Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1024/08. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The final report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Gemma Trainor is employed as a consultant nurse in child and adolescent mental health services.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Hannigan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Mental health in children and young people

One in 10 children and young people between the ages of 5 and 16 years living in Britain has a diagnosable mental health problem. 1 In England the total number affected is projected to increase by over 13% in the period to 2026. 2 In this context a priority for the NHS and its partner agencies is to make sure that the needs of each child are met in a tailored and timely way. To this end, child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) in England and Wales continue to be organised using a tiered approach. 3,4 This is represented in Box 1.

Tier 1: child and adolescent mental health services are provided by professionals whose main role and training is not in mental health, such as GPs, health visitors, paediatricians, social workers, teachers, youth workers and juvenile justice workers.

Tier 2: tier 2 CAMHS are provided by specialist trained mental health professionals, working primarily on their own, rather than in a team. They see young people with a variety of mental health problems that have not responded to tier 1 interventions. They usually provide consultation and training to tier 1 professionals. They may provide specialist mental health input to multiagency teams, for example for children looked after by the local authority. Tier 2 also consists of those practitioners and services from specialist CAMHS that provide initial contacts and assessments of children and young people and their families.

Tier 3: tier 3 is reserved for those more specialised services provided by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) or by teams assembled for a specific purpose on the basis of the complexity and severity of children’s and young people’s needs or the particular combinations of comorbidity found on specialist assessment.

Tier 4: tier 4 services are very specialised services in residential, day patient or outpatient settings for children and adolescents with severe and/or complex problems requiring a combination or intensity of interventions that cannot be provided by tier 3 CAMHS. Tier 4 services are usually commissioned on a subregional, regional or supraregional basis. They also include day-care and residential facilities provided by sectors other than the NHS such as residential schools, and very specialised residential social care settings including specialised therapeutic foster care.

Source: information in this table has been directly extracted from the Wales Audit Office/Healthcare Inspectorate Wales document Services for Children and Young People with Emotional and Mental Health Needs,4 and is Auditor General for Wales and Crown copyright.

Inpatient child and adolescent mental health services: a component within a complex system

With multiple groups of people and organisations located at different tiers, all interacting in mutual interdependence, CAMHS are an example of a complex system. 5–7 Within this system, as Box 1 shows, the most specialised services are available at tier 4 to young people with the greatest need. Those who use services at this level often have multiple disorders and difficulties, and, until relatively recently, tier 4 was largely synonymous with hospital care. 8 New service developments reflect the idea that care at this highest level should be provided in the least restrictive environment possible. Against this background a team funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation programme systematically reviewed alternatives to hospital admission for children and young people and the evidence of their effectiveness, acceptability and cost. 9 This team described a number of alternatives to inpatient care in a typology of evaluated models, and from its mapping exercise reported a variety of services in use across the UK.

This evidence, plus evidence secured by the independent CAMHS review team3 and by the National CAMHS Support Service,8 points to a diversification at tier 4 which includes an expanded array of highly specialised and/or intensive community and out-of-hospital services. However, inpatient CAMHS units continue to play a major part in overall systems of mental health care, and, reflecting the terms of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme’s call under which this project was funded (NIHR HS&DR 11/1024: Innovations in secondary mental health services), it is hospital services that have exclusively been focused on here. Over the lifetime of this evidence synthesis, important reminders have appeared of the need for locally accessible, age-appropriate, hospital-based mental health care for children and young people. New data published in February 2014 following a joint British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC)/Community Care investigation pointed to the continuing problem of young people being admitted to adult wards and to wards many miles from their homes, with detrimental effects on individuals and on the maintenance of relationships with family and friends. 10 This, plus the fact that highly specialised, institutional health care also constitutes a substantial component of health service costs, makes this evidence review in the tier 4 hospital services field particularly timely.

At the turn of the new century it was estimated that over 2000 young people are admitted to English and Welsh CAMHS inpatient units each year, with the majority of specialist centres catering exclusively for those over 11 years old. 11 Variations in the characteristics of young people admitted are believed to exist, reflecting differences in the socioeconomic features of regions and differing levels of bed availability. Pressure on inpatient beds is considerable, and many who are referred for inpatient treatment are not accepted. 12 The admission of young people to adult mental health wards has been recognised as a problem for some time,13 with the recent BBC/Community Care investigation including vivid first-person testimony of the difficulties this causes. The increased use of adult wards in England has also happened in the face of active monitoring by the Care Quality Commission, which requires services to report each occasion on which an under-18-year-old is placed on a ward intended for adults for a continuous period of more than 48 hours. 14

It is notable that, until relatively recently, little was known of the actual interventions offered to young people admitted to mental health hospitals or the advantages of providing inpatient care. This general situation is changing, helped by the commissioning (including by the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme, the predecessor to the body funding this current evidence synthesis) of investigations such as Tulloch et al. ’s15 into costs, outcomes and satisfaction in inpatient CAMHS. The wider evidence base has also been strengthened by new knowledge of systems and processes supporting young people making the transition from CAMHS to adult mental health services. 16 What has not been attempted hitherto is a synthesis of the evidence in the area of risk in the way that has been accomplished here.

Identifying, assessing and managing risk: the case for an evidence synthesis

Within the inter-relating CAMHS system, the identification, assessment and management of risk are key considerations for practitioners and managers working at the interface between community and hospital services. Work across this interface includes making decisions on the transfer of young people from one tier to another. Decisions made at this juncture, and risk-related decisions made in the within-hospital context, can have lasting consequences for young people, families and services. In preparing our bid for NIHR support we were aware of individual (and sometimes small-scale) investigations being conducted in the areas of risk identification, assessment and management in inpatient CAMHS. To the best of our knowledge, however, no previous studies have systematically brought together research and other evidence in the way that has been done here.

The word ‘risk’ in everyday mental health services is overwhelmingly used as a shorthand referring primarily to the possibilities of direct harm to self or others, or harm through self-neglect and physical deterioration. Risk-management interventions, including the admission of people to hospital as places of safety in which round-the-clock care and observation can be provided, are then introduced as means of minimising the likelihood of harm happening. Action in response to identified risks of this type is vitally important for young people. Beyond this, an ambition of this project has also been to search for evidence in the area of inpatient CAMHS risk where risk is understood in the broadest of senses, with the word itself having a number of different meanings. ‘Risky behaviour’ and ‘posing a risk’ are two, correlating closely with the dominant ways in which risk is thought of in mental health services but contrasting with the ideas of ‘risk factors’ and ‘being at risk’. 17 To this Coleman and Hagell17 add the idea of ‘risk reframing’, through which behaviours typically seen as risky might be reinterpreted as opportunities to develop resilience. In the mental health service context, this connects with the idea of ‘positive risk-taking’,18 used as a route to the promotion of individual responsibility and personal development.

As a project team we view risk as complex and multifaceted. Our original case for funding support included the idea that, in addition to the risks of harm to self and others and self-neglect, attention ought also to be given to the identification, assessment and management of other, less obvious, risks for young people using inpatient mental health services. In a context of bed scarcity and regional variations in patterns of provision, it is known, for example, that CAMHS clinicians describe the most significant reasons for hospital admission as a young person’s high risk of suicide, risk of physical deterioration owing to mental illness, need for round-the-clock observation and the presence of serious deliberate self-harming behaviour. 12 Pursuing the example of self-harm is illustrative of the thinking behind this study. Although good practice involves care and treatment in the least restrictive environment possible, for young people who seriously self-harm, safety can be difficult to achieve in the community, making this risk a common trigger for hospital referral. Anecdotal, practice-based evidence included in our original bid for support suggests that managers and professionals in hospitals also find self-harm difficult to manage because of problems of contagion. Contagion is the copying of harmful behaviours and, while important, is a risk that may not feature highly when hospital admission decisions are made. It is also a risk that may be underexamined in the research context, and about which little is therefore known.

Informing this project is also the idea that mental ill-health and hospital admission present risks to young people’s achievement of developmental milestones, psychological maturity, educational attainment, social integration with family and peers, and personal physical well-being. This overall perspective has informed the production of an evidence synthesis which embraces a broad view of risk, along with the idea that action to reduce the chances of one type of unwanted event happening potentially increases the chances of another occurring. For example, admitting a young person to hospital may represent a reasoned response to the risk of harm to self but is also an action potentially increasing the risk of other, undesired, events happening (including contagion, but also disruption to family and friendship networks, educational continuity and increased stigma). Just as risks are connected, so too are the people and services who might collectively respond to them. Addressing the full range of risks for young people admitted to mental health hospital is likely to draw on the efforts of workers located across the system: in health, social care and education services. The intention in this report has been to bring together the available evidence in ways that are helpful to this broad group of workers and to young people using services and their families.

Overarching research question and objectives

This project was funded under a NIHR HSDR programme call focusing on innovations in secondary mental health services in order to answer the overarching research question:

What is known about the identification, assessment and management of risk (where ‘risk’ is broadly conceived) in young people (aged 11–18 years) with complex mental health needs entering, using and exiting inpatient child and adolescent mental health services in the UK?

Objectives for the overall project were:

-

to summarise and appraise the evidence for the identification, assessment and management of risk for young people: as they make the transition into inpatient CAMHS; as they are cared for in inpatient CAMHS; as they make the transition from inpatient CAMHS to the community; and as they make the transition from inpatient CAMHS to adult mental health services

-

to identify and describe any underlying theoretical explanations for approaches used in the identification, assessment and management of risk

-

to understand the views and experiences of risk of young people (aged 11–18 years) with complex mental health needs using inpatient mental health services, and of those involved in the identification, assessment and management of risk in these settings

-

to synthesise the evidence for the identification, assessment and management of risk in young people (aged 11–18 years) with complex mental health needs entering, using and exiting inpatient services

-

to synthesise the evidence on the costs and cost-effectiveness to the NHS of different approaches to identifying, assessing and managing these risks

-

to identify the future priorities for commissioning, service development and research for young people (aged 11–18 years) with complex mental health needs entering, using and exiting tier 4 inpatient services.

A two-stage framework to evidence synthesis: the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre approach

The project team was commissioned to meet these objectives using a specific approach to the identification, review and synthesis of the evidence. In recent years a variety of review approaches suitable for the health-care field have emerged,19 of which the EPPI-Centre (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre) framework is one. This has developed over a period of two decades, led by researchers located primarily at the Institute of Education at the University of London and their affiliates. Documents outlining EPPI-Centre methods (and other materials) are freely available from http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/, where reviews informed by this framework are intended to have particular utility in informing policy and practice for public services. Recent published examples modelling varying degrees of detail and complexity completed by EPPI-Centre members and their collaborators include syntheses of the evidence for the socioeconomic value of nursing and midwifery,20 on commissioning in health, education and social care21 and on the effectiveness of interventions to strengthen national health service delivery in low- and lower middle-income countries. 22 Previous examples also exist of NIHR-funded projects using the broad EPPI-Centre approach. These include an HSDR programme project addressing self-care support for children and young people led by a member of the current research team (SP),23 and a Public Health Research Programme review into the effects of schools and school environment interventions on health. 24

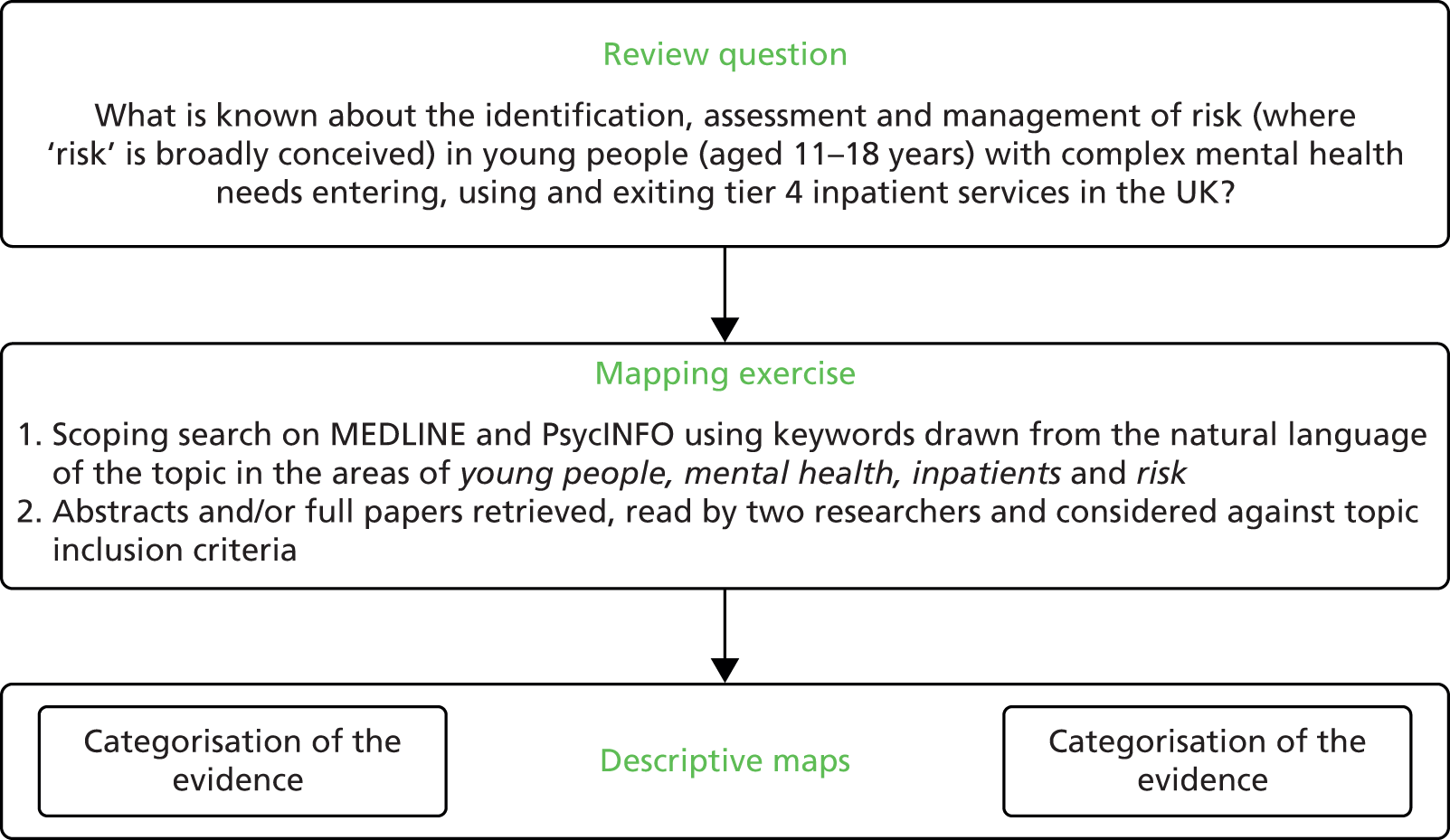

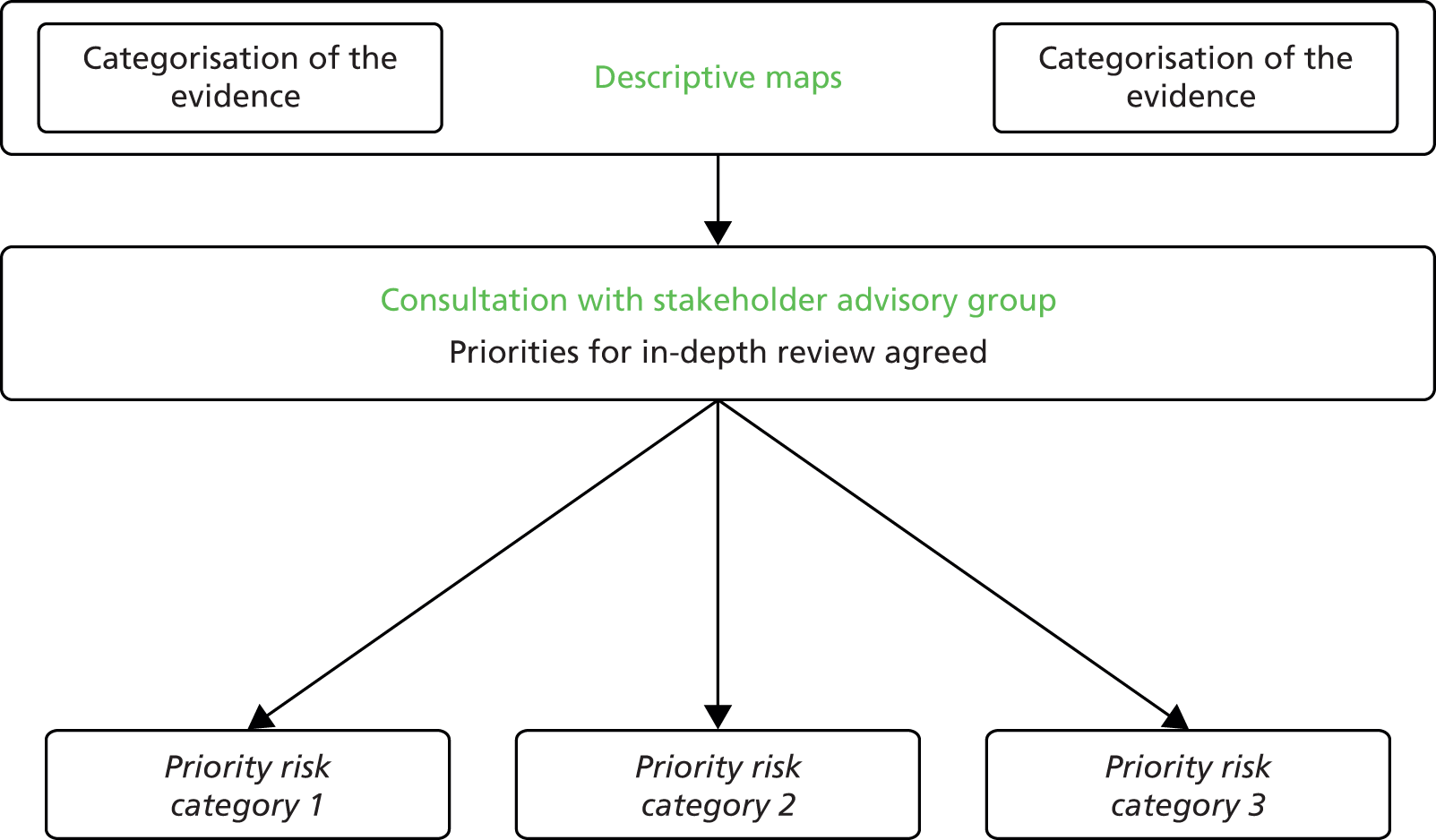

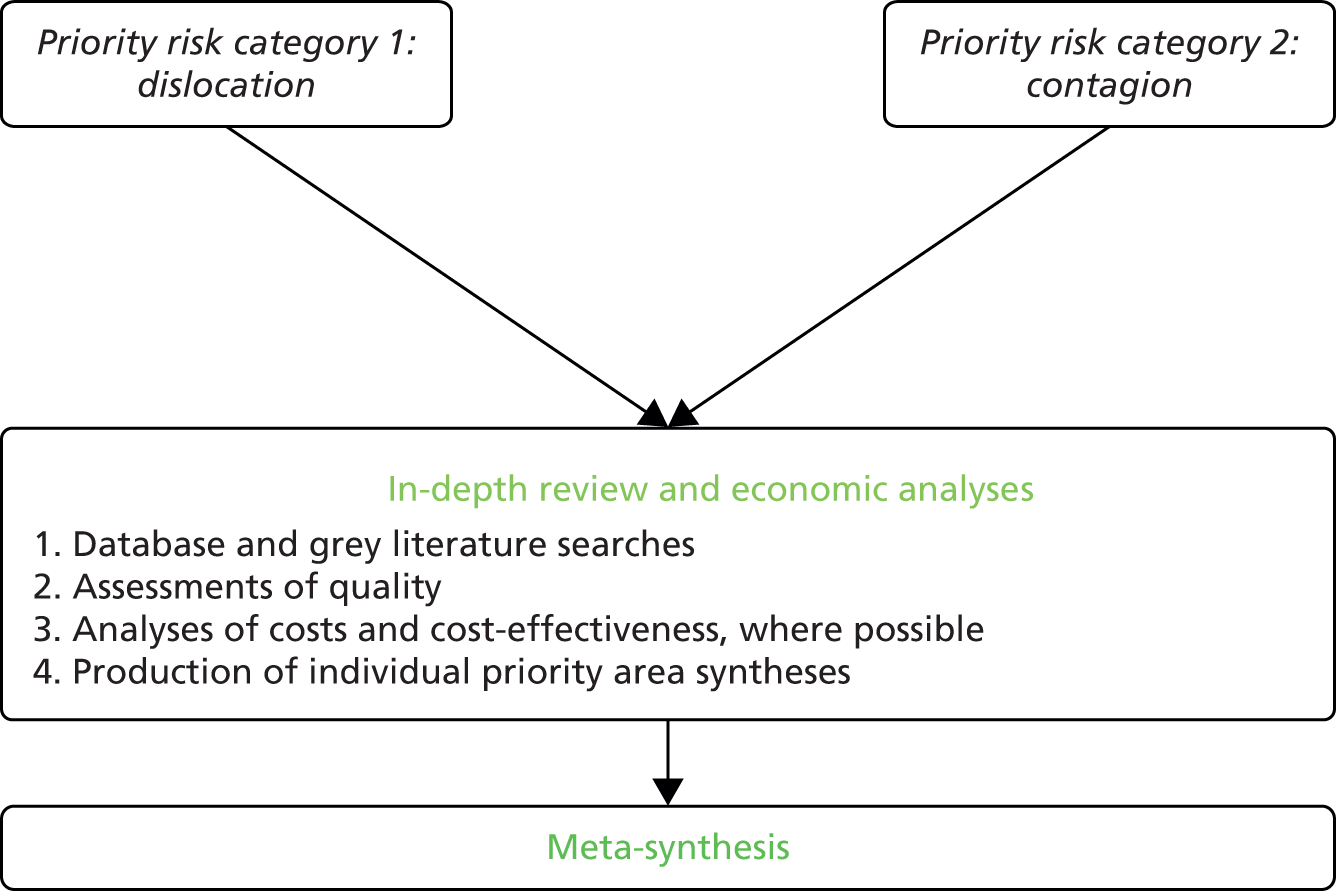

Our use of the EPPI-Centre approach throughout the totality of this project is summarised in Figure 1.

Like other frameworks guiding the review and synthesis of evidence, the EPPI-Centre approach stresses the importance of transparency and rigour. It also has a number of distinct, novel features. A first is an explicit acknowledgement that choice of research topic and specific focus (in the cases of both primary studies and syntheses of existing evidence) reflect particular sets of values and interests. 26 Research questions are not self-evident, but are constructed by particular people for particular purposes. In the case of the child and adolescent mental health field, the range of people with active interests in this complex system is wide indeed, potentially yielding a large variety of candidate priority research topics. Managers, practitioners from different backgrounds, commissioners, policy-makers, young people, families and others may have varying ideas on what kinds of research questions ought to be asked and what methods should be used to answer them. Often the authority to shape priorities remains limited to a relatively powerful few. These ideas underpin the observation that:

Involving representatives of all those who might have a vested interest in a particular systematic review helps to ensure that it is a relevant and useful piece of research.

(p. 1)26

In any project informed by the EPPI-Centre approach a crucial task must therefore be the effective engagement of concerned people. Involvement in an EPPI-Centre synthesis is typically secured through the setting up of an advisory group or something similar, in which representatives of groups with clear interests and experiences relevant to a study’s broad focus and eventual findings participate. In reviews conducted in the health-care field, members of advisory groups are likely to be drawn from communities of practitioners and managers as well as from those with direct experience of using services. A representative stakeholder advisory group, in turn, assumes particular responsibilities at key moments in the lifetime of a project. One critical moment for a group’s involvement is the point at which major decisions need to be made on the direction of travel an evidence synthesis is about to take.

This idea that in-progress decisions have to be made on the future direction an evidence synthesis will take is a second hallmark of the EPPI-Centre framework. This is particularly evident through the EPPI-Centre’s commitment to the combining of an initial scoping and mapping phase with a second, more targeted, review in one or more negotiated priority areas. In EPPI-Centre reports a detailed account is often included of how an initial mapping of the territory (in our case, the territory relating to risk in inpatient CAMHS) has been presented to stakeholder participants drawn from across a system, and how this has been used as the basis for the considered selection of candidate subareas for subsequent, detailed, quality review and synthesis.

A third component of the EPPI-Centre framework relates to the sharing of information on a project’s methods and findings in ways that are sensitive and accessible to the needs of larger stakeholder groups. Representatives of these groups are offered opportunities to advise project members on the most suitable ways of disseminating new knowledge, through the use of varieties of media including briefing summaries, online materials and articles of varying lengths and complexity tailored for particular audiences. Again, in this report we show how we worked with stakeholders to develop strategies to share what we learned. We also include plans for further work in this area once this final report has been accepted for publication as an NIHR journals library monograph.

Structure of this report

This opening chapter has set the scene for this evidence synthesis in the area of risk for young people moving into, through and out of tier 4 inpatient child and adolescent mental health services. It has introduced the CAMHS system as a tiered one, in which hospitals fulfil important functions within a dynamic and inter-related network of services. The existence of risks, both obvious and less so, has been introduced and a case made for a project of this type. An overarching research question has been given, along with a series of objectives. The project team’s commitment to the EPPI-Centre approach to evidence synthesis has been stated, and an overview given of some of the key distinguishing characteristics of this framework. In the chapter immediately following, methods and findings are given of the project’s phase 1 scoping and mapping exercise. Chapter 3 describes the approach taken to working with stakeholders, and the process through which priority categories of risk were identified and carried forward into the second, in-depth, phase of the project. Chapter 4 addresses the concepts and methods used in the phase 2 review, beginning with a summary of the research questions and objectives guiding this segment of the project. Chapter 5 synthesises the evidence in the phase 2 priority risk areas. Chapter 6 discusses the study overall and its findings. It includes a single-page matrix summarising the project overall and outlines plans for dissemination and knowledge exchange informed by discussions with stakeholder collaborators. It also draws out the implications of this project for policy, services and practice and makes recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Scoping exercise

Using the EPPI-Centre framework to map risk in inpatient child and adolescent mental health settings

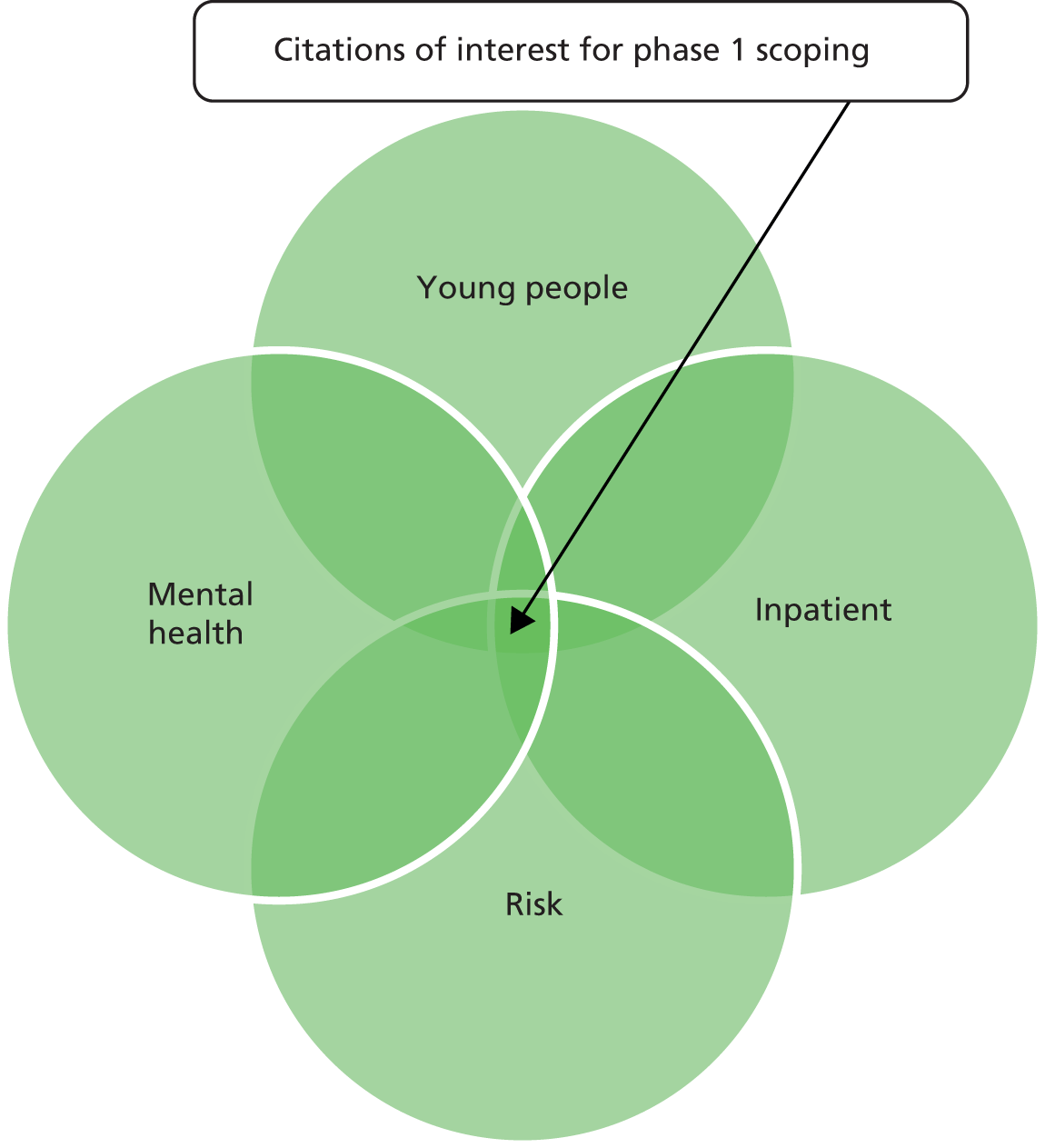

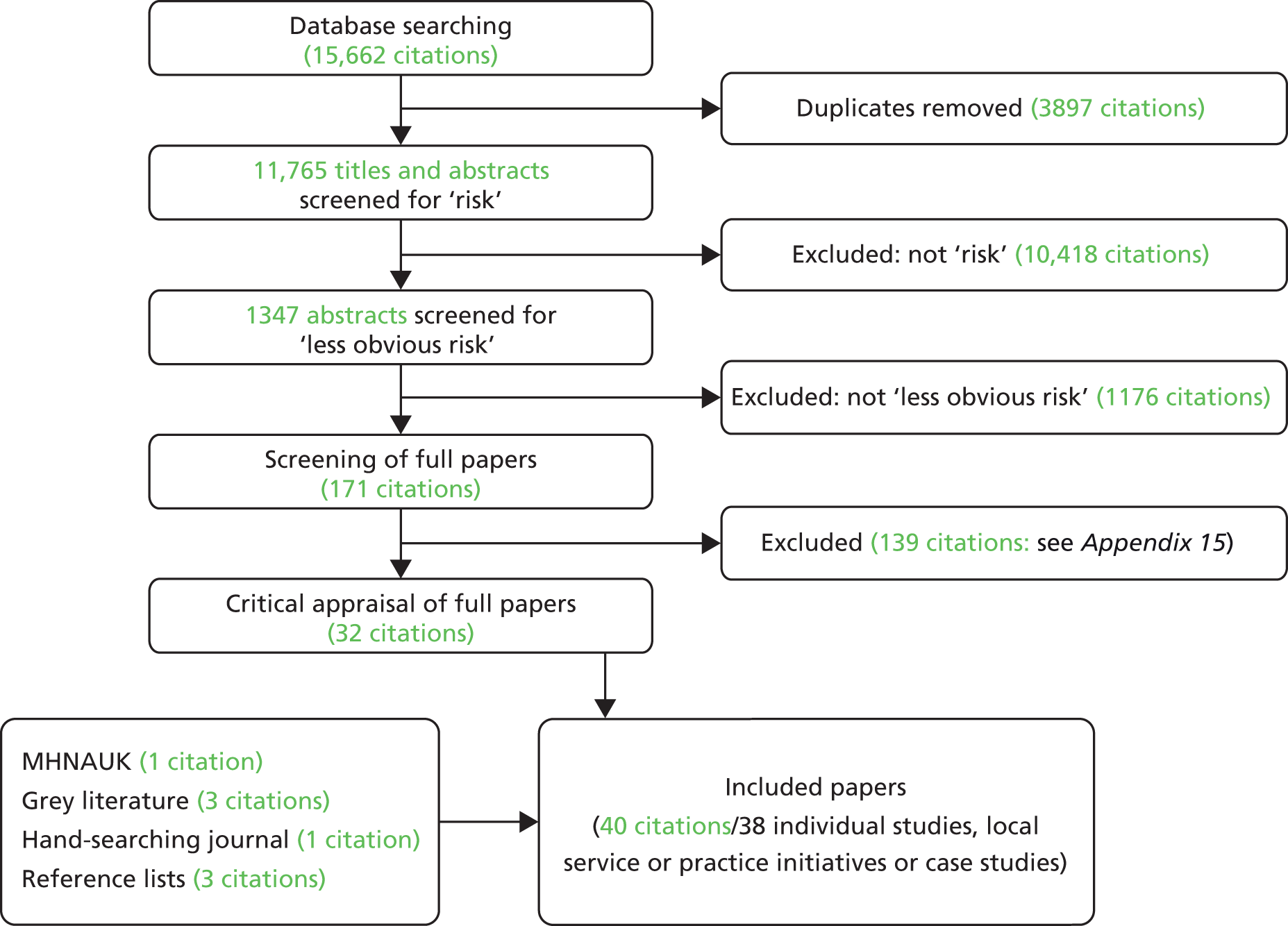

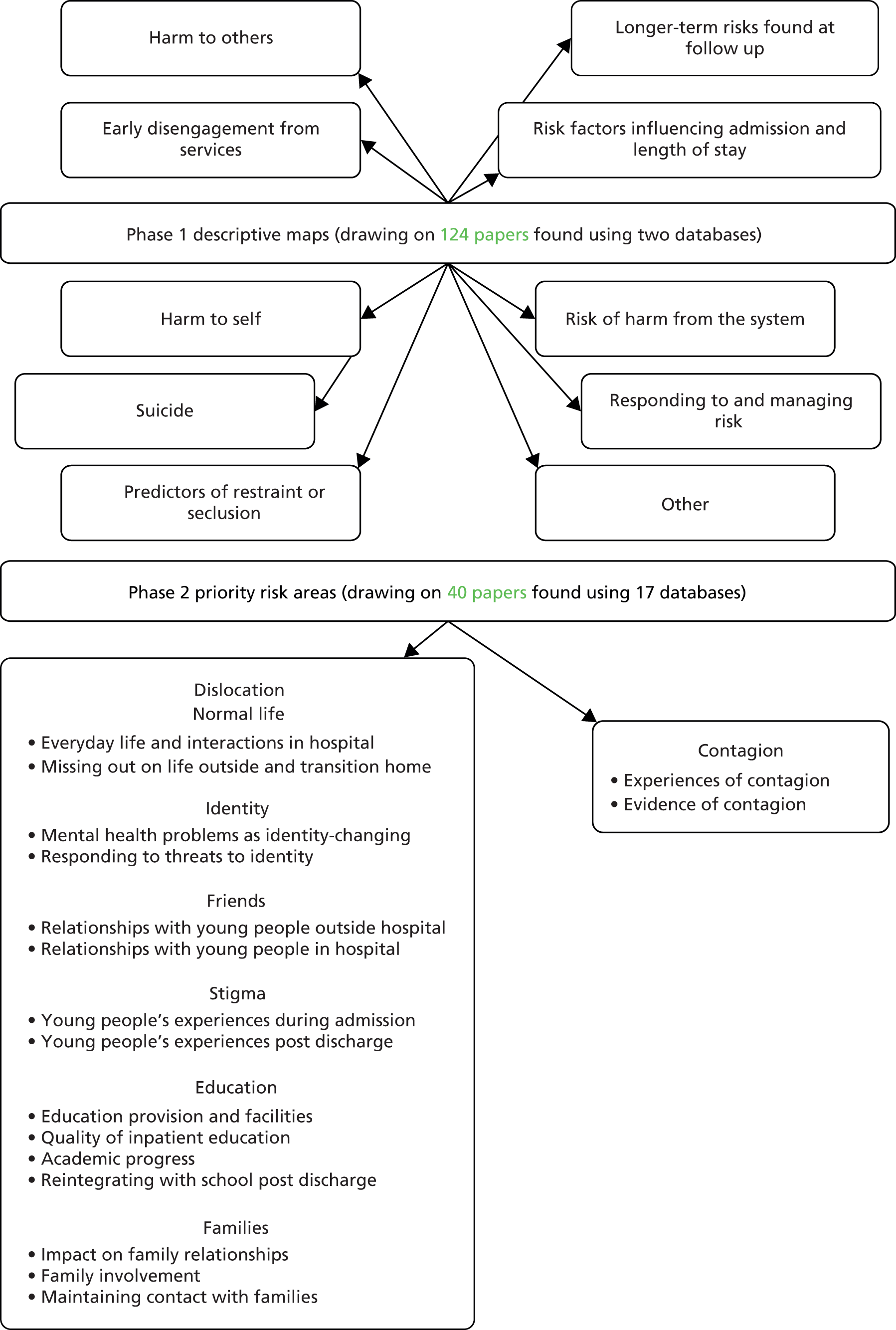

The team’s use of the EPPI-Centre framework commenced with a scoping exercise (see Figure 2) to identify the broad contours of the research field relating to risk in inpatient child and adolescent mental health settings. The aim of this first phase was to identify and categorise research and other evidence at the intersection of the four key areas of young people, mental health, inpatients and risk (see Figure 3). During this phase no attempts were made to assess the quality of materials retrieved, the aim being instead to scope and map out the existing evidence at the meeting point of the areas lying at the heart of this project. In this initial searching, scoping and mapping, no attempts were made to determine which types of risk should be either included or excluded, and no attempts were made to identify underpinning theory or to identify costs or cost-effectiveness.

FIGURE 2.

Phase 1 of the EPPI-Centre framework in action.

FIGURE 3.

Phase 1 search.

As per the study’s commissioned protocol, searching for papers was conducted using the electronic databases MEDLINE and PsycINFO. For these two databases, controlled vocabulary and free-text terms which covered the four key areas above were combined. Details of the search strategies used are given in Appendix 1 (MEDLINE) and Appendix 2 (PsycINFO). This search was guided by a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria described immediately below and (in summary) by the four-arm strategy depicted in Figure 3. The end date for searching was March 2013.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be included in this scoping exercise, a citation (which could be a research report, a review paper, a discussion piece, a published opinion, an editorial or something similar) had to:

-

Be written in the English language.

-

Focus on young people aged 11 to 18 years by:

-

focusing exclusively on young people aged 11 to 18 years or

-

focusing on a wider age group but including sufficient detail to enable the accurate identification of data relating to young people specifically or

-

relating to a study sample where the mean age was between 11 and 18 years.

-

-

Focus on moving into (admission), through and/or out (discharge) of inpatient mental health services. As not all citations retrieved included unambiguous descriptions of service types, the decision was taken to consider ‘inpatient mental health services’ as any inpatient hospital services (and, in the case of US citations, residential treatment centres) staffed by mental health professionals.

-

Address risk identification and/or risk assessment and/or risk management. Reflecting the purpose of the review, risk was viewed in broad terms, with no a priori exclusions placed on citations because of the way risk was thought about and/or used by authors. Citations were therefore included which addressed the risks of (for example) harm to self or harm to others, but also the risks mental ill-health and hospital admission pose to young people’s physical, psychological, social and educational development.

All citations retrieved were downloaded into Endnote Web™ (2013, Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) and duplicates removed. For the purpose of this scoping exercise, all citations to dissertations, theses or books were excluded. Each remaining citation retrieved was independently assessed for relevance to the review by two members of the study team, using the information provided in the title and abstract. Where any doubt existed, the full text was retrieved. In all cases, the full text was retrieved for all citations that at this stage appeared to meet the scoping review inclusion criteria.

Describing relevant papers

To achieve a high level of consistency, reviewers screened each retrieved citation for inclusion using a purposely designed form (see Appendix 3). Disagreement was resolved by discussion with a third reviewer. This phase 1 form included space for the extraction of key data from each citation: the country in which the study (in the case of research reports) had been carried out; if the citation focused on moving into (admission), through or out of (discharge) inpatient mental health services, or any combination thereof; the characteristics of the population studied (if relevant); the type of risk focused on; and, in the case of original research, the design used (e.g. cohort study, longitudinal study).

Evidence map

Figure 4 illustrates the flow of citations through the scoping exercise and shows how 124 individual items were eventually identified for inclusion. Details of the included papers are given in Appendix 4. Of these, the majority were primary research papers (115 articles describing 118 studies). The remaining papers (n = 9) described the development of guidelines (n = 1) or were a recommendation statement (n = 1), general discussions (n = 4), reviews (n = 2) and a letter (n = 1). In the following section we describe the characteristics of the 118 research studies according to the country in which projects were undertaken, the age of study participants, research design, the size of study populations and the year of publication.

FIGURE 4.

Flow of citations through phases of the scoping review.

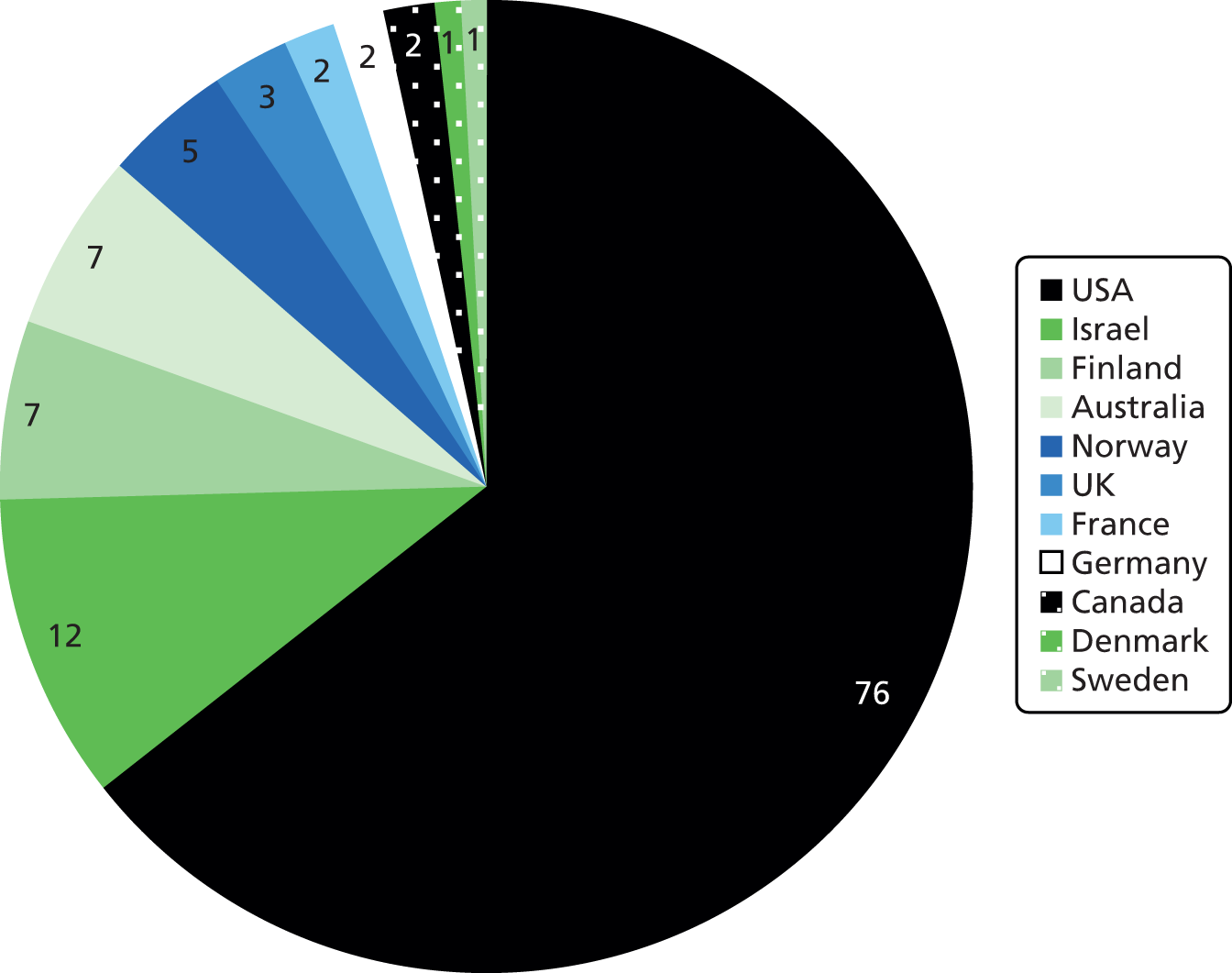

Country where research was undertaken

Information on the country in which each research study had been carried out was obtained from the methods section of the retrieved full-text version of each paper, or where this information was not directly given from the country location of the corresponding author. The distribution of research by country in Figure 5 shows that by far the largest number of studies (over 60%) were conducted within the USA, with only 2.5% conducted within the UK. This preponderance of studies from the USA may reflect the limiting of the phase 1 scoping search to English-language citations only, this having a direct effect on the country of origin of papers retrieved.

FIGURE 5.

Country of origin of the 118 studies included in the scoping review.

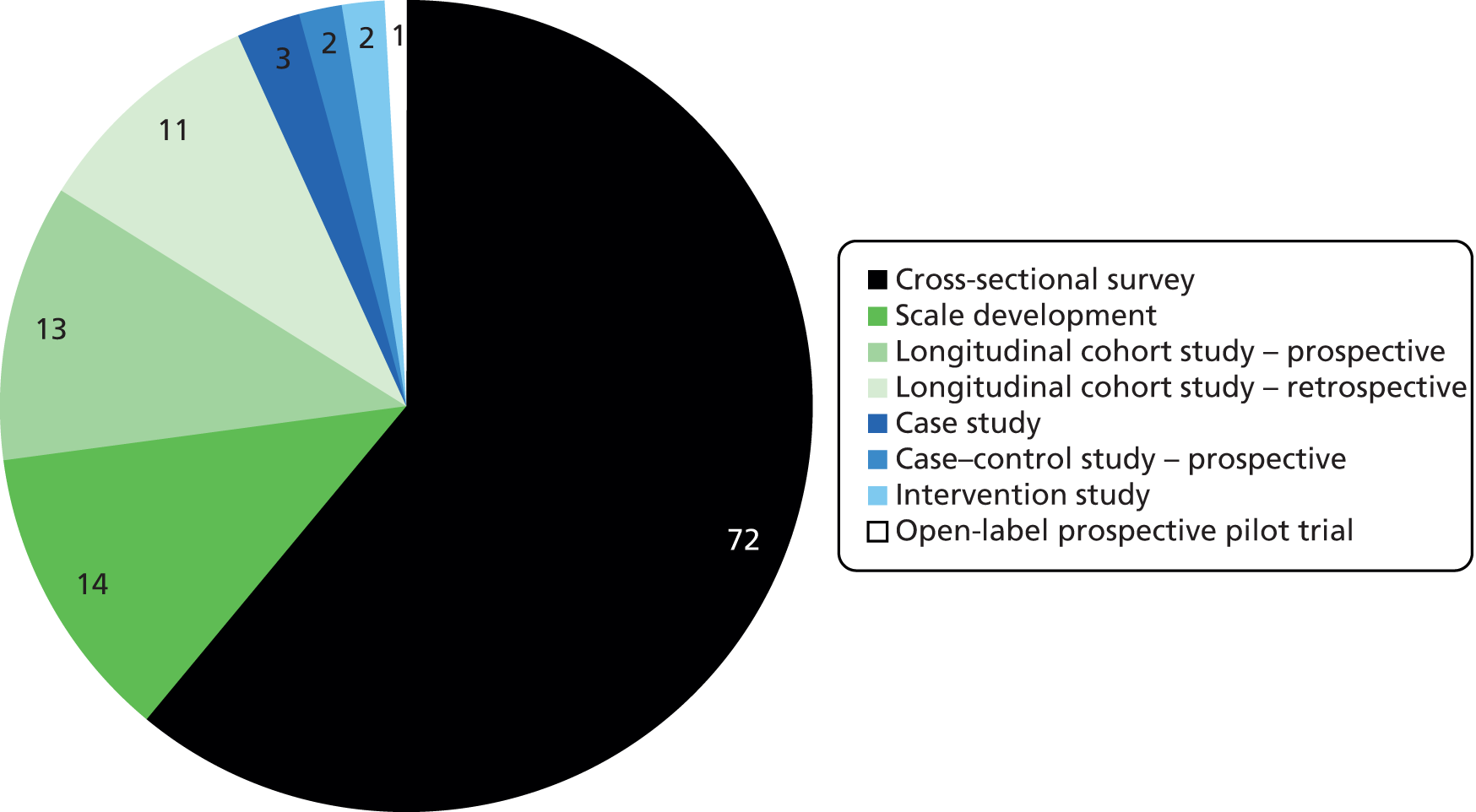

Research design

Figure 6 summarises the research design used in the 118 research studies included in the phase 1 scoping exercise. Seventy-two of the studies used a cross-sectional design, of which 24 involved the collection of retrospective data from young people’s inpatient medical notes or charts.

FIGURE 6.

Research design used in the 118 research studies included in the scoping review.

Age of study participants

The mean age of the young people whose data were included in each of the 118 studies in the phase 1 scoping fell between 11 and 18 years. The age ranges of young people participating, or whose data were used, in individual studies are summarised in Table 1.

| Age range (years) | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| 11 to 18 | 13 |

| 12 to 18 | 27 |

| 13 to 18 | 14 |

| 14 to 18 | 6 |

| 15 to 18 | 4 |

| 16 to 18 | 2 |

| 11 to > 18 | 3 |

| 12 to > 18 | 10 |

| 13 to > 18 | 8 |

| 14 to > 18 | 1 |

| 16 to > 18 | 1 |

| < 11 to 18 | 10 |

| < 11 to > 18 | 9 |

| Age not specified but sample described as adolescents | 10 |

| Total number of studies included in phase 1 | 118 |

Size of study populations

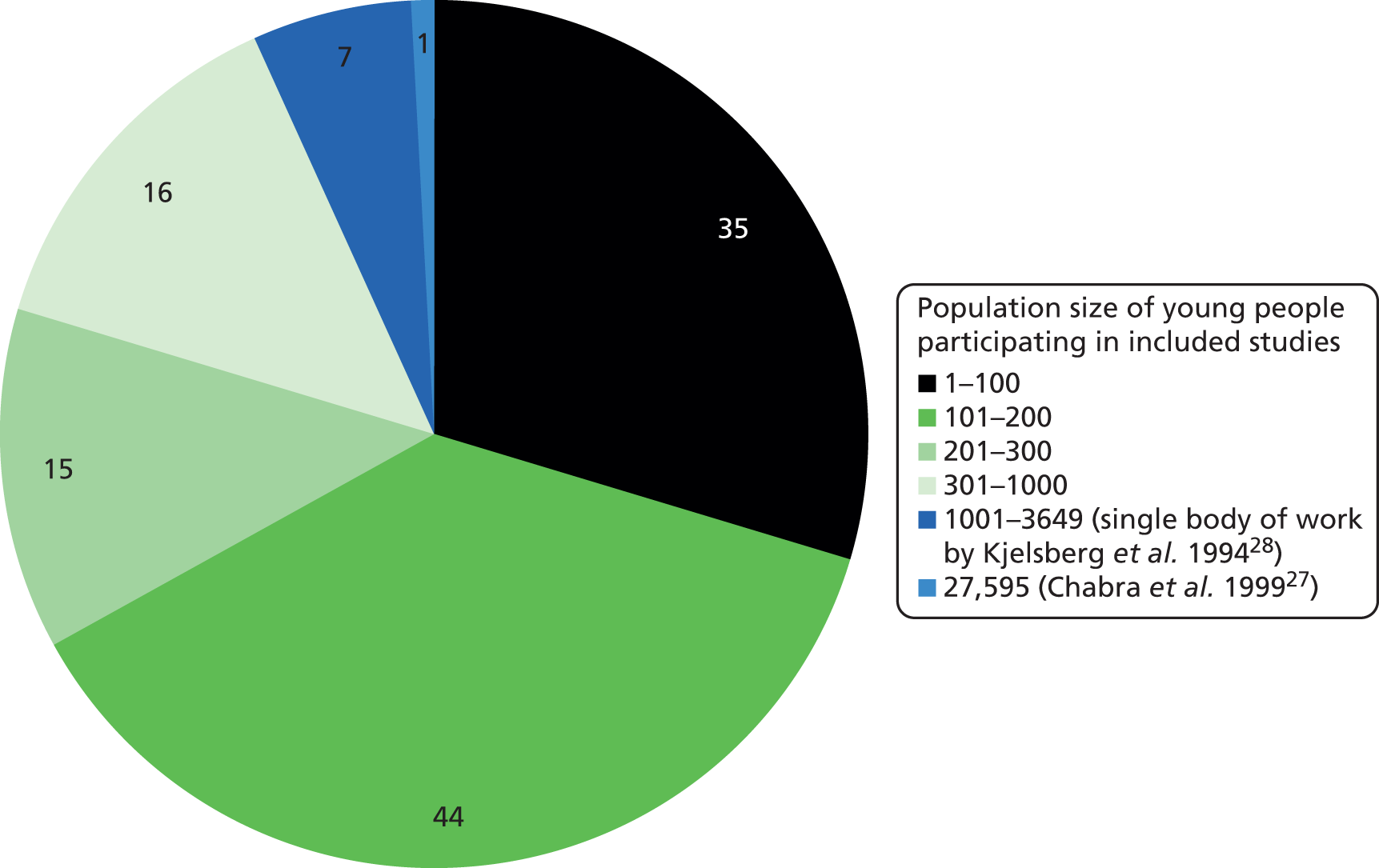

The size of the populations included in each of the 118 phase 1 studies varied, with the largest number being 27,000 included in the single study by Chabra et al. 27 Figure 7 summarises this information.

FIGURE 7.

Size of the populations participating in phase 1 included research studies.

Year of publication

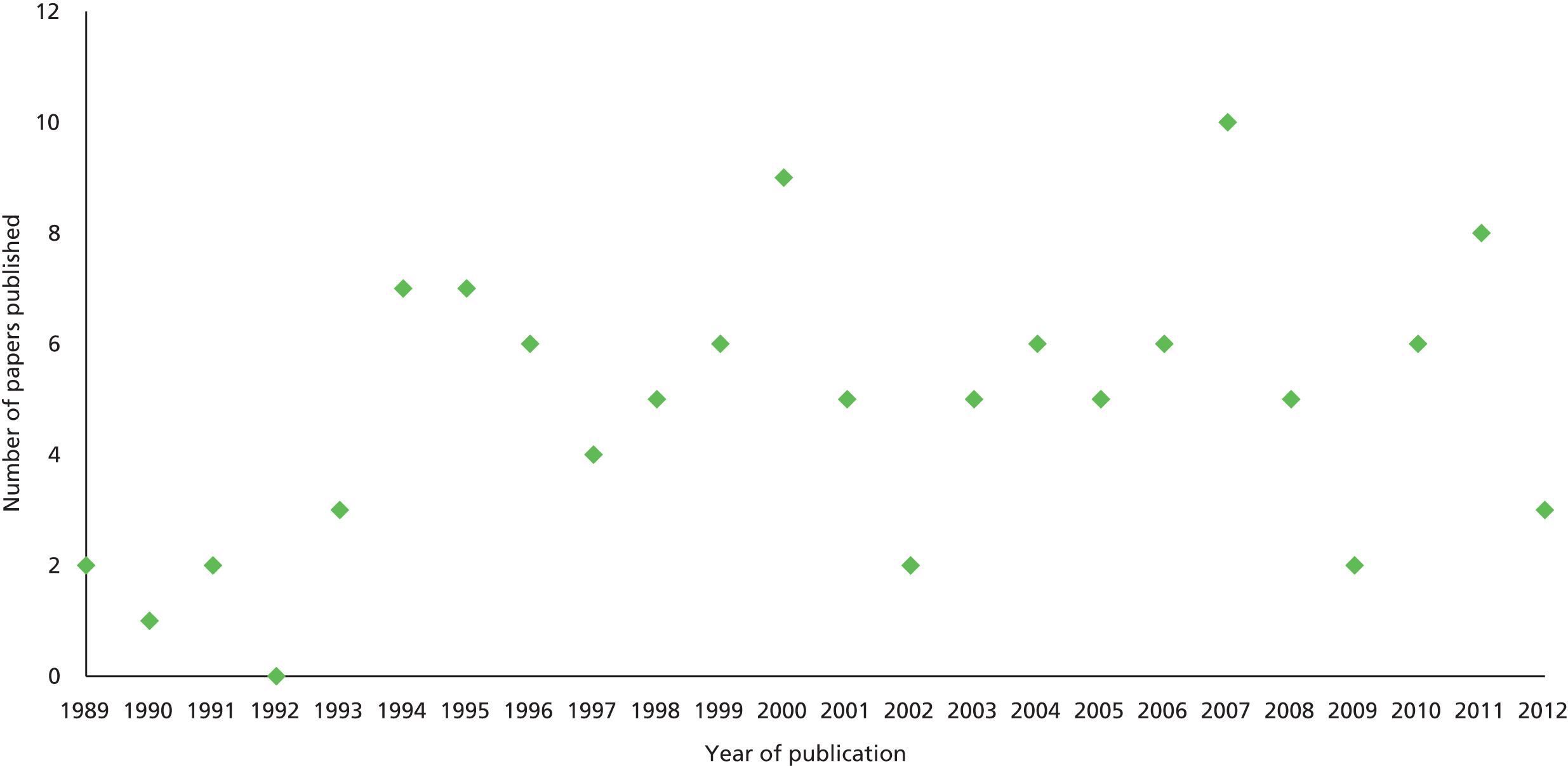

Data on the year of publication of the 115 papers reporting findings from the 118 studies included in phase 1 are given in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

Year of publication of phase 1 included papers.

Mapping exercise

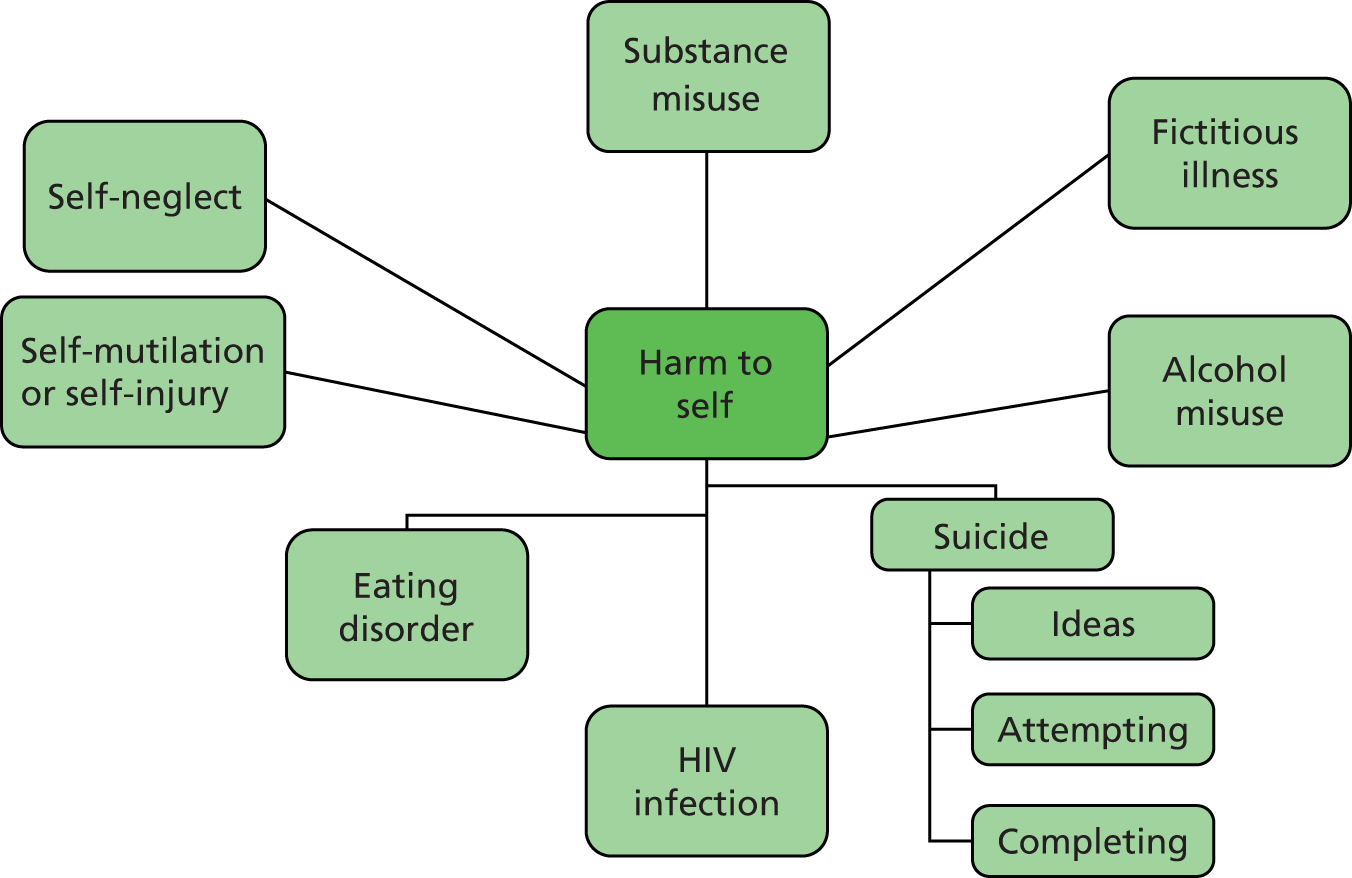

As a way of presenting the evidence located and included in this phase 1 scoping, a number of broad, descriptive maps of the different ways in which risk has been identified, assessed and managed in the inpatient CAMHS area were produced. These are presented in this report as Figures 9–17. To group included papers thematically, an initial typology of risks was used, drawing on the work of Subotsky. 29 Subotsky uses four categories of risk: harm to self; harm to others; harm from others; and harm from the health-care system and its staff. In order to capture the full range of risks addressed across all 124 included papers, further categories were added by the project team as necessary, each reflecting the content of papers retrieved. Examples included the category of longer-term risks found at follow-up of young people previously admitted to inpatient CAMHS units, and risks of early disengagement from services. This full range of risks identified is reproduced in the figures immediately below, where the content of each map thematically summarises the main areas addressed by the papers included in each category.

FIGURE 9.

Descriptive map of ‘harm to self’.

Risk of harm to self (65 papers)28,30–93

Given what is known about the general usage of the term ‘risk’ in mental health services and the types of risk that attract most attention in policy and practice, it was not surprising to the project team to find that the category with the largest number of included phase 1 papers addressed the risks of harm to self (see Figure 9 for the associated descriptive map). Of the 65 papers included here, overwhelmingly most (n = 53)28,30–81 were concerned with the identification and/or the assessment and/or the management of suicide risk, followed by the risks to self which are associated with alcohol and drug abuse (n = 7). 82–88 Smaller numbers of included papers focused on general self-harm (n = 3)89–91 and the risks associated with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) (n = 2). 92,93 Noting the high volume of papers addressing risks associated with suicide, a decision was made to produce a separate descriptive map for this area alone (see Figure 10).

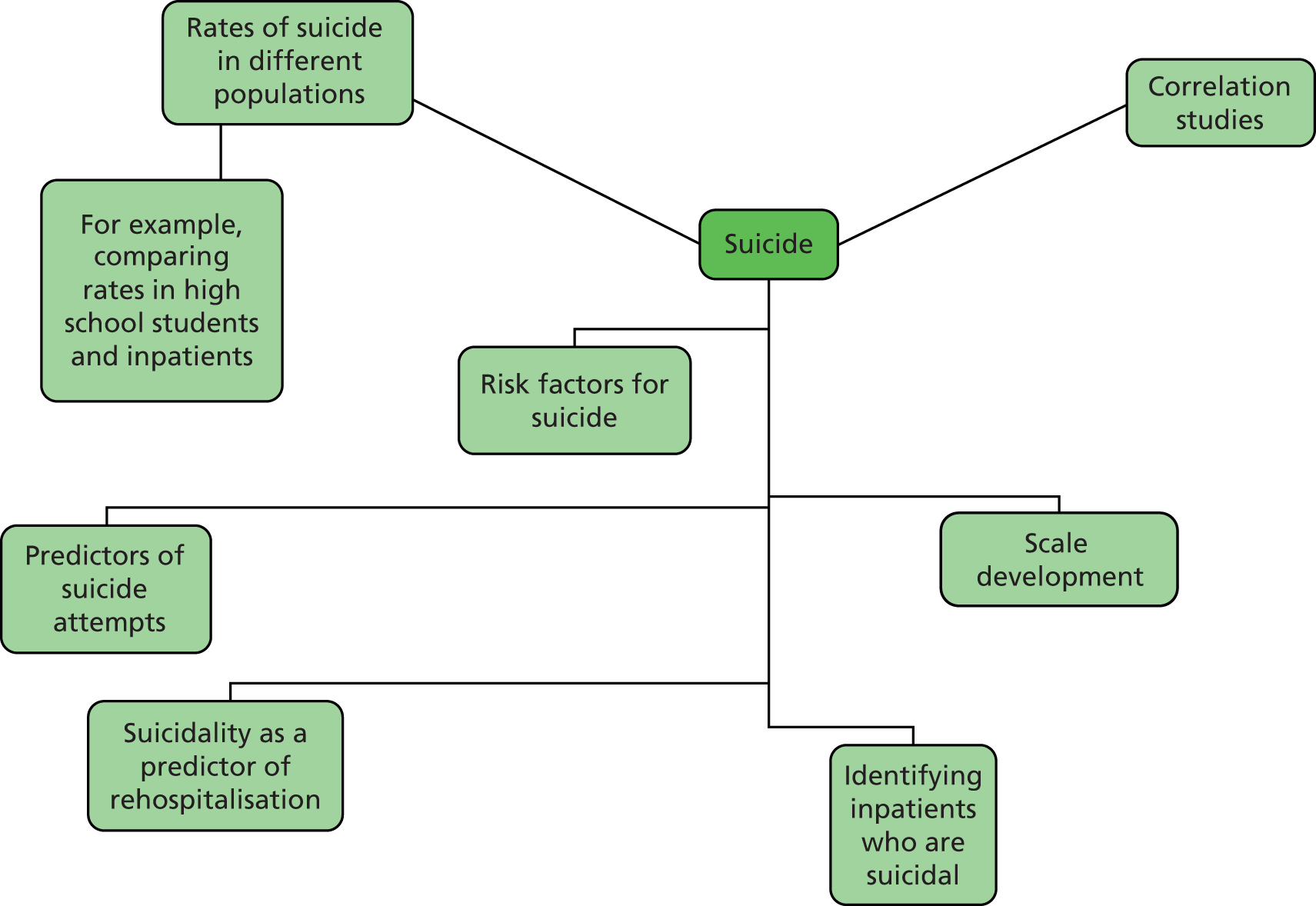

FIGURE 10.

Descriptive map of ‘suicide’.

Suicide (53 papers)28,30–81

As noted above, the volume of papers addressing the identification, assessment and management of suicide risk in young people moving into, through and out of inpatient mental health services warranted a separate thematic map. This is reproduced in Figure 10. Papers included in the correlation studies category investigated the associations between suicide and a variety of personal and clinical characteristics (e.g. depression, delinquency).

Harm to others (20 papers)94–113

This category included a large number of papers addressing the risk of harm to others, with papers focusing on both aggression and violence (n = 18)94–111 and bullying (n = 2)112,113 (see Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Descriptive map of ‘harm to others’.

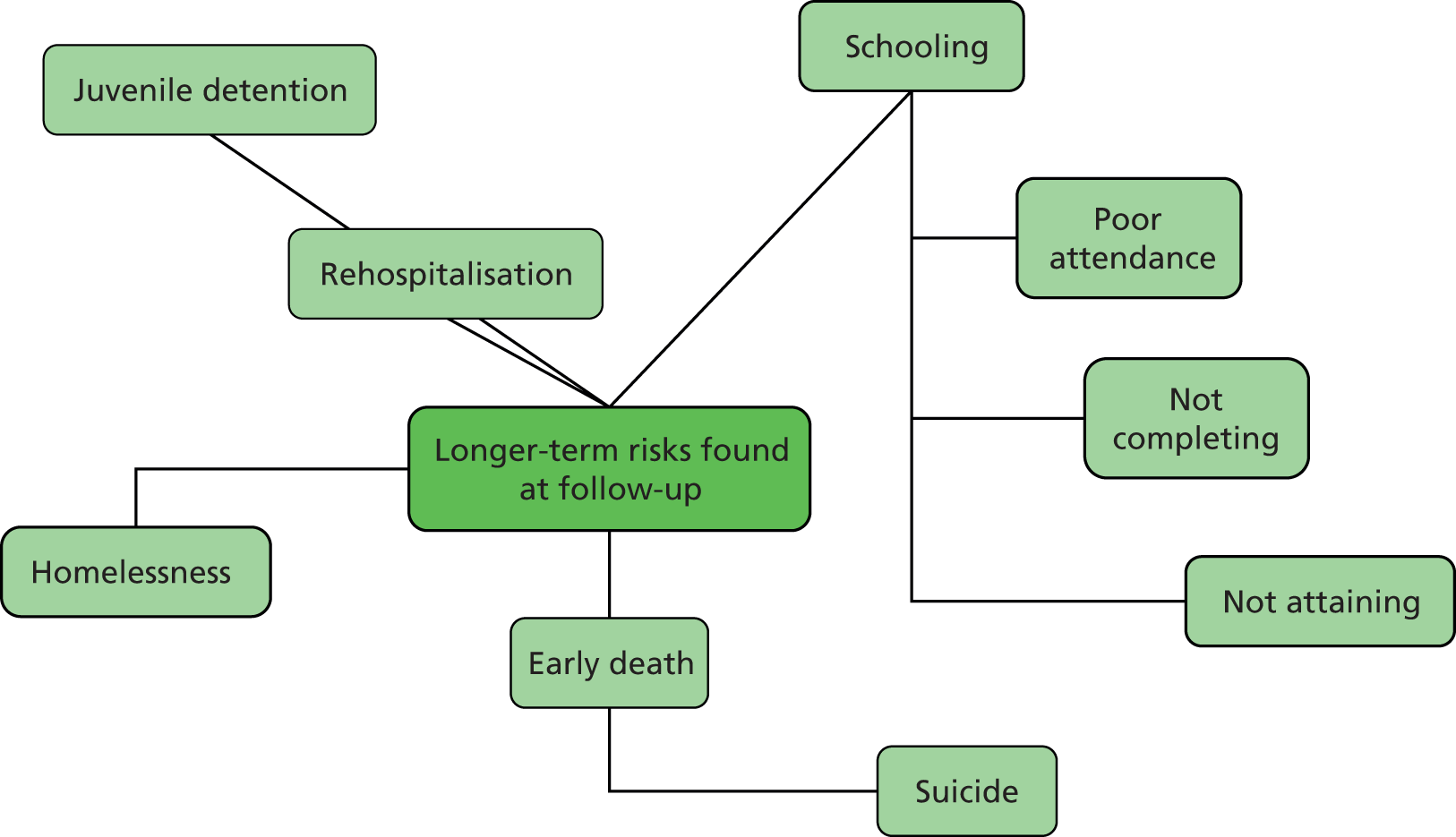

Longer-term risks found at follow-up (15 papers)114–128

This category was independently created by the project team to group together a series of papers focusing on the longer-term risks of being admitted to inpatient CAMHS units (see Figure 12). Included papers variously addressed the risks of readmission (n = 9),114–122 early death (n = 2),125,126 disrupted schooling (n = 2),127,128 homelessness (n = 1)123 and delinquency (n = 1). 124

FIGURE 12.

Descriptive map of ‘longer-term risks found at follow-up’.

Early disengagement from services (five papers)129–133

This category is depicted in Figure 13 and was developed by the project team to bring together papers concentrating on the risk of young people running away (n = 3),129–131 being discharged against medical advice (n = 1)132 and dropping out from treatment (n = 1). 133

FIGURE 13.

Descriptive map of ‘early disengagement from services’.

Risk factors influencing admission and length of stay (five papers)27,134–137

This category is depicted in Figure 14 and was created to bring together papers addressing factors influencing admission to, and length of stay in, inpatient CAMHS care. Factors identified included gender, ethnicity, general predisposing factors, and young people being adopted and living in disrupted family homes.

FIGURE 14.

Descriptive map of ‘risk factors influencing admission and length of stay’.

Risk of harm from the system (five papers)138–142

Directly drawn from Subotsky’s29 typology, this category includes the negative effects of treatment along with the risks of other adverse consequences of inpatient admission, such as loss of educational continuity, or exposure to risks, such as abuse by staff. Included in the mapping (see Figure 15) were papers dealing with the side effects of medication (n = 3),138–140 sexual abuse by staff (n = 1)141 and contagion (n = 1). 142

FIGURE 15.

Descriptive map of ‘risk of harm from the system’.

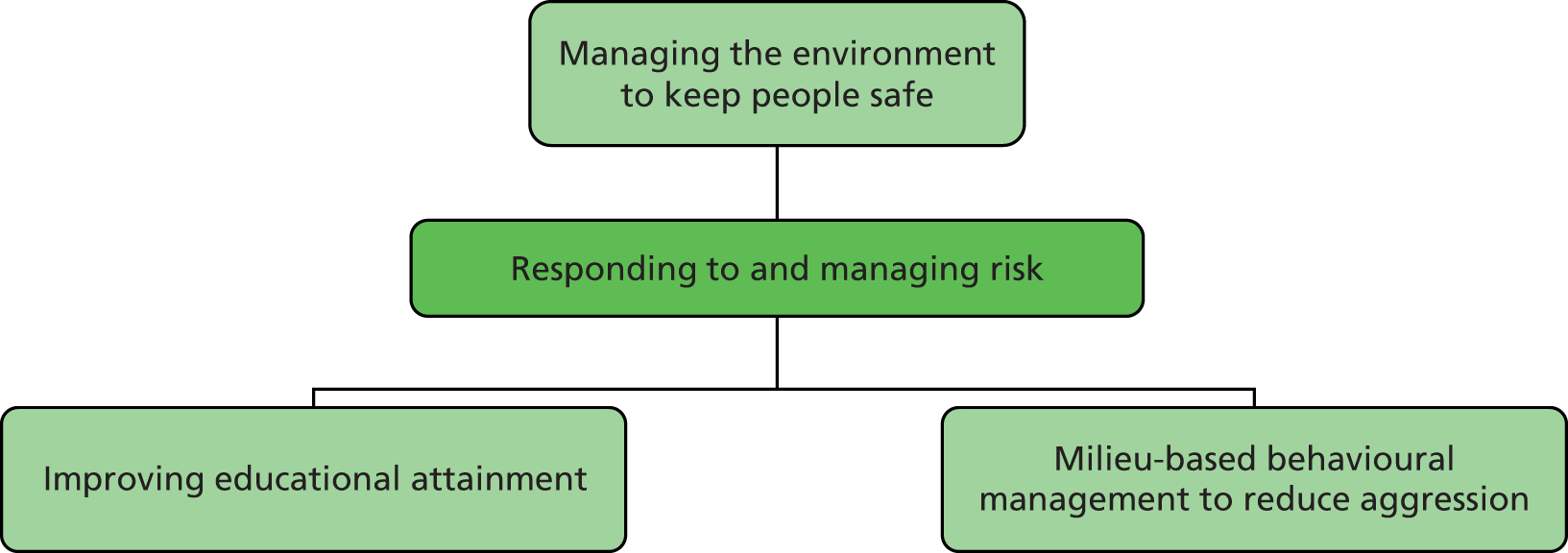

Responding to and managing risk (three papers)143–145

A small number of papers were brought together in this category, created by the team for the purposes of this mapping because they specifically addressed actions designed to manage or reduce risk (see Figure 16). These papers variously addressed improving educational attainment (n = 1),143 managing the environment to keep people safe (n = 1)145 and milieu-based behavioural management to reduce aggression (n = 1). 144

FIGURE 16.

Descriptive map of ‘responding to and managing risk’.

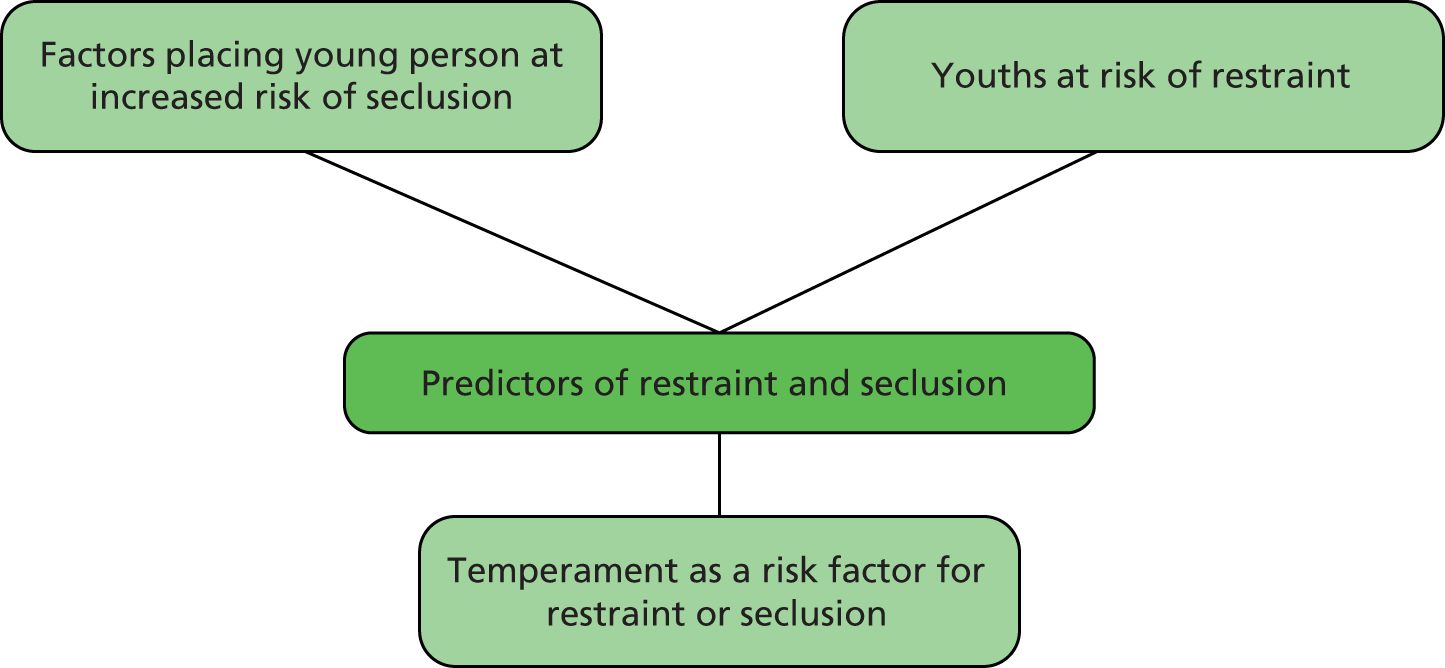

Predictors of restraint or seclusion (three papers)146–148

This set of three papers looked at predictors of restraint, seclusion or both (see Figure 17). Specifically, they sought to identify the factors that place a young person at increased risk of seclusion during his or her admission (n = 1),146 to establish whether or not a particular group of young people are at risk of restraint (n = 1)147 and to examine whether or not temperament characteristics (e.g. fear, anger) are risk factors for restraint and seclusion for young people in inpatient mental health hospital (n = 1). 148

FIGURE 17.

Descriptive map of ‘predictors of restraint or seclusion’.

Other

Three final papers were included, none of which could be mapped to the categories above and each of which addressed a distinct area. One paper focused on the risk of functional impairment, reporting on two studies which assessed the validity of a measure (the Functional Impairment Scale for Children and Adolescents). 149 The second reported from a study into the risks to, and the effects of, young people in inpatient mental health services playing fantasy role-playing games. 150 The third was a non-empirical paper included because it scoped the challenges facing inpatient CAMHS mental health services. 151

Summary of phase 1 findings

Each of the 124 papers included in phase 1 of this project was identified following a search of two databases combining terms from four arms (mental health, young people, inpatients, risk). Each was reviewed by at least two members of the study team, who agreed that it met the project’s criteria for inclusion. Data (e.g. focus of paper, country of origin, type of study in the case of papers reporting original research) were extracted from each and summarised.

The central purpose of this first phase of our overall evidence synthesis was to scope and map out the territory in the area of risk for young people moving into, through and out of inpatient mental health services. This was achieved by grouping together included papers using categories developed by Subotsky,29 and by using new categories created specifically for this study by the project team. This theming of retrieved papers demonstrated that, overwhelmingly, it is clinical risks (particularly the risks of suicide, self-harm and harm to others) that have featured most prominently in published papers (or, at least, in the papers published in journals indexed in the two databases searched in this phase of the project).

This was not an unexpected finding. It suggests that the risks that dominate policy and practice in mental health services are the risks that occupy most researchers and writers in the field. With regard to the characteristics of the research in this area, few papers retrieved reported data from inpatient CAMHS risk studies conducted in the UK. Most papers reported findings from prospective or retrospective cross-sectional surveys designed to establish associations between the personal and clinical characteristics of young people using inpatient CAMHS and the chances of certain unwanted events (e.g. self-harm, violence, running away) happening. Very few papers were directed at establishing what might be done to respond to or manage risk.

Chapter 3 Consulting with stakeholders and determining priorities for in-depth review

Using the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre framework to consult with stakeholders

The EPPI-Centre approach obliges researchers to pause at the point where the territory has been scoped and mapped out, and to consult with people with interests in the field. The purpose of this consultation is to share knowledge of what has been found and to invite views to be given on the priority areas to be taken forward into the in-depth phase of the review which follows. In this project, key groups to involve in the consultation process included young people with personal experience of using inpatient mental health services; family members; service managers; practitioners drawn from different occupational groups; and workers from non-statutory organisations campaigning for young people’s mental health and the development of services. Figure 18 illustrates the use of the EPPI-Centre framework in this phase of the project.

FIGURE 18.

Using the EPPI-Centre framework to consult and determine phase 2 priorities.

Young people

In order to engage with young people with experience of using inpatient mental health services, members of the project team formed an early collaboration with representatives of the leading mental health charity YoungMinds. To inform our involvement strategy more generally, project members also consulted with two Cardiff University colleagues otherwise unconnected to the study but with expertise in involving young people in the research context (Professor Lesley Lowes in the School of Healthcare Sciences and Professor Sally Holland in the School of Social Sciences). From the project’s initial meetings onwards, members of the team were determined that the approach to working with young people should be sensitive to experiences, informed by an awareness of relative power relations and (during face-to-face project-related meetings) interactive in style. 152

The earliest approach to YoungMinds was made during the preparation of the project’s outline proposal for funding. It was set in the context of an existing collaboration between this organisation and a member of the project team (SP) in another, then-current, NIHR HSDR programme study involving young people with mental health needs. 23 YoungMinds was approached because it is the UK’s leading charity in its field, describing itself as:

committed to improving the emotional wellbeing and mental health of children and young people. Driven by their experiences we campaign, research and influence policy and practice. 153

Following confirmation of this project’s funding award, a key meeting was held in Cardiff at the beginning of March 2013 involving team members (BH, DE and NE) and YoungMinds’ then national Training and Development Coordinator (Matthew Daniel). This was convened with a view to mapping the fine detail of how young people might most effectively be engaged in the work of determining phase 2 priorities. Project team members were aware of the pitfalls of inviting young people to formal advisory group meetings without support, in which other contributors were likely to be drawn from more powerful groups such as management and the professions. An important guiding principle, therefore, was to agree an approach to involvement that ensured that the voices and experiences of young people were properly heard and their priorities around risk attended to.

At this key planning meeting, a number of strategies were considered and a two-part plan negotiated drawing on YoungMinds’ expertise in participation and consultation. First, the document specifying YoungMinds’ contribution emphasised the plan to involve experienced staff from the organisation’s national young people’s participation project and from its training and development team. It also emphasised YoungMinds’ then-current Very Important Kids (VIK) project, funded by the National Lottery and established with one aim of increasing young people’s involvement in service design and delivery. The VIK project enabled regionally based workers to support and engage with groups of young people affected by mental health difficulties, to both hear and represent their views and experiences. With staff already skilled in involvement work, and with networks of young people already engaged with YoungMinds, it was agreed that the part of the project budget devoted to involvement would first be used to support YoungMinds to conduct a series of independent priority-setting consultations with young people on the project team’s behalf. With our project classified as an evidence synthesis, rather than as a primary research study, we were clear to distinguish this consultative activity from the activity of directly participating in research. NHS or university research ethics committee approval is always needed for primary, data-generating, studies where people are recruited as research participants. Active involvement in projects to help identify and prioritise research topics and/or to join advisory groups is a different type of participation, a distinction made clear in national guidance. 154 Second, it was agreed that YoungMinds’ Training and Development Coordinator would participate in the project’s formal priority-setting event and, through his organisation’s networks, invite a number of young people to join him.

Following this planning meeting and throughout the remainder of March 2013, YoungMinds conducted a series of five separate consultative conversations with young people who had previously been admitted to inpatient CAMHS. Identification of people was made using YoungMinds’ existing networks. Broad questions guiding these discussions were agreed in advance by project team members (BH, DE and NE) collaborating with our YoungMinds colleague Matthew Daniel, and were explicitly designed to inform the process of research priority setting as opposed to eliciting research data. These focused on understanding young people’s perceptions of risks and what is done about them, including (reflecting current concerns in the CAMHS field) risk for young people admitted to adult wards. Noting the purpose of these consultations in the context of this as a two-phase evidence synthesis, a clear request was also put to young people taking part to identify those risks that the project team should focus on in the second phase of the overall study.

The five consultation questions put to five young people are reproduced here:

-

What do you think the risks to children and young people in inpatient settings are?

-

How do you think those risks are assessed?

-

What do you think is done about those risks?

-

Do you think there are a different set of risks for young people who are inpatients in adult wards?

-

What risks do you think the research team should focus on in its in-depth review?

To facilitate a record and to inform the study’s priority setting, each consultative conversation was audiorecorded and segments transcribed, so that young people’s ideas could be drawn on to stimulate debate and discussion among members of the project team and stakeholder advisory group. A formal report on this consultation was also delivered to the project team (see Appendix 5), in preparation for tabling at the subsequent priority-setting meeting of the combined project team and stakeholders for phase 2. The summary from this report included this extended section:

Though we spoke to a relatively small number of young people there were some clear themes that emerged from all of the conversations and those themes came out of the direct experiences of the young people. They told us that there were a number of risks that were not adequately being assessed or addressed and that this might be because of a lack of resources or training. All of the types of risks that we discussed were seen as equally important and the assessment of risk was highlighted as an area that needed to be carefully considered, as a poorly done risk assessment could feel extremely punitive and could therefore have a negative effect on the individual’s emotional wellbeing. Most of the young people talked extensively about the risk of emotional harm caused through exposure to distressing experiences as well as negative peer group influences. The young people also mentioned the risk of having their social lives put on hold indefinitely and the lack of opportunity to get any high quality educational provision. One young person used the term ‘fragmented’ to describe how what had happened to their life felt and the result of this fragmentation was their self-identification as ‘ill’. This new identity was seen as damaging as it prevented recovery and made it more difficult for the young people to move back into a ‘normal’ life off the ward. The young people said that they were put on wards to get better but that in many cases there were reasons why being placed in an inpatient setting was in fact detrimental to them. However they also recognised that leaving too early was equally damaging. The risks are present in the immediacy of the inpatient setting but the failure to address those risks has severe implications on both the young people and services as not addressing them leads to increased emotional distress as well as the increased likelihood of a readmission.

Carers

Along with involving young people to help shape this project, the team was also concerned to involve parents or other carers. One member of the project team combines identities as a mental health professional, academic and carer of a young person with mental health difficulties. An invitation to participate in our planned priority-setting stakeholder advisory group meeting was also extended to a mother whose child had recently been admitted to mental health hospital. This carer was identified as someone interested in participating in broader consultative and influencing activities by the project team’s senior practitioner member (GT). In the event, this person’s preference was to discuss risk in inpatient CAMHS settings and priorities for our in-depth evidence synthesis in a private, one-to-one conversation. This conversation took place in April 2013, involving one team member (BH), and focused on this carer’s views of the risks to young people entering, using and leaving hospital and on identifying phase 2 priorities.

Notes taken during this consultative conversation were prepared for tabling via oral presentation at the planned face-to-face stakeholder meeting. Key carer messages included that admission to inpatient CAMHS can be damaging, with planned short admissions turning into longer spells in which risks of harm to self can increase through the learning of abnormal, dangerous behaviours and the forming of new, unhelpful friendships (i.e. contagion). A further risk identified by this mother was at the transition from hospital to home, where concerns focused on the risks of young people remaining in touch with people met in hospital and thus extending unhelpful relationships.

Stakeholder advisory group meeting: agreeing risk priorities for phase 2

In preparation for a first combined project team and stakeholder advisory group (SAG) meeting, a set of documents was prepared for invited members and posted out in advance. Included were an accessible overview of the project (see Appendix 6), a proposed set of terms of reference for SAG members (see Appendix 7) and an agenda (see Appendix 8). The meeting itself was convened in Cardiff on 24 April 2013, organised for the express purpose of generating candidate categories of risk to serve as priorities for the second, in-depth, phase of this review. The event was chaired by Dr Michael Coffey (Associate Professor, Swansea University), an academic with expertise in mental health services but not associated with the study in any other way.

Decisions on the full range of stakeholders to include in the SAG, and the identification of actual representative individuals to invite, were taken collectively by the project team, drawing on our understanding of the CAMHS system, our knowledge of specific inpatient units and our working relationships with managers, practitioners and others. In addition to members of the project team, participants (drawn from South Wales and Greater Manchester, reflecting the locations of project members) included Matthew Daniel, collaborating representative from YoungMinds (who had already completed the consultation exercise reproduced in Appendix 5); two young people with experiences of using CAMHS; a senior NHS CAMHS manager; a senior child and adolescent psychiatrist; a senior CAMHS therapist; and a senior nurse with inpatient CAMHS responsibilities. Invitations were also extended to individuals with backgrounds in child and adolescent mental health social work, clinical psychology and teaching in inpatient CAMHS settings.

The principles of nominal group technique were drawn on in planning the process designed to lead to the identification of priority risk categories for phase 2 of the project. This is an approach to group decision-making introduced in the early 1970s by Delbecq and Van de Ven,155 which places weight on all participants having an equal opportunity to express a view. Since its emergence it has been successfully used in the research context, including in a study funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme involving a member of this current project team (ML) as a co-investigator. 156 In this current project, the use of an approach explicitly designed to avoid letting group decision-making become dominated by one or more vocal individuals appealed to the team, given our concern that young people, in particular, might find it difficult to contribute in the presence of professionals, managers and academics.

The SAG meeting opened with an overview of the project, along with a presentation of the broad themes arising from the phase 1 scoping and mapping exercise. To facilitate later discussion and priority setting, our maps remained on display throughout the duration of the event, each depicted on an individual sheet of A1 flipchart paper. A presentation from YoungMinds followed, centring on a summary of the outcomes of the consultation exercise previously conducted with young people.

Following a natural break in the meeting, participants were invited to record independently written responses to the question ‘What do you think the risks for young people are as they make the transition into, through and out of inpatient CAMHS?’

The idea of inviting written responses, without conferring, was used as a nominal group strategy to ensure that as a project team we had access to the full range of views available in the room in enduring form once the meeting had ended. With a member of the team (NE) acting as facilitator, all SAG and project team members were then invited to share their written responses individually. These were recorded on flipcharts using the words directly spoken by the participants, and, during this round, the views of the carer who had previously been consulted were also reported and recorded. In the facilitated discussion following, opportunities were taken to seek explanations or further details about any of the ideas that participants had produced that were not clear to all. In this segment of the meeting our aim was to generate as comprehensive a list as possible of the full range of risks associated with inpatient CAMHS, including (but not limited to) the risks which our phase 1 scoping and mapping had identified as occupying the interests of researchers.

By the end of this process, meeting participants had access to a range of materials and ideas presented and discussed in the earlier part of the day. These included the pre-prepared series of maps displaying the themed overview of existing research; the account of the YoungMinds pre-meeting consultation with young people; and a series of flipcharts carrying the words of individual stakeholders (and a carer, previously consulted) in response to the invitation for people to identify the risks facing young people as they make the transition into, through and out of inpatient CAMHS. In a second round of activity informed by nominal group principles, project team and stakeholder group members were then asked to rank, in writing, their personal priorities for the categories of risk to take forward into the second, in-depth, phase of the project. The preamble to this exercise invited people to draw as widely as they wished on the full range of risks as previously described and discussed.

This first combined project team/stakeholder meeting closed with the collection of lists of individually generated, ranked phase 2 priority categories of risk produced by each person taking part. To this collection of lists were added carer priorities previously identified and a composite list of priorities extracted from the YoungMinds consultation report. This exercise gave project team members a long list of candidate categories of risk for the in-depth segment of the project ordered by individual researcher and SAG member, and from the young people collectively consulted (see Appendix 9). From this collated list the top three ranked priorities were taken from each individual (and from the YoungMinds consultation collectively) to produce a new, shorter, list of 45 individual items. In order to group these items under broader categories, this list was independently coded by two members of the project team (DE and NE), who then met to discuss and agree on their categorisation. This joint categorisation was then checked and agreed on with the involvement of a third member of the team (BH).

This process led to the identification of eight ranked priority categories of risk, each having a count of the number of items from the total of 45 subsumed within it (see Appendix 10). This information was included in a summary document for SAG members, which was circulated for final responses before the initiation of phase 2 of the review, and is also summarised in Table 2. Further details are given in Appendix 11.

| Area of risk | Number of times identified |

|---|---|

| Dislocation | 16 |

| Contagion | 6 |

| Harm from organisation | 6 |

| Institutionalisation | 5 |

| Self-harm | 4 |

| Decision-making | 3 |

| Suicide | 2 |

| Aggression | 1 |

| Other: managing dissonance/ambivalence (n = 1) and psychological risks (n = 1) | 2 |

The document for SAG members noted that the top risk category priorities for the in-depth segment of the review were all examples of ‘less obvious’ risks, and, as such, were unlike many of the more ‘clinical’ risks identified in the phase 1 mapping of the literature. The project team’s categorisation of these less obvious risks included a version of this summary information, along with plans for the initiation of the next phase of the synthesis overall:

-

Dislocation is the word the project team has used to describe the top priority emerging for the second phase of this review. This category of risk includes the ideas of young people being removed from ‘normal’ life, of being ‘different’ and of experiencing ‘fragmentation’.

-

Dislocation as a category of less obvious risk also captures the ideas of being stigmatised and discriminated against, and of young people losing their previous identities, social contacts and friendship groups. It includes isolation from, and within, families.

-

Dislocation also includes the risks presented to young people’s educational, psychological and social development.

-

Dislocation implies unhelpful loss, and contagion (the second category of risk prioritised for the next phase of the review) implies unhelpful gaining: the risk of being exposed to and of learning abnormal behaviour, and of new and unhealthy friendships.

The project team’s plan presented to SAG collaborators indicated the aim of taking both dislocation and contagion forward as the two, linked, priority risk categories for the second phase of this evidence synthesis. Team members were aware of an equal number of items having been brought together under the categories of ‘contagion’ and ‘harm from organisation’, but noted that, in consulting with a carer, the risks from contagion (learning new and harmful behaviours) were a particular priority. This informed the plan, also included in the report to collaborators, to take this area forward into the next study phase. The report also drew attention to the fact that the proposed phase 2 plans implied a move away from the more ‘clinical’ risks identified in the phase 1 mapping towards a consideration of some of the ‘less obvious’ risks, and in this context invited feedback on three questions:

-

Have we reflected stakeholders’ priorities accurately?

-

If we have reflected the priorities for the in-depth part of our review accurately, then we welcome ideas on where we need to go for evidence in these areas. If we are gathering information on how the risks of ‘dislocation’ and ‘contagion’ are identified, assessed and managed as young people move into, through and out of inpatient CAMHS, then where should we look and whom should we approach?

-

What other words can you think of that reflect the ideas of ‘dislocation’ and ‘contagion’, which we might use to continue to search for evidence?

One stakeholder participant from our April 2013 meeting responded to the summary and phase 2 initiation document by advising the team to be mindful of the dangers of ‘demonising tier 4 admissions’, noting that hospitals are a crucial and very scarce resource playing an important part in overall systems of care. Our response as a team, then and now, is that we concur: inpatient admission for young people with mental health difficulties is indeed sometimes necessary, as it is here that round-the-clock specialist care is provided to people with the greatest need. What the consultation exercise indicated, however, was an appetite among project members and collaborating stakeholders for a phase 2 review of some of the risks less often considered for young people passing into, through and out of inpatient care.

Summary of consultation with stakeholders

Following EPPI-Centre principles, a series of broad, phase 1 maps of the literature on risks for young people admitted to mental health hospitals were taken to a stakeholder advisory group with a view to determining the focus for the second, in-depth, phase of this study. Project team members engaged with the charity YoungMinds, which conducted a consultation on the team’s behalf. A series of maps arising from the phase 1 scoping exercise were devised and presented to people taking part in a key stakeholder advisory group meeting convened in April 2013. Collaborators were then asked to identify what they thought the risks to young people moving into, through and out of mental health hospital were. Responses were displayed alongside the risks occupying earlier teams of researchers identified from the scoping exercise. Informed by nominal group techniques, all team members and collaborators were invited individually to rank the categories of risk they saw as priorities for the in-depth phase of the project. These priorities were grouped together under a series of broader categories, with a large number of risks brought together under the umbrella category ‘dislocation’. The team determined to make this a first priority risk category for phase 2 alongside a second category, ‘contagion’.

Chapter 4 Phase 2 in-depth evidence synthesis: concepts and methods

Introduction and conceptual framework

During the phase 1 scoping of the literature using two databases, a preponderance of research and other outputs was found that concentrated on the clinical risks to young people admitted to mental health hospitals, and particularly in relation to the risks of suicide and self-harm. Typically, it is in response to these risks that young people are admitted to tier 4 inpatient settings, as it is in hospitals that round-the-clock specialist care and treatment in conditions of safety can be provided. The risks of suicide, self-harm, physical deterioration and harm to others are vitally important ones: for young people, their families, friends, practitioners, managers and the wider society. Nonetheless, the steer from young people contributing to the YoungMinds consultation exercise conducted on the project team’s behalf, and from stakeholders participating in the end-of-scoping priority-setting meeting, was to conduct a search and synthesis of the evidence across a series of other, less obvious, risks.

This part of the project was again informed by the idea that inpatient CAMHS units exist within a larger, complex and inter-related system of people and organisations. Young people themselves are part of this system, as are their families and friends, the schools they attend and the community-based health services they may use. Decisions to admit young people to mental health inpatient units are often made in the context of high levels of clinical risk, and have important consequences: for the individuals admitted, for families and friends and others immediately surrounding, and for those providing direct services. Hospital admission also has consequences at the system level, at which services are organised and delivered: where teams and workers in inpatient and community health and social care services, in schools and elsewhere have responsibilities to manage young people’s transitions into, through and out of hospital in as seamless and integrated a manner as possible. In this context a consideration of the broader, less obvious, risks of ‘dislocation’ and ‘contagion’ for young people and those around them is consistent with a systems perspective and it is these largely non-clinical risks that form the focus of this part of the project.

Having identified dislocation and contagion as the categories of risk to prioritise, the task of searching comprehensively for research and other evidence in these areas in the context of young people passing into, through and out of inpatient mental health hospital proved challenging. This segment of the report sets out the research questions guiding phase 2. It also addresses the approach used in the interrogation of databases, and the sequential strategy developed for sifting through citations and making decisions on including and excluding materials identified. Reflecting EPPI-Centre commitments to seeking out evidence of the widest variety (rather than research outputs alone), a description is also given of the steps taken to locate and secure grey literature, clinical case reports and reports of local practice initiatives on how inpatient CAMHS units identify, assess and manage the categories of ‘less obvious’ risk focused on in phase 2. A detailed account is then given of the materials included in this in-depth component of the project and how decisions were made on the quality of these.

Phase 2 research question and objectives

The research question for phase 2 was:

What is known about the identification, assessment and management of dislocation and contagion in young people (aged 11–18 years) with complex mental health needs entering, using and exiting tier 4 inpatient services in the UK?

Objectives for the in-depth evidence synthesis were:

-

to identify and appraise the evidence for the identification, assessment and management of the risks of dislocation and contagion for young people using inpatient CAMHS

-

to identify and describe any underlying theoretical explanations for approaches used in the identification, assessment and management of the risks of dislocation and contagion

-

to understand the views and experiences of dislocation and contagion of young people (aged 11–18 years) with complex mental health needs using inpatient mental health services, and of those involved in the identification, assessment and management of these risks in these settings

-

to synthesise the evidence for the identification, assessment and management of dislocation and contagion in young people (aged 11–18 years) with complex mental health needs moving through inpatient services

-

where possible, to synthesise the evidence on the costs and cost-effectiveness to the NHS of different approaches to identifying, assessing and managing the risks of dislocation and contagion for young people using inpatient mental health services.

Review design

As with the first phase of the project, the design of this second segment was informed by the approach developed by the EPPI-Centre, as Figure 19 illustrates.

FIGURE 19.

Phase 2 of the EPPI-Centre framework in action.

Review methods

As per the approach described in the project protocol, once we had agreed the focus for this second phase of the project, work commenced with electronic searches of specified databases. In the case of citations finally included, reference lists were searched to identify additional materials for possible inclusion (back-chaining). Searches were conducted for UK-only grey literature, and the project team published (and widely circulated) a call for evidence. This requested examples of local service responses to the less obvious risks and was sent to all NHS and non-NHS inpatient CAMHS units in the UK and was additionally distributed via online discussion and mailing lists.

Types of participants

To be included, research and other materials needed to be written in the English language and to focus on young people aged 11–18 years by:

-

focusing exclusively on young people aged 11–18 years or

-

focusing on a wider age group but including sufficient detail to enable the accurate identification of data relating to young people specifically or

-

relating to a study sample where the mean age was between 11 years and 18 years.

Types of intervention and phenomena of interest

All citations were considered which addressed ‘dislocation’ and ‘contagion’ for young people moving into, through and out of inpatient mental health services.

Context

All citations were considered where care was provided in inpatient mental health services. Following the decision made in phase 1, ‘inpatient mental health services’ was defined in this phase of the study as any hospital setting staffed by mental health professionals. In the case of US studies retrieved, the decision was again taken to include citations centring on residential treatment centres (RTCs) or residential treatment programmes. These facilities are comparable to hospitals, with the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry defining them as providing:

intensive help for youth with serious emotional and behaviour problems. While receiving residential treatment, children temporarily live outside of their homes and in a facility where they can be supervised and monitored by trained staff.

(p. 1)157

Types of evidence

This part of the review considered a variety of types of evidence: published and grey literature original research; review, discussion and opinion papers; reports of local practice initiatives or service developments; clinical case studies; and policy and guidance documents. All evidence relating to outcomes, views and experiences, costs and cost-effectiveness, policies, and service and practice responses in the areas of ‘dislocation’ and ‘contagion’ for young people (11–18 years) with complex mental health needs using inpatient mental health services was sought. Materials published in the English language since the introduction of the tiered system in CAMHS in 1995 were sought.

Exclusion criteria

Excluded materials were those not in the English language; addressing inpatient mental health services for adults over 18 years; centring on inpatient mental health services for children under the age of 11 years; relating to any community-based mental health services (e.g. outpatient, day care or wraparound); addressing juvenile justice services.

Search strategy

Preliminary scoping searches of MEDLINE and PsycINFO performed for phase 1 of the project (see Chapter 2 and Appendices 1 and 2) highlighted a number of potential challenges to be considered when developing the in-depth searches required for phase 2, principally surrounding the use of the term ‘risk’. The outputs from phase 1 had predominantly focused on the clinical risks to young people in inpatient mental health settings, such as the risk of suicide and self-harm. Comparatively little evidence was found focusing on the less obvious risks such as the risk to young people admitted to mental health hospital of negative peer group influences or the loss of educational opportunities. The priority risk categories, to be taken forward to the second, in-depth, phase of the study and decided in consultation with the stakeholder advisory group, were all examples of these less obvious risks. An examination of the papers known to the investigators from phase 1 discussing these less obvious risks confirmed the challenge ahead, with very few using the term ‘risk’ and the language used within each varying considerably.

Led by one member of the project team (EG), an initial attempt was made to try to define and describe the two priority areas of ‘dislocation’ and ‘contagion’, with the intention of directly including these in one arm of the phase 2 search strategy. Potential keywords reflecting these areas were generated, drawing on contributions from the project team and from members of the stakeholder advisory group. Examples of candidate keywords connected to the priority risk areas are given in Table 3.

| Areas identified | Keywords for stage 2 |

|---|---|

| Dislocation | |

| Dislocation (loss or gain) | Dislocation, disrupt*, disconnect*, fragmentation |

| Removal from ‘normal life’ | Life in proximity to normal, abnormal. ‘Fitting in’, marginali?ation |

| Losing out educationally | Education or school in proximity to achievement, attendance, performance, progress, continuity, interruption*, attainment |

| Falling behind in psychological and social development | Social in proximity to network, support, development, relations, influences, isolation, media. Development* in proximity to milestone*, psychological, social, education*, risk |

| Being stigmatised/discriminated against | Stigma*, discrimination |

| Loss of previous identity | Identity, social contact*. Friend* or peer* in proximity to missing, loss, separation |

| Isolated within families | Family or parent* in proximity to breakdown, relationship*, dislocation, missing, separation, problem*, support, change, isolation |

| Contagion | |

| Contagion | Contagion, copy, mimic, imitate |

| Developing new and unhealthy friendships | Friend* or peer* in proximity to loss, separation, bad, manipulative, abnormal, detrimental, harmful, disruptive, negative, damaging, pressure |

However, testing these terms in pilot searches produced an unmanageable volume of citations. Following consultation with colleagues, including Mala Mann [an information specialist associated with the Systematic Review Network (SysNet) at Cardiff University], the decision was made to remove this arm of the search entirely. This decision produced a highly sensitive final search strategy for phase 2 comprising three arms: (1) young people, (2) mental health and (3) inpatient. This was recognised as the best approach to capturing all relevant material, leaving project investigators the task of reviewing all search results and manually identifying citations that also addressed the priority risks of dislocation and contagion, from which any papers addressing costs and cost-effectiveness could also be located. Searches were developed using a combination of controlled vocabulary [e.g. medical subject headings (MeSHs) in MEDLINE] and text words, and, before proceeding, this strategy was thoroughly tested to ensure that it retrieved all of the core papers identified as relevant during the phase 1 scoping. Information on search strategies used across all databases is provided in Appendix 12. The 17 individual databases searched were:

-

American Economic Association Database (EconLit)

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)

-

British Nursing Index (BNI)

-

Cochrane Library (including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Methodology Register, HTA and NHS Economic Evaluation Database)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature

-

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC)

-

Excerpta Medica (EMBASE)

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC)

-

Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE)

-

PsycINFO

-

Scopus

-

Social Care Online

-

Social Services Abstracts

-

Sociological Abstracts

-

System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (OpenGrey)

-

Turning Research into Practice (TRIP) Plus

-

Web of Science.

To ensure that the project remained manageable in the time frame given, a number of limits were also applied to contain the number of results. Text word searching was used for titles and abstracts only, and, as per the inclusion criteria given in Types of evidence above, the search was limited to English-language publications from 1995 to September 2013. When numbers of results were particularly large, the option of restricting the search to ‘human’ was also utilised.

As described in our Review methods section above and in Call for evidence below, a range of snowballing techniques were also used to increase the sensitivity of the search. References from citations located and included in phase 2 were searched for additional studies (back-chaining), and the Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychiatric Services were hand-searched for the previous 2 years to ensure that any relevant papers that may not have been indexed in the major databases were located. Searches for relevant grey literature were conducted using directories of conference proceedings, HMIC, OpenGrey and Index to Theses. A search was also made using the website of the NIHR, including for information on studies funded by the HSDR programme and its predecessors.

Searching for policy and guidance