Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1002/09. The contractual start date was in February 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

During part of the duration of this project, Jonathan Klein received a grant from Southampton Clinical Commissioning Group for another project, which did not constitute any conflict of interest.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Wye et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Changes to health-care commissioning during the lifetime of the study

Recent history suggests that there will always be some mix of public sector, clinician and commercial involvement in NHS health-care commissioning, even if the balance shifts under successive governments. This research spanned 6 turbulent years within the NHS, during which that balance changed considerably.

This study was conceived in 2008, at the time the then Labour government emphasised improving the competencies of commissioners through World Class Commissioning (WCC). 1 At this time, NHS commissioning was mainly led by managers in about 150 organisations known as ‘primary care trusts’ (PCTs). The main vehicle to draw on clinical expertise was known as ‘practice-based commissioning’ (PBC), which was established in 2005, and later promoted under the WCC initiative. PBC, however, struggled to engage clinicians. 2 Meanwhile, commercial providers were gaining greater ground with the advent of the Framework for procuring External Services for Commissioners (FESC), launched in November 2007. FESC was an initiative whereby 14 commercial providers went through an authorisation process and were approved to aid PCTs in commissioning health-care services.

When this study was designed and submitted at the outline stage in August 2009, NHS health-care commissioners were defined as ‘PCT managers’, clinical input to commissioning was relatively minimal or variable across the country and the outlook for commercial companies was promising.

This changed substantially after funding for the study was awarded in June 2010. After the 2010 election, the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government brought in a major NHS reorganisation with the stated aim of transferring commissioning power from managers to clinicians, specifically general practitioners (GPs). With Liberating the NHS,3 PCTs were to be abolished by April 2013 and their commissioning responsibilities allocated to over 200 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and NHS England. Public Health, which for many PCTs had been an important conduit of research evidence, moved to local authorities. The analytical function of PCTs was hived off into independent commissioning support units (CSUs) expected to be self-sufficient by 2016. A major impact of the Health and Social Care Act of 20124 was to externalise much of what had been previously internal to local commissioning organisations (e.g. analytics, Public Health).

Unsurprisingly with this degree of flux, identifying the ‘commissioners’ became increasingly difficult during fieldwork, as PCTs moved into PCT clusters, shedding staff through reconfigurations, CCGs emerged out of General Practice Commissioning Groups and PCTs, and CCGs negotiated the transition of commissioning responsibilities. PCTs no longer contracted commercial companies for commissioning support, as PCTs were soon to be defunct, and neither did CCGs, as CCGs often did not hold budgets because they were in shadow form. The term ‘external provider’ became synonymous with ‘commercial provider’, although the implications of Liberating the NHS3 meant that the health-care market was increasingly open to not-for-profit organisations such as social enterprises and the voluntary sector.

When fieldwork began in early 2011, a commissioner could be defined as either a PCT manager or a GP commissioner and clinical input was increasing, but contracts with external providers such as commercial companies and not-for-profits were limited. Protests led by groups such as 38 degrees (www.38degrees.org.uk) and Keep our NHS Public (www.keepournhspublic.com) were common, because of fears that Liberating the NHS3 would privatise the running of the NHS. Moreover, the proposed changes had limited support from doctors, without whom they would flounder. 5 In the summer of 2011 in light of the controversy, the coalition government instituted a ‘pause’ for further consultation, which added confusion and delay to the commissioning reforms and our project. Over the 2 years of data collection since, the situation has settled and it is possible to delineate commissioners and those who provide commissioning support and advice. This culminated with authorisation of CCGs in April 2013.

At the time of writing (early 2014), about 60% of the commissioning budget and contingent responsibilities lay with CCGs, which had substantial clinical leadership. Commercial companies were steadily increasing their business, with the aid of the ‘Lead Provider Framework’ which included assured suppliers of health and social care support services. 6 These suppliers were winning contracts from CCGs and, in some cases, forming partnerships with CSUs, many of which employed former PCT staff. In addition, a host of external providers taking multiple organisational forms had sprung up. 7,8

Research questions and objectives

Throughout the span of the study, our chief interest was exploring knowledge exchange processes between those responsible for NHS health-care commissioning with others internal and external to their organisations, even as those classified as ‘internal’ and ‘external’ were continually changing. We used the term ‘knowledge exchange’ (rather than ‘knowledge transfer’ or ‘research implementation’) as information, research evidence, expertise, skills and innovations such as research-based software are all forms or applications of ‘knowledge’, and ‘exchange’ best describes how knowledge is transformed through the interaction of two or more parties. We wanted to know what knowledge was needed, where it was obtained and how it was transformed and fed into NHS commissioners’ decision-making. Although we had a particular interest in research-based evidence, for the purposes of this study all sources of knowledge were included.

The reorganisation of commissioning following the 2012 Health and Social Care Act4 impacted on our exploration of the research questions. The upheavals were a major part of the context in which the participants in our research were operating, and the impact of the Act was a running theme throughout our data. However, that process of change was a unique event that we were not funded to evaluate. Although this inevitably remained an important part of the context, we eventually took the view that it should not form a major part of our analysis.

The focus of enquiry on knowledge exchange remained constant, although the research questions and aims were regularly updated because of the changing NHS landscape. By adopting a qualitative approach using ethnographic techniques, the study was flexible enough to adapt. Moreover, it complemented other research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Services Delivery and Organisation research programme such as the use of evidence in health-care management decisions,9 health-care managers’ use of and access to management research,10 management practice among middle managers and GPs11 and the commissioning of long-term conditions. 12 Those studies have given a valuable picture of how PCT managers and GPs drew on research evidence and other sources to inform their commissioning decisions. This study builds on that literature by providing early insight into CCGs and the growing band of external purveyors of knowledge and information including commercial providers, not-for-profit agencies, CSUs and Public Health.

The study was structured around four research questions. They were:

-

How do health-care commissioners access research evidence and other sources of knowledge to aid their commissioning decisions?

-

What is the nature and role of agencies that provide commissioning expertise from the public (e.g. Public Health), private (e.g. commercial providers) and other sectors (e.g. not-for-profit)?

-

What are the processes by which health-care commissioners transform information provided by other agencies into useable knowledge that is embedded in commissioning decisions?

-

What are the benefits and disadvantages?

In answering these questions, this study had the following objectives:

-

to describe models of commissioning expertise, including private (e.g. commercial providers) and public sector (e.g. clinical consortia, specialist commissioning)

-

to elucidate how diverse health-care commissioners and other providers of commissioning expertise access, assimilate, integrate and utilise managerial and clinical research

-

to establish how existing professionals with expertise in commissioning from the public (e.g. Public Health practitioners) and private sector (e.g. management consultants) transform and market their managerial and clinical knowledge

-

to examine how knowledge is exchanged between commercial agencies and public sector bodies and how that knowledge is embedded and applied in the commissioning process

-

to explore the perceived benefits and disadvantages of these exchanges

-

to identify actionable messages and disseminate them to commissioners, policy-makers and external providers using effective knowledge exchange strategies.

Structure of this report

The next chapter of this report covers the methods used in the study, including information on the case sites. Chapter 3 is the first results chapter and discusses the nature of commissioning. Chapter 4 covers models of commissioning to provide greater understanding of what commissioners do, before going on to describe the contributions of others such as commercial providers to commissioning processes. Chapter 5 focuses on the knowledge acquisition and Chapter 6 discusses knowledge transformation. Chapter 7 covers the role and function of external providers. Chapter 8 offers in-depth accounts of three contractual relationships. Chapter 9 reports the benefits and disadvantages of these processes and Chapter 10 details the key findings and implications of this study.

Box 1 summarises the key points of this chapter.

-

The aim of this research is to study knowledge exchange between those responsible for commissioning NHS services and external agencies.

-

Since this project was conceived in 2008, the NHS landscape has changed remarkably as a result of the organisational changes set out in Liberating the NHS. 3 Consequently, several functions that were formerly considered ‘internal’ in PCT structures (e.g. analytics or Public Health) now have ‘external’ status.

Chapter 2 Methods

Research design

The aim of this research was to study knowledge exchange between NHS commissioners and internal and external agencies. We chose a case study design as case studies are useful in answering exploratory questions, especially when the investigator has little control over events and when the focus is a contemporary phenomenon with real-life context. 13 Within the cases, we collected data through a variety of ethnographic techniques such as semistructured interviews, observations and documentary analysis. We provide more details about data collection and analysis later in this chapter, but first, we discuss recruitment. Because of the complexities, a major portion of this chapter is dedicated to explaining how, who and why we recruited participants as we did. This detail has been provided also because the scientific advisor from our funders, NIHR Health Service and Delivery Research, asked for a full description to give guidance to those wishing to study commercial providers in the future, as this has rarely been accomplished before in this context.

The phenomenon in this research was knowledge exchange, but identifying case boundaries proved challenging. Reassuringly, Ragin and Becker argue that it is counterproductive to have strong preconceptions of the case boundaries as this hampers conceptual development. Instead, researchers need to continually ask themselves ‘What is the case?’, to reconfigure what is inside (and outside) case boundaries and reclarify the phenomenon under study. 14 This was certainly our experience.

Initially, our intention was to construct cases around contracts of 6 months’ duration or more with significant knowledge exchange between commercial providers and their NHS clients. These criteria were selected to exclude one-off consultancy activities such as contract negotiation or pathway development, where knowledge exchange was presumed to be minimal. Our assumption was that each contract would clearly engage a set of external providers and their NHS clients and data collection would involve gathering sets of accounts from both.

Ethical permission was obtained from South West Research Ethics Committee 2 on 25 November 2010 (10/H0206/52). Local research governance approvals were obtained from all 11 PCTs where the study external providers were working. Service support costs were agreed to cover the study costs of participants, but no one asked for financial reimbursement for taking part.

Recruitment of external providers

To recruit commercial providers, our starting point was that the study lead (LW) had a long-standing relationship with the chief executive of one commercial provider. Relying on these types of prior contacts to recruit study participants is an accepted feature of ethnographic15 and case-study research. 13 The chief executive first informally sounded out the key leads from other commercial providers verbally and then by e-mail, furnishing an information sheet about the study, which was then supplied by the research team. Where a commercial provider showed interest, contact details were supplied to LW, who followed up with a telephone call and further written information. Only two commercial providers were approached and both agreed (see Recruitment and data collection via the first commercial provider and Recruitment and data collection via the second commercial provider for further details). We attempted to recruit a third commercial provider without this introduction and received no response.

Through our work with Swallow, we encountered a not-for-profit agency that offered a software tool marketed and supported by Swallow. Given that our fieldwork with Swallow and Heron suggested that antipathies towards the for-profit sector might hamper knowledge exchange, we recruited this not-for-profit (Jackdaw – pseudonym) to learn more about how such organisations fared (see Recruitment and data collection via not-for-profit agency for further details).

Four CCGs located in areas where Swallow and/or Heron had worked were also recruited (see Recruitment of Clinical Commissioning Groups for a fuller explanation). Through fieldwork with these CCGs, we encountered many other external providers offering support to commissioners including freelance analysts and former NHS commissioners, for-profit organisations with particular subject and methods expertise and not-for-profit agencies lobbying for particular patient groups. Furthermore, as discussed in Chapter 1, several units that started out as ‘internal’ moved to external provider status such as Public Health. Wherever possible, we interviewed these providers to augment our understanding of the type, range and usefulness of external provider input to commissioner decision-making.

Recruitment and data collection via the first commercial provider

Data collection started with Swallow, a medium-sized UK-based commercial company that worked exclusively with public sector clients in health, education and government. Offering a suite of software tools for invoice validation, auditing best place of care, risk prediction and predictive modelling, Swallow consultants often had NHS or public service backgrounds in analytics or commissioning.

When fieldwork began in early 2011, Swallow was engaged in two contracts that met our criteria, but one was nearly finished; we therefore chose the second, which was just beginning the second of 4 years. Worth over £20M with 40–50 Swallow staff involved, this contract was one of the largest ever negotiated between commercial providers and NHS commissioners. With the contract covering an entire region, the aim was to deploy the suite of software tools to the analytics units of local commissioning organisations, train NHS analysts in using the tools and supply ‘wrap around’ support from consultants with commissioning expertise to help commissioners translate output from the tools into commissioning decisions. Importantly, the contract dictated that although Swallow staff could operate the tools and recommend actions to ‘realise benefits’ (estimated at £200M), the NHS staff were tasked with putting those recommendations into effect. Swallow received payment only once both parties agreed that the ‘deliverables’ had been met.

With respect to our study, this contract afforded multiple avenues of enquiry (and potential cases), as several commissioning organisations were involved. Interviewing began with the Swallow director and programme manager for the contract. Through snowball sampling, we interviewed a further 13 Swallow staff including analysts and those with commissioning expertise, making a total of 15 Swallow interviews. We also observed one internal and one mixed Swallow/NHS meeting and one informal and three formal training events led by Swallow staff for NHS participants. Moreover, Swallow was particularly generous in sharing documentation such as training materials, progress reports, PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentations and software guides.

By the end of the summer of 2011, saturation was reached with Swallow professionals, as little new information was emerging, but further data collection with their NHS clients was necessary. Wherever possible, we approached NHS staff observed and named in interviews by Swallow staff; however, few NHS staff agreed to be interviewed, partly because of the heightened turbulence resulting from the recent reorganisations and possibly because our independence might have been questioned as our introductions had come via Swallow. We planned to recruit more through future observations, as the changes in the NHS settled. However, our potential pool of NHS clients suddenly dried up as Swallow was bought out by a much bigger company (Tern), which abruptly discontinued involvement in the study in September 2011, preventing the identification of potential new candidates. In total, we interviewed 10 NHS staff in direct contact with Swallow before losing access.

This left us with murky case boundaries. The data did not fall neatly into matched Swallow–NHS accounts within specific geographical areas around a clear contract, partly because of the paucity of NHS data but also because Swallow consultants worked across several PCTs, making data concentration more difficult. An exception was the use of a Swallow tool for auditing best place of care.

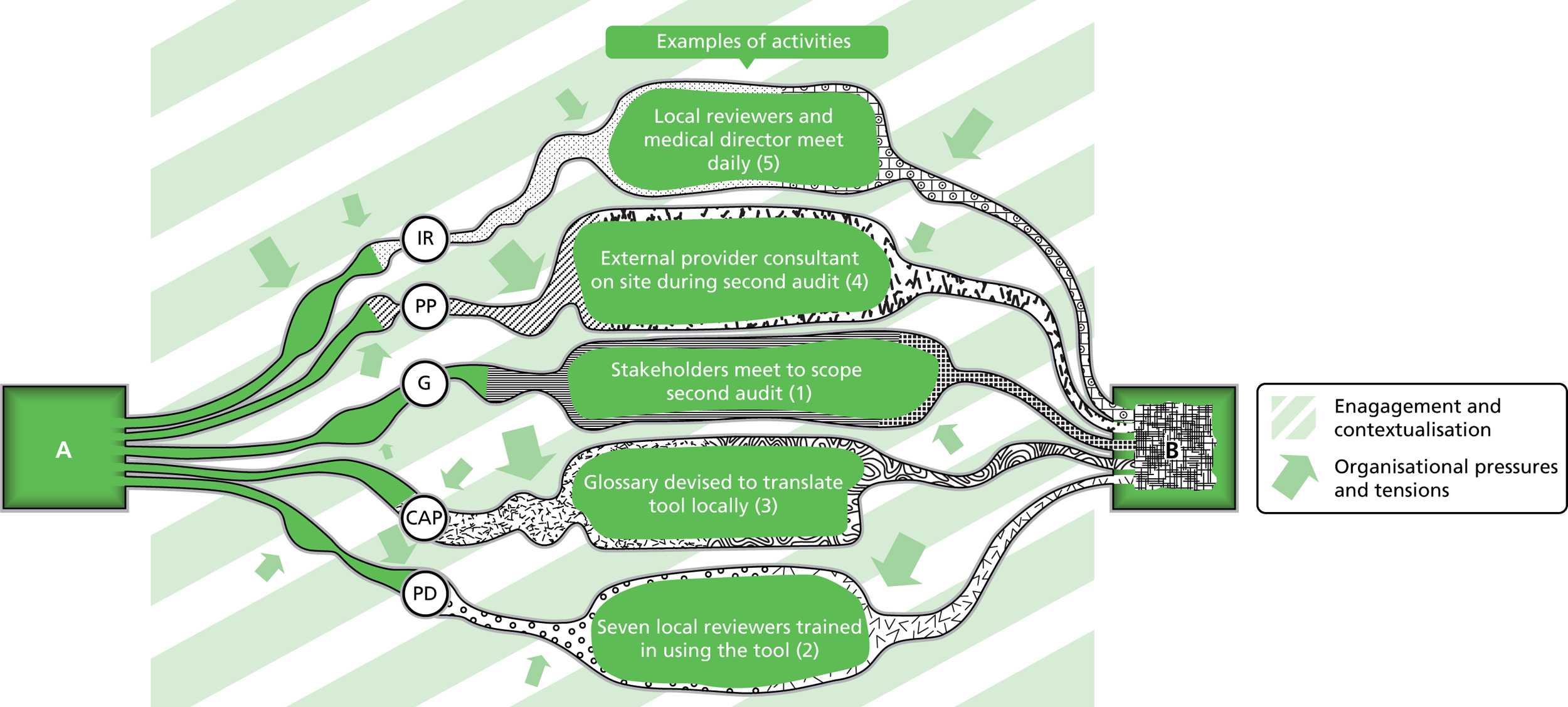

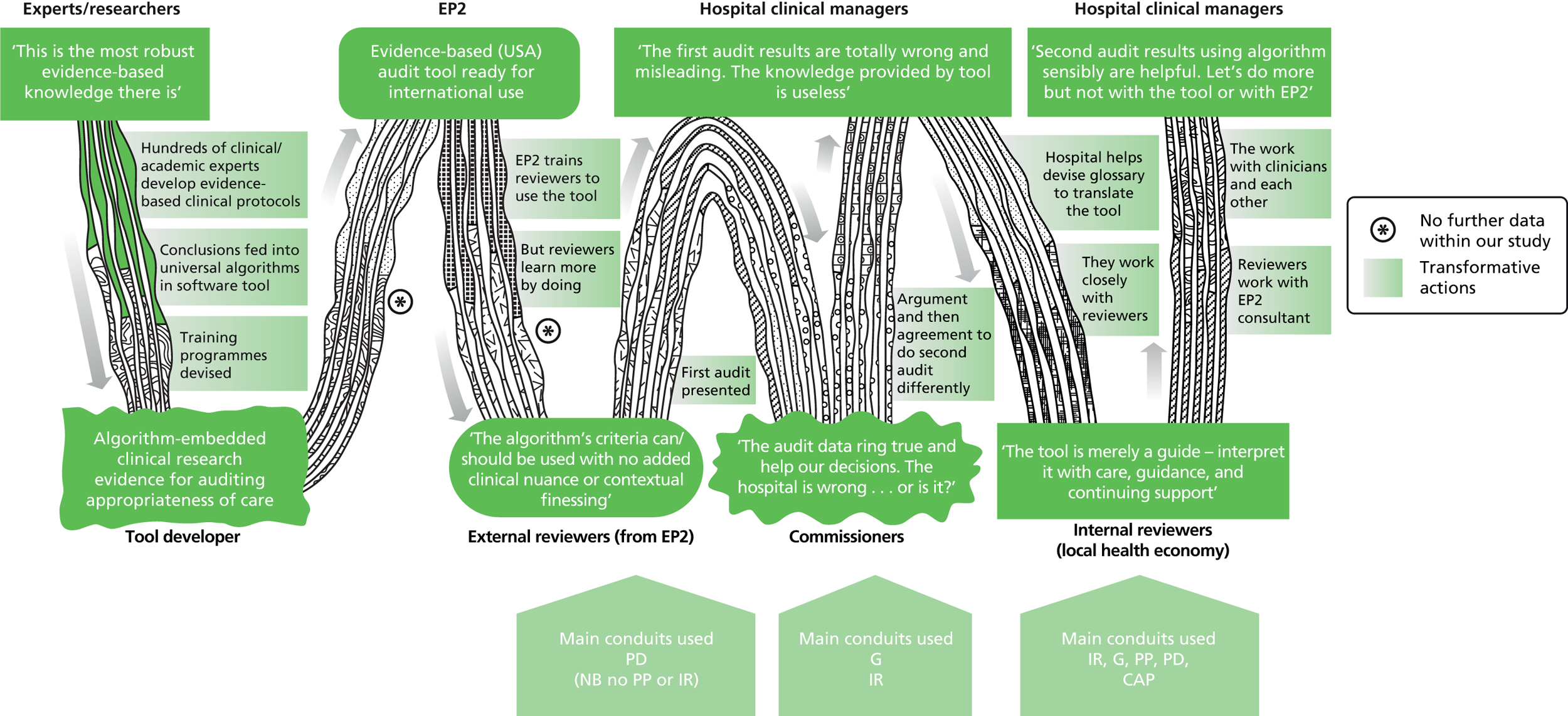

Developed in North America, this tool consisted of care standards informed by research-based evidence and expert opinion. Clinical auditors applied the standards in real time, inputting data from patient notes to determine if current inpatients were in the best place of care. A previous audit using this tool at a local hospital had not been very successful. Swallow staff had exclusively conducted the first audit and their results were challenged by the acute providers. Nine months later, a second audit was initiated, which coincided with our fieldwork. This second audit was led jointly by the PCT and acute and community providers with Swallow support. In this instance, we interviewed the Swallow tool lead, observed a NHS/Swallow planning meeting, interviewed four NHS staff (two commissioners and two senior provider managers) and attended a CCG meeting where the results of the audit were presented. Documentary evidence included meeting minutes, the audit tool template, the software product guide, a draft action plan for the PCT, an audit report and e-mails between LW and commissioners several months after the audit.

This body of evidence gave useful, balanced information about the phenomenon of knowledge exchange between commissioners and commercial providers and so became a separate Swallow ‘case’ known as ‘Swallow tool’. Other Swallow interview, observation and documentary data were amalgamated into this second distinct Swallow case, albeit with only a few NHS accounts dispersed across several geographical areas known as ‘Swallow’. Some NHS participants appear in more than one case study and only three are exclusive to the ‘Swallow’ case. The Swallow data provided valuable information about the methods and mind-set of Swallow consultants. Moreover, two of the commissioning organisations ultimately recruited in the latter half of fieldwork were located in the region of the original Swallow contract.

Recruitment and data collection via the second commercial provider

Shortly after our contact with Swallow was prematurely terminated, data collection started with Heron in the autumn of 2011. Heron was a UK subsidiary of a much larger international company. Heron offered software tools for invoice validation and risk prediction, in addition to an electronic tool that advised GPs on the most clinically effective and cost-effective medications for their patients during consultations.

Heron’s staff of around 130 people with analytical, project management and clinical backgrounds included approximately 10% who were North American. Again, data collection started with senior leaders, specifically the head of Heron UK and a director, and continued with Heron personnel identified through snowball sampling. At the close of fieldwork, saturation with Heron was reached, with 16 interviews with project managers, analysts and clinical staff, one observation of a training session and documentation such as marketing brochures, e-mails and the website.

Findings emerging from Swallow suggested that little knowledge exchange with commissioners occurred in the early to mid-point of contracts. So, with Heron, we wanted contracts that had either finished or were towards their end. Data collection started with Heron during the ‘hunger gap’ between the PCTs disbanding and CCG authorisation in the autumn of 2011 to summer 2012, when few commercial opportunities arose. Our quest to find mature or completed contracts was well timed, because Heron had four contracts with former PCTs that met our criteria. This was rapidly reduced to three, because relationships with NHS clients at a fourth site were somewhat precarious. Although Heron were not averse to including this site in the study, they felt that limited knowledge had been exchanged, compared with the others.

One contract was for Westhide (pseudonym). Starting in 2009, the remit of this 3-year rolling contract was for Heron to directly manage a portfolio of contracts with a group of acute trusts offering specialist care to patients with rare conditions. This provided unique insight into how commercial providers would manage commissioning responsibilities if these functions were outsourced. Unfortunately, although we interviewed four of the eight frontline Heron staff working on this project, only two NHS participants were willing to be interviewed. One was interviewed in 2012 when we were in the field and she suggested three other possible NHS participants, none of whom agreed to be interviewed. In fact, two sent an identically worded e-mail:

Many thanks for your e-mail but I am going to have to decline your request to assist with this research.

Surmising that perhaps the timing of interview invitations was unfavourable, we made a final attempt to find NHS candidates for this potential case in early 2014. Three new NHS names were suggested, of whom one responded to requests for an interview. Although this was better than before, two NHS client interviews were not sufficient to include Westhide as a case site in its own right. Instead, its data formed part of the ‘Heron’ case study (see Chapter 4, Commercial provider commissioning model).

Heron also put forward a second contract with Deanshire. We contacted the NHS project manager lead for Deanshire on several occasions by e-mail and got no response. Heron also contacted this lead on our behalf without success. Eventually, we bypassed this individual, requested permission to recruit the CCG directly from its board and were given approval. Three NHS participants subsequently interviewed had contact with Heron.

In contrast, recruiting from the third Heron contract was relatively smooth. The ‘Penborough’ contract initially ran for 2 years and was renewed for a third. It had three aims: (1) to increase the competency of commissioners for WCC assurance; (2) to develop a community engagement model to feed into commissioning decisions; and (3) to support the integration of health and social care in commissioning. With a few reminders and some prodding, three NHS participants with direct contact with Heron were interviewed.

Once again our data did not neatly fall into paired Heron–NHS accounts around a clear contract, except for Penborough. So, we separated out the Penborough data into their own case (see Penborough, below) and amalgamated the 16 Heron interviews, one observation, documentation and five NHS participant interviews into a case called ‘Heron’.

Recruitment and data collection via not-for-profit agency

As previously mentioned, having collected data from two commercial providers, we were interested in learning more about the not-for-profit sector. Our point of contact with Jackdaw was a Swallow NHS participant, who took part in Jackdaw training. This training came about when the Swallow contract was renegotiated (for a second time), following the takeover of Swallow by Tern in the summer of 2011. The NHS negotiators stipulated greater contact between the original developers of Swallow’s tools (i.e. Jackdaw and several other companies) and the wider NHS clients.

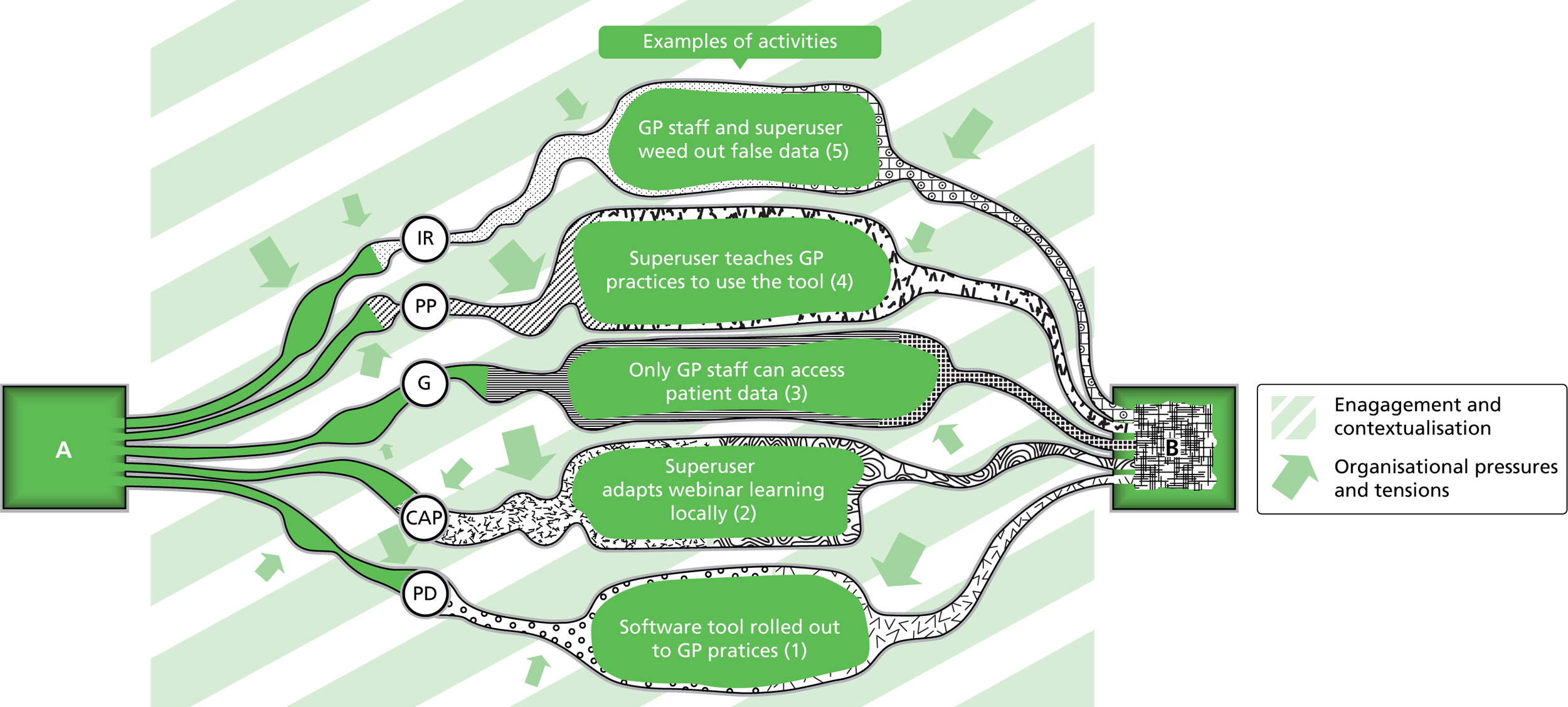

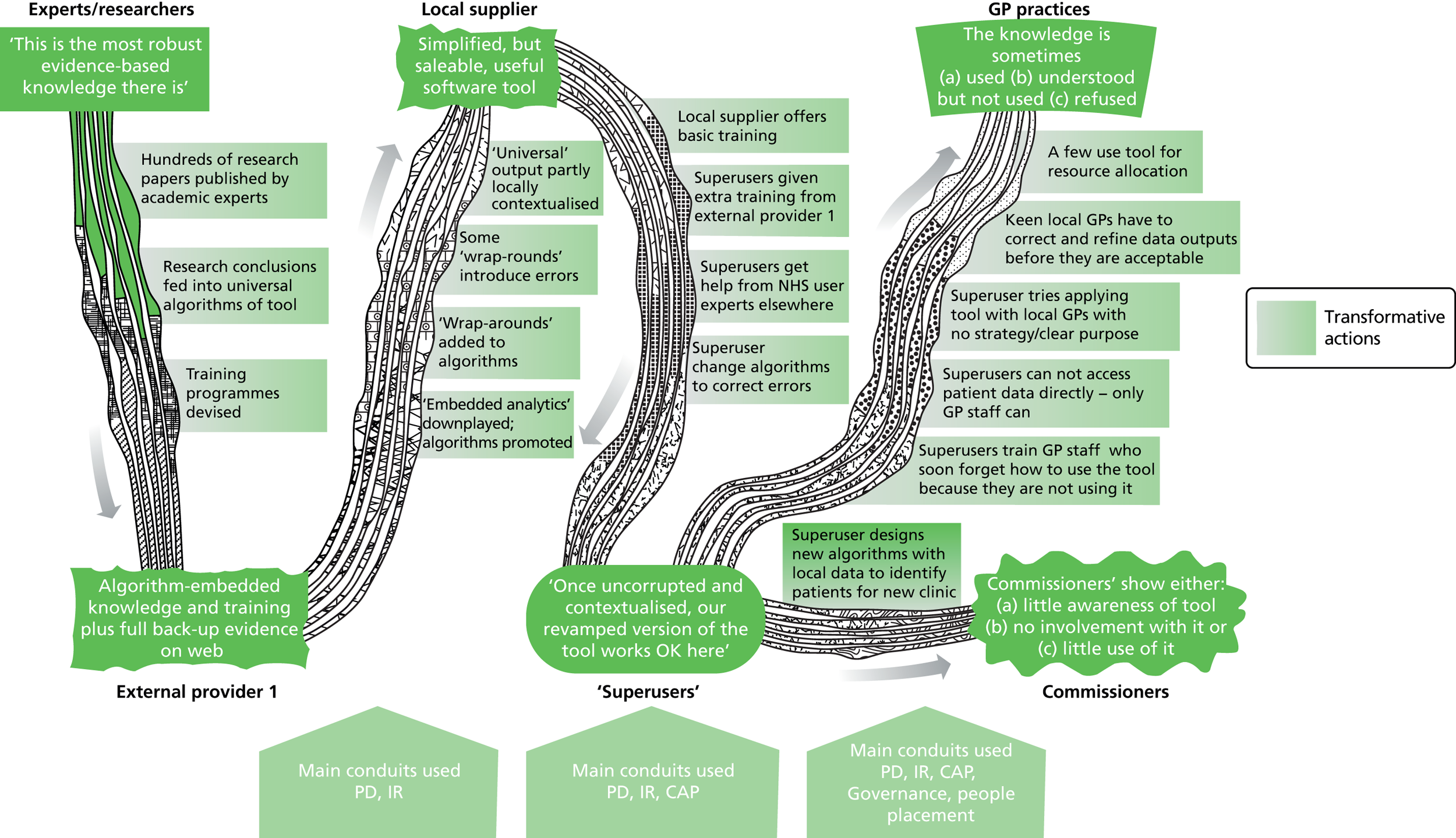

Jackdaw was a very small not-for-profit provider, which had developed and refined a risk prediction tool through research carried out over 30 years, and continued its strong links with academic institutions. At the time of data collection, the UK branch of Jackdaw consisted of one full-time consultant who reported to a managing director in Europe, both of whom were interviewed. Through didactic, online webinars, the knowledge exchanged in this particular case study was between Jackdaw staff (nationally and internationally) as tool experts and seven NHS clients of diverse backgrounds (analytics, commissioning) from different commissioning organisations to help the NHS clients become ‘superusers’. We invited all seven NHS participants to interview and three accepted. We also ‘observed’ a virtual webinar session. Data were collected from May 2012 to January 2013.

We would have liked to have recruited further not-for-profit organisations, but the only other potentially suitable candidate did not respond to requests for interview. Thus, our conclusions about the role of not-for-profit agencies are somewhat tempered.

Recruitment of Clinical Commissioning Groups

By May 2012, when data collection with Swallow and Heron was complete, concerns were rising about the lack of NHS participation in the study. Moreover, preliminary findings suggested that capturing impact on commissioning decisions was difficult, as it was largely analysts who benefited (or not) from the use of the software tools. This meant that answering our research questions about how commissioners (i.e. decision-makers) accessed, transformed and used external knowledge was impeded. We had shied away from more direct recruitment of CCGs as commissioners’ attention was understandably absorbed by changes in the NHS. However, in the summer of 2012, we decided to proactively target the CCGs where Swallow and Heron had been most active, inviting staff from these CCGs into the study regardless of their previous level of contact with Swallow and Heron. Two CCGs were recruited from Swallow’s geographical patch (Norchester and Carnford) and two from where Heron had previous contracts (Penborough and Deanshire).

Norchester

To recruit Norchester, LW opportunistically met an influential Norchester GP at a conference. This academic GP agreed to an interview and then liaised with the chief operating officer of the CCG on our behalf to recruit the CCG.

Norchester CCG was a highly research-aware organisation, largely because of the involvement of this GP academic. Although Norchester was in an affluent area in England, the CCG was facing considerable financial challenges with targeted savings of over £20M by 2014. Nationally known for its pioneering initiatives, the CCG’s primary, somewhat high-risk, strategy for reducing unsustainable spending was to modify about 40% of their contracts by (1) rewarding providers on the basis of achieving outcomes such as fewer deaths in hospital rather than activity (e.g. number of procedures) and (2) commissioning a lead provider who then subcontracted other providers. Information and knowledge to support this work came from local CSU analysts employing Swallow’s risk prediction tool and several commercial and not-for-profit agencies with expertise in Public Health, contracting, business case development and condition expertise.

Norchester was split into localities of different sizes; the largest locality covered a population of 150,000. The CCG was in considerable flux during the first period of fieldwork (summer 2011), which had stabilised by the second period of fieldwork (December 2012 to May 2013), shortly before authorisation. Public Health and CSU colleagues (formerly known as the ‘Decision Support Unit’) were colocated in the same building, although some Public Health professionals also worked in local authority premises. Participants for Norchester were selected on the basis of involvement with Swallow and its tools and role in organisation (e.g. senior leaders). Again, snowball sampling was the principal method of identifying appropriate candidates. Data collection is itemised in Table 1.

| Data type | Data source |

|---|---|

| Observations and associated documents (two observations, total duration 5 hours 50 minutes, 28 documents) | CCG shadow governing body meetings December 2012 (held in public, 10 meeting papers) and January 2013 (not held in public, 18 meeting papers) |

| Interviews (11 interviews, total transcribed duration 8 hours 4 minutes) | Four members of the CCG shadow governing body: a CCG accountable officer (GP), two locality leads (both GPs), and a practice manager |

| Four analyst/information staff: a PCT lead analyst, a chief information lead, a PCT/CSU analyst and a freelance analyst | |

| CCG R&D lead (GP), ex-PCT chairperson (GP), CCG associate director of strategy and governance | |

| Additional documents (11 documents, seven websites) | CEO’s report November 2013, commissioning report Phase 1 March 2013, report of workshop event January 2013, three board papers November 2013 Questions to the board September and December 2013, statements on procedures of limited clinical value from 2009, 2012 and 2013 (accessed from Norchester website 6 December 2013) |

| Websites of three organisations working with the CCG |

Carnford

We were directed to Carnford via a Swallow NHS participant. Carnford covered a 210,000+ population with generally low deprivation in England, and was one of several CCGs operating in the same county. They were under serious financial pressure, having received one of the lowest allocations in England, and felt that ‘operating at the edge of bankruptcy’ had been normalised in their area. There was a lot of interest in data and tools as a route to finding solutions to their problems, and those offering knowledge based on research evidence were enthusiastically received. Public Health and the local CSU were both working closely with the CCG to find ways to provide the knowledge and support they wanted, but the CCG had also engaged an external provider with an accountancy background (Bullfinch: pseudonym) to work on a number of specific projects.

Our first interview was with a GP who was using the Swallow risk prediction tool for end-of-life care. This GP was a member of the Unscheduled Care Board (UCB) that reported to the ‘Clinical Cabinet’, which was described as the CCG’s ‘engine room’ where clinical priorities were identified and work streams were monitored. Perhaps because our entry point was via the UCB, data for this CCG were more operational than strategic. Participants for Carnford were selected on the basis of role in the organisation (e.g. senior leaders, purveyors of research or data) and involvement with Swallow and its tools. Observation at meetings and snowball sampling were the principal methods of identifying appropriate candidates. Data collection ran from May 2012 to May 2013 and is itemised in Table 2.

| Data type | Data source |

|---|---|

| Observations and associated documents (five observations, total duration 13 hours, 12 documents) | November 2012 (five meeting papers), January 2013 (minutes only) and February 2013 (four meeting papers) meetings of UCB |

| March 2013 meeting of Clinical Cabinet (agenda only) | |

| May clinical reference group meeting (agenda only) | |

| Interviews (11 interviews, total transcribed duration 6 hours 55 minutes) | Five members of the Clinical Cabinet: CCG accountable officer/Clinical Cabinet chairperson, unscheduled care lead (also chairperson of UCB), research/education/innovation lead, IT lead and Public Health representative |

| Three other members of UCB: lead on integrated care teams, integrated services programme manager (contractor), and Public Health consultant | |

| CSU information analyst working with UCB, CSU director of performance and development, and a freelance analyst who was involved in evaluating risk stratification tools for the local PCTs | |

| Additional documents (five documents, one website) | Briefing paper from Public Health on unplanned hospital admissions, two issues of the local ‘Clinical Bulletin’, and two ‘pathway tool project’ documents |

| CCG website |

Penborough

Penborough CCG had contracted Heron for 3 years. This CCG covered a population of about 160,000 and was in the most deprived quintile of local authority areas in England. NHS commissioners in Penborough had a history of working in close partnership with the local authority to achieve an integrated commissioning strategy for health and social care. With the Health and Social Care Act 2012,4 this partnership was maintained and many key staff from the former commissioning structure were retained. Working collaboratively with providers, the local authority, the community and other CCGs was an ethically driven approach, but was also seen as the most efficient and effective way of commissioning. They were idealistic, positive and regarded themselves as an effective commissioning organisation. They also had the confidence to openly admit in CCG board meetings and interviews where improvements could be made.

As stated previously, our entry point to this CCG was two Heron consultants. In keeping with a CCG that prioritised patient involvement and integration with social care, this case had the broadest range of participants. These were selected to include senior leaders, and those involved with Heron and its tools, but also to reflect the organisation’s focus on including knowledge from clinical, managerial and community perspectives. Observation at meetings and snowball sampling were the principal methods of identifying appropriate candidates. Data collection took place from February 2012 to May 2013 and is itemised in Table 3.

| Data type | Data source |

|---|---|

| Observation and associated documents (five observations, total duration 12.5 hours, 54 documents) | Three sequential bimonthly public meetings of the CCG governing board, covering January to May 2013. Documents: 14 to 16 papers available in advance of each meeting |

| One bimonthly CCG governing board workshop (April 2013). Documents: agenda and copies of two presentations | |

| One monthly meeting of the council formed of representatives from each practice in the CCG (May 2013). Documents: agenda and copies of four presentations | |

| Interviews (12 interviews, total transcribed duration 7.5 hours) | Seven members of the CCG governing board: chairperson, vice chairperson (who is also chairperson of the Council of Members), finance director/deputy chief executive, Public Health director (who is also lead for well-being and prevention), sustainable services director, adult social care advisor and GP representative (who is also clinical lead for the unscheduled care) |

| Four other CCG members: deputy chief finance officer, innovation and research lead, service manager lead for unscheduled care and community representative for unscheduled care | |

| Two staff from private provider Heron Ltd who had worked with the organisation before the transition to CCG structure (joint interview) | |

| Additional documents (seven documents, two websites) | Set of six documents and one web-based tool relating to business case/service proposal development processes |

| Memorandum of Understanding with Public Health | |

| CCG website |

Deanshire

Coterminous with its local authority, Deanshire was a county-wide CCG serving a largely rural population of approximately half a million. The practices making up the CCG were organised into localities, each of which nominated a representative to sit on the Clinical Operations Group, the ‘engine room’ of the CCG. Deanshire had a somewhat conservative ethos in ensuring that the CCG ticked the right boxes and was seen to be above board, possibly to maintain its reputation as a leading commissioning organisation, but there were also several examples of innovative, inspiring projects focusing on improving patient care carried out by committed staff.

Like Penborough, Deanshire had formerly contracted Heron but our entry point to this CCG was through the director of commissioning development, who suggested that we focus our enquiry on two commissioning initiatives: the reablement project and the acute stroke project. Work on the reablement project began in 2010 and rollout of the redesigned reablement service across the county was ongoing at the time of data collection. The acute stroke project was at a much earlier stage and grew out of broader work around stroke, which had been instigated by the CCG in response to poor outcomes in Deanshire.

Heron’s presence in the data collected from the CCG was minimal, largely because the contract had stopped several years prior to fieldwork, but other commercial providers of commissioning expertise were visible. These included a commercial company that had worked on the reablement project and a project management contractor who was working on the acute stroke project. Participants for Deanshire were selected basis of role in the organisation (e.g. senior leaders) or in one of the two projects which had been selected as foci. Observation at meetings and snowball sampling were the principal methods of identifying appropriate candidates. Data collection took place from January to April 2013 and is itemised in Table 4.

| Data type | Data source |

|---|---|

| Observations and associated documents (four observations, total duration 9 hours 45 minutes, 43 documents) | December 2012 CCG governing body public meeting. Documents: agenda and 10 meeting papers |

| February and May 2013 Clinical Operations Group meetings (March/April meetings closed to non-CCG members). Documents: agenda and eight meeting papers (February), plus agenda and 17 meeting papers | |

| Acute stroke project meeting in February 2013. Documents: agenda and four meeting papers | |

| Interviews (14 interviews, total transcribed duration 9 hours 44 minutes) | Seven members of the CCG: governing body chairperson, clinical operations group vice chairperson, director of clinical commissioning development, director of strategy and patient engagement, head of pathway development, head of federation development and a commissioning manager |

| One member of local authority staff, who had worked with the NHS commissioners on the reablement project, and one Public Health consultant | |

| Five commercial providers of commissioning expertise: two staff each from two large companies which had worked in the area, and one project manager who worked as a contractor on the acute stroke project | |

| Additional documents (one document, one website) | ‘Prioritisation principles’ document for planning |

| CCG website |

Summary of cases and data collection methods

At the completion of fieldwork, eight cases were identified from the data and we had a spread of data with NHS and external provider accounts. In total, we collected interview data from 92 participants [47 NHS clients, 36 external provider consultants and nine other participants (e.g. freelance consultants, lay representative and so on)] and conducted 25 observations.

Interview participants were sent information sheets electronically before interviews and written (or recorded) consent was obtained. The initial topic guide was devised by the research team and covered type of information wanted, sources of information, and how that information was accessed and fed into decision-making. The topic guide was regularly revised as new questions emerged and others appeared to have been answered. Interviews were face to face or by telephone, depending on the preference of the participant and practicalities. Lasting 20–60 minutes, all interviews were recorded and transcribed.

Prior permission to observe activities was obtained by researchers before attending events. Chairpersons and training leads mentioned the research and researcher’s presence at the start of events, sometimes with the researcher absent from the room. Observation notes were taken, with the help of an aide memoire based on the research questions. Notes taken during observation included details of who was present, room layout, verbal exchanges, participant reactions and researcher reflections. Observation notes were typed up as soon as possible after the data were collected. All interview and observation participants were given pseudonyms.

A range of documentary data were collected to supplement, confirm and challenge emerging findings from interview and observation data. These included meeting minutes, reports, websites, marketing material, press releases and e-mails. These data fed into the second phase of data analysis (Table 5).

| Case | NHS | Total NHS | External provider | Total external | Total NHS plus external | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP commissioner | Commissioner | Analyst | Other NHS | Commercial/not-for-profit | Freelance | Public Health | Local authority | Lay | ||||

| Swallow | 1 | 2 | 15 | 25a | ||||||||

| Swallow tool | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | ||||||||

| Heron | 2 | 1 | 16 | 17 | ||||||||

| Jackdaw | 2 | 1 | 2 | 5 | ||||||||

| Norchester CCG | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 11 | |||||||

| Carnford CCG | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 11 | |||||||

| Penborough CCG | 2 | 5 + 1 | 2 | 2b | 1 | 1 | 12b | |||||

| Deanshire CCG | 2 | 5 | 2 + 2b | 1 | 1 | 14b | ||||||

| Total | 15 | 17 | 9 | 6 | 47 | 36 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 47 | 92 |

Data analysis

Several theoretical influences were present in our thinking while we were analysing the data, including ideas from the knowledge management literature.

Brown and Duguid’s notion16 of the ‘social life of information’ was useful. They argue, for example, that innovative knowledge ‘flows in social rather than digital networks’, and see successful innovation as dependent on ‘the bringing together of abstract information and situated knowledge’. They emphasise the importance of local knowledge and the role of social networks in grounding knowledge in practical contexts. They stress that informal exchanges such as stories are key to the way that knowledge moves through organisations. 17 Consequently, the notion of ‘communities of practice’ was also key to our analysis, as an important way in which people share knowledge and also connect informally and formally across boundaries, such as departments, disciplines and organisations, to share expertise and learning and to develop knowledge-in-practice. 18,19 Gabbay and le May’s work on collective mindlines provides a further dimension to the role of collective sense-making in primary care decision-making. 20,21 These ideas are concordant with Weick’s analyses of collective ‘organisational sense-making’, where context and understanding are mutually enacted. 22

Nonaka’s model of knowledge creation,23 which describes how knowledge is created and assimilated, also seemed relevant. This suggests a sequence of conversions of knowledge between tacit and explicit that enable people in organisations to share (mostly practical) knowledge. This author originally described a continuing cycle of socialisation (learning how things are actually done day to day in that organisation), externalisation (exposing implicit and tacit knowledge, e.g. through story-telling and mutual observation), combination (of that explicit knowledge with other sources of knowledge often in guidance documents, manuals or intranets) and internalisation (by individuals working in that environment). However, subsequent critiques have suggested that this so-called ‘SECI cycle’ misunderstands the nature of tacit knowledge and that a more nuanced view is required. Cook and Brown, for example, argue that organisations come to know by ‘bridging epistemologies’ in a process of productive enquiry termed a ‘generative dance’. 24 Nonetheless, the underlying SECI elements still seemed germane to the way commissioners might treat knowledge.

Analysis was guided by constant comparison methods, whereby data were compared across categories, continually refined and fed back into further data collection (and analysis) cycles, as is usual with high-quality qualitative studies. 25 Preliminary analysis started in June 2011, a few months after data collection began. The research team had regular face-to-face meetings every 6 months and teleconferences in between (about every 6–8 weeks). In preparation, individual team members were sent two to three pieces of data (e.g. two interviews and an observation) and asked to read through these documents, identify emerging themes and key learning points, reflect on the research questions and suggest any possible new questions for the topic guide. Covering all eight cases, eight batches of data were analysed and discussed successively.

The next phase of analysis began in May 2013, when fieldwork came to a close. The research associate (EB) developed a coding framework, in collaboration with LW and AC, based on the research questions. Using NVivo software (QSR International, Warrington, UK), she systematically coded cases independently. In addition, EB and LW developed 20–50-page case summaries for each case. Drawing on all interview, observation and documentary data for each case, these summaries included a ‘thumbnail sketch’, key findings, details of data collection and useful quotes. Each summary was structured into:

-

models of commissioning

-

external providers

-

knowledge/information accessed

-

knowledge transformation processes

-

benefits/disadvantages.

From October 2013, every member of the research team read the summaries independently and wrote up their reflections. Drawing on the research questions, each researcher conducted a cross-case analysis, identifying key themes common to the cases as well as discrepant data. In January 2014, we held a day-long meeting to discuss and agree themes. As in past team meetings, discrepant data were debated, with data confirming/negating particular positions presented, until agreement among the group was reached. In fact, disagreements tended to be more about nuances rather than clear differences in perspectives.

A final stage of analysis took place while writing up the report. Data were compiled and compared separately for each of the five domains (e.g. models of commissioning, external providers) from the data summaries, analyses from previous team meetings and sometimes the sound files from digitally recorded steering meetings. Draft chapters were produced, distributed to the team for comment and revised.

One key question was whether or not to undertake, as part of this report, a substantial analysis of the impact of the 2012 Health and Social Care Act4 on the world we were studying, or whether or not to allow it be included just as a part of our findings on knowledge exchange. The arguments in favour of the former were that we had considerable (if serendipitous) data about the NHS participants’ experience of the changes, that these underlay the relationships that underpinned the knowledge exchange, and that this unique context needed to be explicated in full. The counterarguments were that we had not designed our data gathering to answer questions about that context. Our job was to understand knowledge exchange between the various agencies involved, whose changing roles would inevitably emerge as we presented the findings. What mattered for our study was that commissioners were always operating in difficult organisational and political circumstances, and so we should focus not on the features of a unique event, but those that were likely to be common to a wide range of circumstances. There was also, it must be said, an underlying set of political tensions to our debating this point: the desire to provide evidence that exposed the disruption to commissioning versus the professional necessity of maintaining the political neutrality of a research report about knowledge exchange. Our final decision was that although the results and discussion chapters refer to the vicissitudes created by the 2012 Health and Social Care Act4 as it pertains to knowledge transfer, we would not explicitly present data on the impact of this Act on the NHS.

Challenges

There were several challenges in working with commercial and not-for-profit providers. The first concerned research governance. External provider consultants moved around NHS organisations quickly and freely, but as researchers we could not. For example, initially the second audit using the Swallow tool was planned for the week after the stakeholders’ meeting. This audit was to take place in two settings: an acute and a community trust. To understand more about informal ways of exchanging knowledge, the research team were keen to observe the audits in practice. However, obtaining the necessary permissions from these two NHS settings took several weeks. In this instance, the date of the audit was fortunately postponed and local permissions came through for the acute trust in time. Other opportunities were missed, though, because local governance processes were not quick enough.

Research governance issues also affected the study methodology. In the original protocol, we had planned to shadow five commercial consultants over several time periods to observe where they obtained their knowledge and how this was fed into client decision-making; but, in addition to difficulties with research governance processes, which meant that the research team was unlikely to have permission to enter the same premises as the external consultants, a further complication was that few consultants were willing to be observed. They were highly (and understandably) sensitive to the impression an accompanying researcher might make on their clients. Several also voiced concern about patient confidentiality, fears that were not assuaged on presentation of documents evidencing local research and development permissions. Moreover, external consultants were highly autonomous and readily refused requests to take part in shadowing, despite their line manager’s encouragement. So, we abandoned the idea of shadowing and instead carried out observations of meetings and training events, which helped to identify study participants.

Another challenge centred around anonymisation and confidentiality. Given the commercial sensitivities of the data, transcripts, summaries and observation notes were password protected. It is always problematic to write an account of this sort while holding to one’s assurance to participants that the data will be kept anonymous and unattributable. In drafting this report, the demands of providing enough information for ‘rich description’ were weighed against the possibilities of unmasking. This was challenging in an arena where commercial providers knew their competitors well. In addition, the commissioning organisations were also quite distinct. Thus, in presenting quotes, participants’ professional backgrounds are cited and a distinction is made between NHS and external providers, but employing organisations are not identified. In order to not single out the one not-for-profit provider, this company and its two commercial competitors have all been identified as ‘commercial provider’. We have done our very best to maintain anonymity by giving the sites fictional names and using false names for specific individuals, but, inevitably, some readers will still be able to identify the sites. We hope that participants will accept that anyone who recognises a site will probably already be close enough to them to be well aware of most of the matters raised, and that no harm will result.

Dissemination

As this was a study about exchanging knowledge, dissemination of findings to target audiences such as commissioners and external providers was an essential part of the original bid. Accordingly, we put forward the idea of setting up a reference group of interested commissioners and external providers from the case sites who would act as a dissemination group, helping us to find key messages for wider dissemination throughout the lifetime of the study. This plan was modified, because early attempts to feed back to commercial providers as ‘critical friends’, with a view to having them subsequently join such a dissemination reference group, created significant consternation.

For example, in March 2011, a few months after fieldwork began with the first case (Swallow), we were asked to furnish Swallow with our observation notes of a Swallow team meeting. These were raw data, noting who sat where and who talked to whom, and appeared fairly innocuous. However, subsequently, a Swallow team member got in touch to say:

I have to say I wasn’t aware you’d be feeding back in this way. I’d certainly value an opportunity to discuss your interpretation of my performance given what has been written.

E-mail, 21 March 2011

We subsequently learnt that several members of the team were under consideration for promotion and felt that our account of their behaviour (e.g. X looking at computer) did not reflect well on them. For a short time, the continuing participation of Swallow hung in the balance. Ultimately, a key senior leader decided that the notes were not prejudicial and they should continue with the study. Unsurprisingly, those who had objected refused all further invitations to take part in the study.

Moreover, we were becoming increasingly aware of the commercial sensitivities of our research. Although regular feedback to research participants through reference groups was our original intention, we did not want to endanger the study. Consequently, we left dissemination to towards the end, although an independent academic met with us mid-study to identify any emerging findings.

Significant dissemination opportunities arose about 9 months before the study ended. A NHS manager was seconded from a commissioning organisation and attached to the project to develop and carry out knowledge mobilisation. Modelled on the defunct Service Delivery and Organisation Management Fellow scheme and paid for by local Research Capacity Funding, this NHS manager became invaluable as the study drew to a close. She helped to interpret the commissioning data (e.g. reports, business cases), clarified anomalies in the data and identified local commissioners who would be willing to develop a knowledge mobilisation strategy. The outputs of this work are presented in Chapter 10 and Appendix 1.

Reflexivity and the research team

The use of external providers in NHS commissioning is highly sensitive and controversial. We were aware of the potential research team members to unwittingly view the data through preconceived prejudices. To address this, three measures were adopted.

The first was the composition of the research team. This included two commissioners (one clinical and one non-clinical) and academics with policy, management, Public Health and methodological backgrounds. The research team also had a mixture of views including sceptics and those who were more neutral about the contributions of commercial providers, including one who had previously worked for a commercial provider. Thus, throughout the duration of the project, team members challenged each other’s views.

The second was the introduction of explicit reflexive activities when fieldwork began (January 2011) and at our final analysis steering meeting (January 2014). The key question asked of all team members was:

What are your preconceptions, assumptions, prejudices and views about: a) the use of external providers in the NHS, b) the implications of the White Paper [Liberating the NHS], especially shifting commissioning to GP consortia?

Team members provided either written or verbal accounts, which were recorded and transcribed. Interestingly, these individual accounts charted a similar trajectory with regard to the use of external providers. The more sceptical members of the team initially had an ‘antipathy’ towards commercial providers that ‘softened’ through data collection with Swallow consultants, as this agency was ‘populated with people who shared the ideology/aims of the NHS [and] genuinely wanted to make a difference to patient care’. However, once the senior management team at Swallow was replaced and former Swallow interviewees found jobs elsewhere, original ‘fears/prejudices were (utterly) confirmed’. These were not shifted much with further collection of Heron data. Meanwhile, those with more neutral views remained relatively constant. However, overall team members did develop a more nuanced perception of the advantages and disadvantages of commercial providers. With regard to the implications of Liberating the NHS,3 the team was unanimous in having serious concerns about the abilities of GPs to take on their new commissioning roles.

Another measure to encourage reflexivity was that the final steering group meeting was chaired by an external academic with a background in knowledge exchange. Apart from summarising key findings and helping us to clarify our thoughts, an important task of this chairperson was to ensure that suppositions and hypotheses were backed with data. However, interestingly, the research team reached consensus with rapid accord.

The impact of these activities was that as we were aware of each other’s (and our own) preconceptions, we became quite adept at ensuring that contributions were challenged, especially during analysis. Often, the contributor themselves would flag up that a particular insight might be due to a preconception or attitude. It meant that the team frequently questioned each other and explored assumptions.

Box 2 summarises the key points of this chapter.

-

Using a case study design, although the phenomenon under study remained constant, identifying the case and its boundaries was challenging. Eventually, eight cases of knowledge exchange between NHS commissioners and other agencies emerged. Four were case studies that had external providers as the unit of analysis and four had a commissioning organisation as the unit of analysis.

-

Data collection included 92 interviews of NHS and external provider staff, 25 observations of meetings and training events and documents such as meeting minutes, websites and marketing brochures.

-

Challenges included variable willingness for potential interviewees to participate, slow research governance processes that stopped researchers from shadowing external consultants, safeguarding of commercially sensitive data and maintaining participant anonymity.

-

Our initial intention to disseminate findings as the study progressed was reversed early on because of sensitivities around data sharing. Instead, a NHS commissioner was seconded into the team towards the end of the project to set up a group of commissioners to identify actionable messages. Similarly, she also worked closely with a former commercial provider consultant to develop actionable messages for this audience.

-

Given the controversial nature of this project, the research team considered it appropriate to generate and share their observations about their own preconceptions and changing views at key points in the study trajectory.

Chapter 3 Processes of commissioning

Introduction

Before presenting findings about how commissioners access, transform and apply knowledge from different sources, greater awareness is needed of what health-care commissioners actually do. It is also important to contextualise this study by elucidating how commissioning was understood at the time of fieldwork.

This chapter presents background information from other literature (e.g. Department of Health and other studies) and findings from our own data. The background section begins with a brief history of commissioning and contracts. This is followed by a discussion of theoretical models of commissioning and a description of ‘real-life’ commissioning from other studies. The chapter concludes with findings from our study on the various pressures that commissioners needed to satisfy when making commissioning decisions.

A brief history of commissioning and contracts

Commissioning in England and Wales has had many incarnations. Before 1991, the commissioning of health care was carried out by local authorities. With the 1990 NHS and Community Care Act,26 the Conservative government created ‘purchasers’ and ‘providers’, whereby purchasing was carried out by health authorities and family health service authorities, the latter focusing on general practices. Primary care groups were established in 1999, bringing together health authorities and family health service authorities. Primary care groups, however, were short lived, and by 2002 they had amalgamated into the larger organisational form of PCTs. PCTs were allocated about 80% of the NHS budget, incorporating Public Health and community health services. They were also responsible for the broad clinical governance of general practices and some types of contracts with general practices, although GPs were still personally responsible under law and professional regulations for their clinical practice. 11 In April 2013, as part of the Health and Social Care Act 2012,4 PCTs were abolished and their functions distributed among local authorities, CSUs, NHS England and CCGs.

Clinical Commissioning Groups became the latest attempt to involve clinicians in commissioning. The first was in the 1990s, when the Conservative government brought in GP fundholding. Fundholding general practices negotiated their own contracts with hospitals, made decisions about which providers and services they would use and often deployed surpluses to develop innovative new services. GP fundholding was abolished by the Labour government in 1998 in response to accusations that it had been creating a two-tier NHS. 27

‘Total purchasing pilots’ were another variation of general practice commissioning that also operated in the 1990s. 28 Results from an evaluation suggested that the level of achievement varied widely between pilots and included reductions in the length of stay and emergency admissions. However, total purchasing pilots were also associated with higher direct management costs per head and needed heavy financial investment in their organisational development. In 2005, PBC was introduced. This gave general practices the power to spend NHS allocations locally, but the engagement of GPs was patchy,2 perhaps partly because no real funding followed the decision-making.

As commissioning organisations have evolved with more (or less) clinical input, so have the nature of provider contracts. Initially, most contracts were ‘block’, whereby an amount was agreed for a predetermined set and number of activities. The disadvantage of block contracts was that those providers that performed more than the anticipated number of activities did not get paid for this extra work. In 2003–4, Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs) were established, and so instead of paying an average price for an activity, activities were split into different clinical categories that were aligned on a cost basis. However, more detail was still needed and so ‘payment by results’ was brought in, whereby each patient event had a HRG converted into a price for individual item billing. A limitation of payment by results was that often activities outside acute hospitals had no set price, such as those carried out in community services. Moreover, the emphasis continued to be on activity rather than quality of care or outcomes.

More recently, interest has grown in ‘outcomes-based commissioning’, whereby payment is contingent on meeting an agreed set of outcomes. Sometimes more than one provider is necessary to deliver these outcomes and a lead provider will subcontract relevant services from other providers. The advantage of this approach is that services are purchased on the basis of needs but, thus far, outcomes-based commissioning has proved difficult to implement, with substantial resistance from powerful acute hospitals. 29 Another contractual innovation originating from social care is ‘micro commissioning’, whereby clients/patients have personal budgets and agree a care package in collaboration with social workers/GPs. Outcomes-based commissioning and micro commissioning are still relatively rare within the health-care sector, although we encountered both during this study. Generally, we found that commissioning organisations tended to use a combination of block and activity-based contracts when negotiating with providers.

What do commissioners do?

Definitions of commissioning

A literature review by the University of London found many definitions of ‘commissioning’, which varied across public sectors. 30 In asking for definitions of commissioning from our study participants, a NHS commissioning director said that ‘ideal’ commissioning was the ‘right balance’ between ‘strategic focus on needs assessment and service strategy delivered through contracting’ utilising Public Health and analysts to understand needs, commissioning staff with service specific knowledge to ‘build up a picture of what the whole system needs to look like’ and contracting staff ‘with technical skills to make sure that we use the contracts to deliver that’ (Paula, NHS senior commissioning manager).

Other answers included ‘everything but provision’ (Donald, CCG chairperson) but others argued that provision was also a form of commissioning, as every time a GP issued a prescription or made a referral it had commissioning implications (Jen, commercial consultant). A long-term conditions study also concluded that the ‘strict separation’ of commissioning and provision was notional. 31 The definition of commissioning has even inspired several YouTube™ videos (search www.youtube.com under ‘what is commissioning?’).

Commissioning frameworks

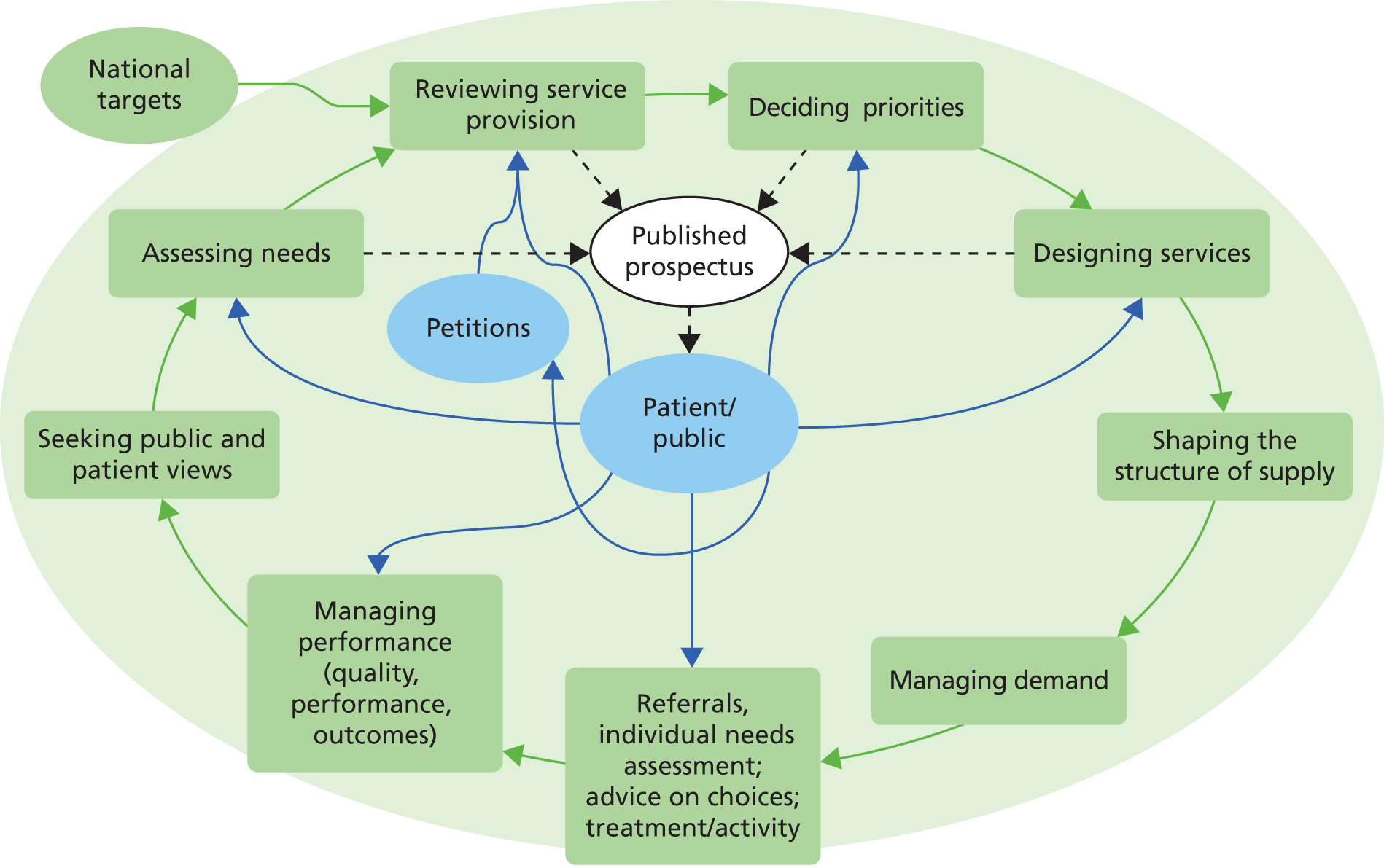

An early, simple conceptual framework of purchasing (the forerunner of commissioning) was suggested by Øvretveit and colleagues using the plan-do-study-act model. 32 Several years later, the Department of Health developed a much more complex model to include functions such as assessing needs, designing services, managing demand and managing performance (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Commissioning framework. Source: Health Reform in England: Update and Commissioning Framework. 33 Copyright Yorkshire and the Humber Public Health Observatory.

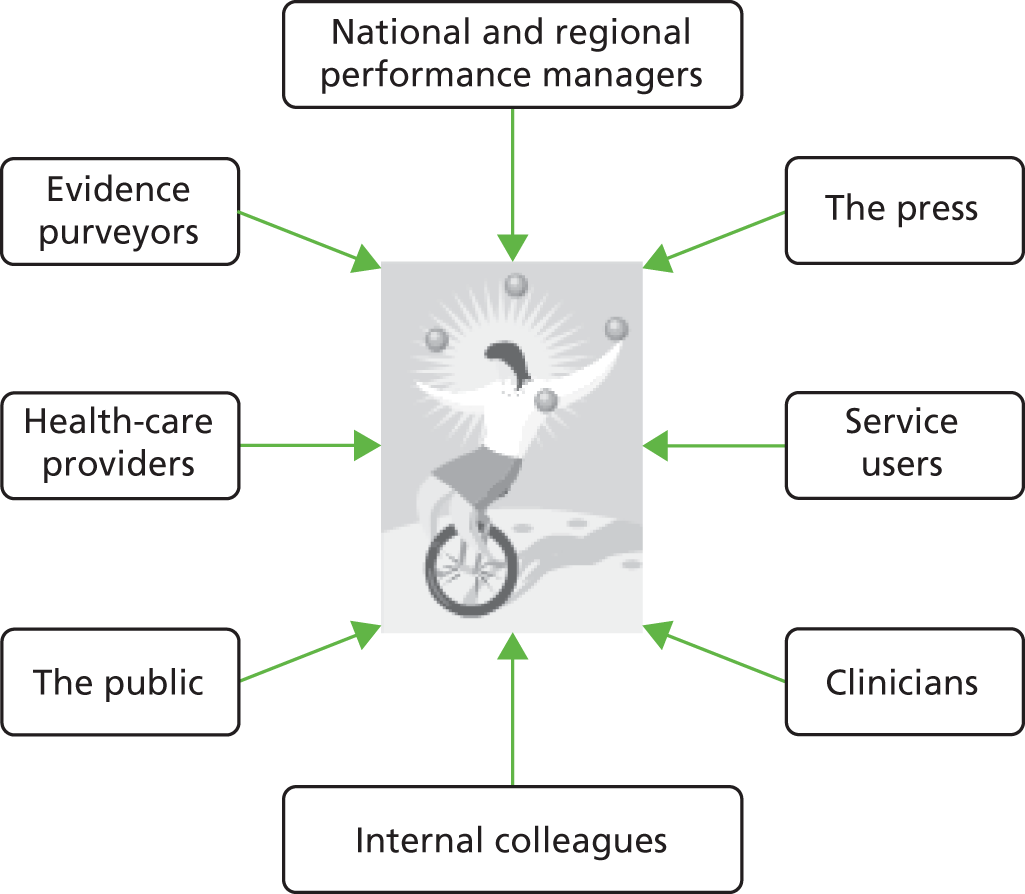

The Institute of Public Care split commissioning activities into commissioning and procurement. They expanded and refined the framework to include other common commissioning activities such as gap analysis, business case appraisal, service evaluation, development of service specifications, contract management, performance management and resource allocation Figure 2. Clearly, over the past 20 years, the role of commissioners has evolved substantially.

FIGURE 2.

Institute of Public Care model of commissioning. Reproduced with permission from Developing Intelligent Commissioning Yorkshire and the Humber Joint Improvement Project. Commissioning Model: IPC Joint Model for Public Care. URL: www.yhsccommissioning.org.uk/index.php?pageNo=594. 34

The literature

In comparing these frameworks with ‘real-life’ commissioning, recent studies found that the work of commissioners is complex, disjointed, mutable and fast paced. Moreover, high-quality, effective commissioning is difficult to achieve, not least because the link between commissioning processes and outcomes is tenuous.

In their study of health-care middle managers in four PCTs,11 Checkland and colleagues concluded:

The generic managerial work undertaken by PCT middle managers was messy, fragmented and largely accomplished in meetings . . . [There was] evidence of confusion and overlap between the various commissioning teams and groups. Managers struggle with this and appear to compensate by dividing up their personal responsibilities into ‘pieces of work’.

p. 11

The aim of an action research study led by Smith and colleagues was to learn more about the ‘nitty gritty’ of commissioning long-term conditions in three PCTs. 12 Based on their findings, plus previous work, they suggested that there were two cycles of commissioning. The first was the annual contractual cycle, which was labelled as ‘transactional’. The second cycle was ‘interpersonal’, built on trust, common values, and established and new networks. They identified nine activities of effective commissioning (e.g. getting the balance right between interpersonal and transactional aspects, strong focus on monitoring and using information to inform review). The researchers also detailed seven key themes:

-

The ‘commissioning cycle’ is a misnomer as developmental commissioning running over many years ran in parallel with annual contractual aspects of commissioning.

-

An ‘extraordinary’ level of effort went into commissioning, and this often seemed ‘disproportionate’ to the anticipated or actual outcomes.

-

Many different individuals carried out commissioning tasks including managers and clinicians from providers, GPs, voluntary sector representatives and PCT commissioners. Clinicians’ role was primarily as champions for change.

-

Money was at times peripheral, with the majority of spending remaining in block contracts.

-

Changes brought about through commissioning were incremental. Success was more likely with ‘bite-sized’ completion of tasks within a wider plan.

-

External drivers such as national guidance played a powerful role.

-

Commissioners within this study worked within a context of uncertainty, as fieldwork took place while PCTs were winding up and CCGs emerged.

In our study, participants also mentioned the fast-paced nature of commissioning, whereby those providing support had to be highly flexible to changing needs.

You have to go in with a blank sheet of paper and almost listen to their requirements from the ground up again and see has the landscape changed? Commissioning requirements are a moving feast. Does your tool still – is it still relevant?

Randall, freelance analyst

Our study participants highlighted several processes, skills and viewpoints necessary for commissioning not previously mentioned. With their strategic overview, commissioners took ‘a whole systems approach to the way we develop services and pathways’ (Jane, NHS commissioning manager), because providers may be overly focused on ‘their services, their staff, their accountability’ (Abbie, NHS commissioning manager). Furthermore, leadership and persuasion skills were crucial to link providers together and manage tensions that competing agendas invariably generated. Commissioners, however, did not just have to influence providers. Successful commissioners also continually worked with and competed against their commissioning colleagues. For example, in one CCG we observed a commissioner present a business case for a lymphoedema service to the CCG board. The board had to consider the merits of funding this business case compared with several others recently submitted by other local commissioners; the lymphoedema business case was in direct competition with other proposals.

Having outlined the processes that commissioners engage in and provided a flavour of the shifting, challenging nature of their role, the rest of this chapter focuses on results from our study. The next section covers the reasons that prompted commissioners to look for information and the various pressures they needed to satisfy.

Commissioning decision-making

Observations of CCG meetings, reinforced and explored through interview and documentary evidence such as CCG meeting minutes, suggested that the push for commissioners to seek information arose either because they were told to take a course of action or because they wanted to take a course of action and they needed to find out how best to proceed. In both situations, which occurred commonly across the sites, relevant information was necessary to justify the decision and to persuade others to approve and/or follow the suggested course. Decision-making was assisted through repeated cycles of finding information, persuading others, justifying proposals, finding more/different information, persuading others, etc.

The impetus when commissioners were ‘told’ might be a top-down edict from the Department of Health or Strategic Health Authority; for example, the implementation of NHS 111 and ‘telehealth’ were major national initiatives during fieldwork. One CCG found that generating their own data from the first few patients using telehealth (specifically looking at hospital utilisation) was helpful in beginning to persuade some sceptical colleagues and to start developing an ‘evidence base’ to justify the decision. Commissioners might not have agreed with the directive or believed in its merit for their local population but, regardless, such activities became a ‘must do’ which led to the search for viable supporting information.

Alternatively, commissioners sometimes looked for information when no predetermined course existed. Sometimes, local information prompted changes. For example, in response to service user feedback one commissioning organisation needed information to develop a reablement project for those with long-term conditions. To help to decide a course of action, persuade others and justify their decisions, commissioners drew substantially on several sources including mapped patient pathways, shadowing key clinicians and meetings between service users and senior commissioners. These senior commissioners needed to be convinced of the priority of the problem and merit of the proposed solution to allocate funding and give senior-level support.

In either situation (being told to or wanting to make changes), commissioners searched for and pulled in information, when information was needed. Commissioners required information to build a cohesive, convincing case. In comparing GP decision-making with GP commissioner decision-making, one participant said that as a GP the decision was between the GP and the patient, but as a commissioner the decisions ‘have to stand up to extremely close, possibly legal scrutiny and have to be owned by the organisation’ (Angus, GP commissioner). As they came from publicly accountable organisations, commissioning decisions had to be resilient to challenges from many possible directions.

For example, challenges might come from clinicians and health-care provider organisations that needed to make changes themselves in order for the initiative to be a success. We encountered multiple examples of this, including commissioners in two case site CCGs who were rolling out risk assessment tools to general practice staff, with variable success.