Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5001/14. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The final report began editorial review in June 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Galdas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Long-term conditions

Improving the treatment and management of long-term conditions (LTCs) is currently one of the most significant challenges facing the NHS. 1 Around 15 million people in the UK suffer from a LTC such as hypertension, asthma, diabetes, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease or other health problems that cannot currently be cured but can be managed through medication, therapy and/or lifestyle modification. 2 The figure is set to grow dramatically over the next 10 years, particularly those individuals living with three or more LTCs at once.

The increasing burden of LTCs coupled with the financial pressures facing the NHS in the coming years is leading to a shift in health-care delivery. Offering existing LTC care and services as currently configured – that is ‘doing more of the same’ – will not be adequate if NHS and social care services are to be sustainable in the future and are to appropriately target need while being resource efficient. 3 The current NHS therefore requires a ‘paradigm shift’ in the provision of health care to meet the needs of a population in which most of the disease burden is attributable to LTCs. 4

Empowering and supporting the increasing number of people living with LTCs to develop their knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their own health has become a key strategic objective of the NHS. 5 So-called ‘supported self-management’ is seen as a core platform for optimising quality, effectiveness and efficiency of LTC care because of the potential to improve health outcomes, help patients make better use of available health-care support, and avoid interventions that are burdensome for patients, inappropriate to their needs and inefficient for the NHS. 3,6 Delivered on a large scale, self-management support interventions have the potential to help reduce the overall costs of care in the NHS without compromising patient outcomes. 7

Self-management

There is currently no universally accepted definition of self-management, and the terms ‘self-care’ and ‘self-management’ are often used interchangeably in the literature. In this report, ‘self-management’ is considered as distinct from ‘self-care’. ‘Self-care’ refers to a set of behaviours which individuals perform to prevent the onset of illness or disability and maintain quality of life. 8 ‘Self-management’ refers to an individual’s ability to effectively manage the symptoms, treatment, physical and psychosocial consequences and lifestyle changes inherent in living with a LTC. 9 Thus, in this review we have adopted the definition of a ‘self-management support intervention’ used in the recent Health Services and Delivery Research Reducing Care Utilisation through Self-management Interventions (RECURSIVE) review:7

An intervention primarily designed to develop the abilities of patients to undertake management of health conditions through education, training and support to develop patient knowledge, skills or psychological and social resources.

Knowledge of the most effective ways to support patient self-management of LTCs is growing. Significant investment has been made by a number of research funders in studies to explore the role of various forms of self-management support, including studies of the Expert Patient Programme10 and assistive technologies through the Whole System Demonstrator. 11 A number of systematic reviews have also been carried out on different aspects of self-management support. These have focused on interventions targeting specific conditions (e.g. diabetes or mental health),12,13 types of intervention (e.g. lay-led programmes)14 or particular outcomes (e.g. medicines adherence). 15 Despite a developing evidence base, there remains a lack of clarity concerning the effectiveness of self-management interventions, and major ‘knowledge gaps’ remain, especially around ‘what works, for whom, and why?’

Men and self-management support

Despite growing evidence for their effectiveness, self-management support interventions are considerably limited in their ‘reach’, that is the numbers of patients able or willing to access and engage with the intervention. 16–18 Existing self-management support services have tended to engage only a minority of the eligible population. Evidence suggests that, despite men being more likely than women to develop the most common and disabling LTCs such as chronic pulmonary disease, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases,19,20 fewer than one-third of participants engaging with existing support services are male. 13,21–23 This pattern of attendance is consistent with a growing body of research into male identity and the management of illness that is revealing preventable risk factors, poor engagement in self-management and reluctance to access existing health services may account for a high proportion of mortality and morbidity in men. 20,24–29

Increasing recognition of the evidence pointing towards men’s gender-specific needs has led to calls for tailored and targeted health-care interventions to be delivered to men,19,29 including the recent European Commission report on the State of Men’s Health in Europe. 20 Delivering gender-sensitive health services to meet the statutory requirements of the Public Sector Equality Duty30 is also a matter of great concern to the NHS at present. The duty, which forms part of the Equality Act 2010, places statutory responsibility on all NHS organisations to take account of any evidence that men and women have different needs, experiences, concerns or priorities when developing policies and services. This means fully integrating an awareness of male and female health needs strategically and operationally throughout an organisation. 31,32

Compliance with the Public Sector Equality Duty30 is currently being implemented by the vast majority of NHS organisations through the refreshed Equality Delivery System. 32 Considering the different needs of men and women in the commissioning, design and delivery of NHS services to meet the legal requirements of the Public Sector Equality Duty30 will remain a crucial factor in service planning in the future, and the area of self-management support is an example of where gender-related differences are likely to exist.

However, existing data on self-management support are not available in a form suitable for assessing whether or not gender has an impact on the effects of these types of interventions; therefore, the data cannot be used as a basis for supporting evidence-based decisions about commissioning and designing services to meet the specific needs of men with LTCs and the legal requirements laid out in the Public Sector Equality Duty. 30 The relative effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, accessibility and acceptability of self-management interventions for men with LTCs have yet to be established. 14

The aim of this review was to address this ‘knowledge gap’ by conducting a comprehensive assessment of the current evidence to judge if self-management support interventions are effective and cost-effective in men. In addition, the review aimed to identify men’s experiences of, and perceptions of, self-management support to identify whether or not interventions and activities aimed at supporting self-management are acceptable and accessible to men.

Our synthesis was designed to make a conceptual and empirical contribution to the evidence base on both self-management support and men’s health. A key goal of this project was to provide clear guidance on whether or not self-management support interventions need to be adapted so that they are more effective in, accessible to and acceptable for men; this would help commissioners and practitioners meet the legal requirements of the Public Sector Equality Duty30 and allow men to gain appropriate support to limit any adverse consequences of living with a LTC.

The results of the SELF-MAN review should be considered alongside the recent Practical systematic Review of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions (PRISMS)33 and RECURSIVE7 reviews, which offer broader assessments of the role and effectiveness of self-management support in LTCs, and the degree to which current models of support reduce health service utilisation, respectively.

Research questions

-

How effective, cost-effective, accessible and acceptable are self-management support interventions for men with LTCs?

-

What are the key recommendations for service commissioners and research funding bodies on delivery of self-management support for men with LTCs and the research priorities of the future?

Review objectives

-

To assess the effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, accessibility and acceptability of self-management support interventions in men with LTCs.

-

To identify experiences of, and perceptions of, interventions and activities aimed at supporting self-management of LTCs among men of differing age, ethnicity and socioeconomic background.

-

To identify gaps in the available evidence and identify critical areas for future research.

Chapter 2 Quantitative review methods

A systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted based upon a protocol published on the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42013005394, URL: www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42013005394).

Deviations from the original protocol are presented in Box 1.

The target population are male adults (aged 18 years or over) living with one or more long-term conditions.

The 1-year time frame of this project made consideration of all possible LTCs impracticable. We therefore focused on a range of ‘exemplar conditions’ informed by the strategy adopted by the recent PRISMS review:33 asthma, type 1 diabetes, type 2 diabetes, depression, hypertension, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, arthritis, chronic kidney disease, chronic pain (including back pain) and human immunodeficiency virus. In addition, we also considered the literature on generic non-disease-specific interventions (such as the Expert Patients Programme) as well as self-management interventions for men-only conditions (i.e. disorders of the prostate and testicles).

Identifying and locating studies of relevance from existing high quality systematic reviews via the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and PROSPERO.

Dual screening of the systematic review literature on self-management support interventions led to the identification of 706 potentially eligible reviews that met our study inclusion criteria via the CDSR, DARE and PROSPERO. The team considered the screening, extraction and synthesis of all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) included in these 706 reviews to be unmanageable within the project time frame and an inefficient use of research resources to answer our research questions. We therefore limited the review to relevant RCTs identified through Cochrane systematic reviews (n = 116). We considered the incremental benefit of including studies identified through non-Cochrane systematic reviews to be low, as the majority of relevant high-quality RCTs are likely to be included in Cochrane systematic reviews.

A data extraction tool will be created to extract data on patient populations (e.g. gender, age, other demographic factors, long-term conditions and other clinical characteristics), self-management interventions (including details on components using the BCT [behavioural change techniques] taxonomy as a guide).

We found that coding and synthesising interventions using the BCT taxonomy and methodology developed by Michie et al. 34 was not feasible because a shared language was not used to describe ‘active ingredients’ of interventions; there was a lack of precision and detail reported in studies to enable coding at a granular level; and reporting was inconsistent on whether or not an intervention was intended to target a specific behaviour change. We therefore extracted data on intervention components and structured aspects of our analysis using the categories of self-management support informed by the PRISMS and RECURSIVE projects.

Search strategy

We searched the following databases using a search strategy developed in conjunction with an information specialist from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York (see Appendix 1): Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR); Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (up to July 2013); PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) (up to July 2013); and Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online (MEDLINE) (January 2012 to July 2013). The breadth of the literature identified meant we took a pragmatic approach and limited our search to CDSR; see Box 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating self-management support interventions in men with LTCs (identified via Cochrane systematic reviews of self-management support interventions) were included. Studies which analysed the effects of self-management support interventions in sex groups within a RCT were also identified and synthesised separately.

The following population, intervention, comparison and outcome criteria were used:

-

Population and setting: adults, 18 years of age or older, diagnosed with a LTC.

We limited the review to studies of patients with 14 ‘exemplar’ LTCs (informed by disease areas prioritised in the PRISMS study and team discussions): asthma, diabetes, depression, hypertension, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), arthritis, chronic kidney disease, chronic pain, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), testicular cancer, prostate cancer, prostate hyperplasia and chronic skin conditions in any setting. Studies including inpatients with depression were excluded. Studies including patients with multimorbidity involving at least one ‘exemplar’ condition were considered.

-

Intervention: a self-management support intervention.

We adopted the broad definition of a self-management support intervention used in the recent Health Services and Delivery Research RECURSIVE review:7

An intervention primarily designed to develop the abilities of patients to undertake management of health conditions through education, training and support to develop patient knowledge, skills or psychological and social resources.

There is no single agreed definition of what a self-management support intervention encompasses; interventions are highly variable. We therefore developed further standardised criteria which more clearly defined what we considered to be a self-management support intervention of relevance to this review. They are outlined in Box 2.

In line with the recent RECURSIVE7 and PRISMS33 reviews, we excluded any self-management that did not involve some level of professional or peer-led input, guidance or facilitation. For example, we included physical activity-based interventions if they involved an element of education, training or service support, but we excluded studies which involved exercise only. Although we recognise that self-management can be undertaken without any support from health services, we took this stance because it is seldom the subject of intervention studies. 7

We excluded studies involving only self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension and glucose monitoring in diabetes, as we considered these to be well-established practices with a well-developed evidence base. The substantial nature of this literature also meant that reviewing these studies was not feasible within the project time frame.

-

Comparison: any comparison group.

We considered studies using ‘care as usual’ or any other intervention.

-

Outcomes: effectiveness, cost-effectiveness.

We extracted data on the effect of interventions on health status, clinical measures, health behaviour, health-care use, self-efficacy, knowledge and understanding, communication with health-care professionals (HCPs) and effects on members/carers.

-

Study design: RCTs identified via eligible Cochrane systematic reviews.

Only papers published in the English language were included, as translation was not feasible in the time frame of the project. In instances where records were unobtainable, attempts were made to contact authors to request the information.

The intervention should, through some means of education, training or support, help people with a LTC by:

-

developing knowledge, skills, psychological or social resources relating to the management of their condition

-

adopting healthy life habits

-

helping individuals recognise the signs of deteriorating health status

-

planning actions to take at signs of relapse or exacerbation

-

knowing what resources are available and how to access them

-

developing skills for helping individuals adhere to a treatment plan

-

communicating effectively with health professionals and/or a support network

-

solving problems

-

identifying objectives and goals and developing action plans.

Identification of studies

We piloted the screening criteria on a sample of papers before undertaking the main screening, in order to identify and resolve any inconsistencies. Screening was conducted in two phases:

-

identification of relevant Cochrane systematic reviews

-

identification of relevant RCTs within included Cochrane systematic reviews.

For phase 1, an initial screen by title and abstract was conducted by one researcher. Two researchers then screened each article independently according to the screening criteria to identify relevant systematic reviews. Disagreements were resolved by a third researcher (principal investigator) as required.

For phase 2, each Cochrane review was screened independently for eligible RCTs by two researchers. The eligibility of each RCT was checked using the study information presented within Cochrane reviews before full papers were sourced. Full texts of each RCT were independently screened by two researchers and disagreements were resolved by a third researcher (principal investigator) as required.

For this review we focused on identifying male-only RCTs and trials which analysed the effects of interventions by sex groups. Agreement on Cochrane review eligibility was 89% and agreement on male-only RCT inclusion/exclusion and identification of RCTs containing sex group analyses was > 90%.

Data extraction

We designed a data extraction sheet and piloted this on a sample of papers prior to the main data extraction. Relevant data from each included article were extracted by a member of the review team and checked for completeness and accuracy by a second member of the team. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by a third person (principal investigator) as required. In instances where key information for meta-analysis was missing, efforts were made to contact authors. We extracted data on study and population characteristics, intervention details (setting, duration, frequency, individual/group, delivered by), outcome measures of health status, clinical measures, health behaviour, health-care use, self-efficacy, knowledge and understanding, communication with HCPs and items for quality assessment (Cochrane risk of bias tool35). Items for economic evaluations [hospital admission, service use, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), incremental cost-effectiveness ratios] were also extracted.

Where studies were reported in multiple publications, each publication was included and relevant data were extracted.

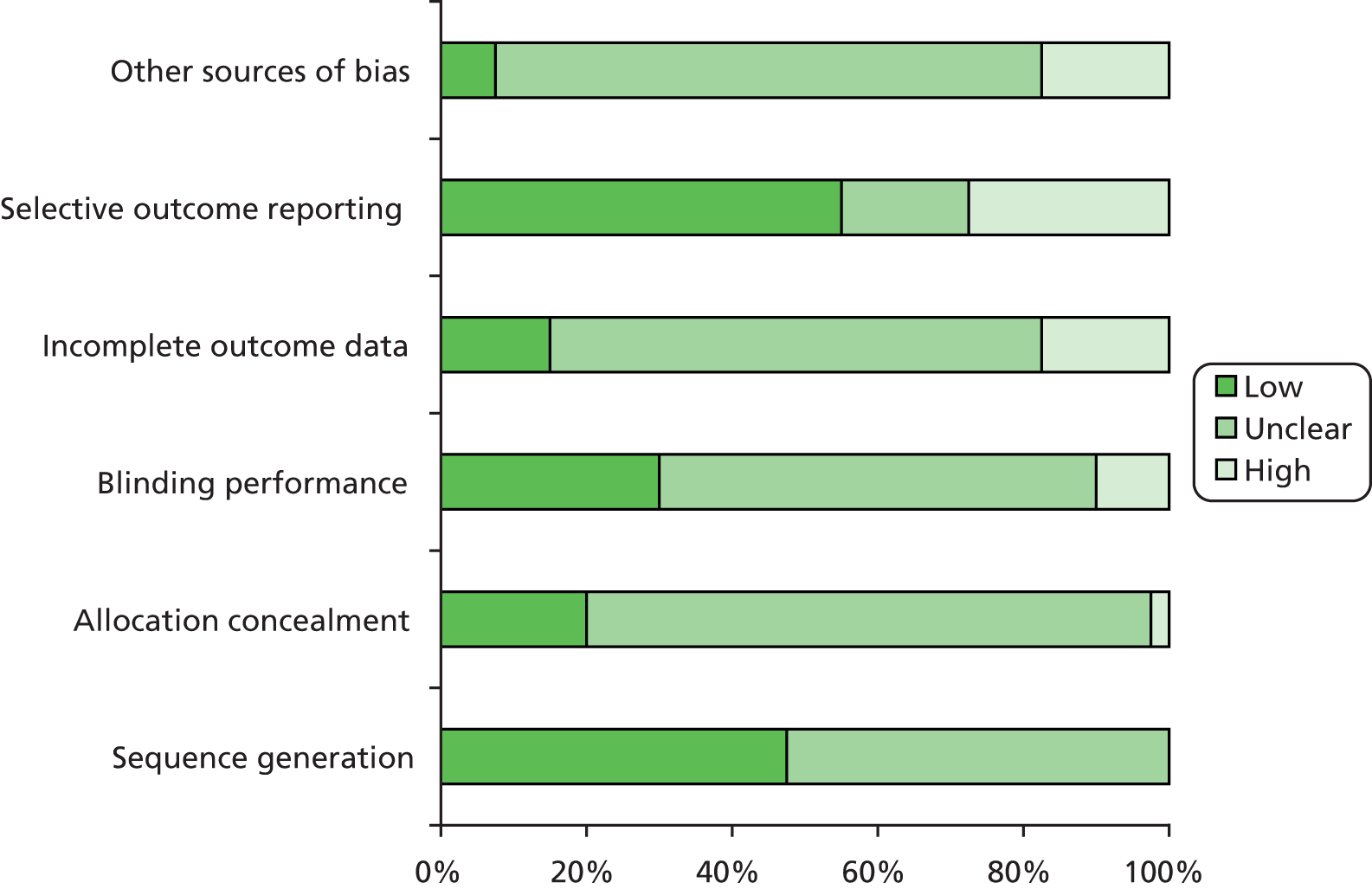

Quality assessment strategy

We extracted data on the methodological quality of all included male-only RCTs and appraised this using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Quality appraisal was undertaken by two researchers independently and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias were assessed, assigning low, high or unclear risk of bias, as appropriate. The purpose of the quality appraisal was to describe the quality of the evidence base, not to give an inclusion/exclusion criterion.

Randomised controlled trials containing sex group analyses were assessed for quality using assessment criteria adapted from Pincus et al. 36 and Sun et al. 37 ‘Yes’, ‘No’ and ‘Unclear’ were recorded as responses to the following quality appraisal questions:

-

Was the group hypothesis considered a priori?

-

Was gender included as a stratification factor at randomisation?

-

Was gender one of a small number of planned group hypotheses tested (≤ 5)?

-

Was the study free of other bias (randomisation, allocation concealment, outcome reporting)?

Data analysis

Meta-analysis was conducted using Review Manager version 5.2 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark).

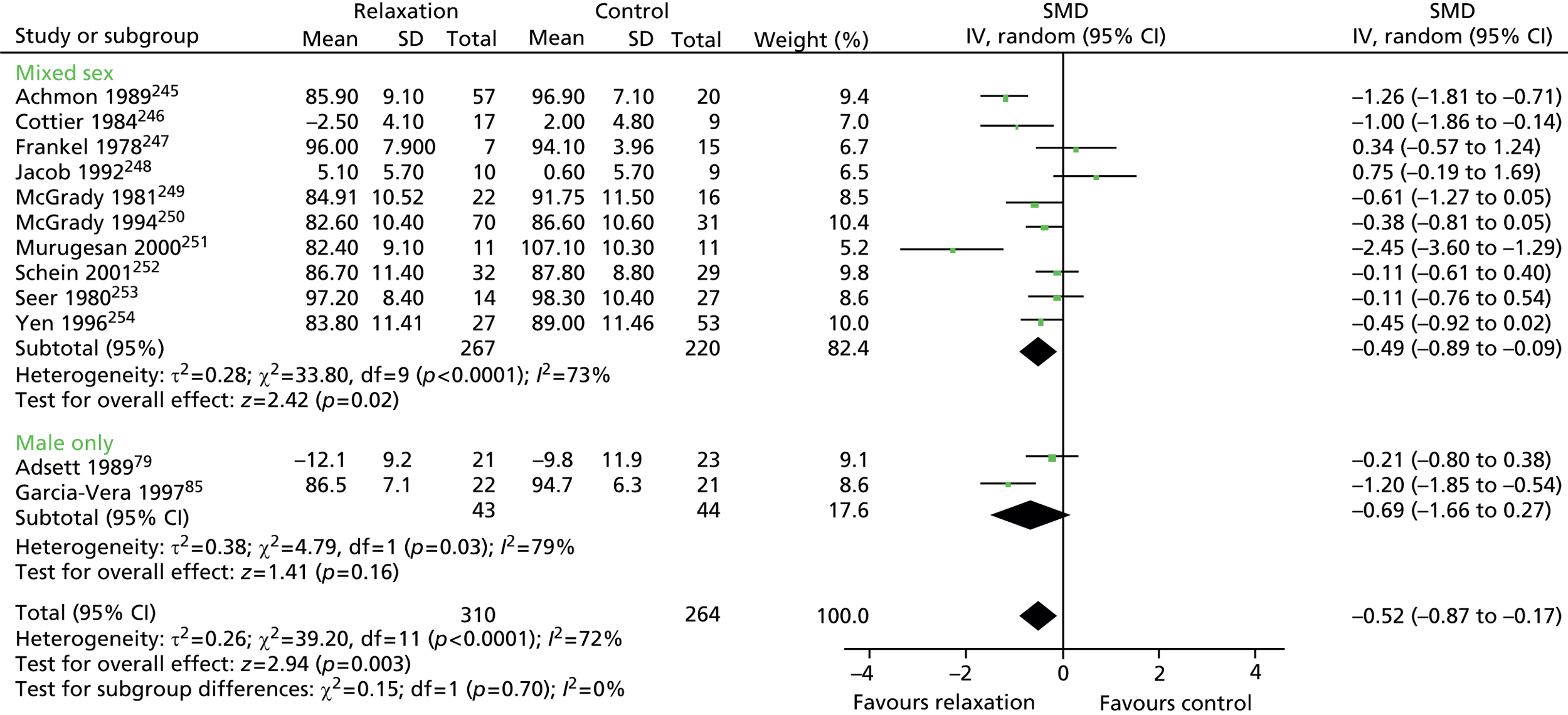

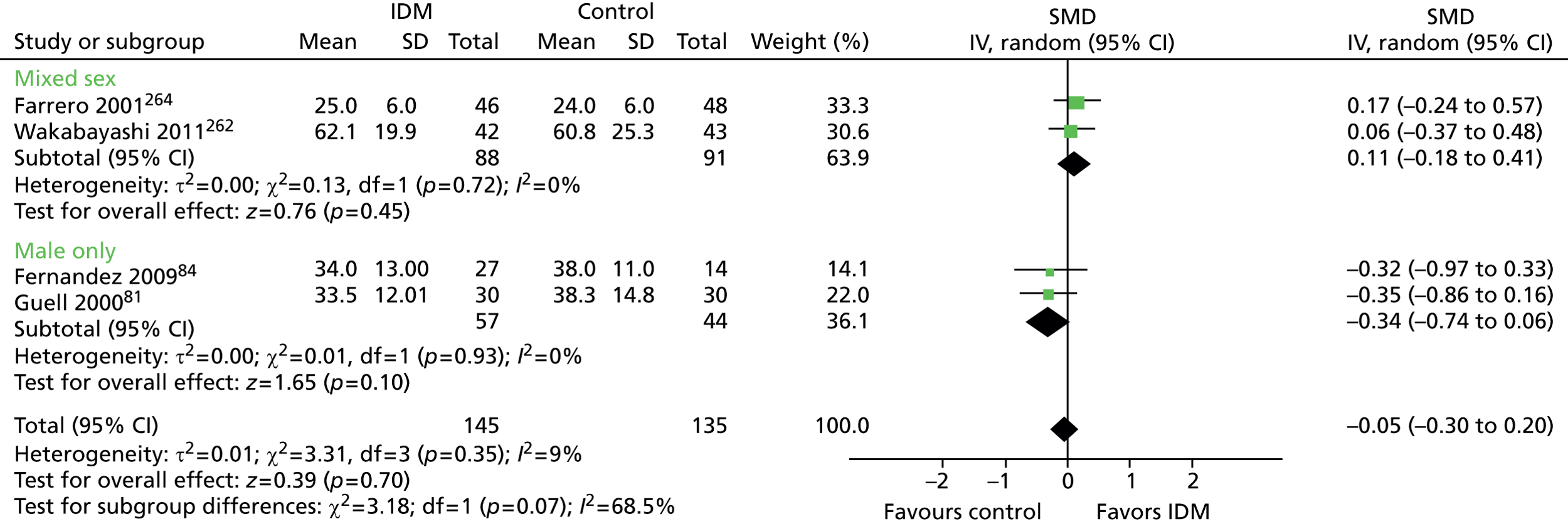

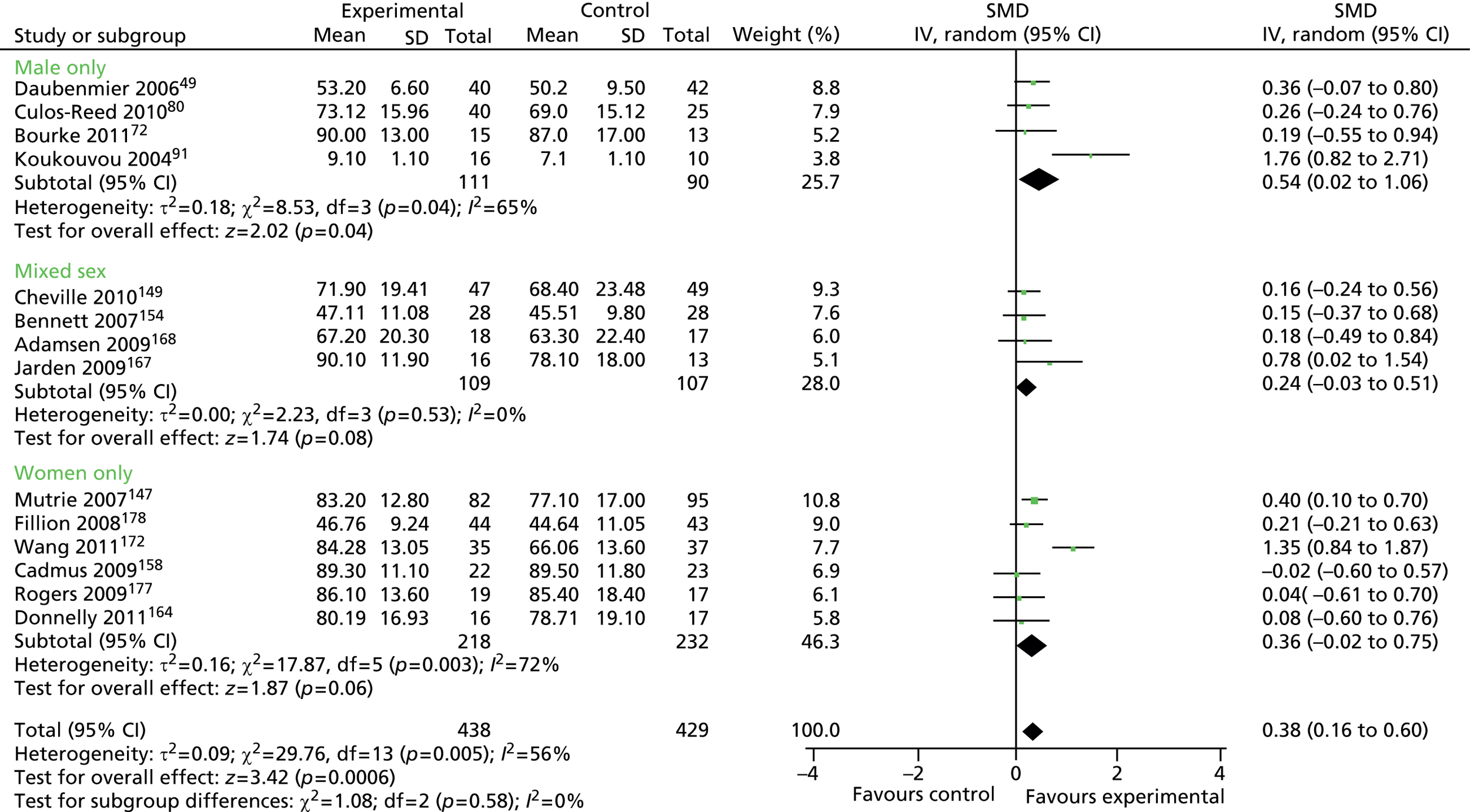

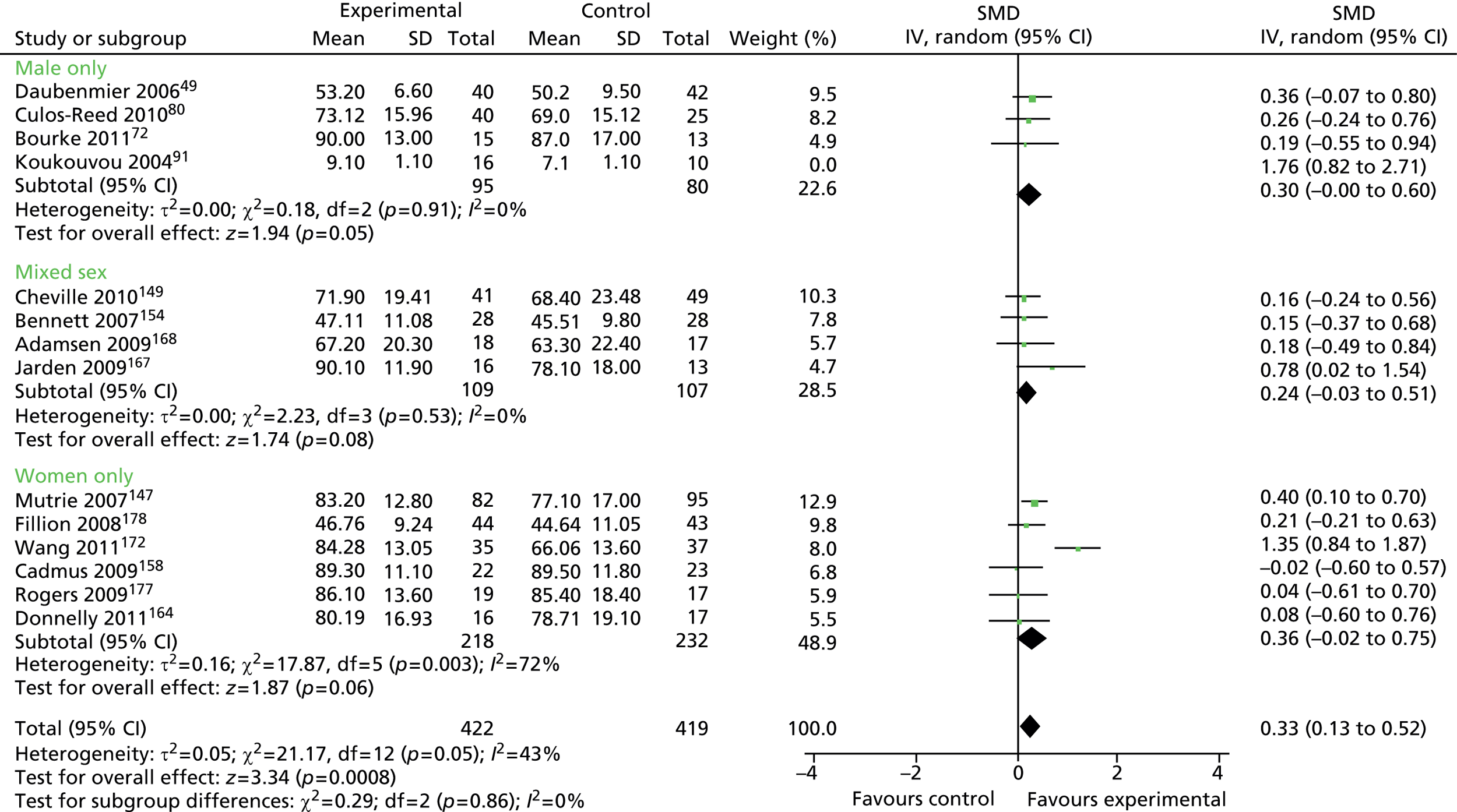

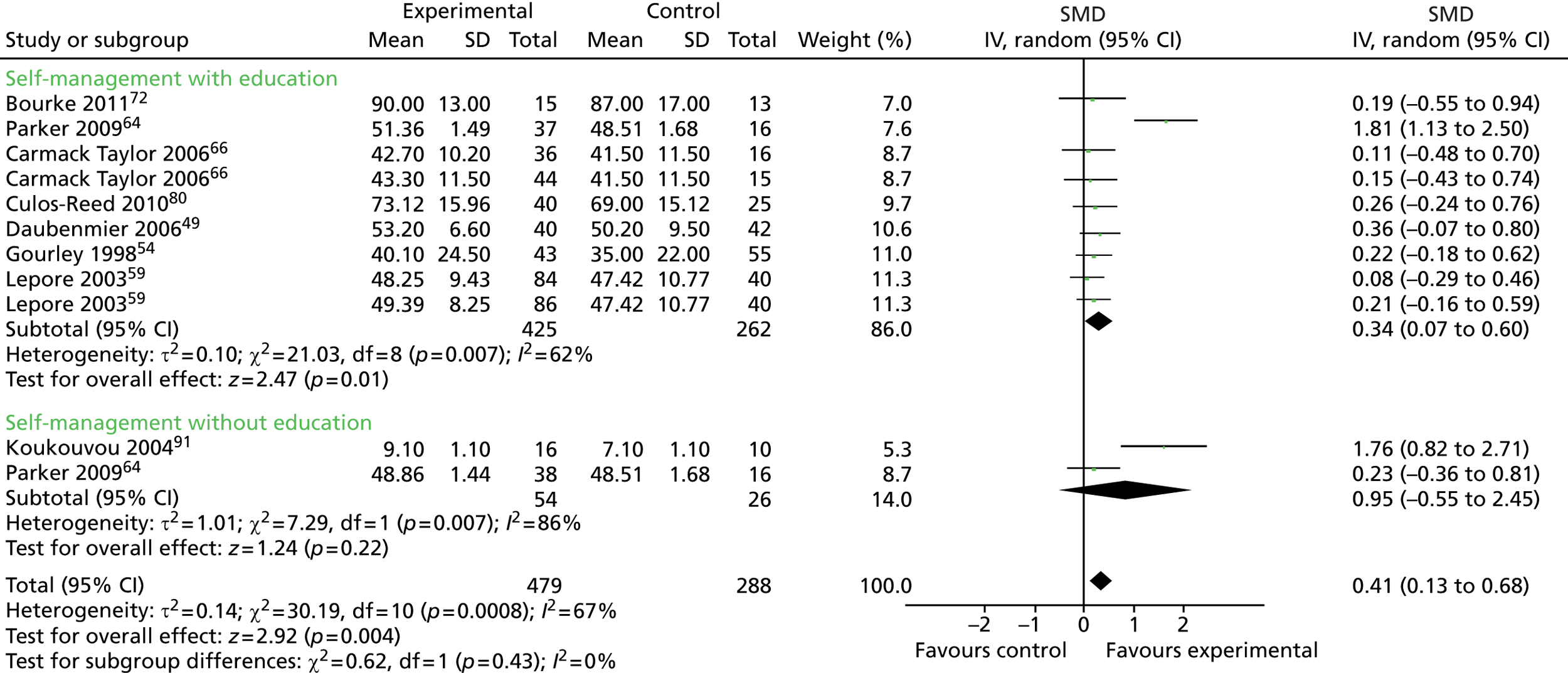

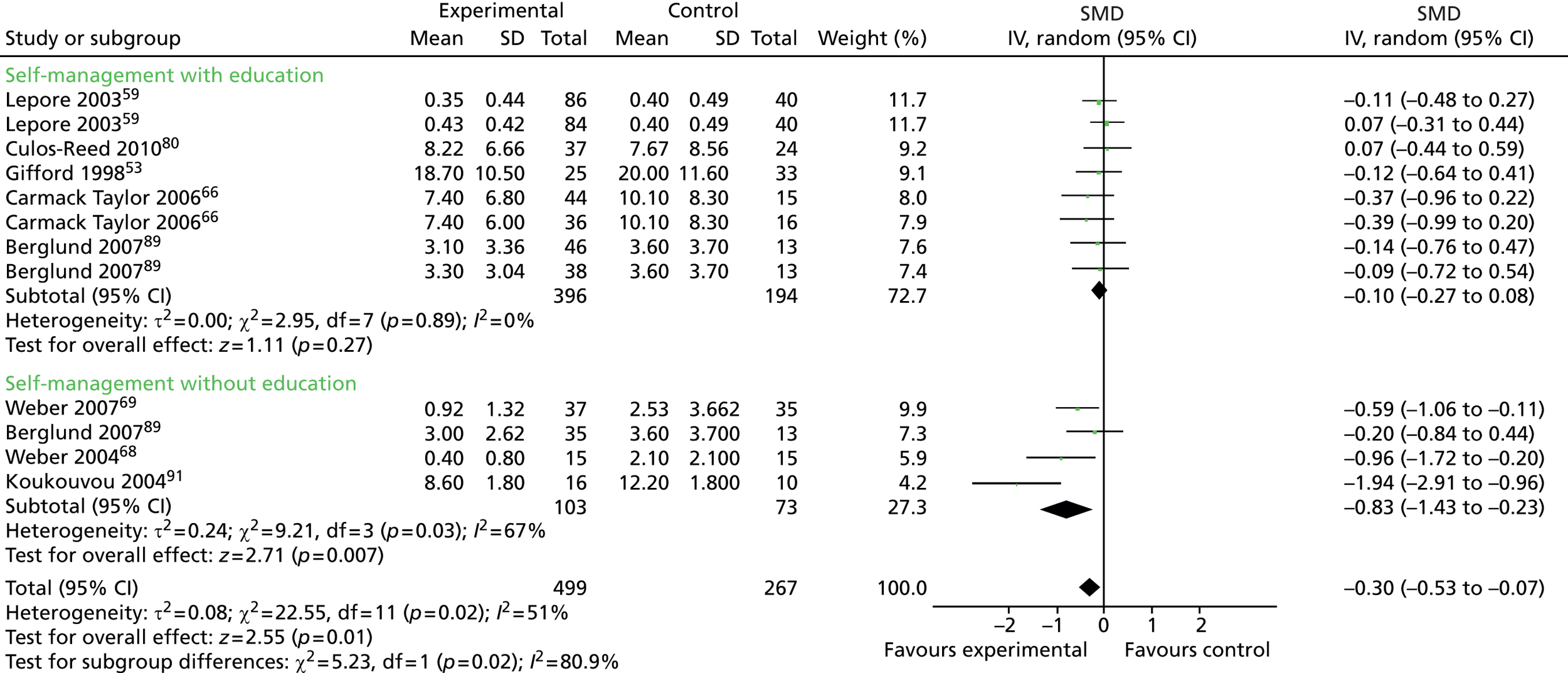

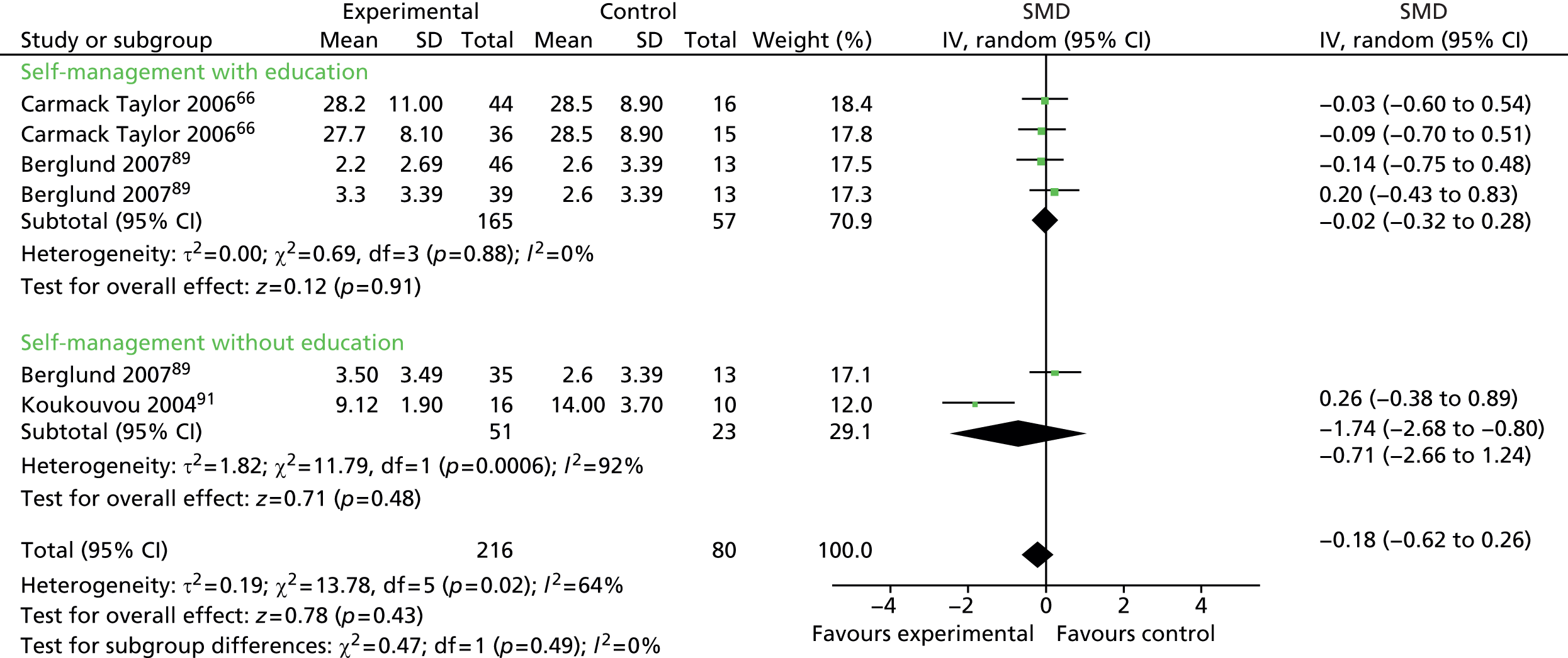

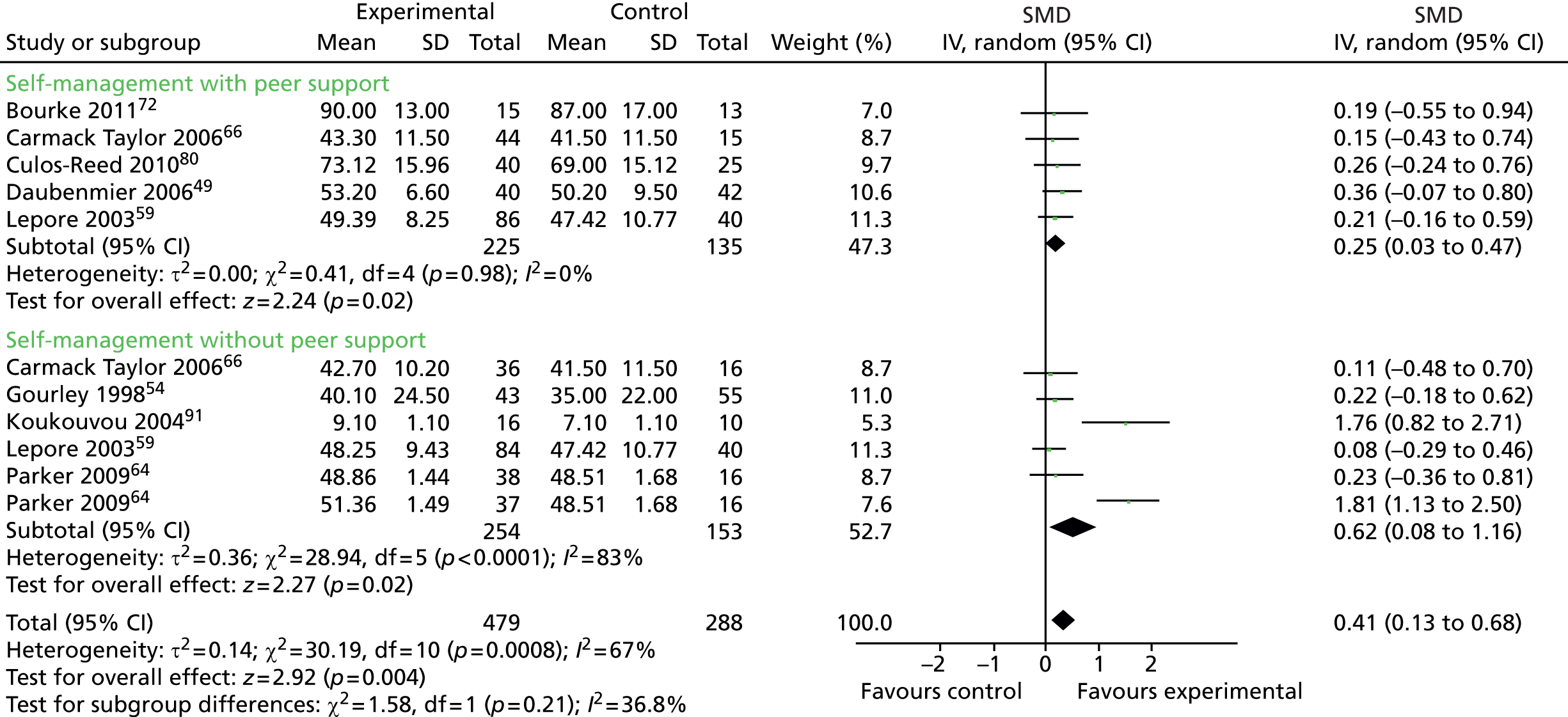

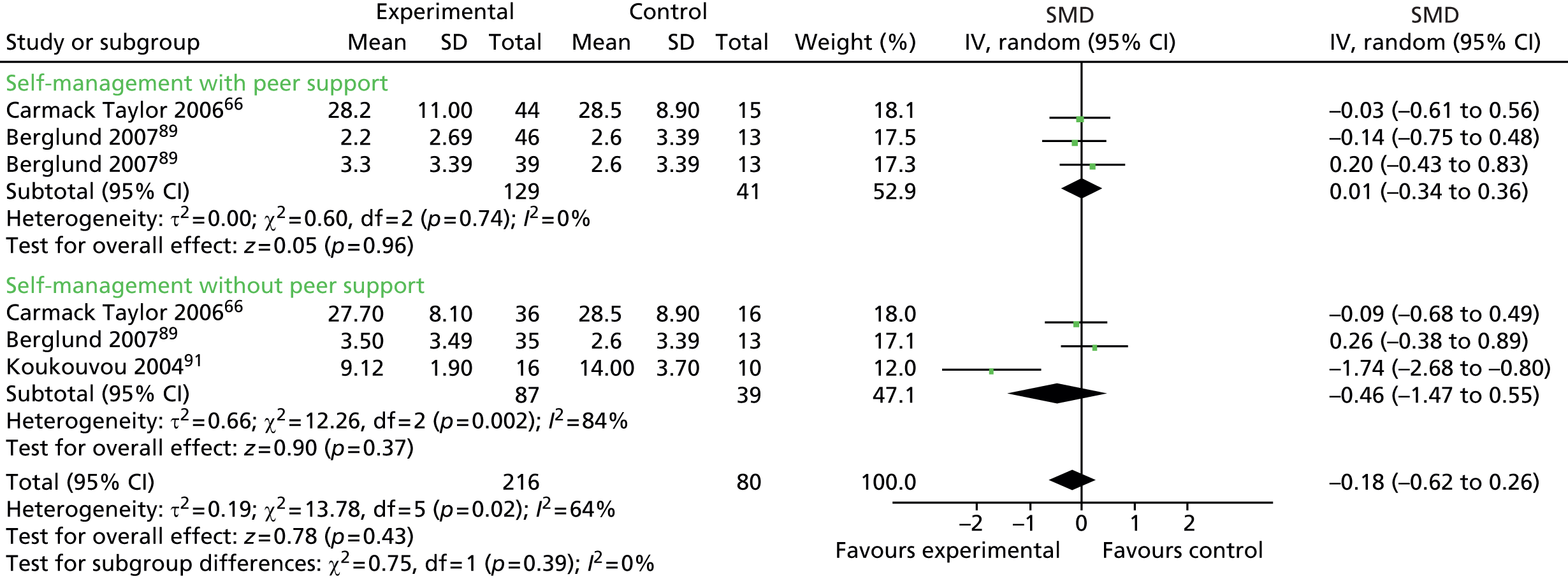

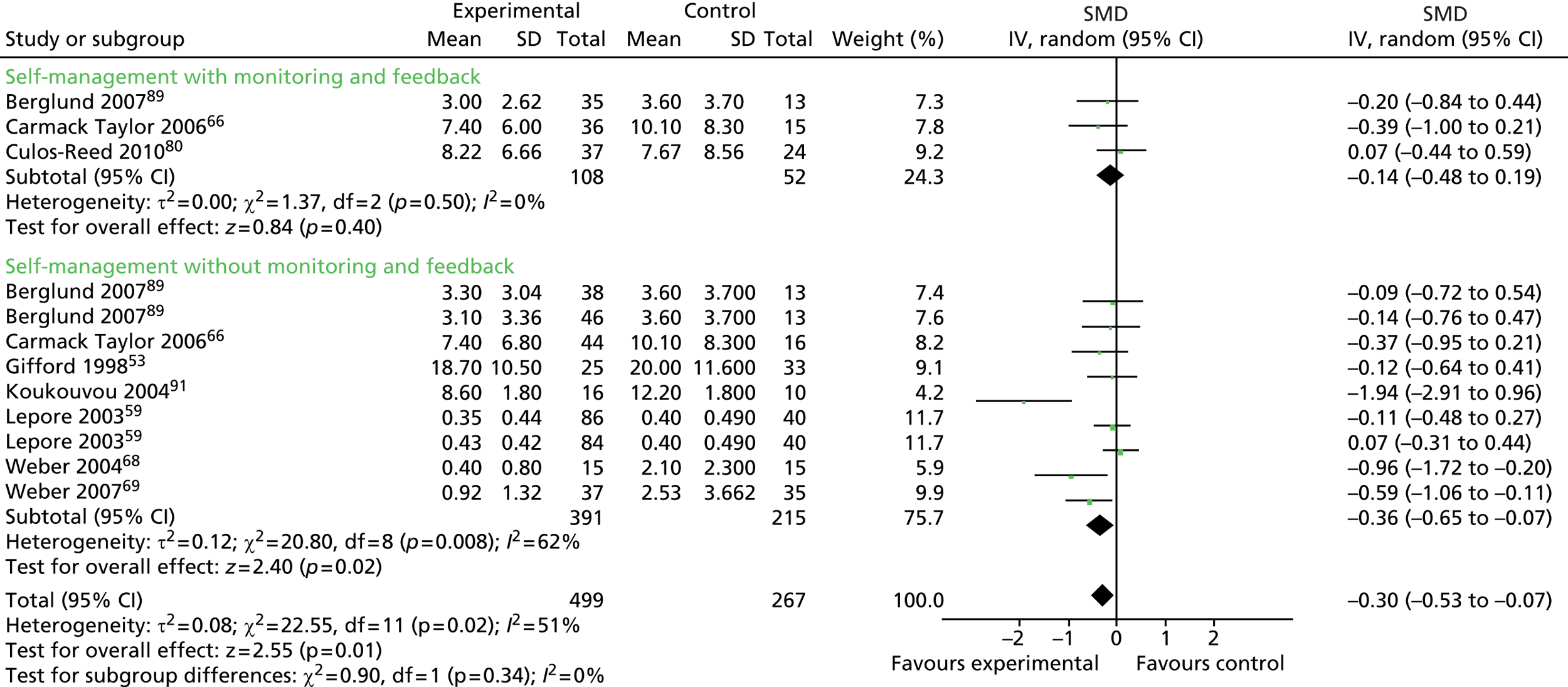

Data were extracted, analysed and presented as standardised mean difference (SMD) to account for the different instruments used, unless otherwise stated. As a guide to the magnitude of effect, we categorised an effect size of 0.2 as representing a ‘small’ effect, 0.5 a ‘moderate’ effect and 0.8 a ‘large’ effect. 38

A random-effects model was used to combine study data. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed with the I2 value, with ‘low’ heterogeneity set at ≤ 25%, ‘moderate’ 50% and ‘high’ 75%.

In instances where studies contained multiple intervention groups, each group was extracted and analysed independently, dividing the control group sample size to avoid double counting in the analysis.

The following outcome measures were used in the analysis where possible: HRQoL, depression, anxiety, fatigue, stress, distress, pain and self-efficacy. Where a study contained more than one measure of a particular outcome (e.g. depression measured by the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale39 and Beck Depression Inventory40), the tool most established in the wider literature was chosen for meta-analysis. If the tool had multiple subscales, a judgement was made about the most relevant subscale. Where studies reported at multiple time periods, outcome measures reported at or closest to 6 months were used, as measures around this time were by far the most frequently reported.

Unless otherwise specified in the results section, positive effect sizes indicate beneficial outcomes for HRQoL and self-efficacy outcomes, while negative effect sizes indicate beneficial outcomes for depression, anxiety, fatigue, stress, distress and pain outcomes.

We conducted four types of analysis, described below.

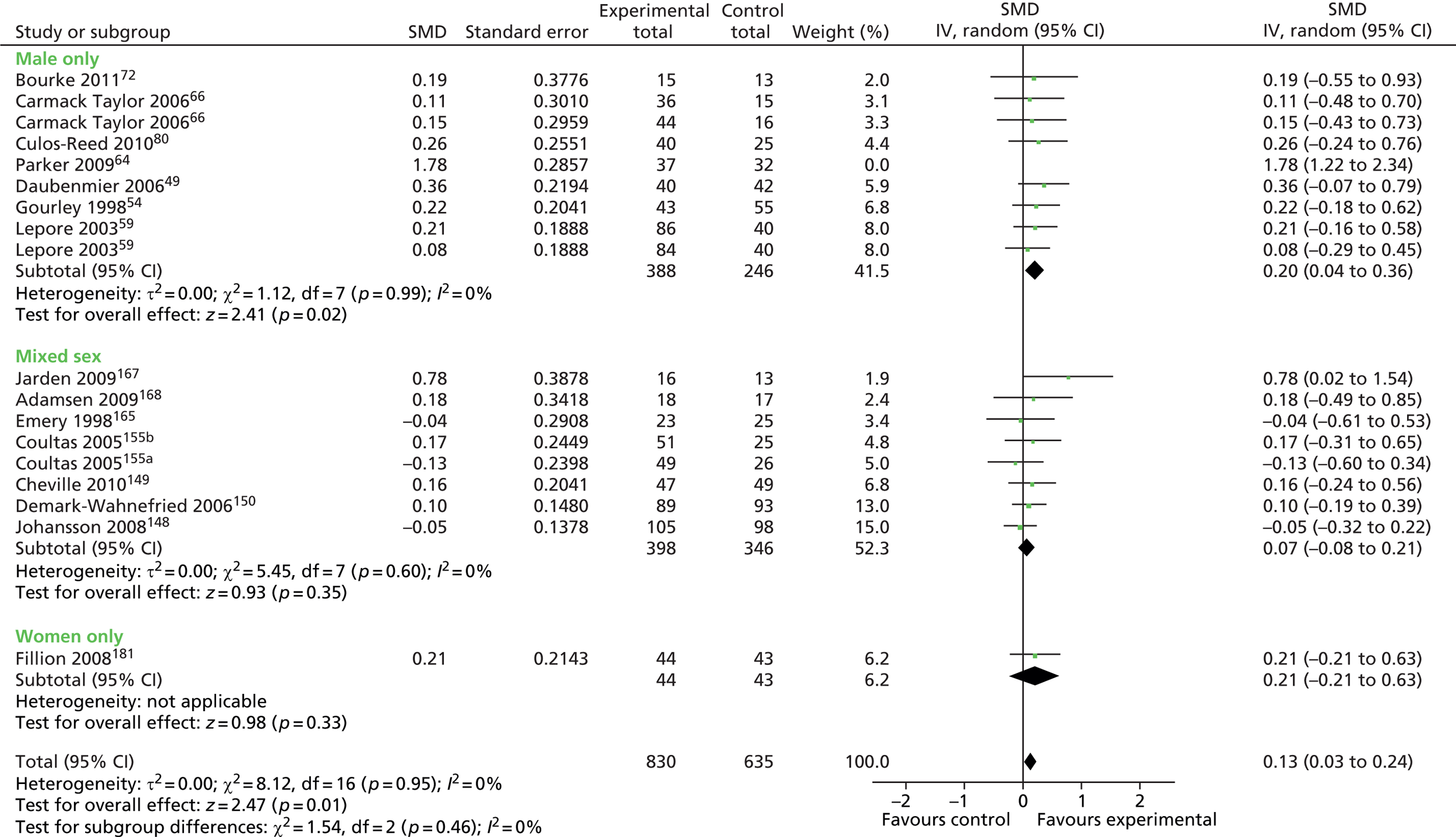

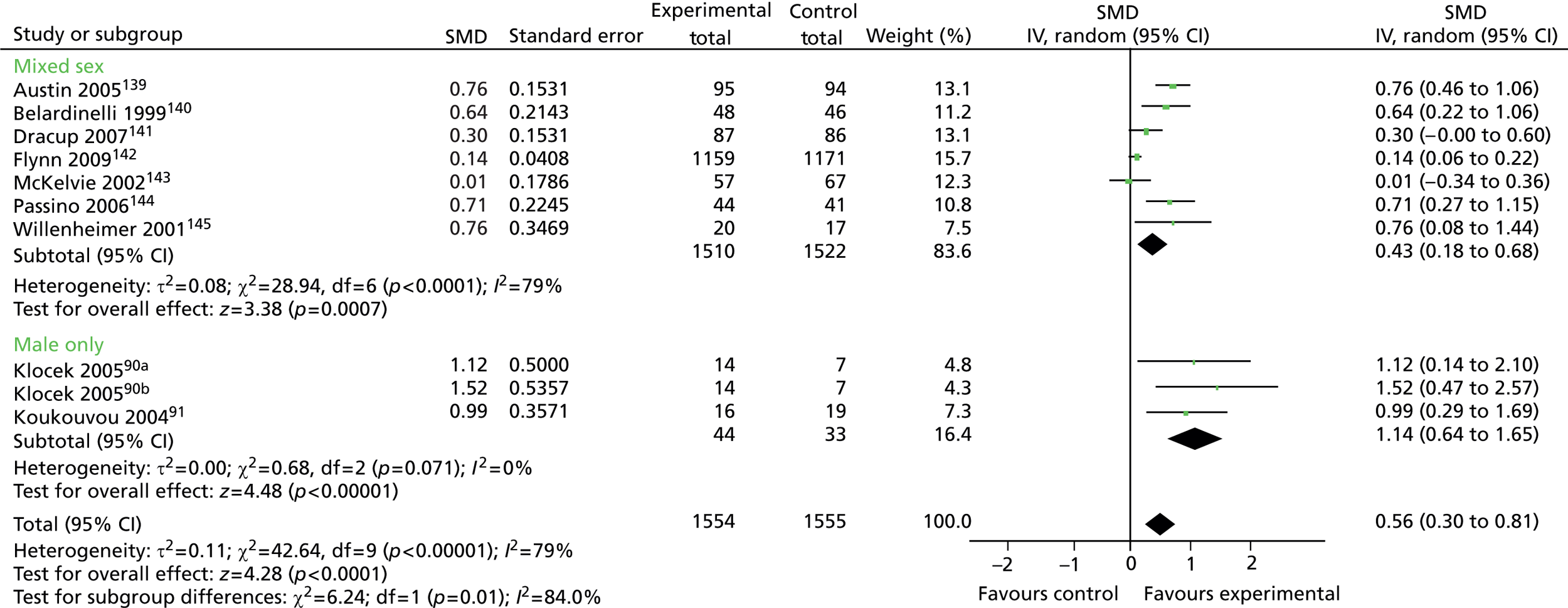

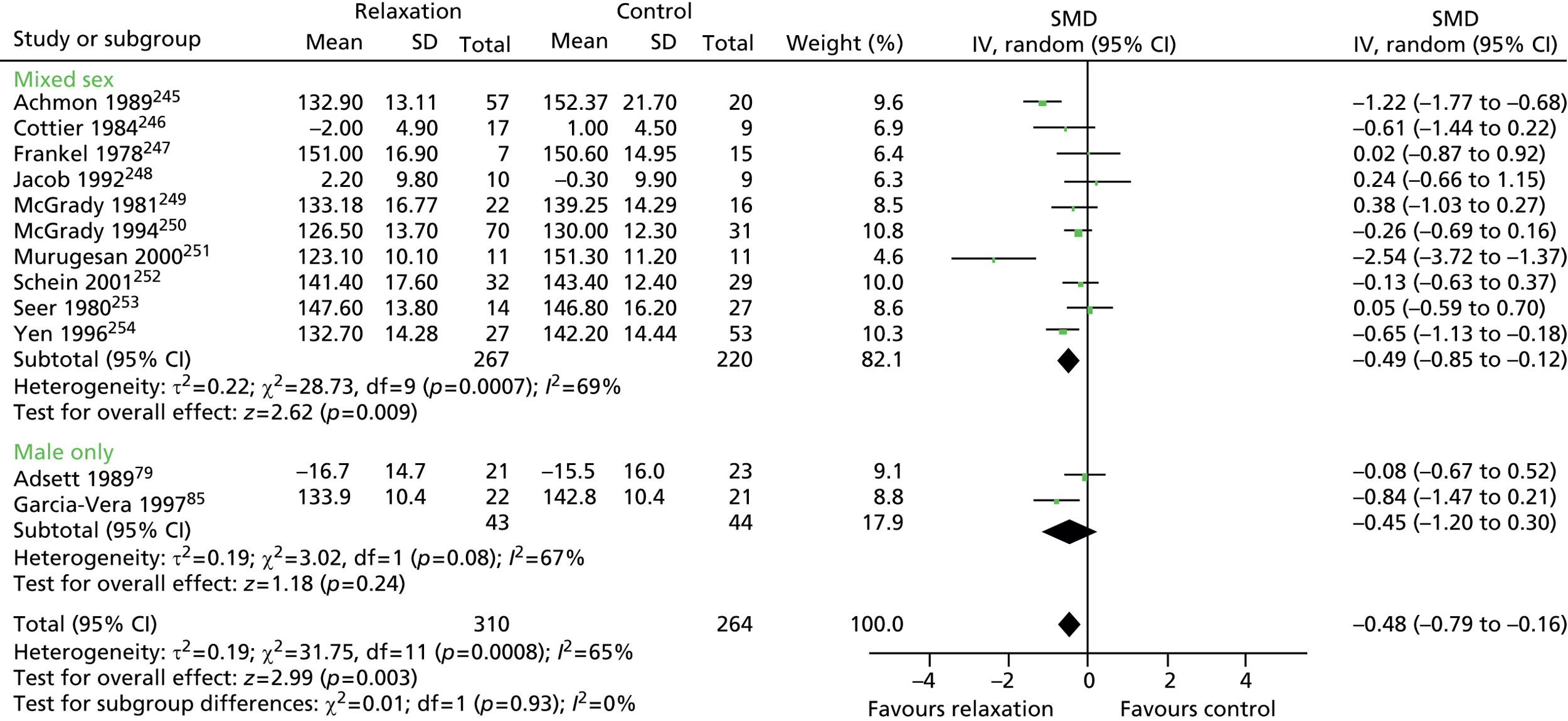

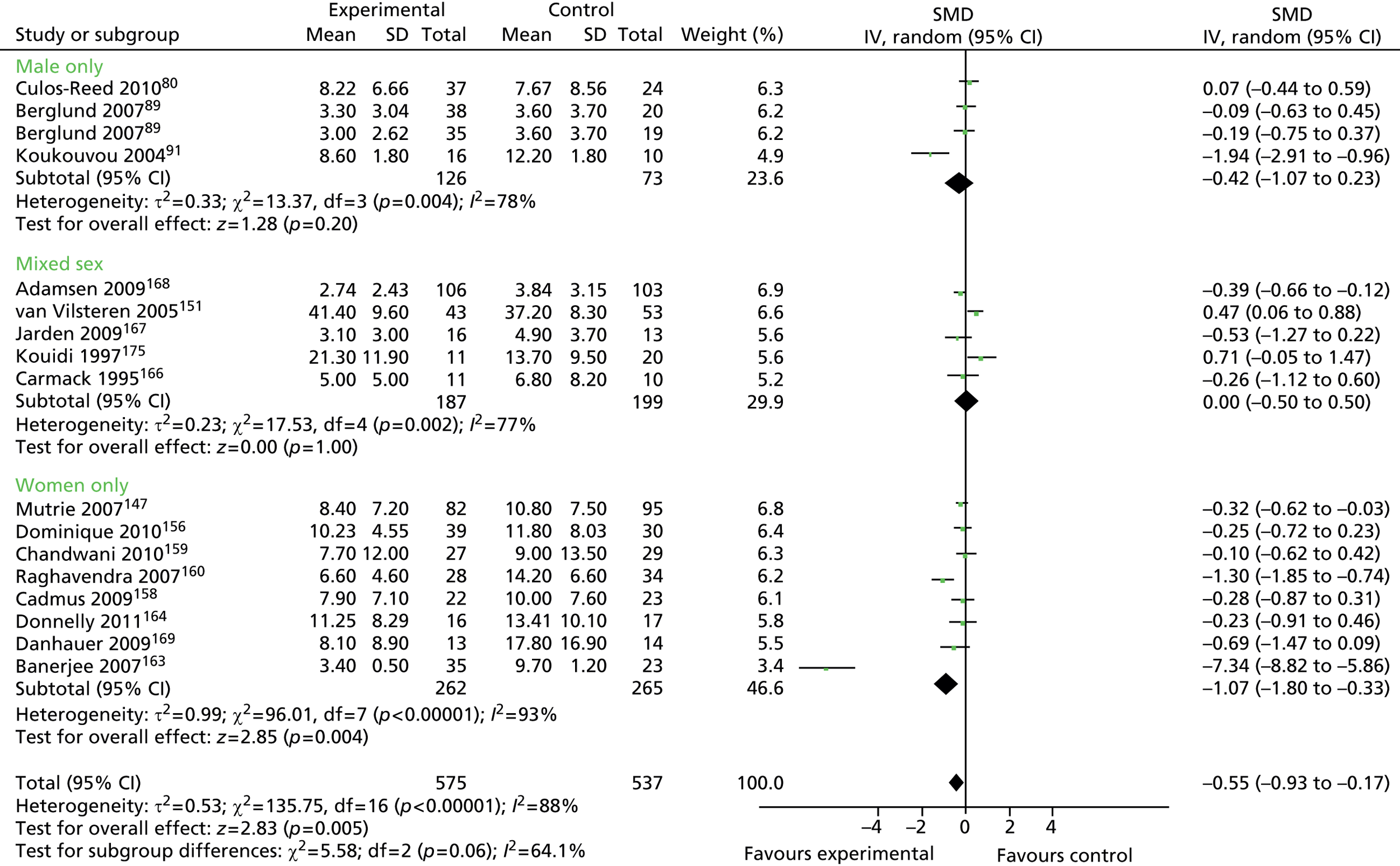

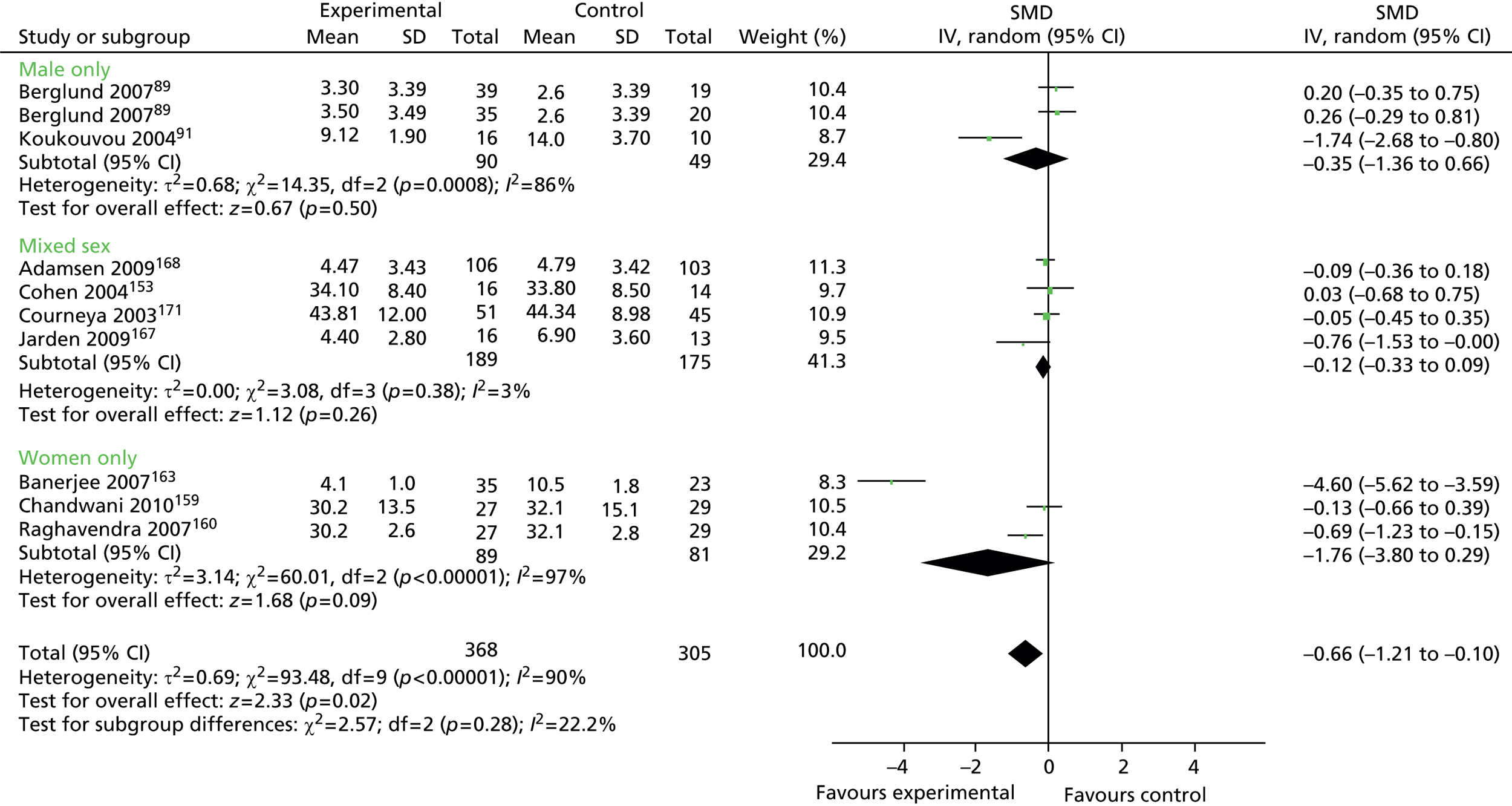

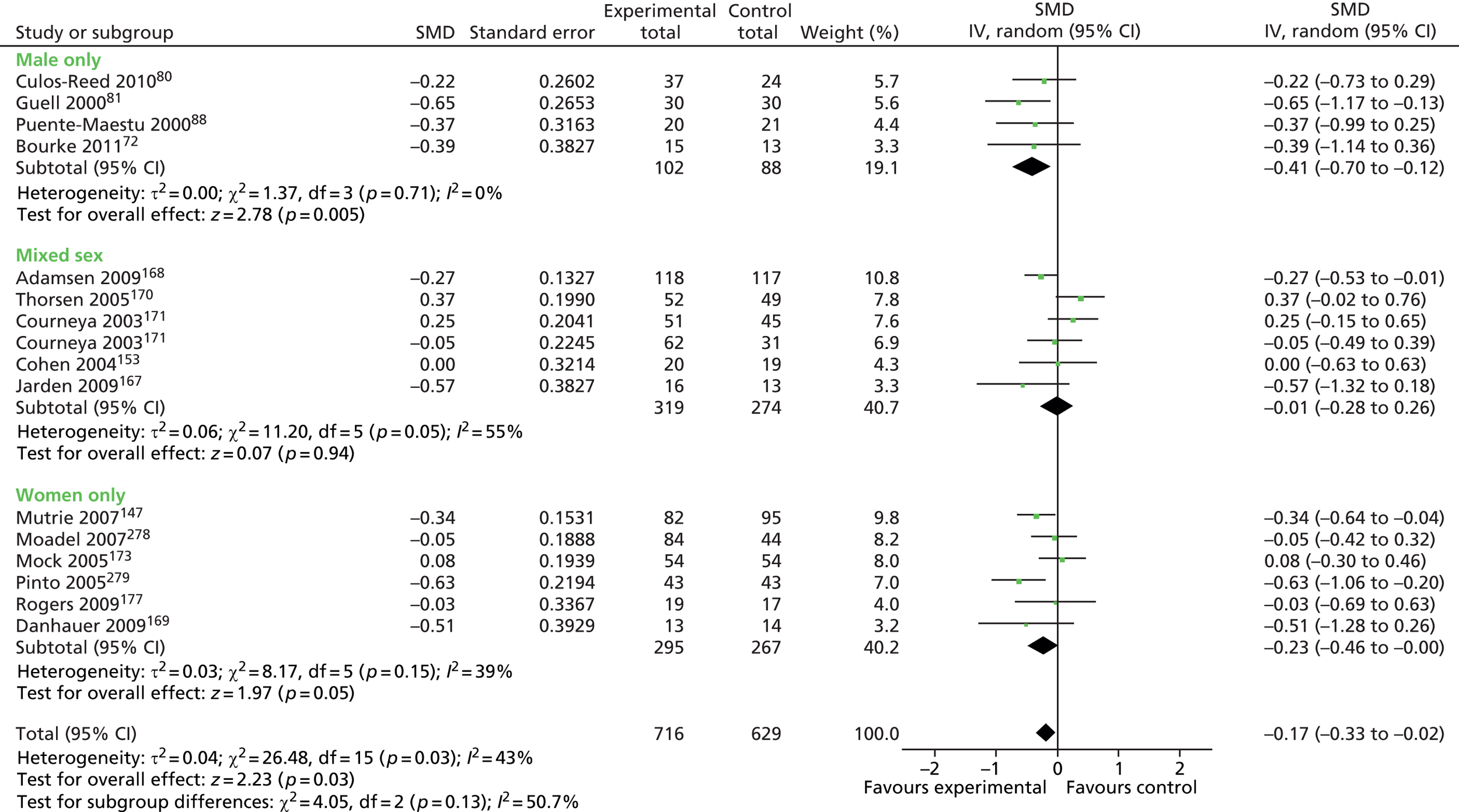

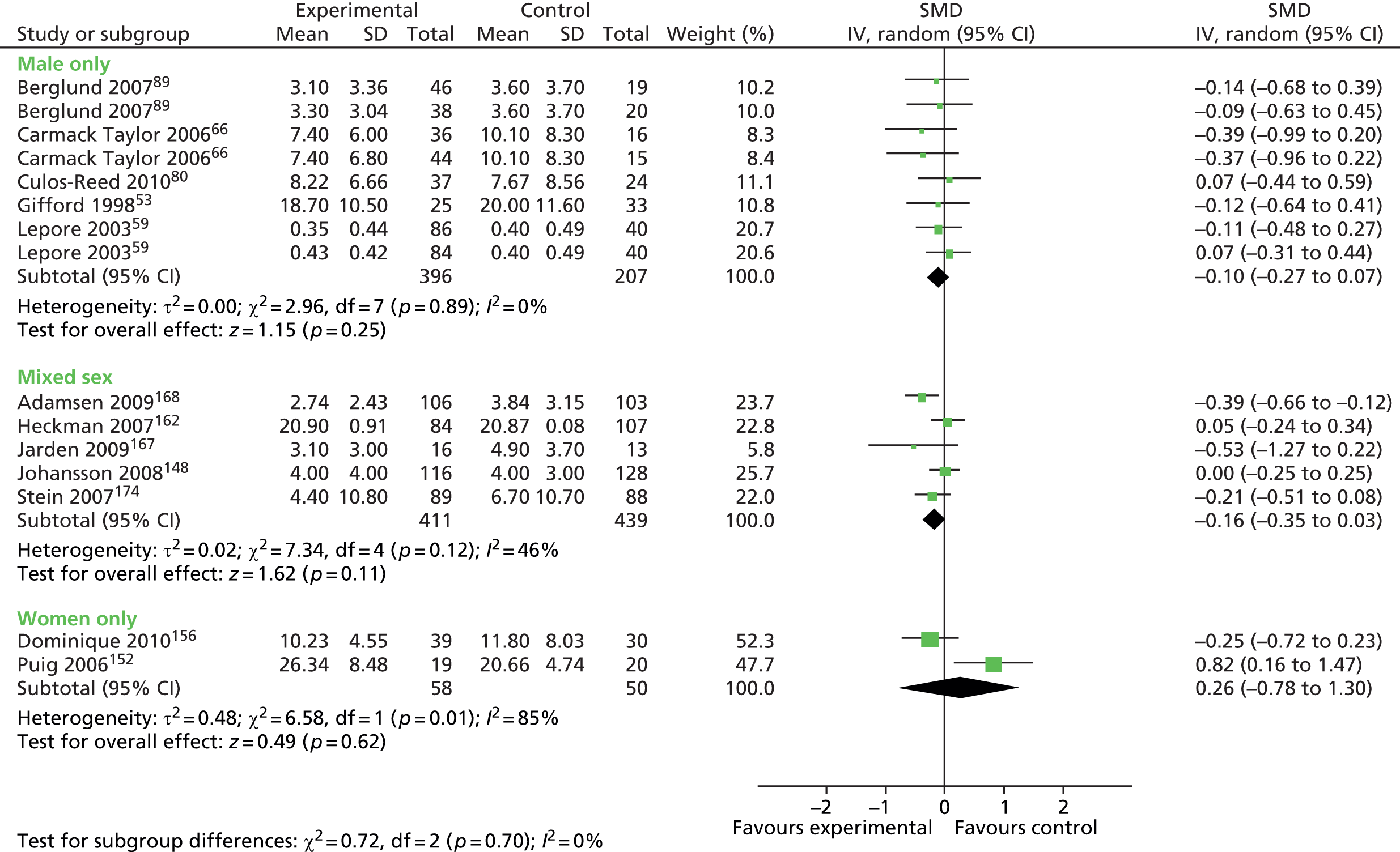

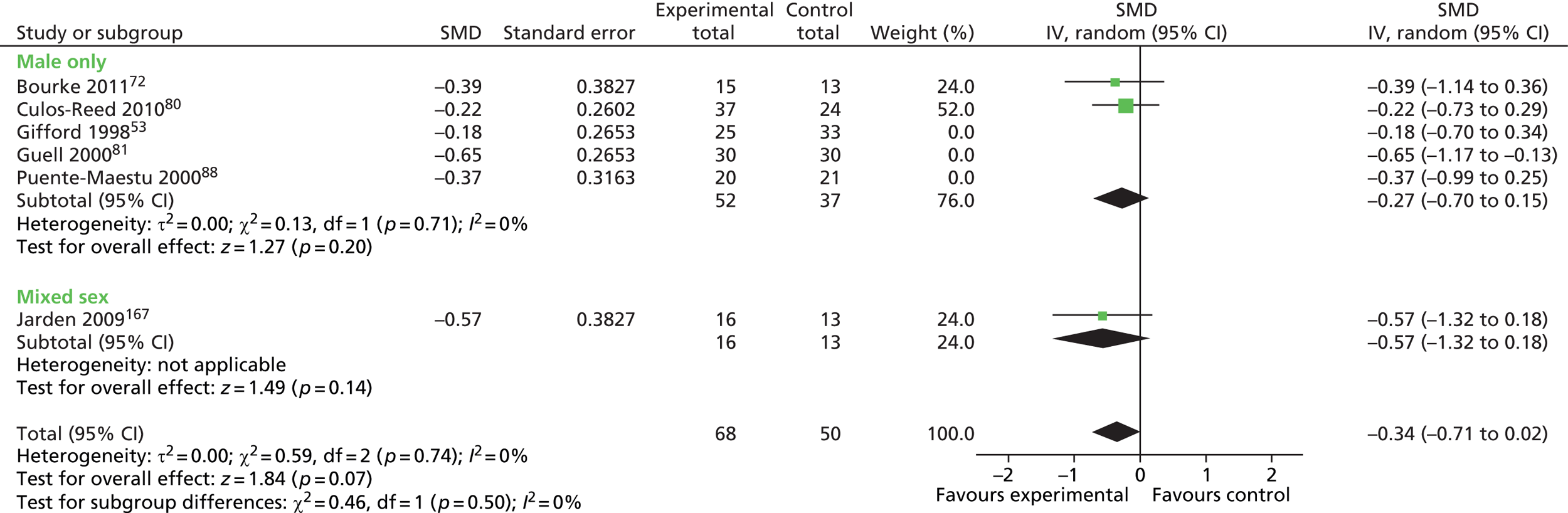

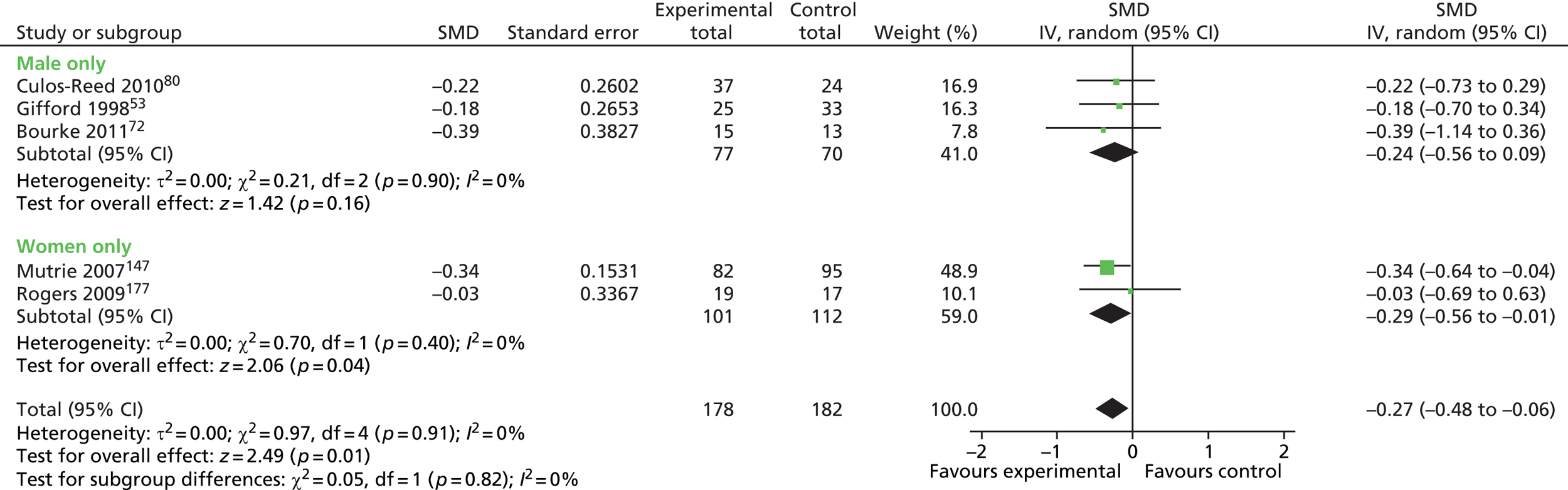

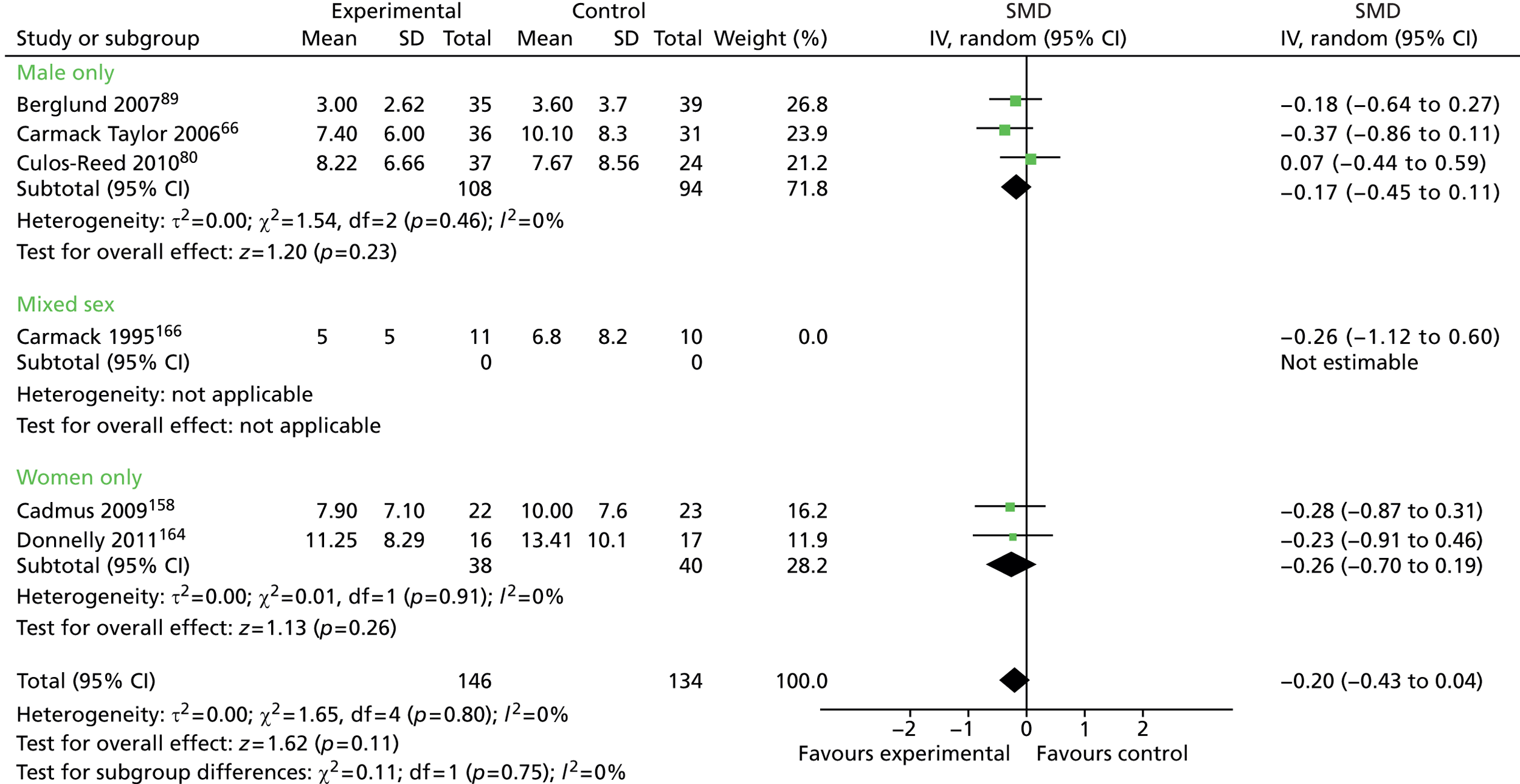

Analysis 1: ‘within-Cochrane review analysis’

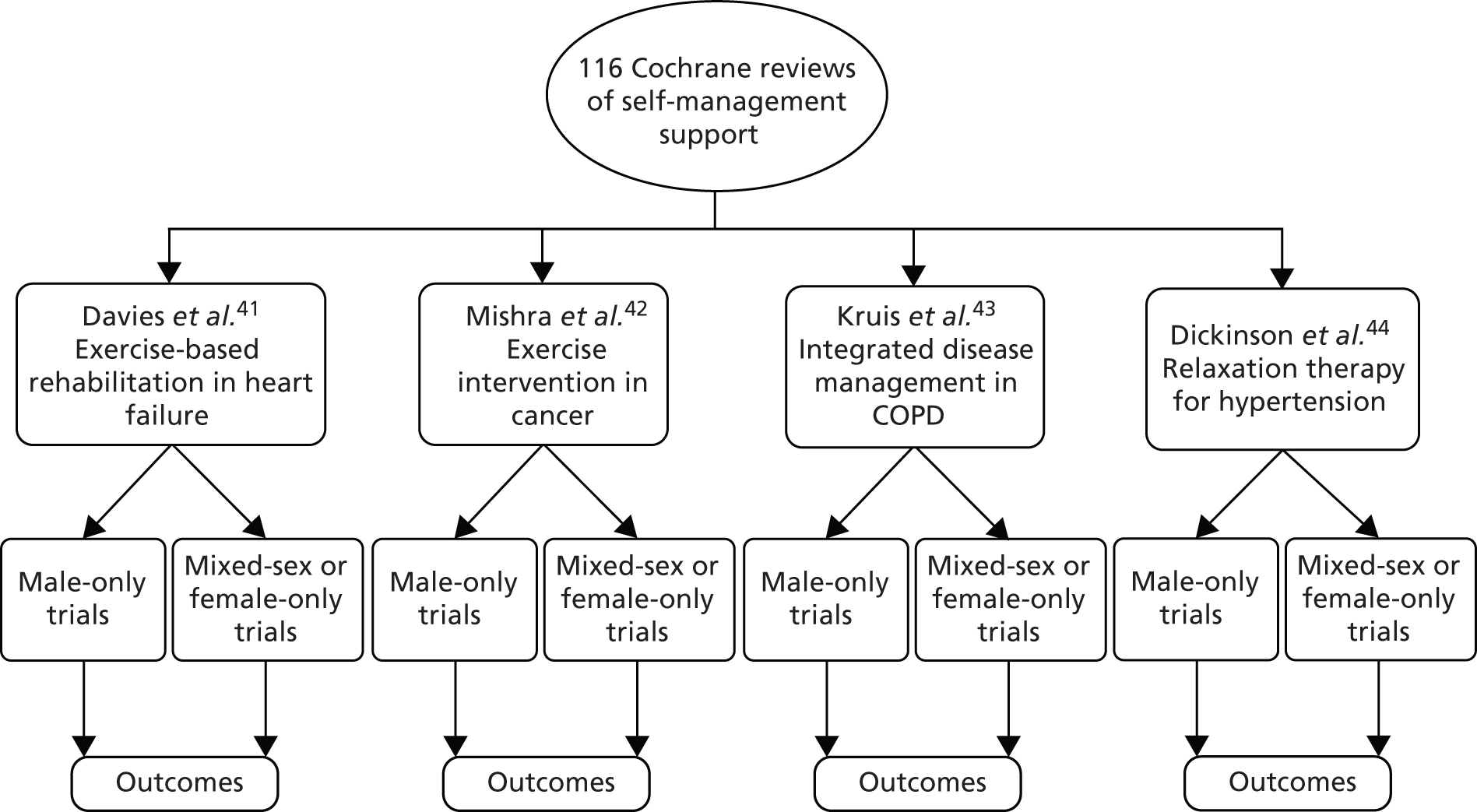

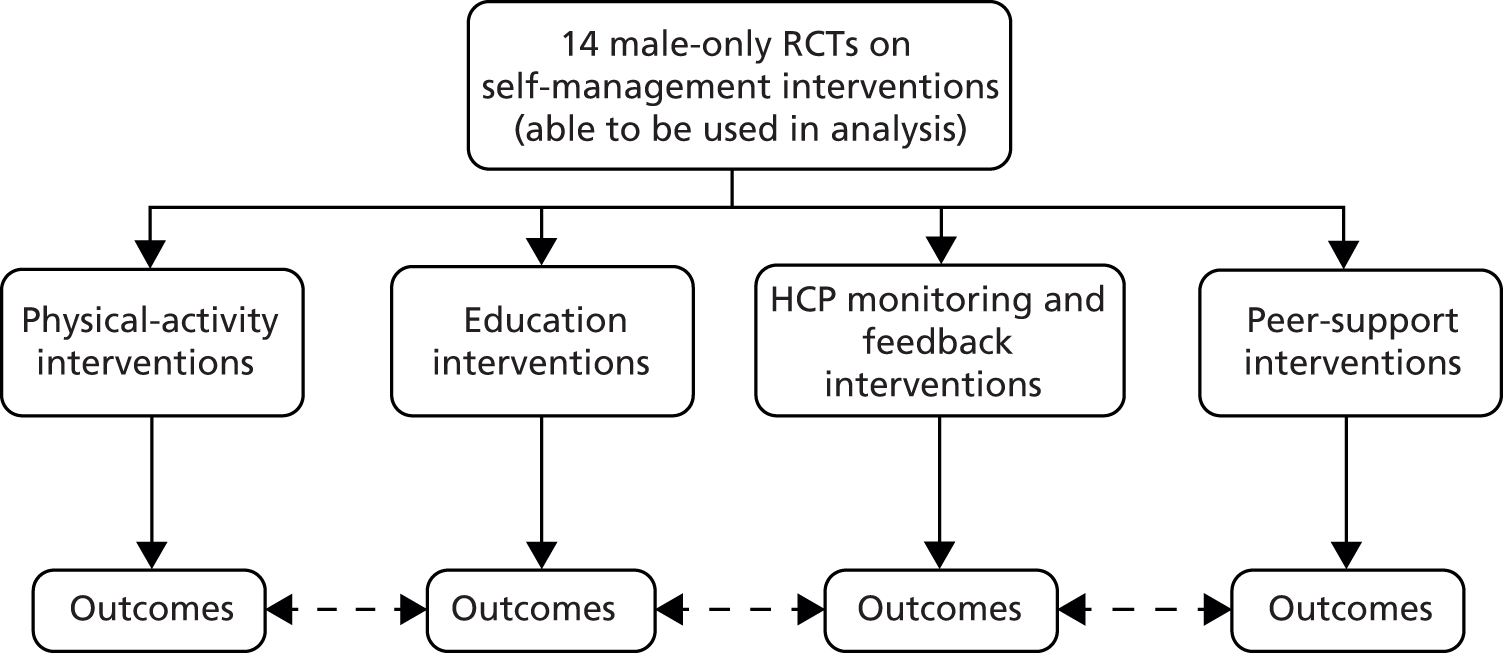

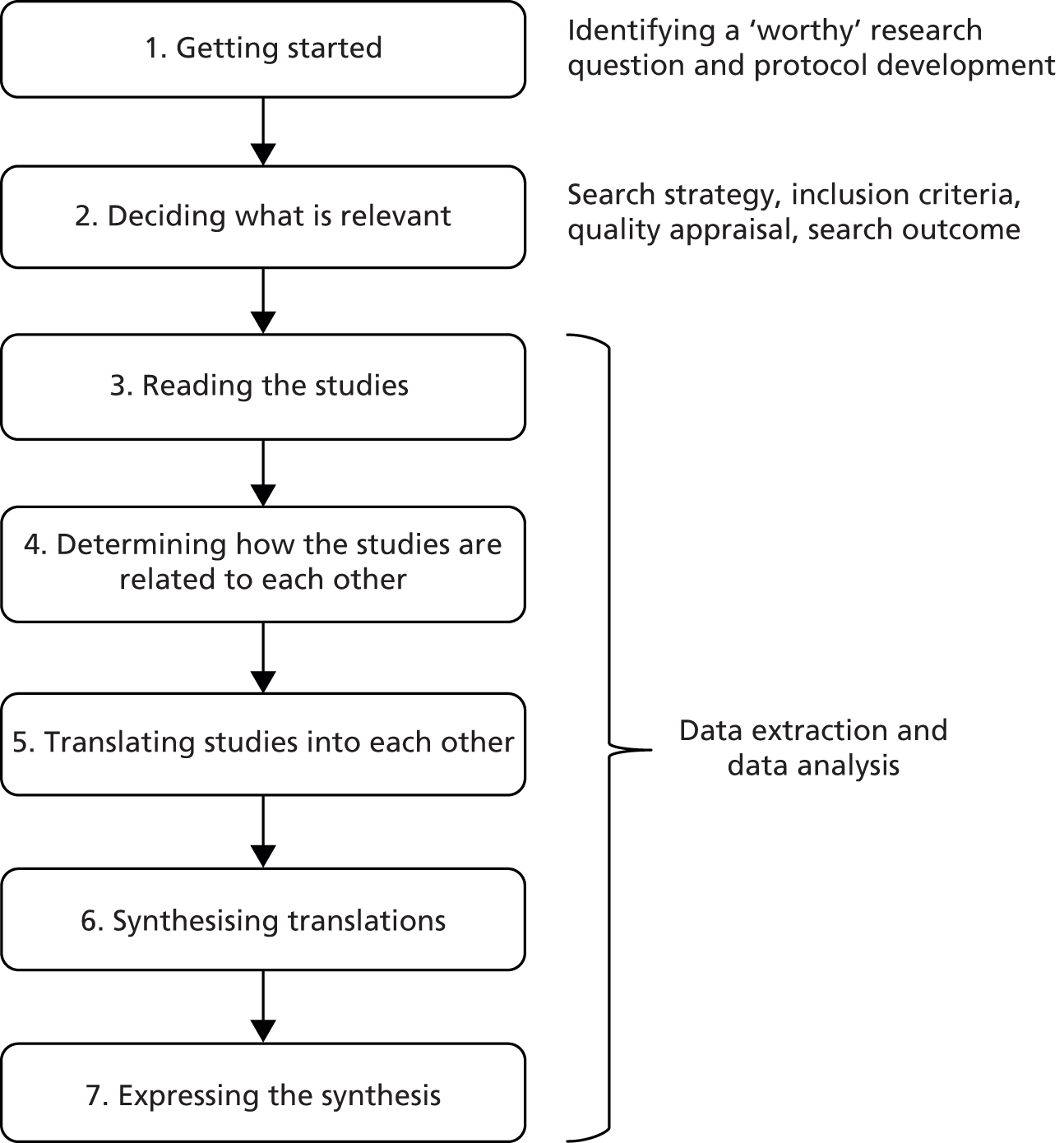

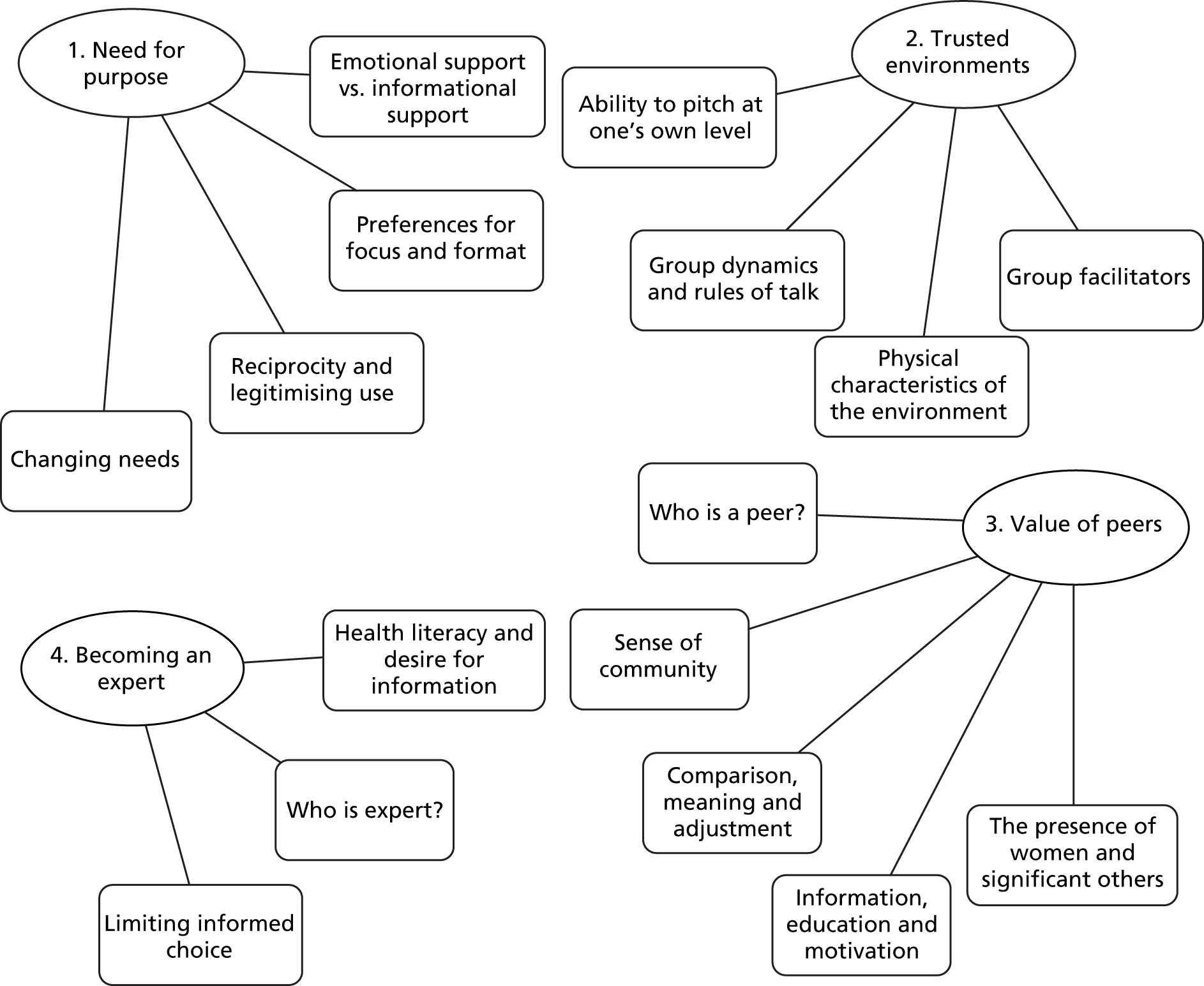

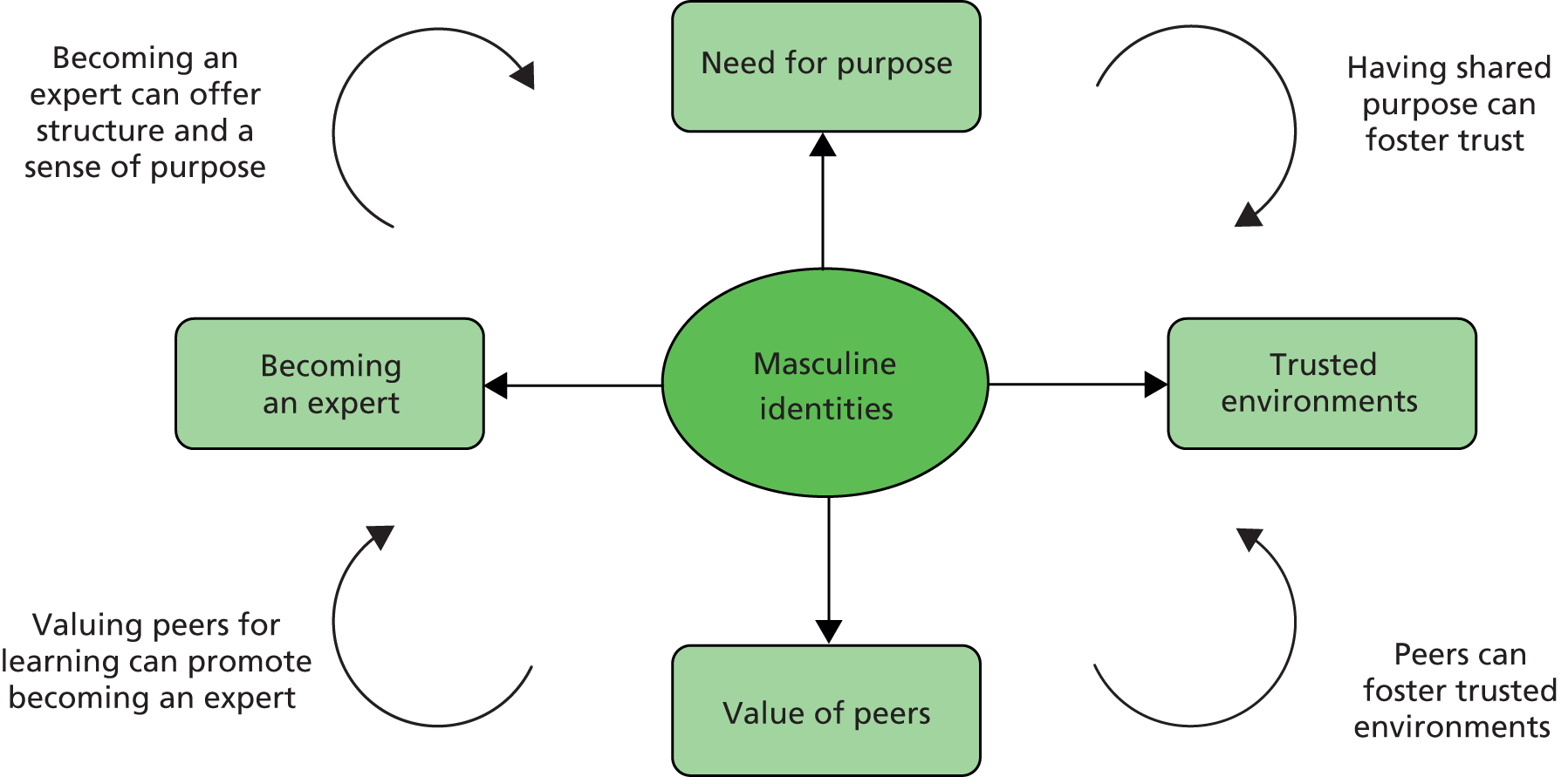

Analysis 1 sought to determine whether studies in males show larger, similar or smaller effects than studies in females and mixed-sex groups within interventions included within the ‘parent’ Cochrane review. We screened all included Cochrane reviews of self-management support interventions to identify those that contained analysis on outcomes of interest and at least two relevant male-only RCTs. Where an eligible review was identified that met these criteria, the studies were categorised as male only, mixed sex and female only (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Analysis 1: ‘within-Cochrane review analysis’.

Such comparisons across trials do not have the protection of randomisation, and there may be differences between the studies included in each sex group which account for differences in effects between groups. We presented data on the comparability of these trials within these three categories, including the age of the included patient populations, and on the quality of the studies (using allocation concealment as an indicator of quality).

We report the effect size [together with significance and 95% confidence interval (CI)] of self-management support in each sex group (male only, mixed sex, female only). We conducted analyses to test whether or not interventions showed significantly different effects in sex groups. It should be noted that the power to detect significant differences in such analyses can be limited.

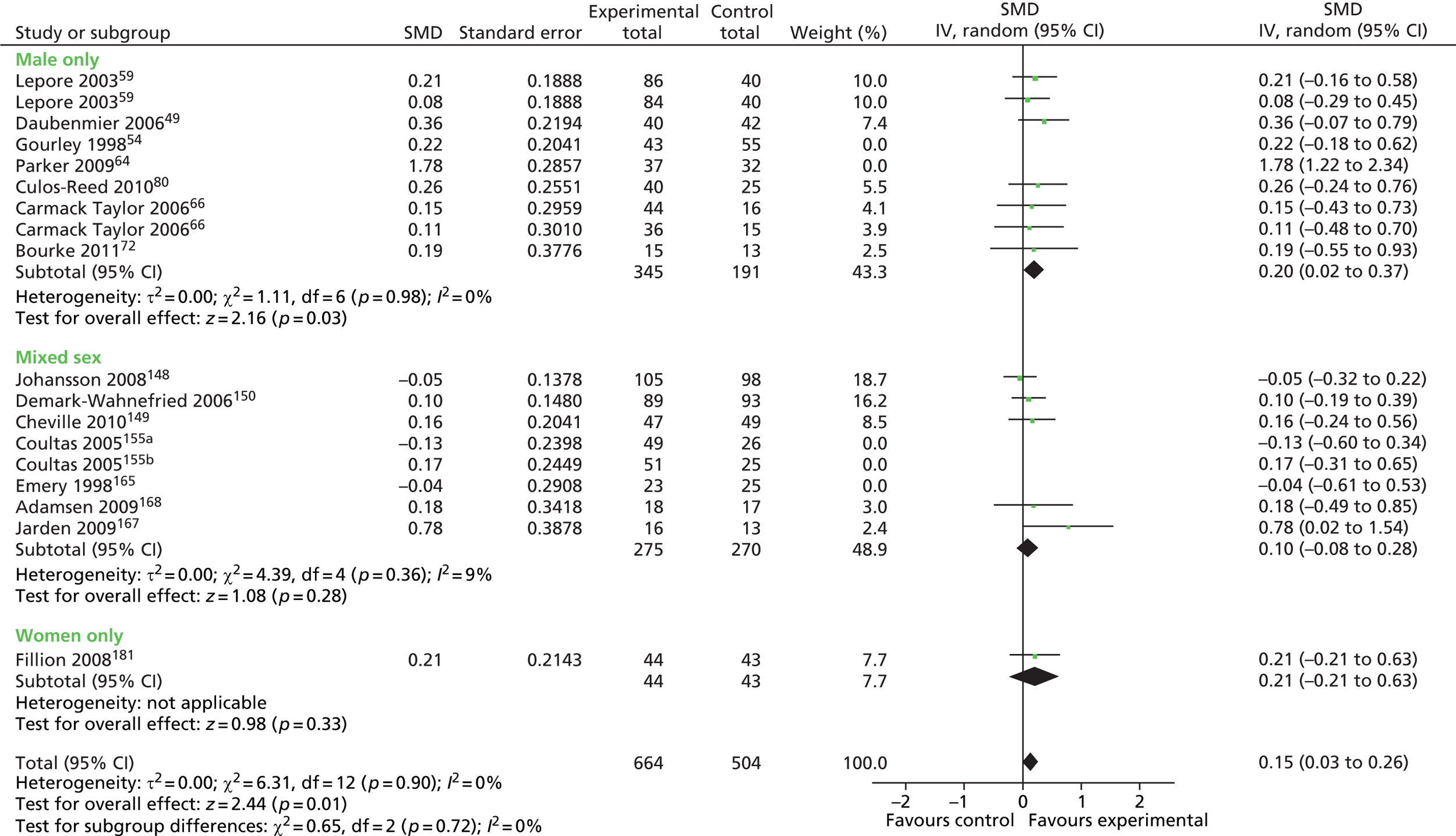

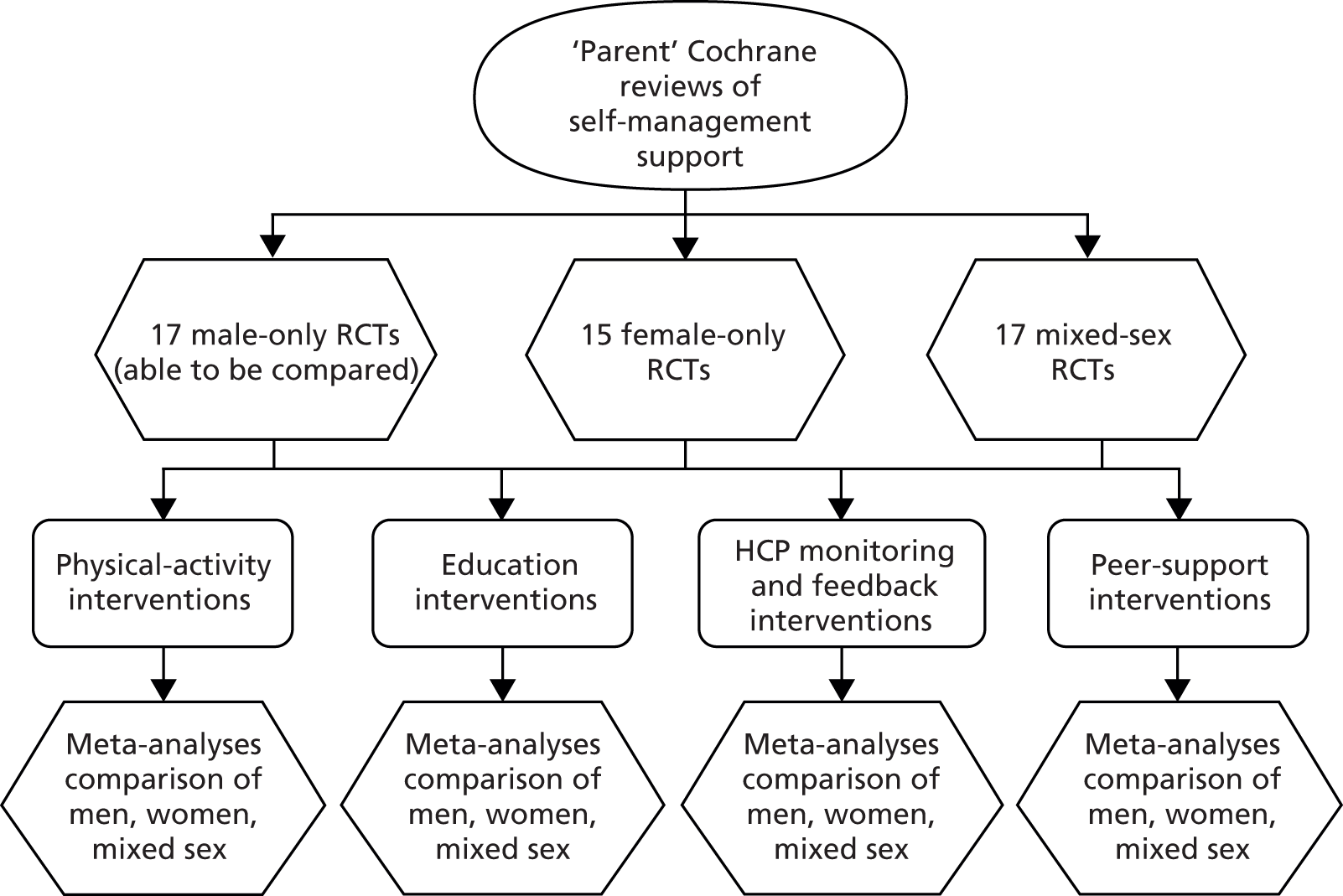

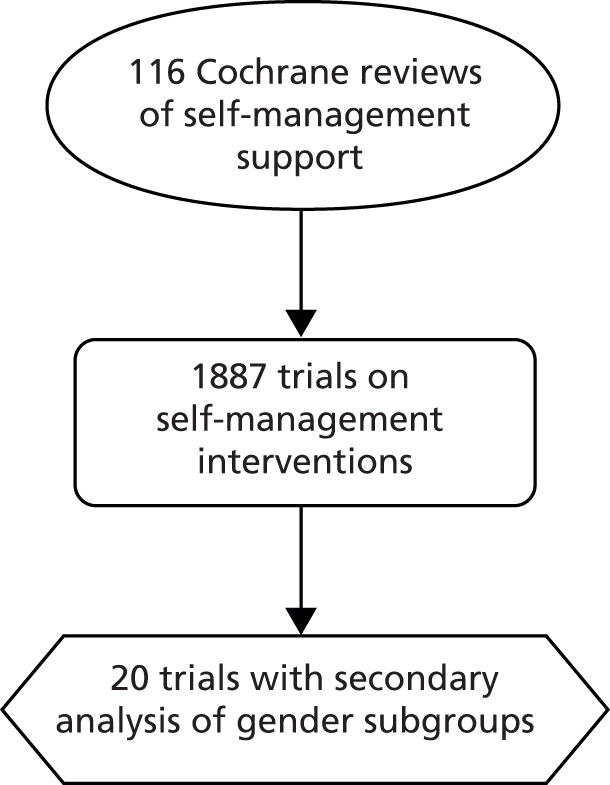

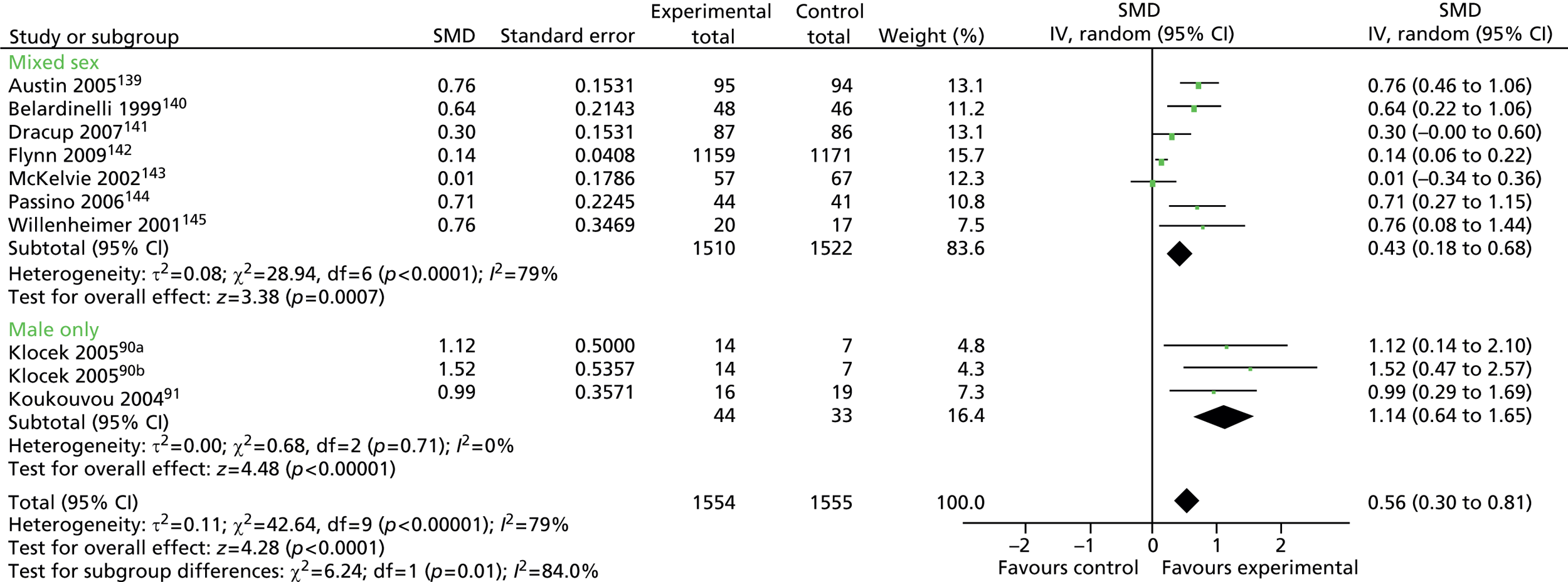

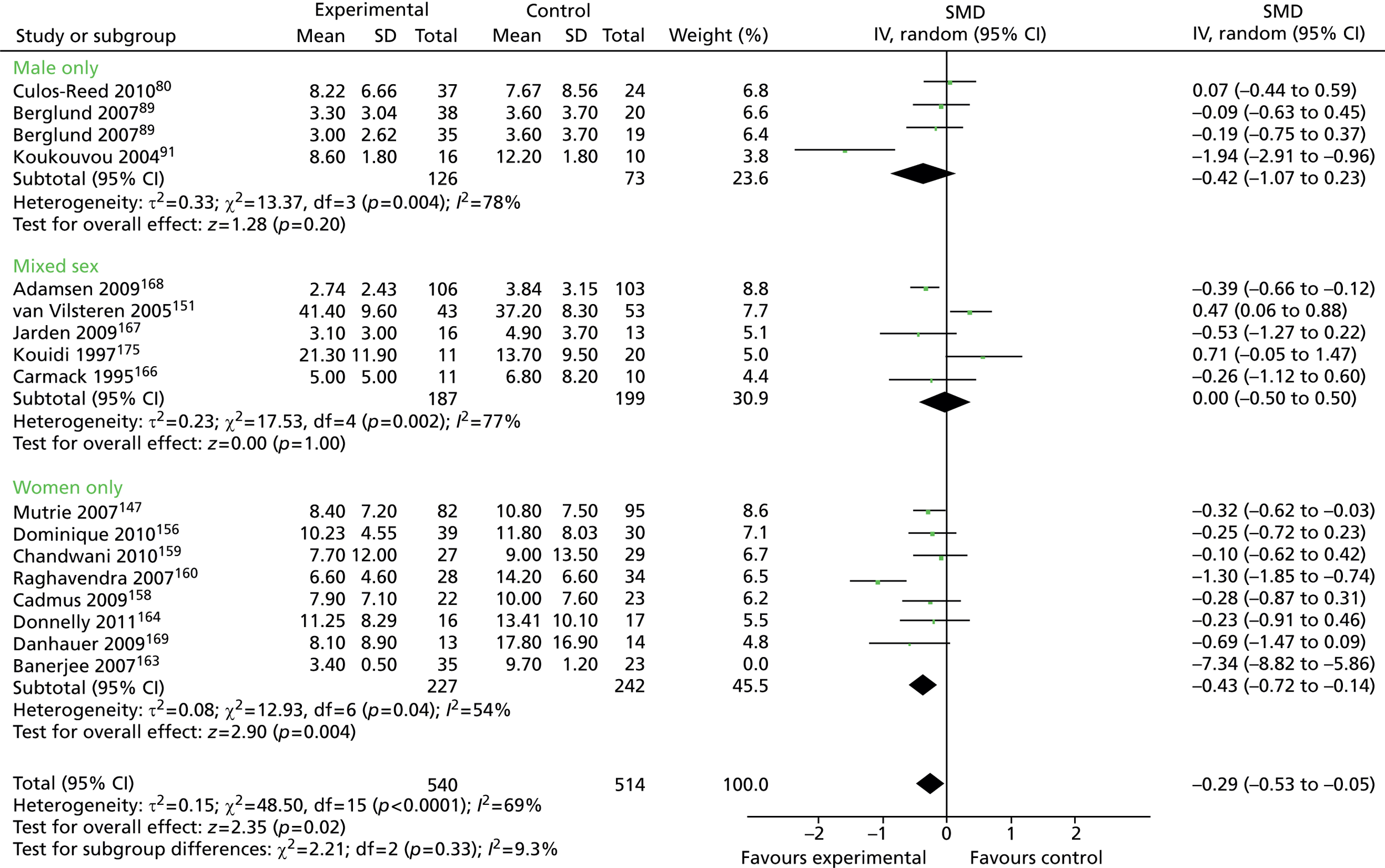

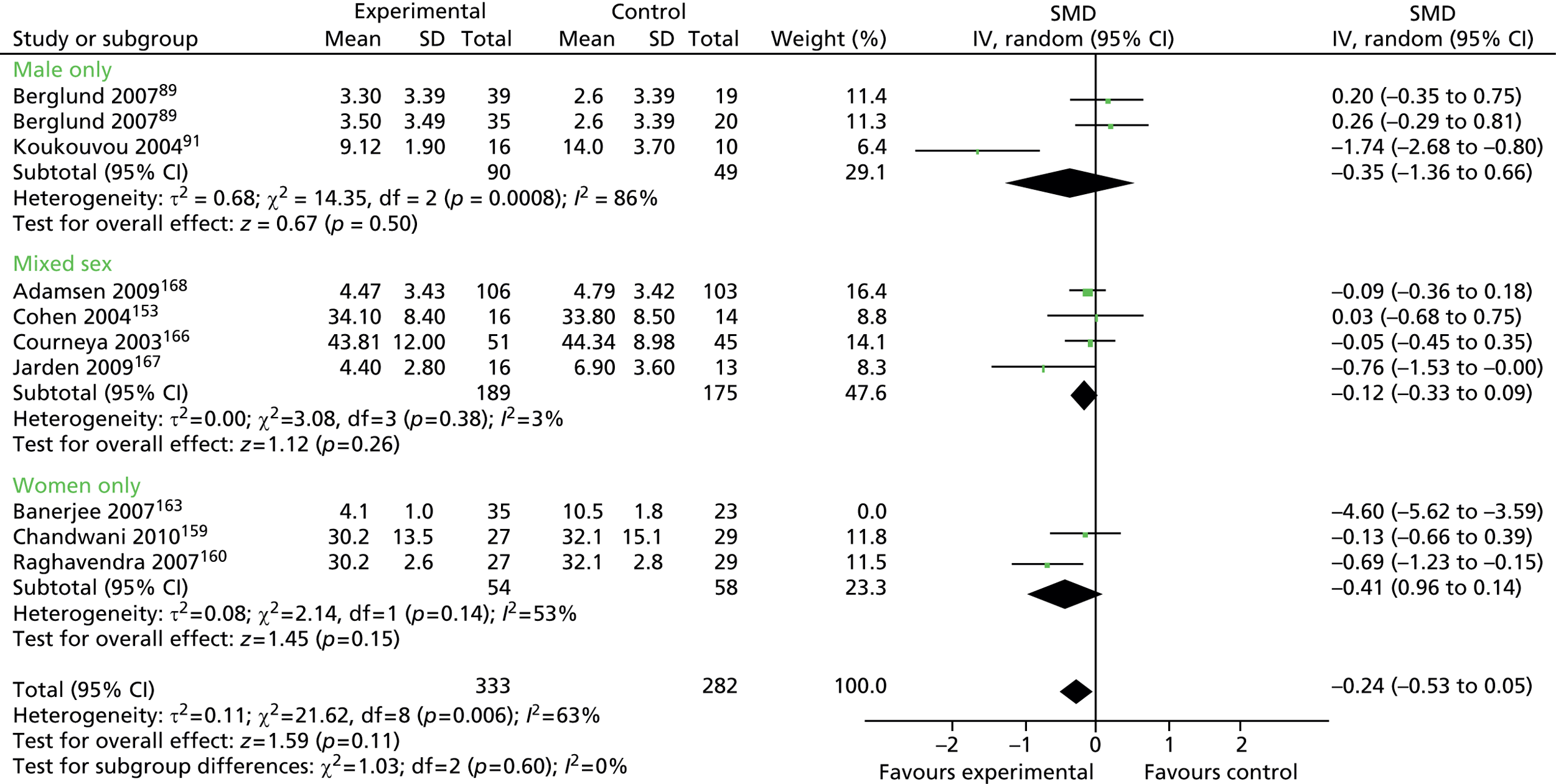

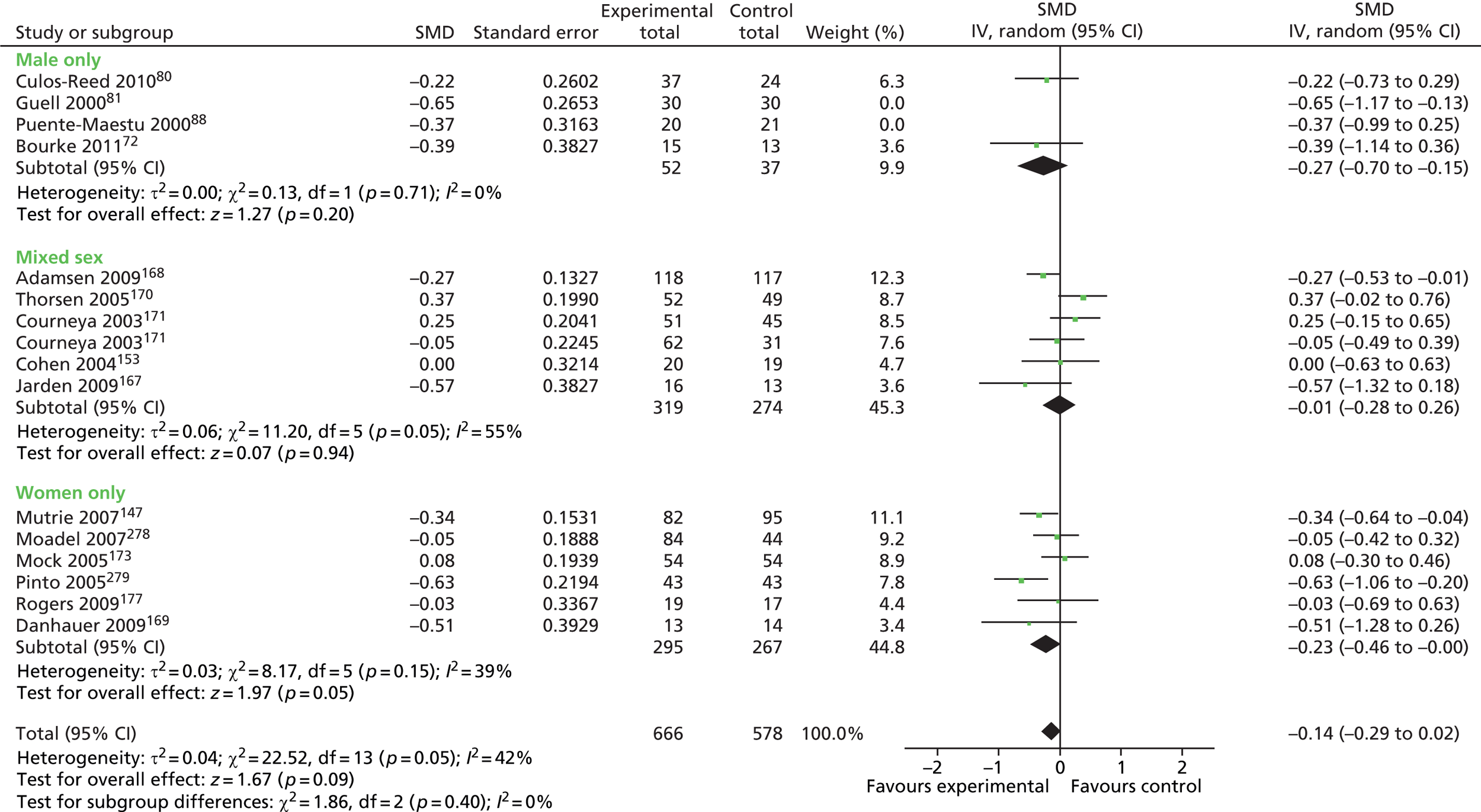

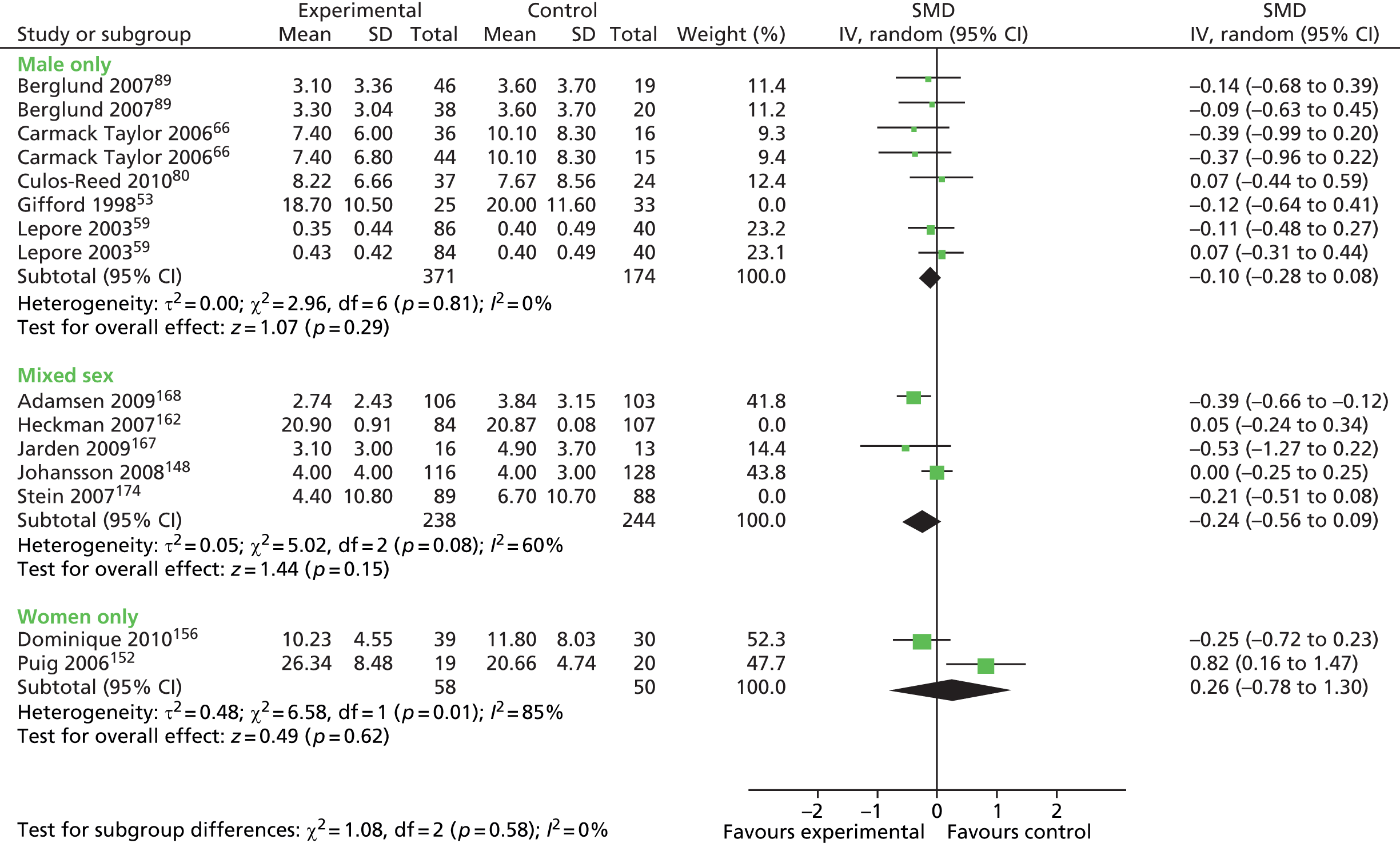

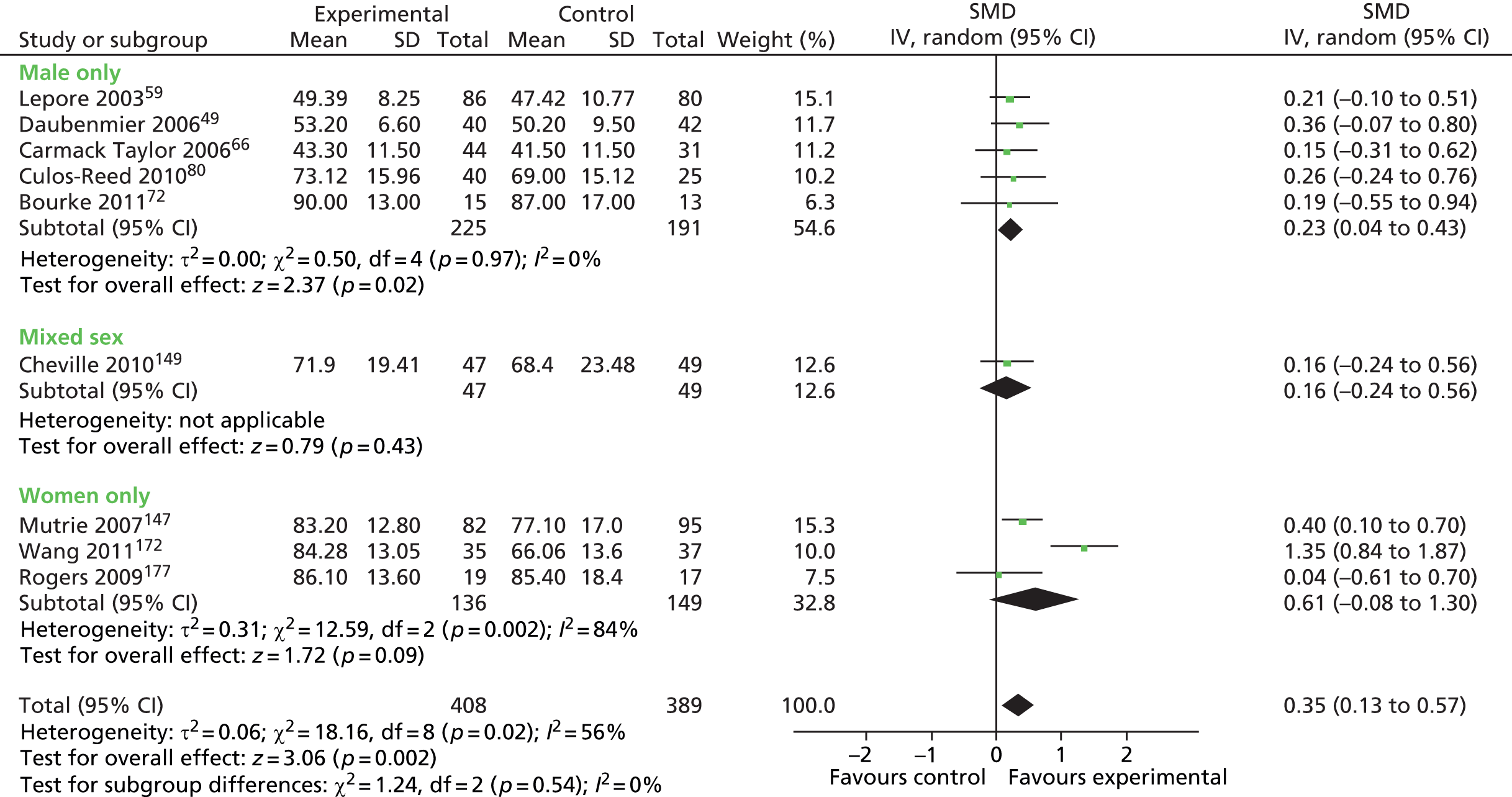

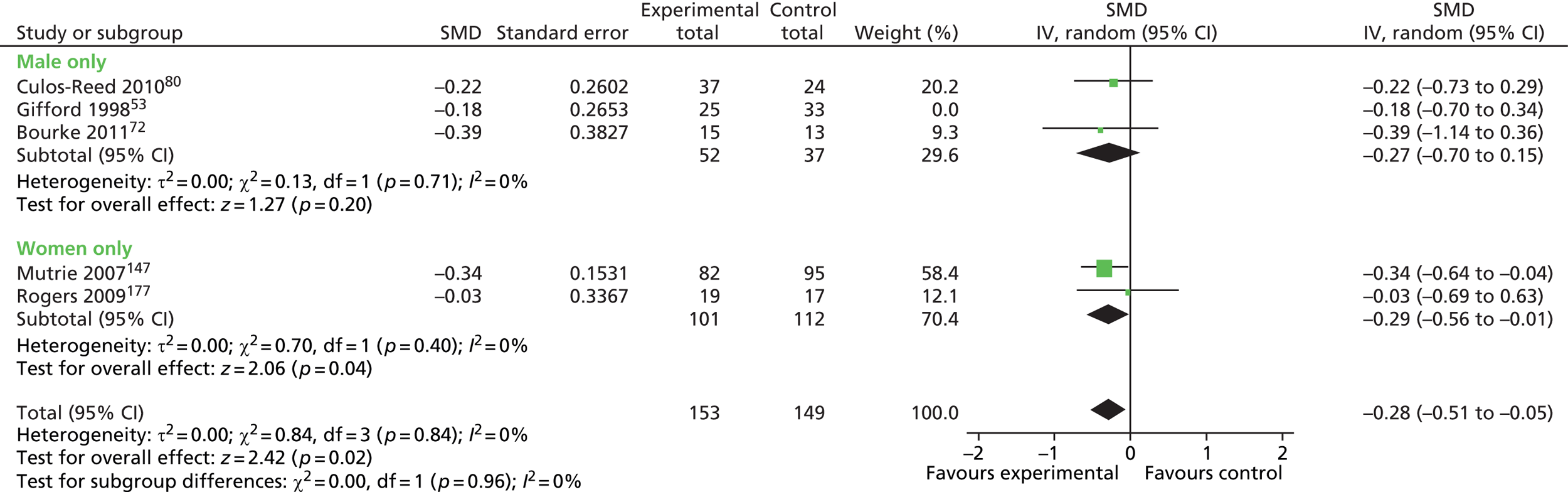

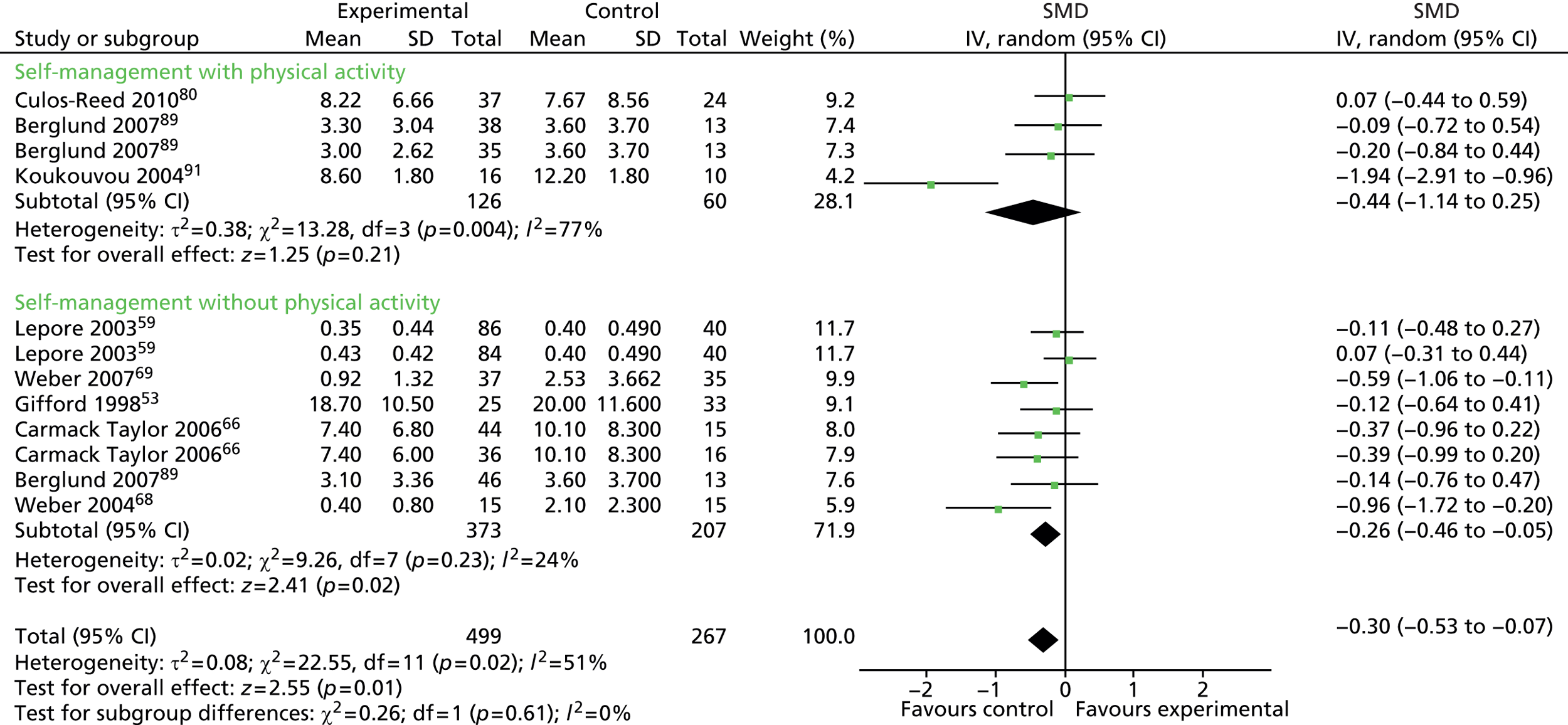

Analysis 2: ‘across-Cochrane review analysis’

Analysis 2 sought to determine whether studies in males show larger, similar or smaller effects than studies in females and mixed-sex groups within types of self-management support pooled across reviews.

In analysis 2, data were pooled according to broad intervention type across reviews, rather than within individual reviews as in analysis 1 (Figure 2). This allowed us to determine whether broad types/components of self-management support interventions show larger, similar or smaller effects in males than in females and mixed populations. Limitations in the data meant that we were able to conduct analyses on only physical activity, education, peer support, and HCP monitoring and feedback interventions.

FIGURE 2.

Analysis 2: ‘across-Cochrane review analysis’.

Such comparisons across trials do not have the protection of randomisation, and there may be differences between the studies included in each sex group which account for differences in effects between groups. We presented data on the comparability of these trials within these three categories, including the age of the included patient populations, and on the quality of the studies (using allocation concealment as an indicator of quality).

We report the effect size (together with significance and 95% CI) of self-management support in each sex group (male only, mixed sex, female only). We conducted analyses to test whether or not interventions showed significantly different effects in sex groups. It should be noted that the power to detect significant differences in such analyses can be limited.

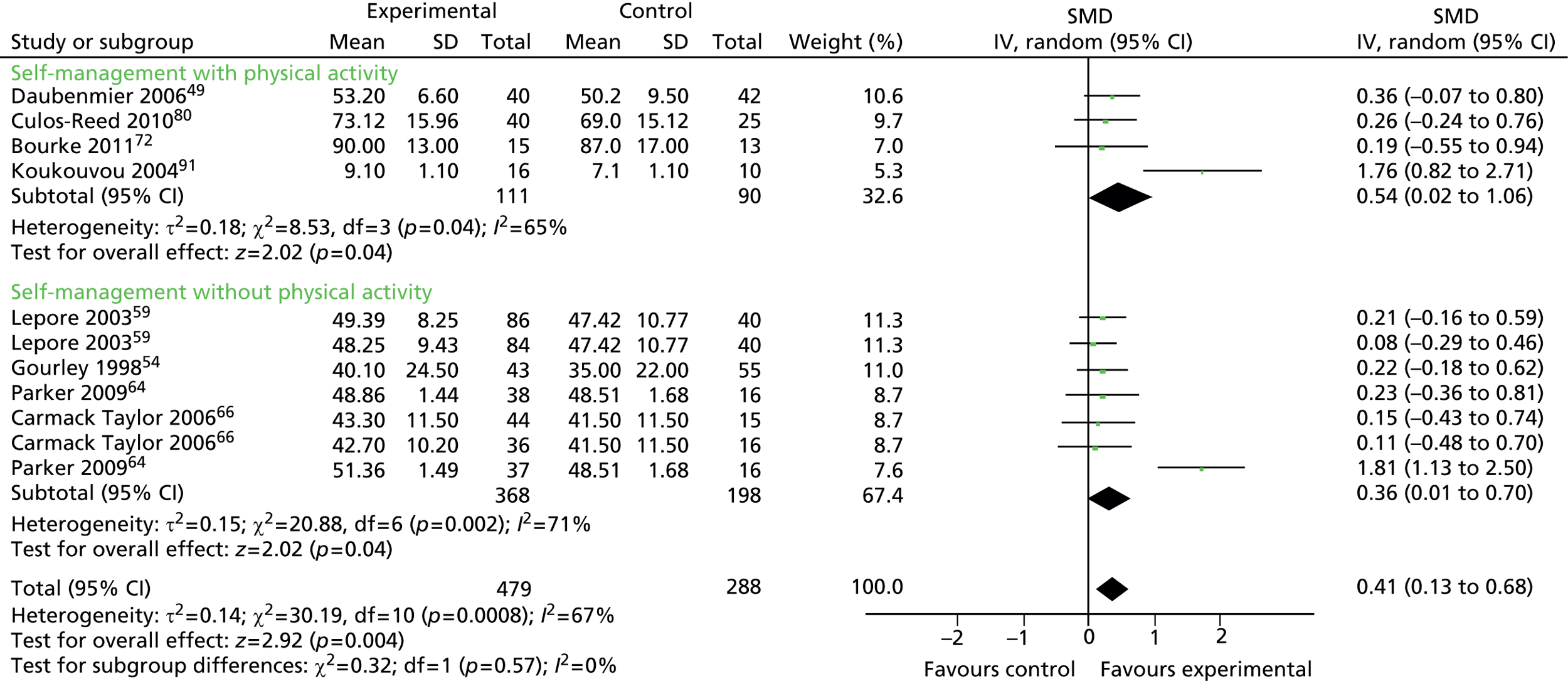

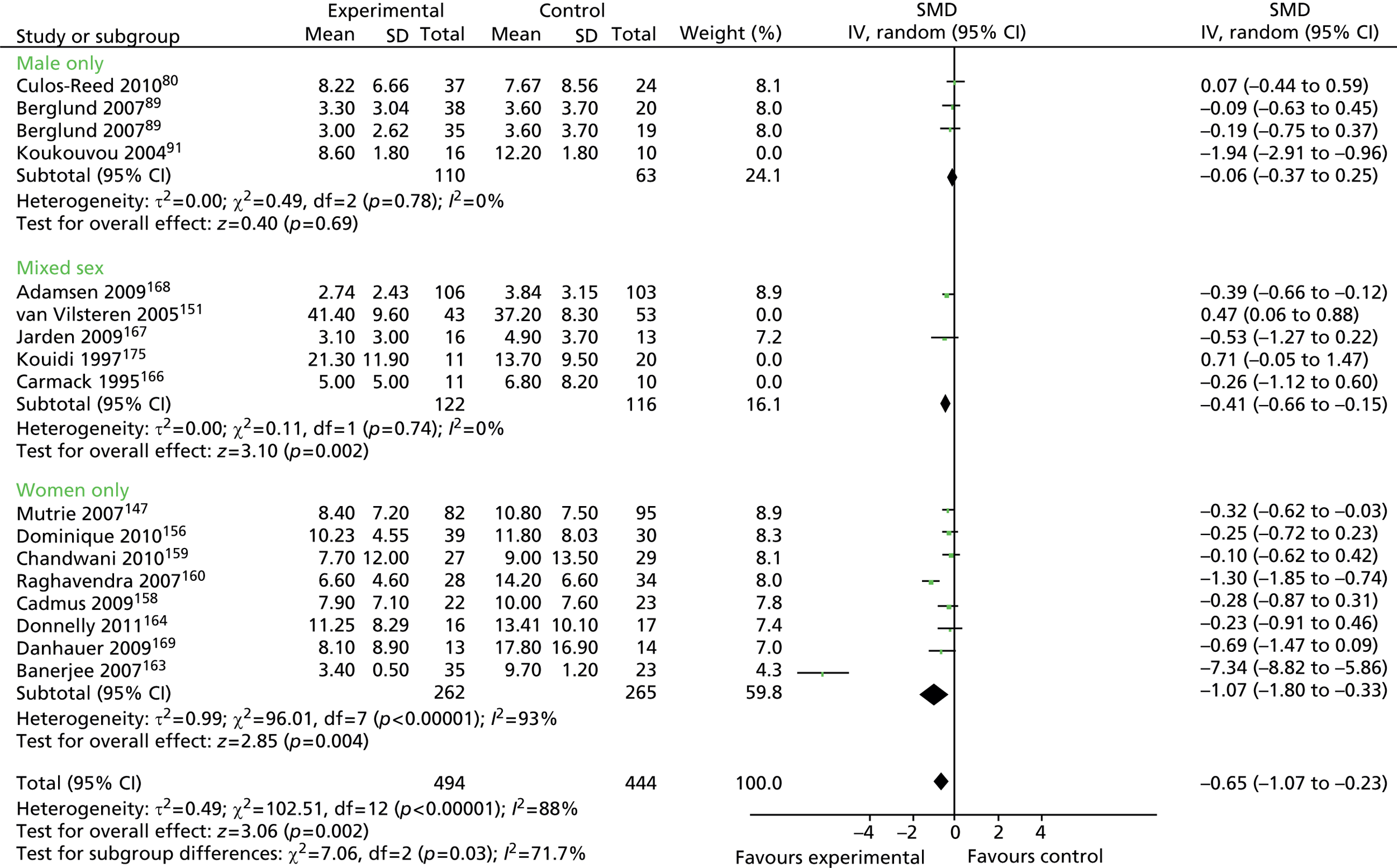

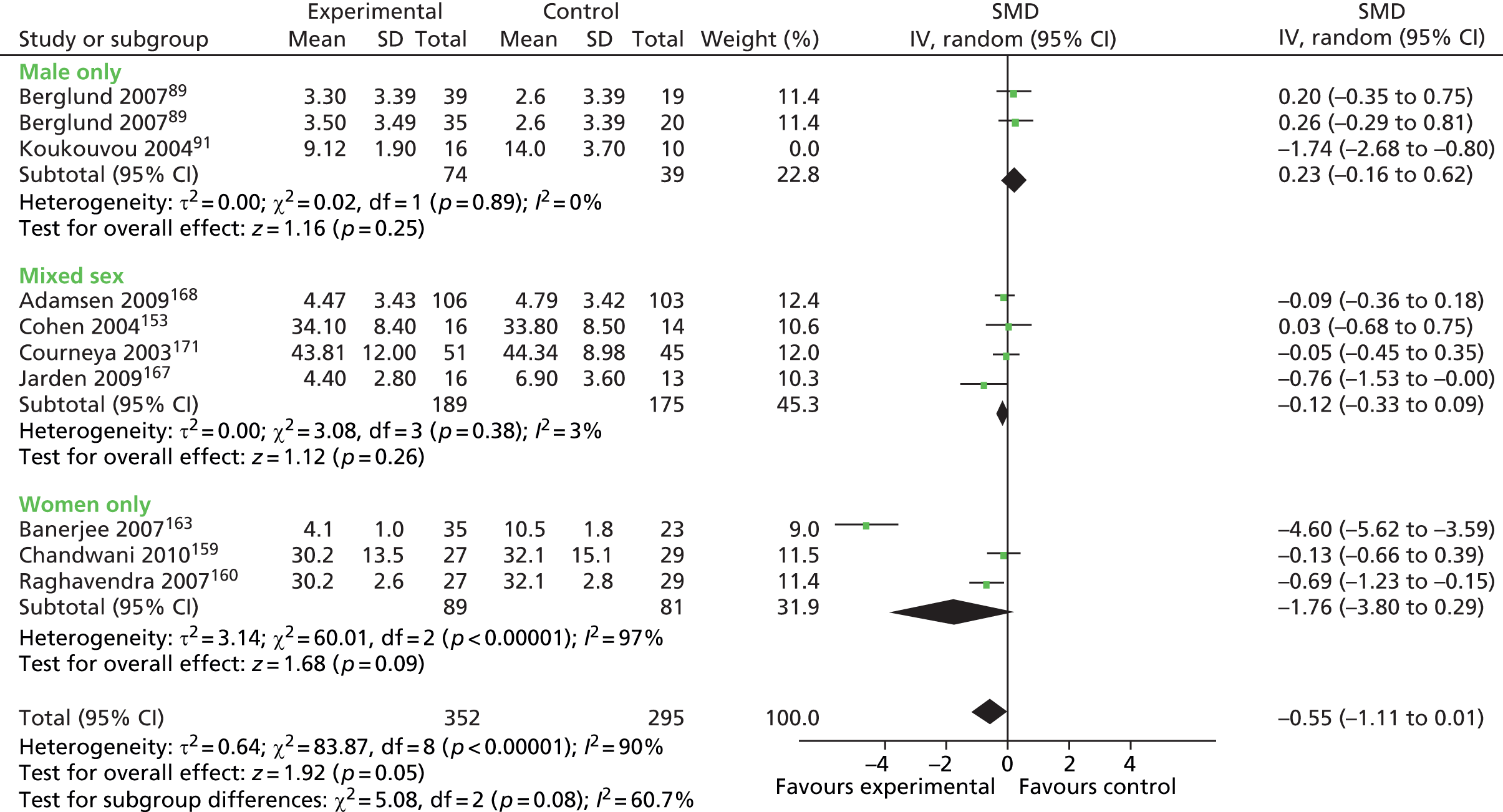

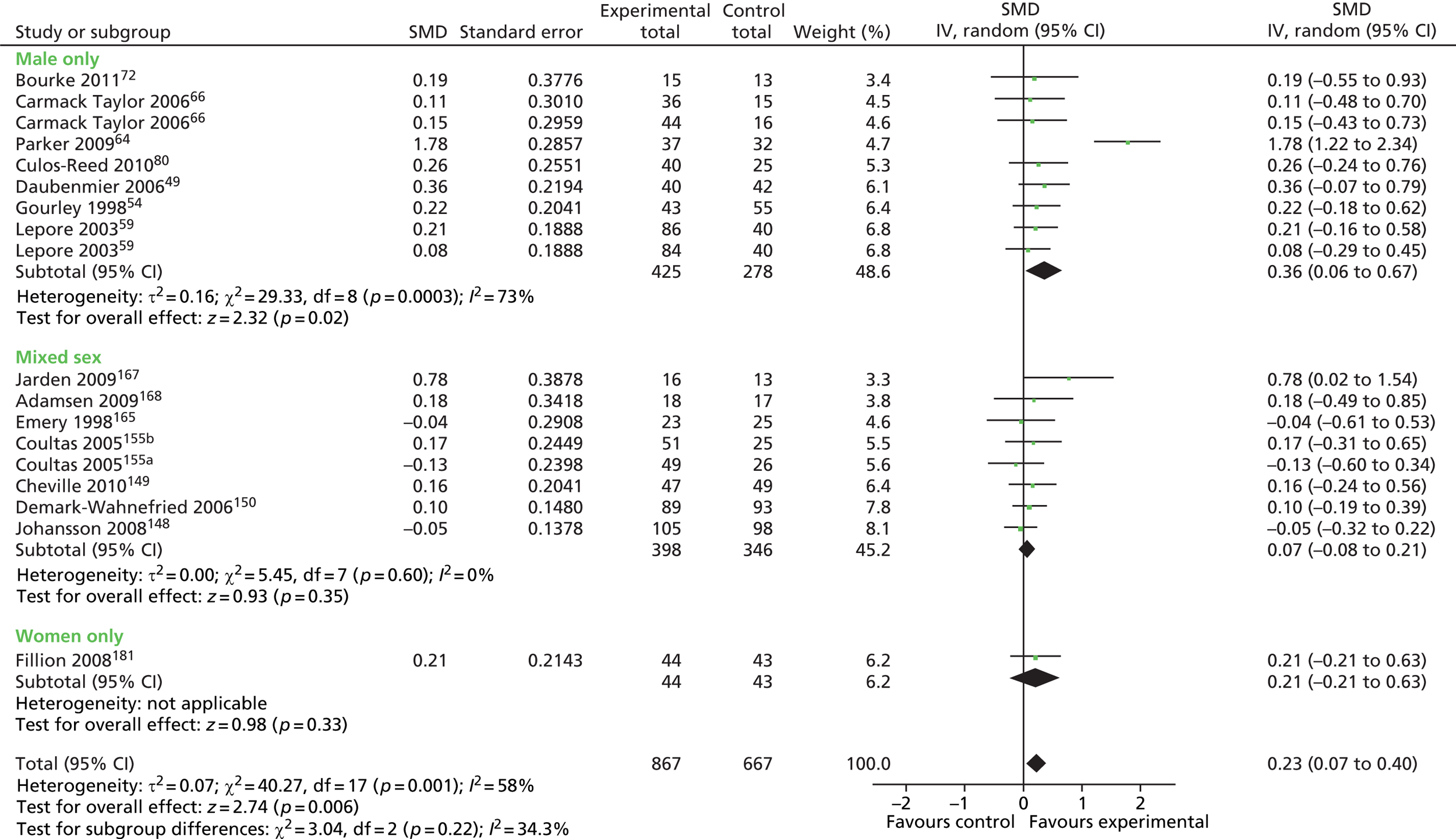

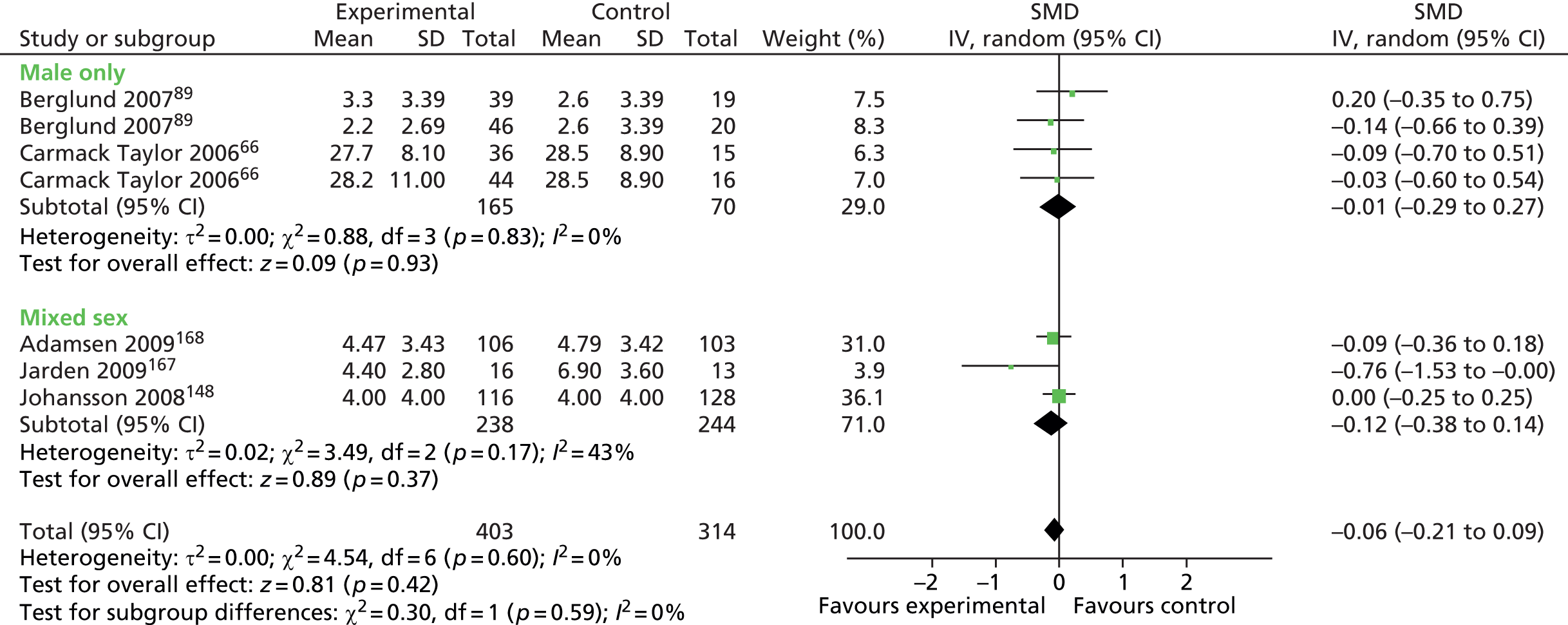

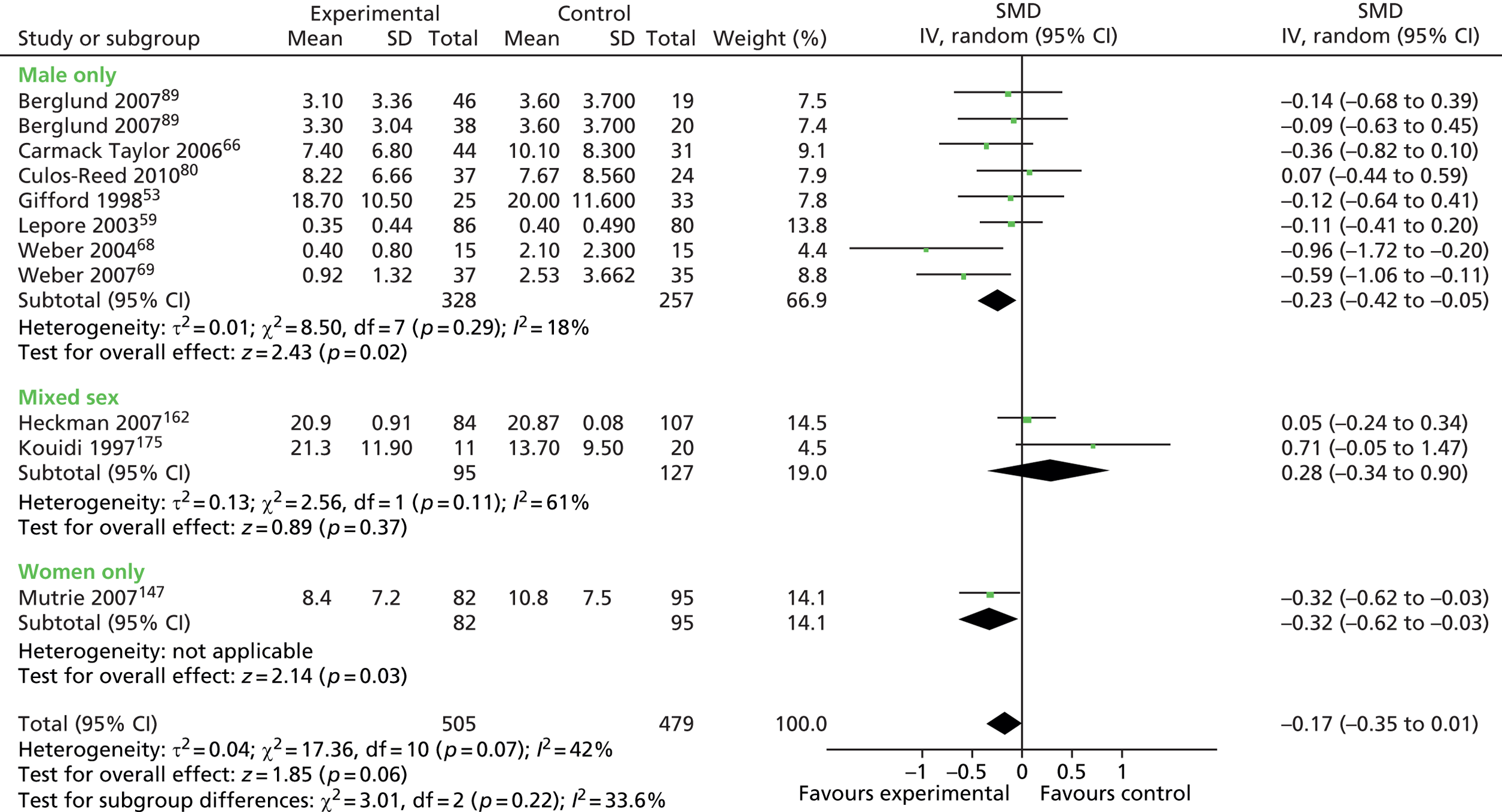

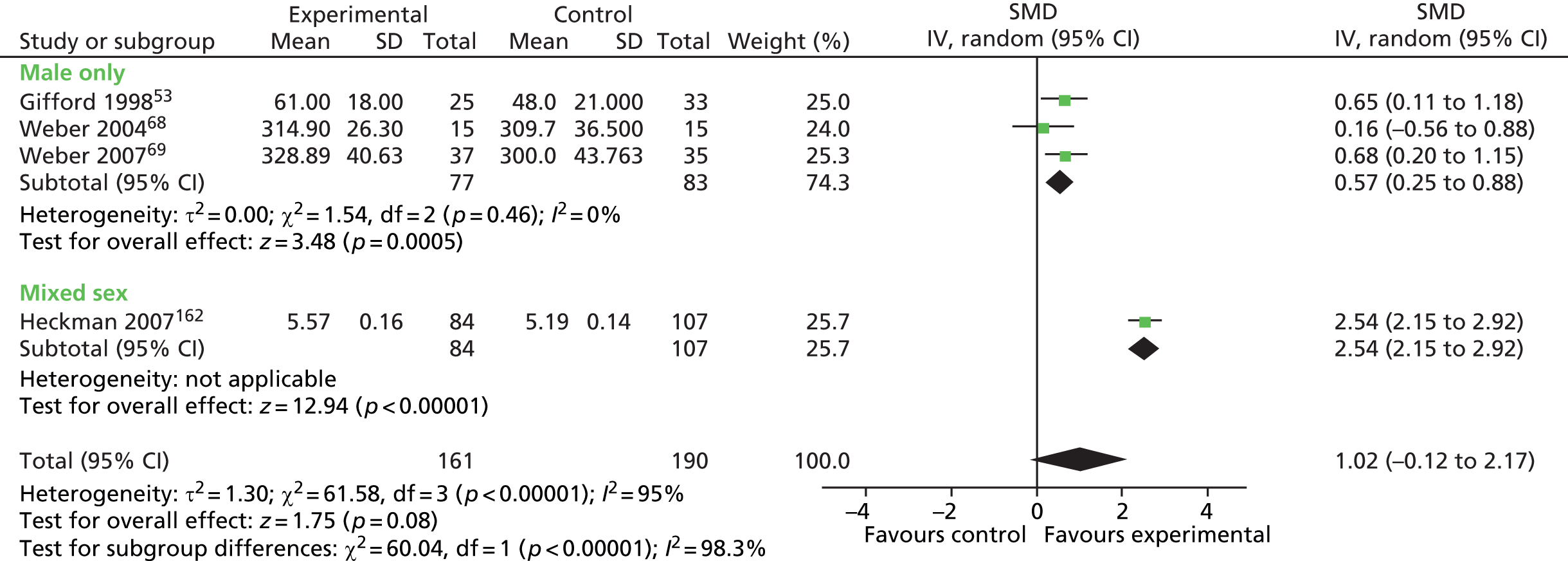

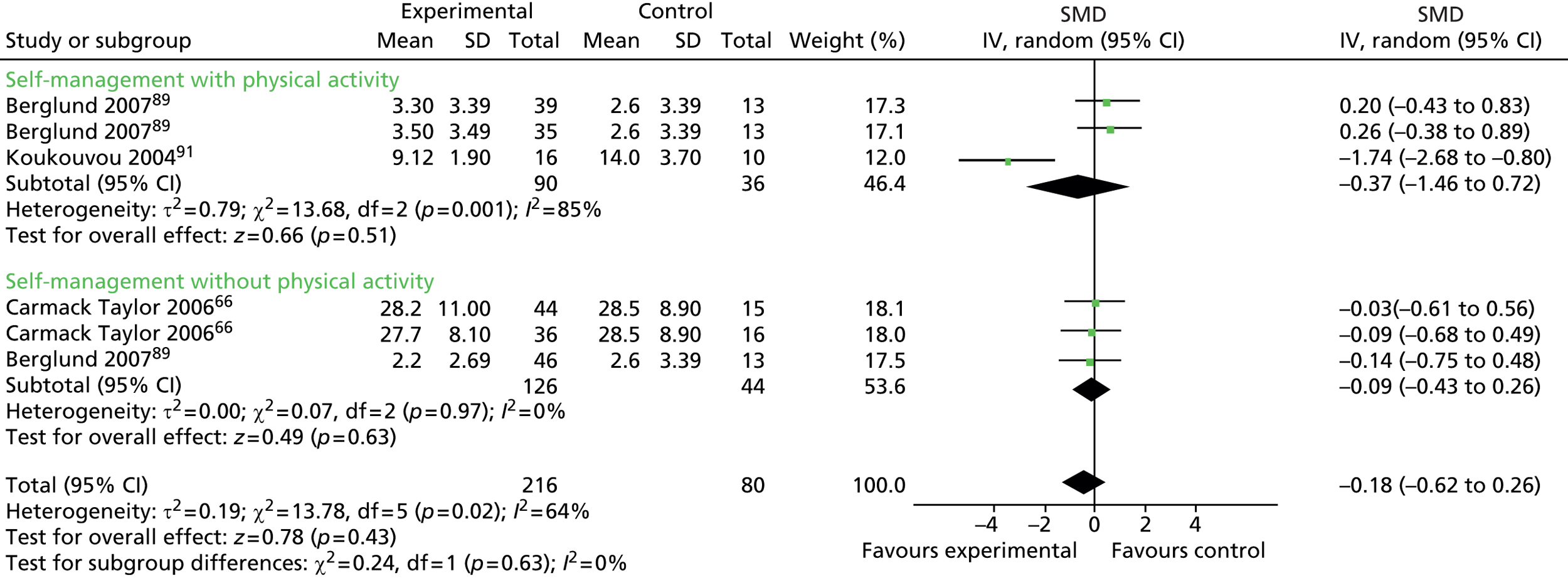

Analysis 3: ‘male-only intervention type analyses’

We conducted a meta-analysis on trials including males only, according to broad intervention type – physical activity, education, peer support, and HCP monitoring and feedback – and compared effects between intervention types (Figure 3). This allowed us to determine whether or not certain broad categories of self-management support intervention were effective in men.

FIGURE 3.

Analysis 3: ‘male-only intervention type analyses’.

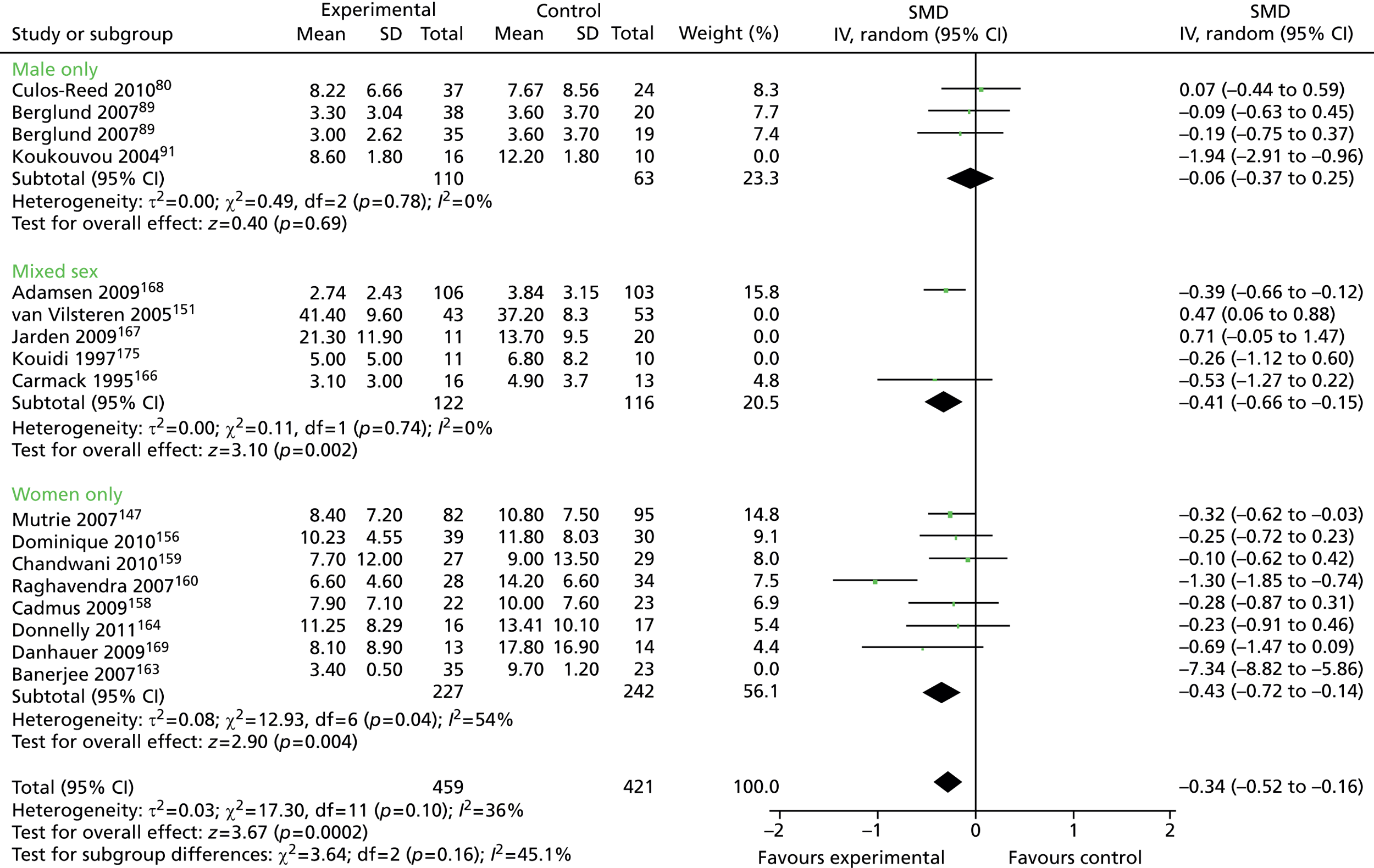

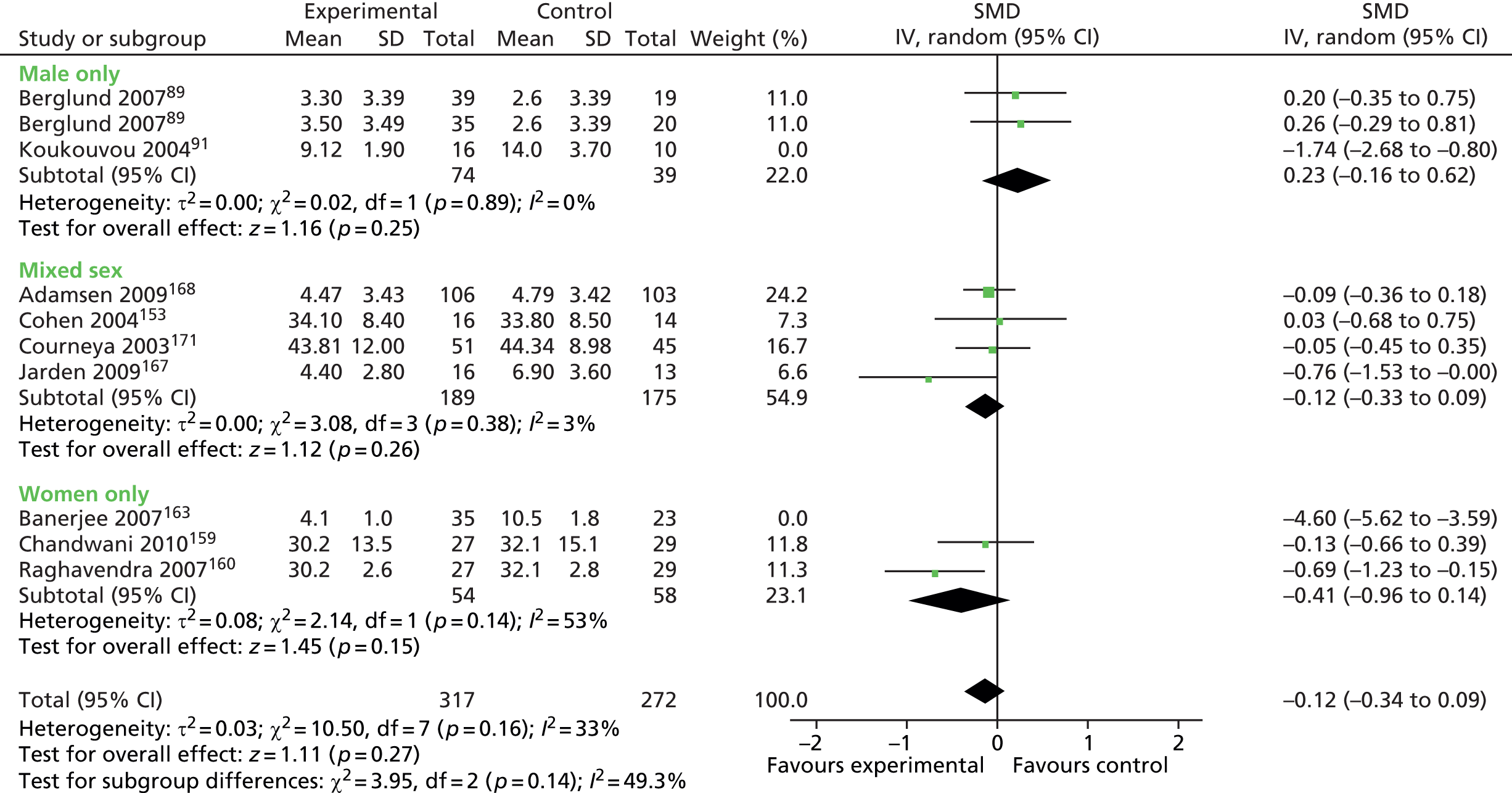

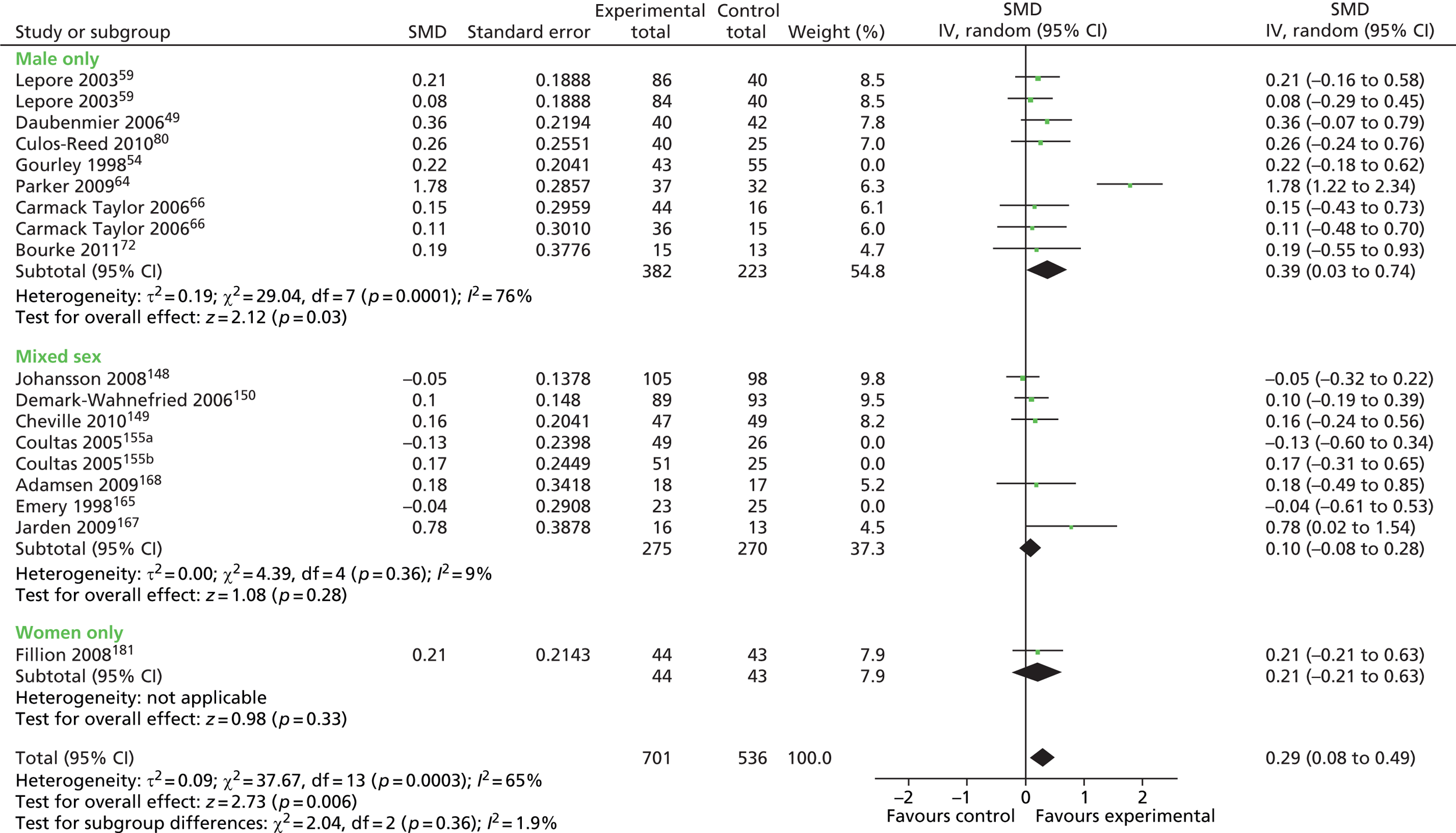

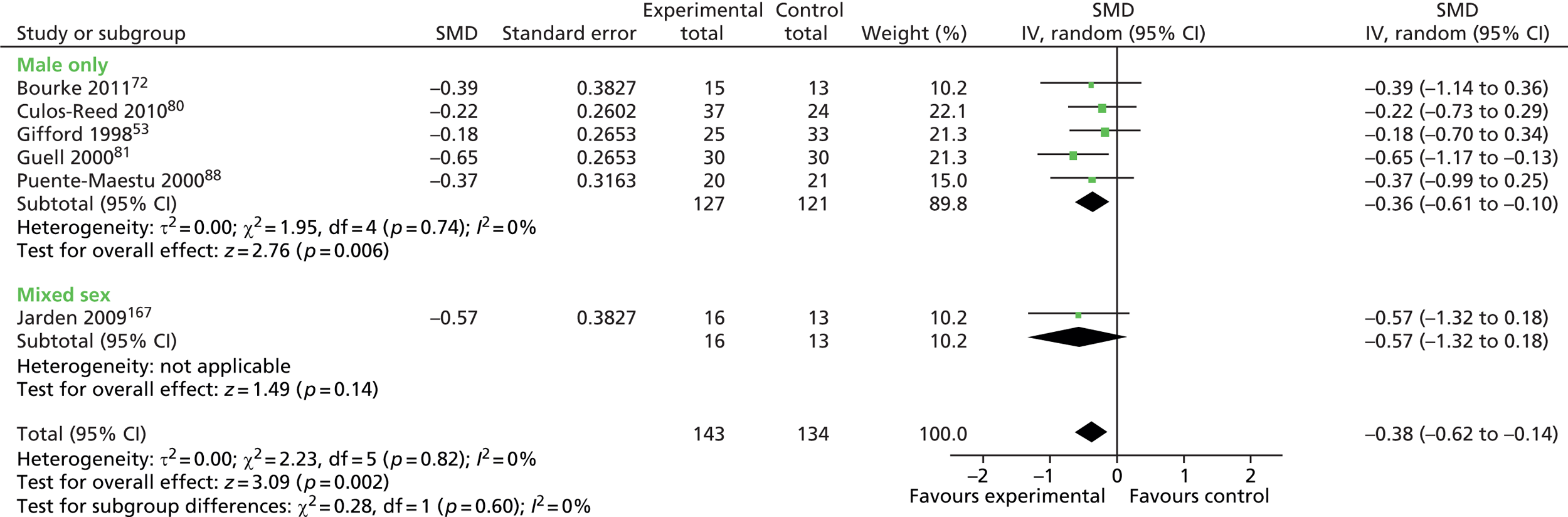

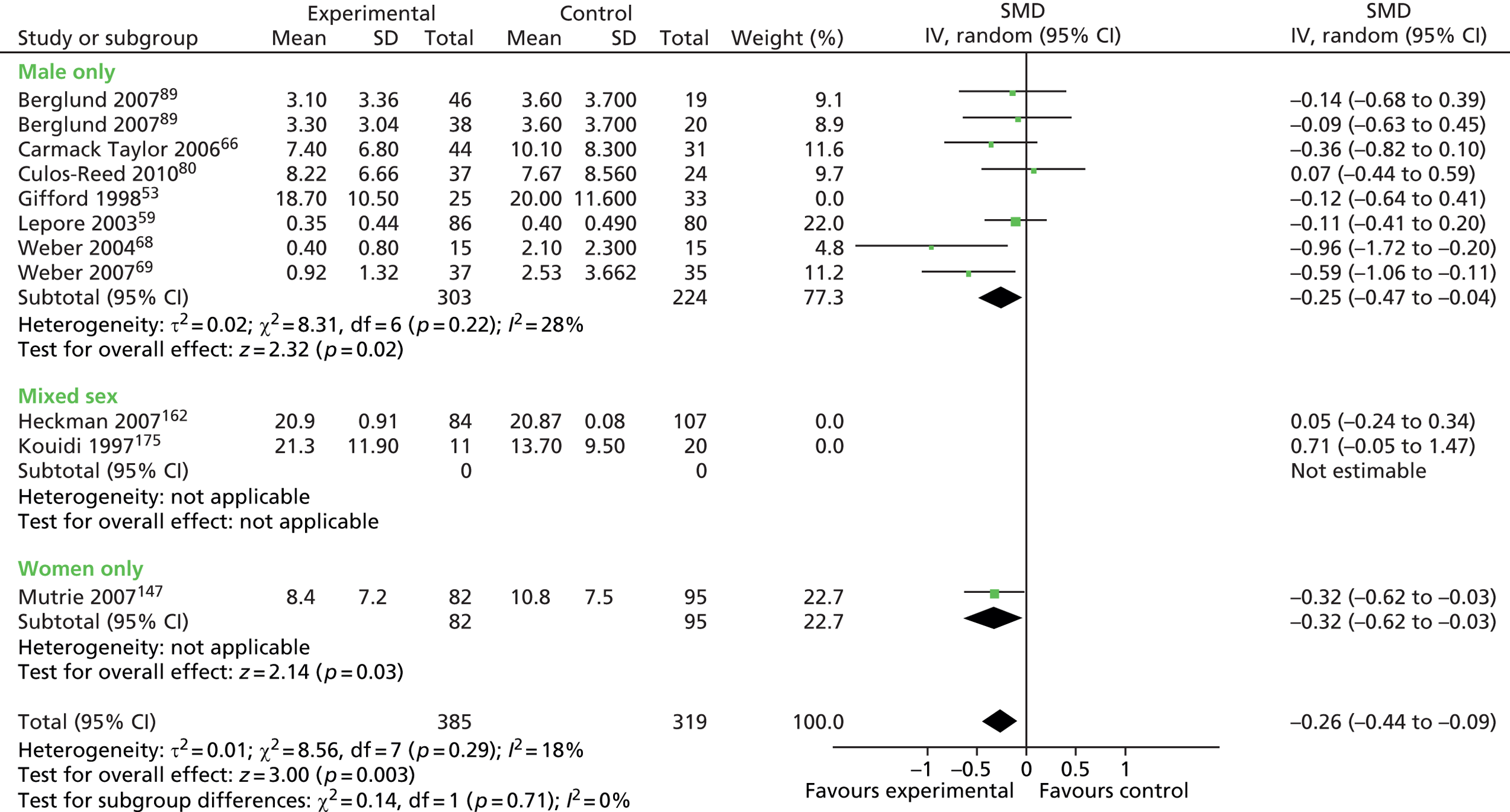

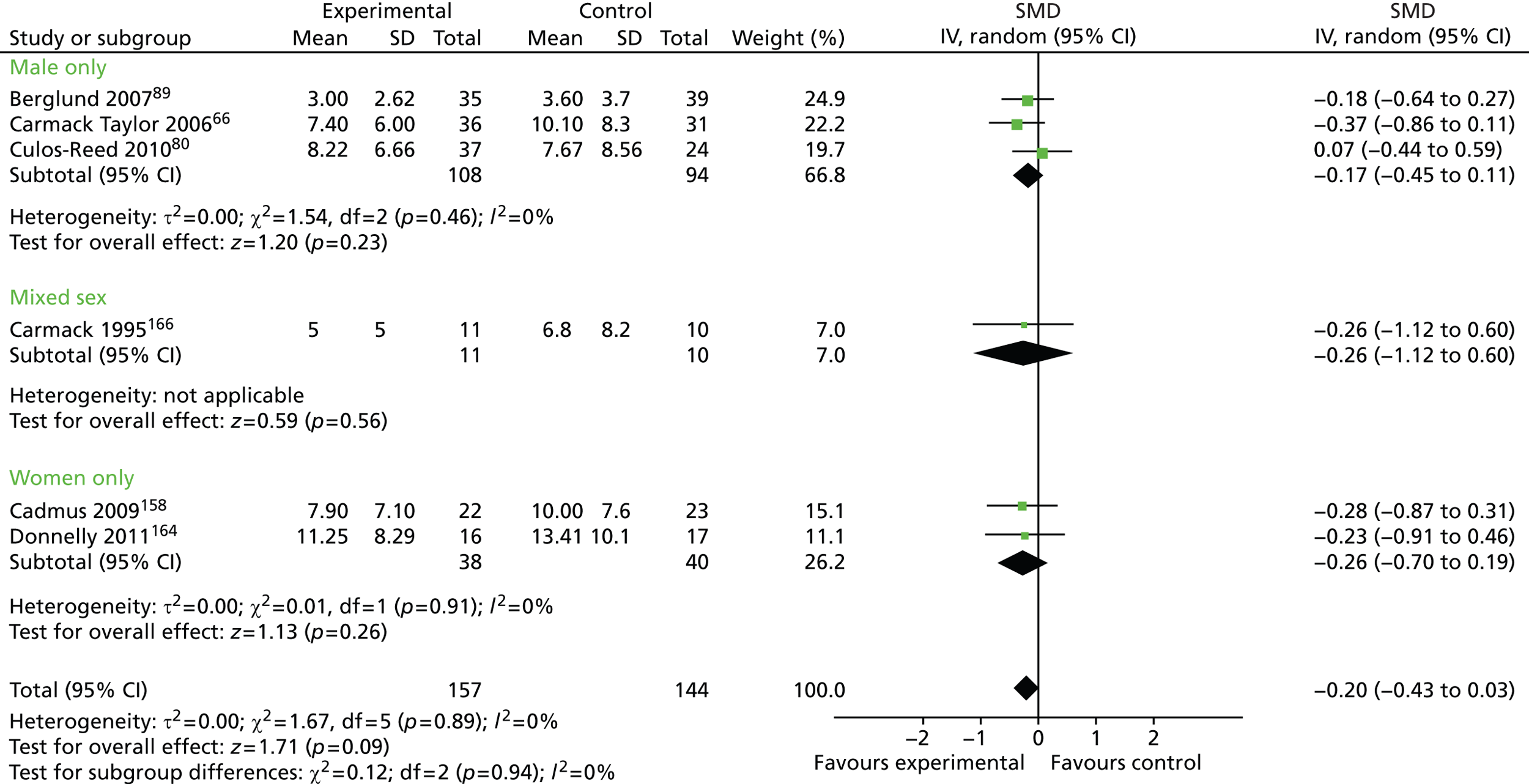

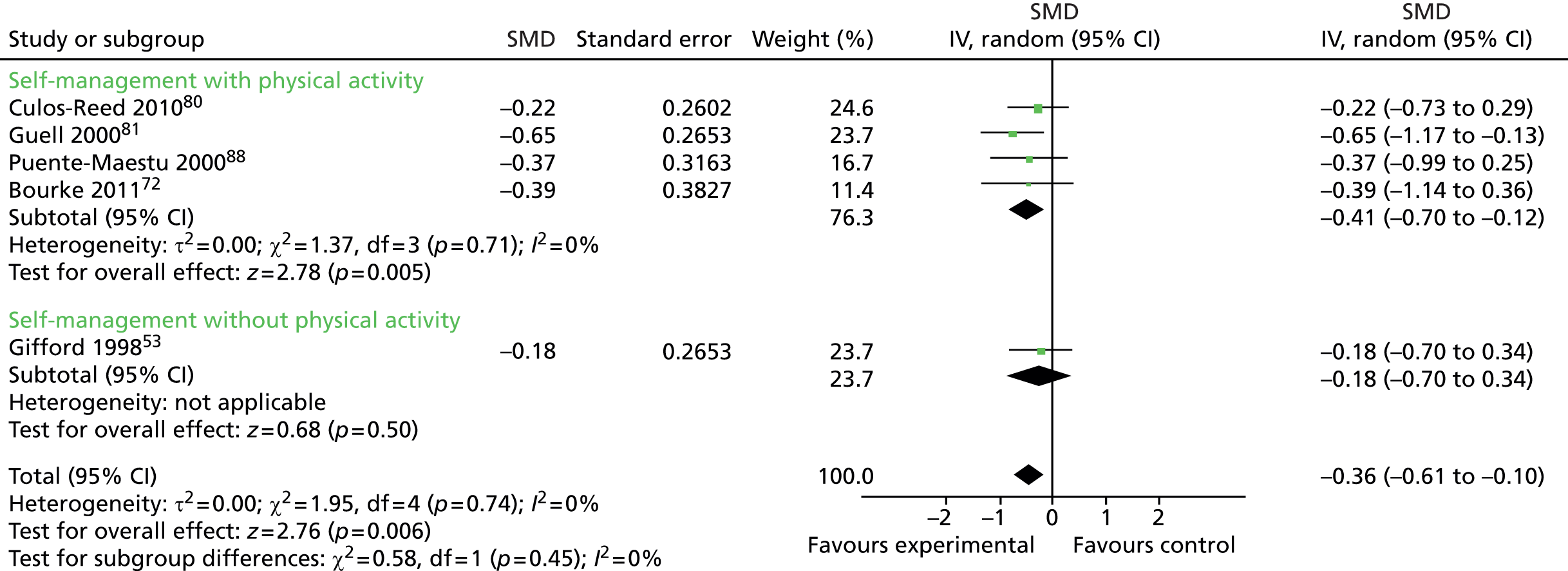

Analysis 4: ‘within-trial sex group analysis’

We identified RCTs which analysed the effects of self-management support interventions in sex groups. We sought to extract relevant data on the direction and size of moderating effects in secondary analysis (i.e. whether males show larger, similar or smaller effects than females), and assess these effects in the context of relevant design data, such as sample size, and the quality of the secondary analysis (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Analysis 4: ‘within-trial sex group analysis’.

Sex group analyses within trials do in theory provide greater comparability in terms of patient and intervention characteristics than analyses 1–3.

A mixture of LTCs was included within each analysis, constituting the main analysis. Although this was not in the original protocol, we attempted to conduct an analysis by each disease area. We found there were sufficient data to conduct a sex-comparative analysis in only cancer studies; the results are presented in Appendix 2.

Coding interventions for analysis

The plan to use the behavioural change techniques (BCT) taxonomy was dropped (see Box 1 on protocol deviations). Post hoc, we took a pragmatic approach to coding interventions. Development of the intervention categories was informed by the published literature identified in this project and previous work conducted by the PRISMS and RECURSIVE project teams. 7,33 Table 1 provides a list of the categories and their associated description. Categories were designed to be broadly representative of the interventions identified and facilitate comparison of intervention types in the analysis. Two members of the review team independently assessed the ‘type’ of self-management support intervention in each study in order to categorise it, and disagreements were identified and resolved by discussion with a team member.

| Self-management support intervention category | Description |

|---|---|

| Physical activity | Includes any study where physical activity occurs, that is a class or self-directed home-based work. Those containing purely advice or promotion should be captured under education |

| Education | Includes any study where education is taught or educational materials are provided to patients. This may include skills training and dietary or physical activity guidance |

| Peer support | Peer support provided by ‘peers’, that is other patients. This may be in the form of a ‘buddy’ system or through interaction at support groups. HCP support may be captured under HCP monitoring and feedback |

| Psychological interventions | Includes professional counselling or therapy |

| HCP monitoring and feedback | Support in the form of health monitoring and/or feedback on a regimen/promoted lifestyle change. Excludes support provided by peers, which should be captured under peer support |

| Action plans | A plan of actions or responses agreed with and used by the patient in response to particular situations; for example, if symptoms exacerbated, dose adjustment according to symptoms |

| Financial incentives | Includes any intervention where financial barriers are removed or incentives are used to motivate patients to follow a particular intervention or lifestyle change |

Economic evaluation

The review of cost-effectiveness studies was initially planned as a two-stage review. First, we would review economic evaluations of self-management interventions on males only. Subsequently, we would review all economic evaluations with group analyses in which the costs and effects for males and females could be separated.

Study quality was assessed using a modified version of the Drummond checklist where appropriate. 45

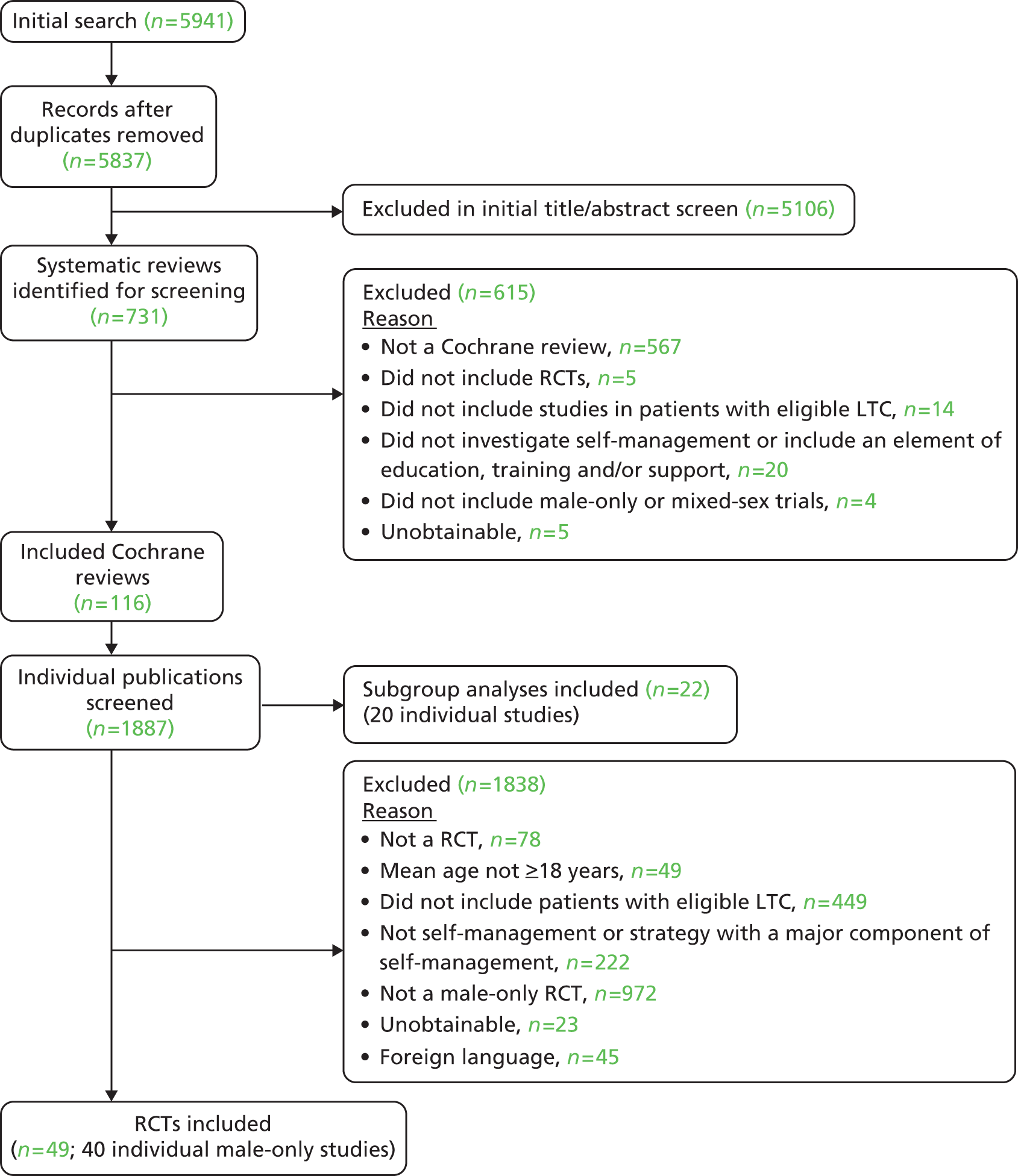

Study characteristics

Setting and sample

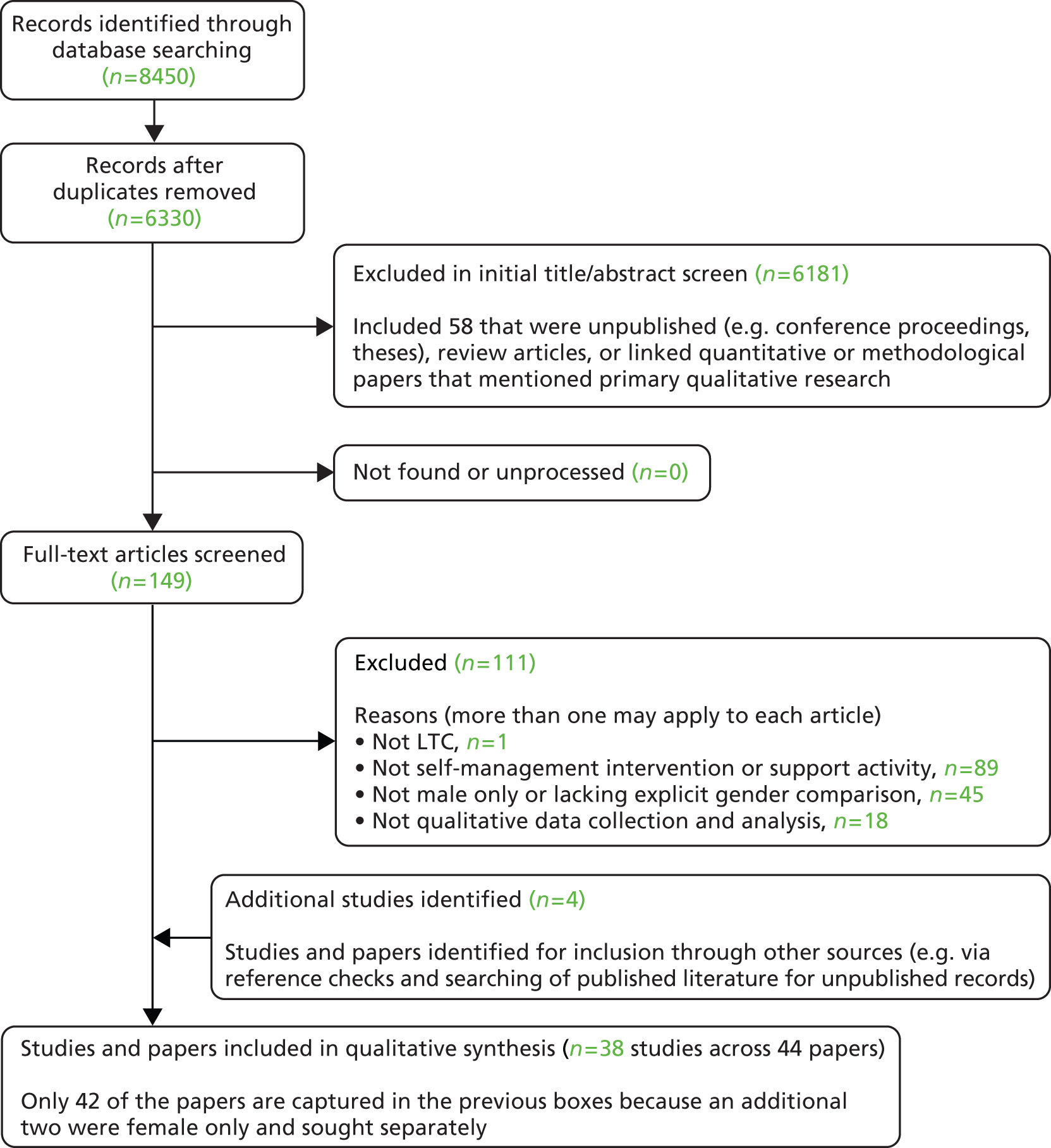

We identified a total of 40 RCTs on self-management support interventions conducted in male-only samples (some trials have more than one reference) (Figure 5). The majority of the studies were conducted in the USA (n = 23),46–70 with the remainder conducted in the UK (n = 6),71–78 Canada (n = 5),79–83 Spain (n = 3),84–88 Sweden (n = 1),89 Poland (n = 1)90 and Greece (n = 1). 91 Males with prostate cancer were the most frequently studied male-only population (n = 15) included in this review. 48,49,52,58,59,61,64–66,68,69,72,78,80,89 Other disease areas included hypertension (n = 6),47,71,79,82,83,85,86 COPD (n = 6),54,55,73–76,81,84,87,88 heart failure (n = 4),62,67,90,91 type 2 diabetes (n = 3),46,50,51,70 diabetes of unspecified type (n = 1),56 arthritis (n = 1)63 and testicular cancer (n = 1). 77 One multimorbidity study recruited obese men with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. 57 The age of participants ranged from 25 to 89 years and, where reported, ethnicity was predominantly white. Only one study reported socioeconomic status using a validated tool;63 the majority of other publications included a description of education or annual income.

FIGURE 5.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram for the quantitative review.

Self-management support interventions

A total of 51 distinct self-management support interventions were reported across the 40 included male-only studies. Physical activity (n = 16),49,57,62,72–76,78,80,81,84,87–91 education (n = 36),46–55,58–61,63–67,70–72,77,79–81,83–88 peer support (n = 17)47,49,53,56,68–72,80 and HCP monitoring and feedback (n = 25)46,47,50–52,56,57,60,61,66–68,70,71,75,76,78–80,82–89 were the most frequently reported components of these interventions. Three interventions with a psychological component,64,77 two interventions containing a financial incentive component82,83 and one study containing an action plan component19 were also identified.

Twenty-three of the interventions were aimed at individuals,46,48,50–52,54,55,60,61,64,65,67–69,75–78,82–86 20 were aimed at groups47,53,58,59,62,66,70,71,79,89–91 and the remainder used a mixed individual and group approach (n = 6). 49,56,72–74,80,81,87,88 It was unclear what approach was used in two studies. 57,63 Over half of the interventions lasted 0–5 months (n = 28),47,53,58–64,67–69,71–80,85,86 12 interventions ranged between 6 and 11 months,46,52,54–57,66,70,84,90,91 six interventions were 12 months or longer49,65,81,82,84,87,88 and in five cases the total programme duration was unclear. 48,83,89

The mode of administration of the interventions varied. They included telephone-based support (n = 6),60,61,65,67 face-to-face delivery (n = 21),47,53–55,58,59,62–64,66,68–70,77,83,89–91 remote unsupervised activities (n = 2),75,76,78 a combination of face-to-face delivery and remote unsupervised activities (n = 20),46–51,57,71–74,79–82,84–89 and a combination of face-to-face delivery and telephone support (n = 2). 52,56

In terms of setting, interventions were reported to be home-based (n = 11),46,52,60,61,65,67,75,76,78 at a non-home location such as a dedicated gym, pharmacy, hospital clinic, work, university laboratory, coffee shop or other community-based venue (n = 12),53–55,62–64,68–70,77,85,86,90 a combination of home and non-home-based venue (n = 14)48–51,56,57,72–74,79–84,87,88 or not clearly reported in the publication (n = 14). 47,58,59,66,71,89,91

Half of the studies79–82,46,48–51,53,56,58,59,66,70,72,78,84,87,88 reported on some aspect of compliance with the self-management intervention and most participants were followed up for 6 months or less (n = 24) following participation in the intervention.

Table 2 provides an overview of study details and Table 3 includes detailed descriptions of the self-management support intervention.

| Author, year, country | Study aim | Participants: intervention | Participants: control | LTC | Self-management support strategy: intervention group | Self-management support strategy: control group | Follow-up from baseline | Attrition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsett et al. 1989,79 Canada | To compare compliance and efficacy of relaxation therapy with medication, alone or in combination, in reducing the effects of physical and psychological stressors, anxiety and anger | n = 11. Mean age 42.45 years (± 8.24 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 12. Mean age 47.50 years (± 9.35 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Hypertension | Relaxation therapy with placebo drug | Relaxation therapy with beta blocker | 1 month, 3 months | n = 15. No further detail |

| n = 12. Mean age 46.58 years (± 7.77 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 12. Mean age 49.42 years (± 6.84 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Education with placebo drug | Education with beta blocker | |||||

| Allen et al. 1990,46 USA | To compare the effectiveness of self-monitoring with blood glucose testing and routine urine testing and their respective costs | n = 27. Mean age 58.2 years (± 9.7 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 59% white. Mean education 11.1 years (± 4.0 years) | n = 27. Mean age 57.9 years (± 10.7 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 67% white. Mean education 10.9 years (± 3.1 years) | Type 2 diabetes | Blood testing and dietary guidance | Urine testing and dietary guidance | 6 months | Five removed because of inappropriate randomisation. I, 1; C, 1 |

| Bennett et al. 1991,71 UK | To investigate the effectiveness of minimal stress management or stress management, through TAM, on cardiovascular reactivity and behaviour | n = 15. Across-group mean age 46 years. Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 14. Across-group mean age 46 years. Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Hypertension | Minimal SMT | Waiting list | 2, 6 months | SMT I, 2; TAM I, 0; C, 0 |

| n = 15 (TAM). Across-group mean age 46 years. Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | SM including behaviour modification (TAM) | |||||||

| Berglund et al. 2007,89 Sweden | To assess the effect of a psychosocial rehabilitation programme on anxiety and depression and HRQoL | n = 53. Across-group mean age 69 years. Across-group age range 43–86 years. Ethnicity N/R. Elementary school education 52% | n = 51. Across-group mean age 69 years. Across-group age range 43–86 years. Ethnicity N/R. University graduate 28% | Anxiety and depression | Physical training | Standard care | 6, 12 months | 23 dropouts at baseline. Missing data at 6 months n = 23, 12 months n = 19 |

| n = 55. Across-group mean age 69 years. Across-group age range 43–86 years. Ethnicity N/R. Elementary school education 30% | Information | |||||||

| n = 52. Across-group mean age 69 years. Across-group age range 43–86 years. Ethnicity N/R. Elementary school education 39% | Physical training and information | |||||||

| Bosley and Allen 1989,47 USA | To evaluate training procedures to alter psychological responses to stress, to reduce blood pressure | n = 41. Across-group mean age 57 years. Across-group age range 42–68 years. Ethnicity 100% black. Majority skilled/unskilled labour | n = 41. Across-group mean age 57 years. Across-group age range 42–68 years. Ethnicity 100% black. Majority skilled/unskilled labour As above |

Hypertension | Cognitive self-management | Standard care | 2 months | N/R |

| n = 41. Across-group mean age 57 years. Across-group age range 42–68 years. Ethnicity 100% black. Majority skilled/unskilled labour | Attention placebo | 2 months | N/R | |||||

| Bourke et al. 2011,72 UK | To assess the feasibility of a tapered exercise programme in combination with dietary advice in men with prostate cancer | n = 25. Mean age 71.3 years (SD 6.4 years). Across-group age range 60–87 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 25. Mean age 72.2 years (SD 7.7 years). Across-group age range 60–87 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Prostate cancer | Exercise and dietary advice | Standard care | 3, 6 months | I, 10; C, 12 |

| Burgio et al. 2006,48 USA | To test the effects of preoperative pelvic floor muscle training vs. usual care on continence | n = 57. Mean age 60.7 years (SD 6.6 years). Across-group age range 53–68 years. Ethnicity 22.8% black. 83.3% high school graduates. 50% employed outside home | n = 55. Mean age 61.1 years (SD 7.2 years). Across-group age range 53–68 years. Ethnicity 32.7% black. 85.7% high school graduates. 54.7% employed outside home | Prostate cancer | Exercise | Standard care | 1.5, 3, 6 months | I, 6; C, 4. |

| Carmack Taylor et al. 2006,66 USA | To evaluate the efficacy of a 6-month group-based lifestyle physical activity programme on QoL for prostate cancer patients | n = 46. Across-group mean age 69.2 years. Across-group age range 44.8–89.0 years. Across-group ethnicity 73.1% white. Across-group employment status 54.5% retired. Across-group education status 48.9% college or advanced degree | n = 37. Across-group mean age 69.2 years. Across-group age range 44.8–89.0 years. Across-group ethnicity 73.1% white. Across-group employment status 54.5% retired. Across-group education status 48.9% college or advanced degree | Prostate cancer | LP | Standard care and information leaflets | 6, 12 months | LP I, 11; EP I, 7; C, 3 |

| n = 51. Across-group mean age 69.2 years. Across-group age range 44.8–89.0 years. Across-group ethnicity 73.1% white. Across-group employment status 54.5% retired. Across-group education status 48.9% college or advanced degree | EP | |||||||

| Cockcroft et al. 198174 and 1982,73 UK | To examine the effects of exercise on chronic respiratory disability | n = 18. Mean age 61.2 years (± 5.02 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 16. Mean age 60.2 years (± 4.72 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | COPD | Exercise | Waiting list | 2, 4, 8–9 months | I, 1; C, 4 |

| Culos-Reed et al. 2010,80 Canada | To investigate the effects of physical activity, for men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer treatment, on activity behaviour, QoL and fitness | n = 53. Mean age 67.2 years (SD 8.8 years). Age range 46–82 years. Ethnicity N/R. Completed university/college 32.7%. Annual income > CA$80,000 31.3% | n = 47. Mean age 68 years (SD 8.4 years). Age range 49–86 years. Ethnicity N/R. Partially completed university/college 25.5%. Annual income CA$20,000–CA$39,999 31.8% | Prostate cancer | Exercise, education and peer support | Waiting list | 4, 6, 12 months | I, 11; C, 23 |

| Daubenmier et al. 2006,49 USA | To assess the impact of a lifestyle intervention on HRQoL, perceived stress and self-reported sexual function in those electing for active surveillance | n = 44. Mean age 64.8 years (SD 7.1 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 84.1% white. Graduate degree 46%. Full-/part-time work 54% | n = 49. Mean age 66.5 (SD 7.6 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 96% white. Graduate degree 35%. Retired/disabled 51% | Prostate cancer | LP | Standard care | 12 months | I, 4; C, 7 |

| Fernandez et al. 2009,84 Spain | To determine if a simple home-based pulmonary rehabilitation programme for patients with severe COPD is safe and effective | n = 30. Mean age 66 years (± 8 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 20. Mean age 70 years (± 5 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | COPD | Exercise and education | Standard care including education | 12 months | One removed from analysis. I, 3; C, 5 |

| Gallagher et al. 198451 and 1987,50 USA | To evaluate the effect of an unmeasured diet on control of blood sugar, insulin dosage, serum lipids and weight as compared with traditional calorie-defined diet | n = 28. Mean age 47.8 years (SD 16.2 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 23. Mean age 44.5 years (SD 12.7 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Type 2 diabetes | Unmeasured diet and dietary education | Calorie-defined diet and dietary education | 48 months | I, 1; C, 3 |

| Garcia-Vera et al. 199785 and 2004,86 Spain | To evaluate whether or not SMT reduces blood pressure and blood pressure variability | n = 22. Mean age 45.6 years (± 9.9 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 21. Mean age 45.1 years (± 7.8 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Hypertension | SMT | Waiting list | 4 months | I, 1; C, 3 |

| Giesler et al. 2005,52 USA | To assess the efficacy of a cancer-care intervention on QoL | n = 48. Mean age 66.7 years (± 8 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 92% Caucasian. High school diploma 29% | n = 51. Mean age 61.1 years (± 8 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 88% Caucasian. College degree 35% | Prostate cancer | Psychoeducational strategy | Standard care | 12 months | 14 dropouts, nearly equal between groups |

| Gifford et al. 1998,53 USA | To evaluate the acceptability, practicality and short-term efficacy of a health education programme to improve disease self-management with symptomatic HIV/AIDS | n = 25. Mean age 45.2 years (SD 9.4 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 68% white. Some graduate school education 36%. Unemployed 56%. Annual income < US$20,000 55% | n = 33. Mean age 45.3 years (SD 8.1 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 82% white. Completed college 33%. Unemployed 70%. Annual income US$20,000–40,000 40% | HIV/AIDS | Education | Standard care | 3 months | I, 9; C, 4 |

| Gourley et al. 199854 and Solomon et al. 1998,55 USA | To determine patient satisfaction with pharmacist-led care | n = 43. Mean age 69.3 years (SD 5.9 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 90.7% Caucasian (sic). Some college or technical school education 37.2%. Mean annual family income US$20,908 | n = 55. Mean age 69.3 years (SD 9.2 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 83.6% Caucasian (sic). Some college or technical school education 40.0%. Mean annual family income US$21,022 | COPD | Education and support | Standard care | 6 months | N/R |

| Guell et al. 2000,81 Canada | To examine the short- and long-term effects of an outpatient pulmonary rehabilitation programme | n = 30. Mean age 64 years (± 7 years). Across-group age range 46–74 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 30. Mean age 66 years (± 6 years). Across-group age range 46–74 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | COPD | Education, breathing exercise and general exercise | Standard care | 6, 9, 12, 24 months | I, 6; C, 7 |

| Haynes et al. 1976,82 Canada | To assess the application of behavioural-oriented strategies on compliance and blood pressure control | n = 20. Mean age N/R. Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 18. Mean age N/R. Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Hypertension | Behavioural strategies | Standard care | 12 months | I, 0; C, 1 |

| Heisler et al. 2010,56 USA | To compare reciprocal peer-support with nurse care management | n = 125. Mean age 61.8 years (SD 6.1 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 80% Caucasian (sic). Some college or technical or vocational training 73%. Annual income ≤ US$30,000 63% | n = 119. Mean age 62.3 years (SD 6.6 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 84% Caucasian (sic). Some college or technical or vocational training 70%. Annual income ≤ US$30,000 63% | Diabetes (type not specified) | Peer support | Nurse care management | 6 months | I, 9; C, 5 |

| Klocek et al. 2005,90 Poland | To examine changes in QoL and oxygen consumption compared in two exercise programmes | n = 14. Mean age 54 years (± 7 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Years of education 12 | n = 14. Mean age 55 years (± 9 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Years of education 13 | Heart failure | Rehabilitation programme with constant level of workload | Standard care | 6 months | N/R |

| n = 14. Mean age 57 years (± 8 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Years of education 14 | Rehabilitation programme with progressive level of workload | |||||||

| Koukouvou et al. 2004,91 Greece | To investigate whether or not exercise-based rehabilitation affects psychological profile and QoL and examine correlations between changes in cardiorespiratory capacity and psychological status | n = 16. Mean age 52.3 years (SD 9.2 years). Across-group age range 36–66 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 10. Mean age 52.8 years (SD 10.6 years). Across-group age range 36–66 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Heart failure | Supervised exercise rehabilitation programme | Standard care | 6 months | I, 2; C, 1 |

| Leehey et al. 2009,57 USA | To measure if exercise improves cardiovascular health and weight loss, decreases proteinuria, improves glucose and lipid control and decreases inflammation | n = 7. Across-group mean age 66 years. Across-group age range 55–81 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 6. Across-group mean age 66 years. Across-group age range 55–81 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Kidney disease and type 2 diabetes | Exercise | Standard care including disease education | 1.5, 6 months | I, 0; C, 2 |

| Lepore 1999,58 USA | To investigate if psychoeducational support groups enhance QoL | n = 12. Age N/R. Age range N/R. Ethnicity 100% Caucasian (sic). Median annual income US$50,000–75,000 | n = 12. Age N/R. Age range N/R. Ethnicity 100% Caucasian (sic). Median annual income US$50,000–75,000 | Prostate cancer | Psychoeducational support group | Standard care | 2 months | N/R |

| Lepore et al. 2003,59 USA | To compare QoL outcomes of patients randomised to standard care, education alone or education and peer discussion | n = 84. Mean age 64.8 years (SD 7.7 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 76% Caucasian (sic). High school graduate 26%. Retired 43%. Latest occupation professional/technical 34% | n = 80. Mean age 65.6 years (SD 6.6 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 72% Caucasian (sic). College graduate 21%. Retired 38%. Latest occupation professional/technical 33% | Prostate cancer | Education | Standard care | 0.5, 6, 12 months | 29 lost to follow-up |

| n = 86. Mean age 64.8 years (SD 8.0 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 78% Caucasian (sic). College graduate 29%. Retired 42%. Latest occupation professional/technical 30% | Education and peer discussion | |||||||

| Lucy 1994,60 USA | To measure the impact of a psychosocial intervention on psychological distress | n = 9. Mean age 38 years (± 8.1 years). Across-group age range 25–68 years. Ethnicity n = 7 Caucasian (sic). Full-time employment n = 6. Annual income US$20,000–29,000 | n = 8. Mean age 38.75 years (± 12.7 years). Across-group age range 25–68 years. Ethnicity n = 5 Caucasian (sic). Full-time employment n = 4. Annual income US$30,000–39,000 | HIV | Telecare support | Waiting list | 4 months | N/R |

| McGavin et al. 197776 and 1976,75 UK | To evaluate a home-based exercise scheme | n = 12. Mean age 61.4 years (± 5.6 years). Age range 53–69 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 12. Mean age 57.2 years (± 7.9 years). Age range 40–69 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | COPD | Exercise | No intervention | ≈ 3 months | I, 4; C, 0 |

| Mishel et al. 2002,61 USA | To test the efficacy of an individualised uncertainty management intervention | Overall n = 239. Group n N/R. Across-group mean age 64.0 years (SD 6.9 years). Age range N/R. Across-group ethnicity 56% Caucasian. Across-group income > US$3000 per month 45%. > 12 years education 57% | Overall n = 239. Group n N/R. Across-group mean age 64.0 years (SD 6.9 years). Age range N/R. Across-group ethnicity 56% Caucasian. Across-group income > US$3000 per month 45%. > 12 years education 57% | Prostate cancer | Patient uncertainty management | Standard care and general health information | 7 months | 5% dropout across groups |

| Overall n = 239. Group n N/R. Across-group mean age 64.0 years (SD 6.9 years). Age range N/R. Across-group ethnicity 56% Caucasian. Across-group income > US$3000 per month 45%. > 12 years education 57% | Patient and close family member uncertainty management | |||||||

| Moynihan et al. 1998,77 UK | To determine the efficacy of adjuvant psychological therapy in patients with testicular cancer | n = 36. Across-group mean age 62 years. Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Across-group social class III n = 25 | n = 37. Across-group mean age 62 years (± 85 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Across-group social class III n = 25 | Testicular cancer | Psychological therapy | Standard care | 12 months | I, 3; C, 2 |

| Mueller et al. 2007,62 USA | To assess exercise capacity, mortality, cardiac events and physical activity patterns in chronic heart failure patients undergoing a rehabilitation programme | n = 25. Across-group mean age 55 years (± 10 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 25. Across-group mean age 55 years (± 10 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Heart failure | Residential rehabilitation programme | Standard care | 1 month, 6.2 years | I, 11; C, 12 |

| Parker et al. 1984,63 USA | To compare patients receiving a comprehensive arthritis education programme with a standard-care control group | Overall n = 18. Group n N/R. Mean age 55.3 years (± 10.8 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Hollingshead index 56.9 (± 7.5) | Overall n = 18. Group n N/R. Mean age 55.8 years (± 10.2 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Hollingshead index 56.9 (± 16.7) | Arthritis | Education | Standard care | 3 months | n = 22 selected; n = 18 with complete data. No further detail |

| Parker et al. 2009,64 USA | To assess the short- and long-term effects of a SM or SA intervention | SM: n = 53. Mean age 59.8 years (SD 6.9 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 71% white. College graduate 39% | n = 52. Mean age 60.9 years (SD 5.9 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 92% white. College graduate 35% | Prostate cancer | SM | Standard care | 12 months | SM I, 21; SA I, 17; C, 20 |

| SA: n = 54. Mean age 60.7 years (SD 7.2 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 70% white. College graduate 39% | SA | |||||||

| Puente-Maestu et al. 200088 and 2003,87 Spain | To compare two exercise training programmes and evaluate any long-term effects | n = 20. Mean age 65.6 years (SD 43.7 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 21. Mean age 63.3 years (SD 4.3 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | COPD | Unsupervised exercise | Supervised exercise | 2, 15 months | I, 10; C, 8 |

| Sackett et al. 1975,83 Canada | To evaluate strategies for increasing medication compliance. Factorial design | Overall n = 230. Group n N/R. Age N/R. Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Augmented convenience n = 114, normal convenience n = 116, mastery learning n = 115, no mastery learning n = 115 | Hypertension | Augmented convenience and mastery learning | Normal convenience and no mastery learning | 6 months | Augmented convenience, 6; normal convenience, 4; mastery learning, 8; no mastery learning, 2 |

| Scura et al. 2004,65 USA | To evaluate the feasibility of a telephone social support intervention to increase physical, emotional, functional and interpersonal adaption of men to prostate cancer | n = 7. Across-group mean age 66 years (SD 8.3 years). Across-group age range 51–78 years. Across-group ethnicity 59% Caucasian (sic). Across-group mean annual income ≤ US$40,000 | n = 10. Across-group mean age 66 years (SD 8.3 years). Across-group age range 51–78 years. Across-group ethnicity 59% Caucasian (sic). Across-group mean annual income ≤ US$40,000 | Prostate cancer | Telephone support and education | Education | 2.5, 7.5, 12 months | N/R |

| Wakefield et al. 2008,67 USA | To compare a telephone intervention and a videophone intervention on changes in communication, nurse perception and patient satisfaction | n = 14. Mean age 72 years (± 9.2 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 86% Caucasian (sic). High school education 29% | N/R | Heart failure | Telephone support | Standard care | 3 months | Telephone I, 39; video I, 18; C, N/R |

| n = 14. Mean age 68.1 years (± 8.3 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity 100% Caucasian (sic). High school education 57% | Video call support | |||||||

| Weber et al. 2004,68 USA | To investigate the effects of a peer support programme between men recently treated with radical prostatectomy and long-term survivors | n = 15. Mean age 57.5 years (SD 6.7 years). Across-group age range 48–67 years. Ethnicity 87% white. High school education 40%. Mean annual income US$50,000–74,000 33%. Full-time employment 80% | n = 15. Mean age 59.7 years (SD 6.6 years). Across-group age range 48–67 years. Ethnicity 80% white. High school education 40%. Mean annual income > US$75,000 33%. Full-time employment 47% | Prostate cancer | Peer support | Standard care | 2 months | I, 2; C, 0 |

| Weber et al. 2007,69 USA | To enhance self-efficacy through dyadic support in men who have undergone radical prostatectomy for prostate cancer | n = 37. Mean age 59.5 years. Across-group age range 47–74 years. Ethnicity 86.5% white. Four-year degree education 29.7%. Mean annual income > US$75,000 37.8% | n = 35. Mean age 60 years. Across-group age range 47–74 years. Ethnicity 80% white. Some college education 28.6%. Mean annual income > US$75,000 29.4% | Prostate cancer | Peer support | Standard care | 2 months | Two patients relocated/lost to follow-up, unclear which group. I, 2; C, 5 |

| White et al. 1986,70 USA | To compare the effectiveness of advice and education vs. group management with peer support | n = 16. Mean age 62.4 years (± 5.5 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Employment 25%. More than high school education 31.3% | n = 16. Mean age 60.7 years (± 6.4 years). Age range N/R. Ethnicity N/R. Employment 31.3%. More than high school education 37.5% | Type 2 diabetes | Group management and peer support | Education and advice | 6 months | I, 4; C, 5 |

| Windsor et al. 2004,78 UK | To determine if aerobic activity reduces fatigue incidence and prevents deterioration of physical functioning during radiotherapy | n = 33. Mean age 68.3 years (± 0.9 years). Across-group age range 52–82 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | n = 33. Mean age 69.3 years (± 1.3 years). Across-group age range 52–82 years. Ethnicity N/R. SES N/R | Prostate cancer | Exercise and HCP support | Standard care | 1 month | I, 1; C, 0 |

| Author, year, country | Self-management intervention description and intervention coding | Method of recruitment | Setting of intervention | Duration of intervention session and frequency | Total duration | Individual or group | Mode of administration | Delivered by/intervention training |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsett et al. 1989,79 Canada | Training in progressive muscle relaxation, monitoring practice and strategies for stressful situations. Education on hypertension, lifestyle and stress. Patients were given a take-home tape of first relaxation session for home practice and kept daily logs. Compliance was assessed weekly (Edu, M&F) | Recruitment from work place (Dominion Foundries) | Work and home based | 1 hour, weekly | 8 weeks | Group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Therapists trained on intervention |

| Education (same as relaxation group) on hypertension, lifestyle and stress. Weekly logs of activities, food intake and exercise were kept and reviewed weekly (Edu, M&F) | Work and home based | 1 hour, weekly | 8 weeks | Group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Therapists trained on intervention | ||

| Allen et al. 1990,46 USA | Patients were trained to perform blood glucose tests at least 36 times per month. Proficiency was checked prior to the start of study and throughout. Each patient was also instructed on a diet, which largely focused on increasing fibre intake. Booklets on diet and weight loss were provided and compliance was checked at 3 and 6 months (Edu, M&F) | Medical centres | Home based | N/A. Follow-up at 3 and 6 months | 24 weeks | Individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Dietitian, diabetes teaching nurse, physician or physician associate. Intervention training N/R |

| Bennett et al. 1991,71 UK | Stress management training: small groups were educated on BP, stress and relaxation techniques, self-instruction techniques, cognitive restructuring and meditation. Sessions involved role-play and group problem-solving. Participants were set behavioural assignments and kept a diary (Edu, Peer, M&F) | Medical centres | N/R | 2 hours, weekly | 8 weeks | Group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Therapist. Intervention training N/R |

| Type A behaviour management: same content as stress management training. Additionally, specific attention was paid to the identification and modification of type A behaviours including time urgency management and anger control (Edu, Peer, M&F) | N/R | 2 hours, weekly | 8 weeks | Group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Therapist. Intervention training N/R | ||

| Berglund et al. 2007,89 Sweden | The training programme involved light physical fitness training, relaxation, breathing exercises and pelvic floor exercises. A booster session was held after 2 months (Phy, M&F) | Consecutive hospital patients within 6 months of diagnosis | N/R | 1.25 hours, 7 sessions | N/R | Group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Physiotherapist. Intervention training N/R |

| Information was provided on prostate cancer, treatment and potential side effects in the form of lectures. Opportunities for group discussion and demonstration of products for incontinence and sexual aid formed part of the sessions (Edu, Peer) | N/R | 1.25 hours, 7 sessions | N/R | Group | Face to face | Nurse. Intervention training N/R | ||

| This programme combined the physical and information programmes (Phy, Edu, Peer) | N/R | 2.25 hours, 7 sessions | N/R | Group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Physiotherapist and nurse. Intervention training N/R | ||

| Bosley and Allen 1989,47 USA | Education on stress, emotional arousal and hypertension. Participants were trained to monitor own behaviour and physiological responses in stressful situations. Group practice, identification of faulty appraisal, recognition of inaccurate labelling of situations and home practice formed part of the intervention (Edu, Peer, M&F) | Community recruitment | N/R | 45 minutes, weekly | 8 weeks | Group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Psychologist with matched ethnicity. Intervention training N/R |

| Presentation on the dynamics of stress and hypertension, followed by group discussion sessions on how to handle stressful situations (Edu, Peer) | N/R | 45 minutes, weekly | 8 weeks | Group | Face to face | Psychologist with matched ethnicity. Intervention training N/R | ||

| Bourke et al. 2011,72 UK | Supervised aerobic and resistance exercise training and self-directed exercise. Incorporating exercise into daily activities and available support structures were explored for each patient. All participants received a nutrition advice pack, which recommended reductions in saturated fat and refined carbohydrates, increased fibre and moderate alcohol consumption. Small group healthy eating seminars were also held (Phy, Edu, Peer) | Sedentary patients from outpatient clinics | Dedicated exercise suite and home based. Healthy eating seminar location N/R | ≥ 0.5 hours, three times per week. Healthy eating seminar fortnightly, duration N/R | 12 weeks | Group and individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Exercise physiologist. Intervention training N/R |

| Burgio et al. 2006,48 USA | A single session of biofeedback to learn pelvic floor control, reinforced with verbal instructions. Patients were provided with written instructions for 45 pelvic floor exercises and encouraged to continue at home in various positions and to integrate into daily activities (Edu) | Pre-surgery patients at urology clinics | Hospital and home based | One session, duration N/R. Frequency of home practice N/R | N/R | Individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | N/R |

| Carmack Taylor et al. 2006,66 USA | Cognitive behavioural skills training including self-monitoring, goal-setting, problem-solving to overcome barriers, cognitive restructuring and self-rewards to integrate physical activity into daily life. Patients self-monitored and were followed up to solve issues and set new goals (Edu, M&F) | Cancer centres. Recruitment in five cohorts | N/R | 1.5 hours per session; one orientation session, 16 weekly sessions and four sessions twice a week | 24 weeks | Group | Face to face | Expert speakers, physical and lifestyle co-ordinator. Intervention training N/R |

| Facilitated group discussion on various topics: diet and prostate cancer, side effects of treatment and sexuality. Expert speakers presented at some sessions (Edu, Peer) | N/R | 1.5 hours per session; one orientation session, 16 weekly sessions and four sessions twice a week | 24 weeks | Group | Face to face | Expert speakers | ||

| Cockcroft et al. 198174 and 1982,73 UK | Rehabilitation centre-based exercise including stationary cycle pedalling, rowing machines, swimming and daily walks. Recommended home exercises included stair climbing and level walking (Phy) | N/R | Rehabilitation centre and home based | Twice-daily walks, duration unknown | 16 weeks | Group and individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | N/R |

| Culos-Reed et al. 2010,80 Canada | Group exercise tailored to ability consisting of walking, stretching and light resistance work. Exercise equipment was provided to facilitate home-based exercise. Peer support was encouraged and education/discussion sessions were held on goal-setting, monitoring behaviour, overcoming barriers, role of positive attitude, social support, relapse support and nutrition (Phy, Edu, Peer, M&F) | Prostate cancer survivors on long-term therapy | Home based and fitness centre | Home-based exercise 3–5 times per week, duration N/R. Fitness centre exercise weekly for 1.5 hours, then monthly during maintenance phase | 16 weeks | Individual and group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Fitness professional. Intervention training N/R |

| Daubenmier et al. 2006,49 USA | A plant-based vegan diet with 10% of calories from fat, 3 hours of moderate exercise per week and 1 hour of stress management practice per day. Participants attended a 1-week retreat to familiarise themselves with the intervention. Subsequently, weekly support group meetings were held to enhance programme adherence (Phy, Edu, Peer) | N/R | Residential retreat and home based. Support group meeting location N/R | Recommended 3 hours of exercise per week and 1 hour of stress management per day. Support group meetings weekly, duration N/R | 48 weeks including 1-week residential retreat | Individual and group | Face to face and remote unsupervised | N/R |

| Fernandez et al. 2009,84 Spain | Respiratory education combined with inspiratory, upper and lower limb muscular training. Training logs were kept and patients were followed up by a physiotherapist. Educational materials were also provided on exercises (Phy, Edu, M&F) | Patients receiving long-term oxygen therapy | Hospital and home based | Two education sessions for 1 hour each. 1 hour of exercise, five times per week | 44 weeks | Individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Physiotherapist and nurse. Intervention training N/R |

| Gallagher et al. 198451 and 1987,50 USA | Diet with an unspecified calorie intake consisting of three meals per day and a snack avoiding refined sugars and saturated fats. Education on the diet and dietary consultations occurred every 3 months (Edu, M&F) | Hospital diabetic outpatient unit | Home based | N/A. Consult every 3 months | 4 years | Individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Dietitian |

| Garcia-Vera et al. 199785 and 2004,86 Spain | Education and training on hypertension, relaxation and problem-solving. Patients received a self-help book, problem-solving sheets, relaxation tapes and recording sheets to track medication use and stressful events. Homework assignments were set and reviewed by a therapist (Edu, M&F) | Referrals from medical centres | Health centre and university laboratory | Five sessions over 1 week and then two sessions every 2 weeks | 8 weeks | Individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Therapist. Intervention training N/R |

| Giesler et al. 2005,52 USA | A programme of symptom management and psychoeducational strategies. The intervention focused primarily on sexual and urinary problems, bowel dysfunction, cancer worry, dyadic adjustment and depression (Edu, M&F) | Medical centres and hospital cancer units | Home based | Monthly, duration unknown | 24 weeks | Individual | Face to face and telephone | Nurse. Intervention training N/R |

| Gifford et al. 1998,53 USA | Self-care education sessions covering evaluating symptoms, seeking care for new symptoms, medication use and problems, communication skills with caregiver/health professionals, coping with symptoms using cognitive–behavioural therapy, and relaxation. Additionally exercise, fitness programmes, nutrition plans and goal-setting. Interaction was encouraged through role-playing, information sharing and other forms of participation (Edu, Peer) | Community recruitment and medical centres | Community settings | Weekly, duration unknown | 7 weeks | Group | Face to face | Lay leaders from community trained on intervention |

| Gourley et al. 199854 and Solomon et al. 1998,55 USA | A pharmacist provided regular assessment and educational interventions to optimise disease management. Patients’ questions and concerns were also managed (Edu) | Hospital and medical centres | Pharmacy clinic | Monthly, duration unknown | 24 weeks | Individual | Face to face | Pharmacist. Intervention training N/R |

| Guell et al. 2000,81 Canada | Breathing retraining and relaxation techniques, low-level stair walking, flat surface exercise, stationary cycle pedalling and walking with arm and leg co-ordination. Education sessions covered anatomy, basic respiratory physiology, nature of the disease and interventions. Physiotherapy for effective cough and postural drainage was offered (Phy, Edu) | Consecutive eligible patients at an outpatient clinic | Hospital gym and home based. Unclear where educational classes held | Phased exercise programme: 30 minutes of supervised classes and 30–60 minutes of home-directed exercise up to 5 times per week. Education component details N/R | 48 weeks | Group and individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | N/R |

| Haynes et al. 1976,82 Canada | Each patient was interviewed to identify habits and tailor medication taking. Loaned BP devices were provided and BP and medication taking were tracked. During fortnightly follow-ups, if BP had lowered, financial credit was given towards owning the BP device. Patients were also praised and encouraged on progress (M&F, Finance) | N/R | Work and home based | 30 minutes, every 2 weeks | 48 weeks | Individual | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Female programme co-ordinator |

| Heisler et al. 2010,56 USA | Action plans were generated based on individual laboratory and BP results. Each patient was then paired with a peer and encouraged to make regular contact with automated reminders. Each pair received training on communication skills and topic guides for phone calls. In addition three optional group sessions to raise queries, discuss concerns and review action plan progress were held (Peer, M&F, Action) | Patients from two medical centres with poor glycaemic control | Home based. Group session location N/R | One 3-hour training session. Weekly peer calls encouraged. Three optional group sessions lasting 1.5 hours each | 24 weeks | Individual and group | Face to face and telephone | Care manager trained on motivational interviewing and empowerment. Patient peer supporters trained on peer communication |

| Klocek et al. 2005,90 Poland | Exercise consisting of warm-up, then consistent workload training on a cycle ergometer (60% maximal heart rate for age) and post-training relaxation (Phy) | Consecutive patients from hospital cardiac unit | Cardiac rehabilitation outpatient unit | 1 hour, three times per week | 24 weeks | Group | Face to face | Physician and rehabilitation specialist |

| Exercise consisting of warm-up, interval training with gradually increasing workload on a cycle ergometer and post-training relaxation (Phy) | Cardiac rehabilitation outpatient unit | 1 hour, three times per week | 24 weeks | Group | Face to face | Physician and rehabilitation specialist | ||

| Koukouvou et al. 2004,91 Greece | A gradually modified physical training programme incorporating stationary cycling, walking or jogging, calisthenics, stair climbing and step aerobic exercises. Resistance exercises were added in after the first 3 months (Phy) | Referrals from hospital cardiac clinic | N/R | 1 hour, 3–4 times per week | 24 weeks | Group | Face to face | N/R |

| Leehey et al. 2009,57 USA | Education and instruction on walking, shoe selection and developing a walking programme. Gradually increasing treadmill walking and unsupervised home-based walking programme. Patients were followed up and monitored by staff (Phy, M&F) | Individuals from an outpatient clinic | Laboratory gym setting and home based | Gradually increasing from 30 minutes, thrice weekly | 24 weeks | N/R | Face to face and remote unsupervised | N/R |

| Lepore 1999,58 USA | Patients and partners were invited to expert lecture and question sessions followed by separate peer discussions for men and wives. Topics were prostate cancer overview, nutrition and exercise, side effects, stress management, communication and intimacy, and follow-up care. Those missing meetings received a tape recording of the lecture and any handouts (Edu, Peer) | Patients after treatment for prostate cancer | N/R | 1.75 hours, weekly | 6 weeks | Group | Face to face | Clinical psychologist and oncology nurse. Intervention training N/R |

| Lepore et al. 2003,59 USA | Expert-delivered lectures on prostate cancer biology and epidemiology, control of physical side effects, nutrition, stress and coping, relationships and sexuality, follow-up care, and future health concerns. Printed materials were provided in each lecture and 10 minutes of questions were permitted, minimising group discussion (Edu) | Urology and radiology clinics | N/R | 1 hour, weekly | 6 weeks | Group | Face to face | Expert speakers. No further detail |

| Expert lectures as above as well as facilitated group discussion with a male psychologist for men and separate discussion for partners with a female oncology nurse (Edu, Peer) | N/R | 1.75 hours, weekly | 6 weeks | Group | Face to face | Expert speakers, male psychologist and female oncology nurse. Intervention training N/R | ||

| Lucy 1994,60 USA | Psychosocial support, monitoring of health, stress, mood and interpersonal satisfaction. Monitored weekly over the phone. Information and education on HIV/AIDS. Referrals to other services when appropriate (Edu, M&F) | Press release | Home based | 0.4–0.75 hours, weekly | 16 weeks | Individual | Telephone | N/R |

| McGavin et al. 197776 and 1976,75 UK | Home stair-climbing exercises starting from a minimum of two steps up and down for 2 minutes building to 10 steps for 10 minutes. Participants recorded their progress and the programme was reviewed after 2 weeks and monthly thereafter (Phy, M&F) | N/R | Home based | 2–10 minutes ≥ once a day, ≥ 5 times per week | 12 weeks | Individual | Remote unsupervised | N/R |

| Mishel et al. 2002,61 USA | Patients’ concerns directed the skills training. Strategies included information, cognitive reframing, directing to local resources, problem-solving techniques, encouragement and patient–doctor communication skills to enhance participation in care (Edu, M&F) | Medical centres and community | Home based | Weekly, duration unknown | 8 weeks | Individual | Telephone | Nurse trained in the intervention |

| Patients’ concerns directed the skills training. Strategies included information, cognitive reframing, directing to local resources, problem-solving techniques, encouragement and patient–doctor communication skills to enhance participation in care. In addition, the spouse or family support member also received weekly telephone calls (Edu, M&F) | Medical centres and community recruitment | Home based | Weekly, duration unknown | 9 weeks | Individual | Telephone | Nurse trained in the intervention | |

| Moynihan et al. 1998,77 UK | A cognitive and behavioural treatment programme, designed for cancer patients, covering current problems, coping strategies, muscle relaxation, raising self-esteem, overcoming feelings of helplessness and promoting a ‘fighting spirit’ (Edu, Psy) | Newly diagnosed hospital patients | Hospital based | 1 hour. Six sessions offered although exact number tailored per patient | ≥ 8 weeks | Individual | Face to face | Experienced cancer/mental health nurse trained in therapy techniques |

| Mueller et al. 2007,62 USA | Patients resided at a rehabilitation centre for 1 month, undertaking cycling and walking. Exercise levels were adjusted accordingly (Phy) | Consecutive referrals to rehabilitation centre | Residential rehabilitation centre | 1.5–2 hours, seven times per week | 4 weeks | Group | Face to face | N/R |

| Parker et al. 1984,63 USA | Intensive education programme covering disease process, therapies and medication, joint protection and conservation, coping with psychological stresses, and unproven treatment methods (Edu) | Hospitalised patients | Hospital based | One session for 7 hours | 7 hours | N/R | Face to face | Rheumatology patient educators |

| Parker et al. 2009,64 USA | Individual clinical psychologist sessions and stress management guides covering relaxation skills (60% of the time), problem-focused coping strategies, having realistic recovery expectations and an imagined exposure of day of surgery. Further information on cancer and the adverse effects of treatment were also provided (Edu, Psy) | Patients before prostate surgery | Hospital based | 1–1.5 hours, four sessions around surgery | < 3 weeks | Individual | Face to face | Clinical psychologist |

| Individual clinical psychologist sessions providing support to patients (Psy) | Patients before prostate surgery | Hospital based | 1–1.5 hours, four sessions around surgery | < 3 weeks | Individual | Face to face | Clinical psychologist | |

| Puente-Maestu et al. 200088 and 2003,87 Spain | Each participant was supplied with a pedometer and asked to walk 3–4 km in 1 hour, 4 days per week. Subjects were followed up and encouraged to continue with training during a maintenance phase. During this period, patients were interviewed every 3 months to reinforce compliance. Education sessions were also held on medication use and nutrition (Phy, Edu, M&F) | Respiratory physician referrals | Home based. Location of education sessions N/R | Exercise 1 hour, four times per week. Education session 0.75–4 hours, frequency N/R. Maintenance phase N/R | 56 weeks | Individual. Education sessions N/R | Face to face and remote unsupervised | Nurse and dietitian. Intervention training N/R |