Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/2000/61. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in June 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Reuber et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background to the study: ‘patient choice’ in the National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) has made a firm commitment to offering patients more choice. Yet the concept of patient choice is a contested one, used in diverse ways across different academic, political and policy literatures. 1 Even within the context of the NHS, patient choice is taken to mean very different things. As a key part of the (Labour) government-driven public service reforms, for example, the patient choice initiative had a limited, measurable definition: it referred to a set of deadlines by which patients were to be offered choices that were previously unavailable within the NHS (such as which hospital to attend for elective surgery). Laid out clearly in the NHS 2013/14 Choice Framework, there are now a series of such legal rights to choose (with explicit limitations), which all patients are accorded. 2 These include choosing one’s general practitioner (GP) practice, having a right to ask to see a particular GP or nurse, choosing where to go for a first outpatient appointment if referred to secondary care, and which consultant will be in charge of one’s treatment.

Yet a much broader notion of patient choice is also evident within NHS policy. For example, the 2000 NHS Plan3 announced that ‘[t]he relationship between service and patient is too hierarchical and paternalistic’ [p. 30 reproduced from The NHS Plan: A Plan for Investment, a Plan for Reform, © Crown Copyright 2000 (this attribution applies to all quotations from this source)], and promised reforms that would ‘shape [NHS] services around the needs and preferences of individual patients, their families and their carers’ (p. 3). As Sir Nigel Crisp,12 then Chief Executive for the NHS, put it: ‘The ambition for the next few years is . . . to change the whole system so that there is more choice, more personalised care, real empowerment of people to improve their health – a fundamental change in our relationships with patients and the public’ (p. 2). Working towards this goal, the NHS provides a public information service – NHS Choices,5 with the strapline, ‘your health, your choices’ – which is intended to ‘symbolise the type of personalised healthcare that the NHS is moving towards’6 (p. 13). This vision is reflected in the NHS Constitution,7 which states not only that patients have ‘the right to accept or refuse treatment that is offered’ (p. 8), but also that they ‘have the right to be involved in discussions and decisions about [their] health and care . . . and to be given information to enable [them] to do this’ (p. 9). The NHS Constitution includes the following pledge to patients: ‘The NHS also commits: . . . to offer you easily accessible, reliable and relevant information in a form you can understand, and support to use it. This will enable you to participate fully in your own healthcare’ (p. 9). 7

It is this broader notion of patient choice that the present study addresses. Our aim is to examine how the drive to involve patients in decisions about their health care – including treatment decisions and decisions about further investigations – is currently being enacted by practitioners. In so doing, we address a gap both in the empirical literature and in the guidance available to health professionals. As we discuss further in our review of the literature below, fine-grained observational studies of doctor–patient interaction have focused overwhelmingly on how doctors deliver treatment recommendations. There is very little comparable research on how they might seek, instead, to hand the decision over to the patient. Moreover, practitioners are explicitly told, within the NHS Constitution,7 that they should aim ‘to involve patients, their families, carers or representatives fully in decisions about prevention, diagnosis, and their individual care and treatment’ (p. 15), and the NHS Choices website5 assures patients that NHS clinicians are trained to involve them in decision-making.

Yet the available guidance tends to be at a rather general level. For example, the General Medical Council in the UK has issued a guidance document, entitled Consent: patients and doctors making decisions together,8 which came into effect in 2008. This ‘provides a framework for good practice’ and provides health professionals with a set of principles to guide their decision-making with patients, including the requirement to work in partnership with patients and, among other things, to:

(c) . . . share with patients the information they want or need in order to make decisions

(d) maximise patients’ opportunities, and their ability, to make decisions for themselves

(e) respect patients’ decisions

Reproduced from Consent: Patients and Doctors Making Decisions Together. © 2008 General Medical Council (this attribution applies to all quotes from this source), p. 68

Such principles are clearly important. However, we are not aware of any guidelines on how they might be put into practice during interaction with patients. This matters for two reasons. First, as we discuss below, there is growing evidence that small differences in doctors’ talk can make a big difference to patient involvement in the consultation. 9 Directives like those shown above inform doctors about what they ought to do during interaction with their patients, but not how best to do it. Second, as we have argued on the basis of the pilot analysis we conducted for this study:10 ‘our findings suggest that the concept of “choice” in the context of doctor–patient interactions is not as simple as the literature may suggest, and that the simple course of telling clinicians to “offer patients more choice” may not achieve its objective’ (p. 319). This echoes conclusions drawn about choice in the context of interactions in care homes for people with learning difficulties:11 that ‘analyses of real-time interactions reveal the complexities of offering choice’, and imply that the best starting point for understanding the delivery of choice is ‘not from the top down but from the ground up’ (p. 264).

Searching for guidelines on how to ‘maximise patients’ opportunities, and their ability, to make decisions for themselves’ (p. 6),8 we located only the Dr Foster marketing health workbook Patients Choosing their Healthcare. 12 Subtitled, How to Make Patient Choice Work for Patients, GPs, and Primary Care Trusts, this looked promising – and is, indeed, a useful document. However, it focuses entirely on the first, more limited, concept of patient choice, outlined above. Likewise, seeking information on any formal training in shared decision-making (SDM) given to students at the Hull–York, University of Sheffield and University of Glasgow medical schools, we were told that – while there is some training included in the curriculum – these communication skills are predominantly acquired through observation and on-the-job learning. There is a need, then, for empirical research to address the gap in our understanding of how practitioners actually go about offering choice, as a crucial step towards developing well-founded guidelines for use in practice.

Aims and objectives

This report discusses findings from a 2-year study, funded by the UK’s National Institute for Health Research, Health Services and Delivery Research programme. In order to identify what works in practice and from the participants’ perspective, the study depends largely on the fine-grained analysis [using conversation analysis (CA); see Chapter 2] of over 200 audio- and video-recorded consultations. These took place in two neurology clinics (one in Glasgow and one in Sheffield), where decision-making around chronic conditions – such as epilepsy, migraine, non-epileptic attack disorder and multiple sclerosis (MS) – occurs on a regular basis. In the broadest terms, our core research questions are:

-

What communication practices are clinicians using to give patients choice in decision-making processes?

-

How do patients respond to the different practices used by clinicians?

More specifically, in answering these questions, the study aims to address three main objectives. These are:

-

to contribute to the evidence-base about whether or not, and how, patient choice is implemented

-

to identify the most effective communication practices for facilitating patient choice

-

to disseminate these findings to clinicians and patients in order to help translate into practice the policy directives to increase patient choice (where appropriate).

It is worth noting that there are situations in medicine when patients are physically unable to contribute directly to decision-making processes (for instance when they are unconscious or lack competence or when decisions have to be made so quickly that there is no time for deliberation). Our study focuses on the many other situations in which decisions about tests or treatment can reasonably be discussed between clinician and patient.

Setting: why neurology?

Neurology is an ideal setting for addressing these aims because ‘a person-centred service’ (p. 4)13 is an explicit quality requirement for neurological practice. This underpins 10 other requirements listed in the National Service Framework for Long-Term Conditions, which states that ‘People with long-term neurological conditions . . . are to have the information they need to make informed decisions about their care and treatment . . .’ (p. 15). 13 More specifically, two neurological conditions – epilepsy (the most common serious neurological disorder in the UK) and MS (one of the most common disabling central nervous system diseases) – are among seven chronic conditions identified by the UK’s Department of Health as particularly suited to a SDM approach. 14 In part this reflects health professionals’ recognition that patients with chronic conditions often understand their disease as well as (or even better than) they do, but that ‘this knowledge and experience by the patient has . . . been an untapped resource’ (p. 5). 14 The Department of Health14 has advocated a ‘fundamental shift . . . which will encourage and enable patients to take an active role in their own care’ (p. 6), arguing that patients with chronic diseases are able to ‘become key decision-makers in the treatment process’ (p. 5). This increased involvement is argued to be of benefit both to ‘the quality of patients’ care and ultimately their quality of life’ (p. 5). 14

Moreover, because many neurological conditions have an uncertain trajectory, decision-making in this context is seldom cut and dried. Indeed, in our pilot work for this study (discussed further in Building on our pilot work), we found that decisions were frequently made against a backdrop of ongoing diagnostic uncertainty. This means that a simple recommendation for the ‘known to be best’ option is often not possible. Even where the diagnosis is certain, the effects of the different treatment options may not be. For example, McCorry, Chadwick and Marson15 note that antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) have ‘dose-related and idiosyncratic effects’ and that ‘ultimately the choice of an individual AED will be determined by an individual risk-benefit assessment’ (p. 730). Decision-making, then, will at least partly rest on factors that only the patient can assess, such as his or her willingness to risk certain side effects, which side effects are more or less manageable in the context of the patient’s personal circumstances, and the extent to which the patient’s condition is affecting his or her quality of life. As Pietrolongo et al. 16 put it in relation to MS: SDM ‘is especially important in gray-zone situations where available treatments have important risks as well as benefits, and where evidence is lacking’ (pp. 1–2). Similarly, the NHS Choices website5 tells patients that, although health professionals can provide information, advice, and treatment recommendations, only the patient will know what matters to him or her with respect to any decisions that need making.

Yet there is some evidence that neurology patients may experience the decision-making process as clinician dominated. For example, an interview study17 of AED treatment decisions found that most of the patients (42 of 47) attributed ‘decisional ownership’ to the neurologist: ‘He just said, “We’re best leaving them as they are for now,” that was it really’ (p. 213). The authors argue that this may be particularly common for conditions which engender feelings of desperation (e.g. to be seizure free), and hence a willingness to defer to any recommendation. Similarly, a study16 that rated the ways in which physicians at four Italian MS centres spoke with patients about disease-modifying treatments, concluded that SDM was ‘not a prominent part of patient care’ (p. 6). There is also evidence that MS specialists in the UK are exerting a significant influence over patients’ selection between four disease-modifying treatments. Although the same options were available in all 72 prescribing centres, Palace18 found that the relative use of these options varied significantly. Moreover:

. . . the percentage of MS specialists in each centre prescribing the disease[-]modifying drugs to patients with secondary progressive (versus relapsing remitting) MS varied from 0% to nearly 50% These variations are likely to be due to physician preference and opinion and not patient influenced

Palace, p. 618

Such findings indicate a discrepancy between the Department of Health’s vision, and (some) patients’ experience. By identifying the key practices for offering patients choice that are evident in current neurology consultations, this study will be of relevance to any neurologist wishing to engage patients (at least under certain circumstances) in decision-making about their health care. More broadly, because our focus is on communication strategies, our findings should not be assumed to be limited to neurology. Although the content of a choice may be condition specific (e.g. different drug or surgical options), practices for making choice available in interaction with patients are not. The findings from this study should therefore be of relevance to clinicians working in a range of settings.

Models versus practices: our methodological starting point

Three main models of decision-making in medical consultations have been described in the research literature: paternalist, shared and consumerist (or informed). 19,20 These have been summarised as follows:

In a paternalist model, doctors make health care decisions based on what they believe to be the best interests of the patient. At the other end of the scale is the consumerist model, where the patient makes the decisions . . . In the middle is shared decision-making, where [both parties] deliberate together

Murray et al. 2007, p. 18921

These models have been widely adopted in research on doctor–patient interaction and have been particularly useful for unpacking decision-making – conceptualised as a process – into its key components. For example, Charles et al. 20 have influentially distinguished between the following three steps: ‘information exchange, deliberation about treatment options and deciding on the treatment to implement’ (p. 654). In practice, ‘these may occur together or in an iterative process’ (p. 654). 20 Crucially, the naming of these steps makes it possible to distinguish analytically between different forms of patient engagement in decision-making, including information seeking (by asking questions), information provision (e.g. about preferences or values) and actively selecting a course of action to implement. Thus, patients may be analysably engaged in the decision-making process even in consultations where they do not make the final choice.

By their very nature, however, models must smooth over the many subtle differences that are evident in the detail of real interactions. Even when based on observation (as opposed to self-report methods or theory), models are typically derived from code-and-count studies which unavoidably lose interactional detail. This is a problem because there is a growing body of evidence that the precise wording used by clinicians can make a significant difference to patient involvement in the consultation. For example, Heritage and Robinson22 investigated the ways in which primary care physicians in the USA elicited patients’ problem presentations – the only phase in such visits ‘that is institutionally designed to provide patients with interactional space in which to present their concerns in accordance with their own agendas’ (p. 99). They identified a key distinction in physicians’ problem solicitation turns: general enquiry questions, which do not constrain the content, extent, or precise form of patient’s responses (such as what can I do for you today?), and questions that request confirmation either of a general gloss of the patient’s problems (e.g. sounds like you’re uncomfortable) or of specific symptoms.

In the last formats, the physician orients to the patient’s concerns as already (partly) known – a state of affairs which arises in this context because patients typically describe their symptoms first to a nurse, who records this in the patient’s notes, which are handed to the physician. The patient is therefore more constrained – relative to the general enquiry questions – with respect to how he or she may answer this kind of question; the relevant response entails a confirmation or disconfirmation of what has already been stated by the physician, rather than a more open account of the patient’s concerns. Heritage and Robinson22 showed that this has a statistically significant effect not only on the length of patients’ problem presentations, but also on the number of symptoms described. They also showed that, of seven demographic variables assessed in addition to question design, only age was significantly associated with longer problem presentations (but not with numbers of symptoms presented). For the most part, then, it was the design of the physician’s question that best predicted the nature of the patient’s response.

Another study9 investigated two question forms used in US primary care to elicit additional concerns that patients may not have raised during their initial problem presentations: ‘is there ANYthing else’ compared with ‘is there SOMEthing else you want to address today?’. Patients recorded their reasons for the visit in a pre-consultation questionnaire and doctors were randomly assigned to use one or other of the question forms during the consultation. The study found that ‘the multivariate odds of unmet concerns were less than one-sixth as high for the SOME intervention when compared to the non-intervention group (i.e. not asking the question at all)’9 [odds ratio = 0.15, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.054 to 0.45; p = 0.001] (pp. 1431–2). By contrast, ‘the ANY intervention could not be significantly distinguished from the non-intervention condition’ (odds ratio = 0.213, 95% CI = 0.030 to 1.5; p = 0.122) (p. 1432). 9 Crucially, the study also showed that neither of the intervention arms had a statistically significant effect on visit length. They conclude that, although, it may seem surprising that a range of demographic factors were not found to have a significant impact on their main outcome, this provides a reminder of the centrality of communication to health care. Moreover, they argue that it is encouraging to discover that interactional factors (such as a minor change of wording) can have such an influence on outcomes, given that these are far more amenable to change than many demographic variables.

The significance for patient participation of how doctors design their turns (i.e. word their contributions to the interaction) has also been demonstrated in health-care settings outside the USA. For example, investigating interactions in Finnish primary care, Peräkylä23 found that patients produced extended responses to doctors’ diagnostic statements in about one-third of his cases. Crucially, he showed that the responses were ‘strongly associated with the way in which the doctor referred to the evidence for the diagnosis: After diagnostic statements in which the evidence is verbally explicated, the patients start to talk about the diagnosis more often than after diagnostic statements in which such explication is not done’ (p. 219). 23 These findings have a close parallel in data collected in secondary care cancer consultations in the UK. Focusing on discussions of test results, Murtagh et al. 24 found evidence of a relationship between the way in which the results were delivered and whether or not patients asked direct questions. ‘Plainer’ announcements, which did not include sharing of the diagnostic evidence (e.g. ‘your scan is fine’), were less likely to receive patient-initiated questions than were more ‘elaborate’ announcements, which did include such evidence. In addition, reference to the scan or X-ray appeared to encourage patient participation. The authors conclude that: ‘Incorporating and explaining the evidence appears to be interpreted by patients as an opportunity to contribute to the consultation and establish their information needs in an environment within which the patient’s queries/opinions are welcomed’ (p. 5). 24 This was of particular significance in the study setting as the authors also found that, in general, patients’ levels of involvement were relatively low, and that patients seemed largely ‘disinclined to ask questions’ (p. 5). 24

These (conversation analytic) findings demonstrate how the same activity (e.g. eliciting the problem presentation, giving patients an opportunity to raise additional concerns or delivering a diagnosis and/or test results) can be done in different ways; and that these differences can have significant consequences for what happens next in the consultation. These are precisely the sorts of details that are lost in ‘code-and-count’ studies, which typically code for whether an activity occurred, rather than how it was performed. By contrast, all of the above findings depend on fine-grained, sequential analysis of recorded consultations in order to identify specific interactional practices and their consequences for patient participation. They did not start with a model of doctor–patient interaction and then seek to code their data in accordance with that model. This is vital because, as we will highlight in Chapter 7, Conclusion there is no one-to-one correspondence between specific practices that doctors use to initiate decision-making in interaction with patients and the three core decision-making models that are so prominent in the literature. Indeed, the very same practice can be used in ways that are analysably paternalist, consumerist or shared. Our aim, then, is not to assess the extent to which neurologists are adopting any of these three styles. Rather, our aim is, in the first instance, a more descriptive one: to identify the practices that neurologists are using to initiate decision-making in a way that is demonstrably oriented to patient choice – whether or not a shared decision is actually achieved.

This distinction between practices and models is crucial here for an additional reason. In searching for practices, we sought to adopt – as our starting point – as neutral a position as possible with respect to the value of patient choice. We wanted to avoid starting from an assumption that being offered a choice is inherently better than not being offered one – an assumption that is evident in much of the current NHS literature, which tends to associate increased patient choice with a shared model of decision-making. For example, the NHS Choices website5 explains that medicine today should be understood as a partnership between doctor and patient.

There is good evidence to support NHS policy on choice. For example, research25 suggests that patients who think they have chosen their treatment have better health outcomes than those who think they have not – despite receiving the same treatment. Patients have also been found to be more likely to follow a treatment plan they have chosen, and increased patient satisfaction with the consultation, confidence in the doctor’s recommendations and greater psychological well-being are all associated with more involvement in decision-making. 26 However, it has also been observed that too many options can leave consumers feeling anxious and overwhelmed,27 with patients at particular risk owing to the nature of clinical decision-making: as a health-care consumer, the patient is, by definition, sick, dependent on the professional for treatment and often lacking the knowledge to make an independent decision and the time to deliberate. 28 Moreover, it is well documented that not all patients want to choose their treatment;29,30 and, as Pilnick and Dingwall31 highlight, reviews of the literature on patient centeredness show mixed results with respect to positive health outcomes (although they suggest increased rates of patient satisfaction).

We did not start, then, from the assumption that choice ought to be more widely offered to patients. We also wanted to avoid the opposite assumption that patient choice must necessarily be conceptualised in terms of the consumerist model and that therefore calls for its increase should be rejected – on the grounds, for example, that these are not really directed towards patient empowerment but rather towards (neo-liberal) competition-based reforms of UK health-care provision, as some critics of the NHS choice agenda have argued. 32–34 Our focus on patient choice does not start from either of these normative positions. Rather, it reflects the recognition that (like it or not) patient choice has become increasingly prominent within NHS policy35 and is, as we outlined above, a feature both of the NHS’s commitment to patients and its directives to health professionals. Yet, as we discuss in What do we already know? A focused review of conversation analysis research into how decisions get made in real clinic encounters and What we already know about practices for offering choice existing research has largely overlooked the ways in which this policy is actually enacted through the interactions that occur in NHS clinics on a daily basis. There is a need, then, for an evidence-based understanding of how, if at all, doctors are orienting to the choice agenda in consultation with patients, as a precursor to assessing the value of such practices.

What do we already know? A focused review of conversation analysis research into how decisions get made in real clinic encounters

Existing CA research – with its fine-grained analysis of recordings of real medical consultations – has clearly demonstrated a range of (often subtle) ways in which patients may take the initiative in order to participate in the various activities that make up these interactions. For example, patients may answer ‘more than the question’ during comprehensive history-taking,36 make inexplicit requests for a diagnostic test,37,38 self-initiate problem presentations during prenatal check-ups39 and resist a doctor’s diagnosis23,40 or treatment recommendation. 41–43 In addition, as we discussed in the previous section, there is a handful of studies that have demonstrated how the turn designs selected by doctors can be more or less conducive to subsequent patient participation. 9,22–24 However, CA studies of decision-making in clinical practice have rarely investigated the ways in which doctors might actively invite patients to participate. Instead, as we discuss next, the focus has been predominantly on doctors’ recommendations.

This focus began with Stivers’43–45 influential work on US primary care consultations. Investigating treatment decision-making between doctors and parents of children presenting with upper respiratory tract infections, Stivers showed that when parents responded to treatment recommendations with a full acceptance (such as ‘OK’ or ‘let’s do that’), doctors typically moved towards closure of the consultation. However, when parents responded with silence or minimal receipts (such as ‘mm’), doctors continued to talk about treatment, justifying their recommendation or revising it. On this basis, Stivers convincingly argued that the doctors were treating such responses as passive resistance and were hence working to secure a full acceptance before moving to close. Where this failed, patients were sometimes prescribed antibiotics even when these were medically unnecessary. Stivers concluded that treatment recommendations are better understood as proposals to be accepted or resisted by parents (and patients) than as directives ‘simply handed over to patients who passively receive them’46 (p. 1036; also see our previous discussion of this work47).

Comparable patterns are evident in other settings. For instance, a study in Finnish primary care41 showed that – even when doctors produce a recommendation in a manner that appears to expect no response – patients sometimes go on to introduce their own views in ways that succeed in initiating negotiation and subsequent shaping of the final decision delivery by the doctor. Maynard and Hudak42 have shown how orthopaedic surgeons (in the USA) pursue acceptance of their recommendations and, like Stivers’45 paediatricians, do not always succeed. By introducing small talk, patients can produce a topic shift away from the recommendation-relevant talk, avoiding the sought-after acceptance. Similarly, Costello and Roberts48 found that, if faced with patient resistance, clinicians in US oncology and internal medicine clinics also pursue acceptance. However, in the former setting they typically work to secure acceptance of the original recommendation; in the latter, they usually reformulate the recommendation. In UK neurology consultations, Monzoni et al. 49,50 have shown that the neurologist may sometimes abandon the treatment recommendation altogether: when patients fail to accept a psychosocial explanation for their symptoms, it becomes difficult for the neurologist to propose psychological treatment. Further, Costello and Roberts48 demonstrated that – whether or not patients display resistance – doctors in both oncology and internal medicine clinics routinely orient to the patient’s right to accept or reject their recommendations through the interactional work they do to justify them. Medical recommendations may be understood, then, as a form of ‘joint social practice’ (p. 241).

Indeed, Koenig51 has shown how even so-called passive resistance from patients (in the form of minimal responses to treatment recommendations) can ‘create an opportunity to actively participate in how a treatment recommendation ultimately emerges as acceptable’ (p. 1112). In an instance which he presents as a candidate example of best practice, Koenig shows how a primary care doctor in the US responds to a patient’s passive resistance with an invitation to discuss the patient’s treatment preferences: ‘uh::m, do you- how do you feel about that?’ (p. 1112). 51 This leads to an understanding that the patient is worried about the cost of the recommended referral to secondary care. Once this is resolved, the patient accepts the recommendation. Koenig concludes that: ‘Including patients into the construction of the treatment recommendation ratifies patient active participation in making treatment decisions’ (p. 1112)51 (see Ijäs-Kallio et al. 41 for a similar conclusion in the Finnish primary care context). There is also evidence that this may be done quite routinely – not only in response to patient resistance. For example, Hudak et al. 46 have shown how orthopaedic surgeons design their recommendations in ways that address what they know – from talking with the patient – about the patient’s preferences (for or against surgery). Even when the surgeon disagrees with those preferences, he or she will typically display a sensitivity to them, designing the recommendation in a way that is ‘fitted’ to the recipient. As a result, it is possible for patients to ‘contribute to the joint accomplishment of recommending not only once a recommendation is given, but also by influencing how recommendations are designed from the beginning’ (p. 1029).

Although such studies have shown convincingly that patients are not simply passive recipients of doctors’ recommendations, there is also compelling conversation analytic evidence that doctors routinely influence or even direct patients’ decisions. For example, in the context of decision-making – in Hong Kong – around whether or not to undergo further testing for Down syndrome following a preliminary high-risk result, Pilnick and Zayts52 showed that doctors could be ‘quite directive . . . both explicitly by appearing to assume that testing will take place, and implicitly through the information which they offer or withhold in particular circumstances’ (p. 270). Similarly, Quirk et al. 53 showed how psychiatrists – working in the NHS in the UK – could design their questions about antipsychotic treatment in such a way that they demonstrated a clear ‘preference’ for agreement to a particular course of action. For example, although the question, ‘can I give you a prescription (for that)?’ (p. 101) ostensibly places the decision in the patient’s domain, it clearly implies that this treatment is the psychiatrist’s recommended option. Likewise, Karnieli-Miller and Eisikovits54 identified eight approaches used by paediatric gastroenterologists in northern Israel to ‘market’ their recommended treatments for inflammatory bowel disease. These included ‘various ways of presenting the illness, treatment and side effects; providing examples from other success or failure stories; sharing the decision only concerning technicalities; and using plurals and authority [e.g. ‘We are in favour of. . .’]’ (p. 1). 54

Taken together, these findings imply that the practices used by clinicians to initiate decision-making are indeed best understood as lying along a continuum with respect to how free the patient is to make a choice – just as the three main models of decision-making suggest. This has been described55 as a ‘spectrum of pressure’, running from ‘pressured decisions’ through ‘directed decisions’, to ‘open decisions where the patient is allowed to decide’ (p. 95). Similarly, a well-cited study of UK primary care consultations about diabetes, and secondary care ear, nose and throat cancer consultations, identified a spectrum of clinician approaches to decision-making, ranging from more ‘unilateral’ (or clinician-determined) to more ‘bilateral’56 (or shared). Moreover, the Finnish study,41 discussed above, showed that unilateral decision deliveries themselves lie along a spectrum, both with respect to the extent to which they incorporate the patient’s perspective and the extent to which they indicate that a response from the patient is relevant and expected. Our pilot study,10 likewise, described a ‘spectrum of openness’ in relation to neurologists’ practices for initiating decision-making. At the same time, as we have argued above, it is clear that patients have their own strategies for getting their voices heard. Concluding his review of the CA literature pertaining to medical authority, Heritage57 argued that the evidence points to more of a balance between authority and accountability on the part of health professionals ‘than is traditionally observed in the sociological literature’ (p. 99). Decisions about treatment and testing should, then, be understood as always negotiated in various ways – regardless of which model might best capture the nature of the decision-making overall.

Nevertheless, as we have demonstrated through our pilot work for this study, recommending as an action does not invite the patient to make a decision. 47 As Pilnick58 has argued, there is a real difference between ‘a decision that simply requires assent to a recommended course of action, [and] the production of an independent choice’ (p. 519). By exploring how clinicians may work to create an explicit slot for the latter, the present study will show that it is not only that medical authority may be subject to ‘a tacit bargaining process’57 (p. 99) triggered by patient resistance; clinicians may actively seek to create space for the patient’s voice during decision-making. In widening our focus beyond the recommendation sequence, then, we will be able to examine the more overt ways in which clinicians might be orienting to current policy directives to give patients ‘more choice’, and to evaluate the impact of these practices on the consultation.

What we already know about practices for offering choice

Quirk et al. ’s55 spectrum of pressure and the unilateral to bilateral spectrum described by Collins et al. 56 both provide a good springboard for our research in that they show how health professionals may work to minimise the extent to which they direct patients’ decision-making. For example, Quirk and colleagues list a range of interactional features that contribute to a more open decision, including that ‘the doctor’s wishes are communicated weakly’, that ‘the doctor allows the patient to reformulate the decision and reconsider it once made, and immediately acquiesces to patient resistance to treatment proposals’, and that ‘the decision is constructed as one that will be easy to reverse if the patient experiences difficulties’ (p. 110). 55 Similarly, Collins and colleagues show how, when taking a more bilateral approach, the health professional ‘actively pursues [the] patient’s contributions, providing places for the patient to join in, and building on any contributions the patient makes: e.g. signposting options in advance of naming them; eliciting displays of understanding and statements of preference from the patient’ (p. 2625). 56

However, we are aware of only two previous studies that have examined practices for offering choice specifically. Neither of these has focused on choices relating to a patient’s own health (at least not directly), but both have sought – like the present study – to understand how policy may be enacted through interaction. Pilnick’s58 study of antenatal, nuchal translucency screening for Down syndrome in the UK addressed the question of how the decision to screen (or not) is made in real interactions between pregnant women and midwives. Pilnick notes that guidelines produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) state that the pregnant woman has an explicit right to make this choice and, indeed, Pilnick showed that the existence of a decision to be made was routinely articulated by the midwives. Nevertheless, she also found that they presented the decision in ways that made it more a matter of ‘assent’ than of independent choice on the part of the women. For example, the midwives (sometimes) gave information in a way that required only ‘minimal acknowledgment rather than active participation’ (p. 526),58 treated the lack of an explicit refusal as implicit acceptance, and portrayed the test’s benefits in non-neutral ways. Pilnick concludes that ‘a key difficulty in practice’ (p. 527)58 is moving beyond simply telling women that they have a right to choose, which clearly does happen in this setting, ‘to creating an interactional environment in which that choice can actually be exercised’ (p. 527). 58

Although focusing on a different environment, Antaki et al. 59 reached similar conclusions. Investigating how professionals enact the policy requirement in UK care homes to offer choice to people with intellectual difficulties, they identified six practices for offering choice. These included two-option alternatives in a single question (e.g. ‘Do you want to get the glasses or are you drinking them out of your mugs this morning?’), open questions plus various follow-up types [e.g. open question plus multiple-option alternatives, such as ‘what do you want for pudding=look there’s (0.8) prunes, peaches, . . .’ (p. 1167);59 or open question plus a single option], and closed questions [‘a’we still happy f’Chris to come, (.) and do the filming?’ (p. 1170)59]. Like Pilnick,58 Antaki et al. 59 showed how, despite overt orientations to choice for the service users, the way in which the decision-making process was accomplished often actually made it difficult for residents to choose. Antaki et al. 11 also showed that there is a clear discrepancy between policy-level conceptualisations of choice – emphasising fundamental life decisions, like who to marry and what job to do – and the far more frequent choices of everyday life, like what to eat and what to do for fun. They conclude that ‘an account of what actually happens in utterly mundane, routine examples’ (p. 1166)59 is needed to translate policy into effective practice. Likewise, Pilnick has argued that:

. . . what the offering and exercising of choice actually looks like in practice . . . remains unclear. The potential implications of these interactional processes, though, are immense, since . . . ‘good’ practice is ultimately achieved through interaction rather than through policy or regulation

Pilnick, p. 51258

In the present study, we apply this approach to choice around testing and treatment in routine practice in neurology outpatient clinics.

Building on our pilot work

In addition to building on the literature, the present study also builds on the pilot analysis we carried out – published in Epilepsy & Behavior10 and Sociology of Health & Illness47 – on consultations between 13 seizure patients and one epilepsy specialist. We found that the neurologist introduced a range of possible next steps for the patient using two broad approaches: he either recommended a single course of action, which the patient could accept or reject, or he used a practice which we have termed ‘option-listing’, in which he gave the patient a menu of at least two alternatives from which to choose.

Based on this pilot work, we argued that, even when a menu is offered, the choice can be substantially constrained in a range of ways, including how the options are described (e.g. making a case for or against), when the options are provided (e.g. after a discussion in which the neurologist builds a case for or against one of the options) and which options are included (e.g. some may be ruled out explicitly or simply not listed at all). Analysis of even this small data set indicated, therefore, the complexity of putting into practice the apparently simple directive to offer more choice. The presentation of such an offer does not, in itself, ensure that an independent choice is made; and, conversely, the absence of explicit choice does not necessarily mean the clinician has not taken into account the patient’s preferences, which may be built into the design of a recommendation. 10

The present study extends this preliminary work in a number of ways. We examine decision-making in:

-

two geographical settings (Sheffield and Glasgow)

-

a wide range of neurological complaints (not just seizures)

-

a much larger patient sample (n = 223)

-

a more diverse sample of neurologists (14 participants, including women and men with a range of different subspecialties and years of experience; for more information about the sample see Chapter 3).

Through analysis of this substantial data set, we develop our understanding of option-listing as a practice for offering choice and also examine a second practice that was not identified in our pilot work [i.e. the use of patient view elicitors (PVEs): see Chapters 6–8]. But first we turn to a discussion of our methodology.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Introduction

In this chapter we first describe the approach taken to sampling and data collection. We then provide an overview of the methodological approach taken, including an introduction to our core method, CA, and a description of the main stages of analysis undertaken for this study.

Setting and sampling strategy

To identify the strategies clinicians use to offer patients choice, and the interactional consequences of the different strategies, we recorded and analysed actual clinic appointments. The study was conducted in the outpatient departments of two major clinical neuroscience centres (the Southern General Hospital in Glasgow and the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield). The recordings were made between February and June 2012 in Glasgow, and between April and September 2012 in Sheffield.

These two sites were chosen for a number of reasons. First, access was facilitated by Professor Reuber (in Sheffield) and Professor Duncan (in Glasgow), both of whom have extensive experience with medical communication research and, at the time, were practising in these clinics (Professor Duncan has since relocated to New Zealand) and so were able to manage recruitment directly. Second, each of these sites serves a diverse population, meaning that patients from a range of different backgrounds participated in the study (see Chapter 3, Data collection sites for further details). Third, each site employs a diverse team of neurologists, with different specialties, ensuring a broad range of consultations (see Chapter 3). Sampling at these sites therefore offered a cost-effective, closely managed approach to capturing the communication strategies used by a range of clinicians with different patient groups.

The eligible sample population was all neurologists (20 in Sheffield and 23 in Glasgow) at the two sites and all patients (aged 16+ years) attending the clinics over a 6-month period, provided they were able to give informed consent in English. Each neurologist typically sees around 10–20 new patients, and 10–20 follow-up patients, per week, meaning a target of 200 recordings (100 per site) with at least 10 clinicians was attainable (these targets were in fact exceeded; see Chapter 3, Recruitment figures for each site for details). Although this is a substantially larger sample size than is common in much qualitative research, similar samples are now commonplace in CA studies of medical interaction. 45,56,60 Larger data sets are desirable for CA research because they provide more instances of the same action (e.g. offering choice), making it easier to identify patterns and deviations from these,61 as we discuss further below.

Recruitment and consent

The two collaborating neurologists were responsible for making initial contact with their colleagues and providing written information sheets describing the study and what involvement would entail. The collaborating neurologists then passed on the details of any potentially interested colleagues to the research assistant at each site, who explained the study face to face and obtained written informed consent from participating colleagues. The nature of the sample was, therefore, partially determined by which neurologists were willing to participate.

A full-time research assistant (henceforth, researcher, for short) was employed at each site for a period of 6 months: Fiona Smith (Glasgow) and Zoe Gallant (Sheffield). These researchers liaised with participating neurologists and, for each upcoming clinic, generated a list of eligible patients. The initial approach to these eligible patients was a letter of invitation to participate, plus patient information sheet, enclosed in the appointment reminder letter from the neurology clinic (sent out 2 weeks before patients’ appointments). The purpose of sending the invitation letter (and information sheet) was to give the patient adequate time to think about the study and (potentially) to ask the research team questions (via e-mail, letter or telephone).

Patients were then subsequently approached in the waiting room for each clinic, prior to the start of the patient’s appointment. When approaching patients, the researchers checked if patients had received the information, asked whether or not they were willing to take part and ensured that patients had a chance to discuss the study prior to the start of the appointment. This initial approach also ensured that the appointment itself could proceed as it normally would (without a consent procedure being undertaken at the start by the neurologist). This not only saved on valuable clinic time, but also allowed the neurologists to follow their usual approach to the appointment. This was important for this study given the aim to investigate what happens in ordinary practice.

The clinical encounters (first and follow-up visits) between consenting patients and neurologists were audio- or video-recorded, depending on participants’ preference. Signed consent was obtained from all participating patients prior to administering questionnaires or making any recordings (see Ethical considerations). Patients and neurologists (and any accompanying others, including spouses, partners, carers and friends) were also asked to indicate whether or not they agreed to clips from the recordings being used in presentations. The researchers operated the recording equipment, but did not attend the consultations. They did, however, remain close by in case the recording equipment malfunctioned or the patient or neurologist asked for the recording to be stopped (in no case did the latter occur).

Pre- and post-appointment questionnaires

The main source of data for this study was the audio- and video-recordings of clinic appointments. In addition, quantifiable information was collected by means of questionnaires, which patients completed immediately before and after the consultation, and neurologists completed after (see Appendices 2–7). The researchers administered these. The pre-appointment questionnaires (for patients) captured:

-

demographic details (see Appendix 4)

-

the patient’s agenda (‘Please list your reasons for seeing the doctor today, including the problems you want to talk about and any tests or treatments you hope to receive’; see Appendix 2).

The post-appointment questionnaire captured patients’ impression about whether or not they were given a choice using a short series of questions devised for this study (e.g. were they given a choice; do they think the clinician had a preference; how do they feel about whatever is going to happen next; did they think the clinician had a preference) (see Appendix 3). The clinicians’ questionnaire asked about the diagnosis and any decisions reached (e.g. did the clinician have a preference; did they think the patient had one; do they think the clinician had a preference; how do they feel about whatever is going to happen next;). Clinicians’ levels of diagnostic certainty were self-reported on a scale from 1 for ‘very uncertain’ to 10 for ‘very certain’ (see Appendix 5).

In the data analysis section below, we detail how these self-report data were analysed alongside the recordings. It should be noted that the pre-appointment questionnaire (see Appendix 2) responses were, mostly, not detailed enough to be useful (patients tended not to provide much detail about their agenda prior to the appointment).

In addition, we took the opportunity to collect follow-up patient satisfaction data using the Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale 21(MISS-21), which has been validated in UK patient populations,62 and used in previous CA research to measure patient satisfaction in primary care63 (see Appendix 7).

These data were collected as a pilot for a potential follow-up, quantitative evaluation of the interactional strategies identified in the present study. This is an increasingly common approach when applying CA to medical interactions (i.e. the foundational, fine-grained, qualitative analysis is done first, followed by various statistical measures of evaluation). 61 The purpose of the pilot was to assess the suitability of the above questionnaires for encounters in secondary care, and to provide information for group size calculations for future quantitative or mixed methods studies (see Chapter 9). We also carried out some exploratory analysis on the MISS-21 data within the present study (see Quantitative analysis).

Ethical considerations

The main ethical issue for this study was to ensure that patients and clinicians were able to make an informed choice about participation. As noted above, study information was sent to patients (through the clinics) at least 2 weeks in advance, with an invitation to contact the team with questions. On the day of the patient’s appointment, a researcher with experience of recruiting in the NHS explained the study further (if patients were willing to consider participating) and answered any questions. Clinicians were approached at the start of the study by the two neurologists on the research team, who provided an information sheet. However, to ensure that they did not feel under pressure to participate by virtue of being approached by colleagues, they were subsequently recruited by the researchers, who provided a verbal explanation of the study and answered questions. All participants were assured that they could refuse to participate without any repercussions, and, if they decided to take part, were able to choose between video- and audio-recording. Participants could also ask for the recording to be stopped at any time during the consultation. All who agreed to participate (patients and clinicians) completed a written consent form, which guaranteed the confidentiality of their data.

A further important ethical consideration was the safe storage of all data in accordance with the Data Protection Act (1998). 64 Code numbers (for labelling questionnaires and recordings) and pseudonyms (in transcripts) have been used to ensure that all personal information collected for the study is kept strictly confidential. All data are stored on secure, password-protected servers, encrypted hard drives and/or in locked filing cabinets, as appropriate.

Ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Committee for Yorkshire & the Humber (South Yorkshire) on 11 October 2011, following revisions to supporting documentation requested following the Research Ethics Committee meeting held on 29 September 2011 and attended by Dr Toerien on behalf of the research team.

Analytic approach

The core analytic approach for this project was one that allowed for the identification of those interactional practices already being used by neurologists to offer patients choice about their treatment and/or further investigations. The methodology through which we analysed the recorded consultations is known as CA. Because of the specialist nature of this approach, we include, below, an introduction to CA and a description of the main ways in which we applied it. In addition, as we also describe below, we carried out some quantitative analysis of our questionnaire data and sought to link some of these findings with our analysis of the recordings.

An introduction to conversation analysis

As we have also noted elsewhere, CA is a qualitative, microanalytic, systematic method for studying real-life interaction. 65 It is widely recognised as the leading methodology for investigating how doctor–patient communication operates in practice. 66,67 It uses audio- and video-recordings of authentic interactions to enable direct observation and fine-grained analysis, focusing not only on what is said but how it is said (e.g. the exact words used, and evidence of hesitation, emphasis, interruptions, laughter or misunderstanding). Its key advantages are that it does not rely on recall – which can often be incomplete or inaccurate68 – and it investigates how people behave at a level of detail that they could not be expected to articulate (e.g. in a research interview). Although CA originated through the study of everyday interaction, this approach has been applied to numerous institutional settings, including (among others) medical interactions,67 psychotherapy69 beauty therapy sessions,70 helpline calls,71 interviews with state benefits claimants72 and courtroom interactions. 73

In everyday interactions, we accomplish a wide range of social actions with others. We make and accept or reject offers, we agree or disagree with one another, we make suggestions or invitations, we announce news, we apologise, complain and account for our actions, and so forth. In neurology outpatient appointments, neurologists are, similarly, engaged in a range of context-specific activities with their patients, such as history-taking, diagnostic questioning, delivering diagnoses and discussing treatment and investigation options. It is the accomplishment of such activities – specifically, how they are done and how certain approaches appear to influence the ensuing interaction – that forms the focus for a CA study of institutional interaction. The aim is not to uncover people’s hidden meaning (conceptualised as lying beneath their words) or to interpret their underlying intentions, feelings or desires. 66 Rather, CA focuses on participants’ objectively observable, empirical conduct, based on detailed analysis of actual interactions. It offers advantages, therefore, in expanding our knowledge and understanding of decision-making in the context of neurology outpatient services, by providing detailed information about what actually takes place, as a basis for future effective practice recommendations.

Importantly, CA enables us to focus on the patients as much as the neurologists, because:

CA begins from the presumption that physicians and patients, with various levels of mutual understanding, conflict, cooperation, authority, and subordination, jointly construct the medical visit

Heritage and Maynard, p. 36361

As we have argued elsewhere,65 the key advantages of a CA approach may be summarised as follows:

-

It does not rely on patients’ or neurologists’ recall, which may be incomplete or inaccurate.

-

It is less susceptible to ‘socially desirable’ reframing according to what people think they should say.

-

It investigates directly how people talk, in a level of detail that the speakers are unlikely to be aware of and could not possibly recall.

-

It allows us to explicate and give voice to patients’ orientations as well as those of clinicians.

For general introductions to CA, see Drew,74 Sidnell75 and Toerien. 76 For introductions to CA as applied to interactions in institutional settings, see Antaki,77 Drew and Heritage78 and Heritage and Clayman. 79

Analytic methods

In this study, all recordings were transcribed verbatim (and anonymised) by a professional transcriber. All questionnaire data were entered into Excel (version 14.4.4.; Microsoft corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheets by the researchers at each site and checked/cleaned by members of the research team. Thereafter, the research team undertook both quantitative and qualitative analyses using IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS; Version 20; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Quantitative analysis

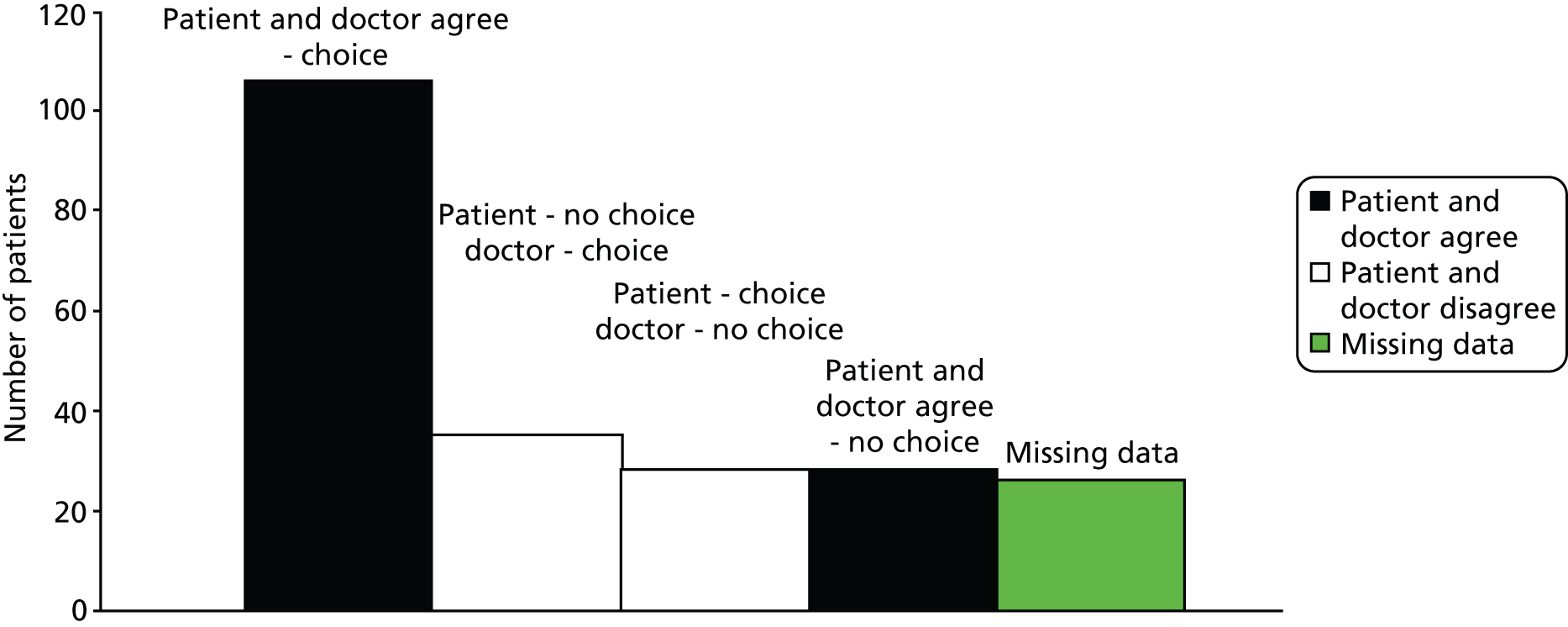

First, the responses from patient and clinician to the following post-appointment questions were summarised and compared, asking of clinicians ‘Did you give the patient a choice about treatment or further management?’ and of patients ‘Did the doctor give you a choice about any tests or treatment you might have or the next step in the management of your condition?’ (see Chapter 4). This gives an indication of the perception of choice for the recorded consultations and the degree of agreement/disagreement about this across our sample.

Patients had also completed the MISS-21 questionnaire after their appointment with the clinician. For the purpose of our exploration of MISS-21 findings, missing values were replaced by median replacement if less than 10% of responses were missing from a particular patient. Replies with 10% or more of missing data were discounted. Total MISS-21 scores were calculated and analysed and examined.

In our exploration of the data we first compared the data sets collected in the two study centres. Bivariate analyses were conducted using chi-squared statistics for categorical variables and two-tailed t-tests for continuous data (after Levene’s test had revealed equality of variance). Two-tailed p-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In view of the exploratory character of these statistical analyses, no procedures were undertaken to reduce the risk of type 2 errors.

In the statistical examination of associations of perceptions of choice, we initially carried out univariate tests of differences between categorical variables using chi-squared statistics, and of differences between the means of normally distributed continuous data (age, MISS-21 score) using two-tailed t-tests. If differences between grouping variables were found on univariate tests, forward logistic regression analysis was carried out to determine the predictive value of the findings in the univariate analyses.

Qualitative analysis

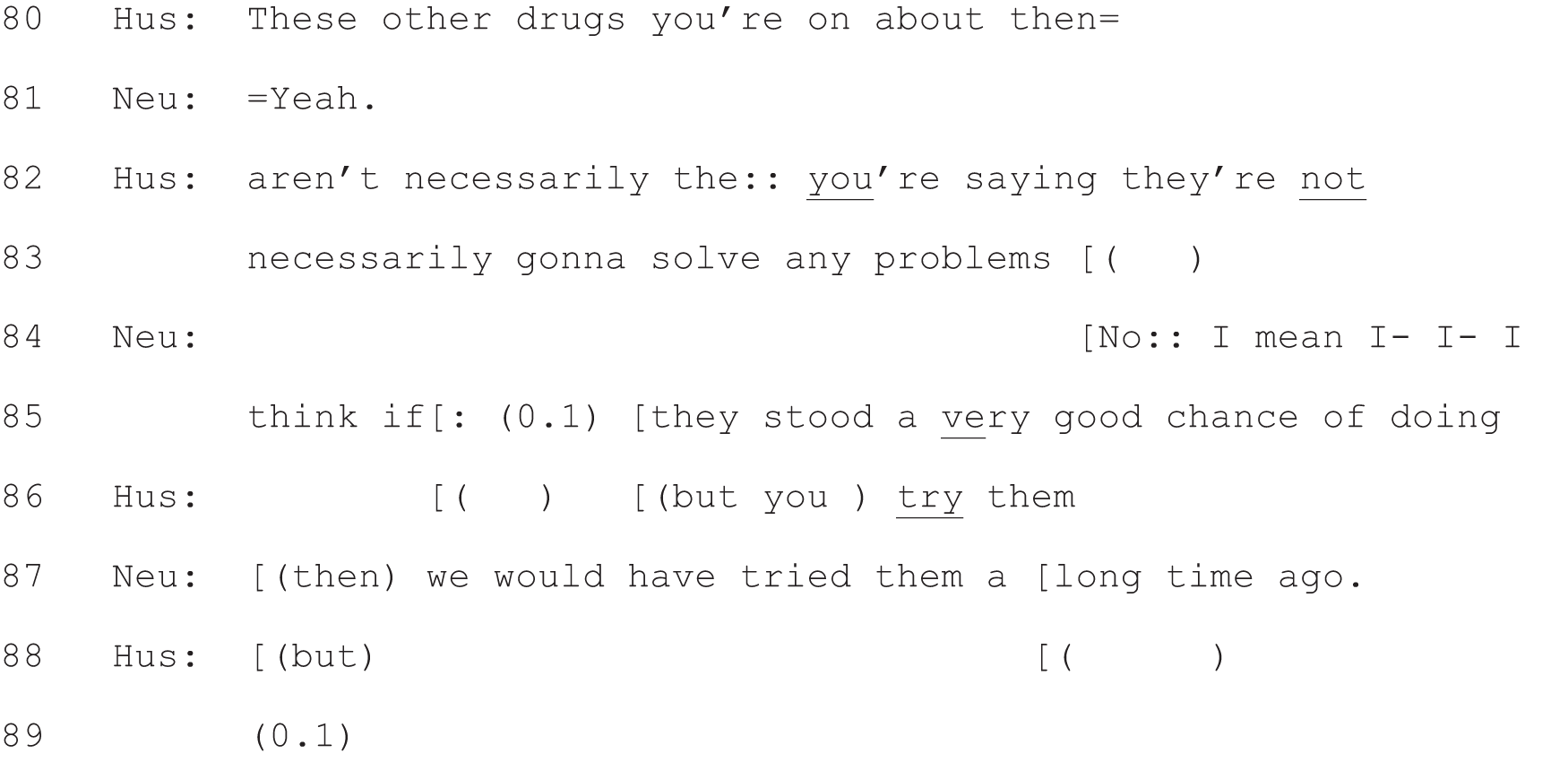

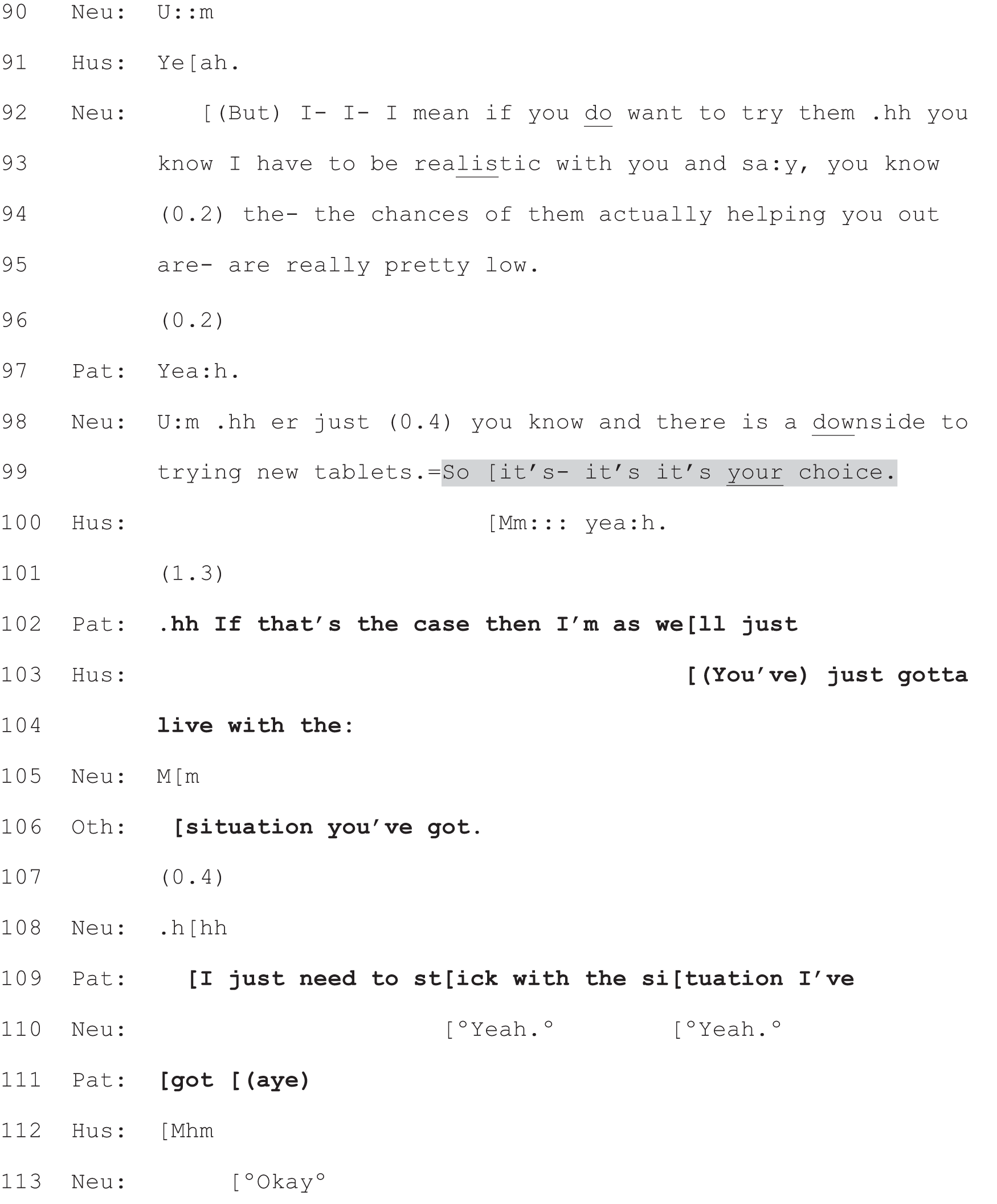

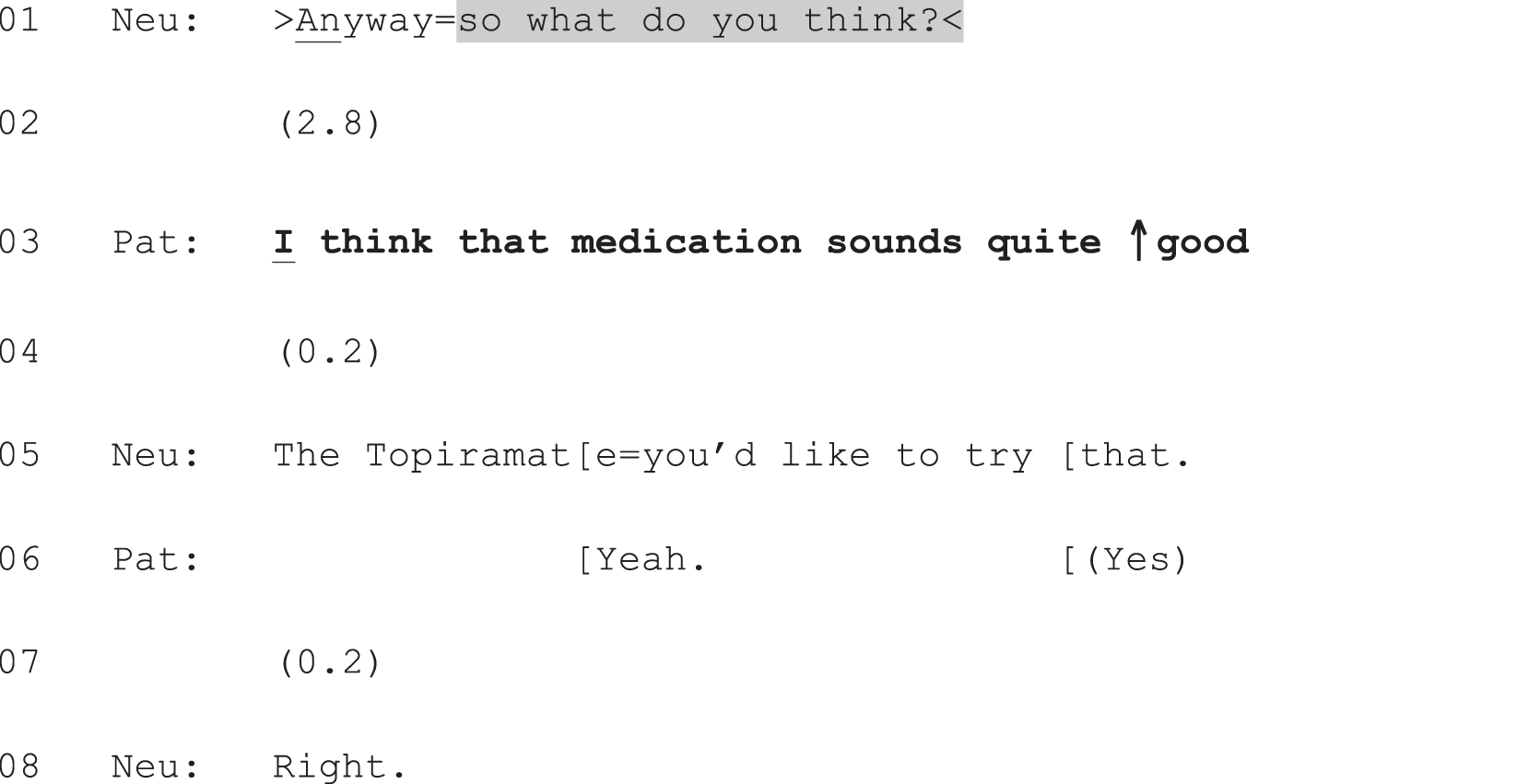

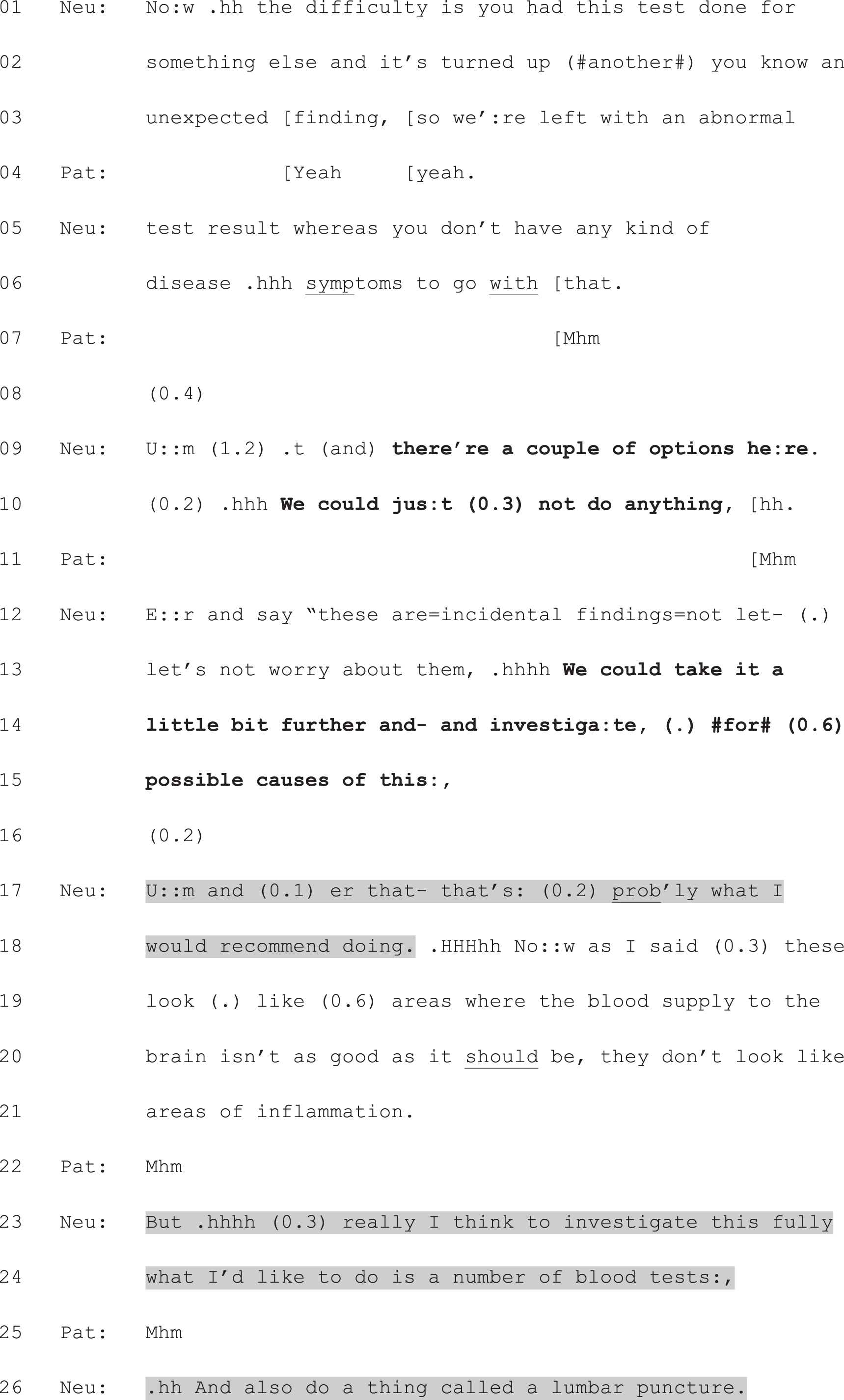

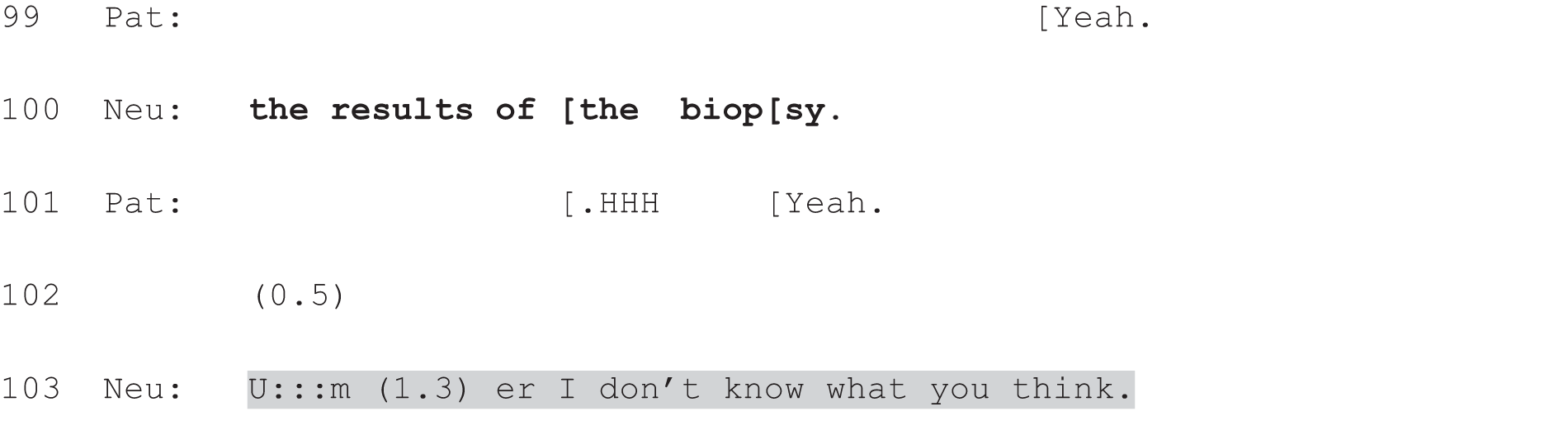

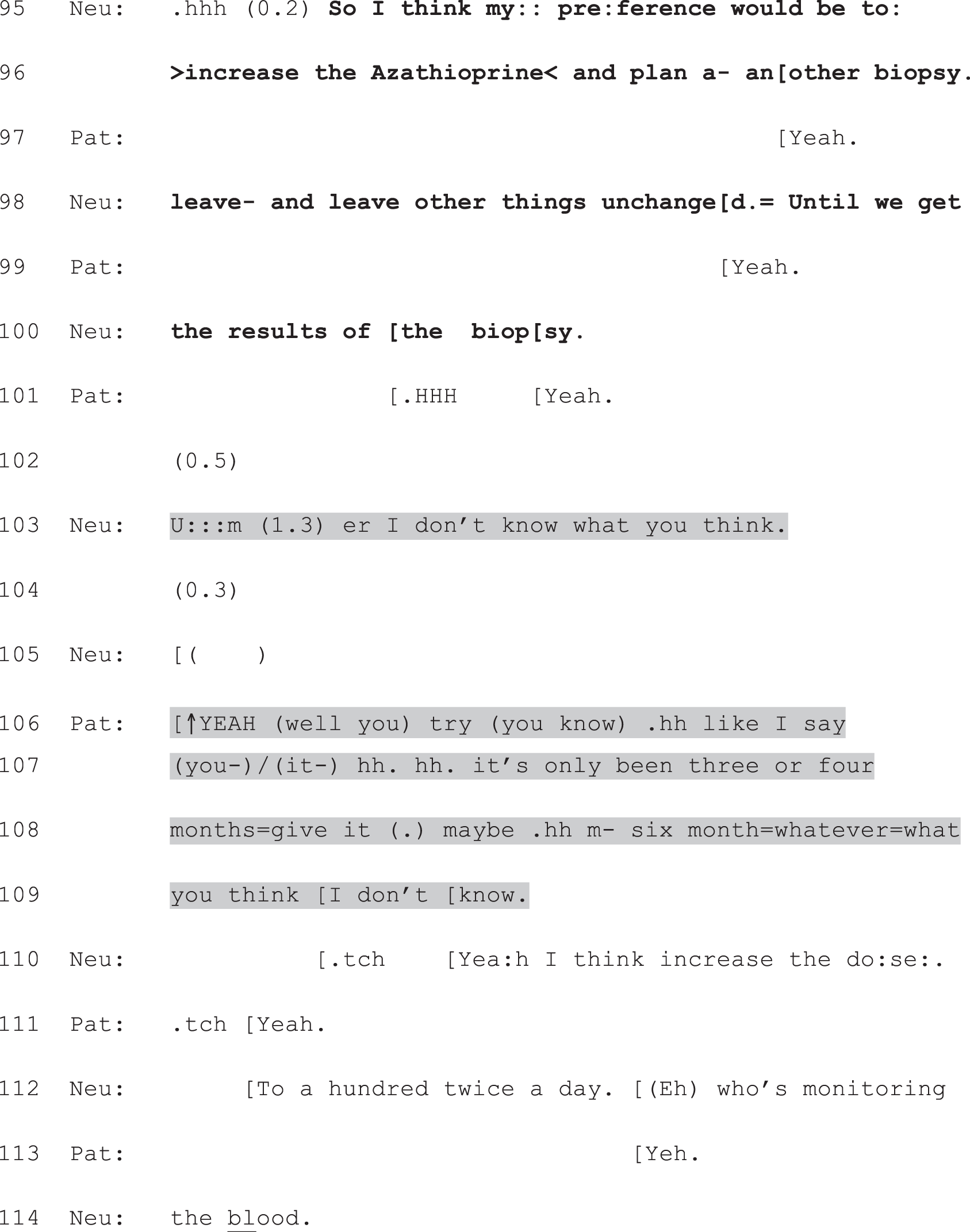

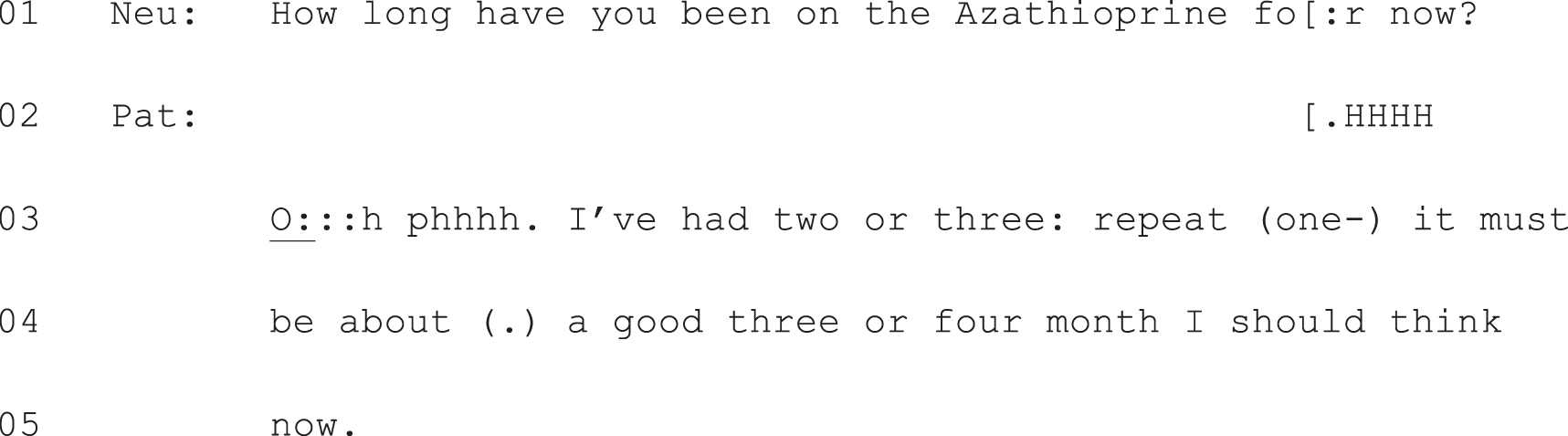

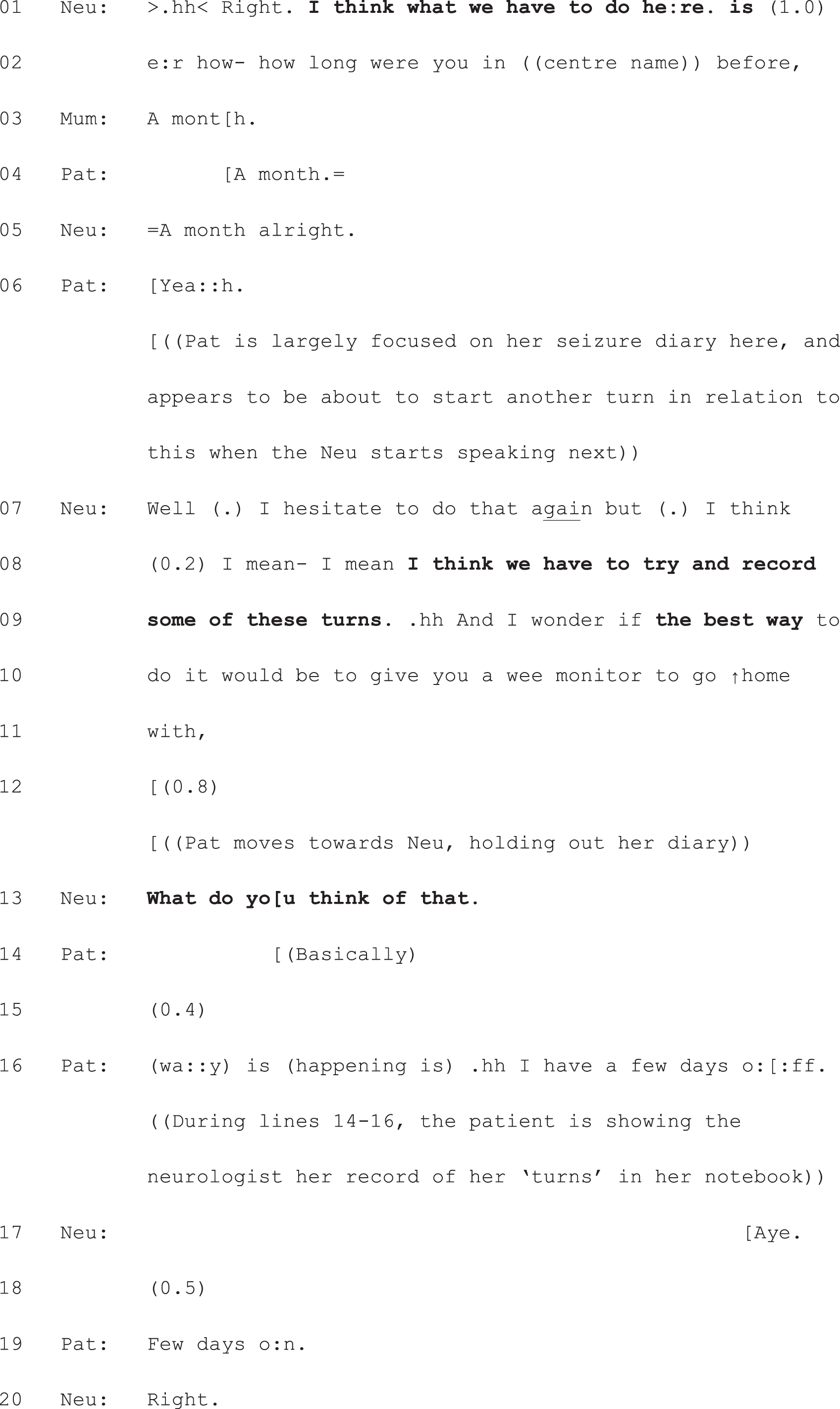

Initially, all recordings were viewed/listened to repeatedly in conjunction with their transcripts. The goal was to identify all instances of the interactional activity of making a decision about treatment and/or investigations. These decision points were transcribed in considerable detail, to show not only what was said but how it was said, using symbols to represent features of both the timing of speech and the manner of speaking. For example, transcriptions show overlapping speech between speakers, pauses, and aspects of intonation and prosody (for explanation of transcription symbols, see Appendix 1).

As a means of comparing patient and neurologist reports of choice in the encounter with what took place in the recordings, we also divided the recordings into four subsets based on the self-report findings (those for which participants agreed either that a choice or no choice had been offered, and those for which either patient or neurologist thought a choice had been offered when the other did not). The aim was to discover, inductively, what was hearable in the recordings – for participants – as choice. It was intended to be exploratory and to suggest directions for the central analysis, which followed the standard methodology of CA. That is, as we discussed in Chapter 1, we did not want to approach the data set with preconceptions about what patient choice might look like on the basis of one theory or another. Rather, we analysed, in depth, those consultations for which participants agreed that there was/was not choice, for evidence of what was being heard in this way. In addition, we examined points of disagreement, again to see if this could help us define, inductively, what counts (for participants themselves) as choice. Consultations with missing self-report data were also examined to see if there was anything unusual about them. As we could not see anything that distinguished them as a group, they were excluded from the analysis on the grounds that we were not sure which subset they fell within.

On the basis of the above exploration of the recordings, we built collections of practices that were demonstrably being used by the neurologists to offer patients choice. The most substantive phase of analysis entailed close examination of these practices (and patients’ responses to them) using the techniques of CA. The analysis was systematic (not selective), incorporating all cases of each practice rather than just the most striking ones. Focusing on details of the talk, we looked for patterns of similarity and difference (e.g. in words or phrases used) in the design of neurologists’ turns. A core aim was to see whether or not some practices were more effective at engaging patients in decision-making. This is a complex question, but patient responses provide an important internal indicator of effectiveness. By internal, we mean ‘within the interaction itself’65 – such as forms of patient resistance or alignment with the neurologist’s prior turn or displays of (mis)understanding – as opposed to some kind of correlational assessment of external outcome measures (such as questionnaire scores for patient satisfaction, measures of adherence to treatments or measures of health outcomes following the consultation).

Internal measures are important for two reasons. First, they are measures of the direct, immediate consequences of the clinician’s approach to decision-making – they tell us precisely what happened next in response to practice x compared with practice y. If there are significant patterns to these consequences – such as one approach routinely shutting down the decision-making process compared with another routinely engaging the patient – then we gain strong evidence for the likely effect of using these practices in the future. By contrast, outcome measures are indirect ways of assessing effectiveness. For example, a measure of adherence can allow us to infer the role and significance of the consultation in whether or not the patient went on to take the prescribed treatment, but that consequence will always be at one remove from the exact approach used by the neurologist to initiate decision-making. Moreover, numerous other factors are likely to have been relevant to the patient’s subsequent level of adherence.

Second, clinicians only have direct control over what they do in the consultation itself – not what happens in patients’ lives afterwards. For example, they can influence, but not directly control whether or not the patient goes on to take the prescribed medication. By contrast, if it turns out that practice x routinely blocks patient engagement in decision-making, clinicians can choose to stop using that practice. In so doing, they may be able to directly affect the process of decision-making as it unfolds in future consultations. So, by scrutinising the internal consequences of neurologists’ talk, we sought to provide insights upon which clinicians can act directly.

Patient and public involvement

We set up a service users’ group (SUG) comprising five users of neurological services, recruited through the Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield (four patients and the husband of one patient). The group met before recruitment for the study commenced and during data collection and analysis periods in order to facilitate engagement with every stage of the research process. In addition, a service user representative took part in the study’s Steering Committee meetings. The service users have been engaged with the study in the following ways:

-

Informing the drafting of the participant invitation letter, information leaflets and consent forms. Concrete changes that occurred as a direct result of discussion with the SUG included substantive amendments to the invitation letter to make it less formal and more explicit about why the study matters.

-

Informing the design of the open-ended questions for the pre- and post-appointment questionnaires. Again, we made concrete changes to our questionnaires on the basis of service user feedback. For example, a service user noted that our list of options relating to educational qualifications on the demographic questionnaire did not include professional qualifications; these were added.

-

Informing our study aims. Discussion of our work in progress with service users – and also with our Steering Committee (which included a service user) – has highlighted an important issue that the language we were using to talk about patient choice (including in our initial grant application) tended to imply that we thought choice was always better than no choice. The service users called this assumption into question. We therefore amended our study aims accordingly (see aims 1 and 3 in Chapter 1). This has also impacted our thinking about choice more broadly throughout our analysis.

-

Providing feedback on the acceptability of the recruitment approach. The group confirmed that they would be happy to be approached regarding study participation in the manner described above.

-

Feeding into the analytic process by reading and commenting on transcripts and work in progress by the study team. Discussion of our work in progress has significantly contributed to our understanding of service user perspectives on decision-making in neurology. For example, lively debates about what constitutes choice and (often poignant) anecdotes about service users’ experiences of their health conditions and engagement with health services have had two kinds of impact on the study: they have helped redirect our thinking about particular data extracts; and, more broadly, have served as powerful reminders of the very real consequences for patients of their interactions with clinicians.

-

Facilitating access to patient groups for presentation of our work in progress. The service users have advised on, and enabled access to, wider patient groups. For example, they have helped arrange opportunities for us to speak at Epilepsy Action meetings in Sheffield, Scarborough and Harrogate and at a Parkinson’s UK meeting in Sheffield.

We are currently in the process of arranging two dissemination workshops on the basis of our findings. Two service users have volunteered to assist with the delivery of these. They are also involved in the ongoing task of commenting on the clarity and accessibility of all publications (including plain English summaries) arising from this research.

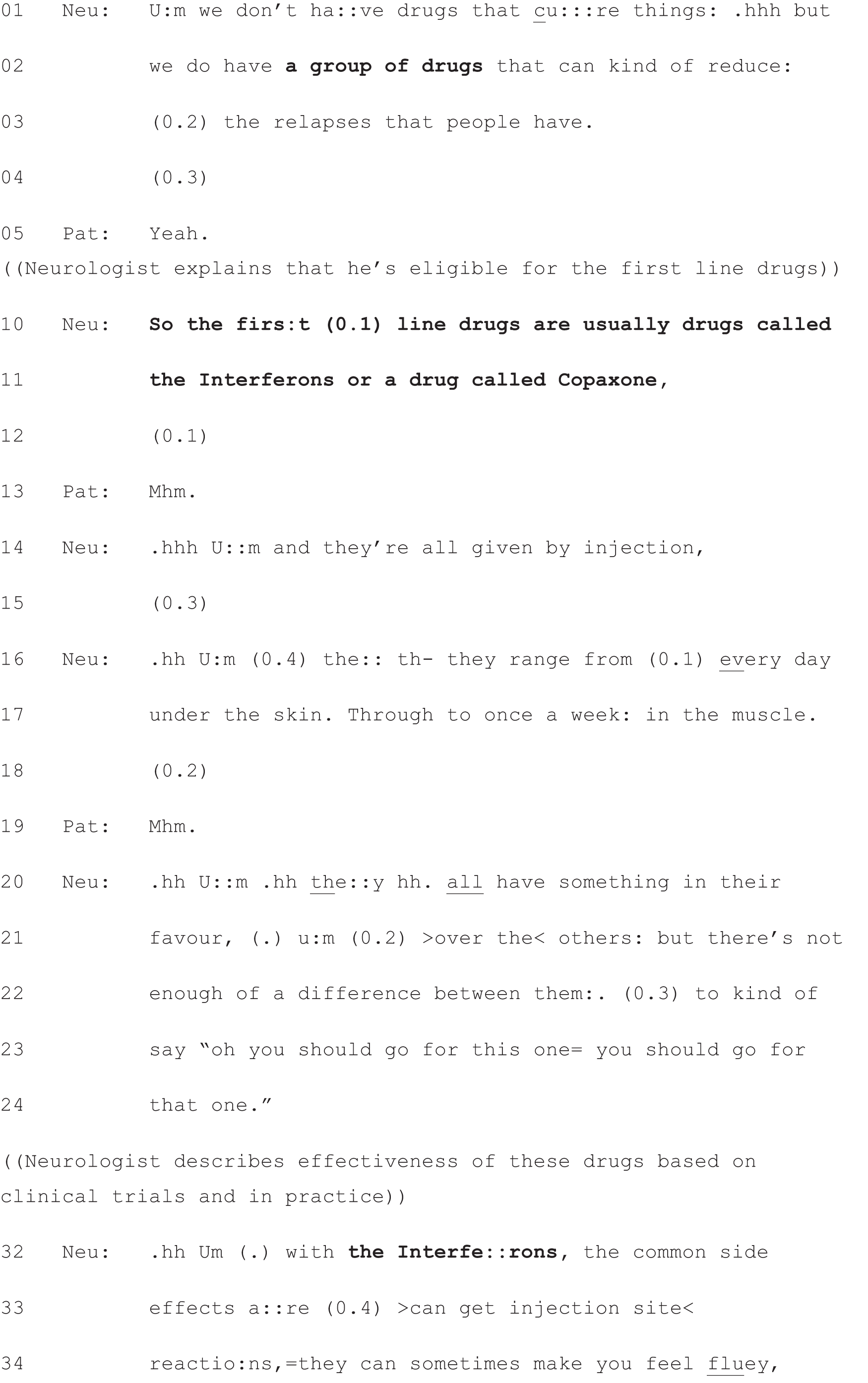

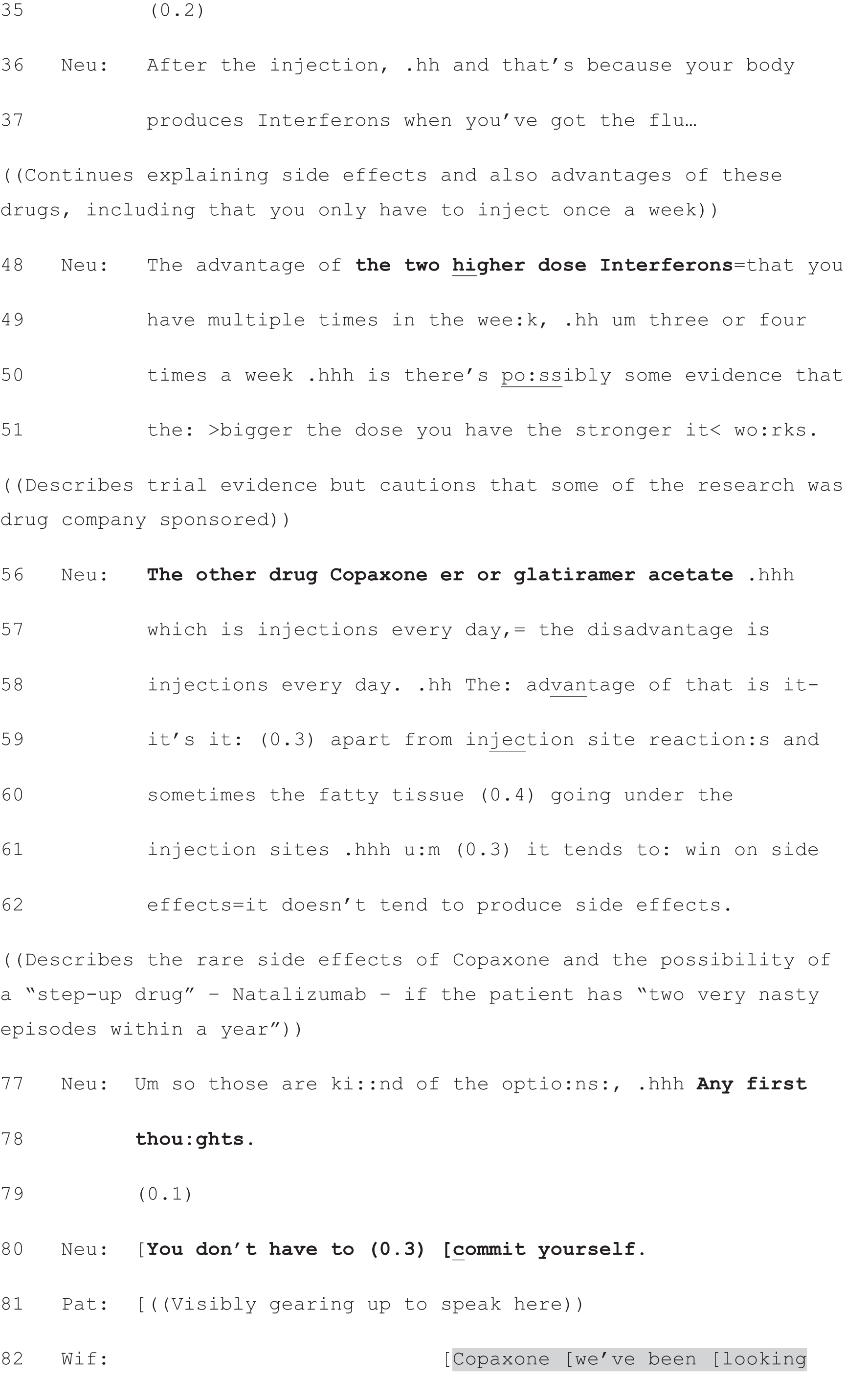

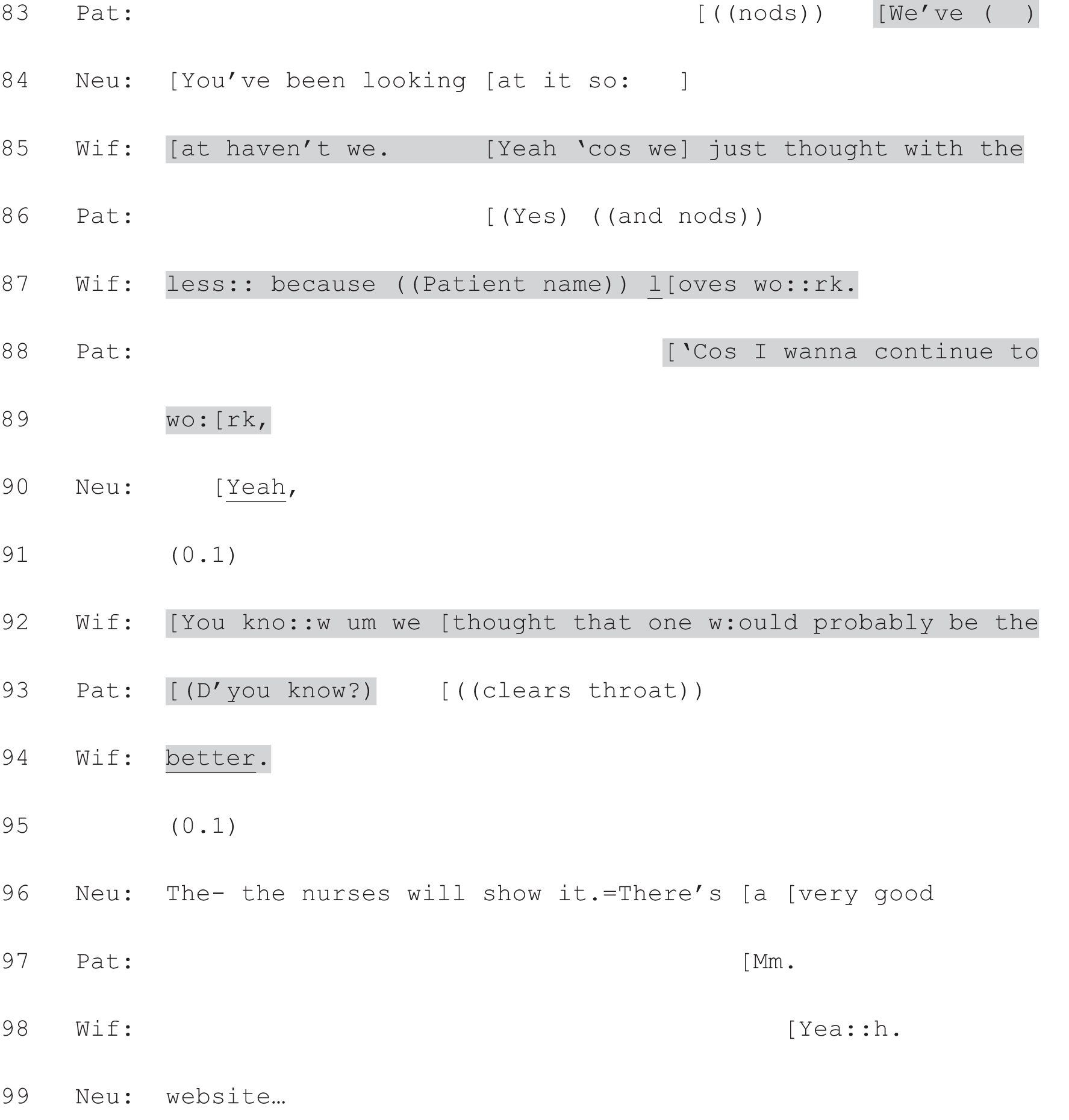

Structure of the results sections of this report

The remainder of the report is structured as follows: we begin with an overview of the study data set, including our recruitment figures and sample characteristics (see Chapter 3). We then present a quantitative analysis of the questionnaire data pertaining to choice (see Chapter 4). We also provide a brief overview of the ways in which neurologists in our data set constructed the patient’s condition as involving no choice (see Chapter 5). In Chapters 6 and 7 we analyse option-listing – the only practice demonstrably oriented to offering choice that was only evident (with one exception, which, as we show, proves the rule) in the subset of recordings in which neurologists and patients agreed a choice had been offered. In Chapter 8, we consider two alternative practices for offering choice, this time focused on single-option decisions. Chapter 9 discusses the implications of our findings and our recommendations for future research.

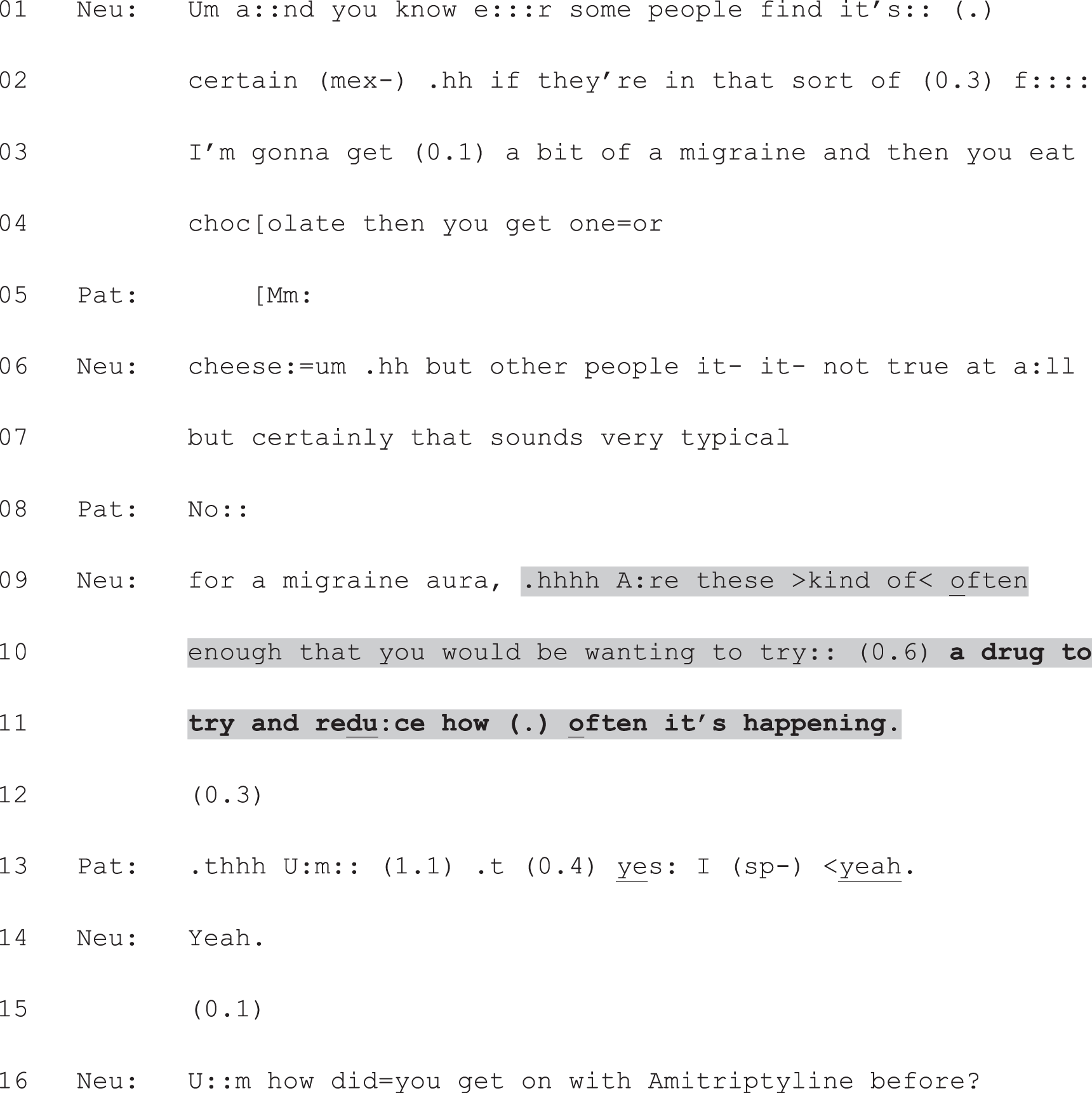

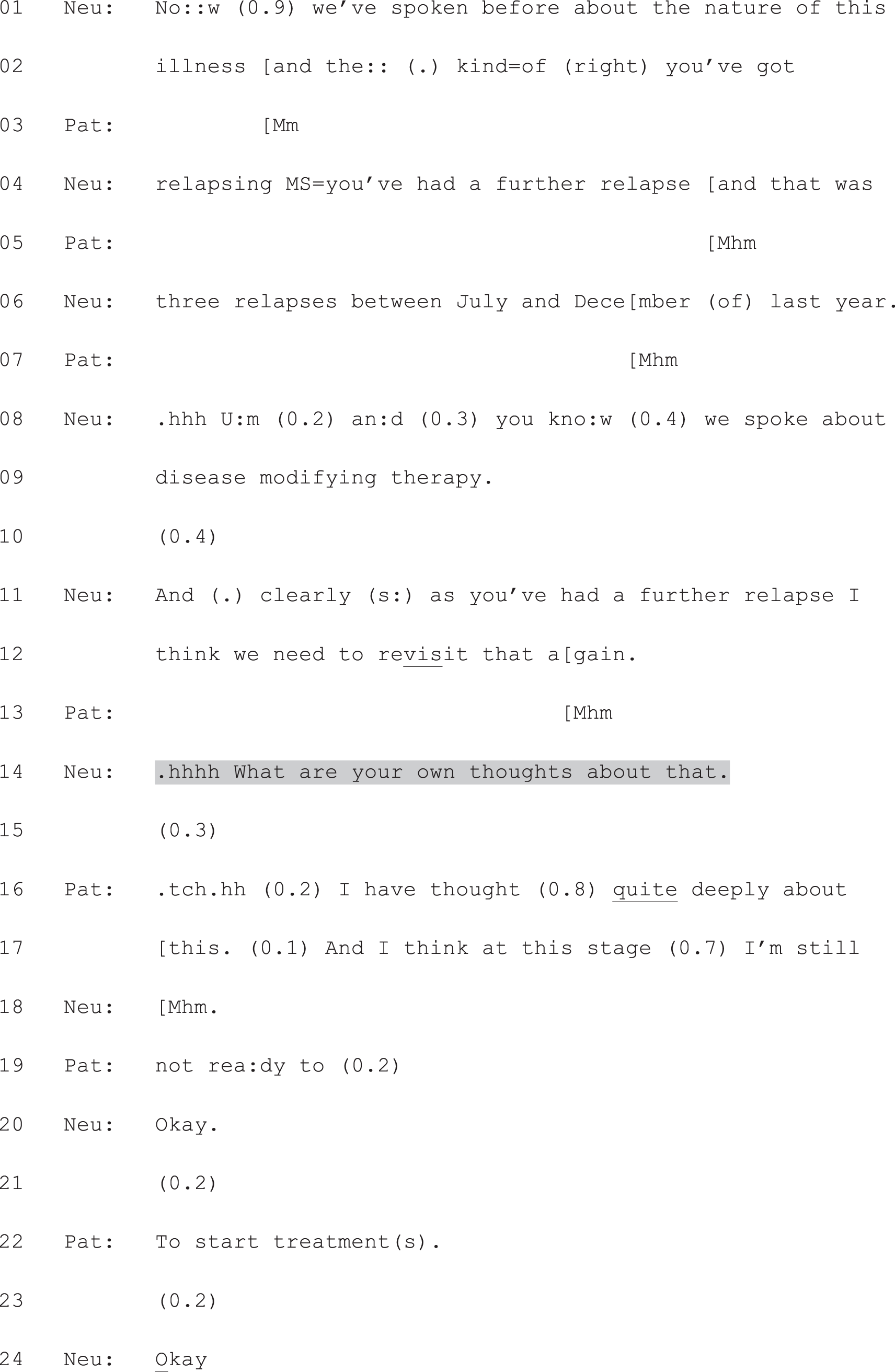

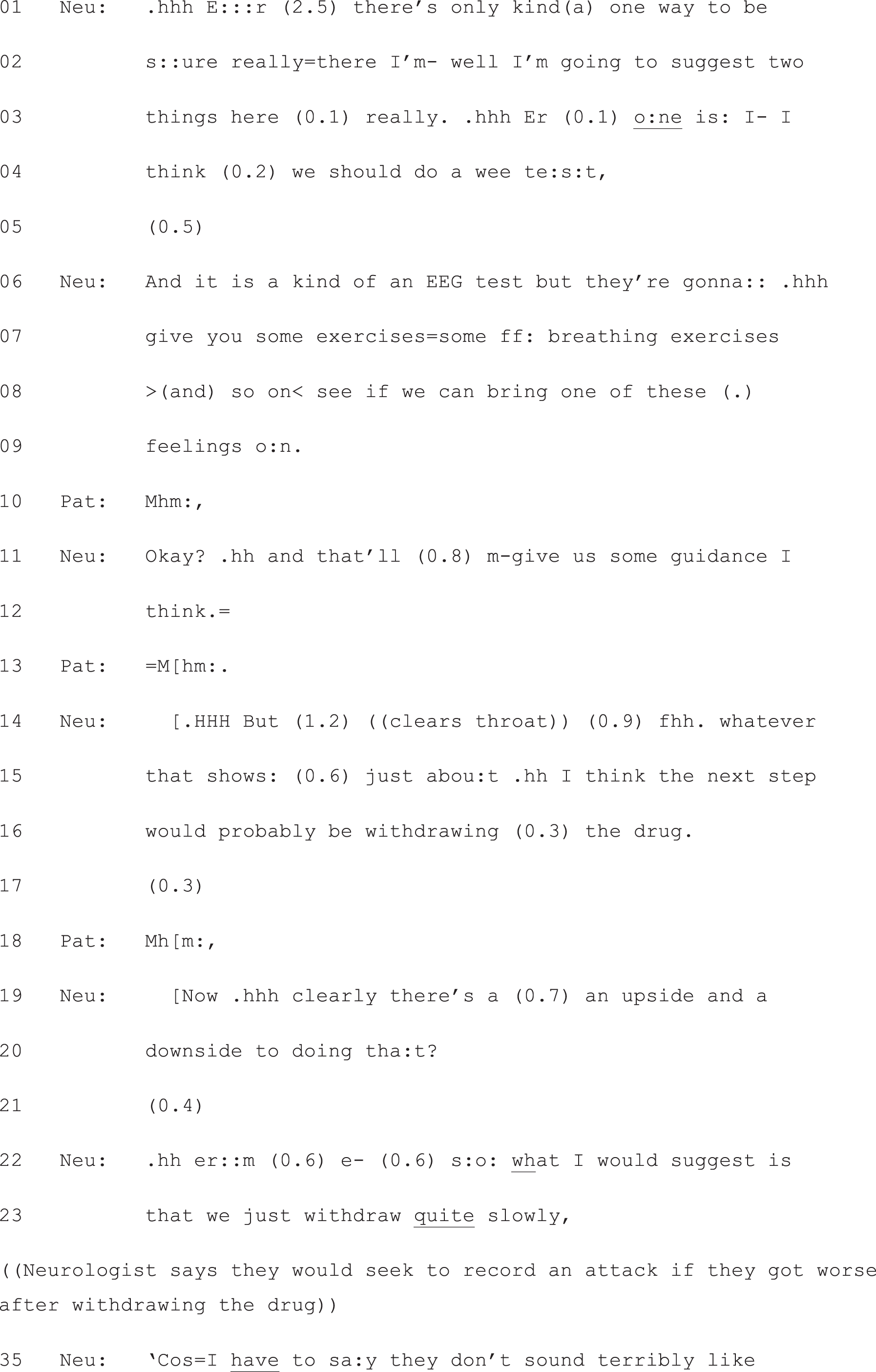

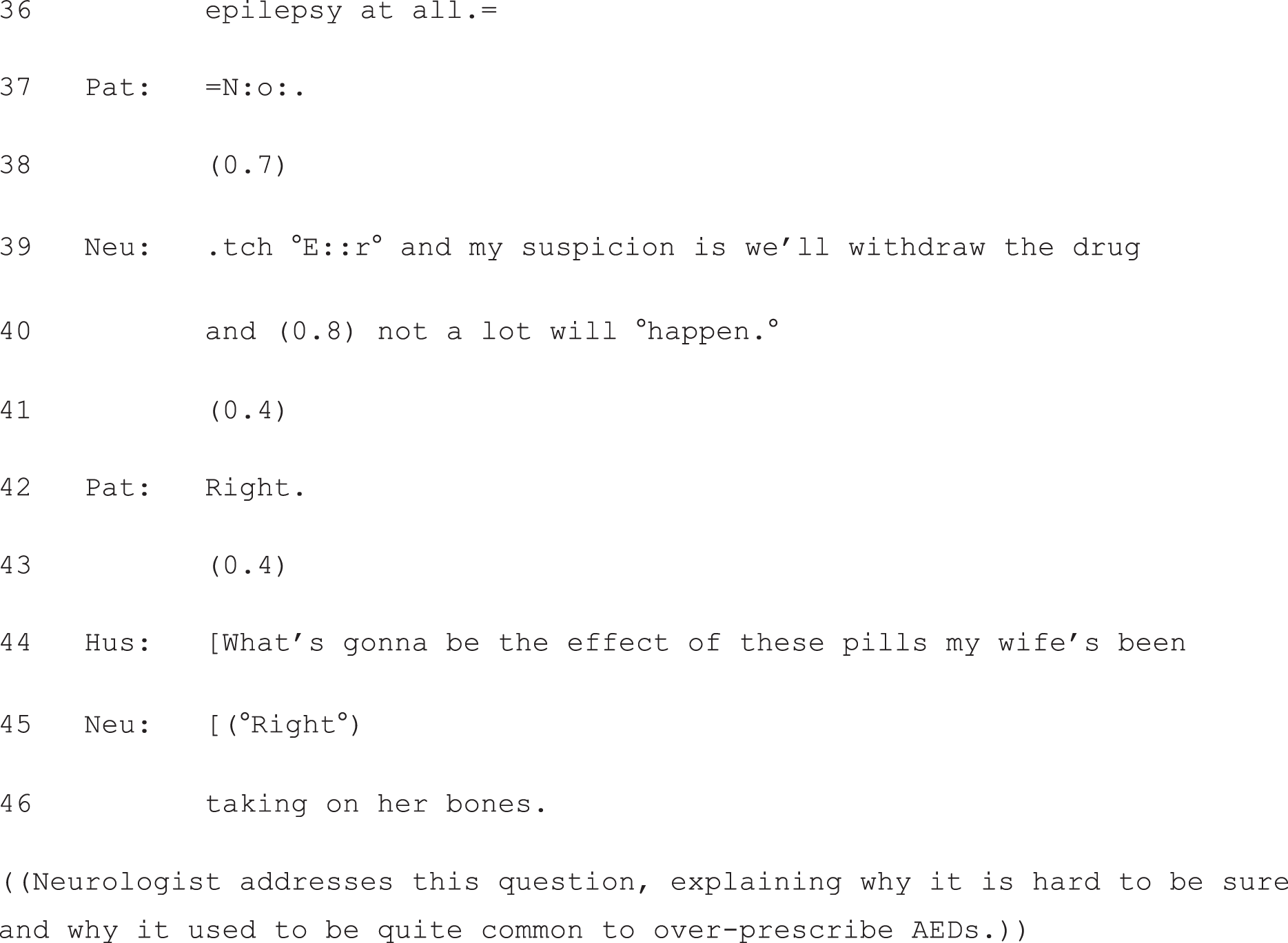

Throughout the report, findings are illustrated with extracts from the transcribed recordings. Some of these extracts may seem rather long. However, we ask the reader to bear with this as it partly reflects the nature of our phenomenon (e.g. option-listing involves information provision and, typically, rather extended discussion between neurologist and patient) and partly reflects the nature of our methodology – its key advantage is the fine-grained analysis of what really happened rather than summaries thereof. We hope that readers will avoid the temptation to skip over the extracts and will see the benefits of the transparency that they allow with respect to evaluating our analysis.

Each transcript is numbered consecutively to make it easier to refer to consultations shown in different chapters. The transcript labels include the following information: the study site (‘G’ for Glasgow, ‘S’ for Sheffield); a three-digit patient number; a two-digit clinician number and the diagnosis that the neurologist reported (in the post-consultation questionnaire) as most likely.

Chapter 3 Overview of the study data set

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to describe the data set on which this study is based. We start by describing the two data collection sites, then present our recruitment figures, and finally map out the nature of the sample with respect to factors such as the type of appointments recorded and a range of participant demographic variables.

Data collection sites

All data were collected at the outpatient departments of two major clinical neuroscience centres (one in England and one in Scotland). The Royal Hallamshire Hospital in Sheffield, South Yorkshire, is part of Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and has approximately 800 beds, of which 50 are sited within the neurology department. The Southern General Hospital in Glasgow, Lanarkshire, is a large teaching hospital with an acute operational bed complement of approximately 900 beds. The hospital is sited in the south-west of Glasgow and provides a comprehensive range of acute and related clinical services. The Royal Hallamshire Hospital serves as the clinical neuroscience hub to a population of 2.2 million. The general population served by the Southern General in Glasgow is 2.5 million.

Each site employs a diverse team of consultant neurologists (20 in England and 23 in Scotland) and offers general neurology as well as a range of subspecialty clinics (such as epilepsy, MS, dementia, ataxia, headache, cerebrovascular disease, neuromuscular disorders and movement disorders) ensuring a broad range of consultation types. New patient appointments are usually scheduled to last 30–45 minutes and follow-up appointments 15–20 minutes.

Recruitment figures for each site

Fourteen clinicians (seven in Glasgow and seven in Sheffield) agreed for recordings to be made in their clinics subject to patient consent. As detailed in Chapter 2, the eligible patient population included all patients (aged 16+ years) attending clinics run by the participating clinicians, provided they were able to give informed consent in English. In total, 223 patients agreed to take part (114 in Glasgow and 109 in Sheffield). One appointment per patient was captured. In addition to patients and clinicians, 120 accompanying others (including spouses, parents, carers and friends) consented to contribute to the study (63 in Glasgow and 51 in Sheffield).

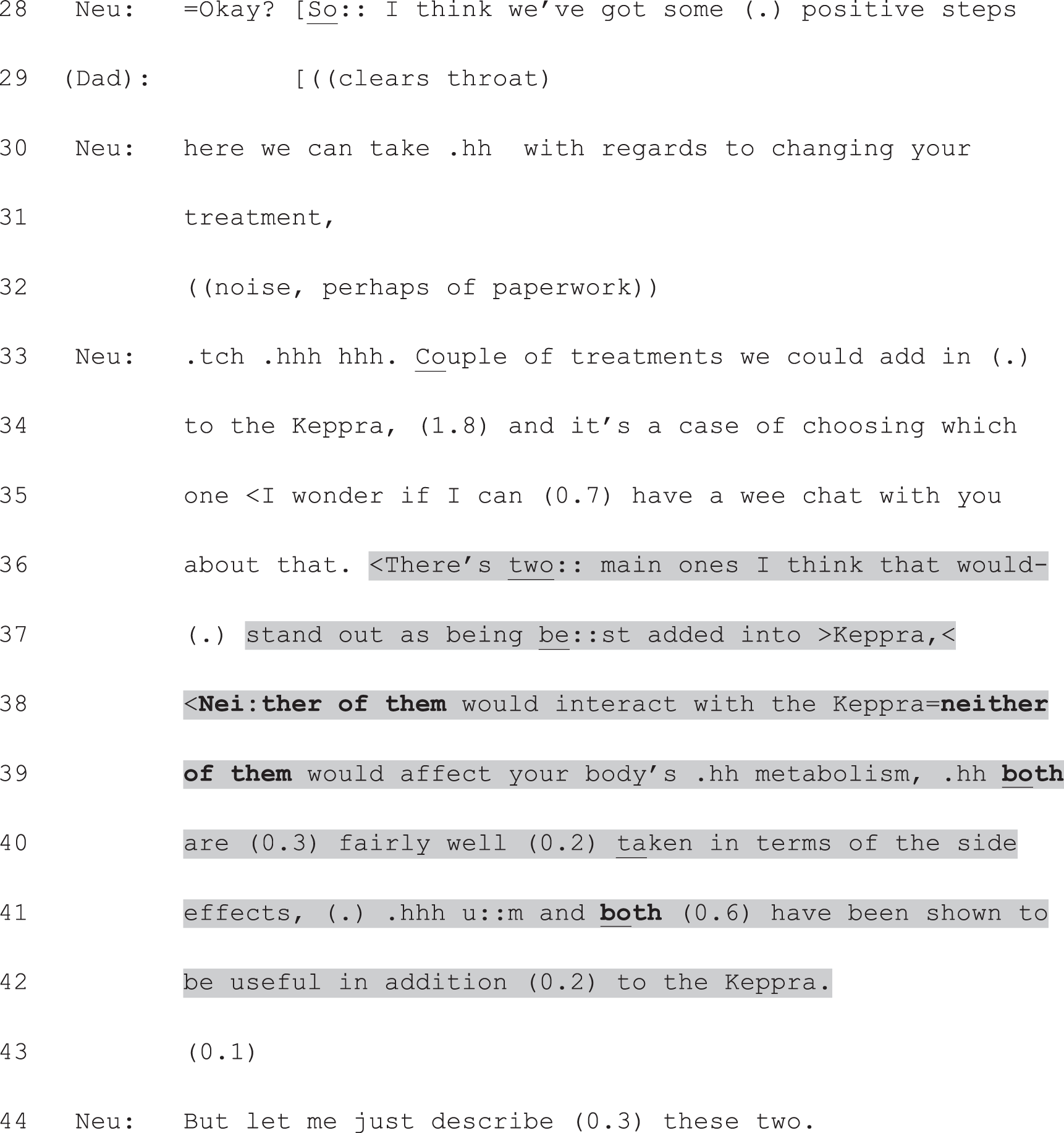

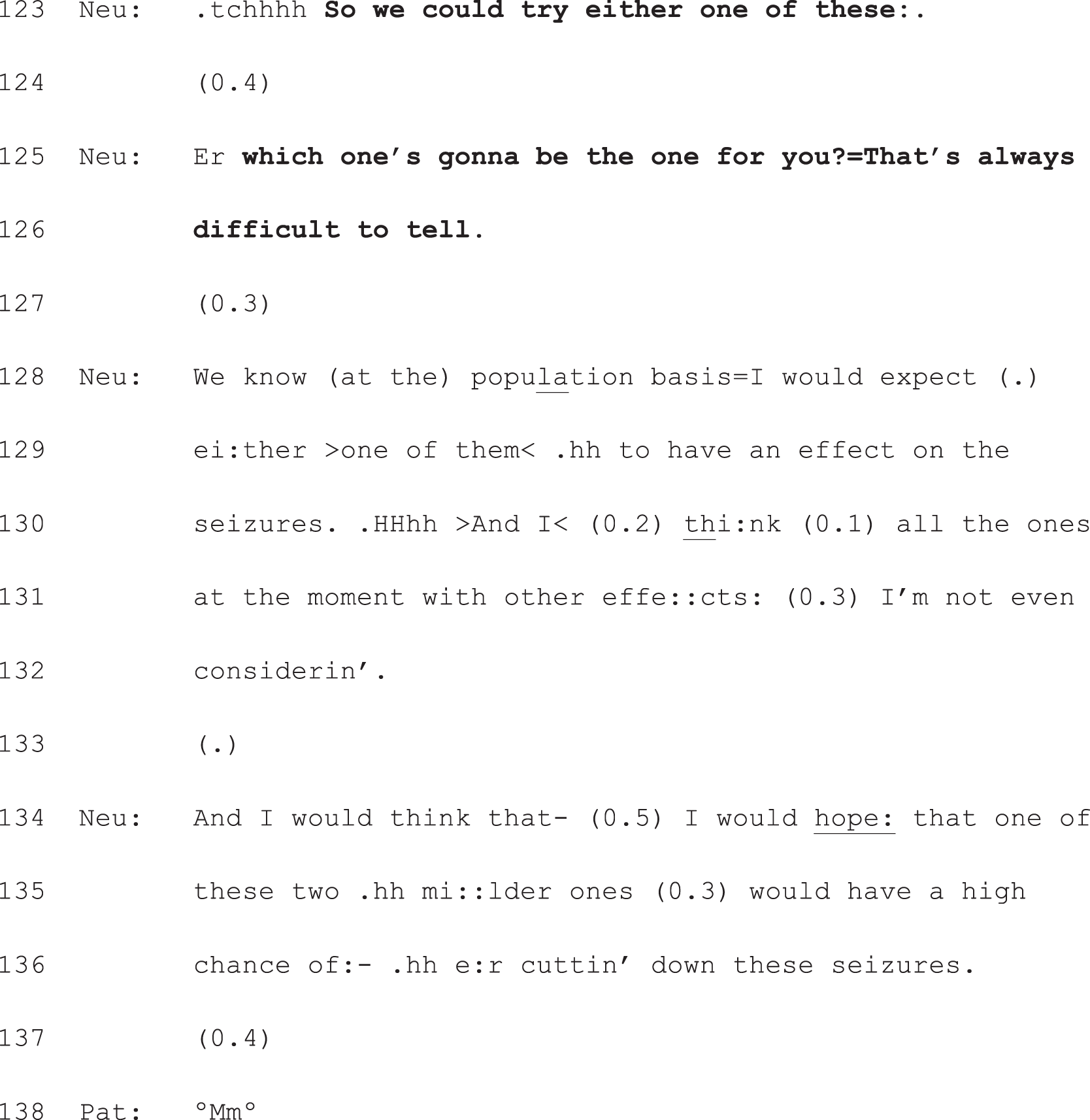

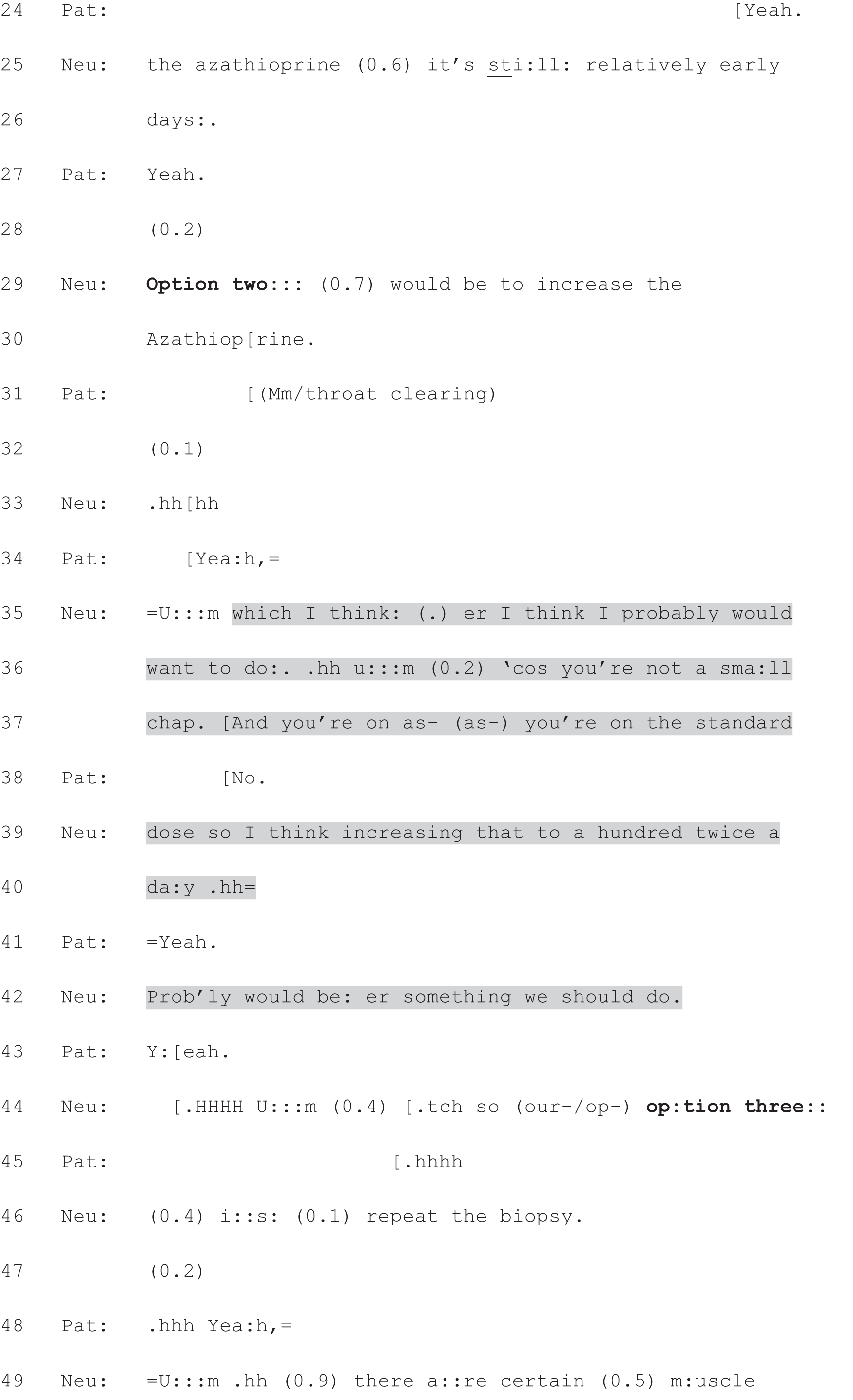

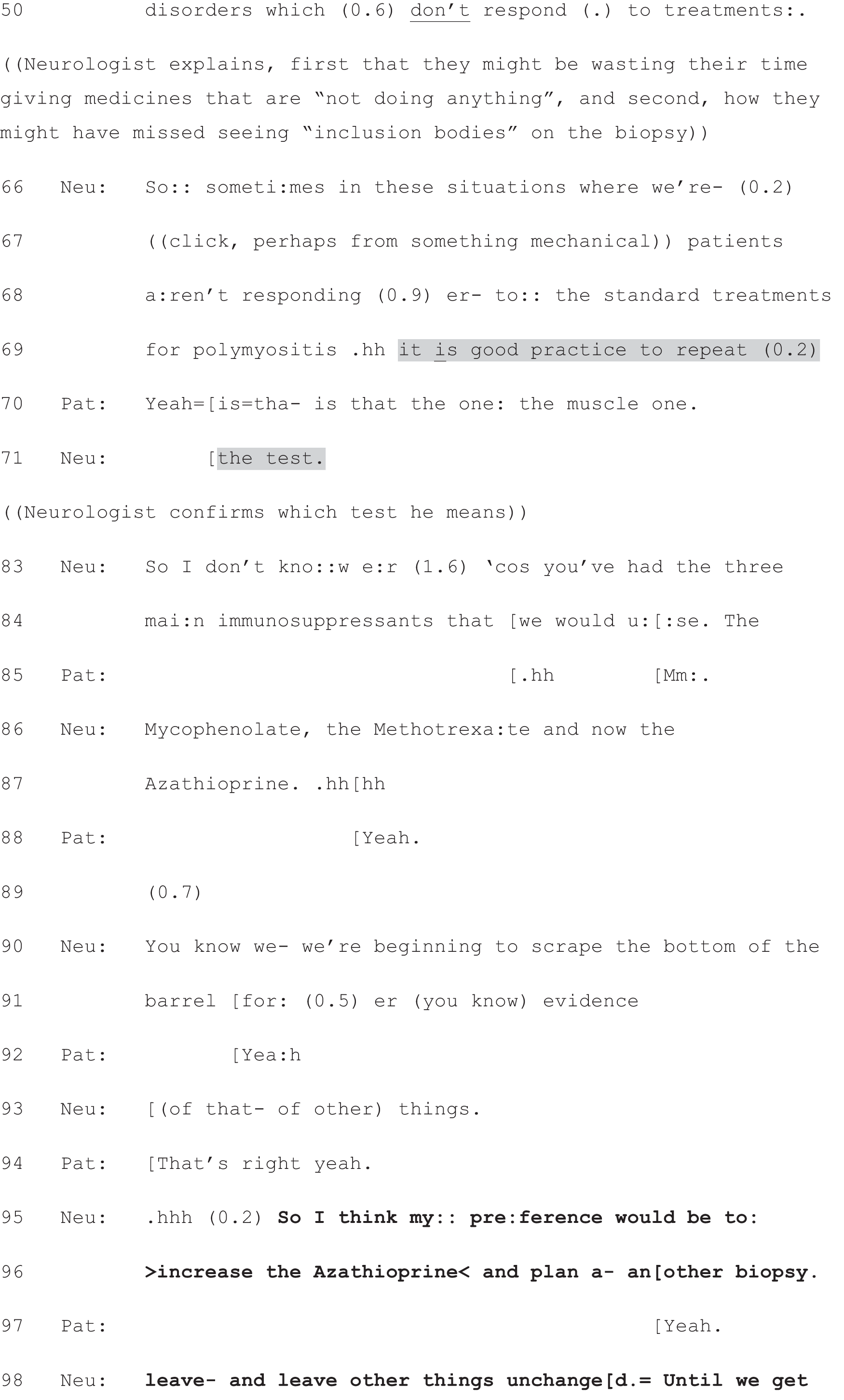

Figures 1 and 2 describe the data collection process at Glasgow and Sheffield, respectively. Patients who attended on the day of the clinic (there were a number of non-attenders at each site) were approached in the waiting room, prior to the start of the patient’s neurology consultation. If patients agreed to participate, signed consent was obtained (see Chapter 2 for more information about our approach to recruitment).

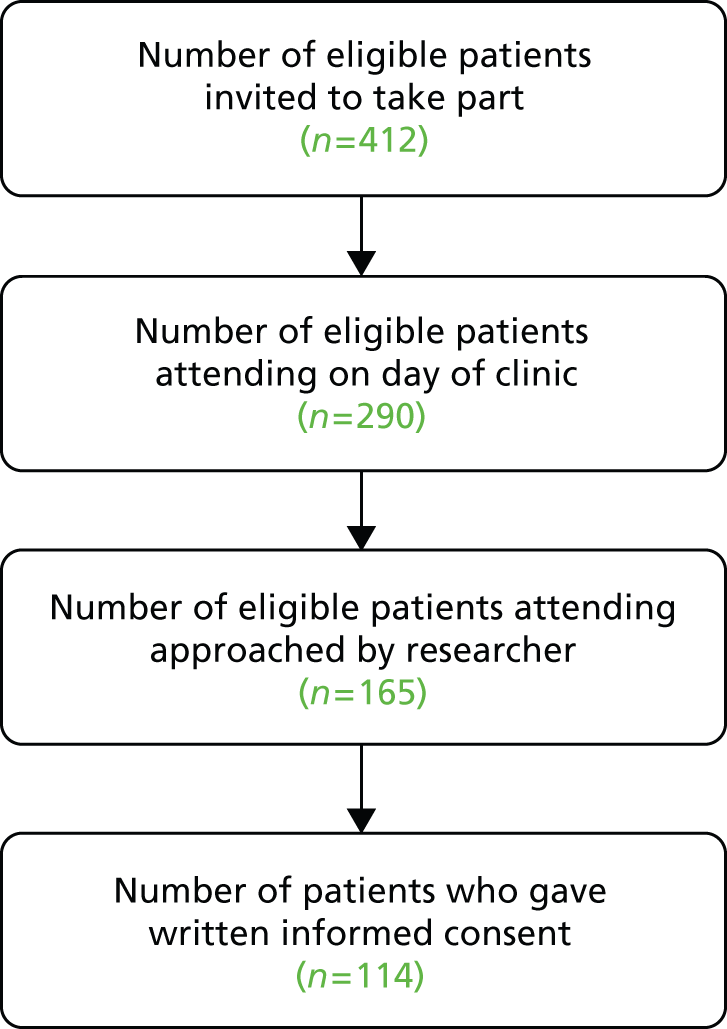

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment of participants at the Glasgow site.

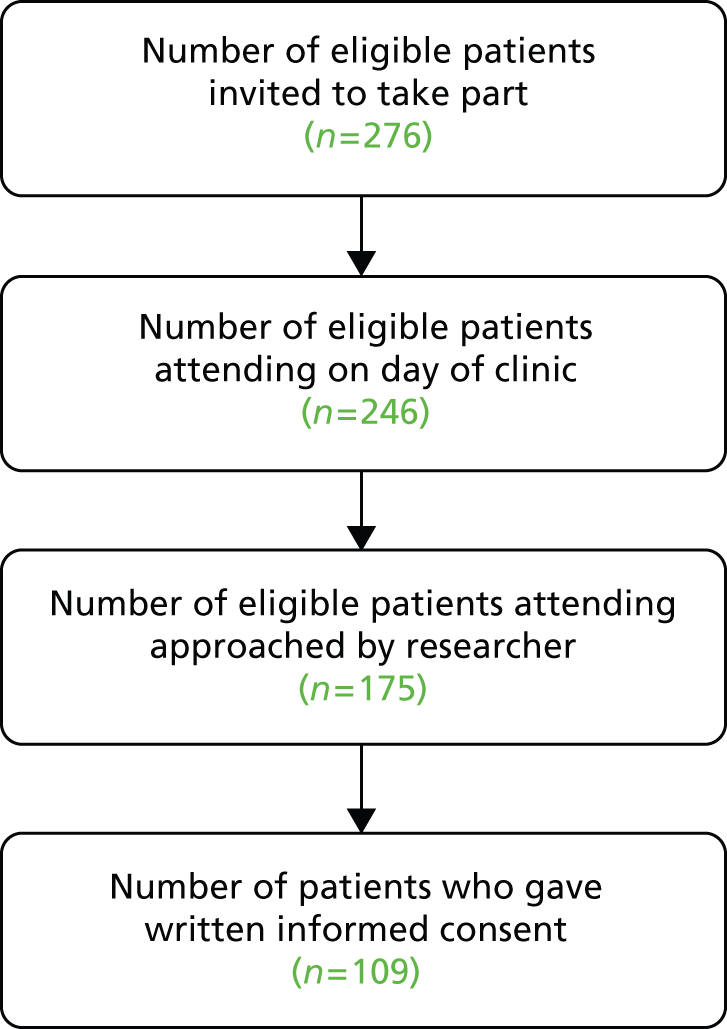

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment of participants at the Sheffield site.

In total, 69% of those approached to consent by a researcher in Glasgow agreed to take part and 62% of those approached in Sheffield agreed to take part – an overall response rate of 66%. It should be noted that researchers were not able to approach all patients attending, as researchers had competing demands on their time (e.g. they were handling the consent procedure with another patient, setting up recording equipment or administering questionnaires).

Participant demographics

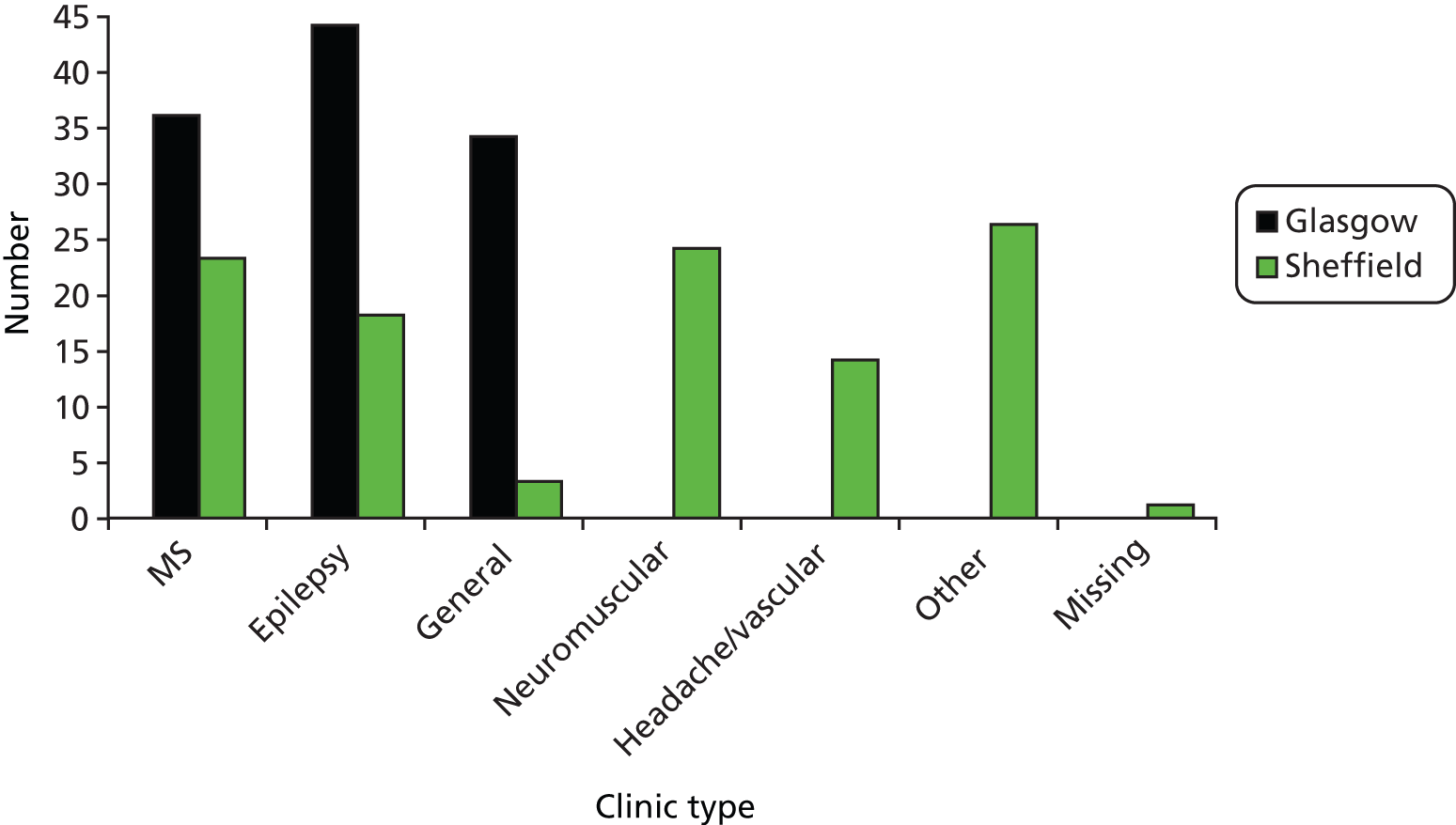

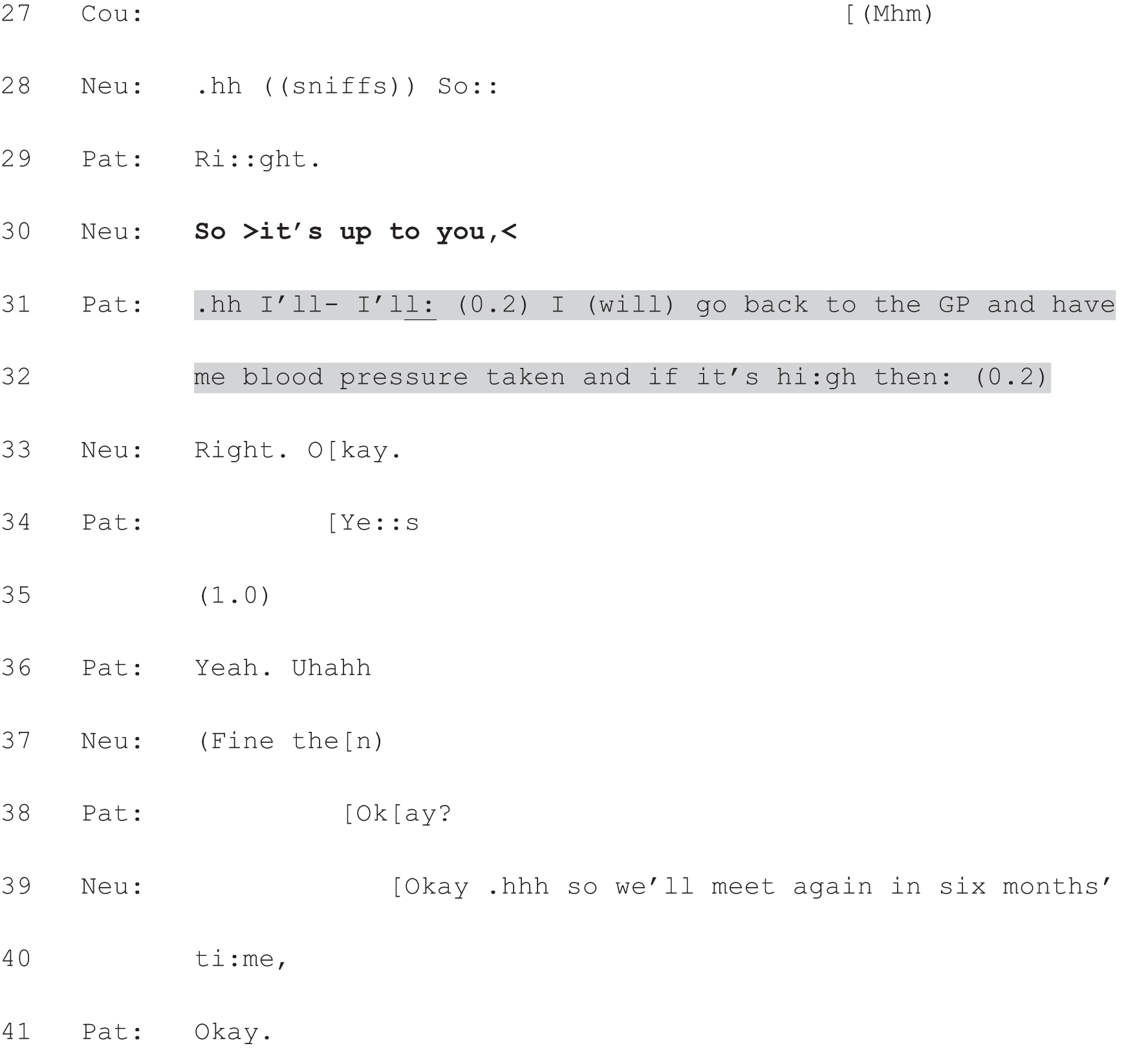

The overall sample of patients ranged in age from 17 years to 80 years, with a mean age of 46 years. More than half the patients recruited were female (60%). Ninety-three per cent described themselves as white (English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British). Forty-two per cent of the sample was in employment (full- or part-time) or education. Educational qualifications beyond school leaving age (16 years) had not been obtained by 40.5%, while 40% had received a high school or university education. The neurologist sample ranged in age from 31 years to 57 years, with a mean age of 43 years. The neurologists consisted of eight men and six women, 12 consultants and two registrars. Seventy-nine per cent of the neurologists described themselves as white. Table 1 shows the demographic features of the study sample in more detail, including a breakdown per study site. More Glasgow patients were seen in general neurology clinics than Sheffield patients. Glasgow patients were a little older and more likely to be out of work or on sick leave because of their illness or disability.

| Feature | Sheffield (109 patients, seven doctors) | Glasgow (114 patients, seven doctors) | Difference: Sheffield vs. Glasgow | Combined (223 patients, 14 doctors) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultations | ||||

| Percentage accompanied | 46.8 | 52.6 | N/S | 49.8 |

| Percentage of first appointments | 27 | 32 | N/S | 29 |

| Percentage seen in general clinics | 2.8 | 29.8 | p < 0.0001 | 16.7 |

| Patients | ||||

| Patient age (years) | 49.1 (SD 15.2, range 17–80) | 43.7 (SD 14.9, range 17–80) | p = 0.005 | 46.3 (SD 15.3, range 17–80) |

| Percentage male patients | 46.2 | 34.2 | N/S | 40.1 |

| Percentage white (English, Welsh, Scottish, NI or British) | 89 | 96.5 | N/S | 92.8 |

| Percentage without post-school qualifications | 39.2 | 42.1 | N/S | 40.5 |

| Percentage with university qualification | 35.3 | 25.5 | N/S | 29.9 |

| Percentage in work/education | 45.9 | 37.7 | N/S | 41.7 |

| Percentage on leave/out of work because of sickness/disability | 33.6 | 16.7 | p = 0.005 | 25.3 |

| MISS–21 scores | 101.0 (SD 9.2) | 95.0 (SD 11.9) | N/S | 98.0 (SD 11.0) |

| Neurologists | ||||

| Neurologist age (years) | 43.7 (SD 5.3, range 37–53) | 41.4 (SD 9.86, range 31–57) | N/S | 42.6 (SD 7.7, range 31–57) |

| Percentage male neurologists | 57.1 | 57.1 | N/S | 57.1 |

| Percentage white (English, Welsh, NI or British) | 100 | 57.1 | N/S | 78.6 |