Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was joint funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceeding programmes and INVOLVE as project number 10/2001/29. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in June 2014 and was accepted for publication in March 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Hanley reports personal fees from the Medical Research Council and personal fees from User Involvement in Voluntary Organisations Shared Learning Group, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Gamble et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

What is patient and public involvement?

Public involvement in research is described as research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them. 1 The role of patients and the public therefore extends far beyond that of a research ‘subject’ or participant. Increased recognition that patients and public are stakeholders in research has led to increasing calls that they be represented within that research process, resulting in a growth of patient and public involvement (PPI) in health research both nationally and internationally, and also within the peer review process of that research. 2–4 This includes the USA, where it is known as stakeholder engagement, and Australia, where it is termed consumer and community participation.

It has been suggested that clinical trials are particularly likely to benefit from PPI. 5,6 Health research funding bodies strongly encourage researchers to implement PPI at every stage of the research process and specifically to include PPI contributors on Trial Steering Committees (TSCs). 7–12 Assimilation of PPI into grant applications is therefore becoming commonplace, with clinical trial funding bodies requiring that plans for PPI be submitted by investigators to ensure trial participants’ needs are respected, and to maximise research quality and relevance. 7,12–15

When should patient and public involvement start?

Patient and public involvement can start at various stages of a trial and may influence many aspects. The ability to have an impact on a trial has to be considered in line with the opportunity to exert influence. Staniszewska et al. 16 discuss the importance of PPI in the design of research to optimise its impact and relevance. During the design stages of a trial, many decisions are made that determine the relevance and conduct of the proposed research: the precise specification of the research question including the outcomes to be measured; visit schedules; methods of data collection; and recruitment and consent procedures. Fudge et al. 17 suggest that decisions made by professional researchers at the outset of a study have a cumulative and significant influence on the potential for PPI to have an impact on a study and that involvement is more difficult to achieve once studies are under way. It is therefore important to consider the stage of the trial at which PPI begins alongside the process of involvement when identifying impact.

Boote et al. 18 reviewed published case examples that focused solely on PPI at the design stage of primary health research; they identified just six peer-reviewed journal articles reporting on PPI in the development of a clinical trial. The PPI methods entailed group discussions. Although the methods of PPI may not be considered representative of the diverse nature of PPI, suggesting the presence of selective reporting, the key contributions identified have been reported from other models of involvement: review of patient information sheets and consent procedures; suggestion of outcome measures; review of acceptability of data collection procedures; and recommendations on the timing of potential participants being approached for the study and timing of follow-up. 5 To understand how frequently these contributions occur and the factors associated with their occurrence there is a need to investigate PPI in an unselected cohort of trials.

The UK Department of Health guidelines, Best Research for Best Health,7 state that PPI must be included in all stages of the research process including priority setting, defining research outcomes, selecting research methodology, patient recruitment, interpretation of findings and dissemination of results.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme has encouraged PPI, previously asking researchers to consider the benefits of its incorporation and now requesting evidence of PPI from researchers submitting their proposals. Oliver and Gray19 assessed the impact of public involvement in the HTA research-commissioning programme; however, the impact of public involvement in the research funded by the HTA programme is yet to be assessed.

How should patient and public involvement be implemented?

Challenges to the realisation of plans for PPI include debate regarding its purpose, lack of evidence regarding the impact of PPI, complexities in researchers and contributors sharing power, and difficulties in ensuring sufficient resources for PPI. 5,15,18,20–22 Alongside such challenges are uncertainties regarding how best to plan PPI. Guidance drawing on the opinions and experiences of those involved in PPI activity within trials is available21,23 and a 2011 review examined case studies of PPI in the design and conduct of trials. 6 However, the evidence base is limited in terms of the range of trials, researchers and patients that have informed this previous work, and there has been no systematic evaluation of the extent to which triallists’ intentions for PPI are put into practice.

Little is known about how or when researchers incorporate PPI in clinical trials, or what impact may stem from that involvement. There are indications that PPI can have favourable impacts upon every stage of the research process5,24–28 by helping to ensure that research funds are appropriately prioritised and that research evidence is relevant to patients, by improving recruitment and retention rates and by supporting the uptake of research in practice. Indications that PPI may have unfavourable impacts upon research24,29 or no impact at all30 have also appeared. In this intensely moral and political arena, the rarity of such reports has raised concerns that the benefits of PPI have been selectively reported. 5,31 Concerns have been expressed that the existing literature is selectively reported to make the case for or against PPI, with many reports aiming to make the case or convince the sceptics about PPI, and these concerns have led to questions about the quality of the evidence base for PPI in trials. Furthermore, as much reporting has involved single case studies, generalisability of the PPI literature is limited and may provide a misleading account of how PPI is implemented and its impact. 31 Crucially, these problems make it difficult to predict what type of involvement is most effective and where.

The relationship between the nature of involvement and the control of PPI contributors in the decision-making of the research process has been debated, with higher levels of control often being considered as of higher quality, and lower levels of control being criticised as tokenistic. 32 However, this approach has been critiqued. 33 For example, while it is often assumed that approaches that are described as limited, tokenistic or of low quality are ineffective, they may still achieve valuable impacts; conversely, those considered to be better models of involvement might not.

Who can be a patient and public involvement contributor?

The NIHR states:34

We need people with everyday experience of health, education, social care or services delivered in your home or near where you live. We often look for people who have experience of specific health services as a patient or carer, and who have an interest in research. We welcome individuals and representatives of voluntary organisations and patient groups.

However, there is debate about whether or not it is acceptable for individuals employed within a medical or research capacity to provide PPI. Current NIHR HTA guidance states that ‘To achieve the aim of bringing fresh eyes to the work of the HTA programme a patient or member of the public should not normally be a health practitioner, manager or researcher’. 35 Concerns have also been raised about PPI contributors becoming professionalised. 36 This may happen either as a result of contributing across a number of separate research projects or as a result of their role in facilitating or supporting PPI contributors within the remit of their employment, and may be extended to those undertaking leading roles in charities and patient organisations. The debate on the professionalisation of PPI contributors also has implications for training provisions.

Patient and public involvement contributors may be selected because their attributes or experience are considered to strengthen their ability to contribute to their role in the research. Others may be selected based on the perception of their ability to ‘represent’ the wider population of interest. Little is known about how PPI contributors are identified or the selection process used by researchers. This may affect the training and support needs of the PPI contributor in fulfilling their role.

Whereas the evidence on PPI activity in research is expanding, PPI training has received little research attention. Training demands time and resource, and also has potential to shape the future conceptualisation, implementation and impact of PPI in research. INVOLVE, the UK-based advisory body on PPI in health and social care research, reports that most PPI training courses have been developed within particular organisations or in the context of individual research projects. 37 It defines training broadly as any activity ‘that aims to help members of the public and researchers develop their knowledge, skills and experience to prepare them for public involvement in research’ (p. 5). 37 An examination of training and educational provision of PPI in research confirms the diversity of aims, content and delivery of training. For example, education and training for PPI contributors ranges from a year-long formally assessed and certificated course on the discovery, testing and evaluation of medical products and technologies,38 to one-day informal workshops to help contributors identify suitable research roles and build confidence. Examples of training for researchers are almost as variable, ranging from formal modules on the theory, policy and current practice of PPI within accredited master’s courses39,40 to single ‘awareness raising’ workshops on the aims and implementation of PPI in research. 41

Although this diversity of training may be appropriate, it raises questions about how to ensure training is fit for purpose. INVOLVE proposes that training be provided for both PPI contributors and researchers,37,42 tailored to their needs and roles, delivered on an ongoing basis and in ways that allow contributors and researchers to learn from each other. 37 These principles were drawn from consultations with over 30 stakeholders who had direct experience of PPI training either as providers or recipients. However, few details of the methods of consultation are available and little is known about the perspectives of those researchers and PPI contributors who have not participated in training. A key consideration for any training is that it engages with the diversity of learners’ needs and is meaningful from their perspective. 43 Insights on how members of the clinical trials community perceive PPI training, regardless of whether or not they have had prior experience of training, will help to ensure its relevance and uptake.

Should we assess impact of patient and public involvement?

Robust evidence on the effectiveness of PPI in research is absent. It has been argued that PPI in research is ‘the right thing to do’ and should occur irrespective of impact. 44 However, incorporating PPI within research requires time and resource,5 so we should be expected to learn from both the positive and negative experiences of researchers and PPI contributors to determine facilitators and barriers to impact for the benefit of future research. 45

For PPI contributors, getting involved in research has been reported to lead to ‘personal development’ such as boosting confidence, empowerment and a sense of purpose. 46 Similarly, there can be personal benefits for researchers, who have reported that their attitudes, values and beliefs about the worth of PPI had been heightened as a result of such involvement. 20 However, as well as being a vehicle for improving research validity, there are indications that ‘patient influence’ can pose a potential threat to the validity of research if it is not drawn upon appropriately. 14 For example, PPI in technical decisions may result in worse as opposed to improved project outcomes. 47

It is important that accounts of researchers and PPI contributors be accessed in establishing an evidence base to guide future approaches to the implementation of PPI. Each brings different perspectives and, consequently, the two parties may differ in their views of how PPI impacts on trials. This position is supported by the evaluation of PPI in the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC). 48 Indeed, much of the existing literature looks at the experience of PPI representatives or advisory groups, but there is less research on the experiences of professional researchers and clinical trials units (CTUs). An examination of the experience of PPI from all perspectives is needed to strengthen understanding and develop a more robust evidence base for future implementation.

A national questionnaire survey on the role of PPI in designing, conducting and interpreting randomised trials managed by clinical trial coordinating centres concluded that PPI was still uncommon. 49 Since the publication of this survey there have been many changes in the clinical research environment, including those brought about by the establishment of the UKCRC in 2004 and the UKCRC Registered Clinical Trials Units (RCTUs) in 2007. 50 RCTUs are assessed as having the expertise necessary to ensure high-quality, successful and timely trials, and to meet regulatory and governance requirements. There is limited knowledge about the engagement of RCTUs with PPI contributors, and challenges to early PPI for trials competing for public funding have been identified. These include the short time frame for completion of applications, the lack of resources to support PPI and difficulties in identifying appropriate PPI contributors. It is expected that a growing proportion of publicly funded clinical trials will be co-ordinated via a RCTU. Therefore, there is an important need for new work to be conducted within the network of RCTUs to explore the current role they have in determining the process and quality of PPI, and to aid strategic planning for future practices drawing strength across RCTUs.

How should the impact of patient and public involvement be assessed?

The assessment of impact is difficult because of the complexity of PPI. Problems with the conceptualisation and measurement of the impact of PPI have also been identified,51 and few studies have accessed the perspectives of both PPI contributors and researchers. Moreover, much of the literature on the impact of PPI in research has not focused specifically on randomised trials, although these are regarded as particularly likely to benefit from PPI. 5

In assessing impact stemming from PPI in clinical trials, there is a need to consider the empirical evidence on how PPI was actually implemented in its broadest form. For example, direct impact may be observed in terms of suggested improvements to patient information sheets, logistics or the visit schedule, which in turn may be thought to lead to improved recruitment. Direct impact may be observed in relation to the choice of outcomes to be measured, either by suggestions to include outcomes otherwise considered unimportant by health professionals or by suggestions to improve the likely completion rate of participant questionnaires. In turn, these may lead respectively to research that patients are more likely to use to help them make decisions and to research of higher quality. Impact may also be less direct, for example, with PPI providing an opportunity for dialogue between researchers and PPI contributors; the improved awareness of patient perspectives may not only help to guide researchers’ attention towards clinical problems that are most relevant to patients, but also drive their motivation to address these problems.

Despite its importance, there is a lack of well-accepted approaches to the assessment of the impact of PPI in health research. 5,52,53 Staniszewska54 commented that the varied methods used to assess and report the impact of involvement caused difficulties when trying to synthesise evidence across studies. More recently a Public Involvement Impact Assessment Framework (PiiAF)55 has been developed to help researchers at the beginning to identify the issues that could affect the impacts public involvement can have on their research and to develop an approach to assessing these impacts during their research.

Aim

The overall aim of this project, known as EPIC (Evidence base for Patient and public Involvement in Clinical trials), is to increase knowledge of PPI within randomised trials by:

-

establishing an unselected evidence base of how PPI has been implemented within randomised trials

-

identifying associated impact to inform the future optimisation of PPI by systematically describing and critically evaluating the process, challenges and impact of PPI from the perspectives of the PPI representative, chief investigator (CI) and CTU staff.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

The EPIC project aimed to investigate PPI in a cohort of randomised trials funded by the NIHR HTA programme between 2006 and 2010. EPIC comprised four phases:

-

Phase 1 examined triallists’ plans for PPI as described within their funding applications.

-

Phase 2 was a questionnaire survey of CIs’ and PPI contributors’ opinions and activities concerning PPI.

-

Phase 3 involved semistructured interviews with CIs, PPI contributors and trial managers (TMs).

-

Phase 4 examined the role of CTUs in identifying and supporting PPI needs by means of a questionnaire survey.

Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Liverpool Institutional Ethics Board (reference RETH000489).

Establishing the cohort

The cohort was identified as randomised trials that were actively receiving funding from the NIHR HTA programme between 2006 and 2010. The cohort included randomised trials at different stages, from recently funded applications to randomised trials that had reached the final report stage, providing data on PPI across all stages of the research process.

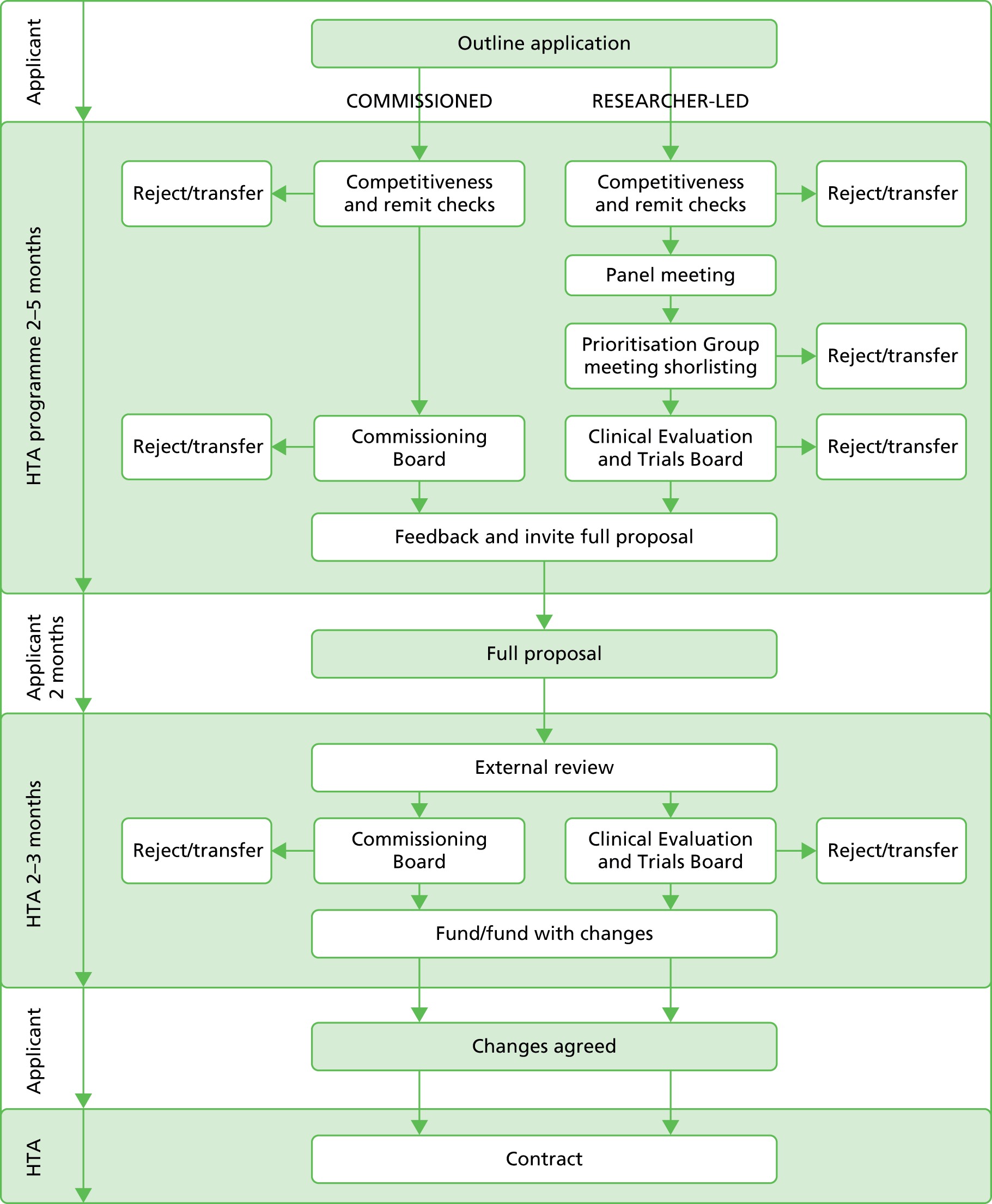

The NIHR HTA programme has a two-stage application process (Figure 1). In summary, the outline application is considered by the funding board and applicants are asked to address feedback from the board if a full application is requested. The full application is sent for external peer review and considered by the board to determine if it should be rejected or any changes made prior to funding. The full application consists of a completed application form and a detailed project description.

FIGURE 1.

National Institute for Health Research HTA programme application process.

We requested all available documentation relating to the application process. This comprised outline applications; the minutes of the board meetings at which the outline applications were considered and which contained feedback for the applicants to consider in submitting the full application; the full application form and the detailed project description; external referee reports; and the minutes of the board in which the final decision on funding was made. Prior to the release of these documents the NIHR HTA programme contacted the CIs of the trials involved, informing them of the intention to release their names, which were readily available within the public domain. We signed a confidentiality agreement and the NIHR HTA programme redacted sensitive information regarding budget information and names of coapplicants (not available within the public domain) before releasing the documentation.

Phase 1: documentation, data extraction and coding

A Microsoft Access® version 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database was developed to assist in extracting and analysing the information on PPI within the applications. Each application was given a unique identifier within the database and this identifier, rather than the NIHR unique identifier, is used to maintain confidentiality throughout. A PPI advisory group of five members with experience of providing PPI in randomised trials was established for this project (see Appendix 1). The advisory group commented upon the data extraction tool and made recommendations for changes. Data were extracted to characterise the cohort and to describe PPI activity within the two-stage application process and plans for involvement once trial funding was secured. Trial characteristics linked to trial complexity, or thought to be barriers or facilitators to recruitment,56 were also extracted. In brief, the extracted data included characteristics of the trial design and setting, disease or condition under study, type of intervention, participant characteristics, recruitment setting and any text that described or was relevant to PPI. Data were extracted by three reviewers (LD, JP, CG). Extracted text was anonymised by replacing any identifying details with a general term in brackets [term], or using [. . .] to indicate removed text.

Text extracts describing PPI were examined to determine the stage of its actual or planned initiation; for example, the outline application (submitted in the first stage of the application process) may have specified that PPI was planned to occur during the development of the full application (submitted in the second stage of the application process). The stages of initiation were the development of the outline application; the development of the full application; and following a positive funding decision or during the trial.

The text was also examined to determine the role of the PPI contributor’s input. This was categorised as managerial, responsive or oversight. We categorised PPI contributors as managerial if they were described as coapplicants or involved in the management of the trial, for example a member of the Trial Management Group (TMG). We categorised PPI contributors as having a responsive role if descriptions of their input were largely confined or targeted towards a particular aspect of the application or trial, or if PPI contributions were on an ‘as required’ basis. An oversight role was defined by appointment as an independent member of either the TSC or the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). Descriptions of PPI in the application documentation were often limited, and coding ‘rules’, informed by our knowledge of grant application development and clinical trial implementation processes, were devised to categorise the descriptions. The codes were developed by CG and LD after reading the PPI descriptions and then reviewed by JP. CG and LD independently categorised the PPI descriptions. Disagreements between CG and LD were discussed and agreement reached by referring back to the documentation. All categorisations were cross-checked by JP. The coding rules (Box 1) and the classifications were reviewed by the PPI advisory group and no changes were suggested.

-

If a PPI contributor is described as a member of the research team or ‘lay member’, categorise them as inputting across all future stages of the study.

-

The design of the study is determined within the full application stage so if a PPI contributor is described as inputting in to the design of the study, categorise their input as starting no later than at development of the full application.

-

If a PPI contributor’s role is confined to TSC membership (which is usually agreed by the funders and follows the funding decision), categorise their input as starting after the full application regardless of the tense of the sentences describing their involvement.

-

If a PPI contributor’s role is described as managerial or as a coapplicant, or referred to as a part of the team, categorise their level of involvement as managerial.

-

If a PPI contributor’s role is confined to a panel or advisory group, categorise their contribution as responsive.

-

If a PPI contributor’s role is limited to a specific aspect of the trial, categorise their input as responsive.

The external referee assessment forms that were completed by each referee began requesting referees to comment on any aspect of the proposal that they considered relevant from the perspectives of patients or service users. In addition, within a section on resources and feasibility, referees were asked to consider whether or not there is ‘appropriate representation from all relevant groups in the research team (this might include consumers, researchers from different disciplines, managers and professionals) and is the role of each collaborator/co-applicant clear (particularly important for multi-centre studies)?’ All areas of the form were examined for references to referee assessment of PPI.

Comments from external reviewers and the funding board were coded as positive, negative or factual. Positive comments implied that the referee or board considered the PPI to be satisfactory or sufficient, and did not contain suggestions for adding to the existing PPI plans. Negative comments were those which indicted that PPI was considered weak or unclear, or gave direction on strengthening PPI from that proposed within the application. A comment may indicate the absence of PPI in an area, such as membership of TMG or TSC, but not specifically indicate that this was required. Where this occurred it was interpreted as a negative comment in that it was aiming to highlight a gap in the approach to PPI. Factual statements were those which outlined the importance of service users without commenting on the plans proposed, or identified PPI plans without any indication of the respondent’s view on their appropriateness.

Phase 1 analysis

In considering trends over time, the year the outline application was submitted was used. The cohort was identified as randomised trials that were in receipt of funding from the NIHR HTA programme between 2006 and 2010, but the year the outline applications were made ranged from 2003 to 2008.

The following specific conditions were selected to consider in more detail: mental health, pregnancy and childbirth, human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, cancer, stroke, paediatrics, diabetes, and dementias and neurodegenerative diseases. These were identified either by their strong history of PPI or by the establishment of a NIHR clinical research network for a specific condition. 57

Categorical data were summarised using descriptive statistics with numbers and percentages. Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used as appropriate.

Phases 2 and 4: surveys of chief investigators, patient and public involvement contributors, and UK Clinical Research Collaboration Registered Clinical Trials Units

Three surveys were planned as part of the EPIC project targeting CIs, PPI contributors and the network of RCTUs. Each survey was web-based and developed in SurveyMonkey (www.surveymonkey.com), with portable document format (PDF) versions available from the EPIC website. Each survey consisted of both closed and open questions to avoid constraining responses. In addition, further free text was collected when ‘other’ was selected as a closed response. The surveys were initially developed by LD and CG and sent for comments to BY, JP and PRW prior to being considered by the PPI Advisory Group. Surveys were piloted within the Clinical Trials Research Centre, University of Liverpool, prior to being finalised. The CI and PPI survey questions targeted opinions and motivations about PPI, methods of engagement, areas of contribution and level of impact within the cohort of trials. The RCTU survey questions focused on the experience and processes of the RCTUs across trials rather than within the cohort.

The link for the CI survey was emailed to the CI of each trial within the cohort. The e-mail addresses of each CI were obtained from the funding application but were checked against web searches on the CI names to ensure that they were up to date. The invitation e-mail described EPIC in brief, explained why they were being contacted and referred to the initial contact made by the NIHR HTA programme about the project. E-mails to the CIs also contained a link to a website which contained PDF versions of the survey and information sheets. The CI surveys were sent out on 13 March 2013 and two reminder e-mails were sent to non-responders on 17 April 2013 and 28 June 2013. Non-responders known to members of the EPIC research team were contacted to encourage completion.

Names of the PPI contributors for each trial were not available in the public domain. To obtain their contact details we requested the CI of each trial to contact their PPI contributor(s) asking them to contact the EPIC team so that we could send them information about the project and the PPI survey. An additional e-mail was sent to the trial CIs reminding them to contact their PPI contributors about EPIC. In addition an advert was drafted by JP and sent to the PPI Advisory Group for comments. The advert was placed on the websites of Involving People and North West People in Research. Finally we contacted the NIHR HTA programme to ask if it could contact the PPI contributors to inform them about EPIC; however, PPI contact details were not held by the NIHR HTA programme. The NIHR HTA programme contacted the chair of each of the TSCs asking them to contact any PPI contributors known to them.

The directors of the 46 RCTUs were contacted by e-mail requesting them to complete the CTU survey. The names of the fully and provisionally registered CTUs were obtained from the UKCRC website58 following the publication of the results of the 2012/13 Review Process. Websites for each RCTU were identified and contact details of the directors obtained. The survey could have been circulated on our behalf by the UKCRC across the directors using the group UKCRC directors e-mail list, but it was hoped a personal e-mail would encourage response. The initial e-mail was sent on 27 March 2013. The e-mail contained a brief summary of EPIC and the purpose of the survey along with links to the EPIC website, which contained a PDF version of the survey. The RCTU directors were asked to complete or delegate completion of the survey, which targeted PPI processes across trials in their units rather than focusing on individual trials. Reminder e-mails were sent on 29 April 2013 and, if it was unclear whether or not contact had been made, we used their websites to identify an alternative senior person within the RCTU.

Analysis of phase 2 and phase 4 surveys

All surveys were analysed using descriptive statistics, and chi-squared tests were used for cross-tabulations between questions. Recurring themes were identified within the free-text responses and used to group responses provided.

Phase 3: interviews

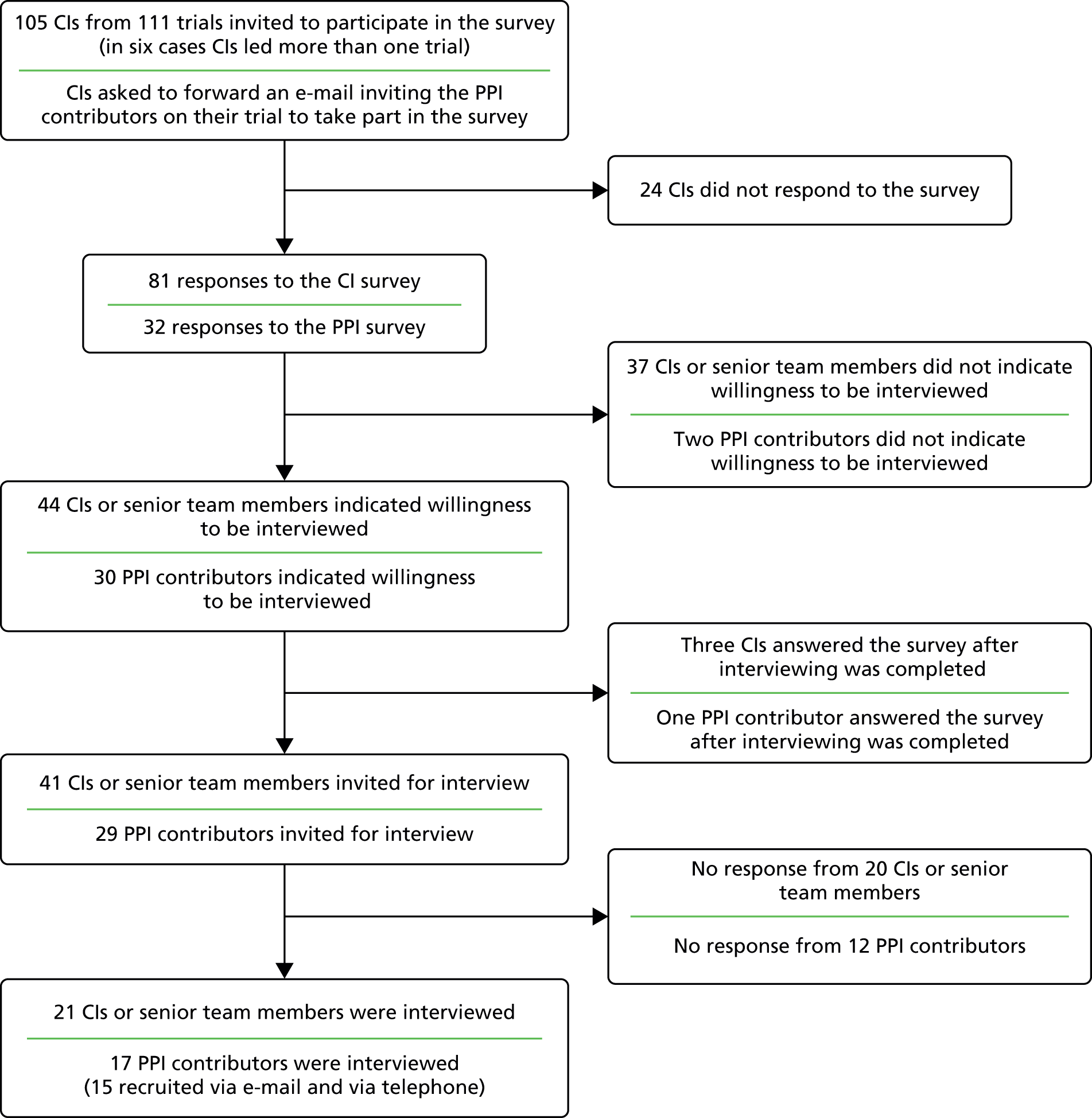

Within the CI and PPI surveys, respondents indicated if they were willing to be contacted to take part in an interview to further explore their experiences of PPI within the trial.

We initially sampled CIs for maximum diversity based on their survey responses, although we eventually invited all but three of the CIs who had responded to the survey and indicated their willingness to be interviewed. We invited for interview all PPI contributors who returned a survey response and indicated their willingness to take part. Additionally, we invited TMs for all trials for which the CI or PPI contributor had been interviewed. We obtained contact details for TMs from CTUs, trial websites and protocols, or via CIs.

We contacted all potential informants by e-mail and provided an information leaflet inviting them to contact the EPIC research associate to arrange an interview. Non-responders were sent one reminder e-mail. We expected that some PPI contributors might access their e-mail accounts infrequently so we subsequently telephoned those who had not responded. All informants provided signed or audio-recorded verbal consent before being interviewed.

A psychologist, LD, conducted audio-recorded semistructured telephone interviews with informants between April 2013 and November 2013. Before starting interviews, she explained that study data would be anonymised and kept confidential. Interviewing was conversational to allow informants to voice their views and experiences of PPI freely. In order to minimise the risk of idealised accounts, LD adopted a neutral stance in her interviewing. This was to avoid creating a sense that informants had to justify or defend their approach to PPI, which might have inhibited or coloured their accounts. LD familiarised herself with each of the documents for each trial before interviews to tailor questions to specific aspects of the trial. Nevertheless, we used topic guides to steer the interviews (see Appendix 2, Topic guides). We developed three versions to ensure interviews were appropriate for each of the three informant groups (CI, PPI contributor and TM), although the topic guides mirrored one another to ensure core topic areas were explored. Table 1 provides summary topic guides for researchers and PPI contributors. Topic guides were informed by the previous literature, reviewed by EPIC team members and the PPI advisory group, and developed in the light of the ongoing data analysis. In addition, the PPI advisory group read transcripts from early interviews and fed back on the interview with implications for the topic guide. Interviewing paralleled the analysis and continued until theoretical saturation had been reached,59 and additional data ceased contributing to the analysis. Interviews were transcribed using an ‘efficient’ verbatim style that involved transcribing the content of informants’ accounts, rather than detailed features of speech such as subvocalisations and duration of pauses and hesitations. All transcripts were checked for accuracy and anonymised.

| Topic | Researchers | PPI contributors |

|---|---|---|

| Expectations | Understanding of PPI Experience of including PPI in research Goals or plans for PPI in current trial |

Previous experience of being a PPI contributor Expectations about what working on the current trial would be like |

| What happened? | Stage of PPI implementation Identifying and selecting PPI contributors Roles of the PPI contributors Overall experience of including PPI in the current trial |

How did they become involved in the trial? PPI contributor’s role Relationship with research team |

| Impact | Perceived contributions of PPI Challenges of including PPI |

Differences made to the trial as a result of their input Benefits to themselves of being involved Challenges of being involved |

| Training and support | Training or support given to PPI contributors PPI training received by researchers |

Training or support for their role Views on PPI training for researchers |

This qualitative workstream of EPIC allowed us to access CIs’ and PPI contributors’ accounts of PPI in their own words and to analyse them inductively. Given the moral and political expectations surrounding PPI, we thought it was particularly important to adopt an interpretive approach60,61 and consider how informants talked about PPI. Therefore, we focused on the language informants used to describe PPI and on the aspects of PPI they gave little emphasis to in their interviews, as well as what they emphasised. Before each interview we reviewed the documents for each trial on their PPI plans, in order to tailor our questions and identify particular lines of enquiry to pursue. The interviews enabled us to seek clarification and prompt informants to elaborate on their experiences and perspectives. Similarly, informants were able to seek clarification from us, to elaborate on their perspectives and to raise topics that they considered important which we had not foreseen.

Phase 3 analysis

Analysis was informed by the principles of the constant comparative method62,63 with elements of content analysis. 64 We used procedures to support rigour in qualitative research65 and, as we note above, our approach was interpretive. To ensure a contextualised analysis we referred to transcripts as a whole as well as to particular data segments. We initially analysed CI and PPI contributor transcripts at the informant group level for evidence of their beliefs and experiences about the process and impact of PPI as well as their views and experiences of training and support for PPI. Subsequently, we triangulated CI and PPI contributor transcripts within each trial, before comparing them with the TM transcripts within each trial. Where trials did not have a full data set (i.e. did not include all three groups of informants), we compared the two available accounts. Where only one account was available, analysis was at the informant group level.

The analysis was led by LD, who read CI and PPI contributor transcripts several times before developing open codes. BY also read multiple transcripts, and she and LD met regularly to compare interpretations of the data and review the ongoing analysis. Open coding took place at multiple levels, from line-by-line coding of detailed descriptions to the general stance informants took towards PPI. Open codes were grouped into categories and organised into a framework. Coding and indexing of data was assisted by NVivo 9 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and we continually compared categories with new data and amended them to ensure that they reflected the data while accounting for deviant cases. For TM transcripts we conducted some open coding of sections relevant to the categories emerging from the CI and PPI contributor analysis. Subsequent discussion and review of detailed analysis reports by other members of EPIC team including DB, who led an analysis of the same data set on the implementation of PPI, helped to refine the analysis and corroborate the findings. To evidence our interpretations we present illustrative extracts from the data. Extract codes indicate informant group (CI; PPI contributor 1 or 2, where more than one were interviewed for the same trial; TM) and trial identification numbers.

To compare what PPI actually happened in the trial with that planned within the application (implementation of PPI), the following primary and secondary data sources were used.

Primary sources of data were trial documentation (full application forms, reviewer comments, detailed project descriptions and study protocols), from which we extracted data about trial teams’ plans for PPI; and CI and PPI contributor interview transcripts, from which we determined whether or not the documented plans were implemented.

Secondary sources of data were outline application forms, CI survey responses and TM interview transcripts. We used the secondary sources in cases of ambiguity, that is where it was unclear from the primary sources whether or not aspects of a particular set of plans had been implemented. We also used the secondary sources to elucidate the illustrative examples that we present in the results.

The implementation of PPI analysis, led by DB, used a thematic analysis approach to analyse the interview data regarding the implementation of plans for PPI, alongside data extracted from trial documentation about written plans for PPI. Thematic analysis is a useful method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. 66 DB familiarised herself with the interview data by reading the transcripts several times, and then drew on the Framework technique,67 which is a manual method to develop and apply open codes to the interview data. Codes were grouped into broader categories within the framework and compared with data extracted from the documented plans. Other members of the EPIC team, who were familiar with the interview transcripts and trial documentation, examined the early stages and ongoing refinements of the descriptive coding framework, as well as the tabulated comparisons of planned and implemented PPI, thus providing confidence in the credibility and ‘confirmability’ of the findings. 68

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement in the application process: results of phase 1

Cohort documentation

One hundred and eleven randomised trials were identified as being in receipt of funding from the NIHR HTA programme between 2006 and 2010, and were therefore eligible for inclusion within the cohort. Complete documentation for each trial was requested. The initial batch of documentation was provided by the NIHR HTA programme and then supplemented by LD visiting the NIHR HTA offices to access missing documentation. All included trials had at least one of the outline application form, the full application form or the detailed project description available, from which we could assess PPI plans.

Cohort summary

Table 2 summarises the completeness of trial documentation available across the cohort. Of the 111 trials eligible for inclusion, 110 were required to submit an outline application. The dates of submission of the associated outline applications were between 2003 and 2008.

| Documentation (N = 111) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Outline applicationa | 90 (82) |

| Board feedback on outline | 77 (70) |

| Full application form | 106 (95) |

| Detailed project description | 99 (89) |

| Referee comments on full applicationb | 111 (100) |

| Board feedback on full application | 100 (90) |

Table 3 provides a summary of the trial characteristics. Trials were funded across a wide range of clinical conditions, with the most common area of study being trials in mental health (16%). The majority of trials (79%) were aimed at treatment of a condition, with 17% working on prevention. The trials used a wide range of interventions. Over one-third investigated a medicinal product and just under one-fifth each evaluated behavioural interventions (18%), surgical techniques (15%) and devices (16%).

| Condition/intervention (N = 111) | Number of trials (%) |

|---|---|

| Long-term conditiona | 61 (56.5) |

| Rare condition | 2 (1.8) |

| Condition expected to reduce lifespan | 36 (32.4) |

| General shortening | 20 of 36 (55.6) |

| Rapid mortality | 16 of 36 (44.4) |

| Condition under studyb | |

| Mental health | 18 (16.2) |

| Heart disease/condition | 4 (3.6) |

| Haematology/phlebology | 8 (7.2) |

| Infections | 9 (8.1) |

| Musculoskeletal | 7 (6.3) |

| Cancer | 7 (6.3) |

| Renal | 4 (3.6) |

| Childbirth and pregnancy | 4 (3.6) |

| Obstetrics and gynaecology | 2 (1.8) |

| Addiction | 5 (4.5) |

| Dermatology | 3 (2.7) |

| Gastroenterology | 7 (6.3) |

| Diabetes | 2 (1.8) |

| Obesity/nutrition | 3 (2.7) |

| Falls in the elderly | 3 (2.7) |

| Sleep disorders | 3 (2.7) |

| Stroke | 5 (4.5) |

| Dental | 2 (1.8) |

| Degenerative neurological disorders | 4 (3.6) |

| Respiratory | 5 (4.5) |

| Other | 6 (5.4) |

| Aim of intervention | |

| Treatment | 88 (79.3) |

| Prevention | 19 (17.1) |

| Diagnostic | 4 (3.6) |

| Nature of interventions useda | |

| Drug | 44 (39.6) |

| Behavioural | 20 (18.0) |

| Device | 18 (16.2) |

| Surgery | 17 (15.3) |

| Physical, e.g. exercise | 11 (12.2) |

| Educational | 10 (9.0) |

| Community care | 5 (4.5) |

| Other | 4 (3.6) |

| Commissioned brief | 45 (40.5) |

Table 4 describes the characteristics of trial participants and features of the trial designs. Three-quarters of the trials recruited adults only, with paediatric trials accounting for 18% of the cohort. The majority of the trials were not gender specific and approximately a quarter recruited participants at the time of diagnosis. Trial recruitment was most commonly conducted within secondary care (61%). Just under one-quarter of the trials (25 of 111) involved blinding of the treating clinical team or the participants, with 28 of 111 blinding the outcome assessor only. Just over 15% of trials used a placebo, and all participants received an active intervention in one-third of these, indicating the use of a double dummy design.

| Trial participant and design characteristics (N = 111) | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| Adults only | 83 (74.8) |

| Paediatrics only | 20 (18.0) |

| Adults and paediatrics | 7 (6.3) |

| Unclear | 1 (0.9) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 10 (9.0) |

| Male | 1 (0.9) |

| Male and female | 100 (90.1) |

| Recruiting newly diagnosed patients | 27 (24.3) |

| Trial recruitment settinga | |

| Secondary | 68 (61.3) |

| Primary | 24 (21.6) |

| Community | 12 (10.8) |

| Emergency | 8 (7.2) |

| Tertiary | 8 (7.2) |

| Social care | 7 (6.3) |

| Blinded trialb | 53 (47.8) |

| Clinician blind | 19 of 53 (35.8) |

| Participant blind | 24 of 53 (45.3) |

| Trial involves a placebo | 17 (15.3) |

| Placebo involved, but all participants receive an active intervention | 6 of 17 (35.3) |

To develop understanding of PPI within the earliest stages of clinical trial development we placed an emphasis on the outline application process. The specific objectives were to identify if, and how, PPI is described within the early development of a grant application for funding; examine how PPI contributions within the development of the outline application were reviewed by the funding board; consider how applicants describe their proposed PPI plans for the development of the full application and the trial once funded; and describe variations in PPI in relation to time of funding and trial characteristics.

Patient and public involvement within the first stage of the application process

Outline applications were available for 90 of the 111 randomised trials in the cohort. The trial and participant characteristics restricted to these 90 trials are summarised elsewhere. 69 Of these 90 outline applications, 49 (54%) provided some level of detail on PPI. Table 5 summarises the stage of initiating PPI and role of PPI across the trials. The first row of Table 5 shows that there were 19 applications in which the text provided within the outline described PPI occurring at all three stages (within the outline application, in the full application and once the trial was funded). Of these 19 applications the role was managerial at each stage in 13. In the remaining six there was variation in the roles across the stages, or it was unclear, when a statement indicated that PPI would occur but no details were provided to allow classification. An example of a description that we were unable to categorise is ‘Investigators have, and will continue to, collaborate with service users.’

| Stage | Number of outline applications (%), n = 90 | Role | Number of outline applications | Comments | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outline | Full application | Trial once funded | Outline | Full application | Trial once funded | |||

| Y | Y | Y | 19 (21.3) | M | M | M | 13 | Two had multiple approaches alongside M in the main trial (TSC; TSC plus R) |

| R | M | M | 1 | |||||

| R | R | R | 2 | |||||

| R | U | U | 1 | |||||

| U | R | R | 1 | |||||

| U | U | U | 1 | |||||

| Y | Y | NS | 2 (2.2) | R | R | – | 1 | |

| O | R | – | 1 | O = described as informal contacts | ||||

| Y | NS | Y | 2 (2.2) | R | – | O | 1 | O = scale development |

| R | – | TSC | 1 | Consulted in pilot study | ||||

| Y | NS | NS | 3 (3.4) | O | – | – | 3 | O = clinical studies group; survey; service user forum |

| NS | Y | Y | 8 (9.0) | – | M | M | 3 | In one also TSC and R in trial |

| – | R | R | 2 | In one TSC too | ||||

| – | R | M | 1 | |||||

| – | U | U | 2 | |||||

| NS | Y | NS | 1 (1.1) | – | R | – | 1 | |

| NS | NS | Y | 12 (13.5) | – | – | M | 3 | |

| – | – | R | 1 | |||||

| – | – | TSC | 7 | Two above also listed TSC alongside higher-order approach | ||||

| – | – | O | 1 | O = piloted and then refined with users | ||||

| NS | NS | NS | 41 (45.6) | – | – | – | 41 | |

| NS | U | U | 2 (2.2) | – | U | U | 1 | |

| – | M | M | 1 | Unclear when PPI initiated but when it starts it is at M level | ||||

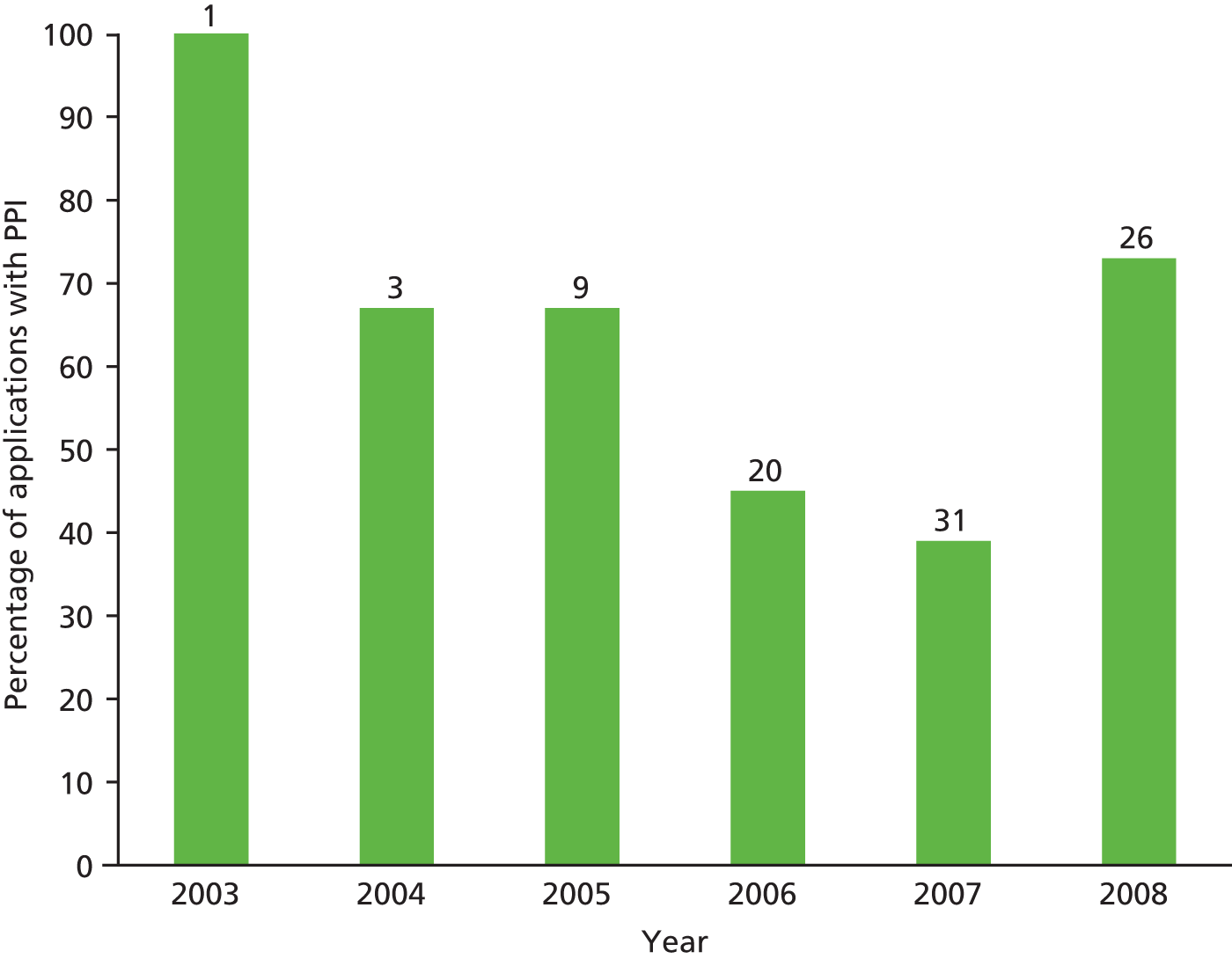

Twenty-nine per cent (26 of 90) specified a level of involvement within the development of the outline application. This was managerial in 13, on a responsive basis in 7, unclear in 2 and other approaches used in 4 (e.g. a patient survey or pilot feedback). Within the ‘other’ approaches it was difficult to determine conclusively whether this was PPI or they were examples of data collection aimed at ascertaining public opinion. In the three applications that specified use of a survey, the extent of the distribution of the survey was unclear in two. PPI was planned to occur within the full application for 32 trials (36%). This was managerial in 18, responsive in 9 and unclear in 5. Forty-three (48%) applications indicated that PPI was planned after the trial was funded. This was as managerial in 22, responsive in 6, a member of the TSC in 8, unclear in 5 and other in 2. The numbers of outline applications by year with and without details of PPI are displayed in Figure 2, with Figure 3 showing the percentage of applications with PPI. These figures show a general trend for an increasing number of funded applications; however, the proportion of those containing PPI fluctuates. The proportion ranges from approximately half to two-thirds (see Figure 3), with the exception of 2003, for which only one application was available.

FIGURE 2.

Number of outline applications by year in which the application was made.

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of outline applications containing PPI details by the year in which application was made. The number of trials included within each year is indicated at the top of each bar.

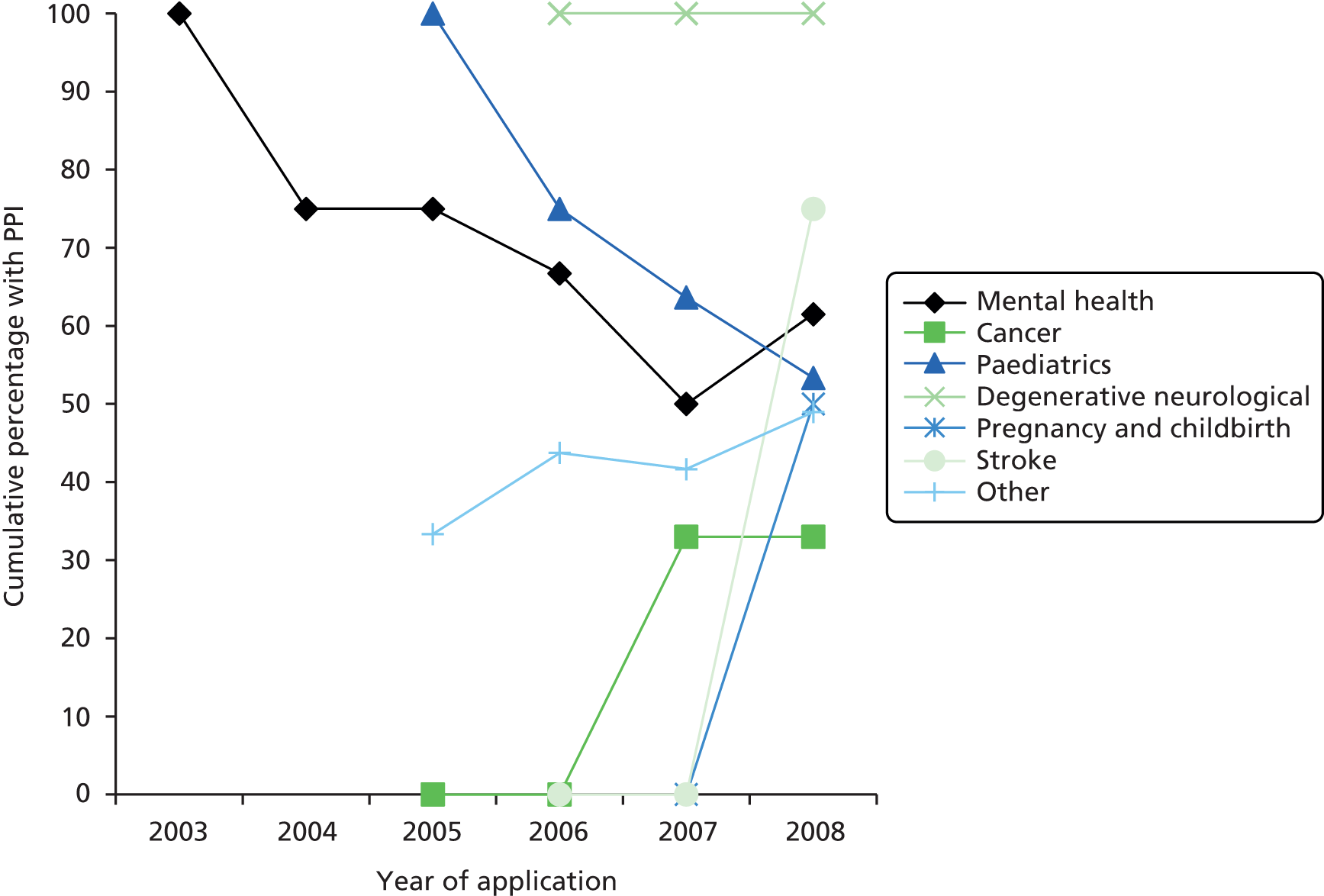

Figure 4 displays the data by year for specific conditions. Both of the diabetes trials were in children and were coded as paediatric, and there were no human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome trials within the cohort with outline applications available. Figure 4 suggests declining rates of PPI in paediatric and mental health, with other areas, including the general ‘other’ category, demonstrating an increase over time. However, as shown in Table 6, the numbers in some categories were small and therefore limit conclusions based on disease areas. Table 7 suggests an absence of association between specification of PPI within the outline application and disease area (n = 0.51).

FIGURE 4.

Cumulative percentage of outline applications by disease/condition.

| Disease/condition category | Cumulative number of outline applications by year | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | |

| Mental health | 1 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 10 | 13 |

| Cancer | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 |

| Paediatrics | 0 | 0 | 5 | 8 | 11 | 15 |

| Degenerative neurological | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 |

| Pregnancy and childbirth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Stroke | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 3 | 16 | 36 | 49 |

| Disease/condition category | PPI details in outline text | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (% of category total) | No (% of category total) | Total (% of overall total) | ||

| Pregnancy and childbirth | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (2.2) | 0.51a |

| Cancer | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Stroke | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | 4 (4.4) | |

| Mental health | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 13 (14.4) | |

| Paediatricsb | 8 (53.3) | 7 (46.7) | 15 (16.7) | |

| Degenerative neurological | 4 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.4) | |

| Other | 24 (49.0) | 25 (51.0) | 49 (54.4) | |

| Total | 49 (54.4) | 41 (45.6) | 90 (100.0) | |

Table 8 shows the associations between trial design characteristics, or characteristics of the condition under study, and consideration of PPI within the outline application.

| Intervention | PPI details in the outline application | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (% of category total) | No (% of category total) | Total (% of overall total) | ||

| Aim of intervention | ||||

| Treatment | 40 (54.1) | 34 (45.9) | 74 (82.2) | 0.66a |

| Prevention | 8 (61.5) | 5 (38.5) | 13 (14.4) | |

| Diagnostic | 1 (33.3) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (3.3) | |

| Nature of interventionb | ||||

| Drug | 16 (51.6) | 15 (48.4) | 31 (34.4) | 0.70 |

| Device | 7 (46.7) | 8 (53.3) | 15 (16.7) | 0.51 |

| Surgery | 4 (25.0) | 12 (75.0) | 16 (17.8) | 0.01 |

| Education | 6 (60.0) | 4 (40.0) | 10 (11.1) | 0.75a |

| Behavioural | 11 (64.7) | 6 (35.3) | 17 (18.9) | 0.35 |

| Physical | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 11 (12.2) | 0.19 |

| Settingb | ||||

| Primary care | 10 (47.6) | 11 (52.4) | 21 (23.3) | 0.47 |

| Secondary care | 30 (56.6) | 23 (43.4) | 53 (58.9) | 0.62 |

| Emergency care | 4 (50.0) | 4 (50.0) | 8 (8.9) | 1.00a |

| Community | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | 12 (13.3) | 0.77 |

| Social care | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (6.7) | 0.68a |

| Tertiary | 4 (66.7) | 2 (33.3) | 6 (6.7) | 0.68a |

| Blinding | ||||

| Yesc | 30 (69.8) | 13 (30.2) | 43 (47.8) | 0.01 |

| No | 19 (40.4) | 28 (59.6) | 47 (52.2) | |

| Involved a placebo | ||||

| No placebo | 39 (51.3) | 37 (48.7) | 76 (84.4) | 0.17 |

| Placebod | 10 (71.4) | 4 (28.6) | 14 (15.6) | |

| Received an active intervention | ||||

| Received placebo onlye | 8 (88.9) | 1 (11.1) | 9 (10.0) | 0.04a |

| Received an active intervention | 41 (50.6) | 40 (49.4) | 81 (90.0) | |

| Recruitment at diagnosis | ||||

| Yes | 8 (33.3) | 16 (66.7) | 24 (26.7) | 0.02 |

| No | 41 (62.1) | 25 (37.9) | 66 (73.3) | |

| Long-term conditionf | ||||

| Yes | 31 (60.8) | 20 (39.2) | 51 (58.6) | 0.17f |

| No | 17 (47.2) | 19 (52.8) | 36 (41.3) | |

| Impact of condition on life expectancy | ||||

| None | 36 (57.1) | 27 (42.9) | 63 (70.0) | 0.72 |

| General shortening | 7 (50.0) | 7 (50.0) | 14 (15.6) | |

| Rapid mortality | 6 (46.2) | 7 (53.9) | 13 (14.4) | |

Of the intervention aims, numbers were too small to draw conclusions about involvement in diagnostic studies, but prevention trials described PPI more frequently than treatment trials. Trials involving educational, behavioural or physical interventions were more likely to have provided details of PPI in the outline application than trials involving drugs or devices. Surgical trials were significantly less likely to have provided details of PPI.

The settings for trial recruitment did not appear to affect specification of PPI, whereas recruiting participants at the point of diagnosis was associated with less PPI.

Forty-three trials were described as being blind and these trials were associated with increased frequency of describing PPI. Of these trials 23 involved blinding of the outcome assessor only. Only 14 trials involved a placebo and, of these, participants in five trials all received an active intervention, with the placebo used as a double dummy. The allocation of a placebo only to one arm of the trial was significantly associated with greater frequency of PPI detail.

Only two trials were in rare conditions. Both of these trials provided details of PPI within the outline application. Although there appeared to be some increase in describing PPI when the condition was long term, there did not appear to be any influence based upon impact on life expectancy.

Board comments on outline applications

National Institute for Health Research HTA Board minutes were available for 70% (77 of 110) of the outline applications. Only nine (12% of 77) board minutes gave feedback on PPI and two of these did so indirectly (Table 9). One comment was supportive of the PPI described in the outline, which involved a PPI contributor as a coapplicant.

| Unique identifier | Year outline application submitted | Text from board minutes for outline applications |

|---|---|---|

| 28 | 2007 | The applicants should consider involvement of disadvantaged groups |

| 65 | 2006 | There was no clear service user involvement and this needs to be addressed |

| 70 | 2006 | The Board would be pleased to see letters of support from appropriate PCTS [primary care trusts] & patient groups that the trial is feasible. The Board wish to see patient and public involvement in any full proposal |

| 34 | 2008 | The Board noted it was a well designed study that has received input from patients |

| 92 | 2007 | Ethical aspects including acceptability to parents must be fully considered |

| 39 | 2008 | Consideration should be given to increasing service user involvement |

| 42 | 2008 | Patient representation is required |

| 98 | 2007 | An explanation and demonstration of acceptability to parents must be included |

| 105 | 2007 | The application would benefit from strong patient and public involvement |

Of the 77 trials for which board minutes were available, the corresponding outline applications were also available for 64 (84%). Of these applications 39% (25 of 64) gave no information about PPI.

Eight of the nine sets of board comments that were made about PPI expressed the need for applicants to increase PPI. Six of these contained no detail about PPI within the application. Of these six, two were drug trials, three were exercise interventions and one was comparing an invasive with a non-invasive intervention. Two were recruiting participants with addiction (smoking and alcohol), two were recruiting elderly participants, one was recruiting infants and one was recruiting participants with a long-term, chronic, debilitating condition.

In the two outline applications which had given some details on PPI, comments from the board were to increase PPI. In one application the PPI contributors were employed within a NIHR condition-specific network in roles relating to PPI. These individuals also had relevant experience as carers or patients of the condition. In the other application the PPI contributor was a coapplicant with an unrelated clinical background (midwife) and was the mother of a child with the condition being studied.

Patient and public involvement within the second stage of the application process

Documentation within the second stage of the NIHR HTA application process requires submission of a full application form and a detailed project description. Ninety-five per cent (106 of 111) of the full applications were available and 89% (99 of 111) of detailed project descriptions. The level of information about PPI within the full application forms was limited, with greater detail generally provided within the detailed project descriptions.

Full application forms

Within the full application form only 38% (40 of 106) provided any level of detail about PPI, with 19% (20 of 106) of trials including a PPI contributor as a coapplicant. The classifications used within the outline applications were applied and are summarised in Table 10. In applying the classifications to the text in the full application form the presence of a PPI coapplicant was used.

| Stage | Number of full applications (%), N = 106 | Role | Number of full applications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full application | Trial once funded | Full application | Trial once funded | ||

| Y | Y | 18 (17) | M | M | 8 |

| M | M/TSC | 2 | |||

| R | R | 1 | |||

| R | R/TSC | 2 | |||

| M/R | M/R | 1 | |||

| M/R | M/R/TSC | 1 | |||

| R | U | 1 | |||

| U | R | 1 | |||

| U | U | 1 | |||

| Y | NS | 5 (5) | R | – | 4 |

| U | – | 1 | |||

| NS | Y | 16 (15) | – | R | 6 |

| – | TSC | 4 | |||

| – | TSC/R | 3 | |||

| – | U | 3 | |||

| U | U | 1 (1) | U | U | 1 |

| NS | NS | 66 (62) | – | – | – |

Twenty-three (22%) applications indicated that PPI had occurred within the development of the full application; 34 (32%) provided some indication that PPI would occur once the trial was funded; and 18 (17%) indicated involvement in the development of the full proposal and once the trial was funded. Among these 18 applications PPI occurred most frequently in a managerial role (12 applications).

A total of 10 trials included a responsive approach within the development of the full application, and 15 planned it once funding had been obtained. Twelve trials planned to include a PPI contributor on the TSC.

In five trials details of involvement in the full application were provided, but continued involvement within the trial post funding was not specified. In four of these trials a responsive approach to PPI was used in the development of the full application.

In 16 applications details of PPI were not specified within the development of the full application, but some text was provided on their plans for implementation in the trial once funded. Nine of these planned a responsive approach, and three of these combined it with a PPI contributor on the TSC. Four planned to include a PPI contributor on the TSC only, and in three applications this was unclear.

In three trials qualitative research was described as an approach to address the objectives of PPI.

We have conducted in depth interviews with 7 patients who have survived [condition/intervention] and their spouses concerning the design of the trial and key outcome measures.

Of the 40 full applications that provided any detail of PPI, the process for recruiting or identifying PPI contributors was frequently unclear; 17 provided no information or used the term ‘service users’ without further detail. In 10 applications use of an already established support group was proposed, while in six representation was proposed to stem from leaders such as directors or chairs of support groups or charities. Three included participants identified from previous trials or feasibility work, and four specified identifying contributors from local patients.

Detailed project descriptions

The detailed project descriptions, submitted alongside the full application, were available for 89% (99 of 111) of the cohort. Ninety-three per cent (92 of 99) provided some text of relevance to PPI. A summary of PPI described in the detailed project descriptions is provided in Table 11.

| Stage | Number of full applications (%), N = 99 | Role | Number of full applications | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full application | Trial once funded | Full application | Trial once funded | ||

| Y | Y | 57 (58) | M | M | 2 |

| M | M/R | 1 | |||

| M | O/M | 5 | |||

| M | O/M/R | 1 | |||

| M | O/M/R/Q | 2 | |||

| M/R | O/M/R | 3 | |||

| M/R | O/M | 3 | |||

| M/R | R | 1 | |||

| M/R | M | 1 | |||

| M/S | M | 2 | |||

| M/R/Q | M/R | 1 | |||

| R | R | 6 | |||

| R | O | 9 | |||

| R | M | 1 | |||

| R | O/R | 5 | |||

| R | O/R/Q/S | 1 | |||

| R | O/M | 1 | |||

| R | O/R/Q | 1 | |||

| R | O/M/R | 1 | |||

| R | M/R | 1 | |||

| R | R/Q | 1 | |||

| R/Q | O | 1 | |||

| R/Q | R | 2 | |||

| R/S | O/R | 1 | |||

| Q | O/R | 1 | |||

| Q/S | R | 1 | |||

| Q | O/R/Q | 1 | |||

| S | O/R | 1 | |||

| Y | NS | 4 (4) | R | – | 4 |

| NS | Y | 24 (24) | – | O | 7 |

| – | M | 1 | |||

| – | R | 3 | |||

| – | O/R | 7 | |||

| – | R/Q | 1 | |||

| – | M/Q | 2 | |||

| – | O/Q | 1 | |||

| – | O/M/R | 1 | |||

| – | O/R/Q | 1 | |||

| N | Y | 3 (3) | – | O | 1 |

| – | O/R | 1 | |||

| – | O/M/R | 1 | |||

| N | N | 4 (4) | – | – | 4 |

| NS | NS | 7 (7) | – | – | 7 |

Within the detailed project description 31% of applications (31 of 99) did not specify whether or not any PPI had occurred within the application development; however, 24 of these described plans for PPI once the trial was funded. Sixty-one (61%) provided some details of PPI during the development, with 57 of these also providing some text of relevance to plans for PPI once the trial was funded. The remaining seven provided reasons for not incorporating PPI within the application development; however, three of these planned to attempt PPI once the trial was funded:

The planned work does not directly focus on patients; [. . .] it will recruit people with and without medical conditions. We are actively considering the involvement one or more members of the general public, possibly someone from [name], but are struggling to identify how he/she could be involved beneficially.

In all our previous [condition] research we have tried to incorporate user involvement although we have met with limited success. Often the biggest challenge has been finding people who wish to be involved and developing this involvement. In writing this application we planned to discuss the content with service users whom we have previously collaborated, but this was not possible due to death and illness. [. . .] we are hoping to develop such a local group (independently from this trial) that will be initiated and run in line with the PPI good practice.

Twenty-two applications described PPI contributions as being managerial within the development of the application, with 44 describing a responsive approach. Responsive PPI contributors were frequently described as ‘lay members’, ‘patient representatives’, ‘patients’, ‘carers’ or ‘user groups’ (42 of 44). Managerial PPI contributors were described as ‘Chairs’ of charities or support groups (7), members of charities (5), patients, carers and patient representatives (10).

Few applications indicated that the approach to incorporating PPI in the development of the application would remain the same during the funded trial. Among those that had PPI contributions within the application development and planned for PPI in the trial, only 14% (8 of 57) indicated that the approach to PPI would continue unchanged in the trial. Forty-seven per cent (27 of 57) planned to increase the variety of approaches used, 25% (14 of 57) would make changes but maintain the same number of approaches and 14% (8 of 57) intended to reduce the routes for PPI input.

Five applications described the use of surveys to inform the development of the application, while seven used qualitative research to obtain patient perspectives and opinions. Although qualitative research and surveys do not fall within the definition of PPI, they do partner some of the objectives of PPI and have therefore been included here. Of the seven applications that used a qualitative approach with their development, three also used a responsive or managerial approach to PPI. Of the 11 that planned to include qualitative research within the trial once funded, only one had used qualitative research in the application development and all planned to include oversight, managerial or responsive approaches. However, the level of detail provided about the qualitative research was low. Many used the terminology ‘focus group’ but in all but one it was unclear that these would be carried out by qualitative researchers:

Towards the end of the study, when the provisional results are available, we will use the expertise and contacts of our panel of commissioners/trainers/users’ representatives to form focus groups to assist in the understanding and dissemination of findings.

It is clear from our contact with the [local topic-specific research network] user group that consumers welcome the proposed study. The members of the group have already contributed to the design of the study, with feedback from qualitative interviews with service users confirming the relevance of [intervention/assessments], and supporting the plan to identify target symptoms for individual participants, with the involvement of the clinical team and participants themselves.

From the [condition] clinics at [name] Hospital and [name] Hospital, 88 [participants] with a history of [condition] were interviewed with a set of open and closed questions to identify their opinions regarding the need for the trial, [intervention delivery], duration of therapy, suitability of [trial processes], and the choice of outcomes.

Service users have already contributed to the design of the study; with feedback from qualitative interviews with service users resulting in our amending our secondary outcome measures by including a measure of well-being.

We have consulted widely, including with patients to seek their views on trial design and relevant outcome measures: [. . .]. We have involved services users (n = 7) in the design of the trial. We used the patient information pack and part of the questionnaire that has been developed and validated in collaborative research with the [name] Institute as a basis for in-depth interviews to identify patient perspectives on trial design and outcomes. We have identified one service user, [name] who will advise the trial management committee on patient perspectives.

This will allow us to convene 1 or 2 focus groups consisting of 5 to 10 individuals selected by us on the basis that they might represent regular users of [service]. Costs of convening that group along with appropriate honoraria will be met from the project budget. These focus groups will be run by an experienced qualitative researcher. The group will have the opportunity to comment on the proposal, suggesting amendments and modification in the light of their lived experience [. . .]. Finally, we will invite two representatives from these groups to sit on the project advisory board.

Changes in patient and public involvement between the first and second stages of application

There were 80 trials in the cohort for which we had the outline application, the full application and the detailed project description.

Plans for patient and public involvement in the development of the full application provided in the outline application

At the outline stage 36% (29 of 80) of the applications indicated plans for PPI during the development of the full application. In the full application 86% (25 of 29) indicated that this had occurred; 13 specified it within the text of both the full application form and the detailed project description, 11 in only the detailed project description, with one application providing detail in the full application form only. Seventy-two per cent (18 of 25) were consistent in their approach to PPI; for example, they had specified within the outline application that a managerial approach would be used within the development of the full application and, judging from the text provided within the full application form or detailed project description, this had occurred.

In six, there were changes or inconsistencies; for example, five specified a managerial approach in the outline but indicated that a responsive approach had been used in the development of the full application. Inconsistency also occurred between the approaches described in the full application form and the detailed project description. One application could not be assessed because of an ‘unclear’ classification at the outline stage.

Of the four outline applications that had planned to include PPI in the development of the full application, but did not provide any text to show that it had occurred, two had planned a responsive approach, one managerial, and in one the approach was unclear.

No plans for patient and public involvement in the development of the full application provided in the outline application

Fifty-one per cent (26 of 51) of outline applications that did not indicate plans for PPI in the development of the full application did obtain PPI input in its development. PPI activity in the development of the full application was reported in both the full application form and the detailed project description for three, in the detailed project description only for 22 and in the full application form only for one. Within these applications a responsive approach was used in 20 and a managerial approach in eight (approaches not mutually exclusive).

Consistency in plans for patient and public involvement for the funded trial between the two stages of the application process

Plans for PPI once the trial was funded were included within 49% (39 of 80) of the outline applications. Of these, 38 also provided plans in the full application to incorporate PPI once the trial was funded.

Of the 18 outline applications that planned to use only a managerial approach in the trial, three continued with these plans in the full application but 10 increased this planned PPI to include other approaches too (oversight in nine and/or responsive in five). Of the five that changed the managerial approach, three planned to use both oversight and responsive, with one using oversight only and one responsive only.

Nine outline applications planned to use oversight PPI only. This was maintained as the only approach in three, and expanded to include responsive in three and managerial in one. In two applications the approach was changed to be responsive (one application) or managerial (one application).

Four of the five outline applications that had planned to use only responsive PPI kept that approach but three also planned to include oversight, while the remaining one planned to use oversight instead of responsive PPI.

Multiple approaches to PPI were specified in three outline applications. All three had specified oversight as an approach in the outline; two dropped it from the full application, leaving managerial and responsive in one trial and only responsive in one. In three the classification was unclear at the outline stage, preventing comparison.

Of the 51% (41 of 80) of outline applications that did not suggest that PPI would occur in the trial once funded, 78% (32 of 41) did provide plans within the detailed project description; the remaining nine provided no mention of PPI plans for the trial.

The single approach to PPI in the main trial was planned to be responsive in six, managerial in three and oversight in seven. In eight, oversight was planned to occur in conjunction with either managerial (two applications) or responsive (six applications), with four applications using all three approaches. Four applications specified plans for qualitative research to obtain patient perspectives but plans for this occurred alongside PPI in responsive, oversight or managerial approaches.

The level of information varied between the full application form and the detailed project description; discrepancies in approaches planned were common.

Within the section of the detailed project description which asked applicants to specify changes between the outline and full applications, only three specified that changes to PPI had occurred and that these changes were in response to board comments.

Referee comments on the full applications

There were 515 sets of referee comments for the 111 trials in the cohort. The minimum number of referees for a trial was one, the maximum was nine and the median was five.

Across all referee comments only 41% (211 of 515) gave a comment in relation to the PPI. The median number of referee comments relating to PPI per trial was two, with a minimum of zero (occurring for 11 applications) and a maximum of six.

Thirty-four per cent (72 of 211) of comments were positive, 51% (107 of 211) were negative and 15% (32 of 211) were factual. Sixty-three applications had more than one set of referee comments that contained text relating to PPI; after factual comments were removed, 52 applications remained, of which 56% (29 of 52) had referee assessments that disagreed in their assessment of PPI. Table 12 provides examples of conflicting referee comments.

| Unique identifier | Referee comments |

|---|---|

| 11 | It is positive to note the extent to which the trial team have gone to attempt to obtain user involvementThe research team acknowledge that they have not consulted with service users in the preparation of this proposal. However they give no indication of what efforts they made to try and remedy this situation or if they consulted with INVOLVE or service user groups who could advise them. The only limitation here is the lack of service user involvement |