Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1010/05. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in September 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Wilson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

This study was based on three premises: first, that a major challenge for health and social care is in reducing unplanned admissions is in those aged 85 years and over; second, that reducing unplanned admissions requires interventions at several inter-related points in a complex system; and, third, that an understanding of the practical challenges in implementing policies to reduce admission is necessary for successful adoption.

The challenge of unplanned admissions in those aged 85 years and over

The number of people aged 85 years and over in the UK is projected to more than double between 2009 and 2034, from 1.4 million to 3.5 million, compared with a 12% growth in the overall population. 1 Between 2001 and 2011, the number of people aged 85 years and over increased at three and a half times the rate of the rest of the population. 2 The proportion of emergency admissions contributed to by this age group rose between 2004/5 and 2008/9 from 9.5% to 11%,3 and will continue to increase as a result of these demographic trends.

Many, but not all, patients aged 85 years and over presenting to acute care have multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, cognitive impairment and disability. Such patients are challenging to assess and manage, as the clinical presentation may be non-specific and difficult to interpret and relevant information may not be readily available. This leads to the high ‘conversion rates’ (the proportion of people attending acute care who are subsequently admitted to a bed). 4 Once admitted to hospital, older people have longer stays, are more prone to hospital-acquired complications, both physical and psychological (e.g. delirium), and may experience more difficulty returning home or to their usual place of residence due to disruption of previously established care packages. 5

Explanations for rising admission rates

Reasons for the rise of unplanned admissions in all age groups have been examined in detail in several reports. 2,3,6–10 A consistent finding was of unexplained variation in trends of admission rates, at hospital trust, primary care trust (PCT) and local authority levels, suggesting lessons can be learned from these different experiences.

In part, the increase in numbers of admissions is due to an ageing population; it has been estimated that demographic change accounted for 40% of the rise between 2004 and 2009. 3 There is no evidence of increased morbidity in the population, and so the consensus is that the majority of the increase is due to service factors, professional behaviour and public expectations.

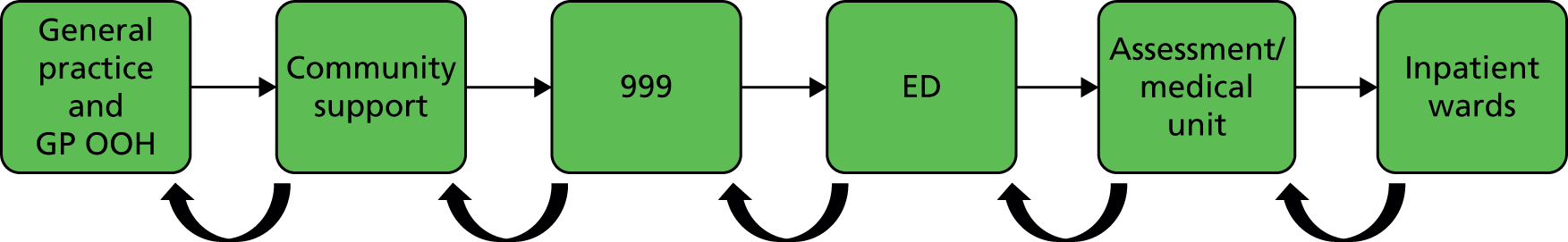

The patient journey from community to inpatient wards involves several steps, including all or some of the following: management in primary care, community support, emergency/ambulance services and emergency department (ED). The contribution of these to rises in admission is summarised below.

Primary care

Primary care can influence admission rates in two ways: first by optimal control of long-term conditions, such as blood pressure management to reduce risk of stroke, and second by early intervention in an acute condition to avoid the need for admission; for example, appropriate management of heart failure and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) can prevent admissions. These have been referred to as ‘preventable’ and ‘avoidable’ admissions respectively,11 although the literature does not always use these terms consistently. Ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) have been defined as those for which effective management in primary care should prevent admission to hospital, and include chronic and acute conditions as well as those that are vaccine preventable (e.g. influenza). Which conditions are included as ACSCs varies between reports. In 2009/10 in England, 19 ACSCs accounted for 16% of acute admissions overall, and 30% in those aged 75 years and older. 10 Using a broader definition of 27 ACSCs, Blunt reported that in England, between 2010 and 2013, rates of admission for these conditions rose by 26% after adjusting for an ageing population. 8 Within the older population, the biggest increases were for COPD, pneumonia and pyelonephritis, whereas in all age groups the rate of admission for chronic conditions declined. 8 This suggests that primary care (as well as public health measures, such as tobacco control) has been more effective in managing chronic conditions, but less effective in dealing with some acute conditions that could, in principle, be managed in the community.

There is some empirical evidence that lack of investment in primary care may contribute to increasing admissions. In a study of 16 acute trusts, it was found that, after adjusting for other factors such as age and deprivation, those serving communities with higher investment in primary care had lower ED attendance rates in those aged 65 years and above (admission data were not presented). 12 There is increasing evidence that access to and continuity in primary care affect ED attendance and admissions. 13 Evidence from the USA suggests that lower continuity of primary care (which includes family physicians, paediatricians and geriatricians) increases admission rates,14 a finding supported by recent work conducted by some of the authors. 15 Using the same data set from one English county, and adjusting for all known confounders, there was also a relationship between ED attendance rates and perceived access to general practice. 15 A similar study found the same relationship with emergency admissions. 16 National data, adjusting for age, also show that, where overall satisfaction with general practice and satisfaction with telephone access are lower, ED attendance rates are higher. 2 It has recently been estimated that, in England, over 5 million ED attendances (26.5%) were preceded by patients being unable to obtain an appointment with their general practitioner (GP). 17

The contribution of out-of-hours general practice, especially following the changes in 2004 which led to GPs being able to relinquish responsibility for this task, has been contested. Some authors have linked rising rates of ED attendance to these contractual changes,18 while others have noted that rates were already rising before they were introduced. 19 More certain is the fact that out-of-hours services vary in quality, including the proportion of patients they refer to hospital. 20 Although the introduction of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in 2004 has improved management of individual long-term conditions, it has been suggested that this is at the expense of a more holistic approach, especially with older people. 21,22

Community support

One reason cited for rising admission rates of older people is the lack of community-based alternatives available to respond to the demographic changes outlined earlier. As far back as 2000, it was recognised that 50% of older people in hospital needed rehabilitation rather than acute care and that inappropriate use of in-patient bed-days by older people was greater than 20%. 23,24 This led to a commitment in the NHS plan25 to expand intermediate care provision, but evaluations have suggested that this has not been introduced on a sufficient scale and that, in many cases, these services have offered additional rather than substitute care. 26 Lack of community support has also been identified as a factor in the rising rates of readmission in the elderly. 27

Emergency departments and acute assessment units

By far the largest contributor to rises in emergency admission rates is the number of patients who come through EDs (accounting for 71% of admissions in 2012). Between 2003 and 2012, the number of attendances at major EDs increased by only 12.5%, but the percentage of attenders admitted (the conversion rate) increased from 19% to 26%. The National Audit Office estimated that this increase in the conversion rate accounted for 75% of the rise in emergency admissions through major EDs. 2 In 2010/11, people aged 80 years and over accounted for 6.5% and those aged over 90 years for 1.8% of first attenders to English EDs and, of those aged 85 years and over, 62% were admitted to hospital. Other factors identified in the report as explaining the rise in admissions include the 4-hour target (within which time ED attenders must be seen, treated, and admitted or discharged) and the introduction of acute assessment units, in which patients can be further assessed before a decision on management is made. Typically these units admit for a maximum of 72 hours. 28 Unfortunately, routine data do not distinguish between admission to such units and admission to an inpatient ward. It has recently been estimated that the increasing number of older people attending EDs between 2011/12 and 2012/13 accounted for 11% of the decline in reaching the 4-hour target. 29

In summary, the increase in the number of admissions from EDs has largely comprised short-stay admissions of less than 2 days (which increased by 124% in the 15 years to 20132) and has been driven more by a rise in conversion rates than by a rise in numbers attending. Clinical practice and government directives are likely to have contributed.

Initiatives to stem the rise of acute admissions

Several initiatives have been introduced to stem the increase in acute admissions, with many focused on the oldest old. The evidence base for these was summarised by Purdy in 2010. 6 They can be conceived as attempts to achieve the left-to-right shift illustrated in Figure 1, as proposed in the ‘Silver Book’. 30

Primary care

As outlined earlier, there is some evidence that improved access and continuity in general practice may reduce ED attendance. There have been several initiatives to improve access, particularly concerning targets for appointments to be offered within a defined time frame, but the effect of these on admission rates has not been evaluated. Risk profiling, to identify and support those at high risk of admission, was also introduced in 2005,31 but there is no firm evidence of effectiveness; for example, an evaluation of case management of those at high risk of admission showed no impact on admission rates,32 a finding supported by more recent evidence. 33

Additional services to improve access have been introduced in the last decade, including walk-in centres, minor injuries units, and telephone and web-based services such as NHS Direct. The first two of these are classified as accident and emergency (A&E) services in some data sets, and increased use of these services was reported by the Audit Commission as explaining the majority of the 32% increase in overall ED attendances between 2003/4 and 2012/13. In principle, these services could reduce emergency admissions by providing prompt management of acute conditions and by diverting people away from major EDs. Alternatively, they could increase admissions if their staff are less prepared to manage risk than standard primary care services. There are no empirical data to support either of these assertions and a recent systematic review found no evidence of effect, noting the lack of good-quality studies. 19

Community support

Community support to reduce acute admissions has focused on intermediate care, a term first used in the NHS Plan. 25 Intermediate care comprises services, primarily catering for older people, which seek to prevent unnecessary hospital admissions, facilitate earlier discharges and avoid premature admissions to long-term care. 34 Admissions avoidance schemes are services designed to provide an alternative to hospital admissions. Examples of such schemes include ‘rapid response’ (rapid assessment and access to short-term nursing/therapy support and personal care in the service user’s own home), ‘hospital at home’ (intensive support in the patient’s own home) and ‘residential rehabilitation’ (a short-term programme of therapy and enablement in a residential setting). There is good evidence from systematic reviews that, for selected patients, hospital at home can deliver similar or better outcomes than inpatient care, potentially at a lower cost;35,36 however, these schemes have not been implemented on a sufficient scale to show an effect on reducing admissions. The evidence base for early-discharge hospital at home schemes is less clear, although for some patient groups they may reduce long-term admissions to residential care. 37

A key driver of improving care for older people has been the promotion of ‘integrated care’. Although this concept includes ‘vertical’ integration (e.g. between primary and secondary care), in practice most activity has been improving ‘horizontal’ integration between general practice, community nursing and social services. Several such initiatives included the aim of reducing acute admissions. Surprisingly, a national evaluation of 16 schemes found that they resulted in a significant 2% increase in emergency admissions, but reduced planned admissions and outpatients attendances by 4% and 20% respectively. The authors suggest that increased availability of planned care in the community could explain these findings. 38

A specific area of activity aimed at reducing admissions has been work with care homes (nursing and residential). A number of different schemes have been introduced, including enhanced payments and different models for GP provision,39 specialist nursing and pharmacy teams, and input from geriatricians. A 2011 review included anecdotal reports that such initiatives could be effective in reducing admissions, but no one model of care was pre-eminent. 40

Ambulance and paramedic services

A recent trial of providing an emergency response by paramedics with enhanced skills found that this new service reduced ED attendances by 28% and admission rates by 13%. The mean age of participants was 82 years, and the most common conditions were falls, accounting for over 85% of cases. 41 A later systematic review supported this approach to falls,42 and there is evidence for the effectiveness of community management of these cases. 43 However, there is a lack of evidence for other conditions. 2

Emergency departments and acute assessment units

Several interventions have been introduced to reduce the proportion of ED attendances that result in admission. In 2007, the NHS published a list of conditions which could be managed in EDs without admission, for example pulmonary embolism. 44 Review by a senior clinician has been found to reduce admission rates to wards by 12% and to medical assessment units by 21%, compared with actions taken by a more junior clinician. 45 Similarly, the introduction of comprehensive geriatric assessment in an ED setting was found to reduce the ED conversion rate for people aged 85 years and over from 69.6% to 61.2%,46 a finding in line with other studies. 47–49

Although, as discussed earlier, admissions to acute admissions units are counted in the same way as those to traditional inpatient wards, there is good evidence that their introduction can increase the proportion of patients discharged within 72 hours, thereby reducing pressures on inpatient wards. 28

The need for a systems-level approach

The above sections demonstrate that, in experimental settings, individual initiatives can be shown to affect admission rates of older people. It is clear, however, that all elements of the system are inter-related; for example, the impact of senior medical assessment in EDs cannot be fully realised unless there is access to a range of services offering alternatives to acute admission. As The King’s Fund report notes:

in the real world, interventions will rarely be implemented in isolation. A combination of interventions intended to reduce admissions may be expected to have a ‘cumulative’ effect and, although each may have little effect individually, there may be greater benefit overall than the combined effects of single interventions.

p. 176

The need to understand how interventions inter-relate and contribute to the total system of care is particularly important in providing care for older people. 50 More recently, the National Audit Office concluded that ‘The effective management of the flow of patients through the health system is at the heart of reducing unnecessary emergency admissions and managing those patients who are admitted’. 2

Such a systems approach is attentive to the interconnections and configurations between various elements, transitions of care and handover, entities and processes that contribute to the performance, sustainability and capacity of an organisation or service. It suggests that complex social and organisational processes cannot easily be explained, or indeed changed, by focusing on single interventions, but rather that it is the relationships between these that contribute to both success and failure.

Systems theory therefore provides a holistic approach to understanding complex social and organisational processes, as exemplified by present-day health-care services that involve the co-ordination of multiple agencies, care processes and organisations. It is based on four underlying ideas: first, that ‘the whole is greater than the sum of the parts’ or that when different entities and processes interact there are emergent properties, including both intended and unintended consequences; second, that systems comprise entities or components with specialised functions and processes that often evolve in isolation and can be poorly aligned; third, that specialised elements are often grouped and over time brought together into subunits or organisations; and, fourth, that the challenge for systems thinking is the appropriate alignment and co-ordination of these elements and processes. This is because the components of the system have a tendency of organising themselves based on simple external rules. This self-organisation may not be aligned to the needs of the system as a whole. A systems approach offers a middle-range perspective to understanding complex organisations and processes, such as initiatives to reduce admissions of older people.

Implementing system change

The literature offers a range of models and approaches for understanding and implementing organisational change within organisations, including the health service. 51 This often centres on modifying the goals or mission of a unit, the culture and values of staff, the structures and operations within which people work, or looking for innovation or new technology. Much of this research, however, is focused at the organisational or unit level, with little attention given to the introduction of change at the system level, as outlined above. In other words, understanding the processes of change requires attention and the energy to change within the individual units or components that constitute the system together with the interconnections between them. This also means recognising that change management strategies that work within one unit, such as hospitals, might be very different from those needed in other units, such as commissioning groups. Utilising this ‘systems perspective’ therefore requires paying greater attention to the wider institutional conditions within which care services are organised and delivered. This includes the institutional pillars, such as regulatory systems, normative conditions and cognitive-cultural influences, that have been shown to shape health-care services and hinder strategic change. 52 Analysis of strategic change includes considering several ‘receptive conditions’ for change:

-

coherence of policy

-

leaders of change

-

environmental conditions and pressures

-

organisational cultures

-

managerial–clinical relations

-

co-operative interorganisational networks

-

clarity of goals and strategy

-

fit between the change ‘agenda’ and the local conditions.

System change, by its nature, is highly related to both the structure of an organisation and also its strategy. Strategy and structure are themselves tightly connected. Implementation will therefore always require a number of essential components that we can identify as being a strategy. Of strategy, Chandler53 identified three generic parts: it is the determination of long-term goals, followed by the adoption of courses of action, and finally the allocation of resources to meet the goals. Dealing with systems and, more accurately, ‘complex systems’ is difficult. In order to understand what a system is, we need to understand some of its key characteristics:

-

the interdependence of individual elements (objects, people, tools)

-

a holistic view (insight, obtained by observing the system as a whole, that observance of small elements would not provide)

-

entropy (accept there is a level of disorder in the system)

-

regulation (the complexity of feedback and controls within systems)

-

recursion (the manner in which the larger system is composed of smaller, similar systems, embedded within it, at lower hierarchical levels and aggregation)

-

differentiation (how smaller elements fulfil specific system tasks).

In summary, for a complex system to operate in an optimum manner, all subsystems must do so as well and in co-ordination with each other. Therefore, when systems elements are not working well, the ‘whole’ is compromised.

In the case of this change project, an effective way to identify that which we want to change was required. There are a number of different approaches or model structures that can help us to understand and analyse complex organisations. Among these are Porter’s Value Chain,54 McKinsey’s 7S framework,55 Beer’s Viable System Model,56 Galbraith’s Star Model57 and Mintzberg’s conceptual description of the organisation. 58

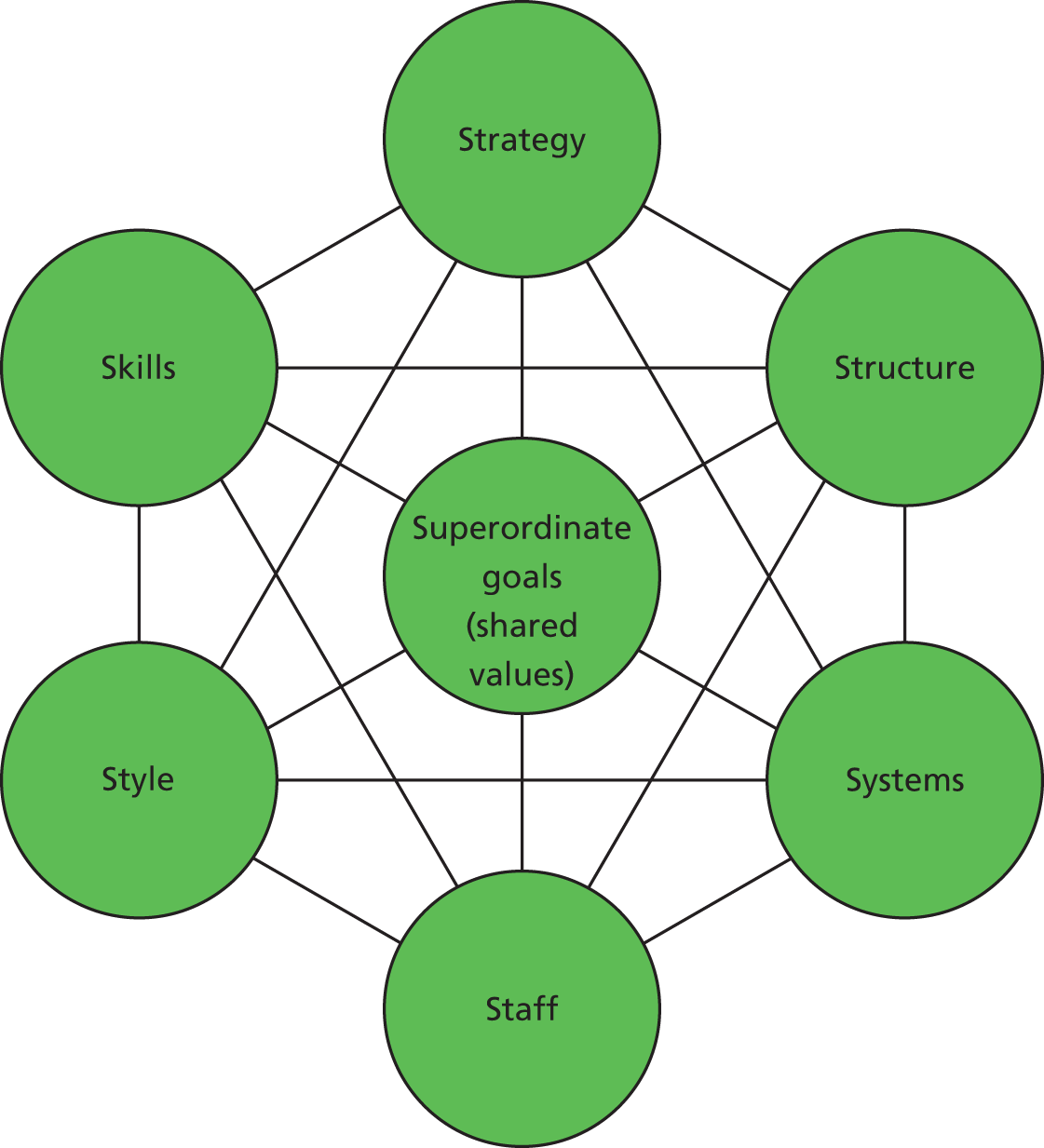

Of these models, the McKinsey 7S framework was seen as the most appropriate tool to capture and analyse the complex organisational structures we were to encounter. The 7S framework was originally designed to diagnose how the existing organisation operates and then to find ways to implement change. Moreover, the 7S framework has been proven in organisational study and design since its inception in the early 1980s. It has been widely adopted by researchers and managers in the NHS. 59 Its particular strength, relevant to this project, is in focusing on a systems-based approach, emphasising that, for change to be effective, changes in any one component must be accompanied by complementary changes in others. 51 It is often used in conjunction with PESTELI, a tool for analysing the environment in which an organisation operates (comprising Political factors, Economic influences, Sociological trends, Technological innovations, Ecological factors, Legislative requirements and Industry requirements). In this project our focus was more on the internal than the external environment, so PESTELI was not used. Although it might have contributed to contextual understanding, we considered this would be adequately covered by the 7S model.

The 7S framework segments different parts of the organisation (elements of the systems) so that they can be observed, studied, measured and understood at a meaningful level of aggregation. In addition, this tool crucially allows different organisational systems to be analysed by a common, simple yet effective framework (Figure 2).

The framework enables consideration of the key elements of the organisation/system as follows:

-

Structure: this is the way the organisation is structured, and specifically includes the reporting structure.

-

Strategy: this is the plan of activity for the system; importantly, it is also about how aligned the whole system is towards its objectives.

-

Systems: these are the processes and procedures of the system: the daily activities and routines.

-

Shared values: these are the norms and standards that guide the behaviour of the human elements within the system.

-

Style: this is essentially about the style of management used by the system leadership.

-

Staff: this element is concerned with the training, motivation and rewards of the staff.

-

Skills: this element is about the specific skills existing and required by staff in order to best execute their duties. It is also important during change management.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

Aims

To identify system characteristics associated with higher and lower increases in unplanned admission rates in those aged 85 years and over; to develop recommendations based on best practice to inform providers and commissioners; and to investigate the challenges of starting to implement these recommendations.

Research questions

-

What system characteristics (including commissioning arrangements and pathways of care) are associated with higher and lower than average changes in unplanned admission rates in those aged 85 years and over?

-

What are the antecedents, contextual and internal factors that influence these different characteristics of the management of care of those aged 85 years and over?

-

What are the lessons to be learned in terms of commissioning, system configuration and system change to reduce unplanned hospital admissions for those aged 85 years and over more widely across the NHS?

-

What are the practical challenges faced by providers and commissioners in starting to implement system change to reduce unplanned admissions in those aged 85 years and over?

Chapter 3 Methods

Overview

Our conceptual framework is the premise that emergency admissions are one outcome in a complex system which includes a range of inter-related services. Additionally, improvements will emerge not just from reconfiguration of services, but also from effective leadership and implementation. We define the system of interest as a healthy economy serving a defined population and comprising an acute hospital trust, commissioning groups, GPs, intermediate care services, care homes, ambulance service and social care. The principal method is a qualitative multiple explanatory case study. 61 This approach is designed not to be generalisable to a population but to develop and test theory. Multiple cases strengthen the results by replicating pattern matching, thus increasing confidence in the robustness of the theory. We examined three cases at each extreme of changes in admission rates, a sample large enough to develop and test theory while being small enough to be feasible. Other multiple case studies, including the national evaluation of intermediate care, to which several of this report’s authors contributed, included a similar number of sites. 62

Selection of study sites

A key consideration in multiple case study designs is the basis of case selection. This can be representative, purposive or guided by theoretical concerns, with the aim of providing a relevant basis for comparison. 63 For example, selection might include outliers or deviant cases with the express purpose of identifying and analysing factors potentially unique to the case and capable of generating novel conceptual insight. 61 For this study, the definition of case was the local health economy serving a defined population and comprising an acute hospital trust, commissioning groups, GPs, intermediate care services, care homes, ambulance service and social care. The basis of case selection was purposive and guided by prior statistical analysis; that is, cases were selected according to their distribution in relation to unplanned admission for people aged over 85 years, where case selection aimed to compare high- and low-performing cases as a means of understanding the factors (common and unique) that might account for unplanned admission.

We used PCTs as the basis of site selection, as these have a population base that can be used to derive admission rates. We chose changes in rates of admission for older people as the main criterion for selecting sites. This was chosen rather than absolute rates, as the latter are highly dependent on demographic factors such as age and deprivation. 6 By identifying and examining sites where rates had risen fastest and slowest we hoped to be able to understand how changes (or lack of changes) in systems of care influenced changes in admission rates.

A second criterion was a strong linkage between the PCT and an acute trust. This was applied because we wanted to explore areas in which there was at least a potential partnership between these organisations so that system change could occur. We defined this criterion as being achieved if more than 80% of acute admissions for people aged 85 years and over from a PCT were admitted to one acute trust. We excluded London PCTs, as their acute trusts have partnerships with several PCTs, even if the index PCT used one acute trust for a high proportion of its patients. Finally we excluded any site that was known to be experiencing significant reconfiguration as reflected in national publicity.

A third criterion in sample selection was to use a mix of urban and rural sites, and a range of deprivation. Finally, we excluded sites that were potential participants in the implementation phase of the project.

Admission rates for people aged 85 years and over were calculated for the latest 3 years for which Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data were available (provided by the Nuffield Trust). These data are based on admissions, not individuals, and also provide information about the trust to which admissions were made. Data were not available for some PCTs because of mergers, etc. For the 143 PCTs for which we did have data, a regression coefficient was calculated for the change in admission rates over the 3-year period, adjusting for population size and age. The value of the slope indicates the annual change in admission rates, with a positive slope value indicating an increased admission rate.

Primary care trusts were ranked according to this statistic. The change in rates of admission of older people ranged from + 10% per annum at the bottom of the ranking to –6% per annum at the top. Of the 143 PCTs, 120 (84%) had increased admission rates. Sites at the top and the bottom of the ranking were considered as potential participants.

Table 1 shows a selection of sites at the top of our ranking. After we applied our criteria, sites ranked 4, 5 and 9 were selected. The selection at the bottom of the ranking is shown in Table 2. After applying our criteria, we selected sites ranked 132, 133 and 135.

| PCT rank for slope | 85 years and over admission rate (number of admissions/population) | Slope (per annum change) | % admissions to linked hospital trust | % aged 85 years and over | Reference in report | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |||||

| 1 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.49 | –0.06 | 66 | 1.5 | |

| 2 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.50 | –0.03 | 52 | 1.5 | |

| 3 | 0.71 | 0.69 | 0.67 | –0.02 | 43 | 1.5 | |

| 4 | 0.55 | 0.51 | 0.51 | –0.02 | 89 | 2.6 | I1 |

| 5 | 0.61 | 0.60 | 0.57 | –0.02 | 87 | 2.6 | I3 |

| 6 | 0.66 | 0.70 | 0.63 | –0.02 | 40 | 1.0 | |

| 7 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.50 | –0.02 | 40 | 2.5 | |

| 8 | 0.57 | 0.55 | 0.55 | –0.01 | 78 | 2.3 | |

| 9 | 0.41 | 0.41 | 0.39 | –0.01 | 83 | 2.2 | I2 |

| 10 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.38 | –0.01 | 66 | 2.2 | |

| PCT rank for slope | 85 years and over admission rate (number of admissions/population) | Slope (per annum change) | % admissions to linked hospital trust | % aged 85 years and over | Reference in report | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | |||||

| 132 | 0.48 | 0.54 | 0.59 | 0.06 | 92 | 2.2 | D1 |

| 133 | 0.41 | 0.45 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 87 | 1.7 | D3 |

| 134 | 0.41 | 0.44 | 0.52 | 0.06 | 76 | 2.3 | |

| 135 | 0.49 | 0.59 | 0.61 | 0.06 | 83 | 1.8 | D2 |

| 136 | 0.51 | 0.58 | 0.64 | 0.06 | 90 | 2.1 | |

| 137 | 0.47 | 0.51 | 0.60 | 0.06 | 89 | 2.0 | |

| 138 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 0.60 | 0.07 | 75 | 1.6 | |

| 139 | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.64 | 0.07 | 83 | 1.8 | |

| 140 | 0.41 | 0.56 | 0.56 | 0.07 | 80 | 2.2 | |

| 141 | 0.56 | 0.68 | 0.71 | 0.08 | 73 | 1.4 | |

| 142 | 0.33 | 0.51 | 0.50 | 0.09 | 50 | 1.8 | |

| 143 | 0.39 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.10 | 46 | 2.1 | |

Recruitment at sites

In the selected sites, invitations to participate were sent to the chief executives of the PCT and acute trust (see Appendix 1). In all cases, there was initial agreement from both parties. We then invited participation from the organisation responsible for community health services and social services. Table 3 shows final agreement of organisations by site. At site I1 there was a change of chief executive, and the incoming one withdrew the site from the study because of competing priorities. In site D3 the contract for delivering community health and adult social care was awarded to a social enterprise organisation. We were unable to obtain the confidentiality agreement from the university that this organisation required, so it did not participate.

| Site | Acute trust | PCT | Community health | Social services |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | No (withdrew support) | Yes | Yes | No |

| I2 | Yes | Yes | Yes (Care Trust Plus for both services) | Yes (Care Trust Plus for both services) |

| I3 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| D1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| D2 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| D3 | Yes | Yes | No (community enterprise) | Yes |

Quantitative methods

Improving and deteriorating sites were compared with national data using publicly available data and enhanced HES data. Publicly available data comprised the following:

-

HES online:64 admissions by PCT and hospital provider, aged 75 years and over (data on those aged 85 years and over were not available).

-

NHS Information Centre Indicator Portal:65 emergency admission rates (aged 85 years and over), changes in age structure of population, admissions for acute and chronic ACSCs, readmissions within 28 days of discharge (aged 75 years and over), deprivation.

-

NHS Better Care, Better Value Indicators:66 standardised emergency admissions rates for 19 ACSCs, financial and volume opportunities (i.e. potential financial and bed occupancy savings) rank.

-

GP Patient Survey:67 GP access, including out-of-hours services.

The enhanced HES data set enabled us to examine admissions in those aged 85 years and over up to the year 2011/12. These were used to calculate the following: admission rates, length of stay, seasonal variations and rank of admission rates, readmissions within 28 days, deprivation, ethnicity, health and disability index, breakdown of admissions by acute and chronic ACSCs, and admission from and discharges to care homes. Data are presented descriptively; given the small number of sites in each grouping and the purposive method of selection, it was not felt appropriate to apply statistical testing.

Qualitative methods

Following agreement to participate, two rounds of data collection were conducted at each site. In preparation for these interviews a profile was prepared for each site, using the quantitative data described earlier, and this was used to stimulate discussion during the interview.

In the first round, an understanding of the system’s history and drivers was sought in interviews with high-level key informants, including commissioners and managers of health and social care with responsibility for those aged 85 years and over, and clinicians and care providers with leadership roles in primary care, ED, social care, and intermediate and secondary care services. These interviews explored known system-level issues such as commissioning, interagency working, communication and knowledge sharing, culture, power relationships, incentives, boundaries, and successes and failures in implementation. We sought to understand what changes have been instigated in an attempt to reduce admissions in the 85 years and over bracket, the extent of their adoption, their outcome and reasons for success or failure. Respondents were also asked to allow the team access to any internal documents, audits, etc.

In the second round of data collection, we examined specific components of the system, using in-depth interviews and focus groups with those involved in delivering care, to explore issues involved in translating policy directives to changes in the actual provision of care. These included clinicians in ED and acute medical units, managers of intermediate and integrated care provision and clinicians in primary care. We had planned to conduct focus groups composed of individuals with similar roles, but in practice these were logistically difficult to arrange because of potential participants’ other commitments and so took place at only some sites.

In each site we aimed to convene a focus group, including representatives of carers and service users, to capture their perspectives on the impact of initiatives to reduce admissions in those aged 85 years and over. Participants were selected who were able to present a user perspective on service changes focused on admissions in those aged 85 years and over, and were drawn from local patient and public involvement (PPI) groups in primary and secondary care and charities such as Age UK.

Development of topic guide

The topic guide for interviews and focus groups with professionals was developed using the McKinsey 7S model as a starting point. The major themes were based around:

-

Strategy

-

Structure

-

Systems

-

Style

-

Staff

-

Skills

-

Shared values.

These areas for exploration were refined based on the topic of emergency admissions of older people. The project team discussed the areas which they believed would have an impact on emergency admissions in each of the seven major themes. The topic guide was further developed based on these discussions and was piloted on members of the project group. The topic guide was designed to be used in sections, whereby questions on the strategy and organisational structure were asked of senior staff and questions on service delivery and staff skills were given to frontline staff. The final topic guide can be found in Appendix 2.

Qualitative analysis

Interviews and focus groups were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Qualitative data analysis was undertaken in a stepwise approach following completion of data collection from the six case study sites. In the preliminary phases, all data from each case site were assigned to individual members of the project team for an initial phase of inductive, open coding. The aim of this initial stage was to develop a general descriptive account of each health system, paying particular attention to the management of care for people over 85 years old, and to determine the relevance and usefulness of systematically applying the 7S framework for subsequent data analysis. The initial case descriptions were shared and discussed among the wider project team with the aim of developing a common coding framework for the 7S model. Selection bias at the individual level was therefore minimised by group discussion and conferring.

The second and main stage of data analysis involved two independent researchers developing detailed case reports for each health system. This was informed by the 7S model and the preliminary phase of data analysis. Following a framework approach,68 all data items were systematically scrutinised, with extracts of data coded and sorted according to the 7S categories. This involved the close reading of all electronic data items, coding data extracts according to the 7S categories and copying these into the appropriate column of the framework spreadsheet. Guidance for coding was agreed by team members, including how items would be categorised according to the 7S framework (e.g. it was agreed that ‘Structure’ would be used to capture information about inter-relationships of services and ‘Systems’ for items related to individual component services). Where items of data did not easily fit within the 7S headings, a new open heading was produced. Throughout this phase, and in line with the principle of constant comparison, each category was systematically checked for its internal consistency and inter-relationships. 69,70 After this initial phase, data items within each category were further reanalysed to identify sub- and grouped themes. Through this process an initial narrative was produced to describe and characterise the findings within each category. The aggregated coding framework and initial descriptions were finally brought together to produce an initial case report for each site.

These case reports were then shared with the wider research teams for clarification and conceptual development, paying particular attention to the recommendations and learning points. At this time, one member of the study team used the data from each case report to produce a summary table for each case study site. For each of the 7S categories the table aimed to present the headline positive or negative features, for example those aspects of ‘Strategy’ that contributed either positively or negatively to the management of care for people aged over 85 years. For each of the identified features the table also sought to draw out from the case reports the possible reasons, source or influences that might explain these aspects, for example how local strategy was influenced by national policies, resource limitations or leadership structures. In this way, the table also starts to identify linkages between 7S categories, such as how Strategy and Skills are linked.

The final stage of data analysis involved members of the wider study team reviewing individual case reports and looking for overarching themes and accounts that might explain similar systems, features and processes. Comparison between case study sites provided the basis of conceptual and theoretical elaboration whereby tentative explanatory models were identified, developed and discussed among the study team with the aim of explaining similarities and differences among the study sites, especially between the improving and declining sites. These tentative propositions were then tested against the empirical data with the aim of producing recommendations for service improvement, before being validated through consultation with wider stakeholders and project advisors.

Ethics and governance

The project team applied for NHS ethics approval but was advised in September 2011 that the committee did not consider the project to be research. We therefore applied to the University of Leicester Ethics Committee, which granted approval in January 2012. Approval was also sought from the Research Group of the Association of Directors of Adult Social Services which in October 2012 agreed to recommend the project to social services departments. This study was included in the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network Portfolio in August 2012, and sponsorship was agreed by University of Leicester.

Chapter 4 Results

Overview of quantitative data for improving and deteriorating sites

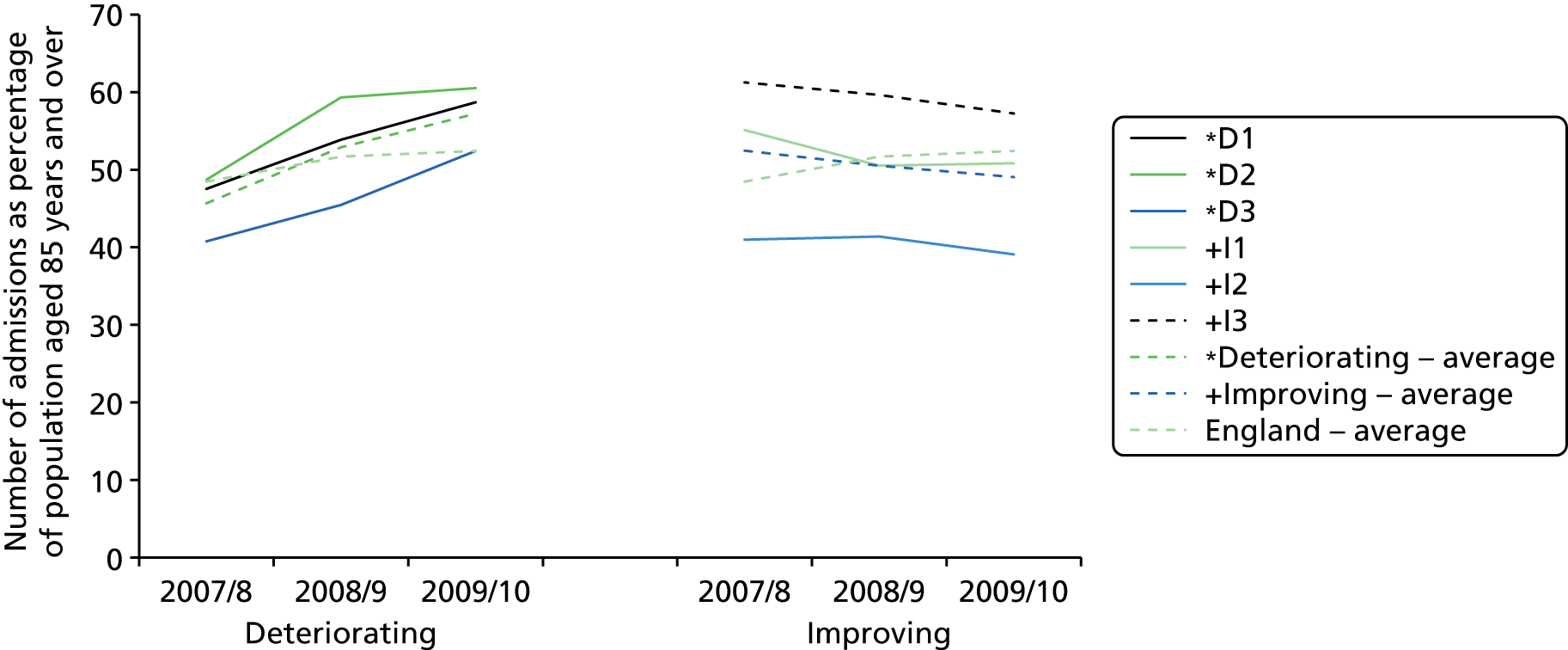

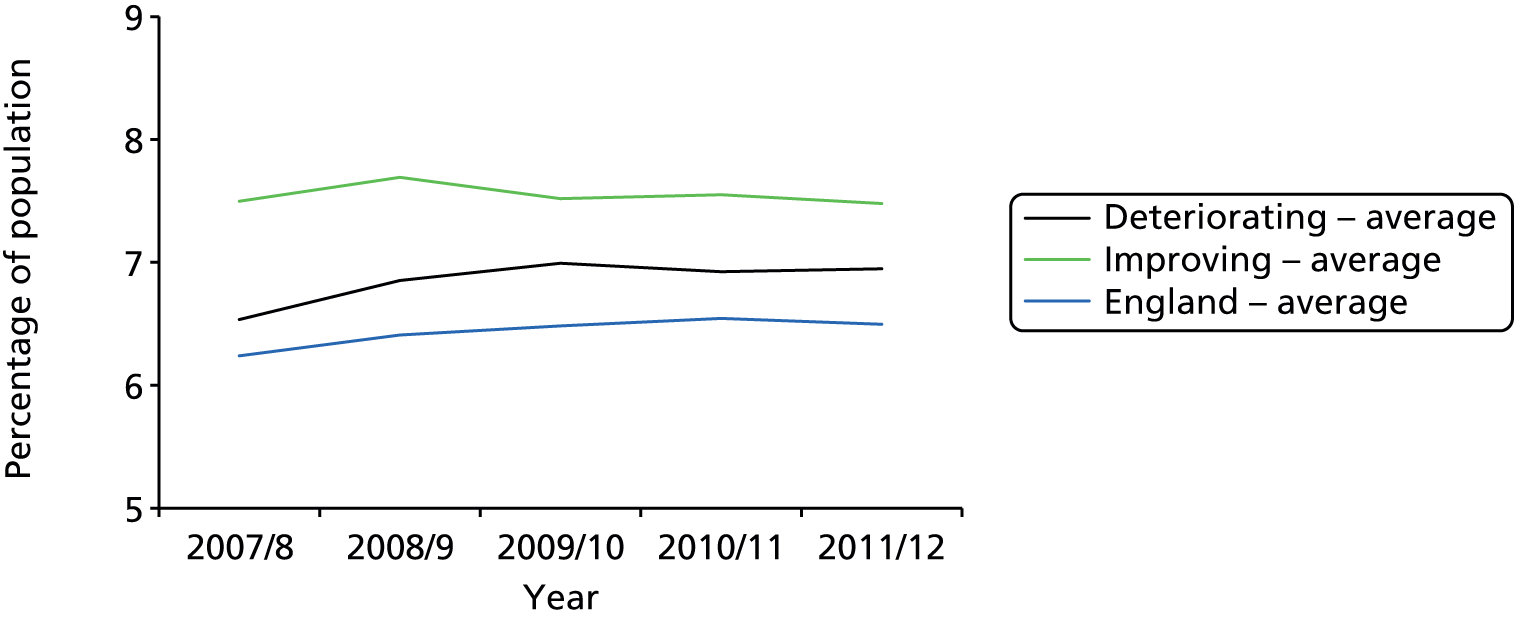

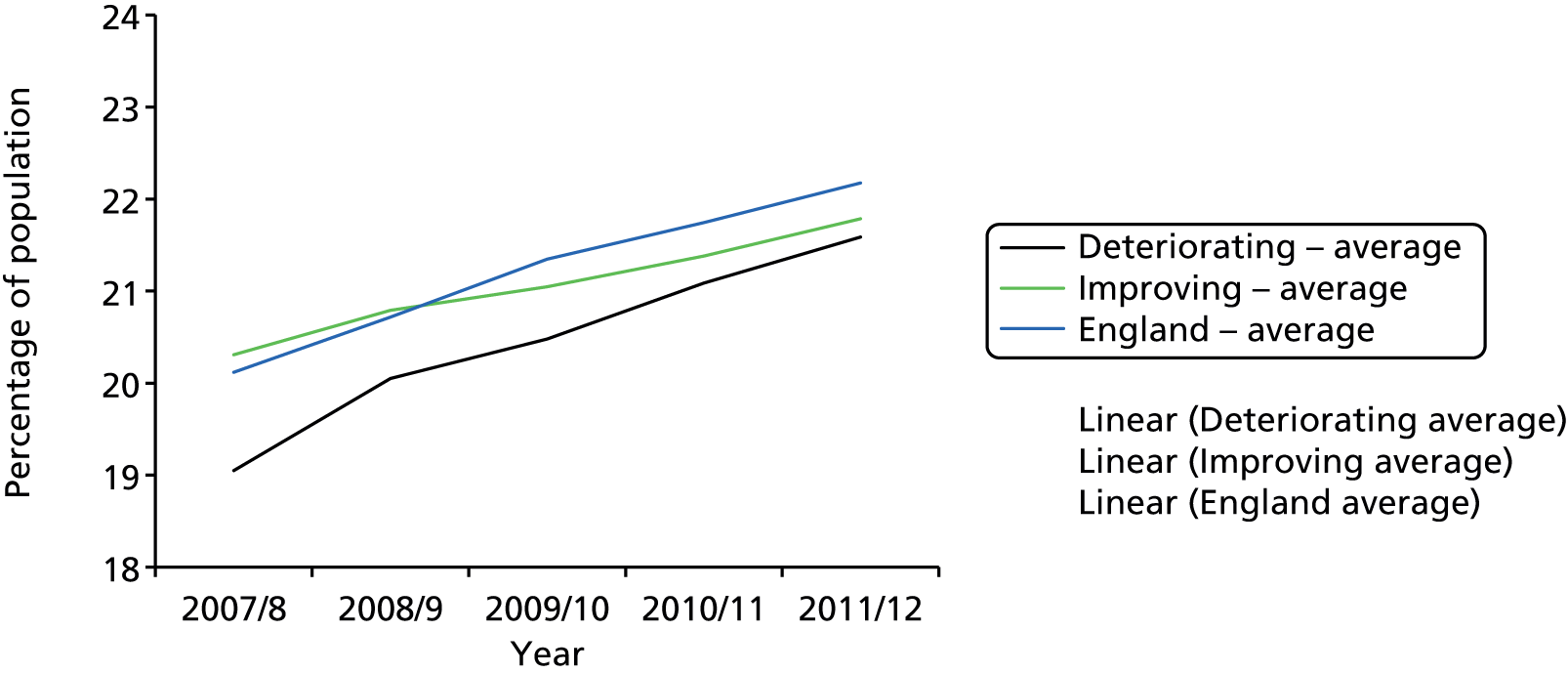

Emergency admission rates of people aged 85 years and over

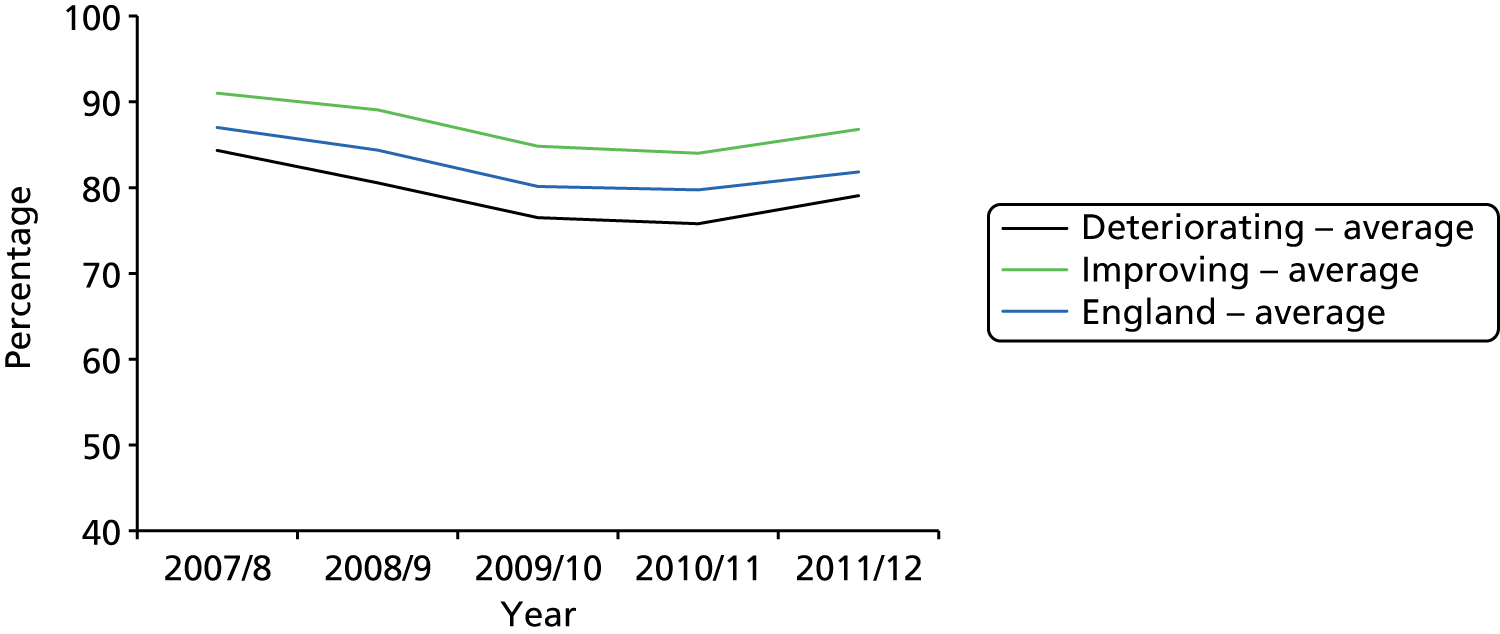

Our selection of deteriorating and improving sites was based on their admission rates, expressed as number of hospital admissions in the age group of 85 years and over divided by the population of 85 years and over for each PCT, between 2007/8 and 2009/10. On average, the deteriorating sites experienced a rise in admission rates by about 5.5% annually during the period 2007/8–2009/10, higher than the average for England of 2% (Figure 3). In contrast, the improving sites experienced a fall in admission rates by 1% annually for the same period. At the start of the period, the deteriorating sites had, on average, rates below the English average, but at the end of the period these were higher than average. In contrast, improving sites started above the English average but were below at the end of the period. There was greater variation in absolute rates in improving sites than in deteriorating sites. As no sampling was used, error bars are not included.

FIGURE 3.

Eighty-five years and over admission rates for the period 2007/8–9/10 for study sites. Adapted from Ian Blunt, Nuffield Trust, 2011, personal communication.

Data for later years show that in improving sites admission rates remained stable, whereas there was a small reduction in rates in deteriorating sites (Figure 4). Between using HES data for selection and this analysis, some corrections had been made to 2007/8 data, meaning the overall trends in reduced rates for improving sites were less pronounced.

FIGURE 4.

Eighty-five years and over admission rates for the period 2007/8–11/12 for study sites. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

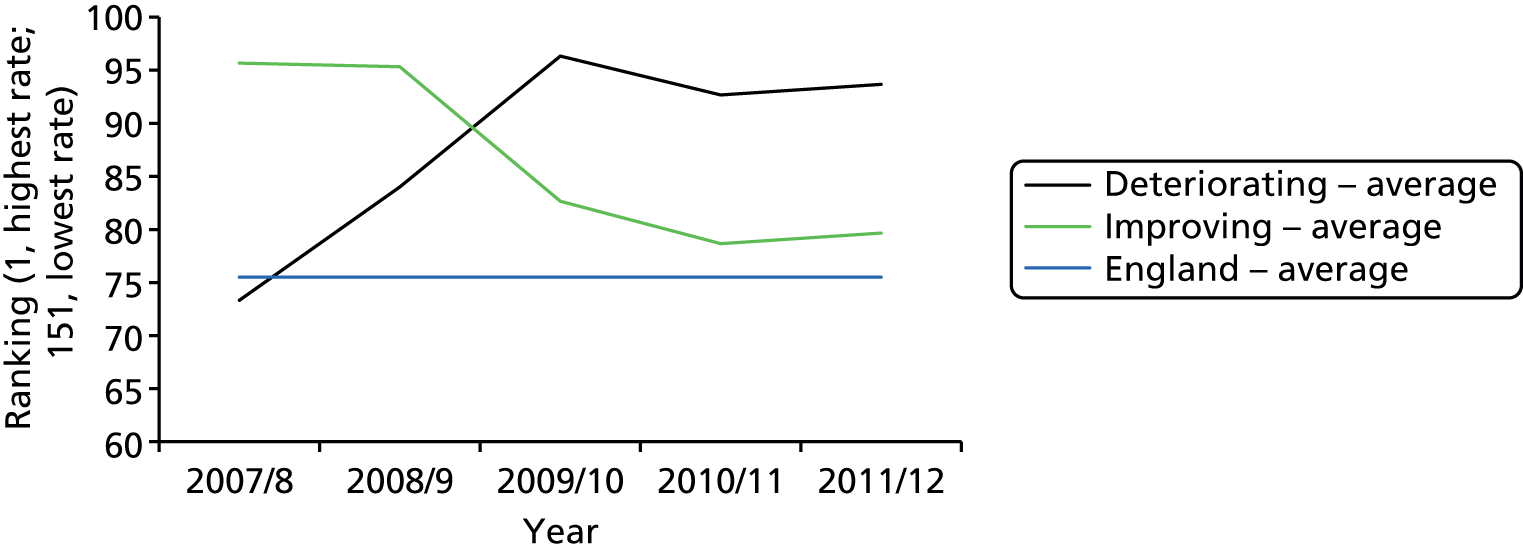

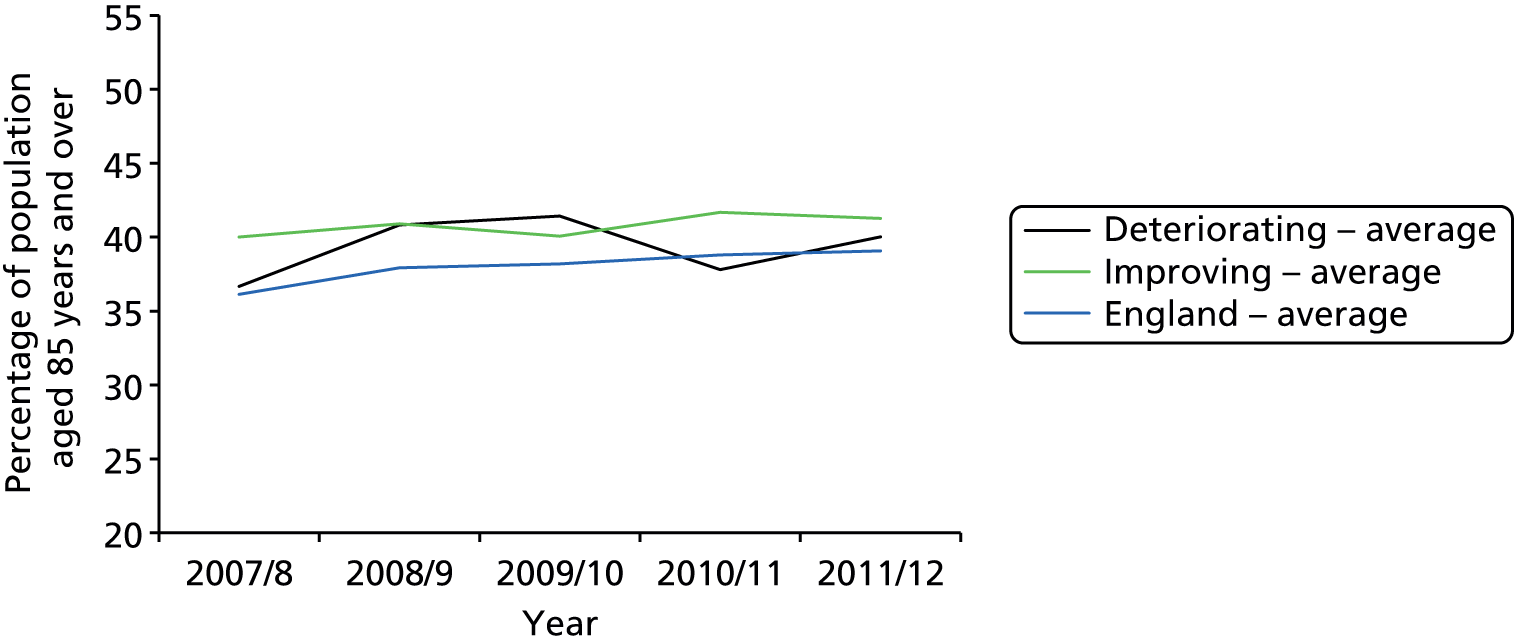

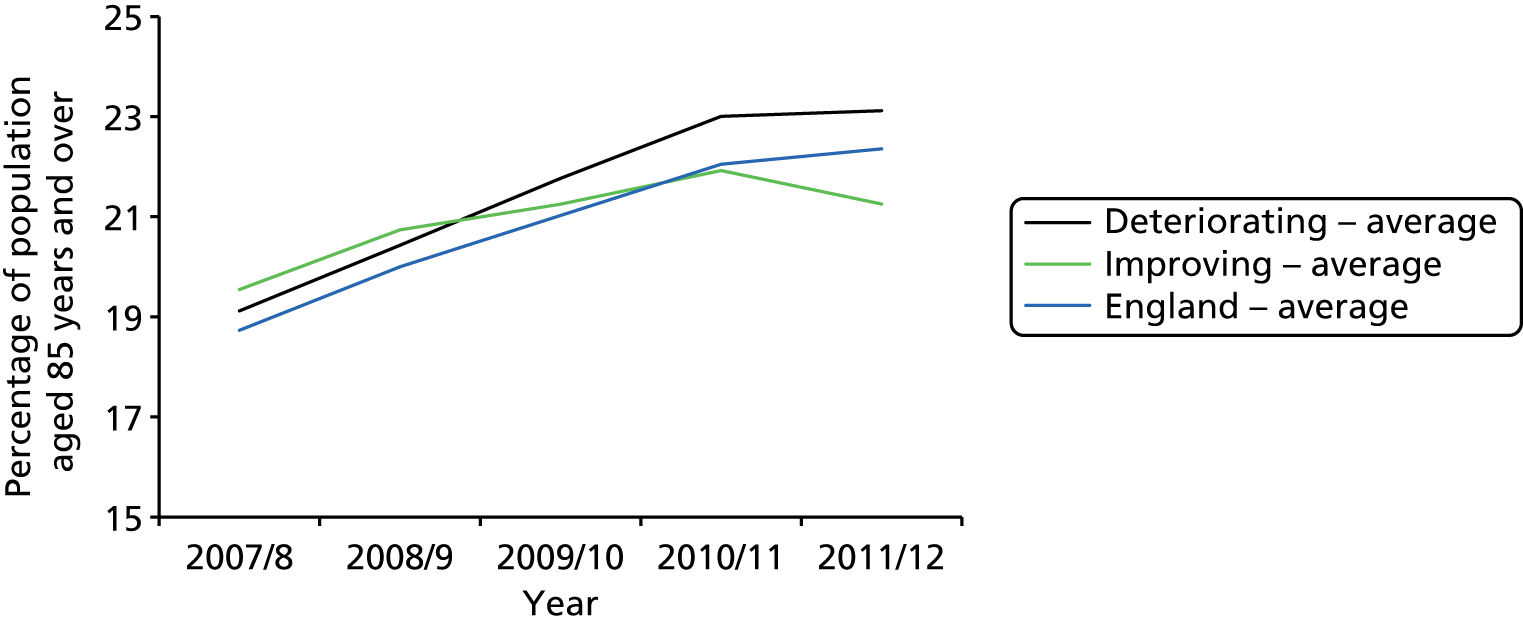

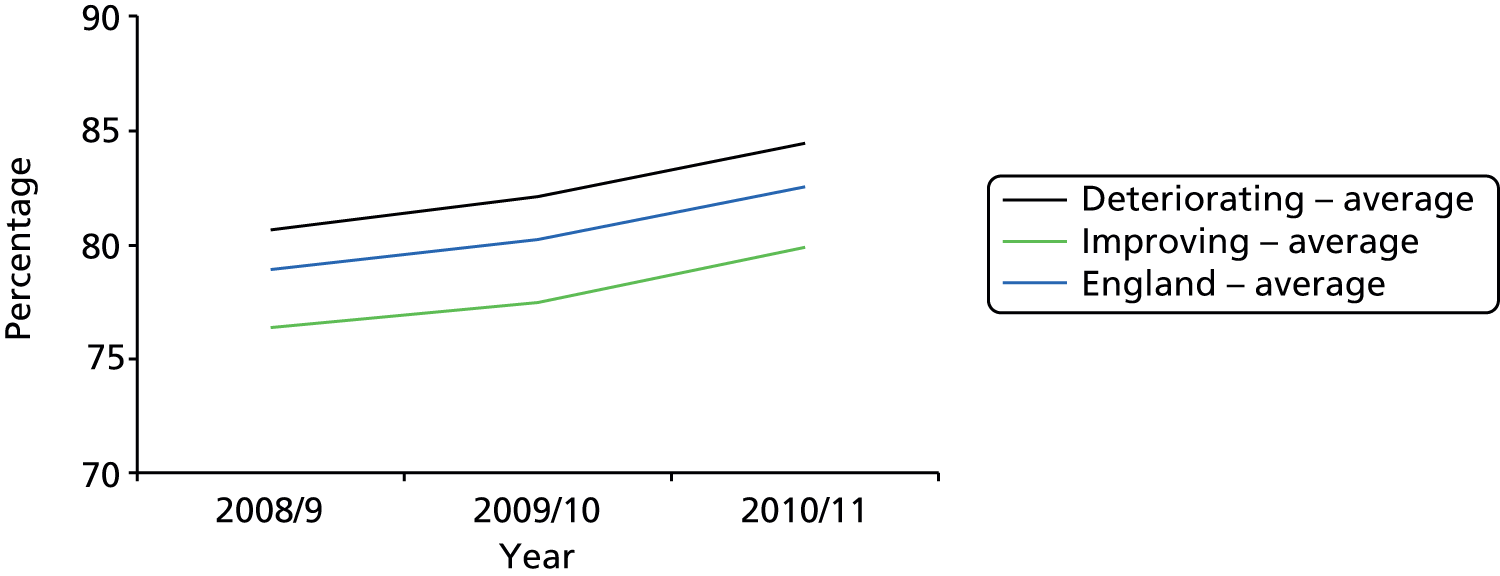

Differences in performance between improving and deteriorating sites were also explored by calculating their ranking in total admission rates compared with all 151 PCTs (Figure 5). In the first 3 years, the improving sites climbed the rankings and deteriorating sites fell back. Over the subsequent 2 years, the performance of both groups was stable.

FIGURE 5.

Rank fluctuations in total admission rates. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

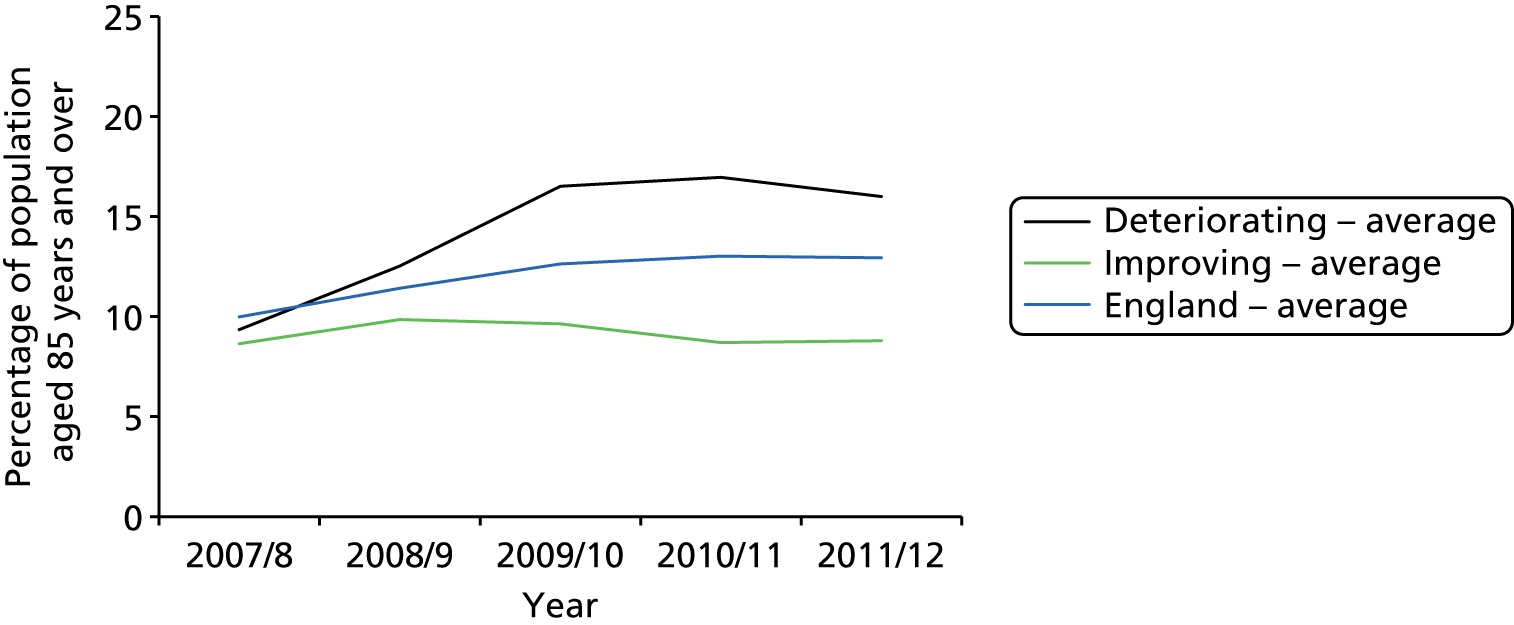

We examined demographic changes as a possible explanation for differences between improving and deteriorating sites. During the period 2007–10 the population of 85 years and over residents in the deteriorating sites rose by 3.4%, which is above the England average of 2.8% for all 151 PCTs, while the population in the improving sites rose by only 1.3%. This pressure on services for older people may have increased more in deteriorating than improving sites.

Admission rates for ambulatory care sensitive conditions

As discussed in Chapter 1, the rising tide of admission for ACSCs is largely due to acute conditions, with an average annual increase of 2.7% from 2002/3 to 2009/10. Rates for chronic ACSCs remained fairly stable during this period. Acute conditions included in this group are H660–H664, suppurative otitis; I500, heart failure; J02–J06, acute upper respiratory infections; N159, renal tubulointerstitial disease; N300, acute cystitis; N39, urinary tract infection; I11, hypertensive heart disease; and J31, rhinitis, nasopharyngitis and pharyngitis. Chronic conditions included are J45–J46, asthma; and E10–E14, diabetes. 71

We examined admissions for ACSCs in study sites using the NHS information portal. The latest year for which data were available was 2009/10, and no data were available specifically for those aged 85 years and over. Emergency admissions for acute ACSCs exhibited a similar pattern to the overall admission rates for the age group of 85 years and over, which suggests that acute ACSCs may be a significant factor in explaining differences between improving and deteriorating sites. More specifically, the numbers of admissions in the deteriorating sites rose, while the numbers of admissions in the improving sites fell (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Emergency hospital admissions: acute conditions usually managed in primary care. Indirectly age- and sex-standardised rate per 100,000, all ages. Adapted from https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/. 65

Admissions for chronic ACSCs in the study sites were fairly stable during the period examined (Figure 7), although some variation is probably due to the low numbers of this type of admission (between 200 and 250 per 100,000 people).

FIGURE 7.

Emergency hospital admissions: chronic conditions usually managed in primary care. Indirectly age- and sex-standardised rate per 100,000, all ages. Adapted from https://indicators.ic.nhs.uk/. 65

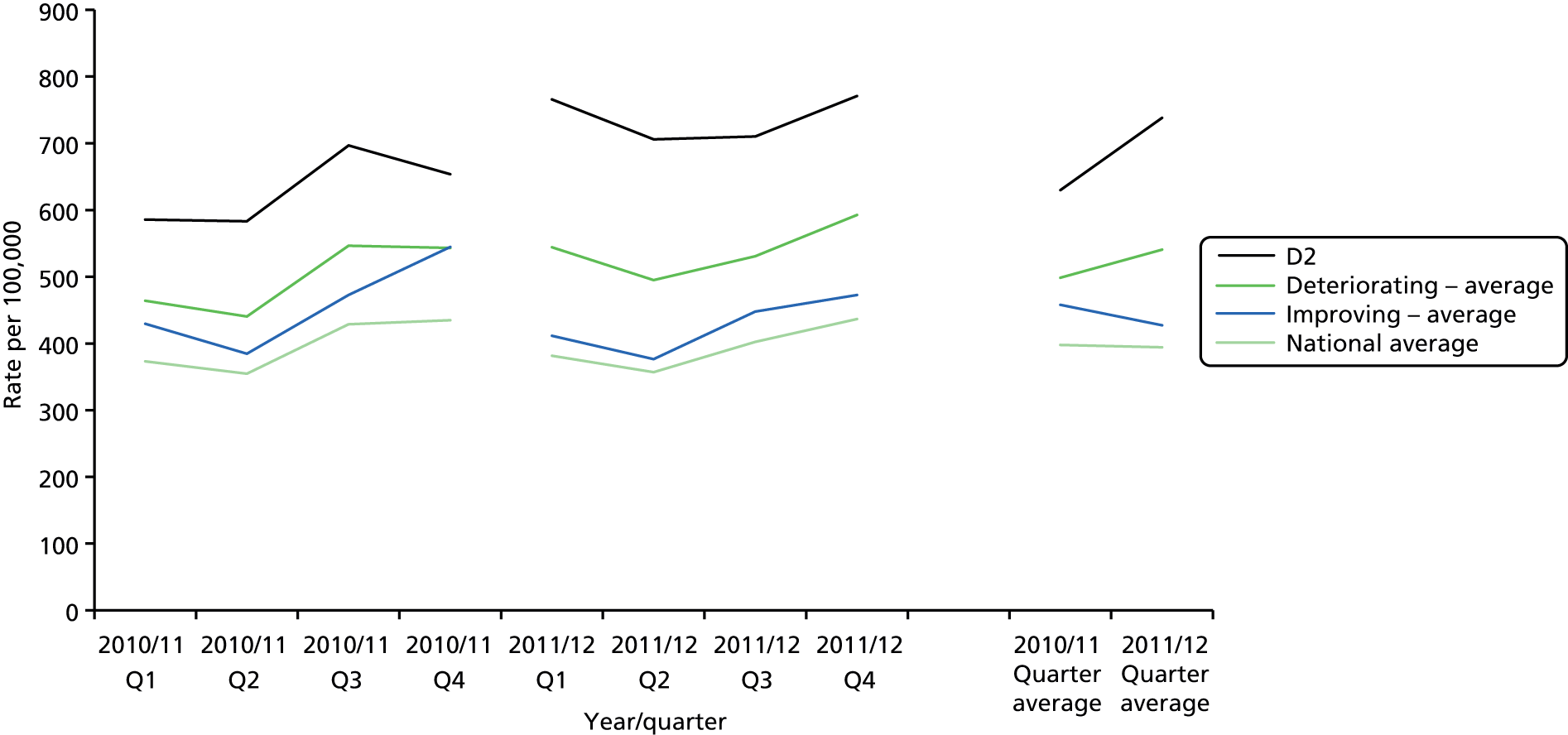

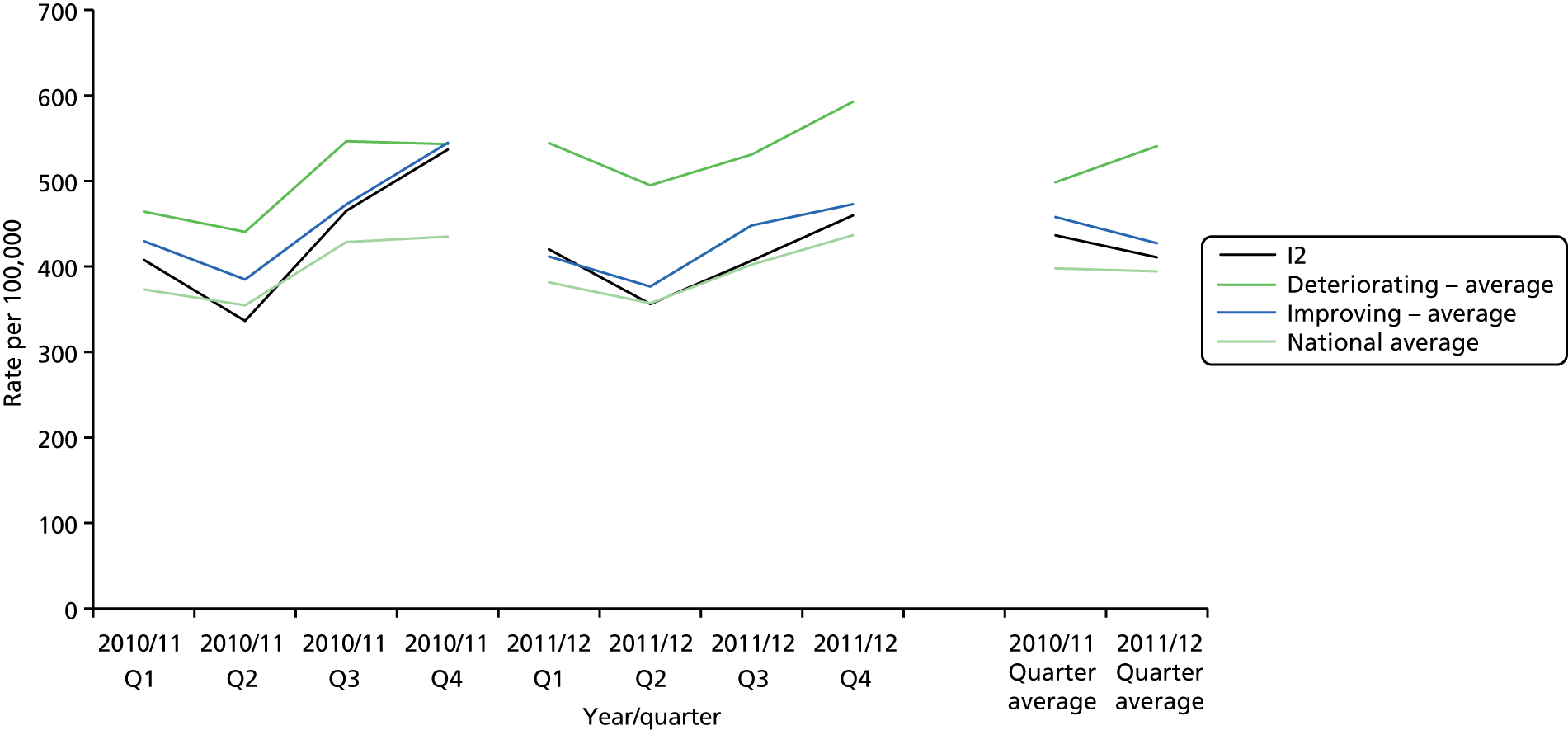

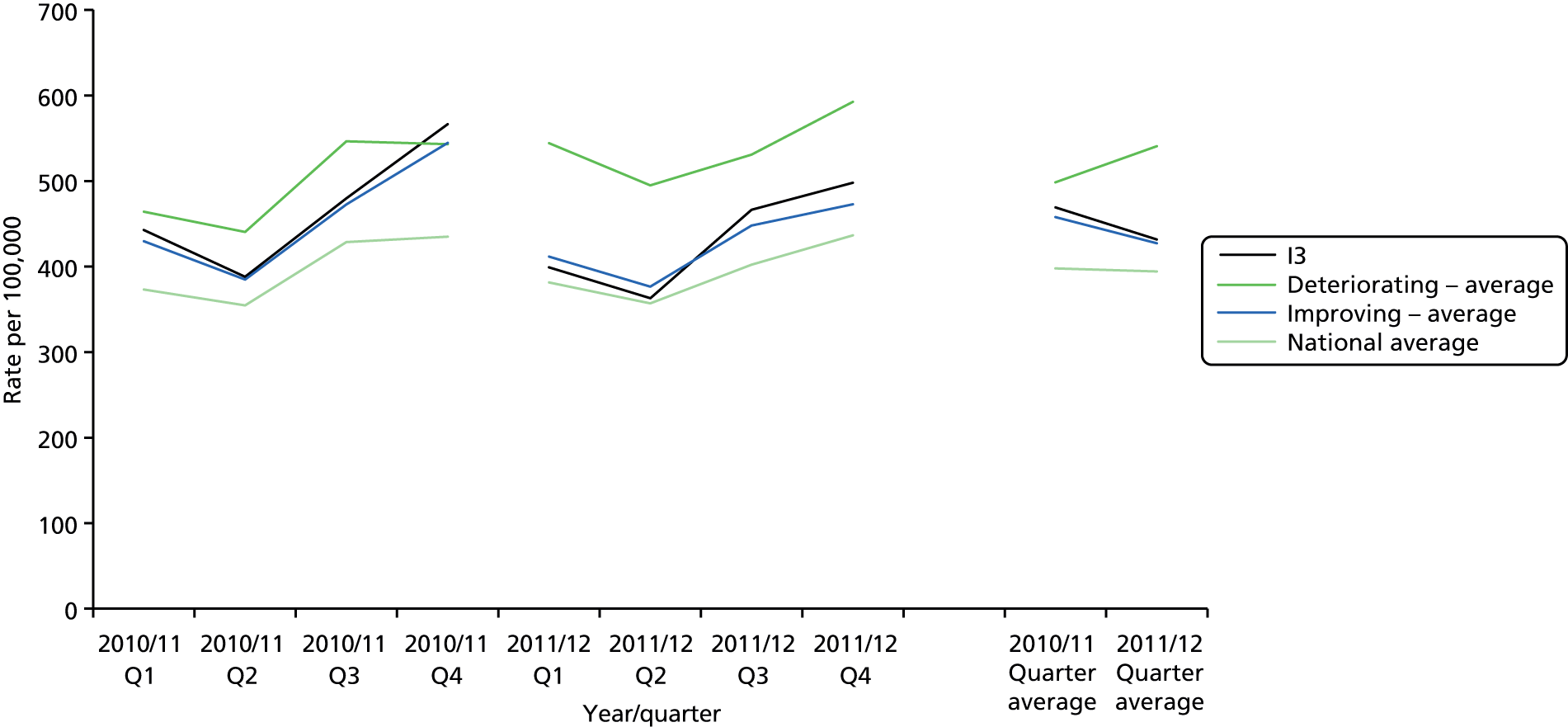

Further information on ACSCs was obtained from the NHS Better Care, Better Value Indicators website. 66 It provides information on the emergency admissions for 19 ACSCs aggregated for patients from all ages. When accessed, this data set included admissions in 2010/11 and 2011/12 for the following conditions, standardised for age, sex and social deprivation: COPD, angina (without major procedure), ear, nose and throat infections, convulsions and epilepsy, congestive heart failure, asthma, flu and pneumonia (> 2 months old), dehydration and gastroenteritis, cellulitis (without major procedure), diabetes with complications, pyelonephritis, iron-deficiency anaemia, perforated/bleeding ulcer, dental conditions, hypertension, gangrene, pelvic inflammatory disease, vaccine-preventable conditions and nutritional deficiencies.

These data show that the changes in standardised average quarterly ACSC admission rate (per 100,000) between 2010/11 and 2011/12 were from 498 to 541 in deteriorating sites and from 458 to 427 in improving sites. Expressed as rankings of 151 PCTs, deteriorating sites moved from 90th to 96th, and improving sites from 87th to 85th.

This indicator also shows the financial opportunity per quarter of reducing the rate of emergency admissions per population head to those of the PCT at the 10th percentile. The estimate for national savings in quarter 4 of 2011/12 was £323M. From 2010/11 to 2011/12, this changed from £1.51M to £1.65M in deteriorating sites and from £1.30M to £1.38M in improving sites.

Length of stay

We examined whether or not differences in admission rates could be explained by differences in the length of stay of patients with acute admissions. Emergency admissions (all ages and 85 years and over) were divided into two categories: zero-day admissions (i.e. discharge on the same date as the admission) and multiday admissions (i.e. those discharged on a later date). For the latter category, average length of stay was calculated by dividing the sum of the bed-days by the number of admissions. Rates for zero-day admissions were calculated as a proportion of the population and as a proportion of the total number of admissions.

Multiday admissions

Across England and in both improving and deteriorating sites, there was a steady decrease in the length of stay (Figure 8). The average length of stay fell from 6.5 days in 2007/8 to 5.2 days in 2011/12, with no differences between types of site.

FIGURE 8.

Multiday admissions: average length of stay 2007/8–11/12, all ages. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

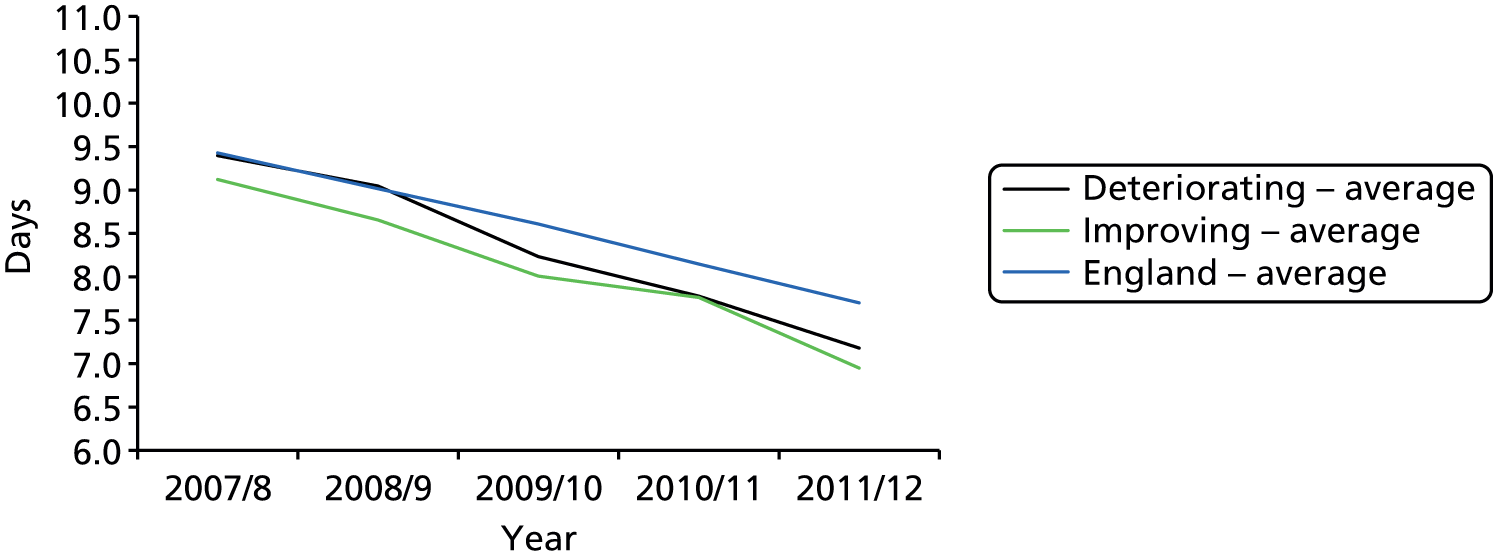

For those aged 85 years and over, stays were longer, but showed the same trend in reduction, from 9.3 days on average in 2007/8 to 7.2 days in 2011/12 (Figure 9). In the final year, both types of site had lengths of stay below the English average.

FIGURE 9.

Multiday admissions: average length of stay 2007/8–11/12, 85 years and over age group. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

Zero-day admissions

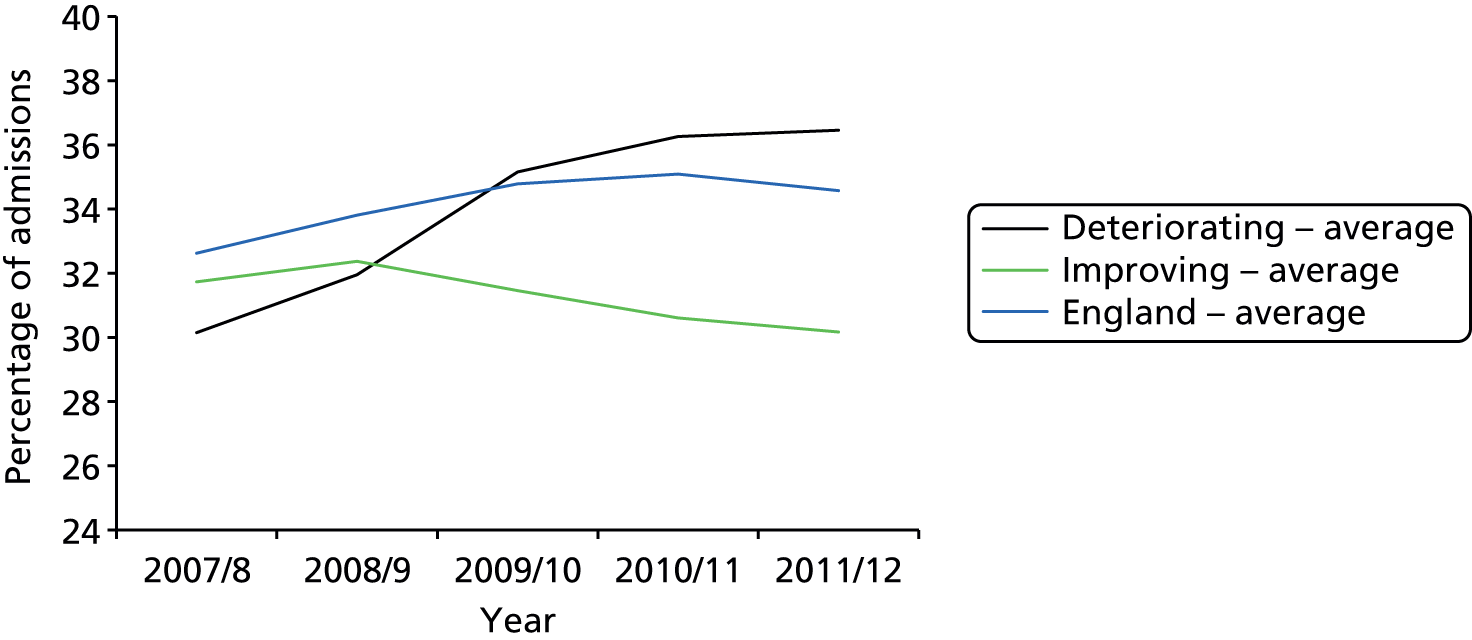

Across England, same-day admissions constitute about one-third (28% to 30%) of all admissions. Their share was slightly rising from 2007/8 to 2010/11, when it seemed to peak (Figure 10). The two groups of sites differed markedly in trends for the proportion of 1-day admissions. The improving sites started out close to the England average in 2007/8 but the share declined until 2010/11. In contrast, the deteriorating sites started out well below the England average but increased the share of one-day admissions to that level by 2010/11. During the last year (2011/12) trends remained stable.

FIGURE 10.

Zero-day admission rate as a percentage of admissions, 2007/8–11/12, all ages. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

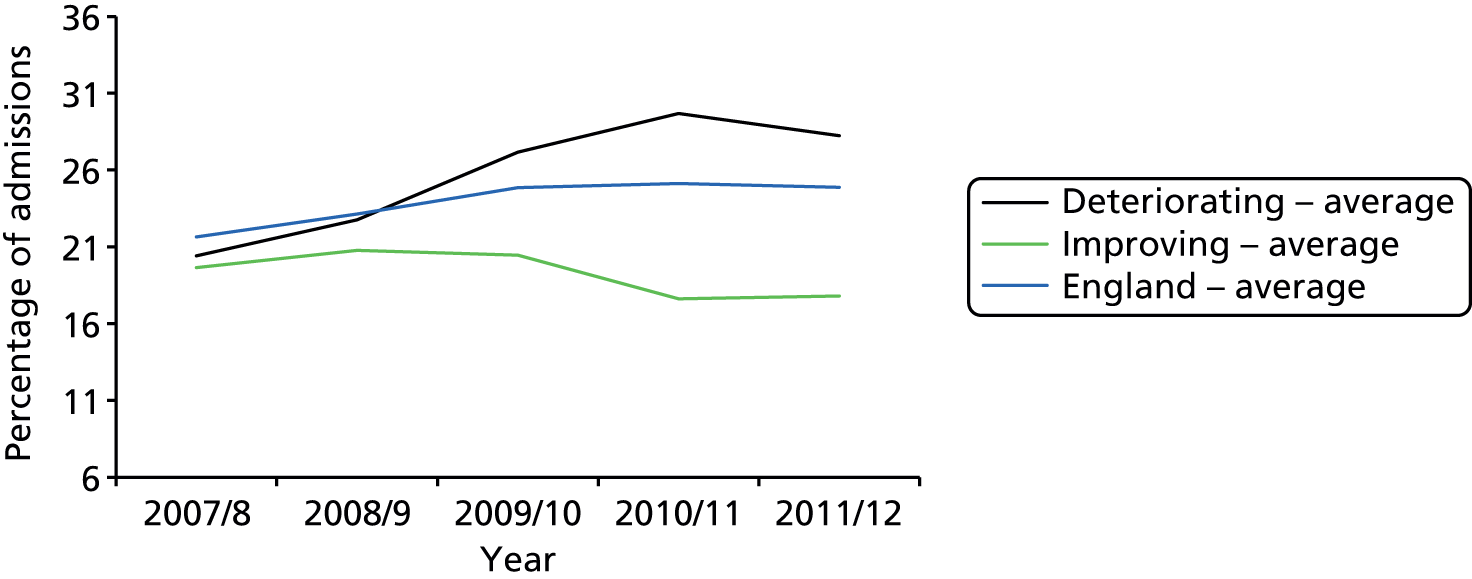

The zero-day admissions rate as a percentage of all admissions for the group aged 85 years and over followed the same trends as the rates for the whole population, with the exception that both the improving and deteriorating sites started out near the England average but then diverged (Figure 11). In 2010/11 the percentage of zero-day admissions in this age group was 30% in deteriorating sites, compared with 18% in improving sites.

FIGURE 11.

Zero-day admission rate as a percentage of admissions, 2007/8–11/12, 85 years and over age group. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

Rates of zero-day and multiday admissions were also examined for all age groups and those aged 85 years and over (Figures 12–15). In the latter group it can be seen that rates of zero-day admissions started close to the English average, but increased to 4.1% in deteriorating sites and fell to 3.0% in improving sites. Conversely, multiday admissions in those aged 85 years and over were stable in both types of site, and close to the national average. This trend was noted also by Blunt et al. ,3 who suggest that it is complex in nature, probably because of the interplay of several factors, and does not offer a causal explanation of the trend of increasing overall admission rates on its own.

FIGURE 12.

Zero-day admissions rate as a percentage of population, all ages. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

FIGURE 13.

Zero-day admissions rate as a percentage of population, 85 years and over age group. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

FIGURE 14.

Multiday admissions rate as a percentage of population, all ages. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

FIGURE 15.

Multiday admissions rate as a percentage of population, 85 years and over age group. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

Emergency readmissions within 28 days of discharge

The numbers of emergency readmissions within 28 days of a previous admission were calculated by populating an additional field in the HES database table with the date difference in days from the discharge date to the admission date. This was done regardless of the type of index admission, and so included planned admissions. This yielded the number of emergency admissions following an earlier discharge within 28 days. The number of readmissions for the first year was adjusted by half of 28/365 (= 0.038356) to account for lack of data on admissions in the preceding 28 days.

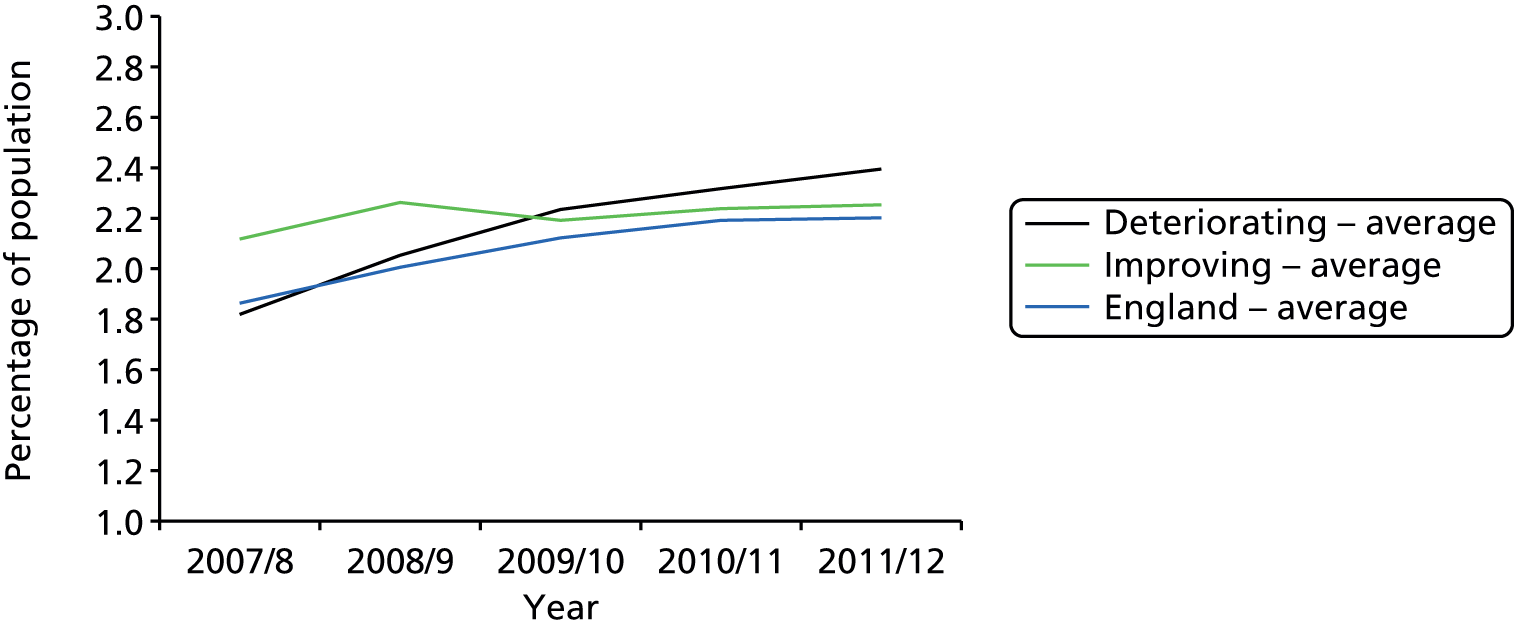

Emergency readmission rates as a percentage of the population

All ages

Across England, readmission rates increased from 2.0% to 2.2% of the total population between 2007/8 and 2011/12. Deteriorating sites started at close to this average, but showed a larger increase. In contrast, improving sites started above average but finished below (Figure 16).

FIGURE 16.

Emergency 28-day readmissions rate as a percentage of population, 2007/8–11/12, all ages. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

Age group 85 years and over

Readmission rates in this age group were higher but showed similar time trends. Both improving and deteriorating sites started close to the English average, but at the end of the period rates were 12.3% in the deteriorating group compared with 10.4 in the improving group (Figure 17).

FIGURE 17.

Emergency 28-day readmissions rate as a percentage of population, 2007/8–11/12, 85 years and over age group. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

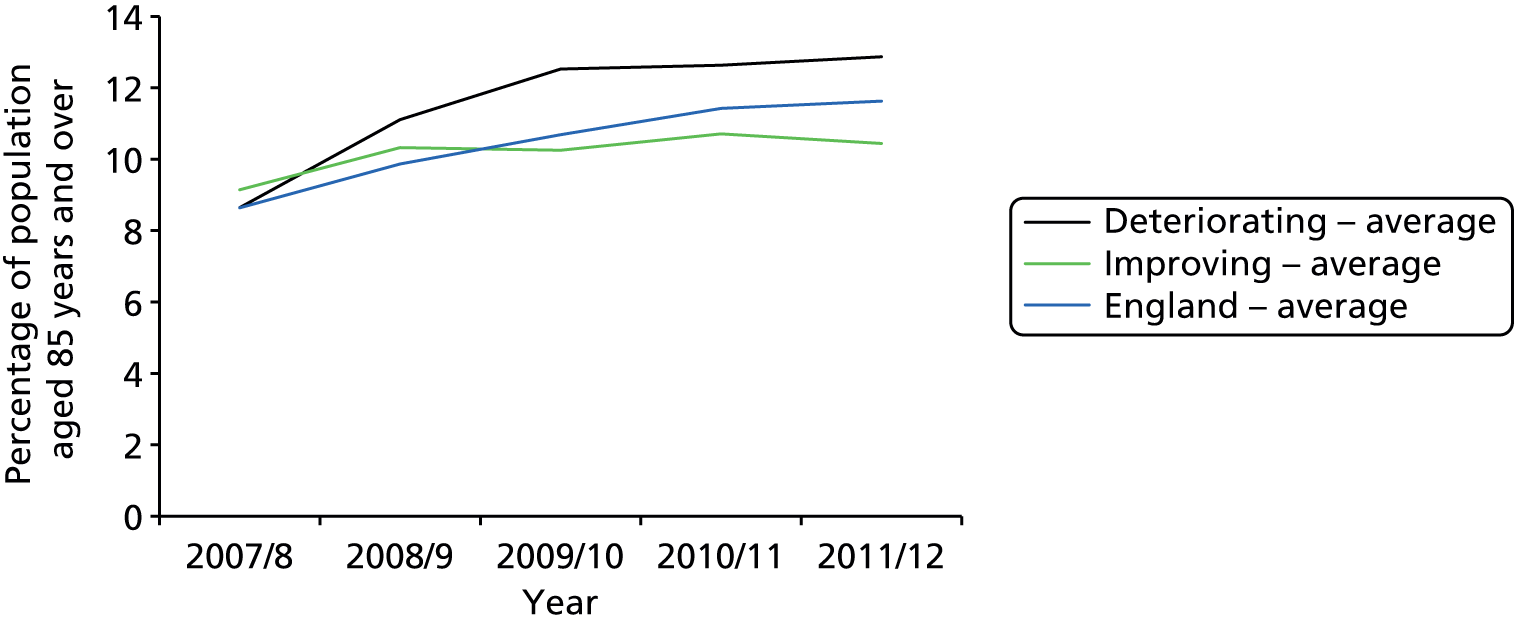

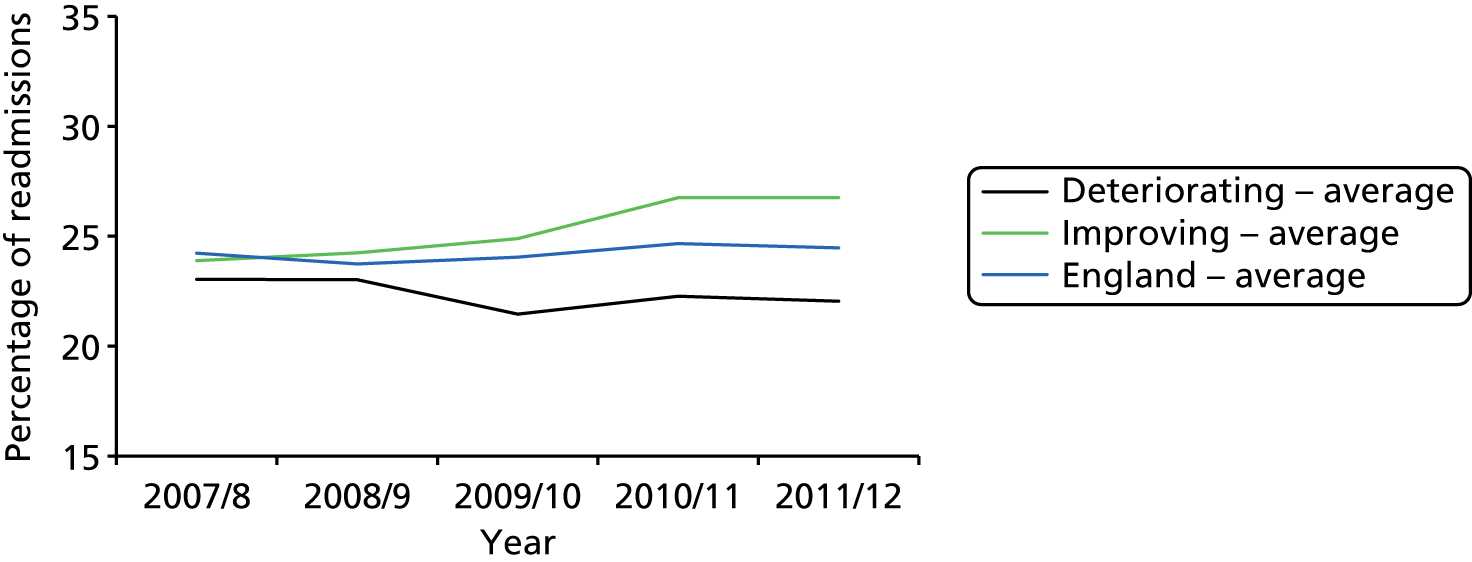

Emergency readmission rates as a percentage of admissions

Since admission rates and the readmission rates show similar trends, the ratio between them should be close to constant. This is what we observe in both graphs: for all ages (Figure 18) and for the age group 85 years and over (Figure 19). There is a slight trend of increase in the ratio, with the slope of the trendline for all ages in the deteriorating sites (= 0.61%) being higher than the slope of the trendline for the improving sites (= 0.35%) and closer to the England average (= 0.51%), which suggests that readmission rates are rising more than admission rates in the deteriorating sites. In 2011/12, for those aged 85 years and over, emergency readmissions comprised 23% of admissions, compared with 21% in improving sites.

FIGURE 18.

Emergency readmissions rate as a percentage of admissions, 2007/8–11/12, all ages. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

FIGURE 19.

Emergency readmissions rate as a percentage of admissions, 2007/8–11/12, 85 years and over age group. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

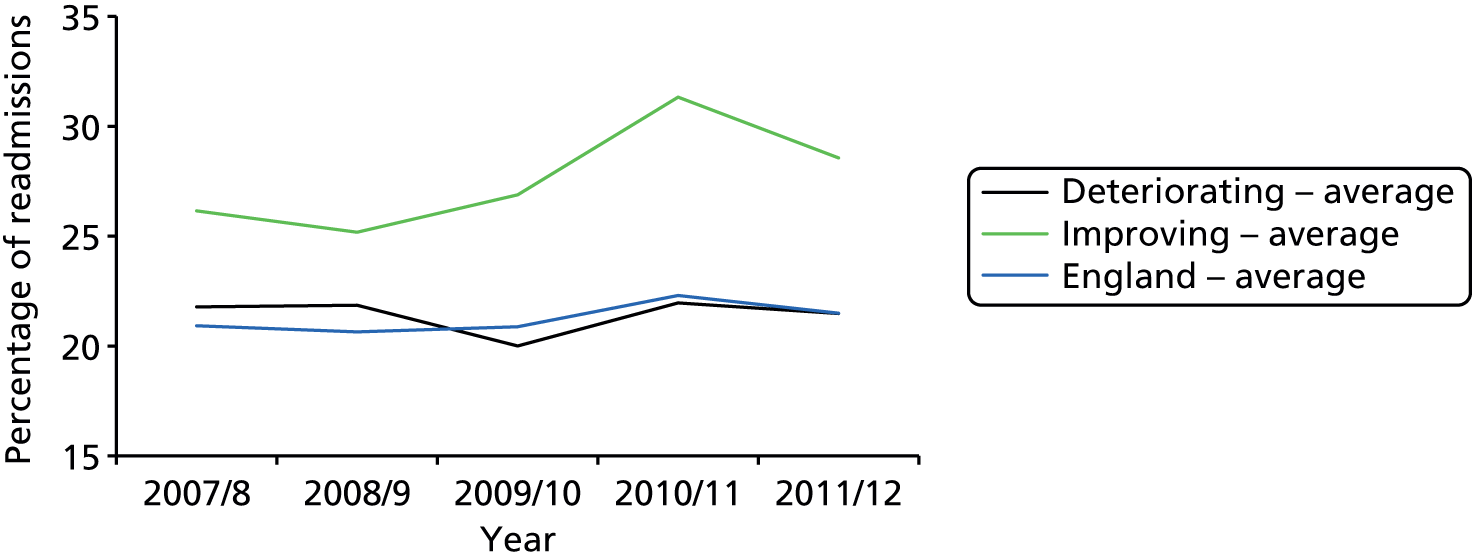

Emergency readmission rates following zero-day admissions

Emergency readmission rates following zero-day admissions were higher in improving sites, and this was more pronounced in those aged 85 years and over. There was an inverse relationship between zero-day admission rates and readmission rates following this type of admission. In the deteriorating sites, 1-day admission rates for all age groups rose from about 3% to about 4%, while the associated readmission rates fell from 23% to 22%. Conversely, the 1-day admission rates for all age groups in the improving sites fell slightly, from 3.2% to 3.0% of the population, while the associated readmission rates rose from 24% to 27% (Figure 20). This suggests that the absolute numbers of readmissions tend to remain stable, and the rates are affected mainly by the rising and falling admission numbers. It might also suggest that, in improving sites, people admitted for zero days are more ill and so more likely to be readmitted.

FIGURE 20.

Emergency readmissions rate following zero-day admissions, 2007/8–11/12, all ages. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

The pattern for the age group of 85 years and over (Figure 21) resembles the one for all ages. Deteriorating sites are very close to the English average, whereas readmission rates for improving sites are much higher.

FIGURE 21.

Emergency readmissions rate following zero-day admissions, 2007/8–11/12, 85 years and over age group. Adapted from HES data set (Dean White, Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2012, personal communication).

Admission to and from care homes

We aimed to examine differences in admissions from care homes, as the literature suggests initiatives based in these settings may be effective in reducing unplanned admissions. Unfortunately it was clear from examining HES data that, as shown in Table 4, these fields had not been reliably completed, so no conclusions are possible. Similarly, there were no reliable data for discharges to care homes.

| Site | 2007/8 | 2008/9 | 2009/10 | 2010/11 | 2011/12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 91 | 54 | 17 | 13 | 6 |

| D2 | 57 | 59 | 21 | 32 | 24 |

| D3 | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 | 8 |

| Deteriorating average | 50 | 38 | 13 | 15 | 13 |

| I1 | 9 | 5 | 5 | < 5 | < 5 |

| I2 | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 | < 5 |

| I3 | 367 | 370 | 377 | 143 | 28 |

| Improving average | 126 | 125 | 128 | 49 | 10 |

General practitioner survey

Primary care trust-level results from the GP survey72 were examined for study sites. This survey is conducted regularly by Ipsos MORI. In 2014, 2.63 million patients were sent a questionnaire, which they could complete by post, by telephone or online. As in previous years, a response rate of around 34% was achieved and from 2009/10 onwards the results are adjusted for age, ethnicity, deprivation, etc.

Two questions about access which were included in 2008/9–2010/11 are shown in Figures 22 and 23. Similar questions were asked in 2007/8 and 2011/12, and these data are combined with the other 3 years. In all years, access scores were higher in improving than deteriorating sites, falling below and above the English average respectively. In all groups of sites, ease of access declined between 2007 and 2009 and then levelled off, and differences between improving and deteriorating sites persisted. Similar results were found in response to a question about ability to obtain an appointment (data are available only for 2008/9–2010/11).

FIGURE 22.

Able to see a doctor fairly quickly (question 7), percentage ‘yes’ answer. In 2007/8 and 2011/12 the question was defined differently. Adapted from GP Patient Survey. 72

FIGURE 23.

Reasons for not being able to be seen fairly quickly (question 8), percentage ‘there weren’t any appointments’ answer. Adapted from GP Patient Survey. 72

The 2010/11 survey included a question about ease of contacting out-of-hours GP services by telephone. In deteriorating sites 23% reported it was ‘not very easy or not at all easy’, compared with 16% in improving sites.

Summary of quantitative findings

This analysis has revealed several factors that might explain differences in performance between improving and deteriorating sites, despite differences in admission rates for the 85 years and over being attenuated in the years after the period used to identify sites. The most important differences are the much lower proportion of zero-day admissions in improving sites, and lower overall readmission rates, suggesting that improving sites have been able to provide alternatives for these patients. The finding that readmission rates following 1-day admissions are higher in improving sites supports the suggestion that in these places admissions include a higher proportion of severely ill patients. Another reason for differences in performance is changes in admission rates for acute ACSCs, which rose sharply in deteriorating sites and declined in improving sites. This could reflect lower provision of community and GP services in these locations, as supported by evidence from the GP survey that access to GP services, including out-of-hours services, was poorer. Furthermore, problems with GP access are associated with increased use of EDs, which could itself increase admission rates, particularly for admissions for less than 1 day. The suggestion that both primary and secondary care services are under more strain in deteriorating sites is also supported by our finding that the oldest old population increased more rapidly in these locations.

Participants in qualitative interviews

We were able to gain participation from all key organisations in four of the six study sites. As outlined in Chapter 3, in site I1 the acute trust withdrew following a change of chief executive and the social services department declined to participate. In site D3, we were not able to secure an agreement with the social enterprise organisation with responsibility for community services. As shown in Table 5, we interviewed over 140 individuals in total, including some focus groups, with the number of participants at each site ranging from 15 to 43. Table 6 shows the background of those we interviewed. Across the sites we were able to capture the views of a range of professionals, including senior managers involved in commissioning and delivery, operational staff and clinicians from medicine, nursing and rehabilitation.

| Site | Acute trust | PCT/Clinical Commissioning Group | Community services | Social services | PPI | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Declined | 2 | 13: 7 individual, 2 focus groups (n = 2 and 4) | Declined | 0 | 15 |

| I2 | 6 | 6 | 16: 7 individual, 2 focus groups (n = 9)a | Focus group (n = 5) | 33 | |

| I3 | 5 | 3 | 24: 4 individual, 3 focus groups (n = 6, 6 and 8) | 2 | Focus group (n = 9) | 43 |

| D1 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 2 | Focus group (n = 5) | 20 |

| D2 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 4 | Focus group (n = 5) | 24 |

| D3 | 2 | 3 | Declined | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Total | 30 | 20 | 58 | 9 | 25 | 142 |

| Site | PCT/CCG | Community services | Acute trust | Social services | Patient participation group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1 | Locality transformation manager Commissioning manager, urgent care |

Manager, rehab Head, reablement Manager, end of life care Head of adult services Demand, capacity and resilience team leader Deputy head, community services Advanced nurse practitioners Head occupational therapist Head nurse Team manager, integrated care Team manager, falls (physio) GP and lead for roving GP services |

|||

| I2 | Service lead, unplanned care Clinical lead, unplanned care Nurse commissioner Strategic advisor, adult social care Director of commissioning Commissioning chairperson (GP) |

Chief executive (nurse) Head of service, intermediate tier Team manager, intermediate care Discharge team manager (nurse) Advanced nurse practitioner, rapid response Manager, older people Head of service, demand management and commissioning |

Clinical director, ED Assistant director of operations Director of operations Manager, medicine group Operations centre manager Clinical director for medicine (geriatrician) |

Manager, adult social services Manager, access and assessment |

Chairperson of Engage Voluntary worker Care home manager Lay member, CCG |

| I3 | Commissioning manager planned care (nurse) Commissioning manager urgent care Chief operating officer Chief operating officer (nurse) |

Medical director (GP) Manager, community nursing Service lead, therapies Clinical director (GP) Discharge co-ordinator (nurse) Team leaders, intermediate care (3) Alternatives to hospital nurses (2), administrators (2) Nurse practitioner, older people Community matrons (4) Community nurses (3) |

Older People’s Parliament: chairperson and five members Age UK project manager |

||

| D1 | GP member, CCG Head of development Service redesign manager |

Director of operations Deputy director of operations General manager |

Co-ordinator, services for older people Clinical director, acute and elderly medicine Consultant in acute medicine Associate director, non-elective care Nurse specialist, older people Practice facilitator (matron) |

Assistant director, adult social care Assistant director |

Older people’s partnership Age UK |

| D2 | CCG chairperson (GP) Urgent care lead (GP) Director of commissioning |

Clinical lead reablement (nurse) Mental health and dementia lead (nurse) |

Clinical director, unscheduled care Divisional nurse manager Manager, unscheduled care (2) Matron Manager, clinical assessment unit Clinical lead, clinical assessment unit Manager, medical assessment unit (nurse) Manager, acute nursing |

Head, adult care services Commissioning manager Hospital social worker Manager, community rehab |

Chairperson, user carer forum Members, user carer forum (4) |

| D3 | CCG board member (GP) CCG lead, unscheduled care (GP) Locality commissioning director |

Chief executive (medical) Geriatrician |

Head of policy, adult social care | Head of Healthwatch |

Site reports

A detailed qualitative case report can be found for each in-depth study in Appendix 3. These reports provide more detailed analysis of each site in terms of broader system configuration in line with the 7S framework and include illustrative extracts of data from study participants and other empirical sources. These case reports also provide summary tables that draw out the main findings from each site, which were subsequently used to inform and develop recommendations for system improvement (see Chapter 5). In this chapter, we draw on both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a brief descriptive overview of each study site and present an account of their main learning points. After reviewing each site, the chapter provides a cross-case comparison to draw out the main learning points from both the deteriorating and improving groups with the aim of elaborating recommendations. It is worth noting that the primary focus of these short case summaries is on the organisation and delivery of unplanned care for patients aged 85 years and over between 2007 and 2010, but many other aspects of service configuration were described to the research team through comparison with current practices. For example, participants often talked of more recent initiatives as a way of highlighting previous shortcomings. Given this, there is an inevitable hindsight bias to some of the accounts provided by participants and possibly a desire to present an improving picture. Readers are also encouraged to examine the more detailed case reports found in Appendix 3, where primary data support the summary account provided below.

Deteriorating sites

Site D1

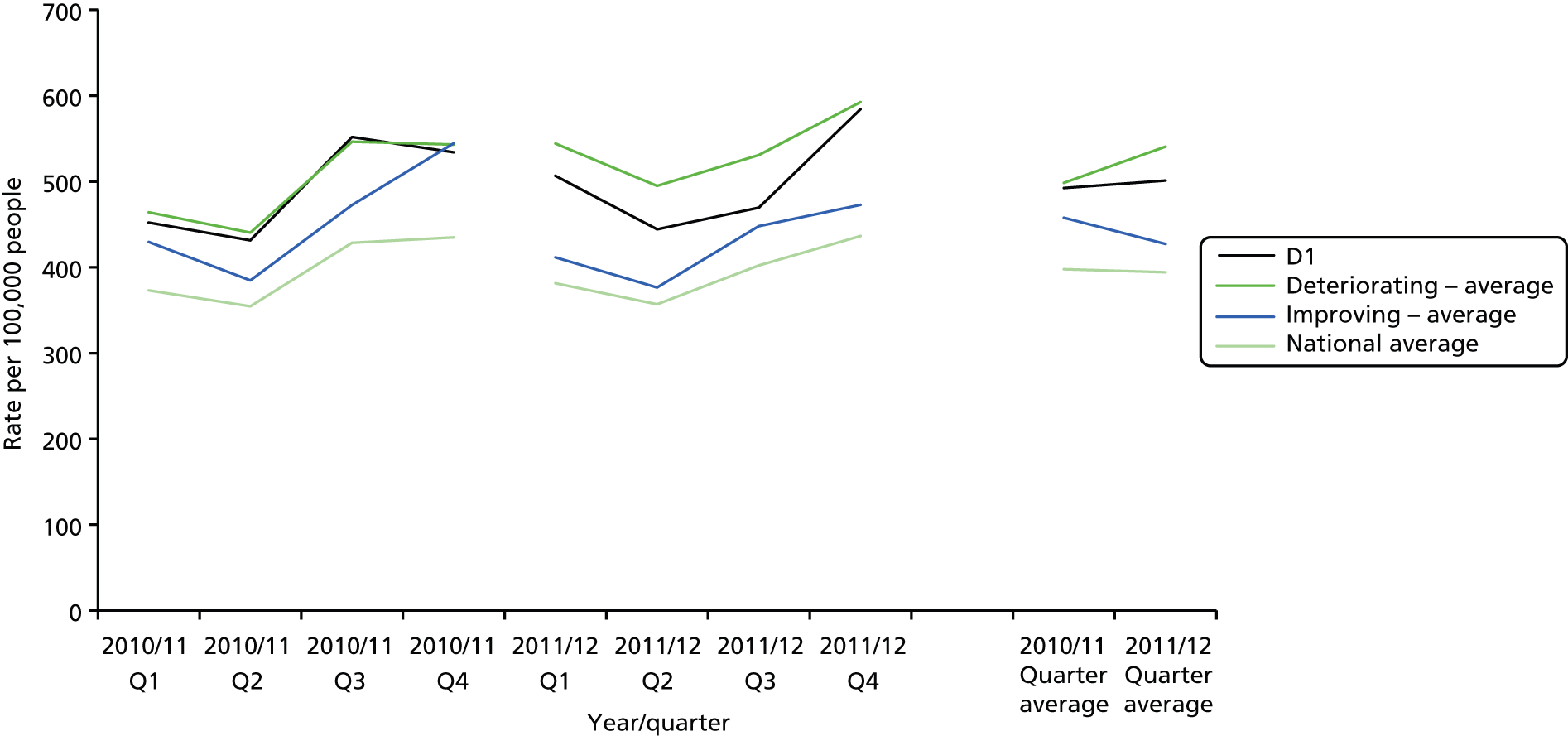

The PCT of D1 has a large urban population base, classified as a ‘centre with industry’ by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). 73 For total population it ranked 56th out of 151 PCTs, and had higher than average population growth, including in those aged 85 years and over. Its deprivation rank is 43rd of 151, meaning it is in the most deprived third of PCTs. Its admissions rate for the age group of 85 years and over ranked 37th out of 143 PCTs, which is the second highest of the sites included in this report. As many as 92% of acute admissions from the PCT are to the linked acute trust. As shown in Tables 7 and 8, admission rates for people aged 85 years and over and readmission rates for those aged 75 and over rose more rapidly than the average for our deteriorating sites. Between 2010 and 2011, emergency admission rates for ACSCs rose slightly, but less than the average for deteriorating sites (Figure 24). Results from the GP survey for access to GP services and out-of-hours services were similar to the average for deteriorating sites.

| Site | 2007/8 | 2008/9 | 2009/10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 48 | 54 | 59 |

| Deteriorating sites – average | 46 | 53 | 57 |

| England – average | 48 | 52 | 52 |

| Site | 2007/8 | 2008/9 | 2009/10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| D1 | 15.5 | 16.0 | 18.0 |

| Deteriorating sites – average | 15.3 | 15.9 | 16.7 |

| England – average | 14.4 | 14.9 | 15.4 |

FIGURE 24.

Emergency admissions for ACSCs 2010/11–11/12 (per 100,000 people, all ages, sum of 19 conditions), site D1.

Site D1 comprised a large acute teaching hospital (NHS trust) formed in 2006, consisting of over 1200 beds and providing an extensive range of acute and specialist services. The hospital was located in the main administrative city of the county and provided acute services to city and county, and specialist services to bordering counties. Two smaller NHS trusts provided a selective range of acute and non-acute services to the wider county area and surrounding catchment populations. A community health-care NHS trust was formed in 2006 and provided a range of community services and rehabilitation to the city and county. This trust provided inpatient, community and day clinics as well as specialist services to a population of over 850,000. The organisation provided services from more than 80 locations and employed more than 4000 dedicated staff. Over 60 GP practices served the principal administrative city, with many being operated by single-handed GPs or in small practices. An urgent care walk-in centre was also provided in a city-centre location.

The over-riding finding from D1 was the absence of any coherent or system-wide strategy for managing urgent, unplanned care, particularly for those aged 85 years and over. Specifically, the strategy developed over the preceding 5 years had largely been in relation to the formation and development of specialist acute services within the NHS acute trust provider, rather than primary or community services. Linked to this, participants described an operational strategy driven by prevailing national targets, especially for 4-hour ED attendance, which could admit patients with more complex needs as inpatients. Where innovations and changes had been adopted across the wider health system, they often lacked strategic leadership or alignment between acute and community care, focusing instead on expanding acute care. In addition, many innovations were based around rapid improvement projects, many of which failed to complete or were overtaken by new initiatives before being completed and evaluated.

Reflecting the above strategy, the structure of the health system at site D1 was largely centred around the main acute NHS trust, with the emphasis on building up the expertise and resources of this trust to meet the growing needs of older people. Accordingly, a number of systems had been put in place in and around the ED to improve the flow of patients into and through the acute hospital and avoid breaches of the 4-hour target. This also seemed to drive a set of values around the importance of meeting targets.

The organisation and delivery of community care had recently undergone change, with care being provided by multidisciplinary care teams, but with limited evidence of integration with either acute or primary care services. However, with increased admissions to the acute trust and evidence that certain patient groups were receiving restricted packages of care, there had been a move to develop alternative forms of community provision based upon care at home. The involvement of GPs in the management of longer-term and acute care for those aged over 85 years was uneven and widely seen as a problem, especially for smaller practices, which struggled to respond to urgent patient needs. In particular, urgent access to GPs was commonly identified as a problem, although where access was available it was believed that medical expertise was usually adequate to manage patient care needs. Some areas of primary care witnessed increased specialisation in the care of older people, including specialist nurses and geriatricians working in the community, but this recent development was not necessarily meeting demand throughout the entire city and county. Additional concerns were also raised about the management, resources and inspection of nursing homes. As well as difficulties with recruitment and training for complex care needs, it was reported that nursing home staff were poorly supported by primary or community health-care specialists, making it difficult to manage urgent care needs without referring the patient to the ED. It was also felt that patients aged 85 years and over struggled to navigate the care system and that there was a growing reliance on families and other carers to service the needs of these groups.

In sum, site D1 illustrated a system highly centred on acute care, with some degree of fragmentation of other primary and community services. The problems of urgent care attendance at the ED for those aged 85 years and over was, accordingly, managed by streamlining the acute care system to avoid breaches of targets over and above the better management of complex care needs in the community. The lack of integration and planning at a wider system level was further evidenced by widespread concerns about the lack of communication between care providers, and a lack of shared vision or strategy about the management of care for older patients.

Site D1 offers possible lessons for the management of urgent care for patients aged 85 years and over. These include:

-

Strategy

-

Define a specific strategy for the care of patients aged 85 years and over.

-

Align this strategy with existing local and regional service strategies.

-

National pressures and targets need to take into account the impact they have on older people.

-

Learn from pilots and implement good practice.

-

-

Structures

-

Better integrate acute, community and primary care.

-

Restrengthen relationships between GPs and community nursing where these are no longer colocated.

-

-

Systems

-

Provide greater transparency of service availability and provision.

-

Longer-term packages of care need to be provided.

-

Systems to access GPs may need to improve.

-

-

Shared values

-

Service providers should unite around the quality of care and communicate with each other.

-

Alignment of staff and public values regarding care and funding of care for older people.

-

-

Style

-

Overcome cultural differences between care providers.

-

Improve communication and manage expectations between different professional members/roles, between staff and family, and between practitioners and patients.

-

-

Staff

-

Consider specialised roles such as community geriatricians and specialist nurses.

-

-

Skills

-