Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 08/1806/262. The contractual start date was in December 2009. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in February 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Sheaff et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 NHS commissioning practice and health system governance

Background

Few questions are more important to the NHS than how its commissioners exercise governance over local health economies. Commissioners pay for health care on behalf of patients who cannot do so themselves and on the state’s behalf; in the absence of public ownership and direct managerial control by the state, they also exercise governance over the service providers. This study aims to examine the means, contexts and effects of commissioning practice that was current in 2010–12, that is the activities of assessing health needs, selecting and contracting providers to meet them, monitoring the outcomes and then repeating the cycle. 1,2 We focus on the ways in which health-care commissioners can influence health-care providers within a quasi-market health system.

NHS commissioning: the policy context

Policy initiatives related to commissioning since 1991 have set the basis for current NHS commissioning policy and the system introduced in April 2013. Since 1991, three distinct main commissioning structures have evolved:

-

Population-based commissioning. A single body commissions health services for the entire resident population within its geographical boundaries. This structure includes public health activity, for evaluating population health-care needs and initiating preventative activities. In England, District Health Authorities began commissioning services for populations of 200,000–500,000 people in 1991.

-

General practice-based commissioning. General practices, or another gatekeeper and budget holder, individually or collectively commission services, the general practitioners (GPs) acting as proxies or advocates for their registered patients when making referral decisions. These commissioners tend to serve perhaps 5000–100,000 patients. GP fundholding was the best-known English variant.

-

Client-based commissioning. Patients themselves choose a health provider, which a commissioning organisation then pays on their behalf. Consequently the provider has to be paid per episode of care; in most health systems, through a diagnosis-related group (DRG)-based tariff system. Another variant is to give patients a voucher or budget to pay for care. Client-based commissioning is still an emergent structure in England, represented by the Patient Choice policy, personal health budgets and the ‘payment by results’ (PbR) system (see section Phase 5: 2006–10 – client-based commissioning).

Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), introduced in April 2013, are essentially a variant of population-based commissioning, but also resemble general practice-based commissioning in that GPs play a pivotal role in their governance. One can distinguish six phases of the evolution of NHS commissioning in England.

Phase 1: unitary system (before 1991) and the impetus behind the 1991 reforms

Until the late 1980s, contiguous health authorities (HAs) planned and managed NHS hospital and community health services for a geographically defined population. Services could be organised across the district and integrated, since just one body managed them. Transaction costs were low because decisions were enacted through line management. However, HAs were subject to provider capture, becoming beholden to clinicians (especially doctors) both for technical reasons (to help inform their decision-making) and in consequence of the 1947 settlement between the state and the medical profession, through which the NHS was established. 3 There was also an efficiency trap: ‘good’ providers who attracted more patients incurred greater costs and their service ‘quality’ (especially waiting times) deteriorated.

The NHS financial ‘crisis’ of the late 1980s prompted the Conservative government to announce a widespread review. Though financial in origin, the crisis was to be solved by organisational restructuring. The Working for Patients White Paper4 heralded the end of the unitary system. Enthoven, whose work5 anticipated it, had proposed contracts with individual consultants, but the White Paper was less radical and proposed a market-style relationship between commissioners (‘purchasers’, i.e. HAs) and service providers, albeit with a heavy dose of management intervention and regulation. At varying speeds, NHS providers became self-governing trusts. A late addition to the proposals was GP fundholding, seen as a way of introducing competition between purchasers. Hence the NHS quasi-market was born in April 1991.

Phase 2: 1991–7 – the ‘plurality of purchasing’

Although allegedly incompatible,6 population-based commissioning and GP fundholding coexisted for several years.

Although HAs had sufficient financial clout to engender improvements in provision, they were not so responsive to local needs. Some HAs sought to introduce locality purchasing initiatives, not only to be responsive to local need but also to stem the flow of GPs electing to become fundholders. 7 GP fundholders had relatively little financial power (given the size of their budget compared with a provider’s), but were more agile in securing improvements in certain services for particular groups of patients. The analogy between HA ‘supertankers’ and GP fundholder ‘speedboats’ was apt.

Much concern about GP fundholding centred on fears of ‘cream skimming’ (GPs might avoid ‘unhealthy’ patients in case they cost the GP’s budget more), a two-tier service (some patients might enjoy ‘better’ access to services), higher transaction costs (of negotiating and monitoring contracts) and possible adverse effects on the doctor–patient relationship. In the event there were few cases of cream skimming and few patients were aware whether their GP was a fundholder or not,8 although transaction costs were approximately twice those of HAs. Over time, GP fundholding schemes became smaller and their remit expanded, which complicated the evaluation of them. 9 Some GP fundholders also sought to leverage their financial power by combining in networks (‘multi-funds’), which evolved into more formal total purchasing pilots (TPPs),10 the nearest equivalent commissioning organisation so far to CCGs. Each served about 300,000 people, similar to an HA. By 1997, the variants of GP fundholding covered 53% of the English population,11 equivalent to 10% of the hospital and community health services budget. 12

At this stage client-based commissioning barely existed. Although patients were given some encouragement to move between practices, few did. 8,13 Policy talk about ‘choice for patients’ was thus largely rhetoric.

Phase 3: 1997–2001 – the fall and rise of the practice commissioner

Labour’s 1997 election manifesto declared that it would replace GP fundholding with more collaborative commissioning,11 in language that symbolised a shift away from explicitly market-style relations towards a system of service ‘delivery agreements’ of longer duration than existing contracts. Whereas GP fundholders had real budgets, the replacement system would give general practices ‘indicative’ budgets. Crucially, all GPs in an area would belong to a primary care group (PCG). The 481 English PCG boards were mandated to include nurse and local authority representatives,14 but GPs were in the majority, albeit ‘not very effective’15 in wielding influence. Although the ‘ghost of GP fundholding’ lived on,15 the tension between general practice-based commissioning and population-based commissioning was resolved in favour of the latter, attenuated with strong GP input.

Primary care groups evolved into primary care trusts (PCTs), taking on the former HA role to

become the lead NHS organisation in assessing need, planning and securing all health services and improving health. They will forge new partnerships with local communities and lead the NHS contribution to joint work with local government and other partners. 16

Health authorities were abolished, while NHS performance management regimes and the authority of the Secretary of State were significantly reinforced. 17

Phase 4: 2001–6 – shifting the balance of power?

In 2005, practice-based commissioning (PBC) was introduced to give GPs greater influence over commissioning. PCTs gave general practices ‘virtual’ budgets for health services for their practice patients, but retained the ‘real’ money;18 a system similar to the TPPs. Since PBC budgets were not held at practice level but collectively, PBC represented another variant of the population commissioner model, with stronger GP input than hitherto. PBC practices tended to collaborate to share expertise and resources, designed care pathways jointly19 and encouraged GP engagement with commissioning. However, on balance:

Progress to date has been slow in all sites: very few PBC-led initiatives have been established and there seems to have been little impact in terms of better services for patients or more efficient use of resources. 18

See also Coleman et al. (p. viii). 20

By 2012, ‘David Colin-Thomé, the health department’s lead doctor in primary care, declared it [PBC] to be a “corpse”. A corpse which he judged was “not for resuscitation” ’. 15

Phase 5: 2006–10 – client-based commissioning

In 2006, PCTs were amalgamated, reducing their number from 303 to 152. The number of Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs) was reduced to eight, in ‘what looked remarkably like the reinvention of the regional offices that had been abolished earlier’ (pp. 241–2). 21 Ministers were starting to consider PCTs underpowered in controlling healthcare providers and began considering ‘demand side’ (p. 11)22 reforms. World-class commissioning (WCC) was an attempt to upgrade PCTs’ managerial performance of their commissioning role, and to strengthen PCT commissioning by developing, and evaluating PCT performance against, a set of 10 competencies (www.hsj.co.uk/resource-centre/world-class-commissioning-nhs-sets-out-to-lead-the-world/211288.article) – a development that also illustrated population-based commissioners’ ongoing search for legitimacy. Under the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) scheme, up to 2.5% of the value of provider contracts was linked to compliance with quality standards; the selection of quality standards changed from year to year, and within limits could be varied at regional level.

Client-based commissioning thus emerged. Hitherto, NHS providers (except GPs) had been paid through block or cost-and-volume contracts. The PbR policy introduced a prospective payment system of paying providers a tariff for each episode of care. These ‘Healthcare Resource Group’ (HRG) tariffs were a variant of the DRG system originally developed in New York. PbR was intended to encourage providers to reduce their costs (to below tariff level) and increase patient throughput (hence reducing waiting times for treatment). Concurrently, the ‘Patient Choice’ policy obliged GPs to offer patients a choice of provider for planned secondary care,23 and the chosen provider was guaranteed the corresponding tariff payment. Following similar schemes for social care,24 a pilot scheme to develop and evaluate personal health budgets was launched. In 2009, a policy that NHS organisations would be ‘preferred providers’ was announced. Nevertheless, the policy of promoting provider competition (including competition between NHS providers) continued during and after 2009.

Phase 6: coalition government

Originally billed as ‘GP commissioning groups’, CCGs are membership organisations of all the GPs serving a geographically defined resident population. Although the nature of this membership role is still emerging, it means that individual practices will not hold commissioning budgets; only the CCG will do so collectively. Thus CCGs represent yet another variant of population-based commissioning, but with still stronger GP input. This time, GPs are ‘required to assume the driving seat of commissioning’ (p. 12). 15 CCGs will also have greater leverage over individual general practices’ performance than did earlier commissioners. CCGs were intended to become responsible for 80% of NHS spending (their 2014 share is almost certainly lower) compared with the initial 30% budget responsibility for GP fundholding in 1991. It remains to be seen whether CCGs will become more like large-scale GP fundholders or more like PCTs.

The Any Willing (later, Qualified) Provider policy widened the range of providers from which patients or GPs could choose, with the aim of adding private providers. The Transforming Community Services (TCS) policy (2011) transferred community health services from PCT ownership and management into separate organisations, most often NHS trusts. The monitor’s role became one of fostering ‘level playing field’ competition between public and private providers. Private firms were permitted to participate in NHS commissioning, through selling data analysis services that model patient demand (as two US health maintenance organisations (HMOs) have done), helping commissioners manage programme budgets, or selling more general commissioning support to NHS commissioners. Further commissioning support work could, according to some, be tendered for private-sector provision.

So, at the time of writing (June 2013), the NHS mainly uses two commissioning structures: a population-based (but GP-controlled) structure and a client-based structure [PbR plus Any Qualified Provider (AQP)]. Traces of general practice-based commissioning are more rhetoric than reality.

Continuities

Certain structural continuities have persisted since 1991. Competing governance structures coexist. 25 Health policy rhetoric about competition has often been accompanied by a strong undercurrent of control and market management, such as brokering individual organisations’ losses at the end of the financial year. 26 Concomitantly, the level of competition has waxed and waned. Throughout the past 20 years, commissioners have preferred to spend their budget on local providers – ‘localism’. 27 While commissioning structures have varied over time, whether NHS funding was expanding or being retrenched, commissioners have retained a rationing role and a function in ensuring equitable allocation of NHS spending.

There has been constant tension regarding the scale of population at which commissioning should take place. 28 The range goes from personal budgets (n = 1) to CCGs and, for rare or specialised treatments, millions. The Secretary of State did not prescribe how many CCGs there should be, but the number authorised (n = 211) is smaller than the original number of PCTs (n = 303), larger than the last generation of PCTs (n = 152) and similar to the number of HAs in 1992 (n = 192). General practice, specialised services and health visiting are commissioned at national level by NHS England.

There has also been a clear shift away from letting general practices decide if they want to commission other services. GP fundholders were volunteers. All practices had to be members of their local PCT, and now CCG. The GPs managing CCGs will have to take responsibility for, and intervene to influence, any apparently poorly performing GPs or general practices in their territory. They will hold individual practices to account for the practice’s commissioning expenditure. In some areas general practices are already being performance managed on this responsibility. General practice itself has been gradually drawn into the orbit of NHS management, partly but not only through successive changes to GP contracts, especially the new general medical services (NGMS) contract introduced in 2004. 29

Contracting methods have also become more sophisticated, block contracts being gradually replaced by cost and volume contracts (sometimes with caps and/or cost-per-case variations at the margin). Starting with a small range of planned acute treatments, PbR tariffs now cover most planned acute care and are being extended into mental and community health services.

Overview

Although the commissioning–provision split is generally accepted, the precise roles that either side plays are not. Given the alleged ‘failures’ of commissioning (and commissioners) over the past 20 years,30 it might appear that the balance of power within the NHS remains weighted towards the providers, in primary31 and secondary care. Equally, commissioners have not always been willing to exercise their powers fully, often ‘colluding’ with providers in support of local services. 27 Their limited data and expertise also put NHS commissioning organisations at a further disadvantage compared with providers. Managerial careers in commissioning, for example, might be short compared with those in NHS trusts. Mean salaries for commissioner chief executives were about £10,000 less than their acute-sector counterparts. 32 Throughout there has been an ongoing tension between the need for a publicly funded service to be answerable to Parliament and the neo-liberal desire for markets and competition, which policy-makers think deliver locally responsive services.

Attributing impacts to commissioning and commissioning practice is a complex and contested activity. Because evaluation was not built into the early periods of commissioning, the evidence for improved outcomes is equivocal. Two reviews8,13 point to some positive outcomes, although other commentators33 are less convinced. This brings us to the question of what existing research shows about the mechanisms by which commissioning works and their effects.

Chapter 2 The research context: commissioning as governance

Governments introducing quasi-markets in health care still wish to avoid uncontrolled ‘market forces’ damaging such politically salient services. An apparent solution is to construct governance structures34 that retain a degree of state control, hence exercise power, over the increasingly independent health-care providers. Someone must also be ‘payer’ on behalf of patients who cannot pay providers directly. Commissioning serves both purposes.

‘Commissioning’ is a very English concept. Elsewhere, diverse organisations fulfil these roles to varying extents: social health insurers [social health insurers (SHIs), e.g. Krankenkassen (Germany), Siekenfonds (the Netherlands)], state bodies [e.g. Medicare (USA)], corporate insurers, charities or mutuals [e.g. Group Health (USA)]. To develop an initial theory of how commissioning works, we therefore drew on research about this range of organisations (and for brevity call them all ‘commissioners’).

International comparisons of health systems35–37 report that commissioners use diverse and multiple means of exercising governance over providers. Many quasi-market health systems hybridise contractual with hierarchical38,39 and networked governance structures. To explain and analyse such complexes therefore required a theoretical framework which accommodated, and related, these diverse governance mechanisms, one capable of combining and integrating more specific theories (e.g. of contract) within a wider, more complex framework. Consequently, and because governance is an exercise of power, we selected the theory of (the multiple) ‘technologies of power’40–42 as an overarching analytic framework. Within it, we applied (a) more specific analytic framework(s) for each of the main media of power (enumerated below), choosing a framework relevant to, and used in, preceding research into commissioning, but with two exclusions. When incompatible alternative theories were available (e.g. negotiated-order versus institutionalist explanations of organisational value-systems), we selected the one most consistent with the overall framework and complementary to the other elements in it. We also excluded essentially normative frameworks, such as neo-classical theories of perfect competition43 or normative managerial accounts of governance. The resulting framework supplements the markets–hierarchy–networks trichotomy of governance structures44 with a more nuanced, specific account of the media of power through which, in different combinations, commissioners might exercise governance over providers.

Many commissioners are also, even mainly, agents of employers, subscribers (consumers),45 shareholders and other interests besides the state. In some health systems, commissioners compete, which in Germany and the Netherlands has led to market concentration on the commissioner side of the market. 46,47 Commissioner competition may accentuate adverse selection, requiring a risk-equalisation system to make risk selection unprofitable. 46 Even competing commissioners often negotiate collectively with providers, attempting to wield power through a de facto monopsony35 (one buyer confronting many sellers), which in a health system with flexible prices would help reduce those prices. 48

Media of power

The ‘therapeutic state’ (p. 254)40 co-opts and adapts the ‘technologies of power’ that it believes will reinforce its control over the population, promote and implement policies (e.g. regarding population health, reproduction, the control of deviancy) and discipline the medical profession accordingly. Foucault argued41 that control within and between organisations occurs through a dispositif: a structured complex of diverse, coexisting technologies of power42 including professional disciplines, surveillance, task sequencing, task distribution, coercion and panoptical control. 49,50 Commissioners generally try to exercise governance over health-care providers by combining several methods in parallel. 51 We call each such method a ‘medium of power’, because each embodies a collection of ‘technologies of power’. 52 These complexes of technologies of power are historical ‘positivities’ that can be identified only empirically, case by concrete case. 53 International overviews35–37 suggest that health-care commissioners generally use one or more of six media of power: managerial performance of commissioning; negotiated order; discursive control; resource dependency and financial incentives; provider competition; juridical control.

Managerial performance of commissioning

Strong management systems are necessary to ensure provider compliance. 54 Some English GPs see commissioning as a substantial ‘job’, others as a supplementary task. They often lack time and skill (e.g. in data analysis) to participate intensively in commissioning; PCTs also lacked the necessary resources. 55 Delegating those tasks to other staff may be cheaper, but can also send an adverse message about the relative importance of these tasks and problems. 56 Although GP fundholding may have fragmented strategic planning,13 their small size and organisational independence enabled fundholding practices to make small local service changes more easily than PCTs. 57

As noted, the managerial performance of commissioning is often regarded as a cycle involving evaluating the health needs of the population that the commissioner serves and then specifying the corresponding services, which requires epidemiological and public health expertise. Few recent studies examine how needs assessment relates to commissioning, although cf. Pickin and St. Leger58 and Milne. 59

A second step is procurement. There are again few studies of NHS procedures for recruiting and selecting providers, letting the contract and negotiating its terms and conditions. At times these procedures have been erratic. PCTs have been known to change their requirements for procuring alternative provider medical services less than 24 hours before the competitors were due to present bids. 60 Furthermore, the choice of provider inherently has a value-laden ‘political’ aspect. 61 Outside the health sector, Cousins and Lawson62 among others describe how corporations normally manage procurement through a supply portfolio approach, relationship management and performance measurement. Socialisation mechanisms, incorporating relational aspects such as supplier conferences and on-site visits, help establish effective communication and information sharing. These in turn support the integration of suppliers and providers into product development. Managerial attention becomes focused on specific aspects of procurement and product development, such as innovation and communication, through performance management processes. Competitive procurement for military equipment produced substantial savings even when the provider did not change,63 for instance. One difficulty, though, is co-ordinating different providers in parallel, especially under conditions of organisational instability. 64,65

Thirdly, commissioners have to audit and monitor provider performance and compliance with commissioners’ aims, and prevent provider ‘opportunism’. 66,67 Transparency of provider activities and costs assists commissioners in these activities,35,68 as does professional expertise in the services concerned. 54 PCT scrutiny of out-of-hours services was least rigorous when the PCT itself supplied them69 and most rigorous when social enterprises did. Bevan and Hood,70 Bevan71 and Gray72 describe how performance targets encouraged upcoding or ‘gaming’ of data returns by both NHS hospitals and general practices, although other studies39,73,74 report the opposite. Bevan71 attributed the weakness of PCT monitoring and control of providers partly to the removal of a regional level mediating between PCTs and the Department of Health (DH),75 and recommended introducing more uncertainty into how NHS provider managers are assessed in order to impede gaming. English GPs valued monitoring data only when they had selected information that would be meaningful and useful to them. 56 ‘Hard’ (measurable) outcomes make it easier for commissioners to monitor providers’ activity,76 even independently of the provider. 77 US local government commissioners self-report more active monitoring than providers perceive. 76 Where only soft outcomes apply, US practice is often to monitor multiple stakeholders’ satisfaction levels with providers. 76 Providers who perceive that their commissioner lacks monitoring expertise, and those who are highly resource dependent on one commissioner, are likely to try to negotiate monitoring methods with their commissioner. 77 US studies also report that commissioning managers often lack the skill and understanding to obtain monitoring data and interpret it in non-simplistic ways. 78–80 To address this point, the NHS introduced the WCC assurance framework, requiring PCTs to evaluate their competencies in procurement and ‘managing the local health system’, among others.

A second-order managerial task is to minimise the transaction costs of the above activities. Divergence between commissioner and provider goals, and hence the cost of monitoring services, is likely to be greater when publicly owned commissioners face corporate rather than ‘third-sector’ providers. 81 Transaction cost theories imply that contractual negotiations demand more resources for infrequently commissioned services that display asset specificity, uncertainty and immeasurability. 82–84 Thus the negotiation of, say, residential care contracts is simpler, cheaper and better adapted to quasi-market institutions than is the negotiation of contracts for mental health services. 85 In services with hard-to-measure outcomes, negotiative monitoring becomes necessary, with raised transaction costs;65 which may partly explain why US non-profit providers are over three times more likely to negotiate outcome monitoring than are for-profit providers. 77 Increased contracting out (of US social care) may come at the price of reducing commissioners’ own capacity ‘to be a smart buyer of contracted goods and services’,86(p. 296),87 although a study of US municipal contracts suggested that including contract management activities in the services bought can offset this problem. 54 However, some US commissioners doubt the probity of contracting out service-monitoring work. 76 In some US states, Medicare has subcontracted health-care commissioning entirely to managed care ‘plans’ (insurers) but how far this arrangement improves health outcomes to compensate for the additional managerial complexity is not well understood.

Economies of scale in commissioning management may be exhausted at quite small population sizes (< 200,000), although the threshold varies by care group (e.g. > 1,000,000 for organ transplants). 88 Qualitative studies83,89 suggest that moving from block to tariff payments (see subsection Resource dependency and financial incentives) raised NHS transaction costs. Longer-term contracts spread the initial transaction costs over a longer period, and flexible, relational working saves the cost of contract revisions. 83 Negotiating with an ‘umbrella group’ for numerous, similar small providers (e.g. general practices) also makes contract negotiation simpler and cheaper. 83 In theory, cheaper or more effective service provision might outweigh higher commissioning transaction costs, although an early New Zealand study cast doubt on this claim. 83 Greaves et al. 90 found no empirical basis for defining an optimal PCT size.

Negotiated order

Commissioners can also influence providers by agreeing with them a division of labour, rights of non-interference91–93 and arbitration procedures should disputes occur,35 establishing an explicit or tacit ‘negotiated order’. 91(p. 147),84,94 Although it might include contract negotiations as a special case, a negotiated order is wider than that. The parties exchange mainly non-monetary benefits: promises of action (or restraint), help in kind, authorisations, material resources, public support and so on. The negotiation may be multilateral and is highly ‘relational’,95,96 reflecting social capital already accumulated, local organisational cultures, micro-politics and personal antagonisms or affinities. The character of a negotiated order is determined by the selection of participants and by agenda control,97–99 that is what is not discussed and how the issues that are discussed are framed. The weaker a commissioner’s bargaining position, the more prudent it may be for them to negotiate about one variable (e.g. price or quality or volume), not several,100 letting other ‘sleeping dogs lie’ (p. 1). 101 English NHS structures at all levels reflect a negotiated order with the medical profession. 3 Bate et al. 102 describe ‘backroom commissioning’ in six PCTs where the chief executives of the largest local NHS organisations struck local deals about resource allocation. With few commissioners and providers, community health services also support negotiative rather than contractual relationships. 27,103 In contrast, commissioner–provider relationships in English social care, with its numerous small providers, ‘barely go beyond the mere business of contracting’ (p. 560). 104

Negotiated order is often criticised for allowing provider ‘capture’ of commissioning because of information asymmetry, because details of providers’ working practices and cost become negotiable only insofar as they are transparent and intelligible to the commissioner;105 professional loyalties and career paths transcend the commissioner–provider split; and commissioners assume that providers always behave in ‘knightly’, not ‘knavish’, ways (p. 67). 106 Such conditions may inhibit commissioners from radically changing existing patterns of provision. 107 Strong relationships between providers and government can also undermine commissioners:

contracting out presumes that the . . . contractor’s job is to act as agent of the government’s policy. The relationship is fractured, however, if contractors create independent political ties with policymakers and thus outflank their administrative overseers. In such cases contractors are less agents than partners, helping to shape the very design of the program, free from any significant oversight, and beneficiary of state and local governments’ dependence on their performance (p. 176). 107

As instances of negotiated order, in the early 2000s PCTs negotiated away financial control in return for providers realising other targets, rapidly increasing PCT deficits. 71 A New Zealand study found that non-governmental organisations were discouraged from participating in commissioning activities that they thought existing providers had already captured. 108

Nevertheless, some health policies encourage primary care doctors to ‘capture’ commissioning. Fundholding and TPPs appeared on balance to reduce elective referral and admission rates, emergency-related occupied bed-days (TPPs only), waiting times for non-emergency treatment109–111 and growth in prescribing costs. They appeared to improve the coordination of primary, intermediate and community support services, financial risk management (TPPs only) and clinicians’ engagement in commissioning. 112,113 However, they also reduced patient satisfaction (fundholding only) and equity of access, increased management and transaction costs and had little impact on how hospital care was delivered. Fundholding furthermore gave commissioning GPs an incentive to refer conservatively,111 despite GPs being insensitive to provider prices. 114

Discursive control

Where the parties trust each other, a stewardship model of governance115,116 applies and the negotiated order rests on discursive control. For persuading providers, commissioners can apply two main types of discursive ‘orders’. 117

Emic discourse is intelligible and morally persuasive to those who inhabit a particular culture, though not necessarily to others. It invokes what are regarded as legitimate normative claims on others’ behaviour, such as the demands of ‘policy’, ‘public opinion’, wider social ideologies (religion, economics, ethics, etc.) and professional ‘discipline’. 52 Thus, strong professional norms of treatment standards prevented Danish hospital ownership making much difference to the clinical quality of orthopaedic care;118 for England, see Waring and Bishop. 119 In the English NHS, managerial targets and their role as agents of central policy120 appear to have the strongest emic influence on NHS trusts, although less upon GPs. 31 A study of three English PCTs found that they regarded central government authority as more influential on providers than contractual mechanisms. 57 Similarly, ‘targets and terror’ were the main influence on providers’ waiting times. 71 Most variants of New Public Management ideas and practices are ‘aimed at “normalising” public sector employment on private sector models’ (p. 1). 121 As a special case of emic discourse, ‘soft coercion’ is the technique of threatening that, if one’s demands are not satisfied, a third party – for instance, a government – will impose a worse solution. 122 Thus, ambulatory care cost control occurred in Germany because SHIs could allude to government threats to control ambulatory doctors’ professional autonomy, which the doctors valued above marginal income gains. 46

Etic discourse (evidential, technical or scientific knowledge) nowadays means, above all, evidence-based medicine (EBM) and epidemiology, whose persuasive power lies in its objectivity and putatively scientific basis, which clinicians regard as authoritative. For commissioning purposes, EBM has the advantage of making increasingly explicit what health impacts and outcomes commissioners can expect from each service they commission, or expect to lose when rationing health care, facilitating commissioners’ monitoring of services provided. By tending to standardise descriptions of treatments and their outcomes – ‘commodification’123 – EBM facilitates the comparison of providers, hence provider competition. In practice, though, evidence is often used as post facto justification of decisions made for other reasons:102 ‘policy-based evidence’. The choice of performance measure itself reflects managers’ and other parties’ interests. 124 Its availability also varies by care group.

Discursive control can also be applied where trust is weak, but then negotiators rely more on other mechanisms to align provider and commissioner interests artificially. 125

Resource dependency and financial incentives

By threatening to reduce or remove resources, a commissioner can exercise power over providers who depend on the commissioner for their resources. 77,126,127 How much power depends upon whether the provider depends heavily or only slightly upon the commissioner for resources;128 on the unit of payment (whether the provider is paid, say, for each episode of care or by large block contracts);35,108 on whether the commissioner pays the provider directly or through an intermediary; on whether the payment is made before or after treatment occurs;1,35 and on whether or not the commissioner’s threat to withdraw resources is credible (the ‘credibility’ of an incentive).

There is strong evidence that using fee for service (FFS) units of payment raises treatment volume and costs: ‘Consequently, not to introduce unregulated fee-for-service reimbursement is one of the few unequivocal lessons of health care financing’ (p. 1580). 46

Block payments enable commissioners to cash-limit the cost of health services, as do spot contracts24 and payments to individual professionals for working a specified period of time. 129 Theoretically, block contracts create an incentive to undertreat, but there is only slight evidence130 that this actually occurs in the NHS. Capitation (subscription) payments for a defined population theoretically have a similar effect per patient, but are also incentives to recruit patients. Flat fees prevent monopoly providers using price discrimination and price fixing. 46 Incentives also motivate data collection regarding the activities and outcomes being incentivised. 89,131

Tariff (e.g. DRG-like) payments incentivise providers to treat more patients. In England, HRG payments to hospitals appeared to reduce average length of stay (ALoS) and increase throughput and the proportion of day cases, with little effect on three quality indicators (changes in in-hospital mortality, 30-day post-surgical mortality and emergency readmission after treatment for hip fracture), and exerted downward pressure on costs. 132,133 In Taiwan, switching from FFS- to DRG-based payments reduced length of stay and intensity of treatment for coronary artery bypass graft and angioplasty patients. 134 Tariff payments may remove incentives for hospitals to transfer services to community care. 135

Pay-for-performance incentives are typically used to incentivise specified care processes,136 on the assumption that if they are evidence based the desired health outcomes will follow. The NHS general practice Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) produced high compliance with the stipulated care processes, and little evidence of providers ‘gaming’ the data. 137 Nevertheless, two recent systematic reviews suggest that, overall, evidence about the effects of such payments is ambivalent, especially regarding the integration and continuity of care. 129,138 The effects of incentive payments for service quality may wear off after a few years, both in (US) hospitals139 and in general practice. 140 Financial penalties for high levels of hospital-acquired infection had little effect,141 although incentive payments did improve asthma and diabetes management in a large care network. 142 Penalties were only one mechanism among several for reducing late discharges from NHS hospitals. 143 A systematic review of incentives for individual professionals129 found that payment for working for a specified period was generally less effective, and payment for providing care for a patient or specific population or pre-specified activity or care quality more effective, at influencing care processes, referrals, admissions and prescribing, but not compliance with guidelines. Another systematic review140 found that financial incentives had a small positive effect on the quality of general practice.

Retrospective reimbursement of patients’ treatment costs (e.g. by tariff payment) usually leaves commissioners somewhat passive unless probity problems arise (e.g. overclaiming). Commissioners can influence provider selection only indirectly by framing (‘nudging’) patients’ or gatekeepers’ choices,144 for instance through promotional or ‘educational’ activities. Cost reimbursement appears to be a suitable payment for simple services whose outcomes and production processes are clearly definable, while fixed-cost payments (which can be prospective) are suitable for complex services that have multidimensional, unstable and uncertain goals. 145

The effect of incentives also depends on their credibility. Danish and Swedish hospitals that knew they would be financially supported for other reasons (e.g. rurality) were less dependent on, hence less sensitive to, DRG-like payments than private hospitals. 118,146 NHS hospital managers also initially doubted the stability of the HRG tariffs, hence their value for long-term planning. 132

Prospective payments give commissioners scope to construct incentives and, if they can, to choose how to allocate work between providers, to plan the provision and cost of health care for their population. Strict monitoring of performance targets, coupled with direct incentives to managers, has functioned partly as an alternative to competition as a mechanism for controlling NHS providers. 147 It has also been argued that financial incentives can displace non-financial incentives to provide high-quality care. 148

Provider competition

A credible threat of losing income to another provider accentuates a provider’s resource dependency on the commissioner. 96,149 Yet the mere presence of alternative providers does not necessarily suffice to increase bargaining power; US self-pay patients are charged up to 2.5 times as much as insurers and Medicare are per patient. 150 Rather, commissioner power is maximised by creating a monopsony. 151 During 1997–2002 the fragmentation of English HAs into PCTs, and numerous hospital mergers,152 increased market concentration on the provider side. 153 A common NHS scenario is a large commissioner (HA, PCT, CCG) facing one main provider (e.g. a hospital, mental health trust) with insufficient ‘numbers’ for competition to occur. 147 In, say, Italy, commissioners can take a ‘make-or-buy’ decision66 to operate their own services, which is likely also to make them more proficient in other aspects of commissioning154 and more micro-economically ‘efficient’ for low-contestability, low-measurability services. 66 GP fundholders,11 and later PBC commissioners, as often used their commissioning budgets to ‘make’ new services and care pathways as to ‘buy’ secondary care. Commissioners can also encourage untried providers to tender. The creation of preferred provider organisations offered US insurers a way to control health-care costs without eliminating patient choice. 155 Providers at the margin of financial or technical viability become more susceptible to competitive pressures; cf. Hinings et al. 156 Technical complexity creates asset specificity, reducing providers’ capacity to find alternative commissioners. 157

Commissioners may also be able to set the criteria by which to select providers: at its crudest, price versus non-price (‘quality’) competition. Fixed tariffs are usually thought to force providers to compete only on service quality, but variable tariffs give commissioners greater power to safeguard competition itself and to influence providers in other ways. 158

English147 and US159 studies in the 1990s found an inverse relationship between competition and quality of care but, when prices were fixed, competition improved hospital care quality. Mortality from acute myocardial infarction (AMI) fell in NHS hospitals exposed to greater competition. 160 A review of 68,000 discharges from 160 hospitals during 2003–7161 found, that where competition was more ‘feasible’, AMI mortality rates decreased faster, lengths of stay were shorter and treatment cost the same as elsewhere. Increasing the number of an NHS hospital’s competitors by three was associated with improved hospital management practices estimated to cause a 6% reduction in AMI mortality. 162 The effects of hospital competition on quality, however, appeared different inside and outside London. 163 Even after 2006, patients were more likely to ‘choose’ hospitals that their GP had referred patients to previously. 152 Patient choice effected a small reduction in waiting times. 164 UK studies mostly define health-care ‘markets’ in terms of the distance between patients’ general practices and hospital, an approach that they say ‘accurately reflects the choice sets open to NHS users’ (p. F238). 160 However, what matters for understanding how commissioners (hitherto PCTs, predominantly) harness competition for controlling providers is the choice set open to them. Studies from that angle are rare.

Providers of different ownership in the UK also appear to concentrate on different aspects of service design as their distinct competitive advantage. Corporate independent-sector treatment centres (ISTCs) brought new models of care into the NHS rather than clinical innovation. 165 Personal budgets for social care gave people who employed personal assistants directly (not via a care agency) greater control, continuity and quality of life. 166 Competition between care homes seems to keep prices in check but has little effect on quality. 167 Third-sector providers often have difficulty dealing with NHS commissioners’ procurement systems. 168,169

Findings from the USA are also equivocal, and have to be applied to the very different NHS context with caution. On balance they suggest that provider competition raises hospital quality, particularly for high-risk AMI patients;170–172 but the opposite has also been reported. 173 Some studies have found that competition improved outcomes for HMO-funded hospital patients but worsened them for Medicare-funded patients. 174 Competition had no quality effects for insured patients although it worsened outcomes for the uninsured. 175 Incentive payments for quality improvement had greater effects in less competitive markets. 139 Lower Medicare payments were associated with higher mortality, especially in more competitive markets. 171 Although increased market concentration and hospital volume have contributed to declining mortality with some high-risk cancer operations, declines in mortality with other procedures are largely attributable to other factors. 176 US data from 1990–97 suggested that hospital efficiency increased as one moved away from a very competitive market [Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) < 0.25], but began to decrease again at HHI > 0.7. Furthermore, HMO market share had a stronger association than HHI with hospital efficiency. 177 Non-profit providers may also be less opportunistic and self-interested,87 which may explain why they were less responsive than for-profits to financial incentives. 178 However, under competitive pressure, non-profit providers began to mimic corporate pricing strategies and merger tactics to increase their market power. 179 Provider competition in the USA reduced the costs of services to institutional180 but not individual payers. Competition made no difference to how closely social service providers in Florida complied with contracts. 181

Juridical control

Commissioners can also use juridical processes to influence providers. In some health systems (e.g. Germany, Russia) commissioners have the right to audit or inspect providers (e.g. to see medical records) to verify if treatments were necessary and/or correctly billed. Commissioners everywhere can seek enforcement of contracts, laws and regulations through the courts or regulators, although, in the ‘new public contracting’, contracts between commissioners and publicly owned providers are enforced – sometimes only weakly or one-sidedly – through hierarchical governance structures rather than the legal system. 38 If they have such discretion, commissioners can simplify contract formulation by supplementing a standard base contract,182 with optional additional clauses per provider, speciality or care group. 83 Complete, presentiated contracts (i.e. contracts which anticipate all main contingencies and specify what will be done should each event occur) are hard to formulate for ‘complex services’ (p. 1). 145 Writing them increases transaction costs. 39 Nevertheless, managed care (with contracts stipulating such practices as making primary and preventative services available to patients and controlling secondary care utilisation) reduced US preventable admissions of over-65-year-olds compared with fee-for-service reimbursement, especially for sicker patients. 183 Long-term contracts reduce transaction costs but also provider contestability, and remove a disincentive for providers to engage in staff development and training. 83 In England, zonal contracts for social care provision create, in effect, local monopolies of provision. 24 NHS hospital contracts generally had greater flexibility at the margin, the more the provider’s spare capacity. 184,185 Yet, however tightly a commissioner tries to specify contract terms, there are always practical limits to the completeness and presentation of contracts;84,186 in practice, a negotiated order (see above) is required to complement them. 39,187 Stable contracts become increasingly relational and may engender stable networks,188 eventually even the replacement of a market or quasi-market with an integrated hierarchy. 82

Although these six media of power are distinct, they interact. Negotiation demands certain managerial skills (performance). A negotiated order rests on agreement about norms and a shared discourse. These norms may include juridical principles besides beliefs about evidence basing, what the law requires, and wider social ideologies. If a competing provider is available, a commissioner’s negotiating position may become stronger. However, whether it has competitors or not, each provider depends on its commissioners for resources, so a commissioner can exploit that resource dependency even when negotiating with a monopoly provider, and even in non-market health systems. To understand how commissioners might exercise governance over providers, it is therefore necessary to understand in a more concrete way how the media of power combine and interact, reinforce or negate each other depending on circumstances.

Modes of commissioning

As noted, commissioners try to exercise governance over providers through particular combinations of media of power. We call each such combination a ‘mode of commissioning’. Globally, many different modes of commissioning are found. The above research findings suggest, in sum, that differences in modes of commissioning help explain:35

-

patterns of provider development, the spread or absence of specific kinds of provider or services; corporatisation and concentration of capital

-

health systems’ capacity for cost control

-

the development and use of evidence-based medicine

-

patterns of managerial development of commissioning and medical involvement therein.

Different types of commissioning organisation are likely to develop different modes of commissioning, whose effects partly depend on how providers react. 24 Except in the extreme case of ‘gridlocked’ governance,189 each mode of commissioning leaves providers some room for manoeuvre. Each medium of power might therefore be expected to have different effects even on similar providers (e.g. university hospitals) according to the institutional context. One might expect different modes of commissioning to develop for, say, diverse care groups. This brings us to our research questions.

Chapter 3 Aims and research questions

Contingency theory83,190 predicts that observed commissioning practice is likely to evolve by trial and error towards the mode(s) of commissioning best adapted to the commissioners’ roles, environment and the specific characteristics of different care groups and services. Furthermore, one mode of commissioning may contain elements of use to another, and the different modes of power interact (whether synergistically or the opposite).

The research aimed to assist this learning by examining existing commissioning practices and their contexts and effects on providers, that is to:

-

examine which commissioning practices emerge and are adapted to different organisational and care-group contexts, including other health systems

-

contribute thereby to governance theory, institutional economics, organisational sociology and organisational theory.

Comparing NHS commissioning with that in other health systems would help illuminate which commissioning practices – those which recur across health systems – are adapted to the structure of quasi-markets per se, and which reflect only the circumstances of the NHS during 2010–12. However, we used the English NHS of 2010–12 as the main context within which to address these aims. Our research questions (RQs) therefore were:

-

How do English health policy-makers and NHS commissioners understand the policy aims of commissioning, and how can governance over providers be exercised through commissioning?

-

How has the reconfiguration of commissioning structures occurred in practice and what shapes this reconfiguration?

-

How far does their commissioning practice allow commissioners to exercise governance over their local NHS health economies?

-

How much room for manoeuvre do NHS commissioners have?

-

What are the consequences, and how do commissioners try to manage them, when commissioning is distributed across different organisations and when it shifts to being client based?

-

How do provider managers respond to commissioning activity?

-

-

How do commissioning practices differ in different types of commissioning organisation and for specific care groups, taking the following care groups as contrasting tracers: unscheduled inpatient care for older people; mental health; public health; and planned orthopaedic care? On which aspects of service provision do different commissioning organisations tend to focus?

-

What factors, including the local health system context, appear to influence commissioning practice and the relationships between commissioners and providers?

We took RQ3 to ask what media of power commissioners use, how and with what limitations. By ‘client-based commissioning’ we mean specifying and paying for services on the basis of each episode of care for each individual patient (tariff payments, personal health budgets). We defined ‘distributed commissioning’ as the joint commissioning of a health-care provider or pathway by several commissioners collaboratively, and ‘room to manoeuvre’ as ‘scope for exercising the media of power over providers’.

Chapter 4 Methods

Research design

Our research design was a multiple mixed-methods191 realistic evaluation. 192 Its components were:

-

Content and discourse analysis of policy documents and interviews with policy-makers and managers to elicit their programme theories of NHS commissioning, answering RQ1 by identifying their understanding of:

-

the intended policy and service outcomes of NHS commissioning

-

the mechanisms that would produce these outcomes.

-

-

A cross-sectional analysis of publicly available managerial data about local health economies (commissioners, providers, socioeconomic context), testing for any associations between commissioners’ characteristics and the policy outcomes identified in the programme theory of NHS commissioning. In agreement with the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme, this analysis was regarded as an initial exploration of the value and uses of reanalysing published managerial data to characterise and evaluate the impacts of NHS commissioning. The unit of analysis (‘local health economy’) would for practical purposes be the PCT, considering what data would probably be available. This method contributed to answering RQ3 and RQ5.

-

A systematic comparison of case studies of commissioning in five English case study sites, with induction of common patterns, and exploration and explanation of contrasts. Within each site these case studies were longitudinal, tracing the formation of commissioning structures and practices in recent years. The framework structuring the comparison was the analysis of the media of commissioner power outlined in Chapter 2. This method contributed to answering RQ2, RQ3 and RQ4.

-

A systematic comparison, using the same framework, of patterns across the English case studies with case studies in Germany and Italy. This method contributed to answering RQ3, RQ4 and RQ5.

-

Action learning sets of commissioners from the English, German and Italian case study sites. This contributed to answering RQ1, RQ2 and RQ3.

-

Framework analyses to synthesise the above findings, contributing to answering all of RQ2, RQ3, RQ4 and RQ5 and to testing the programme theory’s underlying assumptions.

These methods fitted together as follows. The discourse and Leximancer analysis revealed the empirical and causal assumptions (programme theory) on which current commissioning policy rests, especially about how commissioners can influence the providers of NHS services (RQ1). Case studies of the development of local commissioning then explored how far the assumed commissioning organisations and systems were present to begin with (RQ2). The case studies were also used to explore which commissioning mechanisms commissioners were using, how they did so (RQ3), if they used different mechanisms for different care groups (RQ4), how providers responded and what contexts appeared to influence providers’ reactions to commissioning (RQ5). Within the data availability constraints, the cross-sectional analysis of managerial data served the same purposes. Action learning was another way to explore, in ‘real time’, what mechanisms commissioners were using. We used the international comparisons to explore and differentiate which commissioning contexts, mechanisms (above all, media of power) and outcomes appear common to quasi-markets more widely, and which are peculiar to English NHS commissioning. Each method contributed some parts of an overall, perforce incomplete, jigsaw of the complex relationships between commissioning organisations, contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Table 1 gives an overview.

| Research question | Method | Data sources | Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Programme theory | Discourse analysis | Interviews; documents | Leximancer analysis; cognitive frame analysis |

| 2. Development of commissioning | Cross-sectional comparison of longitudinal narratives | Fieldwork (interviews, document collection); published managerial data | Pattern induction from systematic cross-sectional comparison of longitudinal case studies |

| 3. Commissioning practice and governance | Comparative case studies; cross-sectional analysis of published managerial data | Fieldwork (interviews, document collection); published managerial data | Framework analysis comparing uses and limitations of media of power across health economies; inductively classifying commissioning practices; testing associations between commissioning practice and service outcomes |

| 4. Modes of commissioning for different care groups | Framework analysis comparing commissioning practices between tracer groups | ||

| 5. Commissioning practice and commissioner–provider relationships | Framework analysis; empirical testing of programme theory | Results of analyses for RQ1, RQ2, RQ3 | Compare these relationships and their contexts across countries, with programme theory and with initial theoretical frameworks |

Because all the above were undertaken during 2010–12, the cross-sectional study data are for 2008–9 (the latest available in 2010–12). Comparison with published managerial data, where available, helped indicate the likely generalisability of our findings. We also compared our own findings with relevant empirical findings emerging from research studies in the Health Reform Evaluation Programme, HSDR, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the DH Health Policy Programmes.

We involved patient representatives [through PenPIG, the Patient Involvement Group of the SW Peninsula Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC)], consulting them before research started about the research questions and overall research design (as expressed in the lay summary) and afterwards about our conclusions (expressed in an executive summary). We involved key commissioning stakeholders – clinicians and managers – through the action learning set described below, and will involve them again in the post-project dissemination activities.

Discourse analysis

Design

The discourse analysis of commissioning policy was carried out to identify the programme theory of NHS commissioning that would apply to CCGs. We analysed key policy documents’, policy-makers’ and managers’ accounts of these matters; cf. Millar et al. 22 We focused on actually occurring texts and utterances rather than their ‘genre’ or ‘conclusion rules’ (p. 278),193 but did regard the texts as a systematic set of ideas, values and problematics. 194

Sampling

Documents

Our sampling strategy was purposive, selecting what policy-makers emphasised as seminal policy statements, hence widely distributed to NHS managers between the general election and the start of legislation (July 2010 to September 2011). The two main documentary samples were:

-

Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS195 and its official support documents; this was the most widely distributed policy document concerning NHS commissioning (43,351 downloads in 2012; followed by the NHS Operating Framework at 32,869)

-

the 2012 Act196 and its explanatory ‘factsheets’, including one on service quality subsequently withdrawn from the DH website.

These (see Appendix 1) were downloaded from DH, NICE, Healthcare Commission and National Patient Safety Agency websites.

Oral material

We assembled transcripts of interviews with policy-makers and top-level NHS managers. Returns from interviewing diminished after about 20 interviews but we interviewed 23, whose roles Table 2 summarises. The transcripts (with speeches mentioned below) were inputs for the cognitive frame analysis (see Chapter 5, section Cognitive frame analysis) which supplemented the Leximancer analysis.

| Role | n |

|---|---|

| Current and former parliamentarians | 4 |

| DH policy directors | 5 |

| Directors of national and regional NHS organisations | 5 |

| National local authority organisation representative | 1 |

| Directors of national voluntary organisations | 2 |

| Heads of national medical organisations | 2 |

| Senior official of think-tank | 1 |

| Former NHS Director | 1 |

| Other | 2 |

Many informants were so senior that fuller details would compromise their anonymity. However, their careers and status gave good reason to believe that they would know the rationales for NHS commissioning policy, having been involved in formulating it. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Interviewees were offered the chance to see and correct their transcript.

Besides the above interviews, we also analysed transcripts of (existing) speeches by national politicians and the NHS Chief Executive about the aims, mechanisms and implementation of the new commissioning system. These included speeches to the House of Commons, Royal College of General Practitioners, British Medical Association, NHS Confederation and The King’s Fund, selected to cover both supportive and unsupportive audiences. We also included evidence to the Commons Health Select Committee from civil servants and NHS managers. Evidence given by independent experts was not included, as they would not necessarily be among the policy authors. For the same reason we did not include evidence, or other speeches and writings, from opponents of the policy.

Leximancer and cognitive frame analyses

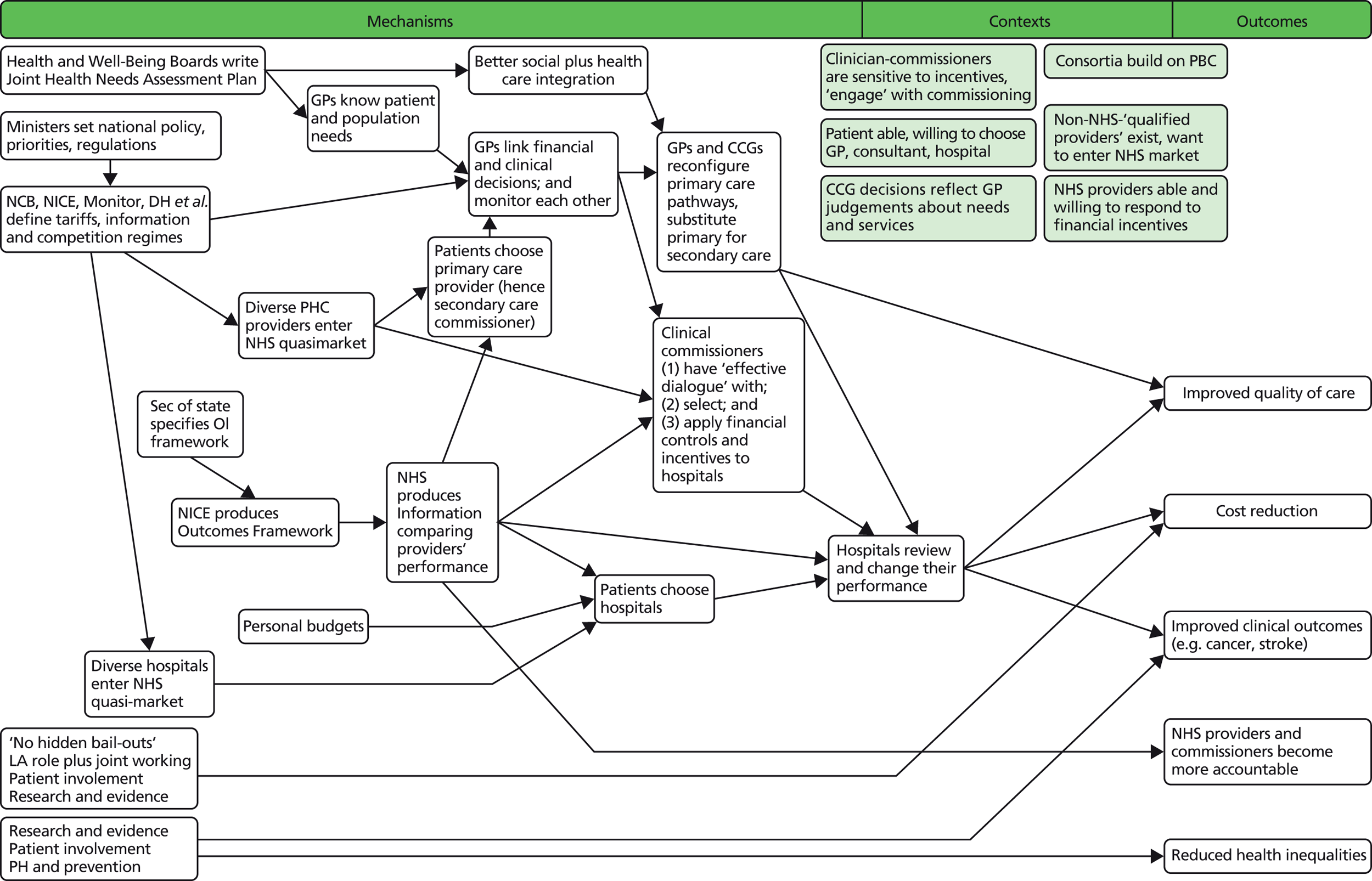

To expose the programme theory underlying commissioning policy for the English NHS required exposing what context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) relationships the sample texts stated or implied. Appendix 2 describes Leximancer analysis more fully, but in brief it is an automated form of quantitative content analysis which outputs lists of associated terms (‘concepts’), counts and measures of their co-occurrence, and indexes their original textual occurrences.

Although Leximancer analysis located which CMO relationships the texts most often mentioned, the original documentary formulations were mostly too broad, ambiguous or brief to specify clearly how these mechanisms would work. We therefore conducted a cognitive frame analysis of data from our interviews with parliamentarians and top-level health managers, making a logic analysis197 to elaborate and supplement the policy texts’ accounts of CMO relationships. In doing so, again seeking to relate our informants’ accounts and explanations (frames) to the categories (CMO, media of power) required for a realistic evaluation. Mostly the informants’ accounts were consistent, but where they differed (in emphasis rather than contradicting each other) we took the more prevalent interpretation as more likely to guide commissioning practice. Appendix 2 further describes the cognitive frame analysis. We collated the descriptions of CMO relationships found by these methods and paraphrased them as statements in the form required for empirically testing CMO assumptions, namely ‘Doing X in circumstances M will cause agent A to do Y’, or a logical equivalent.

Cross-sectional analysis of published managerial data

Insofar as data were available, the cross-sectional analysis of published routinely collected managerial data was designed to:

-

provide a sampling frame for the English case studies

-

describe the profile (mix) of commissioning organisation(s)’ practices and resources in the English NHS, allowing categorisation of local health economies in terms of these variables

-

test for associations between health economies’ organisational characteristics (profiles), commissioning practices and published indicators of service outcomes.

The second and third of these also contributed to answering RQ3 and RQ5.

Indicators and measures

Three groups of measures were selected by the following methods and criteria (Appendix 3 explains more fully):

-

Independent variables [(Governance Variable) in the model below] were selected from the published data sets as measures or prima facie proxies for the media of power described in Chapter 2. Suitable data were mostly available only for 2008–9, and only for two media of power (provider competition, managerial performance).

-

Control variables were selected on the basis of existing research into the factors that influence the need and demand for health services. Ideally one would control for all likely confounders that are not under PCT control: population age, sex, ethnicity, income and education profiles and case mix (primary diagnosis, comorbidities, severity of illness). 198,199 Published data allowed only limited controlling for these factors (for instance, PCT income is allocated by criteria intended to reflect – so, in this context, standardise for – population health needs and local service input costs). It would have been desirable to have a control variable that enabled us to control directly for differences in hospital case mix, but in the absence, at the time of the study, of a suitable published variable, deprivation appeared to be the nearest proxy among the control variables available.

-

Dependent variable selection started from lists of the generic health service and health policy outcome indicators200,201 that the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and World Health Organization (WHO) use for international comparisons of health systems, and Greaves et al. ’s list,90 which, so far as we were aware, was then the only published study similar to this one.

Table 3 lists the independent variables, controls and dependent variables that we used. Appendix 3 explains more fully how and why they were selected.

| Category | Variable | Mean | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Commissioning governance (independent variables) | |||

| Generic provider competition | HHI | 0.511 | 0.200 |

| Client-based commissioning | Proportion of ‘Choose and Book’ patients | 0.539 | 0.178 |

| Personal health budget pilot (Y/N) (dummy) | N/A | N/A | |

| Practice-based commissioning: % GP participation | 94.766 | 17.494 | |

| Population based competitive commissioning | % of budget spent on local authority and voluntary providers | 5.036 | 5.479 |

| % of budget spent on independent-sector health care | 3.447 | 3.798 | |

| Number of provider contracts | 6.020 | 2.470 | |

| Proportion of PCT budget spent on main provider | 0.572 | 0.318 | |

| PCT management | WCC score | 109 | 21 |

| Controls | Number of PCT mergers | 1.513 | 1.884 |

| PCT income per capita | 1.393 | 0.505 | |

| PCT weighted population | 337,689.4 | 170,141.5 | |

| Indices of deprivation, average score | 23.722 | 8.376 | |

| Service outcomes (dependent variables) | |||

| Quality of care and primary–secondary care co-ordination | Amenable mortality annual rate, all causes, under-75-year-olds, directly standardised | 0.961 | 0.213 |

| Unplanned hospitalisation rate for ambulatory care sensitive chronic conditions, adults, directly age and sex standardised, as % of 2007–8 | 112.516 | 33.176 | |

| Emergency admissions for primary care preventable acute conditions, indirectly standardised, % change since 2007–8 | –3.482 | 13.365 | |

| Emergency admissions for primary care preventable chronic conditions, indirectly standardised, % change since 2007–8 | –6.201 | 15.828 | |

| Emergency readmissions within 28 days of discharge from hospital, adults over 16, indirectly standardised for age, method of admission, spell, diagnosis (ICD-10) and procedure (OPCS version 4), % change since 2007–8 | –3.690 | 6.052 | |

| Ratio of observed to expected emergency admissions for conditions not usually requiring hospital admission, indirectly standardised | 90.502 | 26.213 | |

| Access to care | Mean time waited for admission | 47.461 | 9.218 |

| % change 2007/8 to 2008/9 in proportion of trauma and orthopaedics patients waiting less than 18 weeks from referral to planned treatment | 0.103 | 0.455 | |

| % change 2007/8 to 2008/9 in proportion of all admitted patients waiting less than 18 weeks from referral to planned treatment | 0.579 | 3.348 | |

| % change 2007/8 to 2008/9 in proportion of all non-admitted patients waiting less than 18 weeks from referral to planned treatment | 0.820 | 1.084 | |

| Proportion of patients waiting more than 4 weeks for a first outpatient appointment following GP referral | 0.010 | 0.057 | |

| Monthly mean waiting list, IP and day cases, proportionate to weighted population | 0.011 | 0.004 | |

| Cost control | PCT surplus (deficit marked with –) as proportion of income | –0.273 | 0.501 |

| Hospital activity | Ratio of day cases to admissions | 0.365 | 0.045 |

| Average (mean) length of stay | 5.742 | 0.801 | |

| Finished consultant episodes proportionate to weighted population | 0.325 | 0.117 | |

Although the range of publicly available data at PCT level about the media of power increased during 2010–12, lack of suitable data still limited the scope of the cross-sectional analysis. Only qualitative data can describe discursive control, negotiated order and the contents of contracts. Ad hoc financial incentives to providers also evade managerial data sets. When available at all, quantitative data about patient complaints, prosecutions or disciplinary proceedings against providers record only exceptional events. We could identify which PCTs had personal budget pilot schemes, but NHS managerial data contained little further information about them. Consequently our cross-sectional analysis concentrated on managerial performance and provider competition.

The mean and SD for each measure were calculated from data sets noted in Appendix 3. The independent and control variables shown in Table 3 all had variance inflation factor (VIF) scores between 1.164 and 2.273. In general the different quality indicators for hospital services were not highly correlated,163 but among our selection there were five exceptions (see Appendix 4). Note that PCT budgets did not include the majority of general medical practice (funded from DH budgets).

Data collection

Deprivation data were downloaded from www.gov.uk/government/publications/english-indices-of-deprivation-2010. WCC scores were published in the Health Services Journal. 202 Data from which to estimate hospitals’ ‘market’ shares were obtained from the 2011–12 PCT recurrent revenue allocations exposition book. 203 Otherwise, data were downloaded from the NHS Information Centre website (www.hscic.gov.uk/searchcatalogue). We assembled a database in which the rows were PCTs and the columns contained the above measures and data about PCT characteristics (e.g. extent of practice-based commissioning, presence of personal health budgets, number of recent PCT mergers). Data were for the financial year 2008–9 except for referral to treatment time and WCC data scores, which were reported by calendar year; we used 2009. According to their accompanying documentation the deprivation data were ‘mainly’ for 2008, but reported for 2011 administrative boundaries. We trimmed percentages back to 100% when higher figures (e.g. for data completeness, percentage of GPs involved in practice-based commissioning) were obviously wrong.

Analysis

To measure the relationships between the media of commissioner power (‘governance variables’), dependent variables (policy outcomes) and the main potentially confounding variables, and the relative contributions of each explanatory variable, we used stepwise multiple linear regression with backwards elimination, that is removing all non-significant and/or trivial independent variables until only those that satisfied our declared criteria remained. Our basic model was:

We used four variants of this model, changing the independent [GovernanceVariable] variable to reflect different media of power, including the different quasi-market architectures that coexist in the NHS. The variants of independent variable were therefore:

-

a measure of managerial competence (WCC scores)

-

a generic measure of competition (HHI)

-

four measures indicating the extent of competitive tendering commissioning

-

three measures indicating the extent of individualised commissioning.

For each variant of the independent variables, we repeated the regression with different dependent [Service Outcome] variables, explained below. In all cases PCT Deprivation Index, per capita PCT income and PCT weighted population were included as controls. (It was a policy aim that PCT income should reflect the PCT’s weighted population size, but this was not achieved during PCTs’ existence.) The unit of analysis was the PCT, the main NHS commissioner for the pre-CCG period that the data described, approximately 2 years before the case study fieldwork began. The implications of this time difference are discussed below.

We declared negligible correlation to be one where the estimated standardised beta (β) coefficient was in the range 0.001 > β > –0.001 or adjusted R2 < 0.01. Significant correlation was declared where p ≤ 0.05. Statistical calculations were performed with R (version 3.1.1, The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). In analysing the data we have erred towards conservatism, that is towards statistically underprocessing rather than overprocessing the data. The method of analysis is described more fully in Appendix 2.

Systematic comparison of case studies

Design

Using the frameworks described below, we systematically compared case studies of English local health economies. Because health-care processes (types of interventions, models of care, etc.) are likely to influence commissioning practice, we selected four care groups as ‘tracers’ likely to reveal contrasting commissioning practices:

-

unplanned admissions of people with chronic conditions

-

mental health

-

public health: prevention of diabetes and coronary heart disease through both clinical activity (e.g. statin prescribing) and intersectoral action (e.g. to influence diet and exercise)

-

scheduled orthopaedic surgery.