Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/2002/52. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in June 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by White et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Hospitals feature significantly in the lives of many children who come to harm at the hands of their parents or carers, and diagnostic and other errors are not uncommon. These have proved resistant to standard policy responses, and reviews into decision-making in high-profile cases tend to reassert familiar imperatives – particularly that professionals should ‘share information’ in order to identify and protect children at risk. Despite radical reforms to safeguarding processes and systems over the last 10 years, errors and failures persist in detection and intervention when children at risk present in secondary care. There is no ‘gold standard’ for the diagnosis of child abuse. Harmful incidents to a child are rarely independently witnessed and, unless there is perpetrator confession, reliance is placed on substantiation of reasonable suspicion at case conferences or in the civil courts (that the occurrence of abuse was more likely than not). The consequences of an incorrect diagnosis of child maltreatment in either direction can be catastrophic. A false-negative diagnosis of a ‘sentinel’ or ‘harbinger’ injury, such as facial bruising or oral injury, in a non-independently mobile infant may precede severe and sometimes fatal abuse. 1 A false-positive diagnosis of inflicted injury in a child presenting with, say, a scald could have serious consequences, including needless separation of the child from his or her family. 2

The last decade has seen the rise of the patient safety paradigm in health, with three major reviews taking place in England in 2013 – the Francis, Keogh and Berwick reports – arising from the events at North Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. 3–5 These emphasise, variously, social and organisational processes, including the importance of communication, feedback loops, confidential reporting and organisational learning. However, these are rarely modelled in detail to take account of the social and cultural dynamics of child health settings and children’s safeguarding. This remains a relatively neglected area, despite being associated with high risks, including child deaths. For example, while tools exist for detecting risk [it has been estimated that 91.7% of emergency departments (EDs) have some form of written protocol6], little is known of their effectiveness in influencing clinical behaviour, and follow-up of child protection outcomes is typically absent. 7,8 To date, mainstream patient safety research has tended to emphasise safety within clinical specialities, departments or units, such as operating theatres or EDs, with less attention paid to multiagency systems, the wider organisation and beyond. In children’s health care, the complexity of human factors is somewhat broader than in many other clinical domains, not least because the decision-making network is dispersed and the potential risks to children are outside rather than inside the hospital walls. Thus, the interface between hospital-based services for children and local authority children’s social care (CSC) is crucial. Very recently, there has been increased attention to this domain, which is beginning to draw attention to the importance of human and interactional factors,9 with increased emphasis placed on clinical governance through the use of best evidence, audit and, more recently, supervision and peer review. 10

Alongside developments in patient safety, the child protection system has also been subject to a number of major reviews, with the most recent11 making recommendations about the need to move away from a compliance culture, to support professional judgement and to develop learning cultures in CSC organisations. These chime with the recommendations of the Francis,3 Keogh4 and Berwick5 reports, potentially providing an opportunity for a system redesign that takes into account the specific challenges of safeguarding children at risk. This study examines the interstices between hospitals and CSC. It looks in detail at the factors affecting decision-making and knowledge sharing in secondary health-care settings to argue for a more sophisticated engagement with the complex factors at play. It draws substantially on the patient safety paradigm and associated concepts relating to organisational culture and change.

Specifically, the study is focused on supporting and evaluating clinician-led service design in an acute trust in the north-west of England, where the relative neglect of safeguarding in patient safety initiatives had prompted senior clinicians, with strong support from the executive board, to rethink their processes and practices. A suite of initiatives and artefacts has been designed to combine both bottom-up initiatives and top-down governance,12 which has been shown to be effective in promoting cultural change. Their intended outcome is to create a positive safety culture, characterised by openness, justice and learning, where learning from error is regarded as the norm. 13 The various initiatives are described in detail in Chapter 6 of this report, but are summarised below (Table 1).

| Module | Cultural emphasis | Components |

|---|---|---|

| Governance | Promoting board-to-ward communication and feedback | Walkround |

| Electronic reporting | Promoting a reporting culture | Electronic information sharing form based on patient safety principles |

| Quality control (co-mentoring) | ||

| Special circumstances form for maternity cases | ||

| Storytelling | Safeguarding awareness and the sharing of professional knowledge | Case discussions based on systemic incident analysis |

| Digital stories |

Research aims and objectives

This project follows a ‘whole systems’ approach aimed at addressing these deficits in the knowledge base, and is also oriented to action and to creating a culture of safe practice with children at risk, using a user-centred design methodology. It is designed to address the following primary question:

‘Can a safeguarding culture be designed within the hospital environment that will provide the conditions for the detection of children at risk of abuse and support protective actions before discharge, including collaboration with external agencies?’

More specifically, the objectives comprise:

-

the development of a sociologically rich understanding of why diagnostic failures and communication breakdowns occur

-

the design of a suite of integrated interventions for promoting a positive safety culture, following a user-centred approach

-

the evaluation of the effectiveness of this package, including its generalisability across sites.

The project addresses cultural and organisational issues, uses applied methodologies within a multidisciplinary team, makes better use of existing research knowledge through system redesign, and is centrally concerned with knowledge transfer within and between organisations, seeking to provide measurement of quality improvement.

In addition to contributing to the design of innovations in the primary site, the project has been concerned with the adoption of the safeguarding system in new sites. Understanding the transfer of technologies between contexts is crucial if benefits are to be accrued across the NHS. In a review of research on the diffusion of service innovations, Greenhalgh et al. 14 concluded with a call for research to address the following key question:

By what processes are particular innovations in health service delivery and organization implemented and sustained (or not) in particular contexts and settings, and can these processes be enhanced? This question would benefit from in-depth mixed-methodology studies aimed at building up a rich picture of process and impact. 14

The present study aimed directly to address this gap, following the requisite disciplined, eclectic approach. In a recent comprehensive review of technology adoption in health care, the provision of ‘firm evidence of clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness’ was identified as a primary determinant of successful adoption. 15

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 reviews a diverse range of literature on safeguarding and on organisational systems and cultures. Chapter 3 outlines the methods and natural history of the project. Chapter 4 primarily addresses the first objective of the study – the development of a sociologically rich understanding of why diagnostic failures and communication breakdowns occur – using data from the study to illustrate the everyday complexities of knowledge making and sharing in relation to safeguarding concerns in the hospital context. Chapter 5 builds on this to explore the perspective at the receiving end of information in CSC. Chapter 6 addresses objectives 2 and 3 and details the artefacts in use in site 1 and their evaluation, and also includes a description and formative evaluation of systems in use in site 2. Chapter 7 concludes the study, with particular reflection on the potentialities and challenges of innovation and technology transfer in complex public service bureaucracies. It attends to the principal research question of whether or not a safeguarding culture can be designed that will provide the conditions for the more accurate detection of children at risk of abuse and support protective actions before and after discharge.

Chapter 2 ’Wicked issues’ in safeguarding children

This chapter reviews a range of extant literatures which underpin the study. It begins with an examination of what is known about child protection practice and the complexities of the reasoning processes involved. Attempts to reform policy are critically reviewed. It is argued that the ‘process paradigm’, which sees organisations as technical networks of business processes and has been dominant in the public services [as a central feature of the new public management (NPM)] for at least two decades, is not optimal for children’s safeguarding. 16,17 The chapter then reviews the literature on safety cultures, pivotal to understanding the innovations in our primary site, and concludes with a brief review of some of the seminal work on technology adoption, given our interest in transferring these innovations to other settings.

Policy context

[C]hild protection raises complex moral and political issues which have no one right technical solution. Practitioners are asked to solve problems every day that philosophers have argued about for the last two thousand years . . . Moral evaluations can and must be made if children’s lives and well-being are to be secured. What matters is that we should not disguise this and pretend it is all a matter of finding better checklists or new models of psychopathology – technical fixes when the proper decision is a decision about what constitutes a good society.

p. 24418

Written 30 years ago, this closing paragraph of a detailed ethnography of child protection underscores the ethical imperatives and dilemmas at the core of clinical practice in this area. This counsel has not been heeded, and ‘the child protection system’ has arguably been subject to a series of technical fixes. Thus, the key moral debates have not taken place and service design has tended to be based on a series of misreadings of the realities of the work. This study is focused directly on the pressing matter of ‘design’ and has entailed a detailed examination of everyday safeguarding practices in secondary health settings where problems of detection and action to protect children at risk have proved recalcitrant, despite the fact that statutory frameworks and policy/practice guidelines are well established and that there are ongoing attempts to refine and improve them.

The Children Act 198919 introduced the concept of significant harm as the threshold for justifying compulsory intervention in family life in the best interests of children or unborn babies. 19 Much professional activity in relation to safeguarding children is oriented to deciding whether or not the presenting circumstances constitute ‘reasonable’ cause for referral to CSC for a section 47 investigation. Section 47 of the Act places a duty on local authorities to make enquiries, or cause enquiries to be made, where there is reasonable suspicion that a child is suffering, or is likely to suffer, significant harm. When this threshold for intervention is deemed to be reached, the duty to seek parental consent for information sharing is dispensed with. In many cases, particularly those presenting in secondary health settings, knowledge about the family or child is either too ambiguous or too incomplete to warrant a section 47 referral, even though professionals may have serious concerns about children’s well-being. In these circumstances, they may make a referral under Section 17.1(a) of the 1989 Act19 which gives local authorities a duty to ‘safeguard and promote the welfare of children within their area who are in need’. In relation to both of these categories, local authorities will, in turn, make decisions about whether or not the criteria are met. Thus, a case may be referred to children’s services, but may still fail to make it over the threshold of the ‘front door’. This makes this interface particularly thorny and elevates the importance of professional ‘information practices’, namely the way professionals handle and present information in particular ways to serve particular purposes.

The importance of ‘sharing information’ is underscored in statutory guidance. In 1988, the then Department of Health and Social Security began attending to the need to ensure multiagency working in child protection, producing the first version of Working Together, which provided detailed prescriptions for competent interagency working. 20 These measures were intended to protect children from ‘inter-agency dangerousness’ (p. 13), by ensuring that significant details were passed between agencies. Working Together has been through a number of iterations since, and in its penultimate form in 2010 the document had grown to 393 pages in length as the government tried to pre-empt every communicative eventuality. This has recently been stripped back to 97 pages following attempts to cut the bureaucratic burden in child protection practice,21 but it remains the primary guidance for multiagency working in child safeguarding. The new Working Together to Safeguard Children has the explicit aim of shifting the focus away from processes and onto the needs of the child. 22 However, most of the responsibilities and procedures in this 2013 document remain the same as the 2010 guidance. These are underpinned by a key principle, that ‘safeguarding is everyone’s responsibility’, but this is a deceptively complex imperative in everyday practice, particularly when services are under pressure.

Brandon et al. 23 estimate that, currently, the total number of violent and maltreatment-related deaths of children (0–17 years) in England is around 85 per year. In 50–55 of these cases, death was directly attributable to violence, abuse or neglect, with a further 30–35 in which maltreatment was a factor but not the primary cause. Despite policy changes, the numbers of child deaths has remained relatively constant and, in contrast with their political significance, comparatively low. 24 The most recent data suggest that fewer such deaths are occurring in children already known to the child protection system and in infancy, although this remains the period of highest risk. 23,24 Nevertheless, accurately detecting children at risk without encroaching on the privacy of family life has proved a very vexing problem with a turbulent recent history. Moreover, while secondary health-care settings should provide opportunities to prevent children returning to unsafe situations, or to alert other agencies to potential dangers, there is strong evidence that clinicians under-report child protection concerns9,25,26 and that triggers for reasonable suspicion are highly variable, particularly in relation to older children. 27,28 In one of very few studies examining the interface between hospital services and CSC, Lupton et al. 29 found that clinicians in EDs believed that other agencies and professionals had unrealistic expectations of their role in child protection work. Clinicians’ thresholds for reasonable suspicion are variable and highly subjective. In a ‘judgement analysis’ of the decision-making of a hospital-based child protection team in respect of referral to Social Services,30 involving 915 cases over a 7-year period, it was found that 81.7% of reported cases were substantiated through systematic decision processes that reflected current knowledge. However, single-parent families in financial difficulties were more likely to be reported, a finding that echoes other studies. 31 The authors were unable to determine whether this reflected a true association between low-income, single-parent families and child maltreatment, or a prior bias or stereotypical view of such families.

Under-reporting of suspected child abuse cases tend to reflect clinicians’ personal experience, beliefs and attitudes. 32 Factors associated with under-reporting include prior knowledge of the family,33 lack of confidence in the child protection system and its perceived adverse consequences for the child and family,33,34 and previous negative experiences of the child protection system and the courts. 33–35

Clinicians’ interpretation of ‘reasonable suspicion’ is also highly subjective,36 although a central diagnostic tenet, of an injury being suspicious when the history is inconsistent or implausible, is generally adhered to. 32 Using case vignettes abstracted from real clinical situations, Lindberg et al. 37 showed that experienced paediatricians agreed substantially at either pole of an ordinal scale, from definitely not inflicted (e.g. disinterested witness to a road traffic injury, mimic of bruise such as a birth mark) to definitely inflicted (e.g. unexplained multiple fractures, patterned bruising) injury, but showed considerable variability in agreement with ‘intermediate’ case scenarios (e.g. bruising in a setting of possible ‘easy bruising’). This accords with clinical experience, where diagnostic uncertainty that accompanies such ‘grey’ cases can lead to circumspection and indecision. 38

Despite the emerging evidence base, there are signs of physical injury that remain equivocal and situations where the likelihood of physical abuse is difficult to determine. For example, the characteristics of bruising suggestive of physical abuse are, to some extent, seen in children with an underlying blood coagulation or connective tissue disorder. Both physical abuse and bleeding disorders may coexist and the diagnoses are not mutually exclusive. 39

A suspicious injury may remain the only concern when a child protection investigation has been concluded and known risk factors have been eliminated as far as possible. In these situations, the investigating team will turn to the paediatrician to adjudicate, as the balance lies with the medical evidence alone. This is a very difficult and uncomfortable position for the professional. Could this be a non-intentional, ‘one-off’ injury that, for some reason, was not witnessed; or is the nature of the injury, whether abusive or otherwise, being concealed out of fear of repercussions; or will this be regarded as a ‘harbinger’ if the child represents with a more serious injury?

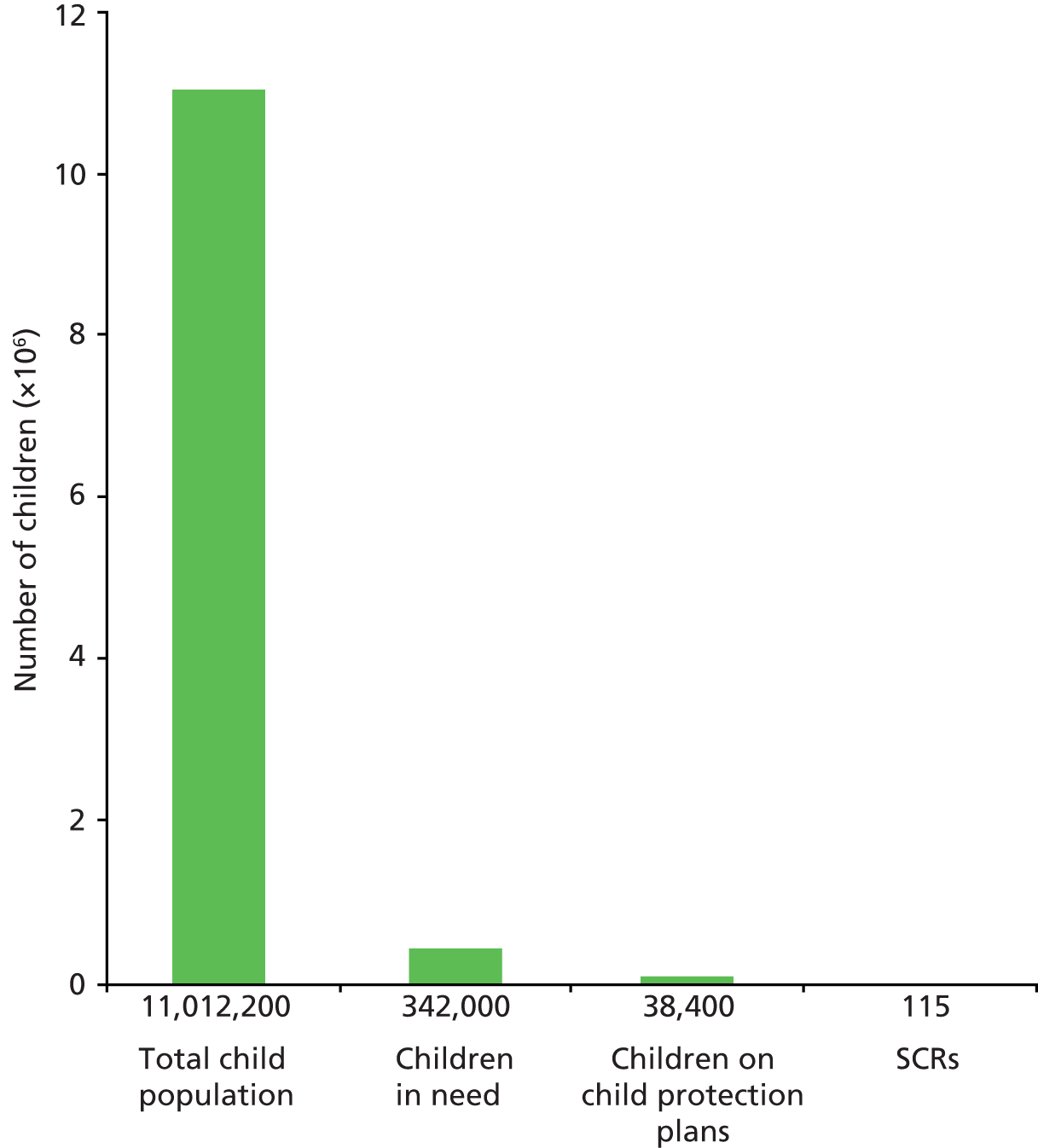

In their review of serious case reviews (SCRs), Brandon et al. 23 note that one-third of the 40 children they studied had a history of missed health appointments; six had been admitted to hospital, one child nine times; and 18 had at least one attendance at an ED. Serious harm is only the tip of the iceberg: the number of other errors is unknown, but will be substantially greater than SCRs suggest. Moreover, the number of children experiencing serious harm clearly hugely outweighs the number of fatalities. This is illustrated in Figure 1, using data from Brandon et al. 23

High-profile stories and media outrage about children who have been neglected or fatally abused at the hands of their parents or carers have driven policy since the death of Maria Colwell in 1973. 40 With the inquiry reports into the deaths of Jasmine Beckford,41 Tyra Henry42 and Kimberley Carlile,43 the late 1980s saw the translation of the notion of danger into one of ‘risk’. As Mary Douglas44 notes, the beginnings of the notion of ‘scientific’ risk assessment had implications for professional and organisational accountability:

The charge of causing risk is a stick to beat authority, to make lazy bureaucrats sit up, to exact restitution for victims. For those purposes danger would once have been the right word, but plain danger does not have the aura of science or afford the pretension of a possible precise calculation.

p. 24

Dingwall et al. ’s18 study of the child protection practices in two social services departments appeared to support the view that the State was reluctant to intervene in family life. The authors referred to the ‘rule of optimism’, by which they meant the pervasive liberal democratic belief that children are usually best cared for within their (birth) families. This idea was (mis)appropriated by the Beckford Inquiry and was taken to mean that it was social workers who were overly optimistic and easily duped by dangerous parents. After the inquiry, Dingwall45 underscored the more general societal meaning of the original statement through the use of the first person plural:

the child protection system contains an inherent bias against intervention anyway. If we wish to change that, then we must confront the social costs . . . that some children will die to preserve the freedom of others.

p. 503

This perspective was more recently reiterated in the family courts:

Society must be willing to tolerate . . . diverse standards of parenting . . . [and] children will inevitably have both very different experiences of parenting and very unequal consequences flowing from it . . . These are the consequences of our fallible humanity and it is not the provenance of the State to spare children all the consequences of defective parenting.

J Hedley, cited in the matter of B (A Child)46

This central moral tension remains between the rights of the many to freedom from scrutiny and intrusive intervention into the intimate spaces of family life, and those of the relatively few who come to serious harm at the hands of their carers. This is rarely, if ever, addressed in policy and procedure, but it renders the accurate detection of children at risk a really ‘wicked issue’ for the human actors involved. The precautionary principle is constantly in a discursive and moral dance with proportionality. Many more children die in road accidents, for example, than at the hands of their significant others. 47 Each violent and retrospectively tragically preventable death has its own effect on this fickle pendulum, potentially shifting the point of balance. The high-profile cases of Victoria Climbié48 and Peter Connelly have had their impacts on policy, which are discussed below. The more recent cases of Keanu Williams and Daniel Pelka in autumn 2013 have provoked further political and media scrutiny of systems and practices, again and understandably with a focus on the prevention of false negatives (i.e. avoiding missed cases) and an assumption that more referrals to CSC will keep children safe. It is easy for these tragic events to drive precipitous policy initiatives which tend to move towards the precautionary pole.

The post-Climbié reforms: strong but wrong solutions?

Victoria Climbié died in London in 2000 as a result of longstanding cruelty at the hands of her great aunt, Marie-Therese Kouao, and Kouao’s partner, Carl John Manning. 48 This triggered a highly influential inquiry into professional and institutional failure, which proved a pivotal catalyst in New Labour’s modernisation agenda for children’s services. Resulting legislative changes, first outlined in the Every Child Matters Green Paper,49 include the establishment of local children’s safeguarding boards, with the responsibility for safeguarding children in local authority areas, conducting reviews on all child deaths, and increased regulation and audit of child protection responses. The government put in place a series of measures intended to enhance information sharing and early intervention, drawing heavily upon information and communication technologies (ICTs) to support their ambitions. 50 These included the establishment of a children’s database (known as ContactPoint), which was intended to hold basic information on all children in an area, with an option for practitioners to record their involvement with a child/young person and, as an early warning, place a ‘flag of concern’ on a child’s records. This has subsequently been scrapped, but there are currently plans to develop a national database by 2015 to record every child who visits hospital accident and emergency (A&E) departments or has out-of-hours general practitioner (GP) consultations. It is proposed that medical staff will be able to see if the children they treat are subject to a child protection plan, meaning that they have already been identified as being at risk. Thus, the search for technical solutions to mediate and augment human communication continues, and these matters are discussed further in later chapters of this report.

The post-Climbié reforms also included aspirations for a ‘common assessment’ process. The common assessment framework (CAF) has been developed as the standard tool for all professionals working with children and families, which can be used for both assessment and referral purposes. 51,52 The aspiration was that a ‘common language’ may develop to improve information sharing and communication between professionals. The inspectorate Ofsted currently uses the numbers of CAFs completed by agencies as a proxy measure for early help, with the apparent assumption that more is better. 53 This places pressure on hospital services to use this rather than other forms of assessment, as we discuss in Chapter 6.

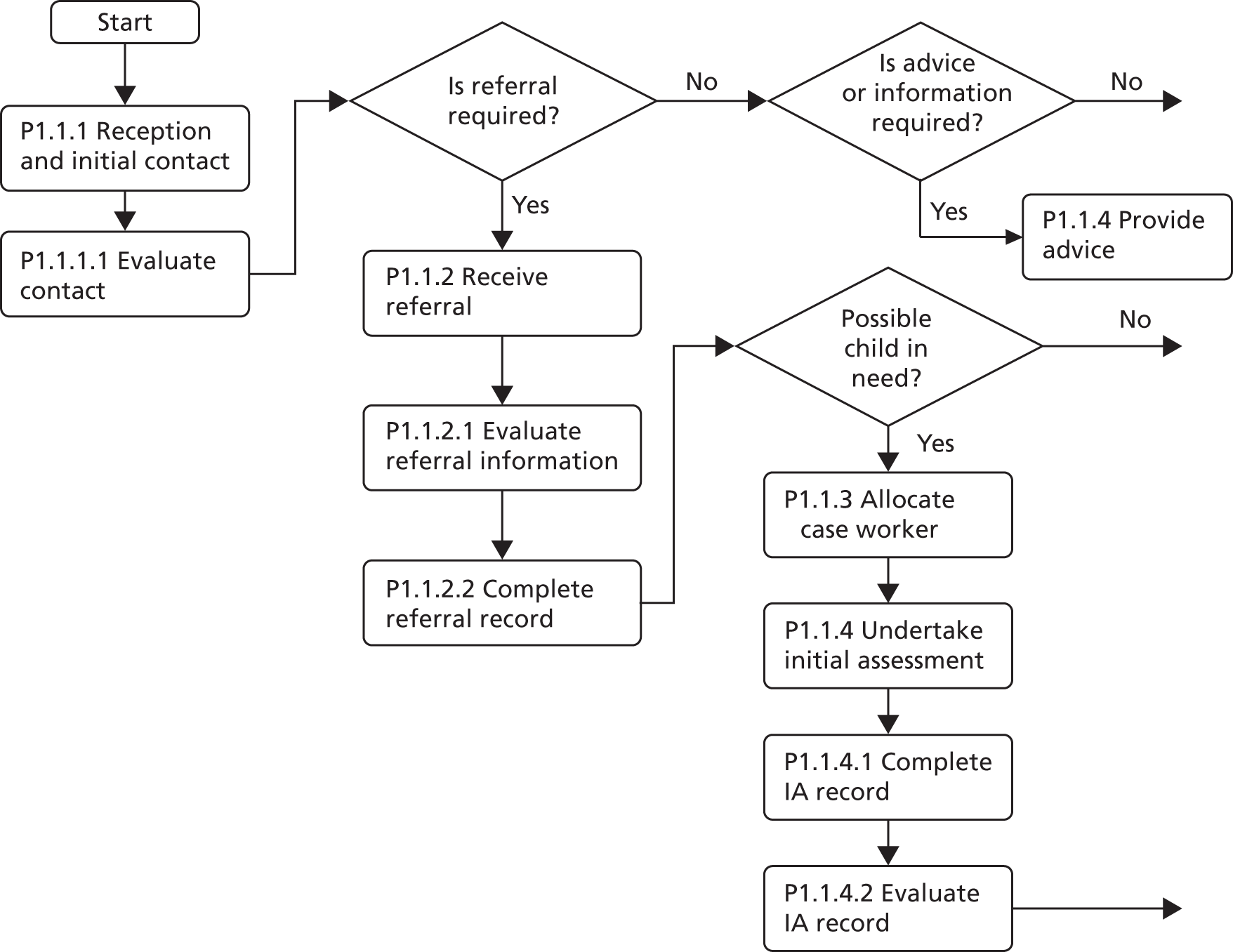

The developments in England post Climbié have led to a highly centralised ‘command and control’ approach to regulating the activities of professionals in the area of child protection. New Labour’s approach to public administration provided a medium for NPM to flourish. 54 The defining contours of NPM were that strong top-down management is the key to quality and performance; that workers are apt to be self-interested and inefficient; that the standardisation of processes and explicit targets drive quality; and that these are ensured by rigorous micromanagement using performance indicators. 55 In the context of human services, and particularly child protection, NPM has been centrally concerned with managing institutional risk,56 and has been accused of creating a climate of ‘targets and terror’. 57 It is in this context that the then New Labour government put in place a series of reforms drawing heavily on concepts of ‘business process management’ (BPM), electronically enacted through the Integrated Children’s System (ICS). 58,59 The ICS attempts to re-engineer and micromanage practice through the imposition of a detailed, workflow model of the case management process and other processes, as Figure 2 demonstrates.

FIGURE 2.

The diagram is adapted from the Children’s Social Care Services Core Information Requirements Process Model. 60 It shows only the initial stages of a much more comprehensive flow chart covering an A3 sheet; the open arrows on the right indicate that the flow continues after these initial steps have been performed. The labelling of the process steps (P.1.1.1, etc.) reflects the hierarchical notational system in the original process model to designate successive steps. IA, initial assessment.

Many of Laming’s48 broad diagnostics of the failures contributing to Victoria’s death are accurate. However, the relative neglect of human, interactional and social factors in the report means that the policy responses, particularly the emphasis on standardised processes and ‘information sharing’ initiatives, have been based on a set of contestable assumptions. 16,61 The most notable of these is that catastrophic child deaths are substantially the result of professionals failing to record or share information. Such failures clearly are not trivial, indeed they are crucial, but they are not necessarily causal. For example, they are ubiquitous features of many cases which do not end catastrophically, as Wastell17 notes:

[T]o be sure that this evidence is decisive, we need to know how often it was present in other cases but did not lead to calamity . . . Unless it can be shown . . . that assessments, information gathering and multi-agency collaboration were conspicuously worse in the serious cases, how can it possibly be claimed that these were critical causal features?

p. 168

For the causal factors in the death of Victoria, it is necessary to look elsewhere. A re-examination of some of the evidence submitted to the Climbié inquiry48 will illustrate this point. In July 1999, Dr Schwartz, consultant paediatrician at Central Middlesex hospital, examined lesions on Victoria’s body. Her clinical opinion was that the marks were self-inflicted due to intense itching from a scabies infection. This opinion differed from a previously expressed and documented diagnosis by a locum registrar, who produced detailed body maps of Victoria’s injuries and was of the view that there was a strong possibility that she had been physically abused. While Dr Schwartz testified to the inquiry that she had made it clear to social services that she could not exclude physical abuse, the production of a medical explanation for some of the injuries proved a highly consequential red herring.

The contact with social services to inform them of the ‘change’ of diagnosis was made by Dr Dempster, a junior doctor unfamiliar with social services and the child protection system. Dr Dempster followed up several unsatisfactory conversations with social workers with the following letter:

Thank you for dealing with the social issues of [Victoria]. She was admitted to the ward last night with concerns re: possible NAI [non-accidental injuries]. She has however been assessed by the consultant Dr Schwartz and it has been decided that her scratch marks are all due to scabies. Thus it is no longer a child protection issue.

There are however several issues that need to be sorted out urgently: 1) [Victoria] and her mother are homeless. They moved out of their B & B accommodation 3 days ago. 2) [Victoria] does not attend school. [Victoria] and her mother recently arrived from France and do not have social network in this country. Thank you for your help.

Laming, p. 25148 (The Victoria Climbié Inquiry, Crown Copyright 2003)

The letter’s communicative intent was to prompt a visit to the hospital by a social worker, but was read by social services as a recategorisation of the case, triggering a quite different organisational response. Brent children’s services had two initial assessment teams: referrals were considered first by the duty team, and, if the referral appeared to relate to ‘a child in need’, the case would remain with them for initial assessment. If, on the other hand, there were child protection concerns, it would be transferred to the child protection team for urgent action. Under the Children Act 198919 and the associated guidance, the category of ‘child in need’ was introduced to signal the importance of offering support to families with a range of needs such as housing. Thus, within the assumptive world of Brent Social Services, the crucial line of Dempster’s letter becomes, ‘Thus it is no longer a child protection issue’ and not the documented ‘urgent’ social matters. The case, therefore, entered a bottleneck in an overstretched duty team, who were dealing with backlog of 200–300 cases per week. While these circumstances are clear, such formal organisational systems and the dysfunctions they produce escaped scrutiny in the enquiry process; indeed, subsequent reforms have prescribed more of them, with time scales imposed on decision-making and assessment, regardless of case complexity. 62 Thus, the interface between other agencies, including hospitals, and CSC became dogged by a preoccupation with ‘thresholds’ and their ‘consistency’, ascribing a technical rationality to what is in fact a complex sense-making process with the potential to distract attention from human factors in the decision process. 63

Thresholds are dynamic. They bend in response to the balance between demand and resources, and are affected by a range of human, social and organisational factors. For example, analysis of the child protection system at a national level has demonstrated that as referral rates increase, the number of ‘non-urgent’ cases allocated falls,62 reflecting rational adaptation and prioritisation at the local level. In such a system, an immobile baby presenting at the ED with an unexplained skull fracture will always make it over the threshold regardless of competing demands, but most children and families referred from health settings to social work services are not like that. A family struggling to cope is also going to struggle to get through the front door of many local authority CSC departments, and they are going to struggle harder on some days than others. Yet a great deal of organisational time is spent crafting ‘thresholds’, and waste in the form of ‘failure demand’ enters the system as cases are batted back and forth, and universal services try to second-guess responses. 64

It is clear that complexities arise from the need to pass what might be speculative and ambiguous information across service boundaries. Communications within a system are embedded in a range of interpretive dichotomies: signal/non-signal; information/noise and pattern/randomness. 65 One reader/hearer may find information where another detects only noise. For the receivers of the referrals, for example, the categories ‘non-accidental injury’ or ‘child protection case’ are the signals they are seeking in the ‘noise’ of the genuine deliberations of doctors, as the latter try to make sense of equivocal cases.

Interactional factors in child health: sharing knowledge

There are two principal literatures which pertain to the complexities of sense-making and knowledge sharing in children’s safeguarding at the agency interface. First, there are problems in translation, interpersonal trust and technological systems where the individuals involved, including sometimes the child, are separated from each other in time and space. Second, there are intrinsic complexities in all clinical and professional decision-making, which are amplified in safeguarding because the presenting ‘symptoms’ are often ambiguous and contestable, and judgements about parenting often require moral evaluations.

Beginning with the first set of factors, research shows that knowledge sharing and learning is influenced by multiple interpersonal, social and organisational factors, including the inhibitory impact of distinct knowledge domains, social hierarchy and low trust. 66 Knowledge sharing throughout child health and social care is, therefore, both ‘slippery’ (difficult to codify) and ‘sticky’ (difficult to share across boundaries), not readily responsive to simplistic exhortations to ‘share information’. 67,68 Mainstream patient safety research has tended to focus within clinical specialities, departments or units, such as operating theatres or EDs, with less attention paid to the interconnections between these areas and the wider organisation and beyond. 69

The identification of children at risk and the sharing of knowledge and decision-making across time and space may properly be conceived as a complex system, whereby interdependencies and couplings between professionals and agencies can be the source of both safety and risk, depending on how they are co-ordinated. The promotion of multiagency working in social work with children and families is promoted as a way to prevent children ‘slipping through the net’ of services, and of ensuring that professionals have the ‘full picture’. 70 Yet research from social psychology71,72 on helping behaviours, and from the USA73–75 on interagency collaboration, has found that where there are increased numbers of people involved, the individual sense of responsibility for a case can, contra to the policy aspiration, be radically reduced. The literature repeatedly emphasises that good communication has the potential to reduce this complexity and support co-ordination, but, thinking back to the example from the case of Victoria Climbié, what does communication mean and how does one know when it has taken place?

Knowledge sharing is more than the transmission of information. It denotes the exchange and use of diverse knowledge, and often more tacit ‘know-how’, between different groups to engender shared understanding and collaborative learning. 76 Knowledge is often elaborated along two lines. For many systems and improvement strategies, such as knowledge management, knowledge is conceived as an explicit, abstract and tangible resource that can be accessed, codified and exchanged (e.g. in formal policies or incident reports). In other words, it is a substantive thing to be shared with others in the form of documents or evidence. This contrasts with the idea that knowledge or know-how is often tacit, experiential, taken for granted and inextricably situated in practice. 77 In this sense, knowledge is difficult to share and it is typically acquired and developed through participation in ‘communities of practice’78 rather than management information systems. In short, knowledge is not a ‘thing’ that a community ‘has’, but rather it is what they ‘do’ and ‘make’, and who they ‘are’. 78 This distinction is important because efforts to understand and, indeed, promote knowledge sharing and collaboration should focus not only on the formal assemblages of knowledge, but also on the more informal and unarticulated manifestations of know-how. Knowledge sharing is, therefore, more than the communication of information, referring also to how the meanings, ‘know-how’ and practices of one group or organisation can be shared and integrated into the practices of another. 79 Recognising these differences, knowledge sharing requires different strategies and practices. So, the sharing of explicit knowledge (e.g. evidence, guidelines or data records) is often related to how it is described, presented and articulated; the extent to which different actors are aware of its availability and utility and can access it; and the ease with which it can be used. In contrast, the sharing of tacit knowledge is often based on more informal, day-to-day interactions around common problems, the creation of opportunities to enable social intercourse and creative problem-solving.

More than this, however, knowledge sharing and collaborative learning involves transforming the form of knowledge. For example, Nonaka80 suggests organisational learning involves the ‘externalisation’ of tacit know-how, so that it can be used by others, but also the ‘internalisation’ of explicit knowledge, so that it can be integrated into daily practices. As such, activities are often needed to translate and transform knowledge between different communities. Returning to our previous example, if a non-mobile infant presents at an ED with a skull fracture, which the parents say has been caused by the infant turning over in his or her cot, there is little externalisation or translation of tacit knowledge required: it is self-evidently implausible, and both the police and CSC will have no difficulty understanding it as such. In this case, the technological systems, whether these be telephones, faxes or information technology (IT) systems, will usually be sufficient to ‘pass’ the information. Any system failure would be readily evident, probably technological in nature, and easily remedied.

However, if the mother of a 5-year-old child on a paediatric ward is seen by the parent of another patient to be shouting at the child ‘inappropriately’, and nursing staff also have a ‘bad feeling’ about the way the parent and child interact, the process of translation is much harder. If the nursing shift changes and the new staff do not directly encounter the parent in contact with the child, further problems ensue. The sense-making is constrained by the local organisational temporal practices which disrupt relationships and reduce or eliminate proximity. This has consequences for the embodied knowledge of the interaction between parent and child, the subsequent production of an externalised ‘rationalisation’ of the observation, and, crucially, a waning of the moral imperative to act. 81 One can now easily see the complexities of knowledge sharing in safeguarding. As Bauman82 notes:

The only space where the moral act can be performed is the social space of ‘being with’, continually buffeted by the criss-crossing pressures of cognitive, aesthetic, and moral spacings. In this space, the possibility to act on the promptings of moral responsibility must be salvaged, or recovered, or made anew.

p. 183

Research points to a range of factors that facilitate or inhibit knowledge sharing. 76,79,83,84 These include the characteristics of both ‘donor’ and ‘recipient actors’, such as their motivations, accessibility, strategies, levels of trust, shared values, hierarchies and absorptive capacity. 85,86 For example, in the commercial world, competitive pressures can inhibit inter-organisational knowledge sharing where it threatens competitive advantage. 76 As discussed, CSC is under systemic pressure to reduce demand on its services and, accordingly, has developed locally ‘rational’, rationing and gatekeeping practices. The structural configuration of relationships between agencies can also channel knowledge flows through ‘central actors’ rather than between peripheral actors,87 or indeed through actors who ought to be peripheral, such as call centre operators, at the expense of a proper dialogue between clinicians and social workers, for example. 88 Similarly, power hierarchies and cultural difference between actors can impact knowledge sharing, especially where powerful actors maintain control of knowledge to advance their own interests. 84,89 For professional work, these issues are exacerbated where expert knowledge is closely linked to sociolegal jurisdictions within the division of labour. 90 CSC is the lead agency for child protection investigations under section 47 of the Children Act 198919 and, as noted above, has a number of systemic pressures which incentivise ‘screening out’ ambiguous referrals by recategorising them as ‘below the threshold’ for intervention.

Making knowledge: the problematics of sense-making

As explained above, there are vexing problems in ensuring effective knowledge sharing in relation to children at risk. However, there are also complex problems in knowledge making for individuals and groups of professionals and clinicians. For example, often children present with a complaint for which there may be biological, neurological, genetic and/or psychosocial explanations. In accomplishing diagnosis, the boundary between biological and psychosocial aetiology is especially problematic. 91 For example, are frequent hospital admissions the result of an intrinsic metabolic disorder, a consequence of emotional maladjustment, because of poor nutrition or inadequate parenting, or do all factors apply?

To find possible clues to diagnostic certainty and avoidance of error in child protection, it is useful to examine the process of decision-making. Munro92 describes two major forms of reasoning as the basis of decision-making practice: intuitive and analytic. Intuition is a cognitive process that ‘somehow produces an answer without the use of a conscious, logical process’. Analytical reasoning is the opposite, ‘a step-by-step, conscious, logical process’ (p. 2). This is akin to the decision-making framework described by Almond93 and Dowie and Elstein,94 which portrays intuition as a subconscious and experiential process, based around ‘common sense’, ‘gut feeling’ and ‘cue and pattern recognition’, in contrast to the analytic or rational model, which is based on logical and systematic methods of gathering information. Both Munro92 and Almond93 argue persuasively that these models exist on a continuum, the process of decision-making often involving decisions within decisions, all of which require careful deliberation and reflection, both at a rational and an intuitive level. Over-reliance on intuition may, in some circumstances, lead to a persistent, negative bias towards, say, low-income, single-parent families in reporting child abuse concerns. On the other hand, evidence-based checklists may be a valuable aid to decision-making, but cannot provide a satisfactory replacement for intuitive judgement.

Furthermore, children frequently injure themselves and the injuries may be medically trivial,95 creating a potential bias towards the default assumption of accidental injury. Children are usually accompanied by parents whom clinicians may find difficult to confront, and their moral evaluations of the parents can also be decisive, especially when the child cannot communicate directly. 25,91,96,97 These difficulties are exacerbated by other human factors. Human beings have particular cognitive biases. We tend to reach conclusions quickly and develop a ‘psychological commitment’ to our first formulation. 94 This is confounded by a tendency to seek out evidence that confirms a hypothesis rather than to search for ‘disconfirming’ evidence, known as ‘confirmation bias’. 98

The case of Peter Connelly (Baby P) illustrates some of these complexities. Peter was observed to be injured very frequently, with a variety of bruises and bumps which became increasingly serious over time. However, Tracey Connelly, Peter’s mother, alleged that he would frequently injure himself and had behavioural disturbances such as head banging, which were also observed by the social worker. A strong (but wrong) hypothesis thus took hold that Peter had a behavioural disorder. In his last few months of life, Peter’s weight was falling dramatically. His father had also raised significant concerns, and told agencies that Tracey Connelly had a new boyfriend. Many agencies were involved with Peter, but the different professionals seemed to be failing to notice or to respond to the deterioration in Peter’s health and development, and to act appropriately in relation to his injuries. Tracey Connelly had been apparently co-operative with services, frequently presenting Peter at the doctor’s surgery, for example, to seek help with what she said was his difficult behaviour.

The intuitive judgements that the professionals had made about Tracey Connelly’s character, and their cognitive commitment to the ‘behavioural disturbance’ hypothesis, led them to pay insufficient attention to clear signs that Peter was being abused. These pressures are challenging to counteract, resisting interventions such as training. 25 Moreover, attempts to increase the reporting of concerns carry their own unintended consequences: the generation of false positives, overloading child protection services, together with buck-passing and discrimination against vulnerable communities. 99 For example, there are concerns that the use of screening instruments and protocols in health services, to assist in the identification of cases where children could be at risk, may not increase accuracy but may instead lead to a rise in the rate of false positives, putting more pressure on strained child protection25,100–103 resources, which could in turn generate more rather than less risk. There are also potentially direct adverse effects on children; for example, a full skeletal survey to screen for unseen injuries can be very distressing, especially for preverbal infants.

Further complicating the picture, as co-operative social animals, humans are equipped with abilities for making intuitive judgements about each other, often of a moral nature. For a long time, at least as far back as Plato, emotions were seen as distinct from our capacity to reason. Emotions were things to be tamed, allowing reasoning to take place uncontaminated. There is now clear evidence that a good deal of ‘rational’ decision-making relies on our capacities as human beings to make sense of the world using our emotions. 104–106 Gut feelings are not impeccable guides to judgement, but neither are they silly and ‘irrational’. They are not inferior to reason. They rely on the capacities of our evolved, social brain, and enable us to act quickly, often with a high degree of accuracy in many different situations. 107 However, intuitive judgments are vulnerable to error, and so critical debate with others is vital in order that professionals learn to recognise and interrogate such biases, choosing whether or not they need to correct them for this particular case, in these individual circumstances. Human beings’ judgements about each other normally stay in the realm of what we think of as common sense. 108 A ‘gut feeling’ can make an individual particularly resistant to change or challenge,109 especially if that gut feeling is masked by a ‘technical’ vocabulary using, for example, psychological theory of one sort or another. A ‘cold’ mother can thus become redescribed as a ‘mother who has failed to bond with her child’, obscuring the fact that the underlying judgement was made on intuitive grounds, not through systematic scientific observation and critical self-questioning.

The presence of other human actors in the right atmosphere of circumspection, challenge and debate may properly work to ‘trouble’ the intuitive reading of a case, but it will not do so unless the organisational cultures encourage this kind of critical questioning. Without such a culture, professionals all too frequently remain in an unquestioning, comfortable, collective settlement about the reality of a family’s circumstances. This may often prove to be right, but is sometimes strong but wrong. This means that the cultures in organisations, and the dominant ideas in a profession at a particular point in time, will affect the rational/emotional/intuitive responses of individual clinicians and teams. It has recently been argued that more attention must be paid to human factors and the interactional complexities of decision-making regarding children at risk of harm. 61 Within CSC, there are promising signs of growing interest in and potential government support for more systemic solutions, focused on human factors, human-centred design, systemic understandings and more complex conceptualisations of culture and governance. 21,110–112

Protecting children: fatal flaws in the process paradigm

In this section, we develop further our analysis of the failure of systems such as the ICS (see The post Climbié reforms: strong but wrong solutions?) which contribute to the mounting evidence that top-down, bureaucratic approaches to safeguarding children, which privilege process over practice, are not the solution; indeed, they can make matters worse, for instance by restricting knowledge sharing between professionals. 59,62,113–115 We argue that such approaches are based on a process paradigm, the assumption that the key to enhancing reliable performance is to standardise the process and enforce compliance to that standard. This paradigm is problematic not only in health and social case, but in the commercial world, too, from which it derives. This is attested by the high rate of failure of BPM initiatives, estimated to be as high as 80%116 The ‘critical success factors’ for BPM initiatives have been well investigated,116 and the degree to which processes can be validly standardised is the decisive factor. Technologies for process management will thus only be effective for standard, routine processes and it is vital to distinguish between these and non-routine counterparts;17 put simply, the message is ‘do not standardise processes which are not standard’. Lillrank and Liukko117 capture this distinction in their ‘quality broom’ metaphor. Using the metaphor of a sweeping brush, they suggest that quality systems work for routine processes requiring compliance with procedure and protocol (the handle end of the broom), whereas flexible, interpretive processes are required for decisions which are non-routine and taken in conditions of uncertainty (the flexible ‘swishing’ end of the broom). For the latter, a quality culture is required. Treating the processes at the interpretive end as though they were processes at the ‘handle end’ will erode the quality culture, trapping professionals in rigid processes.

Lillrank and Liukko117 argue that non-routine processes differ from standard routines ‘in that input is vague and not readily classified into categories . . . Therefore the assessment of an input is an interpretation which must be derived through the search for new information, iterative reasoning, and trial-and-error’ (ibid. p. 42). While standard processes can be managed directly through procedural or technological means, non-routine processes, on the other hand, are often controlled more effectively through indirect means such as professional beliefs and values, personal responsibility; through culture, in other words. 118 Or, as Weick119 put it:

Either culture or standard operating procedures can impose order . . . but only culture also adds in latitude for interpretation, improvisation, and unique action.

Much of the professional task in children’s safeguarding lies at the ‘brush’ end of the quality broom, which explains why rigid process standardisation at the interagency interface is, fundamentally, the wrong approach. The argument encapsulated in the quality broom metaphor is not simplistically for or against standardisation, but for recognition of the diversity within a system and for the deployment of standardisation only in the correct context.

Managers need to decide what should be strictly regulated and what should be left to empowered individuals and groups . . . A great deal of trouble follows, if processes are interpreted as being different from what on closer examination they really are.

Lillrank and Liukko117

The fundamental need to distinguish routine and non-routine processes also appears in the work of the sociotechnical theorist, Calvin Pava. 120,121 In contrast to routine processes, where work follows a linear, sequential ‘conversion process’, non-routine work (the work done by skilled professionals and managers) addresses unstructured or semistructured problems; it is driven by ‘plausible but imprecise information inputs, varying degrees of detail, extended or unfixed time horizons’, and is characterised by fairly broad discretion (p. 48). 120 Non-routine work is characterised by the management of many activities at the same time; non-linear flow (‘a disjointed zigzag process’ of problem-solving on uncertain, shifting terrain); and vocational separatism (professionals are educated experts with a high degree of autonomy). Pava sees non-routine work as consisting of multiple, overlapping deliberations carried on by flexible and fluid networks of individuals (discretionary coalitions). Deliberations are defined as ‘reflective and communicative behaviours’ concerning equivocal, problematic topics. One example of this in social work is the assessment of a child and family’s circumstances and discussion with other professionals, while in medicine an example is differential diagnosis.

Enhancing non-routine work involves the technical analysis of deliberations, looking in particular for important ‘information gaps’. As a sociotechnical theorist, Pava is equally concerned with the social analysis of deliberations, the ‘role network’ identifying who interacts with who, attempting to understand the ‘characteristic values’ for each party and whether they align, converge or conflict. The key to improving performance is to optimise the joint design of the technical subsystem (the deliberations) and the social subsystem (the role networks). Pava suggests, as example interventions, human resource measures to support the formation of effective coalitions (e.g. team-based pay schemes) and technical innovations to support deliberations (e.g. computer conferencing). In relation to safeguarding children, organisational systems are not optimally designed from a sociotechnical perspective, with the social system often neglected. For example, team relationships may be fractured by efficiency-based interventions such as hot-desking and the use of call centres in local authorities.

Safety cultures

The concept of organisational culture is ubiquitous in the discourses of health-care reform and patient safety. 122 Cultures speak themselves through articulations of ‘the way we do things around here’. Especially where work is non-routine and interpretive, they are likely to have profound effects on case formulations and so forth. Culture is known to be a key factor in, for example, the successful adoption of clinical guidelines. 123 The concept has a long history but came strongly to the fore in the 1980s, promoted by management gurus such as Tom Peters. Culture is a promiscuous, protean concept, amorphously defined and difficult to measure,122,124 but always to hand as convenient slogan, explanation, manipulandum, mediating variable, outcome, and so on. In a survey,124 90% of health managers routinely used ‘culture’ to describe the way things happen in the organisation and 99% agreed that understanding culture was important for effective management (53% strongly agreed), yet almost all managers agreed that local cultures can provide significant obstacles to improvements in health-care quality. 124

Schein’s125 conceptualisation of culture as shared basic assumptions, articulated in values which govern how the organisation behaves and visibly manifests itself, has been seminal. Hofstede’s126 framework is also popular, characterising culture in terms of several key dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism, masculinity and long-term orientation. 126 The competing values framework (CVF) is also widely used in the management literature. The CVF defines culture in terms of two axes: flexibility versus control, and internal versus external orientation. The intersection of these two axes generates four distinctive cultures: clan, adhocracy, hierarchic and market. The CVF has been used, for instance, to study the mediating effect of culture on the success of organisational change initiatives. For instance, Shih and Huang127 found that the process improvement programmes, based on the rigorous management of work processes, tended to fare better in organisations with a hierarchical culture.

A further popular framework is that of Martin128 who argues organisations are not homogenous cultural entities, but comprise different subcultures. In health care, for example, nursing could be characterised as having a stricter disciplinary code than other professional groups. 129 The current study concerns interagency work, and the multiple cultural contexts of different professional groups can be expected to affect the tractability of professional behaviours. Martin identifies three broad categories of subculture: enhancing subcultures (characterised by strong support for the centre), countercultures (characterised by scepticism and dissent) and orthogonal subcultures (defined by occupational group or demographic features). Such subcultural features can modulate change efforts. Ravishankar et al. ,130 for instance, show how the enhancing subculture of one business unit led to the smooth adoption of a centralised IT initiative, whereas a countercultural business unit largely rejected it.

In this work, we are concerned with a very specific aspect of organisational culture, its ‘safety culture’, defined in general by Vincent131 as follows:

[T]he safety culture of an organization is the product of the individual and group values, attitudes, competencies and patterns of behavior that determine the commitment to, and the style and proficiency of, an organization’s health and safety programmes.

p. 273

A positive safety culture is characterised by communication based on mutual trust, shared perceptions of the importance of safety and confidence in the efficacy of safety mechanisms. Vincent131 writes of the importance of an ‘open and fair’ culture, in contrast to the normal organisational tendency to blame people for errors which, by producing defensive strategies, works against safety in the long term by inhibiting the reporting of important safety concerns and incidents:

Punishing people for honest error is not simply unfair and pointless; it is dangerous . . . suppress[ing] the very information you need to create and maintain a place of safety.

p. 277

In a similar vein, Dekker13 has written extensively of ‘Just Cultures’ which simultaneously address the twin, and potentially conflicting, imperatives for accountability and organisational learning. Dekker13 distinguishes two forms of accountability: backward looking (looking for culprits to blame and shame) and forward looking, a form of accountability which ‘brings forward information about needed improvements to people or groups that can do something about it’ (p. 135).

An important strand in the literature on safety culture deals with the characteristics of ‘high-reliability organisations’ (HROs), such as nuclear power plants, aircraft carriers and air traffic control. Some authors believe that health care has much to learn from the culture and practices of such organisations; Vincent131 explicitly likens the typical day in an ED to the situation aboard an aircraft carrier. In both cases, a complex, dynamic situation must be managed: planes must be landed, often in bad weather on a heaving deck; patients must be treated, each different, always under time pressure, sometimes with the threat of violence. In both situations, there is the same overarching imperative: ‘try not to kill anyone’. Dealing with constantly shifting contingencies requires rapid decision-making, co-ordination and mutual adjustment by those involved in the action. This requires a relaxation of hierarchy (of rank and authority), an emphasis on local autonomy and a flexible attitude to procedures. Vincent sees the HRO as a more appealing model for health care than manufacturing, the source of conventional ideas about safety, because production line processes seem to have so little in common ‘with the hands-on, hugely variable and adaptive nature of much work in healthcare’ (p. 278). Vincent cautions, though, that this can be overplayed, as much of health care, such as pharmacy distribution, is routine and predictable.

The distinctive cultural characteristics of HROs are articulated by Weick et al. 132 using the concept of mindfulness. HROs are contrasted with conventional organisations: whereas the dominant concern in the latter is efficiency and success, for the HRO the priority is reliability. Reliability may be defined as ‘the lack of unwanted, unanticipated, and unexplainable variance in performance’ (p. 51). 133 The traditional approach seeks to achieve reliability through the development of highly standardised routines, but this focus on repeatability is problematic: ‘it fails to deal with the reality that reliable systems must perform the same ways even though their working conditions fluctuate and are not always known in advance . . . the idea that routines are the source of reliability . . . makes it more difficult to understand the mechanism of reliable performance under trying conditions’ (p. 35). 132

This brings us back to the ‘quality broom’ metaphor, and the need to distinguish between routine and non-routine processes, also echoed in the work of Pava. What is distinctive of the HRO is not process stability but cognitive stability, i.e. stability in the processes that make sense of the variability; reliability is not the outcome of ‘organisational invariance’, but results from the continuous management of fluctuations. The law of requisite variety is, therefore, at the heart of reliable performance. Crudely speaking, this law stipulates that the ‘variety’ of a ‘control system’ must equal or exceed the variety of that which is being regulated (variety is defined as the number of possible ‘states’ a system can be in). 17 For an organisation to survive in a particular environment, it must be attuned to the variety of its surroundings. If the environment becomes more complex, the organisation must adapt itself in order to manage this variety and to preserve its viability. Two adaptive mechanisms are available:17 variety attenuation describes the process of reducing the variety of the relationship between the organisation and its environment (e.g. a CSC agency restricting its services to only those children at very high levels of risk); variety amplification describes the reverse, for example a hospital sets up a new diabetic clinic, thereby increasing its variety from the perspective of the local population.

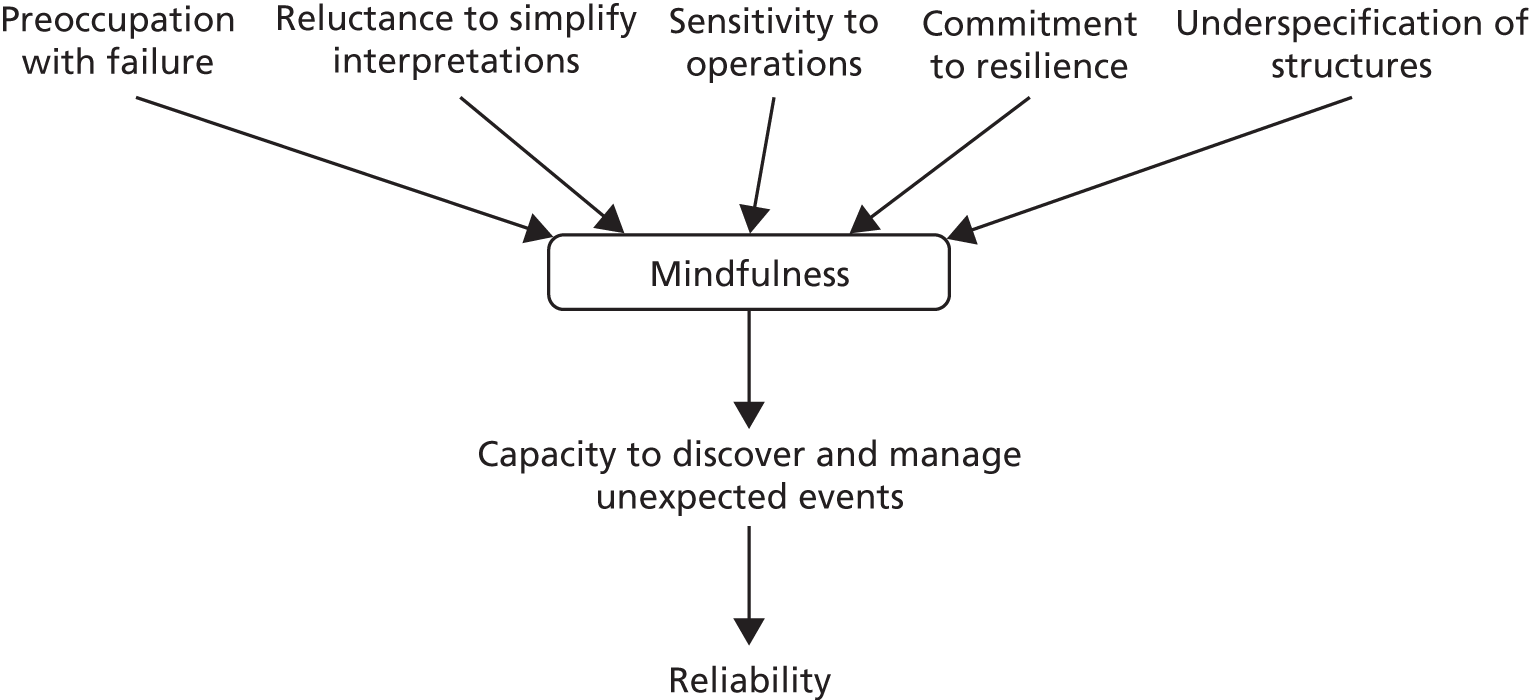

For Weick et al.,132 the ability to anticipate, detect and adapt to unexpected events is key. When new or unexpected events occur, practitioners need ‘to revise their understanding of the situation, their evidence collection and evaluation tactics, or their response strategy’ (p. 35). Continuous awareness of variations, adaptive cognition and flexible action produces orderly, reliable behaviour. Weick and Sutcliffe134 designate this state of cognition ‘mindful infrastructure for high reliability’. It has several key determinants, as depicted in Figure 3.

Weick and Sutcliffe134 define mindfulness as:

The combination of ongoing scrutiny of existing expectations, continuous refinement and differentiation of expectations based on newer experience, willingness and capability to invent new expectations that make sense of unprecedented events, a more nuanced appreciation of context and ways to deal with it, and identification of new dimensions in content that improve foresight and current functioning.

p. 42

The five determinants are briefly explicated as follows. Preoccupation with failure is what gives HROs their distinctive character; because failures are rare events, not only is constant vigilance needed, but there must also be a readiness to seek out more data and broaden the variety of failures given attention. Effective HROs thus encourage the reporting of errors, including near misses. Simplification is an intrinsic property of organisation, enabling complexity to be made cognitively tractable and action to be taken. However, it is potentially dangerous, as it ‘limits the precautions people take and the number of undesired consequence they envisage. Simplification increases the likelihood of surprise’ (p. 41). 134 Sensitivity to operations essentially means having an ‘integrated big picture of operations in the moment’ (p. 43),134 a concept similar to ‘situation awareness’, which has been extensively studied in the human factors literature. Whereas anticipation refers to the prediction of dangers in advance, resilience refers to ‘the capacity to cope with unanticipated changes after they have become manifest, learning to bounce back’ (p. 46). 134 Finally, underspecification of structures refers to the need to create flexibility, building in requisite variety and avoiding procedures that are followed mechanically. These factors are crucial and will be returned to in later chapters of this report.

Technology adoption

The practical centrepiece of the present work is the development of a package of tools aimed at fostering a safeguarding culture. The tools will be developed primarily at one site, and an important aim was to test their general validity by evaluating their adoption by other participating partners. The adoption of innovations is an enterprise fraught with risk, and has been the subject of scholarly research for several decades. Initiatives involving IT, such as those featured here, are notoriously risky: all too many IT projects miscarry, with failure rates as high as 80% reported at one time or another. 17 When information systems involve more than one organisation, the risk of failure is inevitably higher. Research has sought to tease out the ‘critical success factors’, which predispose projects to achieve the desired benefits, and a strong consensus has emerged. Failed projects typically represent management failures of flawed decision-making and lack of engagement; technology per se is seldom to blame. Many in senior positions see technology as a ‘magic bullet’. Markus and Benjamin135 argue that such ‘blind faith’ in technology is the predominant mind-set among managers and executives. There is general agreement that users must be engaged in the development of systems, and that strong commitment at the top of the organisation is also required. It is vital that managers engage with technology, seeing it as an instrument for redesigning their organisation; passively implementing technology developed elsewhere is a recipe for failure. We will return to the need for such a ‘design attitude’ in the chapter on the design and evaluation of the safeguarding package.

The literature on technology innovation and adoption is voluminous and a review is beyond the scope of this work. The seminal work is that of Everett Rogers. Rogers136 portrays the innovation process as a linear sequence of stages, beginning with the initial idea and its development into an adoptable entity, be it product, artefact or service. Whether or not the innovation is adopted is held to depend on a number of critical factors, grouped into three areas: the intrinsic attributes of the innovation itself (e.g. its ‘relative advantage’, complexity and compatibility with existing practices), the effectiveness of marketing and communication on the part of change agents, and the degree of ‘felt need’, resources and capacity for change within the adopter. Rogers’ original work has spawned a vast profusion of derivative models, such as the technology adoption model, which with its various embellishments dominates the research in the field of information systems on technology adoption and diffusion. 137 Alternative theorisations have begun to spring up, such as those based on actor-network theory (for a recent discussion of applications in health care, see Cresswell et al. 138) but models based on Rogers’ continue to hold sway. 137

A pertinent limitation of Rogers’ model is its focus on adoption decisions made by individuals rather than organisations. As Van de Ven139 argues, the process of organisational innovation and adoption is considerably more complex, with multiple potential initiatives unfolding in parallel, all competing for priority in a politically contested milieu. Van de Ven proposes an extension of Rogers’ model to address organisational innovation and its management: the model depicts the organisational innovation process as made up of multiple, non-linear activities and events progressing through time. These can be inventive, developmental or adoption activities, or reflect evolving features of the organisation context (such as changes in norms or reward systems). At any time, the flow of activity can be perturbed by ‘process events’ (shocks, setbacks, learning events, gestating events), which can influence the trajectory of particular innovations.

Conclusion

Patient safety is an international priority140 and the subject of a high-profile NHS initiative, Patient Safety First141 (PSF). There has been a reconceptualisation of clinical risk focusing on latent ‘error provoking conditions’ which create ‘accident opportunities’. 142 It has become increasingly recognised that most harm to patients is not deliberate, negligent or the result of serious incompetence. Instead, harm more usually arises as an emergent outcome of a complex system where typically competent professionals and managers interact in inadequate organisational configurations (inter alia Mannion et al. 122). There has been a gradual recognition within the wider health policy arena that safeguarding (both adults and children) is inextricably linked with quality, governance, safety and dignity. 143 Although these developments have begun to address the safety of children presenting in hospitals, very little reference to safeguarding is made in the Operating Framework for the NHS in England 2011–12,144 and PSF focuses exclusively on ‘in hospital’ threats, not the extra-mural risks to which the children are usually exposed. This reflects general concern that protecting the welfare of children is insufficiently embedded within the thinking and practices of acute NHS trusts. 145

Much research on patient safety to date has also focused on a single clinical environment or organisational setting. 146 There has been a relative neglect of threats to patient safety arising across settings, or where the decision-making depends on a dispersed network. This is often the case in secondary settings where retrenchment of local government services has led to the loss of many hospital-based social work teams. 147 Safeguarding children is interactionally, emotionally and cognitively complex. Signs and symptoms are often ambiguous. It often falls into the interstices between organisations and governance systems, with a consequent lack of clarity about responsibility compounded by endemic problems in communication and knowledge sharing across space, time, and organisational and professional boundaries. 148 As a high-risk, high-blame activity, it is also buffeted by media scandals and political buck-passing,149 which create further barriers to co-operation. Only a thorough understanding of human, social and organisational challenges will afford effective solutions. Chapters 4–6 present data from the study to illustrate, explore and evaluate attempts to provide such remedies.

Chapter 3 Research design and methods

Design science

The proposed investigation follows a design science approach. In contrast to conventional social science (which aims to describe, explain or predict social phenomena150), the aim of design science is to develop a corpus of practically oriented knowledge regarding the design, implementation and use of a general class of artefact, technology or service innovation. 17 In the field of information systems, design science enjoys a well-established tradition with a lineage reaching back over several decades. 151 It also has its votaries in management research. Van Aken152 distinguishes two modes of management research. Mode 1 corresponds to conventional explanatory science. In contrast, the aim of mode 2 research (i.e. design science) is the production of field-tested and grounded ‘technological rules’, i.e. chunks of ‘general knowledge linking an intervention or artefact with an expected outcome in a certain field of application’ (p. 22). 152 Importantly, such rules should be used not as instructions but as design exemplars, to be invoked because of their relevance to resolving a problem. Practitioners then ‘have to translate this general rule to their specific problem by designing a specific variant of it’ (p. 27). 152 The question must always be ‘why does this intervention in this context produce this outcome?’ The rationale of mode 2 research is, thus, to furnish a body of knowledge informing design, which must be applied critically and sensitively to important features of the local context. 17

Design is a core feature of the patient safety paradigm and has been shown to be integral to its success. 12 Design science intrinsically involves the construction and evaluation of an exemplar of the innovation in question, reflexively learning from this real-world action. This is the broad approach to be adopted in this study. A mixed-methods153,154 research design will be followed to evaluate the impact of a package of initiatives (including an electronic reporting tool) designed by clinicians within our primary hospital site, aimed at promoting a safety culture. In the spirit of design science, we will seek to understand if, and in what aspects, this intervention has been effective and the key causal and contextual factors bearing on this outcome. The primary interest will be the impact of the intervention on improved communication and knowledge sharing, particularly with external agencies. For this reason, much of the research has been devoted to understanding generic issues regarding the exchange of knowledge and information between hospitals and community bodies, in particular local authority CSC departments.