Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1002/37. The contractual start date was in December 2011. The final report began editorial review in February 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Rushmer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

What is the problem and why should we care?

Across the world, considerable time, effort and money invested in health research are creating a better understanding of effective and efficient health interventions (the evidence base). National and international policy documents clearly reflect the need to use, where possible, the evidence base to inform effective practice. 1–5 These policy calls, to ‘close the gap’ between what we know works (the evidence base) and frontline practice, occur across multiple policy areas as diverse as health, planning and information technology (IT) development,6–9 attesting to the prevalence, complexity and persistence of this problem. Evidence from the late 1990s suggested that, on average, it takes 17 years for evidence to shape frontline practice8 and, 12 years on, despite more than a decade of translational research efforts in health-care research, the same conclusion was reached by different authors. 10 The problem is one of wasted resources (money and effort) creating an unused evidence base, suboptimal care provision (based on less effective care or poor delivery) and a moral argument that so much time and effort is expended in doing the ‘wrong thing’ to achieve ‘less than the best’ results. This seems to suggest an ideal where research evidence, policy drives and practice align to deliver optimal care, and where practice does reflect a strong evidence base, we know that outcomes can improve. 11 However, in practice, this may be simplistic. It is to address these issues that this project was undertaken.

In public health there are specific challenges to research utilisation. The very nature of public health problems is that they are complex, multifaceted, interlinked and difficult to address with simple interventions. 12 Solutions may need to address health, social and political factors, take time and require support from various stakeholders, making it difficult to establish clear evidence of effectiveness. 12 Specific difficulties are threefold.

First, the evidence base is often patchy or not proven and may be contested. 13 Key stakeholders may believe that local conditions are counterindicative. 13,14 Additionally, public health agendas span health, local government and voluntary organisations with distinct research cultures, governance and procedural processes and different ‘employee’ members. Efforts to join up public sector services to enhance coherence and co-ordination in the pursuit of ‘joined-up services’ have proved difficult. 15,16 We know that it is still particularly hard to get research information to flow over professional and organisational boundaries. 17–20 All of this suggests that gaining agreement on priorities and actions may be challenging. 14,20,21

Second, the evidence base may not address the questions that practitioners, managers and commissioners (given the exact task in hand) want answered, when they need answers: here the evidence base appears to be less than useful, untimely and largely irrelevant, as Lomas writes:

Decision makers – the patients, the care providers, the managers, and the policy makers – tend to see research as a product they can purchase from the local knowledge store, but too often it is the wrong size, needs some assembly, is on back order, and comes from last year’s fashion line.

p. 13019

Third, a range of contextual factors suggest that the evidence base may not be as objective as it is claimed. Culturally, how participants make sense of their activities22 can inform what counts as evidence (e.g. home births are considered safe in Canada but the USA favours hospital births). 23 In this instance it may be financial and legal concerns, and not research evidence, that define acceptable practice. 23 Politically, evidence emerging from research funded by powerful groups (the drug companies; legislative groups), can squeeze out opportunities to collect competing evidence. 24 Conventionally (see typical online sources that offer guidance to practitioners),25 the ‘hierarchy of evidence’ privileges quantitative, statistical randomised controlled trials (RCTs), largely ignoring plentiful observational and narrative data regarding what the public prefers or what is culturally acceptable and might work. 26 Furthermore, the introduction of evidence-based practice may be seen as an attempt to impose management control on wieldy and costly processes to standardise practice around a politically driven agenda27 rather than public choice or public need. It is not just practitioners who may feel that research evidence can be abused; researchers may feel that evidence is misused or used selectively to support favoured policy positions or practices. 28

The above illustrates that implementing an evidence base and research utilisation is a complex, dynamic process subject to social, contextual and political influence14,17,18,29 and it becomes clear that services do not fall out of policy directives in any simple, straightforward or automatic way. The research reported here was designed to be sensitive to these social processes. Two in-depth, mainly qualitative, case studies were undertaken, working in cocreation with the research participants rather than doing research on them, respecting their situated expertise and mindful of their contexts.

The contextual backdrop to this project

Two factors inexorably shaped this project as it took place. The proposal was written, funded and empirical data collected at a time of international financial downturn, resultant financial constraints and the dawning of an ‘age of austerity’ in the UK. Alongside this, the reforms to the public sector of April 2013 and the transitional period leading up to this created churn, instability and uncertainty within services trying to carry out business as usual. Some of the difficulties and disquiet surrounding the reforms was contextually ‘swept up’ with other data and our findings cannot be fully understood without reference to this troubled context. The influence of this context appears throughout the report.

The project was designed to cross-compare research utilisation across policy contexts (commissioning in England vs. joint planning in Scotland) and this remains the case (see Chapter 3). However, the parallel decision to design and operationalise this project in cocreation with co-applicants and research participants also left a deep footprint on the findings as they are reported here. In particular, in an effort to research a topic of most pressing need, salience and usefulness to our case study participants (and to secure ‘buy-in’), our case study partners picked the topic of the process case study themselves. When each picked a different topic (licensing vs. maternal alcohol consumption), this made little difference to the core conceptual design (investigating evidence use), but substantially impacted on aspects of the proposed work that needed more traditional approaches. The small health economic component of the project was largely neutered, with no like-for-like health issue to compare relative performance on; it became solely reliant (partially as envisaged) on measures of overall organisational performance. However, existing performance measures also changed during the life of the project, making it difficult to tell a longitudinal story around the organisational performance of our case study sites (see Chapter 8, Limitations of the study).

Structure of the report

This report lays out the design, operationalisation and findings of the project. The first three chapters give the background. Chapter 1 introduces the topic area and its importance; Chapter 2 reviews the literature to summarise what we already know about the topic areas, including the ‘promise’ of cocreation; and Chapter 3 outlines the methodology of the project including the ‘plan’ for cocreation, the five workstreams and the methods of data collection and analysis. The next three chapters report on the findings and are interspersed with analysis, comment and discussion. Chapter 4 reports on evidence use in the alcohol licensing process in the Scottish case study site and Chapter 5 reports on evidence use in commissioning to reduce harms related to maternal alcohol consumption in pregnancy in the English case study site. Chapter 6 reports on the findings from the national seminar and the questionnaire issued to explore how the findings from the in-depth case studies play out elsewhere. The final two chapters discuss the significance and implications of the findings, with Chapter 7 reflecting on the ‘experience’ of cocreation and Chapter 8 providing a high-level synthesis of ‘what works’ in relation to the dominant programme theory: Research evidence will enable public health functions to be met more easily. We conclude that research evidence is necessary and useful, but that it is only one part of a complex set of considerations.

Chapter 2 Literature review

Preamble

Best et al. 30 outline three phases through which the conceptualisation regarding what it takes to get evidence into practice has developed: from linear discrete models; through an appreciation of the quintessentially relational nature of the process; and on to a growing understanding of its largely unpredictable and complex nature. One conceptual framework has not replaced the others, and all three understandings, to a certain extent, coexist. We begin this short review of the extant literature with a look at the linear model of knowledge translation and its rise to favour in the evidence-based practice movement of the 1990s, using this as a springboard to explore the developing theoretical understanding of the broad area of translational research.

Methods

We searched academic literature databases: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); The Cochrane Library; Google Scholar; GoPubMed; Scopus; Social Science Research Network (SSRN); and Web of Science. We used (but were not limited to) the following search terms: translational research; knowledge transfer; knowledge translation; knowledge exchange; knowledge exchange and linkage; knowledge integration, evidence-based medicine (EBM); evidence-based commissioning; participatory research; action research; cocreation, co-production; complex systems; and complexity linked to health and public health. The search terms ‘research utilisation’ and ‘public health’ identified 973 papers. We cross-referenced these papers with those identified via other combinations of search terms and 729 papers appeared more than once. We hand-searched all 973 titles (and then abstracts if the titles appeared to be relevant) and 393 papers were of some relevance. We also searched for ‘alcohol’ and ‘licensing’ (availability, affordability, public health and interventions), ‘pregnancy’, and ‘alcohol-related harm’ (health care professionals’ attitudes, fetal alcohol syndrome) linked to public health and interventions. What follows is not a systematic review, nor does it limit itself to one evidence type. It draws on qualitative studies and grey literature (in particular, policy documents, professional guidelines and advice), and reports findings from quantitative controlled studies to give an overall narrative review reporting on relevant findings. In addition to this search approach we also drew on the principal investigator’s knowledge of relevant papers, authors and debates in the area to include papers from their personal archives not directly surfaced via the search terms. This is an approach advocated by Øvretveit31 as more inclusive of cognate conceptual issues and empirical findings in related, but parallel, disciplines.

Producing and getting evidence used: the linear model (push and pull)

Historically, within Western societies universities were acknowledged as ‘the first and foremost knowledge producer’. 32 Dissemination followed a top-down approach with the expectation being that, once produced, knowledge was automatically implemented. 29,33,34 Early models of EBM were based on positivist, quantitative and biomedical modes of understanding (see discussion in Blevins et al. ,33 Golden-Biddle et al. ,34 Øvretveit35 and Goldenberg36).

This process was seen as largely linear, one-way, rational and unproblematic. The aims and purpose of EBM are articulated well by Dopson et al. , who argue that EBM:

. . . is about creating a culture where practitioners automatically think in an ‘evidence’-based way every time they see a new case, where it becomes instinctive to seek out research evidence and base treatment decisions on that evidence.

p. 31737

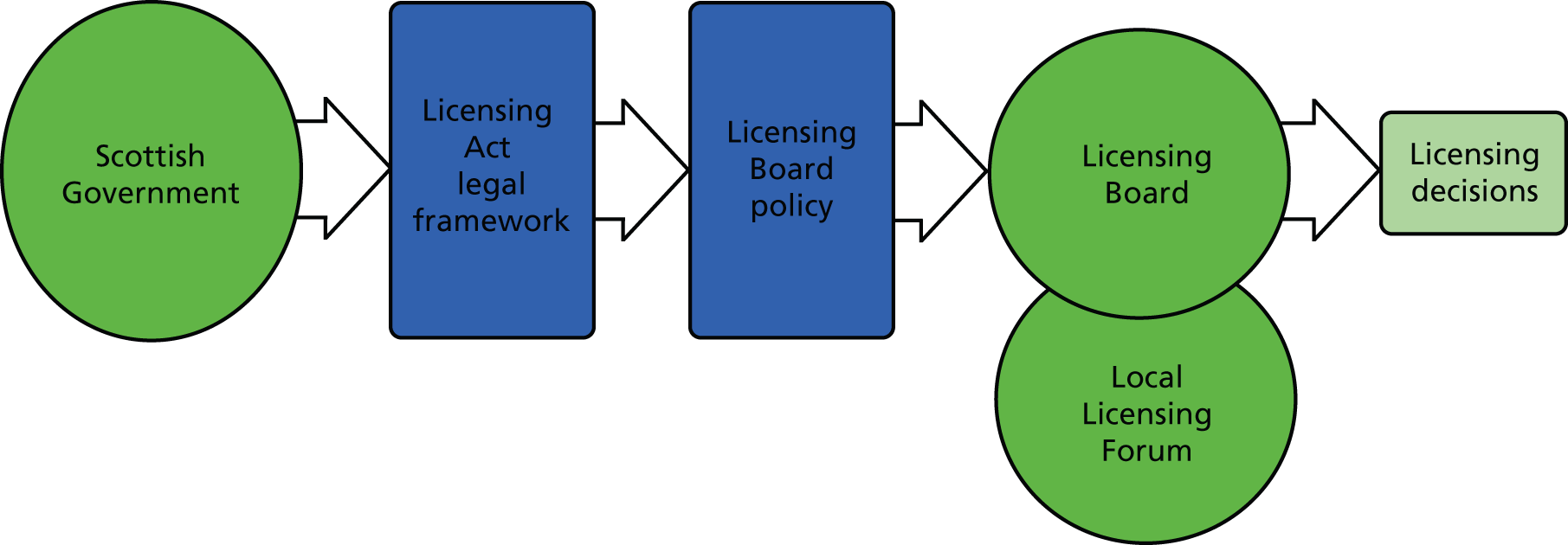

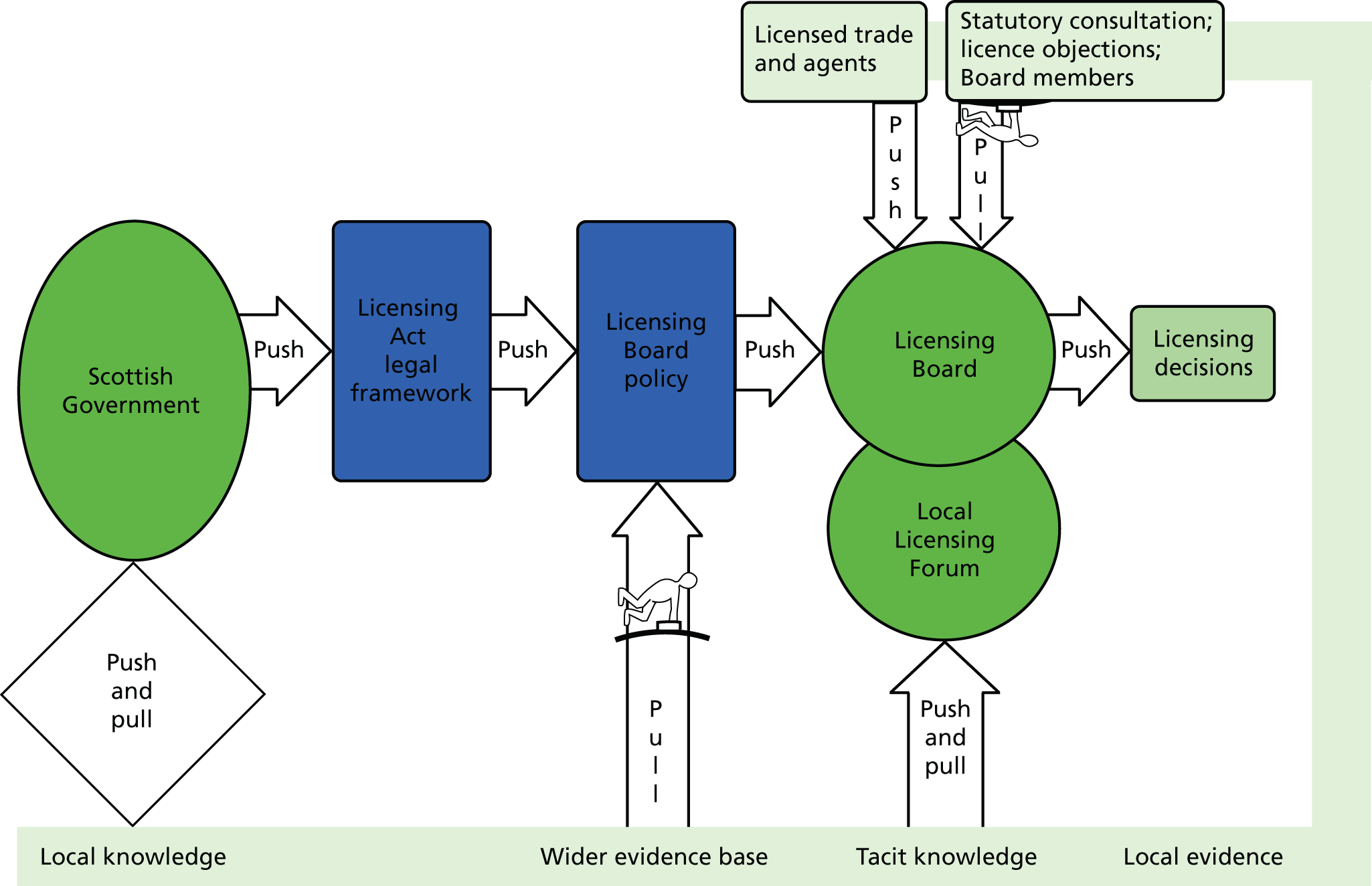

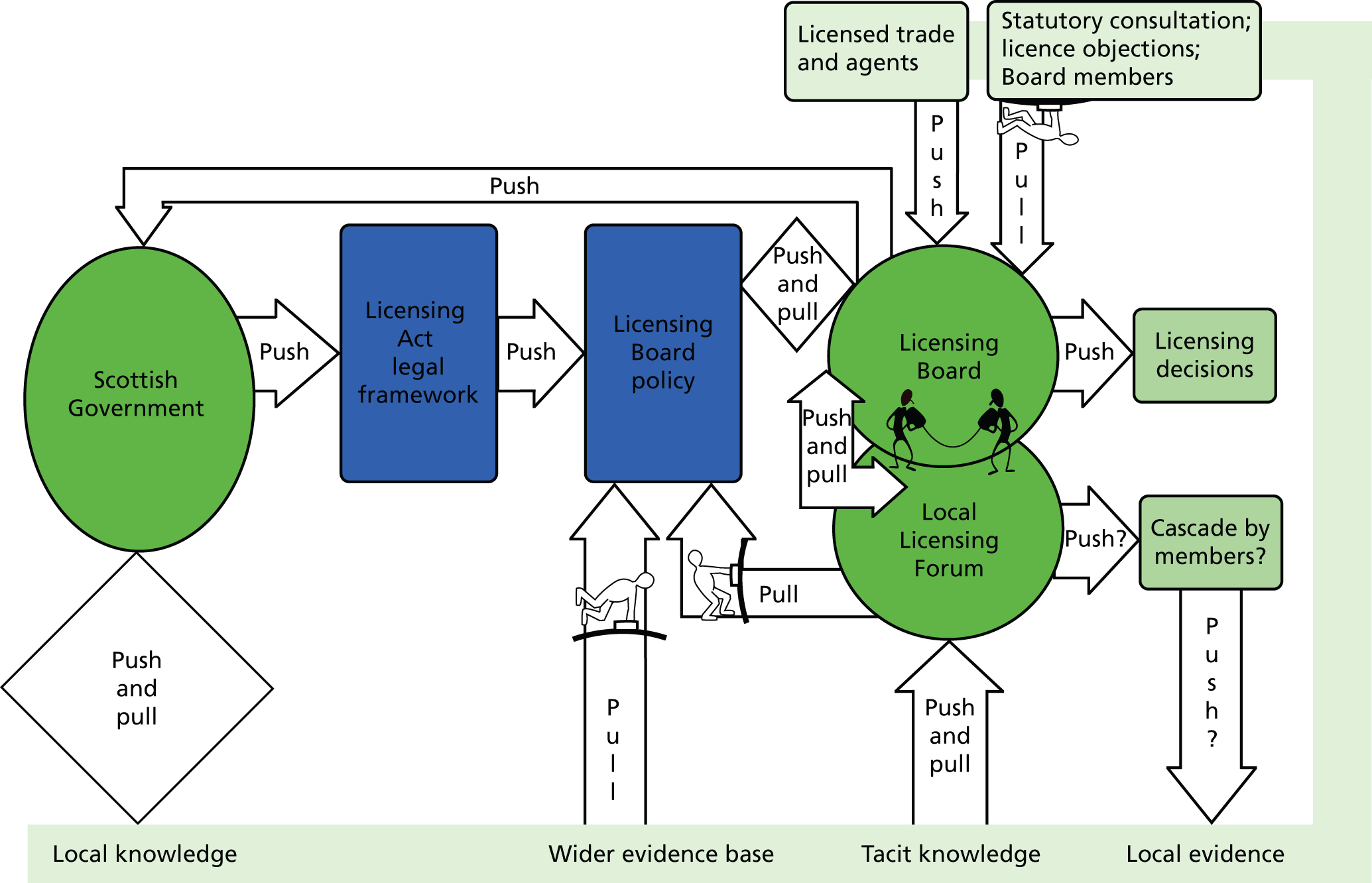

So, if EBM and other linear models worked well, it would not simply result in the ‘push’ of evidence into practice by evidence producers but would also result in practitioners’ desire to ‘pull’ evidence into their practice for themselves. 38,39 Davies et al. 39 conceptualise knowledge transfer as including three activities: knowledge push (from evidence producers to evidence users), knowledge pull (from users) and linkage and exchange (engagement between producers and users). 19,39 Kerner et al. 40 suggest that passive diffusion is generally ineffective in changing practice, and that effective dissemination should be a push–pull process whereby those who can adopt innovations want and are receptive to them (pull) and there are, at the same time, clear efforts to assist the adopters in implementing the innovation (facilitation and support). Furthermore, they suggest that tacit knowledge based on experience drives pull while explicit knowledge from research drives push. Tetroe et al. 41 note that ‘push’ involves diffusion and attempts to disseminate information to a broad audience, ‘pull’ focuses on the needs of users and creates an interest and desire for research results and ‘linkage and exchange’ exchanges knowledge and ideas by building and maintaining relationships through which information and ideas can flow.

It became clear that EBM could not be simply a matter of applying recipes or predetermined guidelines because their appropriate application required the use of clinical expertise in addition to clinical evidence and was heavily influenced by professional and peer opinion,21 although latterly within EBM it is acknowledged that there is considerable variation in what is considered ‘evidence’ (anecdotes, clinical opinion, qualitative data, etc.)42 and not all evidence is seen as equivalent. 37,43 The dominant view of the capacity of different types of evidence to faithfully tell us about the world is reflected in the ‘hierarchy of evidence’, with RCTs at its pinnacle and, more latterly, the meta-synthesis of RCT evidence (see discussion in Lambert44 and Petticrew and Roberts45). At this point in time research evidence (and in particular research evidence produced through particular methodologies) was considered to present a privileged view of the world and offer a superior take on ‘what works’ regardless of context. These views were not without challenge, with others considering that the selection and use of specific methods and research designs was a matter of ‘horses for courses’, with differing approaches being useful for answering different research questions (RQs). 45

A changing view of evidence

The rise of EBM led to calls for such an approach to be adopted in policy and health-care management settings. 46,47 Others have argued that attempts to translate the principles of EBM into evidence-based policy have misunderstood the policy process. They argue that the policy process is already evidence based, but that it draws on a different kind of evidence:

Policy decisions incorporate evidence as to whether a policy will be implementable in practice, and whether it will be politically acceptable. Any policy which cannot meet these criteria is not worth pursuing, whatever the research evidence says.

pp. 325–637

In policy development, the social, political and economic climates in which organisations (and vested economic interests) operate may also be significant considerations. 48 Sanderson49 highlights that, in practice, the complexity and messiness of policy decision-making raises the issue of the role that value judgements play, and suggests that researchers should consider adopting a broader perspective on what counts as ‘evidence’ by investigating how ‘valid knowledge’, as well as research evidence, informs policy-making. 49 In their discussion of the role of evidence in health promotion and public health, Sanderson49 and Armstrong et al. 50 suggest that the complexity of decision-making means that the development and use of evidence is difficult and contentious. Both argue that a collaborative approach is needed for gathering and applying evidence, which requires health practitioners and academics to work across sectors.

What is developing is a growing understanding that evidence and other forms of information flow two ways, influenced by context and the prevailing social dynamics within it, and that to fully understand these issues, understanding context becomes important. The literature begins to acknowledge the way in which different types of evidence are varyingly and competitively used, perhaps with different stakeholders keen to demonstrate that they have (politically) better traction on what will actually work in situ. While Contandriopoulos et al. 51 suggest that for researchers it is the internal validity of a process that leads to ‘best evidence’ (i.e. evidence produced through a recognised research process), they question whether or not this holds the same importance for practitioners. They argue that as evidence users are exposed to diverse forms of information, only some of which has been produced through scientific methods, they are unable to weight information on the basis of internal validity alone. Tacit knowledge, personal values and experience may all carry significant weight. 50 Kothari et al. suggest that tacit knowledge is widely embedded in the planning of programmes and services in health-related areas. 52 In these contexts, practitioners may draw on both personal and professional experiences in the construction of ‘what they know about the world’ (knowledge frameworks), and tacit and professional knowledge may influence practice to a greater extent than evidence based on specific research findings.

Increasingly nuanced views of what constitutes knowledge, evidence and research utilisation appear where practitioners are no longer considered merely consumers of university-produced knowledge. 34 Knowledge produced ‘in the sterile laboratory of the isolated scientist’53 (p. S2.2) is no longer considered ‘real knowledge’53 (p. S2.2), and academic research, which rarely meets the direct needs of policy and practice,51 is often ignored. 30 Tacit knowledge, previous experience and the influence of colleagues, however, have become recognised as powerful guiders of action. 21,32,52,54–56 Boaz and Ashby57 argue that in order to facilitate the development of evidence-based practice and policy, a broader conception of research quality is needed, which includes its fitness for purpose rather than just traditional academic measures of quality. On a more pragmatic level, it has been suggested that commissioners need three types of knowledge: knowledge from research (‘evidence’), knowledge from data analysis (e.g. statistics) and knowledge from clinician and patient experiences. 58

Specific challenges of getting evidence used in public health

Getting evidence from public health research into decision-making and real-world practice is not straightforward;33 it is not the linear process it is sometimes believed to be, and may bring its own challenges. 28 This results in part from the diversity of topics, organisations and environments that form public health,59 and in part because there is little consensus around what constitutes either knowledge or research utilisation in these contexts. 51,60 The issue is further complicated by the increasing range of terms used to describe these processes. 51,61 The terms are often used interchangeably, with an oft-implied assumption that everyone has the same understanding of their meaning.

These debates attest to the view of evidence (and its use) as being not a simple, identifiable ‘thing’ (a product that is portable), but rather a dynamic process which may vary according to what evidence is being used, by whom and for what purpose. What counts as evidence on any one occasion may, in fact, be largely ‘worked up’ in the flow of the setting of its use. What counts as evidence may be what those involved can be persuaded is evidence (proof) on that occasion. 62 Research utilisation may be not simply the instrumental, goal-orientated action that the linear model suggests, but that all types of evidence may be used tactically, strategically and politically to steer action in certain directions, or stall and silence as well encourage debate, and as ammunition in securing the imposition of the desired actions of a few. 22,63

Traditional interpretations propose that barriers to research utilisation exist because researchers and practitioners occupy differing ‘communities of practice’,64 each with their own perspectives of knowledge and utilisation,32,65 where discussion and information sharing flow freely among members but where flow occurs less across community boundaries. 17,32 Each community works to its own identified time scales and priorities, and these may not be well synchronised. 19 However, the interlinked, multifaceted nature of public health issues themselves, the responsibility for which is shared across sector boundaries, may present unique and substantial barriers to evidence use. It can take many years for any health gains to be seen. Decision-makers can feel that the time scales they work to are often too short to ‘prove’ the benefits of using research findings. 66 Furthermore, practitioners have reported that longer-term planning was required in order to have a positive impact on the wider determinants of health or to enable broader societal changes, but that this was constrained by the 4-yearly political electoral cycle in which the short-term political and financial cycles were embedded. 66 The frequent NHS reorganisations also inhibited long-term planning, with high levels of change, inconsistent and disruptive work patterns, a lack of leadership and the loss of tacit knowledge and organisational memory all leading to deflected primary care trust (PCT) focus and lost momentum in relation to commissioning. 67

Greenhalgh et al. 68 suggest that politics, and the way these impact on innovation as well as power relations, can be critical for research evidence uptake. It is argued that health is a ‘political world and while evidence can be brought to the table, there is certainly no guarantee that it will be acted upon’. In light of these multiple social, relational, political and contextual influences on the use of various types of evidence, researchers have been criticised for having an unrealistic view of the importance of research evidence, ‘which is after all just one piece of a rather complicated jigsaw’ (p. 381). 69 Previously, researchers were also criticised for prioritising publication in peer-reviewed journals,20,28 seen as more relevant to other academics, over engaging users and promoting utilisation. 20,32 Criticism is similarly levelled against health professionals; although practitioner involvement in research is recognised to positively influence utilisation,70 the use of research is hampered by bureaucracy, centrally directed organisational structures and the need to provide services on time and within budget. 14,28,39,69–71 In this way, the contemplative nature of research can be considered ‘the opposite of action not the antidote for ignorance’20 (p. 129). 20 The general picture is ‘one of poorly connected worlds lacking knowledge of (and often respect for) each other’ (p. 129). 20 We might speculate that the changes introduced by the most recent research excellence framework assessment (REF 2014) to include impact case studies might prompt closer engagement across the two communities.

Although the two communities theory65 offers some insight into barriers that inhibit research utilisation, its inherent assumption – that researchers and practitioners are homogenous groups – presents an overly simplistic interpretation, in several ways especially when applied to public health. Firstly, within public health, individuals and organisations working in the same fields often come from diverse disciplines and have differing perspectives and values which influence how knowledge is selected and interpreted. 51 Similarly, given the increasing diversity, plurality and multiculturalism of contemporary society,28,40,70,71 many of the issues faced within public health, especially those within the inequalities agenda, are complex, multidimensional and defy the imposition of single or simple solutions. Stakeholders identify different causes of the problems and correspondingly see solutions in different actions. Such ‘wicked problems’72,73 are multifactorial, with any unidimensional solutions offering only ever a partial solution (the ‘problem’ simply morphs to resurface slightly differently elsewhere). For example, if laziness appears to be the cause of unemployment, forcing the idle to take up work is the solution; alternatively, if the lack of locally available jobs is seen to be cause of the problem, relocation may be the solution, or if there are no jobs, then job creation is the preferred solution. No single approach is either fully correct or incorrect, nor will it ‘solve’ unemployment forever. Weber and Khademian74 suggest that in order to tackle wicked issues such as health inequalities it is necessary to synthesise complex sets of evidence from across different disciplines and methodological divides, and to understand the process and context of interventions while using such syntheses to inform real-world decisions.

Lastly, the notion of flow of evidence across two communities ultimately rests on the prevailing metaphor of evidence as a ‘thing on a journey’, from evidence creators to evidence users, with the success of the journey being reliant on the uptake of the evidence in an instrumental way. We have seen from the above that research utilisation is not ‘recipe following’ but ‘cooking’ informed by tried and tested techniques and approaches, with mixing and blending equivalent to drawing on and working around the issues that the current context provides as a backdrop. We move on to consider the use of research evidence in different ways.

Non-instrumental use of research evidence

The Canadian Institute for Health Research (CIHR) argues that all translational research has, at its heart, the desire to accelerate the rate of change. 38 Yet rather than leading to radical shifts in practice, the impact of evidence is more likely to contribute to a general shift in thinking. This may range from major conceptual shifts or simple low-level awareness raising. The new understanding created may remain unspoken and unused, or become gradually absorbed into familiar practices rather than directly influencing new ways of working. 21,22,28 Ward et al. encourage a need for:

moving away from narrow descriptions of knowledge transfer towards a broader sociological explanation of the process, testing the adequacy of alternative models of knowledge transfer, and refining and testing tools for designing and evaluating interventions.

p. 15761

These new approaches to research and data collection would need to look for more subtle and indirect use of research evidence and the evolution of impact rather than seeking out overnight revolution as ‘proof’ of research utilisation. This, of course, takes time and presents problems in directly attributing cause-and-effect inferences to evidence use, perhaps stretching our understanding of what scientific enquiry is and how to understand and ‘measure’ impact.

Kothari et al. 75 suggest that the importance of the end-user’s underpinning value base is key to determining utilisation. Within the context of multidisciplinary working, as is typical within public health, the differing value bases of differing stakeholders may wrestle for credence in relation to a specific issue. A better understanding of the role evidence plays on values would be useful. Contandriopoulos et al. 51 state that it is the extent to which any group working around a specific issue has reached consensus regarding the issue problematisation, the importance of the problem and the measurements of success of potential solutions (how well a group works to achieve issue polarisation) that impact on research utilisation. Best et al. 30 write of ‘knowledge integration’, as opposed to research utilisation, suggesting that it is the ability of the new evidence or knowledge to become part of the culture (values and identity) of the users that influence its use. In this way researching how evidence shapes cultures is also important.

Exchanging knowledge, relational approaches and complexity

The debate has largely moved away from rational, instrumental uses of evidence to a consideration of more subtle effects of evidence as thought-shaping, (re)defining values, and shaping cultures by forming collective views on what is important and how things should be done. Many have noted that interpersonal trust promotes communication21,76 while repeated communications encourage trust. 76 Mitton et al. ,77 too, note that communication, time and timing, context, the quality of relationships and trust can be very important. Greenhalgh et al. 68 also identify that meanings can be re-evaluated and reframed, that the decisions to use research evidence should not be viewed in isolation from other factors, and that it is difficult to predict the size, nature and direction of any changes in advance. 69,78 In summary, research utilisation may accelerate change, but it may not be possible to identify in advance (and therefore control) the direction this takes.

Recent literature has emphasised the importance of interactions between researchers and practitioners75,79 and there has, increasingly, been a move towards collaborative approaches to knowledge translation and research utilisation. It has been argued that the use of a more participatory approach enables a more nuanced understanding of context, a shared enactment of facilitation and transformative leadership. 80

Researching in new ways: participatory approaches and the promise of cocreation

Collaborative research (including participatory action research) describes a partnership between researchers and practitioners to undertake research. Partnerships may be based on many forms of involvement and engagement. Each needs time and genuine resource commitments from all involved in order to succeed. 81 Participatory approaches aim to enhance both the credibility and ownership of research, addressing barriers that inhibit utilisation and allowing each party to develop a greater understanding of each other’s world. 32,39,82–84 To understand the aspirations for cocreated research, we need to refer to Van de Ven’s definition of engaged scholarship:

Engaged scholarship is [. . .] a participatory form of research for obtaining the different perspectives of key stakeholders [. . .] in studying complex problems. By involving others and leveraging their different kinds of knowledge, engaged scholarship can produce knowledge that is more penetrating and insightful than when scholars or practitioners work alone on problems.

p. 982

Collaborative research can enable greater insight into the interpretation of data3,4,82–86 by adding a contextual perspective to findings,85 supporting implementation14 and enabling the development of more focused real-world RQs. 28,85 While outwardly appearing to dissolve the barriers of cross-boundary working, collaborative research is not without its challenges. Researchers and practitioners often do approach issues from differing agendas and bring competing (and complementary) skills to partnerships. 86 Questions have been raised regarding the objectivity and potential bias of collaboratively generated research and also the viability of investing typically large amounts of time developing and sustaining partnerships. Despite the challenges and the professional and organisational compromise that is often needed to develop effective collaborative partnerships,77,87 researchers and practitioners alike report benefits. 53,82–84 Typically it is the strength of the partnership, the people involved and the working relationships developed that are key to determining effectiveness: ‘the best processes in the world are unlikely to produce results without the right people to work within (or sometimes around) them’ (p. S2.5). 53 This suggests that successful relational approaches are partially dependent on structural mechanisms to facilitate and support engagement. For example, the structures (e.g. strategic partnerships committee structures and their prescribed membership, and the softer structures such as job descriptions, roles and reporting channels) can present opportunities to engage across professional and sector boundaries, but may not. Even if these structural opportunities are present, it still takes the agency of those involved to use the role and access created to engage with and promote the use of evidence, with sensitivity to all aspects of the context.

Calls for collaborative working largely assume that practitioners wish to collaborate in the research process and the creation of evidence. However, while research and evaluation skills are key public health competencies,88 for many practitioners they are perceived as additional responsibilities within already constrained professional remits88 and are not necessarily welcomed. In reality, organisations and individuals tasked with commissioning often require support to develop capacity and capability to strive to meet such aspirations. What is needed is not only more accessible and better public health research but commissioners and public health managers able to use the research and skilled in translating it to their local setting. 28,89 In summary, cocreation and other participatory approaches may enhance both research utilisation and evidence creation in multiple ways, but equally they may be as welcome as ‘your cat bringing you a dead rat’. 35

Concluding remarks and the focus of this project

Overall, what we know is that knowledge transfer, exchange and research utilisation are embedded social processes encompassing complex, sometimes context-specific interactions. 14,17,18,51,61,76 In a cross-cutting discipline such as public health, some authors conclude that taking decisions is a balancing act:

The public health approach is not an exact science but more an art, balancing competing voices in decision-making such as the evidence of efficacy and cost effectiveness of interventions, patient demand, clinician or speciality interests, financial constraints, collaborators’ and other stakeholders’ agendas, quality standards, targets and so forth.

p. e38790

However, as yet we have few studies of how evidence is used to address live issues in situ, as the action unfolds to provide empirical examples of how the conflicting factors are pragmatically resolved and how the complexity is pragmatically closed down to achieve action in commissioning and planning decisions. As Dobbins et al. note:

The influence of: key stakeholders, organizational [sic] culture and values, individual decision-making styles, research evidence, and the importance of the decision itself have yet to be comprehensively studied and understood.

p. 15791

While many theories and models seek to explain how and why knowledge is or is not utilised,70,86 gaps still exist,86,92 and sometimes precious resources are spent on research that is never utilised. 60,61 Innvær et al. 70 suggest that much literature focuses predominantly on instrumental use of evidence, while Ward et al. 61 suggest that how knowledge is actually used is often overlooked in discussions, especially in models of knowledge translation, and little exists that identifies specific approaches that make utilisation more or less likely in particular contexts. 61,77,92 It was on addressing these gaps that our research focused. We considered that varying organisational structures (commissioning across a purchaser–provider split vs. joint planning) created by differing policy contexts would provide varying managerial mechanisms for mobilising and using evidence. In turn, we also considered that these managerial mechanisms would simultaneously affect the relationships between those involved and what could be achieved (see Chapter 3).

We now proceed to give a brief synopsis of the extant literature relating to the substantive topic areas selected by our case study partners: alcohol licensing and alcohol consumption in pregnancy. We begin with a short overview of the area of alcohol-related harms as a public health issue.

Alcohol misuse: a clinical and public health issue

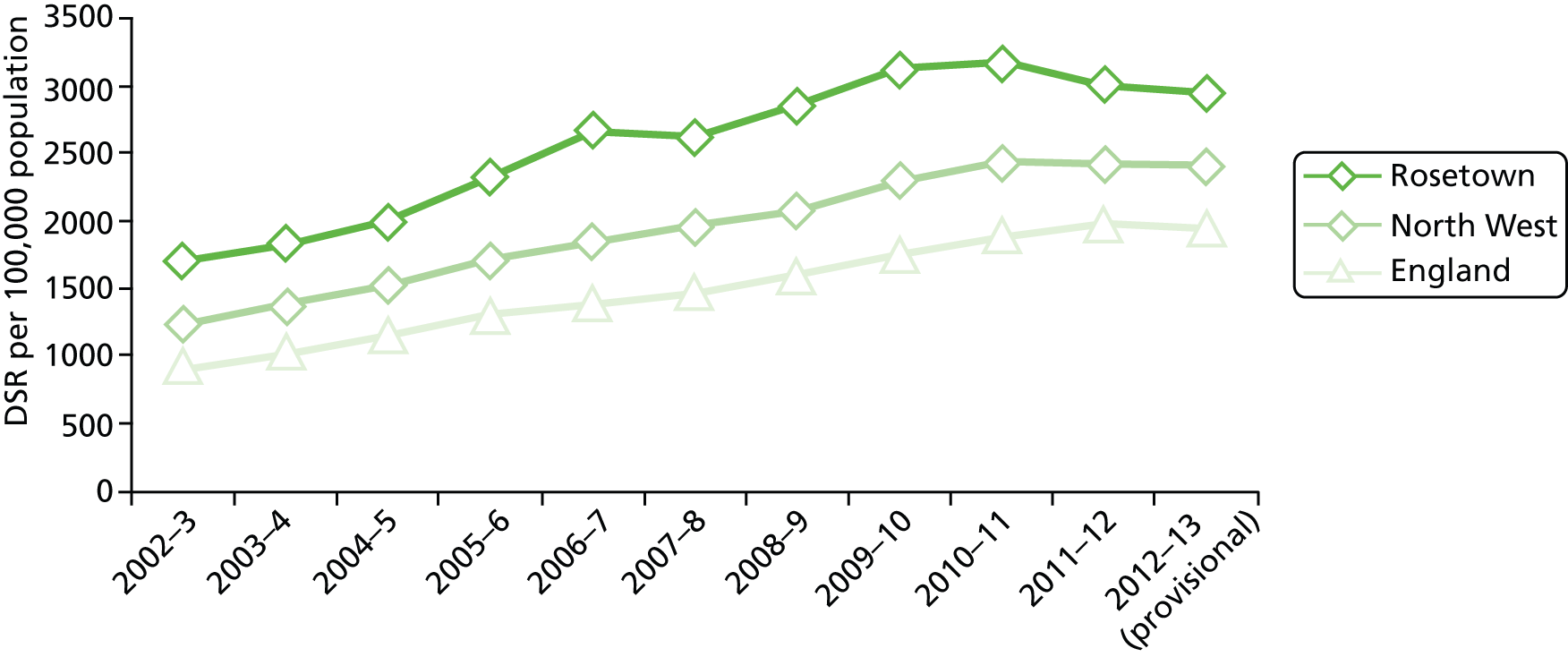

In 2002, in developed countries, alcohol ranked third after smoking and hypertension as a leading cause of ill health and premature death. 93 A key indicator of alcohol harm in the population is measured by mortality due to liver disease. UK cirrhosis mortality rates have risen sharply over the past 30 years, especially in Scotland (104% increase in males, 46% for females). In England and Wales there was a 69% increase in males and 44% for females. 94 What makes this rise more poignant is that corresponding figures from the European Union (EU) over the same time period fell by 30%. 94

For some years, UK drinking patterns have appeared to be out of step with those of the rest of Europe. In the UK, consumption of alcohol has increased by roughly 50% since 1970, compared with France and Italy where consumption has more than halved over the same period. 95 In particular, the number of women who are drinking at harmful levels has increased in some areas of the UK. This has led the Scottish Government96 to report that alcohol-related mortality among Scottish women is now higher than that of English men for the first time. Substantial differences between regions in the UK are noted, with the greatest increases in alcohol-related deaths being seen in Glasgow, north-east England and north-west England, including among younger women, which have led to calls for targeted action. 97 Differences in patterns of drinking have been noted, with older, affluent women tending to drink more frequently than less affluent women. 98 The wider health, economic and social effects of increasing alcohol consumption are well documented elsewhere99,100 and efforts to reduce the harm caused by alcohol101 would result in benefits for women of childbearing age as well for as the wider population. 102

At a population level, ‘alcohol problems’ range further than alcohol dependency or alcoholism. Heavy drinking is believed to contribute to many social problems (e.g. antisocial behaviour and crime, domestic violence, drunk-driving, accidental injuries, assault, and poor street and environmental cleanliness). 103 Heavy drinkers outnumber people with alcohol dependency by 7 to 1. 104 Consequently, the greatest impact in reducing alcohol problems can be made by focusing on prevention rather than the treatment of ‘alcoholism’ (the so-called preventative paradox)105,106 and making alcohol abuse a mainstream public health issue.

Alcohol misuse interventions

In cultures of heavy drinking, the most cost-effective approaches to prevention focus on regulating the environment, particularly focusing on the price, availability and marketing of alcohol. 101,107 Typically, this requires legislative change; however, concerted community-based programmes can be effective at reducing alcohol problems in specific areas following similar strategies. 108 These approaches may include education and information campaigns, controls on selling and other regulations reducing access to alcohol (supported by surveillance and law enforcement), and may be led through community organisation and coalitions. The second most cost-effective strategy is for public sector services (particularly the NHS) to deliver systematic programmes of screening and brief intervention. 107 Here, typically, a conversation between a practitioner [most often in primary care or accident and emergency (A&E) settings] and a heavy drinker takes place. Current alcohol use is discussed and the future consequences of alcohol misuse are explored. There is a large and robust evidence base supporting brief alcohol interventions,109 and this approach is a key component of alcohol misuse prevention guidance published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 110

In addition, the Department of Health advises a co-ordinated approach to reducing alcohol-related hospital admissions, advocating what are called ‘high-impact changes’ (HICs). 102 The seven HICs have been extensively used across the NHS and local government to highlight practical measures that can be implemented at local level. Three HICs suggest how efforts can be best organised to achieve success: work in partnership; develop activities to control the impact of alcohol misuse in the community; and influence change through advocacy. The remaining four HICs suggest services, interventions and activities that can be commissioned to reduce alcohol-related harm and reduce the rate of the rise in alcohol-related admissions. These four HICs are improve the effectiveness and capacity of specialist treatment; appoint an alcohol health worker; offer brief intervention to provide more help to encourage people to drink less; and amplify national social marketing priorities. 102

Alcohol policy and licensing

Anderson111 argues that New Labour alcohol policy framed alcohol-related problems in individual terms, was developed in partnerships with the alcohol industry, ignored the social context of alcohol-related issues or problems, and has increased alcohol-related harm, whereas an effective alcohol policy should flatten trends and reduce harm. 111 In England and Wales, the Licensing Act 2003112 restricted the power of licensing to ‘the prevention of crime and disorder, public safety, the prevention of public nuisance, and the prevention of children from harm, and not with public health’. 111 The Act did not offer any licensing responsibilities for the behaviour of customers after they had left the licensed premise. Moreover, it stipulated that licensing should not interfere with the free market and its understanding of ‘need’ was attached to the commercial demand for an additional premise. 111 In Scotland, the Nicholson Committee report published a review of licensing law in 2003,113 exploring ways in which licensing legislation could be used to modify drinking cultures and binge drinking in particular. Below, we provide more detail of the Scottish licensing policy context in the light of our case study (see Chapter 4).

Licensing law in Scotland has previously been based on the 1973 Clayson Report114 and Licensing (Scotland) Act 1976,115 which had recommended longer opening hours and the option of premises seeking special dispensation for extended hours of opening. 116 At the same time, alcohol became more affordable, with a 54% reduction in real cost between 1980 and 2003117 and a 70% change in affordability between 1980 and 2010. 118 The Nicholson Committee recommended the abolition of statutory permitted hours, including those for off-licences and supermarkets, with Local Licensing Boards agreeing opening hours for specific premises and Liquor Licensing Standards Officers supervising and monitoring the system’s operation in each Licensing Board’s area. 116 It was suggested by the Nicholson Committee that Licensing Boards would have to introduce policy statements to outline both their expectations and their mode of operation. Furthermore, a Licensing Forum, with a broad membership, would review the Licensing Board’s activities and highlight any local issues or concerns. These two structures were intended to provide local accountability for the Licensing Board’s decisions and would sit under a national Licensing Forum headed by the Ministers for Justice and Health, which would review practice and advise on problems, with national guidelines for practice and training. 116 The range of allowed objections and objectors was narrow, covering nearby residents, local community councils, some officers of the local council, chief constables and health and safety officers. 116 Medical and health perspectives were, at that time, potentially absent from this, as the staff of these sectors were not generally included in the permitted objectors.

What ‘works’ in the context?

In the Scottish context, it is suggested that a range of measures are effective in alcohol policy, including regulation, early detection and interventions, treatment and support in addition to education, with controls on price and availability, drink-driving legislation and brief interventions being most effective. 117,118 Alcohol brief interventions are a key element in Scottish alcohol policy, with suggestions that these reduce alcohol consumption for up to 1 year in harmful or hazardous drinkers, and in 2008 a target was set for a total of ≈150,000 interventions by 2011, with each health board achieving an agreed number in line with Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines. 118 It is suggested that front loading (drinking alcohol at home before going out to a licensed premises) is an increasing trend among under 25s and, consequently, more focus needs to be put on off-sales. 117

The 2005 Licensing (Scotland) Act was based on five licensing objectives: (1) preventing crime and disorder, (2) securing public safety, (3) preventing public nuisance, (4) protecting and improving public health and (5) protecting children from harm. 117 It is interesting that while public health is a key objective, the decision-making structures around Licensing Boards do not incorporate health representation. The updated report13 reviewed actions relating to protection and controls, prevention and education, provision of services and ‘getting the framework right’. There is also some discussion of the impact of alcohol and of changing alcohol cultures. Within ‘protection and controls’ intended actions are summarised in relation to licensed premises, actions in the community and action with the UK government. Intended actions in the ‘prevention and education’ category cover those relating to general information and communication, plus those targeted at schools, workplaces and the community. Intended actions relating to ‘provision of services’ are discussed at three levels: nationally, in the community and in primary and secondary care settings. The aims pertaining to ‘getting the framework right’ are discussed in relation to structures, information and evaluation and training.

Further priorities and actions are suggested in the Scottish Government’s 2008 discussion paper96 and the ensuing framework for action. 119 These documents identify targets in relation to the Scottish Government’s three overarching priority themes: ‘improving our productivity and competitiveness’, ‘increasing our labour market participation’ and ‘stimulating population growth’. Alcohol-related actions are outlined in relation to the themes of reduced consumption, supporting families and communities, ‘positive attitudes, positive choices’ and improved support and treatment. Some key actions for consideration in these reports include modifying the Licensing (Scotland) 2005 Act to end the option for off-sales premises to supply alcohol free of charge with a purchase (e.g. ‘buy one get one free’ schemes); ending reduced price sales of alcohol; introducing a minimum price per unit as a condition of both premise and occasional licences; consideration of raising the minimum age for alcohol purchases; applying a social responsibility fee; reviewing test purchasing; improving enforcement; focusing on early intervention through the Community Initiative to Reduce Violence; restricting the display of marketing material and encouraging responsible marketing; working with health and industry partners; introducing mandatory product labelling (ideally as part of a common system across the UK); establishing a working group to update core services for alcohol treatment; supporting the evaluation of brief interventions pilots; supporting NHS boards in reaching brief intervention targets; and exploring the opportunities for developing psychological therapies. The issues of minimum pricing and trade discount bans in Scotland are discussed more thoroughly in a University of Sheffield report,120 which offers a detailed conceptual and statistical discussion and models potential scenarios. At the date of writing, the Scottish Government’s efforts to introduce minimum unit pricing for alcohol is being challenged in the courts.

European policy on alcohol and licensing

While national policies are probably most significant with regard to approaches to alcohol problems and licensing, there are also intersections with European policy. The European Commission’s 2006 Communication on alcohol used research about the effectiveness of different policy measures pertaining to the reduction of alcohol consumption and harm, and identified five priorities for best practice: (1) protecting young people, children and the unborn child, (2) reducing injuries and deaths from alcohol-related road traffic accidents, (3) preventing alcohol-related harm among adults and reducing the negative impact on the workplace, (4) informing, educating and raising awareness about the impact of harmful or hazardous alcohol consumption and highlighting appropriate consumption patterns, and (5) developing and maintaining a common evidence base at EU level. 121 Guidance on advertising has also been set at the European level. It is noted by Gordon and Anderson121 and Anderson and Gual122 that the commission places significant emphasis on education, but this is the least effective alcohol policy option. Moreover, the impact of alcohol misuse on mental health and well-being has been significantly undervalued. 122 Issues such as cross-border shopping are also very relevant, and may become more so with the divergence of English and Scottish policies.

Next, we provide an overview of what is known about women’s alcohol use in pregnancy and explore some of the key themes identified to support the findings from Rosetown (see Chapter 5).

Prevalence of alcohol consumption in pregnancy

First, it is difficult to know the size of the problem. According to national surveys, around one-third of women in the UK drink more than medically recommended levels. 123,124 Estimates of alcohol consumption during pregnancy vary widely, with some national surveys estimating that 5% of women drink alcohol during pregnancy,125 compared with 54% in other studies. 126 However, estimating the amount of alcohol women drink is complicated and inexact, with considerable variation between research studies and countries127 and little standardisation about what constitutes heavy, moderate or light use. This results in imprecise definitions and difficulties of interpretation and comparison. 128 Poor understanding among the population of units and measures of alcohol129 may also lead to under-reporting. It has been noted that alcohol use, particularly in pregnancy, remains a socially stigmatised activity, and surveys of drinking behaviour in pregnancy may underestimate the true extent of alcohol consumption130 through fear of social disapproval. 131

A Swedish study found that older age, living in a major city with low social support and using tobacco during pregnancy, as well as pre-pregnancy drinking, were predictors of women’s drinking in pregnancy. 132 It has been suggested that increased awareness of the dangers of drinking in pregnancy has resulted in changes in women’s behaviour,133 but this may simply be a case of women reporting less alcohol consumption.

Effects of light to moderate drinking in pregnancy

Second, it is difficult to estimate the harms caused. There is considerable debate about the effects of light to moderate drinking in pregnancy in published literature and media reports (e.g. Taylor 2012134). A 2006 systematic review found no robust evidence of poor outcomes among women consuming moderate amounts of alcohol while pregnant,135 whereas a 2009 review from the Swedish National Institute of Public Health found impaired cognitive and socioemotional development in children aged 3–16 years in three of the six studies reviewed. 136 Advice to avoid alcohol in pregnancy is recommended following a study of the Danish National Birth Cohort, which found a strong graded association between alcohol intake and risk of miscarriage in the first 16 weeks of pregnancy. 137 In Australia, no independent effects of light to moderate drinking were found on birth weight or head circumference at 5 years of age. Similarly, a large-scale Danish study (1628 women) found no significant impact on preschool child intelligence. In the UK (Millennium Cohort Study) Kelly et al. 138 suggest there is no increased risk of behavioural or cognitive deficits at the age of 3 years for children whose mothers drank within recommended limits compared with children whose mothers did not drink. Indeed, boys born to light-drinking mothers were less likely to have conduct/hyperactivity problems, showing some apparently protective effects of alcohol, with similar findings in Australia,139 although there may be important confounding factors as light alcohol consumption is noted as a marker of relative socioeconomic advantage, which can influence children’s social and emotional behaviours. These effects were shown to continue until children reached 5 years of age. 140

Elsewhere it is also argued that the risks are not clearly established, and there is a need to understand possible risk factors mediating the relationship between drinking and outcomes. 141 Factors might include difference in drinking patterns (e.g. frequency, quantity, variability and timing) as well as absolute levels of alcohol exposure in utero,142,143 which have all been shown to affect the functioning of young children. Although the likelihood is that individual differences in alcohol metabolism protect most women, it is not possible to predict who is and is not at risk. A recent finding from a large population-based study found variants in genes involved in alcohol metabolism among children and mothers who had drunk in moderation during pregnancy, associated with lower cognitive ability in the children at the age of 8 years. 144 This suggests that in some cases even small amounts of alcohol in utero can affect future cognitive outcomes, leading some authors to conclude that we may never be able to conclusively prove whether or not there are safe levels of alcohol consumption in pregnancy, making it morally and ethically unacceptable to suggest otherwise,143–147 a message at odds with current UK guidelines.

Effects of heavy drinking in pregnancy and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder

We know that fetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD) is a set of conditions which are poorly understood by the general public and health-care professionals, limiting opportunities for appropriate diagnosis, prevention, early intervention and treatment. 130 Children affected by maternal alcohol consumption suffer a range of primary and secondary disabilities, the effects of which are often seen, although not well understood, by education providers and early-years practitioners. 129

Numerous studies have shown the harmful effects associated with heavy drinking in pregnancy,130 with heavy alcohol consumption increasing the risk of low birthweight and preterm birth. 148 Experts agree that there is a dose-dependent effect of alcohol on fetal and child development. 98

The term fetal alcohol syndrome was first coined in 1973 by Jones and Smith in the USA, but as research has accumulated, terms have changed, and they remain inconsistent between countries and institutions. 149 FASD is an umbrella term that covers fetal alcohol syndrome, alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorders, alcohol-related birth defects, fetal alcohol effects and partial fetal alcohol syndrome. Symptoms include changes in facial appearance, hyperactivity, impulsivity, difficulty with abstract concepts, poor problem solving and social skills, and difficulty learning from consequences,150 leading to developmental, health, behavioural, intellectual, learning, emotional and transition-related difficulties. 129 Disabilities range from mild to very serious, and affect individuals throughout their life course.

There are currently no reliable UK data on the incidence and prevalence of FASD, as routine data are not collected, definitions differ and under-reporting is likely. 151 Estimates of the economic impact of FASD are acknowledged as scarce, with studies limited to the USA and Canada, and this calls for a standardised methodology to allow for proper comparisons across countries. 128 One study estimated that the cost of FASD annually to Canada of those affected from birth to the age of 53 years was CA$5.3B, providing a strong rationale for commissioning prevention programmes. 149

Assessment and detection of problem drinking in pregnancy

Third, there is difficulty in knowing where and when to target interventions. Pregnancy is considered to be a ‘teachable moment’, a time of increased motivation to learn and eliminate unhealthy behaviours (including excessive alcohol consumption). 127 Routine screening tools have been developed which are quick, inexpensive and shown to be effective at identifying problem drinkers in the pregnant population in Canada [e.g. the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C), comprising the first three questions of the full Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) tool]. 152,153 In both Australia and the Netherlands, while women found screening acceptable, midwives were reluctant to discuss alcohol with women in their care and felt that they needed additional training in asking difficult questions and in managing those who disclosed that they were continuing to drink alcohol while pregnant. 154,155 A small-scale qualitative study of the factors that influence women’s disclosure of substance use in pregnancy in Australia found that a non-judgemental rather than confrontational approach encouraged disclosure. Midwives reported a good rapport and that trusting relationships were essential; for women, direct questions, continuity of care and addressing child protection issues early and honestly all helped. 156 The booking visit when women first come into contact with antenatal services has been identified as important, alongside multidisciplinary collaboration and co-ordination of services for pregnant women, who may experience embarrassment and stigma regarding alcohol use. 157

Alternatively, given that up to half of all pregnancies are reported as unplanned,133 with many women consuming alcohol unaware that they are pregnant, alcohol consumption in the first trimester is likely to be common, suggesting that intervening at the first midwifery booking appointment may be too late. The latest national alcohol strategy158 recognises that FASD can be caused by mothers drinking before they know they are pregnant, and so preventing them is strongly linked to reducing the levels of heavy drinking in the population as a whole (universal as opposed to targeted interventions). There may be arguments in favour of continuing with both universal and targeted interventions. Although many women are known to reduce their alcohol consumption in pregnancy, a sizable minority who continue are thought to drink moderate amounts or to binge drink. 127 In a systematic review of 14 international studies, women’s pre-pregnancy alcohol consumption appeared to be consistently associated with drinking during pregnancy, alongside exposure to violence and abuse,159 leading the authors to highlight the importance of antenatal providers assessing these factors to improve the detection of women at continuing risk.

International and UK guidelines on alcohol and pregnancy

The official recommendations regarding alcohol consumption in pregnancy differ from country to country. The USA and Denmark advise pregnant women to abstain from alcohol. Since 2009, the Australian government has advised women to abstain, a move away from previous guidelines which suggest that, if they chose to drink, they should consume fewer than seven drinks per week and never more than two drinks on the same day, and never get drunk. 146

In the UK before 2008, NICE suggested that pregnant women limit alcohol consumption to no more than one standard unit per day. Currently, pregnant women and women planning a pregnancy are advised to avoid drinking alcohol in the first 3 months of pregnancy if possible, because this may be associated with an increased risk of miscarriage. 100 The guidance goes on to state that if women choose to drink, they should be advised to drink no more than one to two UK units once or twice a week. [Note: one unit equals half a pint of ordinary-strength lager or beer, or one shot (25 ml) of spirits. One small (125 ml) glass of wine is equal to 1.5 UK units.] NICE110 guidance states that although there is uncertainty regarding a safe level of alcohol consumption in pregnancy, at this low level there is no evidence of harm to the unborn baby. 110

The Department of Health’s guidelines160 endorse this approach, stating that pregnant women or women trying to conceive should preferably avoid drinking alcohol altogether. The recommendations suggest that, if they do drink, women should not exceed the limits outlined above and not get drunk, as getting drunk or binge drinking during pregnancy may be harmful to the unborn baby. After a 2012 review of the evidence base by the UK Chief Medical Officer, the government concluded that ‘current guidance adequately balances the scientific uncertainty with a precautionary approach’. 99 This view is not universally held. NHS Health Scotland161 and the British Medical Association Board of Science130 have produced more conservative guidelines, recommending that women who are pregnant, or who are considering a pregnancy, should be advised not to consume any alcohol at all, as there is no known safe level of alcohol consumption in pregnancy.

A Royal College of Midwives (RCM) guidance paper on alcohol and pregnancy162 (p. 3) recommends that midwives advise pregnant women about the risks of consuming alcohol and to avoid alcohol while pregnant and breastfeeding. The RCM encourages midwives to understand the evidence base, and adopt an individualised approach, which will enable them to discuss the implications of alcohol use. Midwives are expected to support pregnant women who continue to consume alcohol and encourage them to seek further help if abstaining from alcohol is problematic. Overall, evidence on the effects of drinking alcohol in pregnancy is contested and contradictory, resulting in different national and international guidelines. This gives conflicting and somewhat confusing messages to women and to the health professionals who provide their care.

A wider understanding of the stigma and shaming of alcohol use in pregnancy

So far, this short literature review has taken a medicalised view of alcohol consumption, largely ignoring the leisure, pleasure and cultural aspects of drinking alcohol, whereas for most people this may be the only aspect of alcohol consumption that makes sense to them. It has allowed us to focus on the research evidence of alcohol-related harms, but it is guilty of treating alcohol in the ways that sometimes ‘food’ is treated in the obesity literature – as a ‘medicine’, without reference to the pleasure, comfort and social inclusion that eating brings. 163,164 The extant public health literature views alcohol as a toxin and, in keeping with this, continuing to drink during pregnancy is considered irrational, illogical and wilful. Unless we open our understandings to see a competing view that culturally links alcohol with sociability, with ‘having a good time’ or with relaxation (its social and cultural significance) then we may miss some of the reasons why many people drink, where they drink, and why women to continue to drink in pregnancy.

A growing body of literature in the social sciences questions the ways in which pregnant women and their fetuses have become such ‘a potent focal point for regulation, monitoring and control’. 165 Concerns have been expressed about the punitive and value-laden language that is used to describe the exposure of fetuses to damaging substances and the moral assumptions which underpin these discourses,166 generating something of a moral panic. 167 Drawing on Foucauldian concepts of the neoliberal government of citizens, Lupton165 notes that pregnant women are encouraged to take ethical responsibility for themselves and their fetus by avoiding exposure to harmful toxins such as alcohol and tobacco. Failure to respond to expert advice about appropriate health promoting behaviours in pregnancy risks exposing women to critical public gaze, judgement and recriminations for lack of self-discipline and self-sacrifice. 168 Some see policy-makers who advocate abstinence without a clear evidence base as creating new definitions of risk, formalising a connection between uncertainty and danger, transforming health advice into rules ‘less connected to a balanced assessment of evidence’. 169 Empirical research in Australia found high levels of guilt and anxiety reported by women about the welfare of their children, with marked social class differences observed. 170 Interviewees were aware of the judgemental attitudes of others, including other mothers, towards their efforts to conform to the ideal of the ‘good mother’. These findings are important to note in the context of efforts to raise awareness among women of the risks of drinking in pregnancy and enable women to access appropriate services in a timely manner. It may also explain why the routinely collected self-reported data on alcohol consumption during pregnancy are viewed as unreliable (and often are not collected at all).

Chapter 3 Methodology

Overview

The study design, RQs and proposal were a collaboration effort (and jointly written) across the research team. Half of the research team members are senior practitioners in the NHS, local authority (LA) or other national public sector organisations and it was their choice to investigate public health initiatives to address alcohol-related harms. Two in-depth, largely qualitative, cross-comparison case studies (in two sites) were undertaken. Each process case study was designed to investigate research utilisation in a live, real-time process of the commissioning cycle (or joint planning in Scotland) start to finish, in relation to services or interventions to reduce alcohol-related harms. With a strong focus on collaborative working and knowledge cocreation, this study draws primarily on qualitative methods, although a small amount of basic quantitative work was undertaken to help to contextualise the qualitative data. To see if the findings were typical and applied elsewhere, a two-stage Delphi questionnaire was designed and issued to interested stakeholders (followed by the wider issue of this questionnaire; see Exploring the transferability of the case study findings: overview and Delphi questionnaire design). A national workshop was held to share and discuss the findings.

The aim, RQs, objectives, data collection methods and fieldwork details are discussed in more detail below, starting with the overarching analytical (realist) framework and the impact that concurrent public sector reforms had on the project, its design and execution.

Overarching analytical framework

The overarching analytical framework is provided by Pawson and Tilley’s notion of realistic evaluation (that mechanism plus context informs outcomes) to ask the fundamental question: ‘what works where and under what conditions?’. 171

Programme theories

Behind commissioning (and joint planning) processes are programme theories – that is to say the assumptions (or ideas) about how things work or what the active ingredients are in a process that makes it work. A key task was to identify these programme theories and look at how they played out in different contexts. For example, a programme theory may be supplying research evidence into the commissioning (or joint planning) process will ensure that research evidence is mobilised in the decision-making process to secure evidence informed commissioning (or joint planning) decisions. The realist approach asks under what conditions (where and for whom) does supplying research evidence into the commissioning process secure evidence-informed commissioning: where and how does this hold true and why? We were looking for the key components (active ingredients – sociocultural mechanisms) that made this work, or not. Central to the realist approach is an exploration of the context–mechanism–outcome interactions, and this informs the design of this project. Different policy contexts in the UK (English and Scottish health policy) require managers to operate within different managerial mechanisms (commissioning vs. joint planning) to secure public health services and interventions. The realist task is to investigate how and in what ways the interplay between context and mechanism influence the use of research (and other types of) evidence (the outcomes) in order to build mid-range theories. These theories in turn may be modified and developed through their application across additional contexts.

The key to understanding the differences will lie in exploring the extent to which different NHS contexts provide varying managerial mechanisms for effecting change. The potentially hard contractual lever of commissioning across a purchaser–provider split (or joint commissioning across the NHS and local authorities as is more common for cross-cutting public health issues) is the predominant English managerial mechanism. In Scotland, however, single outcome agreements seek to establish a shared commitment to priorities across partners at the level of each LA (with no purchaser–provider split or commissioning arrangements). A pejorative understanding of the difference may be expressed in this way: England – commissioner’s contract, provider’s work; Scotland – shared work. Within these two contexts, the mechanisms managers have available to them may strongly influence what action can, and should, be taken, as well as how that can be achieved. Each context may offer different opportunities (barriers and facilitators) for research utilisation, allowing events to play out in different ways.

A look across contexts will permit initial observations of how these things play out in practice and implications for commissioning approaches. It might allow us to see if forceful commissioning is essential to drive change but potentially damaging to long-term purchaser–provider relationships (or unduly legalistic). The predominant English managerial mechanism is the potentially hard contractual lever of commisioning across a purchaser–provider split. For public health issues this more often takes the form of joint commissioning across the NHS and local authorities.

Conceptually clearing the ground

In line with the realistic approach, it is necessary to ‘conceptually clear the ground’171 and to clarify the wider context of this research. Without wishing to open a complex debate on epistemology, we take a pragmatic approach to defining our terms; throughout the project we use the term ‘evidence’ in its widest sense to mean:

Evidence noun 1 information or signs indicating whether something is true or valid. 2 information used to establish facts in a legal investigation or acceptable as testimony in a law court. verb be of show evidence of: the city’s economic growth is evidenced by the creation of new jobs.

PHRASES in evidence noticeable; conspicuous.

ORIGIN Latin evidentia. 172

Within this definition what counts as evidence is diffuse: facts, information, signs, indications, testimony, documents and material objects may all, in the appropriate context, be considered ‘evidence’ that something is true or valid. We proceeded on the understanding that research utilisation is a socially situated activity – so that what counts as good (useful) knowledge and evidence will depend on the audience and the context – and that this in turn informs how it can be used (or abused?) and to what end. To understand events, we locate them within the context that gave them meaning and made them possible. We adopt this diffuse definition of evidence, as it is the one routinely used by our research participants to inexorably shape their understandings of what counts.

However, where useful, we contrast this lay understanding of ‘evidence’ with ‘research evidence’, to explore the issues raised when an externally coded evidence-base that is widely accepted in rational western society as a privileged way of understanding the world attempts to trump lay and situated understandings of what counts in a given context. By ‘research evidence’ we mean the available body of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or valid as it results from the research process and as analysed through recognised methods. That is:

. . . the systematic investigation into and study of materials and sources in order to establish facts and reach new conclusions. 173

To focus the research gaze within the process case studies (and avoid looking too widely at all types of evidence used in all parts of the process), we concentrated on the times and places where overt use was made of research evidence (and other types of knowledge). For other definitions see the Glossary. 38

The context: researching in a changing public health landscape

The fieldwork for this project (January 2012 to November 2013) coincided with the public sector reforms introduced by the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 174 During this period, public health commissioning in England moved from the NHS to LA control. Between 2012 and 2013, public commissioners (i.e. our research participants) were in transitionary arrangements, and after April 2013 they became LA employees, although some [e.g. the Director of Public Health (DPH)] had already held a joint NHS/LA post since 2007. For much of this time (and in the contracting period before the project officially began) the precise details of the reforms, new organisational structures, and funding arrangements, including ring-fenced funding for public health services, were still being negotiated. It was unclear what public health services and interventions would remain in place post reforms. In addition, the global financial downturn and the resultant public sector financial constraints introduced by the 2010 UK government formed a much wider backdrop of uncertainty regarding the nature and longevity of public health provision, especially given that funding to the NHS was protected, whereas LAs had been subject to substantial reductions in funding.

To cope with this level of uncertainty and to take what steps were possible, at that time, to ‘future-proof’ the project to ensure that it was not derailed by as-yet-unseen changes resulting from the reforms, the research team decided that:

-

The data collection would ‘follow-the-action’175 and not study case study sites (i.e. physical entities which were being dissolved) but follow the process of commissioning (or joint planning) wherever the action was taking place. In accordance with this, as public health moved to the LA, the project moved with it and carried on.

-

To ensure that the commissioning process around the intervention or service being tracked would still exist post reforms, a high profile public health issue was identified. It was decided that reducing alcohol-related harms was likely to remain a priority concern regardless of other organisational or political priorities.

These changes were incorporated into the project design and the project protocol. The case studies became process case studies to follow research utilisation (and use of other types of knowledge) in public health commissioning (or joint planning) to reduce alcohol-related harms.

Design

A qualitative methodology, to focus on the social and situated process of evidence use and the meanings and significance this holds for participants, was selected. Two interpretive, in-depth, multimethod, cross-comparison process case studies (one in each of two sites) were undertaken. 176,177

Key aim

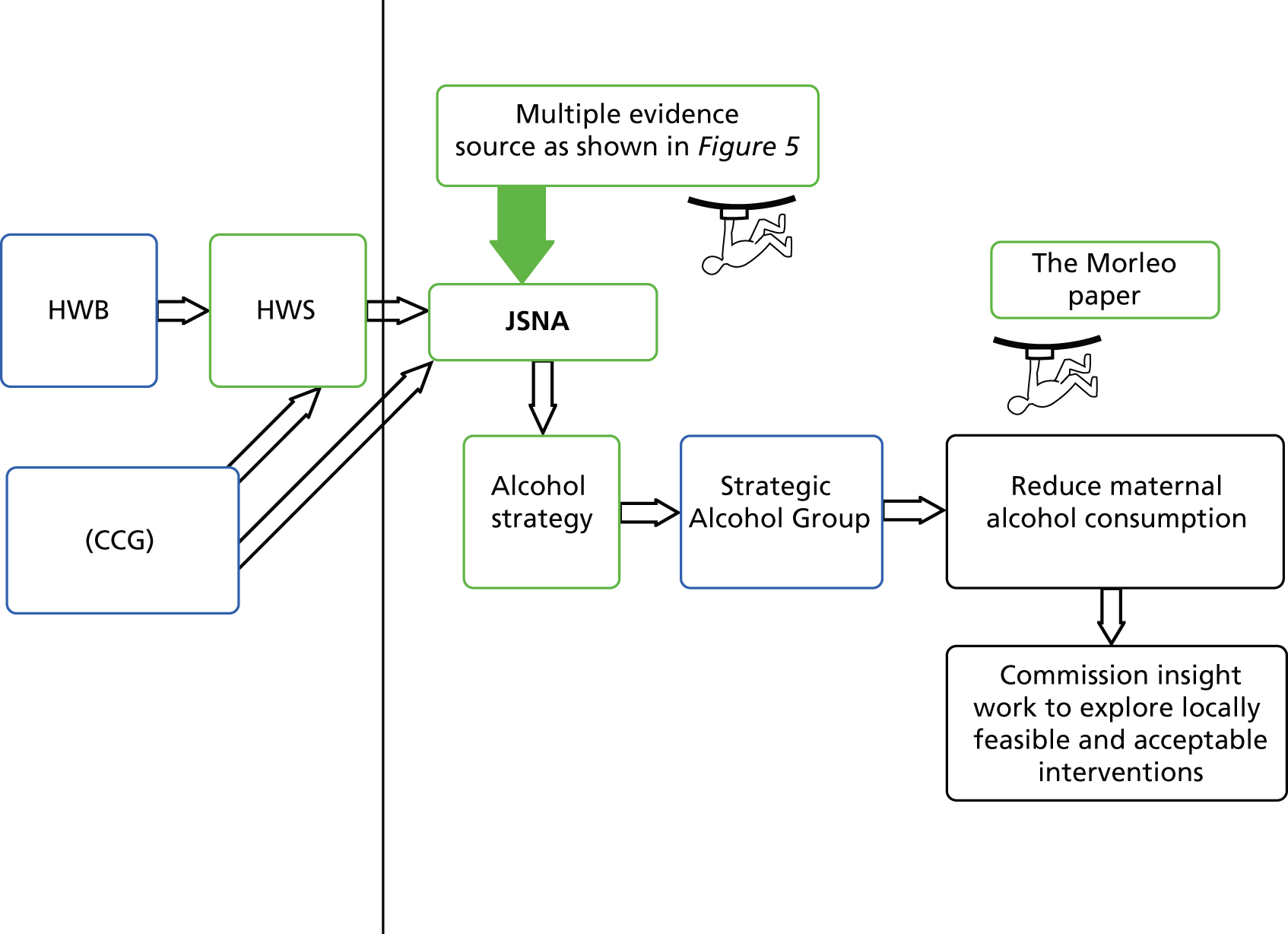

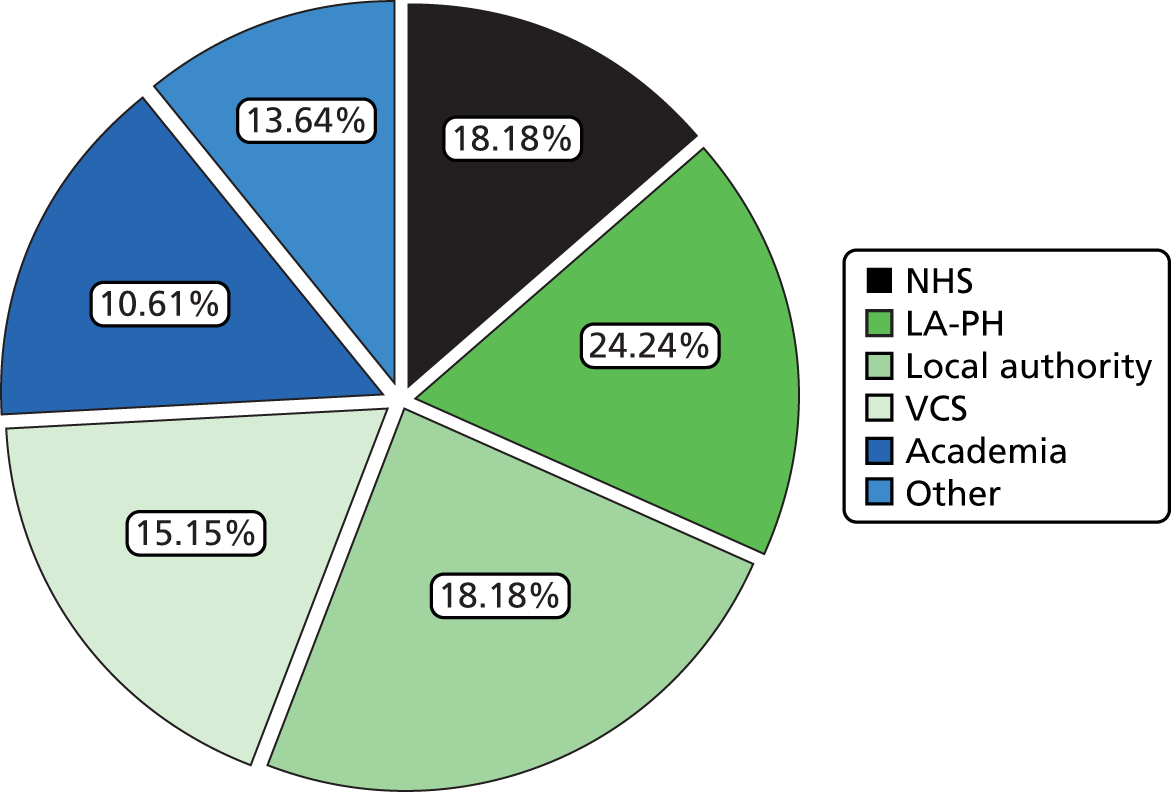

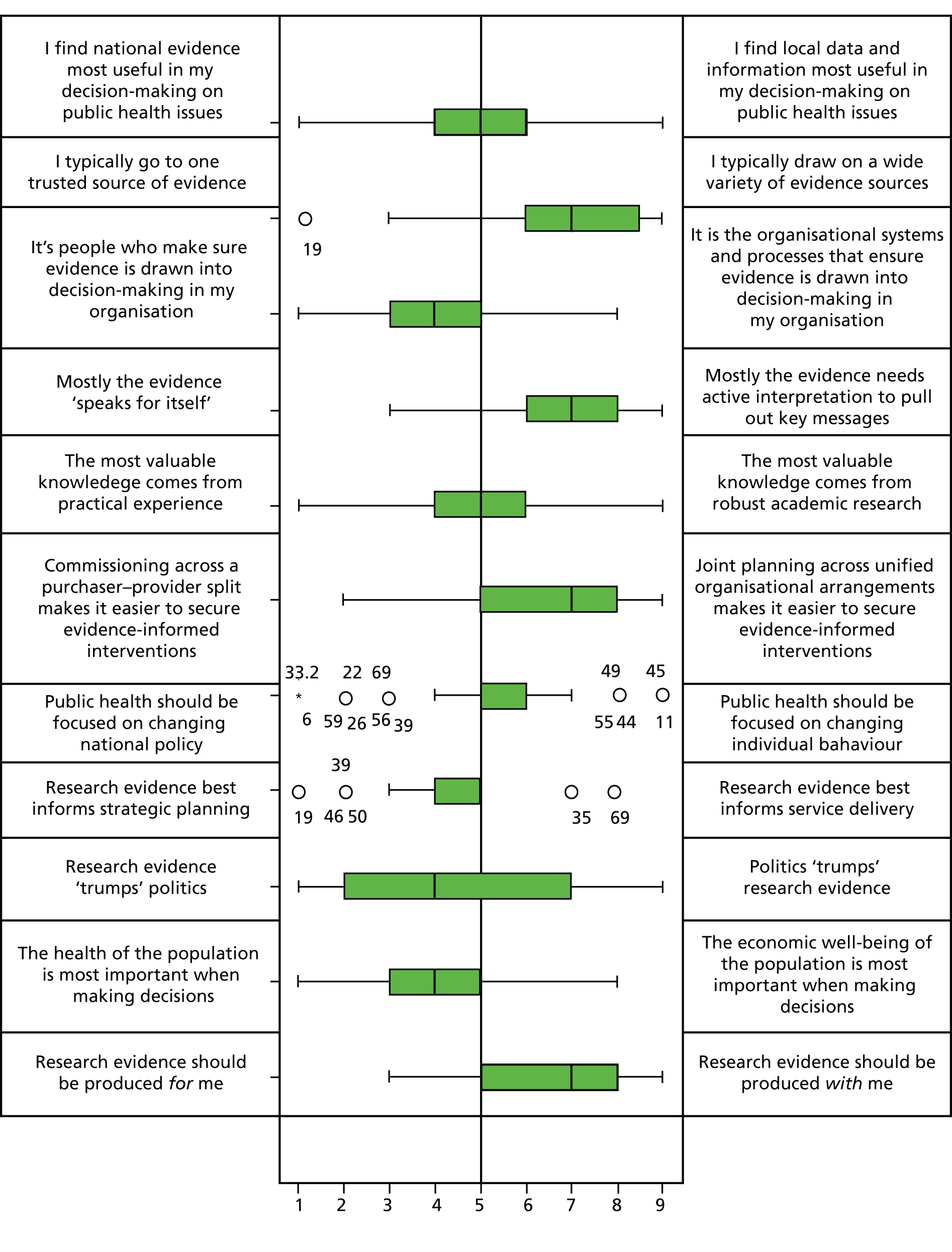

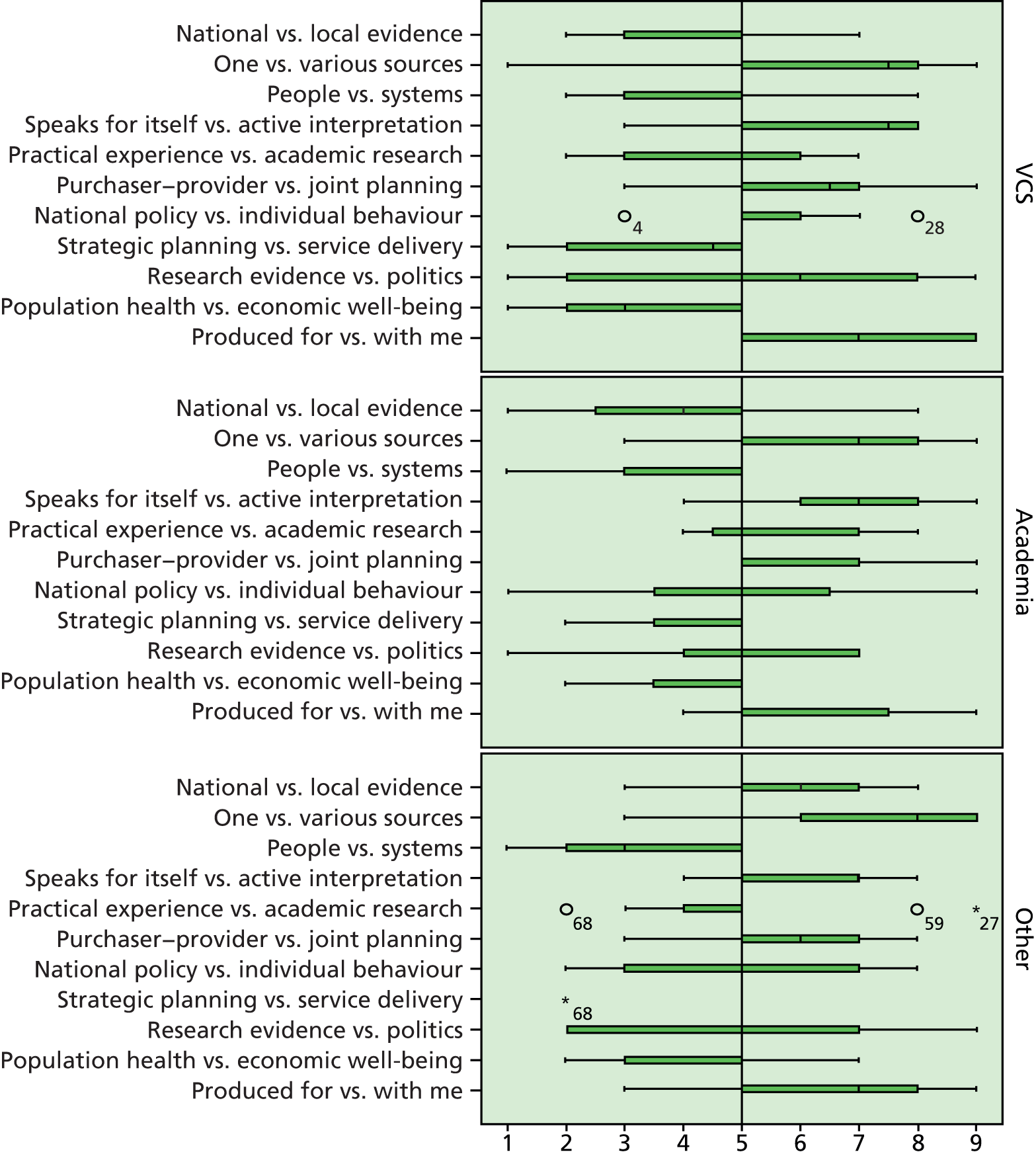

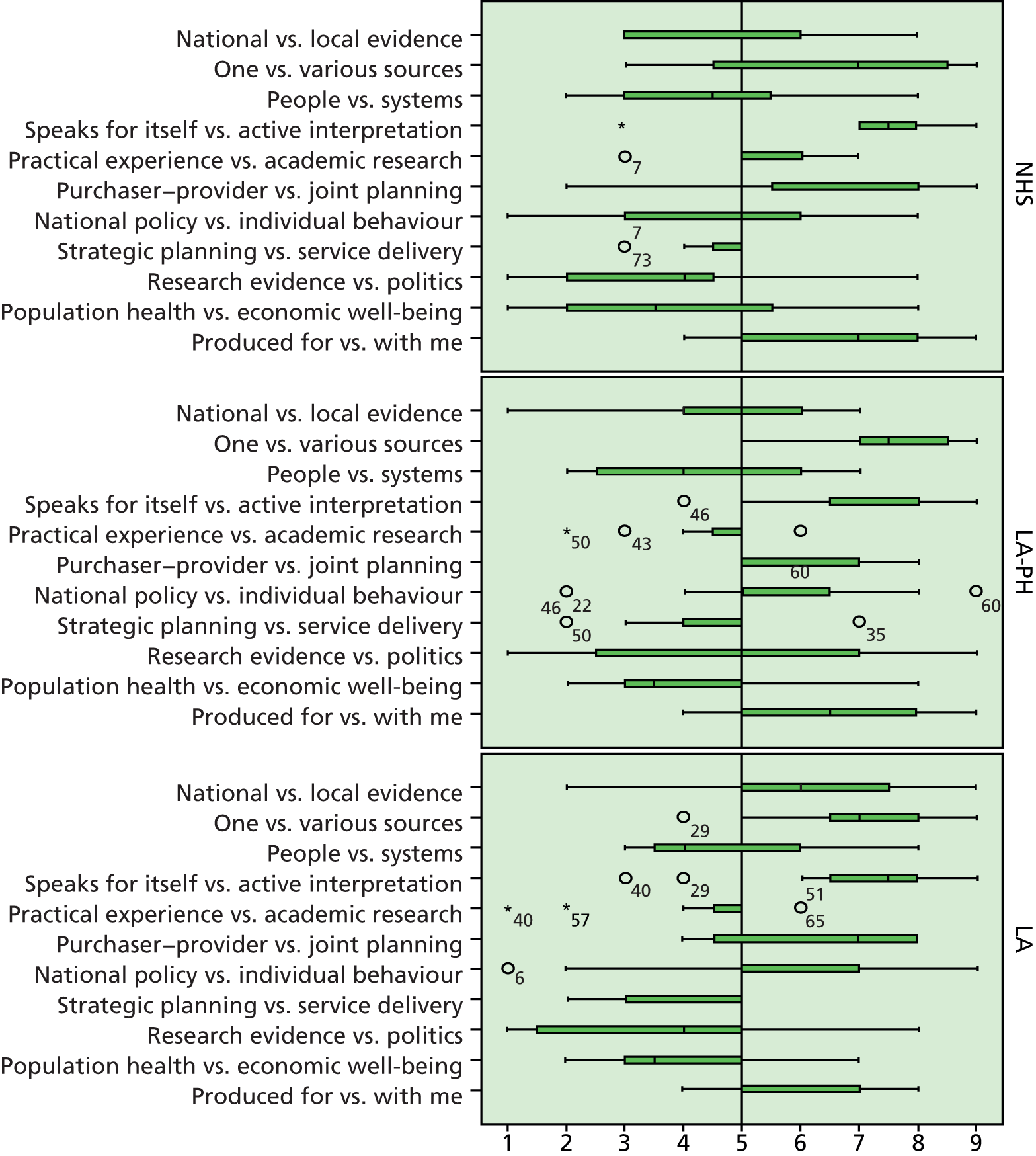

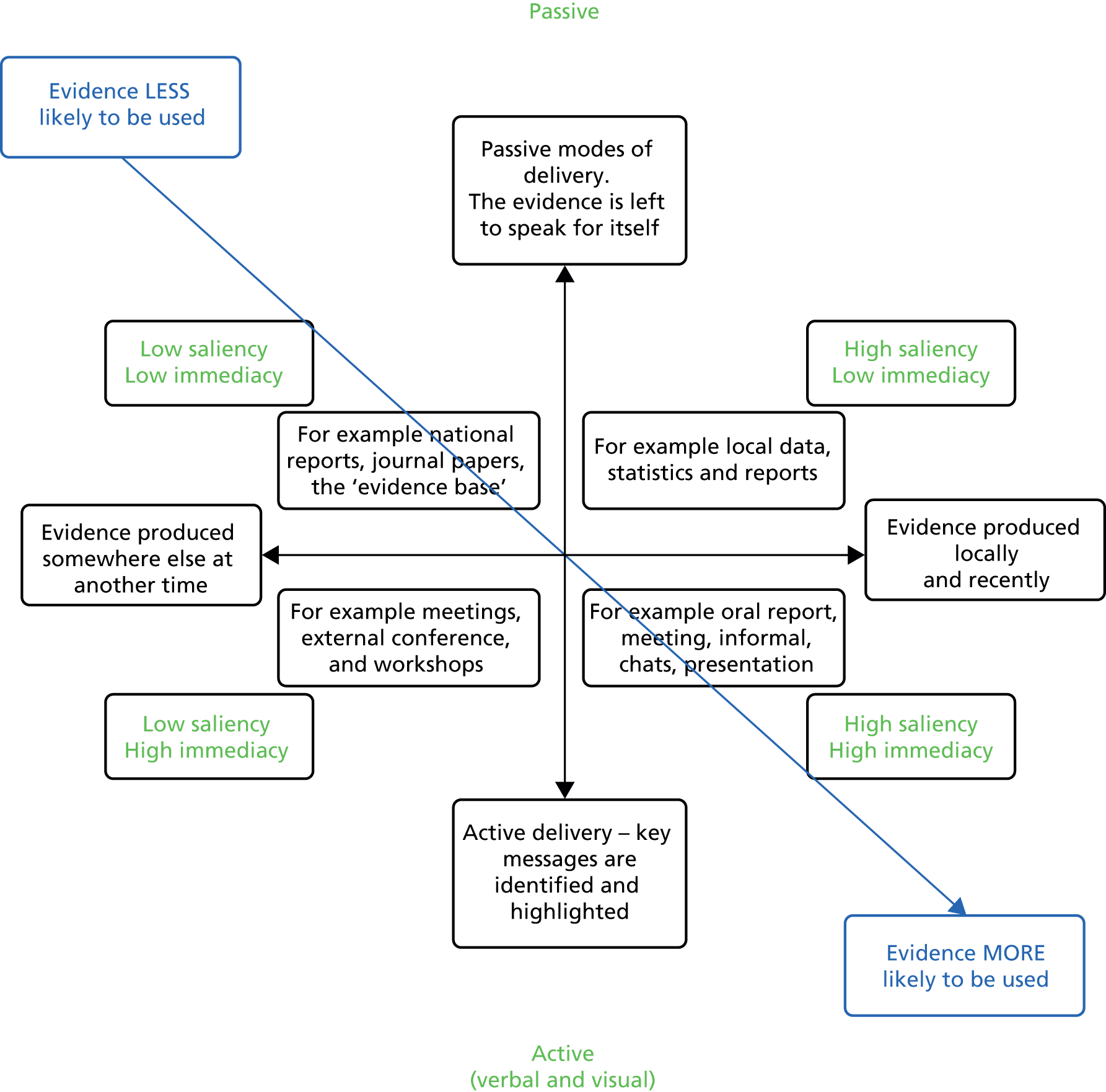

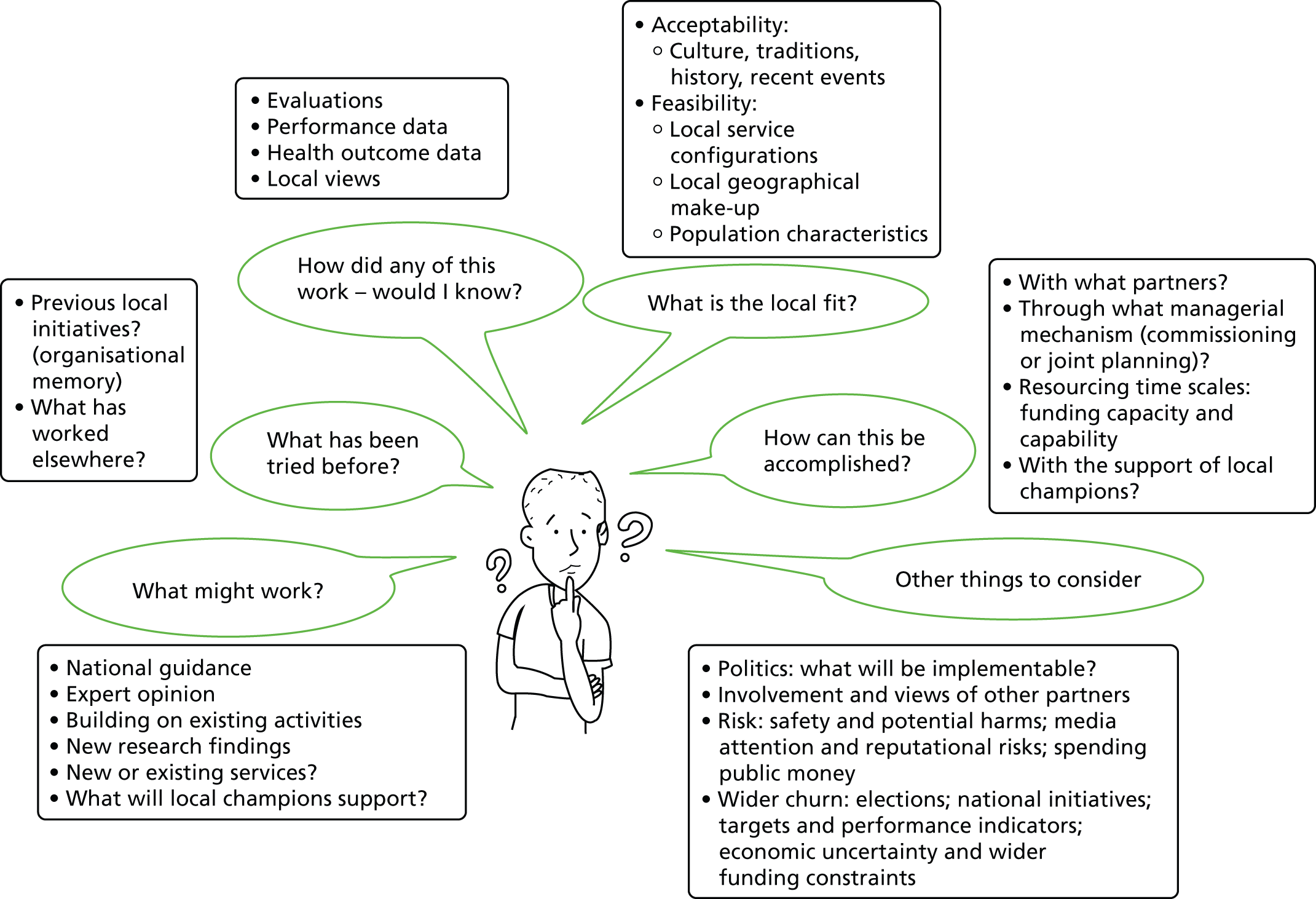

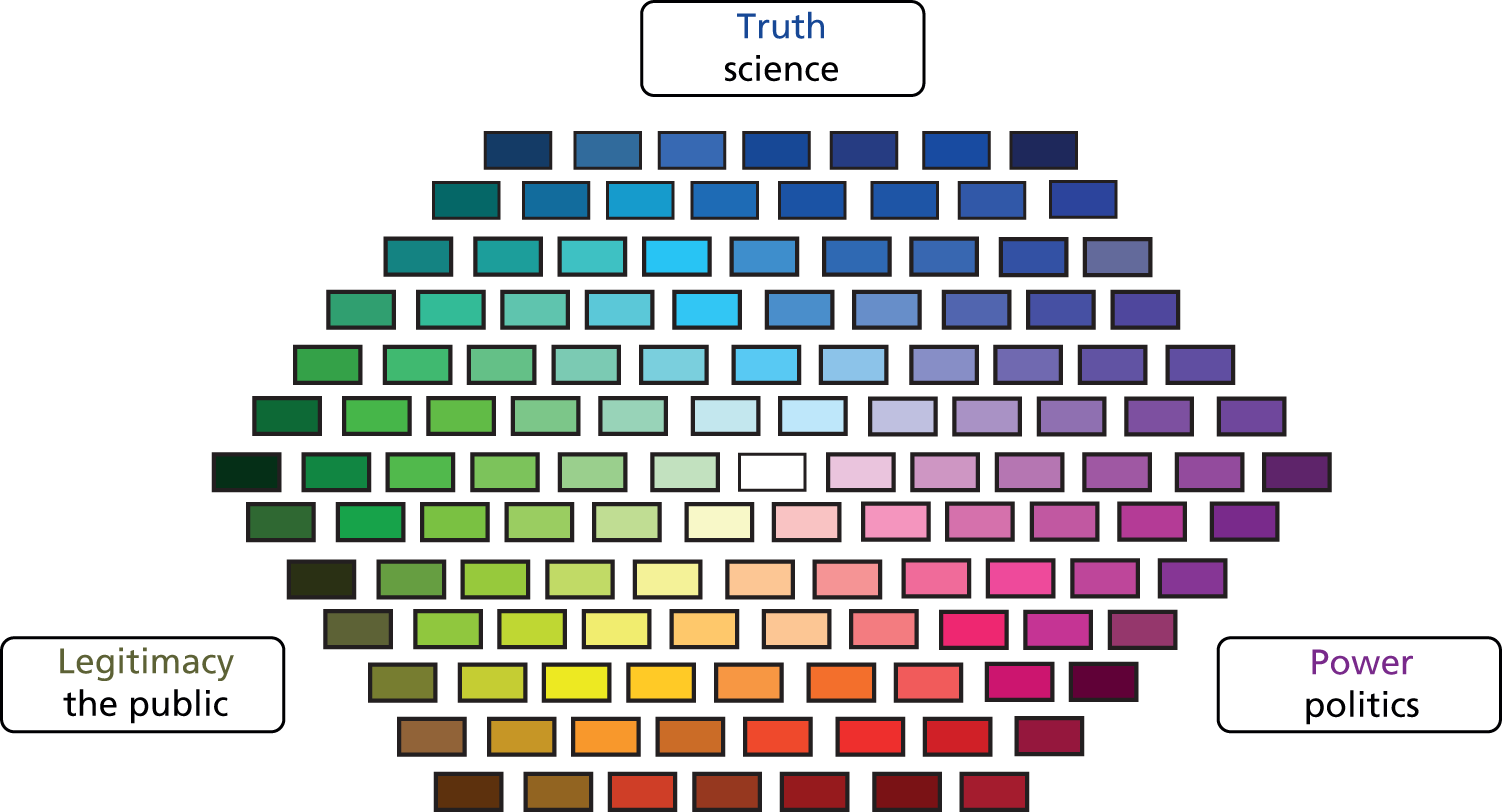

To work collaboratively with research participants to explore and understand how research is utilised and knowledge mobilised by NHS and LA managers (and others) in the commissioning and planning of public health services to reduce alcohol-related harms.