Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1011/01. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

this report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and includes language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Greenhalgh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and literature review

The problem of ‘failed’ information and communication technology programmes in health care

The history of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in health care includes some expensive disasters. For example, England’s National Programme for Information Technology (NPfIT) was established in 2006 with a projected cost of £12.7 billion over the ensuing 8 years,1 but after numerous delays and difficulties, most of its component technologies were abandoned in 2011–12, and expensive penalties were incurred for breach of commercial contracts. 2–5 To accompany the release of a damning summary of the programme’s failures in May 2011, the head of the National Audit Office wrote:

The original vision for the National Programme for IT [information technology] in the NHS will not be realised. The NHS is now getting far fewer systems than planned despite the Department paying contractors almost the same amount of money. This is yet another example of a department fundamentally underestimating the scale and complexity of a major IT-enabled change programme. The Department of Health needs to admit that it is now in damage-limitation mode. I hope that my report today, together with the forthcoming review by the Cabinet Office and Treasury, announced by the Prime Minister, will help to prevent further loss of public value from future expenditure on the Programme.

Amyas Morse, head of the National Audit Office, 18 May 20116

In 2007–10, our team evaluated the introduction of two components of the NPfIT: the Summary Care Record (SCR) and a linked patient portal, HealthSpace (see Chapter 3, The primary data sets). Policy-makers had predicted that these technologies would be widely adopted and would lead to rapid improvements in the quality, safety and efficiency of care as well as empowering patients, promoting choice and reducing health inequalities. 7 Lack of realisation of their hoped-for benefits was attributed mainly to the fact that they were not being used. 8–11 Similar findings were documented by the evaluators of the implementation of hospital records within the NPfIT. 3,12–14 At the time of writing, most of the technologies in the NPfIT (including hospital-based records and HealthSpace) had been withdrawn because of delays in supply and/or non-uptake by clinicians, and a new policy emphasising local development and/or procurement introduced. 15 The SCR was still Department of Health policy but its use in clinical practice remained limited. 16

Both we and other research teams have described numerous other instances of non-adoption, limited adoption or adoption followed by abandonment of ICTs by clinicians, especially when they were introduced as part of a large, top-down change programme. 3,17–19 As one study concluded, ‘Most [healthcare ICT] implementations fail because, despite high investments in terms of both time and financial resources, physicians simply do not use them’ (p. 309). 20

The literature on resistance to ICTs in health care is extensive. In the next few sections, we summarise that literature and introduce our own chosen approach. Immediately below, we consider the (broadly) behaviourist approach taken by many cognitive psychologists and health services researchers to ‘resistance’ to ICTs, which is still the dominant framing taken by many academics or policy-makers. In the section Multilevel models of resistance to information and communication technologies, we review multilevel models of resistance in which group and organisational factors are added to individual ones. Next (see Interactional models of resistance: the sociotechnical perspective), we consider theoretical approaches that take an organic or interactional view of how individuals in organisations use technologies (or not), focusing in particular on Lynne Markus’s classic study from 1983 on technology-system fit, Albert Cherns’ work on sociotechnical systems theory, computer-supported co-operative work (CSCW) and Carl May’s normalisation process theory.

In the section Critical studies of organisational power relations, we outline the literature from critical management studies (and, more specifically, from critical information systems studies) that considers people’s resistance to ICTs in the workplace in terms of the play of power between dominant and ‘dominated’ groups. We then briefly explain actor–network theory (ANT: Bruno Latour) and related perspectives (see Actor–network theory), including important extensions of this approach in the work of Ole Hanseth and colleagues from Norway on standardisation and Marc Berg from the Netherlands on the agency as a product of the network. We introduce the sociological work of Anthony Giddens (see Giddens’ work on structuration, modernity and technology), including structuration theory and its links to modernity and technology. Finally, we explain how an empirically-oriented extension of structuration theory developed by one of us (RS) and known as ‘strong structuration theory’ (SST) can be further enhanced for the study of technologies using selected elements of ANT (see Strong structuration theory). When we originally planned this study, we were drawing on our work on this ‘ANT–SST hybrid’, though as we explain in the Discussion (see Chapter 5), we modified our stance somewhat as our thinking developed and data analysis progressed.

The technology acceptance model

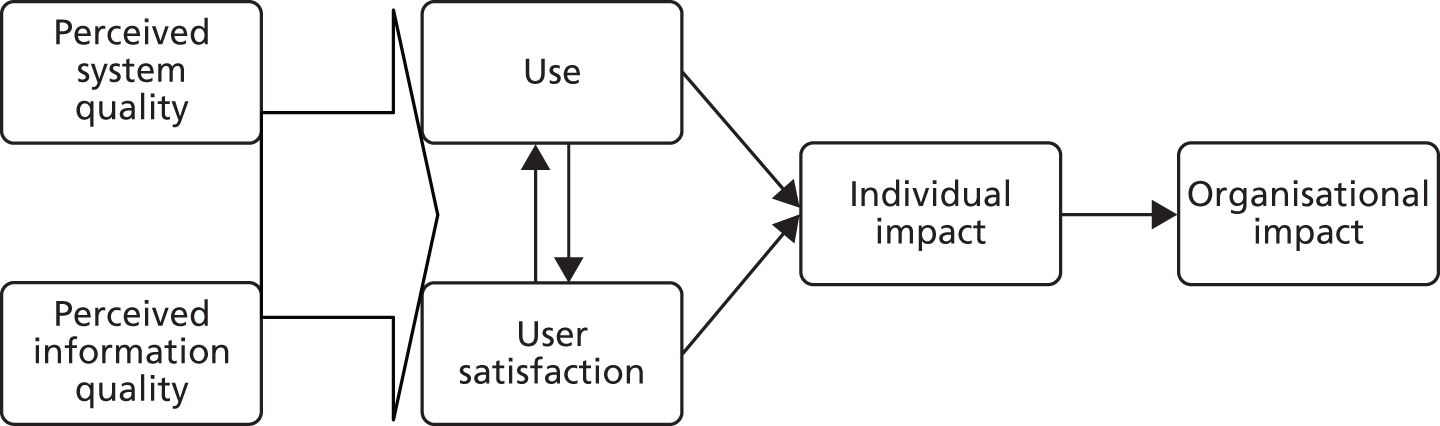

The most widely used model for considering ICT adoption in organisations is probably Davis’ ‘technology acceptance model’ (TAM), located in the cognitive psychology/human–computer interaction literature and cited by over 2000 studies since. 21 It states that a technology is more likely to be adopted by a potential user if it scores highly on a set of attributes including ‘usefulness’ (e.g. the degree to which it helps someone do their job and improves their productivity) and ‘ease of use’ (e.g. features such as user-friendliness, speed and ‘clunkiness’). The TAM, which was originally derived as an adaptation of Rogers’ diffusion of innovation theory, was subsequently extended to produce a model of information system success, seen as determined by user uptake, which in turn was determined by users’ perceptions of the quality of the system and the quality of the information it contained. 22 All of these variables are seen as interconnected and interdependent; the strength of the relationship between any of them, and the influence of particular mediating or moderating variables, will vary with the situation, but according to the model, they can (in theory at least) be measured and quantified.

Delone and McLean later added a third component (perceived service quality, such as helpdesk support) to the first column in Figure 1. 23 They also unpacked the dependent variable (‘organisational impact’) into four dimensions: task productivity (the extent to which an application improves the user’s output per unit of time); task innovation (the extent to which an application helps users to create and try out new ideas in their work); customer satisfaction (the extent to which an application helps the user ‘create value’ for customers); and management control (the extent to which the application helps to regulate work processes and performance). Although their model rests on positivist assumptions (i.e. it assumes an objective reality ‘out there’ that can be measured and whose behaviour can potentially be predicted), Delone and McLean emphasised (drawing implicitly on contingency theory) that it should not be used in a simplistic, deterministic way, as different systems will have different independent variables that impact on the dependent variable.

FIGURE 1.

The Delone–McLean model of information system success. Adapted with permission from Delone WH, McLean ER, Information systems success: the quest for the dependent variable, Information Systems Research, volume 3, number 1, March 1992. 22 Copyright 1992, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences, 5521 Research Park Drive, Catonsville, Maryland 21228, USA.

A 2010 review by Holden and Karsh of the applicability of the TAM in health care considered 16 data sets analysed in over 20 studies of clinician use of health information technology (IT) for patient care across a range of settings. 24 Certain TAM relationships (e.g. between perceived usefulness and the behavioural intention to use) were consistently found to be significant, whereas others (e.g. between perceived ease of use and behavioural intention to use) were inconsistent. The authors concluded that TAM predicts a substantial portion of the use or acceptance of health IT, but that the theory may benefit from several additions and modifications – specifically, with more attention to norms and beliefs of potential adopters of the technology.

A citation track of Davis’ original paper and Holden and Karsh’s later review showed that hundreds of empirical studies of user resistance to technology have been based on the TAM and that several dozen of these relate to ICTs in health care. 25–31 These studies invariably conceptualise the individual user of an ICT as a rational actor who seeks control over his or her work and weighs up constructs such as ‘usefulness’, ‘ease of use’ and the ‘costs’ and ‘benefits’ of change. Indeed, most such studies implicitly or explicitly combine the TAM with the Theory of Planned Behaviour. 32 They depict user resistance as an individual deficit, usually comprising a combination of parochial self-interest, misunderstanding, lack of trust, a belief that change is worthless and low tolerance for change,33 and emphasise measures through which resistance (thus defined) can be overcome – for example, via ‘engagement’ activities, incentives or punishments, firm leadership of the change project and ensuring that staff feel ‘in control’ during implementation. 34 All place a central emphasis on the individual user of an ICT, and all see user acceptance – and its converse, user resistance – as a key focus of enquiry (especially in explaining ‘failed’ ICT projects).

One author in this tradition articulated the problem of resistance thus:

. . . the major challenges to system success are often more behavioral than technical. Successfully introducing such systems into complex healthcare organizations requires an effective blend of good technical and good organizational skills. People who have low psychological ownership in a system and who vigorously resist its implementation can bring a ‘technically best’ system to its knees. However, effective leadership can sharply reduce the behavioral resistance to change--including to new technologies--to achieve a more rapid and productive introduction of informatics technology.

p. 1135

As the following sections show, many researchers have rejected such overt behaviourist framings. However, this section has shown that un-nuanced and uncritically pro-innovation applications of the TAM remain popular in some parts of the research literature. In such studies, the adoption and use of new technologies is seen as a necessarily positive step linked to the promise of greater procedural efficiency (and, implicitly, clinical effectiveness). In such traditions, research has assumed a ‘rational actor’ and been directed mainly at ‘overcoming resistance’ using behaviourist methods. Reflecting this rationalist emphasis, policy measures for introducing ICTs in health care often focus largely or exclusively on ‘overcoming [individual] resistance’ (e.g. see the Department of Health’s consultation36).

Multilevel models of resistance to information and communication technologies

A number of authors have extended the focus of the TAM by nesting it within a multilevel conceptual framework. Sabherwal et al. ,37 for example, propose context-related constructs (top management support for the system, facilitating conditions); user-related constructs (user experience with an information system, user training, user attitudes, user participation in the development of the system); and system constructs (system quality, perceived usefulness, user satisfaction, system use).

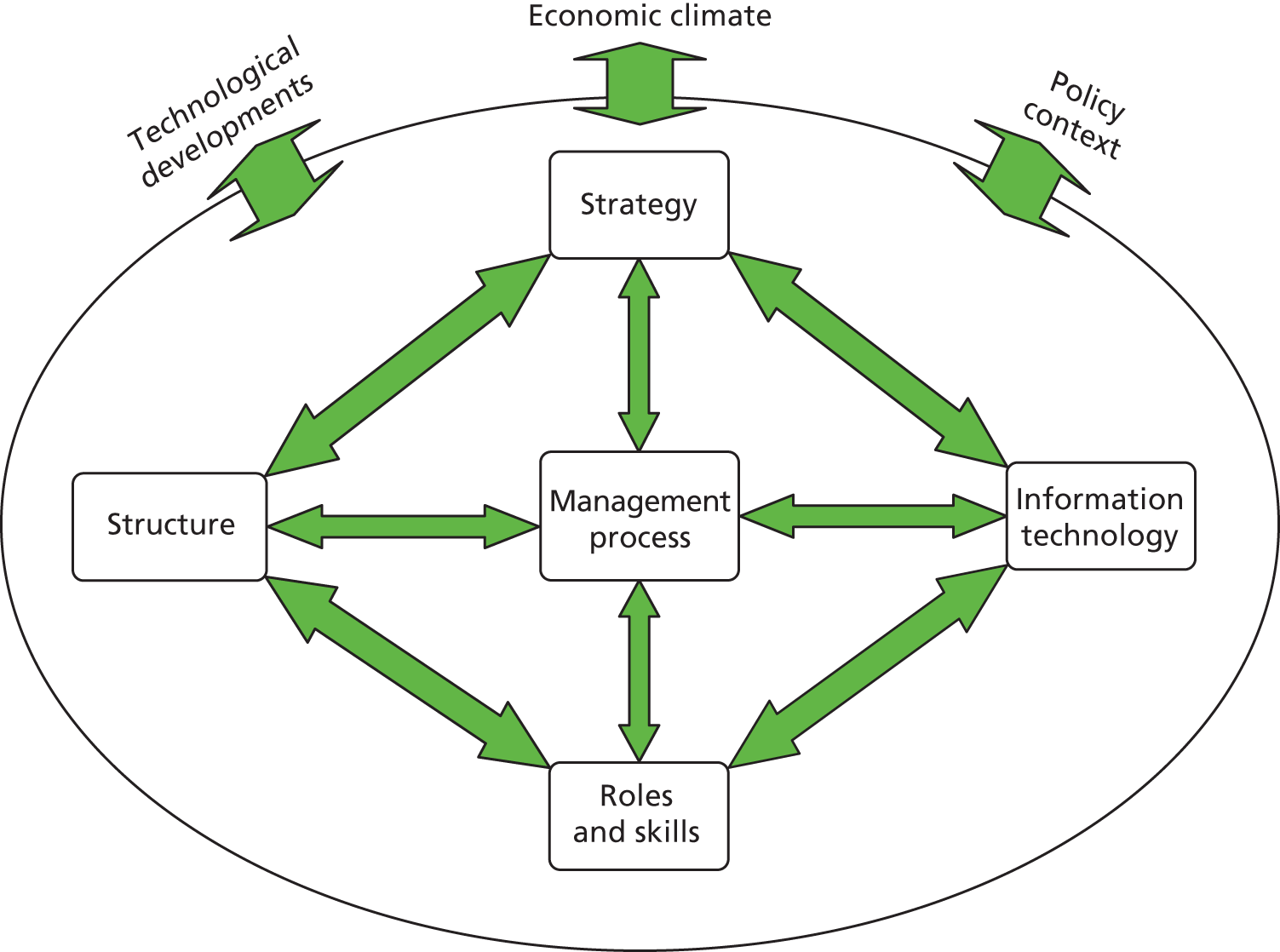

Yusof et al. 38 suggest that the Delone–McLean model lacks attention to certain factors that are particularly important in the healthcare setting – specifically, the ‘soft’ human and organisational factors such as culture, buy-in and so on. They offer a model of ‘fit’ between information systems, organisational factors, and external influences (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

‘Fit’ between information technology, internal organisation factors and external factors. © 2014 IEEE. Reprinted and adapted, with permission, from Yusof MM, Paul RJ, Stergeoulas L. Towards a framework for health information systems evaluation. HICSS ’06 Proceedings of the 39th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. IEEE Digital Library; 2006. 38

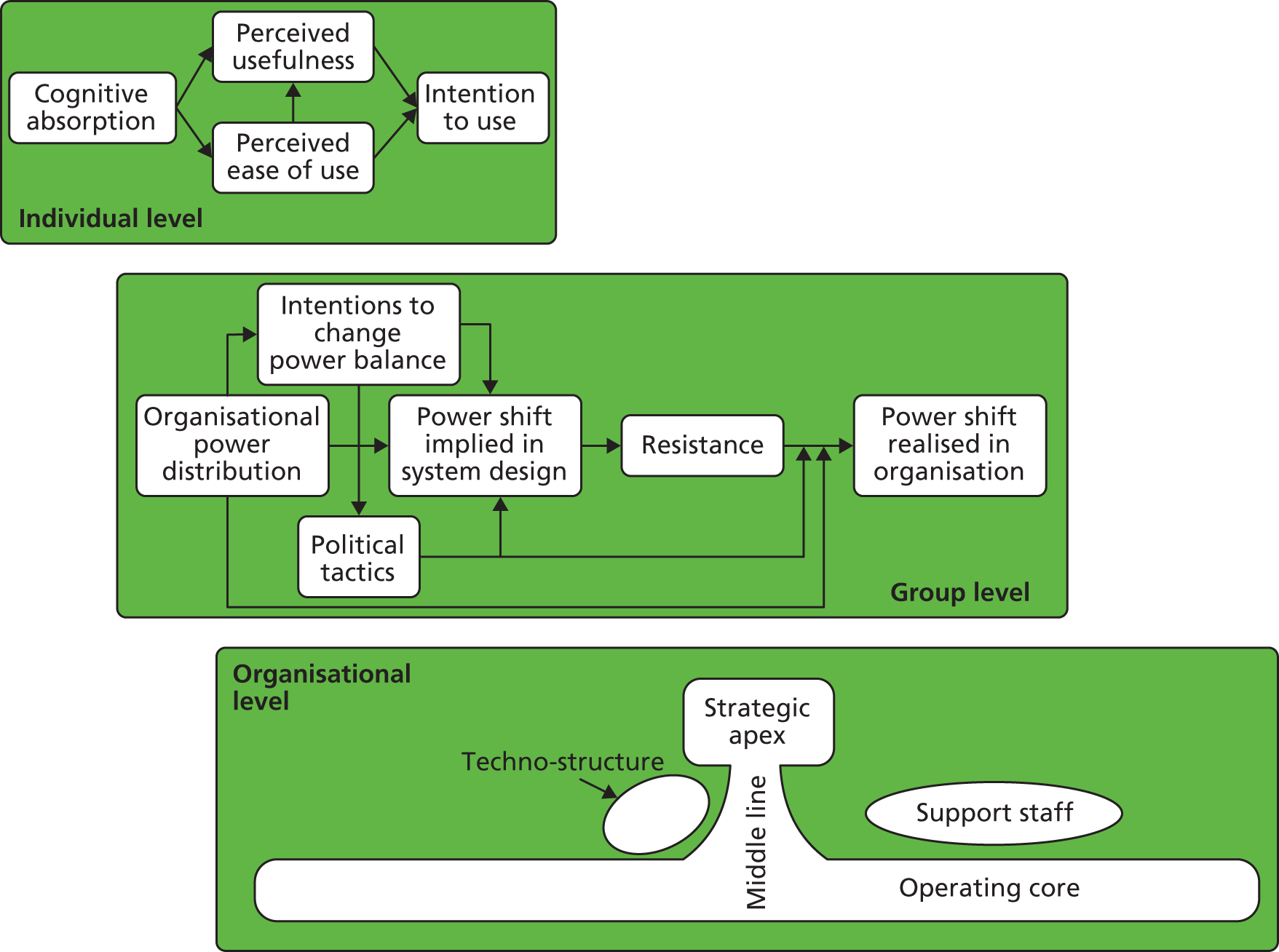

Based on a series of studies of the differing fortunes of ICT systems in different hospitals,39–41 an interdisciplinary group of researchers developed a ‘triple-level’ model of resistance comprising individual (people’s perceptions of the technology), group (the extent to which the new system reinforces or threatens a group’s power base) and organisational (the extent to which the innovation aligns with organisational strategy and goals). This model is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Triple-level model of information system implementation, based partly on Markus. Adapted with permission from Lapointe L, Rivard S, A triple take on information system implementation, Organization Science, volume 18, number 1, 2007. 41 Copyright 2007, the Institute for Operations Research and the Management Sciences, 5521 Research Park Drive, Catonsville, Maryland 21228, USA.

In this ‘triple model’, resistance is seen not simply as a psychological deficit (obstinacy, indolence, ignorance and irrational fear of change) that needs to be overcome (e.g. via top management mandate or the psychological tactics for increasing engagement). Rather, it is a phenomenon that develops over time as users interpret the alignment (‘fit’) between a new technology and individual, group and organisational context. According to this model, when resistance generates conflict and consumes time and attention, it tends to have negative impact, but resistance may also have a positive impact when it stops organisations from investing in systems that would lead to losses in productivity and stress among staff. This is true of any organisation, but Lapointe and Ricard suggest that it may be particularly apposite in health care, where ‘fit’ between an information system and the internal properties of the organisation may be particularly poor.

While this stream of research marks an important step forward from individual-focused models, it remains uncritical of the place of technology in health care and is relatively uninterested in the external forces (political, economic, technological, professional) that give rise to ICT programmes or in the subtle but potentially important ways in which ICTs may influence the nature of clinical work and the quality of the clinical interaction.

Interactional models of resistance: the sociotechnical perspective

Back in 1983, Lynne Markus published a classic review paper in a US management journal of barriers to implementation of information systems in organisations. In it, she divided theories and models into ‘people-determined’ (resistance is explained by people’s personalities, goals, capabilities and so on); system-determined (resistance is explained by features of the technology itself and how it is implemented); and interactional (resistance is explained by what we would now call sociotechnical issues, i.e. the interaction between people and technologies). 42 ‘People-determined’ theories, said Markus, depicted the solution to resistance in terms of education, training, incentives, policies and user participation (to achieve commitment). ‘System-determined’ theories saw the solution in terms of better technical and ergonomic design, better protocols and procedures, and user participation (to achieve better design). Interactional theories suggested that the organisational problems should be addressed before the system is introduced (or even designed), and that the relationships between users and designers were all-important.

At around the same time as Markus’s paper on ‘Power, Politics and Information Systems’ was published in the USA,42 British researchers based at the Tavistock Centre in London, UK (which specialises in the study of organisational dynamics from an interpersonal perspective), were developing sociotechnical systems theory. This proposes that technologies and work practices are best codesigned using participatory methods in the workplace setting, drawing on such common-sense guiding principles as staff being ‘able to access and control the resources they need to do their jobs’, and insisting that ‘processes should be minimally-specified (e.g. stipulating ends but not means) to support adaptive local solutions’. 43 Sociotechnical theory frames resistance to ICTs in terms of poor fit between the micro-detail of work practices and the practicalities of using technology.

Sociotechnical theory, developed in the 1980s, has more recently been taken forward in a number of ways. It inspired the interdisciplinary field of inquiry known as CSCW, in which one key concept is the social–technical gap. 44 A fundamental tenet of CSCW is that the interaction between people and technologies in the workplace is, with few exceptions, far more complex than would initially appear. A key reason for this, argued Ackerman, is that there is a gap between the nuanced, flexible and often unpredictable nature of human activity and what it is possible to deliver technically. 44 This is an inherent problem and can probably never be fully ‘designed out’. It links to a more general mismatch between formal work procedures (as in a manual) and the informal routines that actually occur. Grudin, cited by Symon et al. ,45 put it thus:

Work processes can be described in two ways: the way things are supposed to work and the way they do work. Software that is designed to support standard procedures can be too brittle

p. 2545

Technical solutions, argue the CSCW community, tend to be designed to align with an idealised, formal map of work processes, which may bear limited relation to what actually happens (especially in non-standard and emergency situations). Two partial solutions to this problem are recognised by CSCW: articulation and co-evolution. Gerson and Star (cited by Goorman and Berg46) define articulation as follows:

All tasks involved in assembling, scheduling, monitoring and co-ordinating all of the steps necessary to complete a production task (patient trajectory). This means carrying through a course of action despite local contingencies, unanticipated glitches, incommensurable opinions and beliefs or inadequate knowledge of local circumstances. Every real world system is an open system . . . No formal description of a system (or plan for its work) can thus be complete . . . every real world system thus requires articulation to deal with the unanticipated contingencies that arise. Articulation resolves these inconsistencies by packaging a compromise that ‘gets the job done’ that is, that closes the system locally and temporally so that the work can go on.

p. 2046

‘Articulation’ includes both temporal co-ordination (sequencing the inputs of different actors over time) and spatial co-ordination (ensuring that the right people and artefacts are in the right place). ‘Co-evolution’ refers to the parallel and reciprocal evolution of technologies and work roles or routines. 44,47 It might be a largely unintended consequence of introducing a technology (i.e. it is inadvertently found that work roles and practices have to change), or there might be a deliberate plan for such evolution to occur (i.e. the technology is introduced along with a plan for new roles and routines). This begs the question of when the introduction of a technology can justify prospective job redesign and when it is better for technologies to be closely designed around people’s current jobs. As Pratt et al. 48 put it:

At one extreme, developers carefully design the application to fit the specific work practices of its users. Under this model, users do not change their work practices at all, because the technology accommodates their specific needs and work styles. The alternative extreme is to reshape the processes of the organization around the new application. [. . .] most applications fall in a middle ground: a mixture of supporting some existing work practices and attempting to change others.

p. 13348

It follows from these principles that ‘resistance’ to ICTs by staff in any organisation may be explained by the subtle contingencies – and inherent messiness – of work. One of the leading researchers to apply these principles to the healthcare setting is Marc Berg, who also draws on ANT (see Actor–network theory, below). Berg talks, for example, of ‘growing’ rather than ‘building’ information systems in health care and working to achieve synergy between three fundamental (re)design tasks: the technical system, the primary work process (e.g. clinical care), and the secondary work process (e.g. audit, management). 49 It is perhaps worth commenting that critiques of the NPfIT have (naively, in our view) tended to emphasise poor planning, poor contracting and lack of vision but not the inherently organic nature of information system design. 4

In a contrasting development of sociotechnical theory, Brown and Duguid50 have shown how technologies in the workplace are embedded in networks of social relationships that make their use meaningful. The detail of how to use, adapt, repair or work round technologies is learned through membership of a community of practice; this social infrastructure, local and specific to an organisation, strongly influences whether or not and how particular technologies ‘work’ in particular conditions of use.

Another broadly interactional theory of technology adoption in organisations is Carl May’s normalisation process theory, which he developed to explain the uptake (or non-uptake) of ICTs, especially telemedicine, in healthcare organisations. 51 This theory comprises four constructs: interactional workability (to what extent does the technology fit with the micro-environment of the clinical encounter?); relational integration (to what extent does it fit with the network of relationships within which the clinical encounter sits, and, especially, how does it impact on issues such as interpersonal trust?); skill-set workability (to what extent does it fit with the formal and informal division of labour between staff?); and contextual integration (to what extent does the organisation understand the innovation and agree to allocate material and human resources to its implementation?).

An interview study of NHS clinicians and managers using normalisation process theory identified that Choose and Book referral software was unpopular and little used, and suggested that the main barrier to uptake was poor interactional workability, defined as ‘the impact that a new technology has on interactions, particularly . . . consultations’; in contrast, Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS; a digital image storage and retrieval package), was popular and widely used because it scored highly on all of the four constructs listed in the previous paragraph. 19 Normalisation process theory is presented very explicitly as a ‘rational’ model for considering the uptake (and non-uptake) of complex technology-based interventions. 52 The theory recognises the complex nature of healthcare work and the human relationships on which that work depends, but it lacks a theoretical perspective on the technology itself and remains explicitly couched in assumptions of ‘rationality’ rather than in normative concerns about what constitutes good clinical practice. 52

Critical studies of organisational power relations

Some researchers, especially those aligned with critical management studies, have emphasised the network of power relations in which the introduction and use of technologies is embedded, and especially how ICTs affect domination and power struggles in organisations. The use of ICTs to monitor work, they suggest, inevitably opens the performance of organisational members to administrative surveillance – and it makes them aware that managers may be checking up on them. Drawing on Foucault’s powerful metaphor, Doolin53 describes the impact of this ‘panopticon’ in the healthcare setting:

. . . representational, inscriptional and computational techniques associated with information systems render individuals calculable, and thus knowable and governable. Some activities are given existence and attention, while others remain unrecognized, enabling managerial knowledge to make stronger truth claims and engendering compliance in those subject to such scrutiny.

p. 34553

In such situations, staff may have only limited possibilities to resist the introduction of pervasive ICT systems. Indeed, Doolin suggests that, as suggested by Foucault’s theory of governmentality, staff may come to internalise and hence fail to question the managerialist discourse that is built into, and perpetrated by, the system.

Others, however, have proposed that in such situations, resistance may take subtle forms. In a paper called ‘The failed panopticon’, for example, Timmons describes how hospital managers colluded with nurses to resist a new information system for monitoring nursing work. 54 The system’s abstracted work plans, while in theory producing ‘action at a distance’ (i.e. the quantification and control of nursing work), were recognised by managers as failing to reflect the real work of nursing. When the system appeared to reflect poor performance on a particular ward, the lead nurse was given no more than a sham telling-off by senior managers.

In an ethnographic study in UK general practice, Winthereik55 studied how general practitioners (GPs) managed two potentially conflicting agendas: accountability to external scrutiny [e.g. via the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) and other government-imposed audits and incentive schemes]; and professional autonomy (the need to feel in control of their own clinical practice). Many GPs were largely negative about the new external controls and expectations, and felt that the standards against which they were being judged were arbitrary and sociopolitically driven. Despite this, they engaged actively with accountability tools (e.g. by complying with the use of codes through which their work was being audited), and they were keen to make their work visible and demonstrate good performance against the standards. Winthereik concluded that there was no simplistic zero-sum relationship between being rendered accountable and retaining clinical autonomy. Rather, accountability and autonomy appeared to co-evolve such that new, positive forms of autonomy emerged alongside the accountability agenda.

There is a small but important literature that uses a critical feminist lens to study resistance to new technology in nursing and midwifery. Henwood and Hart,56 for example, conducted a large, multisite case study of the introduction of electronic records in maternity units from the perspective of midwives. They found that in fewer than half of the units had midwives been consulted at all about the nature of their work or the design of the IT system. In interviews and focus groups, there was a marked disinterest among many midwives, who saw the new system as something introduced by management, ‘boring’, or something they might engage with when ‘it’s all sorted out’. This resistance was palpable and widespread; midwives appeared to be actively participating in their own exclusion by defining the electronic record as part of a techno-medical world, imposed by (male) doctors, marginal to the ‘real’ work of midwifery, and detrimental to client care. One interviewee is quoted thus:

I just think it would totally ruin the whole point of being a midwife. You’re supposed to be with the woman, looking after the woman. To have a computer in the corner, where you’re away and typing into it, it’s just not part of what having a baby’s all about, to me. Because that would take over what you’re actually there for, I’m sure . . . So I wouldn’t want there to be any more technology involved – it’s supposed to be a normal process. So all this hi-tech stuff is just not what I think it’s about.

Senior midwife; p. 25756

Having first positioned the ICT as ‘masculine’ and as interfering with the ‘normal’ process of birth, this interviewee went on to distance herself (and midwifery in general) from the low-status administrative work of ‘data entry’. In her symbolic world, technology was either about ethereal, unreal aspects of care or not about care at all. This example of resistance from feminist nursing studies has some resonance with our own findings, described below.

Actor–network theory

One increasingly popular approach to incorporating the material properties of technology in a sociological analysis of ICTs is Latour’s ANT,57 which shares some of its intellectual roots with CSCW (see Interactional models of resistance: the sociotechnical perspective). We have described the key concepts and assumptions of ANT relevant to this topic in more detail elsewhere. 58 Briefly, ANT considers networks that are made up of both people and technologies. A key focus is what people and technologies become as a result of their position in a network, and the power that emerges from dynamic configurations of human and non-human actors. A nurse who takes a job in a 24-hour call centre dealing with ‘emergency’ calls from the public takes on particular characteristics and develops particular skills; his or her role is shaped, enabled and constrained by the (human and technological) properties of the telephone network – and also by the other technologies to which the system is connected (e.g. access to the electronic records of the patients who call in). In such a situation, the electronic patient record becomes a part of this particular enactment of unscheduled care.

Critics of ANT are quick to point out that technologies do not have agency, but its protagonists depict agency as a product of the network, not as something internal to either a person or a technology. In Berg’s59 words:

The elements that constitute these networks should not be seen as discrete, well-circumscribed entities with pre-fixed characteristics. Rather, those entities acquire specific characteristics, roles and tasks only as part of a network. A ‘physician’ is only a ‘physician’ in the modern western sense because of the network of which s/he is a part and which makes his/her work and responsibilities a reality. [. . .] Because of this tight interrelation between elements in a network, the introduction of a new element or the disappearance of an element (as when a hospital stops training junior residents) often reverberates throughout the healthcare practice.

p. 8959

Actor–networks (that is, networks of people and technologies) are typically highly dynamic and inherently unstable. They can be stabilised to some extent when people, technologies, standards, procedures, training, incentives and so on are aligned. When introducing a new technology, this alignment is achieved (or, at least, attempted) through what Latour called ‘translation’, which involves the four stages of problematisation (defining a problem for which a particular technology is a solution), interessement (getting others to accept this problem-solution), enrolment (defining the key roles and practices in the network), and mobilisation (engaging others in fulfilling the roles, undertaking the practices and linking with others in the network). 60

Studies of resistance to ICTs from an ANT perspective tend to focus on two main issues: the efforts made by human actors to achieve (or thwart the achievement of) particular alignments of people and technologies; and the tendency of the inbuilt properties of software (e.g. access controls or pull-down menus) to shape and constrain the possibilities open to organisational actors. 61 While other research traditions have also addressed these issues, ANT offers a novel way of theorising them. Efforts made by groups of actors to influence the codes, architecture and algorithms inscribed into particular ICTs, for example, are interpreted as political moves rather than simply attention to clinical and technical standards. 62–64

Latour has suggested, for example, that if usage of a new technology that aligns with designers’ intentions is a ‘program’, resistant individuals seek to mobilise others into enacting and stabilising an ‘anti-program’ (in which the technology may be used differently for different purposes), and this wider program–anti-program dynamic across the network should be the focus of analysis when studying resistance to any technology. 65

Studies in the ANT tradition have also shown that the tension between standardisation (which helps to stabilise the network) and contingency (which reflects and responds to local needs and priorities) can never be resolved once and for all; rather, it must be actively and creatively managed – and this gets harder as the network gets bigger. 62,66,67 In this framing, ‘resistance’ may simply reflect the practical impossibility of resolving the tension between standardisation and contingency. Hanseth and Monteiro,68 for example, have used ANT to consider the institutionalisation of technology standards – whether in health care or in other fields such as transport, telecommunications or education. Infrastructure is built on an installed base (hardware and software); the (increasingly) large installed base attracts complementary production and makes the standard cumulatively more attractive. As the installed base expands, complementary products and components emerge and this in turn increases the credibility of the standard among the key groups of human actors on which its adoption and sustainability depends. This promotes adoption, which further increases the size of the installed base. Thus, a particular network of technologies and the people who (necessarily) use them emerges and becomes progressively more stable.

Actor–network theory’s framing of resistance is perhaps best illustrated with a detailed example. Constantinides and Barrett69 drew on ANT to address what they called ‘networks of power’ [‘the close interdependencies between institutional arrangements, people, ICTs, and work practices and how these mobilize (spread and extend) each other’s strength and durability, for example, how ICTs can become standardized in organizational practices’ (p. 77)] in the introduction of a region-wide health information network in Crete. They were interested in how particular tools and activities become ‘filtered’ in the habits and routines of different communities, either by becoming integrated into everyday work practice or by being discarded as impractical. The ‘surviving’ tools and activities would become parts of large, sociotechnical systems and influence, in turn, other tools and activities. They were also interested in ‘body politics’ – that is, how different institutions, people and technologies are brought together to form different versions of the diseased body and exercise politics through different rules and resources. 70

The authors interviewed senior managers and IT professionals from the private IT company that initiated the project, healthcare professionals, and senior management from the regional health authorities. They found that political negotiations between these parties were complex and protracted, with multiple competing efforts at problematisation. One early move by the IT company was to recruit three GP enthusiasts (who were already high users of other IT solutions and champions for electronic records) and, through them, engage a ‘community of users’ of fellow GPs (what Latour would call ‘interessement’ and ‘enrolment’). This positive move was to some extent outweighed, however, by the limited interest of the Ministry of Health in the project (hence use of the system remained voluntary for GPs) and also by a large denominator of undertrained GPs whose interest in the project was at best lukewarm (lack of enrolment). Despite having recruited some influential clinical champions, the company’s power was limited to offering ‘free’ computers; it did not extend to enforcing the use of these technologies. The demise of the system was linked to two key events: an acrimonious intellectual property rights dispute between the IT company and a GP who felt that he had contributed to the design of the system, and a key clinical champion who reverted to using paper records.

At the time of that study’s publication, the actor–network was fragile and the authors were unsure whether the electronic record system (which was widely seen as ‘state of the art’ and had won an international e-health award) would be taken up further or abandoned. They conclude (a) that networks of power are key to success – and especially that an IT company should seek to mobilise the enthusiasm and influence of its clinical user base; (b) that large-scale ICT innovation requires access to heterogeneous resources, the control of which can externally influence the process of translation; and (c) that the network is fragile and dynamic [‘large-scale ICTs have distributed and multiple effects on participant organisations and need to be managed over time as use may be transformed into nonuse, resources initially gained may be later lost, and collaboration with key stakeholders may turn into conflict’ (p. 89)]. This example illustrates how individual ‘resistance’ to a particular ICT can be conceptualised as emerging as a product of the actor–network rather than as originating within the person’s ideas, beliefs, competences and so on.

As we have argued previously, some concepts from ANT, notably the notion of a fluid and potentially unstable network involving people and technologies, are extremely useful in theorising large-scale ICT systems in health care. 58 However, ANT does not include a sophisticated theory of either human agency (e.g. embracing a detailed analysis of what actors ‘know’ and how they assess particular small-scale situations) or the macro social structures in which human action is nested. The quote from Berg earlier in this section, for example, suggests that a physician is a physician ‘only’ because of his or her position in the sociotechnical network – a framing that minimises the importance of such things as professional identity, values and virtues (what some sociologists would call ‘agency’). In the next section, we consider an alternative theorisation of people, society and technology, in which the concepts of social structure and human agency are key.

Giddens’ work on structuration, modernity and technology

The theory of structuration links the macro of the social environment (‘social structures’) with the micro of human action (‘agency’) and considers how this structure–agency relationship changes over time as society becomes ‘modernised’. 71 On the one hand, agents are influenced by the context in which they operate (and also, historically, by the contexts in which they were brought up, educated and trained). On the other hand, human action has consequences (intended and unintended) that influence (and, therefore, gradually change) the external social context. People can be thought of as ‘social actors’ who are, to a greater or lesser extent, knowledgeable and reflexive. They contemplate any action by taking account of social structures such as norms (‘structures of legitimation’ – what they see as reasonable and ethical, such as assumptions about the nature of clinical excellence that underpin professional practice), meaning-systems (‘structures of signification’ – the symbolic meanings and significance which they attach to people, experiences and artefacts) and rules and regulations (‘structures of domination’ – what they see as following protocol or obeying external authority). 71

In developing structuration theory, Giddens sought to bring together two apparently contradictory traditions within sociology: on the one hand, that of interpretative scholars such as Goffman and Garfinkel, who emphasised human interpretations and action, and on the other hand, the work of structural sociologists such as Durkheim and Marx, who were more interested in the wider social forces that shape and define society. Far from being mutually exclusive or incommensurable, proposed Giddens, these two perspectives are intimately and dynamically related: structure shapes agency, and agency, in turn, shapes structure.

Giddens’ application of structuration theory focused mainly on four large-scale systems: the world capitalist economy, the international division of labour (and the role of industrialisation in this), the world military order (including the industrialisation of war), and the nation-state system (including the modern revolution in administrative techniques, surveillance and the control of information). 72 The system of medical practice, supported by technological artefacts and shared guidelines and standards, represents another large-scale social system which, while operating semiautonomously and to its own logic, also depends on and interfaces with these four systems.

Giddens also proposed that, as a result of modernity and globalisation, connections between different social contexts become networked, such that local happenings are shaped by events on the other side of the world, and vice versa. Globalised disease surveillance networks linked to national public health systems allow for co-ordinated international responses to potential pandemics, but such responses – typically dictated by distant committees – inevitably restrict the freedom of individuals to attend work, school or leisure activities locally. Similarly, guidelines and protocols developed by distant committees (and, increasingly, standardised at national or international level) restrict the capacity of clinicians to tailor their practice to local needs and circumstances.

Giddens proposed that humans, both individually and collectively, continually reflect on their predicament and try to control their future. However, because they are unable to control the reflexive responses of others, they generate new forms of risk and uncertainty, from financial instability to the threat of nuclear accidents and environmental catastrophe. To this list, we might add the inability of doctors to control the exponential increase in ‘lifestyle’ diseases linked to obesity and inactivity, the failure to date of the expanding industry of ‘risk scores’ (designed to identify high-risk individuals at a sufficiently early stage to intervene and prevent disease) to translate into tangible and scalable gains in health or life expectancy, and the numerous examples of large-scale ICT programmes in health care that have generated recurring technical glitches and operational confusion rather than the predicted efficiency gains. All these disappointments undermine trust in the ability of globalised institutions (the economy, nation-states, industry, the military – and medical science) to create the structural conditions for what Giddens called the ‘ontological security’ of individuals. 73

Social practices (everything from parenting to conducting a job interview or a clinical consultation) depend in part on actors’ personal knowledge of the local context and the network of relationships in which they live and work. Social structures are reproduced because (and to the extent that) people know how to ‘go on’ in a particular social setting. However, in the modern world, social practices become disembedded as a result of the twin social forces of modernity and globalisation, which produce (among other things) ‘expert systems’ – defined by Giddens as ‘[a] system of technical accomplishment or professional expertise that organize[s] large areas of the material and social environments in which we live today’ (p. 27) – that manipulate abstract, impersonal knowledge using new technologies. 74

Social practices are now, in large part, removed from the immediacies of context, with the relations they involve typically being stretched over large tracts of time and space. Local experiences and events are shaped by processes taking place on the other side of the world, and vice versa. These are processes, moreover, that are primarily impersonal and abstract. [. . .] Each of these abstract systems plays a part in coordinating social relations between distant and absent others. Local contexts are cross-cut and ‘emptied out’ by the power and authority of these stretched relations.

pp. 449–5075

A closely related sociological concept is that of distanciation, originally defined by Giddens as ‘[t]he stretching of social systems across time-space, on the basis of mechanisms of social and system integration’ (p. 377). 71 By ‘system integration’, Giddens is referring to the different ways in which the parts of a social system are combined and co-ordinated – activities which increasingly happen at a distance and on the basis of technologically mediated and abstracted forms of information. 76 Global disease surveillance networks replacing (or substantially augmenting) the localised monitoring and management of disease outbreaks are a good example of distanciation: in the 19th century, public health physician John Snow plotted cases of cholera by hand on a street map and thereby traced their source to the Broad St. water pump; removal of the handle of that single pump successfully curtailed the outbreak. Today’s GP or public health physician typically takes action in response to an e-mail from an authorised source that conveys the recommendations of senior experts, derived in turn from calculations undertaken on regionally, nationally or internationally-aggregated data sets. While these data sets are built from locally collected data, the direct link between documenting local cases and taking local action is replaced with an indirect one based on abstracted and distantly processed data.

Another social change characteristic of modernity is the replacement of reason with rationality. As Sayer77 (drawing on various scholars including Aristotle) has argued, rationality is distinguishable by its formal and instrumental character, its abstraction from concrete situations, and its focus on means rather than ends. For example, it is concerned with identifying the most efficient method of getting a job done (‘doing the thing right’) but is not centrally engaged with the appropriateness and reasonableness of the job itself (‘doing the right thing’). In contrast, phronesis (practical reason) is characterised by its concern with the concrete and the particular; its practical, embodied and tacit character; its focus on ends rather than means (in particular, whether the ends are ethically justified); and its focus on people rather than things.

A reasonable person is someone who takes account of the specificities of the people they interact with, their particular capacities, needs and vulnerabilities, as well as other specificities of the situation. [. . .] When we talk of having ‘reasonable expectations’ of people, we mean expectations that take into account their particular characteristics, constraints and resources, including their vulnerability and fallibility, and ‘reasonable behaviour’ also suggests some degree of emotional sensitivity to others. Further, to be a reasonable person is to be able to imagine things from other people’s standpoints – in other words, to be willing to take the standpoint of the other. [. . .] Hence to call someone ‘a reasonable person’ in such contexts suggests an ethical judgement of them.

p. 65, emphasis in original77

Despite the increasing tendency for expert systems to ‘empty out’ the significance of local events and relationships by invoking general rules that apply everywhere and anywhere, the processes of system integration must necessarily be animated by local actors working in specific local situations and dependent on local contextualities. These will include physical and material constraints (such as the availability and cost of broadband) as well as symbolic ones (such as the extent to which doctors are trusted in a particular society). While the general rules governing the expert system might reflect the impersonal logic of rationality, local actors will, to a greater or lesser extent, seek to act reasonably – that is, ethically and practically with regard to the situation at hand and their (perceived) obligations towards their fellow human beings.

Giddens famously said very little about technology in his original formulation of structuration theory apart from recognising that technologies are key components of social systems, and particularly of expert systems. Other scholars, particularly in the information systems tradition, have attempted to theorise technology from within structuration theory. Notably, Barley proposed that the introduction of a new technology provides an ‘occasion for structuring’ – that is, it creates new possibilities for changing the taken-for-granted routines and patterns of interacting (‘scripts’) between actors, potentially allowing new institutional logics (i.e. patterns of interacting that are culturally and cognitively taken for granted) to emerge. 78 However, as Barley emphasised, the technology does not determine these logics since a key component of structuration is the interpretation that human actors place on the technology and the work they choose to do with it. Barley’s early work on the introduction of computerised tomography (CT) scanners in hospitals informed Orlikowski’s ‘technology structuration theory’, which considers how organisational actors, working collaboratively around common tasks, engage in a process of adapting the meaning, properties and applications of technologies to a particular context, and a parallel process of adapting the context to accommodate the technology. 79 Both Barley and Orlikowski are organisational scholars and so have focused their research efforts at the assimilation of technologies in organisations rather than considering issues of national policy.

In sum, structuration theory offers potential to analyse human action (including the use and non-use of technologies) as social practice, influenced by – and, in turn, influencing – the norms, meaning-systems and rules of a particular social system. It potentially allows us to study the fortunes of planned change efforts either as broadly aligned with prevailing social structures (and, in particular, with actors’ internalised norms, meaning-systems and rules) or as cutting across these structures and creating the preconditions for ontological insecurity.

Strong structuration theory

Whereas Giddens formulated structuration theory in a somewhat abstract way (e.g. focusing on ‘structure’ and ‘agency’ as theoretical concepts), Stones has sought to give the theory a more empirical slant in what he has called ‘strong structuration theory’, focusing on the interpretations and actions of particular people in particular circumstances, and especially on their assessment of particular situations and their efforts to act reasonably in those situations. 80,81

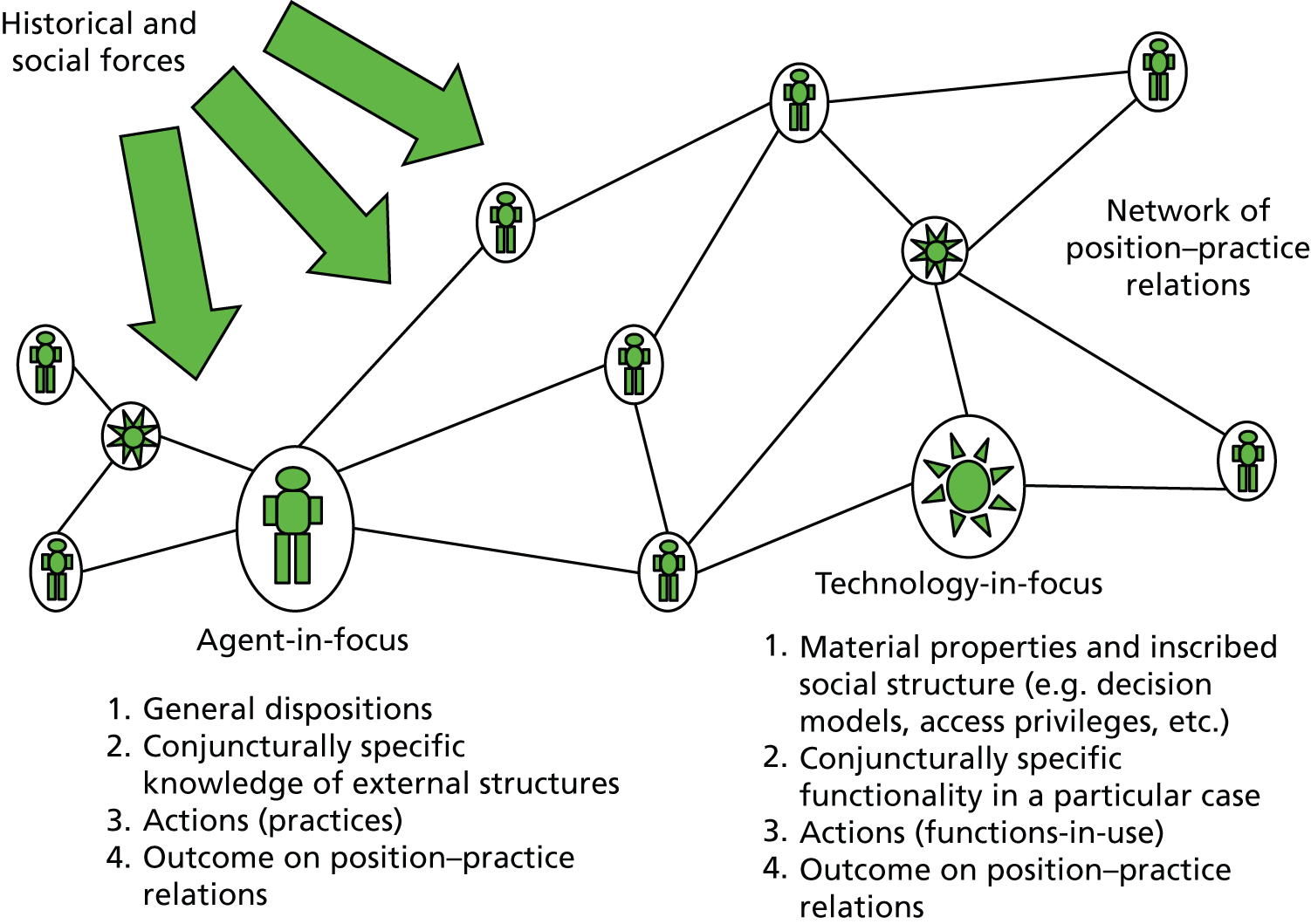

Strong structuration theory’s focus on empirical cases in which individuals are considered as situated in webs of networked relations (Figure 4) resonates with ANT’s focus on dynamic and unstable networks of people and technologies described in the previous section. However, in contrast with ANT’s ‘flat ontology’, SST holds that the recursive (i.e. mutually influencing) relationship between structure and agency remains a useful concept.

FIGURE 4.

Networks of position–practice relations along with technologies in SST. Reproduced with permission from Greenhalgh and Stones. 58

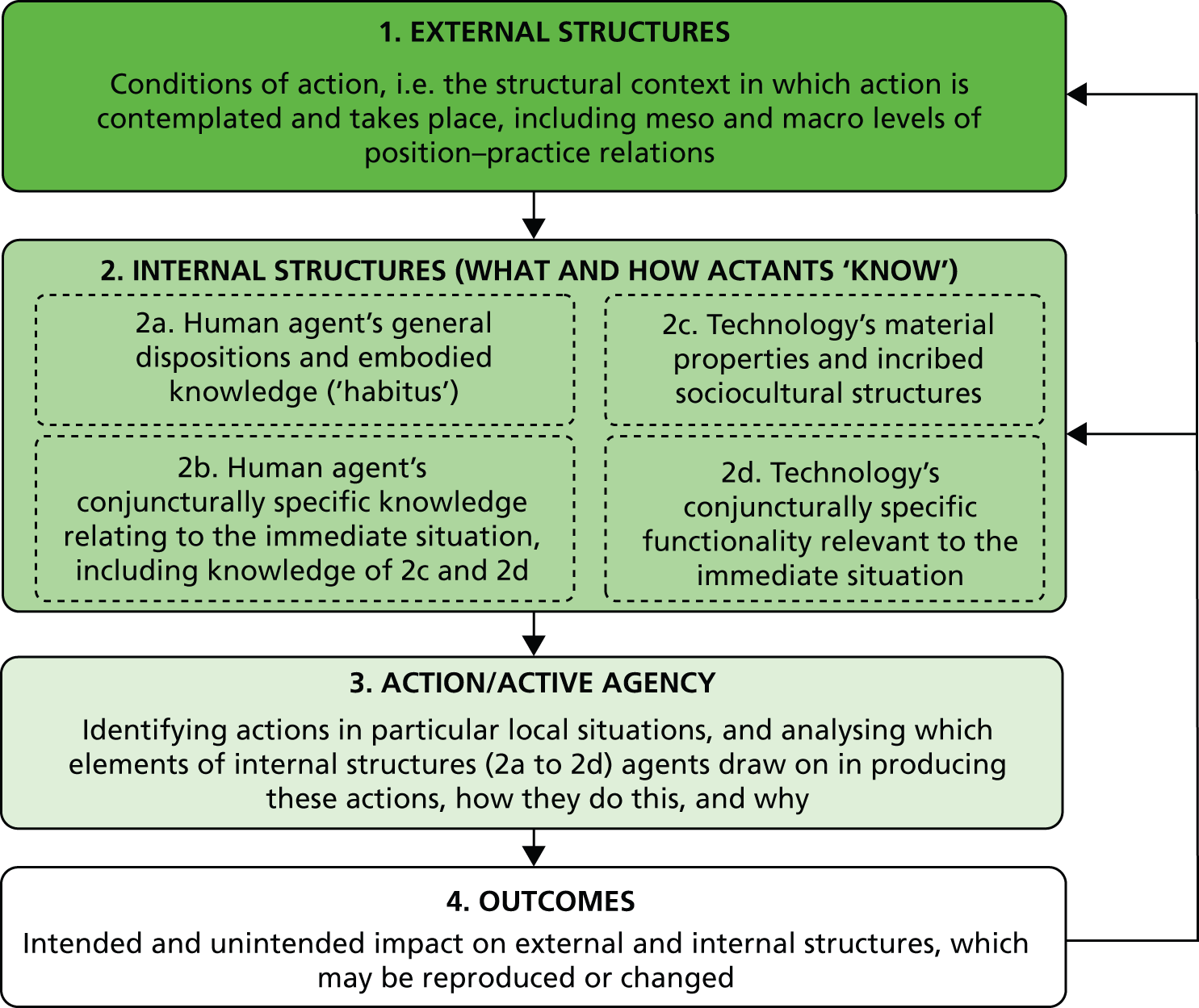

Stones’ quadripartite approach to structuration theory, depicted in Figure 5, considers not only external structures (the macro-level structures that form the contextual conditions of action in any situation) but also internal structures (what agents ‘know’, albeit sometimes imperfectly and even incorrectly, about the external world), actions (observed behaviour) and outcomes (how observed behaviour in a given scenario feeds back to reinforce and/or change internal and external structures). To get an empirical handle on the structure–agency relationship, SST considers the conjuncture (defined as a critical combination of events or circumstances), of which ‘the clinical encounter’ is one example.

FIGURE 5.

Stones’ quadripartite theory of structuration, adapted to encompass a technology dimension. Reproduced with permission from Greenhalgh and Stones. 58

Strong structuration theory proposes that external structures are mediated largely through position–practices (defined as a social position and associated identity and practice), together with the network of social relations that recognise and support it (‘position–practice relations’). Agents’ internal structures may be divided into:

-

general dispositions, which include such things as sociocultural schemas, discourses and world-views, moral and practical principles, attitudes, ambitions, technical and other embodied skills, and personal values – roughly what Bourdieu82 called ‘habitus’; and

-

particular (‘conjuncturally specific’) knowledge of the strategic terrain and how one is expected to act within it, based on one’s hermeneutic understanding of external structures.

Within a particular conjuncture, action occurs when the human agent draws actively and more or less reflexively on his or her internal structures.

To study active agency, SST incorporates theories from phenomenology (the study of agents’ shifting fields and horizons of action arising from the focused activity at hand83), ethnomethodology84 and symbolic interactionism (the study of the subjective meaning and interpretation of human behaviour85).

Strong structuration theory emphasises that while each of us brings generic capabilities, dispositions and strategic knowledge to any particular conjuncture, what we actually do in that situation will depend on a host of specificities including our horizon of action and particular features of context.

The healthcare setting is heavily institutionalised: behaviour in healthcare organisations is strongly influenced by such things as regulations and other governance measures, norms, professional codes of practice and deeply-held traditions (all of which are embodied and reproduced by human agents including clinicians, administrators and patients) rather than exclusively by business concerns like efficiency and profit. The agent’s knowledge of these institutional structures (in the language of SST, the ‘strategic terrain’) may be more or less accurate and more or less adequate. Outcomes of human action in any situation may be intended or unintended, and will feed back on both external and internal structures – either preserving them faithfully or changing them as they are enacted.

As we have argued previously, SST can be enhanced by selected concepts from ANT. 58 First, technologies and human actors might usefully be conceptualised as part of the same network, and both may be thought of as having a ‘position–practice’ in that network (see Figure 5). SST can accommodate ANT’s emphasis on studying the complex and dynamic alignments in the network, including efforts by commercial companies (marketing, lobbying) to influence uptake of technologies, coalition-building within and across stakeholder groupings, and local reinterpretation of objects-in-use. However, SST rejects ANT’s assumption of ‘ontological symmetry’ between people and technologies. Humans and technologies ‘act’ in different ways, and a technology can only ever have a limited and qualified form of agency. Secondly, SST can accommodate ANT’s notion that aspects of the social order can be inscribed in technologies and this may to some extent ‘freeze’ certain position–practice relations within the technology. Thirdly, human behaviour will be shaped and constrained by complex forces in the sociotechnical network and hence may in some senses be an ‘effect’ rather than a ‘cause’ of what we are studying, though SST contends that human agency cannot be reduced entirely to network effects. Indeed, from a SST perspective, what ANT theorists call ‘the sociology of translation’ (interpreting the moves of different actors as they seek to build and stabilise a network of human actors and technologies) is likely to be productively enhanced by considering agency as sited within the human actor rather than merely as a product of the network.

Technological orientations of structuration theory have only recently begun to theorise how the material properties of technologies are coconstituted along with the social practices in which they are used. 86 Conversely, ANT has been criticised for overemphasising the material aspects of technologies at the expense of the lived relationship between humans and material objects. 87 Dant’s notion of ‘material interaction’, informed by phenomenology, in which human agents meaningfully experience, perceive and manipulate objects to achieve a task, has some parallels with the notion of sociomateriality which Barley and Orlikowski’s group have latterly begun to embrace. 88,89 It also resonates with SST’s emphasis on how active agency occurs when the actor draws on phenomenological and embodied dispositions and capabilities (see boxes 2a and 2b in Figure 5).

Figure 4 summarises the broad conceptual model for considering ICT programmes, comprising a network of position–practices (humans and technologies), which evolves over time and is influenced by macro historical and social forces (which exist more or less independently of the agents on which a particular empirical study might focus), and they contribute to the external conditions of action in any given conjuncture. Social structures are embodied and reproduced by both human agents (when they use technologies for meaningful social action) and technologies (when external structures, built into the technology, are instantiated when humans choose to use the technologies – or find they cannot use them as intended).

Having developed the above adaptation of SST using insights from ANT, we drew up a provisional list of questions to guide the study of resistance to ICTs:

Macro-level questions

-

What is the prevailing macro-level context within which the (changing) social practice is undertaken and the ICT has been or is being introduced?

-

What does the sociotechnical network consist of (key people and technologies, position–practices, relationships)?

-

To what extent has stability of the network been achieved – and why?

Micro-level questions focused on specific conjunctures

-

Which human(s) and ICTs are ‘in focus’ in this conjuncture?

-

What are the relevant general dispositions of the human agent, and what does he or she know (perhaps imperfectly) about relevant external structures? In particular, how does he or she think other agents view the world; and what does he or she know or believe about the ICT?

-

What are the relevant material properties and inscribed social structures of the ICT(s)?

-

What does the human agent do (i.e. how do they draw on their general dispositions and conjuncturally specific knowledge to produce action)?

-

How do the social structures inscribed (deliberately or inadvertently) in the ICT enable, influence or constrain the human agent?

-

What are the consequences of the use or non-use of the ICT, and how do these feed back on the wider system?

These questions were subsequently refined and focused as set out in Chapter 2 (see Research questions) and also in the more specific questions outlined at the start of each main findings section.

Chapter 2 Aims, approach and research questions

Aims

Our aim was to help policy-makers and change agents move beyond the commonly used (but, we believe, impoverished) rational actor models of the (non-)uptake of ICTs and un-nuanced conceptualisations of clinicians’ resistance to them. We sought, through literature review and secondary analysis of data (collected for previous empirical studies by our team8–10,16,90–95) and building on our previous preliminary theoretical work to link SST and ANT,58 to produce a sociologically informed model that would explain ICT adoption and use. In particular, we sought to account for its non-adoption and non-use in certain social and organisational situations. Our starting position was the assumption that clinical work is a social practice, shaped and constrained by wider social influences including norms, meaning-systems and rules, and that ‘resistance’ to ICTs would be explained at least partially in terms of professionals’ ethically-motivated efforts to do their job well and deliver excellence in clinical practice – and that administrative staff in healthcare organisations were also driven, at least in part, by these ethical and professional concerns.

We wished to produce a multilevel model of resistance that unpacked this notion of excellence and which also incorporated the influence of institutional changes in the healthcare field; the meanings people attach to technologies in the workplace; the complex, situated and unpredictable nature of clinical work; the material properties and affordances of ICTs and how these create possibilities and limit what is possible for the user; and the potential for creative human action to overcome the limitations of technology and bridge the ‘model-reality gap’. We were particularly interested in how nationally mandated ICTs were adopted (or not) by local actors.

A normative anchor: what is excellence in clinical practice?

As the literature review above illustrates, many, but by no means all, previous approaches to ICTs in health care begin with the index technology and ask ‘is this technology being used by its intended adopters, and if not, how can we increase or optimise its use?’. Interactional models consider the fit between the technology, organisational routines and individual capability. ANT considers dynamic changes in, and stability of, the sociotechnical network. In this study, framed in SST, we sought to take a different starting point: the internal structures of human agents – in other words, what people know. By ‘know’, we include what they believe and what they value – and how these beliefs and values are influenced by past experience and by the norms, meaning-systems and rules of society described in the section on SST (see Chapter 1, Strong structuration theory). Thus, we sought to shift the focus from means (the use or non-use of a particular technology) to ends (the purpose for which technology is used – or for which it may be more appropriate not to use a technology).

We begin, therefore, not with a focus on technology or even on the system or network, but by depicting the clinician as a social agent and considering clinical practice primarily from a normative (i.e. professional and ethical) perspective. Professionals are strongly influenced by socially shared notions of what good practice consists of and how they should behave towards patients and towards one another.

Accordingly, a key guiding question in this study was, ‘what is excellence in clinical practice and how is the use and non-use of ICTs influenced by (changing) notions of excellence?’. In this section, we summarise the literature on good clinical practice mainly in relation to doctors (because most of the relevant studies have been done on doctors and their work). We also refer to the nursing literature where available.

Much has been written about good doctoring. Perhaps the pithiest statement of its essence is the motto of the UK Royal College of General Practitioners – cum scientia caritas (‘loving care with expert knowledge’: see www.rcgp.org) – which depicts the professional ideal of delivering the highest-quality bioscience while also attending to the human needs of the patient. While the ‘scientia’ component of good doctoring is often equated with evidence-based medicine (EBM), the original definition of EBM actually incorporates ‘caritas’ too. This definition is reproduced in full below, though only the first sentence is generally quoted.

Evidence based medicine is the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research. By individual clinical expertise we mean the proficiency and judgment that individual clinicians acquire through clinical experience and clinical practice. Increased expertise is reflected in many ways, but especially in more effective and efficient diagnosis and in the more thoughtful identification and compassionate use of individual patients’ predicaments, rights, and preferences in making clinical decisions about their care. By best available external clinical evidence we mean clinically relevant research, often from the basic sciences of medicine, but especially from patient centred clinical research into the accuracy and precision of diagnostic tests (including the clinical examination), the power of prognostic markers, and the efficacy and safety of therapeutic, rehabilitative, and preventive regimens.

p. 7196

Evidence-based medicine was acknowledged by its early protagonists as being dependent on clinical judgement and contingent on patient choice (i.e. the ‘best’ treatment is not necessarily the one shown to be most efficacious in randomised controlled trials but the one that fits a particular set of individual circumstances and aligns with the patient’s preferences and priorities). Unsurprisingly, given its disciplinary roots in clinical epidemiology, the early research literature on EBM focused on the scientific component and sought to build an evidence base of randomised controlled trials and other ‘methodologically robust’ research designs. Later, a tradition of ‘evidence-based patient choice’ emerged in which the patient was assumed to be a (more or less) rational chooser and the clinical challenge was framed as how to convey the research evidence about different treatment options in a way that supported informed patient choice. 97 However, the third component of EBM – individual clinical judgement – has not been extensively theorised within that tradition.

The US bioethicist Kathryn Montgomery, drawing on Aristotle’s notion of praxis, considers clinical practice to be an example of case-based reasoning. 98 Medicine is governed not by hard and fast laws but by competing maxims or rules of thumb; the essence of judgement is deciding which (if any) rule should be applied in a particular circumstance. Clinical judgement incorporates science (especially the results of well-conducted research) and makes use of available tools and technologies (including guidelines and decision-support algorithms that incorporate research findings). However, rather than being determined solely by these elements, clinical judgement is guided both by the scientific evidence and by the practical and ethical question ‘what is it best to do, for this individual, given these circumstances?’.

The dual commitment to ‘scientia’ and ‘caritas’ has been analysed from a philosophical perspective by the Norwegian doctor and philosopher Edvin Schei. ‘Scientia’ requires the practitioner to consider the ‘objective patient’ (i.e., the patient as expressed in terms of measurements and standardised procedures, for which objectively-assessed diagnostic tests and treatments are then considered), whereas ‘caritas’ requires attention to the ‘existential patient’ (i.e. the patient’s subjective experiences and human needs). 99 The notion of evidence-based patient choice can be incorporated in the former (objective) component of good clinical practice but there are also subjective (and intersubjective) aspects of the interaction to consider.

Unlike disease, which can be defined in terms of a typical constellation of symptoms, signs and test results, illness is a personal, lived experience that is both emotionally laden and socially meaningful (e.g. it may come with various connotations of shame and blame100). The good clinician engages reflexively with this lived experience and acts not merely as diagnostician or technical expert but also as active listener101 and professional witness. 102 Using Schei’s definition, good doctoring is ‘a relational competence, where empathic perceptiveness and creativity render doctors capable of using their personal qualities, together with the scientific and technologic tools of medicine, to provide individualized help attuned to the particular circumstances of the patient’ (p. 394). 99 This definition has obvious parallels in nursing and allied professions.

The personal qualities referred to by Schei are strongly aligned with what Aristotle called virtues – character traits that strike a balance between undesirable extremes (such as courage, which lies between the extremes of recklessness and cowardice). 103 Toon has challenged principle-based medical ethics (in which clinical practice is guided by a set of core principles such as beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy and justice) and argued that above all else, doctors must develop their professional virtues through reflection and peer support. 104 Similarly, good nursing practice has also been defined in terms of personal virtues. 105 The UK General Medical Council acknowledges the importance of virtues in the opening paragraph of its guidance ‘Good Medical Practice’: ‘Patients need good doctors. Good doctors make the care of their patients their first concern: they are competent, keep their knowledge and skills up to date, establish and maintain good relationships with patients and colleagues, are honest and trustworthy, and act with integrity’ (p. 1). 106

Whereas the objective dimension of clinical practice has often been tightly defined (and frequently redefined) in terms of adherence to best evidence guidelines, the subjective dimension is something of a mystery107 – depending as it does on a form of knowledge that is tacit, experiential and difficult to codify. 108 The judgements made by virtuous, wise clinicians entail ethical and practical considerations not just about what to do in relation to the particular circumstances of this patient but also about how to balance the competing demands of advocacy (addressing the needs of the individual patient) and distributive justice (balancing this patient’s needs or wants against the wider needs of the population in the context of limited resources) – for example, in relation to the questions of whether or not to prescribe, whether or not to operate, whether or not (and where and how urgently) to refer, and so on. 107

Critical scholars have voiced concerns that the essence of good clinical practice is being lost as society moves from a traditional era in which medicine and nursing were viewed as vocations, health care as a public good and the sick patient as a vulnerable citizen who had a right to care (and to whom the doctor has a duty of care) to a new era of market values where medicine is a business, health care a transaction and the sick patient a customer. In this latter era, informed choice by ‘empowered’ patients is seen as the driving force for achieving excellence, as clinicians (and health services) that do not produce ‘satisfaction’ will quickly go out of business. The doctor’s role is defined either as seller of specialist services or as an information purveyor. It follows from these assumptions that a good consultation is one in which the patient or their nominated advocate has been given sufficient balanced information to make a well-informed choice. 109 The empowerment of the patient is assumed to exist, more or less, in a zero-sum relationship with the disempowerment of the doctor – with the caveat that many patients do not wish to be completely autonomous (and some do not even seek ‘shared’ decision-making).

However, in the vocational model, patient empowerment and ethical practice are all defined differently. For one thing, it is illness itself, and not medical paternalism, that makes patients vulnerable. 99 Doctors’ specialist knowledge has symbolic significance; in many cases, power is not so much seized by doctors as conferred by society (doctors symbolise hope, trust, agency and authority, making possible a powerful therapeutic alliance of reciprocal interpretation and projection110). This ‘cognitive institution’ facilitates doctor–patient interaction and produces a ‘legitimate hierarchy of domination and subordination, recognized by all participants’ (p. 397)99 – though this hierarchy is rightly renegotiated and redefined more progressively as society evolves. In this hierarchy, patients are doubly vulnerable – because they opt (or are compelled) to rely on the doctor’s skill and judgement in potentially life-threatening situations, and because they expose themselves to the potential for shame or loss of dignity as intimate secrets and body parts are revealed (with the risk of loss of face if this is met with ridicule, disbelief or indifference).

For another thing, as Mol has argued, decision-making (shared or otherwise) is only part of the challenge. 111 As health problems increasingly involve chronic, non-communicable diseases which require ongoing effort by both patients (self-management) and health professionals (periodic surveillance, management of exacerbations and long-term support of disability and impairment), so the ‘logic of choice’ (episodic, decision-focused, objective, predictable – as in a decision tree) becomes less relevant than the ‘logic of care’ (continuous, relationship-focused, intersubjective, unpredictable). The logic of care includes the role of the doctor or nurse as witness and active listener – but it also includes the practicalities of care such as the effectiveness of medication in controlling symptoms, the accessibility of the clinician at times of need, and whether or not tools and technologies introduced with the aim of supporting the process of care are usable and useful in particular situations. In this framing, ‘care’ has a substantial physical and material component as well as a socioemotional one.

Good clinical practice is thus – arguably – less about achieving equal distribution of power (as in shared decision-making) than it is about ensuring that doctors draw on their personal virtues (integrity, honesty and so on) to build a healing relationship, wield their socially conferred power and use technologies pragmatically and judiciously in the patient’s best interests. Patients are also influenced by social norms: they will conform to a greater or lesser extent with expectations of what they understand to be the ideal of a good patient – for example, constructing an account of conscientious self-care, acknowledging the needs of other patients (hence not taking up too much of the doctor’s time), deferring to the doctor (or, perhaps, exerting what seems to be a reasonable level of autonomy) and seeking to demonstrate an appropriate level of knowledge and curiosity about their condition. 112 These small acts of deference contribute further to sustaining the established power differential.

In sum, the clinical consultation is not merely an informational transaction or a set of decisions. Rather, it is a complex social encounter in a heavily institutionalised environment. It has symbolic as well as scientific and practical significance. Good clinical practice involves judgement and attention to the particularities of the patient and their situation (the ‘existential patient’) as well as up-to-date knowledge and incorporation of best scientific evidence (the ‘objective patient’). It follows – and this is the point of this discursion into professional practice – that technologies that support the latter at the expense of the former are likely to be experienced by clinicians as interfering with excellent care.