Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1002/05. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The final report began editorial review in September 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Currie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

General background

Patient safety is a global concern. Research suggests that, in line with the USA and Australia, around 10% of patients admitted to acute hospitals in the UK experience an adverse event, of which half are identified as preventable, costing the NHS around £1B a year in terms of additional bed-days. 1 Empirically, our study focuses on the brokerage of patient safety knowledge (PSK) by hybrid middle-level managers (H-MLMs) for quality improvement in the care of older people in a hospital, a knowledge domain considered to be ineffectively mobilised for continuous improvement in clinical frontline care. Data captured via the UK’s National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS, released September 2012) identify inpatient falls within hospitals as the largest single type of patient safety incident (26%), followed by medication incidents (11%), and incidents relating to treatment and/or procedures (11%). This trend remains consistent with previous data releases. Such patient safety issues are the subject of intense policy focus across developed countries, particularly with ageing patient populations, where older patients take up increasing hospital resources to the extent that their care may be characterised as ‘mainstream business’ rather than specialist. Linked to this, older patients may remain in hospital longer than intended (e.g. because they have fractured their hip following a fall), or be discharged but quickly return to hospital (e.g. because the social care package is inadequate in the light of cognitive impairment, such as dementia), both of which are very costly.

Learning from safety events and clinical risks is recognised as vital to enhance patient safety,2 yet the brokering of PSK to the clinical front line remains problematic. The brokering of PSK related to the care of older people represents a high-profile and visible topic to examine more general matters of knowledge brokering by H-MLMs in health-care and social care organisations beyond hospitals, and in service domains beyond elderly care.

The knowledge-brokering role of the hybrid middle-level manager

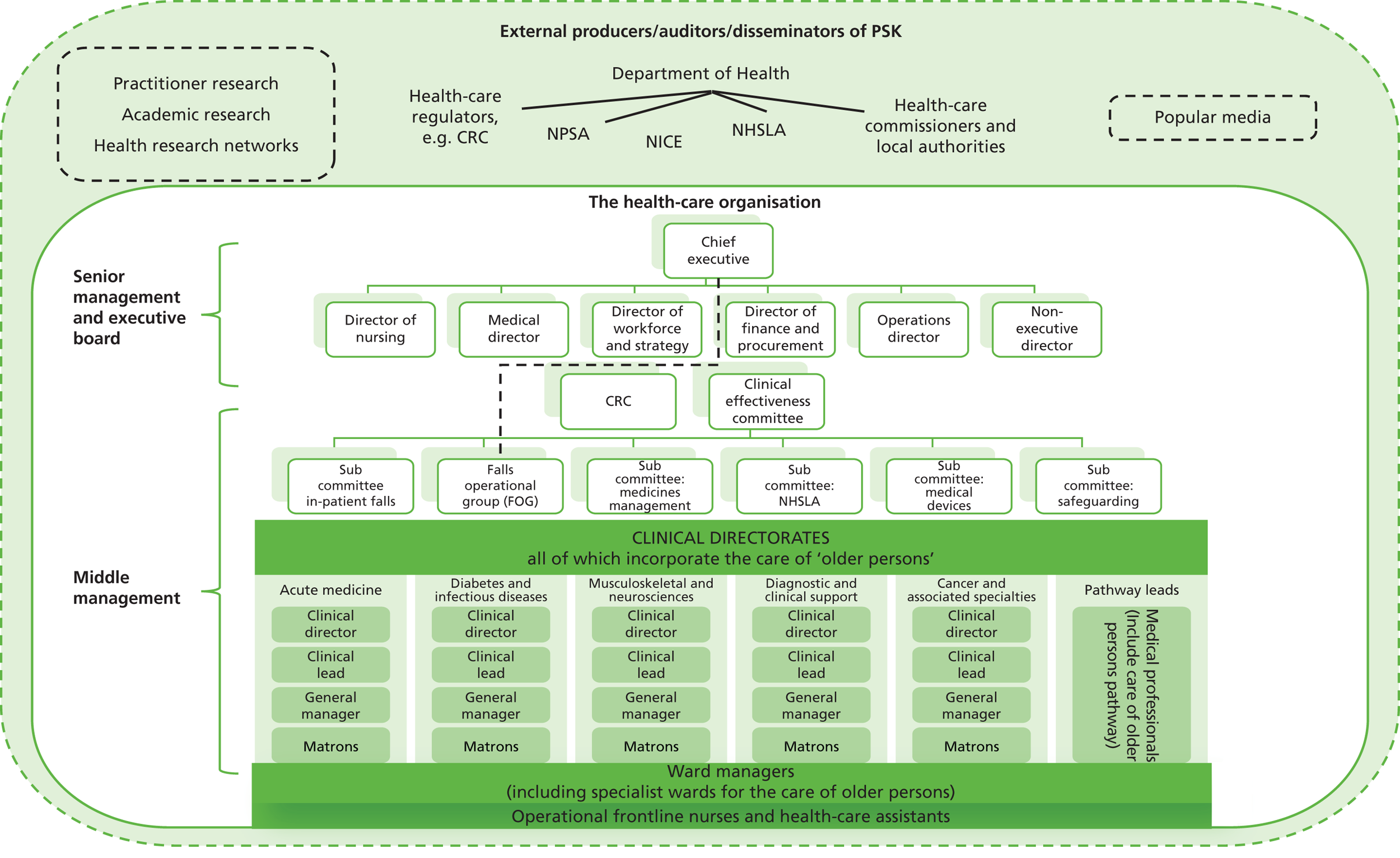

Knowledge brokering across organisational and professional boundaries is particularly crucial for high-quality health-care delivery. Learning from PSK derived from ‘exogenous’ sources [e.g. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines, National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA) alerts, and scientific research and publications], and ‘endogenous’ sources (e.g. experiential knowledge from the clinical front line, and patient safety incidents) is central to enhancing patient safety. 2

A knowledge broker is defined as an individual who uses their in-between vantage position to support innovation through connecting, recombining and transferring to new contexts otherwise disconnected pools of ideas, i.e. they get the right knowledge into the right hands, at the right time. 3,4 Middle-level managers (MLMs) play an important brokering role in understanding the functionality of the knowledge (i.e. for what purposes knowledge may be used) and how they can match the knowledge to potential opportunities. 5 In health-care organisations, a significant number of MLMs are ‘hybrid’, i.e. they hold responsibility for clinical service delivery as well as conduct a managerial role. 6 On the basis that H-MLMs have credibility with their clinical communities and, thus, enjoy legitimacy to broker knowledge within health-care organisations – more so than their generalist counterparts – H-MLMs are uniquely placed within organisations to broker the flows of exogenous and endogenous sources of PSK to improve the overall quality of care in four ways.

We highlight that H-MLMs are able to broker exogenous knowledge ‘downwards’ from external producers and disseminators of evidence – e.g. NPSA ‘safety alerts’ and NICE guidelines – and broker endogenous knowledge ‘upwards’ from within the organisation, for example through incident reporting and investigation, such as framed by the NRLS. 7–9 Further to this, we suggest that H-MLMs span the boundary between managerial structures for brokering PSK, such as clinical governance structures, and frontline clinical practice. They are, thus, uniquely positioned to fuse their understanding of local context (endogenous knowledge) with the more generic evidence base that constitutes exogenous knowledge, to ensure continuous development and implementation of high-quality service delivery that is patient-safe. Finally, if the necessary antecedents for H-MLM knowledge brokering are in place, such as H-MLM interaction with the external environment, then H-MLMs can effectively broker knowledge across organisations, as well as within organisations,10 to influence global best practice. We revisit our conceptualisation of the knowledge-brokering role of the H-MLM in Chapter 2.

Aims and objectives

Our research study examines the role of the H-MLM in brokering PSK relating to the care of older people within hospitals, between hospitals and other health-care organisations, and between hospitals and producers/disseminators/auditors of exogenous PSK and health-care context. We aim to identify contingent factors framing a more strategic role for H-MLMs, which is predicated on knowledge brokering.

The key dimensions of the knowledge-brokering process we analyse are shown in Box 1.

-

DIMENSION 1: The brokering of patient safety knowledge from external sources to inform service development within their local employing organisation.

-

DIMENSION 2: The brokering of patient safety knowledge from internal sources to inform service development within their local employing organisation.

-

DIMENSION 3: The fusing of external and internal knowledge within organisations, to ensure that service enhancement is aligned with global best practice, and simultaneously locally contextualised.

-

DIMENSION 4: The brokering of patient safety knowledge across the constituent organisations of a local health and social care delivery system for service development.

Our research will generate a deep understanding of the processes through which H-MLMs broker knowledge, grounded in the larger social context, aligned with the following RQs (as stated in our original protocol):

-

RQ1. What expectations and perceptions do external regional and national producers/disseminators/auditors of PSK have regarding the brokering of top-down knowledge (‘safety alerts’, broadly defined) through MLMs and risk management structures to influence clinical practice?

-

RQ2. Which MLMs are more likely to enact a knowledge-brokering role within organisations and across the system, and why: e.g. more ‘senior’ or more ‘junior’ MLMs; more or fewer H-MLMs; those affiliated to certain more powerful professional groups, notably doctors?

-

RQ3. What is the contribution of MLMs towards brokering PSK, e.g. when do they broker knowledge, of what type, how, within or across organisations, and qualitative description of outcomes?

-

RQ4. How do expectations and perceptions of knowledge-brokering patterns held by external national and regional producers/disseminators/auditors of PSK diverge or converge from knowledge-brokering patterns at local organisational or system levels?

-

RQ5. How do patterns of brokering associated with top-down PSK differ from knowledge-brokering patterns associated with bottom-up PSK?

-

RQ6. What prescriptions can our analysis of knowledge brokering offer for policy and practice, e.g. how can MLMs be enabled to broker PSK more effectively?

RQ, research question.

Research context

Knowledge brokering

The nature of knowledge, and knowing, is an important starting point for any research that aims to understand how knowledge is mobilised. This has been covered extensively in a recent scoping review of the literature by Crilly et al. for the National Coordinating Centre for the Service Delivery and Organisation (NCCSDO). 11 In essence, we regard knowledge as a resource applied by social actors in an attempt to solve problems. It can never be removed from its context, as it is bound to its use and its user within the organisation. 12 We position the concept of knowledge brokering as one solution to the challenge of knowledge mobilisation.

Our review of the strategic role of the H-MLM in brokering PSK draws upon the knowledge-based view (KBV) of the firm. KBV focuses upon knowledge as the most strategically important resource for any organisation. 13 In this study, we adopt a practice-based view of knowledge,14 distinguishing, first, between knowledge which is tacit (personal) or explicit (can be codified),15,16 and, second, between that which derives externally to the organisation (exogenous knowledge, more likely explicit) or internally (endogenous knowledge, more likely tacit). In complex organisations, and where the dominant core of the organisation is characterised by professional knowledge as in health care, knowledge mobilisation is inherently problematic. 17 Specificity of context, combined with the personal nature of knowledge,18 engenders knowledge that is ‘sticky’ and, thus, difficult to broker within and across organisations. Evidence suggests that clinical professionals privilege more contextualised, endogenous knowledge over and above exogenous knowledge which is explicitly presented and accessible to the whole health-care community,19 a phenomenon that Gabbay and Le May20 have termed ‘mindlines, not guidelines’. Attempts at brokering both explicit and tacit knowledge for patient safety face considerable challenges. 21,22 Generating a deep understanding of the processes through which explicit and tacit PSK is brokered within and across health-care organisations, grounded in the larger social context, is critical to inform quality improvement in health-care delivery.

Strategic management

Strategic management literature considers MLMs to be well placed as brokers because they provide a unique ‘linking pin’ between operational and strategic contexts. 23 Despite this, the role of the MLM has been under scrutiny in the private and public sector since the late 1970s. An increasingly globally competitive environment encouraged senior organisational management to delayer MLMs on the basis that the latter did not add value to the organisation’s activities. 10,24–27 However, organisations have found that the expected reduction in costs has not been realised, in large part explained by the loss of ‘tacit’ knowledge as MLMs ‘walk out of the door’, and management consultants are hired to fill the knowledge gap. 10,28 This highlights that the value of MLMs is linked to their role as a knowledge resource, which may be ‘hidden’ in more populist prescriptions for delayering.

In particular, where they have a relevant professional background, MLMs act as ‘hybrid’ managers10,29 who bridge managerial and clinical contexts, i.e. some MLMs may be better placed than others to enact a strategic knowledge-brokering role. Llewellyn6 describes the hybrid concept using a metaphor of a ‘two-way window’. In the context of health care, H-MLMs with a clinical background act as ‘mediating persons’ capable of working through sets of ideas belonging to management and sets of ideas belonging to clinical practice. The strategic role of the H-MLM lies in their ability to look through a ‘two-way window’, to ‘broker’ tacit as well as explicit PSK across clinical and managerial knowledge domains for service improvement. 4–6,19,30

Summary of research context

In summary, the research brings the following literatures together to frame analysis of the processes through which H-MLMs broker PSK in health care: strategic management literature about KBV of the firm and the role of MLMs; organisation studies literature about knowledge mobilisation and brokering; and a more specific health-care policy and management literature about MLMs and knowledge mobilisation. Our study seeks to understand the external and internal contextual influences that impact the ability and disposition of H-MLMs to broker exogenous and endogenous PSK within the organisation and across the wider elderly care pathway to improve the quality of health-care delivery for older people specifically and other patient groups more generally.

Research approach and report structure

The research adopted a mixed-methods approach incorporating interviews, observation, document analysis, tracer studies, focus groups and social network analysis (SNA). The rationale for a mixed-methods approach follows that of other National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) projects. There is general agreement in the literature that the combination of such methods yields results that are both robust and significant,31 and further that a mixed methods approach is particularly useful in health-care settings. 32,33

The main data-gathering method was semistructured interviews. In total, 127 semistructured interviews were conducted, mostly with H-MLMs, who broker PSK within three hospitals, but also with those involved in the external production/dissemination/auditing of PSK (henceforth referred to as ‘external producers’). Details of respondents and their organisations can be found in Chapter 3.

All interviews were semistructured, allowing for broad exploration of H-MLMs’ brokering of exogenous and endogenous PSK in line with our research questions (RQs). Interviews were conducted in line with work packages 1, 2 and 3 as outlined below.

Work package 1

Seventeen semistructured interviews were conducted with external, national- and regional-level producers, disseminators and auditors of PSK around falls, medication and transition, as outlined in our original proposal and in accordance with our research protocol. The primary purpose of interviews in work package 1 was to ascertain the expectations and perceptions of external producers of PSK regarding knowledge-brokering transfer from the ‘external producers’ to the ‘internal users’ of PSK.

Work package 2

Fifty-four interviews were conducted with individuals on and outside the main clinical governance structure, the Clinical Risk Committee (CRC), across three health-care organisations (two hospitals, cases A and B, and one mental health-care organisation, case C, with which the first two link around cognitive impairment of older patients in hospitals). These interviews focused, firstly, upon knowledge brokering of exogenous PSK produced or disseminated by external parties (e.g. in the form of ‘safety alerts’, broadly defined, or best practice guidelines) into clinical practice, by H-MLMs who are members of the CRC within a hospital. Then, secondly, we analysed the brokering of exogenous PSK from the CRC to the clinical front line. This provided an illuminating counterpoint to the expectations and perceptions of those producing and disseminating external evidence, who are interviewed in work package 1. Work package 2 examines, in detail, the social structures that impact upon knowledge-brokering roles.

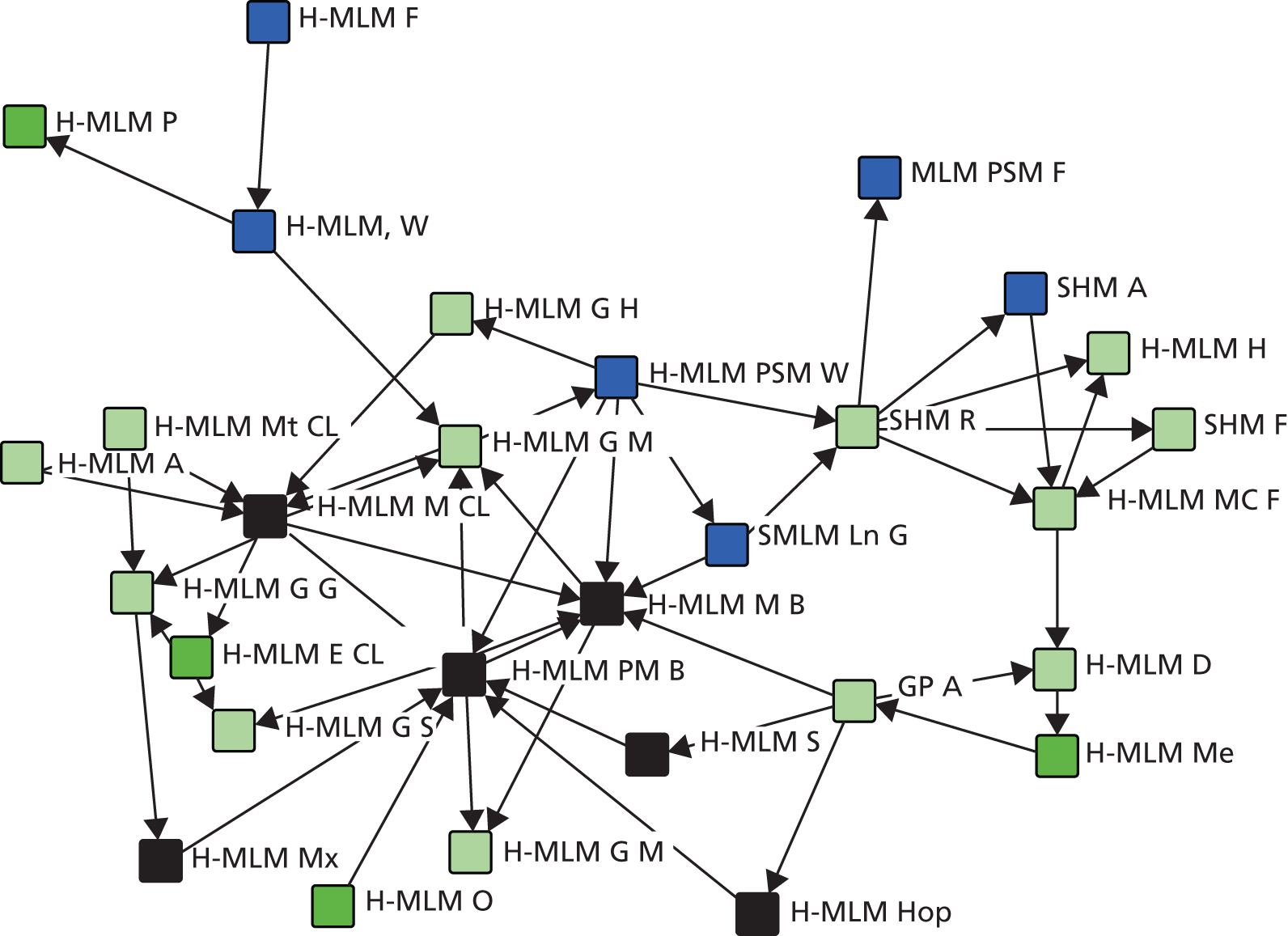

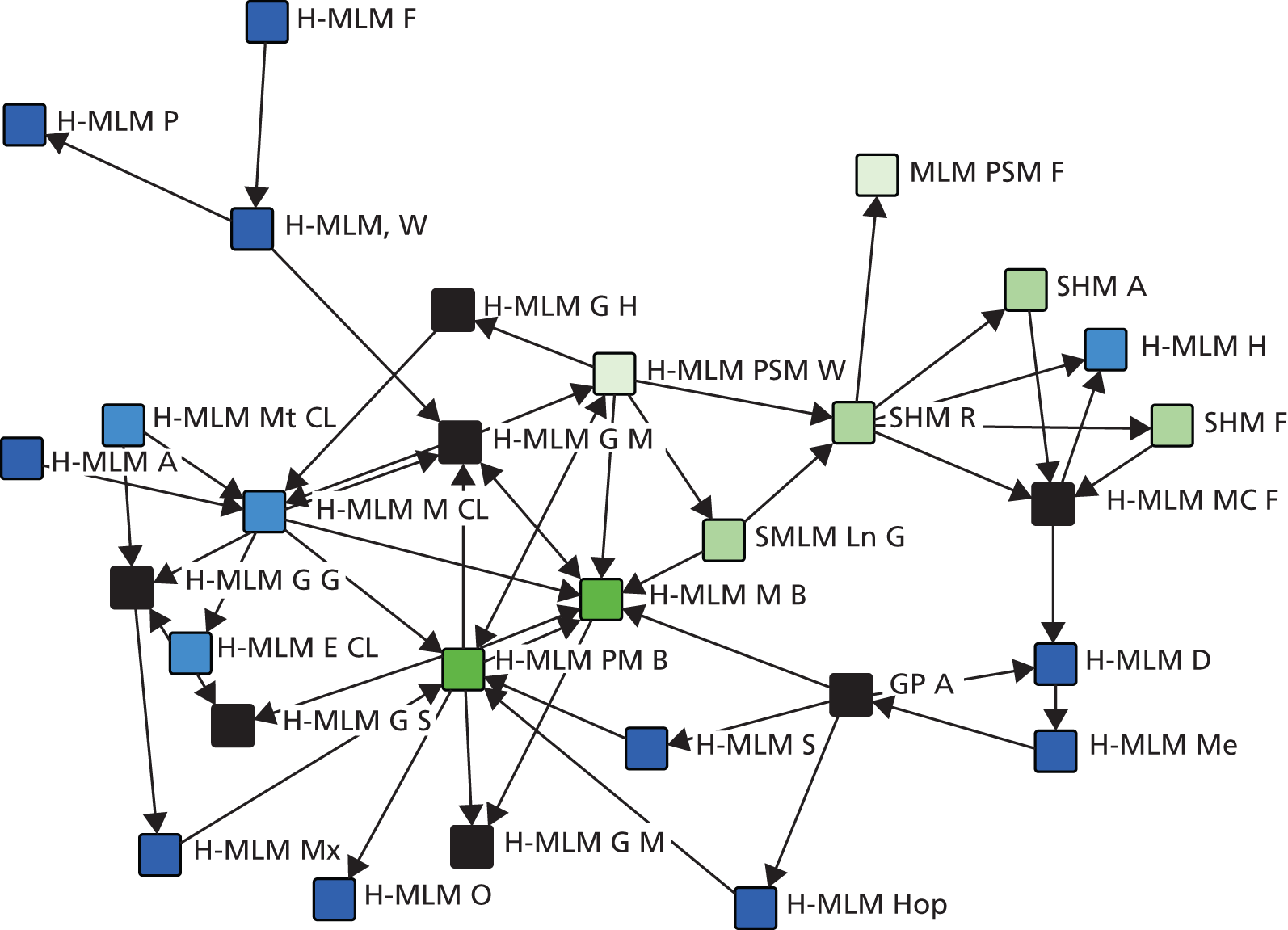

We employed SNA to help us to identify key knowledge brokers and their characteristics. However, while our preliminary SNA data concur with our qualitative data in highlighting H-MLMs as key knowledge brokers, we found the ‘network’ to be very difficult to define. Questions about structural relations in the brokering of PSK yielded a range of answers regarding who was encompassed within the elderly care pathway through which PSK was brokered, commonly veering between ‘everyone’ and ‘no one’. While we do not present a specific SNA within this report, given the difficulties of defining any network in relation to PSK, our more qualitative assessment of the network following SNA, applied to interview transcripts, informs our analysis of relationships between H-MLMs at different levels within the organisation, and between H-MLMs and other actors within our hospital cases, and outside to external producers of PSK.

Supplementing interviews and SNA, we carried out observation of the CRC, and other relevant committees, such as the Inpatient Falls Committee (IPFC) and the Falls Operational Group, in hospital A. This amounted to approximately 20 hours’ observation of discussions related to PSK in elderly care, and helped to contextualise our research analysis.

Work package 3

Work package 3 focused upon the brokering of bottom-up or endogenous PSK. We traced knowledge brokering from serious untoward incidents (SUIs) related to falls, medication management and/or transition that resulted in unexpected patient harm (or death), anticipating that learning and quality improvement ensues. Recognising the importance of this work, one case study organisation, hospital A, requested an evaluation of the effectiveness of root cause analysis (RCA: a systematic investigation technique that looks beyond the individuals concerned and seeks to understand the underlying causes and environmental context in which the incident happened22) as a vehicle for learning and service improvement from patient safety incidents. Subsequently, the research team were asked to conduct focus groups with wards in order to work through problems and devise a plan for improvement. Work package 3 was consequently modified to involve more junior members of clinical staff located closer to clinical practice than participants in work packages 1 and 2 – i.e. registered and non-registered nurses, ward managers, matrons and junior doctors – in order to evaluate whether or not knowledge had been brokered to the clinical front line following a patient safety incident. Data collected in work package 3 provided a valuable insight into the importance of knowledge brokering to facilitate learning from endogenous PSK directly back to the ward where the incident occurred, and the challenge of brokering such knowledge upwards (and across) for wider learning across the hospital and to linked health and social care providers. Following this work, the research team conducted an evaluation of learning and service improvement from SUIs following RCA in a second case study organisation, hospital Z. This second evaluation allowed the research team to consider the generalisability of emergent research findings at hospital A about the brokering of PSK from RCAs for learning and service improvement in elderly care. Within work package 3, 56 interviews were conducted in total, supported by approximately 20 hours of observation of the day-to-day running of the wards and departments related to the SUI.

Feedback and engagement with user groups

Maximising and harnessing research impact is a major objective of our study, facilitated by the coproduction of data and the involvement of stakeholder groups across the health-care organisations. This was facilitated in the following way:

-

holding of three meetings of the Study Advisory Board across the project duration

-

presentation of emergent research findings to the IPFC and the Falls Operational Group (chaired by the chief executive) at hospital A, and to the patient safety team at hospital Z

-

facilitation of focus groups to share findings and work with stakeholders, to improve learning from bottom-up patient safety knowledge, within hospital A

-

presentation of emergent research findings at Health Services Research Network (HSRN) (June 2013)

-

employment of a professional corporate communications company to codevelop high-impact accessible lessons from study for health-care managers, professionals and policy-makers

-

facilitation of national dissemination via end-of-study report and a website, including video presentation (in place October 2013).

Relevance to National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme

Our research fills a knowledge gap that is timely given initiatives in the Next Stage Review,34 which highlighted a need for locally driven innovation located nearer the front line of service delivery, impending constraints on NHS expenditure, and the concerted efforts around innovation adoption by the NIHR. A recent review of the Patient Safety Research Programme, funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme,9,35 highlights a need for system-level analysis and research on older people. The NPSA identifies the following PSK domains relevant to the care of older patients: (i) falls – a major and highly reported area of patient safety; (ii) medication-related safety – a prominent area of concern which exemplifies the challenge of brokering across jurisdiction, for example general practitioner (GP) or pharmacy to acute; and (iii) transition – as an elderly patient moves from one care provider to another, information may be absent, delayed, lost, distorted, misinterpreted or repeated.

The health-care literature about knowledge brokering is relatively normative,36 although there is anecdotal evidence about the effectiveness of knowledge brokering in improving the quality and use of evidence in health-care decision-making. 36–38 There is a particular need to understand how social context impacts upon brokering of evidence for service innovation. 11,39 Prescriptions around effective brokering of PSK by H-MLMs could save the NHS billions of pounds and prevent reputational damage. Finally, we link to the NIHR HSDR commissioning document around the Knowledge Transfer and Innovation (KT&I) programme of research (KM259), the systematic review of Ferlie et al. ,11 its follow up (Crilly et al. 40) and other ongoing research about knowledge mobilisation funded by the NIHR, particularly the study led by Waring, which focuses upon safe discharge and hospital readmission. 41 Regarding our focus upon H-MLMs, this relates to a number of previous studies commissioned by NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation examining the role of middle managers, specifically Annandale et al. ,42 Buchanan et al. ,43 Checkland et al. ,44 Dopson et al. 45 and Hyde et al. 46

Chapter 2 Literature review

This chapter reviews literature pertaining to the knowledge-brokering role of the MLM as a contribution to strategy. Our approach to reviewing literature represents a narrative synthesis,47 one which has previously been used in management sciences. Drawing on the interpretivist approach, adhering to the same principles of organisation, transparency and replicability as standard systematic review approaches in the field of health sciences, and with both quality and relevance as the organising matrix, narrative synthesis is a flexible method that allows the reviewer to be reflexive and critical through their choice of organising narrative. By developing a critical narrative, an evidence synthesis seeks to generate an understanding of the evidence and provide new insights that would not otherwise be apparent, either by focusing on individual or small clusters of studies or by including only certain types of data (e.g. quantitative). Through its emphasis on ‘evidence’ as opposed to ‘statistical significance’, an evidence synthesis thus looks to the nature and scale of the effects in practice but without compromising on quality (i.e. validity) or relevance. It highlights the importance of the social (contextual) as well as the scientific nature of evidence and emphasises the need for reflexivity in conducting evidence reviews. It also emphasises credibility to denote an approach which yields results that are meaningful at both objective (reliable) and subjective (trustworthy) levels. The literature review focused upon those concepts most relevant to our a priori objectives, specifically ‘knowledge brokering’ and ‘the role of hybrid middle managers’. Readers might note, however, that within our empirical sections we draw in other concepts, specifically ‘absorptive capacity’. We highlight analysis that applies the concept of absorptive capacity ensued as a consequence of inductive reasoning derived from thematic coding of data. As later detailed in research design, themes not anticipated in the literature review may emerge during the coding process; thus, ‘absorptive capacity’ did not represent an original search term in our narrative literature review. Such a more inductive or iterative approach to literature review and thematic coding is consistent with academic practice in social science. 48

Following our narrative synthesis, we begin by outlining the ongoing debate concerning the role and value of the MLM in the generic literature and specifically in relation to health care. Following this outline, we draw upon strategic management literature to illustrate the strategic role of the H-MLM as uniquely capable of brokering knowledge to influence and implement strategy in a manner that fuses exogenous sources of knowledge with the organisation’s endogenous knowledge base. Aligned to this, we review literature that adopts a more nuanced view of knowledge brokering and delineates between types of knowledge-brokering roles enacted by individuals within organisations and highlights the influence of context.

We then review the knowledge-brokering literature in health care, which we describe as normative and focusing mostly on external knowledge brokering. On this basis, we extend our review to consider the nature of knowledge in a health-care environment, and compare and contrast two approaches to brokering knowledge: a managed system-based approach (the NRLS) and an informal people-based approach [communities of practice (CoPs)]. We conclude that both approaches have strengths and weaknesses. Finally, we summarise the literature, highlighting key findings that guide our study.

The role and value of the middle-level manager

The role of the MLM has been under scrutiny in the private and public sector since the late 1970s, when an increasingly globally competitive environment encouraged senior organisational management to delayer MLMs on the basis that the latter did not add value to the organisation’s activities. 10,24–27 However, organisations have found that the expected reduction in costs has not been realised, in large part explained by the loss of ‘tacit’ knowledge as MLMs ‘walk out of the door’, and management consultants are hired to fill the knowledge gap. 10,28 This highlights that the value of MLMs is linked to their role as a knowledge resource, which may be ‘hidden’ in more populist prescriptions for delayering.

Cognisant of the hidden value of MLMs, since the early 1990s a less pejorative view of MLMs has emerged among academic commentators, highlighting the importance of their strategic contribution to organisational performance, although this has translated slowly to practice. The less pejorative view highlights the capacity of MLMs to develop, as well as implement, organisational strategy in a way that adds value to, rather than subtracts value from, organisational activities, through both upwards and downwards strategic influence, and which may diverge from, as well as converge with, the strategic intentions of executive management. 28 Central to this notion of strategic influence is the capacity of the MLM to ‘broker’ knowledge from one domain to another, given their position at the ‘nexus’ of the organisation to support innovation through connecting, recombining, and transferring to new contexts otherwise disconnected pools of ideas, i.e. they get the right knowledge into the right hands, at the right time. 3,4

Despite such a view of the more productive MLM, the efficiency drive to target MLMs continues to escalate. A recent column published in Harvard Business Review entitled ‘The end of the middle manager’49 proposes that ‘Technology itself is now the great general manager . . . thanks to the internet and search engines, everyone now knows or can know something about everything’ (p. 36). The underlying suggestion is that those with general management skills are vulnerable, as they no longer have knowledge that is considered valuable to the firm. The ensuing dissension among the ranks of academics and practitioners in response to this article was captured online and was swiftly picked up on in the Financial Times. 50 The general thread of the revolt against the argument by Gratton49 is centred on the increased complexity and velocity of change in modern organisations that require the more contextualised knowledge of those in the middle to shape, as well as to execute, strategy. In response to Gratton,49 Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) professor, Steven Spear, employs the analogy of the human body to emphasise the crucial role of the MLM:

The human body has layer after layer of middle management, across cells, tissue, organ, leading up to the brain. Remove any one of those layers and ask the brain to talk directly to cells and you have something quite different and less efficient.

Steven Spear, cited in Broughton50

Reinforcing such a view, Wooldridge et al. 51 state that ‘Organisations require distributed and interactive leadership throughout the organisation with middle managers as important mediators between levels and units’ (p. 1191). In a related literature, that of distributed leadership, we note similar calls for a more influential role for those actors located at the middle levels of the organisation. 52

Returning to the crux of Gratton’s argument, that technology will supplant the role of the general manager, Dopson and Stewart27 trace this prediction back more than half a century to Leavitt and Whisler. 53 Other commentators followed similarly, from 1960 through to the middle of the 1980s,54–57 yet there was little evidence to support these assertions. 58,59 During the mid 1980s, research was published that suggested that rather than information technology (IT) shrinking the role of the MLM, it was actually reshaping and enhancing their strategic role,60,61 with evidence highlighting a variety of changes to the work of the MLM that had, almost without exception, enriched jobs, with reports of widespread upskilling and increased responsibility and autonomy. 25,58,62 In attempting to make sense of these competing views of the interaction of IT and the role of MLMs, Pinsonneault and Kraemer63 argue that the latter will continue to perform tasks where they have comparative advantage and renounce those tasks that are best performed by IT, ‘Hence IT takes over most informational and structured decisional activities, but few (if any) interpersonal and unstructured decisional activities’ (p .279). The authors also argue that the numbers of MLMs vary according to the degree of centralised decision-making in the organisation. In organisations where decision-making is decentralised (a characteristic of health-care organisations), MLMs are crucial to the synthesis of information to bestow it with meaning and purpose,10,24,63,64 in turn permitting the MLMs to influence strategy and decision-making at a strategic level of the organisation. 28,65–67 In such a situation, the numbers of MLMs may even be likely to increase rather than diminish. 63 Finally, Pinsonneault and Kraemer63 argue that factors other than IT can cause a decay or enhancement of the numbers of MLMs, specifically environmental triggers such as a cost-efficiency drive or changes in the policy environment. These triggers are apparent in the English NHS, as follows.

Middle management and the NHS

The efficiency drive to target MLMs has continued to escalate, with the current coalition government (elected in 2010) pledging a reduction in management costs in the English NHS by more than 45% by 2014. This drive to reduce management costs is reflected in recent figures published by the NHS Information Centre (March 2011), which highlights a decrease in the number of managers and senior managers by 6.2% between September 2009 and September 2010, alongside an overall expansion in the size of the workforce during this time. In their report to the King’s Fund, Walshe and Smith68 suggest that the widely professed rise of bureaucracy may actually be exaggerated. Their report concludes that ‘There is no persuasive evidence that the NHS is over-managed, and a good deal of evidence that it may be under-managed’ (p. vii). Further, they caution policy-makers: ‘the denigration of managers and the role they play in delivering high-quality health care will be damaging to the NHS and to patient care in the short and long term’ (p. vii).

Reflecting the bifurcated debate in generic literature, in the English NHS the attack on the utility of the MLM goes hand in hand with policy drives to reduce organisational costs. 10 We highlight that the justification for reducing the numbers of MLMs appears emotive, linking a strong emblematic association of the NHS with national values, and a need to reduce management costs and distribute savings to safeguard frontline care. 69 Provocative and captivating headlines in the popular press expose the evocative language employed by high-profile politicians in their efforts to reduce the numbers of MLMs in health care. 68 Disparaging terms have emerged to describe MLMs in health care within daily printed media and online communities, such as ‘faceless bureaucrats’, ‘idle pen pushers’ and ‘men in grey suits’. The depth of negative feeling about MLMs in health care is evidenced in the use of satirical language; for example, see ‘nhsmanagerturnedtrader.blogspot.com’ (last accessed 21 March 2013), describing one ex-NHS manager’s journey from ‘faceless bureaucrat to bad-assed trader’ [sic], and the ‘idlepenpusher.blogspot.com’, where the writer describes himself as ‘a public sector nobody’.

At the same time, from a strategic perspective, reflecting the more generic literature, arguments that MLMs should be delayered in health care lack an empirical evidence base. Rather, it may be that an enhanced role for MLMs is required. Developing this line of argument further, we now review the strategic management literature in line with a reconceptualisation of the MLM role as strategic. Our assertion is that MLMs, specifically H-MLMs, are central to the brokerage of PSK, meaning that they play a crucial role in enhancing service quality.

The strategic role of the middle-level manager

The classical view of strategy suggests strategy formulation is an isolated, planned and deliberate process. The senior manager formulates strategy and the MLM executes the strategy. 70,71 During the past 25 years, the scope of strategy process research has expanded to include not only senior managers but also MLMs. 51 Quinn72 was among the first to challenge the classical view with his concept of ‘logical incrementalism’, suggesting that strategy is gradually adapted over time through experimentation and learning. 73 Since 1980, strategic management theorists have agreed that strategy is neither completely deliberate nor completely emergent. Instead, the two approaches represent polar ends of a continuum upon which ‘real world strategies would fall’ (p. 259). 74 Thus, to varying degrees, strategy is as much emergent as it is planned. 66,74 Reflecting this, Nonaka75 describes the process of strategy at Honda using the term ‘compressive management’. The author explains that this ‘middle up–down’ style of management involves the translation of senior management vision to resolve the contradiction between their visionary (but abstract) concepts and the experientially grounded concepts originating from the ‘shop floor’. Thus, by virtue of their structural location at the nexus of the organisation, the MLM acts as a linking pin between senior management vision and bottom-up reality. 23 This suggests that the MLM is an important catalyst for change, as opposed to being a passive recipient. 24 Specifically, the MLM has an important strategic role of mediating and resolving the knowledge gap between the top and bottom layers of the organisation, as strategic change emerges.

In common with Nonaka’s75 findings, empirical research conducted by Floyd and Wooldridge28,65,67,76 has shown a positive relationship between MLM involvement in strategy and organisational performance. 26 Based on this research, Floyd and Wooldridge65 developed a typology of MLM roles that illustrates their ability to influence strategy through their upwards and downwards relations. MLMs influence strategy upwards through interpreting information and channelling this information upwards to senior management (synthesis). Upwards influence may also occur through the championing of strategic alternatives as a result of divergent activities that combine the experience of the ‘shop floor’ (i.e. those at an operational level) with the strategic intentions of the top. Championing alternatives closely aligns to Nonaka’s15 view of the MLM role in mediating the conceptual knowledge at the top with the experiential knowledge on the shop floor (a ‘middle up–down’ style of management, in Nonaka’s terms75). In influencing strategic implementation (downwards influence), the MLM fuses their knowledge of top-down strategic objectives with bottom-up situated knowledge to facilitate adaptability, preparing the bottom for change,24 as well as the more traditional role of merely implementing deliberate strategy. 70

Floyd and Wooldridge23 conceptualise the process of influencing and implementing strategy as an iterative process that involves the conversion of new ideas into strategic initiatives. Over time, this process develops into organisational capabilities. They state that ‘Information flows and patterns of social influence that transform ideas and initiatives into new capabilities have their nexus at middle levels of management hierarchy. . . This is “where the action is” in a capability-based view of strategy’ (p. xvi). Floyd and Wooldridge imply that the role of the MLM is more than a ‘linking pin’. The MLM has the capability to fuse divergent ideas that arise at an operational level with top-down strategic issues based on their knowledge and experience, to shape strategy and influence change. 23 Such a view aligns with KBVs of the firm that have emerged in the strategic management literature. 13,77,78

The knowledge-based view and the strategic role of the middle-level manager

Grant13 argues that organisations exist because they are more efficient at integrating and applying specialised knowledge than markets are. The KBV of the firm is an innovation within the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm. 13,79–81 Underpinning KBV is an assumption that knowledge is the most important resource of any organisation and, thus, strategy should be concerned with the development, protection and transfer of knowledge. 77,78 In many ways, KBV, with its emphasis on knowledge development and transfer, may be thought of as the link between the traditional static conceptualisation of the RBV and more recent developments surrounding dynamic capabilities theory,82 combinative capabilities83 and absorptive capacity. 84 As such, KBV suggests a significant role for MLMs in the management of an organisation’s knowledge for improving quality through the successful transformation of new knowledge for service improvement. To explain, MLMs, given a set of knowledge resources, play an important brokering role in understanding the functionality of the knowledge (i.e. for what purposes knowledge may be used) and how they can match the knowledge to potential opportunities. In doing so, ‘knowledge broker’ MLMs bridge multiple domains, learn about the knowledge resources within those domains, link that knowledge to new situations, and finally build new networks around the innovations that emerge from the process. To emphasise, a knowledge broker is defined as an individual who uses their in-between vantage position to support innovation through connecting, recombining and transferring to new contexts otherwise disconnected pools of ideas, i.e. they get the right knowledge into the right hands, at the right time. 3,4

The hybrid middle-level manager

Strategic management literature argues that MLMs are well placed as knowledge brokers because they provide a unique ‘linking pin’ between operational and strategic contexts and are capable of shaping strategic change. 23 Particularly where they have a relevant professional background, MLMs act as ‘hybrid’ managers10,29 who can bridge managerial and clinical contexts, i.e. some MLMs may be better placed than others to enact a strategic knowledge-brokering role. 85 ‘Hybrid’ refers to MLMs who are skilled in an alternative profession, hereafter referred to as ‘H-MLMs’. Llewellyn6 describes the hybrid concept using a metaphor of a ‘two-way window’. In the context of health care, for example, H-MLMs with a clinical background act as ‘mediating persons’ capable of working through sets of ideas belonging to management and sets of ideas belonging to clinical practice. 6 This dual sense-making activity requires skills of ‘discursive competence’,86 described as the ability to ‘perform the conversation’ and ‘set the scene’, skills which Rouleau and Balogun86 assert go beyond the capacity to speak the right words to the right people, additionally involving the use of language to trigger linkages and build acceptance of their position among others.

The two-way window implies greater communication between clinical practice and management, which were previously opaque to each other, i.e. constituted as one-way windows. On the basis that there are now both people and organisational tasks that cross the boundary between clinical practice and management, management within health care is no longer about ‘oiling the wheels’. 87 Instead, management represents an organisational arena where difficult and contentious clinical management decisions are required, which H-MLMs are well placed to make. H-MLMs command credibility within their clinical communities and, thus, enjoy a legitimacy to broker knowledge within health-care organisations – more so than their generalist counterparts – and, further, have a zeal for service improvement. 24,88,89

In health care, professionals value and pursue local and tacit knowledge in making clinical decisions about patient care. Indeed, clinical professionals may privilege more contextualised knowledge over and above knowledge which is explicitly presented and accessible to the whole health-care community, a phenomenon that Gabbay and Le May20 have termed ‘mindlines, not guidelines’. Consequently, any attempt at managing professionalised and tacit knowledge in health care through the mobilisation of explicit and codified knowledge faces significant challenge. 21,22 The significance of tacit knowledge in the professionalised setting of health care leads us to assert that IT is unlikely to supplant the role of the H-MLM. We posit that the strategic role of the H-MLM lies in his or her ability to look through a ‘two-way window’, to ‘broker’ tacit, as well as explicit, clinical and managerial knowledge domains for service improvement. 4–6,19,30,90 Conceptually, based on the extant literature, we characterise the potential knowledge-brokering role of the H-MLM in relation to PSK for service improvement in the following way. Firstly, H-MLMs are able to broker exogenous knowledge ‘downwards’ from external producers and disseminators of evidence, for example, in England, from NPSA ‘safety alerts’. Secondly, H-MLMs are able to broker endogenous knowledge ‘upwards’ from the clinical front line to inform learning and improvement at a systems level, for example through incident reporting and investigation. 9 Thirdly, H-MLMs who hold responsibility for clinical service delivery span the boundary between managerial structures for brokering PSK, such as clinical governance committees and frontline clinical practice. Thus, they are uniquely positioned to fuse their understanding of local context (endogenous knowledge) with the more generic evidence base that constitutes exogenous knowledge, so as to ensure continuous development and implementation of high-quality service delivery that is patient-safe. Fourthly, H-MLMs can effectively broker knowledge across organisations, as well as within organisations, where they interact with the environment.

Having reviewed at length the literature with regards to the strategic role of the H-MLM, we now turn to a more nuanced discussion related to the range of knowledge-brokering roles enacted by the H-MLM.

A typology of knowledge-brokering roles

Fernandez and Gould91,92 delineate a typology of knowledge-broker roles: ‘liaison’, where knowledge is brokered across a triad of individuals each belonging to different groups, in which contact between sender and ultimate receiver is only indirectly reached through an intermediating party;93 ‘representative’, where the knowledge broker transfers knowledge received from an actor within his own professional group to an actor in another professional group, representing his own group to the outside; ‘gatekeeper’, where the broker screens knowledge to distribute within their own group; ‘co-ordinator’, where all of the actors are in the same group, and an individual brings two persons from his own divisions into contact with each other; and the ‘cosmopolitan’ broker, who mediates between actors in the same professional group, but where the broker is not part of this group. Shi et al. 85 extend this typology of brokerage roles, through considering how the knowledge-brokering roles relate to Floyd and Wooldridge’s typology of MLM strategic roles. 28,65–67 Like Fernandez and Gould,91,92 Shi et al. 85 conceive the knowledge broker sitting within a triad consisting of one knowledge broker and two ‘alters’ (i.e. lower, peer or more senior managers). However, they extend the number of brokerage types identified by Fernandez and Gould91,92 from five to eight, incorporating the notion that some roles (cosmopolitan, gatekeeper and liaison) involve different subgroups within the cadre of MLMs. To clarify, the authors explain: ‘In a cosmopolitan role, the middle-manager broker can have relationships either with two lower-level managers or with two top managers . . . such alternate scenarios [create] different brokerage roles because they involve different subgroups (the group of lower-level managers and the group of top managers) and consequently, they dictate different contexts’ (p. 1461). It is context, they argue, that impacts a broker’s strategic agency to engage a ‘union’ or ‘disunion’ strategy. A ‘disunion’ strategy refers to the bridging of a structural hole between two ‘alters’, i.e. for a H-MLM to keep them apart while brokering knowledge between them on a continuous basis. Conversely, a ‘union’ strategy94 refers to the joining of two previously isolated actors, and might occur where there may be more value in closing the structural hole and bringing the ‘alters’ together than in keeping them apart. This is more akin to blurring organisational and professional boundaries, and hints at an approach to knowledge brokering aimed more at developing community-like tendencies across disparate professional or managerial groups.

The work of Fernandez and Gould91,92 assumes that there is no potential linkage between the two alters, and, thus, the role of the broker is always to bridge a structural hole, rather than to close the hole altogether. Shi et al. 85 consider this view to be flawed. They argue that there may be instances where a ‘union’ strategy (bringing two alters together and closing the structural hole) may bring more benefits than a ‘disunion’ strategy (bridging the structural hole). The contention is based on two scenarios. The first is a straightforward situation where more value can be created through bringing two alters together rather than mediating information flows. The second situation may arise where the strategic intention of the broker is viewed with suspicion by the alters and reflects the ability of the alters to set up their own linkage, cutting out the broker altogether. The contribution of Shi et al. ’s85 work lies in the assertion that context surrounding the alters’ ability and desire to close the structural hole will also impact upon the broker’s intention to bridge or close it. In short, the strategic role of the knowledge broker is more complex than a mere linking of actors to broker knowledge. Consideration of context is vital to our understanding of the processes of knowledge brokering within professional organisations where more powerful actors may work together to ‘shut down’ a knowledge broker’s role in bridging a structural hole, or where an individual may benefit from closing a structural hole in a bid to conjure credibility and legitimacy to broker knowledge across professional groups and influence strategy.

In summary, the work of Shi et al. 85 supports the view of the knowledge broker as more than a ‘linking pin’ between senior and other managers/professionals and alerts us to the MLM’s potential to broker between two actors at higher levels of status than him or her.

Knowledge brokering literature and health care

Literature about knowledge brokering in health care resonates with strategic management literature, in emphasising the potential for MLMs to add significant value to organisations. 3,36,95–103 However, we suggest that the literature about knowledge brokering in health care is relatively normative regarding the role of MLMs. Further, it focuses mostly on external knowledge brokering (i.e. between research and practice), suggesting that health services are not very well organised or receptive to the application of exogenous knowledge for service development. 101 While this is relevant for our study, we highlight that brokering of endogenous knowledge remains under-researched, yet crucial where evidence is ‘complex’, i.e. not easily codified. Furthermore, the political dimension of knowledge brokering remains relatively unexplored, with a particular need to understand knowledge brokers’ legitimacy claim to carry out their activity, and also how others respond to brokerage activity, i.e. to shut it down where their interests are threatened. 85

In the next section, we build upon The hybrid middle-level manager in our discussion of the nature of knowledge and how this relates to the brokerage of PSK in the NHS.

The nature of ‘knowledge’ and approaches to broker patient safety knowledge in the NHS

What constitutes knowledge and the appropriate mechanisms for brokering knowledge both across and within occupational and organisational boundaries has been widely debated in academic circles. The debate is polarised around whether knowledge is an objective or a more subjective phenomenon. Those who hold an objective view of knowledge tend to privilege technological or structural aspects of storing and retrieving knowledge. 59 Those holding a more subjective view of knowledge focus on the conduciveness of the environment, emphasising human factors of trust, learning ability and information sharing among communities. 104,105 For those holding an objective view of knowledge, it is conceivable that technology may supplant the role of the MLM. However, for those holding a more subjective view which characterises knowledge as ‘fluid’ – i.e. cannot be stored as ‘stock’106,107 – then the concept of ‘knowledge management’ becomes something of a paradox, as how can knowledge be formally managed when it resides in practice and is a contextualised phenomenon?104 Bridging diverse views of knowledge, Styhre107 argues that such a division between objective and subjective views of knowledge is not helpful, as ‘Tacit and explicit knowledge are not discrete categories, but always co-exist in one another. All explicit knowledge pre-supposes some tacit skills, and tacit knowledge is always based on the use of explicit knowledge’ (p. 183). In short, we might consider how exogenous knowledge, which is explicit, fuses with endogenous knowledge, which is more contextualised and tacit.

Mobilising patient safety knowledge across the NHS

Reflecting the competing views of knowledge, as above, which coexist in health care, the problem of mobilising knowledge in this environment can also be conceptualised as one of two extremes. At one end, there exists a professionalised body of knowledge that develops increasing degrees of tacitness over time. This knowledge is localised, specialised and closely guarded within professions. 108 At the other extreme, there is a body of explicit knowledge, commonly presented as formal evidence, which is vast, expanding at a phenomenal rate and is ubiquitously accessible. 21 A literature review of knowledge management in health care by Nicolini et al. 21 finds that the highly fragmented and dispersed nature of clinically related knowledge lends itself well to electronic storage and retrieval to support the clinical decision-making process. The use of IT-based tools is considered important to enable health-care clinicians to access the vast array of scientific knowledge that is relevant to managing their practices and delivering quality of care to patients. 105 Perhaps paradoxically, the extant literature also portrays compelling evidence that professionals value and pursue local and tacit knowledge in making clinical decisions about patient care (e.g. Gabbay and Le May20). One might conclude that any attempt at brokering professionalised and tacit knowledge in health care through its conversion into explicit and codified knowledge is unlikely to succeed. 21 Overall, managing knowledge at the extremes is wrought with difficulty. Knowledge that is tacit-dominant tends to remain isolated in select circles with knowledge brokering ‘retarded’. 109 Knowledge that is explicit-dominant tends to be too voluminous, and so, despite its universal accessibility, the ability to first identify such knowledge and then broker it to the right person(s) in order to impact service is a formidable challenge.

The following section outlines two approaches to brokering knowledge across health-care organisations, which highlight this challenge. The first represents a structural solution designed to extract and codify ‘situated’ PSK (i.e. embedded in context) from individual health-care organisations in order to generate new PSK that is then brokered back to hospital organisations as ‘safety alerts’, usually prescribing remedial action regarding a patient safety issue. It exemplifies the challenge of pulling endogenous PSK upwards through a health-care system and converting this to exogenous PSK, which is then pushed back into health-care organisations for service improvement. The other approach is a much more informal arrangement, whereby tacit or endogenous knowledge is shared within CoPs110,111 to inform ongoing service improvement locally, but which remains insulated from other parts of the health-care organisation and system.

National Reporting and Learning System: a national approach to brokering knowledge across occupational and organisational boundaries

Following the publication of the Department of Health’s report entitled An organisation with a memory,2 in which it was estimated that around 10% of hospital admissions lead to the occurrence of an adverse event, i.e. unintended harm or near harm, a NRLS was implemented in England and Wales. The NRLS comprises a dedicated system for incident reporting throughout the health service. NRLS requires frontline clinicians to systematically report patient safety incidents (or near incidents) that they have experienced in order to generate national guidance and learning in the form of patient safety alerts. Patient safety alerts are issued to all NHS Trusts and are received through a central alert system, i.e. they represent exogenous sources of PSK for learning and service action to improve patient safety. Trusts are duly required to respond to alerts and to indicate when they have completed the actions required, or else to confirm that no action is required.

After a decade of incident reporting in England and Wales through the NRLS, the increasing number of incidents reported year on year by hospitals, and by other health-care providers, suggests that a responsible culture of incident reporting is being cultivated in the NHS England and Wales. Correspondingly, empirical research by Sheldon112 and Lankshear et al. 113 suggests that hospitals and other health-care providers are willing to follow guidance of this type. However, Lankshear et al. 113 find that, while health-care providers in the NHS England and Wales have succeeded in setting up systems to disseminate alerts to MLMs, implementation of recommendations by doctors is suboptimal. In a later study, the same authors found that medical directors were much less likely to be aware of medication-related alerts and rapid response reports (RRRs) than their nursing and clinical governance colleagues. Furthermore, around half of health-care providers in the NHS England and Wales reportedly struggle to communicate effectively and reliably with their junior doctors. 114,115 Such research raises questions about the efficacy of a national agency that systematically codifies knowledge from patient safety incidents across the NHS for transfer into practice and, correspondingly, the ability of MLMs to broker patient safety knowledge effectively to inform service action or influence strategy.

In summary, the NRLS comprises a dedicated system for incident reporting throughout NHS England and Wales, which requires frontline clinicians to systematically report patient safety incidents (or near incidents) that they have experienced. NRLS pulls endogenous and tacit-dominant PSK from the clinical front line as a basis for generating exogenous sources of PSK for brokerage across NHS England and Wales as a whole. It represents an approach that attempts to convert tacit knowledge into explicit for durable improvements for patient safety.

Conceptually, the efficacy of the NRLS as a vehicle for brokering PSK is challenged on the basis that the system is founded on a number of assumptions that violate both the nature of knowledge and the nuances of a professionalised context. For example, the first assumption is that incident-related PSK can be meaningful when codified and extracted from nuances of context. Second, that risk is a unified concept shared across professional occupations. Third, there is a misperception that doctors are amenable to being managed (and conceivably monitored) in a technocratic and managerial manner. 7,9,116,117 Waring and Currie9 subsequently report the unintended consequences of this approach as the strengthening (or blurring) of professional and managerial boundaries, as doctors seek to circumvent the NRLS through offering bespoke situated responses, which begin to cohere around a CoP110,111 and which limit management control over knowledge and reinforce claims to medical autonomy.

Communities of practice

Dopson and Fitzgerald88 are not entirely positive regarding the effects of CoPs upon knowledge brokering. The authors emphasise that professionalised contexts, such as health care, have differentiated knowledge domains, which are decoupled, and that this inhibits knowledge brokering. 85,88,109 So, there exist uniprofessional communities, which are self-sealing and highly institutionalised. These shut out neighbouring communities, and defend their professional jurisdiction, so creating a ‘cognitive lock-in’ to members of that community, and community ‘lock out’ to non-members. 85,88 In short, the challenge remains to join up self-sealing CoPs, so that a community of practitioners or interest is developed.

Oborn and Dawson118 offer a more optimistic view of the ability of CoPs to broker knowledge in a specialist health-care setting, where they encompass multidisciplinary activity. The authors initially observe the type of barriers to knowledge brokering typically associated with CoP, as outlined by Dopson and Fitzgerald. 88 However, they assert that the ability to broker knowledge across CoPs was gradually learned. Such learning was assisted by the development of boundary objects and processes such as the use of ‘ambassadorial’ brokers, who facilitated ‘a level of transparency into the knowledge held by the various CoPs’ (p. 853), enabling others to make sense and personalise the knowledge presented by the various CoPs.

In essence, Oborn and Dawson118 echo the knowledge-brokering role of the H-MLM as described earlier (see The hybrid middle-level manager). The ability of the H-MLM to broker clinical and managerial knowledge domains for service improvement is afforded not just by their epistemic ‘two-way’ window, but also in their ability to conjure credibility and legitimacy among others for their role to fuse knowledge from multiple perspectives in a multidisciplinary clinical setting.

To reiterate the value of two approaches to brokering knowledge, those that assume an objective view of knowledge, such as the NRLS, appear insufficiently contextualised. 9 Meanwhile, those assuming a subjective view of knowledge, such as CoPs, may suffer from ‘cognitive lock-in’ and the potential isolation of members from other knowledge perspectives. 88 Both approaches may be deficient, with potentially significant implications for the quality of care to service users and, ultimately, the long-term sustainability of the organisation, unless H-MLMs play a knowledge brokering role.

Our next section builds upon the KBV of the firm to explore literature relating to ‘combinative capabilities’. We consider how brokering of knowledge by H-MLMs is framed by the organisation’s ability to process knowledge for service improvement. Our focus upon combinative capabilities allows us to surface features of organisational context and its environment that represent contingencies that frame H-MLM’s knowledge brokering.

Combinative capabilities and knowledge brokering

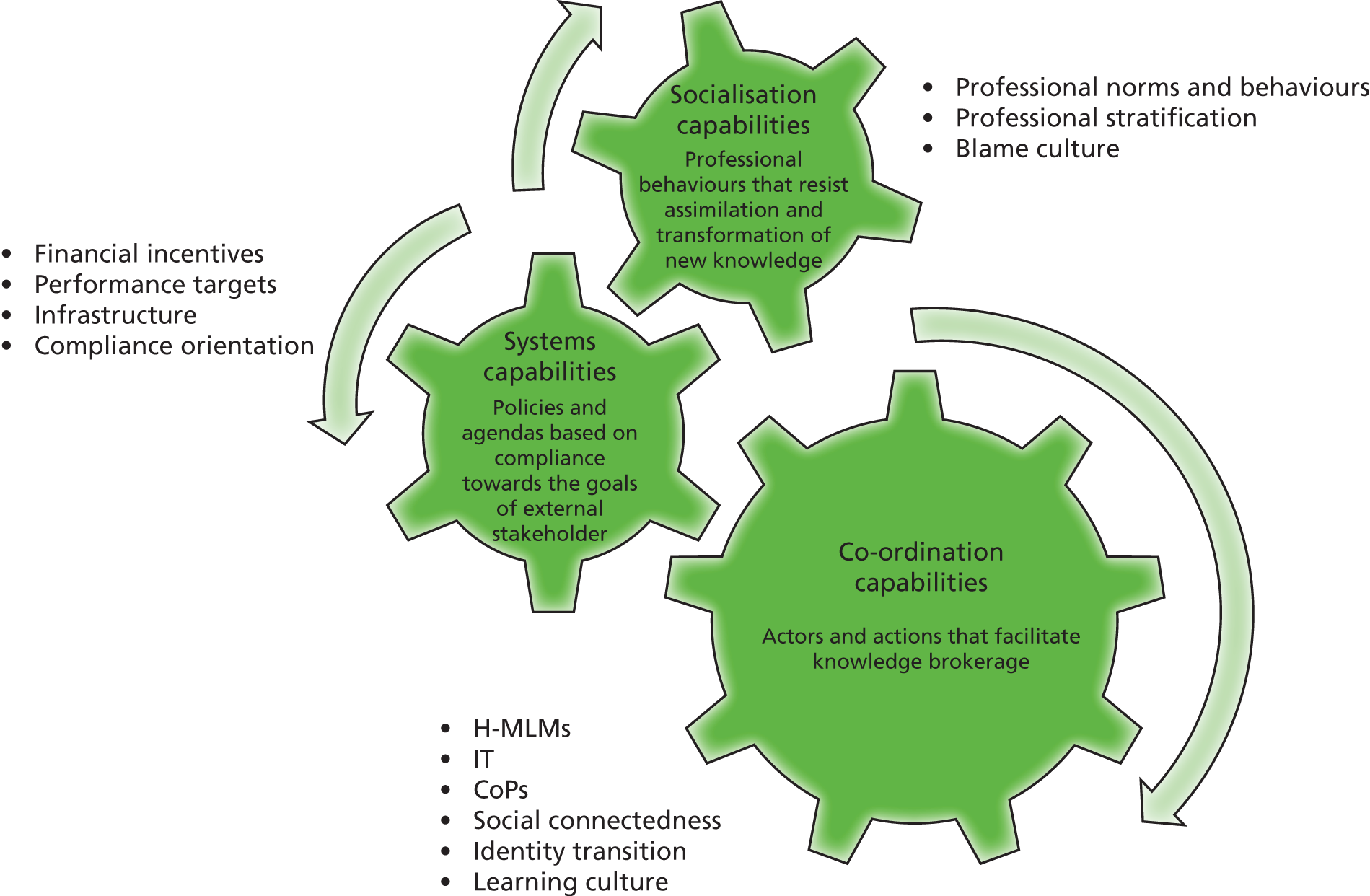

Combinative capabilities refer to the knowledge-processing activities of an organisation to generate, synthesise and apply new knowledge. 83,119 Van den Bosch et al. 119 distinguish three types of combinative capabilities: systems capabilities, socialisation capabilities and co-ordination capabilities. Systems capabilities refer to formal knowledge exchange mechanisms, such as written policies, procedures and manuals, that are explicitly designed to facilitate the transfer of codified knowledge. Socialisation capabilities refer to cultural mechanisms that promote a shared ideology and collective interpretations of reality within an organisation. Co-ordination capabilities refer to lateral forms of communication such as education and training, job rotation, cross-functional interfaces and distinct liaison roles.

Regarding their effects upon knowledge brokering, combinative capabilities work in different ways. The shared culture or ideology that socialisation capability represents can transform and exploit new knowledge quickly, but may also represent a ‘mental prison’ that leaves little room for absorbing outside sources of knowledge that contradict shared beliefs. We see this in the example of CoPs outlined in the previous section. An organisation’s systems capabilities provide a memory for staff handling routine situations in an organisation, and mean that staff know what to do and can react very quickly. Like socialisation capabilities, they therefore increase the efficiency of knowledge exploitation, while narrowing the search for new external knowledge and the scope for information processing. In contrast, co-ordination capabilities increase the scope of external knowledge acquired and assimilated, and flexibility in knowledge absorption. In essence, managers might attend to organisational mechanisms associated with co-ordination capability to enhance the brokering of new knowledge for service improvement. 119,120

However, despite the burgeoning literature examining combinative capabilities, it remains unclear how to impact knowledge-brokering activity for service improvement. 121,122 From the literature, we can discern the following. First, organisations do not absorb knowledge without effort; rather, it is dependent upon deliberate will and individual agency. Second, the absorption of new, external knowledge proves easier where it is linked to that knowledge already embedded within the organisation, rather than representing a significant departure from pre-existing knowledge. Third, knowledge is more likely to be transferred between those within the organisation where they have common knowledge in terms of expertise, training or other background characteristics, i.e. socialisation capability effects. 121 Finally, powerful groups of actors, both within and outside an organisation, may influence knowledge absorption processes to achieve their own goals. 123,124 The implication is that employees need to be exposed to diverse knowledge sources, but these need to have complementarity with existing knowledge sources. 122 Organisational managers need to establish ties with external sources of new knowledge and support this through establishing dense networks of ties within the organisation. 120 However, mediating socialisation capability to allow this to happen is likely to prove challenging, as employees and managers may not ‘see’ or ‘understand’ the potential value of new, external knowledge. 124 They may be encouraged to do so in the presence of ‘activation triggers’, such as internal crises or performance failures. 121,122 This is more likely where co-ordination capabilities are developed in the domain of ‘social integration mechanisms’, such as boundary-spanning or liaison mechanisms, CoPs, and decentralising authority and decision-making. 84,120,121,125 Based upon this analysis, H-MLMs would appear to represent co-ordination capability, but may need to be supported through other social mechanisms to mediate the effects of systems capabilities and socialisation capabilities within health-care organisations.

In the next section, we consider how individual, organisational and interactional antecedents, linked to combinative capabilities, bound the brokering of PSK for service improvement within health-care organisations.

Brokering new knowledge for service improvement

Health-care organisations exemplify the professional bureaucracy archetype,126 within which professional organisation is likely to represent a key influence upon socialisation capability, limiting knowledge brokering in the following ways. Firstly, knowledge brokering interacts with strong organisational cultures and structures, so that socialisation capability restricts the development of critical review capacity in the organisation important for such knowledge brokering. 119 Power and status linked to professional roles are likely to impact an organisation’s ability to exploit new knowledge. 127–129 For example, Berta et al. 130 note the role of doctors in subverting an organisation’s learning capacity in relation to the adoption of clinical guidelines and the assimilation of new knowledge into practice. Similarly, Ferlie et al. 109 note that deeply ingrained organisational structures and social networks engender institutionalised epistemic CoPs, which exist in silos, relatively decoupled from one another. This stymies the search for new knowledge that lies outside current ways of thinking among powerful professional groups.

Secondly, public service organisations (PSOs), such as those in health care, are subject to New Public Management reform, which frames performance through financial incentives and regulation. Reflected in systems capability, such government policy affords access to external resources, and directs and formalises knowledge acquisition and assimilation. However, it narrows the search for new knowledge and the scope for information processing, as managers in health-care organisations ‘game play’ to ensure compliance with policy requirements around their governance. 131–133 Volberda et al. 121 highlight the importance of the ‘classical’ managerial logic, which portrays organisations as tools to achieve pre-set ends, and so limiting the level of knowledge brokering for service improvement. Knowledge brokering within health-care organisations towards patient safety appears particularly directed towards compliance with government regulation and performance management,22 in a way likely to limit external knowledge search and utilisation, hence limiting the level of brokering for service improvement.

Thirdly, in mediating the effects of socialisation and systems capabilities, Hotho et al. 134 highlight a health-care organisation must attend to co-ordination capabilities, particularly social mechanisms for bridging the gap between sources of exogenous knowledge and brokering of the knowledge for service improvement. Confirming assertions in the more generic management literature, commentaries on the development of combinative capabilities in health care highlight the following specific social mechanisms which engender co-ordination capabilities: they are the development of learning relationships through establishing internal and external networks; staff development and training; appropriate leadership; organisational strategy; investment in information support systems; and participation in decision-making. 128,129

In summary, extant literature suggests that systems and socialisation capabilities act to reduce knowledge brokering at the operational front line119,120 in a more pronounced way in health-care organisations. This highlights the need for health-care organisations to develop co-ordination capabilities, to offset the effects of systems and socialisation capabilities, and support knowledge brokering for service improvement in elderly care.

Summary of literature review

We highlight that health-care organisations are characterised by professional hierarchy, with power and status linked to professional roles likely to impact an organisation’s ability to exploit new knowledge. 127–129 Knowledge brokerage and learning interact with strong organisational cultures, systems and structures to restrict the brokering of knowledge for service improvement. 119 Deeply ingrained organisational structures and social networks engender institutionalised epistemic communities of professional practice that exist in silos, relatively decoupled from one another. 109 Of further relevance, systems capabilities such as pre-existing policy in the realm of organisational incentives, legislation and system-level dissemination mechanisms or initiatives, which afford access to external resources and influencers, formalise knowledge acquisition, but may restrict brokering of knowledge across organisational and professional boundaries within health-care systems. 130 In mediating the effects of the above, co-ordination capabilities, incorporating social processes and mechanisms, seem most influential within a health-care context, particularly for bridging the gap between the acquisition of new exogenous knowledge and service action. 84,122,128,129,134,135

In summary, in adopting a KBV of the organisation, we posit that the H-MLM has a pre-eminent strategic role as knowledge broker. However, aligned with Berta et al. ,130 our literature review highlights that the knowledge brokerage process is one that is highly complex and iterative, with considerable but variable agency for actors to affect the process. Aligned to this, we adopt a critical, social and political examination of approaches and mechanisms to broker knowledge for quality improvement in the care of older people.

Chapter 3 Methods

The research study was conducted across three sequential research phases. Phases 1 and 2 were exploratory, using semistructured interviews to help to develop a deep understanding of the knowledge-brokering activity of H-MLMs in relation to PSK and the care of older people. Phase 3 was more a validation phase regarding earlier findings, which we sought to elaborate at the same time, through a tracer study: this involved tracing the brokerage of PSK from the ‘ward to the board’ and back onto the ward for service improvement through the brokering activity of H-MLMs. Work packages 1, 2 and 3 (outlined below) align to each of research phases 1, 2 and 3, respectively. Permission to conduct field research was obtained in accordance with the recommendations of the UK’s National Research Ethics Committee. In line with such permission, readers should note that we were required to obtain voluntary consent from individuals where we wanted to interview or observe them. All individuals approached for interview and observation consented to our request.

Data collection

The main data-gathering technique was that of interview. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed (except in two instances where respondents declined to be recorded). See our original research protocol for indicative interview schedules that relate to work packages 1, 2 and 3.

Work package 1 (17 interviews)

Work package 1 was particularly concerned to identify what PSK was generated and disseminated by external stakeholders and their expectations and perceptions of how that knowledge was brokered and by whom, thus linking to RQ1, RQ3 and RQ4. We also asked respondents in work package 1 about their perceptions of the contingencies of the knowledge-brokering process, i.e. what (do you perceive) are the limiting and facilitating contextual features for H-MLM knowledge brokering, and how can H-MLMs be enabled to broker PSK more effectively in older persons’ care? Thus, work package 1 also contributes to RQ6.

We conducted 17 semistructured interviews with external, national- and regional-level producers, disseminators or auditors of PSK around falls, medication and transition, as outlined on our original full proposal. Representatives from the following organisations were interviewed:

-

Department of Health (three respondents)

-

NPSA (two respondents)

-

National Professional Applied Research Network (three respondents)

-

strategic health authority (one respondent)

-

local government commissioners of health and social care (two respondents)

-

Royal College of Nursing Institute (one respondent)

-

Age Concern (one respondent)

-

university-based health-care professors (four respondents)

-

GP representative on regional commissioning and quality structures (one respondent).

To summarise, in the interviews with external stakeholders, our aim was to elicit their expectations and perceptions (expectations and perceptions may differ) of how exogenous knowledge is brokered, and who they perceive is likely to broker knowledge into the local organisation, and onwards to clinical practice.

Work package 2 (54 interviews)

Work package 2 aligns to RQ1–6. We conducted 54 semistructured interviews with H-MLMs, from lower-status MLMs such as ward managers through to more senior MLMs such as directorate managers and patient safety governance managers, in order to examine the brokerage of exogenous and endogenous sources of PSK. These respondents helped us to identify further respondents for interview, based on their knowledge-brokering role within our case-study organisations. These interviews took place across three separate health-care organisations: two hospital trusts (cases A and B) and one mental-health-care provider (case C). We asked what knowledge gets brokered, to whom, how and why. We began by conducting interviews with more senior H-MLMs who are members of the CRC within our case-study hospital organisations in order to ascertain details about the brokering of PSK produced or disseminated by external parties (e.g. in the form of ‘safety alerts’, broadly defined, or best practice guidelines) into clinical practice, and details of endogenous PSK at the clinical front line brokered upwards into the clinical governance system. Table 1 outlines who we interviewed and whether or not they were members of the CRC. Within Table 1, we also identify where H-MLMs were research active (i.e. held a research grant in last 5 years), as well as delivering and managing clinical services.

| Role | Committee: yes/no | Hybridity and manager level |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital A | ||

|

Yes | Hybrid senior manager |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

No | Academic H-MLM |

|

No | Academic H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | Academic H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

No | Academic H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

Yes | Senior manager |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

| Hospital B | ||

|

Yes | Hybrid senior manager |

|

Yes | Senior H-MLM |

|

Yes | Senior H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | Senior H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |

|

Yes | General MLM |

|

No | H-MLM |

|

Yes | H-MLM |