Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1011/67. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in February 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

this report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Lea et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

A lack of ‘joined-up’ working between the health and social care sector and the criminal justice system (CJS) has been reflected in a number of tragic events, resulting in serious case reviews and subsequent inquiries. 1–5

The aim of the Interface Project was to examine and explore current practice relating to the management of individuals with enduring moderate to severe mental health needs (EMHN), specifically at those points where they interface with the NHS and CJS, and to ascertain how such practice can be enhanced. Three stages of work were conducted, each guided by a set of research questions.

Stage 1

-

1. How are the practice implications of current national policy relating to the management of individuals with EMHN being interpreted at local level?

-

2. How has Cornwall articulated national policy into practice benchmarks where the NHS and police are required to work together?

Stage 2

-

3. What are the organising principles that precipitate a joint working decision, by either the NHS or the police?

-

4. What is the decision-making process and who is involved in it?

-

5. Is the decision-making process consonant with local practice guidelines and national policy implications?

-

6. What is the impact of these decisions on the service user?

-

7. What is the impact of these decisions on the NHS and police organisations?

-

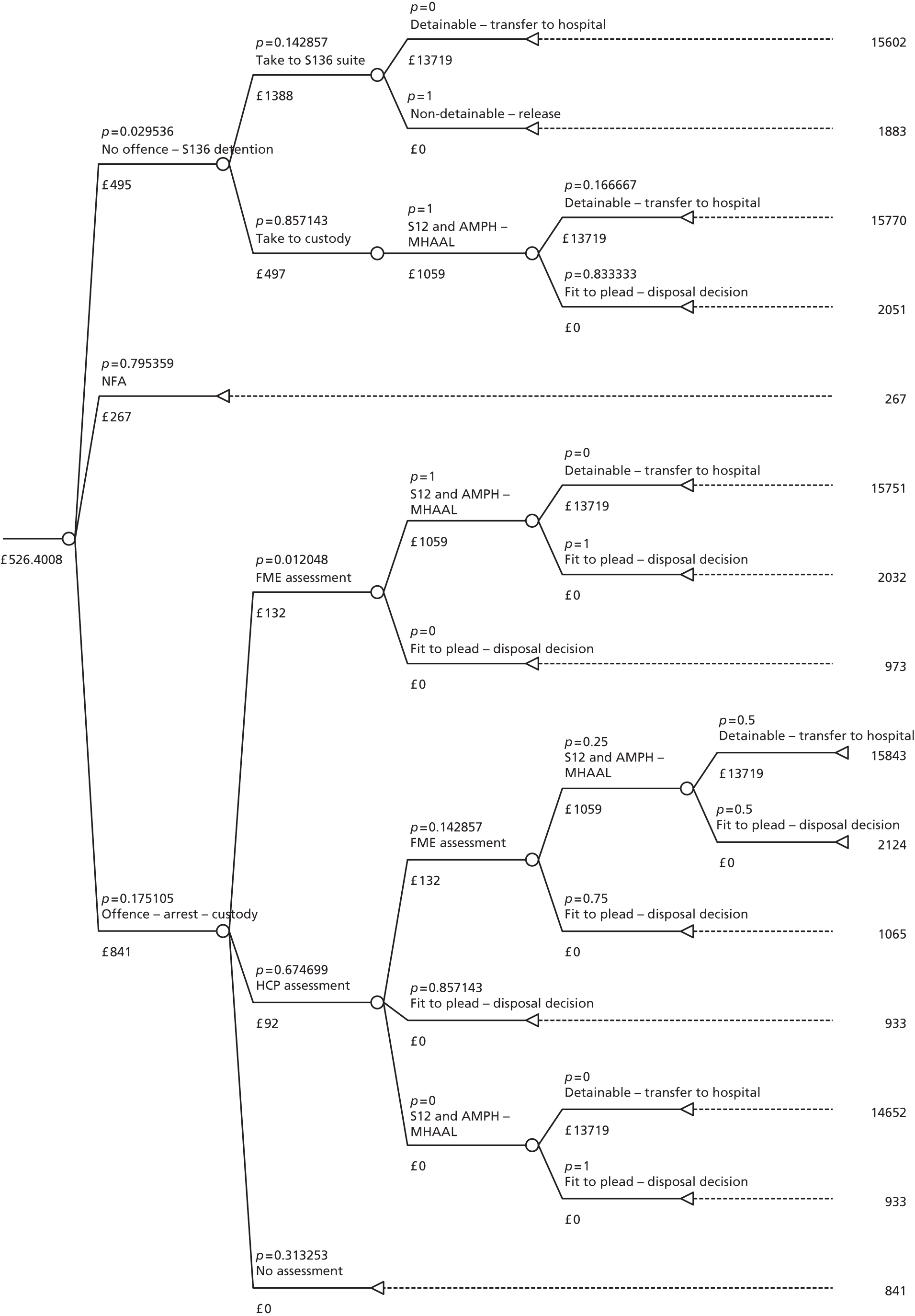

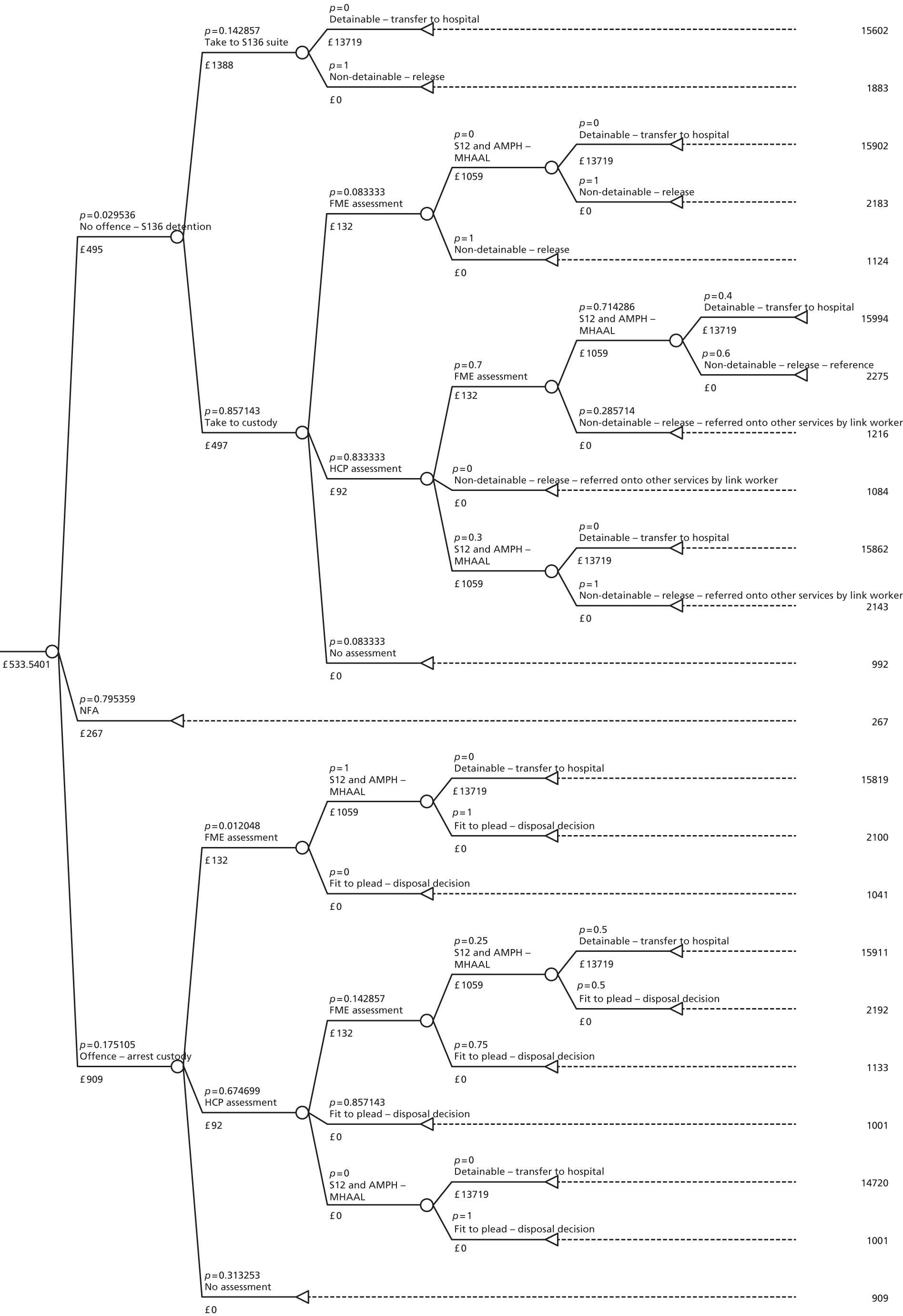

8. What are the economic costs associated with current and potentially enhanced practice?

Stage 3

-

9. What are the barriers and facilitators to the multiagency management of individuals with EMHN?

-

10. What are the implications of the research for national policy and practice?

The research project became known as the Interface Project in the early stages of the work in order to contextualise the work and provide the research with an identity. The terms ‘research project’ and ‘Interface Project’ are therefore used interchangeably throughout the report.

Chapter 2 Background

The national context

Throughout the last 20 years, and especially the latter part of the last decade, there has been an escalating debate about how individuals with EMHN might best be managed within and between the NHS and CJS. It is widely recognised by mental health practitioners, the police and the courts that these individuals repeatedly come to the attention of the CJS, with their journey into and out of the CJS being conceptualised as a ‘revolving door’. 6 The Department of Health (DH) has been proactive in commissioning a considerable amount of research in an effort to understand how this cycle might be broken. In 1992, Dr John Reed, in the first of a series of reports, reviewed ‘health and social services for mentally disordered offenders and others requiring similar services’. 7 Among the many recommendations made, Reed stressed that a flexible, multiagency, partnership approach was essential to bring about change.

It is unfortunate, but telling, that 21 years on, Reed’s primary recommendation has been only partially heeded. Indeed, the term ‘silo working’8 has been used to describe the paucity of interaction and engagement between services. Lord Bradley’s inquiry into how people with ‘mental health problems or learning disabilities’ fare within the CJS conceded that since Reed, little had changed except the ‘political and social context’. 6 Baroness Corston’s equally wide-ranging review of ‘women with particular vulnerabilities in the CJS’ identified similar shortcomings to Bradley, but suggests too that where women are concerned, a radically different and holistic approach is required. 9 Rutherford explored the extent to which interagency working or ‘convergence’ has developed, the obstacles that still exist to a wider take up, and the limits that (may) need to be applied to the convergence process to retain professional and ethical boundaries. 8

Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) has encouraged the police to embrace the operational and financial benefits to be had from partnership working in all areas of policing;10 Flanagan, in his comprehensive review of policing, arrived at the same conclusions. 11 Perhaps with one eye to the extensive post-Bradley implementation process, the National Policing Improvement Agency in conjunction with the DH produced detailed guidance on how the police should respond to people with ‘mental ill-health and learning disabilities’. They, like others, identify that police officers have little or no formal training in diagnosing or dealing with mental ill-health. 12

Although mental ill-health is not indicative of any latent propensity to criminality or dangerousness, stereotypically, those who live with it are invariably perceived to be predisposed or inclined to both. On the street, where the police are both the first and last resort in dealing with individuals deemed to be experiencing mental ill-health, the ‘successful resolution’ of an incident – the bridge jumper, for example – depends on the unique contextual details of the event in question. These, in turn, will determine the legal powers available to the officer and the sort of action he or she may take. The process of rationalising and interpreting these contextual and legal elements is, of course, informed by the ideological imperatives (the received wisdom) of the police organisational milieu; this may well be quite different to the occupational imperatives of the mental health professional, the social worker, ambulance staff, or general medical practitioners. Moreover, the police imperative may very well conflict or compete with the occupational imperatives of others and the long-term prognosis of the individual concerned. For those whose levels of ‘dangerousness’, criminality and psychiatric diagnosis are such that they are not subject to any formal interagency process such as Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements (MAPPA) or Safeguarding Children or Vulnerable Adult protocols and procedures, this is especially so. As many practitioners within the CJS and the statutory and voluntary mental health services have long been aware, these ‘gaps’ in the system are what ensure that many individuals with mental ill-health are destined to make unnecessary and inappropriate forays into the CJS. For a large number of people, this experience is as damaging as it is avoidable.

The need for research

The research literature calls for increased cross-sectoral case- or data-linkage studies to examine service users’ interaction with services to enhance service user outcomes (e.g. Ferrante13). Furthermore, such methods are useful in enabling researchers to identify service user outcomes for populations such as those targeted in this study, which are often considered marginalised or hard to reach. 14 Triangulating data contained in routinely collected data sources with primary data enables not only a holistic picture of the service user experience to be obtained, but also connections between and utilisation of findings to be understood. For example, there has been a recent call for longitudinal studies that include the analysis of administrative or secondary data in combination with validation through primary data collection to provide comprehensive understanding of interactions between services. 15 The Interface Project responded to these suggestions through the qualitative analysis of predominantly secondary data together with a small amount of primary data to enable a ‘thick description’16 of service user journeys and inter- and intra-agency decision-making to be obtained, examined and understood. This broad application of qualitative methodologies fulfils recommendations for the wider use of qualitative methodologies in mental health research to enable the exploration of research areas that are not conducive to the application of purely quantitative methods. 17 The current study also seeks to address three research priorities identified through a consultation exercise:

-

researching care pathways and transitions between services (in this case within and between the CJS and mental health services)

-

research to improve the quality of mental health care in the CJS (through understanding the interactions between CJS staff and service users and mental health professionals)

-

enabling meaningful involvement of service users in the planning and delivery of services (through involvement and consultation of service users on and with the project team and via consultation with service users regarding project findings, and developing implications for research through focus groups). 17

A great deal of the existing research identifies or acknowledges the ‘gaps’ that exist in the interface between CJS and NHS mental health service provision, and the sort of individuals who regularly find themselves falling into those interagency voids. The practicalities of implementing a ‘national intention’ are complex, and necessarily subject to a local interpretation: for example, for a variety of contextual reasons what works well in cosmopolitan inner city London may be less likely to succeed if transplanted to the more isolated districts of rural Cornwall. This project sought to illuminate the nature of these gaps both nationally (through a practice-focused review of existing documentation) and locally (through a detailed study of Cornwall’s attempt to translate EMHN policy into practice guidelines for NHS/CJS interface working), in order that interagency decision-making, communication and service delivery are improved.

It is essential that rigorous academic research is conducted in order to understand the disparate processes and outcomes in relation to individuals with EMHN across the country, in order to address the inevitable inconsistency and lack of coherence between policy and practice. Furthermore, as the current situation demonstrates, a lack of dialogue within the same organisation and between organisations ensures that individuals ‘known’ to all or some of them are frequently not dealt with in a truly integrated or genuinely informed way. If the ‘silo mentality’ stifles interagency dialogue and inhibits practitioners and managers from exploring every option when dealing with those individuals who are known to a number of organisations, it also exaggerates the distinct and seemingly competing occupational aims and cultures of those involved. Thus, an important aim of the research was not only to find ways to promote greater interagency dialogue, but also to explore how practitioners from different organisations might develop genuine partnerships in dealing with individuals who are known to a range of organisations. A ‘case-linkage’ methodology offered a useful and exciting means of finding ways to include a range of relevant practitioners and professionals into the health-care process and improving continuity of care and access.

Reflecting local need

Against the above background, the research arose out of a small pilot project, set up to scope the need associated with individuals having EMHN and care plans who are also known to the police. The project was set up as a partnership between the local policing area in East Cornwall and the Cornwall Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (CFT) funded by the NHS. This pilot identified the scale of the need and resulted in a partnership bid to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to conduct the Interface Project.

Cornwall’s partnership working with individuals who may encounter health and social services and the CJS has pockets of exemplary practice. These include co-ordinated activities around the use of Section 136 of the Mental Health Act (MHA),18,19 the operation of drug treatment requirements as part of Community Rehabilitation and Punishment Orders, the enactment of the MAPPA and maintaining performance with regard to prison transfer targets for mentally disordered offenders. Multiagency collaboration is underpinned by a local forum, the Peninsula Criminal Justice Agencies Group (formerly the Mentally Disordered Offenders Group), where major stakeholders (Crown Prosecution Service, probation, primary care trusts, local authorities, police and provider trusts) are represented. Inevitably, where specific services or activities are underpinned by statutory requirements, clarity and delivery are enhanced. Local experience is that where the legal and statutory basis of provision is unclear and risk is possible but uncertain, then co-ordination of activities relies on the interpretation of service mandates by authoritative individuals who may have competing agendas (e.g. risk management vs. capacity management).

Research into practice

It is widely acknowledged that the translation or implementation of research findings into practice must occur more frequently and widely. Indeed, implementation in mental health practice has been described as ‘embryonic’. 20 Within the Interface Project, therefore, an iterative process of ‘translational forecasting’ enabled potential opportunities for the translation of research findings into practice to be explored and optimised as they become available in real time.

Within the research framework, specific models and strategies for facilitating the implementation of findings were reviewed. The literature recognises that innovation adoption fails to achieve long-term implementation due to deficiencies in the implementation strategy rather than due to those in the innovation itself (e.g. Klein and Sorra21). Therefore, the concept of a translational continuum was of particular relevance, involving an explicit focus on translating research findings into practice from the outset of the research to ensure adoption, early and enduring implementation of recommendations and actions based on the research findings. 20,22

Chapter 3 Methodology

Overview

A three-stage methodology was used to achieve the aims and objectives outlined in Chapter 1 (two using secondary data and one gathering a small amount of primary data). Stage 1 involved a review of documentation pertaining to the translation of national policy into regional/local practice guidance in the area of EMHN. Stage 2 represented the main body of work and was a case-linkage study involving NHS case records and police case records for individuals with multiple mental health episodes, deemed of moderate risk, and known to the police. Stage 3 explored the barriers and facilitators to the effective multiagency management of this vulnerable group in the light of evidence from the review exercise against the findings from the case-linkage study. The three stages are presented in this report as distinct sections containing methods and findings for each stage. Quotations are provided in the findings of stages 2 and 3 to illustrate the themes emerging from the analysis; it should be noted that the use of offensive language in quotations has been retained to remain true to the original voice of the participants.

Conceptual framework and design

The project was informed by a conceptual and methodological framework developed by the project team to successfully evaluate a range of multiagency services and initiatives through the rigorous application of mixed methods. 23 This framework was responsive to identified need,24 adopting Burke’s25 principles of participatory evaluation. Burke (1998, pp. 44–5)25 posits seven principles of participatory evaluation:

(1) The evaluation must involve and be useful to the program’s end users; (2) the evaluation must be context-specific, rooted in the concerns, interests and problems of the program’s end users; (3) the evaluation methodology respects and uses the knowledge and experience of the key stakeholders. (4) the evaluation is not and cannot be disinterested; (5) the evaluation favors collective methods of knowledge generation; (6) the evaluation (facilitator) shares power with the stakeholders; (7) the participatory evaluator continuously and critically examines his or her own attitudes, ideas and behavior.

These principles were operationalised in the Interface Project through the engagement of stakeholders at all stages of the research/evaluation process to ensure the meaningful utilisation of project findings26 and enhance multiagency working and service user outcomes. The framework was further informed by the tenets of community psychology, which espouse collaborative working with traditionally marginalised groups and understanding people within their social contexts. 27

Implementation science in action

The current research constituted a single-site study in Cornwall. The research team adopted a two-pronged approach to the dissemination and implementation of the research findings:

-

thorough and considered implementation of the findings in the county of Cornwall across police, NHS and third sector organisations

-

dissemination of the research findings nationally to both academic and practice communities through a consultative process focused on the translation of the findings into different local contexts.

Implementation in Cornwall: the praxis-oriented dialogue model

A social constructionist epistemology and central tenets of community psychology form the basis for what the authors’ term the praxis-oriented dialogue (PoD) model of implementation. Social constructionism is a theory of knowledge which is broadly concerned with the ways in which reality is actively constructed, rather than pre-existing. 28 Psychological and social phenomena, in particular, are constructed or coconstructed with others and there is an emphasis on the role of language and discourse as the medium through which meaning and understanding are created. As presented above, community psychology advocates explicitly focussing on the experience of those individuals traditionally marginalised by society within a democratised research process.

This model was explicitly defined within the Interface Project, building on the methodology that Lea and Callaghan had been using in their work for many years. It articulates implementation as integral to the research process, considered from research conception and embedded in research design, rather than simply constituting a ‘research phase’. The PoD model reflects a set of principles that inform the process of research, to maximise engagement, ownership and translation into practice. Thus, the PoD model set the context for the way in which qualitative and quantitative data would be collected and analysed as part of a mixed-methods approach to research design. The PoD model is particularly appropriate for health-care research relating to interagency and joint service development, delivery and innovation. A set of three core and three operational principles define the model representing its epistemological basis and methodological foundation.

Knowledge is socially constructed

The discipline of the sociology of scientific knowledge reminds us that all knowledge is socially constructed, and recognises the existence of powerful ‘ideological commonplaces’ relating to the tacit ‘how to’ knowledge associated with socialisation into different professions, disciplines and their respective cultures. Understanding the intersubjective, intertextual and fundamentally dialogic nature of social life and being mindful that all language is dynamic, relational and engaged in the redescription of the world is fundamental to the effective and successful implementation of research findings. Understanding that knowledge is socially constructed enables researchers to acknowledge that as research findings are translated into practice contexts they will be redefined and reinterpreted in that context; a new set of meanings may be created. Furthermore, in mental health service delivery, benefits can be derived from researchers, practitioners and service users working together to coconstruct the meaning of the research. Specially, the ‘over to you’ approach that characterises much dissemination activity can create a barrier between research and practice and risks the impact of research being ‘lost in translation’.

Research is explicitly committed to critiquing the status quo and building a more just society

The notion of ‘research as praxis’29 is fundamental to the PoD model. Praxis involves putting ideas or theories into action or practice through a reflective process, which aims to achieve change. The elements at the core of research as praxis are that those being researched are involved in the research through a ‘democratized process of inquiry characterized by negotiation, reciprocity, empowerment’, acknowledgement that research cannot ever be neutral30 and that research thus framed is ‘explicitly committed to critiquing the status quo and building a more just society’;29 that is, it aims to transform. Indeed, at the core of much health and social care research is a concern to provide an evidence base for practice to transform services such that they offer enhanced user care. As researchers, practitioners and service users, we are committed to using the rigours of research to enable positive social change and ensure ‘sustainable co-creation processes that model, seed, and support progressive change agendas’. 31

Practice-informed research is as important as research-informed practice

Evidence-based, or research-informed, practice is central to best practice. However, the authors argue that the notion of ‘practice-informed research’ is equally important in health-care research generally and particularly in relation to research into mental health care service delivery. Thus, research arises from challenges in the current practice context, and is developed and designed in relation to that context. For example, the benefits of ‘bottom-up, clinician-conceived and directed clinical intervention research, coupled with collaboration from research experts’32 have been noted. This approach increases the likelihood that research is relevant, appropriate and significant to practice and, therefore, that the potential for effective and sustained implementation will be realised. Research-informed practice and practice-informed research lead to both improved practice and improved research in the challenging context of mental health care service delivery.

‘Implementation’ should be thoroughly embedded within the research

Building on the first three principles, the PoD model asserts that researchers should contemplate implementation from the outset of a research project, and that this approach should inform both the governance and process of the research. Although many funding bodies require dissemination and implementation strategies to be included in research proposals, research suggests that these are often insufficient to effect successful translation of findings to practice. Research-driven change is complex and invariably impacts on individual practitioners and support staff at various levels of the target organisation, as well as potentially affecting ways of working between individuals, sections, departments and other agencies. In order for implementation to be effective, Eccles et al. 33 noted the importance of having a health-care workforce that can sustain implementation in the clinical setting as a matter of routine. Including practitioners as members of the research team assists in privileging the importance of implementation right from the start and in being mindful of the context within which research findings will need to be applied. Furthermore, permitting the dialogic and intertextual nature of social life into the research team allows for the development of a sensitive, appropriate and realistic implementation strategy. Operationally, thoroughly embedding implementation within the Interface Project will enable timely identification of barriers and facilitators to implementation, key gatekeepers and champions, relevant practice meetings and events to attend. This allows projects to map out a ‘timeline of engagement’, informing the implementation strategy over the lifetime of the project.

Key stakeholders need to be engaged in a meaningful, authentic way

In a context of increasing ‘transdisciplinarity’,34 considerable benefit can be derived from establishing a multidisciplinary research team, including academics from different disciplines as well as practitioners and service users, and from key stakeholders’ meaningful and authentic engagement in the research. Although the attendant diversity of views can be challenging, the consequent reciprocal understanding enables appropriate contextualisation of the research and lays the foundations for effective implementation while building joint accountability, responsibility, investment and ownership. This aligns with Baker et al. ,35 who regard translation as a ‘new, broader, collaborative approach that brings clinicians, researchers, patients, and managers together to improve care’.

Stakeholder engagement and the associated successful implementation of research can be facilitated further through the integration of researchers within health-care organisations as Eccles et al. 33 noted: ‘Implementation research and implementation researchers need to be embedded within the NHS’. The benefits of this approach include enabling key elements of the research to progress (e.g. data collection, case-linkage); increased engagement of individuals and organisation with the research; increased collaborative working; increased shared investment in the successful outcome of the research; enhanced understanding and appreciation of roles (both research and practice); and increased rapport and trust leading to joint problem-solving in the face of gate-keeping. Taken together, these benefits positively influence the likelihood of the successful implementation of research findings in the service context.

The relationship between researchers and practitioners is respectful and appreciative

Shotter has argued that ‘too often’ researchers act as ‘external observers of others’ conduct’ (unpublished paper cited in Lather31). This leads to a divide between ‘researcher’ and ‘researched’ (whether health-care provider or user) and fuels the translation gaps identified by Cooksey. 36 Therefore, the PoD model asserts that although the nature of stakeholders’ engagement may vary, both researcher and researched should be involved together in the research process. Furthermore, such relationships must be characterised by genuine mutual respect and appreciation, the valuing of all contributions, and equality. Achieving such relations involves overcoming the sometimes competing cultures that define different professions, and the mistrust that can exist between researchers and practitioners that is sometimes fuelled by perceptions that researchers are making ‘diagnostic pronouncements’31 about current service delivery. However, it is through effective, constructive relationships that translation can best be achieved.

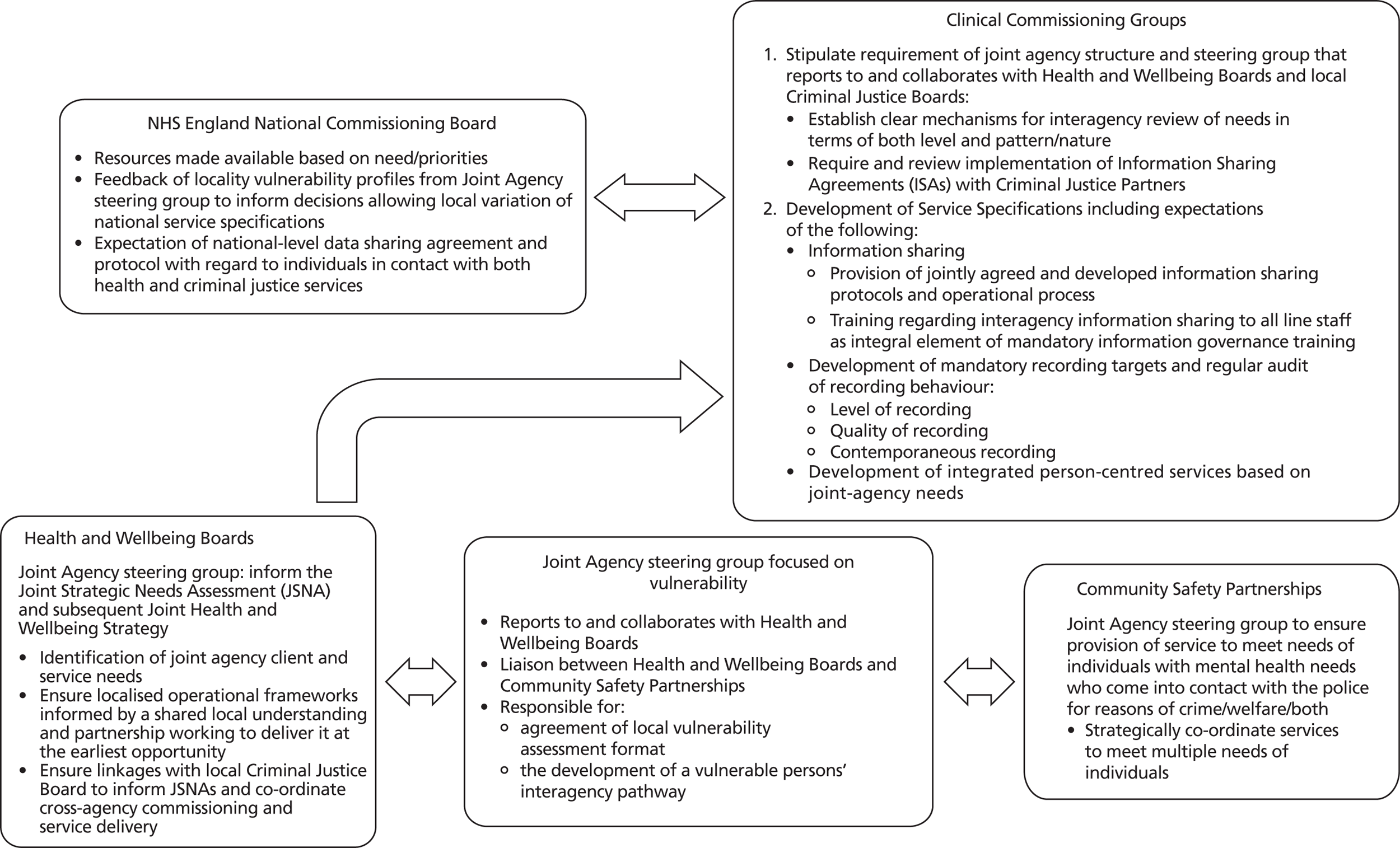

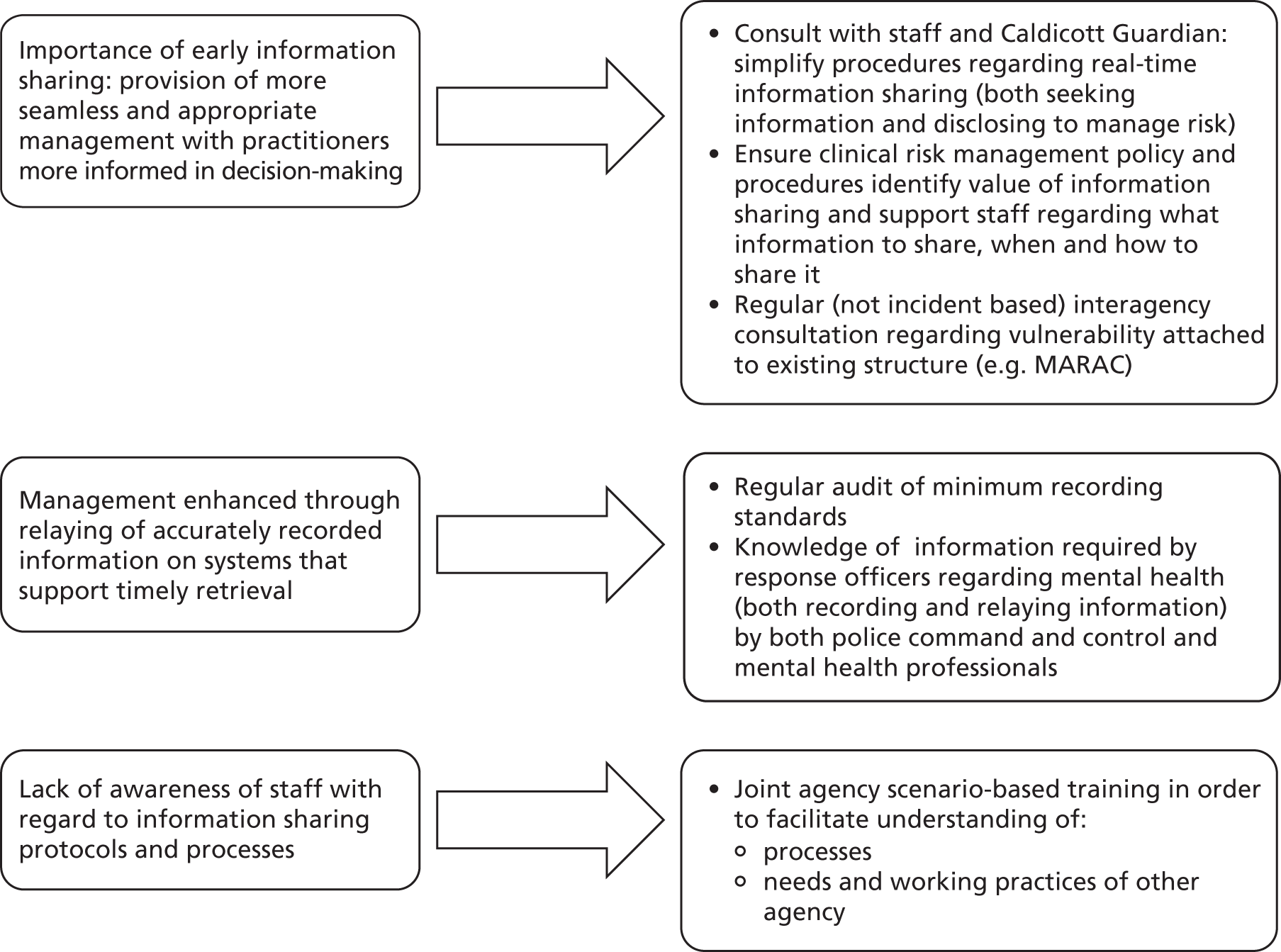

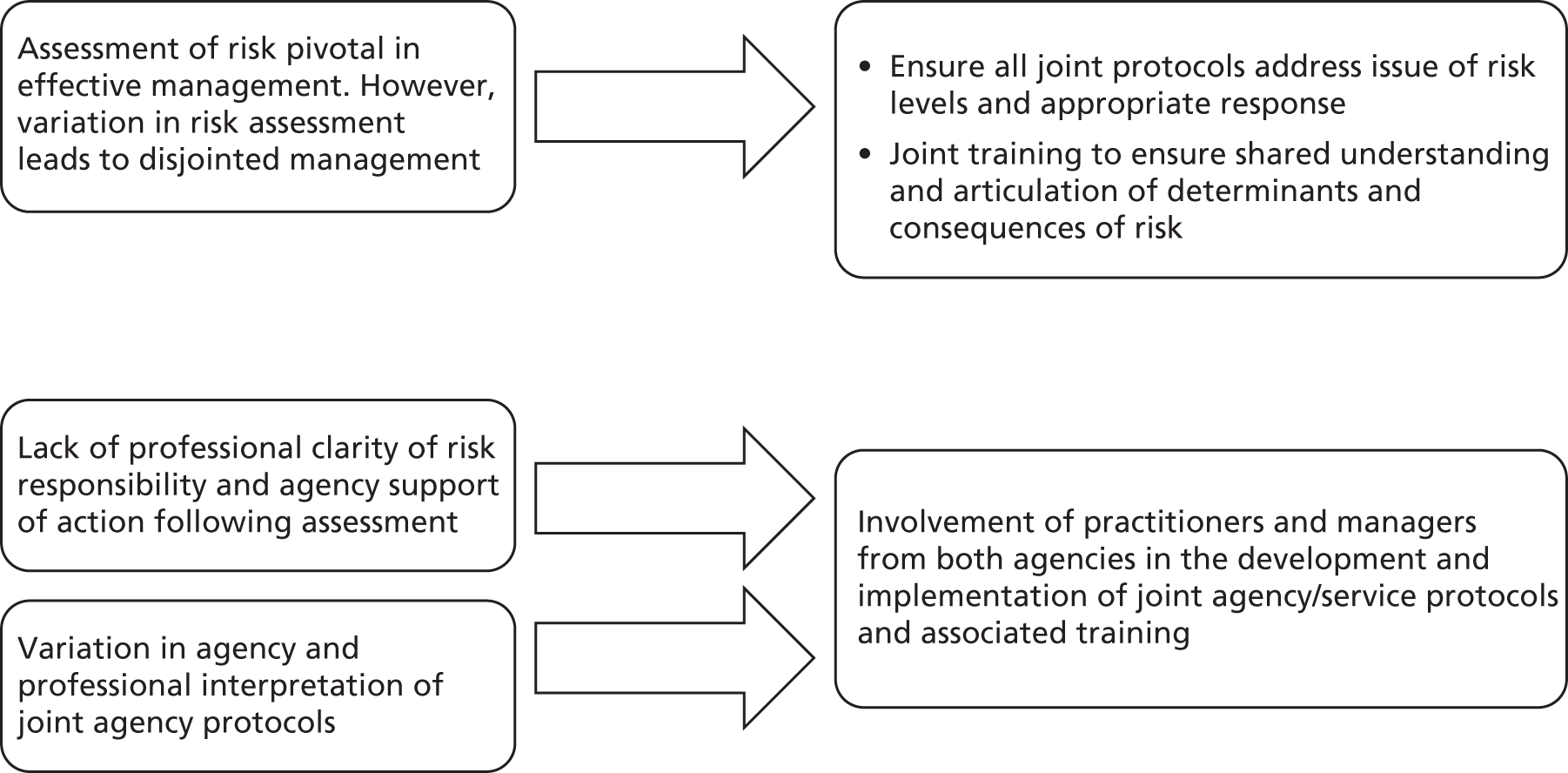

National consultation and dissemination: moving beyond Cornwall

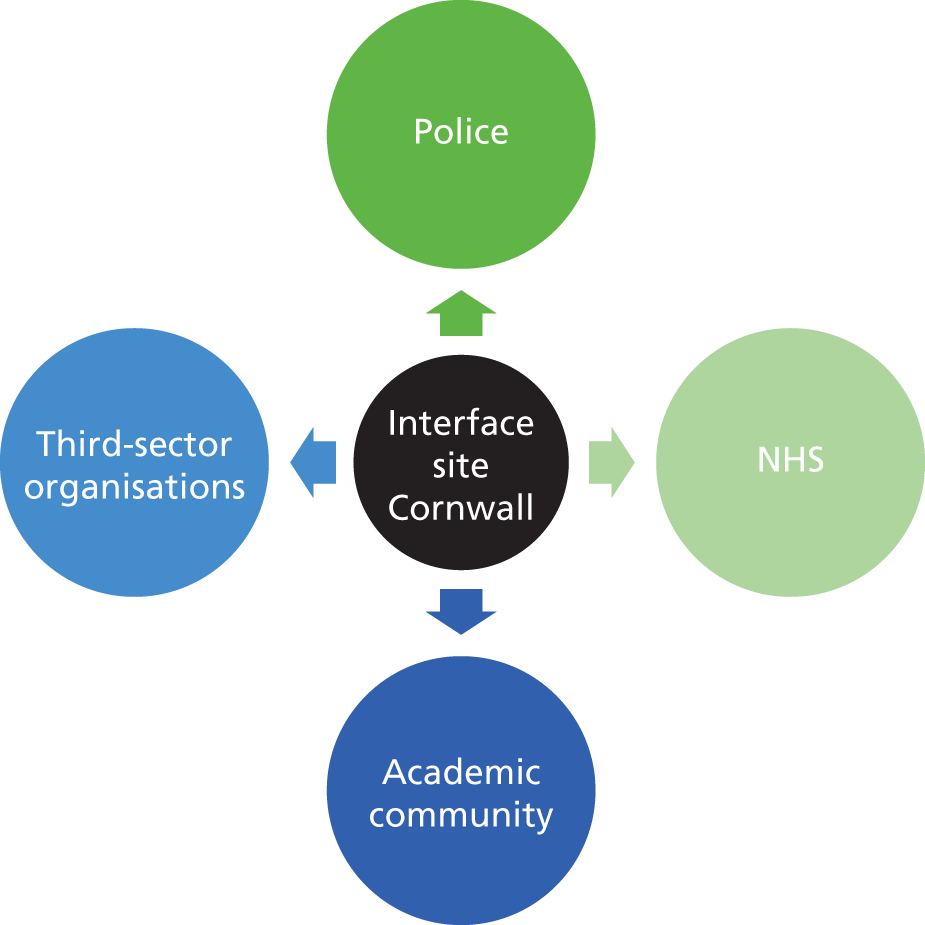

Although this study involved a single site, given the rationale for the research and the ongoing challenges of managing this vulnerable, marginalised and under-researched population, it was decided to explore the applicability of the research findings beyond Cornwall. A national consultation and dissemination strategy was developed early on in the project to address this. Four sectors were identified and targeted, as illustrated in Figure 1, mirroring the key stakeholder groups engaged in the research and responsible for the management and research of individuals with EMHN. These were the police, the NHS, third-sector organisations and the academic community. Within each of these sectors, key individuals and/or organisations as relevant were directly targeted with a view to sharing the research findings and consulting on their implications for differing contexts. This process (illustrated in Figure 2), was greatly facilitated by the academic–practice collaboration described above and informed by the PoD model, as the team had knowledge of and access to a wide variety of influential individuals nationally through academic and practice contacts and networks.

FIGURE 1.

Key national sectors for consultation on and dissemination of findings.

FIGURE 2.

Dissemination strategy beyond Cornwall.

A central focus of this strategy was a targeted Interface National Stakeholder Consultation event, held at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, on 10 September 2013.

Research capacity building

The research team were committed to ensuring that research capacity was developed within the partner organisations. Although elements of the PoD model support the activity of research capacity building, this was seen as an element of the project that required explicit action to ensure that the research had both positive and lasting impact in practice organisations. In order to ensure that this was being achieved, the team used the components of Cooke’s framework for analysing research capacity building to ensure a holistic approach. 37 Each of these components are presented below, detailing how they were fulfilled by the Interface Project.

Skills and confidence building: developing appropriate skills and confidence through training and creating opportunities to apply skills

Due to the participatory approach of the PoD model, members of the research team from practice organisations received research training and development from the proposal stage of the research. Academics ensured that practice-based members of the team were able to develop according to their interests and the needs of the research. The success of this approach is reflected in the development by practice staff of a bid for research funding to investigate the efficacy and utility of a custody service innovation. The approach also contributed to a police research team member successfully applying for a Winston Churchill Fellowship to examine the implementation of Mental Health Courts and Crisis Intervention Teams in Chicago and Baltimore, USA. Furthermore, through the embedding of the Interface research manager in the CFT Centre for Mental Health and Justice, staff and trainees were able to access expertise and advice as appropriate when embarking on evaluations and audits to monitor aspects of work of the team and scope for further funding.

Close to practice: to enable implementation/utility

As described, the research manager and research assistant were integrated into CFT and Devon & Cornwall Police (DCP), each receiving honorary contracts in order to undergo relevant training to facilitate access to systems and sites. Part-time (approximately 2 days a week) situation of the research manager in the CFT Centre enabled the formation of links to facilitate:

-

development of the detailed process of case extraction and linkage according to protocols and guidance within each organisation

-

implementation of findings of current research

-

potential opportunities for research/evaluation support

-

potential opportunities for collaboration beyond the current project

-

potential opportunities for staff development

-

potential opportunities for service delivery research/evaluation as a follow on/beyond the current project.

Linkages and collaborations

Although three members of the original project team had worked together previously on a variety of criminal justice-related projects, Interface Project funding enabled the development of a team that not only strengthened the partnership with DCP but also extended to the CFT (including mental health and social care), primary care (through the health for homeless service that were instrumental in the service user consultation) and third-sector agencies. This not only enhanced the implementation of the findings of the Interface Project as described above, but developed both academic–practice relationships and collaborations between practice organisations. Examples of how such collaborations have impacted on practice as a result of this project include:

-

provision of support for the development of a business case for the innovative custody liaison and diversion service

-

provision of advice with regard to the development of the street triage service delivery model for Section 136 detentions and associated evaluation

-

a successful collaborative proposal developed to support pump prime of evaluation of service delivery model from the Institute of Health and Community, Plymouth University, Plymouth

-

development of CFT risk assessment training.

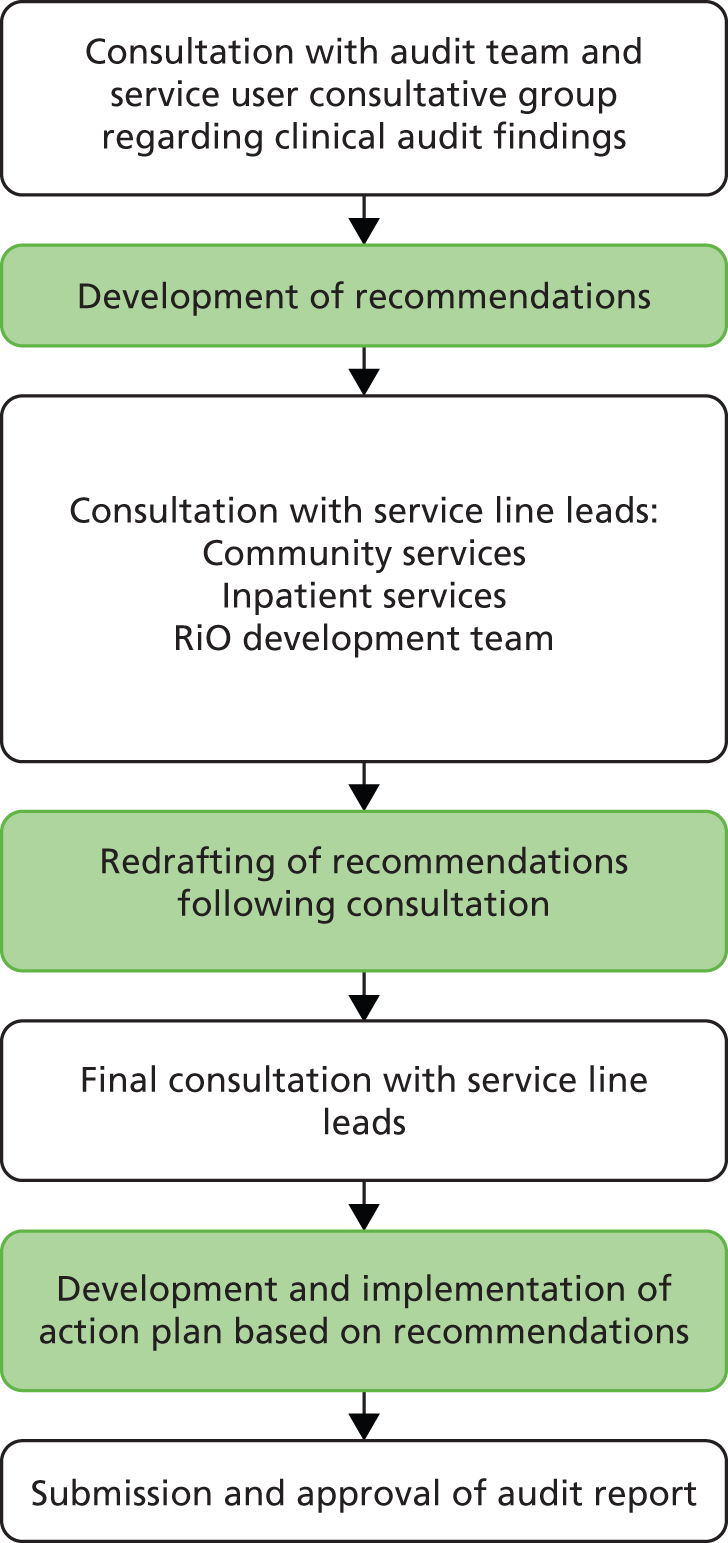

Appropriate dissemination: to maximise impact

Dissemination was undertaken from the earliest available opportunity in order to embed the research in the practice organisations. Presentations were made at a CFT Research Continuing Professional Development event to raise awareness among CFT staff, at an event held on World Mental Health Day in order to disseminate information to service users, and at a police joint health commissioning day to ensure that members of DCP were aware of the research. Meetings also took place with Mental Health Team (MHT) leads in order to disseminate project aims and objectives and plan implementation from the outset. Additionally, following completion of the clinical audit, meetings and consultations were held between inpatient and community service line leads to disseminate clinical audit findings and support the development of recommendations and actions. The research manager was also a member of the CFT Research and Innovation Committee.

Continuity and sustainability: maintenance and continuity of newly acquired skills and structures to undertake research

Through the participatory approaches highlighted above, practice members of the team were able to gain experience in a range of research skills including writing funding proposals; applications to the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) and the National Information Governance Board (NIGB); research design; data collection; data analysis and service user consultation. As such, team members gained confidence to enable them to disseminate these newly acquired skills within their organisations. Furthermore, and importantly, the embedding of researchers and conduct of the project directly in and with practice engendered the development of a research culture within these organisations with consideration of the value of research and evaluation to support practice and in the design and development of service.

Infrastructures: structures and processes set up to enable smooth and effective running of research projects

The methodology employed to conduct the case-linkage study necessarily relied on access to systems, including mental health records and police intelligence systems. The researchers worked with the practice organisations to develop information-sharing protocols to support the work of the project. This was facilitated through the inclusion of the force data protection officer and the CFT information governance manager on the Project Steering Group to monitor the requirements of the project in the light of the agreements in place. These structures and processes, set up early in the project, were invaluable in the application to the Ethics and Confidentiality Committee of the NIGB for Section 251 support. Owing to both the established collaborative relationships and the clear protocols already in place, a successful application was made that received Secretary of State approval to access records for the purpose of the research. Additionally, these structures and processes enabled the development of further interagency work that required cross-system access and analysis such as the current CFT audit of the new custody liaison and diversion service.

Finally, the formal buyout and associated subcontracts between the practice organisations and lead academic institution enabled planned, effective and sustainable management of protected time for practitioner members of the research team. This also enabled an explicit link to be made between practitioner–researchers’ current roles and their role in the research team, which further underlined research as a core activity for these individuals and more generally in their teams.

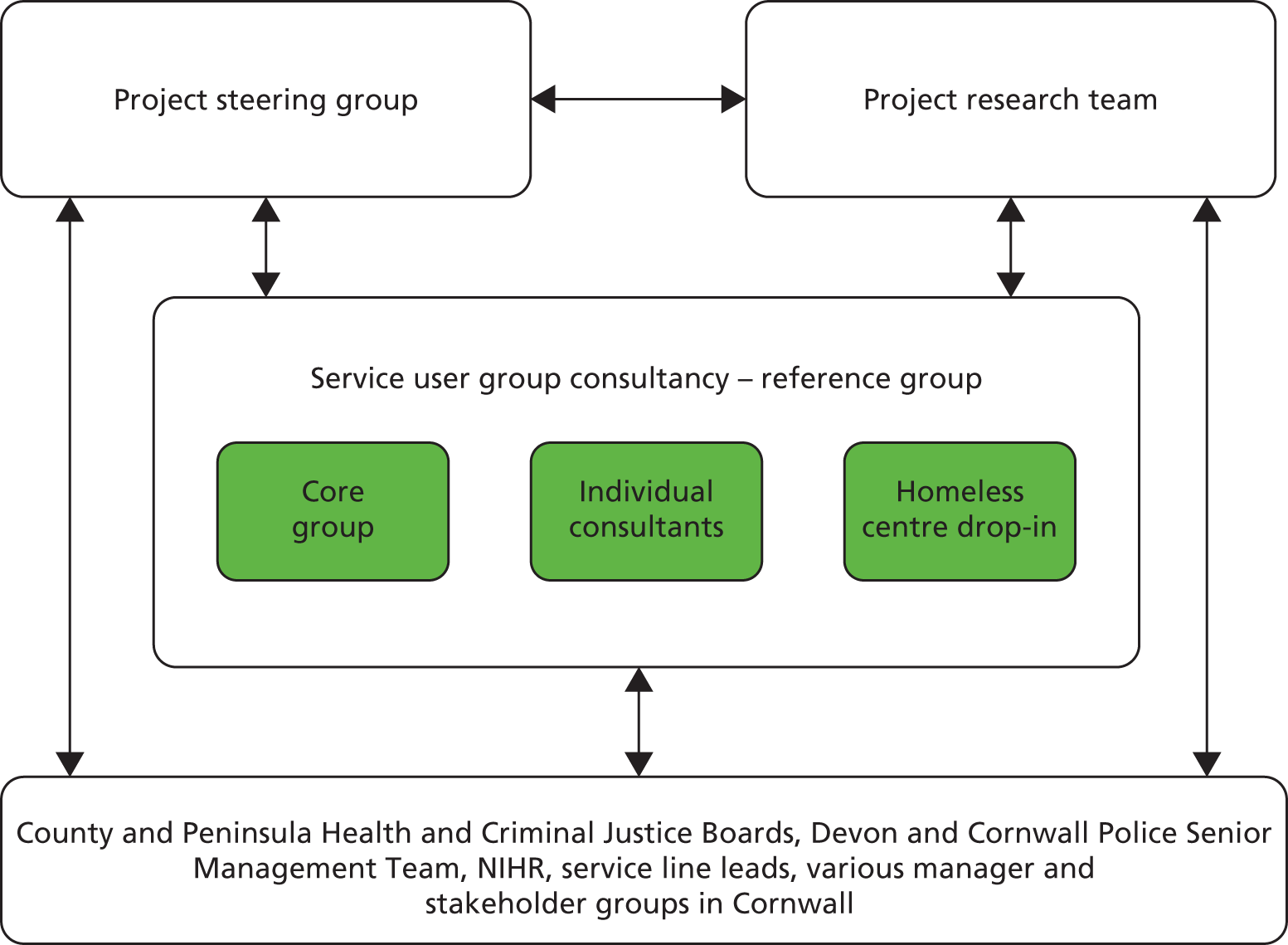

Project management

As per the protocol, the project was managed by a collaborative team of academics, practitioners and service user researchers, experienced in working in multisite, multidisciplinary initiatives. The project was headed by Professor Lea (Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London) who has considerable experience in leading this type of academic and community work, including having occupied key roles in the Local Strategic Partnership of Plymouth with responsibility for co-ordinating and delivering outputs and outcomes. Regular monitoring and reporting was undertaken in order to ensure project progress and success. Figure 3 presents the project management structure and associated communication and dissemination channels.

FIGURE 3.

Project management structure.

Three distinct groups conducted, monitored and consulted on the research, these being the research team, the steering group, and the service user reference group respectively. The research manager and research assistant were present at all steering group, research team and patient and public involvement (PPI) sessions, providing continuity and a single point of reference across the groups. A service user consultant, employed by the trust, sat on both the steering group and reference group, liaising and communicating between the two. Wider collaboration and consultation with service users is described in detail in the methods and discussion sections of this report. Practice members of the research team took on additional dissemination roles, promoting the project at regional and local meetings, which they attended as part of their formal roles. The research manager represented the project specifically at the Local Health and Criminal Justice Boards, Section 136 meetings and in communicating findings to trust service line leads and force staff as appropriate. The interactions between the different elements of project management within the project are illustrated in Figure 3.

Steering group

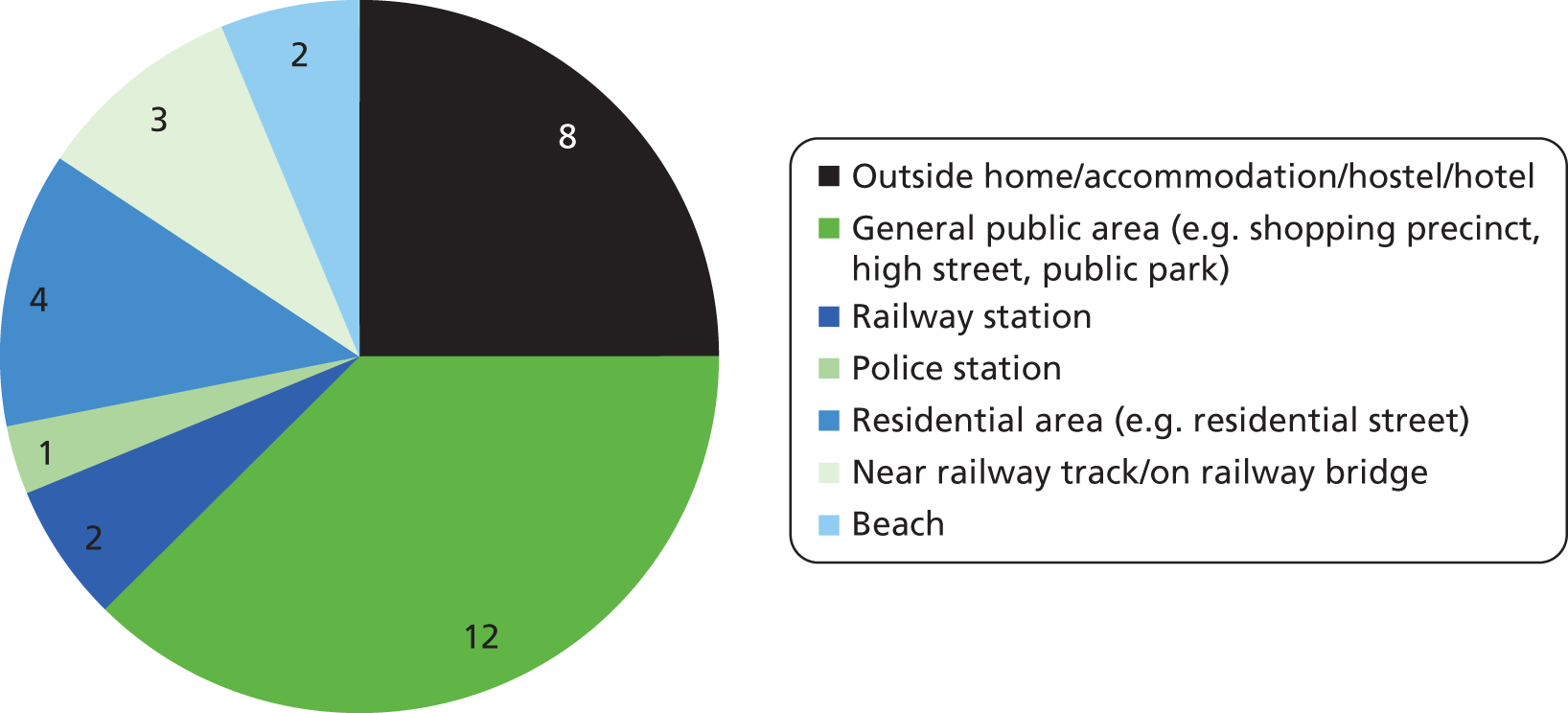

The project reported to a steering group comprising team members, stakeholders from the NHS, police, third sector and service users – representing the main organisations with an interest in the research. The terms of reference of the group included responsibility for monitoring the delivery of milestones to time and on budget, ensuring the appropriateness of the communication and dissemination strategy associated with the project and receiving interim and final reports. Membership of the steering group extended during the course of the research to include individuals within statutory and third-sector organisations with key strategic and practice-based roles in both the management of individuals with EMHN and/or information governance in the practice organisations in which the research was based. The steering group was chaired by an independent chair, Professor Rod Sheaff, who has experience as a principal investigator on NIHR-funded projects. Meetings were held quarterly throughout the project until the last meeting on 20 September 2013.

Research team

The full project research team met bimonthly [in person or via telephone conferencing/voice over internet protocols (in this case Skype™; Skype Ltd, Rives de Clausen, Luxembourg)]. The meetings were held in the south west in various locations hosted by each of the participating organisations. Each meeting was chaired by Professor Lea or Dr Callaghan (research manager) in person and included the regular evaluation of project performance, both financial and non-financial, ensuring that any necessary corrective actions were undertaken in a timely manner. The research team meetings were important in ensuring that the research was being conducted rigorously and answering the research questions defined in the protocol. Furthermore, practice-based research team members were able to highlight changes in policy and practice that could affect the conduct of the research and/or the context in which implications from the research would be drawn. The membership of the research team changed from the original fund holders, specifically in relation to the police fundholders and health economics academics, with all changes to the team approved by the Health Services and Delivery Research (HS&DR) programme.

The roles of the members of the research team were as follows: Dr Callaghan (Research Manager, Plymouth University) was responsible for day-to-day operational project management and liaison with NHS and police colleagues; Susan Eick (Research Assistant, Plymouth University) supported the work of the Research Manager and day-to-day operation of the project; John Morgan (fund holder, CFT) facilitated the conduct of the project and implementation strategy within the Trust; Chief Inspector Mark Bolt (fund holder, DCP) facilitated the conduct of the research within the force; Dr Diana Rose (fund holder, Institute of Psychiatry) guided the development of the PPI strategy for the project; Dr Anita Patel (fund holder, Institute of Psychiatry) led the health economics component of the Interface Project until she went on maternity leave, specifically she was responsible for overseeing the development of the methodology and data collection; and Professor Graham Thornicroft (fund holder, Institute of Psychiatry) provided specialist advice and guidance on elements of the project.

In summary, a framework of robust governance structures ensured effective delivery of outputs and outcomes including project management, financial tracking, risk management and performance management. These structures also provided a forum for robust discussion and appraisal of the research and the associated implementation and dissemination activity.

Changes to the original protocol

A number of necessary changes were made to the original project protocol as described in the original application. Where required, changes were submitted to and approved by the NRES and substantial changes to the project were approved by the HS&DR programme (refer to Appendix 1 for full details of changes). Most significant were the changes to the identification of cases for the case-linkage study following support from the NIHR and Section 251 approval from the NIGB, and changes to the recruitment strategy for the stakeholder consultation. A 3-month funded extension to the project was also permitted to allow the application to the NIGB and an amendment to the original NRES application to take place.

Ethical approval for the study was sought from the South West Research Ethics Committee of the NHS NRES, the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London (as the sponsor) and the Faculty of Health, Education and Society Human Ethics Subcommittee of Plymouth University (responsible for the delivery of the research). Approval was also obtained from the Royal Cornwall Hospitals Trust Research and Development Department as the research site. The research team sought appropriate approval for all amendments. The research was also adopted by the NIHR Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) and was supported by the team based in CFT.

Inclusion of a clinical audit

Originally, as described in the project proposal, the researchers anticipated that the participant pool for the case-linkage study (stage 2) would be drawn from a clinical audit that would be undertaken by CFT as part of their Skillshare initiative. However, Skillshare was disbanded due to funding issues and the audit was not conducted as planned. This therefore necessitated the CFT to conduct the audit as part of the Interface Project with the support of the researchers so that case-linked individuals could still be identified to form the participant pool for the research.

Application for support in terms of Section 251 of the NHS Act (2006)

An application was made to the Ethics and Confidentiality Committee of the NIGB for their support in terms of Section 251 of the NHS Act (2006),38 by setting aside the common law duty of confidentiality. The application process is described in the following section.

Team changes

As the project progressed, the roles of team members evolved, particularly in the case of two of the police representatives on the original bid who retired during the project. As they were no longer representative of the police, they were transferred from the research team to the steering group (Police Constable Dr Nick Lynn and Detective Superintendent Iain Grafton OBE). Changing team members allowed the project to retain the two retired police representatives’ expertise and advice while allowing a new team member from the force to join the research team (Chief Inspector Mark Bolt). In addition, the lead for the health economics component of the study, Dr Anita Patel, had to suspend involvement on the project at the point where health economic data collation for analysis was started. Ms Margaret Heslin conducted the health economic component under the supervision of Dr Barbara Barrett.

Recruitment process

After the protocol was amended to take into consideration the change to the recruitment process supported by Section 251 support from the NIGB, a decision was taken to seek support from the local MHRN to gain consent from potential service user participants in stage 3 of the project. As a project on the MHRN Portfolio, the MHRN local team were able to liaise with care teams to locate potential service users and distribute recruitment packs on behalf of the researchers.

Stakeholder consultation

Changes were made to aspects of the data collection in stage 3. For the stakeholder focus groups, it was envisaged that a nominal group technique would be used. Once the framework analysis progressed in stage 2, it was realised that not all decisions applied to each of the stakeholder groups, making it difficult to use the technique with the same questions across all the groups. Therefore, the findings related to service decision-making were presented to the stakeholders and groups selected the decisions most relevant to them for further discussion. Questions were developed to prompt discussion of experiences in relation to presented findings, specific to the police, mental health services and service users. The national stakeholder element of stage 3 was originally envisaged as involving telephone focus groups. However, this was replaced with a face-to-face consultation event to increase participation, group synergy and rapport. The event reflected the PoD implementation model used in the project and event feedback suggested that it was very well received (see Chapter 6, National consultation findings).

The original proposal, original protocol and final protocol approved by the NIHR are provided in Appendix 1 for further reference.

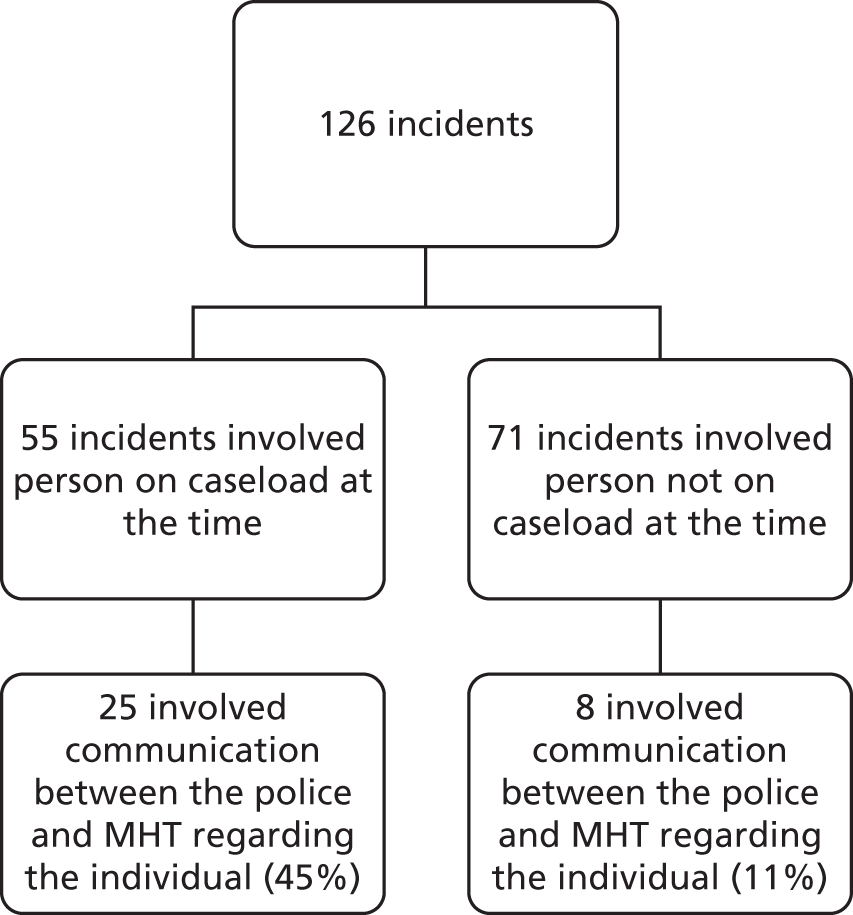

Application to the National Information Governance Board

In the early stages of the clinical audit conducted in stage 1 it became clear that the recruitment process through care teams that had originally been envisaged would not fulfil the sample requirements for the case-linkage study (stage 2). Findings revealed that approximately 35% of the potential participants for this research were not on the current caseload of a secondary MHT at any one time. Consequently, this proportion of the potential participant pool for the case-linkage study could neither be screened according to the agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria, nor invited to provide their informed consent to participate in the research. This group of identified cases arguably included the most vulnerable of individuals who were at the centre of this research and who Lord Bradley argued to be most at need. 6 Not only do they continually enter and leave the CJS through a revolving door but further, as the audit revealed, this pattern is mirrored in their use of mental health services. In order to include this group, it was deemed necessary (by the research team, steering group and service user consultants) to apply to the Ethics and Confidentiality Committee of the NIGB for Section 251 support of the NHS Act (2006). 38 This permission sets aside the common law duty of confidentiality to enable access to mental health records without consent.

Application to the NIGB was a rigorous process involving all four partner agencies in the rewriting of the study protocol, development of a secure data extraction and pseudonymisation process, and the implementation of data transfer risk assessments and system security policies to enable the lawful and secure extraction and transfer of data for the purpose of the research. The research received Secretary of State approval for Section 251 support on 12 October 2012 and it was noted by the NIGB that the research was of ‘huge public benefit’.

Patient and public involvement: the Interface Service User Consultative Group

Introduction

Patient and public involvement has been an integral and informative part of the project from the outset. PPI through direct consultation and collaboration on elements of the study methods has occurred from the early stages of the research through to the findings in this report.

Summary of patient and public involvement

Integrally, the project has been supported and directed by Dr Diana Rose, Co-Director of the organisation Service Users in Research Enterprise (SURE). Dr Rose was an original fund holder and as such, has had input on the study methods and the development of PPI consultation throughout the project. Dr Rose is a member of the research team and the project steering group; the latter also included a further member, Kate Atkinson, who is employed by CFT as a service user consultant. Additionally, some members of the research team have had life experience of being users and/or carers in receipt of the services explored in the research. Direct PPI in the project management provided expert knowledge to develop a ‘reference group’, an independent group of service users who could be consulted on the project as it progressed.

The aim of having a strong PPI component in the project was to provide meaningful advice for the project from service users’ perspectives, ensuring the research findings were relevant to service users, and to improve implementation and translation of the findings. Adhering to the collaborative nature of the research, all stakeholders, including professionals and service users, needed to be involved in directing the research and interpreting the findings.

Through discussions with Dr Rose, it was decided that a reference group, representative of service users who had experience of mental health services and the police, should be created. No such reference group within the target population existed in Cornwall.

Method of consultation

The following describes the process used to set up the reference group.

Initially, recruitment was to be attempted through information packs distributed via care teams in Cornwall. In a similar vein to the original methods for the case-linkage study, care teams were asked to identify people they believed would be willing to take part and whose involvement would not impinge on their care. Unfortunately, only one person volunteered through this process (and did not actually take part once consultation began). To improve the chances of recruitment, all groups in Cornwall in contact with mental health service users were approached and provided with recruitment leaflets to distribute to their clients. Additionally, a précis of the project was provided to display in open access areas and on organisation websites. The choice of dissemination contacts and the recruitment leaflet were guided by Miss Atkinson.

Once this process was initiated, interest in the project snowballed, with professionals and service users getting in contact to ask for leaflets to distribute. Over 300 leaflets were distributed throughout Cornwall. From this recruitment, a core reference group of 12 individuals was formed. The consultants met as a group on a bimonthly basis and individually with members of the research team depending on their mental health needs (one individual consistently met the researchers on a singular basis and two interchanged between group and one-to-one meetings). Six group meetings (with an average of nine attendees) were held in a public building in central Cornwall and five individual meetings were held (on university property or in the locale of a third-sector organisation) over the lifetime of the project. Two researchers attended each meeting and facilitated the group. Consultants were given £20 and paid travel expenses for each meeting they attended. Copies of claim forms and group meeting minutes/individual meeting notes were circulated to service user consultants after each meeting.

Once the group commenced, it was realised that although the group members had experience of both services as service users or carers, they did not represent the majority target group represented in the research. The initial group was 75% female, > 35 years old and had limited recent experience with the police. Results from the audit in stage 1 illustrated that the consultation needed to target young males in repeat contact with the police for suspected substantive offences in hard to reach populations. To address this, the research team liaised with ‘Health for Homeless’ to set up drop-in sessions in a homelessness centre in Cornwall. To approach the homeless population was a suggestion made by the main consultative group. This resulted in consultation with three young males and one female with recent contact with the services.

When devising a format for the reference group, discussions were held with administrators of existing service user groups and Plymouth University’s Human Resources and Finance departments. Literature and guidance from organisations such as the MHRN and SURE were reviewed. Advice was sought from the facilitator of an existing service user consultative group for a social work programme at Plymouth University. The following key aspects of administering a reference group were adopted:

-

terms of reference and ground rules

-

fully minuted group meetings

-

summarised individual meetings

-

clear accounting, with claim forms copied to consultants

-

secure and confidential storage of contact details.

Contributions of the group to the research

As well as the PPI support received from Dr Rose and Miss Atkinson described above, the reference group has contributed to the following aspects of the project, resulting in formal changes to research methods and the interpretation of findings. Changes to the research design were formalised in the information sheets, consent forms and other relevant documents; in turn, these changes led to amendments to the research ethics application and changes to the research protocol. The input of the reference group has helped to frame the findings. The challenges and impacts of the group are discussed in Chapter 7 of this report.

-

NIGB application The group was consulted on the appropriateness of applying to the NIGB for permission to access data without consent. The group agreed with this approach and emphasised the importance of gaining accurate data to help improve services over the concern about accessing data without permission.

-

Information sheets and consent form The documents developed by the research team early in the project were reviewed by the group. Following their suggestions, changes were made to the layout; the principal change was a bulleted summary on the first page, highlighting the main points from the information sheet. From reviewing the consent form, the group decided that potential research participants should be offered the option of taking part in an interview and focus group, rather than one or the other.

-

Research participant recruitment method The group provided advice on recruitment methods for the stakeholder consultation in stage 3, including the concept of drop-in sessions at homeless centres (which was used as a method of recruitment for the service user consultation and for recruiting participants for stage 3).

-

Logistics of service user consultations and research participation The group provided guidance relating to suitable times to start and finish consultations and research interviews/focus groups with mental health service users, for example:

-

hold meetings in the afternoon to allow people to travel and time for medication to take effect, but finish in time for people to leave before it gets dark

-

hold meetings in neutral locations acceptable to users of police and mental health services

-

pick suitable days of the week to ensure support services were available post consultation (not on a Friday so people were not in crisis over a weekend)

-

suitable length of time for consultation meetings, research interviews and focus groups with an emphasis on the ability to take breaks during participation.

-

-

Dissemination The group suggested outputs for the research that would be meaningful for service users, including dissemination to third-sector organisations such as Mind, the Revolving Doors Agency and Age UK. Representatives of these organisations were invited to the national stakeholder event.

-

Discussion of findings At each stage of the research, results were presented to the reference group as they became available. This allowed the group to discuss the findings and compare them with their own experiences. Throughout the consultation, the group has made suggestions as to how services could be improved, in addition to their advice on the research itself.

-

Review of implications for research and final report At the end of the project, a final meeting was held with the group in the form of a workshop to present the findings and ask for feedback on the main implications of the research. Further consultation was sought from the group on the following topics, which arose from the process of setting up the group and from feedback given by group members.

-

UK Border Agency requirements Due to new requirements from the UK Border Agency, universities have to ask for proof of identity before making payments to anyone employed in any activity, even if this is to pay expenses to volunteers. The consultants were asked for their feedback on this requirement and how it might affect their participation in research and service consultations as it seemed to pose some challenges. This consultation was written up in a short report and disseminated internally to the Human Resources and Finance departments at Plymouth University.

-

Disclosure barring service checks A recurring theme was the impact of police records on future employment prospects. Due to this, a police force data protection officer was asked to provide a summary of information that could be given to service users on request during the project relating to disclosure barring service checks. The group reviewed the information in terms of applicability and ease of understanding.

Chapter 4 Stage 1: policy into practice review and clinical audit

Introduction to stage 1

A short practice-focused review was undertaken to illuminate how national policy has been interpreted and translated at the regional/local level. This involved two elements: a review of relevant regional/local documents nationally; and an audit to identify and analyse local need within offender populations at the stages of the CJS identified in the Bradley report (Custody and Neighbourhood Policing6). This work extended the pilot review that formed the impetus for this research and complements existing policy-focused reviews and a local trust-based audit.

Policy review

Policy review method

A review was conducted of national and local policy, guidelines, supporting documents and related reports. The search process was internet based, searching government departmental sites, third-sector organisation sites, and using the search engine Google (Google Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). Search terms for regional/local documentation included formal descriptors (e.g. mental health issues, suicidal, Section 136). Information on national recommendations was collated into single documents to understand the policy landscape post the Bradley report. 6

Pertinent documents were analysed using thematic analysis to identify core features and themes associated with the developing practice guidelines or benchmarks with which to assess practice quality and standards. Standards on which to assess the audit findings were developed from this review. The recommendations pulled from the review were used to frame and compare the findings from the case-linkage component of the research in stage 2.

Policy into practice review

The practice-focused review illuminated how national policy relating to individuals with EMHN has been interpreted and translated at the regional (south west) and local (Cornwall county) levels to inform practice. The main aim of the review was to answer the first two project research questions:

-

How are the practice implications of current national policy relating to the management of individuals with EMHN being interpreted at local level?

-

How has Cornwall articulated national policy into practice benchmarks where the NHS and police are required to work together?

Commissioned national recommendations for practice

Much of the national focus for the management of EMHN stems from Lord Bradley’s review. 6 Building on the key recommendations of the 2009 review, the DH responded with New Horizons: A Shared Vision for Mental Health,39 providing a broad overview of actions that could be taken to improve the lives of individuals with mental health issues. Actions generated from the report included specific suggestions for improving the journeys of service users through the CJS pre and post prosecution. These actions were further defined in Improving Health, Supporting Justice: The National Delivery Plan of the Health and Criminal Justice Programme Board,40 which reiterated Bradley’s recommendations,6 devising objectives to meet the recommendations nationally. Key deliverables were suggested for each of the main services involved in the care of individuals as they progressed through the CJS. There were six overall strands from the plan:40

-

The need for a systematic and joint NHS/CJS approach to offender health.

-

Needs assessments to help inform commissioning decisions about mental health services for offenders, both in the community and for those in prison or in secure mental health services.

-

A systematic approach to supporting people with mental health problems at police stations and at courts, through liaison and diversion services: provision of high-quality assessments; diversion of people to health and social care services as appropriate; support of decisions about the range of sentencing options by the courts.

-

Continued investment in mental health awareness training for frontline CJS staff.

-

Embedding the care programme approach (CPA) throughout the CJS.

-

Working to reduce the transfer times from prison to mental health bed for individuals under Section 47/48 of the MHA. 19

In line with the Interface Project’s research questions, the specific recommendations of the Bradley report6 pertaining to types of police contact that are particularly relevant for this research have been explored. Service users with EMHN may interact with the police in one of three ways: detention under Section 136 of the MHA;18,19 detention in custody for a substantive offence; or police contact not resulting in detention but pertaining to welfare issues, low level offending, antisocial behaviour (ASB), etc.

The Bradley report6 remained the key source of recommendations throughout the research window (18 April 2011 to 8 June 2012). However, in 2013 two major reports were published. 41,42 They both propose new recommendations, although the reports also call for some of Bradley’s original recommendations to be actioned 14 years on. The latest recommendations are important in providing a context for how the findings of this research are relevant to current and future practice. These new recommendations form part of the framework for the implications for research provided at the end of this report. The specific recommendations relating to detention under Section 136 are provided in Boxes 1 and 2.

All partner organisations involved in the use of Section 136 of the Mental Health Act 2007 should work together to develop an agreed protocol on its use.

Discussions should immediately commence to identify suitable local mental health facilities as the Place of Safety, ensuring that the police station is no longer used for this purpose.

The Codes of Practice should be amended to bring detention times for those detained in police custody under section 136 in line with the PACE [Police and Criminal Evidence Act 198443], allowing a maximum of 24 hours in police custody (out of the maximum of 72 hours for which they can be detained overall). The period of detention should be subject to regular, independent reviews by both police and health officials to ensure that:

action is taken to transfer the detained person to a health-based Place of Safety as soon as is practicable; or

An assessment is carried out as soon as possible at the police station, where any transfer to a health-based Place of Safety may cause unnecessary delay.

Any assessments which are needed, once the 24 hours in police custody has elapsed, should be undertaken in a hospital.

Clinical Commissioning Groups and local social services should assure themselves that they have commissioned sufficient capacity to meet the demand for assessment under section 136, and that multiagency working is effective.

Commissioners and providers of social services and health services should ensure that they identify periods of demand for the reception and assessment of persons detained under section 136 and that they effectively manage resources to meet this demand.

Police custody officers should ensure that a full explanation is recorded in the custody record as to why a person detained under section 136 has not been accepted into a health-based Place of Safety.

The Mental Health Act 1983 should be amended to remove a police station as a Place of Safety for those detained under section 136, except on an exceptional basis (namely, where a person’s behaviour would pose an unmanageably high risk to other patients, staff or users of a health-care setting).

The recommendations relating to custodial detention for individuals who are suspected of committing a substantive offence are provided in Boxes 3 and 4.

Information on an individual’s mental health or learning disability needs should be obtained prior to an Anti-Social Behaviour Order or Penalty Notice for Disorder being issued or for the pre-sentence report if these penalties are breached.

All police custody suites should have access to liaison and diversion services. These services would include improved screening and identification of individuals with mental health problems or learning disabilities, providing information to police and prosecutors to facilitate the earliest possible diversion of offenders with mental disorders from the CJS, and signposting to local health and social care services as appropriate.

Liaison and diversion services should also provide information and advice services to all relevant staff including solicitors and appropriate adults.

The MPS [Metropolitan Police Service] and its NHS partners should immediately implement the Bradley Report recommendation so that all police custody suites should have access to liaison and diversion services.

Additionally, a group of recommendations from the reports relate to all forms of detention in a custody centre, therefore are relevant to both Section 136 and custody detentions in a police custody centre. These recommendations are provided in Boxes 5 and 6.

A review of the role of Appropriate Adults in police stations should be undertaken and should aim to improve the consistency, availability and expertise of this role.

Appropriate Adults should receive training to ensure the most effective support for individuals with mental health problems or learning disabilities.

The NHS and the police should explore the feasibility of transferring commissioning and budgetary responsibility for health-care services in police custody suites to the NHS at the earliest opportunity.

Mental health nurses with experience related to offenders must be available to all custody suites as required. The MPS should conduct a 360 degree review every six months to ensure that they are accessing the proper advice from psychiatric nurses in the delivery of health care in custody suites.

Practices and policies in custody suites must acknowledge the needs of people at risk on grounds of their mental health issues as part of pre-release risk assessment and take appropriate steps, to refer them to other services and to ensure their safe handover to relatives, carers or professionals.

The MPS [Metropolitan Police] should adopt the Newcastle health screening tool or one that meets the same level of effectiveness for risk assessment in all custody suites.

The main recommendations from the earlier Bradley report6 and the two recent reports41,42 concern Section 136 and custody, and are related to the detention and management of individuals in both these processes. However, Bradley also suggested preventative measures that could be taken to reduce offending, including two measures of particular relevance to the non-detention contact group identified within this research:

1. Local Safer Neighbourhood Teams should play a key role in identifying and supporting people in the community with mental health problems or learning disabilities who may be involved in low-level offending or anti-social behaviour by establishing local contacts and partnerships and developing referral pathways.

2. Community support officers and police officers should link with local mental health services to develop joint training packages for mental health awareness and learning disability issues.

Reproduced with permission from the DH6

Although the above recommendations are important for practice relating to individuals with EMHN in the CJS, the main underpinning factors for practice arise from legislation defined in Acts of Parliament and the related Codes of Practice pertaining to those Acts. The main acts are discussed in the following section. These acts, in part, inform the recommendations made by Bradley and others.

UK legislation

Framing all government guidelines and reports are the legal requirements of Acts of Parliament relating to mental health and the CJS. Legislatively, the main Acts of Parliament that inform practice relating to individuals with EMHN and their interactions with the CJS are:

-

the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA)44

-

the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE)45

-

the Criminal Justice Act 2003 (CJA)46

-

the Data Protection Act 1998 (DPA). 47

For each of these acts, a code of practice has been developed which guides national interpretation of the acts to inform practice.

Mental Health Act 1983 c.20, revised 2007 c.12

The code of practice for the MHA48 notes that the guidance is not mandatory. Principally, the purpose of the MHA code of practice is:

Decisions under the Act must be taken with a view to minimising the undesirable effects of mental disorder, by maximising the safety and wellbeing (mental and physical) of patients, promoting their recovery and protecting other people from harm. 48

In reviewing the MHA code of practice, the most relevant sections to management of individuals with EMHN in the CJS were from the section on ‘Guidance on Section 136: mentally disordered people found in public places’ (pp. 74–86). 48 This section of the code of practice defines that to be sectioned the individual needs to be in a public place and in immediate need of care or control. Removal to a place of safety (which could be a purpose built Section 136 suite, custody, the individual’s home or other care settings) may take place if a police officer believes it is necessary in the interests of that person, or for the protection of others. A person can be taken to a place of safety to enable the person to be examined by a doctor and interviewed by an approved mental health professional (AMHP), so that care and treatment can be arranged:

It is not a substitute for an application for detention under the Act, even if it is thought that the person will need to be detained in hospital only for a short time. It is also not intended to substitute for or affect the use of other police powers. 48

The maximum allowable period of detention is 72 hours (consecutive detentions are unlawful).

The MHA code of practice highlights the importance of jointly agreed local policies to govern the use of Sections 135 and 136. Section 135 is a magistrates order applied for by an AMHP for a person who is refusing to allow mental health professionals into their residence for the purposes of a Mental Health Act assessment (MHAA). Police officers are provided with the right to enter the property and to take the person to a place of safety.

Local Social Services Authorities, hospitals, NHS commissioners, police forces and ambulance services should ensure that they have a clear and jointly agreed policy for use of the powers under sections 135 and 136, as well as the operation of agreed places of safety within their localities. 48

When considering service users who come into contact with police and the health service for incidents other than sections 135 or 136, there is guidance in the code of practice relating to police powers for conveying patients between hospitals and returning patients who abscond (p. 93)48 and for dealing with patients who are absent without leave (AWOL) (pp. 174–7). 48

Mental Capacity Act 2005 c.9

The MCA came into force in 2007, providing a legal basis for providing care and treatment for adults lacking mental capacity to give consent. 49,50 The MCA is primarily aimed at health professionals and the code of practice indicates that decisions about mental capacity should be taken by a health professional. The code of practice does provide guidance that:

All reasonable steps which are in the person’s best interests should be taken to prolong their life

Paragraph 5.31 (p. 79)50

Sometimes people who lack capacity to consent will require emergency medical treatment to save their life or prevent them from serious harm. In these situations, what steps are ‘reasonable’ will differ to those in non-urgent cases. In emergencies, it will almost always be in the person’s best interest to give urgent treatment without delay.

Paragraph 6.35 (pp. 104–5)50

Police do not have the power to detain under the MCA, but may be in a position to act in the best interests of a person where an officer perceives that an individual does not have mental capacity. The MCA was not used in any of the incidents discussed in this report.

Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 c.60

Police guidance comes directly from the PACE43 and other relevant criminal acts. Relevant sections for custodial detention of individuals with mental ill health are in Code C: code of practice for the detention, treatment and questioning of persons by police officers. Within Code C, particularly the following referenced pages, there are guides for police officers dealing with people defined as a ‘mentally disordered or otherwise mentally vulnerable person’. 45 Of particular relevance to the findings in this research and to individuals with EMHN are the general descriptions of custody management (pp. 2–5), assigning an appropriate adult (AA) (pp. 9–10, 16), and the conditions of detention and the care and treatment of detainees (pp. 23–29). 43 Guidance for dealing with detainees is further provided in sections relating to cautions, interviews, detention extensions and charging in Code C of PACE.

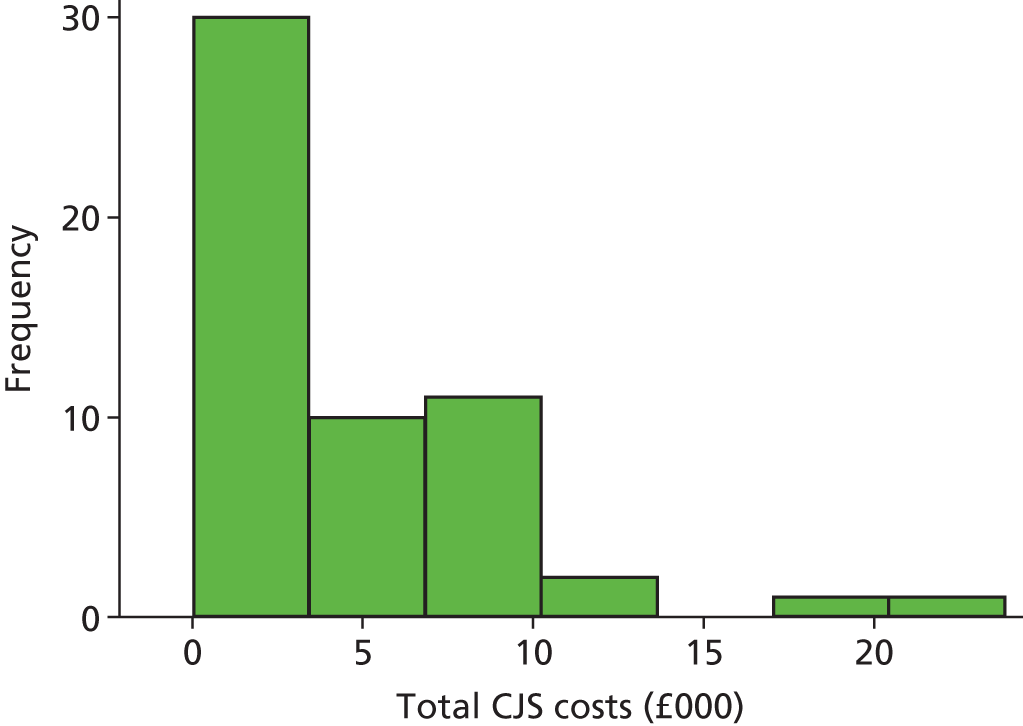

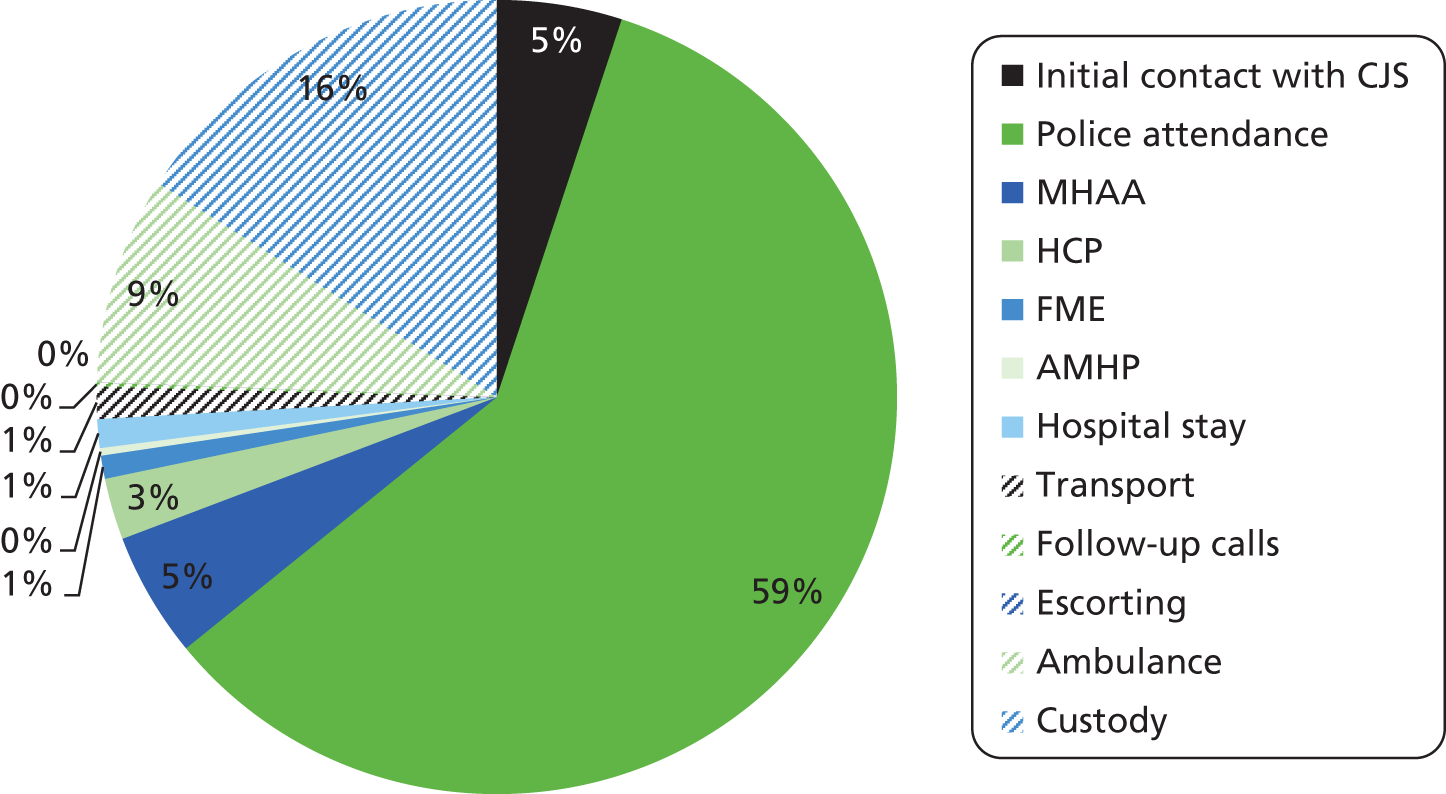

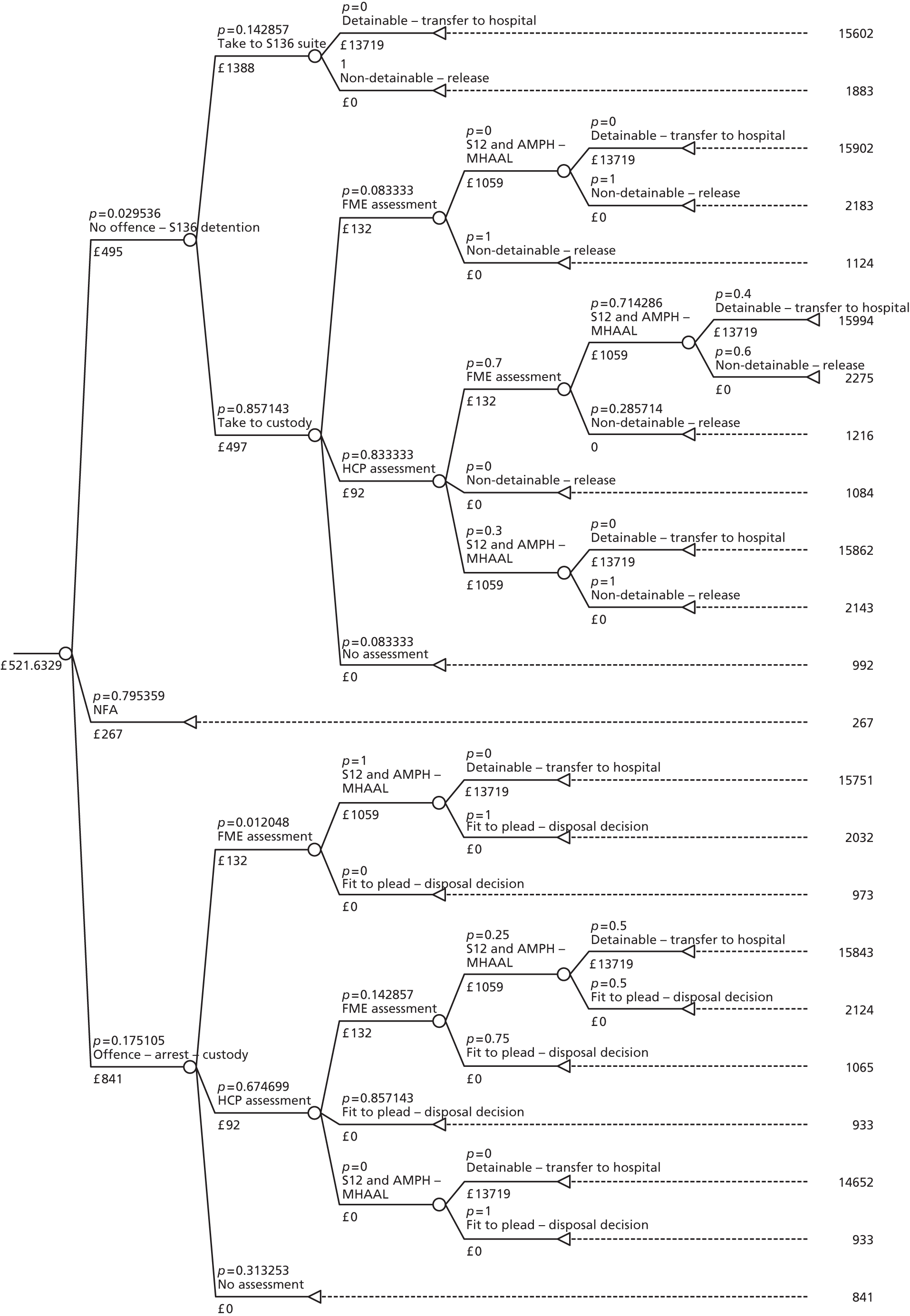

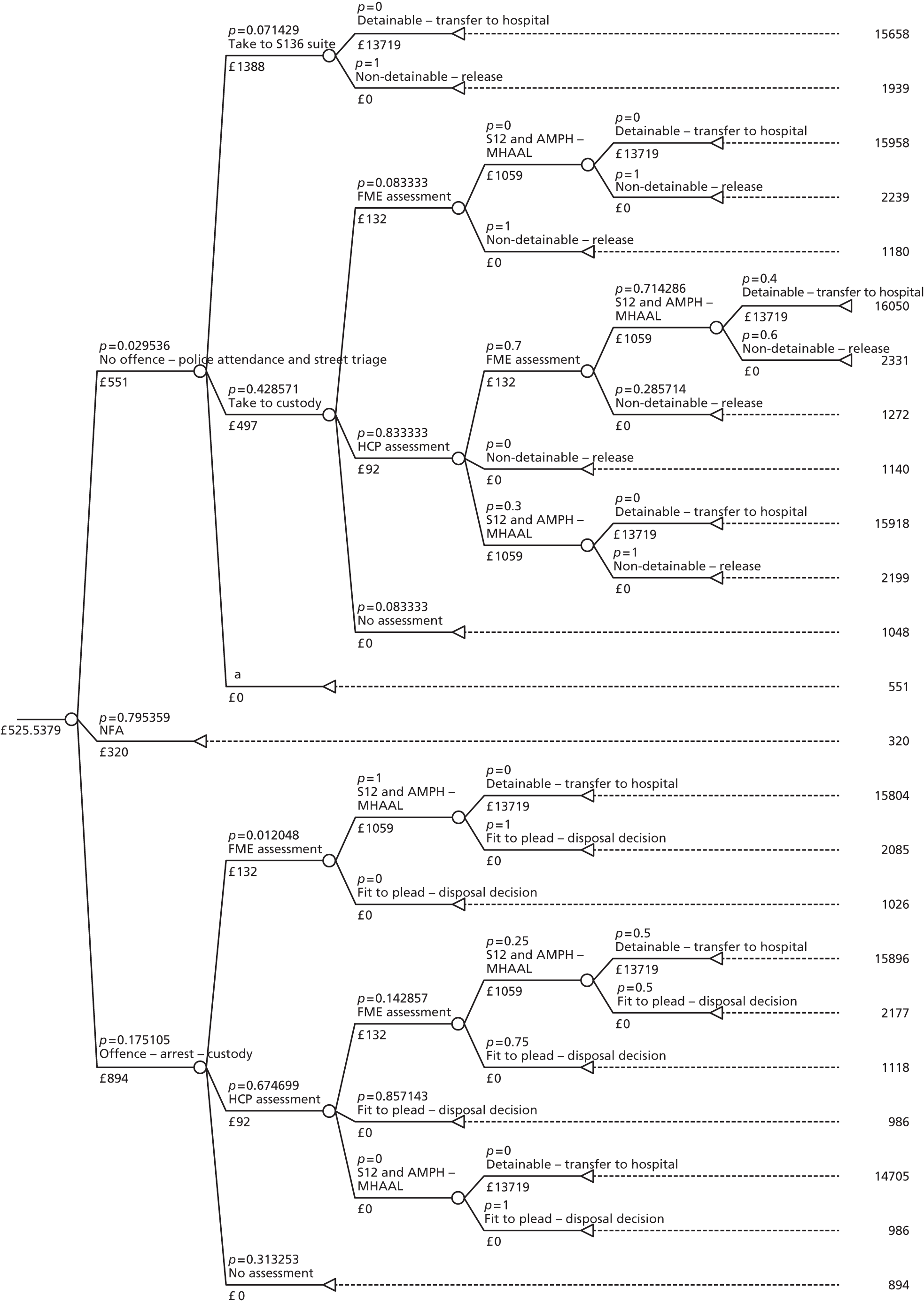

Criminal Justice Act 2003 c.44