Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2004/10. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Davies et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background: evidence and health care

It is likely that the quality and effectiveness of health care could be significantly enhanced if services were aligned more closely with the available research evidence. 1,2 Improvements could be seen in both the nature and types of services and treatments provided and the processes by which these services are delivered (e.g. their location and duration, the financial and organisational infrastructures underpinning them and the personnel involved).

There are growing bodies of research knowledge from a range of fields that have the potential to inform all aspects of health-care organisation and delivery. 3 For example, studies on diagnostics, prognostics and therapeutics provide fine-grained understandings about the nature of ill-health, its assessment, potential causal pathways and likely trajectory, and the scope for amelioration through health-care intervention. Epidemiological and clinical epidemiological studies are augmented and complemented by a wide variety of health services research – research aimed at exploring the lived experience of ill-health, understanding health-care-seeking behaviours, and predicting responses of patients to service encounters (e.g. clinic attendance/reattendance and concordance with treatment regimes).

Knowing what to do, how to do it, and the likely consequences of clinical interventions are only parts of the knowledge picture to which research contributes. 2 Substantial bodies of research contribute to important policy questions by, for example, mapping health inequalities and health-care disparities and the dynamics of these, tracking the consequences of system incentives, and clarifying the challenges and opportunities of various performance and regulatory frameworks.

Macro policy and frontline practice are not the only domains in which research has much to offer: on managerial and organisational matters too there is now a large and growing research resource that explores, for example, the dynamics of change and leadership in health-care organisations; the development and composition of multidisciplinary teams; and the costs/consequences of different models of service design. 4,5 An important subset of this work is that devoted to understanding quality and safety issues in health care (improvement science). 6 In this area, many diverse models of quality improvement have been developed or (more often) imported from industry, models such as ‘lean’, ‘six sigma’ or ‘business process reengineering’. Many of these now have associated research literatures offering insights and evaluations as to their impacts, challenges, prerequisites and (more rarely) costs. 7,8

Evidence making a difference

Despite this growth of research activity and despite the considerable attempts to focus and prioritise research effort on areas of greatest knowledge needs,9 it is widely recognised that the linkages between research effort, knowledge enhancement and informed action are not yet working to best effect. 10–13 Better understanding of how research-informed knowledge can be shared and applied in health care remains a key challenge.

Recognition of this gap between what is already known and what is carried out in practice has led to a number of initiatives to close the gap between evidence and policy and practice in health care and in other sectors such as education, social care and criminal justice. These initiatives exist alongside growing recognition of the challenges inherent in attempting to change complex social systems and the need to attend to a wide range of political, psychological and organisational factors. 14

Framing the problem

How the problem of closing the gap between research evidence and policy and practice has been framed in the literature has altered in the past two decades. Traditional thinking on research use in health care suggested that it was a largely linear, rational, instrumental process and that the provision of particular organisational supports (e.g. continuing medical education; mechanisms to increase access to information and guidelines; clinical audit, etc.) would be sufficient to ensure that health professionals’ practice was in line with the evidence. This view has been subject to increasing challenge from a growing body of evidence that suggests that, far from being a simple linear process, research use is instead an intensely social and relational process. 15–17 This means that a range of interventions (around system design, organisational infrastructures and the facilitation of relational and interactive approaches) are required to better connect research to policy and practice. Such interventions seek to enable research-based knowledge to be combined with other forms of knowledge, to be tested, refined and assimilated, and to be integrated into the thinking and behaviour of individuals and groups.

Building on this interactive, social and situated understanding of how research-based knowledge actually has influence, more sophisticated models of knowledge mobilisation strategies have been developed. In health care, recent reviews of these1,16,18–21 have identified the diverse languages used to describe new models – such as knowledge translation, knowledge exchange, knowledge interaction, knowledge intermediation and knowledge mobilisation. 22,23 These reviews have also begun to map out the empirical support for various mechanisms thought to promote effective knowledge sharing.

Terminological debates are important, as they have the potential to reveal unexamined assumptions about the nature of knowledge and the processes of knowledge sharing. 3,24 Moreover, the multiplicity of terms can sometimes act as a barrier to clear communication and be an obstacle to engagement with non-academic actors. 1,22,23,25 Subsequently, in this study we explore with our field sites the breadth and value of diverse terminology; here, for simplicity’s sake, we consistently use the broad term ‘knowledge mobilisation’ as a shorthand for the range of active approaches deployed to encourage the creation and sharing of research-informed knowledge. Such a convenience is not intended to short-circuit the legitimate debates about terminology, to which we return in due course.

As the ‘knowledge mobilisation’ literature expands, several developments are apparent. Knowledge mobilisation researchers20,26,27 have argued that the ‘complex systems’ theories that are beginning to permeate thinking on health care delivery need also to be applied in thinking about knowledge use. There is growing emphasis on the need to attend to issues around power and conflict over what constitutes ‘knowledge’ in a given time and context16,24,28–30 rather than treating it as an objective and unproblematic entity. There have been increasing calls31 for researchers to take a more multidisciplinary approach to knowledge use in health care while recognising that seeking convergence across these diverse fields (e.g. technology, organisational learning or political science) is neither feasible nor desirable. 16,32 The growth of implementation science as a discipline has called attention to the need for more robust evidence on all of the stages of implementation and on the ways in which organisational change is effected,33,34 including sustainability and scale-up. 35 At the same time there has been recognition of the need for focused knowledge mobilisation rather than pursuing the ‘knowledge translation imperative’ in a more scattergun manner. 36 There have also been calls for careful prior consideration of existing ‘naturalistic’ knowledge exchange processes within an organisation prior to planning and implementing formal knowledge exchange interventions. 37

Innovations in the field

Alongside, and at times independently of, these new ways of thinking about knowledge use, there have been a range of organisational and policy initiatives which have created new structures, networks and configurations aimed at increasing the use of research-based evidence in health-care policy and practice. In the UK these have included the second round of 5-year funding (2013–18) for the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) and the second phase of funding (2013–18) for the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) Public Health Research Centres of Excellence aimed at integrating research, policy and practice in public health. Internationally, we have seen the development of the Global Implementation Initiative (www.globalimplementation.org), and considerable investment by many countries in a range of knowledge mobilisation infrastructures and processes. 11,12 The European Commission has recently undertaken several initiatives to endorse the use of evidence in policy-making in relation to children’s services. 38

Innovation has also been seen in other areas of public service delivery, such as social care and education. For example, the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) was established in 2011 as an independent grant-making charity dedicated to breaking the link between family income and educational achievement. In addition to identifying, funding and evaluating promising innovations, it works to encourage schools and other stakeholders to apply evidence and adopt innovations found to be effective. It has developed a widely used toolkit and is currently funding a series of studies to test various ways of improving research use. These include testing the effectiveness of research champions, research learning communities, and a structured school improvement process. Many of the EEF’s funded studies are led by schools.

In social care, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Collaborating Centre for Social Care (NCCSC) has been established to co-produce guidance about social care with people who use care, their families and friends, care providers and commissioners. The NCCSC is a consortium led by the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). SCIE has been at the forefront of efforts to involve users and carers in all aspects of its activities. It has also been innovative in the way in which it supports organisations to learn and use evidence, for example through its Learning Together programme of support that helps organisations to learn systems thinking and improve how they safeguard adults and children.

These parallel developments in other sectors have the potential to give additional insights for application in health care. 15,39 In addition, cross-sector initiatives are springing up. One recent addition to the landscape here is the Alliance for Useful Evidence (www.alliance4usefulevidence.org/), which aims to provide a focal point for increasing the use of social research evidence in the UK in a wide variety of settings.

Linking theory and practice in mobilising knowledge

Despite rich conceptual development in the literature on knowledge mobilisation and a wide variety of practical initiatives to mobilise knowledge, to date there has been little systematic research effort to map, conceptualise and learn from these practical initiatives, or to investigate the degree to which they are underpinned by contemporary thinking as set out in the published literature. This gap is particularly apparent when looking at knowledge mobilisation at the ‘macro’ level: the activities undertaken by organisations that are major research funders, major research producers or key research ‘intermediaries’ (e.g. policy organisations, think tanks or boundary spanners). More attention has been paid to knowledge mobilisation at the organisational level (understanding service redesign and organisational change) or to initiatives focused at the individual level (e.g. on changing the behaviour of health professionals). This study aimed to fill this gap and to learn from the macro-level knowledge mobilisation strategies developed and applied in health care, both in the UK and internationally. In addition, the study aimed to learn from the experience of the social care and education sectors in the UK, which face similar kinds of challenges in applying social science research to the delivery of public services.

Study aims and objectives

The overall aim was to harness the insights from a growing body of new approaches to knowledge creation, sharing and use and to draw out practical lessons that could be used to make current and future NHS initiatives around research use more effective.

The study had three key objectives with associated research questions (RQs):

-

Mapping the knowledge mobilisation landscape

-

What knowledge mobilisation strategies have been developed in health care (in the UK and internationally) to better promote the uptake and use of research?

-

What analogous knowledge mobilisation strategies have been developed in social care and education within the UK?

-

-

Understanding the models, theories and frameworks that underpin approaches to knowledge mobilisation

-

What models, theories or frameworks have been used explicitly – or can be discerned as implicit underpinning logics – in the development of the knowledge mobilisation strategies reviewed?

-

What evidence is available from existing reviews and secondary sources on the mechanisms of action of these models, theories and frameworks?

-

-

Learning from the success or otherwise of these enacted strategies

-

What evaluative data are available on the success or otherwise of enacted strategies (i.e. the strategies and approaches being used by agencies), and what do these data suggest are the most promising approaches to successful knowledge mobilisation?

-

What formative learning has accumulated through the practical experience of the programmes as implemented?

-

Concluding remarks

Having set out the rationale for this project, and laid out the study aims and objectives, we have organised the rest of the report as follows. The next chapter (see Chapter 2) sets out the methods of the interlocking strands by which we explored these RQs. Chapter 3 presents the findings from our review of reviews, including the creation of a conceptual map. There then follow three chapters that present, analyse and interpret the data collected: Chapter 4 focuses on the interview data; Chapter 5 provides an account of the findings from the web survey; and Chapter 6 provides an integrative analysis across theory and practice by exploring the deeper patterns of agency activities and emphases. The final chapter (see Chapter 7) develops the discussions further and returns to our original research aims as a means of drawing further conclusions.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

This chapter describes how the different stages of the study were carried out. In brief, data were collected in the following ways:

-

Desk research (literature) (months 1–15): we conducted a review of published reviews (total of 71 reviews uncovered) in order to be able to map the theoretical and conceptual literature. A key output from this work was a visual and textual ‘conceptual map’ of key issues in mobilising knowledge.

-

Desk research (agencies) (months 1–15): we identified key agencies for further examination (major research funders, research producers and key research intermediaries: 186 in total), gathering basic descriptive information on their knowledge mobilisation activities from websites and other publicly available resources. Health-care agencies were explored internationally (with the obvious limitations imposed by the need to find English-language resources); social care and education agencies were limited to those in the UK. With regard to education agencies, our focus was on those that concerned themselves with education in schools (i.e. age 4–18 years).

-

Interviews (months 4–12): in-depth qualitative interviews with key individuals in agencies analysed using a thematic framework supplemented the data gathered from desk research (52 interviews with 57 individuals drawn from 51 agencies).

-

Web survey (months 13–15): a bespoke web survey was used to add greater breadth to the understanding drawn from earlier strands of the work (response rate 57%; n = 106).

-

Participatory workshops: two workshops (month 6 and month 16) were used to create discussion and greater insight into our emergent findings (28 and 25 participants, respectively).

-

International advisory board: we used regular teleconferences and e-mail discussion with our international advisory board (eight members) to deepen and strengthen the work.

Table 1 shows how the RQs map to the different strands of the study.

| RQs | Study strands |

|---|---|

|

RQs 1a and 1b:

|

|

RQ 2a:

|

RQ 2b:

|

|

|

RQ 3a:

|

RQ 3b:

|

An account of each of these aspects is provided in sequence, but in practice there was a lot of interplay between the different strands of the project. For example, the interviews were shaped by the review of reviews and the desk research on key agencies; the content of the web survey drew on the review of reviews and on the interview data; and the initial development of the conceptual map was accomplished using the review of reviews, but the conceptual map was then developed further by the addition of the knowledge mobilisation archetypes (see Chapter 6) which were derived from the interview data.

Ethics committee approval

In accordance with the policies of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme and the University of St Andrews, we applied for (and received) ethical approval from the University Teaching and Research Ethics Committee of the University of St Andrews.

A large part of the work involved accessing publications and collating information which was already in the public domain or gathering data about activities that are carried out in the public domain. As such, no significant ethical issues applied to the study beyond the standard ethical requirements common to all research with participants (informed consent; voluntary participation; safeguarding confidentiality). Those requirements were met by the following actions during the study:

-

providing participants with detailed information about the study

-

advising participants that participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time without having to provide an explanation

-

obtaining written consent for the interviews and making clear to potential participants that attendance at the workshops or participation in the online survey would be regarded as consent to take part in the research

-

advising interview participants that the nature of the study was such that it would be inappropriate to withhold details of organisations carrying out specific knowledge mobilisation initiatives or programmes (particularly as much of this knowledge was already in the public domain) but that data would not be attributed to individuals

-

advising interview participants that they were entitled to ask for sensitive data to be kept confidential or disclosed only in aggregated/anonymised form

-

advising workshop participants that the workshops would be conducted under the Chatham House rule [i.e. that participants agree that they are free to use the information received but not to reveal the identity or affiliation of the speaker(s) or of other participants]

-

advising survey participants that the quantitative survey data would be published in aggregate form and would not refer to individual organisations or respondents and that where free-text quotations were used they would not be attributed to specific organisations or individuals but would refer only broadly to sectors (e.g. health-care research funder) unless specific permission had been obtained from the respondent.

During the conduct of the study, no significant ethical issues or concerns arose, although we did gain a heightened sense of the sensitivities of talking about individual agencies by name even when there was extensive information on their knowledge mobilisation activities in the public domain. For this reason we have refrained from identifying agencies by name in the findings section of this report.

Desk research

Review of research reviews of knowledge mobilisation

The first stage of constructing the conceptual map involved reviewing key research reviews of knowledge mobilisation to identify the main knowledge mobilisation models and strategies in health care, education and social care.

We were already aware of many of the key reviews in this field from our prior work in this area. In order to augment this collection systematically, we contracted with The King’s Fund Information and Library Service (health and social care databases) and with the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre (EPPI-Centre) (education databases) to design and carry out systematic searches of key databases in each field. We had detailed discussions with the information scientists, both in advance of and during the searching process, to clarify the objectives and parameters of the search and to refine the search terms. Details of the searches, including the databases searched and the search terms used, are given in Appendix 1.

Excluding duplicates, the search yielded 142 items in health and social care databases and 362 items from the education databases; the larger number of items from the education databases resulted from the more limited indexing facilities in these databases which led to a greater number of less relevant items being retrieved.

The abstracts were then read by the three members of the research team (at least two members for each of the searches) who allocated ‘scores’ to each review on the basis of its apparent relevance to the study: 1 = include (core paper); 2 = of some interest; 3 = marginal; and 4 = not relevant. Those papers which attracted a score of 1 or 2 from either or both of the assessors were then retrieved and read in full by one member of the research team (AP). Papers which met both of the following criteria were retained: substantial research review of the field of knowledge mobilisation; of relevance to health care, social care or education. This included conceptual development papers that contained within them a substantial review section relevant to our concerns. We identified further relevant reviews from reference lists of our key reviews and drew on the expertise of members of the advisory board and our key contacts in social care and education to check whether or not there were any additional key reviews (published or in press) that we had missed. Thus, we were satisfied that we had identified the main research reviews relevant to the development of a conceptual map.

This process resulted in our identifying a total of 71 reviews (listed in Appendix 2), which formed the core set of reviews. At the outset of the study we had anticipated that there would be around 30–40 relevant reviews; however, the process described above uncovered rather more. This somewhat increased the scale and scope of the task, but provided a rich set of conceptual concerns on which we could draw.

Initial development of the conceptual map

The initial development of the conceptual map was carried out as part of the desk research and is described here and in Chapter 3. The conceptual map was then developed further by the addition of knowledge mobilisation ‘archetypes’, which were derived from the interview data; this part of the process is described in a later chapter (see Chapter 6).

The aim of the conceptual map was to provide a ‘map’ of the knowledge mobilisation terrain as it applies to key research funders, producers and intermediaries developing their knowledge mobilisation strategies. The objective was to develop a tool that could be used both for analytic purposes (for the exploration of data gathered later in the study) and for communication purposes (as a practical way into the literature for use by agencies considering the development of their knowledge mobilisation strategies). The first stage of developing the conceptual map was to set out visually the domains identified inductively by our reading of the major reviews of knowledge mobilisation. One member of the research team read all of the reviews and prepared a document for the other researchers summarising the key points from each review as they related to the focus of the study, that is the knowledge mobilisation strategies and approaches of research funders, research producers and research intermediaries; on average, each review took up around one side of A4 in this summary document.

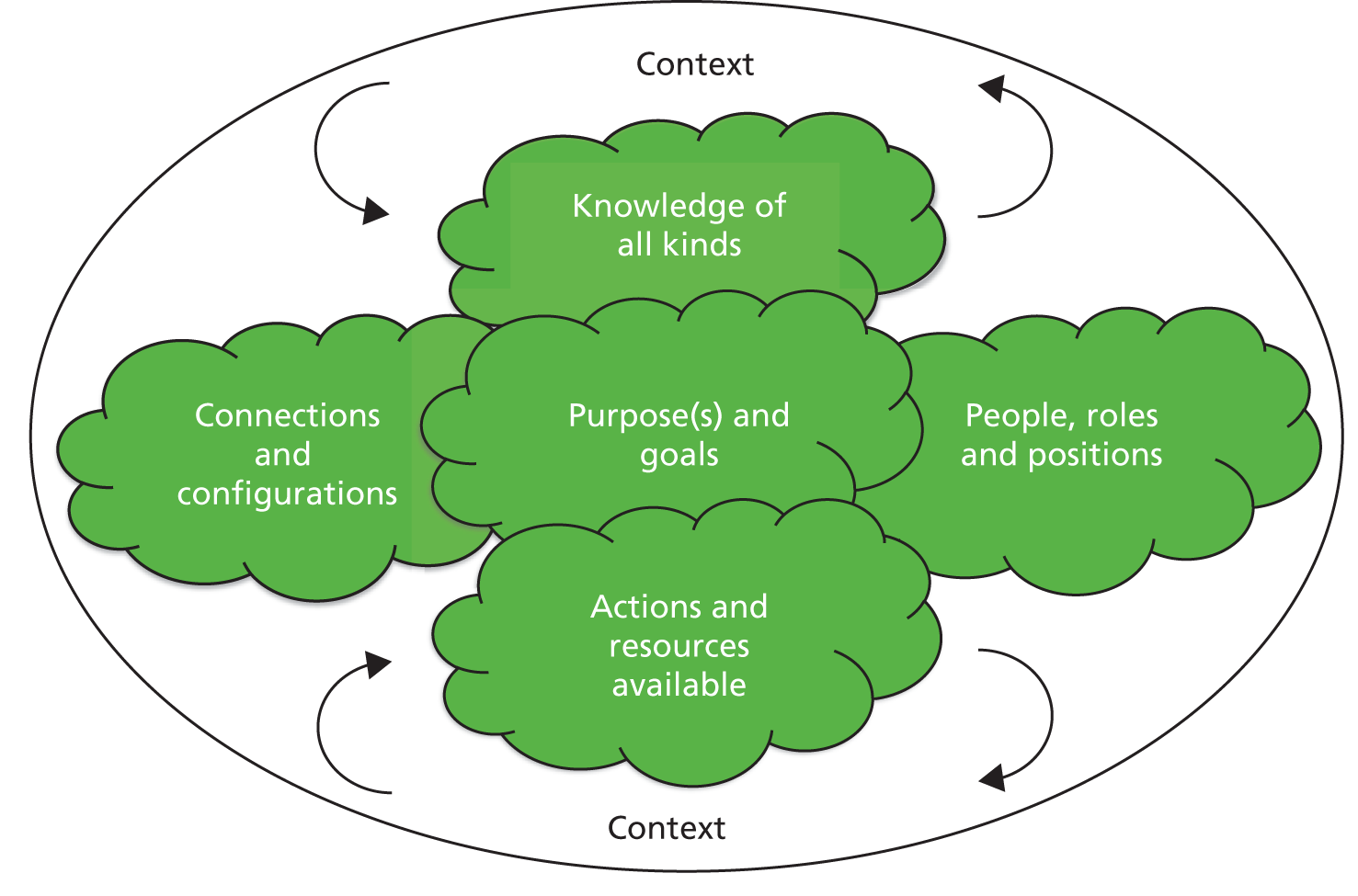

Having read the summary document and drawing on their existing knowledge of the literature, the research team then discussed the key domains that needed to be included in the conceptual map; the aim was to distil the core conceptual areas underpinning knowledge mobilisation and to do so with knowledge of the existing typologies but without seeking to follow or reproduce these. This discussion resulted in six domains being agreed on: knowledge of all kinds; connections and configurations; purpose(s) and goals; people, roles and positions; actions and resources available; and context.

The members of the research team then independently reread the summaries of 10 of the key reviews to check whether or not these initial six domains appeared sufficient to capture the core conceptual areas. One member of the research team then read through the whole of the summary document again to extend this initial ‘checking’ process to the whole group of key reviews (i.e. to check whether or not all of the key issues raised by the reviews could fit well under these domains or if there were additional domains that needed to be added). No further domains were added to the conceptual map as a result of these two processes.

Once the main domains for the conceptual map had been agreed, these domains were used to structure the further exploration of the key reviews (e.g. to consider the key concepts, issues and theories covered under each domain, the evidence underpinning them and the implications for agencies). The findings from this work are set out in Chapter 3.

Mapping of the key agencies

Early in the study we carried out careful mapping of the key research funders, major research producers and key research intermediaries (e.g. research collation agencies, think tanks, charities, professional and membership organisations) in health care in the UK and internationally, and in social care and education in the UK. Our focus was on agencies that had substantial investment in programmes of knowledge mobilisation rather than on delivery units, policy settings or other sites of research application. Throughout the study we used the terms ‘agencies’ and ‘organisations’ interchangeably as useful shorthand terms to cover a variety of organisations.

In order to compile a list of organisations to research, we first drew up from our own previous work and from key reviews an initial list of potential organisations in each sector. In the case of health care, we included organisations in the main English-speaking countries/regions outside the UK known to be active in knowledge mobilisation; in the case of social care and education, we included organisations in the UK alone, in line with the remit of the study. For the UK, we also compiled a cross-sector list in recognition that many UK organisations work across more than one sector. We then consulted two key contacts from each of the social care and education sectors for their comments on the initial lists (social care and cross-sector and education and cross-sector as appropriate) and their suggestions of additional organisations. This was an additional stage carried out in preparing the list of education and social care agencies in recognition that these sectors were less familiar to two members of the research team.

The initial lists were then circulated to contacts in each sector so that they could be ‘validated’ (described below) and expanded further. The social care and education contacts were different from those who had been consulted when the initial lists were being drawn up. All of the contacts at each stage were individuals who were known to have considerable expertise and experience of both knowledge mobilisation and their sector. Individuals were asked to review the lists of organisations in their region/country and sector as follows: UK social care and cross-sector (two contacts); UK education and cross-sector (two contacts); UK health care and cross-sector (three contacts); continental Europe health care (three contacts); health care USA (three contacts); health care Canada (four contacts); and health care Australia and New Zealand (three contacts).

Reviewers were asked to give a ‘broad brush’ rating to each organisation on the list using a scale from 1 (lowest) to 3 (highest) to show which of these organisations were responsible for a significant scale of knowledge mobilisation activity and/or pursuing especially innovative approaches to knowledge mobilisation. We were not looking for absolute consensus but instead were seeking a pragmatic assessment from experts in the field to help us to compile a list that was comprehensive and yet manageable within the constraints of the project.

As an additional check on organisations that we might have missed, participants were also asked to add any key organisations to the list. The process was augmented by e-mail and telephone conversations with some of the participants, which provided additional detail on organisations, particularly those outside the UK with which the research team was less familiar.

We then used the ratings and the additional comments that participants provided to allocate organisations to three groups according to the following criteria:

-

Group A: major players in scale or degree of innovation in knowledge mobilisation: selected for interview (preceded by website research); included in sample for web survey (n = 55).

-

Group B: agencies with significantly interesting knowledge mobilisation activities: included in website research, with the possibility of an interview if the website research uncovered particularly interesting initiatives that merited further research by the team; included in sample for web survey (n = 131).

-

Group C: organisations that carried out knowledge mobilisation activities as part of their role and were, therefore, part of the wider knowledge mobilisation field, but that did not appear to be conducting knowledge mobilisation activities that were significant in terms of scale or degree of innovation – no further action (this broader hinterland of knowledge mobilisation agencies was not fully enumerated and included all of those agencies that came to our attention but which were not considered further for more detailed review).

In order to seek wider confirmation that the list of organisations we had compiled was comprehensive, we posted messages to two key e-mail discussion lists used by the UK research communities (and with some reach beyond the UK): JISCMail Health Services Research list (around 550 subscribers) and JISCMail Evidence Use list (around 200 subscribers). We asked subscribers to review our provisional combined list of organisations and to contact us if they were aware of any prominent research funders, major research producers and key research intermediaries that were particularly active or innovative in knowledge mobilisation but that did not appear on our list. These postings resulted in our being notified of 20 additional organisations, of which we added six organisations to group A (website research, interview and web survey) and eight organisations to group B (website review and web survey); six of the organisations suggested fell outside the remit of the study or were subsumed under other organisational entities already considered.

At the end of this mapping exercise we had a list of 186 organisations for inclusion in the study, of which we had categorised 55 organisations as being in group A (30 in health care, 10 in social care, seven in education and eight cross-sector organisations) and 131 as being in group B. Analysis of the activities of these organisations addresses RQs 1a and 1b, and the organisations themselves are listed in Appendix 3. Interview organisations appear in Appendix 3 in bold font.

In line with our RQs, our aim was to map the knowledge mobilisation strategies that have been developed at the agency level, to understand the models, theories and frameworks underpinning them, and to learn from their success or otherwise (so addressing RQs 1a, 1b, 2a, 3a and 3b). Thus, our primary objective in compiling the list of organisations was to ensure that we had captured the main strategies, approaches and innovations in use. Our intention was not to compile an inventory of all of the organisations carrying out knowledge mobilisation in their respective sectors, and our final sample of agencies should not be interpreted in this way.

This sampling of agencies underpins our interview strategy and web-based survey work described later in this chapter and reported in Chapters 4 and 5.

Review of evaluations of knowledge mobilisation work by the agencies

As part of our review of agencies’ knowledge mobilisation work from their websites, we looked for evidence of evaluations by the agencies of these activities, we considered the evaluation methods used, and we looked for any formative or summative learning reported in the evaluations (addressing RQ 2b). We supplemented these web searches by specifically asking interviewees for information about any informal or formal, internal or external evaluations of their knowledge mobilisation activities, the criteria and methods used for such evaluations and the key findings. Where such evaluations were publicly available, we requested copies of relevant material from the interviewee or downloaded them from the agency’s website as appropriate. We report findings from this work in Chapter 4.

Interviews

The aim of the interviews was to supplement the picture gained from the website review by exploring in more depth key issues about each organisation’s approach to knowledge mobilisation. The specific objectives in relation to the RQs were to elicit clearer understandings about the models, theories and frameworks that (explicitly or implicitly) underpinned the development of specific knowledge mobilisation strategies by agencies (RQ 2a); to identify formal and informal evaluative work (RQ 3a); and to tease out the local learning from implementation challenges (RQ 3b).

The organisations selected for interview were those responsible for a significant scale of knowledge mobilisation activity, and those highlighting especially innovative approaches. The detailed process of selecting organisations to approach for interview was described above. We approached 55 organisations by e-mail and invited them to participate. The approach included brief details of the study together with links to the project website and to the project webpage on the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HSDR programme website. Attached to the e-mail were a participant information sheet, giving further information, and a consent form (see Appendix 4 for both documents). Four of the 55 organisations approached did not proceed to interview because the organisation declined to participate or did not respond to the interview invitation. In total, we conducted 52 interviews with 57 individuals from 51 organisations. This included five interviews which had two participants and three organisations for which we carried out two interviews at their suggestion of additional participants. Two interviews spanned the work of two organisations. The majority of the interviews were conducted by phone, although seven of them were conducted face to face. Most of the interviews lasted for 30–60 minutes, although a few extended to 80–90 minutes.

The interviews were semistructured and, therefore, followed a topic guide (see Appendix 5) while allowing scope for participants to raise other issues. The main topics covered were the interviewee’s perception of the organisation’s role in knowledge mobilisation and the main innovative activities; the terminology commonly used in the organisation to describe these activities (e.g. knowledge transfer or knowledge exchange); the history, origin and development of the knowledge mobilisation approaches used; any models, theories and frameworks that had been used in developing and using these approaches; the nature of and results from any formal or informal evaluations that had been carried out by the agency or of which the agency was aware; any formative learning or practical experience that had accumulated through the agency’s use of the approach.

Prior to each interview, the organisation’s website was reviewed to obtain initial information on the organisation’s remit, knowledge mobilisation approach and knowledge mobilisation activities. Interviewees were supplied with a further copy of the participant information sheet together with a broad list of topics that the interview would cover to assist in brief preparation if they wished. Interviewees were asked to sign the consent form prior to the interview. This included giving consent for the publication of identifiable or attributable data (i.e. data that would clearly identify and attribute data collected to the participant’s organisation but not to a named individual), except where the interviewee requested that material be anonymised or kept confidential or where material was particularly sensitive (interviewees were advised that such data would be anonymised, e.g. by aggregating findings). The research team reflected further on this requirement during the process of analysing the interview data. The initial rationale, as set out in the information sheet given to interview participants, was that attributing data to organisations was important in terms of contextualising the data and maximising the potential learning for other organisations from the study. Furthermore, many of the knowledge mobilisation initiatives would already be in the public domain. However, it became clear during the process of analysing the interview data that much of the interview material was sensitive (e.g. around formative learning in relation to individuals’ roles or ongoing issues involving key stakeholders) and, as a result, needed to be anonymised. It was, therefore, agreed that all of the interview data would be anonymised; we allocated each organisation a number and these numbers are used to label verbatim quotations in this report.

All three academic members of the project team were involved in conducting the interviews and in data analysis to make the interviewing task manageable within the time scale and to contribute to the richness and robustness of data collection and analysis. Additional assistance with conducting 13 of the interviews was given by an experienced research assistant. This meant that the 52 interviews were spread fairly evenly across the four interviewers. The team held regular discussions during the interview phase of the study to consider the emerging data and to ensure consistency of approach between interviewers.

The interviews were taped and transcribed. Thematic analysis formed the first stage of data analysis: the data were first reviewed to draw up a preliminary framework of emergent themes around the development of knowledge mobilisation approaches by the agencies. This initial framework was augmented and adapted with reference to the main themes underpinning the interview topic guide. The revised framework (Table 2) was then applied iteratively to the data. Disconfirming data were sought out at each stage. This stage of the analysis led to a detailed account of the knowledge mobilisation activities of the 51 organisations, their underpinning theories, the factors that had led to their development and the formal and informal learning that had resulted. These findings are the dominant focus of Chapter 4.

| Main theme | Subthemes |

|---|---|

| How the agency sees its role in relation to knowledge mobilisation | Terms that are commonly used in the agency to refer to knowledge mobilisation activities |

| The main groups that the agency sees as their audience/users | |

| PPI activities around knowledge mobilisation | |

| The main knowledge mobilisation activities, approaches and strategies | Activities or approaches that the agency describes as innovative |

| The origins of these activities, approaches and strategies being used in the agency | Factors contributing to the development of these knowledge mobilisation activities, approaches and strategies |

| Models, theories and frameworks used in developing and using these activities, approaches and strategies | |

| Planned or recent changes in knowledge mobilisation activities, approaches and strategies and the origins of these | |

| The influence of other organisations on the agency’s knowledge mobilisation activities, approaches and strategies | |

| Formal and informal evaluation of the agency’s knowledge mobilisation activities | Formal and informal evaluations of the agency’s knowledge mobilisation activities carried out by or on behalf of the agency: the nature of these evaluations, the evaluation criteria used, the main findings and any changes that resulted |

| Evaluations planned for the future | |

| Formative learning and practical experience | Advice that the interviewee would give to a colleague in a similar organisation |

| Any additional themes emerging from the data |

By this stage of the analysis, it had become clear that there were patterns of knowledge mobilisation activity emerging from the interview data and that there was scope for deriving knowledge mobilisation ‘archetypes’ from these data. Secondary analysis of the interview data was therefore carried out: from repeated reading of the interview transcripts and an assessment of them in the light of the literature reviewing and the conceptual map, eight archetypes emerged inductively from our data. This is described more fully in Chapter 6.

Web survey

The aim of the web survey was to provide some assessment from the wider field of key agencies involved in knowledge mobilisation in health care, social care and education of the degree of consensus and contention about the emerging findings. The interviews focused on those agencies responsible for a significant scale of activity and those using particularly innovative approaches, but the web survey utilised a broader group of agencies as described earlier.

Web surveys are a relatively new form of survey, but emerging research literature suggests that they provide results that are comparable with those of traditional surveys and are often of higher quality, and that they have the additional benefits of speed of data collection, reduced cost and reduced potential for human error. 40–42 The research literature does suggest that web surveys may encounter response problems when they are conducted with groups of people who are infrequent or unconfident users of the internet. 43 However, the recipients of the web survey in this study were a highly information technology (IT)-literate group of individuals who worked in largely desk-based jobs at research-related organisations: key research funders, major research producers and key research intermediaries. Thus, the web survey was an appropriate research method to use with this group.

The web survey was drawn up by the research team, drawing on the published reviews and on the emerging data from the review of websites and the depth interviews. The web survey consisted of a brief section on agency type (covering the geographical location of the organisation, the sector and whether the organisation was predominantly a research funder, producer or intermediary), followed by six main sections which are briefly described below. The final version of the survey is available at www.st-andrews.ac.uk/business/km-study/documents/kmstudy-text-of-web-survey.pdf.

Terminology

The first section, on terminology, explained that the survey was ‘using the term knowledge mobilisation to cover activities aimed at sharing research-based knowledge’ and asked respondents to indicate all other related terms commonly used in that organisation (e.g. knowledge transfer, knowledge translation or research use). The list of terms was drawn from the key reviews.

Knowledge mobilisation activities

This section, consisting of three questions, provided a list of activities that might be carried out as part of a knowledge mobilisation strategy and asked respondents to indicate which of these activities were carried out in that organisation and with what frequency (often; sometimes; planned for the future; never/does not apply). The list of activities was drawn from the reviews and from the interview data. It included (but did not signpost as such) some activities which might be associated with ‘push’ approaches, some that are related to ‘pull’, some which might be associated with ‘linkage and exchange’ and some which specifically involved patients or service users.

Models and frameworks used in knowledge mobilisation

The third section invited respondents to indicate which of a list of models and frameworks were used in developing knowledge mobilisation activities. The models and frameworks listed were those described most often in the key reviews and in the interviews. Respondents were invited to name any other frameworks the organisation used in developing its knowledge mobilisation activities.

Ideas around knowledge mobilisation

The fourth section asked respondents to indicate, on a Likert scale, the degree of agreement with key propositions drawn from the published reviews and from comments made in the interviews.

Developing knowledge mobilisation activities

The fifth section asked respondents to weight in terms of importance (very important; fairly important; not that important; do not know/does not apply) factors that might be considered in developing knowledge mobilisation activities (e.g. acceptability to stakeholders; attention to context; feasibility of evaluating the approach; previous use in that organisation). These factors were drawn from the reviews.

Evaluating the organisation’s knowledge mobilisation activities and measuring impact

A final section concerned the evaluation of the organisation’s knowledge mobilisation activities. Respondents were first asked to indicate whether or not the organisation evaluated their knowledge mobilisation activities (little/no formal evaluation; some evaluation; a comprehensive approach to evaluation) and then to indicate the relative importance of measuring different types of impact (e.g. change in users’ attitudes and intentions; impact on outcomes for service users). The types of impact were drawn from the reviews.

Finally, free-text boxes were provided for respondents to add additional comments or clarifications at appropriate points during the survey. A further free-text box was provided for any further comments at the end of the survey.

Reviewing, piloting and running the survey

International advisory board members (in conjunction with colleagues where possible) reviewed the draft survey and suggested changes which were then incorporated into the survey. The final version was piloted for comprehension and ease of use with a small number of colleagues who were familiar with the field but were not themselves due to receive the survey; these responses were not included in the survey findings.

The survey was sent out by e-mail to a named recipient in each of the 186 agencies. To deal with situations where individuals had more than one institutional affiliation, the covering e-mail specified which organisation was of interest. Recipients were asked to advise the research team if an alternative contact in that organisation would be more appropriate. In addition to careful piloting of the survey to assess comprehension and ease of completion, a range of further strategies was used to ensure a good response rate: sending a personalised invitation to participate in the survey; emphasising to participants the relevance of the study and the importance of participation; sending prompt follow-up reminders, together with an invitation to nominate an alternative contact if appropriate; and changing the wording of reminders rather than sending out successive reminders with identical wording. 44–48

A total of 186 contacts were sent the survey with a request for completion, and after two reminders (one after 2 weeks and one after a further 3 weeks) useable data were obtained from 106 of these giving an overall response rate of 57%. Fifty-one respondents responded to the first invitation, followed by 30 who responded to the first reminder and a further 25 who responded to the second reminder. The level of missing data was generally low (as shown in the results set out by question in Chapter 5), although, as explained in Chapter 5, around one-third of respondents skipped the question on models, theories and frameworks used in knowledge mobilisation. Analysis of the survey data involved compiling descriptive statistics (e.g. frequency counts of use of particular models or frameworks; extent of agreement/disagreement with key propositions) as well as thematic content analysis of free-text comments.

Workshops

We held two stakeholder workshops during the study. In line with the thinking behind the study (that there is no neat separation between knowledge production and knowledge use), these workshops were not used primarily as dissemination mechanisms but instead formed an integral part of the enquiry methods. The first workshop was held early in the study (month 6) and the second workshop towards the end (month 16). The aims of the workshops were to share the research thinking, emerging data and analysis, and future empirical and analytic direction, and thereby to identify (a) areas for refined data gathering, (b) clearer articulation of the mapping domains and supporting literatures, (c) creative ways of presenting findings and insights from our data, and (d) mechanisms for encouraging key actors in the UK to interact with our emerging findings. By actively engaging with and harnessing the insights of the potential research users in this way, we aimed to enhance the impact of the research by ensuring that our explorations and the outputs from the study were meaningful to, relevant for and readily usable by these organisations. Participants were invited from key research funders, major research producers and key research intermediaries in health care in the UK and from equivalent social care and education organisations. In addition, we sought participation by a number of key academic experts in the field (largely from the UK, but also with participation from some members of our international advisory board). To promote continuity, we invited participants from the first workshop to attend the second workshop. We were keen to ensure that the voice of service users involved in knowledge mobilisation in the agencies was also represented at the workshops and we therefore invited relevant agencies to send two participants to the workshops: a lay person (e.g. a service user/public member of a funding panel or board) and a member of staff.

The first and second workshops were attended by 28 and 35 participants respectively (plus the study team). A list of participant organisations at each workshop is given in Appendix 6.

The workshops used a range of interactive methods and processes to ensure the active engagement of all participants. Participants were actively encouraged to explore and critique the findings from their own organisational standpoints. The first workshop (month 6) provided an early opportunity to discuss the emerging findings and informed the subsequent data collection and analysis. The second workshop (month 16) provided an opportunity for further discussion of the data and for refining the study’s conclusions. The second workshop also enabled us to discuss with the stakeholders creative ways of engaging stakeholder organisations with the findings and insights from the study, including the potential for developing a practical tool from the study findings.

Engagement with the international advisory board

We recruited from the study team’s existing network of professional contacts an advisory board of international experts in the field of knowledge mobilisation (n = 8) to provide additional expertise and ‘insider’ knowledge throughout all stages of the study. Given that the intent of this study was primarily to inform developments in the health sector, all of these experts were drawn from this background. The composition of the advisory board is given in Appendix 7. Members were involved throughout the study. Via e-mail, telephone contact and in person, they advised on the theoretical aspects of the research; provided information on key agencies and key reviews; provided insights into the knowledge mobilisation strategies in their own countries; assisted with access to key agencies and individuals; commented on the emerging findings from the study and on the developing conceptual map; commented on the draft web survey; and participated in the two workshops.

Concluding remarks

While the various stages of data gathering and analysis have been set out sequentially, many aspects of data collection, collation, analysis and interpretation took place in parallel, and there was much interplay between the different strands. Subsequent chapters elaborate (where appropriate) on the detailed analytic approaches deployed to make sense of the data. The remainder of this report unfolds as follows. The next chapter (see Chapter 3) explains how we made sense of the conceptual material contained in the 71 reviews, leading to the creation of a ‘conceptual map’ of the field customised to the interests and perspectives of agency knowledge mobilisation. Chapter 4 describes the key findings from the interview data; Chapter 5 does the same for the web-based survey data. Chapter 6 develops an argument that there are identifiable in agency practices and accounts certain patterns that relate to different aspects of the conceptual map. We articulate these as specific ‘archetypes’ of knowledge mobilisation (eight in total). These are derived inductively and are presented for discussion. Finally, Chapter 7 assesses the implications of the findings for the development of more effective knowledge mobilisation strategies.

Chapter 3 Mapping the conceptual literature

Introduction

An early part of the initial desk research for this project involved a ‘review of reviews’ in the area of knowledge mobilisation. Our aim here was to identify and understand the main knowledge mobilisation models, theories and frameworks in health care, education and social care. Further, we also wanted to develop some accounts of the conceptual thinking that lay behind these framings. The search strategy used to uncover and select the relevant reviews is described in Chapter 2, and led to 71 reviews being included. These are listed in Appendix 2.

In reviewing this substantial set of reviews our aims were pragmatic and twofold. Our first was to develop a set of understandings that could be used for analytic purposes in exploring the data gathered in other parts of the study (websites review; depth interviews; web-based survey). This related to RQ 2a, which explores the logic(s) underpinning agency activities:

What models, theories or frameworks have been used explicitly – or can be discerned as implicit underpinning logics – in the development of the knowledge mobilisation strategies reviewed?

The second goal of the review work was to develop a mapping that might have utility to the agencies as they sought to find ways into the complex and growing conceptual literature, something that might be useful to them in developing their knowledge mobilisation strategies. This second goal will receive further development as part of our ongoing collaboration with agencies.

Having uncovered the 71 reviews, we used an inductive, iterative, dialogical process within the research team (and subsequently, with the advice of the advisory board) to distil the key domains (see Chapter 2). As the domains surfaced and were fleshed out (six in total), repeated reading of the reviews was used to provide an account of issues within each of the domains. This chapter provides an integrated account of these domains alongside a visual map.

Understanding the academic literature that links knowledge, knowing and change is a challenging and boundary-less task: relevant literatures sit in a wide range of disciplines (psychology, sociology, organisation studies, political science and more) and ideas appear and reappear within and across these disciplines in sometimes chaotic fashion. In making sense of these conceptualisations it is abundantly clear that debates have not proceeded in a wholly linear, cumulative or convergent manner. While there are some areas of widespread agreement, there are also areas where contestation, problematisation and conflict are evident.

In developing this review we have been guided by a number of framing choices:

-

We have concentrated on that literature which has itself attempted to review the field rather than seeking to collate and synthesise across primary work whether theoretical or empirical (i.e. this is a review of reviews).

-

We have focused on reviews in the three key areas of application of health care, social care and education.

-

We have sought to review work that specifically addresses the creation, collation, communication, implementation and impact of research-based knowledge (albeit that such knowledge is often seen in the context of other forms of knowledge/knowing).

-

We have provided an account that speaks to the action-oriented concerns of the agencies at the heart of this study (i.e. funders, major research producers and intermediaries); that is, we have kept in focus the agencies’ needs to develop practical knowledge mobilisation strategies and portfolios of specific activities.

-

We have sought to lay out the key fault-lines of debate rather than forcing order and convergence where the literature does not readily support this.

Reading across these reviews we first identify a wide range of models, theories and frameworks that have been used to describe and inform knowledge mobilisation. Looking at these models and the empirical work that has been carried out to explore and (occasionally) evaluate them, we can discern a number of insights for the effectiveness of particular approaches. We then read across these models and the wider conceptual literature to create a conceptual map that surfaces key issues, debates and conceptualisations. These are discussed under the six domains that emerged inductively from the set of reviews (see account in Chapter 2). Finally, we note the limited literature that has explored the roles that the public and service users can play in mobilising knowledge.

Models, theories and frameworks, and associated evaluative work

The review papers document a bewildering variety of models, theories and frameworks. Even within individual review papers, 60 or more distinct models are sometimes considered (e.g. Ward et al. ;19 Graham et al. 1), but the actual set included varied significantly between review papers. From this review of reviews, we extracted the key models that seemed to have potential for use in knowledge mobilisation work in the kinds of agencies that we were considering. Additional checking of this list with our advisory board and other knowledgeable experts in the field reassured us that we were capturing the main models of interest. The set of distinct models and frameworks are listed in Box 1 and are elaborated on further in Table 3. These formed the basis of some of our discussions with agencies (see Chapter 4) and the development of the web-based survey (see Chapter 5).

The Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Model for Improvement (Langley 199649).

Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (Kilo 199850).

Ottawa Model of Research Use (OMRU) (Logan and Graham 199851).

The Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) Framework (Kitson et al. 199852).

Push, pull, linkage and exchange (Lomas 2000;10 Lavis et al. 200653).

Knowledge Dissemination and Utilisation Framework (Farkas et al. 200354).

Lavis et al. ’s framework for knowledge transfer (five questions about the research, four potential audiences) (Lavis et al. 200355).

Mindlines (Gabbay and le May 2004;56 Gabbay and le May 201157).

The Greenhalgh model for considering the diffusion of innovations in health service organisations (Greenhalgh et al. 200431,58).

The Levin model of research knowledge mobilisation (Levin 200459).

Walter et al.’s three models of research use (Walter et al. 200460).

The Knowledge to Action (KTA) Cycle (Graham et al. 20061).

Collaborative knowledge translation model (Baumbusch et al. 200861).

The Interactive Systems Framework (ISF) for Dissemination and Implementation (Wandersman et al. 200862).

The Knowledge Integration framework (Best et al. 200863).

The three generations framework (Best et al. 2008;63 Best et al. 200964).

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al. 200965).

The Critical Realism and the Arts Research Utilization Model (CRARUM) (Kontos and Poland 200966).

Normalisation Process Theory (May et al. 200967).

Participatory Action Knowledge Translation model (McWilliam et al. 200968).

Ward et al.’s conceptual framework of the knowledge transfer process (Ward et al. 200919).

The Knowledge Exchange Framework (Contandriopoulos et al. 201021).

The National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP) KTA Framework (Wilson et al. 201169).

Knowledge translation self-assessment tool for research institutes (SATORI) (Gholami et al. 201170).

School Improvement Model (EEF71).

| Model or framework | Key features |

|---|---|

| The IHI Model for Improvement (Langley et al. 199649) | The Model for Improvement asks three questions, which can be addressed in any order:

|

| Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (Kilo 199850) | PDSA cycles are a tool from the quality improvement field that has been applied to knowledge mobilisation activities. Originally developed by Shewhart as the Plan-Do-Check-Act cycle, PDSA cycles have four steps: Plan: plan the change to be tested or implemented Do: carry out the test or change Study: study the data before and after the change and reflect on what was learned Act: act on the information and plan the next change cycle The rationale for PDSA cycles comes from systems theory and the concept that systems are made up of interdependent interacting elements and are, therefore, unpredictable and non-linear: small changes can have large consequences. Short-cycle, small-scale tests, linked to reflection, are seen as helpful because they permit experimentation and enable teams to learn on the basis of action and its observed effects. |

| The Ottawa Model of Research Use (OMRU) (Logan and Graham 199851) | The OMRU has six key elements to be assessed, monitored and evaluated before, during and after knowledge translation initiatives. The first three are assessed as barriers or facilitators: practice environment; potential research adopters; and the evidence-based innovation. The other three elements are research transfer strategies; evidence adoption; and health-related and other outcomes. The OMRU is an example of a planned change theory (i.e. one that views innovation adoption as a deliberately planned process). |

| The PARIHS Framework (Kitson et al. 199852) | The PARIHS Framework was developed to address problems with linear models and their failure to account sufficiently for context. It proposes that successful implementation is a function of the relationship between evidence, context and facilitation. It can be operationalised as a practical tool through diagnostic questions and a grid-plotting device to assess ‘readiness’. |

| Push, pull, linkage and exchange (Lavis et al. 2006;10 Lomas 200053) | This framing differentiates between: ‘push’ efforts, which are led by the producers or purveyors of research who push research out into policy or practice settings; user ‘pull’ approaches, in which research users ‘reach in’ to the research world to obtain information to help with a decision they face; and linkage and exchange approaches, which involve the development of a partnership between the producers or purveyors of research and the (potential) research users. |

| Knowledge Dissemination and Utilization Framework (Farkas et al. 200354) | The Knowledge Dissemination and Utilization Framework is a typology of diffusion strategies intended to help researchers to integrate knowledge utilisation into the research process. It distinguishes strategies according to goal (increased knowledge; increased knowledge and positive attitudes; increased competence; increased utilisation over time) and audience (researchers; providers and administrators; consumers or families). |

| Lavis et al.’s framework for knowledge transfer (five questions about the research, four potential audiences) (Lavis et al. 200355) | Lavis et al. provide an organising framework for a knowledge transfer strategy. The framework can be used to evaluate a strategy as a whole over long periods of time or to evaluate and fine tune elements of it over shorter periods of time. There are five questions that provide an organising framework:

|

| Mindlines (Gabbay and le May 2004;56 Gabbay and le May 201157) | This theory proposes that health professionals combine knowledge and information from a wide range of sources into ‘mindlines’ (internalised, collectively reinforced tacit guidelines), which they use to inform their practice. Diverse forms of knowledge are continually being built into these mindlines and result in ‘knowledge-in-practice-in-context’. The authors propose that closer, more realistic relationships between the worlds of research, education and practice are needed to ensure that research findings feed into this ‘knowledge-in-practice-in-context’. |

| The Greenhalgh model for considering the diffusion of innovations in health service organisations (Greenhalgh et al. 200431) | This major systematic review of 495 sources (213 empirical and 282 non-empirical papers) identified 13 distinct disciplinary research traditions that may be relevant in considering factors affecting dissemination and implementation. The conceptual model for considering the determinants of diffusion, dissemination and implementation of innovations is intended to be a memory aid for considering the different aspects of a complex situation (‘illuminating the problem and raising areas to consider’) and not a prescriptive formula. The authors note that the components do not represent a comprehensive list of the determinants of innovation: they are simply the areas on which research has been published. |

| The Levin model of research knowledge mobilisation (Levin 200459) | Levin’s model emphasises three kinds of contexts for the use of research: one in which research is produced, one in which research is used and the third that consists of all of the mediating processes between the two. There are multiple dynamics at play within each context and many connections between the contexts. Some people or groups operate in more than one context. The model sees research use more as a function of systems and processes than of individuals. |

| Walter et al.’s three models of research use (Walter et al. 200460) | The three models of research use proposed by Walter et al. and derived from a review of the social care field are:

The review found that evidence of the effectiveness of the three models is largely absent and that there is little evidence about potential barriers and enablers to their development. |

| The KTA Cycle (Graham et al. 20061) | The KTA cycle is based on a review of 31 different KTA frameworks. It illustrates the key requirements of linkage and exchange between knowledge development and implementation and makes explicit the action-reflection process. This framework divides the KTA process into two concepts, knowledge creation (funnel) and action (cycle), with each concept comprising ideal phases or categories; in reality the boundaries between the two concepts and their ideal phases are fluid and permeable. The action phases derive from planned-action theories, frameworks and models (i.e. deliberately engineering change in groups that vary in size and setting). Both local and external knowledge creation or research can be integral to each action phase.

|

| Collaborative knowledge translation model (Baumbusch et al. 200861) | The collaborative knowledge translation model is based on a collaborative relationship between researchers and practitioners. It consists of a knowledge translation cycle (the process dimension) and a sequence of collecting, analysing and synthesising knowledge (the content dimension). |

| The Interactive Systems Framework (ISF) for Dissemination and Implementation (Wandersman et al. 200862) | The ISF provides a heuristic for understanding systems, functions and relationships relevant to dissemination and implementation. The authors argue that traditional research-to-practice models tend to focus on separate functions in dissemination and implementation rather than on the infrastructures or systems that support and carry out these functions. The ISF uses aspects of research-to-practice models and of community-centred models. It suggests three systems:

The authors suggest that the framework can be used to identify the key stakeholders and to consider how they could interact. |

| The Knowledge Integration framework (Best et al. 200863) | Best et al. define knowledge integration as ‘The effective incorporation of knowledge into the decisions, practices and policies of organizations and systems’ (p. 322).63 The Knowledge Integration framework builds on the National Cancer Institute of Canada (NCIC) 1994 cancer control framework and looks at the types of science (basic, clinical and population) and the domains of inquiry (individual, organisational and system/policy). Best et al. comment that, although this is not explicit, the framework recognises the field as a complex adaptive system (i.e. options must reflect local context while guiding overall system change). The authors argue that a systems-oriented approach to knowledge into action is lacking from other models. The model attempts to provide guidance that will align knowledge to action strategies across individual, organisational and system levels, recognising that actors in knowledge mobilisation processes occupy positions in systems that affect their outlook and behaviour. The model is operationalised as a nine-cell matrix characterising the philosophy and some possible implementation strategies appropriate to three domains of inquiry (individual, organisational and system/policy) and three types of science (basic, clinical and population). |

| The three generations framework (Best et al. 2008;63 Best et al. 200964) | Best et al. suggest that there have been three generations, or types, of models: linear (dissemination, diffusion, knowledge transfer, knowledge utilisation), relationship (knowledge exchange) and systems (knowledge integration). The authors define knowledge integration as ‘The effective incorporation of knowledge into the decisions, practices and policies of organisations and systems’.63 |

| The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al. 200965) | The CFIR consolidates 19 different conceptual frameworks relevant to implementation research and suggests that implementation is influenced by implementation characteristics, the outer setting, the inner setting, the characteristics of the individuals involved and the process of implementation. The starting point for this framework was the 2004 synthesis by Greenhalgh et al. 2004;58 the CFIR builds on this work by reviewing 17 other models that were not specifically included in the Greenhalgh review. The CFIR has five major domains with their own constructs: intervention characteristics (eight constructs), outer setting (four constructs), inner setting (12 constructs), characteristics of the individuals involved (five constructs) and process of implementation (eight constructs). The framework suggests that implementation may necessitate the use of a range of strategies that exert their effects at multiple levels. |

| The Critical Realism and the Arts Research Utilization Model (CRARUM) (Kontos and Poland 200966) | The CRARUM is an adaptation of the OMRU, borrowing additional concepts from critical realism (generative mechanisms, structural and agential powers) and incorporating arts-based methodologies with the potential to foster critical awareness and transformation. It is a more dynamic model than OMRU, with more room for agency by the adopters of research. |

| Normalisation Process Theory (May et al. 200967) | Normalisation Process Theory draws on social constructivism and implementation theory. Its key elements are the social organisation of the work (implementation), making practices routine elements of everyday life (embedding) and sustaining embedded practices in their social contexts (integration). It defines activities, mechanisms and actors’ investments that are crucial to the outcome of an implementation process. It can be operationalised as a planning or evaluation tool by means of questions about the work required for normalisation and the actors who accomplish it. |

| Participatory Action Knowledge Translation model (McWilliam et al. 200968) | The Participatory Action Knowledge Translation model combines a social constructivist approach with elements of the PARIHS Framework and the KTA framework. It takes the components of PARIHS (evidence, context, facilitation) and the idea of a dynamic relationship between ‘science push’ and ‘demand pull’ from the KTA framework. |

| Ward et al.’s conceptual framework of the knowledge transfer process (Ward et al. 200919) | This conceptual framework of the knowledge transfer process emerged out of a review of 28 different models which seek to explain all or part of the knowledge transfer process. Five common components of the knowledge transfer process were problem identification and communication; knowledge/research development and selection; analysis of context; knowledge transfer activities or interventions; and knowledge/research utilisation. These five components are connected via a complex multidirectional set of interactions (i.e. the individual components can occur simultaneously or in any given order and can occur more than once during the knowledge transfer process). The review identified three types of knowledge transfer processes: a linear process, a cyclical process and a dynamic multidirectional process. The authors suggest that their framework can be used to gather evidence from case studies of knowledge transfer interventions; they comment that at present it is analytically and empirically empty: it does not contain details about the relative importance or applicability of each of the five components or details of the practical actions which can be associated with the components. Note that the authors subsequently tested the framework empirically and refined it.37 A revised diagram of the framework was created illustrating the point that the five components could occur separately or simultaneously and not in any set order and illustrating some of the possible connections between them. |

| The Knowledge Exchange Framework (Contandriopoulos et al. 201021) | The Knowledge Exchange Framework focuses on collective knowledge exchange systems (i.e. interventions in organisational or policy-making settings rather than those aimed at changing individual behaviour) and on active knowledge exchange interventions (rather than passive information flows). The framework has three basic components of knowledge exchange systems: the roles of individual actors in collective systems; the nature of the knowledge exchanged and the process of knowledge use and situates knowledge exchange interventions in larger collective action systems with three core dimensions: polarisation; and cost-sharing and social structuring. |