Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/2001/04. The contractual start date was in November 2010. The final report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Raine et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter overview The structure of the report

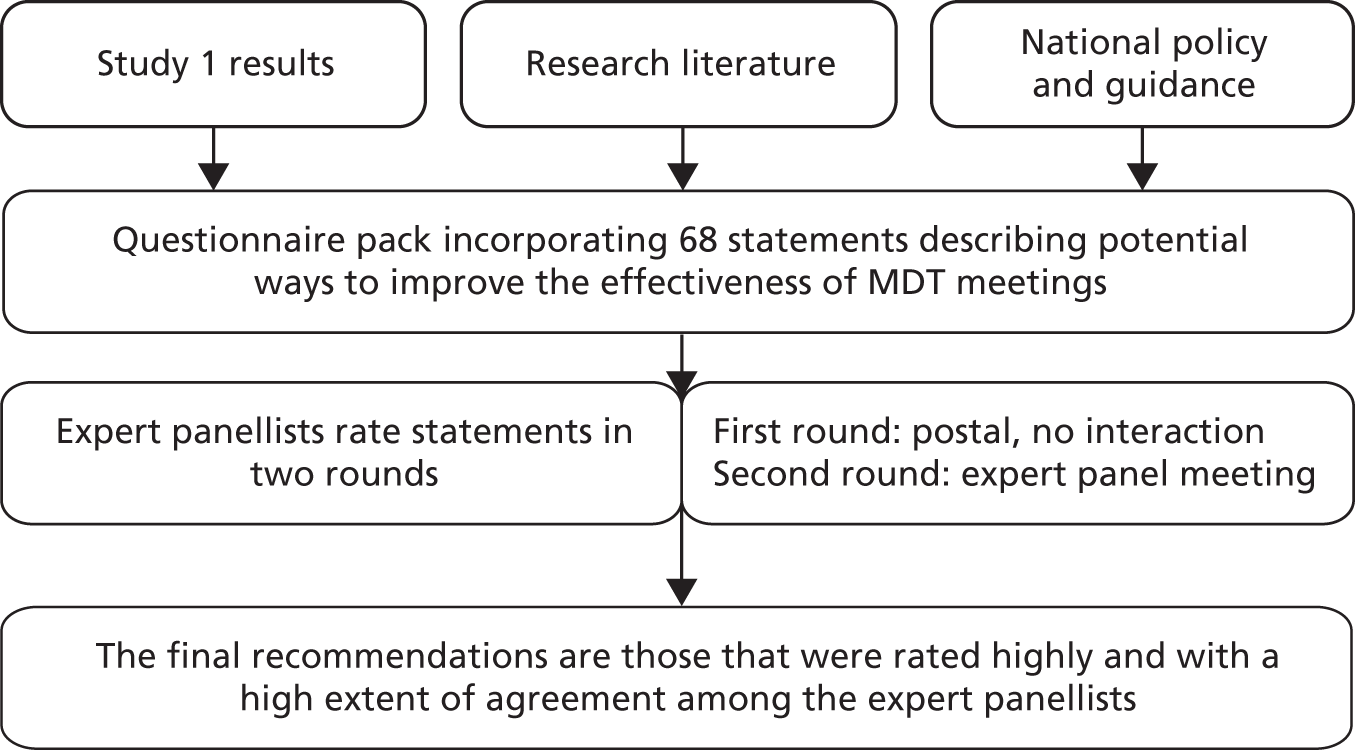

This project consists of two studies. Study 1 examines the determinants of effective decision-making and areas of diversity across MDT meetings. Study 2 uses a consensus development method to develop a list of indications of good practice for MDT meetings. In this report each of the studies is introduced, presented and discussed in turn. Study 1 encompasses Chapters 1–5, study 2 is reported in Chapter 6, and Chapter 7 brings together the findings from the two studies and highlights issues warranting further investigation.

Chapter 1 Study 1: examining the determinants of multidisciplinary team meeting effectiveness and identifying areas of diversity

Background

Multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings are central to the management of chronic disease and they have become widely established across the NHS1–4 and internationally. 5 The proliferation of MDT meetings in health care has occurred against a background of increasingly specialised medical practice, more complex medical knowledge, continuing clinical uncertainty and the promotion of the patient’s role in their own care. In this environment, it is believed that MDT meetings ensure higher quality decision-making and improved outcomes,6–8 for example by providing a better assessment of treatment strategies and safeguarding against errors. 9

However, the evidence underpinning the establishment of MDT meetings is limited and mixed, and the degree to which they have been absorbed into clinical practice varies widely across conditions and settings. 10–12 One recent trial found multidisciplinary care is associated with improved survival for patients with breast cancer. 13 However, another trial comparing multidisciplinary memory clinics with general practitioner care found no evidence of improved effectiveness. 14 Several recent systematic reviews of MDTs working in cancer, mental health and other disciplines have concluded that there is insufficient evidence to determine their effectiveness. 15–17 In the light of this ambiguity, there have been calls for empirical research on MDT meeting decision-making in routine practice to understand how and under what conditions MDT meetings produce effective decisions. 11

Team features and group processes

Research into the critical factors which have the greatest impact on team effectiveness has established the importance of certain features including clear leadership,18,19 clearly defined goals with measurable outcomes19 and team reflection. 20,21 Some studies have found team ‘climate’, defined as shared perceptions of policies, practices and procedures,22 to be associated with improved performance;23 however, others have found no association. 24 Taylor and Ramirez25 surveyed cancer MDT members, assessing the extent to which they agreed with an extensive list of statements regarding team features potentially important for effective MDT working. They identified several domains that were considered important, including the physical environment, meeting administration, leadership and professional development. However, virtually all respondents agreed with the majority of the statements, making it difficult to prioritise particular issues, and the narrow distribution of responses makes it uncertain whether they are an accurate representation of views or the result of a design effect. Furthermore, their findings may not be generalisable to non-cancer MDTs.

Team structure and group processes are also likely to influence the effectiveness of teamwork. Professional boundaries and hierarchies have the potential to undermine the benefits of multidisciplinarity. 21,26 Previous research has demonstrated that team diversity can create communication barriers arising from differences in knowledge, skills, ability, professional identity21 and status. 27 The unidisciplinary nature of professional education may hinder collaboration as professional groups struggle to assert the primacy of their own theories of illness. 28,29 A recent survey of community mental health teams (CMHTs) across 67 mental health trusts found that CMHT members felt satisfied with multidisciplinary working, but that there were still cases of ‘silo working’ and concerns about the ‘dilution’ of core professional skills. 30

Hierarchical differentiation and the inability of some MDT members to freely communicate may undermine decision-making. A recent systematic review of cancer MDT meetings found that MDT decisions are typically driven by doctors, with limited input from nurses. However, where there was active involvement of nurses, this improved perceptions of team performance. 17 Howard and Holmshaw31 found that a lack of engagement in MDT discussions and a lack of ownership and follow-up of discussed plans hindered effective teamworking.

Context

Context is the environment or setting in which the MDT meeting is located. This incorporates social, economic, political and cultural influences. 32 Organisational research has demonstrated the influence of context on team behaviour and performance. 33 However, a recent systematic review found that the majority of studies investigating health-care team effectiveness have not addressed the impact of the context in which teams operate. 34 Health-care management research has drawn a distinction between the outer (national, sectoral or health-care issue-based) and the inner (local) context, which includes both ‘hard’ features such as the degree of structural complexity and ‘soft’ features such as culture. 35 Team climate (described in the previous section, Team features and group processes) may be considered an aspect of the local ‘soft’ context. Models of ‘receptive contexts for change’ have suggested that improvement in health care is most likely to occur where relationships are good, learning, teamwork and a patient focus are emphasised, and the larger system and environment are favourable. 36

Comparative assessments of a range of MDT meetings are needed to explore how contexts vary and how MDT meetings respond to both national and local influences. Although MDT working has been endorsed at a high level for chronic disease management,2 each of the disease types under study in this report is underpinned by different policies and guidance, which contain varying levels of detail.

Cancer multidisciplinary teams

Specialist multidisciplinary teams in cancer were initially introduced in response to the Calman–Hine Report published in 1995. 37 This was followed in 2000 by the NHS Cancer Plan,38 which documented the progress made in establishing specialist teams for the most common cancers (breast, colorectal and lung) and recommended the extension of MDTs for other cancer types. Specifically, the NHS Cancer Plan committed to ensuring that all patients were reviewed by tumour-specific cancer MDTs from 2001. 38 Additional resources were made available, and there was significant commitment at both national and local levels to support these reforms.

By the time the Cancer Reform Strategy was published in 2007, approximately 1500 cancer MDTs had been established in England. 39 The strategy confirmed that MDT working was to remain the core model for cancer service delivery. This was reiterated when the coalition government published its national policy document for cancer in 2011, which concluded that MDTs should remain the cornerstone of cancer care, in recognition of support for the model from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and clinicians. 40

In addition to these national policies, tumour-specific guidance has been published by NICE41 and the National Cancer Action Team (NCAT). 1,42,43 The NCAT guidelines set out measures relating to the composition of teams, attendance at MDT meetings and the frequency of meetings, in addition to stating which patients should be discussed and the need for documentation of MDT decisions. Since 2001, MDTs have been audited annually to ensure they fulfil these requirements. 10

Community mental health teams

In contrast, although MDTs are long established in mental health, their development has been much more ‘bottom up’, more locally varied44 and less well defined than in cancer. Multidisciplinary teams providing mental health services for adults based outside hospitals began to emerge in the 1970s, bringing together social workers from local authorities and NHS clinicians in ‘community mental health centres’. 45 These were criticised, however, for having a lack of clear service objectives, and for providing limited services. 46 The National Service Framework for Mental Health (NSF), published in 1999, provided significant funds to reorganise and improve the quality of mental health services to address the wide geographical variations in provision. 47 However, there are still concerns that mental health services are underfunded. 48 The NSF promoted the use of more specialist teams, including Crisis Resolution and Home Treatment teams as well as teams for those experiencing a first episode of psychosis (Early Intervention Services). Generic CMHTs have retained an important role, however, continuing to care for the majority of mentally ill people in the community and functioning as a key source of referrals to these more specialist teams. 49

In contrast with the detailed tumour-specific guidance for cancer MDTs, there is little guidance on the structure and processes that teams should follow for MDT meetings within community mental health. Recommendations that do exist state that assessments and reviews of patients should be routinely discussed by the whole team in a timetabled weekly meeting where actions are agreed and changes in treatment are discussed, and that these weekly meetings should include the consultant psychiatrist. There is also some guidance about the different professions that should be members of the team, but the guidance explicitly avoids being ‘too prescriptive’ in order to allow local flexibility. 49 Recently, however, the Care Quality Commission has committed to developing definitions of ‘what good looks like’ in mental health and is currently developing an assessment framework of indicators to facilitate quality inspections. 50 It remains to be seen whether or not this will lead to more specific guidance on multidisciplinary working.

Heart failure multidisciplinary teams

The detailed guidance for cancer MDTs is also in marked contrast to heart failure MDTs, where they appear to have evolved in response to local needs. In 2003, NICE recommended that heart failure care should be delivered by a multidisciplinary team. 51 The August 2010 NICE update reiterated the pivotal role of the multidisciplinary team in the continuing management of the heart failure patient. 52 This specified that patients should be referred to the specialist multidisciplinary heart failure team for initial diagnosis of heart failure; management of severe heart failure; heart failure that does not respond to treatment; and heart failure that can no longer be managed effectively in the home setting.

In addition to this national guidance, the NICE commissioning guide, Services for People with Chronic Heart Failure,53 provided a number of best-practice service models for integrated care. It proposed that regular MDT discussion of patients should involve review of people with chronic heart failure covering outcomes, current care plans and possible improvements as well as potential discharge or onward referrals. 53 However, there is no further detail on processes or structures for heart failure MDT meetings.

Memory clinics

In 2001, the National Service Framework for Older People was published, which recommended that all specialist mental health services for older people include memory clinics. 54 Memory clinics specialise in the diagnosis and treatment of people with memory impairment, delivered by a core multiprofessional team. 55 However, existing evidence demonstrates that there are major variations in practice between teams. 56 Guidance on formal team meetings to make diagnosis or treatment decisions is limited, with recommendations on developing a service specification for memory clinics stating that only care providers should draft a care plan for dementia patients ‘in consultation with other relevant disciplines’. 57

Summary

This overview of the different national policies that underpin MDT working highlights the degree of variation in the context within which different MDTs operate. While NHS policy for cancer, and to a more limited extent in mental health, provides guidance on MDT meetings, in other specialties the format is locally determined. It is unknown whether such flexibility is appropriate or undermines the productivity of meetings.

Patient-related factors

The impact of patient-related factors upon MDT meeting decisions also requires examination. Although reducing health-care inequalities is a key aim of government policy,58 there remains evidence of inequalities in health-care use according to socioeconomic circumstances, age, ethnic group and sex, having adjusted for clinical need. 59–61 In heart failure, some studies have found socioeconomic variations in the use of services such as angiography and heart surgery. 62–64 In mental health, there is mixed evidence of an association between socioeconomic circumstances and contact with psychiatric services, with some finding associations between socioeconomic variables, such as low income, low education and unemployment, and contact with psychiatric services65 and other studies finding no such association. 66–68 One of the main aims of the NHS Cancer Plan for England was to tackle inequalities in cancer survival for people from deprived or less affluent backgrounds. 38 Whereas some studies have reported no difference in treatment by socioeconomic circumstances,69 others have demonstrated evidence of lower rates of surgical treatment for patients in more deprived areas70,71 as well as differences in the use of chemotherapy72 and radiotherapy. 73,74

If patients’ sociodemographic characteristics influence MDT effectiveness, then explanations such as the influence of patient preferences and comorbidities should be sought. The involvement of patients in decision-making is now widely advocated75 and guidelines state that patient preferences should be taken into account when managing their care. 40,50,76–78 The influence of patient-centred factors such as patient preference and comorbidity on MDT decision-making has been shown to be partly dependent on variation in the presence and participation of particular professional groups (e.g. specialist nurses). 79,80 There is also some evidence to suggest that MDT decisions that take account of patient preferences are more likely to be implemented. 81,82 There is, therefore, a need to explore how best to obtain and consider patient preferences in MDT meeting decision-making.

Measuring effectiveness

There is debate in the literature concerning the most appropriate outcome for evaluating the effectiveness of MDTs. Measures used include health-care use, patient and team member satisfaction, and well-being, as well as various health outcomes. Each measure has limitations; for example, for patient satisfaction, it is difficult for patients to separate satisfaction with a clinical intervention from the benefits of teamwork. 8

The underlying rationale for MDT meetings is to produce higher-quality decisions that lead to improved health outcomes. However, health improvement is affected by factors other than the quality of care. These factors include subsequent onset of unrelated morbidity, change in patient’s personal circumstances, extent to which patients adhere to treatment and efficiency of care provision. 8,83 Furthermore, intended health outcomes may not be evident for a year or more. Finally, many outcomes are specific to particular illnesses, making it impractical to compare MDTs for different conditions. It is for these reasons that other researchers have robustly defended the use of process measures over outcomes, provided that the process measure clearly lies on the pathway to health improvement. 84

However, the identification of an indicator of high-quality decisions is also difficult. While some decisions can be compared with best practice guidelines, the latter rarely specify recommended courses of action for every management decision made for a patient. Moreover, guidelines rarely consider how decisions should be modified for patients with comorbidities or other factors (such as their social circumstances or preferences) which will influence decision-making. Finally, guidelines are not available for all the conditions considered in MDT meetings. We identified decision implementation as a useful process measure of effectiveness because it lies on the pathway to health improvement and reflects effective team decision-making that has taken account of relevant clinical and non-clinical information. For example, MDT meeting decisions may not be implemented because of a lack of meaningful patient involvement, failure to consider comorbidities, lack of agreement with the decision among those who have to implement it, and incomplete clinical information available. 85,86 Furthermore, decision implementation can be measured and compared across MDTs for different conditions. Investigation of a diverse range of MDT meetings may enable identification of factors associated with effective decision-making that are generalisable across health care. For these reasons, the measure of MDT meeting effectiveness used in this research is decision implementation, and when the term ‘MDT meeting effectiveness’ is used in this report it refers to decision implementation.

Given the widespread presence of MDTs, the opportunity costs for the NHS of unwarranted variations in team membership and processes and the consequences for patients of inequitable care, we undertook a prospective cohort study of chronic disease MDT meetings across the North Thames area (North London, Essex and Hertfordshire).

Study 1 examined the effect of a range of team and patient features on decision implementation. We collected quantitative and qualitative data, including clinical and sociodemographic data, through non-participant observation of MDT meetings, review of patients’ medical records and interviews with professionals and patients.

In study 2, we drew on these quantitative and qualitative findings and used formal consensus methods to derive a series of generalisable recommendations for modifying the structure and process of MDT meetings to improve the quality of decision-making.

Purpose of the research

Main research question

How can we improve the effectiveness of decision-making in MDT meetings for patients with chronic diseases?

Aims

-

To identify the key characteristics of chronic disease MDT meetings that are associated with decision implementation.

-

To derive a set of feasible modifications to MDT meetings to improve effective MDT decision-making for patients with chronic diseases.

Objectives

-

To undertake an observational study of chronic disease MDT meetings to identify factors which influence their effectiveness in terms of decision implementation (study 1).

-

To explore the influence of patient preferences and comorbidity on any socioeconomic variations in implementation found (study 1).

-

To explore areas of diversity in beliefs and practices across MDT meetings (study 1).

-

To use the results from study 1 in an explicit structured formal consensus technique to derive a set of feasible modifications to improve MDT meeting effectiveness (study 2).

Chapter summary

In this chapter we have outlined the background to the study and described the relevance to MDT team effectiveness of the national and local contexts within which MDTs operate, of their distinctive features and group processes, and of patient characteristics. We have discussed the complexity of measuring effectiveness in this context, and outlined our rationale for investigating treatment plan implementation. Finally, we outlined the aims and objectives of the study. In Chapters 2 and 3, we discuss the methods through which these aims and objectives were addressed.

Chapter 2 Study 1 methods

We undertook a prospective cohort mixed-methods (quantitative and qualitative) study of MDT meetings in 12 adult chronic disease MDTs across North Thames between December 2010 and December 2012. We examined one skin cancer, one gynaecological cancer, two haematological cancer, two heart failure, two psychiatry of old age (memory clinic) and four community mental health MDTs (including one early intervention service for psychosis).

Ethics and research governance permissions

This study was approved by East London Research Ethics Committee (10/H0704/68) and the National Information Governance Board (NIGB) for Health and Social Care [Ethics and Confidentiality Committee (ECC) 6-05 (h)/2010]. The NIGB ECC provided permission, under Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006,87 to process patient identifiable information without consent. We gained permissions from the relevant research and development (R&D) departments to collect data following submission of site-specific information forms (using the Integrated Research Application System) at each of the NHS organisations that participated in the study.

Recruitment of multidisciplinary teams

We aimed to include a diverse range of teams and chronic conditions to allow examination of key issues about MDT decision-making and implementation. We sought to include teams which varied in terms of health-care context, professional mix of team, conditions which affected patients from different parts of the adult life range, and fatal versus lifelong conditions. When deciding which and how many chronic diseases to include, we also had to take a pragmatic approach to ensure feasibility, because the data collection phase involved extended periods of observation at multiple sites.

Teams which might have been interested in participating in the study were identified by our clinical coapplicants. The principal investigator (PI) wrote to the lead clinician of each MDT inviting them to take part. This was followed by a discussion with each MDT lead to clarify any issues or concerns.

Following this, the research team visited each MDT meeting to introduce the study. We provided participant information sheets and obtained members’ signed consent to observe, record data from and audiotape MDT meetings (see Appendix 1). Other professionals occasionally attend MDT meetings on an ‘ad hoc’ basis, so we also displayed a printed notice at the entrance to the meeting room during every meeting we recorded. This explained the nature of the observation and provided the researcher’s contact details. We made it clear that if individuals did not wish to take part in the study we would delete their contributions from any transcripts. Nobody requested this.

We initially aimed to recruit 10 teams. This was based on estimates made by our clinical coapplicants of the number of patients discussed in each specialty. In practice, we found considerable differences in the number of patients discussed at each MDT (even within the same specialty), so we had to vary the observation period in each team to maximise data collection in those teams which discussed fewer patients (Table 1). In addition, one mental health team disbanded during the observation period. We therefore asked one of our coapplicants (with a background in mental health) to identify other suitable mental health MDTs. We subsequently recruited an additional two mental health teams (in order to increase our capability of achieving the required sample size), taking the total number of teams in the study to 12. Three field researchers observed a total of 394 meetings (including two meetings for each of the 12 teams where the data collection tools were piloted) and collected quantitative and qualitative data from 370 meetings.

| Team | Observation period (months) | Number of meetings observed |

|---|---|---|

| Gynaecological cancer | 5 | 18 |

| Haematological cancer 1 | 13 | 38 |

| Haematological cancer 2 | 12 | 36 |

| Skin cancer | 11 | 31 |

| Mental health 1 | 5 | 15 |

| Mental health 2 | 8 | 20 |

| Mental health 3 | 17 | 55 |

| Mental health 4 | 8 | 23 |

| Heart failure 1 | 13 | 42 |

| Heart failure 2 | 9 | 24 |

| Memory clinic 1 | 12 | 43 |

| Memory clinic 2 | 9 | 25 |

| Total | 370 | |

| Pilots (two per team) | 24 | |

| Total | 394 |

We also planned to include semiurban and metropolitan teams but, in the event, only one MDT from outside London accepted our invitation to participate.

Quantitative methods

We collected both quantitative and qualitative data. In the rest of this section (Quantitative methods) and the next (Qualitative methods) we first describe how we collected and then analysed the quantitative data, and then describe how we collected and analysed the qualitative data.

Quantitative data collection

Non-participant observation

Non-participant observation included collection of both quantitative and qualitative data. The quantitative data collected are described here (see below under Qualitative methods for a description of the qualitative data).

In collaboration with our clinical coapplicants and patient advisors we designed a standard proforma to collect quantitative data on each patient discussed. This included information on patient features (e.g. presenting problems, comorbidities, medical and social history) mentioned during the discussion. The clinically active members of the research team identified the most important and common comorbidities and other health behaviour risk factors which could have an impact on the MDT decision and/or whether or not it was subsequently implemented. Examples of data collected are provided in Box 1. The proforma also included a space for free text on additional clinical or social factors mentioned during a discussion but not already included in the standard proforma. We also used this proforma to record discussion features (e.g. whether or not patient preferences were mentioned, whether or not the presenter was questioned), and decision features (e.g. decision, whether responsibility for implementing the decision was given to a named individual or not, and whether the agreed decision was written down or verbally summarised) (see Appendix 2).

-

Comorbidities including other chronic diseases, for instance anaemia, diabetes and transient conditions (e.g. broken leg, bladder infection, flu).

-

Medical history (e.g. history of breast cancer, history of substance misuse).

-

Health behaviours (smoking, drinking, physical inactivity).

-

Obesity.

-

Terms that indicate comorbidity without being given a diagnostic name (e.g. back problems, memory problems).

-

Allergies, hypersensitivity to medication/side effects.

-

Learning disabilities.

-

Behavioural problems.

-

Family history (e.g. BRCA gene).

Patient preference included any preference indicated by a patient, even if it was not directly related to the decision ultimately made, for example general mention of the fact that a patient was reluctant to see doctors.

A decision was defined as a resolution about patient management, either with or without discussion (e.g. a decision based on local protocols) between MDT members. This did not include:

-

mention of a decision that had been made outside the MDT

-

when team members provided feedback or updates regarding a case but no decisions were made

-

when a patient was listed for discussion on an agenda but the discussion was deferred until the following week because key information or people needed to make a decision were absent.

We completed the proforma during observation of each team’s weekly MDT meetings. We also audiotaped each meeting and collected data on meeting attendance (number of attendees and their professional category). Following the meeting, a researcher listened to the audio recording to double-check that the information had been recorded accurately.

Follow-up of medical records

We reviewed patients’ medical records to ascertain sociodemographic information, whether or not their MDT decisions had been implemented, and reasons for non-implementation where applicable (Table 2). This involved accessing electronic patient records, paper records, or both, at the hospital or clinic where the MDT meeting took place. On some occasions, files had been moved to other sites for storage. In these instances, we either requested that the specific records be returned to the MDT site or we obtained permission to review the records at the site where they were stored. We followed up each individual decision observed, and we recorded all information directly into an IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) database, version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

| Type of information | Data collected |

|---|---|

| Patient details | Information recorded |

| Date of birth | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Postcode (used to derive indicator of deprivation) | |

| Recorded diagnosis | |

| Decision details | Response options |

| Decision implementation | Implemented |

| Partially implemented | |

| Not implemented | |

| Not documented | |

| Patient not identifiable | |

| Records not available | |

| Reasons for non-implementation recorded in notes | Patient choice |

| Carer/family choice | |

| Patient and family/carer choice | |

| Comorbidity present but not mentioned at MDT meeting | |

| Comorbidity deteriorated post MDT meeting | |

| New comorbidity arose post MDT meeting | |

| No reason recorded | |

| Clinician notes decision not implemented | |

| Patient died | |

| Other | |

| Patient did not attend | |

| Change in circumstances | |

| Condition not met | |

| Was implementation rescheduled? | Rescheduled by patient |

| Rescheduled by staff | |

| Not applicable |

These data were collected at least 3 months after each MDT decision was made. The Department of Health national targets for cancer services state that MDT decisions should be implemented within 31 days of patients receiving their diagnosis of cancer. 58 For the other conditions studied, although there is no national standard, MDTs commonly aim to have the investigations complete and the patients and carers offered an appointment for discussion of diagnosis and plan 6 weeks after being seen. Hence, 3 months after the MDT was deemed a reasonable time to check for MDT decision implementation, even allowing for unavoidable delays in beginning treatment. For longer-term decisions, where it was explicit that a decision would not be implemented within 3 months (e.g. follow up in 4 months), we followed up after the requisite time period.

Examples of partially implemented decisions included ‘cancel existing appointment and write to patient confirming no diagnosis of cancer’, where the records showed ‘wrote to patient but still saw in clinic to discharge’, or ‘biopsy of left sided nodules’ where the records showed ‘biopsy attempted but had to be abandoned after patient lost consciousness’. The research team met to review all cases that were recorded as ‘partially implemented’ to ensure the category was used consistently across the data set.

Team Climate Inventory

During the final month of observation, core team members (as defined by the lead clinician or based on a team list, where this existed) were invited to complete the Team Climate Inventory (TCI), which is a 44-item questionnaire. This validated measure88–90 assesses members’ perceptions of team processes in four domains: team vision, participative safety (i.e. a facilitative atmosphere for involvement), task orientation and support for innovation. Responses for each item on the TCI are given on a 5-point Likert scale, with a rating of 1 indicating strong disagreement with the statement, and a rating of 5 indicating strong agreement. 91 Lower TCI scores reflect poorer perceptions of team climate.

Additional questions

In addition to the TCI items, we added two items to the TCI questionnaire. The first asked respondents to rate their agreement with the statement ‘I believe that the [team name] MDT meetings are an effective use of my time’ on a scale of 1 to 5. The second was an open question: ‘Is there anything you would change about these meetings?’

Planned sample size

We calculated the sample size using the conservative assumption (based on published research and clinical experience) that 18% of decisions would not be implemented. 92 Using Peduzzi’s rule of 10, we required 80 non-implemented decisions to estimate eight coefficients in our regression model; this would require approximately 440 patients. 93 To allow for clustering by MDT, the sample size was inflated using estimates of the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) and the average cluster size. 94 Directly relevant estimates for the ICC were not available, but published models associating the ICC and outcome prevalence for a range of outcomes in community and health services settings suggested an ICC of between 0.01 and 0.05. 95 Thus, we assumed an ICC of 0.025 and that across MDTs the average number of patients with relevant decisions during the study would be approximately 230. Based on this information we aimed to include 3000 patients with a decision from the 12 MDTs.

The sample size calculation, based on decision implementation, assumed one decision for each patient. Some patients had more than one decision per meeting. We grouped these decisions into a ‘treatment plan’. This is described below under Summary measures.

Summary measures

The data were categorised for analysis using the following summary measures.

Treatment plan

We limited our analyses to the first presentation of each patient at an MDT meeting within our observation period. Discussion of a patient often resulted in more than one decision being made which cannot be assumed to be independent. We therefore grouped decisions into a ‘treatment plan’. This is consistent with cancer guidance, which refers to treatment plans rather than individual decisions. 42

In the majority of cases (88%) implementation of the treatment plan was consistent, that is either all or no component decisions of treatment plans were implemented. In cases where some decisions in the plan were implemented and others were not, we classified a treatment plan as implemented if more than 50% of the component decisions were implemented. This definition was agreed to be reasonable by our study team but was investigated further in sensitivity analyses (see Appendix 3).

Team Climate Inventory

The overall team TCI score was obtained by averaging the scores of team members. Team members with missing responses for more than 25% of items in one of the four dimensions of the TCI were excluded. There is no advice given about an acceptable team completion rate for the TCI. Previous studies using the TCI have ranged from including teams where at least 30% of members responded96 to including any teams where at least two members responded. 97 For this study we included all team responses in the main analysis.

We averaged the scores of team members in response to the statement ‘I believe that the [team name] MDT meetings are an effective use of my time’ and summarised responses to the additional open question about things they would change for use in the qualitative analysis.

Skill mix (Adjusted Teachman’s Index and number of professional categories)

There is no consensus on the best measure of skill mix or team diversity. 98 We therefore considered both the number of professional categories represented and the more complex Adjusted Teachman’s Index (ATI). This index captures both the number of professional categories represented and the evenness of representation within each of these categories. A higher value reflects a more even spread across a greater number of categories. 98 By including both measures we could assess whether or not the more complex index added any predictive value over a count of professional categories. These were classified as diagnostic doctor, surgeon, doctor, MDT co-ordinator, nurse, researcher, social worker, allied health professional and psychologist (Table 3). Both core and occasional members were included. Observers such as students were excluded.

| Professional category | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Allied health professional | Includes occupational therapists, support workers and Age Concern representatives |

| Diagnostic doctor | Includes radiologists, pathologists, consultants in nuclear medicine, clinical scientists |

| MDT co-ordinator | Includes individuals whose role focuses on facilitating the smooth running of the meeting (MDT co-ordinator may not be their official job title). They may have limited clinical input, prepare notes for patients discussed and take minutes |

| Nurse | Includes clinical nurse specialists, community psychiatric nurses, palliative care nurses and visiting crisis team nurses |

| Doctor | Includes junior doctors, consultants and staff grade doctors (medical students were excluded) |

| Psychologist | Includes assistant psychologists and clinical psychologists |

| Social worker | Includes junior and senior social workers |

| Surgeon | Includes subspecialist trainees, specialist registrars and consultants |

| Researcher | Includes clinical research fellows, research nurses, clinical trials practitioners and clinical trials co-ordinators |

Index of Multiple Deprivation

We used the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2010 as an indicator of patient’s socioeconomic circumstances. 99 This index is a widely used area-based measure that combines seven domains into a single deprivation score for each small geographical area (i.e. each ‘lower layer super output area’, which covers about 1500 people) in England. The domains comprise income; employment; health and disability; education; skills and training; barriers to housing and services; and crime and living environment. 99 We grouped IMD scores into quintiles, where quintile 1 encompassed the least deprived and quintile 5 the most deprived areas. The postcode address of patients was linked to the lower layer super output area and hence to the corresponding deprivation quintile.

Health behaviours/other clinical factors

We combined data on comorbidities (physical and mental health), health behaviour risk factors, medical history and family history into a binary variable which we referred to as ‘health behaviours/other clinical factors’ (see Box 1).

Primary statistical analysis

Data were collected on all patients discussed, although only those about whom at least one decision was made were included in the primary quantitative analysis, which aimed to identify factors predicting MDT decision implementation. The factors we investigated were patient characteristics (age, sex and socioeconomic circumstances) and MDT and decision characteristics (team climate, disease type, skill mix, discussion of patient preferences and health behaviours/other clinical factors).

For the primary analysis, the implementation response categories were collapsed into a predefined binary outcome where partially implemented was combined with implemented. We also combined decisions where implementation was not documented with those decisions which were not implemented. This was because, on the basis of our clinical experience, non-implementation is commonly not explicitly recorded in patients’ records.

The influence of MDT and patient-related factors on treatment plan implementation was investigated using random-effects logistic regression models, allowing for clustering by MDT. We fitted unadjusted models for each factor of interest. We then undertook the following predefined selection process to obtain a final adjusted model. Initially we fitted two separate models. Model 1 included patient characteristics (age, sex and IMD quintile) and model 2 considered MDT and decision related characteristics (TCI score, disease type, ATI score, number of professional groups, mention of patient preferences and health behaviours/other clinical factors). Factors identified as having potential importance from these models (p < 0.3)100 were then fitted in the final model (model 3).

The suitability of models was investigated, including considering normality of the random effect, goodness of fit (using a Hosmer–Lemeshow test) and evidence of overfitting (using bootstrapping). 100 We examined the pattern and extent of missing data and considered its potential impact on our results. We also carried out a set of sensitivity analyses to investigate some assumptions made in our main analysis. We refitted model 3 including adjustment for the number of decisions making up the first treatment plan. The impact of using the first recorded treatment plan in analysis was examined by refitting the model based on a randomly chosen treatment plan for each patient. We also refitted model 3 collapsing the five IMD quintiles into two groups (IMD 1–3 and IMD 4–5) in order to produce an eight-coefficient model (as specified in our sample size calculation).

We undertook exploratory investigations to further understand the associations observed in our model and whether these differed by disease type. We extended model 3 to examine interaction terms between the number of professional groups and disease type, and between IMD and guideline-driven cancer compared with non-cancer MDTs.

Quality assurance: clinician validation

The field researchers were not clinicians, but there were several quality assurance procedures in place to safeguard against this potential limitation. Clinical members of the research team (the PI and several of the study coapplicants) were involved throughout data collection and analysis, and were available to respond to any specific queries the field workers had throughout the project (e.g. relating to specialist terminology).

In addition, the clinical members of the research team ensured accurate recording of the primary outcome, decision implementation. During the follow-up period, a clinician from each specialty (SG for heart failure, AL for cancer and GL for dementia and mental health) reviewed a random selection of approximately 20 treatment plans from each of the specialities, and examined the medical records to independently ascertain whether or not the decision had been implemented. Any discrepancies between the outcome recorded by the field researcher and the clinician were discussed with the wider research team. Discrepancies were rare and the process gave us confidence in the accuracy of data collection. We also sought advice from the clinical coapplicants on any other clinical queries that had arisen throughout the medical record follow-up.

Qualitative methods

The qualitative aspect of the study served two purposes: firstly, to provide insights into possible explanations for the quantitative findings, and, secondly, to identify areas where there were diverse beliefs or practices with respect to MDT meetings.

To achieve this we collected qualitative data using three data collection methods:

-

non-participant observation of MDT meetings

-

interviews with MDT members

-

interviews with patients.

The steps taken to collect and analyse the qualitative data are described below.

Non-participant observation

In addition to the quantitative data collected during non-participant observation of MDT meetings, we also developed a qualitative observation coding sheet to obtain a detailed understanding of the meeting context and processes.

Developing the qualitative observation coding sheet

The observation coding sheet (see Appendix 4) was based on an adaptation of an inputs–process–outcome model. 33,34,101,102 It included sections on the meeting environment, mention of national or local policies, features of the team and task, levels of participation, and mediators of team processes and outcomes. This provided a framework to map out the potential factors influencing implementation of MDT decisions.

Data collection

Although we attended a total of 394 meetings, the purpose of the first two meetings we attended at each team was to test the data collection instruments and to enable the team to get used to the presence of the researcher. We took observational field notes at 370 MDT meetings. These notes focused on significant events and interactions observed by the researcher. Within 24 hours of each meeting, the researcher categorised these field notes according to the observation-coding sheet. The researcher also listened to the audio recording of each meeting, adding further notes and noting the timing of key events on the recording for future reference.

Interviews

We conducted semistructured interviews with MDT professionals and with patients to gain an understanding of MDT meetings from different perspectives.

Developing the interview topic guides

Draft topic guides for the MDT professional and patient interviews were developed based on reviews of the literature and the research aims. These were revised based on emerging issues identified during non-participant observation and suggestions from the study steering group.

The MDT professional interview topic guide included open-ended prompts about the purpose of the MDT, areas of diverse beliefs or practices, and what participants saw as their role in the meeting (see Appendix 5). This was piloted with a clinical coapplicant and amended on the basis of their feedback.

The patient topic guide covered issues such as whether or not patients were aware of the MDT meeting and what issues they believed should be considered when the MDT was making decisions about their care. This topic guide was piloted with two patient representatives and amended on the basis of their comments (see Appendix 6).

Recruitment of multidisciplinary team professionals

We purposively selected interviewees to ensure diversity in terms of professional group, seniority and level of participation in MDT meetings (based on the observation data).

Interviewees were approached after observation for each team was completed. This was done either in person or by e-mail, and individuals were provided with an information sheet and consent form. While we suggested that the interview would take approximately 1 hour, some clinicians requested shorter interviews (e.g. 30 minutes) to fit in with their schedules.

The interviews were all conducted at the place of work of the participants and were audiotaped. Researchers wrote reflective field notes following each interview, including comments on setting, the main issues discussed and new perspectives on the research questions prompted by the interview.

Recruitment of patients

We aimed to interview patients or carers across all four disease types and to maximise diversity in terms of sex, age and ethnicity. Patients were recruited from the MDTs under observation. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for these are detailed in Box 2. To increase the likelihood that interviewees would still be under the care of the team, the 30 patients who had been most recently discussed by each team at the end of the observation period were selected. From this group, we gave the relevant lead clinician or team manager a list of the patients we sought to invite for interview. We asked clinicians to highlight any cases where they thought the interview would present a risk to the patient or to the interviewer. These patients were not approached for interview.

Diversity of age, sex and ethnicity.

Under the care of the team.

Summary of exclusion criteriaNon-English speaker.

Clinician deems a risk to interviewer.

Clinician deems too vulnerable for interview.

Not living in England.

Declines to be interviewed.

The relevant key worker was then asked to contact the selected patients, provide them with a study information sheet and consent form, and seek permission for the researchers to contact patients directly to discuss the study further. Patients who agreed to be contacted were telephoned by a member of the research team to confirm participation, address any questions they had and arrange the interview. Interviews took place in either the hospital/clinic or the patient’s home and were audiotaped. As with the professional interviews, researchers wrote reflective field notes directly after each interview.

Qualitative analysis

We devised a strategy for qualitative data analysis to enable us to manage the large volume of data generated. The analysis was an iterative process, using a combination of both inductive and deductive coding and ethnographic methods such as constant comparison and coding frame revisions. Analytic conferences of the field researchers and the wider research team were used to scrutinise and revise codes and themes and to encourage reflexivity.

Analysis of non-participant observation data

This was undertaken in two stages, as described below:

Stage one: initial coding and selective transcription

Verbatim transcription of MDT meetings was not practical given the large number of participants at some meetings, overlapping talk and variable audio quality depending on the layout of the meeting rooms. Instead, we used selective transcription to document relevant parts of the meetings. 103

In the first instance we inductively coded the observation coding sheets (i.e. our field notes) for the first 16 meetings (excluding the initial 2-week ‘test’ period for each team) of each of the teams observed (with the exception of one team, which disbanded after 15 weeks of observation). We used NVivo 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to organise the data. Each observation was labelled with a basic descriptive code, and recurring and salient issues were compiled into an initial coding framework. Exceptions were noted within the relevant codes and some codes were relevant to only specific teams or specialties.

This coding framework was then used to identify and selectively transcribe at least two discussions illustrating each code. This ‘data reduction’ technique allowed us to manage the huge volume of data collected, while still reviewing the excerpts in the context in which they occurred by listening to the audio recordings.

These selective transcripts were imported into the NVivo database alongside the observation coding sheets and were read, reread and further coded using the initial coding framework. Thus, codes included data from both observation notes and transcripts. The coding framework was revised iteratively and additional codes were added where new issues that were relevant to the research questions arose. Code definitions were discussed by the team and revisited regularly throughout the analysis to ensure they were being applied consistently. The list of observation code definitions is provided in Appendix 7. This pool of codes was drawn upon throughout the analysis, as appropriate to the question at hand. For example, for the qualitative investigation of the primary quantitative findings, relevant codes were grouped as shown in Appendix 8.

Stage two: analytic conferences

Conducting qualitative research as a team is recognised to have a number of potential benefits, such as increasing rigour by providing an opportunity to challenge and clarify conflicting understandings and encouraging a richer conceptual analysis. 104 We drew upon the expertise and experience of project team members to devise a strategy for the analysis of the qualitative data that would be both reflexive and rigorous. This involved using analytic conferences to discuss the analysis and interpretation of the findings.

Analytic conferences were attended by the researchers who conducted the observation and senior members of the team with clinical and research experience. For each of the 12 MDTs, the researcher who completed stage one of the observation analysis provided each member of the analytic team (CN, IW, PX, AL, AC) with an audio recording of a different meeting from the same team. Each team member listened to their allocated audio recording, making notes of potential codes, exemplary quotes and deviant cases. Following this, the team met to discuss and review the appropriateness of the codes allocated.

Once this process had been completed for half the teams, an analytic conference was dedicated to refining and integrating the codes across the data set, merging synonymous codes and splitting compound codes to form a coherent framework. Analytic conferences were also held for the remaining six teams to monitor the consistent application of the framework.

Analysis of interviews

All interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed thematically using NVivo 9. Transcripts were anonymised and identifying details (such as names and specific job titles) were removed where necessary to preserve anonymity.

The initial analysis of professional interviews was conducted independently of the patient interviews.

In order to manage the large volume of data, and to build on our observation analysis (as described above), we adopted a hybrid inductive and deductive approach to analysing the interview data.

The deductive themes were based on our research objectives and our preliminary qualitative analysis of the observation data. These are listed in Box 3. We applied these in the first instance to collate the data relevant to each theme. We then inductively analysed the data to generate subthemes. This allowed us to explore relevant issues identified in the data more fully. Tables 4 and 5 provide illustrative examples of these levels of analysis for the professional and patient interview analyses respectively.

Added value of the MDT meeting, in relation to (1) decision-making, (2) other formal and informal functions of the MDT meeting.

Areas for improvement/weaknesses/problems of the MDT meeting, in relation to (1) decision-making, (2) other formal and informal functions of the MDT meeting.

Patient preferences and decision-making.

Comorbidities and decision-making.

MDT patient interviews: deductive themesPatient preferences.

What should and should not be considered when making a decision in the MDT meeting.

Most appropriate methods for implementing patient preference.

Feedback (what kind of feedback patients received and would want in the future).

| Deductive theme | Inductive subthemes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| Added value of MDT in relation to decision-making | Improving decision-making | Consistency of decision-making (acting as a ‘check’) |

| Having access to all the information to inform decision-making | ||

| Context within which MDT decision-making is most helpful | When the ‘right’ people attend | |

| When there is good leadership/management | ||

| When people make meaningful, significant contributions | ||

| Difference as strength | Sharing professional knowledge and expertise | |

| Providing a different perspective |

| Deductive theme | Inductive subthemes | Codes |

|---|---|---|

| What feedback do patients want? | Content of feedback | Symptoms/test results |

| Options | ||

| Decisions | ||

| Other | ||

| Life expectancy | ||

| Impact on life: side effects | ||

| Feedback format | No paperwork/a phone call | |

| No feedback wanted | Feedback would not change anything | |

| Best for others to decide | ||

| Too much information can be confusing | ||

| Might not be able to understand | ||

| Need for basic information in order to recover | ||

| Control over feedback | Asking for information that you want to know | |

| Feedback dependent on the person/situation | ||

| Feedback wanted | Full feedback of all the options | |

| Information about the MDT discussion |

Analytic integration and triangulation across data sources

The term ‘triangulation’ has been ascribed several meanings. Two of the most common uses are the corroboration approach (assessing whether or not accounts derived from different data sets are consistent) and complementarity approach (using different methods to assess different aspects of the same issue to gain a more complete picture). 106,107 We adopted a complementarity approach106 using multiple methods to gain a more comprehensive, multidimensional understanding of a complex issue. 107 We integrated our three qualitative data sources with two specific objectives in mind: firstly, to provide insights into possible explanations for the results from the quantitative analysis, and, secondly, to identify areas of diverse beliefs or practices in MDT meetings.

-

To provide insights into possible explanations for the quantitative findings

-

This analysis drew upon each of the different methods (non-participant observation and semistructured interviews) to explore possible explanations for variation in treatment plan implementation. We undertook a deductive analysis of both the observation and interview data, where each finding from the logistic regression formed the basis of a deductive theme (see Appendix 8 for an illustration of how the observation codes were grouped according to the quantitative variables examined). We drew on the entire pool of inductive codes, grouping them according to their relevance to each deductive theme, as illustrated by Table 6. This allowed us to identify the relevant transcripts and field notes to illuminate possible reasons for each finding. Additional analytic conferences were held to facilitate these analyses.

-

-

To identify areas of diverse beliefs or practices in MDT meetings

-

In order to identify themes for study 2, we distinguished issues around which there were differences in beliefs or practices, either within or across teams. This was achieved by synthesising findings from the three qualitative data sources to produce overarching ‘metathemes’ relating to these differences and issues of contention.

-

Throughout the analysis, we drew on the ‘following a thread’ technique108 where key themes and topics identified in the initial analyses of each data source were further explored in the other data sets. Since we gathered the observational data before the interview data were collected, we were able to follow up ‘promising’ findings when analysing the other data sets, as well as in the questions we asked interviewees. This allowed us to collect richer interview data on ‘promising’ codes than would have been possible by integrating the findings in the analytic stages alone.

-

Once we had undertaken preliminary analyses of the three qualitative data sources, we convened an analytic synthesis meeting attended by the chief investigator (RR), the three field researchers (CN, IW, PX), two senior clinical members of the research team (AL, AC) and two patient representatives (DA, MH). At this meeting, we reviewed the outputs from each of the preliminary analyses (observational codes, professional interview themes and patient interview themes) and, taking the comprehensive data set as a whole, we identified all the issues around which there were different opinions or practices (which we called metathemes, e.g. differing opinions about the role of the patient and differing chairing practices). We then collated the relevant themes, codes and quotes from all sources related to each of these issues.

Quality assurance

Non-participant observation

Observation notes and selective transcripts of the meeting discussions were coded and analysed in a constant comparative manner, with repeated inspection of each data source between three researchers, and at regular analytic conferences with other members of the research team. We used multiple coding to address the issues of subjectivity sometimes levelled at the process of qualitative data analysis. 109 As new codes were introduced, they were assigned a working definition to ensure they were used consistently by the different researchers. These definitions were debated and revised repeatedly throughout the process. The analytic conferences allowed the researchers to check whether or not codes were being applied according to the definition, and that definitions were iteratively revised where appropriate. The analytic conferences also facilitated group reflexivity and safeguarded against individual bias by providing opportunities to make each researcher’s assumptions explicit and open to challenge. 110 Together with regular meetings between the field researchers, the chief investigator and other members of the team, these formed a kind of auditing that was ‘built into the research process to repeat and affirm researchers’ observations’. 111

Professional and patient interviews

In order to establish consistency of coding for the interview data, two researchers initially independently coded 20% of the transcripts. Following this, the researchers met to discuss any incongruence, going through each transcript line by line to check for differences in terms of both sections coded and the specific code applied in each case. Differences were resolved by discussing the differing interpretations, identifying any misunderstandings and refining code definitions as necessary. A third researcher was present to give an independent perspective if the two coders failed to reach agreement.

Steering group meetings

Throughout the study, we convened four steering group meetings (between July 2011 and March 2013), which provided a mechanism for peer review and guidance (see Appendix 9 for collaborators and steering group members).

In these meetings, as well as providing general support and advice (e.g. with recruitment), the steering group members discussed methodological issues, reviewed the definitions of variables and outcomes and the interview topic guides, and helped to develop data-auditing strategies, hence providing further quality assurance.

Patient and public involvement

We had two active patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives on our project steering group (MH and DA, coauthors on this report), who were actively involved throughout. They attended steering group meetings and provided in-depth and valuable contributions to our study design and analysis. In particular, they reviewed and amended the information sheets for the patient interviews, to ensure these were clear and informative. They also collaborated in the design of the patient interview topic guide and helped to organise pilot interviews to test and refine them. In addition, they reviewed the anonymised patient interview transcripts and participated fully in the analytic conference where these were discussed.

The collaboration of patient representatives in this research was integral to both its design and delivery. We found that having continuous rather than sporadic PPI engagement was invaluable, because their in-depth knowledge of the background and progress of the study meant that they could respond quickly when their patient perspective on particular aspects of the study was needed.

Chapter summary

We began this chapter by outlining the ethics and recruitment procedures undertaken. We then described the data collection and analysis methods for the quantitative components (i.e. non-participant observation of meetings and medical record review) and the qualitative components (i.e. non-participant observation of meetings, interviews with patients and professionals) of the research. Finally we explained how we integrated these data to address the study aims. Chapters 3 and 4 present the quantitative and qualitative results.

Chapter 3 Study 1 quantitative results

A shorter version of the results presented in Chapters 3 and 4 has been published in Raine et al. 105

Team characteristics

We observed 370 MDT meetings during which 3184 patients were discussed. Characteristics of the 12 teams and their meetings are summarised in Table 7. There was considerable variability among the 12 teams in the number of patients discussed at each meeting. The average for each team ranged from 4 to 49 patients. The average meeting size across the 12 MDTs ranged between 5 and 28 members, with one to seven professional groups represented (an overall median of four). Of the patients discussed, 83% had a least one treatment plan made, but this proportion was notably lower for the mental health teams.

| MDT characteristics | Haematological cancer | Gynaecological cancer | Skin cancer | Memory clinic | Mental health | Heart failure | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Team 1 | Team 2 | Team 1 | Team 2 | Team 1 | Team 2 | Team 3 | Team 4 | Team 1 | Team 2 | |||

| TCI score | 4.32 | 3.79 | 3.49 | 4.11 | 4.10 | 3.89 | 4.01 | 3.31 | 3.64 | 4.01 | 4.00 | 3.75 |

| Number of meetings | 38 | 36 | 18 | 31 | 43 | 25 | 15 | 20 | 55 | 23 | 42 | 24 |

| Number of patients discussed per meeting: mean (SD) | 14.5 (4.1) | 14.2 (4.8) | 34.5 (5.0) | 21.7 (5.6) | 11.2 (5.4) | 4.3 (1.3) | 29.1 (11.5) | 14.6 (4.4) | 14.0 (4.9) | 49.3 (12.1) | 8.0 (2.3) | 6.0 (2.2) |

| ATI: mean (SD) | 1.38 (0.14) | 1.29 (0.10) | 1.70 (0.12) | 1.52 (0.12) | 1.75 (0.14) | 0.86 (0.33) | 1.26 (0.17) | 1.34 (0.14) | 1.34 (0.13) | 1.47 (0.08) | 1.36 (0.13) | 0.89 (0.14) |

| Number of professional categories represented: median (25th–75th percentile) | 5 (4–5) | 5 (5–5) | 6 (6–6) | 6 (5–6) | 5 (5–6) | 3 (2–3) | 3 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (3–4) | 4 (4–4) | 4 (4–5) | 2 (2–2) |

| Number of MDT members at the meeting:a mean (SD) | 11.79 (1.65) | 28.25 (4.43) | 18.28 (2.89) | 17.48 (2.66) | 9.23 (1.60) | 6.92 (1.75) | 7.73 (2.60) | 8.35 (2.13) | 9.09 (2.21) | 9.70 (1.94) | 15.02 (2.96) | 5.38 (1.58) |

| Number of patients discussed during observation period (at least once) | 390 | 371 | 324 | 384 | 403 | 106 | 231 | 134 | 314 | 169 | 225 | 133 |

| Patients with at least one treatment plan: number (%) | 330 (85) | 321 (87) | 281 (87) | 335 (87) | 356 (88) | 106 (100) | 145 (63) | 71 (53) | 251 (80) | 131 (76) | 197 (88) | 130 (98) |

Team Climate Inventory and additional questions

Of the 211 TCIs issued, 161 were returned, giving a response rate of 76%, ranging from 50% (mental health team that disbanded) to 100% (skin cancer).

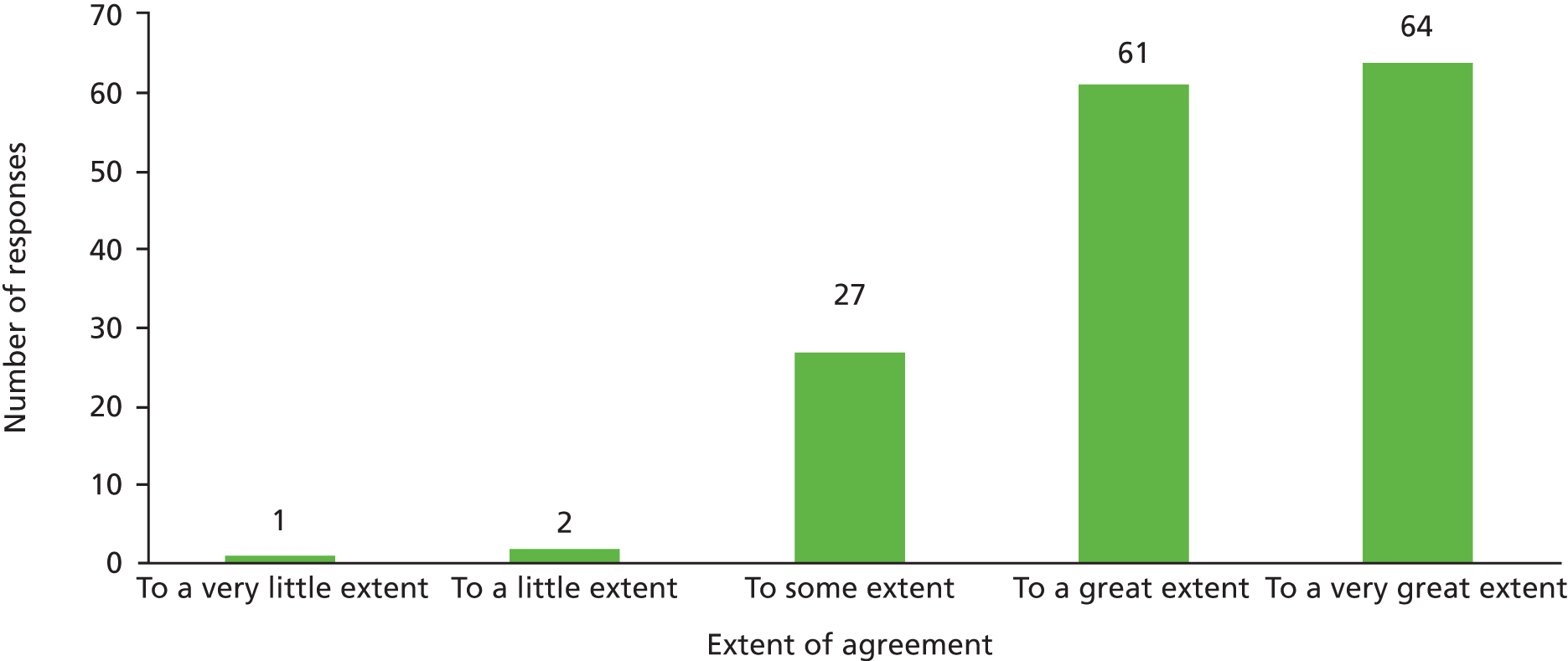

Across all teams, 155 members responded to the additional question, with almost all agreeing to a great or very great extent with the statement, ‘I believe that the [team name] MDT meetings are an effective use of my time’ (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

MDT member response to ‘I believe that MDT meetings are an effective use of my time’ across 12 MDTs.

Treatment plan implementation

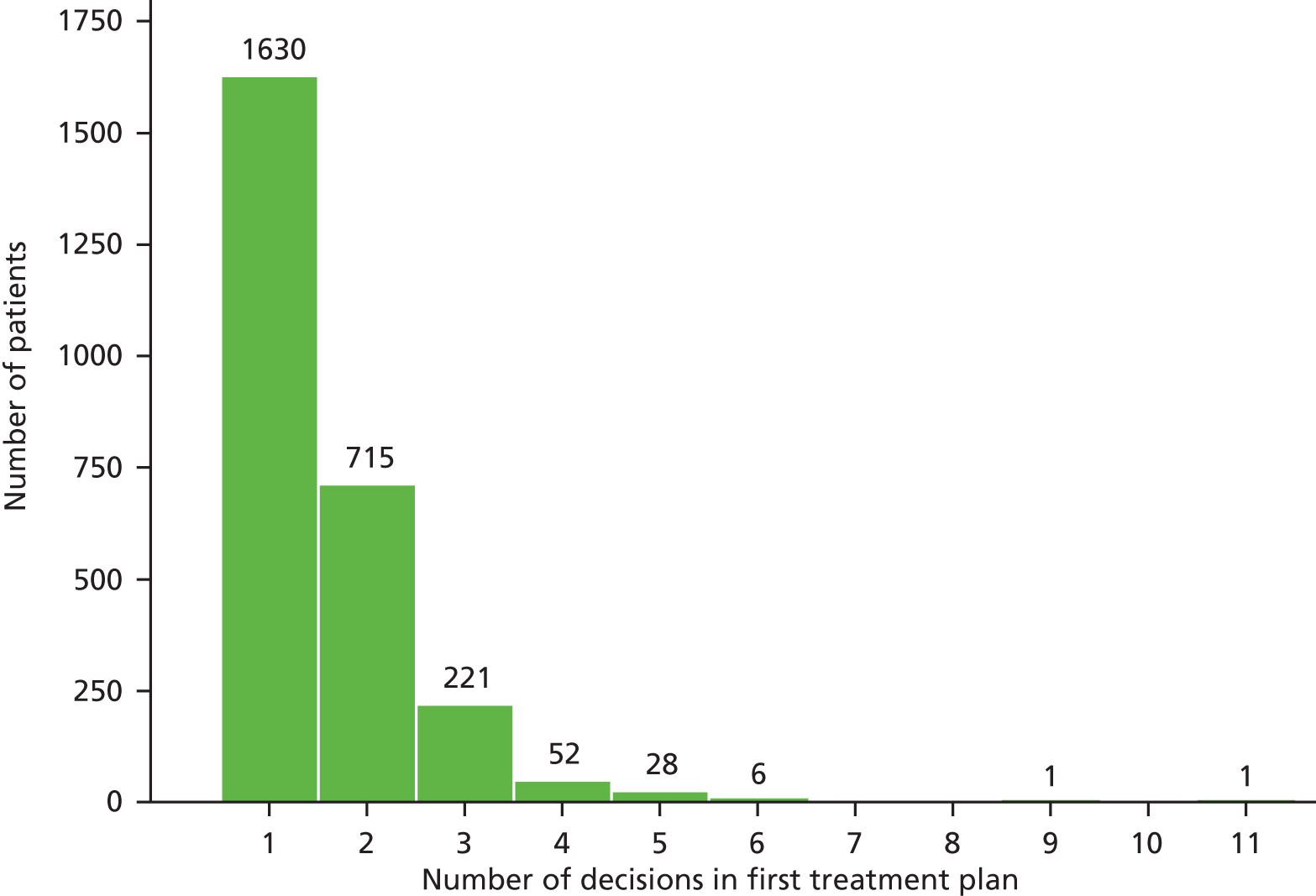

Overall, 2654 patients had a treatment plan. The number of decisions making up the plan ranged between 1 and 11 (Figure 2) with an average of 1.6 decisions per plan.

FIGURE 2.

Number of decisions making up the first treatment plan recorded for each patient. Average number of decisions = 1.6, number of decisions for first treatment plans = 4127.

Of the patients with treatment plans, 2512 (94.6%) had adequate implementation data recorded for implementation status to be classified, and 1967 (78.3%) of these had implemented plans. Treatment plan implementation is summarised by patient, MDT and discussion characteristics in Table 8. By disease type, implementation was highest in the gynaecological cancer team and lowest in the CMHTs, although implementation also varied by team. There was a trend for non-implementation with increasing patient deprivation.

| Characteristic | Treatment plan implemented, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) (n = 2504) | |

| 20–39 | 355 (73) |

| 40–59 | 488 (79) |

| 60–79 | 739 (81) |

| 80+ | 381 (80) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 945 (78) |

| Female | 1022 (79) |

| IMD quintile (n = 2431) | |

| Least deprived | 197 (85) |

| 2 | 331 (82) |

| 3 | 395 (82) |

| 4 | 541 (76) |

| Most deprived | 442 (73) |

| TCIa,b | |

| < 4 (median score) | 853 (78) |

| ≥ 4 | 1114 (79) |

| Type of diseasea | |

| Haematological cancer | 502 (81) |

| Gynaecological cancer | 228 (84) |

| Skin cancer | 229 (78) |

| Memory clinic | 362 (81) |

| Mental health | 403 (70) |

| Heart failure | 243 (80) |

| Teama | |

| Haematological cancer 1 | 276 (85) |

| Haematological cancer 2 | 226 (76) |

| Gynaecological cancer | 228 (84) |

| Skin cancer | 229 (78) |

| Memory clinic 1 | 263 (76) |

| Memory clinic 2 | 99 (94) |

| Mental health 1 | 106 (77) |

| Mental health 2 | 42 (65) |

| Mental health 3 | 163 (68) |

| Mental health 4 | 92 (70) |

| Heart failure 1 | 148 (81) |

| Heart failure 2 | 95 (79) |

| ATIc | |

| < 1.2 | 349 (82) |

| 1.2–1.4 | 538 (76) |

| 1.4–1.6 | 591 (78) |

| > 1.6 | 489 (78) |

| Number of professional groupsc | |

| 1–3 | 312 (81) |

| 4–5 | 1199 (77) |

| 6–7 | 456 (79) |

| Patient preferences considered | |

| Yes | 361 (75) |

| No | 1606 (79) |

| Health behaviours/other clinical factors mentioned | |

| Yes | 1069 (79) |

| No | 898 (77) |

| Total | 1967 (78) |

Adjusted associations (Table 9) showed no evidence of a relationship between treatment plan implementation and patient’s age or sex, or with discussion of patient preferences or health behaviours/other clinical factors. ATI and number of professional groups were highly correlated (correlation coefficient 0.8) but did not appear to have an association when fitted together (model 2). When included individually in the model, however, each showed a relationship such that an increase in team diversity or number of professional groups was associated with a reduced odds of treatment plan implementation.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted (n = 2512)b | Adjusted model 1 (n = 2431) | Adjusted model 2 (n = 2512) | Adjusted model 3 (n = 2431) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age (at first decision) | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.60 | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | 0.84 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Male | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Female | 0.99 (0.80 to 1.21) | 0.89 | 1.01 (0.82 to 1.24) | 0.96 | ||||

| IMD quintile | ||||||||

| Least deprived | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 2 | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.30) | 0.83 (0.53 to 1.30) | 0.80 (0.52 to 1.25) | |||||

| 3 | 0.91 (0.58 to 1.40) | 0.91 (0.58 to 1.40) | 0.87 (0.56 to 1.34) | |||||

| 4 | 0.64 (0.43 to 0.98) | 0.65 (0.43 to 0.99) | 0.64 (0.42 to 0.97) | |||||

| Most deprived | 0.60 (0.39 to 0.93) | 0.04 | 0.60 (0.39 to 0.93) | 0.04 | 0.60 (0.39 to 0.91) | 0.05 | ||

| TCI (0.1 increase) | 1.05 (0.97 to 1.15) | 0.25 | 1.09 (1.03 to 1.15) | 0.004 | 1.07 (1.01 to 1.13) | 0.01 | ||

| Type of disease | ||||||||

| Haematological cancer | 1 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Gynaecological cancer | 1.22 (0.62 to 2.38) | 2.76 (1.58 to 4.83) | 2.48 (1.48 to 4.15) | |||||

| Skin cancer | 0.81 (0.42 to 1.56) | 0.97 (0.67 to 1.39) | 0.97 (0.67 to 1.39) | |||||

| Memory clinic | 1.21 (0.67 to 2.20) | 1.11 (0.74 to 1.67) | 1.05 (0.76 to 1.45) | |||||

| Mental health | 0.56 (0.35 to 0.90) | 0.60 (0.37 to 0.99) | 0.57 (0.39 to 0.82) | |||||

| Heart failure | 0.93 (0.52 to 1.54) | 0.03 | 0.78 (0.49 to 1.21) | < 0.001 | 0.75 (0.50 to 1.14) | < 0.001 | ||

| ATI | 0.64 (0.35 to 1.17) | 0.15 | 0.65 (0.24 to 1.76) | 0.40 | ||||

| No. of professional groups | 0.90 (0.77 to 1.06) | 0.21 | 0.84 (0.65 to 1.10) | 0.21 | 0.75 (0.66 to 0.87) | < 0.001 | ||

| Patient preferences considered | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 0.86 (0.67 to 1.11) | 0.24 | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.14) | 0.34 | ||||

| Health behaviours/other clinical factors mentioned | ||||||||

| No | 1 | 1 | ||||||

| Yes | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.27) | 0.80 | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.32) | 0.55 | ||||

Factors with an association (p < 0.3) in models 1 and 2 were fitted together in the final model (model 3). The adjusted odds of implementation increased by 7% (95% CI 1% to 13%) for a 0.1-unit TCI score increase (indicating improved team climate). In contrast, the adjusted odds of implementation were reduced by 25% for each additional professional group represented, and were lower for patients living in more deprived IMD quintiles. Adjusted odds of implementation also varied by disease type.

We had sufficient data on 2512 (92%) patients to include them in the final model. Data were missing for age (2%), IMD quintile (6%) and treatment plan implementation (5%), mainly because of missing patient notes. The only characteristic associated with ‘missingness’ was MDT disease type. Given the small proportion of missing values, we did not consider it necessary to account for this in our analysis.

Sensitivity analyses for model 3 included adjusting for the number of decisions making up the first treatment plan (which varied between 1 and 11 decisions); examining the impact of using the first recorded treatment plan in analysis by refitting the model based on a randomly chosen treatment plan for each patient; collapsing the five IMD quintiles to two groups (IMD 1–3 and IMD 4–5) to produce an eight-coefficient model; and altering the definition of an implemented treatment plan such that implementation is when > 80% of component decisions are implemented. None of these analyses substantially changed our conclusions (see Appendix 3).

We further explored the observed trend between implementation and number of professional groups to examine whether this was dependent on disease type. Tabulations suggested that this association was mainly apparent in memory clinic and mental health teams, and an interaction term added to model 3 indicated some evidence of a differential effect by type of disease (p = 0.06) (Table 10). We also considered whether the relationship between IMD and implementation differed for cancer and non-cancer specialties. This interaction term was not significant (interaction p = 0.13) (Table 11).

| Disease type | Number of professional categories represented | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | |

| Haematological cancer | 60 (85%) | 442 (81%) | |||||

| Gynaecological cancer | 42 (86%) | 151 (82%) | 35 (90%) | ||||

| Skin | 96 (76%) | 133 (79%) | |||||

| Memory clinic | 3 (100%) | 37 (97%) | 34 (94%) | 73 (87%) | 78 (76%) | 137 (74%) | |

| Mental health | 146 (76%) | 257 (67%) | |||||

| Heart failure | 84 (79%) | 8 (72%) | 110 (81%) | 41 (80%) | |||

| Total | 3 (100%) | 121 (84%) | 188 (79%) | 500 (74%) | 699 (80%) | 421 (78%) | 35 (90%) |

| Disease type | IMD quintile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (least deprived) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (most deprived) | |

| Haematological cancer | 62 (86) | 127 (80) | 144 (85) | 93 (78) | 59 (76) |

| Gynaecological cancer | 32 (94) | 43 (84) | 49 (85) | 59 (82) | 42 (78) |

| Skin cancer | 30 (77) | 45 (74) | 67 (87) | 57 (75) | 23 (72) |

| All cancer | 124 (86) | 215 (79) | 260 (85) | 209 (78) | 124 (76) |

| Memory clinic | 40 (89) | 69 (90) | 64 (74) | 119 (81) | 63 (75) |

| Mental health | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | 15 (63) | 159 (71) | 208 (70) |

| Heart failure | 33 (85) | 43 (83) | 56 (88) | 54 (75) | 47 (77) |

| All non-cancer | 73 (84) | 116 (87) | 135 (78) | 332 (75) | 318 (72) |

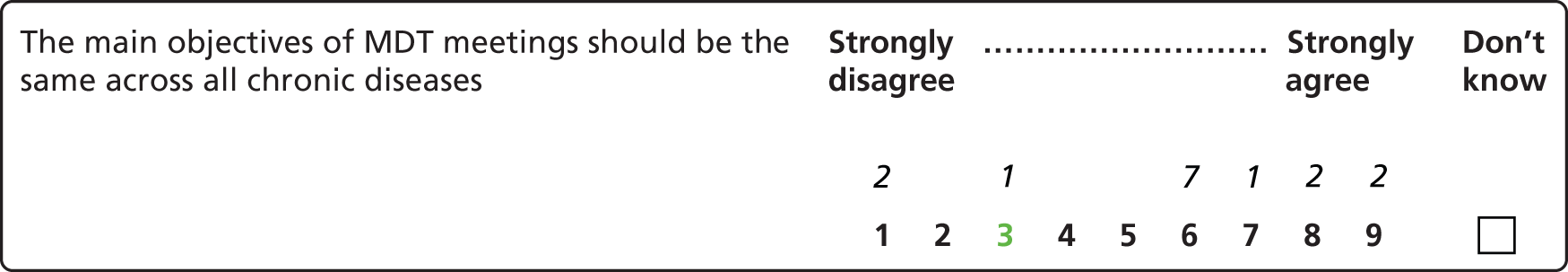

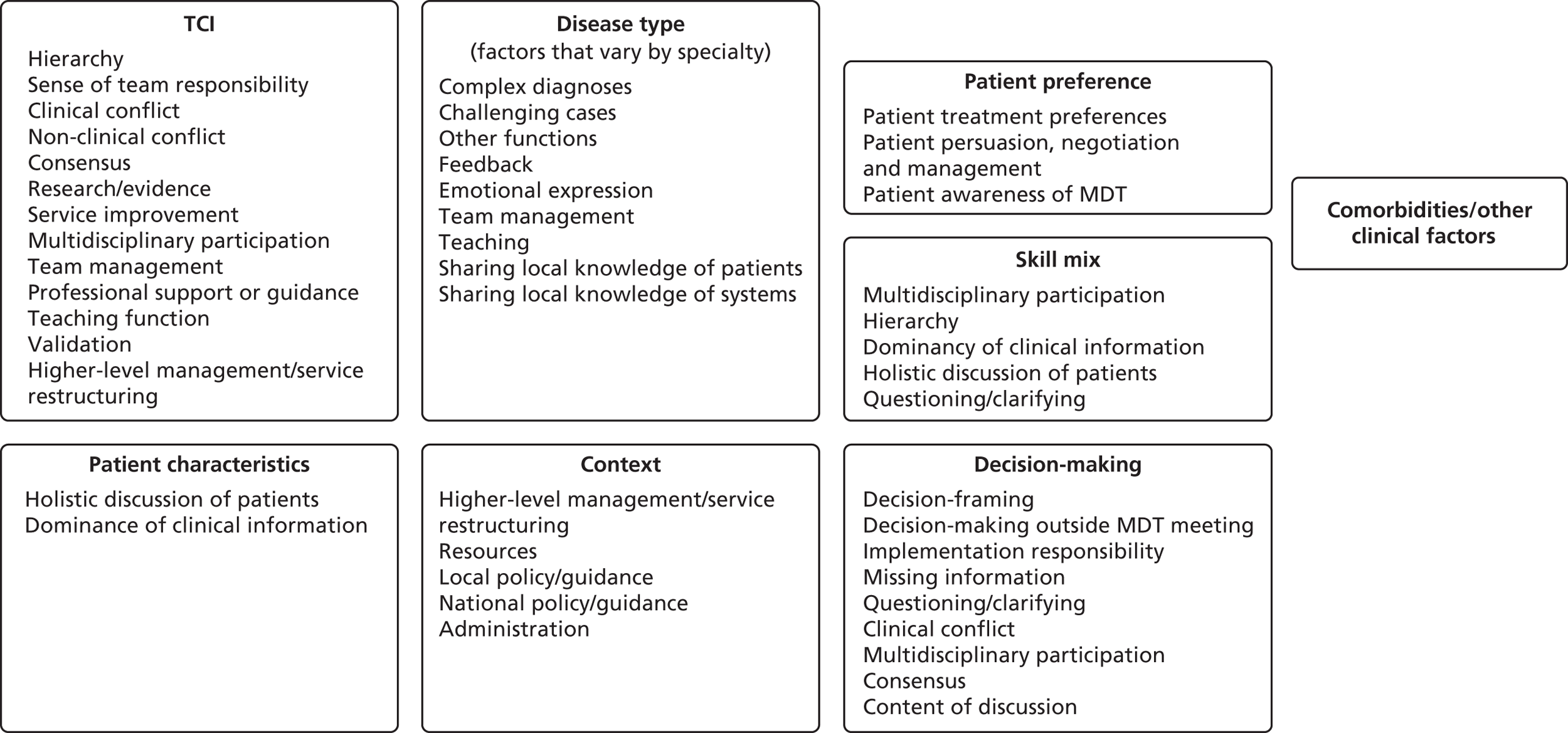

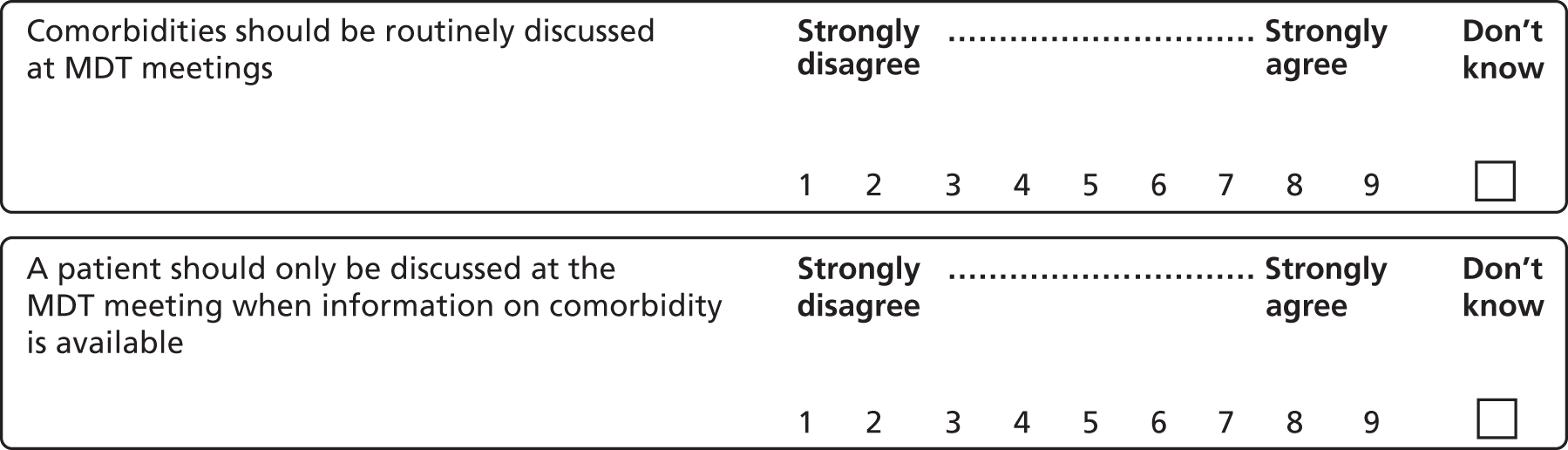

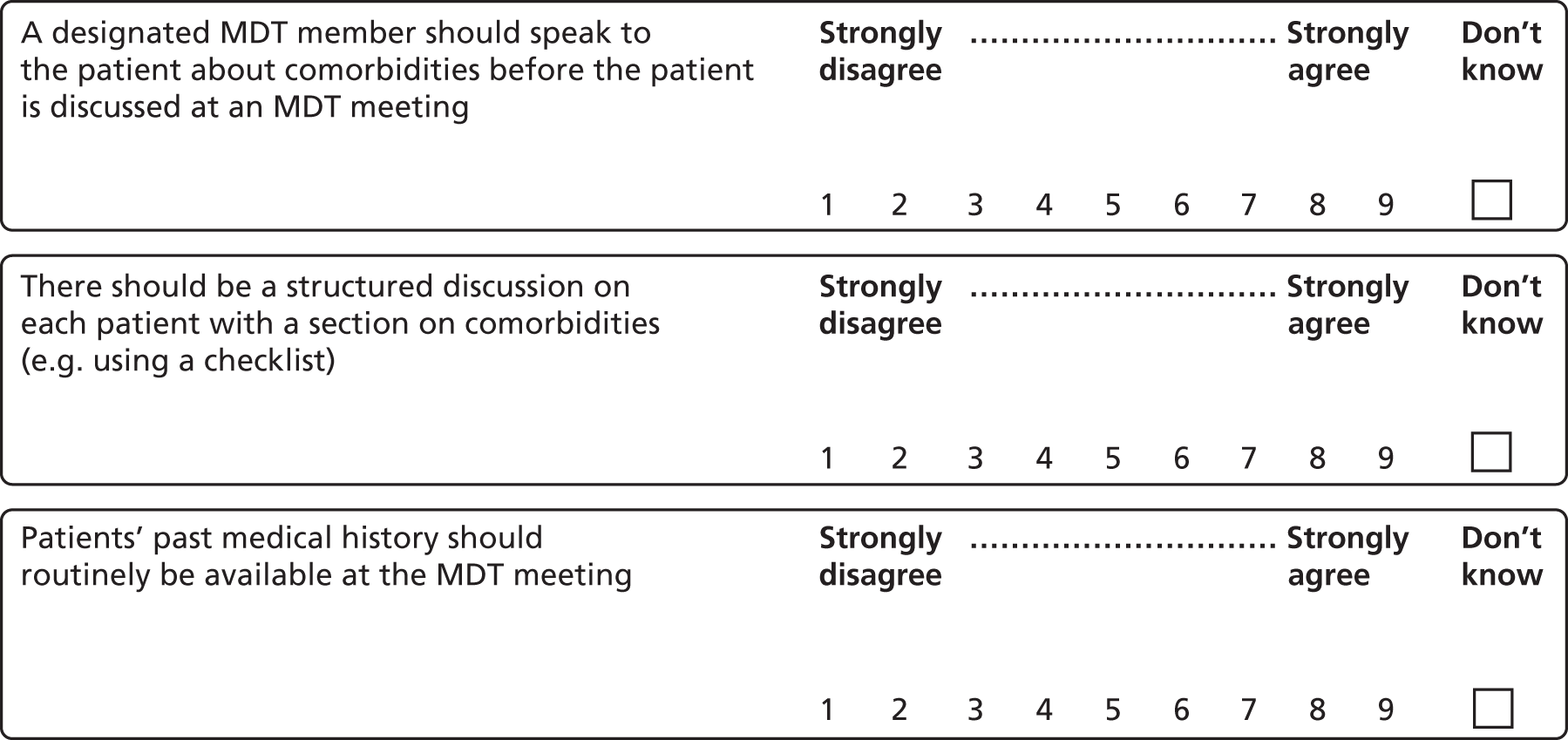

| Total | 197 (84) | 331 (82) | 395 (83) | 541 (76) | 442 (73) |