Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme as project number 13/05/11. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The final report began editorial review in September 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jane Dalton is a publicly elected governor at York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Dalton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The need to fully engage staff, patients and the public in discussions and decisions about changes to the way health services are delivered has been recognised for many years. In England, local authority health overview and scrutiny committees must be consulted by local NHS bodies about proposals for substantial changes to services. Committees can refer proposals to the Secretary of State for Health if they are not satisfied with the consultation process or consider that the proposals are not in the interests of the health service in their area. The Independent Reconfiguration Panel (IRP) provides independent advice to the Secretary of State in such cases. 1 More recently, the Health and Social Care Act 20122 established a new mechanism (Healthwatch) to drive patient involvement locally and nationally across the NHS. Best-practice guidance is available from several sources, such as NHS England’s Planning and Delivering Service Changes for Patients3 and Transforming Participation in Health and Care. 4 Proposals for service changes by commissioners and other bodies are required to pass four tests, the first of which is to be able to demonstrate evidence of strong public and patient engagement. The remaining tests seek to demonstrate consistency with current and prospective need for patient choice; a clear clinical evidence base; and support for proposals from clinical commissioners.

While much of the guidance reflects common sense, there is a need to establish the strength of the evidence base around different approaches to public engagement and involvement and in terms of impact. Proposed changes to health service delivery are often controversial locally and sometimes nationally. Effective public engagement may help resolve controversy and result in a broad consensus on the way forward. Successful implementation of this process may, in turn, bring about greater satisfaction that services adequately reflect public preferences; and may ultimately improve clinical outcomes or better access to services. In contrast, inadequate consultation may result in lack of agreement, leading to proposals being delayed or referred to the IRP or ultimately the courts. Any evidence that can clarify factors associated with positive public engagement will be of value both to NHS decision-makers and to society as a whole.

A wide variety of approaches to public engagement and involvement are available. Examples include surveys, face-to-face and telephone interviews, public meetings, focus groups, online consultations (including use of social media), local referenda and citizens’ juries (also known as citizen panels or stakeholder dialogues). The available literature describing and evaluating how these approaches have operated in practice appears to be disparate and widely scattered. Recent systematic reviews have looked at the impact of patient and public involvement (PPI) on UK health care in general5 and at strategies for interactive public engagement in development of health-care policies and programmes. 6 In the primary literature, examples include an academic study of a ‘decision conference’ including patients and caregivers, to consider eating disorders services;7 a general discussion of the issues in a journal aimed at health service managers;8 and a number of case studies published by the NHS Confederation. 9–13

The objective of this project was to bring together evidence from published and grey literature sources, to assess what is known about effective patient and public engagement in reconfiguration processes and to identify implications for further health-care practice and research.

Chapter 2 Methods

General approach

The project was resourced as a rapid evidence synthesis. There is no generally accepted definition of this term and a number of other terms have been used to describe rapid reviews incorporating systematic review methodology modified to various degrees. Our intention was to carry out a review using systematic and transparent methods to identify and appraise relevant evidence and produce a synthesis that goes beyond identifying the main areas of research and listing their findings. However, we foresaw that the process would be less exhaustive and the outputs somewhat less detailed than might be expected from a full systematic review. Added to this, we expected to find limited evidence on the subject in the peer-reviewed primary literature.

Research questions

We sought to address the following five questions:

-

How have patients and the public been engaged in decisions about health service reconfiguration in the past?

-

How has PPI affected decisions about health service reconfiguration?

-

Which types of PPI have had the greatest impact on these decisions?

-

Which methods of PPI are likely to be sustainable/repeatable?

-

How have differing opinions about reconfiguration between patients, the public, clinical experts and other senior decision-makers been negotiated and resolved?

Scope and definitions

The focus of the review is reconfiguration of health service provision in the NHS. We also considered evidence on health services delivered by non-NHS providers (e.g. voluntary sector/private sector) and the joint provision of health and social care where this impacts directly on NHS provision. Where relevant, we considered international evidence from other health systems which are comparable and relevant to the NHS. In addition to England/the UK, the included systematic reviews covered studies conducted worldwide; other research and case studies additionally covered Scotland and Canada.

Reconfiguration includes large-scale system change, such as relocation of hospitals, (re)location of specialist care and changes in provision of urgent/emergency/out-of-hours care. We did not consider small-scale change, for example at hospital ward level or within a general practitioner (GP) practice. Reconfiguration has been defined in the literature as a deliberately induced change of some significance in the distribution of medical, surgical, diagnostic and ancillary specialties that are available in each hospital or other secondary or tertiary acute care unit in locality, region or health-care administrative area. 14

In the literature, the terms ‘engagement’ and ‘involvement’ are often used interchangeably. For the purposes of public involvement in research, INVOLVE (www.invo.org.uk) distinguishes between active involvement of patients or members of the public in research projects and engagement, which provides information and knowledge about research in an accessible way (e.g. through science festivals or open days). This distinction is difficult to sustain in the context of proposals for service reconfiguration where provision of information may (or may not) lead to active involvement. Events such as public meetings or citizens’ juries have elements of both information provision and active contribution of patients or members of the public to developing or modifying (or rejecting) proposals for change. In this review we define patient/public engagement or democratic involvement as including any means of seeking and responding to the views of patients and the wider public at any stage of the process of reconfiguration (including identifying possible options for change). We have not attempted to standardise the various terminology used to indicate service user engagement across the included studies. In our search strategy, other terms included ‘user’ and ‘carer’ engagement and involvement (see Appendix 1). The scope included existing patients, carers and their representative groups; and the general public and their representatives [e.g. local councillors and Members of Parliament (MPs)].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We looked for relevant evidence in three main areas:

-

Systematic reviews of methods of/approaches to patient/public engagement. We included only reviews that were relevant to PPI in decisions about health service reconfiguration. Reviews of PPI in research were excluded.

-

Empirical studies of any design evaluating methods of/approaches to patient/public engagement. Studies that focused on involvement in research were excluded.

-

Case studies examining how PPI worked in specific examples of system change in the recent past. We expected that these were more likely to be found in the grey literature than in peer-reviewed publications. Case studies of this kind were likely to provide a biased sample of ‘successful’ rather than typical PPI but were more likely to provide useful data to inform future practice. We also searched for case studies where public involvement failed to produce an agreed way forward or resulted in unintended consequences, using the website of the IRP as a starting point.

The following were excluded:

-

‘emergency’ reconfigurations triggered by failure of a service provider, such as a NHS trust

-

consultation/involvement of NHS staff, except as part of a broader consultation where staff and PPI could not be separated

-

patient/public representation on bodies where reconfiguration was part of the remit but was not the main focus

-

patient/public engagement methods where complaints management was the focus (e.g. patient advice and liaison service and the Healthwatch independent advocacy arm).

Literature search

Search strategy for reviews

A search strategy was developed on the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Wiley) to identify any systematic reviews or overviews of systematic reviews of user engagement. As user engagement is described in a variety of ways in the literature, a wide range of text words, synonyms and subject headings were included in the search strategy. Key terms for user engagement were identified by scanning key papers, discussion with the review team and use of database thesauri. Searches were restricted to reviews published from 2000 onwards. No language restrictions were applied to the searches. The search strategy was adapted for use in each of the review databases searched. Text word searches were limited to searching in only the title field for databases where this was possible. The following databases were searched in March/April 2014: the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Campbell Library, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Database of Promoting Health Effectiveness Reviews, the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre), Evidence Library and Health Systems Evidence (www.mcmasterhealthforum.org/hse/).

Search strategy for primary studies

A search strategy for primary studies was developed using MEDLINE (OvidSP). The existing strategy for reviews described above (containing terms for user engagement) was combined using the Boolean operator ‘AND’ with a second set of terms for reconfiguration. As this was a rapid review, a number of limits were used to focus the strategy: focusing of subject headings, a date limit of 2000 onwards and restriction to English-language studies. The range of databases searched was more limited than would be usual for a full systematic review. In particular, no specific databases of conference proceedings, theses or foreign-language studies were searched. Relevant databases covering literature from health, health management and social science were searched in March/April 2014: MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Health Management Information Consortium, PsycINFO, Social Care Online and the Social Science Citation Index. The MEDLINE strategy was adapted for use in each database.

Search strategy to locate grey literature

In addition to the database searches, a wide range of websites relevant to UK health policy, health service delivery and organisation, and user engagement were searched to identify any policy documents, reports, case studies or grey literature. Websites were selected on the basis of expert knowledge and judgement. A list of relevant websites was drawn up by the review team and further additions to the list were suggested by our collaborators and external contacts. Each website was browsed manually and/or searched using the website search function where available, depending on the size of literature contained on the website. Searches were carried out in April/May 2014. Relevant documents hosted on the websites relating to user engagement in the reconfiguration of services published since 2000 in English were retrieved and downloaded. Further links within each website to documents on other websites were not explored. To supplement the website searches, a focused search of Google was carried out to locate UK reports on service reconfiguration. Using the Google advanced search facility, the search was limited to UK portable document format files (PDFs) published in English from 2000 onwards with the term ‘reconfiguration’ in the title of the web page. The first 100 results were scanned for relevance. Further case studies were identified through contact with local hospitals and other experts and researchers working in the field of user engagement.

Records were managed within an EndNote library (EndNote version X6, Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). After deduplication, 2322 records in total were identified.

Further details of the search strategies and results can be found in Appendix 1.

Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment

Search results were initially screened by a single reviewer to eliminate obviously irrelevant items. Full-text copies were ordered or downloaded for potentially relevant records. Final study selection was carried out by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved by discussion or involvement of a third reviewer if necessary.

We used EPPI-Reviewer 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK) to record decisions about study selection and for data extraction and quality assessment. We developed separate data extraction forms to record key information for different evidence sources (systematic reviews, case studies and other research). For case studies, data extraction was done in two stages: basic details were extracted for all included case studies; then a number of ‘exemplars’ were selected for more detailed data extraction and analysis. Exemplars were those case studies that provided most detailed and current information about the methods used for patient/public engagement and involvement and/or assessed the impact of engagement/involvement in reconfiguration decisions. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and checked by a second.

We assessed systematic reviews for methodological quality and reliability using the approach of DARE. We planned to assess published primary research studies using appropriate design-specific tools described in the guidance of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination for undertaking systematic reviews in health care (2009). 15 Unpublished case studies and non-peer-reviewed reports were not formally assessed for quality (risk of bias) but we sought to identify any instances of more rigorously conducted and fully reported case studies. Issues considered were:

-

the extent to which an appropriate diversity of perspectives (e.g. across service user and NHS) was considered in assessing the impact of patient/public engagement

-

the extent to which the case study was conducted and reported with transparency

-

reflexivity on any specifically adopted perspective, together with adequacy and clarity of reporting on intervention context, methods and impact.

Synthesis

We carried out a narrative synthesis using multiple frameworks to guide our analysis. In addition to the five research questions specified in the study protocol, we considered chronological aspects of reconfiguration decisions in terms of the seven stages specified in the NHS England guidance on planning and delivering service changes (Box 1). 3 Levels of engagement/involvement were assessed where possible, using the version of Arnstein’s ‘ladder of engagement and participation’ presented in the NHS England guidance on transforming participation in health and care (Table 1). 4 We used the available literature to determine the extent to which evidence supported or disagreed with the recent guidance and to highlight areas where the evidence was conflicting or insufficient.

-

Setting the strategic context.

-

Proposal.

-

Discussion.

-

Assurance.

-

Consultation.

-

Decision.

-

Implementation.

Source: Planning and Delivering Service Changes for Patients (pp. 14–15). 3

| Devolving | Placing decision-making in the hands of the community and individuals, for example Personal Health Budgets or a community development approach |

| Collaborating | Working in partnership with communities and patients in each aspect of the decision, including the development of alternatives and the identification of the preferred solution |

| Involving | Working directly with communities and patients to ensure that concerns and aspirations are consistently understood and considered, for example partnership boards, reference groups and service users participating in policy groups |

| Consulting | Obtaining community and individual feedback on analysis, alternatives and/or decisions, for example surveys, door knocking, citizens’ panels and focus groups |

| Informing | Providing communities and individuals with balanced and objective information to assist them in understanding problems, alternatives, opportunities and solutions, for example websites, newsletters and press releases |

In synthesising the case studies, we focused on those case studies identified as exemplars (those case studies that provided more detail, see Study selection, data extraction and quality assessment). We were particularly interested in identifying case studies with an element of independent evaluation by an organisation not involved in the reconfiguration being examined.

Given the resources available for the project, we planned to focus on only a small number of exemplars. For other case studies, we extracted basic details only and used these studies to supplement the analysis of themes emerging from the exemplar case studies.

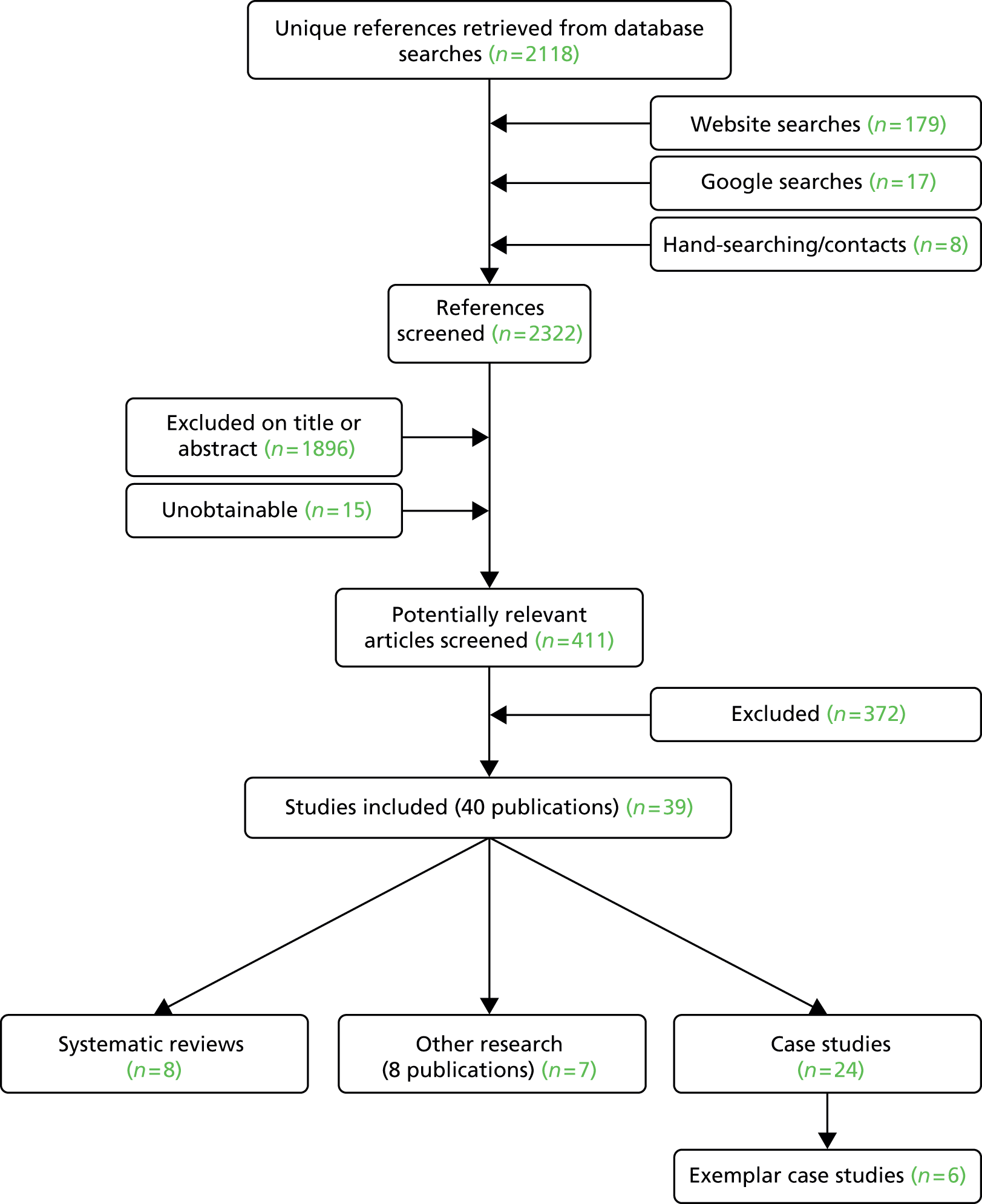

Chapter 3 Nature of the evidence

We included eight systematic reviews,5,6,16–21 eight papers (describing seven distinct pieces of work) that were classified as other health-care-related research1,22–28 and 24 case studies. 7–13,29–45 See Figure 1 for details.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Full data extraction tables for the systematic reviews, other research, case studies and case study exemplars are available in the appendices, along with details of the systematic reviews quality assessments (see Appendices 2–6).

Overview

We identified eight systematic reviews conducted between 2002 and 2012 (see Appendix 2). The number of included studies in these reviews ranged from 8 to 344. Study locations included various European countries, the USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Israel and Japan. All reviews included some proportion of UK studies. Four reviews contained a majority of studies located in the UK16–18,21 and two reviews5,19 had a complete focus on the UK setting (Table 2 and Appendix 2). Reading across the reviews, there was some overlap of studies. Owing to resource limitations, further examination of the nature and extent of this overlap was not carried out.

| Study reference | Type(s) of reconfiguration | Who was engaged/involved? | Method(s) of engagement/involvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conklin et al. (2012)16 | Relevant studies (where reconfiguration was the goal). Examples: resource allocation relating to local health integration networks; shaping policies and decisions about primary care provision and delivery; health-care priority setting; health policy decisions about the delivery of women’s health services; decision-making about local health services | Special interest groups; the public; patients; staff; NHS lay board members. More specific definitions of ‘the public’ varied and were generally unclear across the studies. Terms used by the study authors: representatives of patient organisations; ordinary citizens; individuals with no particular axe to grind; those whose voices might not otherwise be heard | Surveys; conference and website; community health councils; public meetings; local patient groups; citizen panels/juries; group simulation using roulette wheel; collaboration between agencies/groups/individuals |

| Crawford et al. (2002)17 | Various services, including primary care, mental health, learning and physical disability, general health care, community services, inpatient and outpatient, social care, maternity, neurology and human immunodeficiency virus. Most studies looked at smaller-scale change. Approximately one-quarter of studies focused on larger-scale change, including changes to organisation of care and/or services. Of these studies, two involved a plan for hospital closure | Most studies described participants as patients. Others reported involvement of carers, service users, staff, Health and Welfare Council, Community Health Council, citizens, lay board of directors or mixed populations | Patient groups; consultation meetings; committees and forums; interviews; citizen’s juries; survey; focus groups; representation on planning boards and panels; mixed methods |

| Crawford et al. (2003)18 | Specific reconfiguration not described. Reconfiguration contexts described as various within health, social and community care; non-health public sector (including postal services, social security, education, housing); private sector (including consumer goods, travel, entertainment); and voluntary sector (disability/neurological services) | Current, past and potential service users and their representatives; providers | Various, covering time-limited methods (to elicit user perceptions/preferences) and long-term approaches (building relationships with service users). Some initiated by provider; others initiated by service users. Public sector tended to use more deliberative approaches. Examples: surveys; focus groups; deliberative approaches (such as citizen’s juries, public conferences); user/community groups; formal bodies (such as Community Health Councils, patient groups, advocates and link workers) |

| Daykin et al. (2007)19 | General/strategic development; cancer services; mental health; older people’s services | Staff; members of the public; patients | Employment of an individual to work with community groups; interprofessional cancer education programme; user groups; forums for service users and officials; community-based exercise facility for people with mental health problems; citizen’s juries; community initiative to elicit and respond to the views of older people; regional-level action research programme with staff |

| Mockford et al. (2012)5 | General | Patients/carers; public | Lay membership of boards, panels and working groups; user groups |

| Rose et al. (2003)21 | Promoting democracy and representation and/or cultural change (over 50% of included studies). Strategic planning, restructuring of services (very few studies), and policy initiatives. New service provision and the employment of service users in organisations | Most studies focused on service users and professional staff. A quarter of studies involved carers. Others involved: user groups, carer groups, public, Community Health Councils | Most studies focused on collective consumerism, involving consultation, representation, partnership, evaluation, involvement in staff recruitment. Methods not explicitly stated |

Quality of the reviews

The quality of the eight systematic reviews varied. Seven reported an adequate search and provided study details, and all presented implications for research and/or practice. However, the extent to which review conclusions were reliably supported by the evidence presented (in the traditional sense of critically appraising systematic reviews) was limited by the fact that only two reviews formally assessed the quality of included studies. Seven of the reviews involved mixed evidence sources such as reviews, qualitative and quantitative (largely observational) studies, grey literature and discussion papers.

Types of reconfiguration

Although all eight reviews were related to service reconfiguration, not all framed their objective in these terms. Where reconfiguration was described beyond general terms, review authors referred to priority setting, local planning and policy development, and decisions about health service resource allocation. Service user engagement was explored across a range of specialist services and generic service or policy development. Examples of specific clinical service changes included those which were related to cancer,6,19 mental health,17 women’s health and maternity,16,17 and older peoples’ services. 19 Reviews also examined system-wide change, such as the shaping of primary care and community services;17,18 one review included two studies concentrating on plans for hospital closure. 17 Some reviews adopted a wider remit, capturing more than merely health implications. These particular reviews focused (in addition to health-care services) on proposals for change in areas such as environmental planning, education and housing. 18,20

Engagement methods and who was involved

There was no consistent definition of service user engagement or involvement. Where this was reported, engagement was specified in the review authors’ terms and did not appear substantially linked to any wider conceptual or theoretical framework.

A range of methods was employed in the engagement process. The extent to which methods were explicitly specified varied. Those that were primarily informative in nature included, for example, communication via traditional publicity and the provision of website materials. 16,20 Other methods indicated more active involvement of service users in eliciting feedback by opinion polls and surveys. 17,18,20 Consultation and deliberative methods featured in all reviews, being largely operationalised as collaborative partnerships, citizens’ juries, working groups, consensus conferences and other mechanisms. Where public meetings and community forums were described, without further detail it was often difficult to determine their positioning on the ladder of engagement and participation (see Table 1). Across many reviews, a mixture of methods was used to capture the service user voice. Four reviews discussed the potential sustainability of methods. 6,16,18,20

Across the reviews, service users were frequently described as ‘the public’, although this term tended to be defined loosely and variably. Others engaged in the process were patients, carers, staff, local residents, councillors, MPs and stakeholders (invariably not defined). The engagement of multiple audiences was referred to in many cases.

Impact

Most reviews were broadly agreed on the paucity of evidence of impact in relation to service user engagement and reconfiguration. More robust evaluative research was generally recommended. Many review authors cited the critical influence of contextual variables on successful engagement; one referred in particular to geographic variability. 16 The absence of measurable outcomes was a problem;5,16,21 the lack of independent research was reported to be a considerable limiting factor. 18

Successful engagement was defined variably across the included studies, with many describing impact on processes rather than service reconfiguration per se; for example, changes in service user views about services, organisational culture change with regard to commitment to user engagement, and shifts in learning about future processes represented outcomes in two reviews. 16,17

There was some evidence of impact on service delivery outcomes in terms of changes to service provision5,17 and, in particular for location and access issues,5 priorities integrated into a regional programme and new resources found for services resulting from the activities of citizens’ juries and other community collaborations. 16 One review included two studies that reported a successful challenge to hospital closure, resulting in the proposal being modified or abandoned. 17

Negative consequences of engagement were rarely reported. However, two reviews referred to service users interpreting the engagement process as tokenism,17 and community stakeholders were reported to experience unintended consequences (feeling ostracised) when challenging statutory sector partners. 16

While there was little evidence to support the isolated success of any particular engagement method,19,20 there were positive indications for those characterised as more deliberative in nature and involving face-to-face interactions,6,16,19,20 and for engagement efforts comprising multiple methods. 19 There was mixed support for partnership working, which was seen as central to success in one review6 and as having no systematic relationship with any form of organisational change in another. 21

Tentative success factors in service user engagement appeared to be organisational support for the process; a willingness of users to engage; clarity surrounding the aims of engagement; and adequate resourcing of evaluations. 6,18,19,21

There was little discussion about the potential sustainability of methods. In one review, the institutionalisation of partnerships was seen as a key driver,6 while regional meetings were seen as potentially repeatable in another. 16

Systematic reviews in summary

Reviews were conducted with a reasonable level of attention to methodological rigour. Because of the diversity and nature of the study designs, the quality of the studies included in the reviews was difficult to determine. A variety of health services were studied, and a range of engagement methods (described by various terminologies) adopted. Not all systematic reviews focused completely on health service reconfiguration. Where this was the case, review objectives seemed closely aligned to reconfiguration (e.g. the focus was on priority setting or decisions about resource allocation for future services).

The isolated impact of service user engagement (as distinct from the engagement of staff and other stakeholders) was sometimes difficult to distinguish. Reviews focused largely on the impact of service user engagement on outcomes related to process (e.g. shifts in organisational views about engagement) rather than those related to the impact of engagement on reconfiguration success.

Positive indications were noted from engagement methods that were more deliberative, those involving face-to-face interactions and those comprising multiple methods. Tentative factors leading to successful service user engagement were organisational support, willingness of users to engage, clarity about the aims of engagement and adequate resourcing of evaluations.

Other research

Overview

We identified eight publications that described seven other research projects in the area (see Figure 1). All were located in the UK (four in England, two in Scotland and one UK-wide). The papers were selected based on relevance to this review. They were not evaluated for methodological quality. Although they were diverse in methodology, it was possible to identify three broad categories of discussion papers about service user engagement and reconfiguration.

Influencing factors, trade-offs and options appraisal

Three papers focused in part on engagement in proposed changes in accident and emergency services. 22–24 Changes to community hospital provision were additionally explored in the Scottish-based paper; in this paper, discussion of services involving day-long deliberative panels, surveys and interviews with the public and NHS stakeholders resulted in the identification of several key drivers underpinning successful service user engagement. 24 These were reported primarily as the need for common understanding on the case for change, careful selection of methods of public engagement, focus on location and access, and a strong clinical case for change.

In-depth interviews and flash cards were used to elicit information about preferences and trade-offs among patients and members of the public in two English localities. 22,23 Discussion revealed that most participants were unwilling to accept trade-offs (particularly longer journey times to access higher-quality care). A key message for commissioners and policy-makers was to avoid assuming that presenting the clinical case for change, together with very visible clinical leadership of the proposals, would result in associated community support. While this could be viewed as a negative or unexpected consequence of engagement, hostility to the proposal identified in this research demonstrated an important step in the process of arriving at a democratically derived solution.

Mechanisms for independent scrutiny and lessons from failures

A review of IRP reviews sought to highlight common themes arising from various cases of service reconfiguration referred to the organisation between 2003 and 2010. 1 The report illustrated the following precursors to referral: inadequate community and stakeholder engagement in the early stages of planning and change; inadequate promotion of the clinical case for change; overlooking the broad vision of integration; underplaying benefits of change; limited content and methods of conveying information; lack of preparedness to respond on key issues such as money, transport and emergency care; and inadequate attention to responses throughout and beyond the consultation.

The issue of independent scrutiny was further discussed in an expert opinion paper exploring the robustness of local and national scrutiny mechanisms (local overview and scrutiny committees, judicial scrutiny and the role of the IRP) relating to a range of NHS service reconfigurations. 25 The report concluded that local overview and scrutiny committees were assertive in questioning and challenging proposals. Uncertainties were uncovered relating to decisions about exactly when consultation was required and the definition of ‘substantial’ change. Costs and benefits of local authority scrutiny were also discussed.

Recommendations for local leaders of service reconfiguration from a further expert opinion paper placed strong emphasis on involving patients in the coproduction of services (where patients and organisations were engaged from the start as equals in shaping the case for redesigning services to meet their needs and preferences) and having less reliance on formal consultation. 28

The nature of communication and role of the media

The first of two papers focused on how primary care trusts (PCTs) could most effectively communicate proposals for service reconfiguration to the general public. 26 Using focus groups and case studies, the authors discussed the use of language. Results showed that certain words and phrases (such as ‘budget’, ‘value for money’ and ‘competitive tendering’) were not fully understood and sometimes misunderstood by service users. Consequently, the potential tension between organisational transparency and communicating in a way that successfully engaged people was exposed. In Scotland, media coverage of changes to rural maternity services was observed in another report. 27 This report documented variations in reporting across a number of newspapers and British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) coverage, with positive and negative accounts of the service change.

Other health-care-related research in summary

Other health-care-related research comprised discussion papers and debates, with some examination of public views about engagement and/or service reconfiguration. The research highlighted the existence of key steps in the reconfiguration process that could result in referral to the IRP if not followed correctly (see Mechanisms for independent scrutiny and lessons from failures). 1 The research also indicated where service user engagement could be construed negatively; the importance of effective use of language in communicating with multiple audiences; variations in media opinion about service change; and consequent potential to influence service users in their decision-making.

Case studies

Overview of case studies not examined in depth

We identified 24 case studies, but detailed data extraction was not carried out for 18 of these because of variability in the consistency and depth of reporting. The basic details of these case studies are summarised as follows.

Most case studies highlighted potential indicators of success but failed to provide enough detail about methods of engagement and/or report the association of these methods with specific impact. 8,10,11,13,29–38 Most studies were located in England and in the NHS setting. Specific types of reconfiguration included hospital mergers, integration of health and social care, and changes linked to primary care, maternity, emergency, acute care and pain services. Other types of reconfiguration were less well specified, such as the centralisation of services or unspecified large-scale reconfiguration. A wide range of participants was involved in the engagement process, including patients and the public, NHS staff, foundation trust members and governors, voluntary sector organisations, MPs and others.

Two reports focused on the history and development of specific models of patient and public engagement. These included a detailed account of activities from the Somerset Health Panels39 and a description of how a Public Involvement Network model was developed in Dorset, England. 40 Another report which looked at the planning of regional supportive cancer services in Ontario, Canada, focused generally on barriers to effective patient involvement. 41

The final case study reference was a web link to 24 reports produced between 2005 and 2012 by the Scottish Health Council on behalf of the Scottish Government. 42 As with the English NHS, Scottish Health Boards are required to involve patients and local communities adequately in relation to significant NHS service change. Across these reports, types of reconfiguration varied. Details centred on aspects of the consultation process and on learning points to improve future public consultations.

Case study exemplars

Six case studies were identified as being exemplars of good practice on the basis of one or more of the following: completeness and quality of reporting (particularly on methods and impact); diversity of perspectives employed; reflexivity in reporting; and demonstrable impact resulting from a specified engagement process. 7,9,12,43–45 See Tables 3 and 4, and Appendix 6.

| Study reference | Setting | Type(s) of reconfiguration | Who was engaged/involved? | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airoldi (2013)7 | PCT eating disorder service | Priority-setting in eating disorder services, with emphasis on improving services in a climate of decreasing resources | Patients, caregivers, clinicians, health-care managers. There were five patients/carers out of 24 in the group. Follow-up was conducted with a wider set of stakeholders (not specified) in the local health economy | Decision conferences: working meetings attended by key stakeholders, led by an impartial facilitator. Participants assessed the value of services based on (1) cost and (2) population health benefit. Additionally: semistructured and unstructured interviews; e-mail correspondence; direct observation of workshops; use of flipchart notes and minutes of board meetings; follow-up events and interviews at 1 and 2 years after consultation. A steering group and an independent evaluator oversaw the process, in addition to input from the case study author |

| Gamble and Sloss (2011)43 | Urgent care/ED | Redesign of minors care within the ED. To include integration of a walk-in centre (separately located at the time; engagement work on the walk-in centre does not form part of the present study); improved integration with the out-of-hours GP service; and consideration of a potential GP triage service | Patients, carers, staff, hospital governors | Observation sessions in ED; focus group; real-time feedback (patient experience questionnaire via standpoint machine); inpatient national survey results specific to York ED. Other engagement work was proposed (no details in this report) as part of the trust’s wider communications strategy on proposals to create an urgent care centre. The proposed work included attendance at local events, presentations to specialist interest groups and information-giving at the hospital open day |

| NHS Confederation (2013)12 | Acute and emergency care | ‘Better Healthcare in Bucks’: centralisation of emergency care. Providing care closer to home for most patients. Establishment of clinical centres of excellence | Patients, public, primary care and hospital-based clinicians, other health service staff, MPs, local health overview and scrutiny committee, voluntary organisations | Public meetings, clinical summits, online surveys, website, video showing interviews with lead clinicians, printed materials, local media campaign, presentations and site visits. A wide-reaching communications programme (internal and external) was implemented to support the service change |

| NHS Confederation (2013)9 | Acute hospital (maternity services) | Redesign of maternity services | Patients and their representatives: women and their families, GPs, local councillors and MPs, including the Joint Health Overview Scrutiny Group. Parent groups, Sure Start. Others engaged in the process: community midwives, hospital-based clinicians | Online responses, public meetings, face-to-face meetings with key stakeholders, letters, articles in relevant local and national media, website updates, ‘ground-breaking events’, posters and postcards, employment of a redesign lead at the trust. Public engagement ran alongside a comprehensive staff-training programme |

| Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2010)44 | Mental health day and vocational services | Service redesign as part of a wider review of modernising day and vocational services for people with mental health problems | Service users, commissioners, external consultants | A working group (comprising eight service users) was established to take part in the review of services, in response to invitation leaflets and posters distributed to local day centres. Three members of the working group joined a separate project steering group, which also included representatives from commissioners and external consultants. The group’s remit included design of the review of services; research with service users to gather views about services; contributing to decisions about service redesign; contributing to the development of service specifications and tender documents; and helping to select future providers in the tendering process |

| NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (2014)45 | Primary care | Urgent care services | Patients, public, clinicians, partner organisations (representatives from primary care, secondary care, local authority, voluntary sector), local and regional scrutiny committees, local media | Distribution of consultation document and video; interactive workshop for clinicians and partner organisations; presentations to local and regional health scrutiny committees; surveys; public meetings; focus groups; Facebook (Facebook Inc. CA, USA) posts |

| Key factors of successful engagement/reconfiguration from case study exemplars | |

|---|---|

| Study and reference | Key themes |

| NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (2014)45 |

|

| York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Gamble and Sloss 201143) |

|

| Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire PCT/Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust (NHS Confederation 201312) |

|

| Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust (NHS Confederation 20139) |

|

| Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (201044) |

|

| NHS Sheffield PCT (Airoldi et al. 20137) |

|

Overview

Consultations took place between 2007 and 2014. All were conducted in the UK. Four case studies were commissioned by NHS organisations [foundation or acute care trusts, PCT, Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG)], one was carried out by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health and the other was commissioned by The Health Foundation.

Quality of the case studies

Based on our three assessment criteria, the overall quality of these case studies was good (defined as adequate and clear reporting; evidence of reflexivity; and diverse perspectives considered). Report authors had generally considered diverse perspectives in the conduct of their case studies. There was evidence of reflexivity in the reporting (authors had reflected on findings and discussed the implications for practice in many cases), and reporting depth and clarity was considered largely good to excellent.

Types of reconfiguration

Proposed changes to services covered urgent and emergency care;43,45 centralisation of emergency care, providing services closer to home and developing clinical centres of excellence;12 acute hospital maternity services;9 mental health services;44 and priority-setting for eating disorder services. 7

Populations engaged

Multiple audiences were involved in all except one case study where the consultation focused more narrowly on patients and members of the public (although this piece of work was part of a wider engagement and communication strategy). 43 Across the case studies, other people engaged in the process included patient representatives, NHS staff and clinicians, overview and scrutiny committees, carers, local councillors and MPs, partner organisations (including the voluntary sector), specific statutory bodies (e.g. Sure Start), media, commissioners and external consultants.

Case study exemplars in focus: engagement methods and impact

NHS Scarborough and Ryedale Clinical Commissioning Group

A 3-month consultation was commissioned by Scarborough and Ryedale CCG in relation to urgent care services. 45 The consultation was intense and wide-reaching (an estimated 200,000 people were contacted), and this involved gathering the views of service users and the general public about their experiences of current provision, together with their thoughts about a proposed new model of urgent care. Clinicians, partner organisations (representatives from primary care, secondary care, local authority and voluntary sector organisations) and local media were also consulted.

Multiple engagement methods were employed, including the distribution of a consultation document and accompanying video; an interactive workshop for clinicians and partner organisations; presentations to local and regional health scrutiny committees; questionnaires (paper and online); a series of public meetings and focus groups; and use of social media.

The demonstrable impact of this consultation was a number of key considerations being taken forward to inform a service tender specification for urgent care services. Important issues identified by service users were the need for appropriate location of services with attention to parking, transport, and security (a significant finding was that people would not be willing to travel further for an improved service, echoing findings from other research). 22–24 Service users also called for the appropriate design of services for a range of potential users; appropriate access to medical records and liaison with NHS 111 (where necessary); and adequate information to aid decision-making about how and when to access urgent care. It was strongly felt that patient experience should form part of ongoing performance and quality measures for urgent care services. In November 2014, the successful provider of these services was announced with effect from April 2015. From the CCG’s press release, it was evident that issues raised in the public consultation (such as access and car parking) had been taken on board in the reconfigured service.

This case study highlights the potential effectiveness of wide-reaching stakeholder consultation including those opposing change. Use of an extensive range of engagement methods (including those to access hard-to-reach populations and others most likely to access urgent care services) and intensive reflection on local context appeared to be significant drivers. The direct impact of this engagement on successful service reconfiguration will require further evaluation.

York Teaching Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

The trust conducted a 3-month consultation focusing on public and patients/patient representatives in relation to redesigning the minors care pathway with a view to developing an integrated urgent care service within its emergency department. 43 This piece of work formed part of a wider consultation on urgent care services including the integration of a walk-in centre (separately located at the time), improved integration with the out-of hours GP service and consideration of a potential GP triage service. The project was set in the broader strategic context of helping to maximise effective future streaming of patients across minor and major care within the emergency department.

Uniquely in this series of exemplars, the methodology underpinning the particular engagement exercise was experience-based design. 46 This methodology focuses on capturing and understanding patient, carer and staff experience of services, with a view to using them to inform actions for the physical redesign of systems and processes.

Three key engagement methods were used: observation sessions in the emergency department by hospital governors and members of the local involvement network; focus groups with service users who had attended the emergency department in the preceding year; and real-time feedback (a questionnaire on a standpoint machine located in the emergency department waiting area).

A number of key issues arising from this engagement exercise were fed into an action plan for the emergency department redesign at micro and macro levels. Various aspects relating to physical redesign were linked directly to the trust’s capital works programme (e.g. major alterations to the reception area and the provision of a designated quiet area for people with particular clinical needs such as those suffering from dementia). Indeed, in identifying the needs of patients with dementia as a priority, the emergency department consultation proposed a review of wider activity around the referral and service access for these patients.

This case study highlighted the potential effectiveness of consultations that were more narrowly focused, time-limited and based on a specific methodological framework.

Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Primary Care Trust Cluster/Buckinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust

The redesign of emergency care featured again in the next case study reported by the NHS Confederation and carried out across NHS hospital sites in Buckinghamshire. 12 This study focused on the proposed centralisation of emergency care, alongside other objectives to provide care closer to home and to establish a number of clinical centres of excellence. Similar to York (previous subsection), this was a short-term consultation but with wider reach involving patients, public, primary care and hospital-based clinicians and other NHS staff, MPs, local overview and scrutiny committees and voluntary sector organisations.

A range of engagement methods was used, including public meetings, clinical summits, online surveys, website access, video recordings showing interviews with lead clinicians, printed materials, a local media campaign, presentations and site visits. Public meetings were seen as opportunities to provide assurance on fears about service closure.

Results of the engagement programme led to direct action in response to patient concerns about transport and access to services. Concerns were considered in more depth by a multidisciplinary task group comprising council members, hospital representatives and ambulance service representatives. A direct outcome of this partnership work was the subsequent provision of free travel on local bus networks and the establishment of a county-wide community transport hub.

For service redesign, implementation began 6 months after the consultation had ended. An emergency medical centre at one site was replaced with a new minor injuries unit, together with the transfer of some inpatient medical wards, a new day unit and a step-down ward. The engagement process was reported to continue beyond the implementation stage.

Key messages from this case study were the importance of reaching a shared understanding of the case for change at local level (involving partnerships with primary and secondary care) and possibly by focusing on one aspect of care to encourage wider debate about services; starting public engagement early and listen to/accommodate the views of all interest groups where possible; encouraging clinicians to make the case for change, focusing on the potential to improve services rather than cost savings; and engaging face-to-face with local politicians and stakeholders. This case study also demonstrated the direct impact of engagement in bringing together a multidisciplinary team to address a specific issue of patient and public concern (transport and service access), and how positive action could result from collaboration with agencies outside the health-care system.

Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust

Maternity service redesign was the focus of an engagement exercise spanning 4 years at Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust, reported by the NHS Confederation. 9 The proposed redesign arose from a pre-consultation exercise that resulted in three options for the delivery of maternity care across the region. On these three options a range of participants were consulted over a 3-month period. Participants included patients and their representatives, GPs, local councillors and MPs, community midwives and hospital-based clinicians.

Methods of engagement include online activities, public meetings, face-to-face meetings with key stakeholders, use of local and national media, ‘ground-breaking events’, posters and postcards, and the employment of a redesign lead at the hospital trust.

Response to the consultation was reported to be overwhelmingly in favour of the option to establish a community birth centre, with specialist care taking place at an inner-city hospital location. It was proposed that women and their families would contribute to the design of the new facilities. The option was approved and its implementation ran in parallel with an intensive communications and engagement programme and a staff training programme.

The nexus between engagement, service reconfiguration and health outcomes was tentatively demonstrated in this case study. The maternity services at Sandwell and West Birmingham NHS Trust resulted in the highest normal birth rate in the country in 2011/12, a national award from the Royal College of Midwives for promoting natural birth was received in 2013, and in the same year the trust’s maternity services were upgraded to level 2 of the Clinical Negligence Scheme in recognition of safety standards. The unforeseen consequence of this reconfiguration (and one which will reportedly be taken forward as a lesson for future consultations) was that some women preferred to give birth in the Black Country, rather than in the specialist unit in Birmingham. It was unclear from the report whether this was potentially related to socioeconomic status or to broader cultural influences.

Many of the key messages for future service user engagement mentioned earlier were illustrated in this case study. Additionally, this study provided novel insight to cultural factors that can exert a strong influence on patient choice of service location and thus potentially affect the success of reconfiguration.

Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health

A case study carried out over 2 years by the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health focused on engagement as part of a wider review of modernising day and vocational services for people with mental health problems. 44 Participants included in the process comprised service users, commissioners and external consultants.

A working group (consisting of eight service users) was established to take part in the review of services. Three members of the group joined a separate project steering group, which also included representatives from commissioners and external consultants. The group’s remit was to design the review of services, gather service user views and contribute to decisions about service redesign (e.g. the development of service specifications and tender documents, and helping to select future service providers).

This case study focused heavily on a process evaluation of the consultation, and several key considerations were highlighted relating to the need for clarity of purpose; attention to detail (e.g. the provision of background contextual information to aid the process of service redesign); openness between commissioners and staff about the implications of service change; and effective management and resolution of conflict and hostility. A list of specific issues was presented in terms of what worked well and what worked less well. Key indicators of successful engagement were reported to be suitable practical arrangements (inclusivity, minimal use of jargon and an agreed working agreement); decision-making based on genuine and valued partnerships with service users; consideration of service user well-being (in terms of whether or not they felt their input was worthwhile); and commitment to ongoing development of the engagement process.

Outcomes directly relating to service redesign were less well documented. Many service users were reported to feel positively about their involvement in the process, in terms of personal lives and services offered. Three new models were proposed in relation to the provision of future day and vocational services.

NHS Sheffield Primary Care Trust

The final case study in this section focused on a 6-month engagement programme relating to the redesign of eating disorder services in Sheffield (delivered by the PCT at that time), reported by The Health Foundation. 7 Participants in the process included patients, caregivers, clinicians and health-care managers. Follow-up was conducted with a wider set of stakeholders (unspecified) in the local health economy.

Methods of engagement included decision conferences attended by key stakeholders and led by an impartial facilitator; interviews; e-mail correspondence; direct observation of workshops; use of flipchart notes and minutes of board meetings; and post-consultation follow-up events.

Results of the decision conferences had a direct impact on the development of a business case. The objective of the business case was to reallocate resources by expanding capacity in primary care and increasing community or outpatient services, with a view to reducing the number of referrals of patients to residential care. The case was approved, spending for the eating disorder service was reduced by more than 15% and reductions were sustained in subsequent years.

Key messages for overcoming resistance to service change were the collective character of deliberations and encouraging ownership of the model and its results; analysis of the whole pathway and helping to identify opportunity costs of alternative budgetary choices; strong patient presence; development of a model based on cost-effectiveness analysis principles; and strong managerial leadership.

Exemplars in summary

The series of case studies chosen as exemplars of good practice were conducted across a range of health-care services and implementation contexts, with diverse audiences and using multiple engagement methods. Key messages focused mainly on the potential mechanisms for successful engagement, and less so on possible negative outcomes. In two case studies attempts were clearly made to link engagement efforts with impact on service reconfiguration and further on health9 and financial outcomes. 7

Chapter 4 Synthesis

This chapter focuses on evidence emerging from the review (but particularly the case study exemplars). We first summarise the evidence in relation to the ‘ladder of engagement and participation’,4 second we consider the NHS England guidance3 and finally we draw together the material to answer our five research questions.

Ladder of engagement and participation

The NHS England guidance on transforming participation in health and care uses a ‘ladder of engagement and participation’4 (based on the work of Sherry Arnstein47) to classify different ways in which patients and the public can participate in health (see Table 1). The ladder has five levels: informing, consulting, involving, collaborating and devolving. It is argued that participation becomes more meaningful towards the top of the ladder (devolving). Although there is academic debate about the limitations of this model, in terms of its narrow focus on transfer of power between providers and services,48 it has been widely used in studies of engagement and participation in health.

For the included case studies, we assessed only the levels of engagement reported in those selected as exemplars. Among the six exemplars, the highest level was devolving in one case,7 collaborating in four12,43–45 and involving in one. 9 Thus, these generally well-reported case studies were characterised by relatively high levels of engagement, which would be expected to allow meaningful interaction between participants and NHS decision-makers. This sample of case studies was too small to allow any assessment of whether or not levels of engagement had increased over time.

The levels of engagement in the studies reported in the included systematic reviews were also high. The highest level reported was collaborating (which involved working in partnership with communities and patients on all aspects of a decision) for all except one review. The broad review of user involvement in change management by Crawford et al. was judged to include examples of devolving (placing decision-making in the hands of the community or individuals). 18 The high levels of engagement may partly reflect the broad coverage of the included systematic reviews.

The levels of engagement reported or discussed in studies in the ‘other research’ category were generally lower than in the case studies or reviews. Two reports related to the collaborating level. 15,28 The Scottish Health Council report sought input from public panels and NHS stakeholders on how to enhance public involvement in NHS service change. 42 The other report was an expert opinion report on how NHS managers should seek to frame debates around reconfiguration. 28 As with the systematic reviews, both reports were broad in scope, although much more specifically focused on service change.

Overall, the ‘ladder of engagement’ was of some help in differentiating among studies but its use was based on the assumption that the methods reported provide genuine opportunities for engagement and were not just offered to meet legal or bureaucratic requirements. The extent to which this was true may depend on contextual factors that were difficult to assess from paper reports.

NHS England stages of reconfiguration

The NHS England guidance covers seven stages (Table 5), ranging from ‘setting the strategic context’ through to ‘implementation’, although the boundaries between these are not always clear-cut. Some themes and issues arose at multiple stages of the process. It should be noted at the outset that most of the evidence appeared to adopt the perspective of health system decision-makers responsible for the process of service change, and comments about ‘successful’ engagement or service change should be seen in those terms.

| NHS England stage | Guidance/recommendations | Relevant exemplars | Findings/comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: setting the strategic context | Continuous dialogue with communities on local health priorities and needs | Airoldi et al. (2013);7 Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2010);44 NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (2014)45 | Limited evidence of this from reports |

| 2: proposal | Identify range of possible service changes. Statutory duty to involve service users. Good practice to involve patients, the public and wider stakeholders in the early stages of building a case for change | Airoldi et al. (2013);7 Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2010);44 NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (2014)45 | Difficult to identify as a discrete stage; often mixed with wider public consultation |

| 3: discussion | Formal discussion with local stakeholders, including relevant health and well-being boards and local authority health scrutiny bodies | Airoldi et al. (2013);7 Gamble and Sloss (2011);43 NHS Confederation (2013);12 NHS Confederation (2013);9 Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2010);44 NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (2014)45 | Also difficult to identify as a discrete stage. Limited research |

| 4: assurance | Demonstrate clinical case for change, the robustness of the reconfiguration programme, workforce and financial plans, and the alignment between the proposal and commissioning plans (where relevant) | Airoldi et al. (2013);7 Gamble and Sloss (2011);43 NHS Confederation (2013);12 NHS Confederation (2013);9 NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (2014)45 | Limited evidence to demonstrate explicit attention to the assurance stage of the guidance, other than three exemplar case studies reporting that clinical case for change was proposed |

| 5: consultation | Continuous engagement with service users throughout the period of reconfiguration, with options to focus on specific reconfiguration and allow for a range of approaches for appropriate tailoring | Airoldi et al. (2013);7 Gamble and Sloss (2011);43 NHS Confederation (2013);12 NHS Confederation (2013);9 Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health (2010);44 NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (2014)45 | Continuous engagement with service users throughout the period of consultation featured heavily across the evidence base. Many engagement activities were designed with specific populations in mind |

| 6: decision | The need for commissioners to determine which (if any) of the configuration options are to be pursued; at the same time notifying all relevant stakeholders | Airoldi et al. (2013);7 NHS Confederation (2013);12 NHS Confederation (2013)9 | Some evidence that decisions had been made and communicated to service users and stakeholders in respect of reconfiguration. The particular influence of overview and scrutiny committees in this process was highlighted |

| 7: implementation | The need for clarity about implementation plans, and maintenance of an ongoing dialogue with service users in relation to the bedding down of service reconfiguration | Airoldi et al. (2013);7 NHS Confederation (2013);12 NHS Confederation (2013)9 | Some attention to the implementation stage was evident in a limited number of articles, mainly in the exemplar case studies in terms of follow-up with service users or communication at this stage |

We did not systematically attempt to assess the extent to which stages of the NHS guidance were addressed in the case studies not selected as exemplars. When considering the stages of the NHS guidance addressed in the other research studies, the extent to which attention to specific stages influenced the overall success of the engagement process and other outcomes was unclear.

Table 5 summarises which of the stages were covered by the literature, with a focus on the relevant exemplar case studies.

Stage 1: setting the strategic context

Exemplar case studies

Three of our exemplar case studies covered this phase of reconfiguration. 7,44,45 The extensive literature on public involvement in commissioning and other decision-making bodies was excluded, as we looked only at examples that were explicitly focusing on service change and reconfiguration. The main issue emphasised by the guidance was continuous dialogue with local communities and representative bodies on local health priorities and needs.

Of the three case studies, only the NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG urgent care redesign involved a broad public consultation. 45 The other case studies involved setting the strategic context with small groups of service users/carers. 7,44 The Scarborough and Ryedale report noted the involvement of CCG governing body members, local clinicians, voluntary/third sector organisations and local authority scrutiny committees prior to the wider public consultation. However, the extent to which the urgent care consultation was influenced by a process of continuous dialogue with local communities and stakeholders was unclear from the report of the consultation. 45

We did not systematically attempt to assess the stage(s) of engagement covered by case studies not selected as exemplars. However, a number of case studies reported attempts by UK health authorities to engage the public and patients in discussion of broad strategic issues prior to developing proposals for service change. An example is the ‘Big Health Debate’ organised by Liverpool PCT in 2006 and involving structured discussion and voting on different options to inform redesign of primary care and community services. 34 Another case study, referring to work done in Cornwall and the Isles of Scilly, stressed the importance of engaging with the public to gain information and establish trust in a situation where there had been a history of conflict over proposals for service change. 35 In a case study in Surrey and Sussex, where some hospitals faced a potential loss of acute services, extensive ‘pre-consultation’ in the absence of firm proposals was reported to have increased public concern. 37 These examples reinforced the importance of local contextual factors in influencing how proposals for service change are received and discussed; the Surrey and Sussex example, in particular, may reflect a lack of success in engaging with the public to discuss the strategic context and drivers of change before introducing potentially unpopular proposals.

Systematic reviews

Among the included systematic reviews, a 2009 scoping review by Mitton et al. looked at public participation in health-care priority-setting. 20 The review included a wide variety of empirical studies, mainly focusing on macro-level priority-setting. Despite a lack of rigorous evaluations, two-thirds of included studies reported that participation processes were successful (as defined by the original study authors). Use of deliberative methods (often as part of an ongoing process rather than one-off events) and face-to-face contact were associated with higher levels of perceived successful participation. In studies where affecting an actual decision was the intention of the engagement process, this was reported to be achieved in 60% of cases, not achieved in 10%, and unclear or not reported in 30% (actual numbers of studies unclear). Other systematic reviews provided limited information about this stage of the service change process.

Other research

Three pieces of ‘other research’ were judged to address this stage of the service change process. 1,27,28 The IRP report on lessons from reviews identified inadequate community and stakeholder engagement in the early stages of planning change as a key factor in proposals referred to the panel for formal review. 1 In Scotland, the study of media coverage of reconfiguration of maternity services at Caithness General Hospital reported that the issue was framed as a conflict between Highland Health Board management and local people, with a lack of information about issues underpinning the proposed changes. 27 Issues around how proposals for service change were framed were also central to an expert opinion report published by the NHS Confederation. 28 This report stressed the need to focus on drivers of change and potential benefits of new models of service without overusing the term ‘reconfiguration’.

Summary

Overall, the limited available evidence suggested that early strategic engagement with patients and the public along with other stakeholders could contribute to the process of developing and implementing proposals for service change. Although there was a lack of rigorous evaluations, opportunities for ongoing face-to-face interaction appeared to be viewed positively. 20 One-off deliberative approaches allowing groups of patient or public representatives to express views on possible service changes in a structured way have also been reported as successful. 7,34 This early stage of discussing service change is important because it can influence how the issue is framed and perceived by the patients and public with whom decision-makers are trying to engage. Case studies emphasised the importance of local contextual factors which those responsible for service change may or may not be able to influence. The Surrey and Sussex case study cited in Exemplar case studies37 involved a phased roll-out of engagement to different groups, which could have had a negative impact on those who entered the process later.

Stage 2: proposal

Exemplar case studies

At the proposal stage, the NHS England guidance stresses the importance of identifying a range of potentially viable options for change and involving patients, the public and other stakeholders at an early stage in building a case for change. Three of our exemplar case studies assessed methods and impact of public and patient involvement at this stage;7,44,45 these were the same three exemplars as for the previous stage, emphasising the difficulty of separating the two stages. In addition, a further case study from the NHS Confederation reported in some detail the methods of public engagement at the proposal stage in Greater Manchester but without evidence of impact. 11

As with the previous stage, the NHS Sheffield PCT eating disorders7 and Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health44 case studies involved small groups of service users/carers rather than the general public. Key themes of the eating disorder case study included collective deliberation encouraging ownership of the process and its results; analysis of the pathway as a whole; and framing the problem in terms of patient benefit, seen as a result of the presence of patients as part of the group developing the proposal. In this case study, the group was able to identify the opportunity cost of alternative budget allocations and develop a model based on theoretical principles which provided a credible rationale for difficult decisions. 7 Some similar themes of service users and commissioners working together to identify potential new models of service emerged from the Sainsbury Centre for Mental Health case study, although this did not involve a cost-effectiveness analysis. 44

The NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG case study45 reported on a broad public consultation that primarily included elements of stages 2, 3 and 5 of the NHS England guidance (proposal, discussion and consultation). It appeared that patients and the public were involved from an early stage, although the exact details of how the CCG had developed its ‘vision’ for urgent care services were not clear. The CCG did use a wide variety of methods to involve patients and the public in the process. The consultation had an impact in identifying issues that needed to be considered in the specification and tendering process for a new urgent care service. Overall, this case study did not fit closely to the NHS England model, as a broad public consultation appeared to have begun at an earlier stage than envisaged in the NHS England guidance. This may reflect the context of reconfiguring the service by means of a service specification and tendering process. However, although not included as an ‘exemplar’ case study, the ‘Healthier Together’ consultation in Greater Manchester also involved early engagement of wider groups of patients and the public in discussing the need for change and broad principles involved rather than commenting on specific proposals for service change. 11

Systematic reviews