Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/2002/49. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by McLean et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Against the backdrop of monumental efficiency challenges facing health and social care, the NHS needs to achieve up to £20B of efficiency savings by 2015 through a focus on quality, innovation, productivity and prevention (QIPP). 1 The QIPP programme was developed to ensure value for money through cost efficiencies and improved productivity, while simultaneously working towards better patient outcomes. 1 Missed health-care appointments are a major source of potentially avoidable cost and resource inefficiency that impact on the health of the patient and treatment outcomes.

Since 1999, the cost of missed appointments to the NHS has tripled, and in 2009 was estimated to be more than £600M for that year. 2,3 A recent report by the Department of Health, England, reported that, of the 15 million appointments offered at consultant-led clinics between October and December 2012, around 1.5 million patients did not attend. 4 In the UK, more than 12 million general practitioner (GP) appointments are missed each year, costing the tax payer in excess of £162M. 2,5 There has been little research into the costs of missed appointments at outpatient clinics led by Allied Health Professionals (AHPs) and nurses; however, Gleeson et al. 6 reported that the average annual cost of missed appointments to one occupational therapy department was equivalent to a full-time member of staff. In addition, several studies indicate that non-attendance rates at physiotherapy clinics are frequently between 6% and 30%7–9 and could be as high as 46% in some services. 10 Nursing studies have found similarly high non-attendance rates. 11,12

In addition to the costs identified above, non-attendance may lead to increased waiting times for appointments,5,13 increased cost of care delivery,11,12 under-utilisation of equipment and personnel,12 reduced numbers of appointments available for all patients,5,11 reduced patient satisfaction14,15 and negative relationships between the patient and staff. 5,13 The delay in presentation at health-care departments and consequent lack of monitoring of chronic conditions may predispose patients to exacerbations of their condition and its related complications, leading to unnecessary suffering and possible costly hospital admission. 12,16 In addition, the impact of patient non-attendance, coupled with pressure from referring agents to manage waiting list length, can potentially increase health-care practitioners’ stress, anxiety and fatigue levels. 17

Reducing the rate of missed appointments may lead to many benefits, including reduced NHS costs and improved treatment outcomes. 18 At an estimated cost of around £100 per appointment,3 a 1% reduction in missed appointments could result in savings of £6M per year on consultant clinics in England and in excess of £16M per year in savings to GP practices. Potential cost savings to AHP and nursing clinics are also considerable. Reducing the number of missed appointments may be a relatively inexpensive way to support the intentions of the NHS to treat patients within 18 weeks of GP referral,19 while simultaneously supporting the NHS QIPP agenda.

In an attempt to manage the negative effects and improve the efficiency of appointment systems, many health-care organisations are increasingly investing in short message service (SMS), telephone and e-mail reminder systems. Many patients welcome the use of reminders, and patients who did not attend their appointment report that they would have been more inclined to attend if they had received a reminder. 20 However health-care organisations frequently employ a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, with little evidence of differential effectiveness or acceptability for particular populations or subgroups. This research systematically examined the published evidence around different models of patient reminders and their effectiveness for, and acceptability to, particular population groups who use outpatient clinical services. Identification of those reminder strategies that are most appropriate for particular subgroups of patients may help health-care organisations to improve attendance at outpatient clinic appointments. The output of this study is a practice guide to help managers identify which approaches are likely to be most effective for reducing non-attendance rates for their service and client groups.

Chapter 2 Objectives

The aim of the project is to explore the differential effect of alternative types of reminders (written and automated) for scheduled health service encounters for different segments of the population on fulfilled or rescheduled appointments, substitutions and satisfaction. In order to achieve this, the following questions will be addressed:

-

Which types of reminder systems are most effective in improving the uptake of health service appointments?

-

Do any systems effectively support the cancellation of appointments?

-

-

Do different reminder systems have differential effectiveness for particular subgroups of the population (e.g. by age group, ethnic group, socioeconomic status, gender, etc.)?

-

What factors influence the effectiveness of different reminder systems for particular population subgroups?

-

How do the perceptions and beliefs of patients, their carers and health professionals regarding specific types of reminder systems, and patient/carer resources and circumstances, influence their effectiveness?

-

How do external factors (e.g. content, delivery, setting, frequency, notice period) influence the effectiveness of reminder systems?

-

How do organisational factors (e.g. person sending the message, perceived status, proximity to delivery of care, et cetera) influence the effectiveness of reminder systems?

-

-

What factors or possible disadvantages should be considered when introducing reminder systems for specific populations for health care and health services?

-

Can potential economic impacts of any interventions be identified?

Chapter 3 Methods

Overall rationale

We performed an effectiveness review following conventional systematic review methodology [i.e. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidelines] utilising systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 21 As the scoping review revealed an overall pattern that reminder interventions are effective in many circumstances, albeit to varying degrees, we complemented this with a review informed by realist principles supplementing effectiveness information with non-randomised and qualitative research and engaging with specific and general theory. This review was informed by a conceptual review of relevant theories; thus, the overall project comprised three components:

-

conceptual review of relevant theories (review 1)

-

systematic review of effectiveness studies (systematic reviews and RCTs) (review 2)

-

review informed by realist principles (review 3).

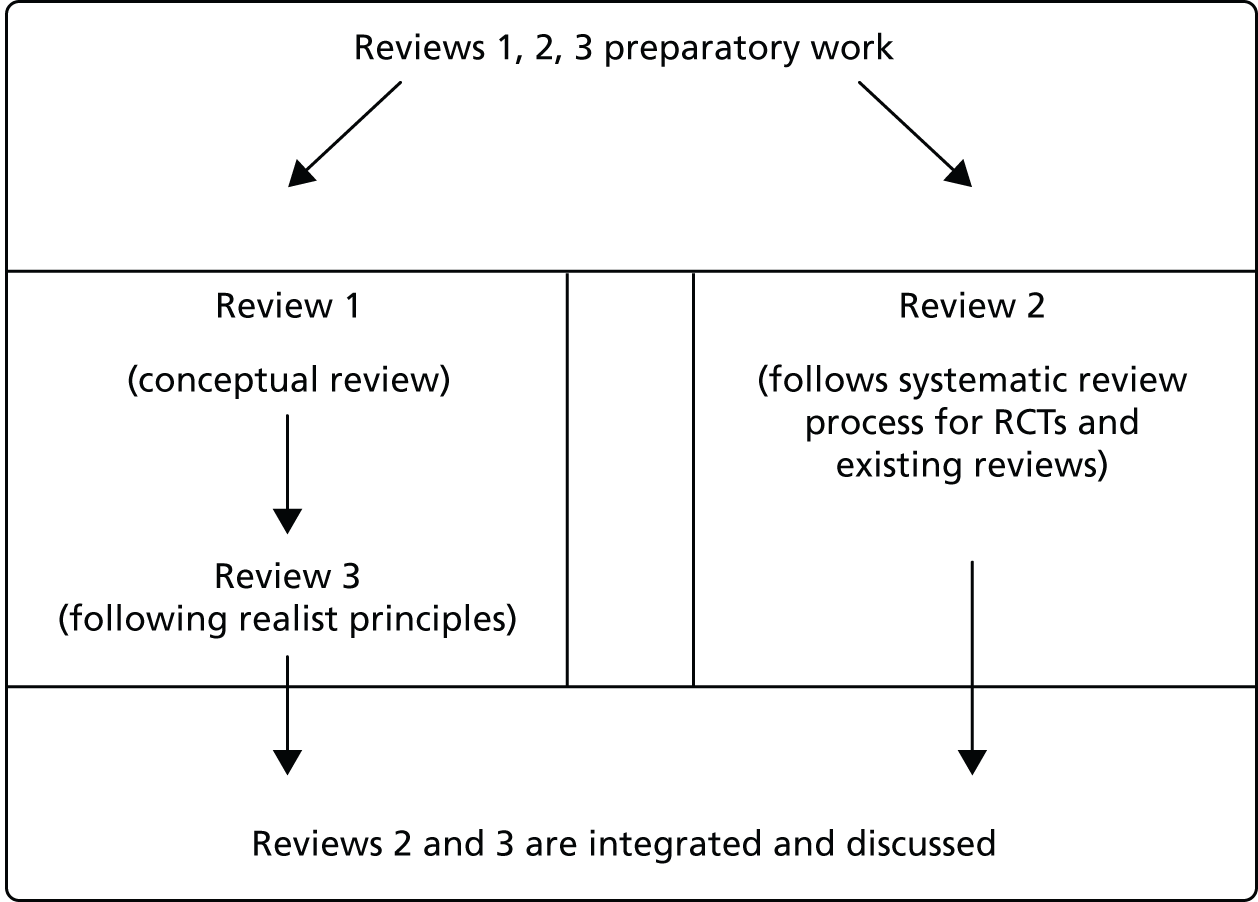

Figure 1 outlines the chronological process by which the three reviews were conducted, their relationship to each other and their overall contribution to the project.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart summarising the review process.

Review questions

The review question for review 1 (the conceptual review) was: how has appointment non-attendance been characterised and explained in existing considerations of behavioural and sociological theory?

The review question for review 2 (the systematic review of effectiveness) was: what is the differential effectiveness (in terms of such outcomes as attendance/non-attendance, cancellation, rebooking, patient satisfaction and cost, etc.) of various appointment reminder systems (interventions and comparators) for users of health services and specific user groups (e.g. populations) when examined through RCTs and systematic reviews (study types)?

The review question for review 3 (the review informed by realist principles) was: which mechanisms are most able to explain the differential effectiveness (outcomes) of various appointment reminder systems (interventions) in different contexts and populations?

For ease of navigation, the relevant review components are indicated alongside the section headings below.

Literature searches (reviews 2 and 3)

Preliminary searches

The objective of the preliminary searches was to identify published studies and reviews relating to outpatient appointment reminder systems. A broad search strategy was used to capture relevant papers reporting the outcomes of the use of reminder systems or exploring attitudes, barriers or facilitators to their use, but not in technical papers describing reminder systems per se. However, technical papers describing reminder systems could be readily identified and eliminated at the title/abstract stage.

Searches were conducted on the following databases: Allied and Complementary Medicine (via Ovid, 1 January 2000 to 15 February 2012), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus with Full Text (via EBSCOhost, 1 January 2000 to 11 January 2012), The Cochrane Library (1 January 2000 to 15 February 2012), EMBASE (via NHS Evidence, 1 January 2000 to 15 February 2012), Health Management Information Consortium database (via NHS Evidence, 1 January 2000 to 15 February 2012), Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers digital library Xplore (1 January 2000 to 15 February 2012), The King’s Fund Library catalogue (1 January 2000 to 8 February 2012), Maternity and Infant Care (via Ovid, 1 January 2000 to 15 February 2012), MEDLINE (via EBSCOhost 1 January 2000 to 11 January 2012), Physiotherapy Evidence Database (1 January 2000 to 8 February 2012), PsycINFO (via ProQuest, 1 January 2000 to 8 February 2012), SPORTDiscus (via EBSCOhost, 1 January 2000 to 11 January 2012), Web of Science (1 January 2000 to 2 February 2012).

The strategy used the concepts of reminders, prompts or alerts in proximity to appointments. If supported, appropriate database headings/thesaurus terms were also used. The search terms considered and investigated but rejected (as they did not yield any additional items of relevance but did return several irrelevant papers), included appointment recall and follow-up. The results were limited to papers published in or after 2000 and to English-language articles. See Appendix 1 for the search strategy for CINAHL Plus with Full Text, MEDLINE and SPORTDiscus (which were searched concurrently). The references were managed in a RefWorks database, version 2.0 (ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA).

Supplementary searches

Forward citation searches in Google Scholar were carried out for papers citing the RCTs about reminder systems selected for inclusion and alerts were set up to capture additional citing references. A cut-off publication date of 30 June 2012 was used for new primary studies, but there was no cut-off date for new reviews (i.e. all reviews published up to 28 February 2013 that cite any included RCTs about reminder systems, were screened for inclusion). The team checked reference lists of reviews selected for inclusion to identify additional post-2000 RCTs relating to reminder systems. The reference lists of RCTs selected for inclusion were checked for papers relating to the same named study or by at least one of the same authors and for papers that provided further theoretical material to supplement/inform the development of the conceptual framework. The reference lists of other studies selected for inclusion were checked for papers by at least one of the same authors and for papers that provided further theoretical material to supplement/inform our conceptual framework. Additional references were uncovered from general current awareness.

Sifting/categorisation of search results (reviews 2 and 3)

Title/abstract screening and categorisation of studies

Following removal of duplicate citations, all records were reviewed for initial inclusion and categorisation based on their titles and abstracts. The purpose of this initial screening and categorisation was to eliminate obviously irrelevant records and to start to map out and prioritise the relevant literature. The project team agreed screening and categorisation criteria following a pilot activity in which a test set of 150 randomly selected records were screened by five reviewers (AB, MG, SMc, SN and SS). This activity proved essential in reaching consensus among the team members as to what is meant by ‘appointment reminders’ and what would definitely fall outside this remit. As a result, the team agreed to exclude reminders sent to a patient to book an appointment, e.g. the type of ‘reminder’ prevalent in vaccination or screening. To be considered in this review as an ‘appointment reminder’, a reminder would need to be in respect of an appointment that had already been booked.

For review 2 (the systematic review of effectiveness studies), RCTs and systematic reviews about reminder systems, in any geographical context, published in or later than 2000 (as operationalised by the search strategy) were included.

For review 3, which utilises realist synthesis principles, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were less clear-cut. The team decided to be broadly inclusive, in recognition of the wider contribution from the evidence needed by the realist-based approach. Considering relevance as more of a continuum than a straightforward ‘in or out’, the analogy of an onion was invoked in moving outwards from a ‘core’ set of records that addressed exactly our research question, towards further outer ‘layers’ likely to be informative but perhaps less directly so. Thus, included papers comprised studies examining the effectiveness of outpatient appointment reminders in a UK context, studies of various quantitative and qualitative designs around appointment attendance behaviour in the UK and elsewhere, studies of adherence to treatment (including appointment attendance behaviour) in the UK and elsewhere, and theories/models/frameworks relating to appointment attendance. Included papers were categorised accordingly to aid focus for data extraction and synthesis. An ‘include other’ category was also applied to records that were felt to inform the review but did not necessarily fall within any of these categories. All included papers were published from 2000 onwards (as per the search strategy).

Five reviewers (AB, MG, SMc, SN and SS) performed the screening using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The records were randomised and divided between the reviewers, with overlap sets of 20 records being double reviewed to explore inter-reviewer reliability. Discrepancies were resolved with reference to a third reviewer (SMc).

During the screening process, ‘included’ records were categorised to specify, for reminder system interventions, the reminder system technology used (e.g. letter/telephone/SMS, etc.) and whether or not the paper related to reminder effectiveness/acceptability/cost-effectiveness/factors influencing effectiveness. Studies were also categorised according to patient age, target population (gender and ethnic minority/social deprivation, etc.), the purpose of the appointment, study type and country. These data were used to populate a ‘PopInS’ (population/intervention/study-type) matrix to help visualise the ‘landscape’ of the literature.

Full-text screening

Full-text screening took place in conjunction with data extraction and is described below, see Production of draft conceptual framework and draft propositions (review 1).

Production of draft conceptual framework and draft propositions (review 1)

The multidimensional nature of health problems, health service settings and their interactions with individual service users implies that the mechanisms supporting or undermining patient attendance at outpatient appointments following receipt of a reminder are likely to be varied, complex and context dependent. Therefore, we sought to develop a comprehensive conceptual framework that could guide our review of the available literature systematically in order to explore the wide range of contextual and mechanistic factors that may influence reminder effectiveness. To construct this framework, we initially conducted a rapid review of our available literature base to identify any prior conceptual models or frameworks that had been employed to explain why and how reminder systems do, or do not, work. It was established early in this process that the majority of the reminder-focused literature was theory light, with a noticeable lack of attention within the identified RCTs to process evaluation that could explain why, how and in what circumstances reminders are effective and there were few and limited theories being advanced by authors to explain reminder system functioning. Indeed, it was apparent that much of the literature was framed very narrowly around the notion that reminders simply remind forgetful patients, with little consideration of the broader range of factors that could be at play.

We identified only one conceptual model specifically about appointment reminder systems. This model, developed by Coomes et al. ,22 proposes that communication functionality of SMS reminders (e.g. single or multicomponent, interactivity, frequency of reminder, timing of reminder and tailoring of the message) and patient psychosocial factors (e.g. patient involvement, social support, medication adherence, risk behaviours, and health and well-being) could mediate the impact of SMS reminders on health-care quality and health outcomes for people living with a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. 22 For the purposes of the current project, this model was limited in two regards: first, it dealt only with SMS reminders rather than the spectrum of available reminders; and, second, it dealt with mechanisms leading to health-care outcomes rather than considering the mechanisms leading to appointment attendance. However, it did identify features of SMS functionality that were potentially useful to consider within our own framework, which aimed to be more comprehensive.

Given the limited theoretical understanding available from the prior literature on reminder systems, it was decided to conduct a focused review of the conceptually close topic area of medical compliance and adherence. It was known to the team that at least some of the research in this area had been theoretically driven and it was decided that this literature could therefore yield conceptual insight of relevance to the topic of the current review. From this literature, we identified a number of conceptual models specifying factors that can explain medical adherence (including appointment attendance behaviour). These were:

-

theory of planned behaviour,23 which had been adapted to explain attendance at screening appointments,24 adherence with psychological therapies25 and attendance at a cardiac rehabilitation programme26

-

transtheoretical model (also known as ‘stages of change’),27 which had been adapted to explain adherence with psychological therapies25 and attendance at dental check-ups28

-

self-determination theory,29 which had been used to explain adherence with psychological therapies25 and dental clinic attendance30

-

health-care utilisation model,31 which has been adapted for use to explain medication adherence. 32

A further three models which appeared to have some relevance to our topic of enquiry were also identified during this stage of our work, although they had not been used to guide empirical work on adherence/attendance specifically. These were:

-

protection motivation theory,33 which contends that how a person behaves will be broadly explained by a person appraisal of the threat and an appraisal of how to cope with that threat and can, therefore, potentially be related to health behaviours such as making and attending appointments

-

rational choice theory, a development of William Glasser’s choice theory34 that has been discussed in relation to the role of message framing to motivate healthy behaviours35

-

complexity theory,36 which provides a scientific framework for understanding complex phenomena in the natural, biological and human sciences.

Although none of the above models specifically dealt with our topic, they provided a useful starting point for mapping out the contextual factors, mechanisms and outcomes that were important to consider in any attempt to explain how reminder systems work, for whom and in which circumstances. In addition to these behavioural models, which were predominantly informed by psychological theory, we also engaged with relevant sociological literature. This approach was in keeping with our desire to develop a comprehensive conceptual framework that mapped the range of influences operating at different levels, thereby seeking to understand the functioning of reminder systems within a broad psychosocial-systems perspective, rather than locating the phenomenon entirely at the individual level. Although our review did not identify any sociologically driven research papers that dealt specifically with responses to appointment reminders, a number of contributions were felt to be useful in relation to expanding our conceptual framework to encompass a broader range of potentially important factors. First, we noted earlier work on the uptake of screening interventions that highlighted the way in which attendance can be understood as a response to normative expectations about what constitutes responsible and legitimate action – a form of moral obligation – rather than an individual choice or decision (e.g. Griffiths et al. 37 on breast screening). 38 This strand of work can be seen to be influenced by Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of habitus:39 the embodiment of social rules, values and dispositions. Individuals, he argues, acquire a ‘sense of one’s place’ within hierarchically structured society and include/exclude themselves from goods, persons and places that are inside/outside their social group. 39 Understanding differential patterns of appointment behaviour between ‘groups’ may be enhanced by considering the way in which such behaviours may be supported or undermined by other taken-for-granted ‘ways of being’ or ‘sticky habits’ that exist within particular groups or communities. 39 Second, we identified work that seeks to highlight the roles of concrete, situated contingencies that shape and constrain behaviours, such as the practical demands of daily living, including health-related adherence/attendance. For instance, Rosenfield and Weinberg38 alert us to the need to counter the tendency for adherence research to focus on thought processes, knowledge and beliefs, thereby overlooking the importance of ‘the contours and rhythms of situated domestic practices’. 37 Understanding more about the day-to-day lives of patients can potentially throw light on how people respond to appointment reminders. Finally, we saw value in critical sociological contributions that take a more macro focus seeking to explore and expose the linkages between the health-care system and the broader political, economical and social systems of society in historical perspective. Critical theory has enriched various bodies of work exploring patient experiences of health care, revealing the ways in which medical ideology helps to maintain and reproduce class structure (as well as other social divisions, e.g. gender, race/ethnicity). These perspectives tend to challenge the way in which health-related behaviours and their promotion are frequently presented as unproblematic by health professionals and health researchers, while downplaying the complex costs and benefits that may be involved for the patient, particularly patients from more marginalised groups. These sociological contributions complemented the more individualistic focus of the psychological models and allowed us to usefully expand our conceptual framework.

At an operational level, team members drew on this wide-ranging theoretical literature together with evidence gathered during early data extraction and synthesis to develop a series of internal concept notes that were then discussed in team meetings. The multidisciplinary make-up of the project team meant that different members were well placed to engage with different literatures and to produce summaries for the rest of the team to consider. Deliberative discussions were combined with visual tools to iteratively consider alternative ways of representing reminder system functioning, considering:

-

Process maps of attendance charting patient decisions, appointment attendance/cancellation/rescheduling behaviour and consequent outcomes, looking at the day of initially receiving the appointment, the day of receiving a reminder closer to the appointment (if applicable) and, finally, the day of the appointment itself.

-

Balance-sheets focusing on patient decision(s) to attend or not, in terms of a weighing-up of the advantages of attending compared with the advantages of not attending. It was felt that, overall, the balance would tend to be weighed heavily in favour of not attending (as this is the easier option for the patient in the short term), but that various factors, including reminder interventions, may help tip the balance the other way.

-

A ‘tumblers in a safe’ model whereby various factors need to align if a patient is to attend the appointment. Such factors include individual patient characteristics, the wider social system (including norms, expectations and enablers such as transport) and the health service system (including flexibility of the appointment system and the effectiveness of the reminder system). Similarly, for an appointment reminder system to be effective, various elements must ‘line up’, namely the reminder should be received in time and its content should be accurate, the patient should be receptive and genuinely not forget and the service should be sufficiently flexible to enable cancellation/rebooking.

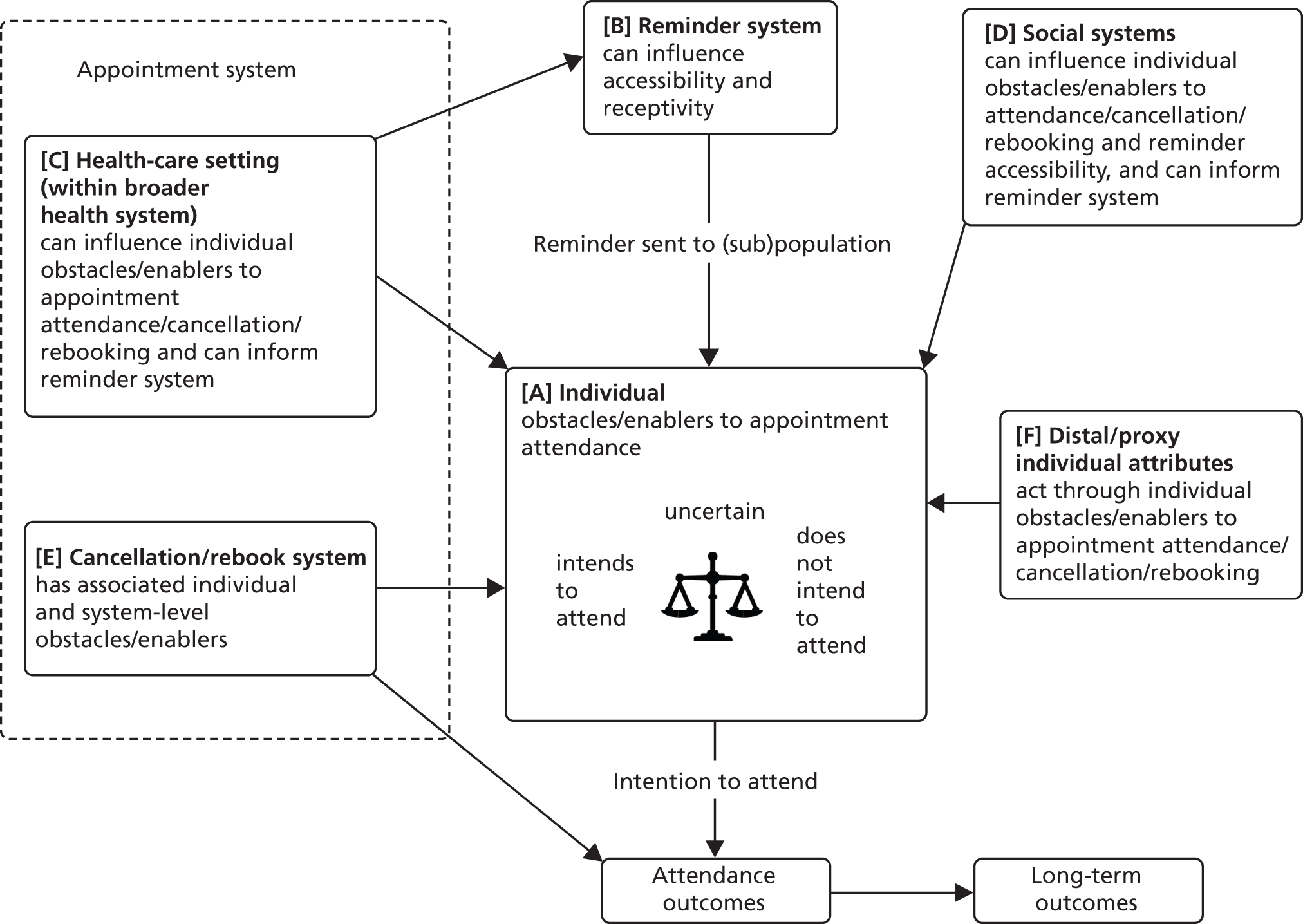

This process enabled the development of our conceptual framework, which is depicted in its final iteration in Figure 2. In this framework, propositions A–F identify various important contextual elements that are hypothesised to contribute to attendance outcomes. The individual (proposition A) is placed at the centre to convey the centrality of the patient role in deciding whether or not he or she will attend (or at least intends to attend). Each patient can be perceived as mentally constructing a balance sheet by which they weigh up perceived obstacles to attendance against enablers. The centrality of the patient interaction with the reminder system further indicates its central importance within this review. There are different factors that will influence the ‘baseline’ of where the patient is ‘at’ with respect to attendance obstacles or enablers when he or she receives an appointment notification. These include various social factors (proposition D) and health-care setting factors (proposition C), with the appointment system located at the heart of the latter. The model shows some possible ‘distal/proxy attributes’ (proposition F) – attributes that could be used to characterise a patient (or patient group) that may tend to give that patient or group a certain ‘baseline’ or which may predict the effectiveness of different types of reminder system. The reminder system (proposition B), depending on its characteristics and depending on where the patient weights the balance of obstacles/enablers before receiving the reminder, may tip the balance in favour of enablers so that the patient intends to attend. Other factors outside the reminder system per se, but within the control of the health-care system, may be modifiable in order to tip the balance in favour of intention to attend. Finally, the model recognises that there may be individual- and system-level obstacles and enablers to cancellation and rebooking (proposition E) that warrant consideration. An accompanying articulation document expands/explains the elements of the conceptual framework and highlights possible causal pathways between them (see Appendix 2). These propositions form the basis of our evidence statements and discussions in Chapters 4 and 5.

FIGURE 2.

Targeting the Use of Reminders and Notifications for Uptake by Populations (TURNUP) conceptual framework.

Preliminary data extraction: randomised controlled trials (review 2)

Full-text screening took place in conjunction with data extraction. The team prioritised RCT studies of appointment reminder interventions in order to draw out effectiveness data to address the objective concerning which types of reminder systems are most effective in improving the uptake of health service appointments. These data fed into review 2, to identify whether or not any studies conducted subgroup analyses, and to start to identify (if possible) any trends in terms of ‘what works’ and in ‘which context’. We mapped the studies to the draft propositions derived from the conceptual framework (Table 1 and see Figure 2). A data extraction tool was designed, piloted, refined and ultimately used in Google Forms (Googleplex, Mountain View, CA, USA) to extract data from included RCTs. Google Forms allowed the five reviewers to use the extraction tool concurrently and to view interim patterns from the data as soon as each study was submitted. Preliminary analysis of these data was used formatively by the review team to identify contextual patterns that might influence the effectiveness of reminder systems and, therefore, to support the development of the preliminary conceptual framework [see Production of draft conceptual framework and draft propositions (review 1)].

| Proposition | Hypothesised association with attendance |

|---|---|

| [A] The reminder–patient interaction | A reminder increases intention to attend (and, therefore, likelihood of attendance) when it (1) reduces patient-specific obstacles to attendance and/or (2) increases patient-specific enablers to attend. The patient will intend to attend when the enablers outweigh the obstacles |

| [B] Reminder accessibility | The aggregate impact of a reminder will vary between service settings because of variations in the patient population profile and the accessibility of the reminder to patients in different patient subgroups |

| [C] Health-care setting | The aggregate impact of reminder systems on intention to attend (and, therefore, likelihood of attendance) will vary between service settings (and patient subgroups) because health-care system factors and patient-/procedure-specific factors can influence patient-level obstacles/enablers (i.e. the ‘baseline’ of obstacles/enablers that are potentially modifiable by the reminder) |

| [D] Wider social systems | The aggregate impact of reminder systems on intention to attend (and, therefore, likelihood of attendance) will vary between service settings (and patient subgroups) because the wider social systems within which patient subgroups are situated vary and elements of these can influence reminder accessibility and patient-level obstacles/enablers (i.e. the ‘baseline’ of obstacles/enablers that are potentially modifiable by the reminder) |

| [E] Cancellation and rebooking | Intention to attend may not result in attendance because additional obstacles can arise for patients who would otherwise intend to attend. This will include patients whose intention to attend has been influenced by the reminder (i.e. whose obstacles–enablers balance has been shifted by the reminder) and those who already intended to intend but for whom the timing/location was not convenient |

| [F] Distal/proxy attributes | A range of factors can act as markers/proxies for proximate individual factors that are enablers or obstacles to attendance |

Testing the draft propositions: further data extraction (reviews 2 and 3)

Testing of the draft propositions (see Table 1) and populating them with evidence for the review informed by realist principles required further exploration of the included studies. Previously extracted data from the included RCTs about reminder systems were augmented with fields for data to be extracted directly against the contextual factors and potential explanatory variables identified in the preliminary conceptual framework (propositions A–F in Table 1). Other fields included gender, age, other population categories, description of study population, country, setting, stated underlying purpose of the study and, for each reminder intervention described, description of reminder intervention(s), reminder timing, reminder medium, reminder interactivity, reminder content, reminder source/bearer, reminder intensity, comparison/control, reported outcomes, economic analysis and disadvantages of introducing reminder systems. This process was also extended to papers reporting other study designs (both qualitative and quantitative), again utilising the same fields, to allow mapping against the research questions addressed by each study (see Review questions). The propositions are expanded in the results section (from Proposition A: the reminder–patient interaction onwards), with evidence statements demonstrating the strength of the findings for each proposition.

The extraction forms also provided a facility for memoing by each reviewer, including identification of any relevant references for follow-up and a field for noting any quality issues. See Quality appraisal (reviews 2 and 3) for a discussion about this.

From the outset, the team recognised that they would not be extracting from all eligible papers; therefore, the papers were prioritised for extraction, based on study type and likely relevance to a UK NHS context. All RCTs about reminder systems were prioritised for full extraction, as they could be seen to contribute to both the systematic review (review 2) and the review informed by realist principles (review 3). We also prioritised all reviews (systematic and otherwise) about reminder systems and appointment systems. We then turned to qualitative, mixed-methods and non-RCT quantitative studies about reminders and appointments for the UK, Ireland, Europe, Australia and New Zealand. In accordance with realist principles, we did not extract data from all possible studies. Having extracted from a sizeable number of the above categories of paper, we found that we were not routinely uncovering new ideas and concepts. Thus, during synthesis we focused on identifying potentially ‘rich’ sources of data from the remaining studies. The methodological justifications for this approach, predicated on considerations of data saturation, were subsequently endorsed by our project steering group (see Involvement of patient steering group).

Data extraction was carried out independently by six reviewers (AB, MG, SB, SMc, SN and SS). Although the team did not undertake double data extraction, individual reviewers were able to refer back to the original articles when interpreting their assigned section, thus corroborating the initial extraction process.

Synthesis (reviews 2 and 3)

Thematic synthesis

The extracted data from the RCTs and other study designs were exported from Google Forms into a single Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that was shared between four of the reviewers (AB, MG, SMc and SS). Each reviewer examined different propositions from the conceptual framework, in order to perform a thematic analysis of the evidence in respect of the different propositions. As described above [see Preliminary data extraction: RCTs (review 2)], the data extraction forms included fields for extracting directly to the different framework factors. A complete list of the different framework factors can be found in Appendix 3. One example of the different framework factors is item B.4 which refers to ‘the format of the reminder may or may not compromise the delivery of the content to the patient’; however, in most instances, it was necessary for the reviewer to ‘read across’ the extraction row in order to contextualise the excerpt or observation. The reviewers formulated evidence statements for each of the six areas of the model using the summary categories for bodies of evidence laid out in Table 2.

| Category | Factor type | Definition | Recommendation options |

|---|---|---|---|

| I. Strong consistent evidence (for/against) |

|

Studies pointing in the same direction (either for or against factor) with a general pattern of statistical significance | Factor must definitely be taken into account when planning change |

| II. Strong equivocal evidence |

|

Studies divided with statistical significance shared between positive and negative effects | Alternatives for practice tailored to local context. Factor may be of local importance and, if so, should be taken into account when planning change. Ongoing evaluation required |

| III. Weak consistent evidence (for/against) |

|

Studies pointing towards a general trend (either for or against factor) without statistical significance | Further sufficiently powered studies supplemented by local data. No basis for change in practice unless initiated by local considerations |

| IV. Weak equivocal evidence |

|

Studies divided between positive and negative effects without statistical significance | Further sufficiently powered studies required. No basis for change in practice except in the context of rigorous evaluation |

| V. Indicative evidence |

|

Studies suggesting that a factor may be considered important (e.g. results from isolated quantitative study or findings from qualitative studies/surveys) | Need for well-designed studies exploring putative factor as hypothesis. No basis for change in practice except in the context of rigorous evaluation |

| VI. Confounded evidence |

|

Studies include factor but have not been designed to isolate its importance | Need for well-designed studies specifically isolating factor. No basis for change in practice except in the context of rigorous evaluation |

| VII. No evidence |

|

No empirical studies | Need for well-designed studies exploring putative factor as hypothesis. No basis for change in practice except in the context of rigorous evaluation |

Consideration of meta-analysis

Following data extraction of all the included RCTs, the reviewers were in a position to examine the heterogeneity of this body of evidence. Identification of existing systematic reviews had revealed limited previous instances for which studies had been combined in meta-analysis. However, these previous meta-analyses were characterised by having very tightly specified population–intervention characteristics (i.e. a specific reminder technology being used in a specific clinical context). There is widespread recognition that uncritical use of meta-analysis is unhelpful – a review team should not perform a meta-analysis simply because it is technically possible. In the case of review 2 the commonality of a limited number of attendance outcomes (i.e. attendance/non-attendance, cancellation, rebooking, patient satisfaction, et cetera) was not to be allowed to determine the appropriateness of meta-analysis.

Two principal considerations must be taken into account when examining heterogeneity: clinical heterogeneity and statistical heterogeneity. Typically a qualitative examination of clinical heterogeneity (i.e. is combining results together statistically a clinically meaningful exercise?) precedes, and may indeed obviate, the need for a quantitative analysis (i.e. is combining results together statistically a valid statistical exercise?). The reviewers identified significant areas of clinical heterogeneity relating to the clinical context of the reminder, the purpose and timing of the appointment, the technology used, the content of the reminder message, the ’dosage’ and timing of the reminder, the patient’s relationship with the health-care provider, the credentials of the one delivering the reminder, the patient’s relationship with the one delivering the reminder as well as variations in definitions of non-attendance [e.g. whether rebooking was treated as a negative outcome (i.e. non-attendance) or as a positive outcome (eventual attendance)]. Therefore, the team decided that it would be unhelpful to mask these significant areas of variation either within a single meta-analysis display or within a series of ostensibly comparable displays.

Notwithstanding this decision not to employ formal meta-analysis, the team did map and investigate relationships between areas of clinical variation and attendance outcomes in order to inform the qualitative synthesis and analysis that was to follow. So, for example, the team arranged intervention and control attendance rates for each trial in a single display, from high to low, which revealed several clusters of studies with shared characteristics. To cite two such patterns, studies of blood donors tended to have relatively low overall ceilings of attendance and studies in paediatric populations shared high overall rates of attendance. Although such patterns were not conclusive, they did help to inform discussion about such important issues as symptomatic compared with asymptomatic attendance rates, the characteristics of attendance for ‘universal’, generalised health contacts, and the role of agency (of parents, partners or carers) in affecting the receipt of the reminder and/or subsequence attendance at an appointment and/or adherence to a programme of treatment.

Narrative synthesis

The reviewers also developed a narrative synthesis explaining the volume and strength of evidence underpinning the evidence statement and the potential mechanisms influencing how reminders support attendance, cancellation and rebooking. In addition, reviewers also provided a supplementary synthesis of evidence to explore emergent factors that might possibly explain patient attendance behaviours. This was not one of the original objectives of the review; however, owing to a relative absence of literature surrounding the contextual and mechanistic factors that influence the effectiveness of reminders, it was considered relevant to review our included studies for these explanatory factors because understanding why patients do and do not attend appointments may lead to useful insights and explanations about the differing circumstances in which different types of reminder systems may be more effective.

The final stage of synthesis involved bringing together the findings of the review. This synthesis will be used to support production of practice guidelines (see Development of materials for health service users).

Quality appraisal (reviews 2 and 3)

The data extraction forms included a field for the reviewer to memo any methodological quality issues noted, flagged up either by the author of the paper being reviewed or by the reviewer. Quality appraisal was not used as a mechanism for study inclusion or exclusion, as realist review principles (review 3) recognise that it is perfectly acceptable to use informative ‘nuggets’ from a methodologically flawed paper. 40 For the RCTs included in the systematic review (review 2), full formal quality appraisal was carried out using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) appraisal tool for those RCTs that had not already been quality assessed by a previous systematic review. 41

Review complexity

The sequential process outlined in this chapter belies the complexity of the project. Two specific areas of complexity were identified: complexity at a macro level, evident in the inter-relationship and interdependency of the three reviews with their methodologies; and complexity at a micro level, relating to the numerous factors that interact to impact upon appointment behaviour, a complexity acknowledged in the choice of a methodology informed by realist principles.

This complexity was explored, and largely resolved, through team discussions and by drawing on advice from the project steering group. The steering group drew on its experience of realist synthesis methodology, and of systematic reviews more generally, to help refine details of the review procedures. Group members facilitated fruitful discussion on the complementary strengths of the systematic review and the review informed by realist principles. They advised on strategies for managing and stratifying large volumes of qualitative literature and deciding when to stop pooling literature. The steering group confirmed the team’s perception that theoretical saturation was likely to occur with fewer new ideas and concepts being likely to emerge as extractions progressed. This served to inform the subsequent prioritisation and process of the remaining identified articles. The review team were, therefore, able to proceed with their more selective approaches utilising theoretical sampling, as mandated by realist synthesis methodologies. As a consequence, the team decided to scan the remaining papers for conceptual richness and to prioritise papers with particular richness or that offered unique perspectives on an issue, while proceeding with the thematic synthesis described above.

Furthermore, the steering group acted as a sounding board for theories identified from review 1, which sought to explain why patients do not attend appointments and the mechanisms by which reminder systems work to improve appointment attendance. Such discussions informed the subsequent development of the candidate propositions.

Development of materials for health service users

The findings of reviews 1, 2 and 3 were finally synthesised to support the development of materials for use by health service managers to support decision-making regarding the management of non-attendance at outpatient departments. The materials have been developed in three parts:

-

an outline of all known reasons for patient non-attendance and incorporating potential reminder and wider solutions for managing those reasons for not attending

-

clinical scenarios that focus on the managing attendance, cancellations and rescheduling

-

advantages and disadvantages of different reminder systems.

Involvement of patient steering group

In February 2013, two members of the project team (SMc and MC) met with a group of six patient representatives at Sheffield Teaching Hospital. These representatives were invited from a group of public governors from Sheffield Teaching Hospitals. They were presented with a draft of the clinical scenarios for managing attendance, cancellations and rescheduling, and were asked to review this from a patient perspective (see Chapter 6, Other emergent interpretations for a fuller explanation). Each scenario was discussed openly and frankly, with the patient representatives providing comments about the draft document and additional information around each scenario and suggesting additional clinical scenarios for inclusion in the document. These comments were utilised to refine our final clinical scenarios document.

Chapter 4 Results

In this chapter we report the results of the search process and the findings of the systematic review of effectiveness studies (review 2, see Figure 1 and Chapter 3, Review questions). When relevant, the findings of these systematic reviews and RCTs are supported by evidence from other study types. The findings from systematic reviews and RCTs are reported separately.

Results of searches

The preliminary database searches and supplementary searches are described in Chapter 3, Literature searches (reviews 2 and 3).

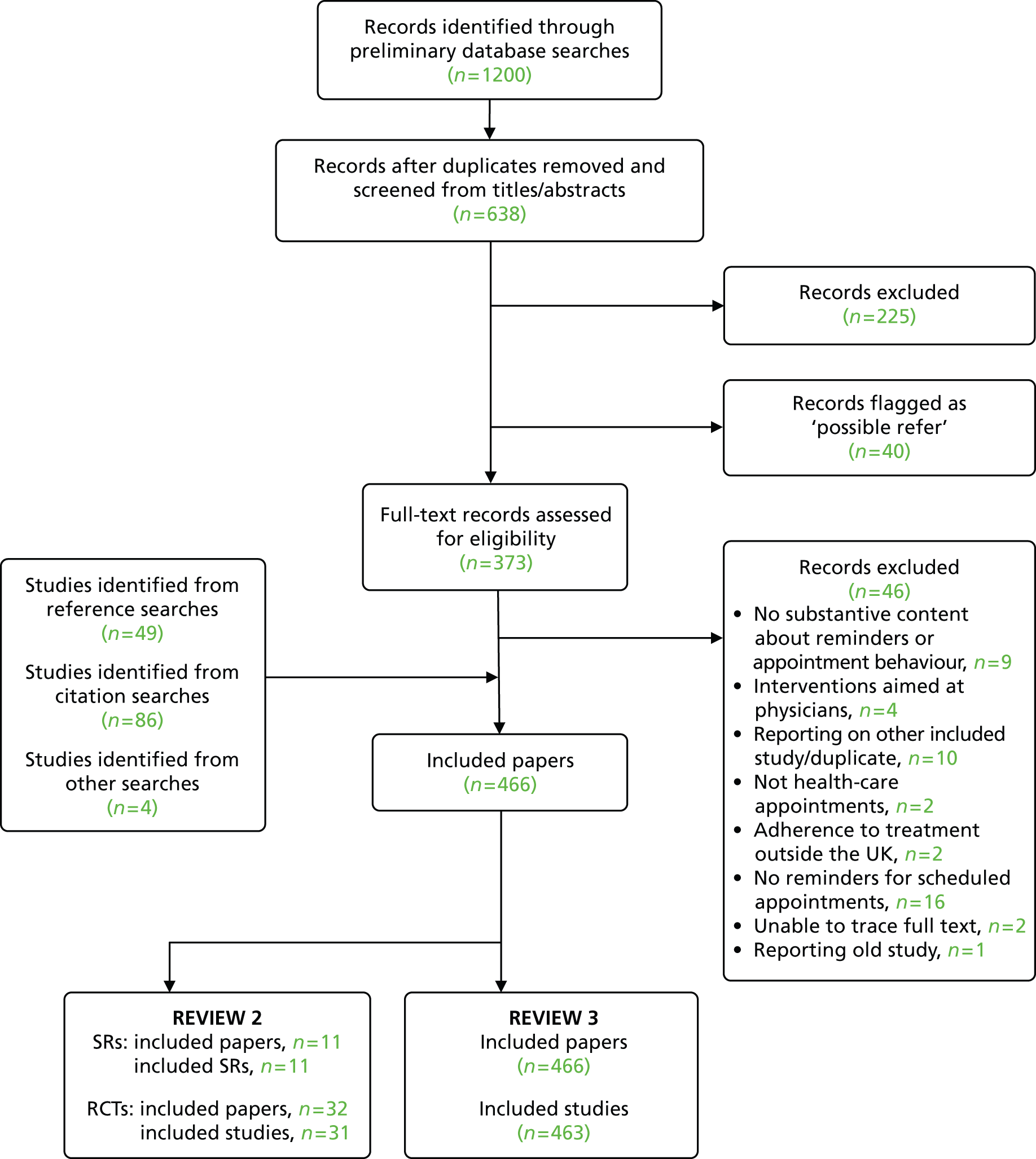

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart (Figure 3) shows the numbers of papers included at each stage of reviews 2 and 3. The preliminary database searches yielded 1200 records and, after duplicates were removed, 638 records proceeded to screening. Citation and reference searching yielded 86 and 49 additional references, respectively, that were deemed relevant after screening by title and abstract. Four additional references were added from the team’s general current awareness activities.

FIGURE 3.

The PRISMA flow chart. SR, systematic review.

A total of 225 records were excluded at the title/abstract screening stage and a further 40 were placed in a ‘holding’ category (‘possible refer’) for reconsideration during the realist stage of the review (review 3). A further 46 records were excluded at the full-text screening/extraction stage. Thus, 466 records were included for reviews 2 and 3. Of these, 31 RCTs and 11 systematic reviews were included for review 2 (see Appendix 4). An additional 424 papers were identified for potential inclusion for review 3. See Appendix 5 for a list of studies excluded at the full-text screening/extraction stage.

In addition to items included from the formal bibliographic searches as documented, the review team drew on a wider evidence base when seeking to understand or explain the possible mechanisms impacting on appointment attendance. In accordance with agreed methods for reviews employing realist synthesis principles these items, which are primarily incorporated and referenced within Chapter 6, are not formally documented within the PRISMA flow diagram, as they do not constitute ‘included studies’ in the accepted sense of the phrase.

Evidence from systematic reviews

Our literature searches (see Chapter 3) identified 11 systematic reviews42–52 that met our inclusion criteria, namely systematic reviews that:

-

partially or completely examined appointment reminder systems, and

-

included studies published since 2000.

The identified reviews tended either to examine a single technology, e.g. a systematic review of SMS reminder systems (e.g. Guy et al. 44), or to explore the role of information technologies for multiple aspects along a patient care pathway, one of which might be appointment reminder systems (Table 3). As a consequence, existing systematic reviews did not match our own review question, being either narrower in terms of technology or health condition or including only a limited number of eligible studies within their broader inclusion criteria.

| Study | Letter | Manual telephone | Automated telephone | Mobile/SMS | Voice messaging | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atherton et al., 201242 | ✓ | ||||||

| Car et al., 201243 | ✓ | ||||||

| Free et al., 201345 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Glynn et al., 201046 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Guy et al., 201244 | ✓ | ||||||

| Hasvold and Wootton, 201147 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Henderson, 200848 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Jacobson Vann and Szilagyi, 200949 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Krishna et al., 200950 | ✓ | ||||||

| Reda and Makhoul, 201051 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Personal visit | |

| Stubbs et al., 201252 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Open-access scheduling |

Characteristics of included systematic reviews

Reviews were published in the period 2008–13. Four of these are Cochrane reviews on mobile phone messaging for general health-care appointments,43 use of e-mail for appointment reminders42 and for immunisation specifically. 49,51 Several of the other reviews, although using elements of systematic review methods, did not meet the criteria used by the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) for selecting systematic reviews for more detailed appraisal. 42,47

Quality of included systematic reviews

The quality of the included systematic reviews was assessed against the criteria used by the CRD when evaluating reviews for inclusion in the DARE. 53 Potential systematic reviews are independently assessed for inclusion by two researchers using the following criteria:

-

Were inclusion/exclusion criteria reported?

-

Was the search adequate?

-

Were the included studies synthesised?

-

Was the quality of the included studies assessed?

-

Are sufficient details about the individual included studies presented?

To be included in the DARE database, reviews must meet at least four criteria, with the first three criteria being considered mandatory. Our own pragmatic approach focused on the need to address our review questions and did not exclude any reviews on the basis of quality alone. Instead, we use judgements on quality to moderate our interpretation of review findings.

As can be seen from Appendix 5, the quality of included reviews was very variable. Two very recent reviews42,43 and two earlier reviews49,51 are Cochrane reviews and are therefore scrutinised against the highest quality standards. Four reviews44,45,50,52 all passed the CRD systematic review quality threshold. The review by Hasvold and Wootton,47 although an extremely informative source for our subsequent review, did not pass the minimum essential criteria for systematic reviews required by the CRD. The main limitation of this review lies in its incomplete coverage of possible database sources. The reviewers searched only PubMed in seeking to locate relevant studies. The implications of this relate to possible location bias in that, although PubMed typically approaches coverage of 70–80% included studies in a wide range of systematic reviews,54 it is possible that studies not identified could be substantively different in their findings from those discussed by the reviewers. Another useful review48 also fell short of the CRD criteria having been performed by a single reviewer and, therefore, open to possible reviewer bias.

Evidence from randomised controlled trials

Our literature searches (see Chapter 3) identified 31 RCTs55–86 that met our inclusion criteria for our review 2, namely they included RCTs that investigated the use of appointment reminder systems for a health-related outpatient appointment and were published in English between 2000 and 2012. For the purpose of this review, appointment reminders had to prompt patients to attend a health-related appointment that had already been scheduled; studies investigating reminders to make an appointment were excluded.

Characteristics of included randomised controlled trials

The majority of the included RCTs examined either the use of automated telephone reminders (15/31) or the use of SMS texting services (12/31). Seven out of 31 examined personalised telephone calls and 9 out of 31 studies examined postal (letter/postcard) reminders. In most studies, the comparator was no intervention. Tables 4–7 provide a breakdown of the interventions investigated. A variety of attendance-related outcomes were measured, including attendance, cancellation, rescheduling and patient satisfaction (see Table 7).

| Study | Letter | Personalised telephone | Automated telephone | Mobile/SMS | Voice messaging | Other | Comparator | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bos et al., 200555 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | ||||

| Can et al., 200356 | ✓ (plus reply slip) | No reminder | ||||||

| Chen et al., 200857 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Chiu, 200558 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Cho et al., 201059 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Christensen et al., 200160 | ✓ (telephone at 24 hours and 48 hours) | No reminder | ||||||

| Comfort et al., 200061 | ✓ | No engagement | ||||||

| Costa et al., 2008;62 Costa et al., 201063 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Fairhurst and Sheikh, 200864 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Goldenberg et al., 200365 | ✓ [telephone (doctor) and telephone (secretary)] | No reminder | ||||||

| Griffin et al., 201166 | ✓ | ✓ IVR (IVR at 3 and 7 days) | No reminder | |||||

| Hashim et al., 200167 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Irigoyen et al., 200068 | ✓ (postcard and postcard/telephone) | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Kitcheman et al., 200869 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Koury and Faris, 200570 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Kwon et al., 201071 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Leong et al., 200672 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Liew et al., 200973 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Maxwell et al., 200174 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Nelson et al., 201175 | ✓ (SMS) | Mobile | ||||||

| Oladipo et al., 200776 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Parikh et al., 201077 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Perron et al., 201078 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | ||||

| Prasad and Anand, 201279 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Reti, 200380 | ✓ (telephone from hospital and telephone from GP) | No reminder | ||||||

| Ritchie et al., 200081 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Roberts et al., 200782 | ✓ | Usual care | ||||||

| Rutland et al., 201283 | ✓ | SMS plus health promotion message and no reminder | ||||||

| Sawyer et al., 200284 | ✓ | ✓ | No reminder | |||||

| Taylor et al., 201285 | ✓ | No reminder | ||||||

| Tomlinson et al., 200486 | ✓ (postal reminder and leaflet) | Standard information – no reminder |

| Study | Sample size | Country | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bos et al., 200555 | Four groups (N = 301) | Netherlands | Orthodontic clinic |

| Mail (n = 85) | |||

| Telephone (n = 73) | |||

| SMS (n = 51) | |||

| No reminder (n = 92) | |||

| Can et al., 200356 | Two groups (N = 231)a | UK | Orthodontic clinic |

| Mail plus reply slip (n = 115) | |||

| No reminder (n = 116) | |||

| Chen et al., 200857 | Three groups (N = 1859) | China | Health promotion centre |

| SMS (n = 620) | |||

| Telephone (n = 620) | |||

| No reminder (n = 619) | |||

| Chiu, 200558 | Two groups (N = 311) | Hong Kong | Radiology outpatients |

| Telephone (n = 154) | |||

| No reminder (n = 157) | |||

| Cho et al., 201059 | Three groups (N = 918) | Republic of Korea | Hospital-based family practice outpatients |

| SMS (n = 327) | |||

| Mail (n = 294) | |||

| No reminder (n = 297) | |||

| Christensen et al., 200160 | Three groups (N = 232) | USA | Children’s dental clinic |

| Telephone (24 hours) (n = 77) | |||

| Telephone (48 hours) (n = 71) | |||

| No reminder (n = 84) | |||

| Comfort et al., 200061 | Two groups (N = 102) | USA | Substance abuse treatment |

| Engagement (n = 51) | |||

| No engagement (n = 51) | |||

| Costa et al., 2008;62 Costa et al., 201063 | Two groups (N = 3362) | Portugal | Outpatients clinics |

| SMS (n = 1685) | |||

| No reminder (n = 1677) | |||

| Fairhurst and Sheikh, 200864 | Repeated non-attenders;b 2 groups (N = 418) appointments | UK | Inner-city general practice |

| SMS (n = 191) | |||

| No reminder (n = 227) | |||

| Goldenberg et al., 200365 | Three groups: (N = 723) | USA | Teaching clinic |

| Telephone – doctor (n = 193) | |||

| Telephone – secretary (n = 200) | |||

| No reminder (n = 330) | |||

| Griffin et al., 201166 | Three groups (N = 2381) | USA | Colposcopy |

| Interactive voice reminder 7 days (n = 797) | |||

| Interactive voice reminder 3 days (n = 794) | |||

| No reminder (n = 790) | |||

| Hashim et al., 200167 | Two groups (N = 930) | USA | Urban family practice |

| Telephone (n = 479) | |||

| No reminder (n = 451) | |||

| Irigoyen et al., 200068 | Four groups (N = 1273) | USA | Paediatric Vaccination Clinic |

| Postcard (n = 314) | |||

| Telephone call (n = 307) | |||

| Postcard and telephone call (n = 306) | |||

| No reminder (n = 346) | |||

| Kitcheman et al., 200869 | Two groups (N = 764) | UK | Inner-city outpatients |

| Prompt letter and appointment card for clinic (n = 388) | |||

| Appointment card for clinic only (n = 376) | |||

| Koury and Faris, 200570 | Two groups (N = 291) | UK | ENT clinics |

| Mobile phones (n = 143) | |||

| No reminder (n = 148) | |||

| Kwon et al., 201071 | Two groups (N = 404) | USA | Electrodiagnostic laboratory |

| Telephone (n = 223) | |||

| No reminder (n = 181) | |||

| Leong et al., 200672 | Three groups (N = 993) | Malaysia | Primary care clinics |

| SMS (n = 329) | |||

| Telephone (n = 329) | |||

| No reminders (n = 335) | |||

| Liew et al., 200973 | Three groups (N = 931) | Malaysia | Primary care clinics |

| Telephone (n = 314) | |||

| SMS (n = 308) | |||

| No reminder (n = 309) | |||

| Maxwell et al., 200174 | Three groups (N = 2034) | USA | Inner-city clinics |

| Automated telephone reminder (n = 700) | |||

| Postcard reminder (n = 664) | |||

| No reminder (n = 670) | |||

| Nelson et al., 201175 | Two groups (N = 318) | USA | Paediatric dental clinics |

| SMS (n = 158) | |||

| Mobile (n = 160) | |||

| Oladipo et al., 200776 | Two groups (N = 189) | UK | Colposcopy clinic |

| Telephone (n = 111) | |||

| No reminder (n = 78) | |||

| Parikh et al., 201077 | Three groups (N = 9835) Telephone from clinic staff (n = 3266) Automated telephone message (n = 3219) No reminder (n = 3350) |

USA | Academic outpatient clinics |

| Perron et al., 201078 | Two groups (N = 2123) | Switzerland | HIV/primary care clinics |

| Telephone call (fixed or mobile) reminder then if no telephone response: a SMS reminder; then if no mobile phone number a postal reminder (n = 1052) | |||

| No reminder (n = 1071) | |||

| Prasad and Anand, 201279 | Two groups (N = 206) | India | Dental preventative care |

| SMS (n = 96) | |||

| No reminder (n = 110) | |||

| Reti, 200380 | Three groups (N = 109) | New Zealand | Hospital outpatients department |

| Hospital (n = 37) | |||

| GP (n = 35) | |||

| No reminder (n = 37) | |||

| Ritchie et al., 200081 | Two groups (N = 400) | Australia | Hospital outpatients department |

| Telephone call (n = 200) | |||

| No reminder (n = 200) | |||

| Roberts et al., 200782 | Two groups (N = 504) | UK | Respiratory clinics |

| Telephone reminder (n = 246) | |||

| Usual care (n = 258) | |||

| Rutland et al., 201283 | Three groups (N = 252) | UK | GUM clinic |

| SMS notification of defaulted appointment and invitation to attend clinic (n = 88) | |||

| As per group 1 plus health promotional message about Chlamydia (n = 79) | |||

| No reminder (n = 88) | |||

| Sawyer et al., 200284 | Two groups (N = 53) | Australia | Adolescent clinics |

| Mail (n = 29) | |||

| Telephone (n = 24) | |||

| Taylor et al., 201285 | Two groups (N = 679) | Australia | Physical therapy clinic |

| SMS reminder (n = 342) | |||

| No reminder (n = 337) | |||

| Tomlinson et al., 200486 | Two groups (N = 500) | UK | Colposcopy clinic |

| Postal reminder and leaflet (n = 267) | |||

| No reminder (n = 233) |

| Interactivity | Frequency | Timing | Tailoring of message | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bos et al., 200555 | ||||

| None | Single reminder | 1 day before | No details | |

| Telephone | No details | Single reminder | 1 day before | No details |

| SMS | No details | Single reminder | 1 day before | No details |

| Can et al., 200356 | ||||

| Mail with confirmation slip | Stamped-addressed postcard – reply required | Single reminder | 2 weeks before | No details |

| Chen et al., 200857 | ||||

| SMS | None | Single reminder | 72 hours before | Participant’s name and appointment details |

| Telephone | None | Single reminder | 72 hours before | Participant’s name and appointment details |

| Chiu, 200558 | ||||

| Telephone | No details | Single reminder – three attempts | Within 3 working days before | No details |

| Cho et al., 201059 | ||||

| SMS | None | Single reminder | Week 16 after enrolment |

|

| Telephone | No details | Single reminder | Week 16 after enrolment |

|

| Christensen et al., 200160 | ||||

| Telephone | No details | Single reminder | 1 working day before | No details |

| Telephone | No details | Single reminder | 2 working days before | No details |

| Comfort et al., 200061 | ||||

| Engagement (including telephone reminders) | Opportunity to ask questions about the program | No details | No details | Remind clients of intake appointments, to brief them on what to expect and to follow-up on missed appointments |

| Costa et al., 2008;62 Costa et al., 201063 | ||||

| SMS | None | Single reminder | 2 working days before | Messages written/sent by informatics department of hospital. Characteristics included name of institution, patient’s name, type of episode, date and hour. When necessary, included advice to arrive earlier |

| Fairhurst and Sheikh, 200864 | ||||

| SMS | None | Single reminder | Between 08.00 and 09.00 for morning appointments; and between 16.00 and 17.00 for afternoon appointments. Reminders for Monday morning sent on Friday afternoon |

|

| Goldenberg et al., 200365 | ||||

| Doctor call | No detail | Single reminder – two attempts | Within 48 hours before | No details |

| Secretary call | No detail | Single reminder – two attempts | Within 48 hours before | No details |

| Griffin et al., 201166 | ||||

| Nurse phone call | No data on whether or not patients spent more time engaged with nurses during telephone calls than they spent receiving IVR messages. Nurses answered any questions during call | Single reminder – two attempts | 7 days before procedure | Appointment reminder, information about preparation for examination and encouragement to prepare for and attend examinationa |

| IVR system call | None | Telephone calls programmed for morning. If answering machine picked up on initial call, IVR system left general message about purpose of call. System programmed to call again in afternoon and then again in evening until patient answered. Messages left only on first attempt. If IVR not completed that day, process repeated following day. Patients answering call had option for IVR call back at later time | 7 days before procedure | Appointment reminder, information about preparation for the examination and encouragement to prepare for and attend examination |

| IVR system call | None | Same call protocol as for 7-day reminder above | 3 days before procedure | Appointment reminder, information about preparation for the examination and encouragement to prepare for and attend examination |

| Hashim et al., 200167 | ||||

| Telephone | No details | Single reminder | 1 day before | No details |

| Irigoyen et al., 200068 | ||||

| Postcard | No details | Single reminder | 1 week before | No details |

| Telephone | Bilingual clerk | Single reminder – three attempts | Weekday evening before | No details |

| Postcard and telephone | No details | Single reminder – three attempts | 1 week before and weekday evening before | No details |

| Kitcheman et al., 200869 | ||||

| Orientation letter | No details | Single reminder | Sent out 72 hours before; received 24–48 hours before | Letter very short, taking 30 seconds to read. Written on headed paper: time of appointment, name of doctor, short description of clinic and its routine, a map, request to bring medication and a friend or family member |

| Koury and Faris, 200570 | ||||

| No details | No details | No details | No details | |

| Kwon et al., 201071 | ||||

| No details | No details | 1 day before | No details | |

| Leong et al., 200672 | ||||

| SMS | None | Single reminder – maximum of three attempts | 24–48 hours before | No details |

| Mobile | No details | Single reminder – maximum of three attempts | 24–48 hours before | Mobile phone conversation similar to SMS reminder. No clinical or laboratory information included |

| Liew et al., 200973 | ||||

| SMS | None | Single reminder | 24–48 hours before | No details |

| Telephone | To avoid caller bias, research assistant trained to deliver same message as in SMS group. Further enquiries from patient redirected to appointment counter | Single reminder – up to three further attempts made at 4-hourly intervals. | 24–48 hours before | No details |

| Maxwell et al., 200174 | ||||

| Automated telephone | None | Single reminder | 1 day before | No details |

| Mailed postcard | None | Single reminder | 5 days before | No details |

| Nelson et al., 201175 | ||||

| SMS | None | 48 hours before |

|

|

| Mobile | No details | No details | 48 hours before | No details |

| Oladipo et al., 200776 | ||||

| Telephone | No details | No details | 12–24 hours before | No details |

| Parikh et al., 201077 | ||||

| Clinic telephone | Appointment confirmed or rescheduled at patient’s request | 3 days before | No details | |

| Automated telephone | Recipient had option of confirming or cancelling appointment | System attempted to reach patient each night for three nights before appointment. After three attempts if appointment not confirmed, patient remained registered for appointment | 3 days before | Practice-customised computerised or live voice recording played after telephone call was answered |

| Perron et al., 201078 | ||||

| Phone call (fixed or mobile) plus SMS plus postal reminder | Languages used by research assistant for telephone calls were French, English or Spanish | Three ‘escalating’ reminders includes three attempts on telephone | 48 hours before. Postal reminder to reach patient on next day | SMS sent in French. Included name of physician, day and time of appointment, but no medical information |

| Prasad and Anand, 201279 | ||||

| SMS | Successful delivery assumed when indication showing that message had been sent. | Two reminders | 24 hours before and also on day of appointment | Included dentist’s name, date, time and location of the appointment. Reminders in local language for non-English language patients. Picture message of institution sent to seven patients |

| Reti, 200380 | ||||

| Hospital | Hospital waiting-list clerk | No details | 24 hours before | No details |

| GP | Patient’s GP | No details | 24 hours before | No details |

| Ritchie et al., 200081 | ||||

| Telephone | Telephoned by one of authors or research nurse | Single reminder | 1–3 days after attendance at A&E | To remind patient about appointment (and importance for medical follow-up) if one had been made and to offer to make an appointment if one had not been made. General enquiry made about their health and importance of medical follow-up explained in general terms |

| Roberts et al., 200782 | ||||

| Telephone | By researcher | Single reminder – two attempts. If patient not available, no message left | Between 09.00 and 17.00 during week prior to appointment | No details |

| Rutland et al., 201283 | ||||

| No details | No details | 1 week after defaulted appointment | No details | |

| Sawyer et al., 200284 | ||||

| No details | Single reminder | 5 days before | No details | |

| Telephone | Single administration officer made all telephone calls | Three attempts before contact deemed not to have occurred (leaving message on answering machine deemed as contact). Number of calls required and time required for each call noted | 1 day before | No details |

| Taylor et al., 201285 | ||||

| SMS reminder | Sent using automated system at clinic 1; manually by administration assistant at clinic 2 | No details | 2 days before if appointment made more than 3 days before, or day before appointment for appointment within 2 days. Timed to allow appointment slot to be offered to another patient and filled in event of cancellation | Reminder

|

| Tomlinson et al., 200486 | ||||

| Postal reminders | No interactivity | Single reminder | 7–10 days before | Detailed explanatory leaflet on implications of abnormal cervical smear, description of colposcopy, outpatient treatment using sensory information and detailing importance of follow-up (available in summary in most common ethnic languages) |

| Study | Attendance outcomes | Overall effect |

|---|---|---|

| Bos et al., 200555 | Standardised failure rate; respondents attitudes to receiving reminder; respondent’s reminder preferences | No-show rate reduced by 4.5% |

| Can et al., 200356 | Attendance rates | No-show rate reduced by 4.2% |

| Chen et al., 200857 | Attendance rates; cost per attendance of interventions | No-show rate reduced by 7% |

| Chiu 200558 | Attendance rates | No-show rate reduced by 9.4% |

| Cho et al., 201059 | Attendance rates; cost per attendance | No-show rate reduced by 3.4% (SMS) and by 1.1% (telephone) |

| Christensen et al., 200160 | Punctuality for appointment (15 minutes); rate of broken appointments | No-show rate reduced by 21% (48 hours) and by 26% (24 hours) |

| Comfort et al., 200061 | Engagement with services | No statistically significant differences |

| Costa et al., 2008;62 Costa et al., 201063 | Non-attendance rate | No-show rate reduced by 3.5% |

| Fairhurst and Sheikh 200864 | Non-attendance rates | No-show rate reduced by 5.3% |

| Goldenberg et al., 200365 | Attendance (show) rates | No-show rate reduced by 10% |

| Griffin et al., 201166 | Appointment non attendance; patient perceptions about the call | 38%, 42% and 41% did not attend in IVR7, IVR3 and nurse delivered call groups, respectively; 33% (FS) and 38% (colonoscopy) non-attendance at baseline |

| Hashim et al., 200167 | Outcome of call (confirmed, unable to leave message, appointment cancelled by patient/family, appointment rescheduled by patient/family or no active telephone number); cost of reminders | No-show rate reduced by 6.9% (95% CI 1.5% to 12%) |

| Irigoyen et al., 200068 | Appointment rates; cancellation coverage; cost of reminders | No-show rate reduced by 6.7% |

| Kitcheman et al., 200869 | Attendance at first appointment; continuing attendance; hospitalisation, transfer of care, discharge, presentation at A&E and death by 1 year | No-show rate reduced by 6.5% |

| Koury and Faris, 200570 | Non-attendance rate; willingness to receive SMS | No-show rate reduced by 8% |

| Kwon et al., 201071 | Non-attendance without prior notification | Non-attendance reduced by 2.6% but not significantly. For appointments of particular test, e.g. electromyography (EMG), non-attendance rate reduced by 21.7% |

| Leong et al., 200672 | Attendance rates; costs of interventions. | No-show rate reduced by 10.9% (SMS); no-show rate reduced by 11.5% (mobile); cost of SMS reminder lower than mobile phone reminder |

| Liew et al., 200973 | Non-attendance rates | No-show rate reduced by 9.3% (telephone); no-show rate reduced by 7.4% (SMS) |

| Maxwell et al., 200174 | Appointment adherence rates | No-show rate reduced by 3.2% (mailer); no-show rate reduced by 2.1% (phone) |

| Nelson et al., 201175 | Attendance rates | 8.97% improvement in voice over text |

| Oladipo et al., 200776 | Attendance rates | No-show rate reduced by 22% |

| Parikh et al., 201077 | No-show rate; cancellation rate; patient satisfaction | No-show rate reduced by 9.5% (personalised); no-show rate reduced by 5.8% (automated) |

| Perron et al., 201078 | Rate of missed appointments, cost of intervention and profile of patients missing their appointment | No-show rate reduced by 3.6% |

| Prasad and Anand, 201279 | Attendance rate | No-show rate reduced by 43.7% |

| Reti, 200380 | No-show rates | No-show rate reduced by 22% |

| Ritchie et al., 200081 | Making the recommended appointment; attendance at scheduled appointment; and reasons for non-attendance at scheduled appointment | No-show rate reduced by 16.2% |

| Roberts et al., 200782 | Attendance rate; cost of intervention | No-show rate reduced by 15% compared with control (71%, n = 258) and with patients who could not be contacted (68%, n = 142) (p = 0.007; p = 0.004) |

| Rutland et al., 201283 | Reattendance rates | Non-reattendance rate reduced by 3.7% for text reminder only. Non-reattendance rate reduced by 10.7% when reminder accompanied by health promotional message |

| Sawyer et al., 200284 | Clinic non-attendance, reason for non-attendance and satisfaction with the booking system | No-show rate reduced by 12% |

| Taylor et al., 201285 | Rate of non-attendance without cancellation; cancellation and attendance rates; factors associated with non-attendance | No-show rate reduced by 5% |

| Tomlinson et al., 200486 | Attendance and default rates | No-show rate reduced by 17% |

The majority of studies have been conducted in the USA (10/32), UK (8/32) and Australia (3/32), with New Zealand (1) and Canada (1) also being represented. Other European countries include the Netherlands (1), Portugal (1) and Switzerland (1). More recent years have seen the emergence of an active research agenda in Asia, including India (1/32), Malaysia (2/32), Republic of Korea (1/32) and China (including Hong Kong) (2/32).