Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1809/1074. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The final report began editorial review in April 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Soper et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

CLAHRC aims and functions

In 2008 the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) established nine Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) to develop forward-looking partnerships between universities and local NHS organisations focused on improving patient outcomes through the conduct and application of applied health research. 1 The NIHR made £88 million available over 5 years for this initiative with the requirement that each CLAHRC also obtained matching funding from local NHS organisations. The aims of the CLAHRCs, as defined in the original call for proposals for external evaluations of the CLAHRC initiative, were:2

-

to secure a step change in the way that applied health research is done and applied health research evidence is implemented locally

-

to increase capacity to conduct and implement applied health research through collaborative partnerships between universities and NHS organisations

-

to link those who conduct applied health research with all those who use it in practice across the health community covered by the collaboration

-

to test and evaluate new initiatives to encourage implementation of applied health research findings into practice

-

to create and embed approaches to conducting and implementing research that are specifically designed to take account of the way that health care is increasingly delivered across sectors and across a wide geographical area

-

to focus on the needs of patients, and particularly on research targeted at chronic disease and public health interventions and

-

to improve patient outcomes across the geographic area covered by the collaboration.

The CLAHRCs’ remit was to identify and address problems facing the NHS and population health more widely. This involves three interlinked functions: conducting high-quality applied health research; supporting the ‘translation’ of research evidence into practice; and increasing the capacity of NHS organisations to engage with and apply research. The focus was therefore not only on the translation of research (whether undertaken locally or elsewhere) but also on developing ways of doing applied research that maximise its chances of being useful to the service and of being implemented.

From the start the CLAHRCs were encouraged to develop a community-wide outward-facing approach based on partnerships between academia and the NHS across the widest possible local geographical area, that also actively involved patients and the public and other relevant stakeholders. 3 They were also intended to be experimental, conceived as pilot projects with a common vision but considerable discretion as to how they achieved their goals.

Policy context and the emergence of the CLAHRCs

There has been long-standing recognition of the gap between findings generated by research and their implementation in daily practice. It was against this background that countries have set up programmes to encourage the implementation of research findings that is directly relevant to health care through collaboration,4 including the 10-year Quebec Social Research Council grant programme to encourage collaboration between researchers, practitioners and policy-makers set up in 1992,5 the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) programme launched in 1998 by the US Veterans Health Administration6 and the Need to Know project in Manitoba, funded in 2001 by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. 7 In 2001, the US Institute of Medicine further highlighted the gap between research findings and health-care practice, in the context of its seminal work on quality improvement in health care,8 and it subsequently set up a clinical research round table that identified two ‘translational blocks’ or ‘translational gaps’ in clinical research:9

-

the transfer of new understandings of disease mechanisms, gained in the laboratory, into the development of new methods for diagnosis, therapy and prevention, and their first testing in humans

-

the translation of results from clinical studies into everyday clinical practice and health decision-making.

In the UK, the NHS Research & Development (R&D) programme was launched in 1991 to strengthen public health and health services research and ensure that the content and delivery of health care were based on high-quality research. 10 It built on previous government attempts to generate research to meet the needs of policy-makers which had emphasised the importance of users of applied health research and researchers working closely together. 11 The NHS R&D programme was intended to be driven by the needs of the service and be fully integrated into its management structure, with regional R&D offices providing a local focus for collaboration. 12,13

However, in practice, effective collaboration between researchers, clinicians and managers has sometimes proved elusive and the UK experience illustrated how entrenched cross-cultural differences and ongoing reorganisations of NHS structures hindered the full realisation of the hoped-for exchanges. 12

The establishment of the CLAHRCs represents one of the more recent attempts to integrate the health research system into the health-care system. 14 It followed the launch, in 2006, of a new 5-year research and development strategy for the NHS in England which aimed to create a health research system in which the NHS supported leading-edge research that focused on the needs of patients and the public. 15 This led directly to the creation of the NIHR. In the same year, the Cooksey Report on UK health research funding highlighted, among other findings, the two gaps in translation of health research previously identified by the Iinstitute of Medicine. 16 Specifically, it noted that a crucial stage in the second gap was the identification and evaluation of new interventions that are effective and appropriate for everyday use in the NHS, and their implementation into routine clinical practice.

Meanwhile, in 2007, the High Level Group on Clinical Effectiveness, which had been asked by the Chief Medical Officer to suggest a programme of action to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of clinical care, recommended in the field of health research that ‘the health service harnesses better the capacity of higher education to assist with this agenda through promoting the development of new models of community-wide “academic health centres” to encourage relevant research, engagement and population focus and embed a critical culture that is more receptive to change’ (p. 14). 17

Parallel efforts to strengthen translation of research into patient benefit and promote innovation following the Cooksey Report included the establishment, in 2007, of 12 NIHR-funded biomedical research centres. 18 These were designed to address the first translation gap, drive innovation in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of ill health, and translate advances in biomedical research into benefits for patients. Shortly afterwards, 16 smaller and more specialist biomedical research units were established with the same remit and a similar focus. 19

There was also continuing activity in the NHS, and the 2008 NHS Next Stage review addressed the same broad themes. 20 Specifically, it argued that there were cultural, professional and organisational barriers to effective innovation and relevant research, which would require new initiatives; these included academic health science centres and health innovation and education clusters (HIECs). In 2009, five UK-based academic health science centres were designated by the Department of Health with the aim of focusing on world-class research, teaching and patient care and competing internationally with comparable centres in the USA, Canada, Singapore, Sweden and the Netherlands. 21 The HIECs initiative was launched in 2009/10, with 17 HIECs set up across England for an initial period of 2–3 years. 22 These sought to promote innovation in the NHS by combining the expertise of industry, health and education at a local level.

Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care were originally foreseen as NIHR ‘Academic Health Centres of the Future’. 3 However, against the background of other ongoing initiatives, there was a perceived need to identify a designation that would more appropriately emphasise the collaborative nature of the proposed partnerships and their role in applied health research and the implementation of research evidence, as well as avoiding ‘any confusion with Academic Health Science Centres’ given their different purpose and structure. 23 The distinctive feature of CLAHRCs was that they had a wider, integrating role in promoting collaboration across a range of local organisations, including NHS trusts, primary care trusts, universities and industry, and a key focus on addressing the second translation gap. Depending on local circumstances, they might also relate to the work of other parts of the landscape such as biomedical research units/centres. In Chapter 5 we will return to the question of how CLAHRCs have assumed a unique role in this wider, and constantly evolving, landscape, and discuss their role in relation to developments in both the health research system and the health service.

The conceptual background

A wide range of thinking about the conduct and translation of research informed the development of the CLAHRCs and considerations of how their role is best interpreted. However, the literature on the diffusion of health-care research, knowledge transfer and dissemination is complex, reflecting the contributions made from a variety of disciplines, each bringing their own conceptual frameworks and terminology, such as ‘research’, ‘evidence’, ‘knowledge’ or ‘innovation’, and ‘diffusion’, ‘dissemination’, ‘exchange’, ‘transfer’ or ‘learning’. While we acknowledge this complexity and the resulting difficulties of summarising this literature without losing significant detail and risking misinterpretation, we also believe that there was a need to draw on insights from a wide range of theories and approaches in order to guide our work and help interpret observations from CLAHRCs as they evolved. Building on a targeted review of the literature which we undertook early in the evaluation,24 and which we have updated in light of more recent evidence, we describe here different insights from some key approaches that have explored the causal relationship between research production and research use.

Research diffusion and knowledge utilisation

Research diffusion and knowledge utilisation are concepts central to the working of CLAHRCs. Two key papers are discussed here. Estabrooks et al. suggest that research on knowledge utilisation has evolved through a series of paradigms in which certain disciplines seem to have dominated at different stages. 25 In contrast, Greenhalgh et al. suggest that many streams of research have explored research diffusion in parallel and attempt to identify the interactions and linkages between them, developing ‘a unifying conceptual model’ to consider the diffusion of innovations in health-care organisations. 26 Both groups of authors emphasise the wide range of research traditions involved and explain how an early emphasis on diffusion research (Greenhalgh et al. ) or knowledge utilisation (Estabrooks et al. ) broadened to cover other fields. Greenhalgh et al. cite the emergence of development studies (covering the different contexts and meaning or value of innovations) and health promotion;26 Estabrooks et al. note the emergence of diffusion of innovations and technology transfer. 25 Both comment on the emergence of evidence-based medicine in the mid-1980s, and Greenhalgh et al. also discuss the relevance of the organisation and management literature. 26

Greenhalgh et al. ’s attempt to provide an underlying framework was ambitious, and their suggestions for (and against) further research have been helpful. They highlight the importance of context and ‘confounders’, which ‘lie at the very heart of the diffusion, dissemination, and implementation of complex innovations’ and how these are ‘not extraneous to the object of study; they are an integral part of it’. 26 Therefore, future research should be multidisciplinary and multimethod, meticulously detailed and participatory, and should acknowledge the central importance of context. They further suggest that the next generation of research on the diffusion of health service innovations should be empirically driven but theory-guided so that consistent processes can emerge.

We were persuaded by the arguments brought forward by Greenhalgh et al. and informed by their recommendations on how research translation should be studied. For CLAHRCs, the important lesson is that when discussing research diffusion and knowledge utilisation there is no single, stable and agreed conceptual framework and this requires being sensitive to how terms are being used and recognising that the same concept may have different meanings. It also means that there is no off-the-shelf conceptual model that can be used without the potential for confusion.

Implementation and the use of theory

Eccles et al. also call for greater use of theory in promoting the uptake of research findings, and describe the current situation as ‘an expensive version of trial-and-error, with no a-priori reason to expect success or to have confidence of being able to replicate success if it is achieved’. 27 Following other work, they describe theory as ‘a coherent and non-contradictory set of statements, concepts or ideas that organises, predicts and explains phenomena, events, behaviour, etc.’ (p. 108), and, along with Ferlie and Shortell,28 note that interventions that seek to improve health care operate at four levels: the individual health professional, the health-care group or team, the organisation providing health care (e.g. NHS trusts) and the larger health-care system or environment in which individual organisations are embedded. In a comment that could have been tailored specifically for the CLAHRCs, Eccles et al. also note: ‘Because implementation research lives in a policy-relevant context where clinicians, managers, and policy makers may erroneously believe that they already know what is best to do, it will always be prey to the demands for a quick fix and the political solution’ (p. 111). 27

In a similar vein, Grol et al. refer to the need for a ‘better understanding of the black box of change in health care’ and also call for a more systematic use of theories in planning and evaluating improvement interventions in clinical practice. 29 Following other work, they describe ‘theory’ as ‘a system of ideas or statements held as an explanation or account of a group of facts or phenomena’, and distinguish two types:

-

impact theories: hypotheses about how specific interventions will facilitate a desired change, as well as the causes, effects and factors determining success (or the lack of it) in improving health care

-

process theories: how implementation activities should be planned, organised and scheduled in order to be effective (the organisational plan) and how a target group will utilise and be influenced by the activities (the utilisation plan).

According to Grol et al. ,29 the ideal model for change in health care would encompass both types of theory. They summarise and recommend a set of 16 theories about change in health care, and, in a taxonomy that closely reflects that used by Eccles et al. ,27 differentiate these by ecological level (individual professional, social setting, organisational context, political and economic context). Cognisant of the limited empirical evidence of the effectiveness and feasibility of theoretical approaches to produce the intended change, they emphasise the need to draw on different theoretical perspectives simultaneously to inform change plans.

Building on Greenhalgh et al. ’s26 work, Damschroder et al. developed a consolidated, metatheoretical framework for implementation research that is based on 19 published theories. 30 This again is a very broad approach (the authors use the term ‘theory’ to refer to published models, theories and frameworks) that encompasses five major, interactive domains:

-

intervention characteristics: source, evidence base, relative advantage, adaptability, trialability, complexity, design quality and packaging, and cost

-

outer setting: economic, social and political context in which organisation resides

-

inner setting: structural, political and cultural contexts through which the implementation will proceed

-

characteristics of the individuals involved: knowledge and beliefs about implementation, belief in own capabilities, identification with organisation and other personal attributes such as tolerance of ambiguity, intellectual ability, motivation, values, competence, capacity, innovativeness, tenure and learning style

-

process of implementation: planning, engaging, executing, reflecting and learning.

The aim was to provide a pragmatic structure for identifying potential influences on implementation and organising findings across studies.

Knowledge mobilisation and research utilisation: the potential contribution of the management literature

The relevance of the organisation and management literature is explored more fully by Crilly et al. ,31 who note that there is a well-established literature on the utilisation of clinical evidence in health care but that there has been less consideration of the utilisation of management evidence and research by health-care organisations. Crilly et al. 31 identify 10 thematic categories from the management literature: the nature of knowledge and knowing; information systems and technology; communities of practice; organisational form; organisational learning; resource-based view of the firm; critical theory; knowledge transfer and performance; barriers and facilitators; and culture. A review of the health and social science literature identified two further domains: the evidence-based movement and ‘super structures’, which they define as ‘the infrastructure of institutions and funding that commission healthcare research’ (p. 45). 31

Based on their review, the authors provide a series of propositions, including the general thesis that productivity and efficiency will become increasingly important in the context of spending restrictions in England, and that, as a result, knowledge transfer and the diffusion of innovations will be crucial to the sustainability of NHS organisations. Overall, they argue, the NHS would need to consider how knowledge and information can be used to improve productivity, innovation and performance. These arguments have been adopted in the establishment of Academic Health Science Networks (AHSNs) in England in 2013,32 to which we return later in this report.

Crilly et al. 31 also put forward propositions that are more specific to entities such as the CLAHRCs. They highlight the lack of consensus on what constitutes evidence-based management and suggest that ‘all management knowledge is contested’ (p. 216). 31 They draw on evidence about barriers to, and facilitators of, transfer, and propose that knowledge mobilisation is not just a mere technical activity, arguing that it is also cultural and political. A further proposition that Crilly et al. 31 put forward is extremely germane to the CLAHRCs: they suggest that partnership and network-based organisational forms are more effective at knowledge-sharing than markets or hierarchies and they emphasise the value of collaboration. This last proposition was also identified as important in studies of organisational culture, which we discuss further below. 33

Crilly et al. 31 observe that learning processes and their relationship with organisational design emerged as an important theme in their review. However, it is their further observation that is particularly telling, especially in relation to the CLAHRCs. Crilly et al. 31 note that the question of organisational form has received little attention in the health-care literature despite major reorganisations designed to promote bench to bedside research translation and organisational learning.

Knowledge transfer and exchange

A closely related field is the ongoing work on knowledge transfer and exchange (KTE), which Mitton et al. define as ‘an interactive process involving the interchange of knowledge between research users and researcher producers’ (p. 729). 34 In a wide-ranging review that examined the evidence base for KTE, the authors note that knowledge transfer emerged in the 1990s as a process by which research messages were pushed by the producers of research to the users of research but that, more recently, knowledge exchange emerged as a result of growing evidence that the successful uptake of knowledge requires more than one-way communication, calling instead for genuine interaction among researchers, decision-makers and other stakeholders. They also note a growing emphasis on generating knowledge that can have a practical impact on the health system, which has been a key driver of the CLAHRC scheme.

Mitton et al. list the key KTE strategies mentioned in the literature, including:34

-

face-to-face exchange (consultation, regular meetings) between decision-makers and researchers

-

education sessions for decision-makers

-

networks and communities of practice

-

facilitated meetings between decision-makers and researchers

-

interactive, multidisciplinary workshops

-

capacity building within health services and health delivery organisations

-

web-based information, electronic communications

-

steering committees (to integrate views of local experts into design, conduct and interpretation of research).

They also identify a variety of mechanisms to facilitate KTE, such as joint researcher–decision-maker workshops, the inclusion of decision-makers in the research process as part of interdisciplinary research teams, a collaborative definition of research questions and the use of intermediaries who understand both roles, known as ‘knowledge brokers’.

These lists suggest that a possible blueprint might be emerging for subsequent programmes (such as the CLAHRCs) to follow. However, Mitton et al. reiterate the concern about the lack of empirical evidence raised by others, noting that ‘despite the rhetoric and growing perception in health services research circles of the “value” of KTE, there is actually very little evidence that can adequately inform what KTE strategies work in what contexts’ (p. 756). 34

Research dissemination

There is some overlap between Mitton et al. ’s34 work on knowledge transfer and exchange and a review undertaken by Wilson et al. on the conceptual or organising frameworks relating to research dissemination. 35

While their focus is on dissemination, Wilson et al. 35 reiterate the debate about terminology mentioned earlier and note that the terms ‘diffusion’, ‘dissemination’, ‘implementation’, ‘knowledge transfer’, ‘knowledge mobilisation’, ‘linkage and exchange’ and ‘research into practice’ are all used to describe overlapping and interrelated concepts and practices. The authors define ‘dissemination’ broadly as ‘a planned process that involves consideration of target audiences and the settings in which research findings are to be received and, where appropriate, communicating and interacting with wider policy and health service audiences in ways that will facilitate research uptake in decision-making processes and practice’ (p. 2)(a formula that resonates with CLAHRC objectives). They note that there are currently a number of theoretically informed frameworks available to researchers that could be used to help guide their dissemination planning and activity, and identify 33, of which 28 are underpinned at least in part by one or more of three theoretical approaches: persuasive communication, diffusion of innovations theory and social marketing.

The authors do not provide a blueprint, although they caution against over-reliance on linear models of health communication. They also reiterate the need to use theoretically informed strategies and, specifically, suggest that funding agencies could consider encouraging grant applicants to develop theoretically informed plans for research dissemination.

Knowledge translation

The call for applications to establish the CLAHRCs stressed their role in addressing the second translation gap. 3 However, the terms ‘translation’ and ‘translation gap’ can be variously interpreted. Moreover, additional gaps have subsequently been identified to complement (and complicate) the two identified by the US Institute of Medicine 8 and the Cooksey Report. 16 Thus Westfall et al. propose a third translational step involving research in ambulatory clinical practices. 36 This proposal is based on the observation that much of clinical research is undertaken in an academic clinical setting whereas the majority of patients receive medical care in a primary care setting. It is at this interface, Westfall et al. 36 argue, that practice-based primary research is required to support primary care physicians to incorporate new discoveries into daily clinical practice, with the third translational step involving dissemination and implementation research. Khoury et al. add a fourth step that, beyond implementation, considers the impact of a given ‘discovery’ on population health outcomes. 37

However, it is increasingly recognised that this terminology may be unhelpful, and that a linear, basic-to-applied model which assumes that ‘gaps’ can somehow be ‘bridged’ does not fully capture the complexities of moving knowledge into action. 38 The translation and implementation of research in practice depends, in part, on the relevance, quality and usefulness of the research itself to service needs. That, in turn, depends on the ways in which research agendas are set, research processes implemented and research knowledge communicated and exchanged. Generating, translating and adopting knowledge is likely to involve iteration and feedback between multiple actors involved to varying degrees in different phases; therefore, implementation activity cannot be studied in isolation from research generation activity.

Research impact assessment

There is growing interest in understanding and measuring the return on investment in medical research. In a systematic review of the associated literature, Hanney et al. identified 200 papers, but relatively few were empirical studies. 39 One approach has been the descriptive categorisation of payback and the payback analytical framework developed by Buxton and Hanney,40 which originally assessed the impact or payback from health services research funded by the health department in England but is now applied more widely. The categorisation covers a wide range of measures of impact, including knowledge, benefits to future research and research use, informing policy and product development, health sector benefits and broader economic benefits. The payback framework focuses attention on the whole process including research production and use. Of specific relevance to the CLAHRCs and their potential influence in local health economies is another study identified in the review. This assessed the impact of the NHS South and West Region’s Development and Evaluation Committee’s technology appraisal reports and compared the impact in the south-west with that elsewhere in England. 41 It found considerable impact in the south-west but less elsewhere, suggesting that having local authors known to local decision-makers was influential in encouraging translation, a finding of interest given the local remit of the CLAHRCs.

Capacity building: collaborative research and absorptive capacity

The main purpose of the CLAHRCs was to develop collaborations that are a ‘mutually beneficial, forward-looking partnership between a university and the surrounding NHS organisations, focused on improving patient outcomes through the conduct and application of applied health research’ (p. 2). 3 Denis and Lomas traced the development of a collaborative approach to research in which researchers and potential users work together to identify research agendas, commission research and so on. 4 They identified the 1983 study by Kogan and Henkel of the R&D system of the health department in England42 as an important early contribution. According to Kogan and Henkel, a critical feature of the collaborative approach, as applied to research and policy-making, is that researchers and policy-makers should join forces ‘to identify research needs against policy relevance and feasibility’ (p. 143). 42 Work to analyse and operationalise this collaborative approach was subsequently undertaken by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation, led by Lomas, whose concept of ‘linkage and exchange’ between users and researchers has been particularly influential. 43,44 Collaborative approaches to research somewhat mirror the concept of ‘Mode 2′ research: research that is context-driven, problem-focused and interdisciplinary. 14,45–47

The CLAHRCs were also required to increase ‘the capacity of NHS organisations to engage with and apply research’ (p. 4). 2 The concept of absorptive capacity was first described by Cohen and Levinthal in the context of industrial research;48 they suggested that conducting R&D within a firm helps that firm to develop and maintain its broader capabilities to assimilate and exploit externally available information from research. 49,50 The original theory could apply at different levels, including individual and organisational levels, and it can be argued that, when clinicians and managers in a health-care system are seen as stakeholders in the research system, their engagement in research is a way of enhancing their ability and willingness to use research from wherever it might originate. For example, Buxton and Hanney51 include increased capacity to use research as one of the benefits identified in their multidimensional categorisation of benefits from health research,40,51–53 and this approach is replicated in other health research impact assessment frameworks that build on the payback framework. 54–56 Part of the theoretical underpinning that research engagement contributes to building absorptive capacity is the notion that, in practice at least, knowledge is not a pure public good but instead requires a level of understanding of research before it can be absorbed. 57 Such understanding can be built up by undertaking research.

Cultural change

Another requirement of the CLAHRCs was to ‘embed a critical culture [in the NHS] that is more receptive to change’ (p. 14). 17 Shortell et al. 58 explored the relationship of organisational culture, quality improvement and selected outcomes in hospitals in the USA, showing that an organisational culture characterised as participative, flexible and risk-taking was significantly related to quality improvement implementation. More recently, Mannion et al. classified the extant cultures in NHS organisations into four types – clan, hierarchical, developmental and rational – and explored how these cultures change over time. 33 In general they identified ‘developmental’ culture, characterised by innovation, dynamism, growth and entrepreneurship with an external, relational focus, as one in which change was viewed as a ‘positive organisational attribute . . . [and there was a] . . . willingness of senior management to embrace innovative approaches to delivering services’ (p. 209). 33 It is this developmental culture that most closely matches the culture the CLAHRCs are seeking to instil. This is a considerable challenge; Mannion et al. found that this development culture was dominant in only a small percentage of NHS hospital trusts and general practitioner (GP) practices. 33 However, they also suggest that cultural change can happen when it is triggered by a perception of crisis, initiated and shaped by strong leaders, consolidated by perceived success and mediated by relearning or re-education.

Organisational change and system shift

Some health-care organisations have paid particular attention to the role of research in their overall approach to improve performance. 59 For example, the Veterans Administration in the USA sought to promote research engagement throughout its health-care delivery system as part of a comprehensive re-engineering exercise designed to improve the quality of the health care provided. 60 Veterans Administration investigators are nested in a fully integrated health-care delivery system with a stable patient population with a high prevalence of chronic conditions, which provides them ‘with unparalleled opportunities to translate research questions into studies and research findings into clinical action’ (p. I–10). 61 One way in which this integration has been achieved is through the aforementioned QUERI programme. Launched in 1998, it sought to accelerate the implementation of new research findings into clinical care by creating strong links between those performing research and those responsible for health systems operations: a remit that resonates strongly with that of the CLAHRCs. An evaluation of the QUERI programme described this approach as achieving a ‘paradigm shift to an action-oriented approach that meaningfully engages clinicians, managers, patients/clients, and researchers in research-driven initiatives to improve quality’ (p. 1). 62 In language that echoes that later used by the CLAHRCs, the authors concluded that this shift is towards coproduction of knowledge, or ‘Mode 2′ knowledge production.

Organising for quality

In the context of CLAHRCs, work on quality improvement also provides important insights. Bate et al. ,63 in a study of the quality of nine high-performing health-care organisations in the UK and the USA, took an approach that was grounded in the examination of actual processes at different organisational levels. Reflecting the observations of Grol et al. described earlier in this section,30 Bate et al. point to the underuse of theory in the quality improvement literature and note that much of the evidence that is available is descriptive rather than explanatory. 63 Furthermore, they contend that quality improvement has been dominated by a form of ‘menu mentality’,63 characterised by lists of factors seen as important, such as leadership support, team-based structures and composition, and information technologies (and their failings), instead of focusing on the processes that will bring these factors together to achieve change.

Emphasising that quality improvement has to be seen as a complex process, they suggest that the keys to quality improvement lie in the distinct characteristics and dynamics of organisational and human processes. In theoretical terms this is a shift from a variance or variables theory (e.g. more of X and more of Y produce more of Z) to a process theory (e.g. do A and then B to get to C). In empirical terms it is the shift from seeing quality improvement merely as a method, technique, discipline or set of skills to seeing it as a human and organisational achievement, that is a social process. Bate et al. identify six common challenges that all the organisations they studied faced, which they describe as structural (organising, planning and co-ordinating quality improvement), political, cultural, educational, emotional, and physical and technical. 63

Like others, Bate et al. 63 argue that there is no single best way to achieve service excellence. The case studies they report underscore the notion that quality improvement processes are interconnected and symbiotic. Organisational processes may form cycles or closed loops, which may be virtuous (upward improvement) or vicious (downward degrading) spirals. This step beyond the ‘menu mentality’ focuses on sequencing and transformation, and provides important insights for the CLAHRCs about the need to examine organisational processes and their interactions over time.

Normalisation process theory

Normalisation process theory (NPT) was developed by May et al. 64,65 and is concerned both with the implementation of new ways of thinking, acting and organising in health care and with the integration (‘routine embedding’) of new systems of practice into existing organisational and professional settings. NPT proposes what May and Finch refer to as a ‘working model of implementation, embedding and integration in conditions marked by complexity and emergence’ (p. 535). 66 It covers the relationships between a complex intervention and the context in which it is implemented. It is interested in the processes by which implementation proceeds – including interactions between people, technologies and organisational structures – and the work that proceeds from these. It proposes that (1) innovations become embedded in practice as a result of people working, individually and collectively, to implement them; (2) the work of implementation is operationalised through four generative mechanisms identified as coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring; and (3) organising structures and social norms specify the rules and roles that frame action. 66 The four mechanisms are described further as:64,67

-

coherence or sense-making: how complex interventions are formed in ways that hold together and people make sense of, and specify, their involvement in it

-

cognitive participation: how communities of practice are built and sustained, that is how actors enrol themselves and others into a complex intervention

-

collective action: the collective work that people do to enact a set of practices

-

reflexive monitoring: the appraisal that people make to understand the ways in which a new set of practices affects them and those around them.

May considers NPT a generic and middle-range theory of implementation that examines what people do and how they work. 64 This distinguishes it from theories of the cultural transmission of innovations (such as diffusion of innovations) that seek to explain how innovations spread, theories of collective and individual learning and expertise that seek to explain how innovations, are internalised, and theories of the relationships between individual attitudes and intentions, and behavioural outcomes. NPT emphasises the need to look for processes. It provides an important frame for CLAHRCs in that the outcomes of the CLAHRCs can be seen to result from the integration of a complex intervention into a complex system achieved by the accomplishments of its stakeholders.

Conclusions

This section has discussed theories of the diffusion of innovation, research use, quality improvement, collaboration and process theory that can inform CLAHRCs’ activities and their evaluation. The main observations are further summarised in Table 1. While we would not want to place too much weight on this brief overview, we believe that a number of key lessons can be learned:

| Approach | Focus | Features/strategy | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation | |||

| Diffusion of innovation | Conceptual framework for implementation developed by Greenhalgh and others26 based on systematic literature review | Captures many of the features of implementation in the health services context and identifies some key attributes for success | Health-service specific Builds on a range of existing literature Broad and generalisable |

| Research use, includes research-based practitioner model, embedded research model and organisational excellence | Implementation by various groups/at various levels | Responsibility for implementation is at various levels, with an emphasis on creating a research-oriented mind-set | Context-driven Emphasises capacity building May help to clarify thinking about research uptake |

| Quality improvement | Several different models | Clear definition of the necessary, but not sufficient, conditions for the implementation of change | Importance of a combined approach, using relevant aspects from various models |

| Collaboration | |||

| Linkage and exchange, and knowledge brokering | Theoretical model focusing on personal interactions | Emphasis on frequent interpersonal interactions as crucial for learning | Recognises the importance of learning and capacity-building |

| Process | |||

| Organising for quality | Focusing on the characteristics and dynamics of organisational processes | Emphasis on key constituent processes in organisations and their interrelations over time | Sees improvement as a social process as well as a set of techniques or methods |

| NPT | Theoretical model focusing on process evaluation | Emphasis on what people do and how they work | Specifically aimed at the implementation and integration of complex interventions in health-care settings in relation to the work that it involves |

-

There is no ‘industry standard’ to guide the CLAHRCs; CLAHRCs are involved in both developing their own solutions and delivering these.

-

The causes of problems are understood differently, and consequently solutions vary (although these are often at a high level of abstraction).

-

It is widely recognised that context is very important.

-

There is a general scepticism about overly rigid linear models (but in all there is a sense that processes can be managed to make progress over time).

-

It is likely that successful change will be multifaceted and therefore evaluations must be equally multifaceted if they are to understand the range of processes involved.

We have identified a body of literature reflecting an area of research characterised by conceptual pluralism, alternative ways of framing the evidence and competing causal explanations. The conceptual terrain might be described as dynamic, pluralistic and competitive. With terminologies that evolve over time and compete one with another we need to define our terms with care. Given the wide range of theories and metatheories it is not always clear how to translate research into practice, although three general messages do emerge. The first is that context is increasingly identified as crucial to shaping outcome. If practitioners do not understand the context within which they operate, and evaluators fail to assess this accurately, then it is unlikely that we will develop a good understanding of why the CLAHRCs work in some contexts and not in others. Secondly, while there is a flow of knowledge it is not always clear that this is simply from research to practice and, even when this is largely the case, there will be a variety of ways in which information flows ‘back’ the other way. In the language of economists, there will be supply push as well as demand pull. Thirdly, and following from the first two, the metaphor of a single bridge, linking research to practice and with a steady flow of traffic moving one way, is unhelpful. Competing metaphors might include an ecosystem or a marketplace. 68

Structure of this report

This introductory chapter briefly set out the aims of and the policy context within which the CLAHRCs were established, as a means to illustrate the complexities involved and the innovative nature of the initiative. It also summarised the conceptual background against which the CLAHRCs were developed. Chapter 2 describes the methods used, setting out our approach and the phased nature of the work undertaken. Chapters 3 and 4 present the core findings of the work, with Chapter 3 presenting the observations from phase 1 of our evaluation while Chapter 4 focuses on findings emerging from phase 2 and is structured according to major themes that were identified in phase 1 of the study. Chapter 5 discusses our overall findings, seeking to relate them to the wider literature on research use and impact. We also review current developments in the NHS, in particular the new AHSNs, and explore how they, and the CLAHRCs in their second round of funding, have been tasked to work together in an integrated and synergistic way. Finally, we draw some general conclusions, highlight some practical implications and make recommendations for further research in an area that is continuing to evolve.

Chapter 2 Methods

This evaluation explored how effectively the CLAHRCs supported the translation of research into patient benefit, and how they developed ways of doing applied research that maximised its chances of being useful to the service and the capacity of the NHS to respond.

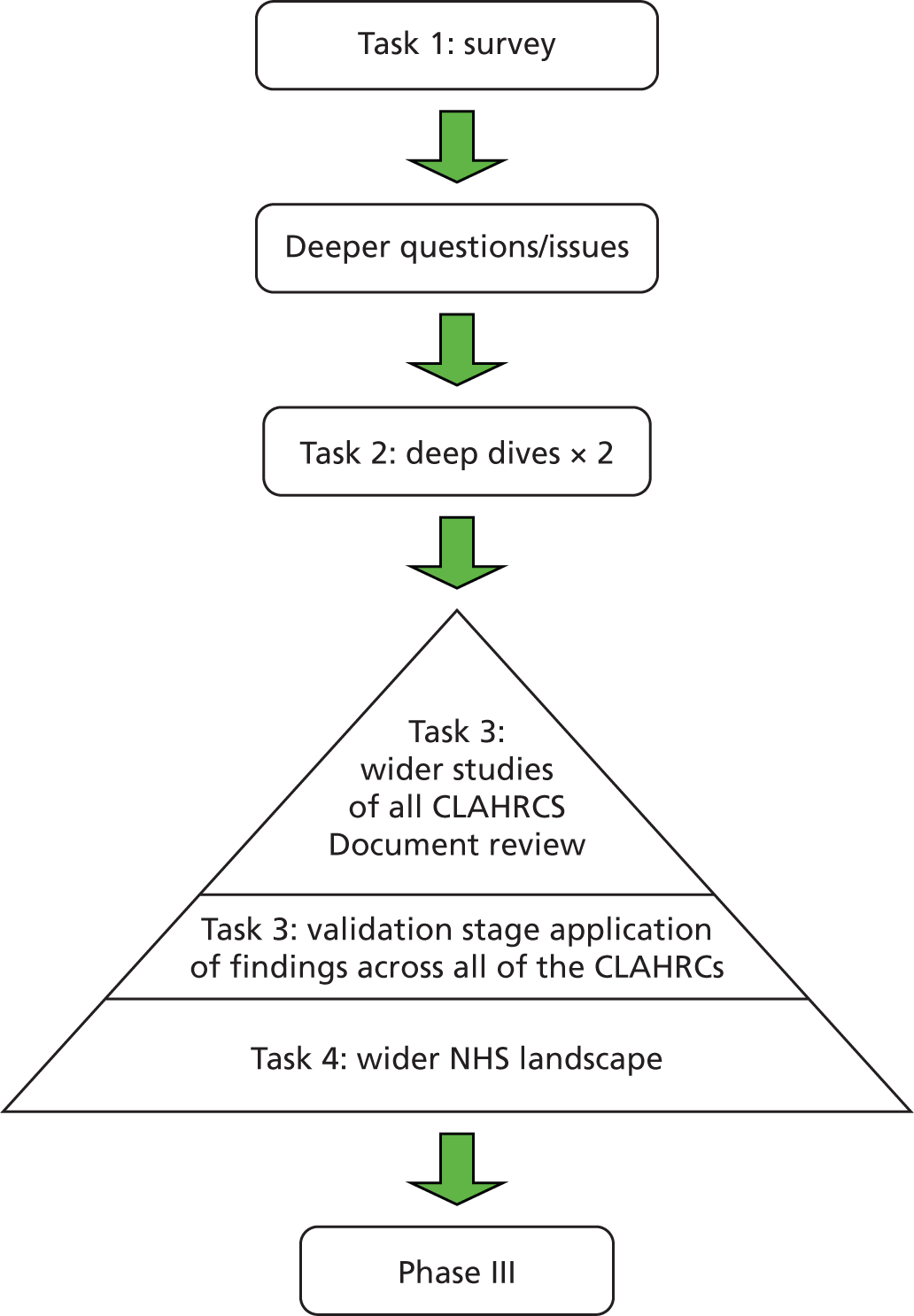

In developing the design for our study we sought to take account of the evolving and changing nature of the context within which CLAHRCs were established. We note how there were many paths that CLAHRCs could have taken to generate knowledge and enable its adoption for the improvement of patient care. Against this background, our approach to evaluation had to be emergent and ready to develop with the CLAHRCs’ phases. We thus adopted a tiered design to enable an adaptive and emergent approach69 and incorporated the formative evaluative components that were requested in the NIHR’s research brief for the evaluation of CLAHRCs. We did this to ensure that findings from the evaluation informed learning as the CLAHRCs evolved in the early years of their implementation. 2

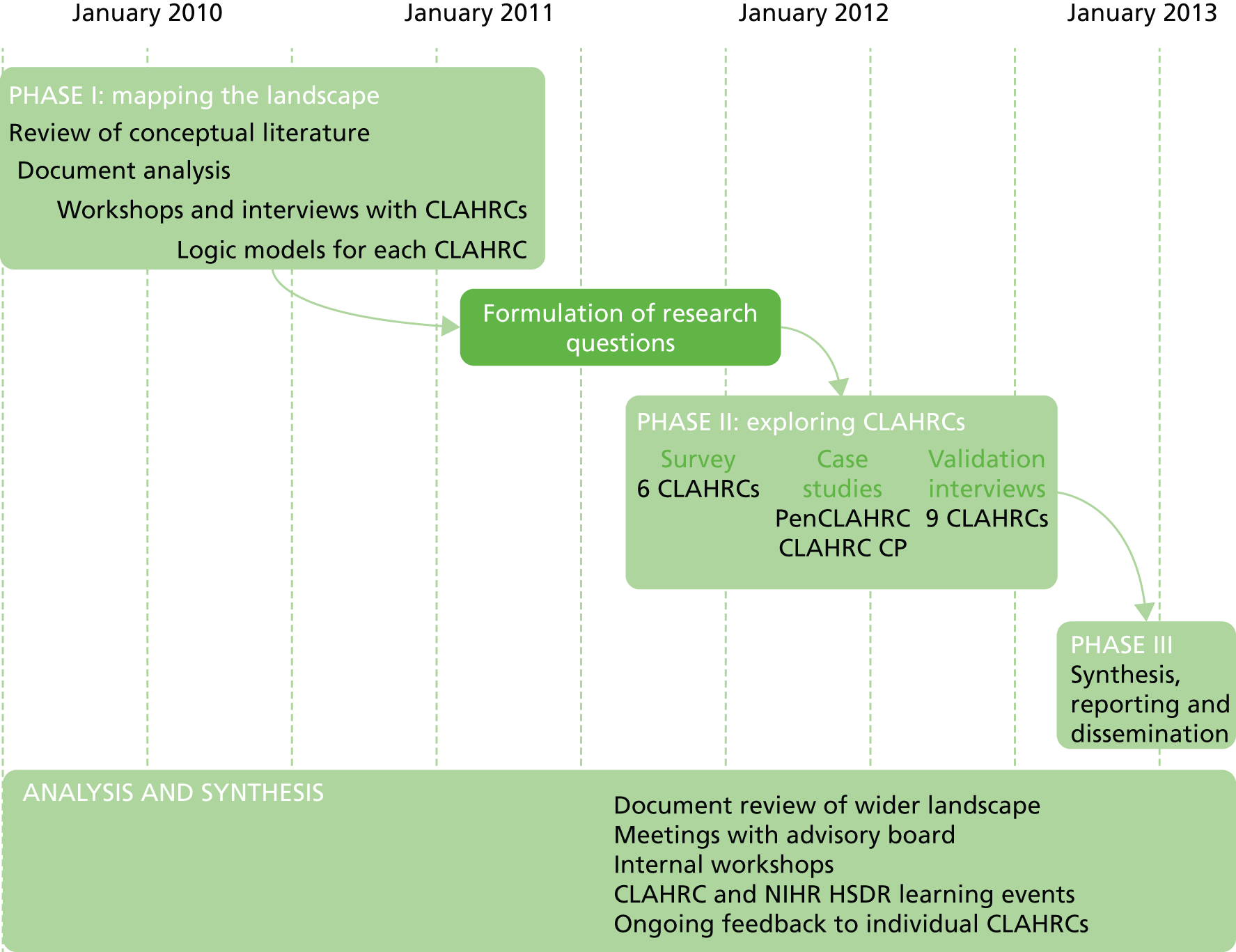

Recognising the breadth and complexity of the CLAHRC initiative, we developed a ‘research map’ to guide our work (Figure 1). This allowed us to formulate the preliminary evaluation questions that constituted a generic starting point for the analysis of specific CLAHRCs and the identification of specific research questions. These were:

FIGURE 1.

Key evaluation questions guiding the study.

Overarching research question: How, and how effectively, do CLAHRCs address the second translation gap?

Subsidiary questions:

-

How, and how effectively, do CLAHRCs support local health research?

-

How, and how effectively, do CLAHRCs build local infrastructures to utilise globally and locally generated health research for local patient benefit?

-

Does bringing together activities for health research and activities for delivering health research benefit both sets of activities?

In line with the tiered approach, the study consisted of three phases, each building on the insights from the preceding phase. Phase 1 sought to map the landscape of the nine CLAHRCs and the context in which they were established. Through this mapping exercise, and in consultation with the nine CLAHRC directors and the Health Services and Delivery Research Programme (HSDR), we identified three core research questions, which we explored in detail in phase 2, using qualitative and quantitative methods. These were:

-

How does the NHS influence CLAHRCs’ evolution, outcomes and impact (and indeed how does having a CLAHRC influence NHS behaviour)?

-

How are effective multistakeholder and multidisciplinary research and implementation teams for service improvement built: what can we learn from the CLAHRC model and what mechanisms are being used to enable it?

-

What can we learn from the CLAHRCs that can provide new understanding of how to use research knowledge and evidence to change commissioning and clinical behaviour for patient benefit?

The final phase of the study, phase 3, sought to synthesise the findings. Figure 2 illustrates how the three phases of our study interlinked and facilitated the emergence and refinement of our research questions over time. This approach was devised in response to the initial research brief,2 which also meant adapting the research protocol as the study evolved, in consultation with the advisory board to the project and following agreement by NIHR HSDR. The final revised research protocol is presented in Appendix 1 to this report.

FIGURE 2.

Study design and timeline. CP, Cambridgeshire and Peterborough; PenCLAHRC, South West Peninsula Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care.

Phase 1: mapping the CLAHRC landscape

We drew on a theory-of-change-led realist evaluation framework to help inform the identification of the various strategies that different CLAHRCs were pursuing to generate and use new forms of knowledge. 70 Specifically, we sought to understand the CLAHRCs by exploring their perceptions and behaviours, in order to reveal some of the implicit assumptions underlying the approaches adopted by individual CLAHRCs. Thus, we did not set out with pre-specified hypotheses on how CLAHRCs would evolve, and seek to test them, because we expected that such hypotheses would become outdated and made irrelevant almost as quickly as they were formulated.

Phase 1 of the study considered all nine CLAHRCs, and involved the collection of data to identify and make explicit the diversity of strategic approaches being used, and identify how the strategies were being implemented.

Before describing our approach to data collection in phase 1, it is important to reiterate that NIHR HSDR commissioned four teams to evaluate aspects of CLAHRCs. 71 There was, therefore, a need to minimise unnecessary duplication of data collection so as to not overburden CLAHRCs, in particular in the early phases of their establishment. As a consequence, the quantity and range of evidence collected in the first phase of our evaluation varied. However, we were able to collect sufficient data that allowed us to understand the key resources being used, the range of CLAHRC activities, the outputs achieved and the intended outcomes of all nine CLAHRCs, and the facilitators and barriers encountered.

Data collection primarily included document analysis, interviews with senior individuals, workshops or mini-conferences with some CLAHRCs and non-participant observation of key meetings in others, as well as drawing on existing literature in implementation science and the sociology of knowledge to inform our enquiries. Documents reviewed included CLAHRCs’ individual application forms to the NIHR and other documentation; Table 2 provides an overview of the range of interviews and workshops we carried out across the nine CLAHRCs.

| CLAHRC | Interview participants | Workshop and events |

|---|---|---|

| Birmingham and Black Country (CLAHRC-BBC) | 4 | Limited their involvement to interviews |

| Cambridgeshire and Peterborough (CLAHRC-CP) | 8 | Half-day workshop |

| Greater Manchester (CLAHRC-GM) | 4 | Non-participant observation at board and theme leads meeting |

| Leeds, York and Bradford (LYB-CLAHRC) | 7 | 2-hour workshop and attendance at business meeting |

| Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland (LNR-CLAHRC) | 8 | CLAHRC mini-conference and half-day workshop |

| North West London (Northwest London) | 7 | Half-day workshop |

| Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire (CLAHRC-NDL) | 3 | CLAHRC conference and mini-session |

| South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC) | 5 | Half-day workshop |

| South Yorkshire (SY-CLAHRC) | 2 | Limited their involvement to interviews |

| Total number of interviews | 48 |

In-depth interviews

Interviews in the first phase of the evaluation sought to provide background information on the details of CLAHRC implementation strategies, approaches and activities, motivations for the selection of specific strategies and activities to achieve the CLAHRC goals, processes and structures in place for managing and delivering the activities, expected milestones and targets for outputs, and the nature and role of local and national factors as enablers or potential barriers to success.

We purposely sampled senior individuals who were likely to play a key role in implementing CLAHRC interventions across all nine CLAHRCs. We sought to interview three or four senior people per CLAHRC, covering clinicians, academics, managers and commissioners. Potential interviewees were identified in consultation with individual CLAHRCs. As indicated above, the final number of individuals agreeing to be interviewed varied across CLAHRCs, from two participants in South Yorkshire CLAHRC to eight participants representing Cambridgeshire and Peterborough (CP) CLAHRC and eight representing Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland CLAHRC (Table 2); roles and functions covered CLAHRC directors, clinical leads and theme leads. Interviews were conducted face to face or as telephone interviews, lasting an average of 60 minutes (the interview protocol is presented in Appendix 2). Interviews were recorded and transcribed following prior permission by the participant. Transcripts were analysed according to the themes guiding the interviews.

Workshops

The workshops sought to develop the themes identified in interviews with senior CLAHRC individuals. Specifically, the workshops aimed to explore innovative ways of delivering CLAHRC activities as well as the facilitators and challenges/barriers to their success, expected or intended outcomes, early and future impacts, and views on how to improve each CLAHRC’s performance. Participants were also asked to suggest issues on which the evaluation might focus in the succeeding period. An outline of the workshop agenda is presented in Appendix 3.

Our aim was to hold one workshop with each CLAHRC, which was to take place at the lead institution and involve five or six representatives of different stakeholder groups and organisations within the CLAHRC. However, as indicated in Table 2, the number and format of workshops varied, with two CLAHRCs limiting their participation in our evaluation to interviews only. Following the workshops, the evaluation team prepared a workshop report which summarised the issues discussed and the findings. These were shared with workshop participants to validate the evaluation team’s report.

Synthesis

Drawing on the primary and secondary data collected, we sought to identify and make explicit the theories of change and intervention logic of each CLAHRC. Specifically we explored:

-

the types of intervention being used to identify problems and promote evidence-generation and evidence-based improvement in health-service practice

-

the mechanisms through which these interventions operated (interactions, social influence, facilitation, etc.)

-

the diversity of stakeholders involved in the intervention approaches

-

the various levels at which these interventions operated:

-

the micro level, that is interventions that promoted improvements in the identification, conduct, application and integration of research by individual researchers, managers, practitioners and patients within a single organisation

-

the meso level, namely interventions that promoted improvements in the identification, conduct, application and integration of research by researchers, managers, practitioners and patients across different organisations

-

the macro level, interventions that promoted improvements in the identification, conduct, application and integration of research from organisation to organisation and across research and health-care sectors.

-

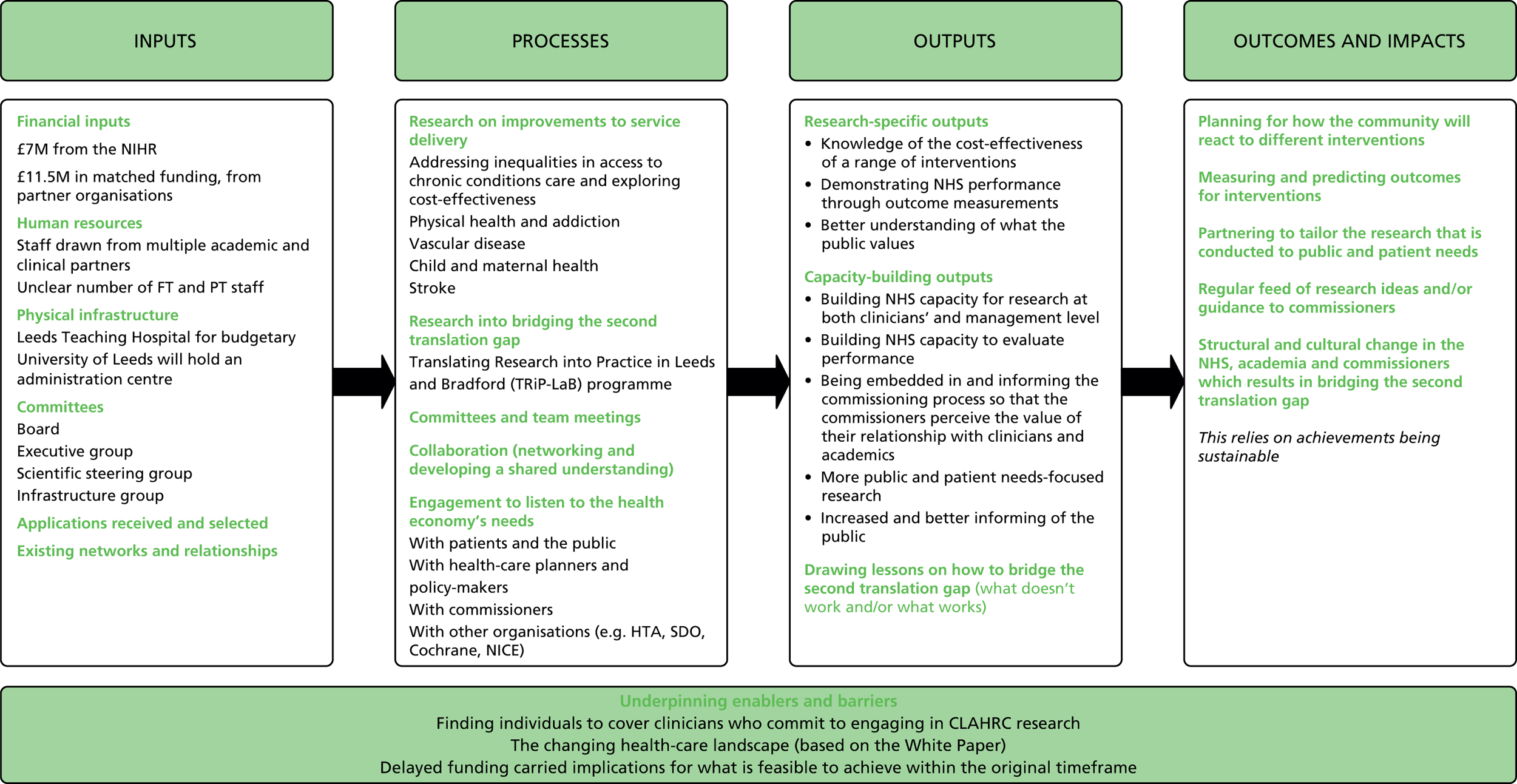

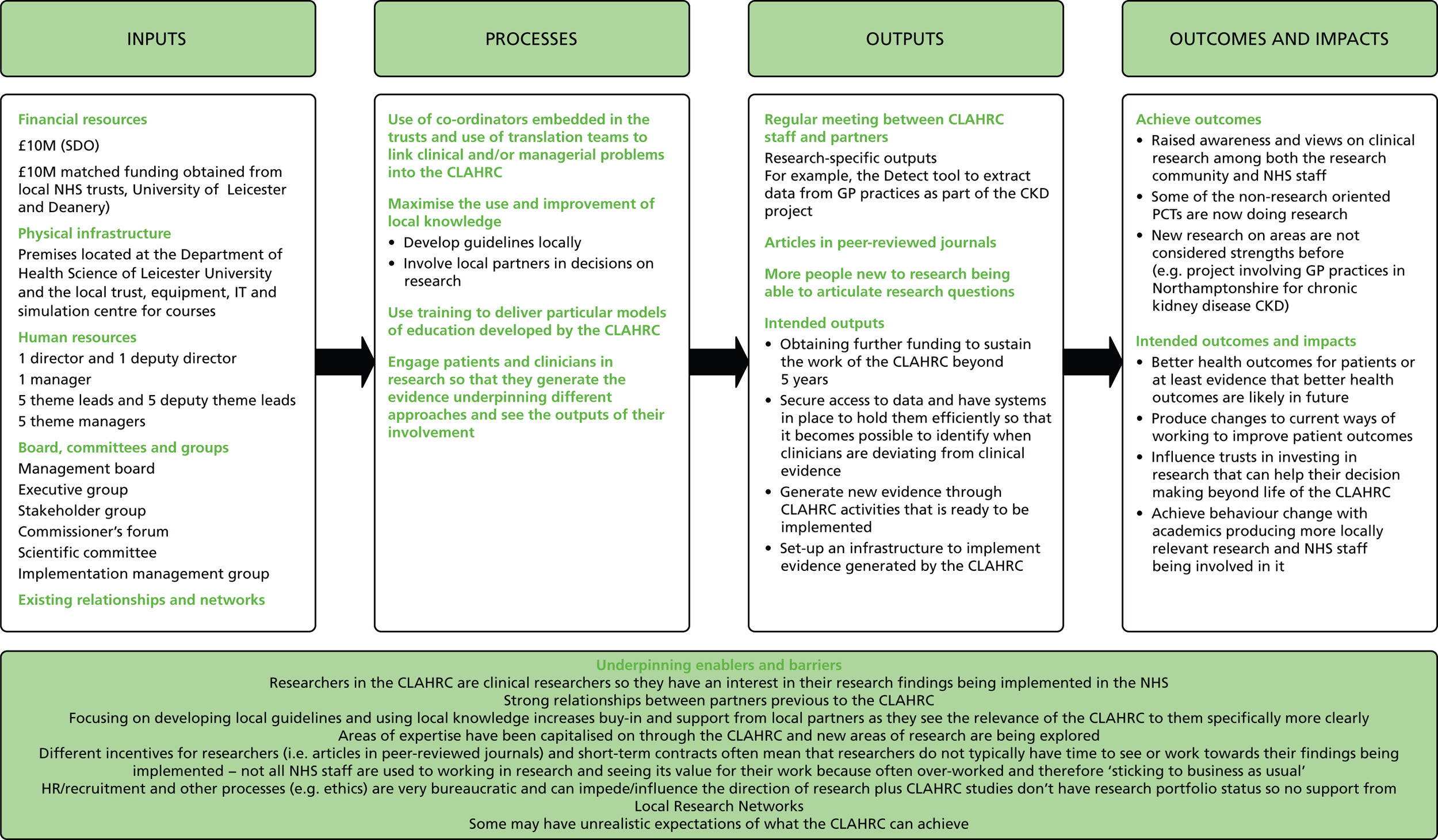

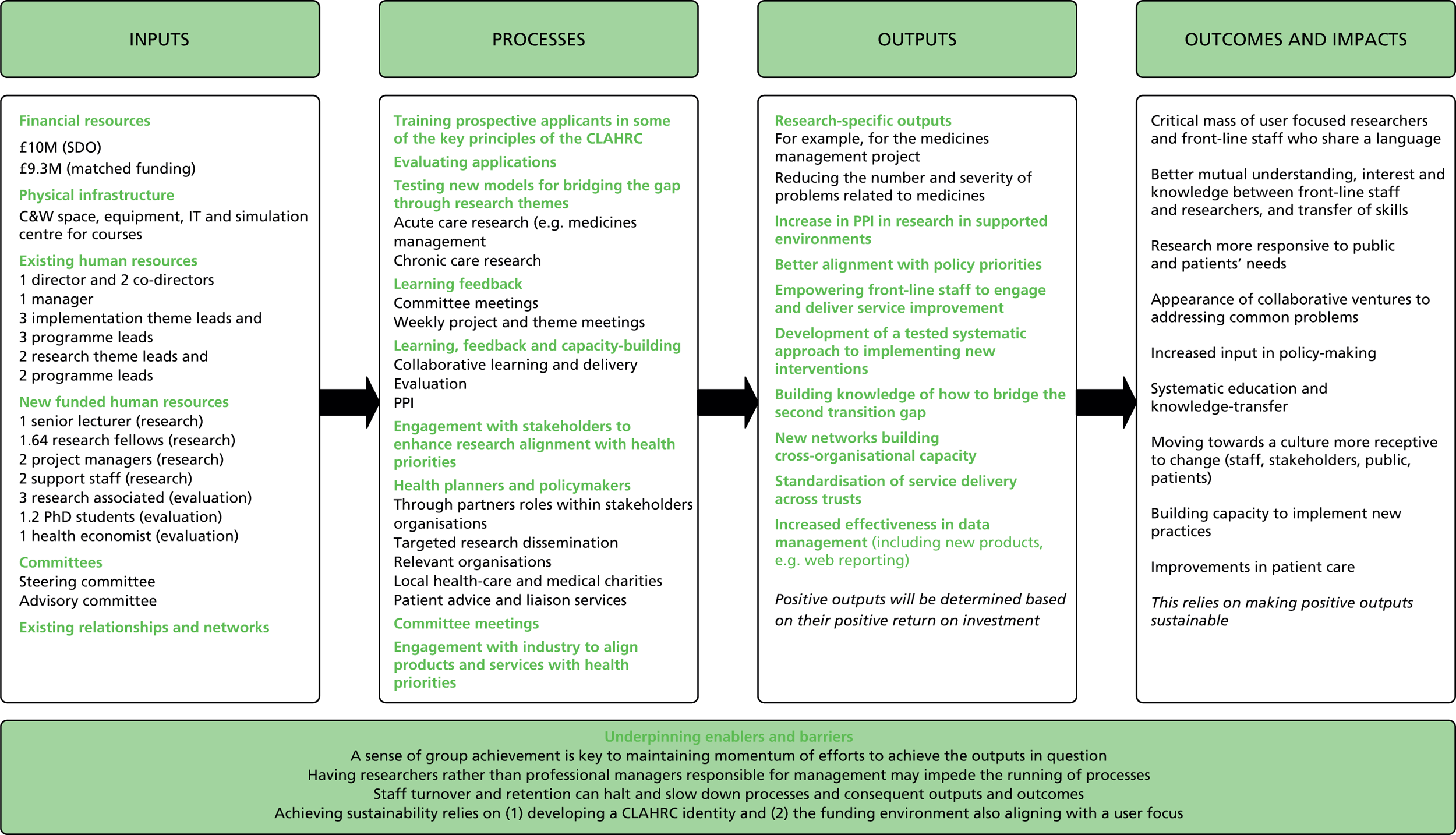

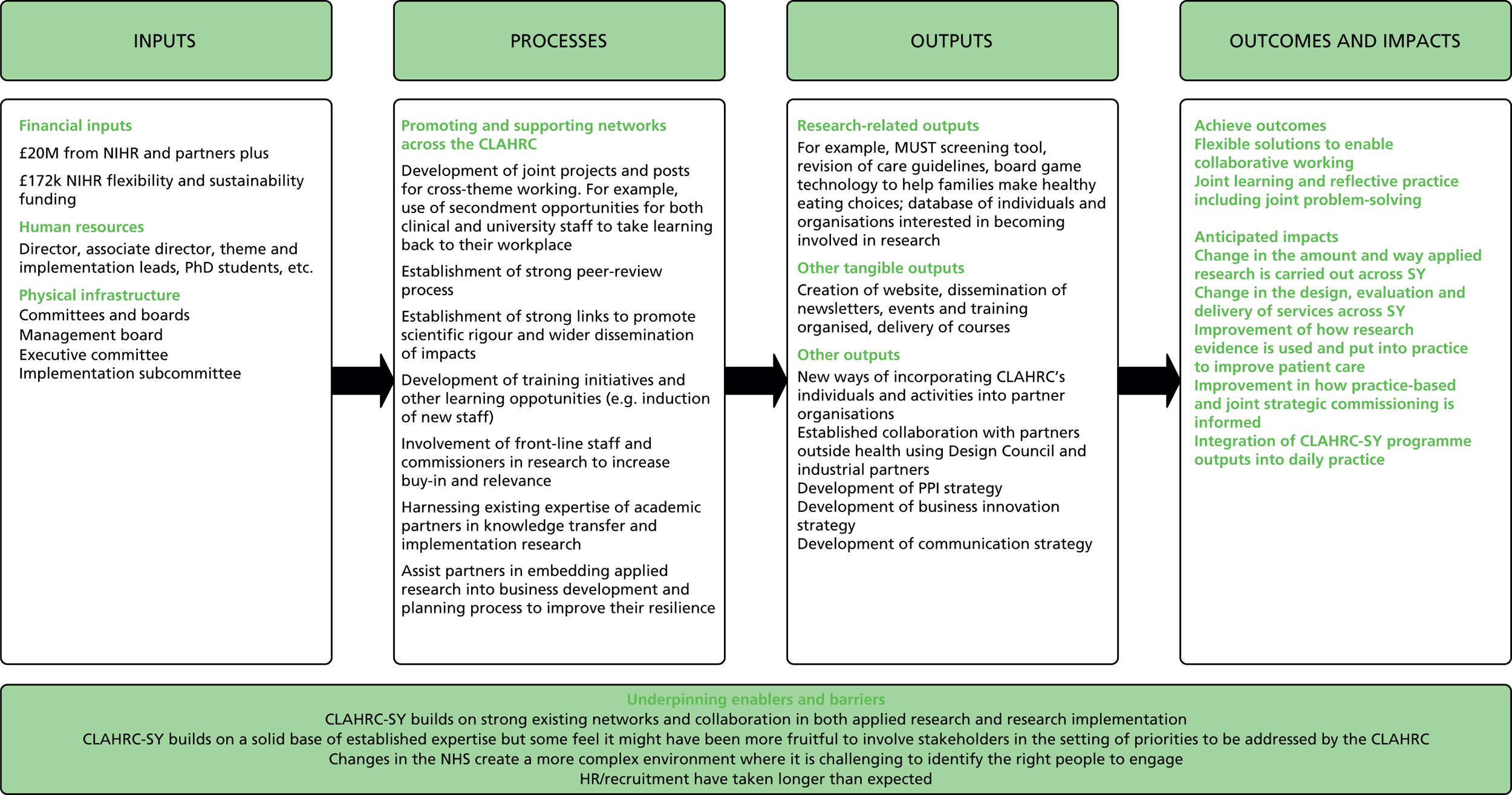

Guided by this information we developed logic models for each of the nine CLAHRCs, to illustrate and explore the theories of change underlying each CLAHRC.

In keeping with the formative emphasis of the evaluation, we fed early findings back to all the CLAHRCs, NIHR HSDR and other key stakeholders at a dedicated learning event in early 2011. We also provided a detailed report to the NIHR and others on progress achieved in the first year of the evaluation. 24

In addition to identifying and make explicit the diversity of strategic approaches adopted by individual CLAHRCs, phase 1 of our study also sought to identify the most pertinent research questions for detailed exploration in phase 2 of the evaluation. Informed by work undertaken in phase 1 and guided by the overarching question of how, and how effectively, CLAHRCs address the second translation gap, we identified a set of priority areas for further exploration. These priority areas were further informed through consultation with the advisory board to our study, and by consideration of the focus of the three other NIHR HSDR-commissioned evaluation teams. 71 Following this process, we identified three core areas for further analysis in phase 2 of the project, which we described in the introduction to this chapter:

-

How does the NHS influence CLAHRCs’ evolution, outcomes and impact (and indeed how does having a CLAHRC influence NHS behaviour)?

-

How are effective multistakeholder and multidisciplinary research and implementation teams for service improvement built: what can we learn from the CLAHRCs model and what mechanisms are being used to enable it?

-

What can we learn from the CLAHRCs that can cast new understanding on how to use research knowledge and evidence to change commissioning and clinical behaviour for patient benefit?

Phase 2: exploring CLAHRCs

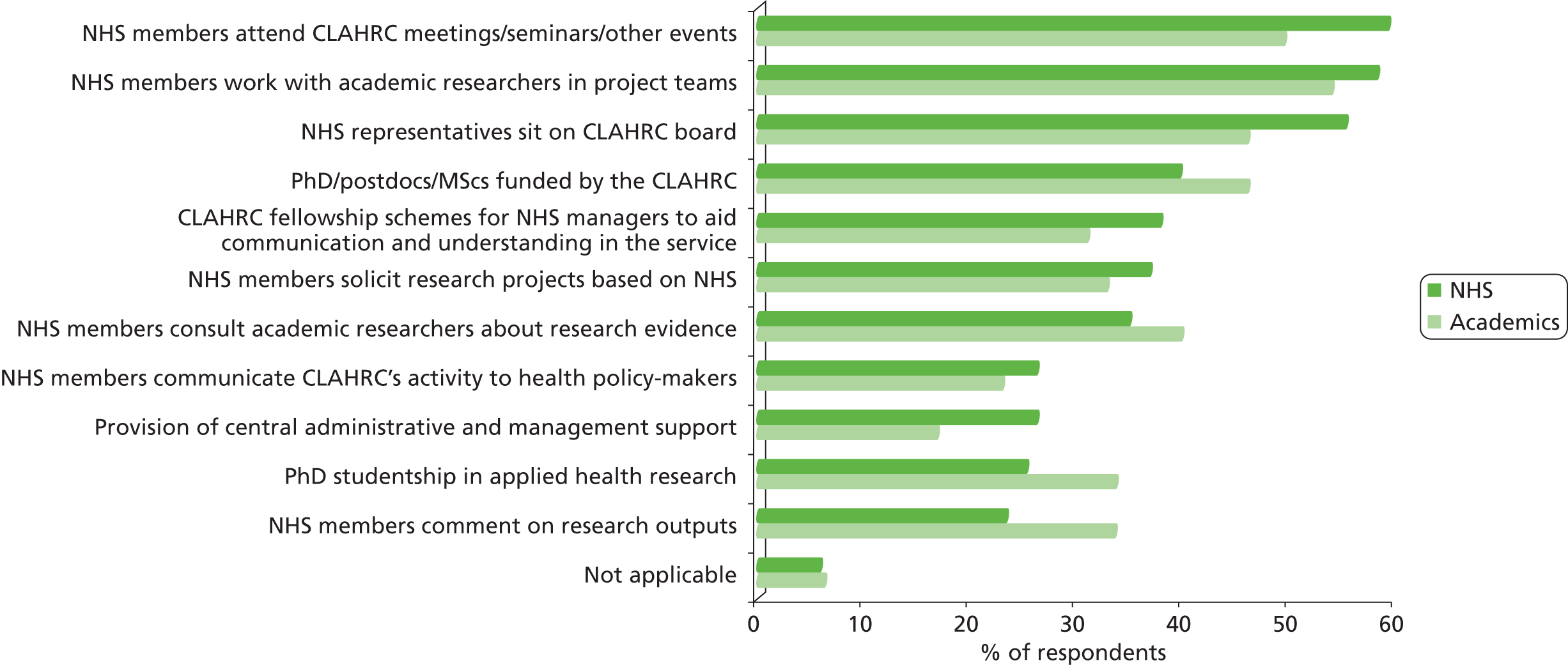

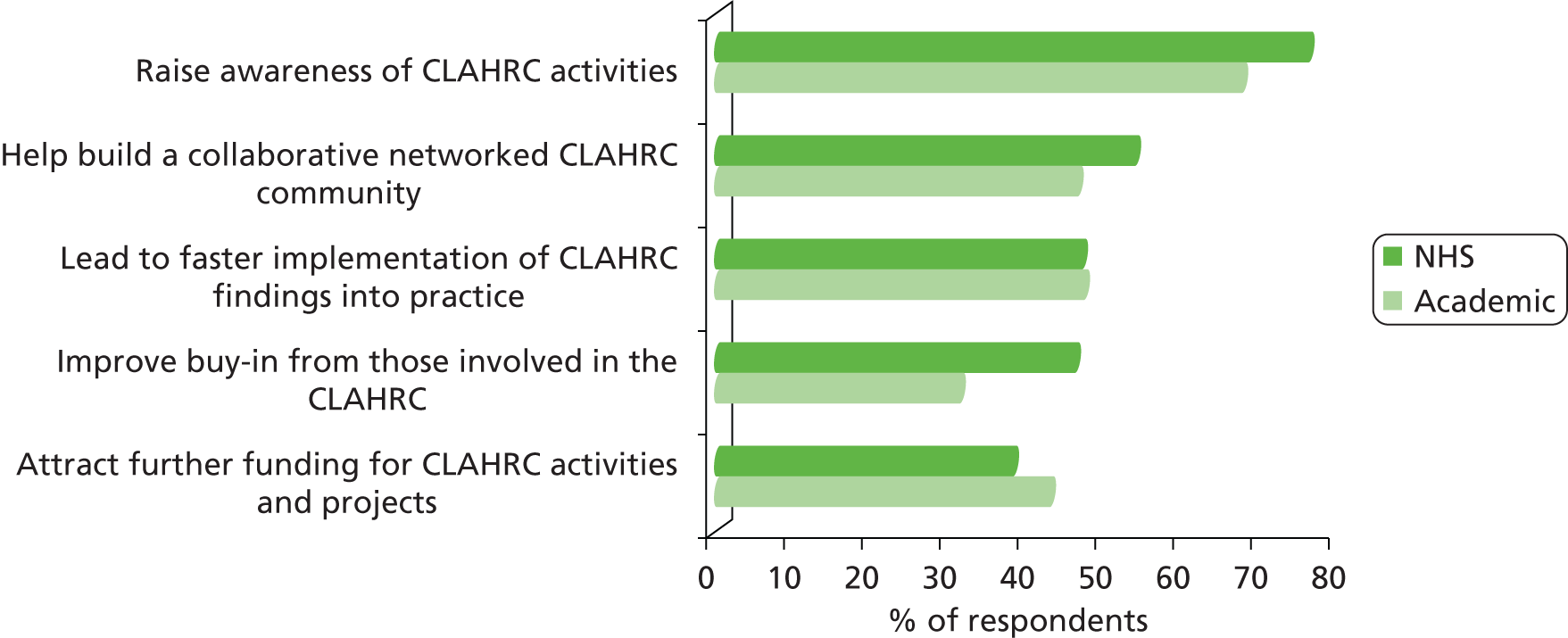

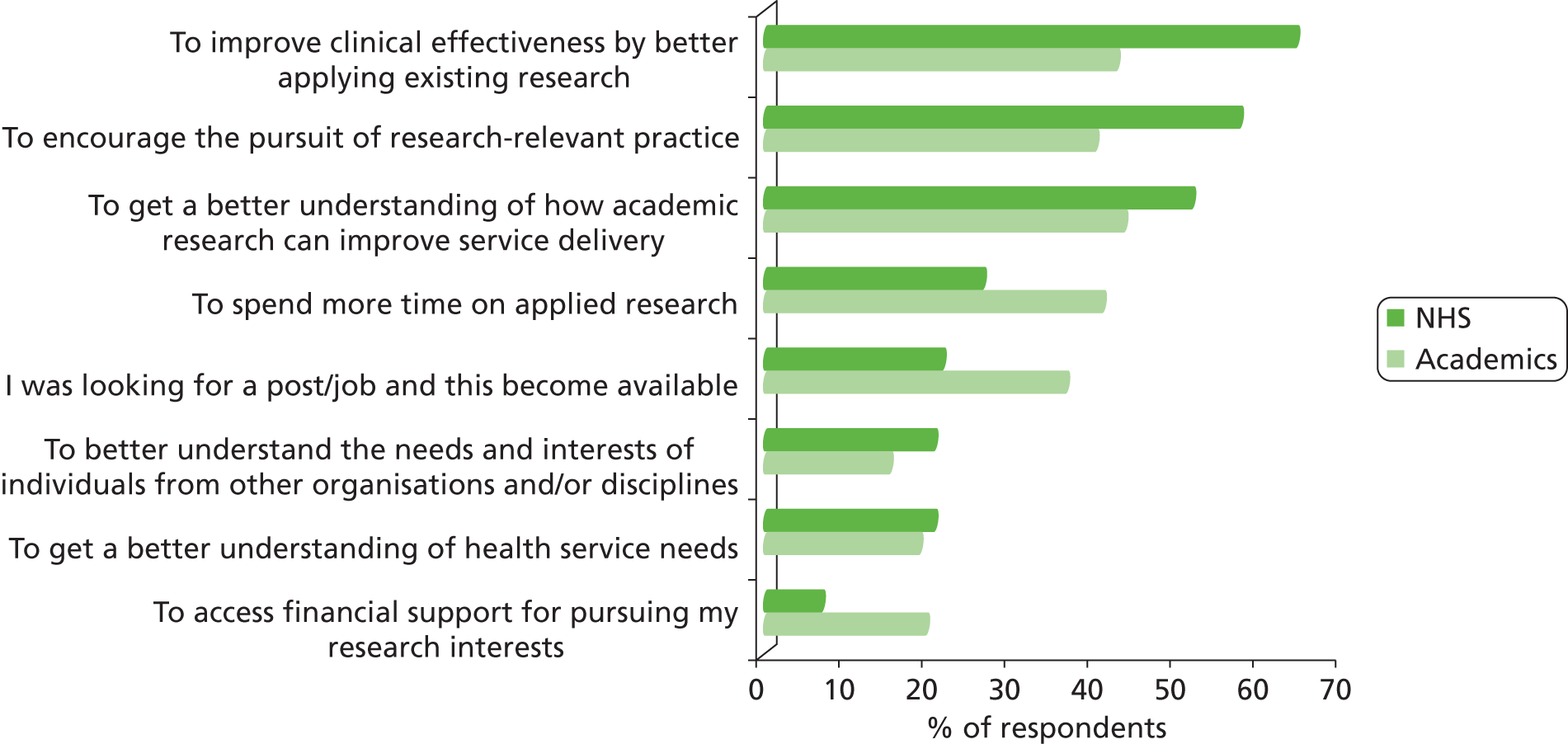

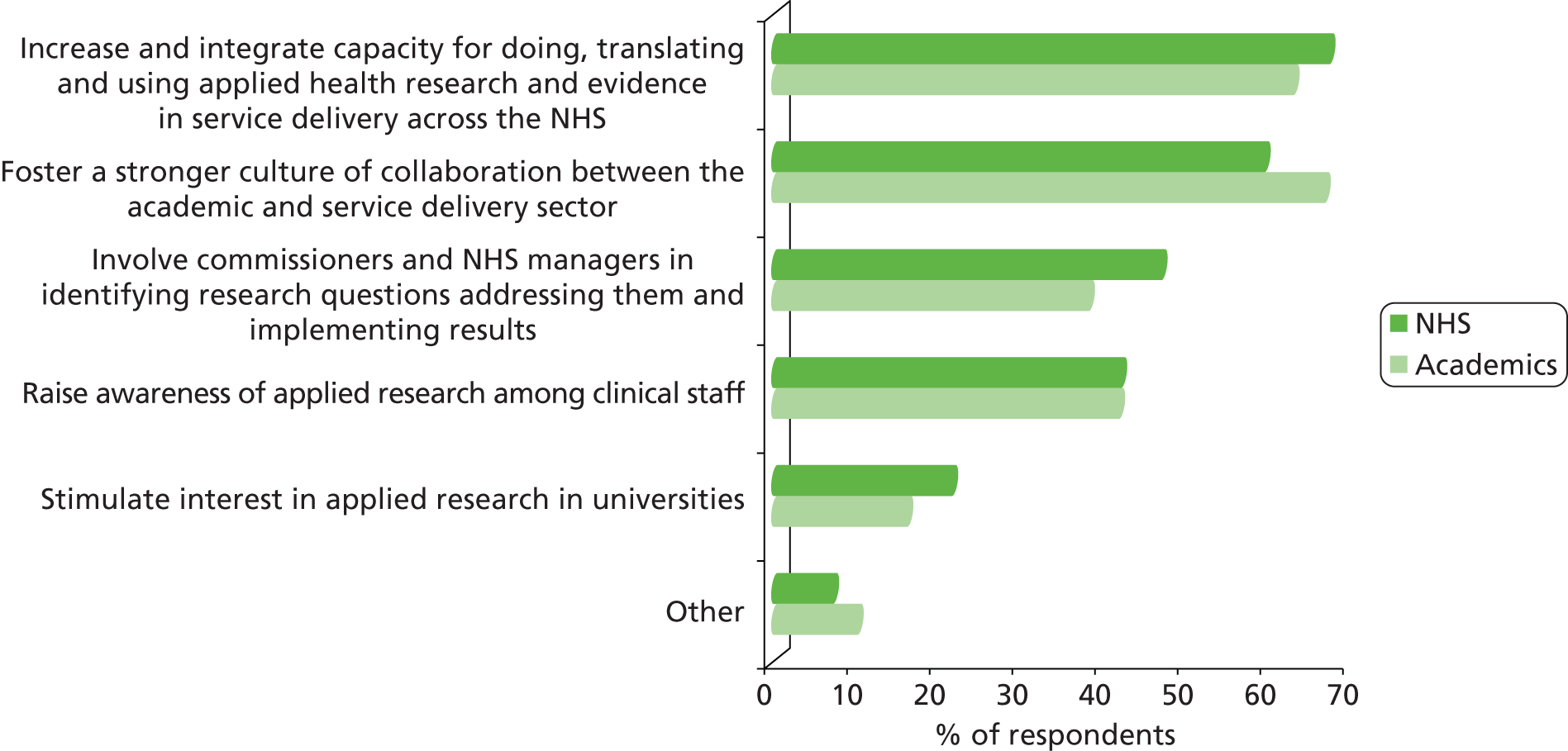

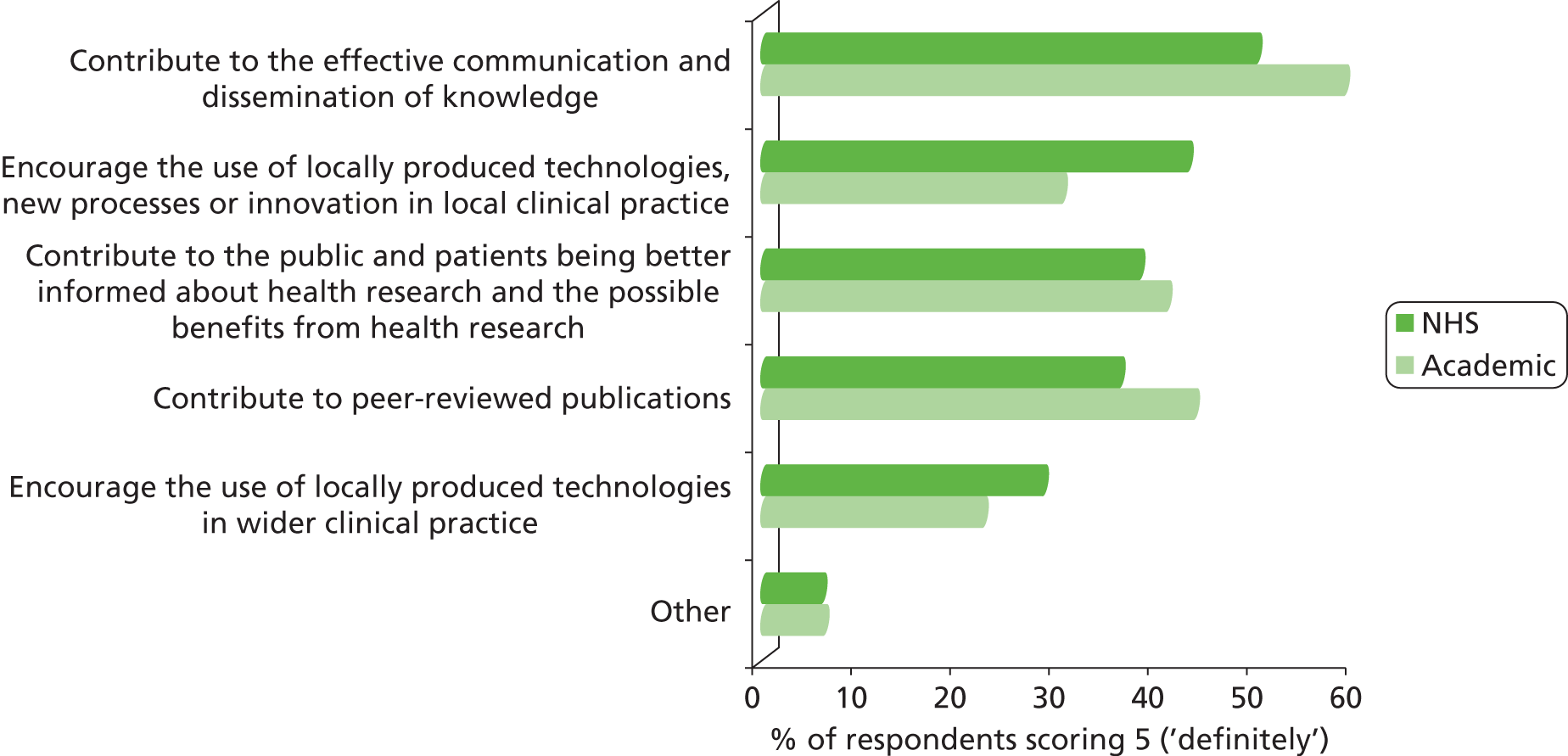

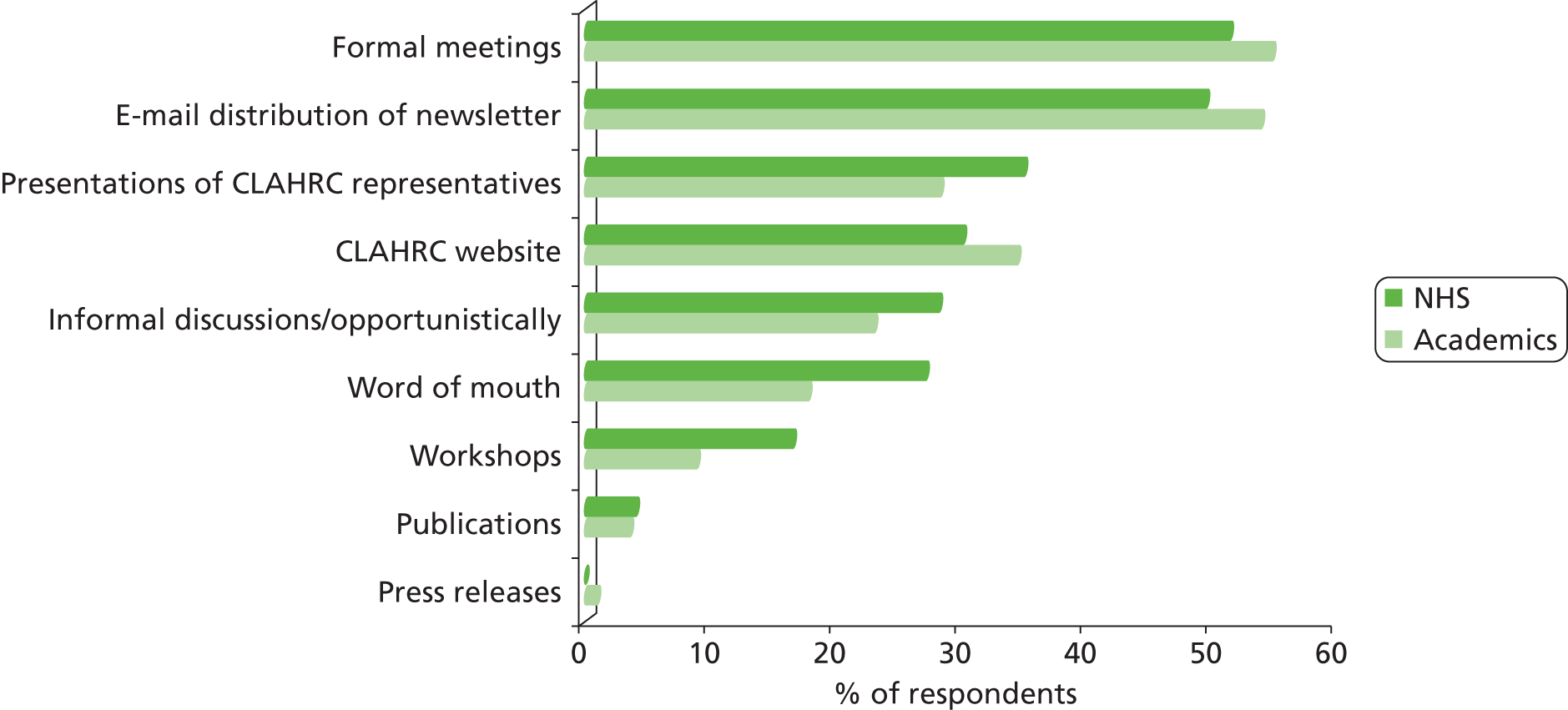

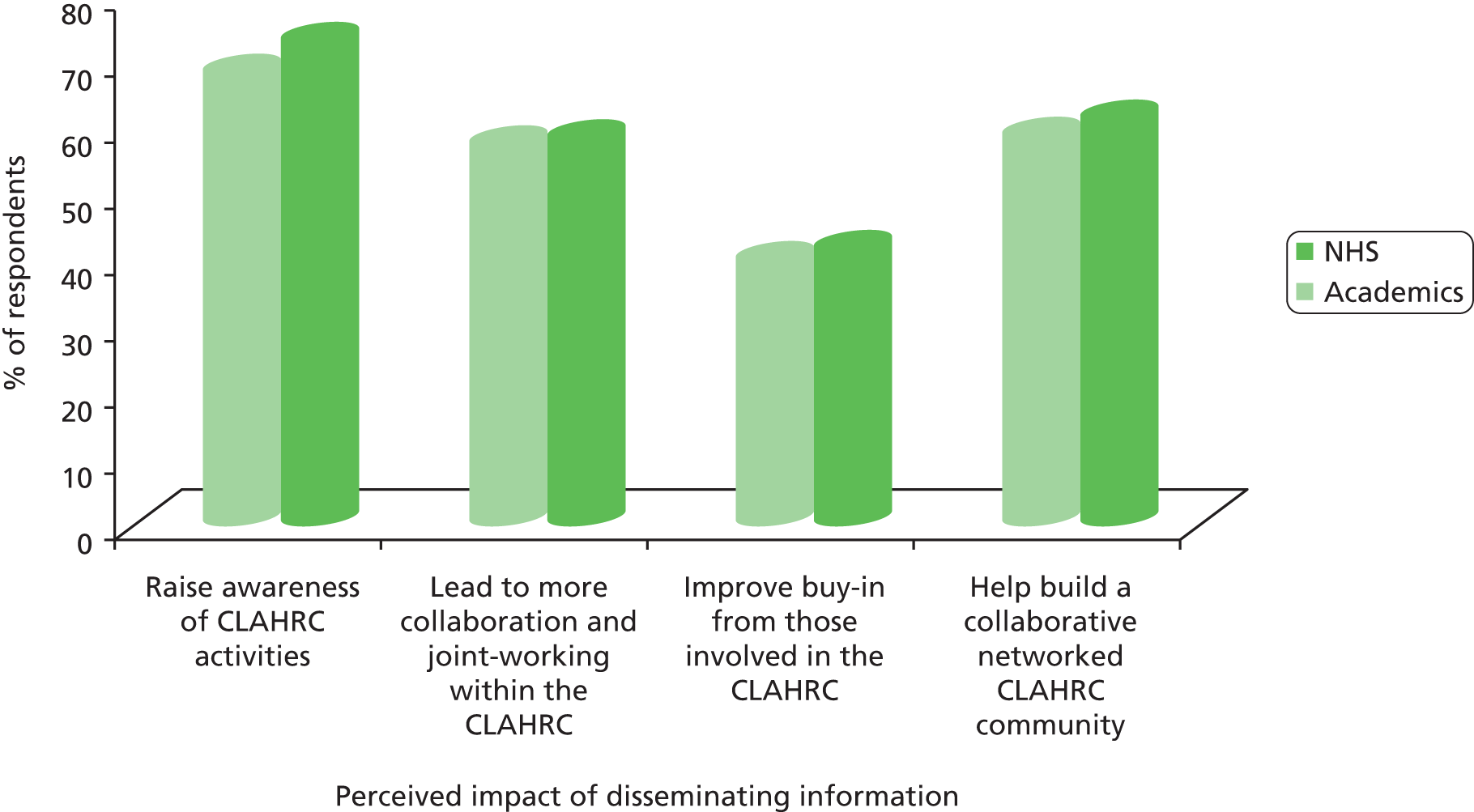

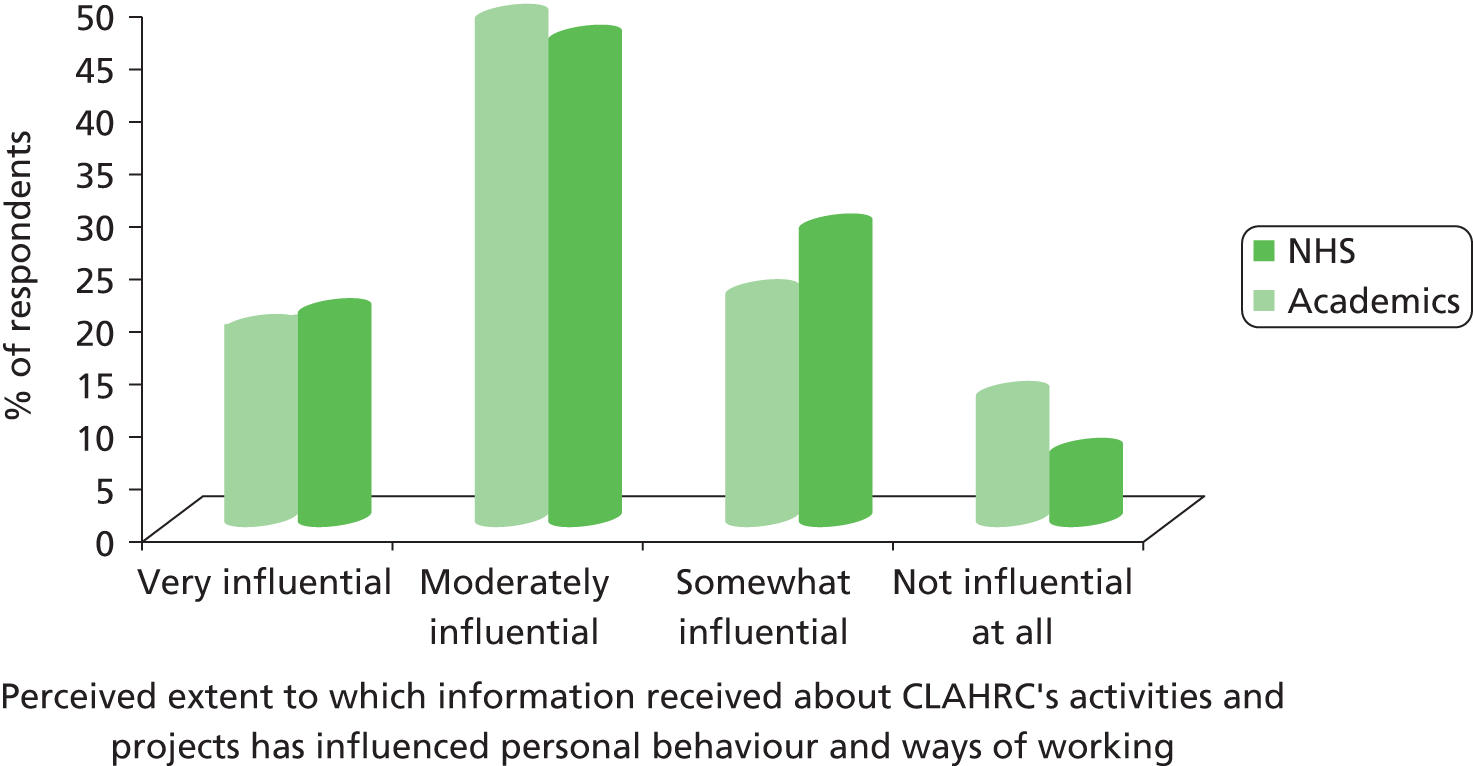

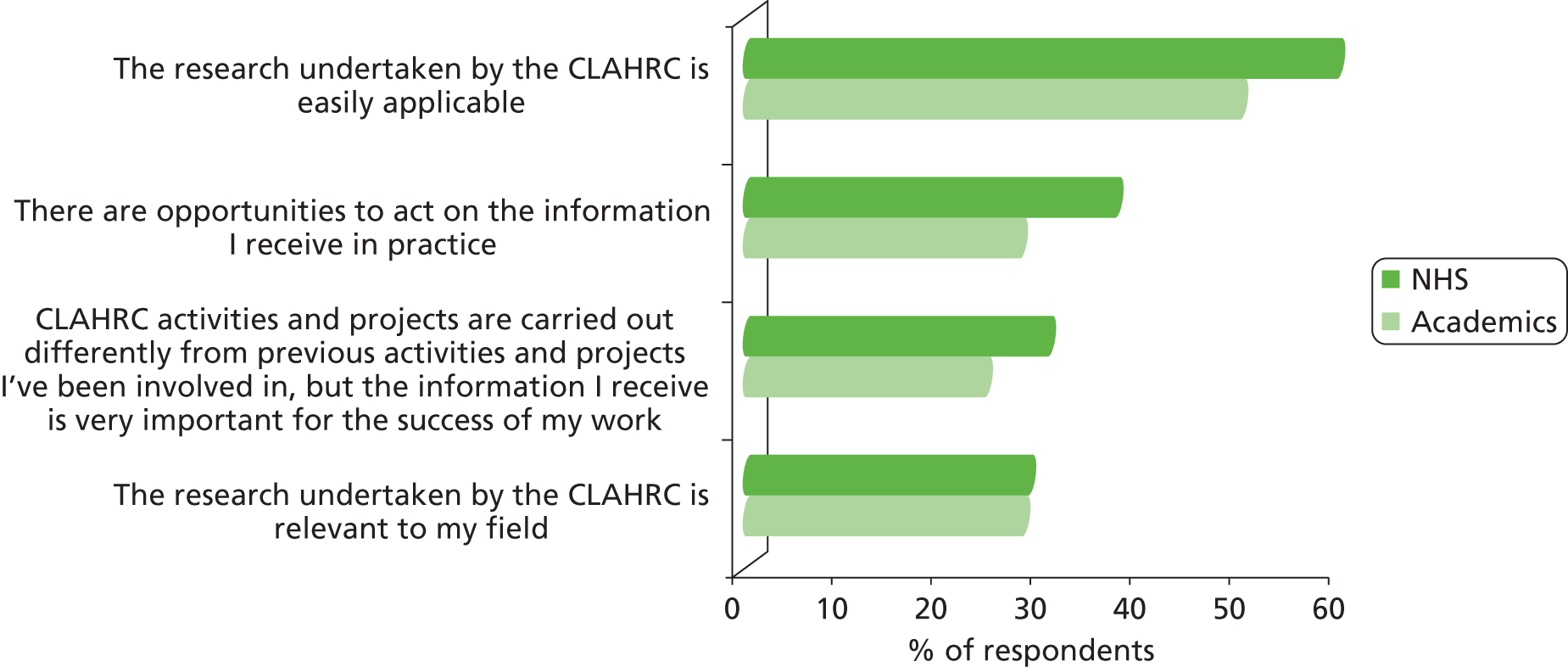

Stakeholder survey

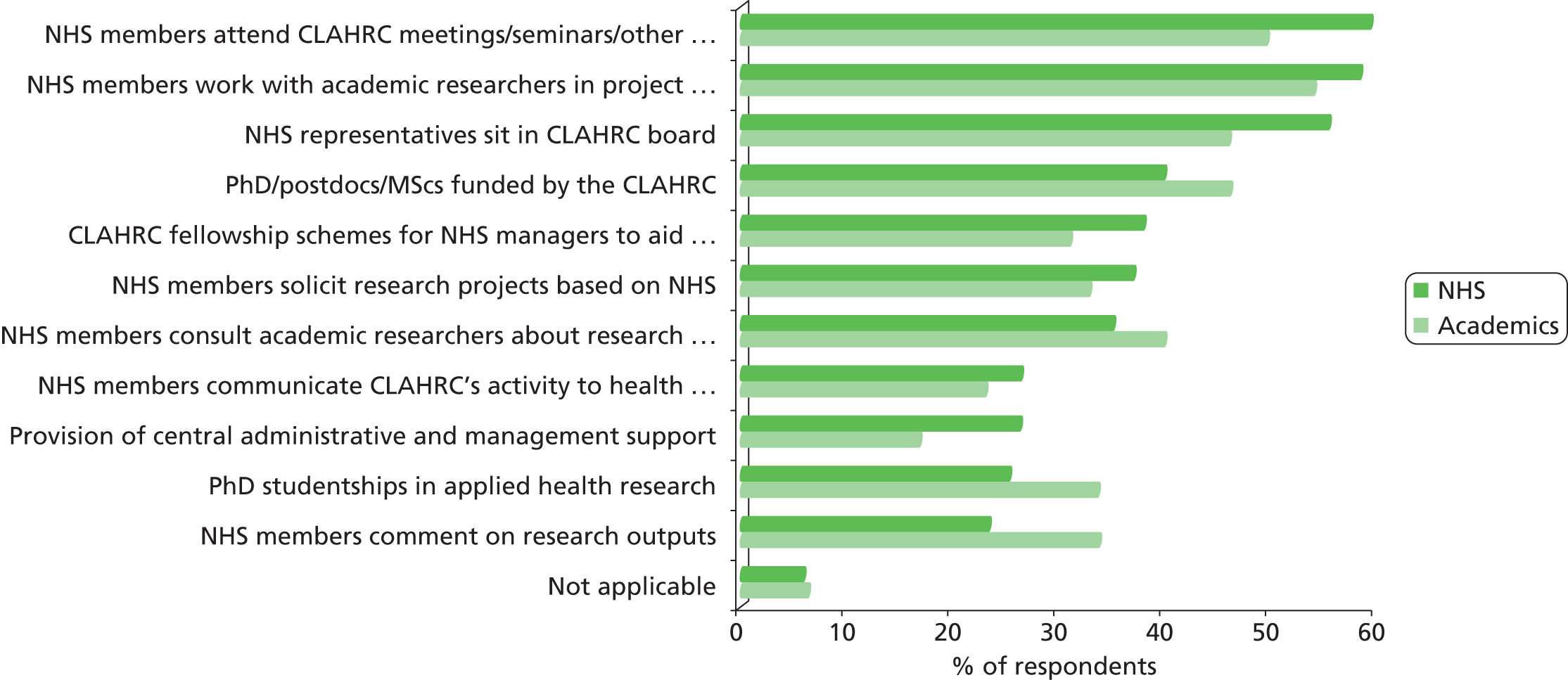

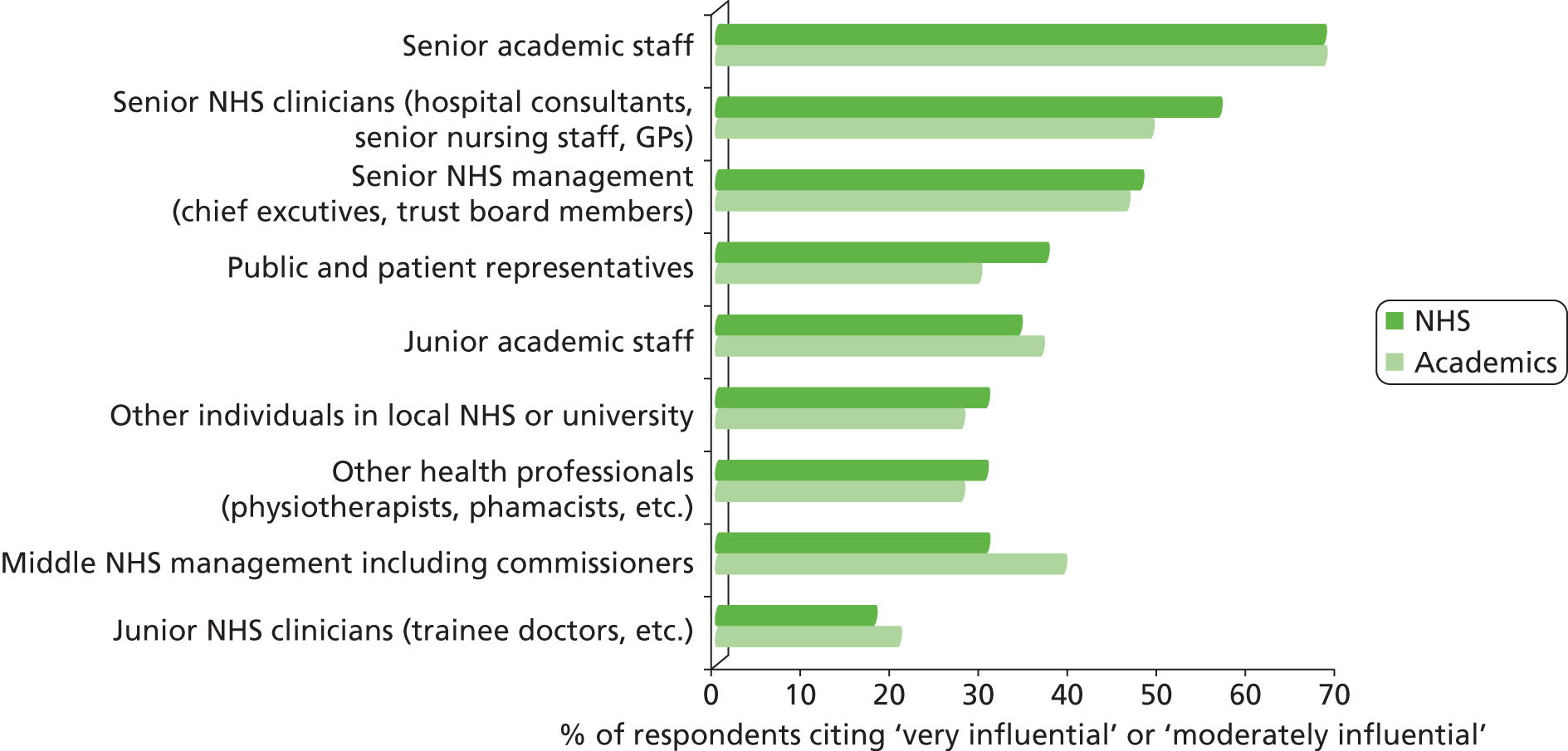

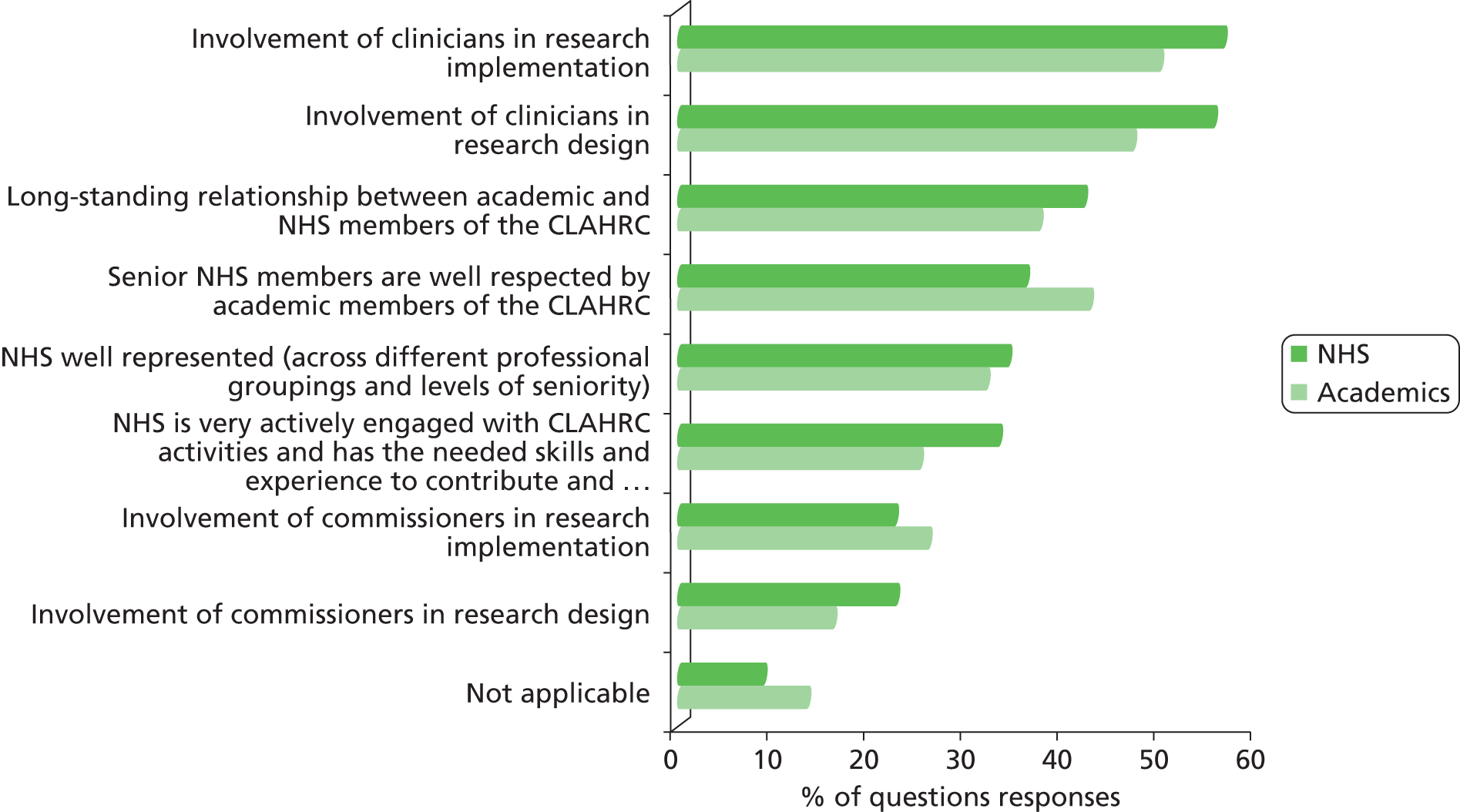

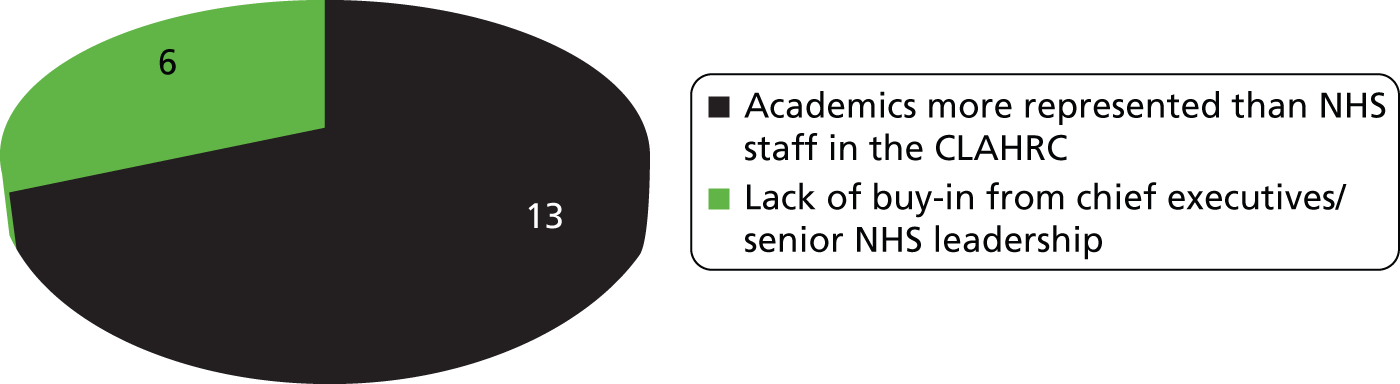

To better understand the inter-relations between the NHS and the CLAHRCs, the (perceived) effectiveness of multistakeholder and multidisciplinary research for service improvement, and how research knowledge and evidence can be used to inform commissioning and clinical behaviour for patient benefit, we carried out a survey of CLAHRCs (see Appendix 4).

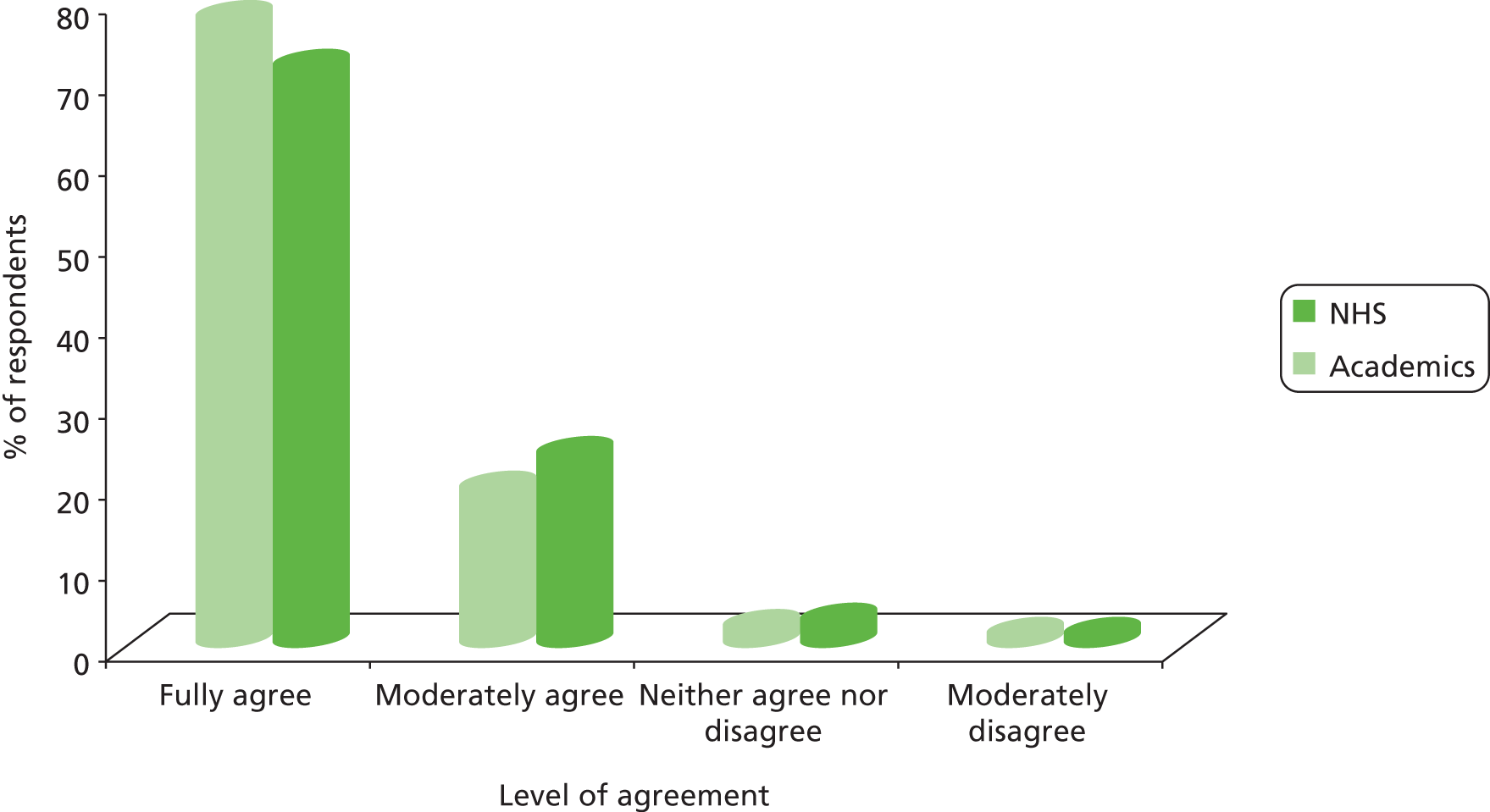

Against the background of the CLAHRCs as a complex intervention, and the interest in learning about how this model might be used in future, the design of the survey instrument was informed by the theory of the normalisation of complex interventions (NPT),54,65,72 which we discussed in Chapter 1 of this report. In developing the survey instrument, we drew on the four components of the NPT and mapped these against the core research questions guiding phase 2 of the evaluation:67

-

coherence and sense-making: why people believe CLAHRCs to be distinctive and have value

-

cognitive participation: how individuals and groups participating in CLAHRCs come to see the role they can play to achieve the value on offer

-

collective action: how individuals and groups participating in CLAHRCs are able in practice to collaborate in pursuit of the goals of the CLAHRC

-

reflexive monitoring: how improvement achieved by CLAHRCs can be sustained by learning and adapting a multifaceted and evolving approach.

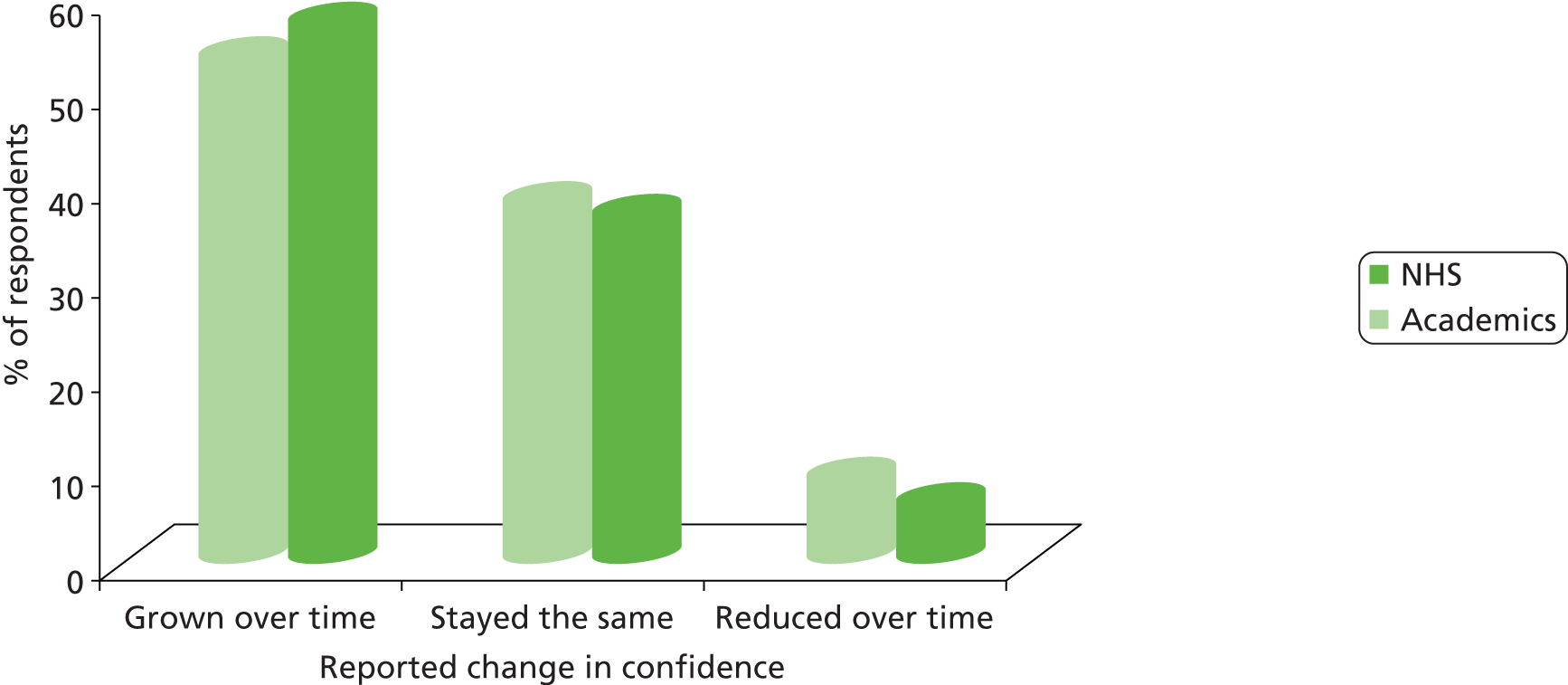

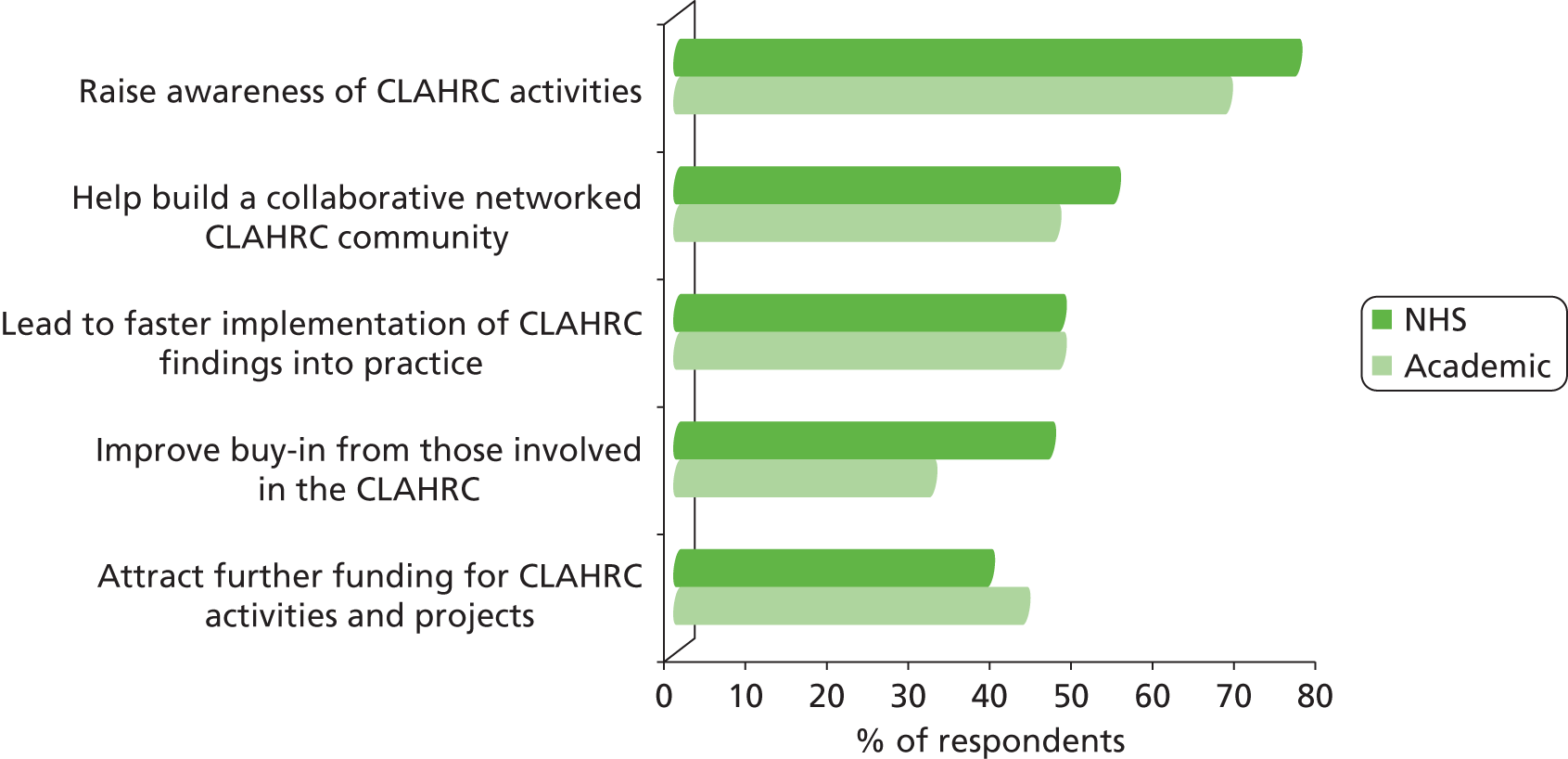

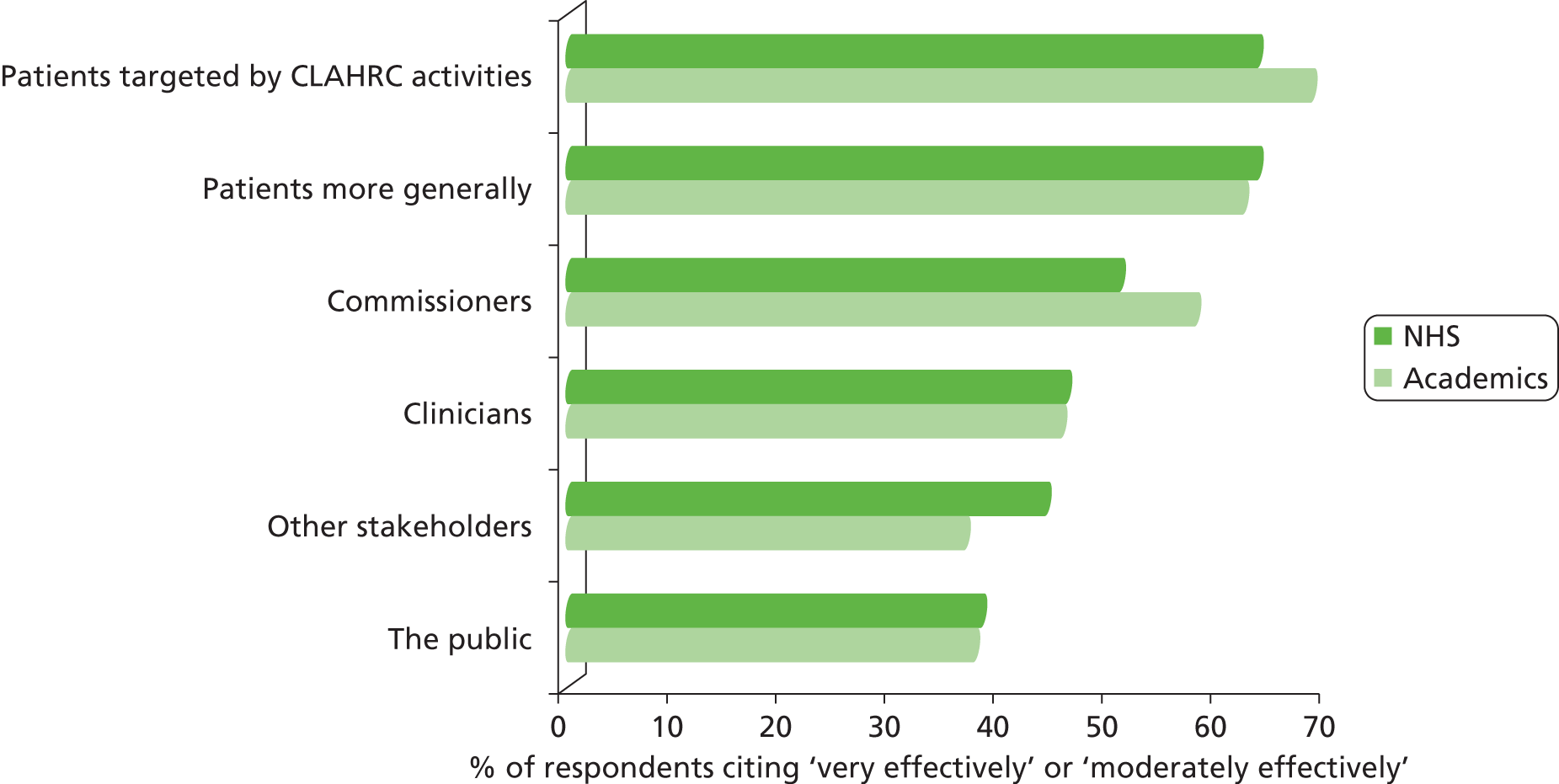

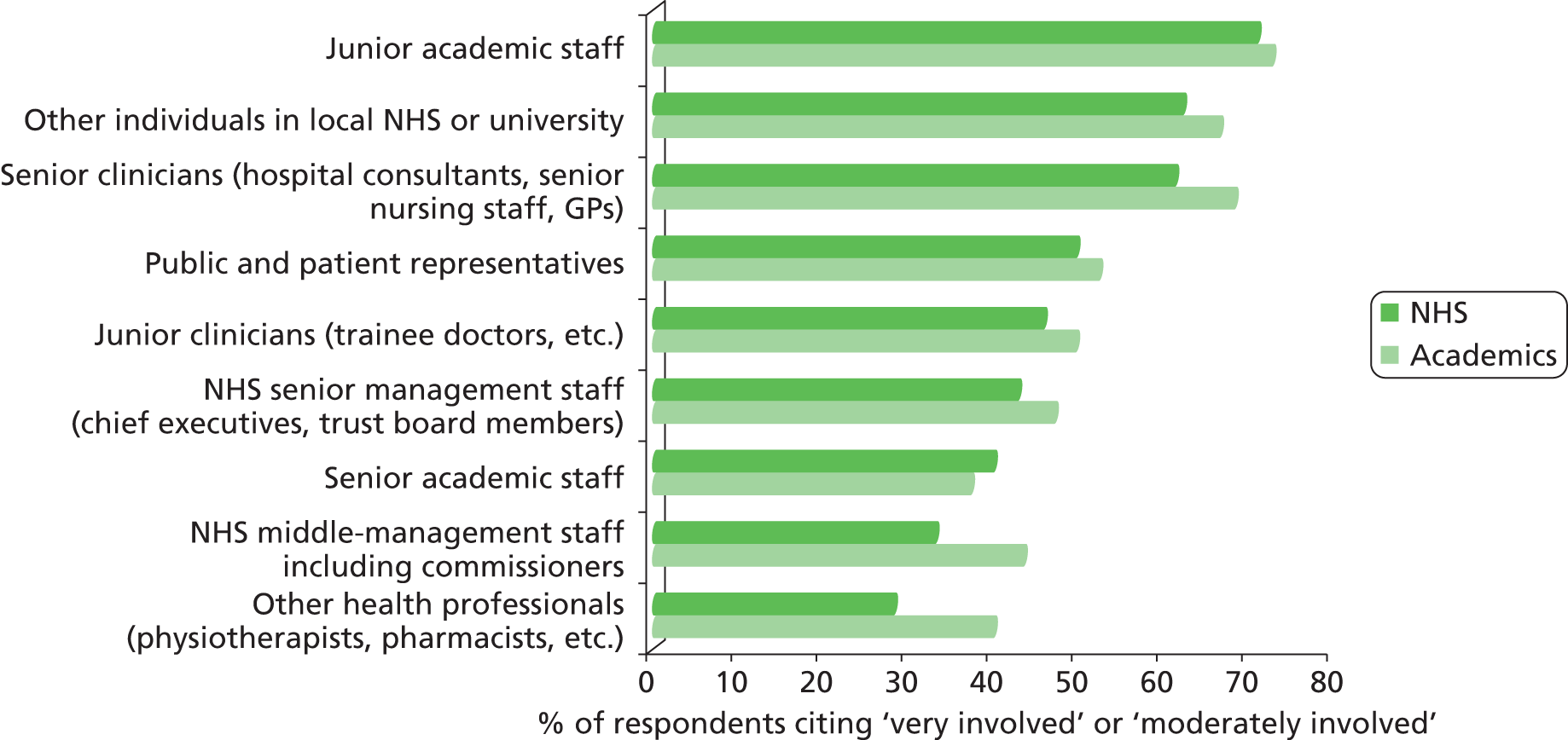

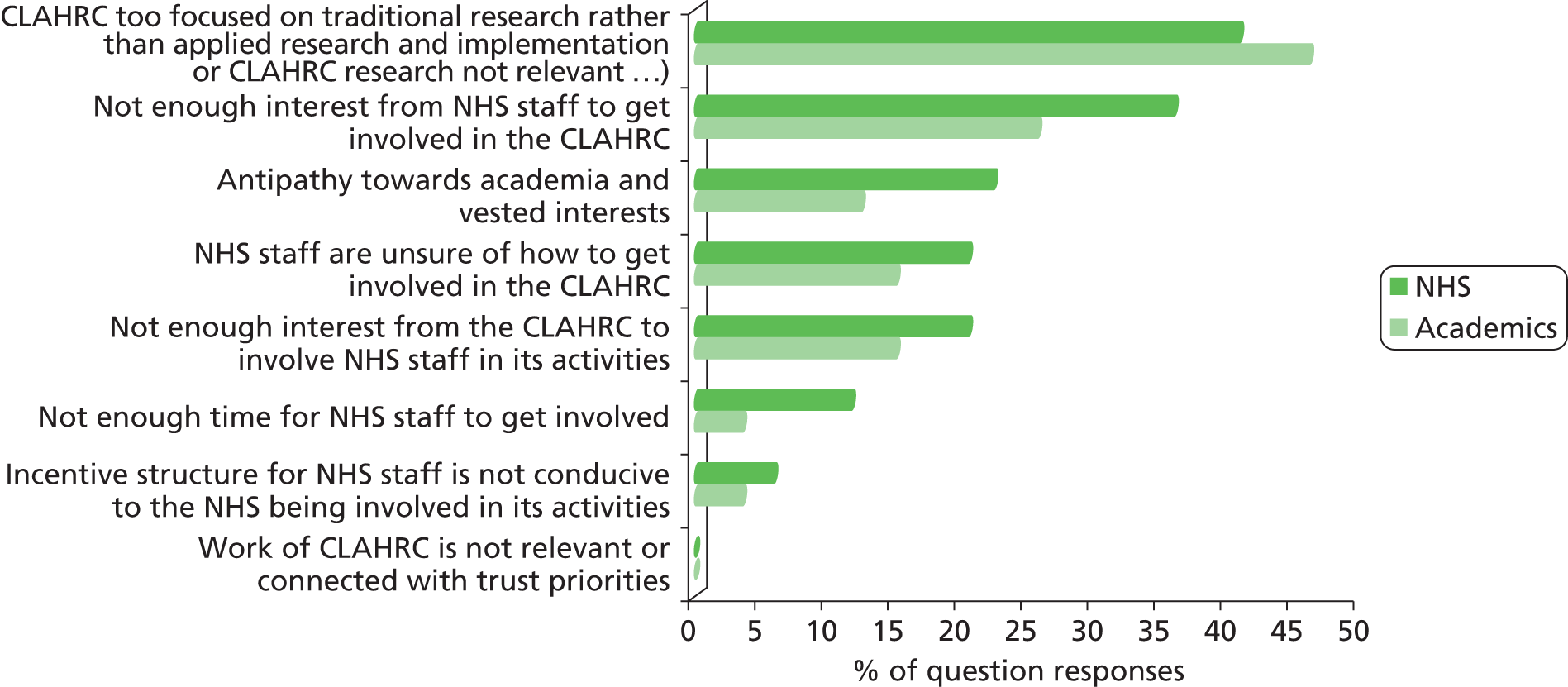

Informed by the NPT, our survey examined the diversity of interventions taking place in CLAHRCs as they related to our three core areas of interest, alongside practical insights into how people work, and perspectives on effectiveness and impact. Using this approach, we identified five cross-cutting themes: building awareness of the intervention; creating buy-in and mobilisation; sustaining engagement with the intervention; learning from the experience of the intervention; and acting on learning. These themes were adapted to the CLAHRC-specific context, with additional questions included on issues that needed to be explored in more depth.

Each of the nine CLAHRCs was invited to participate in the survey, with six agreeing to do so: CP; Leeds, York and Bradford; North West London; South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC); Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire; and Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland.

The survey was conducted online, using SelectSurvey (SelectSurvey.NETv4.126.000, ClassApps.com, Overland Park, KS, USA), a survey software that provides a web interface for creating, administering, deploying and monitoring the uptake of the survey, and analysing results. Prior to roll-out, the survey instrument was piloted with two members of CLAHRC-CP. The participating CLAHRCs were then asked to circulate a link to the survey, together with an explanatory section, to prospective respondents from a number of stakeholder groups involved with their respective CLAHRC. Data were collected over a 4-month period from October 2011 to January 2012.

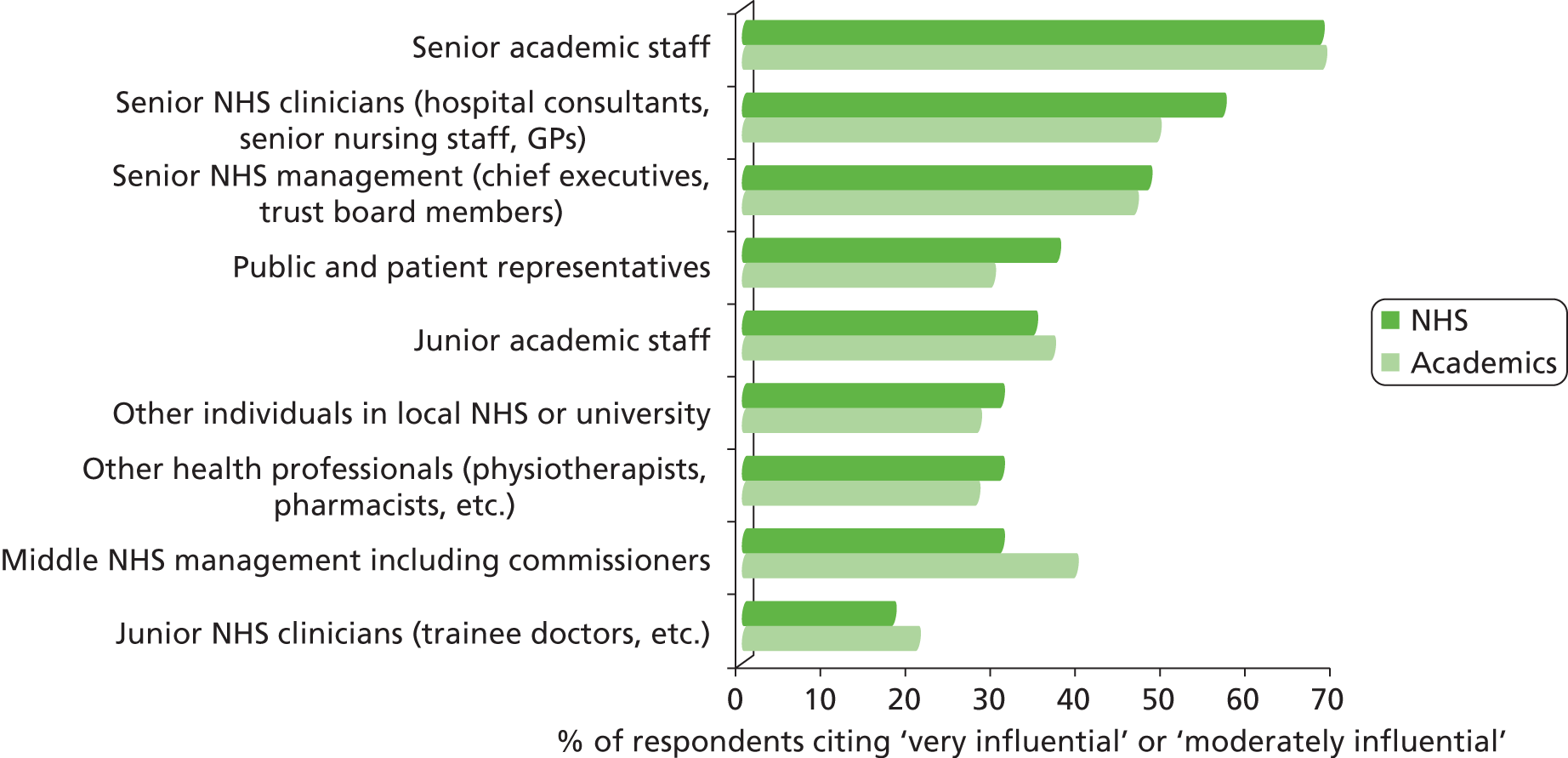

Key characteristics of survey respondents

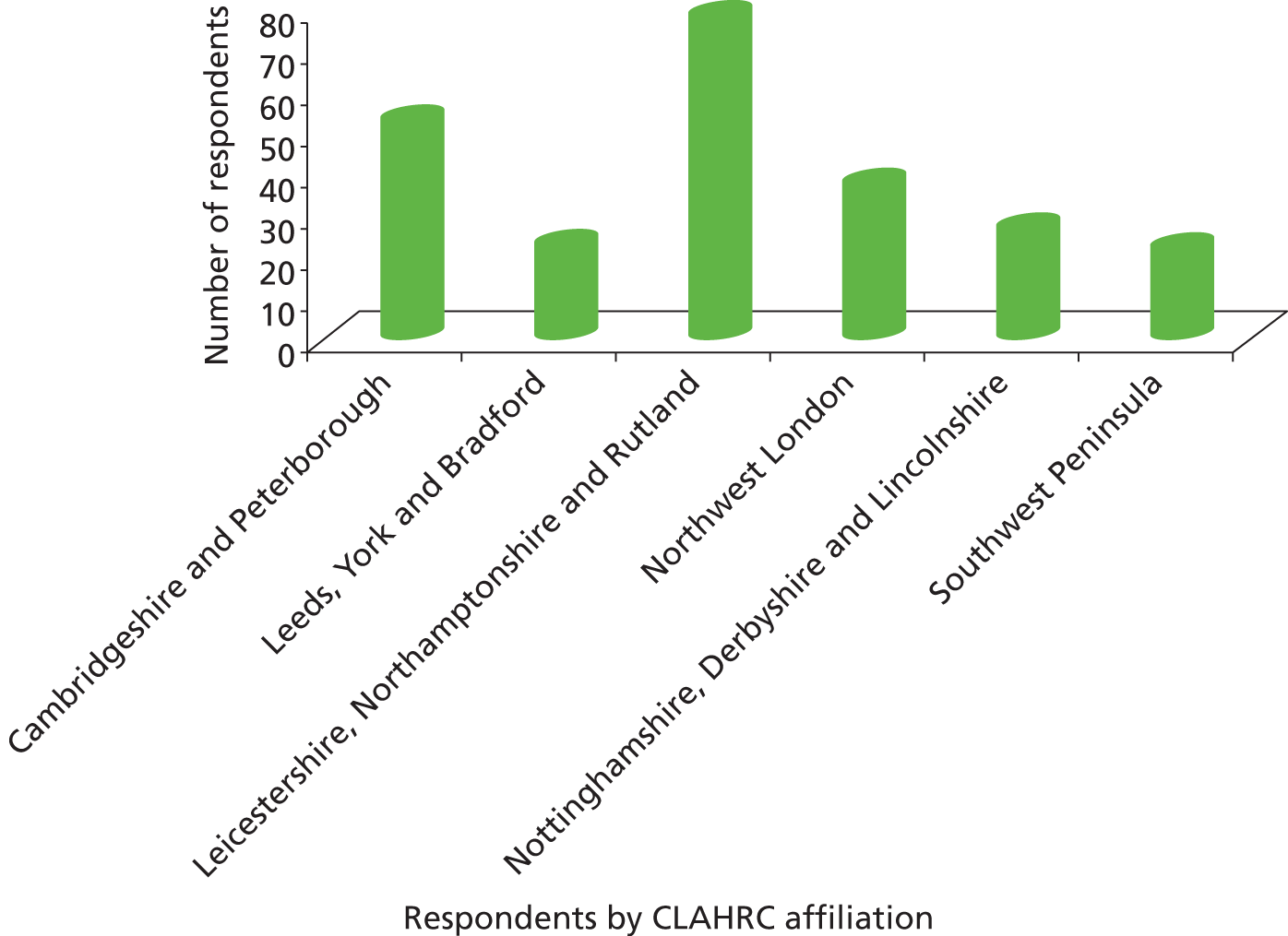

The number of potential respondents invited by the six CLAHRCs ranged from 43 to 145 individuals; of the approximately 500 people who were invited to participate in the survey, a total of 242 across the six CLAHRCs responded.

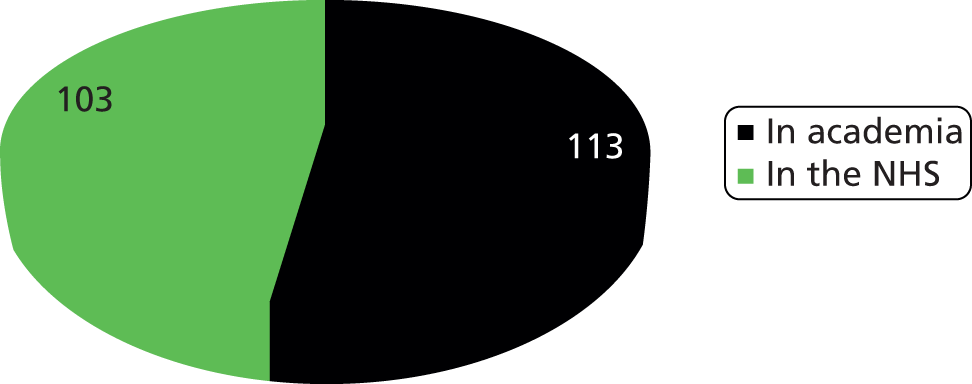

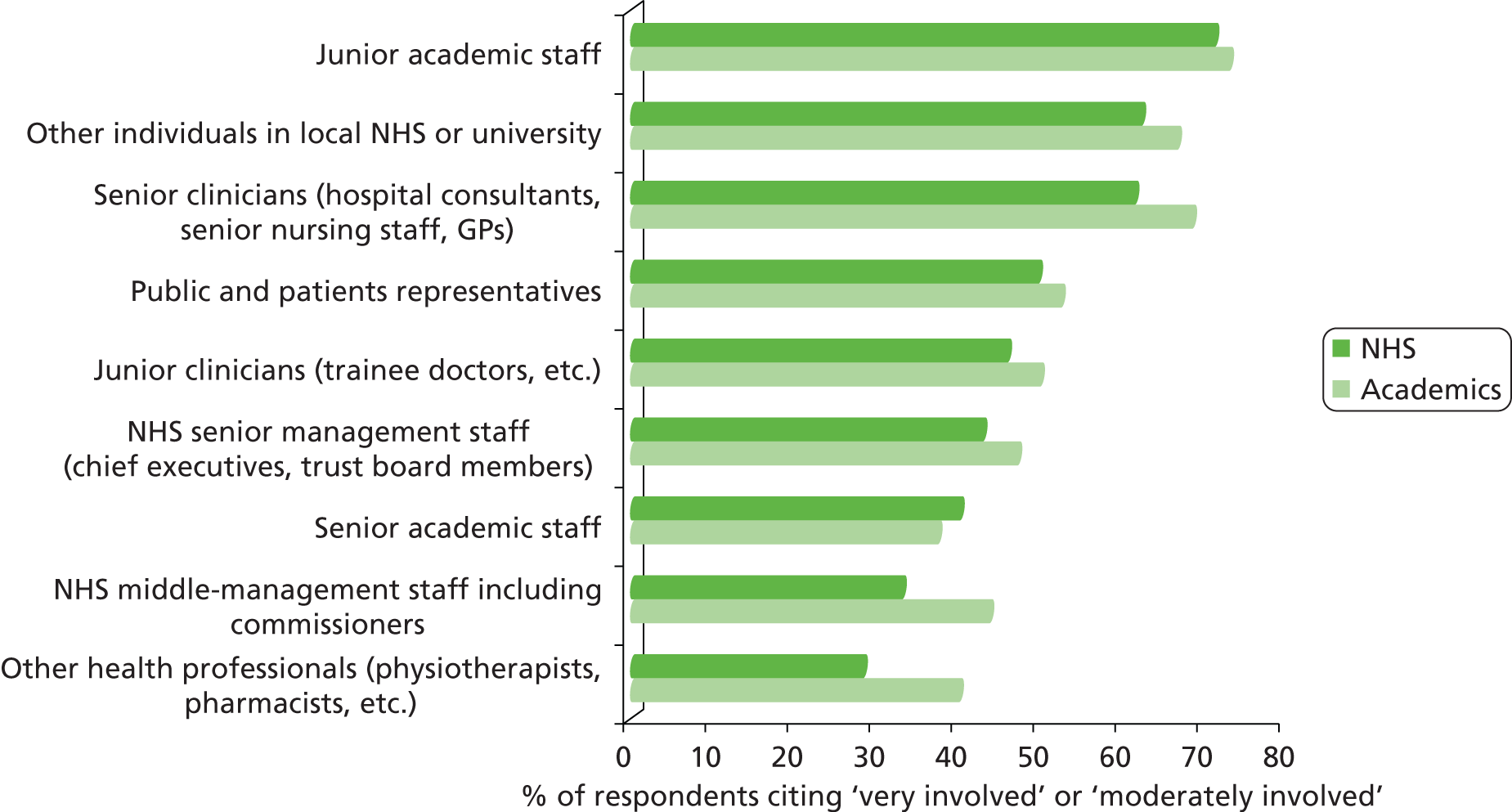

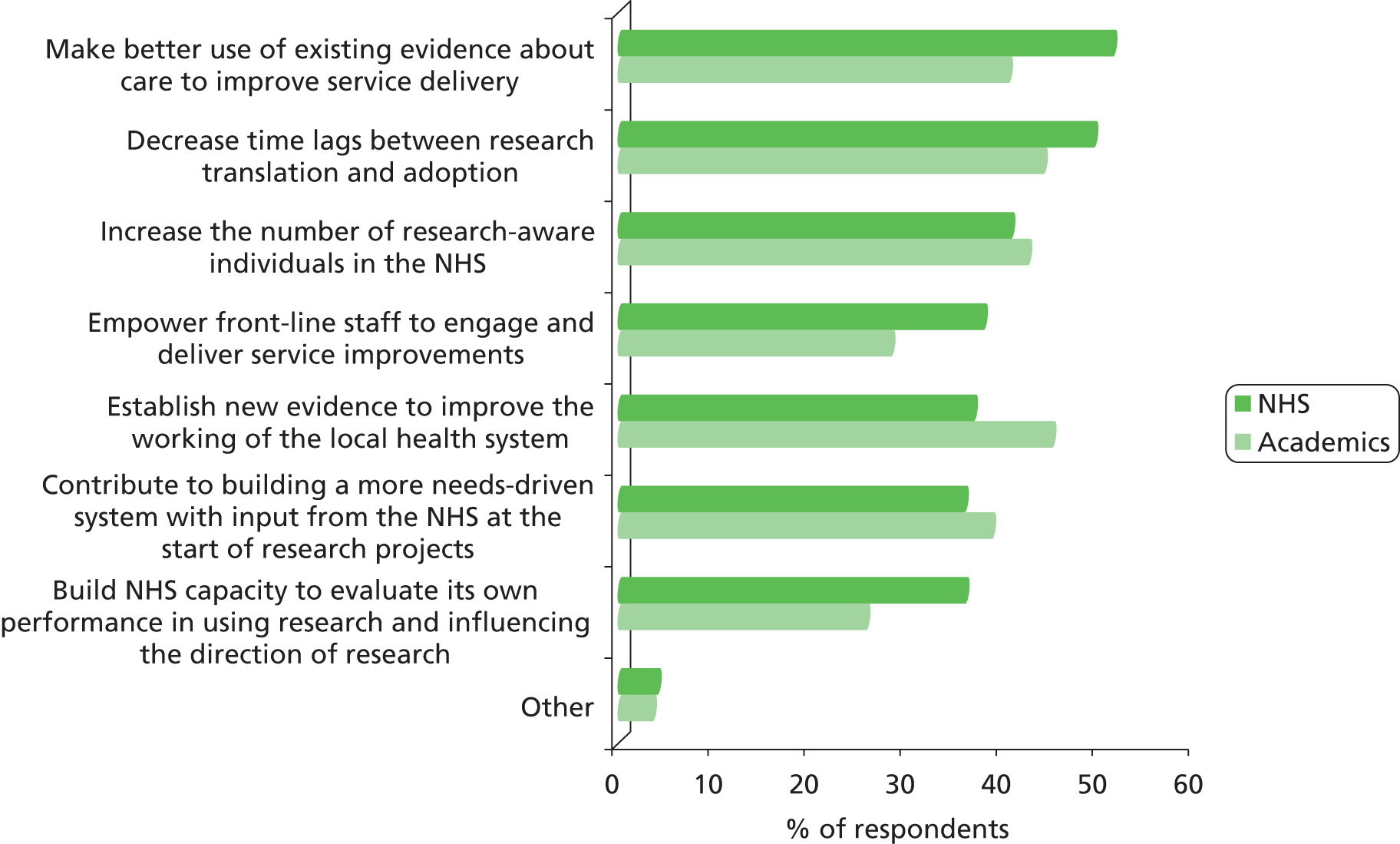

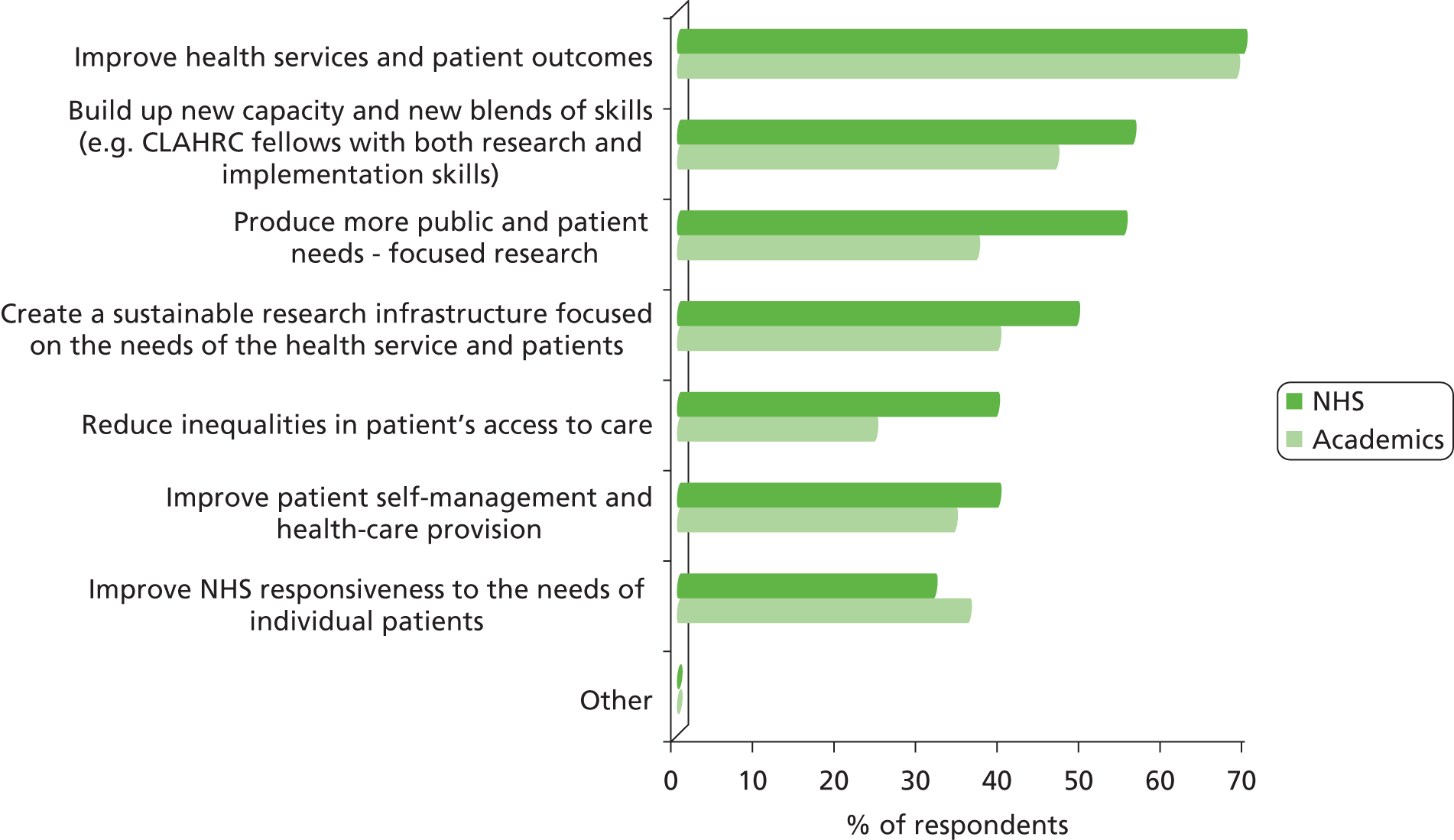

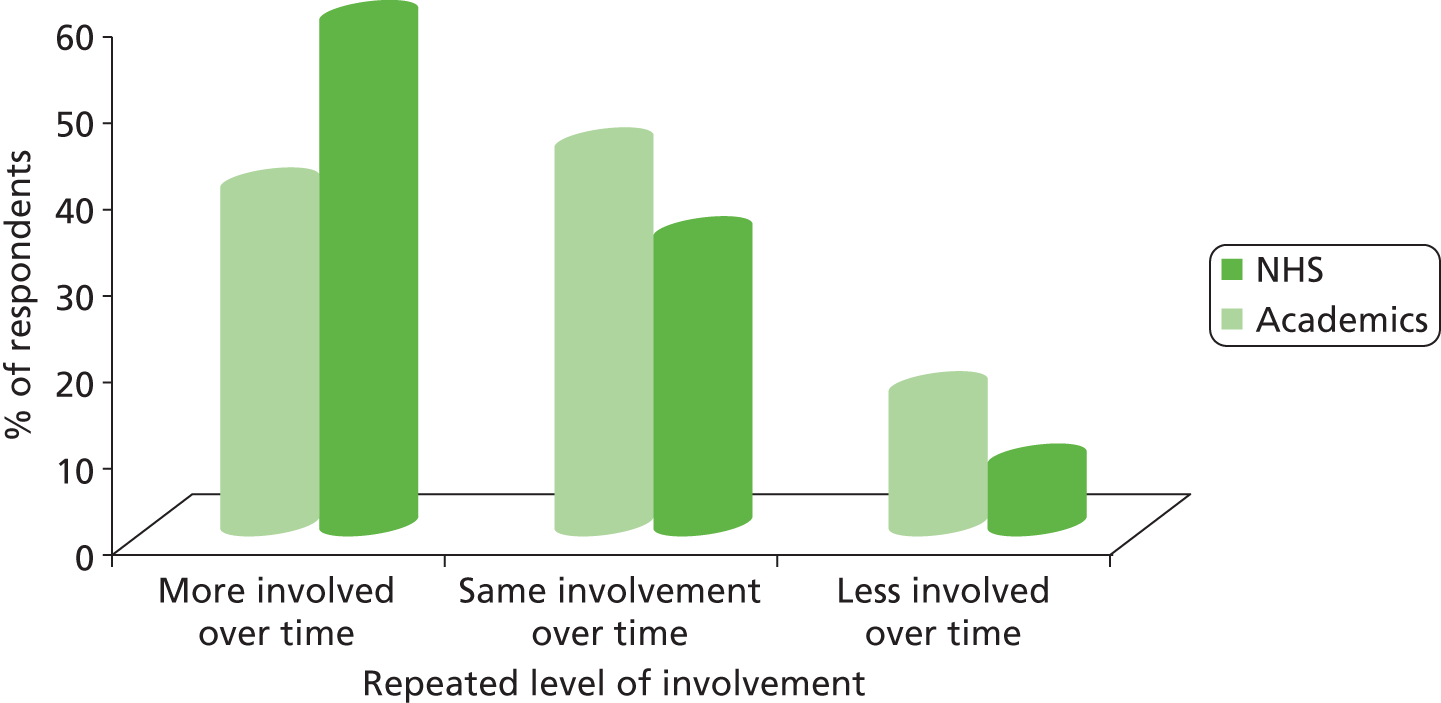

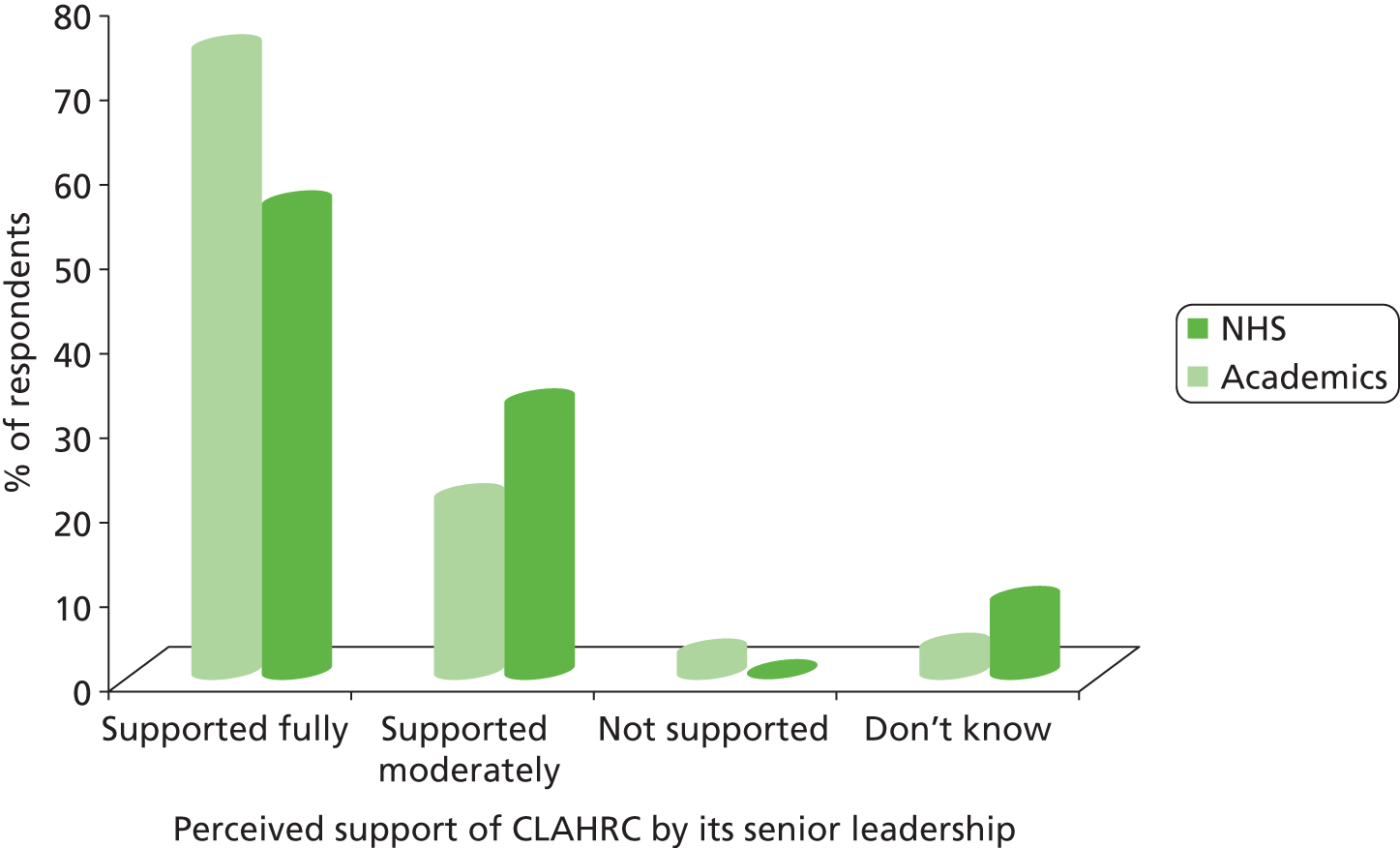

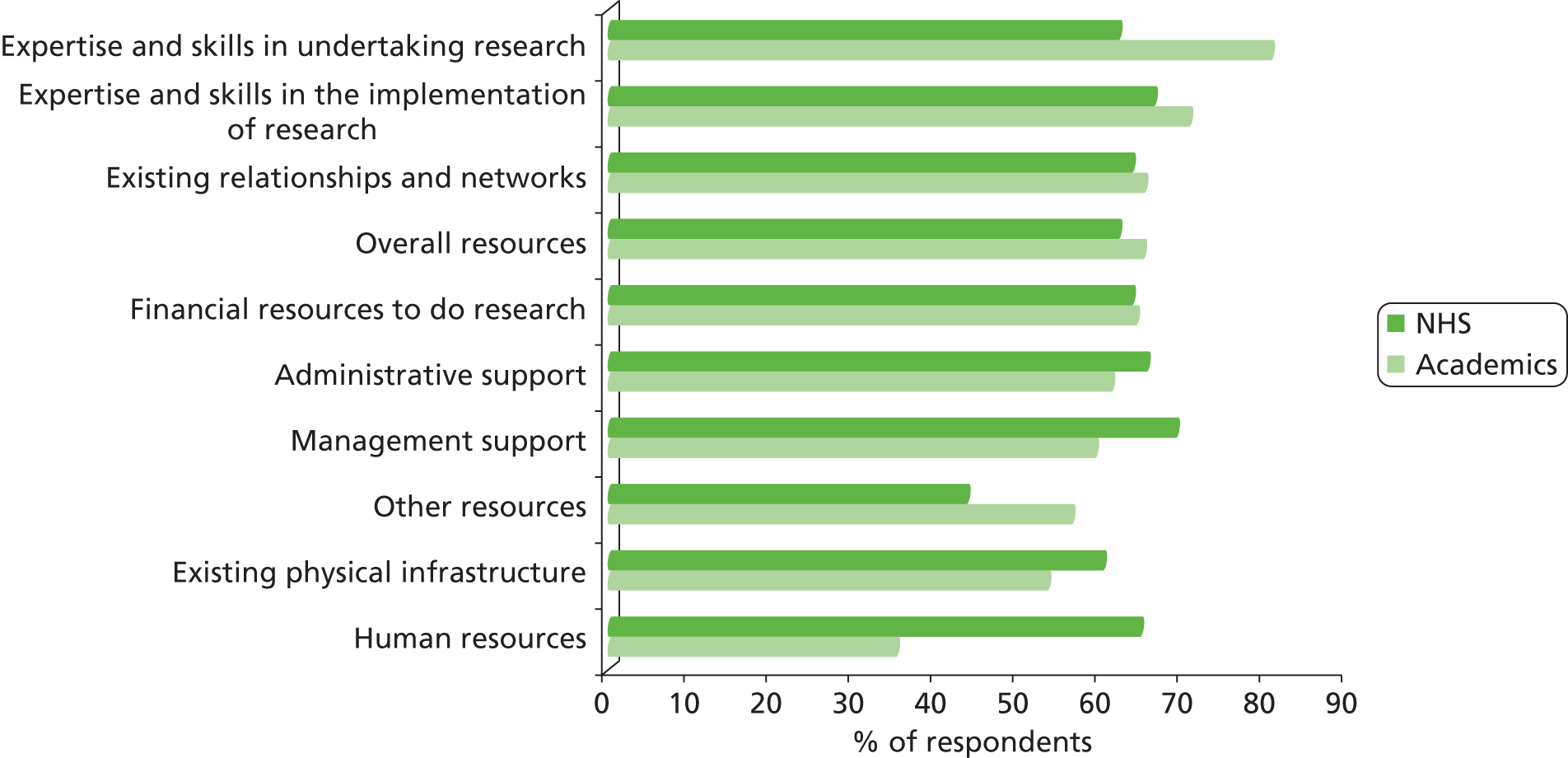

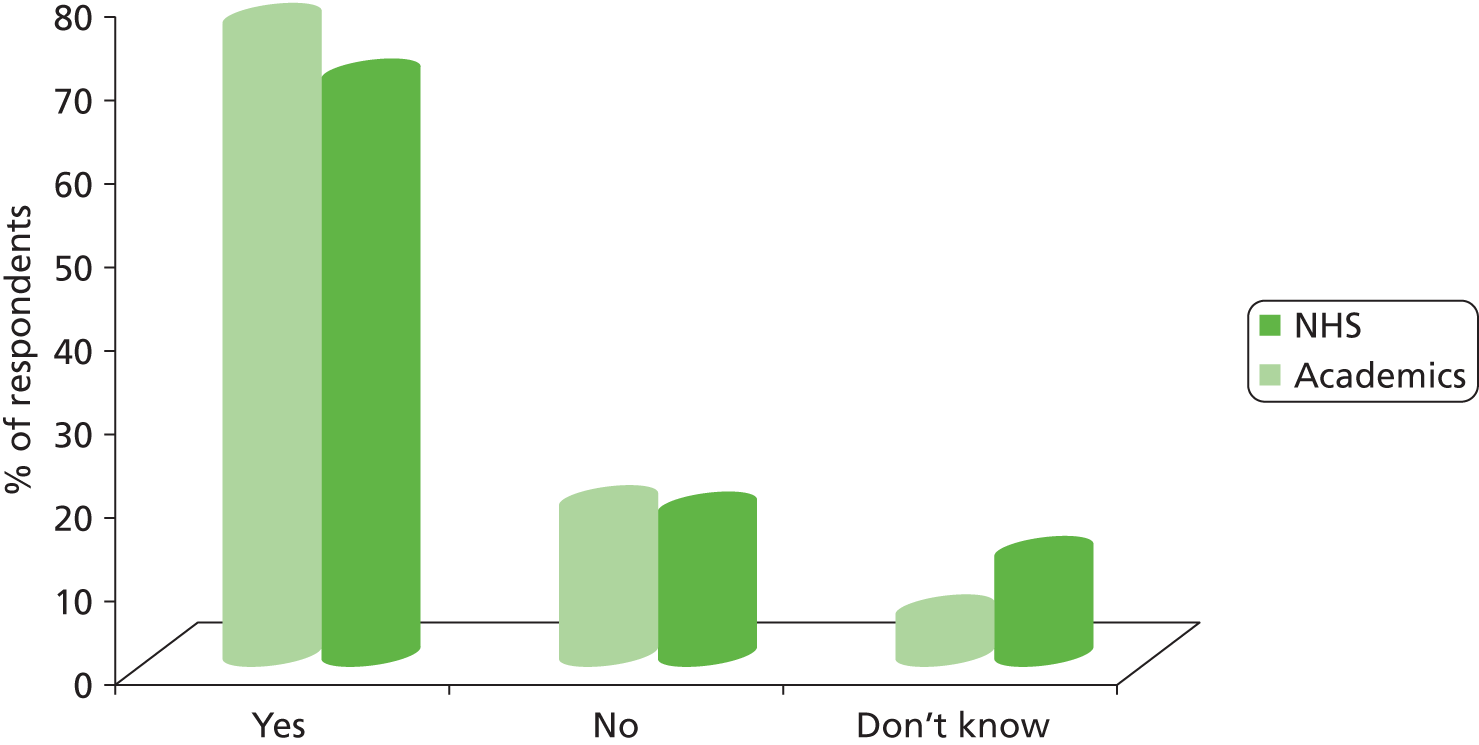

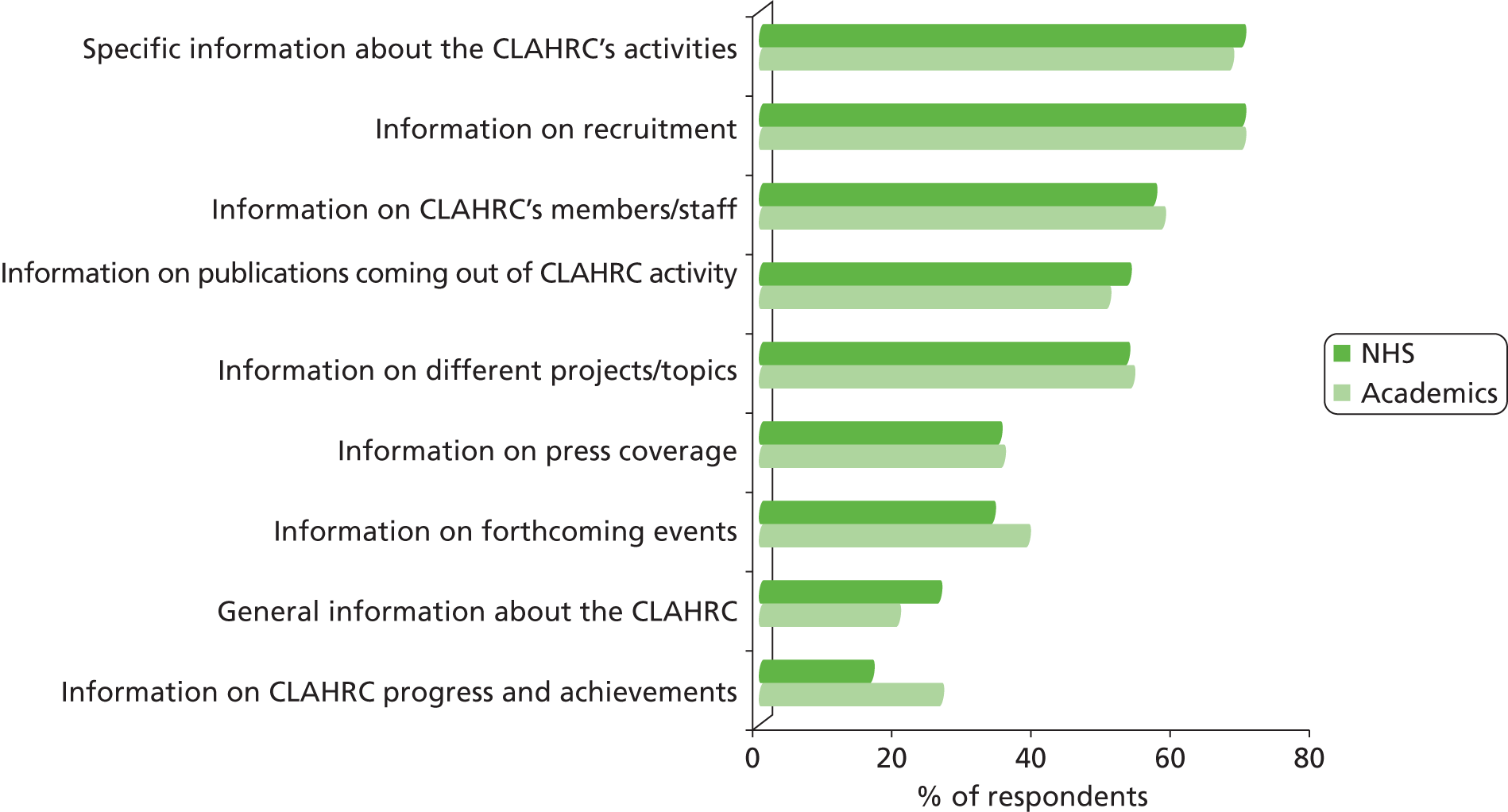

The number of respondents varied across CLAHRCs, from 22 to 79, with response rates ranging from 28% to 51%. There was an average of 40 respondents per CLAHRC (see Appendix 5). Of the 242 respondents, almost half reported spending most of their time working in the NHS (n = 103), with the remainder working predominantly in academia (n = 113) (the remaining 26 respondents did not respond to this question) (Figure 3). This proportion of respondents from the NHS and academia was also reflected across the majority of individual CLAHRCs (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

Number of respondents across NHS and academia.

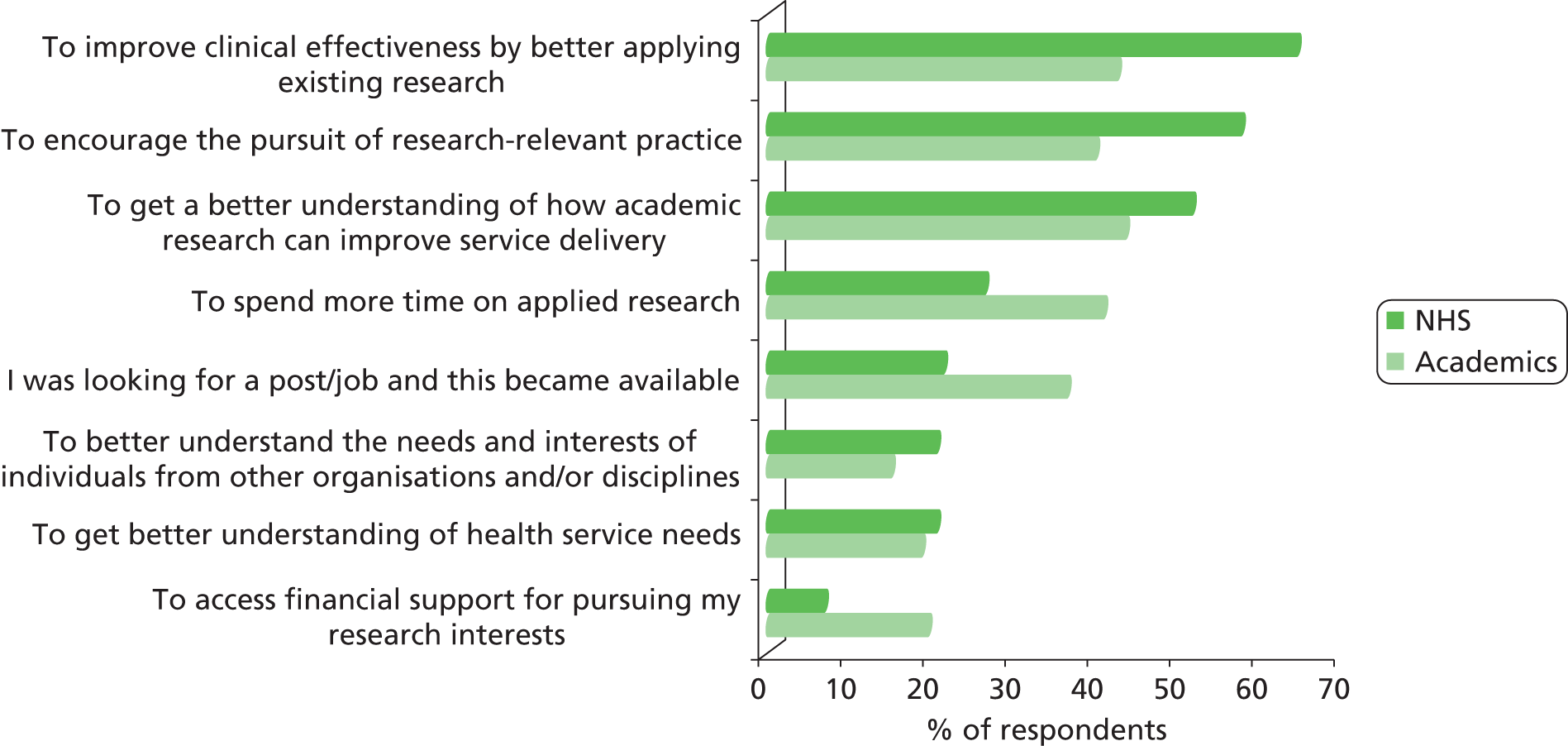

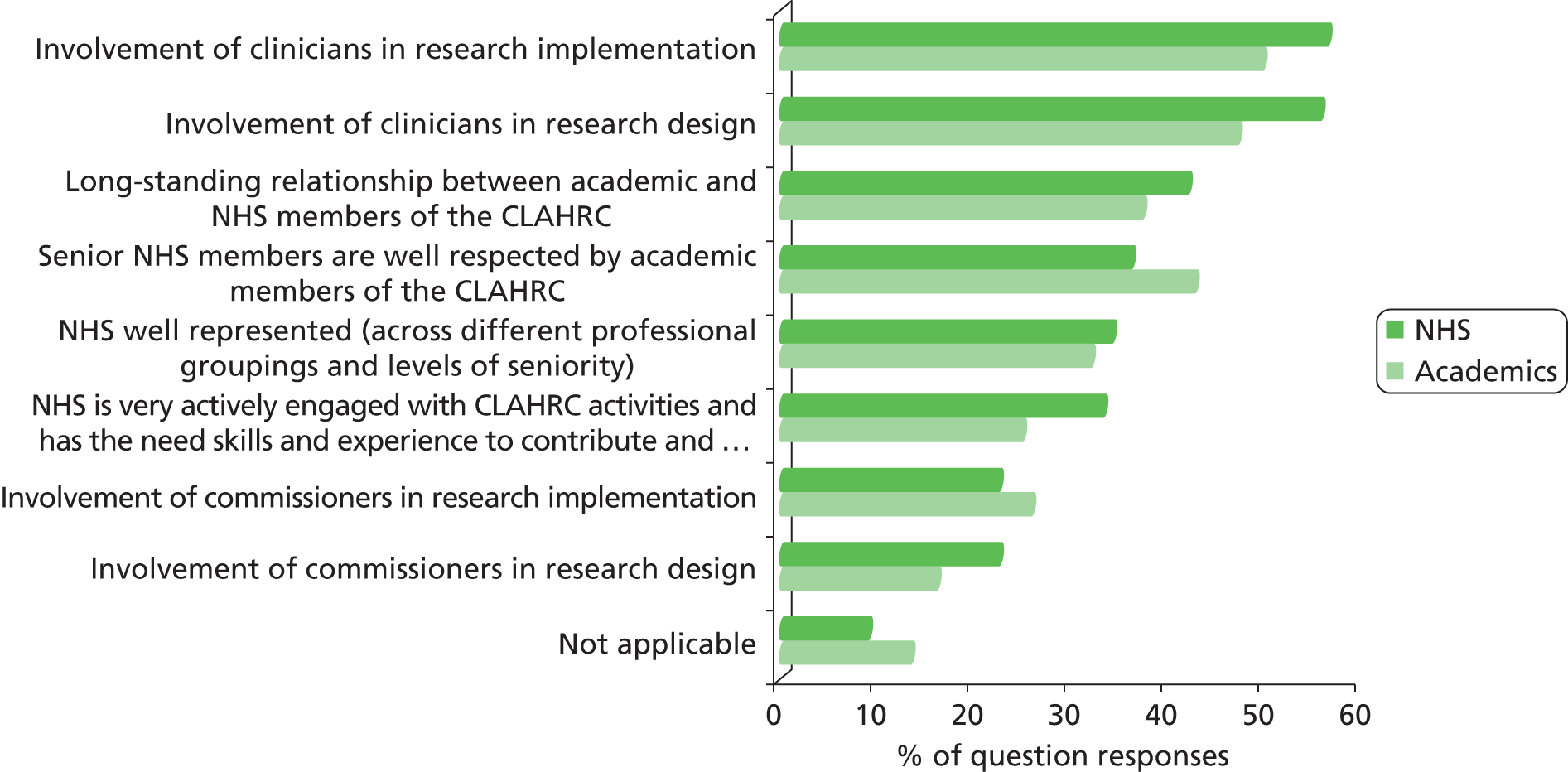

Figure 4 shows the nature of respondent involvement in the CLAHRCs where respondents reported this information (n = 163). A diverse range of job titles were cited, with the highest number being project team members, followed by theme leads, members of the CLAHRC board and research fellows.

FIGURE 4.

Respondent’s nature of involvement in the CLAHRC. PhD, doctor of philosophy; PPI, patient and public involvement.

Case studies

In order to develop a richer and more nuanced understanding of our areas of enquiry, we conducted case studies of two CLAHRCS. As noted earlier, the NIHR HSDR commissioned four teams to evaluate aspects of CLAHRCs. 71 HSDR’s key objectives throughout were to spread the evaluative effort evenly across the CLAHRCs, and to encourage the four HSDR-funded research teams to collaborate with each other so that the different parts of the evaluation were well co-ordinated and there was minimal duplication. All four research teams planned to undertake case studies with selected CLAHRCs. The selection of case study CLAHRCs was discussed by HSDR representatives and the four external evaluation teams at a start-up meeting in October 2009, and took into account the need to ensure an appropriate spread across all nine CLAHRCs and to ensure manageability for CLAHRCs and for researchers. Considerations about the nature and scope of individual CLAHRCs and more pragmatic reasons, such as geographical location, all played a role. As a result we agreed with HSDR that our evaluation should cover two case studies, CLAHRC-CP and PenCLAHRC.

Case studies comprised reviews of documentation relating to the two CLAHRCs, interviews with staff and a 1-day workshop with each CLAHRC to refine and validate emerging insights.

In-depth interviews

The in-depth interviews sought to explore the three core research questions guiding phase 2 of the study: the nature of the relations between the NHS and the CLAHRCs; how multidisciplinary teams for service improvement had been built; and how the CLAHRCs had promoted the use research evidence to influence commissioning and clinical behaviour for patient benefit. Participants were identified based on our prior knowledge of personnel involved with the CLAHRCs as identified in phase 1 of the evaluation, and in consultation with the CLAHRCs themselves. The selection of participants was intended to ensure representation of a wide range of individuals from academia and the NHS, including CLAHRC directors and managers, theme leads, management leads, programme leads, patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives and other stakeholders. Interviewees were contacted directly by the evaluation team with prior agreement of the two CLAHRCs.

We conducted a total of 29 interviews (CLAHRC-CP, n = 12; PenCLAHRC, n = 17). Interviews were semistructured in nature and lasted an average of 60 minutes (the interview protocol is presented in Appendix 6). Interviews for CLAHRC-CP were held face to face in February and March 2012, with 12 of the 16 individuals contacted agreeing to participate. Interviews for PenCLAHRC were conducted in March and April 2012; the majority were conducted face to face (or by telephone where this was not possible), with 17 of the 20 individuals contacted agreeing to participate. The majority of interviews were conducted by one researcher from the evaluation team, and all interviews were recorded and transcribed with prior permission. The transcripts were analysed using a uniform data extraction template structured according to the three research questions and, within each, clustered according to themes developed in the interviews.

CLAHRC workshops

The workshops served to refine and validate insights emerging from interviews in a collaborative way, and aimed to reflect on the evolution and progress of the CLAHRCS to (1) learn from the past and gain summative insights and (2) provide formative value for CLAHRCs to draw upon in informing any renewal of the initiative in the future. A total of 25 persons participated in the CLAHRC-CP workshop, and 14 persons participated in the PenCLAHRC workshop. The list of participants invited to the workshops largely reflected the individuals invited for interview. In the case of CLAHRC-CP, additional staff were approached by the CLAHRC in consultation with the evaluation team. Again, the primary objective was to ensure the presence of a wide range of individuals from both academia and the NHS.

Workshop discussions were facilitated by members of the evaluation team, following a structured protocol as detailed in the workshop agenda (see Appendix 7). Discussions were documented by workshop participants (flipcharts) and facilitators (notes) and the principal data points were organised according to the three research questions guiding phase 2 of the evaluation and, within each, clustered further into common themes.

Validation interviews

Informed by the survey and the case studies, we developed a number of deductive propositions which we sought to test and validate through a final set of interviews with representatives from all nine CLAHRCs. Eighteen interviews were conducted as part of the validation stage during September and October 2012. Interviewees included the directors from each of the nine CLAHRCs; senior members of the CLAHRCs affiliated to the NHS (in seven of the nine CLAHRCs); and representatives from the funder (NIHR). The interview protocol was structured to elicit the views of respondents on four emerging propositions relating to the CLAHRCs that had emerged from the case studies:

-

The task of the CLAHRCs is not just improving health-care research and not just improving patient outcomes, but a combination of both.

-

CLAHRCs are rooted in local relationships (some in place prior to the CLAHRC, providing a platform on which to build, others created during the CLAHRC) and build on local capacities, with implications for critical size and remit.

-

The collaborations CLAHRCs are building are ones that seek to promote integration and culture change, and are not designed simply to develop arrangements for brokerage (including knowledge brokerage) and linkage and exchange.

-

CLAHRCs legitimise a degree of experimentation in finding new ways of identifying and addressing NHS research needs, encouraging the emergence of research questions from the service and from its patients, which can then be funded by the CLAHRC but also by others.

The interviews also aimed to gain insights into how the CLAHRCs had evolved over time, including establishing the collaboration (e.g. the extent to which the original model for the CLAHRC persisted over time); leadership and developing the collaboration (including the scope of the individual CLAHRC and perceived risks surrounding the collaboration); and sustainability (e.g. did interviewees regard CLAHRCs as a persisting entity that would continue to broker the collaboration between the NHS and academia, or as a shorter-term catalyst to encourage a collaboration that could eventually stand on their own?). The full interview protocol is presented in Appendix 8.

Interviews were semistructured in nature and conducted by phone. The majority of interviews were conducted by one researcher from the evaluation team, and lasted an average of 60 minutes. All interviews were recorded and transcribed with prior permission. Interviews were analysed separately by two evaluation team members, using qualitative data analysis software (NVivo version 9, QSR International, Burlington, MA, USA), in order to identify content relating to our research questions and emerging propositions, and to capture any new themes arising from the data. The resulting analyses were cross-checked by the second team member.

Document review

Also as part of phase 2, we conducted two separate document reviews. The first of these aimed to review the wider landscape in which the CLAHRCs were operating, in order to place them in context and provide insights on the future role and potential of the CLAHRCs. To inform the review of the wider landscape throughout the period of the project, we regularly monitored the websites of the Department of Health and the NIHR and the most relevant programmes within them, and, using snowballing, identified documents produced by both the NIHR and the NHS, especially those related to the translation of research. We also conducted web searches to identify, and then review, proposals made in response to the call in 2012 for proposals to establish AHSNs. 73 Key findings from this review are presented in Chapter 5 and Appendix 9 of this report.

In addition, we conducted a document review to complement the validation stage of the study. This was intended to test our emerging propositions by cross-referencing with the documents produced by each of the nine CLAHRCs. We included documents available on the websites of all individual CLAHRCs and also contacted CLAHRC managers to obtain further documents, including publication lists and annual reports. This component of the study did not seek to provide an exhaustive assessment of all documentation produced by CLAHRCs. Its main purpose was to provide additional contextual information to inform our results further.

Phase 3: synthesis

The third phase sought to synthesise the findings from the overall study. It also constituted the reporting and dissemination phase.

Ethics approval

This study was granted ethics approval by Cambridgeshire 4 Research Ethics Committee on 1 July 2010.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement did not form a significant component of our study. This reflected the funder’s requirements that we keep a certain distance from the activities of the CLAHRCs and resist seeking close involvement in their day-to-day activities in order not to overburden managers and other key CLAHRC staff. However, we did strive to incorporate the views of PPI representatives where possible and explore the CLAHRCs’ role in engaging patients and the wider public in CLAHRC activities. Thus, we interviewed PPI representatives from CLAHRC-CP and PenCLAHRC as part of our case studies; they were also present at the workshops for both CLAHRCs. In addition, we attended a meeting of the Peninsula Public Involvement Group (PenPIG, PenCLAHRC’s user involvement group) in order to inform the case study further.

Chapter 3 Results phase 1: mapping the CLAHRC landscape

This chapter describes the findings from phase 1 of our evaluation, which was completed in the second year of the CLAHRC programme. 24 As noted in Chapter 2, a key aim of phase 1 was to identify the main logics of interventions underlying each of the nine CLAHRCs. Drawing on data derived from document review, interviews with senior individuals involved in the implementation of CLAHRCs and workshops with individual CLAHRCs, we explored how the partnerships were set up, their governance arrangements and the contexts in which CLAHRCS were implemented, alongside their aims and objectives, their overall approach (including any theories of change they identified) and the research and implementation themes they covered.

We here present a summary overview of our findings. The detailed accounts of each CLAHRC that emerged are summarised in Appendix 10, alongside the logic models that sought to capture the logic of intervention in each CLAHRC.

This initial overview was designed to obtain a broad picture of all nine CLAHRCs as they were in the second year after their establishment. In what follows we discuss these initial findings, distinguishing between those that were unique to specific CLAHRCs and those that were common, and describe how we used these findings, in discussion with the funder and the CLAHRC directors, to shape phase 2 of our evaluation.

The key themes of the CLAHRCs

A shared vision, but contrasting interpretations

The CLAHRCs involved collaboration between different stakeholders in health research and the NHS. They were intended to be vehicles for improving patient care through efficient and effective services built on improved generation, translation and adoption of knowledge. In this spirit we were interested not simply in the CLAHRCs as emerging forms of collaboration but also in how, through all their diverse impacts and activities, we could learn more about how a closer engagement between communities of researchers, health practitioners, health managers and others might lead to improved patient outcomes. From the detailed summaries (see Appendix 10) it was clear that all the CLAHRCs shared a vision and a vocabulary about the long-lasting change in the NHS that could be achieved by establishing new relationships between applied researchers and NHS decision-makers and new behaviours within each of these groups. There was shared optimism about the new pathways that could be forged, linking applied health-care research and medical research to patient outcomes and experiences. However, along with the similarities there were also more nuanced differences. Table 3 presents the broadly shared story of the CLAHRCs, using the data we obtained from all nine CLAHRCs. In Appendix 11 we show some of the ways in which individual CLAHRCs compare and contrast with others. The structure that we use to organise these summary tables draws upon a conceptualisation widely used to understand ‘improvement journeys’ in the health sector, reminding us that the ultimate aim of the CLAHRCs is to improve health care. See, for example, Bate et al. , who argue that there are six core challenges to organising for quality, and that these are structural, political, cultural, educational, emotional, and physical and technological. 63

| Structural and political | Cultural, educational and norms | Infrastructure: financial and physical | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Governance and accountability | Organisational structure of CLAHRCs including activities and themes | Societal attitudes and behaviours | Individual attitudes and behaviours | Infrastructure (including technology) | Use of resources |

| What needs to be done to bridge the second translation gap? | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| System shifts | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vision for success | |||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Governance, accountability and organisational structure

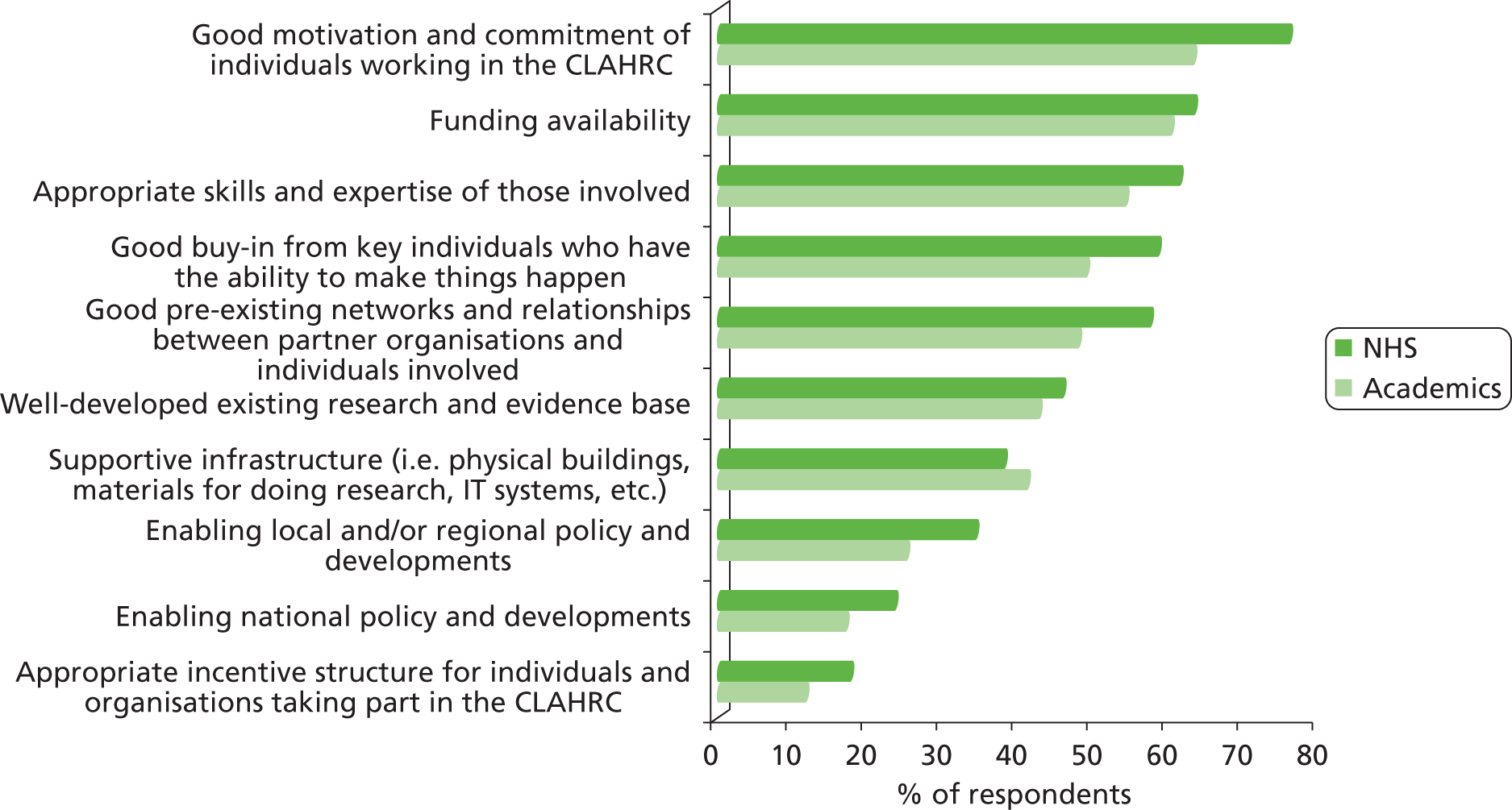

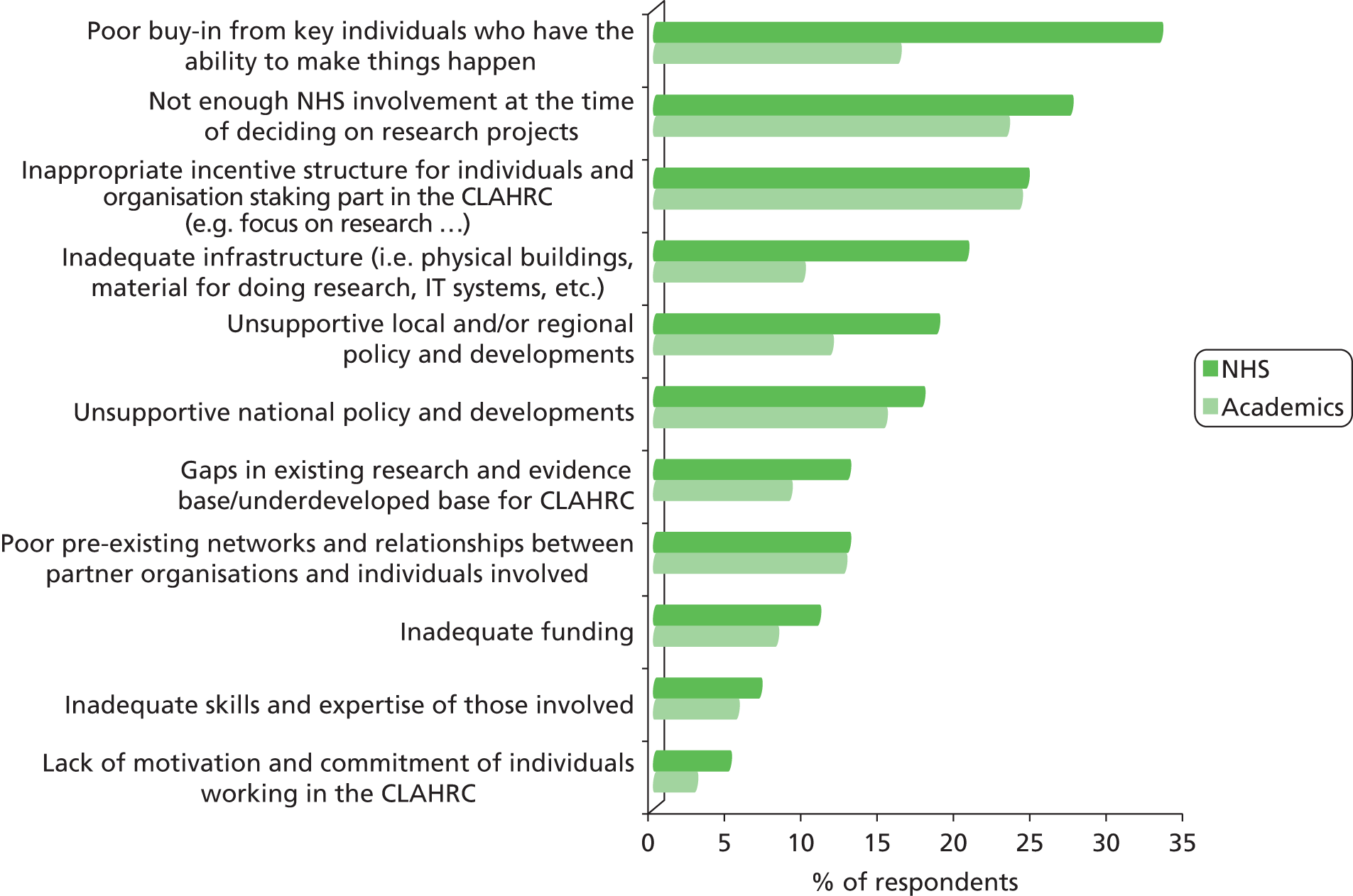

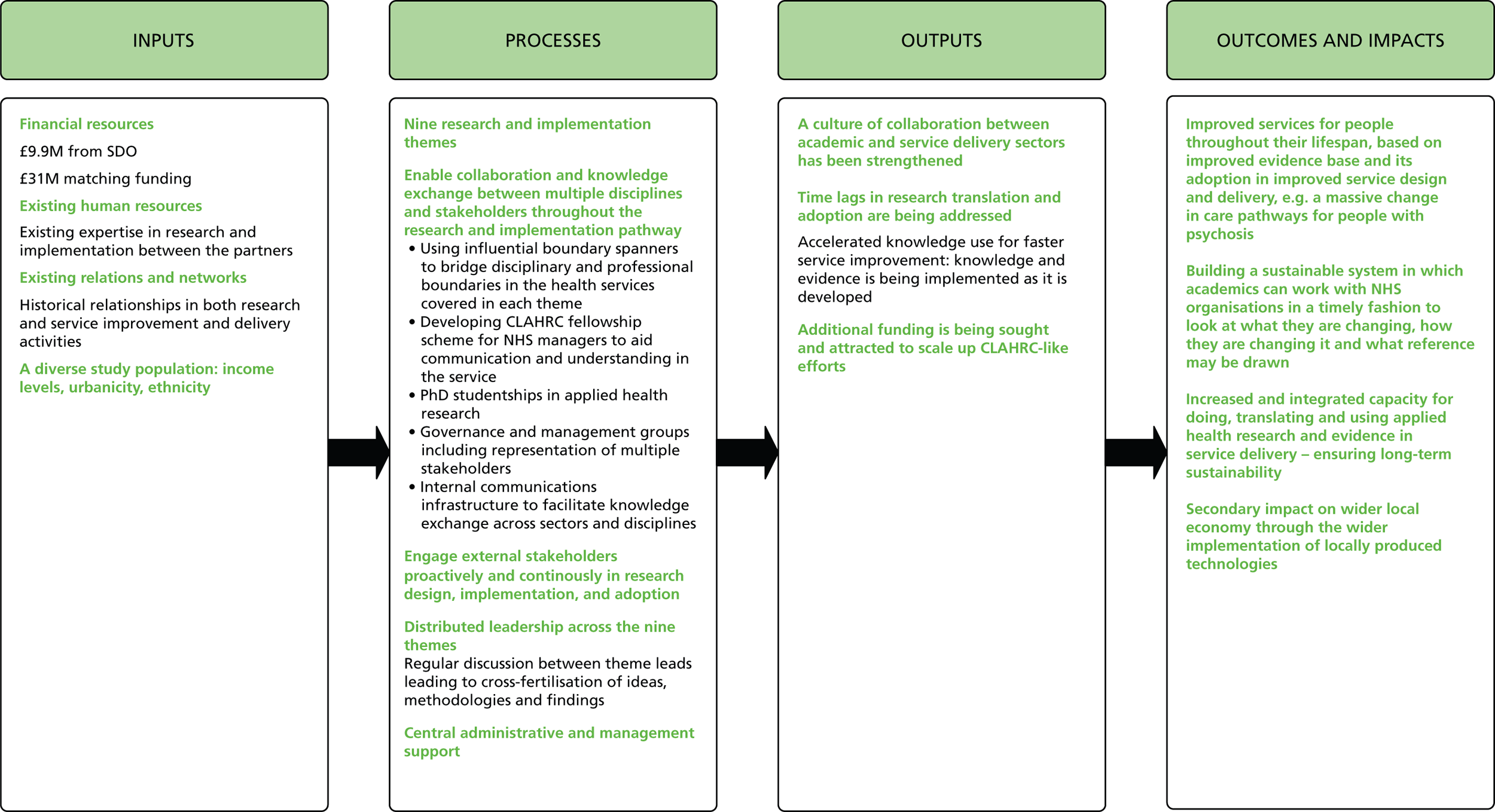

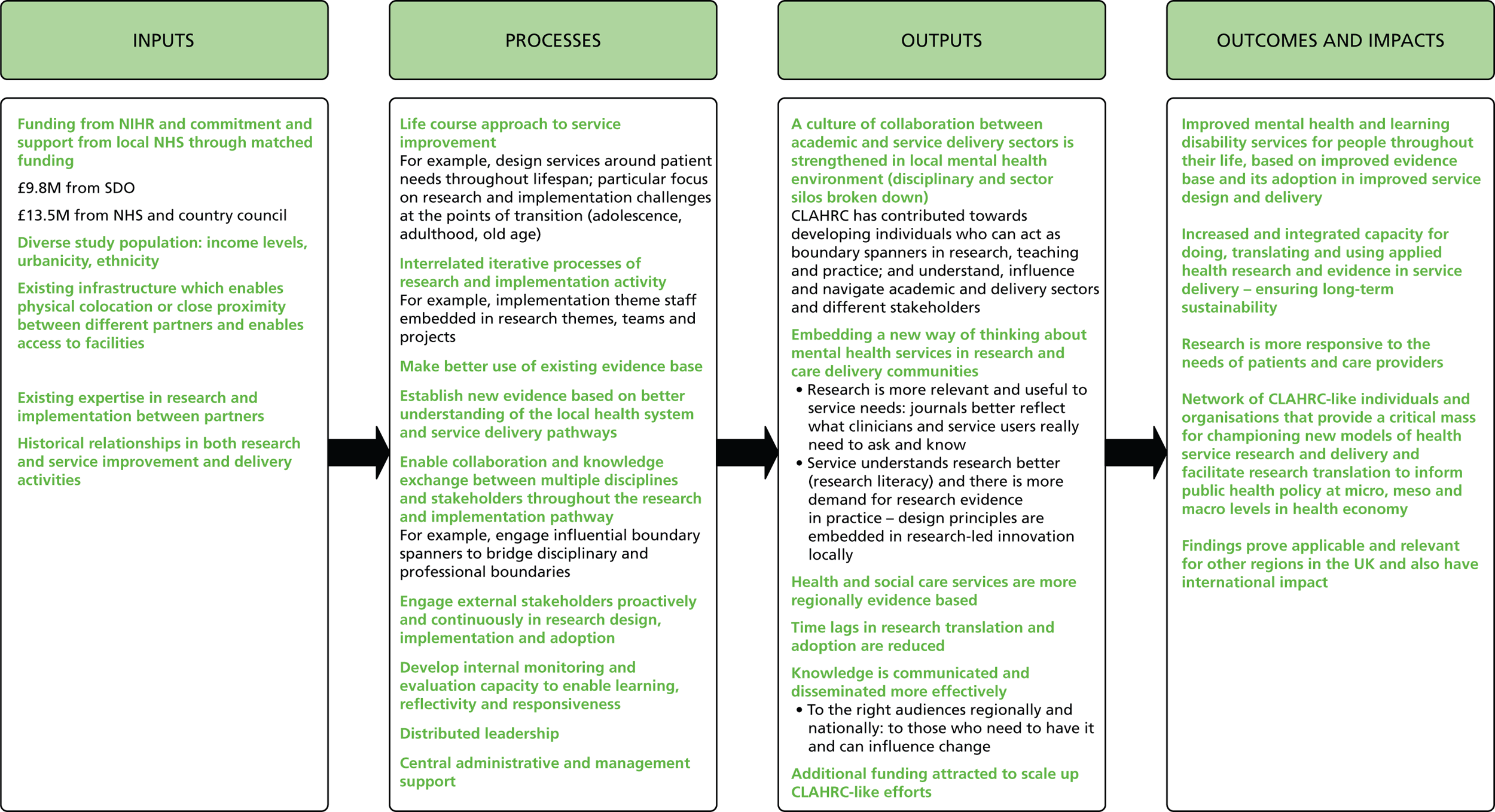

Governance and management arrangements involve the formal structures through which resources are allocated, decisions taken and disputes resolved. They also establish who should be accountable to whom and on what basis. From the outset, all the CLAHRCs involved leading figures with experience in establishing and running such arrangements across academic and service–delivery boundaries. All the CLAHRCs also shared the governance and management challenges that are unavoidable consequences of working in this terrain. These include navigating and managing dual R&D governance systems (NHS and academia) within a single structure and developing capacity, systems, provisions and contingency plans to adapt and respond to changing health-system landscapes (such as changes in the nature of commissioning and uncertainty about long-term funding availability). There were, however, differences in the way in which the fundamental governance principles of transparency, accountability and responsibility were operationalised. Some CLAHRCs had centralised ownership, control and management arrangements, while others devolved significant amounts of responsibility and provided substantial autonomy to constituent partner organisations or to differentiated functional committees. The administrative support in each CLAHRC was, therefore, diverse both in nature and in levels of centralisation.