Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1809/1073. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The final report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in December 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Lockett et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Over recent years with the provision of new funding streams, translational research initiatives have become increasingly important to health-care research in Europe, Canada, the UK and the USA. 1–3 In the UK, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has invested £450M over 5 years to establish five comprehensive and seven specialist biomedical research centres (BRCs), alongside five accredited academic health science centres (AHSCs). 4 Similar initiatives have already been established in the USA, including a consortium of 60 multidisciplinary research centres known as clinical and translational science centres. These were set up to enable collaboration between clinical and basic science and provide training in clinical research. 5

The ‘bench to bedside’ rhetoric has, therefore, seen the creation of research centres and a growth in knowledge in basic sciences and clinical medicine. The role of the translation of knowledge in improving patient care has been strongly argued for ‘effective translation of the new knowledge, mechanisms, and techniques generated by advances in basic science research into new approaches for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease is essential for improving health’. 6

The increasing importance of understanding the knowledge translation (KT) process has led to the identification of two translational gaps. The first gap addresses the translation of ideas from basic and clinical research into the development of new health technologies, products and approaches to the treatment of illness and disease. The second translational gap (T2) focuses on the implementation of these technologies, products, and services in clinical practice. Funded by the NIHR, nine Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) aim to bring together universities and their surrounding NHS organisations to test new treatments and new ways of working. CLAHRCs were seen as a unique way of strengthening collaborations between universities and local NHS organisations. Importantly, they aimed to address the ‘second gap in translation’ as identified by Sir David Cooksey in A Review of UK Health Research Funding. 7

The policy intention is that CLAHRCs have three key interlinked functions: (1) conducting high-quality applied health research, (2) implementing the findings from research in clinical practice and (3) increasing the capacity of NHS organisations to engage with and apply research. The CLAHRCs are regionally focused, and their agendas are determined by partner organisations and the health-care needs of their geographical areas. While mandated by policy, CLAHRCs were regarded by the NIHR as experimental in nature during their inception, with considerable variation allowed for their structures and processes. Academic research and clinical practice were blended in different ways. For example, social sciences were variably integrated into CLAHRC plans, which included engagement with business schools. There were also differences in the disease emphases of CLAHRCs, and the clinical disciplines involved, both medical and non-medical. Overall, all CLAHRCs focused on translational research around long-term conditions.

Institutional entrepreneurship and Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

The ‘translation gap’ between academic research and routine practice in health-care provision is a longstanding global problem8,9 which has given rise to a plethora of translational health research interventions, for example, in the USA, the Veterans Health Administration’s Integrated Health and Research System,10 American Quality Enhancement Research Initiative, and Clinical Translational Science Centres;5 in Canada, the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation;11 and in the Netherlands, the Dutch Academic Collaborative Centres for Public Health. 12 As described above, England has followed suit with investment in BRCs, biomedical research units (BRUs), AHSCs, academic health science networks (AHSNs) and CLAHRCs,4 the last of which we focus on.

Translational initiatives are positioned in a landscape governed by multiple institutional forces from professions with different priorities and values. Academics, for example, are required to meet the academic credentials that underpin their legitimacy and credibility, and clinicians are tasked with translating research into practice to improve patient care. These two professions must, therefore, collaborate successfully to ensure that research is effectively implemented into practice and patient care is improved. However, the paradigm of translational research that underpins translational and collaborative initiatives has not sufficiently considered or reflected the complex realities of these different professional environments.

Existing studies highlight that the uptake of evidence into practice is more complex13 and that the translation of evidence-based innovation is a non-linear process overshadowed by cultural changes and political forces which are intertwined across various organisational and professional boundaries. 14 Such translational initiatives are challenging because they seek to bring together and bridge two institutional worlds, health care and academia, with different structures, cultures and norms. 15,16 Furthermore, Martin et al. 17 have highlighted the role of differences in institutionalised power that can facilitate resistance to policy. Furthermore, Albert et al. 18 offer insights into the particularities of different research practices in the health domain in Canada suggesting that the interaction between different actors in the translational field is affected by an actor’s position and affected by epistemic culture and what constitutes as legitimate science.

Translational initiatives pose a potential space for conflict between different actors, who may interpret such ventures in different ways, resulting in varying practices, systems and ultimately outputs. We consider these conflicts that are nested in the T2 to be institutional in nature. Research, therefore, is required to understand how to support the translation of clinical research into practice where such spaces host knowledge that is multidisciplinary and requires different communities to interact, including clinical scientists and social scientists. 18,19 As CLAHRCs are tasked with overcoming such institutional problems of translating research into practice, through reshaping existing institutions that frame KT, they are an ideal platform to examine such important institutional issues.

To examine the work undertaken by CLAHRC actors to encourage institutional change in promoting CLAHRCs, we have drawn on the emerging theory of institutional entrepreneurship, a subtheme within neo-institutional theory. Drawing on the work of Lockett et al. ,20 based on a recent Department of Health (DH)-funded study of mainstreaming genetics innovation,21 we argue that the theory of institutional entrepreneurship is an important tool for understanding change in health care.

Our focus is on identifying and analysing the actions of the institutional entrepreneurs (IEs) in developing and implementing the CLAHRCs. Consistent with the emphasis on the need for a broad perspective on institutional working by institutional entrepreneurship research,22,23 and the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation’s (SDO) [now encompassed within NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme] call to pay closer attention to the involvement of a wider array of field-level actors and activities;24 and with the introduction of the CLAHRCs, we view institutional entrepreneurship as transcending any one specific role. IEs may be drawn from a range of different stakeholder groups including CLAHRC directors, scientific programme managers, commissioners, clinicians and service users. A broad perspective on institutional work (IW) enables us to encompass internal and external organisational issues both within and across the NHS and universities.

Employing the concept of institutional entrepreneurship to the CLAHRC initiative, the proposed aims of our report were:

-

to provide a formative evaluation of CLAHRCs in relation to the generation of applied research, and the impact on practice and capacity building across CLAHRCs as they were envisaged and enacted

-

to apply institutional theory to identify and examine the challenges facing CLAHRCs

-

to apply the concept of institutional entrepreneurship to make a theoretically informed analysis of how to engender and sustain the translation and exchange of research knowledge into service facing innovation in CLAHRCs.

Feedback and engagement with user groups

Engagement with CLAHRC stakeholder groups was a major objective of our research (see Chapter 3). At all stages of our research process, we engaged with stakeholders, from the shaping our original application for funding of the research through to the final writing of this report. The major forms of engagement were as follows:

-

Scientific and stakeholders’ advisory panel (SSAP). This group was able to meet only twice during the research process as a result of problems in scheduling meetings. The meeting of the SSAP ensured that scientific and user input were garnered into the research direction and interpretation of emerging research findings. Moreover, members of the SSAP were consulted via e-mail and telephone as issues arose outside formal meetings. This included discussions around the findings and analysis of the research, where feedback was sought and subsequently fed into the report.

-

Feedback to or from collaborating sites. Formal and informal feedback sessions were conducted at four of the research sites, through the direct reporting of research findings to CLAHRC directors and deputies, on an ongoing basis. In addition, a number of workshops and presentation events were held in six different CLAHRCs (with as many as five meetings in one CLAHRC) to feed back our results to the wider CLAHRC communities in each region, including advisory boards, learning events and stakeholder boards. All of the feedback sessions enabled us to validate our emerging findings and to provide new learning for those involved.

-

Feedback at CLAHRC directors’ meetings. In addition to individual feedback to individual CLAHRCs, feedback sessions were conducted at periodic CLAHRC directors meetings and wider CLAHRC-wide events. Again, these sessions enabled us to validate our emerging findings and to provide new learning for those involved.

-

National workshop. A 1-day national workshop was conducted in November 2012 to disseminate findings and obtain feedback on our emerging findings. The event included a panel discussion of the emerging results, with the panel comprising four current directors and one ex-director of a CLAHRC.

Report structure

Chapter 2 provides a narrative synthesis of the key concepts related to (1) KT in health care and (2) institutional entrepreneurship. From our synthesis of the literature on KT in health care we conclude that the extant research is under-institutionalised in nature, which motivates our review of the institutional entrepreneurship literature.

In Chapter 3 we present our methodological approach, which encompasses issues of data collection and data analyses. Specifically, we present our mixed methods outlining our approach to qualitative case studies and social network analysis (SNA), and our overarching model of institutional entrepreneurship in CLAHRCs.

In Chapter 4 we outline the founding conditions of each of the CLAHRCs. Building on the tradition of Pettigrew et al. ,25 whose work on strategic change in health care highlighted the importance of history and context, we examine the social positions of the key actors involved in attempting to engage in institutional change, the local field conditions in terms of the extent to which there was pre-existing activity in the local region, and whether the bid formation involved a collective or more autonomous process. Importantly, we argue that it is the founding conditions that shape the local context and influence the nature of institutional change.

Chapters 5–7 outline three distinct phases of institutional entrepreneurship work: envisaging, engaging and embedding. Envisaging (see Chapter 5) relates to the important first stage in any change process in which actors formed an ‘embryonic’ vision, based on the interplay between themselves and the context in which they are situated. 26 Engaging (see Chapter 6) relates to the mobilisation of support from the IEs’ allies27,28 and the cultivation of co-operation and strategic alliances. 29–31 Embedding (see Chapter 7) involved the education of actors both within the CLAHRC and in practice with the skills and knowledge-based tools needed to support the creation of the new institution. 32,33

In Chapters 8 and 9 we examine how CLAHRC actors changed their patterns of interaction over time and, then, reflected on the effectiveness of their work. In Chapter 9 we draw on our SNA, based on the data collected in two survey waves in 2011 (wave I) and 2013 (wave II), to examine how successfully different CLAHRC actors bridged the divide between research and practice and the extent to which the patterns of interaction changed over time. In Chapter 10, we examine how the actors who managed and led the projects reflected on the way CLAHRCs were set up and run, and how they sought to rebalance the activities necessary to improve translation initiatives.

In the penultimate chapter we link our findings back to the KT literature. Here, we present our development of five schematic archetypes of KT. The archetypes are not representative of all the characteristics of one particular CLAHRC partnership, but rather a culmination of distinctive strategies used by CLAHRC entities into an archetype. Finally, in Chapter 11, we present the conclusions from our study.

Chapter 2 Literature: knowledge translation in health care and institutional entrepreneurship

In this chapter we provide a narrative synthesis of the literatures relating to (1) KT in health care and (2) institutional entrepreneurship. We dovetail both syntheses in one chapter as we conclude from our review of the KT in health-care literature that the main conclusions are under-institutionalised in nature, which motivates a synthesis of the institutional entrepreneurship literature.

The KT and health-care literature is characterised by a burgeoning number of articles, a number of which provide exhaustive reviews (e.g. Dopson and Fitzgerald,34 Graham et al. ,35 Mitton et al. ,36 Kitson et al. 9). Given the presence of exhaustive reviews, and as our intention is to employ the literature in this chapter as a means of framing our research, we present an overview that highlights and grounds key debates in the literature. To inform this review, we used Google Scholar, EBSCOhost and Science Direct databases to do a number of searches across relevant literature streams (from November 2009 to April 2010). For example, we did a forward citation of Weiss,37 a seminal paper on research utilisation in the KT field to build our understanding of the conceptual landscape of the KT field. 38 We selected and retrieved 75 scholarly papers from over 400 articles. Three researchers knowledgeable in the field then developed a conceptual map working iteratively between the research papers. Using the references from retrieved papers (original research, review and policy papers), we looked for additional papers that might help further develop and clarify our conceptual development of KT. Rather than seeking to be exhaustive our goal was to synthesise and be integrative.

In contrast to the literature on KT and health care, the literature on institutional entrepreneurship is still in its relative infancy. 39 As such, there is no real formal body of evidence to synthesise; rather, there is an emerging collection of studies that focus on the role of individual (and collections of individuals) agency in promoting institutional change. Consistent with our approach for the KT and health-care synthesis, we used Google Scholar, EBSCOhost and Science Direct databases to do a number of searches across relevant literature streams. We identified 35 main scholarly papers that have informed the emerging debate on institutional entrepreneurship; using the references from retrieved papers (original research, review and policy papers), we looked for additional papers that might help further develop and clarify our conceptual development of institutional entrepreneurship. Rather than seeking to be exhaustive, our goal was to synthesise and be integrative.

In performing both syntheses, our intention was to delineate the main concepts and constructs to be employed when analysing the qualitative data. The advantage of such an approach is that it enables a theoretically informed analysis of the data, thereby avoiding the pitfall of mere data description.

Knowledge translation in health care

A critical concern with KT is that advances in research knowledge can take years to be implemented into practice, and change realised. Given the pace of innovation and research in the health-care field, this ‘knowledge gap’ has generated significant attention within health-care research and policy, and has been the subject of numerous reports7,40 editorials commentaries2,41 and papers. 42,43 Thus, managers, clinicians and researchers are finding themselves increasingly called on to actively participate in the process of KT. This interdisciplinary field draws heavily on perspectives from clinical epidemiology, but also integrates scholarship from innovation studies, management, psychology, public health and sociology. 44 Given the increasing attention on KT in health care, it is important that scholarship crosses disciplinary boundaries and taps into existing resources, so that concepts do not have to be ‘reinvented’ in neighbouring fields. In the section Institutional theory and institutional entrepreneurship we argue that institutional theory provides helpful analytical concepts with which to understand the disciplinary knowledge silos and contrast ways of organising for knowledge production and its application.

A number of models and theories have been developed to overcome the barrier of translating knowledge between research and practice. We review three dominant approaches used in addressing the KT gap. 38,45 Given the burgeoning number of articles in this area, our purpose was not to provide an exhaustive review (which can be found elsewhere)26,27,38,39 but rather an overview that highlights and grounds key debates in the literature.

Linear and unidirectional models

Early conceptualisations of the knowledge–practice gap frequently used the term ‘research utilisation’,37 a term that remains popular in the USA. 46 The early knowledge-driven and problem-solving models conceptualised the process as a linear, unidirectional and passive flow of information from research to practice or vice versa. 37 The ‘knowledge-driven model’ was used mostly within the natural sciences, including the medical fields. The model assumed that basic research would progress to applied research and eventually lead to development stages, such as a new medicine or technology and then find application in the realm of practice. 37 Nonetheless, as highlighted by Mosteller,47 200 years elapsed between the discovery and adoption by the British Navy of a cure for scurvy, which emphasises the difficulty of knowledge ‘moving’ from research into practice. Thus, the passive view of KT has become increasingly questioned.

Although early models of KT accounted for the various modes of relations between research and practice, they generally did not consider the role of normative differences in knowledge flow. Subsequent research proposed a ‘two-communities’ model to highlight cultural differences among academics and practitioners, which was seen to be a major constraint to knowledge transfer or exchange. 48 Although these models emphasised the cultural incommensurability of the professional domains in the process of knowledge exchange between the two worlds, they did little to bridge the KT gap between research and practice. 49

The evidence-based medicine (EBM) movement in the 1990s further highlighted the ongoing concern of the slow uptake of research findings into the domains of health and medical practice. Originating at McMaster University in Canada, EBM sought to maximise the efficiency of medical practice by adopting a more rationally ordered means of predicting health outcomes and organising service provision. This model of medical practice organised knowledge into levels of rational validity, and used double-blind randomised control trials (RCTs), which were considered the most trustworthy forms of explicit medical knowledge as they are based on statistical inference. 50 Though grounded in epidemiology, linear models of KT drew ideas from innovation diffusion studies and technology transfer.

An important premise of EBM was that many clinicians were also researchers and, therefore, familiar with medical science literature, which enabled clinicians to make use of ongoing research updates. This modern, rational approach to formalising and disseminating explicit components of medical knowledge sat alongside the political narrative of medical learning and government policy concerns with the accountability and efficiency of health-care provision. 51,52 The predominant emphasis of EBM was to expect and anticipate that clinical practitioners would initiate the search for knowledge based on their professional motivation to provide the best possible care.

Interactional models with bidirectional knowledge flows

Interactional models developed by the Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) highlighted the social nature of learning and the need for engagement between individuals from research, decision (or policy)-makers and clinical practice communities. 2,53 This view argued for the relevance of new research knowledge as research findings were often conceived as ‘square pegs that need to be fitted into a round hole’. 54 Instead of viewing knowledge flow as a linear process whereby decision-makers would seek out and use knowledge to inform their practice, researchers and those tasked with producing knowledge were encouraged to consider how they could actively facilitate the use of knowledge from research.

This view of bridging the research–practice gap emphasised the two-way nature of knowledge flow and the need for active engagement. The conceptual focus shifted to the process of interaction and collaboration and away from diffusion. Drawing on management and sociology scholarship, the roles of ‘knowledge brokers’ and ‘absorptive capacity’ have been emphasised. For example, Mitton et al. 55 identified that interactively engaging key champions was an important factor for successful ‘knowledge-transfer and exchange’. Others2,56 identified the importance of opportunities for building long-term relationships and highlighted the KT process as cyclical and iterative.

While the EBM logic of efficiency reconciled variations involved in problem selection and analysis, further developments of the knowledge exchange literature recognised and reconciled cultural differences through a symmetrical and reciprocal interaction of researchers and practitioners. 57,58 In particular, ongoing interactions between researchers and practitioners were identified as critical to knowledge use in practice2 and often involved the role of knowledge brokers in knowledge exchange. Other literature has also identified the importance of opportunities for building long-term relationships in enabling knowledge exchange activities. 59,60

A further concept – ‘knowledge linkage and exchange’ – has been developed as a model for the Canadian Health Service Research Foundation. This model suggested that knowledge generation and use is cyclical and that, at different stages in the knowledge translation process, effort needs to be expended in linking knowledge with potential users. The linkage and exchange activities could be conceptualised as either the researchers ‘pushing’ the knowledge out towards decision-makers in the practice communities, or as ‘pulling’ activities, whereby decision-makers initiate the linkage process.

The term ‘knowledge translation’, with a strong emphasis on impact, was also introduced by the CIHR in 2000. The CIHR61 stated that the process of KT included knowledge dissemination, communication, technology transfer, ethical context, knowledge management, knowledge utilisation, a two-way exchange process between researchers and those who apply knowledge, implementation research and the development of consensus guidelines. Rather than emphasising discrete events whereby ‘links and knowledge exchange’ could occur, an ongoing dynamic that reshaped knowledge and its meaning for the various stakeholders affected was highlighted. 62

The World Health Organization then adapted the CIHR’s definition to ‘the synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health’40 (p. 2). The National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR), based in the USA, also adopted and extended the use of the term KT by developing a working definition in its long-range plan for 2005–9. 63 In this light, KT has been an important step towards the recognition of the linkages between diverse communities and constitutes a key assumption in Baumbusch et al. ’s57 ‘collaborative model’ of KT. As emphasised by Harvey et al. ,56 a collaborative model of KT defines accountability regarding roles in relation to KT activity, reciprocity and respect for one another’s knowledge as important for the KT process.

In explaining the notion of reciprocity, Baumbusch et al. 57 made a brief reference to the mutual negotiation of meaning and power. However, the authors did not account for the processes through which these negotiations could be enacted in practice. Moreover, the intricacies of failures to establish common meanings and the rise of conflict over meaning, although crucial in understanding how knowledge is created and legitimated, are absent from their analysis. Although the current emphasis on highly collaborative notions of engagement and reciprocal exchange are increasingly common in the health services KT literature, it is interesting to note that models evaluating the success of KT programmes continue to focus on more linear and quantitative approaches. 64–66

Multilevel implementation research

In recent years, the complexity of changing clinical and organisational practices has oriented health services research to more explicitly include broader contextual features of practice and organisations into their analysis. 67,68 This perspective draws on the fields of change management and service improvement. While a number of scholars focus their discussions around the term ‘implementation science’,43,44,69 the terms ‘KT’ and ‘knowledge exchange’ continue to be used extensively, with overlapping definitions. The launch of the new online open-access journal Implementation Science in 2006 has consolidated a growing body of knowledge around what scholars term ‘implementation research’. In their initial editorial, Eccles and Mittman41 suggested that ‘implementation research is the scientific study of methods to promote the systematic uptake of research findings and other evidence-based practices into routine practice’ and called for papers which include more details around the context and developmental process of moving research knowledge into practice.

While interactional models included the context as an important component, the analytical focus has predominantly been on the interaction and relationships between individuals and groups. Yet Keith et al. 64 highlighted ‘the real-world clinical environment is more susceptible to contextual factors than is the controlled research environment in which interventions are often designed’. As such, there is increasing focus on developing organisational readiness, capacity and capabilities. Wensing et al. ,70 for example, have argued for the importance of tailored implementation, and made the assumption that, in practice, innovations can be successful if they effectively address the most important determinants of practice for improvement in a targeted setting. Furthermore, Wensing et al. 70 have argued that ‘systematic tailoring entails three key steps: identification of the determinants of health-care practice, designing implementation interventions appropriate to the determinants, and application and assessment of implementation interventions that are tailored to the identified determinants’.

Eccles et al. 69 have argued for wider use of theory in implementation research, both for intervention development and for evaluations of intervention effectiveness. By contrast, Oxman et al. 71 have argued for a pragmatic and empirical approach, where pragmatic models specified a list of potentially relevant factors, but did not embed these in a comprehensive theoretical framework. Wensing et al. 70 (p. 2) also note that ‘although tailoring implementation interventions to determinants of practice seems logical and has received growing attention, research evidence that tailored strategies are substantially more effective than other approaches is lacking’.

Chamberlain et al. 72 have set out a model for understanding the stages of implementation completion (SIC), based on Feldstein et al. ’s73 Practical, Robust Implementation and Sustainability Model (PRISM). The SIC model was developed to measure the progression through the stages of implementation in an evidence-based programme in the context of a RCT. Alongside other models, references to, and discussions of, the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) 2004 framework were widespread. 74 The aim of the PARIHS framework was to ‘present successful research implementation as a function of the relationships among evidence, context, and facilitation . . . [which] have a dynamic, simultaneous relationship’75 (p. 289).

In addition to context, evolving implementation research literature has increasingly questioned the epistemological nature of knowledge. 76 As Ward et al. 77 noted, KT literature has, to date, largely assumed a rational, technical view of the problem and has not developed discussion on the nature of knowledge. Harvey et al. 56 divided evidence (as knowledge) into three types (theoretical, empirical and experiential) and called for the use of all three types. This gave experiential evidence a greater role than it had typically held in biomedical sciences. Harvey et al. 56 argued that: ‘Given the inherent complexity and context dependent nature of the implementation process, as well as the insufficiency of empirical evidence about implementation, it becomes impractical to prioritise one type of knowledge over the others.’ (p. 4). 56 In contrast to earlier KT concepts where the critical knowledge was encapsulated as objective and professionally defined research outputs, the current shift towards a more inclusive and expansive evaluation of knowledge begins to acknowledge a wider distribution of relevant expertise.

Conclusions

In summary, the KT literature has largely focused on the individual-level learning and clinical encounter, although with a view to influence a large population of clinical decision-makers. While the level of the individual is important in the health-care industry, as health encounters often occur on a one-to-one basis, recent work has increasingly emphasised the social nature of KT and the need to engage in long-term relationships with bilateral communication processes in order to generate changes in decision-makers’ practices. Furthermore, understanding the context and diverse types of knowledge have been found to be increasingly important in influencing behavioural change.

Based on our reading of the KT literature, we suggest that there is a greater need to attenuate to the importance of context in shaping KT in health care. Following the lead of Pettigrew et al. ,25 we suggest that much research on strategic change is ahistorical and does not take account of context. Importantly, the role of the reshaping of context in influencing KT has implications for the promotion of effective and sustainable KT beyond resource deployment. In the next section we examine the issue of context, and how actors may seek to engage in reshaping context in a manner that promotes KT, drawing on a synthesis of the literatures of institutional theory and institutional entrepreneurship.

Institutional theory and institutional entrepreneurship

As outlined in Chapter 1, we frame the T2 as being institutional in nature. Based on our review of the literature on KT in health care, we argue that many of the models of KT are under-institutionalised and, as such, fail to account for important institutional constraints that shape actors’ work in closing the T2. In this chapter we review the literature on institutional entrepreneurship and frame the discussion within the broader literature on institutional theory and IW.

Traditionally, institutional theory had developed to provide insight into how deeply embedded beliefs, roles and patterns of interaction could structure social practice and compel individuals and organisations into forms of conformity. 78,79 In particular, it has been used to explain how exogenous institutional forces structure organisational processes. For Scott80 these consisted of three elements or pillars: regulative elements, consisting of formal rules, laws and public policies; normative elements, including norms, conventions and practices; and cognitive elements comprising beliefs and understandings as well as scripts and schemas. 81–83

Institutional theory had particular resonance in the study of organisational change and continuity. Organisations are located in organisational fields, which are characterised as clusters of organisations and occupations whose boundaries, identities, and interactions are defined and stabilised by shared institutions. 80 Seen in this way, institutions are resilient social structures, sometimes enshrined in law, that specify field rules, membership, and the appropriate behaviour of its constituents. 84 The more developed a field, the more likely institutions will have become entrenched. A mature field will tend to have a stable membership with a strong mutual understanding of which organisations occupy the field,80,85 and organisational forms will converge to be consistent with the field’s institutions. 78

Field characteristics

Fields are more than just an aggregate of organisational players, and consist of ‘distinctive’ ‘rules of the game’, relational networks, and resource distributions that differentiate multiple levels of actors and models for action’ (p. 251). 86 Fields may be characterised by the presence of multiple institutions or institutional logics. 84,87–89 These fields can have multiple field constituents who are ‘often armed with opposing perspectives rather than with common rhetoric’ and, so, institutional change ‘may more resemble institutional war than isomorphic dialogue’ (p. 352). 90

Pluralistic fields provide actors with the raw materials to challenge existing practices as they are confronted by competing logics and present new potential ways of working that are outside the dominant template. 84,91 Recent work has investigated the diversity in organisations’ responses to the guiding principles of overlapping logics. For example, Greenwood et al. 92 noted the variations in organisational responses to the competing logics of ‘family’ compared with ‘markets’ in different regions across Spain. In doing so they identified how internal organisational factors as well as the local environment shaped individual responses to contradictions in their institutional environment.

We propose that CLAHRCs are located within the overlapping fields of higher education and health care, giving rise to a pluralistic field structure that provides fertile ground in which institutional change may be possible. The pluralistic field means that CLAHRCs faced an institutional landscape of diffuse power structures and divergent objectives, arising from competing institutions, both at the macro and micro level.

Historically, within each health-care region there typically exist one or more teaching hospitals, two or more primary care trusts (PCTs) and a strategic health authority (SHA). However, during the funding period of CLAHRCs, the Health and Social Care Act 201293 replaced PCTs and SHAs with clinical commissioning groups. Historically, NHS organisations formed links with higher education institutions (HEIs) most notably through HEIs’ medical schools. Furthermore, medical schools have been charged with the tripartite mission of excellence in research, education and practice. However, there are strong institutional forces that make the accomplishment of the tripartite mission challenging. Specifically, regulatory/coercive, normative and mimetic forces within the health-care sector impact upon cultural–cognitive processes that underpin knowledge sharing across organisational and professional boundaries. 15

At the macro level, the government sets public policy and creates regulatory institutions for many public sector organisations. A particular issue is that government set performance indicators and priorities can cause the activity of organisations in health care and higher education to diverge, leading to the separation of research and practice. 15

The macro-level regulatory environment in the field of health care has been under considerable flux for the last few years. At present, the NHS is currently in the final year of transition to the new commissioning and management system. In enacting this change, NHS leaders have been required to respond to three inter-related challenges: (1) the need to maintain strong performance on finance and service quality, (2) the need to address the difficult changes to service provision required to meet the quality, innovation, productivity and prevention challenge in the medium term, and (3) the need to complete the transition to the new delivery system set out in Liberating the NHS. 94

At a macro level, HEIs are subject to a centrally driven set of performance measures. In the higher education sector the Research Excellence Framework (REF), previously the Research Assessment Exercise, frames academic activity as ranked within a UK level. This is largely based on research outputs in the form of academic publications (weighted at 60%), with the environment (weighted at 20%) and the impact of research (weighted at 20%) accounting for the remainder. University medical schools, similar to hospitals, are ranked within the UK in a publicly available league table according to their national research rating. Funding varies with research ratings. Crucially, these form part of the basis for the department’s reputation, with an indirect effect on attracting further research income and student numbers. The overall effect appears to be one that enhances, rather than dilutes, boundaries between health care and higher education. Arguably, the explicit tripartite agenda of NHS and HEI organisations has become less pronounced.

Academic research and clinical practice have become unbundled, to the possible detriment of patient care: ‘The strategies for patient care and research are pointing in different directions and driving the integrated ethos into history unless we strive for its preservation’ (p. 38). 95 At an organisational level, Currie and Suholminova15 have suggested that mimetic forces have buttressed the divergence that stems from what can be called ‘coercive pressures’. Organisations tend to imitate the practices of their most successful peers so that, for instance, universities seek to pursue more laboratory-based research, in line with high performers in academia globally.

At the level of the professions, the process of professionalisation has undermined the sense of a tripartite mission. The tendency towards increasing specialisation – and, thus, divergence – in the career paths between clinical researchers and clinical practitioners has acted to pull apart the worlds of research and practice. 15 One consequence of divergent career paths is that medical consultants and aspiring professors are now unlikely to develop a shared perspective on a given problem that is necessary for an effective knowledge exchange across the professional divide. The opportunities for integration of academic research and clinical practice, fostered under the ‘old’ climate of a tripartite mission, are likely to be lost with the decoupling of research and practice, which will have detrimental effects on patient care. Similarly, the rise of professions allied to medicine and the rise in the status of various categories of professionals in the health-care field more generally (vis-à-vis the traditionally high-status hospital consultants), have also contributed to the strengthening of normative pressures operating on those groups and, thus, a further divergence in perspectives between them. Again, mimetic pressures, which have resulted in professional associations and educational institutions following the lead of the most prominent peer organisations, have added to the normative pressures.

Finally, the picture is complicated further by the internal stratification of professions. For example, within HEIs, academics are not a homogeneous group; rather, Becher and Trowler96 have referred to them as being organised into their own tribes seeking to defend and enhance their own territories. Hence, important differences in norms and customs may further drive apart the tripartite mission, whereby different professional groups (inter- and intraprofessionally defined) clash over issues such as epistemology, ontology, methodology, etc. Such stratification is more pronounced in the clinical world, where elite professionals engage in IW when faced with changes in the health landscape and are likely to maintain pre-existing arrangements. 97

Institutional entrepreneurship

The literature on institutional entrepreneurship emerged in response to the strong determinism of institutional theory, which characterised institutional change as largely exogenous. Although organisational fields are structured, and institutional forces influence actors’ behaviours, endogenous struggles between actors still occur in relation to resources and relative positions of power. 98 The literature on institutional entrepreneurship focused on the nature of these struggles and how actors may seek to influence institutional arrangements in order to enhance their position and promote interests which they value. 27,99–101

Institutional entrepreneurs are defined as organised actors who envisage new institutional configurations as a means of advancing interests they value highly, yet are often suppressed by extant logics. 102 These new configurations may be realised through the creation of new institutions or the transformation of existing ones. 27,86,102 The work undertaken by IEs can be diverse, but is inevitably political and contingent on prevailing forms of legitimacy and power. 86

Research suggests that not all individuals or groups may be equally adept at engaging in institutional entrepreneurship. 27,102 Key to an actor’s scope to envisage and enact change is his or her social position, or location within the pre-existing institutional configuration, in terms of their access to resources, participations in activities, formal roles and legitimated identities. 103

In linking the concepts of field and social position, we argue that a given field can be conceptualised as a structured system of social positions, each with interests and opportunities,104 from which actors compete to promote their vision of future states of the world. 98 Social positions are defined in terms of the capital (economic, cultural, social and symbolic) endowments that underpin them and the associated relationships with other field members. 105 These social positions shape actors’ outlook, perceptions, motivation and ultimately their ability to enact institutional change. 106

A key debate for scholars of institutional entrepreneurship has been concerned with the distinction between central and peripheral social positions in a field in terms of their influence on actors’ IW. The distinction between central and peripheral social positions recognises both the differing capacities of actors to establish and sustain institutional arrangements in line with their own interests and their degree of embeddedness in a field. 107,108 Those who occupy central social positions, with the authority and connections to compel change, are arguably best placed to engender an institutional transformation. Conversely, those who occupy peripheral social positions are arguably less able to engender institutional change. The empirical evidence, however, attests to a more complex picture. 24,82,108–113

A number of studies, focusing on a range of different fields including health care and open-source software, have found that instead actors located in peripheral social positions are most likely to bring about institutional change. 25,87,102 Actors located in peripheral social positions are the most disadvantaged by current institutions and, so, will be more able to see the faults, alternatives and ways around living according to institutional expectations. 114,115 Seo and Creed116 have suggested that peripheral organisations are also more likely to be exposed to the contradictions in the current institution, especially when facing pluralistic fields. Therefore, actors and organisations in peripheral social positions will be exposed to alternative fields and, consequently, come into contact with alternative logics and/or ideas, which may help instigate change. 109

In contrast, actors in central social positions that are more privileged by existing institutions may be least likely to promote institutional change. The argument is that: ‘Although central, dominant actors may be able to champion institutional change, they appear unlikely to come up with novel ideas or to pursue change because they are deeply embedded in – and advantaged by – existing institutions’ (p. 199). 117 There are instances in which centrally positioned actors have been seen to promote change; however, they appear to occur when some movement in the wider environment has meant that the current institutions are not fully aligned with the dominant actors’ interests. 28,108,118–120 Greenwood and Suddaby108 examined changes initiated at the centre of the mature field of large accounting firms. In particular, the leading firms sought regulatory changes in order to expand the range of services they offered, in response to demand from clients. Rao et al. 121 examined centre-led change in relation to the rise of nouvelle cuisine, which arrived from restaurants at the top of the French culinary hierarchy. In both examples, although the change promoted was significant, it further cemented the actors’ dominant field position.

Institutional work for entrepreneurship and maintenance

In this review, we highlight the importance of the work of IEs, but also that, in general, a range of different actors may undertake IW. Lawrence and Suddaby22 suggested that IW is a more general category of embedded agency than institutional entrepreneurship, used to describe any ‘intelligent situated institutional action’ (p. 219) of individuals and organisations ‘aimed at creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions’ (p 215). 22 The myriad, day-to-day instances of agency that, ‘although aimed at affecting the institutional order, represent a complex mélange of forms of agency–successful and not, simultaneously radical and conservative, strategic and emotional, full of compromises, and rife with unintended consequences’ (p. 52),122 are missing from accounts of institutional entrepreneurship.

Although the literature on institutional entrepreneurship implies that institutions generally remain stable unless remoulded by a motivated actor, the literature on IW focuses on how actors across a field are continually engaged in the partial re-enactment of routines and practices that may ultimately lead to field-level dynamism, but may also result in the strengthening of existing institutional arrangements. 123 As Lawrence et al. 122 stated, institutions are continued by ‘the everyday getting by of individuals and groups who reproduce their roles, rites and rituals at the same time that they challenge, modify, and disrupt them’ (p. 57). 122 To this end, we argue that institutional entrepreneurship can be seen as one specific type of IW that divergently challenges aspects of the prevailing institutional order with the aim of establishing new institutions in place of old. The development of the concept of IW, therefore, appears to be an important move in presenting a more balanced account of agency within institutions.

Furthermore, there is a risk of the misclassification of the nature of the IW undertaken. Currie et al. 97 suggested that the maintenance of an institutional status quo by elite actors may be more than an act of mere resistance or maintenance. Rather, Currie et al. 97 have argued that elite professionals combine elements of IW such as ‘theorising’ and ‘defining’ in a more creative manner than is presented by the types of IW categorised as maintenance by Lawrence and Suddaby. 22 Powerful actors (re)generate or (re)create institutional arrangements in the face of external threats, in a way that can enhance, not merely maintain, their position. In essence, the elite actors are engaging less in change resistance and more in positive action through IW to shape the change trajectory to ensure continued professional dominance. Consequently, we argue that IW to maintain professional elite status is likely to encompass a wider variety of IW than previously categorised by Lawrence and Suddaby. 22 We observed types of IW for maintenance that Lawrence and Suddaby22 associated with creating institutions.

Based on the above, we suggest that actors are continuously engaged in a struggle to (re)shape the institutional landscape in a manner that promotes the interests that they value highly. The willingness and ability of actors to engage in a process of (re)shaping institutions, however, will vary across actors and institutional fields. In addition, we suggest that the nature of the IW (for maintenance and/or entrepreneurship) will vary by actor and field.

Conclusions

We conclude that the field of CLAHRCs is pluralistic in nature and spans the institutions of the NHS and HEIs. As such, CLAHRCs provided a fertile ground for actors to expose and explore institutional contradictions in promoting institutional change. In addition, drawing on the emerging literature on institutional entrepreneurship we argue that IW for entrepreneurship and/or maintenance will be influenced by the antecedents of the nature of the field, and the social position within it, in which the actor is located. To date, however, there has been a dearth of research that has focused on comparisons of institutional actors within a common institutional field, and how their different subject positions may shape their work for institutional entrepreneurship and/or maintenance. We suggest, therefore, that it is important to examine the work of all institutional actors, located in a range of social positions in a field, and how their work may either promote or hinder institutional change.

Chapter 3 Methods and data

In this chapter, we outline out the research methods we employed, and in doing so, discuss our approach to data collection and data analysis. The study gained ethics approval from the Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland Research Ethics Committee 2 (reference number: 10/H0402/6). In addition, we worked to authenticate our work, as documented in our study protocol, by holding advisory boards, and feeding back to CLAHRC directors regularly, where we presented our emerging findings and discussed issues with the study as we progressed.

First, we outline our approach to qualitative methods, explaining the multistage nature of our research process across the CLAHRC case study sites. Second, we outline the social network methods of data collection and analysis, which complemented the qualitative case study work.

Qualitative methods

We employed a qualitative, induction-driven research design to enable contextualisation, vivid description and an appreciation of subjective views. 124,125 Drawing on institutional theory, with a specific focus on institutional entrepreneurship and IW, we examine the work of a range of different institutional actors as they engage in the CLAHRC initiative. In conducting our research, we employed a multiple case study format as it enabled a more robust basis for theory building,126 and often yielded more accurate and generalisable explanations than single case studies. 127

Qualitative data collection

Our research strategy involved collecting data from three sources: (1) archival data, (2) interview data and (3) observational field notes. In so doing, we sought to strengthen our ideas by triangulating our sources of evidence. 128 As with Pettigrew et al. ,25 the research adopted a longitudinal strategy across comparative cases, which encompassed the three data sources over a period of 4 years (2009–13).

First, documentation was collected, such as initial CLAHRC bids (where possible), annual reports, study protocols, corporate publicity material and minutes of operational and CLAHRC board meetings. In Gephart’s terms, we developed ‘a substantial archival residue’ (p. 1469)129 from the different published sources. All interviews, observational, and documentary material were collated into a case study database, and were organised on a case-by-case basis.

Second, we embarked on a two-stage process of conducting primary data. Data presented in this report encompass the 174 qualitative interviews which took place during the mobilisation phase of CLAHRCs and include a number of bid documents developed prior to the launch of CLAHRCs in late 2008. Overall, 104 interviews were carried out in the first exploratory phase across all nine CLAHRCs. In the second phase of data collection across four in-depth comparative cases, a further 70 interviews were carried out. These second-phase in-depth CLAHRCs were chosen based on the following criteria: variation in antecedent conditions (e.g. site based on existing translational activity or greenfield site) and the social position of the CLAHRC director (NHS or HEI as main employer, clinical or social scientist). The indicative interview schedules are presented in Appendix 1, which were employed as interview prompts. In reality, the discussion engendered in the interviews encompassed much more than is indicated on the interview schedules.

Staff central to the initiatives were interviewed, including CLAHRC senior managers (both HEI and NHS employees, clinical and social scientists), theme leads (clinical scientists and social scientists), researchers, other NHS staff involved in CLAHRCs, such as senior NHS managers represented on the CLAHRC boards and clinicians seconded to work on CLAHRC studies. Given that our theoretical focus was to examine the process of institutional entrepreneurship in CLAHRCs, our interviewees were largely drawn from middle and senior management levels in CLAHRCs and their partner organisations. We did so because such actors were mandated with attempting to enact institutional change.

Our interest lay in examining the motivations of different actors to get involved with the CLAHRC initiative, what they were seeking to achieve and why, and to what extent they thought that they were be able to achieve their aims. The focus of the interviews was broad, but encompassed questions about lead actors’ backgrounds, disposition towards change and vision for CLAHRCs during bid development.

All interviewees and participants of observed meetings were presented with details on the nature of the project and were required to complete a consent form before the interview and/or observation began. As such, the relationship between the researcher and the respondent was made clear at all times. The research was subject to strict NHS research governance and ethical guidelines, and gained ethical approval. Interviews were semistructured in nature, were openly recorded and each lasted between 45 minutes and 2 hours. All interviews were fully transcribed. Interviewing stopped when we reached a point of theoretical saturation – when interviews were only adding marginally to our knowledge. 130

Third, we supplemented the archival and interview data with over 100 hours of site-specific and programme-wide observations. We spent extensive time carrying out observational work, involving attendance at key meetings, workshops, presentations and other educational events. In terms of CLAHRC sites, we undertook observations in six of the nine CLAHRCs. The observation guide is presented in Appendix 1.

At educational events, for example, one or two of the research team would present feedback and facilitate discussion, while a third member of the research team did not participate but observed and took notes with an emphasis on CLAHRC vision and background of participants. The research team attended three CLAHRC directors’ meetings of around half a day in length, facilitated two cross-CLAHRC educational events and gave individualised feedback to four of the CLAHRCs on at least two occasions each. Members of the team were able to attend a range of different intra- and inter-CLAHRC events, involving the CLAHRCs’ senior leadership teams for each case. During the observations, the researchers took detailed notes and then wrote up a more expansive commentary post observation, in which they reflected on what they had witnessed. The notes were written up on the day the visit took place. 131 In collecting the observational data, we were keen to reflect on how the nature of interaction involved by the researchers may have influenced the nature of data we collected.

Qualitative data analysis

Data analysis was iterative and undertaken in an inductive manner, but was informed by key concepts in the literature. 132,133 Each interview transcript, set of observational notes and archival document was read several times, generating and coding themes according to both issues identified in the literature and features of the data that emerged inductively. Analysis was conducted with the assistance of NVivo 8 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, VIC, Australia).

Our data analysis involved three stages. Across all stages, two members of the authorial team who had conducted the fieldwork undertook initial coding of the data. In advance of the analysis, we assembled all of the documents, interview transcripts and field notes for each of the cases into a single data file. This enabled us to share data across the research team. In order to understand the complexity of each project,134 we coded the data on a within-case basis. 132 We began by analysing the data collected in stage one, involving all nine CLAHRCs, with a focus on the initial founding conditions of the nine CLAHRCs and their models for closing the T2. We then analysed the four in-depth cases, where we focused on examining how the CLAHRCs were introduced over time.

Across both stages of analysis, we began with a fine-grained reading of the data. 135 After inductively creating a list of first-order codes from the case evidence, we consolidated all of our codes across the nine and four cases, and progressed with axial coding, structuring the data into second-order concepts and more general aggregate dimensions. 136 In doing so, we engaged in deductive reasoning whereby we linked our inductive codes with existing concepts and frameworks. 137 Although we accept that our accounts are one of many potential interpretations,137 we worked in two ways to ensure that we did not retrospectively fit the data to service our theorising. 138 First, we triangulated between data types. Second, we triangulated across analysts with one member, remaining independent of the data, able to challenge and interrogate the coders’ knowledge and interpretations. 139 Our coding was based on interview and archival data, and we included codes in our work only if we had at least four archival and/or interview sources for each of our cases where relevant. The observational data were employed to contextualise and corroborate the interview and archival coding.

In order to avoid identification of individuals or CLAHRC cases, we reveal the social position of the interview respondent only. To define their specific role in a CLAHRC (e.g. director, etc.) would pinpoint the respondent and organisation in question. The process through which we classified actors by their social positions is outlined in Chapter 4. Our approach aligns with our research protocol following ethics approvals, and a need for particular sensitivity given ongoing CLAHRC refinancing.

Consistent with the preceding point, in presenting our qualitative analysis we do not draw explicitly on our observational data, as many of these data (1) were not intended for public consumption, i.e. were a commentary of others; (2) were highly personal views that were communicated in confidence; or (3) revealed the details of meetings, etc., which may risk revealing the identity of respondents. As such, we drew exclusively on data from formal interviews in the text, but employed the observational data as a means of informing our analysis.

We began by examining the founding conditions for each of the nine CLAHRCs in terms of the local institutional conditions, the social positions of the main actors involved and the nature of the process through which the CLAHRC bid was developed, the analysis for which is presented in Chapter 4. Founding conditions constitute a key concept in institutional entrepreneurship theory, which are used to explain variation of institutional entrepreneurship work and outcomes.

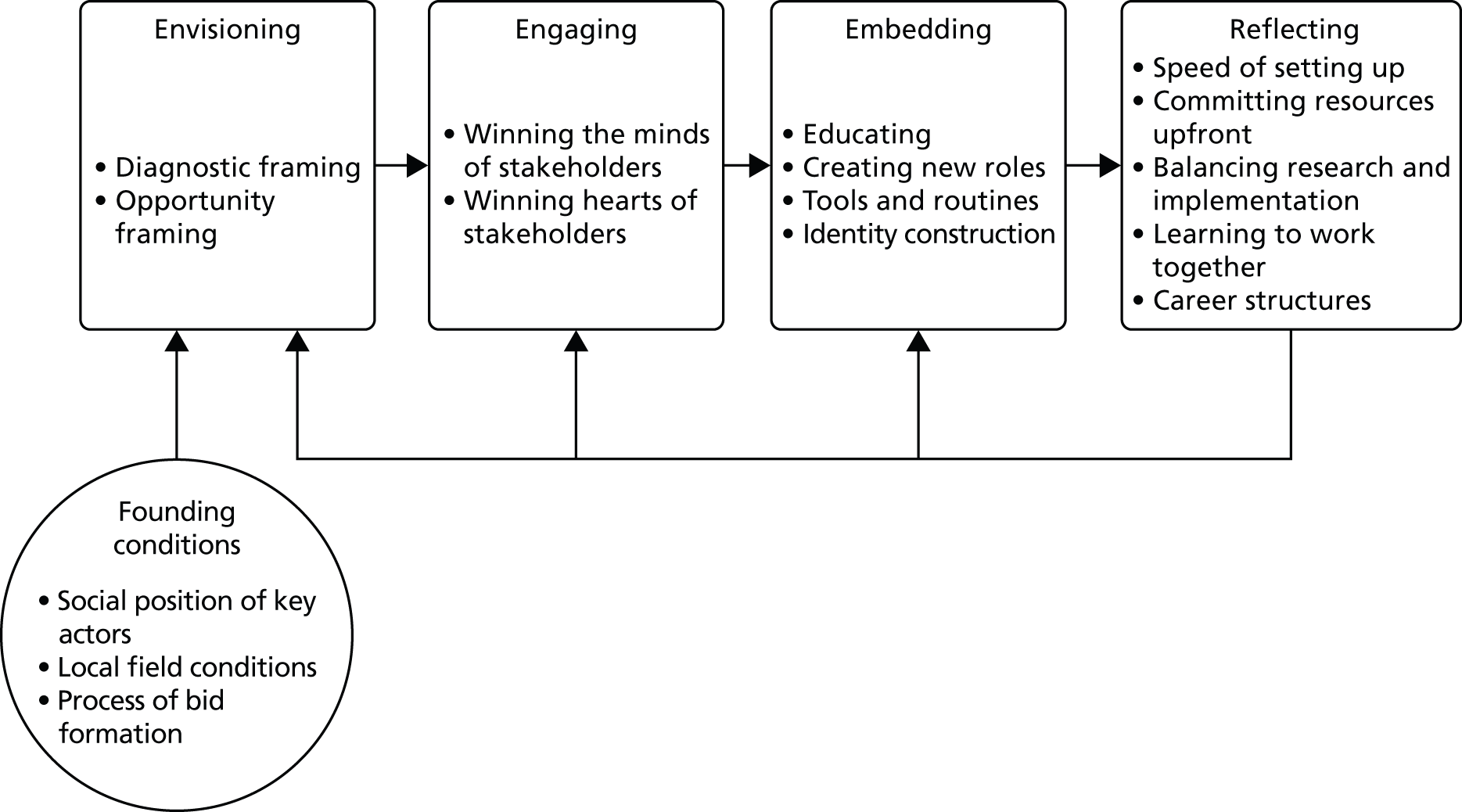

The next stage was to take the data for the nine CLAHRCs and examine how the founding conditions shaped the IW undertaken by the CLAHRC actors. We identified distinct theoretical categories of IW that was undertaken, across the nine cases initially, and then in the four in-depth cases following the later-stage developments. All of the different forms of IW relate to the process of enacting institutional entrepreneurship for institutional change. The themes were developed inductively through first-order coding, which then progressed to axial coding, working back and forward between the data and theory, as outlined above. First, this work was related to the way in which actors interpreted the CLAHRC mission and responded accordingly, as shaped by the founding conditions. We termed this work the ‘envisaging’, which we defined as the process through which actors developed an ‘embryonic’ vision of change, based on the interplay between themselves and the context in which they are situated. 26 This work is presented in Chapter 5. Second, was the work that actors undertook in signing up stakeholders of the CLAHRC, which we term ‘engaging’ and present in Chapter 6. Third, was the work around the sustaining of the CLAHRCs, which we term ‘embedding’ and present in Chapter 7. Finally, there was a distinct area of IW that involved the rethinking of initial decisions and learning from the process of establishing the CLAHRCs, which we term ‘reflecting’, and is presented in Chapter 9. All of the different themes are expanded on in the introduction sections to the relevant chapters. Across these different areas of IW, we were able to identify distinct differences in the nature of the work undertaken by actors, as shaped by the institutional antecedents of the local institutional context and the social position of the actors involved.

The final stage of our analyses involved re-examining our data to understand the temporal sequencing of the theoretical categories of IW and the nature of relationships between them. As is common in process-based studies, it is difficult to establish whether or not a process is entirely linear;140 however, we present the second-order codes in the temporal sequence in which they generally emerged in the case histories. Employing both inductive and deductive reasoning, and travelling back and forth between data and theory, we aimed to develop an understanding of how an actor’s social position shaped the envisaging process. 125,132,135 Our emerging theoretical arguments were based on the interplay between theory and data, drawing on both within-case and cross-case analysis. 141 Based on our analysis of the temporal sequencing of the different forms of IW to promote KT we developed a process-based model of institutional entrepreneurship as presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

A process model of institutional entrepreneurship.

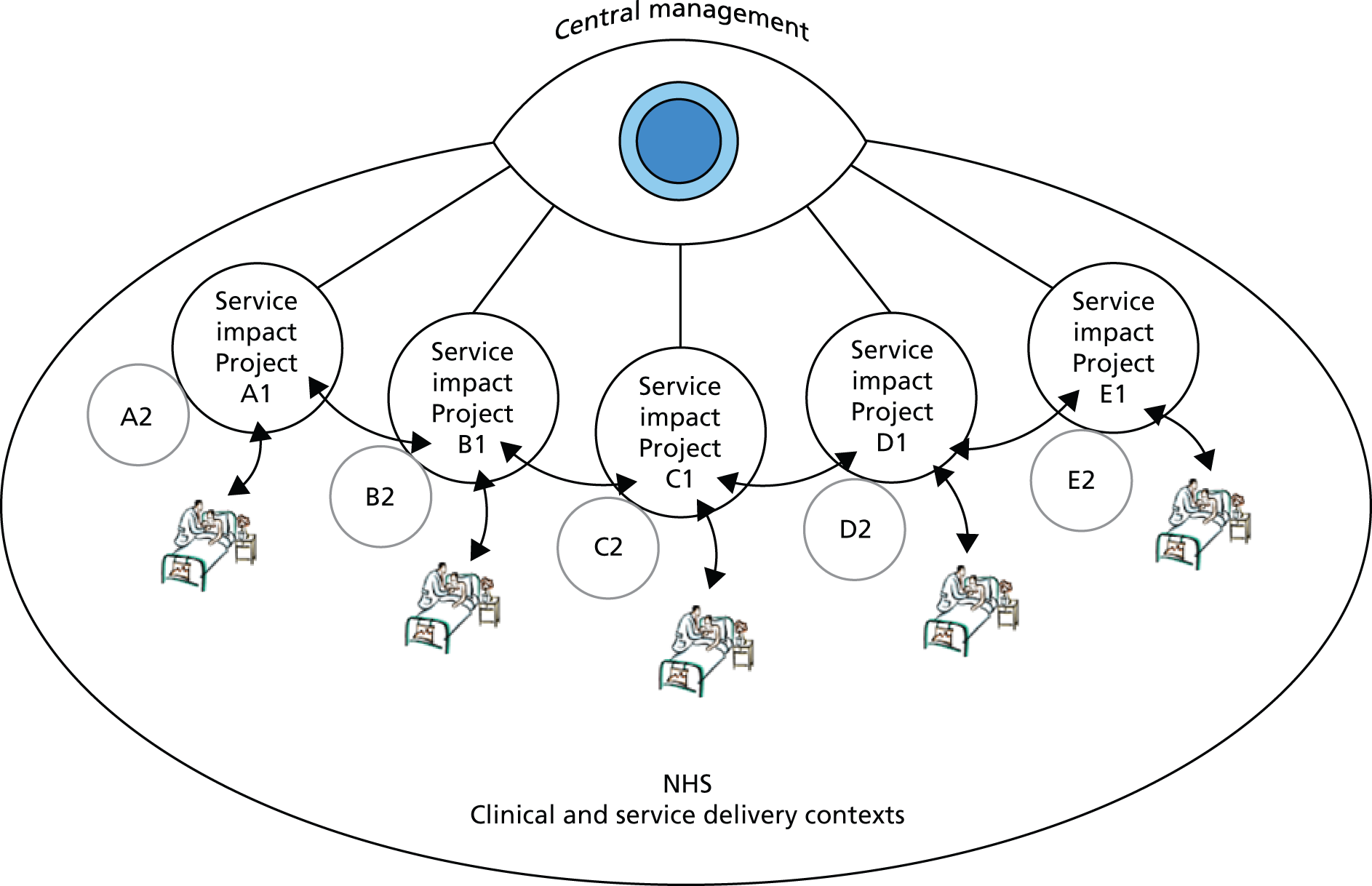

In addition, and based on the work of the different IEs, we identified five different archetype models that were employed by actors to try to close the T2. In Chapter 10 we explore those models and the issues arising from each. In doing so, we emphasise that the models do not represent any one CLAHRC, but rather the elements of the different models that may be exhibited in any CLAHRC.

Patient and public involvement in the research

Patient and public involvement (PPI) in the CLAHRCs was not a theme which we focused on in the project. We recognise, however, that PPI is important to inform and contribute to research,142–144 especially where translational research is concerned. 145 In terms of PPI in the project, two service users were consulted (we use the pseudonyms service user 1 and service user 2), who were ‘experts’ in two different long-term health conditions and were both familiar with CLAHRCs. One service user was consulted at the start of the project to discuss, clarify and provide feedback on our initial thoughts of CLAHRCs. A second service user was consulted for their opinion on the methods employed, specifically on the selection of the four in-depth CLAHRCs and the appropriateness of the interviewees. The second service user was consulted again towards the end of the project for their feedback on the findings of the work and on any further avenues the project should consider taking.

At the start of the project, a discussion took place with service user 1 to discuss and refine our initial thoughts of the CLAHRCs and the view that CLAHRCs were set up differently reflecting the social position of the IEs and focal actors. Service user 1 was asked his view on how CLAHRCs were set up, their mission and the balance between research and implementation:

Each theme is supposed to have a research element and the research element is then supposed to translate into practice through the commissioning of services. Those services should have, research and implementation and both should be brought together and users should be part of that too. That is my understanding of really what the CLAHRC mission is.

Service user 1

Following this initial consultation with service user 1, we proceeded to carry out the data collection across all of the nine CLAHRCs. In choosing the four in-depth CLAHRCs, we consulted service user 2 on his views on the selection of the in-depth CLAHRCs.

I think that it is good picking the different CLAHRCs, and talking to the different directors and other main people, it will provide interesting variations.

Service user 2

Furthermore, service user 2 advised us to consider questioning interviewees on the mission of CLAHRCs and how they were rolled out. His view was that CLAHRCs were led by many ‘powerful researchers’, and that CLAHRCs were ‘to some degree all about research’ – a finding that emerged from the data.

As we began to structure our findings, we consulted service user 2 to discuss and validate the findings. This enabled us to organise the research findings and draw out important points. One of the findings discussed with service user 2 was the variation across CLAHRCs, particularly in relation to the balance between research and implementation.

CLAHRCs talk about getting research quicker into practice but as your findings found not all achieved that. And that’s what I thought CLAHRCs were for, we do the research and then we get it into practice quicker than normal research.

Service user 2

Consulting two service users on different aspects of our research enabled us to think about issues more broadly, refine preliminary results and organise our findings more appropriately. Furthermore, PPI during the project helped us to frame practical recommendations for CLAHRCs and provided useful insights into future avenues of research, specifically around PPI in translational initiatives.

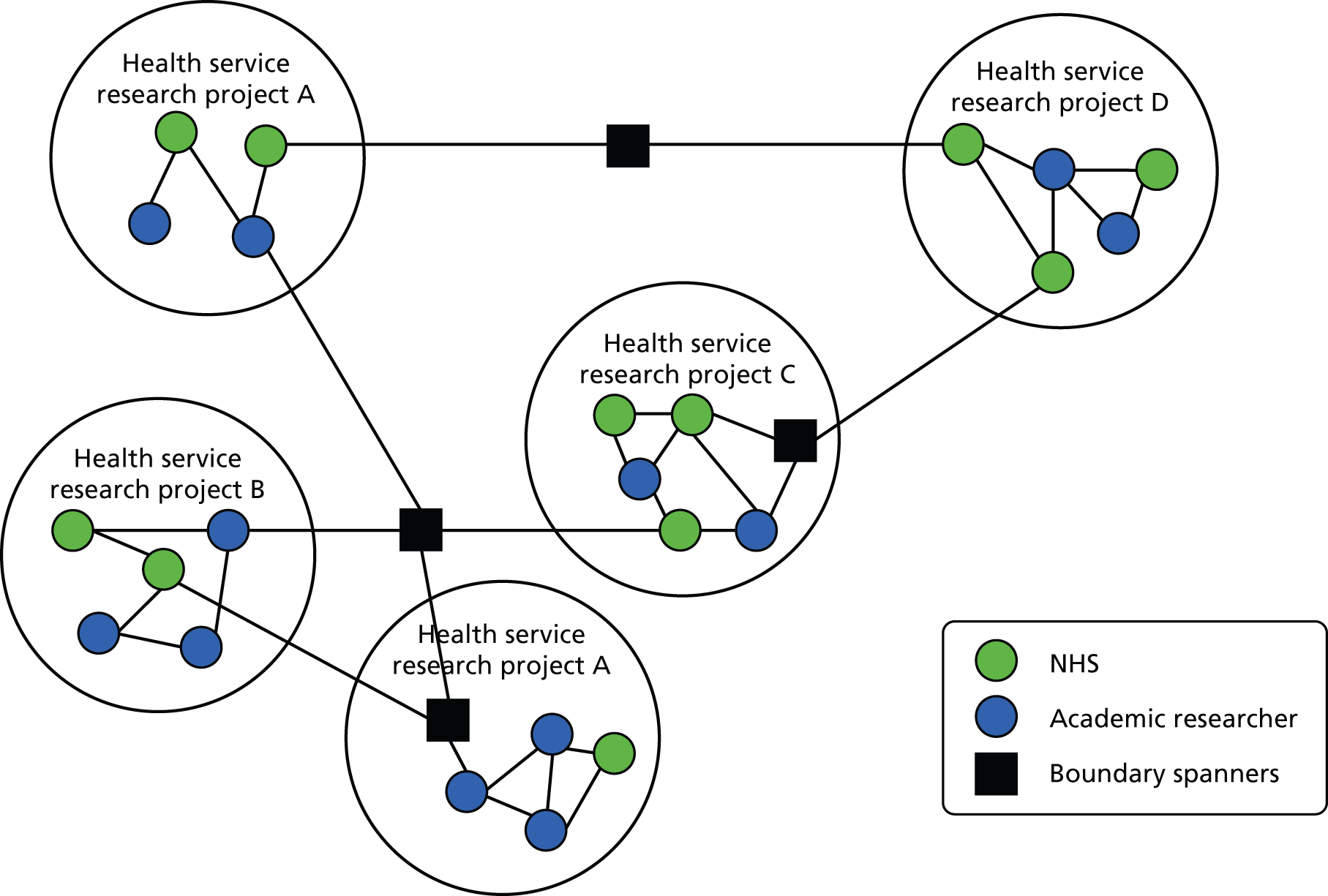

Social network analysis

We complemented our in-depth qualitative research by employing a SNA of the development CLAHRC actors’ ego networks of interaction over two points in time, for the four in-depth sites. Our SNA complemented our in-depth qualitative case studies through providing quantitative evidence as to the extent to which CLAHRCs had enabled the new patterns of working to bridge the T2.

Ego networks relate to an individual actor’s network of relationships and enable us to examine variation across actors’ networks, with a particular focus on the extent to which they bridge the research–practice divide. We examined actors’ ego networks at two points in time: (1) early on in the development of CLAHRCs, and (2) during the run-up to CLAHRC refinancing. In doing so we wanted to gain insights into actors’ ego networks across all levels of the CLAHRC, including those actors engaged in senior and more front-line roles.

To carry out the SNA, we used a web-based sociometric survey [Network Genie146 (Tanglewood Research, Inc., Greensboro, NC, USA)] to capture actors’ personal characteristics and networks, which was e-mailed to a list of CLAHRC staff as agreed with the directors (or deputy directors) of the four CLAHRCs. Each actor was then sent a link to the survey, and we then followed up with a number of additional reminder e-mails. Network Genie enables us to ask actors (the egos) about the people they interact with (the alters). The questionnaire is automatically generated by each actor based on the names they select of people they interact with. The number of names provided for each CLAHRC ranged from 35 to 48, and included actors from a range of different roles including CLAHRC senior managers (both HEI and NHS employees, clinical and social scientists), theme leads (clinical scientists and social scientists) and other NHS staff involved in CLAHRCs, including secondees and researchers. We present an abridged version of the SNA instrument in Appendix 1 because of the problems of presenting a web-based survey.

The first wave of data collection in 2011 (wave I) produced 81 complete responses and the second wave, in 2013, (wave II) produced 86 responses. Sample sizes for each of the four CLAHRCs are presented in Table 1. In wave I we asked actors to outline their networks and patterns of interaction at the inception of CLAHRCs, to capture actors’ actual ego networks as CLAHRCs were first established (i.e. looking backwards). In wave II, we captured actors’ current ego networks (at the end of CLAHRCs 5 years of funding).

| CLAHRC | Survey | |

|---|---|---|

| Wave I | Wave II | |

| CLAHRC A | 22 | 20 |

| CLAHRC B | 17 | 27 |

| CLAHRC C | 27 | 23 |

| CLAHRC D | 15 | 16 |

| Total | 81 | 86 |

Our aim was to examine how individuals’ professional characteristics influenced the four different outcome measures of social interaction for understanding the KT processes in CLAHRCs: (1) formation of networks across academics and clinicians, (2) integration of decision-making practices among CLAHRC academics and clinicians, (3) formation of networks across members of research and implementation themes, and (4) formation of networks across members of clinical and non-clinical departments involved in CLAHRC.

The professional characteristics we focused on were the respondents’ professional background (i.e. academic or clinical), their professional status (i.e. senior vs. junior), the status of professionals in an actor’s ego network, the number of professionals in their network with whom the respondent had not worked with before joining the CLAHRC and the number of professional connections from the same professional category.

Social network research has tended to focus on whole networks, and the extent to which actors find themselves in social structures characterised by dense, reciprocal, transitive or strong ties. These approaches may tell us some interesting things about the entire network and its substructure, but they do not tell us very much about the opportunities and constraints facing individuals. Thus, to understand the variation in the behaviour of individuals, we need to take a closer look at their local circumstances. Describing the variation across individuals in the way they are embedded in local social structures is the goal of the analysis of ego networks.

We collected actors’ ego network data using Network Genie, which asks actors (the egos) about the people they interact with [in our case for the purposes of KT (the alters)]. The typical way to generate ego network data is to create an exhaustive list of alters with whom the respondent has some type of relationship. Termed a name generator, the respondent was asked to list alters who occupy certain social roles, those with whom he/she shares interactions, or those with whom he/she exchanges resources. This approach is used in many classic studies of ego networks. 147

To analyse the SNA data, we employed regression analysis and bivariate analyses where we were limited by sample size. Our analysis consisted of cross-sectional regression models for both waves of data collection independently, thereby providing two snapshots of patterns of interaction. In addition, we conducted longitudinal analyses for the changes in behaviour over time. Specifically, we explored the effects of CLAHRC participants’ professional and organisational characteristics on the change in the measures of the bridging of academic–practitioner networking and decision-making gap, and the formation of connections among members of research and implementation themes and members of clinical and non-clinical departments. The criterion change over time in all cases is measured as the difference between criterion scores in waves II and I (CChange = Cwave II − Cwave I).

We drew on and adopted SNA and in-depth qualitative research to explore institutional entrepreneurship across the different CLAHRCs in facilitating KT. In the following chapters we present our findings, beginning with the founding conditions of CLAHRCs.

Chapter 4 Founding conditions of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

In this chapter we focus on the founding conditions of the nine CLAHRCs. In doing so, we have drawn on the seminal work of Pettigrew et al. 25 that highlighted the importance of context and receptivity for the type of strategic change envisaged by policy-makers in funding CLAHRCs. An important point raised by Pettigrew et al. 25 was that much research on strategic change has been ahistorical. To understand possibilities for future strategic change, we need to understand past patterns of change and stability, which includes consideration of the local context, as well as the national context.

We examined the importance of actors as situated in their local context by drawing on the concept of institutional entrepreneurship. 39 Specifically, we have cast senior CLAHRC leaders as IEs and examined how their position in the structural context of translational interventions impacted on early strategic decisions in bid development. Although organisational fields are in some sense structured by institutional forces, struggles still occur between different stakeholders in relation to resources and social action, and these have the capacity to recreate, and even change, institutionalised practices. Institutional entrepreneurship has focused on the nature of these struggles and how actors seek to influence existing and emerging institutional configurations. 19,88,90,91