Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 12/5004/08. The contractual start date was in September 2012. The final report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in February 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Hinrichs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Policy context

In the UK, the government has made reducing the public deficit its greatest priority, with significant implications for public sector services including health care. 1 Following a decade of growth in National Health Service (NHS) funding, this has slowed substantially from 2011–12. 2 This is set against a need to make efficiency savings of £20B by 2014–15 while improving the quality and delivery of NHS care. 3 NHS organisations are therefore under considerable pressure to contain cost while at the same time meet the growing demand for health care and ensure the quality of treatment and care. 3

There are various options by which the efficiency of the health system and of organisations operating within it may be enhanced. One way of thinking about this is to differentiate between types of inefficiencies that occur at different levels in the health-care production process, considering operational, allocative and administrative processes. 4,5 Thus, operational inefficiencies occur because of duplication of services and inefficient processes, the use of expensive inputs or errors. Allocative inefficiencies result from misalignment of resources against best possible outcomes that could be achieved. Measures to strengthen allocative efficiency would involve rebalancing services across the health system, improving care co-ordination or strengthening preventative care. 5,6 Administrative inefficiencies occur as a consequence of administrative spending which exceeds that necessary to achieve the overall goals of the organisation or system,4 also referred to as ‘back office’ functions. 4,7 Improving administrative efficiency could be achieved through, for example, (de)centralising administrative functions, simplifying administrative procedures and introducing uniform standards.

Ongoing activity in the NHS is seeking to address these different types of inefficiencies in different ways, with the potential for savings in operational and administrative functions. In particular, procurement and back office are seen as important areas to achieve efficiency gains. 2 One area that has come under scrutiny is NHS trusts’ non-pay expenditure, which, on average, accounts for around 30% of their total expenditure. 8 In 2011–12, this expenditure was estimated at £20.6B, of which over one-quarter was spent on drugs and pharmacy and just over one-fifth on clinical supplies and services (Table 1). 9

| Expenditure category | NHS expenditure | Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute (£B) | Proportion (%) | ||

| Drugs and pharmacy | 5.5 | 27 | Generic and branded drugs, medical gases and other pharmacy-delivered supplies |

| Clinical supplies and services | 4.5 | 22 | Medical devices and consumables, dressings, X-ray machines, laboratory and occupational therapy materials |

| Premises | 3.3 | 16 | Rates, electricity, gas, oil, furnishings and fittings |

| Contract and agency staff | 2.4 | 12 | |

| Non-clinical supplies and services | 1.3 | 6 | Cleaning materials, crockery, bed linen, laundry items, uniforms, patient clothing |

| Establishment | 1.0 | 5 | Administration expenses such as printing, stationery, advertising and telephones |

| Rentals under operating lease | 0.6 | 3 | |

| Transport | 0.5 | 2 | Vehicle insurance, fuel, materials and external contracts |

| Consultancy services | 0.3 | 1 | |

| Training | 0.3 | 1 | |

| Health care provided by non-NHS bodies | 0.2 | 1 | |

| Miscellaneous | 0.6 | 3 | |

| Total expenditure | £20.6B | ||

A 2011 review of NHS spending on medical and other consumables found wide variation in purchasing across acute trusts in England, with differences in processes and product ranges procured, alongside variation in prices paid for the same items. 10 The review highlighted the scope for efficiency savings in this area of spending. It estimated the potential of savings to be £500M, which equates to 10% of the annual spend on NHS consumables. Areas identified as offering potential for even greater savings include strengthening the strategic vision for purchasing and logistics.

Procurement in the NHS

Procurement of medical supplies and other consumables by NHS trusts in England can be realised in various ways. NHS trusts can, individually or in collaboration with others, directly contract with suppliers, draw on the national supplies organisation (NHS Supply Chain) or use one of the nine regional collaborative procurement hubs. 10 These hubs are regional purchasing organisations that were introduced during the 2000s in an attempt to achieve savings for partner trusts at regional level through aggregating their procurement efforts. 11 NHS Supply Chain was formed in 2006 from the NHS Logistics Authority and parts of the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency, which had been established in 2000 as an executive agency of the Department of Health. 12 Operated by DHL Supply Chain Limited and managed by the NHS Business Services Authority on behalf of the Department of Health, it provides, at national level, procurement and logistics customer and supplier support. 12 Purchasing decisions are otherwise controlled by individual trusts via the local route of direct contracting between individual providers and suppliers.

More recently, the 2008 Procurement Capability Review of the Department of Health and the NHS,13 conducted by the Office of Government Commerce, identified weaknesses in approaches to procurement in the NHS, for instance lack of agreed strategy and operating model. In response, and as part of its wider strategy for the NHS, the Department of Health set out a new commercial operating model for the Department of Health and the NHS. 14 Among other things, this included the introduction of regional commercial support units (CSUs), which were intended to provide commercial support to both NHS commissioning and provider organisations, and were expected to work alongside NHS Supply Chain to ensure value for money for goods and services procured (Table 2). There was also an expectation for CSUs to merge with the corresponding regional collaborative procurement hub. The new model further involved the dissolution of the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency, and its responsibility for procurement policy and pharmaceuticals procurement was transferred to the Department of Health. 17 At the same time, and in response to Innovation Nation (2008),18 which committed each government department to include an innovation procurement plan as part of its commercial operating model, the Department of Health published the National Innovation Procurement Plan (2009). 15 It highlighted the importance of innovation procurement in safeguarding quality, productivity and sustainability in the NHS. The plan sought to provide a coherent framework for innovation procurement by organising the adoption of technology-led innovation at the regional level, supported by an innovation fund to promote faster innovation and more universal diffusion of best practice. These overall developments took place against a wider reform programme of the NHS that sought to enhance patient choice and competition between providers while emphasising the need to secure quality, innovation and productivity. 19

| Year | Policy document | Aims and core elements |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | Necessity – Not Nicety: A New Commercial Operating Model for the NHS and Department of Health 14 | To create ‘a new commercial operating model which will address past deficiencies and which is fit to meet the opportunities and challenges of the future’a Core elements include:

|

| 2009 | National Innovation Procurement Plan 15 | To ‘bring clarity and coherence’a to innovation procurement in the NHS Core elements include:

|

| 2011 | Innovation Health and Wealth: Accelerating Adoption and Diffusion in the NHS 16 | To ‘support the adoption and diffusion of innovation across the NHS’ through setting a ‘delivery agenda that will significantly ramp up the pace of change and innovation’b Improving arrangements for procurement in the NHS identified as one of the eight themes described as core to the delivery agenda to support the NHS in achieving systematic transformation. Core activities identified under the procurement theme include:

|

| 2013 | Better Procurement, Better Value, Better Care: A Procurement Development Programme for the NHS 9 | To ‘support the modernisation of procurement across the health system and help trusts deliver the efficiencies they need’c The programme comprises four integrative elements:

|

Recognition of the importance of procurement as a means to drive up quality and value, and to stimulate innovation in the NHS more widely, was further emphasised in the 2011 Innovation Health and Wealth: Accelerating Adoption and Diffusion in the NHS report,16 which also noted how procurement would provide an important lever for economic growth. It announced the publication of a procurement strategy by the Department of Health in 2012, which would include a range of measures to help reduce waste and achieve efficiency gains in procurement as identified by the National Audit Office (2011), as described earlier. 10 This strategy was eventually published in August 2013, although referred to as a ‘procurement development programme’ rather than a strategy as such. 9 Highlighting how non-pay expenditure in NHS trusts had continued to increase over time, and at a rate higher than NHS activity and inflation during 2011–12, it set out a programme of work that seeks to stabilise non-pay spending for the period until the end of 2015–16. It proposed four core initiatives that aim to (i) deliver immediate efficiency and productivity gains; (ii) improve data, information and transparency; (iii) revisit the nature of clinical engagement in procurement; and (iv) create a national ‘enabling function’ to support leadership and build procurement capability throughout the system (see Table 2). We will return to the 2013 procurement development programme in subsequent sections of this report as it provides important context for the findings presented here.

Informing NHS learning for procurement

In its 2012 review of progress made in the NHS towards achieving efficiency savings, the National Audit Office highlighted the need for robust evidence to help the NHS make informed decisions about how to make such savings. 2 It pointed to the potential for lessons to be learned from activities and initiatives implemented elsewhere to enable the adoption of good practice.

In the field of NHS procurement, and supply chain management (SCM) more generally, there is potential to learn from other sectors, public and private, and from experiences in other countries, and to identify potential for cost containment and efficiency gains. A growing body of work has studied the applicability of SCM concepts developed in the private sector to public services to inform better use of public funds. 20 Much of the existing literature which draws on good practice in the private sector focuses on manufacturing, with the automotive sector one of the most studied industries. For example, Toyota’s ‘just in time’ supply management model, which aimed at improving return on investment and limiting inventory costs, has been explored in some depth for its transferability to other sectors. 21 The Toyota model relies on developing close links with a small number of suppliers, level production scheduling and continuous quality improvement,22 and this has also informed discourse and practice in health-care settings. 23–25

The public sector may also offer opportunities for learning. For instance, following a review of UK Ministry of Defence routine procurement items in 2007,26 the ministry introduced a number of measures intended to streamline processes and improve the cost-effectiveness of routine procurement by introducing measures such as e-procurement and reverse auctions, and changing some of the low-cost supply routes for routine items. 27 There is also potential for learning from experiences of procurement in health systems other than the English NHS. Countries that may provide useful insights into procurement and SCM in the health-care sector are Italy28 and New Zealand,29 owing to their recent reforms to strengthen efficiency in health-care procurement.

Although available evidence provides potential for models developed in other sectors to be adapted in health-care settings, there is a need to bring together the diverse literature on such approaches that may be relevant to the NHS context. Work that is available has highlighted that the NHS has a substantial potential to influence the supply chain in some of the products it purchases. 30 The 2011 review by the National Audit Office of NHS procurement of consumables argued that more efficient procurement has the potential to save costs without reducing the quality of patient care. 10 At the same time, lessons learned will have to be placed in the wider context of the quality improvement agenda31 and the need to create value in health care. 32 There is therefore a need to better understand the potential of new approaches used in other sectors to inform decision-making in the NHS, and the risks and benefits associated with these.

The work presented in this report seeks to contribute to this process by advancing our understanding of the evidence on procurement and SCM in sectors other than health care that can inform practice in the NHS. Principally drawing on a rapid evidence assessment (REA), we sought to

-

describe approaches to procurement and SCM in selected areas (including, but not limited to, manufacturing and automotive sectors, defence, information and communication technology and pharmaceutical industries)

-

identify best practices that may inform procurement and SCM in the NHS.

Defining procurement

The terminology around procurement in the health sector has proliferated in recent years, with concepts such as procurement, purchasing, commissioning or contracting frequently used interchangeably. 33 However, interpretation of these terms is likely to differ across disciplines and professions,34 and it will therefore be important to apply consistent terminology throughout this report.

At the outset, a core distinction can be made between purchasing for health care and purchasing of health-care services. 35 Purchasing for health care refers to the purchase of any physical items, and their maintenance, by health-care organisations in order to support the delivery of services. Purchasing of health-care services describes the actual process of purchasing the service itself. In the context of the English NHS, this is also referred to as NHS commissioning, although it is important to note that the term ‘commissioning’ is understood as a broader concept than purchasing. Box 1 provides an overview of definitions of a range of terms used in the context of procurement and SCM. It illustrates that boundaries of concepts are frequently not clear-cut and we will use the terms ‘procurement’ and ‘purchasing’ as equivalent while noting their conceptual differences.

Commissioning: oriented towards maximising population health and equity by purchasing health services and influencing other organisations to create conditions which enhance population health. 36 Involves a strategic approach that includes monitoring and evaluating outcomes. 33

Contracting: negotiated agreement about services that a provider will provide in return for payment; includes service specification, tendering, monitoring and reviewing contract performance. 36

Procurement: the process of managing all activities associated with the purchase of goods and services required to operate an organisation. The term ‘procurement’ is more often used within the public procurement context, whereas private organisations may refer to purchasing and/or sourcing.

Purchasing: the process of buying or funding goods and services in response to demand or usage. 33 Purchasing is often linked to resource allocation and thus regarded as a mechanism by which those who hold financial resources allocate them to those who produce health services. 37

SCM: the management of the interconnection of organisations that relate to each other through upstream and downstream linkages between the processes that produce value to the ultimate consumer in the form of products and services. 38

Effects of the changing NHS context on the study

The REA presented in this report was commissioned to commence in December 2012. Since then, the NHS has undergone a series of changes which had direct and indirect impacts on the work undertaken here. First, when submitting the research protocol for this study we had secured commitment from advisors from two hospital trusts, who had agreed to participate in the research as key informants, and to act as multipliers by enabling contacting of other staff members within their trusts for interview. Both trusts were affected by the changing NHS context; one had to withdraw its commitments because of unforeseen difficulties in securing staff time for research within current resource and financial constraints, and the second experienced changes in staff working in procurement. Given that the procurement function in hospital settings tends to work with small teams, any reduction in team size will inevitably affect availability of staff previously engaged in procurement to participate in the research. Against this background, we amended the original research protocol by extending the range of key informants to be interviewed, to include a wider range of stakeholders with expertise and/or experience in NHS procurement from other NHS trusts and related organisations.

Second, and as indicated earlier, in August 2013 the Department of Health released the new procurement development programme. 9 This has not had an impact on our approach to the REA presented in this report, although we set the discussion of findings in the light of the recommendations by the procurement development programme, in the context of insights drawn from the literature. We have, however, amended our approach to include international experiences. The original research protocol for this component of the project foresaw an assessment of general approaches to procurement and SCM strategies in a small number of health systems. However, given that the new procurement development programme for the NHS has now been released and will be implemented in due course, we believed it to be of more use to the NHS to report in detail on specific countries’ experiences that may provide useful insights into the further advancement of the procurement development programme, rather than providing general overviews of different systems as such. Following a preliminary review of the evidence, we narrowed the international component to an in-depth review of approaches in France and New Zealand. We describe the reasoning for our choices in Chapter 2, Assessing the experience of procurement and supply chain management in the health sector in selected high-income countries. It is important to note, however, that we have considered experiences in other countries by means of the REA also, and report on these throughout the evidence review.

Structure of the report

This introductory chapter has briefly set out the aims of the research and the policy context within which it was commissioned. Chapter 2 describes the methods used. Chapter 3 presents the core findings of the work, structured according to the major themes identified in the academic and grey literature, and with reference to interview findings to highlight the NHS context. Chapter 4 specifically reports on the international approaches studied. We close with Chapter 5, which discusses our overall findings, seeking to relate them to the wider health-care context, and offers recommendations for further research.

Chapter 2 Methods

The principal approach used in this study was a REA of the academic and grey literature. We complemented the assessment of evidence with interviews with a small set of stakeholders involved in procurement in the NHS, representing both the NHS and the private sector, to help place the findings of the evidence review in the NHS context. We also undertook an in-depth assessment of approaches to procurement in the health-care sector in two countries other than England to understand the potential for learning for the NHS.

Rapid evidence assessment

A REA is a comprehensive, systematic and critical assessment of the scope and quality of available evidence which follows the general principles of conducting literature reviews in health care. 39 The choice of REA was informed by the requirements for this project as set out in the commissioning brief40 and was based on the need to provide the best possible value for money within a relatively limited time frame. In contrast to formal systematic reviews, REAs tend to place more explicit limits on the scope of the review, whether by number and type of databases or other sources searched, types of research included or the language and time period in which the research was conducted. However, the REA follows the same principles as a systematic review: defining the research question; developing the review protocol, including defining inclusion and exclusion criteria, search terms and sources to be searched; undertaking the review, that is, study selection, data extraction, quality assessment and data synthesis; and reporting.

Search strategy

The literature on procurement and SCM stretches beyond peer-reviewed journals to trade publications and government reports. Given the highly theoretical nature of most of the academic publications, we included examples from smaller studies or empirical data from case studies in practice, regardless of whether this was academic or grey literature.

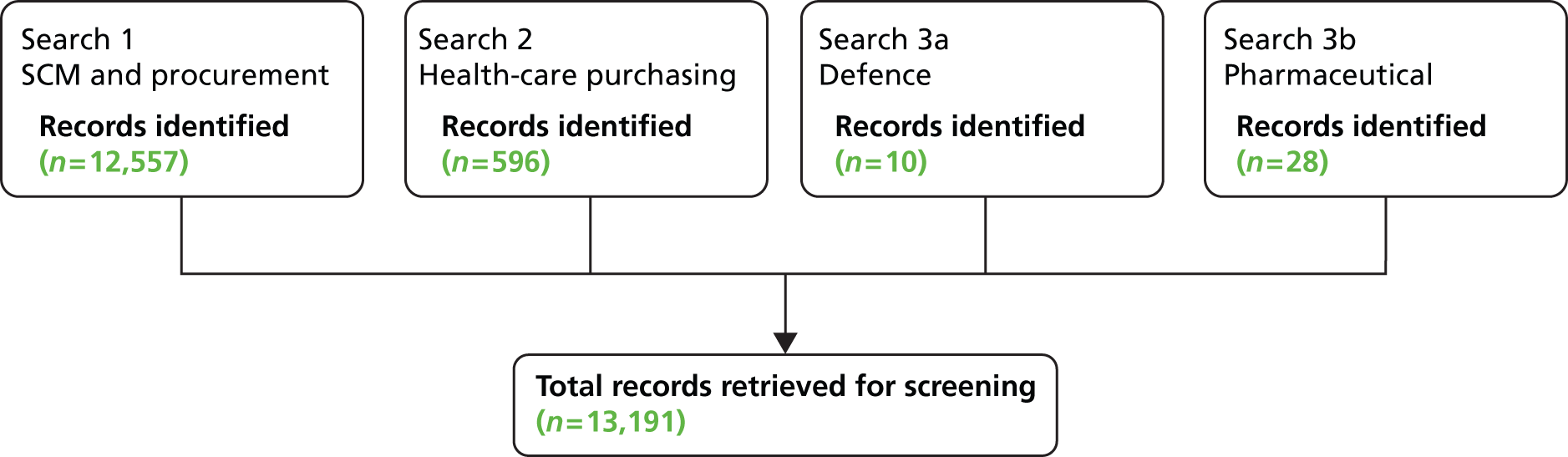

Our pilot testing of the search terms underwent several iterations, and the search was conducted in three stages, focusing on (1) SCM and procurement, (2) procurement in health care and (3) targeted searches of procurement and SCM in the defence and pharmaceutical industries. Here we summarise our principal approach; further details are described in Appendix 1.

-

General SCM and procurement As a first step, we undertook a systematic search for studies that described any initiatives and mechanisms in procurement and SCM across any sector. We searched MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, Academic Search Complete, Social Sciences Abstracts, Military and Government Collection, EconLit and Business Source Complete from January 2006 to November 2013.

-

Procurement in health care In a second step, we conducted a further targeted search of studies of procurement in health care, using MEDLINE only. We used medical subject headings, with the search extending from 2007 to 2013.

-

Procurement and SCM in the defence and pharmaceutical industries We conducted targeted searches of studies of procurement and SCM in the defence industry, using Google Scholar, for the period 2008–13, and procurement and SCM in the pharmaceutical industries, using Google Scholar, Web of Science and Business Source Complete, for the period 2006–13.

The first search was the most extensive with respect to databases and date range as this was the main source for evidence, whereas the two additional searches were more targeted towards the nature of studies in each particular field.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Table 3 summarises the inclusion and exclusion criteria which we applied when selecting studies for review.

| Type of study | Inclusion: we considered reviews and primary studies that presented empirical evidence, for example testing a hypothesis or demonstrating practice, as well as case studies of specific experiences in the sector under review Exclusion: we excluded studies that presented conceptual or theoretical work only and did not provide lessons for practice. We further excluded news articles and opinions |

| Outcomes | Inclusion: the outcomes of interest were cost savings, efficiency (e.g. time saving or general business performance) or effectiveness (improved delivery of the organisation’s aim, quality improvement). Outcomes could be reported qualitatively or quantitatively Exclusion: empirical studies that did not report outcomes were excluded |

| Time period | Searches were undertaken from 2006 onwards (in the main search), coinciding with the introduction of technologies such as RFID, which had a significant impact on approaches to SCM |

| Transferability | Inclusion: we only considered studies conducted in high-income countries. Eligible studies had to report on aspects of procurement or SCM that were potentially transferable to the NHS Exclusion: studies reporting on experiences in low- and middle-income countries were excluded unless they were incorporated as part of a multicountry comparative study |

| Type of article | We considered studies published in academic journals as well as trade and professional journals and the grey literature, as long as these provided examples of procurement and SCM applied in industries in different sectors, including health care |

Study selection

To ensure consistency in study selection, three reviewers screened the same 200 articles, each using the inclusion and exclusion criteria described in Table 3. Disagreements and discrepancies were resolved by discussion or involvement of a fourth reviewer where necessary. The full list of records (n = 13,191) was then divided between three reviewers for further screening according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data extraction

Data from studies identified as eligible for inclusion in the review were extracted into a spreadsheet template. We extracted information on context, study design and objective(s), methodological approach, reported outcomes and identified limitations. Data extraction was undertaken by three researchers. Consistency of data extraction across reviewers was checked through duplicate extraction of a random sample of studies (n = 100) by two reviewers independently. Disagreements and discrepancies were resolved by discussion or involvement of a third reviewer where necessary. Given the wide range of types of studies, to aid with the extraction and reporting of the review we have utilised the Context, Interventions, Mechanisms, Outcomes (CIMO) extraction approach, a framework used in management and organisational settings. 41 Details of all studies selected for review are included in Appendix 2.

Quality assessment of studies

Given the heterogeneity of study designs considered in this review, we did not apply a formal quality rating system, such as the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system for evaluating the quality of evidence for reported outcomes, and typically used for health-care randomised trials. Initial scanning of identified records revealed that many studies were theoretical in nature and did not present empirical data, or that recommendations were not tested in practice. Thus, as a pragmatic approach we applied the following criteria to assess the quality of the studies:

-

The research question or aim of the study is clearly stated.

-

The approach/mechanism/intervention is clearly defined.

-

The study design is rigorous and clearly reported.

-

The results are clearly reported.

Study analysis

Data were analysed drawing on the principles of narrative synthesis, which has been recommended as the most appropriate approach for analysing diverse evidence. 42 Building on tabular presentation of findings as described above (see Data extraction), we first grouped data according to emerging themes and particular areas of learning, including, but not limited to, the following:

-

types of ‘end product’: service, product or product–service system

-

types of improvement gained: efficiency, effectiveness, other forms of optimisation and streamlining

-

types of cost savings: transaction costs, items costs, other optimisation costs

-

types of opportunities for innovation: e-procurement, collaborative agreements

-

types of outcomes achieved: purchaser experience, wider economic impacts.

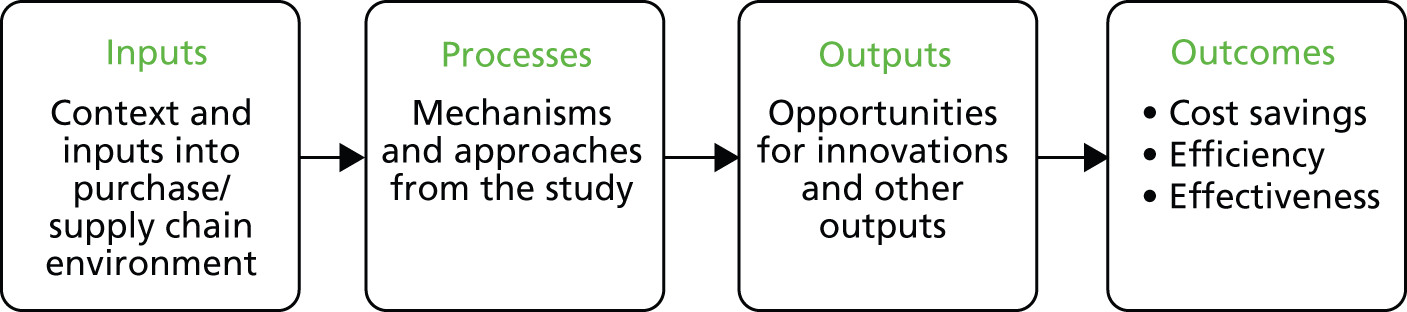

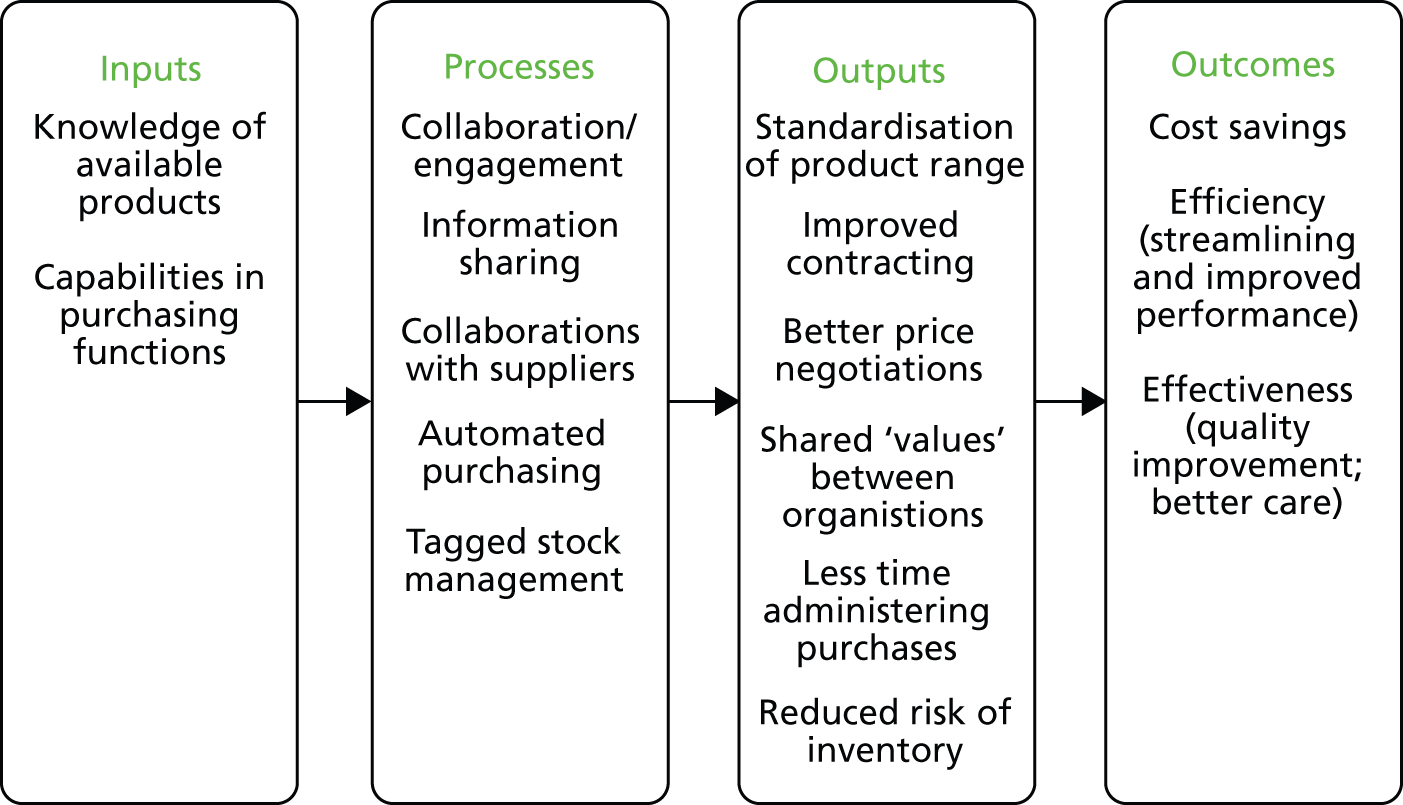

In a further step, we organised our learning from the literature into a logic model format as a means to group the emerging themes and areas of learning into a hypothetical NHS context (Figure 1). In line with the established approach to logic modelling, we distinguished inputs into an organisation (i.e. the context and environment in which purchases are made), the processes or mechanisms used for purchasing, and purchasing outputs and outcomes emerging. In line with our inclusion criteria, we sought to identify outcomes that were (or could potentially be) associated with cost savings, efficiencies and general effectiveness in achieving a given organisation’s aims. We return to a further development of this model, containing the emerging themes from the study, in the discussion (see Chapter 5, Although the evidence remains limited, it is possible to draw some general lessons).

FIGURE 1.

Framework for analysis of studies.

Key informant interviews

Purchasing practices depend on a range of industry and contextual factors which are not easily identifiable or documented in the published literature. Interviews with a small number of key informants, working with or within the health-care sector, helped to ground and validate the themes identified through the literature. They also furthered our understanding of the more practical issues facing NHS procurement in the current climate. This component of the research was designed to be exploratory only, to help place the findings of the evidence review in the NHS context and so inform how our findings might best be used to meet the needs of the NHS.

As indicated in Chapter 1, Effects of the changing NHS context on the study, the original protocol for this research foresaw the commitment of advisors from two hospital trusts who had agreed to participate in the research as key informants and to act as multipliers to identify further staff members for interview. However, the changing NHS context since commencement of the study in December 2012 has meant that one trust had to withdraw, while the second was affected by changes in staff working in procurement, so reducing the number of potential participants in the research. In consultation with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), we amended the original research protocol by extending the range of key informants for interview to consider a wider group of stakeholders with expertise or experience of NHS procurement, including participants from the private sector.

As a consequence of these changes to the protocol, interview participants were identified from different sources. First, we approached the trust still involved in the study in an advisory function for potential interview participants. Second, we used a combination of purposive and ‘snowball’ strategies using official websites, expert advisors’ contacts and the authors’ professional networks. These two approaches identified 21 potential interviewees, who were invited to participate by e-mail explaining the background of the study. Of those invited, five agreed to be interviewed. Table 4 provides an overview of the roles of study participants.

| Label | Sector | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Interviewee 1 | Private sector | Senior manager; provider of data management services to NHS suppliers |

| Interviewee 2 | Private sector | Senior manager; provider of procurement and business services to the NHS |

| Interviewee 3 | Private sector | Senior manager; provider of data management and joint purchasing services to the NHS |

| Interviewee 4 | Private sector | Consultant provider of procurement and improvement services to the NHS |

| Interviewee 5 | NHS | Responsible for strategic procurement in a general acute teaching hospital (foundation trust) |

| Interviewee 6 | NHS | Head of medical device procurement committee in a general acute teaching hospital (foundation trust) |

Depending on the location of the study site under consideration, interviews were undertaken face to face or by telephone, using a semistructured interview guide which was shared with the interviewee beforehand upon request. Interviews explored broad themes around issues facing procurement in the NHS today. They included questions about drivers behind buying practices, problems with NHS buying, best practices in procurement for the NHS, and challenges to and enablers of implementing best buying practice in the NHS (the full interview protocol is presented in Appendix 3).

Interviews were carried out between June and August 2013. All but one interview were undertaken by two researchers. Interviews lasted an average of 45 minutes; they were audio recorded following consent and key notes were transcribed. Transcripts were manually coded, with analyses informed by key themes guiding the interviews with respect to the interview protocol, while also seeking to identify additional emerging themes.

As indicated above, the purpose of key informant interviews in this study was exploratory only, complementing the evidence review as the main component of the study. Given the small number of interviews, data are presented only as a means to further illustrate findings from the evidence review, rather than as confirmatory evidence in their own right.

Assessing the experience of procurement and supply chain management in the health sector in selected high-income countries

The international component of this study initially sought to systematically explore the experiences in a set of countries of procurement and supply chain strategies within their health systems. However, as noted in Chapter 1, in August 2013 the Department of Health released the new procurement development programme. 9 Against this background, and given that the programme will be implemented in due course, we have amended our approach to examining countries’ experiences by focusing on specific examples that may provide useful insights into the further advancement of the procurement development programme, rather than providing general overviews of different systems as such.

Based on a preliminary review of the evidence, we considered five countries for in-depth review: France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand and the USA. Following further assessment of publicly available documentation, we have narrowed the international component to an in-depth review of approaches in France and New Zealand. These were chosen because both countries recently introduced system-level changes in the approach to procurement in the health-care sector through nationally mandated programmes, but they did so through different means. Thus, New Zealand established a national agency mandated with facilitating and leading national initiatives and managing the implementation of common administrative functions of regional health agencies [district health boards (DHBs)], while in France, a national programme seeking to advance hospital performance through sustainable procurement made systematic use of existing collaborative purchasing groups [group purchasing organisations (GPOs)] to help building and disseminating efforts at regional and local levels.

Data collection involved first a review of the published and grey literature as identified from bibliographic databases (PubMed, EBSCOhost), the World Wide Web using common search engines (Google Scholar) and relevant governmental and non-governmental agencies and organisations in the two countries under review, generally following a snowballing approach. Based on information and data extracted from publicly available documents, we drafted a report on each country. Each followed a similar structure, including (i) a summary overview of key features of the health system, (ii) a description of the policy or reform leading to system changes in procurement, (iii) an overview of the key agencies involved in delivering the changes and (iv) an assessment of achievements.

Second, the draft report was informed by one expert in each country. Experts were identified from the professional networks of the authors of this report. They were asked to review the report on their country for comment and verification of the information presented. Experts were also invited to participate in a telephone interview to further explore the nature of the system-level changes in procurement and provide additional information where appropriate, in particular on areas that are not well documented or require in-depth understanding of the country context. Interviews followed a topic guide, exploring perceived challenges around procurement in the health-care sector; the general approach to procurement and policy framework; the role of stakeholders; the role of procurement in the wider system; and the perceived effectiveness and achievements of changes in the procurement function. Interviews lasted an average of 60 minutes; they were recorded upon verbal consent by the interviewee and notes were taken. Interviews were not formally analysed as their purpose was to provide additional information only.

Ethics review

The research protocol was reviewed by the National Research Ethics Service, Research Ethics Committee East of England – Cambridge Central. It confirmed that this study would not require ethics review. However, RAND Europe is committed to following good ethical principles and practice in all research studies. In light of this, key informants were approached in their professional roles only and no sensitive personal information was collected. All references to interviewees were anonymised throughout the report. Information about the project was shared in advance and participants were given the opportunity to ask questions before consenting to take part. Verbal consent was obtained before the interview and interviewees could withdraw from the study at any point.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) did not form a significant component of our study. However, we consulted with members of the public from INsPIRE (patIeNt & Public Involvement in REsearch), a PPI in health and social care research group for Bedfordshire and Cambridgeshire43 on the research protocol and the conceptual framework. Four individuals shared comments, especially regarding the importance of this study, the value of the international component of the study and the need to find genuine efficiency savings, if possible. We considered these in the data extraction and analysis phase. One panel member suggested that SCM professionals should be interviewed, in view of their knowledge of good practices; these individuals were included in our interviewee selection.

Chapter 3 Findings: evidence assessment

This chapter presents the findings from the REA according to the themes that emerged from the data extraction and analysis. Within this section we also report on observations from interviews with reference to the current context of working within and with the NHS.

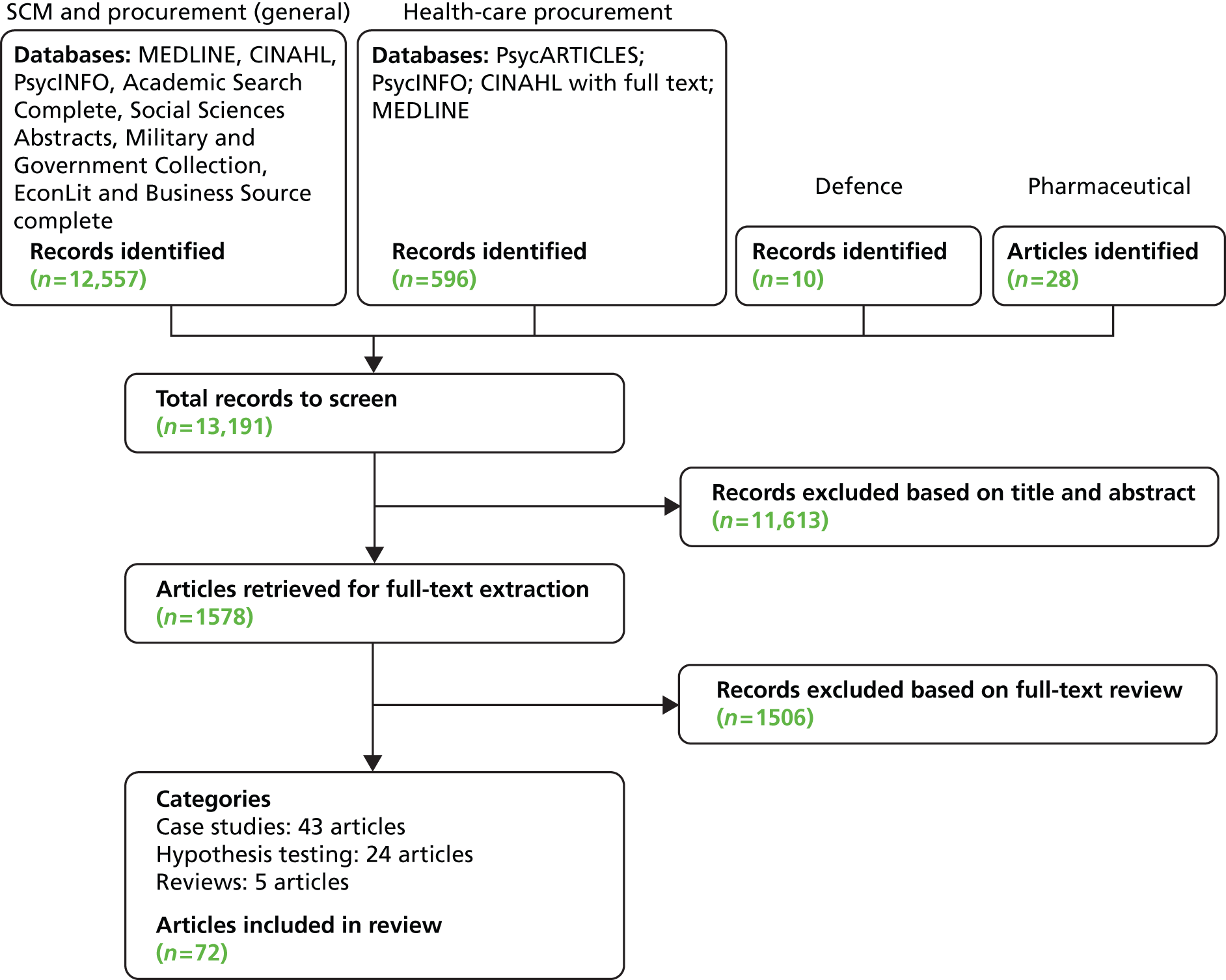

Description of studies

Our search identified a total of 13,191 records across the databases searched, following removal of duplicates; after initial screening of titles and abstracts, we considered 1578 references for full-text review. Of these, 72 studies were identified as eligible for inclusion in the review (Figure 2). 44–115

FIGURE 2.

Process of selection of articles for review.

It was challenging to judge the quality of studies and documents considered as eligible as these often lacked descriptions of methods and strategy of analysis. Our main aim was to capture examples of approaches in practice and, where available, evaluations of such approaches, or studies which contained at least some form of empirical evidence. Frequently, studies did not specify the precise details of the nature of the practice and reported outcomes could not be attributed to single interventions or practices. The studies included in the review were of three types:

-

Studies testing a hypothesis about practice (n = 24),47,50,51,58,63–66,68,71,74,76,77,79–82,84,85,91,93,95,102,104 validated empirically through surveys or interviews, or exploring concepts through interviews, surveys or observation; in the following we refer to these as ‘hypothesis testing’.

-

Studies describing current practice, typically in the form of case studies (n = 43). 45,46,48,49,52–57,59,60,67,69,70,72,73,78,83,86–90,92,94,96–101,103,105,106,108–115 Primary studies were set mostly in the USA (n = 20),48,52–54,57,70,87,88,90,94,96,97,99–101,105,106,108,110,113 Canada (n = 2),72,115 Australia (n = 1),92 Europe (n = 8)45,46,67,69,89,103,109,112 and the UK (n = 3);49,73,78 a few were set in multiple countries (n = 6),55,56,59,83,111,114 or their country information was not reported (n = 3)60,86,98 or unavailable. In the following we refer to these as ‘case studies’.

An overview of the studies included is shown in Table 5. Identified studies covered a range of sectors and industries, including textiles, information technology (IT),99 the automotive industry45,46,68 and manufacturing. 57,63,65,71,76,77,79,80,86,102,104,113 We further identified 21 studies addressing the health-care sector specifically. 48,49,52,54,58,62,70,72,87,88,90,94,96,97,103,105,106,108–110,115

| Theme | Case study (n) | Hypothesis testing (n) | Review (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organisation and strategy | 13 | 9 | 3 |

| Collaboration and relationships | 9 | 10 | 1 |

| Materials and information management | 21 | 5 | 1 |

Analysis of studies identified three overarching themes: organisational and strategic issues; collaboration and relationships (within an organisation and with suppliers); and materials management and information flows within an organisation. Table 5 summarises the included studies according to theme, although it is important to note that studies might address more than one theme. Further detail of individual studies is presented in Appendix 2.

The following sections are organised according to the three main themes we have identified. Each section begins with a summary table of studies reporting on the theme, describing selected characteristics; further details of studies are documented in Appendix 2. We then report on a subset of studies in some more detail, to illustrate the type of evidence under each identified theme. We complement the evidence assessment presented with findings from interviews with key informants working in or with the NHS in England, where appropriate.

Organisation and strategy

A common theme identified across studies reviewed here concerned strategic and organisational issues in relation to SCM, although only a small number of studies (n = 13)45,46,48,49,52–57,59,60,67 provided examples of how this was achieved in practice. The remainder of the studies reviewed comprised those testing hypotheses (n = 9)47,50,51,58,63–66,68 and literature reviews (n = 3). 44,61,62 The studies are summarised in Table 6. Under the overarching theme, we identified further subthemes; these were green and environmental issues, group and collaborative purchasing, and supply chain integration, alignment and general quality improvement. We discuss each of these in turn.

| Reference | Country | Industry | Study type | Study aim and principal methods | Outcomes/learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlSagheer and Ahli (2011)44 | Multiple | Multiple | Review | To assess and analyse the impact of supply chain integration on business performance and associated challenges, using review of literature | Supply chain integration had a ‘mostly’ positive impact on business and enhances profitability, financial stability, customers’ satisfaction and accomplishing business goals |

| Azevedo et al. (2011)45 | Portugal | Automotive | Case study | To study the relationship between green practices and the supply chain performance, using interviews and secondary data | Environmental cost, quality and efficiency were the performance measures with most significant relationships with green practices (e.g. environmental packaging implies utilisation of reusable packages), but differences in opinion on other aspects |

| Azevedo et al. (2012)46 | Portugal | Automotive | Case study | To use a theoretical framework applied to a case study to determine the relationship between green and lean practices and the economic, social and environmental performance of businesses, using interviews and secondary data | Operational costs decrease with one green practice, i.e. reusable packaging, and decrease with a selection of lean practices (such as ‘just-in-sequence’, deliveries direct to point of use, geographical concentration, using electronic data interchange to share information, single sourcing) |

| Baier et al. (2008)47 | Multiple | Multiple | Hypothesis test | To look at the effect of strategic alignment and purchasing efficacy on financial performance, using survey and interviews | Results supported hypotheses which suggested that the relative fit between business strategy and purchasing strategy (labelled as strategic alignment) and between purchasing strategy and purchasing practices (referred to as purchasing efficacy) was key to achieving financial performance |

| Birk (2009)48 | USA | Health care | Case study | To report on effects of implementing a purchasing coalition | One hospital group, as members of the purchasing coalition, saved $1,105,309 on medical supplies in the year prior and $11M in capital acquisitions was saved across members. Cost saving estimated 10–25% for group buys depending on the product |

| Boniface (2012)49 | UK | Health care | Case study | To see the benefits delivered by effective purchasing, related to sustainability (e.g. switching to thinner gloves to deliver smaller carbon footprint) | Cost saving of 30% reported on gloves, due to price environmental incentives set by industry |

| Bose and Pal (2012)50 | Multiple | Multiple | Hypothesis test | To examine the effect of green SCM initiatives on stock prices of firms | Greatest impact was on manufacturing firms, and firms with high R&D to asset ratio |

| Brau et al. (2007)51 | Not reported | Multiple | Hypothesis test | To explore SCM initiative impact on the performance of small firms, using surveys | Higher integration strategy, internal integration support, external integration support, supply chain alignment, supplier integration and customer integration all positively (and significantly) associated with asset utilisation, revenue generation and competitive performance |

| Carpenter (2008)52 | USA | Health care | Case study | To report on the implementation and benefits of quality management initiatives, using surveys | 55% of respondents with quality initiatives said that the initiative reduced waste or cost, 49% said that it improved patient satisfaction, 45% that it increased communication, 44% that it reduced hospital-associated infections and 43% that it improved staff satisfaction |

| Carroll and Coker (2007)53 | USA | Military | Case study | To provide an overview of the impact of the army’s LMP | LMP benefited by streamlining processes (decreasing project time) and accessibility worldwide |

| Case (2011)54 | USA | Health care | Case study | To investigate reasons for SCM-attributable success in a health-care setting. Intervention comprised switching to a low-unit-of-measure distribution and a switch to the combined medical–surgery and pharmacy departments | Combined departments avoided the need for multiple supply chain agreements and adopted a single 7-year master agreement including medical–surgical supply, pharmacy distribution and pharmacy data analytics. Leaders estimated savings potential in tens of millions of dollars. Low-unit-of-measure distribution logistics service reduces high cost of storing, maintaining and distributing by delivering low-unit-of measure orders straight to hospital departments |

| Childerhouse and Towill (2011)55 | Multiple | Multiple | Case study | To test whether or not enhanced performance of supply chains can be attributed to the five arcs of integration – inward facing (lower quartile for suppliers and customers), periphery facing (middle range for both supplier and customer integration), supplier facing (upper quartile for suppliers, below for customers), customer facing (upper quartile for customers, below upper quartile for suppliers) and outward facing (upper quartile for suppliers and customers) – using interviews, attitudinal survey and document analysis | More integrated supply chains (i.e. more outward facing) were more productive for four out of seven productivity indicators (most relevant: customer delivery frequency; outward-facing value streams deliver average of 687 times/year compared with 77 for periphery-facing arc). Non-productivity indicators: no positive difference found between product variety and arc of integration, outward-facing arc had highest level of streamlined information flow (but it is only significant at 90% level) |

| Constantine et al. (2009)56 | Multiple (Europe and North America) | Multiple | Case study | To assess the link between supply chain performance and underlying practices driving it, using interviews | Organisations displaying strength across six broad practices (link supply chain to company strategy, segment supply chain to master most important product/service complexity, tailor the supply network to optimise service/cost/risk goals, use lean tools end to end, create integrated/robust sales and operations planning, find top talent/hold people accountable) outperformed competitors in service, inventory and logistics costs. Top companies achieved the discipline required to excel in these areas partly by improving the skills of their employees. Investments in formal IT systems did not appear to improve supply chain performance as much as some managers expected |

| Elmuti et al. (2008)57 | USA | Manufacturing | Case study | To examine the impact of a SCM system on organisational performance (ROI, productivity, expenses), using surveys and interviews | Organisational performance measures increased (between 52% and 81%) |

| Elmuti et al. (2013)58 | USA | Health care | Hypothesis test | To examine the effect of various SCM interventions (e.g. inventory control, centralising supply chain data, strategic alliances), using surveys, interviews and secondary data | Positive relationship between SCM activities and organisational performance/effectiveness, and positive correlation between outsourcing decisions and performance/effectiveness |

| Font et al. (2008)59 | UK and Europe | Tourism | Case study | Various sustainability initiatives implemented (e.g. the development of standards and assessments, environmental auditing and management, renewable energy use), using document analysis and interviews | Increased revenues and reduced costs; increased staff morale, improved relationship with suppliers and client retention |

| Fugate et al. (2006)60 | N/R | Multiple | Case study | To explore how co-ordination mechanisms in different disciplines are effective, using interviews | Price co-ordination mechanisms (i.e. discounts for the buyer) had a negative impact on firms’ and trading partners’ performance. Non-price co-ordination (e.g. allocation rules) turned out to be contrary to the literature as the interviewees saw it as detrimental to performance |

| Golicic and Smith (2013)61 | N/R | Multiple | Review | Meta-analysis to understand variables, measures, contexts or other factors that might be influencing impacts of environmental practices specific to the supply chain and their performance | The mean effect (0.294) was significant; overall environmental supply chain practices were associated with positive firm performance |

| Guimarães and de Carvalho (2011)62 | Germany, UK, Australia/New Zealand, USA, Greece | Health care | Review | To compare outsourcing activities, drivers, benefits and risks of outsourcing, using literature review | Five countries studied showed different benefits and attitudes towards outsourcing; all reported positive outcomes such as best access to technology and increased efficiency, but highlighted contextual risks such as adaptability time and some dissatisfaction with outsourced suppliers |

| Kroes and Ghosh (2010)63 | USA | Manufacturing | Hypothesis test | To evaluate the degree of congruence between a firm’s outsourcing drivers and its competitive priorities, assess the impact of this congruence on supply chain performance and investigate the relationships between the supply chain and the business performance, using surveys | Outsourcing congruence was associated with higher levels of supply chain performance, i.e. aligning outsourcing with firm strategy |

| Meehan and Muir (2008)64 | UK | Multiple | Hypothesis test | To assess SMEs’ attitudes towards benefits and barriers of SCM (defined as the degree of internal co-operation and external integration, implying end-to-end co-ordination, representing a strategic shift in a firm’s culture rather than just a business practice), using surveys | Most important benefits of SCM were a reduction in duplication of interorganisational processes, reduction in product development cycle time processes, reduction in risk, improvement in supply chain communications and improvement in customer service responsiveness |

| Merschmann and Thonemann (2011)65 | Germany | Manufacturing | Hypothesis test | To analyse the relationship between environmental uncertainty, supply chain flexibility and firm performance, using surveys and interviews | Companies that matched supply chain flexibility and environmental uncertainty performed better than those that did not (i.e. those with high environmental uncertainty should have high supply chain flexibility) |

| Paulraj and Chen (2007)66 | USA | Multiple | Hypothesis test | To illustrate that the implementation of strategic supply management initiatives can ultimately lead to a sustained competitive advantage for buyer firms and their suppliers, using surveys | There was a significant association between strategic supply management and supplier performance, and buyer performance, and a significant association between supplier performance and buyer performance |

| Rudberg and Thulin (2009)67 | Sweden | Farming | Case study | To show the implementation of advanced planning system for logistics, using case study descriptive methods | Total costs reduced by 13% annually |

| Zhu et al. (2008)68 | Multiple (UK and China) | Automotive industry | Hypothesis test | To compare pressures, practice and performance of environmental SCM (UK and China), using surveys | Performance improvement based on environmental SCM practices was only weakly supported (in the UK mainly due to fines and financial incentives for adopting environmental practices) |

‘Green’ supply chain

Our review identified seven studies45,46,49,50,59,61,68 which specifically reported on initiatives to create a more environmentally sustainable, or ‘green’ supply chain as referred to in this section (other studies also alluded to this theme but are not referenced here). For example, one meta-analysis examined the relationship between environmental SCM (environmental effort targeted towards creation, development and/or delivery of a product to end user) and the firm’s operational performance. 61 It found that, overall, environmental supply chain practices were associated with improved firm performance. An association between ‘green’ supply chain practices and organisational performance was also demonstrated by Zhu et al. (2008),68 in a study surveying automotive organisations in the UK (n = 39) and China (n = 89). It found the association to be positive, if only weakly so, with impacts of the use of environmental SCM practices on performance being due to decreased fines for environmental accidents (UK companies) and an increased volume of goods delivered on time.

Within these articles we found some examples of primary studies. One concerned the tourism sector in the UK and in Europe more widely, and sought to identify examples of good practice to promote sustainability across the whole supply chain among tour operators. 59 Drawing on interviews and document analyses across tour operators (n = 18), tour operators’ associations (n = 3) and non-governmental organisations engaged in tourism (n = 4), the authors documented changes in the supply chain such as the development of standards and assessments, environmental auditing and renewable energy use. These developments were reported to have resulted in financial gains to the organisation such as increased revenues and reduced costs, as well as non-financial gains such as improved brand reputation, staff morale and retention, long-term business relationships with suppliers, retention of clients, operational efficiency and risk management, as well as staying ahead of legislative requirements and protection of the core assets of the business. 59

Azevedo et al. (2011)45 reported one example in the automotive industry in Portugal, finding that, in one firm, operational costs and business wastage decreased following the introduction of one ‘green’ intervention (reusable packaging). Cost savings may also arise from the financial incentives for switching to green product choices; an article in a professional journal reported on various trusts switching to more sustainable practices which in some cases resulted in cost savings of around 30%. 49

In summary, evidence reviewed here suggests that a ‘green’ supply chain can increase staff morale and organisational reputation. There is also some evidence to suggest that moving to a green supply chain may be associated with cost savings. However, studies frequently failed to provide a detailed account of how such reported savings were arrived at and often relied on savings ‘implied’ as a result of incentives for purchasing more sustainable products.

Collective purchasing

We identified one study which reported empirical evidence of cost savings associated with the use of collective purchasing, by which organisations come together to aggregate purchasing. Birk (2009)48 reported on a case of 14 hospitals in the USA that formed a purchasing ‘coalition’ which secured volume purchases, committing to a specific volume as a single unit. Reported savings achieved through group purchases were in the region of 10–25%, with a reported total of US$11M of capital acquisitions saved across the hospitals participating in the coalition; one hospital was reported to have saved just over US$1M on medical supplies in a year.

The limited empirical evidence of collective purchasing as identified in the evidence review does not permit drawing general conclusions about the likely effectiveness and potential of such practices. Interviews with a small number of key informants working in or with the NHS in England highlighted that such practices formed a necessary requirement for effective procurement, mainly because of a perceived lack of specialised purchasing skills within individual NHS trusts (interviewee 3, private sector). There was recognition among interviewees that collective purchasing can help to negotiate lower product prices. This was seen to be particularly important for smaller facilities with limited ‘purchasing power’, whereas a larger hospital ‘with the international reputation gets the better deal than the small little hospital’ (interviewee 5, NHS); however, the usefulness of such collaborations would depend on the nature of products to be purchased:

Collaborative procurements hubs are probably more powerful than they’ve ever been . . . and that can only be beneficial. But that’s only for small medical devices, mainly disposables . . . Really the ones we’re talking about are the electro-medical capital equipment.

Interviewee 5, NHS

In this particular case it was suggested that direct negotiation with suppliers on larger equipment remained the preferable option for services providers.

Overall, the evidence on the effectiveness of collective purchasing identified in our study is limited and it is difficult to predict whether or not collective purchasing would be a successful strategy based solely on evidence from elsewhere. Therefore, although we note that the use of collective purchasing may have the potential to increase the purchasing ‘power’ of service providers through strengthening their position in price negotiations, further empirical evidence is needed to assess the extent to which this is effective, the specific roles of market size and volume of purchases, and the further implications for the supply chain as a whole.

Supply chain integration, alignment and quality improvement

We identified 10 studies44,47,51,55,60,63–67 which discussed the role of supply chain improvement in the context of streamlining and integration and quality improvement as a means to improve organisational performance (other studies also alluded to this theme but are not referenced here). The notion of integration was generally discussed with reference to aligning general corporate strategies and priorities among different organisations within a supply chain, and measures of success included enhanced profitability and customer satisfaction,44 as well as increased revenue. 51 The importance of strategic alignment was also discussed in the context of outsourcing of purchasing functions or other functions within an organisation. For example, one study of the manufacturing sector reported that companies whose drivers and motivations were better aligned (in this instance, the drivers for outsourcing were compared with its general competitive priorities) demonstrated better supply chain performance. 63 One study specifically focused on quality improvement measures in relation to SCM. Carpenter (2008)52 surveyed the implementation and benefits of quality management initiatives within their materials management departments across 710 health-care organisations, of which 58% were reported to have implemented a defined quality improvement programme. Initiatives included programmes such as Six Sigma, lean and rapid cycle improvement, all within their materials supplies departments. Reported outcomes included reduced waste or cost (mentioned by 55% of respondents), improved patient satisfaction (49%), increased communication (44%), reduced hospital-associated infections (44%) and improved overall staff satisfaction (43%).

Collaboration and relationships

Evidence reviewed in this study pointed to the role of the ‘softer’ features of SCM and procurement activities which may influence their effectiveness. Less than half of the studies were empirical case studies (n = 8);69,70,72,73,78,83,86,87 the remainder comprised hypotheses testing (n = 10)71,74,76,77,79–82,84,85 and one literature review. 75 The studies are summarised in Table 7. Specific areas within this category that emerged from the literature as pertinent were stakeholder engagement within an organisation; capabilities of procurement stakeholders; and relationships with suppliers. We discuss each in turn.

| Reference | Country | Industry | Study type | Study aim and principal methods | Outcomes/learning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abrahamsson and Rehme (2010)69 | Sweden | Food retail | Case study | To find the role of logistics in retailers’ profitability, growth and market expansion by comparing the Swedish food retailing industry with modern retailers, using interviews and document analysis | Fast-growing companies (IKEA, H&M, Tesco, etc.) were ‘flow-oriented’ by managing flow of goods through constantly adapting operational resources and capacity in manufacturing and logistics to customers’ demands, partly through co-operation with suppliers |

| Barlow (2006)70 | USA | Health care | Case study | To show the impact on an organisation as a result of investing heavily in materials management via physical, mental and emotional reorganisation, a strengthened engagement of clinicians and streamlining | New contract for gloves resulted in reduced nosocomial infections translating to $1.2M in savings in one hospital and $334,000 in another. A further $750,000 in savings resulted from dealing with fewer vendors |

| Barnes and Liao (2012)71 | USA | Manufacturing | Hypothesis test | To look at the impact of strategic partnerships on firm performance (the extent to which a company can meet end-customer requirements, and operate efficiently to deliver high-quality performance), using surveys | Positive relationship between a company’s investment in strategic partnership (i.e. long-term relationships) and its overall performance |

| Bilyk (2008)72 | Canada | Health care | Case study | To examine effects in a hospital where managers, physicians and nurses take a close look at supplies they are using, streamline inventory, store information on supplies using IT inventory management databases and other best practices | A major hospital in Alberta managed a 34% reduction in direct-buy spending on operating room supplies in 1 year, and in just over 3 years decreased overall operating room supply costs by 42%, increasing on-contract spending by 52% |

| Cadden et al. (2013)73 | UK | Consumer goods | Case study | To investigate what cultural dimensions between a buyer and its supply chain partners are compatible in supporting high and poor performance outcomes, using survey and qualitative research | High-performing supply chain organisations had significantly different cultural profiles across all six dimensions. Low-performing organisations had identical profiles with significantly lower mean scores across every dimension |

| Ciliberti et al. (2011)74 | Multiple, Europe (Italy and the Netherlands) | Various | Hypothesis test | To investigate whether or not specific code of conduct is followed, using four case studies with interviews, observations and document analysis | Codes of conduct could lead to communication flows and improved supplier selection processes and solve moral hazard issues |

| Cox and Chicksand (2008)75 | UK | Food | Review | To review the demand and supply in pig and beef supply chains and provide an analysis of two red meat supply chains using power and leverage methodology; framework development for policy options | The success of collaboration practices (such as lean thinking) were context dependent |

| Danese and Romano (2011)76 | Multiple | Manufacturing | Hypothesis test | To analyse the impact of CI and SI on efficiency and the moderating role of SI, using secondary data | CI was not significantly associated with efficiency performance |

| Kannan and Tan (2010)77 | Multiple (USA and Europe) | Manufacturing | Hypothesis test | To examine whether or not performance benefits accrue to firms that involve extended supply chain partners, using surveys. The ‘extent of integration’ is the extent of the supply chain that is integrated (i.e. beyond first-tier suppliers) | Firms incorporating broad spectrum of supply chain partners in integration efforts had stronger emphasis on building interorganisational linkages; statistically significant differences between integration constructs (supplier focus, customer focus, information focus and supply chain focus). They also had a stronger relationship performance; relationships had a greater positive impact in sales improvements, new product development time and quality, but not cost reduction. Finally, they had strong customer service performance level, but not a higher market share, ROI or overall competitive position – likely because these last factors had to do with non-supply chain elements of a firm |

| Ogden and McCorriston (2007)78 | UK | Hospitality | Case study | To report the findings from a survey of UK conference and event managers, which highlights the benefits that can accrue from supplier management within this sector, using surveys | A significant proportion of venue managers reported having long-term supplier relationships, placing considerable value on the non-financial benefits that could accrue from long-term supplier relations featuring mutual trust and good working relationships |

| Pagell et al. (2007)79 | Multiple (USA and Taiwan) | Manufacturing | Hypothesis test | Implementation of two investments: greening supply chain and buyer–supplier relationships; using surveys | Buyer–supplier relationship and environmental investments were significantly associated with sustainability performance, but not with cost, quality or responsiveness performance |

| Paulraj and Chen (2007)80 | USA | Manufacturing | Hypothesis test | To explore the connection between strategic buyer–supplier relationships and logistics integration, along with the subsequent impact on a firm’s agility performance | Results show that effective external logistics integration is engendered by strategic buyer–supplier relationships and IT, and logistics integration has a positive impact on firm agility |

| Periatt et al. (2007)81 | USA | Multiple | Hypothesis test | To investigate the degree to which personality factors (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness) affect customer orientation of logistics personnel, using surveys | Openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness were significantly positively related to customer orientation of logistics employees (neuroticism and extraversion were not) |

| Richey et al. (2008)82 | N/R | Retail | Hypothesis test | To explore the direct impact of retailer technology utilisation behaviours on operational effectiveness, using surveys. ‘Operational effectiveness’ relates to the sales per employee. ‘Technological intensity’ refers to the variety of technologies used | Intensive technology utilisation between supplier and retailer led to better retailer operational effectiveness. Technological intensity was a particularly important determinant of retailer effectiveness for retailers who are optimistic about the use of technology |

| Roloff and Aßländer (2010)83 | Multiple | Consumer toys | Case study | To investigate a particular safety case in terms of buyer–supplier relationships and corporate autonomy; approach to data collection not reported | In this context it was found that supplier–buyer partnerships can harm corporate autonomy through mistakes made by suppliers or the company |

| Schloetzer (2012)84 | N/A | Petroleum manufacturing | Hypothesis test | To investigate the effect of process integration and information sharing in supply chains, using secondary administrative data | Process integration and information sharing could lead to productivity, sales growth and profitability |

| Thai (2012)85 | Australia | Multiple | Hypothesis test | To investigate the skills and knowledge required for logistics personnel to be successful, using surveys | The five most important skills and knowledge (in order), as currently perceived by respondents, were personal integrity, managing client relationships, problem-solving ability, cost control and the ability to plan |

| Van der Vaart and van Donk (2006)86 | Not reported | Manufacturing | Case study | To identify which business characteristics make suppliers choose buyer-focused operations as a supply chain strategy in their relationships with key buyers, using interviews as part of site visit case studies | The study found that buyer-focused operations are chosen for reasons of flexibility in mix, volume, specification and timing |

| Williams (2008)87 | USA | Health care | Case study | To provide some examples of cost containment through better SCM and increased physician engagement; approach to data collection not reported | Cost savings reported for both of the organisations examined ($4.5M and $13M respectively) |

| Kehoe (2006)88 | USA | Health | Case study | To report on the improvements in SCM due to the adoption of an electronic supply chain and engagement of stakeholders; approach to data collection not reported | One of the outcomes included an average bid savings of 21%. An average bid savings of 21% and a 70% reduction in bill completion cycle time was seen |

Stakeholder engagement

Stakeholder engagement, although alluded to as an important factor across sectors, emerged as a particular theme within the procurement literature in health care. Evidence identified for this review drew mostly on single case studies, with three studies70,72,88 reporting on four case studies located in the health-care sector in the USA and one in Canada. For example, Williams (2008)87 reported on experiences in one hospital in North Carolina which created teams of supply chain personnel, finance professionals and clinicians to inform procurement decisions. Teams reviewed data on types of products used in departments, and consulted and negotiated reduced prices with suppliers. This resulted in the standardisation of some products, which was interpreted by the authors as promoting patient safety through the use of ‘similar’ devices across the hospital. Williams (2008)87 also reported on experiences of a group of 20 hospitals in Arizona operating under the same health-care provider, where finance staff and clinicians together developed a pricing model which set a fixed price for physician preference items and was informed on a comparison of prices in the national market. This was reported to have saved the provider more than US$3M per year in cardiology, and US$13M overall. A proportion of the cost savings was invested in new equipment and technology, hypothesised to have sustained engagement of physicians. A related example of clinician engagement was reported by Kehoe (2006). 88 Inspired by SCM systems used by local groceries stores, the executive team of a financially challenged group of hospitals in Pennsylvania combined end-users, such as chief nurses, pharmacists and materials management staff, with engagement and IT investment to improve organisational performance through streamlining, standardisation and overall better materials management. The collaboration of clinicians was reported to have enabled the implementation of new processes and contributed to the success of the initiative.

An analysis of stakeholder engagement in one hospital in Canada was reported to have led to a 34% reduction in 1 year in direct spending on operating room supplies, and a reduction of overall theatre supply costs by 42% over 3 years. 72 This was achieved through involving managers, physicians and nurses in streamlining purchasing and taking a more active part in storing information on supplies and inventory to inform new purchases. Finally, Barlow (2006)70 reported on experiences of two hospitals which invested in improved materials management, while also strengthening clinician engagement in procurement decisions. This was reported to have resulted in a new contract for surgical gloves, which in turn was linked to a reduction in nosocomial infections, estimated to have equated to a total of US$1.5M in savings in the two hospitals combined.

Stakeholder engagement was also identified as an important factor in effective procurement decision-making in our exploratory interviews with key informants. In addition to the value placed upon engaging a wider range of stakeholders in itself, engaging clinicians in particular in the purchasing process was felt to lead to better information about the requirements of the purchase, as well as knowledge of other products on the market, which may lead to a more informed negotiation position for a hospital:

Clinician engagement in procurement decisions is key. They have to be involved. One of the things we’re trying to do . . . is actually set up focus groups. So we have focus groups for various types of equipment. But the focus group is involved in various types of procurement elements in their categories of equipment. And it’s bringing in expert clinicians and nursing staff in those areas to advise and to provide input into that process.

Interviewee 5, NHS

In summary, evidence reviewed here suggests that team collaboration and the engagement of practitioners such as clinicians in the health-care sector may have a core role in the procurement process. Selected examples of stakeholder engagement in health-care procurement in North America point to the notion of ‘engagement’ as good practice. However, the empirical evidence demonstrating the value of engagement with regard to overall organisational performance remains weak.

Capability