Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1011/51. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The final report began editorial review in November 2012 and was accepted for publication in June 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stuart Parker declares National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) grants for Health Services and Delivery Research 12/5003/02 and was Deputy Director for the NIHR South Yorkshire Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Ariss et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Objective 1 To identify those patients most likely to benefit from intermediate care and those who would be best placed to receive care elsewhere

Chapter 1 Which patients are most or least likely to benefit from intermediate care?

Introduction to the chapter

This chapter begins with an exploration of the literature regarding patients who are most or least likely to benefit from intermediate care (IC) services. The chapter considers descriptions of some commonly found types of IC services and some specific clinical needs of service users. The review moves on to look at reported patient characteristics, including age and sex, cognitive impairment, living arrangements and functional status on admission and examines how these impact on outcome. This chapter then focuses on the secondary analysis of data from the two previous studies. 1,2

Background

If IC is to contribute to the current NHS agenda by using resources in the most effective way while maintaining service quality, then it is essential that it is offered to those patients who are most likely to benefit from these services.

In order to target services appropriately, evidence is clearly needed to inform the development of appropriate criteria in order to identify both those patients who are most likely to benefit from IC and to identify which patients are least likely to benefit in terms of both physical functioning and quality of life (QoL). The reasons for this are outlined below.

Introduction of intermediate care

The need to provide services to facilitate early discharge and to prevent admission to hospital has been identified in Department of Health guidance over two decades, with winter pressures resources being made available in 1997. 3 The concept of IC was first articulated as formal policy in the UK NHS Plan4 and National Service Framework (NSF) for older people. 5 A review of these policies can be found in the National Audit Report (2012). 6 The framework identifies the range of community-based services that should be used to prevent hospital admission, to facilitate timely discharge from hospital and provide active rehabilitation in the community following discharge. The concept arose from concerns about the unnecessary use of acute hospital inpatient care to meet the needs of older people. 7 More information to ensure that services are tailored to support the needs of those they support is required.

Demographics

The proportion of older people in the population continues to rise, leading to concerns about the appropriateness and sustainability of current models of care. The rising prevalence of long-term conditions, which are often multiple, concurrent and associated with the development of acquired disability and complications – such as acute exacerbations, cognitive decline and institutionalisation – has been associated with an intention to reorient health-care systems from acute hospital-based services to more care in the community. However, it is likely that some patients will respond better than others to the different forms of intervention available in the community.

Public policy to treat close to home

Public policy is to treat close to home; in England, the Department of Health has directed that more people with long-term conditions be supported to retain independence in the community, using innovations in health technologies and improved carer support. 8,9 It is recognised in policy that, within this context, services that function at the interface between primary and secondary care are crucial. They influence the setting in which acute care can be provided, the durations of stay in different compartments of the care system (home or other community setting, hospital emergency service, acute inpatient care, inpatient or home-based rehabilitation and reablement services) and can be constructed to influence capacity for self-management and community care. This in turn may affect demand for hospital bed use (influencing admissions, durations of stay and readmissions). Therefore, it is important to understand who benefits (and, crucially, who does not benefit) from service interventions that are targeted at people with care needs which fall between traditional hospital inpatient and community care needs.

Literature review

Review methods

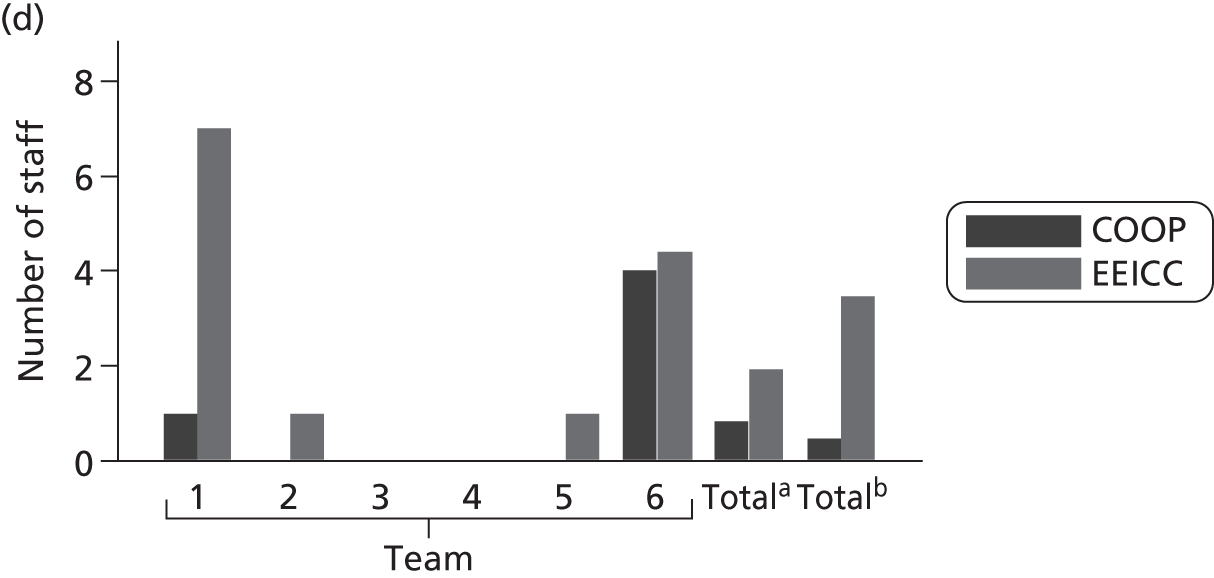

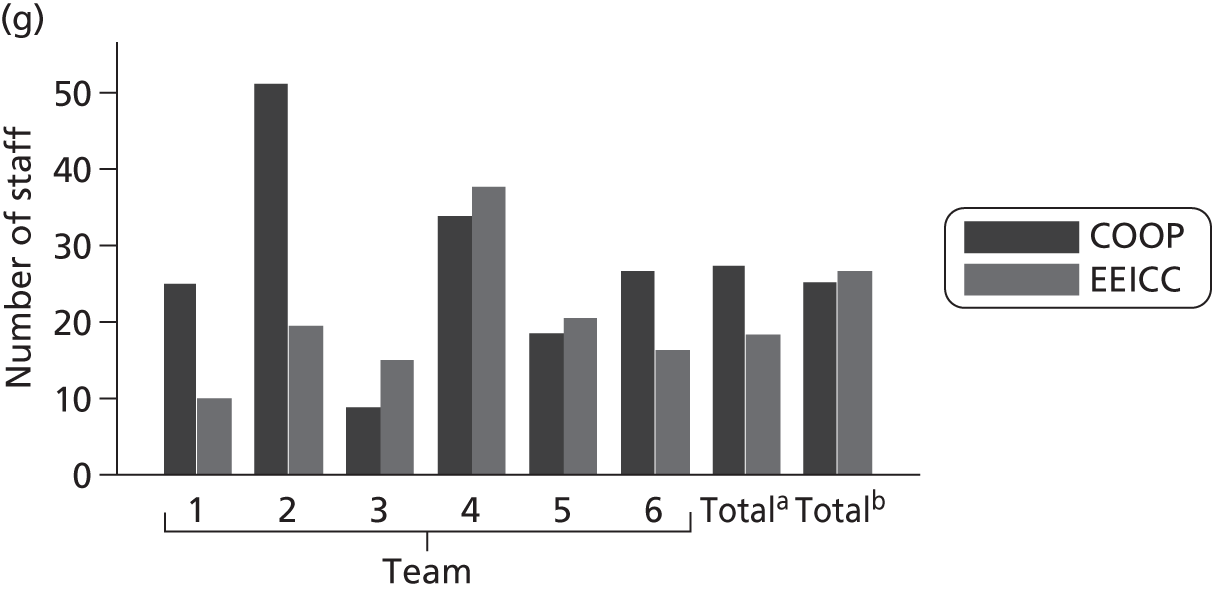

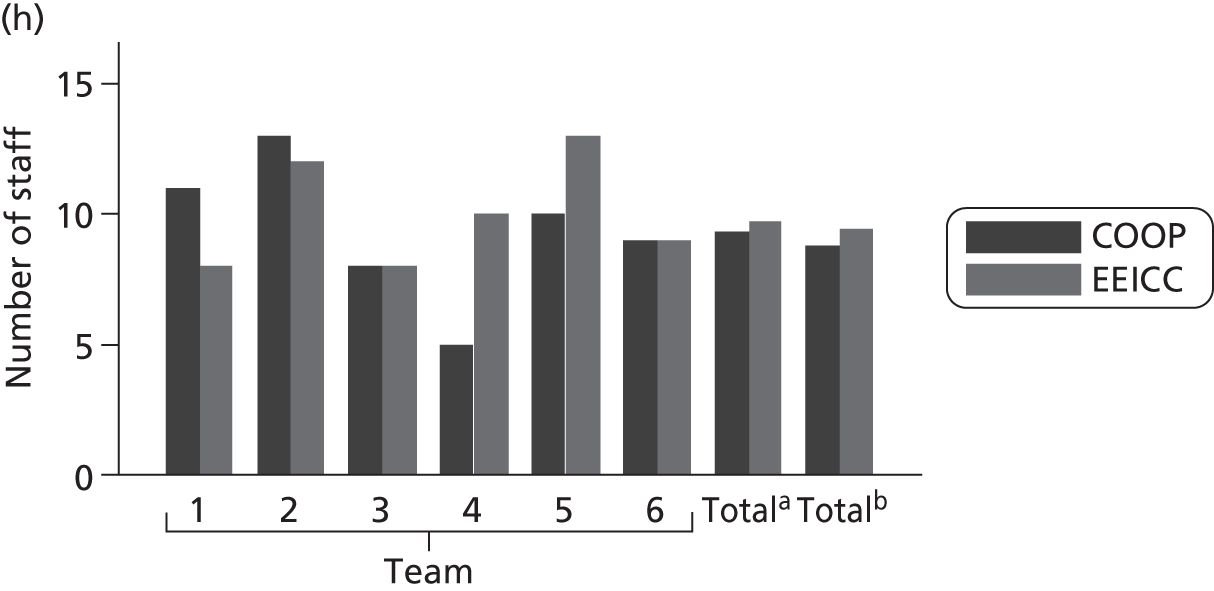

Details of the literature search undertaken to support this chapter are located in Appendix 1. The review built on the reviews conducted as part of the costs and outcomes of older peoples’ services (COOP)1 and enhancing the effectiveness of interdisciplinary working (EEICC)2 studies, as well as a number of systematic reviews, specifically a review of the evidence for the effectiveness of IC conducted as part of the National IC evaluation10 and three Cochrane reviews of non-disease-specific IC services. Two of these focused on hospital at home (HAH) for admission avoidance11 or early discharge12 and one focused on rehabilitation of older people. 13 Relevant studies from a systematic review of HAH were also considered. 14

We drew on evidence from a number of sources to identify English-language studies published since 2000, in which the intervention or setting is IC (including descriptions of services offering similar provision) and for which the outcomes assessed were any measure of physical functioning or QoL. We defined IC services as community-based services provided mostly for older people, aiming at avoiding unnecessary admission to hospital and/or facilitating discharge from hospital and preventing admission to long-term residential and nursing care.

It should be noted that this review has focused on patients who may or may not currently benefit from IC. It was somewhat beyond the scope of the focus of this chapter to explore the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of IC services or to compare effectiveness with other forms of service delivery.

Findings from the literature

Seventy-two studies met the inclusion criteria for this review. Of these, six studies explore the patient characteristics associated with changes in physical functioning or QoL (Table 1). However, these six outcomes studies are heterogeneous in terms of type of intervention, country and care setting, and this limits the conclusions that can be drawn. What does emerge from them though is a consistent and clear message that not all patients benefit from IC.

| Study ID | Type of service | Objectives of care | Disease/condition | Country | Care setting | Study design | Relevant outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landi et al. 200215 | Community hospital rehabilitation | Post-acute rehabilitation | Frail older people | Italy | Geriatric hospital | Cohort study | The Minimum Data Set for Post Acute Care which includes physical and cognitive function and health status was assessed on admission, then every 2 weeks |

| Analysis and findings | Logistic regression. In the unadjusted mode, patients aged > 85 years with cognitive or sensory impairment were less likely to improve. After adjusting for age, sex, social and functional status, indicators of disease severity and ‘all possible negative factors affecting rehabilitation’ only cognitive impairment remained significant | ||||||

| Findings reported in Kaambwa et al. 200816 | Various forms of IC | Various including rehabilitation, supported discharge and rapid response | Elderly patients | UK | Various including patients homes, residential homes and day hospitals | Cohort study | EQ-5D and Barthel Index |

| Analysis and findings | Regression modelling. Mean improvement (SD): 0.16 (0.32) increase in EQ-5D score and 1.68 (2.89) increase in Barthel Index. For EQ-5D, a lower score on admission was associated with a greater improvement in EQ-5D score on discharge. Those who live alone were more likely to improve. Lower score on admission for Barthel Index and EQ-5D was associated with a greater improvement in independence on discharge. Older patients were less likely to improve. Those who live alone were more likely to improve. No effects for sex | ||||||

| Pereira et al. 201017 | Rehabilitation in a day hospital | Admission avoidance, rehabilitation | Frail older people | Canada | Day hospital | Cohort study | Barthel Index, instrumental ADLs using the Older Americans Resources and Services, EQ-5D, Timed Up and Go test for general mobility, 6-minute walk test, gait speed, Berg Balance Scale and grip strength |

| Analysis and findings | Logistic regression. Overall 58% (134 out of 233) patients achieved a ‘successful improvement’ (significant improvement in ≥ 3 tests). Patient characteristics associated with ‘successful improvement’ were lower admission score on Barthel Index, Older Americans Resources and Services, Timed Up and Go test, gait speed and 6-minute walk test, with a trend for lower scores on the Berg Balance Scale and EQ-5D. No significant differences for age or sex | ||||||

| Fusco et al. 200918 | Home-based rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Frail older people | Italy | Home | Cohort study | Functional status was assessed using the Minimum Data set for Home Care at the end of treatment, 6 months and 12 months. One of the summary scales describes ADLs |

| Analysis and findings | Only 30% of patients improved significantly after 6 months. When adjusted for potential confounders, there were four ‘negative factors’: (1) cognitive impairment (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.85); (2) urinary incontinence (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.70); (3) bowel incontinence (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.27 to 0.81); and (4) visual impairment (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.92). Similar results when the main diagnoses were considered in the main model. After adjustment for baseline ADLs, impaired cognitive performance, depression, urinary and faecal incontinence and sensory impairment were associated with the outcome | ||||||

| Gitlin et al. 200819 | Home-based rehabilitation | Rehabilitation | Frail older people | USA | Home | RCT | Functional ability was assessed at 6 and 12 months using a self-report measure of difficulties in 17 areas including six IADLs, six ADLs and six mobility/transferring items. Each item was self-rated on a 1 to 5 scale. Mean difficulty was calculated across all items |

| Analysis and findings | Analysis of covariance. For ADLs at 6 months, sex, age and education moderated treatment outcomes with women, the oldest (aged > 80 years) and those with less education benefiting more. When all three interactions were entered into one model only age and sex remained significant. At 12 months, only age was significant. For mobility difficulties at 6 months, there were significant effects for age and sex only – women had a bigger decrease in mobility. At 12 months, age as well as education were significant. For IADLs, there were no differences at 6 months, but at 12 months, race was significant, with whites having less difficulty than non-whites | ||||||

| Comans et al. 201120 | Community rehabilitation service | Rehabilitation, admission avoidance | Frail elderly following falls or poor balance/functional decline | Australia | Home | RCT | EQ-5D and a visual analogue scale |

| Analysis and findings | Factors negatively impacting on QoL were depression, impaired hearing and vision and poor nutritional intake. EQ-VAS was positively associated with level of participation in normal activities and perceived HRQoL. Negatively impacting factors were depression, having poor reading vision and poor nutrition. Test of physical capabilities were not found to have significant associations with HRQoL. Age, sex, living alone and comorbidities were not associated with differences in QoL | ||||||

The Cochrane database of systematic reviews includes three highly relevant reviews of disease-unspecific services provided in the home and compared with hospital-based alternatives,11–13 and three reviews of disease-specific services providing home-based IC for patients with stroke21,22 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 23

In a review examining HAH and comparing it with hospital inpatient care, a study found that early discharge in certain patients groups may reduce pressure on acute beds,11 but that there was insufficient evidence of economic benefit. A review of HAH for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive airways disease shows that mortality and readmission rates are not significantly different between intervention and control groups and suggests that both patients and carers prefer the HAH services to inpatient acute care. 12,23 Few other outcomes were reported.

A review of services to help acute stroke patients avoid hospital admission concluded that there was no evidence from clinical trials to support a radical shift in the care of acute stroke patients from hospital into the community. 21 Whereas, a review of services for reducing duration of hospital care for acute stroke patients concluded that supported early discharge services for stroke have significant effects on inpatient length of stay (amounting to a reduction in length of stay of about 9 days). The risk ratios (RRs) for adverse outcomes, including death, institutionalisation and benefits (on functional outcome) and costs remain unclear. 22

Key point 1: a substantial number of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted in populations including frail older people, for whom disease-specific inclusion criteria have not been set. These populations include older people at risk of adverse outcomes including delirium, polypharmacy and urinary complications. These trials demonstrate a reduction in pressure on acute beds and are preferred by patients.

Models of care

The main models of service delivery relevant to UK IC that have been researched are HAH, nurse-led clinical services and home-based rehabilitation. The trials fall naturally into two groups: those that have investigated the use of IC services in non-disease specific conditions, such as frail older people and elderly medical admissions, and those that have investigated specific service models in patients with particular diagnosed health conditions.

Recently reported trials have tended to focus on interventions in specific chronic diseases and some have demonstrated quite significant reductions in inpatient hospital stays. Early supported discharge services after stroke typically include rehabilitation and are associated with reduced length of inpatient stay. 24–27 Discharge support services in a range of other specific conditions which have been associated with significant reductions in inpatient length of stay including after surgery for breast cancer28 or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG),29 treatment for acute exacerbations of COPD30 or diabetes. 31 Interventions of specific relevance to frail older people that achieved significant reductions in inpatient length of stay included home-based rehabilitation for a range of conditions32,33 and after fractured neck of femur. 34

Key point 2: many RCTs of IC services have been conducted with patient groups with specific conditions, mostly medical conditions such as stroke, COPD and heart failure and demonstrate reduced length of stay.

Most studies have been conducted in the home setting, with some including patients in special facilities in acute hospitals. No studies were found which employed interventions in non-clinical institutions. One of the Cochrane Database reviews specifically addresses the use of residential care settings for rehabilitation for older people, but has not identified any trials that the met the inclusion criteria for this study.

Key point 3: RCTs investigating IC for frail older people have not investigated alternative non-clinical residential facilities such as nursing and residential homes. Nevertheless, these settings are routinely used by IC services.

The question of ’who may benefit from intermediate care’ has been tested in RCTs for the following main groups:

-

Patients with a medical condition including:

-

patients at risk of delirium

-

patients at risk of urinary tract complications

-

frail older people.

-

-

Patients in need of rehabilitation:

-

after stroke

-

after fractured neck of femur

-

after CABG

-

after breast surgery

-

with ischaemic heart disease.

-

-

Patients with exacerbation of specific long-term conditions:

-

COPD

-

heart failure.

-

It is worth noting that none of the trials contributing to the above list specifically included patients with cognitive impairment or dementia. There is current debate on assessment and rehabilitation for people with dementia and other comorbidities, but for now it is not an area that has been extensively investigated in controlled trials.

Key point 4: RCTs do not address the use of IC services for people with physical rehabilitation or recuperation needs, which are complicated by the presence of cognitive impairment.

Another important issue is related to whether or not IC and community rehabilitation can provide benefits for those coming to the end of their life.

Key point 5: the literature suggests that there is a case for integrating palliative care services for older people with IC/community rehabilitation as the complexity of cases being cared for in the community is increasing. However, no controlled trials have been conducted to evaluate the use of IC services (e.g. HAH, early supported discharge teams) in the provision of palliative and end-of-life care.

More recently, the notion that home-based care for a range of acute care needs may be superior to inpatient hospital care has begun to emerge. For example, RCTs of ‘hospital in the home’ (HITH) for acute care35 and rehabilitation36 suggest that home-based care which substitutes for, and meets, clinical care needs that would otherwise be provided in an inpatient hospital setting reduces the incidence of delirium and urinary tract complications, that may lead to further illness and/or admission. A recent and extensive meta-analysis of this concept, substitution of care at home for hospitalisation using HITH and similar schemes, included 61 RCTs that demonstrated reduced length of stay in hospital. 14 The authors of this review concluded that HITH is associated with reduced mortality, readmission rates, costs and increased patient and carer satisfaction. The effect sizes were not small. The odds ratios (ORs) pooled from 42 RCTs with 6992 subjects for mortality was 0.81 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.69 to 0.95; p = 0.008; i.e. a 19% reduction in mortality in HITH] and for readmission was 0.75 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.95; p = 0.02; i.e. a 20% reduction in readmission). The number needed to treat to prevent one death was 50 patients. These effect sizes are similar to those found for many interventions that have been regarded as essential health technologies, for example Streptokinase® (CSL Behring UK Ltd, West Sussex, UK), for acute myocardial infarction.

Key point 6: admission avoidance by the use of HAH services that substitute for acute hospital admission have been shown to reduce the incidence of delirium and urinary tract complications with reductions in mortality and readmission. This indicates that patients who are particularly at risk of such complications should be considered for home management of their acute care episode, where the facilities are available.

A further seven studies meeting the inclusion criteria for this review did not include any exploration of the relationship between patient characteristics and treatment outcomes as one of the study aims, but did include reference to relevant analyses within the papers. These are summarised in Table 2.

| Citation | Type of service | Objectives of care | Disease/condition | Country | Care setting | Study design | Relevant outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fjaertoft et al. 201137 | ESD by multidisciplinary team | Discharge support | Stroke | Norway | At home or in a day clinic | RCT | mRS to measure independence, Frenchay Activity Index, Scandinavian Stroke Scale, Barthel Index |

| Analysis and findings | Logistic regression. Within the ESD group, predictors of good outcome (mRS score ≤ 2) after 5 years were lower age at stroke onset (median age 69.0 years for good outcome/76.6 years for bad outcome), a lower mRS score and cohabitation (living alone 26.4% for good outcome/48.5% for bad outcome) at baseline | ||||||

| Koh et al. (2012)38 | Community hospital rehabilitation | ESD and rehabilitation | Stroke | Singapore | Community hospitals followed by outpatient rehabilitation centre | Cohort study | Barthel Index |

| Analysis and findings | Mixed-model analysis. At all five time points (admission, discharge, 1 month, 6 months and 1 year post discharge) predictors of lower Barthel Index scores were increasing age, hypertension, greater cognitive impairment greater depressive symptoms and greater neurological impairment | ||||||

| Mallinson et al. (2011)39 | Rehabilitation in community or subacute settings | Early supported discharge and rehabilitation | Those aged > 65 years following knee or hip replacement | USA | Inpatient rehabilitation. Skilled nursing facility or Home Health Agency | Cohort study | Functionality using inpatient rehabilitation Facility Patient Assessment Instrument, Outcomes and Assessment Information Set and Minimum Data set 2.0 |

| Analysis and findings | Stepwise regression. Self-care function at discharge unaffected by age and sex, but significant factors were severity of procedure, number of comorbidities, urinary incontinence and level of self-care on admission. For mobility function, only urinary incontinence and mobility on admission were significant | ||||||

| Hogg et al. 200940 | Preventive primary care team | Admission avoidance | Those aged > 50 years at risk of experiencing adverse health outcomes | Canada | Home | RCT | SF-36, HRQoL scales, functional status (IADLs scale) |

| Analysis and findings | Multivariate regression performed for each outcome adjusted for a variety of patient characteristics. Results for QoL and functional status not reported | ||||||

| Courtney et al. (2009)41 | Home-based rehabilitation | Admission avoidance | Those > 65 years of age following an acute medical admission and at least one risk factor for readmission | Australia | Home | RCT | SF-12 at baseline, 4,12 and 24 weeks post admission |

| Analysis and findings | Analysis of covariance. For the intervention group, admission diagnosis had no effect on Physical Component Summary Score of the SF-12 | ||||||

| Allen et al. (2009)42 | Home-based rehabilitation | Discharge support | Stroke | USA | Home | RCT | Neuromotor function (Timed Up and Go test), QoL using stroke specific QoL scale |

| Analysis and findings | Multivariate modelling. For the intervention group, at 6 months, patients with a prior stroke/transient ischaemic attack/atrial fibrillation identified a substantial subgroup interaction benefit in terms of neuromotor function. Severity of stroke, comorbidities, age, sex and race were not significant | ||||||

| Carratala et al. (2005)43 | HAH following discharge from emergency department | Admission avoidance | Community-acquired pneumonia | Spain | Home | RCT | SF-36 |

| Analysis and findings | Multivariate analysis using age, sex, comorbidities and pneumonia severity index scores as confounders. Results not reported in detail | ||||||

Table 3 summarises the effects of patient characteristics on physical functioning and QoL across all the included studies that contained data pertinent to the research question (n = 13).

| Patient characteristic | Effect on physical functioning | Effect on HRQoL | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Improvement | No effect | Reduction | Improvement | No effect | Reduction | |

| Age (increasing) | Gitlin et al.19 | Landi et al.15 | Kaambwa et al.16 | Comans et al.20 | ||

| Pereira et al.17 | Fjaertoft et al.37 | |||||

| Fusco et al.18 | ||||||

| Allen et al.42 | ||||||

| Mallinson et al.39 | ||||||

| Sex (female) | Gitlin et al.19 | Landi et al.15 | Comans et al.20 | |||

| Kaambwa et al.16 | ||||||

| Pereira et al.17 | ||||||

| Fusco et al.18 | ||||||

| Allen et al.42 | ||||||

| Fjaertoft et al.37 | ||||||

| Mallinson et al.39 | ||||||

| Living alone | Kaambwa et al.16 | Fjaertoft et al.37 | Kaambwa et al.16 | Comans et al.20 | ||

| Sensory impairment | Landi et al.15 | Fusco et al.19 | Comans et al.20 | |||

| Cognitive status impairment | Landi et al.15 | Pereira et al.17 | Fusco et al.18 | |||

| Functional status on admission low | Kaambwa et al.16 | Fusco et al.18 | Pereira et al.17 | Comans et al.20 | ||

| Pereira et al.17 | ||||||

| Fjaertoft et al.37 | ||||||

| QoL on admission low | Kaambwa et al.16 | Kaambwa et al.16 | ||||

| Diagnosis/comorbidities | Fusco et al.18 | Mallinson et al.39 | Comans et al.20 | |||

| Allen et al.42 | Courtney et al.41 | |||||

| Incontinence | Landi et al.15 | Fusco et al.18 | ||||

| Mallinson et al.39 | ||||||

| Depression | Fusco et al.18 | Comans et al.20 | ||||

Evidence on the characteristics of patients who do not improve in IC is limited.

In a retrospective cohort study of 233 frail elderly patients undergoing a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme in a geriatric day hospital in Canada,17 only 58% (n = 134) of patients achieved a ‘successful improvement’, which was defined as a significant improvement in ≥ 3 tests of functional status.

A study of rehabilitation in Italy identified the outcomes of 598 elderly patients undergoing a multidisciplinary home-care rehabilitation programme. 18 Only 30% of patients improved significantly after 6 months of rehabilitation when assessed using the Minimum Data set for Home Care which describes activities of daily living (ADLs).

Key point 7: there is scant evidence to indicate which patients are less likely to do well in IC in terms of physical functioning and QoL.

Age and sex

Five studies15,17,18,39,42 assessed the impact of age on physical functioning and found no effect. In three other studies,16,19,37 age was found to have an effect, but the direction of the effect was not consistent. A randomised trial by Gitlin et al. 19 of a home-based intervention in the USA included occupational and physical therapy visits and telephone follow-up for 319 frail older people (> 70 years of age). This found that age moderated treatment outcomes (using self-reported functional ability) at 6 and 12 months, with the oldest (> 80 years) benefiting more from the intervention in terms of both ADLs and mobility.

However, in a UK-based study of IC services for the elderly15 and a Norwegian study of early supported discharge for stroke patients,37 increasing age was associated with a reduction in benefit. The UK study found that older patients were less likely to improve their level of independence as detected by the Barthel Index. Similarly, a study by Fjaertoft et al. ,37 found that age at stroke onset predicted outcome as measured by the modified Rankin Scale. The median age was 69.0 years for good outcomes and 76.6 years for bad outcomes.

There was little indication of the effect of sex on physical functioning or outcome across any of the studies.

Cognitive impairment

There is also some indication that cognitive status may have an effect on physical functioning, although, again, the direction of the effect is not consistent across studies. Landi et al. 15 conducted a cohort study to identify predictors of rehabilitation outcomes in 244 frail older people in a geriatric hospital in Italy following admission to acute care. Cognitive impairment was the strongest predictor of recovery. People with dementia had a 64% reduction in their odds of recovery relative to patients with normal cognitive performance (OR 0.36, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.92). Conversely, in a cohort study to determine predictors of outcome in 598 elderly patients undergoing a multidisciplinary home-care rehabilitation programme, again conducted in Italy,18 cognitive impairment had a negative impact on physical functioning (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.85).

Comans et al. 20 conducted a RCT of a community rehabilitation service in Australia, which received referrals from the emergency department or general practitioners (GPs) and explored the outcomes of 107 frail older patients presenting with falls or poor balance/functional decline, or QoL.

Living alone

Similarly, living alone had both a positive and negative effect on physical functioning. In Kaambwa et al. ,16 those who lived alone were more likely to improve but in Fjaertoft et al. ,37 those living alone were less likely to improve (26.4% for good outcome and 48.5% for bad outcome).

Key point 8: there is some indication that age, cognitive status and living alone may affect outcomes. However, the direction of this effect is inconsistent.

Functional status on admission

The literature indicates that those with lower functional status on admission improve more in terms of their physical functioning and, therefore, those whose scores are higher are less likely to improve. However, it is possible that this is as a result of a ceiling effect of most measures. This effect was clear in three studies,16,17,37 although baseline scores had no effect in another study. 18

There were suggestions that those with sensory impairment,18 more comorbidities,39 incontinence18,39 and depression18 do less well.

Key point 9: those who enter IC with higher levels of independence and health-related QoL improve less than those with lower levels. However, this is likely to be an artefact of the ceiling effect of most measures. The potential to demonstrate improvement on measures may be less for those starting with high scores. Those with sensory impairment, increased number of comorbidities, incontinence and depression may do less well in IC.

Discussion of the literature review

Few studies explicitly set out to answer the question ‘which patients are more or less likely to benefit from IC in terms of QoL and physical functioning?’

However, given that IC can include a wide range of community-based services, such as HAH and community rehabilitation, and can take place in a number of settings (e.g. patients’ homes, community hospitals or care homes) there is a substantial body of literature exploring the impact of IC. For example, within The Cochrane Library alone, there are three reviews of IC which are non-disease specific11–13 and three which are disease specific for stroke21,22 and COPD. 23 Within any single study of IC, there may well be secondary analyses, which have explored the characteristics of patients who are less likely to do well in IC in terms of physical functioning and QoL. This review has taken a pragmatic approach to exploring a selection of this literature since 2000, through a combination of database searches and incremental searching of reference lists of existing reviews of IC services that are non-disease specific. However, given the extensive volume of literature identified, relatively few studies were found.

Key point 10: few studies have aimed to explore which patient characteristics are associated with adverse or improved outcomes in terms of physical functioning or QoL.

Secondary analysis of data

Methods

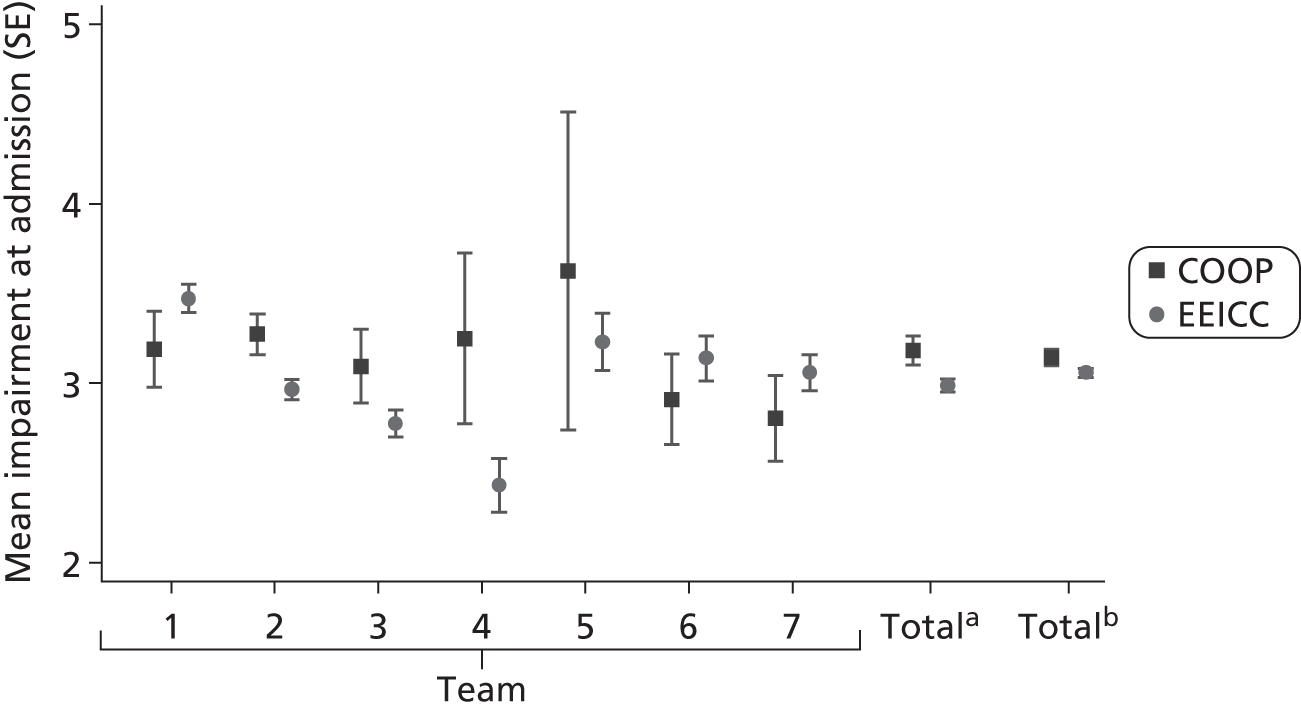

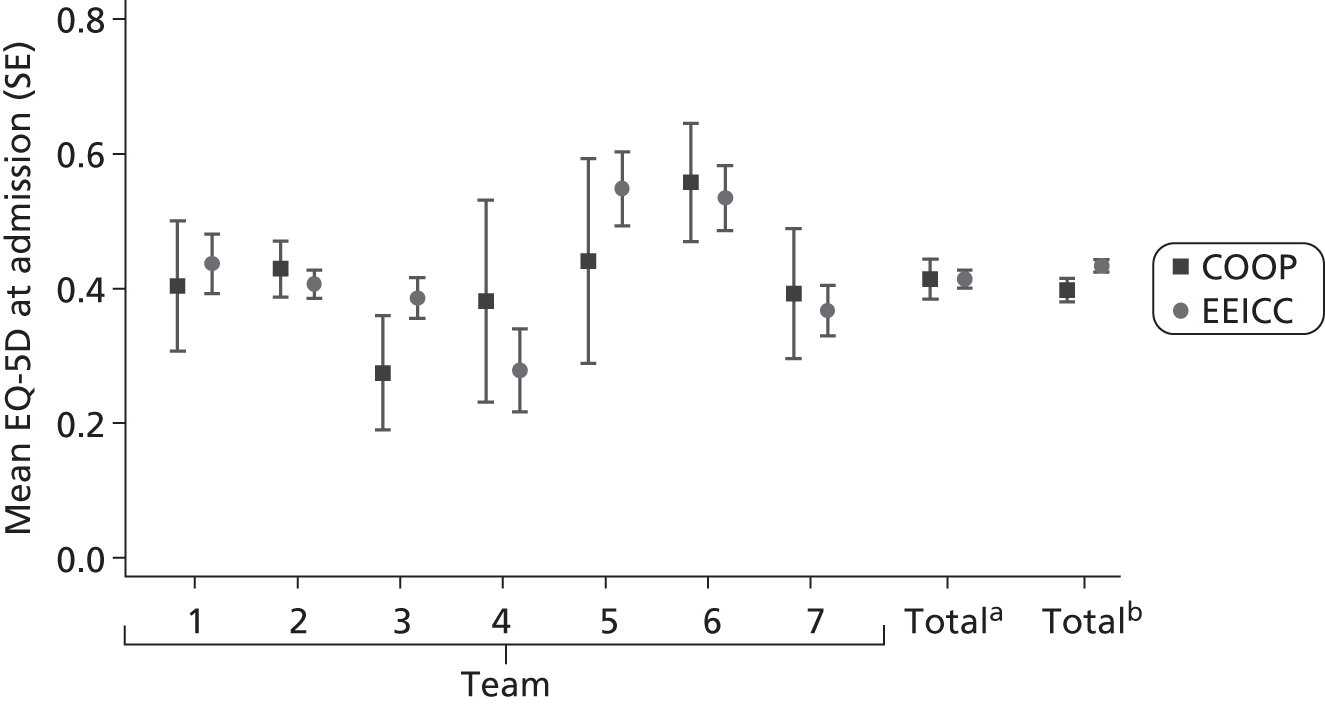

The patient outcomes collected were the four domains from the therapy outcome measure (TOM) scale (impairment, activity, participation and well-being) and the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire. For each of the five scales [impairment, activity, participation and well-being (as measured by the TOM scale) and EQ-5D questionnaire], two outcomes were used:

-

the magnitude of improvement, defined as the change from score at admission to score at discharge

-

the presence or absence of improvement, defined as patient improved (an increase from admission score) or patient not improved (no change or worsened from admission score).

The relationship between these outcomes was assessed against the following patient characteristics: the value of the baseline score of the (EQ-5D or TOM) and each of age, sex, level of care (LoC) on admission, route of referral, the usual living arrangements and place where care was provided. As the last two variables were heavily correlated, it was not appropriate to include both in the model at the same time, instead, they were assessed in two separate models as described in Table 4. The first model assessed whether or not the patient’s residence during IC was associated with outcome, whereas the second was to investigate whether or not there was any additional impact among patients who had left their home in order to receive IC. The results are reported for the most parsimonious model, i.e. for model 1 unless there was an additional impact of leaving home, which was assessed by the likelihood ratio test.

| Model 1 | Model 2 |

|---|---|

| Included in both models: age, sex, LoC at admission, route of referral and baseline value of outcome (EQ-5D or TOM score) | |

| Place where care was provided | Usual living arrangements |

| Did patient leave a home residence to receive care? | |

| If left home to receive care, where was care provided? | |

Missing data

An important consideration for this reanalysis, and one that is also pertinent to Chapters 1–3, 5, 6 and 10, was how to handle patients with incomplete data. There were missing data in a substantial number of patient records, encompassing both baseline data (i.e. patient characteristics at admission) and, more commonly, outcome data at discharge. This presented a challenge, especially with missing outcome data; ignoring patients with missing data makes the strong assumption that these are a random subgroup of the study population (the so-called ‘missing completely at random’ assumption as described by Schafer). 44 This is unlikely to be true; for example, missing data were more common among patients discharged to acute settings or nursing homes, but it is clear (both from available data and from intuition) that these patients had worse outcomes than patients discharged to their own home. Moreover, even if the ‘completely at random’ assumption were met, the ability to detect a difference is compromised by losing a high proportion of data.

We addressed this by a multiple data imputation approach. 45 Missing data were multiply imputed to give a range of plausible values, the details of which are described at length in Appendix 2. In order to assess the extent to which the findings were robust to missing data, analyses were performed on both complete case data and data sets incorporating imputed data. Five augmented data sets were sufficient to ensure that the between-data set variance was negligible in the model coefficients.

Analyses of continuous outcomes (the magnitude of change in TOM and EQ-5D scores) were undertaken by fitting a generalised least square model in which the team was a random effect. An analogous approach was taken for binary (yes/no) outcomes, for which a random-effects logistic regression model was applied. All analyses were undertaken using version 12.1 of the Stata statistical software (2011; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with analyses on imputed data sets incorporating adjusted standard errors as described by Schafer. 46

Results are presented as tables of coefficients (reflecting the difference in means) for magnitude of change and as predicted probabilities for any improvement. The graphs depicting mean change by patient characteristics are adjusted for other model parameters, in each case displaying least square means ± 95% CIs based on analyses of the imputed data.

Results

Remaining or returning home

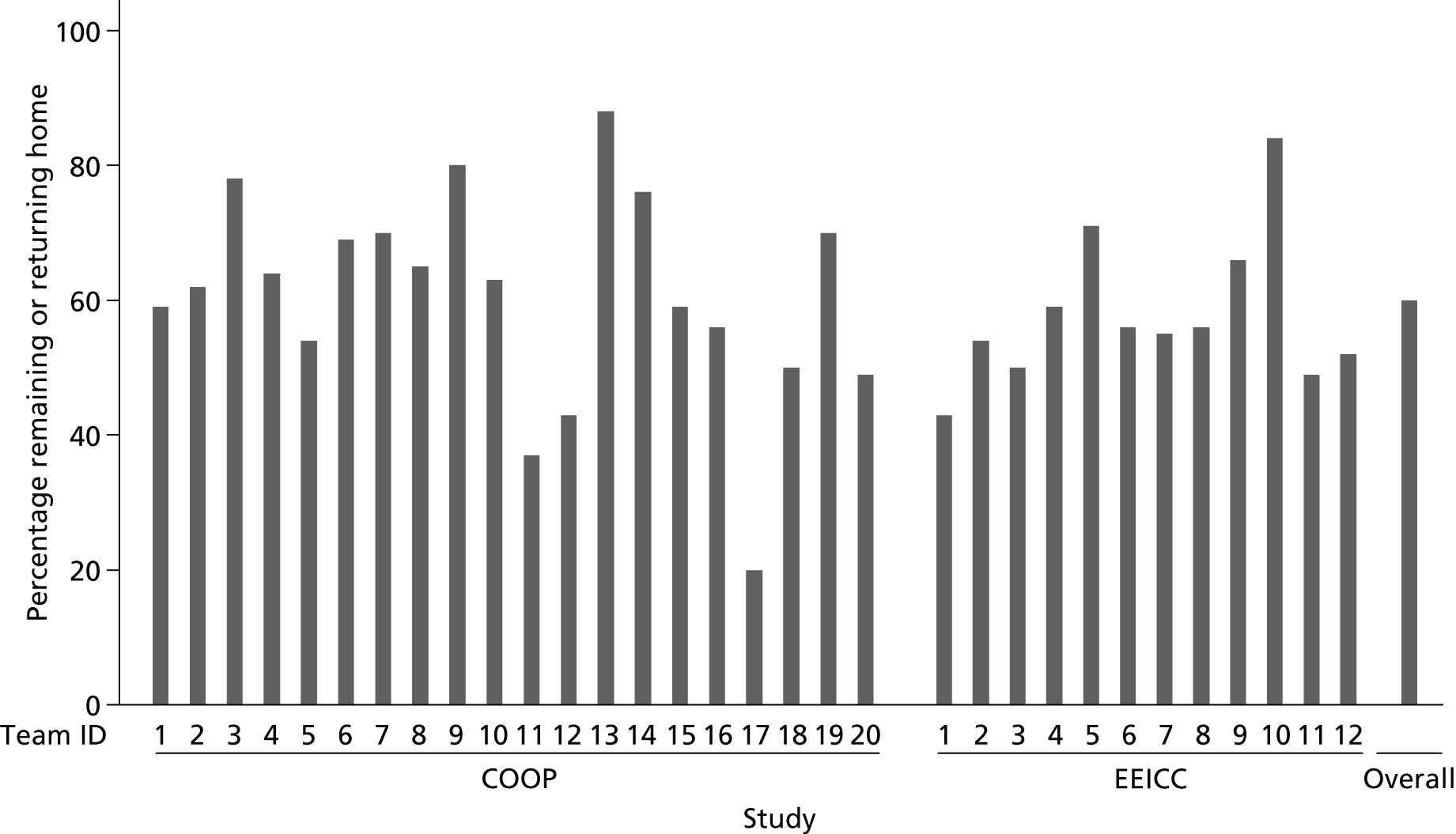

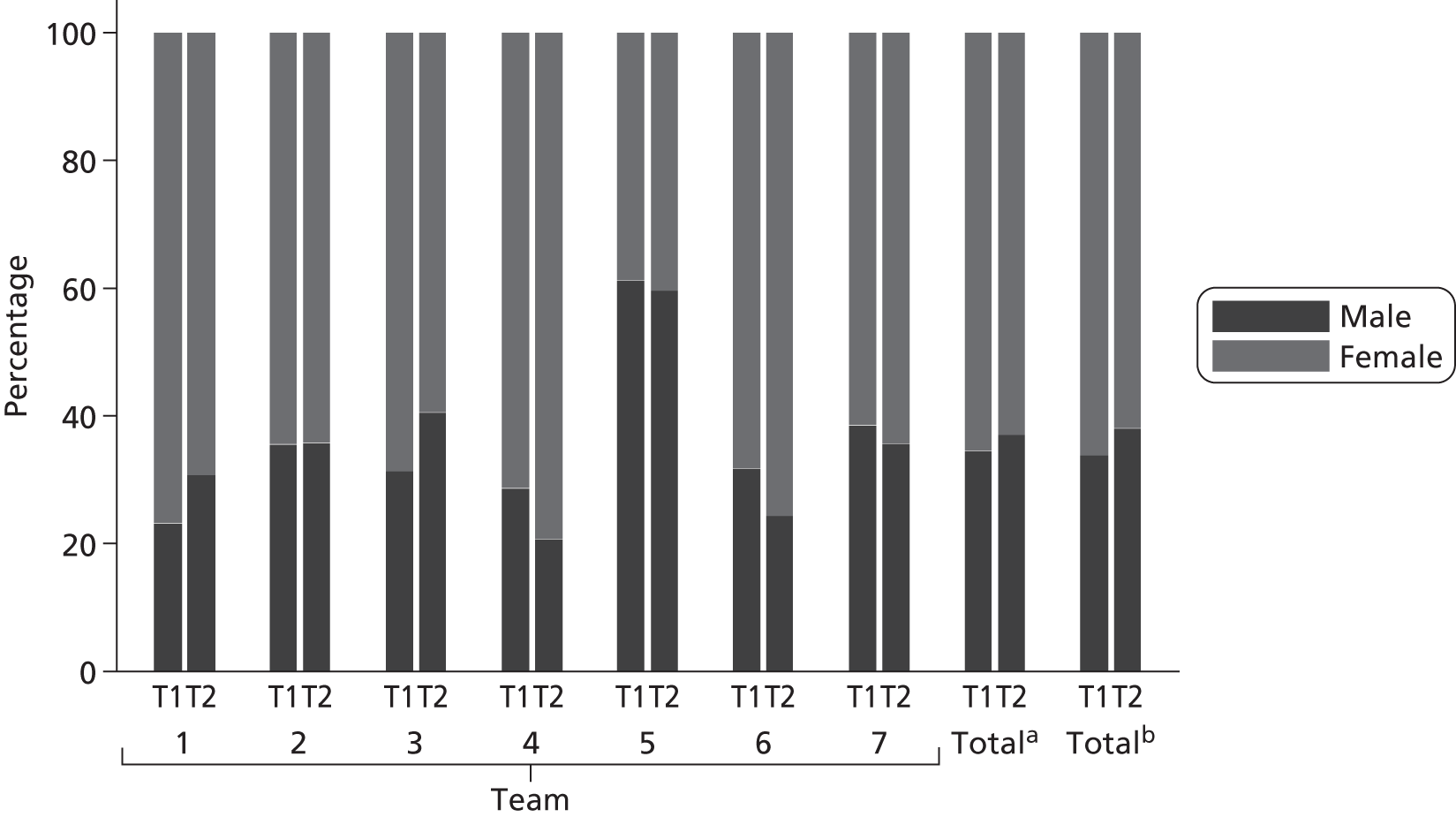

In all 4556 out of 7620 patients (60%) remained or returned home following an episode of IC. The distribution of this outcome is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Frequency of patients remaining or returning home.

The likelihood of returning home shows a large amount of variation between teams. Team COOP PB had the greatest percentage of patients who remained or returned home, with 88% of their patients remaining or returning home. Team COOP SG had the smallest percentage of patients who remained or returned home, with 20% of their patients remaining or returning home.

Level of care at admission

The chance of remaining or returning home is greatest for patients with a LoC, at admission, of 4 (needs regular rehabilitation programme) and 3 (needs slow-stream rehabilitation). Patients with these LoCs, at admission, have a 66.0% and 63.7% chance of remaining or returning home, respectively.

The chance of remaining or returning home is lowest for patients with a LoC, at admission, of 0 (does not need any intervention) for which there was only a 20.4% chance of remaining or returning home. However, many of the patients with a LoC, at admission, of 0 were marked as being an inappropriate referral. Those with a LoC, at admission, of 7 (needs medical care and rehabilitation) had a 34.8% chance of remaining or returning home.

Key point 11: the likelihood of remaining or returning home is related to the LoC at admission to IC. It is greatest for levels 3 and 4 and is lowest (20.4%) for patients with a LoC, at admission, of 0 (does not need any intervention).

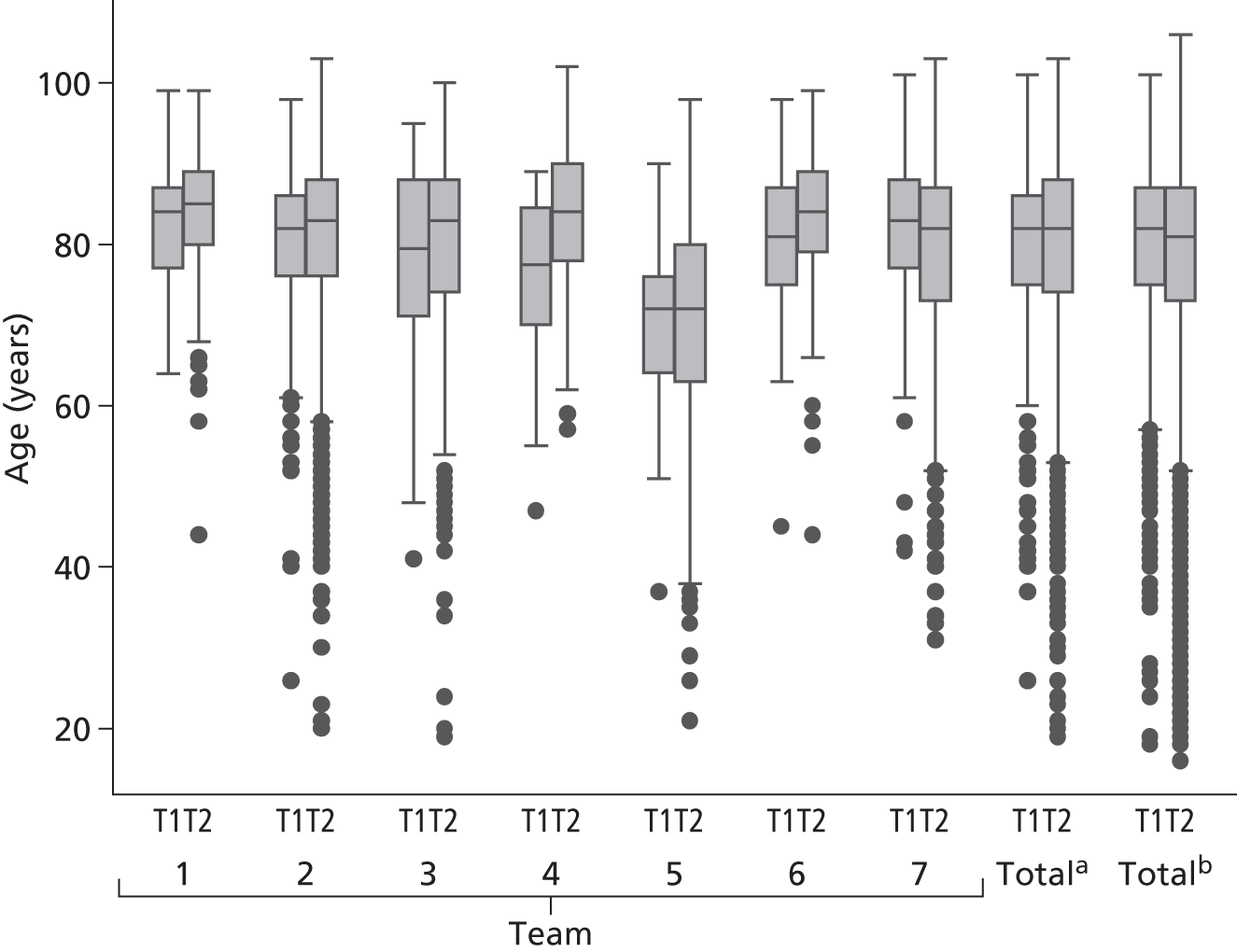

Age and sex

For every 10-year increase in age, there was a 6% decrease in the odds of returning home. The chance of returning home was greater for females than males. Females had a 51.8% chance of returning home and males a 47.4% chance.

Key point 12: for every 10-year increase in age there was a 6% decrease in the odds of returning home. The chance of remaining or returning home was greater for females than males.

Relationship between patient characteristics and therapy outcome measures

For all domains of the TOM scale, around half of all patients with outcome data did not improve or worsen. More patients showed improvement in TOM impairment and activity than in participation or well-being. In the imputed data set, the proportion of patients who failed to improve was slightly higher, as patients with missing outcomes had worse predicted outcomes than those for whom data were available. Table 5 summarises the improvement in these scores.

| Outcome | Complete case | After data imputation (n = 7291)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with data | Mean (SD) improvement | % (n) with any improvement | Mean (SD) improvement | % with any improvement | |

| TOM impairment | 5337 | 0.44 (0.71) | 50% (2659) | 0.28 (0.83) | 43.1% |

| TOM activity | 5339 | 0.46 (0.71) | 51% (2735) | 0.31 (0.84) | 44.4% |

| TOM participation | 5340 | 0.38 (0.71) | 43% (2279) | 0.22 (0.85) | 37.0% |

| TOM well-being | 5330 | 0.30 (0.68) | 37% (1975) | 0.13 (0.87) | 32.1% |

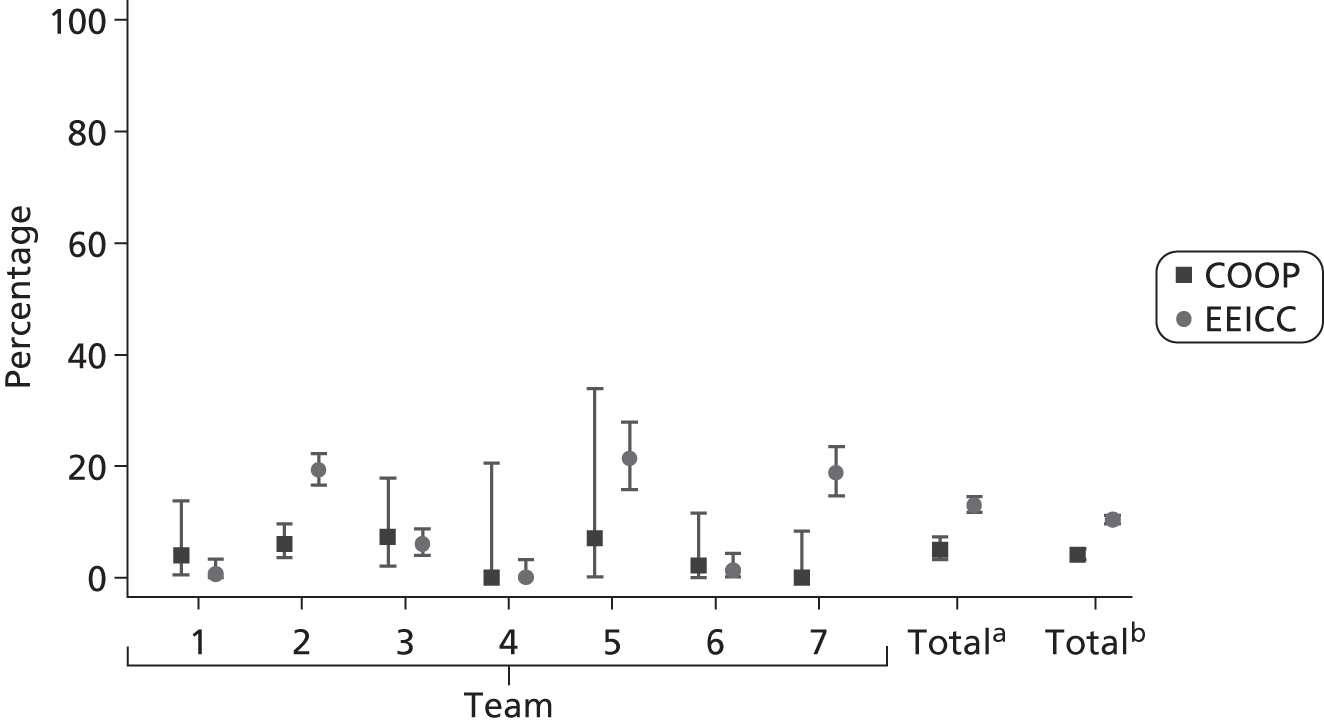

The magnitude of these changes is displayed graphically in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Change in TOMs by domain.

Key point 13: nearly half of all patients with outcome data did not improve on any of the domains of TOM.

Baseline scores

Patients with higher TOM scores on admission were less likely to improve. The relative increase in odds of improvement per 1-point increase in score on admission ranged from 0.53 (TOM well-being) to 0.75 (TOM impairment) using imputed data (see Appendix 2). The extent that this is as a result of a ceiling effect (i.e. because the potential to improve is less for those who already have high scores) is not known.

Age

The magnitude of a TOM score increase was related to patient age, with smaller changes being observed in older patients. Although statistically significant, the decreases were modest. On average, the change in TOM scores decreased by 0.02–0.03 units per additional 10 years of age (see Appendix 2).

Sex

Fewer men than women improved for all domains of the TOM. However, the difference in mean scores between men and women was small, i.e. ≤ 0.1 units for all domains. The odds of improvement were significant for all domains except participation (see Appendix 2).

Level of care on admission

Level of care at admission was associated with change in all TOM domains. Fewer than 20% of patients with a LoC, on admission, of 0 improved their TOM scores for all domains (using imputed data). The patients most likely to improve were those with admission LoCs of 3, 4 or 5 [> 40% for impairment, activity and participation, > 30% for well-being (see Appendix 2)]. However, the magnitude of change was modest, with the average (adjusted) mean changes in the highest (levels 4 and 5) and lowest (levels 0 and 6) groups being within 0.06 units of each other. The probability of any improvement as calculated from the imputed data was between 64% (level 6) and 77% (level 4) (see Appendix 2).

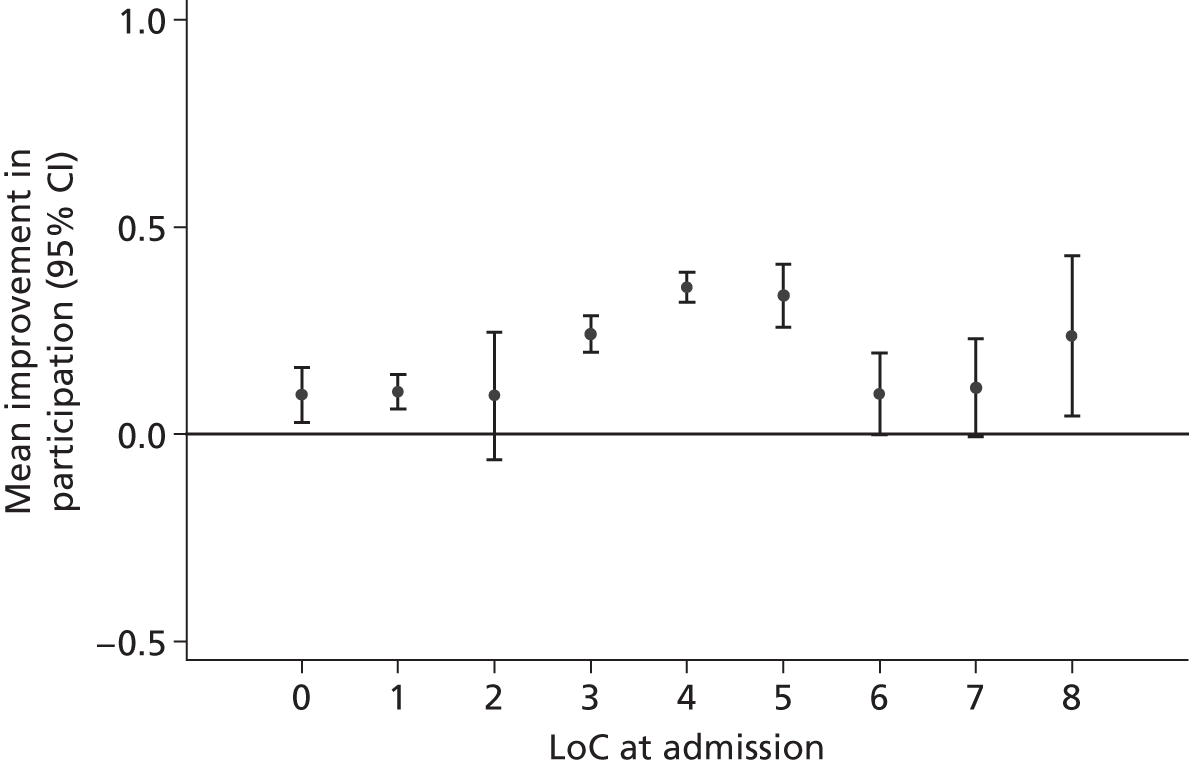

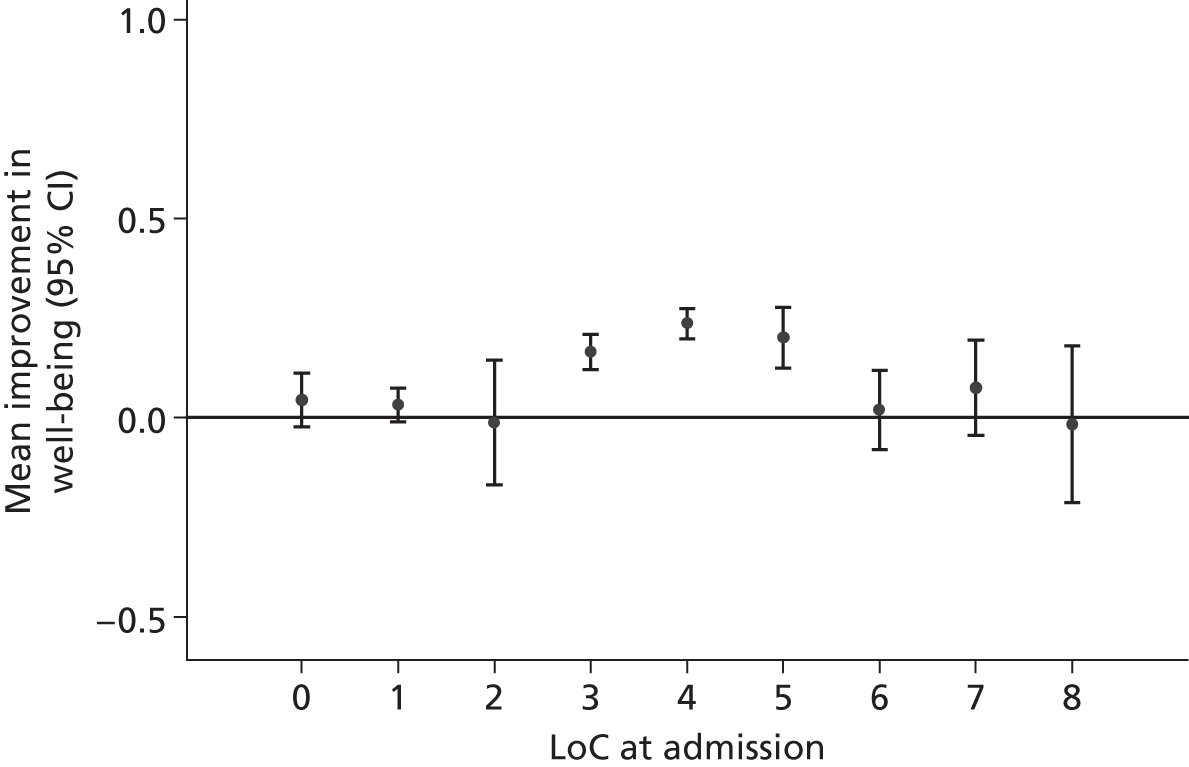

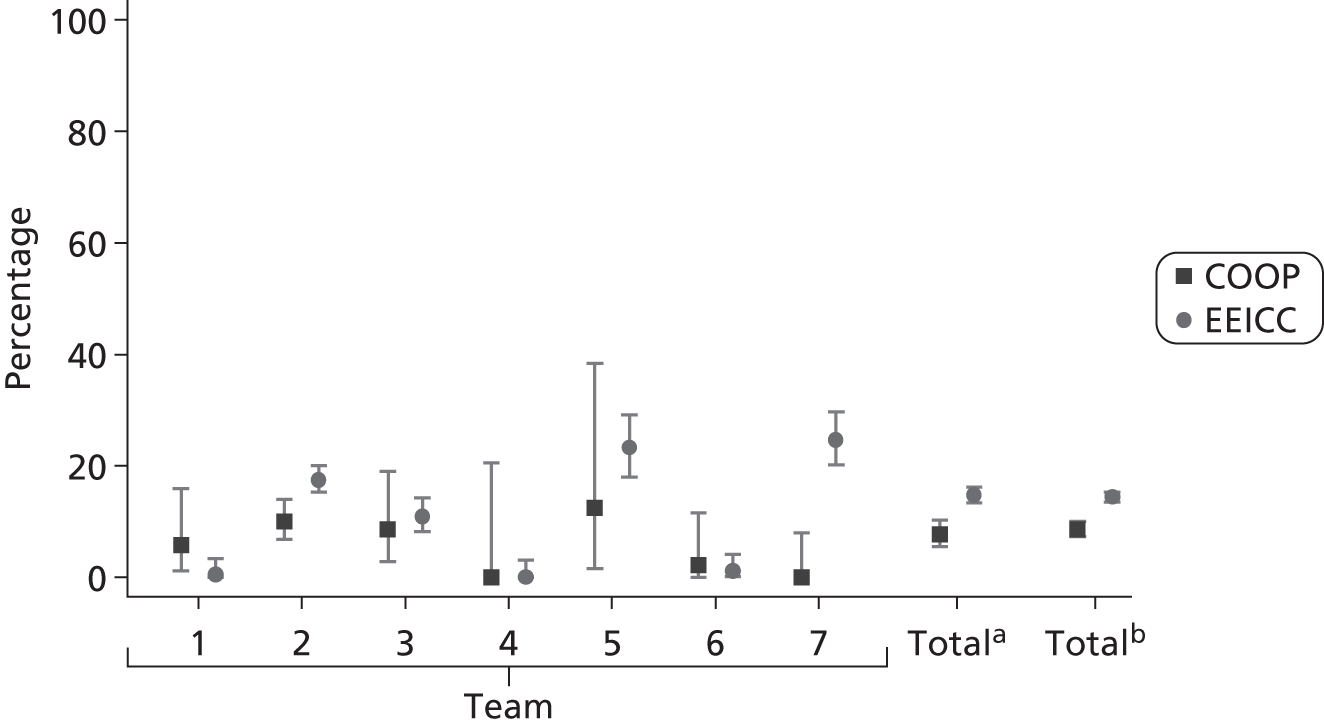

Compared with level 0, levels 1–8 all had a higher probability of having any improvement for impairment, activity and participation. The mean difference between the best and worst LoC group was around 0.3 to 0.4 TOM units. The magnitude of the changes in impairment, activity and participation and well-being, adjusted for other covariates, are illustrated graphically in Figures 3–6.

FIGURE 3.

Change in impairment by LoC at admission (model adjusted).

FIGURE 4.

Change in activity by LoC at admission (model adjusted).

FIGURE 5.

Change in participation by LoC at admission (model adjusted).

FIGURE 6.

Change in well-being by LoC at admission (model adjusted).

Key point 14: patients most likely to improve were those with admission LoCs levels of 3, 4 or 5 (> 40% for impairment, activity and participation; > 30% for well-being). The probability of any improvement as calculated from the imputed data was between 64% (level 6) and 77% (level 4).

Route of referral

Improvement was greatest among patients referred in from acute settings [accident and emergency (A&E), ambulance, rapid response, acute hospital, day clinics and fall clinics]. Of particular note is that baseline TOM scores in these subgroups were similar to those referred in from other settings and so these differences are not obviously an artefact of regression to the mean. Patients referred via a community nurse, social care or social work had the smallest improvements in TOMs. Again, despite statistical significance, the effects were modest with the highest and lowest group means being around 0.2 TOM units different.

Key point 15: improvement was greatest among patients referred in from acute settings (A&E, ambulance, rapid response, acute hospital, day clinics and fall clinics) despite similar baseline scores to those admitted from other settings.

Place of care

The patient location was also associated with outcome for TOM and EQ-5D scores, with better outcomes observed among those who initially live more independently (i.e. in their own home, an IC facility or resource centre), who have bigger changes than those admitted from residential or hospital settings.

As was found with the TOM data, the relationship between the EQ-5D score and different locations of care was affected by the fact that 3738 patients (46%) had missing data.

Smaller proportions of the patients in residential/nursing home or acute hospital settings improved than those receiving care in more independent care settings, such as at home or in an IC facility or resource centre. However, the percentage showing an improvement became more consistent across the groups when the imputed data set was analysed.

The proportion of patients showing any improvement was significantly lower among people receiving care in a residential/nursing home, A&E or acute hospital compared with those in other settings for all domains of the TOM (see Appendix 2). The magnitude of the changes was modest (< 0.4 units in all domains) and smallest for TOM well-being scores. Mean changes ranged from < 0.1 (residential/nursing) to 0.2 units (IC facility) (see Appendix 2).

The chance of remaining or returning home was greatest for patients receiving care at home who had previously lived at home unaided prior to their health complication; these patients had a 71.9% chance of returning home. This variable also suggests that the chance of returning home is smallest for patients receiving IC at residential or nursing homes; these patients had only a 10.1% chance of returning home.

Key point 16: smaller proportions of the patients in residential/nursing home or acute hospital settings improved compared with those receiving care in more independent care settings, such as at home or in an IC facility or resource centre.

Key point 17: the chance of returning home was greatest for patients receiving care at home who had previously lived at home unaided (71.9%).

Key point 18: the chance of returning home is smallest for patients receiving IC at residential or nursing homes (10.1%).

Usual living arrangements and changes during intermediate care

After data imputation, the patients’ usual living arrangements were found to be highly associated with level of improvement across all four TOM domains. Patients who normally live in their own home or in sheltered accommodation had greater improvements than those living with relatives, who in turn had greater improvements than those in residential, nursing or other settings.

The mean improvement in TOM impairment was > 0 for all subgroups, but ranged from 0.32 (patients living alone in their own home) to 0.01 (other settings). The association was stronger for TOM activity, ranging from 0.36 (own home) to –0.06 (nursing home). Changes in TOM participation and well-being were less pronounced, but patients living in their own home fared, on average, 0.4 units better than patients who are institutionalised prior to IC. The patterns observed in the complete case data were less clear cut, but broadly echoed these.

The greatest level of improvement was observed among patients who were transferred to IC facilities, followed by those who did not leave their own home during IC. Patients who were transferred to hospital or nursing home were the least likely to improve during IC. Figure 7 illustrates these changes, which account for health status.

FIGURE 7.

Change in activity by location of care (for those not institutionalised pre entry; model adjusted).

Key point 19: patients’ usual living arrangements were found to be highly associated with level of improvement across all four TOM domains. The greatest level of improvement was observed among patients who were transferred to IC facilities, followed by those who did not leave their own home during intervention.

Relationship between patient characteristics and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions scores

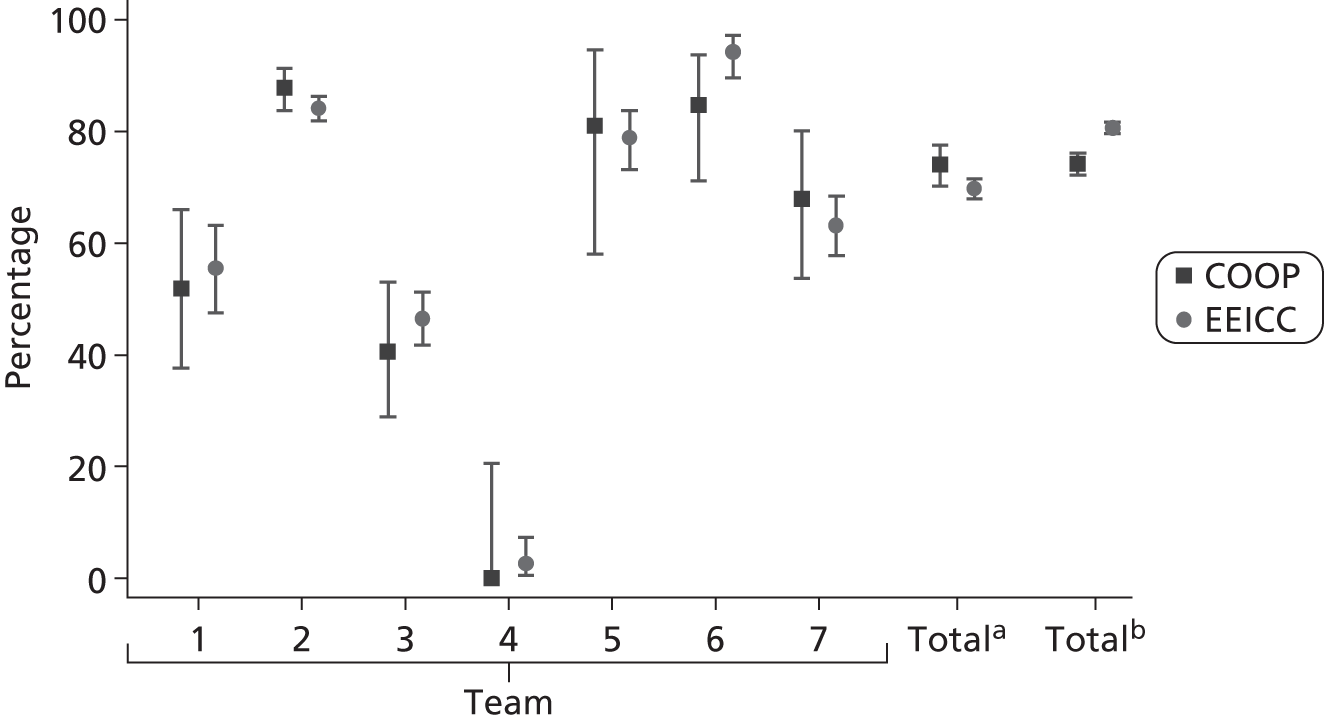

The EQ-5D scores of 38% of patients did not improve during their episode of treatment. This is less than the proportion who did not improve on any of TOM domains. This may be a reflection of the fact that EQ-5D is effectively a continuous measure and is a patient-completed measure (reflecting the patient’s view their own health status), whereas the TOM scale has only 11 possible levels and reflects the health-care professional’s view. Improvements in EQ-5D scores were found to have statistically significant relationships with other variables. For instance, the greatest improvements were seen for LoCs 4, 5 and 7 (approximately 0.04 increase), patients receiving care in their own homes (0.06 increase), referrals from A&E/ambulance service or acute wards (0.05 increase) and lower baseline EQ-5D score (0.05-unit increase per 0.1-unit decrease in baseline). Tables 6 and 7 summarise the improvements in these scores.

| Outcome | Complete case | After data imputation (n = 7291)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with data | Mean (SD) improvement | % (n) with any improvement | Mean (SD) improvement | % with any improvement | |

| EQ-5D | 4332 | 0.18 (0.28) | 62% (2684) | 0.15 (0.25) | 66.4% |

| Characteristic | Relationship with TOM | Relationship with EQ-5D | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistically significant? | Nature of relationship | Statistically significant? | Nature of relationship | |

| Age | Yes | Minimal: TOM reduced by 0.02–0.03 units per 10-year increase in age | No | |

| Sex | Yes | Minimal: on average, females had approximately 0.1 unit greater improvement than males | No | |

| LoC at admission | Yes | Levels 3, 4 and 5 improved greatest. Impairment and activity: levels 3–5 typically 0.2–0.3 units higher than lowest (0 and 6), with other levels between. Participation and well-being: levels 3–5 around 0.15–0.25 higher than other levels | Yes | Levels 7, 4 and 5 had greatest improvement, around 0.04 units more than the remainder |

| Normal living arrangements | Yes | Greatest improvement for patients receiving care in their own home, with an average increase of 0.15–0.3 units more than living in a residential home or relatives home (which showed the least improvement) | Yes | Greatest improvement for patients receiving care in their own home, with an average increase of 0.06 units more than other locations |

| Effect of leaving own home during IC | Yes | Greatest improvement for patients in IC facilities, showing an improvement of around 0.5 greater than acute hospitals, which show the smallest improvement. Patients remaining at home or transferred to resource centre have next greatest improvement overall | Yes | Greatest improvement among patients who transfer to IC facility, resource centres or remain in own home. Improvement approximately 0.05–0.15 greater than other locations. Those transferred to acute settings had least change |

| Who made the referral | Yes | Greatest improvement for wards in acute hospitals of around 0.1–0.25 units more than the remainder | Yes | Greatest improvement for A&E/ambulance service and wards in acute hospitals, this showed an increase of around 0.05 units more than the remainder |

| Baseline score | Yes | On average, improvement in TOM scores reduced by approximately 0.2 units per unit increase in baseline TOM score | Yes | Improvement in EQ-5D reduced by 0.05 units per 0.1-unit increase in baseline EQ-5D |

The magnitude of these changes is displayed graphically in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

Change in EQ-5D score.

Discussion

This chapter has explored which patients are most likely to benefit from IC and those which are least likely to benefit and, therefore, may be best placed to receive care elsewhere. A summary of the main findings is detailed in Table 7.

In order to use resources appropriately, it is important to select patients carefully to receive interventions that are most likely to be of benefit. The data presented here provide information to improve the selection of patients most likely to be assisted by IC. The analysis adds to the evidence in the literature review that the most very elderly patients may be less likely to benefit from IC in terms of rehabilitation outcomes. However, the differential benefits associated with reduced age were small and, therefore, the clinical significance of this is tenuous. The data analysis supports the findings of the literature review that neither age nor sex is likely to be useful criteria on which to select patients for IC.

However, both the literature review and analysis of these data indicate that severity of impairment and health-related QoL (HRQoL) appear to affect outcomes. Patients with higher scores on the TOM scale and EQ-5D questionnaire, on admission, are less likely to benefit, although this may be because patients with higher score are healthier to begin with and have less room for improvement. This assertion is supported by the finding in the data analysis that those with a LoC of 0 (‘client does not need any intervention’) showed less change than other levels. However, it is important to note that many of these clients were discharged on the same day that they had been admitted to the service as they were deemed as not requiring intervention. Patients considered ‘inappropriate referrals’ or who did not need the intervention that they had been referred for are a poorly described group and require further investigation.

Key point 20: the group of patients considered as ‘inappropriate referrals’, or not needing IC services after referral, are poorly understood and require further research.

A similar lack of change in TOM and EQ-5D scores was found for those who need relatively little care (convalescence/respite or prevention/maintenance) rather than those who need slow-stream, regular or intensive rehabilitation, indicating that use of the LoCs may be a useful tool for resource allocation.

The literature provides information about the types of patients included in studies evaluating IC service models using RCTs. The systematic reviews and meta-analyses essentially capture those models for which there has been extensive interest, leading to funding and the conducting of several RCTs.

A key message from the literature review is that RCTs include older people with specific medical [stroke, COPD, congestive heart failure (CHF)] and surgical conditions (fractured neck of femur, CABG). Trials have not included the general population of service users. There is evidence that the rates of improvement in patients admitted to IC are often modest, with two studies showing that only around one-third of patients improve at all. Given the frailty of most of the patients admitted to IC, it could be that no decline in health status is also a positive outcome and perhaps the parameters for success of IC services need to be reconsidered.

The literature review showed evidence that age, cognitive impairment, living alone at admission and functional status at admission may all have an influence on the outcomes of patients using IC; however, the strength and direction of these findings were not consistent enough to draw conclusions for this study.

Analyses of data from our two studies focus on two main sets of characteristics: the assessed need of the subjects in receipt of IC services and the location of care. Age and sex are also included in the analysis but the effects, although statistically significant, were numerically rather small.

For each of the five measures, the extent of change was negatively associated with the baseline score: higher scores at baseline tended to have smaller changes. Increasing age was associated with lower gains in all TOM scores, but the association was small in absolute terms (< 0.05 units of TOMs per 10-year increase). When compared with females, males had marginally higher improvements in impairment and activity, but lower improvements in participation and well-being. EQ-5D score was not associated with age or sex.

The overall outcomes of this study showed that, on average, 60% of patients remain or return home following an episode of IC. Rates of improvement varied according to the outcome measure. On average, 43% of patients improved on the measure of TOM impairment, 44% on TOM activity, 37% as measured by TOM participation and 32% on TOM well-being. Two-thirds of patients (66%) improved on the EQ-5D score measurement after data imputation.

Factors that were statistically associated with a change in TOM scores were patient age (improvement declines with age), sex (females more likely to improve), LoC at admission, living in own home, receiving care in own home or IC facilities, referrals made by acute hospitals and having a lower score at admission.

With respect to all the outcomes (return home, TOM score and EQ-5D score), the analyses generally support the same conclusion: those patients who are more likely to have the most positive outcomes (return to home, large improvement in TOM parameters and EQ-5D score) are more likely to have been assessed as in need of rehabilitation (according to LoC need) by the admitting team.

Levels of care 3, 4 and 5 provide the springboard for most improvement and these represent an assessment that the patient is in need of slow-stream, regular or high-intensity rehabilitation.

Those patients who are likely to do best receive the IC service in their own home. This implies that those who do worst receive IC elsewhere, although it should be noted from the literature review that residential and nursing home settings are largely unevaluated.

However, there are clear indications from the secondary data analysis that place of care is important and that those who improve the least are those who receive care in residential/nursing homes and acute hospital settings. This finding is not surprising given that the level of impairment tended to be more severe for these patients, indicating a higher burden of chronic disease.

Key point 21: those patients who are more likely to have the most positive outcomes (return to home, large improvement in TOM parameters and EQ-5D score) are more likely to have been assessed as in need of rehabilitation (according to LoC need) by the admitting team.

Conclusion

The literature review and data analysis can be seen to agree. Those patients for whom IC may be of benefit include older people with medical and selected long-term conditions for whom a needs assessment suggests that there is potential for rehabilitation, which should be provided, when possible, in the patient’s own home.

Gaps in the evidence base concern the location of care (specifically the use of residential and nursing home settings) and the specific clinical concerns of meeting the needs of patients with dementia, or palliative and end-of-life care needs.

Key point 22: those patients for whom IC may be of benefit include older people with potential for rehabilitation, which should be provided, when possible, in the patient’s own home.

Chapter 2 What factors are associated with increased hospital admissions for patients using intermediate care services?

Introduction

This chapter deals with the question of whether or not the use of IC services changes the use of hospital inpatient facilities by reducing hospital admissions and what factors (if any) are associated with increased rates of hospital admission (and/or readmission) during or after the use of IC services.

Background

In the first instance, there are some conceptual issues which need to be clarified. Admission to acute hospital care is an event that IC services are frequently designed to avoid completely. For example, HITH services can be constructed to bypass the acute hospital, providing substitute acute and/or subacute care in the community and resulting in the total avoidance of hospital admission. A person in receipt of such a service, whose condition deteriorated to require admission to hospital, would be experiencing a first admission to inpatient hospital care for the episode of care in question. Conversely, someone who deteriorated in an IC scheme designed to support early discharge from hospital will be readmitted to hospital (i.e. will experience a second period of inpatient care during the same episode of illness). For example, nurse-led, post-acute care for frail older people was set up to deliver quality transition care (rather than change episode duration). RCTs showed that the nurse-led inpatient units tended to increase the length of inpatient hospital stay. 46–48 However, the subsequent use of health-care resources was different between intervention and control.

In one unit, this was shown to be largely at the expense of community hospital transfers, i.e. total resource use was similar between the intervention group, who had longer inpatient stays, and the control group, who had shorter inpatient stays but made more use of community resources after discharge. These examples are given to illustrate the potential interdependence of the relationship between duration of inpatient stay and subsequent use of services after discharge. 49 Hospital length of stay has become a simplistic metric used as an indicator of efficiency with associated political overtones. Thus, there are incentives for patients to be moved out of hospital, or to avoid hospital, when in fact they may receive more efficient rehabilitation within a hospital setting.

For the purpose of this chapter, the notion of avoiding first admission and avoiding readmission will be conflated, so that we can consider the issue of reducing hospital admissions without worrying about somewhat arbitrary definitions concerning the type of hospital admission.

Admission/readmission as a policy focus

During the first decade of this century, policy-led initiatives focused on reducing recurrent hospital use by patients at risk of multiple admissions. Examples of this include the idea of case management in the community and using specialised nurses or health-care teams to identify at-risk individuals and provide them with additional support in the management of their long-term conditions. The aim of such interventions would be to reduce the use of secondary care and improve health and well-being through encouraging enhanced self-management and providing support in the community for acute or subacute episodes of deterioration.

Although there was some early enthusiasm for these forms of care in England, the potential for them to reduce secondary care use was somewhat overstated in the first instance. Evaluation of the potential for reductions in hospital admissions,50 and the impact of one form of enhanced nurse practitioner working with older people in England,51 was followed by a re-evaluation of the potential for case management to solve the problem of rising numbers of hospital admissions. Case management approaches have been shown to be appreciated by users and carers52 and, in some configurations, to impact on functional health and well-being of recipients. 53 Another approach to targeting interventions to help prevent hospital admissions has involved the use of predictive modelling to identify people at high risk of readmission54 and target additional support in the community. Both of these approaches (anticipatory case management in primary care and predictive modelling) have typically considered hospital admission risk over a 12-month period.

More recently, there have been a series of shifts in policy, directly and indirectly, addressing the issue of unplanned acute hospital readmissions in England. In particular this has included a focus on community care of chronic conditions,8 payment by results, practice-based commissioning55 and, more recently, the setting up of Clinical Commissioning Groups and alterations to the tariff concerning readmissions. 56 The current government has confirmed a policy of altering the remuneration available to NHS trusts (the tariff) for patients readmitted to acute care within a month of discharge. This has been applied to elective care, but in the future may include a proportion of acute care admissions. The key point about this change in policy is that the trust responsible for the initial episode of inpatient care becomes responsible for the cost of subsequent inpatient care if the patient is readmitted within 30 days of the initial discharge. This places the responsibility for managing discharge across the interface between secondary and primary care (i.e between hospital and community care) firmly in the domain of the acute trust and is probably intended to stimulate re-engineering of services at the crucial interface between primary and secondary care so that they become more closely integrated than they may have been in the past.

Literature review

In conducting this review of the relevant literature, we have focused on the evidence from RCTs, evidenced mostly from systematic literature reviews. These sources sometimes report on admission rates and sometimes report on readmission rates, depending on the objectives of the services being reviewed. We have treated these terms as interchangeable for our purpose of describing the literature evidence on interventions affecting hospital admission rates.

Review methods

In developing this literature review, we have drawn on previous systematic literature reviews of discharge arrangements and IC57–59 conducted as part of a series of studies investigating the influence of workforce factors on costs and outcomes in IC. 2,60,61 These reviews have been supplemented with additional literature searches (see Appendix 1) from 2008 to April 2012 and we have identified additional systematic61 and narrative62 reviews, trial protocols63,64 and reviews conducted for the Cochrane collaboration.

Findings from the literature: Cochrane reviews

The Cochrane database of systematic reviews includes three highly relevant reviews of disease-unspecific services provided in the home and compared with hospital-based alternatives. 11,13,65

One review of HAH admission avoidance services addressed the specific research question ‘do readmission rates, or transfers to hospital, differ for patients treated in admission avoidance hospital at home compared with patients who are treated in hospital and are discharged at the standard time?’13 The analysis, combining data from three trials (n = 423), showed a non-significant increase in admissions for patients allocated to HAH [hazard ratio (HR) 1.49, 95% CI 0.96 to 2.33] which persisted even after removing admissions occurring within 14 days of randomisation (HR 1.42, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.30).

A review of early discharge HAH examined services designed to care for patients discharged early from hospital and provide co-ordinated rehabilitation with specialist care. The aim of these services was to relieve the pressure on acute hospital beds. 12 The meta-analysis of the effect on readmission found no significant difference in readmission rates between those allocated to HAH rather than to inpatient care at the 3-month (RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.47 to 2.38) and 6-month follow-up (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.60). No significant heterogeneity was seen.

In a review of trials of IC in nurse-led beds,65 the intervention was complex and involved professional substitution (nurse for doctor) and altered the case mix of the unit. The objective of care was to enhance the quality and quantity of nursing care received by patients in preparation for discharge. In this analysis, the impact of the intervention on resource use was complex and included alterations in duration of stay in the inpatient and community sectors. The impact on readmission (to 30 days) was considered separately and reported in five studies. Overall, odds of readmission were reduced for patients from the nurse-led units (NLUs) (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.80). The effect size was maintained (but the statistical significance lost) when this analysis was repeated for the three methodologically stronger studies.

Key point 23: non-disease-specific IC schemes have not been shown to have a major impact on the numbers of hospital (re)admissions. A possible exception is nurse-led inpatient units, which also have complex effects on other resources used (e.g. skill mix).

A further three reviews from The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews are about disease-specific services providing home-based IC for patients with stroke21,22 and COPD. 23

A review of services aimed at helping acute stroke patients avoid hospital admission concluded that, overall, fewer patients who received the service were admitted to hospital than those who did not receive the service. 21

A review of HAH for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive airways disease showed that readmission rates were not significantly different between intervention and control groups. In these schemes, patients who would usually be managed in hospital have most of their care undertaken by a specialist respiratory nurse who makes regular visits to the patient’s home. Further analyses suggested that both patients and carers prefer the HAH services to inpatient acute care. 23

A review of services in which stroke patients in hospital were offered an alternative to conventional systems of care through a policy of early discharge with community-based rehabilitation [early supported discharge (ESD)] concluded that supported early discharge services for stroke has significant effects on inpatient length of stay (amounting to a reduction in length of stay of about 9 days). 22 Five trials (663 patients) provided data on hospital readmission. Rates during scheduled follow-up (27% vs. 25%) were very similar between the patients who received the ESD services and controls.

Key point 24: services designed to reduce inpatient bed use (such as admission avoidance schemes and early discharge schemes) are likely to do so, but there are no consistent effects on readmissions from these types of intervention.

Findings from other systematic literature reviews

In a systematic review of discharge arrangements for older people (> 65 years of age),59 31 studies were identified for which formal synthesis of readmission data was possible. The results of readmission rates were reported in terms of the readmission rate ratio (RRR). A RRR of < 1 indicates that the intervention was beneficial in reducing the risk of readmission to inpatient hospital care. Overall, the RRR was 0.851 (95% CI 0.760 to 0.953; p < 0.001). Analysis of the RRR by the characteristics of the interventions showed that interventions that were implemented by either an individual or a team had similar effects on the reduction in the RRR. The trend to fewer readmissions in the intervention groups was most marked for those provided for both at hospital and at home. It was less marked among interventions delivered only in the hospital, or only in the home, either face to face or by telephone. Interestingly, analysis of readmission rates by service model (such as discharge planning protocols, use of comprehensive geriatric assessment or discharge support arrangements) did not reveal beneficial effects of specific service models on readmission rates. This observation was repeated in a systematic literature review conducted as part of a national evaluation of IC,10 with no particular benefit for readmission rates for discharge support arrangements, admission avoidance schemes or post-acute care.

A systematic review of complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people61 concluded that the interventions studied reduced hospital admissions by a small but significant amount (about 6%). Subgroup analysis found that the significant effects were attributable to performing a comprehensive geriatric assessment of frail older people (OR 0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.98), and in community-based care after hospital discharge (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.90 to 0.99).

Key point 25: working across the interface between hospital and community is a key characteristic of services that achieve reductions in readmissions to hospital inpatient care.

Key point 26: frail older people are less likely to be readmitted to inpatient hospital care if they have a comprehensive geriatric assessment and receive community-based care after hospital discharge.

Secondary analysis of data

Methods

Hospitalisation was defined as a patient being transferred to an acute hospital following IC. The methods used to analyse predictive factors for hospitalisation were similar to those used in the previous objective in Chapter 1, but with some modifications, which are described below.

The analysis of factors predicting hospitalisation was modelled using random-effects logistic regression in which the team was a random effect. Initially, the covariates considered were age, sex, LoC on admission and route of referral. Variables were chosen more sparingly for this analysis than the previous chapter, as regression models with binary outcomes and relatively low event rates are more prone to either ‘overfitting’66 (spurious associations with too many covariates) and ‘model non-convergence’66 (difficulties in fitting models with very low occurrences in some combinations) than regression models for continuous outcomes. 66 Hence only terms that were found to be statistically significant at the 5% level were included.

Following on from this, the usual living arrangements and place where care was provided were considered. As in Chapter 1, the model did not include both because of their collinear nature. Starting with the model chosen above, the patients’ location during IC was added and assessed for statistical significance using the likelihood ratio test. The model was then refitted, removing location during IC but adding the usual living arrangements, whether or not the patient had left this place for the duration of IC and, if so, where to. The best of these models was chosen based on the significance of the likelihood ratio test. All omitted terms were then tested one last time for inclusion and included terms vice versa, using the likelihood ratio test.

Additional analyses were undertaken to assess the impact of the five TOM and EQ-5D baseline assessments. Again, as these five measures are correlated, these analyses were undertaken by adding each of these five in turn, and separately.

Missing data

Missing covariate (i.e. baseline) data were imputed as detailed in Appendix 2, but outcome data were less commonly missing and no imputation was performed for this analysis.

Results

Table 8 provides information on the numbers of patients transferred back to hospital following admission to their service. In total, 628 patients were transferred to hospital. One team (COOP-D) did not transfer any patients to hospital. The EEICC-PB team had the greatest proportion of people transferred to hospital (21%).

| Team | Number transfered to hospital | % of total number of people transfered (to nearest integer) |

|---|---|---|

| COOP study | ||

| A | 27 | 10 |

| B | 8 | 10 |

| C | 1 | 6 |

| D | 0 | 0 |

| E | 1 | 2 |

| F | 7 | 14 |

| G | 18 | 11 |

| J | 12 | 16 |

| L | 2 | 7 |

| M | 13 | 13 |

| N | 5 | 5 |

| PA | 1 | 7 |

| PB | 1 | 6 |

| Q | 4 | 9 |

| SA | 6 | 10 |

| SB | 30 | 16 |

| SG | 2 | 4 |

| T | 7 | 13 |

| TA | 14 | 6 |

| U | 6 | 13 |

| EEICC study | ||

| B | 17 | 6 |

| D | 16 | 5 |

| DO | 7 | 4 |

| E | 27 | 6 |

| F | 17 | 10 |

| G | 128 | 10 |

| H | 78 | 8 |

| I | 71 | 9 |

| PB | 24 | 21 |

| Q | 8 | 5 |

| R | 58 | 12 |

| U | 12 | 7 |

The location following IC was known for 7084 patients, of whom 628 (9%) were hospitalised at the end of IC. Hospitalisation was found to be associated with age (p < 0.0001), sex (p = 0.004), LoC at admission (p < 0.0001) and the place receiving care (p = 0.002), but not with the route of initial referral (Table 9). In addition, the TOM and EQ-5D scores at admission were associated with hospitalisation as described below.

| Term | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (per 10-year increase) | 1.20 | 1.10 to 1.32 | < 0.0001 |

| Sex (male vs. female) | 1.36 | 1.12 to 1.62 | 0.004 |

| LoC at admission | |||

| 0 | Reference | < 0.0001 | |

| 1 | 1.34 | 0.85 to 2.09 | |

| 2 | 1.51 | 0.66 to 3.48 | |

| 3 | 1.43 | 0.91 to 2.27 | |

| 4 | 1.86 | 1.21 to 2.88 | |

| 5 | 2.87 | 1.72 to 4.77 | |

| 6 | 2.30 | 1.28 to 4.12 | |

| 7 | 6.54 | 3.84 to 11.14 | |

| 8 | 1.73 | 0.63 to 4.75 | |

| Care location | |||

| At home, alone | Reference | 0.002 | |

| At home, not alone | 0.90 | 0.71 to 1.12 | |

| Relatives home | 1.53 | 0.87 to 2.67 | |

| Residential/nursing home | 0.61 | 0.38 to 0.96 | |

| Sheltered housing | 1.18 | 0.68 to 2.06 | |

| Acute hospital | 2.74 | 0.51 to 14.66 | |

| A&E | 2.20 | 1.04 to 4.69 | |

| IC facility | 1.88 | 1.26 to 2.78 | |

| Day hospital or community hospital | 0.29 | 0.04 to 2.22 | |

| Resource centre | 1.18 | 0.39 to 3.57 | |

| Community hospital | 0.91 | 0.54 to 1.54 | |

| Other | 0.35 | 0.08 to 1.47 |

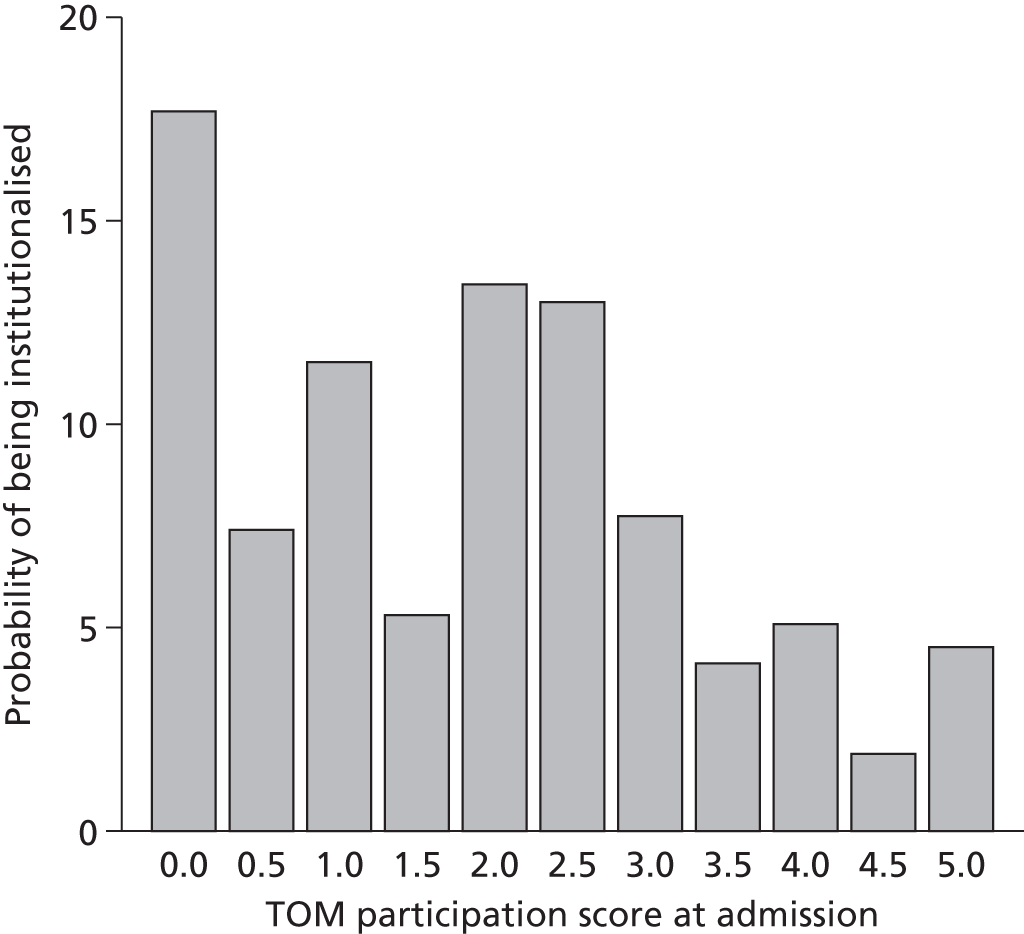

Level of care at admission

The probability of being transferred to hospital was greatest for a LoC of 7 (needs medical care and rehabilitation); for these patients the probability of being transferred to hospital is 25.4%.

The chance of being transferred to hospital is smallest for LoCs of 0 (does not need any intervention) and 1 (needs prevention programme); for these patients the chance of being transferred to hospital is 5.2% and 6.6%, respectively.

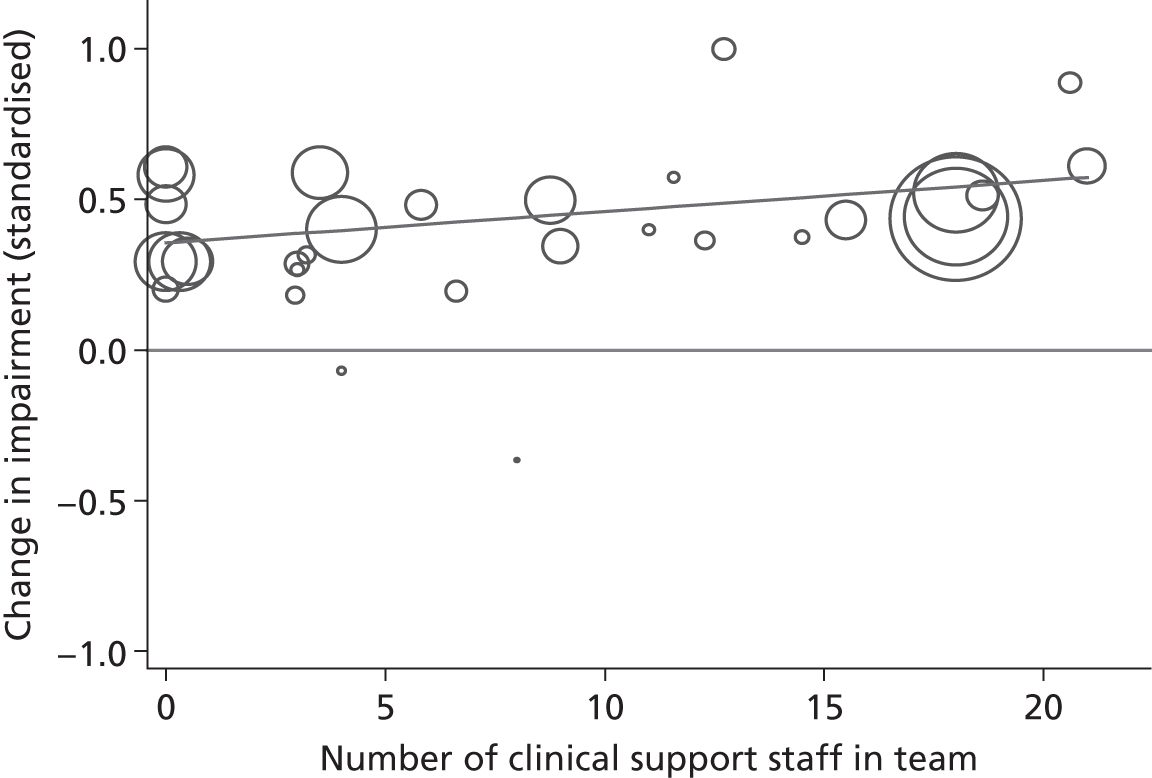

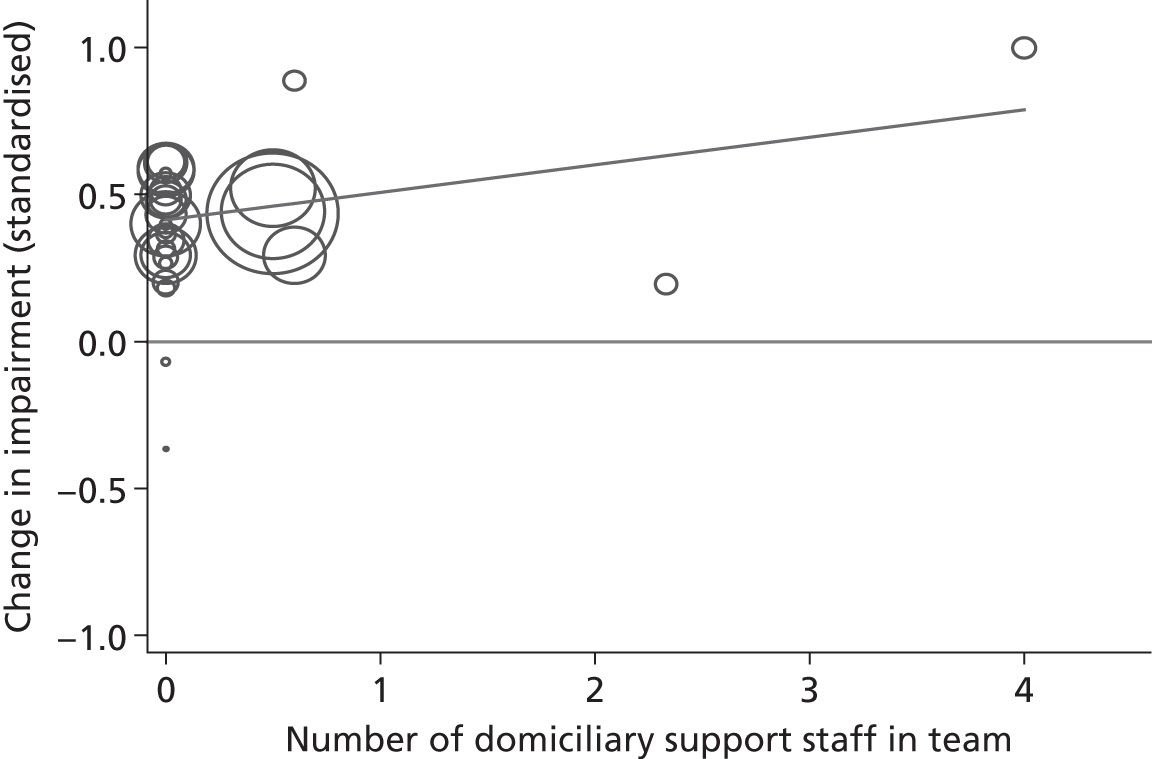

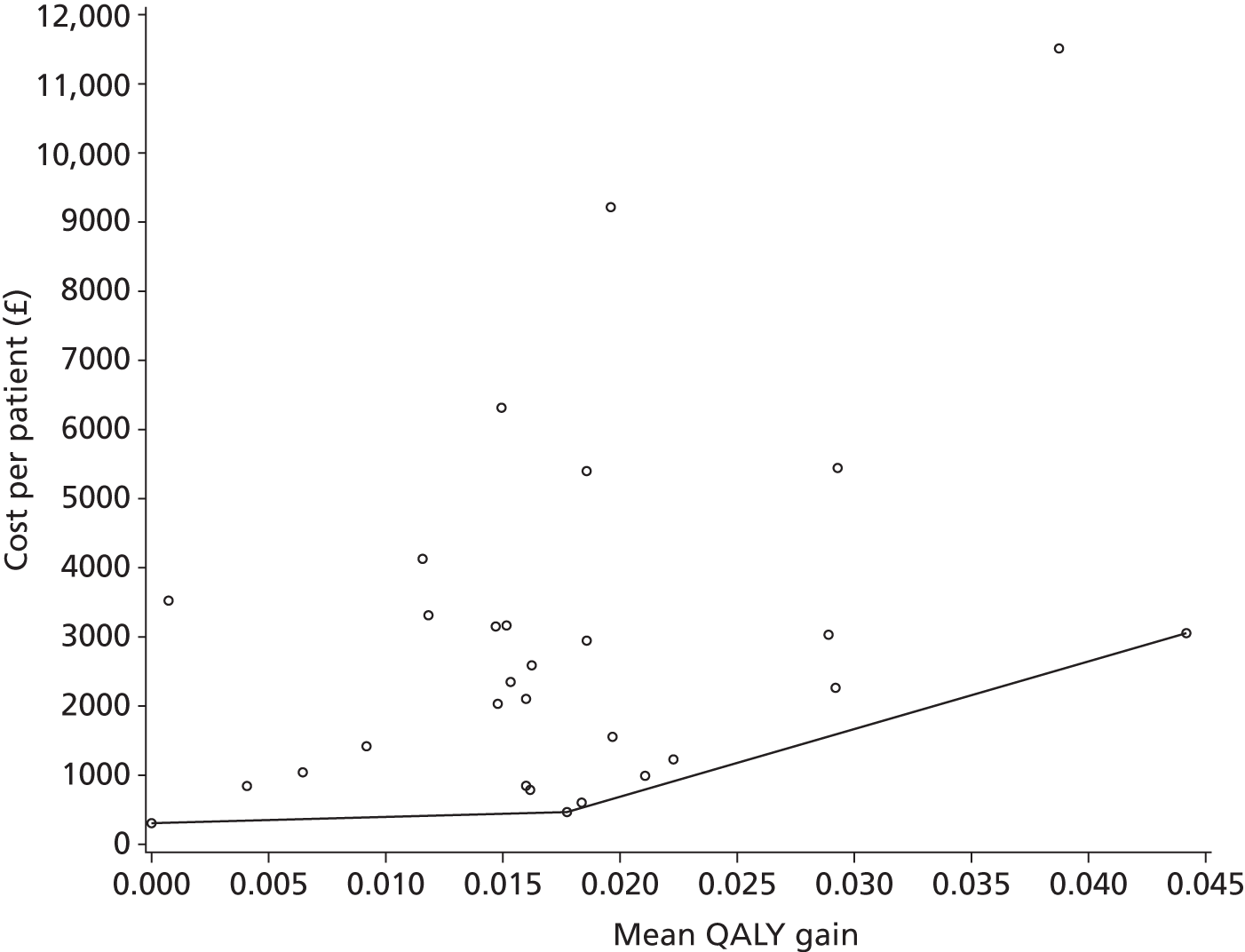

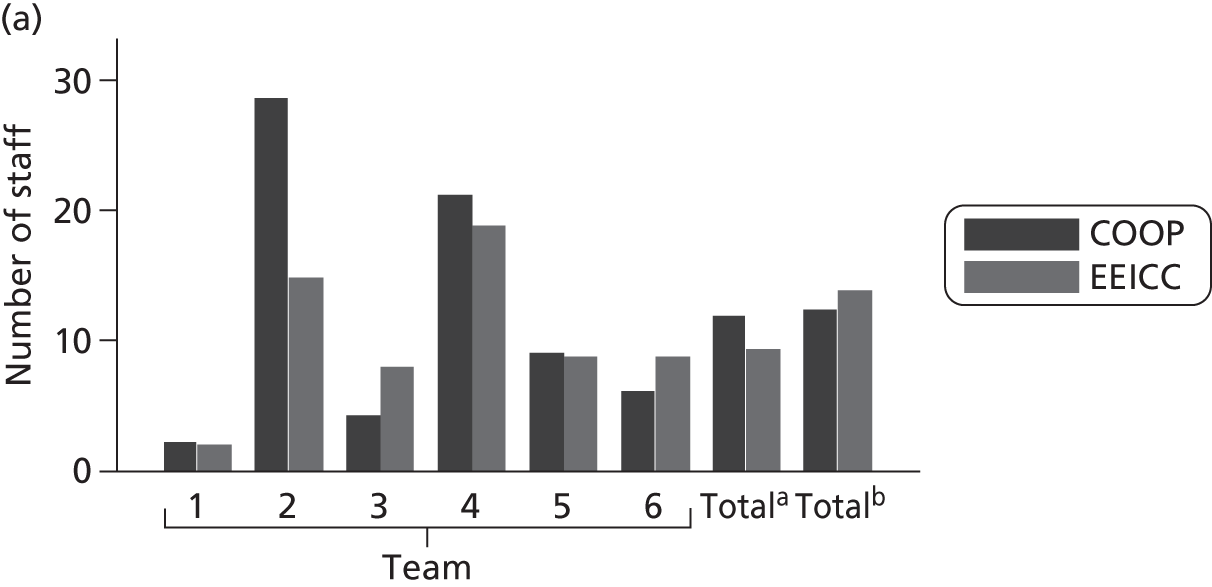

Location of care episode