Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/2000/36. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Roderick et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Chronic kidney disease and end-stage kidney failure in older adults

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is categorised into five stages depending on the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and evidence of kidney damage, as recognised by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and other international guidelines. 1,2 The most severe of these stages, termed end-stage kidney failure (ESKF) is termed stage 5 CKD (CKD5) where the eGFR is < 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2. National guidelines state that renal replacement therapy (RRT) should be considered in all patients with CKD5. The symptoms of ESKF are largely due to the failure of erythropoietin (EPO) production and consequent anaemia, accumulation of toxic metabolites (‘uraemia’), acid base and electrolyte imbalance, and fluid retention. While a lower eGFR is associated with more severe and more frequent symptoms, the effects of a decrease in kidney function can vary between individuals, with some CKD5 presenting as asymptomatic.

The rate of decline of kidney function in CKD5 to a level of eGFR and/or symptoms that would justify starting RRT is variable between patients and can be difficult for clinicians to predict. Clinicians are faced with complex decisions about whether RRT should be started or not and, if so, when. The rationale for initiation of dialysis may be to prevent imminent death from hyperkalaemia (high potassium), fluid overload or uraemic coma, or to maintain quality of life and prevent complications of severe uraemia. These decisions depend on the rate of deterioration of kidney function, on the development and attribution of symptoms and on whether or not clinicians believe that dialysis will improve outcomes. Such decisions are especially difficult in older patients, who often have symptoms related to multiple comorbidities.

Planning for renal services over the past decade has been largely dictated by the National Service Framework for Renal Services published in 2004/5. 3 Services for ESKF (CKD5 which has progressed to a disease state at which dialysis is the default treatment) have been commissioned as specialist rather than general acute services and development of renal services in England has remained centred on teaching hospitals and large district general hospitals. Personalisation of choice in ESKF care has been an explicit policy goal. Increasing emphasis has been given to preparation for ESKF and choice of treatments including conservative kidney management (CKM). The majority of patients with stage 4 chronic kidney disease (CKD4) or CKD5 approaching ESKF are now seen in multidisciplinary renal clinics, where risk factors for progression and major cardiovascular events are managed, advanced CKD metabolic abnormalities and symptoms are treated and preparation for RRT is organised.

The population rate of starting RRT has increased steadily over the last few decades, though with a recent stabilisation. 4,5 This is in part because of the ageing population, the rising prevalence of type 2 diabetes, a decline in competing mortality risk from cardiovascular disease and considerable expansion in the supply of dialysis facilities. 4 This increase in RRT is highest among those over 75 years old, with disproportionate numbers who are frail and have multiple comorbid conditions. 6,7 In 2011, there were over 1500 patients aged 75 years and over who started RRT in the UK. 4 Several small retrospective or prospective cohort studies have raised the possibility that the balance of benefit versus burden in this older frail group may favour non-dialysis (conservative) management,6–12 especially when the patient has a significant burden of morbidity. Those aged 75 years and over with ESKF who have dialysis do have a survival advantage, but this advantage may be small in those with high comorbidity, especially when the effects of establishing access for dialysis, time spent travelling to, receiving and recovering from dialysis three times a week, and complications of dialysis per se, which often result in hospitalisation, are also considered. Moreover, quality of life can be maintained on conservative care pathways. 11 Conservative management may increase the likelihood of dying at home and with input from palliative services. 12,13 Dialysis per se leads to loss of functional status in older frail patients. 14 For selected patients, and in the context of increasing frailty and loss of independence,13,15,16 RRT may therefore be a costly intervention both for patients (in terms of quality of life and treatment burden) and to the NHS (in terms of resource usage).

Providing an alternative to dialysis for end-stage kidney failure patients

We have used the term CKM to describe the management of ESKF without RRT, but with active symptom management, communication and advanced care planning (ACP), interventions to delay progression and minimise complications, psychological support, social and family support, and spiritual care. It is expected that a recent Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) consensus conference will produce a definitive definition.

Such an approach might contribute to a cost-effective strategy for managing the rising number of older people with CKD5. However, there has been a perception that CKM might be seen as rationing care. Rationing means the limiting of access to (usually) expensive interventions from which patients would benefit, in order to control resource utilisation where resources do not permit such patients to be treated. However, consideration of CKM is not to deny dialysis but to recognise that for some patients dialysis may be futile or detrimental to their well-being, and CKM a more appropriate option. Historically the UK RRT programme has had lower uptake rates than in many other countries with comparable populations. It is not easy to disentangle the role of rationing (implicit or explicit) in this, as compared with careful and appropriate use of treatment. CKM is now more accepted in the UK than in many other developed countries; this means that the UK is in a key position to provide the evidence base for its appropriate and effective development.

In recognition of the gap in provision of high-quality care for those dying with ESKF, there have been a number of initiatives to raise the profile of care for kidney patients in the last year of life. The 2005 National Service Framework for Renal Services: Part 23 recommended that people with ESKF receive timely evaluation of prognosis, information about their choices and, for those near the end of life, a jointly agreed palliative care plan, built around individual needs and preferences. 16 Guidelines have been developed for managing the symptoms of kidney patients in the last days of life. 17 The Department of Health introduced policies to improve end-of-life care across conditions, through initiatives such as the End of Life Care Strategy18,19 and, in primary care, the Gold Standards Framework. 20,21 To consolidate and help embed these policies, the Framework for End of Life Care in Advanced Kidney Disease was published22 and piloted across the UK along with advice from NHS Kidney Care. 23

The pathway through ESKF to CKM includes regular CKD management work, dialysis/CKM education to ensure informed decision-making, ongoing discussions about CKM versus dialysis for patients who have chosen CKM, activity to manage sequelae/symptoms of advancing CKD, and when the patient becomes symptomatic escalation of palliative care. It is not simply a ‘no dialysis’ option. 7 Maximum care to slow disease progression,24 management of other comorbidities, assessment and active management of symptoms (e.g. by correcting anaemia and acidosis, maintaining fluid balance and treating troublesome symptoms with drugs) including dietary restrictions,25,26 optimising communication and ACP,27 and improving care at the end of life,28 are all recommended. Services have increasingly been developed to focus on optimising conservative care. 29,30

Potentially, the delivery of such care can be undertaken by renal unit teams in outpatient departments or community outreach, or both, with varying input from specialist palliative care expertise and from primary care. 31 There may be crossover from intended CKM to dialysis and vice versa. Some patients with CKD5 may not be referred to a nephrologist at all or may be referred back to primary care, so receiving all their CKM outside specialist renal services. The physical health of patients and the attitudes of patients and physicians towards the added value of attending kidney clinics for CKM are likely to influence the decision to be referred and then remain in secondary care. Variation at centre level in the spectrum of older patients with CKD5 referred to renal units and managed by dialysis or CKM needs to be taken into account when examining outcomes of CKM patients in renal units.

Assessing optimal delivery of conservative kidney management

Major questions remain unanswered about how to commission and deliver CKM. Analysis of UK Renal Registry data4 suggest there is significant variation between renal units in the mortality rate during the first year of RRT. Although this could reflect variations in the quality of care delivered, variation in case-mix is a more likely explanation. This variation in case-mix is likely to be driven by variation in whether RRT or conservative care is recommended to frail, elderly patients with comorbidities, and by whether or not such patients are referred to the centre at all. There are no recent data on practice patterns for CKM. The last survey, conducted over 5 years ago before the National Service Framework for Renal Services: Part 23 suggested that only half of units even recorded the pathway choice for conservatively managed patients, and only five units had nursing or professions allied to medicine staff devoting over 12 hours per week to CKM. 31 Yet it has been reported that, if late referrals are excluded (patients referred with ESKF who start RRT within 3 months of referral), about 15% of elderly patients in managed nephrology care with CKD5 opt for CKM. 6,8,32 Decisions regarding these choices have been based upon clinical consensus and experience, supported by a very limited number of UK studies. 6–13,33,34 These studies have focused predominantly on survival, and few have captured evidence on other outcomes10 (such as patient preference, symptom burden, quality of life or quality of death) or clarified which patients in the older cohort would or would not benefit from RRT. Given the cost to patients (in terms of quality of life and dialysis treatment burden) and the cost to the NHS (in terms of resource usage), addressing this question has become imperative. The outcomes and costs of different models of care may vary substantially. Currently there is no financial payment for CKM under the Payment by Results tariff scheme and a better understanding of the resources and costs of CKM is needed.

The current study, Conservative Kidney Management Assessment of Practice Patterns Study (CKMAPPS), follows the guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions. 35 CKM is clearly a complex intervention with multiple components and outcomes, and variable patterns of delivery. We first need to understand the intervention and how it is delivered, before we explore how it can be evaluated.

Study aim

The overall aim of this study was to determine the practice patterns for CKM of older patients with CKD5. This information should inform future service development and the design of a future prospective multicentre study to evaluate the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and appropriateness of CKM compared with dialysis for treating elderly patients.

Objectives

The main objectives were:

-

to describe the variation between renal units in the extent and nature of CKM, its relative scale compared with dialysis, the factors influencing service developments and future plans (staff interview study, survey)

-

to explore how and when decisions are made in renal units about the main treatment options for older patients with CKD5, and what are the main clinical and patient factors that influence decisions to opt for CKM (staff interview study, survey, patient interview study)

-

to explore clinicians’ willingness to randomise patients with CKD5 to CKM versus dialysis and to assess the feasibility of a subsequent prospective study (survey)

-

to describe the interface between renal units and primary care in managing CKD5 patients [staff interview study, survey, general practitioner (GP) interview study/data linkage]

-

to identify the resources involved and potential costs of CKM (survey, staff interview study).

Methods

The research programme was a mixed-methods study divided into five parts:

-

patient interview study: a qualitative study with patients over the age of 75 years exploring their experiences of choosing between CKM and dialysis for the treatment of CKD5 in a purposive sample of nine renal units

-

staff interview study: a qualitative study across the nine renal units exploring the views and experiences of staff members who provide care for CKD5 patients over the age of 75 years

-

survey: a national survey of all UK renal units assessing the delivery of CKM

-

data linkage: linking routine data on new ESKF patients from the local clinical biochemistry laboratory records of the nine renal units with subsequent referral to the associated renal units

-

GP interview study: a qualitative study of GPs exploring their views and experiences of managing CKD patients and referring patients to secondary care.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from South Birmingham National Research Ethics Committee (11/WM/0240). Various secondary and primary care NHS trusts were involved in recruiting patients and staff in this research. Site-specific approval was obtained from all the relevant trusts. Research staff had NHS research passports and letters of access.

Chapter 2 Patient interview study: making decisions about treatment for stage 5 chronic kidney disease – a qualitative study with older adults

Introduction

This study set out to address objective 2 of the CKMAPPS project by exploring patients’ decisions to opt for CKM.

Few studies have explored why patients opt for CKM. 36–39 Patients who reported making an autonomous decision gave the following reasons: they felt they were too old for dialysis, they thought dialysis was too strenuous for them to undertake, they felt well without dialysis, they did not want to be a burden on their family, they knew other patients who had had bad experiences on dialysis and they found it difficult to travel to dialysis. 36–39 In addition, some patients believed they had no decision to make if they were told dialysis was unsuitable for them. 36 Researchers also identified that some patients were reluctant to think about the future, which meant decision-making about treatment potentially needed in the future was difficult. 38

While these studies give some indication of the reasons patients choose between treatment options, studies have been small and of a single centre. No research has explored, across different units with different CKM policies and practices, the views of patients on choosing between CKM and dialysis, and the reasons for their choice.

This qualitative study aimed to explore the views and experiences of older adults with ESKF, who had chosen different treatments for CKD5, on their treatment decision and reasons for their decision across nine UK renal units.

Methods

Design and setting

Qualitative study with semistructured interviews with patients recruited from nine renal units in England (Birmingham, Heartlands; Bristol, Southmead; Hull; London, King’s College; Manchester; Middlesbrough; Reading; Stevenage, Lister; Stoke-on-Trent). Renal units were purposively sampled to produce a diverse sample in terms of location in England and the scale of CKM delivery. The latter was estimated by responses provided by clinical directors to a previous survey by the UK Renal Registry. 40

Participants

Consultant nephrologists and nurses in each renal unit were asked to identify patients who were 75 years old or older and whose records indicated that they had an eGFR of less than 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2 or were on dialysis. Patients were required to speak English fluently and be judged by their health-care professionals (HCPs) to be sufficiently fit, physically and mentally, to take part in an interview. The researchers aimed to sample patients purposively by stage of illness and management pathway as follows: (1) following the decision to opt for CKM (CKM pathway), (2) following the decision to have dialysis in the future, but before starting dialysis (pre-dialysis pathway) and (3) following the start of dialysis (dialysis pathway). Staff in each unit were responsible for identifying patients in each of these groups who met the inclusion criteria, and patients were invited to take part in the study either by post or in person. Demographic and other information for all patients invited to take part in the study was recorded (gender, age, ethnicity, date first seen at renal unit and date started CKM or dialysis if applicable).

Interviews

Patients were interviewed by an experienced qualitative researcher (ST-C), either face to face, in the patient’s own home or in their renal unit while they were on dialysis, or by telephone. The type of interview was determined by patient preference except for some interviews which had to be carried out by telephone because of the distance between the researcher and participant. The interviewer introduced herself as a non-clinical researcher to explain that she had both no medical training and no specific allegiance to the nephrology field. All patients gave written informed consent, either at the time of interview or before the interview if carried out by telephone. Interviews followed a semistructured interview guide which asked patients about their medical history in relation to their CKD, their contact with their renal unit, their knowledge and understanding about management options and their reasons for their management decision (see Appendix 1). A semistructured format was deemed suitable to ensure relevant questions were asked to all patients but also to allow patients the opportunity to talk about issues which were important to them. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by an independent transcriptionist. Transcripts were checked by the interviewer to ensure accuracy. Recruitment and interviews continued until the interviewer was satisfied that the data indicated saturation.

Data analysis

Thematic analysis41 allowed an inductive approach to exploring the data, which lessened the likelihood that findings would be influenced by the existing literature or the researchers’ preconceptions. Transcripts were coded line by line, with codes being assigned to each meaningful segment of text. Transcripts were then compared with one another, using a constant comparison approach taken from grounded theory, to search for similarities and differences between interviews. 42 ST-C independently coded 20 interview transcripts and developed an initial set of themes. NVivo 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to facilitate coding. Initial themes were discussed with the wider research team, and themes and subthemes were amended and renamed until a consensus was reached. This agreed framework was used to code the remaining 22 transcripts. Any new data occurring in transcripts which did not fit into the existing themes were highlighted and discussed further. New themes and subthemes were added, and existing themes amended, in the light of these new data.

Results

Participant characteristics

Ninety patients were invited to take part in the study and 44 agreed. Eleven patients declined, five patients were unable to take part for health reasons, four patients died after being invited and 26 did not reply. Patients who did not take part were mostly CKM patients, which meant that more CKM patients had to be invited to take part (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Patients who agreed to take part (n = 44) | Patients who refused/did not respond/were unable to take part (n = 46) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, years) | 81.7 | 82.7 |

| Gender (male) | 30 (68%) | 31 (67%) |

| Ethnicity (white British) | 40 (91%) | 44 (96%) |

| Pathway | ||

| CKM | 14 (33%) | 22 (48%) |

| Dialysis | 14 (33%) | 11 (24%) |

| Pre-dialysis | 14 (33%) | 13 (28%) |

Forty-two patients were interviewed, 14 patients in each group (Table 2). All dialysis patients were on hospital haemodialysis (HD) except for two on continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. Interviews ranged from 27 to 87 minutes with a median of 47 minutes. Interviews were carried out between May 2012 and February 2013 and were carried out in person except for five interviews carried out by telephone. There was no indication from the data that interviews carried out by telephone differed substantially from face-to-face interviews in content although interviews were slightly shorter on average. While some interviews took place with a family member in the same room, three of the CKM patients specifically wanted to be interviewed with a family member for support.

| Unit | Pre-dialysis pathway | Dialysis pathway | CKM pathway | Total for unit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 4 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| 6 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 8 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 14 | 14 | 14 | 42 |

Sociodemographic characteristics did not differ substantially between the three groups. Participants’ ages ranged from 74 to 92 years with a mean of 82 years, most were men and most identified themselves as white British. Many patients were married or had a partner (n = 24, 57%) and most were living with their partner (n = 22, 52%). Other patients lived alone (n = 14, 33%), with their children (n = 3, 6%), their friends (n = 1, 2%) or in a care home (n = 2, 4%). Compared with the pre-dialysis and dialysis groups, patients opting for CKM were slightly older, were more likely to be female and were more likely to live alone or in a care home, but group numbers were small (Table 3).

| Characteristic | Pre-dialysis patients (n = 14) | Dialysis patients (n = 14) | CKM patients (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean, years) | 81.3 | 80.4 | 83.5 |

| Gender (male) | 11 (78%) | 10 (71%) | 7 (50%) |

| Living alone | 2 (14%) | 6 (43%) | 6 (43%) |

| Living in a care home | 0 | 0 | 2 (14%) |

At the time of interview, patients had been in contact with their renal unit for a median of 49 months (range from 5 to 131 months). Dialysis patients had been on dialysis for a median of 10.5 months (range from 1 to 120 months) and patients who had opted for CKM had done so a median of 11 months previously (range from 1 to 83 months). Although recruitment had aimed to interview CKD5 patients, some patients reported that their eGFR was between 20 ml/minute/1.73 m2 and 15 ml/minute/1.73 m2 in interviews, indicating that they had CKD4.

Renal unit characteristics

Results from the national survey (see Chapter 4) confirmed variation in the scale of CKM delivery in the nine units sampled (Table 4). Three of the nine renal units reported that, of their patients over 75 years old, under 10% were receiving CKM, as opposed to other units, where up to 50% of over-75-year-olds were opting for CKM. The same three units reported that the terminology used to refer to CKM was usually phrased as ‘non-dialysis’. Based on these data, units were classified into two groups: those with more established CKM pathways (units 1, 2, 5, 6, 8 and 9) and those with less established CKM pathways (units 3, 4 and 7).

| Unit | Percentage of patients over 75 years on CKM | CKM discussed with all patients over 75 years? | Dedicated staff time for CKM patients? | CKM guideline? | Staff training in delivering CKM? | Dedicated CKM clinics? | Funding for CKM? | Terminology used to refer to CKM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 40–49 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | CC |

| 1 | 20–29 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No, in preparation | Yes | No | CM |

| 2 | 40–49 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | SC |

| 6 | 20–29 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | CKM |

| 5 | 10–19 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | CC |

| 9 | 20–29 | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | CM |

| 7 | 1–9 | Yes | No | No, in preparation | Yes | No | No | CM (non-dialysis) |

| 3 | 1–9a | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Non-dialysis care |

| 4 | 1–9 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Not for dialysis |

Qualitative findings

Four themes emerged from the analysis of all interview transcripts (Figure 1). All themes were relevant to all patients, but differences within themes emerged between patients who had chosen different treatment options and between patients from different units.

FIGURE 1.

A thematic map of the four themes identified from the analysis of 42 interviews.

The diagram indicates how interaction with staff fed into patients’ conceptualisation of the process between understanding CKD and making (and occasionally revising) a management decision for their own CKD.

Theme 1: patients’ understanding of the management of chronic kidney disease

Patients mentioned that information about management had been provided through discussions with staff, written information and education days (meetings at the unit for patients to come and hear about different types of treatment). Although patients reported being given a large amount of information, some felt overloaded by the amount of information and described feeling unclear about what treatment options entailed, and others felt that the information given to them could be improved.

My wife was enraged with the brochure to such an extent that she brought it home and re-wrote parts of it . . . The pictures were meaningless; a woman sitting at a desk with a tube somewhere didn’t mean anything to anyone. So the information was bad.

Male, 79 years, dialysis, unit 5

Education days seemed to be well received by patients, particularly when they were able to hear about others’ first-hand experiences of dialysis. Education days were not available in all units; however, this appeared to be a popular option among patients and may be of benefit if delivered in more units.

Some pre-dialysis and dialysis patients stressed that they did not want, or had not wanted, to know about the details of dialysis until it was time for them to start.

I wouldn’t come down and see the [dialysis] machines. No, I thought wait till it happens and – I don’t want to know until I have to, you know?

Female, 76 years, dialysis, unit 8

All patients were aware of dialysis and the majority had an idea of the differences between peritoneal dialysis and HD, with most describing them as dialysis ‘at home’ or ‘in hospital’. In most units, knowledge about CKM was not common among patients who had not opted for it.

It was presumed that dialysis would work for me, I presume . . . I can’t remember [unit] ever – ever suggesting to me or saying that there is a third option – of not having dialysis. There were two sorts of dialysis.

Male, 82 years, pre-dialysis, unit 5

However, in units with more established CKM pathways, some dialysis patients were aware of CKM as an option which some patients chose.

[The nurse] was leaving the low clearance to go to people who were having – non-dialysis, I think tablets and things.

Female, 76 years, CKM, unit 8

In relation to this, some patients described how dialysis had, in their view, always been inevitable for them.

Going to low clearance, you saw people go off onto dialysis, so you knew that it would come to you, you know?

Female, 76 years, dialysis, unit 8

Conservative kidney management patients also reflected that, at first, they had also been guided towards dialysis because other patients were preparing for it.

Well initially, because you think that’s the right way to go, you’re on the dialysis track. So you’re going that way, everybody’s going that way . . . So that’s the track you’re on. At some stage – then the conservative management comes into play – and it’s when you realise that the dialysis is perhaps not the best track, but something has to tell you that . . . what told me was [the experience of my friends].

Male, 82 years, CKM, unit 5

Theme 2: patients’ perceptions of their own chronic kidney disease

Most pre-dialysis and CKM patients reported that they had no symptoms from their CKD. Others were unsure whether their symptoms were due to their kidneys, another comorbidity or just ageing. A lack of symptoms seemed to be interpreted by some CKM patients as an indication that their CKD was not serious.

They wanted to put me on dialysis, nearly five months ago, but I didn’t want to go on dialysis. Everything is all right, you know, I don’t have to go on dialysis.

Male, 81 years, CKM, unit 2

In addition, two CKM patients felt they could prevent their kidney function from decreasing through diet and medication.

I think if I try, I can sort of get a bit better than what I am, if I had the right – materials, you know, the medication and all that. And what to eat, I think that’s the main thing, what to eat and what not to eat.

Female, 88 years, CKM, unit 6

It was clear that discussions with staff had helped other patients to realise how serious their CKD was. Most had been told when dialysis would need to be started in terms of the level of their eGFR. In addition, patients from one renal unit all reported that they had been given an estimate of which calendar year they would probably need to start dialysis if chosen.

They’ve been watching this graph going down . . . they talked to me about dialysis and they said that in 2012 it looked as if I would reach the time when I should need it.

Male, 83 years, pre-dialysis, unit 5

However, in other examples, patients reported that they had been told different things by different members of staff about their CKD, which had influenced how serious they felt it was and appeared to influence their treatment decisions.

This nurse came to have a talk with me . . . and she says ‘we’ve given you a score of 6 [eGFR]’. So I thought – 6/10, that’s not bad, I can live with that. Then I thought, 6 out of how many? She said ‘6/100 that’s how poorly you are’ and that brought me down to earth.

Male, 87 years, CKM, unit 9

It went from 6 to 5 and the doctor said, ‘don’t worry, it’s alright’, she says, ‘I’ve got a patient on 4, been on 4 for years and she’s still alive, don’t worry’. I said, ‘oh well, that’s alright’.

Male, 87 years, CKM, unit 9

Theme 3: patients’ experiences of making a management decision for their chronic kidney disease

Patients’ assessments of dialysis

Patients who had opted for different treatments appeared to hold contrasting beliefs about the advantages and disadvantages of dialysis. Some dialysis and pre-dialysis patients believed that dialysis was the only way they could continue to live and described a belief that others who chose not to have dialysis were ‘cutting their lives short’.

I don’t fancy the idea of having to lay on the bed there for 4 hours, but, you know, it’s – the alternative is death, isn’t it, so there’s no choice.

Male, 77 years, pre-dialysis, unit 4

Patients from units with a less established CKM pathway reported that they had been told they would live for many more years on dialysis.

[Consultant] said, ‘well it looks as if you will probably have 6 years [on dialysis]’.

Male, 82 years, dialysis, unit 3

In contrast, some CKM patients, from units with more established CKM pathways, believed that dialysis did not guarantee longer life. This appeared to reflect what they had been told by renal staff.

I decided – after seeing this [dialysis] demonstration – that I didn’t want dialysis. I’m told that’s not terribly unusual – and I was told that – if you say no to dialysis, you don’t necessarily live any longer anyway. And as I’ve no discomfort or pain or anything like that, I thought I’d carry on.

Male, 84 years, CKM, unit 9

Alongside longevity, patients considered quality of life. Many CKM patients believed that they would have a better quality of life without dialysis and prioritised this over living longer. In these situations patients seemed to have formed their own beliefs about dialysis rather than from discussing quality of life with staff.

It did occur to me that [on dialysis] you were, sort of, living for tomorrow, for your next treatment, for tomorrow, for your next treatment, for tomorrow. And it made me think, well, I wonder if it’s better to live as best you can, as you can and let time take its course.

Male, 82 years, CKM, unit 5

In contrast, some pre-dialysis patients believed that dialysis could offer them a better quality of life or help them to maintain their current quality of life.

Well I’ve been promised that I shall be ten times better [on dialysis]. (Laughs) I’m being optimistic.

Male, 76 years, pre-dialysis, unit 9

Conservative kidney management and dialysis patients spoke very differently about the time one would have to spend on dialysis. CKM patients saw this time as a ‘waste’ whereas others felt they were gaining additional days or that it was similar to how they would usually spend their time. Again these views seemed to be based on the patients’ own interpretations rather than on information they had been given by their unit.

I don’t want to waste a week of my life all the time – when I can be sat at home, enjoying myself, you know. I mean, to me, I’m going to lose my life if I’m going to have to be on dialysis.

Female, 82 years, CKM, unit 7

I’m 81 so it really don’t matter to me, I thought 4 hours out of your life twice a week, what difference does it make . . . I mean I would only be sat watching the television anyway.

Female, 81 years, dialysis, unit 7

Additional factors which influence patients’ decisions

Transport to and from dialysis was a major concern for patients and was a reason for some not to have dialysis when home dialysis was not an option for them.

Well, I can’t drive and I live out of town and so it’s relying on hospital transport and I mean you could be waiting hours . . . I just couldn’t cope with it.

Female, 82 years, CKM, unit 7

Many patients talked about how family was a consideration in their decision. Several patients on dialysis had family support which made it possible for them to undertake dialysis. Two patients reported that they were carers for their spouses, which had been the major influence on their decision.

I can understand [people choosing CKM], I can quite easily understand that, but whilst the wife is about, if dialysis helped me along, to keep her out of a nursing home, then that would be a good achievement as far as I’m concerned.

Male, 82 years, pre-dialysis, unit 5

Some CKM patients indicated that they did not want to be a burden to others or the health-care system by having dialysis and indicated that it was of little benefit to have dialysis when they felt they had already reached old age. This appeared to stem from patients’ own beliefs rather than anything they had discussed with staff.

At 80, there is a lot of younger people that could benefit from dialysis which, you know, what’s really the good of dialysis when you reach 80 years old?

Male, 82 years, CKM, unit 5

I could see a big disruption to my husband [if I had dialysis], he’s had quite enough to do without having to get me ready to go in [to hospital]. If I was younger, say 50s I might think about it, but I shall be 87 in a couple of weeks’ time, so what’s the point?

Female, 86 years, CKM, unit 1

Four patients said that they knew of a friend or relative who was, or had been, on dialysis. Some had heard about others’ bad experiences with dialysis, which appeared to have influenced their decisions.

I decided not to have dialysis . . . at that time, actually, two of my close friends had dialysis and I don’t ever want to be involved in that, that’s no way to live . . . There was no fun in their lives, it was just hopeless really. We tried to go on holiday but every 2 . . . every 4 hours you had to go back to change and we didn’t get nowhere at all.

Male, 81 years, CKM, unit 3

Staff influences on patient decision-making

Patients also appeared to have been strongly influenced by staff when making their decision. Many patients talked about how staff had explicitly recommended dialysis or presented it as the best option in most units.

[The staff] said ‘well it’s entirely up to you, you’ve got the choice. You can have dialysis or you can have the other thing . . . But if you want not to have dialysis it’s your choice but you’ve got to realise that it is going to kill you . . . But if you’re on dialysis you could last for 10, 15, 20 years’.

Male, 76 years, dialysis, unit 2

However, in some units with more established CKM pathways, staff appeared to have discussed CKM as an alternative to dialysis with patients, presenting this alongside information on dialysis.

They went to great lengths to tell us about the fact that we could opt in or out of the dialysis and that there was an alternative to dialysis, which is this care path.

Husband of female, 74 years, CKM, unit 8

Theme 4: patients’ experiences of revising management decisions

Only patients who had opted for CKM talked about having the option of changing their decision and most seemed to have been told that this option was always available to them.

Two dialysis patients, from the same unit, reported that they had changed their treatment decision in the past. They reported that they had initially chosen CKM because they felt well but then opted for dialysis when they had felt ill as a result of their CKD.

I said at the time no [to dialysis] and then within a fortnight I’d changed my mind. Because my health wasn’t very good at all.

Male, 88 years, dialysis, unit 4

In three of the 14 interviews with CKM patients, participants implied that they would have dialysis if they ‘had to have it’ or if they ‘got really ill’, although this was not usually revealed until late in the discussion. An example is this discussion thread taken from one interview with a CKM patient.

One of the nurses told us that you had decided not to have dialysis?

No. She said that if I did change my mind – you know – but – I don’t think I will, definitely not.

[later in interview]

And [nurse] said to you more recently that you’re able to change your mind if you decide you want to have dialysis?

Oh yes.

And what do you think about having that – that option still available?

Well it’s nice, I think, that it’s there; whether I’ll ever take it up, I don’t know – but – in a way, I suppose it’s a comfort that I could go back, you know, if I was really ill.

[later in interview]

Yes, so do you think that – you might change your mind then, if you got – if you got more symptoms from it or got quite ill?

Well yes, if I got really ill and I wouldn’t be having any – type of life anyway, would I? If I was that ill, you know, so there wouldn’t be that much choice.

This may indicate that the goals of CKM had not been fully explained to patients. These patients attended both types of units, those with more and less established CKM pathways.

Well if it came to the point, I’d have to do [dialysis], wouldn’t it, you know? But it comes to the stage, you know, that then there’s no alternative. You have to do it.

Male, 81 years, CKM, unit 2

The revision of a decision from CKM to dialysis appeared to be linked to a lack of consideration of what would happen in the future. CKM patients differed in whether or not they had discussed the future with staff. CKM patients from units with more established CKM pathways appeared to have discussed the future with staff more than patients from other units. This included talking about how their CKD would progress and setting up ACP.

I mean I don’t think it’s an agonising death like people suffer with bone marrow, cancer and all that . . . they said ‘you could suddenly start to feel very ill . . . and then ultimately probably go into a coma and just disappear.’ Which doesn’t sound pleasant but it’s not that bad to worry about.

Male, 75 years, CKM, unit 1

[Nurse] arranged care to come – they took her away and put her in a hospice for a couple of weeks, just down the road here. They were marvellous, but she went to the hospice and they discussed the end of life with her and, so, I think [nurse] did as well and I think they spoke about it.

Husband of female, 74 years, CKM, unit 8

Summary

Main findings

While CKD patients consider the same factors when making a treatment decision, patients who choose different treatments hold contrasting beliefs about what dialysis can offer. These beliefs appear to be influenced by the information provided by renal staff, which can differ between units, particularly in regard to CKM. It was noticeable that few patients were aware of CKM as an option if they had not chosen it, although patients from units with a more established CKM pathway appeared to be more aware of CKM. While most acknowledged the severity of their CKD, some CKM patients did not appear to think of their CKD as serious because of its asymptomatic nature, despite information from staff indicating otherwise. There was a distinct divide between CKM patients, and dialysis and pre-dialysis patients in whether people believed they would live longer on dialysis or not and whether they expected their quality of life to get better or worse on dialysis. Information from units with less established CKM pathways appeared to focus on the number of additional years a patient was likely to live on dialysis. Patients from units with more established CKM pathways, however, described being told that living longer on dialysis was not a guarantee and in addition that choosing CKM was ‘not unusual’. Finally, few patients reported speaking to staff about the future, in terms of the consequences of either starting dialysis or opting for CKM. Patients from units with more established CKM pathways appeared to have discussed the future with renal staff and some indicated that they had begun conversations about ACP. For others, being unaware of how their disease was likely to progress added to the misperceptions some patients appeared to hold about the severity of their CKD and the need for dialysis.

Comparison with existing research

Particular results mirrored those identified in previous qualitative research. 36–39 CKM patients reported that they had chosen CKM because they felt too old for dialysis, they were worried about being a burden on family/society and they were concerned about travelling to have dialysis. While these factors can be valid reasons for making a decision there is also a sense that some patients may feel dialysis is not really a possibility or that they do not have a right to dialysis. Thinking of oneself as a burden on society, if dialysis is chosen, may lead to feelings of guilt for patients, who may benefit from extra time to talk through their decision with staff. Equally, concerns about whether transport is a possibility or not, rather than a preference to avoid transport, are different thought processes, and equity of access to treatments needs to be assured.

Reluctance to think about the future and feeling well without dialysis have been identified in previous studies37,38,43 and they linked to the current findings about perceptions of CKD severity and revising decisions. Feeling well, with few symptoms, seemed to make some patients think their CKD was less severe, which meant they did not see a reason to consider dialysis. A reluctance to think about the future and possibilities of becoming more ill had led some to choose CKM initially and then change their decision later on. This may be unavoidable for some patients who are unable to understand their CKD until they feel symptoms, although clinicians should be wary about using the term ‘CKM’ to refer to such patients. Patients who are in ESKF often want to know their prognosis but clinicians may feel uncertain or uncomfortable about when to discuss this with patients. 43 Open discussions about prognosis are likely to have a substantial influence on discussions about treatment options and feed into better shared decision-making.

Results also supported previous qualitative and quantitative work which showed how CKM patients may choose quality of life over length of life. 39,44,45 While this indicated different priorities between patients, the current results highlighted how patients held contrasting beliefs about whether dialysis would extend life or not, indicating the importance of patient expectations as well as priorities. Results also supported previous work which indicates that patients may choose CKM if they feel they have achieved everything they have wanted to in life. 39 This contentment and feeling of having had a ‘complete life’ has been suggested to lessen anxiety about death and end of life. 39

In addition to existing research, the current study identified the influence staff, and information from the renal unit, had had on patient decision-making. Patients from different units reported being provided with varying types of information, which presented CKM in a more or less positive light. It appeared that patients from units with a more established CKM pathway were more likely to know what CKM was, had been given more information about CKM and, for those who had chosen it, had discussed the consequences of their decision in more detail. While there may be recall issues with patient reports, results suggest that there are unit variations in the way in which older CKD patients are informed.

Strengths and limitations

This was the first qualitative study to explore patients’ views of choosing between dialysis and CKM across different renal units. Including nine units in the study meant that the sample contained diversity in terms of both patients’ treatment decisions as well as the service delivery experienced. We were able to include units which had more or less established CKM pathways in order to explore variation in what patients had been told.

Qualitative results cannot be generalised to other populations but data gathered can identify important issues and offer conceptual transferability. Indeed, the findings presented resonate with the existing literature. While interviewing methods run the risk of obtaining socially desirable responses, the interviewer presented herself as an impartial observer who had no link to the renal units or staff. Moreover, patients mentioned negative aspects of the care they had received, which suggests that they felt able to speak freely and in confidence. Finally, as with all interview studies, the findings do not provide a window on events as they happened but rather provide insight into how participants construct their experiences of relevant events.

Although the study had clear entry criteria, one participant under 75 years was invited to take part and three participants reported they were CKD4 rather than CKD5. Recruitment was difficult and time-consuming for renal staff and it was not always clear that participants did not match the inclusion criteria until part way through an interview. Data on patients’ eGFR over time were not collected. It is likely that patients with both advanced but stable kidney function and those with a linear, progressive, predictable decline in kidney function were recruited. Such differences may have had implications for how treatment options were discussed because of the clinician’s (un)certainty of how likely a patient was to die from their CKD rather than another condition.

The study excluded participants who did not speak English fluently, in order to ensure that participants were able to provide full responses to questions without the need for a translator. This limitation meant that the study was less likely to recruit patients from black and minority ethnic groups. Recruitment of such patients would have required additional resources which were unavailable and somewhat unfeasible for this study and may be better suited to a more focused qualitative study looking specifically at this population.

Recruitment of advanced CKM patients was particularly difficult. CKM patients most often had an eGFR of over 10 ml/minute/1.73 m2 and few felt they had any symptoms from their CKD. This meant CKM patients who were symptomatic and who otherwise would have started dialysis were not well sampled; interviewing more of this type of patient might have provided additional insights into why CKM is chosen by some and would have allowed more direct comparison of CKM versus dialysis patients. However, such patients may not have been physically and mentally well enough to take part. This is likely to be a limitation of any qualitative work carried out with a chronically ill older population across several centres.

The views of dialysis, pre-dialysis and CKM patients were compared. While all patients were similar in age, patients differed greatly in their physical and mental health, within and between treatment groups. The choice between dialysis and CKM is most relevant to older adults who are frail with other comorbidities. While we tried to recruit such patients, this was not always possible and some CKD patients who were not frail or burdened with multiple comorbidity were recruited to the study. For these patients it may be unsurprising that less emphasis had been placed on CKM as an option by renal unit staff.

The number of renal units in the study captured variety in CKM delivery. However, this influenced the number of patients interviewed per unit, which had to be limited in order to obtain a manageable data set which could be explored in depth. Future qualitative work may benefit from sampling more patients from fewer units in order to follow-up initial data which suggests that patients attending different units are receiving different information about treatment options.

The categorisation of units into two groups representing units with a more or less established CKM pathway was relatively crude. Inevitably there was some overlap in policy and practice between the two groups; however, the categorisation helped us to look at general trends in the data.

Implications

Patient reports indicated that they had been given different types of information, at different time points, by their renal unit and that units with a more established CKM pathway appeared to have provided more detail about the option of CKM than others. While this may have reflected the suitability of dialysis or CKM for the individual patient, it was interesting that patients from units with a more established CKM pathway were aware of both treatments regardless of what their final decision had been. Having fewer resources dedicated to CKM may reflect a general trend in a unit to encourage dialysis for all patients. However, it may also reflect less experience in providing care for CKM patients. Staff with access to fewer resources and less experience in providing a type of care may be less likely to discuss such care with patients, which may bias discussions towards dialysis. Staff may also be less supported in these discussions if they are not provided with materials which help to explain the CKM pathway or with training in how to have such discussion with patients. Finally staff may not feel comfortable discussing CKM with patients if they believe that dialysis will always offer more benefit despite comorbidity or frailty. Research which can provide data on the comparative outcomes of CKM and dialysis patients will help to clarify whether dialysis is beneficial for certain patients or not.

It was interesting to note that some patients had opted for CKM several months before interview, in one instance 7 years previously. It was also apparent that some patients had initially opted for CKM when they were well and changed their mind once they had experienced symptoms from their CKD. Both situations suggest that the label of CKM is being used for a very broad population, arguably one that is much larger and more diverse than the label ‘CKM’ would initially suggest.

Conservative kidney management is an alternative to dialysis and therefore could be strictly defined as applying only to patients who have passed the point at which dialysis would usually have been started, though this point can be difficult to define, especially in patients who may have symptoms related to other comorbidities. While this time point will be different for individual patients and judged differently between clinicians, a consensus based on eGFR or symptoms linked to kidney failure may be possible and would reduce the number of patients with asymptomatic, stable CKD being labelled as receiving CKM. Delaying a label of CKM would allow patients more time to think about their decision. It may lead to patients experiencing more symptoms from their CKD and give them greater awareness of how much their CKD is affecting their life. Having a more standard approach to the labelling of CKM, specifying separately those patients who currently plan to have CKM in the future and those who are currently receiving CKM, would provide a clearer view of the numbers of patients on this pathway and the variation between units. Our interviews emphasise that both categories of patients retain the option of changing their plan or choice of treatment.

Both dialysis and CKM patients reported they had not discussed the future with staff. Regardless of what treatment decision is made, it is important that renal staff discuss the likely trajectory of illness with patients. Previous literature has highlighted this issue and recommended earlier, rather than later, conversations about ACP to promote optimal end-of-life care. 46,47

Finally, quantitative results from the CKMAPPS survey indicate that units use different terminology for CKM and that there is a subgroup who refer to CKM as ‘non-dialysis’. CKM is accepted by most as an alternative to dialysis for a subset of patients, and patients may benefit if the option of CKM is presented in a consistent and unbiased manner across renal units. Units that are organised to support staff in the discussion of CKM options with patients will deliver patient benefit by promoting greater shared decision-making. 48,49 Clinicians should consider the implications of having a pathway framed as a negative option. Consistency in terminology would help establish CKM as a clearly defined and appropriate pathway for some patients.

Conclusion

Our results indicated that older adults with CKD5 who have chosen different treatment options have contrasting beliefs about what dialysis will offer them. Patients’ decisions were influenced by the information provided by their renal units, which differed between units with more and less established CKM pathways. Supporting staff in discussing CKM as a valid alternative for a subset of patients across all renal units will promote informed decision-making and thereby stand to benefit patients.

Chapter 3 Staff interview study: treating older adults with stage 5 chronic kidney disease who opt for conservative kidney management – a qualitative study with renal unit staff

Introduction

This substudy addresses objectives 1, 2 and 4. Semistructured interviews were conducted with renal HCPs to explore the organisation and provision of CKM to patients in their units, and their views and experiences of treating patients who opt for CKM. The primary aim of conducting these interviews was to inform the development of the national survey questionnaire.

Only a few qualitative studies have explored renal staff’s experiences with patients on RRT. One study identified that physicians and nurses found it difficult to meet the complex needs of elderly patients and faced dilemmas when making decisions concerning withholding or withdrawal of dialysis. 50 Another study found that nephrologists working in HD care faced ethical dilemmas where they were forced to make ‘life or death’ decisions, such as whether or not to start or discontinue dialysis. These decisions were made particularly difficult if patients and relatives were in disagreement about a treatment option, and when they were faced with time restraints and professional and personal demands. 51 Nephrologists also found it difficult to explain the complexity of advanced kidney disease to patients with difficulties in managing a disease over which they have little control. Consequently, discussions with patients focused on present clinical status and avoidance of discussions of prognosis and the future. 44

While these studies identify difficulties that renal staff face, they do not give a detailed account of staff’s experiences of discussing alternative treatment options such as CKM with patients. None of these studies was conducted in the UK. This study focused on exploring UK renal staff’s views about CKM and their experiences of the provision and delivery of the CKM option for older adults with ESKF.

Methods

Design and setting

Semistructured interviews were conducted with staff members in nine renal units across England. These units were the same as those involved in the patient interview study (see Chapter 2) and were purposively sampled to obtain a range of locations and scale of CKM practice.

Participants

Consultant nephrologists in each participating unit were approached by the principal investigators and asked to identify a minimum of five staff members who were involved in the care of CKM patients in their unit. For units that had very few CKM patients, staff who cared for patients in low-clearance clinics or for those whose eGFR was less than 20 ml/minute/1.73 m2 were recruited. We stipulated that the staff members interviewed had to include a minimum of one lead nephrologist and one nurse per unit. Allied health professionals were also invited to participate in the study.

Interviews

Participants were interviewed by IO and ST-C, either face to face at their renal unit or by telephone. All participants signed a consent form either at the time of interview or before the interview if they were interviewed over the telephone. Semistructured interviews were conducted following an interview schedule (see Appendix 2). The interview schedule was initially constructed from a literature review and discussion with steering group members and was then developed iteratively as interviews were carried out. The interview schedule asked participants to discuss their views of CKM, their experiences of being involved in decision-making about CKM, how CKM was delivered in units and the role of primary and palliative care services in caring for CKM patients. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and interviewers verified the accuracy of transcription by listening to the interview and reading transcripts.

Data analysis

A content analysis of the 60 interviews was carried out to inform the survey questions (see Chapter 4). This consisted of several steps and included rereading the interview transcripts, identifying frequency of words, phrases and themes, and then developing categories of words, phrases or themes with similar meaning. 52 The data from the qualitative study helped to identify the sections of the survey and facilitated the formulation of the survey questions and multiple choice options.

Subsequently, a more detailed thematic analysis41 of the qualitative data was conducted. NVivo 10 was used to facilitate coding of the data. From the 60 staff interviews, 28 interviews were sampled using maximum variation sampling to ensure variation of units and experience of being involved with renal patients. Fifteen interviews were analysed in the first instance using thematic analysis by IO. 41 ST-C independently coded 10 of the 15 interviews. These interviews were selected from four units, which were the first participants recruited to the study. This sample was selected to ensure variation in units, staff roles and their experience of being involved with renal patients. Researchers reread the interview transcripts in order to identify emerging codes and to develop an initial coding framework. A further 13 interviews were selected to ensure variation of units and experience of being involved with renal patients; they were then coded by IO, ST-C and a third researcher, CE, using the preliminary framework, which was refined and further developed into the final thematic framework. Discrepancies were discussed and resolved by consensus. Data from the remaining 32 transcripts also added to the final thematic framework and facilitated saturation of the themes, which was achieved when no new codes or themes emerged from the data.

Results

Participant characteristics

Sixty renal staff members were interviewed between February 2012 and November 2012. Table 5 summarises characteristics of all those interviewed and of the 28 staff whose interviews were analysed using in-depth thematic analysis.

| Characteristic | 60 participants interviewed | 28 participants whose interviews were analysed in depth |

|---|---|---|

| Gender (n) | ||

| Male | 13 | 7 |

| Female | 47 | 21 |

| Age (years) | ||

| Median | 49 | 47 |

| Range | 28–67 | 36–67 |

| Job title (n) | ||

| Nephrologist | 22 | 14 |

| Nurse | 25 | 9 |

| Palliative care consultant | 1 | 0 |

| Allied health professional | 12 | 5 |

| Time at current unit | ||

| Median | 9 years | 10 years |

| Range | 9 months to 40 years | 10 months to 31 years |

Qualitative findings

Three themes emerged from the detailed analysis of 28 interviews and the analysis of the remaining 32 interviews.

Theme 1: providing conservative kidney management to patients

Many staff discussed how they provided CKM, including what services CKM involved and the resources available for the delivery of CKM. They also talked about how they viewed CKM and how it could be improved in their units.

Staff views about providing conservative kidney management as a treatment option

A variety of terms were used by participants to refer to CKM, such as ‘conservative care’, ‘maximum supportive care’, ‘non-dialysis care’ and ‘renal palliative care’. For example, the term ‘maximum supportive care’ was used at unit 8, which had a developed CKM programme with dedicated staff, CKM clinics, CKM guidelines and CKM funding, whereas unit 3, with a less developed CKM programme, used terms such as ‘non-dialysis care’.

We call it maximum supportive care and I’m sure one of the things that you’re coming across is that people have all kinds of different names for this.

So do I call it non-dialysis care or conservative kidney management?

Well you know, we probably . . . we probably use it . . . we probably use non-dialysis care. I think perhaps everywhere . . . I think we may change with the rest of the world where everybody calls it conservative kidney management.

Conservative kidney management was generally accepted by renal HCPs as a treatment option. Many renal staff described CKM as a valuable option for some patients, particularly for those with multiple comorbidities, and recognised it as an active treatment, managing the symptoms of kidney failure without using RRT. Some staff said that not dialysing someone used to be thought of as a failure by medical staff, and talked about how HCPs had recently started to realise that dialysis was not suitable for everyone. Having CKM as an established care pathway also helped staff, as they described how they were able to provide something to patients rather than just not providing dialysis.

When you are dialysing [patients] you know you are doing the most you can, but now because we have got an active conservative management programme my colleagues feel you know although the patient is elderly we can still offer them something. So you know, you feel that you can do something proactive.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 1, participant 1

While many described CKM as a valuable alternative treatment to dialysis, there was one nephrologist who did not hold this view.

There are amazingly few [CKM] patients [in our unit], whereas most people’s conservative care clinic is filled with people who do not currently need dialysis, who may or may not need dialysis at some point in the future, but it has been decided that they will not get dialysis, at that point in the future. And so these are the same people that we are treating in our nephrology clinics for chronic kidney disease, Stage 4 and 5 [. . .] We remain unconvinced that this is a useful concept for – for managing people with kidney disease. It doesn’t add anything to what we do at the moment.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 4, participant 23

Many interviewees recognised that there were some patients who unexpectedly responded well to dialysis, while others did not respond well and experienced complications as a direct consequence of the treatment. Some staff reported that they sometimes found it difficult to assess whether patients were suitable for RRT or CKM and wondered if they had given their patients the right treatment for them.

I think most of the nephrologists will find it very tricky when a GP sends you a 90-year-old lady with multiple comorbidities, with a GFR [glomerular filtrations rate] of 10 – how do you approach that? Do you say – well you are going to die – without dialysis; you are probably going to die with dialysis – and on dialysis and you’re probably going to have worse quality of life; I really don’t know.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 4, participant 22

Resources available for conservative kidney management vary

Resources available for delivering CKM varied across the units. For instance, only unit 8 had funding dedicated to providing CKM. Some of the units without such funding used alternative funding to develop general CKD services, which partly contributed to the delivery of CKM.

We won a bit of money and what we used that to do was to set up the Cause for Concern Register, the two renal resource days and also communications, so myself and [nurse’s name] have done the advanced communication course, but we want to now – for the whole of the renal services so every consultant, every specialist nurse will do the enhanced communication training. So that’s going to happen in the next year; so that’s what we use our funding for.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 7, participant 42

Many staff did not have allocated time for CKM patients, and their time for CKM was integrated into their normal workload. Some units did have dedicated CKM staff and stressed the importance of having staff who had dedicated time to treat CKM patients. Unit 8 had a dedicated palliative care nurse treating CKM patients as part of CKD patients approaching end of life.

We have a palliative care nurse. I mean one of the things that stops people doing [CKM] is that they know that if they sit down and have a conservative care conversation with someone, that takes an hour. One of the things that’s helped us to do [CKM] over the last couple of years is that we have a dedicated palliative care nurse who can spend all that time having those conversations. We have a dedicated palliative care nurse who can then do all the set ups to the hospice and get all the home care organised.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 8, participant 47

Some units provided their staff with training, which was perceived to improve staff’s confidence to deal with patients who were approaching the end of life, including CKM patients.

We have undergone quite an intensive staff education programme, communication skills mainly; we’ve done it across the board from clerical staff to doctors, right the way across nursing staff, and it really just helps patients. It’s dealing with a distressed patient, so say, somebody on dialysis says – I’m fed up with this, I really don’t want to carry on, I’m quite certain some of our nurses beforehand would have said . . . , I don’t know what to say, so I’ll pretend I didn’t hear it. Now they feel more empowered. So we have champions in each area now, who do feel competent in discussing end of life or death and dying.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 8, participant 47

Many staff reported that patients’ CKM decisions were recorded in their medical notes or database. Some also pointed out that having a clear record of the CKM decision not only within the renal unit but also in the primary care record was very important. Adequate recording was thought to minimise inappropriate hospital admissions and/or dialysis.

I think one of the most important things we do is make a clear record of the decision about dialysis in the hospital and in the primary care records . . . certainly in my letters it says please make it very clear for the out-of-hours doctors, that if they become unwell they would rather not be admitted to hospital and rather not be, you know, started on dialysis.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 5, participant 32

Service components of conservative kidney management

All staff mentioned that CKM offered assessment and management of symptoms caused by CKD. However, the way CKM patients were seen and what service they received varied between the units. At some units, especially those without CKM clinics, CKM patients have the same pathway as pre-dialysis patients until they reached the point when they would have started dialysis if it had been their chosen treatment.

[Patients on] conservative care do all the same [as dialysis patients] up to this point; counselled, chosen, coming back to clinic on anaemia treatment, [GFR] 8 to 10 they start getting symptomatic, then the nurses start visiting. They don’t start doing anything between [GFR] 15 and 8–10, they are not sort of having a different pathway at that point from anybody else, so they have got the same symptoms as the people that would start dialysis. They are not different at that point.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 6, participant 36

Unit 5 also did not have CKM clinics and a consultant nephrologist reported that they saw their CKM patients less often than in a hospital with CKM clinics and that they mainly monitor patients rather than actively manage them.

[At (a hospital name)] it looks like they see [CKM patients] much more often, they see people as if it is an active treatment. For us, we bring people back in 4 months and do a blood test, there is not a lot you can do every 4 months when you are seeing somebody and it sends out the message that well, we are just monitoring things.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 5, participants 32

There were units that had a multidisciplinary approach towards CKM patients. Unit 9 had dedicated CKM clinics and a nurse explained that they provided not only medical but also social care to patients.

If they come to the [CKM] clinic and we ask them very generic things about their social life, how things are going, do you need any more carers putting in, how is the carer, are you managing – mum’s not well, she had a fall. We do all that and then [nurse’s name] does a medical assessment; so they get a social assessment if you like, dietetic assessment and a medical assessment, all in one clinic. And then we’ve got our helpline, our phone as well.

Nurse, unit 9, participant 54

All staff discussed that patients on CKM received palliative/supportive care when they started to approach end of life. Some units mentioned the importance of providing patients with a smooth and timely transition to end-of-life care, which usually happened in the community or at a hospice. Staff from unit 2 reported that they monitored CKM patients carefully so that they could plan the end-of-life care for patients proactively.

We do our RAG [red–amber–green] rating, so we have red–amber–green rating for patients who are on conservative management. We are trying to identify those that would you be surprised if they are here in 3 months? [. . .] When the liaison nurses see one of the conservative management patients in clinic, they attend the clinic visit with them, do their RAG rating and come and readjust it on the supportive care register, and then raise those patients that are flagging up and moving and changing on the register, so you’re becoming more concerned about them. You would raise them at that [quality assurance] meeting and then at that point the liaison nurse should not only have highlighted the increasing need but have actioned it. For example, they would have said, ‘We are thinking of introducing them to the hospice’, ‘I’ve been in touch with the community nurses’, ‘I might have had a conversation with the GP’. We have started an advanced care plan, a social worker would often go out and arrange another home visit to see if there was a carer problem.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 2, participant 7

Staff views about organisation of conservative kidney management

Units 1, 8, and 9 had dedicated CKM clinics. Staff in units without dedicated CKM clinics saw CKM patients in low-clearance or general nephrology clinics. Some units had a small number of CKM patients, and staff discussed not needing dedicated clinics because of this.

[CKM patients] aren’t seen separately. We don’t have a non-dialysis care clinic. I suppose in the future, depending on numbers isn’t it, because what will happen to non-dialysis care patients is they will die off. You know so that the numbers don’t grow huge.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 3, participant 13

In contrast, some talked about the need for such clinics, as they would be likely to help provide better quality of care.

We do feel that it is important for us to develop some sort of service which would be dedicated to the conservative care and that’s one of the driving forces for us to probably think that we should have some sort of dedicated clinic. And one of the advantages of having a dedicated clinic for the conservative care, would be that we could at least spend a bit more time [with patients].

Consultant nephrologist, unit 6, participant 38

Some said that setting up dedicated CKM clinics would not be supported by consultants because they would then lose any continuity of care.

They want to see their patients through, whether they’re dialysis patients or conservative patients, or transplant patients. They want to be able to deal with the whole group of patients rather than . . . as soon as they make the decision then another consultant looks after them.

Nurse, unit 5, participant 30

Conservative kidney management patients were also seen by GPs and the community team towards the end of life, and this was mostly as a result of the patient’s preference. The size of geographical area a unit covered also affected how the unit cared for CKM patients. For example, unit 7 encouraged patients to be cared for by primary care teams once patients had chosen CKM, and they cared for patients in collaboration with GPs and community teams. This is mainly because the unit covered a large geographical area and many of their patients needed to travel a long way to come to the renal unit. Consultants from the unit questioned if it was fair to bring CKM patients, who were usually old and frail, to the clinic when the same care could, in theory, be given in the community.

[CKM] patients want to be followed up in the community and I think that suits them. [Patients] are enjoying what life they have and they are more likely to die at home, rather than coming into hospital and relatives having to take days off just for me to check a blood pressure. I don’t add any value at that point and I know some units tend to bring them back and I don’t approve, I don’t agree with that; I think it’s not fair.

Consultant nephrologist, unit 7, participant 42

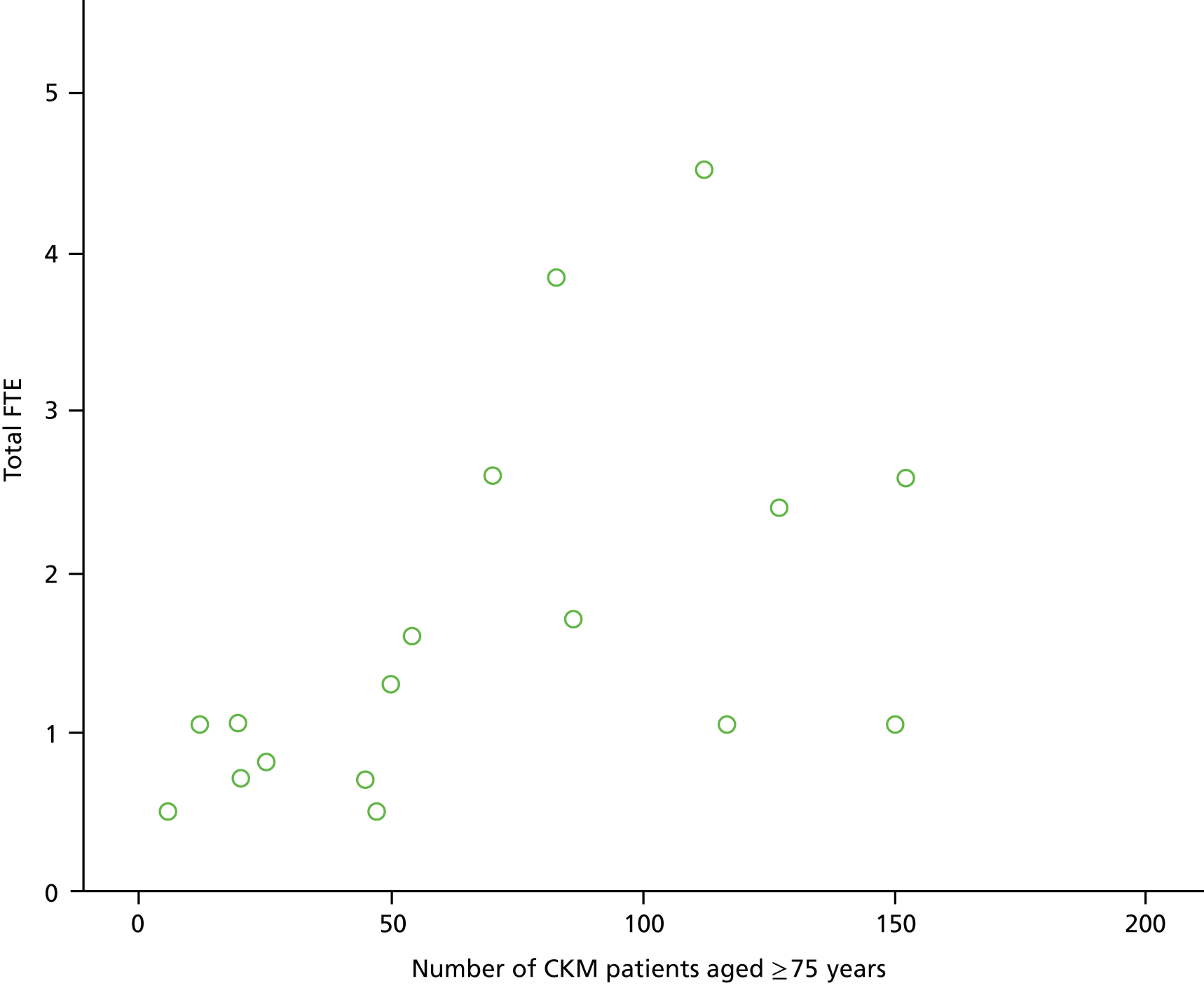

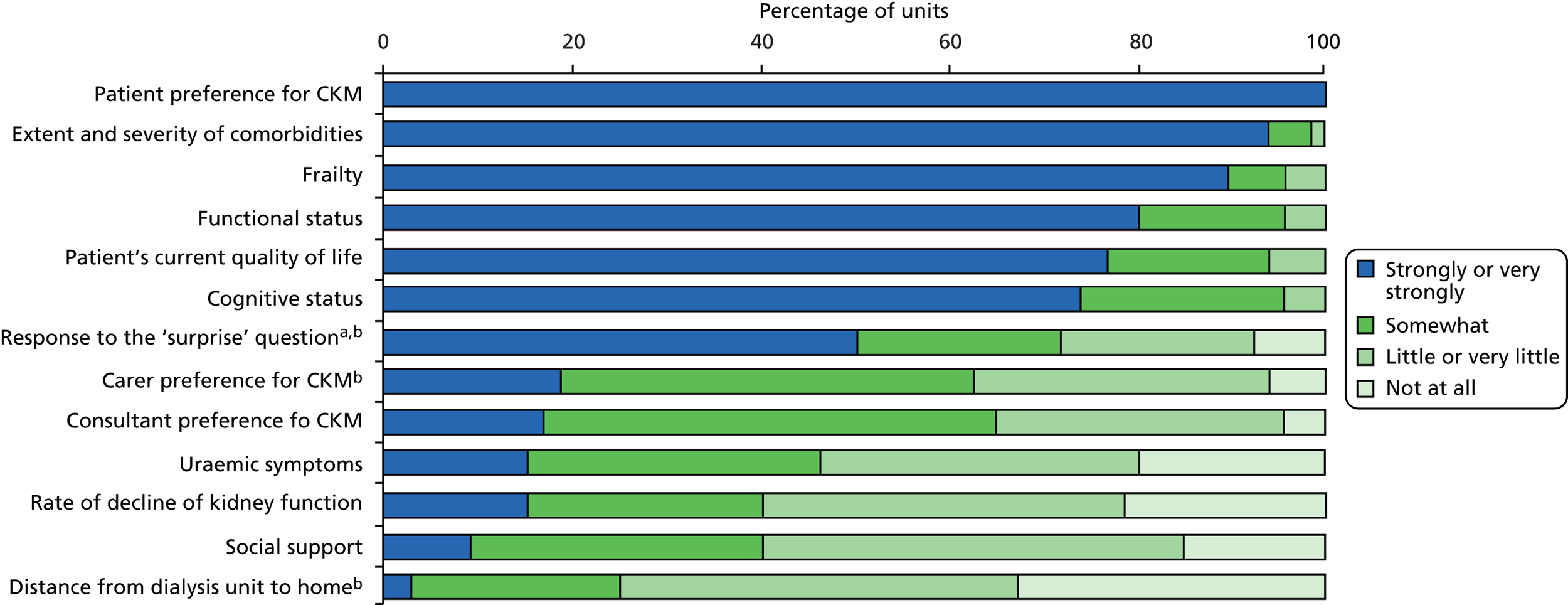

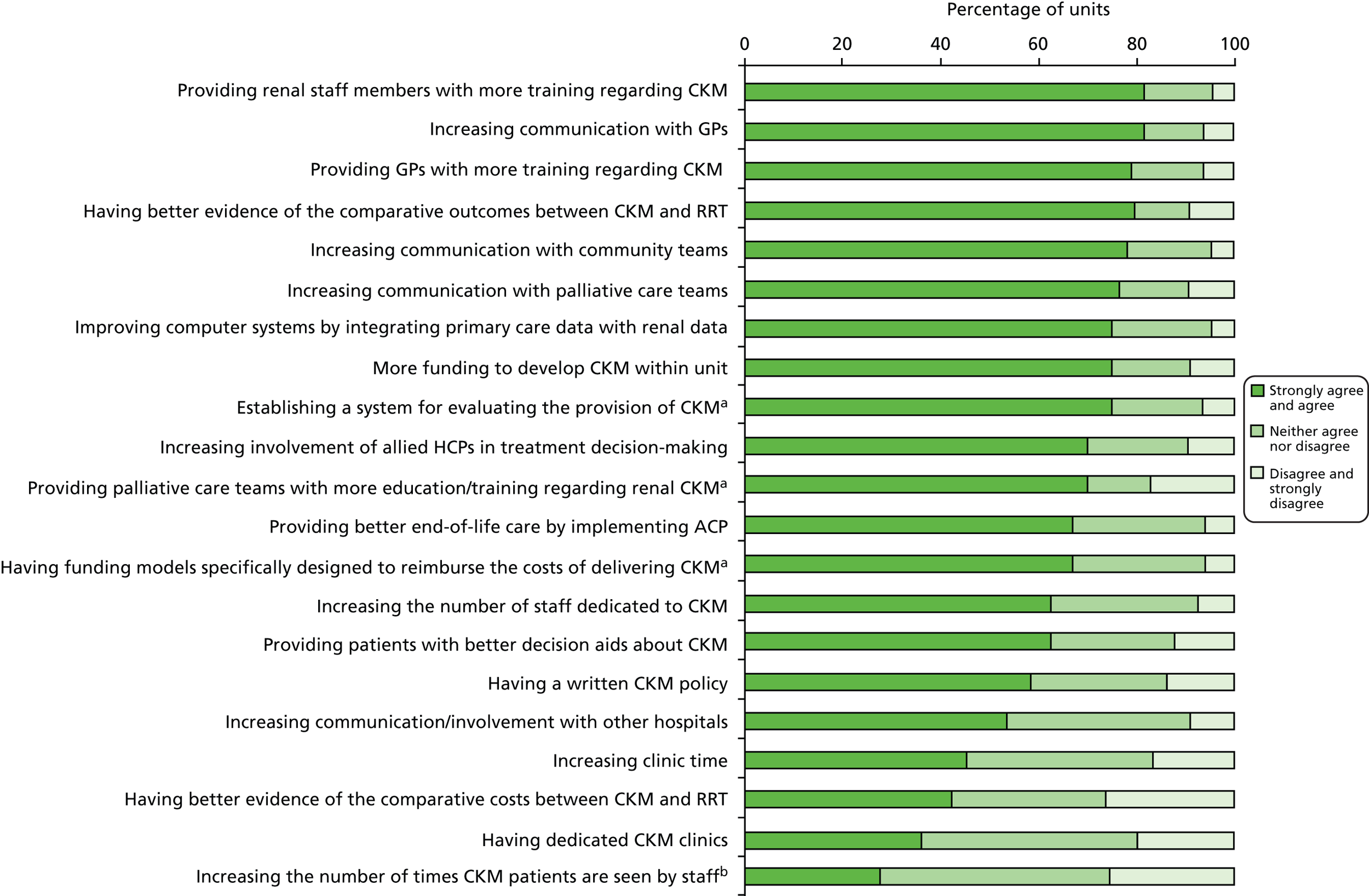

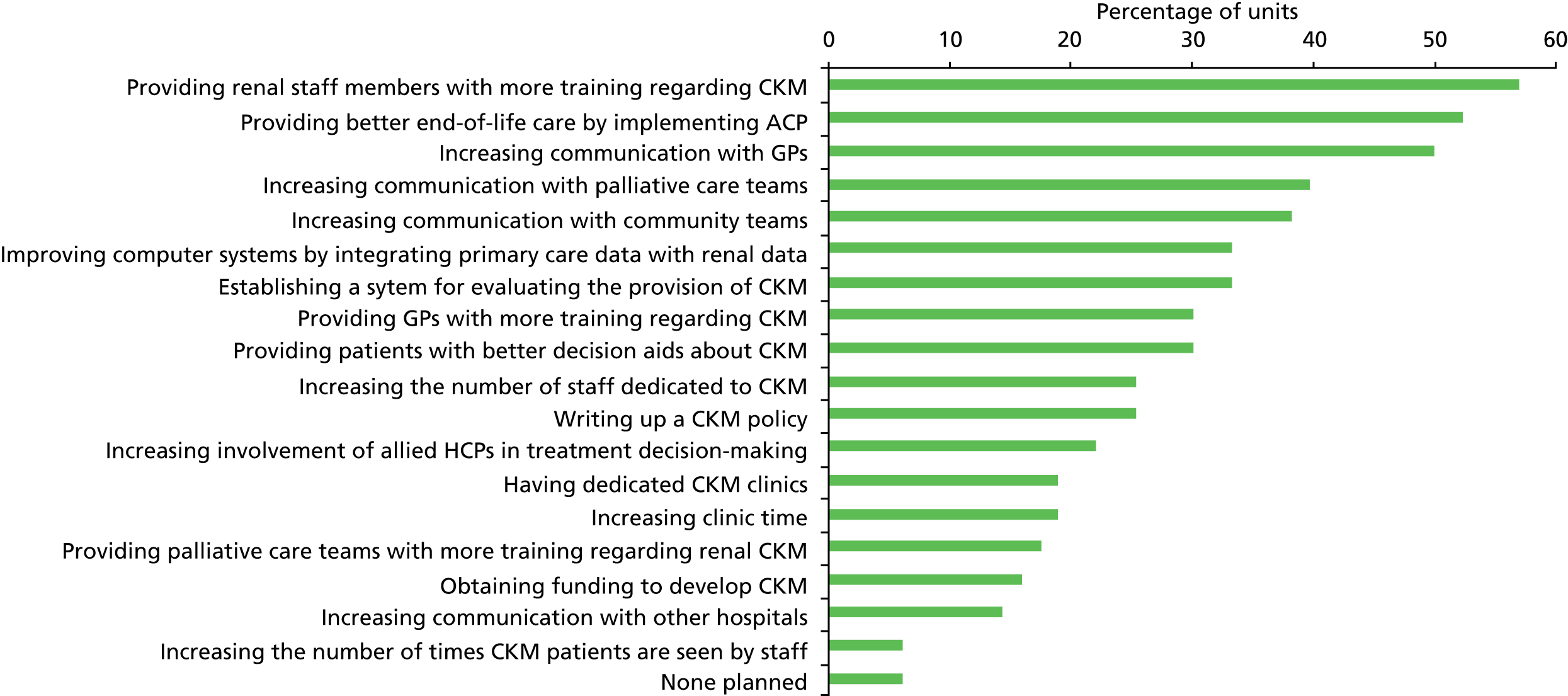

This approach was not supported by all, as other staff had doubts about the quality of care delivered by units that mainly saw CKM patients remotely.