Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1013/42. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in March 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sally Brearley acted as the Chair of the Prime Minister’s Nursing and Care Quality Forum from January 2011 to December 2013.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Maben et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Introduction

This report describes the second phase of a study investigating the impact of a move to all single room accommodation in a new hospital. It draws upon data from phase 1 of the study, which was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) through the Health and Care Infrastructure Research and Innovation Centre (HaCIRIC) at Imperial College London. In phase 1 we carried out in-depth research on care delivery, working practices and staff and patient experiences in the old hospital buildings (Pembury Hospital and Kent and Sussex Hospital) during the period in the run-up to the move to the new Tunbridge Wells Hospital, giving us baseline, ‘before’, practices and experiences in four cases (postnatal ward, acute assessment unit, acute general surgery ward and older people’s ward). We also undertook interviews with 20 key stakeholders including the architects, builders and senior nursing staff and executives in the trust. This phase 1 work was completed in August 2011. 1

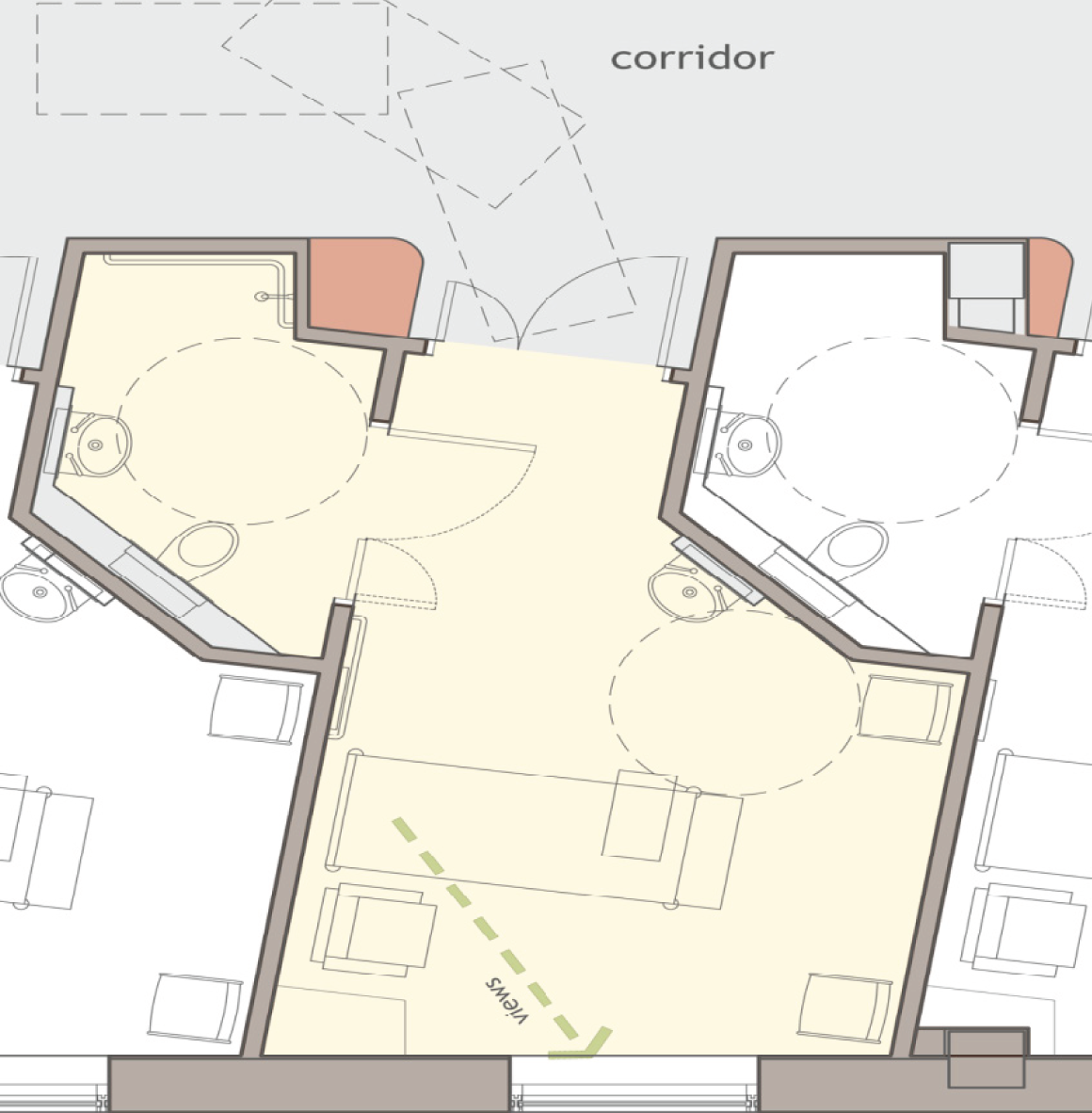

The study reported here (phase 2) was undertaken at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust’s new 512-bed hospital in Pembury, Kent – the Tunbridge Wells Hospital – and two hospitals which acted as controls (steady state and new build) between 2012 and 2013. We have (with the trust’s permission) deliberately chosen not to try to anonymise the 100% single room new build hospital at Tunbridge Wells, as it would be very difficult to do so and by not doing so we have been able to use photographs and plans, which greatly add to the data. Tunbridge Wells Hospital was completed in December 2010, with women’s and children’s services moving into the building in January 2011 and the remaining clinical services following in September 2011. It is the first district general hospital in England with single rooms throughout the inpatient accommodation. Data collection for this phase of the study was undertaken 12–15 months after the move to avoid teething problems and to try to capture working practices and experiences once they had had a chance to bed down.

Together, phases 1 and 2 deliver a project that answers significant questions for health care generally and the NHS in particular: how does the move to all single room hospital accommodation impact upon care delivery and working practices, staff experience, patient experience, costs and safety?

Background

Historically, the principles of hospital design have been based on Florence Nightingale’s 19th-century observations about the advantages of natural light, ventilation and cleanliness. 2 Long open wards of about 30 beds became the standard inpatient accommodation in hospitals globally. 3 Over the years, clinical practice and opinions about health care have changed and the suitability of open wards in modern hospitals has been called into question. 4 In the 1950s, new build hospitals experimented with ‘racetrack’ wards, where beds are arranged round the periphery with a corridor or ‘track’ surrounding the offices and other ancillary areas. 5 More recently, hospital design has used multibedded bays, which usually contain four to six beds. 6 Meanwhile, private health-care facilities have mainly single rooms. At the present time, internationally, the case is being made for more single room accommodation in new hospital designs, and some researchers argue for the abolition of all shared accommodation. 7 This is largely based on the belief that patients prefer single rooms and benefit from improved patient outcomes compared with hospital wards. 8 Hospital designs based on higher proportions of single room accommodation are likely to impact on patients’ health outcomes, staff and organisations but the nature and extent of the impact is as yet unclear. 9

Research on single room accommodation is a relatively new area within hospital design. 10 Evidence-based hospital design aims to improve outcomes for specific design characteristics or interventions,11 including room occupancy, ventilation systems, the acoustic environment, views of nature/landscapes,12–14 lighting, ergonomic design, and floor layouts and work settings. 2,15,16 More is now known about the impact of hospital design on patient safety,17 patient and staff satisfaction, a patient’s stress experience and organisation performance metrics. 18 For example, good design can reduce injury from falls, infections and medical errors; it can minimise environmental stressors19,20 and enhance pain control. 21 However, design decisions about hospital accommodation are not only based on scientific evidence such as patient outcomes; they also involve value-based judgements such as patient preferences for care, operational judgements about demand or changing clinical needs and priorities, and economic considerations. 8 An area of developing research is flexibility of hospital design to accommodate future changes in service delivery based on medical requirements (e.g. acuity-adaptable rooms) and patient preferences (e.g. private or semiprivate). 22 Advances have also been made using participatory ergonomics to involve staff in designing work spaces5 and to involve patients in hospital design. 11,23 Evidence from the USA11 and from UK childbirth environments suggests that the involvement of patients in ward and hospital design can improve health-care outcomes. 24,25

UK context

The proportion of single rooms in UK NHS hospitals is on the rise. 2 In UK hospitals, the percentage of single rooms as a proportion of total available beds increased from 22.6% in 2002–3 to 32.7% in 2009–10. Since 2001, Department of Health guidance has been that ‘the proportion of single rooms in new hospital developments should aim to be 50% and must be higher than the facilities they are replacing’. 3 Thus, increasingly, new hospital design includes greater proportions of single room accommodation and, in some cases, all single rooms. 26

The argument for single rooms in NHS hospitals is gaining prominence in the context of increasing public and political expectations about the quality of health care in general. 27 Political aspirations for more single room hospital accommodation are, in part, a response to a perceived public desire for such accommodation, and to provide greater privacy and dignity in NHS hospitals. 28 Single rooms can address a patient’s dislike of mixed-sex accommodation and difficulties of accommodating patients according to gender, by eliminating mixed-sex wards or bays. 29 Problems with mixed-sex bathrooms can remain, unless the rooms are en suite – a move that is relatively easy with new builds, but may be harder if existing facilities are being converted. 28 Single rooms mean that patients are unlikely to need to be moved because a bay needs to ‘change sex’ or because they need to be isolated;30 this potentially reduces stress for patients and risk of infection spread. 31 In the UK independent sector, the use of single room accommodation is far more common than in the NHS and it has been suggested this contributes to its lower rate of health-care-associated infections (HCAIs). 32 HCAI (also referred to in the medical literature as nosocomial infection) has become more common as medical care has grown more complex, causing significant morbidity, mortality and cost internationally. 33 Reduced HCAI is an important potential outcome of single room hospital design and we examine the issues in several sections of this report. In the next section we summarise existing evidence on infection rates and single room hospital design. Part of the argument in favour of single rooms is that they can also be used to accommodate diverse functions, such as patient recovery after surgery or other procedures and providing in situ medical treatment – for example wound dressing and physiotherapy – as well as offering flexible accommodation for many different types of patient, such as maternity, mental health and paediatric, together with the equipment required for each specialty. 8

At the time of research commissioning, there were no NHS hospitals and few general wards in the UK with all single room accommodation, and the opportunities for evaluation were limited. Bevan ward at Hillingdon Hospital is one of the few test wards in the UK supported by the Department of Health and the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA). Evaluation of Bevan ward based on patient and staff perspectives shows a range of perceived positive outcomes for staff and patients (including patient privacy and comfort, prevention of infection, reduction in medication errors, ease of toileting and bathing). However, Bevan ward is the only ward with 100% single rooms in an otherwise unchanged estate, so it provides limited evidence for whole hospital redesign, where multifunction rooms for nurse breaks, staff bases and communal social spaces for patients and visitors would be needed. 34

At the present time, there is little good-quality evidence from UK hospitals about the likely impact of single room accommodation on patients, staff or health-care organisations. Such evidence is much needed to inform decisions about single rooms and the extent to which they may be associated with inflated capital outlays and capital costs, augmented staffing levels, reduced patient safety and greater staff walking distances. 35 Economic considerations are also important when NHS managers have to make efficiency savings to meet rising health-care costs36 yet maintain the quality of, and access to, health care. Most available evidence (discussed in the next section) derives from studies in the USA and Scandinavia, and, while some evidence may be transferable, not all is likely to directly translate to the UK because of different financial, cultural and organisational systems. Gaps in the evidence are discussed in the next section.

Current state of the evidence

In this part of the report we draw together evidence from the health-care literature to examine what is known about the impact of single room accommodation and to identify gaps in the evidence. We explore impact in terms of the range of potential advantages and disadvantages for patients and staff and potential economic outcomes. These are summarised in Boxes 1–3 and discussed below.

-

Potential advantages for patients include increased privacy, dignity and less disruption from other patients. Improved control over their environment could mean greater comfort, enhanced sleep, enhanced contact with families, better communication with staff and increased patient satisfaction.

-

Potential outcome advantages include fewer medication errors, reduced infection rates and faster patient recovery rates.

-

Potential disadvantages include less surveillance by staff; increased failure to rescue and increased rates of slips, trips and falls; reduced social interaction and greater patient isolation.

-

Perceived advantages for staff include potential for more personalised patient contact and potentially fewer interruptions.

-

Perceived disadvantages include increase in staff travel distances (less time for direct care); potential need for an increase in staffing levels as a result of more single rooms and/or adjustments to staff skill mix; increase in staff stress, staff working in isolation and increased risks to personal safety.

-

Perceived economic advantages include potential for cost savings associated with reduced length of stay, reduced infection rates and fewer medication errors.

-

Perceived economic disadvantages include increased land and building costs, increased maintenance costs and increased staffing costs.

For patients, a potential advantage of single room accommodation could be increased privacy, dignity and comfort. 11,37,38 However, the evidence does not clearly point to a preference for single rooms among patients and little is known about patient preferences across different age and cultural groups. 39 One UK survey (IPSOS Mori) found that around 35% of the public preferred single rooms, while around 40% preferred small (single-sex) bays. 28 However, this was a survey of the perceived (and future) needs and desires of the general public, not of hospital patients, who, when sick, may express different preferences. It is important to note that for many patients the privacy associated with single rooms may not be as important as other aspects of the hospital environment, such as a sense of safety, security or connection. A recent Scandinavian study showed that positive aspects of multibedded accommodation included a patient culture of taking care of one another and enjoying the company of other patients, which gave a sense of security to both patients and nurses. However, these advantages were slight and could easily become disadvantages if roommates were very ill or confused. 40 There is some evidence that single rooms are associated with greater patient satisfaction: a Welsh hospital with 100% single rooms reported 95% satisfaction. 41 Results from the York Health Economics Consortium evaluation of the pilot ward of 100% single rooms at Hillingdon Hospital suggest that patients in single rooms were more satisfied than those in multibedded rooms [yet infection rates did not decrease and length of stay (LOS) was unaltered]. 29

In other studies, patients rated privacy and personal space as important but they also said that when ill they wanted nurses to be closer. 12,13,42 There is also evidence of more speech privacy and higher patient-reported satisfaction with doctor and nurse communication in single room patient accommodation. 11 A study of patient–physician communication in the Netherlands suggested that patients find it easier to raise questions with staff during ward rounds in single rooms than in multibedded rooms and feel that staff are more empathetic towards them. 43

There is potential for improved outcomes for patient safety with single rooms. Single rooms could mean fewer medical errors because of less interruption and distraction,29 and room design that incorporates dedicated space for patient supplies and medication can help to reduce medication errors. 20 In 2007, the NPSA undertook a study including a review of empirical evidence, an analysis of National Reporting and Learning Systems (NRLS) data and interviews with clinicians and staff with experience of current conditions, who would be directly affected by the use of single rooms. 38 These authors concluded that if there is good design (layout which includes observation points and large glazed windows and doors) the evidence does not suggest that single rooms reduce staff-to-patient observation or increase accidents or ‘near miss’ events.

The evidence of associations between single rooms and HCAI, including evidence of causal effects on infection rates is complex. Relevant research is dispersed across clinical, service management and design literatures8,11,44 and extends to include themes of infection control effectiveness, transmission routes, the impact of movement patterns between health-care institutes, the development of antimicrobial resistance and strain competitiveness or cocolonisation. 45 Specific studies relate to different types of impact or measures of infection, clinical settings, population groups, different types of infection site (e.g. respiratory, urine, wound, blood) and organisms, including Escherichia coli (Migula 1895) Castellani and Chalmers 1919, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Rosenbach 1884 (MRSA), Clostridium difficile (Hall and O’Toole 1935) Prévot 1938 (C. diff. ) and Pseudomonas Migula 1984. 33 It is known that HCAIs are spread by numerous paths including surfaces (especially hands), air, water, intravenous routes, oral routes and surgery. 8,9 Some authors suggest that single rooms improve infection control because of better physical design46,47 that enables patient isolation at admission, decontamination after discharge and maintaining clean air. 11 Mechanisms for the reduction of infections through single rooms could include reduction of person-to-person contacts and limiting the spread of infection by person–surface–person contacts. 48 However, the relationships are complex, and multiple organisational and management factors, such as clinical leadership and staffing, are also known to have a significant impact on infection control in hospitals. 49 Staff infection control knowledge50 and risk perceptions of HCAI within different clinical environments may also influence HCAI rates. 51 Models of nursing may also be an important factor; for example, the ‘cohorting’ of patients, by grouping together infectious patients and nursing them within an area of a hospital ward to reduce spread of infection, can be more easily achieved with single rooms. However, to be effective, staff cohorting is also essential (having a cohort of staff who work only with ‘infected’ patients),52 and this may be as hard to achieve in single room accommodation as in other designs. The high degree of heterogeneity of studies, together with inter-related causal factors described above, makes it difficult to draw clear conclusions about causal effects of single rooms on HCAI rate. Two rigorous systematic reviews have been conducted to summarise the evidence on the association of single room accommodation and HCAI. Dettenkofer et al. 53 included 17 historic and prospective cohort studies between 1975 and 2001 in their systematic review (details of these findings can be found in Appendix 1). The majority of studies were conducted in intensive care units (ICUs; n = 9), followed by surgical wards (n = 4), isolation units (n = 2) and general hospitals (n = 2). Three out of nine studies in ICUs reported a reduction of infections, while no reduction was found for postoperative wound infections in the four studies of surgical wards. A subsequent review by Whitehead et al. 54 identified two additional studies between 2001 and 2006. The two studies, in neonatal55 and paediatric intensive care settings,56 showed a reduction of the mean number of infections in isolation or single rooms in comparison with multibedded bays (further detail of these studies is in Appendix 1); reduced HCAI rates may also be related to shorter LOS associated with single rooms. More recent studies all conducted in ICUs57–60 have shown a reduction in several types of infections including MRSA and C. diff. Meta-analysis of infection rate from studies of single rooms is problematic because of different study designs, patient groups, types of infection or organism under consideration, and geographical setting. 53,61 Furthermore, there is evidence that HCAI rates usually show a short-term decline following any move to a new hospital building but that the effect is short-lived. 62 Furthermore, findings from studies of isolation rooms may not be transferable to single room accommodation because of differences in patient confinement, ventilation, barrier nursing or other infection control measures to limit transmission risk. 32,39 While an association of single room accommodation and decreased infection rates is repeatedly shown in intensive care settings including paediatric populations,53,57–61 for all other patient populations evidence of an association of single room accommodation and HCAIs is absent or equivocal. For the purposes of our study and research questions (listed in Chapter 2, Research questions), we consider infection rate as a possible safety outcome associated with single room accommodation, as explained in Chapter 2, Staff travel distances.

There is some evidence that patients in single rooms recover faster than those on wards. 11,37,38 This has been attributed to lower patient stress, but other factors that influence a healing environment, such as being able to see daylight and nature views or infection control practices, may have a more significant impact on patient recovery outcomes. 11

Although some patients may prefer and benefit from single rooms, this is not the case for all patients. Single rooms could mean less surveillance by staff, increased failure to rescue, increased rates of slips, trips and falls,41 and patients experiencing falls unnoticed. 11,37,38,63 Potential disadvantages may also include reduced social interaction64 and greater patient isolation. 11,26,38 For some patient groups, such as people with a stroke65 or mental health problems,66 the isolating effects of single rooms could impede the therapeutic process and overall experience of care. Research on routine isolation of infected patients in hospitals31 provides strong evidence about the negative impact of isolation. In a systematic review of 16 studies, the majority showed that isolation had a negative impact on patients’ mental well-being and behaviour, including depression, anxiety and anger, and that some health-care workers spent less time with patients in isolation,67 which may have implications for patients in single rooms per se. An interview study of people with cancer in Denmark68 found that refuge from fellow patients was hard to achieve in multibedded rooms and the fact that personal conversations might be overheard by fellow patients caused patients to withhold important information from health-care professionals. Despite the challenges, 18 of the 20 patients (10 male and 10 female) preferred the companionship associated with multibedded rooms.

Young people in hospital may prefer the company and security of sharing accommodation with people their own age. 69 Other patient groups may value different aspects of hospital environments; for example, new mothers may want a family-centred environment which can support bonding with their baby and developmental care;70,71 stroke patients benefit from environments that support physical activity;65 and patients who are receiving long-term critical care may benefit most from an environment that enables them to maintain the personal activities of daily living. 72 Patients near the end of life and their families may want an environment that provides a sense of emotional or physical proximity to loved ones. 73 These aspects of the hospital environment may be more important than single rooms in influencing patient satisfaction74 and health-care quality. 75

Aspects of hospital and ward design have the potential to impact on all health-care staff; however, there is little UK research evidence about staff perceptions or experiences of delivering care to patients in single room accommodation or the impact on morale, motivation and staff engagement. A report by the York Health Economics Consortium described advantages of single room accommodation for staff. This included the potential for more personalised patient contact and fewer interruptions to care delivery. 29 However, as these outcomes are so closely linked to staffing and other variables it is difficult to control for these factors or to say what the impact on patient outcomes at ward level might be.

Possible disadvantages of single rooms could include increased distances for staff to walk. However, the evidence relating to ward layout and nurses’ observation,2 walking distances76 and workload4 is complex, making it difficult to draw conclusions about implications for staff, patient care or outcomes. Several authors have suggested the potential need for an increase in staffing levels as a result of more single rooms and/or adjustments to staff skill mix. 26,37,38 The NPSA study refuted the suggestion that single-patient rooms require increased levels of staff to prevent patient alienation. 38 However, no patients were directly involved in the study, suggesting this statement is based on the evidence from other countries. A US study using comparative design to investigate how clinicians perceive, evaluate and adjust to a new hospital environment found the single-patient room model increased the workload of many clinicians and their stress had increased after 15 months. 77 The study showed that employees with 3 or more years of service had significantly higher stress than others, suggesting that staff with established work patterns may find it more difficult to adjust to new hospital designs. Staff stress could be greater if they feel less able to monitor patients, have less time for direct care or are less visible to patients. 30 Staff working in single room hospitals may spend more time working in isolation, which could have negative implications for team working, innovation78 and staff well-being,79 but there is little UK evidence to support these suggestions. Staff working in isolation may experience greater risks to personal safety from violence, aggression or physical assault,80 and factors which are known to trigger anger and aggressive behaviour (e.g. emotional anxiety, patient stress, lack of hydration/nutrition) could be harder to detect and respond to if patients are in single rooms. 81

A study by the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment16 found links between hospital design and nurse recruitment, retention and productivity. Overall, however, there is not yet sufficient evidence available in the UK to be able to draw valid and reliable conclusions in terms of the impact on nursing workforce requirements, or indeed requirements of other staff groups.

The economic advantages and disadvantages of single rooms have also been debated in the literature. As part of the present research study we undertook a focused literature review of the economic impact of single rooms (see Appendix 1). The review explored evidence on building costs, staff costs and outcomes as reported in the research literature. Overall, the review found little comparable evidence about the construction and operating costs associated with single room accommodation. The majority of studies are not based in the UK and, even within the UK, construction costs are likely to vary with geographic setting and hospital design. In general, a single room (and en suite bathroom) requires more space and this may need extra land, depending on the site and building design. 82–84 Acuity-adaptable rooms can cost even more because of the need for more space and equipment, but some cost savings may be made because of a reduced need for patient transfers. 85 Maintenance costs per square metre are likely to be the same, but the greater space requirement for ward areas means that overall maintenance costs may be higher. It is not possible to say whether or not single rooms increase staffing costs because of the scarcity of evidence for impact on staffing levels or skill mix. 6 Although many claims have been made about the cost savings associated with single room accommodation – including reduced LOS, infection rates and fewer medication errors61,86 – there is very little evidence from well-designed research studies to support these claims.

Summary

Internationally, health systems and individual hospitals are keen to explore higher proportions of single room accommodation in new builds, but little is known about the impact of this type of accommodation on patients, staff and organisations.

In the UK, NHS providers are encouraged by Department of Health guidance to provide higher proportions of single room accommodation (the aim is 50%) in any new hospital builds. As yet, there are few wards or hospitals in the UK with all single room accommodation and the opportunities for evaluation have been few.

Evidence-based health-care design is a growing area of research. To date, little empirical work on single rooms has been undertaken in the UK, with most research emanating from the USA and Scandinavia. The available evidence is equivocal, suggesting a range of potential benefits for patients and staff but also a range of potential disadvantages.

Potential advantages of single room accommodation include increased patient privacy, greater dignity and less disruption from other patients. If patients have improved control over their environment this could mean greater comfort, enhanced sleep, enhanced contact with families, better communication with staff and increased patient satisfaction. Improved outcomes could include fewer medication errors, reduced infection rates and faster patient recovery rates. Staff could experience more personalised patient contact and fewer interruptions.

Potential disadvantages of single room accommodation include less surveillance by staff; increased failure to rescue and increased rates of slips, trips and falls; reduced social interaction and greater patient isolation; increase in staff travel distances (less time for direct care); potential need for an increase in staffing levels as a result of more single rooms and/or adjustments to staff skill mix; increase in staff stress; staff working in isolation; and increased risks to personal safety.

The impact of single room accommodation on staff-to-patient observation, staffing levels, adjustments to staff skill mix and staff travel distances is unclear.

However, important issues that require further research include concerns about potential additional workload,4 stress79 and risks to staff;30,77,80,81,85 less patient surveillance;11,37,38 and patients feeling isolated or alienated. 38,68,69

There is limited evidence about the costs and economic outcomes of higher proportions of single room accommodation. 82–84 In the UK there is insufficient strong evidence to be able to draw valid and reliable conclusions about single rooms or models of hospital design based on this type of accommodation. The international health-care literature shows that decisions around ward design are complex and trade-offs are likely to be necessary between evidence-based designs, patient and staff preferences, changes in clinical needs/demand and economic considerations.

Further research and evaluation of UK hospitals is needed to build evidence to inform and improve ward and hospital designs at ward and hospital level and nationally, including:

-

examining impact on patient outcomes at hospital level including implications for having sufficient beds and safe hospital occupancy87,88

-

addressing how to ensure privacy when it is needed and also facilitate communication and social interactions to make a period of hospitalisation more manageable for patients68 and more satisfactory for staff

-

exploring issues of managing risk/safe care practices associated with single rooms, for example staff ability to deliver direct patient care while also monitoring other patients on the ward and making judgements about priorities of caregiving. 12,13,42

These emergent issues reinforce the need for research to examine single rooms not only as physical spaces but as personal, social and cultural spaces of caregiving.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

This report is based on data collected during the second phase of a two-phase longitudinal mixed-methods study. Phase 1 data are reported fully in a separate report,1 although they are used throughout the report as a basis for comparison and to orientate readers to key phase 1 findings. The case study methods and data collected in this study (phase 2) replicate as far as possible the case study methods and data collected in phase 1 (Table 1).

| Aims: to identify the impact of the move to 100% single room accommodation on: | Research question(s) | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Care delivery and working practices | How are work patterns disrupted and reconstituted, including through trial-and-error use of new approaches (and to what extent are these successful/unsuccessful)? | Case study data:

|

| Staff experience | How are staff perceptions and experiences of the move to single rooms shaped by formal organisational and change management processes? What are the advantages and disadvantages of a move to all single rooms for staff? Does the move to all single rooms affect staff experience and well-being, and their ability to deliver effective and high-quality care? |

Case study data:

|

| Patient experience | What are the advantages and disadvantages for patients of a move to all single rooms? How does the move to all single rooms affect patient experience and well-being? Does it affect diverse patient groups differently? |

Case study data:

|

| Safety outcomes (including falls and infection rates) | What are the influence and costs of a move to a new hospital with 100% single rooms compared with the nearest equivalent design with standard proportions of single rooms? What impact do different percentages of inpatient single rooms have on patient safety outcomes (including falls and infection rates) compared with standard accommodation? |

Quasi-experiment secondary data:

|

| Costs | How does the move to all single rooms affect costs, including nurse staffing, patient services and costs associated with adverse patient events? How do different percentages of in-patient single rooms (50–100%) influence costs? What is the influence of a move to a new hospital (compared with no move) on costs? |

Cost analysis secondary data:

|

Research approach

The research includes a pre/post mixed-methods evaluation in a single hospital within which there are three distinct but related workstreams:

-

a before-and-after mixed-methods case study design (with four nested cases) within a single hospital

-

a quasi-experimental before-and-after study using two control hospitals (one steady state and one move to new build with fewer than 100% single rooms)

-

an analysis of comparative costs associated with single rooms.

This chapter provides an overview of the research approach and questions. It also presents the methods used and provides details of the study design, sampling, data collection and analysis.

In our original project proposal we included applying a realist evaluation framework1 to explore the effect of single rooms in different circumstances and on different stakeholder groups. This proposal was reconsidered during the project for a variety of reasons. First, and most importantly, realist evaluation is an approach developed for evaluating large-scale complex social change programmes. While bringing a new hospital into operation has some similarities with implementing a programme, important differences became apparent to the project team that made a realist framework problematic to apply. 89–91 Second, during the course of the project, unresolved methodological issues relating to how to define context–mechanism–outcome configurations that form the basis for realist analysis became the focus of critiques of the approach. 92,93 In view of these, the research team decided that there were few advantages in adopting a realist framework over and above using conventional methods, such as case study and quasi-experimental design. However, our approach has been broadly informed by ‘realist’ perspectives, particularly in terms of identifying stakeholder intentions; utilising their knowledge of ‘how things work’ on the ground; and defining and testing ideas about ‘what works’ in different contexts. Thus, our aim was still to understand what worked and for whom, in what circumstances, and how.

Research ethics and patient and public involvement

The study was approved by Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust Research and Development department as a service evaluation project in July 2009 and access renewed for phase 2 in December 2012 (reference 09/07/049A). Ethical approval was obtained from King’s College London Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Subcommittee (approval granted January 2010 and for phase 2 in January 2012, reference PNM/09/10-30).

Patients and the public were involved throughout this study, as detailed in Appendix 2.

Research questions

The research seeks to identify the impact of the move to 100% single room accommodation on five key areas:

-

care delivery and working practices

-

staff experience

-

patient experience

-

safety outcomes

-

costs.

The overall aim of the project is to explore the implications for the clinical workforce and patients of a move from ‘traditional’ facilities – comprising primarily open-plan ‘Nightingale-style’ wards – to a newly built facility in which all accommodation is in single rooms.

Table 1 provides details of the specific research aims, the research questions that align with these and the principal methods that were used to gather data to answer them.

Before-and-after mixed-methods case study

A before-and-after mixed-methods case study design was used to explore the impact of the move to all single room hospital accommodation on care delivery, working practices and staff and patient experience. Phase 1 data provide a ‘baseline’ understanding of care delivery, working practices and staff and patient experience in four case study wards (see Appendix 3 and phase 1 report). 1

The following sections describe the main components of data collection for the pre-/post-move evaluation: interviews with key stakeholders to explore the organisational context in which the move took place and the ‘nested’ ward case studies. The latter had five components: observation of practice; measurement of staff travel distances; a staff questionnaire survey; interviews with staff; and interviews with patients. A separate section describes how the data were analysed.

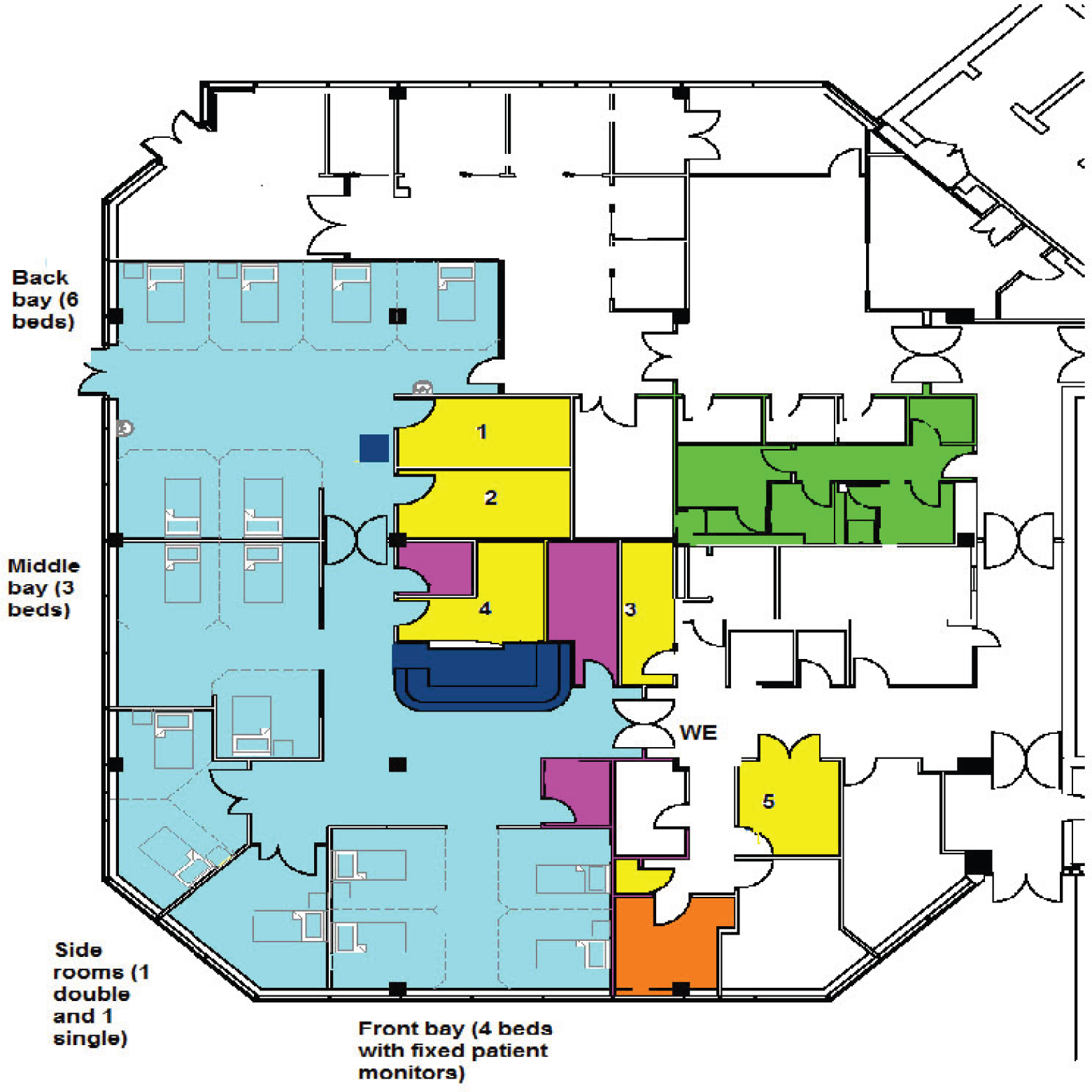

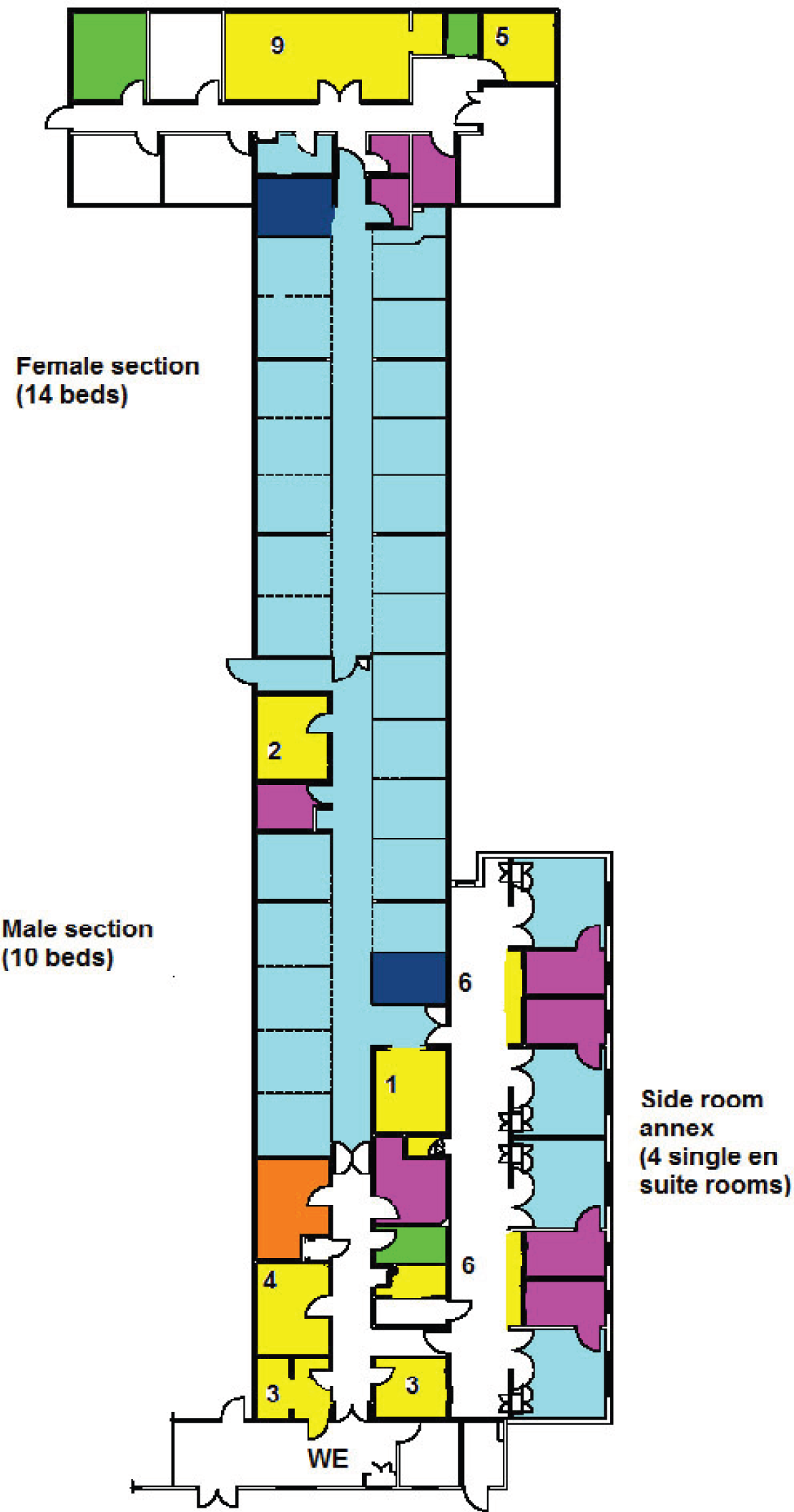

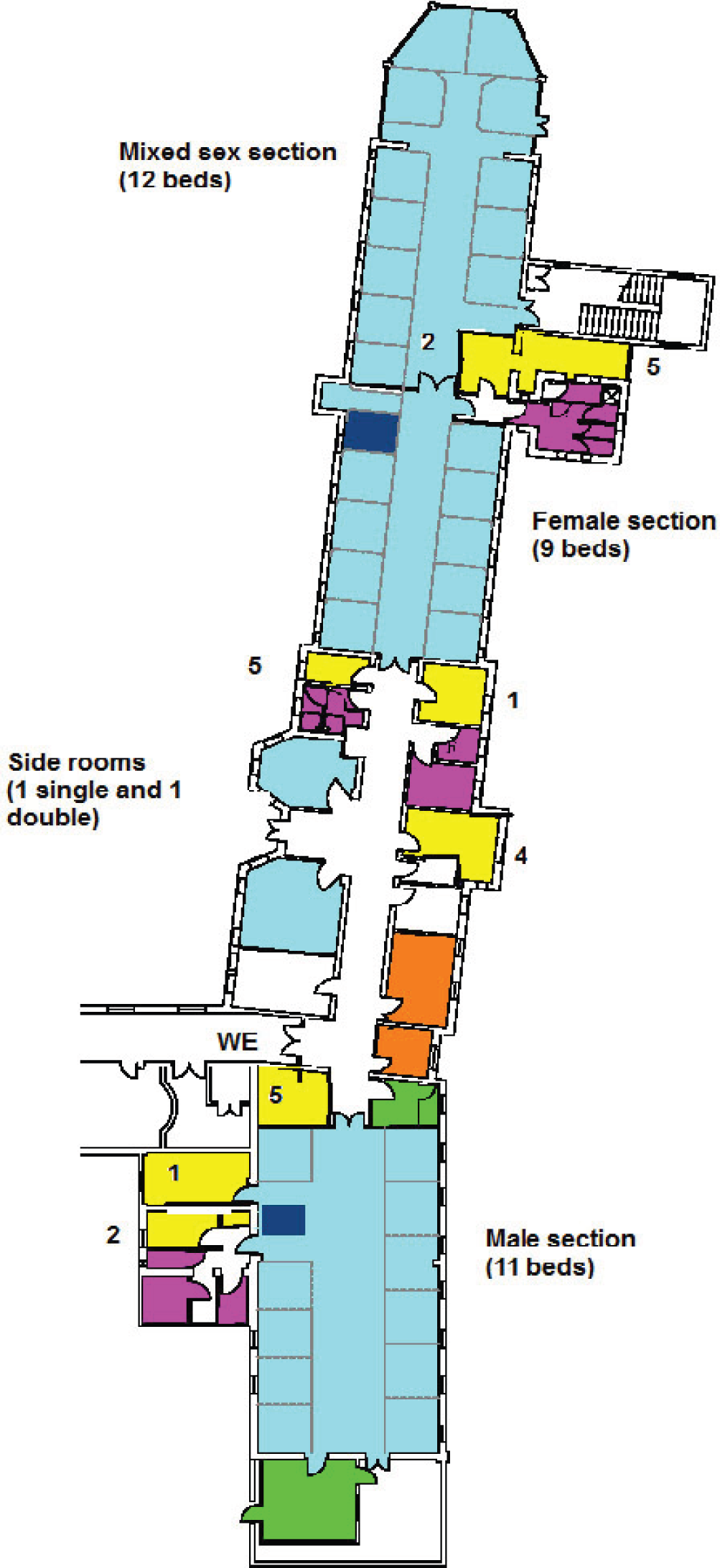

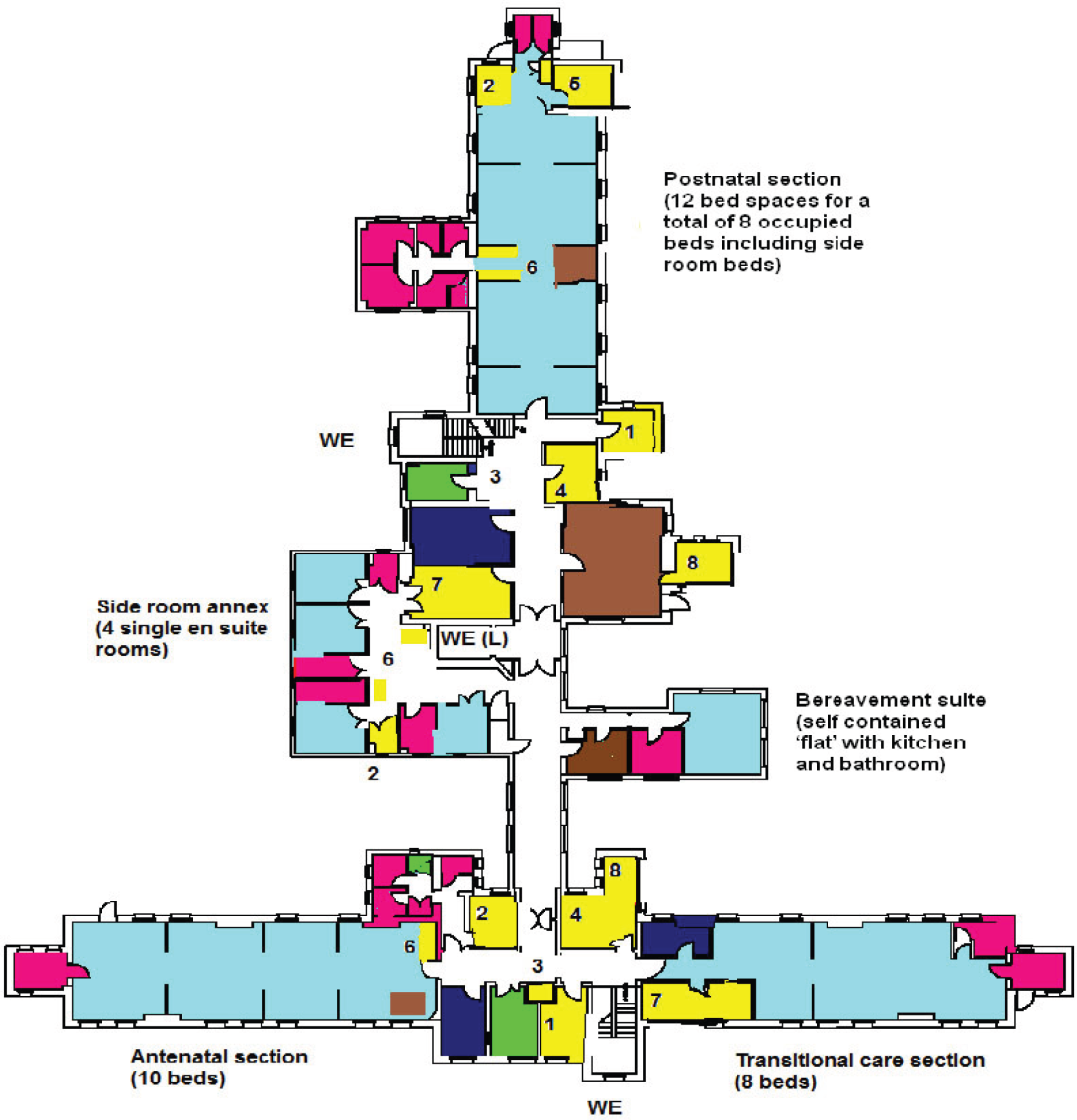

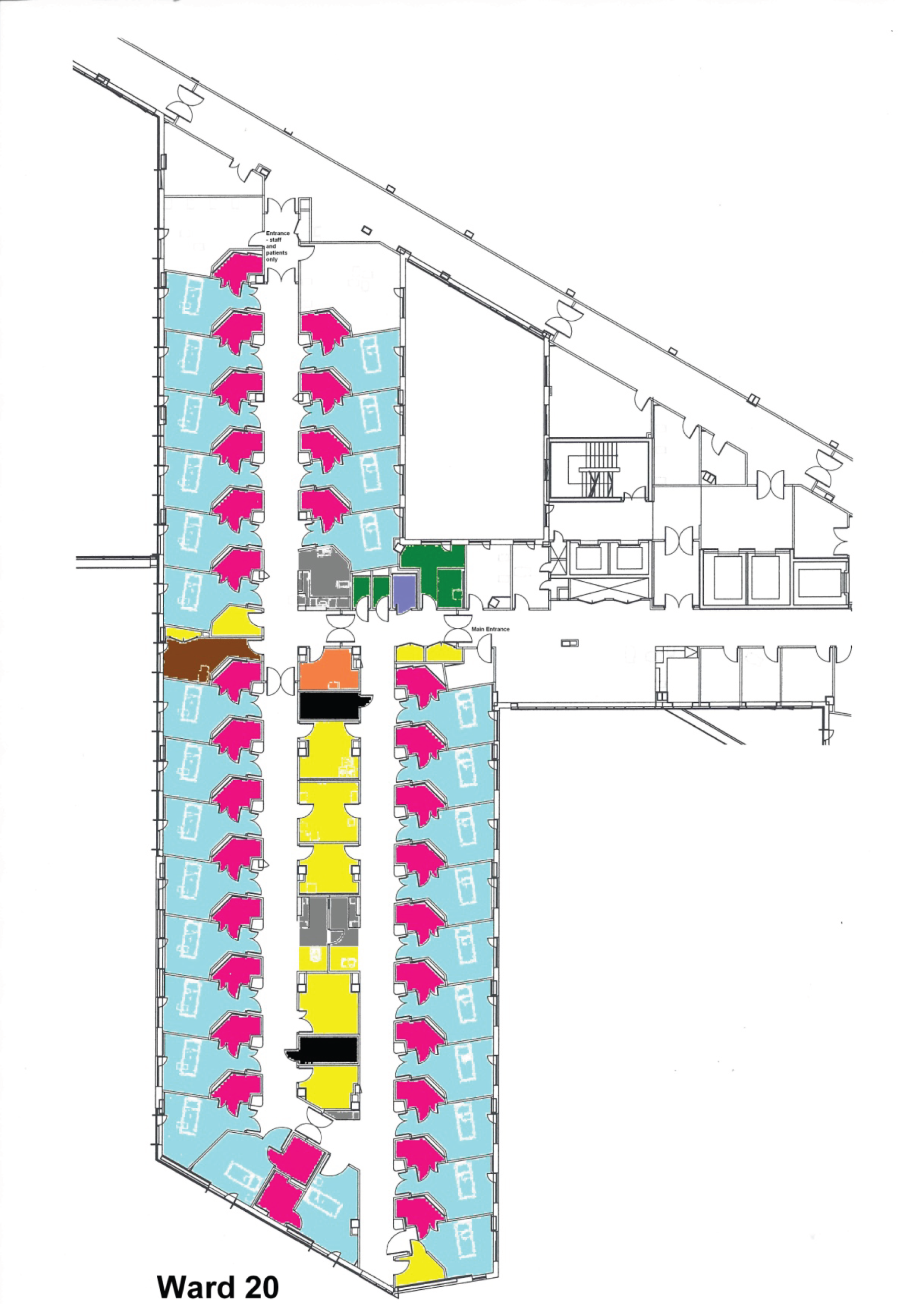

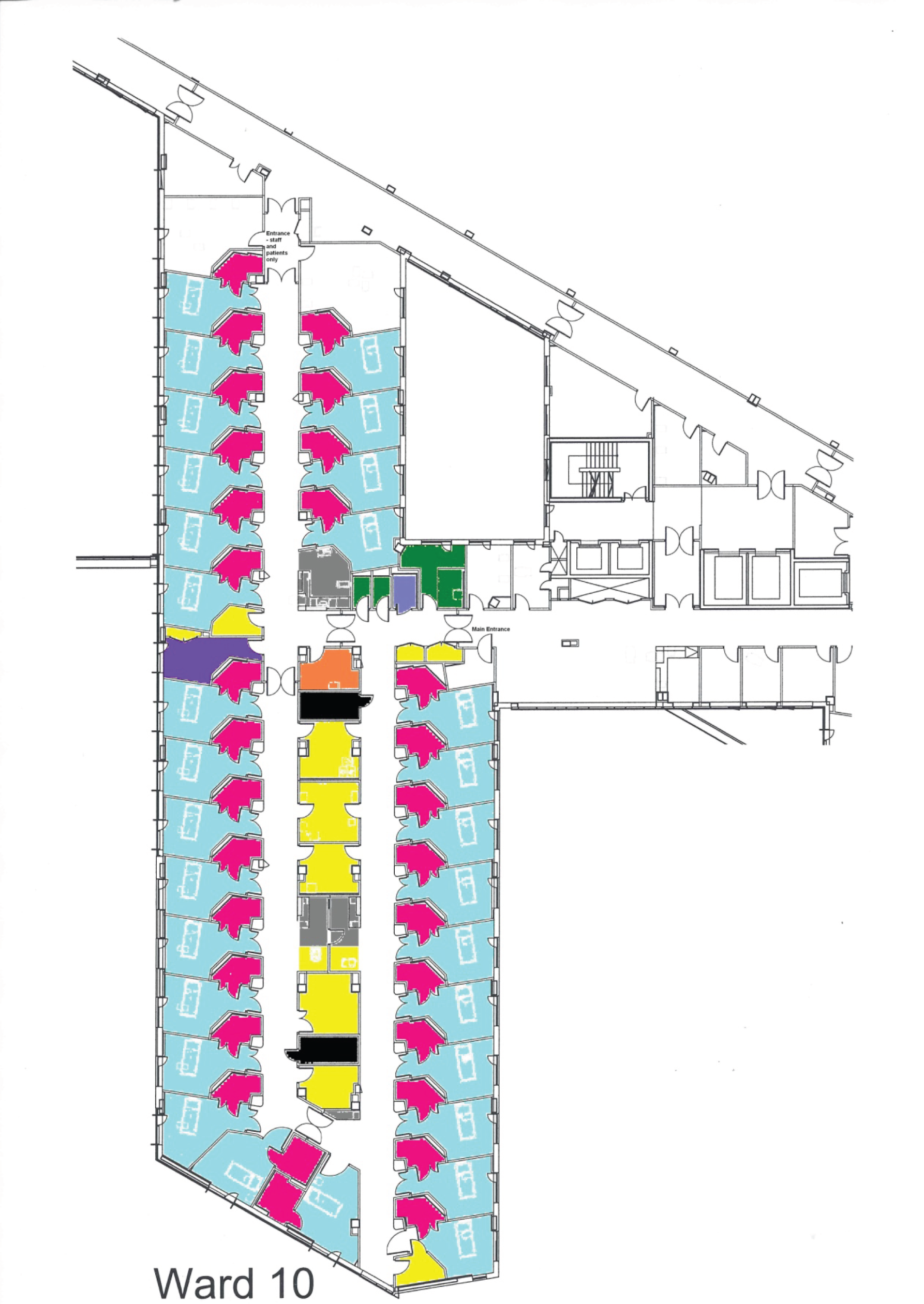

Four case study adult inpatient wards were purposively selected to encompass a range of different clinical areas and patient groups. Wards selected were acute assessment, surgical, medical (older people) and maternity (see Chapter 4 for full descriptions of each case study ward, including their physical layout and staffing). Case study data collection was undertaken between September 2012 and June 2013. Staff and patients invited to take part received an information sheet about the research study (see Appendix 4).

Organisational context: key stakeholder interviews

Data on organisational context were collected through a series of key stakeholder interviews (n = 41) which were undertaken between August 2009 and July 2010 for phase 1 (n = 20) (see Appendix 5 for phase 1 sample and interview guide) and between August 2012 and May 2013 for phase 2 (n = 21). In addition to these interviews in phase 2, a mini focus group was undertaken with Allied Health Professionals (AHPs). Trust staff interviewed were sampled purposively and through snowball sampling (Table 2).

| Senior trust staff | Medical staff and AHPs | Case study ward managers and ward clerk |

|---|---|---|

| Interim director of nursing Head of nursing for emergency services Head of nursing for surgery Head of midwifery/head of women’s, children’s and sexual health services/coclinical director for maternity services Deputy director of infection prevention and control Assistant director estates and facilities Therapy manager Senior matron safeguarding vulnerable adults |

Consultant respiratory physician Medical director (and consultant in anaesthetics and intensive care) Senior physiotherapist (n = 2) (orthopaedic and medical rehabilitation) Senior occupational therapist (n = 2) (acute and orthopaedic) Dietitian Speech and language therapist Mini-focus group with five participants (all different from the above): one dietitian, two occupational therapists and two physiotherapists |

Ward manager – surgery (interview also involved junior sister/practice development nurse) Ward manager – acute elderly care Ward manager – AAU Ward manager – postnatal and transitional care unit Ward clerk/administrator (AAU) |

Key stakeholders were provided with the staff research interview information sheet (see Appendix 4), which lasted 30–60 minutes. The topic guide prompted exploration of the early challenges and experiences across the trust and issues of implementation relating to transition to all single room ward accommodation (see Appendix 6).

Observation of practice

Procedure

The aim of the observation of practice was to understand how and where staff spent their time and determine if the proportion of time they spent on each activity changed following the move. Staff members were approached by either the ward manager or the researcher prior to the shift to assess willingness to be shadowed, and the researcher explained the research and that participation was voluntary, prior to obtaining consent. All observation was carried out by the same member of the research team in order to ensure consistency in data collection across the four case study wards and across study phases. Observation involved shadowing individual nursing and midwifery staff members (both registered and assistant staff) for between 4 and 8 hours and recording their activity using a structured time and motion data collection tool. Observation was undertaken during the day only (between 07.00 and 20.00) and should, therefore, be regarded as indicative rather than representative.

The data collection tool was developed by the research team using HanDBase (version 4, DDH Software, Inc., Wellington, FL, USA) software, and drew on a similar tool used in health-care research designed and developed by Westbrook and Ampt94 (WOMBAT – Work Observation Method by Activity Timing). Time-stamped data were collected using a HanDBase custom form interface on a hand-held computer [personal digital assistant (PDA)]. The form contained a series of categories, each with a popup list of options or subcategories. Additional detail was collected in relation to two activity categories (direct care and face-to-face professional communication), which were predicted to change most in the all single room ward, and via a ‘Twitter’ box allowing the recording of additional short verbatim notes relating to working practices and effectiveness. Activity categories are detailed in Box 4.

-

Direct care.

-

Documentation.

-

Escort/transfer patient.

-

Indirect care.

-

Medication tasks (including medication administration).

-

Personal/social.

-

Professional communication.

-

Ward-related (including cleaning, bed-making, stocking utility room, and linen trolleys).

See Appendix 7 for a full list of the HanDBase form categories and tables of definitions.

Participants

A mix of nurses, midwives and health-care assistants (HCAs) (to be shadowed) were sampled in order to understand differences between these groups. A total of 19 members of staff were observed before the move and 24 after the move to the new build. No members of staff were observed both times, so the design was purely a between-sites comparison. Numbers of staff observed and hours of observation per ward are shown in Table 3.

| Staff group | Phase | Hours observation (number of staff shown in brackets) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute assessment | Medical (older people) | Surgical | Maternity | |||

| Nurses/midwives | Pre | 23 (3) | 13.5 (2) | 19.25 (3) | 14.75 (3) | 70.5 (11) |

| Nurses/midwives | Post | 27.4 (5) | 23.2 (4) | 23.2 (4) | 22 (4) | 95.8 (17) |

| HCAs | Pre | 6 (1) | 15.25 (2) | 12.5 (2) | 14.5 (3) | 48.25 (8) |

| HCAs | Post | 5.6 (1) | 8.5 (2) | 10.5 (2) | 11.2 (2) | 35.8 (7) |

| Total | 62 (10) | 60.45 (10) | 65.45 (11) | 62.45 (12) | 250.35 (43) | |

Staff travel distances

Procedure

Staff travel distance data were collected by pedometer. The researcher had 10 pedometers that could be used at any one time. The pedometer model was the ‘OMRON Walking Style II’ (OMRON Healthcare UK Ltd, Milton Keynes, UK), chosen because it has high accuracy. The mechanism works whether it is in a pocket or attached and does not count false steps such as bending or jumping. The devices recorded the number of steps taken, but not distance. The pedometers were attached to the participant’s belt or placed in a pocket. These were distributed and collected by the researcher before and after the shadowing sessions. The quality of the pedometer was commented on by participating staff, who displayed high motivation to wear the device.

Participants

During the time when observation data were being collected, all staff members on duty were invited to wear pedometers to record the number of steps taken. This usually involved the same cluster of rooms in which the researcher was observing but could involve staff on other clusters. Travel distance data were collected from 109 staff: 53 staff (49%) before the move and 56 (51%) after the move. A small number of staff (n = 5, 4%) were observed at both times: one registered nurse (RN) and four HCAs. A number of staff contributed more than one observation session: 85 provided one session, 18 provided two sessions, 5 provided three sessions and 1 provided four sessions. A total of 140 data collection sessions occurred. There were 73 sessions (52%) collected prior to the new build and 67 sessions (48%) after the new build. The average number of sessions per member of staff was 1.38 and 1.20, respectively. Table 4 shows the number of hours of data collection and the number of participants.

| Staff group | Phase | Hours pedometer data (number of staff shown in brackets) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute assessment | Medical (older people) | Surgical | Maternity | |||

| Nurses/midwives | Pre | 111 (11) | 54 (5) | 74 (8) | 40 (5) | 279 (29) |

| Post | 58 (9) | 27 (7) | 59 (8) | 33 (6) | 177 (30) | |

| HCAs | Pre | 30 (1) | 118 (11) | 49 (6) | 39 (6) | 236 (24) |

| Post | 24 (5) | 62 (12) | 54 (7) | 11 (2) | 151 (26) | |

| Total | Pre | 141 (12) | 172 (16) | 123 (14) | 79 (11) | 515 (53) |

| Post | 82 (14) | 89 (19) | 113 (15) | 44 (8) | 328 (56) | |

| Grand total | All | 223 (26) | 261 (35) | 236 (29) | 123 (19) | 843 (109) |

Staff survey

Survey design

The survey was developed by the research team to probe perceptions of many aspects of the ward environment, and questions were generated by reviewing the literature including previous studies of ward design and the tools they used. 95–97 It included a new 152-item questionnaire designed specifically for this study, and a validated teamwork and safety climate survey98 (see Appendix 8). After generating a pool of potential items, a group of health services researchers reviewed and iteratively revised the items to ensure that there was no overlap or repetition, that the wording was consistent and non-biased, and that all theoretically relevant topics were included. The draft survey was then pilot tested by a group of 20 nurses attending postgraduate training, who provided feedback on timing, wording, clarity and layout. Changes were incorporated into the final version. The survey included categorical questions, using Likert scales and yes/no answers, and open-ended questions designed to capture more nuanced data about staff experiences. The sections in the survey were:

-

perceptions of current ward layout, environment, facilities and information and communications technology (ICT) in relation to patient facilities, staff facilities, effect on teamwork, care delivery, safety and privacy

-

perceptions of the move to 100% single room wards

-

teamwork and safety climate

-

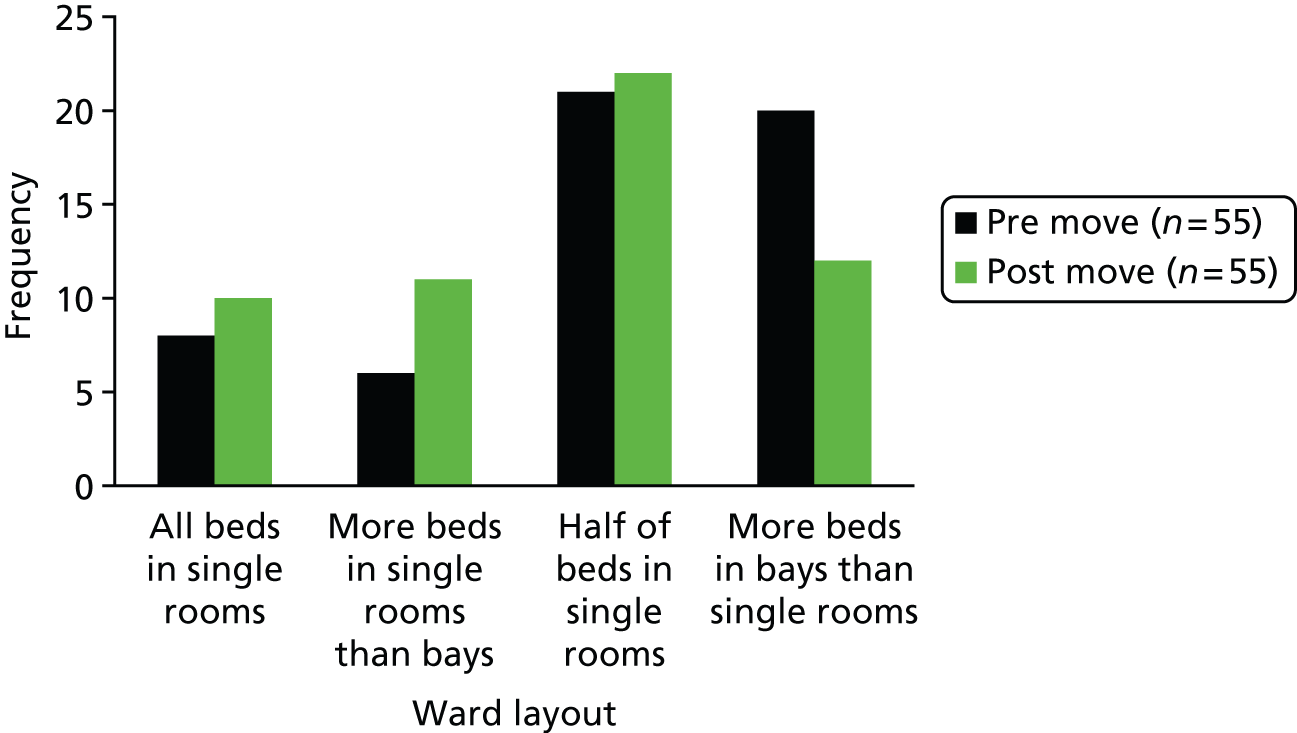

preference in relation to the proportion of beds in single rooms versus bays

-

job satisfaction

-

well-being and stress

-

demographic details.

A small number of questions were rephrased for coherence following the move (see Appendix 9).

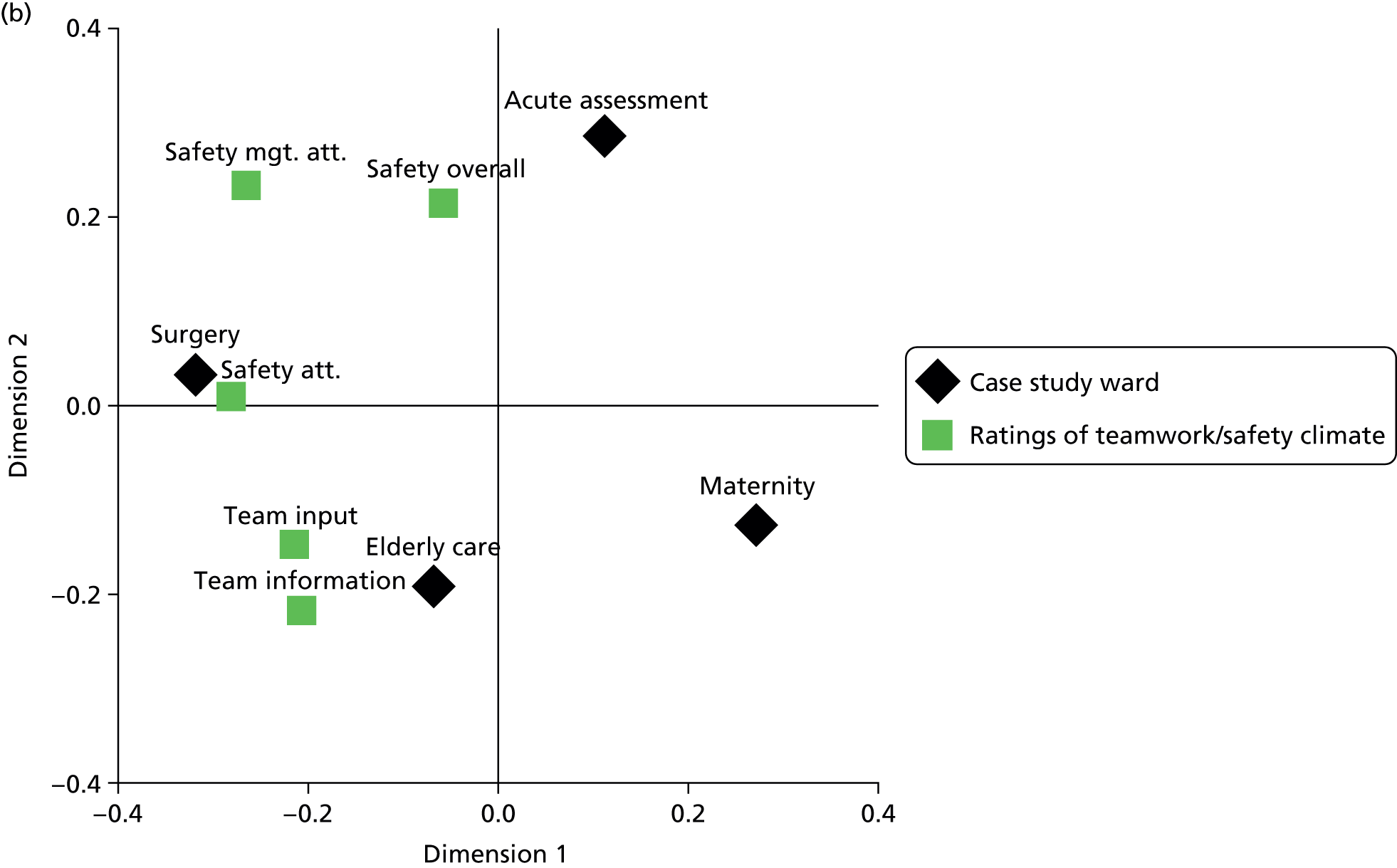

The survey included an adapted version of the 22-item version of the Teamwork and Safety Climate Survey. 98 This is a validated survey consisting of two scales to measure perceptions of teamwork and three to measure safety climate. The final adapted teamwork and safety climate scale within the survey consisted of 24 items with Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) (see Appendix 8).

Procedure

A copy of the survey was addressed to each ward staff member and placed in a box (in either the ward manager’s office or the staff break room) for collection by staff when they were next on duty. Staff were informed about the survey by ward managers (on several occasions) and the researcher during observation sessions. Posters publicising the study and reminder posters (after 2 weeks) were also put up on the wards to encourage responses. A prize draw incentive was offered to staff completing the survey (£75 Marks & Spencer gift card for each ward). Completed surveys were returned directly to the research team using a Freepost reply envelope.

Participants

The total survey population was 176 before the move and 204 after the move. The overall response rate was 31% before the move and 27% after it. Fifty-five participants completed the pre-move survey and the same number completed the post-move survey. Nineteen participants took part in both the before and after surveys. The survey respondents were predominantly female; one male completed the pre-move survey and three males completed the post-move survey. The survey respondents were RNs/midwives and HCAs/care support workers. The number of staff participating from each case study ward before and after the move is shown in Table 5, and the respondents who were RNs or registered midwives (RMs) and HCAs are shown in Table 6.

| Phase | Ward | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternity | Surgery | Older people care | Acute assessment | ||

| Pre | 17 | 15 | 11 | 12 | 55 |

| Post | 26 | 14 | 11 | 4 | 55 |

| Total | 43 | 29 | 22 | 16 | 110 |

| Phase | HCAs | Registered nurses/midwives | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | 16 | 39 | 55 |

| Post | 16 | 39 | 55 |

| Total | 32 | 78 | 110 |

Staff interviews

Procedure

Staff were recruited through the ward managers and by the researcher while conducting observation on the wards. Staff were reminded that participation was voluntary. Of 24 staff interviewed, 10 had also been shadowed by the researcher. Interviews were conducted on the wards in a private room or quiet area and lasted 30–60 minutes. The staff interview topic guide (see Appendix 10) covered the following areas:

-

staff experience – working differently/new ways of working

-

ward layout including layout of single rooms and en suites

-

staff communication and teamwork

-

perceptions of patient experience.

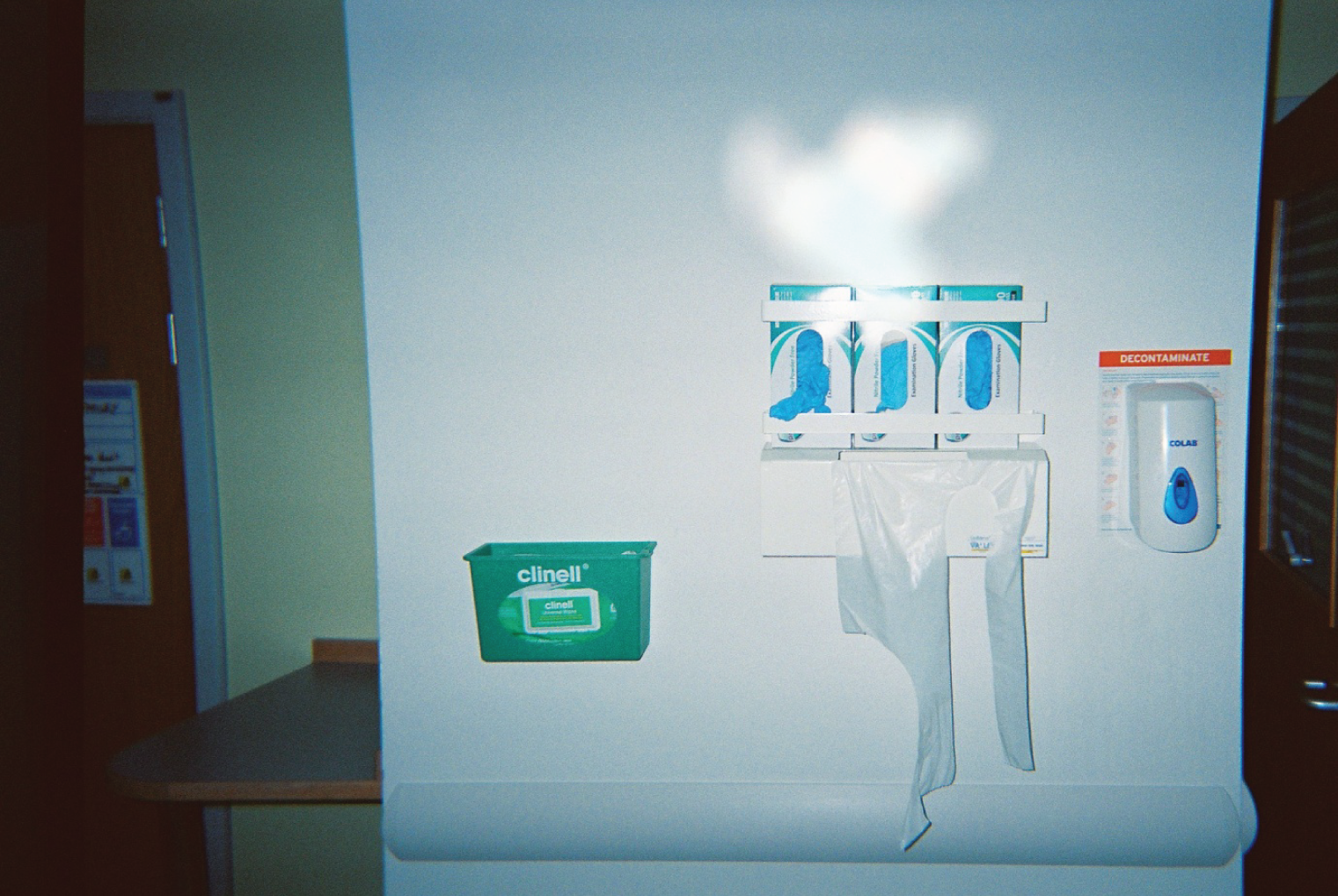

Half of the total interviews additionally involved reflexive photography. 99 Reflexive photography – a type of photo-elicitation technique where research participants take photographs – formed the main focus of ‘reflective’ discussion during the subsequent interview. The approach allows the research participant to talk about the significance and meaning of photographs which represent their perspective on the topic in question. Reflexive photography was used in this research to both generate a visual record of the work environments and also encourage research participants to critically analyse the ward layout, environment and facilities. It was used to prompt deeper consideration of positive and negative aspects of the work environment, and encourage participants to ‘view’ the environment in a new way or light, reassessing those aspects that are taken for granted. 100

Staff taking part in reflexive photography interviews were provided with a 27-exposure single-use disposable camera and a sheet of information and guidelines about reflexive photography (see Appendix 11). Staff were asked to take a minimum of five photographs of aspects of the ward environment. The researcher collected the cameras from the wards and returned at a later date with the photographs, which were discussed during one-to-one photo-elicitation interviews. Staff participating in reflexive photography interviews took between 5 and 27 photographs (phase 1, median 9, total 128; phase 2, median 7, total 114).

Participants

In-depth interviews were conducted with nursing staff (registered and assistant staff) in phases 1 and 2 (a total of 48 interviews). In each phase, six interviews were carried out on each case study ward (Table 7).

| Staff group | Phase | Staff interviews (photo elicitation in brackets) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute assessment | Medical (older people) | Surgical | Maternity | |||

| Nurses/midwives | Pre | 5 (3) | 2 (2) | 4 (2) | 5 (3) | 16 (10) |

| Post | 5 (3) | 3 (1) | 6 (3) | 5 (2) | 19 (9) | |

| HCAs | Pre | 1 (0) | 4 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 8 (2) |

| Post | 1 (0) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | |

| Total | Pre | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 6 (3) | 24 (12) |

| Post | 6 (3) | 5 (2) | 7 (4) | 6 (3) | 24 (12) | |

| Grand total | All | 12 (6) | 11 (5) | 13 (7) | 12 (6) | 48 (24) |

Patient interviews

Procedure

Patients were recruited in two ways. For three wards (acute assessment, surgical and maternity), the trust sent a letter to recently discharged patients on behalf of the research team. Patients could then choose to opt in by returning a reply slip directly to the research team. Patients were interviewed between 2 and 4 weeks following discharge from hospital. The majority of interviews were conducted in respondents’ own homes (n = 24). Three interviews were conducted by telephone and one at another health-care facility at the request of participants. Interviews lasted 60–75 minutes (telephone interviews lasted up to 30 minutes) and patients received a £25 cash payment for giving up their time to participate.

An alternative method was used to recruit four of the patients on the medical (older people) ward because of the importance of identifying patients who were cognitively able to give informed consent, and concerns about the potential burden placed on frail older patients in participating in an interview following discharge. The ward manager, in consultation with staff, recommended patients that the researcher could approach to provide information about the research. The researcher introduced herself to these patients, provided them with a copy of the patient information sheet and returned to discuss willingness to participate 48 hours later. Patients were reassured that participation was voluntary. Patients were interviewed in their single room, were cognitively well and were able to participate fully in interviews, which were tape recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interviews were conducted using a topic guide (see Appendix 12) which focused on patient experiences of the physical environment and their overall experience of care, including:

-

feeling comfortable

-

feeling safe

-

interaction with staff

-

interaction with visitors.

Participants

A total of 32 in-depth patient interviews were conducted in both phases 1 and 2 (with between 4 and 12 patients per case study area) (see Appendix 13 for pre-move sample). Table 8 provides a breakdown of key characteristics of patients interviewed, including LOS, age, parity (maternity patients) and gender.

| Key demographics | Ward | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical assessment unit | Older people | Emergency surgery | Postnatal | ||

| LOS (range) | 24 hours to 7 days | 6 days to 5 weeks | 24 hours to 9 days | 48 hours to 7 days | – |

| Mean age | 62 years (range 44–74 years) | 82 years (range 70–95 years) | 66 years (range 45–84 years) | 35 years (range 26–49 years) | – |

| Paritya | |||||

| Primiparous | N/A | N/A | N/A | 5 | – |

| Multiparous | 3 | ||||

| Female | 4 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 19 |

| Male | 4 | 4 | 5 | N/A | 13 |

| Total (interviews per ward) | 8 b | 8 | 8 | 8 | 32 |

Data analysis

Time and motion personal digital assistant observation, pedometer and survey data analysis

Time and motion PDA observation data were exported from the handheld computers to Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for analysis. Pedometer data were entered into Excel for analysis and staff survey data were entered and analysed in SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions version 22, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) (see Chapter 5 for full details of analysis integrated with results reporting).

Interviews with key stakeholders, staff and patients

Qualitative in-depth interviews with key stakeholders, staff and patients were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Qualitative data were analysed using a framework approach, a method which involves the systematic analysis of verbatim interview data within a thematic matrix. 101 The key topics and issues emerging from the interviews were identified through familiarisation with interview transcripts as well as reference to the original objectives of the case study research, the topic guides and phase 1 data. However, new themes and issues were also allowed to emerge inductively from data. A series of thematic charts was developed and data from each transcript were summarised under each theme (see Appendix 14 for an example). This facilitated detailed exploration of the charted data, in order to map and understand the range of views and experiences in different themes as well as allowing comparison across cases and groups of cases. Recurring and significant core concepts or dimensions of experience themes were identified through an exploration of associations between the themes, and among cases in the coding matrix. This helped to develop an understanding of the range of experience of the study participants.

Data synthesis occurred as part of the analytical process, and connections were made between qualitative and quantitative data sources in order to identify core themes and connections. We aimed to balance the emic versus etic position following Greenhalgh et al. ’s work90 and have drawn upon the work of Happ et al. 102 to undertake a concurrent mixed analysis for complementarity and completeness.

Quasi-experimental before-and-after study

Design

To isolate any effect of single room accommodation on safety outcomes, a quasi-experimental approach (as a before-and-after study with non-equivalent controls) was taken. 103

Selection of comparator sites

The new Tunbridge Wells Hospital is a 100% single room facility. Main characteristics required of potential comparator sites were (1) no change but planning to move in the future (indicating wards that were nearing the end of their expected useful life, to ensure comparability with the ‘intervention’ site) and (2) moving to a new building with mixed accommodation with 50% single rooms (as a control for changes associated with a move to a new facility but not 100% single rooms). After several potential NHS trusts were contacted, one hospital in the South West region (no move, planned move in 2014) and one hospital in London (new building, mixed accommodation, move in 2011) agreed to participate in the study (Table 9).

| Characteristic | Acute assessment | Older people | Surgical | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tunbridge Wells | Mixed accommodation | Steady state | Tunbridge Wells | Mixed accommodation | Steady state | Tunbridge Wells | Mixed accommodation | Steady state | |

| n | 17,457 | 4948 | 24,747 | 1600 | 1779 | 1580 | 4938 | 1821 | 8388 |

| Age | 57.5 | 52.8 | 64.8 | 84.4 | 80.5 | 82.9 | 60.7 | 55.0 | 50.2 |

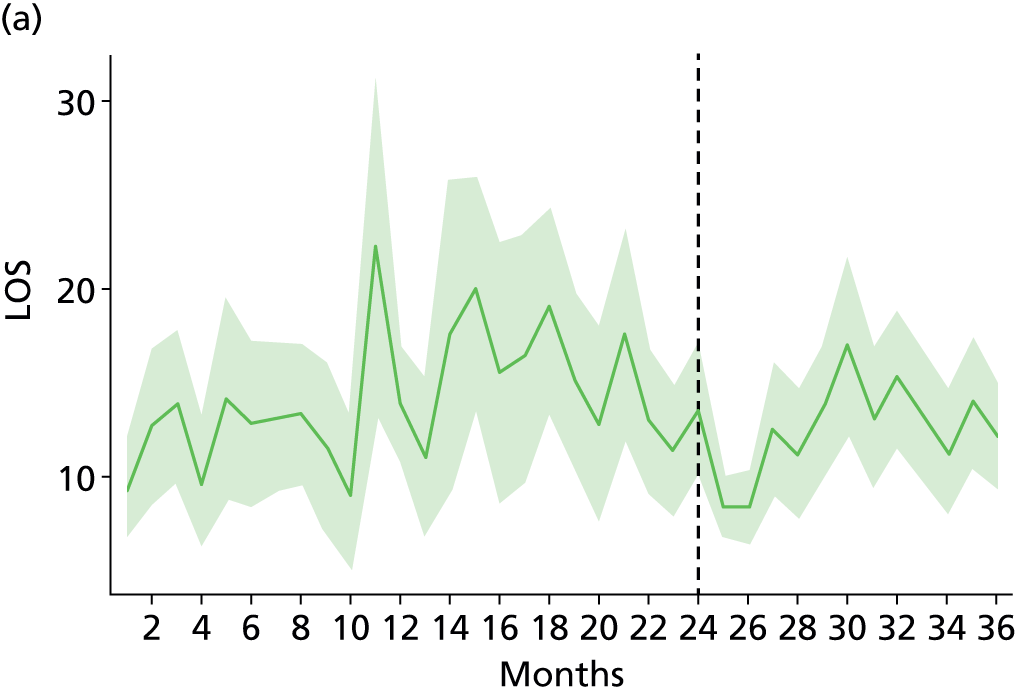

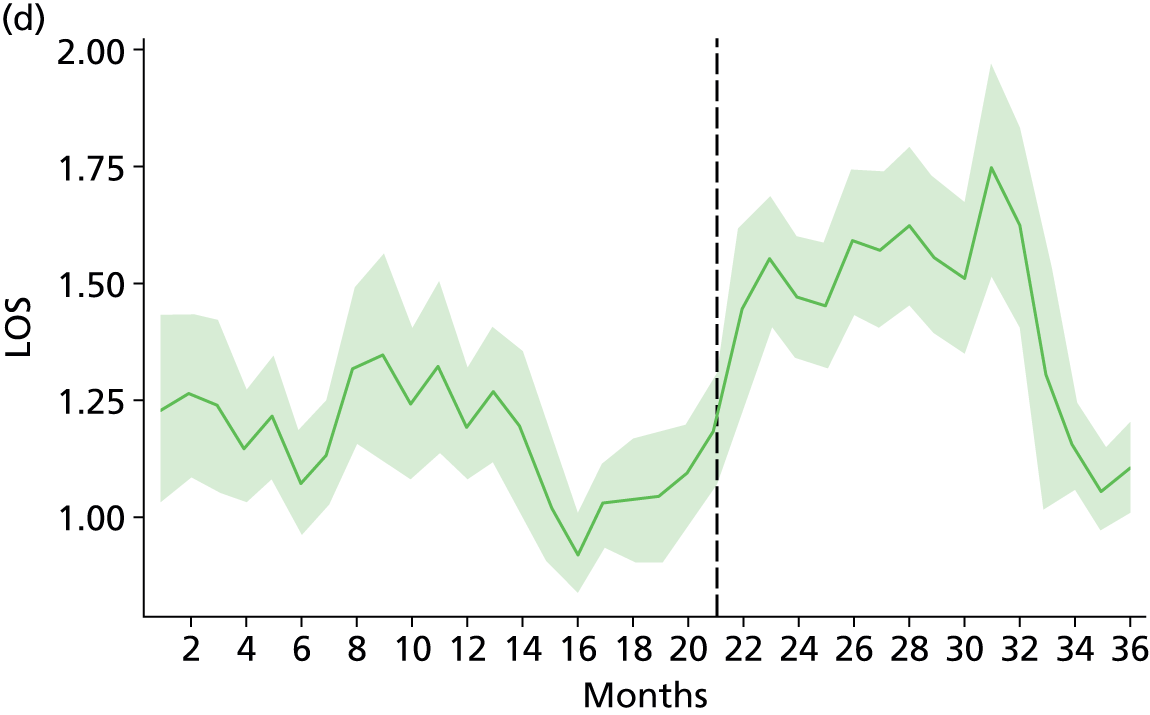

| LOS | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 27.4 | 12.9 | 13.8 | 7.2 | 8.1 | 1.9 |

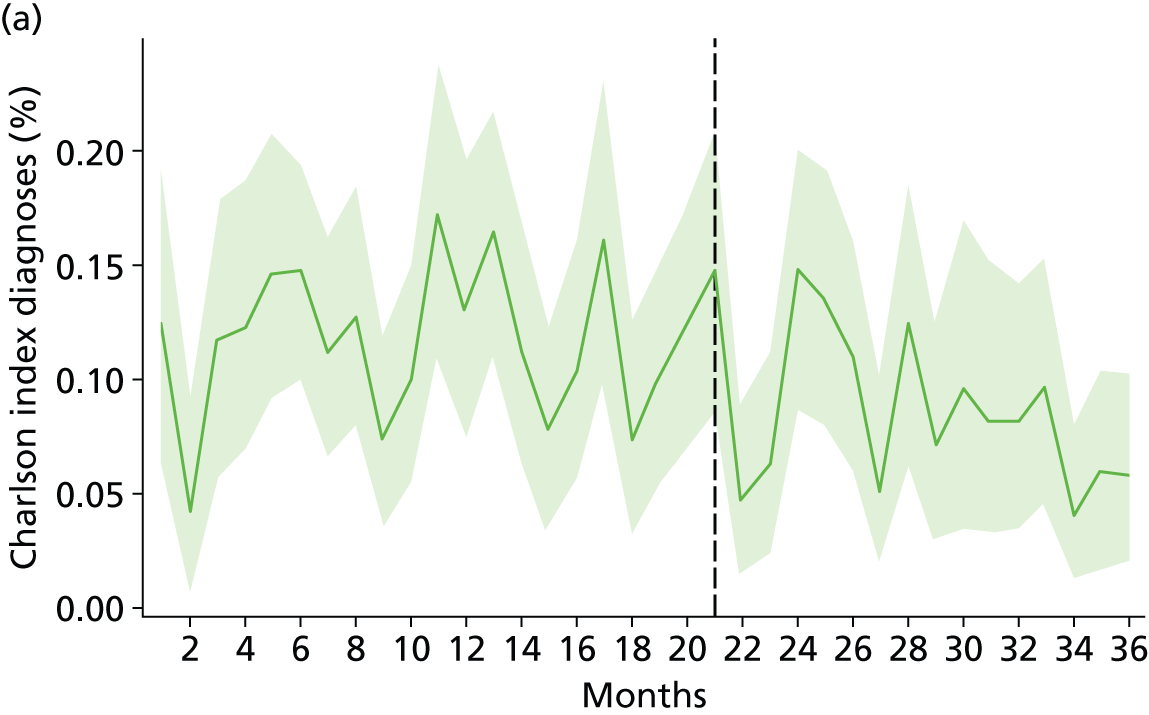

| Charlson comorbidity index (%) | 8.2 | 4.3 | 9.5 | 11.8 | 4.9 | 16.5 | 10.6 | 9.4 | 4.1 |

Analytical approach

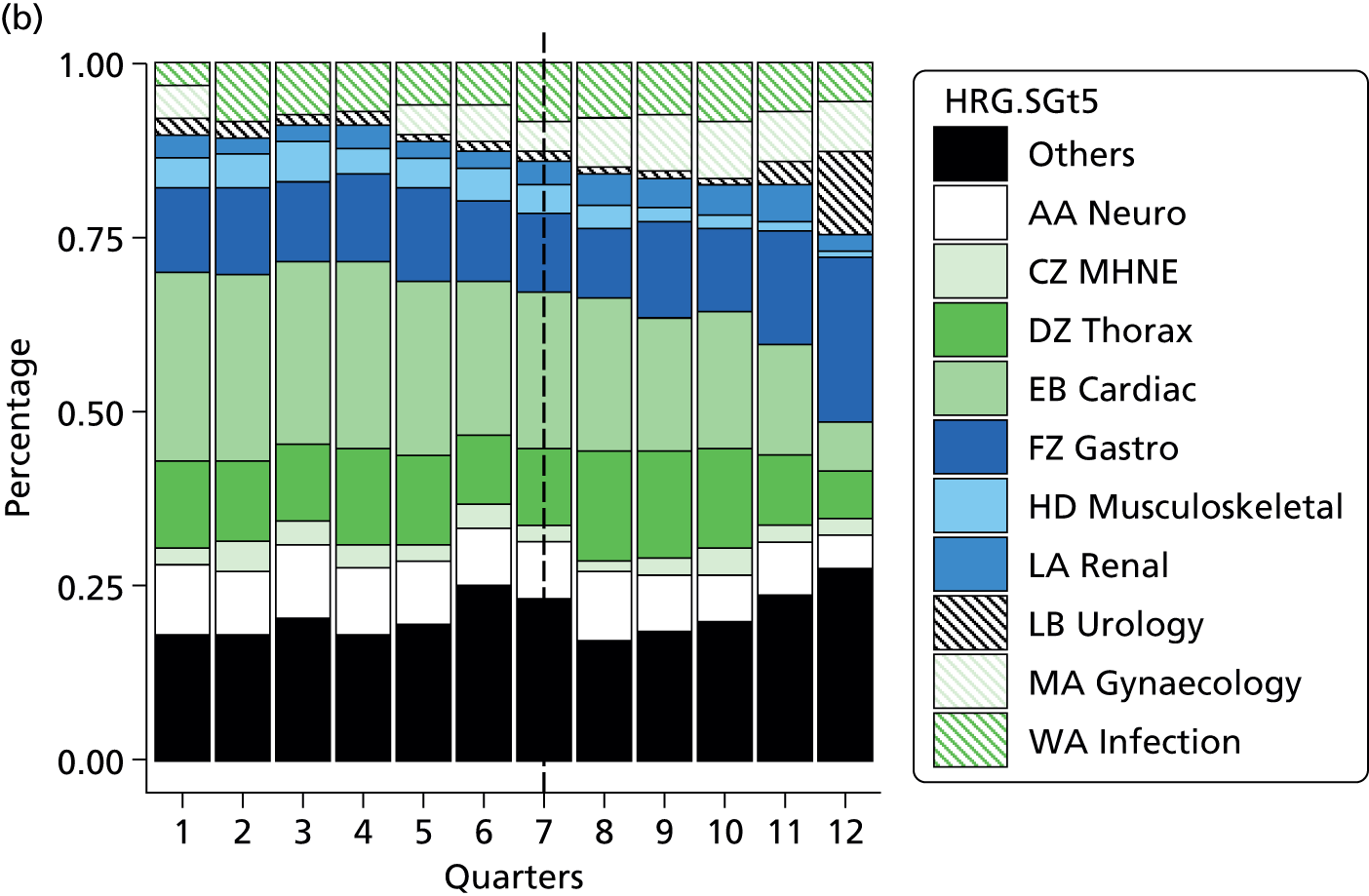

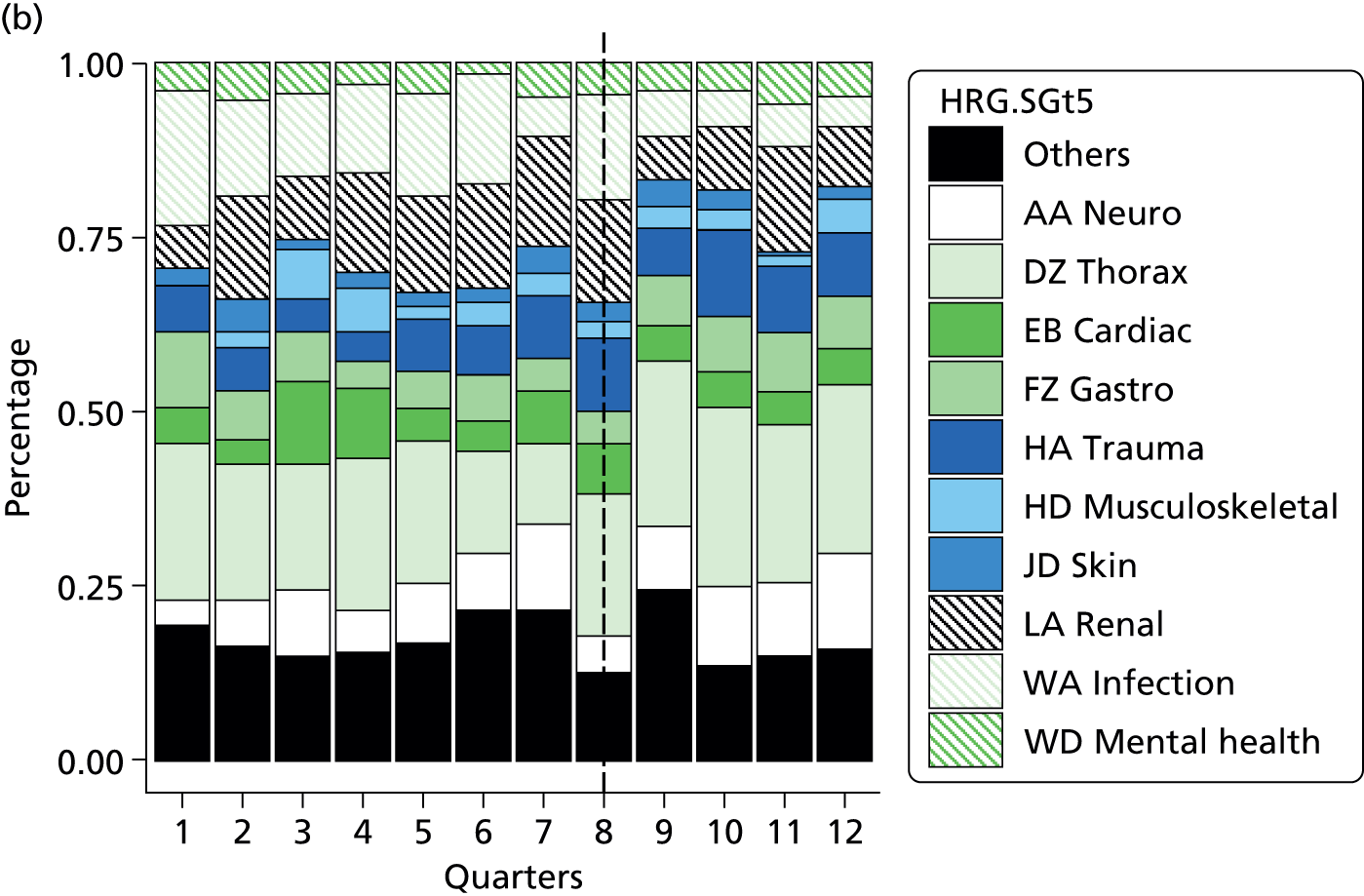

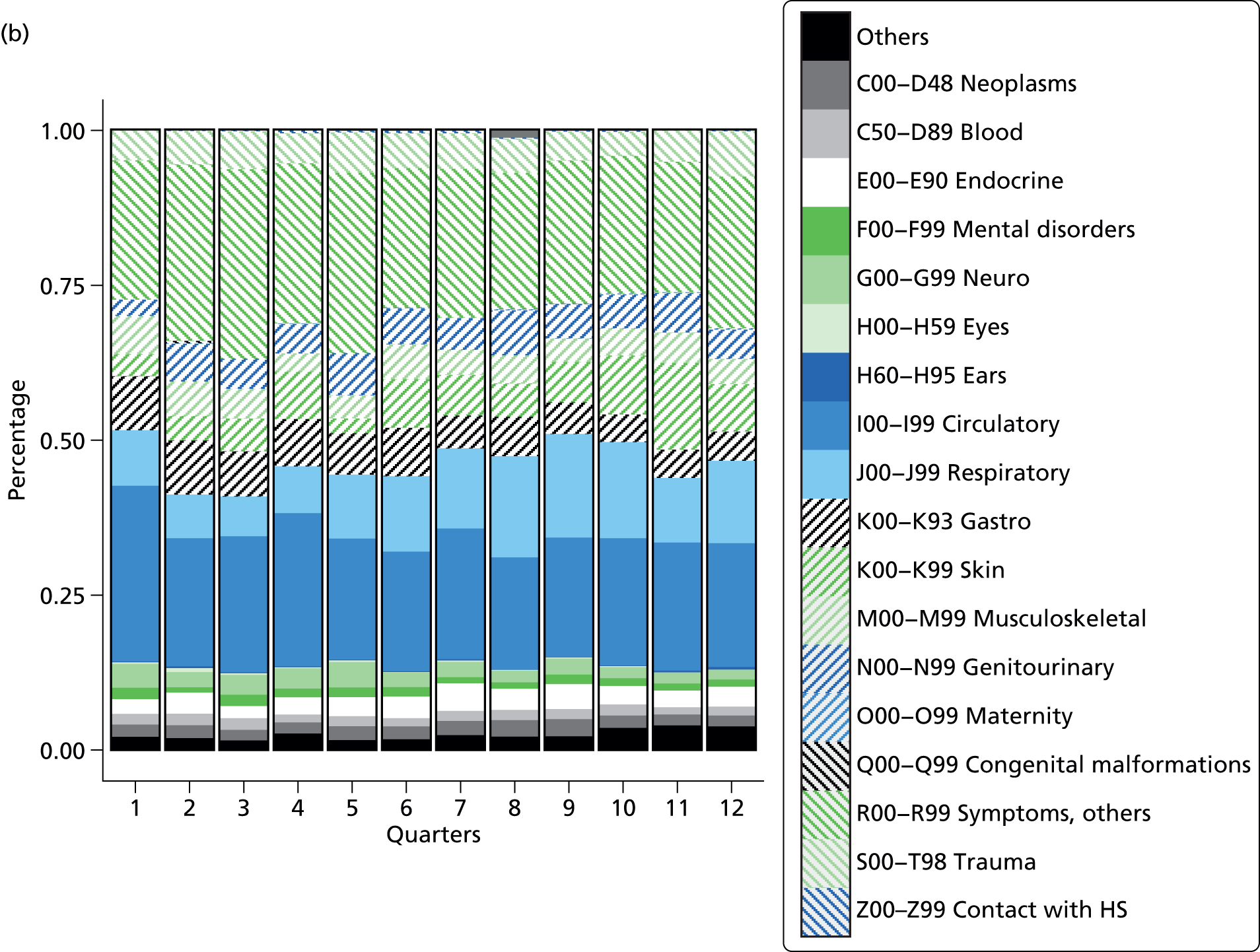

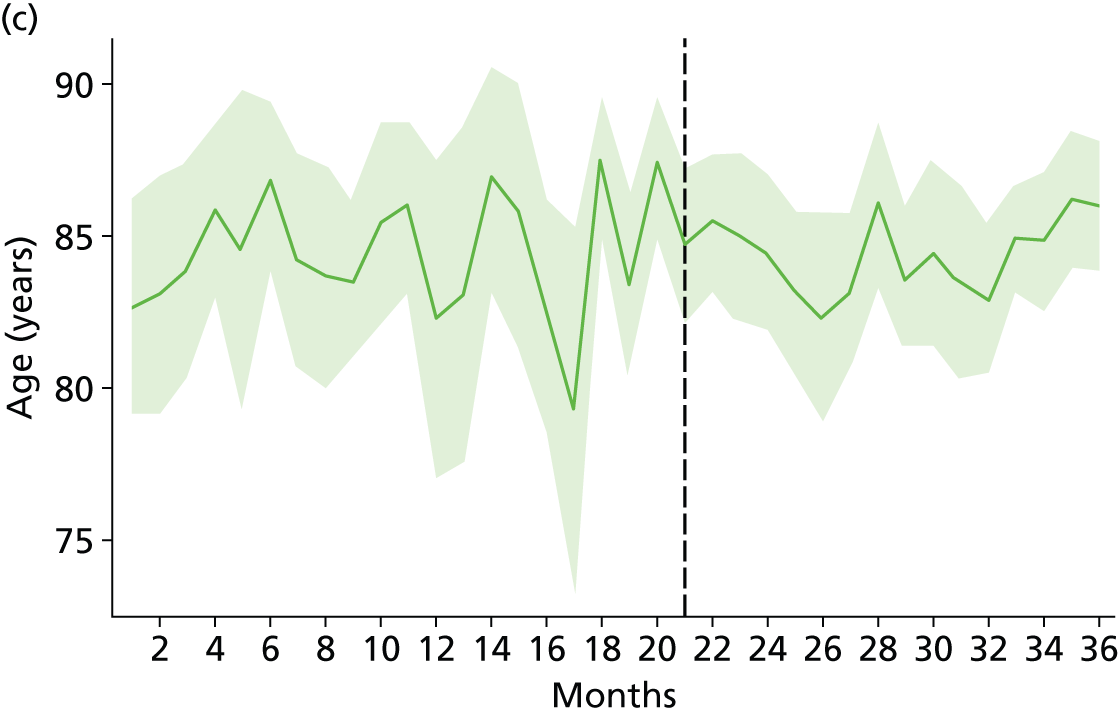

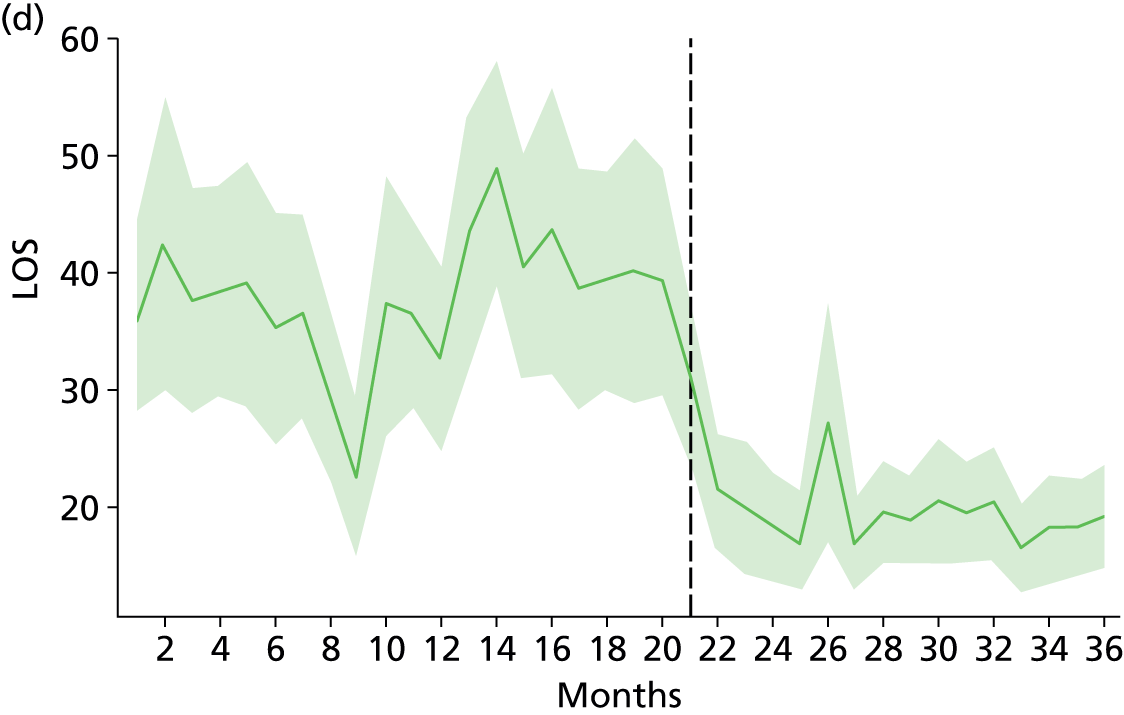

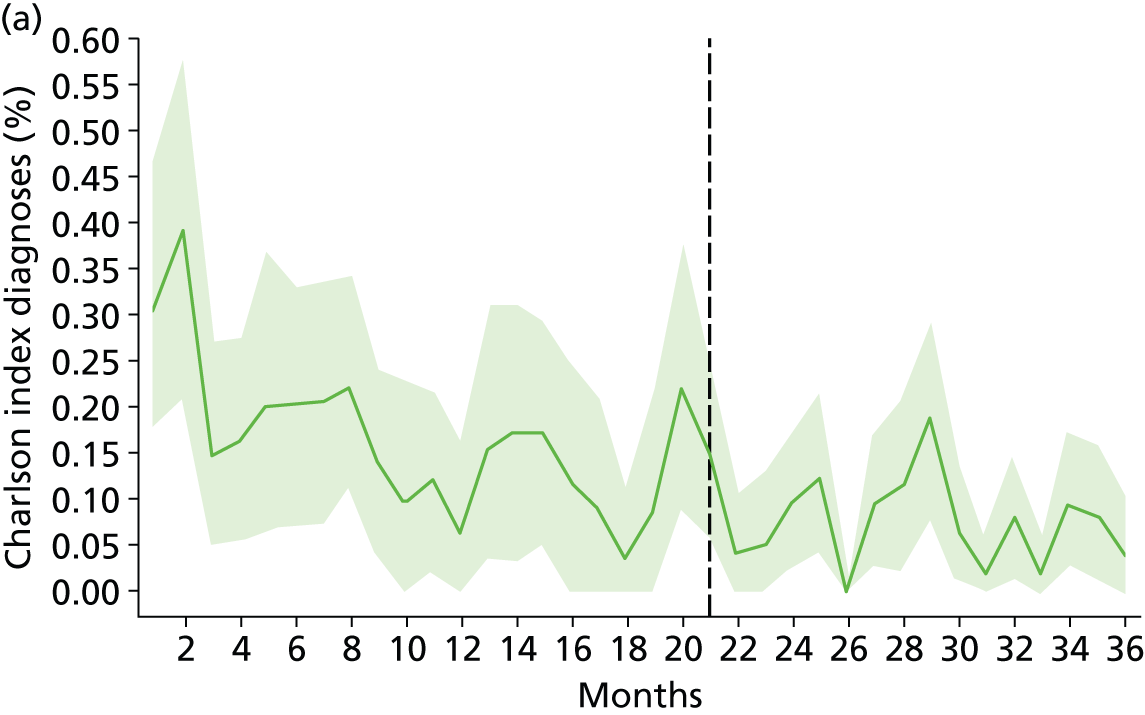

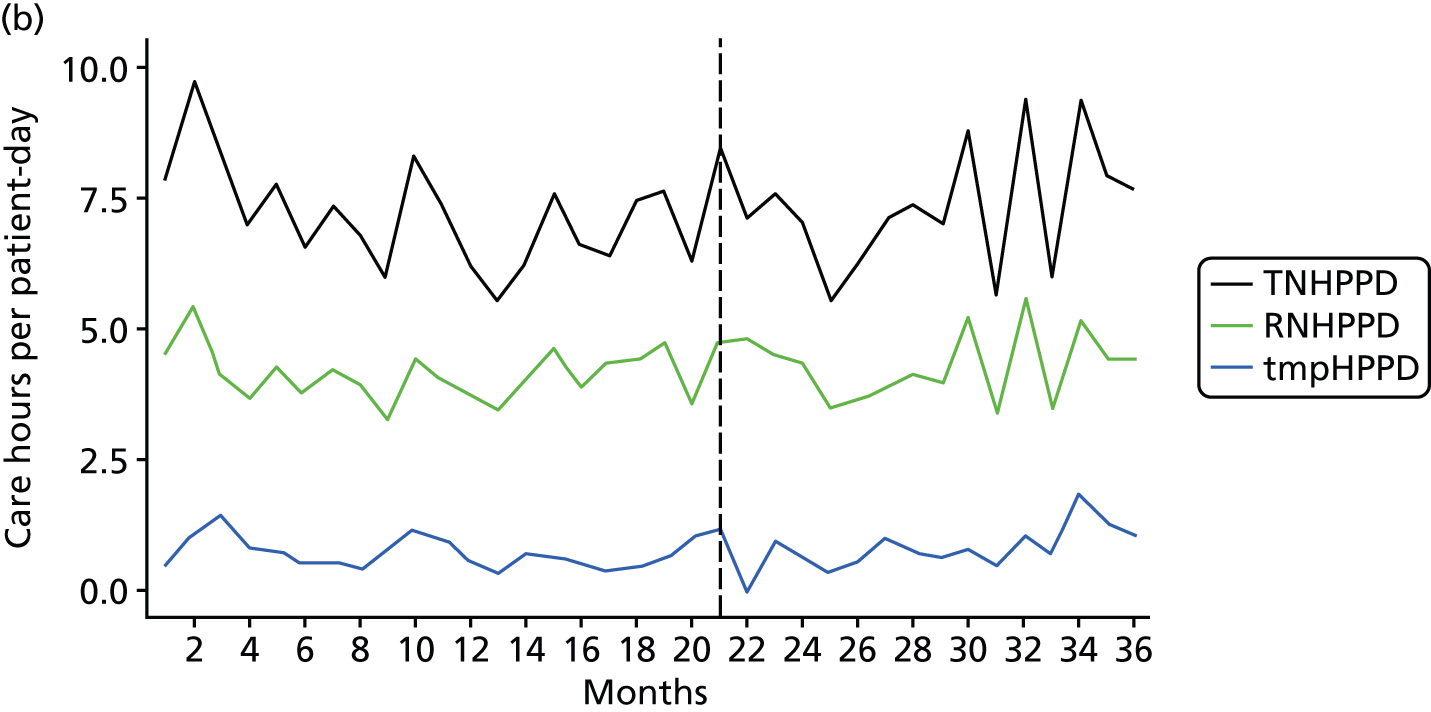

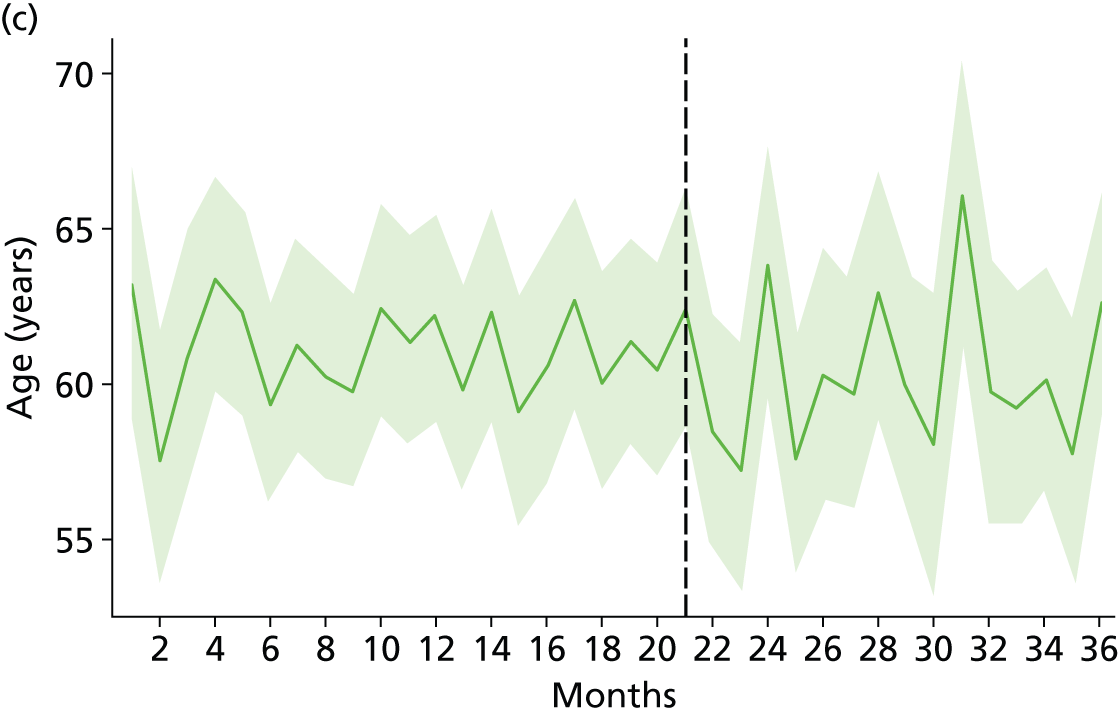

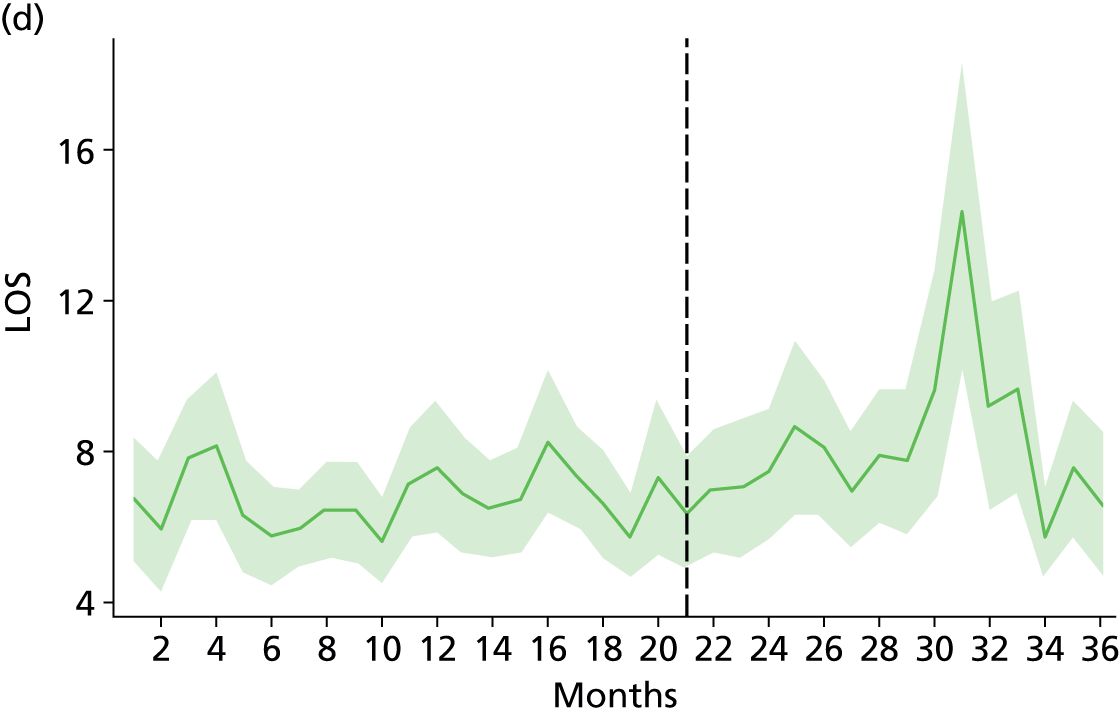

Theoretically, the comparison of trusts by trends of infections or safety events could be conducted at the individual, ward or hospital level. However, safety incidents such as falls, as well as hospital-acquired infections, are usually recorded in dedicated reporting systems, which contain information only about the harmed patients, thereby excluding information about the overall population of the ward or the trust. These data are often used for performance measurement and are available on the ward and/or trust level as volume-standardised rates (e.g. falls per 1000 bed-days). While individual-level data would allow risk adjustment and therefore reduce selection bias in the comparison of trusts or wards, individual-level data are rarely available in routine data. A different way of addressing selection bias is based on risk stratification, which groups in strata patients with similar characteristics. Analysing at the ward level by comparing wards of the same type (e.g. medical ward) partially achieves this goal, since most wards have specific populations where patients share similar characteristics. Therefore, safety incidents and hospital-acquired infection rates are analysed on the ward level. In addition, we use administrative data containing information on age, LOS, primary diagnosis based on the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10),104 Healthcare Resource Group (HRG) codes, and diagnoses used in the Charlson comorbidity index,105 to match wards with similar characteristics between trusts and to identify changes in the population over time.

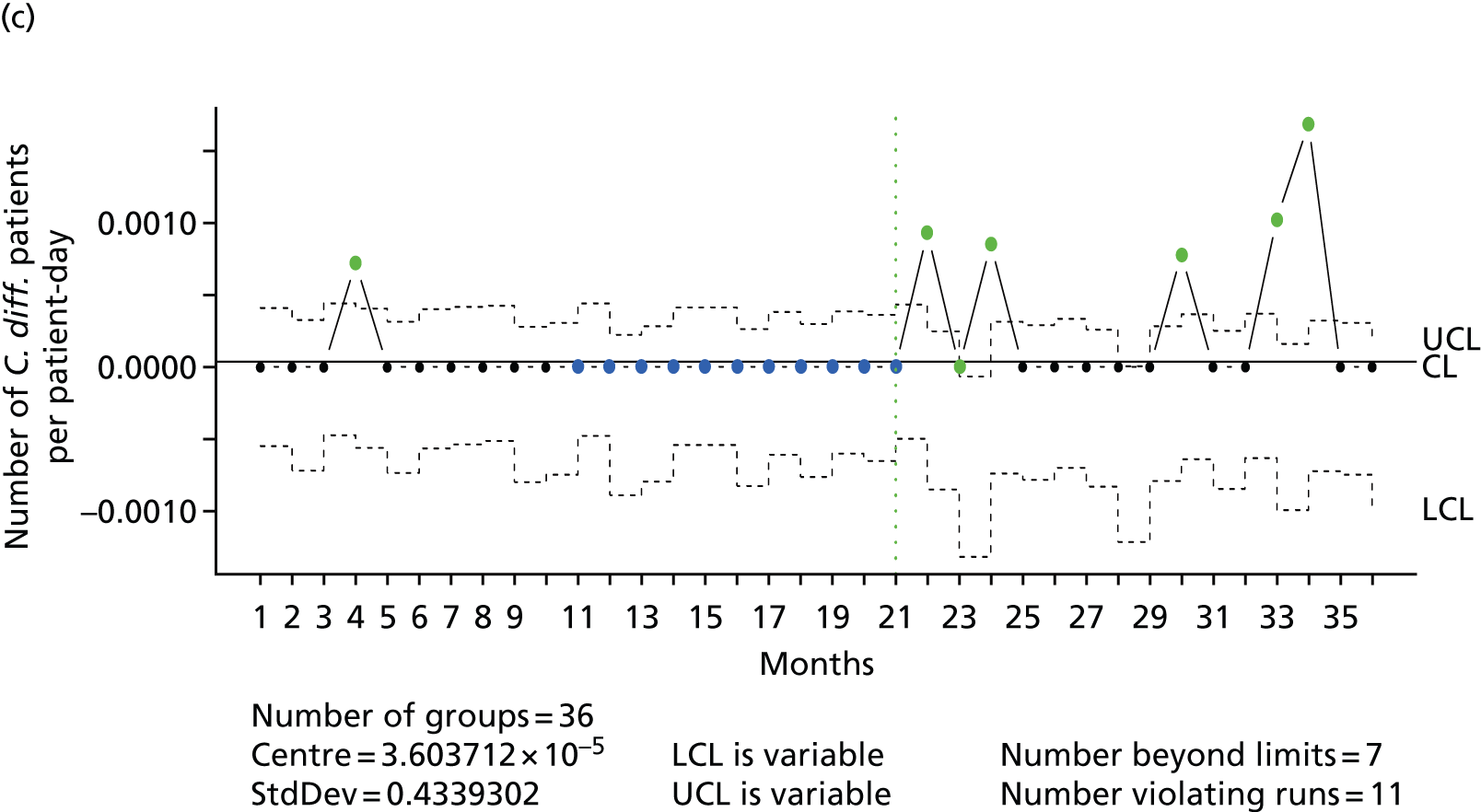

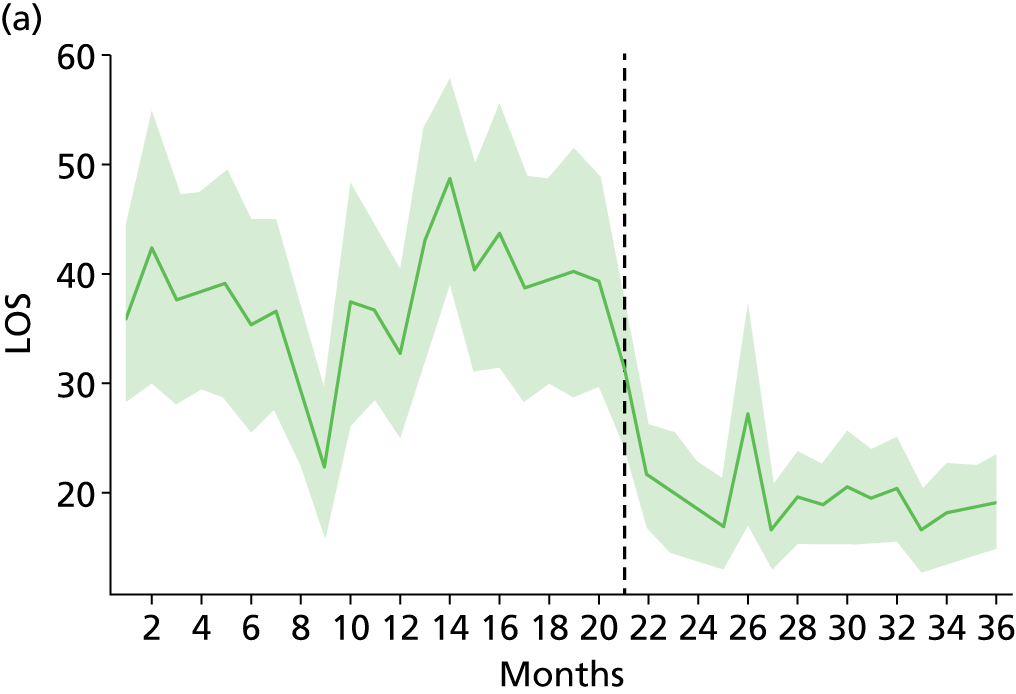

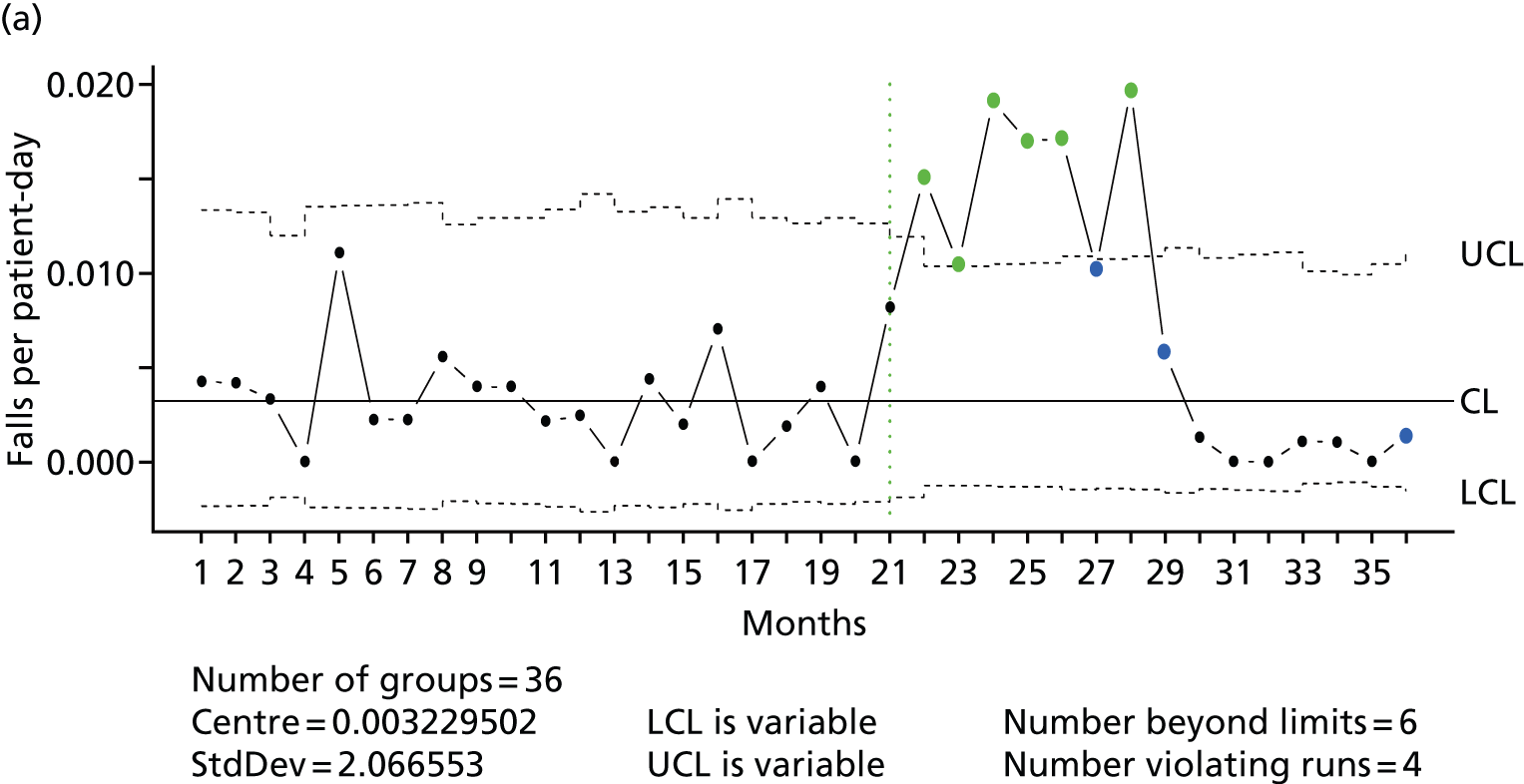

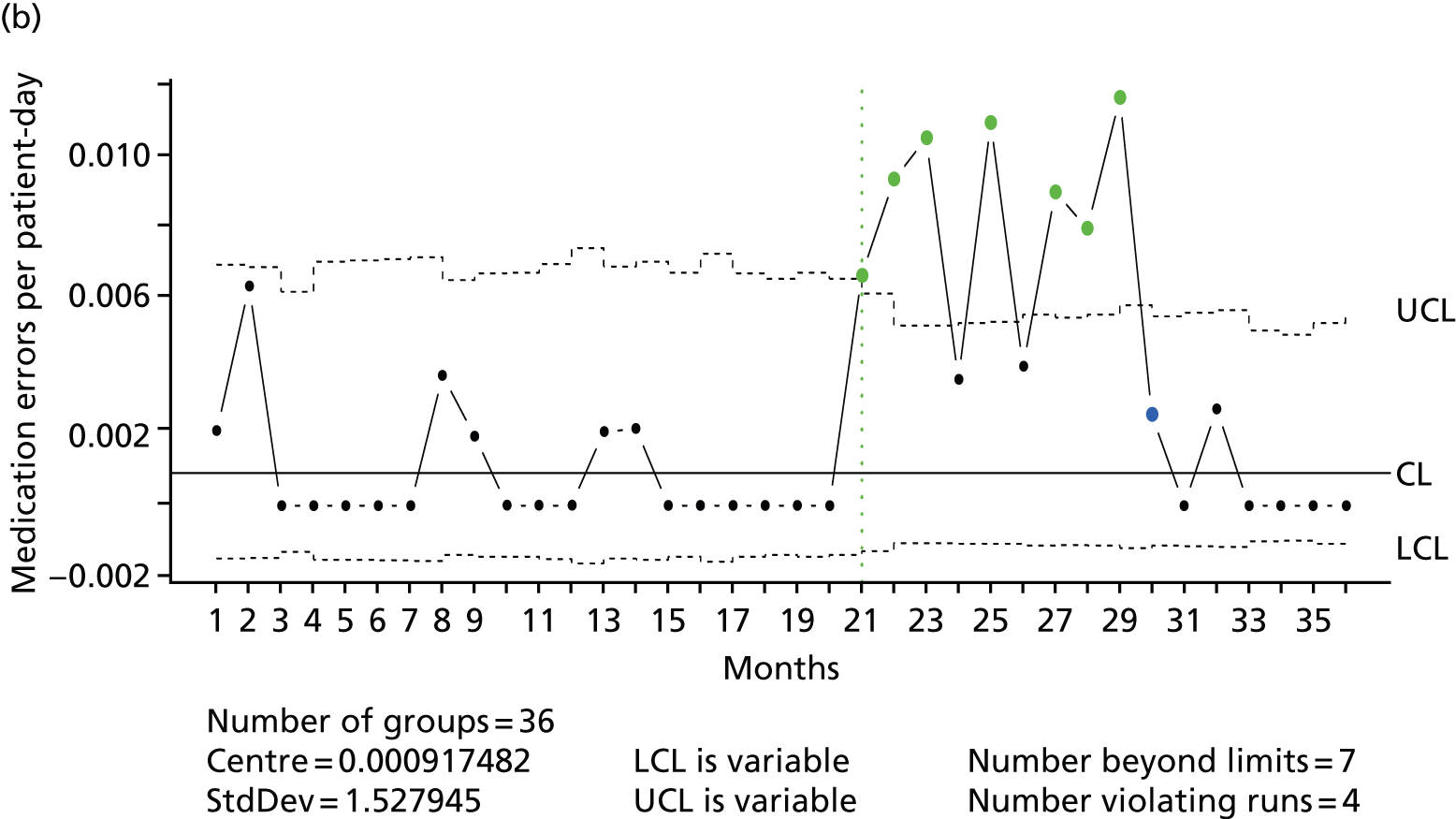

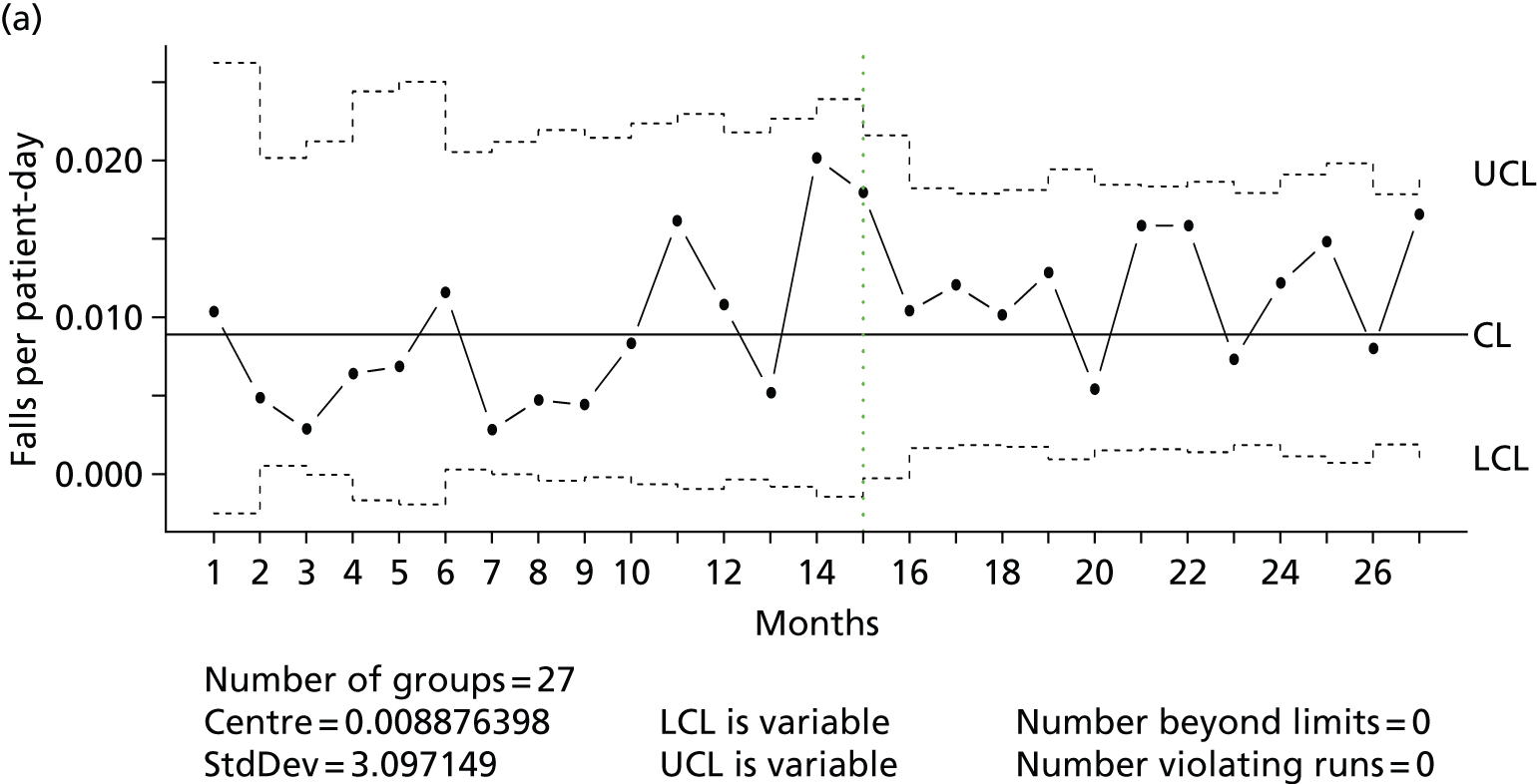

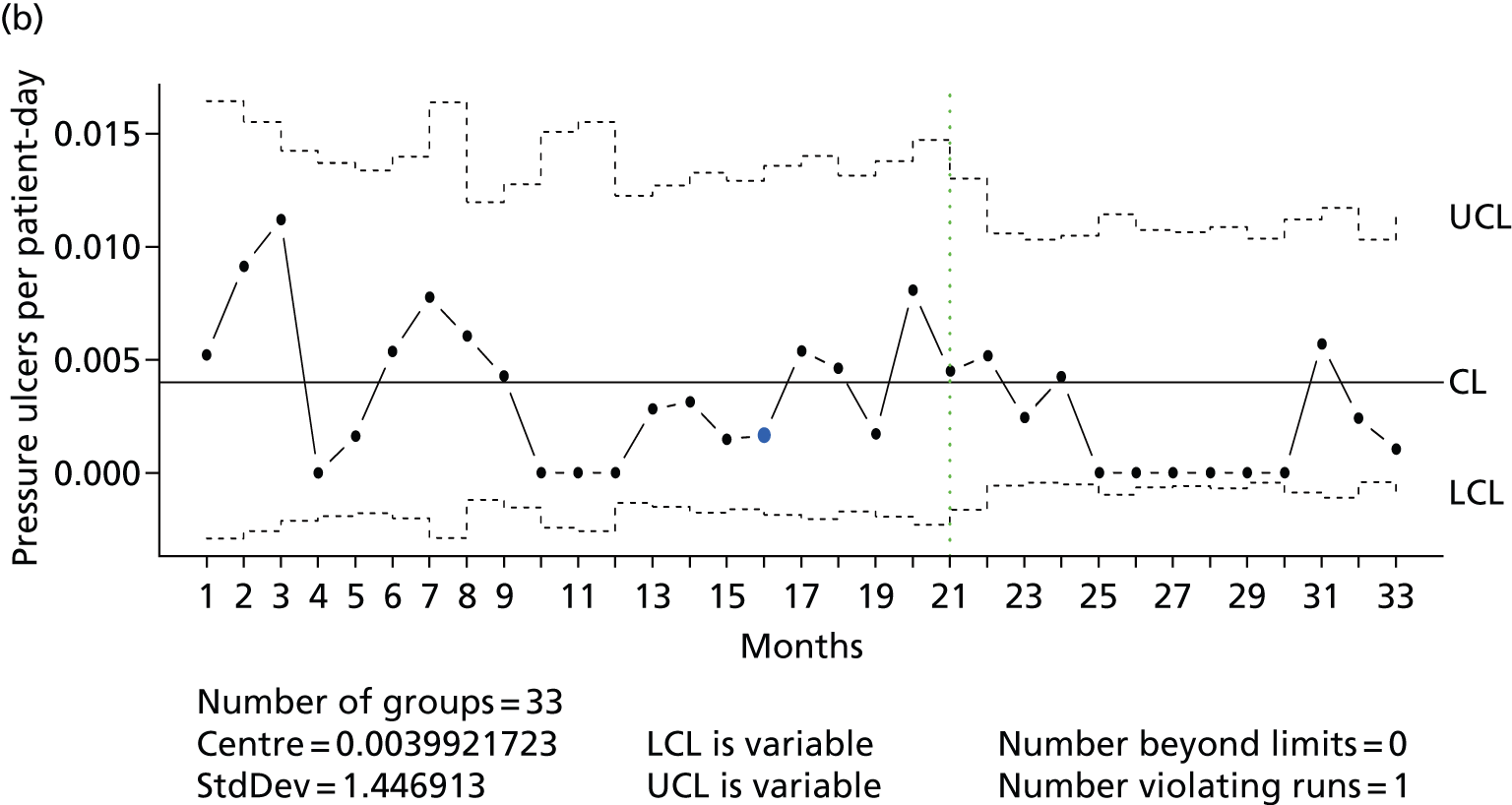

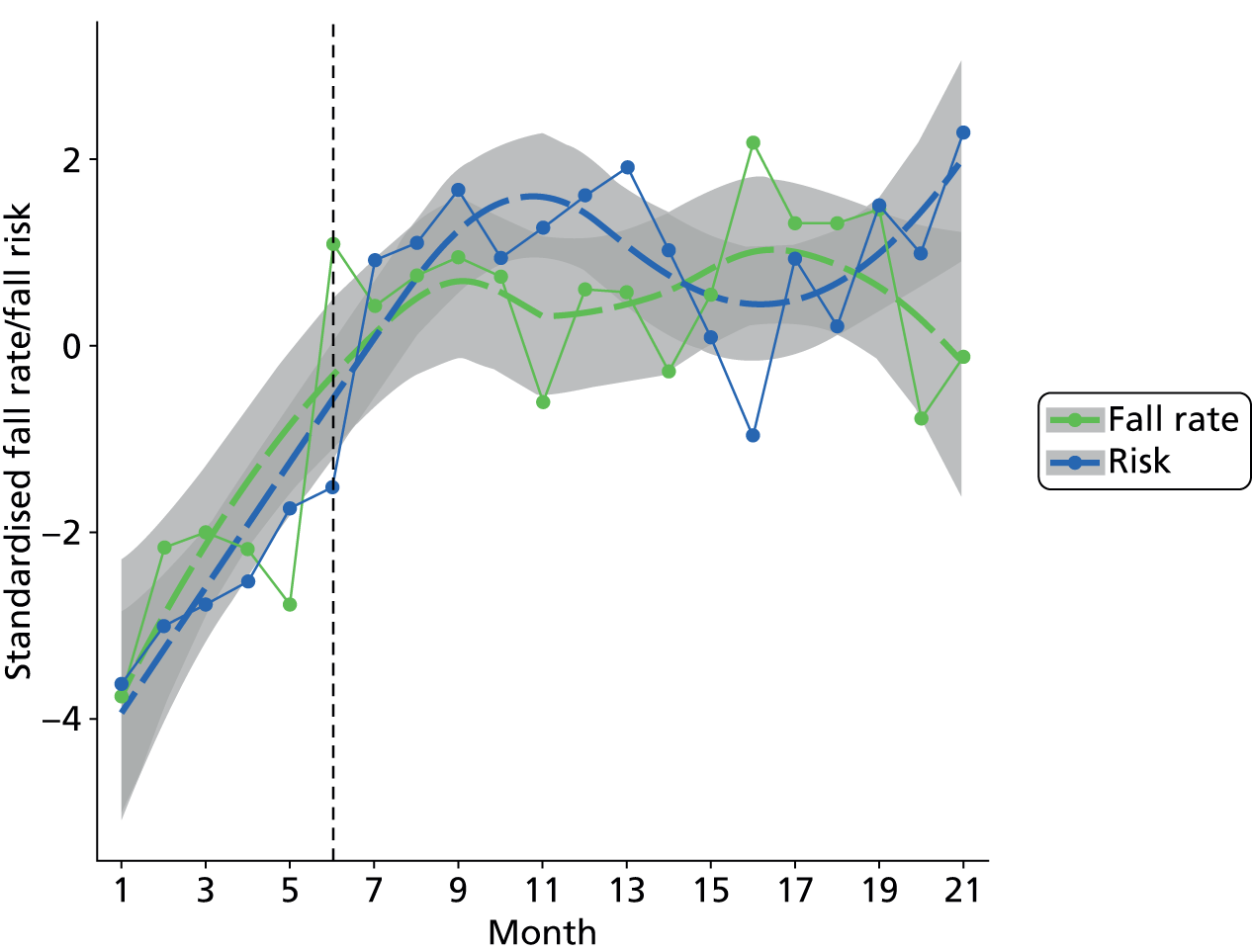

Assessing trends before and after the move, or identifying differences between trusts, and associating these trends with a single room effect requires four conditions to be met: (1) the outcomes of interest (safety events, hospital-acquired infections) change after the move to the ‘intervention’ (single room) site, while (2) the core characteristics of the patient population remain the same over time and (3) the core characteristics of the patient populations of the compared wards at the different trusts are broadly similar. Finally, (4) any identified effect is strongest at the single room site (Tunbridge Wells Hospital), weaker at the new building with mixed accommodation site and not present at the steady state control site. Based on these considerations, we first considered the data from Tunbridge Wells Hospital. When trends of a single room effect supported by statistical process control charts (SPCs) were apparent, we considered the comparator sites to assess if the pattern of results was consistent with a single room effect.

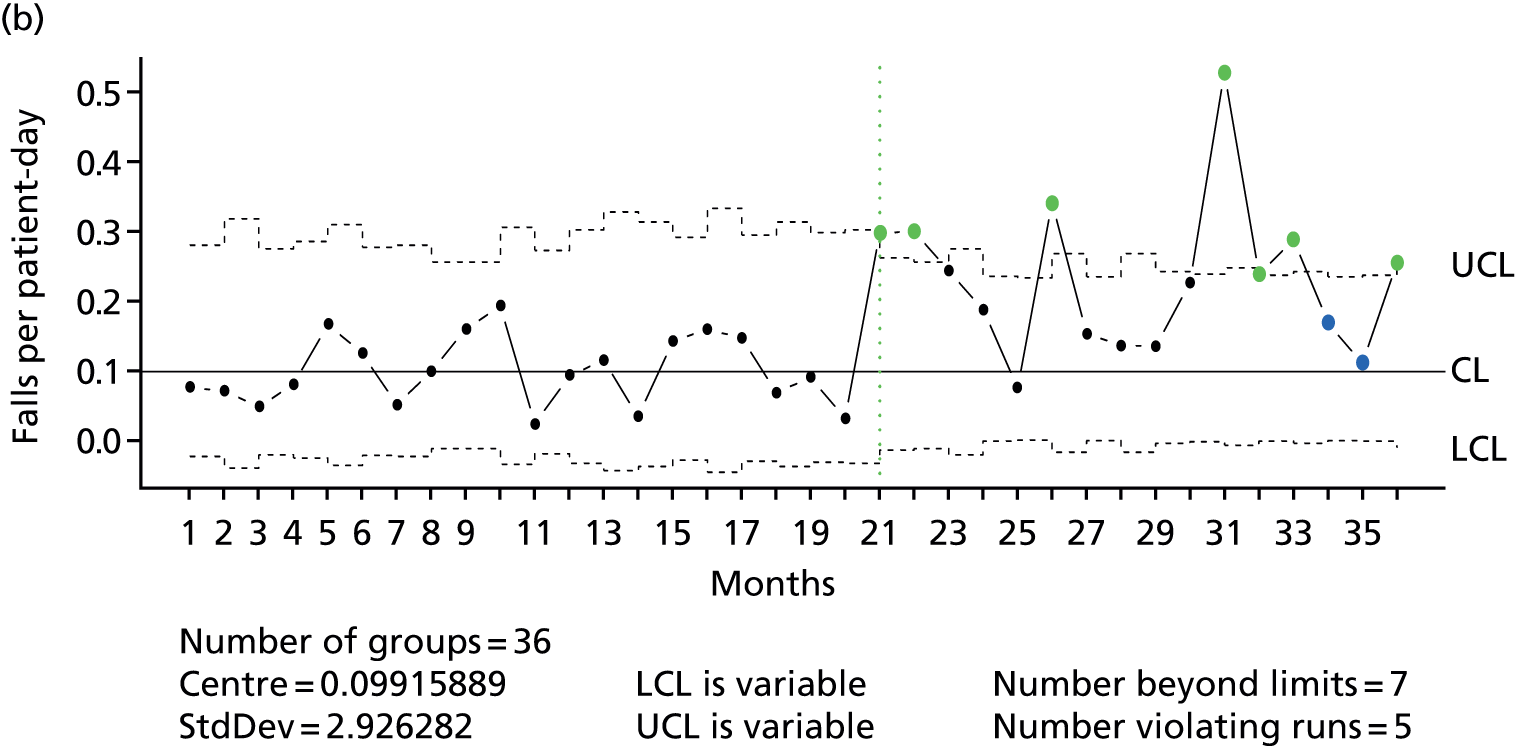

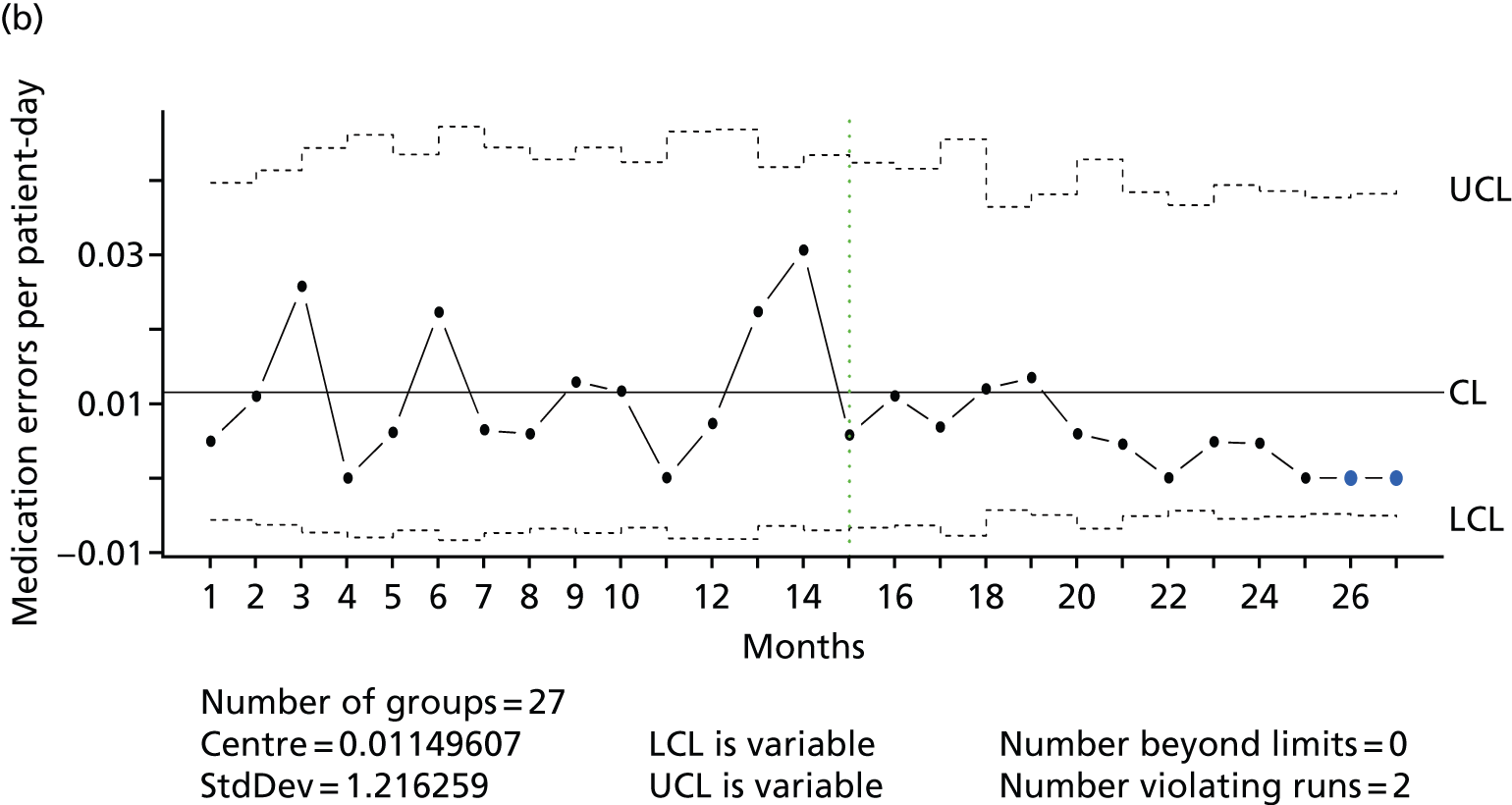

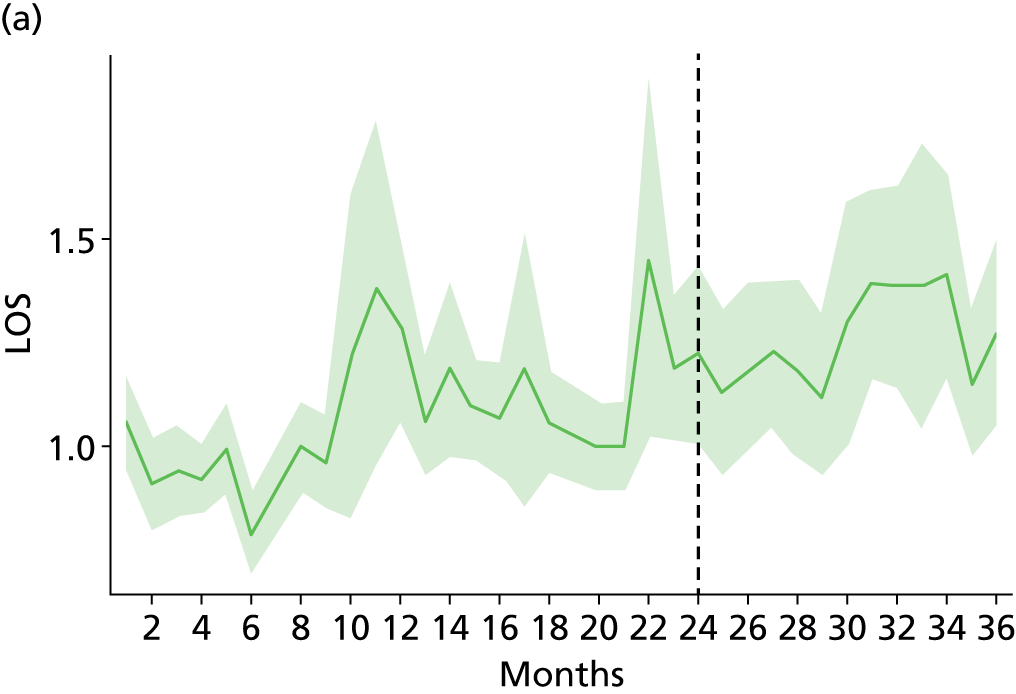

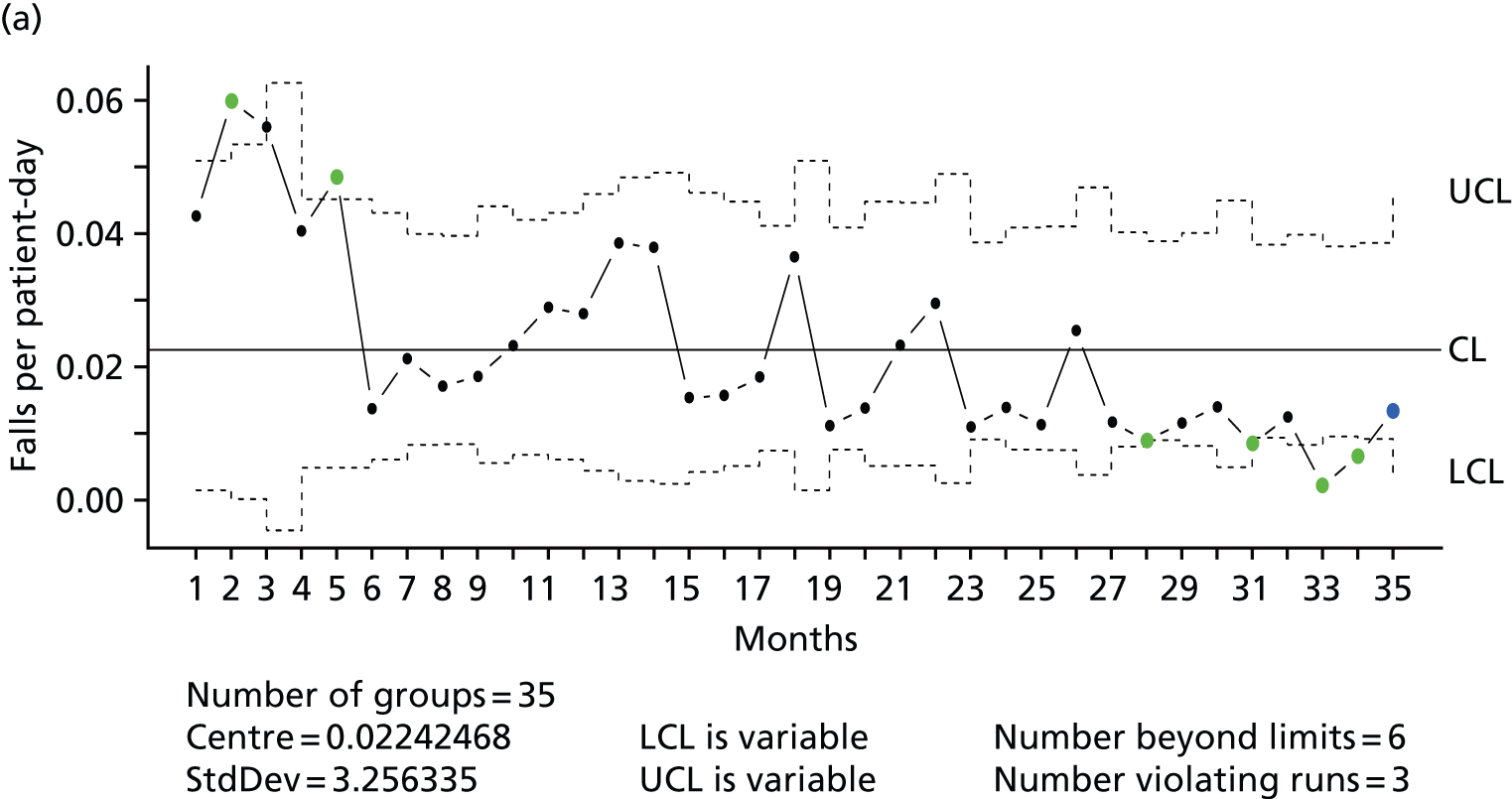

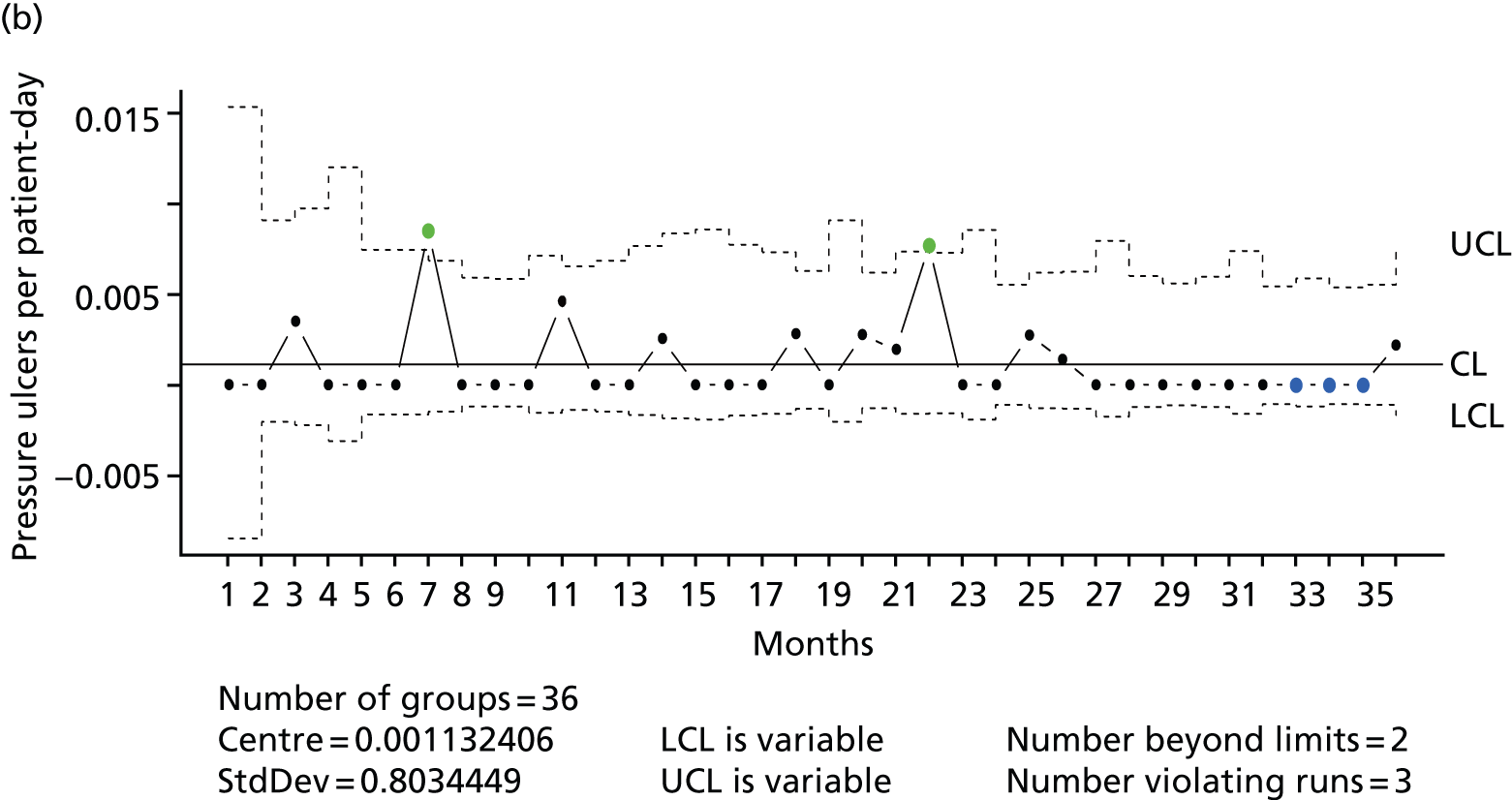

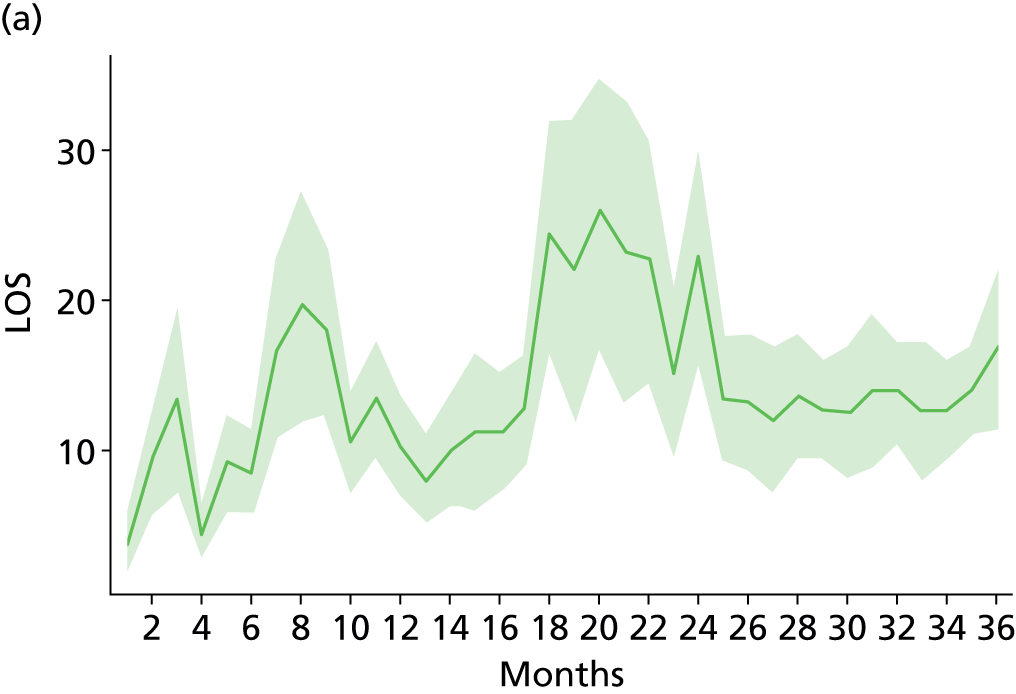

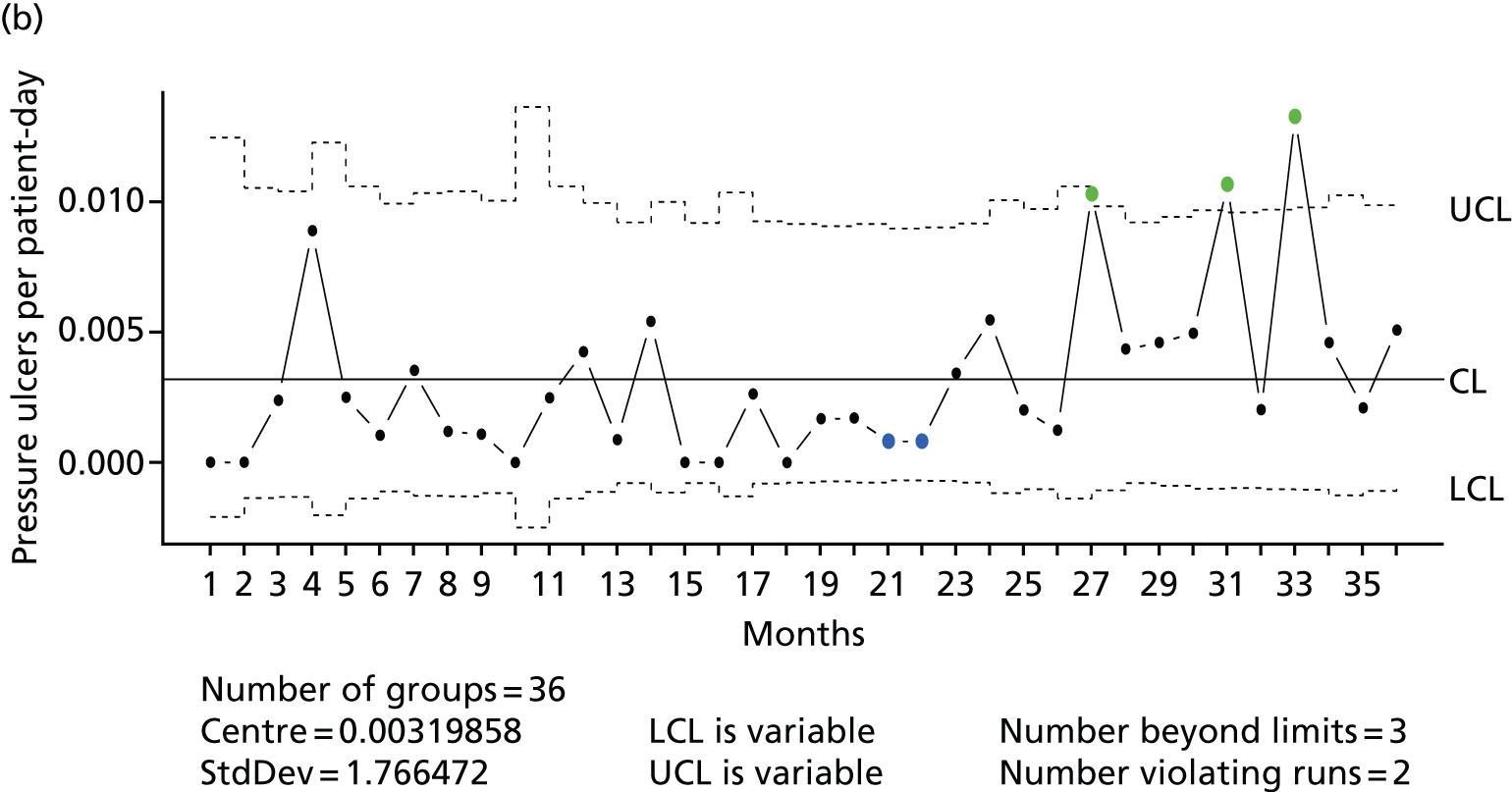

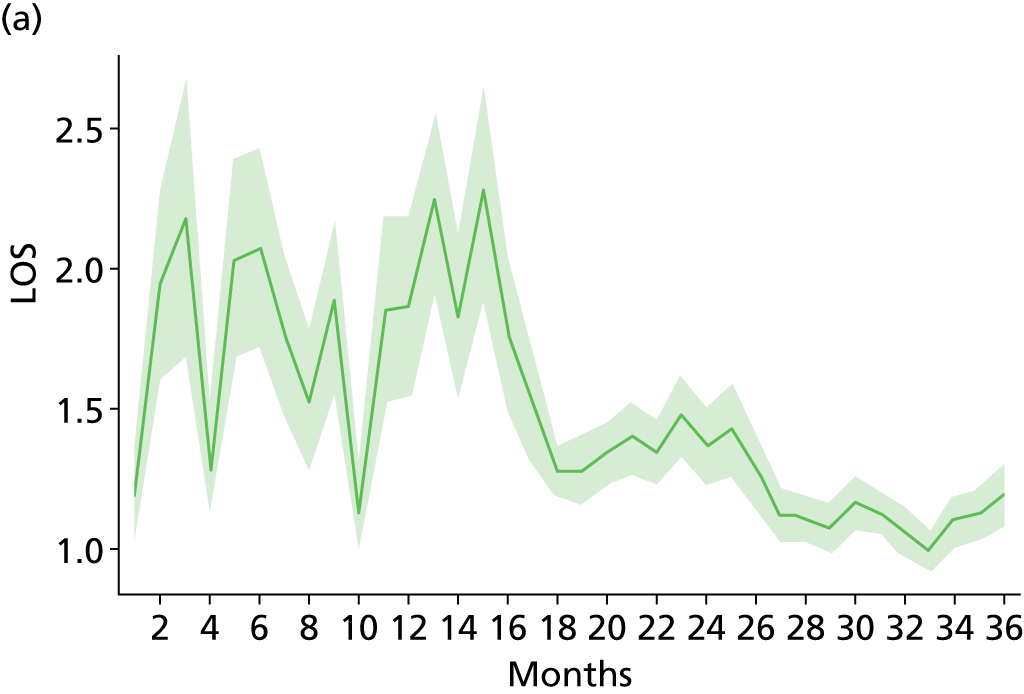

Statistical process control charts

Given the nature of the available data as monthly rates, and to analyse changes in safety events and hospital-acquired infection outcomes before and after the move, the analysis was conducted as an interrupted time-series analysis augmented by SPCs. SPCs plot the outcome of interest over time on a chart which contains a centre line (representing the mean) and upper and lower confidence limits, which are defined as three standard deviations below or above the centre line. SPCs allow differentiating between common cause variation, which refers to random error, and special-cause variation, which arises from actual changes in the level of the variable of interest. 106 Several rules identify special-cause variations, of which two are of particular interest to identify changes to safety events after the move: (1) one data point outside the confidence limits and (2) eight or more data points above the centre line. 106 This approach was taken because of the nature of the available data (generally monthly reports of rates over relatively short time periods). A regression-based analysis would be more appropriate if it were possible to risk adjust for differences in patient characteristics. However, this was not possible given the available data. Another alternative would have been to pool all data before and all data after the move and test for differences. However, this would have not allowed us to identify the patterns we have found. We therefore believe that this was the most appropriate approach to the data that we were able to collect.

For all outcomes, u-charts with Cornish–Fisher (CF) expansion were used, which are appropriate to handle varying sample sizes and count data with a Poisson distribution. 107 All charts were plotted with the Improved Quality Control Charts (IQCC; version 0.5; http://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/IQCC) package in R (version 3.1.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Matching

To identify similar wards across sites, individual-level data for age (mean), LOS (mean) and the percentage of diagnosis included in the Charlson comorbidity index were aggregated at ward level and inspected for matching with existing case study wards. Wards that most closely matched the aggregated measures and were of the same ward type (e.g. surgery) as the case study wards were selected for inclusion in the study (see Table 9). The wards at the new build mixed accommodation control site consisted before the move of eight-bedded, three-bedded and single rooms. With the move, the proportion of single rooms increased from 14% to 38% for the three included wards. The steady state control site had less than 10% single rooms.

Data management

Trusts were asked to provide data for a 3-year period from January 2010 to December 2012. Outcome data (safety events and hospital-acquired infections) were requested for the four case study wards (acute assessment, older people, surgery and maternity) at the old Pembury Hospital and their succeeding wards at the new Tunbridge Wells Hospital. These outcomes are all regarded as being sensitive to the quality and quantity of nursing care provided, with some (falls, infections) reflecting specific challenges or hypothesised advantages attributed to single rooms. 108 The same was requested from four wards of the same type at each of the control sites. Because of the low incidence – pressure ulcers, falls, MRSA and C. diff. – maternity wards were excluded from further analyses.

Routine data are captured in various ways. Table 10 summarises the sources and definitions of the different outcome and risk stratification variables. Data were received from several departments within each trust, including finance, human resources, infection control and nursing management. While definitions of ‘incidents’ recorded in this routine quality data are generally standardised (e.g. using recognised grading systems for pressure ulcers), the approaches to gathering data may not be. There is a risk of under-reporting. However, as the key aim was not to compare trusts but to scrutinise (differences in) changes within trusts, these data remain potentially useful, if limited.

| Variable | Source | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome | ||

| Falls | Incident reports | (Falls per month per ward/bed-days) × 1000 |

| Pressure ulcer | Incident reports | (Pressure ulcers per month per ward/bed-days) × 1000 |

| Medication error | Incident reports | (Medication errors per month per ward/bed-days) × 1000 |

| MRSA | Infection control | (MRSA cases per month per ward/bed-days) × 1000 |

| C. diff. | Infection control | (C. diff. cases per month per ward/bed-days) × 1000 |

| Matching/risk stratification | ||

| Age | Administrative | Mean |

| LOS | Administrative | Mean |

| Primary ICD-10 | Administrative | 10 most frequent four-digit ICD-10 codes |

| HRG | Administrative | Five most frequent HRG subgroups |

| Charlson index | Administrative | Percentage of diagnoses included in the Charlson index |

| Bed-days | Administrative | Sum of LOS per month per ward |

| Staffing | ||

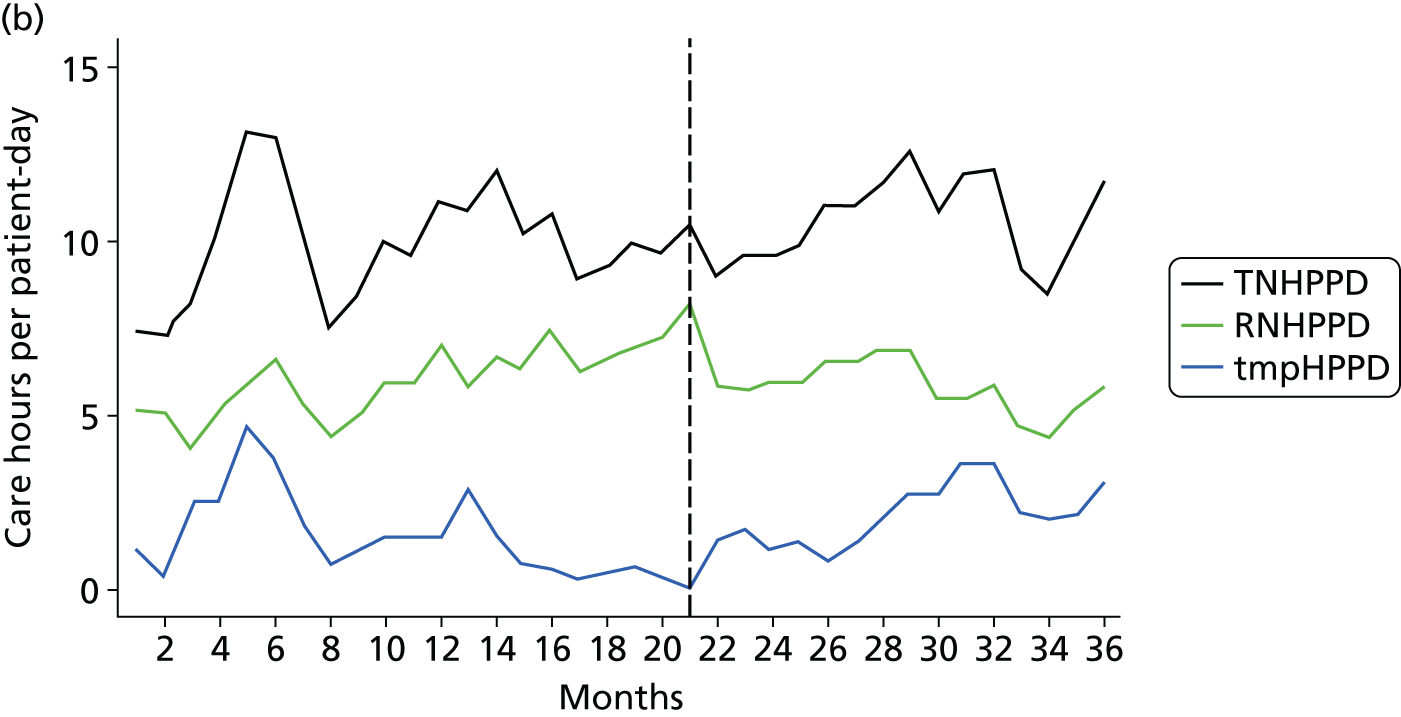

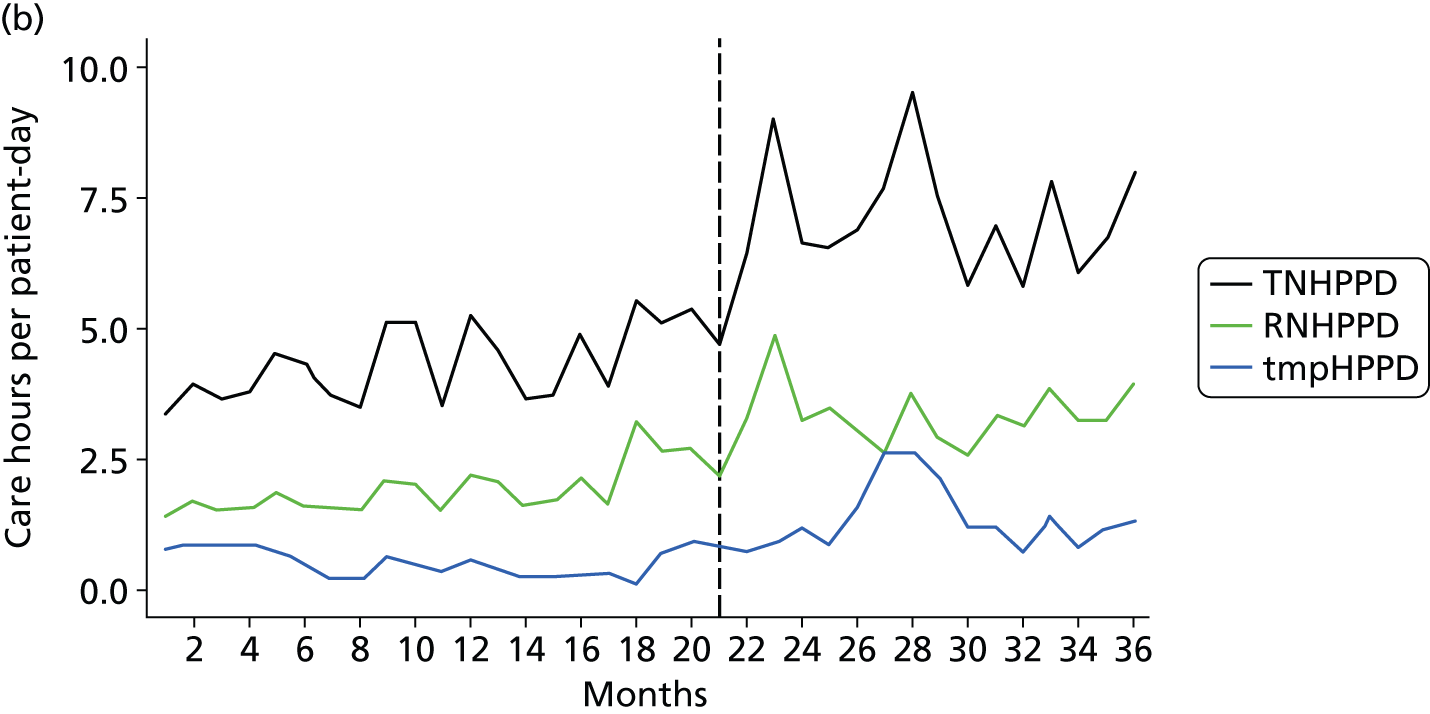

| WTE all nursing staff | Finance | Total nursing hours per patient-day |

| WTE RNs | Finance | Total registered nursing hours per patient-day |

| WTE temporary staff | Finance | Temporary nursing hours per patient-day |

Data availability

Because of the diverse range of sources, analysis on the ward level and changes in the data infrastructure, not all data were available for all wards throughout the investigation period from January 2010 to December 2012 (Table 11).

| Area | Variable | Tunbridge Wells | Mixed accommodation | Steady state | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute assessment | Surgery | Older people | Acute assessment | Surgery | Older people | Acute assessment | Surgery | Older people | ||

| Staffing | Total nursing hours per patient-day | 36 | 36 | 36 | N/A | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Total registered nursing hours per patient-day | 36 | 36 | 36 | N/A | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | |

| Temporary nursing hours per patient-day | 36 | 36 | 36 | N/A | 36 | 36 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| Case mix | Age | 36 | 36 | 36 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| LOS | 36 | 36 | 36 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 36 | 36 | 36 | |

| Volume | 36 | 36 | 36 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 36 | 36 | 36 | |

| HRG | 36 | 36 | 36 | 32 | 32 | 32 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| ICD-10 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 32 | 32 | 32 | 36 | 36 | 36 | |

| Outcomes | Falls | 36 | 36 | 36 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 36 | 36 | 36 |

| Pressure ulcer | 36 | 36 | 36 | 27 | 33 | 33 | 36 | 36 | 36 | |

| Medication error | 36 | 36 | 36 | 26 | 26 | 26 | N/A | N/A | N/A | |

| C. diff. | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | |

| MRSA | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | 36 | |

Missing data handling

For the mixed accommodation new build site, only 32 months of administrative data were available, which would have reduced the observation period that could be matched to outcome data. To impute the missing aggregate bed-days we calculated the mean and standard deviation of the previous 5 months (all post-move phase) and used these values assuming a normal distribution to randomly generate and impute four aggregate values. For missing outcome and staffing data, listwise deletion was used, which subsequently reduced the number of available time points.

Cost analysis

Design

Available data are described above (see Tables 10 and 11). Where possible, we aimed to gather differences in terms of unit of resources and outcomes before and after the move to single room design. Where it was feasible and relevant, changes in resource consumption and outcomes were investigated using real costs (e.g. cleaning and staff costs).

Data collection from expert opinion

A range of experts from the architecture, construction and facilities management industries were consulted, along with experts from hospital management and operations. The aim of these interviews was to seek views on the relative impact of different hospital designs on costs and resource use. These experts also provided opinion on the emerging research findings. Use of expert opinion is a relatively informal technique, but can be useful in clarifying the issues relevant to a particular topic and its evaluation, especially where the available research evidence or data are poor. Individual experts can be consulted, but groups of experts together are generally preferred to draw on a wide range of experience. 109

We drew up a list of experts from personal contacts and used a snowball sampling strategy to add to this list, and to include those connected with hospital construction (Table 12). Experts were contacted directly through e-mails or telephone, and meetings were arranged in person. An interview schedule with the main discussion topics was prepared in advance, together with a list of questions to be addressed (see Appendix 15). Nine experts were gathered in a group setting in order to stimulate and allow different perspectives or opinions to be discussed. One-to-one telephone interviews were arranged with three other experts.

| Institution/role | Skills/expertise |

|---|---|

| Director of Gateway Reviews and Estate Facility Management for NHS | Construction management, PFI |

| Commercial Leader of Laing O’Rourke Construction Ltd | Construction management, PFI |

| Bid Manager at Laing O’Rourke | Architectural design, health care |

| BIM Specialist at Skanska | Architectural design, health care |

| Managing Director at Steffian Bradley Architects | Architectural design, health care |

| Director at Steffian Bradley Architects | Architectural design, health care |

| Strategic advisor at comparator site (new build) | Strategic estate advice |

| General Manager – Facilities at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | Facility management, hospital management |

| General Manager at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | Facility management, hospital management |

| Associate Director of Nursing at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | Nursing management, staff management |

| Head of Domestic Services at comparator site (steady state) | Facility management |

| Head of Financial Management at Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust | Management finance, costing, health care |

Analytical approach

Construction and facilities management costs

Construction and operating/maintenance costs were assessed using a combination of data from the literature (see Chapter 2 and Appendix 1); the outline business case for the new hospital; stakeholder views; the health-care premises cost guides; and Estates Return Information Collection (ERIC) data over a sample of hospitals. Net present value of construction costs and life-cycle operating costs were assessed using a 3.5% discount rate over the first 30 years and a 3% discount rate for the next 30 years, making a total of 60 years.

An estimate of the difference in cleaning costs over 1 year was calculated using administrative data and assuming three different scenarios: 100% single rooms, 50% single rooms and 100% multi-bedded rooms. Costs were assessed assuming each hospital would host the same number of patients but in three different room designs.

Cost of nurse staffing before and after the move to single rooms

The cost impact of changes in nursing whole-time equivalent (WTE) before and after the move using the actual monthly WTE in each case study ward was assessed. The monthly WTE of each staff category (bank nurses, agency nurses, trained and untrained nurses) was costed using the monthly salary in each salary band. This was drawn from Royal College of Nursing (RCN)110 data on pay rates for bands 1–9 for each year from 2009 to 2012110 and data on unit cost of health and social care111 to estimate the unit cost for WTE.

The average monthly WTE has been multiplied for the corresponding monthly pay rate in each month. The 2010–11 pay rate was used for monthly WTE before the move and the 2011–12 pay rate for the monthly WTE after the move. Pay rate differs according to staff band; therefore, we applied the salary corresponding to each band using the average of all pay scales in each band.

Extra nursing time, workload and patient contact time

We used monthly data from January 2010 to August 2011 for the period before the move and data from September 2011 to December 2012 for the period after the move.

We used the time (in seconds) of the activities nurses spent in contact with patients (e.g. direct care, indirect care or medication activities at the bedside) using the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Tables 13–16). Data were carefully analysed to exclude any direct care where the patient was not present (e.g. with relatives or while the patient was away) and included any indirect care, ward-related activity or medication activities where the patient was present with the nurse (e.g. helping the patient in the toilet, taking temperature in the ward, escorting the patient to another ward). The time in seconds before and after the move spent in contact with patients was compared with the total time of a 12-hour shift (in seconds) to calculate the proportion of patient contact activities over all the nurses’ activities during a shift.

| Activity | Location | Comment on activity for inclusion (I) or exclusion (E) | Time (seconds) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | |||

| Direct care | At bedside | All activities of direct care at bedside are in contact with patient (I) | 33,150 | 37,404 |

| No value | If there is no location we assume it is direct care with the patient (mainly all these activities are with the patient, e.g. ‘check male patient ok as walking down ward’) (I) | 782 | 0 | |

| Nursing team | Nurse is clearly with a relative and not with patient (e.g. ‘relative asking re social services’) (E) | (69) | (119) | |

| On ward | Unless it is clearly stated otherwise, nurses are in contact with the patient (e.g. ‘assisting patient walking’, ‘walking with patient to loo’) (I) | 1662 | 2368 | |

| Activities with relatives where the patient is clearly not there (e.g. ‘speak with relative’, ‘bed 20 buzzing’) (E) | 0 | (284) | ||

| Toilet | All activities of direct care in the toilet are in contact with patient (I) | 705 | 612 | |

| Documentation | At bedside | All activities of documentation at bedside are in contact with patient, unless explicitly stated that the patient is away (e.g. ‘care plan re what eaten’) (I) | 2224 | 1031 |

| All other locations (office, nurse station) | Documentation activities away from the bed are not in contact with patient, unless clearly stated (E) | (5475) | (10,243) | |