Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1010/08. The contractual start date was in August 2011. The final report began editorial review in February 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Steve Goodacre is Deputy Chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Evaluation and Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by O’Cathain et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Context of increasing emergency admissions

Provision for emergency hospital admissions is a necessary and important role for the NHS in England. The NHS has faced a large increase in emergency admissions, with a 12% increase between 2004 and 2008. 1 The aging population accounts for at most 40% of this increase, with the increase largely occurring in short-stay admissions of under a day. 1 Not all emergency admissions are necessary. They may even be harmful because they can result in hospital-acquired infections, distress to patients and their families, difficulties for service providers trying to balance elective and emergency care, and unnecessary high-cost intervention in a resource-limited health service. As a consequence, reducing unnecessary admissions has been a focus of policy-makers, commissioners and service providers for many years.

Unnecessary emergency admissions

Definitions of unnecessary emergency admissions focus on either ‘preventability’ or ‘avoidability’. ‘Ambulatory or primary care sensitive conditions’ (ACSCs) have been identified, where emergency admissions are prevented through intervention in primary care. 2 For example, primary care asthma nurses monitor asthma patients regularly to ensure optimum health and thus prevent exacerbations which might lead to an emergency admission. Problems have been identified with this set of conditions, with a recommendation for clarification of what admissions can be prevented. 3 An alternative approach focuses on avoidability; that is, when a person has an acute health problem, or an exacerbation of an existing health problem, it is dealt with without resort to emergency admission. For example, an asthma attack is dealt with immediately in a walk-in centre or general practice before it becomes serious enough to require emergency admission. Responsibility for preventability tends to be focused on primary care, while the responsibility for avoidability lies with the range of services in the wider system of emergency and urgent care that respond to patients suffering an acute health problem. 4

Admissions avoidable by emergency and urgent care systems

In England the range of services that could respond to an acute health problem includes same day appointments in general practice, general practitioner (GP) out-of-hours (OOH) services, walk-in centres, telephone helplines such as NHS Direct/NHS 111, community services such as district nursing, emergency departments (EDs) and emergency ambulances. Some health problems are accompanied by a need for social care and, therefore, social services can be included within an emergency and urgent care system. These services can be viewed as an emergency and urgent care system because patients living within a geographical area seeking emergency or urgent care will make decisions about which service to contact first and will often have pathways of care involving a number of services. 4,5 The availability, accessibility and quality of services within any system, as well as the co-ordination and integration between services, may affect emergency admission rates.

Defining and measuring the avoidable admissions is difficult but is an essential prerequisite to any study of the effect of services on avoidable admissions. Direct measurement would involve detailed analysis of individual admission and a judgment of whether or not the patient benefited from admission. It would not be feasible to undertake such an analysis on sufficient numbers of admissions to support a national study. An indirect measure of the avoidable admission rate is therefore required. In a previous study we used a Delphi exercise to identify health conditions, defined by ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition) code, where experts believed that exacerbations could be managed by a well-performing emergency and urgent care system without admission to an inpatient bed. 6 We combined these conditions to develop a system performance indicator of ‘hospital emergency admission rates for acute exacerbation of urgent conditions that can be managed out of hospital or in other settings without admission to an inpatient bed’. This indicator identifies the rate of potentially avoidable emergency admissions for a given population through calculation of an age- and sex-adjusted rate of admissions from conditions rich in avoidable admissions, rather than a direct measure of avoidable admissions. This allows us to estimate the avoidable admission rate using routinely available administrative data. Although it is not a direct measure of avoidable admissions, it has clear advantages over an unselected analysis of all hospital admissions, which would include many substantial disease categories in which most admissions are unavoidable.

Research is needed on how characteristics of the emergency and urgent care system – its configuration, integration and accessibility – affect avoidable emergency admissions. There is a need to understand more about why some emergency and urgent care systems have lower avoidable emergency admission rates than others. It would be useful to identify the rate of avoidable emergency admissions, consider whether there is variation in rates between different systems and identify system-wide factors explaining variation in order to identify modifiable factors for decreasing these rates.

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework for this study is that patients, health professionals and health services operate within an emergency and urgent care system. 4,5 General systems theorists have suggested that a system can be understood as an arrangement of components, and their interconnections, that come together for a purpose. 7 In the context of an emergency and urgent care system, the parts are the range of services available with a purpose of treating or managing acute health problems quickly. If the availability, accessibility and quality of services in the emergency and urgent care system are good then avoidable admission rates will be low. However, systems are about more than their components. Services are linked by the pathways patients take through a number of services when they need acute care. For example, a patient may call an emergency ambulance, be transported to an ED and be discharged home with support from district nursing, physiotherapists and social care. Co-ordination between services can be as important as the presence of individual services. Mingers and White8 recommend that systems thinking should involve:

-

viewing the situation holistically as a set of diverse interacting elements within an environment

-

recognising that the relationships or interactions between components are as important as the parts themselves in determining the behaviour of the system

-

recognising a hierarchy of levels of systems; for example, an ED operates within the larger system of an acute trust

-

accepting that people within a system will act in accordance with differing purposes or rationalities; that is, services may have differing priorities which are at odds with each other.

Defining emergency and urgent care systems in England

We used two definitions of an emergency and urgent care system in this study. Health-care systems operate at a national level and at a local level. Local emergency and urgent care systems can be virtual entities defined by their shared administration, or physical entities defined by geography. At the time this study was designed, local emergency and urgent care systems could be defined as primary care trusts (PCTs) which commissioned services for a defined geographical population. 9 That is, the geographical boundaries of PCTs identified 152 local emergency and urgent care systems in England in operation between 2006 and 2013. Each of these 152 PCTs managed an emergency and urgent care system, ensuring that their population had access to emergency and urgent care, and that the system of care – as well as individual services – met the needs of their population. PCTs ceased to operate in April 2013 but their geographical basis has historical relevance that is likely to persist in affecting patient pathways in current configurations of health and social care commissioning and provision. Therefore we used PCT resident populations to define 152 geographically based systems in our study. General acute trusts are the focus of emergency admissions. Therefore we used a secondary definition of a local emergency and urgent care system as the catchment population of general acute trusts (acute trust-based systems).

Factors affecting emergency admissions

Many researchers have explored the factors affecting emergency admission rates overall, or for specific conditions, through studying variation between general practices in the UK10–19 and internationally,20 commissioning organisations in the UK12,21–23 or hospitals internationally. 24,25 Factors explaining variation were related to the population, particularly in terms of deprivation and health (Table 1). Much of the focus on health service-related factors affecting variation in emergency admissions has been on primary care (Table 2), for example the quality and supply of,10,12,14,17 and access to, primary care. 10,12,15,16 There is some evidence that factors within hospitals can affect emergency admissions, such as bed numbers and availability,16 physical space24 and clinical decision-making. 25

| Factor | All emergency admissions | Condition-specific | Preventable, avoidable or ambulatory set of conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deprivation | General practice10,11,13,15,18 PCT21 |

General practice: COPD,12,16 asthma,16 MI,17 angina,17 stroke19 PCT: COPD,12,23 diabetes,21 asthma21 |

General practice20 PCT23 Hospital,24 local authority22 |

| Ethnicity | General practice10,15 | General practice: diabetes14 PCT23 |

General practice20 |

| Vulnerability, e.g. living alone | General practice: lone parenthood18 | PCT23 | |

| Urban/rural status | General practice: COPD,16 asthma,16 angina17 | Hospital24 | |

| Distance to hospital | General practice10,15 | General practice: COPD, asthma,16 angina17 | Hospital24 |

| Morbidity and mortality | General practice10,18 PCT21 |

General practice: COPD12,16 asthma,16 MI,17 angina,17 diabetes,14 stroke19 PCT: COPD,23 diabetes21 |

|

| Prevalence of health behaviours such as smoking | General practice: COPD,12,16 asthma,16 MI,17 angina,17 diabetes,14 stroke19 PCT: COPD12 |

||

| Agea | General practice10,11,13,15 | GP: diabetes14 | General practice20 |

| Sexa | General practice10,11,15 | GP: diabetes14 |

| Factor | All emergency admissions | Condition-specific | Preventable, avoidable or ambulatory set of conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quality of primary care | General practice: COPD,12 diabetes,14 angina17 PCT: diabetes23 |

||

| Supply of primary care (i.e. GPs/primary care staff per head of population) | General practice: COPD,12 MI,17 stroke19 PCT: COPD12 |

||

| Access to primary care (single handed GPs, practice size) | General practice10 | General practice: asthma16 | |

| Perceptions of access to general practice | General practice10,15 | General practice: COPD12 | |

| Amount of floor space in hospitals | Hospital24 | ||

| Total bed number/availability | General practice: COPD,16 asthma16 | ||

| ED doctor | Hospital25 | ||

| Hospital variation | General practice18 Hospital25 |

||

| Prescribing | General practice: angina17 | ||

| GP fundholding | General practice18 |

Research has also been undertaken on factors affecting variation in use of a common gateway to emergency admission – EDs. Some studies have found that perceived access to general practice affects ED attendance. 26,27 Less research has been undertaken on system-related factors, such as integration of health and social services. Two limited case studies suggested integration of services was associated with reduced increase in emergency admissions. 1

We designed a study to address gaps in the evidence base. We focused on avoidable rather than all emergency admissions, and on all services in the emergency and urgent care system rather than primary care and hospitals only.

Aim and objectives

Aim

To identify system-wide factors explaining variation in potentially avoidable emergency admissions in different emergency and urgent care systems.

Objectives

-

Calculate the ‘age- and sex-adjusted potentially avoidable emergency admission rate’ for each emergency and urgent care system in England.

-

Explain variation in the ‘age- and sex-adjusted potentially avoidable emergency admission rate’ in different systems using routine data on population, health and system characteristics.

-

Undertake in-depth research in systems with high and low ‘age- and sex-adjusted potentially avoidable emergency admission rate’ to identify further factors which may be influencing variation.

-

Identify modifiable factors which affect potentially avoidable emergency admissions to help policy-makers, commissioners and service providers implement changes to reduce avoidable admissions.

Chapter 2 Overview of methods

Design

We calculated an age- and sex-adjusted potentially avoidable emergency admission rate, that is a standardised avoidable admission rate (SAAR), for emergency and urgent care systems in England in 2008–11. We defined these systems in two ways: geographically based systems (populations of 2006–13 PCTs) and acute trust-based systems (the catchment populations of acute trusts).

The study design was a three-phase mixed-methods design known as ‘ethnographic residual analysis’28 or ‘qualitative residual analysis’. 29 The first phase of this approach involves a regression to identify factors affecting variation between a large set of cases. The second phase involves qualitative research on some cases that the first-phase regression fails to predict well. That is, the qualitative research focuses on cases that are likely to identify factors not already included in the regression model. The third phase involves reassessing the regression in phase 1, in particular looking for variables which measure the additional factors identified in the qualitative research. The strength of this approach is that qualitative research generates hypotheses for testing in the quantitative component as well as helping to explain how factors in the regression affect the outcome of interest. For this study:

-

Phase 1 was quantitative, involving a regression to identify factors that explained variation in the SAAR. We identified routinely available data on the characteristics of these systems and tested whether they explained variation in the SAAR. We then identified systems with large residuals within our analysis, that is systems that had SAARs which could not be explained by the system characteristics in our regression.

-

Phase 2 was largely qualitative. We identified six geographically based systems with large residuals in our phase 1 regression and used in-depth case studies to identify further more complex system characteristics which might explain variation in the SAAR.

-

Phase 3 was quantitative, building on the phase 1 regression by identifying routine data on factors from phase 2 and attempting to explain further variation in the SAAR.

Integration between the quantitative and qualitative components of this mixed methods study was built into the design. The first quantitative component (phase 1) helped to identify the sample for the qualitative component (phase 2) so that the case studies were more likely to offer additional factors rather than simply repeat those found in phase 1. The qualitative component (phase 2) helped to identify further factors for testing in a second quantitative component (phase 3). Further integration took place by displaying the findings from different components together and considering the convergence, complementarity and disagreement between the findings from each component. 30 The design was superior to an alternative design of a regression followed by case studies of high and low SAARs in which the case studies might identify only similar issues to the regression. The design is displayed in Figure 1, which also shows where the methods and findings are reported.

FIGURE 1.

Design of study.

Patient and public involvement

The Sheffield Emergency Care Forum (SECF) is an independent group of members of the public with an interest in emergency care. A member of this group (Enid Hirst) was a coapplicant on the proposal for this study, and an active member of the study management group, contributing to operationalising the study proposal and interpreting the emerging findings. For example, as a member of the public with an interest in emergency care she identified a list of factors to test in phase 1 from the perspective of the general public. Another member of this group (Beryl Darlison) was a member of the Project Advisory Group for this study, offering advice on emerging findings and interpretation. A subset of SECF met with the team at three key points in the study to contribute to the selection of factors for testing in phase 1, the selection of the six case studies, the development of the case studies and interpretation of overall findings.

Chapter 3 Calculation of potentially avoidable admission rate

Based on fourteen conditions

A consensus group of 48 senior clinicians, researchers and health-care commissioners with a special interest in emergency and urgent care identified 14 health conditions where exacerbations could be managed by a well-performing emergency and urgent care system without admission to an inpatient bed. 6 Consensus group members included patient representatives, pharmacists, NHS Direct staff, GPs, pre-hospital care staff, paediatricians, public health officials, psychiatrists, emergency medicine doctors and nurses, acute medicine doctors and nurses, walk-in centre nurses and PCT commissioners. The 14 conditions are displayed in Table 3.

| Condition | ICD-10 codes | Numbers (%) | % aged > 75 years |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-specific chest pains | R07.2, 7.3, 7.4 | 731,758 (22) | 21 |

| Non-specific abdominal pains | R10 | 660,438 (20) | 10 |

| Acute mental crisis | F00–F99 | 340,826 (10) | 15 |

| COPD | J40–J44 | 322,747 (10) | 44 |

| Angina | I20 | 186,394 (6) | 38 |

| Minor head injuries | S00 | 100,178 (3) | 32 |

| UTIs | N39.0 | 356,814 (11) | 54 |

| DVT | I80–I82 | 74,914 (2) | 29 |

| Epileptic fit | G40–G41 | 111,697 (3) | 13 |

| Cellulitis | L03 | 164,499 (5) | 31 |

| Pyrexial child aged under 6 years | R50 | 33,562 (1) | 0 |

| Blocked urinary catheter | T83.0 | 20,277 (< 1) | 61 |

| Hypoglycaemia/diabetic emergencies | E10.0, E11.0, E12.0, E13.0, E14.0, E15, E16.1, E16.2 | 40,299 (1) | 43 |

| Falls not elsewhere classified | W00–W19 cause and diagnosis (based on DIAG_01) S00, S10, S20, S30, S40, S50, S60, S70, S80, S90, T00, R | 128,992 (4) | 100 |

| All avoidable admissions | 3,273,395 (100) | 29 | |

There were a total of 15 million emergency admissions in the 3-year period 2008–11, approximately 5 million in each year and increasing over time. Twenty-two per cent (3,273,395 of 14,998,773) of these admissions were for the 14 conditions identified as rich in potentially avoidable admissions. That is, our avoidable admissions accounted for one fifth of all emergency admissions in this time period. Chest pain, abdominal pain, urinary tract infections (UTIs), acute mental crisis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) accounted for over two-thirds of these potentially avoidable emergency admissions (see Table 3). Twenty-nine per cent occurred in people aged over 75 years old. Admissions came from a number of sources: EDs, GPs, bed bureaus, outpatients and other.

Calculation of avoidable admission rate

Geographically based systems

Numbers of emergency admissions for the set of 14 conditions for each emergency and urgent care system were calculated using Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) for the 3 financial years April 2008 to March 2011. Admissions from all sources were included. The most common admission route was EDs, with an average of 69% of avoidable admissions through this route, although this varied by system between 44% and 92%.

The condition code for the first finished consultant episode was used. PCT mid-2009 resident populations were then used as the denominator to calculate the rate of potentially avoidable emergency admissions per 100,000 population. The directly age- and sex-standardised admission rates per 100,000 per year were calculated for each PCT for the 3-year period using seven age groups (0–4, 5–14, 15–44, 45–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85+ years), standardised to the whole population for England in 2009. A 3-year period was selected to ensure that the effect of annual variability in emergency admission rates at a system level was minimised. It is important to understand that this rate is an indicator of avoidable admissions. It is based on conditions rich in avoidability; that is, not all admissions from these conditions were avoidable in practice. For shorthand, we call this the SAAR even though it was a directly standardised rate.

Acute trust-based systems

Catchment populations for acute trusts were needed to calculate admission rates for the 14 conditions. There are different ways of calculating catchment populations for hospitals, with debates about which approach is best. 31,32 We used estimates of acute trust catchment populations for emergency admissions in 2009 calculated by Public Health Observatories in England. 33 These catchment areas were defined as the number of people in each sex and age group who live in the catchment of the acute trust. They were calculated using HES data between April 2006 and March 2009 to count the number of patients in each age and sex group admitted from small areas called Middle Super Output Areas. These areas have a minimum population of 5000, with an overall mean of 7200. Mid-year population estimates for 2009 were supplied by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). Within each 5-year age and sex group, the proportion of patients who went to each acute trust as a proportion of patients who used any acute trust was calculated. For each small area, this proportion was multiplied by the resident population in that age and sex group to give the small area catchment population for each acute trust. Then the small area catchment populations for each acute trust were summed to give the total catchment population for each acute trust.

We calculated the SAARs per 100,000 per year for each acute trust for the 3-year period April 2008 to March 2011 using seven age groups (0–4, 5–14, 15–44, 45–64, 65–74, 75–84, 85+ years) standardised to the whole population for England in 2009. A 3-year period was selected to ensure that the effect of annual variability in emergency admission rates was minimised.

Some specialist acute trusts offer care to specific age, sex or condition groups only. We wanted to compare similar types of acute trusts and focused on general acute trusts because they account for the majority of emergency admissions. 1 We included any acute trusts where the estimated population in each age and sex group was > 1000. This was an arbitrary cut-off point which successfully excluded children’s hospitals, women’s hospitals and condition-specific hospitals. It also excluded some general acute trusts located near children’s hospitals because they did not admit children.

Variation in the standardised avoidable admissions rate

Geographically based systems

There were 152 geographically based systems (based on PCT populations). The reliability of the HES data was checked by looking for consistency between numbers of emergency admissions per year within each system. The only large differences between years for any system were two systems with zero emergency admissions for 2010–11. We excluded them from the analysis, leaving 150 systems.

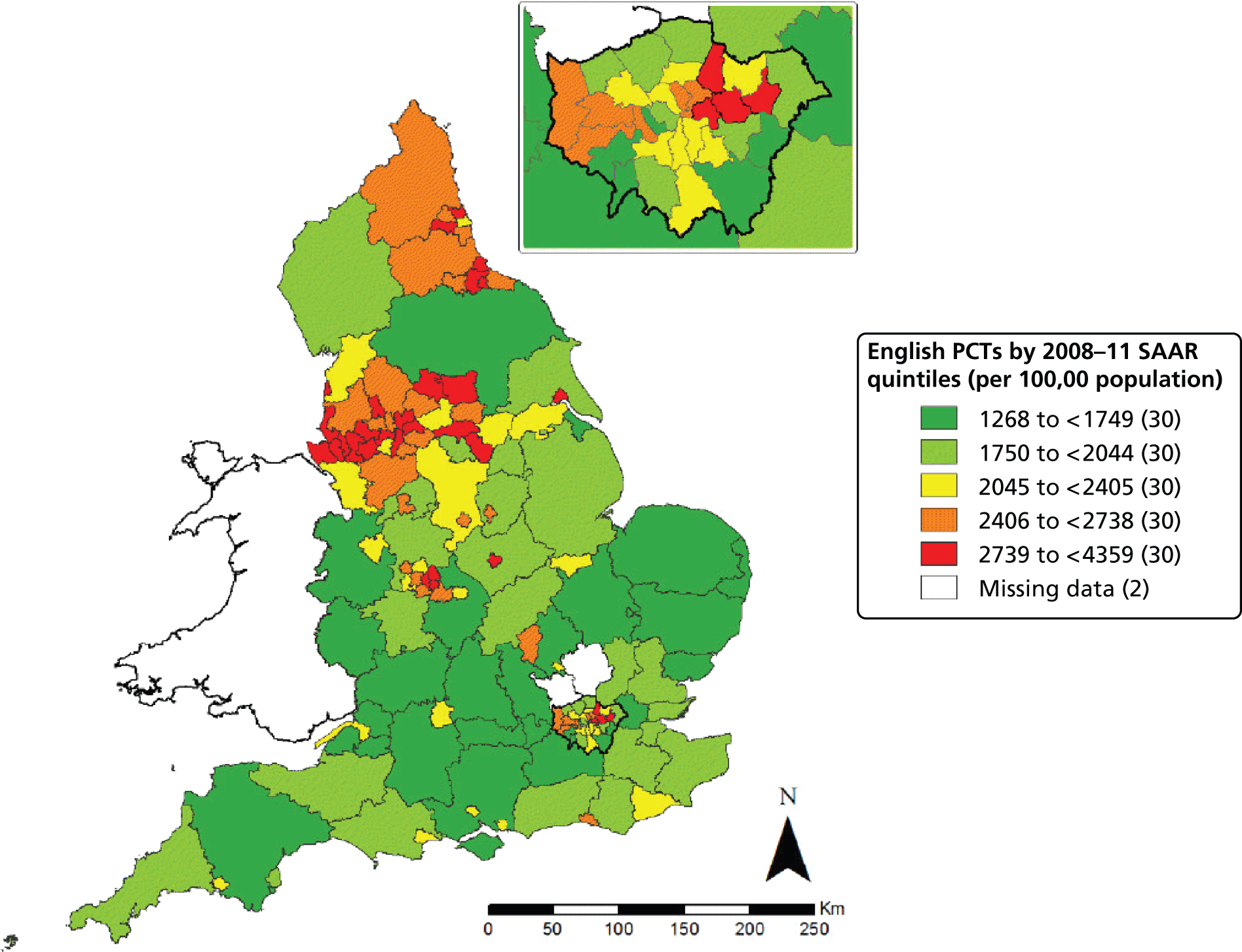

The median SAAR was 2258 [interquartile range (IQR) 1808–2662], with a 3.4-fold variation between systems ranging from 1268 to 4359, and a 1.9-fold variation between the 10th and 90th percentiles. Geographical variation in the SAAR was apparent, with highest rates clustering in the north-west of England, the north-east of England and east London (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Variation in SAAR in 150 geographically based systems in England.

Acute trust-based systems

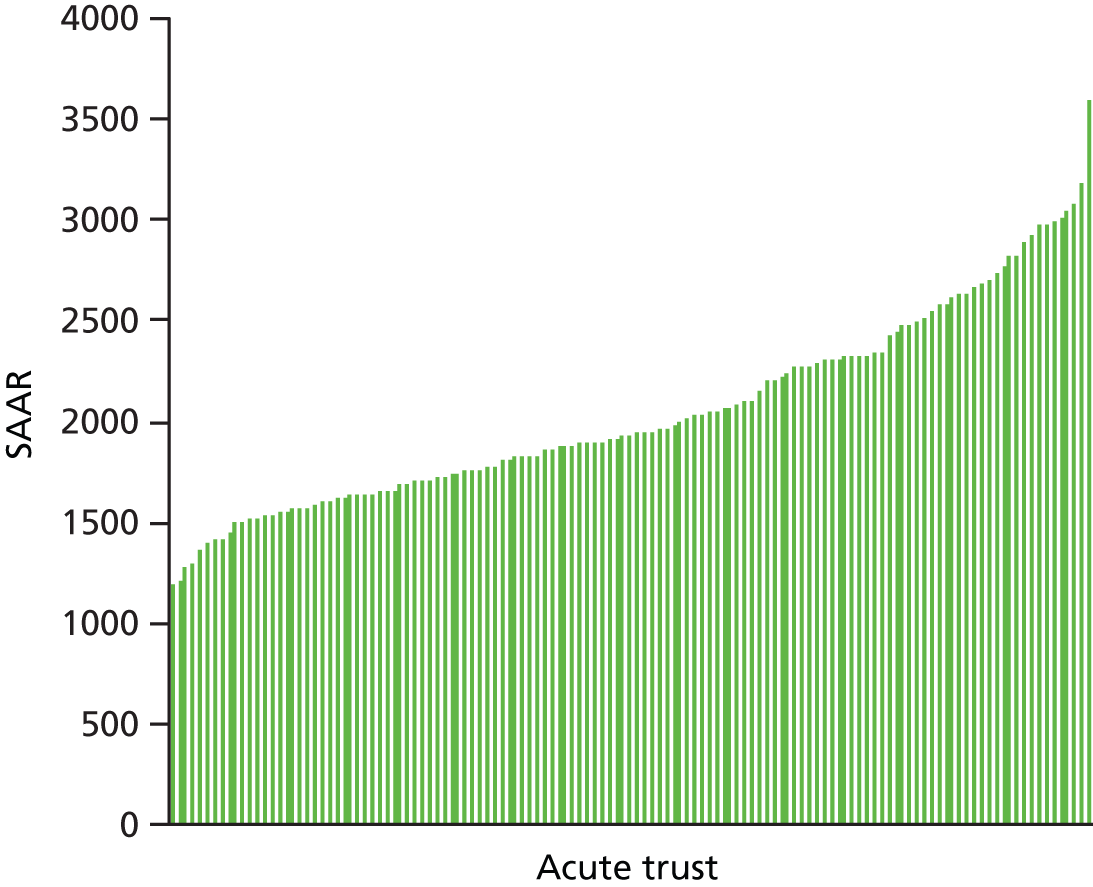

There were 131 acute trusts after exclusion of specialist hospitals. Two acute trusts had missing data for admissions in 2010/11 and were removed, leaving 129 acute trusts. The median SAAR was 1939 (IQR 1676–2331) per 100,000 population per year, with threefold variation between acute trusts ranging from 1194 to 3601, and a 1.8-fold variation between the 10th and 90th percentiles (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Variation in SAAR in 129 acute trust-based systems in England.

Relationship between the standardised avoidable admissions rate and similar measures

It is useful to understand the relationship between the SAAR and other related emergency admission rates. Other indicators are available for PCTs and, therefore, we compared our geographically based system SAAR with other measures.

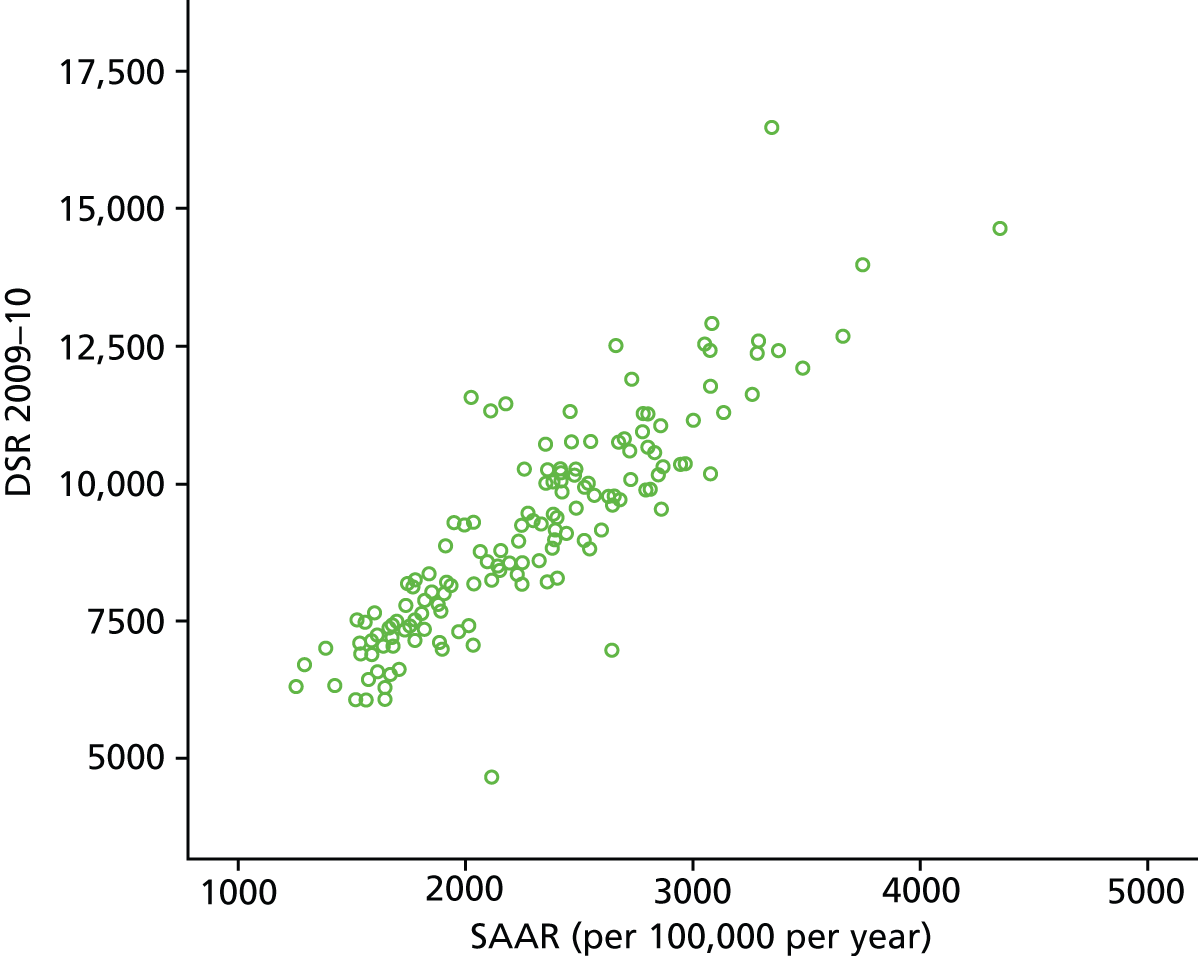

Standardised avoidable admissions rate and all emergency admissions

There was a strong association between the SAAR (2008–11) and the directly standardised rate for all emergency admissions for geographically based systems (2009–10) (Figure 4). Systems with high SAARs tended to have high rates of emergency admissions (Pearson’s r = 0.88, p < 0.001).

FIGURE 4.

Relationship between SAAR and directly standardised rate of all emergency admissions rate by geographically based systems. DSR, directly standardised rate.

It is also worth noting that five of the conditions in our SAAR appeared in the top 10 diagnostic groups contributing to an increase in emergency admissions over recent years. 1

Standardised avoidable admissions rate and ambulatory emergency admissions

Ambulatory or primary care sensitive conditions are conditions for which hospital admission could be prevented by interventions in primary care. There are various definitions34 but the King’s Fund list is the most frequently used in England. 22 There is some overlap between these 19 ACSCs and our 14 conditions (indicated by * below):

-

influenza and pneumonia

-

other vaccine-preventable conditions

-

asthma

-

congestive heart failure

-

diabetes complications*

-

COPD*

-

angina*

-

iron-deficiency anaemia

-

hypertension

-

nutritional deficiencies

-

dehydration and gastroenteritis

-

pyelonephritis

-

perforated/bleeding ulcer

-

cellulitis*

-

pelvic inflammatory disease

-

ear, nose and throat infections

-

dental conditions

-

convulsions and epilepsy*

-

gangrene.

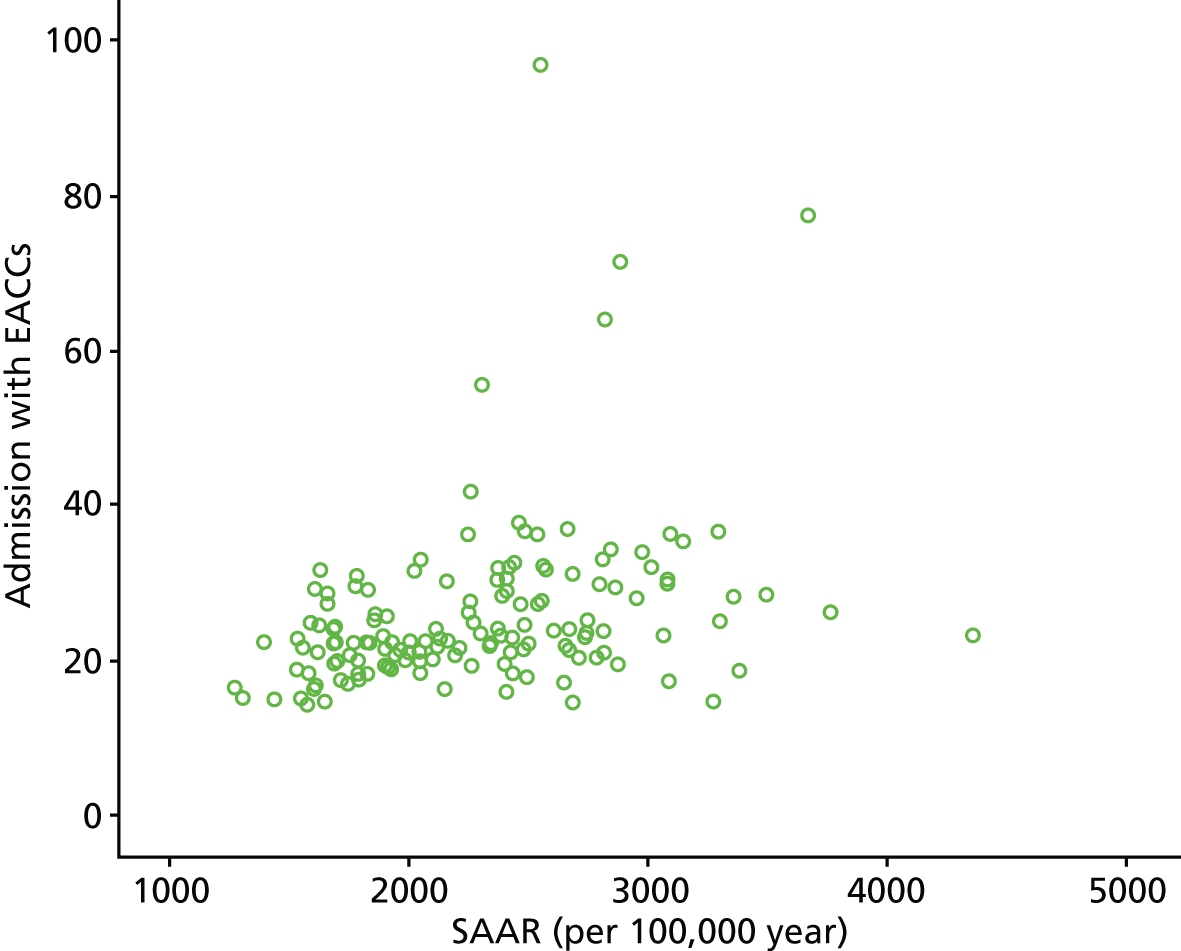

Our SAAR is based on injuries as well as illness and includes mental as well as physical health problems. We could not locate ACSC rates for our systems but we did locate the rate of admissions with emergency ambulatory care conditions (EACCs) per population by PCT. 35 This is a directly age-, sex- and deprivation-standardised admission rate based on 49 emergency conditions with the potential to be managed on an ambulatory basis. The 49 conditions were developed by the National Institute for Improvement and Innovation. Figure 5 shows that there is correlation between our SAAR and the EACC (Pearson’s r = 0.34, p < 0.001) but that it is weaker than that between our SAAR and all emergency admissions.

FIGURE 5.

Relationship between SAAR and admissions with EACCs by geographically based systems.

Conclusion

Over one fifth of all emergency admissions in England between 2008 and 2011 were accounted for by 14 conditions that are likely to be rich in avoidable admissions. There was considerable variation in an age- and sex-adjusted rate of potentially avoidable admissions – the SAAR – for emergency and urgent care systems defined in two different ways, with high rates clustering in the north of the country and east London. There was correlation between the SAAR and other types of emergency admission rates.

Chapter 4 Phase 1: explaining variation in potentially avoidable admissions rates for geographically based systems

Objective

In this chapter we present the methods and findings of a regression to explain variation in the SAAR for geographically based systems. This was published during the course of the study. 36

Methods

Identification of factors

Based on previous research on variation in emergency admission rates, and the focus here on the emergency and urgent care system, it was necessary to locate factors relating to the population, geography, health and range of emergency and urgent health services for the 150 geographically based systems. We searched national databases of routinely available data for relevant data on factors reported at PCT level. Where factors were available by financial year, we selected 2009–10, which was the mid-point year of the SAAR, or the calendar year 2009, or summed quarterly data for 2009. The source of data for factors is reported in Appendix 1.

Population factors

The SAAR was adjusted for age and sex, using 5-year age groups. We attempted to locate data on social deprivation, minority ethnic groups, density of elderly people and social isolation. The Index of Multiple Deprivation has often been identified as an explanatory factor for variation in emergency admissions. We used two domains of this index – employment and income deprivation – because the index itself includes standardised emergency admission rates. 37 The employment deprivation domain reports the proportion of the working age population unable to work because of unemployment, sickness or disability. The income deprivation domain reports the proportion of the population in families who are out of work or have low earnings. We included a factor on the percentage of the population aged over 75 years old even though the SAAR was adjusted for age in case the density of older people in an area created pressure on services.

Geography

We tested one geographical factor, which was a six-category urban–rural scale. We started the analysis with a three-category scale. A patient and public involvement (PPI) representative drew attention to the effect of geography on the SAAR when we presented preliminary findings. We then sought out a more detailed scale to represent geographical differences between systems.

Health

The standardised mortality ratio has been shown to explain variation in emergency admissions overall (see Table 1). We decided not to include it because it may be an indicator of both health status of a population and performance of services for that population. Instead we used indicators of morbidity: we found data on the prevalence of three conditions included in the 14 conditions in the SAAR.

Services in an emergency and urgent care system

We located factors about key services in the emergency and urgent care system: general practice, GP OOH, EDs, acute trusts and ambulance services. We wanted to locate data on the availability, accessibility and quality of all services but could locate data on only some aspects of these services.

The Atlas of Variation was a source of health service-related factors but the authors have expressed concerns that some variation may be accounted for by data management problems. 35 We replaced very high values with the median value for two factors: ED attendance rate (replaced two high values) and admissions from nursing homes rate (replaced five high values).

We calculated two factors using HES data. The first was the percentage of all emergency admissions staying less than 1 day because this had been identified as explaining the recent increase in emergency admission rates. We felt that this factor could indicate one of two things: either (1) coding differences between hospitals, for example, with patients waiting in the hospital for a few hours without using a bed coded as admissions in some hospitals and as ED discharges in another, or (2) different ways of managing patients within the hospital; for example, some hospitals may have been able to put community services in place to discharge ED attendances while others admitted patients to a hospital bed to arrange community services to allow discharge. Second, we calculated the percentage of all emergency admissions referred by GPs to identify the direct influence of general practice on emergency admissions.

Two factors about the emergency ambulance service – percentage of incidents not transported to hospital (non-conveyance) and the percentage of incidents meeting the 8-minute response target – were available only for ambulance services rather than PCTs. We allocated the ambulance service rate to each of the PCTs nested within that ambulance service, an underestimate of the variation at PCT level.

Services we could find no data for

We found no routine data for community/intermediate care, social care or system integration.

Analysis

We undertook general linear modelling in SPSS version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) weighted for the size of the system population to account for larger uncertainty of estimates for smaller systems. The dependent variable was the SAAR for 150 systems. The independent variables were tested in a hierarchical multiple regression in two blocks, using forward stepwise regression within each block. Variables were included if the p-value for the t-test was < 0.05. The blocks were determined by the extent to which service providers could affect a factor. Block 1 was population-related factors. We used the residuals from block 1 as the dependent variable in block 2 and then tested the effect of service-related factors.

After we had completed the analysis and moved on to phase 2 of the study, we felt that this regression did not capture enough of the conceptual framework of the study. Although our conceptual framework led us to include factors which other researchers had not – that is those from services other than primary care and hospitals – we had ignored the fact that factors might operate in sequence. That is, services outside the hospital would affect numbers who turned up at the hospital. For example, difficulty getting a GP appointment has been shown to explain higher rates of attendance at EDs. 26,27 We undertook a three-block analysis to reflect this:

-

block 1: population-related factors: population, geography, health

-

block 2: out of hospital service-related factors – GP access, GP quality, ambulance service performance, GP OOH service

-

block 3: in hospital service-related factors: ED attendance, conversion rate at ED, short length of stay in hospital.

Findings

Univariate linear regression

We display descriptions of the variables tested in the multiple regression (Table 4). It is interesting to note that two factors explained a very large amount of variation in the SAAR. Both were population factors related to deprivation: income deprivation and employment deprivation, explaining 60% and 72% of variation respectively. These are likely to be correlated. We explore correlation between factors in the next section.

| Factor | Sourcea | Median (IQR) | Range | Pearson’s r2 (%) | p-value | Direction of correlation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | ||||||

| INCOME: % population in an area that live in income-deprived families | IMD 2010 | 15 (11–19) | 7–33 | 60 | < 0.001 | + |

| EMPLOYMENT: % population with employment deprivation | IMD 2010 | 6 (5–8) | 3–12 | 72 | < 0.001 | + |

| ETHNICITY: % population minority ethnic | ONS | 9 (5–20) | 3–63 | 9 | < 0.001 | + |

| OVER75: % population aged 75 or over | ONS | 7 (7–9) | 3–13 | 18 | < 0.001 | – |

| ALONE: % pensioners living alone | ONS | 6 (5–6) | 3–8 | < 1 | 0.547 | + |

| Geography | ||||||

| URBAN/RURAL | ONS | No PCTs (%) | 29 | < 0.001 | – | |

| Major urban | 58 (39%) | |||||

| Large urban | 19 (13%) | |||||

| Other urban | 23 (15%) | |||||

| Significant rural | 26 (17%) | |||||

| Rural 50% | 22 (15%) | |||||

| Rural 80% | 2 (1%) | |||||

| Healthb | ||||||

| CHD: prevalence of coronary heart disease | QOF | 4 (3–4) | 1–5 | 3 | 0.032 | + |

| COPD: prevalence of COPD | QOF | 2 (1–2) | 1–3 | 20 | < 0.001 | + |

| DIABETES: prevalence of diabetes | QOF | 5 (5–6) | 3–9 | 18 | < 0.001 | + |

| Hospital | ||||||

| MANAGEMENT/CODING: % emergency admissions with length of stay < 1 day | HES | 28 (24–30) | 14–41 | 16 | < 0.001 | + |

| MANAGEMENT: % population waiting 4 or more weeks for elective admission | Department of Health | 62 (53–68) | 35–98 | 1 | 0.198 | – |

| EDs | ||||||

| EDUSE: directly age-, sex- and deprivation-standardised rate of ED attendances per 100,000 population | NHS Atlas of Variation 2011 | 275 (241–324) | 149–909 | 15 | < 0.001 | + |

| EDCONVERSION: directly age-, sex- and deprivation-standardised rate of conversion from ED attendance to emergency admissions | NHS Atlas of Variation 2011 | 100 (88–112) | 70–148 | 7 | 0.001 | + |

| Community | ||||||

| CAREHOME: admission rate for people aged >74 from nursing home or residential care home settings per 10,000 | NHS Atlas of Variation 2011 | 12 (6–29) | 1–193 | 4 | 0.013 | + |

| General practice | ||||||

| GPSUPPLY: GPs per 100,000 population | London Health Observatory | 69 (64–75) | 54–99 | 0 | 0.855 | + |

| GPACCESS1: % GP single handed | Information Centre | 13 (7–23) | 0–48 | 17 | < 0.001 | + |

| GPACCESS2: % practices offering extended opening hours | Department of Health | 75 (69–86) | 39–100 | 0 | 0.901 | – |

| GPACCESS3: % able to see GP in 48 hours | GP survey | 80 (77–83) | 71–89 | 25 | < 0.001 | – |

| GPADMISSION: % admissions from general practice | HES | 18 (7–26) | 0–44 | 11 | < 0.001 | – |

| GP QUALITY: QOF indicators | QOF | Six indicators tested | 0–9 | < 0.001–0.570 | –c | |

| General practice OOH | ||||||

| GPOOH1: % know how to contact GP OOH | GP survey | 66 (62–69) | 48–79 | 10 | < 0.001 | – |

| GPOOH2: % of GP OOH users reporting ‘very easy’ to contact by phone | GP survey | 38 (34–42) | 20–55 | 1 | 0.231 | – |

| Ambulance service | ||||||

| AMBRESPONSE: % category A response within 8 minutesd | Information Centre | 75 (73–75) | 71–78 | 13 | < 0.001 | – |

| AMBTRANSPORT: % not transported to hospitald | Information Centre | 21 (16–30) | 8–34 | 35 | < 0.001 | – |

Correlations between factors

Some of the factors were correlated with others. It is important to describe these correlations to facilitate interpretation of the final multiple regression. Employment deprivation was positively correlated with income deprivation and the prevalence of some of the 14 conditions (Table 5). Urban/rural status was positively correlated with a number of factors including the proportion of elderly people in a system and some access to general practice factors.

| Factors in multiple regression | Factors correlated with | Pearson’s r |

|---|---|---|

| EMPLOYMENT | INCOME | +0.87 |

| COPD | +0.55 | |

| DIABETES | +0.42 | |

| AMBTRANSPORT | –0.44 | |

| URBAN/RURAL | ETHNICITY | –0.60 |

| OVER75 | +0.62 | |

| CHD | +0.42 | |

| GPACCESS3 | +0.66 | |

| GPOOH1 | +0.61 | |

| GPADMISSION | +0.59 | |

| AMBTRANSPORT | +0.45 | |

| GPACESS3 | INCOME | –0.54 |

| ETHNICITY | –0.63 | |

| OVER75 | +0.71 | |

| ALONE | +0.43 | |

| URBAN/RURAL | +0.66 | |

| CHD | +0.44 | |

| GPACCESS1 | –0.46 | |

| GPOOH1 | +0.62 | |

| GPADMISSION | +0.52 |

Factors affecting standardised avoidable admissions rate in a multiple linear regression

We then undertook multiple linear regression to identify the combination of factors which predicted the SAAR (Table 6). We undertook the block 1 analysis – which tested population-related factors – and identified two factors which predicted the SAAR: employment deprivation and urban/rural status. The more deprived populations and more urban populations had higher SAARs. These two factors together predicted 75% of the variation. In the block 2 analysis – which tested service-related factors – those related to EDs, hospitals, emergency ambulance services and primary care explained further variation (r2 = 85% in a non-hierarchical analysis). Systems with higher SAARs had higher attendance rates at EDs, higher rates of conversion of ED attendances to admissions, higher proportions of very short-stay patients, higher rates of ambulance calls transported to hospital and better perceived access to general practice (see Table 6). This last factor was in the opposite direction from the univariate linear regression and counterintuitive in the context of the conceptual framework of the study. We discuss this in Chapter 10.

| Block | Predictorsa | Unstandardised coefficient | 95% CI | Standardised coefficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: population, geography, health | EMPLOYMENT | 203 | 179 to 227 | 0.78 | 0.001 |

| URBAN/RURAL | –0.17 | 0.001 | |||

| Major urban | 536 | 138 to 934 | |||

| Large urban | 437 | 23 to 850 | |||

| Other urban | 452 | 38 to 867 | |||

| Significant rural | 386 | –14 to 787 | |||

| Rural 50% | 322 | –81 to 725 | |||

| 2: services | EDUSE | 0.9 | 0.4 to 1.3 | 0.30 | 0.001 |

| EDCONVERSION | 7.3 | 5.1 to 9.4 | 0.46 | 0.001 | |

| MANAGEMENT/CODING | 18.4 | 10.1 to 26.6 | 0.29 | 0.001 | |

| AMBTRANSPORT | –5.6 | –10.2 to –0.9 | –0.18 | 0.02 | |

| GPACCESS3 | 16.6 | 6.5 to 26.8 | 0.24 | 0.001 | |

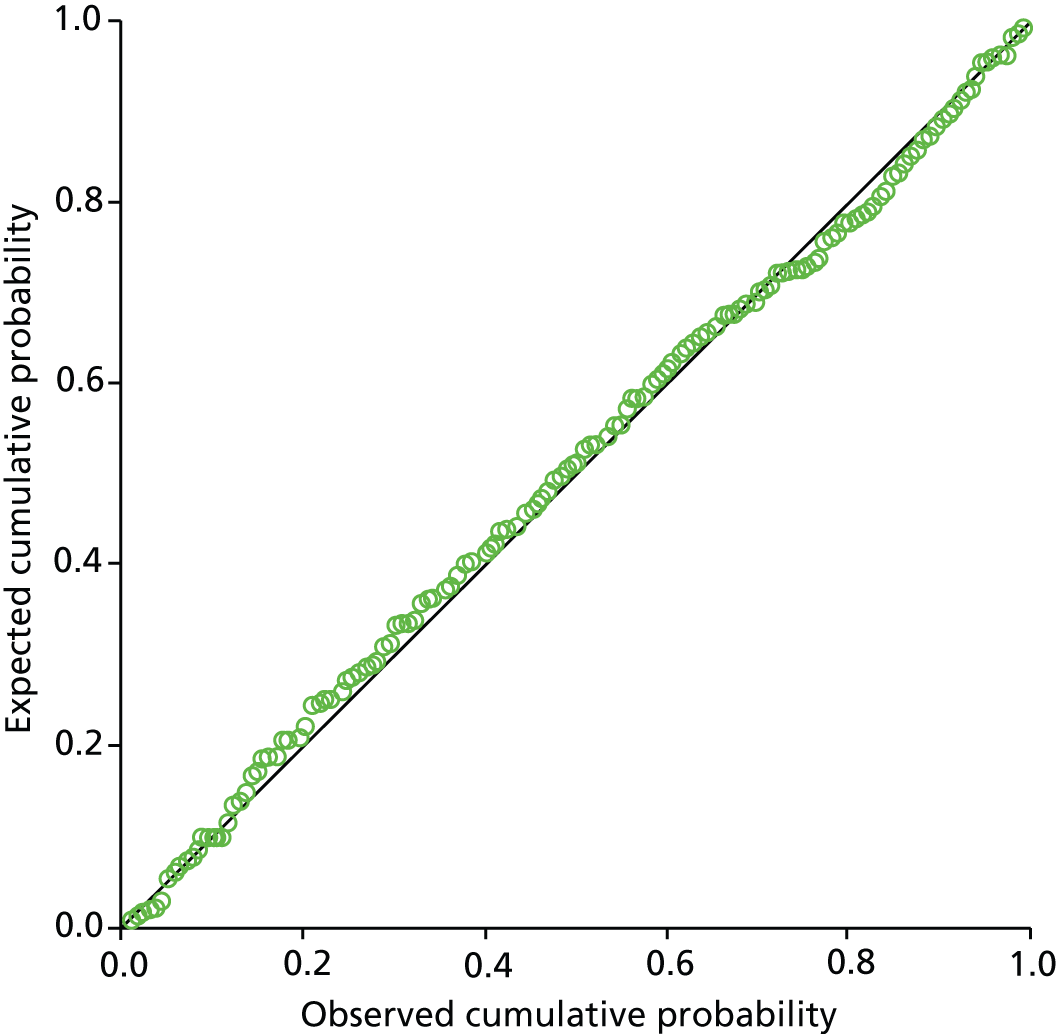

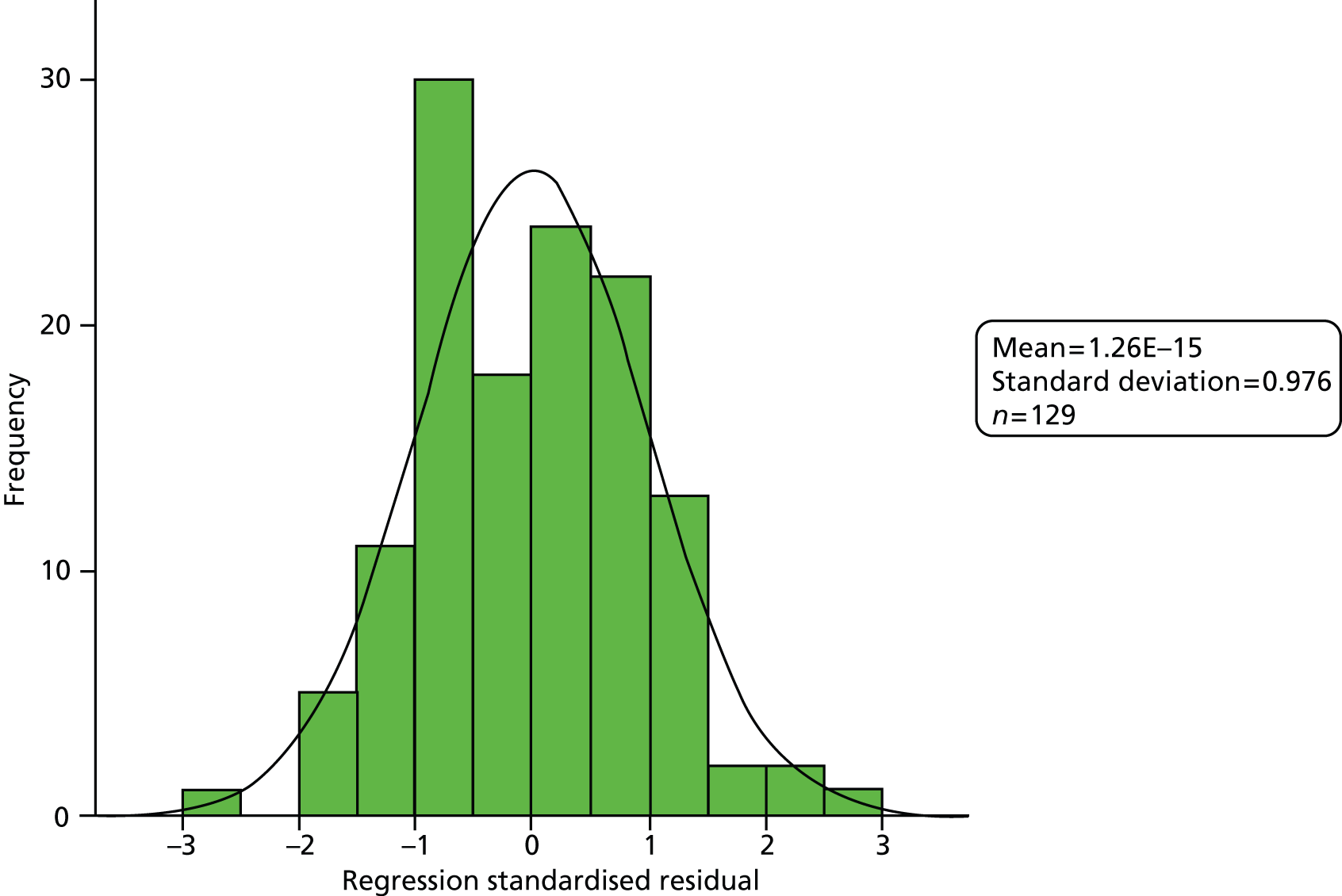

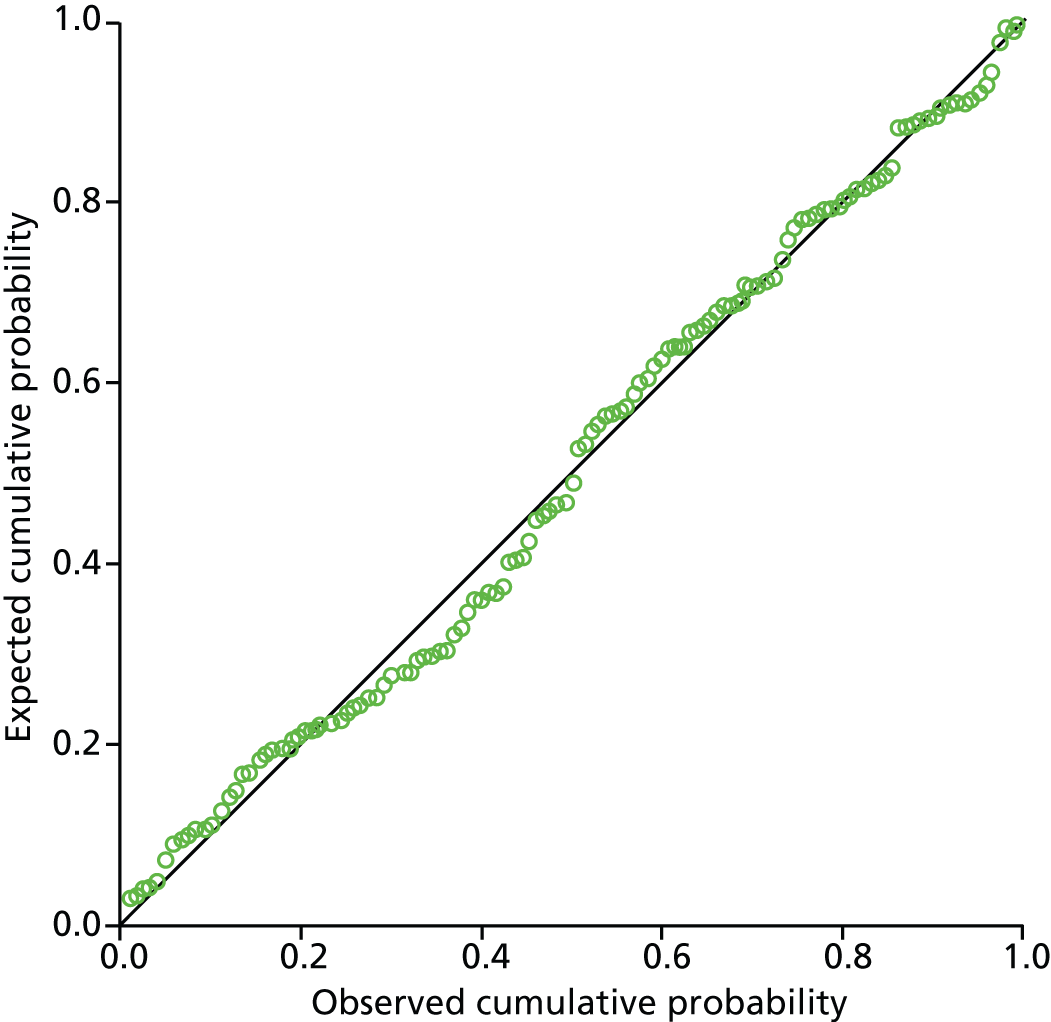

Regression metrics are reported in Appendix 2, showing that the model was a good fit. There was no evidence of multicollinearity in block 2: variance inflation factors varied between 1.1 and 1.4. Some of the factors in the multiple regression were correlated with each other even though there was no multicollinearity: employment deprivation was negatively correlated with the proportion of ambulance callers not transported to hospital; urban/rural status was correlated with perceptions of access to general practice and the proportion of ambulance callers not transported to hospital (see Table 5). Because of the large amount of correlation between factors, it is likely that a number of regressions would fit the data equally well, so there is some uncertainty about the model presented here.

Test of a stronger system-based theoretical model

The first block was the same as block 1 in the primary analysis reported above. In block 2 – out-of-hospital factors – ambulance performance was the only factor adding to the regression. That is, factors about availability of, access to and quality of primary care did not explain further variation at this stage. In block 3 – in-hospital factors – the factors explaining further variation were those in the two-block analysis reported earlier. That is, this approach made little difference to our findings.

Conclusion

Variation in potentially avoidable emergency admissions was explained mainly by population factors. Health-care providers can reduce avoidable emergency admissions by investigating why some populations attend EDs more than others, why some EDs convert more attendances to admissions than others and why some ambulance services transport more of their calls to hospital than others. The greatest potential for reduction in avoidable emergency admissions lies with understanding more about how services can best provide care to deprived communities in ways that avoid emergency admission.

Link with phase 2: identifying residuals and potential case studies

A residual is the difference between the dependent variable for a case and its value predicted by the multiple regression. The description of qualitative residual analysis is brief28,29 and there is no guidance on which type of residual to measure or the size of a large residual. The histogram of standardised residuals from our earlier regression shows that they were normally distributed (see Appendix 2). We identified large standardised residuals as > 1.5 or < 1.5. We noted that some systems with large residuals were in geographical clusters, in that neighbouring systems had similar SAARs and similar residuals. We changed our definition of a large residual to > 1.3 or < 1.3 to include systems within each of these geographical clusters. Twenty-seven systems had large residuals (Table 7).

| Type | System grouped by cluster | Residual | SAAR | Predicted SAAR | Rank | Predicted rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High SAAR (overpredicted) | HO | –2.51 | 2669 | 3238 | 115 | 147 |

| High SAAR (underpredicted) | HU1 | 1.55 | 3493 | 3172 | 147 | 144 |

| HU | 2.41 | 4359 | 3637 | 150 | 148 | |

| HU | 1.31 | 3295 | 3029 | 143 | 138 | |

| HU | 1.72 | 3383 | 3016 | 146 | 136 | |

| HU | 2.16 | 3272 | 2767 | 142 | 127 | |

| HU | 3.07 | 2861 | 2363 | 130 | 87 | |

| HU | 1.85 | 2808 | 2580 | 124 | 107 | |

| HU | 1.43 | 2860 | 2534 | 129 | 103 | |

| Medium SAAR (overpredicted) | MO3 | –1.47 | 2481 | 2710 | 100 | 118 |

| MO | –1.50 | 2432 | 2731 | 96 | 121 | |

| MO | –1.74 | 2427 | 2742 | 94 | 122 | |

| MO | –1.34 | 1961 | 2299 | 53 | 81 | |

| MO | –2.03 | 2116 | 2572 | 65 | 106 | |

| MO6 | –1.45 | 2421 | 2748 | 93 | 123 | |

| MO | –1.32 | 2108 | 2430 | 63 | 92 | |

| Medium SAAR (underpredicted) | MU | 2.10 | 1821 | 1441 | 39 | 2 |

| MU4 | 1.39 | 1905 | 1690 | 48 | 22 | |

| MU | 1.57 | 2270 | 1949 | 77 | 42 | |

| MU | 1.70 | 2661 | 2312 | 113 | 84 | |

| MU | 1.43 | 2530 | 2204 | 104 | 66 | |

| Low SAAR (overpredicted) | LO5 | –2.67 | 1776 | 2300 | 32 | 82 |

| LO | –2.23 | 1754 | 2232 | 31 | 72 | |

| LO2 | –2.98 | 1572 | 1950 | 9 | 43 | |

| LO | –2.02 | 1607 | 2113 | 14 | 55 | |

| LO | –1.66 | 1656 | 2128 | 20 | 59 | |

| LO | –1.78 | 1268 | 1553 | 1 | 8 | |

| Low SAAR (underpredicted) | None | – | – | – | – | – |

We used purposive sampling to identify six systems for our in-depth case studies. We wanted to select cases with high, medium and low SAARs in case the way in which systems operated differed by size of SAAR. The median SAAR was 2258 with an IQR of 1808–2662. We labelled any system in the highest quartile ‘high SAAR’, any system in the lowest quartile ‘low SAAR’ and all others ‘medium SAAR’. We also wanted to select systems where the residual was positive and negative, indicating over- and underprediction of the SAAR. Some systems had predicted SAARs that were higher than the actual SAAR (overpredicted) and some had predicted SAARs that were lower than the actual SAAR (underpredicted). We categorised the 27 cases by size of SAAR and direction of residual (see Table 7). We then grouped geographical neighbours together with the intention of selecting only one case from a cluster in order to maximise variation of selected cases.

Our intention had been to select one case from each ‘type’ (see column 1 in Table 7). However, ‘low SAAR underpredicted’ did not have any cases and ‘high SAAR overpredicted’ was very similar to the ‘medium SAAR overpredicted’. Instead we selected cases that could represent a cluster of systems distributed across the types. We labelled selected cases using H for high SAAR, M for medium SAAR, L for low SAAR, U and O for under- and overpredicted, and 1–6 to indicate case number. Selected cases HU1, LO2, MO3, MU4, LO5 and MO6 are indicated in bold in Table 7.

Chapter 5 Phase 1: explaining variation in potentially avoidable admissions rates for acute trust-based systems

Objective

The majority of emergency admissions occur in general acute trusts. 1 These trusts are a key part of any emergency and urgent care system. How they manage admissions may affect rates of avoidable emergency admissions, and indeed acute trusts can be the focus of efforts to address avoidable admissions. In Chapter 4 we found routine data on a limited number of hospital characteristics for the geographically based systems studied. We found that three of these hospital characteristics explained variation in the SAAR: the conversion rate of ED attendances to admission, the proportion of all emergency admissions with length of stay < 1 day, and the use of EDs. Another characteristic we tested did not explain variation in the SAAR: waiting time for planned admission. Some hospital characteristics are routinely available by acute trust that are not available by PCT, for example numbers of acute beds. Our objective was to test whether or not hospital characteristics explained variation in the SAAR. This work was published towards the end of the study. 38

Methods

Characteristics of acute trusts

We searched databases for routinely available data on the characteristics of acute trusts in England. Ideally we wanted to include characteristics of the acute trust catchment populations because these were important when explaining variation in the geographically based SAAR (see Chapter 4). The best variable we found was the deprivation level of the population in the geographical area in which the acute trust was located. We used the postcode of the ED of each acute trust and identified the percentage of households in poverty in the area around the postcode using the ONS data on Middle Super Output Areas. Where there were two or more EDs based at different geographical sites, we took the mean of these percentages. We found routine data on 11 acute trust characteristics including demand, supply, accessibility and management variables.

Analysis

We undertook linear regression in IBM SPSS Statistics version 20 weighted for acute trust catchment population to account for larger uncertainty of estimates for smaller populations. The dependent variable was the SAAR for 129 acute trusts. The independent variables were tested in a hierarchical multiple regression in two blocks, using forward stepwise regression within each block. Variables were included if the p-value for the t-test was < 0.05. These blocks were determined by the extent to which the factors tested were modifiable by acute trust managers. In block 1 we tested population-related factors: percentage of household poverty in the area in which the hospital was located and demand for the ED in terms of attendance rate. We then used the residuals from block 1 as the dependent variable in block 2 and tested the additional effect of acute trust characteristics.

Findings

Univariate linear regression

We display descriptions of the factors that were tested in the multiple regression in Table 8.

| Factor | Source | Rationale for inclusion | Expected direction of relationship | Median (IQR) | % for variable | Range | Pearson’s r2 (%) | p-value | Direction of effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | |||||||||

| POVERTY: % households in poverty in location of hospital | ONS 2007–8 | Emergency admissions are higher in deprived areas and areas at short distance to hospital | The higher the deprivation, the higher the admission rate | 22 (17–27) | – | 9–52 | 13 | < 0.001 | + |

| Demand | |||||||||

| EDUSE: number of first attendances at EDs per head of population | Health and Social Care Information Centre 2009–10 | People are more likely to be admitted if they attend an ED | The more attendances, the higher the admission rate | 0.29 (0.23–0.33) | – | 0.13–0.53 | 27 | < 0.001 | + |

| Supply | |||||||||

| ACUTEBEDS: number of acute beds per 1000 population | Department of Health website KHO3 2009–10 | Supply-induced demand OR demand-driven supply | The more beds, the higher the admission rate | 1.8 (1.5–2.1) | – | 1.0–2.9 | 16 | < 0.001 | + |

| EDNUMBER:a number of type 1 or type 2 EDs within an acute trust | QMAE Q1 2009–10 | Use of EDs increases when distance is shorter and patients are more likely to be admitted if they attend the ED | The more EDs, the higher the admission rate | – | 1, 56%; 2, 24%; 3+, 20% | – | 0 | 0.994 | + |

| Hospital management | |||||||||

| FT: foundation trust statusb | Name of trust | Foundation Trust status is given to hospitals able to manage services independently | Foundation trusts have lower admission rates | – | FT, 53%; not FT, 47% | – | 1 | 0.199 | – |

| Accessibility | |||||||||

| ACUTEOCC: % acute beds occupancy | Department of Health website KHO3 2009–10 | High occupancy rates cause EDs to look for alternative to admission OR lots of emergency admissions keep acute bed occupancy high | The higher the occupancy rate, the lower the admission rate OR the higher the occupancy rate, the higher the admission rate | 0.86 (0.83–0.89) | – | 0.72–0.97 | 3 | 0.054 | – |

| OPWAIT: % waiting 1 month or less from primary care referral to outpatient appointment | Health and Social Care Information Centre Outpatient statistics 2009–10 | The higher the proportion waiting less than a month, the less likely it is that health will deteriorate and lead to emergency admission | The higher the proportion, the lower the admission rate | 51 (45–56) | – | 34–88 | 5 | 0.009 | + |

| EDWAIT: mean duration in ED (minutes) | Health and Social Care Information Centre 2009–10 | Long waits create pressure in ED to admit OR short waits increase accessibility, which increases demand, which leads to more admissions | The longer the wait, the higher the admission rate OR the longer the wait, the lower the admission rate | 131 (124–149) | – | 98–203 | 5 | 0.015 | – |

| ELECTIVE: mean time waiting for elective admissions (days) | Health and Social Care Information Centre Provider level analysis for admitted care 2009–10 | People waiting longer for elective care may deteriorate and increase the rate of emergency admissions OR a high rate of emergency admissions causes long elective waits | The longer the wait, the higher the emergency admission rate | 47 days (42–51) | – | 20–79 | 6 | 0.005 | – |

| ED management | |||||||||

| LOS0: % admissions which stay less than 1 day in hospital | Calculated from HES 2008–2011 | Hospitals which cannot provide rapid discharge from ED admit people briefly | The higher the percentage of short stays, the higher the admission rate | 28 (23–31) | – | 17–42 | 9 | < 0.001 | + |

| CONVERSION: % ED attendances admitted | Health and Social Care Information Centre AE 2010–11 | Hospitals which convert more of their attendances to admissions will have a higher admission rate | The higher conversion rate, the higher the admission rate | 24 (21–27) | – | 14–39 | 0 | 0.712 | + |

Correlation between factors

Use of the ED and poverty levels around the acute trust were correlated (Pearson’s r > 0.4). There was a negative correlation between use of the ED and the conversion rate (Pearson’s r > 0.4): as use of the ED increased, the percentage of attendances converted to admissions decreased.

Multiple regression

In block 1, only demand for the ED was statistically significant because of the correlation between this factor and poverty levels around the acute trust (Table 9). The residuals from block 1 were used as the dependent variable to then test the added effect of acute trust characteristics. Five factors explained some variation in block 2: supply determined by the number of acute beds per 1000 population, management or coding of admissions determined by percentage of admissions with length of stay < 1 day, management within the ED determined by the conversion rate from ED attendance to emergency admission, the management of the hospital determined by its foundation trust status, and access to planned care determined by percentage of people waiting less than 1 month for a hospital outpatient appointment. Regression metrics are reported in Appendix 2, showing that the model was a good fit. The variance inflation factor for block 2 was approximately 1 for each factor so there was no indication of collinearity. The final multiple regression explained 53% of the variation in the SAAR when all the factors in Table 9 were entered in a single block. Because of the correlation between some factors, it is likely that a number of regressions would fit the data equally well so there is some uncertainty about the model presented here.

| Block | Predictorsa | Unstandardised coefficient | 95% CI | Standardised coefficient | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1: population | EDUSE | 2566 | 1608 to 3524 | 0.445 | < 0.001 |

| 2: acute trust related | ACUTE BEDS | 0.80 | 0.40 to 1.20 | 0.30 | < 0.001 |

| LOS<1 | 0.06 | 0.04 to 0.09 | 0.34 | < 0.001 | |

| CONVERSION | 0.06 | 0.04 to 0.09 | 0.31 | < 0.001 | |

| FT | –0.31 | –0.59 to –0.02 | –0.16 | 0.035 | |

| OPWAIT | 1.56 | 0.16 to 2.97 | 0.16 | 0.031 |

Conclusion

Avoidable admission rates were higher for acute trusts with higher ED attendance rates, higher numbers of acute beds per 1000 catchment population and higher conversion rates from ED attendance to admission. Hospital managers may be able to reduce avoidable emergency admissions by reducing supply of acute beds and by reducing conversion rates from ED attendance.

The factors which explained variation in the SAAR for acute trust-based systems were very similar to those found for geographically based systems in Chapter 4: ED attendance rates, short length of stay and the conversion rate from ED attendance to admission explained variation. One difference was that deprivation levels explained a much lower amount of variation between acute trust-based systems. This is probably to do with the poor quality of the deprivation factor we obtained for acute trust catchment areas. Other differences were related to the availability of data for different definitions of systems. For acute trust-based systems we were able to test the new factor of the number of acute beds per 1000 population and this explained some variation: the higher the number of beds, the higher the SAAR. The model was a good fit (see Appendix 2). There is uncertainty about this model, and other models are likely to exist which explain the SAAR equally well.

Link with phase 2

We identified the large residuals for the regression reported in Table 9. Only two of the acute trusts associated with the six case studies had large residuals in this analysis (emboldened in Table 10). That is, the variables included in this regression predicted the SAAR well for most of the acute trusts in our case studies.

| Case study system | Acute trust | Residual | SAAR | Predicted SAAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HU1 | A | 1.27 | 2985 | 2516 |

| B | 2.17 | 3601 | 2807 | |

| LO2 | A | –0.49 | 2105 | 2310 |

| B | –1.02 | 1287 | 1555 | |

| MO3 | A | 0.99 | 2446 | 2158 |

| MU4 | A | –0.35 | 1814 | 1946 |

| B | –0.40 | 1912 | 2106 | |

| LO5 | A | –1.19 | 1511 | 1943 |

| B | –1.35 | 1719 | 2115 | |

| MO6 | A | 0.15 | 2314 | 2259 |

Chapter 6 Phase 2: case studies of six emergency and urgent care systems – methods and overarching themes

Aim and objectives

The aim was to explore six emergency and urgent care systems in depth to identify further factors that explain variation in potentially avoidable admission rates. A secondary aim of the case studies was to help explain how factors identified in phase 1 affected potentially avoidable admission rates.

The objectives were to:

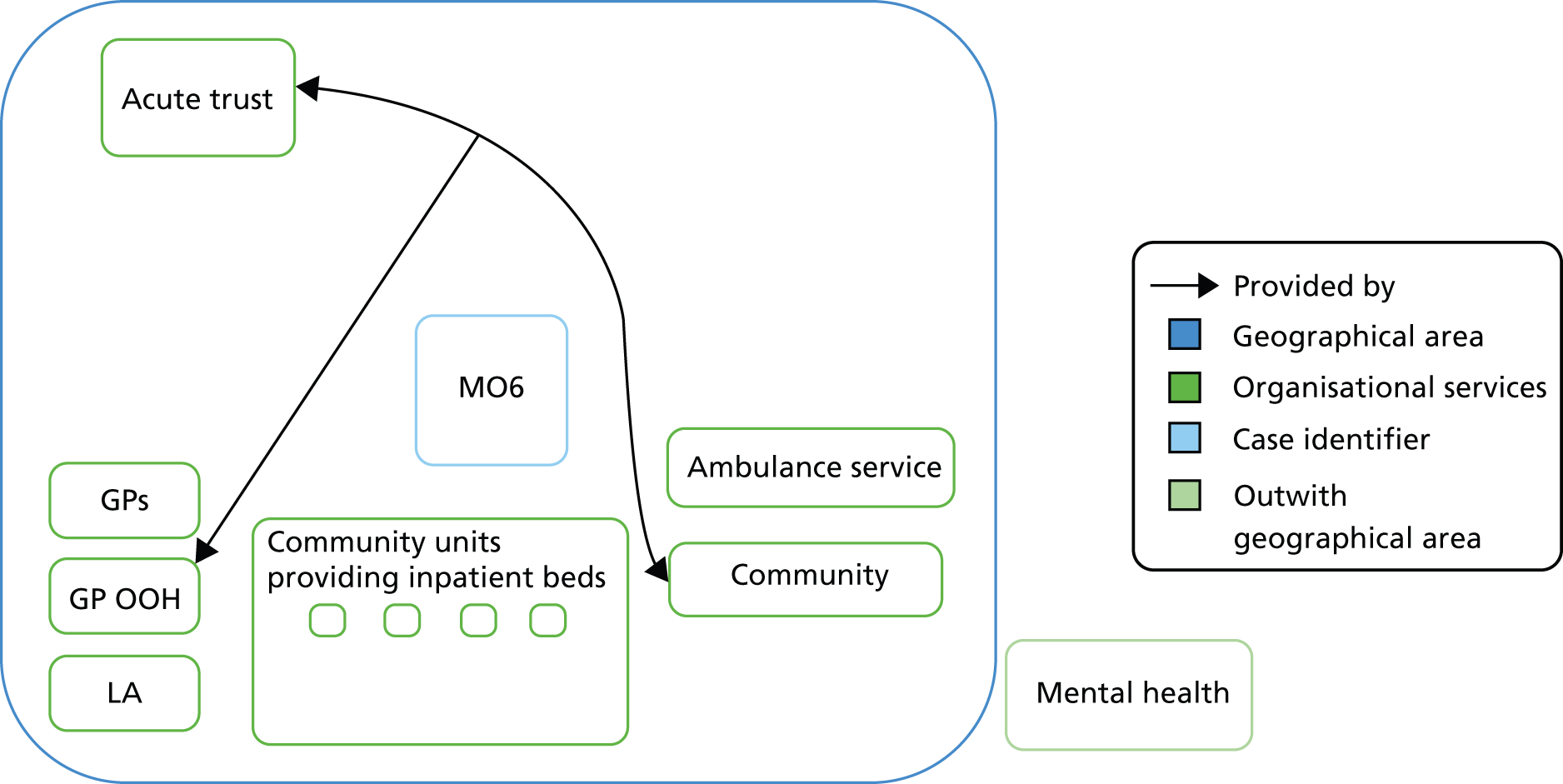

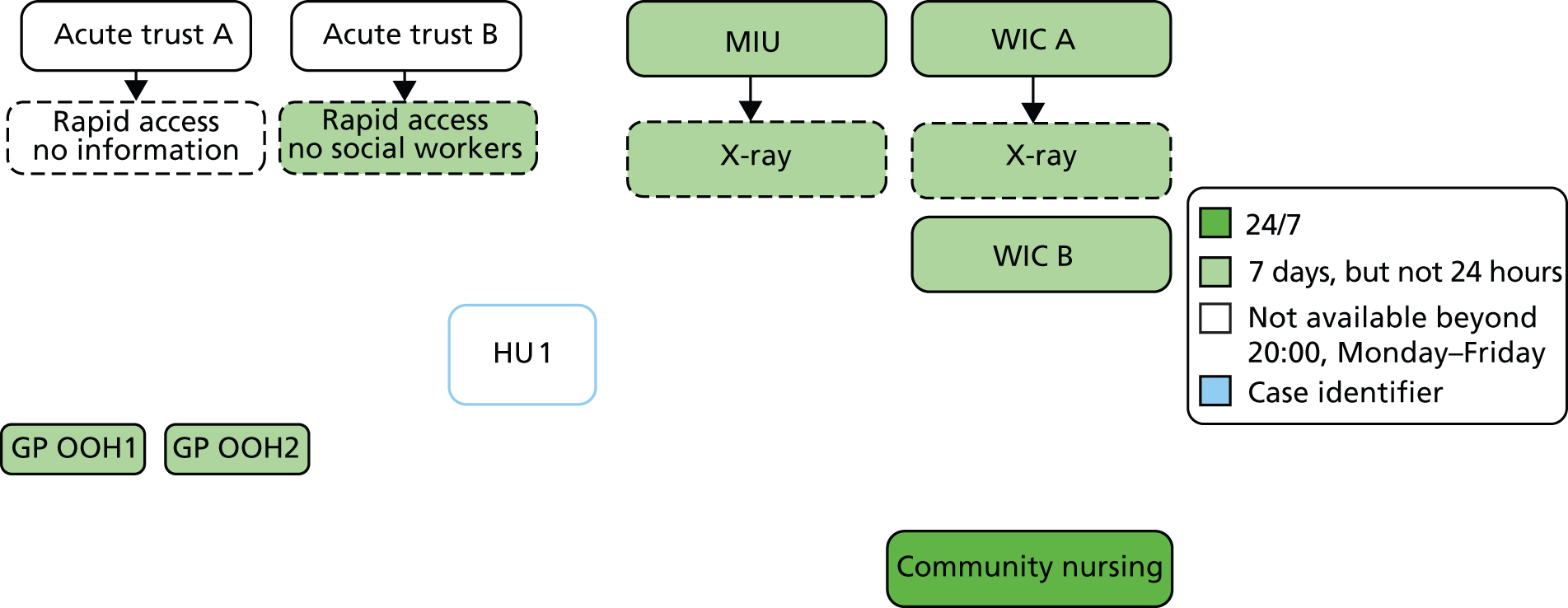

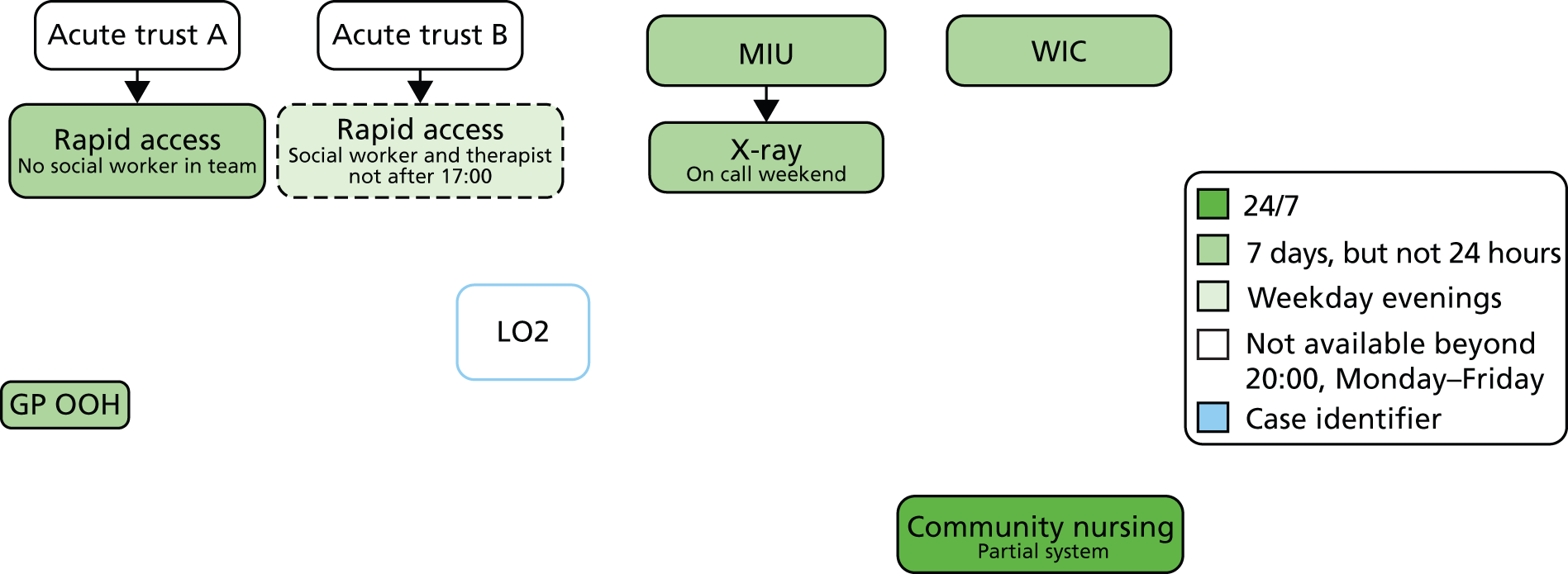

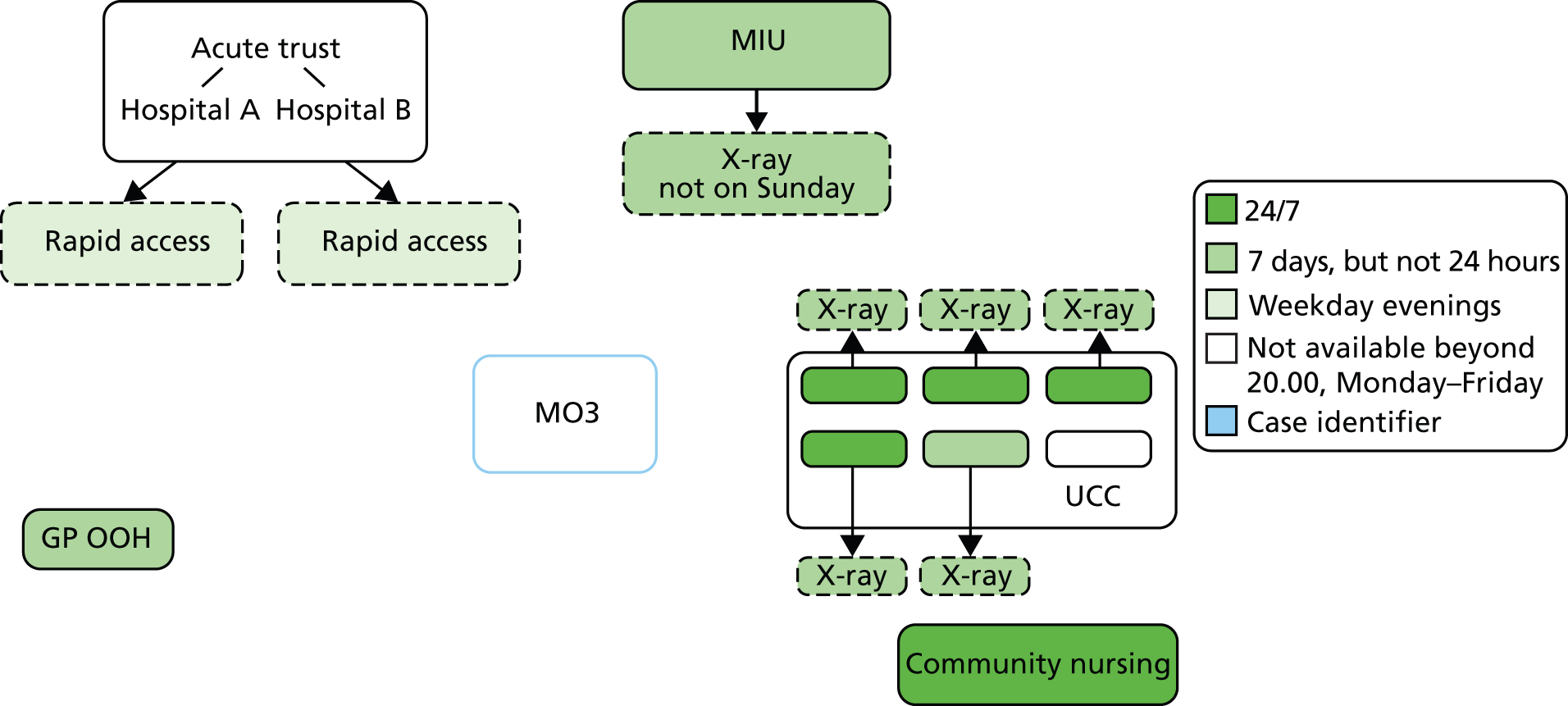

-

describe each system configuration in terms of services available and relationships between services

-

obtain perceptions of key stakeholders about what worked within their system and what needed to be improved.

Design: multiple case studies

For this component of the study we used Yin’s multiple case study approach. 39 Yin’s post-positivist perspective was suitable for our use of case studies within a mixed-methods study. The cases were emergency and urgent care systems defined by our geographically based systems. Yin identifies three types of case studies: exploratory, descriptive and explanatory. Our case studies were both descriptive and explanatory, describing six systems and offering further possible explanation of variation in the SAAR.

Numbers of cases

There is a need to balance selecting a large enough number of case studies to allow patterns to be determined across cases and a small enough number to make full use of the strength of the case study approach to explore issues in depth. Yin points out that ‘A fatal flaw in doing case studies is to conceive of statistical generalisation as the method of generalising the results of the case study’ (p. 32). 39 Rather, analytic generalisation is important, where a theory is generated within one case study and replication – or not – of the theory is considered in the other case studies. We selected six case studies to offer a balance of pattern identification and depth of understanding.

Selection of case studies

The regression undertaken in phase 1 identified 27 candidate systems for in-depth case study, that is with SAARs which could not be fully explained by the factors in the regression reported in Table 5. We explained in Chapter 4 (section Link with phase 2) how we selected the case studies, whereby we purposively selected a mix of high, medium and low SAARs and over- and underprediction by the phase 1 regression. Early in the study the health-care commissioners in two selected cases did not want to participate in the study or did not respond to our invitation. At the time we felt that commissioners were an essential stakeholder because they helped us to define the services providing care to the population of the system. Therefore, we replaced each system with another system within the same geographical cluster. When this occurred again later in the study we kept the original systems because we realised that we could make use of the commissioner’s website to obtain the information we needed about service use by their population.

Data collection

Case studies can draw on six key sources of evidence: documents, records, interviews, direct observation, participant observation and physical artefacts. 39 Because of the complexity and size of each system, observation was difficult. Therefore, within each case we used three types of data: documents, routine data and interviews. The interviews were central to the case studies, with support from documents and routine data.

Interviews

We undertook semistructured face-to-face and telephone interviews with key stakeholders in the system to describe the system configuration and perceptions of issues affecting avoidable emergency admissions within their service and the wider emergency and urgent care system. Our intention had been to undertake one case at a time, visiting the site two or three times to undertake most of the interviews face to face. However, permissions were needed for access to multiple organisations within each system; procedures were time-consuming and occurred at different speeds for different organisations. We made a decision early in the data collection period to undertake interviews for an organisation as soon as the permissions were given and we considered that telephone interviews offered a more efficient approach. EK visited each site once for 1–2 days to undertake as many face-to-face interviews as possible and then conducted the majority of interviews by telephone.

It was important that a wide variety of stakeholders were interviewed to offer different perspectives of the system in which they worked. The sample we attempted to recruit in each case study was informed by our conceptual framework, drawing on commissioners, service providers and patient representatives. Services included the wide range of services within an emergency and urgent care system. Within any acute trust serving a large proportion of the system population, we included parts of the trust responsible for emergency admissions such as EDs, medical admission units and bed managers. Our planned sample included health-care commissioners, ED staff (consultant, lead nurse, manager), acute trust bed manager/medical admissions unit, GP, GP OOH service, ambulance trust operations manager and paramedic, community health service providers, social care staff, nursing/residential care home manager and the Healthwatch lead. We did not attempt to interview patients and their families, so an important set of voices was missing from our work.

A local collaborator was identified in each organisation of our six systems, who helped to identify relevant staff within the local area. Each potential interviewee was contacted by email and formally invited to take part in the study. Non-responders to our initial invitation were contacted again within 1 month. Our intention was to undertake around 15 interviews per case, totalling around 90 interviews across the six case studies.

Emma Knowles began the interviews by being clear about the geographical area we were interested in and the services we included in any emergency and urgent care system. She then read out a list of the 14 conditions rich in avoidable admissions. This ensured that each interviewee was clear about the territory being addressed by our study. The interviews covered key drivers of potentially avoidable admissions within the interviewees’ organisation and the wider system. We clarified when initiatives were in operation, because interviewees liked to discuss new services and future plans whereas we were more interested in services operating in 2008–11. We did not tell interviewees whether their system had a high or low SAAR, or why we had selected their system, until near the end of the interview. A topic guide was developed based on our research objectives (see Appendix 3) and piloted in the first few interviews. The topic guide worked well and few adjustments needed to be made for later interviews. Written informed consent was gained. Interviews were digitally recorded with permission and lasted around 60 minutes. We offered £77 to the organisation (not the individual) for the time given for the interview.

Documents

We searched the websites of commissioners and service providers for information that would help us to describe the system configuration and relationships between services. We also searched for key documents to identify initiatives in operation that might affect avoidable admissions during our SAAR time period. In particular we searched for the annual reports from each PCT, acute trust, community health trust, ambulance service trust, local authority commissioner and Local Involvement Networks (LINks) published between 2008 and 2013, and the annual public health report in each system. We paid particular attention to any references made to major changes to the structure of the organisations or workforce; emergency care; emergency admissions; and our 14 clinical conditions.

Routine data

We had planned to request from the services within each case study any local data on use of key services within the system during the previous financial year. However, as our interviews progressed we became more interested in the routine data about the case in our phase 1 regression and focused on this instead because it was measured consistently for all of our cases.

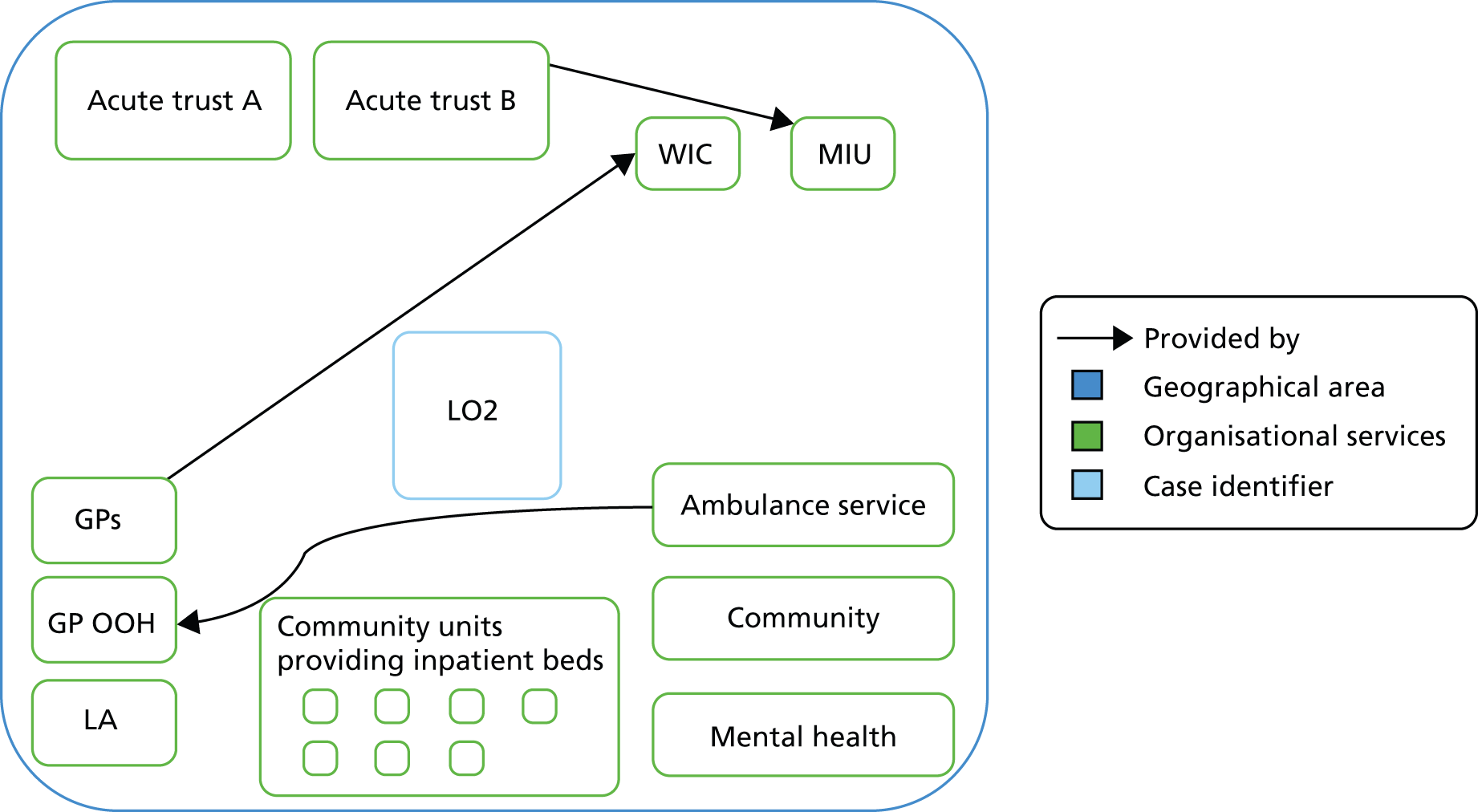

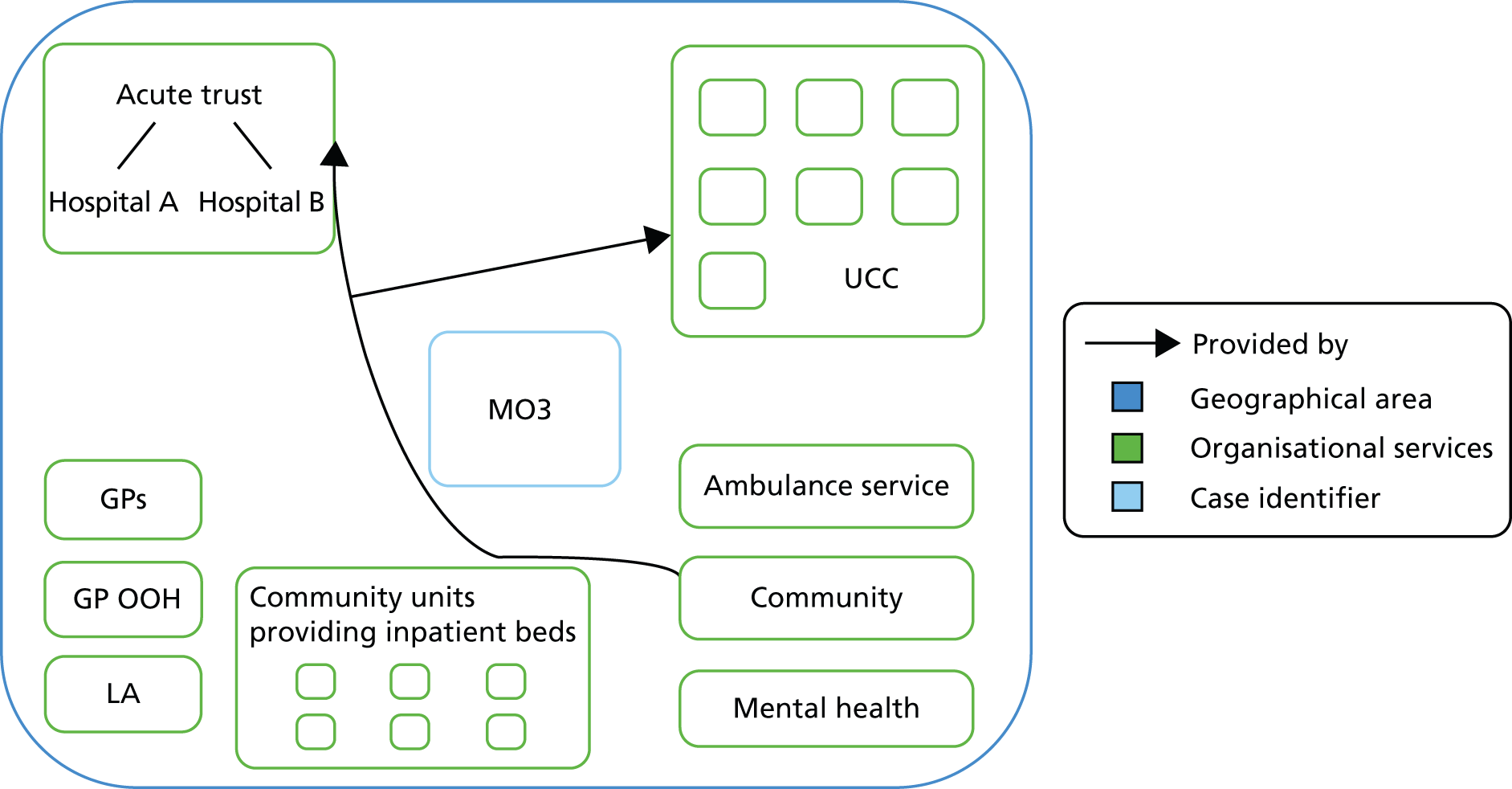

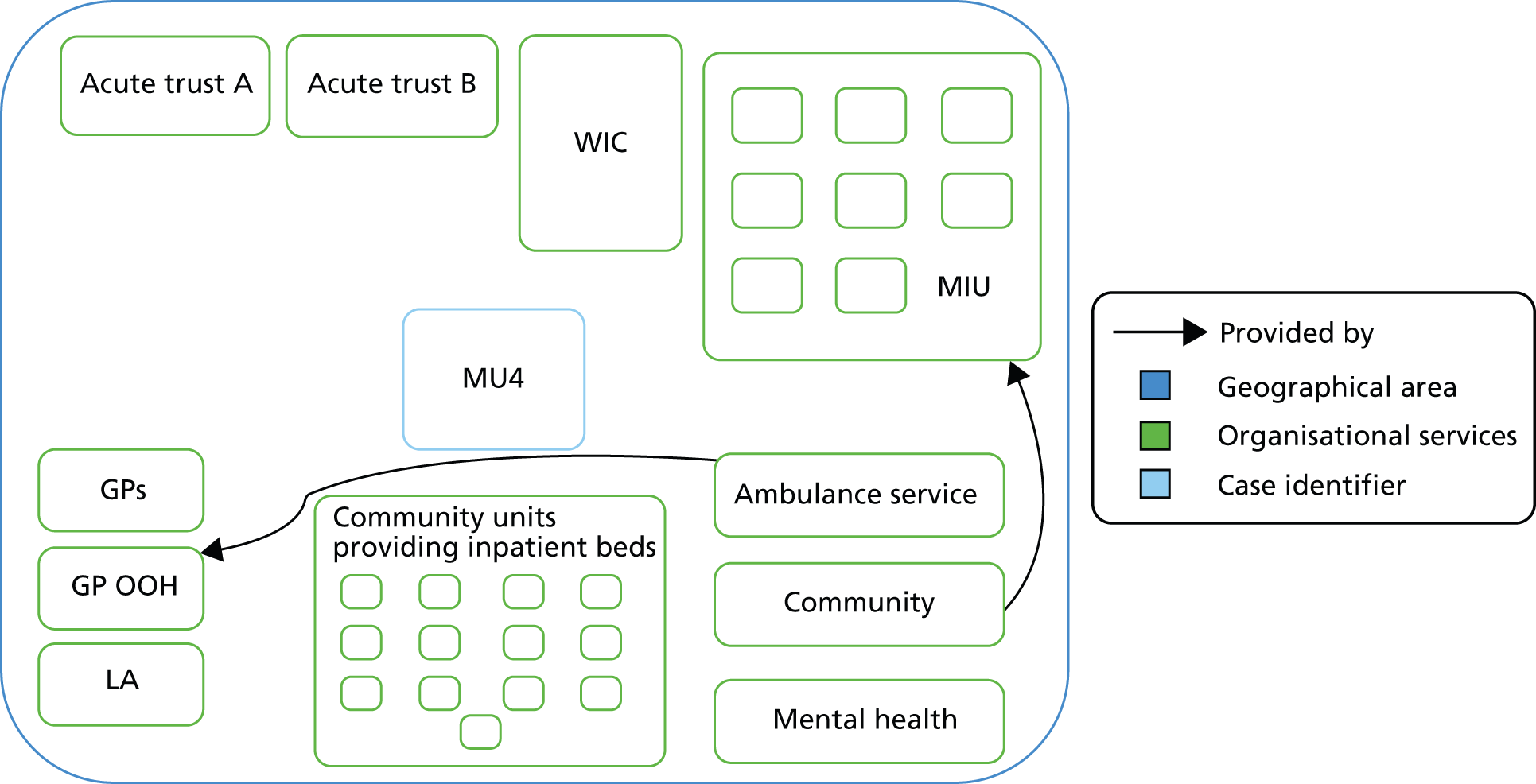

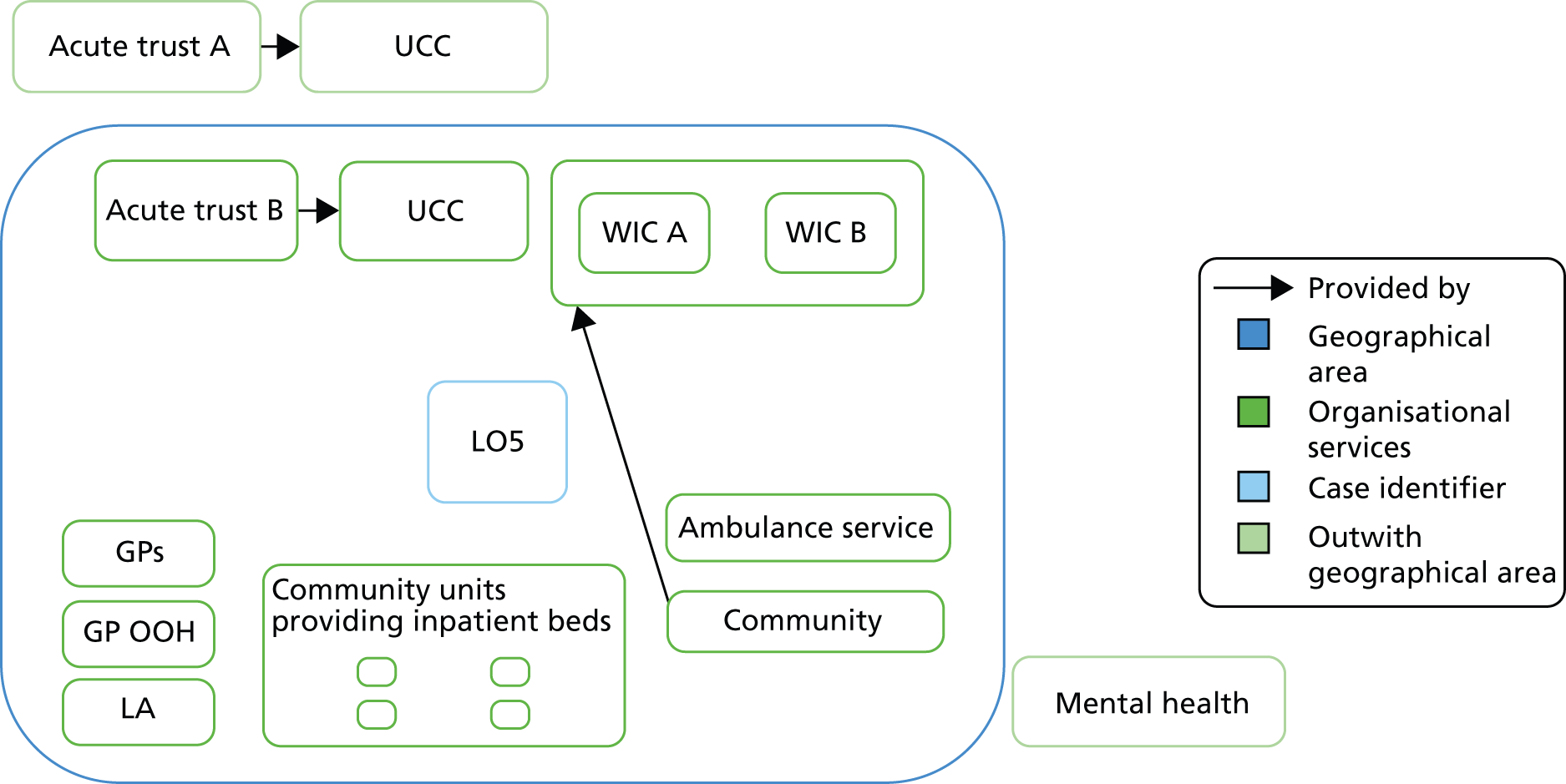

Operationalising the definition of a case

Each case was an emergency and urgent care system defined by the main services used by a population served by the health-care commissioning bodies known as PCTs at the time of the data collection (2011–13). Services included in a case could be within or outside the geographical boundaries of the geographically based systems in the phase 1 regression. We relied on local commissioners and their websites to identify key services to include in a case.

Context in which cases were operating

We were interested in 2008–11, for which the SAAR was calculated. We interviewed stakeholders in 2012 and 2013. As stated earlier, we asked interviewees to clarify when initiatives they discussed were in operation so we could relate these to the findings in the phase 1 regression.

The interviews were undertaken at a time of major NHS reorganisation. PCTs were in the process of being disbanded to make way for Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). Patient representation structures were also changing, with Healthwatch introduced in April 2013, taking over the function of LINks. This made it difficult to identify some stakeholders for interview because they were in the process of leaving their job or had yet to be appointed.

The subject of emergency admissions and their reduction was high on the political and commissioning agenda. Tariffs were in operation nationally which reduced payments to service providers for emergency admissions occurring over the rate of previous years.

Analysis

Analysis of interviews

Interviews were transcribed verbatim. We analysed the data in a number of stages:

-

Alicia O’Cathain selected a case and read 6–10 transcripts from a variety of stakeholders to identify themes based on issues common to the set of transcripts. These themes were written up in conjunction with the quantitative data from the phase 1 regression for that case. The aim was to describe the case and to identify some hypotheses about factors affecting potentially avoidable admissions that we had failed to measure in phase 1 and reasons why we had over- or underpredicted the SAAR for that case. We called these our ‘case personalities’. These documents were read by our research team and discussed at our management meetings and at SECF meetings, where the content was questioned and challenged. This focus on one case at a time helped with analytical generalisation, as subsequent cases were compared and contrasted with previous cases.

-

When we had completed our six case personalities we analysed all the interviews using the first four stages of framework analysis. 40 The framework approach was appropriate because it allows for the exploration of both a priori and emergent issues. The first stage of familiarisation had already occurred during the development of the case personalities. The second stage of developing a thematic framework was based on the issues we identified in our case personalities. These themes were mainly descriptive, based on the key services within the emergency and urgent care system. We had some conceptual themes, such as incentives within the system related to avoiding emergency admissions and how easy it was perceived to be to admit a patient. The third stage involved EK and COK systematically coding transcripts to the themes using NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). During this process, AOC, EK and COK discussed the process of coding to facilitate consistency. The fourth stage involved EK and AOC taking data extractions related to a theme or subtheme and analysing these for three purposes:

-

We identified stakeholder perceptions of an issue without paying attention to the cases.

-

We identified within-case perceptions of that issue in preparation for the multiple case analysis, focusing on summarising the issue for each case in comparison with the other cases.

-

We rewrote our case personality documents to ensure that they reflected the more systematic approach to our interview analysis.

-

Analysis of documents

We extracted data from documents by making summary notes of issues related to emergency and urgent care, documenting date and source. Data extraction was undertaken by a researcher who had not been involved in the interviews (RC), who was therefore not focused on finding issues to support the interviews. After writing up a preliminary case personality based on the interviews, we used this documentary extraction to add to the case personalities by offering context; verifying, contradicting or clarifying interview content; and identifying gaps in the interviews.

Analysis of multiple case studies

After developing full case personalities, and a matrix summarising findings for each case for each theme, we undertook a multiple case study analysis by using ‘pattern matching logic’39 to look for cross-case patterns, particularly issues that appeared distinctly in one type of case (e.g. underpredicted SAAR) and not another (e.g. overpredicted SAAR). The matrix displayed subthemes (rows) for each case (columns) and we used it to identify hypotheses for testing in phase 3.

Validity

There can be concerns about the validity of data collected within interviews in terms of whether or not it represents ‘the truth’. For example, interviewees can give accounts of a situation to show themselves or their service in a good light, while finding fault with others; or they may repeat beliefs that are held within a community of health and social care professionals, which may not be supported by data. Construct validity can be increased by using multiple sources of evidence, and chains of evidence, within a case. 39 Our multiple sources were the interviews, the phase 1 regression and documents. We took the views of interviewees as valid individual perceptions of a system, but we also cross-referenced the views of one stakeholder with those of other stakeholders in the system. Sometimes stakeholders described the service provision differently and we put more weight on the view of the stakeholder providing the relevant service.

Findings

The findings are reported in this chapter and Chapters 7 and 8 for ease of reading:

-

We start by describing the cases and interviewees in the case studies (next section).

-

We consider some overarching themes emerging from the case studies (following section).

-

We describe each case in detail (see Chapter 7).

-

We undertake multiple case study comparison to attempt to explain variation between the six emergency and urgent care systems and develop hypotheses for testing in phase 3 (see Chapter 8).

We chose this order of presentation even though the primary focus of the case studies was the multiple case study comparison. We felt that it was helpful to the reader to lead up to the primary analysis by first understanding the overarching themes emerging from the case studies and then seeing how they played out in the six different cases.

Description of cases and interviewees

Cases

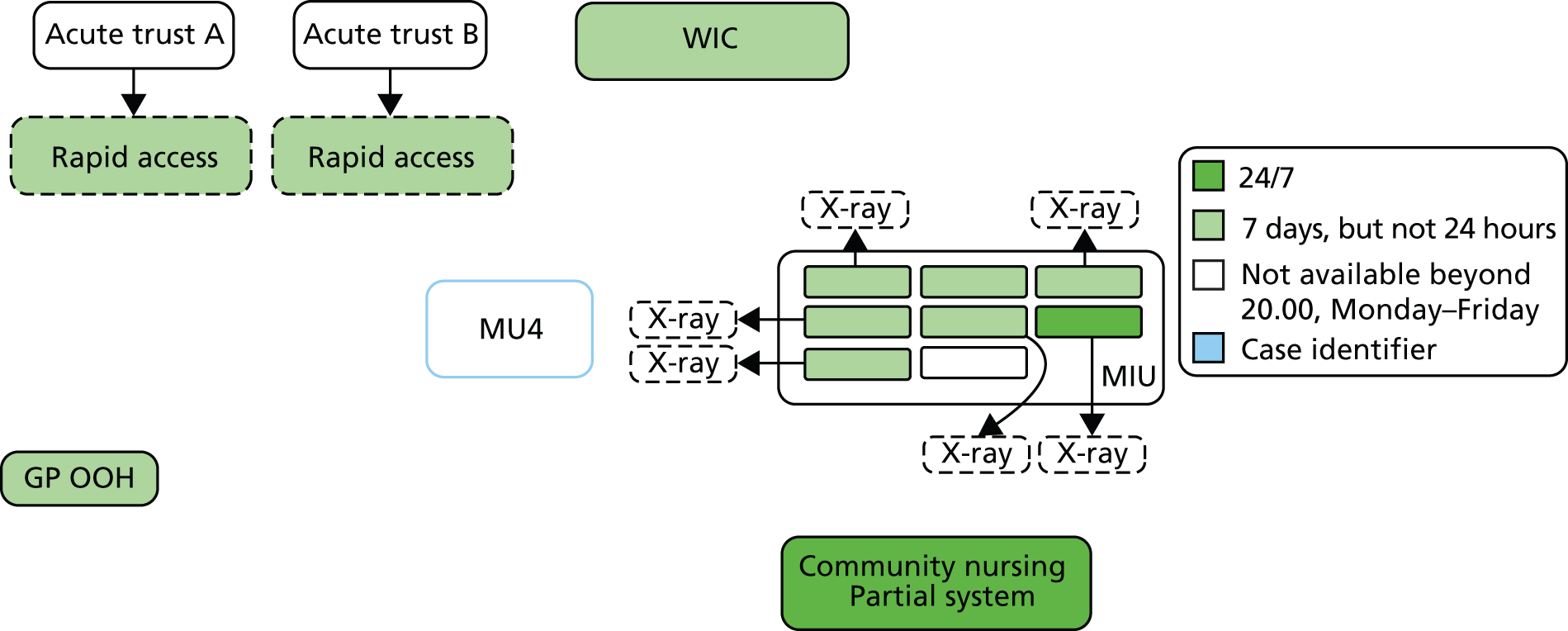

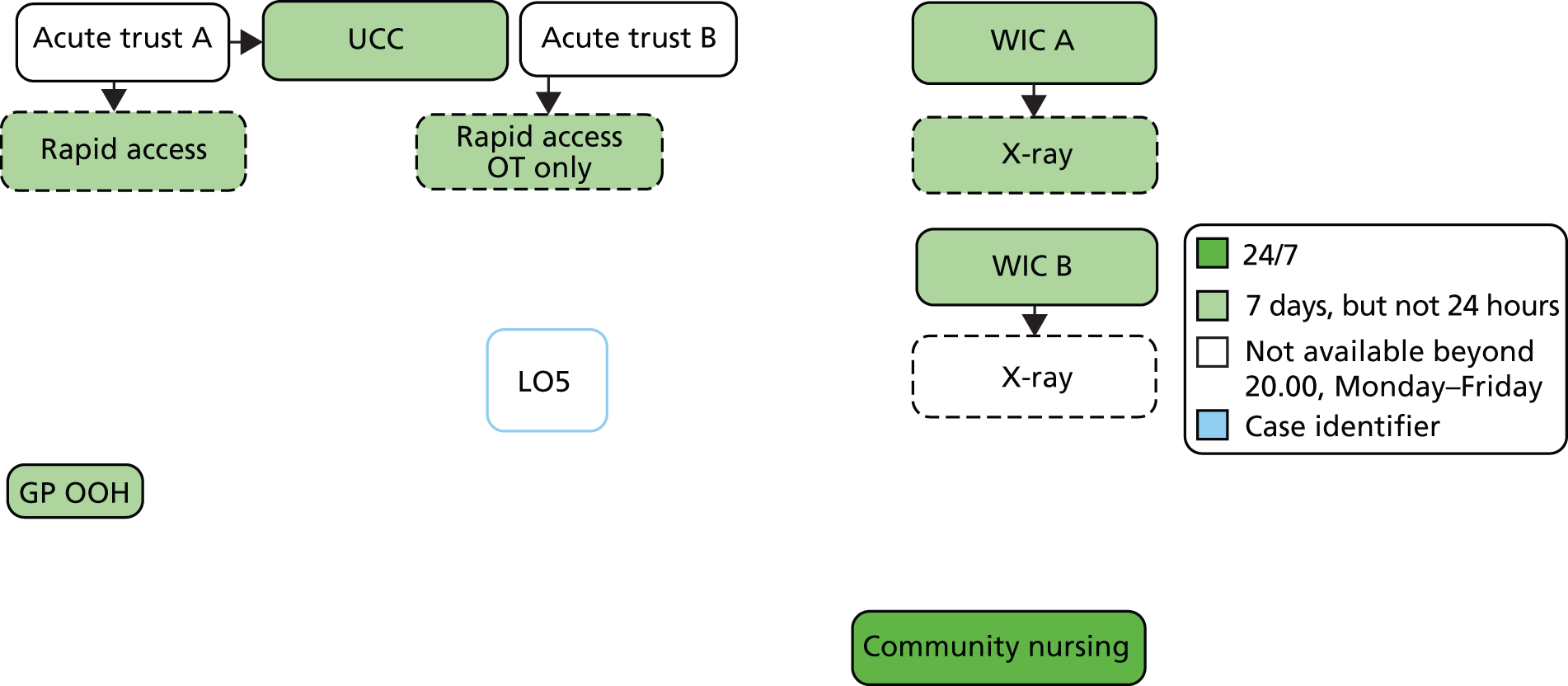

We summarise the findings from the phase 1 regression for each of the cases in Table 11. Some key issues to notice are:

-

HU1 had a high SAAR; it was one of the highest in England.

-

LO2 and LO5 had low SAARs; LO2 had one of the lowest in England.

-

Three cases had medium SAARs, although MU4’s SAAR was rather low.

-

HU1 and MU4 had actual SAARs that were higher than their predicted SAARs (underpredicted) and four had actual SAARs that were lower than their predicted SAARs (overpredicted). One interpretation of this is that HU1 and MU1 performed worse than predicted and the others performed better than predicted in our phase 1 regression. We use the terms ‘better’ and ‘worse’ here for ease of communication, rather than necessarily suggesting that a lower than predicted SAAR is good. The premise of the study suggests that services should aim for a low SAAR, but this involves a value judgement and various assumptions.

-

Three cases were rural (LO2, MO3 and MU4).

-

One case had an exceptionally high ED attendance rate (HU1).

| HU1: high SAAR, underpredicted | LO2: low SAAR, overpredicted | MO3: medium SAAR, overpredicted | MU4: medium SAAR, underpredicted | LO5: low SAA, overpredicted | MO6: medium SAAR, overpredicted | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAAR | 3493 | 1572 | 2481 | 1905 | 1776 | 2421 |

| Rank SAARa | 147 | 9 | 100 | 48 | 33 | 93 |

| Predicted SAAR | 3172 | 1950 | 2710 | 1690 | 2300 | 2748 |

| Predicted rank | 144 | 43 | 118 | 22 | 82 | 123 |

| Deprivation (%) | 9 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 8 |

| Rural status | Urban other | Rural 50% | Rural 50% | Rural 50% | Urban major | Urban major |

| ED attendance rateb | 426 | 175 | 218 | 349 | 319 | 284 |

| Conversion rateb | 94 | 125 | 105 | 74 | 108 | 94 |

| % LOS < 1 day | 32 | 27 | 29 | 27 | 35 | 31 |

| % non-conveyance | 8 | 34 | 20 | 31 | 16 | 8 |

| % able to see GP in 48 hours | 80 | 81 | 82 | 89 | 79 | 77 |

Interviewees