Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1015/21. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The final report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Benn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In the UK, recent policy reports have set a clear agenda to improve the way in which health-care organisations report on the quality of care delivered to patients, alongside the more conventional financial aspects of service performance. With UK acute care trusts now required to produce quality accounts to report on quality of care delivered to patients, there is a need to support specific clinical service areas in the development of criteria for monitoring quality of care.

The NHS Next Stage Review report High Quality Care for All1 aims to make organisations accountable for quality through a focus on the measurement and reporting of quality indicators representing safety, effectiveness and patient experience. 1 More recently, these principles form a core for planned changes to the health service to link payment of providers to performance on clinical quality outcomes as an incentive for continuous improvement in standards of care. 2 The Francis Report called for information that is accessible and useable by all, allowing for effective comparison of performance by individuals, services and organisations. 3

Though recent policy has focused on organisational-level reporting of quality indicators using quality accounts, other research has suggested that robust measurement systems to evaluate progress in improving the quality and safety of care at the clinical systems level are lacking. 4,5 The General Medical Council’s (GMC) work towards the development of revalidation processes for doctors has seen broad consultation and the establishment of task groups in the national clinical bodies to develop criteria and processes that are acceptable to each clinical profession. Within the anaesthetics specialty, the Royal College of Anaesthetists, the Association of Anaesthetists for Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) and the National Institute of Academic Anaesthesia are engaged in work to support the evolving revalidation agenda. This work is being driven by a number of specialist working groups, co-ordinated by the newly formed Health Services Research Centre hosted by the Royal College. A committee has been set up to investigate and develop national frameworks for revalidation of anaesthetists, including specific working groups in the areas of patient and peer feedback (multisource feedback), and quality indicators and outcomes. There is a clear need for health services research to support these activities and the development of the revalidation agenda through understanding how an effective quality indicators framework, data feedback process and the necessary service organisation structures can promote continuous improvement in clinical practice.

Considering the requirements for effective processes to feed back data from anaesthetic quality indicators to clinicians is currently a topical focus. Recent specialty focus on revalidation for anaesthetists has highlighted the requirement for metrics that can provide supporting evidence for individual professional revalidation. 6,7 This requirement places considerable demands on local quality monitoring systems, which will vary in capability. The perception of the revalidation process and the use that is made of personal professional data within it will be important and it has been suggested that multisource feedback is used constructively to support professional development and is separate from the assessment process used to judge doctors. 8 The Royal College of Anaesthetists and the AAGBI have published guidance on revalidation and the necessary supporting documentation for evidence of fitness to practice. 9 Feedback from quality indicators can be used as key support within the multisource feedback required for revalidation. Indeed, participating in quality monitoring and acting on the results is included as one aspect of good medical practice. 10

Chapter 2 Structure of the report

This report begins with a review of the relevant literature and a thorough description of the feedback intervention that was implemented. The remaining sections of the report are then reported by substudy within the mixed-methods design, beginning with qualitative investigation of the initiative, followed by analysis of longitudinal survey data designed to support the evaluation. The report then proceeds with the results from interrupted time series analysis (ITSA) of the impact of the initiative on anaesthetic quality and perioperative outcome indicators.

Each substudy section is designed to be self-contained, including description of the methodological details pertinent to each stream of enquiry, summary of the results or development of qualitative theory and discussion of the findings. The final two sections of the report are designed to draw together the results across the studies that constitute the mixed-methods design and synthesise the key findings and conclusions, prior to a discussion of the important implications for research and practice.

Chapter 3 Background research and theory

The need for quality monitoring

Effective monitoring of the quality of service delivery is central to the capacity of an organisation, unit or individual to maintain and improve standards of care. International studies have found broad variations in care quality and well-publicised examples of the consequences for quality of care and patient safety exist, where unreliable systems and variable professional practices are inadequately monitored. 3,11 Monitoring is essential if clinical units and individuals are to (1) understand the factors underlying variations in care, (2) detect and respond to opportunities to improve standards and (3) evaluate the impact of changes to services.

Drawing on the rationale and past research outlined above, there is a clear need for work in this area to support the current national service agenda to promote improvement in quality of care and revalidation for clinicians across the professions. There is mounting economic pressure for productivity in the perioperative workflow, which focuses effort on the intraoperative stages of care and theatre utilisation efficiency. Anaesthetists as a professional group have a high degree of patient contact in the perioperative pathway and yet receive little routine feedback on patient experience or outcomes specific to the quality of the anaesthetic care process. There is a need for anaesthetists to receive quantitative feedback from the postoperative stage on the quality of care they deliver to patients and the patient experience. Indeed, owing to tight integration within the surgical process and the development of the modern anaesthetist’s role in the perioperative pathway, anaesthesia poses some specific and potentially unique challenges in terms of providing feedback on quality of care to departments and individual clinicians.

Feedback on postoperative nausea or pain control often occurs on a periodic basis through successive audit cycles, but these information streams are discontinuous and may not be geared towards continuous improvement actions. Feedback on the quality of recovery (QoR) experienced by patients on waking from surgery often occurs only on an ad-hoc basis, through personal interactions with patients and recovery room staff or when anaesthetists have the opportunity to personally follow-up patients in between busy theatre list schedules or are requested to attend a patient by recovery room staff. There are few reported examples of systematic, routine monitoring of quality indicators in the recovery room to provide rapid, continuous feedback on the quality of anaesthetic care delivered. Similarly, few evaluative studies of personal professional monitoring programmes for anaesthetists or trainees exist. 12,13

Perioperative quality indicators

As a precursor to consideration of how data might best be used to monitor quality of care in anaesthetic services, it is important to consider how quality can be defined and measured. Contemporary practice in development and application of quality indicators to monitor and improve care owes much to the early work of Avedis Donabedian. 14–16 Donabedian made the distinction between structure, process and outcome metrics according to the relationship and proximity of a variable to the desired performance result. 14

In accordance with policy developments, considerable work has been undertaken in specialty areas, including anaesthesia, to identify the potential metrics by which quality of service delivered can be reported and evaluated. Within anaesthetics in particular, there is a lack of reliable, evidence-based quality indicators to quantify quality of care, patient experience and process efficiency, and capable of guiding service development efforts and improvement in professional practice. The close integration of the anaesthetist’s function with that of the surgeon and other proceduralists within the perioperative pathway means that identification of routine outcome metrics that are sensitive to variations in quality of anaesthesia is difficult. A recent review of quality indicators for anaesthesia concluded that conventional perioperative morbidity and mortality data largely lack the sensitivity and specificity necessary for analysis of variation in quality and safety of anaesthesia. 17 In Haller’s review,17 108 quality indicators in use within the anaesthetics research literature were identified. Around half of the indicators looked specifically at anaesthesia; the other half also measured surgical or postoperative ward care. Only 1% of indicators looked at structure of care; the majority (57%) measured outcome and 42% measured process of care.

Mortality and serious morbidity attributable to anaesthesia has decreased significantly over the last 50 years to the point where mortality is considered a poor quality indicator because it is both rare and frequently related to factors outside the anaesthetists’ control. Anaesthesia has been considered at the forefront of improving safety in health care18 and, currently, with around 2,300,000 general anaesthetics (GAs) performed every year in the UK, the risk of death and major complications after surgery in the general surgical patient population is relatively low: < 1% of all patients undergoing surgery die during the same hospital admission, with perioperative mortality occurring in only 0.2% of healthy elective patients. 19

While variation in perioperative morbidity and mortality are influenced by a range of patient, surgical and anaesthetic factors, variation in the quality of anaesthetic care may be more directly assessed in the immediate postoperative period, in which the patient’s experience of recovery is closely linked to the quality of the anaesthetic and the selection of analgesic and antiemetic properties. Although outcomes such as mortality are concrete and therefore easier to measure, outcomes such as patient experience and satisfaction require quantification of subjective perceptions, usually along multiple dimensions. It may be this reason that underlies the observation that there are few validated indicators available that incorporate the patient’s perspective on quality of anaesthetic care. 17 Indeed, Haller reported that only 40% of clinical indicators had been validated beyond face validity. 17

In terms of patient satisfaction with anaesthesia, a number of postoperative patient satisfaction questionnaires have been developed and validated. 20–26 Myles26,27 developed a nine-point QoR Scale, measuring patient-reported dimensions of quality, for use as a perioperative outcome measure and for clinical audit. The scale included items derived from a larger questionnaire used to determine patient priorities, and included aspects such as general well-being, support from others, understanding of instructions, respiratory function, bowel function, nausea and pain, among others. 28 Psychometric analysis found that the scale showed good internal consistency and validity, with factors such as invasiveness of surgery, duration of hospital stay and gender all being significant predictors of QoR scores. 27,29 Capable systems for routine monitoring of quality of anaesthetic care as experienced by perioperative patients lags some way behind research-based development of patient satisfaction measures, however, representing a clear gap for operationalisation and translation of research evidence into clinical practice.

A large body of established evidence, linked to national guidelines, supports the impact of various anaesthetist perioperative practices such as patient temperature control, antibiotic administration and management of anaesthesia on care quality and perioperative outcomes [e.g. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)30].

Two of the most important dimensions of QoR in the postoperative period are postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and postoperative pain. 31 PONV is both common and among the most important factors contributing to a prolonged postoperative stay following ambulatory surgery. 32 PONV and incisional pain during recovery has a strong negative influence on patient satisfaction, and studies have shown that vomiting and nausea are among the most undesirable complications from the patient’s point of view31 as well as posing clinical risks. Pain is commonly measured in a post-anaesthetic care unit (PACU) by a variety of means, including visual analogue scales, numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales and behavioural scales. 33 Research suggests that 10.9% of surgical patients experience severe pain. 34 A range of risk factors have been identified for PONV, and guidance has been produced for antiemetics administration to patients that are moderate and high risk. 35 Aside for the importance patients place on experience of the immediate postoperative period, patient-reported pain and PONV represent important anaesthetic quality indicators for the attending anaesthetist, as they are interrelated and dependent on the balance between analgesic and antiemetic properties, matched to the patient’s characteristics and procedural requirements.

Many quality metrics are routinely measured by staff working in the postoperative environment; temperature on arrival in recovery and time spent in recovery are important aspects of a patient’s experience, and are readily quantifiable. Evidence demonstrates that perioperative normothermia results in a reduced incidence of wound infection36 and has been established as a NICE guideline. 30 Despite this, a recent UK review of perioperative care for surgical patients found that 34% of hospitals had no policy for the prevention of perioperative hypothermia. 20

Research on the development of effective quality indicators for clinical practice suggests that they should be transparent, reliable, evidence-based, measurable and improvable. 37 However, it is clear that there are certain challenges in the measurement of quality of care in anaesthesia which must be overcome, and some consensus is emerging as to what may be useful and reliable basic metrics for anaesthetic quality, collected in the recovery period.

Further study to identify sensitive and useful quality indicators for anaesthesia is warranted. From a practical perspective, while variation attributable to the anaesthetic component of care may be determinable in perioperative morbidity and mortality data through well-powered research studies, the requirements of local clinical units differ. Anaesthetic quality indicators must be useful when monitored longitudinally in small numbers of cases, with limited opportunity for case-mix adjustment. Quantification of dimensions associated with the patient’s experience of immediate postoperative recovery may provide valid and reliable outcome measures for anaesthesia if evidence and consensus based.

Data feedback interventions

Monitoring involves collecting data on important quality indicators. However, identifying practical metrics that are valid and reliable indicators of the quality of service delivery is only one part of the challenge. Effective quality control requires clinical units to not only develop reliable data collection mechanisms, but to put in place systems and processes for effective feedback and use of the data to support quality improvement. Considerable research and development has been undertaken to define the processes by which valid, reliable and useful clinical quality indicators can be defined, using systematic approaches such as review of scientific research and expert consensus. 37–39 The question of how the resulting quality indicators can best be used in practice, however, is not currently supported by a coherent body of literature. The conventional clinical audit model often fails to deliver sustainable, effective change40,41 and clinicians do not routinely use or engage in quality improvement. 42–44 Crucially, quality indicators generate data representing variation in an underlying parameter of the care process (plus measurement error). How those data are turned into information and useful, actionable intelligence to support quality assurance and improvement is an important issue and is as central to the design of effective quality monitoring systems in health care as defining the right measures in the first place. 45 Within the patient safety domain, for example, the lessons from incident reporting suggest that simply focusing on data collection and building large databases, without feedback to the front line, is insufficient to sustain engagement and action. 46

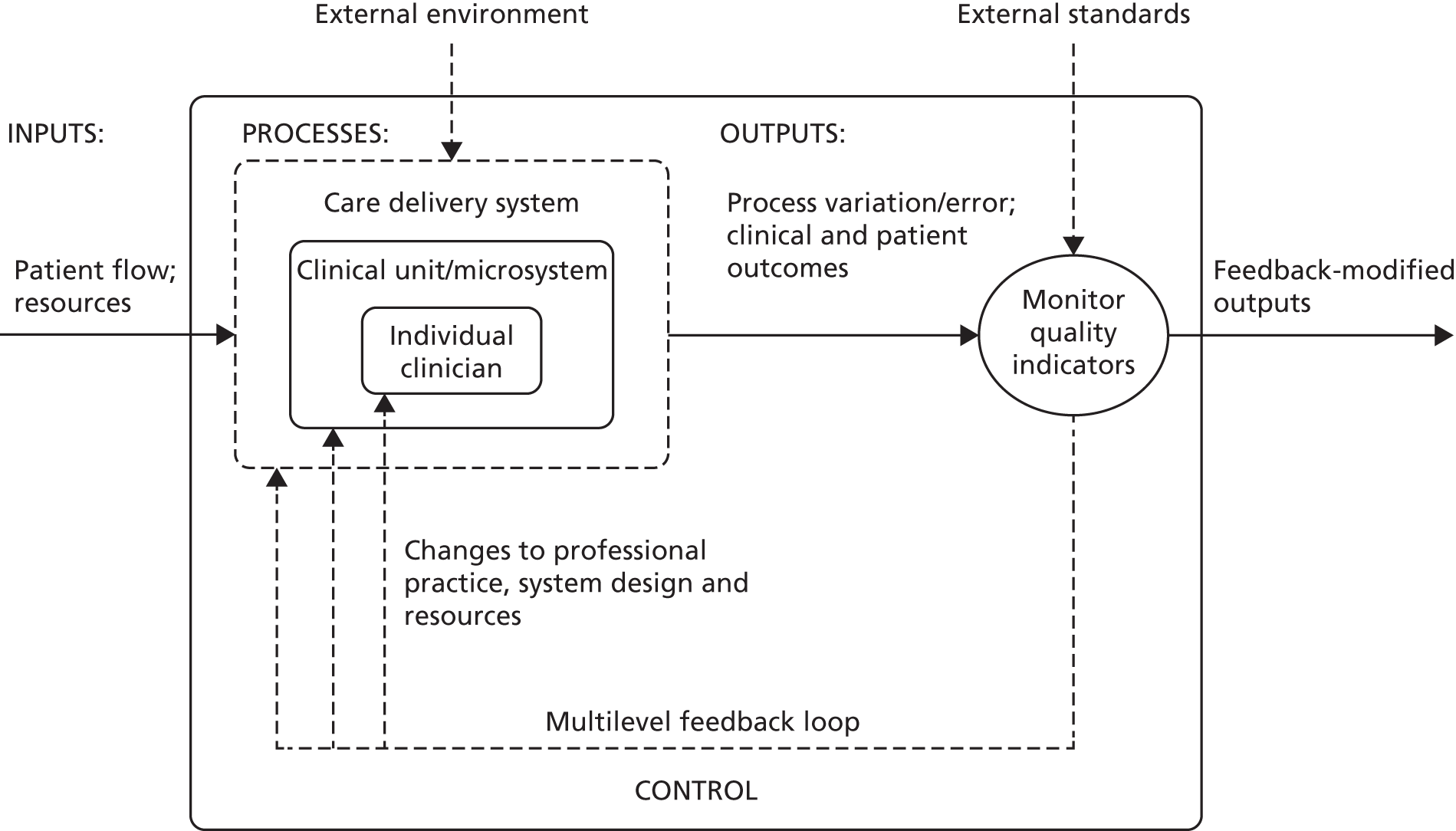

The term ‘feedback’ is most often used to describe the act of providing knowledge of the results of behaviour or performance to the individual. 47,48 Within a health-care context, information feedback has been defined as ‘any summary of clinical performance of health care over a specified period of time, given in a written, electronic or verbal format’. 49 A related and useful perspective is that of control systems engineering or cybernetics, in which feedback refers to the process by which data describing the output from a system are returned to an earlier stage of the system to modify their behaviour in order to affect future outputs (Figure 1). Crucially, information by itself is not feedback by the engineering definition; rather, feedback must incorporate some action or response to close the identified gap. 50 From an organisational perspective, feedback from operational experience over time is an important mechanism of organisational learning, resulting in incremental and large-scale modification to care systems and processes. 51

FIGURE 1.

The health-care system as a basic cybernetic feedback loop based on monitoring quality indicators. Information concerning outputs from the current system is fed back to an earlier stage to modify processes in order to achieve enhanced future.

In recent studies, many different feedback strategies are applied in clinical settings, but the type of feedback strategies as well as results produced are often heterogeneous. 52–54 The current available evidence is certainly not conclusive, but, taken as a whole, providing feedback results in generally small to moderate positive effects on professional practice49 and process-of-care measures may be more sensitive to data feedback initiatives than outcomes. 52 The literature shows that initiatives that do not use feedback reports are less effective than those that do use feedback reports, regardless of whether or not the feedback is accompanied by an implementation plan. 53,55 A number of published systematic reviews are relevant to the efficacy of performance feedback to improve professional practice and quality of care. These are summarised in Table 1.

| Review | Year | Effect of feedback | Characteristics of effective feedback |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Veer et al.52 | 2010 | Process-of-care measures are more positively influenced by feedback than outcome of care measures. Adding elements to a feedback strategy positively influences its effectiveness | The most mentioned factors influencing the effectiveness of feedback were (trust in) data quality, motivation of the recipients, intensity of feedback, organisational factors, outcome expectancy of recipients, timeliness, dissemination of information and confidentiality/non-judgemental tone |

| De Vos et al.53 | 2009 | Effective strategies to implement quality indicators do exist, but there is considerable variation in the methods used and the level of change achieved | Feedback reports in combination with an educational implementation strategy and/or the development of a quality improvement plan seems to be most effective in improving quality. Analysis of barriers led to the identification of the following barriers in quality improvement: unawareness, lack of credible data, no support management to units and lack of hospital resources |

| Hysong et al.45 | 2009 | The effect size estimate of 0.40 (96% confidence interval) suggests that audit and feedback has a modest though significant effect on the outcome of interest | Identified characteristics that augment feedback effectiveness are correct solution information and written feedback delivery. Verbal and graphic feedback delivery attenuated feedback effectiveness. There seems to be a trend in that both individual- and group-level feedback may be beneficial but data could not significantly confirm this |

| Jamtvedt et al.54 | 2006 | Audit and feedback can improve professional practice, but effects are variable. Effects are generally small to moderate | Low baseline compliance with desired practice and higher intensity of feedback were associated with higher adjusted risk ratios across studies, and therefore are more effective in improving quality |

| Veloski et al.56 | 2006 | Forty-one studies evaluated the independent effect of feedback. Of these, 32 (74%) demonstrated a positive impact on physician performance | Feedback can change physicians’ clinical performance when provided systematically over multiple years by an authoritative, credible source |

| Mugford et al.57 | 1991 | Feedback of information most probably influences clinical practice if it is part of an overall strategy which targets decision-makers who have already agreed to review their practice | Information feedback is likely to have a more direct effect on practice if presented close to the time of decision-making |

The practical value of this literature lies in the descriptions it provides of the range of potential feedback mechanisms that have been developed to improve clinical practice and the conclusions drawn about the value of specific system characteristics in terms of their contribution to effective feedback capable of engendering improvement. Van Der Veer’s review identified different barriers and success factors concerning feedback. The most frequently cited barrier was lack of trust in data quality, followed by lack of intensity of feedback and lack of motivation. Success factors included sufficient timeliness (time between data collection and the forthcoming feedback report), dissemination of information, trust in data quality and having a confidential or non-judgemental tone. 52

Jamtvedt found that low baseline compliance with recommended practice and higher intensity of audit and feedback were associated with a greater effectiveness of the feedback intervention. 49 Other important characteristics of feedback seem to be the source and the duration of the feedback. 56 Physicians are more influenced by an authoritative, credible source that will continue to monitor the physicians’ performance over several years. 56 Mugford concluded that information feedback was most likely to influence clinical practice if the information was presented close to the time of decision-making and the clinicians had previously agreed to review their practice. 57 De Vos found that feedback reports in combination with an educational implementation strategy or quality improvement plan seemed to be most effective. The following common barriers to quality improvement were identified: unawareness, lack of credible data, no support management to units and lack of hospital resources. 53

Such findings from systematic reviews of primary empirical sources are echoed by experience in quality improvement projects, which identify effective feedback that supports improvement in care as being sustained or continuous, timely, locally relevant, credible, non-punitive and supportive of remedial action. 58 Other reviews of the evidence linked to the efficacy of professional behaviour change interventions have found that there are ‘no magic bullets’, that information dissemination alone was rarely effective and that moderate positive results can be achieved using more complex interventions. 59 Similarly, synthesis of evidence on professional education and quality assurance found that simple passive intervention approaches were generally ineffective and unlikely to result in behaviour change, whereas multifaceted interventions involving educational components were found to be more effective. 60 This finding echoes that of reviews of data feedback interventions, in which multifaceted approaches that involve adding elements to basic data feedback were found to be most effective. 52

The distinction between passive data dissemination and more active forms of feedback is of importance to the effectiveness of a data feedback intervention, with several reviews concluding that maximum impact was achieved through embedding data feedback in targeted reporting, quality improvement strategies, educational programmes or similar multicomponent initiatives. Mugford defines passive feedback as the unsolicited provision of information with no stated requirement for action. Active feedback occurs where the interest of clinicians has been stimulated and engaged in aspects of practice, perhaps through the process of agreeing standards, involvement in continuing education or consideration of the implications of the information for improving care. 57

Integrating the lessons from the diverse literature described previously into coherent guidance for practice in the anaesthetic service area is a somewhat difficult task. Taken at face value, an effective feedback strategy should be timely, intensive, originate from a trustworthy and credible data source, be confidential and non-judgemental, and be supported by the broader organisation, supplied continuously over time and integrated within a broader quality improvement framework. Future research into the application of quality indicators in anaesthesia must take a holistic view of quality monitoring systems that incorporates the whole feedback cycle from data collection, through analysis and dissemination, to actual use of the data to improve practice.

From consideration of the range of characteristics that previous studies have suggested to be features of effective feedback systems, it is apparent that these systems are sociotechnical in nature, governed by a range of human, social, organisational and design factors. 61 The organisational context and culture into which a quality monitoring programme is implemented is, therefore, clearly important to its success, especially in terms of whether or not there is open disclosure and constructive discussion on performance issues within the professional group. How a community of end-users views the system and its output, and how acceptable they consider the system to be, is likely to affect adoption and use of the technology. 62 Performance measurement systems, in particular, are likely to be sensitive to end-user perceptions of utility, fairness and the opportunities inherent within the system for misuse of the data, from different perspectives. Such considerations require multidisciplinary study that includes clinical, health services, human factors and psychological investigation.

In terms of the effects of performance feedback on individual clinicians and clinical units, research evidence suggests that positive changes in systems and practice can result, especially where feedback from quality indicators is sustained and linked to a quality improvement framework. 13,49,52,54 Other reviews of the evidence linked to the efficacy of professional behaviour change interventions have found that there are ‘no magic bullets’,59 that dissemination alone is rarely effective and that moderate positive results can be achieved using more complex interventions. Similarly, synthesis of evidence on professional education and quality assurance interventions aimed at changing professional behaviour found that passive intervention approaches were generally ineffective and unlikely to result in behaviour change. 60 Multifaceted interventions involving educational components were found to be more likely to be effective. There is generally a lack of evidence in this area underpinning the understanding of the causal mechanisms that drive professional behaviour change in health care and a clear need exists for future work in this area to identify the effective modifiers, barriers and facilitators. 63

A growing body of research across a range of diverse areas suggests that selection of appropriate quality indicators and providing actionable feedback linked to quality improvement mechanisms can support detection of problem areas and timely action to improve effectiveness, efficiency, safety and the patient experience. Various models for feedback from quality indicators have been proposed and implemented, and yet there is little robust evidence for the efficacy of any one specific model or its fit within the local clinical service context. From both the health services and research perspectives, there is a need to build on existing work on effective use of data and quality indicators to drive local service improvement and to better understand the requirements for effective quality monitoring and feedback processes at the clinical departmental level to support personal professional development among doctors.

Quality improvement in health care as an approach

In the UK and elsewhere, a number of national and local initiatives have been launched to improve care through the application of industry-derived quality improvement methods, for example Quality Collaboratives, The Safer Patients Initiative, The Productive Series and Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC). An alternative approach to the question of how clinical units can best use data on quality of care to improve local systems is provided by popular quality improvement programme models which utilise industrial process control principles. 64–73 Drawing on the evolving improvement science discipline,74,75 in the UK and elsewhere, a number of national and local initiatives have been launched to improve care through the application of industry-derived quality improvement methods. 76,77 Such programmes adopt a Continuous Quality Improvement philosophy78,79 and often employ statistical process control as a measurement and evaluation model to guide improvement activities.

Process control has received some attention as a means of monitoring variations in clinical practice at the individual, unit and organisational levels within various clinical disciplines, including anaesthesia. 80–84 The dominant rationale for this approach is that continuous, longitudinal monitoring of local clinical processes, in near real-time, can detect and correct significant variations in care in a more proactive manner while providing useful information on the reliability of a process over time. 66 Such information on longitudinal variation is often masked by reporting aggregated data infrequently. Plotting data from process measures longitudinally on run charts or control charts permits the detection of non-routine underlying causes of variation as giving rise to violations in control limits. 64 Special causes of variation may be identified and addressed through application of quality improvement methods to alter the underlying process in some way, with the dual aim of improving both the reliability and performance of the process. 73,85

Although some evidence exists supporting the efficacy of process control as an approach to monitoring and improving care,86 reviews of quality improvement models in health care have suggested that the effects of dominant improvement models which utilise the technique are likely to be highly context-specific. 87–89 The large volume of published case reports suggest that initiatives using a quality improvement model can be highly effective within a conducive local context90 or tailored interventions. 91 The penetration of statistical process control as a means of monitoring and evaluating the impact and sustainability of serial interventions, such as quality improvement initiatives, remains underutilised in health care and there is limited mention of the method in the anaesthetics research literature. Varughese reports one example of a multicomponent quality improvement initiative in paediatric anaesthesia, which utilises run charts and control charts to evaluate the local impact of improvement work. 80

Perhaps one of the most interesting features of continuous quality improvement and statistical process control as an approach is the ways in which it contrasts with conventional clinical audit as it is often applied in practice. The conventional clinical audit model may be limited in its ability to support or drive quality improvement activities, due to a range of design, organisational and other barriers. 40,41 Discontinuous or periodic audit provides an aggregated snapshot of practice at a single time point and, therefore, cannot account for prior or baseline trends without multiple follow-up periods. As data collection is not continuous, there may be issues with the reliability of measures and the possibility of a Hawthorne effect within the teams being observed, meaning that the knowledge of being measured actually changes behaviour and poses a threat to external validity. Common experience is that audit can be a data collection exercise, undertaken by junior staff, that fails to prompt corrective action. Where action is taken, there may be a lack of follow-up measurement to evaluate the impact on care and, subsequently, to determine if any gains made have been sustained. Through embedding continuous process monitoring in routine operations following the industrial model, many of these limitations are overcome due to the creation of a data-rich environment in which to assess current practice over time and evaluate the impact of changes to the care system. In continuous monitoring programmes, the onset and offset of data collection introduce variations due to the Hawthorne effect. Feedback over extended time periods has, additionally, proven to be more effective,56 although this must be at the expense of considerable additional investment in data collection and administration.

Chapter 4 Research aims

Table 2 states the primary and secondary research aims that were included in the original research protocol for this project and an explanation of how they link to the existing literature in this area.

| Research aim | How will it contribute to the existing literature | Key references |

|---|---|---|

| To evaluate the impact of a departmental continuous quality monitoring and multilevel feedback initiative on the quality of anaesthetic care and efficiency of perioperative workflow within a London teaching hospital over a 2-year period. Data will be analysed at multiple time points over the course of the project in order to generate both formative and summative information to support development and evaluation of the initiative | Test whether or not the characteristics we are using as part of our initiative are effective Provide research evidence to support others in developing feedback initiatives of this type |

Bent et al.,12 Bolsin et al.13 |

| To employ a quasi-experimental time-series design to provide robust evidence concerning the impact of a serial data feedback intervention on anaesthetic quality indicators while controlling for baseline variance | Evaluate the effectiveness of this quality improvement methodology for these purposes | Varughese et al.,80 Thor et al.86 |

| To contribute to the evidence base for valid and reliable quality indicators for anaesthetic care, including effective patient experience measures | Identify which quality indicators and patient experience measures are effective/ineffective for these purposes Identifies characteristics of effective quality indicators and patient experience measures as perceived by end-users |

Haller et al.,17 Myles et al.,26 Wollersheim et al.,37 Bradley et al.58 |

| To document the main features of the data feedback intervention as it develops through the CLAHRC programme for replication at other sites, including definition of metrics, data processes, feedback format and action mechanisms | Understand whether or not our intervention is effective and how others can learn from it | Bent et al.,12 Bolsin et al.13 |

| To assess the perceived acceptability and utility of this information system for individual end-users, the clinical department and other organisational stakeholders, using a formative, mixed-methods design | Comment on how useful these data will be for the purposes of revalidation, i.e. do clinicians trust in and want to use this type of data as evidence for their fitness to practice? If not, then what data do they want/need? Provide a sociotechnical view of the system |

Bradley et al.,58 Eason,61 Holden and Karsh62 |

| To collaborate with relevant specialty groups within anaesthesia and perioperative care, including the Royal College of Anaesthetists, the AAGBI and the National Institute of Academic Anaesthetists, to support the agenda around revalidation and quality indicators within this specialty | Contribute to the development of quality indicators for the purposes of revalidation and the perioperative specialty agenda to develop standards and guidance for a core set of perioperative quality measures | Moonesinghe and Tomlinson,6 Rubin7 |

Chapter 5 The intervention: a continuous monitoring and feedback initiative for anaesthetic care

The intervention implemented and evaluated in this study (and as part of the CLAHRC North West London quality improvement project on which it is based) was conceived as a continuous quality monitoring and feedback initiative for anaesthetic care. Drawing on an industrial approach to quality measurement and improvement, the initiative took the form of continuous audit of anaesthetic quality indicators in the PACU (recovery room) coupled with continuous feedback of personal-level case data to consultant anaesthetists and perioperative professionals. In the later phases of the programme, basic data feedback was enhanced with broader professional engagement activities and rapid, responsive development of the feedback model in response to user feature requests, in order to increase the capability of the feedback to stimulate improvement in professional practice, learning from case experience and quality of anaesthetic care delivered by the perioperative system.

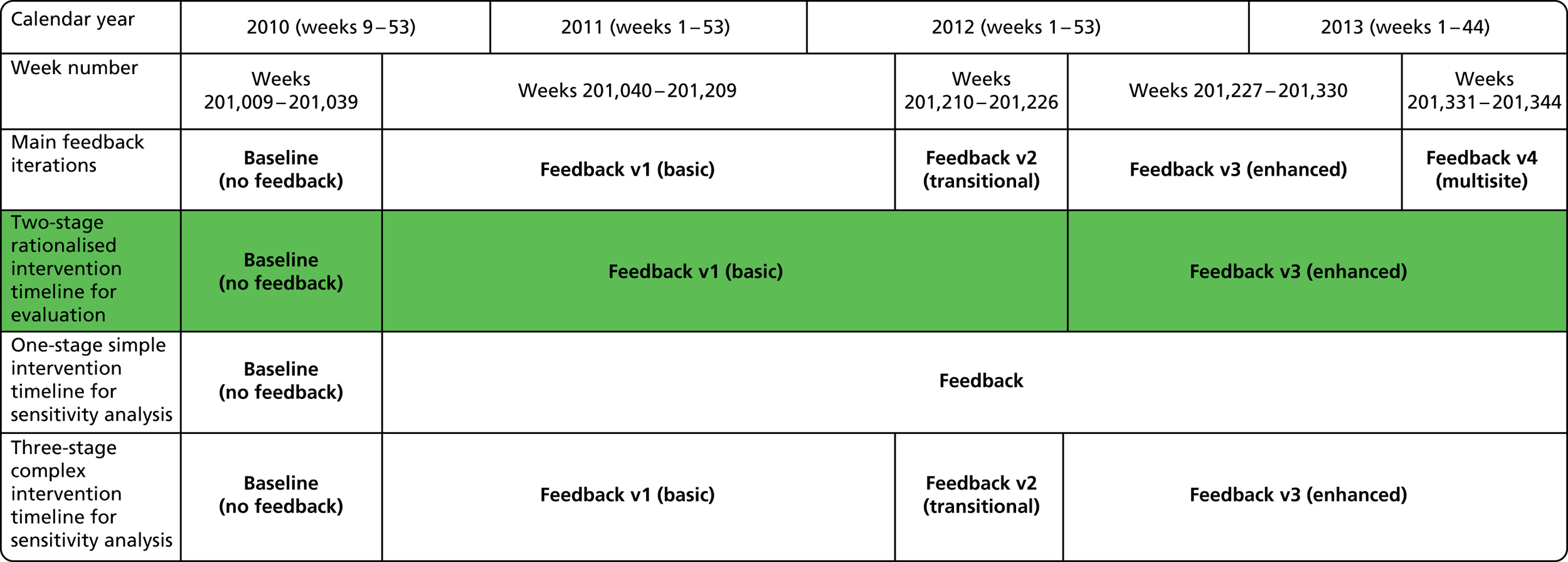

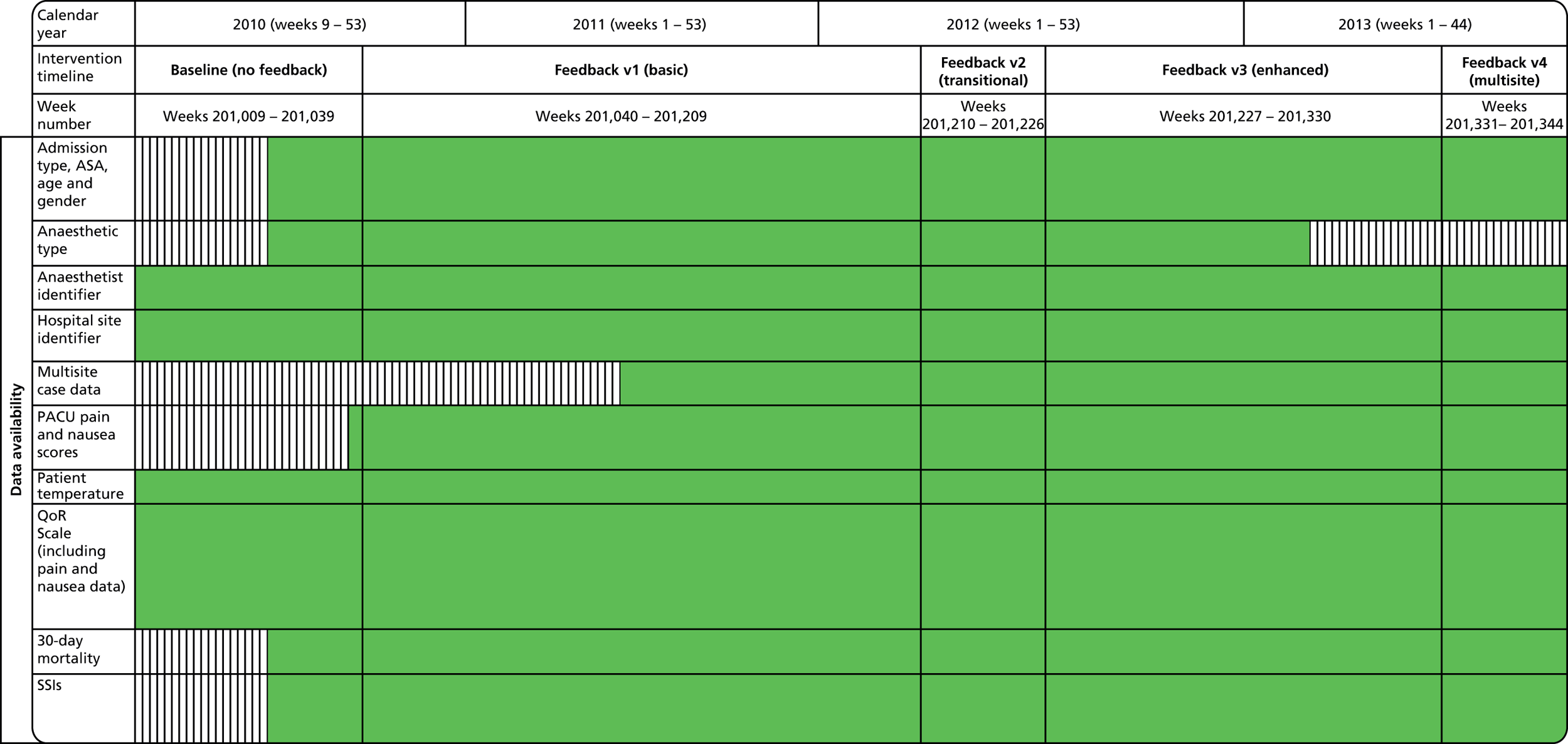

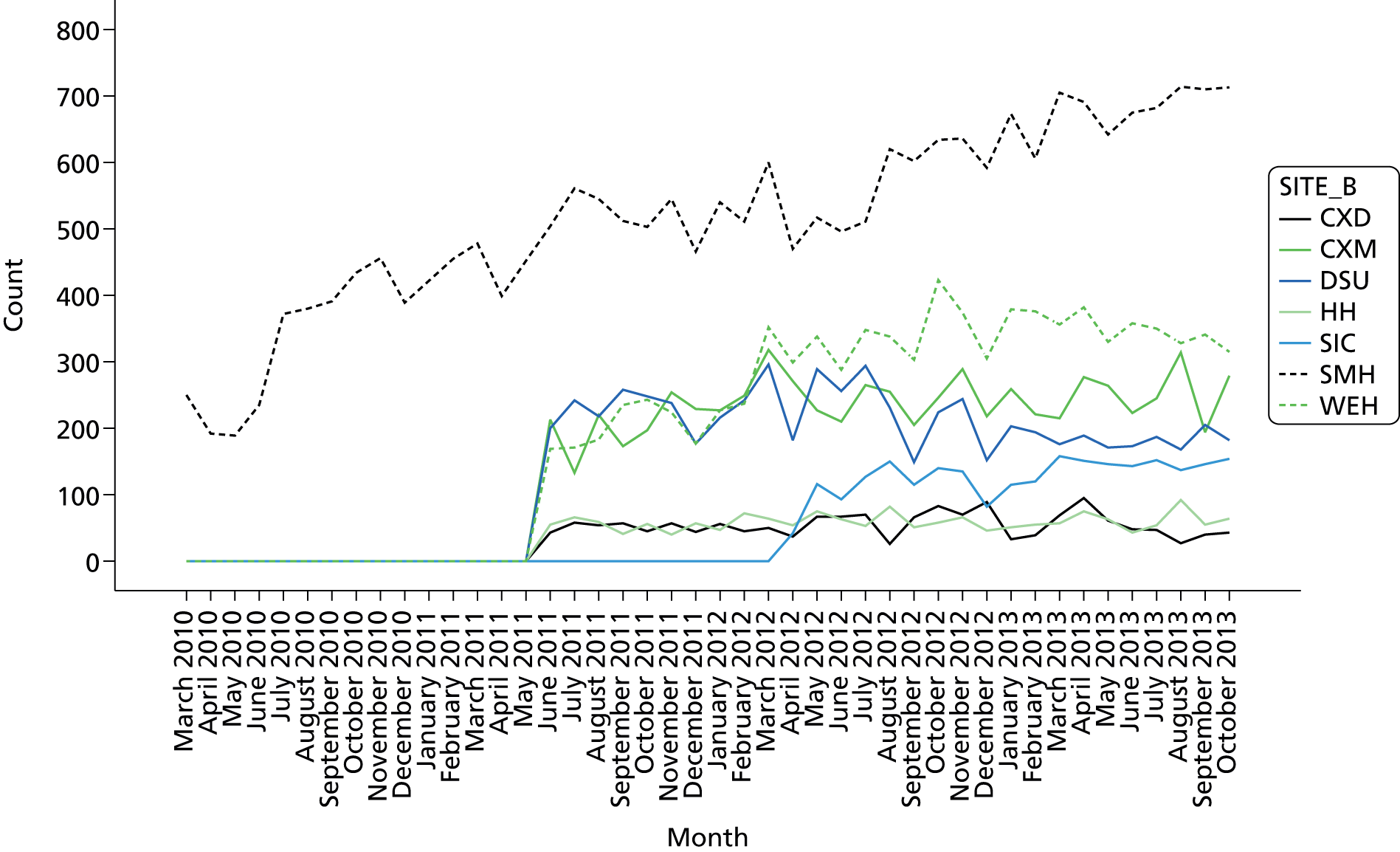

Baseline data collection of anaesthetic quality indicators began in March 2010 at St Mary’s Hospital main theatre suite, with basic feedback (version 1 of the report) introduced 6 months later in October 2010. Enhanced feedback (version 3 of the feedback report) was introduced in July 2012 and ran until the end of the project in November 2013. During the course of the project, many minor iterations were made to the feedback that consultant anaesthetists received, both due to development in the available quality indicator data set and in response to specific requests and feedback from the anaesthetist group. The project developed following the CLAHRC programme quality improvement model, which draws on established improvement science in health care and advocates rapid-cycle iterative development of quality improvement solutions.

Basic feedback consisted of the provision of monthly personal data summaries in tabled form for a limited number of summary quality metrics, compared with group-level averages without adjustment. Limited longitudinal and normative comparisons were included in graphical format. In contrast, the enhanced feedback phase of the intervention employed a design rationale that was driven by more active engagement with users and with a view towards providing specific data and statistical perspectives geared towards supporting personal learning from case experience. Provision of enhanced feedback included, in addition to the basic feedback content, monthly detailed case category breakdown, specialty-specific information, deviant case details, enhanced comparative and longitudinal data and institution-wide dissemination. During the enhanced feedback phase, engagement with the anaesthetist group was much more active, involving regular presentation of statistical results at meetings, consultative interviews by the research team for formative evaluation of the preferred features of the feedback for end-users and more focused engagement and facilitated peer interaction on specific specialty areas in which potential quality issues were identified (e.g. pain management after gynaecological surgery). During the enhanced feedback phase, the scope of data collection was increased to include multiple sites, which increased the prominence of the quality monitoring and feedback activities within the broader perioperative department across the trust as a whole.

Main approach and design rationale

Development of the feedback reports proceeded iteratively over time in response to several key categories of design rationale.

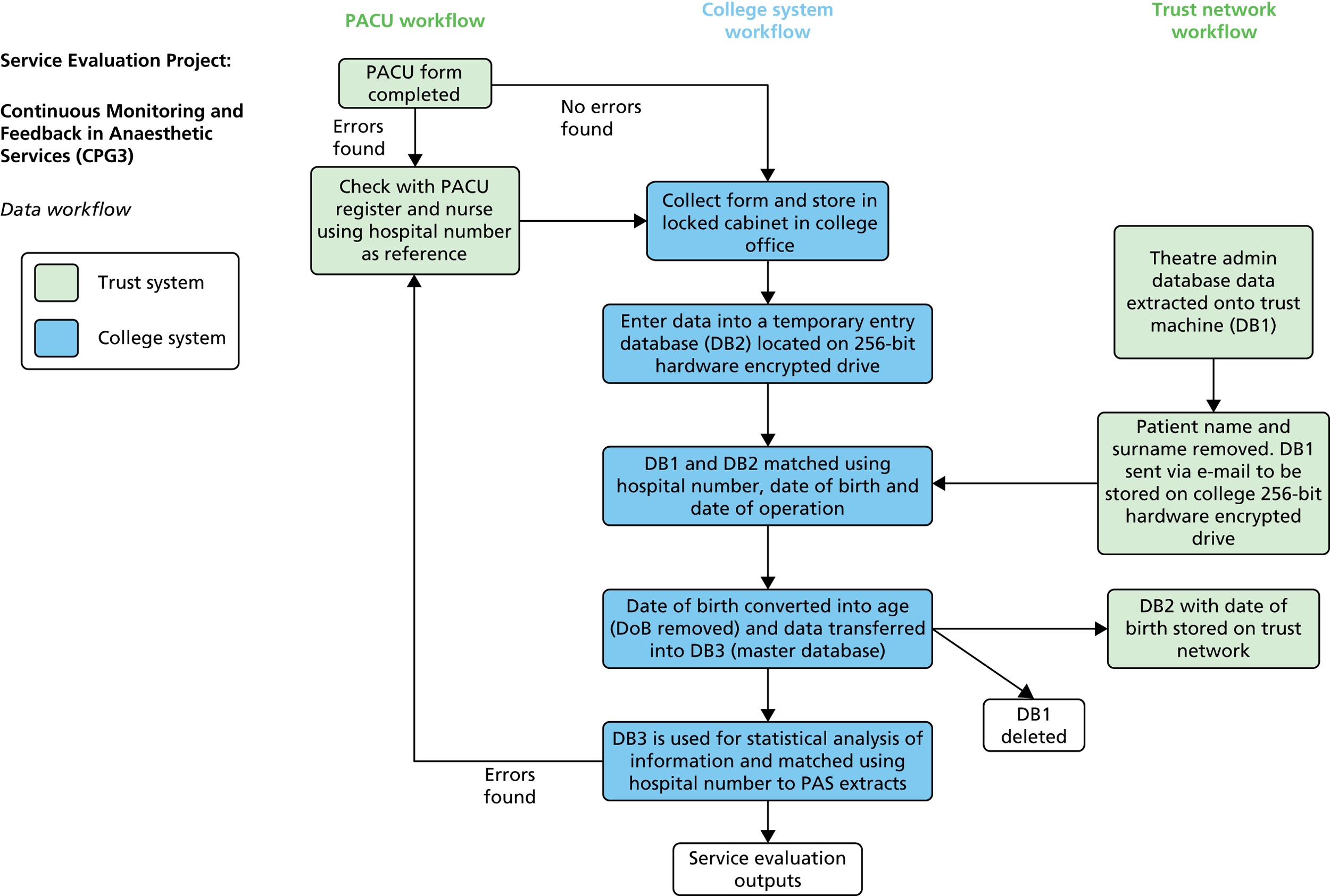

Increasing integration of the post-anaesthetic case unit form with the post-anaesthetic case unit nursing workflow and post-anaesthetic case unit patient information/data-logging requirements

The PACU nurses were required to maintain both a patient log book and, in later stages of the project, a computer-based theatre administration system database (‘TheatreMan’; Trisoft, Peterborough, UK), along with an electronic patient experience tracker (tablet PC-based). These requirements were in addition to the PACU form data collection to support the Improving Anaesthetic Quality (IMPAQT) initiative. Only the last two requirements could be completed in a flexible way at the patient bedside, and it soon became apparent that the PACU nurses were using the PACU form as a flexible record of patient recovery data, which was massed for multiple patients and then periodically entered into the log book and PC-based databases. This was an efficiency measure for staff, which overcame the need to repeatedly move between the patient bedside and the PACU PC workstation in order to enter recovery data. Our project team responded by ensuring that data items and definitions on the PACU form were compatible with the other data entry requirements and to make it clear which metrics were directly comparable (duplicate items) and which were unique to the IMPAQT initiative. The design rationale was that this would both reduce workload and enhance efficiency in terms of PACU workflow, while improving the reliability of our data entry system for the IMPAQT project.

Increasing availability of comparative databases, contextual information for individual patient records, quality indicator data available and analytic capability

Development of the PACU form to include additional/revised data items and enhanced definitions and guidance, usually in response to evidence that there was variation in consistency in the way in which the scales and items were being completed or in response to an identified need for additional metrics or more fine-grained analysis. With the introduction of the electronic theatre administration system (June 2011) and subsequent iterations made to that system by trust information services, the IMPAQT project had access to additional data that were automatically uploaded from the hospital patient administration system as well as enhanced theatre workflow data. Standardised contextual information at case level, such as specialty category and procedure type, allowed finer-grained analysis of caseload and disaggregation of QoR indicators by specialty in later versions of the anaesthetist feedback report. It should additionally be noted that, at first, with the introduction of this database, the additional data entry requirements and recovery metrics that needed to be collected interfered with PACU staff’s ability to accurately and reliably generate data against the original IMPAQT project items, and so the PACU form was streamlined to reduce the data collection burden, as described above, in an effort to improve data capture reliability. Subsequently, however, the availability of the TheatreMan database, along with the presence of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded researcher dedicated to the project, provided the opportunity to both validate the PACU form-based data set on which the IMPAQT project relied and complete missing data items identified in the IMPAQT database.

Theoretically and evidence-informed practice resulting from the research effort

As part of broader research undertaken at the Imperial centre and strategic collaborations with academic partners, the IMPAQT project team was able to draw on a range of health services research theory and practical experience in order to inform the design of the data feedback programme. Research into effective forms of feedback from quality monitoring identified by a systematic review suggests that effective feedback is timely, continuous, specific to the local context, non-punitive, is accompanied by a sense of local ownership of the data and is issued by trusted/credible sources. Similarly, the longitudinal perspective adopted in the data feedback reports was informed by quality improvement methodology (specifically, theory in the area of process control), which holds that useful data for improvement are generated through sampling small units repeatedly over time rather than large aggregated data collection time points. Evolving theory and research evidence in the science of improvement suggests that data for improvement have a number of distinct characteristics that distinguish them from data for judgement, research or audit (Solberg), and the IMPAQT anaesthetists’ reports were compatible with this perspective.

Responses made to feedback from the anaesthetist user group

The IMPAQT project involved close collaboration with the anaesthetist user group, and every opportunity to actively engage with the clinicians who were receiving and using the data was made. This occurred formally, through interviews with individuals and meetings with groups led by the research team, and informally through dialogue between individuals and the lead clinician for the IMPAQT project (GAr), who often received queries and feedback from the recipients of the monthly reports. The requested enhancements to the feedback reports included features such as elaborated details and contextual information for statistically outlying cases, and specific breakdown of case types/specialty to support personal case log books and to support professional appraisals. Analysis of user feature requests was a component of the formative qualitative investigation that was conducted as part of the evaluative research. Illustrative findings from this component of the work are described in the subsequent section.

User feature requests: formative input from the evaluation

In terms of future developments, 75% of respondents expressed an interest in a longer report with a more detailed breakdown that would increase the comprehensiveness of the quality metrics. Sixty-one per cent of respondents felt that in order for the reports to reach their potential they needed to contain a combination of both longitudinal and normative approaches to enable end-users to benchmark their performance both against their own baseline and within a comparable peer group. Table 3 illustrates the main types of feature requests that were requested during the formative qualitative investigation, which involved consultation with the anaesthetist group and individuals that volunteered to be interviewed by the research team.

| Requested change | Related codes from original analysis |

|---|---|

| More detail/specificity in the reports | Reports can afford for data to be added as long as they are meaningful |

| Feedback reports are not detailed enough to be used for revalidation and need to consider external factors | |

| Reports are too simplistic | |

| Information could be added to the report and it would not become too long | |

| The introduction of more complex information onto the reports would allow anaesthetists to identify what they need to change to improve | |

| Individuals should be able to request further information from the providers of the reports | |

| Measures need to be specific enough to make improvements based on them | |

| Request for more information on reports | |

| Need to be able to funnel down further in the reports to patient-specific information | |

| Need for more detail regarding the pain indicator | |

| Trainees to receive separate reports rather than being included under their consultant | Trainee data should not be automatically recorded under the on-call consultant |

| Data being recorded inaccurately under the anaesthetist who is on call rather than the anaesthetist on duty | |

| It would be useful to compare trainees with consultants | |

| Comparison based on case mix | Metrics that take case mix into consideration need to be incorporated into the feedback reports |

| Information on caseload is useful | |

| Information about an individual’s case mix needs to be more specific | |

| Without reference to case mix the feedback reports are not interpretable | |

| People are more likely to act on comparisons if case mix is considered | |

| Need to understand case mix in order to make valid comparisons | |

| Data presented at an individual level over time to enable the identification of trends | Anaesthetists want to see their own personal feedback over time |

| Individual feedback is more useful than normative feedback | |

| It would be useful to be able to instantly see your own feedback over time | |

| Need combination of normative feedback and individual feedback over time | |

| Simplification of the key messages | Summary pages are useful |

| Graphs displaying caseload need to be simplified | |

| Reports should be as simple and to-the-point as possible | |

| A more visual approach | Preference for graphics over numbers and statistics |

Main iterations to the data feedback intervention

The following sections of the report provide a detailed overview of the main developmental sequence of the data feedback component of the intervention.

September 2010: version 1.0

Initial version: the monthly anaesthetist feedback report is based on a rolling 12-month snapshot of the data (‘year-to-date’). It includes summary statistics for patient demographics and average/summary scores for pain/PONV/temperature of patients in the last month on the first page. Both basic time series and distribution charts were included based on key indicators: pain, PONV (PACU form data, simple three-point rating scales based on QoR audit tool). Time series depicts monthly score for individual anaesthetist compared with the average for the department. The report also included the ward wait time (WWT) data summaries and breakdowns based on the PACU form data.

March 2011: version 1.1

Moderate iteration (interim/transitional version): this includes rankings of anaesthetists among colleagues in response to feedback on the first version of the report. It also adds a case logbook with breakdown of personal caseload by specialty type to support anaesthetists’ requirements to maintain a case log record for appraisal purposes. Quality indicator score distributions for the anaesthetist group were focused on (i.e. a comparative view) in the reports, and the longitudinal (time series) charts depicting personal variation over time were dropped from this version of the report in order to accommodate the changes. These were subsequently reintroduced at the request of the research team with the view that the longitudinal view was important and compatible with the principles of measurement for improvement and process control, drawing on improvement science theory. In this version of the report, the data source switched from the PACU data set (which was maintained by an anaesthetic trainee at the time) to the theatre administration system. Pain and nausea metrics were recorded slightly differently in the theatre administration system, and pain scores in particular were now recorded using an 11-point visual analogue scale (the PACU data source was subsequently brought into alignment). The PACU data were also removed to allow focus on anaesthetic quality indicators. QoR scores were included.

May 2011: version 1.2

Minor iteration: personally identifiable position within the group distribution. The format was as above with some additional graphical views of personal caseload by specialty and over time. Time series graphs to enable longitudinal comparison with own scores over time were reintroduced. Crucially, in this iteration, identification codes were introduced for each individual anaesthetist so that an individual could identify his- or herself and where he or she fell within the group distribution compared with his or her colleagues (who were not identifiable to the individual). This is the first version of the report that includes full comparative and longitudinal perspectives. This report additionally flagged variation in quality of anaelgesia as an issue in the introductory text, as evidenced by variations in pain scores. Initial TheatreMan data were, however, incomplete and unreliable in places. QoR score data collected in recovery were not included in this version of the report as they did not appear to show any variation across the group (i.e. a potential ‘ceiling effect’ in the QoR measure).

October 2011: version 1.3

Minor iteration: expansion of the data set to include data collected in day surgery and the Western Eye Hospital, to ensure that anaesthetists who did a significant proportion of their cases in these locations received adequate data coverage. There were additionally some minor changes to the way in which the descriptive summary statistics were presented. These were included within more detailed text descriptions and explanations within each relevant section of the report, rather than presented in a summary table at the start of the report, largely owing to the need to define the origin of each data source in more depth now that multiple database sources were utilised. The log book section similarly expanded to accommodate multiple data sources, and the focus of the graphical data presentations was streamlined to depict the proportion of cases that fell out of acceptable threshold (e.g. proportion of cases arriving in recovery with core temperature < 36 °C), rather than to summarise based on the statistical mean.

February 2012: version 2.0

Major iteration: introduction of detailed breakdown by site of origin and comparison of pain scores by specialty. This version of the report represents a more mature format that consolidated several key features of previous versions into a single format, including the breakdown of personal and departmental summary data by specialty, which allows the user to account for case mix to a degree (i.e. compare themselves with a score based on comparable colleagues’ cases only). Key features include the development of a detailed breakdown by site of origin and comparison of pain scores by specialty. Note that this version of the report did not contain any longitudinal data views (time series charts). These were reintroduced partially in April 2012 and more fully later. This version of the report functioned as a pre-release mock-up of the intended final report design, developed with formative input from the evaluation and designated ‘version 3’. Version 2 was, therefore, an early release designed to gauge end-user reactions and opinions concerning the new format. The final version 3 report was implemented in June 2012.

The main structural sections and metrics included in this version of the report are as follows:

-

cover sheet and message

-

12-month personal caseload by anaesthetist and site

-

caseload breakdown by gender, age and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score (ASA’s classification of fitness of cases before surgery)

-

percentage of cases by specialty

-

distribution of anaesthetists’ patient temperature data (proportion of cases over 36 °C)

-

distribution of anaesthetists’ patient nausea data (proportion of cases without PONV)

-

distribution of anaesthetists’ patient pain data (proportion of cases with visual analogue pain scale scores below 4)

-

proportion of anaesthetist’s patients in pain by specialty, compared with departmental proportion.

April 2012: version 2.1

Minor iteration: as above but with addition of two longitudinal time series charts based on pain data.

June 2012: version 3.0 (final report implementation)

Major iteration: previous version consolidated and addition of a number of enhanced functions and features requested by anaesthetist group in response to exposure to various version 3 candidates since February 2012.

Version 3 of the anaesthetist feedback report represented a large development effort with enhanced input from the research team and from formative data from the evaluation project. Version 3 represented the consolidation of key features from previous iterations along with intensive development of the underlying database structure, Excel macro for report generation (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and addition of numerous enhanced data views and features derived from qualitative analysis of the requests and requirements of end-users interviewed as part of the evaluation project in early 2012. Crucially, version 3 of the report included full cross-sectional (peer comparison) statistics for all quality indicator measures, full longitudinal time series graphs tracking trends over time, flagged cases and contextual details to allow identification of specific case instances that violated set thresholds for quality indicators, and comprehensive specialty and site comparisons, to allow adjustment for case mix and selection of a comparable peer subgroup.

Version 3 report structure:

-

12-month caseload breakdown by anaesthetist and site (Surgical Innovation Centre, Western Eye Hospital, day surgery unit, Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother Hospital).

-

Annual logbook of cases broken down by surgical specialty as recorded in Theatre administration software.

-

Patient ASA score, age and gender breakdown.

-

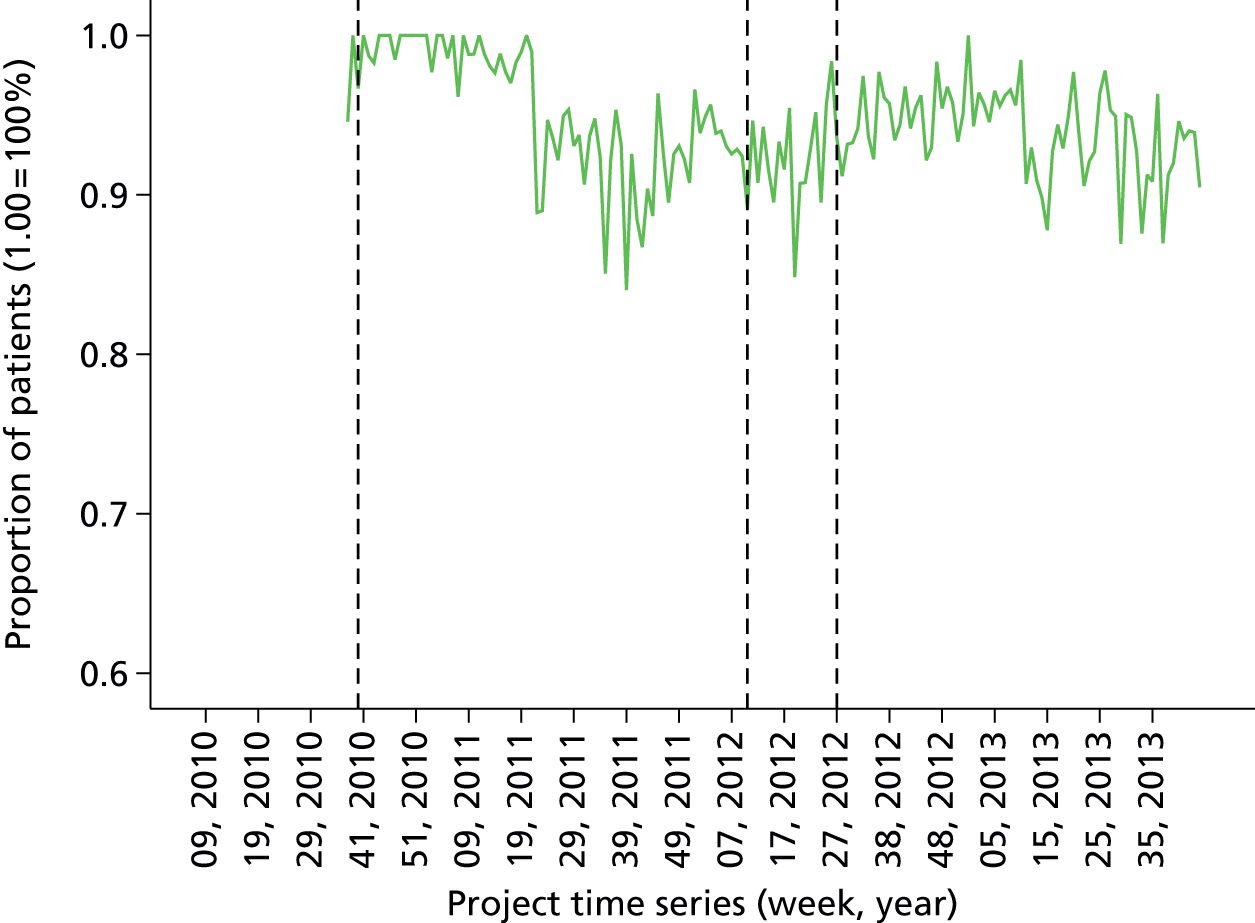

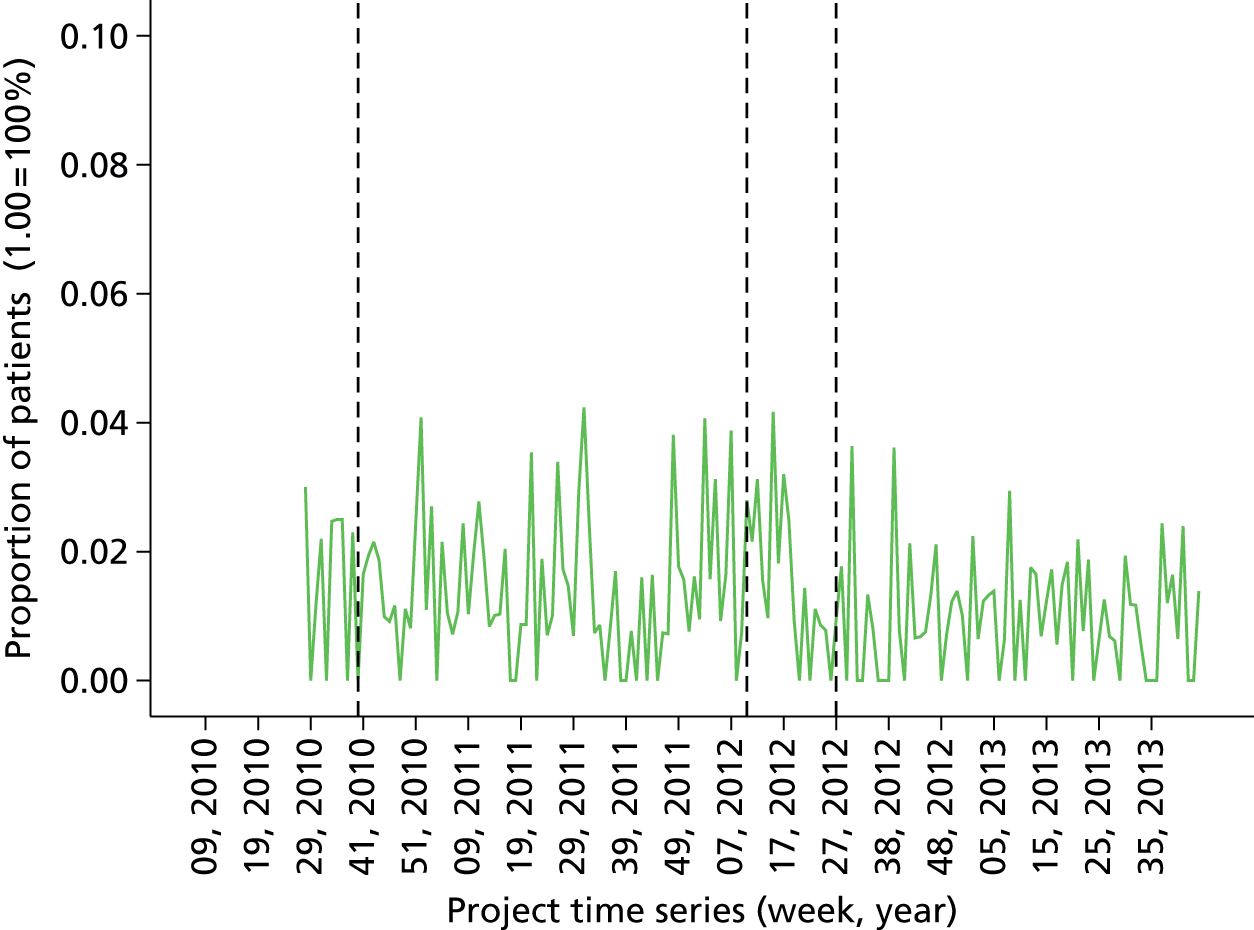

Proportion of all patients with temperature over 36 °C in last 12 months (cross-sectional comparison with peer group and longitudinal data over time by month). Breakdown by site over last quarter. Flagged cases and case details of patients that fell below threshold for temperature.

-

Proportion of all patients free from PONV in last 12 months (cross-sectional comparison with peer group and longitudinal data over time by month). Breakdown by site over last quarter. Flagged cases and case details of patients that fell below threshold for PONV.

-

Proportion of all patients with pain below score 4 in last 12 months (cross-sectional comparison with peer group and longitudinal data over time by month). Breakdown by site over last quarter. Comparison of pain scores with peer group by specialty (i.e. case mix adjusted). Flagged cases and case details of patients that fell below threshold for pain.

-

QoR Scale score distribution by anaesthetist.

July 2013: version 3.1

Minor iteration to version 3 format and site categories to reflect inclusion of data from other non-St Mary’s Imperial sites.

October 2013: version 3.2

Minor iteration to the way data were recorded in TheatreMan in response to requests to distinguish between cases in which a consultant was present and cases in which they were ‘supervising consultant’. No major changes to report format.

Chapter 6 Qualitative evaluation

This chapter reports the rationale, methodology and findings from the qualitative work stream of the evaluation. The chapter is divided into three key sections. Section 1 contains the qualitative process evaluation of the feedback initiative. The second section is a critical appraisal of the applicability of a number of pre-selected theories to the mechanisms of data feedback effectiveness. Finally, in section 3 we present core conclusions and recommendations from the work stream as a whole. Box 1 contains all key research aims from the original project protocol, with those of greatest relevance to the qualitative component presented in bold.

To evaluate the impact of a departmental continuous quality monitoring and multilevel feedback initiative on the quality of anaesthetic care and efficiency of perioperative workflow within a London teaching hospital over a 2-year period. Data will be analysed at multiple time points over the course of the project in order to generate both formative and summative information to support development and evaluation of the initiative.

To employ a quasi-experimental time series design to provide robust evidence concerning the impact of a serial data feedback intervention on anaesthetic quality indicators while controlling for baseline variance.

To contribute to the evidence base for valid and reliable quality indicators for anaesthetic care including effective patient experience measures.

To document the main features of the data feedback intervention as it develops through the CLAHRC programme for replication at other sites, including definition of metrics, data processes, feedback format and action mechanisms.

To assess the perceived acceptability and utility of this information system for individual end-users, the clinical department and other organisational stakeholders, using a formative, mixed-methods design.

The qualitative work stream of the project addresses these aims by providing a comprehensive requirements analysis for the sociotechnical design of the system based on multiple end-user and broader stakeholder perspectives. These outcomes provided formative input to the development of the feedback reports throughout the life of the project. The interviews assessed the perceived acceptability and utility of the information system for individual end-users, the clinical department and other organisational stakeholders. They also explored perceptions of the impact of the programme on local culture and attitudes towards quality of care and quality improvement including any associated organisational change issues. This component of the evaluation enabled us to qualitatively explore the mechanisms by which individuals and groups use the data to change practice by capturing specific narratives and use case scenarios. Alongside this it also supported the identification of key barriers and enablers to the successful development, implementation and utilisation of this type of quality monitoring and feedback system within a specific service context.

Qualitative process evaluation of the initiative

Introduction

In this section we report the qualitative process evaluation of the quality monitoring and feedback initiative. The purpose of the evaluation was to assess whether or not clinicians would engage with an initiative of this nature, whether or not they would find the quality indicator data provided useful and whether or not they would use the feedback to change their professional practice. Given the broader specialty focus on clinician revalidation and establishing quality indicators for anaesthesia, understanding the causal mechanisms by which an intervention of this type might result in changes to practice and outcomes is an important aim and precursor to further evaluative work. From a practical point of view, it can additionally provide important information concerning the role that the local context for implementation plays, which might influence the degree to which the intervention will generalise to other contexts. If the professional culture within a clinical department is reflective, with open and constructive sharing of past performance data in order to learn and strive for excellence, then the effects of any feedback initiative are likely to be enhanced compared with a unit which is characterised by closed or punitive dialogue on variations in care. Such an approach has been termed ‘process evaluation’ in the improvement science literature and advocates investigation of social, cultural and organisational factors in addition to effective intervention design. 92

Methods

Design

The design was a longitudinal, qualitative work stream which ran parallel to the intervention work and took a realist evaluative perspective on the project. The realist position provides a framework for identifying not only what outcomes are produced by an intervention, but how they are produced and how the intervention interacts with varying local conditions to produce the outcomes. Complex, multifaceted interventions are subject to phased implementation and intensive iteration. We therefore expected effects to be serial and cumulative over time. We also expected levels of engagement and impact of the initiative to vary as a result of ongoing interaction with contextual and organisational preconditions.

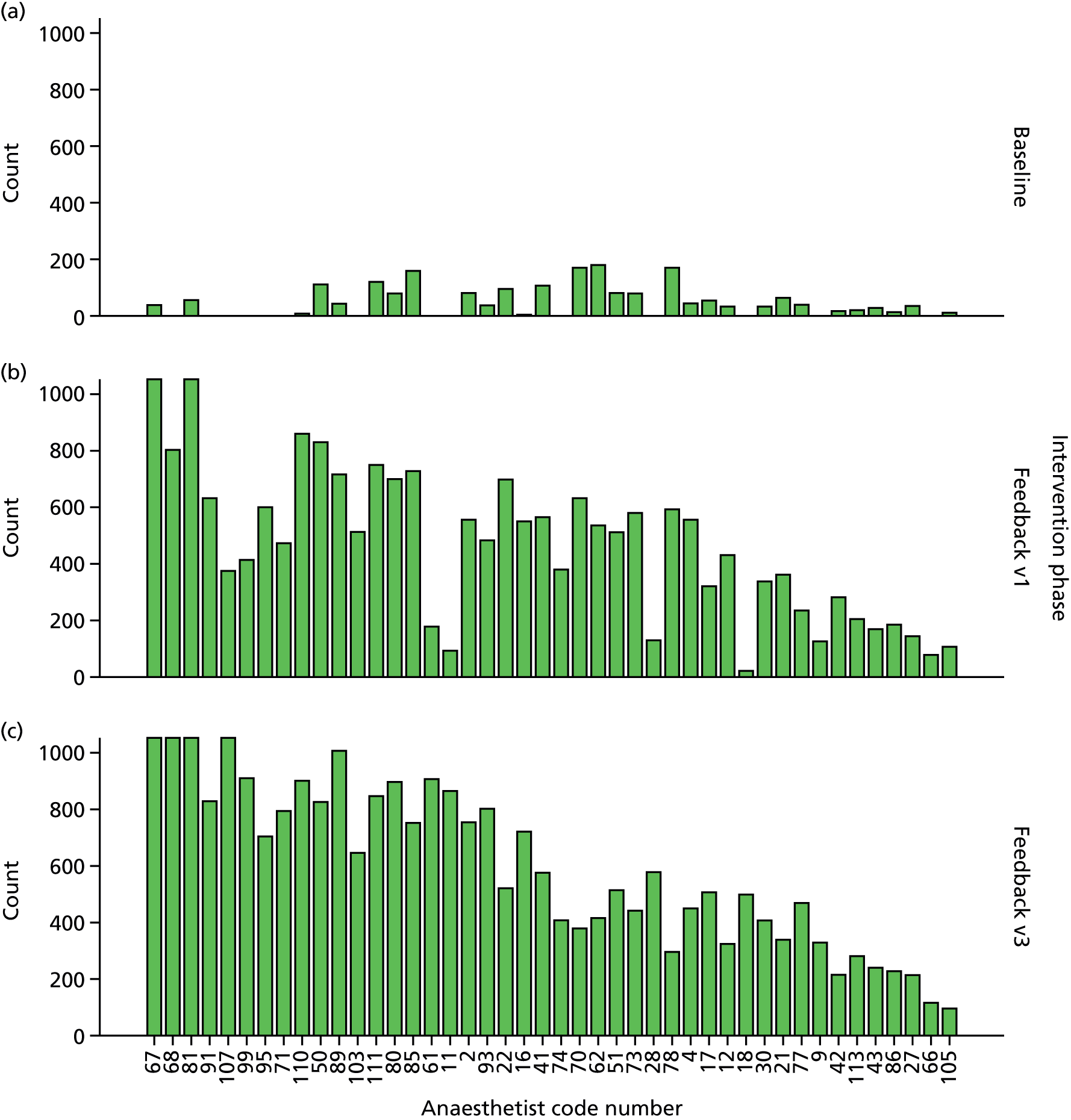

Participants

Participants for the interviews were perioperative service leads (including the lead nurse for the PACU), consultant anaesthetists and surgical nursing leads from the primary site at which the initiative took place. Potential respondents were approached to give feedback to assist in developing the programme and as users of the information it provided. These perioperative service stakeholders represent an array of actors in the processes of the previously described feedback initiative and enabled us to explore the different mechanisms of change that were under way. Forty-four consultant anaesthetists were contacted to participate along with specific perioperative service lead, surgical ward lead and recovery nursing roles that were selected based on professional position and level of expertise.

Data collection

Interviews were conducted by a research team including one senior social science researcher, two research associates in quality and safety, and two clinicians in training undertaking a research placement. Interviews determined the perceived value of specific quality indicators in anaesthesia and impact of feedback design. Furthermore, factors optimising engagement with the initiative were investigated as well as the mechanisms by which data were used to create behaviour change. Multiple interview schedules were used by the research team (dependent on the professional role of the participant, the time point at which they were being interviewed and their previous participation in the project). Table 4 provides a simplified overview of the topic areas with example questions covered. The research team received strong clinical input into the design of the interviews. The initial interview schedule was piloted with a senior consultant anaesthetist using a cognitive walkthrough technique in which the interviewers’ questions were first answered, and then discussed in depth in terms of wording, relevance and duplication. Appendix 1 reproduces the final interview schedule for consultant anaesthetists at time point 1 and Appendix 2 reproduces the final interview schedule for consultant anaesthetists at time point 2. The research team engaged in ongoing reflexivity throughout the data collection process. This involved individual researchers continuously reflecting on and discussing their own personal influence on the interviews that they were conducting and how this impacted on their understanding and interpretation of the data. The fact that the interviewers were already engaged in the operational process of delivering feedback to end-users raised potential issues of subjectivity and bias. This was counteracted by ensuring that multiple researchers engaged in the interview process and that any arising issues associated with the action research style approach to the project were discussed and reviewed at regular steering group meetings.

| Topic | Example questions |

|---|---|

| General views on feedback | In your view, what are the most important aspects of quality of care relevant to anaesthetics practice? |

| Do you think anaesthetists/PACU staff/ward staff generally get adequate feedback on these aspects of quality of care? | |

| Evaluation of the current initiative | What are your general thoughts about this initiative and the feedback reports that you receive? |

| What was your initial reaction to seeing your data? | |

| How do you use the information contained within the reports? | |

| Departmental perspective | What is the potential value of this initiative to the department? |

| How do you think the department itself should use the data? | |

| Project stakeholder questions | What are the implications of this initiative for the anaesthetics specialty? |

| Can you see a role for initiatives of this type in revalidation? | |

| Future development | Are there any measures, features or functionality that you would like to see included in future versions of the reports? |

| What further support could be provided for anaesthetists/PACU/wards to use these data to improve care? | |

| Broader context | Do you see any barriers to engagement with and utilisation of this initiative? |

| Is there anything about the organisation or context in which you work that might make a system like this one more or less successful? | |

| Do you think there is an atmosphere of transparency here among the clinical group/nursing directorate concerning quality? | |

| Longitudinal component | Have your views about the feedback reports changed or developed in any way over time? |

| Have your perceptions about anonymity changed over time? |

Analysis

Analysis was led by a research associate in quality and safety and took an inductive approach, informed by principles of grounded theory and social constructionism. 93,94 This enabled themes to emerge naturally from the data without the influence of prior theory. Interview recordings were transcribed, read and reread until the data were familiar. The transcripts were then open-coded into units of meaning using NVivo software (version 10, QSR International, Warrington, UK). Units of meaning were later coded and grouped into broader themes and subthemes. The emerging qualitative template was reviewed and discussed with strong clinical input from three consultant anaesthetists and a junior doctor, as well as ongoing academic input from the senior social sciences researcher. Results were presented to the project steering group on two occasions to gain further senior academic perspectives on the work, and findings with high relevance to the development of the feedback reports were regularly sent to operational leads. A number of iterations were developed until no new categories of meaning were derived. Content analysis was also employed where appropriate to quantify responses. 95

Results

Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes each. In total we analysed approximately 22 hours of interviews with 24 consultant anaesthetists, six surgical nursing leads and five perioperative service leads.

Content analysis

The results of the content analysis are displayed in Table 5. Results are shown in figures as well as percentages to accommodate the fact that not all participants responded to all questions. Ninety-five per cent of respondents felt that they did not generally get systematic and objective feedback on the quality of care that they provided. However, 57% of respondents described specific changes that they had made to their practice as a direct result of the current initiative, and 90% of respondents agreed that the reports had strong potential for use as part of the upcoming revalidation process.

| Question | Response |

|---|---|

| Do you think anaesthetists generally get adequate feedback on these aspects of quality of care? | Yes: 1 (5%) |

| No: 18 (95%) | |

| Are there any examples of changes you have made to your practice? | Yes: 8 (57%) |

| No: 6 (43%) | |

| Would you rather see your data compared with others’, your data displayed over time, or both? | Normative: 1 (8%) |

| Individual: 4 (31%) | |

| Both: 8 (61%) | |

| Would you be interested in a longer report with a more detailed breakdown/analysis of your data? | Yes: 9 (75%) |

| No: 3 (25%) | |

| Can you see a role for initiatives of this type in revalidation? | Yes: 9 (90%) |

| No: 1 (10%) |

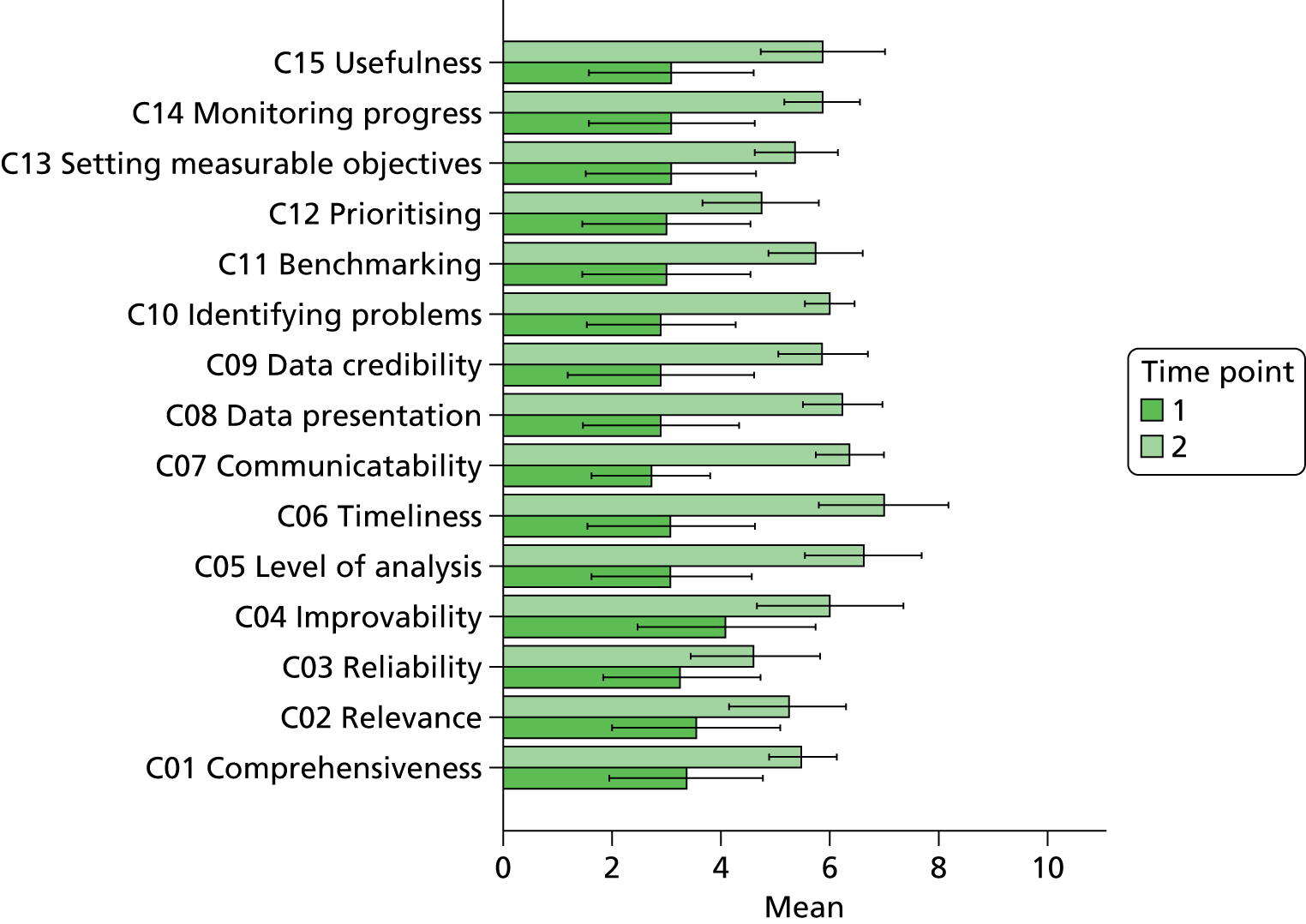

In terms of future developments, 75% of respondents expressed an interest in a longer report with a more detailed breakdown that would increase the comprehensiveness of the quality metrics. Sixty-one per cent of respondents felt that in order for the reports to reach their potential they needed to contain a combination of both longitudinal and normative approaches to enable end-users to benchmark their performance both against their own baseline and within a comparable peer group.

Formative evaluation (feature requests)

Throughout the interviews a number of requests were made for iterations to the feedback reports. These were fed back to operational leads and where possible were integrated into the development of the project. Table 6 lists the requested changes with links to their original qualitative codes and example quotations from the time point 1 analysis.

| Requested change | Related codes from original analysis | Example quotations |

|---|---|---|

| More detail/specificity in the reports | Reports can afford for data to be added as long as they are meaningful Feedback reports are not detailed enough to be used for revalidation and need to consider external factors Reports are too simplistic Information could be added to the report and it would not become too long The introduction of more complex information onto the reports would allow anaesthetists to identify what they need to change to improve Individuals should be able to request further information from the providers of the reports Measures need to be specific enough to make improvements based on them Request for more information on reports Need to be able to funnel down further in the reports to patient-specific information Need for more detail regarding the pain indicator |