Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/2000/63. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Simpkin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Aim

Our aims were to develop longitudinal age-related reference ranges that predict how prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels change over time and to examine their use in identifying abnormal (cancer-related) PSA increases in men with clinically localised prostate cancer (PCa).

Objectives

-

To use data from four cohorts of men with PCa to investigate whether or not data collected during diagnosis about the type, quantity and aggressiveness of the cancer (e.g. Gleason score, number of positive biopsy cores) improve the accuracy of our previously published reference ranges.

-

To use data from three cohorts of men with PCa to (1) calibrate the thresholds of the reference ranges to identify when an increase in PSA might be indicative of progressing cancer; (2) calculate the sensitivity, specificity and predictive value of the reference ranges to predict clinical cancer progression; and (3) compare these predictive abilities to those of standard PSA kinetics.

-

To develop an easy-to-use instrument based on the reference ranges that would assist in the clinical management of men with clinically localised PCa who have opted for active monitoring [(AM) regular PSA tests to monitor the cancer], and to explore the acceptability of various formats and presentations of the instrument to patients and clinicians.

-

To design a randomised controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the effectiveness of the most acceptable AM instrument compared with existing AM methods.

Background

Prostate cancer

For men in the UK, PCa accounts for 24% of cancers diagnosed and 14% of cancer mortality;1 yet, currently, its natural history is not fully understood. Autopsy results have shown that approximately half of men over 50 years of age have some form of PCa. 2 However, based on data from the USA, there is a 16.5% lifetime chance of being diagnosed with, and a 3% chance of dying from, PCa. 3,4

Screening for prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is one of the most common newly detected cancers in men worldwide, primarily because of the increasing use of PSA as a screening test. 5 PCa screening is, however, a controversial issue in contemporary health care. 6 Screening using PSA can detect cancers that are still confined within the prostate7 when radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy could possibly achieve a cure. However, current tests cannot differentiate between tumours with biological potential for progression and the majority of slow-growing tumours, which will not cause clinical disease in a man’s lifetime. The recent publication of the results of screening trials in Europe and the USA have further fuelled the controversies in this area, showing, for example, that 1410 men needed to be screened to find 48 cancers to prevent one cancer death. 8

Treatment for clinically localised prostate cancer

Men diagnosed with clinically localised PCa are often treated by either radical prostatectomy (surgery to remove the prostate) or some form of radiotherapy. Radical treatments can cause serious side effects, particularly incontinence and impotence. 9 There is currently a lack of robust evidence about the comparative effectiveness of treatment for PCa. A recent systematic review10 sought to compare monitoring with radical treatment but found no comparative trials. Two randomised trials have evaluated the effectiveness of a passive strategy called watchful waiting (WW). WW historically involved palliative treatment once symptoms appeared and was aimed at older men who were not suitable for surgery or radiotherapy. The Prostate cancer Intervention Versus Observation Trial (PIVOT) recently found no difference between WW and radical prostatectomy for either all-cause mortality or PCa-specific mortality (PCSM) after at least 10 years of follow-up11 for men with PSA-detected PCa. The Scandinavian Prostate Cancer Group study number 4 (SPCG4) trial12 found that radical prostatectomy reduced PCSM compared with WW among men who had been diagnosed clinically (rather than screen detected as in PIVOT). This trial started recruitment prior to the use of PSA and, consequently, the majority of participants had clinically detected disease. 13 The Prostate testing for cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) trial is comparing AM with radical treatment (surgery and radiotherapy) in men with PSA-detected clinically localised PCa, but the long periods of follow-up required for clinically relevant outcomes to be observed means that it will not report for at least another 2 years. 14,15

Interest in the safety and acceptability of monitoring for clinically localised PCa, which avoids unnecessary intervention, has grown over the past decade. Although it is accepted that AM protocols involve closer monitoring than that which is employed in the WW arm of SPCG4, recent systematic reviews have concluded that there is little evidence or expert consensus over the most effective monitoring protocol. 10,16–18 Serial measures of PSA level are used consistently, but various aspects of PSA kinetics are used to trigger further clinical review, including PSA doubling time [(PSADT) length of time for PSA to double] and PSA velocity [(PSAv) rate of PSA change per year]. Hence, there is increasing interest in using PSA levels to monitor men with low-risk clinically localised tumours and in using strategies that would indicate when further clinical review and radical treatment would be appropriate and when men could remain monitored without intervention. 19

Active monitoring or surveillance

Active monitoring and active surveillance (AS) have developed as management strategies for men with clinically localised PCa to avoid overtreatment of low-risk disease. 20 AS involves regular follow-up by PSA testing, digital rectal examination (DRE), review of symptoms and scheduled repeat biopsy, whereas AM only uses a rebiopsy in the presence of changing PSA or DRE findings, because a rising PSA can be indicative of worsening PCa. Under an AM protocol, men with stable PSA remain on monitoring, whereas those with rapidly rising PSA are recommended for clinical review. At clinical review, a biopsy of the prostate can be performed and, depending on the specific protocol, a patient may be recommended for or suggested to consider radical intervention (e.g. radiotherapy or prostatectomy) or continuation on AM. The key tenet of AM/AS is to balance the risk of harm of intervention in men with non-lethal cancer, with the risk of not intervening where cancer is progressing. A previous systematic review16 based on five AM/AS cohorts20–24 found little consensus on the eligibility criteria, optimum protocol for monitoring, the trigger(s) for radical intervention or the role of PSA kinetics in monitoring. 16 Two more recent systematic reviews10,17 again found no consensus on eligibility criteria for AM/AS or the AM/AS regimens used.

Prostate-specific antigen kinetics

In order to use PSA in AM/AS, a model for normal PSA levels is needed as a comparator for observed PSA levels in men on AM/AS. PSADT, PSAv and absolute level of PSA are commonly used measures for monitoring a man’s PSA level. 18 There is little consensus on which of these to use or what threshold should be employed for each measure. There remains an absence of clinical or statistical evidence for their use in AM, and retrospective analyses have found very little association with clinical outcomes, such as metastases or PCSM. 18,25–28 Furthermore, there are concerns about the various methods of calculation of PSADT29,30 and PSAv,31,32 as well as a great deal of variation and uncertainty about how many PSA values should be used for calculation. 33 PSA levels increase naturally with age, so a method is needed to indicate when increases in PSA are beyond normal age-related change to avoid reviews being triggered when they are not necessary.

Modelling prostate-specific antigen change with age

Modelling PSA in AM/AS has received little attention in the literature,33–36 despite the fact that repeated measures of PSA from a cohort of men represent a wealth of information about the behaviour of PSA. An accurate model for PSA change would allow men to observe where they lie in comparison to the general trend of PSA in similar men and whether or not any increase in their PSA is consistent with normal age-related change. Multilevel models37,38 allow such data to be fully exploited by modelling the variation in PSA between men in an AM cohort, as well as the variation in PSA within each individual during follow-up. We have previously used multilevel models to model PSA change with age in men without cancer and compared this with men with screen-detected and clinically presenting cancer. 35 Limitations of this previous work include the use of only two cohorts of men with cancer and the derivation of the model on cancer-free men which meant that potential explanatory variables such as Gleason score, or age at diagnosis, were not included in the model. Initial examination of the comparison of observed PSA to that predicted for a cancer-free man of the same age indicated that this model might result in fewer alerts for clinical review. 35 However, clinical outcomes were not available for comparison. In order to study the effect of PSA change on clinical outcomes, it may be necessary to combine AM/AS cohorts, because very few deaths or cases of metastases have been reported at this stage. 10,16,17

Qualitative research in active monitoring/active surveillance

Qualitative methodology has not been widely applied in AM/AS research. Few studies have considered patients’ and clinicians’ views and experiences of AM/AS in depth, and the published literature largely refers to protocols that more closely follow AS than AM.

A considerable proportion of the qualitative literature relating to AM/AS considers men’s treatment decision-making. Qualitative evidence largely places clinician recommendations and communication as principal drivers for patients’ decisions to opt for or against AM/AS. This has tended to be framed in the literature as patients deferring the decision-making process to the clinician,39–42 or justifying their decision to opt for AM/AS in light of clinicians’ recommendations. 39,41,43 Similar decision-making tendencies are seen in earlier studies of localised PCa management that do not make specific reference to AM/AS. 44,45 Of these studies, one suggests that passing on the decision-making power to the clinician can be an active choice on the man’s part. 45 Qualitative interviews also suggest that men come to the decision to choose AM/AS by reading cues from their clinicians (e.g. descriptive terminology of the low-risk status of the cancer). 39,41

The qualitative findings provide insight into how clinicians may shape the decision-making process, but do not represent the prevalence of treatment decision-making preferences. A review of the literature found that men prefer to be actively involved in the treatment decision-making process. 46 Despite this, there is a substantial body of evidence that suggests that men’s values and preferences are not reflected in the final treatment choices made. 47 A systematic review of treatment decision-making concluded that men’s treatment choices tend to be reflective of information they receive, rather than their underlying values and preferences. 48

Only one qualitative study has considered AM/AS men’s information needs, focusing broadly on psychosocial and educational needs. The single focus group study found that men had poor knowledge of their disease and tended to turn to the internet as their main source of information. 49 A number of studies have designed decision-support interventions to increase men’s involvement in, and satisfaction with, decision-making in relation to treatment of PCa through increasing knowledge and education. Successful interventions have included providing audio-recordings of consultations, presenting individualised information to men and their partners,50,51 and providing counselling via nurses. 52

A handful of qualitative studies have sought to explore men’s experiences of being on AM/AS. These have tended to focus on psychosocial issues, particularly issues of uncertainty. Two qualitative interview-based studies in Sweden and Canada report uncertainty as a major theme to emerge from interviews with men on AM/AS. 53,54 Men talked about uncertainty across a number of domains, including disease progression, prognosis, symptom interpretation and morbidity associated with potential imminent treatment. However, there was a suggestion that uncertainty was temporal, peaking at times of PSA testing or rebiopsy. Receipt of reassuring test results enabled men to ‘continue with their normal lives’. The study by Oliffe et al. 53 also reported that men’s strategies for coping with uncertainty included attempting to ‘live a normal life’ and to do all they can to assert control over their bodies (i.e. through lifestyle and diet changes, and use of complementary/alternative therapies).

Some qualitative studies have intentionally focused on the issue of uncertainty in AS, rather than identified this as a key theme through grounded theory approaches. 55 A study by Bailey et al. analysed men’s accounts of being on AM/AS through the lens of a pre-existing theoretical model of uncertainty. 55 The authors identified uncertainty surrounding cancer progression and the questioning of whether or not one had made the ‘right choice’ as major themes to emerge from interviews. Linked with the uncertainty related to cancer progression was men’s perceptions of how PSA monitoring was not a fail-safe indicator of disease status. 55

The issue of uncertainty has also been identified as a key issue through survey-based research. A survey asked men to provide open responses to a question that asked about the key advantages and disadvantages of being on AM/AS (n = 103). 56 One-third of men reported the risk of disease progression being a key disadvantage, one-quarter made non-specific reference to ‘uncertainty’ and ‘distress’ and 10% talked about the bothersome nature of regular follow-up.

Although research focusing on men’s experience of AM/AS is limited, qualitative studies on decision-making have made some reference to men’s AM/AS experiences. Davison et al. reported that men felt able to ‘live a normal life’, although the authors also emphasise patients’ reported relaxed mentality. 39 A systematic review of psychological effects of AM/AS concluded that men could experience anxiety in response to the prospect of ‘no intervention’, uncertainty and lack of patient education/support. The authors suggest that these concerns are likely to be particularly relevant to men on AM/AS. 57 Overall, the literature on measures of anxiety/psychological distress and/or health-related quality of life suggests there are no significant negative outcomes associated with following an AM/AS programme,58–63 although this can depend on other factors (e.g. personality type, how men conceptualise the role of the clinician, marital status). 59,64 However, it has also been reported that PSA testing and rebiopsies can raise anxiety levels in men on AM/AS, usually temporarily. 65 Furthermore, comparisons of psychological distress/health-related quality of life in men on AM/AS compared with men who undergo radical treatments is somewhat mixed. 59,60,65–67

To our knowledge, there has been no qualitative research that seeks to understand patients’ and/or clinicians’ experiences of AM/AS protocols. More generally, men’s understanding of and views surrounding AM/AS protocols, including thresholds for moving off AM/AS, have not yet been reported. Furthermore, although guidance on AS protocols has been produced by authoritative bodies [e.g. the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the British Association of Urological Surgeons, the European Association of Urology], AM/AS protocols adopted by clinicians have not yet been explored in practice.

NHS policy and practice

The recently published 2014 NICE guidelines68 suggest that men with low-risk localised PCa should be offered AS, which acknowledges that many men would not benefit from radical treatment. NICE recommends a protocol for the management of men on AS, including frequency of PSA testing, DRE and rebiopsy. NICE also suggests that AS could be offered to men with intermediate-risk localised PCa if these men do not wish to undergo immediate radical treatment. There is only a little information about treatments, including AS, as part of the NHS Prostate Cancer Risk Management Programme (see www.cancerscreening.nhs.uk/prostate/faq17.html).

Overview of this report

In Chapter 2 we present a systematic review of AM/AS, which includes a summary of the included studies along with a meta-analysis into the factors affecting management change from AM/AS to radical treatment. A model for PSA change is developed in Chapter 3, using data from men following AM as part of the ProtecT trial. This model for PSA change is then validated in four external cohorts in Chapter 4 and used to derive 95% reference ranges for PSA with age. Chapter 5 compares the PSA reference range (PSARR) method against PSADT and PSAv in predicting several PCa outcomes in three external cohorts. Chapters 6 and 7 summarise the qualitative interviews conducted with clinicians and patients about AM/AS and the active monitoring system (AMS). Chapter 8 discusses several potential RCTs and summarises the issues surrounding any RCT of AM/AS strategies. Chapter 9 contains recommendations for future researchers and health-care professionals in the area.

Chapter 2 Systematic review of active monitoring for prostate cancer

Aim

The aims of this stage of the project were to identify how AM/AS is carried out in ongoing studies worldwide and to assess whether or not any study protocols (such as eligibility) appeared to be beneficial for PCa outcomes. We also wished to investigate the PSA monitoring procedures used in modern AM studies, in order to compare these to PSARRs.

Search strategy

We conducted a systematic search of the online databases MEDLINE, EMBASE and Web of Science for articles/abstracts published between October 2004 (the end date of the previous systematic review by Martin et al. 16) and April 2013. Reference lists of included articles and recent reviews were searched by hand for additional citations. A forward citation search of the five studies20–24 included by Martin et al. 16 was also performed using the Web of Science database. Where potentially relevant conference abstracts only were available, authors were contacted to enquire about full publications of their work or to elicit further details of their AM/AS programme.

Inclusion criteria

Studies involving men with T1–T2 localised PCa, which was initially managed conservatively, were included if pre-defined clinical, pathological or biochemical criteria for clinical review were outlined. Studies involving recurrence after radical prostatectomy or radiotherapy (i.e. not initially managed conservatively) or non-clinical studies were excluded. We excluded any conference abstracts, non-systematic reviews, editorial comments, background papers or studies involving different treatments or diseases of the prostate. Where several papers reporting on the same cohort of men were found, the latest full analysis of the study was included. Title and abstract screening was undertaken independently by AJS, CM, KT and RMM. Each full paper was screened by AJS and independently by one of CM, KT and RMM.

Data extraction

Eligibility criteria, monitoring protocols, sample size, age, PSA, follow-up times, management change triggers, management change rates, metastases, PCSM and reasons for changing treatment were extracted manually from each paper by AJS and checked by one of CM, KT or RMM. Authors of publications found in our search were contacted to provide information where specific values were not given in a publication and to check that data extraction was correct. Management change rates are considered here as key short-term outcome measures for AS, whereas occurrences of metastases or PCa death are considered to be longer-term outcomes.

Data synthesis

Person-years per study were estimated as the median follow-up time multiplied by the sample size for each study; total person-years were the sum of these across included studies. A metaregression was conducted to investigate whether or not elements of study design were associated with the rate of management change per person-years. This rate was calculated for each study as:

Heterogeneity between studies was measured using the I2 statistic;69 the higher the I2 value, the more between-study heterogeneity is present. The covariates for the metaregression were (1) year of first recruitment; (2) whether or not a Gleason score of 3 + 3 or less was used for eligibility; (3) whether or not a PSA level of 10 ng/ml or less was used for eligibility; (4) the number of PSA tests in the first 3 years; (5) whether or not mandatory rebiopsy was specified in the protocol; and (6) whether or not PSA or PSA kinetic measures, such as PSADT or PSAv, were used to recommend clinical review or radical treatment. Together with univariable analysis, two multivariable metaregressions were performed grouping eligibility variables (1)–(3) and monitoring procedure variables (4)–(6). Average variable effects on management rate are presented alongside 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Meta-analysis was performed in Stata 1270 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to combine the effects of prognostic factors for management change. Factors were combined if they appeared in more than two studies that reported estimates of the association with change to radical treatment. Where applicable, a sensitivity analysis was used to check if the pooled combination of odds ratios and hazard ratios (HRs) led to different results from just pooled HRs or pooled odds ratios. We also used meta-analysis to study the reasons for management changes. Reasons for changing to radical treatment were given within studies and the proportions of each reason were combined to get an overall average estimate.

Bias in reporting

Publication bias could be an issue in our review, as we examined only abstracts published in English. However, we would expect that studies showing that AM/AS was not a safe option would be more likely to be published in English-language journals, and, therefore, if anything, this systematic review will overestimate the number of adverse events.

Results

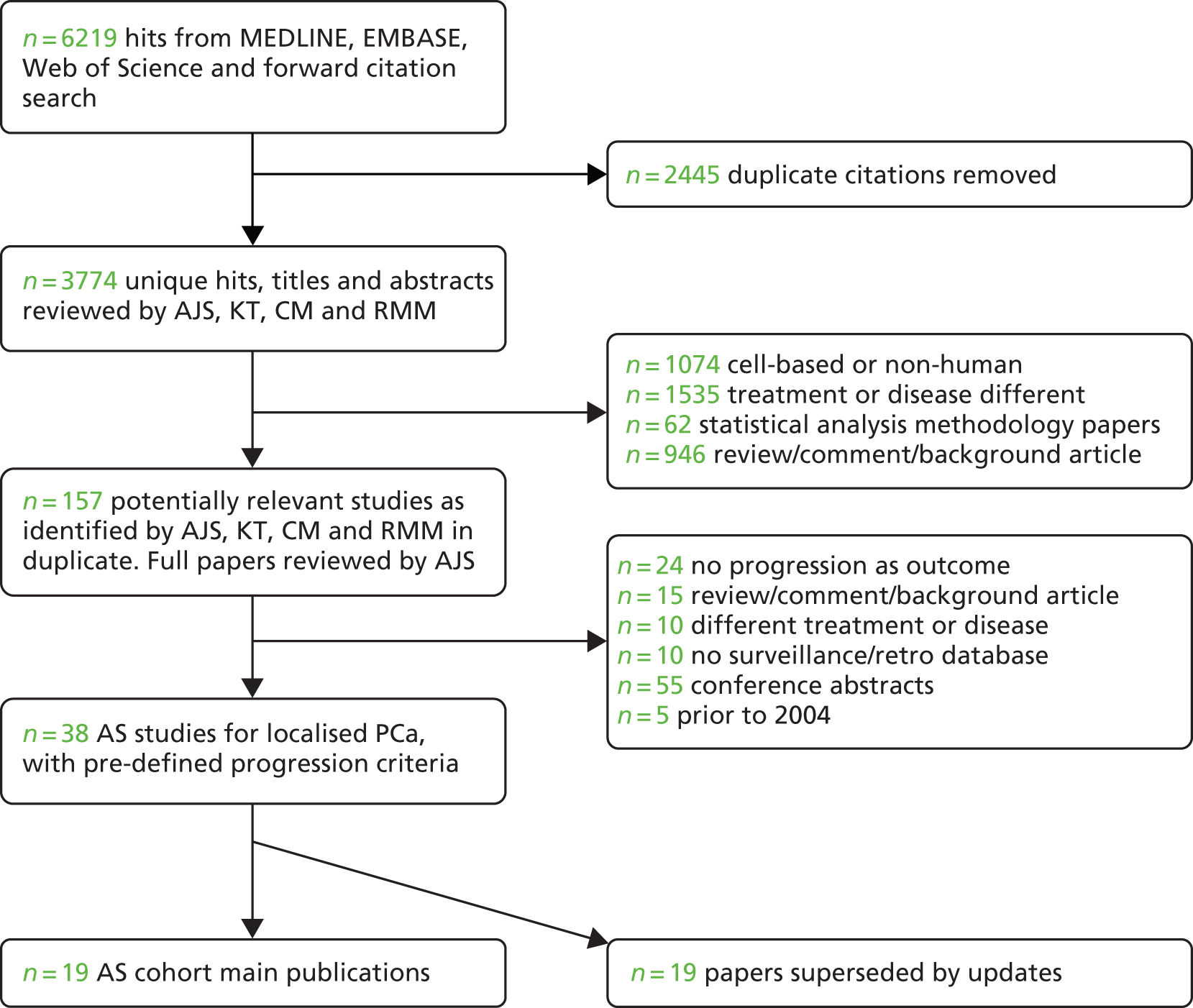

Authors of potentially relevant conference abstracts were contacted to provide full papers if available, although we identified no publications by this route. We found 157 potentially eligible studies for full-paper screening, of which 38 papers met the inclusion criteria, reporting on 19 unique cohorts of men on AS (Figure 1). 71–89 Two of these were updates of the five studies from the previous review by Martin et al. 16 Updated cohort information was volunteered by one author. 78 We also included the three papers21–23 without update from the previous review, leading to 22 cohorts and 7111 men. The median age at entry ranged from 64 years to 70.5 years, with the youngest participant being 36 years86 and the oldest being 97 years. 73 The median follow-up time between the cohorts was 3.7 years. Four studies had < 2 years’ median follow-up23,77,88,89 and seven studies had > 5 years,21,71–73,79,80,85 up to a maximum of 7.5 years. 71

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart of the screening process.

Eligibility criteria

Table 1 contains a summary of eligibility criteria, monitoring protocol and baseline characteristics. A combined Gleason score of 6 (3 + 3) or lower was required for entry into 12 of the 22 studies. 71,72,74,77–79,82–84,87–89 A further five cohorts broadened this criterion to include a Gleason score of 7 (3 + 4),75,76,81,85,86 and two allowed up to a Gleason sum of 7,22,80 leaving three cohorts without an explicitly specified Gleason entry requirement. 21,23,73 Additional pathology findings were used with some degree of consistency across the studies. Five studies allowed only those men with < 50% cancer in any single core into the study,74,77,82–84 with one study allowing only 20% involvement in any single core. 78 The number of positive cores allowed varied between an absolute number or a proportion; two studies required no more than half of the biopsy cores to be positive,85,88 whereas seven allowed two or fewer positive cores,74,78,82–84,86,89 and one study raised this to allow those men with three positive cores to enter. 77

| Setting | Study design | Patient baseline characteristics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligibility | Monitoring protocol | |||||||||

| PSA | Gleason score ≤ | Tumour stage ≤ | Other | PSA | DRE | Biopsy | Sample size (years recruited) | Median age (years) | Median PSA (ng/ml) | |

| Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung City, Taiwan21 | – | – | 1a | TURP for benign hyperplasia | Every 3–6 months (after 1990) | Every 3–6 months | As a result of DRE/PSA | 52 (1983–96) | Mean 71.5 (SD 7) | Not specified |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA22 | – | 4 + 3 | – | No significant comorbidities; eligible for radical treatment | Every 3 months for 1 year, then every 6 months | Every 3 month for 1 year, then every 6 month | At 6 months or as a result of DRE/PSA | 88 (1984–2001) | Mean 65.3 (range 44–79) | 5.9 (range 0.09–30.2) |

| Hospital Universitano Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain71 | – | 3 + 3 | 1a | – | Every 6 months | Every 6 months | Restaging biopsy post diagnosis then as a result of DRE/PSA | 16 (1986–99) | Mean 64 (range 49–71) | Not specified |

| McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada72 | – | 3 + 3 | – | Patient choice, limited life expectancy, presumed insignificant cancer | Every 3–6 months | Every 3–6 months | Every 12 months or as a result of DRE/PSA | 186 (1987–2006) | 67 (range 49–78) | < 4 (23%), 4–10 (65%), 10–20 (10%), > 20 (2%) |

| Cochin Hospital, Paris, France73 | – | – | 1a | – | Within 2 months then every 6 months for 2 years, then every 12 months | – | As a result of PSA | 144 (1988–2005) | Mean 69 (range 52–97, SD 9.2) | 7 (range 0.6–29) |

| University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT, USA74 | < 10 | 3 + 3 | 2a | ≤ 2 positive cores; < 50% cancer in any core; age < 75 | Every 6 months or every 3 months if PSA increasing | Every 6–12 months | Within 2 years or as a result of DRE/PSA or patient choice | 40 (1990–2006) | 68 (range 52–75) | 6.3 (range 4–9.1) |

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA23 | – | – | 1c | – | At 3 months then every 6 months | At 3 months then every 6 months | Not routinely taken | 27 (1991–6) | Mean 65 (SD 5) | Mean 5.3 (range 2–24, SD 9.8) |

| ERSPC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands75 | ≤ 15 | 4 + 3 | 2 | – | Chart reviews every 6 months | Chart reviews every 6 months | Not routinely taken | 278 (1993–9) | 69.8 (IQR 66.1–72.8) | 3.6 (IQR 3.1–4.8) |

| Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK76 | ≤ 20 | 4 + 3 | 2 | Fitness for radical treatment | 3–6 months, then every 6 months after 2 years | 3–6 then 6 after 2 years | Not routinely taken | 80 (1993–2002) | 70.5 (range 59–81) | < 4 (20%), 4–10 (52%), 10–20 (25%), > 20 (1%) |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA77 | < 10 | 3 + 3 | 2a | ≤ 3 positive cores (out of at least 10); < 50% cancer in any core; confirmatory biopsy before starting surveillance | Every 6 months | Every 6 months | Within 12–18 months, then every 2–3 years or as a result of DRE/PSA | 238 (1993–2009) | 64 (IQR 58–68) | 4.1 (IQR 2.5–5.6) |

| University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA78 | ≤ 10 | 3 + 3 | 2a | ≤ 2 cores; ≤ 20% cancer in any core | Every 3–4 months for 2 years, then every 6 months | Every 3–4 months for 2 years, then every 6 months | Within 1 year then every 1–2 years | 276 (1994–2011) | Mean 63 (range 42–79) | 4.8 |

| University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada79 | ≤ 10, 2000– ≤ 15, 1995–1999 |

3 + 3 2000– 3 + 4 1995–1999 |

– | Age > 70 years 1995–1999 | Every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months for stable patients | – | Within 6–12 months then every 3–4 years or as a result of PSADT | 450 (1995–2010) | < 70 (48.7%), ≥ 70 (51.3%) | 0–2.5 (12%), 2.5–5 (25%), 5–10 (48%), 10–15 (12%), 15–20 (2%), n/a (0.4%) |

| ERSPC, Gothenburg, Sweden80 | < 10 (low-risk group) < 20 (intermediate-risk group) |

3 + 3 (low-risk group) 4 + 3 (intermediate-risk group) |

1 (low-risk group) 2 (intermediate-risk group) |

Very low risk group defined as T1c, Gleason score of ≤ 6, PSAD < 0.15 ng/ml, < 3 positive cores, ≤ 50% involvement in any core | Every 3–6 months | Every 3–6 months | As a result of signs of PSA or T-stage progression | 439 (1995–2010) | 65.4 (51–70) | Not specified |

| University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA81 | Within CAPRA score | 3 + 3 (low-risk group) 3 + 4 (intermediate-risk group) |

2 | Low risk = Gleason score of 2–6 and CAPRA score of 0–2; Intermediate risk = Gleason score of ≤ 7 or CAPRA score of 3–5 | Every 3 months | Every 3 months | Every 12–24 months | 466 (1995–2010) | Mean 62.8 (SD 8.1) | Low risk 4.99 (range 0.3–11); intermediate risk 10.3 (range 3.14–37.91) |

| JH University, Baltimore, MD, USA82 | PSAD < 0.15 ng/ml/cc | 3 + 3 | 1c | ≤ 2 positive cores; < 50% cancer in any core | Every 6 months | Every 6 months | Every 12 months | 769 (1995–2011) | 66 (range 45–92) | 5 (range 0.3–19) in men eventually treated; median 4.7 (range 0.2–24) in untreated |

| Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA83 | – | 3 + 3 | 2c | ≤ 2 positive cores; < 50% cancer in any core | Every 6 months | Every 6 months | Every 12–18 months | 135 (2000–10) | Not specified | Not specified |

| Multi-institutional, Kagawa, Japan-based84 | ≤ 20 | 3 + 3 | 1c | ≤ 2 positive cores < 50% cancer in any core Age, 50–80 years |

Every 2 months for 6 months, then every 3 months | – | At 12 months | 118 (2002–3) | 50–59 (5%), 60–69 (43%), 70–74 (37%), 75–80 (16%) | Mean 7.2, 81% < 10, 19% ≥ 10 |

| Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK85 | < 15 | 3 + 4 | 2 | ≤ 50% positive cores Age, 50–80 years |

Every 3 months in first year, every 4 months in second year, every 6 months after 2 years | Every 3 months in first year, every 4 months in second year, every 6 months after 2 years | Within 18–24 months then every 2 years | 471 (2002–11) | 66 (range 51–79) | 6.4 (range 0.2–14.5) |

| Southern Health, Melbourne, Australia86 | < 10 | 3 + 4 | – | ≤ 2 positive cores; < 3 mm in each core of cancer T1a if TURP diagnosed | Every 3 months | Every 6 months | Within 12–18 months then every 3 years | 154 (2003–10) | 63 (range 36–81) | Mean 6.5 (range 0.3–22) |

| Cleveland Clinic, USA87 | ≤ 10 | 3 + 3 | 2a | Confirmatory rebiopsy within 6 months | Every 6–12 months | Every 6–12 months | At least every 2 years | 89 (2004–9) | 67 (range 52–83) | 4.8 (range 0.6–18.4) |

| Frimley Park Hospital, Frimley, UK88 | ≤ 15 | 3 + 3 | 2a | ≤ 50% positive cores; ≤ 10 mm of disease in single core; age ≤ 75 years | Every 3 months | – | Within 12 months then every 18 months | 101 (2006–10) | 68 (range 51–75) | 6.4 (range 0.9–15) |

| PRIAS (International), Rotterdam-based, Holland89 | ≤ 10 ; PSAD < 0.2 ng/ml/cc | 3 + 3 | 2 | ≤ 2 positive cores | Every 3 months for 2 years, then every 6 months | Every 6 months for 2 years, then every 12 months | 1, 4 and 7 years or annually if 3 ≤ PSADT ≤ 10 | 2494 (2006–12) | 65.8 (IQR 61.0–70.4) | 5.6 (IQR 4.4–7.0) |

Clinical tumour stage (T-stage) was used in 17 cohorts with thresholds of T2 (six cohorts75,76,80,81,83,89), T2a (five cohorts74,77,85,87,88), T1c (three cohorts23,82,84), T1b73 and T1a (two cohorts21,71). There was no consensus among the 15 cohorts that used a PSA threshold for entry, with seven cohorts permitting men with PSA ≤ 10 ng/ml,74,77–79,86,87,89 three cohorts allowing PSA ≤ 15 ng/ml75,85,88 and three cohorts allowing PSA < 20 ng/ml. 76,80,84 Two further studies used PSA density (PSAD) as an eligibility criterion, with limits of PSAD < 0.15 ng/ml/cc82 and PSAD < 0.2 ng/ml/cc. 89 Seven studies did not explicitly use PSA for eligibility,21–23,71–73,83 although six of these involved men diagnosed between 1983 and 199121–23,71–73 (i.e. in the pre- and early-PSA-screening era). Age restrictions were used in just four studies. 74,79,84,88

Surveillance or monitoring protocol

Serial PSA measurement as a measure for surveillance or monitoring during follow-up was common to all studies, but the frequency of measurement was not consistent. Eleven studies maintained PSA testing every 3–6 months throughout;21,71,72,75,77,80–83,86,88 eight reduced the frequency of PSA testing after men had been on surveillance beyond 1 or 2 years. 22,23,73,76,78,84,85,89 Frequent testing occurred in the Kagawa and modern Royal Marsden Hospital (RMH) studies, with men scheduled for 2284 and 1885 PSA tests, respectively, in the first 3 years.

Digital rectal examination was regularly performed in all but five73,79,84,86,88 of the studies, with inconsistency of frequency between the study protocols. In the 17 studies with both DRE and PSA testing, 14 assessed both at the same frequency, whereas the other three had DRE less often than PSA tests. 74,85,89

Repeat biopsy testing was used by 19 studies, with 16 having a scheduled biopsy within 2 years of beginning surveillance. 22,74,77–79,81–89 Biopsies were repeated at least every 2 years in nine studies. 72,78,81–85,87,88 Three studies undertook repeat biopsy only where worsening PSA or DRE results were evident or at the request of the patient or clinician. 21,73,80 Three studies did not include routine rebiopsy or rebiopsy as a result of worsening DRE or PSA. 23,75,76

Triggers for clinical review or radical treatment

Triggers for recommending clinical review and radical treatment are summarised in Table 2. Almost all studies used histological findings such as an increase in Gleason score (18 cohorts22,71–74,77–89), number of positive cores or percentage of cancer on a single core (15 cohorts22,71–74,77–79,82–86,88,89) to recommend radical treatment. Less commonly, T-stage (six cohorts77,79,80,82,84,89) and PSA (13 cohorts21–23,76,77,79–82,84–86,89) were used as triggers to recommend rebiopsy or radical treatment. In four studies, a threshold of PSADT was used, with this being 2 years in two of those studies81,84 and 3 years in the other two studies. 79,86 In one study, radical treatment was offered to men with a PSA velocity > 1ng/ml/year,85 while in another such men were rebiopsied. 71 In two studies, a combination of PSA kinetics with other factors such as DRE and rebiopsy findings was used to recommend radical intervention. 22,87

| Setting | Trigger for clinical review and management change criteria | Median follow-up years (range) | Percentage changing to radical treatment (median time, years) | Percentage ‘progressed’ objectively (median time, years) | Progression-free probability | Treatment-free probability | Reasons for changing treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Taichung City, Taiwan21 | Abnormal DRE or progressive elevation of PSA | 7.3 (0.5–15) | 8 (2.5) | 8 | – | – | All four had abnormal DREs and elevation of PSA |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA22 | Three or more points coming from system including Gleason score increase, PSAv > 0.75 ng/ml/year, DRE/TRUS findings, biopsy findings | 3.7 (0.6–13.5) | 35 (7.3) | 25 (3.75) | 95% at 1 year, 88% at 2 years, 67% at 5 years, 56% at 10 years | 93% at 1 year, 84% at 2 years, 58% at 5 years, 41% at 10 years | 17 had three or more points Seven scored two and were anxious Seven patient choice |

| Hospital Universitano Miguel Servet, Zaragoza, Spain71 | PSA > 4 or PSAv > 1 ng/ml/year leads to rebiopsy where upgrade can lead to treatment | 7.5 | 0 | 0 | – | – | Not specified |

| McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada72 | Any of: predominant Gleason score of 4 pattern; > 2 positive cores; > 50% cancer/core, ≥ T2b | 6.3 (1.7–14.1) | 16 (3.7) | 18 | 82% at 5 years for negative first biopsy group, 50% at 5 years positive first biopsy | – | Nine patients ≥ T2b 13 > 50% cancer/core Five Gleason score 22 > 3 positive cores Two patient choice |

| Cochin Hospital, Paris, France73 | Doubling of PSA from baseline leads to rebiopsy where upgrade can lead to treatment | 5.1 | 19 | 21 (mean 5.1) | 75% at 5 year | – | Not specified |

| University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, CT, USA74 | Any of: increase in Gleason score; increase in number of positive cores; onset of urinary symptoms; change in DRE; patient request | 4 (1–14) | 23 (2.75) | Not specified | – | 74% at 5 year | Not specified |

| University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA23 | Abnormal DRE or three consecutive PSA increases with total increase of 5 ng/ml | Mean 1.9 (0.5–5.1) | 19 (1) | 33 | 80% at 1 year | – | Five PSA increases |

| ERSPC, Rotterdam, the Netherlands75 | Patient desire and/or clinician advice | 3.4 | 29 (2.5) | Not specified | – | 86% at 2 years, 78% at 4 years, 66% at 6 years, 53% at 8 years, 31% at 10 years | Not specified |

| Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK76 | Any of rate of PSA increase, subjective decision by patient and clinician | 3.5 (0.1–9.7) | 14 | 11 (1.1) | – | 79.2 at 5 years (95% CI 63.9 to 88.6) | Nine based on rate of PSA rise Two patient choice |

| Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY, USA77 | No longer meet study criteria (i.e. any of PSA ≥ 10, Gleason score of ≥ 7, > 3 positive cores, > 50% tumour/core, > T2a) | 1.8 for untreated; 11% ≥ 5 years | 36 | 26 | 80% at 2 years, 60% at 5 years | – | 34 PSA ≥ 10 23 Gleason score of ≥ 7 Seven positive cores > 3 One T-stage Two tumour/core > 50% (Five men had two or three of these factors) 25 patient choice |

| University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL, USA78 | Any of Gleason score of ≥ 7, increase in number of positive cores, increase in percentage of cancer/core or personal choice | 3.3 (1–17.3) | 26 | 22 | – | 85.7% at 5 years | 15 Gleason 24 tumour volume (i.e. no. cores or percentage cancer/core) 28 both tumour volume and Gleason Eight patient choice |

| University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada79 | Any of PSADT < 3 years, histological upgrade on rebiopsy or clinical progression | 6.8 | 30 | 30 | – | 84% at 2 years, 72% at 5 years, 62% at 10 years | 65 patients PSADT < 3 years 36 Gleason increase Six T-stage Four volume Two urethral obstruction 14 patient choice Eight unknown |

| ERSPC, Gothenburg, Sweden80 | Established PSA, stage or Gleason score progression | 6 (0.08–15.1) | 37 | Not specified | – | 76% at 2 years, 61.5% at 5 years, 45.4% at 10 years, 37.1% at 14 years | 77 Gleason Seven T-stage 45 PSA Four anxiety Four other symptoms |

| University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA81 | Upgrade to PSADT ≤ 2 years, Gleason score of ≥ 4 + 3 if already 3 + 4 or to 3 + 4 otherwise | 3.9 (1–15.2) | 30% of low risk (4) 35% of intermediate risk (4) |

39 | 54% at 4 years for low risk 61% at 4 years for intermediate risk |

– | 73 reclassified on repeat biopsy 17 on PSADT 38 on PSA Nine other pathological 11 other |

| JH University, Baltimore, MD, USA82 | Any of: PSAD ≥ 0.15/ml/cc, Gleason score of ≥ 7, > 2 positive cores, > 50% tumour/core | 2.7 (0.01–15) | 33 (2.2) | 24 | – | 81% at 2 years, 59% at 5 years, 41% at 10 years | 91 number of positive cores or tumour involvement 106 Gleason 67 patient choice |

| Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, USA83 | Any of: Gleason score of ≥ 7, > 3 positive cores, > 50% tumour/core | 2.4 | 27 | 27 | 95% at 1 year, 82% at 2 years, 72% at 3 years, 59% at 4 years, 45% at 5 years | – | 18 number of cores 11 Gleason Six number of cores + Gleason score |

| Multi-institutional, Kagawa, Japan based84 | PSADT ≤ 2 years or pathological upgrade on rebiopsy | 4.5 | 47 | 29 | – | 49% at 3 years | 17 PSADT ≤ 2 years One T-stage change 16 pathology change 15 patient choice Eight comorbidities Seven unknown |

| Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK85 | Any of PSAv > 1 ng/ml/year, Gleason score of ≥ 4 + 3, > 50% tumour/core | 5.7 | 31 (5.4) | 22 | – | 89% at 2 years (95% CI 86% to 92%), 70% at 5 years (95% CI, 65% to 75%) | 18 histological alone 56 PSAv alone 23 both histological and PSAv 40 patient choice |

| Southern Health, Melbourne, Australia86 | PSADT < 3 leads to rebiopsy, any Gleason score or mm cancer/core increase | 2.4 (0.2–7.9) | 16 (2.4) | 17 | – | 62% at 5 years, 45% at 10 years | 26 reclassified on repeat biopsy One patient choice |

| Cleveland Clinic, USA87 | Either Gleason score of ≥ 7 or a combination of PSA, PSA kinetics, DRE cancer quantity, Gleason score; never PSA alone | 2.75 (IQR 1.7–3.75) | 18 | 39 | 93% at 3 years (95% CI 85% to 97%) | 87% at 3 years (95% CI 78% to 93%) | 10 patient choice Six increased Gleason score One percentage of cancer/core One number of cores |

| Frimley Park Hospital, Frimley, UK88 | Any of: upgrade on TTB increase in Gleason score, > 50% positive cores, ≥ 10 mm tumour in 1 core | 1.5 (1–2.3) | 33 | 33 | – | – | 25/34 reclassified on TTB chose treatment 10 patient choice |

| PRIAS (International), Rotterdam based, the Netherlands89 | Any of PSADT < 3 years, Gleason score of ≥ 7, > 2 positive cores, stage > T2 | 1.6 (IQR 1.0–2.8) | 21 | 16 | – | 77% at 2 years, 68% at 4 years | 387 patients on biopsy or PSADT 47 anxiety, 93 other |

Radical treatment rates

In 17 studies, up to 33% of men received radical treatment after a median of 3.6 years. 21,23,71–76,78,79,82,83,85–89 In one of these studies, all 16 men remained on monitoring after 7.5 years, having started with very low-risk T1a disease. 71 The University of California, San Francisco intermediate-risk group radically treated 35% of men after 3.9 years;81 the early Memorial Sloan Kettering study radically treated 35% of men after 3.7 years;22 and the later Memorial Sloan Kettering cohort changed the treatment of 36% of men. 77 In Gothenburg, 37% of men received radical treatment after a median follow-up of 6 years. 80 The highest proportion of men who changed from AS to radical treatment was in Kagawa, with 47% leaving surveillance for radical treatment by 4.5 years of follow-up. 84

Study factors associated with the rate of management change

Total person-years were estimated to be 22,545 in the 22 cohorts. The average rate of change of management (found through metaregression) was 84 (95% CI 61 to 106) per 1000 person-years. In the context of the follow-up found here (i.e. roughly 4 years), we estimate that 84 out of 250 men on monitoring would receive radical treatment during four years of follow-up (Figure 2). There was evidence (I2 = 96%; p < 0.0005) that the rate of change differed substantially between cohorts. The minimum rate of change was 11 per 1000 person-years21 and the maximum was 218 per 1000 person-years. 88

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of the proportion of men changing to radical treatment per person-years, sorted by year of beginning recruitment. ERSPC, European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer; PRIAS, Prostate Cancer Research International: Active Surveillance; UNC, University of North Carolina.

The rate of management change was greater in studies with recruitment periods that started in more recent years; for each calendar year increase in start date, an extra four men changed treatment per 1000 person-years (95% CI 1 to 7 treatment changes per 1000 person-years; p = 0.014). Admitting men with higher Gleason scores was associated with an average decrease of 50 treatment changes per 1000 person-years (95% CI 9 to 88 treatment changes per 1000 person-years; p = 0.025), compared with studies with eligibility criteria including Gleason score of ≤ 6. Studies that had a mandatory scheduled rebiopsy had, on average, 50 more men change treatment per 1000 person-years (95% CI 7 to 94 treatment changes per 1000 person-years; p = 0.025) compared with those that rebiopsied on worsening results from PSA tests or DRE only. Each of these associations was found in univariable analyses. Two multivariable metaregressions were performed to account for mutual confounding. In these models, the results were slightly attenuated, although there still remains some evidence for associations with Gleason score of > 3 + 3 (46 fewer changes, 95% CI –5 to 96 fewer changes; p = 0.07) and regular biopsy (49 more changes, 95% CI –5 to 98 more changes; p = 0.07).

Reasons for changing management

Eighteen studies reported reasons men had for changing treatment. 21–23,72,76–89 Up to an average of 37% of changes to radical treatments were a result of a reclassified Gleason score (95% CI 23% to 51%),72,77–89 whereas an average of 38% were caused by men meeting PSA, PSADT or PSAv triggers (95% CI 25% to 51%). 76,77,79–81,84,85,89 Other tumour-related reclassifications, such as the number of positive cores, caused an average of 23% of the management changes (95% CI 8% to 37%). 72,77–79,81–83,89 Among those studies detailing reasons, an average of 21% (95% CI 13% to 30%) of treatment changes were a result of patient choice or anxiety. 22,72,76–80,82,84–89 Not all of these four types of reasons (Gleason score, PSA, other tumour and patient choice) were possible for all studies and, hence, the sum of the given averages is over 100%. For example, if study 1 has 100 men who change management from AS to radical treatment, with 50 changing as a result of Gleason score reclassification and 50 changing as a result of a rising PSA, then each reason contributes 50%. In study 2, 100 men receive radical treatment; however, in this study, men can only receive radical treatment as a result of Gleason score. Thus, averaging the two studies, we can either say that Gleason score contributes 75% [= (50% + 100%/2)] and PSA 25% [= (50%+ 0%)/2] of the reason why men receive radical treatment or we can ignore the PSA contribution from study 2 (i.e. 0%) and calculate that Gleason score contributes 75% [= (50% + 100%/2)] and PSA contributes 50% (= 50%/1) of the reasons for a change in management. We present the second method of reporting, which results in a total value over 100%.

Prostate-cancer-specific mortality and metastases

Overall, eight PCa deaths were reported among the 7111 men and 22,545 person-years of follow-up. In Gothenburg, one man changed to hormone therapy after 8.6 years on surveillance; he developed distant metastases and died 12.7 years after diagnosis. 80 Five PCa-specific deaths occurred in the Toronto cohort, with all having a PSADT < 2 years, such that triggers for intervention were met and treatment recommended; two men received radiation therapy, one underwent radical prostatectomy and two refused treatment. The deaths occurred 3.7, 5.2, 5.3, 8.7 and 9.6 years after diagnosis. 79 In the RMH cohort, two men died from PCa 4 years and 8 years after diagnosis, respectively. 85 Both had a PSAv of > 1 ng/ml/year, subsequent Gleason score upgrade on rebiopsy and received androgen-deprivation therapy. Six further cases of metastases have been reported among the remaining men. 21,72,80,89

Summary

We reviewed 22 studies of men with localised PCa on AS, more than four times the number published in our previous review. 16 Follow-up times were generally short, with 15 studies having < 5 years median follow-up. Eight PCa deaths and five further cases of metastases were found in 7111 men in short-term follow-up.

Eligibility and triggers for management change vary across studies, leading to different study populations and difficulty in making comparisons between studies. All studies used regular PSA testing, combined with repeat biopsy testing in 19 of the 22 studies. An increase in Gleason score was the most common trigger for recommendation of switching to radical treatment. 19,23–27,30–41 The frequencies of PSA testing, DRE and rebiopsy during surveillance were inconsistent across the studies. The rate of change from AM/AS to radical treatment was found to be 30% or less in 15 of the 22 studies. The primary cause of management change was an upgraded Gleason score. In addition, across studies describing reasons for management change, an average of 21% of men who changed from AS to radical treatment did so without meeting triggers for clinical review.

Studies including men with a Gleason score of > 3 + 3 had 50 fewer men changing per 1000 person-years (95% CI 9 to 88 fewer men changing per 1000 person-years). One explanation could be that those with a Gleason score of 6 have an increased chance of receiving an upwards reclassification compared with those with an original Gleason score of 7. Many men who receive a Gleason score of 6 at diagnosis will be undergraded,90–92 such that on rebiopsy they are deemed to have progressed. Another reason could be that those studies with Gleason score of 3 + 4 eligibility have higher treatment-switching thresholds.

Studies with scheduled rebiopsy were shown to have an increased rate of management change. This is to be expected given that rebiopsy offers the opportunity to detect small areas of high-grade tumour missed by initial biopsies, particularly among men with the most common 3 + 3 Gleason score baseline results. It is well established from surgical series that such upgrading (as opposed to true progression) at a rate of around 25–30% is to be expected. 90–92

A higher baseline PSA and T-stage were also found to be associated with a higher rate of change to radical treatment. PSA change in its various forms (doubling time, velocity, etc.) was also responsible for many changes of management, although evidence for its veracity in this regard is lacking. 25,28

Further follow-up data, which will include definitive outcomes, are needed to clarify the long-term impact of AM/AS, in terms of management change and PCa mortality. The use of the word ‘progression’ by several studies to mean a worsening condition rather than treatment switching is misleading. Furthermore, not all studies explicitly provided a breakdown of what caused men to leave surveillance and switch to radical treatment, making comparisons difficult. In the metaregression, explicit information about those leaving treatment was not available for all studies. Thus, all those receiving radical treatment were grouped together and not separated by the reason for changing treatment, the radical treatment received or PCa outcome. To this end, it would be beneficial in future publications of ongoing AM/AS cohorts for detailed reasons for management change to be given. A breakdown of radical treatment received by reason for leaving monitoring would also be helpful in determining whether or not men opt for radical treatment or WW, particularly as they age.

Chapter 3 Building a model for prostate-specific antigen during active monitoring

The material from this chapter has been published as an article. 93

Aims and background

This part of the project involved:

-

the development of a model for PSA change with age in one cohort of men with clinically localised PCa

-

deciding whether or not baseline diagnostic variables or characteristics improve the model.

Here, we present the decisions made in formulating a model for age-related PSA change in men with PCa. We introduce the AM data set and detail the methods to be compared (see Methods). In Results, we summarise the modelling of PSA by each approach and in Choosing a model for PSA reference ranges we choose the optimum method for PSARRs.

Methods

Study population

The ProtecT study is a large UK-based multicentre clinical trial comparing surgery, radiotherapy and AM in the treatment of screen-detected (PSA ≥ 3 ng/ml) and clinically localised PCa. 14,15 Data were available from 512 men who declined random allocation of their treatment but chose to be managed according to the AM protocol. They had been followed over an average period of 4.8 years [standard deviation (SD) 2.4 years] with a median of 14 visits per individual (7438 total PSA tests). Covariates collected include Gleason score (or grade),94 a histological grading system for PCa, which allows for the two main patterns of tumour-cell structure evident upon biopsy to be graded and combined into a single score. All participants in this cohort have a Gleason score of 6 or 7; however, a Gleason score of 7 can refer to either a 3 + 4 (pattern 3 predominant 4, also present) or a 4 + 3.

We have centred age at 50 years (i.e. considering age 50 years to be the baseline age), given that the inclusion criterion for ProtecT is men aged between 50 and 69 years old. Follow-up of men is irregular, as both the duration and timing of blood tests vary across men and, because of this, classical longitudinal approaches for balanced designs are inappropriate. Furthermore, age, rather than time in the study, is used as the covariate over which change in PSA is estimated. Using age makes the model more portable to populations where age at, and method of, diagnosis for PCa may vary. Furthermore, as there is a great deal of variation in when a diagnosis is made, and, consequently, in when treatment is started in relation to the natural history of the disease, and as no PSA altering treatment is used in this cohort of men, changes in PSA level will be aligned with age rather than the date of diagnosis. Here, given that we are interested in model comparison, we treat Gleason score as a binary variable (score of 6 vs. 7) for simplicity.

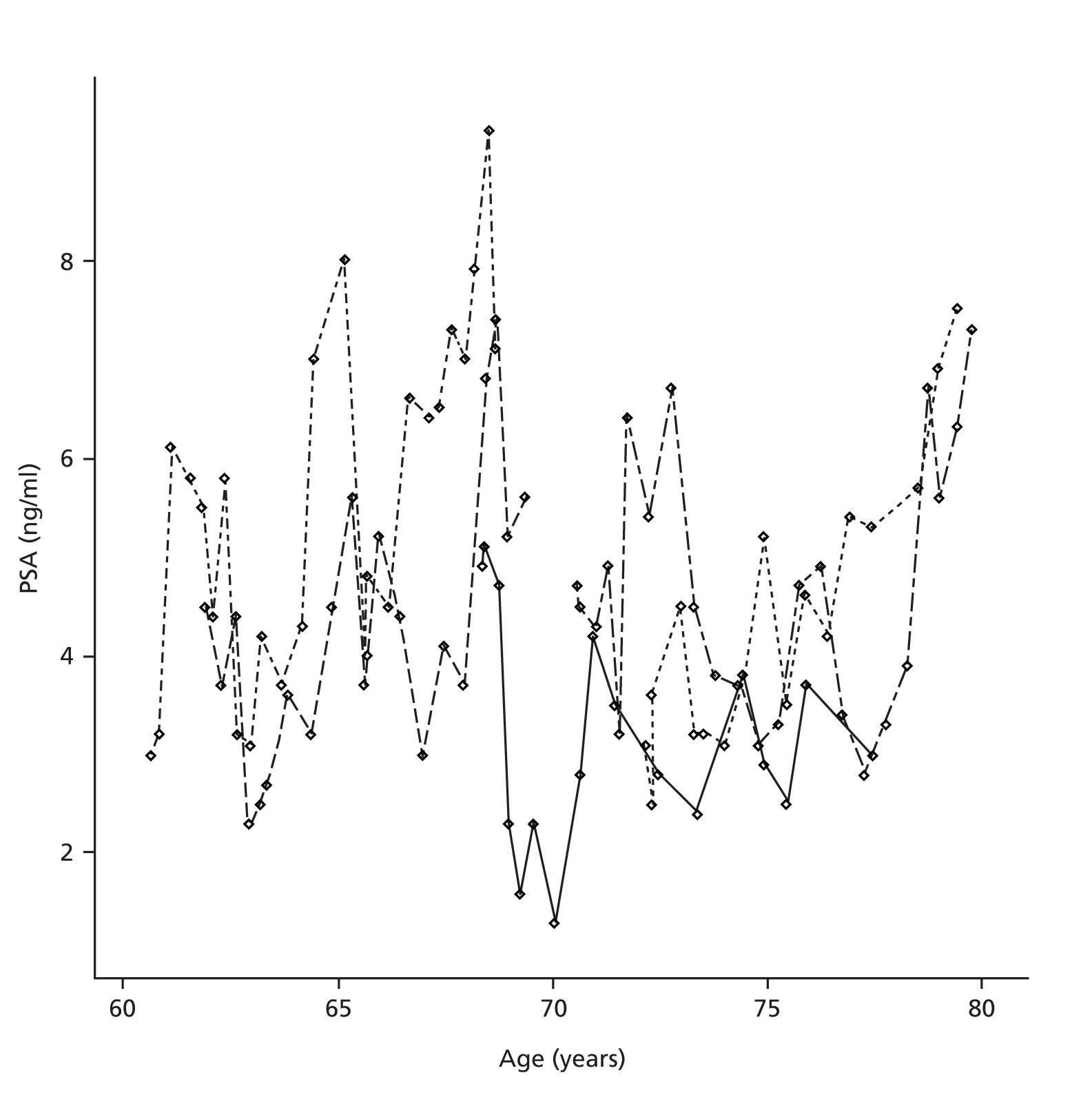

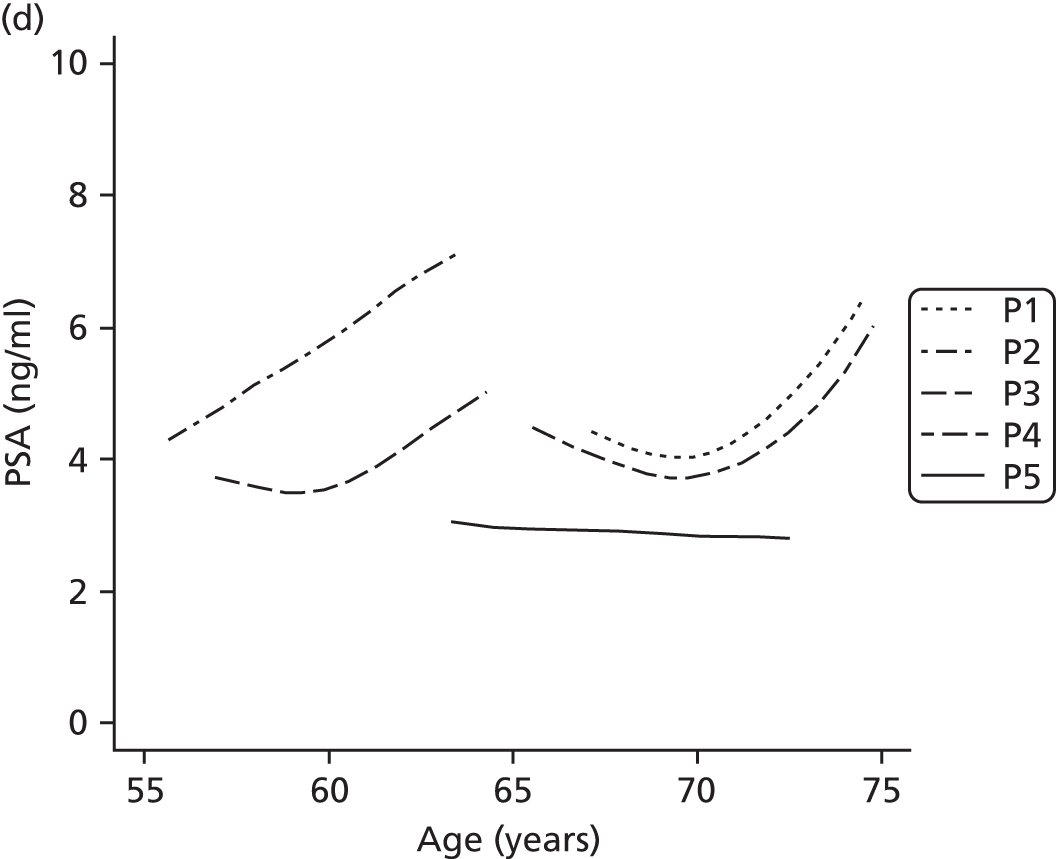

Prostate-specific antigen has a positively skewed distribution and, for this reason, a log transformation of the response is the usual initial step in its analysis. 29,35,95,96 Figure 3 displays simulated PSA trajectories for five men on AM, the high variation in PSA level and steady upwards trend being typical of a real data series from men on ProtecT. These data are simulated, because presentation of post-randomisation results from the trial is restricted until primary analysis in 2015.

FIGURE 3.

Plot of PSA trajectories for five simulated men.

Methods for modelling repeated measures of prostate-specific antigen

Four approaches were used to fit the PSA data from ProtecT, namely linear mixed models (LMMs), fractional polynomial mixed models (FPMMs), regression spline mixed models (RSMMs) and principal components analysis through conditional expectation (PACE). These methods are described in detail in Appendix 4.

Prostate-specific antigen reference ranges

A suitable model for PSARRs must satisfy two criteria. First, it must offer an accurate description of the trend of PSA on average and in individuals. Second, it must be able to make accurate predictions about new PSA observations for an individual and about the entire PSA trajectory for a new individual. Once the model is chosen, 95% of observations will be below:

We are only interested in an upper bound for PSA, given that the method would be used to alert men with high observations of PSA.

Conditional predictions for multilevel models

Using methods developed for LMMs by Pan and Goldstein97 and Tilling et al. ,98 we can enhance predictions for future observations by conditioning on already observed PSA. This allows us to make better use of models when moving to a different population of interest or for new individuals from the same population. To predict a future PSA for an individual, conditional on a previously observed PSA, we regress the deviation from the fixed part of the model at the second measurement on the observed deviation from the model at the previous measurement. Mathematically, to condition the prediction of PSA2 on PSA1:

Results

Linear mixed models, FPMMs and RSMMs were estimated in Stata70 and the PACE method was fitted using MATLAB version 7.14 (R2012a) (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA). 99 The resulting models were used to obtain fitted values of PSA using both unconditional and conditional methods where applicable. Prediction performance was measured using the root-mean-square error (RMSE), whereas model fit was assessed using Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the residual error σε2.

Linear mixed model

A linear mixed model was used to estimate the linear effect on log(PSA) of age, Gleason score and their interaction. The fixed parameter estimates are given in Table 3. Those with a higher Gleason score have an almost 30% increased exponential growth rate per year in their PSA (i.e. from 0.073 to 0.106). Given that the model must follow a log-linear trend, the mean LMM fit is lower to begin with in order to fit the data across later ages where PSA is generally higher.

| Covariate | LMM | FPMM | RSMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSA at age 50 years | 0.628 (0.068) | 1.33 (0.079) | 1.30 (0.075) |

| Age | 0.073 (0.004) | 0.011 (0.008) | 0.023 (0.007) |

| Age3 | – | 6.8 × 10–5 (1 × 10–5) | – |

| a(Age – 12.8)+ | – | – | 0.030 (0.011) |

| a(Age – 17.7)+ | – | – | 0.026 (0.012) |

| Gleason score = 7 | –0.311 (0.168) | –0.140 (0.131) | –0.119 (0.138) |

| Age × Gleason score | 0.033 (0.011) | 0.025 (0.009) | 0.024 (0.009) |

The interpretation of this model is straightforward for use in a clinical setting. Its simplicity also allows for easy transfer to different populations, where more complex models may not fit well as a result of, say, knot placement or polynomial degree being too sample specific. This model could be used to predict PSA trajectory for a newly diagnosed man aged between 50 and 70 years at diagnosis, given his Gleason score. Once an initial PSA is observed, the model can be updated by conditioning on this new observation, thus making a second prediction more accurate.

Fractional polynomial mixed model

The fractional polynomial model of degree 1 (FP1) with the lowest deviance was that with a cubic age term as a covariate, the FP2 selected involved linear age and cubic age. Table 4 shows how the FP2 model was chosen in favour of the FP1 and linear model. We include random coefficients for both polynomial terms to allow for each individual to have their own linear and cubic effect of age on log(PSA).

| Model | Deviance | Power(s) | Step | Comparison | Deviance difference | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FP2 | 1067.27 | 1, 3 | – | – | – | – |

| Null | 4543.64 | – | 1 | FP2 vs. null | 3476.37 | < 0.001 |

| Linear | 1415.82 | 1 | 2 | FP2 vs. linear | 348.55 | < 0.001 |

| FP1 | 1351.46 | 3 | 3 | FP2 vs. FP1 | 284.19 | < 0.001 |

The interaction between the cubic effect of age and Gleason score is omitted because it was not found to improve the model fit. The inclusion of the cubic age term indicates the inadequacy of the linear model for age. It is important to realise that the cubic term-only model was found to be the best FP1, and the addition of the linear term to it (in the FP2 model) was found to improve the fit through a hypothesis test (i.e. Table 4, Step 3). The interaction between age and Gleason score more than trebles the effect of age on log(PSA) for those in the higher Gleason category (from 0.011 to 0.036). If a Gleason score by cubic age interaction were included, the interpretation of this interaction coefficient would not be useful or straightforward.

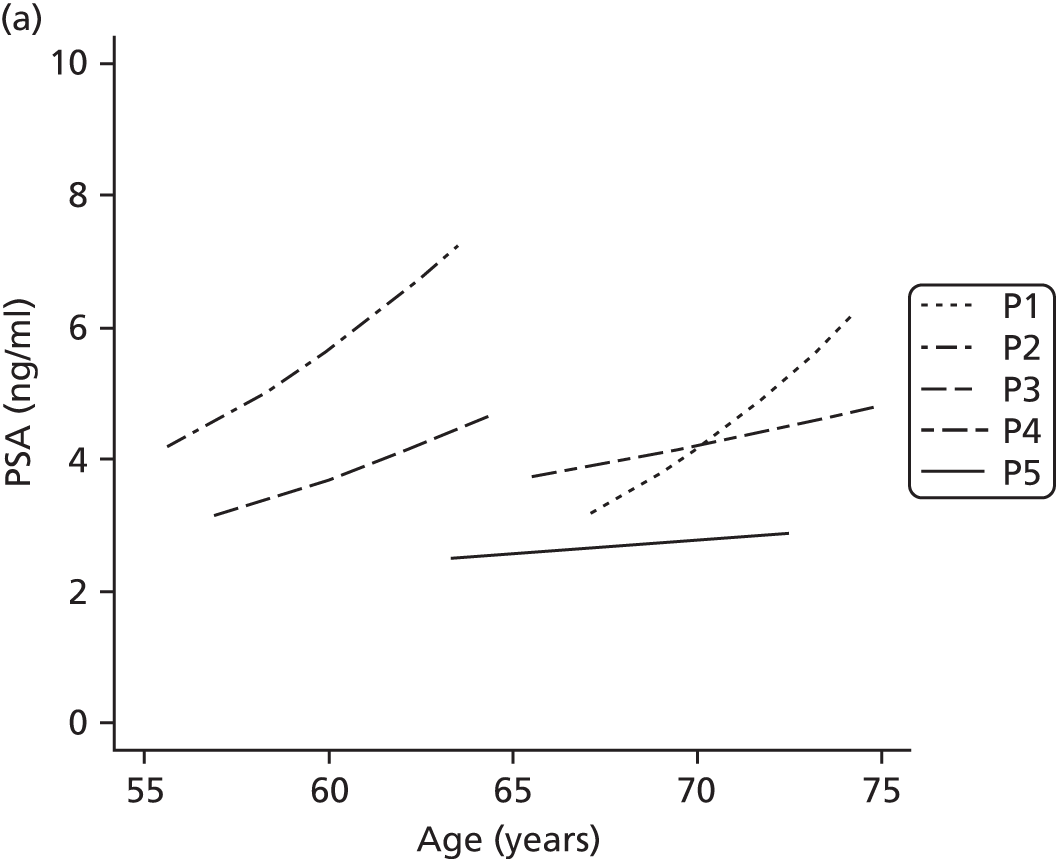

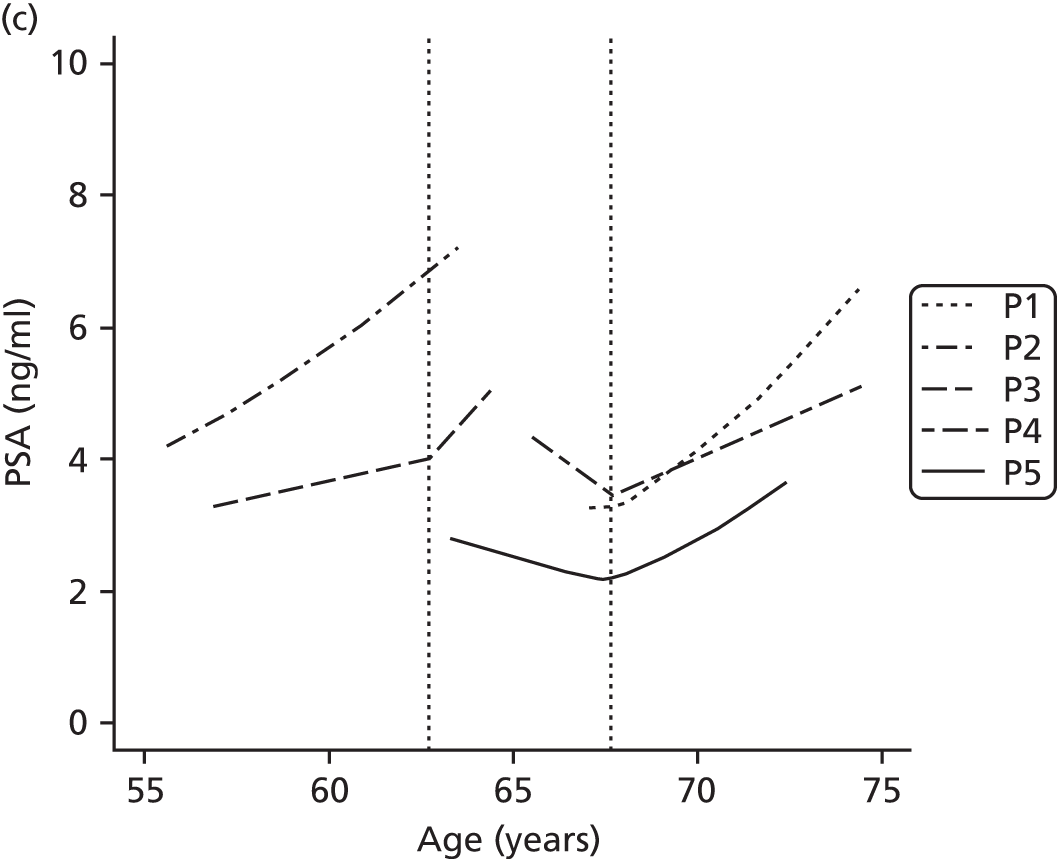

The intercept [estimate of log(PSA) at age 50 years] is much larger here than in the LMM. In Figure 4 we see that the FPMMs allow a more versatile range of fits to the simulated PSA profiles compared with LMMs. The cubic term allows for a steeper gradient in PSA for older people. Overall, there is a positive effect of age on log(PSA), which concurs with the LMM.

FIGURE 4.

Fits to the five simulated PSA profiles. (a) LMM; (b) FPMM; (c) RSMM; and (d) PACE.

Regression spline mixed model

Here, K = 2 knots were selected, based on AIC, to gain modelling flexibility while avoiding potential overfitting of these PSA profiles. Given that no evidence of natural ‘jumps’ of PSA occur at any particular age for all men, these two knots were globally placed at the 33.3 and 66.7 centiles of the distribution of age. All interactions between spline terms and Gleason score were added initially but then removed owing to no model improvement.

Table 3 shows that the linear relationship between age and PSA becomes stronger as a man gets older. Indeed, the strength is doubled at 63 years and trebled at 68 years, compared with the trend for a man aged < 63 years. As can be seen in Figure 4, the fits are allowed to break from a linear trend to capture some features missed by the LMM.

Functional principal components analysis

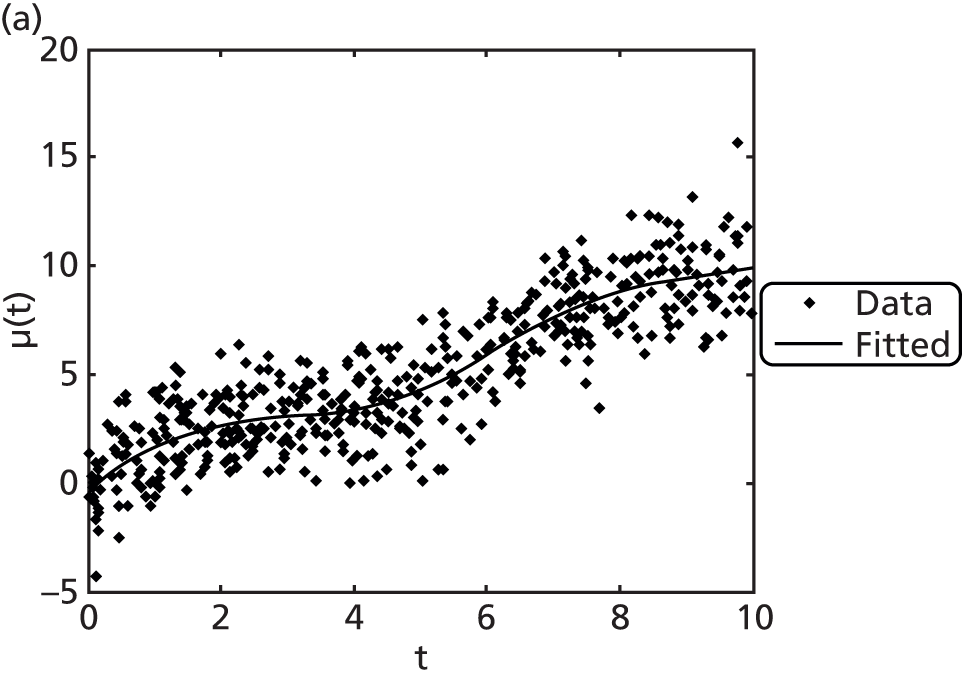

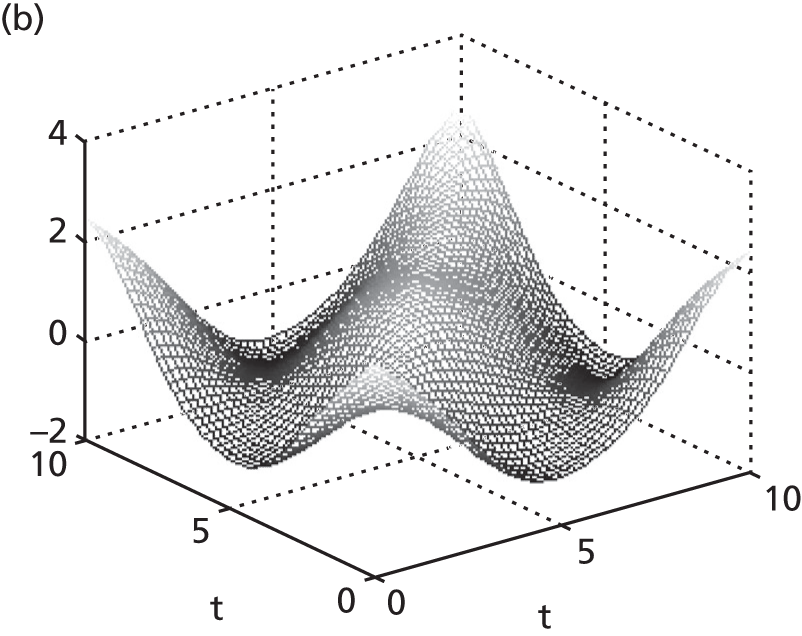

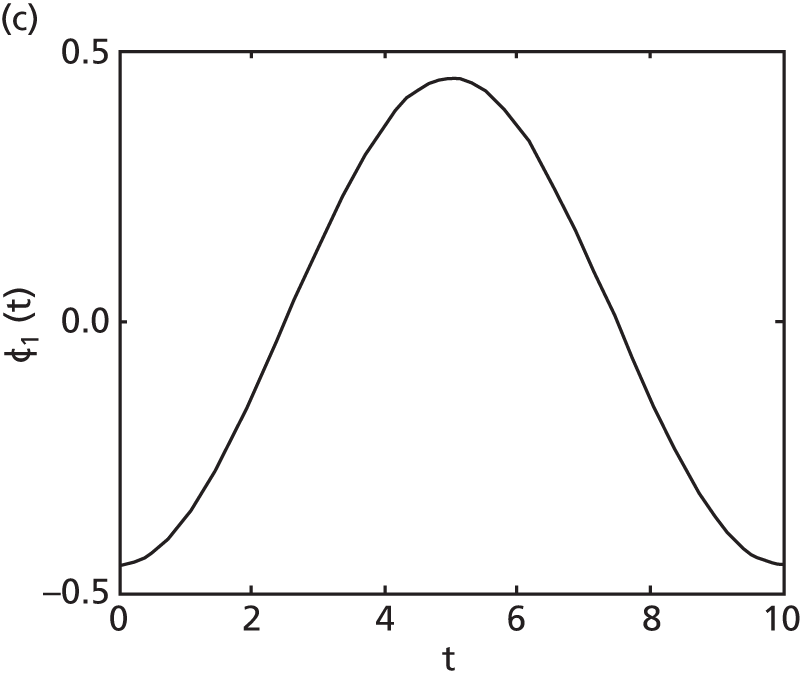

The first two principal components of the PSA data accounted for 92% of the variation in PSA. In Figure 4 the serial PSAs for each man are fitted with smooth curves, which are deviations from the overall mean function μ(t) displayed in Figure 5. These individual curves are not restricted by a parametric shape. The mean curve μ(t) suggests a much less extreme trend than each of the other approaches. PSA is estimated to rise slowly up to the age of 70 years, at which point a sudden change of slope occurs with PSA rising at a faster rate. This fit appears similar to a linear regression spline fit with one knot at 70. The underlying model gives this fit far more flexibility, and, of all methods, it estimates the slowest trend for PSA.

FIGURE 5.

Mean PSA over age (solid line) with fits using LMM (dashed), FPMM (dotted), RSMM (dash dotted) and PACE (long dashed).

Choosing a model for prostate-specific antigen reference ranges

Describing the mean pattern of prostate-specific antigen change

Tables 5 and 6 summarise the difference in fitted and observed PSA and the RMSE, respectively, across age categories. In each age category, PACE is superior for describing these data. Apart from in the right tail (at ages > 71 years), the difference between the observed PSA and that fitted by the model is smaller for PACE than for the other methods. If the sole interest here was in representing PSA trend for this group of men on AM, then PACE would be the best choice. Among the other methods, from ages 50–60 years, the LMM performs quite badly. As can be seen in Table 5, the fitted PSA values are obviously not high enough on average. Over half of the total observations of PSA were taken from men aged 61–70 years, and this range sees comparable performance of the parametric methods. Figure 5 serves to illustrate the benefit of using RSMM instead of FPMM in this example. Up to the age of roughly 70 years, both have a similar mean estimate. The FPMM then continues on this path because it uses a global polynomial basis for model fitting, which leads to severe overestimation of mean PSA in the right tail of age. However, the regression spline fit has the flexibility to change at the second knot (i.e. at age 68 years) and this change then becomes apparent with a flatter fit of the regression spline in the right tail. Outlying PSA measurements in older age affect only the spline-based estimate of the age effect in that region, whereas with FPMM they have a global effect on the estimate.

| Age category (years) | Number of observations | Mean LMM fitted: observed PSA (SD) | Mean FPMM fitted: observed PSA (SD) | Mean RSMM fitted: observed PSA (SD) | Mean PACE fitted: observed PSA (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–55 | 485 | –2.9 (2.9) | –1.5 (2.9) | –1.4 (2.9) | 0.66 (2.5) |

| 56–60 | 1222 | –2.3 (3.9) | –1.5 (3.9) | –1.3 (3.9) | 0.18 (3.6) |

| 61–65 | 2422 | –1.1 (3.9) | –0.88 (3.9) | –0.88 (3.9) | 0.08 (3.7) |

| 66–70 | 2320 | 0.86 (4.2) | 0.80 (4.2) | 0.52 (4.2) | –0.09 (3.8) |

| 71+ | 989 | 2.0 (5.9) | 3.4 (6.3) | 1.6 (5.9) | –0.52 (4.2) |

| All | 7438 | –0.39 (4.5) | 0.80 (4.5) | –0.24 (4.4) | 0.0005 (3.7) |

| Age category (years) | Number of observations | LMM RMSE (SD) | FPMM RMSE (SD) | RSMM RMSE (SD) | PACE RMSE (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–55 | 485 | 2.98 (2.9) | 2.08 (2.3) | 2.11 (2.4) | 1.75 (1.9) |

| 56–60 | 1222 | 2.72 (3.6) | 2.39 (3.3) | 2.39 (3.3) | 2.24 (2.8) |

| 61–65 | 2422 | 2.63 (3.0) | 2.63 (2.9) | 2.63 (2.9) | 2.30 (2.9) |

| 66–70 | 2320 | 3.08 (3.0) | 3.02 (3.0) | 2.93 (3.1) | 2.25 (3.1) |

| 71+ | 989 | 4.85 (3.9) | 5.53 (4.1) | 4.66 (3.95) | 2.48 (3.4) |

| All | 7438 | 3.11 (3.3) | 3.06 (3.3) | 2.92 (3.3) | 2.26 (3.0) |

From Table 7, the FPMM and RSMM have lower AIC compared with the LMM, but only marginally more variation is explained by the two more complex models. The RMSE is lowest using PACE followed by the RSMM approach, which corroborates the results from Table 6. Based on these diagnostic elements, the RSMM is the best fitting of the three parametric models for PSA in men on AM.

| Model performance measure | LMM | FPMM | RSMM |

|---|---|---|---|

| AIC | 1412 | 1084 | 994 |

| σε2 | 0.045 | 0.043 | 0.042 |

| RMSE of conditional prediction (ng/ml) | 2.15 | 2.19 | 2.10 |

Table 3 compares the estimates of the associations between Gleason score and PSA trajectory from the three parametric models. There are some similarities in the effect of Gleason score and its interaction with age; however, the intercept is much lower in the LMM than in either of the other two methods (which have very similar estimates). In the LMM, with a constant trend over time, the intercept must be low to allow for the model to fit the higher PSA values in the right tail of age. We can see in Table 5 that this leads to an underestimate of PSA when age is between 50 and 60 years. For the same reason (i.e. to allow those with higher Gleason score to have higher PSA in later age) the LMM underestimates the association between Gleason score and PSA at age 50 years and overestimates the association between Gleason score and PSA slope, compared with the FPMM and RSMM. The RSMM or FPMM methods are preferred here for estimating the effect of Gleason score on PSA change over time.

Predicting prostate-specific antigen for a future patient

Here a parametric model is preferred, given that, by using methods that condition on new observations of the response,98,100 we can allow the parametric models to become individualised to newly diagnosed men on monitoring. Without a ‘factor loading’ ξi1, a new individual i would simply be predicted to lie on the mean PACE trajectory given his age.

Table 7 presents the RMSE of fitted PSA for each of the 512 men conditioned on their initial PSA. Here we can see that the conditioning improves on the parametric methods such that they are better at fitting these data than PACE. Between the three approaches, the RSMM is still preferred. Surprisingly, the LMM performs slightly better than the FPMM when fitted values are conditioned on the first observation of PSA.

Regression splines offer the optimum performance among parametric methods overall (with the lowest AIC and RMSE for both unconditional and conditional predictions) and also perform well in all segments of age, as shown in Table 5 and Table 6. Thus, using regression splines for prediction of PSA in men in the future seems appropriate. This reflects the changing trajectory of PSA over age, given that the RSMM allows for three separate effects of age on PSA.

Summary

This chapter has compared three parametric multilevel models (LMM, FPMM, RSMM) and a non-parametric smoothing method in order to choose a model for longitudinal PSARRs. Using PACE gave the best descriptive fit to the data initially, but, using methods that condition on initial PSA, the parametric methods displayed lower RMSE. As a predictive model, the linear RSMM, with two knots placed at the 33.3 and 66.7 centiles of age, offers the best model for PSA in this population.

Chapter 4 Testing the accuracy of the prostate-specific antigen model in four separate cohorts

Aims and background

Here, we test whether or not the model for PSA presented in Chapter 3 is suitable for general application, by using it to predict circulating PSA levels in four external cohorts of men on AM/AS. We summarise the predictions for each cohort comparing the ProtecT model with a model based on all the data from each cohort in turn. If the ProtecT model is found to describe age-related PSA changes in other cohorts, then each PSA measured for a man in any clinic can be compared with the value expected with age-related change.

Methods

Study populations

The RMH AS cohort is an ongoing study into the impact of initial conservative management of clinically localised PCa. 101 Data from 499 men, comprising 9472 PSA tests along with Gleason score and several other clinical covariates, were available. PSA test results were obtained between 1999 and 2012. The study eligibility criteria were baseline PSA < 15 ng/ml, Gleason score of ≤ 3 + 4 and percentage of positive biopsy cores ≤ 50%. In most men, diagnosis was based on a raised PSA and subsequent positive biopsy, so they represent a modern AS cohort. Men on AS were followed up with PSA tests every 3–4 months in the first 2 years and every 6 months thereafter. Biochemical progression was defined as PSA velocity > 1 ng/ml/year, whereas histological progression on rebiopsy was defined as having a Gleason score of 4 + 3 or > 50% positive biopsy cores. Clinical outcomes of metastases and PCSM were collected.

The Johns Hopkins (JH) AS programme began recruitment of men with clinically localised PCa in 1995. 82 Men were eligible if they had a Gleason score of ≤ 3 + 3, T1c, PSAD < 0.15 ng/ml/cm3, two or fewer positive biopsy cores and maximum involvement of 50% per core. Data from 961 men, comprising 9993 PSA test results performed between 1993 and 2012, along with diagnostic Gleason score and several other clinical covariates, were available. Radical treatment was recommended once men no longer met the eligibility criteria described above. Clinical outcomes of all-cause mortality and PCSM were included in the data.

The SPCG4 data contained 290 men with 2987 PSA tests. 12 These men were randomised to WW as part of the SPCG4 RCT comparing WW and radical prostatectomy. They were diagnosed between 1989 and 1999, for the most part through clinical presentation with symptoms. To be suitable for randomisation the men were required to be < 75 years of age, with a life expectancy of > 10 years. Data were available on whether or not the men developed metastases and/or died from PCa.

Data received from the University of Connecticut Health Center (UCHC) cohort consist of 114 men with 884 PSA test results102 followed for an average of 4.7 years (SD 3.9 years). Men were diagnosed between 1989 and 1993 (before the advent of widespread PSA testing), for the most part by clinical presentation with symptoms. Fewer baseline clinical exposures were available than from other cohorts, and information was not present on whether or not men developed metastases or died from PCa.

These four cohorts come from two eras, the PSA detection era (RMH and JH) and the clinical detection era (UCHC and SPCG4). As described above, the advent of PSA screening resulted in many more men being diagnosed with PCa at an earlier stage than before. The modern cohorts also come from populations with different screening prevalence. In the USA there is widespread PSA screening, whereby men are likely to have several PSA tests through their lifetime. Thus, men diagnosed with PCa in the USA are likely to have had mostly ‘normal’ PSA results before the raised value, which resulted in a biopsy and subsequent diagnosis. In the UK there is no such screening programme, and the men diagnosed with PCa in RMH may have had any level of PSA before the single high PSA that led to their diagnosis. Hence, the US men are likely to be a lower-risk group with lower PSA on average than their UK counterparts. These issues, and their impact on the poorly understood natural history of PCa, need to be considered when interpreting findings from the cohorts.

The coefficients found in the ProtecT trial model were applied to data from the RMH and JH AS cohorts as well as the UCHC and SPCG4 WW cohorts. However, all data were restricted to PSA test results ≤ 50 ng/ml and to men with an initial PSA ≤ 20 ng/ml. This is to eliminate any atypical values, in terms of a modern AM/AS study. Two cohorts of men without PCa were also included to examine differences in PSA change between men with and without cancer. Data from the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA)103 contained repeated 5012 PSA measurements of 1032 men. A model for PSA change in 1432 men without cancer from the Krimpen study,104 a large prospective community-based study in the Netherlands, has appeared elsewhere. 35

Measuring performance

First, to investigate the behaviour of PSA between cohorts, we fit a simple random intercept and slope multilevel model to log(PSA) in each of these four cohorts:

where u0i is the random intercept, which allows each man to have their own adjustment to the intercept β0 [i.e. the average value of log(PSA) at age 50 years] and u1i is the random slope, which allows each man to have their own adjustment to the slope β1 (i.e. the average change in log(PSA) per year increase in age). This is carried out to compare the age-related change in PSA for men with and without PCa.

The coefficients for our model of PSA change have been previously estimated using a cohort of 512 men with clinically localised PCa participating in the ProtecT study. 93 In the present analysis, the model is used to predict PSA in each of four external cohorts. We measure the accuracy of the predictions using the average difference between observed and predicted PSA value per PSA test:

where PSAij is the observed PSA test result for person i = 1, . . . , n measured at time j = 1, . . . , ni and PSAiJ^ is the predicted PSA test result for person i at time j. The number of PSA tests can be different from person to person, and the total number of PSA tests in the cohort is N. The average absolute difference between observed and predicted PSA will always be positive, with a value of zero if the model predicted PSA perfectly.

For each of the four cohorts, predictions are made using (a) a model with coefficients derived from the external data themselves; (b) the ProtecT model coefficients; and (c) the ProtecT model updated using the first three PSA values for each man in the external cohort. 97,98 Prediction (a) gives the hypothetical upper limit of performance but is not clinically useful, because the model coefficients cannot be estimated until all the PSA measurements have been taken over the duration of AM. Predictions (b) and (c) indicate what could be achieved in clinical practice, as they apply coefficients estimated using the ProtecT cohort to the other data sets, and so can be applied each time a new measure becomes available for a man on monitoring.

To calculate the coverage of the model in predicting PSA, we check whether or not a 95% prediction interval (calculated using unconditional standard errors) from the ProtecT model contains the corresponding observed value of PSA. We measure performance of the models further by tabulating the model failures, which we define as absolute difference between predicted and observed PSA > 5 ng/ml and model successes, defined as predicted PSA within 2 ng/ml of observed PSA. These are tabulated to obtain the proportion of test level failures/successes (i.e. for how many PSA test results does the model fail/succeed) and subject level failures/successes (i.e. for how many men does the model fail/succeed on average across all their PSA test results). These cut-offs were chosen to reflect what we believe to be clinically significant ranges.

Results

Age-related prostate-specific antigen change

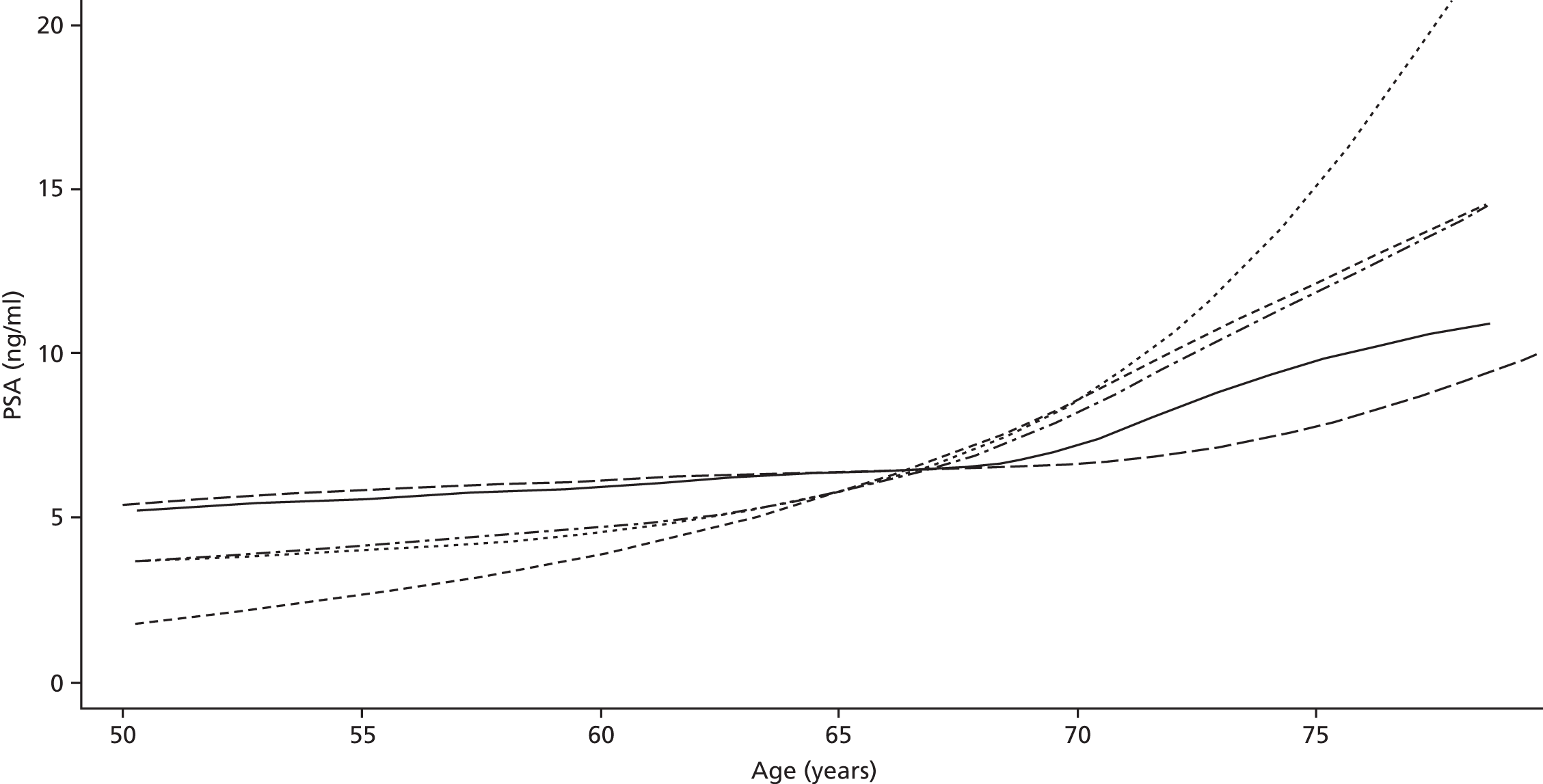

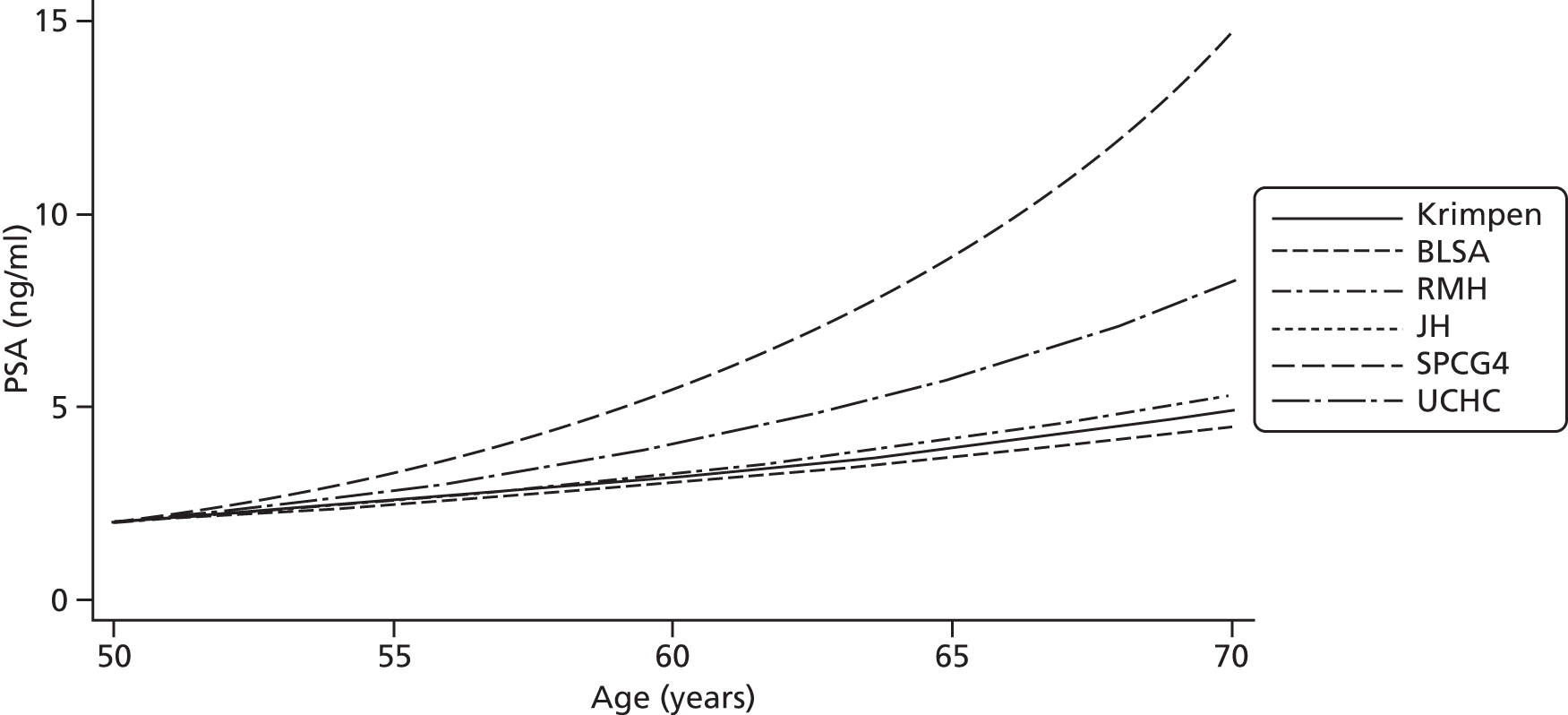

Men on AM/AS and men without PCa have similar age-related PSA change (Table 8). For example, the PSA change per year is very similar in the Krimpen, BLSA, RMH and JH cohorts. Figure 6 shows the predicted average pattern of change if each cohort had an average PSA of 2 ng/ml at age 50 years. This hypothetical graph shows the similarities of the four modern cohorts involving men with or without PCa. However, the results from the multilevel models suggest that men without cancer have much lower average PSA values at age 50 years. In Figure 7 we see that the estimated average PSA at age 50 years is much lower in the Krimpen and BLSA cohorts.

| Variable | Men with no PCa | Men with PCa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krimpen | BLSA | RMH | JH | SPCG4 | UCHC | |

| Average PSA at age 50 years | 0.72 | 0.65 | 2.48 | 2.07 | 1.38 | 1.23 |

| Percentage change in PSA per year in age (%) | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 11 | 7 |

FIGURE 6.

Hypothetical PSA change in the cohorts if average PSA at 50 years was 2 ng/ml in each.

FIGURE 7.

Estimated PSA change in the cohorts.

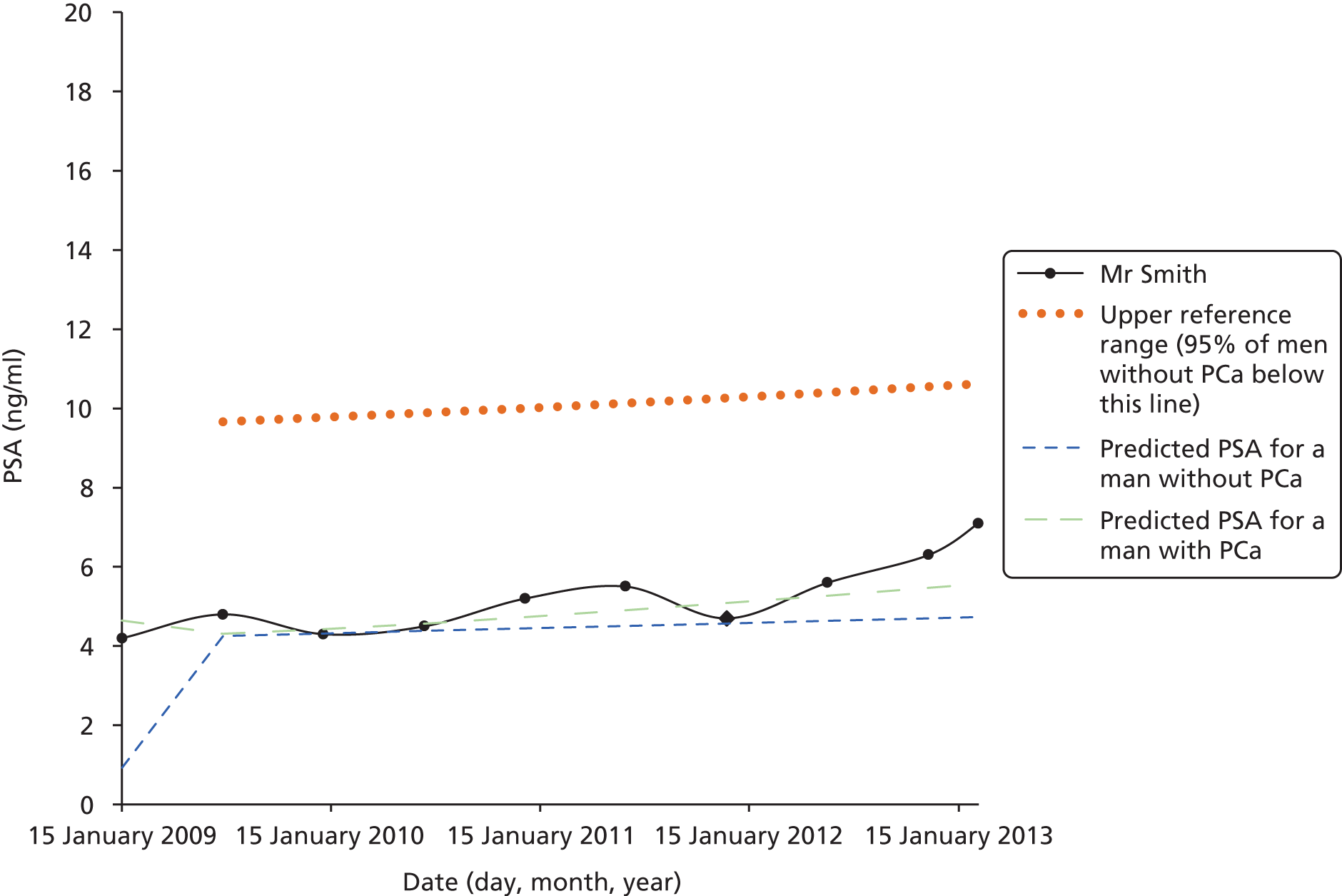

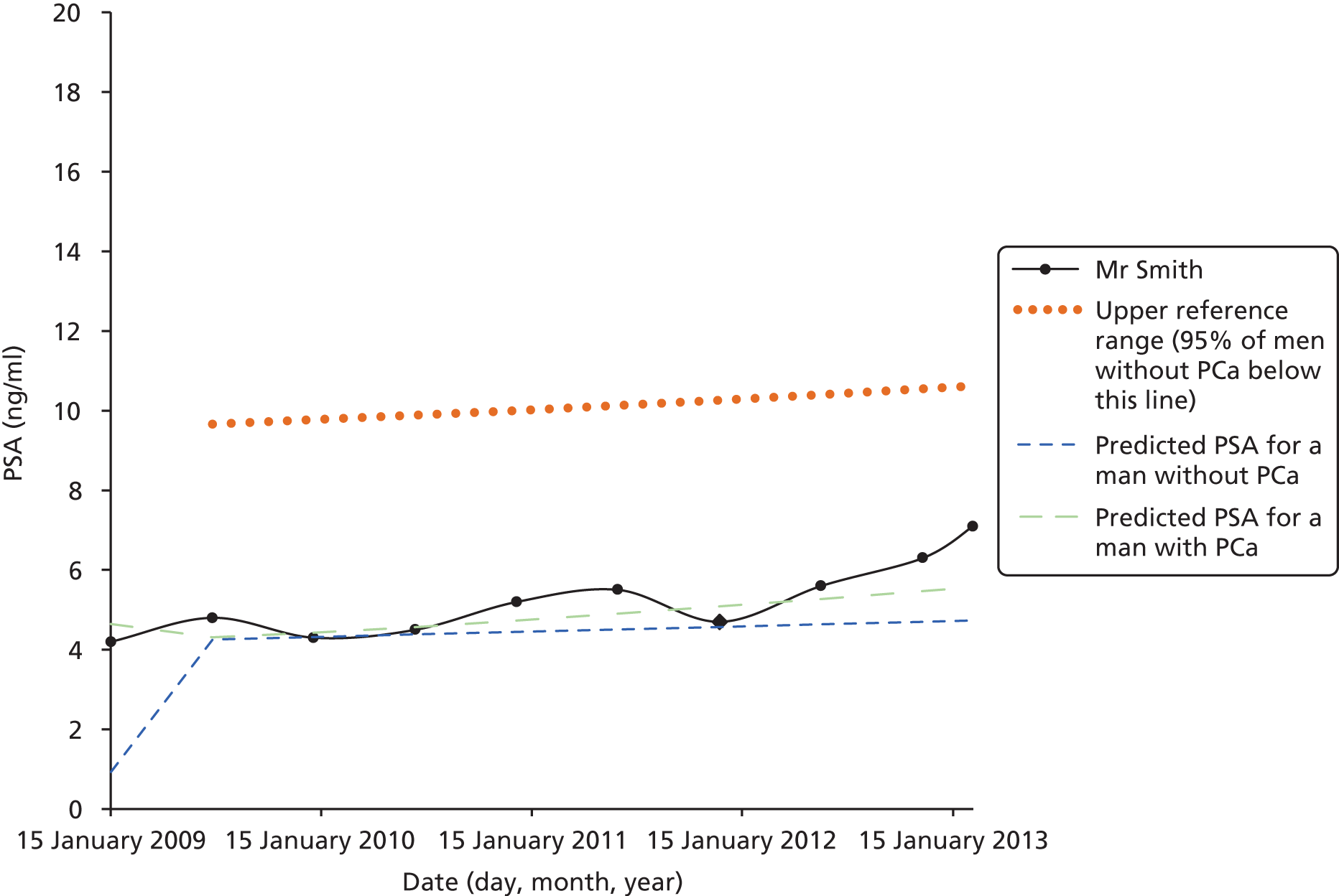

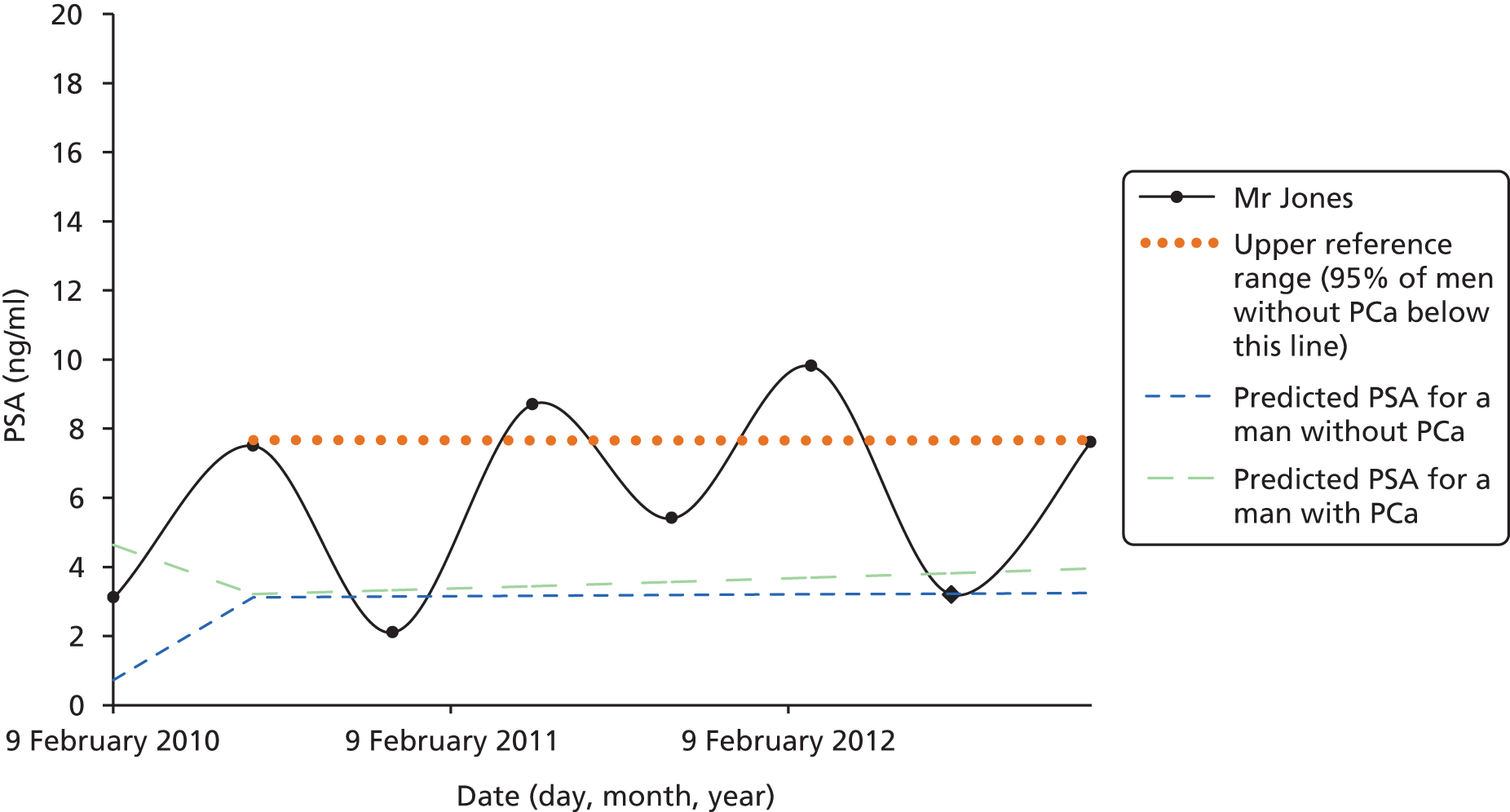

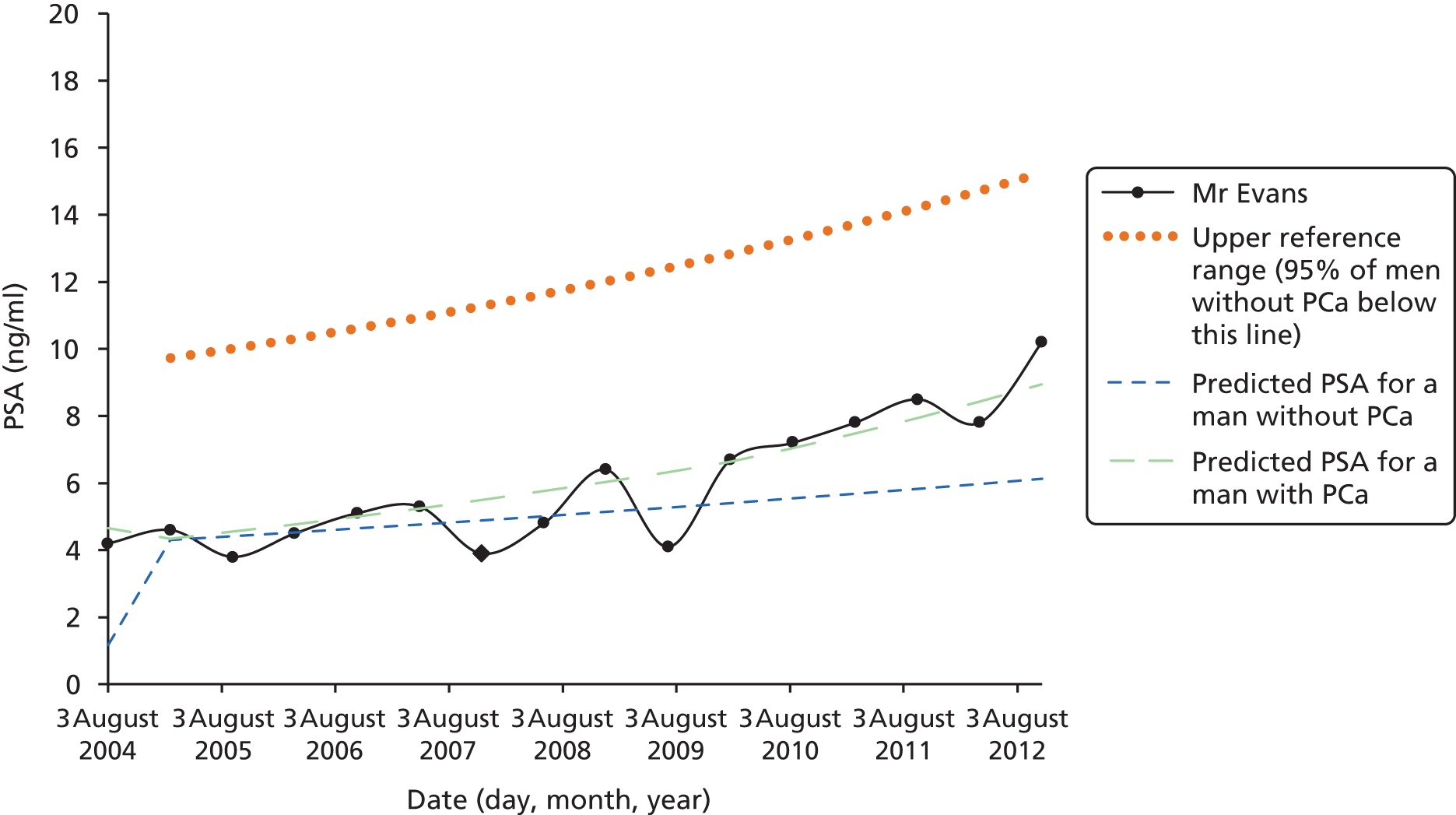

Screen-detected cohorts