Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 08/1809/250. The contractual start date was in March 2009. The final report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Martin Roland has received personal fees from Advice to Brazilian Ministry of Health on pay for performance and personal fees from Advice to Singaporean Ministry of Health on pay for performance, outside the submitted work.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the National Institute for Health Research, the NHS or the Department of Health.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by McDonald et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

A wide variety of pay-for-performance (P4P) schemes have been developed for health-care providers, and such schemes are being increasingly adopted internationally with the aim of improving care quality. 1,2 Increased adoption of P4P is occurring despite a scant evidence base. A review published in 2009 found that only three hospital P4P schemes had been evaluated, and that good evidence was available for only one scheme. This was a US-based initiative called the Hospital Quality Incentive Demonstration (HQID), which was adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in 2003 and supported by Premier Inc.,3 a nationwide organisation of not-for-profit hospitals. These evaluations4–6 and later papers7,8 show, at best, modest impacts on hospital processes of care. Evidence of an effect on patient outcomes is even weaker; HQID was shown to have had no effect on patient mortality9 and a 2011 Cochrane review found no evidence that financial incentives improve patient outcomes. 10 This report details the methods and findings of a 5-year National Institute for Health Research, Health Services and Delivery Research programme-funded project evaluating Advancing Quality (AQ), a hospital-based P4P initiative in the north-west of England.

Advancing Quality is a voluntary programme that provides financial incentives for improvement in the quality of care provided to patients. It has been implemented in the North West region of England since 2008. The programme is based closely on the P4P demonstration project implemented in the USA, HQID, which involved a partnership between CMS and Premier Inc. AQ was initially designed and supported by Premier Inc., and involved similar quality indicators and financial incentive structures. However, it differed from HQID in involving the universal participation of eligible providers and in being implemented in a different health system.

The AQ programme evaluation was undertaken over 5 years from 1 April 2009. Given the changing NHS context, a two-stage process was adopted which involved agreement of aims for the first 3 years of the evaluation, with aims for the final 2 years being agreed in year 3 of the evaluation.

The aims of the evaluation were to:

-

provide a wide-ranging and in-depth evaluation of AQ in the north-west of England

-

identify key lessons for the adoption of P4P systems in the UK NHS

-

add to the evidence base concerning P4P systems.

In order to achieve these aims, the four main objectives were to:

-

identify the impact of AQ on key stakeholders (provider organisations, commissioners and patients) and clinical practice

-

assess the cost-effectiveness of AQ

-

identify key factors that assist or impede the successful implementation of AQ

-

provide lessons for the wider implementation of P4P schemes across the NHS as a whole.

During the first 3 years of the evaluation, we identified that the first 18 months of the programme led to significant reductions in patient mortality and lengths of stay in hospitals. 11 After the initial 18 months, the programme underwent a number of changes (notably a change from financial bonuses to penalties, extension to new disease areas, and a change in supporting contractor). Consequently, the main objectives agreed for the second and final phase of the evaluation were as follows:

-

to analyse how the impact on mortality was generated

-

to examine whether or not the impacts and cost-effectiveness of AQ are sustained over time

-

to assess whether or not the structure of the financial incentives impacts on performance

-

to develop a framework for efficient design of financial incentives in the future.

Chapter 2 Literature review and conceptual framework

Introduction

The literature in the area of incentives is large and growing and much of it is concerned with financial incentives. In addition to studies demonstrating positive effects of changes in incentive structures (financial and otherwise),12 there is a substantial literature derived from a wide range of sectors on the potential for such performance management systems to generate unintended and dysfunctional consequences. 13 Owing to the large volume of theoretical and empirical literature, which may have some relevance to this topic, and the need to limit the review to manageable proportions, it has been necessary to draw some boundaries with regard to the scope of the review.

We have also attempted to avoid duplication of other research. Davies et al. 14 recently undertook a review of the literature on incentives and governance, which provides an in-depth and highly accessible review of the literature in this area. Christianson et al. 15 also reviewed the literature to assess the impact of financial incentives on the quality of care delivered by health-care organisations and individuals, and rather than reiterate its contents in detail here we refer interested readers to this accessible report.

Our recent report The Impact of Incentives on the Behaviour and Performance of Primary Care Professionals16 contains an extensive (c. 5500 words) discussion on incentives and motivation drawing on economic, psychological and sociological literatures. Interested readers should refer to this report for an in-depth discussion of the literature in this area.

In what follows, we present a selective review of some of the literature, chosen for its relevance to the subject of incentives in the context of AQ. The first part of the review discusses issues relating to the design of incentive schemes, highlighting good practice where possible. This is followed by selective discussion of literature relevant to the understanding of change processes in health-care organisations.

Financial incentives for quality in health care

For a number of years, many Western countries have operated fee-for-service payment systems, with payments based on some measure of the volume of care, such as the numbers of procedures undertaken or the total number of bed-days. 17 However, such schemes may not lead to optimal quality, as health-care providers are incentivised to maximise volumes through unwarranted procedures or superfluous lengths of stay. 18 Alternative payment systems, such as bundled payments and capitation, are an attempt to curb unnecessary reimbursement. However, these can have the opposite effect of discouraging behaviours by the organisation that, while clinically necessary or desirable, would not provide them with additional remuneration (e.g. screening and other preventative measures or some elective procedures). 19 P4P is intended to act as a middle ground between these two designs, incentivising to a greater extent the completion of behaviours related to improved quality of care, without discouraging the completion of other necessary yet non-incentivised procedures.

Implementation of P4P schemes is a growing trend in health-care settings. 20 In the NHS, several programmes have been introduced in the past 10 years, including the national Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)21 and Commissioning for Quality and Innovation Payment Framework (CQUIN). 22 Frequently, P4P schemes are justified by a need for improved, standardised levels of care quality and as a method to increase transparency, particularly when coupled with a public-reporting element. 3 However, reviews of the ability of P4P to fulfil such goals suggest that improvements are inconsistent and often only temporary. 2

Provider capacity and pay for performance

The introduction of a quality measurement and reward initiative requires reliable technical support and a capable administrative staff. At its most basic, this requires a sufficient data system to gather and (if necessary) analyse data, and requires individuals responsible for advocating and implementing the scheme internally. A number of papers recognise electronic medical records as a key element in implementing both a successful P4P scheme and, in turn, an efficient health-care system. 23,24 In summarising the effectiveness of best practice tariffs, McDonald et al. 25 noted reduced performance on the quality measures that required a large amount of additional data collection and a restructuring of electronic data systems. Additionally, providers identified insufficient capacity in relation to the built environment (e.g. day-case surgery facilities) and workforce (e.g. orthogeriatrician capacity as a result of a failure to invest locally but also as part of a more general scarcity workforce issue). The built environment may help or hinder quality improvement (QI) initiatives. Additionally, where such initiatives require the shifting of responsibilities across professions, a rebalancing of the provider workforce may be needed.

Provider support for pay for performance

McDonald et al. 25 also identified a lack of support for certain aspects of a P4P programme in areas where clinicians disputed the content of best practice pathways. This suggests that obtaining provider support for a P4P scheme is vital for its success. Furthermore, an evaluation of the national CQUIN initiative in a later study by McDonald et al. 26 found that, although support was often present among managers involved in negotiating quality goals and related payment rules, such support was often absent with regard to frontline clinicians. There were various reasons for this, including a failure by managers to engage and inform frontline clinicians in the process.

Additionally, in some cases, commissioners sought to impose quality goals, which led to friction and less collaborative forms of working in addition to a tick box approach in some cases. Other studies highlight how a lack of engagement and ownership reduces the impact of such initiatives. 27 This suggests that scheme content needs to be informed by close discussion with clinicians and experts in order to ensure relevance, feasibility and commitment. Clear and robust communication and support mechanisms are needed between relevant parties during all phases of a scheme’s design and development, in order to avoid implementing a scheme of which clinicians are unaware or unsupportive. 28

The tendency of financial incentives to crowd out intrinsic motivation29 raises concerns that P4P may compromise altruistic desires to maximise the welfare of patients. Such effects may be minimised by ensuring that tangible rewards (such as money) are complemented by symbolic rewards (such as praise or public recognition). Provider support is likely to be more readily forthcoming when P4P initiatives involve applying incentives to standardised, simple processes, rather than more complex processes requiring greater cognitive application; limit commissioner use of coercive methods, such as surveillance and threats, when promoting quality measures; and acknowledge – if not ensure – that the level of incentive reflects the cost of additional effort required by participants. 30 Crowding out of intrinsic motivation may also be reduced by targeting the scheme at teams and groups rather than individuals and by involving clinicians in the development of indicators and exclusion criteria. 31

Pay for performance and targeting at individual health-care professionals versus an organisation/team level

In an aggregated (i.e. team as opposed to individual) measure, poor performance of one contributor may be hidden by high performance from other individuals. 32 Through performance monitoring of distinct individuals, there exists a more direct link between behaviour and output and a greater visibility of free-riding participants. Moreover, some procedures and care practices, such as the provision of discharge information or smoking cessation guidance, rely on the autonomy of single individuals, which may be undermined by team-level measures. 33

Evaluating individual-level performance for providers that see a low relevant caseload in the scheme timeframe may be overly complex when individual contributions to care are unclear, and misleading when individual physicians see only a small relevant caseload. 34 It may be unfitting to reward just one individual involved in a patient’s care where such care has spanned a number of health-care professionals. Rewards across clinical teams place greater emphasis on incentive schemes as a form of altruism and a way of improving welfare for patients, rather than as a source of additional income for individuals. 35

A team-level incentive scheme may still be supplemented with individual-level performance reporting, minimising issues of accountability and free-riding in group schemes. However, setting a sufficiently challenging minimum target for performance within a team may be preferable because this can also substantially reduce free-riding, by allowing peer effects to increase motivation.

Pay-for-performance and single indicators versus whole-pathway incentives

It may be inappropriate to incentivise single-indication quality measures without consideration of the patient’s other conditions, which may advance the risk of drug adverse events or treatment contraindications. 36 Furthermore, providing health care often involves the expertise of several individuals, across a substantial time period, and this is particularly the case for patients with chronic diseases or multiple comorbidities.

Many health conditions lack a clear care plan, particularly when the patient remains undiagnosed or with an unclear course of treatment. 37 Patient interactions with primary and secondary care services – hospitalisations, repeat prescriptions, rehabilitation, and so on – are often unpredictable in chronic health conditions such as diabetes or mental health disorders. This complicates the development of incentivised measures significantly, as they need to span the whole care pathway.

Pay-for-performance schemes based on care plans have been introduced, for example in Germany and Australia, and designed around a package of care spanning prevention and treatment, with several co-ordinated providers incorporated within one payment contract. 38 Rather than externally assessing the relative contributions of clinical teams or individuals, bonuses are often received at the system level, with teams and individuals rewarded at the provider’s discretion. However, these care plan P4P schemes have yet to be evaluated for effectiveness. 38

Voluntary versus mandatory participation

Voluntary P4P schemes allow providers with a sufficient level of infrastructure to join the scheme at their discretion, without the need to wait for lesser-resourced providers to develop their labour or IT capabilities. Voluntary P4P schemes may only attract those who are already performing highly, excluding those most in need of the programme. Furthermore, highly resourced providers may reap benefits from early participation, further widening the performance gap between providers. 39 Mandatory participation in P4P would therefore remove inequity between providers resulting from self-selection. However, coercing participation is likely to impact adversely on intrinsic motivation. 27

Evidence of over-representation of high performers in voluntary P4P schemes is inconclusive. One study of a Hawaiian quality initiative suggests that low- and high-performing providers were uniformly represented in the scheme. 40 A study of HQID, the US-based predecessor of AQ, suggests that those who volunteered for the scheme exhibited significantly different levels of patient volume and mortality. 9 Overall, conclusive evidence on the extent to which voluntary or mandatory participation affects performance is relatively absent from the literature.

Structuring bonuses

There are four principal structures for rewards under P4P:

-

a predefined, single threshold of achievement (benchmarking/target – e.g. completion of a given measure among x% of eligible patients)

-

multiple thresholds of achievement at predefined intervals (e.g. a small incentive for completion of a given measure among x% of eligible patients, followed by a larger incentive for completion among x + 10% of patients)

-

continuous reward systems, with incentive provided on a per-completed measure/patient basis

-

relative performance (a tournament – e.g. incentives shared among the top x performing providers).

These are often used in combination to reward a mixture of absolute, relative, and improvement in, performance.

Single performance thresholds

Rewarding providers based on a single threshold of performance has the benefit of simplicity both at the point of scheme design and in communication with participants. However, a threshold that is set at a very high level could discourage lower-performing providers from engaging, particularly when there is no secondary reward for improvement. If thresholds are not increased relative to achievement levels, high performers may find themselves eligible for incentive with no additional effort required and providers may disengage from the scheme (as occurred in one US programme41).

Multiple performance thresholds

Multiple performance thresholds, however, create incentives for both high and low performers. Much like in a single-threshold structure, however, motivation to improve could decrease past the point of attaining threshold performance – an issue predicted among high performers in the QOF. 42 Increasing targets in a threshold scheme as providers improve should reduce the likelihood of this, but creates an additional administrative burden. Multiple thresholds35 and continuous rewards work to reward all providers in proportion to their level of achievement, and, thus, they are more likely to be effective in rewarding absolute performance and improvement over time simultaneously.

Continuous reward systems

Much like a single-threshold system, continuous reward structures have the benefit of simplicity and also guarantee a reward for all participants (in the absence of a minimum performance threshold). Unlike threshold systems, however, rewards are directly proportionate to performance. In the absence of any additional bonus for improvement, the structure by its very nature guarantees that lower-performing providers will receive lower payments; several studies suggest that this can widen inequalities in service provision. 39,43 At the same time, providers that can quantify performance to date may feel sufficiently rewarded and discouraged from exerting any further effort for the remainder of the period, particularly on quality measures that require significant investment.

Furthermore, the idea of rewarding participants irrespective of achievement could be contentious among stakeholders who feel that a minimum standard should be met before any incentive is given, particularly when the indicator represents standard clinical guidelines of care. A minimum threshold of achievement could be set, below which providers would be ineligible for reward (or even penalised). Performance on quality measures often exhibits a plateau effect past a given level of achievement; assuming constant returns to effort, there will be a point at which the marginal cost of initiating the measure in another patient outweighs the marginal benefit to the provider.

Relative performance (tournaments)

Tournament schemes, based on a ranking of providers, incentivise providers to compete against one another for rewards. In the absence of perfect knowledge of other participants’ behaviour, the level of performance required for reward is unknown, eliminating the risk that providers would slow performance past a given level of achievement and instead motivating participants towards a system of continuous improvement. 44

In other scheme types, commissioners may risk a shortfall of funds if achievement is higher than expected. In a tournament scheme, on the other hand, the number of winners is fixed. Commissioners therefore possess a greater level of certainty of the final reward value. 33 However, the fact that providers do not know what level of performance is required could discourage large-scale investment in QI, on the basis that the expected return on investment is uncertain. Similarly, if some providers believe that they are low performers relative to their competitors, they could disengage from a programme that rewards solely on relative performance, under the impression that they are unlikely to receive payment. 45

When the incentive is contingent upon outperforming other providers, evidence suggests that collaboration and knowledge sharing is less likely. 46 Tournament-style schemes can be inappropriate where there exists low variability in performance across participants. 47 In this case, the differences in performance that decide who receives a bonus and who does not can be very small and may undermine confidence and credibility in the scheme.

Size of the incentives

Historical evidence suggests that incentive values in P4P schemes are rarely correlated with subsequent improvements in care quality. 20 Kristensen et al. 22 note that many systematic reviews of the effectiveness of P4P often only touch on the notion that bonus values and subsequent performance may be correlated or that bonuses should be equated with the marginal costs and benefits of the scheme.

Provider costs of pay for performance

Increased effort results in a cost to providers. This can involve communication, administration and data-collection costs, as well as the cost of the behaviour change itself. Some quality indicators will be more straightforward and/or less costly to implement than others: persuading individuals to receive a vaccination, for example, is generally easier than convincing them to quit smoking; and, conversely, provision of either service would be cheaper than administering magnetic resonance imaging or computerised tomography for a patient.

In converting the cost savings of QIs into provider tariffs, rewards reflect the impact of high performance on cost savings in the system – a tariff design used in the first major Medicare demonstration48 but yet to be seen in the UK. However, many improvements in quality are difficult to quantify in financial terms, such as programmes to raise patient satisfaction or to target long-term primary prevention. Furthermore, using expected savings to set incentive levels would represent a significant administrative burden and require frequent re-evaluation as clinical evidence evolves. Cost savings-based incentives that do not explicitly refer to the provider and commissioner costs of implementing and maintaining the programme when estimating returns result in flawed and/or partial evaluations of cost-effectiveness.

Many P4P schemes (such as AQ) have been introduced with an intentionally minimal direct focus on cost savings; the principal objective is often instead to improve and standardise care quality for patients, with any subsequent cost saving superfluous to the general cause. Setting bonuses proportionate to cost savings automatically places emphasis on the scheme as a method for saving money, rather than for any altruistic reasons, which may lead to disengagement from participants (see Provider support for pay for performance).

Applying optimal bonus values to pay-for-performance schemes

Optimal service provision, from the perspective of a provider, is to continue implementing quality measures until the cost of doing so for one extra patient is equal to these marginal benefits. Hypothetically, providers would still choose to participate in the absence of a financial bonus, as long as the return from the altruistic component and marginal benefits to patients outweigh the costs. In reality, however, this perspective would be financially unsustainable, from the perspective of the commissioner at least; all NHS funds have an opportunity cost in terms of the potential health gains foregone in other areas.

Evaluating the benefit associated with increased service quality among providers is difficult: altruism as a concept would be complex to quantify and measure, and individual physicians and providers would obtain differing levels of personal satisfaction from improving patient care via P4P measures.

In practice, the cost savings and altruistic sentiments resulting from P4P are often unknown or unquantifiable. In a recent evaluation of the CQUIN scheme, although some attempt was made to mirror incentives to effort required or the level of priority assigned to a measure, decisions on reward weightings were taken on an ad hoc, localised basis, rather than with any formalised evidence to hand. 26

Pay for performance and penalties

Economic theory49 suggests that ‘people impute greater value to a given item when they give it up than when they acquire it’. 50 Although this implies that penalties may more effectively encourage behaviour changes among providers than would equivalent rewards, more recent evidence suggests an increased level of gaming of the system and a greater demotivating effect when providers are faced with potential losses. 30 Penalties may also reinforce a cycle of poor performance, often penalising providers most in need of investment that already lack the financial ability to innovate and implement change (see Werner et al. 39 for an example comparing safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals in the USA).

Contents of incentivised measure sets

A key consideration in scheme design is whether or not measures should focus on processes or outcomes. Patient outcomes are often driven by factors outside the control of providers; mortality and morbidity rates are likely to be higher in areas of high poverty, with greater disease prevalence and with lower patient education. Process or structure measures are less likely to be influenced by environmental factors outside the control of the provider and so may reduce provider concerns. Some specialties may be more ideally suited to specific measure types, owing to the way in which care is provided and care quality measured. 51

Some quality measures, such as smoking cessation, have applicability across a number of conditions; often, however, quality measures suffer from a lack of applicability past one or two similar clinical areas. Indicators are therefore often targeted at specific diseases, particularly those with a significant patient population, within which such schemes may have a greater potential impact. P4P is suited to standardised, well-defined procedures; it is less well suited when measures of performance are difficult to define, obtain or evaluate. 47

Process measures should be within the provider’s control to implement. For example, patient compliance with lifestyle changes such as diet or exercise would be difficult for a physician to monitor and verify. 52 P4P measures should be visible in terms of accountability, applicability and effectiveness; there may exist significant gaps between processes that can be viably quantified and subsequent patient health outcomes.

Quality measures will be most easily monitored and reported at the point at which providers collect appropriate data as part of standard procedure. Providers need to ensure that they are collecting the relevant data for measurement; calculating risk adjustments for patients, for example, may require non-standard, supplementary demographic or clinical information.

Measures should be designed such that at the point of evaluation there exists a clear distinction between high- and low-performing participants;34 a reduction in the spread of achievement across providers is a key identifier of improvement and a need to amend the scheme’s design. In the absence of baseline variability, evidence of provider improvement is less clear. 53

Rewarding care quality in a limited number of measures may lead to a more narrow focus on only incentivised measures or conditions, whereas larger bundles of measures may induce more general improvements in care quality. However, using a large number of measures increases the overall size and burden of the scheme and correlations between indicators are more likely to exist in a larger set, thereby increasing the risk of large gains and losses between participants. 54 Increasing the number of measures also dilutes the importance attached to each, which may result in a lack of effort and therefore improvement, if the influence of a measure on overall performance is perceived to be insignificant.

Locally developed measures have the potential benefit of greater relevance to local health needs. Providers can develop P4P schemes aligned to their own long-term QI efforts, with local schemes used to pilot indicators for later use at national level. In promoting CQUIN to providers, the NHS advocated the new framework as ‘an opportunity for commissioners and providers to focus on delivering higher levels of quality of care for their populations, rather than responding to centrally directed targets’. 55

National measures, however, allow participants to benchmark progress and achievement against other providers and are more likely to represent a cohesive, comparable set of quality standards. Evidence from the CQUIN evaluation suggests that, although local contribution to quality measures was considered vital to the success of the scheme, frontline clinicians were rarely encouraged to involve themselves in the development of CQUIN goals and the technical design may have been better suited as a centrally directed initiative. 22 A mixture of national- and local-level targets may be best suited – although clinicians may quickly tire of the multiple requests for data potentially resulting from schemes in place at both local and national levels, with a risk of overlap or conflict in quality measures as their volume increases.

Provider case mix issues

The significant resource requirements of unusual patient case mixes are likely to affect achievement potential for P4P participants, with slower improvement rates and lower achievement levels. For example, specialist providers may treat and manage patients with more severe diagnoses and may therefore have greater difficulty meeting certain process and outcomes indicators. Participants in areas with greater poverty will perform less well on outcomes indicators that measure risky behaviours such as smoking and drinking levels. Low levels of education are likely to affect patient adherence and co-operation, thereby slowing improvements in process measures relying on actions from the patient, such as attending support groups or adhering to medication. 56

Setting risk adjustments across providers creates a method for standardising performance across different population groups. However, risk-adjustment methods represent an additional administrative cost and, for the most part, remain underdeveloped and unsupported by clinicians. 57 Categorising participants into comparator groups based on patient demographics would limit benchmarking to a smaller number of similar providers and is therefore limited to situations where a sufficient number of comparator providers exist.

Pay-for-performance schemes often incorporate a system of exclusion reporting for patients considered to be ineligible for receipt of one or more quality indicators (such as a contraindication for a particular pharmacological product or opting for palliative care instead of treatment). Such criteria are seen as important in ensuring that patients are not given unsuitable care and allowing health-care professionals to exercise their clinical judgement without fear of being penalised. Eligibility criteria must, however, be clearly defined in order to avoid providers viewing exclusion reporting as an opportunity to exclude seriously ill or non-compliant patients who would otherwise reduce achievement in quality measures.

Unintended consequences and pay for performance

Exception reporting and patient selection

More sick or less adherent patients may be excluded from treatment within a P4P scheme, on the basis that such patients risk contributing negatively to the provider’s quality measures. 52 The potential for manipulation of exception reporting, in which providers exclude certain patients who, on face value, should have been included in the initiative, has attracted studies into whether or not providers manipulate this to their personal advantage.

Evidence from the QOF suggests that the majority of general practitioners (GPs) did not participate in unwarranted exception reporting, despite some wide variations in the level of reporting across practices. 58 Gravelle et al. ,59 however, identified that a small proportion of practices gamed exception reporting to maximise their income. The presence of perverse incentives induced by P4P is strongly suggested in surveys of US physicians,60 particularly when risk adjustments are non-existent or considered inadequate and inaccurate.

Focusing on process or structural measures, rather than final outcomes, should discourage providers from selecting patients based on their predicted response to treatment. Commissioners could monitor for changes in provider case mix following the introduction of P4P or use risk-adjusted bonuses based on relative patient complexity, in order to discourage the exclusion of more severe patients. Both strategies, however, represent a time and cost burden.

Effort diversion and multitasking

Much like the issues encountered in fee-for-service reimbursement systems, participants may be encouraged to overuse incentivised measures for the sake of additional reward unless the scheme is properly monitored and audited. 61 P4P schemes may lead to the prioritisation of incentivised conditions or measures, at the possible expense of non-incentivised areas. Overall quality of care may decrease, owing to an inefficient redistribution of investment between indications resulting from P4P incentives. 62 However, evidence of such an effect is mixed. One study claims systematic effort diversion present in QOF,42 whereas another, conversely, notes a relative absence of effort diversion, instead identifying substantial positive spillover effects (see Positive spillover effects) within the same policy. 63 Ensuring that incentive monies are not sourced from clinical areas in need of the finance should help to minimise effort diversion; measures that encapsulate the whole provider system, such as patient experience or ward hygiene ratings, would also be less discriminatory in nature.

Positive spillover effects

Some QI measures have the potential to bring broader quality changes to non-incentivised conditions or aspects of care. A US P4P scheme incentivising completion of measures for diabetes patients under a managed care programme encouraged the rollout of the measures to patients across all health plans, despite the absence of an incentive provision for such patients. 52 Such positive spillover effects are likely to be amplified when participants are encouraged to communicate and collaborate with non-participating departments and providers, and when quality measures are applicable across a number of indications (such as discharge documentation) rather than strictly limited to incentivised conditions.

Supporting levers to accompany the financial incentives

Performance reporting

A number of P4P schemes include a reporting element, enabling internal staff and external stakeholders to view provider performance. An effectively designed public reporting initiative can have significant effects on commissioner and provider behaviours, even in the absence of a monetary incentive,64 and can also act as a useful preparatory tool for providers that are new to a P4P scheme. 65 The sole act of reporting quality measures can encourage the development of standardised reporting systems. 65 De-anonymised reporting measures at individual level may also reduce problems with accountability and free-riding in group incentive schemes. Even if bonuses are distributed to individual physicians or providers, performance reporting can be produced at ‘multiple levels of the care delivery system – physician, physician group, hospital, community – to identify gaps in performance and foster accountability at each level’. 66

However, much like a reward scheme, performance reporting carries a risk of unintended consequences, such as gaming the system and patient selection. Indeed, physicians often react more negatively to a P4P scheme that includes external reports, with greater concern placed on the quality of the data and measurement. 67 As quality measures are often a small subset of a provider’s services, publication of individual performance may be considered to provide an incomplete picture of care provision. 68

Public reports may also be difficult to interpret for their intended audience. Composite scores and statistical and clinical derivations of provider achievement may hinder the use of public reports as decision-making tools for patients. 68 Reports that use a system of ranking participants may be misleadingly detrimental to low performers in schemes where provider scores exhibit limited variability. Regarding the use of reporting procedures as a complement to financial incentives, provision of bonuses allows participants to further invest in QI, and may therefore accelerate changes in care above that achievable with performance reporting alone. 69

Feedback provision for participants

Negative feedback can reduce individuals’ perceptions of their competence, leaving them feeling demotivated. 70 Positive feedback can make people feel happier and more competent. However, although praise may increase motivation, the relationship between feedback and performance is complex, with feedback that supplies the correct solution more effective at improving performance than praise. 71 A moderate supply of timely feedback,72 complemented with serviceable suggestions for improvement, may be an optimal method for reporting results of P4P performance. 65,71 Such feedback may be best originating from the clinicians themselves, rather than commissioners, in order to ensure actionable methods for improvement. 69

Funding pay-for-performance initiatives

The source of funding for P4P schemes has implications on how providers view such programmes. Withhold schemes encourage the view that high-quality care should be standard practice, rather than an action warranting additional rewards. However, they may also encourage the view that P4P acts as a way for commissioners to hold back much-needed funds, a sentiment acknowledged in an evaluation of CQUINs. 73 There is also evidence that suggests that clinicians view withholds as unfair, coercive and contrary to the spirit of collaboration that should characterise P4P initiatives. 27 The use of a system whereby any unearned bonuses or capitation are paid out as bonuses to high performers on top of their original incentive value – termed a challenge pool in US literature74 – might encourage motivation when participants receive a reward greater than that of the original withheld funds, although this has yet to be used systematically. Similarly, in a combined reward–penalty scheme the income generated from fines to low performers would be used as bonus monies for high performers. Expected returns from penalties also need careful calculation in order to avoid owing bonuses greater than available funds (see Kahn et al. 75 for an example of this in HQID).

Designing achievement targets

Measure targets should be based on the capacity of a provider to improve in the subsequent period; although wealthier, highly resourced providers can be set a more challenging target than providers experiencing greater cost constraints, targets should maintain achievability among all participants. For tournament-style schemes, this could mean the grouping of providers based on resource availability, with rewards provided to winners in each group. For threshold-style schemes, participants may each work within their own set of performance thresholds or, again, may share targets with other similar providers. Alternatively, instead of benchmarking to competitor providers, targets may be set based on an individual participant’s performance in the preceding period (with a predetermined level of performance in the baseline period). Nevertheless, targets for all providers should lead to sufficient QIs (and, in turn, health benefits) so as to justify the opportunity cost of the scheme.

However, participants may become aware that targets in a subsequent period are based on current performance and may, therefore, reduce effort levels in the preceding period in order to maintain a lower future target. Furthermore, if targets do not actively encourage low performers to catch up with higher achievers, performance disparities may become institutionalised across providers. Targets must therefore be based on both the capacity and the relative need of the provider to improve relative to its peers.

Phasing in pay-for-performance schemes

In the early stages of a P4P scheme, when provider engagement is still in formation, the intense focus on specific procedures of care may be a shock for participants not yet acquainted with the nature of P4P. Larger schemes require the recruitment of, and support from, a greater number of health-care professionals, which may be difficult to achieve from the outset. The use of a pilot system has therefore been suggested as a valuable method for phasing in P4P initiatives. 65 This could involve testing the scheme in a limited geographical area or within a select number of indications or providers. In addition, baseline data during the piloting period can be used to set benchmarks and performance targets for when the scheme is fully implemented. Participation in the scheme may be voluntary for a set period, so that those providers requiring additional time to bring internal systems up to requirement need not be penalised in the interim.

Alternatively, participants could be incentivised on quality measure reporting levels alone (i.e. with no targets set for performance in the quality measures). Providers are then able to learn which areas of their infrastructure need investment prior to entering a full P4P scheme. Such a system of pay for reporting (P4R) was implemented in the USA prior to HQID, albeit not with the original intention of using it as a transition method into P4P. However, authors of a study into the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative concluded that P4R would act as a useful preparation technique for providers subsequently involved in P4P. 65

The process by which providers join a P4P scheme will affect the ease with which performance can be evaluated. As discussed previously, allowing providers to volunteer to participate in a scheme is likely to attract participation from those who expect to obtain a net benefit from opting in. In turn, extrapolating performance potential and applying to the (non-participating) remainder of the provider network may bias a priori estimates upwards. Mandatory participation of all providers, however, removes the ability to compare performance with a control group of non-participants, so that the counterfactual performance across the same time period may be determined. 76

Random selection into a compulsory scheme can instead ensure that the scheme maintains a mixture of providers operating at various levels of baseline performance. Subsequent achievement in P4P should therefore more accurately reflect the achievement potential of non-participating organisations. Alternatively, limiting performance to a small number of providers, selected on the basis of sharing some common characteristic, creates the ideal basis for a natural experiment. This is the case with our evaluation and enables us to compare performance in AQ providers in the north-west of England with those in the rest of the country. By observing performance across comparator organisations over the same time period, the relative effects of the P4P scheme may be isolated from national trends in performance. Ensuring that other contemporaneous shocks are accounted for when evaluating performance is vital, as is the ability to gather equivalent performance data from non-participating organisations from baseline onwards. In the case of AQ, although performance on process measures outside the NHS North West is not routinely available, we obtained outcomes (i.e. mortality rates) and use those for comparative purposes.

Quantifying achievement in pay for performance

Performance in P4P is often quantified by amalgamating achievement on individual indicators into a single composite score. Although methods for developing this score are numerous, two of the most frequent are the composite process score (CPS) and the appropriate care score (ACS). 77 The CPS represents the proportion of situations in which P4P measures have been appropriately administered. The ACS represents the proportion of patients receiving all care-quality measures for which they are eligible (Figure 1 shows an example calculation of each in AQ). Performance as measured by an ACS is likely to be poor if one or more measure is particularly difficult to complete, suggesting the use of a CPS in the initial stages of a scheme when measures are often re-evaluated for feasibility. The ACS is particularly useful when performance in the CPS has little variation and when there exists scope for additional measures: ‘it is more difficult to provide all the required measures of a large set than a small one’. 66 This makes the ACS more challenging as more measures are added. If measures complement one another, in the sense that the completion of a full set of measures leads to a superior outcome for the patient than completion of single measures alone, the ACS would be the appropriate score to use.

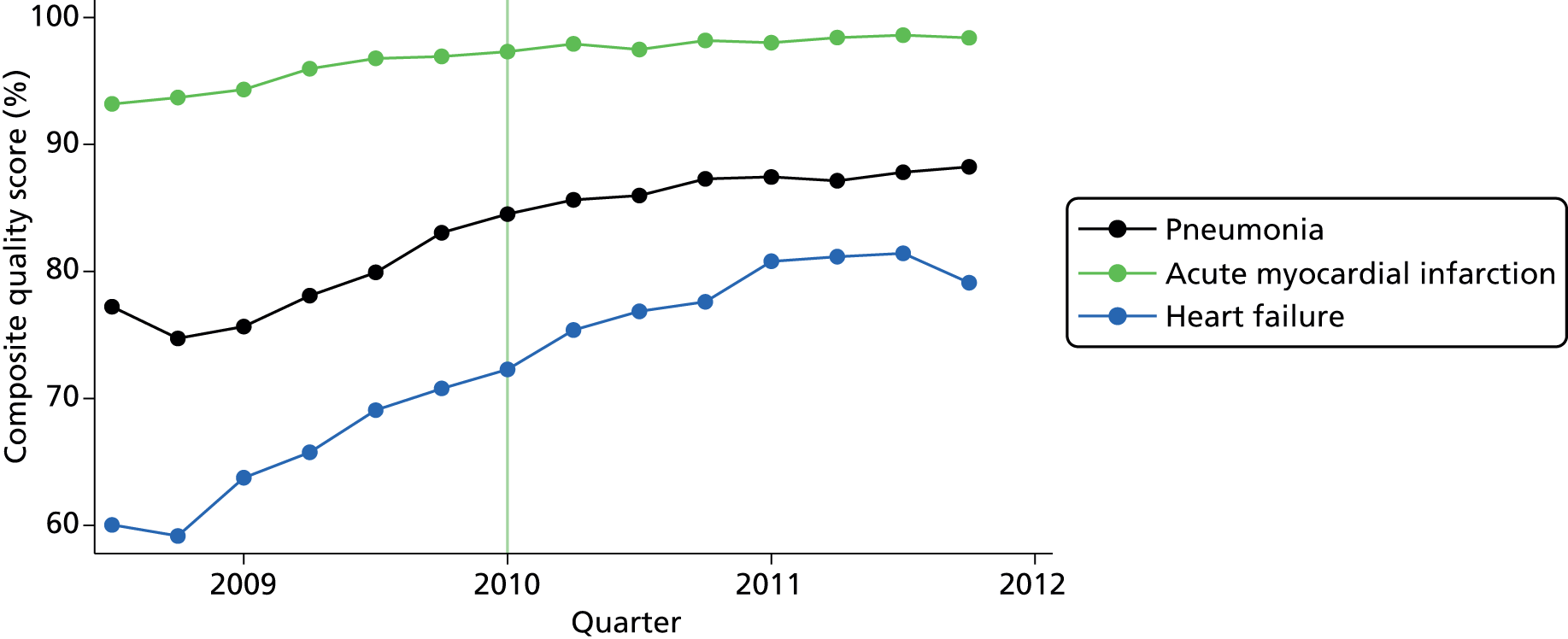

FIGURE 1.

Average quarterly hospital achievement for each condition across indicators. Note that the vertical line indicates start of long-term period (month 19 of the programme).

In amalgamating indicator-specific scores into a composite value, it may be desirable to weight each indicator relative to its clinical benefit or financial cost of completion. As a result, performance in a heavily weighted indicator will influence substantially a provider’s subsequent achievement. From the perspective of commissioners, however, individual weightings often represent additional analysis time and costs; from the perspective of clinicians and patients, they represent a complex obstacle to understanding performance. 78

Adjusting the pay-for-performance scheme over time

Some targets may require amending or retiring in order to reflect new evidence, such as those relating to clinical effectiveness or safety (see Reeves et al. 79 for an example in the QOF). Some quality measures may become more difficult or impractical to attain, owing to changes in either the internal provider environment, such as the supply of hospital beds (see CMS80 for an example in pneumonia), or the external environment, such as changes in socioeconomic conditions. 81 For most measures there exist natural ceiling or plateau effects and decreased returns to effort and investment, at which point financial incentives will no longer be sufficient to improve quality further. Finally, some incentivised behaviours may become so ingrained into standard practice that rewards are no longer necessary: a justification for re-evaluation again noted in a formal summary of QOF. 82 This may be seen as the ultimate success for a P4P programme.

If attainment in a particular measure is peaking at a suboptimal level, further investment or higher rewards may be required. As noted previously, certain internal and external barriers to achievement may mean that the marginal cost of initiating a quality measure on additional patients outweighs the marginal return in incentive. Inducing greater effort would therefore require a rebalancing of incentive value. Performance on a measure may be sufficiently high to warrant its discontinuation. Rather than an immediate removal of an indicator, however, it may be more appropriate to phase out the performance measure. If quality metrics are expected to change radically on a regular basis, support from providers may be more difficult to achieve, particularly for targets requiring significant investment, under the expectation that insufficient returns would be seen within such a short implementation period. 26

This idea of gradually evolving P4P measures has been used in QOF. Instead of requiring participating GPs to measure the blood pressure of patients with diabetes, for example, participants were subsequently required to ensure that the patient’s blood pressure was maintained below a predetermined threshold for the 15 months preceding evaluation. This has the benefit of maintaining focus on the same objective across both measures, while shifting the goalposts in the level of effort required from the provider. 79 Furthermore, a gradual shift from a process to outcomes measure should allow low-performing providers to continue towards the original (easier) quality measure, at the same time as encouraging continuous improvement from high performers.

Retired indicators should continue to be monitored in order to check for depletions in performance following their removal, as occurred in one process measure for the QOF. 79 Such occurrences may be a result of a lack of support from participants prior to incentive provision or because they represented a significant burden on workloads.

As we explain in this report, the AQ programme embodied many aspects of what might be seen as desirable design features of P4P schemes. However, this is no guarantee of success, as the implementation of P4P initiatives is likely to require substantial changes to practice. Evidence suggests that efforts to introduce such change frequently fall short of intentions, resulting in variable outcomes. 83

Conceptualising change: overcoming challenges

In addition to the burgeoning literature on change in health-care settings, there are also various frameworks conceptualising the change process. In our proposal for funding we chose to use a framework developed by Bate et al. 84 as part of their examination and explanation of quality journeys in a range of health-care organisations internationally. They discuss the findings in terms of six common challenges facing organisations undertaking QI initiatives in health-care settings. They conceptualise change as an ongoing journey and suggest that there is no one best way to achieve intended outcomes. The challenges they identify emphasise the multidimensional nature of change. What is important, they suggest, is the ability to address multiple challenges simultaneously and to adapt solutions to the local organisational context.

The challenges in their framework are:

structural (organising, planning and co-ordinating quality efforts)

political (addressing and dealing with the politics of change surrounding any QI effort)

cultural (giving quality a shared, collective meaning, value and significance within the organisation)

educational (creating a learning process that supports improvement)

emotional (engaging and mobilising people by linking QI efforts to inner sentiments and deeper commitments and beliefs)

physical and technological (the design of technological infrastructure that supports and sustains quality efforts).

Bate et al. 84

Addressing structural challenges is described as requiring strong and decisive executive leadership giving clear direction. A focus around QI in general and specific programmes in particular is likely to improve the impact of QI processes. In addition to structures to facilitate leadership and whole systems working, developing structures to overcome challenges related to data collection and monitoring systems is seen as hugely important. Furthermore, the provision of slack resources85 to enable staff to stand back from everyday pressures is likely to facilitate the implementation of QI processes.

Boundary spanning refers to roles with a ‘hybrid, dual bridging aspect, such as clinical leader/manager, which allow for lateral contact and communication between different groups and the linking of resources, people and ideas’84 around QI efforts. In a professional bureaucracy86 such as the NHS, institutionalised occupational boundaries and related epistemic communities87 and subcultures result in a landscape which is replete with ‘structural holes’. 88 The holes between two groups do not mean that people on either side of the hole are unaware of one another, but that they are focused on their own activities and do not pay attention to what people outside their group are doing. ‘Holes are buffers like an insulator in an electric circuit. People on either side of a structural hole circulate in different flows of information. Structural holes are thus an opportunity to broker the flow of information between people and control the projects that bring together people from opposite sides of the hole’. 89

Political challenges relate to dealing with conflict and opposition, stakeholder buy-in and engagement and securing commitment to a common agenda for improvement. Political issues to consider include the extent of empowerment (of staff and patients to exercise control over their environment), clinical engagement, politically credible leadership and relationships between clinicians and managers in terms of their agreement to work together on improvement initiatives. Additionally, making and maintaining constructive relationships with relevant external partners is viewed as an important part of overcoming political challenges.

These are challenges that are connected with established cultures of working practice and the way in which work is performed and perceived by staff members. Bate et al. 84 identify various strands in relation to culture, which are important for QI. These include a group collaborative culture, which refers to a strong group culture that promotes teamwork and co-operation between staff and places a premium on values such as respect, integrity, trust, pride, honesty, inclusion and openness. Formal culture refers to an emphasis on formalised disciplines to ensure efficiency and effectiveness. A culture of mindfulness involves a working environment that promotes vigilance and reflective practice while discouraging habitual and mechanical approaches to work. A scientific culture concerns a commitment to evidence-based practice, and a culture of learning refers to a culture that values risk-taking and experimentation, constantly encouraging people to do more and do it differently, developing and sharing new knowledge, skills and expertise.

The educational challenges refer to a process of ‘[e]stablishing and nurturing a continuous learning process in relation to quality and service improvement issues, including both formal and informal mentoring, instruction, education and training, and the acquisition of relevant knowledge, skills and experience’. 84 In addition to education and training generally, a focus on evidence- and experience-based learning, as well as experimentation and piloting is emphasised. These involve learning and developing new understanding from analysis of routine evidence and data, together with a willingness to try out new ideas and assess their impact.

Emotional challenges relate to the task of ‘[e]nergizing, mobilizing, and inspiring staff and other stakeholders to want to join in the improvement effort by their own volition and sustain its momentum through individual and collective motivation, enthusiasm and movement’. 84 Important aspects in any efforts to overcome emotional challenges are the use of champions to engage peers, as well as quality activists driving improvement via informal networks. Quality should be seen as a mission or calling, rather than merely a job. It is crucial that people engage with their hearts, as well as with their heads.

Physical and technological challenges refer to the ‘[d]esign and use of a physical, informational and technological infrastructure that improves service quality and the experience of care’. 84 The emphasis here is on the built environment and the extent to which it supports and encourages (as opposed to inhibits) QI efforts. Additionally, supportive information technology, in terms of both its functionality and its location, is a key aspect enabling organisations to drive and maintain QI processes.

Conceptualising change: understanding processes and mechanisms

Studies of change in health care often provide explanations that describe the what. 90 Exploration of the how and why can range from black-box explanations to fairly detailed descriptions which distil a wealth of observational and interview data to identify common features. In relatively few cases (although this is becoming increasingly common91), researchers identify underlying mechanisms that lead to particular outcomes in specific contexts. In practice, however, identifying what constitutes a mechanism as opposed to aspects of the context can be difficult. 92 Additionally, identifying what counts as relevant in relation to contexts that span micro-, meso- and macro-level factors is no simple task. For this study, therefore, although we have attempted to go beyond describing surface characteristics or common ingredients, we have approached the understanding of the how and why of the programme from a different, but complementary, angle. This entails consideration of different kinds of explanation as we explain in the next section.

In order to understand how initiatives such as P4P programmes work, it is important to consider the broader field in which these are situated. ‘An organisational field can be defined as a social area in which organisations interact and take one another into account in their actions. Organisational fields contain organisations that have enduring relationships to each other’. 93 In this case, the field is the social area where the 24 health-care providers operate and this area includes other organisations with which they interact.

Formal rules: these provide a regulatory framework to guide behaviour.

Network structures: people are positioned in different spaces in the field, with some more powerful than others. Many of these people may never meet each other, but there is often a dependency relationship between them.

Cognitive frames: individual and collective perceptions of field values and activities.

Fields are characterised by formal rules, but understanding what happens within the field requires consideration of other factors. 94 It is important to take into account the part played by network structures and cognitive frames. For example, as part of the process of applying and implementing formal AQ rules, staff from participating organisations were involved in collaborative learning events similar to those commonly used within a QI collaborative approach. This process can be conceptualised as part of a process of creating new network structures given that new staff members (recruited specifically for the AQ programme) initiated these events. These events also involved bringing people together to develop collective understanding (cognitive frames). To understand how this was related to change, it is important to examine who participated and what participation involved (e.g. in-person learning was chosen as opposed to webinars). Additionally, this ‘what’ does not merely mean the ingredients of these events. The meaning should also include network structures and rules of the field more generally, because change programmes such as AQ are not free-floating but operate as part of a broader organisational field. For example, an examination of network structures reveals, among other things, the position of those involved, some of whom will be more powerful in the field than others. Furthermore, although many of these people may never meet each other, there is often a dependency relationship between them. For example, staff who code data from patient records rely on the information clinicians provide therein. Even assuming that we can capture some or all of this, we need to go beyond formal rules and network structures to consider other factors that may exert an influence (Box 1).

In recent years, partly as a reaction to a reliance on structural explanations which underplay the active part played by individuals and groups, various studies of change in organisational fields have focused on the ways in which actors within the field have interpreted events and structures and how this has influenced activities. For example, institutional theorists conceptualise fields in terms of prevailing social norms95 and are concerned with understanding how things within the field achieve legitimacy. The emphasis here is on shared meaning (e.g. Reay and Hinings96) and understanding how changes in what counts as important and legitimate within the field occur. Attending to interpretation and the development of collective cognitive frames is important, but focusing solely on shared meanings is likely to produce a partial explanation at best.

Furthermore, there is a tendency within such accounts to blur or ignore completely the distinction between the cognitive frames of groups and individuals and the network structures in which they are positioned. Some view perception and meaning in terms of network relationships where ‘interactions between people gradually acquire an objective quality, and eventually people take them for granted’. 97 Such an approach implicitly recognises cognition and perception but makes it indistinguishable from network structures, thereby conflating different types of factors. Other explanations attempt to endogenise cognition. Networks are interpreted as ‘networks of meaning’98 which express mental maps of the structure of social relations. Here the existence and structure of connections are ignored, as what is important is the dominant interpretations that characterise the network. In such cases, a focus on perception and interpretation underplays or fails entirely to acknowledge the ways in which formal rules, on the one hand, and network structures, on the other, influence activities within the field. 94

To understand how changes do or do not happen, it is therefore important to acknowledge all three sets of factors (rules, network structures and cognitive frames) and the interplay between them in a way that does not privilege one over another.

Using the literature to inform our analysis

The foregoing outlines lessons pertaining to scheme design in relation to P4P initiatives. However, although it is necessary to pay careful attention to design in order to increase the likelihood of success, it is unlikely to be sufficient. The burgeoning literature reporting problems with implementation in relation to attempts to change practice in health-care settings draws our attention to the challenges involved. We combine the lessons on scheme design with Bate’s84 framework and, in particular, the nature of challenges involved when exploring the implementation of the AQ programme. We also seek to go beyond the details of the AQ programme to conceptualise change in the organisational field more broadly drawing on Beckert’s94 ideas of how change occurs in such fields. We do not suggest that this is the only way to approach the issues. Instead, we suggest that it is a useful approach which enables us to consider change as a dynamic process involving the interplay of various factors and challenges in a way that resonates with our findings.

Chapter 3 Advancing Quality: background

In this section we present a background description of AQ. This description has been kept to the minimum information required to enable readers to understand the findings. An accessible and detailed description of AQ is available on the AQ website (see www.aquanw.nhs.uk). AQ has evolved over time and new indicators and clinical areas have been added, but this report is mostly concerned with describing and evaluating AQ in relation to the five clinical areas included at October 2008.

Defining quality

Quality of care, for the purpose of the financial incentive programme, at the outset, was intended to be measured in three different ways as follows:

-

Clinical process and outcome measures in five clinical areas – acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), pneumonia, and hip and knee replacement. (See Appendix 1 for a full list of clinical process and outcome measures used in AQ.)

-

Patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) – patients undergoing elective hip and knee surgery are asked a series of questions about their health status before their procedure and a series of questions 6 months after their procedure.

-

Patient experience of care provided – various approaches to measuring patient experience were trialled during the programme. These included two questions based on questions contained in the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey instrument used in the USA. Patients were asked to rate the hospital on a scale of 1 to 10 and to indicate the likelihood (on a scale from definitely no to definitely yes) that they would recommend the hospital to family and friends. A further six questions, ‘Six of the best’, covered experience of service delivery, staff and information.

The choice of clinical areas was based on high-volume conditions and availability of metrics to measure processes and outcomes of care. The clinical measures used at the start of AQ are contained in Appendix 1. As an illustration of the nature of AQ measure, the community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) measures are listed in Box 2.

-

Percentage of patients who received an oxygenation assessment within 24 hours prior to or after hospital arrival.

-

Initial antibiotic selection.

-

Blood culture collected prior to first antibiotic administration.

-

Antibiotic timing, percentage of pneumonia patients who received first dose of antibiotics within 6 hours after hospital arrival.

-

Smoking cessation advice/counselling.

Payment rules

The first year of AQ was run as a pure tournament, with hospitals that scored in the top quartile on the incentivised quality metrics receiving a 4% bonus payment and those in the second quartile a bonus of 2%. For the next 6 months, financial incentives were awarded based on three criteria. Providers for which performance in this period was above the median score from the first year were awarded an attainment bonus. Those earning this attainment bonus were then eligible for two further payments, which were awarded to the top quartile of improvers and those that achieved quality scores in the top two quartiles. There were no penalties or withholds for poor performers during these first 18 months.

After the first 18-month period, payments were made under a new P4P framework that applied across the whole of England. Under this CQUIN framework, a fixed proportion of the hospital’s expected income was withheld and paid out only if hospitals achieved required performance thresholds. The majority of topics, quality measures and threshold values were negotiated and agreed between the hospital and the primary care trust (PCT), the NHS organisation responsible for planning and commissioning health-care services on behalf of the local population. 14 However, the regional authority could also specify some CQUIN requirements, and the North West region included the AQ indicators in the CQUIN requirements of all 24 hospitals. Required levels of achievement were based on the quality scores that had been achieved by each hospital in the first year of AQ.

The potential total amounts of money linked to performance were kept constant throughout the period. In total, £3.2M in bonuses was paid to hospitals in the North West region for the first year and £1.6M was paid for the next 6 months. The transfer to the CQUIN framework meant that the P4P scheme effectively changed from bonuses to penalties. The CQUIN agreements were designed so that hospitals would lose £3.2M in total each year if they all failed to meet all of the targets for the five AQ conditions. At the same time, although comparative league table performance data continued to be reported, AQ was no longer a tournament-style system in that payment was not intended to be made to only a subset of providers.

Relative performance and payment was initially based on the CPS, an aggregate score that reflects the number of opportunities to do the right thing and the proportion that were achieved. The ACS is a reflection of what happened to individual patients. It measures the proportion of patients that received all of the relevant interventions (i.e. perfect care with regard to AQ measures). Although payment was based on CPS performance initially, recent changes mean that the ACS is used as a basis for payment.

Participants and set-up

All 24 acute trusts and the North West Ambulance Trust participated in AQ from its inception to the end of the period covered by the evaluation, although only four trusts undertook CABG. (During this period Trafford Healthcare NHS Trust was taken over by Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; therefore, the number of participating organisations was reduced to 23.) AQ was led from the (then) NHS North West Strategic Health Authority (SHA).

The AQ programme went live for all participating trusts on 1 October 2008, although only the clinical process and outcome measures were being collected from this date. PROMs data collection commenced on 1 January 2009 and patient experience data collection was anticipated to commence winter 2009/10. Seven trusts participated in a first-wave pilot. Wave 1 sites were recruited in May 2007 and site selection was informed by geographical location (because the intention was to obtain geographical spread), willingness to participate, readiness of systems, good evidence of partnership between primary and secondary care and organisation type. First-wave organisations received twice as much in set-up costs as second-wave trusts (£60,000 vs. £30,000).

The clinical-measures component of AQ was based on the HQID in the USA, which was a collaboration between the CMS and Premier Inc. (hereafter Premier), a nationwide organisation of not-for-profit hospitals. Following a competitive process, in November 2007 Premier was selected by the SHA as the partner organisation for AQ. Premier’s role involved the provision of advice and support from staff based in the north-west of England as well as telephone and e-mail support from US-based staff who worked on the UK time zone. This was supplemented with occasional visits from these US-based staff to provide face-to-face training and advice workshops in the north-west of England. In addition, Premier provided software tools and data-management and reporting facilities adapted from its experience of helping to support the delivery of the HQID in the USA. Following Premier’s decision not to tender for the new contract in 2010, an alternative provider undertook this role for the remainder of the period covered by this evaluation. [Clarity Informatics took on this role from December 2010. The new service provider designed a new online tool for data entry and analysis, called Clarity Assure, which has now replaced Premier’s Quality Measures Reporter (QMR) tool.]

Seven trusts participated in a first-wave AQ pilot. Wave 1 sites were recruited in May 2008 and site selection was informed by geographical location (because the intention was to obtain geographical spread), willingness to participate, readiness of systems, good evidence of partnership between primary and secondary care, and organisation type. First-wave organisations received twice as much in set-up costs as second-wave trusts (£60,000 vs. £30,000).

Advancing Quality went live for all participating trusts on 1 October 2008, although only the clinical process and outcome measures were being collected from this date. PROMs data collection commenced on 1 January 2009 and patient experience data collection went live on 1 January 2010.

Data definition, submission and monitoring

The clinical-measures component of AQ is based on the US HQID. AQ measures are supported by a detailed data dictionary, compliance with which is intended to ensure standardisation within and between providers.

The NHS data for patients discharged within a particular month were sent to Premier 58 days after the end of that month. Once the data had been checked for completeness of general data elements, the patients were grouped to the five clinical areas (if they qualified). The data were then made available by Premier to participating providers using a web tool for data collection. These data showed patients for each of the clinical areas. Trusts were then able to complete data entry for the fields relevant to AQ measures, run reports on their data using this web tool, verify that their understanding of eligible patients tallied with Premier’s data, check for missing data and resolve mismatches when appropriate. No changes were permitted after the resolution deadline and the process from month-end to the production of final reports by Premier took 158 days. Individual trusts submitted clinical data sets to Secondary Uses Service (SUS), the NHS comprehensive data repository. These data included information on dates of admission and discharge, primary diagnosis, procedure codes, age, sex, and so on, from their patient administration systems. This is a routine data-collection process for all trusts nationally. Patient data were extracted from SUS. For AQ, three organisations, the Greater Manchester Commissioning Business Service (CBS), the Cheshire & Mersey Contract Information Shared Services Unit and the Cumbria & Lancashire Contracting Information Service, extracted data sets for patients covered by their area of the north-west of England. CBS agreed to collate the three extracts, format them to fit Premier specifications and transmit them to Premier on behalf of all North West region providers. This enabled data extraction exercises to be reduced from 24 to three. This took place 45 days after the month-end. Preparing the data sets, including removing patient identifiers, meant that the data were not transmitted to Premier until day 58. Premier identified the relevant AQ population for each provider and then returned this to that provider on day 68. All providers had 30 days to enter data relating to AQ processes. For example, did the pneumonia patient receive the first dose of antibiotics within 6 hours after hospital arrival? Providers submitted these data via the web tool (QMR) and 30 days later the deadline for issue resolution was reached and the data set was closed (day 128). AQ reports were produced 30 days later (158 days).

Developments during the evaluation period

Commissioning for Quality and Innovation Payment Framework

From 1 April 2010, AQ became part of the NHS North West CQUIN payment framework, which meant that changes were made to payment rules. Whereas AQ was a tournament-style system that (in year 1) rewarded top performers, CQUIN involved setting provider-specific stretch targets that reward an agreed level of improvement from the previous year’s baseline. This meant that all providers that achieved the agreed performance were eligible for CQUIN payment. The local stretch targets for each provider for AQ year 3 were set by the SHA AQ team, which used year 1 results as baseline owing to the unavailability of year 2 data at the time CQUIN targets had to be disseminated to providers (March 2010). In some cases, low year 3 targets resulted in payments to providers that had performance below the average performance of year 2.