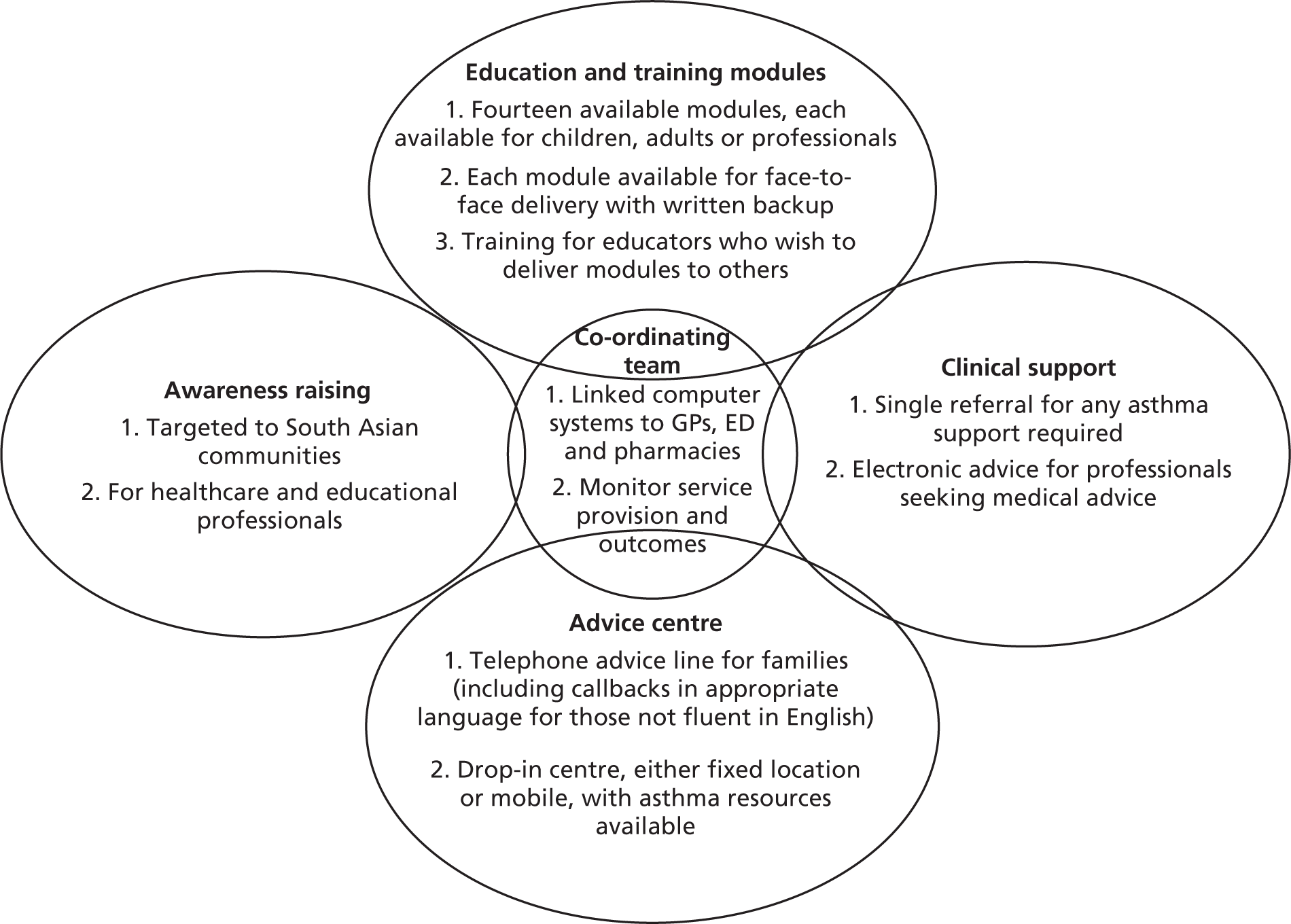

Phase 4: development of potential collaborative intervention strategies

The aim of this substantial and iterative phase was to synthesise the data from all previous stages and to develop an intervention planning framework and exemplar programme for South Asian children with asthma. The objectives were to enable collaborative intervention development, and produce an acceptable and achievable intervention plan for asthma management. Findings from the phase 1 review, the phase 2 community study and the phase 3 family and HCP study were integrated, discussed collaboratively at workshops with families, HCPs and community members and refined into the final intervention planning framework and exemplar programme. This complex process was guided by principles of intervention mapping and took place following the process described in more detail in Chapter 1. Following on from the collaborative intervention development, the research team gathered data on participants’ experiences of the methods of intervention development to feed into a reflection and review of the process of collaborative development. Short semi-structured interviews were conducted with a sample of study participants, team members and advisory group members to explore their experiences of this method of intervention development. The data from these interviews was used to contribute to the team’s reflection on the process; a component of the iterative approach adopted, with a view to improving the process when applied to future projects.

The research team and advisory group

The multidisciplinary research team included academics from the following disciplinary backgrounds: academic and clinical paediatrics (ML, DB), social science (MJ, LC and NH), clinical psychology (NR), nursing (MMcF), respiratory paediatrics (JG) and health psychology (CHW). A South Asian parent representative, (NJ), was also a member of the core research team and worked in partnership in each phase of the study, from the initial design of the protocol and research design, to managing the study, taking part in project activities such as team meetings, running workshops, discussions and reviewing related literature including the final report. Additionally, the core team were supported by a group of ‘community facilitators’: bilingual members of South Asian communities who were trained as lay researchers to assist with all stages of the research. This method was employed as part of the participatory, inclusive research design and is described in more detail below.

A multidisciplinary advisory group was set up in order to assist the team to carry out the research and to include the perspectives of those with a stake in the research. The group therefore included representation from the following areas: paediatrics, public health, general practice, commissioners and children’s services (including service managers, school nurses and paediatricians). South Asian parents of children with asthma were also represented on the advisory group. Both parent representatives on the project (NJ and SA) had children with asthma and were involved at all stages of the research. As part of her role in the advisory group, SA also participated in study recruitment, development of data collection tools and in the running of the children’s workshops.

Collaborative research engagement: the role of community facilitators

The communities which collectively constitute the category ‘British South Asian’ represent approximately 4% of the UK population, yet as with most minority ethnic groups, South Asians remain significantly under-represented in clinical research trials. 86,126 This tendency to exclude certain groups from research persists despite the fact that there is now a well-established and growing body of literature that describes how and why members of minority ethnic communities should, and can, be effectively engaged in research. 127,128 Researchers from the USA and the UK suggest that, to successfully recruit South Asian participants, developing a sense of trust between researchers and participants is of vital importance,128 in addition to consideration of specific language needs in securing informed consent. 127

The MIA project engaged community members as partners rather than subjects, involving them in all stages of research, from identifying research questions to recruitment, developing an intervention, interpreting research findings and disseminating results.

Engaging community members as collaborators is powerful on multiple levels. 129 Developing a research project from the bottom up and working with the community members to identify important issues and factors has the potential to improve a population’s participation and enthusiasm for a project, which can subsequently mobilise the community in addition to improving the effectiveness of the intervention.

Previous research has suggested that, to engage successfully with minority ethnic groups, earning the trust of potential study participants is important. 87 Strategies to achieve this include ensuring ongoing involvement with community groups, key community representatives and faith organisations, with emphasis placed on the employment or involvement of community representatives as study personnel. 66,127 Personal contact with key community representatives is also described as essential by those with positive previous experiences of recruiting minority participants. 87 A personal touch, including face-to-face contact, is seen as instrumental to building relationships between research staff and members of minority ethnic communities. 87 In the MIA study, this collaboration and engagement was achieved by tailoring recruitment, consent and participation in the study in a number of ways.

A team of male and female CFs were actively involved in all stages of the study. The inclusion of CFs in carrying out research is an approach adopted previously by members of the team130,131 and was designed to facilitate the engagement of participants from across a number of South Asian communities. This approach was designed to allow participation by those whose first language was not English; to provide participants with a choice of facilitator or interviewer in terms of sex and ethnicity; and to ensure that the research was relevant to the communities involved. 131 The CFs facilitated a relationship between the research team and the local communities, with many authors suggesting that the role community partners and liaisons play in recruitment may significantly improve the effectiveness and retention of minority participation in research. 129

All of the female CFs had previous experience of research involvement in studies with South Asian communities, while the male CFs were recruited following recommendations from the existing CFs. The facilitators were chosen based on their relevant language skills (Bengali, Gujarati, Punjabi and Urdu), sex, and identification with and knowledge of the four communities to which the study was being undertaken in. Linguistic skills alone were not considered adequate and, to ensure that a positive rapport was developed between the CFs and the participants, cultural and religious familiarity with the intended research participants was also essential. 131 Training on both research methods (e.g. refresher training) and asthma management was provided for the CFs by the research team.

The CFs utilised personal contacts and a snowball sampling method to recruit participants from within their respective communities. They provided verbal explanations of the research process and discussed the study information with potential participants in their preferred language. The CFs were instrumental in enabling verbal-consent procedures when English was not the participant’s preferred language, having been previously trained in this method in sessions with the research team. The use of spoken study information and verbal consent was essential as there were no agreed written consent forms in several South Asian languages, such as the Sylheti and Mirpuri dialects. Research indicates that literacy, even in a native tongue, can be very low among some South Asian communities. 132,133 While informed consent is considered preferable in written format, verbal consent was considered more appropriate at times when participants were non-literate134–137 (see Appendix 2).

The CFs were involved in the development of the data collection tools, organised and facilitated focus groups in the appropriate languages and assisted the research team in conducting family and key informant interviews when necessary. When focus groups or interviews were held in languages other than English, the CF also worked in partnership with the research team, asking questions in the chosen language and providing brief on-the-spot translations for the research team such that any follow-up questions could be asked spontaneously by either the research team or the participants, supporting an interactive, real-time dialogue between the two. At the study workshops, the CFs provided translations of the verbal presentations in five languages and facilitated table discussions. During the analysis process, the CFs attended group meetings to review and discuss the interim results, and to ensure correct understanding of translations and to ensure cultural sensitivity.

The CFs advised the research team throughout the study on how best to maximise community engagement. This was an iterative process and at different phases the research team sought advice from the CFs in order to ensure that engagement with the community was as successful as possible through the utilisation of appropriate financial and human resources. Examples of advice provided included profiles of key informants that they considered important to be approached for the study, venues for workshops that would be more appealing to the different groups, considerations required when choosing the day on which workshops should be held and considerations regarding cultural acceptance of food to be served at the workshops.

Participatory workshops were part of the collaborative design of the study. Dialogue between the research team and the participants at the workshops allowed the team to collect direct feedback on the processes involved. Members from the voluntary sector organisation, Asthma UK, also attended the workshops, providing an opportunity for families who attended to opportunistically learn more about asthma and the support available.

Several community-based organisations were actively involved in the recruitment or provision of key informants. These included Clarendon Park Temple (where study participants and key informants were recruited from); Bengali women’s groups (where Bangladeshi women were recruited for the focus groups); the Federation of Muslim organisations (aided with recruitment and provided several key informants); and Leicester Central Mosque (provided a key informant). A number of other local community centres were used for events and workshops as well as providing key informants.

Collaborative research engagement: the role of children

Children were involved in several aspects of the MIA study to enable us to effectively include their perspectives. It is considered good practice to engage children in decisions about their own health; however, parents are often invited to speak on behalf of their children. The age range of children included in the MIA study was 5–12 years and can be considered young. Research has demonstrated, however, that even young children can effectively respond to research participation. 97 A variety of approaches were utilised to encourage children to communicate with us, both in interviews and at the workshops. This encouraged the bidirectional sharing of information and enhanced the relevance of the whole research project. The children were actively involved in the workshops and contributed to the intervention design through helping to prioritise specific research areas. Teenage ‘peer’ facilitators (aged 14–16 years) were used to put the children at ease, to promote engagement between the research team and the children and, therefore, to enable meaningful participation by the children at the workshops. Further information regarding children’s involvement in the MIA study can be found in Chapter 4.

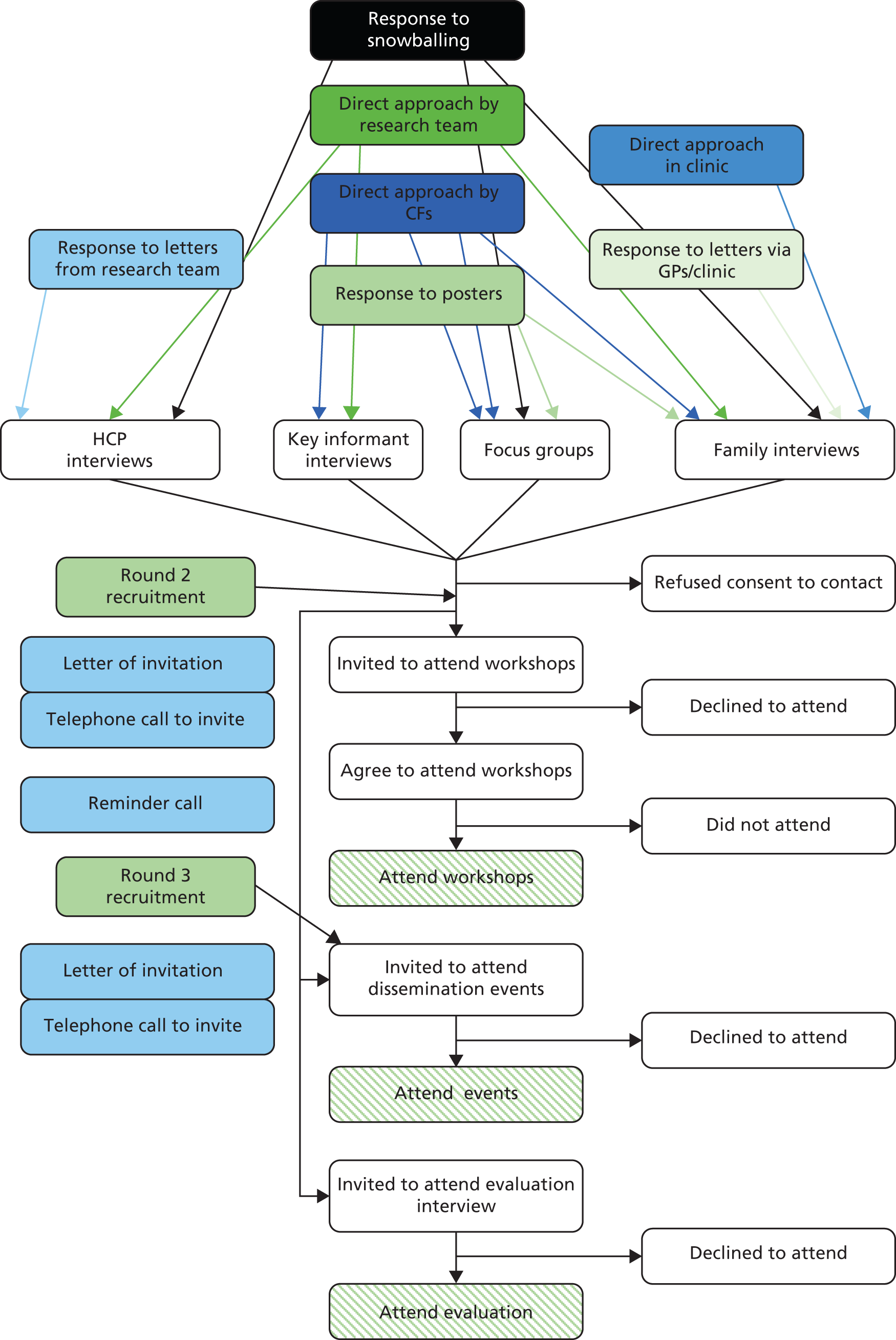

Recruitment

There were two avenues for recruitment in the MIA project: through the NHS or directly through the community. NHS recruitment drew on primary care research networks (PCRNs) and comprehensive clinical research networks (CLRNs) to recruit through pharmacies, GP surgeries, emergency primary care, and hospital and community paediatric clinics using standard NHS ethics and recruitment procedures (see Appendix 3). Community-based recruitment involved CFs who drew on methods such as snowballing, telephone and mail shots (for all recruitment methods see Appendix 3). The recruitment process used by the CFs (and throughout the study) was a standard three-step approach (see Appendix 2). In addition to through the CFs, the study was advertised using posters, flyers, and university and research websites. A study website (www.http://mia.ocbmedia.com) was designed to signpost individuals to study information in English and translated into the main South Asian languages relevant to our study, available in both written and audio formats to enable those with low literacy to still engage with the research project.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was gained through the local NHS ethics committee, university ethics and NHS research and development (R&D) approval. National Research Ethics Service (NRES) procedures were used throughout the study to minimise distress to participants and safeguard anonymity and confidentiality, as well as providing a guarantee for a continued standard of care (see Appendix 2 for further details regarding ethics and consent procedures).

Chapter summary

This chapter has given a brief overview of the research design, the methods used, the team structure and the overall participatory approach. Individual chapters provide a more detailed description of the methods as well as a breakdown of the resulting sample for each phase.

Chapter 3 The community study: perceptions of childhood asthma in South Asian communities (phase 2)

In line with recommendations to consider not only an individual’s attitudes and beliefs towards health but also the influence of the environment and community relationships,5 the first phase of the MIA project focused on exploring lay understandings and perceptions of asthma and its management in South Asian communities. This was regarded as an important contextual phase of the project, and was in accordance with the socio-ecological model underpinning MIA. The attitudes, beliefs and health behaviours of parents/carers and children living with asthma (and other health problems) do not exist in a social vacuum. 2 It is argued that the social context of the wider family and community understandings and attitudes may have a significant influence on parents and children living with asthma2 and this broader context merits further investigation if we wish to fully understand this setting. This phase was also regarded as an opportunity to identify any general community concerns regarding barriers to meeting the needs of the community so that they could be taken into consideration when developing the MIA asthma intervention planning framework. This phase enabled the research team to take the first steps to engaging with South Asian communities, an important starting point in participatory research (see Chapter 4). The focus group participants were, thus, recruited not on the basis of having direct experience of living with a child with asthma, but to gather data on the wider social meanings of childhood asthma within the communities engaged in the study, and to gather general suggestions on improvements in the health system that participants felt could contribute to improvements along the whole asthma management pathway.

This phase of the study was separated into two parts: focus groups representing the main South Asian communities and individual interviews with ‘key informants’ considered to be individuals of influence within their community. The ‘key informants’ were an important inclusion in this phase of the MIA project as they were seen as potentially helpful in assisting the team to interpret and contextualise the community understandings of asthma and its management emerging from the focus group data.

The aims of this phase of the study were therefore to understand lay perceptions of asthma and the potential impact that cultural, religious and wider socioenvironmental factors have on a child with asthma. In addition, this phase also provided an opportunity to engage with individuals who were invited and encouraged to contribute to phase 4 of the study. This phase was therefore designed to take account, as much as possible, of generational, sex and ethnoreligious differences within heterogeneous South Asian communities. As a consequence, the recruitment process, described below, reflected this approach.

Sampling and recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to ensure that at least one community focus group and key informant interview was carried out with participants from each of the main South Asian ethnic, religious and linguistic groups: Indian Gujarati Hindu, Indian Gujarati Muslim, Indian Punjabi Sikh, Indian Punjabi Hindu, Pakistani Muslim and Bangladeshi Muslim. We were also keen to recruit focus group participants from a wide age range, recognising the potential significance of generational differences, and held focus groups with both men and women (Table 1).

| Group | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Community focus groups | Adults aged 18+ years | None |

| South Asian descent | ||

| Key informant interviews | Adults in a position of authority or influence within South Asian communities | None |

Community focus groups consisted of between 6 and 10 participants. In some cases, these were divided by sex to take account of religious/cultural requirements. Key informants were interviewed individually.

Participants were recruited to the focus groups by CFs and members of the research team, using the three-step approach described in Appendix 2. Identification of key informants was predominantly carried out by direct recommendations from the community focus groups to identify persons of influence and tasking each CF to identify key people within their respective communities. All participants in the community focus groups and key informant interviews gave formal verbal or written consent (see Appendix 2).

Methods

Facilitation of community focus groups

A pre-set interview/discussion schedule was devised by the research team (see Appendix 4), informed by findings from the systematic evidence synthesis in phase 1 and consultation with the CFs, and the project advisory group. Discussions took place in both English and the appropriate South Asian language. The CFs were asked to convene eight focus groups: one Bengali female, one Bengali male, two Indian Gujarati, two Indian Punjabi, one Pakistani female and one Pakistani male. The language of the focus group was then a pragmatic choice based on the participants’ needs, for example both Pakistani groups were run in a mixture of English and Urdu with the CFs translating when necessary, one Indian Gujarati group was conducted in Gujarati, and the other Gujarati group was conducted predominantly in English. All discussions were recorded; those taking place in English were directly transcribed and interviews that took place in a South Asian language were translated into English by the CFs and subsequently transcribed.

Facilitation of key informant interviews

The key informant interviews used a semi-structured format with a question schedule informed by the findings of the systematic review and input from external advisors and the advisory group (see Appendix 4). Interviewees were offered their choice of language for the interview. The remaining interviews were conducted by a member of the research team in English. All interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and translated where necessary. The data analysis utilised a framework based on the principles of IM (see Chapter 1, Intervention mapping as a structured process for intervention design). The themes from the data were extracted and transferred to standardised tables (charted) (see Appendix 5 for an example of the tables) used for phases 2 and 3 in preparation for the development of the intervention programme in phase 4. A narrative summary was also produced and is presented in this chapter.

Results

Participants

Seventy-five participants were recruited to the community study in total, of whom 63 participants attended a total of eight focus groups (Table 2).

Community focus groups

As part of best practice, individuals were allowed to self-assign their ethnicity.

| Focus group | Ethnicity | Sex | Religions | Age range | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–34 years | 35–54 years | ≥ 55 years | Did not answer | ||||

| 1 | Indian Punjabi | Male, n = 2 | Sikh, n = 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Female, n = 4 | |||||||

| 2 | Indian Punjabi | Male, n = 4 | Sikh, n = 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Female, n = 6 | Hindu, n = 5 | ||||||

| Did not answer, n = 0 | |||||||

| 3 | Indian Gujarati | Male, n = 0 | Hindu, n = 7 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 |

| Female, n = 8 | Muslim, n = 1 | ||||||

| 4 | Indian Gujarati | Male, n = 5 | Hindu, n = 5 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Female, n = 0 | |||||||

| 5 | Pakistani (female group) | Male, n = 0 | Muslim, n = 6 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Female, n = 6 | |||||||

| 6 | Pakistani (male group) | Male, n = 9 | Muslim, n = 9 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Female, n = 0 | |||||||

| 7 | Bangladeshi (male group) | Male, n = 8 | Muslim, n = 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| Female, n = 0 | |||||||

| 8 | Bangladeshi (female group) | Male, n = 0 | Muslim, n = 11 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Female, n = 11 | |||||||

| Totals | Eight groups | 63 participants | 14 | 29 | 14 | 6 | |

Key informant demographics

Twelve key informants were interviewed, comprising seven men and five women. Examples of their roles included religious leaders, community centre managers, community liaison officers, school–home liaison officers and support workers (Table 3).

| Ethnicity | Sex | Religion | Age range (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Asian, n = 2 | Male, n = 7 | Hindu, n = 2 | 18–34, n = 0 |

| Indian, n = 7 | Female, n = 5 | Sikh, n = 1 | 35–54, n = 4 |

| Bangladeshi, n = 2 | Jain, n = 1 | ≥ 55, n = 2 | |

| Pakistani, n = 1 | Muslim, n = 3 | Did not answer, n = 6 | |

| Did not answer, n = 5 |

Community focus groups: key themes

One of the aims of this phase was to inform the development of the interview schedules for the family interviews as well as informing the development of the intervention planning framework and exemplar intervention programme. The interviews, therefore, focused on organisational issues within the health system as well as issues related to the community or families. Several key themes relevant to asthma and its impact on families were identified from the focus group data and are discussed briefly below: understandings of asthma; impact of having a child with asthma; expectations for a child with asthma; influence of community attitudes; diet and asthma; using inhalers and other medicines; perceptions of the NHS; and suggestions for interventions to help families.

Understandings of asthma

Public awareness is known to be a driver of optimal management, for example by encouraging early recognition and intervention. By identifying community understanding of asthma, the language used to describe it, the symptoms of asthma and what the management involves, an insight into the public awareness of the condition can be gained.

Understandings of asthma were similar across all groups regardless of religion, culture or sex. A key area of discussion included participants’ perceptions of the causes and symptoms of asthma.

Awareness of asthma symptoms

To identify the level of awareness of asthma in the community, participants were asked to discuss, very generally, their thoughts about asthma. Participants reported that they were unsure of the symptoms of asthma and that awareness of symptoms in the community was generally poor. The most commonly identified symptoms mentioned by the participants were difficulty with breathing and ‘being wheezy’.

There are different symptoms that I think a lot of people are not aware of.

FG4, Indian Gujarati

From the breathing you can tell that someone is suffering from asthma yeah – cos they’ll get a tight chest and they can feel their chest getting tight and then you know they struggle to breathe.

FG5, Pakistani female

I always thought asthma was when you can’t breathe properly. It’s not really just that . . . she has a very heavy cough.

FG4, Indian Gujarati

Language used to describe asthma and their relevance: asthma versus wheeze

‘Medical’ language is known to be a barrier to optimal management due to its contribution to communication difficulties between HCPs and patients/carers. Having knowledge of the presence of this barrier should lead HCPs to establish ways of overcoming it and improving communication. The terms ‘wheeze’ and ‘asthma’ are key terms used when communicating about asthma. The research team wished to explore participants’ understanding of these terms, what they meant to participants and the level at which they were used interchangeably.

Wheeziness is mostly related to asthma but I don’t think generally it’s always asthmatic.

FG5, Pakistani female

I wouldn’t say wheeziness was like having asthma; it could be due to chest infections . . .

FG2, Indian Punjabi

People have wheeziness if they have asthma, but some people are wheezy if their chest is weak.

FG1, Indian Punjabi

Some participants felt that asthma was an intermittent periodic condition or was present only when the individual had related symptoms, such as when the child was actually wheezing or having an acute asthma attack.

Sometimes my younger son has it [asthma].

FG3, Indian Gujarati

If they’ve got a cold or bad cough or chesty cough they will get wheeziness and perhaps that instance you can classify as asthma but they not asthmatic children.

FG5, Pakistani female

It’s not a constant thing like diabetes or heart trouble. Asthma is very periodic, your get it at certain times.

FG5, Pakistani Muslim female

While standard medical definitions describe a wheeze as a whistling noise heard on breathing as a result of narrowed airways in the lungs, many participants struggled to define ‘wheeze’ using various definitions, with many relating wheezing to coughing.

It’s a kind of cough you can hear in the chest. You know you have a bad cough and you are kind of chesty.

FG4, Indian Gujarati 2

I would say if anyone has a chest problem they would be wheezy.

FG1, Indian Punjabi

When it’s hard to breathe, the throat makes loud sound.

FG7, Bangladeshi male

There may be blockages in your arteries and you can’t breathe properly, infection swelling of that sort. There is some form of difficulty in breathing.

FG2, Indian Punjabi

It means the child is coughing. When the child has very chesty cough.

FG3, Indian Gujarati

In summary, participants highlighted a difficulty with the language used when describing asthma as a chronic illness and the medical terms commonly used to describe asthma symptoms.

Causes of asthma

Health professionals require a knowledge of the perceptions of an illness’s causes so that any myths or misunderstandings can be addressed; this would help to improve early diagnosis, increase the likelihood of the presentation of an individual suspected of asthma and disclosure of an illness within their community and, in turn, improve adherence to asthma management strategies.

When asked about the causes of asthma, participants either responded that they did not know or referred to either genetic/hereditary factors or factors relating to the weather and general environment.

I have no idea.

FG2, Indian Gujarati

Something to do with inheritance and a family history problem.