Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5004/01. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The final report began editorial review in March 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Bailey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Context for the evidence synthesis

Employee engagement has been a topic of growing significance in recent years, bolstered in the UK by the work of the ‘Engage for Success’ movement, which has asserted that there is evidence of a link between high levels of staff engagement, organisational performance and individual well-being, as well as lowered rates of absenteeism and intent to quit. 1,2 This association was also underlined by Dame Carol Black in her 2008 report to the UK government, Working for a Healthier Tomorrow, in which she argues that features of job design, management and leadership are linked to the health of the workforce. 3

Academics have similarly argued that a range of positive organisational outcomes are associated with high engagement levels, such as improved performance,4 productivity,5 customer service6 and organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB),7 as well as positive individual outcomes such as well-being,8 reduced sickness absence9 and reduced intent to quit. 10

Engagement has grown in significance to the extent that it has been identified by the UK’s Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development as one of the core professional competencies for human resource management (HRM) practitioners, and is frequently cited as being one of the key challenges facing the HRM profession.

Within the NHS, engagement has come increasingly to the fore, with the establishment of a ‘Staff Engagement Policy Group’ at the Department of Health in 2008, the creation of a staff engagement indicator within the annual NHS Staff Survey in 2011 and the development of a range of resources on engagement by NHS Employers. 11 Sir David Nicholson, Chief Executive of the NHS in England, has been a member of the Sponsor Group supporting the work of the current Engage for Success Taskforce. The 2013 Francis Report12 indicated the potential risks of low engagement levels within the NHS and concluded that the NHS needs to foster a culture where the patient is put first, and staff are fully engaged.

However, the 2012 NHS Staff Survey results suggest that, although the staff experience is very positive in some respects, there is also cause for concern. 11 For example, only 26% said senior managers acted on staff feedback, 35% felt that communication between senior managers and staff was effective and 40% felt that their trust valued their work, while 38% reported feeling unwell as a result of work-related stress. 11 All of these factors have been found in academic research to be linked with levels of engagement. 8,10,13 Furthermore, 55% would recommend their organisation as a place to work; although an improvement on 2011 and comparable with findings elsewhere,10 this means that a large proportion of employees still do not feel positive enough about their employers to recommend them. Despite a growing demand for resources and advice on engagement within the NHS, there has hitherto been no systematic evidence synthesis that summarises the findings of research on engagement and shows how these may be relevant for developing and embedding engagement strategies in a NHS context. The purpose of this report is to address this overarching question and to provide a synthesis of the evidence relating to engagement, both within the workforce as a whole and within health contexts in particular.

This task is by no means clear-cut. There is a great deal of uncertainty over what engagement means, and its theoretical underpinnings. For instance, MacLeod and Clarke1 found over 50 different definitions of engagement while preparing their Engaging for Success report, and academics frequently refer to the definitional complexity of the field. 14–16 Definitions drawn from the practitioner domain tend to focus on engagement as an active verb, ‘engaging’, and highlight the notion that employee engagement is something done to employees to ensure they ‘buy in’ to the organisation’s overarching goals and values, often with the expectation that, if employees are engaged, then they will want to give something back to their employer. 1 This conceptualisation is closely linked to the more established constructs of involvement and participation: ‘doing engagement’. 17

However, this conceptualisation of engagement is not necessarily aligned with the development of the field within the academic literature. 18–20 Here, the construct of employee engagement was first introduced by Kahn21 to signify the authentic expression of self in role, involving physical, cognitive and emotional dimensions, and Kahn’s work has heavily influenced subsequent writings. 4,8,10,22 Engagement is thus considered within the organisational psychology field to be a multifactorial behavioural, attitudinal and affective individual differences variable,23–25 ‘being engaged’. 17 More recently, attention has turned to the topic of engagement from a critical HRM and organisational sociological perspective,26 raising new and as yet unanswered questions about the ontological status of engagement.

Linked to this, there is also considerable debate over the factors deemed to drive up levels of engagement, and the evidence is not so clear-cut as advice in the management literature would suggest. Academic research has suggested that a very wide range of factors at the levels of the individual, the job, the line manager and the employer may all be relevant. 27 These include, for instance, aspects of job design such as autonomy, meaningfulness and person–job fit4,21 and aspects of organisational climate such as voice and value congruence. 4,10 Specifically within the context of health-care workers, experiences of negative affect within the context of the job demands–resources (JD-R) model have been shown in one study to impact on engagement outcomes,28 while research by the Institute for Employment Studies found that the key drivers of engagement were staff perceptions of feeling valued by and involved with the organisation. 13

Equally important is an understanding of the underlying process by which engagement is thought to operate, and the theoretical frameworks that may be especially relevant. A number of theories have been proposed that might ‘explain’ how engagement works. For example, psychological traits such as perceived self-efficacy and a proactive approach to work, together with positive affect, are argued to generate an energetic, enthusiastic and engaged state. 29 Job design theory has also been found to be relevant, since for instance Kahn’s21 theory of engagement is rooted in Hackman and Oldham’s30 proposal that job characteristics drive attitudes and behaviour. Bakker and Demerouti31 also argue that the JD-R model demonstrates how job design can generate engaged states. However, there is as yet no agreed theoretical framework that may be of particular relevance in explaining engagement within the NHS context.

Bearing in mind these gaps in knowledge, the purpose of this evidence synthesis is to systematically bring together the research and evidence on engagement that is relevant in the health sector, in order to provide a thorough grounding for the development of a set of practice guides and materials that will be of direct, practical benefit to NHS managers and organisations. As Briner et al. 32 argue, ‘a synthesis of evidence from multiple studies is better than evidence from a single study . . . it is the collective body of evidence we need to understand’ (p. 24). It is therefore hoped that assembling evidence from a wide range of studies into engagement will bring about a more nuanced understanding of what engagement is, and how it works.

Review aim, scope and questions

The aim of this report is to present the results of a systematic evidence synthesis on engagement. Specifically, there are four research questions:

-

How has employee engagement been defined, modelled and operationalised within the academic literature?

-

What evidence is there that engagement is relevant for staff morale and performance?

-

What approaches and interventions have the greatest potential to create and embed high levels of engagement within the NHS?

-

What tools and resources would be most useful to NHS managers in order to improve engagement?

Thus, the first aim is to examine the ways in which engagement is defined and measured within the academic literature. The second is to examine the nature and quality of the evidence available that links engagement with morale and performance outcomes through a systematic review of the literature. The third is to examine the research findings that purport to demonstrate the antecedent factors to engagement. Based on the first three questions, the final research question concerns identifying other resources and evidence (‘grey literature’) that are of practical relevance to practitioners in the NHS. The results of this question are addressed through the production of a series of practitioner outputs provided in the appendices to this report. The main part of the report provides evidence from a systematic evidence synthesis on engagement. A core aspect of the evidence synthesis is to critically evaluate the quality of evidence currently available from a variety of sources in order to ensure that the report and other outputs from the study are based on best evidence. A problem that we have faced in the preparation of this report has been the wide variety of terms used to refer to employee engagement. These include ‘work engagement’, ‘personal engagement’, ‘job engagement’, ‘task engagement’, ‘organisational engagement’ and ‘employee engagement’. For simplicity, we have tended to use the term ‘engagement’ throughout.

Structure of the report

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 describes the rationale underpinning the methodology for the evidence synthesis, and details the stages of the process of piloting and refining search terms, searching for studies, sifting studies against inclusion and exclusion criteria, and extracting and synthesising data.

Chapter 3 addresses the question: ‘What is engagement?’ Engagement is a contested term that has been defined and operationalised in many different ways. 16 In this chapter, we provide an overview of definitions and measures used within the academic literature, and evaluate the areas of both strength and concern. We also present the major theoretical frameworks used to explain the engagement process, and report on the occurrence of both measures and theories within the selected studies. The chapter concludes with some consideration of how engagement as a construct relates to the wider field, and an evaluation of its construct and discriminant validity.

In Chapter 4, we examine the results of the evidence synthesis relating to the link between engagement and morale, and in Chapter 5 we examine the results relating to the association between engagement and performance outcomes. Chapter 6 focuses on the antecedents of engagement, and evaluates the strength of the available evidence concerning approaches within the workplace that can create and embed high levels of engagement.

In Chapter 7, we bring together the evidence presented in the earlier chapters and synthesise the overarching themes emerging from the review of the literature. We highlight areas of strength within the extant literature, as well as areas where further development is required. We present the overall conclusions based on our evidence synthesis, indicate the implications for policy and practice, and make recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Introduction

This chapter outlines the methodological approach to the evidence synthesis. This commences with an examination of the engagement literature from a methodological perspective and is followed by an explanation of the rationale for the use of a narrative approach to evidence synthesis. The remainder of the chapter then details the specific methods used at each stage of the synthesis, explaining how the search terms and strategy were developed and the data were produced. The chapter also explains the methods used to review the grey literature sources in conjunction with the main data collection and analysis process. The grey literature was evaluated for its relevance to the evidence synthesis report, and for inclusion in the practitioner outputs arising from this project that are detailed in this chapter.

The engagement literature and evidence synthesis

The engagement literature

Engagement is a relatively recent construct; its first modern iteration, by Kahn,21 was followed by a period of seeming lack of interest, but, from 2003 onwards, ‘an explosion of scholarly and practitioner interest’ has taken place (p. 57). 33 We have therefore witnessed a very significant increase in the volume and diversity of the engagement literature in the ensuing years, leading Guest18 to term engagement an evolving concept rather than a construct in its own right with a clear theoretical underpinning. This diverse body of literature poses significant challenges for undertaking a systematic review and evidence synthesis; as Rafferty and Clarke note:

The danger with concepts like engagement is that they can become unwieldy, fuzzily-defined terms invoked as panaceas for the dilemmas of workforce management . . . conceptual clarity and definitional precision around measurement of engagement and its organisational outcomes are imperative.

(p. 876)34

However, as Bargagliotti35 states, the need to understand engagement in the context of health has become strategically important for a number of reasons, in particular the increasingly complex demographic and institutional challenges of providing health care and their impact on the quality of health outcomes. The potential for engagement to help address the complex challenges of health governance, management and delivery creates a strong imperative for a synthesis of available evidence. 36 The key methodological challenges in pursuing the research questions of this evidence synthesis, therefore, have been to seek to establish the nature and qualities of engagement that might distinguish it from other similar and/or related concepts, such as job satisfaction, and to understand its role within a causal model of antecedents, mediators, moderators and consequences. 25,37

There is a growing demand for resources and advice on engagement within the NHS, particularly in the absence of a rigorous approach that systematically evaluates how engagement strategies can be developed and operationalised within the NHS context. However, the risk remains that advice given to NHS managers and staff may be based on studies that demonstrate persuasive yet spurious correlations and linkages, rather than on robust academic research grounded in theory. The lack of clarity and unity of approach means that, although a great deal of this research has been reviewed and deemed to be methodologically and conceptually valid, there is a risk of committing a type 3 error, whereby the wrong problem is being solved correctly. 38

Briner and Denyer39 comment that more systematic approaches to reviewing the research literature are needed, otherwise ‘there is a danger that managers searching for “quick fixes” to complex problems may turn to popular books that seldom provide a comprehensive and critical understanding of what works, in which circumstances and why’ (p. 336). In this regard, systematic reviews and systematic evidence syntheses are proposed as more effective ways to determine both the quality and the relevance of the research evidence. By ‘systematic’, what is meant is an approach which adheres to the following principles: organised around specific review questions; transparent, such that methods are explicitly stated; replicable so that how the review is reported would enable others to repeat the review using the same procedures and where appropriate update the findings; and summarising and synthesising findings in an organised way.

Gough states:

Being specific about what we know and how we know it requires us to become clearer about the nature of the evaluative judgements we are making about the questions that we are asking, the evidence we select, and the manner in which we appraise and use it.

(p. 214)40

What is an evidence synthesis?

Like a systematic review, an evidence synthesis enables reviewers to reach conclusions, but there are a number of different approaches that may be appropriate. What should determine the approach is the nature of the question based upon the evidential gap; the nature of the analyses and evidence which are available for review, whether quantitative, qualitative or mixed, empirical, conceptual or critical; and whether it is premised upon objectivist or interpretivist orientations. According to Rousseau et al. ,41 methods of review fall into four categories: aggregation, integration, interpretation and explanation.

Aggregation is an approach to evidence review that is essentially quantitative, the purpose of which is to maximise the sample size and thus render a particular finding more valid by minimising bias. It is an approach commonly associated with randomised controlled trials and the pursuit of clinical evidence, but excluding insights into the social and organisational contexts from which data are drawn and which consequently discount the contextual mechanisms that might influence results. Integration is an approach which similarly seeks to strengthen the validity of research findings, but here this is pursued through triangulation of quantitative and qualitative findings, particularly in seeking to contextualise results. A fundamental problem of this approach relates to the fact that quantitative and qualitative data are generated from different epistemic assumptions. Moreover, there is rarely a comparable volume of quantitative and qualitative research available, and the weight of evidence is often imbalanced, leading to similar acontextualised results to those above.

Interpretation is an approach to evidence review which is underpinned by a hermeneutic tradition in social research and thus is fundamentally different from aggregative and integrative approaches. Issues of validity are often overlooked for thematic viability between studies, using mapping or narrative techniques, yet weaknesses emerge because bodies of data are incomparable. Finally, explanation is an approach which ‘focuses on identifying causal mechanisms and how they operate. It seeks to discover if they have been activated in a body of research and under what conditions’ (p. 497). 41 Again, the epistemic basis differs from the positivist and interpretivist underpinnings evident in the above, to include a critical realist approach which rejects traditional approaches of identifying causal relationships through plausible associations (‘coincidences’) between variables. Explanation commences from an examination of the construct validity of variables used in research, and challenges quality on these grounds, offering alternative explanations of the data based on a different set of underlying causal mechanisms. Although its value is seen to lie in dealing with evidence from disparate sources and methodological bases, it ultimately rests on a hermeneutic approach to knowledge generation.

To this list, Briner and Denyer39 add a fifth approach of narrative synthesis, which has previously been used in management sciences. Drawing on the interpretivist approach, it adheres to the same principles of organisation, transparency and replicability as all the approaches detailed above, and with quality–relevance as the organising matrix. ‘Narrative synthesis’ refers to a way of embracing a wide body of disparate evidence through a range of clear review questions with the aim to ‘tell the story’ of the findings from the included studies (p. 1)42 by

describing how they fit within a theoretical framework and the size or direction of any effects found. Narrative synthesis is a flexible method that allows the reviewer to be reflexive and critical through their choice of organizing narrative.

(p. 356)39

Its strength lies not simply in being able to address complex and discursive constructs, such as engagement, where other forms of synthesis are not feasible, but in providing a critical narrative which explains how an existing or ‘long established policy or practice makes a positive difference’ (or not) (p. 5). 42 By developing a critical narrative, an evidence synthesis seeks to generate an understanding of the evidence and provide new insights that would not otherwise be apparent either from focusing on individual or small clusters of studies, or from including only certain types of (e.g. quantitative) data.

Through its emphasis on ‘evidence’, as opposed to ‘statistical significance’, an evidence synthesis thus looks to the nature and scale of the effects in practice but without compromising on quality (i.e. validity) or relevance (i.e. ‘germaneness to the issue at hand’) (p. 7). 43 This highlights the importance of the social (contextual) as well as the scientific nature of evidence and emphasises the need for reflexivity in conducting evidence reviews. It is important, for example, not to confuse ‘evidence’ with ‘truth’, because evidence rests on a body of research, local information, individual experience and professional knowledge as well as conceptual frameworks that are constantly evolving and open to reinterpretation depending on current circumstances. 44 In its broadest sense, evidence is therefore defined as ‘knowledge derived from a variety of sources that has been subjected to testing and has been found to be credible’ (p. 83). 44

Therefore, to the list of principles that give shape to an evidence review we add credibility to denote an approach which yields results that are meaningful at both objective (reliable) and subjective (trustworthy) levels. However, evidence syntheses can be vulnerable to publication bias because of the ways in which evidence is selected for publication. 45 Too narrow an approach can result in deeming other forms of evidence, including counter-evidence, inaccessible or inadmissible, thus making the synthesis less credible. To maintain a systematic approach and address possible bias, it is important to be as inclusive as possible to ensure that other sources of evidence, including ‘grey literature’, are considered for potential relevance. 46 Grey literature includes materials produced in the form of conference papers/proceedings, statistical documents, working and discussion papers, unpublished studies and websites, material that would not necessarily be found in peer-reviewed journals.

Evidence review methodology

Briner46 sets out the process whereby a systematic evidence review is conducted according to these core principles within the field of management. He suggests it is a process that should be moulded around the issues and review questions, but it is not expected to proceed in a linear fashion. Systematic review is a method of choice because it can be ‘applied or modified depending on the questions being asked’ (p. 21). 45 Nonetheless, the first principle of organisation means that a systematic approach must be taken in which the basis of all decisions about quality, relevance and credibility is clearly defined, alongside the outcomes of those decisions. To achieve this, Briner46 sets out five stages to the review process:

-

planning, which includes developing the research questions

-

locating studies through a structured search

-

evaluating identified material against eligibility criteria for inclusion/exclusion as evidence

-

analysis and thematic coding (data extraction)

-

reporting.

We have set out below how these stages were applied in this project.

Planning

Developing the research questions

The purpose of planning is to agree the overall search strategy and criteria, and to develop and break down the review questions into manageable sections. Getting the research questions right is generally regarded as the most important step in any review process, as it guides all subsequent lines of enquiry and decision-making. This was achieved through the participation of the project team in consultation with the project adviser and the advisory group. The four overarching research questions were refined into nine specific questions, as shown in Table 1. As Briner and Denyer39 suggest, the purpose of involving the advisory group and other experts is to ensure that the research questions make sense, are specific in order to help inform the search strategy and search terms, and provide a robust basis for later judgements about quality and relevance. This was an iterative process which ensured that the research questions were adapted as the search strategy and search terms developed.

| Research objective | Review question | Specific research question |

|---|---|---|

| To review and evaluate theory and practice relating to models of staff engagement | 1. How has employee engagement been defined, modelled and operationalised within the academic literature? | 1.1 How is employee engagement defined within the academic literature and in the health context? |

| 1.2 How has engagement been measured and evaluated within the academic literature? | ||

| 1.3 What theories are used to underpin models of engagement within the academic literature? | ||

| 2. What evidence is there that engagement is relevant for staff morale and performance? | 2.1 What is the evidence that engagement is relevant for staff morale (a) within the workforce in general or (b) within the context of health? | |

| 2.2 What evidence is there that engagement is relevant for performance at the (a) individual, (b) unit, team or group, (c) organisational or (d) patient/client level either within the workforce in general or in the context of health? | ||

| To produce a set of evidence-based outputs that help and guide NHS managers in fostering high levels of staff engagement | 3. What approaches and interventions have the greatest potential to create and embed high levels of engagement within the NHS? | 3.1 What evidence is there concerning approaches and interventions within an organisational setting at the (a) individual, (b) unit, group or team, or (c) organisational level that create and embed high levels of engagement within the general workforce? |

| 3.2 What evidence is there concerning approaches and interventions within an organisational setting at the (a) individual, (b) unit, group or team, or (c) organisational level that create and embed high levels of engagement within the health context? | ||

| 4. What tools and resources would be most useful to NHS managers in order to improve engagement? | 4.1 What tools and resources are currently available for NHS managers? | |

| 4.2 What tools and resources would NHS managers find useful? |

Developing the search terms and strategy

The initial list of possible search terms (Table 2) emerged from a number of meetings involving the project team and wider discussions with advisory group members. Within the project team, this process was facilitated using the context, interventions, mechanisms and outcomes framework (see below) as advocated by Denyer and Tranfield47 as a mechanism to map the issues, focus the research questions and test their logic. Thus, the overall search strategy and terms were developed through scrutiny of the research questions with regard to:

-

context (the setting in which evidence has been gathered, whether health or other)

-

interventions (what is being researched/tested)

-

mechanisms (through which the intervention affects outcomes)

-

outcomes (the effects or results of the interventions).

| Psychology/HRM | Sociology/philosophy | Economics |

|---|---|---|

| Employee engagement | (Worker) participation | Stakeholder engagement |

| Personal engagement | (Employee) involvement | Authentic engagement |

| Staff engagement | Organisational involvement | Integration (economic, social) |

| Organisational engagement | Labour process (theory) (and autonomy) | Intrinsic reward |

| Relational engagement | Organisational action | |

| Workplace engagement | Enactment | |

| Team engagement | Employee voice/employee silence | |

| Job engagement | Employee integration (decision making) | |

| Continuous engagement | Worker/employee identity | |

| Emotional engagement | Employee empowerment | |

| Cognitive engagement | Industrial/workplace democracy | |

| Behavioural engagement | Choice (and links to motivation) | |

| State engagement | Democratic engagement | |

| Trait engagement | (Employee) experience of work | |

| Job involvement | Marginalisation (disengagement) | |

| Employee voice | Exploitation/alienation | |

| Work engagement | Engagement with demographic attributes | |

| Professional involvement/integration | Control/resistance | |

| Disengagement | Resistance/’misbehaviour’ | |

| Professional engagement | Trust | |

| Social engagement | ||

| Affective engagement | ||

| Intellectual engagement | ||

| Strategic narrative | ||

| Integrity | ||

| Vigor/vigour | ||

| Dedication | ||

| Absorption | ||

| Physical engagement | ||

| Active engagement/actively engaged |

By interrogating the research questions with this framework, it became apparent that the engagement literature spanned a number of different disciplines with parallel themes in the fields of psychology; business and management; sociology and philosophy; and economics. Discussions with the advisory group also led to a widening of the search strategy to reflect these concerns and other interests. The advisory group contained two patient representatives and five NHS stakeholders, one of whom was a clinician and two of whom were trade union representatives. Every member of the group had an opportunity to contribute suggestions to shape both the search strategy and the practitioner outputs through inputs to the discussion at advisory group meetings. The group also commented on the review findings as the study progressed. Finally, one of the patient representatives attended the practitioner conference in February 2014, and one of the NHS stakeholder representatives presented at the same event. Discussions with its members resulted in the inclusion of terms which they felt might yield particular insight into engagement through the lens of, for example, patient safety, medical leadership and care quality.

Table 2 details the 54 search terms initially generated across these three disciplinary fields through these discussions. Through subsequent meetings and discussion, these terms were then refined into a shorter ‘search string’, the antecedents or drivers of engagement and outcomes having been distilled from the list of search terms. (Refer to Appendix 1 for a complete record of all search terms and strategy.)

Using search strings is regarded as a good way to optimise search strategies. Through further discussion with a specialist librarian at the University of Kent, it was recommended that the search string should be pre-tested on three separate databases: Business Source Complete, which includes Academic Source Complete, PsycINFO and PsycARTICLES; International Bibliography for the Social Sciences (IBSS), which includes Proquest, is more inclusive of books and is regarded as less biased towards North American sources; and Scopus, which has a greater scientific and health orientation. Two strings (A and B) were initially agreed and trialled with differing field specificity (i.e. open text, abstract, title and key words) using Boolean search terminology. These were:

A. (employee OR staff OR job OR work OR organi* OR personal OR team)

B. AND (engagement OR participation OR involvement)

In open text fields, these two strings initially identified 712,550 separate items of literature, up to 30% of which could be explained by duplication between the three databases, but which still left an unmanageable volume of data. The results were analysed according to source (publication type and location), peer review (listed in Thomson Reuters Web of Knowledge or Association of Business Schools Journal Ranking List) and disciplinary origin. Based on this analysis, the search string was further refined:

‘employee engagement’ OR ‘staff engagement’ OR ‘job engagement’ OR ‘organi* engagement’ OR ‘personal engagement’ OR ‘team engagement’ OR ‘psychological engagement’ OR ‘work* engagement’

This extended string of terms was viewed as more likely to capture some of the engagement literature in North America, where terms such as ‘workforce engagement’ are in use, hence the use of the wildcard character (*) in ‘work* engagement’. Because of the large number of results achieved when using the open text filter, it was agreed that field specificity for the search string should be limited to abstracts, as these are supplied by authors, whereas keywords can sometimes be assigned by database administrators and thus may be inaccurate. It was discussed and agreed with the advisory group and a wider group of experts in the field that, although the terms ‘participation’ and ‘involvement’ were frequently used interchangeably with ‘engagement’, they referred to different, albeit often related, constructs. Results of the pilot study suggested that it would be possible to narrow the focus of the structured search by removing these as explicit terms, since their inclusion very significantly increased the number of returned results. It was discussed and agreed with advisory group members who were interested in these and other terms that where terms such as ‘participation’ and ‘involvement’ had been studied in relation to engagement, along with other terms reflecting interests in patient involvement (e.g. ‘voice’), evidence about these would be picked up via the structured search in any event, thus obviating the need for their inclusion.

In order to acknowledge the importance of practitioner-led research, as well as address the risk of publication bias, the development of the search terms and strategy was shaped by the need to include ‘grey literature’ on employee engagement from the health sector and beyond. At this stage the project team, in consultation with other experts and advisory group members, discussed possible sources of grey literature in order to make the search strategy as inclusive as possible and to be able to address the fourth research question: ‘What tools and resources would be most useful to NHS managers in order to improve engagement?’

It was agreed it would be useful to have a list of ‘mandated sources’ of this literature deemed by the experts to be of the highest quality and relevance, including professional or membership organisations and networks (e.g. various royal colleges, NHS Federation, NHS Employers), research centres (e.g. Institute of Work Psychology, Royal Society of the Arts), unions and third-sector organisations (e.g. Nuffield Foundation, The King’s Fund), as well as various conferences (Healthcare Conferences UK, British Academy of Management), independent consultancies and think-tanks, along with government-led or -sponsored agencies (Department of Health, Nursing and Midwifery Council, UK Commission for Employment and Skills).

The full search strategy subsequently adopted a dual approach: the first element focused on research databases in which it is possible to search tens of thousands of journal titles simultaneously; and the second focused on sources of grey literature.

Locating studies through a structured search

The second stage of the study involved three phases: (1) development of a review protocol, (2) scoping study and (3) undertaking the structured search of the literature.

Developing the review protocol

The project protocol includes a description and rationale for the review questions, the proposed methods and details of how studies will be located, recorded and synthesised, as well as outlining the eligibility criteria. 46,48,49 It is the formal plan for the project in which the reviewers’ intentions for exploring the topic and the methods are clearly explained. 50 It sets out what methods will be used at every stage of a review, linking the research questions to the synthesis of extracted data. In so doing, it reduces researcher bias by minimising subjective judgements and making all processes and criteria used in the review both explicit and accessible. 51 Briner and Denyer state:

A protocol ensures that the review is systematic, transparent and replicable – the key features of a systematic review. Having a protocol also means the review method can be challenged, criticized, and revised or improved in future reviews.

(p. 348)39

The timing for the production of the protocol is open for some debate, but good practice indicates that a final protocol should emerge as the outcome of the planning stage of a review. 45 While protocols are commonly associated with clinical trials and quantitative research, they are increasingly seen as a critical aspect of narrative reviews which engage with discursive bodies of literature generated through different methodological approaches. Particularly in relation to narrative reviews, a protocol should be used as a ‘compass’ rather than an ‘anchor’ (p. 190),52 so, while the intent and the methods of the review should be made clear at the end of the planning stage and before the structured searches begin, it should also allow for changes due to unforeseen circumstances. Being bound to an original statement of intent when problems arise is counterproductive. 50 However, this should not prepare the ground for post hoc decision-making. For this project, a draft protocol was prepared as part of the proposal documentation and was then amended as a result of the pre-test search exercise, with the agreement with the project sponsor, once the likely effect of literature volume on time scales and resources was realised.

Scoping study

Academic literature

A scoping study is essentially a way of reproblematising research objectives with the goal of mapping the underpinning assumptions and concepts, as well as exploring the available sources and types of evidence relevant to an issue. It is a way of ensuring that the right questions are being asked before the full search is undertaken53 and that they can be answered using the identified strategy. Here, this took the form of a formal pilot of the refined search terms and strategy using the three databases and fields as described. This yielded 5295 results, as shown in Table 3.

| Database | Number of results | Main source types |

|---|---|---|

| Business Source Complete | 3951 | Academic journals (1863) |

| Magazines (1136) | ||

| Trade publications (620) | ||

| Dissertations (172) | ||

| Books (113) | ||

| Other (47) | ||

| IBSS | 132 | Academic journals (129) |

| Books (3) | ||

| Scopus | 1212 | Academic journals (1066) |

| Conference proceedings (110) | ||

| Books (23) | ||

| Trade publications (13) |

The overall total (5295) included 3058 items published in academic journals, 1136 articles in magazines, 633 articles in trade publications, 172 dissertations and 139 books. From the outset of the project, the intention had been to restrict the evidence review to include research and literature published in the English language after 1990, as this is the date when Kahn’s21 seminal paper on engagement was published. These initial scoping searches before the pilot trials revealed that, apart from Kahn’s21 paper, very little was published on engagement until 2003, after which the ‘explosion’ (p. 57)33 in interest seems to have occurred. These results were fed back to the advisory group and other expert advisers, who made a number of suggestions to improve the search strategy for the full structured search. For example, in order to minimise publication bias and be as inclusive as possible,39 it was suggested that our search strategy should be expanded to include two further databases: Nexis, which gives access to practitioner outputs including media/trade reports, and Zetoc, an extensive research database based on The British Library’s table of contents.

Grey literature

In order to identify evidence-based grey literature on the topic of employee engagement likely to be of relevance to the evidence synthesis and/or the production of practitioner materials, an initial scoping exercise was completed to locate primary sources from which these items might be obtained. Using team members’ expertise in the field of engagement, combined with their familiarity with the NHS and reference aids (such as listings of health-related organisations in Binley’s Directory of Management),54 the project team produced an initial list of 121 grey literature sources that they believed warranted a preliminary search. A useful by-product of the scoping exercise was the identification of additional sources of grey literature through secondary references to reports or resources provided by other organisations in the area of employee engagement. These included materials identified during the main academic search but which did not meet the quality threshold for inclusion there. In total a further 15 potential sources of grey literature were identified. This helped to address publication bias and brought the total number of grey literature sources to 136 (see Appendix 2).

It was also decided that any individual item which was still considered to have relevance for the grey literature search would be referred to the grey literature search team for review. Based on the academic search strategy, an initial list of six broad search terms was devised by those members of the project team leading the grey literature extraction. These were ‘employee engagement’, ‘staff engagement’, ‘employee involvement’, ‘employee participation’, ‘social partnership forum’ and ‘employee voice’. The aim of this broad list of search terms was to gather material which could then be assessed for both rigour and relevance to the NHS. A record was kept of the search results for each source along with reviewers’ comments on the overall relevance and rigour of the source and materials.

Relevance was assessed initially in terms of the occurrence of search terms in the title, abstract or main body of the text, but mainly in terms of utility to NHS practitioners. Rigour was assessed in terms of whether or not supporting evidence was derived from primary research conducted by the author(s), organisation(s) and/or affiliate(s) involved in the production of these materials. Material of low rigour and/or low relevance was excluded (Table 4). Of the 136 sources of listed grey literature, a substantial proportion (n = 53) returned no materials of relevance to the present evidence review. However, the scoping exercise still returned a substantial quantity of materials from the remaining sources (Table 5), and the term ‘staff engagement’ alone returned 52,840 results.

| Relevance | Rigour | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | |

| High | Include | Include | Exclude |

| Medium | Include | Include | Exclude |

| Low | Exclude | Exclude | Exclude |

| Search term | Number of returned results | % |

|---|---|---|

| ‘employee engagement’ | 27,604 | 15.2 |

| ‘employee involvement’ | 34,640 | 19.1 |

| ‘employee participation’ | 17,571 | 9.7 |

| ‘employee voice’ | 13,500 | 7.5 |

| ‘social partnership forum’ | 34,869 | 19.3 |

| ‘staff engagement’ | 52,840 | 29.2 |

| Total | 181,024 | 100.0 |

Of the 136 potential sources of grey literature, 38 were deemed to be of high quality on the basis of the criteria described above. These are listed in Appendix 3.

The structured search

Academic literature

The full search of the academic literature was conducted using the revised search string on five databases in October 2013: Business Source Complete (including Academic Search Complete, PsycARTICLES and PsycINFO), IBSS, Scopus, Nexis and Zetoc. As these databases differ in functionality, it was necessary to adjust some of the terms according to the field formats of the databases. In total, the search produced 7932 items of literature (Table 6), which were imported into RefWorks (version 2.0, Proquest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) a licensed reference management system with the capacity to hold and manage these items and their full references. Using RefWorks’ internal management function it was possible to reduce this number to 5746 items for inclusion in the next ‘sifting’ stage of the review by cleaning the results. Although the scale of duplication was troublesome throughout this project, the inclusion of multiple databases did ensure a more inclusive approach and provided a degree of triangulation in the later sift and data extraction stages.

| Database | Results |

|---|---|

| Business Source Complete | 4391 |

| IBSS | 226 |

| Scopus | 1666 |

| Nexis | 676 |

| Zetoc | 973 |

| Total | 7932 |

| After removing duplicates | 5746 |

| After citation/additional searches | 5771 |

Briner and Denyer39 observe that a structured search alone is unlikely to generate every item of relevant literature. In this project, our structured search was supplemented by a number of additional approaches, including citation tracking of particular authors, scanning reference lists and footnotes for additional materials not identified by the databases and using new publication alerts, as well as taking advice from a body of experts in the field. This led to a number of additional terms and searches being added to the formal search, including, for example, an additional search using the term ‘medical engagement’. In total, this identified 25 additional items, bringing the final number of items identified in the structured search to 5771. This does not include three books from which multiple chapters were included in the ‘sift’ stage of the synthesis.

Grey literature

The large volume of results returned by the scoping search of grey literature, partly a result of the limited functionality of search mechanisms within the grey literature sources (i.e. compared with the academic databases), meant that the grey literature search strategy had to be refined and refocused to ensure greater relevance. Having reduced the number of sources of grey literature to 38, the team agreed that relevance could be achieved through more specific searches for materials using internal website search engines where available, rather than manual key word searches, etc. In line with the academic search strategy, it was also agreed that the terms ‘involvement’, ‘participation’, ‘voice’ and ‘partnership’ were yielding too many results that were not directly relevant to engagement at all (e.g. they addressed issues of ‘empowerment’). In those instances where terms such as ‘participation’, ‘involvement’ or ‘voice’ were relevant, these were being included using the two key terms ‘employee engagement’ and ‘staff engagement’. In the structured search of grey literature sources these terms were used both within inverted commas (i.e. ‘staff engagement’) to ensure specificity and without inverted commas to avoid overexclusiveness through this more refined and targeted search strategy.

Of the 38 identified sources of grey literature, only 34 produced results in the structured search; these are reported in Table 7. Despite refinements, the nature of these sources and their limited search functionality meant that there were still high levels of duplication of materials across and within websites as well as a high volume of material that was neither relevant to the evidence review nor of sufficient quality for inclusion in it (e.g. press releases, role descriptions and conference details).

| Sources | Terms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employee engagement | ‘Employee engagement’ | Staff engagement | ‘Staff engagement’ | |

| ACAS | 418 | 208 | 328 | 28 |

| BlessingWhite | 178 | 139 | 156 | 16 |

| CBI | 209 | 209 | 344 | 344 |

| Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development | 864 | 469 | 314 | 17 |

| Corporate Leadership Councila | – | – | – | – |

| Department for Business, Innovation and Skills | 50 | 50 | 50 | 50 |

| Engage for Success | 153 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gallup Business/Management Journal | 40 | 30 | 13 | 1 |

| GSR | 23 | 9 | 34 | 0 |

| Harvard Business Review | 262 | 262 | 262 | 262 |

| Hay Group | 764 | 736 | 35 | 1 |

| HSJ | 5321 | 47 | 16,777 | 200 |

| Hewitt Associates (now Aon Hewitt) | 403 | 297 | 179 | 10 |

| Institute for Employment Studies | 797 | 500 | 570 | 23 |

| ILO | 2469 | 40 | 2589 | 7 |

| Involvement and Participation Association | 186 | 96 | 191 | 191 |

| Ipsos MORI | 42 | 33 | 54 | 9 |

| Kenexa | 137 | 21 | 42 | 0 |

| McKinsey | 567 | 84 | 567 | 11 |

| Mercer | 110 | 41 | 11 | 1 |

| NHS Employers | 126 | 48 | 512 | 256 |

| NHS Institute | 24 | 2 | 2890 | 76 |

| NICE | 113 | 1 | 564 | 2 |

| Nursing Times | 1934 | 6 | 9081 | 84 |

| Optimise Ltd | 3 | |||

| People Management | 2201 | 699 | 1720 | 0 |

| PSI | 0 | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| Roffey Park | 15 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| SHRM | 4150 | 997 | 1690 | 7 |

| The Boston Consulting Group | 367 | 115 | 253 | 8 |

| The King’s Fund | 10 | 10 | 201 | 7 |

| The Work Foundation | 92 | 60 | 50 | 10 |

| Towers Watson | 288 | 288 | 46 | 46 |

| UK Commission for Employment and Skills | 281 | 91 | 368 | 27 |

| Grand total | 22,597 | 5588 | 39,901 | 1694 |

Evaluating material against eligibility criteria for inclusion/exclusion

The quality of any evidence review depends almost entirely on the quality of included studies. 55 Before any data can be extracted from the studies, it is therefore crucial to assess each one using clear and explicit inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to evaluate the relevance and quality of each contribution. 46,49 This process should be free from bias and as replicable and systematic as possible. 45 Korhonen et al. 55 state that this evaluation should be carried out as transparently as possible, as this is ‘a key requirement for the reliability of the synthesis and transferability of the results, as well as for the identification of theoretical possibilities’ (p. 1030). We critically evaluated all the studies in two phases: (1) sifting the abstracts of all identified material against a series of inclusion criteria and (2) extracting data from included material as the basis of the synthesis.

Sifting the results

Academic literature

All the identified titles, abstracts and referencing information from the structured search were downloaded onto RefWorks. Patterson et al. 45 recommend that each item be ‘sifted’ by two members of the research team independently and evaluated against a pro forma which sets out clearly the quality and relevance thresholds for inclusion. Using a checklist of agreed criteria in this way helps to address the potential impact of reviewer bias. Where there is some dispute or doubt over inclusion, the item should be referred to a third reviewer. The agreed inclusion/exclusion criteria and categories for the sifting process are:

-

include

-

exclude – dated before 1990

-

exclude – not in English language

-

exclude – empirical but study design does not include employees

-

exclude – opinion piece only/no evidence

-

exclude – item not related to research questions

-

exclude – other (specify).

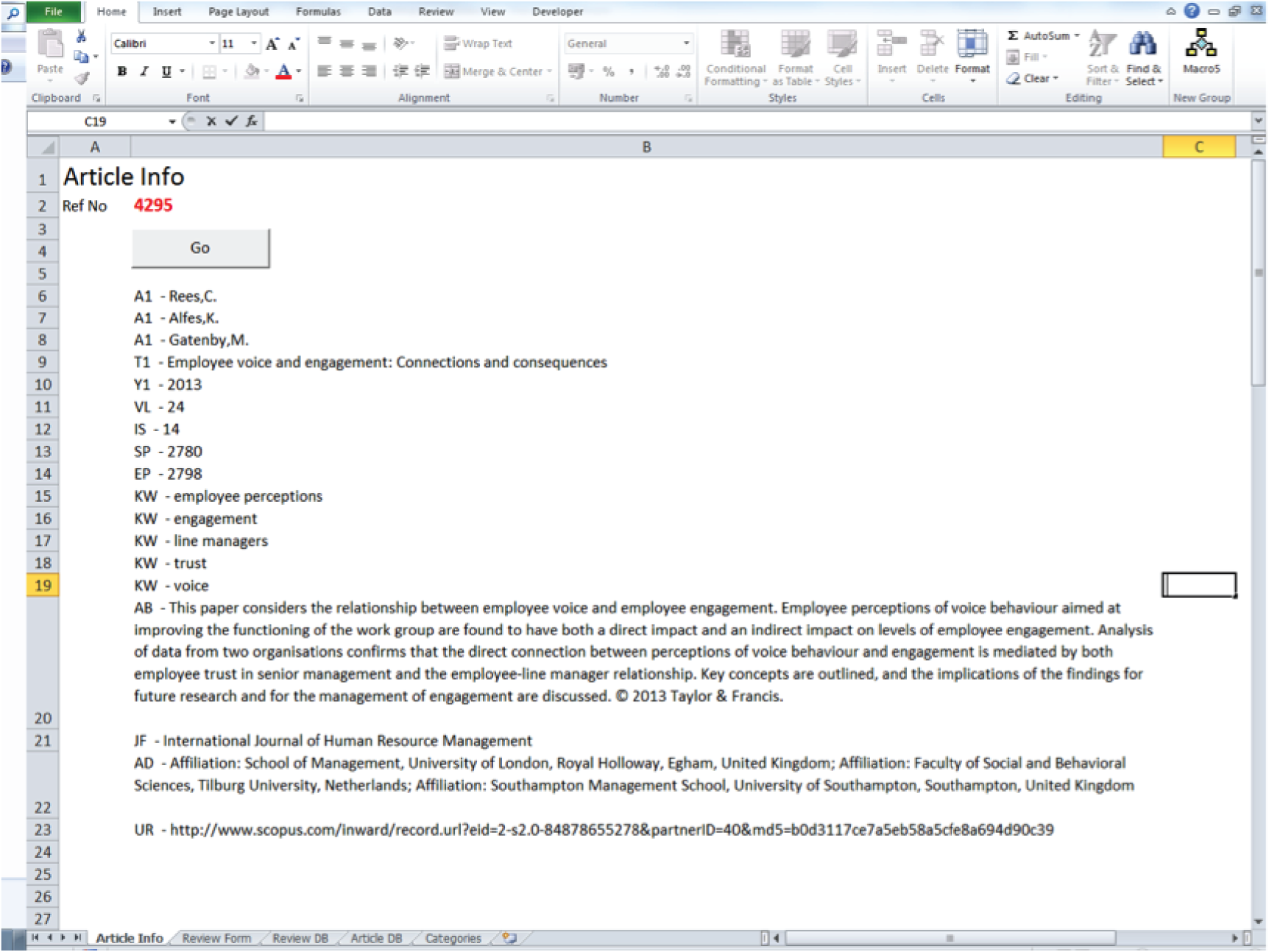

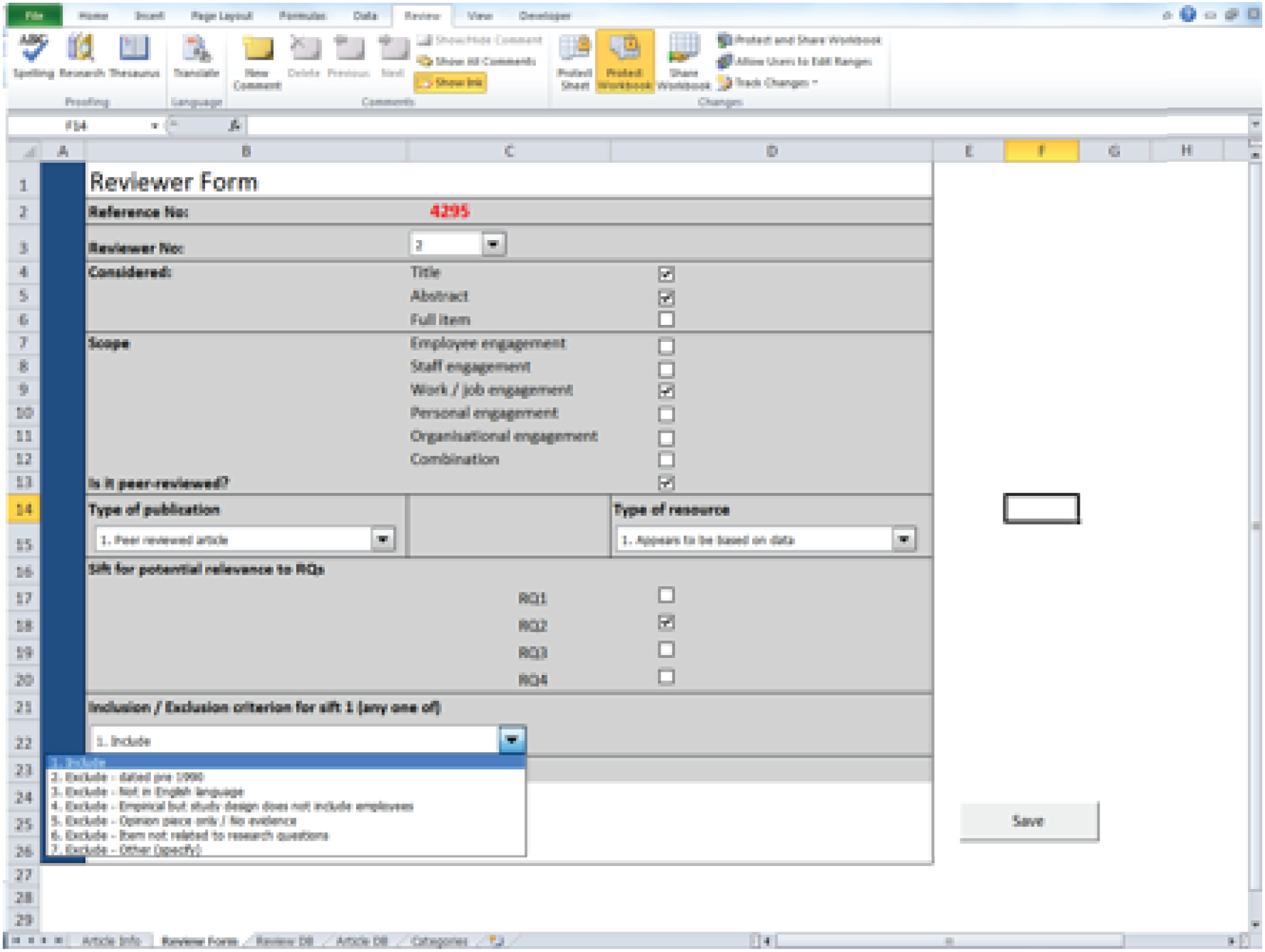

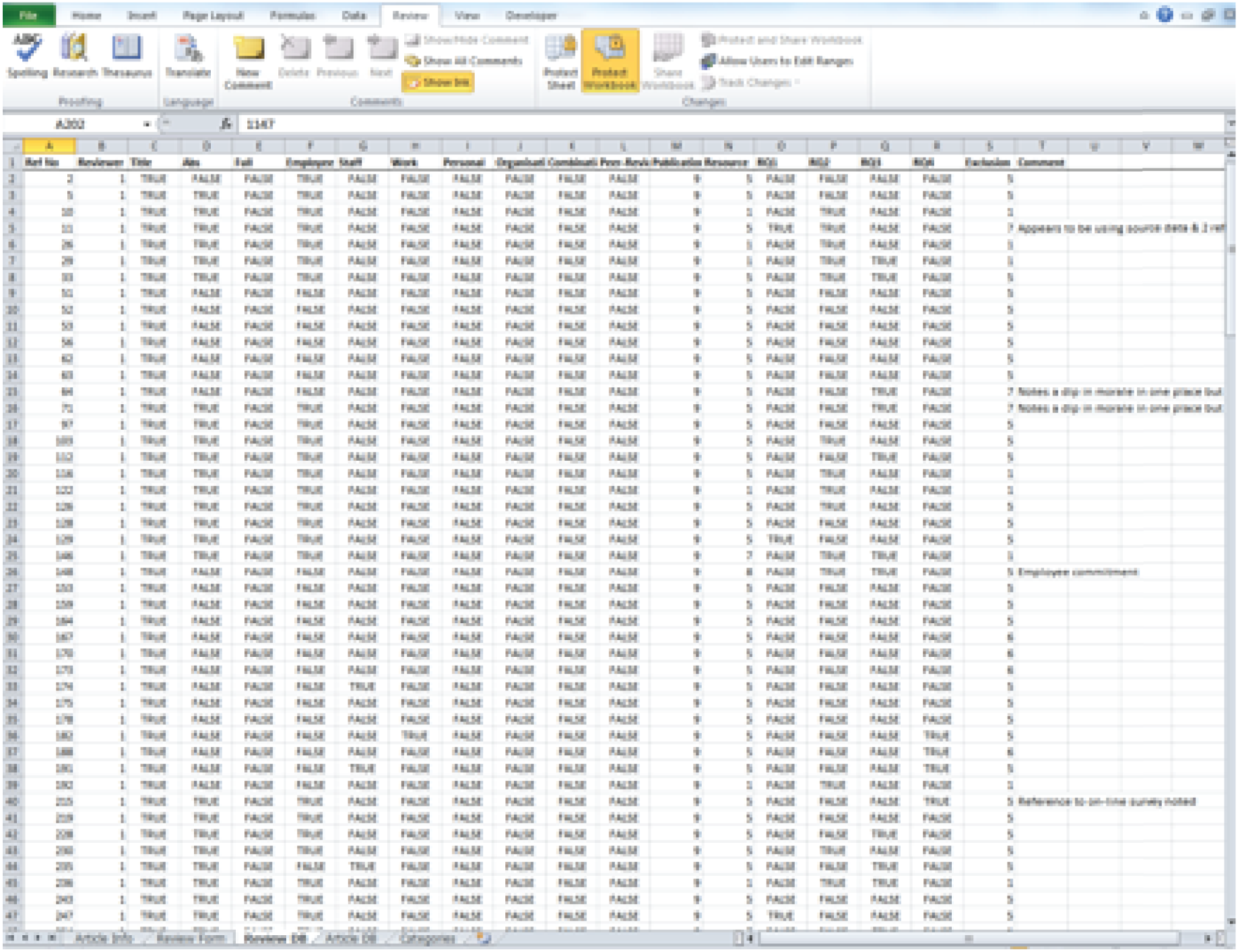

Given the volume of literature to be sifted as well as the dispersed nature of the project team, it was important to develop a systematic and co-ordinated way of sifting the material. Thus, a bespoke database was developed using Excel Professional Plus 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), into which all items of literature were imported and assigned a unique reference number. Each member of the team was then randomly assigned an equal share of the 5771 items identified in the structured search as either first or second reviewer for assessment against the stated criteria.

The database included a series of user-friendly worksheet-based interfaces, the first of which allowed project team members to call up each individual item from the 5771 results (title, author, source, abstract and referencing information) using the allocated reference numbers. A second enabled the reviewer to evaluate relevance and quality according to the agreed criteria. Given that the item abstracts (or, in a minority of cases, titles only) were the initial basis for assessment, the criteria as shown above were weighted more towards relevance (e.g. ‘dated before 1990’, ‘not in English language’, ‘empirical but study design does not include employees’, ‘opinion piece only/no evidence’ and ‘item not related to research questions’), with the view that quality would be better evaluated at the second stage once full items were obtained. Items were included in the next stage where they appeared to be of direct relevance to the research questions, and appeared to include either empirical evidence from employees or a theoretical contribution to the field.

A third interface of the bespoke database was designed to systematically record the outcome of the sifting process by logging the following information: item reference number, reviewer’s name, fields within each record that had been checked, type of engagement discussed, whether peer-reviewed or not, specific relevance to the research questions and, if excluded, the exact reason why. From these records, it was possible to identify disputed items easily and reallocate them to a third reviewer (sample screenshots from these interfaces are illustrated in Appendix 4).

In order to develop inter-rater reliability and further minimise the potential impact of reviewer bias, prior to starting the sift process the project team undertook a number of pilot ‘sifts’ followed by tele-meetings to identify areas and causes of uncertainty, and to build critical reflection and consensus into the evaluation process. 42 A kappa rating was calculated from the results of pilot sifts using all six reviewers from the team, and only when a score of 0.75 was achieved [generally interpreted as ‘substantial agreement’ (p. 361)56] was it agreed to proceed with the sift.

However, as the project team sifted the results of the structured search, it was clear that, while a great many of the results met the relevance criterion, they would not be included at the data extraction stage because of the quality criterion. As with the grey literature material, the search identified a large quantity of material that simply did not contain any substantive evidence or duplicates. Thus, after consulting with the project adviser, it was agreed that only items from peer-reviewed academic sources should be put forward to the next stage. The project protocol was amended to reflect this change. Of the original 5771 items identified in the full search, 5168 were excluded on grounds of relevance at this stage (i.e. not peer-reviewed, duplicated or not in English). This left a total of 603 items to be potentially considered for data extraction. These 603 items are included in the References section of this report.

Each of these 603 items was then reviewed in greater depth by two members of the project team, and 389 of them were excluded on grounds of quality (e.g. rigour), relevance (e.g. conflation of engagement with other concepts such as job satisfaction) or other reasons (Table 8). This left a total of 214 items to be included for full data extraction.

| Basis for exclusion | Total (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Lacking empirical data | For example, opinion piece/normative | 35 (6) |

| Quality | Poor quality of item (e.g. improper scales; missing values or values not reported; measures not stated; sample issues; data not analysed) | 95 (16) |

| Measuring engagement using one dimension only of UWES | 7 (1) | |

| Measuring engagement using two dimensions only of UWES | 46 (7.5) | |

| Not peer-reviewed | 6 (1) | |

| Relevance | Study measures only individual/demographic factors as antecedents | 31 (5) |

| Not focused on concept of engagement, employees or work context | 124 (20) | |

| Other | Duplicated items evident only on close scrutiny | 14 (2.5) |

| Validation study only (of existing scale/not testing variables) | 6 (1) | |

| Item unobtainable via usual sources | 25 (4) | |

| Total excluded | 389 (64.5) | |

| Total included for full data extraction | 214 (35.5) | |

Grey literature

To assess the quality and identify materials suitable for data extraction from the grey literature identified in the structured search, a series of ‘sift’ questions were applied to each of the materials. These ‘sift’ questions were devised within the project team with particular reference to the more explicitly practical emphasis within research question 4 and the production of practitioner outputs. These were:

-

Is the material relevant or useful to an NHS practitioner (in the context of staff engagement)?

-

Does the material contain evidence?

-

Does the material include a described methodology?

-

Is the research original to this source?

-

If the material forms part of a series, is this the most recent?

By applying these quality criteria to the results of the structured search of grey literature revealed, the team deemed only six grey literature sources to be of sufficient quality for inclusion in the data extraction, including one referred from the academic literature search (Table 9). It enabled a greater focus on a small number of high-quality materials from these sources in the production of practitioner outputs.

| Source | Number of suitable items |

|---|---|

| Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development | 5 |

| Institute for Employment Studies | 3 |

| Kenexa | 3 |

| The King’s Fund | 1 |

| GSR | 1 |

| Referred from main literature search: Strategic Human Resources Review | 1 |

| Total number of items | 14 |

Data extraction

Academic literature

The second stage involved obtaining complete versions of the 214 included items in order to evaluate and extract data from them. To facilitate analysis, a data extraction form (see Appendix 5) was devised to record the evaluation of items against a range of quality criteria including methodology (robustness of design and analysis), relevance to health-care contexts and relevance to the research questions (see Appendix 6). This approach was agreed with the advisory group.

Of the 214 items included for full extraction in the synthesis, five were qualitative studies and four were meta-analyses. These were organised according to their specific relevance to the research questions (Table 10). A total of 67 out of the 172 empirical papers (39%) within this evidence review were included in at least one of the four meta-analyses, while nearly half of these (n = 32) had been included in all four meta-analyses. However, to avoid distorted effect, none of these meta-analyses was included in the data extraction tables detailed in Chapters 4–6 but they are discussed separately within each chapter. Throughout the extraction process, additional studies were being added to the search results and sifted as a result of the citation and reference tracking strategy, along with others identified by ‘alert’ services from journals and databases using keywords.

| Research question | Number of relevant studiesa |

|---|---|

| 1. Models and theories | 38b |

| 2.1. Morale | 47 |

| General | 35 |

| Health | 12 |

| 2.2. Performance | 42 |

| General | 36 |

| Health | 6 |

| 3. Antecedents | 155 |

| General | 113 |

| Health | 42 |

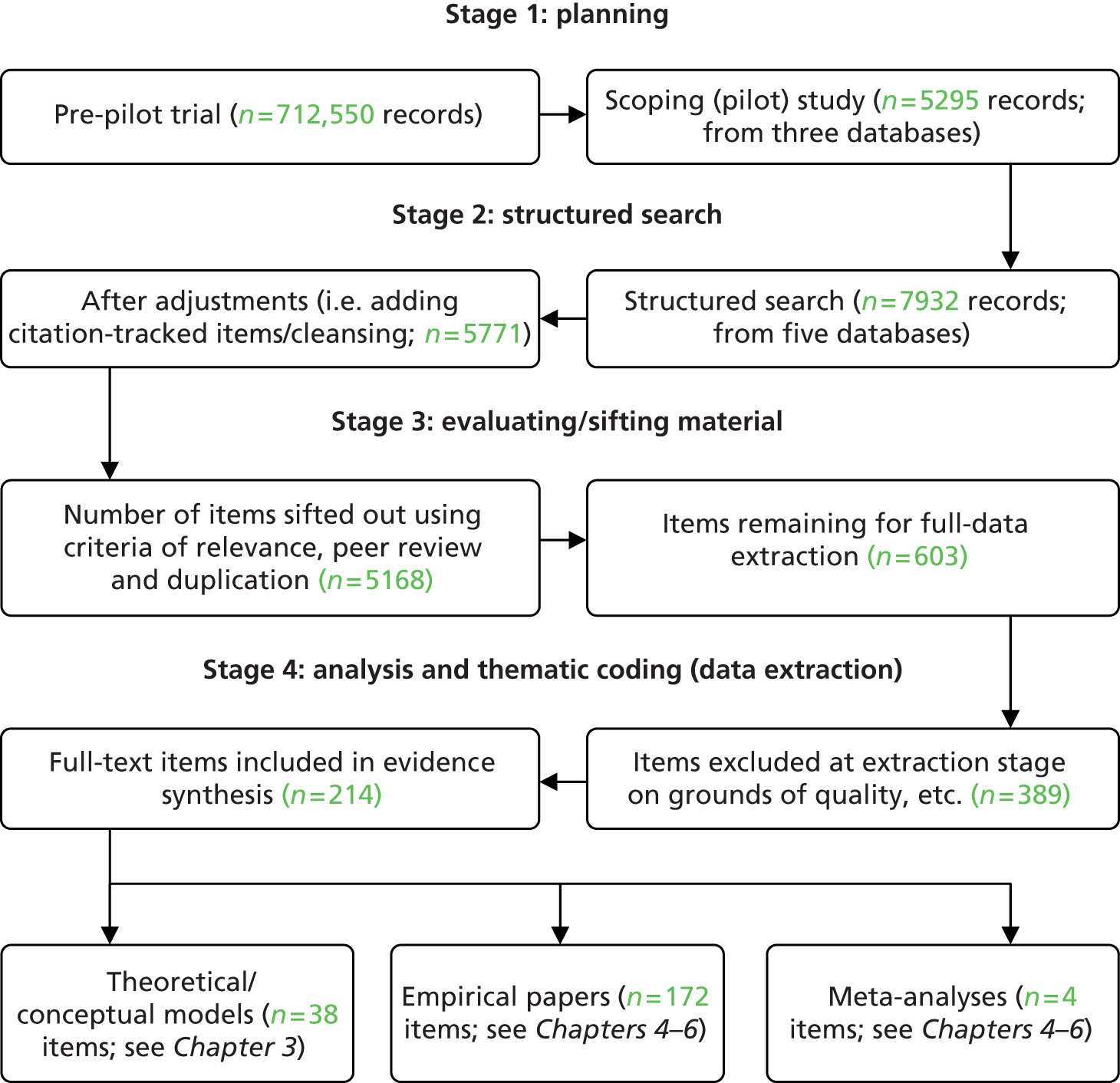

Originally, it had been proposed that each full item would be evaluated by two researchers and coded to identify its primary contribution to knowledge. Given the volume of included studies, it was decided that each item would be reviewed in full initially by one researcher, who completed the data extraction form. However, in practice the vast majority of items, about 75%, were evaluated twice anyway as the report authors reassessed the items included for each of their respective chapters. To describe stages 1–4 of the search and data extraction process, a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-style flow chart57 (Figure 1) was prepared according to the format proposed by Liberati et al. 57 The flow chart summarises the process of evidence synthesis from the planning to the data extraction stage of the project.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-style flow of information through stages 1–4 of the evidence synthesis.

Grey literature

The 14 materials identified in Table 9 were taken forward for data extraction for use in the production of the practitioner materials arising from this project (see Appendices 7–16). The dates of materials from which data were extracted ranged from 2004 to 2013. They included two single-organisation case studies, while the other papers discuss data from more than one organisation. Studies were based in the UK, the USA or mixed-country settings, and four were based either uniquely or partially in a health-care setting. A copy of the data extraction form is provided at Appendix 17. Although none of the practitioner (‘grey’) literature was able to satisfy the peer-reviewed criterion for inclusion in the main evidence review, a review of good-quality practitioner materials was conducted in order to inform the practitioner outputs and address research question 4. This material was therefore separated from the main evidence review and is the subject of a separate review of practitioner material (see Appendix 7).

Analysis, thematic coding and synthesis

Academic literature

The purpose of this stage of the review was to examine the evidence and identify underlying themes in order to relate the findings from the various studies together to develop new insights into engagement within the workforce in general, and within the context of health care. Three members of the research team each took responsibility for one of the data analysis chapters of the report, which corresponded to the first three overarching research questions. In preparing their chapters the three team members iterated between the data extraction forms and the original full-text items to ensure the accurate capture of information.

Hannes and Lockwood58 recommend adopting a pragmatic approach to synthesising evidence using a process that ‘is guided by the lines of action’ that can inform decision-making at clinical, policy or research level, based on the argument of utility and the ‘philosophy of pragmatism’ (p. 1633). While there is no generally accepted approach to narrative synthesis, the approach adopted to synthesising our data largely mirrors that suggested by Popay et al. ,42 who recommended that a narrative synthesis should seek to explore (and interrogate) the relationships in the extracted data within and between studies, noting that these relationships are likely to emerge between characteristics of individual studies and between findings of different studies. It is at this stage that the synthesis should begin to account for the heterogeneity of the data (including types of intervention; context; sample; qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches). The narrative should thus provide insights into what outcomes are attributable to particular interventions, or how conceptual frameworks can explain observed variations. The approach taken by the research team to extracting data for specific research questions and their corresponding chapters is shown in Table 11.

| Research question | Specific approach to data extraction |

|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2 | |

|

|

| 3 | |

|

The project team worked collaboratively throughout these processes to identify and develop emerging themes in the data. Discussions were held to identify similarities and differences between study findings, and explore conceptual and methodological issues. The approach involved initial coding and grouping of data into clusters using descriptive rather than analytic labels in the first instance, to avoid closing themes down prematurely. The approach showed that, while the academic literature does tend to weigh towards the idea of engagement as a psychological state, there are other emerging ‘narratives’ in the data as well, including, for example, the idea of engagement as managerial practice. Through team discussions these initial labels were developed and refined as more data were coded to reflect critical assessment and comparison between and within studies, and then between and among clusters of studies as these expanded. This critical approach process ensured that the inclusion criteria of quality, relevance and credibility were constantly revisited and consistently applied throughout.

Grey literature

The purpose of the grey literature review was to try to include any relevant materials in this evidence synthesis to enhance rigour and overcome bias and, specifically to address research question 4, to consider what materials and tools from this wider resource might be of relevance to practitioners in the health-care context. In the end, only six sources of relevant, good-quality evidence were identified, from which 14 items describing various tools and resources were obtained. Analysis of these materials identified a number of important themes linked to engagement, including meaningfulness, senior manager effectiveness, perception of line manager, appraisals and employee voice. Although there were broad similarities between the overall themes in the academic and the grey literature concerning engagement, the review of grey material (see Appendix 7) suggests that the practitioner material focuses more on wider managerial issues (including performance management and training) rather than on psychological factors of engagement.

Reporting

The aim of this project is to summarise the evidence base on employee engagement in the form of an evidence synthesis and to make this evidence base more accessible within the NHS by disseminating findings about effective interventions, tools and resources. The dissemination strategy for the research has two strands: first, in the form of this report, which documents the overall approach and findings of the project, and, second, in the form of a series of practitioner outputs of direct relevance to NHS managers. The aim has been to ensure that these practitioner outputs are based upon and reflect the findings of a systematic, replicable and credible synthesis of the data. The practitioner outputs are set out in Appendices 7–16.

Summary

In this chapter, we have described the methodological approach underpinning this evidence synthesis. Following the recommendations of Briner,46 we adopted a narrative approach in five stages (planning, locating studies, evaluating material, analysis and coding, reporting).

In collaboration with the project advisory group, we refined the project protocol, detailed research questions and search terms, and conducted a series of pilot searches in order to help refine and focus our search strategy. The full search of academic literature was conducted using five databases and a wide range of grey sources. A total of 5771 studies were included in the preliminary sifting exercise whereby the abstract and/or title for each item was reviewed by two or in some cases three members of the research team.

The application of quality and relevance criteria along with the removal of non-peer-reviewed items led to the inclusion of 172 empirical articles, four meta-analyses and 38 theoretical papers in the final data extraction exercise. Items that were published in the English language after 1990, and that met the appropriate quality and relevance thresholds for the type of study, were included in the evidence synthesis. Items identified from six sources through searching the grey literature are included in the practitioner-oriented materials arising from this project.

In the next chapter, we examine the results of the evidence synthesis in relation to research question 1: what is engagement?

Chapter 3 What is engagement?

Introduction

In this chapter, we address the first research question, namely:

How has employee engagement been defined, modelled and operationalised within the academic literature?

This overarching question can be broken down into the following three subquestions:

-

How is employee engagement defined within the academic literature?

-

How has engagement been measured and modelled within the academic literature?

-

What theories have been used to underpin models of engagement within the academic literature?

In order to address these, we undertook the following analysis:

-

Extraction of information relating to the definition, measurement and theorisation of engagement from all the studies included in the evidence synthesis for research questions 2 and 3 (see Chapter 2): a total of 172 papers.

-

Review of relevant information from a number of literature reviews and conceptual papers focused on defining engagement that were identified in the second stage of the data extraction process but that either did not contain empirical data or contained empirical data that did not meet the quality threshold and so were excluded from the data extraction for research questions 2 and 3: a total of 38 papers.

-

Consultation of three recent academic books focusing on engagement. 16,59,60 The research team identified these as being the only academic books with an exclusive focus on engagement.

-

Consultation of further conceptual articles focusing on defining engagement that were known among the research team or that were identified through a snowballing approach.

-

Consultation of a number of conceptual articles or literature reviews that critiqued or questioned the engagement construct.

The chapter is organised as follows. First, we present an overview of the broad history and development of engagement, and outline the definitions and measures of engagement used within the literature. Next, the findings relating to question 1, the extraction of definitions and measures used in the empirical papers that formed the substance of our data extraction, are presented. This delineates the principal approaches that have been used within the empirical literature. Next, we outline the theoretical frameworks that have been used to explain the processes of engagement, before presenting an analysis of the critiques that have been proposed of the engagement construct. We conclude by highlighting the principal areas of agreement and disagreement with regard to engagement at a theoretical level, a topic that is explored further in Chapter 7, in the light of the evidence presented in Chapters 4–6.

The origins and definitions of employee engagement

Interest in engagement first arose as part of the wider development of the positive psychology movement that has burgeoned in recent decades as a counterbalance to the predominant focus on negative psychological states. As Youssef-Morgan and Bockorny61 note (p. 36), the earlier emphasis on factors such as stress, burnout and poor performance offered limited opportunity to understand strengths, optimal functioning and fulfilment at work.

William Kahn is widely acknowledged as being the first academic to research and write about engagement, which he referred to as ‘personal engagement’. In his seminal article,21 Kahn claimed that personal engagement or disengagement arises when ‘people bring in or leave out their personal selves during work-role performances’ (p. 702). Thus, personally engaged workers are those who express themselves authentically at work in three ways: cognitively, emotionally and physically. This authentic expression of self-in-role is contrasted with disengagement, whereby the individual ‘uncouples’ his or her true self from his or her work role, and suppresses his or her involvement. Since Kahn’s original research, interest in engagement has mushroomed, leading to the publication of significant numbers of publications, especially since 2005. 62

Kahn’s original notion that engagement is the investment of the self into work roles has been developed further into the concept of ‘work engagement’, or the ‘relationship of the employee with his or her work’ (p. 15). 62

However, along with this burgeoning interest has been considerable confusion and uncertainty about what engagement means, leading Christian et al. 27 to conclude: ‘engagement research has been plagued by inconsistent construct definitions and operationalizations’ (pp. 89–90). A range of different terms has been used, including ‘work engagement’, ‘job engagement’, ‘role engagement’, ‘organisational engagement’ and ‘self-engagement’, with associated variations in the measures and theoretical underpinnings used. 63 Some have gone so far as to argue that engagement may be no more than old wine in new bottles. 18,19,64,65

There has been uncertainty over whether engagement is a relatively stable personality trait or a state that is susceptible to fluctuation over time, as well as whether it is a one-, two- or three-dimensional construct. However, the emerging consensus is that engagement is a psychological state, as summarised by Christian et al. :27 engagement is ‘a relatively enduring state of mind referring to the simultaneous investment of personal energies in the experience or performance of work’ (p. 90). Parker and Griffin29 extend this by arguing that engagement is an active rather than a passive psychological state, and therefore is associated with energetic states of mind. There is, additionally, broad agreement that engagement is not a one-dimensional construct but rather comprises several facets. 66

Below, we explore the most widely used definitions and conceptualisations of engagement found through our data extraction process. Drawing on and extending previous typologies such as that of Shuck63 and Simpson,36 we categorise the definitions and operationalisations of engagement within the literature under six headings, and review each in turn (Table 12):

-

Personal role engagement, including the work of Kahn21 and researchers who have sought to operationalise his theoretical framework.

-

Work task or job engagement, including the work of the Utrecht Group,71 which has focused specifically on the notion of engagement with work tasks.

-

Multidimensional engagement, drawing on the work of Saks,72 who distinguishes between engagement with work and engagement with the organisation as a whole.

-

Engagement as a composite attitudinal and behavioural construct, drawing on the work of various consultancy firms and researchers who regard engagement as a broadly defined positive attitudinal state; this approach is what is commonly referred to as ‘employee engagement’.

-

Engagement as practice: scholars within the HRM field have recently begun to focus on engagement, and there is a small emergent literature on engagement as an employment relations practice. 16,17

-

Self-engagement with performance: one measure has been developed that regards engagement as the extent to which high levels of performance are salient to the individual.

| Reference | Definition | Measure | Number of occurrences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personal role engagement | |||

| Kahn (1990)21 | The authentic expression of one’s preferred self at work | N/A: qualitative study | 1 |

| May et al. (2004)22 | Engagement at work was conceptualised by Kahn21 as the ‘harnessing of organisational members’ selves to their work roles; in engagement people employ and express themselves physically, cognitively and emotionally during role performances’ (p. 12) The scale was also adapted by Shuck67 and Reio and Sanders-Reio;68 see below |

Three subscales of one higher-order factor:

|

4 |

| Reio and Sanders-Reio (2011)68 | ‘Engagement is being psychologically present when performing an organizational role. Engaged employees are more likely to have a positive orientation toward the organization, feel an emotional connection to it, and be productive’21 (p. 464) | Shuck’s67 16-item Workplace Engagement Scale, based on a modified version of May et al.’s22 three scales of meaningfulness, safety and availability, including:

|

1 |