Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was joint funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceeding programmes and INVOLVE as project number 10/2001/36. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in March 2014 and was accepted for publication in January 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Wilson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Since the late 1990s, a plethora of policies have emerged aimed at embedding public involvement within the NHS,1–4 and this impetus has been mirrored within health research within the UK. Researchers have increasingly been required through national governance frameworks5,6 to involve members of the public through working with them, rather than conducting research on them. This has been further encouraged through the integration of patient and public involvement (PPI) by most of the main UK funders of health research. 7 This drive towards public involvement in research is not limited to the UK; internationally there has been an increasing recognition of the importance of involving patients and the public in health-care governance and research. 8–11

The PPI in health has its roots in the increasing unease with and challenges to the medical institution. 12 The ethical argument for PPI grew and was taken up by policy-makers as characterised by the phrase ‘nothing about me without me’. 13 Politically, PPI is also seen as a way of addressing the democratic deficit by giving voice to the public in publicly funded health organisations and research. 14 In addition to the moral and political rationales for PPI, there are also a number of methodological claims regarding the positive impact of PPI in health research. These include increased relevance of the research through identifying research questions and prioritising research agendas, appropriate research conduct, addressing ethical tensions and matching research with policy objectives. 12,15–19

These three drivers have resulted in PPI being imperative for health research in the UK. However, despite this, PPI is poorly defined and conceptualised,20,21 with varied definitions and terms used to describe it. 22

Definition of patient and public involvement within the RAPPORT study

Within the ReseArch with Patient and Public invOlvement: a RealisT evaluation (RAPPORT) study, we define the process of PPI in research according to the definition offered by INVOLVE ‘as research being carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them’ (p. 6). 23 However, while the underpinning process of PPI is relatively clearly defined, albeit potentially not embraced or understood by the entire research community, the name is perhaps more contentious. INVOLVE and others24,25 use the term ‘public involvement’, as they argue this covers ‘patients, potential patients, carers and people who use health and social care services as well as people from organisations that represent people who use services’ (p. 6). 23 Conversely, others suggest that this fails to capture the ‘expert’ nature of the experiential knowledge brought specifically by patients or service users. 22 Equally, the connotation of passivity that the term ‘patient’ brings has also been criticised,26 as has the political dimension to the term ‘consumer’ involvement. 27 Jordan and Court22 suggest that controversy around the different labels used is unsurprising, as they are derived from a multitude of contexts and interests. They suggest that the term ‘lay’ is to be preferred, as it denotes a broader alternative perspective to that of the professional. What is clear is that no single label will be acceptable to everyone,28 and we took a pragmatic approach by agreeing with the RAPPORT PPI representatives what terms should be used within the report. We use two terms interchangeably: ‘PPI representatives’ to emphasise individuals undertaking diverse roles from patient representative through to a member of the general public, and ‘lay representatives’ to emphasise the overall perspective these individuals bring.

Rationale for the study

The relatively small amount of empirical evidence on the impact of PPI in research29 has been criticised as poorly reported21 and methodologically weak, often failing to fully explore the contextual factors surrounding PPI as a complex intervention. 30 Not only is there a notable lack of evidence on outcomes and impact of PPI,31 but what little there is tends to be observational evaluations which rarely consider the links between the context (when and where PPI happens), models of PPI (how it functions) and the outcomes of PPI (what difference it made). 32 As outlined in the next section, the RAPPORT study aimed to address these significant gaps in the evidence.

Aims and objectives of the RAPPORT study

The RAPPORT study sought to evaluate how different approaches to public involvement in research with different populations influence the identification of priorities, research conception, design, process, findings and knowledge transfer. Specifically, it aimed to identify what PPI approaches have applicability across all research domains, which are context specific and whether or not different types of public involvement achieve different outcomes for the research process, findings, dissemination and implementation of PPI. The RAPPORT study objectives are listed in Box 1.

The study objectives were to:

-

determine the variation in types and extent of public involvement in funded research in the areas of diabetes mellitus, arthritis, cystic fibrosis, dementia, public health, and intellectual and developmental disabilities

-

describe key processes and mechanisms of public involvement in research

-

critically analyse the contextual and temporal dynamics of public involvement in research

-

explore the experience of public involvement in research for the researchers and members of public involved

-

assess the mechanisms which contribute to public involvement being routinely incorporated in the research process

-

evaluate the impact of public involvement on research processes and outcomes

-

identify barriers and enablers to effective public involvement in research.

Structure of the report

The report presents the main findings from the RAPPORT study and discusses them within the context of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network portfolio. This portfolio consists of high-quality clinical research studies that are eligible for support from the NIHR Clinical Research Network in England. In Chapter 2 we provide scene setting through presenting the dominant arguments for PPI and an overview of the roots of PPI in health research, and summarise the existing available evidence of PPI impact. Chapter 3 sets out the underpinning methodology and methods used. We provide a discrete chapter to describe PPI within the RAPPORT study and evaluate the impact on the RAPPORT study itself. Chapter 5 presents findings from the national scoping and survey of PPI in research, and in Chapter 6 we provide the findings from our 22 case studies. Chapter 7 discusses our findings and in Chapter 8 we summarise the main conclusions of our research with particular regard to our key research questions. Drawing on our findings and discussion, we then identify implications for the research community and PPI representatives, and make recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Background

This chapter of the report sets the scene for PPI in health research. We set out the dominant arguments for PPI within the UK health system: the moral argument, founded on ethical and democratic principles, and the methodological argument. We briefly overview the roots of PPI within the NHS as a whole, then focus specifically on PPI in research and map out the policy frame for PPI in research. Although we have not undertaken a structured review of the literature, we provide an overview of a broad range of papers reporting PPI in research, and complete the chapter by presenting evidence from five structured reviews of the evidence on PPI in health research.

Search strategy

Literature was searched from 1995 to 2013 on the following electronic databases: MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and The Cochrane Library. The InvoNet database was also searched for grey literature and published papers. Lateral searches were conducted from retrieved papers to provide historical background. Papers were restricted to those in English. Combinations of terms, one from each column in Table 1, were searched for.

| Population 1 | Population 2 | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| Patient* Carer* Public* Citizen* User* Consumer* Lay Caregiver* Representative* |

Health Research* Health service Public health Primary health care Community |

Participate* Involve* Engage* Collaborate* Partnership Consult* Consumer panel Advisory group |

Links with experts in PPI also provided further papers and grey literature.

Patient and public involvement: historical roots

Patient and public involvement in health and social care is emblematic of the postmodern democracy. Challenges to the unquestioned authority of medicine from health service user groups can be traced back to the 1950s, with growing disillusionment over health-care decisions being made which failed to include the views and perspectives of the service user. 12 In the UK, health service users have evolved a collective voice and formed a number of groups which actively campaign for the right to have a voice in decisions directly affecting them. While such groups are often organised in relation to a specific health condition (such as diabetes mellitus) or a shared experience (such as domestic violence), the overall movement has questioned conventional assumptions of, for example, disability, and also provided the means for advocacy, political lobbying, provision of alternative forms of health and care services, and user-led research and training. 33,34 Further impetus for the challenge against biomedical authority was provided by a series of high-profile medical scandals including the retention of deceased children’s body parts for research without the knowledge or consent of parents35 and unexpectedly high mortality rates for children undergoing heart surgery. 36,37 This backdrop of a changing health service user response to established biomedical authority underpins one of the three main claims of PPI legitimacy: the moral argument. It has also actively shaped the second claim: the policy argument.

Patient and public involvement: the moral argument

A clear case for PPI is laid out as the right of citizens to have a voice in the public services for which they are paying through taxes and labour; this is particularly relevant to health and care services or publicly funded health research. This argument is founded on the notion of a previous democratic deficit38 and the concepts of rights and citizenship. 39 This right to be involved as a citizen has been further developed internationally,11 but it has also been criticised as often comprising too narrow a view of citizens, with the reality that the involved citizen is generally retired, white, middle-class and highly educated. 38 An alternative viewpoint is the ethical argument that the individual has a right to be fully involved about any health care or research intervention being done ‘to’ them as a person. As well as this ethical standpoint, there are also a range of emancipatory approaches40 that explicitly validate subjective knowledge and openly challenge the traditional medical model of knowledge. Characterised by user-led research, this approach attempts to give voice to knowledge that is seldom heard. 41 A key influence on this movement was the work of Paul Hunt, a resident of Leonard Cheshire Homes who was an early campaigner for residents’ rights in the 1970s and 1980s. The then Department of Health and Social Security commissioned research to explore the potential for residents’ participation in the running of care homes; the resulting report was heavily criticised by Hunt for failing to include the resident perspective. 42 That event was seen as a catalyst in the development of service user-led research. 43 However, while there is growing recognition of the importance of experiential knowledge being addressed alongside scientific understanding,44 there is also clearly often an intrinsic resistance to acknowledging lay knowledge, particularly in the sphere of biomedical research. 44,45

Patient and public involvement: the policy argument

Although some parts of the scientific community have contested what knowledge is credible,46 the public crisis in confidence in the way health and care services were being run contributed towards a policy shift through the 1990s whereby governance moved towards partnership and community involvement. 37 The consumerist movement in the 1980s provided a focus on customer satisfaction, and the involvement of patients and the public was perceived as a feedback system to ensure that the NHS was meeting the needs of service users. 47 However, with the advent of the 1990s and a procession of significant changes to the NHS48 there began a concerted effort to involve patients and the public in key decisions about the purchasing and delivery of health and care services. 49 The pace of policy change speeded up considerably with the new Labour government in the late 1990s. ‘Third way’ policy, with its emphasis on concurrent rights and responsibilities,50 produced a number of initiatives including developing patient expertise in self-management26 as a tool to increase an individual’s confidence and skills in involvement in their care. Public involvement became a statutory duty within the NHS and all organisations were required to involve patients and the public in planning and operational decisions about services. In the light of increasing political expectations of PPI, the NHS has had a succession of involvement bodies including community health councils (abolished in 2002), PPI forums (abolished in 2007), local involvement networks and, from 2013, Healthwatch. This frequent restructuring of mechanisms designed to enable the patient and public voice suggests that policy-makers are still seeking more effective ways of operationalising PPI. 47

While the policy argument has been presented in terms of PPI within the NHS as a whole, PPI within health research, although more recently established,46 has equally been shaped by policy-makers.

The policy approach to patient and public involvement in research

Since the 1990s, and mirroring the policy changes outlined above, there has been increasing mainstream acceptance of PPI in research. In 1996 the Department of Health set up an advisory group to support PPI in research. Originally known as Consumers in NHS Research (now INVOLVE), it commissioned a literature review on service user involvement51 which highlighted the need for flexibility, funding, shared values and the importance of the political philosophy. These key areas are reflected in the main policy papers, whereby PPI became a statutory part of the research governance framework,5 and which made the case for PPI to improve the relevance and more likely implementation of research findings. 6 The 2008 Health and Social Care Act consolidated legislation around PPI in the health service and health research, and in a relatively short time PPI has become embedded within the main UK health research funding streams, regulators and medical Royal Colleges. 52 Researchers applying to NIHR and most medical charity funding streams are now required to demonstrate how PPI has shaped the research proposal and how service users and the public will continue to be involved in the study.

Patient and public involvement: the methodological argument

In addition to the moral arguments, policy-makers have been receptive to the consequentialist case that PPI improves quality within the health service, particularly in terms of service delivery and patient outcomes. There is a growing body of evidence that involvement in care leads to improved health outcomes53,54 and patient experience,55,56 but less evidence on any impact of PPI on the planning and commissioning of health services. 57

Within the health research arena, the policy approach to PPI has been underpinned by various claims regarding the impact of PPI. It has been suggested that PPI in setting research priorities has had an impact on the amount of research conducted on rare conditions,28,29 and has shaped the research agenda for more common conditions, such as breast cancer. 58 Beyond priority setting, PPI is seen as having an important role in identifying specific research questions,59,60 with subsequent applications for funding being more successful. 61 Furthermore, PPI can ensure that the patient and carer perspectives are explicitly addressed within the research questions,62 and may result in research questions being further refined17,63 or even abandoning a research application if PPI suggests that the research questions are not meaningful for the target patient and service user population. 64

In addition to influencing researchers’ priorities, PPI has increasingly played a part in advising funding bodies on priority setting, for example in medical products,65 spinal cord injury66 and burns research. 67 Lay involvement in the review of research grant applications is seen to raise issues not previously identified and challenges scientist reviewers to think more about the service user perspective within their deliberations. 68,69 Overall, making PPI explicit within the research proposal development is seen as lending more credibility to the proposal and hence offering a greater chance of funding. 70,71 In particular, PPI is seen as being key to the development of plain English summaries as a requirement in many grant applications. 24,62

There are also claims that PPI improves the overall design in trials,72 particularly by ensuring the design is acceptable for potential participants. 73 Contributing to the design of interventions is reported as being an important aspect of PPI; examples include stroke research interventions74 and advising on the timing of interventions within Parkinson’s disease research. 75 PPI also has a role in ensuring that research tools are refined to more closely reflect the issues important for the target research population,76 ensuring tools are culturally sensitive and designing measures of patient expectations of treatment. 77 However, the most frequently cited claim for the value of PPI is in recruitment to studies,78 most commonly by ensuring that protocols and participant information are more relevant and accessible to participant groups. 70 PPI input is also seen as having importance in shaping the recruitment strategy by bringing local knowledge,79 or important links to the target population. 80 There are also examples where PPI has contributed to accessing marginalised and seldom heard populations81,82 and those with rare conditions,83 and played a role in promoting acceptance of researchers by previously sceptical communities. 84 More active involvement in mainly qualitative data analysis has been identified as improving interpretation of findings through the drawing out of relevant themes. 79,85–87 Moreover, qualitative data collection by service users as co-researchers has been claimed to improve validity and provide better-quality data. 88–90 Dissemination of research findings is also reported as gaining from PPI networks to increase access to peers81 and relevant sections of the community,15 and making information more broadly readable. 31,72 There are fewer published claims for PPI as playing a significant role in implementing findings, but, in a US public health research programme, Krieger et al. 86 report PPI-related implementation of changes by increasing their cultural relevance. Several researchers have identified that PPI has helped them address ethical dilemmas,17,71,78,85,91 for example ethically appropriate ways of contacting women with recently diagnosed breast cancer and the use of routine patient data. 92 There is also some suggestion that lay co-researchers have a role to play in helping safeguard potentially vulnerable participants. 82

The impact of PPI has a moral dimension in the reported outcomes for service users and the public involved in the study. This includes an increased sense of self-worth,87,93 peer support,94 improved quality of life95,96 and acting as a stepping stone to employment. 88 Being involved with a research team also provides service users and the public with a means of becoming more knowledgeable about health conditions, services and the research process. 58,93,95 Within community-based public health research, benefits of PPI are also reported in enhancing the capacity of community-based organisations to raise their value to their communities. 86

Finally, there are claims that PPI brings benefits to researchers beyond just the research study. Working with the public and service users is found to be a process whereby researchers learn to share control and develop facilitation skills. 88,97 PPI not only increases researchers’ confidence in their studies72 but perhaps most importantly fosters their greater understanding of the service user or patient perspective. 81,98

The evidence base for patient and public involvement in research

Despite the growing body of literature outlined in the previous section, there is relatively little evidence of PPI’s impact and outcomes. 99 Several factors contribute to the weak evidence base for PPI. First, previous evaluations have failed to use methodologies that take into account its complexity,100 arising from PPI being an interconnected, multifaceted social process, making it difficult to pinpoint specific impacts and contributions. 19 Second, there is little systematic appraisal and reporting of PPI impact and outcomes,101 further constrained by the conventions of academic publishing. 21 Nevertheless, there is a limited number of evidence reviews,19,29,99,101,102 here presented chronologically to illustrate the developing evidence base.

The systematic review by Oliver et al. 102 was the first to examine the evidence base on the impact of PPI on identifying and prioritising possible topics for research and development. They found detailed reports of 87 examples of PPI influencing the identification or prioritisation of research topics. While these reports highlighted the collective experience of research programmes in involving patients and the public, gaps were identified in training and preparing lay people. It also highlighted multiple barriers to service users’ ideas influencing research agendas, and a lack of collaborative working between the research programmes and lay people to address the way forward in collective decision-making. In addition, the majority of included reports were descriptive accounts written by researchers rather than service user representatives.

Staley’s 200919 review of the literature appraised papers published from 2007 within the INVOLVE collection of articles, systematically searched electronic databases and drew on grey literature obtained through networks via INVOLVE. A total of 89 articles (71 published papers and 18 from ‘grey’ informally published literature) were included in the review. While there was some evidence around the impact of PPI on influencing research questions, design, data collection, dissemination, implementation and research ethics, the most substantial body of evidence was on PPI’s impact on recruitment. However, particular gaps in evidence were found on PPI impact around grant-funding decisions, and on involvement in data analysis apart from qualitative methodology. There was some evidence of both positive and negative impacts of PPI on the public and researchers involved, and there were examples of positive impact for research participants in terms of PPI influencing a better research process, and impact on the wider community. However, as with Oliver et al. ’s review,102 because of the nature of the evidence available, inconsistent reporting and the context-dependent nature of PPI, it was not possible to carry out an in-depth analysis of different kinds of impact, or to judge the quality of the evidence and determine how generalisable the results were.

The Patient and Public Involvement in Research: Impact, Conceptualisation, Outcomes and Measurement (PIRICOM) systematic review29 aimed to examine the conceptualisation, measurement, impact and outcomes of PPI in health and social care research. Ninety papers published between 1995 and 2009 were included. Data were extracted from 83 papers (the remaining seven were not written in a format suitable for data extraction but were deemed sufficiently important to include within the conceptualisation of PPI). Of the 83 papers, 2 were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), 52 qualitative studies, 15 case study methodology, 4 cross-sectional studies and 10 structured reviews. As in Staley’s review,19 the papers provided more evidence around the processes of PPI rather than impact and outcomes, and found scant evidence of PPI impact on funding decisions. Hence, while there appears to be a reasonably robust level of evidence around the ‘architecture of PPI’, reporting of outcomes continues to be poor. Brett et al. 29 argue that most studies have attempted to conceptualise PPI mainly around context and process and have not sufficiently theoretically grasped the complexities of PPI. They did not find any evidence around systematic measurement of PPI outcomes, and furthermore found a lack of clarity on the differences between PPI impact and outcomes.

Jagosh et al. 103 addressed the complexity of PPI by utilising a realist review design. 104 Focusing on participatory research, which they define as the ‘co-construction of research between researchers and people affected by the issues under study . . . and/or decision-makers who apply research findings’, they reviewed published papers and grey literature on 23 studies or programmes of research where both service users and researchers either identified or set the research questions, selected the methodology, collected or analysed data and used or disseminated the research findings. In each example they attempted to map out the relationship between the context (any condition that triggers or modifies the behaviour of a mechanism), mechanism (a generative force that leads to outcomes) and outcomes (intended and unintended). As part of their realist review they generated three hypotheses to test within each example. Drawing on the concept of ‘partnership synergy’,105 their hypotheses were that partnerships are not always synergistic (e.g. because of previous history); that multiple stakeholder collaboration will enhance research outcomes beyond that which would be expected without the collaboration; and that partnerships may become more synergistic with time. They were unable to test the first hypothesis because of a lack of information about the history and previous context of each example. However, the other two hypotheses were supported in several examples. They conclude that partnership synergy often generates a virtuous circle, so that conflict and disagreement between the stakeholders is not necessarily a bad thing, as it may build more robust synergies through successful negotiation and resolution. However, as with the earlier reviews, Jagosh et al. 103 highlight the limited reporting of PPI and also suggest that negative outcomes are less likely to be reported.

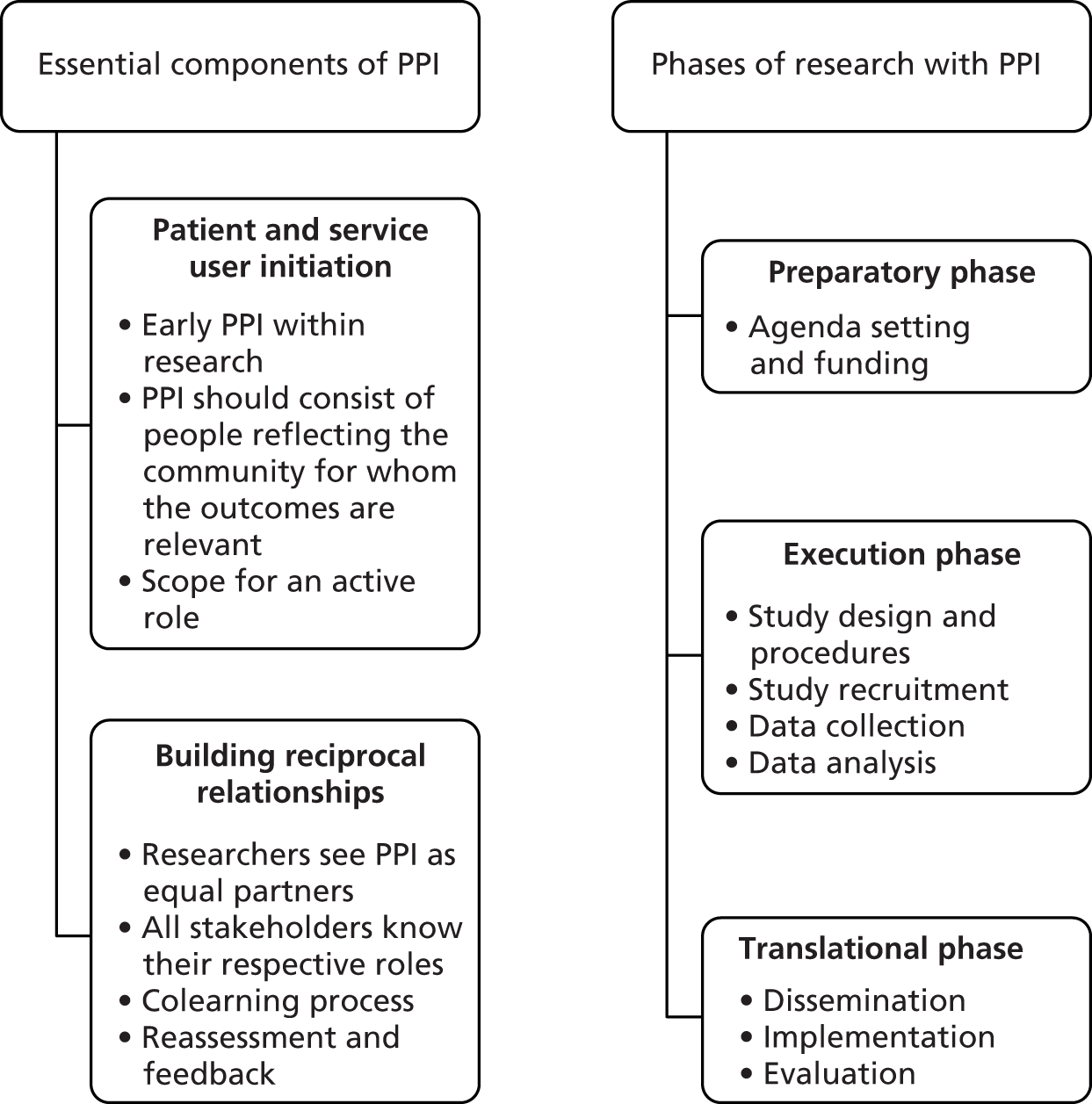

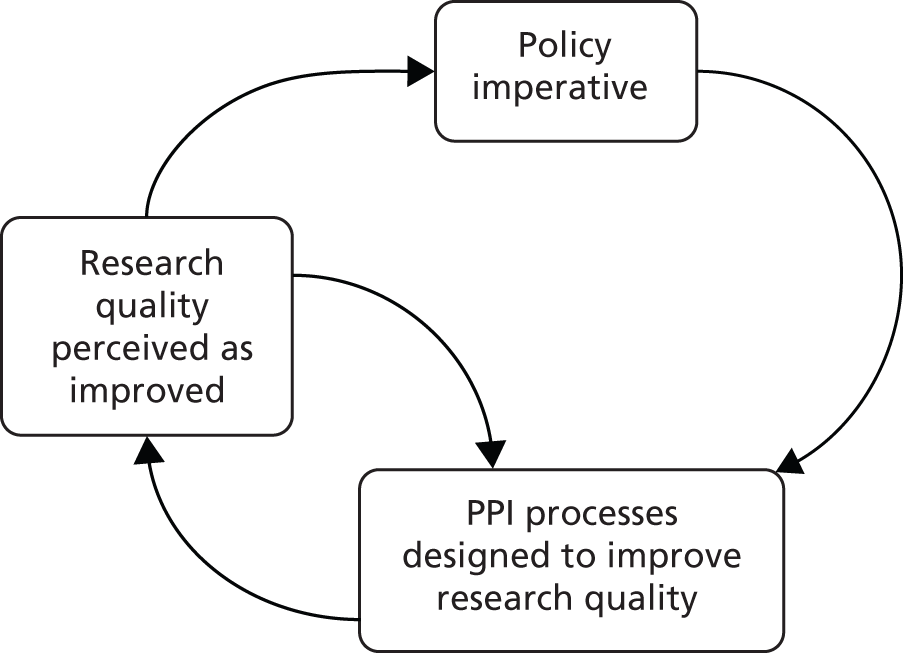

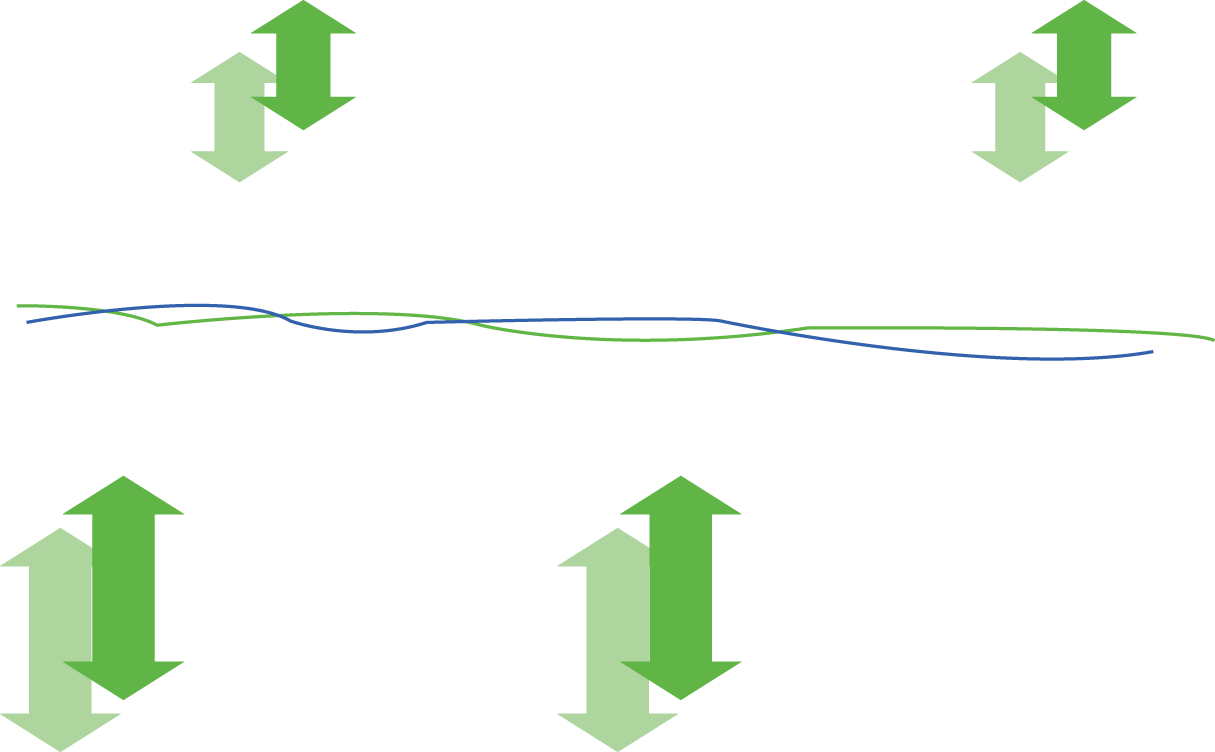

In a study published a year later, Shippee et al. 101 develop a conceptual framework (Figure 1) from their systematic review. They critique previous reviews as focusing on only one part of their proposed framework, suggesting that their approach is more comprehensive and recommending its use to guide future reporting of PPI. From an original 202 papers, the review included 41, with the findings mapped against the framework. They conclude that the evidence of PPI impact on funding decisions continues to be weak, with a notable lack of studies identifying the impact of PPI in data collection and analysis. In contrast, there is a growing body of evidence on the impact of PPI in addressing ethical issues and enhancing the validity of findings. The authors recommend that research be undertaken to compare and systematically report different methods of PPI, and that there be more robust indexing of such studies.

Conclusion

Embedding PPI in research continues within an overall policy framework which is built on specific contemporary moral and consequentialist arguments. However, while the body of literature describing PPI processes and the architecture required to enable PPI continues to grow, it still provides only comparatively weak evidence for impact and outcomes. One reason for this is the difficulty that confused terminology or poor reporting poses for finding evidence of PPI impact in the literature. What evidence there is tends to be descriptive, largely qualitative, often retrospective case studies,19,29,106 with only a few exceptional prospective longitudinal case studies,15 comparative multiproject evaluations107 or studies employing quantitative designs. 108 This reflects the significant methodological challenges in evaluating PPI as a complex intervention, and the length of time before impact may become visible. Key messages from the cumulative reviews of evidence on PPI in research suggest that an appropriate methodological approach must be sensitive to context and processes and their influence on outcomes, that PPI within a research study may shift and develop with time so that there is a need for a longitudinal approach, and that different models of PPI need to be evaluated and compared through a standardised design. In the next chapter we present our methodology designed with these conclusions in mind.

Chapter 3 Research design and methods

As outlined in the previous chapter, PPI in research is a complex social phenomenon, and can act as an ‘intervention’. 109 Providing a more robust evidence base for PPI policy requires moving beyond observational evaluations of PPI. 29,30 More conventional approaches to empirical evaluation would seek to examine whether or not programmes, interventions or innovations are effective using controlled trial designs to measure specified effects of each of a number of variables on outcomes. Although such designs are well suited to assess the effectiveness of clinical treatments, it has long been recognised110 that such research designs are less able to identify how exactly variables combine to create outcomes111 or to fully explain the processes through which programmes actually work. Furthermore, controlled trials are, by definition, able neither to examine the dynamic nature of those interventions which, will, of necessity, evolve over time nor to explore the effect and complexity of the wider social systems within which PPI takes place. For example, an experimental evaluation (RCT) which investigated the impact of PPI in developing participant information sheets (PISs) for a clinical trial108 concluded that PPI had little or no impact on participants’ understanding of the trial or on recruitment and retention, and the authors were able only to speculate that a wide range of contextual factors and limited understanding of the mechanism of gaining consent were responsible for this negative outcome. Yet, as Staley et al. argue:

If an experimental evaluation is not designed in a way that considers the contextual factors and aspects of the mechanism that have the potential to influence impact, then it may produce inaccurate or over-simplified conclusions about when and how involvement makes a difference.

p. 632

Realist evaluation (RE) is one of several theory-based approaches to evaluation developed within the social sciences, which seeks to address dynamism and context, rather than control for them, to explain more adequately how and, importantly, under what circumstances programmes, interventions or innovations will ‘work’ in real-world complex systems, such as those related to health care/research systems. 112 Such social science approaches highlight, specifically, how it can be the reasoning and actions of people (social actors), rather than inherent characteristics of the interventions themselves, that make them work. 113

In conclusion here, the evaluation of PPI in research necessitates a method of enquiry capable of capturing the interplay between outcomes and processes and the context in which PPI is conducted. As other authors have advocated in reviewing the evaluation evidence for PPI,32 a realist evaluation approach114,115 offered this research the capability of more fully investigating and understanding what type of PPI provided what kind of outcome in relation to different types of research and settings. We employed an overarching critical realist framework116,117 focused on the mechanisms embedded within PPI, to facilitate our understanding of outcomes present or absent depending on how they were triggered, blocked or modified. 118,119 RE,115 which draws upon this perspective, was used to inform the research design.

We continue this chapter with a brief introduction to RE and its application in this study. We then explain the three-stage research design and methods employed to test the links between context, mechanisms and outcomes of PPI. We also introduce Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) as the candidate programme theory to explain the ‘work’ required to embed PPI as normal practice. In particular, the focus of NPT on social action can help understand how and how far PPI may be ‘embedded’ within and across contemporary health-care research.

Method of enquiry: realist evaluation with Normalisation Process Theory

Both RE and NPT are theoretically informed approaches that can help researchers to further investigate, develop and refine middle-range theories (MRTs) to explain specific parts of programmes and interventions. Merton defines MRTs as ‘theories that lie between the minor but necessary working hypotheses and the all-inclusive systematic efforts to develop a unified theory that will explain all the observed uniformities of social behaviour, social organisation and social change’ (p. 39). 120 MRTs are thus sufficiently abstract to be applied to differing spheres of social behaviour and structure, but do not offer a set of general laws about these at societal level. Specifying the range of the theory is important here. The limited scope, conceptual range and claims of MRTs are what make them practically workable in analysing practice; both approaches (RE and NPT) can be applied across different types of social programmes at different scales.

The bodies of literature on empirical applications of both these approaches are relatively recent,112 especially NPT; its third and final development phase was reported only in 2009. 121

Realist evaluation is rooted in the philosophy of science situated between extremes of positivism and relativism, known as realism. 115,122 Realism understands the world as an open system, with structures and layers that interact to form mechanisms and contexts. RE research is concerned with the identification of underlying causal mechanisms, how they work, under what conditions and for whom. 115,123 The approach employs three key terms, for which definitions are provided in Box 2.

Context often pertains to the ‘backdrop’ of programmes (PPI in research): those conditions within which programmes are introduced that are relevant to operating the programme mechanisms (e.g. the research arena, previous working relationships or funding body). As these conditions change over time, the context may reflect aspects of those changes while the programme is implemented. Context can be broadly understood as any condition that triggers and/or modifies the mechanism.

MechanismMechanisms are the unit of analysis of RE. Mechanisms describe what it is about programmes and interventions (PPI in research) that bring about any effects (outcomes). Mechanisms are often hidden, as with a clock’s workings; they cannot be seen but drive the patterned movements of the clock’s hands. Mechanisms are linked to, but not synonymous with, the programme’s strategies (e.g. a strategy may be an intended plan of action for PPI in research, whereas a mechanism involves the researchers’ and PPI representatives’ reaction or response to the intentional offer of incentives or resources). Identifying the mechanisms (e.g. the design of PPI roles within research projects) advances the synthesis beyond describing what happened to theorising why it happened, for whom and under what circumstances.

OutcomesOutcomes are either intended or unintended consequences of programmes, resulting from the activation of different mechanisms in different contexts (e.g. if the research recruited more successfully because of PPI). Outcomes can be proximal, intermediate or final.

Because causal mechanisms are always embedded within particular contexts and social processes, their complex relationship with the effect of context on their operationalisation and outcome needs to be understood. Pawson and Tilley115 describe this as: context (C) + mechanism (M) = outcome (O). Rather than identifying simple cause-and-effect relationships, RE is concerned with finding out about what mechanisms work, in what conditions, why, to produce which outcomes and for whom. 124 RE does this through testing and refining configurations of context, mechanism and outcome (CMO) within analysis of data, as described in Box 3.

Context, mechanism and outcome configuring is a heuristic tool used to generate causative explanations pertaining to outcomes in the observed data. The process draws out and reflects on the relationship of CMO of interest in a particular programme. A CMO configuration may pertain either to the whole programme or only to certain aspects. One CMO may be embedded in another or configured in a series (in which the outcome of one CMO becomes the context for the next in the chain of implementation steps). Configuring CMOs is a basis for generating and/or refining the theory that becomes the final product of the evaluation. RE thus develops and tests CMOs conjectures empirically.

Although Pawson and Tilley did not provide a set of methodological rules for RE, and these are still much debated,112,125 they nonetheless suggest some principles for guiding evaluators. These include the identification of mechanisms and testing/refining of CMO configurations; stakeholder involvement and engagement; and a generative conception of causality (i.e. an explanation not of variables that are inter-related to one another but rather of how they are associated). 124

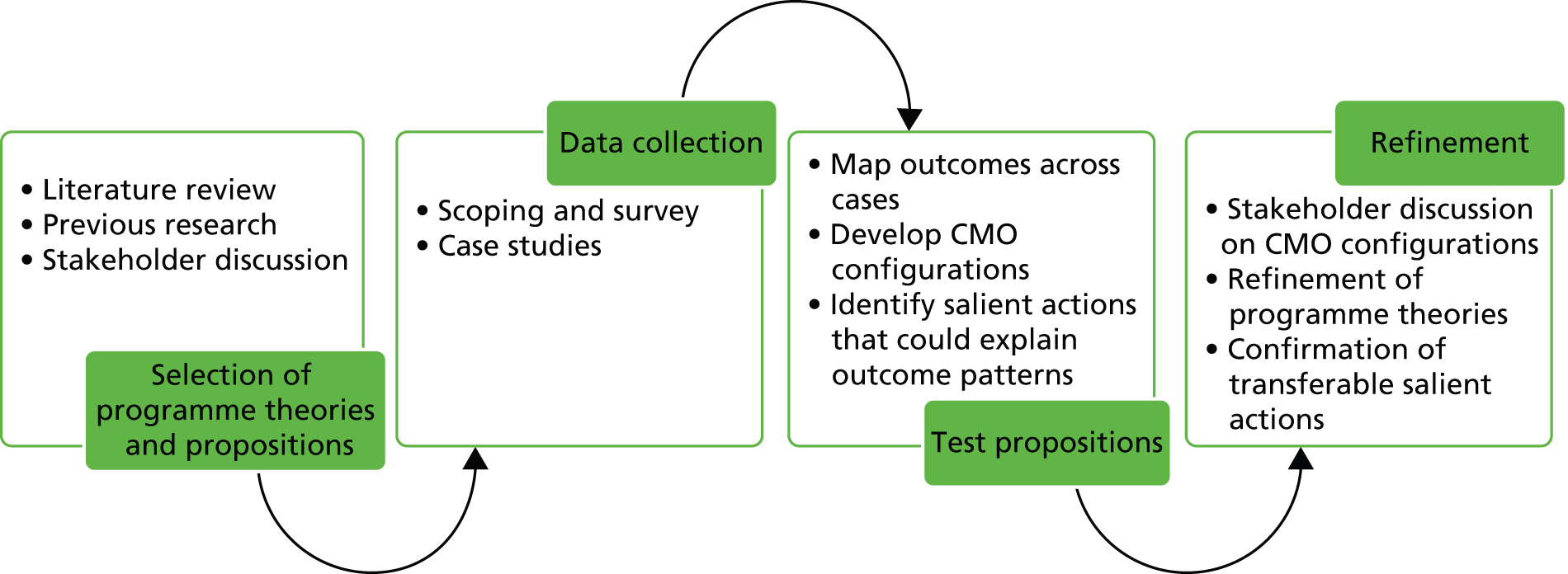

In practice, REs start with a MRT and end with a refined MRT, following four main stages as described by Pawson and Tilley. 114 The MRT can be formulated on the basis of existing theory, past experience and previous evaluations or research studies. The result is discussed with the stakeholders and finally results in the MRT that will be tested. The field study is then designed in relation to the MRT: the design, data collection tools and analysis tools are developed to enable testing the elements of the MRT. The outcomes of the fourth stage should lead to policy advice and recommendations. The application of these four stages in this research is shown in Figure 2.

Both a published literature review112 and critical discussions in the applied literature cite several methodological challenges associated with a RE approach, including deciding what constitutes a mechanism,127 and indeed differentiating between what is a mechanism and what is context. Barnes et al. ,128 for example, also caution against interpreting context as a purely external factor, arguing that context is shaped by actors as much as it constrains their activities.

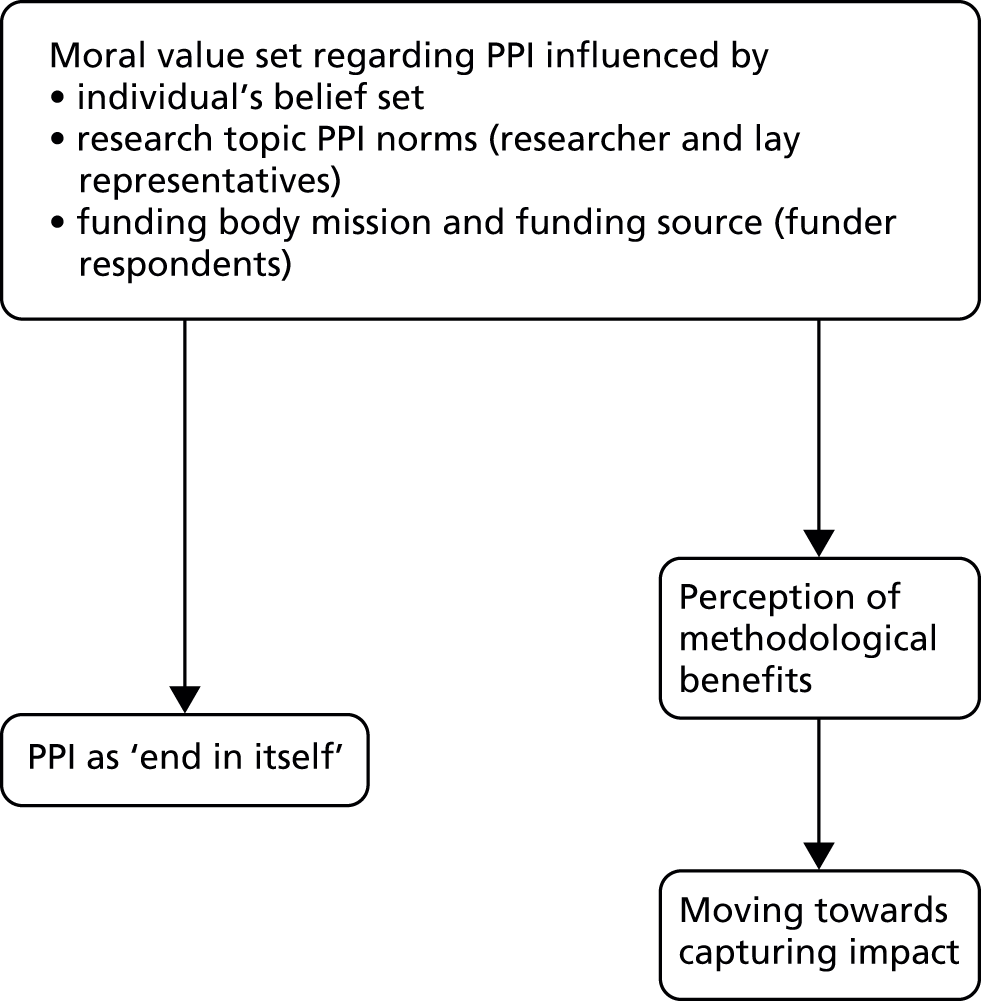

Middle-range theories and hypotheses

Before the empirical work, we conducted a search of the literature to identify programme theories that would inform candidate CMOs. As described in Chapter 2, PPI can be defined through three different perspectives: moral, methodological and policy. We therefore sought explanatory theories that would underpin these approaches and predict outcomes. These are illustrated in Table 2.

| Dimension | Moral | Methodological | Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Purpose | To ensure citizens’ rights and the moral imperative | To improve research processes, outcomes and impact | To support and embed PPI in health research as normal practice |

| Expected outcomes of the programme (PPI) | Researchers ‘working with’ rather than ‘doing to’ patients and the public Patient and public satisfaction with levels of involvement Democratic deficit addressed |

Prioritisation of research questions with greatest relevance for patients and the public Improved overall research design leading to safer and more ethically robust research, participant-sensitive data collection tools, better recruitment rates, increased validity of interpretation of findings, wider dissemination, public engagement and longer-term impact Psychological benefit for patients and the public involved, and for researchers |

Democratic deficit addressed Researchers ‘working with’ rather than ‘doing to’ patients and the public Patient and public satisfaction with levels of involvement Lay people and researchers who are prepared for and supported in PPI Prioritisation of research questions with greatest relevance for patients and the public Improved overall research design leading to safer and more ethically robust research, participant-sensitive data collection tools, better recruitment rates, increased validity of interpretation of findings, wider dissemination, public engagement and longer-term impact |

| Expected developmental approaches to the programme (PPI) | Development of partnership approaches User-led research Emancipatory research |

Development of models of PPI and supportive infrastructure that optimises PPI impact on the research process | Governance frameworks Advisory organisations and guidance Public engagement |

| Programme theory | Critical theory (Habermas 1972129) Emancipatory concept of PPI (Gibson et al. 2012130) |

Architecture of involvement (Brett et al. 2010131) Multidimensional conceptual framework of PPI in health research (Oliver et al. 2008132) Partnership synergy (Lasker et al. 2001105) |

Normalisation Process Theory (May and Finch 2009121) |

We drew on the work of Habermas129 to predict the outcomes of PPI when operationalised through the moral perspective. Habermas proposes that critical theory challenges the traditional superiority of scientific knowledge and unmasks ideologies that seek to prevent the voice of marginalised groups from being heard. The case for emancipatory knowledge is put forward where personal knowledge is gained through self-reflection and leads to personal empowerment. This is amplified through communicative action where the interpersonal knowledge of groups comes together through mutual understanding. 129 Habermas’s work, alongside others, is used by Gibson et al. 130 to develop an emancipatory concept of PPI.

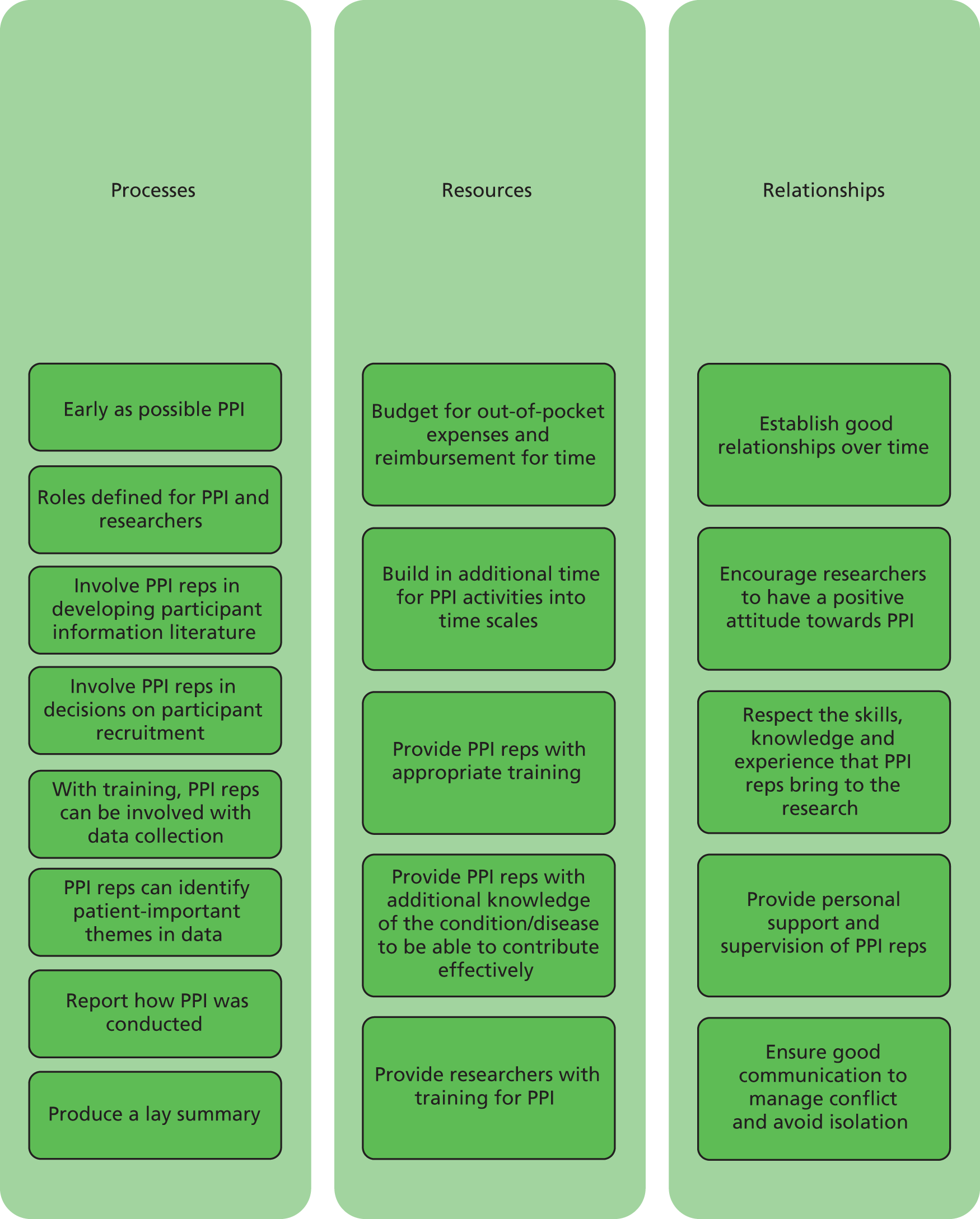

For the methodological perspective on PPI we used the multidimensional conceptual framework of PPI proposed by Oliver et al. ,132 the indicators of successful PPI developed by Boote et al. ,133 through consensus methodology, and the systematic review of Brett et al. ,29 which suggested the architecture required to enable effective PPI. As the methodological paradigm also depicts PPI in research as leading to improved outcomes for the research and for all those involved, we also drew on the partnership synergy model of Lasker et al. ,105 which proposes that synergistic partnerships (between PPI representatives and researchers) lead to high-quality (research) plans with more chance of a successful outcome.

A key MRT that informed our research approach was NPT. 121 Specifically, it is a candidate MRT to inform the policy perspective on PPI, but we found in practice that its constructs systematically inform all three viewpoints and therefore we used it explicitly to similarly inform our methodological approach (see Table 2).

Normalisation Process Theory

In attempts to help understand why it is that seemingly effective innovations often fail to flourish when rolled out in practice (context), NPT addresses two important problems that face service improvers as they try to get innovations into practice:

-

process problems – about the implementation of new ways of thinking, acting and organising

-

structural problems – about the integration of new systems of practice into existing organisational and professional settings.

Because PPI in research is not an entirely ‘new’ innovation, intervention, programme or phenomenon, but also is not yet fully normalised within contemporary research practice, it has been suggested15 that NPT offers unique potential for helping theorise how PPI is/is not routinely operationalised (embedded) and sustained (or not) in practice.

As an ‘action’ theory, NPT also sharpens our analytical focus on the actual work that people performing PPI do, or do not do, rather than people’s attitudes (how they feel about what they do) or their intentions (what they say they are going to do). 134 NPT distinguishes action according to a set of four constructs. Each of these represents a generative mechanism of social action. That is, each construct represents different kinds of work that people do in orienting themselves to a set of practices of PPI in research. These constructs and their components (domains) (Table 3) address the ways that people make sense of the work entailed in implementing and integrating PPI (coherence); how they engage with this work (cognitive participation); how they enact it (collective action); and how they appraise its effects and modify it (reflexive monitoring).

| NPT construct | Description | Components (domains) |

|---|---|---|

| Coherence | The sense-making work that people do individually and collectively when they are faced with the problem of operationalising some set of practices | Differentiation |

| Communal specification | ||

| Individual specification | ||

| Internalisation | ||

| Cognitive participation | The relational work that people do to build and sustain a community of practice around a new technology or complex intervention | Initiation |

| Enrolment | ||

| Legitimisation | ||

| Activation | ||

| Collective action | The operational work that people do to enact a set of practices, whether these represent a new technology or complex health-care interventions | Interactional workability |

| Relational integration | ||

| Skill set workability | ||

| Contextual integration | ||

| Reflective monitoring | The appraisal work that people do to assess and understand the ways that a new set of practices affect them and others around them | Systematisation |

| Collective appraisal | ||

| Individual appraisal | ||

| Reconfiguration |

Normalisation Process Theory has been developed for using in a flexible and dynamic way and can both direct and sensitise the practical and analytic trajectories of a research project. There is currently no published review of its empirical application, but it has been seen to have been applied to good effect in a number of social and health-care settings. 121,134,135 Of relevance in the RAPPORT study, and discussed in the following sections, is that case study methods have been seen to be more robust when theoretical propositions to guide data collection and analysis have been previously developed. 136 We have used NPT constructs and domains both to direct our data collection and to guide our analysis, particularly within our case study work. In effect, these domains map across to the RE, and are most significant in theorising PPI mechanisms and outcomes, and to some extent the context, but, as discussed below, were combined with additional questioning and coding to inductively explore other emerging significant themes.

We also drew on previous work focused on the architecture and infrastructure29,137 required for PPI to be operationalised.

Research design and methods

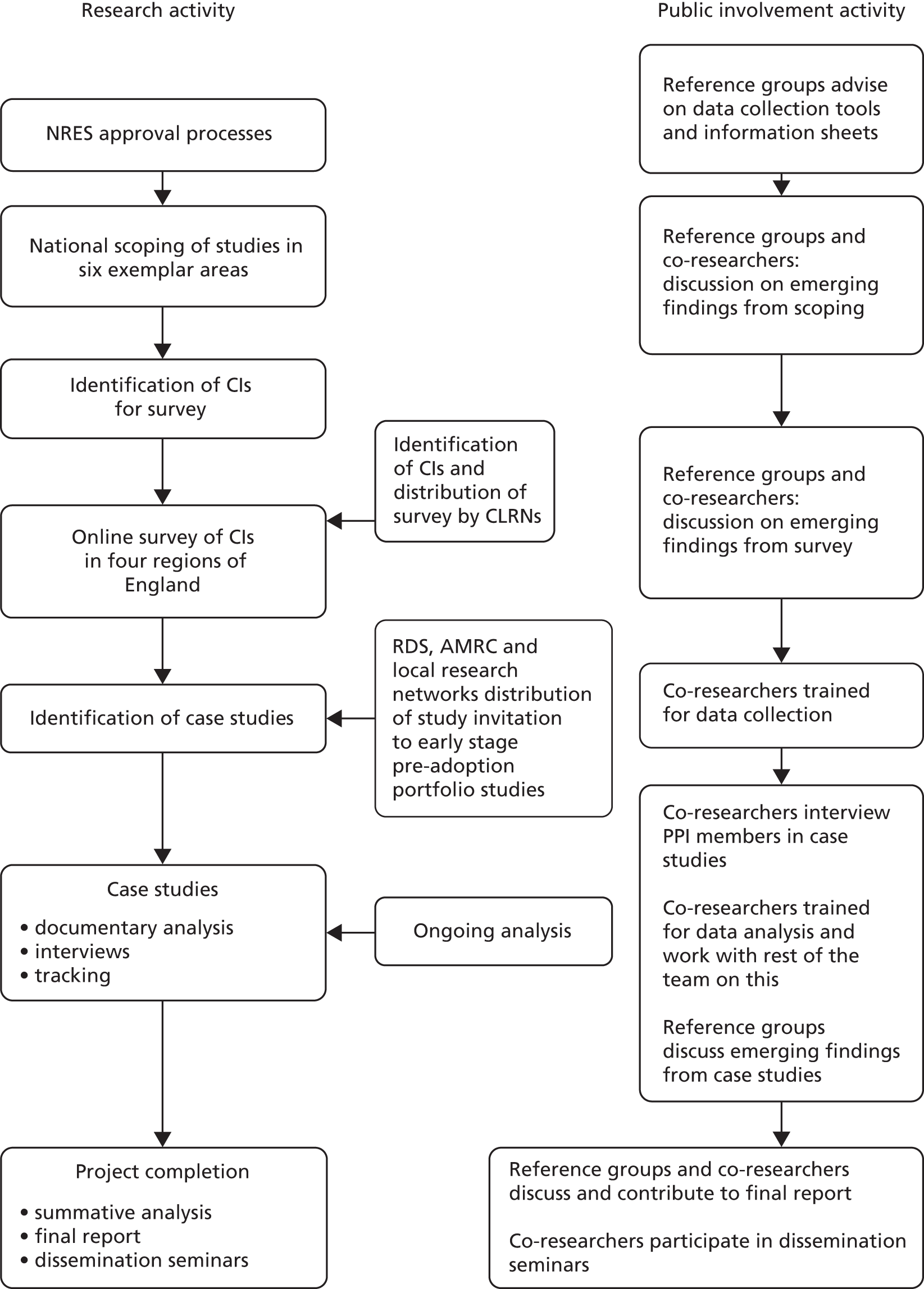

Both RE and NPT are method-neutral and often employ both qualitative and quantitative methods to collect sufficient information on the context (the setting and focus of the research), processes (type of involvement and formal support processes), structure and agency (organisational structures such as PPI frameworks and actions of stakeholders including researchers and lay representatives) within each case. Utilising a sequential, mixed-methods approach, the study was conducted in three stages, from May 2011 to February 2014. The project flow chart, shown in Figure 3, illustrates the phases of the research and methods employed and PPI.

FIGURE 3.

RAPPORT flow chart. AMRC, Association of Medical Research Charities; CI, chief investigator; CLRN, comprehensive local research network; NRES, National Research Ethics Service; RDS, Research Design Service.

The first two stages of the study comprised a scoping and survey which provided us with a contextual backdrop to PPI in current and recent research. These methods also informed us about what is recognised as PPI, and gave us an indication of the current level of PPI across six health research topic areas (see below). These findings informed the development of a sampling frame for the subsequent (third) phase, in-depth case studies.

To demonstrate which elements of PPI in research influence its outcomes, regardless of setting, those that are context specific, and what different approaches can and cannot achieve, we purposively selected six exemplar areas that by their focus and research tradition could capture the full continuum of PPI. These are:

-

Cystic fibrosis (CF). This life-limiting condition affects children and younger adults. Services are located within secondary care and specialist centres. There is a strong current laboratory-based research focus on gene therapy. Compared with the other topic areas, there is less of a history of PPI, with particular challenges in recruiting children and younger people.

-

Diabetes mellitus. This is characterised by a clear clinical diagnosis and its treatment emphasises self-management and lifestyle change. The disease affects people across the lifespan and services are predominantly delivered in primary care. PPI is well established particularly through powerful patient organisations.

-

Arthritis. This occurs through the lifespan but predominantly in older people. There are a range of treatments in a range of settings with an emphasis on preventing further deterioration. A strong patient organisation and recent history of involvement in research have informed the development of Expert Patients Programme.

-

Dementia. This is a condition of later life with a limited life expectancy. Characteristics that can shape PPI include the unclear trajectory of the disease, the stigmatising nature of the condition, reduced mental capacity and a population predominantly of older persons within a primary care setting. There is a well-established history of PPI in the identification of research priorities in the Alzheimer’s Society Quality Research in Dementia Network and an increasing recognition of the need to develop research to be inclusive for this population.

-

Intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDDs, also known as learning disabilities). Widely varying conditions mark out a marginalised group in terms of health-care delivery and health research. Despite the challenges of making research accessible for this group, there are a well-established history of PPI and well-developed theoretical and policy participative frameworks that inform policy, practice and research.

-

Public health. This includes participants across the lifespan who do not see themselves as service users. It may include community interventions and user-led projects in a variety of settings, but faces challenges in PPI, particularly in harder-to-reach groups.

These topic areas represented a diverse range of studies and associated models of PPI. They included studies with participants recruited across the lifespan (such as children and young people in CF studies, and older people in dementia studies), as well as different research designs (basic science to qualitative), settings (acute care, primary care) and traditions and history of PPI. For example, diabetes mellitus has a strong national patient organisation with a record of being involved in research and commissioning of health services. Both diabetes mellitus and dementia have a national research infrastructure that has well-established PPI mechanisms,78,138 and the IDD community at both policy and research levels has focused on inclusive practice. 139 Public health was incorporated to include community interventions and user-led projects and local populations who may not consider themselves as patients.

We built quality and rigour into the research process, from the method of sampling research studies for each stage, through data collection, to the ‘audit trail’ created during analytic phases.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included researchers and service users and members of the public who:

-

were involved in a study eligible for adoption on the UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) portfolio in one of the six exemplar areas

-

were 13 years old and over

-

gave informed consent.

We excluded researchers and service users and members of the public who:

-

were not involved in a study eligible for adoption on the UKCRN portfolio in one of the six exemplar areas

-

were under the age of 13 years

-

did not give informed consent.

Ethical approval

This project had NHS approval (REC reference: 11/EM/0332), obtaining favourable approval by Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 1 Proportionate Review Sub-Committee on 13 August 2011 with no changes to the research protocol.

Ethical issues

It was not expected that any major ethical issues would emerge from this project. However, we were aware that we might be including younger people, people with IDDs and users of dementia services. The team was skilled in working in sensitive areas and with these groups, although few such participants were involved with or recruited to the case study phase of this research. We also foresaw that there might also be sensitivities in discussing experiences of a project with the potential to expose bad practice and misuse of PPI, so we were careful to remain neutral in our reactions to reports of practice, while also probing carefully in order to clarify understandings and gain fuller explanations. Informed consent was taken from all participants participating in interviews in stage 3.

Stage 1: national scoping of studies

To address objective 1, a national scoping of studies within the six exemplar areas was undertaken (October–December 2011).

Sample

Our sample here included current studies or those completed in the previous 2 years in the six exemplar areas and being undertaken in England. To ensure relevance to the NHS and scientific robustness, studies were limited to those registered with the UKCRN portfolio, excluding commercially funded studies. To ensure inclusion of studies most likely to have been designed since the embedding of PPI in the research governance framework,1 we excluded studies older than 2 years (end date of recruitment before 1 September 2009). We also excluded studies funded by commercial organisations because, despite current criticisms of the lack of transparency in drug trials,140,141 access to the study documents required was likely to be limited.

Data collection

Studies were identified using the using the search terms in Table 4.

| Topic area | Focus and key words/terms |

|---|---|

| CF | Key word ‘cystic fibrosis’ |

| Diabetes mellitus | Type 1 and type 2 and other |

| Arthritis | Musculoskeletal, inflammatory and immune, genetics, primary care |

| Dementia | Dementia and neurodegenerative diseases, Huntington’s disease, motor neurone disease, Parkinson’s disease, other |

| IDD | Searched on key words: ‘learning’, ‘attention’, ‘Downs’, intellectual’, ‘autism’, ‘Asperger’. Mental health: learning difficulties theme. Specific syndromes listed by Royal College of Psychiatry142 |

| Public health | Primary care, infection, key word ‘public health’ |

| All topics | Generic relevance and cross-cutting themes |

Details of each study were electronically searched via funding body databases. Relevant documentation such as reports, abstracts and protocols was reviewed for the type of research (e.g. laboratory based or qualitative) and any evidence of the nature and extent of PPI. Where information was not available electronically, the funding body was contacted and requested to provide further relevant details of the study. Indeed, one of our findings from this initial scoping exercise is that there is minimal direct open access to such study documentation. Significantly, even when the protocol was available on the funder’s or study’s website, there was little information about PPI. Therefore, we also contacted study teams directly or through collaboration with the Association of Medical Research Charities (AMRC) for PPI information.

Scoping response

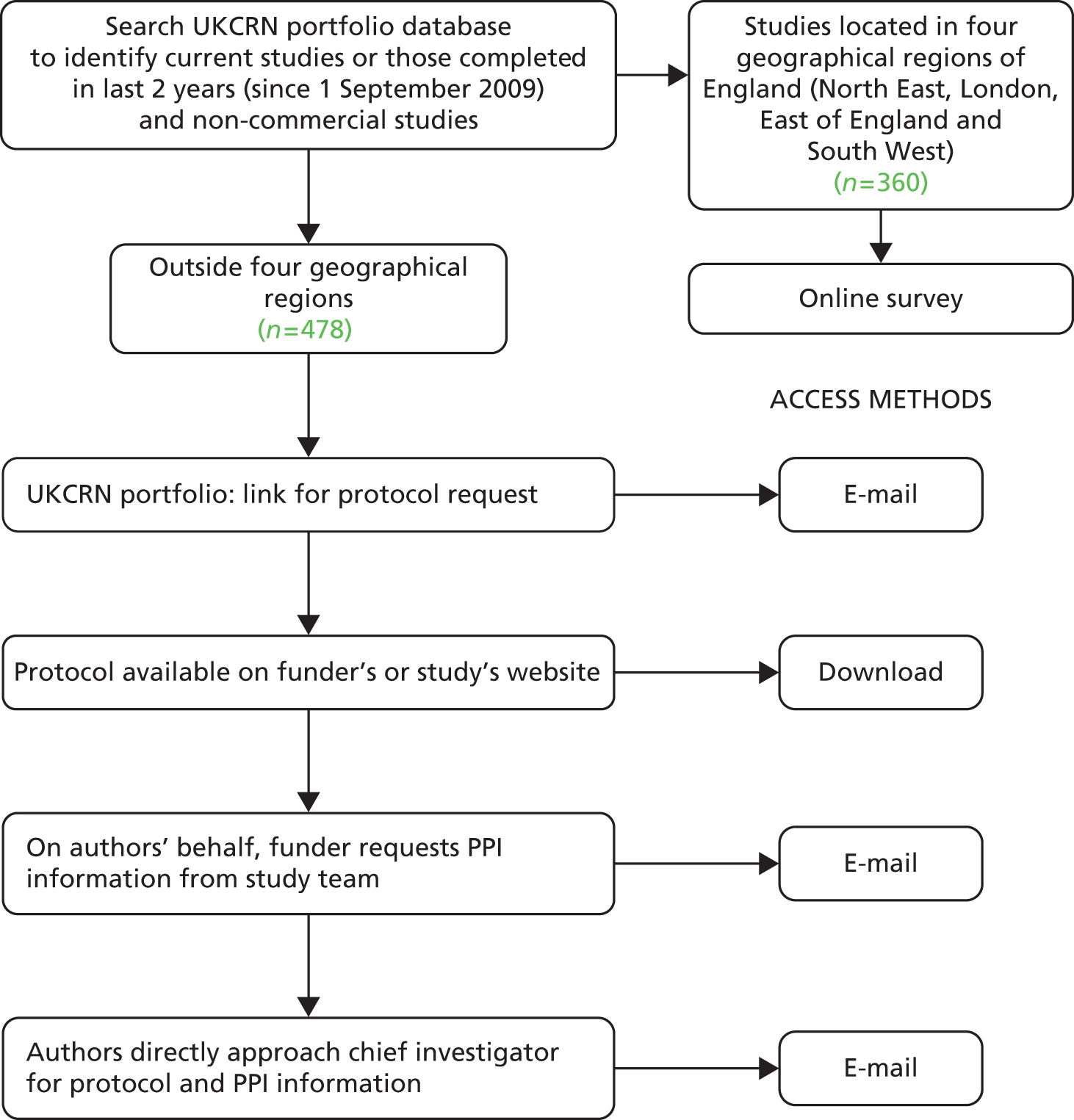

In total, 1464 studies in the six broad topic/exemplar areas were downloaded from the UKCRN database. One hundred and two were excluded as not in the specific topic areas, 263 as more than 2 years old and 261 as commercially funded. A total of 838 studies were included (Table 5). These were then divided into the 478 included in the scoping, and 360 for the online survey. All of the latter group were within the four selected regions of England (Figure 4).

| Topic area | Number of studies identified on UKCRN portfolio | Number of studies for inclusion | % of total on UKCRN |

|---|---|---|---|

| CF | 23 | 8 | 35 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 512 | 277 | 54 |

| Arthritis | 399 | 188 | 46 |

| Dementia | 282 | 192 | 68 |

| IDD | 90 | 51 | 57 |

| Public health | 158 | 122 | 77 |

| Total | 1464 | 838 | 57 |

FIGURE 4.

Flow diagram of scoping and survey.

In the UK, clinical research networks have been established in each of the four UK nations funded by their health departments. These national networks form UKCRN. The UKCRN portfolio of studies was used as one single database to identify relevant research studies, and information including study title, sample size, end date of recruitment and contact details was downloaded into an Excel® (version 14, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet.

For studies not covered by the online survey, that is running outside the four selected geographical regions, including studies in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, direct requests were made. Documents or e-mail replies were then reviewed by two team members independently for background study information and any evidence of the nature, extent and activities of PPI. The scoping exercise obtained information about PPI from 182 studies out of a possible total of 478 (38%) (Table 6). Documents received in response to requests for PPI information included 93 protocols, 12 journal articles, 64 e-mail replies, 10 interim/final reports and 3 Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) forms. Other documents (such as grant applications, reports to funders and lay summaries) were also provided. Some studies provided more than one source of information. The studies in the scoping had sample sizes ranging from 12 to 250,000, with a median of 250. The two main funders were NIHR (29%) and charities (29%). The remaining funders were a mix of government departments, the European Union, research councils and others. Forty-two per cent of the scoping studies were clinical trials, 33% were mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative non-clinical trials), 10% were basic science and 15% were tissue bank/database.

| Topic | Scoping response rate (%) |

|---|---|

| CF | 40 (n = 2 of 5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 34 (n = 46 of 137) |

| Arthritis | 42 (n = 55 of 132) |

| Dementia | 38 (n = 35 of 93) |

| IDD | 38 (n = 11 of 29) |

| Public health | 40 (n = 33 of 82) |

| Total | 38 (n = 182 of 478) |

Analysis

Variations in PPI were mapped against the type of research, topic area and funding body. Drawing on the conceptual framework of Oliver et al. 132 and the PIRICOM systematic review,29 a scoping framework was used to assess the stages of the research at which PPI took place, whether involvement was of lay groups or individuals and where it was located on the continuum of PPI from user-led to minimal PPI. We also assessed evidence of the ‘architecture of involvement’:29 those processes needed to enable PPI in research, which included a budget for PPI, defined roles for lay people, training and support, and means of communication between researchers and lay people. This was used to evidence the range of resources supporting PPI. The results from this analysis are presented in Chapter 5.

Stage 2: survey of lead researchers

Objectives 2, 3 and 6 were addressed by conducting an online survey (see Appendix 1) of lead investigators (January–February 2012). The design of the survey was drawn from indicators of successful PPI identified by Boote et al. ,133 including roles, resources, training and support, and recruitment. Informed by the findings of stage 1, the survey was conducted in four regions.

Sample

Four geographical regions in England were purposively selected for the survey to ensure maximum variation: the South West has a relatively large rural population and a long history of PPI;143 the East of England has established PPI networks144 with rural and urban areas; there is less evidence of any long-established PPI history in the North East, which has one major research hub and socioeconomic factors affected by a heavily industrialised past; and London is the most densely clustered in terms of research centres and has a relatively high population of people from black and minority ethnic (BME) groups.

Data collection

Drawing on the findings of the PIRICOM study,29 a validated online survey tool (Bristol Online Surveys, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK) was designed to collect data to assess how PPI is operationalised and its perceived impact on each study. Although the PIRICOM study found little evidence of PPI being theoretically conceptualised, there has been some work to develop a consensus on the principles and indicators of successful PPI,133 and this was used to underpin the survey design. The research team’s previous experience of using online survey tools suggested that good response rates are achieved when the survey remains focused, it takes no longer than 15 minutes to complete and rapid feedback is promised to participants. There was close working with the appropriate comprehensive local research network, specialty networks and local specialty groups to publicise and disseminate information about the study. The survey was electronically distributed to lead investigators across the four diverse regions and its findings also provided the test-bed for stage 3. Participants received a summary of findings.

Survey response and study characteristics

From the UKCRN portfolio 360 studies across the four regions were identified and an e-mailed invitation and link to complete the survey was sent out to all named chief investigators (CIs) or researchers. From the first e-mail there was a 17% response rate and following the reminder there was a total of 101 responses to the survey (28% response rate) (Table 7).

| Topic | Number replying | Total number sent |

|---|---|---|

| CF | 2 | 3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 28 | 140 |

| Arthritis | 14 | 56 |

| Dementia | 31 | 99 |

| IDD | 5 | 22 |

| Public health | 21 | 40 |

| Total | 101 | 360 |

The 101 studies surveyed ranged in sample size from 5 to 300,000, and grants awarded ranged from less than £50,000 (8% of sample) to 30 over £1M (30% of sample). Funding was split evenly between NIHR (40%) and charities (40%). The survey included 40% clinical trials, 33% quantitative and qualitative, 12% basic science and 7% tissue/bank database and a further 7% were coded ‘other’ (as insufficient information to classify).

Analysis

The focus of the stage 2 survey was to describe researchers’ experiences and perceptions of positive and negative outcomes of PPI, and benefits and challenges of PPI for researchers. The focus of analysis in this stage was therefore the use of summary statistics alongside qualitative analysis of open-text responses. Using an electronic survey tool enabled rapid access to data that were readily transferred to SPSS (version 20, IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY, USA) for analysis. This analysis was mapped against the results of the scoping in stage 1 to identify any recurring patterns within and between types of research, stages in research process where PPI occurred and topic areas. The findings from these two phases were used to develop a sampling frame for the final case study phase. The survey findings were then used as one of the ways to identify research teams likely to be interested in taking part in stage 3.

Stage 3: case studies

Objectives 2–7 were addressed through in-depth case studies. Stages 1 and 2 provided a contextual backdrop, and findings from these stages informed what was recognised as PPI in current and recent research. Stage 3 delivered an in-depth RE of the CMO in specific research settings to increase understanding of at what points PPI has the most impact and effect on outcomes.

Case study methods are a recognised and well-established approach to conducting research in a variety of ‘real life’ settings including health care. 145 Yin146 defines case study research as ‘an empirical study that investigates contemporary phenomena within a real life context, when the boundaries between the phenomena and context are not clearly evident and which multiple sources of evidence are used’ (p. 18). This approach allowed us to employ a range of social science research techniques and designs, mainly qualitative, to gain in-depth understanding of the nature of engagement between service users, the public and local NHS organisations within their specific organisations. It also provided the methodological flexibility to generate some theoretical insights from our results. 147 We were thereby able to adopt an interactive approach to data collection and analysis, allowing theory development grounded in empirical evidence, which was the main strength of this design. 148

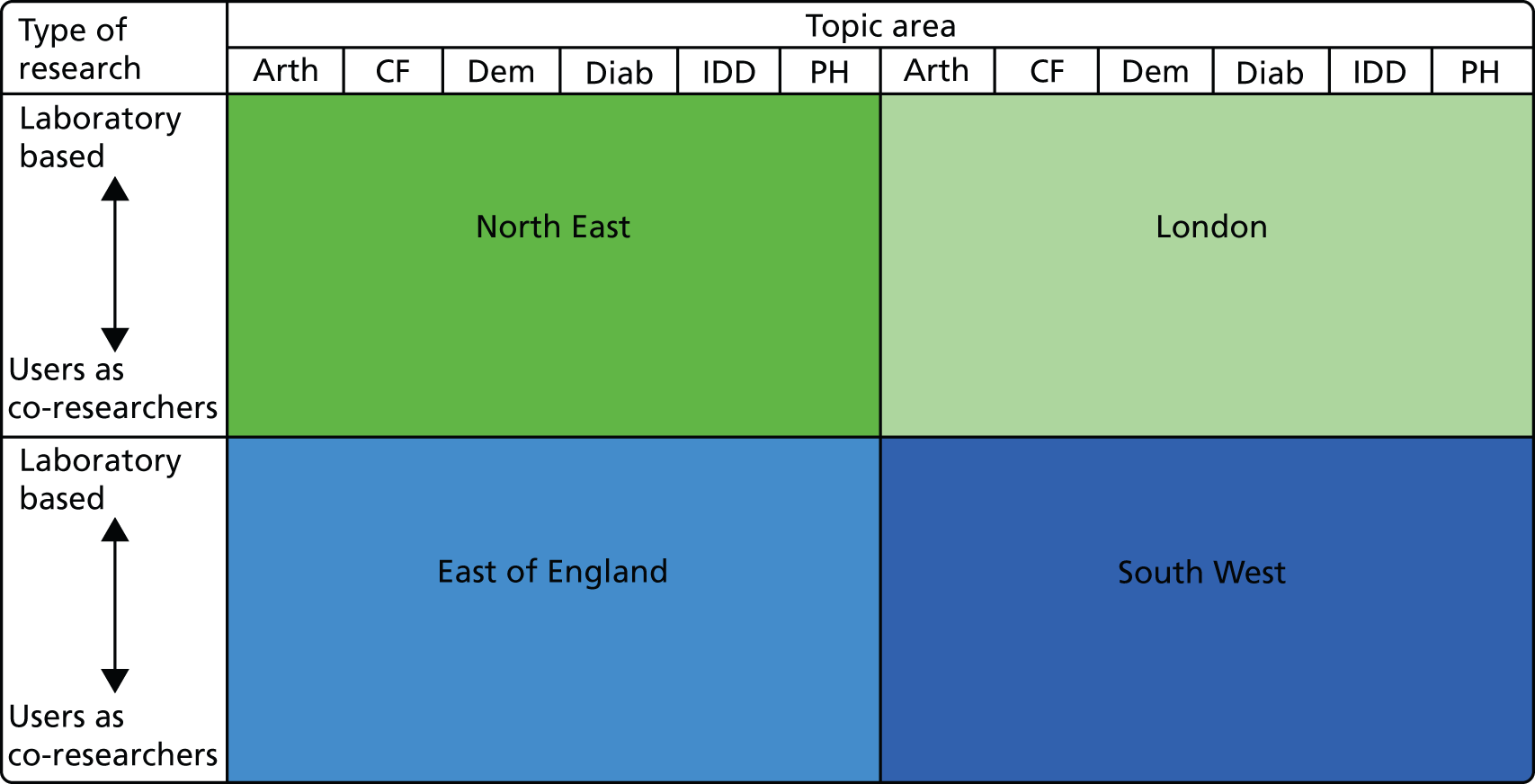

Sample

To ensure typicality and sufficient variation across topic areas, types of research and geographical regions, a sampling frame (Figure 5) developed from the previous stages was used to purposively select up to 20 case studies where the case is a single research study. This enabled maximum variation, but also allowed comparison within and between region, topic area and type of research.

FIGURE 5.

Sampling frame. Arth, arthritis; Dem, dementia; Diab, diabetes mellitus; PH, public health.

Data collection and recruitment

To ensure a range of studies that varied in their stage of research implementation, several recruitment strategies were employed:

-

Potential studies were identified from the survey.

-

Suitable early stage studies that had been awarded funding but had not yet been adopted on the UKCRN portfolio were identified by local Research Design Services (RDSs), by relevant charitable funding organisations from the AMRC, and by networks such as the Primary Care Research Network from their futures list. The RDSs, AMRC organisations and local research networks such as the Primary Care Research Network sent out information about the RAPPORT study and investigators interested in participating were asked to contact the RAPPORT study team.

Data were collected from each case study to inform the three stages of realist enquiry – context, generative mechanisms and outcomes119 – using the methods of documentary analysis, semistructured interviews with key informants from case studies, tracking and semistructured interviews with research funders and networks as follows:

Documentary analysis

Key documents from each project were requested and analysed149 to situate the project historically and capture the temporal dynamics of PPI at three levels of scale: micro (project), meso (host organisation) and macro (funding body). Documents requested included those pertaining to PPI policy, structures and support mechanisms (e.g. training) in the host [e.g. higher education institution (HEI)] and funding organisations. Project team and advisory/steering group meeting notes or minutes were also requested from participating case studies and (once anonymised) were added to the documentation collected in stage 1. Other relevant documents included, for example, PISs or publicity materials, which provided records or evidence of PPI impact/outcomes. Documents were requested and added to analysis throughout the data collection period of the RAPPORT study. A total of 278 documents were collated and analysed in the case study phase.

Semistructured interviews

Semistructured interviews were conducted with key informants in each case study. Depending on the study, this included the PPI members, lead/senior researcher, coapplicants, researchers, clinical partners and sometimes PPI co-ordinators within a host organisation. To maximise recruitment and participant convenience, interviews were conducted mainly by telephone and designed to take about half an hour to complete. The option of face-to-face interviews was also open to participants where preferred.

The interview guides developed (see Appendix 2) drew on, and were cross-referenced to, NPT,121 and focused on mechanisms and associated impact and outcomes of PPI. In the case of children and people with learning disabilities involved in studies, we had planned to review and modify data collection tools in collaboration with a reference group of people with learning disabilities, and a reference group of younger people with CF and their parents. However, all participants in this research were over the age of 18 years and, as seen below, a few participants with IDDs were recruited to the RAPPORT study. The only interviewee with a learning disability was high functioning and had experience of media interviews. Participants received an ethics committee-approved information sheet (see Appendix 3) and signed a consent form (see Appendix 4). All scheduled interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed for analysis, and researchers checked them for accuracy and anonymised them upon receipt.

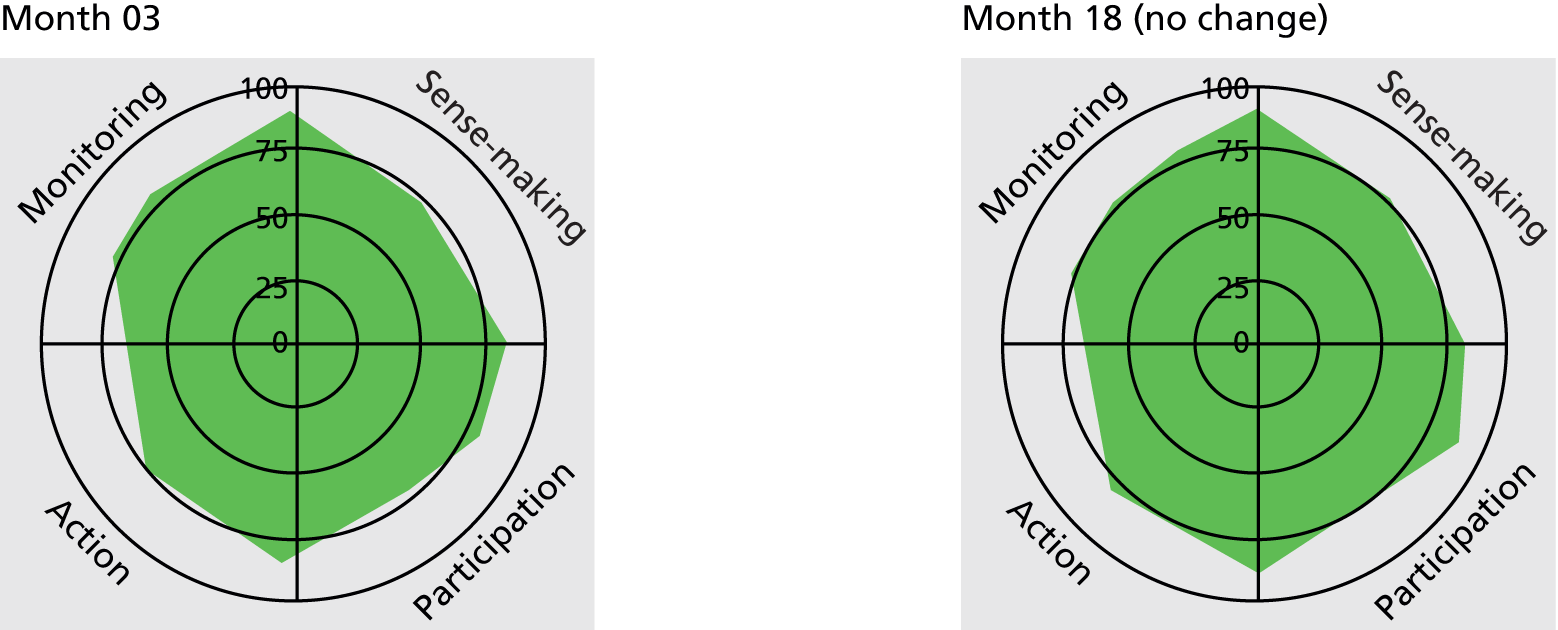

Tracking

Ongoing case studies were tracked over an 18-month period to identify public involvement processes. In negotiation with the study team this was expected to be a regular focused (telephone or occasionally face-to-face) interview with the lead investigator or other nominated member(s) of the research team but, as shown below, more often we were able to track PPI processes more fully by interviewing more than one researcher and/or a PPI member and supplement this data collection with e-mail exchanges/updates. The frequency of this contact depended on study characteristics and PPI milestones within the project, but occurred approximately every 12–16 weeks.

Semistructured interviews with research funders and research networks

To develop a fuller understanding of the dynamic and historical context of PPI, telephone interviews were also conducted with research funders and research networks. Key informants here included those professionals with responsibility for setting PPI policy and/or process for the funder/network and the studies funded within their research grant programmes. Other key informants here also included those with a PPI role within the funding body or network funding body – often as PPI representatives on research priority-setting panels or funding panels.

Interview guides here again drew on NPT (see Appendix 2), participants received an ethics committee-approved information sheet and signed a consent form (see Appendices 2 and 3) and interviews were audio-recorded and professionally transcribed for analysis and anonymised upon receipt.

Response and case study characteristics

In total we recruited 23 case studies in accordance with our sampling strategy as shown in Table 8.

| Topic | Region | Study design | Funder |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia | North East | Basic science involving humans | NIHR |

| East of England | CTIMP | NIHR | |

| Diabetes mellitus | North East | CTIMP | NIHR |

| London | Trial, cohort, qualitative | NIHR | |

| Mixed qualitative/quantitative | NIHR | ||

| Process of care, qualitative | Non-commercial | ||

| East of England | RCT to compare intervention | NIHR | |

| South West | Basic science involving humans | Charity | |

| Genetic epidemiology | Charity | ||

| Intervention (mixed quantitative/qualitative) | Charity | ||

| Arthritis | London | CTIMP | Charity |

| Research database | Research council/charity | ||

| East of England | Cohort | Charity | |

| South West | Qualitative methods | Research council | |

| Public health | London | RCT to compare intervention | NIHR |

| East of England | RCT to compare intervention | NIHR | |

| Survey admin questionnaires/interviews | Charity | ||

| South West | RCT | NIHR | |

| IDD | London | Questionnaire | NIHR |

| East of England | RCT to compare intervention | NIHR | |

| South West | Qualitative | NIHR | |

| Systematic review | NIHR | ||

| CF | London | CTIMP | NIHR/research council |

Considerable efforts were made to balance the recruitment of case studies according to region, topic area and research design. Other factors considered were the range of PPI models, PPI approaches, the stage the case study was at in its research process/cycle and the duration of the study. The cases we achieved appeared remarkably balanced, especially since the body of research in progress at any one time cannot be balanced according to our project’s specifications, but will be dictated by wider historical and political trends, biases and service needs.

Reflecting our emphasis on PPI processes and the tracking element of our research design, we over-recruited case studies in order to compensate for any potential dropout from the study. Standard consent to participation in research respects the right of individuals to withdraw from participation at any time, and for a variety of reasons research projects can be stopped before completion. Although we started with 23 case studies, after about 9 months into the RAPPORT study one withdrew from the study. There were two PPI representatives and two researchers in this study. These data were destroyed and removed from the analysis presented here.

Case studies were at various stages of progress during our RAPPORT data collection period and were tracked for between 8 and 18 months. Most case studies (17 of 22) had already begun before we started data collection, and approximately half (12 of 22) continued after RAPPORT data collection ended.

Initial and ongoing correspondence with case study CIs or a nominated research colleague identified potential documents and personnel (by role) to invite for interview for the RAPPORT study. In some cases it was acknowledged that some PPI representatives, more often those who had taken part in a larger one-off PPI event in the past, could no longer be identified or approached, as their contact details had been destroyed in line with the Data Protection Act (1998). 150 In addition, where studies in their development had been put to PPI panels that advise on a wider portfolio of research proposals [e.g. case study 01 (CS01)], it was deemed that they would have little to say regarding one of many studies they had reviewed in recent years.

Case studies were allocated to one of the three qualitative RAPPORT researchers at the University of Hertfordshire (PW and EM) and the University of East Anglia (JK). PPI co-researchers on the RAPPORT study (MC, DM and another PPI co-researcher) were affiliated to the University of Hertfordshire PPI group and thus were involved in case studies allocated there.