Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1007/01. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Waring et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The challenge of patient safety

Patient safety remains a health policy priority. Over the last two decades, and following the publication of To Err is Human1 and An Organisation with a Memory,2 advances in patient safety research and policy have been significant. In the UK, for example, a dedicated portfolio of research led the development and application of new theories, research methods and improvement interventions to enhance patient safety. 3 This body of work has transformed thinking about the sources of unsafe care and the possibilities for safety improvement. In particular, a new conceptual approach has emerged that draws attention to the ‘upstream’ risk factors located within the wider organisation of care and how these can influence the ‘downstream’ safety of clinical practices. These ideas have provided the conceptual basis for many safety-enhancing interventions that aim, for example, to improve team communication, simplify complex activities and foster a culture of safety.

Despite advances in ‘systems thinking’, research continues to highlight worryingly routine levels of substandard care and patient harm. 4 The recent public inquiry into Mid-Staffordshire NHS Trust again highlights the complex social, cultural and organisational factors that influence the quality and safety of patient care. 5 The study presented here addresses recent calls for research to examine the more complex sociocultural and organisational context of patient safety. 6,7 Elaborating this need, the study suggests that patient safety research to date has tended to focus on the sources of safety and risk located within clinical domains, such as the operating room or the emergency room, but with less attention to the sources of safety and risk located between care settings, such as between health and social care. 3 The sociology of organisational failure shows how catastrophes and errors are often ‘rooted’ within complex intra- and interorganisational processes. 8,9 Such complex structures and processes are often recognised by current ‘systems approaches’ as applied to patient safety, but they are not fully developed in the sense of complex systems of interdependencies that cut across or between care settings and processes. As such, this study suggests that the delivery of high-quality patient-centred health care requires the co-ordination and collaboration of multiple professionals, agencies and organisations working and interacting in the manner of a complex system.

This study aims to extend theory in patient safety through elaborating and understanding the complex interdependencies that frame the safe delivery of patient care across occupational and organisational boundaries.

In line with this aim, the study suggests that the co-ordination of health-care professionals, organisations and other agencies is enhanced where there is shared understanding, common values and aligned ways of working. In other words, system complexity can be mitigated, in part, by system actors knowing how to integrate their distinct activities to meet common goals. Research suggests that such collaboration is typically based upon enhanced patterns of communication and, importantly, knowledge sharing. 10 Knowledge sharing is more than the communication of information, relating instead to how meanings, beliefs, values and ‘know-how’ are shared with and used by groups or networks of actors to support collaborative working. 10–12 Knowledge sharing might therefore be interpreted as a source of system safety, which can support system-level integration through helping different actors to co-ordinate and align discrete practices. Research highlights a number of sociocultural factors that facilitate and inhibit knowledge sharing, including the extent of difference in the forms of knowledge, cultural values and norms, and organising factors that support knowledge sharing. 10–13

This study aims to identify interventions and practices that support knowledge sharing across organisational and occupational boundaries, which in turn can support collaboration and mitigate systems complexities.

The challenge of hospital discharge

The study takes as its focus the complex patterns of care organisation associated with hospital discharge. Specifically, hospital discharge exemplifies the problems of interorganisational dependencies within a complex health and social care system. National policies suggest that timely, integrated transition of care from hospital to a community setting is integral to patient recovery, quality of life, independence and longer-term care. 14 Inappropriate or poorly planned hospital discharge can introduce risks to safety and additional resource costs, inhibit recovery and lead to readmission. 14,15 Data provided by the former National Patient Safety Agency16 indicate that ‘transfer/discharge of patient and infrastructure’ accounted for 7%–8% of reported safety incidents in 2009. This figure is likely to be a significant underestimate given that reporting systems are not well utilised across health and social care boundaries. In their study of 400 patients discharged from hospital, Forster et al. 17 found that nearly 20% experienced some form of adverse event, with those related to drug reactions being the most common. The range of threats to safety in hospital discharge is diverse, often linked to the needs of individual patients. Common risks include the management of medicines, the provision of appropriate health and social care, the fitting and use of home adaptation to support recovery, and the risks of falls, infections or sores. 13–26 Hospital discharge is therefore interpreted as a ‘vulnerable stage’ in the care pathway that exemplifies the opportunities for ensuring patient safety located between care settings.

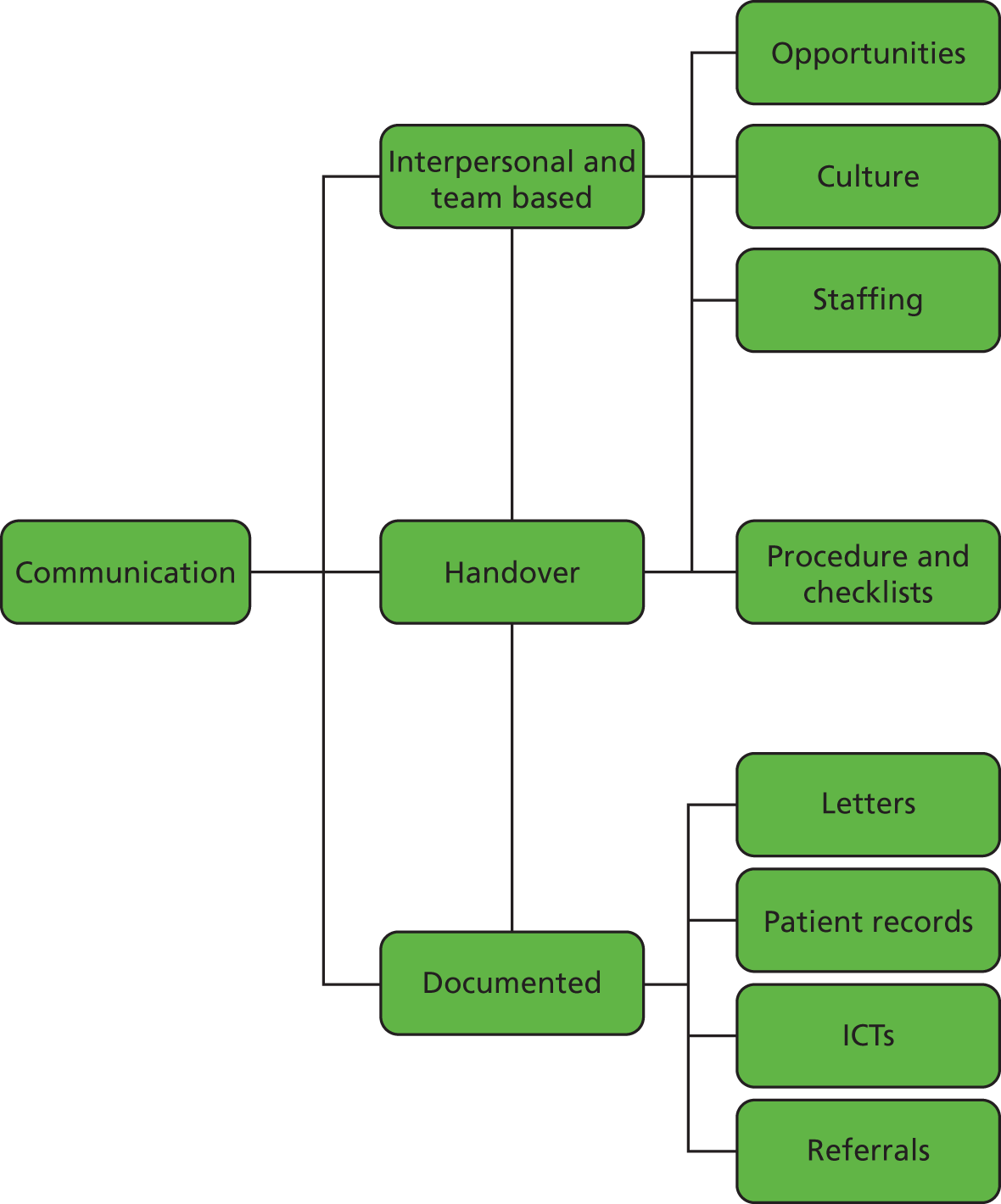

Research repeatedly highlights communication as integral to the quality and safety of hospital discharge. 14,27,28 Returning to NPSA data, ‘notifying and organising external services’ was identified as the most common category related to hospital discharge. 16 Kripalani et al. ’s (2007) systematic review29 of information transfer between hospital and primary care, and the links to patient safety, found that communication was often rare, piecemeal and poorly timed. Communication and information sharing, particularly in the processes of referrals and discharge planning, are consistently seen as underpinning the quality of hospital discharge. 14,27–31 In line with the above theoretical approach, this study examines how knowledge sharing can be a source of quality and safety in the context of organising hospital discharge.

This study aims to identify interventions and practices that support knowledge sharing across care settings, and thus promote safe hospital discharge by mitigating systems-level complexity.

Research objectives

-

To determine the stakeholders and agencies involved in discharge, including their distinct roles, responsibilities and relationships, as elaborated in terms of (a) their specific knowledge and practice domains; (b) their prevailing cultural norms and assumptions; and (c) organisational context.

-

To determine the patterns, media and content of knowledge sharing between stakeholders with a particular focus on interventions to facilitate communication, including (a) multidisciplinary teams(MDTs); (b) guidelines and toolkits; (c) co-ordinators; and (d) information communication technologies (ICTs).

-

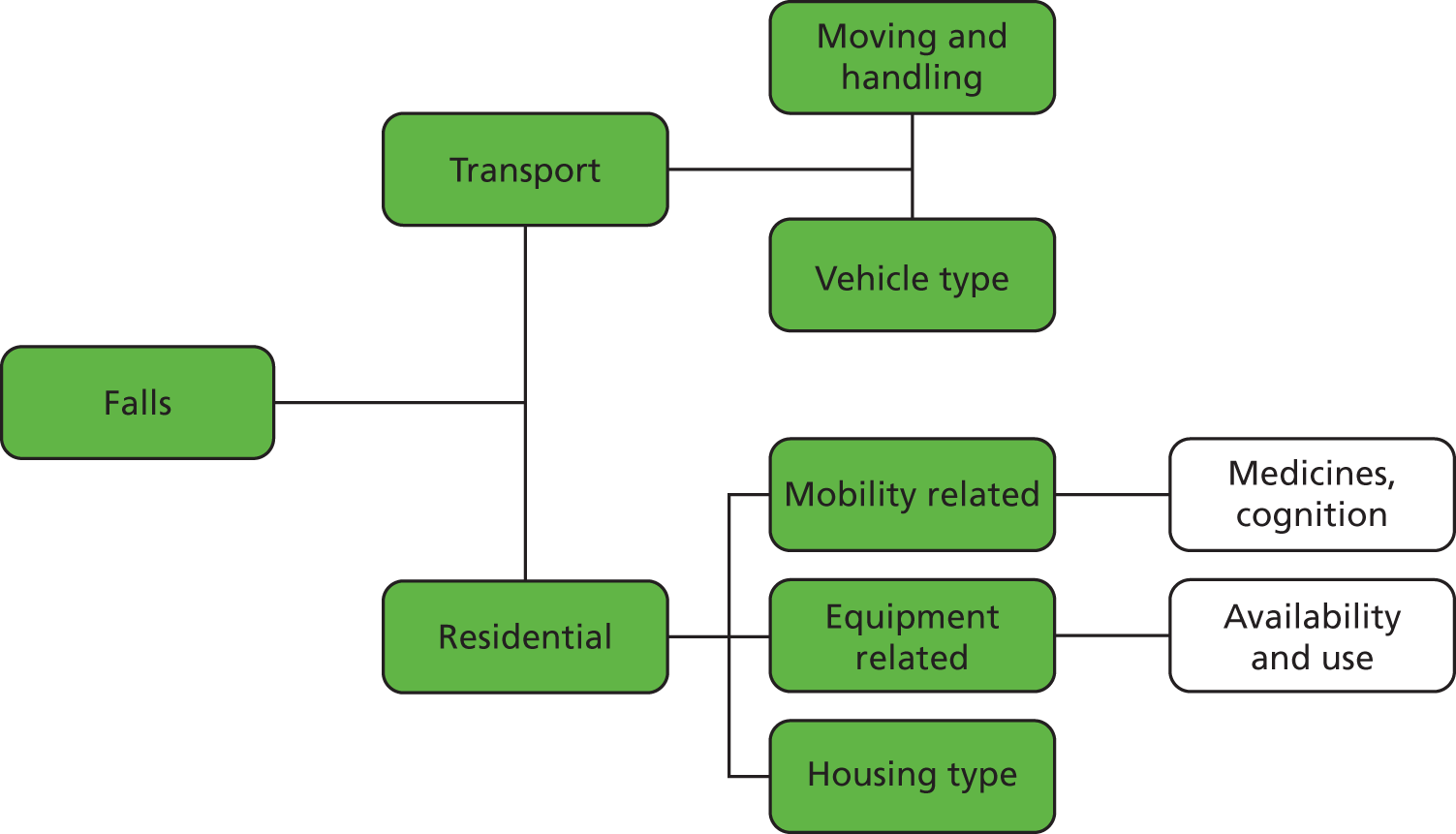

To determine stakeholders’ relative perceptions of the threats to ‘safe’ discharge, with a particular focus on known risks and sources of readmission, including (a) falls and (b) medicines management, as well as other perceived risks.

-

To determine how knowledge sharing represents a latent threat to patient safety and source of delayed discharge, including known factors such as ‘delayed’, ‘missing’, ‘fragmented’ or ‘repetitious’ communications and the persistence of communication ‘boundaries’.

-

To explain the patterns of knowledge sharing as threats to patient safety based upon the heuristic categories of knowledge, cultural and organisational factors.

-

To identify lessons and interventions that support knowledge sharing and, in turn, integrated, efficient and safe hospital discharge and reduced readmission.

The clinical context

The study focuses on the discharge of stroke and hip fracture patients. These represent high-demand areas of NHS care and national priorities for service improvement. Although the majority of patients in both tend to be elderly, they offer an opportunity for comparison in terms of how services might be organised differently, or indeed how resources could be shared across the two areas.

Stroke discharge

Stroke is the third leading cause of death in the UK and the single largest cause of disability in community settings, where over 50% of strokes result in some form of permanent disability. 32 The annual cost to the NHS of providing stroke care is over £2.8B. 33 The threats to safe discharge for stroke patients are considerable, including falls, the use of take-home medicines, psychological distress and cognitive recovery, access to and use of therapists, and the associated complications of personal care, such as incontinence. 19,21,22 Highlighting the contribution of ‘systems’ thinking, such risks often have their origins in the wider organisation and integration of stroke services. 34

For the last decade, health policies have promoted standards in the organisation and delivery of stroke care, culminating in the National Stroke Strategy. 35,36 These include the introduction of dedicated stroke units, thrombolisation pathways, specialist rehabilitation services and early supported discharge (ESD) services in the community. Each aims to diminish long-term disabilities and promote improved outcomes for patients and families. Evidence suggests, however, that there remain many inequalities in stroke care provision and subsequent outcomes related to age, location, professional skills, organisational strategies and service provision. 37,38 A growing body of research demonstrates the potential benefits of initiatives to support safe and timely discharge, including the use of ESD models. 39 Such techniques bring together service providers and users located in different settings to plan discharge. The National Stroke Strategy,36 for example, sets out the aspirations for ‘life after stroke’ by emphasising the importance of integration between stakeholders to plan and support the transfer of patient care. Similarly, it emphasises the importance of ‘working together’ through stroke networks that bring together stakeholders to review, organise and deliver services. Linked to this, the National Clinical Guideline for Stroke40 suggests stroke rehabilitation should include a MDT of relevant agencies to plan care needs after hospital.

Hip fracture discharge

Each year in the UK around 310,000 patients, the majority of whom are elderly, present to hospital with fractures. Around a quarter of these, up to 80,000, are hip fractures. 41 Projections suggest that, if this continues, numbers will rise from the current figure of approximately 80,000 to 101,000 in 2020. The average age of hip fracture patients is 81 years; 74% are female and they are among the most vulnerable groups to be admitted to hospital. Many have multiple comorbidities, including cognitive and physical impairment, which leads to longer lengths of stay, more complex discharge planning and higher readmission rates. 42 More than 60% have diagnosed dementia. 43 The median length of stay in acute hospital is 26 days, probably an indication of the general frailty of the patients, increased survival rates and increased longevity.

Care of fragility fractures is expensive. Direct medical costs to the UK health-care economy have been estimated at £1.8B in 2000, with most of these costs relating to hip fracture care. 41,42,44 Patient frailty is reflected in the outcome of hip fracture: 10% of people die in hospital within a month, and one-third are dead at 1 year. The fracture is responsible for less than half of deaths,44 but patients and families will often identify the hip fracture as playing the central part in a final illness. Hip fracture can seriously damage quality of life for survivors, of whom only half will return to their previous level of independence. Most can expect long-term discomfort and half will suffer deterioration in mobility, such that they will need an additional walking aid or physical help. Between 10% and 20% of people admitted from home will move to residential or nursing care. Length of hospital stay varies considerably between units, reflecting variability in service structures and provision, such as in early rehabilitation and the availability of downstream beds. After discharge, additional costs for health and social aftercare average £13,000 in the first 2 years.

Like stroke patients, hip fracture patients experience many potential threats to patient safety around hospital discharge, including the risks of falls, social and personal care planning, and management of medicines. Also in common with stroke care, there remains little evidence of the latent sources of risk manifest in these interagency patterns of interaction and knowledge sharing. Many specialities and agencies are involved in hip fracture care, and when discharge is planned and co-ordinated effectively through interagency working, this is shown to reduce length of stay and improve patient recovery. 45–47 Again, this requires effective and timely knowledge sharing between agencies. Alternatively, ‘offsite’ rehabilitation units are commonly aimed at frailer patients who require further rehabilitation; however, the complexities around discharge planning are often more significant given the additional level of care introduced before the patient is ultimately returned home.

Taking the discharge of stroke and hip fracture care as its focus, the study investigates the patterns of knowledge sharing across occupational and organisational boundaries and relates these to the perceived and observed threats to patient safety.

Report structure

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 reviews contemporary policies, practices and interventions for hospital discharge, and relates these to research and theory on organisational safety, complexity and knowledge sharing. Chapter 3 describes the study design and methods. Chapters 4 and 5 present the main empirical findings from the study. Chapter 4 provides a comparative ethnographic analysis of discharge planning and care transition, focusing on the main ‘situations’ or opportunities for knowledge sharing that structure the discharge process. Chapter 5 describes the threats to safe discharge as perceived by stakeholders and attempts to explain these with reference to the observed patterns of knowledge sharing discussed in Chapter 4. Chapter 6 draws out the learning from the study to tentatively outline those aspects of discharge planning and care transition that promote knowledge sharing and mitigate the threats to safety in hospital discharge, on which future interventions might be based. It also discusses the limitations of the study, summarises the main contributions to theory and research and offers suggestions for future research.

Chapter 2 Hospital discharge and patient safety: reviews of the literature

Introduction

This chapter reviews the two literatures that inform this study. The first addresses the safety challenge of hospital discharge, elaborating this as a problem of co-ordination and collaboration among various health and social care agencies. Attention is given to major policy changes and interventions aimed at enhancing discharge, as well as research evidence on clinical risk and patient safety. The second literature develops the analysis of patient safety as applied to hospital discharge, suggesting that the transition from acute hospital to community care might be interpreted as a complex system with vulnerable connections between multiple actors. The chapter draws together these literatures to explore how knowledge sharing might be a source of system safety through helping to co-ordinate and integrate the activities of different agencies and, in turn, reducing system complexity.

Understanding hospital discharge

Locating hospital discharge

Hospital discharge describes the point at which inpatient hospital care ends, with ongoing care transferred to other primary, community or domestic environments. Reflecting this, hospital discharge is not an end point, but rather one of multiple transitions within the patient’s care journey. 14,48 The organisation and provision of this transitional care typically involves multiple health and social care actors, who need to co-ordinate their specialist activities so that patients receive integrated and, importantly, safe care. The inherent complexity of co-ordinating a large number of actors, often based in distinct organisations, leads to the view that hospital discharge can be a vulnerable, time-dependent and high-risk episode in the patient pathway.

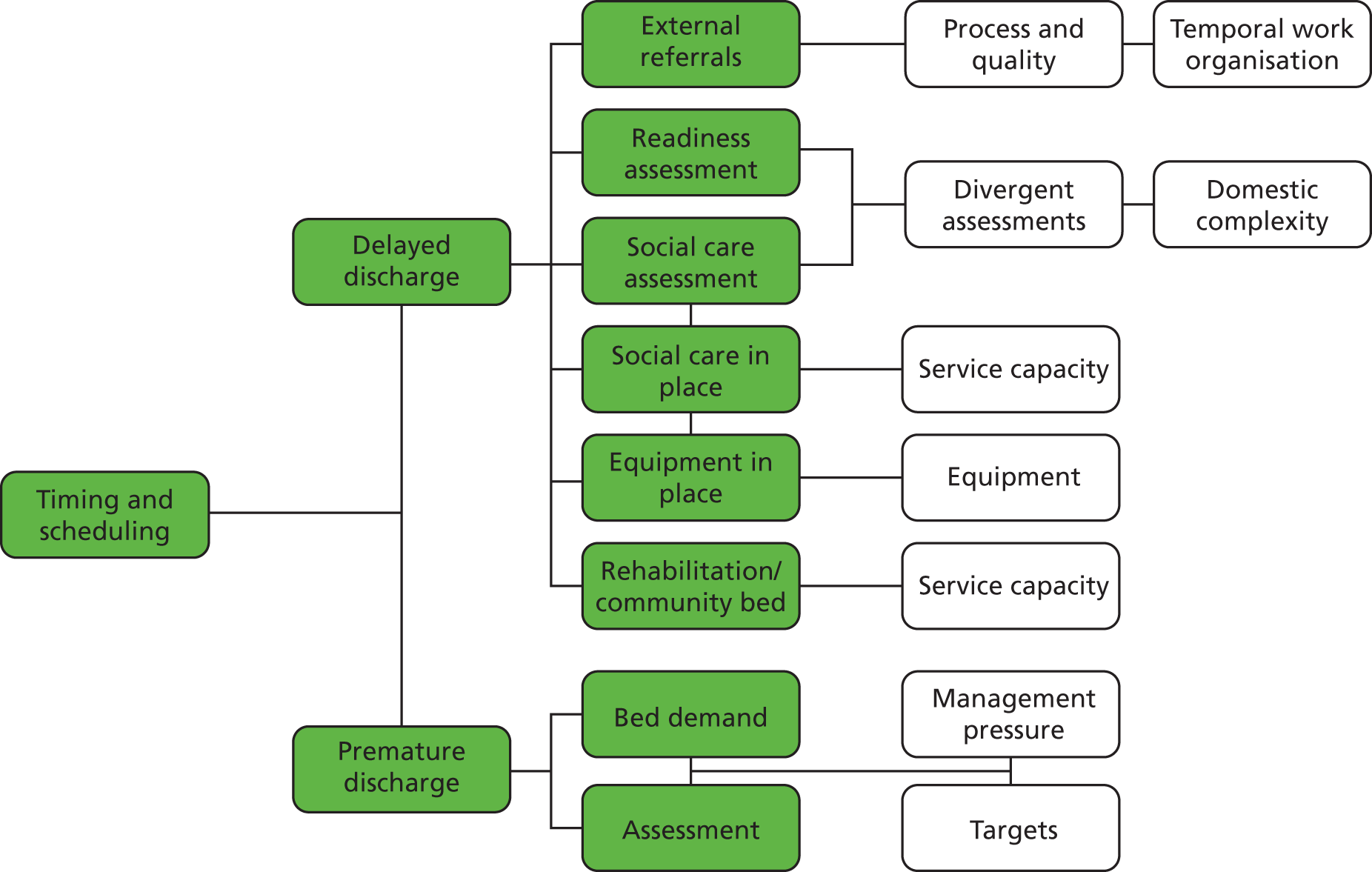

A prominent example of this complexity is ‘delayed discharge’, where the patient remains in hospital because of the failure to appropriately co-ordinate care between agencies. 27,48 According to Victor et al. ,49 nearly 30% of older people experience some delay in their hospital discharge, which is known to expose patients to additional hospital-related risks, create emotional and physical dependency, incur additional hospital costs and restrict the availability of inpatient beds. In parallel, premature discharge or discharge without appropriate arrangements for onward care can also lead to complications for patient recovery. For example, the 28-day readmission rate for older people has doubled from 103,000 in 2001–2 to 201,000 in 2010–11,50,51 suggesting that more needs to be done to support patient recovery following acute care.

The problems of delayed or poorly planned discharge illustrate the broader challenge of integrating health and social care. 27 Analysing the causes of these delays, Tierney et al. 31 point to a range of common factors, including (a) poor communication between health and social care; (b) lack of assessment and planning for discharge; (c) inadequate notice of discharge; (d) inadequate involvement of patient and family; (e) over-reliance on informal care; and (f) lack of attention to the special needs of vulnerable groups. Reflecting this and other evidence,27 policies have repeatedly sought to improve discharge planning, especially the integration of health and social care agencies. A review of these initiatives is outlined below.

Discharge planning

Improved ‘discharge planning’ has been a consistent recommendation of policy and research. 27,52–54 Over the last two decades, the precise form of discharge planning guidelines has varied to reflect wider health and social care reforms, changing economic imperatives and emerging concerns about care quality. 55–58 Furthermore, they have been developed both locally, by individual care organisations, and nationally, for example by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, and there is no commonly agreed model. Despite efforts to promote discharge planning, the recent European HANDOVER study found that health-care professions still did not prioritise discharge planning or interagency communication as supporting enhanced discharge. 59 In 2010, the Department of Health published its new discharge workbook, Ready to Go? Planning the Discharge and Transfer of Patients from Hospital and Intermediate Care,30 which outlined 10 ‘steps’ to ensuring a timely, safe and patient-centred transition from hospital, including:

-

effective communication with individuals and across settings

-

alignment of services to ensure continuity of care

-

efficient systems and processes to support discharge and care transfer

-

clear clinical discharge management plans

-

early identification of discharge or transfer date

-

identified named lead co-ordinators

-

organisational review and audit

-

7-days-a-week proactive discharge planning.

Effective discharge planning is usually associated with a number of common activities and procedures along the care pathway:14,30

-

On admission Prepare detailed and accurate patient record; review assessment information and estimate date of discharge with reference to standard care pathway and complexity of patient circumstances.

-

During admission Undertake regular multidisciplinary assessment of patient condition to identify and assess opportunity for discharge; discuss with patient and family ongoing and continuing needs.

-

At least 48 hours prior to discharge Inform MDT about estimated date of discharge and review assessment criteria; initiate referrals to community health-care providers and social care agencies; contact agencies responsible for ordering and/or installing patient equipment or home modification; social work/care assessment and referrals; complete referral for social care; finalise care package; order take-home medicines; arrange transport.

-

Day of discharge Contact family and carers to confirm follow-up care arrangements; check documentation completion; issue discharge letter to general practitioner (GP); reinforce patient behaviour recommendations and rehabilitation; confirm and finalise transport.

-

Follow-up care Initiate social care package and continuing health-care package, where relevant in consultation with GP.

As these policies suggest, a number of specialist roles and activities are promoted as supporting the integration of different agencies. A longstanding objective has been to promote the use of MDTs in discharge planning. 14,53 These are normally organised as formal, usually weekly, meetings between relevant health and social care specialists with the aim of supporting timely communication, inclusive decision-making and continuity of care. Research often describes MDTs as comprising a core team including the named doctor and nurse, occupational therapists (OTs) and physiotherapists (PTs), and representatives from community and social care agencies, as well as family representatives, GPs and other specialist therapists. According to Bull and Roberts,52 MDTs help break down barriers between professional groups and foster a sense of common purpose and trust. Importantly, MDTs provide an opportunity for communication, first between professionals, second with patient and family, and third with community health-care providers. Furthermore, MDTs can help make clear the lines of responsibility for different tasks and create opportunities for individuals to take the lead in co-ordinating the planning process. In practice, however, convening all representatives for individual patients can be challenging in terms of time or resources. 27

A further initiative has been the introduction of discharge co-ordinators. 14,30 These are individuals, usually experienced nurses, who take lead responsibility for both strategic planning and co-ordination of discharge at the interorganisational level. 60 Research suggests that discharge co-ordinators can improve hospital discharge through supporting the integration of different professionals, overseeing and directing planning and addressing emergent problems in a more responsive way. 61 In particular, co-ordinators acquire both deeper understanding of and extended relationships with a wider range of care agencies that help them better navigate and align divergent ways of working that usually delay or undermine discharge. 52,61,62

Integrating care services

In line with the developments in discharge planning, policies have also introduced new or extended statutory powers, financial opportunities and penalties to support more integrated discharge pathways. For example, the Health Act 199963 enabled health and social care agencies to pool resources to codeliver rehabilitation services. Similarly, in 2005, delayed discharge grants were made available to social service authorities across England to develop reablement services. In contrast, the Community Care (Delayed Discharges) Act (CCDDA) 200364 addressed the problems of integration by allowing hospitals to claim financial reimbursements from local authorities where they delayed discharge by not providing timely services. Against this backdrop, a variety of integrated services and new care pathways have emerged to support the transition from hospital to community, but in doing so have extended (and made more complicated) the range of services involved in discharge planning.

One significant development has been the introduction of ESD. ESD is often associated with the care and rehabilitation of mild-to-moderate stroke patients. It enables patients to return home early with a dedicated package of rehabilitation and reablement of a similar intensity to that provided by inpatient care. ESD is shown to reduce the burden on acute providers and support patient recovery. 65 The funding of ESD through joint commissioning between the acute NHS providers, GPs, social services and central government highlights the role of joint working and resource pooling, but there remain variations across the UK, especially in rural areas, where a lack of funding can limit provision. 66,67

Intermediate services provide transitional, ‘step-down’ care between acute hospital and the domestic environment (usually for 30 days). Patients are typically declared as ‘medically fit’ but requiring ongoing care or rehabilitation, for example those at risk of readmission or with complex care needs. Rather than receiving rehabilitation at home or in hospital, intermediate care offers a form of residential, hospital-like care, but with a focus on rehabilitation. Research suggests that intermediate care services have been effective in both reducing financial costs and improving patient outcomes. 68 Owing to their close proximity to patients’ homes and relatives, community (NHS) hospitals or nursing homes are often used for intermediate and post-discharge rehabilitation. Stays in such units can be longer than in other intermediate care services, yet research suggests patient outcomes are generally favourable. 69 The recent Cochrane reviews of long-term rehabilitation in care homes show no evidence of negative health outcomes. 65,70

A similar initiative is the introduction of reablement services. These usually involve a dedicated package of social care to support daily living in the immediate period following discharge (e.g. personal care, cooking and cleaning). They are usually managed and provided by local authority social services, although in some cases they are funded through both health and social care budgets. In 2012, the Department of Health allocated £150M for reablement linked to hospital discharge,30 to be allocated through primary care commissioners working in partnership with social care authorities. Significantly, these services are normally arranged and provided by social services to ease transition from hospital for a period of 4–6 weeks, with the expectation that ongoing social care will be reassessed and provided by other agencies.

A further example of service innovation, with particular reference to end-of-life care, is the introduction of ‘fast-track’ discharges. This normally relates to supporting early discharges from hospital for those patients wishing to spend the last days of life in the community with palliative support. This end-of-life discharge can exemplify effective joint working and rapid prioritisation, whereby the patient can be discharged within 48 hours with all specialist support and medications in place. 71 For example, funding decisions are established post discharge to remove delays; the needs of the patient and family are met by deliberate use of a continuous dialogue with one specialist co-ordinator; and the emphasis is on timely collaborative working to ensure the patient gets home as requested. 72

The threats to ‘safe discharge’

Multiple sources of evidence suggest that care quality can be suboptimal in, or as a consequence of, hospital discharge. 28 In a major telephone survey of 400 patients following discharge, Forster et al. 17 found that nearly 20% reported some form of adverse event, of which 6% were preventable and 6% ameliorable. Research highlights a number of common discharge-related risks associated, for example, with the management of medicines, the provision of appropriate health and social care, incomplete tests and scans, the fitting and use of home adaptation, and the risks of falls, infections or sores. 17–28 The underlying sources of these risks can range from factors related to the patient’s condition or comorbidities, to the assessment of patient need, the availability of specialist resources in the community, and wider organisational and cultural factors. For example, research shows that the patient’s condition, such as hip fracture, and other comorbidities, especially cognitive function and fragility, can represent a cluster of risks, particularly for older patients, that can complicate the discharge process. 73,74 Research also suggests that time of day, week or year can also have an impact on discharge planning and quality. In particular, discharges during the weekend have been shown to increase the likelihood of death compared with those taking place between Tuesday and Friday, accounting for 34% of all post-discharge deaths. 75,76

Although studies highlight the importance of clinical risk in discharge planning, it is not always clear how ‘risk’ is measured. Moreover, the causal analysis of risk is often implicit or an emergent feature of wider trial research. Reviewing the recent literature (Table 1), a number of risks (direct threats to safety) and identified causes (suggested or inferred) are catalogued.

| Study | Identified risks | Identified causes |

|---|---|---|

| Lankshear et al.77 (Research) |

Anti-coagulant medication risks: non-compliance, polypharmacy, lack of monitoring | Poor documentation, communication between acute and primary care providers, accessibility of clinics |

| Hansen et al.78 (Research) |

Rehospitalisation and link with quality of discharge documentation | No direct association found except in patients with follow-up and larger number of medications |

| Laugaland et al.28 (Review) |

Transitional care safety risks among older people | Lack of discharge planning and post-discharge support |

| Hagino et al.79 (Research) |

Risk factors for hip fracture patients: a prognostic approach | Age (over 85 years), chronic disease, dementia, mobility prior to fall (walking disability) |

| Howard et al.80 (Review) |

Identification of drugs and underlying drug-related issues most likely to cause readmissions | Four groups of medicines account for 50% of drug-related readmissions. Three underlying causes related to patient adherence, monitoring and prescribing errors |

| Romagnoli et al.81 (Research) |

Discharged patients with unmet information and communication needs | Limited medication information, non-medication issues about care/safety/follow-up, functional limitations, severity of condition and communication problems |

| Clarke et al.82 (Research) |

Experience of risk in ESD scheme | Lack of patient consent, patients not ready for discharge, feeling unsafe, medication supply problems, transport home problems, lack of home nursing |

| Goulding et al.83 (Interview study) |

Patient safety among patients on clinically inappropriate wards | Placement of patients on to clinically inappropriate wards poses a latent threat towards safe discharge planning; specifically, patients are more likely to be deemed medically fit before they actually are |

| Härlein et al.73 (Systematic review) |

Risk factors for patients with dementia | Identified eight risk factors for falls in older people with dementia on discharge from hospital, which could be used prospectively on admission |

| Courtney et al.84 (Research) |

Risks of readmission for individualised 24-week post-discharge programme of rehabilitation and telephone support. Randomised controlled trial | Intervention group had lowered readmission rates, lowered emergency GP contact and improved quality-of-life indices |

| Coffrey85 (Research summary) |

Discharging older people and risks | Summary of evidence about discharge risks among older people |

Although the sources of these risks can be complex and variable, research frequently highlights incomplete, inaccurate and inaccessible information as undermining collaborative workings and contributing to unsafe patient discharge. 27–29,86,87 A systematic review conducted by Kripalani et al. 29 found that communication between hospital and family doctor was often partial or missing, relying primarily upon discharge summaries which were often incomplete, lacking in detail and not provided in a timely manner. Similarly, poor communication between the hospital and social care providers is a long-standing risk factor in adverse events. 27,29,88 There remains little extensive research, however, examining the causes of poor communication and adverse events. 29,89 Less is known about how communication breakdowns and patient safety are experienced by patients and carers. 54 A number of studies propose, and in some cases evaluate, interventions to support communication and information transfer at discharge, including structured communication tools, discharge planning guides, discharge checklists, medicine reconciliation guides and patient education strategies. 84,90–94 These suggest that effective discharge planning depends upon effective communication and collaboration between health and social care agencies. 28,86,95 In his analysis of the factors that support or hinder such communication and collaboration, Glasby27 highlights three dimensions:

-

occupational factors related to the particular knowledge, cultures and practices of different professionals

-

organisational factors related to the working patterns, capabilities and resources of different agencies

-

compatibility and co-ordinating factors related to how occupational and organisational factors are aligned, or differences reconciled.

Attention to these and other factors is needed to better understand and enhance communication and collaboration in discharge planning and care transition. Furthermore, greater appreciation is needed of how communication might undermine not only co-ordination but, in turn, safety. In this sense, communication might be seen as a latent (or active) factor that influences the safety of hospital discharge. The next section develops this idea through relevant theory and research on organisational complexity and safety.

Understanding discharge safety

The quality and safety of hospital discharge is framed by a variety of contextual and system-level factors related to the type of discharge, the configuration of different providers, the availability of resources and, importantly, the relationships between actors in terms of communication, decision-making and joint planning. These issues, as identified in the research literature,27–29,86,87 represent possible upstream sources of risk, for example where the failure to communicate and jointly plan services can lead to reduced integration of care agencies and substandard patient care. To better understand this, the present chapter considers relevant patient safety literatures.

The systems approach to patient safety

Current thinking in patient safety is largely informed by theories and research within the fields of ergonomics and human factors. In broad terms, this suggests that performance mistakes are not necessarily brought about by individual negligence, malice or incompetence, but more often by pressures located within the work environment. 96 This line of reasoning makes the distinction between ‘active’ and ‘latent’ errors. The former refers to individual slips, mistakes or omissions that lead to patient harm; the latter to the unsafe conditions that create, enable or exacerbate the potential for active error or patient harm. This can include poorly designed working arrangements, poor defence and early-warning mechanisms or an over-reliance on automation. This approach suggests that risk reduction should attend, not to individual performance alone, but to the upstream factors that make performance error prone, for example by standardising task design, improving team cohesion and communication, alleviating situational ambiguity and recognising the influence of resource management and culture. 96

This ‘systems approach’ to patient safety has been articulated through policies such as To Err is Human1 and An Organisation with a Memory,2 and developed through major programmes of applied health research. 3 For example, it has been used to highlight how a range of ‘task’, ‘team’, ‘situational’ and ‘organisational’ factors contribute to front-line clinical safety. 97 Of specific relevance to this study, this conceptualisation of safety draws attention to the way health care is organised and delivered through a system of interdependent elements interacting to achieve a common goal. 1 Based upon these ideas, various strategies have been promoted to better understand and address the threats to patient safety. These include, for example, the use of incident reporting procedures to enable clinicians to share their experiences of clinical risk and engender system-wide learning of the root causes;98,99 the creation of a safety culture that is mindful of danger, blame free and responsive to organisational learning;100 and a variety of safety-enhancing interventions, such as ICTs or single-use devices which limit unsafe behaviour; checklists, guidelines and the standardisation of practices to reduce variability; and staff training and culture change activities. 3 The ‘human factors’ approach provides a framework (drawing on Vincent101) for conceptualising and investigating the threats to safe discharge (Table 2).

| Dimension | Risk-producing/enabling factors | Discharge risks |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Complexity, severity, personality, demographics | Comorbidities and complexity of patient need; cognitive impairment, cultural and language barriers to engagement |

| Task factors | Clarity, complexity, standardisation | Clarity of the discharge pathway and the steps involved in organising and arranging discharge |

| Individual factors | Knowledge, skills, motivation | Clinical understanding of discharge requirements, attitude towards discharge in context of wider care process |

| Team factors | Communication, decisions, supervision, structure | Communication breakdowns between health and social care teams, limited joint decision-making |

| Work environment | Staffing, skill mix, workload, support structures | Demand for inpatient beds, social care staffing changes and health-care workload placing pressure on discharge arrangement |

| Organisational and management factors | Resources, policy/strategy, culture | Extent of resource sharing and joint working between health and social care agencies |

| Institutional context | Socioeconomic and regulatory systems | Changing policies and regulatory arrangements for discharge, such as compensation for delayed discharge placing pressure on social care staff |

Extending the systems approach

Despite the enormous advances in patient safety research, it has been suggested that the distinctive sociocultural and political dimensions of health care are sometimes overlooked. 6 A related view suggests that the human factors approach tends to, although does not always, focus on what might be considered the ‘clinical micro-system’ or local work environment. Take, for example, the emphasis on team skills, communication aids, decision-support tools and checklists. This approach considers less frequently (and in less detail) the wider cultural, institutional or system factors related to workplace practice. Similarly, research has tended to focus within clinical specialities, departments or units, such as operating theatres, care homes or emergency departments, with less attention to the interconnections between these areas and the wider organisation. 3 Although organisational and societal factors are recognised,96,101 they are not well developed theoretically or empirically as distinct and interconnected levels of analysis.

Attention to the sources of risk and safety between care settings and processes is important for hospital discharge as relates directly to broader organisational and interorganisational factors. It calls for attention to the nature of the relationships and interdependencies between care organisations as patients pass from hospital to community care. These interdependencies constitute ‘system-level’ (latent) sources of safety, and where research does attend to these interdependencies it shows that the organisation of health care is often so complex and non-linear that the idea of creating a reliable, standardised and safe system remains a ‘wicked problem’. 102–106 Extending this line of thinking, Hollnagel107 suggests that although the human factors approach goes beyond a simple (single agent) model of error causation to identify instead environmental causation, it too often neglects the non-linear and more complex dynamic coupling involved in many organisational or system processes.

Developing this perspective, a ‘system’ describes a collection of actors, units or parts that together, and through their various connections, form the basis of a structured and relatively bounded entity. Through combining these constituent elements, systems produce particular effects; in many instances these are positive, but they can also be unpredictable, unanticipated or unsafe. 108 Broadly speaking, ‘complex systems’ have emergent properties that result from the non-linear or complex connections between their heterogeneous units, subsystems, variables or actors. 108,109 Furthermore, complex systems can produce effects that are not always evident from the actions or attributes of the individual parts, owing to the potential for the actions of one component to transform the contexts and actions of others. 108 More than this, complex systems are characterised by the absence of structural design and by patterns of self-organising and adaption. For example, the constituent parts within a system interact according to local rules (e.g. customs or cultures) without any overarching direction or control (e.g. leader). 110

Health-care systems are increasingly identified as complex systems. 102,111–114 The organisation and delivery of health care typically involves a vast number of agencies that span different economic sectors (public, private, voluntary), health domains (primary, secondary, tertiary) and care domains (health, social, personal), with distinct roles and responsibilities (commissioners, providers, regulators) and caring specialities. Moreover, the interactions between these actors are not always well defined, but remain dynamic, non-linear and multifaceted, from micro-level clinical interactions, to the meso-level interactions of service planning or commissioning and the macro-level interactions of policy-making and professional associations. As such, health-care systems can change in ways that are not always easily anticipated by policy-makers or service leaders. Extending this line of thinking, hospital discharge might have been conceived as a complex system involving a network of diverse, often heterogeneous actors, interacting in dynamic and non-linear ways that over time produce unpredictable and unanticipated behaviours or outcomes, both positive and negative.

One seminal analysis of organisational complexity that specifically demonstrates the potential for negative consequences is Charles Perrow’s study of Normal Accidents. 8 This was developed through an investigation of the system failures that contributed to the Three Mile Island nuclear disaster. His analysis suggests that organisational accidents might be interpreted as inevitable for complex organisational systems, not simply because of the high-risk nature of the work or potential for ‘operator error’, but because of the way organisational processes are configured. In particular, his research elaborates how relatively small, isolated or ‘discrete failures’ that occur in one part of a complex system can cascade and escalate into more substantial disasters. In other words, risks do not develop through linear causal chains but through unpredictable interactions. Where organisational activities are ‘tightly coupled’ there are higher levels of interdependence between work processes, meaning that what happens in one area is influenced by, or influences, the work of others. In health care, research has demonstrated how errors and failures from one department have consequences in other tightly coupled activities across the health-care system. 106,115

Although health policies call for greater attention to, and learning about, the systemic threats to patient safety,2 research has largely centred on the latent threats located within discrete and often localised parts of the health-care system. 3 There remains limited understanding or evidence of the threats to, and opportunities for, patient safety located within the wider health-care system, especially in the complex interdependencies and non-linear interactions that exist between care providers located in diverse occupational, organisational and sectoral domains.

Applying these ideas to the problem of hospital discharge, it becomes apparent that the complex interdependencies and non-linear couplings between health and social care agencies can be the latent source of poorly timed, inappropriate or unsafe transition from hospital to community care. Policies to support integrated discharge planning have repeatedly looked to introduce improved or more stable couplings between these agencies through, for example, resource pooling and MDTs, and more routine and robust methods of information sharing. 30 There remain, however, enduring compatibility factors27 that inhibit co-ordination, and hence discharge safety, given the persistence of heterogeneous, tightly coupled and interdependent working practices.

Integration and safety through knowledge sharing

The above literatures show that hospital discharge is a vulnerable or unsafe stage in the care pathway, often because of the challenges of co-ordinating different health and social care agencies. Extending this idea, this study suggests that hospital discharge might be thought of as a complex system, whereby interdependencies and couplings between caring professionals and agencies can be a source of and threat to patient safety, depending on how they are co-ordinated. The literature repeatedly emphasises communication as helping to reduce this complexity and support co-ordination, for example, in discharge planning or the use of checklists. 27–29,86,87,94 Extending this idea, we propose the concept of knowledge sharing as a way of supporting the co-ordination and integration of health and social care agencies and mitigating the uncertainties inherent within complex health-care systems.

Knowledge sharing involves more than the communication of information, but instead denotes the exchange and use of meanings, assumptions, practices and know-how between different groups to engender shared understandings and collaborative practices. 11 For many improvement strategies, such as knowledge management and evidence-based medicine, knowledge is conceived as an explicit, abstract and tangible resource that can be accessed, codified and exchanged, for example in the form of formal policies or incident reports. In other words, it is an explicit ‘thing’ to be shared with others in the form of documents or evidence. This contrasts with the idea that knowledge or know-how is often tacit, experiential and situated in practice. 116 In this sense, knowledge is difficult to share and is typically acquired and developed through participation in communities of practice. 117 In short, knowledge is not a ‘thing’ that a community ‘has’, but rather it is what they ‘do’ and who they ‘are’. 117 This distinction is important because efforts to understand and indeed promote knowledge sharing should not only focus on the formal assemblages of knowledge, but also the more informal and unarticulated manifestations of know-how. Knowledge sharing is therefore more than the communication of information; it refers to how the meanings, ‘know-how’ and practices of one group or organisation can be shared and integrated into the practices of another. 10

The research literature highlights a range of factors that facilitate or inhibit knowledge sharing. 10–12,118 This includes the characteristics of both ‘donor’ and ‘recipient’ actors, such as their motivations, accessibility, levels of trust, values, hierarchies and absorptive capacity. 119–121 For example, competitive pressures can inhibit knowledge sharing where it threatens competitive advantage. 11 The ‘structural configuration’ of relationships can also channel knowledge flows through ‘central actors’ or knowledge brokers, rather than between peripheral actors. 122 Similarly, power hierarchies and cultural difference between actors can have an impact on knowledge sharing, especially where powerful actors assume control of knowledge to advance their own interests. 12,123 For professional work, these issues are exacerbated where expert knowledge is closely linked to sociolegal jurisdiction within the division of labour. 124 In this context, knowledge sharing can threaten professional boundaries and identities. 13,125 The research literature highlights a number of key dimensions that shape the potential for knowledge sharing. 117,122,126–128 Drawing together this literature, three inter-related factors are identified as shaping knowledge sharing and collaboration within and between health-care organisations:

-

Knowledge Related to differences in epistemology, cognition and sense-making, for example how actors make sense of discharge; the types of knowledge that guide practice; and whether or not knowledge represents a competitive resource.

-

Culture Related to the shared norms, attitudes and values that guide practices, for example when knowledge should be shared and with whom; how identities and trust reinforce knowledge hoarding; the different philosophies of care that guide work organisation.

-

Organisation Related to the influence of (inter/intra)organisational structures, processes, regulatory factors and management priorities that shape knowledge sharing, such as sociolegal rules, professional jurisdictions, organisational connections and resource constraints.

Knowledge sharing for safe discharge

Applying the above literatures to hospital discharge, this study investigates how patterns of knowledge sharing among health and social care agencies influence discharge planning and care transition. Developing this view, knowledge sharing is conceptualised as a latent source of safety that, through shaping the patterns of co-ordination, shared decision-making and integrated working, can mitigate system complexity. As such, understanding the barriers to and drivers of knowledge sharing can contribute to the development of new knowledge on the possibilities for improved integration and safety in hospital discharge. These lines of analysis are tentatively outlined in Table 3.

| Dimension of knowledge sharing | Examples in context of hospital discharge |

|---|---|

| Knowledge |

|

| Culture |

|

| Organisation |

|

Summary

This chapter has reviewed research literatures on hospital discharge and patient safety to suggest that discharge from hospital to community is located within a complex and vulnerable system, involving a diverse range of heterogeneous actors interacting in dynamic and non-linear ways. Policy and research highlight the need for improved integration, especially in discharge planning and care transition; however, given the complex, dynamic patterns of interaction and the variable institutional environments in which caring professionals work, this integration remains problematic. The idea of communication and collaborative decision-making is frequently cited as a basis for integration. 27–29,86,87 The study extends this idea by suggesting that knowledge sharing can support enhanced integration and collaboration among system actors, based upon the exchange and alignment of different meanings, assumptions and know-how, as well as more explicit knowledge and information. Knowledge sharing is therefore presented as a source of (and threat to) safety within the complex systems involved in hospital discharge, and requires further empirical understanding.

Chapter 3 Study design and methods

Study aims and objectives

This exploratory study investigates how knowledge sharing, as a latent factor, contributes to discharge planning and the transition of care, with the broad aim of identifying interventions and practices that support knowledge sharing and thus mediate system complexity and promote patient safety. As outlined in Chapter 1, the study focuses on the discharge of stroke and hip fracture patients as two comparator groups, but with the intention of developing broader lessons for improving care transitions. In line with this, the research objectives include:

-

to determine the stakeholders and agencies involved in discharge, including their distinct roles, responsibilities and relationships, as elaborated in terms of (a) their specific knowledge and practice domains; (b) their prevailing cultural norms and assumptions; and (c) organisational context

-

to determine the patterns, media and content of knowledge sharing between stakeholders with a particular focus on interventions to facilitate communication, including (a) MDTs; (b) guidelines and toolkits; (c) co-ordinators; and (d) ICTs

-

to determine stakeholders’ relative perceptions of the threats to ‘safe’ discharge, with a particular focus on known risks and sources of readmission, including (a) falls and (b) medicines management, as well as other perceived risks

-

to determine how knowledge sharing represents a latent threat to (sources of) patient safety, including known factors such as ‘delayed’, ‘missing’, ‘fragmented’ or ‘repetitious’ communications and the persistence of communication ‘boundaries’

-

to explain the patterns of knowledge sharing as threats to patient safety based upon the heuristic categories of knowledge, cultural and organisational factors

-

to identify lessons and interventions that support knowledge sharing and, in turn, integrated, efficient and safe hospital discharge and reduced readmission.

Methodological considerations

The proposed study methodology combined two complementary approaches for identifying, analysing and understanding patterns of knowledge sharing within complex social systems. This included social network analysis (SNA) and ethnography. SNA is an approach for identifying, mapping and measuring social systems and relational processes through analysing the relationships (ties) between people, groups and organisations (nodes). 129–132 Despite a resurgence of interest in more qualitative approaches to understanding social networks,132,133 quantitative approaches for measuring and statistically analysing social relationships remain dominant in organisational research. 131 Although the study obtained a range of qualitative data to describe and understand the patterns of knowledge sharing involved in hospital discharge, these data have not been analysed in the form of SNA, i.e. looking for structural relationships, actor centrality or network density. 131 Through consultation with methodological advisors, and reflecting the comments of the study reviewers, it was determined that, although a range of qualitative data on the patterns of knowledge sharing were collected, these were not of a consistent format and character to enable more standardised SNA. As such, the report draws upon these qualitative data to develop a ‘thick’ description and interpretative understanding of the patterns of knowledge sharing involved in discharge planning and care transitions. 132,133

In broad terms, ethnography is concerned with developing a rich description and interpretative understanding of how different peoples, communities or cultures ‘experience, interpret and structure their lives’. 134 Ethnography is particularly suited to organisational research,135 providing insight into how knowledge is constructed through intersubjective and culturally informed sense-making; how beliefs and assumptions are shared among different groups or communities; the importance of shared language and stories in expressing and reinforcing shared values; how ceremonies and rituals guide interaction and convey shared meaning; how social activities occur and unfold in context; and how wider sociocultural and institutional pressures shape everyday life. 136–138 The ethnographic approach is associated with specific methods for understanding social and cultural processes, especially observations that allow for an emic or insider’s perspective. 136

With reference to this study, ethnography affords exploratory understanding of hospital discharge as a situated social activity involving the sharing of knowledge between multiple actors, each with distinct cultures and modes of social organisation. Ethnography facilitates the identification and analysis of the distinct knowledge and practice domains that characterise different groups involved in hospital discharge; how their distinct cultural norms, values and identities have an impact on their discharge practices; and how wider social and organisational customs frame social practices. As well as providing a detailed and holistic understanding of the social and cultural world of health and social care professionals,138 ethnographic research is well suited to investigating issues of patient safety,139,140 including how latent factors located within this wider sociocultural fabric interact with and make clinical practice potentially (un)safe. 106

Sampling and selection

The study was designed as two system (and two patient group) case studies of discharge planning and care transition. The case study approach enables in-depth and contextual insight within cases, but also comparison and theoretical generalisation between cases. 141 In line with the case study approach, the selection of care systems and patient groups purposively aimed to investigate known differences between these cases.

System and organisational selection

The primary unit of analysis was the local care ‘system’, within which patient discharge is planned and organised. This ‘system’ is conceptualised as comprising an acute NHS hospital around which other primary, community, rehabilitation and social care services are arranged. Discharge is seen as the planning and transition of care from the acute NHS hospital to community-based health and social care. In line with this view, the study was undertaken in two geographically distinct English care systems, broadly defined by county boundary. Each has a principal administrative city and conurbation (Farnchester and Glipton), with smaller towns, and villages located in rural areas. For the purpose of maintaining anonymity of participating organisations and individuals, the city, country and organisational names have been changed. Sampling of these geographical areas took into account their relative size, ethnic diversity and urban/rural balance (Table 4). Sampling also considered variations in the configuration of the care systems in these counties. Each was served by a single NHS acute trust; one was a large teaching and research-active health-care provider, operating over three large organisational units (Glipton), and the other was a smaller district general hospital with limited teaching and research activities (Farnchester). Sampling also considered the geographic spread of community-based care services, the proportion of single-handed GPs and structure of social care services. These differences are summarised in Table 4 [data were obtained through National Health Profiles143 and the Office for National Statistics (ONS)142 from 2010 to 2012].

| Study site | Population (n) (2011142) | Geography (square miles) | Ethnic diversity | Life expectancy, male (years) | Life expectancy, female (years) | Life expectancy variance between most deprived and least deprived city areas (years) | Number of GP practices | Hospital arrangements | Community services | Social services | Ambulance service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glipton city | 307,000 | 60% white | 75.4 | 80.1 | Male, 9.4 Female, 5.0 |

65 | Three large city acute and specialist hospitals with extensive teaching and research (NHS acute trust) | Dedicated rehabilitation centres, ESD services, intermediate care, mental health care and large number of private care providers | City providers | Single NHS provider for acute response; private provider for planned discharges | |

| Farnchester city | 90,000 | 95% white | 76.5 | 81.2 | Male, 10.6 Female, 5.8 |

24 | Two medium-sized district general hospitals with limited teaching (NHS acute trust) | Limited range of generic rehabilitation services with small range of private care homes | Single care provider | Single NHS provider for acute response and planned discharges | |

| Glipton county | 649,000 | 823 | 80% white | 79.8 | 81.2 | Male, 6.2 Female, 5.7 |

145 | Two general community hospitals (NHS community health-care trust) | Large number of private providers and approximately six social service-run homes with registered dementia care units | County providers | Single NHS provider for acute response; private provider for planned discharges |

| Farnchester county | 703,000 | 2350 | 98% white | 78.7 | 82.4 | Male, 7.3 Female, 4.9 |

102 | One general community hospital in remote town | Limited range of private providers with no registered dementia care homes | One single care provider | Single NHS provider for acute response and planned discharges |

| England average | n/a | n/a | 86% whitea | 78.6 | 82.6 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

Farnchester NHS Trust comprises two medium-sized district general (acute) hospitals, one located in the administrative city of the county and the other in another market town (Farnchester and Fallow), and a third, smaller community hospital located in a remote small town (Ribble). The hospitals were merged in 2000 under the management of a single NHS trust, with headquarters based at Farnchester Hospital. According to available records, the Trust employs over 7500 staff and treats more than 180,000 emergency patients, 500,000 outpatients and 100,000 inpatients every year. Farnchester Hospital is the main provider of specialist services across the majority of the county, including stroke and hip fracture patients. At the time of data collection, two primary care trusts (PCTs) (east and west of the county) commissioned specialist and acute services. Following the Health and Social Care Act 2012, services are commissioned by four Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) (north, south, east and west), which operated in shadow form during the last year of the study. The Trust works closely with Farnchester Community Healthcare NHS Trust, which was formerly managed by one of the PCTs but became a separate provider of health care. It also works closely with a single unitary local authority for the county, whose social service department assesses and provides social and personal care, or contracts care provisions from private or third sector agencies.

Glipton NHS Trust comprises three distinct hospitals (City, General and District), located in different areas of the same city and also brought under the management of one NHS trust in the early 2000s. The Trust employs over 10,000 staff and provides services to over 1 million residents in the local population. It is an established site for health education, with strong links to the local universities, and the site of an extensive portfolio of clinical research. At the start of the research, the Trust worked closely with two NHS PCTs (city and county), who commissioned the majority of its acute and elective services. Following the Health and Social Care Act 2012, three new CCGs operated in ‘shadow’ form until assuming responsibility for commissioning in April 2013. Two community NHS trusts (city and county) provide continuing health care, rehabilitation and home-based care, including the management of two community hospitals. The social services departments of the city and county local authorities were involved in assessing, providing or commissioning social care through a mixed market of public, private and third sector organisations. This includes a specialist reablement service for immediate postdischarge care. The regional NHS ambulance trust supports the transition of patients both to and from Glipton and Farnchester NHS Trusts, and a private transportation firm is also contracted to provide patient transports from hospital.

Sampling started with the two acute NHS hospitals, and included other primary, community and social care agencies. It was anticipated that the variety and number of agencies involved in discharge planning and care might be considerable, and variable according to patient need. Reviewing the literature, a range of common agencies was identified. Although many of these groups could be identified in advance of the study, such as social services, it was difficult to determine the exact profile for each county. As such, a snowball sampling strategy was used to identify agencies and organisations involved in hospital discharge. This group included:

-

GPs and primary care administrative and commissioning units (PCTs, now CCGs)

-

community health-care services (some formerly managed by PCTs)

-

specialist community in-reach/outreach services (possibly managed by PCTs)

-

community pharmacies

-

local authority, social services

-

social care providers working in private, public or third sector (including reablement)

-

intermediate care and rehabilitation services

-

residential and nursing homes

-

ambulance and transportation services

-

voluntary sector support groups.

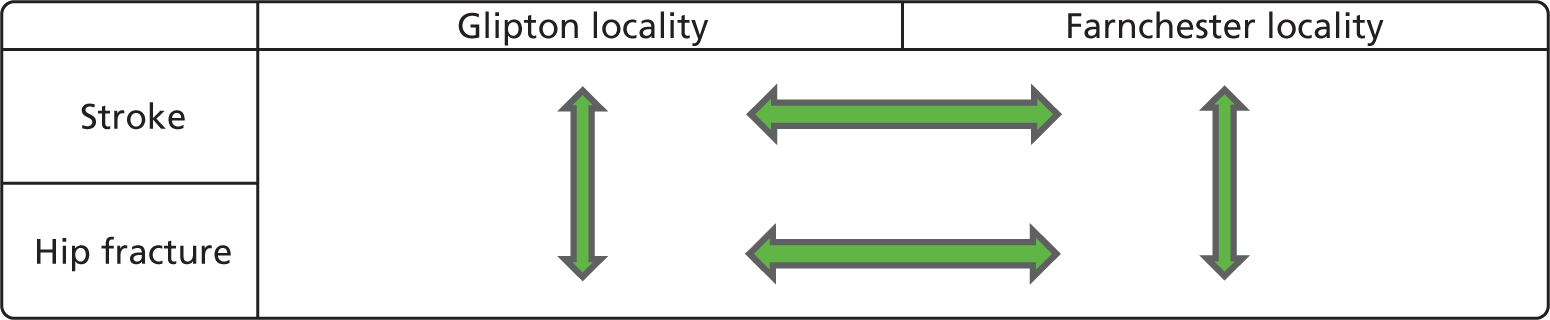

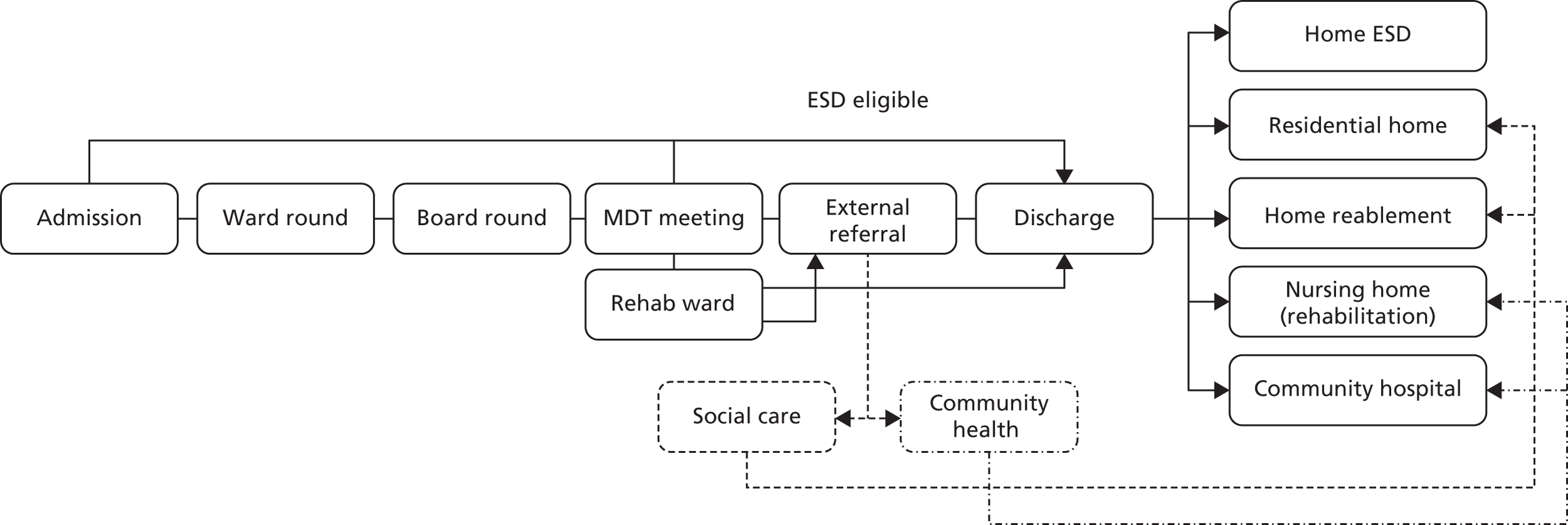

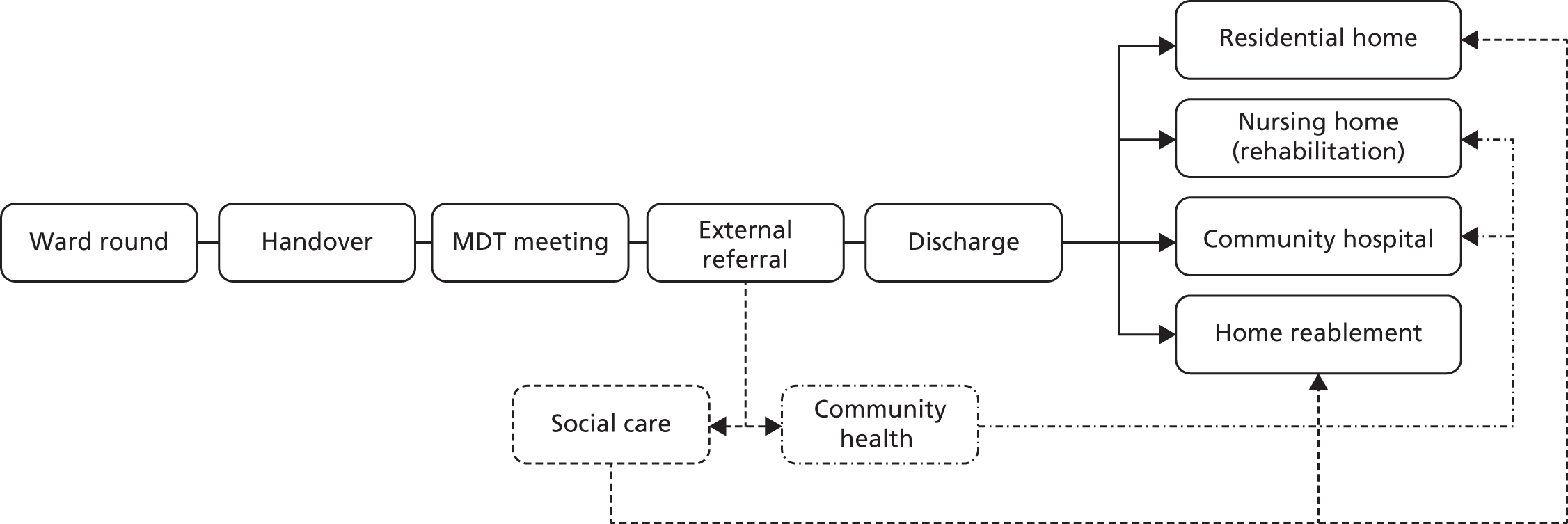

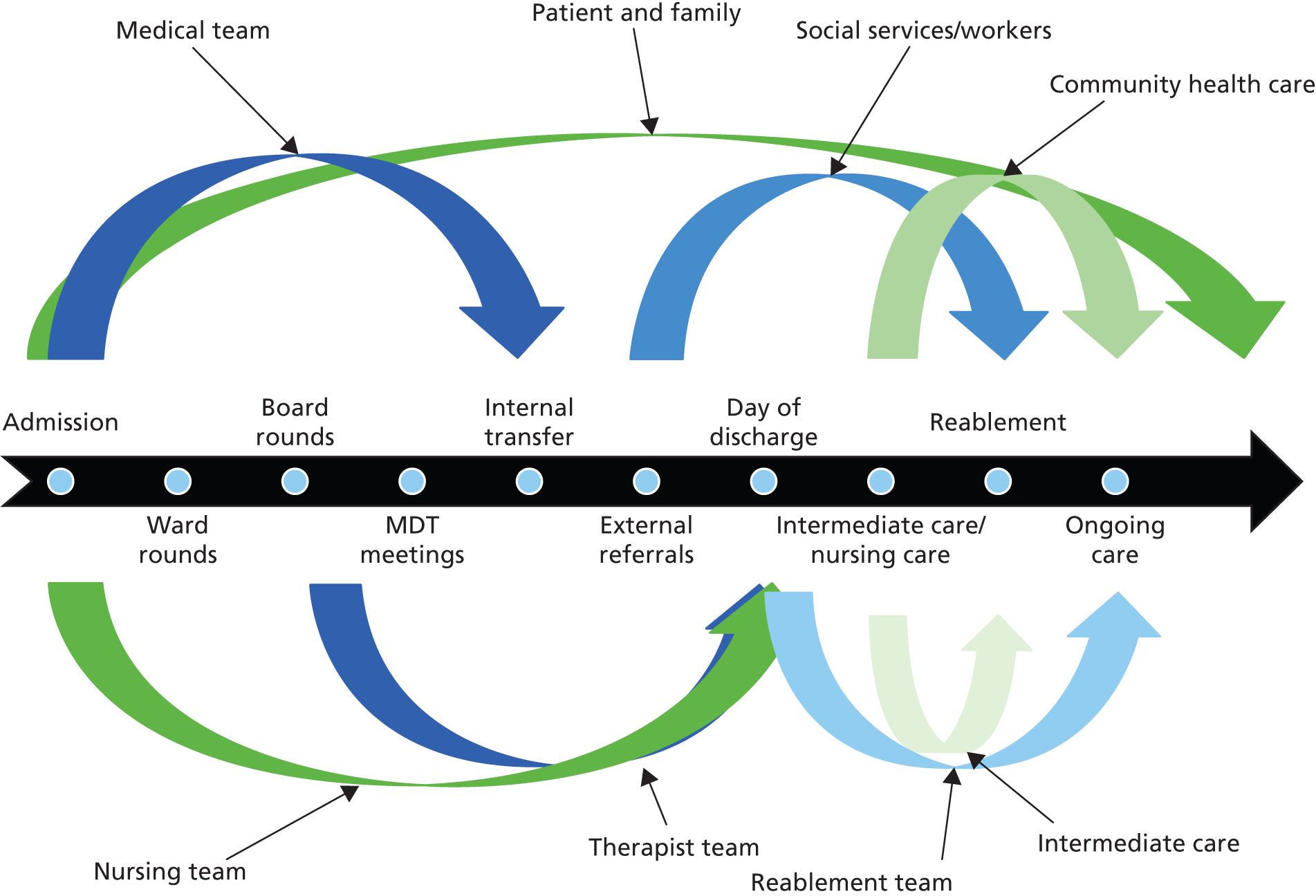

Through purposively selecting differences in health system configuration and patient group (stroke and hip fracture patients), it was possible to develop comparison along four dimensions: between different hospital types and system properties (e.g. single site vs. multisite), where some degree of control is obtained through looking at the same patient group, and between different patient groups (e.g. stroke and hip fracture patients) within the same hospital (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Selection and basis of analytical comparison.

Patient selection

The research used ‘patient tracking’ to develop a patient-centred understanding of hospital discharge (see Patient tracking). This involves focused observations and interviews with patients and families as they experienced discharge planning and care transitions. To facilitate representation across patient groups, a sampling strategy was devised in consultation with clinical specialists on the project team, patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives and clinical leaders at each site. This recognised key variables and comorbidities known to influence discharge activities, such as cognitive impairment or family situation. Sampling included participants with and without cognitive capacity to reflect the general adult hospital population.

Essential criteria

-

Treated in acute hospital for hip fracture (non-elective) or stroke.

-

Expected day of discharge within 7 days of initial information giving by researcher.

-

Lives within the study site boundary.

-

Aged over 18 years.

-

Able to hear and speak to respond to interview questions or has family member able to assist with communication.

Additional selection criteria for each study site

-

Ages: 1 × over 85, 3 × over 65 and 1 × under 65 years.

-

Cognition: at least two patients with recognised confusion or cognitive difficulties (as determined by care team).

-

Place of discharge: 2 × living in residential or nursing home, 1 × home alone, 1 × sheltered housing, 1 × with family.

-

Fast-track can be included but must fit essential criteria and researcher to have made direct contact with family prior to discharge.

Based on these criteria, the study aimed to recruit eight patients within each service area (a total of 32 across all four sites). Selection involved identification of potential participants in consultation with senior members of the care team around the time of admission, before inviting patients and families to take part in the research. This technique proved to be highly successful within three sites. In the Farnchester hip fracture service, difficulties were experienced in sustaining the required number of participants because of frequent transfers between wards, staff shortages and ‘out of area’ patients. In total, across all sites a total of 32 patients were recruited (see Table 7). Reasons for withdrawal during the data collection periods included death, deterioration of condition, loss of discharge destination information, discharge out of the study area, readmission, transfer to a new location and patient or family not wishing to continue.

Research methods and data collection

Data collection involved two sustained periods of data collection within each local care system (Glipton and Farnchester), starting in the respective stroke and hip fracture services of each hospital before moving to the wider health and social care system. Data collection typically involved 2–3 months of research in and around each stroke and hip fracture service (i.e. 5–6 months of research in each hospital) and a further 2–3 months of research in the local community health and social care sector, including patient tracking (i.e. approximately 8 months of research within each health-care system). Patient tracking commenced around the same time that community health and social care agencies were involved in the research.

Qualitative interviews

Semistructured qualitative interviews were used to understand how hospital discharge is planned, organised and experienced from the perspectives of different health and social care professionals, patients and family members. Interviews were especially important for identifying the roles and responsibilities of actors within the discharge process, the patterns of knowledge sharing between actors and how actors’ knowledge domains, cultures and organisational context shaped their interactions. The interviews were designed to be conducted in a semistructured, conversational style, giving participants the opportunity to explore emergent issues. All semistructured interviews were guided by a topic guide developed to reflect the study objectives. Draft questions were developed by the project team and representatives from the PPI group and piloted at one research site with three clinicians. These topics (see also Appendix 1) included:

-

career biographies and backgrounds

-

details of roles and responsibilities, with a specific focus on discharge activities

-

an account of the discharge process, including the broad process, planning issues, and working with patients and families

-

the role of communication and knowledge sharing in discharge processes

-

identification of individuals or groups contacted during discharge activities

-

exploratory accounts of knowledge-sharing relationships with identified individuals

-

perceptions and experiences of risk and safety

-

recommendations and improvements.

A modified guide was developed for patients, family members and carers, based on the advice and feedback from the PPI representatives. This included:

-

ways in which discharge plans were discussed and planned with patient and carer

-

how the discharge was expected and experienced

-

whether or not the plan met the needs of the patient

-

ways in which discharge can be improved.

An important feature of the interview questions was that they were structured to generate participant narratives, or stories of discharge processes. These stories were not read necessarily as ‘truths’ but rather as analytical windows into how participants make sense of and give meaning to discharge, thereby highlighting differences in knowledge and culture. These narratives were particular insightful when exploring how participants make sense of the discharge process, and especially the sources of safety and risk. A further feature of the interviews was that they were used to inform snowball sampling, that is, to help identify other potential, unanticipated actors or groups involved in the discharge process and the patterns of knowledge sharing with these actors. For example, all participants were asked to describe the different people, groups or organisations they communicate and share knowledge with in the processes of discharge planning and care transition.

Most participants were invited in writing to participate in the study. This invitation included a participant information sheet and an opportunity to contact the project team for further information. Other participants were recruited during ethnographic observations; for example, where an individual was observed as having an important role they would be asked to participate in the study and provided with a participant information sheet. All participants were asked to confirm that they had understood the participant information sheet and give written consent. The majority of interviews were digitally recorded with the consent of participants and all were transcribed verbatim for the purpose of subsequent data analysis. Table 5 details the interview participants according to location and number, and Table 6 further details the interview participants by their occupational background.

| Organisational location | Number of interviews |

|---|---|

| Glipton system total | 98 |

| Glipton Hospital: stroke unit | 45 |

| Glipton Hospital: hip unit | 16 |

| Glipton Hospital: management | 2 |

| Glipton community hospitals | 7 |

| Glipton Community NHS Healthcare | 9 |

| Glipton social care | 6 |

| Glipton community health care | 7 |

| Primary care/CCG/GP | 6 |

| Farnchester system total | 64 |

| Farnchester Hospital: stroke unit | 17 |

| Farnchester Hospital: hip unit | 20 |

| Farnchester Hospital: management | 2 |

| Farnchester community health care | 7 |

| Farnchester social care | 5 |

| Farnchester community others | 10 |

| Primary care/CCG/GP | 3 |

| Ambulance service (regional) | 2 |

| National organisations | 5 |

| Total interviews | 169 |

| Group | Glipton | Farnchester | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical (hospital) | 10 | 8 | 18 |

| Nursing | 18 | 15 | 33 |

| HCAs | 5 | 2 | 7 |

| OTs | 10 | 10 | 20 |

| PTs | 16 | 8 | 24 |

| Other therapists (speech, dieticians) | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Pharmacists | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Ambulance (regional) | n/a | n/a | 2 |

| Administrative | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Managerial/leadership | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Social work | 9 | 5 | 14 |

| Social care | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Community nursing | 2 | 7 | 9 |

| GPs | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| GP/CCG administration | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Support group/voluntary | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Patients (interview stage 1) | 16 | 14 | 30 |

| Carers/family (unpaid) | 12 | 11 | 23 |

Alongside semistructured interviews, the research involved more informal ethnographic-type interviews with participants, normally as part of observations. These ranged from small interactions or ‘chats’ to clarify an observed occurrence or activity (i.e. asking a participant what they are doing or to explain a technical procedure) to more open, unstructured and lengthy exchanges (i.e. to explain a series of events or a particular situation in greater detail). Many of these interviews occurred when shadowing participants or in other informal settings, such as rest areas or cafés. As such, it was not always feasible to digitally record these interactions and most were recorded as handwritten notes in field journals.

Observations