Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5001/67. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The final report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Corbett et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Historically, chemotherapy treatment for cancer patients was delivered in hospital. More than 10 years ago, a BMJ editorial noted a shift in chemotherapy practice in the UK from inpatient to outpatient ambulatory therapy. 1 The editorial highlighted a small but growing body of evidence suggesting that chemotherapy in the home was both safe and acceptable, but also identified a need for further exploration of patient selection and cost-effectiveness.

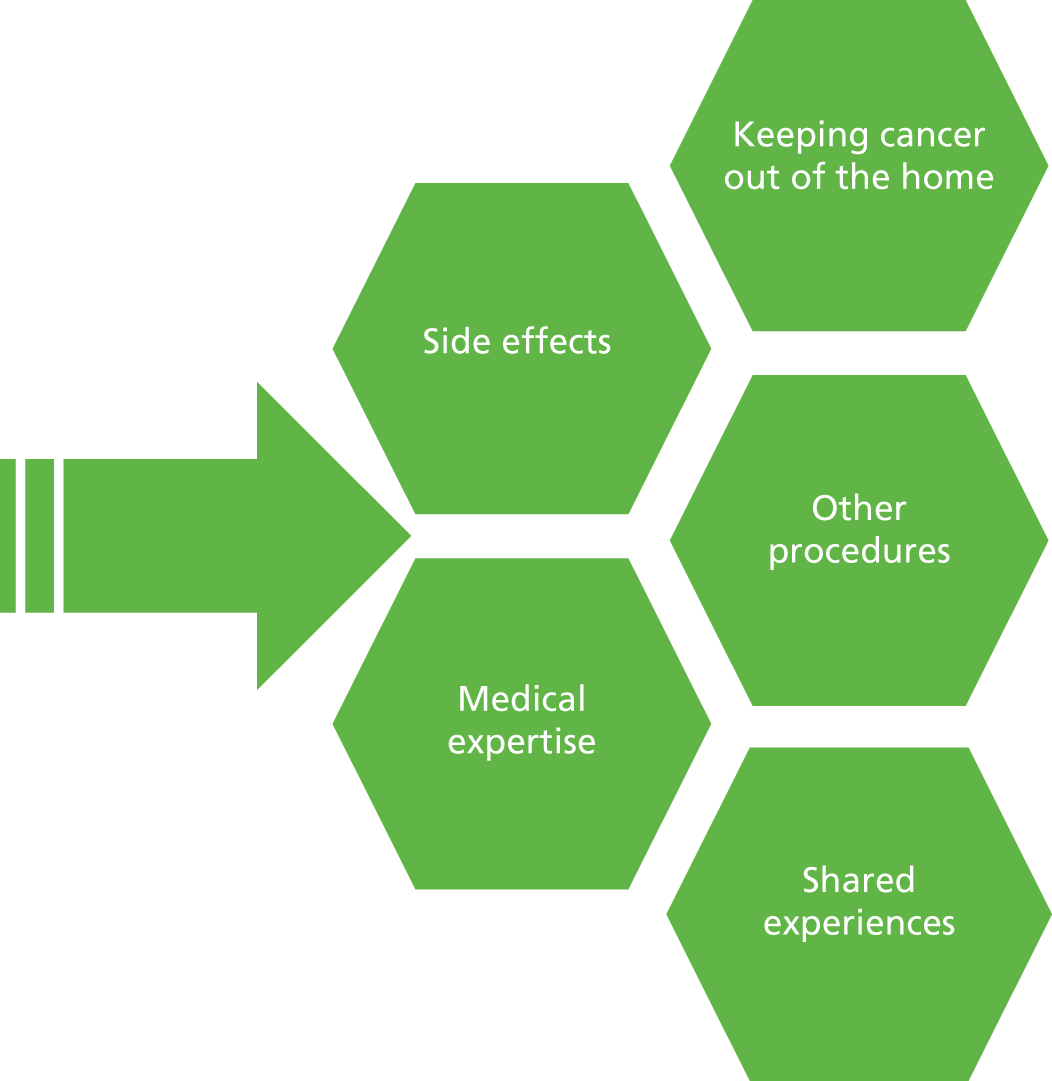

Potential benefits of receiving chemotherapy treatment at home include less travelling to hospital facilities, reduced risk of hospital-acquired infection, receiving treatment in the comfort and security of the home, less disruption to family life and an increased feeling of control over treatment and illness. 2 Potential concerns for patients include increased feelings of isolation, decreased contact with hospital staff (such as specialist nurses) and other patients, feelings of insecurity from a perception of reduced support outside the hospital setting, and the possibility of less continuity of care. 3

Safety is often perceived as being a key issue in the delivery of chemotherapy owing to the toxicity of the drugs, the costs of management of preventable toxicities and the need for specialist skills to administer and monitor treatment. The OUTREACH trial report indicated that clinicians were reluctant to refer patients for home or general practice chemotherapy in part because of patient safety concerns. 4

It is important to ensure that the risks of toxicity are managed by a cohesive multiprofessional team, that problems with toxicity are identified promptly and correctly managed and that concordance with treatment is optimised if outcomes are to be maintained. Severe side effects can be very disturbing and may influence a patient’s decision to continue with treatment; this is true in any setting, but may possibly have a longer term impact on patients when experienced at home. Whatever the treatment setting, severe adverse events mostly occur between treatment-days and so even outpatients experience them outside hospital. Appropriate pre-treatment assessment and patient education are key issues that apply to patients in any setting. Health-care professionals involved with the administration and monitoring of treatment need to have the relevant skills and expertise.

Throughout the NHS there has been an increasing focus on making care more centred on the needs and preferences of patients. 5 In the area of cancer services, the Cancer Reform Strategy has pledged that care will be delivered in the most clinically appropriate and convenient setting for patients. 6 The Department of Health Cancer Policy Team has produced guidance to develop chemotherapy services in the community [such as in general practitioner (GP) surgeries or patients’ homes],3 which builds on best practice guidance provided in the National Chemotherapy Advisory Group report published in 2009. 7 These documents promote the consideration of opportunities to devolve chemotherapy from cancer centres and cancer units to community settings while maintaining safety and quality, and delivering an efficient service. However, a report on how effectively strategies laid out in the Cancer Reform Strategy have been utilised to improve cancer services for patients found a lack of activity in the commissioning of services, with only 26% of primary care trusts having undertaken a cost–benefit analysis looking at different ways of delivering cancer services. 8

These initiatives should be considered within the context of plans in England to reduce the number of centres commissioned for specialised services and focus provision in a smaller number of centres. 9 It is currently unclear if chemotherapy will be included within the definition of a specialised service, or if this will depend on the nature of the cancer being treated. Such a policy change may have implications for where cancer chemotherapy is prescribed and administered, including options for delivery closer to home.

It is likely that many outpatient facilities across England and Wales are delivering chemotherapy services at full capacity (assuming a 15% year-on-year growth in demand), and increasing strain to the service is anticipated. 7 Future demand for services is likely to increase further; increasingly early detection of cancer, improving cancer survival and an ageing population are key factors. For hospitals without the resources to appropriately expand their capacity in terms of either staffing levels or physical space, it is likely that future patients will face longer waiting lists or a reduced service. Delivering chemotherapy closer to the home may enable hospitals to relieve the demand for hospital ward services while maintaining patients’ care.

The various chemotherapy delivery practices used in the UK reflect the different challenges of, for example, large cancer centres and district general hospitals. 10 Nurse-led chemotherapy is well established within the outpatient setting but home and community delivery of chemotherapy is not currently widespread. Different geographic challenges exist for provision in remote and rural communities compared with urban centres. The Department of Health lists exemplars of NHS community chemotherapy services in Sunderland, Dorset, West Anglia, East Anglia and East Kent, and there are health-care companies who undertake chemotherapy in the community, offering services to both private and NHS providers, for example Healthcare at Home (HaH), BUPA Home Healthcare, Baxter, Calea and Alcura. 3

Successful services are likely to be closely tailored to the local requirements and available resources, and as such are expected to vary considerably. For example, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust does not provide intravenous chemotherapy at home, at least in part because of the logistics of covering a large and diverse catchment area; patients can receive intravenous chemotherapy in the community (at Otley community hospital) and would attend pre-treatment assessment clinics at St James’s University Hospital in Leeds. Conversely, the Sunderland model covers a relatively small urban area, which allows for a range of services to be provided (Box 1).

In the Sunderland model, intravenous chemotherapy is available across three different settings according to patient choice where eligibility criteria are met (drug is given in short infusions lasting < 5 hours, or as bolus treatment that is not associated with a high risk of anaphylaxis). This model of care has been in operation since 2009 and is entirely provided by the local NHS hospital, covering a 15-mile radius from the main hospital. Initial assessments are carried out by the chemotherapy nurse prior to treatment being scheduled.

From initiation of treatment, patients choose their preferred setting. Bookings are made through a single appointment system, which allows flexibility so that patients can move between locations to suit their schedules.

-

Hospital outpatient (one venue, provided 6 days per week with a Saturday clinic 8.30 a.m. to 2.30 p.m., extended working until 7.00 p.m. midweek, approximately 40 patients per day).

-

Outreach service (one venue, primary care centre provided 3 days per week, approximately 15 patients per day).

-

Patient home (try to group geographically, provided 4 days per week, six to eight patients per day).

Chapter 2 Introduction

Aims

This aim of the project was to investigate the impact of the delivery of intravenous chemotherapy in different settings on quality of life, safety, patient satisfaction and costs. Our focus was the provision of intravenous chemotherapy led and managed from the oncology department and delivered in the patient’s home, in the community or in the hospital outpatient department.

Objectives

The project comprised four elements:

-

a systematic review of the clinical and economic literature to bring together and assess the existing evidence

-

a brief survey to gather information about the structure of services and variation in practice across the NHS

-

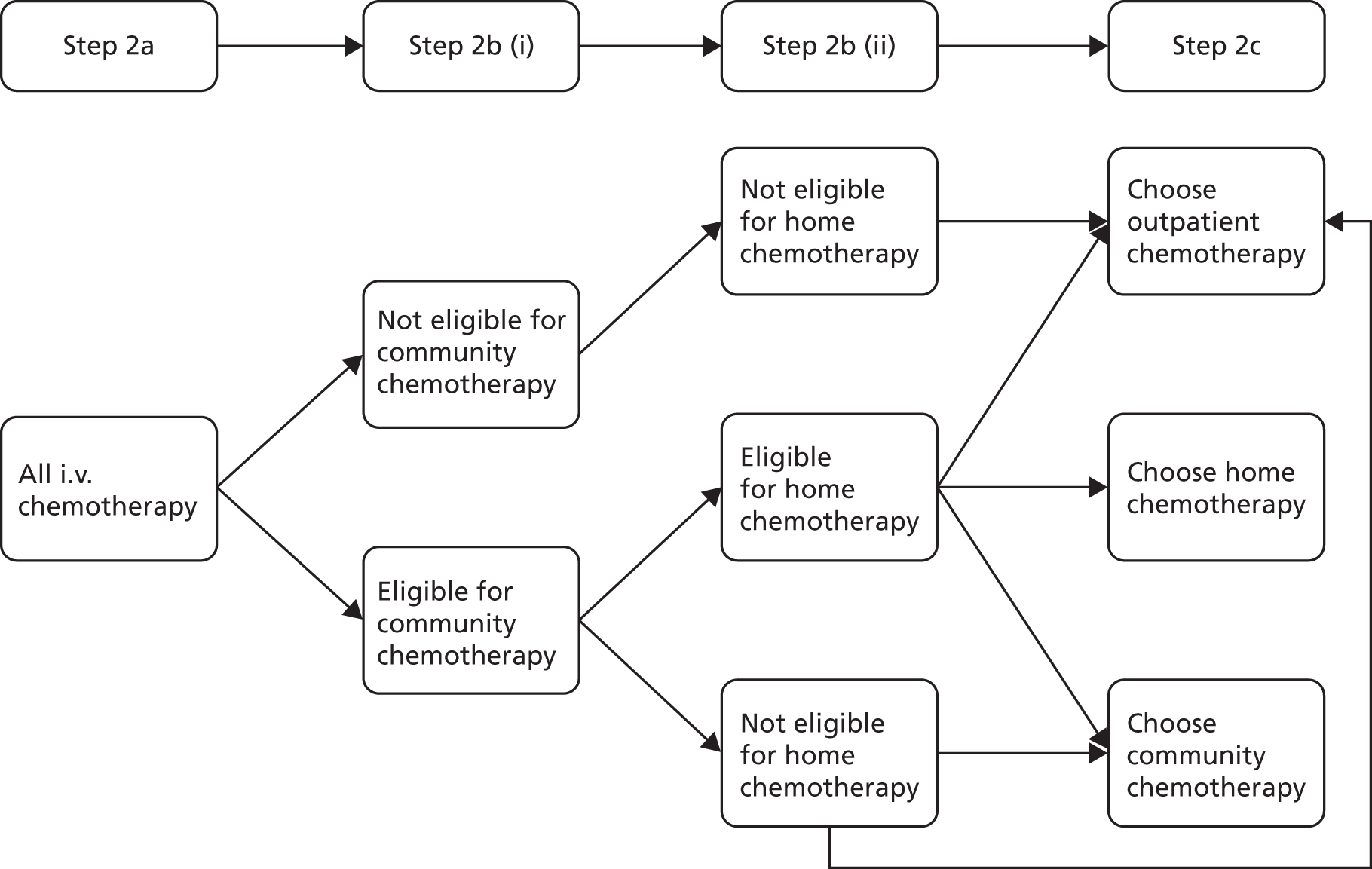

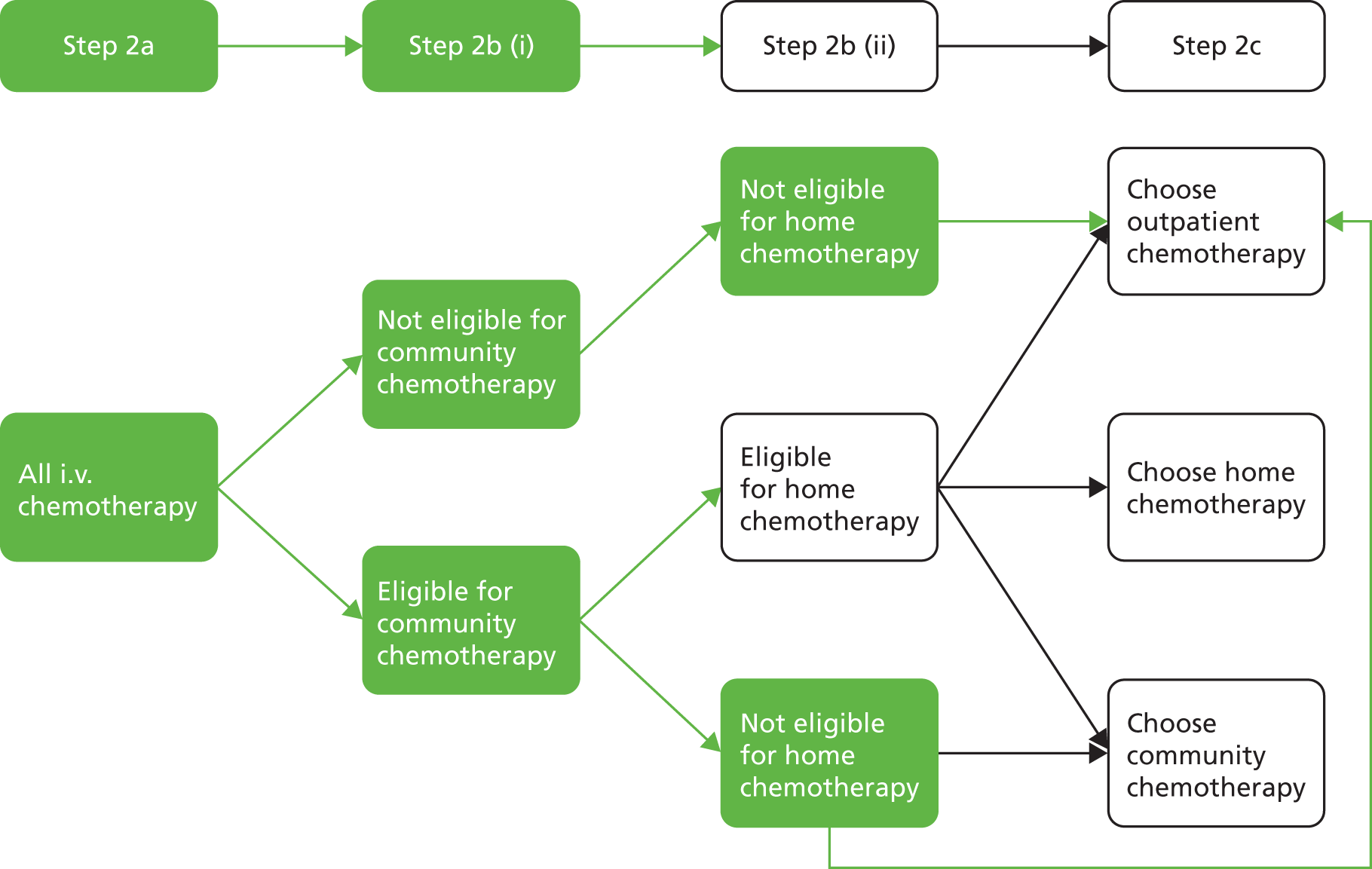

a description of the general pathway for patients who will be offered chemotherapy

-

the development of a decision model to compare delivery of chemotherapy for an eligible population in three settings.

In addition to the project team, an advisory group of specialist nurses, pharmacists, and patient representation was formed to help to guide each of the elements from the proposal stage through to the final report. This report details the methods and results for each element, draws together and discusses the findings and identifies the implications for health care and future research.

Chapter 3 Systematic review

Introduction

To provide a complete overview of the current published evidence base for the delivery of intravenous chemotherapy closer to home, a series of three interlinked systematic reviews was undertaken. Each review assessed a different type of evidence: comparative clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and qualitative studies. We used the same methodology across reviews except where different types of evidence precluded this; any alternative methods are clearly described and signposted.

Together, the three reviews summarise the totality of the evidence base by addressing particular questions and focusing on the most appropriate type of evidence. The reviews were conducted in parallel within an explicit and pragmatic mixed-methods framework based on principles of complementarity. This approach is based loosely on the approach pioneered by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information (EPPI) and Co-ordinating Centre (the EPPI approach). 11

The same researchers worked on each of the three reviews to ensure a collaborative approach. Regular team meetings and discussions during study selection, data extraction and analysis promoted cross-fertilisation of ideas. Matrices were used to collate the summary findings from each of the three reviews. Commonalities and divergences between the results were identified and integrated with the findings informing the decision model. Chapter 6 presents the meta-synthesis of all elements from the project.

Methods

Searches

The aim of the literature searches was to systematically identify research on the impact of setting (closer to home) on the delivery and outcomes of intravenous chemotherapy.

The base search strategy was constructed using MEDLINE and then adapted to the other resources searched (Box 2).

Date range: 1946 to week 2 March 2013.

Date of search: 25 March 2013.

1564 records identified.

Search strategy-

exp neoplasms/ (2,406,640)

-

(cancer$ or neoplas$ or tumor$ or tumour$ or malignan$ or oncolog$ or carcinoma$).ti,ab. (2,073,583)

-

oncologic nursing/ (6088)

-

or/1-3 (2,889,785)

-

drug therapy/ (33,151)

-

Antineoplastic Combined Chemotherapy Protocols/ (97,247)

-

chemotherapy, adjuvant/ or consolidation chemotherapy/ or maintenance chemotherapy/ (27,648)

-

administration, intravenous/ or infusions, intravenous/ (46,068)

-

chemotherapy.ti,ab. (223,465)

-

systemic therapy.ti,ab. (5856)

-

intravenous drug therapy.ti,ab. (39)

-

adjuvant therapy.ti,ab. (14,653)

-

or/5-12 (357,679)

-

home care services/ or home care services, hospital-based/ (28,037)

-

*Outpatients/ (2136)

-

*Ambulatory Care/ (14,592)

-

*ambulatory care facilities/ or *outpatient clinics, hospital/ (13,416)

-

community health services/ or community health nursing/ or community health centers/ (47,800)

-

general practitioners/ or physicians, family/ or physicians, primary care/ (16,406)

-

general practice/ or family practice/ (61,185)

-

((service$ or therapy or treatment$) adj6 (home or community or outreach or out-reach or ambulatory or domicil$)).ti,ab. (42,475)

-

(hospital at home or hospital in the home or own home$ or home care or homecare or closer to home).ti,ab. (15,680)

-

or/14-22 (207,550)

-

4 and 13 and 23 (1144)

-

home infusion therapy/ (579)

-

(chemotherapy adj6 (home or community or outreach or out-reach or ambulatory or domicil$)).ti,ab. (719)

-

(chemotherapy adj6 service$).ti,ab. (184)

-

(chemotherapy adj6 (general practitioner$ or family practitioner$ or family doctor$ or family physician$ or primary care physician$)).ti,ab. (19)

-

(self-infusion adj6 home).ti,ab. (21)

-

home infusion.ti,ab. (254)

-

or/25-30 (1591)

-

4 and 31 (751)

-

24 or 32 (1595)

-

exp animals/ not humans/ (3,782,734)

-

33 not 34 (1564)

The search included the following components:

-

cancer terms AND

-

chemotherapy terms AND

-

generic home care/ambulatory care terms.

These terms were combined with (OR), the following terms:

-

cancer terms AND

-

home chemotherapy terms.

No date, language or other limits were applied and, where possible, animal-only studies were excluded.

The strategy was constructed by an information specialist within the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and subsequently peer reviewed by another information specialist prior to use.

Search terms were identified by scanning key papers known at the beginning of the project, through discussion with the review team and the use of database thesauri.

The full strategies from all of the databases are given in Appendix 1.

Sources of both published and unpublished information were identified by an information specialist with input from the project team. MEDLINE and MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; Allied and Complementary Medicine Database; British Nursing Index; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; The Cochrane Library; Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science; Dissertation Abstracts; EconLit; EMBASE; Google; Health Management Information Consortium; Inside; Office for Health Economics Health Economic Evaluations Database; PsycINFO; PubMed; Social Policy and Practice; ClinicalTrials.gov and Current Controlled Trials databases and the Google search engine were searched.

Databases were searched from date of inception to March 2013. Update searches were undertaken in October 2013.

Reference searches of all included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and relevant systematic reviews were undertaken. Where necessary, authors of eligible studies were contacted for further information and experts in the field were contacted to see whether or not they had access to further material. We contacted private providers of home care through the National Clinical Homecare Association (including HaH, Bupa, Baxter, Calea and Alcura) to identify unpublished reports, evaluations or resource information.

We also contacted the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency to request information on suspected adverse drug reactions and adverse events for intravenous home chemotherapy drugs. Route of administration was available, but the system does not store information on the setting where the drug was given or the adverse event occurred. Therefore, no data relevant to this project could be collated.

Inclusion criteria

Population

Cancer patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy.

Interventions and comparators

Studies comparing intravenous chemotherapy in two (or more) of the following settings:

-

home setting (includes nursing homes)

-

community-based setting (e.g. GP practice, community clinic, community hospital or mobile units)

-

hospital outpatient setting.

Within-setting comparisons were eligible if the study compared different organisational or management approaches.

Outcomes

Any of the following:

-

safety

-

patient quality of life

-

preference

-

satisfaction (including treatment compliance/adherence)

-

social functioning

-

clinical outcomes

-

patient and carer opinions and experiences

-

costs

-

resource/organisational issues (including access).

The clinical outcomes of interest were self-rated health or measures of performance status.

Study designs

Any type of comparative design was eligible. To obtain information about patient quality of life, satisfaction, preferences and opinions, studies that reported results for only one eligible setting and qualitative research (any of the three settings) were considered, providing that they had a stated aim to evaluate one or more of these outcomes. Given the review focus on home and community settings, and the potential diversity and likely volume of these studies in an outpatient setting, we focused on studies of the home and community settings.

Full economic evaluations that compared two or more eligible settings and considered both costs and consequences (including cost-effectiveness, cost–utility or cost–benefit analyses) were eligible.

Screening and study selection

Two researchers independently screened all titles and abstracts obtained using the predefined eligibility criteria. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus, with recourse to a third researcher where necessary. Full manuscripts of potentially relevant studies were obtained where possible and were screened in duplicate. Studies in any language were eligible for inclusion.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Studies were assessed for quality as part of the data extraction process using criteria relevant to the topic and study designs included. Data were extracted into structured forms using a pre-piloted form in EPPI-Reviewer (EPPI-Centre, Institute of Education, University of London, London, UK). Piloting was undertaken by each researcher involved with the process and refined as necessary prior to full data extraction to ensure consistency. Data extraction and quality assessment was conducted by one researcher and checked by a second researcher for accuracy, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion or by recourse to a third researcher where necessary.

Clinical studies

Data were extracted on details of study methods, country and geographical region in which the study was conducted, whether it was single or multicentre, dates over which the study was conducted, patient characteristics, interventions, comparators where appropriate, all relevant outcome measures and results.

The quality of included comparative studies was assessed using criteria appropriate to the study design, adapted from published checklists. 12

Randomised controlled trials

Randomised controlled trials were assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, which focuses on the domains shown to impact on the trial results in particular (selection, performance and detection biases and attrition). 13 The tool was modified to incorporate assessment of baseline imbalances when we evaluated selection bias. 14

Non-randomised comparative studies

Study quality evaluations were based on recently published papers detailing methodological issues and assessment of bias in non-randomised studies. 15–18 Confounding variables (variables other than the intervention being studied, which might affect study outcomes when groups are compared) are known to be a very important source of bias in non-randomised studies. 19 As there were many potentially important confounders for our review question, we focused our assessment on evaluation of the risk of bias due to confounding. This was done by answering the following questions:

-

How were the groups formed?

-

Were the effects of any confounders taken into consideration during the design and/or statistical analysis stages?

-

What methods were used to control for confounders?

-

Were data on the measured confounders recorded precisely enough?

-

Were any key confounders not controlled for?

The important confounders we considered were type of cancer, stage of cancer, type of chemotherapy, age, performance status [e.g. Karnofsky, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) or Lansky scores], quality of life, treatment intent (curative or palliative) and distance from hospital. These confounders were chosen for their potential to affect outcomes such as quality of life and patient satisfaction. Some of these confounders are correlated.

Where these confounders were not measured, and not taken into account in the design or analysis of the study, the study results were deemed likely to be at a high risk of bias. Studies where such details were not clear were judged to have an unclear risk of bias. Given the non-randomised nature of the studies and the lack of assurance provided about the methods used, the implications of an unclear risk of bias judgement are similar to those of a high risk of bias judgement and the study results should not be interpreted as being reliable.

Where the answer to question 2 was ‘yes’, the details of which confounders were controlled for were recorded and the remaining questions were answered; the overall risk of bias judgement (from confounding) was then made based on the answers to questions 3, 4 and 5. Where the answer to question 2 was ‘no’ or ‘not reported’, a high or unclear risk of bias judgement was made and the remaining questions were not answered. An assessment of whether or not there was evidence that potential confounders did not actually result in confounding was also made when considering question 2.

For non-randomised studies there is evidence that confounding may not, on average, cause bias in the estimation of adverse effects. 17 We considered this during our assessments according to how likely a given adverse effect (as defined in individual studies) might be affected by confounding.

As cost and resource outcomes were extracted to inform the review’s economic modelling, formal synthesis and quality assessments were not routinely performed for these outcomes.

Non-comparative studies were not extracted or quality assessed, but they are listed for reference in Appendix 2.

Cost-effectiveness studies

Data extracted from economic evaluations included interventions compared study population; dates to which the data related; measures of effect; direct costs (medical and non-medical); currency used; utilities/measure of health benefit; and results and details of any decision modelling applied. The quality assessment of the economic evaluations was informed by use of the Drummond 36-point checklist. 20 The purpose of the review was to provide an overview of the current cost-effectiveness evidence base and help to inform the development of a de novo decision model. Any additional information that could aid development of a de novo decision model was also extracted.

Qualitative studies

Qualitative studies were assessed for methodological quality using criteria based on the work of Mays and Pope, among others. 21–23 As with the quantitative studies, the focus was on those domains which are expected to influence the reliability of the findings. Domains included transparency and documentation of the data collection and analysis processes, description and justification of sampling, validity appropriate to the method being used, reflexivity and clear distinction between data and interpretation.

The results sections from each included study [apart from one Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.)] thesis were extracted from portable document format files and entered into NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) as text documents. 24 We used online translation for one paper in Danish. This unconventional approach appeared to generate reasonable approximations of the original meaning and avoided the expense and delay of professional translators; this was balanced against the possibility of losing some meaning in translation.

The Ph.D. thesis24 was read through with the other papers, but not extracted and coded until nearer the end of the process. The thesis was useful as a way of checking for gaps or absences in the data as a whole, but it was too dense and, in places, of less immediate relevance to warrant full extraction.

Synthesis

Clinical effectiveness data

Our detailed narrative synthesis explored the methodology and reported outcomes of included studies. Key study characteristics, patient outcomes and quality assessment were tabulated to provide clear summaries of the included studies. The clinical and statistical heterogeneity of the accumulated evidence was assessed. Differences between studies were discussed in the text and the potential impact of these differences on outcomes was explored. The results were interpreted in the context of the quality of the individual studies.

As anticipated, the available data were too heterogeneous for quantitative synthesis.

Cost-effectiveness data

The findings of the systematic review of full economic evaluations were summarised in a narrative synthesis.

Qualitative data

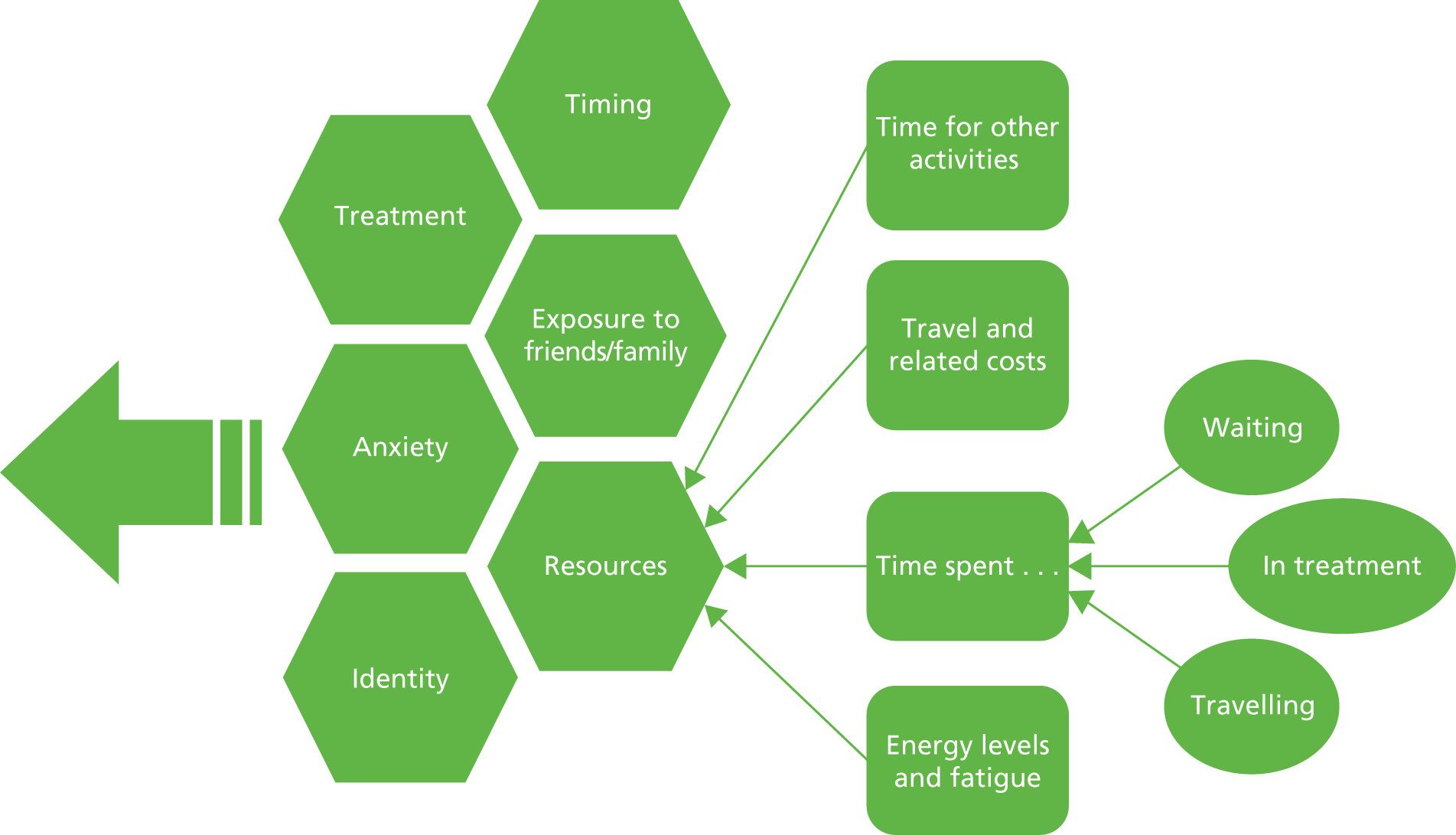

The qualitative studies were synthesised using meta-ethnography, an approach which searches each primary study and systematically extracts key findings and interpretations. 25,26 These data are then compared using a constant comparison method, which categorises key concepts to look for overlapping themes in order to enable linking of material. Each finding is subsequently assessed for similarity or difference to the other studies, and the goal is to develop, in an iterative manner, this reciprocal translation. Ultimately, new lines of argument can be developed which go beyond the data contained within the original studies.

The focus of the analysis was on themes and ideas relating directly to the provision of intravenous chemotherapy with particular reference to treatment location, rather than the experience of having cancer treatments per se.

Each results section was read closely on multiple occasions and coded line by line using participants’ words where possible. Initially, codes were tagged according to the setting (e.g. code ‘prefer to go home after treatment’ was linked to ‘outpatient setting’). Subsequent readings of the texts and resultant codes led to the reworking of the coding framework into key elements rather than distinguishing by treatment location. Codes were collapsed where possible and a process of diagramming used to explore links and interactions between the key lines of argument and categories.

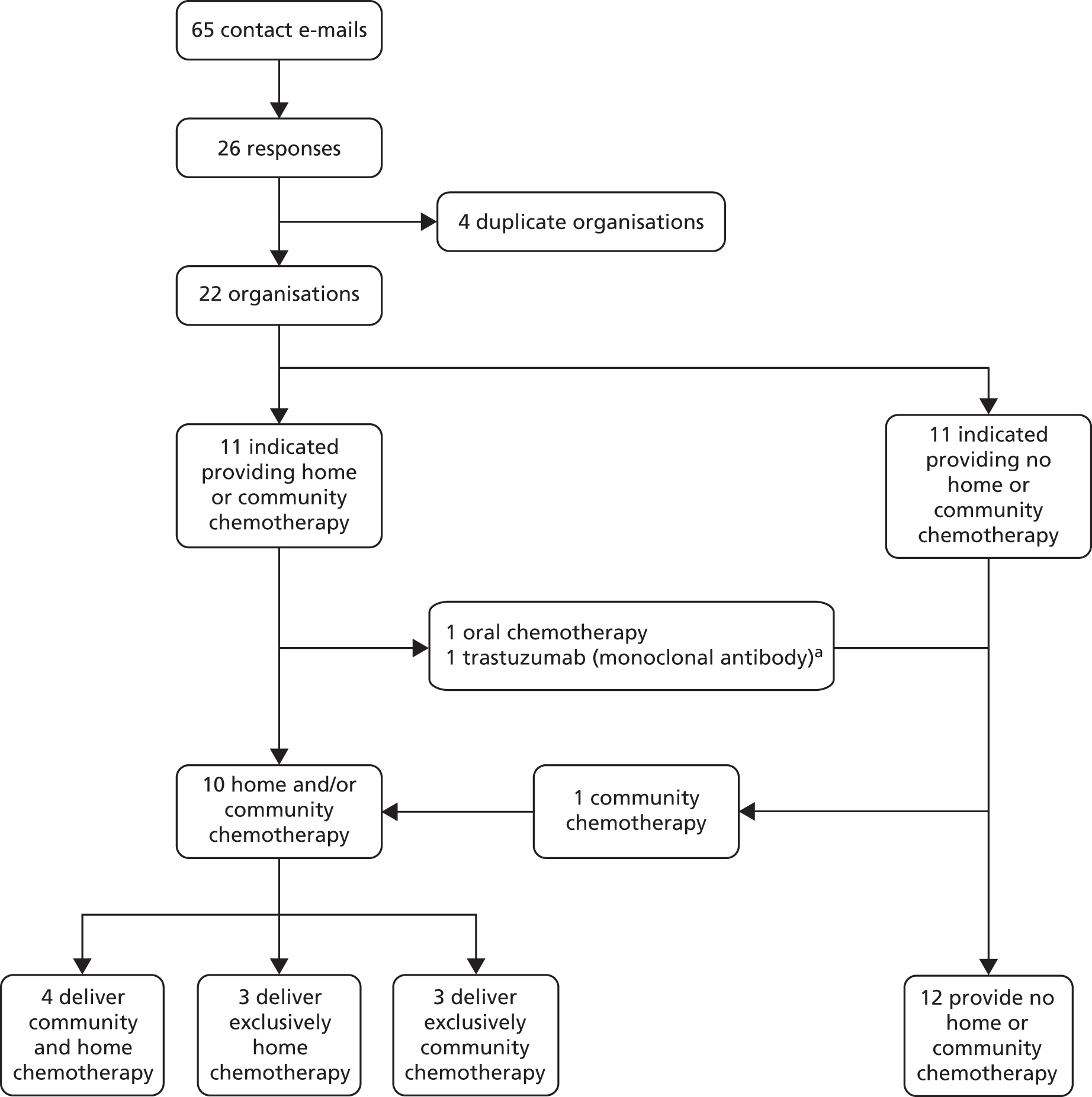

Results

The electronic database searches identified 4260 references. A further 12 references were found by Google searches or by checking reference lists of included randomised trials and relevant systematic reviews. After screening titles and abstracts, full copies of 245 papers were assessed for inclusion in the review. Figure 1 illustrates the flow of studies through the review process. Fourteen references were of papers related to another reference already included. Sixty-seven eligible studies were identified. Nine of the 25 comparative studies (10 RCTs and 15 non-randomised studies) fully evaluated in the review undertook concurrent full economic evaluations; these were evaluated separately in the review to enable a more detailed assessment. The 42 studies of single-settings are listed in Appendix 2. We identified a larger than expected number of comparative studies, and so we evaluated only those single-setting studies which might usefully add to the synthesis of the comparative studies. Consequently, single-setting studies were used only to inform the evaluation of qualitative data on patient, relative or caregiver experience of intravenous chemotherapy (see Chapter 3, Results, Qualitative studies). As we anticipated there to be a large number of single-setting outpatient studies, we ordered full papers only for studies that appeared likely to report qualitative data.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study selection. N/A, not applicable.

The following sections present a detailed breakdown of the results of the RCTs, non-randomised studies and economic evaluations. For each study design, study characteristics, risk of bias or quality assessment and results are presented.

Clinical effectiveness studies

Randomised trials

Study characteristics

Ten randomised trials investigated the effect of setting for patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy (Table 1). Six trials used a crossover design (where participants act as their own controls, and typically receive all interventions in succession). Three trials used a parallel design (where participants typically receive only one intervention). One study reported only as an abstract appeared to use parallel groups and incorporated elements of a crossover design. 27 Most studies were reported as full published papers; two were reported only as conference abstracts. 27,28 Studies were published between 1999 and 2013. Three studies were conducted in the UK (England),4,29,30 two were conducted in Australia,31,32 and one study was conducted in each of Canada,33 Denmark,28 France,34 Japan27 and Spain. 35

| Study | Country | Sample size | Recruitment ratea | Setting | Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | Community | Outpatient | |||||

| Corrie et al. 2013 (OUTREACH)4 | England | 97P | 1.7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Quality of life, anxiety, depression, health status, costs, satisfaction, serious adverse events |

| bChen and Hasuimi 199927 | Japan | 10P | NP | ✓ | ✓ | Quality of life, anxiety, nursing time | |

| bChristiansen et al. 201128 | Denmark | 51C | 1.4 | ✓ | ✓ | Quality of life, adverse effects, time spent receiving chemotherapy, preference, costs | |

| Pace et al. 200929 | England | 42C | 3.2 | ✓ | ✓ | Preference, anxiety, depression, safety, resources | |

| Hall and Lloyd 200830 | England | 15P | 2.5 | ✓ | ✓ | Experience and satisfaction, costs | |

| King et al. 200031 | Australia | 74C | 1.5 | ✓ | ✓ | Preferences and strength of preference, satisfaction, unmet need, quality of life, costs | |

| Rischin et al. 200032 | Australia | 25C | 1.8 | ✓ | ✓ | Preference, satisfaction, complications, costs | |

| Stevens et al. 200633 | Canada | 29C | NP | ✓ | ✓ | Quality of life, social/psychological interactions, adverse events, costs | |

| Remonnay et al. 200234 | France | 52C | 1.6 | ✓ | ✓ | Satisfaction, costs, quality of life, anxiety | |

| Borras et al. 200135 | Spain | 87P | 6.7 | ✓ | ✓ | Toxicity, withdrawals, health-care resources, quality of life, satisfaction, Karnofsky Index | |

Eight studies27,28,30–35 compared chemotherapy in the home setting with chemotherapy in a hospital outpatient setting. One study29 compared a community setting with a hospital outpatient setting. One study4 was a three-armed trial that compared home, community and outpatient settings. Setting details were generally not well reported; for example, aspects such as the number of nurses per patient, the degree of access to parking, and facility details were only occasionally provided. The two community settings studies assessed treatment delivered in GP surgeries and community outreach centres. 4,29 Treatment durations were often not stated explicitly or were expressed in terms of cycles; however, most studies reported chemotherapy durations ranging between approximately 2 and 8 months.

All of the trials except Stevens et al. 33 studied adults, with reported mean (or median) ages ranging from 57 years to 64 years. Around half of the studies were of mixed populations; patients with colon, breast, and pancreatic cancer were the most frequently studied. Studies were also conducted solely in populations with ovarian,27 colon28 or breast cancer. 30 The study in children was of a population with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. 33

The treatment intention was not always reported. Where reported it varied both within and across studies, with chemotherapy administered with either palliative or curative intent (sometimes as an adjuvant treatment). Few studies reported details on where chemotherapy drugs were prepared: in two trials drugs were prepared in the hospital pharmacy4,29 and in one trial a community pharmacy was used. 33 Full study characteristics are reported in Appendix 3.

Recruitment and participation

In total, 482 participants were randomised across 10 trials. Sample sizes ranged from 10 to 97. Six studies reported a target sample size; three of these achieved or exceeded their small recruitment targets of 30 or fewer patients. Three studies did not achieve their targets: in one study a target of 20 patients was not reached (reasons unclear); one study was terminated early when 52 of a targeted 160 participants had been randomised,34 because a large majority preferred the home setting; and the largest included study (OUTREACH) was stopped owing to the poor recruitment rate when 97 of a targeted 390 participants had been randomised (the decision was made on the advice of the independent data monitoring committee). 4 Despite this early termination, the OUTREACH trial rate of recruitment (estimated at around 1.7 patients per month per centre) was similar to the estimates for many other trials (rates ranging from 1.4 to 2.5 patients per month per centre), except for the Borras et al. 35 trial (around 6.7 patients per month/ per centre) and the Pace et al. 29 trial (around 3.2 patients per month per centre) (see Table 1 for details).

Five of the nine trials where the outpatient setting was the standard care setting (the only routinely available setting) reported details of eligible patients who were not randomised. Between them, these five trials randomised 294 participants, but 100 eligible patients chose not to participate for setting-related reasons. Generally, these participants withdrew from the trial to revert to standard practice (which was their preferred setting). In one trial home chemotherapy was already an option before the trial began – and eligible patients had to be registered on the ‘chemotherapy in the home program’. 32 In this study several patients chose not to participate because they wanted only home treatment. These data highlight the inherent bias (in terms of the types of population recruited) often encountered in trials that evaluate settings (see Chapter 6, Limitations of the evidence and of the review for more discussion of this point).

No consistent trends were found in the setting-related reasons for participants who withdrew or dropped out of trials (some studies reported limited details or none at all).

Risk of bias

Results of the risk of bias assessments are presented in Appendix 4. Even though only the OUTREACH trial clearly reported on both the sequence generation and allocation concealment methods,4 most studies can be judged as being at a low risk of selection bias overall. This is largely because treatment groups had similar characteristics at baseline, a factor which was mainly a result of the use of a crossover design.

All studies were judged to be at high risk of performance bias; study participants and personnel will have been aware of which setting had been allocated, and avoidance of such bias is impossible. Similarly, results for the subjective patient-reported outcomes, such as quality of life and satisfaction, were judged to be at high or unclear risk of bias in all studies. Conversely, the risk of detection bias was judged low for studies reporting adverse events because they are mostly not subjective outcomes.

In four of the 10 trials the risk of attrition bias was judged to be low. There were insufficient details for the remaining six trials; accordingly, these trials were judged to be at an unclear risk. Four trials were found to be at a low risk of reporting bias, two were at a high risk of bias owing to missing results (or result detail), and in the remaining trials the risk was unclear.

Of the six crossover trials, only three clearly reported using appropriate statistical analyses. In three crossover trials the use of a crossover design appeared questionable, because of the number of patients withdrawing or dropping out because of disease progression.

Results and synthesis of randomised clinical effectiveness trials

Quality of life

Seven of the 10 randomised trials reported that they evaluated some measure of quality of life; actual result data were available for only four trials (see Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (30 items) (EORTC QLQ-C30) self-rated quality of life between any settings (home vs. outpatient;4,28,35 home vs. GP, outpatient vs. GP4). Both home and outpatient settings were associated with statistically significant better results for the EORTC QLQ-30 Emotional Function outcome than in the GP surgery setting in the OUTREACH trial; there were no statistically significant differences between home and hospital settings. 4,35

One trial used Functional Living Index Cancer (FLIC) scores as a measure of quality of life and found that setting (home vs. outpatient) had no effect on either total FLIC scores or any of the seven dimension scores. 31 The remaining trial studied 23 children using the Paediatric Oncology Quality of Life Survey (POQOLS). 33 It found statistically significant improvement associated with the home setting, compared with the outpatient setting, in terms of sensitivity to restrictions in physical functioning and the ability to maintain a normal physical routine. There were no statistically significant differences between the settings in terms of emotional distress and reaction to current medical treatment.

Clinical and psychological outcomes

Two trials reported results for EORTC QLQ-C30 self-rated health (see Table 1). 4,35 Both suggested that there was no difference between the home and outpatient settings. One trial compared GP and outpatient settings and GP and home settings and reported no statistically significant differences. The other study evaluated Karnofsky Index scores and reported identical scores for the home and outpatient settings.

Two trials evaluated participants using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 4,29 Results from one trial suggested that higher levels of both anxiety and depression were associated with the GP setting, compared with the home or outpatient settings, but the results were statistically significant only for the GP versus outpatient comparison (for depression). There was little indication of any meaningful differences between the home and hospital settings. The other trial did not report any data, but stated that there were no significant differences between the community hospital and outpatient settings for both anxiety and depression.

Satisfaction and preferences

Five trials reported quantitative results for satisfaction (and related outcomes). Specific outcomes varied between studies (see Table 1). Two trials reported statistically significant results suggesting satisfaction benefits in terms of nursing care for the home and community settings, compared with the outpatient setting. 29,35 The largest study (OUTREACH) that compared home, GP surgery and outpatient settings in the UK reported that 78% of participants were satisfied with their treatment setting, regardless of location. 4 An Australian trial reported that significantly more patients found the outpatient setting more depressing than the home setting, although no significant differences were found for patient needs. 31 Other studies suggested no differences between groups in terms of global satisfaction,29 or doctor-care outcomes. 35

Five trials reported quantitative results for preferences, but only one of these trials evaluated strength of preference. 31 In the four trials where patients experienced two settings (because a crossover design was used) between 70% and 95% of patients preferred the home setting,31,32,34 and 97% preferred a community outreach setting,29 when compared with the outpatient setting. One trial stopped recruiting participants early owing to the strong preferences expressed for home treatment. 34

Results from the study that considered strength of preference suggested that preferences were not very strong. It found that 34% of the participants who preferred home treatment changed their preference to outpatient treatment if home treatment was to involve waiting an extra hour, and that 27% of participants who preferred outpatient treatment changed their preference to home treatment if faced with an extra hour of waiting. 31 These results suggest that for some patients time is more important than setting. This trial was the only study to consider the issue of recruitment bias. The authors performed an additional analysis of patient preference by also including the 13 patients who chose not to participate in the trial for setting-related reasons, which they interpreted as a preference for the outpatient setting; similarly, this analysis also included the eight patients who chose not to receive home treatment after experiencing outpatient treatment (see Appendix 3). The results indicated that the proportion of patients who preferred home care to outpatient care was 48%.

Safety

Six trials reported on adverse events (see Table 1). Four trials provided some assessment of whether adverse events were related to setting (e.g. in one trial a nurse was unable to cannulate an outreach patient, who was consequently treated at the cancer centre). 4,29,32,33 They found no evidence to suggest significant differences existed between settings for any type of adverse event. Two studies evaluated only toxicity and also found no differences between settings. 28,35

Full result details for all outcomes are presented in Appendix 5.

Non-randomised studies

Study characteristics

Fifteen non-randomised, comparative studies investigated the effect of setting for patients receiving intravenous chemotherapy; they were reported between 1989 and 2013 (Table 2). 24,36–49 Several studies were not easy to identify or access: four were reported only as conference abstracts,42,44,47,48 one was only available as a Ph.D. thesis,24 one was an unpublished internal report36 and one was only available as an online report. 37 Five studies took place in England,24,36,39,44,46 four in the USA,42,43,47,48 two in Denmark38,41 and one each in Wales,40 Australia,45 Canada37 and France. 49

| Study | Country | Sample size | Setting | Outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | Community | Outpatient | ||||

| Taylor 200824 | England | ≈ 140 | ✓ | ✓ | Qualitative data on provision of care at home from health professionals and patients | |

| NHS Bristol 201036 | England | 848 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Patient experience |

| Pong et al. 200037 | Canada | 435 | ✓ | ✓ | Self-reported health status, costs, satisfaction; reasons for choosing setting | |

| Hansson et al. 201338 | Denmark | 75 | ✓ | ✓ | Patient- and parent-reported health-related quality of life, psychological impact on family, costs | |

| Mitchell 201139 | England | 20 | ✓ | ✓ | Patient experience (qualitative), satisfaction, costs | |

| Barker 200640 | Wales | 14 | ✓ | ✓ | Toxicity, satisfaction | |

| Frølund 201141 | Denmark | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | Qualitative data on experiences of chemotherapy | |

| aGrusenmeyer et al. 199642 | USA | NR | ✓ | ✓ | Costs, satisfaction | |

| Herth 198943 | USA | 80 | ✓ | ✓ | Hope, coping | |

| aIngleby et al. 199944 | England | 25 | ✓ | ✓ | Costs | |

| Lowenthal et al. 199645 | Australia | 179 | ✓ | ✓ | Safety, costs, resource use | |

| Payne 199246 | England | 53 | ✓ | ✓ | Quality of life, Karnofsky performance | |

| aSatram-Hoang and Reyes 201147 | USA | ≈ 2800b | ✓ | ✓ | Time to treatment initiation, duration of treatment, number of cycles delivered, compliance | |

| aSouadjian et al. 199248 | USA | Unclear | ✓ | ✓ | Costs, complications, quality of life, preference | |

| Vergnenègre et al. 200649 | France | 20 | ✓ | ✓ | Adverse events, costs | |

In three studies,24,39,41 the only review-relevant outcomes were qualitative (see Results, Qualitative studies). In the remaining 12 studies, eight compared the home and outpatient settings,38,42–46,48,49 two compared community settings with outpatient settings,37,47 one compared home with community settings40 and one compared all three types of settings. 36 Population sizes were not always clearly reported, but ranged from 14 to around 2800 patients (more than half of the studies were of fewer than 100 patients). Most studies were of mixed populations; most patients had colorectal cancer, breast cancer or lung cancer. Mean ages ranged from 50 years to 75 years, where reported. One study was in children with leukaemia or lymphoma and was the only study which indicated where the chemotherapy drugs were prepared; this study also clearly reported setting details (e.g. home care was provided by one or two nurses, depending on the tasks involved). 38 In other studies the setting details were not generally well reported; exceptions were descriptions of a community mobile chemotherapy unit,39 and community oncology clinics. 37 Full study characteristics are reported in Appendix 7.

Risk of bias

Table 3 details the results of the risk of bias assessment of the non-randomised studies. Most studies were judged to be at a high or unclear risk of bias due to confounding. Although four studies did consider the effect of confounders in their study design and/or analysis plan, they did not investigate all the likely confounders. The two studies which were given a low-risk judgement both reported adverse events as their only review-relevant clinical outcome; the types of adverse event assessed were unlikely to have been affected by any confounding factors in the populations studied.

| Study | 1. How were the groups formed? | 2. Were the effects of any confounders taken into consideration during the design and/or statistical analysis stages? | 3. What methods were used to control for confounders? | 4. Were the data on the measured confounders recorded precisely enough? | 5. Were any key confounders not controlled for? | Risk of bias from confounding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowenthal et al. 199645 | Oncologist decision as to which patients were offered a choice (based on having satisfactory home circumstances, and type of chemotherapy) | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | Likely to be low risk, as complications (requiring hospital admission) was the only clinically relevant outcome (unlikely to be affected by confounding) |

| Payne 199246 | Oncologist preference | Yes, diagnostic category, Karnofsky score and age were found not to be related to several quality-of-life variables | Stratified analyses for age. Stepwise multiple regression for Karnofsky score. Unclear for diagnostic category | Yes | Yes, stage of cancer. The authors acknowledged that patients who were more severely ill were more likely to be treated in the outpatient setting. Illness severity was not assessed | High |

| Herth 198943 | Non-random, convenience sample | Yes, stage of disease, age and extent of illness were considered | Matching for stage of disease. No details provided for age and extent of illness, just that they ‘were not identified as confounding variables’ | Yes | Yes, type of cancer, type of chemotherapy, performance status, and quality of life were not considered | High |

| Satram-Hoang and Reyes 201147 | Selection of retrospective cohorts from a database | It appeared so, but the study was only reported as an abstract so details were limited | Stratification and ANOVA | Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

| Souadjian et al. 199248 | Unclear | Not reported – reported only as an abstract | N/A | N/A | N/A | Unclear |

| Hansson et al. 201338 | Based on distance from home to hospital. Historical controls were also used for outpatient setting | Yes, age, diagnosis, gender and time since diagnosis | Multiple linear regression | Unclear whether or not categories were used for ‘age’, and ‘time since diagnosis’ (rather than treating them as continuous variables) | Yes, stage of cancer, type of chemotherapy, quality of life and distance from hospital | High |

| Pong et al. 200037 | Retrospective random selection of patients from a database | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | High |

| Barker 200640 | Unclear | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | Higha |

| NHS Bristol 201036 | Patient choice | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | High |

| Vergnenègre et al. 200649 | Unclear (beyond home eligibility criteria) | Not reported | N/A | N/A | N/A | Likely to be low risk since incidence of grade III or IV toxicity was the only outcome of interest, unlikely to be affected by confounding |

Non-randomised study results

Three studies evaluated quality of life but their results did little to augment the RCT evidence: two studies were small, with a high risk that confounding would affect the reliability of their results; and one study was reported only as an abstract (making it difficult to interpret the results). 38,46,48 There were similar issues for the four studies of patient satisfaction. 37,39,40,42 One study included 435 patients but they were selected retrospectively, with no consideration made for confounding factors; and the study was in Canada, where the travel time and distances are different from those likely to be encountered in the UK. 37

Only one of the four studies which had a safety outcome yielded informative results;45 this Australian study reported that complications in the home setting were rare, although no comparative data were reported for the outpatient setting for this particular outcome. Two of the three other studies that looked at safety had very small sample sizes,40,49 and the other was only reported as an abstract. 48 Three studies that looked at qualitative patient experience are discussed in Results, Qualitative studies.

Only one comparative study looked at the issue of treatment compliance in any detail. 47 It was conducted in the USA and studied approximately 2800 follicular lymphoma patients receiving chemotherapy [with or without rituximab (Mabthera, Roche)]. The study concluded that patients treated in the outpatient setting tended to have longer times to treatment initiation and fewer cycles across all regimens, and were less likely to receive a compliant dosing schedule than patients treated in a community clinic setting. However, the reliability of these conclusions was unclear as the study was only reported as an abstract (the risk of bias due to confounding was unclear). The results for all the non-randomised studies are presented in Appendix 5.

Cost data

Fourteen comparative studies reported costs as an outcome (see Tables 1 and 2). Cost data were recorded only to help inform the decision modelling part of the report and are presented in Appendix 6.

Clinical results evidence summary

The included studies revealed inherent difficulties in conducting randomised trials of chemotherapy settings. Even trials that were designed appropriately to minimise avoidable biases faced problems not only of patient accrual but also of recruiting a population to enable an unbiased evaluation of the settings. These seemingly unavoidable selection biases might be expected to produce results that favour home (or community) settings. Even so, there was little evidence of clinically relevant differences between settings in terms of quality of life and clinical and psychological outcomes. The only potentially meaningful differences were seen for some patient satisfaction and preference outcomes. However, strength of preference was studied in only one trial, with preferences appearing not to be strong in around one-third of patients. The limited safety evidence available suggested there were no differences between settings.

The non-randomised studies added little to the randomised trial evidence (although community settings were more frequently studied). The main limitations were the small populations and the high risk that study results were biased due to confounding.

Cost-effectiveness studies

Study characteristics

Nine economic evaluations published between 1996 and 2013 met the criteria for inclusion. The key characteristics, methods and results for the nine studies are summarised in Table 4. Details of patient characteristics and treatment regimens can also be found in Table 4. All nine evaluations also met the inclusion criteria and have been assessed independently as comparative studies.

| Study characteristics | Main analytical approaches | Primary outcomes and health-related quality of life | Resource use | Cost analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rischin et al. 200032 (full paper) Country: Australia Settings: home; hospital outpatient |

Economic evaluation alongside a RCT (crossover, n = 25 recruited, n = 20 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CCA) Perspective: hospital Time horizon: two chemotherapy cycles |

Patient preference and satisfaction All patients preferred remaining treatment at home. 0% reported concerns with home treatment, 20% had concerns with hospital. 90% felt that there were advantages to home, 5% hospital |

No resource use data reported Cost categories: nurse time and travel, vehicle costs, one meal in hospital. Unclear if drug costs included |

Price year NR Home associated with average increased cost of AUS$83 per treatment vs. hospital (95% CI AU$46 to AU$120; p = 0.0002) First treatment AUS$57 more expensive than second treatment on average (95% CI AUS$20 to AUS$94, p = 0.0044) |

| King et al. 200031 (full paper) Country: Australia Settings: home; hospital outpatient |

Economic evaluation alongside a RCT (crossover, n = 74 recruited, n = 40 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CCA) Perspective: health service Time horizon: 4 months |

Patient preference and strength 73% (95% CI 59% to 86%; p = 0.008) preferred home. Strength of preference was low. Preference dropped to 48% (95% CI 35% to 60%; p = 0.61) when accounting for preferences of withdrawn patients (p-value testing if = 50%). No apparent differences in quality of life (FLIC score) between settings |

No resource use data reported Cost categories: nurse cost, travel time, vehicles, equipment, cost of capital and overhead costs. Individual category costs reported |

Price year NR Net additional cost of home vs. hospital: AUS$68.81. Additional cost attributed to extra nurse time Cost of new chemotherapy ward = AUS$70,581. Home chemotherapy less expensive per treatment than a new ward used with up to 50% ward capacity. New ward less expensive above 50% ward capacity |

| Lowenthal 1996 et al.45 (full paper) Country: Australia Settings: home (included workplaces, GP offices, day-care centres); hospital outpatient |

Analysis based on a retrospective non-randomised audit (n = 184 recruited, n = 179 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CMA) Perspective: hospital Time horizon: 5 years for safety, 1 year for costs |

Safety: single setting (number of major complications at home only) One major complication among visits to 179 patients. Assumed this would be at least as safe as in the hospital (no data for hospital) The authors appeared to assume equal efficacy between settings |

Reported number of visits, duration, travel and preparation time Cost categories: labour, travel, hospital resources, pharmaceuticals and overheads (drug costs assumed the same). Individual cost category costs reported |

Price year: 1994 AUS ($) Cost per home chemotherapy treatment: AUS$49.93. Hospital: AUS$116.00 Annual cost to deliver 345 chemotherapy treatments and additional services for 65 patients in the hospital (extending hours): AUS$38,207. Home: AUS$45,767 |

| Corrie et al. 20134 (full paper) Additional data from personal communication with author Country: UK Settings: home; GP surgery; community (GP + home); hospital outpatient |

Economic evaluation alongside a RCT (n = 97 recruited, n = 57 evaluated) Analysis: CUA Perspective: NHS Time horizon: 12 weeks |

EORTC QLQ-C30 QoL Emotional Function domain: No difference for community vs. hospital. Home vs. GP: 15.2, 95% CI 1.3 to 29.1; p = 0.033 (favoured home). GP vs. hospital: –16.6, 95% CI –31.4 to –1.9; p = 0.028 (favoured hospital) EQ-5D: No significant differences. Unadjusted mean (SD) QALY home: 0.165 (0.036); GP: 0.191 (0.04); hospital: 0.174 (0.034). Based on 14 hospital patients, 15 GP, 19 home (complete-case analysis) Patient preference: 57% of hospital patients preferred future treatment in hospital, 81% GP, 90% home |

Resource use data collected from nurse diaries and Client Service Receipt Inventory Unit costs from PSSRU (included salaries and overheads) Cost categories: inpatient, outpatient, day hospital, A&E visits, community care, medication, and nurse diaries contact. Nurse travel (not patient) included |

Price year: 2010 GBP Home: £2139 (SD £1590); GP: £2497 (SD £1759) Hospital: £2221 (SD £1831) ICER GP vs. hospital = £16,235/QALY gained |

| Pace et al. 200929 (full paper) Country: UK Settings: community hospital; hospital outpatient |

Economic evaluation alongside a RCT (crossover, n = 42 recruited, n = 31 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CCA) Perspective: NHS and patient Time horizon: completion of treatment |

Patient preference and satisfaction 30/31 (97%) patients chose to receive remaining cycles of treatment in the community hospital and would have preferred to receive all their chemotherapy there |

Service-related resource Average round-trip mileage from main hospital to community centres = 24.2 miles Total time of 104 minutes for each treatment Two nurses for each treatment Patient-related resource Average patient distance from community clinic = 10.25 miles vs. 19 miles to hospital |

Price year NR Service costs: Average cost of round-trip = £12.83 per clinic session. Opportunity cost of travel for each nurse (based on £29,538 salary) was £32.08 (£64.16 for two nurses, £384.96 for six cycles = marginal cost of clinic) Patient costs: Mean cost of travel and parking for patients to outreach = £4.85/treatment vs. £8.77 for hospital. Including private car and public transport cost, average cost to attend outreach = £8.07 vs. £14.99 to hospital |

| Stevens et al. 200633 (full paper) Country: Canada Settings: home; hospital outpatient Paediatric population |

Economic evaluation alongside a RCT (crossover, n = 29 recruited, n = 23 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CCA) Perspective: societal Time horizon: 1 year |

POQOLS QoL questionnaire Factor 1 (normal physical routine): switching to home led to an improvement, switching to hospital led to a worsening (–10.5 for home vs. + 5.2 for hospital p = 0.023) Factors 2 and 3 (emotion and reaction): no significant differences due to crossover. Comparison using end of 6-month data; children at home had significantly higher emotional distress than at hospital (p = 0.043) Child Behaviour Checklist No significant differences |

No resource use data reported Parents provided resource use data for physician/care provider visits, medications/supplies, babysitting, travel and productivity losses. Cash transfer effects were assessed (unemployment insurance, workman’s compensation, mother’s allowance) Costs excluded health professionals who administered chemotherapy and drug costs |

Price year NR Total societal costs were reported for each setting at three time points. At 1 year (last time point): home (n = 13), median CAD$851 (range $147–8726); hospital (n = 9), median CAD$1050 (range $29–10,278); p = 0.95 Home had higher costs at baseline, and lower costs at 6 and 12 months. No evidence that costs were affected by location of treatment The difference between family costs associated with home vs. hospital was not significant (p = 0.79) (no family costs reported) |

| Vergnenègre et al. 200649 Country: France Settings: home; hospital outpatient |

Analysis based on non-randomised comparative study (n = 20 recruited, n = 20 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CCA) Perspective: health service Time horizon: NR |

Adverse events Home: two adverse events in 24 cycles Outpatient: seven adverse events in 30 cycles Not statistically significant difference (p = 0.27) |

Resource use for home Home visit nurse time = 130 minutes (€0.25/minute) Administrative costs = 30 minutes (€0.19/minute) Co-ordination costs = 30 minutes (€0.40/minute) Hospital costs were reported as aggregates with/without comorbidities. Home treatment costs included chemotherapeutic drugs, nursing, co-ordination, administration, disposables, transportation, GP visits and non-chemotherapeutic drugs |

Price year NR Average cost per cycle was €2829.51 (95% CI €2560.74 to €3147.02) for hospital infusion, €2372.50 (95% CI €1962.75 to €2792.88) for home-based care (–16.15%). Difference was €–457.01 by cycle (95% CI –€919.74 to €26.82) in favour of home. Real costs by injection for home was €484.42 (95% CI €424.18 to €540.32) vs. a fee of €699.89 (95% CI €643.64 to €750.23) (–30.79%)a |

| Remonnay et al. 200234 (full paper) Country: France Settings: home (managed by an external association – Soins et Santé); hospital outpatient |

Economic evaluation alongside a RCT (crossover, n = 52 recruited, n = 42 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CCA) Perspective: societal Time horizon: four treatments |

Patient satisfaction 95% of first 52 patients preferred chemotherapy at home, recruitment discontinued after that point |

No resource use data reported Costs categories: personnel, medication, transport, laundering and overhead |

Price year: 1998 USD Marginal cost (i.e. excluding overhead costs) for one treatment home vs. hospital: US$232.5 vs. US$157; p < 0.0001 Average cost (including overheads): $252.6 vs. $277.3; p = 0.002 Category costs reported in paper |

| Hansson et al. 201338 (full paper) Country: Denmark Settings: home; hospital outpatient Paediatric population |

Economic evaluation alongside a non-RCT (n = 89 recruited, n = 75 evaluated) Analysis: CEA (CCA) Perspective: hospital Time horizon: 2 years |

PedsQL scale Trend towards higher home-care QoL Parent Proxy Cancer Module Significantly better physical health and less worry for children in the home-care group Child Self-Reported Cancer Module; Family Impact Module No significant differences |

No resource use data reported Cost of home-care service included nurse wages, car hire, fuel, parking, new nurse uniforms, nursing bags, equipment, safe storage and hospital overhead costs (administration) |

Price year NR Hospital charge for home visit: US$597 Hospital visit: US$600 Disaggregated costs for categories of home-care cost reported in Danish krone in linked study |

Three of the evaluations were conducted in Australia,31,32,45 two in the UK (England),4,29 two in France34,49 and one in each of Canada33 and Denmark. 38 Most studies assessed adult populations; two studies assessed paediatric populations. 33,38 Six evaluations were conducted alongside RCTs, two alongside non-randomised controlled studies,38,49 and one was conducted as part of a retrospective audit. 45 Most studies did not conduct a full incremental analysis i.e. to produce [incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs)], but instead reported cost and health outcomes separately. Costs and outcomes were generally assessed over a short time horizon (1 year or under).

All of the non-UK studies compared treatment delivered in the home with treatment delivered in a hospital outpatient setting. 31–34,38,45,49 The two UK studies included community settings: Pace et al. 29 compared treatment delivered in a community hospital setting with treatment delivered in a hospital outpatient setting; and OUTREACH4 compared home, GP surgery and hospital outpatient settings. None of the economic evaluations assessed the delivery of chemotherapy by mobile bus units. One study assessed the delivery of home chemotherapy by a third-party charity organisation. 34 In all other studies it was implied that home/community care was delivered by the health service.

As highlighted in the clinical study sections, most studies assessed mixed populations with various cancer types, including breast cancer, colon cancer, lung cancer, gastrointestinal cancer, lymphoma, pancreatic cancer and leukaemia. One study assessed only patients with acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. 33 An array of treatment regimens was used for a mixture of curative, supportive and palliative intent. The populations appeared to be heterogeneous in terms of disease severity.

The nine evaluations conducted alongside clinical studies recruited a total of 593 patients and 487 participants were evaluated in the concurrent economic evaluations. Most of these participants were evaluated in the two non-randomised studies; 179 patients were evaluated in the retrospective audit45 and 75 were evaluated in the controlled study. 38 The six evaluations made concurrently with RCTs were based on small data sets:4,29,31–34 the largest study (OUTREACH)4 had complete primary outcome data (EORTC QLQ-C30 Emotional Function subdomain) on only 57 participants across three treatment arms/settings. Chapter 6 contains an overview of recruitment and participation within the RCTs (see Limitations of the evidence and of the review). The number of participants informing the concurrent cost-effectiveness analysis is presented in Table 4, alongside other study characteristics and findings.

Economic quality assessment

The Drummond checklist was used to assess methods and reporting in the nine included economic evaluations. 20 Clinical studies undertaken alongside the economic evaluations were assessed for risk of bias as part of the quality evaluation of comparative studies (see Table 3 and Appendix 4). All of the evaluations suffered from limitations, as highlighted by the checklist. Many did not undertake appropriate data collection and/or sensitivity analyses. Seven of the nine studies reported no data on resource use outcomes, which significantly reduces the transparency and transferability of the results. Five studies reported disaggregated costs (costs for each of the included cost categories rather than a total cost only), but the usefulness of such costs in terms of informing potential UK NHS cost estimates is limited without resource use data. Reporting of methods used to derive cost and resource use outcomes was limited and this made the validity of the cost estimates unclear. Most studies failed to report the price year or any cost adjustments applied. None of the studies conducted an adequate analysis of the potential impact of uncertainty on the results; all three studies that included sensitivity analyses were limited in scope. Most studies failed to consider the generalisability of their results. Full results for the quality assessment can be found in Table 5.

| Item | Response by study | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rischin et al. 200032 | King et al. 200031 | Lowenthal et al. 199645 | Pace et al. 200929 | Stevens et al. 200633 | Vergnenègre et al. 200649 | Remonnay et al. 200234 | Hansson et al. 201338 | Corrie et al. 20134 | |

| Study design | |||||||||

| 1. The research question is stated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2. The economic importance of the research question is stated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3. The viewpoint(s) of the analysis are clearly stated and justified | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No |

| 4. The rationale for choosing the alternative programmes or interventions compared is stated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. The alternatives being compared are clearly described | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6. The form of economic evaluation used is stated | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| 7. The choice of form of economic evaluation is justified in relation to the questions addressed | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Data collection | |||||||||

| 8. The source(s) of effectiveness estimates used are stated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9. Details of the design and results of effectiveness study are given (if based on a single study) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 10. Details of the method of synthesis or meta-analysis of estimates are given (if based on an overview of a number of effectiveness studies) | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 11. The primary outcome measure(s) for the economic evaluation are clearly stated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 12. Methods to value health states and other benefits are stated | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| 13. Details of the subjects from whom valuations were obtained are given | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No |

| 14. Productivity changes (if included) are reported separately | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 15. The relevance of productivity changes to the study question is discussed | N/A | N/A | N/A | No | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 16. Quantities of resources are reported separately from their unit costs | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Partially | No | No | No |

| 17. Methods for the estimation of quantities and unit costs are described | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 18. Currency and price data are recorded | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 19. Details of currency of price adjustments for inflation or currency conversion are given | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 20. Details of any model used are given | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 21. The choice of model used and the key parameters on which it is based are justified | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Analysis and interpretation of results | |||||||||

| 22. Time horizon of costs and benefits is stated | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | No | No | Unclear | Yes |

| 23. The discount rate(s) is stated | No | N/A | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | No | No | No |

| 24. The choice of rate(s) is justified | Unclear | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

| 25. An explanation is given if costs or benefits are not discounted | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 26. Details of statistical tests and confidence intervals are given for stochastic data | Yes | Yes | N/A | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 27. The approach to sensitivity analysis is given | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | Yes |

| 28. The choice of variables for sensitivity analysis is justified | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | No | N/A | No |

| 29. The ranges over which the variables are varied are stated | N/A | Yes | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes | Yes | N/A | N/A |

| 30. Relevant alternatives are compared | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Partially |

| 31. Incremental analysis is reported | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Partially |

| 32. Major outcomes are presented in a disaggregated as well as aggregated form | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Partially | Yes | N/A | No |

| 33. The answer to the study question is given | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 34. Conclusions follow from the data reported | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 35. Conclusions are accompanied by the appropriate caveats | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 36. Generalisability issues are addressed | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No |

Overall, the studies were deemed to be of low or uncertain quality due to small sample sizes; limited reporting on resource use, costs and methodology; and lack of robust sensitivity analyses. There is likely to be significant uncertainty around the cost-effectiveness results.

Economic study results

Health outcomes

Several health outcomes were assessed in the nine economic evaluations: EORTC QLQ-C30, FLIC scores, safety and adverse events, patient satisfaction and patient preferences. It was unclear why only one economic evaluation reported quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) outcomes when these would better facilitate modelling.

There was no robust evidence of any meaningful between-setting differences for most health outcomes (EORTC QLQ-C30, FLIC scores, safety and global satisfaction). There was less than robust evidence that emotional functioning, anxiety and depression were improved in the home and outpatient settings compared with a GP surgery (OUTREACH)4 and that satisfaction was higher in the home than in the outpatient setting in terms of nursing care and the depressive nature of the setting. 29,31 Evidence in the child population was limited. Children’s quality of life was improved in the home setting, compared with an outpatient setting. 33 A full description of these health outcome results, as measured in the trials, is presented in Results, Clinical effectiveness studies.

OUTREACH measured patient utility across outpatient, home and community (GP practice) settings in a UK population using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire. 4 The study recruited 97 participants: 57 patients provided data for analysis of the primary end point EORTC QLQ-C30 and 48 provided EQ-5D utility scores; there were no details of why nine patients provided data on the primary outcome but not for EQ-5D.

The OUTREACH publication4 reported total QALYs gained but not baseline values. Mean differences from baseline over a 12-week period showed that the community setting produced the largest change [0.191 QALYs; standard deviation (SD) 0.04 QALYs], followed by hospital outpatient (0.174 QALYs; SD 0.034 QALYs), and home (0.165 QALYs; SD 0.053 QALYs).

The OUTREACH authors provided us with an analysis of the difference in mean differences adjusted for baseline EQ-5D utility values. With adjustment for differences in baseline QALYs, hospital outpatient chemotherapy was found to produce the most QALYs and was used as the reference for other treatment settings. Compared with the outpatient setting, the community setting (GP practice) had a mean difference of –0.009 (p = 0.0471) and the home setting had a mean difference of –0.010 (p = 0.374) (P McCrone, Centre for the Economics of Mental and Physical Health, Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, personal communication). These data implied that patients treated in a GP/community and hospital settings had a lower health-related quality of life at baseline, suggesting that they might have been in a poorer health state than participants who were treated at home.

There were significant limitations with these data. In particular, they were based on a small number of patients (19 or fewer in each treatment arm) and both the adjusted and unadjusted QALY results were subject to significant uncertainty. None of the results achieved statistical significance and it would be inappropriate to draw definitive conclusions on the basis of these data.

Resource use and costs

Reporting for resource use and costs across the nine economic evaluations was variable. Cost categories and perspectives were similarly inconsistent. These inconsistencies in resource use and perspectives across the economic evaluations make it difficult to ascertain any objective trend in favour of one treatment setting over another.

Only two studies reported resource use, an Australian study45 and a UK study,29 but details were limited to travel and labour. Both studies reported resource use for nurse travel to community or home settings. 29,45 Pace et al. 29 reported resource use for patient travel, in addition to nurse travel, to a community outreach site, and the number of nurses needed to deliver the service in the community setting. Lowenthal et al. 45 reported hours spent on delivering treatment as well as time spent travelling and preparing treatments.

Costs across the included evaluations varied widely. Most studies were from non-UK settings, which can limit the generalisability of resource use and cost data to the NHS and reduced their usefulness in informing a de novo model for this review. Costs and resource use across the countries vary greatly owing to differences in health-care delivery systems and differences in the prices paid for services.