Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1006/25. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The final report began editorial review in August 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Padmanabhan Badrinath co-ordinates the Clinical Priorities Group in Suffolk. Claire Beynon is a member of South West Commissioning Support. Christine E Hine was a consultant in public health employed by NHS South Gloucestershire and NHS Bristol to provide independent public health advice to health services commissioning during the research period. She was a member of the Bristol, North Somerset and South Gloucestershire Commissioning Advisory Forum. Hayley E Jones reports personal fees from Novartis AG and personal fees from the British Thoracic Society, outside the submitted work. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Hollingworth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

National pressures on health-care spending

Health-care expenditure in the UK more than doubled from £42.8B (5.4% of gross domestic product) in 1996/7 to £94.7B (7.0% of gross domestic product) in 2006/7. 1 However, health-care spending in the UK NHS and many other high-income countries has stagnated since the economic crisis of 2007. The 5% annual increases in real expenditure that existed before the crisis have been replaced by flat-line funding, which is projected to persist in coming years. 2 This financial constraint is already pushing some NHS budgets to breaking point. 3 These pressures are thought to arise from ever-increasing demands on health services due to population growth, increasing population health needs and rising patient expectations of health care in wealthier societies. Supply-side factors are also clearly important, with factor costs (e.g. staff salaries) and technological progress often cited as drivers of increasing health-care costs. 4 Studies that have tried to unpick the relative contribution of these factors have identified technological change as a predominant cause of increased health-care spending. 5 Therefore, one natural response to the current financial pressures is for health-care policy-makers to revise the methods that they use to evaluate and regulate new and existing health-care technologies.

The policy context

The aftermath of the economic crisis coincided with a major reconfiguration of NHS care in England, as laid out in the 2012 Health and Social Care Act (HSCA). 6 Prior to the Act, local commissioning of most health-care services was the responsibility of 151 primary care trusts (PCTs) across England. One key legislative aim of the 2012 HSCA was to promote clinically led commissioning by abolishing PCTs and transferring most local health service commissioning to 211 newly established Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) supported by 23 commissioning support units (CSUs) before April 2013. 7 CCGs are responsible for approximately £65B (70%) of NHS funding and are required to plan, commission and monitor services such as elective and emergency hospital care, community, and mental health services. 8 NHS England now directly commissions primary care and specialised services while Public Health England and local authorities are responsible for public health services.

Clinical Commissioning Groups must pay for new technologies mandated by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and find the necessary savings from elsewhere in their budgets. CCGs have a statutory duty to ensure their annual expenditure does not exceed their budget. Primary care doctors [general practitioners (GPs)] play a leading role in the new CCGs; the HSCA envisages that by giving more budgetary responsibility to front-line clinicians it will encourage them to redesign health-care provision more efficiently in their locality. It is too early to judge how CCGs will differ from PCTs in commissioning local health care. However, it is clear that they have taken on the role of commissioning in extremely challenging financial circumstances and that appropriate diffusion of new cost-effective health technologies and discontinuance of existing inefficiently applied health technologies will remain high on their list of priorities. 9

Theories of technology diffusion and discontinuance

Rogers identified seams of diffusion and discontinuance theory in anthropology, sociology, economics, communication and marketing. 10 He argues that discontinuance of inefficient or inappropriately applied technologies will depend on characteristics of the technology (e.g. perceived relative disadvantage), characteristics of individuals who use it (e.g. training and receptiveness to change), systems within which they operate (e.g. financial incentives) and interactions among each component. Rogers distinguishes between replacement discontinuance, which occurs when more efficient technology displaces the existing technology (e.g. radiography replaced by computerised tomography in head trauma) and disenchantment discontinuance, which results when new information indicates that the benefits of the existing technology do not justify the costs or adverse effects (e.g. the decline in tonsillectomy rates in the 20th century).

Discontinuance can be spontaneous or managed (i.e. disinvestment, see Figure 1). Reliance on spontaneous discontinuance will fail if there are imperfections in the market for health care. In particular, imperfect evidence about the costs, effects and safety of existing interventions or lack of communication of this evidence to clinicians and patients may delay optimal discontinuance.

FIGURE 1.

Schema of health-care technology adoption and withdrawal.

Overview of discontinuance and disinvestment in the health sector

In an extensive systematic review of the diffusion of innovations in health care and other service organisations, Greenhalgh et al. 11 build on theoretical work from 13 multidisciplinary research traditions to build a conceptual model of innovation diffusion and dissemination in health service delivery and organisation. The model depicts the interactions between the innovation characteristics (e.g. relative advantage), system antecedents (e.g. absorptive capacity) and readiness (e.g. innovation–system fit) for innovation, adopter characteristics (e.g. motivation), communication channels (e.g. peer opinion) and the outer context (e.g. incentives and mandates). Where active dissemination or disinvestment is the goal, the linkage (e.g. shared meanings and mission) between the agency promoting change and the target audience is essential to achieve sustained implementation. Greenhalgh et al. 11 note that, in the context of medicine, ‘the evidence base for particular technologies and practices is often ambiguous and contested and must be continually interpreted and reframed in accordance with the local context and priorities, a process that often involves power struggles among various professional groups’. However, they found little empirical work in the service sector on internal politics, such as doctor–manager power balances.

Very little is known about the rate of spontaneous health technology discontinuance, managed disinvestment or factors that facilitate them. The Greenhalgh et al. review included more than 400 studies, but identified only one study that explicitly and prospectively studied discontinuance. 11 Therefore, while there is growing recognition of the importance of disinvestment, there is little theoretical foundation or empirical evidence to inform practice. However, there are good reasons to believe that health-care disinvestment may be considerably more challenging than dissemination.

Elshaug, who has done much to reinvigorate research interest in this area, defines disinvestment in health care as ‘processes of (partially or completely) withdrawing health resources from any existing health-care practices, procedures, technologies or pharmaceuticals that are deemed to deliver little or no health gain for their cost’. 12 By stating that disinvestment may be only partial, this definition acknowledges that existing health-care technologies typically do not suddenly become completely obsolete. Instead this process is more likely to be gradual and incomplete as evidence emerges that a new intervention is more clinically effective and cost-effective for some clinical subgroups. Alternatively, it might reflect growing disenchantment if an existing intervention is revealed to have been overdiffused based on inadequate or outdated evidence. The economic concept of opportunity cost is central to this view of disinvestment. 13 Full or partial disinvestment from inefficient health care in one area of medicine gives health policy-makers the opportunity to spend the money to achieve larger improvements in patients’ health in another area.

In order to be evidence-based, disinvestment in health care will rely on a programme of health technology reassessment (HTR)14 analogous to the technology appraisal process implemented by NICE to evaluate new medicines and treatments in England and Wales. HTR has been defined as ‘A structured, evidence-based assessment of the clinical, social, ethical and economic effects of a technology currently used in the healthcare system, to inform optimal use of that technology in comparison to its alternatives’. 14 Elshaug et al. 15 identified five key challenges to health-care disinvestment: (1) lack of resources to support disinvestment policy mechanisms; (2) lack of methods to identify and prioritise technologies with uncertain cost-effectiveness; (3) political, clinical and social challenges to changing established practice; (4) lack of evidence on the efficiency of many existing technologies; and (5) lack of funding for research into disinvestment methods. This lack of evidence on the cost-effectiveness of existing technologies is an example of what have been described as the first (from knowledge need to discovery) and second (from discovery to clinical application) translation gaps in health-care knowledge. 16 Policy-makers and commissioners have a need for more extensive knowledge about particular clinical subgroups of patients for whom a given intervention is cost-effective and, as importantly, those for whom it is either less cost-effective or not cost-effective at all. However, high-quality evidence is often lacking because randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are scarce and are not large enough to provide robust evidence on subgroups. The third translation gap (from clinical application to action) is also likely to be particularly challenging for disinvestment even when robust evidence is available. Lack of familiarity with the evidence, scepticism about the evidence or its applicability, and external pressures (such as patient expectations or financial and professional rewards for procedure use) are just a few of the powerful influences on clinicians towards inertia rather than disinvestment. 17

The quantitative analyses described in this report are based on the hypothesis that high geographical variation in clinical procedure rates is an indicator of interventions where clinicians are uncertain of the diagnostic threshold or the clinical value in particular patient groups and therefore may be using the procedure inappropriately or inefficiently. As NHS commissioners can easily benchmark procedure rates, this is a potentially valuable method of addressing the second key challenge described by Elshaug et al. The qualitative components of our project explore some of the barriers to disinvestment emphasised by Elshaug et al. ’s third key challenge.

Geographical variation in procedure rates and clinical uncertainty

Glover, comparing pre-1945 tonsillectomy rates, found such high geographical variations that he concluded that it was ‘a prophylactic ritual carried out for no particular reason with no particular result’. 18 Wennberg has developed this into the ‘professional uncertainty hypothesis’. 19 That is the theory that geographical variations occur because of differences among physicians in their diagnostic thresholds or in their belief in the value of the procedure, rather than any differences in clinical need. For example, hip fracture repair, where the diagnosis is clear cut and consensus on the value of surgery is high, has a low geographical coefficient of variation (CV), indicating little variation between regions of the USA. In contrast, for lumbar spine fusion surgery, where there is less agreement on the indications for surgery or the benefit of surgery, the CV is much higher. 20

Geographical variation remains after adjustment for demographic factors and is unlikely to be due to differences in disease prevalence or patient preferences. Small area variations are prevalent in the UK. 21,22 It is thought that variations build up over time as clinicians arriving in a region conform to existing practice patterns, because of local opinion leaders and educational forums that generate enthusiasm (or lack thereof) for a procedure. 23 These local patterns may become entrenched as more hospital diagnostic, specialist and surgical resources are devoted to a particular procedure and may be further exacerbated by hospital reimbursement or surgeon prestige which encourages more intensive care. 23 Bisset24 observed that, as Scottish appendectomy rates declined (from 2.89 per 1000 in 1973 to 1.47 per 1000 in 1993), there was a concurrent decrease in the amount of variation in procedure rates between the 12 health boards. She concluded that the reduced variation ‘supports the view that improved management policies may have helped reduce “professional uncertainty”, unnecessary operations and variation in surgical practice’. Where there is marked practice variation, there is potential for evidence synthesis to identify current gaps in knowledge to guide the national research agenda and to inform local commissioning to standardise current practice around current best evidence.

Structure of the project report

This project was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme in response to a call for research on ‘NHS responses to financial pressures’. Specifically, we studied whether or not clinical practice variations can be used by commissioners and clinicians to identify and priorities opportunities for disinvestment in health care. We used six interlinked projects using quantitative and qualitative methods to address a series of related research objectives described in Chapter 2.

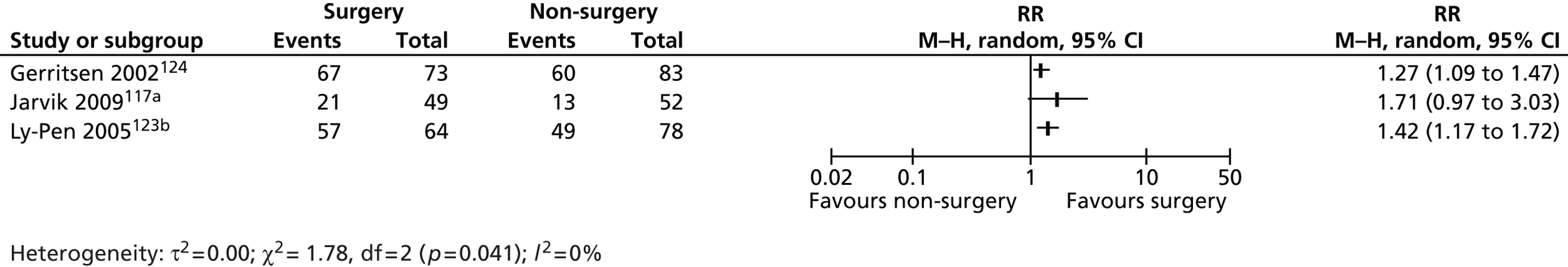

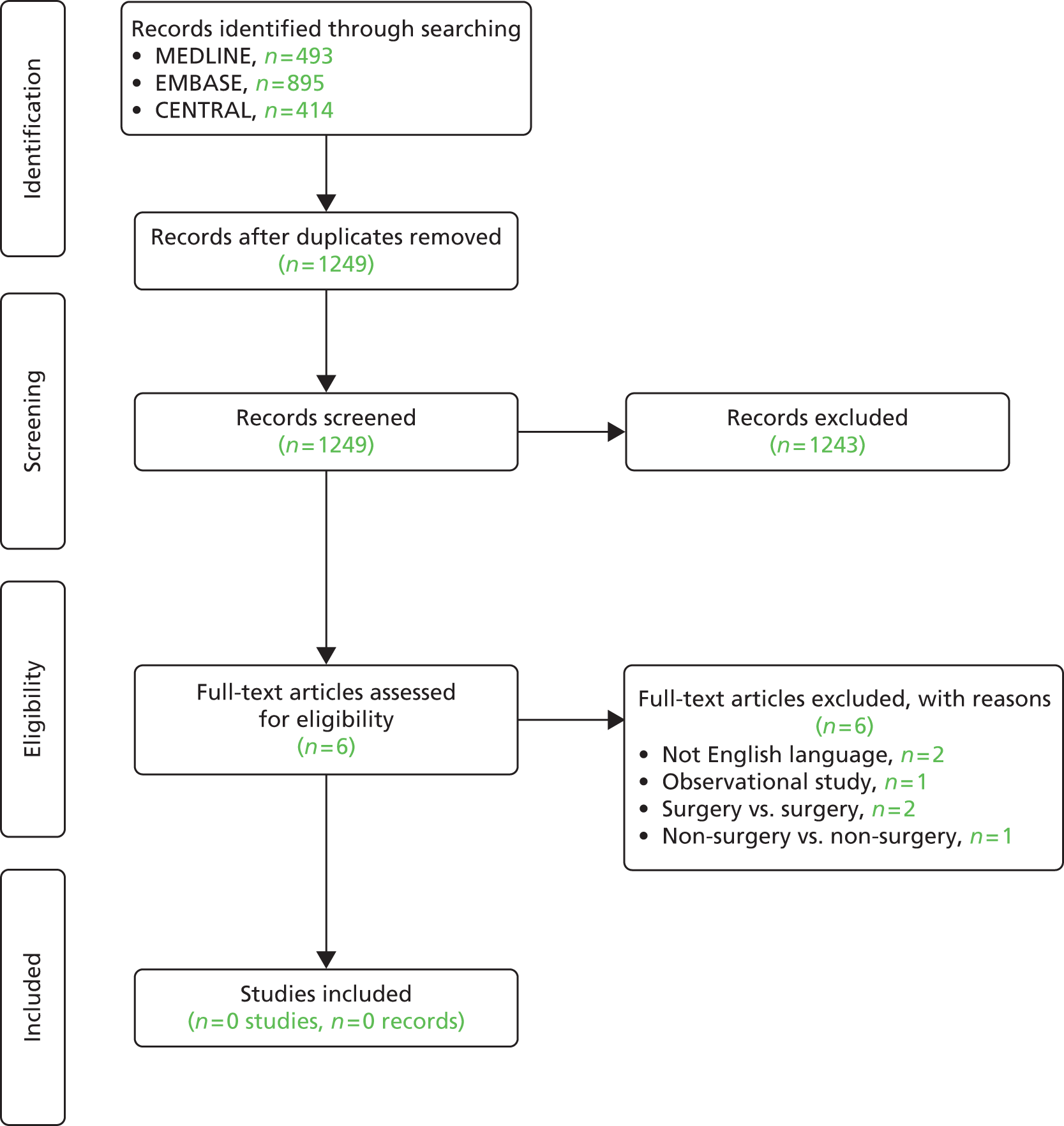

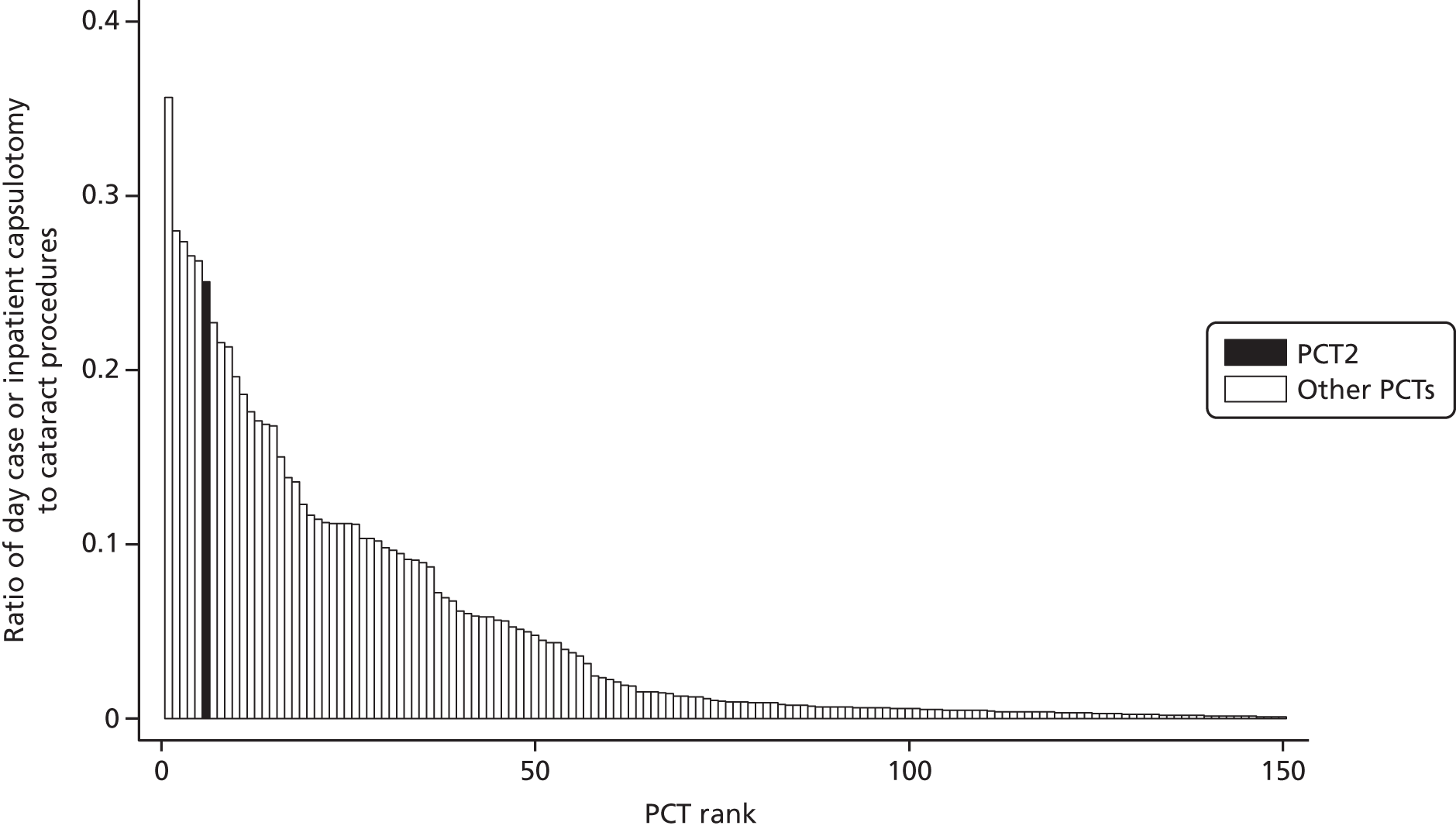

At the national level, we assessed whether or not high geographical variation in procedure rates between PCTs is associated with uncertainty about the clinical value of the procedure and therefore might be used by research funders to identify topics where better evidence can lead to more appropriate use of resources (see Chapter 3). At the local level, we worked with two PCTs to evaluate the potential of benchmarking procedure rates against other PCTs to identify procedures that might be overutilised in their area and that were potential candidates for disinvestment (see Chapter 4). In collaboration with both PCTs we selected one high-utilisation procedure to explore if existing evidence could help commissioners work with providers to establish appropriate rates of procedure use, potentially leading to partial disinvestment. In PCT1 we conducted a rapid systematic review of carpal tunnel release (CTR) surgery to synthesise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this procedure for patients with carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) and discuss potential options for the PCT to regulate the procedure rate based on the evidence (see Chapter 5). In PCT2 we conducted a rapid systematic review of laser capsulotomy to synthesise the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this procedure for patients with posterior capsule opacification (PCO) following cataract surgery (see Chapter 6). We then discuss the probable causes of the high national variation in rates and high local use of this procedure.

In qualitative work we used observations of local commissioning advisory group meetings and semistructured interviews with group members and other stakeholders to understand the facilitators of and/or barriers to disinvestment at the local level (see Chapter 7). We used carpal tunnel surgery as a case study and, through semistructured interviews with patients and surgeons, explored their perspectives on the role of local commissioners in regulating access to surgery in order to regulate procedure rates and contain costs (see Chapter 8). Each of these chapters addresses different aspects of the challenges facing disinvestment. 15 Chapters 3 and 4 evaluate the potential for clinical practice variations to identify and prioritise existing technologies with uncertain cost-effectiveness. Chapters 5 and 6 examine the role of evidence in guiding appropriate use of existing procedures and preventing overutilisation. Chapters 7 and 8 highlight some of the political, clinical and practical challenges to changing established local practice.

In the final chapter we synthesise the main findings of our work and discuss the potential for research funders, commissioners and clinicians to use clinical practice variations and benchmarking to identify and priorities opportunities for disinvestment in health care. We highlight the most important barriers to local commissioners in achieving disinvestment and discuss the implications for the health service and for future research (see Chapter 9).

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The overall aim of this project is to develop and refine the process by which NHS policy-makers identify existing clinical procedures where there is uncertainty about appropriate use and the process by which local commissioners identify procedures that might be over-utilised in their area and are potential candidates for disinvestment.

Our specific objectives are:

-

To use routine inpatient data [Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)] to identify procedures with the highest inter-PCT variation in use. We explore whether or not high inter-PCT variance is a marker of clinical uncertainty about the value of the procedure in some patient subgroups or in some settings (see Chapter 3).

-

To work with two PCT commissioning groups to use benchmarking against the national average procedure rate to select two procedures that might be overutilised by their local NHS trusts (see Chapter 4).

-

To conduct rapid systematic reviews and assemble national and local guidelines for these two procedures to summarise the current evidence on clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. In the light of these technology appraisals, we discuss the likely causes of high local utilisation and the options available to commissioners to regulate local procedure rates to achieve disinvestment (see Chapters 5 and 6).

-

To use qualitative research methods to understand obstacles and solutions to local commissioners achieving evidence-based disinvestment (see Chapter 7) and to explore patient and surgeon perspectives on regulating access to care (see Chapter 8).

Over the course of the project our objectives have evolved to some extent. In part this has been because of the fallout from the large-scale reconfiguration of the NHS and, in particular, PCTs that took place during our project. One of our original objectives had been to evaluate the effectiveness of existing PCT commissioning criteria in reducing the volume of procedures of uncertain value. However, our freedom of information requests to PCTs to access historical threshold policies resulted in insufficient detail about threshold policies and in particular the dates when they were introduced and modified. Previous work25 has found that PCTs have lower response rates to freedom of information requests than other health-care agencies and our complex request coincided with a period of huge upheaval due to the introduction of the HSCA. We therefore decided to drop this original objective in favour of a more detailed exploration of the association between geographical variation and clinical uncertainty described in Chapter 3.

The original objective of the qualitative components of this study was to investigate how two PCT commissioning groups implemented disinvestment from procedures with high local utilisation. However, one of the key findings to emerge from the benchmarking and rapid systematic review process (described in Chapters 4–6) was the dilemma faced by commissioners who are aware of high and unexplained procedure rates locally but lack sufficient evidence to regulate procedure rates through local commissioning policies. In light of this, the revised aim of our qualitative study was to investigate how disinvestment currently works at the local level of health-care commissioning. Specific objectives included investigating the processes underlying local disinvestments, identifying barriers to successful implementation of disinvestment decisions and investigating patients’ and surgeon’s perspectives on disinvestment processes.

Chapter 3 Understanding the causes of national variation in hospital procedure rates

Introduction

In 2011/12 there were over 17 million inpatient and day case episodes in the English NHS,26 costing the tax payer £22.5B. 27 Just under 60% of these episodes involved some form of procedure or intervention. 26 There have been substantial increases in both the number of episodes (92% increase) and the number of episodes involving a procedure (68% increase) since 2001/2. 26 These trends have been accompanied by concerns that some inpatient admissions and procedures are inappropriate or avoidable. 28,29

Current disinvestment initiatives at the national level

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence was established to provide ‘guidance on the use of new and existing medicines, treatments and procedures’ (emphasis added). 30 In fact, the first technology appraisal published by NICE, on wisdom teeth removal, concluded with a disinvestment message that ‘The practice of prophylactic removal of pathology-free impacted third molars should be discontinued in the NHS’. 31 However, the focus of NICE technology appraisals quickly shifted away from reassessment of existing medical technologies towards appraisals of new interventions, particularly new and expensive pharmaceuticals. By 2006, NICE had published 113 technology appraisals, of which only two (wisdom teeth extraction and electroconvulsive therapy) targeted existing technology rather than innovations.

In 2008, NICE was strongly criticised by the House of Commons Health Committee, which recommended ‘that more be done to encourage disinvestment. No evaluation of older, possibly cost ineffective therapies has taken place to date; . . . it is not acceptable that NICE continues to ignore this recommendation’. 32 Since then, NICE has developed numerous tools to help the NHS respond to efficiency challenges. These include the ‘Cost saving guidance’ and ‘Spending to save’ initiatives, which identify investments in, for instance, optimal prescribing of drugs for hypertension, which are expected to save money through preventing subsequent events (e.g. heart attacks and strokes) and therefore GP and hospital visits. NICE has also developed a number of commissioning guides (e.g. surgical management of otitis media in children) to help PCTs/CCGs commission local services in line with best evidence on clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness outlined in NICE clinical guidelines. Of most relevance to disinvestment from existing procedures, NICE has developed a database of more than 850 ‘do not do’ recommendations since 2007. 33 Drawn predominantly from NICE clinical guidelines, technology appraisals and interventional procedures guidance, these recommendations aim to stop premature diffusion or achieve disinvestment from procedures which are not supported by the evidence (e.g. ‘scleral expansion surgery for presbyopia should not be used’). 33 However, these recommendations are derived ad hoc, NICE does not have a formal HTR process for judging the cost-effectiveness of existing medical procedures, analogous to the technology appraisals process for new pharmaceuticals. NICE has tried to launch a more formal HTR programme in 2006 to ‘reduce spending on [existing] treatments that do not improve patient care’. However, this programme faced immediate difficulties, as, ‘in conversations with its stakeholders, NICE has received enthusiastic backing for the idea of appraising existing technologies to seek opportunities for disinvestment; but, when followed by requests for specific suggestions, the subsequent silence has been striking’ (p. 162). 34

The current economic downturn has reignited international interest in how publicly funded health services might manage disinvestment from health care that no longer represents, or perhaps never represented, value for money. 12,35–39 Many countries have emulated the NICE process for evaluating new technologies to ensure that they are safe, clinically effective and cost-effective before diffusion. However, most are struggling to develop any structured process for identifying medical technologies which might be overutilised in patient groups where they offer little benefit. Leggett et al. 14,40 conducted a survey of international HTR initiatives to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of existing non-drug technologies. They concluded that HTR was in its infancy and, although HTRs were being conducted in a few nations, there was no standardised approach.

The HTR process involves the identification and prioritisation of potential candidates for reassessment and potentially disinvestment, a fair and transparent HTR of the evidence that has accumulated over years of use, and robust systems for implementing decisions and monitoring compliance. 14 The process faces challenges at every stage. 15 Unlike innovation, there is rarely a commercial, professional or patient group lobbying for existing practices to be re-evaluated with a view to disinvestment. In fact, hospitals and clinicians often have a vested interest in maintaining the status quo to protect income or prestige. 41 Therefore, the first barrier is to identify technologies where there is clinical uncertainty about appropriate use.

One promising approach is to monitor variations in clinical practice in routinely collected data to help identify where best practice is uncertain and overtreatment may be prevalent. 21,41 Wennberg’s professional uncertainty hypothesis19 postulates that many geographical variations in care are unwarranted and occur because of differences among doctors in their diagnostic thresholds or in their belief in the value of the procedure, rather than any differences in clinical need. This idea has historical precedent. Glover demonstrated 20-fold variations in tonsillectomy utilisation among English boroughs in 1938. 18 In the same decade, a study in the USA (published in the 1940s) found minimal agreement among physicians in judging which children would benefit from tonsillectomy. 42 These initial doubts belatedly led to dramatic declines in tonsillectomy rates on both sides of the Atlantic43 and RCTs to better define the small subgroup of children where tonsillectomy is effective. 44

The interpretation of observed geographical variation in routine data is not straightforward. 21 Variance may be spurious, merely a reflection of random fluctuations in care or inconsistent coding. Furthermore, variation in care may be warranted, caused by differences in clinical need or patient preferences. Despite these considerations, the large and persistent variation brought to light by the publication of documents such as The NHS Atlas of Variation in Healthcare45 and international equivalents46 suggests that some variation reflects more than simple differences in population health need. It is possible that high variation in practice may help policy-makers identify existing health care where HTR is needed and partial disinvestment might be appropriate. In exploring this issue further, we need a better understanding of the causes of observed variation in health care. In this chapter we use routinely collected data on day case and inpatient procedures performed by the NHS in England to quantify the extent of variation across all commonly performed procedures and explore potential causes of ‘high-variance’ procedures.

Methods

Identifying and categorising procedures

We used the HES26 admitted patient care data set to identify inpatient procedures. HES is a routinely collected data set that records all episodes of care provided to all patients (NHS funded and privately insured) admitted, as a day case or inpatient, to NHS hospitals and NHS-funded patients treated in independent sector hospitals. We extracted pseudoanonymised individual episode records on all admissions contained in the HES data set between the financial years 2007/8 and 2011/12. Up to 24 clinical procedures per episode may be recorded using Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) (fourth revision) codes. OPCS codes are hierarchical and include more than 9000 four-character codes defining procedures at the finest level of detail. However, most of these codes are used infrequently, so we elected to define procedures using the three-character OPCS codes (n ≈ 1500).

We focused on the most clinically and economically consequential procedures by including only the 264 most widely used procedure codes, which accounted for over 90% of all inpatient procedures, in our analysis. OPCS codes include some very minor procedures (e.g. blood withdrawal) and diagnostic procedures (e.g. diagnostic echocardiography), which were predominantly not the primary reason for hospital admission. We decided to focus on more major therapeutic procedures, which were thought more likely to be recorded accurately and consistently between hospitals. We excluded diagnostic (n = 53), minor (n =38) and obstetric (n = 5) procedures from our analysis to focus on major therapeutic procedures. We removed a further three procedures because postcode of residence was missing in more than 10% of episodes. We excluded 11 procedures from all analyses because of changes in OPCS procedure codes between years (version 4.4 used in 2007/8 to version 4.6 introduced in 2011/12) which may have led to inconsistent clinical coding. This left 154 therapeutic procedures for analysis. These include procedures that are predominantly elective and those that are more frequently performed as an emergency procedure. A single stay in hospital may comprise more than one episode as patient care is transferred from one consultant to another. Therefore, a hospital stay may contain many procedures, all of which were eligible for inclusion in our analysis. When multiple records of the same procedure were recorded on the same patient with the same admission date, we included only the first record in our analysis in order to avoid the risk of double-counting procedures which were recorded more than once as a result of coding errors. 47

Estimating variation in procedure rates

Geographical variation was measured using PCT boundaries. Until April 2013, PCTs were responsible for commissioning most NHS services for their resident population; they represent geographically contiguous areas of England. In 2007/8 there were 152 (which decreased to 151 in April 2010) PCTs in England; on average each PCT was responsible for approximately 340,000 residents. Since April 2013, PCTs have been replaced by 212 CCGs.

We denote the observed number of utilisations of procedure j on residents of PCT i by ‘Observedij’ (i = 1, . . . , 152 PCTs; j = 1, . . . , 154 procedures). We used a two-stage approach to quantifying variation. In stage 1 we calculated expected numbers of procedure utilisations for procedure j on residents of PCT i based on demographic factors and factors that might affect clinical need for NHS care, denoted by ‘Expectedij’. These expected numbers were calculated using indirect standardisation48 for age and sex (using quinary age groups and gender for England as the standard population49), to account for differences in the size and the age/sex composition of PCT populations. Then Poisson regression was used to further adjust rates for the ethnic50 and socioeconomic composition51 of PCTs, the prevalence of chronic diseases (asthma, atrial fibrillation, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, dementia, diabetes, hypertension, stroke, all-cause cancer),52 and markers of unhealthy lifestyle (binge drinking, smoking and obesity). 52 We also adjusted for the prevalence of private medical care, which might substitute for NHS treatment, based on the number of private hospital beds within a 30-mile radius of the PCT headquarters,53 using mean imputation for the 29% of private hospitals where bed numbers were not recorded.

In stage 2 of our statistical analysis we quantified the residual inter-PCT variability in utilisation rates by using the expected counts as a covariate in random effects Poisson regression models:

The crucial parameter is σ2j, which quantifies the remaining variability in utilisation of procedure j across PCTs, having adjusted for all factors reflected in the expected counts. Importantly, focusing attention on the inter-PCT standard deviation (SD) from a random effects model (or equivalently on a function of it, as we describe in the next paragraph) also appropriately adjusts for chance variability. In what follows, we refer to this parameter as the inter-PCT SD.

Models were fitted within a Bayesian framework using the WinBUGS software (version 1.4.3, MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK),54 which allowed us to estimate the probability of this unexplained variation in utilisation of each procedure exceeding a given threshold. We estimated the probability that a procedure was ‘very highly’ or ‘highly’ variable, which we arbitrarily defined as an inter-PCT SD greater than three or two times the median variability across all therapeutic procedures respectively. To improve interpretability, we transformed each model-based inter-PCT SD estimate into a ‘utilisation ratio’ (UR), which we defined as the rate in a high-utilisation PCT (at the 90th centile of the random effects distribution) divided by the rate in a low-utilisation PCT (at the 10th centile).

Estimating temporal changes in geographical variation and exploring factors associated with high variation

If variation is a proxy for clinical uncertainty about the value of a procedure, then temporal growth in variation could be an indicator of procedures where evidence is evolving, creating either local enthusiasm or disillusionment about the value of a procedure. In order to explore this possibility, for each procedure we performed a linear regression of the log of the estimated inter-PCT SDs on year, to quantify the change in inter-PCT variation between 2007/8 and 2011/12. The log transformation was applied to the SDs because of the large positive skew in the distribution and unequal variation in the error terms. We also conducted exploratory analyses to examine five factors that might be associated with high geographical variation in hospital procedure rates: (1) coding uncertainty; (2) variation in the quality of community care; (3) uncertainty about the appropriate setting for the procedure; (4) urgency and invasiveness of the procedure; and (5) evolving or uncertain evidence. The eight variables selected as potential proxies for these five factors, their definition and our rationale for their potential association with high inter-PCT variation are documented in Tables 1 and 2. We conducted a multivariable linear regression of the log of the inter-PCT SD for each of the 154 procedures on these eight variables.

| Variables used in the multivariate regression | Variable definition | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Coding uncertainty | ||

| Miscellaneous procedure code | Catch-all OPCS codes (e.g. other operations on the mouth) | Variation may be higher among miscellaneous procedure codes because of coder uncertainty about when to use them |

| Variation in community care | ||

| Procedure often performed in elderly patients | % of patients receiving the procedure who are ≥ 70 years old | Variation may be higher among procedures commonly used in elderly or chronically ill patients because of variations in community care that might have prevented the need for the procedure |

| Procedure often performed in patients with chronic disease | % of patients receiving the procedure who have chronic disease (see Table 2) recorded in the episode record | |

| Uncertainty about the setting of care | ||

| Procedures that could be performed in the outpatient setting | Procedures where ≥ 10% are performed in the hospital outpatient departmenta | Variation in admitted patient procedure rates may be high if some hospitals have switched to providing the procedure in an outpatient setting (and therefore it is not included in the admitted patient care data set that we analyse) |

| Urgency and invasiveness of the procedure | ||

| Less invasive procedures | Median length of stay for episodes where the procedure was performed | Variation may be higher in less invasive procedures, where there is less potential harm for the patient and therefore may be more leeway for clinical discretion about the need for the procedure |

| Emergency procedures | % of patients receiving the procedure classed as emergency rather than admitted from a waiting list | Variation may be lower in predominantly emergency procedures, where there may be less leeway for clinical discretion about the need for the procedure |

| Evolving or uncertain evidence | ||

| Procedures with rapidly increasing or decline utilisation | Procedures with ≥ 3% or ≤ –3% growth since 2007/8 | Variation may be higher in procedures with rapid diffusion or discontinuance, where uncertainty about appropriate use exists |

| Procedures with one or more substitute procedure codes | Procedure dyads (or triads, etc.) within the same OPCS chapter that have an intra-PCT correlation of ≤ –0.15b | Variation may be higher if two (or more) procedure codes are substitutes for each other (e.g. hip replacement with cement, hip replacement without cement) and there is uncertainty about which procedure is preferable |

| Condition | ICD-10 codes included (three character) |

|---|---|

| Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome/human immunodeficiency virus | B20, B21, B22, B23, B24 |

| Arthritis | M0X, MX1, M20, M21, M22, M23, M24, M25 |

| Asthma | J45 |

| Cancer | CXX |

| Cerebral infarction | I6X |

| Cerebrovascular disease | I6X |

| Chronic liver disease | K70, K73, K74 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | J40, J41, J42, J43, J44, J47 |

| Diabetes | E10, E11, E12, E13, E14 |

| Heart failure | I50 |

| Ischaemic heart disease | I20, I21, I22, I23, I24, I25 |

Results

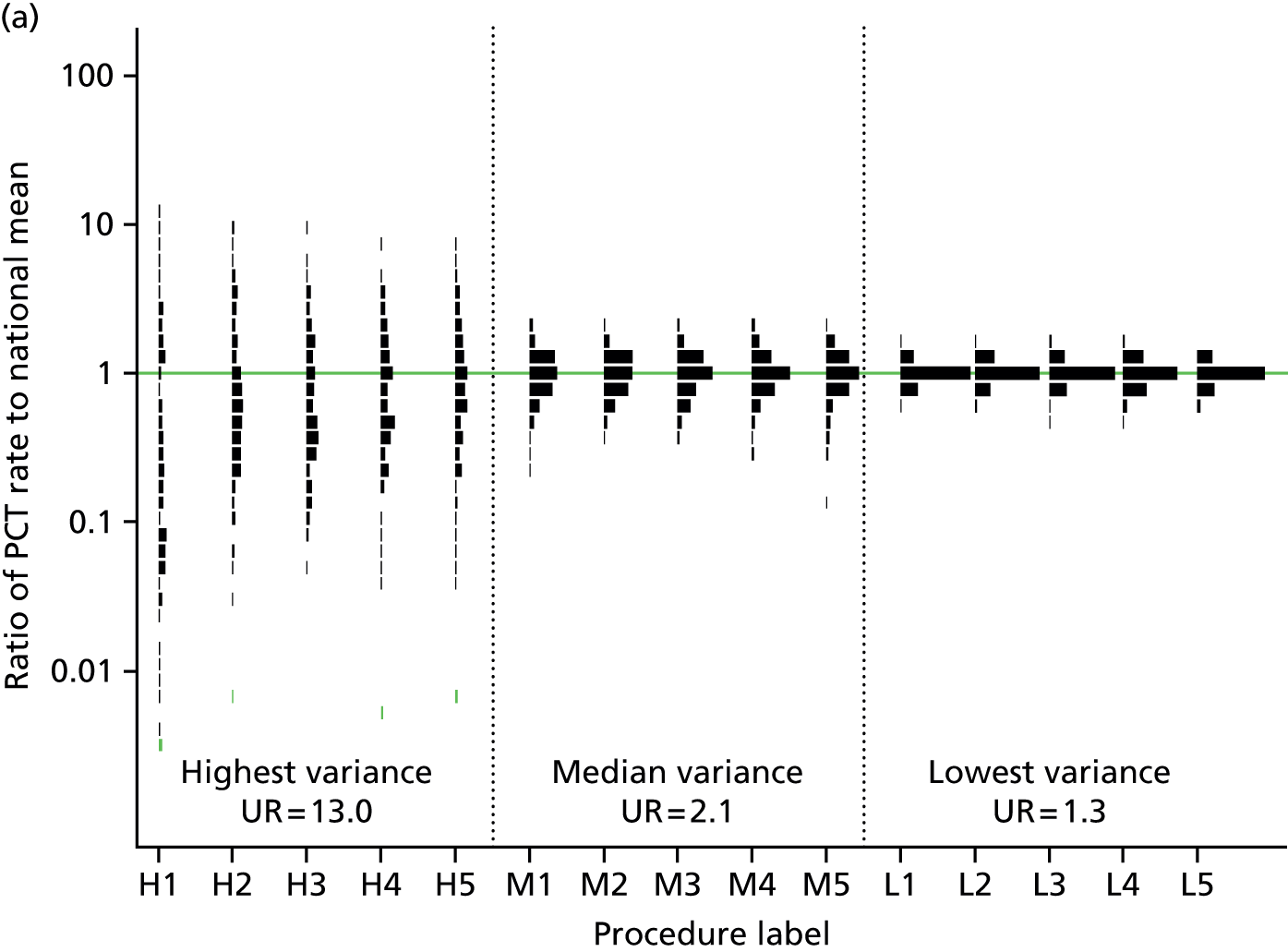

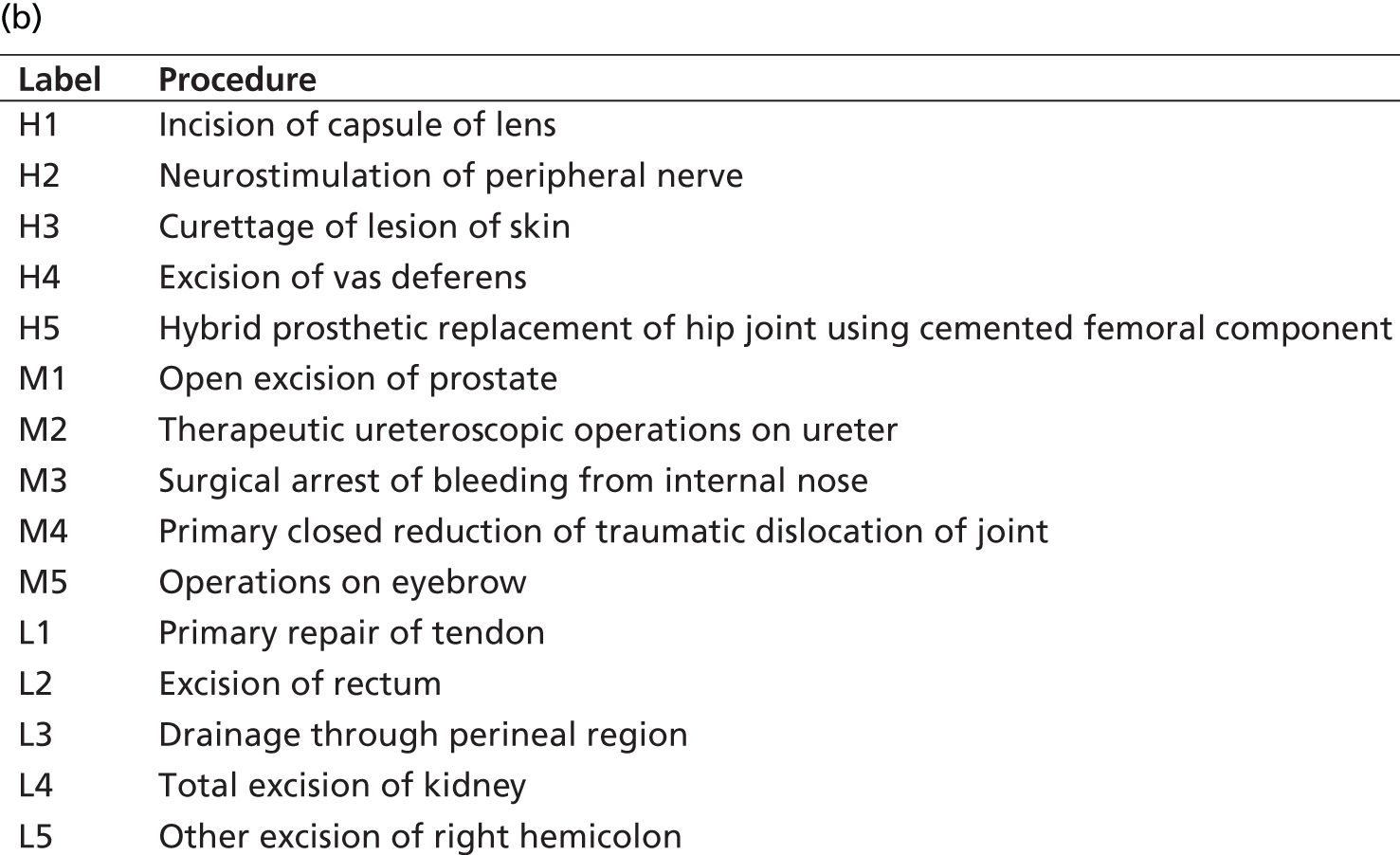

During the analysis period there were 17.8 million episodes which contained one or more of the 154 therapeutic procedures (for a total of 20.6 million procedures) included in our analysis. In 2011/12 this ranged from prosthesis of lens (1.6 million procedures) to other total prosthetic replacement of knee joint (5560 procedures). The degree of inter-PCT variation in procedure rates differed vastly from procedure to procedure. The median estimated UR among the five procedures with the highest inter-PCT variance was 13.0, indicating that the procedure rate was 13 times higher in the PCT at the 90th percentile than the PCT at the 10th percentile (Figure 2). In contrast the median estimated UR among the five procedures with least variation was 1.3. High variation is not solely driven by a small number of PCT outliers but, instead, reflects a spread across all PCTs.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of high, median and low variance procedures in 2011/12. (a) Graph displaying the median UR within the group of five procedures with the highest, median and lowest intra-PCT SD; (b) key of procedure label.

Further analysis of the 20 procedures with the highest estimated inter-PCT variability (Table 3) demonstrates that they represent a range of clinical specialties and include both relatively uncommon (e.g. denervation of spinal facet joint) and common (e.g. destruction of lesion of retina) and both minor (e.g. excision of vas deferens) and major (e.g. hip replacement) procedures. Many of the procedures with highest variance were those which could be performed in the outpatient setting (e.g. incision of capsule of lens) or procedures which were potential substitutes for one another (e.g. transluminal versus combined varicose vein procedures). A full listing of all procedures is provided in Appendix 1.

| Procedure | Number of procedures | Inter-PCT SD (95% CI) | Inter-PCT SD, age/sex (95% CI) | UR (95% CI) | Probability ‘highly variable’ | Probability ‘very highly variable’ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incision of capsule of lens | 15,131 | 1.8 (1.6 to 2.0) | 1.9 (1.7 to 2.1) | 109.1 (59.8 to 196.1) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Neurostimulation of peripheral nerve | 7983 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 16.7 (12.0 to 23.2) | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Curettage of lesion of skin | 13,046 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 13.0 (9.6 to 17.7) | 1.00 | 0.99 |

| Excision of vas deferens | 10,192 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.3) | 12.1 (8.9 to 16.7) | 1.00 | 0.96 |

| Hybrid prosthetic replacement of hip joint using cemented femoral component | 7882 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 1.2 (1.0 to 1.3) | 11.3 (8.3 to 15.5) | 1.00 | 0.91 |

| Transluminal operations on varicose vein of leg | 10,262 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.4) | 10.7 (7.9 to 14.7) | 1.00 | 0.82 |

| Prosthetic replacement of head of femur not using cement | 6287 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 9.7 (7.2 to 13.3) | 1.00 | 0.61 |

| Denervation of spinal facet joint of vertebra | 10,168 | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 9.4 (7.2 to 12.6) | 1.00 | 0.56 |

| Restoration of tooth | 14,720 | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) | 8.9 (6.9 to 11.8) | 1.00 | 0.39 |

| Destruction of lesion of retina | 23,007 | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.0) | 8.1 (6.4 to 10.5) | 1.00 | 0.17 |

| Other vaginal operations on uterus | 13,256 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 0.9 (0.8 to 1.1) | 6.6 (5.2 to 8.4) | 1.00 | 0.01 |

| Combined operations on varicose vein of leg | 10,269 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 0.8 (0.7 to 1.0) | 6.2 (5.0 to 7.8) | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Operations on vitreous body | 101,606 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9) | 5.8 (4.8 to 7.2) | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Excision of cervix uteri | 15,886 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.7) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 5.6 (4.6 to 6.9) | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Intramuscular injection | 28,293 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.7) | 0.7 (0.7 to 0.8) | 5.7 (4.7 to 6.9) | 1.00 | 0.00 |

| Other operations on bladder | 64,605 | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.7) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 5.3 (4.4 to 6.5) | 0.98 | 0.00 |

| Other excision of appendix | 14,360 | 0.6 (0.6 to 0.7) | 0.6 (0.6 to 0.7) | 5.1 (4.2 to 6.4) | 0.94 | 0.00 |

| Other operations on urethra | 9672 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 5.0 (4.2 to 6.1) | 0.91 | 0.00 |

| Destruction of haemorrhoid | 27,387 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 4.7 (4.0 to 5.8) | 0.79 | 0.00 |

| Other operations on sympathetic nerve | 6978 | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.7) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | 4.8 (3.9 to 5.9) | 0.79 | 0.00 |

Six procedures (incision of capsule of lens, neurostimulation of peripheral nerve, curettage of skin lesion, excision of vas deferens, hybrid hip replacement and transluminal operations on varicose veins) had estimated URs in excess of 10. These procedures all have a probability of 1 of meeting our definition of a ‘high variance’ procedure, and a probability of at least 0.82 of being ‘very high variance’. Sixteen procedures had a greater than 95% probability of being ‘high variance’ procedures according to our definition (see Appendix 1). Estimates of procedure variation were similar between the age- and sex-adjusted model and the model adjusted for all markers of clinical need (see Table 3).

Among all 154 procedures included in the variation trend analysis, the mean annual change in the variation between 2007/8 and 2011/12 was –2.3% [95% confidential interval (CI) –3.7% to –1.8%], indicating that variation in utilisation of procedures decreased on average during the study period. Substantial increases (Table 4) and decreases (Table 5) in geographical variation were observed for some procedures. Procedures with increasing geographical variability included those where utilisation was generally declining (e.g. combined operations on varicose vein) and those with more stable (e.g. hip replacement using cement) and increasing (operations on vitreous body) trends in use.

| Procedure | Number of procedures | Inter-PCT SD | Estimated annual % inter-PCT SD increase (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/8 | 2009/10 | 2011/12 | 2007/8 | 2009/10 | 2011/12 | ||

| Operations on vitreous body | 35,076 | 69,058 | 101,606 | 0.333 | 0.619 | 0.693 | 14.2 (8.5 to 19.5) |

| Combined operations on varicose vein of leg | 20,081 | 15,486 | 10,269 | 0.567 | 0.592 | 0.699 | 4.2 (0.1 to 8.0) |

| Repair of recurrent inguinal hernia | 6066 | 5893 | 6221 | 0.128 | 0.165 | 0.176 | 3.5 (–2.0 to 8.9) |

| Combined operations on muscles of eye | 6834 | 6721 | 7082 | 0.205 | 0.244 | 0.270 | 3.4 (–1.6 to 7.6) |

| Other total prosthetic replacement of hip joint | 10,633 | 10,492 | 9830 | 0.349 | 0.406 | 0.416 | 3.3 (–0.3 to 7.0) |

| Drainage through perineal region | 12,046 | 12,431 | 12,656 | 0.044 | 0.050 | 0.098 | 3.1 (–2.2 to 9.0) |

| Drainage of middle ear | 45,760 | 45,448 | 40,680 | 0.203 | 0.188 | 0.244 | 2.7 (–1.5 to 6.6) |

| Total prosthetic replacement of hip joint using cement | 33,182 | 29,167 | 32,020 | 0.370 | 0.441 | 0.422 | 1.9 (–3.8 to 5.5) |

| Release of entrapment of peripheral nerve at wrist | 56,037 | 58,150 | 54,093 | 0.249 | 0.223 | 0.298 | 1.7 (–1.8 to 4.8) |

| Primary repair of umbilical hernia | 21,547 | 22,129 | 24,529 | 0.131 | 0.116 | 0.149 | 1.7 (–3.4 to 7.5) |

| Procedure | Number of procedures | Inter-PCT SD | Estimated annual % inter-PCT SD increase (95% CI) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/8 | 2009/10 | 2011/12 | 2007/8 | 2009/10 | 2011/12 | ||

| Clearance of external auditory canal | 8116 | 6787 | 7406 | 0.732 | 0.365 | 0.379 | –14.6 (–17.6 to –10.7) |

| Endoscopic operations to increase capacity of bladder | 3472 | 4629 | 10,946 | 0.729 | 0.597 | 0.463 | –9.8 (–13.4 to –5.8) |

| Debridement and irrigation of joint | 10,999 | 16,141 | 16,835 | 0.545 | 0.493 | 0.374 | –8.8 (–12.5 to –5.2) |

| Transluminal operations on varicose vein of leg | 4609 | 10,347 | 10,262 | 1.553 | 1.147 | 0.889 | –8.7 (–12.2 to –3.8) |

| Intramuscular injection | 28,695 | 26,860 | 28,293 | 1.034 | 0.919 | 0.664 | –8.4 (–12.1 to –5.3) |

| Orthodontic operations | 7518 | 8020 | 8649 | 0.343 | 0.212 | 0.228 | –8.4 (–12.6 to –4.0) |

| Cardioverter defibrillator introduced through the vein | 4621 | 6933 | 8443 | 0.332 | 0.254 | 0.201 | –8.0 (–13.0 to –3.1) |

| Percutaneous transluminal balloon angioplasty and insertion of stent into coronary artery | 53,173 | 60,340 | 65,673 | 0.237 | 0.184 | 0.173 | –7.8 (–11.2 to –4.7) |

| Extracapsular extraction of lens | 305,669 | 330,161 | 324,345 | 0.207 | 0.135 | 0.153 | –7.1 (–10.3 to –3.8) |

| Excision of lung | 4505 | 5621 | 6815 | 0.258 | 0.201 | 0.176 | –7.1 (–11.3 to –2.6) |

The multivariable analysis (Table 6) provided strong evidence of a U-shaped relationship between procedure diffusion/discontinuance and geographical variation in use. Variation in PCT procedure rates was high where the diffusion or discontinuance of a procedure was most rapidly evolving. Variation in PCT procedure rates was also higher for procedures where alternative procedures were available. We also found evidence that variation was higher for procedures which were predominantly performed in elderly patients, had a length of stay less than 1 day, were more likely to be elective and could be performed in an outpatient setting.

| Variable | Average ratio of inter-PCT SD (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Miscellaneous code | ||

| No | 1.000 | |

| Yes | 1.006 (0.891 to 1.137) | 0.443 |

| Elderly patientsa | ||

| < 50% | 1.000 | |

| > 50% | 1.320 (1.016 to 1.586) | 0.012 |

| Patients with chronic disease | 1.000 (0.998 to 1.002) | 0.500 |

| Outpatient procedureb | ||

| No | 1.000 | |

| Yes | 1.454 (1.260 to 1.645) | < 0.001 |

| Median length of stay | ||

| ≥ 1 day | 1.000 | |

| < 1 day | 1.430 (1.247 to 1.595) | < 0.001 |

| % elective admission | 1.002 (1.000 to 1.004) | 0.008 |

| Relative increase since 2007 | ||

| < –3% decrease | 1.570 (1.125 to 2.085) | < 0.001 |

| –3% to 3% increase | 1.000 | |

| > 3% increase | 1.390 (1.274 to 1.499) | < 0.001 |

| Substitute | ||

| No | 1.000 | |

| Yes | 1.881 (1.534 to 2.390) | < 0.001 |

Discussion

Main results

There is a high degree of geographical variation in procedure rates for many commonly performed procedures that cannot be explained by proxies of clinical need. For six procedures, rates in PCTs at the upper and lower deciles still differed by more than 10-fold, after adjustments for chance variation and proxies of clinical need. Variation was most pronounced in procedures where utilisation was increasing or decreasing most rapidly and those where a substitute procedure was available. Policy-makers could use geographical variation as a starting point to identify procedures where HTR or new RCTs might be needed to inform investment and disinvestment decisions.

Strength and weaknesses

The main strengths of this study lie in the large sample, novelty of the research question and breadth of procedures considered. Our model-based approach accounts appropriately for statistical chance, and the UR provides a simple summary measure of disparity between PCTs. In order to make valid comparisons of procedure rates between PCTs we have adjusted for a number of indicators of clinical need. However, bias may still occur because of unmeasured aspects of clinical need or if the accuracy of demographic and morbidity measures varies by PCT. In particular, local variations in the quality of community and primary health services could plausibly cause variation in procedure rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions. 28 Future work could use proxies for ambulatory care quality such as community health service expenditure or the primary care Quality and Outcomes Framework to assess their association with procedure rates. We used the number of private hospital beds as a proxy measure for the number of private hospital procedures which may be inappropriate, particularly for some conditions (e.g. excision of appendix), where private treatment is less likely. It is also possible that some of the residual variation in procedure rates observed in our study actually reflects differences in local PCT criteria for allowing access to procedures paid for by the NHS. We do not have the data needed to test this hypothesis, but, as PCTs typically did not have access criteria for many of the procedures included in our study, we do not think it would be a predominant factor. Arguably, such PCT criteria ‘lotteries’ still reflect uncertainty about the value of care that might be reduced by better evidence informing more uniform criteria. PCTs have now been superseded by CCGs. We cannot use the CCG as the unit of analysis because demographic and morbidity statistics are not currently available for CCGs. Although it is unlikely that boundary changes will have any immediate impact on geographical variation of procedure rates, new CCG approaches to commissioning will have an impact in the medium term. 9

Our analyses are reliant on the OPCS coding framework, which was not developed for this purpose. The OPCS codes are reviewed annually, but contain anomalies whereby some substitute procedures can be distinguished by the primary OPCS three-character code, for example cemented versus uncemented joint replacement, whereas others cannot, for example open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel decompression. Furthermore, some OPCS procedure codes span more than one diverse clinical group, for example adenoidectomy in children with chronic tonsillitis or sleep apnoea. Methodological research is needed to create an OPCS/International Classification of Diseases (ICD) diagnosis code algorithm that would define a clinically nuanced matrix of distinct procedure/diagnosis group pairings. As both coding frameworks contain thousands of codes, such research would be time-consuming and was beyond the scope of this study. It is important to recognise that different levels of procedure code aggregation will be useful in different circumstances. By using three-character OPCS codes we were able to identify high inter-PCT variation in how varicose vein procedures are conducted (e.g. transluminal or combined), but could not explore variation between PCTs in whether or not to do perform varicose vein procedures.

We have restricted our analysis to major therapeutic procedures to reduce the likelihood of inconsistent coding of minor medical and diagnostic procedures affecting our results. However, inaccurate coding of procedures is still a concern which may contribute to high variation. As hospitals have moved to ‘payment by results’ there is a stronger incentive for complete coding of procedures, but also a possibility of up-coding to increase revenues. 56 We have focused on inpatient and day case procedures because outpatient procedures and those performed in other settings tend to be poorly recorded in routine data. An ideal analysis would include procedures across all settings to provide a more comprehensive picture.

Comparison with other studies

Geographical variation in hospital procedure rates has long been documented in the UK21,22,57 and internationally. 58,59 Indeed, its persistence between countries and through time may give the impression that it is an intractable issue. However, practice variation can be reduced;60 in Scotland, a 50% decline in appendectomy rates between 1973 and 1993 was accompanied by increasing uniformity of procedure rates between health boards. 24 Our findings demonstrate that there is now relative uniformity in tonsillectomy rates between PCTs.

There has been relatively little work exploring the potential causes of geographical variation in health care. Westert and Groenewegen23 and Weinstein et al. 61 describe how an individual clinician’s conservative or liberal use of a procedure might be transferred to colleagues, creating local signatures of procedure use that persist over time. They also stress that the development of these practice patterns may be intensified by fee for service clinician and hospital payments. Birkmeyer et al. 58 and others have demonstrated that geographical variation was higher in discretionary procedures, such as back surgery, where indications are fuzzy and the appropriateness is debated than for procedures, such as hip fracture repair, where the diagnosis and the need for surgery is clear cut. Our analysis also found that procedures that were predominantly performed electively had higher variation.

Unlike most other studies on variation, we did not begin with a list of procedures where we suspected clinical uncertainty existed. Instead, we selected all commonly performed NHS procedures and allowed the data to identify extreme variation. Many of the usual suspects for clinical uncertainty did not appear at the top of our list (e.g. excision of tonsil had a low estimated UR of 1.5; excision of lumbar intervertebral disc had a modest estimated UR of 2.5), underlining the potential of this approach to identify emerging areas of clinical uncertainty.

Implications

Our finding that variation is high in rapidly diffusing or declining procedures, and procedures where a substitute is available, supports the theory that variation is a marker for clinical uncertainty. This suggests that regular monitoring of geographical variation might help NHS regulators and commissioners identify procedures ripe for HTR. However, the appropriate HTR question may take many forms. For some of the ‘high variance’ procedures identified, the question is likely to be ‘which of two procedures (e.g. traditional versus various endovenous varicose vein procedures)62 is more cost-effective and for which patient subgroups)?’63 In other cases, the question may be ‘is this procedure (e.g. radiofrequency denervation of spinal facet joints) more cost-effective than conservative care and if so in which patients?’64 Answering these questions and disseminating the findings is vital if patients across the NHS are to receive best care. However, it is important to realise that, while this should lead to disinvestment from procedures that are not being used cost-effectively, it will not necessarily save the NHS money if they are replaced by more effective but more expensive procedures.

We can only speculate on whether or not our data contain a modern-day equivalent of tonsillectomy, where the clinical indications will narrow drastically in the future. The rise of evidence-based medicine should reduce this risk, but large high-quality RCTs of surgical procedures are still not commonplace and many longstanding procedures have never been fully evaluated in rigorous RCTs. 65 Lack of evidence about which clinical subgroups benefit from a procedure and which do not is the major challenge for commissioners and clinicians. 15 A natural response from commissioners with high local procedure rates is to try to enforce convention through criteria-based access (CBA) and referral management, and many new CCGs have adopted this approach. 9 However, the convention might be wrong66,67 and a more far-sighted response would be for research funders to use geographical variation to prioritise procedures where primary research assessing value in specific clinical subgroups is most needed.

It is also likely that the approach outlined in this chapter, being reliant on coding accuracy, will identify some red herrings. In early iterations of our analysis, in vitro fertilisation (IVF) procedures had extremely high apparent inter-PCT variation with a substantial number of PCTs documenting zero procedures. Media reports have highlighted variations in access to IVF across England;68 however, on closer inspection of the data, we felt that the zero rates in some PCTs were in fact more probably due to variable practice in recording the postcode of patient residence for potentially sensitive fertility treatments. 69

Unanswered questions and future research

Similar studies of unplanned admissions,70 diagnostic tests,71 referral, prescription rates72 and other process measures45 will be useful in identifying other aspects of health care where uncertainty manifests through variation. We chose hospital procedures because there are a nationwide routine data set and a financial incentive for hospitals to document procedures. The integration of routine primary and secondary care data sets has the potential to provide much richer analyses of the intersectorial causes of variation. However, such analyses are dependent on complete and accurate coding and may be jeopardised by any future fragmentation of data sets between NHS and independent sector providers. Additional qualitative research in areas with extreme procedure rates would help us gain a better understanding of the causes of observed variations.

Conclusions

The widespread geographical variations in hospital procedure rates in England are not solely due to variance in clinical need and are likely to reflect clinical discretion regarding appropriate procedure use and setting (e.g. day case or outpatient). NICE and NHS England might, with appropriate caution, use geographical variation to identify candidates for HTR and potential disinvestment. These variations should also be used to set a research agenda for investment in RCTs in surgery.

Chapter 4 Benchmarking for local commissioners to identify potential candidates for disinvestment

Introduction

After a sustained period of growth, health-care spending in many high-income countries has stagnated since the economic crisis of 2007. The 5% annual increases in real NHS expenditure in England that existed before the crisis have now disappeared. In the meantime, chronic diseases in ageing populations with high expectations of new health technologies continue to pressurise these constrained budgets. 2

Around £65B (70%) of NHS funding is allocated to local commissioners, formerly called PCTs but recently reconfigured and named CCGs. 8 CCGs are responsible for planning, commissioning and monitoring services such as elective and emergency hospital care and community and mental health services. CCGs must pay for new technologies mandated by NICE and find the necessary savings from elsewhere in their budgets. Since the formation of the NHS internal market in the early 1990s, local commissioners have been challenged with translating economic evidence into cost-effective pathways of health-care provision by hospitals, GPs and community health services. A survey of NHS decision-makers conducted by Drummond et al. 73 in the mid-1990s revealed that key barriers to greater use of economic evaluation included mistrust of the validity of economic evaluations and an inability to move resources from secondary to primary care to achieve efficiencies. 73 A more recent systematic review of local commissioners’ decision-making echoed some of these findings and reported a number of institutional, political, cultural and methodological obstacles to greater use of evidence on cost-effectiveness. 74 Annual budgets allocated in silos make it difficult for commissioners to reallocate resources from secondary to primary care or to invest this year in the expectation of savings in future years, even when the economic case for reallocation is clear cut. National political objectives, for example waiting list targets, can deflect attention from achieving cost-effective care for the local population. In addition, lack of high-quality evidence on cost-effectiveness and lack of time to consider the available evidence have both been cited as barriers to more efficient local health-care commissioning. 74

Primary care doctors (GPs) play a key role in the new CCGs; one goal of the reconfiguration is to give more budgetary responsibility to front-line clinicians to encourage them to redesign health-care provision more efficiently in their locality. However, identifying opportunities to save the NHS money is challenging, particularly at the local level. It is very difficult to investigate or challenge historical levels of provision for the vast majority of services commissioned. Furthermore, since local commissioners purchase the majority of secondary care services from a very small number hospital trusts, maintaining positive and balanced working relationships is vital. Collaborative approaches to disinvestment in some services to provide an optimal mix of health care for the local population can easily degenerate into mutual mistrust, with hospital trust representatives suspecting commissioners of unthinking cost cutting and commissioners presuming that hospital trusts primarily want to protect income.

There are a variety of options available to local commissioners who wish to regulate procedure rates in line with the best available evidence. Referral management strategies that target the transfer of care from GP to specialist include guidelines, structured referral sheets, GP financial incentives, peer review and feedback, and referral management centres. 75 Other strategies aim to direct surgeon decision-making by introducing CBA, also known as threshold policies, for surgical care, which may be reinforced by retrospective audit or a prospective prior approval process. These criteria aim to target medical procedures on the patient subgroups most likely to benefit from them, based on current evidence. At the extreme, procedures deemed to be of very little or no health benefit can be designated as ‘not routinely funded’. Contracting or putting contracts out to tender can also be used to provide financial incentives to hospitals and surgeons to modify their practice. Other approaches focus on increasing the patient’s role in the process through shared decision-making and decision aids. By informing patients of the potential benefits and harms of surgery, these tools could redress the information asymmetry between surgeon and patient. 76

Most local commissioning groups have developed some form of regulation process for procedures commonly viewed as relatively ineffective or largely cosmetic. 77 However, these ‘usual suspects’ might not be most relevant locally. Instead, benchmarking39 a broad range of local procedure rates against the national norms might provide a more flexible way to identify areas where local service provision is inappropriately high or inefficient. The recent development of the NHS Atlas of Variation in Healthcare45 and similar tools allow commissioners to readily benchmark local health-care provision. However, benchmarking might be counterproductive if the data on which it is based misrepresent actual care patterns, adjustment for clinical need is inadequate or evidence on the appropriate procedure rate is lacking. 67

In this chapter we used routinely collected HES data, adjusting for proxies of clinical need, to identify local variations in 181 procedure rates. In collaboration with two local PCT commissioning groups, we benchmarked local procedure rates against national rates. One case study procedure was selected with each PCT commissioning group and, in the next chapters, we conducted rapid systematic reviews to summarise the evidence on clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness and explore potential reasons for high local use. Our aim is to explore the potential usefulness and pitfalls of using benchmarking and technology assessment to inform local commissioning and potentially disinvestment.

Methods

Benchmarking inter-PCT variation in procedure rates

The methods for identifying inter-PCT variation in procedure rates and adjusting for proxies of clinical need are explained in detail in the previous chapter. However, as the number of procedures, study dates and method for adjusting for private health-care provision are different for the benchmarking work, we briefly recap those methods in this section.

For the benchmarking work, we extracted anonymised individual episode records from HES between 1 April 2007 and 31 March 2010. All interventions and procedures performed during each episode are recorded using OPCS fourth revision codes. OPCS codes include more than 9000 four-character codes defining procedures at the finest level of detail. However, most of these codes are used infrequently, so we categorised procedures using the three-character OPCS codes (n ≈ 1500). We focused on the most clinically and economically consequential procedures by including only the 269 most widely used procedures, which accounted for over 90% of all inpatient procedures. We excluded minor (n = 45) and diagnostic (n = 34) procedures and procedures where codes changed between OPCS version 4.4 (2007/8) and version 4.5 (used since 2009/10), (n = 9). This left 181 major therapeutic procedures for analysis. The number of included procedures differs from Chapter 3, as prior to the analysis in Chapter 3 we tightened our procedure exclusion criteria to focus on major therapeutic procedures and because of coding changes in 2011/12. Up to 24 procedures can be recorded during each episode and a single stay in hospital may comprise more than one episode as patient care is transferred from one consultant to another. All procedures from both admission and subsequent episodes were eligible for inclusion in our analysis.

Crude annual procedure rates (per 100,000) were calculated by dividing the number of procedures undertaken on PCT residents by the total PCT population. 49 We counted the observed number of each procedure within every PCT, ‘Observedij’, and estimated the expected number, ‘Expectedij’, indirectly standardising48 for age and sex and accounting for differences in PCT ethnic and socioeconomic composition and the prevalence of chronic disease and unhealthy lifestyle as described in the previous chapter. However, in the local benchmarking work we used data on the regional prevalence of private medical insurance, which might substitute for NHS treatment, from the British Household Panel Survey to adjust for private health-care provision. 78 The observed number of procedures within each PCT, ‘Observedij’, was divided by the expected, ‘Expectedij’, and multiplied by the national rate of procedure use (i.e. rate in the standard population) to yield adjusted PCT rates.

Benchmarking

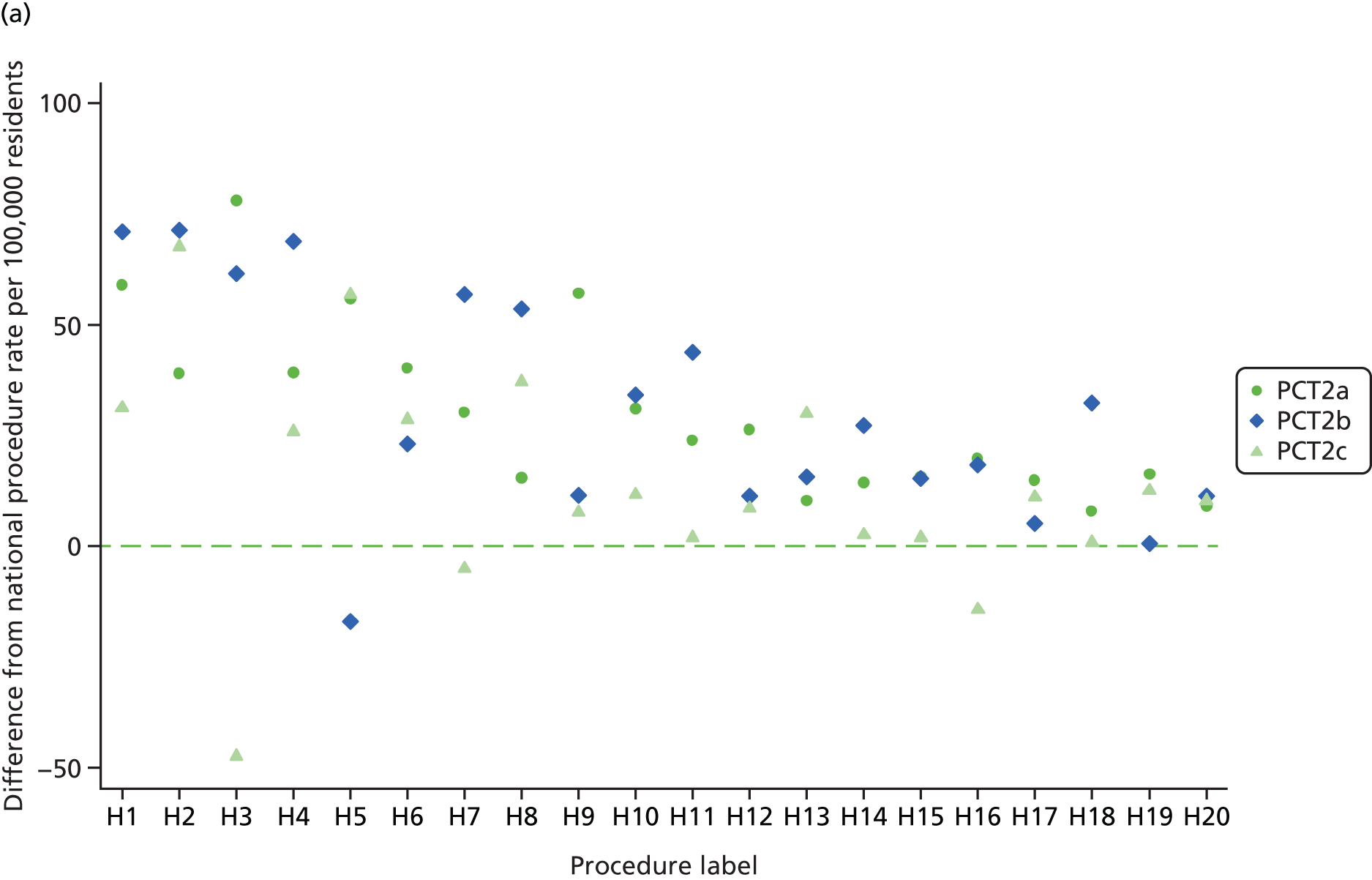

For the work in this chapter, we studied procedure utilisation rates in two PCT commissioning groups in more detail. The first PCT commissioning group (henceforth PCT1) served a region that was relatively rural, with a predominantly white and comparatively wealthy population. The second PCT commissioning group (henceforth PCT2) served a predominantly urban region, consisting of areas with high proportions of ethnic minority populations and pockets of high deprivation. Although we label them as a PCT throughout, one of the commissioning groups supported more than one neighbouring PCT. For each procedure, we quantified the difference between the individual PCT’s rate and the national rate using both the absolute and the relative difference. For each of the two PCTs we presented the 20 procedures with the largest estimated absolute difference as candidates for further study. We calculated a summary measure of the national geographical variability of each of these 20 procedures (described in more detail in Chapter 3). We defined procedures as ‘very high’ variance if there was a greater than 0.95 probability that inter-PCT variation in procedure utilisation was more than three times as high as the median inter-PCT variation for all 181 procedures. Similarly we identified ‘high’ (> 2 times as high as the median), ‘average’ (> 0.5 times as high as the median) and ‘low’ (> 0.33 times as high as the median) variance procedures. The remaining procedures were classified as ‘very low’ variance procedures. In addition, for each procedure, we present the estimated national rank of the specific PCT, where a value of 1 would indicate that the PCT had the largest (of all 152 PCTs) estimated absolute difference in rate from the national rate.

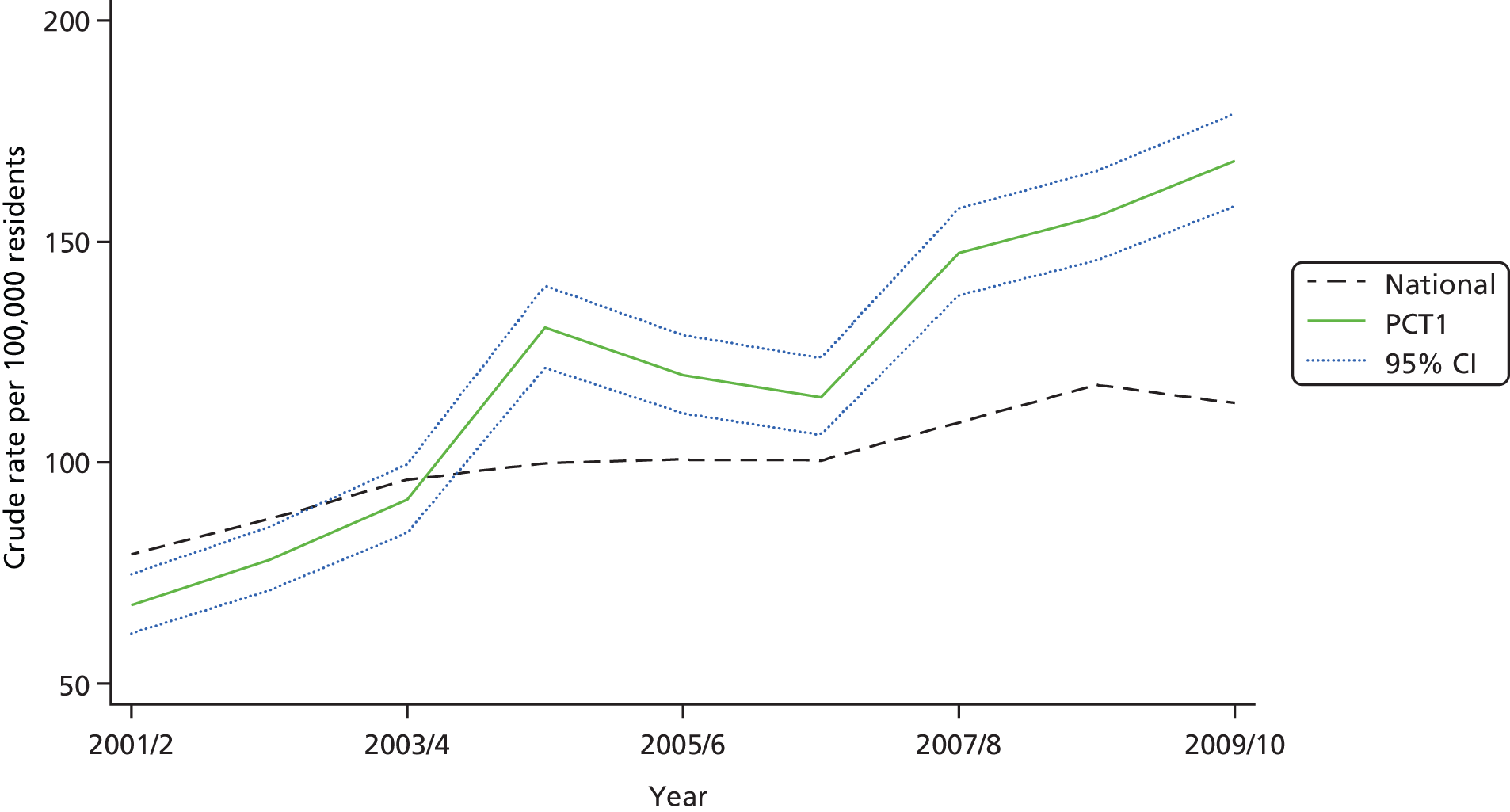

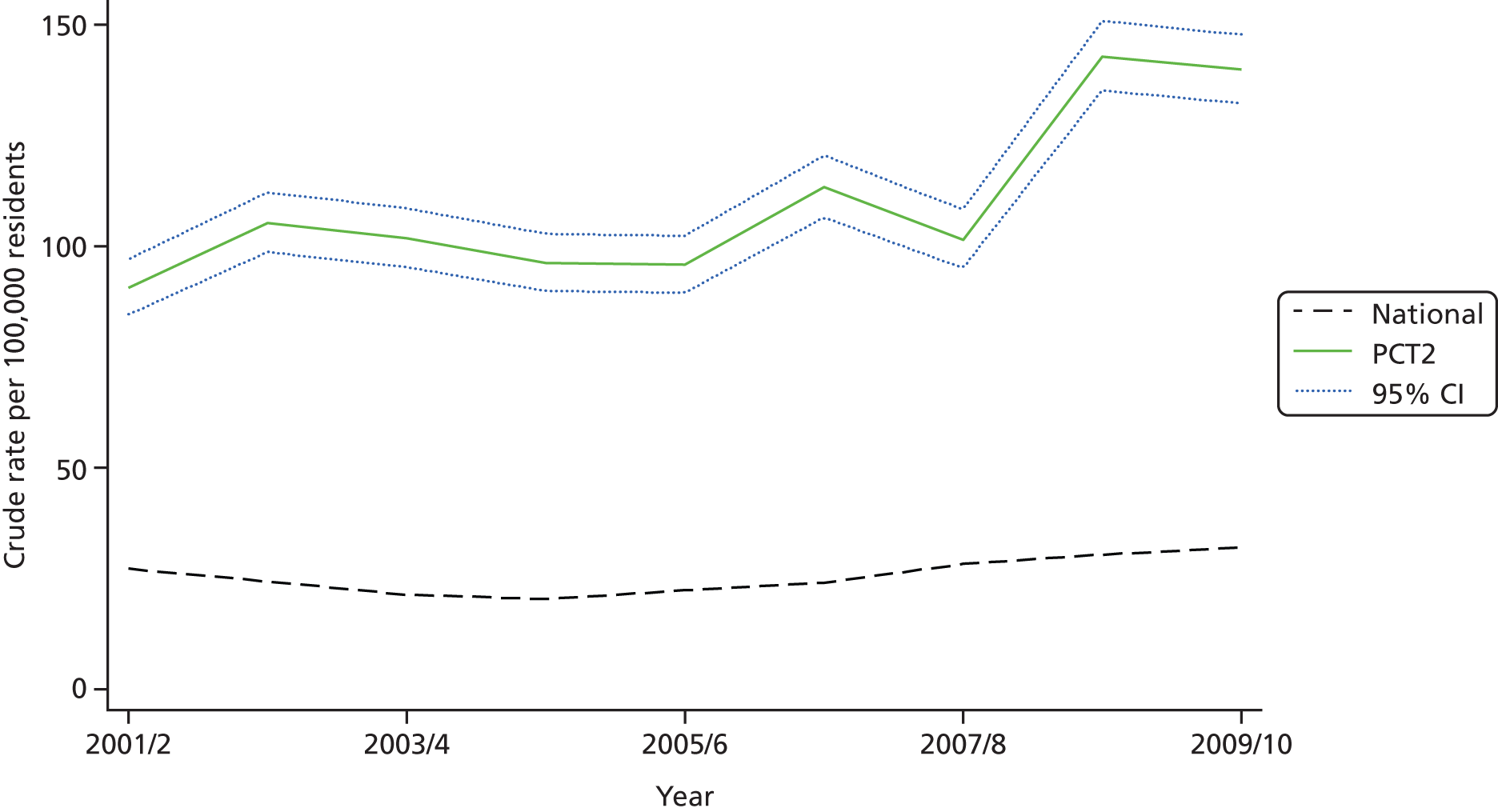

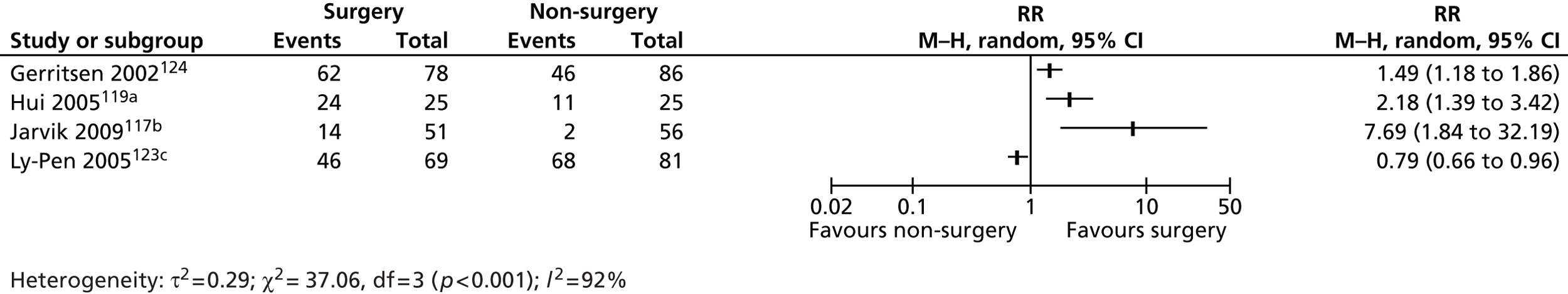

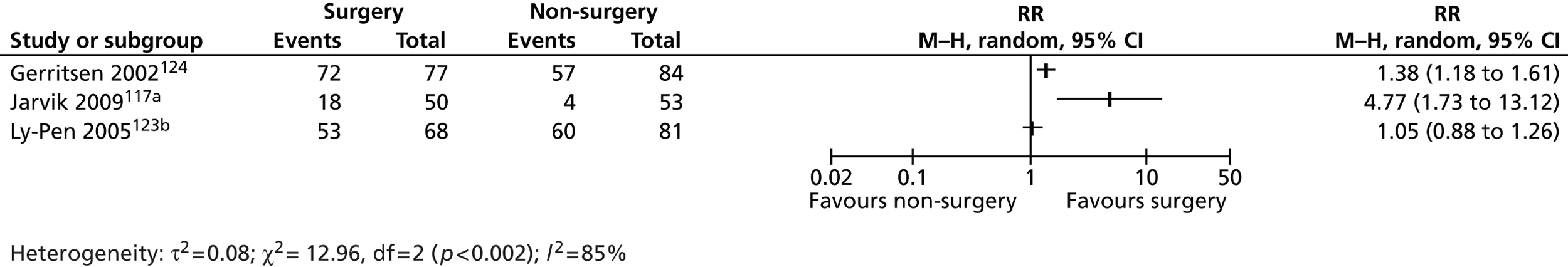

We further explored intra-PCT variation by tabulating procedure numbers by hospital, geographical variation at the sub-PCT (i.e. local borough) level and temporal variation in local procedure rates since 2001/2. A list of 20 procedures with the highest estimated absolute differences between the local PCT rate and national rate was discussed at a project team meeting in October 2011 with public health and commissioning representatives from the two PCT commissioning groups. As a result of the project team meeting we selected one procedure for rapid technology assessment at each PCT. These were ‘release of entrapment of peripheral nerve at wrist’ (OPCS code A65) at PCT1 and ‘incision of capsule of lens’ (OPCS code C73) at PCT2. The choice of procedures was a joint one between the research team and representatives of the two PCTs. These procedures were selected because procedure rates were substantially higher than the national average after adjustment for clinical need and were thought worth further investigation by the PCT representatives. Both procedures were thought likely to have had an important financial impact on PCT spending. Additionally, each procedure code was thought to represent a relatively well-defined procedure and patient population which would allow a subsequent technology appraisal to be undertaken.

Results

Benchmarking: PCT1

The adjusted rate of procedure use is much greater in PCT1 than the national average for a large number of procedures (Table 7). In 2009/10 the procedure with the largest estimated absolute difference from the national rate was ‘operations on spinal nerve root’, where adjusted local use was 62 (95% CI 55 to 70) procedures higher per 100,000 residents than the national mean. If PCT1 reduced its rate of this procedure to the national rate, a reduction of around 370 procedures per annum would be made, leading to substantial cost savings. For three procedures PCT1’s utilisation is in the top 10% of all PCTs. Furthermore, three of the 20 procedures with the largest absolute differences between PCT1 rate and the national rate also exhibit high or very high national variation, suggesting that there may be uncertainty about the appropriate procedure rate across England. For 17 of the procedures (the exceptions being ‘excision of gall bladder’, ‘excision of tonsil’ and ‘endoscopic resection of outlet of male bladder’) utilisation in PCT1 remained above the national median for each year between 2007/8 and 2009/10.

| Procedure name (OPCS code) | Adjusted local rate (95% CI)a | National rate (95% CI) | Absolute difference (95% CI) | Relative difference (95% CI) | 2009/10 estimated national rank(2007/8 rank) | National procedure variabilityb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operations on spinal nerve root (A57) | 110 (103 to 118) | 48 (47 to 48) | 62 (55 to 70) | 2.3 (2.1 to 2.5) | 7 (1) | Average |

| Combined operations on varicose vein of leg (L84) | 60 (54 to 66) | 30 (30 to 31) | 29 (23 to 35) | 2.0 (1.8 to 2.2) | 11 (36) | Average |

| Release of entrapment of peripheral nerve at wrist (A65) | 141 (133 to 150) | 113 (112 to 114) | 28 (20 to 37) | 1.2 (1.2 to 1.3) | 19 (25) | Average |

| Total prosthetic replacement of hip joint using cement (W37) | 83 (77 to 89) | 55 (55 to 56) | 27 (21 to 33) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.6) | 20 (21) | Average |

| Excision of gall bladder (J18) | 145 (136 to 154) | 119 (118 to 120) | 23 (15 to 32) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 7 (86) | Very low |

| Excision of cervix uteri (Q01) | 59 (54 to 65) | 41 (40 to 41) | 19 (13 to 24) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.6) | 37 (36) | High |

| Other therapeutic transluminal operations on vein (L99) | 39 (36 to 44) | 23 (23 to 24) | 16 (12 to 20) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.9) | 20 (19) | High |

| Therapeutic ureteroscopic operations on ureter (M27) | 48 (44 to 53) | 35 (35 to 36) | 13 (8 to 18) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.5) | 22 (52) | Average |

| Other operations on outlet of male bladder (M70) | 72 (67 to 79) | 60 (60 to 61) | 12 (6 to 18) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 51 (71) | High |

| Prosthetic replacement of head of femur using cement (W46) | 37 (32 to 41) | 25 (25 to 26) | 11 (7 to 15) | 1.4 (1.3 to 1.6) | 21 (71) | Average |

| Therapeutic spinal puncture (A54) | 37 (33 to 43) | 27 (27 to 28) | 10 (5 to 15) | 1.4 (1.2 to 1.5) | 25 (19) | Average |

| Primary repair of inguinal hernia (T20) | 137 (129 to 146) | 127 (127 to 129) | 9 (1 to 17) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.1) | 38 (27) | Very low |

| Operations on prepuce (N30) | 76 (69 to 83) | 67 (66 to 68) | 8 (2 to 15) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 33 (43) | Average |

| Other operations on lacrimal apparatus (C29) | 22 (19 to 25) | 13 (13 to 14) | 8 (5 to 12) | 1.6 (1.4 to 1.9) | 16 (13) | Average |

| Abdominal excision of uterus (Q07) | 69 (63 to 77) | 60 (60 to 61) | 8 (2 to 14) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 23 (41) | Low |

| Excision of tonsil (F34) | 105 (97 to 114) | 97 (96 to 98) | 7 (0 to 16) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 42 (95) | Low |

| Destruction of lesion of cervix uteri (Q02) | 21 (18 to 23) | 14 (13 to 14) | 7 (4 to 9) | 1.5 (1.3 to 1.7) | 26 (38) | Average |

| Primary closed reduction of traumatic dislocation of joint (W66) | 42 (37 to 48) | 35 (35 to 36) | 7 (2 to 12) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 37 (26) | Average |

| Other operations on spine (V54) | 148 (138 to 159) | 142 (140 to 143) | 7 (–4 to 17) | 1.0 (1.0 to 1.1) | 62 (63) | Average |

| Endoscopic resection of outlet of male bladder (M65) | 57 (52 to 63) | 50 (50 to 51) | 7 (1 to 12) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 40 (86) | Average |

The procedure ‘release of entrapment of peripheral nerve at wrist’ (i.e. CTR surgery) was selected for further evaluation in PCT1. The adjusted local rate was 28 (95% CI 20 to 37) procedures higher than the national rate per 100,000 residents. PCT1 had the 19th-largest estimated absolute difference from the national rate. Nationally there was ‘average’ variation between PCTs in the use of this procedure, which suggests reasonable agreement in appropriate procedure rates across England.