Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/2000/43. The contractual start date was in June 2011. The final report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Roberts et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This study tested a British Sign Language (BSL) version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) and so by its nature recruited participants who use sign language as a part of their lives. However, as discussed in later chapters, many children who regularly use sign language as a main language also have experiences of living in hearing families or attending mainstream hearing schools and many also use oral English, Sign Supported English (SSE: signs from BSL following English grammar structures) or other languages in their everyday lives, alongside their sign language. This diversity in multimodal use of language and the heterogeneous backgrounds of these young people means that it is not always possible to capture this diversity by the simple use of conventions to describe Deaf cultural experiences. However, for the purposes of this report we use ‘deaf’ to describe the majority of deaf people. We will use the word ‘Deaf’ with a capital D when referring to Deaf culture or Deaf identity.

This chapter outlines the main focus of the present research study, with particular reference to the key issues faced by deaf young people, and how the additional risk factors that they face lead to increased risk of mental health problems. We highlight how these issues would be identified earlier if there were better access to a mental health screening tool that is linguistically and culturally appropriate. We describe the process that this team followed in translating a mental health screening instrument for children and young people.

Finally, the validation process is outlined, whereby deaf young people, deaf parents and deaf teachers across England completed the newly developed screening questionnaire. Their responses were compared with a ‘gold standard’ clinical assessment by clinicians experienced in working with deaf children and young people who have child mental health problems. These clinicians were experienced at working over several years with deaf children who have mental health problems and they always worked with qualified interpreters who also had experience of working in the deaf child mental health field. We refer to this as the gold standard. Currently there is no validated tool which we can use to compare the SDQ’s responses from each group. It would be standard research practice to validate any standardised instrument against a clinical interview with experienced clinicians, as this interview will give the best way of detecting mental disorders.

Background: review of literature

Mental health in deaf children

Prevalence of mental health disorders

In Great Britain, the reported prevalence of mental health disorders in children and young people is 12–20%. 1 Various studies across the world have suggested that the prevalence of mental health problems is higher in deaf children than hearing children2–8 and that when deaf children receive care they need more resources and spend longer in treatment than hearing children and young people. 9 For example, in studies using the parent/carer version of the Child Behaviour Check List in both Holland (n = 238)5 and England (n = 84)6 deaf children and adolescents had two to three times the rates of mental health problems (about 40% in the samples studied) compared with hearing children.

Another English study using screening instruments followed by a structured diagnostic interview using a sign language interpreter found that 50.3% of 11- to 16-year-old deaf adolescents had a psychiatric disorder (42% of those in a school for deaf children and 61% in a hearing-impaired unit in a mainstream school). 2 Forty-one deaf boys (aged 6–11 years) had more internalising and externalising problems than hearing boys10 and the younger boys had more behaviour problems.

A sample of 111 Swedish deaf children also had higher levels of mental health problems using the SDQ11 in written English forms. Of 120 deaf children in Canada, 23% were thought to have moderate to severe psychiatric problems. 12 In the USA, deaf 4- to 17-year-olds receiving outpatient care had higher rates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct disorder, autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and bipolar disorder than hearing children. 9

There are several problems in interpreting this literature. First, the research shows large variations in rates across studies. Second, most studies are in small or selected samples or very heterogeneous samples with no analysis of subgroups. Third, in all studies, the instruments are not validated in deaf children and are inaccessible to many children, as they are not in their first language (where BSL is their first or main language). There is evidence in the study by Cornes that screening of deaf young adults using a questionnaire in BSL picked up higher rates of mental health difficulties than using the written English version13 although the translation methodology for that study did not follow accepted standards. 14

In summary, researchers tend to study heterogeneous samples with instruments not fit for purpose and this may partly explain the wide differences in findings between studies.

Why are mental health problems more common in deaf children?

There are various factors that are proposed to influence mental health negatively in deaf children, including degree of deafness, age at onset, and the presence of additional neurological difficulties. 15 Factors that are purported to increase the likelihood of behavioural and emotional problems include low intelligence quotient (IQ) and comorbid physical7 and neurological problems, severe or profound deafness,16 poor development of language and communication,17 and poor parent–child communication. 5 Factors that increase risk of ADHD are lower intelligence, acquired deafness (compared with hereditary deafness)18 and significant communication difficulties. 19 ADHD is thought to be more common in deaf children. 18 It has been suggested that people who are deafened by rubella infection have five times the likelihood of experiencing subsequent psychosis. 20

Physical problems, learning disability and syndromes

Children with glue ear (otitis media with effusion)21 and rubella (German measles)22 have higher rates of behaviour problems. There is considerable research showing that children with physical illness, chronic illness or chromosomal syndromes have higher rates of mental health problems23 and, as it is estimated that up to 40% of deaf children have some additional needs, with approximately 6% having complex syndromes,24,25 they are found to have higher rates of mental health problems. 22,23,26–30 Children with high-frequency, mild or unilateral deafness (sometimes grouped together and called minimal sensorineural hearing loss) have more problems with behaviour, anxiety and self-esteem than hearing children. 28 In CHARGE syndrome [coloboma of the eye, central nervous system anomalies; heart defects; atresia of the choanae; retardation of growth and/or development; genital and/or urinary defects (hypogonadism); ear anomalies and/or deafness], which is a chromosomal condition involving heart, kidney and visual problems as well as sensorineural deafness, many young people will have severe repetitive behaviours. 29 Usher syndrome, which can involve visual and balance problems as well as deafness, is associated with affective disorders,30 self-injury and aggression. 31 About two-fifths can be aggressive to self or others31 and about one-third in one study had received a psychiatric diagnosis, with 47% on some kind of psychotropic medication32 for problems including anxiety disorders, ADHD, obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and ASD. Some have suggested increased risk of psychosis in deaf people33 and there have been case reports of psychosis in Usher syndrome. 34,35 However, there is no clear systematic evidence for an increased likelihood of psychotic disorders in deaf people. 36 Although many deaf children (especially those with no neurological deficits or neurological damage, and with healthy cultural and linguistic experiences) have an IQ similar to hearing counterparts,37,38 many deaf children with neurological damage have learning disabilities32,39,40 and there is ample research to show that children with learning disabilities have higher rates of mental health problems than those without. 41

Diagnosis of deafness and adjustment of family

Currently in the UK there is a well-established New Born Hearing Screening Programme, which is picking up 1 in 1000 children as having a significant hearing loss. 42 This enables early detection and support from professionals, but also generates potential anxiety around parenting and how to interact with a deaf baby. 43

Some families find it difficult to accept their deaf infant and may treat their deaf child as hearing. Other families may struggle to accept the feelings of loss and overcompensate for this by engaging in increasingly ‘professional parenting’. This may hamper development in many ways including communication, social learning, emotional literacy, and social and emotional development. 44

It is now well established that early social and emotional learning is a complex process that relies heavily on communication. Much vicarious learning45 and communicative reciprocity is absent for deaf children in early life46 because over 90% of deaf children are born to hearing families unprepared for the communicative challenges that they face.

High levels of stress in parents are associated with more emotional problems in the young person,44 although the direction of the association is unclear. Behaviour problems are seen less where positive family support is available. 47,48

In one sample of 86 children, whose deafness was identified late, there were more behaviour problems, as rated using the parent and teacher report Rutter Scales,49 than in hearing children,50 and there were also increased rates where those with low levels of loss were not using hearing aids. 28

Educational experiences and life choices

For families where a child is identified as deaf, there are a number of difficult choices to make, most significantly with respect to education. Parents receive early support from the peripatetic teacher of the deaf (ToD), who advises them on early communication and education. The advised approach often depends on the views and beliefs in the local authority education department. Some areas promote bilingual language development and education, whereas others recommend a strongly oral approach where signed communication is discouraged. Most deaf children are now educated within mainstream provision, with or without a hearing-impaired resource unit. 51 In some areas, families and children are encouraged to have access to Deaf adults and the Deaf community, but this is by no means the norm. Families who find it difficult to accept that their child is deaf may not be discerning about school choice, and there is tentative evidence that schooling has a stronger effect on outcomes for deaf children than in hearing children. 52 Good in-school support is particularly important. 53,54

More than one-third of deaf pupils have additional educational needs beyond communication needs,55 and deaf children consistently achieve less in school than their hearing counterparts. 56–58 They experience delays in written language, vocabulary, grammar, syntax, reading59–62 and verbal intelligence on testing,63 although the process of assessment disadvantages deaf young people in itself because tools are inadequate and the oral assessment process is in English. Typical reading delay on leaving school is approximately 5 years. 64,65 All of these educational and learning challenges lead to lower levels of self-esteem, satisfaction and achievement, all of which are associated with poorer mental health outcomes. 66

Emotional development and theory of mind

Socioemotional developmental delay has been shown to correlate with delay in the ability to infer the thoughts or feelings of others. 67 This has been shown to be significantly delayed in deaf children from hearing families,60,68–71 but not usually delayed in fluent signers in deaf families. 70,72,73 This is the case even when attempts are made to test it in their first language and in culturally sensitive ways68,74–78 or if the child has a cochlear implant. 79,80 This is important because it maps on to empathy skills, which in turn affect social and emotional development and potential emotional or psychological problems in the future. Although deaf children appear to catch up later, early delays create significant problems for deaf children socially and emotionally. 81,82

Abusive experiences

Surveys of adults in Norway and North America suggest that deaf children are between two and three times more likely to be sexually abused than hearing children, and less likely to disclose their abuse. 83 These experiences may lead to subsequent substance misuse behaviours and negative mental health outcomes,84 and abuse is in general associated with higher rates of negative mental health outcomes. 85

Social anxiety and social skills

A review of over 30 studies concludes that children who are deaf are delayed in the development of their social skills. 86 Many deaf children experience anxiety related to social difficulties in communication with hearing children. 87

When researchers have used quality-of-life measures such as the Child Health Questionnaire,88 which is a parent-report measure, there are significant differences between deaf and hearing children. 50 For example, some deaf children in mainstream schools face social difficulties89,90 and may not feel as accepted as their hearing peers even when losses are mild or moderate,91 although many do as well as hearing peers. 92 Fellinger and colleagues found that parents/carers viewed their children’s quality of life more positively than their deaf children, who reported higher levels of dissatisfaction when using a self-report questionnaire in German and Austrian Sign Language. 93

Other factors

Some specific problems are more common in deaf children for reasons that are not fully understood and have not been fully researched. For example, autism appears to be more common in deaf children94,95 and is more likely to be diagnosed later than in hearing children. 96,97 However, it remains unclear whether this is related to high rates of neurological problems, comorbidities or common pathways in deaf children or it is an artefact of the autism assessment process, as many of the behaviours associated with deafness in young children can be mistaken for those seen in autism (e.g. differences in eye and lip gaze, not being responsive to their name being called). 82

Resilience factors

Mental health problems are generally less frequent in deaf children who have greater intelligence,5 are good at sport (boys) and have good peer relationships (girls). 98 As with all children, social successes are likely to be related to resilience factors including intelligence, personality, developmental pathways (e.g. social problem-solving skills), good communication at home and school, support from key adults,48 supportive peers and school ethos.

Cochlear implantation

Cochlear implants are increasingly offered to deaf children as standard. They consist of an internal and external component. The receiver is surgically implanted in the mastoid bone behind the ear, with electrodes inserted into the inner ear (cochlea). The microphone and speech processor, sited externally, convert sound into an electrical signal which is sent to the electrodes in the inner ear. These then send the signal through the auditory nerve to the brain, where it is perceived as sound. Parents have to make a choice about implantation at a very young age, because of concerns around critical stages of language acquisition. Given this, the average age of implantation is 12–18 months. The trend is now for bilateral cochlear implants,99 which offer access to sound to both ears.

There is little consistent evidence about the impact of cochlear implantation on mental health and well-being, but Dammeyer noted that, although some studies suggested that those with an implant had fewer mental health difficulties than those deaf children who were not implanted, the evidence is far from convincing, and the studies were of poor quality. 100 It is certainly true that having an implant can enable speech development and the ability to manage in face-to-face individual conversations. 101 However, for others, group situations are more difficult; people often do not make allowances for good communication, as they do not understand the impact of the deafness and consider the person to be ‘hearing’. This gives rise to several complex issues around participation, identity and belonging. 92

Long-term outcomes

In deaf children, mental health is associated with long-term psychological morbidity, poor educational attainment, increased unemployment, increased crime and delayed social skill development. 58,86

The rates of mental disorder in the adult deaf population are higher than for hearing people. This is particularly true for diagnoses of personality disorders102 and emotional disorders,103 which are unlikely to receive treatment in their early stages for lack of access to appropriate interventions.

Deaf people are more likely to enter the criminal justice system and are overrepresented in the prison population. 104 It has been reported that over 30% of offenders have significant hearing loss, with suggestions that this may be related to the increased risks in deaf people of school-related failure, limited social relationship networks, poverty and unemployment. 105

As a result, many organisations have highlighted the need for better access to mental health services for deaf children and young people. To identify difficulties at the earliest opportunity, in order to be able to intervene to alter the trajectory of these young people, we need to have a valid screening instrument.

Early-intervention programmes for deaf children benefit parents and their deaf children63,106–111 but most of them are focused on language development and communication. Identification of mental health problems earlier would allow clearer understanding of need, proactive development and assessment of support or therapeutic programmes, and potentially better outcomes.

Difficulties identifying mental health problems in deaf children

There is very little research with high-quality methodologies in the area of mental health in deaf children, partly because of the lack of any suitable screening or outcome measures. The research reported here will provide a foundation on which further research studies can build both in terms of translation methodologies (from spoken to visual language) and in validating a mental health instrument with deaf people, and using it in the future. It is important to identify mental health problems in deaf children for the multitude of reasons already outlined.

However, the mapping of need is not accurate because, at present, we do not have an appropriate tool to screen deaf young people for mental health problems, nor are we able to evaluate whether the specialist National Deaf Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (NDCAMHS) in England generates positive outcomes for clients or not. Deaf children may communicate in a range of different ways: 78% of children use spoken English only, 14% speak another spoken language either on its own or in combination with spoken English and 8% use sign language either on its own or alongside spoken English. 51

Until the development of this questionnaire, there was no instrument or questionnaire that focused specifically on those young people who use BSL as their first or main language. Within child and adolescent mental health service assessments, it is standard for parents and teachers also to complete proxy questionnaires to contribute to the assessment. The BSL questionnaire resulting from this research will support clinicians in making more accurate clinical screening and assessments. It will also enable future researchers to map out the prevalence of various mental health problems in deaf young people, therefore allowing NHS services to target interventions and spending where it is most needed and most likely to be of benefit. It will allow us to measure outcomes more effectively and will lead to improved skills in developing screening and assessment instruments that are accessible to deaf children.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

The SDQ is a multi-informant mental health questionnaire that can be used as a screening tool and a treatment evaluation measure. The ‘informant-rated’ version of the SDQ can be used for children and young people aged 4–16 years, and is completed by either a parent or a teacher; the ‘self-report’ version can be completed by young people aged 11–16 years. 112 Each version of the questionnaire comprises 25 questions. All questions are scored on a three-point Likert scale, which can be divided into five subscales measuring:

-

emotional symptoms

-

conduct problems

-

hyperactivity–inattention

-

peer problems and

-

pro-social behaviour.

This last subscale is a ‘strength’ subscale. The first four are ‘difficulties’ subscales. 113 The SDQ11 has been translated into over 60 spoken languages (www.sdqinfo.com) but not BSL. It is a self-report questionnaire, initially developed to improve the detection of child psychiatric disorders in the community. 1 There are three versions: one for children and young people, one for parents/carers and one for teachers. Together, the three SDQs show good sensitivity (63.3%) and specificity (94.6%). 114 The SDQ can be completed at the beginning and end of treatment to assess treatment efficacy115 and it is frequently used to evaluate Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS). 116 The SDQ has a satisfactory internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.80 to 0.87) and specificity ranging from 94% to 95% and sensitivity ranging from 23% to 47% for each version (parent, teacher and child). 113

Barriers to developing or validating screening instruments for deaf children

Generic CAMHS have only relatively recently started prioritising the measurement of outcomes. In the UK, the SDQ is recommended for national use within NHS mental health services by the CAMHS Outcome Research Consortium (CORC) guidelines117 and is a core part of the new national CAMHS data set required by commissioners of services and the UK government to evaluate services across the country, as from April 2013. 118 The newly funded CAMHS Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative119 also requires better outcome monitoring. Local CAMHS often report that deaf children go to services in smaller numbers than expected. 120 There are several apparent reasons for this, including deaf families having a poor experience of services designed for hearing people with often limited understanding of Deaf culture and deaf developmental issues as well as limited and inconsistent availability of appropriately trained interpreters.

Research funding has not been sought or granted very often for deaf child mental health over the last 20 years in the UK. There are also considerable practical and theoretical boundaries to translating and validating screening instruments in a visual language, with no well-developed methodologies. 13,121

Few widely used mental health instruments are available in a format that is culturally and linguistically relevant to the Deaf population. 122 ‘Inappropriate tests, unsatisfactory administration, and the unrealistic norm referencing of results’123(p. 249) remain the biggest challenges to overcome in mental health research with deaf people.

Although sign language versions of the SDQ have been produced previously,124,125 they have not been fully and rigorously translated or validated. The methodology that this study has adapted was developed for translation of spoken and written languages, which outlines the process of translation/back-translation. 14 This methodology is widely used to translate mental health questionnaires by organisations such as the World Health Organization (WHO). Additional methodological considerations that pay close attention to cultural and linguistic differences126 can result in questionnaires and screening tools that are more meaningful to deaf participants as long as this is conducted rigorously and systematically.

In clinical practice, sign language interpreters may be called upon to do on-the-spot translations of diagnostic and screening instruments, but this process can present problems. Interpreters make a linguistic and conceptual leap based on the experience of a deaf person to relay information that is contextually relevant to a hearing mental health professional. 127 Each interpreter will bring something different to this interaction, based on their own experiences, background or training, so the information given may not be consistently expressed. Working with interpreters means that variability in the translation and meaning of questionnaires is inevitable. The other reality is that deaf young people and deaf parents are likely to meet these BSL interpreters in other areas of their life, such as education meetings, financial or social care appointments. The impact of this is that it is likely that clients will not communicate as openly or as honestly as they might, because of confidentiality concerns. There is significant value in a self-report measure.

Such inconsistency could be overcome by using a validated instrument. Arguably the best way of achieving culturally sensitive instruments is to develop them empirically from first principles. However, this process is expensive and time-consuming. An alternative solution is to translate existing instruments into BSL, but the current evidence base outlining best practice is small. Rogers and colleagues gave an in-depth account of the issues regarding translation of standardised mental health assessments into BSL. 128 These issues included the direction of the signing; influence of modality; emotional state in BSL; confirmation of statements; and statements in a social context. Cornes and colleagues13 have noted that pencil/paper tests tend to underestimate prevalence of common mental health difficulties in deaf people, particularly emotional problems, hypothesising that this is partly because of the written language gap often present in deaf people in hearing environments. Linguistic delays, particularly in younger children, may invalidate standardised instruments validated for their hearing peers. For clinicians this presents additional difficulties, particularly those who have little knowledge of deafness or Deaf culture in assessment and diagnosis. The consequences of this may be that many deaf young people do not receive appropriate treatment or they may develop more complex, long-term difficulties.

Previous research has highlighted the difficulties translating into sign languages128–131 but few studies give detailed descriptions of the translation process from English to sign language, and its challenges. We describe here the process employed in translating the SDQ into BSL.

The policy context for deaf children

A National Audit of Families Support listed lack of specific support for mental health issues as one of the areas of most concern to deaf children and their families. 132 Standard 8 of the National Service Framework for children requires all children to ‘have equal access to CAMHS’ and Towards Equity & Access133 highlighted the importance of improving provision and access to mental health services for deaf people. The Human Rights Act and Disability Discrimination Acts mean the inaccessibility of such services is hard to defend. Voluntary organisations such as the Royal National Institute for Deaf People (RNID, now Action on Hearing Loss), UK Council on Deafness,134 the Social Research with Deaf People (SORD) unit at Manchester University135 and the Social Policy Research Unit at York University136 have called for improved services and research in this group. The National Deaf Children’s Society (NDCS) sees it as one of its priorities. Improving screening instruments enables tier 1 professionals such as GPs, health visitors, school nurses and paediatricians to have an adequate tool to identify children with mental health problems. This research therefore provides an accessible tool for deaf children, deaf parents or deaf teachers whose main language is BSL to participate in the identification of individual or population needs of deaf children and young people.

What is the service context in the NHS?

In October 2009 the NDCAMHS was set up in England, specifically to target the needs of deaf children and young people with mental health problems. Its ethos is to be accessible to all service users no matter what their cultural or linguistic background. There are four main bases for NDCAMHS across the country: York, London, Dudley and Taunton. As a national research project, recruitment was led from these sites.

The outcome of this research was a validated translated questionnaire, which was then used both in practice for clinical screening and for research to determine prevalence and types of psychiatric morbidity in deaf young people.

This research involved the collaboration of a comprehensive network of national centres (in four main centres and six outreach centres that map onto the 10 old strategic health authority regions in England). This allowed us to screen children from across England. The research will, therefore, be generalisable nationally. One of the NDCAMHS’s aims is to improve accessibility of services to deaf children and this will be a vital tool in furthering this aim. It will enable better and earlier identification of deaf children with emotional and behavioural problems.

How could a new screening instrument be used?

The development of this screening instrument for those whose first or main language is BSL will become a routine part of the NDCAMHS’s ability to screen for mental health problems and to monitor mental health outcomes. This will be part of a set of outcome measures that will meet the government’s target that high-quality services should have good measures that monitor outcomes routinely. This has been prioritised in the National Services Framework, through CORC137 and through CAMHS IAPT119 and the new ways of working in the NHS.

With more accurate estimates of the prevalence and types of psychiatric morbidity in deaf young people, the organisation and delivery of CAMHS for deaf young people can better reflect the needs of this population. This could enable the development of appropriate care pathways for deaf children, which necessarily and appropriately involve professionals at tier 1 (e.g. social workers, teachers, youth workers), tier 2 (e.g. educational psychologists, mental health workers), tier 3 (e.g. specialist mental health teams including child psychologists, clinical psychiatrists) and tier 4 (e.g. residential units). Currently, deaf children find accessing mental health support difficult,138 and more accurate mapping of mental health needs will enable more appropriate targeting of services. It will also enable the NDCAMHS teams to monitor the outcome of their interventions and build up the evidence base of what works with this population, as there is very little evidence at the present time.

Summary

In summary, deaf children have higher rates of mental health problems, they do not easily access mental health services, and services or commissioners have no mechanisms (such as questionnaires or tools) for screening deaf children or monitoring outcomes.

This study set out to translate the SDQ into BSL and to validate its use in England.

Study aims and objectives

The overarching aim is to create a valid BSL translation of the SDQ for children, parents/carers and teachers.

There were two main objectives of the study:

-

To translate the SDQ into BSL.

-

To use the BSL version of the translated SDQ with a cohort of BSL-using deaf children, deaf parents and deaf teachers sampled across England and to validate it by comparing it with a gold standard clinical interview assessment to elicit true psychological morbidity in the children and young people.

Chapter 2 Stage 1: cross-cultural translation of a screening tool for mental health in deaf children

This chapter describes the translation of the most commonly used mental health screening questionnaire for children and young people into BSL. We took a cross-cultural perspective to accommodate the differences between spoken and signed languages. In order to do this, representation from the Deaf community was sought consistently throughout the study. This section also summarises some of the challenges faced throughout this translation work and how all the final materials for the study were produced and agreed.

Aims

The aim for this phase of the study was to create a valid BSL translation of the SDQ for children, parents/carers and teachers.

Methodology

This study was reviewed and approved by Leeds West Ethics Committee on 7 March 2011 (reference number 09/2000/43).

This study followed the translation model provided by Beaton and colleagues,14 which provides guidance for written translations. However, there are issues that make the current evidence base on translation less well-equipped for sign languages. This is not to say that sign language itself is a problem, rather that the problem is that the guidance outlined by Beaton and colleagues is designed for written languages. BSL is a language with its own syntax, morphology and prosodic features differentiating it from written languages. For example, BSL syntax uses three-dimensional space and, as distinct from written or oral languages, several morphemes can be signed at the same time. Prosody presents in visual space through eye gaze, facial expression, sign production and other visual features. Additionally, the difference in using visual media (i.e. videos) means that the respondent will be watching an actual person on the screen and the questions are being signed, which can have potential implications on understanding to whom the question is referring. In the written questionnaire, the questions do not involve having a person reading out the question. Finally, as BSL is a visual language, this means that substantial modifications need to be made to the standard model of translating for written languages. These differences are well illustrated through the use of words in the English version of the SDQ which represent aspects of frequency: words such as ‘often’ and ‘frequently’, or verb forms which express regularity such as simple present tense forms (‘steals’, ‘shares’) are most naturally expressed in BSL through inflections to manual signs, such as repetition of the sign or aspects of its articulation. Therefore, what is expressed by separate words in English is often expressed through prosodic features in BSL, as part of a complex morphological system that expresses meanings differently from English. 127

Identifying translation teams

Stage 1 was built around the structure of translation/back-translation methodologies, requiring a forward translation team and a back-translation team, independent of each other. The translation teams were made up of bilingual BSL/English professionals who had experience of translation work. Beaton and colleagues14 suggested that there should be two people each in the translation and back-translation teams. We included three in each team because several factors affect variation in BSL (or differences in BSL production, including age, educational background, previous communicative and linguistic experiences, and family history of deafness139–141) and it was important to have geographical diversity in the translation and back-translation groups. BSL varies dialectically across regions. Whereas English dialect varies largely according to accent and syntax, BSL variation is more related to lexical differences. It was therefore important to find more widely used signs and phrases where possible. 142 As there are questionnaire versions of the SDQ for young people, parents, and teachers, having a range of ages represented within the translation groups was essential.

Consultation with professional deaf researchers suggested that there was benefit to having Deaf translators on both teams, as Deaf and hearing cultures are very different. We utilised the skills of bilingual deaf translators as they could more readily discriminate the sign meanings, which was more useful for translation purposes.

Beaton and colleagues suggested that having a balance of expert and lay members on a translation team assists in retaining focus on both the academic aspects of translation (e.g. reliable knowledge of the constructs being measured) and the meaning of the language as it would be perceived by a wider population. 14 This was reflected in the construction of the translation teams, which comprised equal numbers of clinical psychologists and those experienced in translation work across the teams. Equally, members of an expert panel overseeing the translation process were selected on their ability to comment on the different psychological, linguistic, psychometric and cultural aspects of the translation. This group comprised the project leaders (two psychiatrists working in the field of deaf child mental health), a linguist with sign language expertise and a range of deaf professionals experienced in mental health, research and translation work.

The team also considered the issue of agency, in that sign language has to be signed by someone, whereas a written questionnaire involves no other person. This carries with it potential transference143 issues that may resonate in terms of perceptions or feelings, and attributions or unconscious feelings about the signer. For example, a questionnaire signer that reminds a child of their critical mother may affect responses and emotions. There may be a preference of adults/young people for certain types of signers. Separate versions of the SDQ were filmed, presenting different characteristics of the signers (male/female, younger/older, etc.) with a final version chosen by the focus groups of young people. A written test is neutral in this respect.

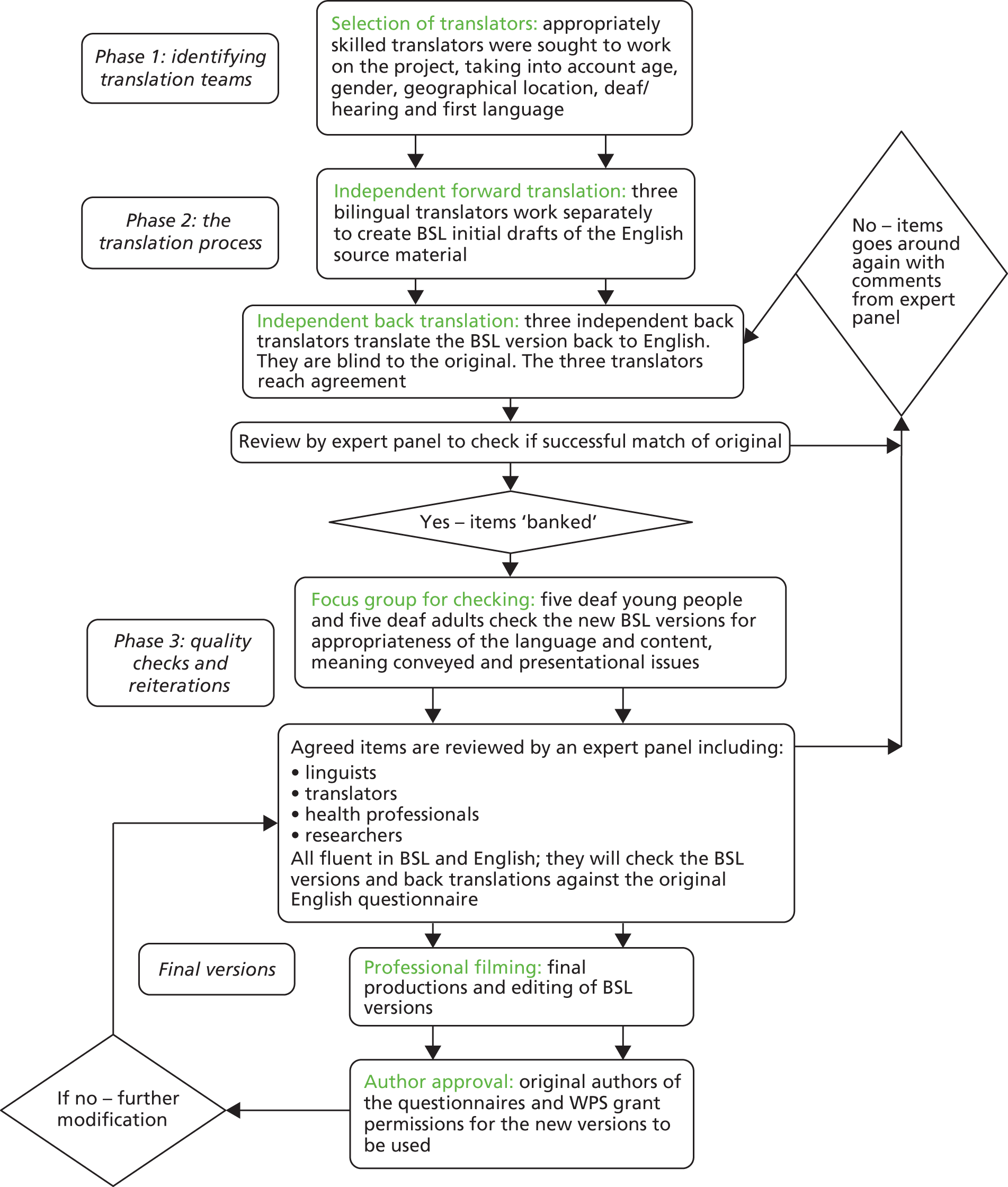

The translation methodology

The translation process is illustrated in Figure 1. Initially, three forward translation team members each filmed independent BSL translations of the SDQ materials, resulting in an initial unbiased signed translation. The translations were collated, presented and then discussed among the three forward translators as a group. The decision-making followed a systematic process of discussion and consideration of alternatives and appropriateness for the target audience (whether young person, parent or teacher). As a result, each item was filmed again, by one of the translators at the meeting, after agreement was reached on the best version. These final versions were then passed to the back-translation team.

FIGURE 1.

The translation process.

The back-translation team, three bilingual translators who were blind to the original versions, each individually produced English translations from each BSL item. These are called back-translations because they are taking the translated versions (now in BSL) and translating them back into English. The back-translations were collated and presented to all three translators for discussion as a group, where the appropriateness of each English word and phrase selection was scrutinised, and a final version agreed. This differs from the recommended process whereby independent back-translations are used only as a validity check for ‘gross inconsistencies’. 14 However, because sign languages are visual languages using the hands, face and body, it is possible for several meanings to be conveyed simultaneously. 144,145 Translating these meanings from signs into words is challenging because some elements that may be represented by words in spoken languages are expressed in sign languages through timing, aspects of sign articulation or facial expression.

Quality checks

The emphasis on service user involvement is highly important in the context of translation work; although efforts were made in order to balance the translation teams, as the Deaf community is such a heterogeneous group, the translators may not be representative of the population as a whole. Their linguistic ability in both BSL and English may mean they selected signs from a wider and more complex vocabulary than the average deaf person. In particular, this applies to young deaf people, whose exposure to sign language is likely to be limited compared with the exposure of a hearing English young person’s exposure to English. As many deaf young people are born to hearing families, their exposure to fluent sign language may be delayed, and potentially restricted. Often these young people will develop their sign language skills when they enter a deaf peer group within education, and the language is developed in a naturalistic and not necessarily grammatically correct way.

On completion of a full translation/back-translation cycle, the expert panel reviewed the equivalence of each back-translation to the original English SDQ in terms of meaning, linguistic structure and cultural/experiential sensitivity. 14,129 Translations that were agreed by the team as faithful and appropriate were judged as accepted (or ‘banked’), meaning no further translation of that item would be necessary. Where there were disparities, the questions were sent back to the forward translation group with comments on specific relevant issues. Versions of the items where the translation needed further iterations (the ‘un-banked items’) were translated again to make the meaning clearer. These items went round the translation/back-translation cycle again. The process was reiterated until all items were successfully banked.

This process was carried out for the young person’s SDQ, the parent’s/carer’s SDQ and the teacher’s SDQ. The BSL questionnaires produced were visual (e.g. available on a DVD and computer screen). The online computer version included both the questionnaire and an online method of providing an answer to each question on the SDQ explained in BSL and inputted interactively. We also produced a DVD version, which had a paper ‘fill in’ corresponding to the visual display.

Following this process, the newly translated SDQs were shown to two focus groups. The young person version was shown to five deaf young people and the parent and teacher versions were shown to five deaf adults (deaf parents/carers and deaf teachers) who all use BSL as their first language. These participants were approached through existing networks of the NDCAMHS throughout the country. This ensured that a variety of dialects and levels of BSL were represented in the focus group. We sought to utilise common mainstream signing forms. We also asked about the accessibility and cultural sensitivity of the delivery of the SDQ. This included presentational issues including characteristics of the presenter (e.g. gender, age, clarity of signing and pace).

Young people involved in the discussion group were given a £10 voucher for their contribution and adults were given a £50 voucher as a thank-you gift for giving their time. The focus groups were held at a geographically appropriate location at one of the NDCAMHS bases. Because of the visual nature of BSL we recorded the focus group on video. This has been discussed with deaf young people and parents (patient and public involvement, PPI) in the research team and it was felt that the full meaning of the discussion could not be captured using audio recording or process notes alone. Videoing allowed us to capture the language of the deaf people whom we are working with and provided us with rich qualitative data. A DVD of this session was produced and filed, as further evidence of the translation and discussion processes. This was destroyed at the end of the study.

Professor Robert Goodman, the original author of the SDQ, was then asked for feedback on the translated SDQ. He approved items and made suggestions for those not approved. These went back through the translation cycle until final and complete approval was achieved.

Results

The outcome was an instrument translated into BSL with versions that were understandable to both young people and adults whose first or main language was BSL.

Versions were successfully translated for:

-

11- to 16-year-old young people

-

parents or carers (adults)

-

teachers.

They could view it at their preferred location with a researcher’s work laptop hosted on an online forum, or play it on DVD.

Discussion

The translation process posed many unique challenges, which had to be overcome to ensure valid translation. These are discussed below, as are the study limitations with regard to translation.

Signer characteristics

As discussed, the characteristics of the signer were considered by the focus groups and expert panel. It had been hypothesised that a male signer would elicit lower response rates for emotional disorders, whereas a female signer might cause a young person to respond to questions about conduct or aggression less readily. Despite our initial belief that there may be preferences or biases in this area, both the young people and adult groups stated that, as long as the presenter was comfortable and clear in their signing, age and gender were of limited relevance to them. It is the content of what is being said that is of most relevance. (This was qualitative feedback and was not tested in any quantitative way.)

Culture, experience and language level

Deaf people’s experiences are very different. This includes differences in family background and makeup, differences in educational experiences, and changes across time and development. 146–148 They may be part of a Deaf culture, a hearing culture or both, and this may change over time. 149,150 For example, there is a question in the self-report SDQ about ‘playing alone’. This does not capture the fact that a deaf child might play alone because they struggle to communicate with their peers, rather than play alone because they do not have the necessary social skills to play with others. Thus, they might play alone at a school where they have only hearing peers, but play quite happily with other deaf children with whom they can communicate in their home environment. This may have the effect of creating disparities between parent and teacher responses. Another example of this is the question about whether or not the child is nervous in new situations; commonly deaf children will be nervous in situations with hearing groups, but will be much more confident at the Deaf club. This makes it very important for the clinician using the screening questionnaire to understand why any particular child might answer in any particular way and to have a good understanding of that child and the deaf experience.

A major point of discussion during the initial filming and reiteration of the young person informant version of the SDQ was around the level of signing in 11- to 16-year-olds. The discussion group was carried out with deaf young people, where the level of signing ability varied within the group. The translation strategy used to overcome this was to pre-pilot the SDQ in focus groups of young people. This allowed a ‘road test’ of the BSL SDQ, highlighting issues in vocabulary choice and structure of sentences. By including bilingual deaf signers as well as two psychologists on the forward translation team, the translators were able to adjust to an appropriate language level, as they had an understanding of the types of language that young people used in real-world environments.

Feedback from the focus groups highlighted a range of issues reflecting diversity of needs in the Deaf community. Whereas, in spoken language translations, questionnaires would be piloted in the hearing population, deaf young people often grow up with a mixture of language experiences, and may use many multimodal strategies in order to gain maximal information from messages. Though the fluent signers among the young person’s focus groups understood the items with relative ease, those from oral English families found this more difficult, despite using sign language as their main mode of communication. Despite ‘successful’ back-translation before the focus groups, it became apparent that the focus group did not understand some of the more complex BSL constructions in the questionnaire. Discussion with the focus groups led the team to believe that the level of language was inappropriate for this group, and therefore some BSL items were retranslated to simplify the language, though care was taken to preserve meaning.

Non-manual features

Non-manual features of sign languages (such as facial expression) can change meaning or imply hidden meaning. This may influence the answer given or alter how a person interprets a question, similar to the way that tone of voice in a spoken language can convey different meanings. This was the case in one of the items on the SDQ, which asked ‘do you take things that are not yours?’ The first translation of this was produced with non-manual features for a question, but with a facial expression indicating that, if the respondent were to choose ‘certainly true’, there would be a negative judgement made on the person answering the questionnaire. It is important at all times for the signer to produce sentences in an attitudinally neutral and non-leading way using only obligatory grammatical features; paralinguistic features should be avoided as much as possible, unless they are required to convey clear meaning, in order not to bias responses.

However, in the translation/back-translation process these features make it harder to obtain total linguistic fidelity. For example, the English SDQ response set for the main test items is on a scale of ‘certainly true’, ‘somewhat true’ and ‘not true’. In BSL, the degree of truthfulness is expressed on a continuum by facial expressions. These represent degrees of certainty simultaneously articulated with the sign ‘TRUE’. Facial expression thus inflects the sign and alters its meaning in the way that the modifiers ‘certainly’, ‘somewhat’ and ‘not’ change meaning. Selecting a sign-for-word substitution, as in SSE, would also be to negate a natural linguistic feature of BSL production. Content-for-content translation is common in interpreting scenarios but this elaborative process means that psychometric properties of a standardised questionnaire may be compromised if not done with great care. 127 In terms of finding suitable translations, we worked according to procedures outlined in previous research. 129 Discussions about the exact meaning and context of each statement were considered first by the bilingual translation terms, then by the expert panel and the focus groups and finally by the author. This process presented a range of checks and balances to obtain cultural and linguistic fidelity in our translation that was not without difficulty, but was thorough.

Statements as questions

The original English SDQ is formatted as a series of statements with which the respondent does or does not agree. In this way, the statement reads ‘I . . .’ In BSL the sentence must instead be produced in the second person, as the presenter and the respondent are not the same person. This, therefore, means that the sentence must also be interrogative, or something to be agreed or disagreed with, in order to elicit a response. This means that there are two key changes to the statement’s linguistic structure: a change of pronominal deixis, and a change of sentence format from declarative to interrogative.

Previously, sign language translation studies have made this reference to the self clear by using a technique of finishing each statement with the index finger pointing outward with head tilted to indicate questioning. 20,24 This might be glossed as ‘YOU WHAT?’ Using this second person singular pronoun denotes that the item is referenced to the test taker, rather than the person signing on screen, and the sign glossed as ‘WHAT’ makes it clear that the sentence is designed to elicit a response. Despite this, feedback from focus groups indicated that this format of questioning seemed unnecessary and was, in some cases, confusing.

Based on this, forward translators attempted to further clarify the distinction between the presenter and the respondent. For parent and teacher statements, asking about the child, ‘THIS CHILD’ was placed at the beginning of each statement. At the end of a sentence, an appropriate sign more related to the question was chosen (such as ‘YOU HAVE?’, ‘YOU BEEN?’ or ‘YOURS?’) rather than the more generic ‘YOU WHAT?’ Although it is not then standardised throughout the questionnaire, it fits more closely with the natural characteristics of BSL sentence structure.

Sign placement

The English version of the SDQ contains the item ‘nervous or clingy in new situations, easily loses confidence’. Many signs in BSL require the location to be marked. For example, in a class of verbs known as ‘directional verbs’, the location of the subject and object determine the start and end point of the sign when articulated. This is known as placement.

In translating ‘clingy’, the forward translators had to show that a young person might be clingy to a parent or guardian. In English this might be implicit, but in BSL needs to be referenced as the sign is visual and clinginess is directional towards somebody.

General and specific wording in oral English and British Sign Language

Having an understanding of Deaf culture within the core research team is highly important, in order to understand the functional ways in which BSL is commonly used. Category words or words with ambiguous meaning can be difficult to translate without further concrete explanation of what that word or concept might include (e.g. in BSL the signing for ‘considerate of other people’s feelings’ might include noticing those feelings in others, thinking about them and moderating one’s actions based on this observation). The SDQ tends to give examples where this has been felt to be necessary. Where examples are not given in the English version, the challenge is to avoid choosing signs that narrow the options too greatly (e.g. considerate of a specific person’s feelings). Research has shown this to be a key problem for interpreting in mental health settings. 127 An additional complication here is that lack of access to situational cues and incidental learning may mean that deaf young people struggle to ‘get the gist’ or understand when context is general as opposed to specific. Without a certain degree of openness to the statement, they may believe that the question relates only to a very specific context. To overcome this, translators must be aware of how they are contextualising situations in their sign choices and placements, and try to strike an appropriate balance between clarity and scope. Having psychological and psychiatric expertise within the research and translation teams allowed choices to be made based on the original intent behind each item.

This also links with an additional concern that any concrete explanation may be a judgement by the translator that goes beyond the meaning that is intended in the original. This is a particular concern between spoken and sign languages, as some English words have a more general sense than their BSL equivalents. The SDQ has an item in the parent version ‘Often complains of headaches, stomach-aches and sickness’. The word ‘sick’ in English can be translated into BSL with two different signs, which can also be glossed as ‘VOMIT’ (which is more specific than ‘SICK’) or as ‘ILL’ (which refers to more general illness or malaise). The English word ‘sick(ness)’ is ambiguous between these two meanings, but in BSL, as in other languages, one is explicitly forced to make a choice because there is no sign that covers both meanings in the way that ‘sick’ does in English. Thus, within the translation process it was important to consult with the author as well as mental health professionals, to understand how intended meaning is received, so that it is clear to the respondent; hence the need for culturally aware translation and focus groups.

Structural characteristics of the questionnaire

A key structural difference between a language presented in writing and one presented on film/video such as BSL is that, in responding to a written test, instructions are always present at the top of the page, and a respondent can keep checking back. However, with a visual questionnaire, this may need to be reiterated within the content or technical solutions sought to readily access instructions. Time frames, scales and instructions may need to be reinforced, and it may be necessary to give a specific contextual placement in each case rather than assuming that the information will be retained through several items.

Limitations

As discussed above there were a number of limitations inherent within the translation element of the study.

British Sign Language, like English, has numerous dialects. A commonly given example of dialectal variation within BSL is the numbering systems, which vary around the country. Variation in English is typically at the phonological or morphological level, and occasionally at the level of syntax; in BSL, the commonest variation is lexical. Typical semantic fields for variation in BSL are numbers, colours and some signs for family members: relatively common signs. This poses some difficulties in terms of intelligibility across the whole of the country. One way we tried to address this was by including translators and back-translators from different geographical regions to try and ensure that we used widely recognised signs to make the material intelligible to as wide a group of users as possible. Clearly, as the translation group had three bilingual adults within it, as did the back-translation group, it was not possible to cover all geographical regions and all possible dialects. This represents a limitation to both the trial methodology but also perhaps the very possibility of having a signed version in BSL that is universally accessible. As a way of attempting to overcome some of these issues, there was extensive discussion within both the translation teams and expert panels about the most commonplace or widely understood signs. For example, the London numbering system was felt to be more widespread and therefore was used throughout the videos. However, some of the qualitative feedback given by participants within the research suggested that throughout the questionnaire they had a strong preference for the signs common to their region. Providing local or regional forms in the video is not practical, so the team took the pragmatic decision to use signs that they believed would be most widely understood.

Another issue is that many deaf children are now in mainstream schools in the UK and, as it is estimated that around 90% of deaf children are born to hearing families,51 many deaf children do not have early life experiences that expose them to BSL from birth and through infancy. This means that many deaf children who do use BSL as their main language as teenagers or adults have learned the language late. Some may have a language impairment in sign language151 and this may be influenced by linguistic experiences in early life. 152 This in turn means that it may be more difficult for deaf people to understand a questionnaire in sign language.

Translation is not an exact science in that meaning may not be fully preserved even when the translation is considered accurate across both forward and back-translation. In this way back-translation may achieve literal equivalence but may struggle to convey full conceptual equivalence or achieve full comprehension of meaning in the target audience. 153 It is important to consider cultural usage, syntax and concept interpretation. 154 There is no gold standard method for translation of scales in cross-cultural research, and many of the issues apply across any two languages and cultures. 155,156 The need to make translations culturally appropriate is important in translations between any two languages157,158 and this is no different in cross-modal translations,159 although translating cross-modally from oral/written language forms to visual forms adds additional complexity. 150

The use of representatives of the Deaf community alongside a research team has been recommended as enhancing the process. 160 We applied additional measures such as focus groups of deaf parents and deaf young people and expert panel review (including a linguist) to review the work of the teams of bilingual translators and back-translators.

Summary

There are relatively few studies translating mental health instruments or questionnaires into sign languages, and fewer still focusing on the additional difficulties this presents when applied to deaf young people. There is a great need for further research in this area, and consideration of the impact of the circumstances of deaf young people in undertaking translation work. As an inclusive process, it is imperative to involve deaf people in the construction and assessment of the translation. The UK population of signing deaf people is comparatively small and tight knit, and encouraging deaf people to lead in the development of the study and early on in the process can be important to the overall success of such a pursuit.

Deaf culture embraces information sharing, and international collaboration on sign language translation processes could improve the quality and efficacy of mental health questionnaires, allowing services to more accurately map the prevalence rates of mental health in this population. Equally, it will allow the National Deaf Children, Young People and Family Service, and its collaborators, to better understand the needs of deaf children and young people.

Chapter 3 Stage 2: validation of the screening tool

Following approval of the translated questionnaires, the research proceeded to a validation stage.

Aims

To validate the new assessment tool, external validity was applied by testing the BSL SDQ version against a clinical interview assessment of parent and child together by an experienced hearing clinician from NDCAMHS with a qualified BSL/English interpreter. We refer to this henceforth as the ‘gold standard’ for assessment of mental health morbidity. All of these clinicians had level 3 BSL or above but always worked with a qualified interpreter.

We also carried out measures of internal consistency: exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to check dimensionality, test–retest reliability and cross-informant validity. Finally, structural validity was tested by analysing the fit of the data to the subscales of the questionnaire through a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA).

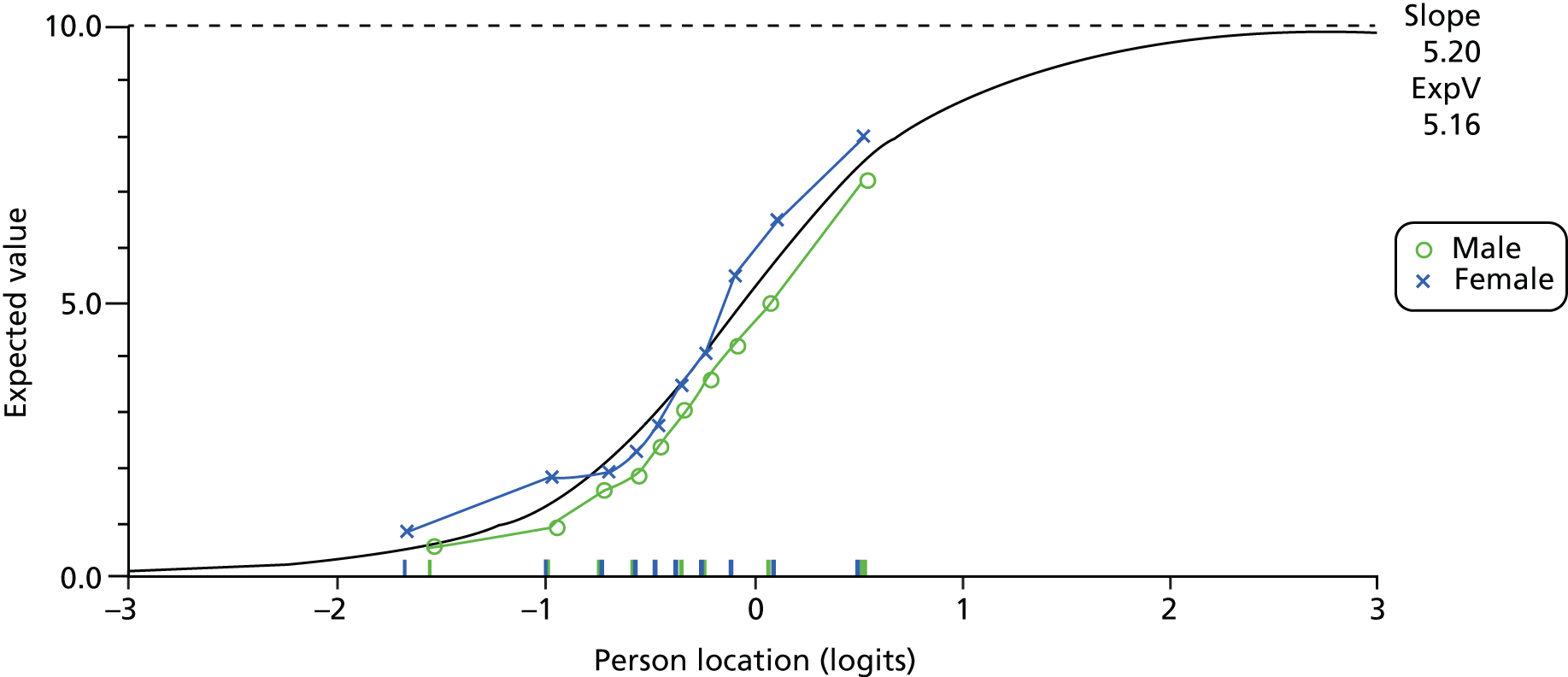

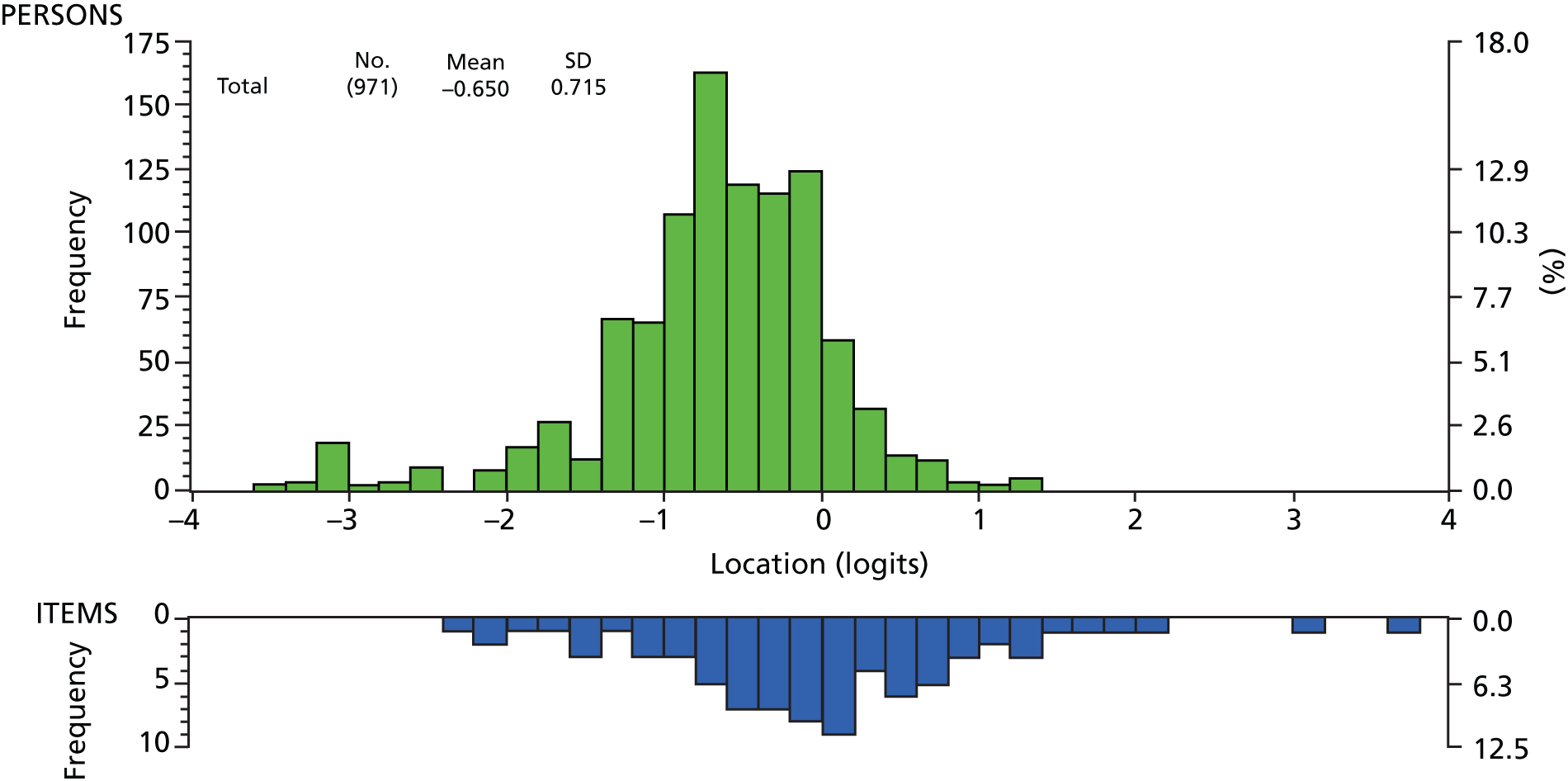

After this, the Rasch measurement model was used to see if the data from the BSL satisfied current measurement standards for invariant measurement, including invariance by gender. 161

Methodology

This study was reviewed and approved by Leeds West Ethics Committee on 7 March 2011 (reference number 09/2000/43).

Power calculations

Proposed sample size

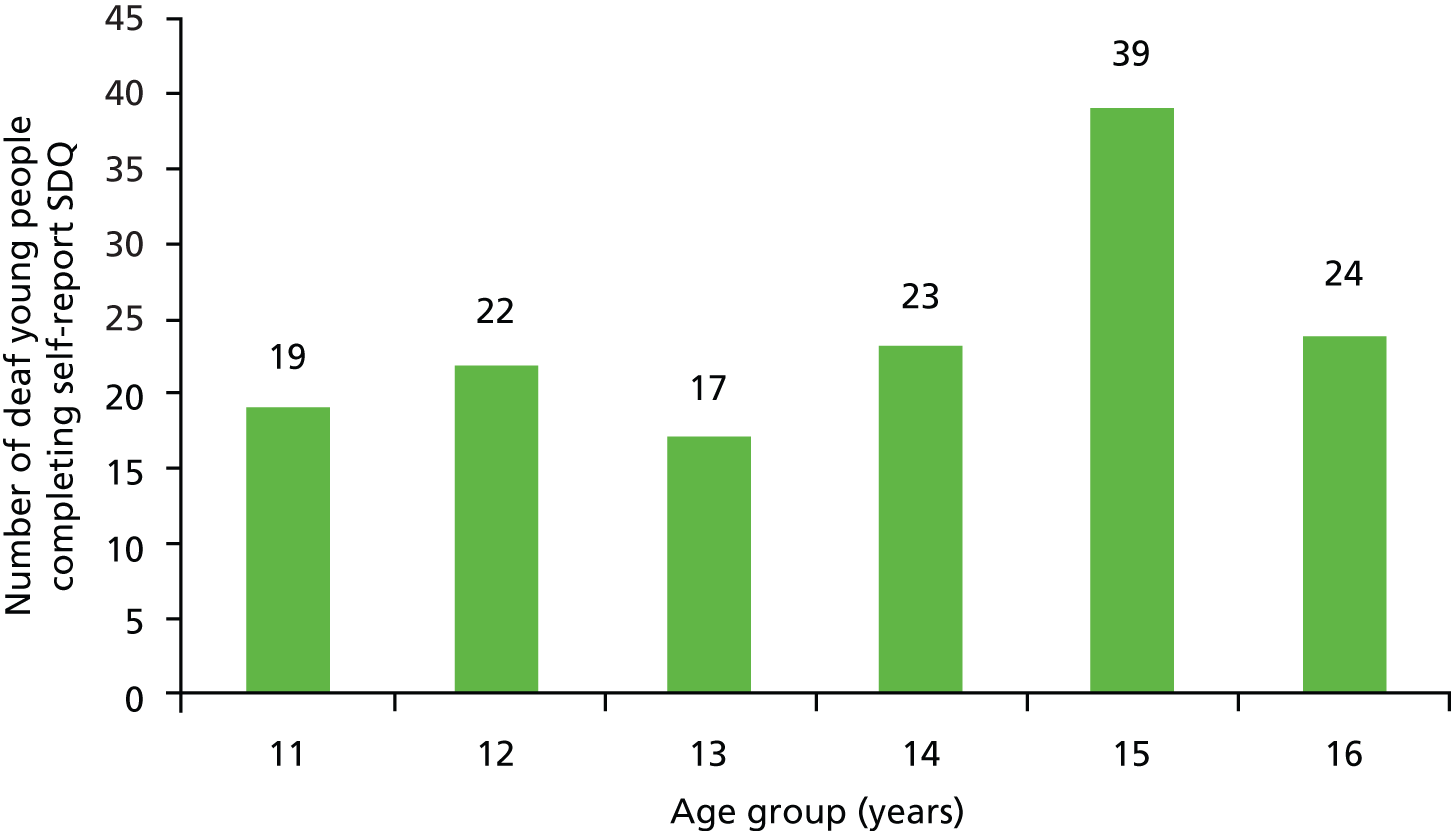

Before the study, power calculations suggested that to have data that were comparable to normative SDQ data in the general population we would require 138 young people aged 11–16 years to participate. This was based on estimating the mean within a 95% confidence limit of ±1.0. This calculation was based on the standard deviation (SD) of 6 found in a normative population using the SDQ. 162

With regard to using clinical interviews of children in validation, a sample size of 80 in each category (young people, parents and teaching staff) achieves 80% power to detect a difference of 0.20 between the null hypothesis correlation of 0.70 and the alternative hypothesis correlation of 0.50 using a two-sided hypothesis test with a significance level of 0.05.

Based on the sample size for this study, we expected that we would be able to recruit enough parents (of children aged both 4–11 years and 11–16 years) and teachers to meet the numbers required in power calculation estimates, with 80 in each group (but recognising limitations in the availability of practising deaf teachers). With respect to the validation of the BSL teacher’s version of the SDQ, we were aware that the sample size would be small. This was because we were constrained by the very limited number of deaf teaching staff in England. To combat this we sought to add deaf teaching assistants to the sample. Deaf teaching assistants often know deaf young people very well and we would be able to tentatively explore the reliability of teaching assistants filling out SDQs, in comparison with teachers.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Three main groups we sought to include were:

-

Deaf 11- to 16-year-old young people who are BSL users compared with the clinical interview and the SDQs from their parents and teachers (deaf and/or hearing).

-

Deaf parents who are BSL users (with 4- to 16-year-old children) compared with the clinical interview and the SDQs from the young people and teachers (deaf and/or hearing).

-

Deaf teachers or teaching assistants who are BSL users (teaching 4- to 16-year-old children) compared with the clinical interview and the SDQs from the young people and parents (deaf and/or hearing).

Where additional disabilities were felt to affect the language of the young person, as determined by Deaf bilingual BSL researchers, they were excluded from the study. An example of this is when a young person requested to take part in the study at school but when the Deaf researcher met him it was clear he was unable to understand BSL because of his learning difficulties. Participants currently experiencing an active episode of psychosis were also excluded, but those with an existing diagnosis of psychosis without active symptoms were included in the research.

Procedure and recruitment

To recruit the clinical sample, staff from the 10 NDCAMHS outreach centres and the residential unit Corner House in London identified which children or young people had BSL as a main language. Their clinician then sent each of these families information leaflets about the study.

To recruit from the community we used a variety of strategies. Since each child in England with a loss of more than 40 dB has been routinely referred to a ToD, each locality keeps a register of such children. Using this, teachers passed an information pack containing consent forms and an information sheet about the study to children and their parents/carers. These information packs were available in plain English and BSL on DVD.

Researchers also visited all deaf schools across the country, as well as large hearing-impaired units in mainstream schools, and known youth clubs. Information about the study was posted on NDCS newsletters. It was established very quickly that prospective participants preferred face-to-face contact to sending out letters or advertising online. This may be because of a number of factors that the team considered. These included a possible preference of the Deaf community to converse directly with researchers whom they met and recognised and were able to ask as many questions as they would like. It also may have been that, because of the delay in English language comprehension, sending letters without having first made contact to explain the research may have been confusing for several families.

In order to recruit deaf teaching staff, we actively approached all the deaf educational establishments across the country. Many centres were extremely receptive to the aims and needs of the research team and were very happy to facilitate recruitment within the school environment. This made a marked difference in levels of recruitment and emphasised the importance of getting educational establishments on board with research of this nature. Deaf education is a hotly debated area, and many schools have different stances on the promotion of BSL or sign languages, inhibiting possibilities for successful recruitment in some areas. However, collaborative relationships with staff members who understood the relevance of mental health research to the well-being of their students and a clear understanding of the commitments involved in taking part in the study was of vital importance to the recruitment of deaf young people to this study.

Once consent was obtained, young people, parents/carers and teachers were asked to complete the SDQ. All parents and young people were also asked to complete a screening questionnaire confirming their eligibility to participate in the trial, and provide basic demographic information about themselves.

For completion of the SDQ, young people were asked to complete the BSL online version or the BSL DVD version with paper fill in. Depending on their preferred language, parents/carers and teachers were able to choose between the standard version of the SDQ and the BSL online version or the BSL DVD version with paper fill in. Where necessary a clinician or researcher fluent in BSL was available to support the process, but did not influence the answering of the questions or interpret them in any way. They gave gentle prompts and encouragement.

Young people were given a £10 gift voucher in order to thank them for their participation.

To produce the online version, we used the software Select Survey version 3 (Atomic Design, Kansas City, MO, USA), which enabled us to develop an interactive online video questionnaire. The software had been used in the past by experienced Deaf researchers from the SORD unit, who are collaborators on this study. We were able to upload the final BSL translations, and participants were able to select and input corresponding answers online. This program also allowed us to obtain consent online; the personal identifiable information from this was stored separately from any questionnaire data provided for the initial test. All data were stored centrally by the University of Manchester, and only members of the research team had password-protected access. The university is an established research centre with many years of experience in research methods and information governance, and we were confident that this was a secure method of retaining our data. This method of consent was visual and preferred by deaf people who use BSL.

Validation against a ‘gold standard’

In order to ensure that the new questionnaires were successfully eliciting true psychological morbidity, the newly translated BSL versions of the SDQ were validated by comparison with a blinded clinical interview administered by experienced deaf child mental health clinicians making use of research diagnostic criteria using the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases version 10. 163

These interviews generally happened in the young person’s home. The interview process involved a hearing clinician, working with a qualified BSL interpreter experienced in working with child mental health teams. As would be the process in clinical practice, the interview involved both the parent and the young person.

Validation of the young people’s (11–16 years) self-report Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Eighty randomly selected deaf young people and their parents were seen for a structured clinical interview for validation purposes, as described above.

The children’s parents and teachers (hearing or deaf) also completed the appropriate version of the SDQ about their child.

Validation of the parent (4–16 years) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

We aimed to interview the children of all deaf parents taking part in the study. Their children could be deaf or hearing. A clinical interview was completed involving the deaf parent and their child as described above.

The deaf or hearing teachers of these children and young people were also asked to complete the SDQ, and the 11- to 16-year-olds completed a self-report SDQ in whichever language (English or BSL) was appropriate for them.

Validation of the teacher (4–16 years) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire

Deaf teachers and teaching assistants completed the BSL SDQ with respect to children and young people. As deaf teachers are almost always involved in the teaching of deaf children, we minimised the number of validation interviews by seeking to recruit as participants the deaf children taught by the deaf teachers.

The parents of the young people were asked to complete an SDQ and the 11- to 16-year-olds completed a self-report version. Deaf and hearing parents of the young people involved were recruited when they gave informed consent.

Test–retest reliability

We sought to recruit 65 participants in an evaluation of test–retest reliability. This sample size was based on the following calculation for estimating the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). When the sample size is 65, a two-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for an ICC for the test–retest will extend about 0.157 from the observed ICC when the expected ICC is 0.600. The ICC coefficient provides the test–retest reliability estimates in a sample of 50% of the children chosen randomly to complete the questionnaire on two occasions. (A sample size of 65 subjects with two observations per subject within 3 weeks achieves 81% power to detect an ICC of 0.70 under the alternative hypothesis when the ICC under the null hypothesis is 0.50 using an F-test with a significance level of 0.050.)

Contacting clinicians to recruit the clinical sample

We circulated information to all the clinicians working within the NDCAMHS including child psychiatrists, clinical psychologists, community mental health nurses, child mental health occupational therapists, family support workers, deaf clinical advisors, deaf child mental health social workers and other therapists. These clinicians passed on information leaflets to families who were eligible.

Contacting schools

In an attempt to recruit participants across England, the following educational establishments were approached:

-

11 deaf residential schools (nine with primary/secondary provision and two with secondary provision)

-

two deaf secondary schools (day pupils)

-

four deaf primary schools (day pupils)

-

54 mainstream secondary schools with hearing-impaired units

-

two mainstream secondary schools without hearing-impaired units

-

50 mainstream primary schools with hearing-impaired units

-

two mainstream primary schools without hearing-impaired units

-

five colleges with deaf services

-

five specialist schools for children with complex needs (four of which have residential provision).

Contact with deaf schools and hearing impaired units enabled us to identify deaf ToDs who were also eligible to participate, meaning that we were able to validate the deaf teacher version of the SDQ whilst simultaneously recruiting deaf children and young people. We had already developed good links with many of these schools through the NDCAMHS and built upon our existing relationships. Many ToDs were already aware of the research.

Initial contact with deaf schools and mainstream schools with units was made through telephone calls and letters. Once the rapport was established, we supplied information in accessible formats to parents and families through the schools. We were aware that accessibility issues might arise if too much written information were sent, so we encouraged teachers to make families aware of the study. Teachers provided families with information leaflets and consent forms, and noted which families were approached. All potential participants were given the option to contact a member of the research team for further information. Teachers and clinicians maintained records of those contacted, those who had been sent follow-up information and those who consented to participate in the study.

Contacting teachers of the deaf and other professionals working with deaf children

There were some independently located ToDs and professionals who were not based at any one particular school. They were contacted through either telephone calls or e-mails. We supplied information packs to ToDs and professionals working with deaf children and encouraged them to make families aware of the study. They acted as a third party between the research team and families to provide and collate the consent forms. A visit was arranged if they provided consent to either the ToDs or other professionals. ToDs maintained records of those who were contacted and we collated information about who consented to be involved in the study.

Advertising