Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/2002/23. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in August 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Pollock et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

This report presents findings of a 2-year study (the Care and Communication study) funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme. 1 The study investigates how seriously ill patients, their relatives and the health professionals caring for them understand and experience discussions about end of life care (EOLC) involving advance care planning (ACP) (Box 1).

. . . a voluntary process of discussion and review to help an individual who has capacity to anticipate how their condition may affect them in the future and, if they wish, set on record: choices about their care and treatment and/or an advance decision to refuse a treatment in specific circumstances, so that these can be referred to by those responsible for their care or treatment (whether professional staff or family carers) in the event that they lose capacity to decide once their illness progresses.

National End of Life Care Programme. Capacity, Care Planning and Advance Care Planning: A Guide for Health and Social Care Staff. Leicester: National End of Life Care Programme; 2011. 2 p. 6. Reproduced under Open Government licence. Crown Copyright 2011.

Advance care planning is a key component of current UK health policy to improve the experience of death and dying by enabling patients and their significant others to consider their options and preferences for future care. 3 It is considered important that patients have the opportunity to do this while they retain capacity to make and communicate decisions. ACP aims to enable family and professional carers to take account of, and where possible to implement, patients’ expressed wishes for care and treatment. ACP is considered an important means of protecting personal dignity and extending personal autonomy through the end of life. Evidence of the nature, frequency and outcomes of ACP discussions remains limited and frequently conflicting. 4 However, it is apparent that ACP remains uncommon in most areas of professional practice and that both professionals and patients tend to avoid discussions they find difficult. 5–14 Patient and family responses to ACP and its effect on EOLC outcomes remain poorly understood. This study contributes to the currently limited evidence relating to the nature and impact of ACP as well as a critical appraisal of its contribution within current EOLC policy. It employed qualitative methods to conduct an in depth investigation into how ACP is initiated and implemented in community health-care settings. It is based on two workstreams: a series of interviews with health professionals and a series of longitudinal patient case studies involving patients, family carers and nominated health professionals followed up over a period of approximately 6 months.

The rest of this chapter provides the background to the study, and considers the policy context in which it is set and the evidence available from earlier studies. Chapter 2 outlines the design and methods of the study before three findings chapters, which present demographic findings, the findings from the professional perspectives interviews and the findings from the patient case studies. Chapter 6 gives a discussion and critical appraisal of the findings in relation to the current literature, provides a summary of the study findings and their significance, and considers their implications for further research. Care of the dying is one of the most significant services to be provided within the NHS: it touches every person in the land and is a signal marker of the quality of national health care. EOLC has become a particular concern within modern industrial societies characterised by a changing demographic in which most deaths occur in great old age, after an extended period of increasing frailty and decline. These trends will continue, and even accelerate, far into the future. 15–17 They bring challenges to people’s experience and expectations of living as well as dying, and impose unprecedented social and economic demands in the organisation and resourcing of health and social care. 18,19 The difficulty of responding to these demands, and deep concern about the quality of care for dying patients, have been graphically documented in recent reports of gross shortcomings in institutional care for older people, including dying patients. 20 Care and treatment at the end of life are recognised to have often been inadequate and crisis driven. 15,21–23 In addition, there are ongoing concerns about the continuation of invasive and futile treatment for dying patients and the lack of recognition among professionals, as well as families, that patients are dying. 24,25 Although the Liverpool Care Pathway (LCP) for EOLC was introduced to implement a palliative approach towards the care of dying patients in hospital and community care settings,26 its widespread misapplication, and frequent reduction to a tick-box exercise rather than a holistic programme of care, has resulted in its withdrawal from service. Difficulties of communication between clinicians and patients and their families were identified as being a major contribution to the pathway’s demise. 27 In response, a coalition of 21 organisations, known as the Leadership Alliance for the Care of Dying People, has published a review prioritising the provision of compassionate care and emphasising the importance of early discussion and planning for death substantially in advance of the point at which an individual is recognised to have reached the end of life. 28

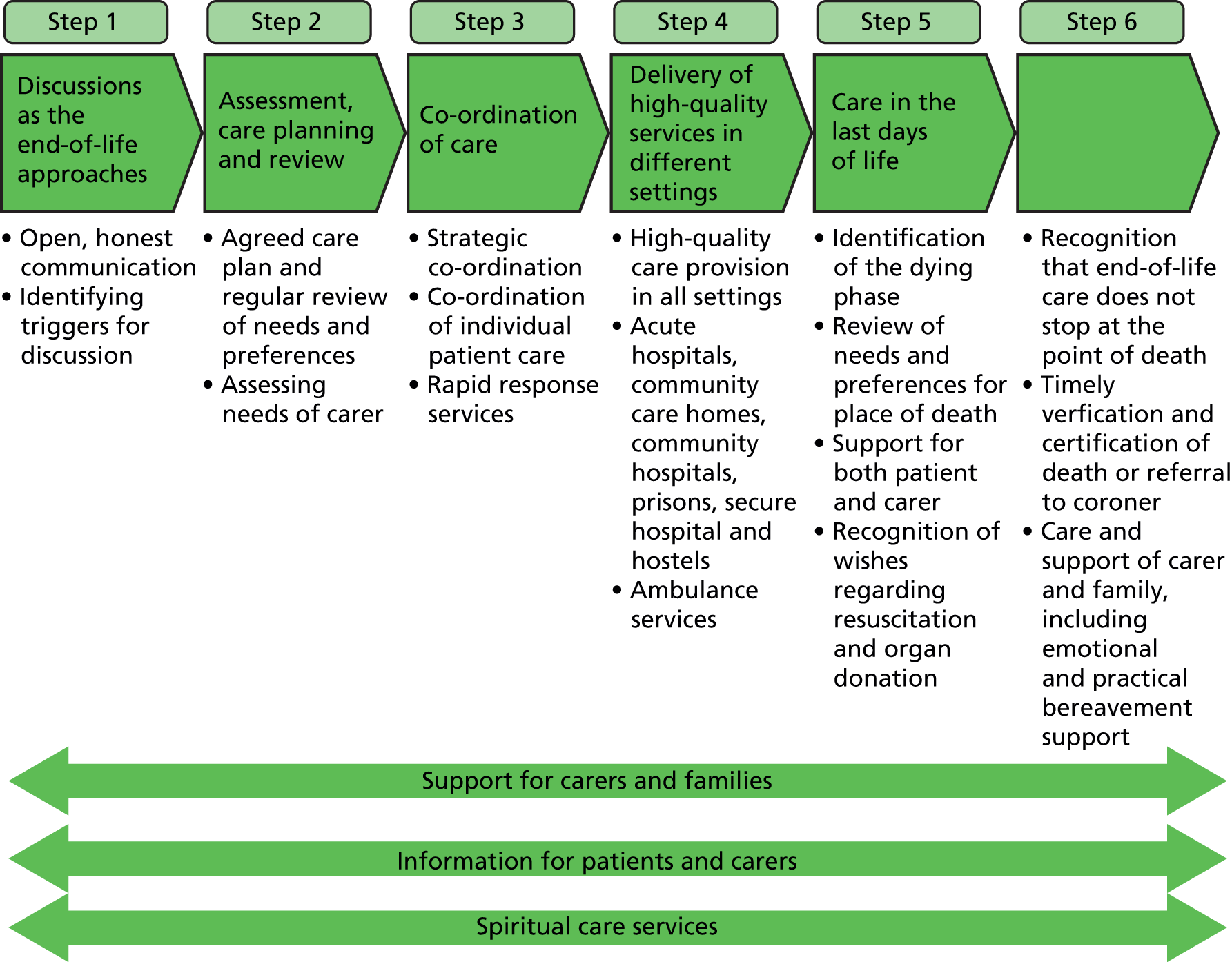

Concerns about the quality and equity of EOLC have arisen in the context of a well-established and progressive national End of Life Care Strategy (EOLCS), initially implemented in 2008 and subsequently supported by the National End of Life Care Programme (NEoLCP). 21,29 The EOLCS promoted the use of a six-stage EOLC pathway, beginning with, and hinging on, successful identification of patients who were in their last year of life. It also sought to promote patient involvement in decision-making about future care, and in particular, the fulfilment of patient choice of place of death, assumed in most cases to be home. 15,30,31 The NEoLCP incorporated a commitment to develop services to enable dying patients to be supported in the community. Reduction in unscheduled hospital admissions and their associated costs, and an increase in the proportion of patients dying at home have become key performance indicators within the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention workstream of the NEoLCP. Between 2008 and 2012 the number of home deaths (defined as usual place of residence, including care homes) had increased from 38% to 42%, with hospital deaths reducing to 51%. 29 The Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention workstream has concentrated on the early part of the six-stage pathway: identifying people who are in their last year of life as a prerequisite for planning and co-ordinating care. ACP is one of the key initiatives involved in this programme of work.

Advance care planning

The current definition of ACP as a process of expressing and documenting preferences for future care to support autonomy refers to recent UK legislation regarding how decisions should be made in circumstances where individuals lose mental capacity. 32 However, the end of life care pathway (EOLCPW) and the very considerable body of resources and materials that have been developed to support it are oriented more broadly to ACP as a means of helping patients prepare for death and professionals to foresee, and make practical arrangements to meet, patient preferences for future care. Skilled communication, in broaching the topic of ACP and helping patients to explore their preferences and options, is essential to an ACP discussion. 21

Talking about death and dying: developing a public conversation

Discussion about ACP is the first step in implementing the pathway set out in the EOLCS, within which greater public openness and willingness to communicate about death and dying is seen as key to improving EOLC. However, public reluctance to talk about death and dying is widely assumed, and death is frequently regarded as a cultural taboo. 21,33 Consequently, the EOLCS set out a plan for an ‘information revolution’ to overcome this resistance, among professionals as well as patients and the public. This aimed to raise awareness and normalise the topic of death and dying as part of a process of encouraging people to consider and express their preferences for end of life well in advance of its occurrence. This campaign has been spearheaded by the Dying Matters Coalition, set up in 2009 and led by the National Council for Palliative Care. 34 There is expected to be a synergistic relationship between increased public awareness of death and dying and increased personal receptivity to the offer of an ACP discussion. Initiatives have also been directed towards health professionals, including a ‘Find your 1%’ campaign. This is led by the NEoLCP and aims to encourage general practitioners (GPs) to identify the expected 1% of patients within their practice lists who are in their last year of life, with a view to initiating a process of ACP and interdisciplinary planning and co-ordination of future care. 35

The origins and development of advance care planning

Advance care planning has developed within a movement to generalise the benefits of palliative care from hospice to wider hospital and community care settings. 36 It thus reflects the core components of a particular professional ideology and commitment to the nature and achievement for all patients of a particular construct of ‘the good death’. 37–40 This involves the excellent control of symptoms within a holistic approach to care, which acknowledges death as a natural, rather than a pathological, process. It incorporates a commitment to open awareness and communication about dying between all participants: patient, family and professionals. The good death occurs in a comfortable, non-medicalised environment: home is usually the preferred place, where dying can most easily be accompanied by the patient’s significant others. Open awareness of dying enables patients to engage actively with decisions about treatment, or their refusal, to foresee and plan for how they wish EOLC to be provided, to put their affairs in order and possibly also to realise personal goals and plans for living while these remain options available to them. Open awareness and communication about dying and patient involvement in planning for a future, however limited, satisfy a deeply held cultural commitment to preserving the dignity and autonomy of patients throughout their experience of greatest vulnerability and even to the end of life.

The protection of personal autonomy and patient determination of her or his own best interest was given a legal underpinning by the implementation of the Mental Capacity Act in 2005. 32,41 This set out the patient’s right to refuse particular forms of treatment, even when the outcome was life-threatening. It also supported the principle of precedent autonomy, whereby the expressed wishes of a competent individual were held applicable in the event that she or he subsequently lost capacity to make decisions, or the ability to communicate these, at some point in the future. Extending these principles to patients who are dying is a natural extension of the principled commitment to individual choice and self-determination.

Advance care planning does not need to be a formal process requiring documentation. It is recognised that some patients may be willing to discuss their preferences for future care, but may not be willing, or may not feel it necessary, to write these down. However, if patients’ wishes are not recorded and shared among the family members, health professionals and services involved in providing care, it is less likely that plans can be known and implemented, or that changes to previous plans may be acted on. Advance care plans carry no legal force [unless they involve the writing of a valid and applicable advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT)], but should be taken into consideration by clinicians managing patient care in the process of determining best interests when the patient no longer has the ability to contribute to the discussion. Patients may record anything they like about their preferences for future care, and the environment and circumstances they would like to be in place during dying.

Advance decisions to refuse treatment and lasting power of attorney

Patients cannot command specific treatments or interventions, but they can refuse them. In the event that such refusal would have life-threatening consequences, it is necessary for a legally binding ADRT to be drawn up. In this case, if it is determined to be valid and applicable to the patient’s circumstances, clinicians must comply with the terms specified. In addition, patients may appoint persons to have a lasting power of attorney to make decisions on their behalf, in relation to property and financial affairs and/or health and well-being, in the event that they should lose capacity at some point in the future. Drawing up legally enforceable documents involves a level of bureaucratic complexity and, in the case of lasting power of attorney, a financial cost that act as a strong deterrent for many people. In practice, ADRTs have not been widely adopted or implemented. Even when clinicians have access to valid documents at the appropriate time, their content may be hard to interpret, or may fail to apply to the context in hand. 42–47 It is difficult for patients to foresee precisely what may happen, and yet accurate prediction and very precise specification are essential to the successful application of an ADRT. 48–50 In practice, and in consequence of these difficulties of application, ADRTs have been widely disregarded. The recent trend has been to shift the focus of anticipatory planning towards more informal processes of discussion and reflection about goals of care. 3,43,51–53

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

A key decision in relation to patients who are extremely ill or frail relates to cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and how this is communicated to patients and their families. CPR is an emergency procedure to restart the heart and/or breathing following a cardiac or respiratory arrest. In the absence of an order not to attempt resuscitation (do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation, DNACPR), it is a clinical decision whether or not to do so based on individual assessment of each patient’s case. 54 If there is doubt, the presumption must be towards preservation of life. Practice in relation to DNACPR decisions was re-emphasised in a court ruling after completion of data collection for this study. Unless such discussion is believed to cause the patient extreme psychological distress and harm, clinicians have an obligation to make sure decisions about resuscitation are clearly communicated to the patient (provided she or he has capacity) and her or his family and, ideally, their agreement obtained. 55 The decision that resuscitation should not be attempted on the grounds of futility remains a clinical responsibility and hence where the ‘expected benefit of attempting CRP may be outweighed by the burdens the patient’s informed views are of paramount importance’ (p. 3). 54 Thus, it is important that all patients with a significant chance of respiratory or cardiac failure should have the opportunity to understand the risks and benefits of CPR and state their preference about whether or not resuscitation should be attempted. Discussion of CPR and documentation of the patient’s wishes are a key component of ACP.

Preferred place of death

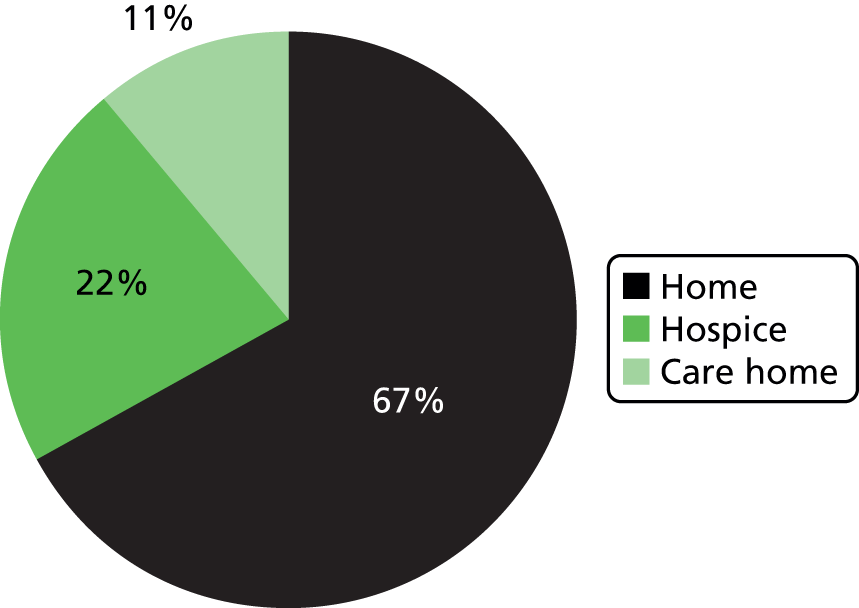

The focus of ‘choice’ in relation to EOLC has centred on supporting patients to die in their preferred place of death (PPOD). This is understood, in the great majority of cases, to be their home or usual place of residence. 16,56–61 It is widely stated that many people do not die in their preferred place, and that most of the 52% of patients who currently die in hospital would have preferred to die at home. 57,62,63 Hospital is regarded as an undesirable and expensive place of death and considerable efforts have been made to increase the resources available to community services to avoid ‘unnecessary’ hospital admissions at the end of life and enable patients to die at home. These include the introduction of specialist roles such as community matrons (CMs), practice liaisons and palliative care nurses (PCNs). 21,64

The proportion of home deaths is frequently taken to be a proxy indicator of quality of EOLC. 29 Indeed, a recent White Paper introduces the consideration that patients should be given the right to die at home. 29 Nevertheless, the evidence base underlying the axiom that home is most people’s PPOD is questionable. Much is derived from population surveys, often involving healthy adults representing a wide range of ages, and at a single point in time. 33,57,65 Responses to a question when it is purely hypothetical may be very different from those made in the light of hard experience. It is evident that preference for home as a place of death decreases as people get older and as the prospect becomes a more pressing reality. 51,59,66–69 Evidence from qualitative studies suggests that terminally ill patients may often feel uncertain about their preferences, which are likely to change throughout the course of illness. Such preferences are often not formulated clearly, especially in the face of uncertainty about what will happen throughout the experience of dying. Patients are pragmatic, also, about their options and how these depend on the circumstances that materialise. 6,22,43,50,51,67–73 Running like a leitmotif throughout the literature is that patients strongly desire not to impose a burden of care on their family members5,22,69,73–79 and it is evident that most people depend on the availability and willingness of informal carers to support their ability to die at home. 69,73,80 As the population ages, increasing numbers of the very old live alone and may not have carers available to help. However, dying alone is generally regarded as a very bad outcome, and for most patients it is not an acceptable option. 77,81,82

Death at home is frequently portrayed as a core component, perhaps even a prerequisite, for achieving a ‘good death’, in contrast to the impersonal, institutional and medicalised environment of the hospital. However, recent evidence suggests that control of pain and not being a burden are the important priorities for patients and the public. 33,79,83 Moreover, pain is reported to be best controlled in hospice, then hospital, and least well at home. 61

As people get older, they report an increased preference to die in hospice. 58 A recent survey of the English population indicated that 29% of respondents expressed a preference to die in hospice. This compares with 5% who actually do so. 57 Patients’ ability to die at home is limited by the availability of personal, family and service resources. Stated preferences for place of death are shaped by patient perceptions and awareness of the options practically open to them, and these may limit choice. Plans may be subject to rapid change as death draws closer. 22,43,51,67,69,70,72,84,85

The National Survey of Bereaved People (VOICES) of bereaved carers reported that, among the 44% of patients who had expressed a preference, 71% had wished to die at home. However, although the majority had died in hospital, most relatives (82%) subsequently felt that the patient had died in the most appropriate place. 61 Regardless of planning, circumstances may conspire to make hospital the only, and even the best, option. The findings of qualitative studies question the assumption that ‘home is best’ in relation to good-quality EOLC. 68,77,86 In the face of conflicting and uncertain evidence, it is important to establish a better understanding of how patients and caregivers develop their preferences, the role of health professionals in shaping these, the salience of choice and the importance patients attach to place of death. 69,74

The initiation of advance care planning

Advance care planning involves discussion of difficult issues that may be distressing to all participants. It is understandable that engaging in ACP discussions can be challenging for professionals as well as patients and their relatives. There is evidence that many professionals lack confidence in undertaking ACP and tend to avoid such discussions. 13,14,35,53,67,87,88 Several studies suggest that, as there is uncertainty about which professional should undertake discussion of ACP, there is a tendency, particularly among GPs, to defer responsibility to someone else. 9,12,53,64,67,89 Evidence also suggests that, although patients tend to expect professionals to take the initiative, there is a tendency for professionals to wait for patients to open the discussion. 5,43,87,90 As a result of this ‘bystander effect’ it is likely that the discussion never happens, or may occur too late, often in response to critical events, by which time options are restricted. 9,12,14 Reviews of patient preferences regarding discussion of end of life issues indicate they vary but tend towards an expressed desire for honesty and information. 91 However, there is also evidence of a discrepancy between stated and actual preferences for information, particularly about prognosis: people may want to know, but not too much. 92,93 It has been commonly reported that patients’ actual desire for information reduces as their illness progresses, and that this is often tempered by a preference for ambiguity and the ability to negotiate the degree of specificity involved. 25,81,91,93–98

Communication

Skilled communication is critical to ACP. 10,99 Poor communication about EOLC is a frequently cited source of patient and carer dissatisfaction and complaint, particularly in hospitals,100,101 and was identified as one of the key shortcomings which led to the withdrawal of the LCP. 27 Further research into improving communication has been identified as a research priority by patients. 102 Despite considerable promotion of ACP as a means of improving EOLC there is little evidence about how it is carried out, or the communication practices necessary to support successful discussion of patients’ future preferences and goals. 52,87,103 Evidence suggests that professional agendas tend to dominate discussions, which may include negative portrayals of life-sustaining treatments, and that patient goals and values are rarely explored in detail. 43,104 Professional influence on ACP discussions will have a very substantial impact on their outcome. Rather than reflecting established preferences, it is through the process of reflection and discussion involving coconstruction between patient and professional that choices for EOLC are established. 67 Preferences emerge and change through time. In this process, patients are likely to be strongly influenced by professional views and expectations, and to be directed towards what are seen to be ‘appropriate’ choices (dying at home, having a DNACPR order in place and, in some cases, opting to refuse further hospitalisation). Especially where patients are hesitant and uncertain, their ‘choices’ may be directed by professionals in line with prevailing assumptions about best interests. 63,67 Previous studies comment on patient apprehension about feeling coerced into formulating preferences for future care, or that statements made in advance might be abused, introducing euthanasia ‘by the back door’. 76,105 However, professional influence is not necessarily unwelcome or unwarranted. There is variation, and frequently uncertainty, in patient and public preferences to be involved in decisions about EOLC. 106 In a critical situation, many patients and their families may look to professionals for information, and also guidance. 49,67,81,101,107,108 Far from being ‘empowering’ for patients and their families, responsibility for decisions of great difficulty and significance may be experienced as burdensome and subsequently subject to uncertainty and regret. 101,109–111

Many studies describe the caution and circumspection that professionals employ when seeking cues about patient receptivity to ACP. 67,87,88 Open questions may be used as opportunities, or ‘offers’, which patients may elect to take up or ignore, and the use of ‘hypothetical’ questions and scenarios may soften the impact of confronting difficult issues directly. 104,112 Vague and indeterminate language, allusion and euphemism are employed by professionals as well as patients. 12,67,93,104,112,113 Reluctance to destroy hope is a common reason for professionals to avoid end of life discussions,12,88,92 and there is evidence that patients strive to balance understanding of their situation with the maintenance of hope. 95,114 Nevertheless, the outcome of interaction that is based on implicit communication and tacit understanding is likely to be misinterpretation and misunderstanding. 14,115 Several studies describe a process of collusion between patients and professionals in deflecting talk about a bad prognosis and limited life expectancy. 25,113,114 However, as Thé et al. 113 note, if patients remain unaware of their prognosis, they cannot plan. In this study, lung cancer patients who insisted on maintaining a ‘recovery story’ eventually confronted a difficult situation and found themselves unable to adjust or prepare for their impending death.

Barriers to advance care planning

Patient perceptions of professional communication skills strongly influence willingness to discuss EOLC. ACP can be undertaken by a range of professionals in hospital and community settings, so the generalisation of advanced communication skills to non-specialist practitioners is challenging. The complexity of modern health-care systems, the diversity of services involved in individual cases, and the number and turnover of professionals providing patient care militate against the achievement of continuity and sustained relationships that could support ACP as a process of ongoing discussion and review. While accepting the value of ACP in principle, professionals express uncertainty about how it should be implemented, and the feasibility of incorporating end of life discussions into routine practice. 53,89 Practical considerations such as lack of time, or a suitable and private location to hold discussions, which may be difficult and lengthy, are additional constraints. 11,67,87

The difficulty of prognostication emerges as one of the most important barriers to professional initiation of ACP, particularly in relation to patients with long-term conditions such as heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) which are characterised by prolonged frailty and dwindling. 11,43,116–118 Professionals are cautious about predicting how long patients may live, from a reluctance to destroy hope or to be proved wrong. 119 This makes it difficult to identify the ‘right’ time to broach the topic. 52,114 Professionals report uncertainty about recognising appropriate opportunities to initiate ACP and are anxious not to cause distress. This leads to avoidance and procrastination. 11,53 In consequence, when it occurs at all, ACP is often undertaken very late, when the patient is already close to death. 8,96,120,121

Professionals are cautious also about raising discussion of ACP for fear of jeopardising relationships with patients who do not want, or are not ready, to consider this. It is evident that patients vary greatly in their receptiveness to ACP discussions and the point in time, if any, at which they are ready to engage with them. 5,12,67,78,88,92,106,122–124 Several studies report a preference among some patients to focus on living in the present, rather than thinking or talking about dying. This can be regarded as a positive means for maintaining a sense of personal integrity and engagement with life, rather than a negative strategy of ‘denial’. 5,2,70,72,107,125,126 There is evidence, also, that many patients simply do not see the relevance of considering issues of ACP while they are still relatively well. They prefer to leave, or only become receptive to, the invitation to consider the end of life much later, when they have become gravely ill and are clearly facing death. 6,12,24,43,51,96 Even when quite severely ill, patients may not realise, or wish to be aware, that they are dying. 12,61 The normative commitment to open awareness towards death and dying within palliative care and current EOLC policy is not borne out by research evidence of patient preferences. The concept of ‘the good death’ lacks public salience,70 as does the notion that dying may present an opportunity for personal fulfilment and growth. 81 It is evident that many patients do not want an open awareness of their impending death. 70,72,127

Professional caution in approaching the topic of ACP is understandable and frequently well founded and may well be sound in protecting the considerable minority of patients who do not wish, or are not yet ready, to engage in ACP. However, such circumspection deprives other patients, who would welcome such a discussion, of the opportunity to have one. The knowledge that patients are likely to change their preferences as their illness progresses may call in question the value of formulating plans in advance. There is wariness about raising expectations about future care that may prove impossible to meet. Whereas the policy rhetoric emphasises choice, in practice both professionals and patients know that options may be limited or illusory, and depend on the availability of resources to support a preferred death in hospice or at home, which may not be forthcoming. 53,121

Advocates of ACP view anticipatory planning as intrinsically beneficial. However, it is clear that patient and public responses to contemplating death and engaging in end of life discussions are complex and highly variable. Some studies have reported benefits and patient willingness to engage in ACP discussion. 128–132 However, as indicated above, an accumulating body of qualitative evidence suggests that a substantial minority of patients find the discussion of death and dying uncomfortable and distressing and do not wish to engage in ACP, or certainly not before their prognosis has become clearly limited. This applies particularly to older patients affected by chronic degenerative diseases such as COPD or heart failure, who tend to view their illness as a fact of life rather than a terminal condition, and do not see the relevance of discussing death and dying. 10,81 Patients may find it difficult to make decisions or anticipate their responses to a hypothetical future that is beyond imagination. Some patients may opt for denial as a positive coping strategy. Rather than plan for an uncertain future, some older patients confronted with their imminent mortality reportedly prefer to live in the present, and take each day as it comes. Acknowledgement of death and dying is resisted because it threatens to undermine the quality of remaining life lived in the present. 94,98,125 In a study of older UK patients with advanced heart failure, Gott et al. 81 found that patients did not want an open awareness of dying, or a precise prognosis. Nor did they value personal autonomy, choice or control over dying, preferring instead to delegate the burden of decision-making to trusted (professional and family) others. Far from its being dysfunctional, these authors acknowledge the value of denial as a positive coping strategy for patients in their management of chronic and debilitating illness. In another UK study of well older people’s views of ACP, Samsi et al. 98 found that, rather than engage in anticipatory planning, respondents preferred to confront future difficulties when they arose and to delegate decision-making to others. Similar findings are reported by Carrese et al. 94 in a study of chronically ill older patients in the USA. These findings suggest that a substantial number of older people, regardless of their current state of health, may not be receptive to the offer of an ACP discussion.

Advance care planning aims to enable patients to shape the experience of death and dying in accordance with their personal goals and preferences. The focus is on the patient as an autonomous agent. It is consistently reported that, rather than promoting personal preferences and autonomy, a key motivator for ACP is patients’ desire to relieve family members of the burden of care and responsibility for making difficult decisions. 65,76,81,82,133 ACP emerges largely as a professional construct framed as an intervention requiring professional mediation. Little is known about the extent or nature of discussions regarding end of life issues that may go on within families, though some studies report patients may look to relatives as well as, and possibly instead of, professionals for this purpose. 43,75,133,134 The availability and willingness of relatives to provide care is critical to enabling death to occur at home. 69,135 Relatives clearly have an important role to play in decisions about ACP and in providing hands-on care for patients dying at home. 133,136 However, carers’ entitlement to information about prognosis and their role in decision-making and future planning is frequently unclear, and carers assess professional communication about EOLC as inadequate. 100

Evidence for effectiveness of advance care planning

Despite the very considerable policy commitment to ACP in the UK as well as internationally, it remains uncommon in practice. Evidence of its effectiveness is limited and conflicting. 4,137 Some studies have reported benefits. 128,130–132,138,139 These tend to be based on surveys, and to focus on a comparative reduction in days and deaths in hospital and costs associated with care in the last year of life. Detering et al. 128 report the results of a randomised controlled trial in Australia in which patients receiving a structured ACP intervention were more likely to die in their preferred place. Carers expressed increased satisfaction with EOLC, and costs for health care were reduced. Abel et al. 132 conducted a retrospective cohort study of deaths among known hospice users and concluded that those who had an ACP in place spent fewer days in hospital and had lower costs of care than those without. However, a growing body of qualitative evidence gives an indication of the great complexity, ambivalence and variability of patients’ desire to engage in ACP, and their responses to professional invitations to do so. 12,25,67,69,81,88,94,98,122

Uptake and initiation of advance care planning

Despite the considerable efforts to change professional practice and public attitudes to death and dying, few people have made or recorded plans for future care. ACP remains uncommon. 9,65,105,140–143 National surveys report no strong resistance to or discomfort about talking about death among the public. 65,134 However, despite sustained campaigns to encourage public and professional engagement in ACP, only 5–6% of respondents have documented their preferences for EOLC. Fewer than half have discussed their own, or others’, future preferences. 33 Evidence suggests that on the one hand, there is a considerable divergence between current policy for ACP, and on the other, patient and public goals and values for making decisions about the end of life. However, little is known about lay and professional responses to the implementation of ACP, how patients and professionals initiate ACP discussions or how these affect the experience and outcomes of EOLC.

Context and justification for the Care and Communication study

For patients with capacity, discussion about ACP is the first step in implementing the EOLCPW (see Appendix 2) set out in the EOLCS. Poor documentation of ACP and lack of knowledge about patient and carer experiences and preferences, and how these may change and be communicated over time, make it impossible to assess the quality, range and frequency of ACP in the UK. However, the available evidence indicates that ACP remains undeveloped and that such discussions are not common. As part of the implementation programme of the EOLCS, each Strategic Health Authority was required to develop and support an EOLCPW to promote the regional uptake of ACP. The Nottinghamshire EOLCPW was established in 2009 as part of a national initiative to improve quality and increase access and equity of EOLC. 31 The Care and Communication study constitutes an instrumental case study144 of the development of ACP through the implementation of an integrated EOLCPW in the East Midlands. It constitutes an in-depth longitudinal investigation and triangulation of lay and professional perspectives of ACP, which will have local and national application in understanding and improving the patient experience of EOLC throughout the NHS. The study provides new knowledge about how patients and professionals initiate ACP in community care settings and how recorded preferences correspond with EOLC outcomes, and associated needs, for patients experiencing a range of terminal conditions as well as cancer (e.g. COPD, heart failure, stroke).

Chapter 2 Aim and methods

Aim

Within the context of a recently implemented EOLCPW in community care settings, the purpose of the study is to investigate how patients, carers and professionals negotiate the initiation of ACP and the outcomes of discussion and planning for EOLC in terms of how closely preferences for EOLC that have been expressed are realised.

Objectives

-

To investigate patient and professional perceptions and experiences of initiating, and subsequently reviewing, ACP discussions and decisions throughout the last 6 months of life.

-

To investigate patient and carer responses to the offer of an ACP discussion.

-

To identify barriers to the implementation of ACP.

-

To investigate outcomes for EOLC: how patient preferences for care, expressed and recorded during ACP, match care received in the last week of life.

-

To investigate how professionals, patients and carers assess the quality of EOLC.

-

To generate evidence for best practice in implementation of ACP.

-

To establish professional training and support needs for confident and skilful communication in ACP.

Methods

Study design

The study explores the applicability of a conceptual framework in which ACP is understood to involve a process of ongoing discussion, reflection and review, rather than constituting a ‘one-off’ recording of instructions for future medical treatment. This process may involve (1) input from several/diverse persons and perspectives (patient, family, professionals) and (2) change over time. A qualitative study design was employed to gather data in two workstreams:

-

workstream 1: professional perspectives interviews

-

workstream 2: patient case studies.

The research builds on methods and recruitment processes used successfully by the research team in earlier studies of patient choice and decision-making in palliative care145 and community nurses’ (DNs’) experiences of ACP. 53 Qualitative methods of data collection and analysis enable an in-depth exploration of participants’ views and perceptions of their experience. This is particularly valuable in discussion of little-known, complex and sensitive topics, especially where these are being studied over time. Semistructured interviews allow core topics to be raised for discussion, while leaving scope for the identification and exploration of unforeseen issues that may emerge as particularly significant or salient in respondents’ accounts, and to extend the discussion of these to establish clarity and depth of meaning. 146,147 Longitudinal case studies involving serial qualitative interviews have been used successfully to study patients’ evolving needs and experiences of palliative care. 90,148 Case studies are particularly suitable for exploring complex situations involving a variety of perspectives. 149 Detailed insights from well-constructed case studies also have an explanatory potential, in this instance in discerning how ACP practice is negotiated between participants and shaped by contextual factors at play in community care. 150,151

Setting/context

The study was based in generalist community health services providing supportive and EOLC to patients living with life-limiting and terminal conditions in their own or care homes and registered with GP practices in the East Midlands region of England.

Eligibility

Workstream 1: professional perspectives interviews

Health professionals: providing EOLC to patients in the community including GPs, DNs, CMs and clinical nurse specialists (CNSs) in palliative care and other specialities.

Workstream 2: patient case studies

Patients: living in their own or care homes; suffering from a progressive, terminal condition; assessed by health-care professional (HCP) to be within the last 6 months of life; with capacity to give informed consent; aged 18 years or older (there is no upper age limit); fluent English speakers.

Family carers: nominated by patient; in at least weekly contact with patient; with capacity to give informed consent; aged 18 years or older (there is no upper age limit); fluent English speakers.

Health professionals: nominated by patient; working in community health-care services providing palliative and EOLC to patients.

Recruitment

With support from the Primary Care Research Network, 10 GP practices were recruited from the study area. The network identified and contacted a range of GP practices. However, engaging practices willing to participate was a long and protracted process, and subsequently recruitment was extended to include a further practice.

Workstream 1: professional perspectives interviews

Health professionals providing EOLC to patients in the community were invited to take part. The initial plan was to recruit several professionals, including at least one GP and one DN, from each practice participating in the study. However, given the difficulty of recruiting professionals from participating practices, and consequently to ensure adequate representation from the different professional groups, the recruitment strategy was widened. Participants were recruited in a variety of different ways including via the participating GP practices, by accessing professional team meetings, by targeting training events and through direct invitation via a network of local contacts. Some participants were then asked to snowball this invitation to colleagues. In order to achieve inclusiveness and diversity and to gain a range of perspectives and experiences, care was taken to recruit GPs, DNs, PCNs and specialist nurses for a range of conditions such as heart failure, respiratory disease and neurological conditions. The aim had been to recruit 30 health professionals to this part of the study. However, in order to achieve the range of perspectives desired, a total of 37 health professionals were interviewed.

Workstream 2: patient case studies

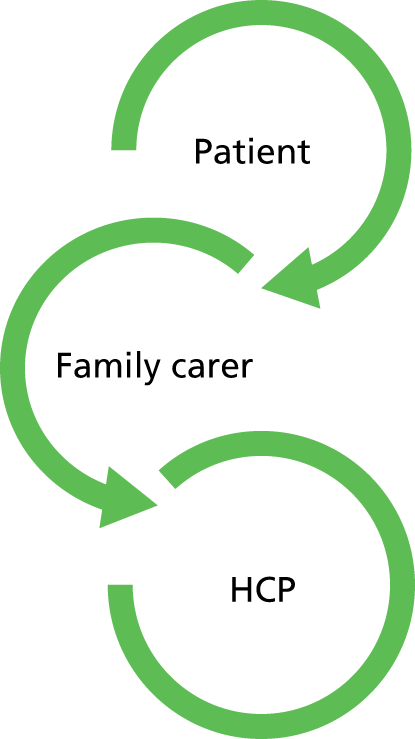

Case studies were prospective, longitudinal and multiperspective, with the patient as the centre of a network involving lay and professional carers148,152 (Figure 1). Initially, the participating GP practices were asked to identify patients considered likely to be within the last 6 months of life, and affected by a range of illnesses and comorbidity, such as cancer, stroke, respiratory disease and heart disease. These patients might be identified by their inclusion on the Gold Standards Framework (GSF) register or by GPs asking themselves the ‘surprise’ question, in this case specified as ‘would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next six months?’148 What was relevant to the study was not the accuracy of prognosis, but the professional perception of the patient’s illness trajectory that was thought to be critical in initiating ACP.

FIGURE 1.

Make-up of cases.

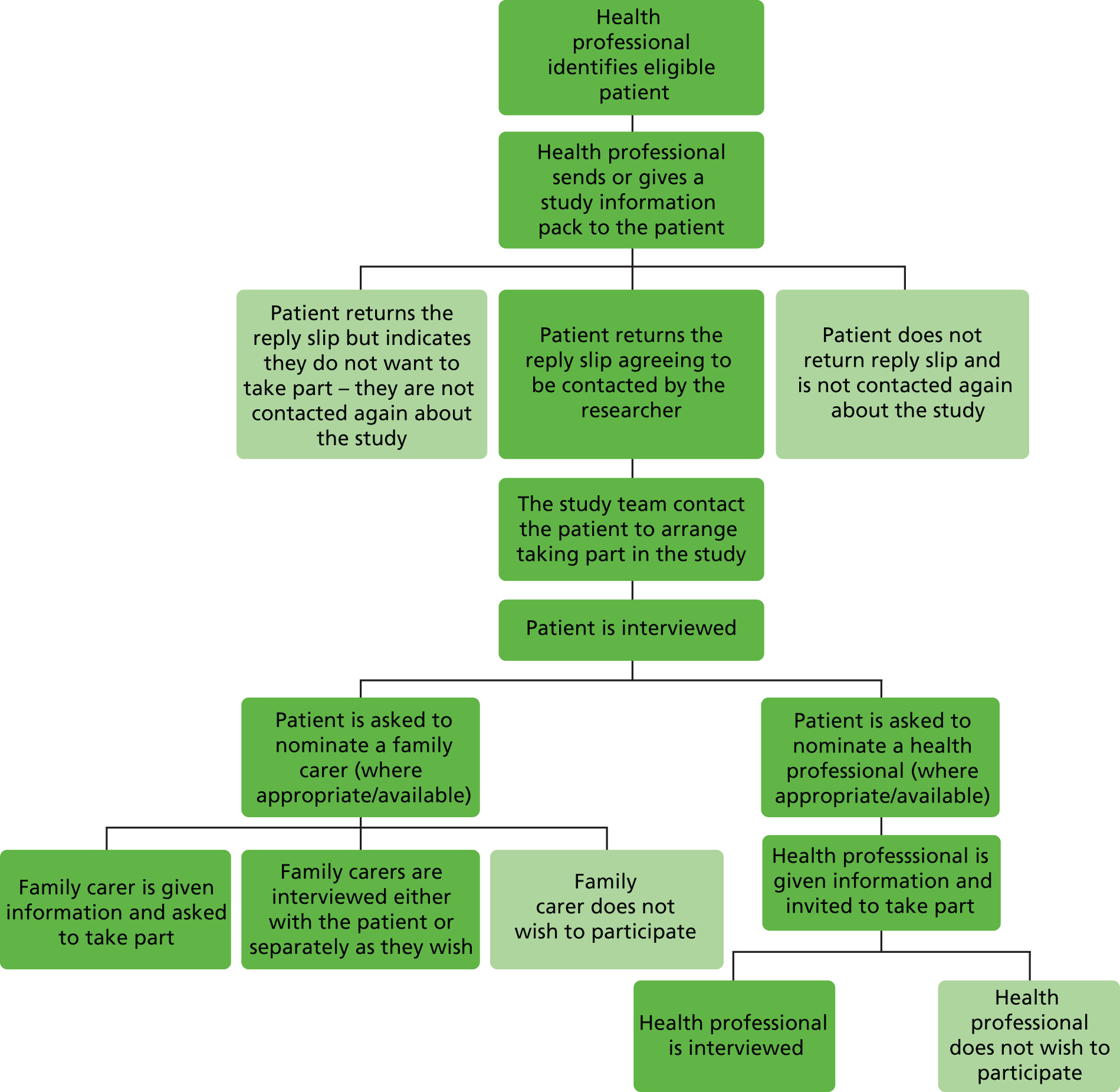

Once a suitable patient was identified, the health professional sent or gave them a pack with information about the study. The patient was then free to decide whether or not to participate by returning a reply form directly to the research team. When a reply slip indicating a wish to take part was received, the research team contacted the patient and arranged to visit for their initial interview. At this stage, written consent was taken and the patient was asked to nominate a family carer and a HCP to be included within the case study, if they wished to do so. Patients without informal carers or a key health professional were still included in the study. Hence the case studies are not uniform. Figure 2 shows the recruitment process.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment process.

Recruitment of cases took place between August 2012 and November 2013, a total of 15 months, exceeding the initial 9-month target. By the end of the first 5 months of the recruitment period, 14 of the proposed 20 cases had been recruited. In order to boost recruitment, participating GP services were revisited, providing an additional four cases. In conjunction with this GP contact, specifically to widen the range of participants beyond those with cancer, recruitment packs were also distributed via CMs for patients with long-term conditions, and secondary care consultants of patients with respiratory and digestive diseases. This yielded three further cases, resulting in a total of 21.

Data collection

In response to a number of challenges, the recruitment period for the study was extended and, with allowance of a 6-month follow-up period for each of the case studies, data collection took place over a period of 22 months from July 2012 to April 2014. In line with the 6-month extension to the recruitment period, follow-up was also extended to allow all those recruited to be followed up for a period of at least 6 months. In addition to the difficulties of recruitment of GP practices, the project had been granted a 4-month no-cost extension to compensate for a period between the departure in May 2013 of Dimitris Vonofakos, who was originally appointed as the full-time research fellow on the project, and Eleanor Wilson’s being able to take up this post in September 2013.

Workstream 1: professional perspectives interviews

Semistructured interviews were used to gather data from a range of community-based health professionals. These interviews focused on respondents’ thoughts and experiences of delivering care towards the end of life, and the use or absence of ACP. Interviews were tailored to suit the time constraints of the participating health professionals. Consequently, one group interview was arranged to gather the thoughts of four CNSs for heart failure. This was initiated by the participants as the most expedient and appropriate approach to participation in the study given their pressures of time and availability. Professionals were also offered a telephone interview if they felt this would be more convenient; only one chose this option. Eight participants in the professional interviews were also nominated health professionals for case studies and took part in both workstreams of the study.

Workstream 2: patient case studies

The processes and outcomes of ACP, or its absence, were explored through (1) initial and follow-up interviews with each patient and each of their nominated family and professional carers and (2) analysis of medical records and documentation of ACP (accessed with permission).

-

Each patient recruited to the case study workstream was followed up for a period of approximately 6 months, or until their death if this occurred sooner. During this time, each member of the case study interview set (patient, family carer and HCP) was interviewed up to four times (Table 1 shows the number of interviews per case, broken down by participant type). The majority of patient and informal carer interviews were held jointly, according to preference. Follow-up contacts with patients and relatives were arranged to take account of relevant developments regarding treatment and care, including respondents’ wishes and state of health. Most follow-up contacts were carried out face to face, a few by telephone (two with patients, one with a family carer and seven with nominated health professionals). Follow-up interviews explored changes to participants’ health and experience of care, how these affected future preferences and plans, and whether or not there had been any changes or developments in discussion, documentation or implementation of planning for future care. Patient and family carer interviews took place in their own home and ranged from 12 minutes to 2 hours and 15 minutes in length.

-

Patients were asked to give permission for the researchers to review relevant parts of their medical records. This provided access to documentation of preferences for future care. Once the case study interviews had been completed, arrangements were made with the relevant GP practice and hospice (where applicable) to view the patients’ medical records. Information was extracted and notes made about recorded evidence of an ACP discussion; subsequent records relevant to ACP; DNACPR status; care in the last week of life; PPOD; and actual place of death. 145 This was possible for all but one case, in which clarity of consent could not be confirmed, without which it was felt inappropriate to access this patient’s medical records.

Patient and public involvement

Public involvement has been sought throughout all stages of this project in accordance with INVOLVE guidance for research. 153 An initial review of the ethical issues, patient recruitment documents and protocol was undertaken by a member of the Lancaster University patient and public involvement group. Further to this, a number of presentations were given to public groups including the Nottingham Older People’s Advisory Group, the Nottinghamshire Chinese Welfare Association, Medical Crises in Older People Patient and Public Advisory Group, Palliative Care Studies Patient and Public Group and the Newark & Sherwood Over 50s Forum. These presentations engaged the public in discussion of the topic and methods of data collection. These discussions raised the profile of the study and reinforced the significance and public salience of the topic and the relevance and value of the research. In preparation for data collection, a focused discussion was undertaken with a volunteer patient who had experience of cancer. This discussion reviewed the content of the patient interview schedule and the different reactions this might give rise to in potential participants. The session was particularly helpful in identifying ways in which interviews could be ended appropriately.

Throughout the recruitment and data collection phases, we engaged with the Nottingham and Sheffield Dementia, Frail Older People and Palliative Care Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Panel for advice, discussion and feedback on the progress of the study. The study findings were presented to the panel for discussion in June 2014. Seven members of the advisory panel reviewed a draft of the project report and their feedback has been incorporated into the final version, particularly concerning points and issues requiring clarification. The reviewer responses to the report were very positive. There was agreement that the study addressed an important topic and made a substantial contribution to the field, particularly in highlighting the gap between current policy and practice. The report was described as clearly written and easy to read. The aims and objectives were felt to be clearly stated and addressed by the study findings. The researchers were commended for the sensitivity and respectfulness with which they approached patients and carers during a very challenging period of their lives. The study findings were felt to have considerable value as a teaching tool for a wide range of professionals delivering EOLC. Panel members also reviewed the plain English summary and amendments were made in the light of their comments.

The Sue Ryder Care Research Group for the Study of Supportive, Palliative and End of Life care (SRCC) works with the panel on a regular basis and provides expenses for travel and time spent reviewing reports. Care is also taken to minimise burden, provide support, create a friendly environment and share research in a way suitable for non-professionals. The panel’s contribution to studies is valued highly, and additional funding is made available for training, education and attending wider meetings and conferences for members who wish to do so. The group meets five times a year and is made up of approximately 15 members, the majority of whom attend meetings on a regular basis.

Throughout the study the team has maintained and updated a web page, which is freely accessible and details the progress of the study. 154 The project has also been featured in a number of local, national, public and professional newsletters. These include national newsletters published by the National Council for Palliative Care, the Palliative Care Research Society and, locally, Nottinghamshire End of Life Care, the Nottingham Clinical Commissioning Group and the Nottinghamshire Chinese Welfare Association. These features have raised the profile of the study and contributed to the public debate around death and dying. All are accessible in the public domain in both hard copy and electronic formats.

Ethical approval

Approval for the study was sought through the National Research Ethics Service and approved by the Leicester NHS Research Ethics Committee on 21 March 2012. A substantial amendment to extend recruitment to a small number of secondary care settings was submitted and approved in September 2012. Research and development approvals and letters of access were issued by the NHS trusts participating in the study.

Ethical issues

The principal ethical issues involved in the study relate to the involvement of patients and family carers confronting the challenge of life-limiting and terminal illness. The research involved a vulnerable patient population and investigation of a topic which participants may find challenging. Previous studies have found that respondents taking part in qualitative studies report this to be a positive experience, despite the discussion involving topics of a potentially difficult and distressing nature, and many welcome the opportunity to contribute to a research effort that may benefit others. 152,155–157 This applies also to patients with terminal conditions, or who knew that they were dying, and bereaved relatives of patients who had died. 156,158 Research has found that such patients may welcome the opportunity for their voice to be included and to make a contribution to research that will benefit others in future. 159–162 Consequently, it has been argued that excluding vulnerable patients from the opportunity to take part in research on the basis of assumptions made about their experiences and preferences is discriminatory and restrictive. 163–167 However, we were well aware of the need to approach contacts with patients and family carers with the utmost care and sensitivity, and to be suitably responsive to patient and family carer reactions and preferences throughout the research. This respect for emotional boundaries relied on the interviewers’ skills in recognising non-verbal cues in order to respond appropriately to each participant. As would be expected, some participants were more willing than others to talk about issues relating to EOLC, and interviewers took care to be guided by the participant on when and how much to discuss these issues. It was important to judge how to elicit relevant information about ACP without forcing people to confront issues or areas they were not comfortable talking about. Sometimes participants would give verbal indications by simply stating that they did not want to think about certain aspects of their care or illness, whereas others specifically introduced these topics themselves. In order to avoid causing distress to respondents who may not have been aware of, or did not wish to acknowledge, the terminal nature of their condition, the study was presented as research into the quality of care and communication about serious, chronic and life-limiting illness between patients, family carers and health professionals in community care settings. Initial discussion with patient and family carer participants was phrased in general terms and great care was taken to allow respondents to reveal their understanding of their condition and prognosis and to frame the interview discussion within the terms of their understanding, rather than assume that the individuals concerned had understood and accepted professional formulations of what these might be.

Care was taken during interviews to maintain clear boundaries between the role of researcher and professional. Researchers took no part in offering advice or support to patients and family carers, while always giving time for respondents to talk in detail about their perspectives on ACP and experience of care.

It is possible that involvement in the research may have altered the behaviour of respondents in such a way as to influence the nature of the data collected. For example, health professionals may have raised and pursued the issue of ACP with patients included in the study, when otherwise they would not have done so. The methodology of the study allowed for the flexibility to monitor and take account of such effects, and where appropriate explicitly address them as a topic of discussion in the interviews. Triangulation of data from workstreams 1 and 2 extended the scope to contextualise this phenomenon.

Written consent was obtained from participants before the first interviews commenced. Patients were also asked to identify whether or not they wished to be withdrawn from the study should they lose capacity either temporarily or permanently. They could also nominate someone to make this decision for them. However, loss of capacity did not materialise as an issue in any of the cases. For those professionals participating in both workstream 1 and workstream 2, a consent form was completed for each part of the study to indicate a clear understanding of the different aspects of the workstreams. Throughout the case studies the notion of process consent was used,168 allowing willingness to participate to be confirmed at each point of contact. This allowed participants to continue in the case studies as they wished. Patients and family carers were given the option of speaking on the phone or a home visit. Times for follow-up interviews were agreed with the participant based on their convenience, preferences and current health.

Confidentiality was a particular issue for the case studies in workstream 2, as most cases involved more than one participant. All participants were informed of the nature of the case studies and consented to participate. None of the participants raised concerns about issues of confidentiality at any point during the study, and they often encouraged the researchers to speak to other family members and health professionals. The majority of interviews with family members were undertaken as a joint interview with the patient, as they preferred.

Open discussion was maintained with all participants about the length of the study, and all patients and family members were happy to participate for the expected 6 months, where possible. In setting up the final interview date it was reiterated that this would be the last time contact would be made. The initial intention had been to conduct rounds of interviews with patients, family carers and professionals at approximately the same time. However, in practice it proved hard to synchronise professional and patient interviews in this way. We adopted a policy of working pragmatically with health professionals in terms of their willingness and availability to be interviewed (which varied) and in the context of what was happening with each case. In some instances where the patient was reasonably stable over part or all of the follow-up period, we judged that there was little to be gained by frequent follow-up with professionals involved,90 especially when they may have had little direct contact with the patient in the interim. In others, it was helpful to obtain an update on the case between patient and family carer follow-up interviews, rather than at the same time.

Analysis of multiple data sets

Most interviews were audio recorded with permission. However, there were three recording failures and four instances when only notes were taken, each when interviews were conducted over the phone. The study findings were derived from a number of data sets across the two workstreams:

-

workstream 1: professional perspectives interviews

-

workstream 2: patient case studies as sequential interviews over a 6-month period with patients, family carers and health professionals involved in their care, and documented records of patient care.

Each data set has been subject to both separate and integrated analysis. Data collected from serial follow-up interviews with case study participants go beyond cross-sectional and static accounts of specific stakeholders. This enables an understanding of communication about ACP and EOLC as a potentially ongoing process of communication between the multiple and changing perspectives of patients, family carers and professionals, by interrogating each case individually.

Coding and analysis was ongoing throughout the study and is an integral part of qualitative research. The qualitative software program NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to facilitate organisation of a complex data set and support a thematic analysis of the data using the constant comparative method based on the principles of grounded theory. 146

Workstream 1: professional perspectives interviews

Once transcribed, checked and anonymised, interviews were imported into NVivo 10 along with written field notes. In addition to the freestanding professional interviews undertaken for this workstream, it became apparent that the nominated professional interviews that contributed to the patient case studies contained much relevant material relating to professional perspectives and experience of ACP. Consequently, relevant content from all professional interviews was incorporated into the professional interview coding frame. Use was made of both the ‘free’ and ‘tree’ node functions in the NVivo 10 software in order to sort and rank codes and to build hierarchical trees of related codes. Core categories and thematic inter-relations were established within and between each data set. 147 The evolving coding frame was discussed regularly by the researchers and within the project group meetings.

Workstream 2: patient case studies

Once data collection was completed for each of the case studies, all data from that case were reviewed and written up as an individual case profile including input from all case participants and data from medical records. This used a process of reconstruction and restorying of each case into an integrated narrative through detailed scrutiny of all relevant data sources. This analysis was extended with the documented evidence established by the review of medical records. Summaries of each case are provided (see Appendix 3). These outline key elements including participation in the study, involvement where applicable of nominated family carers and health professionals, changes over time, key incidents of care and any involvement in ACP. Building these individual narratives prevented cases from becoming swamped or disaggregated by cross-case analysis, enabling presentation of the particularity of each case within its own context. 144 Cross-case analysis was also undertaken to draw out common themes across the individual cases. The progression of each case was explored in relation to the occurrence or non-occurrence, and consequences, of ACP and the light this analysis shed on the salience and implementation of current EOLC policy for patient experience and professional practice.

Immersion in longitudinal studies and complex data collection can result in selective notions of what is important within the data. 169 The analysis was repeated over time and carried out by two researchers employing a systematic approach. Coding frames and data within codes were also presented to the advisory group in order to ascertain how much they resonated with practice. This multifaceted approach allowed a more robust and thorough analysis of the data.

Chapter 3 Findings: demographics

Workstream 1: professional perspectives interviews

Thirty-seven health professionals and allied health professionals (AHPs) were recruited to participate in this workstream of the study (Table 2). All interviews were undertaken on a one-to-one basis with the exception of one group interview, which included four heart failure nurse specialists. Most professional interviews were carried out face to face, with one being conducted by phone. They ranged in length from 12 to 59 minutes.

| Professional | Number interviewed |

|---|---|

| GPs | 12 |

| Community/district nurses | 5 |

| CMs | 6 |

| Heart failure specialist nurses | 6 |

| Specialist PCNs | 3 |

| Specialist nurses (other conditions) | 3 |

| AHPs | 2 |

| Total | 37 |

Eight of the professionals taking part in the professional perspectives interviews were interviewed in relation to one or more specific patient case and also feature in the case data. A further six professionals took part in the case studies as nominated professionals only. In addition to focusing on the individual patient, the case study interviews with professionals contained a considerable amount of more general material relating to respondents’ wider perspectives and experience of ACP. This material was coded in NVivo 10 and included in the analysis of findings relating to professional perspectives. Hence interviews from a total of 43 individual professionals were analysed and are reported in Chapter 4.

Data from the Public Health England website170 show a number of key demographics for all GP practices in England from 2011–13. Data were identified for 10 of the 11 practices included in this study. There were no data available for the remaining practice, which had recently merged with another and moved to new premises (practice L). Table 3 gives features of the different practices, including list size, the number of patients over the age of 65 years and the percentage with long-standing health conditions. These are presented alongside local demographics on deprivation scores, income deprivation for older people, number of Disability Living Allowance claims per 1000 patients, percentage of non-white ethic groups and unemployment status. All these statistics can be compared not only across the participant practices but also with the national average for England.

| Indicator | Practice | England average | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | J | M | ||

| Number of registered patients | 7094 | 2691 | 7918 | 12,048 | 11,360 | 6273 | 13,120 | 13,047 | 5323 | 9287 | 7041 |

| Number of GPs at the practicea | 5 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 6.8/10,000 populationb |

| Percentage (number) of patients on the GSF registerc | 0.35 (25) | 0.18 (5) | 0.48 (38) | 0.29 (35) | 0.18 (21) | 0.19 (12) | 0.14 (19) | 0.41 (54) | 0.3 (16) | 0.16 (15) | National target 1% |

| Percentage of patients over 65 years | 21.8 | 23.7 | 18.3 | 19.2 | 24 | 19.9 | 16.1 | 19.8 | 18.7 | 19 | 16.7 |

| Deprivation score (Index of Multiple Deprivation) | 21.5 | 16.3 | 42.2 | 26.9 | 19.3 | 12.5 | 10.5 | 30 | 31.6 | 23 | 21.5 |

| Income deprivation affecting older people (%) | 16 | 14 | 29 | 18 | 18 | 16 | 11 | 23 | 21 | 18 | 18.1 |

| Long-standing health conditions (%) | 58.9 | 55.9 | 64.3 | 55.4 | 59.5 | 52 | 52.1 | 65 | 66.4 | 48 | 53.5 |

| Disability Living Allowance claims per 1000 | 55.6 | 50.3 | 79.4 | 71.7 | 66.8 | 40.4 | 40 | 74.7 | 77.5 | 63.1 | 48.3 |

| Percentage non-white ethnic groups | 1.2 | 0.8 | 6.7 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 2.4 | 0.9 | 4.8 | Not cited |

| Unemployed (%) | 1.6 | 2.5 | 10 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 6.3 | 10.3 | 9.6 | 4.8 | 1.2 | 5.6 |

These data show that four (D, E, G and H) of the 10 practices have considerably higher than average numbers of patients registered and one (B) is well below the national average. Size of practice and number of GPs are reflected in the number of patients registered. However, these numbers can be considered only a guide, as practice websites did not specify the number of GPs working full- or part-time hours and calculations have been made between the number of GPs and their registered patient lists rather than the total population for the area.

All of the GP practices were registered on the GSF register or kept a register of palliative care patients. For clarity, the term ‘GSF register’ is used throughout the remainder of this document. When the size of practice list is combined with the number of patients registered on the GSF or palliative care register, all practices fell below the national target of 1%. Practices located in urban areas generally had higher deprivation scores. Rural practices in areas of less dense population, such as practice B, had smaller practice sizes and lower deprivation scores despite having a higher than average number of patients over the age of 65 years. All practices, apart from practice G, had higher than average levels of patients over the age of 65 years.

Comparisons between the GP practices used in the study and the national average show that the practices were broadly representative of GP practices in the UK. Marked differences relate to the location of the practices within either large cities or rural areas. Other practices present closer to the national average in terms of population distribution and demographic indicators, demonstrating a good spread of practice types within the study. All GP practices reported data on their GSF registers at one time point between March and April 2014.

Workstream 2: patient case studies

Recruitment

It was not possible to track the number of information packs that different practices and health professionals gave out to patients to invite participation in the case studies. However, from the number of reply slips returned, we are able to identify some characteristics of those who did not wish to take part as well as those who did participate (Table 4).

| Characteristic | Male | Female | Unknown | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participated | 12 | 9 | – | 21 |

| Refused | 6 | 14 | 5 | 25 |

| Ineligible | 3 | 2 | – | 5 |

| Deceased prior to contact | 2 | – | – | 2 |

| Unable to arrange | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Total | 24 | 25 | 5 | 54 |

Profile of cases

Twenty-one patients were recruited to the case studies. In addition, these cases included 13 family carers and 14 individual nominated professionals; four cases were made up of the patient alone. Eight had no family carer they wished to nominate, and seven did not nominate, or we were not able to contact, a HCP. The original intention had been to include only ‘complete’ cases in order to triangulate perspectives of patient, carer and key health professional. However, some patients did not wish to involve family or professional carers or could not identify a suitable individual to take part. It became apparent that a number of patients, particularly those who lived alone, lacked contact or significant relationships with local family members and/or health professionals. It was important to include the experience of such individuals, most likely representative of significant groups within the wider population, within the study. In addition, the sheer difficulty of recruitment called for a pragmatic strategy for inclusion. The demographics of the cases are collated in Table 5. Nominated family carers were predominantly spouses. Slightly more male than female patients took part in the study, resulting in a higher number of female family carers participating. Female patients were more likely to live alone, with the result that only three male family carers took part. Patients were most likely to nominate their PCN or CM. One PCN was nominated by two patients and another by three different patients. A further six nominated their GP or consultant in palliative medicine (CPM). In addition, three AHPs were nominated, demonstrating the range of professionals with whom patients and families built substantial relationships, and with whom they might discuss their end of life wishes. Patient ages ranged between 38 and 92 years. Sixteen were over the age of 65 years and eight of those were over the age of 80 years.

| Type | Characteristic | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Patients (n = 21) | Male (age range 62–91 years) | 12 |

| Female (age range 38–92 years) | 9 | |

| Family carers (n = 13) | Male | 3 |

| Female | 10 | |

| Spouse | 10 | |

| Son/daughter | 2 | |

| Sibling | 1 | |

| None | 8 | |

| Healthcare professionals (n = 14) | GP | 5 |

| PCN | 3 | |

| AHP | 3 | |

| CM | 2 | |

| CPM | 1 | |

| None | 7 |

Table 1 shows the number of interviews per case broken down by participant type. GP-held medical records were accessed for 20 of the 21 patients and, in a further four cases, hospice or care home notes were also reviewed. The names of all patients and family carers have been changed to provide anonymity and preserve confidentiality. Health professionals are referred to by grouped professional roles (see Appendix 1 for further information on these).

A total of 59 interviews were undertaken with patients as part of the case studies. Thirty-three were joint interviews with the patient and a family carer; 26 were with patients alone. In addition, seven interviews were with family carers alone, often after the death of the patient. The 14 individual nominated health professionals took part in a total of 31 interviews as part of the case studies. Apart from a few patients who died in the early stage of follow-up, all interviews took place over a period of approximately 6 months following recruitment to the study and were undertaken as and when was appropriate for each case. In total, 97 interviews were undertaken for the patient case studies. Nine (43%) patients died during the study follow-up period, some after only one interview.

Much previous research has focused on cancer patients. Our original aim had been to recruit patients with a wide range of conditions such as respiratory conditions, heart failure, neurological conditions and diabetes, as well as cancer, to reflect the most common causes of mortality and the type of case most frequently encountered in the community. However, this diversity proved hard to achieve. Patients recruited for the case studies had a range of conditions, and often more than one (Table 6). However, two-thirds (14 of 21) had been referred to the study because of a cancer diagnosis. Part of the struggle with recruitment resulted from the difficulty experienced by many professionals in identifying the end of life phase in patients, particularly those affected by conditions other than cancer, especially those with multiple crises and the frail elderly with multiple comorbidities. Most practices sought to identify eligible cases from their GSF registers, which, although reported to include a diversity of conditions, were predominantly made up of patients with a cancer diagnosis. The difficulty that health professionals evidently experienced in identifying suitable patients, particularly those who did not have cancer, is discussed further in Chapters 4–6.

| Condition | Number of cases | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer (including lung, oesophageal, pancreatic, stomach, brain, bladder and prostate) | 14 | Three had COPD in addition to cancer |

| COPD | 3 | One had renal disease in addition to COPD |

| Renal disease | 1 | |

| Liver disease | 1 | |

| Heart failure | 1 | Several had heart conditions in addition to their primary diagnosis |

| Spinal injury | 1 | |

| Total | 21 |