Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1022/01. The contractual start date was in November 2012. The final report began editorial review in February 2014 and was accepted for publication in October 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Blank et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Demand management defines any method used to monitor, direct or regulate patient referrals. This includes the methods by which patients are referred from primary care to specialist, non-emergency care provided in hospital. This interface between primary and secondary care is a pivotal organisational feature in many health-care systems, including the NHS. In the UK, primary-care physicians act as the gatekeeper for patient access to secondary care and are responsible for deciding which patients require referral to specialist care. Similar models are found in health-care systems throughout the developed world, for example Australia, Denmark and the Netherlands. 1 Elsewhere, self-referral dominates (e.g. France), or the colocation of primary and specialist services leads to a variety of referral pathways (e.g. the USA). As demand outstrips resources in the UK, the volume and appropriateness of referrals from primary care to specialist services has become a key concern within the NHS. Worldwide, shifts in demographics and disease patterns, accompanied by changes in societal expectations and the relationship between professionals and patients (including the influence of the internet), are driving up treatment costs. As a result of this, several strategies have developed to manage the referral of patients to secondary care, with interventions that target primary care, specialist services or infrastructure (such as referral management centres).

Recent reviews of referral management interventions

The effectiveness of interventions to improve outpatient referrals from primary to secondary care has been the subject of a Cochrane review. 1 The Cochrane review searched for only high-quality, controlled studies and found 17 published papers. The authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence on organisational and financial interventions aimed at primary care, and also inconclusive evidence on effective educational interventions. They did, however, suggest that focusing on potentially effective interventions such as secondary care provider-led education activities, structured referral management sheets, enhancement of primary care and in-house second opinions should guide further research. A previous review on the effects of service innovation on the quality and pattern of referrals from primary care predates recent innovations such as referral management centres. 2 This previous review concluded that professional interventions such as guidelines and education, although able to affect clinical behaviour, had limited effect on referral rates, whereas organisational innovations were more likely to affect referral rates. Further to this, Dunst and Gorman3 reanalysed the Faulkner review along with the previous Cochrane review4 and concluded that interventions that more actively involved primary-care physicians were more effective in influencing rates and patterns of referral.

More recently, referral management in the general practitioner (GP) context has been the subject of work funded by The King’s Fund. 5 Their report highlights the concerns of many with regard to the risks of managing demand without taking account of patient safety, acknowledging that referral management has the capacity to increase clinical risk as well as to reduce it. In considering whether or not one approach to referral management is ‘better’ than another, they suggest that ‘light touch interventions’ such as peer review and feedback, alongside the use of guidelines and structured referral sheets, may offer the most cost-effective approach. However, although the report contributes important insights, it does not suggest best practice examples of these interventions or how they would best be implemented in practice.

Theoretical/conceptual framework

It is increasingly recognised that most interventions in health care can be considered to be complex, with individual and organisational factors affecting how and if interventions lead to improved outcomes. 6 This recognition of the complexity of interventions has been accompanied by a corresponding growth in the challenges for standard methods of evaluation and synthesis. Evidence-based practice requires policy-makers and practitioners to have readily available access to information on interventions that have been shown to work or not work, or indeed have the potential to cause harm. Systematic reviews are an established way of exploring the effectiveness of interventions and a cornerstone of evidence-based practice in order to identify, evaluate and summarise the findings of all available research evidence. Methods for carrying out systematic reviews have become increasingly refined, led by Cochrane, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination which details the formal procedures required. Conventional systematic review methods, however, face challenges in establishing clear intervention-outcome links when complex multifactorial processes are operating, and there are few experimental studies to draw upon.

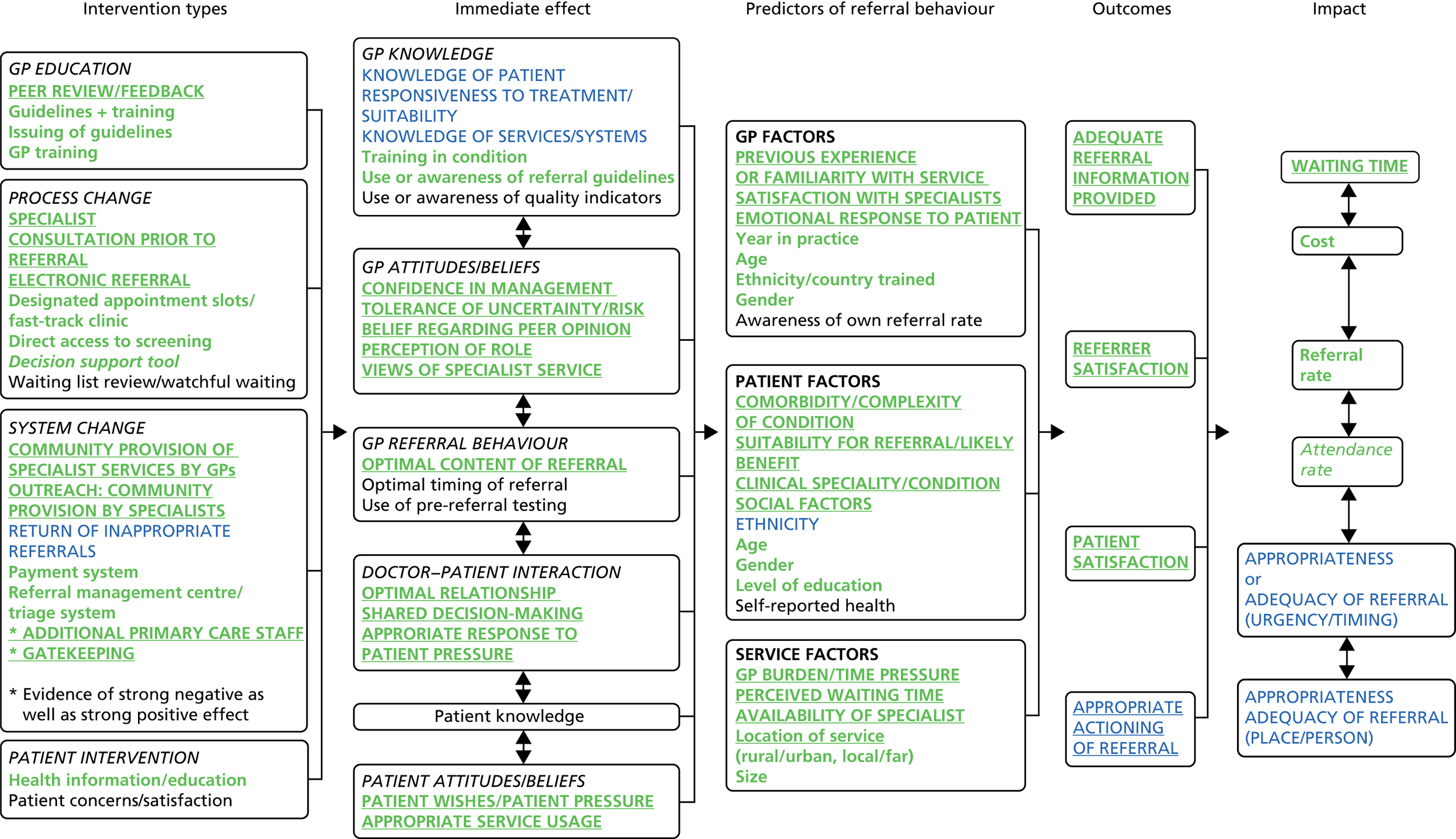

As much of the international evidence in the area of referral management is observational in nature and lacks control comparators, our work builds on previous reviews by taking broader inclusion criteria (to include all study designs and grey literature, as well as evidence from other industries). The review findings are presented via a conceptual model (a logic model), which details the range of interventions identified, evidence of their effectiveness and factors which may influence how and if interventions lead to demand management outcomes. The work not only explores the effectiveness of interventions for demand management, but also aims to uncover detail of the processes whereby interventions may lead to an impact on health-care systems in order to determine applicability to the UK context.

Logic models

Logic model methods are a form of theory-based evaluation that focus on relating hypothesised links between an intervention and its constituent parts to its outcomes and long-term impacts. Logic models are concerned with examining the processes of implementation, mechanisms of change and participant responses in order to develop hypothesised links or a ‘theory of change.’7 In order to develop a theory of change, it is necessary to understand the moderator and mediator variables in the process. 8 These factors are the key to understanding how an intervention works and how interventions may work in different health-care contexts. Logic model evaluation methods begin by mapping out an intervention and then examining conjectured links between the intervention activities and anticipated outcomes to develop a summarised theory of how an intervention works, usually in diagrammatic form. Outcomes are conceptualised as being the end of a chain of intermediate changes which the evaluation process seeks to track, with each intermediate point predicting the outcomes that may occur in the future. 9 Logic models have been suggested as a means to help to provide a strategic perspective on complex programmes and to understand the relationships between various elements of an intervention and outcomes. 10 In particular, they are recommended for evaluating highly complex, multisite interventions with multiple and/or indeterminate outcomes. 11

The area of referral/demand management has many of the same challenges as other complex interventions. A key issue relates to the diversity of the many different referral management approaches that have been investigated, which involve varying degrees of active intervention in referral systems and processes. Understanding how these interventions operate is important when evaluating applicability between different systems and contexts. Logic model methods are underpinned by a systems perspective and provide a mechanism for evaluating system impacts, and for supporting managers in presenting a logical argument for how and why an intervention will address a specific need. There has been growing interest in applying the approach to evaluation of health care. It has been highlighted, for example, that hospitals need to look at the logistics of their patient-pathway processes and use a systems perspective to examine flows through the process. Referral management entails moving from a system that reacts in an ad-hoc way to meet increasing needs to one that is able to plan, direct and optimise services in order to optimise demand, capacity and access across an area. Uncovering the assumptions and processes within a referral management intervention, therefore, requires an understanding of system operation and assumptions which the logic model methodology is well placed to address.

Research questions

This research was designed to conduct an inclusive systematic review and develop a logic model to answer the following research questions:

-

What can be learned from the international evidence on interventions to manage referral from primary to specialist care?

-

How can international evidence on interventions to manage referral from primary to specialist care be applied in a UK context?

-

What factors affect the applicability of international evidence in the UK?

-

What are the pathways from interventions to improved outcomes?

Chapter 2 Review methods

A review protocol was developed for the project and can be found at www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/81178/PRO-11–1022–01.pdf.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants: all primary care medical physicians, hospital specialists and their patients.

Interventions: interventions that aim to influence and/or affect referral from primary care to specialist services by having an impact on the referral practices of the primary physician; in addition, interventions that aim to improve referral between specialists or have the potential to impact on primary care to specialist referrals.

Comparators: the main comparator condition for intervention studies was the usual method of referral practice which is undertaken in the location where the intervention is being implemented. However, alternative comparators have not been excluded. We also included studies with no concurrent comparator (e.g. non-controlled before-and-after studies), as well as qualitative studies where comparators are not relevant.

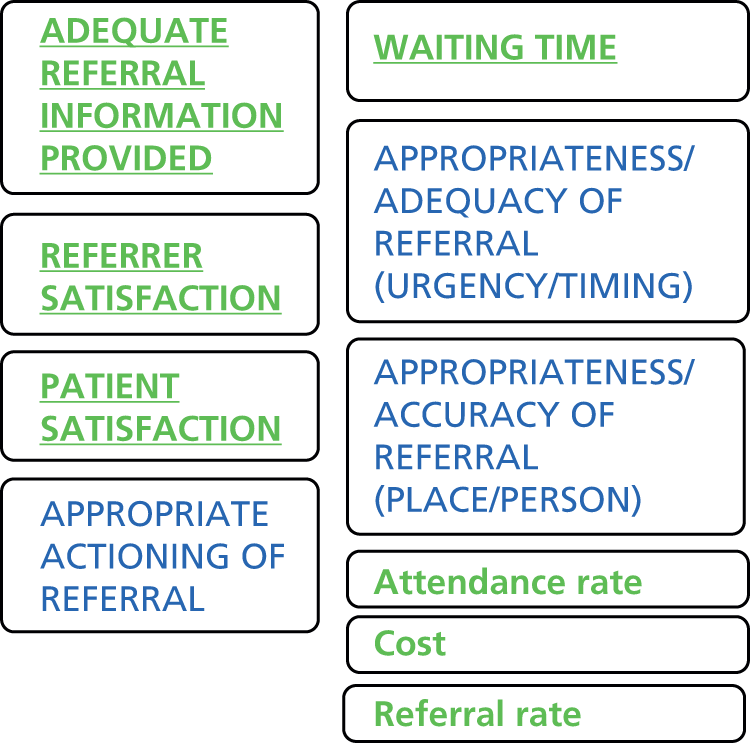

Outcomes: all outcomes relating to referral were considered, including referral rate, referral quality, appropriateness of referral, impact on existing service provision, costs, mortality and morbidity outcomes, length of stay in hospital, safety, effectiveness, patient satisfaction, patient experience and process measures (such as referral variation and conversion rates). All qualitative outcomes were also considered for the relevant papers.

Study design: with the increasing recognition in the literature that a broad range of evidence is needed to inform review findings, no restrictions were placed on study design. The criterion for inclusion in the review was that a study is able to answer or inform the research questions. We have, however, taken note of how quality of study design and execution may affect the reliability of the results generated, as discussed below.

Identification of evidence

Search strategy

Searches were limited by date (January 2000 to July 2013). Articles generated by our searches that consisted of English abstracts only, with full papers published in other languages, were considered for translation, but none was found to meet the inclusion criteria for the review. Our international collaborators did not identify any key articles in other languages, which might have required translation.

All of the literature identified using the above methods were imported into Reference Manager Version 12 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA) and key-worded appropriately. An audit table of the search process was kept, with date of search, search terms/strategy, database searched, number of hits, keywords and other comments included, in order that searches were transparent, systematic and replicable. Searches took place between November 2012 and July 2013. Search strategies and a full list of data sources are given in Appendices 3 and 4.

At the outset of the project a steering group of our international collaborators, relevant patient representatives and other stakeholders was formed. This group had the opportunity to suggest terms to be considered for inclusion in the initial search strategy as well as identifying key articles for potential inclusion.

Initial search

Systematic searches of published and unpublished (grey literature) sources from health care and other industries were undertaken to identify recent, relevant studies. An iterative (i.e. a number of different searches) and emergent (i.e. the understanding of the question develops throughout the process) approach was taken to identify evidence. 12,13

An initial search was generated to address the project research questions, with free-text and subject-heading terms combined to address the concepts of ‘primary care’ and ‘referral’. A broad range of electronic database, including MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and Health Business Elite, was searched in order to reflect the diffuse nature of evidence (see Appendices 3 and 4).

Databases that focus on health management literature, such as the Health Management Information Consortium and Health Business Elite, and management databases such as Business Source Premier and Emerald Management Reviews, were also searched using the initial search strategy.

Additional searches

After the initial search a phrase search was undertaken for ‘referral management centres’ in MEDLINE and CINAHL (for full details of data sources see Appendix 3). This was to make sure that papers had not been missed which described this particular referral method.

As the work progressed, further searches were required in order to seek additional evidence where there were gaps and implicit assumptions that particular outcomes would result following interventions described later.

Citation searches

Citation searches of included articles and systematic reviews were undertaken in the Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index and respective conference papers indices. Where a search returned no results, a search in Scopus was undertaken to double check for any registered citations. Relevant reviews articles were also used to identify studies.

Grey literature

Grey literature (in the form of published or unpublished reports, or data published on websites, in government policy documents or in books) was searched for using the OpenGrey (www.opengrey.eu), Greysource (www.greynet.org) and Google Scholar (http://scholar.google.com; Mountain View, CA, USA) electronic databases.

Reference list checking

Hand-searching of reference lists of all included articles was also undertaken, including relevant systematic reviews.

Selection of papers and data extraction

Citations were uploaded to Reference Manager, and titles and abstracts (where available) of papers were independently screened for inclusion by two reviewers, with disputes resolved by consulting other team members. Full-paper copies of potentially relevant articles were retrieved for systematic screening. A data extraction form was developed using the previous expertise of the review team, trialled using a small number of papers and refined for use here. Data extractions were completed by one reviewer and checked by a second.

Extraction data included country of the study, study design, data collection method, aim of the study, detail of participants (number; any reported demographics), study methods/intervention details, control details, length of follow-up, response and/or attrition rate, context (referral from what/who to what/who), outcome measures, main results and reported associations between elements for the logic model.

Data synthesis

The heterogeneity of the interventions’ aim, design and outcome measures used precluded a meta-analysis of their results. We therefore completed a narrative synthesis of the data, primarily in terms of type of intervention and outcomes. In addition, we built on our previous methodological work14,15 and thematic synthesis methods,16 and used the data to develop a diagrammatic representation (logic model) of the factors that may influence the pathway from interventions to system-wide impacts. The model aimed to portray how interventions operate in order to change practice at individual, local and system-wide levels.

Quality appraisal

Individual studies

The critical appraisal of included evidence is a key part of the review process; however, it is the subject of debate in the field, with no single recognised tool. There is also variation in views regarding the use of scoring systems, with Cochrane discouraging the use of systems which total elements on a checklist, as a single item may jeopardise an entire study. In this review, the quality of studies was assessed using a checklist based on work by Cochrane (see Appendix 2). This approach considers risk of bias and, as it is usually used with experimental studies, required some modification for use with our wider range of study designs. Qualitative papers were evaluated using an adaptation of the Critical Skills Appraisal Program tool. Each paper was assessed by one reviewer and checked for accuracy by a second. Each paper was graded on a three-point scale as being at higher risk of bias, lower risk of bias or unclear risk of bias. The rating was based on not only an aggregate (the number of items) but also an overall judgement of risk of bias. It is important to note that our rating was comparative (higher vs. lower) across the set of papers, with a study classed as being at lower risk not meaning that it was necessarily low risk (see the assessment of each study detailed in Appendix 2). Study design criteria for inclusion in the review were not set as the work was intended to be broad-based and inclusive. Inclusion required only that the paper was able to answer the research question; however, we took account of quality standards in the synthesis and presentation of the evidence as will be outlined below.

Appraising the strength of the evidence

Although there is debate regarding rating of quality of individual studies, there is also considerable variation in views regarding methods for appraising strength of evidence across studies, with a higher number of papers in an area indicating not necessarily greater strength of evidence but only that more work has been carried out. We adopted a system that combined consideration of volume of evidence, and also consistency of evidence, with quality of evidence, based on work by Hoogendoorn et al. 17 Evidence strength appraisal was undertaken by the research team at a series of meetings to establish consensus. Each group of papers was graded as (i) stronger evidence, (ii) weaker evidence or (iii) inconsistent/no evidence.

Stronger evidence (i) was defined as generally consistent findings in multiple higher-quality studies.

Weaker evidence (ii) was defined as generally consistent findings in one higher-quality study and lower-quality studies, or in multiple lower-quality studies.

No evidence or inconsistent evidence (iii) was defined as only one study available or inconsistent findings in multiple studies. Study findings were considered to be inconsistent if fewer than 75% of studies reported the same conclusions.

Validation and applicability of the findings

Following completion of the evidence appraisal and draft logic model synthesis, we undertook a period of stakeholder consultation to seek feedback on the evidence that we had identified and the applicability of the findings to the UK health-care context. This consultation was carried out via presentations to practitioners and patient representatives, via individual meetings to discuss the findings, and by circulating the model to experts in the field (including practitioners, commissioners and academics). In total, 44 individuals contributed to this validation stage. In order to assess how our findings resonated with other work in the field, we also carried out a review of other reviews in the area.

Chapter 3 Results of the review

Quantity of the evidence available

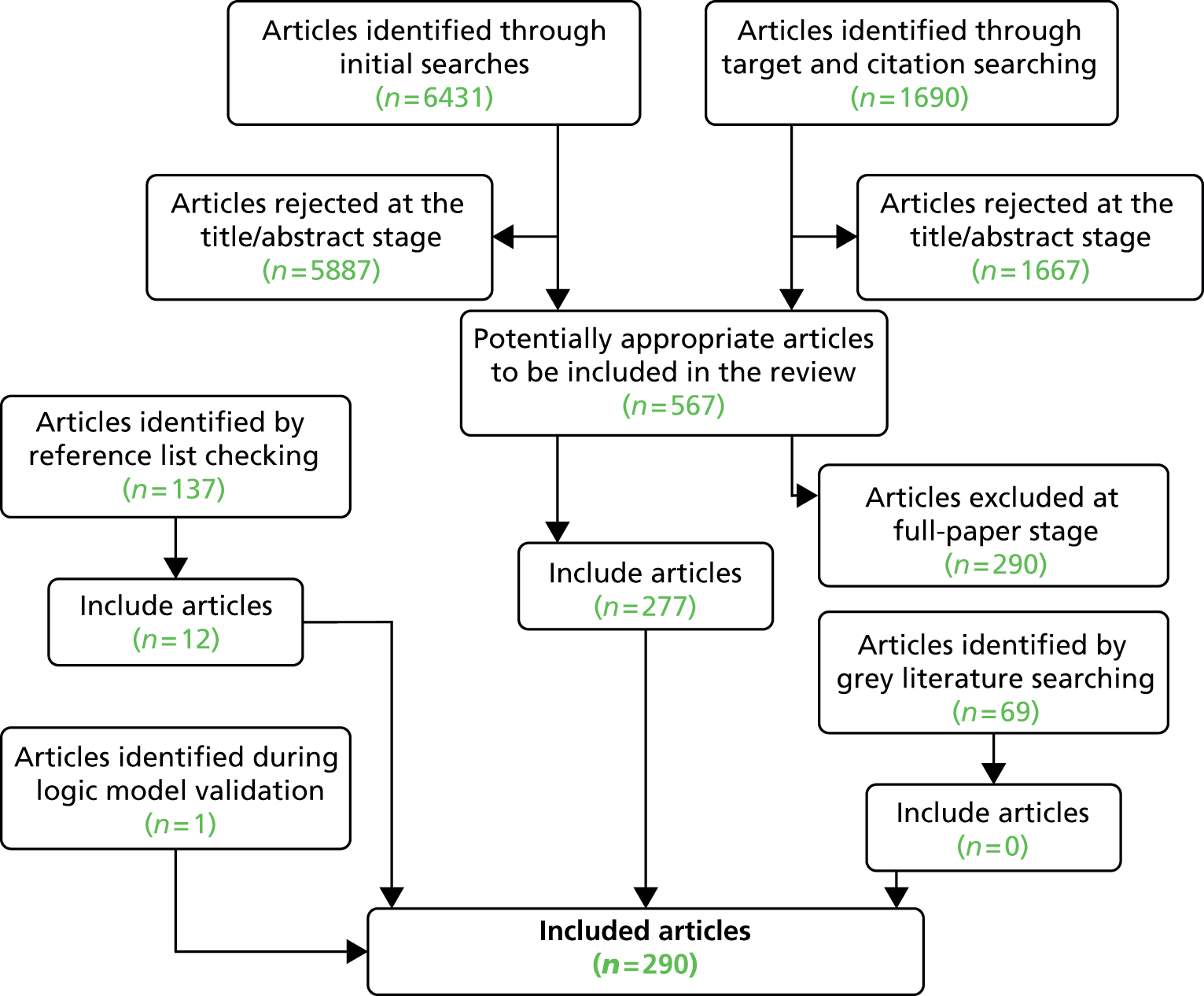

In total, our searches generated a database of 8327 unique papers. Of these, 580 papers were selected for consideration at the full-paper stage. After considering these, searching reference lists and completing the validation stage of the project, 290 full papers were included in the review (Table 1). 18–308 The included papers consisted of 140 intervention papers and 150 non-intervention papers (looking at the views of patients and professionals on the referral process, and factors which predict referral). The 150 non-intervention papers included qualitative studies (n = 33) and non-intervention quantitative studies such as surveys and research reporting associations (n = 117). Grey literature searches generated 69 potentially relevant articles but no additional articles were subsequently found to be within the scope of the review. This was probably due to the fact that a number of grey literature reports had already been identified in the previous searches.

| Source | Number of hits | Number of papers included |

|---|---|---|

| Initial searches | 6431 | 253 |

| Additional searches | 876 | 7 |

| Citation searches of included papers | 814 | 16 |

| Reference list of included papers and systematic reviews | 137 | 12 |

| Grey literature | 69 | 0 |

| Validation stage | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 8328 | 290 |

Of the intervention papers, 114 were identified through the initial database searches, 14 were identified through citation searches, one was identified through additional targeting searching and 10 additional papers were identified through scrutinising reference lists (including those of systematic reviews). One further study was identified at the validation stage of the logic model.

Of the non-intervention studies, 140 were identified through the initial database searches, two were identified through citation searches and six were identified through additional targeting searching, with two additional papers identified through scrutinising reference lists.

In addition, 30 systematic review papers in relevant topics were identified and a synthesis of these was developed in parallel with, but independently to, the logic model development. Comparison with the logic model synthesis is considered in Appendix 6 of this report as part of the validation stage.

We excluded a total of 286 papers which were obtained as full papers but were subsequently found to be outside the scope of the review. A list of these papers and the reasons for their exclusion are given in Appendix 5. Figure 1 details the process of identification of studies.

FIGURE 1.

The process of identification of studies.

Quality of the evidence available

Of the 140 intervention studies, the vast majority (n = 126) were considered to be at lower risk of bias. 19,21–24,27–40,43–71,73–89,92–96,98–100,102–139,141,142,144–150,152,156–160 Fifteen intervention studies were considered to be at higher risk of bias,25,26,42,72,90,91,97,129,140,143,151,153,154 including two studies where the risk of bias was unclear. 19,41 The main risks for bias related to a lack of participant details, only narrative results, percentages reported without supporting statistics, data reported as charts only, inconsistencies in data reporting, poor response rates, attrition rate not reported, weak outcome measures, unclear study design, and evaluation tools which asked questions that strongly led respondents towards positive answers.

Of the 33 qualitative studies, 32 were considered to be at lower risk of bias. 176,177,182,192,194,201,204,207,209,210,212,213,217,218,221,226,228–230,232,237,239,249,252,253,256–258,273,293,306 Only one was considered to be at higher risk of bias due to unclear aim, unclear process for selection of participants and data not clearly distinguished from report of other authors’ work. 20

Of the 117 non-intervention qualitative studies (surveys, etc.), 96 were considered to be at lower risk of bias,98,101,138,161,163–181,183,187–189,191,193,195–200,206,211,215,216,219,220,222,223,225,231,234,235,238,240–243,245–248,250,251,254,259–270,272,274–276,278–294,297,299–305,307 with 21 studies considered to be at higher risk of bias. 162,165,184–186,190,202,203,205,208,214,224,227,233,236,244,255,271,277,295,306,308 The main risks for increased bias were attributable to studies being completed in one small sample only, limited recruitment details, poor response rate, leading questions, recall bias, unpiloted survey tools, unclear methods, limited data presentation, possible overstatement of findings and over-reliance on self-reported outcomes.

Although the higher-risk studies were not excluded from the synthesis and model, the risk of bias was accounted for in assessing the strength of evidence for each element of the model. The detailed quality assessment for each study is provided in Appendix 2.

Study designs

Of the 140 intervention studies, there were 44 randomised controlled trials (RCTs)23,26,27,29–32,36,39,53,54,58–60,63–68,76,77,79,82,85–87,92–95,107,109,111,114,116,117,120,125,126,131,135,144,159 (including 19 of cluster design30–32,39,53,58,63,65–68,77,79,86,111,114,117,120,131), five non-RCTs (nRCTs),62,108,127,130,134 43 before-and-after studies (without a concurrent control group),24,33–35,38,42,43,45,47–52,55,57,69,72–74,89,90,102,103,105,110,112,115,119,122,129,133,136,137,143,145,146,149,154,156–158,160 three controlled before-and-after studies,56,70,81 one case–control study,57 one economic analysis,151 five cohort studies28,46,71,104,128 and 38 evaluation studies (described variably as audits, review, evaluation and retrospective data analysis). 18,19,21,22,25,27,40,41,44,61,75,78,80,83,84,88,91,97–99,106,113,118,121,123,124,132,135,138,140–142,147,148,152,153,155,158

Of the non-intervention views and predictors studies, the 33 qualitative studies consisted of qualitative interview studies (n = 2520,163–165,171,177,178,180,183,192,194,196,201,204,207,210,212,213,237,239,245,249,253,258,260), focus group studies (n = 5217,230,232,252,257), studies using both interviews and focus groups (n = 2196,239) and one study which used transcriptions of video tapes. 182 The non-intervention quantitative studies (n = 117) were mostly cross-sectional surveys (n = 8229,108,161,168–175,178,179,181,183–185,187–191,193,195,198,200,202,203,205,206,208,209,211,214–216,219,220,222,224,225,227,231,232,234–236,238–240,242,244,246,248,250,251,259,261,263,264,268–282,284–287,289,291,292). In addition, one study employed a follow-up survey; two studies used surveys and interviews,176,186 and one further study also included a focus group. 233 There were also 29 studies which consisted of an analysis of patient records, documents, case notes, admissions data and referral forms. 138,166,167,173,197,219,223,235,241,243,254,256,263,265–267 Most of these studies (n = 23) were retrospective designs, but four employed a prospective cohort design. 173,223,254,266 In addition, one study employed Delphi methods196 and one final study used a group-based assessment of referral appropriateness. 255

Populations and settings

Of the 140 interventions, the majority were conducted in the UK (n = 8218,19,21–23,26,28,30–32,34,37,38,41–62,64,65,68,70,71,73,74,76–80,82–85,94,96,99,103,104,106,109,114,116,117,119,122,124–126,128,129,131,133,139,140,142,143,152–157,159,160) or the USA (n = 2024,33,63,87,89,93,98,100,102,112,115,121,132,138,144–147,155,158). There were 10 studies from the Netherlands36,67,86,90,120,123,134,135,141,149 and nine from Australia. 49,72,91,97,105,111,118,136,148 Additional studies were conducted in Canada (n = 327,107,110), Israel (n = 3130,137,150), Italy (n = 369,113,127), Denmark (n = 229,92), Spain (n = 235,75), Finland (n = 195), Norway (n = 1151), Hong Kong (n = 181) and UK/China (n = 125), with one final study where the country of origin was unclear. 101

Of the non-intervention views and predictors studies, the 33 qualitative studies were conducted mostly in the UK (n = 18177,180,182,192,194,201,204,207,209,210,218,228,229,249,252,253,257,258), with additional studies from Australia (n = 5169,176,221,226,245), USA (n = 5170,183,200,202,208), the Netherlands (n = 3212,237), Norway (n = 2164,217), New Zealand (n = 120) and Belgium (n = 1230). The non-intervention quantitative studies (n = 117) were mostly from the UK (n = 35157,174,175,177,187,189,190,193,195,197,198,207,220,224,233,236,241–243,247,251,254–256,265,266,272,273,279,282,284,285,287,291,294) and USA (n = 3198,108,138,171,172,178,184,200,205,214,216,218,219,222,223,225,231,232,235,238,240,246,260,264,267,270,271,274,277,283,286,290,304,305,307), with additional studies from Canada (n = 13107,165,179,196,203,206,227,234,248,263,275,292,299), Australia (n = 1040,91,105,148,162,185,186,188,215,268), the Netherlands (n = 4163,191,212,250), Norway (n = 4164,168,239,244), Israel (n = 3167,261,269), Germany (n = 2173,211), Denmark (n = 229,181), New Zealand (n = 2288,302), France (n = 1161), Ireland (n = 1280), Belgium (n = 1209), Lithuania (n = 1166) and Spain (n = 1276). In addition, two studies were conducted in more than one country, namely the UK/Australia (n = 1169) and USA/Canada/Puerto Rico (n = 1183).

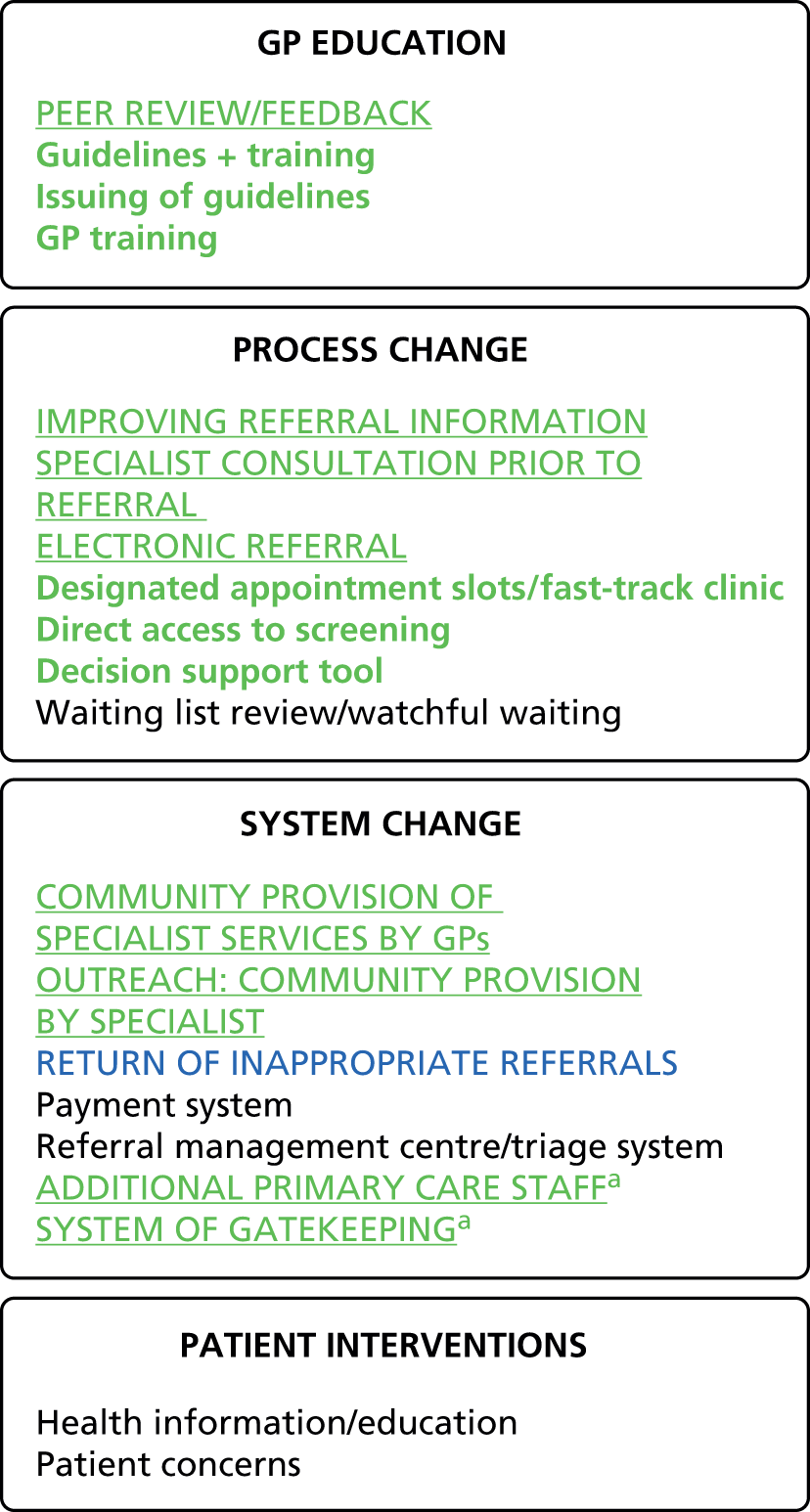

Types of interventions

In total 140 intervention papers were identified and used to create a typology of studies by intervention type. The intervention studies identified may be grouped into four categories: GP education interventions (n = 4919,21,22–69); process change interventions (n = 4770–87,98–120); system change interventions (n = 4118,121–157); and patient-focused interventions (n = 3158–160). It is accepted that this grouping of interventions may have some overlap; however, focus is on the content. Table 2 provides a summary of the intervention studies grouped by typology.

| Intervention category | Intervention type | Studies reporting a positive effect on referral outcomes (first author and year) | Studies reporting no effect on referral outcomes (first author and year) | Strength of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GP education | Peer review and training/feedback | Cooper 2012,19 Evans 2009,21 Evans 2011,22 Jiwa 200423 | i | |

| GP training: professional development | Adams 2012,33 Bennett 2001,30 Donohoe 2000,31 Hands 2001,34 Hilty 2006,24 Kousgaard 2003,29 Ramsay 2003,27 Suris 2007,35 Watson 2001,32 Wolters 200536 | Bhalla 2002,37 Ellard 2012,38 Emmerson 2003,40 Lam 2011,25 Lester 2009,39 Rowlands 2003,26 Shariff 201028 | iii | |

| Guidelines (no training/feedback) | Cusack 2005,43 Idiculla 2000,44 Lucassen 2001,45 Malik 2007,41 Imkampe 2006,47 Potter 2007,46 Twomey 200342 | Fearn 2009,48 Hill 2000,49 Matowe 2002,50 Melia 2008,51 West 200752 | iii | |

| Guidelines with training/feedback/specialist support | Banait 2003,53 Eccles 2001,54 Elwyn 2007,55 Glaves 2005,57 Griffiths 2006,58 Julian 2007,62 Kerry 2000,59 Robling 2002,60 Walkowski 2007,63 White 2004,61 Wright 200656 | Dey 2004,66 Engers 2005,67 Jiwa 2006,68 Morrison 2001,64 Spatafora 2005,69 Wilson 200665 | iii | |

| Process change | Direct access to screening/diagnostic testing | DAMASK 2008,76 Shaw 2006,77 Simpson 2010,78 Thomas 2003,79 Thomas 2010,80 Wong 200081 | Dhillon 2003,82 Eley 2010,83 Gough-Palmer 200984 | iii |

| Designated appointment slots/fast-track clinic | Bridgman 2005,70 Hemingway 2006,73 Khan 2008,71 Sved-Williams 201072 | McNally 2003,74 Prades 201175 | iii | |

| Specialist consultation prior to referral | Eminovic 2009,86 Harrington 2001,93 Hockey 2004,91 Jaatinen 2002,95 Knol 2006,90 Leggett 2004,85 McKoy 2004,89 Nielsen 2003,92 Tadros 2009,96 Wallace 2004,94 Whited 200287 | i | ||

| Electronic referral | Chen 2010,100 Dennison 2006,99 Gandhi 2008,108 Jiwa 2012,105 Kim 2009,98 Kim-Hwang 2010,102 Nicholson 2006,97 Patterson 2004,104 Stoves 2010103 | Kennedy 2012106 | i | |

| Decision support tool | Akbari 2012,110 Emery 2007,111 Junghams 2007,109 Knab 2001,112 Mariotti 2008,113 McGowan 2008107 | Greiver 2005,114 Magill 2009,115 Slade 2008,117 Tierney 2003116 | iii | |

| Waiting list review | Stainkey 2010118 | King 2001,119 van Bokhoven 2012120 | iii | |

| System change | Community provision of ‘specialist’ services by GPs | Callaway 2000,121 Ridsdale 2008,124 Salisbury 2005,125 Sanderson 2002,126 Sauro 2005,127 Standing 2001,122 Van Dijk 2011123 | Levell 2012,129 Rosen 2006128 | i |

| Additional primary care staff | Simpson 2003,143 Van Dijk 2010,141 White 2000142 | i | ||

| Outreach: community provision by specialists | Campbell 2003,131 Felker 2004,132 Gurden 2012,133 Hermush 2009,137 Hughes-Anderson 2002,136 Leiba 2002,130 Schulpen 2003,134 Vlek 2003135 | Johnson 2008,139 Pfeiffer 2011138 | i | |

| Return of inappropriate referrals | Tan 2007,140 Wylie 200118 | ii | ||

| Gatekeeping | Ferris 2001,145 Ferris 2002,146 Joyce 2000,147 Schillinger 2000144 | iii | ||

| Payment system | McGarry 2009148 | Iversen 2000,151 Van Dijk 2013,149 Vardy 2008150 | iii | |

| Referral management centre | Maddison 2004,154 Watson 2002,152 Whiting 2011153 | Cox 2013,156 Ferriter 2006,157 Kim 2004155 | iii | |

| Patient inventions | Patient education | Lyon 2009160 | Heaney 2001159 | iii |

| Patient concerns and satisfaction | Albertson 2002158 | iii |

General practitioner education interventions

The GP education intervention group included peer-review and feedback (n = 4) interventions, which consisted of formal GP training (including continued professional development) (n = 17) and the issuing of guidelines [with (n = 18) and without (n = 11) additional formal training and support for practitioners].

Peer review

Peer-review training/feedback was offered to GPs (plus advanced health-care practitioners and practice managers) in one study19 either in face-to-face meetings19,21,22 or via written feedback. 23 Follow-up was for a minimum of 1 year in all cases. Details of each study are outlined in Table 3.

| Study | Intervention | Design | Country | Specialty | Sample size and details where provided | Study duration (follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cooper 2012 19 | Face-to-face peer review | Audit | UK | Orthopaedics | NR | 5 years |

| Evans 200921 | Face-to-face peer review | Audit | UK | Emergency, orthopaedics | Nine GP practices | 1 year |

| Evans et al. 201122 | Face-to-face peer review | Audit | UK | Seven specialties | 10 GP practices (53 GPs) | 1 year |

| Seven specialties | ||||||

| 21 female GPs, median aged 44 years | ||||||

| Jiwa et al. 200423 | Written peer review | nRCT | UK | Specialists | 26 GPs in intervention group | 18 months (6 months) |

Two studies were at lower risk of bias. Evans21 reported, on average, a significant drop in referrals between the first and fourth quarters (z = 2.25, p = 0.025). The quality of referrals as judged by doctors’ peers improved and referral rates in orthopaedics showed a reduction of up to 50%. However, variability between practices decreased and referral to local services increased. In 2011 they further reported a reduction in variation in individual GP referral rates (from 2.7–7.7 to 3.0–6.5 per 1000 patients per quarter), and a related reduction in overall referral rates (from 5.5 to 4.3 per 1000 patients per quarter). 22 Although the highest individual referrers showed a decrease, the lowest referrers may show an increase in referrals [and a significant negative correlation comparing the first month’s data with the change from first to last month (r = 0.719, p = 0.019)]. 22 Jiwa et al. 23 reported a difference of 7.1 points [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.9 to 12.2 points] in the content scores between the feedback group and the controls after adjusting for baseline differences between the groups. There was a considerable improvement in the content of the referral letters from the feedback group from before to after feedback (mean score 34.1 vs. 39.5). There was no improvement in the scores for the control group in the same period [mean score 34.1 vs. 28.2; mean difference 5.3 (95% CI 1.5 to 9.2)/mean difference 0.55 (95% CI –1.4 to 2.5); t-test degrees of freedom (df) 20/36; p = 0.008/0.6].

One further study was at higher risk of bias. Cooper19 conducted a peer-review scheme for referrals with two guiding principles: the review would benefit the practice and the commissioning group; and there was no blame. GPs, nurses, advanced health-care practitioners and practice managers attended a workshop event and each practice bought two or three trauma and orthopaedic referral letters. Participants worked at mixed tables to understand each practice’s referral profile, share how each practice would handle each situation and then identify any gaps or areas of changed needed. As a result they reported that trauma and orthopaedic expenditure in 2010–11 was 17% less than in 2006–7; in addition, one practice cut ear, nose and throat (ENT) referrals by 20% in the first year and 40% overall.

Formal general practitioner training

Seventeen interventions consisted of formal GP training. Overall, 11 studies reported a positive impact on referral,24,27–36 with six showing no effect or a negative change. 25,26,37–40 Three studies were considered to be at higher risk of bias. 24–26 Overall, the strength of this evidence was graded as inconsistent.

The interventions themselves were varied and it was challenging to separate them further for analysis given the diversity of the interventions delivered. However, seven interventions were delivered in one single session (Table 4) and 10 sessions were delivered over a number of weeks or months (Table 5). The single-session interventions consisted of educational reminders added to radiographs requested by GPs;27 an educational module and 12-page printed guide;28 a structured information pack sent to GPs when their patients attended the department of oncology for the first time;29 an education video;30 in-practice education session plus information pack;31,32 and a 1-day interactive chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) programme. 33

| Study (first author and year) | Intervention | Design | Country | Specialty/treatment | Sample size and details where provided | Study duration (follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adams 201233 | One-day CME | BA | USA | COPD | 351 primary care clinicians | (3–6 months) |

| Bennett 200130 | Video; checklist | cRCT | UK | ENT (glue ear) | 50 practices | (1 year) |

| 177 GPs | ||||||

| Donohoe 200031 | Practice visits; leaflets | cRCT | UK | Diabetic foot | 10 towns | (6 months) |

| 1939 patients | ||||||

| Aged 18+ years | ||||||

| Kousgaard 200329 | Information pack to GPs on first referral | RCT (unblind) | Denmark | Oncology | 248 patients | NR |

| 199 GPs | ||||||

| Ramsay 200327 | Educational reminders on radiographs | RCT | Canada | Radiology (knee and spine) | 81 GP practices | 12 months |

| 2324 referrals | ||||||

| Shariff 201028 | Educational module | Cohort | UK | Oncology (skin cancer) | 460 referrals | 15 months (12 months) |

| Watson 200132 | Practice education session ± information pack | cRCT | UK | Oncology (familial breast/ovarian cancer) | 170 GP practices | 9 months |

| Study (first author and year) | Intervention | Design | Country | Specialty/treatment | Sample size and details where provided | Study duration (follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhalla 200237 | Three or four ENT sessions over a 2-week period once a year | Case control | UK | Otolaryngology (ENT) | Two GP practices | 3 years |

| 1073 referrals | ||||||

| One partner in each GP practice | ||||||

| Ellard 201238 | Six 2-hour interactive sessions on common skin conditions | CBA | UK | Dermatology | 30 GPs from 26 practices | (3 months) |

| Emmerson 200340 | Psychiatric appointments in primary care | Audit | Australia | Psychiatry | Five psychiatrists, 200 GPs | 1 year |

| Hands 200134 | GPs trained at outpatient sessions | BA | UK | All specialties | 22 consultants, 21 GPs | (6 months) |

| Hilty 2006 24 | Regular CME peer review; consultation notes for GPs | BA | USA | Psychiatry | 400 consultations | NR |

| Lam 2011 25 | Diploma in Community Geriatrics | CX | UK/China | Geriatrics | 98 GPs | 1 year |

| Lester 200939 | Video, question and answer, two refresher sessions | cRCT | UK | Psychiatry | 179 patients | (4 months) |

| Two GP practices | ||||||

| Rowlands 2003 26 | Educational referral meetings | CX (part of RCT) | UK | All specialists | 13 GP practices | NR |

| Four or more partners | ||||||

| Suris 200735 | Biweekly educational sessions by specialists | BA | Spain | Rheumatology | 117 GPs | 1 year |

| Wolters 200536 | Distance-learning programme | RCT | Netherlands | Urology | 142 GPs | (14 months) |

Six of the ‘one-session’ interventions (see Table 4) showed positive effects on referral outcomes and were at lower risk of bias.

Adams et al. 33 delivered a 1-day interactive COPD continuing medical education programme. Knowledge/comprehension significantly improved {mean [standard deviation (SD)] pre-test percentage correct, 77.1% (16.4%); 95% CI 76.2% to 78.9%; and mean (SD) post-test percentage correct, 94.7% (8.7%); 95% CI 94.2% to 95.2%; p < 0.001)}, with an absolute percentage change of 17.6% (13.2%). Of the follow-up survey respondents, 92 of 132 (69.7%) reported completely implementing at least one clinical practice change, and only 8 of 132 (6.1%) reported inability to make any clinical practice change after the programme.

Bennett et al. 30 delivered a training video, a checklist or both to three intervention groups. At 1 year post intervention, there was significant improvement in the positive predictive value, adjusted for patient waiting time between GP referral and appointment at the ENT department. The improvement in positive predictive value pre and post intervention was 15% (95% CI –12.1 to 41.7) for the practices receiving both interventions, compared with 20% (95% CI –32.9 to –6.4) for practices receiving only one intervention and a degradation of 34% for those receiving no intervention.

Donohoe et al. 31 delivered an educational intervention aimed at clarifying management of the diabetic foot, referral criteria and the responsibilities of professionals. The intervention included practice visits and education of the whole practice team. Leaflets outlining patients’ role and responsibility were disseminated to the practices. Appropriate referrals from intervention practices to the specialist foot clinic rose significantly (p = 0.05), compared with control practices (p = 0.14).

Kousgaard et al. 29 provided a structured information pack to GPs when their patients attended the department of oncology for the first time. Intervention group practitioners gave a significantly higher score to the information value of the discharge letter than did control group practitioners. The most pronounced difference was seen for psychosocial conditions (p = 0.001) and information about what the patient had been told at the department (p = 0.001).

Ramsay et al. 27 reported that after 6 months of adding educational reminders to radiographs (adjusting for seasonal variation) the frequency of knee radiographs showed a relative risk (RR) reduction of 0.65 and lumbar spine radiographs showed one of 0.64. The mean number of referrals per practice per month for the control group was 2.97 (SD 3.22) knee and 2.88 (SD 3.05) spine, compared with intervention group mean referrals of 1.87 (SD 2.4) knee and 1.76 (SD 2.38) spine.

Watson et al. 32 randomised 170 practices to group A (receiving an in-practice educational session plus information pack), group B (receiving an information pack alone), or group C (receiving neither an educational session nor a pack). There was a 40% (95% CI 30 to –50, p < 0.001) improvement in the proportion of GPs who made the correct referral decision on at least five of six vignettes in group A (79%) compared with the control group (39%) and a 42% (95% CI 31 to 52%, p < 0.001) improvement in group B (81%) compared with the control group (39%). There was no significant difference between groups A and B.

A further ‘one-session’ intervention was not effective. Shariff et al. 28 delivered an educational module that was aimed at building confidence in the diagnosis of lesions not requiring an urgent referral, especially basal cell carcinomas and seborrhoeic keratoses, referred through the ‘2-week wait’ route. After 11 months, the proportion of appropriately referred skin cancers (squamous cell carcinomas and melanomas) was 20.6%, compared with 23.2% before the intervention. The remaining 10 interventions were delivered over several sessions (see Table 5), although the exact number and timing of sessions was not always well described.

Hands et al. 34 reported an intervention where GPs attended outpatient sessions in different clinical specialties of their choice. GPs reported changes in their clinical behaviour which appear to have been maintained at 6 months. GPs stated that referral was discussed/taught in 83% of interactions. Immediately after the session, 25% of GPs reported that this would change their referral behaviour. After 6 months, 29% reported behaviour change in reference to referral.

Hilty et al. 24 implemented the following educational strategies. (1) Regular continuing medical education lectures. (2) GP participation in consultations: GPs present their patients at the beginning of the sessions, and get direct feedback at the end. (3) Consultation notes for GPs: a note by the psychiatrist was sent within 10 minutes of each consultation in a deliberately educational style. A dictation of two to three pages was sent in about 5 working days. (4) Telephone consultations with the psychiatrist. Among the first 200 consultations, only 47.4% of the medication doses for depressive and anxiety disorders were adequate, according to national guidelines. Among the second 200 consultations, dosing adequacy improved to 63.6% (p < 0.001). GPs rated the quality of consultation as significantly higher over time (95% CI 4.45 to 4.83, p < 0.001), as with overall satisfaction (95% CI 4.49 to 4.73, p < 0025). This study was considered to be at higher risk of bias.

Suris et al. 35 carried out biweekly educational sessions with GPs for 1 year (a total of 120 sessions carried out by four rheumatologists). At the end of the pilot year the total number of GP referrals was 31% lower than the previous year (1141 vs. 1652, no significance levels reported). The referral rate to the rheumatology unit decreased significantly from 8.13 per 1000 to 5.53 per 1000 (2.6, 95% CI 2.09 to 3.10; p < 0.001).

Wolters et al. 36 delivered a distance-learning programme accompanied with educational materials or a control group only receiving mailed clinical guidelines. The distance-learning programme comprised: (1) a package for individual learning developed by the Dutch College of General Practitioners; (2) consultation supporting materials: a voiding diary, the international prostate symptom score (IPSS) and Bother score; (3) the guideline summarised into two decision trees [one on clinical management of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) and one on prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing] and a brief explanation; and (4) two information leaflets for patients (on PSA testing and on treatment for LUTS). The intervention group showed a lower referral rate to a urologist [odds ratio (OR) 0.08, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.40], but no effect on PSA testing or prescription of medication.

Six further studies delivered over several sessions did not show a clearly positive effect on referral outcomes. Four of these were at lower risk of bias: Bhalla et al. 37 delivered three or four clinical ENT sessions over a 2-week period, once a year for 3 years to one partner in a GP practice. There was no statistical difference in referral rates (Kruskal–Wallis: p = 0.63) for the trained partner when compared with the other three partners in the same practice. There was also no statistical difference in referral patterns between the intervention and the control practice (Mann–Whitney U-test p = 0.50).

Ellard et al. 38 completed six 2-hour interactive sessions on common skin conditions in early 2011. Appropriate referrals from participants increased from 37.2% in 2010 to 51.8% after training, accompanied by an increase in the mean number of referrals from 20.7 to 25.7. Furthermore, the overall number of appropriate referrals increased from 37.8% to 49.5% at participating surgeries. However, these results were compared with the 36 other local GP practices that did not participate in the training programme, which also displayed an increase in appropriate referrals from 40.8% to 56.4% from 2010 to 2011.

Lester et al. 39 reported an intervention consisting of a 17-minute video, a 15-minute question-and-answer session, and two refresher educational sessions conducted over 4 months. Ninety-seven people with a first episode of psychosis were referred by intervention practices and 82 people from control practices during the study: RR of referral 1.20 (95% CI 0.74 to 1.95, p = 0.48). No effect was observed on secondary outcomes except for ‘delay in reaching early-intervention services’, which was statistically significantly shorter in patients registered in intervention practices (95% CI 83.5 to 360.5, p = 0.002).

Emmerson et al. 40 developed a psychiatric assessment and advisory service for local GPs. Five full-time psychiatrists dedicated a 1-hour appointment per week in their hospital private practice clinics to assess patients referred by local GPs. After 12 months referrals to the clinic were disappointing (n = 30, with 10 referrals from one GP). Feedback from GPs who had used the service showed high levels of satisfaction with the service (mean score 6.2 out of 7). Feedback from GPs who had not used the service showed a strong endorsement of the concept (94%), but there was poor awareness of the service’s existence (26%).

There were also two studies of interventions delivered over several sessions which were at higher risk of bias. Lam et al. 25 conducted an evaluative study to examine the impact of a 1-year part-time Postgraduate Diploma in Community Geriatrics. The diploma includes the components of clinical attachment (20 sessions of clinical geriatric teaching and five sessions of rehabilitation and community health services), interactive workshops, locally developed distance-learning manual, written assignments and examination as well as a clinical examination. Most respondents did not refer elderly patients to private geriatricians and would refer them to public geriatricians or other specialists. After the course, the average percentage of elderly patients being referred to private geriatricians increased from 2.8% to 6.1% and to other specialists decreased from 53.4% to 49.1%. The changes in the referrals to private geriatricians and other specialists were statistically significant. However, no significant change was found in the referrals to public geriatricians. The average percentage remained around 44%. It is unclear which of those outcomes were beneficial or how this study could be applied in a UK context.

Finally, Rowlands et al. 26 implemented an educational intervention consisting of referral meetings. Fewer than half of doctors became involved with development of formal referral or clinical protocols. Eighty-eight per cent noted a change in their referral practice. Overall, there was no change on referral rate in the intervention group. This study was considered to be at higher risk of bias.

Guidelines (no training or feedback)

Interventions that consisted of guidelines mailed to GPs (with no further training, support or feedback) were reported in 12 studies (Table 6). 41–52 The guidelines were for a range of referral conditions and procedures including genetic screening, orthopaedics, complications of diabetes, dementia, dermatology (two studies43,49), radiography (two studies42,50) and cancer (three studies41,46,47). Overall, seven studies reported at least some positive impact on referral,41–47 with five showing no effect or a negative change. 48–52 Two of the positive impact studies were considered to be at higher risk of bias41,42 with all other studies at lower risk of bias. Overall, the strength of this evidence was graded as inconsistent.

| Study (first author and year) | Intervention | Design | Country | Specialty/treatment | Sample size and details where provided | Study duration (follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cusack 200543 | NICE guidelines and a pro forma | BA | UK | Dermatology | 36 GPs | (18 months) |

| 150 referrals | ||||||

| Fearn 200948 | QOF Depression Indicators | BA | UK | Dementia clinic | NR | (18 months) |

| Hill 200049 | Local guidelines | Audit | UK | Dermatology | 33 GP practices | (2 years) |

| 422 patients | ||||||

| Idiculla 200044 | Local guidelines | RCT | UK | Outpatient infertility clinic | 214 GP practices | 1 year |

| 689 referrals | ||||||

| Most aged over 34 years, 84% female only | ||||||

| Imkampe 200647 | Pro forma for breast cancer referral | BA | UK | Oncology (breast cancer) | 2354 referrals | (8 months) |

| Lucassen 200145 | Local guidelines | BA | UK | Regional genetics service | NR | 14 months (6 months) |

| Malik 2007 41 | 2-week wait cancer guidelines | Audit | UK | Oncology (bone or soft tissue tumour) | 40 patients | 2 years |

| Matowe 200250 | Royal College of Radiology referral guidelines | BA | UK | Radiology | 376 GPs in 87 practices | (3 years) |

| 117,747 referrals | ||||||

| Melia 200851 | Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme guidelines | BA | UK | Urology | 200 GP partners in 48 practices | 1–2 years |

| Male patients aged 45–84 years, n = 1520 | ||||||

| Potter 200746 | 2-week wait cancer guidelines | Cohort | UK | Oncology (breast cancer) | 24,999 new referrals | (7 years) |

| Twomey 2003 42 | Local guidelines | BA | UK | Radiology | NR | 2 years |

| West 200752 | Local guidelines | BA | UK | Orthopaedic outpatient department | 471 referrals | 29 weeks |

Seven studies showed a positive effect on at least one referral outcome (although results were often borderline or mixed). Five of these studies were considered to be at lower risk of bias.

Cusack and Buckley43 analysed dermatology referral letters from GPs prior to guidelines and 60 following guideline introduction. NICE guidelines and a pro forma for future referrals were sent to GPs. The percentage of referrals in accordance with NICE guidelines increased from 31% to 45% after introduction of guidelines (p = 0.041). The percentage of inappropriate referrals decreased from 69% to 55%, and 22% of GPs (8 of 36) fully complied with guidelines. However, over 50% of referrals were still inappropriate. The pro forma was used in only 23% of referrals and the provision of data in referral letters remained poor. The number of referrals per month only marginally decreased.

Idiculla et al. 44 analysed 200 GP referral letters submitted before (set 1) and 200 submitted after (set 2) local guidelines on the management of adult diabetes had been issued to local GPs. Following the distribution of the guidelines there was no significant change in the frequency with which specific conditions were documented in referral letters (set 1 vs. set 2): for example, hypertension 72% versus 79%, cerebrovascular disease 89% versus 80%. However, the guidelines did appear to have encouraged the active treatment of hyperglycaemia by GPs before referral.

Lucassen et al. 45 sent referral guidelines for a regional genetics service family cancer clinic to GPs and subsequent content of referral letters was analysed and compared with the previous 6 months. Post guidelines, more referrals met the criteria than before (χ2 = 15.79, p < 0.001). Fewer lower-risk referrals were made: 34% of letters (36/103) were high risk pre guidelines, whereas 47% (46/110) were high risk post guidance (not significant: χ2 for change in proportion of low risk pre and post = 1.34; p = 0.24, and for high risk χ2 = 3.33, p = 0.07). The description of the risk in the GP letter improved so that a greater proportion of generic clinic risks agreed with those described in the GP letter.

Potter et al. 46 used routine data to consider the effect of the introduction of the 2-week wait guideline for cancer referrals. The annual number of referrals increased over 7 years from 3499 in 1999 to 3821 in 2005, a significant increase of 1.6% (95% CI 1.0% to 2.2%). The number of 2-week wait referrals increased by 42% (n = 739) from 1751 in 1999 to 2490 in 2005, an estimated increase of 5.8% per year (5.0% to 6.7%, p = 0.001). By contrast, the number of routine referrals has declined over the same period by an estimated 4.3% a year (3.3% to 5.2%, p < 0.001), giving an apparent reduction of 24% (n = 417) from 1999 to 2005. The percentage of patients diagnosed with cancer in the 2-week wait group decreased from 12.8% (224/1751) in 1999 to 7.7% (191/2490) in 2005 (p < 0.001), whereas the number of cancers detected in the ‘routine’ group increased from 2.5% (43/1748) to 5.3% (70/1331) (p < 0.001) over the same period. About 27% (70/261) of people with cancer are currently referred in the non-urgent group. Waiting times for routine referrals have increased with time.

Imkampe et al. 47 determined whether or not GP grading of referrals into urgent and non-urgent had improved after the introduction of the 2-week rule was introduced. A retrospective review of GP referrals over 8 months, between September 2003 and April 2004, with regard to their urgency, subsequent diagnosis and the use of standardised referral formats was carried out. The results were compared with the 1999 audit. Eighty-two of 1178 patients referred by GP had breast cancer versus 115 of 1176 patients referred in 1999. Sixty-eight per cent (56/82) of breast cancer patients were referred as urgent, compared with 47% (54/115) in 1999 (p = 0.005). A pro forma was used in 47% (548/1178) of GP referrals, while no pro forma was used in 1999. Sixty-five of the 82 cancer patients were referred with a pro forma and 85% (55/65) were referred as urgent.

Two further studies which showed a positive effect on at least one referral outcome were at higher risk of bias. Malik et al. 41 determined if the 2-week wait referral guidelines for suspect cancer referrals had been followed and what proportion of patients referred under the guideline had malignant tumours. Referral letters were evaluated to see if they met Department of Health guidelines for referral of a suspected bone or soft tissue tumour. Most (31 of 40: 78%) ‘2-week’ referrals met the published referral guidelines. However, in 9 of the 40 cases, the patient did not meet the criteria for urgent referral, and none of the nine patients had malignant tumours. Of 40 patients referred under the guideline, 10 of these patients (25%) had malignant tumours, but this was compared with 243 of 507 (48%) of those referred from other sources. Twomey42 assessed GP referral for plain radiography in the areas of hip, knee, cervical spine and lumbar to establish a procedure for the development of care pathways. The proposed guidelines were circulated to all GPs. GP referrals to radiology for plain radiography declined from 2365 the year before the intervention to 1077 the year after intervention, a total reduction of 288 (54%). Similarly, referrals for plain radiography requests declined from 6650 to 4291, a reduction of 2359 (35.5%).

Five further studies (all at lower risk of bias) of dissemination of referral guidelines showed no effect, or a negative effect, on referral outcomes.

Fearn et al. 48 looked at whether or not the introduction of Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) Depression Indicators changed the pattern of referrals from primary care to a dedicated dementia clinic. The percentage of all referrals originating from primary care was about half in both time periods and did not differ significantly between the two time periods (χ2 = 0.88, df = 1, p > 0.1; z = 0.77, p > 0.05). Of the referrals from primary care, about one-third referred in both time periods had dementia. The RR of a diagnosis of dementia in a primary care referral pre and post QOF was 0.55 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.74) and 0.66 (95% CI 0.49 to 0.89), respectively. The proportion of patients referred from primary care with dementia was the same in the cohorts seen both before and after introduction of the QOF Depression Indicator (χ2 = 0.54, df = 1, p > 0.05), a finding corroborated by the z-test (z = 0.60, p > 0.05).

Hill et al. 49 evaluated referral guidelines for dermatology compiled by the dermatologist at the Royal Surrey County Hospital in consultation with local GPs. A 40% increase was seen in the numbers of referrals recorded by the dermatologist as appropriate immediately after the guidelines were sent (from 57% to 80%). The 2-year follow-up audit, however, demonstrated that the improvement had not been sustained, with a decline to 48% appropriate referrals.

Matowe et al. 50 mailed copies of the Royal College of Radiology referral guidelines for chest, limb and joint, and spine radiographs to GPs. There were no significant effects of the intervention on total number of general practice imaging requests. Total referrals decreased by 32 (95% CI –226.7 to 291.4) in the month following guideline dissemination, while the trend decreased by –1.82 requests per month (95% CI –11.8 to 8.2 requests per month). Referral only decreased by average 1.2 per month for the entire 35-month period.

Melia et al. 51 disseminated the Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme (guidelines for GPs on age-specific PSA cut-off levels in asymptomatic men). One year after intervention, awareness of the pack was acknowledged by 112 (56%) GPs (24 were unaware and 64 did not know if they had seen it). The proportion of asymptomatic men referred who had raised antigen levels did not increase significantly from baseline to intervention (24% pre intervention, 29% post intervention; p = 0.42) There was no significant difference in referral rate by area (p = 0.33).

West et al. 52 completed a 13-week audit of referral letters for six specific orthopaedic complaints, namely anterior knee pain, back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, in-toeing in children, sciatica and tennis elbow. Paper copies of referral guidelines produced by orthopaedic consultants were distributed to all local GPs. After a period of 4 weeks for distribution, the process was repeated for a further 13 weeks. The first 13-week period had 195 (64%) referrals that consisted of patients who had not received the recommended management or to whom this had not been mentioned in the referral letter. The second period had 103 (61%). There was no statistically significant difference between the two (p = 0.49).

Guidelines with additional training or feedback

Interventions consisting of guidelines with additional training or feedback were reported in 18 studies (all lower risk of bias), of which 11 showed a positive association with referral outcomes53–63 and six did not (Table 7). 64–69 The guidelines were for a range of referral conditions and procedures including mental health, infertility clinic, dermatology, gynaecology, oncology, colorectal surgeon, urology, cardiology (two studies56,63), low-back pain (two studies66,87), endoscopy (two studies53,55) and radiology (four studies54,57,59,60).

| Study (first author and year) | Intervention | Design | Country | Specialty/treatment | Sample size and details where provided | Study duration (follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banait 200353 | Educational outreach/dyspepsia management guidelines | cRCT | UK | Open-access endoscopy (GI) | 114 practices | (6 months) |

| 233 GPs | ||||||

| Dey 200466 | RCGP guidelines plus outreach visits | cRCT | UK | Low-back pain | 24 health centres | (8 months) |

| 2187 patients; age 18–64 years (mean 42.2 years, SD 12.1) | ||||||

| 54% female | ||||||

| Eccles 200154 | RCGP guidelines, audit and feedback, or educational messages | RCT | UK | Radiology | Six radiology departments; 244 general practices | (1 year) |

| Elwyn 200755 | NICE guidelines plus feedback | BA | UK | Endoscopy (dyspepsia) | 215 GPs | (5 months) |

| Three endoscopy units | ||||||

| Engers 200567 | National guidelines plus workshop | cRCT | the Netherlands | Low-back pain | 41 GPs | NR |

| 531 patients | ||||||

| Glaves 200557 | Guidelines plus return of referrals | BA | UK | Radiology (spine and knee) | Three community hospitals | (1 year) |

| Griffiths 200658 | Local guidelines and training sessions | cRCT | UK | Dermatology | 165 health centres | NR |

| Patients 18+ years with psoriasis n = 188 | ||||||

| Jiwa 200668 | Local guidelines plus visit | cRCT | UK | Colorectal surgeon | 44 practices | (6 months) |

| 180 GPs | ||||||

| 504 patients | ||||||

| GPs 30–60 years | ||||||

| Julian 200762 | Shared care guidelines | nRCT | UK | Gynaecology | 193 GP practices | (8 months) |

| One hospital | ||||||

| Kerry 200059 | Royal College of Radiology guidelines plus feedback | RCT | UK | Radiology (spinal exam) | 69 GP practices | 2 years (9 months) |

| Morrison 200164 | Local guidelines plus meeting | RCT | UK | Outpatient infertility clinic | 214 GP practices | 1 year |

| 689 referrals | ||||||

| Age 34+ years | ||||||

| 84% female | ||||||

| Robling 200260 | Local guidelines plus seminar or newsletter | RCT | UK | Radiology (MRI) | 121 GP practices | NR |

| 182 referrals | ||||||

| Spatafora 200569 | Local guidelines plus meeting | BA | Italy | Urology (outpatients) | 45 urological centres, 263 GPs | NR |

| GPs’ mean age 47 years | ||||||

| 18% female | ||||||

| Walkowski 200763 | Local guidelines, telephone call, e-mail, or in-person visit | cRCT | USA | Cardiology | Five US states | 15 months (3 months) |

| White 200461 | Local guidelines plus implementation strategy | Audit | UK | Mental health | NR | (2 years) |

| Wilson 200665 | Local guidelines plus education meetings and outreach | cRCT | UK | Oncology (familial breast cancer) | GP in Grampian | 4 years (11 months) |

| Wright 200656 | Guidelines, educational meetings, outreach visits | CBA | UK | Cardiology (post TIA for stroke prevention) | One PCT | 50 months (22 months) |

Eleven studies showed a positive relationship between the intervention and referral-related outcomes. 53–63

Banait et al. 53 implemented educational outreach as a strategy for facilitating the uptake of dyspepsia management guidelines in primary care for open-access endoscopy. All groups received the guidelines by post and the intervention groups began to receive education outreach 3 months later. The outreach included practice-based seminars with hospital specialists at which guidelines recommendations were appraised and implementation plans formulated, and was reinforced by visits after 12 weeks. The proportion of appropriate referrals was higher in the intervention group in the 6-month post-intervention period (practice medians: control = 50%, intervention = 63.9%; p < 0.05). The proportion of major findings at endoscopy did not alter significantly, but there was an overall rise in acid-suppressing drugs in the intervention, compared with the control group (+ 8% vs. + 2%, p = 0.005).

Eccles et al. 54 compared two methods of reducing GP requests for radiological tests in accordance with the UK Royal College of Radiologists’ guidelines on lumbar spine and knee radiographs. GPs and consultant radiologists wrote referral guidelines and educational messages for lumbar spine and knee radiographs [based on the Royal College of Radiologists’ guidelines and the Royal College of General Practitioners’ (RCGP) back-pain guidelines]. The referral guidelines were then sent by post to all study GPs. Each practice was randomly allocated to receive audit and feedback or control; and educational messages or control. Feedback covered the previous 6 months’ referrals and was sent to GPs at the start of the intervention period and 6 months later. Educational messages were attached to the reports of every knee or lumbar spine radiograph requested during the intervention. The effect of educational reminder messages (i.e. the change in referral rate after intervention) was an absolute change of 1.53 (95% CI 2.5 to 0.57) for lumbar spine and of 1.61 (2.6 to 0.62) for knee radiographs (relative reductions of ≈20%). The effect of audit and feedback was an absolute change of 0.07 (1.3 to 0.9) for lumbar spine and 0.04 (0.95 to 1.03) for knee radiograph requests (relative reductions of 1%). Requests from doctors who had received audit and feedback were no more likely to be appropriate than requests from other doctors: OR 0.75 (95% CI 0.52 to 1.07) for lumbar spine radiographs and 0.82 (0.50 to 1.33) for knee. For doctors who had received educational reminder messages, the equivalent values were 0.95 (0.63 to 1.67) and 1.36 (0.86 to 2.23).

Elwyn et al. 55 evaluated a system of providing feedback to clinicians following referral requests not adhering to NICE guidelines. Letters were sent to GPs stating that two GPs would be employed part-time to assess all endoscopy letters and referrals for dyspepsia and they would be judged against recently issued NICE guidelines. Where referrals did not meet the criteria, the referring doctor would be informed by letter giving a reason for non-adherence to guidelines. The All Wales Dyspepsia Guidelines based on NICE criteria were circulated to GPs 2 weeks earlier. Adherence to NICE guidelines for referral criteria increased significantly among GPs following the intervention (mean 55% to 75%; 95% CI 13.6 to 26.4; p < 0.001). No similar effect was seen for hospital doctors. The number of gastroscopy referrals for dyspepsia declined after the intervention, but not significantly after inclusion of seasonal effects (p = 0.065). Intervention significantly reduced the referral to procedure time for gastroscopy (mean 52.1 to 39.4 days, 95% CI 6.6 to 18.6 days; p < 0.001).

Wright et al. 56 completed an evaluation of a quality improvement programme for transient ischaemic attack (TIA) referral in three primary care trusts (PCTs). Four local consensus group meetings for relevant stakeholders (including service users and carers) were used to adapt national guidelines to local context and identify barriers and incentives for changing practice. Guideline reminders for clinicians included laminated posters, desktop coasters and electronic referral templates. Guidelines were disseminated via education meetings in each PCT and further education outreach visits to 19 practices. Guidelines were disseminated by post to other practices not requesting a visit. There was a 41% increase in referrals from trained practices, compared with control practices (RR 1.41, p = 0.018). Adherence to best-practice standards was significantly higher in practices that had received the training programme than in the controls.

Glaves57 undertook an intervention where GPs referring to three community hospitals and a district general hospital were circulated with referral guidelines for radiography of the cervical spine, lumbar spine and knee. All requests for these three examinations were checked and requests that did not fit the guidelines were returned to the GP with an explanatory letter and a further copy of the guidelines. If the GP maintained the opinion that the examination was indicated, they had the option of supplying further information in writing or speaking to a consultant radiologist to reach agreement. The total number of examinations fell by 68% in the first year (95% CI 67% to 69%) and 79% in the second year (95% CI 78% to 80%). Knee radiographs fell by 64% in the first year (95% CI 62% to 65%) and 77% in the second year (95% CI 75% to 79%). Lumbar spine radiographs fell by 69% in the first year (95% CI 68% to 71%) and 78% in the second year (95% CI 77% to 80%). Cervical spine radiographs fell by 76% in the first year (95% CI 74% to 78%) and 86% in the second year (95% CI 84% to 88%) (p = 0.001 for all measures).

Griffiths et al. 58 evaluated the effectiveness of guidelines and training sessions on the management of psoriasis in reducing inappropriate referrals from primary care. Guidelines on the management of psoriasis in primary care, developed by local dermatologists, were sent to health centres in the intervention arm, and supplemented by the offer of a practice-based nurse-led training session. Patients in the intervention arm (82/105) were significantly more likely to be appropriately referred than patients in the control arm (49/83), a difference of 19.1% [OR 2.47; 95% CI 1.31 to 4.68; intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) 0]. Only 25 (30%) health centres in the intervention arm took up the offer of training sessions. There was no significant difference in outcome between health centres in the intervention arm that received a training session and those that did not (OR 1.28, 95% CI 0.50 to 3.29; ICC 0).

Kerry et al. 59 evaluated the introduction of radiological guidelines into general practices, together with feedback on referral rates, to see whether or not this reduced the number of GP radiological requests over 1 year. A GP version of the Royal College of Radiologists guidelines was sent to each GP in the 33 practices in the intervention group. Guidelines for examination of chest, hips, knees, spine, skull and sinuses were printed verbatim on two sides of a sheet of A4 paper, which was then laminated. After 9 months’ intervention, practices were sent revised guidelines with individual feedback on the number of examinations requested in the past 6 months. A total of 43,778 radiological requests were made during the 2-year intervention. The number of referrals for all spinal examinations fell by 18% in the intervention group, compared with a 2% rise in the control group (p = 0.05). Taking requests for the lumbar spine alone, there was a reduction of 15% in the intervention group, compared with a rise of 5% in the control group, giving a difference of 20% between the groups (95% CI 3% to 37%). Overall, an 8% reduction in total numbers of radiological requests was observed in the intervention group, compared with a 2% increase in the control group (10% between the two groups, not significant).

Robling et al. 60 investigated whether or not method of access or method of guideline dissemination affects GP compliance with referral guidelines for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in two sequential trials: (1) one group of practices requesting MRI by telephone was compared with a second group requesting in writing using a standard request form. A third group could refer as wished; and (2) one group of practices receiving guidelines via a seminar was compared with a second group who received feedback via a newsletter with practice-specific data on referrals. A third group received both a seminar and feedback, and a fourth group received guidelines only by post. The seminars were facilitated by an academic GP and a researcher. In trial 1, 65% of requests were judged to be compliant with the guidelines and there were no statistical differences between the three groups. Telephone access proved unpopular among participants and written access more cost-effective. In trial 2, 74% of referrals were judged to be compliant with the guidelines and there was no association between method of dissemination of guidelines and compliance. Requests made after dissemination of guidelines were more likely to be compliant: 74% versus 65% (OR 1.62, p < 0.005).

White et al. 61 aimed to use guidelines to improve communication between GPs and community mental health teams (CMHTs). Following a baseline audit of referrals and assessment letters, locally agreed good practice protocols were developed and shared widely, accompanied by a dissemination and implementation strategy (updates at 6-monthly intervals throughout the project). Significant improvements occurred in both the GP and the CMHT letters. These were most dramatic after 1 year but tailed off considerably in the second year despite continued efforts to implement the protocol’s standards. Annual GP referrals (percentage of total) reduced from 661 (63%) to 550 (58%), p-value not significant, and new referrals completing CMHT assessment increased from 369 (66%) to 423 (89%) (p < 0.001).