Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5004/03. The contractual start date was in July 2013. The final report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Sanderson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Objectives and context of the review

Objectives

The main objective of the literature review reported here is to draw out lessons from procurement and supply chain management (P&SCM) theories and from empirical evidence from a range of other sectors and countries, to assist NHS managers and clinicians in developing more effective approaches to commissioning and procurement. The review meets an expressed need in the NHS management community flowing from two primary sources.

First, the NHS is under pressure to save money through a combination of cost cutting, productivity improvements and innovation in service delivery. As we discuss in the next section of this chapter, there have been various organisational and process reforms in NHS commissioning and procurement since 1991 intended to improve cost-efficiency and cost-effectiveness (e.g. the development of national framework contracts by the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency, creation of regional procurement hubs). Despite these reforms, a recent report from the National Audit Office1 shows that there are still significant variations and inefficiencies in current NHS procurement practice. At the same time, the NHS is under massive pressure to make its contribution to the government’s ongoing deficit reduction plans. A more efficient and effective approach to procurement, which accounts for around 30% of hospital operating costs, will play a key role in delivering these savings. 2 Procurement has also been identified as a key part of the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention initiative. 3

Second, the review is needed to assist NHS managers and clinicians in meeting the challenges thrown up by the new commissioning structures and policies introduced by the Health and Social Care Act 20124 in which general practitioners (GPs), other clinicians and managers in Clinical Commissioning Groups and in NHS England are required to exercise commercial skills and make contract award decisions in the context of wider health-care markets of which many have very limited experience and knowledge.

It is useful here to reflect briefly on the differences in NHS parlance between the terms ‘commissioning’ and ‘procurement’. ‘Commissioning’ is used to refer to the planning, acquisition, and monitoring and evaluation of health-care services. 5 As of April 2013 this is the remit of Clinical Commissioning Groups for local services and of NHS England and its area teams for specialist and GP services. One NHS usage of the term ‘procurement’ is to refer to the ‘acquisition’ aspect of this commissioning cycle, whereby NHS commissioners identify, select and contract with providers and monitor their performance in delivering these health-care services. 6 Procurement is also used in the NHS to refer to the acquisition of other goods and services [e.g. dressings, medical equipment, information technology (IT) equipment, temporary staff] needed to support health-care delivery. 2 Procurement defined in this way is undertaken both by NHS commissioning organisations and by NHS health-care providers.

Thus, the common feature of procurement as it is commonly understood in the NHS is a focus on the ‘acquisition’ of goods and services. Service planning, or assessing needs and specifying how and when those needs might be met, is not typically seen as an aspect of the procurement process, particularly as it relates to the commissioning cycle. The suggestion that underpins this review, however, is that the NHS definition of procurement is perhaps too narrow. It is our intention to show that it is unhelpful to see needs assessment and the specification of priorities and requirements as separate, non-procurement activities in the commissioning cycle, because effective procurement practice should begin with a clear statement of what an organisation needs or wants to buy. 7 We do acknowledge that even if one accepts our broader definition of procurement it is not entirely synonymous with NHS commissioning, but suggest nonetheless that there is a more significant overlap than is typically understood in the NHS, which allows us to draw out lessons for the commissioning cycle from the P&SCM literature. The review will, therefore, provide a vital source of knowledge and guidance to GPs, other clinicians and NHS managers responsible for commissioning as the reforms are implemented over the coming years.

The four objectives of this literature review and synthesis are as follows:

Objective 1: To explore the main strands of the literature about P&SCM (e.g. in institutional and production economics, operations management, organisation theory, the resource-based view of strategy, business-to-business marketing, public management) and to identify the main theoretical and conceptual frameworks which relate to decisions about, and the effective management of, providers or suppliers of goods and services.

Objective 2: To understand to what extent existing evidence on the experiences of NHS managers and clinicians involved in commissioning and procurement matches these theories and to provide an explanatory framework for understanding the characteristics of effective policy and practice in the NHS.

Objective 3: To assess the empirical evidence about how different P&SCM practices and techniques can contribute to better procurement processes and outcomes.

Objective 4: To map and evaluate different approaches to improving P&SCM practice, including modelling, diagnostic and facilitation tools, and identify how these approaches relate to theories about effective P&SCM.

Context of the review

In order to set the scene for the rest of the review, the remainder of this first chapter presents a summary of the main policy changes that have shaped commissioning and procurement in the English NHS since 1991. The broad policy context of NHS commissioning and procurement has been defined by the European Union (EU) public procurement rules, which were first introduced in 1993 as part of the Single European Market programme. Since then these rules have been subject to successive waves of reform, broadly intended to achieve simplification and a lightening of the regulatory burden. 8 The detail of how the rules are applied differs for the commissioning of health-care services, where the requirements are less onerous, as compared with the procurement of clinical and non-clinical goods and services. Nevertheless, all NHS commissioning and procurement decisions are expected to conform to the fundamental principles of the rules, namely transparency and non-discrimination in dealings with providers or suppliers.

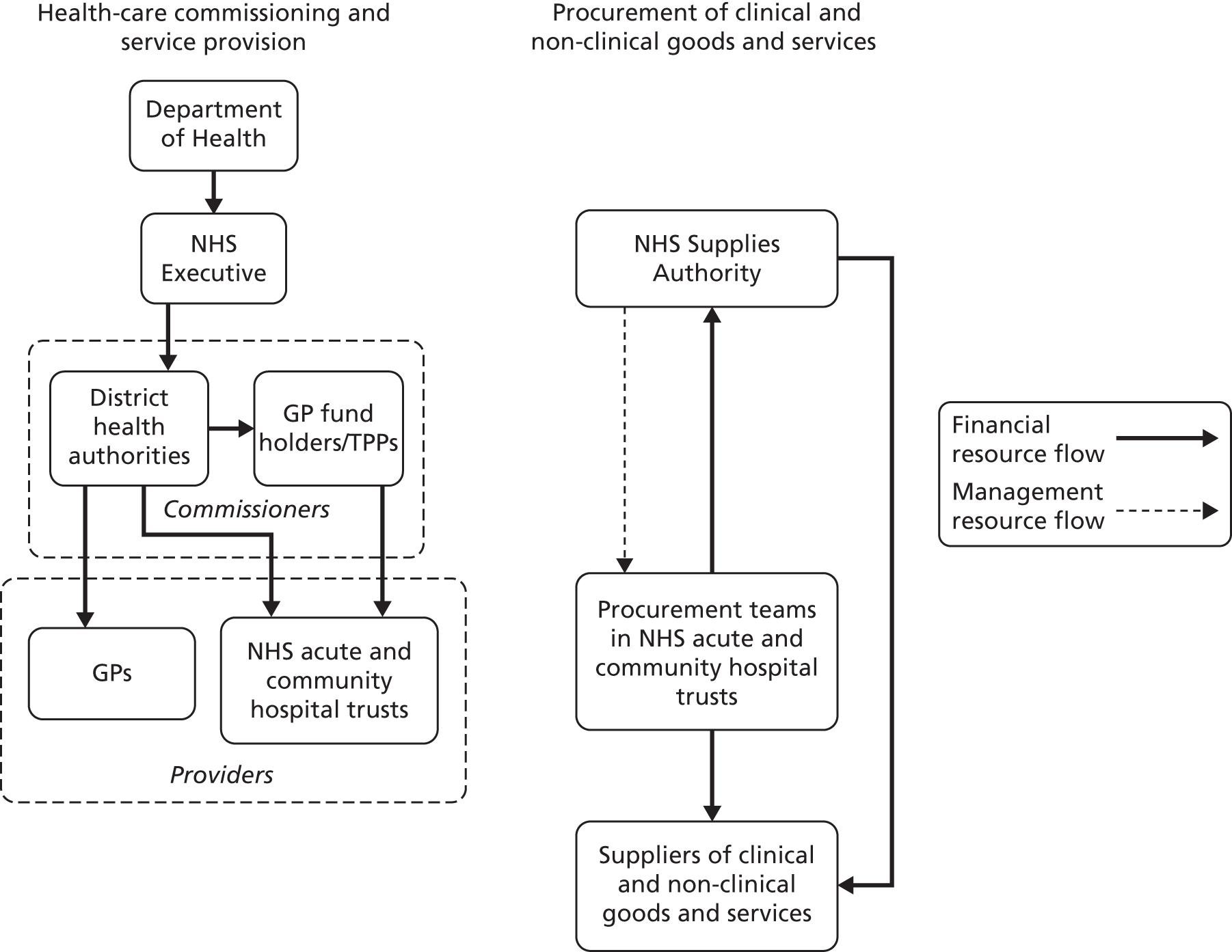

The organisational and structural context of English NHS commissioning and procurement at the time of writing is a result of periodic restructuring and reform over more than 20 years, since the purchaser–provider split was first created in April 1991. 9 This restructuring and reform is characterised to some extent by continuity, in the sense that each successive wave of reform has retained and built on aspects of what went before. This has led to the coexistence of several different, sometimes competing, forms of organisation and governance, what Exworthy et al. 10 call quasi-hierarchy, quasi-market and quasi-network. Each wave of reform has also, however, made some important changes to the organisational ecology and to the distribution of authority over and accountability for the non-pay expenditure of the NHS. This blend of change and continuity can be illustrated if we consider snapshots of the organisational settlement at four points in time, which show the outcomes of significant policy reforms. Each successive snapshot also reveals an increasingly complex set of organisational arrangements. The first, in Figure 1, shows the results of reforms made between 1991 and 1997.

FIGURE 1.

Structure and organisation of NHS commissioning and procurement circa 1997. TPP, Total Purchasing Pilot.

In 1997 two main sets of actors were responsible for NHS health-care commissioning: the district health authorities and GPs acting as fund-holders. This plurality in NHS commissioning arrangements had been established as a key component of the purchaser–provider split in April 1991, with GP fund-holding seen as a way of encouraging service providers to be more responsive to the needs of particular groups of patients. While district health authorities were deemed to have sufficient purchasing power, at least in theory, to extract performance improvements from service providers, they were seen as relatively unresponsive to differing local needs. 11 District health authorities commissioned primary (GP) and secondary (NHS hospital trust) health-care services for a geographically defined population. They negotiated annual block or cost and volume contracts with NHS hospital trusts, based on historical data, for the provision of specified numbers and types of clinical interventions. In principle, hospital trusts in different areas were supposed to compete with one another for these district health authority contracts,12 but in reality most trusts maintained the long-standing relationships with their local health authority that had been in place under the unitary, pre-1991, system.

Commissioning through the GP fund-holding route operated either on the basis of single practices or through co-operative arrangements known as Total Purchasing Pilots. These Total Purchasing Pilots, which had evolved from less formal networks known as multifunds, were designed to give GPs greater purchasing power in their dealings with the financially much larger NHS hospital trusts. They also helped address the lack of co-ordination and higher agency or transaction costs (costs of negotiating, drafting and monitoring contracts) associated with individual GP fund-holding practices. 13 Each Total Purchasing Pilot commissioned on behalf of a population of about 300,000 people, similar to that served by a typical district health authority. By 1997, commissioning through the variants of GP fund-holding accounted for around 10% of the secondary health-care services budget. 14

Turning to the procurement of clinical and non-clinical goods and services, in 1997 this was organised and managed by a combination of the NHS Supplies Authority (NHS Supplies), operating at the national level, and procurement teams based in each NHS trust. NHS Supplies was set up in 1991 to address inefficiencies arising from fragmented procurement and unco-ordinated supply routes that had been identified by the National Audit Office. It initially had a regional structure, with six divisions buying on behalf of trusts in their respective geographical areas and providing a logistics service. In 1995, this regional structure was replaced by a national one. NHS Supplies continued to provide a logistics service, but its remit was extended to provide a national contracting function, which operated through a combination of procurement consultancy advice and framework agreements for use by trusts. A direct customer service function, which managed trust-based procurement teams, was also introduced. A major challenge to the efficacy of NHS Supplies, however, was that NHS trusts were not required to use its services. NHS Supplies competed with other logistics providers and buying agencies to sell its services to trusts; it received no central funding from the Department of Health. Trusts were also free to directly employ and manage their own procurement team, who could select and contract with suppliers without any reference to practice elsewhere in the NHS. 15 It is unsurprising then that, 5 years after the creation of NHS Supplies, the Audit Commission produced a report showing that there were still huge variations in the prices and service levels of suppliers selling the same items to different trusts. 16

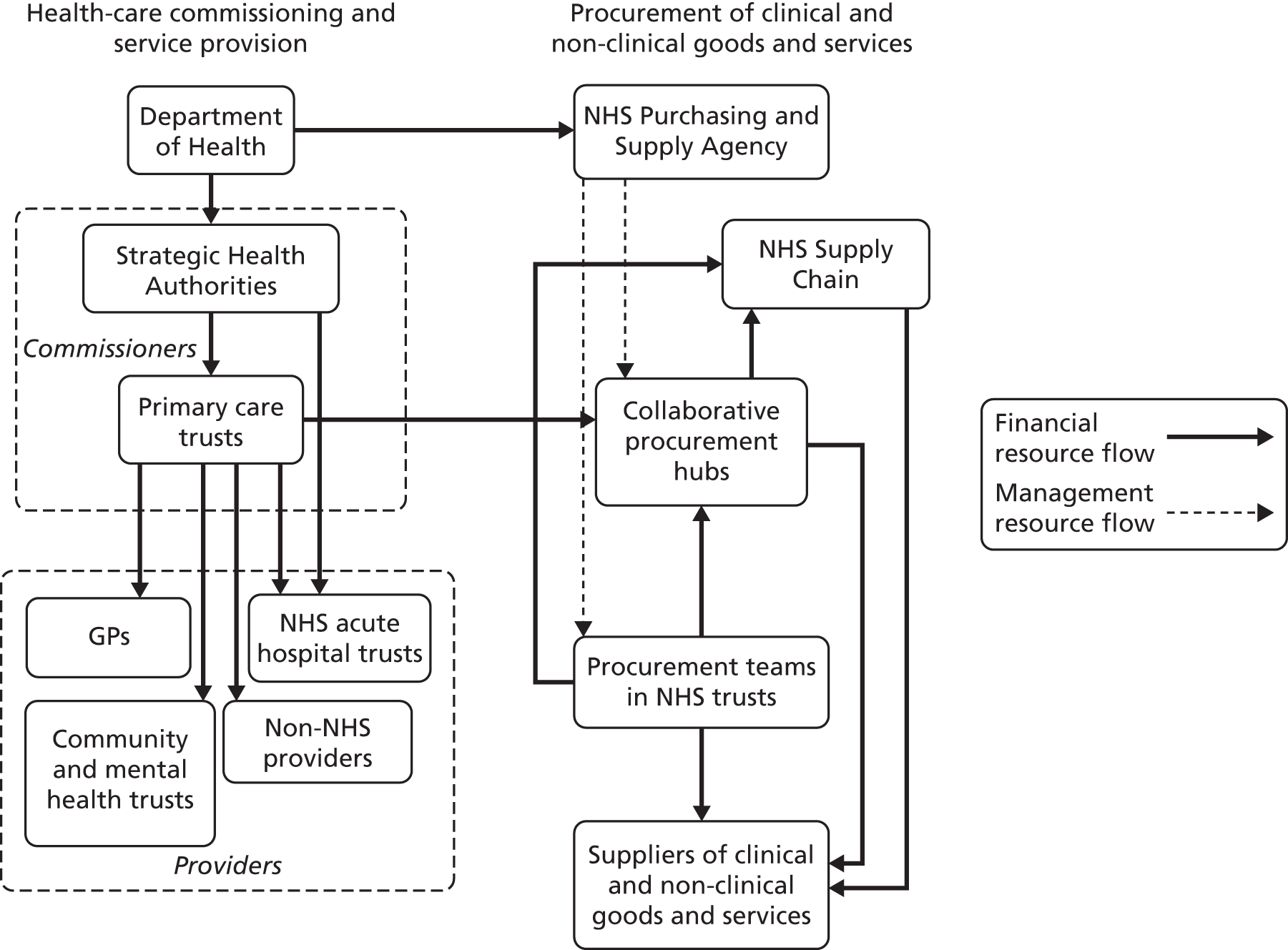

Following the election of the New Labour government in 1997 there were a number of further reforms in the structure and organisation of NHS commissioning and procurement, which meant that by 2001 the picture was markedly different (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Structure and organisation of NHS commissioning and procurement circa 2001.

On the health-care commissioning side, Labour replaced the market-style relations of the GP fund-holding model with what was intended to be a more collaborative system of longer-term service delivery agreements. Under GP fund-holding, practices had real budgets, which they could spend without consulting other practices in their area; this was replaced with a system of indicative budgets. While GP fund-holding arrangements had been voluntary, all GPs were now expected to work in a more co-ordinated way by being required to join a primary care group in their area. Each primary care group was also required to include nurse and local authority representatives to further enhance the scope for collaborative working. 17 By 2001, 481 primary care groups had evolved into 303 primary care trusts, which replaced district health authorities as the lead NHS organisations responsible for health-care commissioning. 18 Primary care trusts also replaced NHS community hospital trusts as providers of community health services such as district nursing and some mental health services. Most mental health services continued, though, to be provided by mental health trusts. Positioned above the primary care trusts, at a regional level, were 28 Strategic Health Authorities. These were responsible for performance management, ensuring that national NHS priorities were integrated into local plans, and the commissioning of some specialist services from NHS acute trusts.

By 2001 there had also been some significant changes in the organisations responsible for procurement of clinical and non-clinical goods and services. Most significant was the replacement of NHS Supplies in 2000 by two separate organisations, the NHS Purchasing and Supply Agency and the NHS Logistics Authority (NHS Logistics), each of which took on some of the functions of NHS Supplies. The Purchasing and Supply Agency was responsible for the national contracting function (consultancy advice to trusts and framework agreements), but it also had a much wider remit to act as the NHS’s centre of excellence on procurement and supply management and to improve procurement performance across all levels of the NHS in England. 19 Unlike NHS Supplies, the Purchasing and Supply Agency was a part of the Department of Health and received central funding, which gave it a much more stable platform from which to carry out its wider policy and practice development remit. NHS Logistics retained the procurement and distribution functions of NHS Supplies, and like its predecessor it was a special health authority funded by charging NHS trusts to use its services. The direct customer service function of NHS Supplies had disappeared, however. All trust-based procurement practitioners were now directly employed and managed by their trust. In addition to this restructuring at the national level, the Purchasing and Supply Agency formally recognised the need for a mechanism to co-ordinate procurement at a regional level by introducing NHS supply management confederations. These were voluntary, virtual organisations without a prescribed structure or dedicated funding. 15 Each confederation was intended to bring together all NHS hospital trusts and primary care trusts within the boundaries of a Strategic Health Authority so that they could procure commonly used goods and services in a more co-ordinated manner. As before, however, NHS hospital trusts remained free if they chose to procure their goods and services directly from suppliers without reference to contracts being agreed by other NHS organisations.

A number of further changes in the structure and organisation of NHS commissioning and procurement over the next 5 or 6 years brings us to the situation in 2007 (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Structure and organisation of NHS commissioning and procurement circa 2007.

On the commissioning side, a policy of practice-based commissioning designed to encourage greater GP involvement and collaborative working between practices was introduced in 2005. This was to some extent a return to the principles of GP fund-holding and Total Purchasing Pilots, but the important difference was that primary care trusts gave GPs only virtual ‘indicative’ budgets to commission health-care services. Accountability for and authority over the actual spending was retained by the primary care trusts. 20 In 2006 the number of Strategic Health Authorities was reduced through amalgamation from 28 to 10, but they retained the same role of performance-managing the primary care trusts and ensuring that national priorities were embedded in local strategies. The number of primary care trusts was also reduced through a process of amalgamation from 303 to 152. This was a response to the argument that they had not been powerful enough in financial and management resource terms to commission effectively, to ‘insist on quality and challenge the inefficiencies of providers’ (p. 3). 21 Finally, under the Transforming Community Services programme primary care trusts were required to formally separate their community health service provider functions from their commissioning function. 22 Community health services were taken on by a range of different providers in the NHS and in the third and private sectors.

Alongside this restructuring of primary care trusts, there were a number of other initiatives designed to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of commissioning. These included the World Class Commissioning initiative introduced in 2007, which involved the evaluation of primary care trust commissioning performance against a set of 10 competencies to identify areas for improvement. 23 One possible solution to weaknesses in any of these competencies was proposed in the Framework for Procuring External Support for Commissioners, which showed primary care trusts how to buy in private sector commissioning support. 24 Commissioners were also given a number of new mechanisms designed to influence the behaviour and performance of providers, under the broad umbrella of the payment-by-results policy. Payment by results replaced the traditional block or cost and volume contracts used in the NHS with a system under which providers were paid a fixed tariff for each episode of a particular type of care. This was intended to encourage providers to reduce their costs to below the tariff level and to increase patient throughput, thereby reducing waiting times. Payment-by-results tariffs were introduced for all elective secondary care from 2005 (representing about 30% of activity); outpatient, non-elective and accident and emergency services were covered by tariffs from 2006; and by 2008 the payment-by-results system covered ‘90% of significant inpatient, day-case and outpatient activity’ (p. 12). 25 An associated reform introduced from 2004 meant that better-performing NHS trusts were given foundation trust status. Foundation trusts had greater autonomy from and less accountability to the central NHS, which crucially allowed them to act in a more business-like way in pursuit of lower costs. 26

Aligned with this was the Commissioning for Quality and Innovation scheme, under which up to 2.5% of the value of provider contracts was linked to compliance with stipulated quality standards. 27 There was also an effort to put providers under some competitive pressure to perform through the ‘Patient Choice’ policy. 22 This gave patients the right, with the support of their GP, to choose their provider for elective secondary care. A similar policy agenda was being developed at this time in social care through the vehicle of personal health budgets. These enabled individuals to commission their own social care services rather than being reliant on their local authority. The ‘personalisation’ agenda is beyond the scope of this review, as we focus on health-care commissioning and procurement, but for a useful discussion see Needham. 28 Patients making these choices were expected to have access to a range of performance data, and consequently commissioning decisions were intended to be a driver for greater responsiveness and cost-effectiveness from providers. 29 The choices available to commissioners were also extended through a policy of ‘Any Willing Provider’, which allowed private sector providers to offer elective secondary care at NHS tariff prices as long as they were able to meet NHS quality standards. Efforts to stimulate a growth in the private provider market came from the Commercial Directorate of the Department of Health, which offered contracts for the setting up of independent sector treatment centres to carry out this elective treatment. One estimate suggested that by 2008 around 15% of NHS elective procedures would be delivered by the private sector,30 but in practice contestability on the provider side was tempered by a policy announced in 2009 that NHS organisations would be ‘preferred providers’ assuming they were delivering satisfactory services (p. 10). 21

On the procurement side, the structure in 2007 was broadly similar to that in 2001. Two important changes had taken place in the intervening years, however. First, the functions of the NHS Logistics Authority and parts of the Purchasing and Supply Agency were outsourced in 2006 to a private sector supplier. A 10-year contract was awarded to DHL, which made a commitment to deliver innovation through significant IT investments and cost savings in excess of £1B. Following this outsourcing, NHS Logistics changed its name to NHS Supply Chain. Second, under the auspices of the Supply Chain Excellence Programme launched in 2003 by the Commercial Directorate of the Department of Health, the Purchasing and Supply Agency established a number of collaborative procurement hubs at regional level. These took the place of the virtual and variously configured NHS supply management confederations. The hubs were relatively homogeneous organisational structures, with their own management and financial resources, designed to undertake co-ordinated procurement on behalf of their member trusts. As before, however, NHS trusts also retained the freedom to procure their goods and services directly from suppliers.

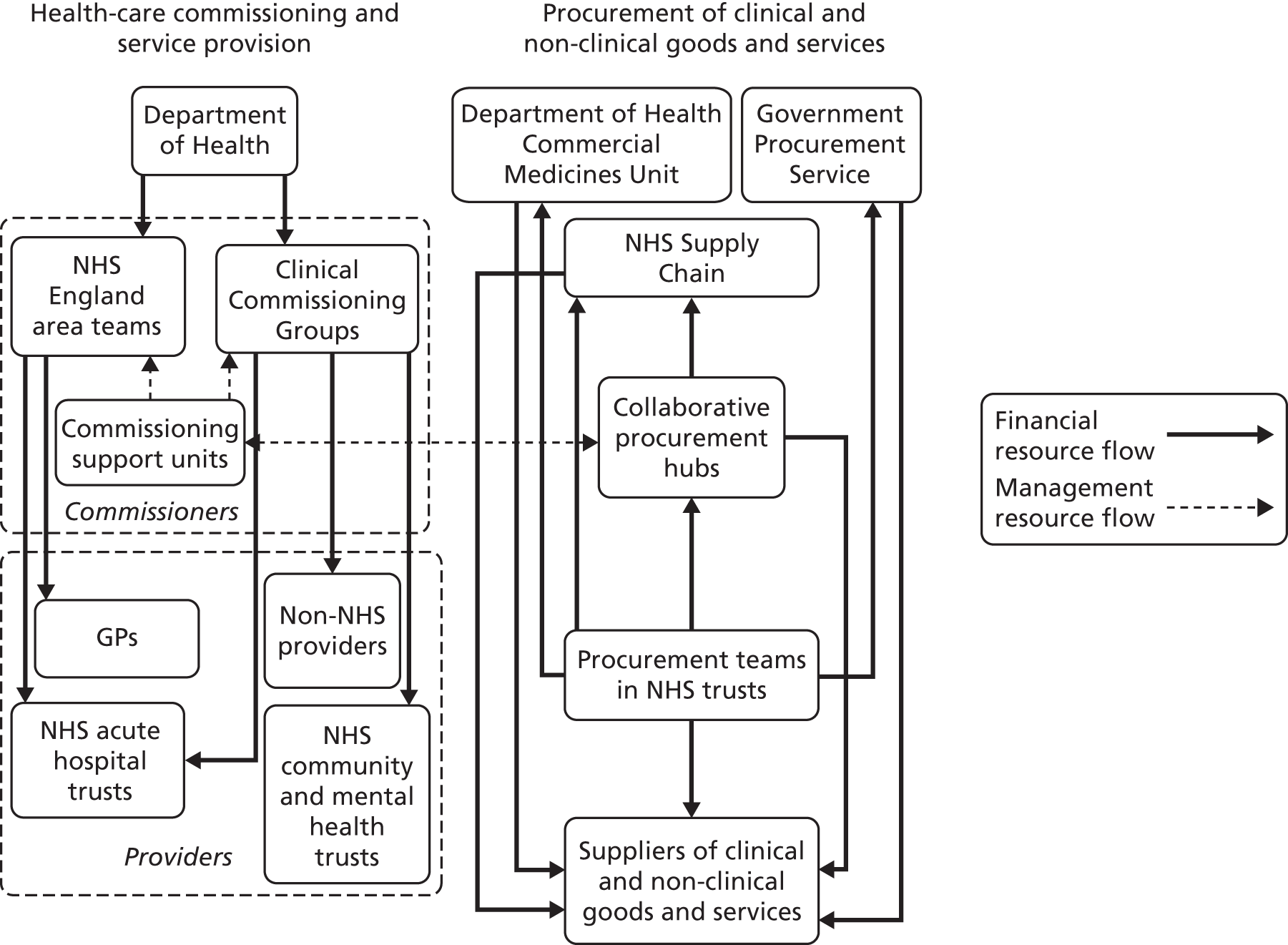

Finally, we turn to the situation in 2014 (Figure 4). On the commissioning side the picture looks significantly different from that in 2007, although there are echoes of previous organisational arrangements designed to get GPs more involved, in particular GP fund-holding and Total Purchasing Pilots. Following the passage of the coalition government’s Health and Social Care Act,4 the 152 primary care trusts and 10 Strategic Health Authorities were replaced in April 2013 by 211 Clinical Commissioning Groups and by NHS England, which comprises 27 area teams. Clinical Commissioning Groups are mandatory membership organisations of all the GPs serving a geographically defined resident population. They must also involve clinicians other than GPs in their governing body, but the legal requirements here are minimal (one nurse and one secondary care clinician in each Clinical Commissioning Group). The division of commissioning responsibilities between the Clinical Commissioning Groups and NHS England has been redistributed to recognise that the former are essentially led by GPs. So, the area teams of NHS England are responsible for commissioning GP as well as specialist services in their regions. They also hold the Clinical Commissioning Groups to account and provide them with developmental support, an echo of the role played by the Strategic Health Authorities. The Clinical Commissioning Groups are responsible for commissioning secondary care, community health and mental health services from NHS and non-NHS providers under the ‘Any Qualified Provider’ policy. To further add to the organisational complexity, the task of public health commissioning previously managed by the primary care trusts has been transferred to the 152 English local authorities. These, in turn, have established health and well-being boards as a forum for strategic co-ordination and to enhance the accountability of Clinical Commissioning Groups to their local population. 31

FIGURE 4.

Structure and organisation of NHS commissioning and procurement circa 2014.

The relationship between clinicians and non-clinical managers looks very different under the new model of commissioning from that under previous commissioning arrangements. The previous relationship, based on a managerial hierarchy, has been replaced by one with a more commercial and contractual edge. A separate group of 19 commissioning support units, staffed by non-clinical managers, has been created to give procurement and contract management support to the Clinical Commissioning Groups. The commissioning support units do not have managerial authority over, or legal accountability for, the commissioning decisions made by the Clinical Commissioning Groups. The Clinical Commissioning Groups are ‘autonomous organisations exposed to full financial risk’ (p. 9)31 and are free to contract with the commissioning support units or to make other arrangements for commissioning support, for instance with private sector service providers. Under previous arrangements, ultimate managerial authority and ‘legal accountability remained with a managerially-led structure sitting above the clinical group’ (p. 9). 31 These were the district health authorities in the case of GP fund-holders and Total Purchasing Pilots or the primary care trusts in the case of practice-based commissioning.

There have also been some significant changes since 2007 on the procurement side of the picture. Perhaps the most significant change was the abolition of the Purchasing and Supply Agency in 2010, which means there is currently no organisation fulfilling its policy role as a national centre of excellence dedicated to improving procurement and supply management practice across the NHS. There has recently been recognition that this was an important and necessary role, and there are plans to create a new Centre of Procurement Development in the Department of Health which will mirror much of what the Purchasing and Supply Agency was previously doing. 32 On the operational procurement side, the Purchasing and Supply Agency’s responsibility for national drugs contracts has been transferred to the Department of Health Commercial Medicines Unit, and its responsibility for negotiating national framework agreements for categories such as energy, telecoms and IT services has been transferred to the Government Procurement Service, which works across all central government departments.

In some areas, though, the picture remains relatively unchanged. NHS Supply Chain is still operating on an outsourced basis under the terms of the 10-year contract agreed with DHL in 2006. Nine collaborative procurement hubs are still operating at a regional level. In some cases these hubs have merged with coterminous commissioning support units, which is a potentially very significant development because those working in the hubs will bring their commercially honed procurement and contract management skills to bear on the commissioning of health care. Finally, NHS hospital trusts remain absolutely free to procure their own goods and services directly from suppliers without reference to contracts being agreed by other organisations such as NHS Supply Chain and the collaborative procurement hubs. Consequently, as was recognised in the recently published Procurement Development Programme for the NHS,32 there are still significant variations in the products being used, the prices being paid and the service levels being received by different trusts.

Round-up

Having established the broad policy context of commissioning and procurement in the English NHS, we turn in the next chapter to a discussion of the approach, focus and method that we have adopted in our review of the P&SCM literature.

Chapter 2 Approach, focus and method

Approach

The approach that we have taken in this study is a theory-based realist review. We chose this route on the basis of our judgement that what constitutes an effective approach to P&SCM is likely to be highly context dependent. We begin by scoping the range of theories and conceptual frameworks used to describe and explain various aspects of P&SCM practice, including a discussion of underlying assumptions about units of analysis, actor behaviour and intended outcomes. We then examine the literature about NHS commissioning/procurement policy and practice to see to what extent the various P&SCM theories provide an insight into what is intended and what happens in this specific context. Next, we examine and assess the empirical evidence about the effect of different P&SCM practices and techniques on procurement processes and outcomes in different sectors and organisational contexts. We end by mapping and evaluating approaches to improving P&SCM practice, drawing on the logic of portfolio analysis to examine the importance of context. Our conclusions offer the basis of an explanatory framework for understanding the characteristics of effective P&SCM practice in the different contexts and types of NHS organisations.

The study is an evidence synthesis of a diverse theoretical and empirical literature on P&SCM. We draw on material from a variety of different disciplines, sectors and countries to identify lessons for more cost-effective policy and practice in the NHS. The research terrain is characterised by considerable complexity in terms of the multiple sources of evidence across different disciplinary traditions, by weakness and ambiguity in terms of association and causation, and by the influence of contextual factors on the appropriateness, effectiveness and outcomes of different P&SCM practices and techniques. Given these characteristics, a conventional systematic review, with its emphasis on a hierarchy of evidence and randomised controlled trials as the chosen research design to address questions of effectiveness, would not be appropriate. Indeed, a traditional literature review would almost certainly be unable to take account of the multiple and interconnected variables that have an impact on the effectiveness of P&SCM practices and techniques.

A realist review approach, on the other hand, emphasises the contingent nature of the evidence and addresses questions about what works in which settings, for whom, in what circumstances and why. Realist review has a ‘generative model of causality’, which argues that ‘to infer a causal outcome (O) between two events, one needs to understand the underlying mechanism (M) that connects them and the context (C) in which the relationship occurs’ (pp. 21–2). 33 A realist review can also be used to generate a theory map exposing the differences between programme theories and theories in use. The purpose is to ‘articulate programme theories and then interrogate existing evidence to find out whether and where these theories are pertinent and productive’ (p. 74). 34 This is appropriate given that a key aim of this study is to illuminate differences between how P&SCM might be carried out and current NHS policy and practice. The value of realist review and evaluation is exemplified by a number of studies of commissioning strategies in the NHS. 35–37 We therefore chose to use this as our overarching research design. Denyer et al. 38 and Jagosh et al. 39 provide a useful discussion of the key terms used in realist review. Box 1 contains a summary.

An implicit or explicit explanatory theory that can be used to evaluate programmes of action or specific interventions. A theory is middle-range if it can be tested with empirical evidence and does not deal with more abstract social, economic or cultural forces (as does a grand theory such as Marxism).

Context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurationsCMO configurations are used to generate causal explanations associated with the empirical evidence. The process draws out and reflects on the relationship between context, mechanism and outcome either in a whole programme of action or in specific aspects/interventions. Drawing out CMO configurations is a basis for generating and/or refining the middle-range theory that represents the final product of a realist review.

ContextThe surrounding factors, the external and internal environment and the characteristics of actors, which influence behavioural change. Programmes of action or interventions are always embedded in a particular context. Factors include the experience and competency of individual actors, the cultural norms or history of a community in which a programme or intervention is implemented, the nature and scope of existing social networks, and the geographical location. Context can be understood as any factor that shapes the behaviour of a mechanism triggered by an intervention.

MechanismThe generative force that leads to outcomes. It typically represents the reasoning of one or more actors in response to the programme of action or the intervention with which they are faced. Mechanisms are about how actors interpret, make sense of and respond to the incentives or resources associated with a programme or intervention. Identifying mechanisms allows realist review to go beyond describing ‘what happened’ (the outcome) to explaining ‘why it happened, for whom and under what circumstances’.

OutcomeThe results of a programme of action or an intervention, which can be intended or unintended, proximal, intermediate or final. Examples of outcomes resulting from P&SCM interventions are supplier/provider cost reduction and improved quality and responsiveness.

Realist synthesis belongs to the family of theory-driven review. It begins with knowledge and theory and ends with more refined knowledge and theory, in the process ‘stalking and sifting’ ideas and empirical evidence. 33 In this research, the synthesis addresses questions in particular about how P&SCM practices (interventions) are carried out, how and why these practices are influenced by context and circumstances, the impact of these practices on procurement outcomes, and the appropriateness and effectiveness of approaches to improving P&SCM. The focus is, therefore, very much on the mechanisms within these practices rather than on the practices per se. Realist review learns from, rather than controls for, real-world phenomena. Our study thereby acknowledges that no two procurement processes are exactly the same in terms of the context or the actors involved.

The limitation of realist synthesis is that it is a relatively new method, still in development and with a relatively small number of exemplar studies. 33 Nevertheless, in 2011–13 there was an effort to propose and codify a set of quality and publication standards for realist synthesis through the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) study. 40,41 These standards represent an important development in establishing realist synthesis as a coherent, consistent and robust review methodology. Moreover, based on the reviews and literature published to date, it is an approach that seems to address the limitations of traditional systematic review methods when dealing with complex social interventions across different circumstances, using a range of mechanisms, and with varying underlying beliefs and assumptions. 38,42,43 Realist synthesis is focused on offering explanations (what is) rather than making normative judgements (what should be), and on developing principles and guidance rather than making rules. Pawson et al. (p. 24)33 comment that ‘realist review delivers illumination rather than generalisable truths and contextual fine-tuning rather than standardisation.’

Gough et al. 44 support this message in their comparison of different types of systematic review. They note that realist synthesis is both configurative, in that it begins by clarifying the nature of the theory or theories that might explain a specific programme of action or a particular intervention, and aggregative, in that it gathers a body of evidence to test those theories. In addition, unlike standard systematic reviews, realist synthesis considers empirical evidence from a broad range of sources and ‘will assess its value in terms of its contribution rather than according to some pre-set criteria’ (p. 6). 44 For the purpose of this evidence synthesis, we believe that this is the most appropriate approach to take. It will offer insights for managers and clinicians to take note of and make use of in enhancing their P&SCM practice. This judgement is further reinforced by Popay’s45 analysis of alternative approaches to systematic review, summarised in Table 1, which underlines that only realist synthesis focuses on mechanisms rather than whole programmes. In our case, this allowed us to focus on particular discrete aspects of the procurement process (specification of requirement, provider selection and evaluation, contract drafting and negotiation, contract and relationship management and so on) rather than having to consider P&SCM practice as the overall unit of analysis.

| Approach | Unit of analysis | Focus of observation | End product | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | Programme | Effect sizes | Relative power of like programmes | Whole programme application |

| Narrative review | Programme | Holistic comparison | Recipes for successful programmes | Whole or majority replication |

| Realist synthesis | Mechanisms | Mixed fortunes of programmes in different settings | Theory to determine best application | Mindful employment of appropriate mechanisms |

One of the principles of realist synthesis is the importance of sense-making. The metanarrative mapping approach to synthesising evidence is attractive, because it acknowledges different disciplinary traditions and changes to dominant narratives over time. This approach has been used, for example, to reveal changing paradigms across different disciplines in relation to studies about the diffusion of innovations. 46 P&SCM is also a good example of an area of practice where the dominant narrative has shifted over time, from the highly technical and rational discourse of production economics to a more hybridised one in which, among others, issues of power, politics and bounded rationality from various branches of organisation theory are now playing a much greater role. We therefore use a metanarrative mapping exercise within the realist framework specifically to address our first research question (RQ), which is to identify and explain the emergence of different theories about P&SCM practice.

It is important to emphasise here that in recognition of the very diverse theoretical and empirical literature about P&SCM we consciously draw on evidence from a broad range of peer-reviewed journals, books and policy documents. This does not mean, however, that our search strategy is comprehensive or exhaustive. Rather we use purposive sampling to focus on literature that helps us to address the context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations that drive the review. In realist review, the relevance and rigour of the literature is primarily judged not by its academic provenance but by the light it sheds on the particular CMO configuration under consideration. 33,44

A key test for studies funded by the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR’s) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme is that the RQs and subsequent research findings are relevant to and useful for the target audience, those responsible for the organisation and delivery of health-care services. Similarly, realist review emphasises the need for theorising to be highly practical, with practitioners helping to shape the investigation of what works, in which circumstances, how and why. 47 In accordance with the principles of realist review, therefore, we saw our RQs as provisional and we discussed, refined and amplified these with an expert advisory and stakeholder group composed of 16 people. This had four representatives of the target audience of NHS managers and clinicians, including a senior manager from a commissioning support unit, the Head of Contracting and Procurement from a Clinical Commissioning Group, a GP and chairperson of the NHS Alliance, and a commissioner of social care services for a local authority. To provide a broader perspective the advisory group also had eight academic researchers and consultants with an active interest in P&SCM, two non-NHS procurement practitioners, the chief executive of a third sector provider of NHS services representing service users/patients, and a representative of the UK Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply (the professional body for procurement managers).

We convened this group on a face-to-face basis in Birmingham in month 3 of the study, and ran a facilitated workshop to elicit and discuss programme theories about different approaches to P&SCM and to explore and amplify the RQs. One outcome of the workshop was a list of additional questions of interest to the advisory group, which are listed in the next section. We held one further face-to-face meeting of the group in month 6 of the study to seek their feedback on some of the early findings. Further provisional findings and a draft of the final report were shared electronically with the group, and feedback comments were received. This embeds the linkage between practitioner and researcher communities, which is advocated as a key feature of realist synthesis and helps to translate findings from research into practice. 48

Focus of the review

According to Pawson et al. 33 there are five key steps in a realist review. These are, first, clarifying the scope, second, searching for evidence, third, appraising the literature and extracting the data, fourth, synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions and, fifth, disseminating the conclusions and implementing recommendations with practitioners and policy-makers. The quality and publication standards developed by the RAMESES study40,41 have added further depth and detail to each of these steps. Our study adheres broadly to this guidance on the realist synthesis approach rather than following it to the letter. So, while we identify a range of alternative theories relevant to the P&SCM process and test their explanatory value in terms of CMO configurations at various stages of the process, we stop short of generating new theory on the basis of this testing. Our broad approach to realist synthesis is justified by complexity and breadth of the research topic. We are looking at aspects of the broad P&SCM process rather than at a specific policy programme or interventions within a programme.

This chapter begins to clarify the scope of our study by identifying the RQs and discussing the purpose of the review. Chapter 3 completes the scoping by articulating the main P&SCM theories to be explored and by using them to create a realist synthesis framework for evaluating the evidence. Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7 focus on the appraisal and synthesis of the evidence, and Chapter 8 draws conclusions.

We used the four research objectives described in Chapter 1 to generate four concomitant RQs. These are presented below. Guided by the realist approach to clarifying the scope of the study, these questions were treated as provisional and they were refined and amplified through discussion with the advisory and stakeholder group. This discussion generated a number of additional questions of interest, also presented below. The study did not explicitly seek to address these additional questions, but rather used them as points of reference during the review.

RQ1: What are the main disciplinary sources of ideas about P&SCM and what are the principal theories, conceptual frameworks and main paradigms?

RQ2: How can theories about P&SCM in general help NHS managers and clinicians in their commissioning and procurement activities, in particular in the light of recent and planned changes to commissioning structures, incentives and processes in the NHS?

Additional questions of interest to members of the advisory group:

-

How does/can the NHS use incentives in commissioning and procurement?

-

How does/can the NHS deliver on contractual obligations? How can NHS managers and clinicians ensure that third party contractual obligations are delivered?

-

How do different sets or layers of rules or guidelines in the NHS affect commissioning activities? What are the differences from private sector practice?

-

How should NHS managers and clinicians commission services for different client groups?

-

How does commissioning differ across different services within the health sector? What is the significance and impact of commissioning from different types of providers (private, third sector)?

-

What is the impact on NHS commissioning of variations in demand between/within health localities?

-

How does commissioning for health vary in different institutional contexts within the UK?

RQ3: What is the empirical evidence about the impact of different P&SCM practices and techniques on outcomes at different stages of the procurement process and in different settings and organisational contexts?

Additional questions of interest to members of the advisory group:

-

Who is responsible for the various P&SCM activities and at which stages of the process? How and where is responsibility handed over, and who is responsible for co-ordinating this?

-

Who is responsible for the overall design of the supply chain? Where is the P&SCM design/management function located within an organisation and what are the implications of this?

-

How can a market be developed and managed? To what extent can alternative suppliers shape the market environment?

-

When and where within a supply chain does competition work? When and where is collaboration better? How can these two approaches be co-ordinated?

-

When, or for which categories of spend, can P&SCM activities be outsourced?

-

For which categories of spend can P&SCM activities benefit from economies of scale? Which categories of spend require local design/implementation of P&SCM activities?

RQ4: What are the different approaches to improving P&SCM practice and which are likely to work best in the different contexts and types of NHS organisations?

Additional questions of interest to members of the advisory group:

-

Is there evidence of ‘best practice’ from the private sector? If so, how useful is this in the NHS context?

-

What constitutes ‘evidence’ in ‘evidence-based commissioning’?

-

What are the particularities of commissioning in health that could lessen the importing and implementation of models and practice from other sectors?

-

What constitutes ‘a success’ in P&SCM activities and what constitutes ‘a failure’?

Research methodology

A detailed description of the research methodology is presented in Table 2. It is worth noting here that the four main objectives outlined in Chapter 1, and their associated RQs, are closely inter-related. For example, the mapping and evaluation of different approaches to improving P&SCM practice (objective 4) is founded on literature presenting and discussing theories about P&SCM, the application of those theories in NHS and other contexts, and evidence about how various practices affect procurement outcomes. Equally, although Table 2 suggests a sequential set of phases, in realist review there is iteration between the phases. So, for example, theories about P&SCM and explanations about effective procurement practices in NHS contexts were shaped and reshaped throughout the course of the study.

| Phase | Actions |

|---|---|

| Define the scope of the review |

|

| Search for, extract and appraise the evidence (see Table 3 for more detail) |

|

| Synthesise findings |

|

| Draw conclusions and make recommendations in relation to the original objectives of the study |

|

Further specific details about the search, appraisal and extraction strategy used in the study are provided in Table 3. With respect to managing a large volume of papers, from diverse sources, a purposive sampling strategy was used to set strict boundaries in relation to relevance, allowing for iteration. Relevance was judged against each of our four research objectives and their associated RQs. Data selection, leading to decisions about inclusion or exclusion, was less linear and predetermined than in traditional systematic reviews. Decisions here were based on pre-existing knowledge of the subject area and the use of expert judgement on what to include in or exclude from the review, drawing upon advice from the research team and from the advisory group as required.

| Phase | Actions |

|---|---|

| Decide purposive sampling strategy |

|

| Define search sources, terms and methods |

|

| Develop data extraction forms |

|

| Test for rigour and relevance |

|

| Set thresholds for saturation |

|

The appraisal process focused on the rigour and relevance of the selected data. Rigour was assessed by looking at the credibility and robustness of the methodology used in a piece of research. Literature reporting anecdotal qualitative evidence and quantitative research drawing on a small data set were judged to be insufficiently rigorous. Relevance was assessed by considering whether or not a particular paper or piece of evidence within a paper was addressing the theories being tested, and by asking whether or not it might add valuable insights for NHS managers and clinicians. Data extraction was done using forms that were specifically tailored to each of our RQs, but in each case we focused on gathering data that revealed the nature of context, mechanisms and outcomes. For RQ1, for example, we extracted data about the contextual assumptions, proposed explanatory mechanisms and intended outcomes embedded in different P&SCM theories. For RQ2, by contrast, we extracted data about the empirical context studied within the NHS, the commissioning or procurement interventions taking place within that context, the mechanisms thought to be triggered by those interventions, and the observed outcomes. Examples of completed data extraction forms are provided in Appendix 1.

Analysis and synthesis of the extracted data were done iteratively and sequentially. First, a body of evidence related to each RQ and expressed in terms of context, mechanism and outcome was built up. This was followed by a process of comparing and contrasting evidence from different studies to identify recurrent patterns of CMO configurations in respect of each RQ. Finally, we undertook synthesis by seeing how far one or more P&SCM theories might be useful in interpreting and explaining these recurrent patterns in our evidence. This sequence of steps was then iterated by analysing further evidence in relation to each RQ through the lens of context, mechanism and outcome. Provisional findings and conclusions from this process were shared periodically with the advisory and stakeholder group to sense-check their relevance and value for NHS managers and clinicians. We also used the expertise and experience of the advisory group to help us frame our final conclusions and recommendations.

Literature search

An initial literature search was conducted in early October 2013 across the electronic resources listed below. The results of this search were then iteratively updated and refined during the remainder of October and early November. The resources used included the leading bibliographic databases in their respective disciplinary fields to ensure both quality and breadth of coverage and to minimise duplication. They were also selected for their relevance to each of our RQs.

-

ABI/INFORM® Global (ProQuest): This is a large business journal database providing the full text of articles from over 2300 business and management journals and abstracts from a further 1000. Coverage includes business, management, marketing and strategy.

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (ProQuest): ASSIA is an indexing and abstracting tool covering health, social services, economics, politics and education.

-

Business Source Premier (EBSCOhost): This complements ABI/INFORM® Global by providing full-text access to more than 2000 business and management journals (mostly different journals from those on ABI/INFORM® Global) as well as trade journals.

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (Ovid): This database brings together information from two key institutions: the Library and Information Services of the Department of Health and The King’s Fund Information and Library Service.

-

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) (ProQuest): This includes over 2.6 million references to journal articles, books, reviews and selected chapters.

-

Scopus (Elsevier): This is a large abstract and citation database, which provides access to 19,000 titles from a wide range of international publishers.

-

Social Science Citation Index (SSCI) (via the Web of Knowledge): This index covers almost 2500 journals across more than 50 social science disciplines and is one of the databases that make up the Web of Science, which is accessible via the Web of Knowledge.

Specific titles

The journals listed below were considered to be particularly relevant by the research team. They were covered by the chosen bibliographic databases as indicated.

-

Academy of Management Journal (1963 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

American Economic Review (1911 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

British Journal of Management (1990 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy (1983 + IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Harvard Business Review (1922 + ABI, BSP, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Health Services Management Research (1998 + ABI, ASSIA, BSP, Scopus, HMIC)

-

Industrial Marketing Management (1971 + ABI, BSP, Scopus, SSCI)

-

International Journal of Operations and Production Management (1980 + ABI, BSP, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing (1994 + BSP, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Journal of Business-to-Business Marketing (1993 + ABI, BSP, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organisation (1984 + ABI, ASSIA, BSP, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Journal of Economic Literature (1969 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, SSCI)

-

Journal of Health Economics (1982 + ABI, ASSIA, HMIC, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Journal of Health, Organisation and Management (1992 + ABI, ASSIA, HMIC, Scopus)

-

Journal of Health Services Research and Policy (1995 + ASSIA, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Journal of Law, Economics and Organisation (1985 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Journal of Marketing Management (1992 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, Scopus)

-

Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management (2003 + ABI, BSP, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly (1996 + ABI, ASSIA, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Policy and Politics (1979 + IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Production and Operations Management (1996 + ABI, BSP, Scopus)

-

Production Planning and Control (1990 + ABI, BSP, Scopus)

-

Public Administration (1965 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Public Administration Review (1965 + ABI, BSP, IBSS, Scopus, SSCI)

-

Supply Chain Management (1996 + ABI, BSP, Scopus, SSCI).

The following titles were also searched individually:

-

Harvard Business Review

-

California Management Review.

The literature search was conducted using keywords relating to the specific focus of each of our RQs as set out in Appendix 2. The keywords were combined with the Boolean operators ‘AND’ and ‘OR’, which narrowed and widened the search respectively. Combinations with Boolean operators were not used if search terms were found to be infrequently employed, to maximise the capture of material. In addition, the terms were variously input into the search function at the level of title, abstract or subject heading in order to ensure adequate breadth and depth of the search as relevant to the RQ. Search terms were truncated (i.e. the root of a word is used with an asterisk) to capture various relevant suffixes of a term for maximum coverage. Speech marks were used if it was necessary to keep multiple words together as a single search term, further ensuring relevance.

The search was limited to retrieve material in English only. It was deemed unnecessary to limit the search by any date of publication, as the purpose of the research involved reviewing the P&SCM and related terms since their earliest usage. The vast majority of the search was limited to peer-reviewed literature, which was taken as an indication of quality, though this was relaxed where appropriate (e.g. for RQ2, to collect relevant grey literature).

The results of the literature search were exported into EndNote X5 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA), an electronic reference management tool. Four EndNote libraries were created, one for each of the RQs. The functions of EndNote enable the references in each library to be sorted into separate subfolders to allow greater focus in the review process, and to be searched and ordered in various ways, for example by keywords, by publication date or by type (article, book chapter, report, etc.). The software also allows electronic versions of the texts to be attached and stored as part of the reference.

In the first phase of the literature review, each of the libraries was examined by the principal investigator (JS) and the researcher (TM) together to ensure that the imported references were relevant to the corresponding RQs, and references were reallocated as necessary. In phase 2, abstracts and summaries were reviewed by the principal investigator and the researcher to remove duplicate references and any material not related to our RQs, for example studies dealing with purchasing power parity and with legal commissions. In the final phase, full articles and texts were scanned and a judgement was made to select for detailed review or to discard based on the exclusion criteria described below. Further hand searching, snowballing and Rich Site Summary updates were also used to add to the literature under scrutiny.

Literature excluded from the review

The following study topics and types were excluded from the review, as they were judged not relevant to our RQs, nor were they of interest to members of the advisory group:

-

studies based exclusively on theoretical/mathematical modelling or simulation, as the realist review approach focuses on experiences of practice

-

studies relating to individual consumer buying/purchasing or related behaviour, rather than business or industrial buying/purchasing

-

empirical studies exhibiting inadequate methodological rigour, for example quantitative research based on a small sample or qualitative research reporting anecdotal evidence.

Literature included in the review

The initial literature search identified 3562 results. Based on the first phase of the review, these were distributed across the RQs as follows:

-

RQ1: 1048 texts

-

RQ2: 720 texts

-

RQ3 and RQ4: 1794 texts.

Following the second phase of the review, with the removal of duplicate references and any texts dealing with unrelated subjects, 1800 texts remained. These were distributed across the RQs as follows:

-

RQ1: 472 texts

-

RQ2: 412 texts

-

RQ3 and RQ4: 916 texts.

In the final phase, after the application of criteria for exclusion and the inclusion of additional material from hand searching, snowballing and updating, 879 texts were selected for full review as follows:

-

RQ1: 191 texts (all of which were journal articles)

-

RQ2: 194 texts (138 journal articles, 25 research reports, 16 book chapters and 15 NHS policy documents)

-

RQ3 and RQ4: 494 texts (all of which were journal articles).

Round-up

Having described and justified the approach, focus and detailed methodology of our literature review, we turn in the next chapter to a discussion of the various theories that have been used to interpret and explain the P&SCM process.

Chapter 3 Theories about procurement and supply chain management

Introduction

The primary aim of this chapter is to address RQ1, which asks: what are the main disciplinary sources of ideas about P&SCM and what are the principal theories, conceptual frameworks and main paradigms? We begin in the next section by identifying what are the main disciplinary sources of ideas about P&SCM. We then discuss the principal theories and conceptual models used to understand, explain and guide P&SCM practice. We also categorise these various theories into a number of broad literatures focused upon particular aspects of the P&SCM process.

In addition, this chapter builds on work by authors such as Giannakis and Croom,49 Halldorsson et al.,50 and Möller51 who have developed metatheoretical analyses to suggest how different theories can inform thinking about and practice in different aspects of P&SCM. The underlying aim of this type of analysis can be either to develop a contingency perspective on middle-range P&SCM theories (Halldorsson et al.,50 Möller51) or to go in search of a unified general theory to support the development of a cognate P&SCM discipline (Giannakis and Croom49). Our aim is to make a contribution to the development of a contingency perspective by adopting a realist review method, focusing on which P&SCM theory works, for whom and under what circumstances. We recognise, as does Möller,51 that the search for a unified general theory is likely to be fruitless given the ontological differences between several of the component theories, and that theory, like practice, ought to be sensitive to context. To this end, the chapter also develops and discusses a realist interpretation framework of P&SCM theories. This framework is then used in the rest of the report as a basis for examining what lessons can be learned from the general literature on P&SCM for practice in the NHS.

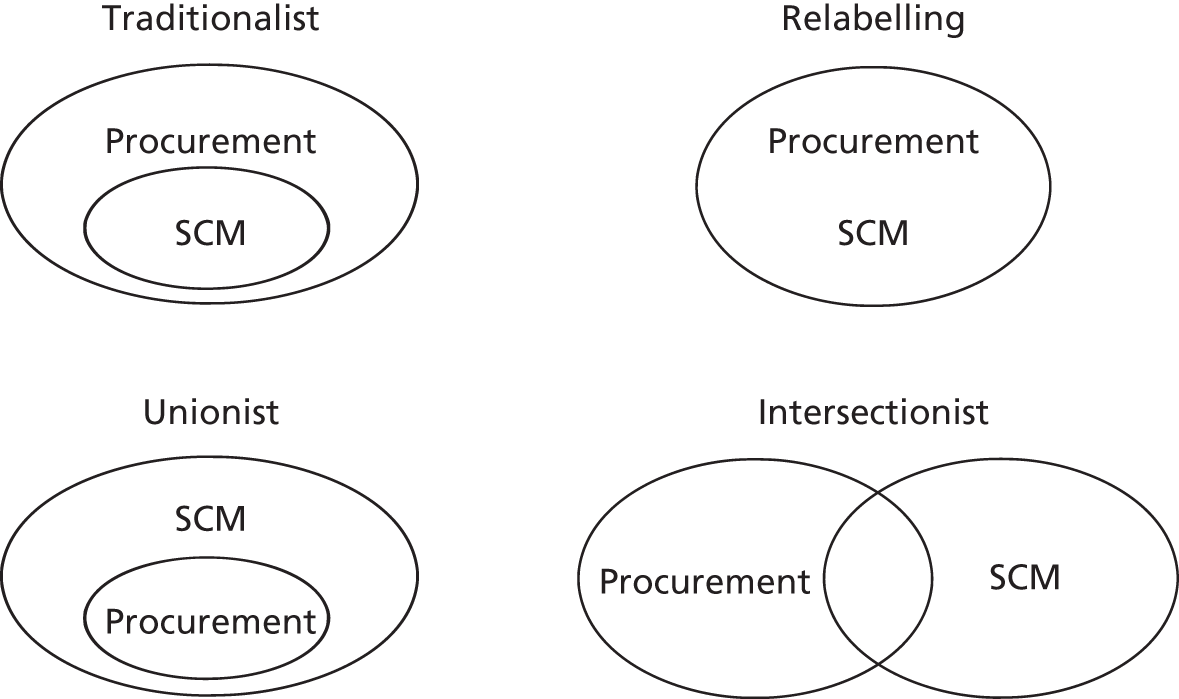

Definitions of procurement and supply chain management

Before turning to the primary task of this chapter we need to define our main terms, ‘procurement’ and ‘supply chain management’, and the relationship between them for the purposes of this report. Larson and Halldorsson52 provide a useful basis for this discussion in a paper which considers the scope and meaning of supply chain management (SCM). They note, as many others have done (e.g. see Svensson,53 Giannakis and Croom,49 Giunipero et al. 54), that the literature offers a multiplicity of definitions of SCM. Some of these definitions share references to the co-ordinated management of both an organisation’s upstream (supplier) and downstream (customer) relationships to achieve superior value for end-customers. Other definitions are solely focused on the integrated management of an organisation’s upstream, supply-side relationships. The interesting question raised by Larson and Halldorsson52 is: how should we define and think about procurement in relation to SCM defined in these two different ways? They identify four perspectives on this question, which they call ‘traditionalist’, ‘relabeling’, ‘unionist’ and ‘intersectionist’. These are illustrated in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Four perspectives on procurement and supply chain management (adapted from Larson and Halldorsson52).

The first two perspectives are associated with the notion of SCM as integrated management of an organisation’s supply-side relationships. The traditionalist perspective sees SCM as a strategic aspect or subset of procurement, concerned particularly with supplier development and building collaborative supply relationships. Procurement in this perspective is broader than SCM and is defined as all activities associated with acquiring and managing the organisation’s supply inputs. The relabelling perspective suggests that in many organisations procurement is ‘evolving’ into SCM. This appears to mean that SCM is seen as a more modern and enlightened version of procurement, involving a generally less aggressive and more collaborative approach to supplier management.

The unionist and intersectionist perspectives are both associated with the idea that SCM involves the co-ordinated management of an organisation’s upstream and downstream relationships. Consequently, these perspectives cast SCM in very broad terms and suggest that it encompasses a wide range of activities and functions including procurement, logistics, operations and marketing. The unionist perspective is perhaps the more radical of the two in that it subsumes and attempts to integrate what have traditionally been seen as separate organisational functions. The intersectionist perspective, on the other hand, retains procurement, operations, marketing, etc. as separate functions and sees SCM as the co-ordination of cross-functional efforts across multiple organisations.

The definitions of ‘procurement’ and ‘supply chain management’ adopted for the purposes of our review are presented in Box 2.

Procurement is the process encompassing all activities associated with acquiring and managing the organisation’s supply inputs. Supply chain management is the subset of procurement activities concerned particularly with the monitoring, management and development of ongoing supplier relationships and the associated flows of supply inputs.

These definitions are perhaps closest to Larson and Halldorsson’s52 traditionalist perspective. We have adopted these supply-side-focused definitions to delimit the scope of our literature review in a way that focuses attention on particular aspects of the NHS and the interactions between its constituent organisations. This review is not concerned with literature that might cast light on an organisation’s management of its relationships with customers or, more appropriately for the NHS, patients or service users. The focus is instead firmly on the literature that addresses an organisation’s interactions with its external suppliers or, in NHS parlance, providers.

Disciplinary sources of ideas about procurement and supply chain management

Reflecting on the findings of a number of extant literature reviews, it is clear that the P&SCM literature is theoretically diverse and fragmented and draws on a very wide range of underpinning disciplines. Burgess et al. (p. 710)55 define a discipline as ‘a body of practice that is well supported by occupational groupings that identify with a defined territory of activity’ and that has an infrastructure (e.g. professional associations, publications) ‘designed to transfer and create knowledge’. They review 100 randomly selected journal articles and identify eight main disciplines, including marketing, logistics, strategy, sociology, economics and operations management, that underpin the P&SCM literature. This disciplinary diversity is further underlined by the fact that these 100 articles are published in 31 different journals covering many disciplinary areas.

Harland et al. 56 review only 41 papers, but with a specific focus on work that considers disciplinary issues and the nature of theory and conceptual development in the area of P&SCM. They find that P&SCM is characterised by ‘borrowing theories from other disciplines’ (p. 745), particularly economics (e.g. game theory and transaction cost analysis) and sociology (e.g. social capital theory). They also identify that their relatively small sample of papers are published in 20 different journals, both specialist and general management, representing disciplines as diverse as production economics, operations management and marketing.

Chen and Paulraj57 review over 400 papers and identify a similar diversity of disciplines contributing to P&SCM thinking, including logistics, marketing, information management and operations management. Giunipero et al. 54 also review just over 400 papers published in nine different journals heavily associated with P&SCM research. They comment that ‘SCM [supply chain management] has been a melting pot of various disciplines, with influences from logistics and transportation, operations management and materials and distribution management, marketing, as well as purchasing and information technology’ (p. 66). Finally, the paper by Chicksand et al. 58 takes a different approach and reviews a much larger sample of 1113 papers, but drawn from three specialist journals only. Despite this narrower search strategy, the paper once again notes the highly multidisciplinary nature of P&SCM research. It identifies economics, strategy and sociology as key sources of theory in topic areas of interest to P&SCM researchers.

Principal theories and procurement and supply chain management literatures

As this brief discussion indicates, P&SCM research is underpinned by a very diverse disciplinary base. Consequently, this area of research is also marked by the use of many different theories and associated models and conceptual frameworks. In an extensive review of organisational buying behaviour research, Johnston and Lewin59 identify the use of several sociologically grounded decision-making process models and frameworks. Buvik60 identifies the use of theoretical perspectives drawing on sociology (organisational decision-making theory, resource dependency theory) and economics (agency theory, transaction cost analysis, game theory). Burgess et al. 55 similarly identify the use of theories from sociology (interorganisational networks and organisational learning) and economics (transaction cost and agency theory), and they add theory drawn from strategic management (resource-based view of firm).

Halldorsson et al. 50 argue that practices in the domain of P&SCM are best understood by applying multiple theoretical perspectives drawn from economics (agency theory and transaction cost analysis), sociology (social exchange theory, resource dependency theory) and strategic management (resource-based view). Shook et al. 61 make the same case for the use of a number of well-established theoretical perspectives as a basis for better understanding and explaining activities such as outsourcing, supplier selection and buyer–supplier relationship management. They make use of 10 different theories, again drawn from sociology (institutional, resource dependency, network, organisational decision, critical), economics (agency and transaction cost analysis), and strategy (resource-based view and strategic choice). They also identify the value of systems theory for thinking about the need for, and the value of, co-ordinated and collaborative relationships in supply networks. This theory was drawn originally from the natural sciences (biology and physics), but has been developed for use in management and organisations.

Finally, Chicksand et al. 58 use their extensive review of articles from three specialist P&SCM journals to identify what they see as the dominant theoretical perspectives. Again, they mention agency theory and transaction cost analysis drawn from economics; network and resource dependency theory drawn from sociology; and dynamic capabilities and the resource-based view drawn from the strategy literature. They also identify a version of systems theory that they call the integrated SCM perspective.

When engaging with the P&SCM literature, then, we are faced with a diverse and fragmented use of theory. Reflecting on the discussion here, though, we can start to discern a picture of those theories that are employed most often. A representative list of the most prevalent theoretical perspectives and models would include various models of organisational decision-making, agency theory, transaction cost theory, social exchange theory, resource dependency theory, dynamic capabilities and the resource-based view, systems theory and game theory. This purely descriptive listing of the dominant theories is only of limited use, however, given our realist review objective of understanding how theory might guide practice in different contexts, for different actors and in different aspects of P&SCM. We therefore need a basis on which to categorise these theories that connects with our realist review objective.

To categorise these theories it is useful to consider Möller’s51 notion of a research domain such as P&SCM as having several inter-related or nested layers (single actor, group, organisation, interorganisational, network, industry). We can also make use of Giannakis and Croom’s49 idea of different P&SCM decision domains (synthesis, synergy and synchronisation) in accordance with the diversity of activities and processes involved. Our approach draws on these notions of nested layers and decision domains by categorising the programme theories in terms of their primary explanatory focus on a particular broad phase in the P&SCM process. As can be seen in Box 3, which illustrates a typical P&SCM process, we can crudely identify four broad phases each associated with one or more steps or activities in the process.

Phase 1: precontract (demand management)

-

Identification of need and development of a specification of the physical and performance characteristics of the required goods or services.

-

Identification of potential sources of supply (market search).

-

Qualification of potential suppliers and their goods or services.

-

Design of the request for proposal/quotation and the solicitation of bids.

Phase 2: selection and contracting

-

Bid evaluation and supplier selection.

-

Negotiation of contractual terms and conditions with selected suppliers.

Phase 3: post contract, relationship management (soft management tasks)

-

Monitoring of supplier performance and the management of ongoing supplier relationships.

Phase 4: post contract, operational delivery (hard management tasks)

-

Establishment of SCM strategies, control systems and performance measurement systems.

-

Management of inventories of purchased parts, materials and supplies.

-

Recycling or disposal of unused materials and obsolete finished products (reverse logistics).

Source: adapted from Corey. 62

By identifying these four broad phases we are able to propose a fourfold categorisation of broad literatures, each associated with particular theories, as shown in Table 4. These are (1) the organisational buying behaviour literature grounded in various theories and models of organisational decision-making; (2) the economics of contracting literature grounded in agency theory and transaction cost economics (TCE); (3) the networks and interorganisational relationships literature grounded in social exchange theory, resource dependency theory and aspects of industrial economics; and (4) the integrated SCM literature grounded in systems theory and behavioural economics, in particular game theory.

| Literature and cognate theories/models | Primary focus in procurement process |

|---|---|

Organisational buying behaviour

|

Phase 1, steps 1–4 (but also concerned with aspects of step 5 and step 7) |

Economics of contracting

|

Phase 2, steps 5 and 6 (but also concerned with aspects of step 7) |

Networks and interorganisational relationships

|

Phase 3, step 7 (but also concerned with aspects of step 6 and step 8) |

Integrated SCM

|

Phase 4, steps 8–10 (but also concerned with aspects of step 7) |

It should be noted that, while each broad literature is primarily focused on one of the four phases, there are inevitably overlaps, as the process steps are not discrete, nor do they occur in a strictly sequential manner. While phases 1 and 2 do occur in sequence, phases 3 and 4 are typically concurrent. Moreover, aspects of phase 3, for example the history of managing a supplier relationship, can affect activities in phase 2 if an existing supplier is being considered for a new or renewed contract.

We now discuss each broad literature in turn, presenting the basic assumptions and the implications for P&SCM practice of the associated theories. We also discuss the major criticisms of each theory.

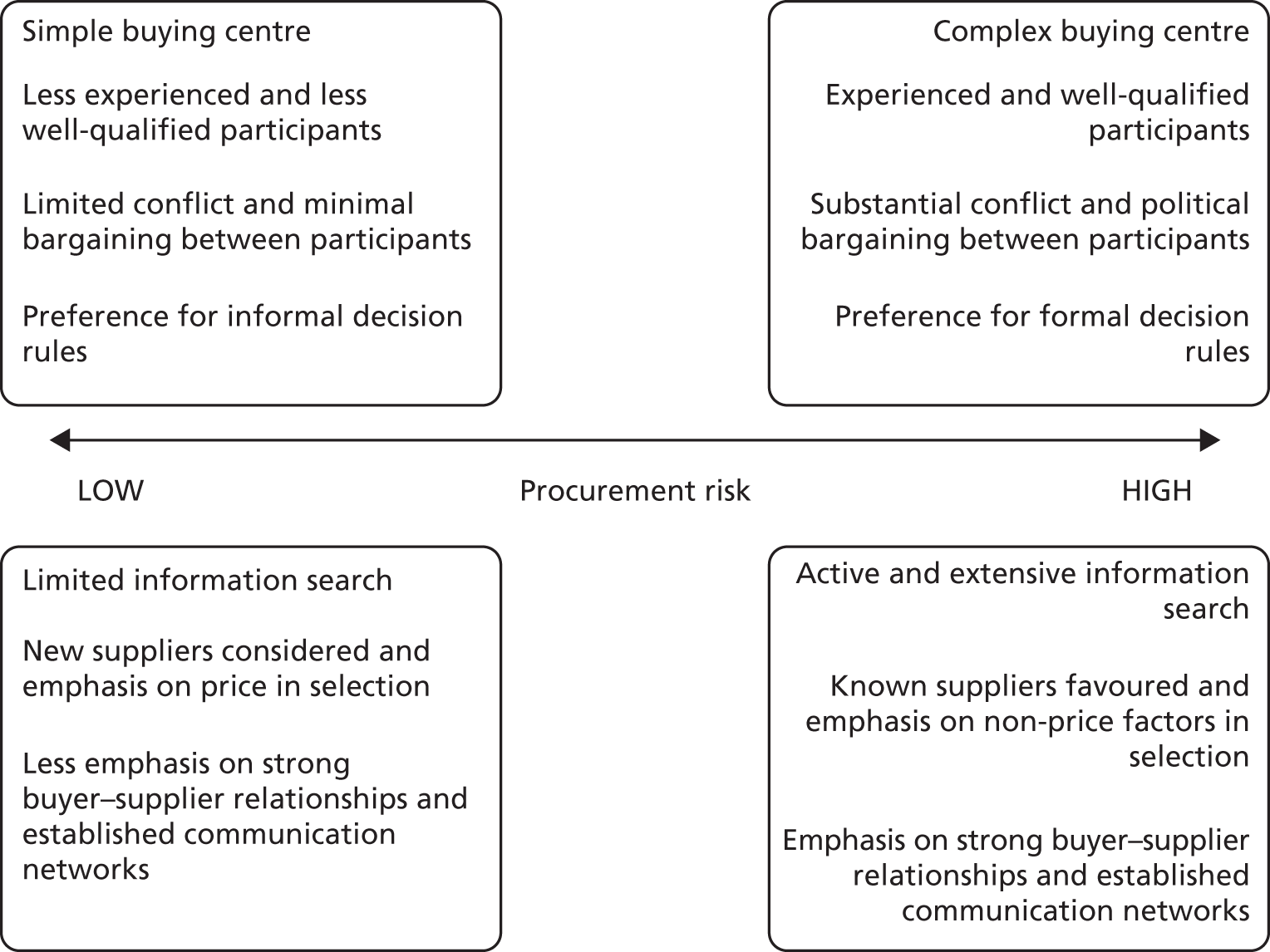

Organisational buying behaviour

The organisational buying behaviour literature focuses primarily on what might be called the precontract or the demand management phase of the procurement process. Box 4 provides a summary of the implications of this literature for P&SCM practice.

-

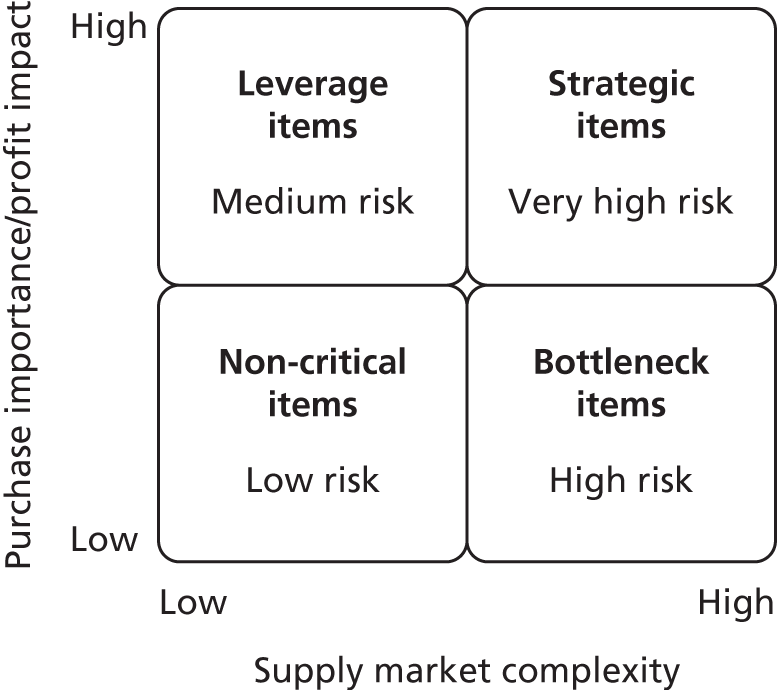

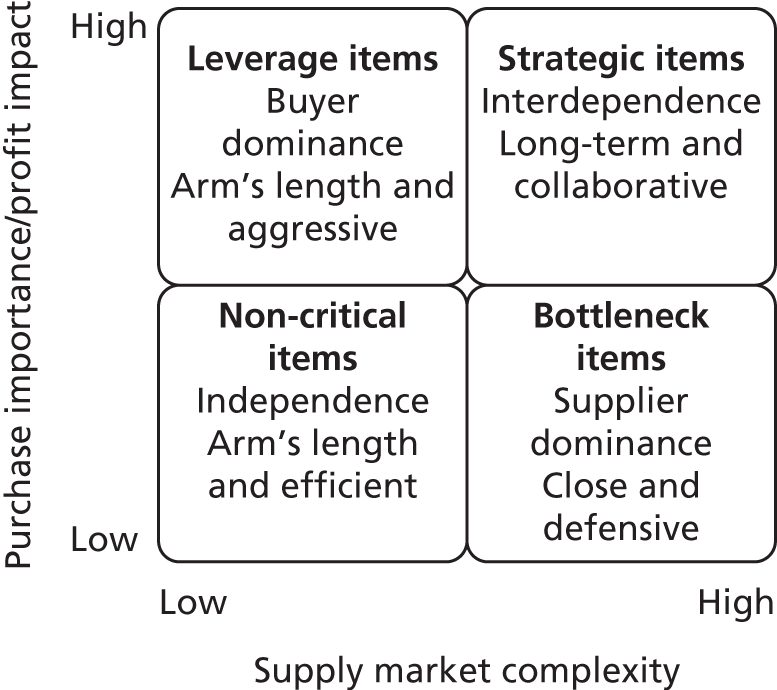

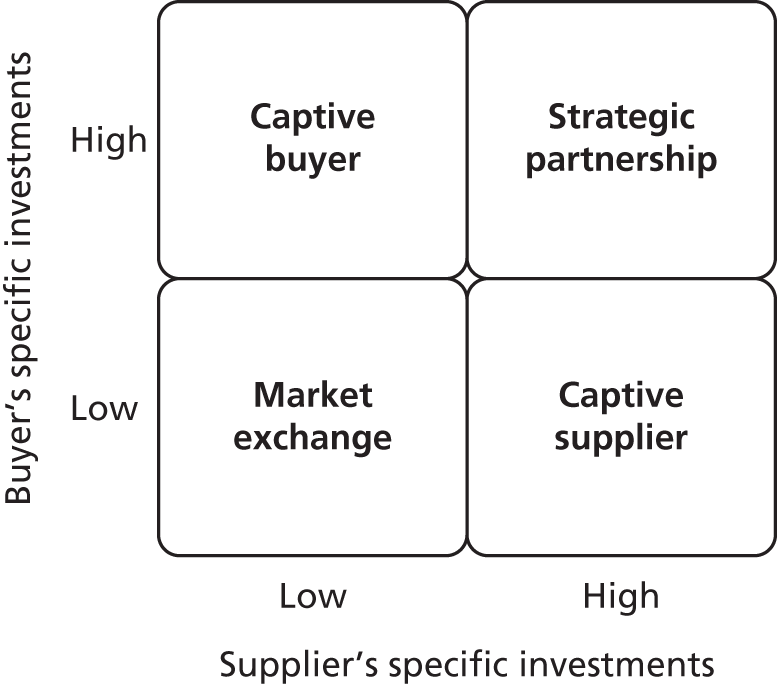

Procurement decisions differ in terms of the level of risk that they pose for the organisation.

-

Organisational buying behaviour is a multiactor, multiagenda process, and consequently procurement decisions are a potential locus of intraorganisational power and politics.

-