Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1007/06. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in January 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Herepath et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Overview

This chapter introduces our study and is presented in three main parts. We begin by discussing the development of patient safety as the field of research that is concerned with one of the most significant social problems of our time: avoidable harm, waste and variation in health-care. Using the available literature, we outline the nature of this problem and present five factors which are thought to represent its foundations: (1) deficits in cultures of care, (2) leadership inadequacies, (3) ineffective team working, (4) problematic governance systems and (5) limited patient and public engagement. We then introduce the current agenda for patient safety improvement across the devolved NHS in the UK.

Second, we discuss the role of patient safety improvement programmes. We consider the design, implementation and evaluation of these complex social interventions and highlight the current lack of systematic analysis of relations between contextual (organisational and environmental) factors and the outcomes of patient safety interventions.

We then introduce the focal case of our study, the 1000 Lives+ national patient safety programme in Wales, and the three interventions selected for our detailed analysis: Improving Leadership for Quality Improvement (ILQI), Reducing Surgical Complications (RSC) and Reducing Health-care-Associated Infection (RHAI). We conclude this chapter by outlining the aim and objectives of our study, the structure of this report and the report’s intended audience.

Patient safety: a major social problem of our time

Since the publication in 2000 of To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System,1 patient safety has become recognised as a major social problem of our time. It now sits at the centre of global debates about the quality, affordability and sustainability of health care. 2–6 Since 2000, understandings of the prevention, detection and mitigation of harm have improved. 4,7–13 Crucially, from an earlier concentration on individual factors, it is now recognised that the consistent delivery of high-quality, safe and effective health care is complex and multidimensional.

Considered at higher system levels of analysis, it has been shown that patient safety is shaped by government policy14–21 and demands a nuanced balance of health-care system design22,23 and resources to create high-reliability organisations. 24,25 At the organisational level of analysis, it has been demonstrated that patient safety is moulded by culture, capacity, processes and governance systems,26–28 and that each is enhanced by distributed (shared, see Glossary) leadership. 28–36 At the level of health-care practice, it is known that patient safety is informed by the beliefs and values of health-care professionals,37–41 and is ultimately underpinned by their personal commitment to care. 42,43

The extent and burden of the problem

Despite growing awareness of the challenges posed by patient safety,44–46 and concerted improvements efforts within some health-care systems,47,48 considerable hospital patient safety problems persist. Global estimates of the burden of harm vary. However, they are normally reported to be around 10% of all inpatient admissions with a range of 3.8–16.6%,49 though such results are influenced by the means of measurement employed. 50–53 In the UK, it is estimated that 1 in 10 NHS hospital patients is harmed during his or her care, and 1 in 300 dies as a result of adverse events such as acquired infection. 54,55 Along with these human costs, safety incidents are a drain on NHS resources, costing an estimated £3.5B per year in additional bed-days and negligence claims. 56

Avoidable harm takes various forms. Errors occurring during drug prescribing, supply and administration represent a significant and persistent burden. 57–62 So, too, do those that arise as a consequence of surgery. 63,64 A more hidden cause is, quite simply, incorrect diagnosis. 65–69 In addition, there is variation in the delivery of medical and nursing care. 70,71 Failure in the safety of care is a particular issue for high-risk patient groups,72,73 but all patients may be at risk of harm, for instance, from communication deficits at handover;74–77 from low staffing,78 especially at weekends; or because the delivery of care coincides with the influx of a new cohort of junior doctors in training. 79,80

Foundations of the problem

Rising concerns about patient safety have led, in recent years, to a number of public enquiries into highly publicised failures of the health-care system, such as patient safety failings at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust,81 events at the Bristol Royal Infirmary82 and the Royal Liverpool Children’s Hospital,83 and the actions of Dr Harold Shipman. 84 The major reports published following these enquiries have helped to identify reasons for the failures85 and have sought ways of improving the safety of patients. 86 Taken as a whole, the findings of successive UK inquiries have emphasised five issues that can be seen as foundations of the problem of patient safety: (1) deficits in cultures of care, (2) leadership inadequacies, (3) ineffective team working, (4) problematic regulatory oversight and governance systems and (5) limited patient and public engagement. We summarise these issues, and the recommendations made to address and eliminate them, in Table 1, as a way of introducing what was known (by us), prior to our study, about the context of patient safety.

| Deficits in culture(s) of care |

|---|

Recommended improvements

|

| Leadership inadequacies |

Recommended improvements

|

| Ineffective team working |

Recommended improvements

|

| Problematic regulatory oversight and governance systems |

Recommended improvements

|

| Limited patient and public engagement |

Recommended improvements

|

Culture(s) of care

Inquiries into the events at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust draw attention to ‘the culture of care in the NHS’. 5,87–89 Unfortunately, as noted by Professor Jon Glasby,81 ‘The trouble with culture is everyone blames it when things go wrong but no-one really knows what it is or how to change it’. This issue is compounded when viewing (as we do) health-care organisations as comprising multiple cultures/cultural frames, rather than as a single culture of care. These points notwithstanding, research indicates that five aspects of culture are of particular salience to patient safety: (1) the need for a culture of compassion in care;81 (2) the problematic intra- and interprofessional hierarchies, which privilege a perceived elite at the expense of the broader health-care team;41,90–92 (3) the culture of blame that retards the promotion of adverse incident reporting and disclosure of harm to patients;42,93–95 (4) the culture of bullying96–98 that, regrettably, appears to be widespread across the NHS;99–104 and (5) the culture of unrelenting pressure to attain government targets, which creates a range of unintended and dysfunctional consequences. 105–111

Leadership

It is well recognised that patient safety improvement requires ‘sustained investment in developing leadership skills at all levels in the NHS’ and its aligned regulatory organisations. 82 Failures in strategic leadership may arise across the public sector,112 with such failures attributed to, for instance, the detrimental impact of external pressures,113–115 structural change16 and the challenges posed by the global financial downturn. 116 Nevertheless, such contextual constraints do not obviate the need for distributed leadership in health care from board to ward. 30,36,117 The detrimental impact on patient safety of a weak board and senior management team, marred by professional disengagement, poor governance and a lack of focus on the standards of care, has been illustrated in the Francis Inquiry. 81 However, at the point of care, professional leadership, especially medical, remains paramount118–121 and may function as catalyst for, or barrier to, patient safety improvement. 28,90,122–125

Team work

Research shows that, given the complexity and multidisciplinary nature of modern health care, effective team working is an important element in patient safety,33,126,127 necessitating good communication and co-ordination,119,128 particularly in high-pressure environments such as the operating theatre. 74,75,129–133 It also requires a degree of consistency in the meanings, beliefs and values that frame different health-care professionals’ commitment to care. 39 Yet effective team working remains vulnerable to the adverse effects of hierarchy,134 poor staffing,81 enmity and conflict30 and the human factors that give rise to team fragility. 135 Greater understanding of such human factors, specifically with regard to (i) human error, (ii) the role of health-care worker performance and (iii) the design of health-care technology, is increasingly recognised as core to patient safety. 136–138 But to be successful, this, too, necessitates careful consideration of the local context and the informal culture of clinical practice. 139

Regulatory oversight and governance systems

Public inquiries into failures in patient safety have consistently sought to enhance regulatory oversight81,82 and heighten both professional and organisational systems of governance. 83,84,140 It has been argued that these pressures have eroded professional self-regulation,141 replacing this traditional mode of control with an increasingly legalised regulatory system. 142 As a consequence, organisational, professional and work group boundaries have shifted. 143 This has the potential to foster defensive activity,144 which, as evidenced in the Francis Inquiry,81 may prove detrimental to the safe provision of health care.

Patient and public engagement

A final foundation of the problem of patient safety that emerges from recent inquiries is the weak representation of patients, their families and carers at all levels of the health-care system. Lauded as a more bottom-up approach to service planning and provision,145 a robust patient-centred focus is increasingly considered a core dimension of health-care quality. 146 This involves providing opportunity for patient, and broader lay, involvement in professional oversight bodies84 and health-care organisations’ formal governance structures,147–150 as well as active patient engagement in decisions about their care and the ensuing evaluation of their experience. 151–156

The patient safety agenda

In 2013, the Francis Inquiry81 was accompanied by two major reports into hospital patient safety. The first was a review into the quality of care and treatment provided by 14 hospital trusts in England, led by Sir Bruce Keogh, National Medical Director for the NHS in England. 157 While this review acknowledged (as other commentators did158–160) the difficulties in adopting mortality measures as an indicator of hospital performance, it also set out core features of high-quality care for patients. The second, a report by the National Advisory Group on the Safety of Patients in England, led by Don Berwick, President Emeritus of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI),161 also endorsed these goals. Each addresses the foundations of the social problem of patient safety that are outlined in Table 1.

The improvement agenda proposed by these two recent reports is exacting. It demands changes in policies, the education of health-care professionals and wider NHS workforce and further research into the quality and safety of health care. 5

Patient safety improvement programmes

Recent reports and inquiries indicate that the global debate has progressed from the recognition and acknowledgement of the foundations of the problem of patient safety to the quest for systemic solutions to the challenges it poses. 88,162–167 In England, a special health authority of the NHS, the National Patient Safety Agency, was established in 2001 with the remit of monitoring patient safety. It identified the need to introduce patient safety improvement programmes to help foster local capacity and progress from a ‘blame’ culture to one that was perceived to be ‘just’ and capable of facilitating the open reporting of errors and near-misses. 168 Informed by the work of the US-based IHI,162 and advances in safety within other industries,22,169,170 NHS hospital patient safety programmes have typically sought to achieve improvements by implementing evidence-based clinical practices and enhancing performance monitoring systems. 171–173 Although the National Patient Safety Agency was dissolved in 2012, these policy goals continue to be pursued, in England, through the NHS Commissioning Board and the Safer Patients initiative sponsored by the Health Foundation, a charitable trust, and in Wales through the 1000 Lives campaign and its successor, the 1000 Lives+ national programme, the focus of this study.

1000 Lives+ national programme in NHS Wales

Patient safety interventions range from isolated interventions within a discrete health-care setting, such as the estimation of intraoperative blood loss174 or the validation of specific measures of harm,175 through to national programmes of the type we are investigating in this study. 176

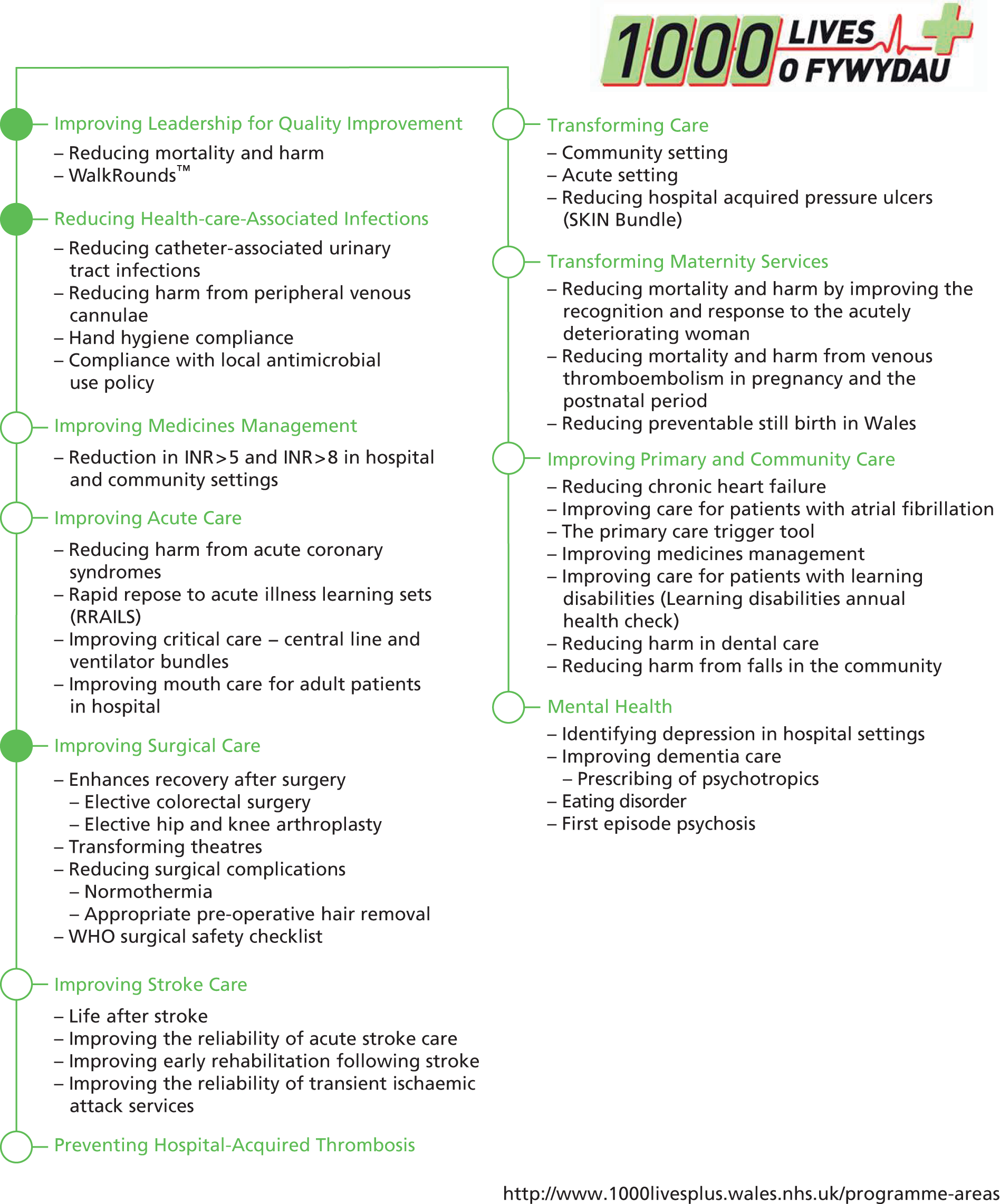

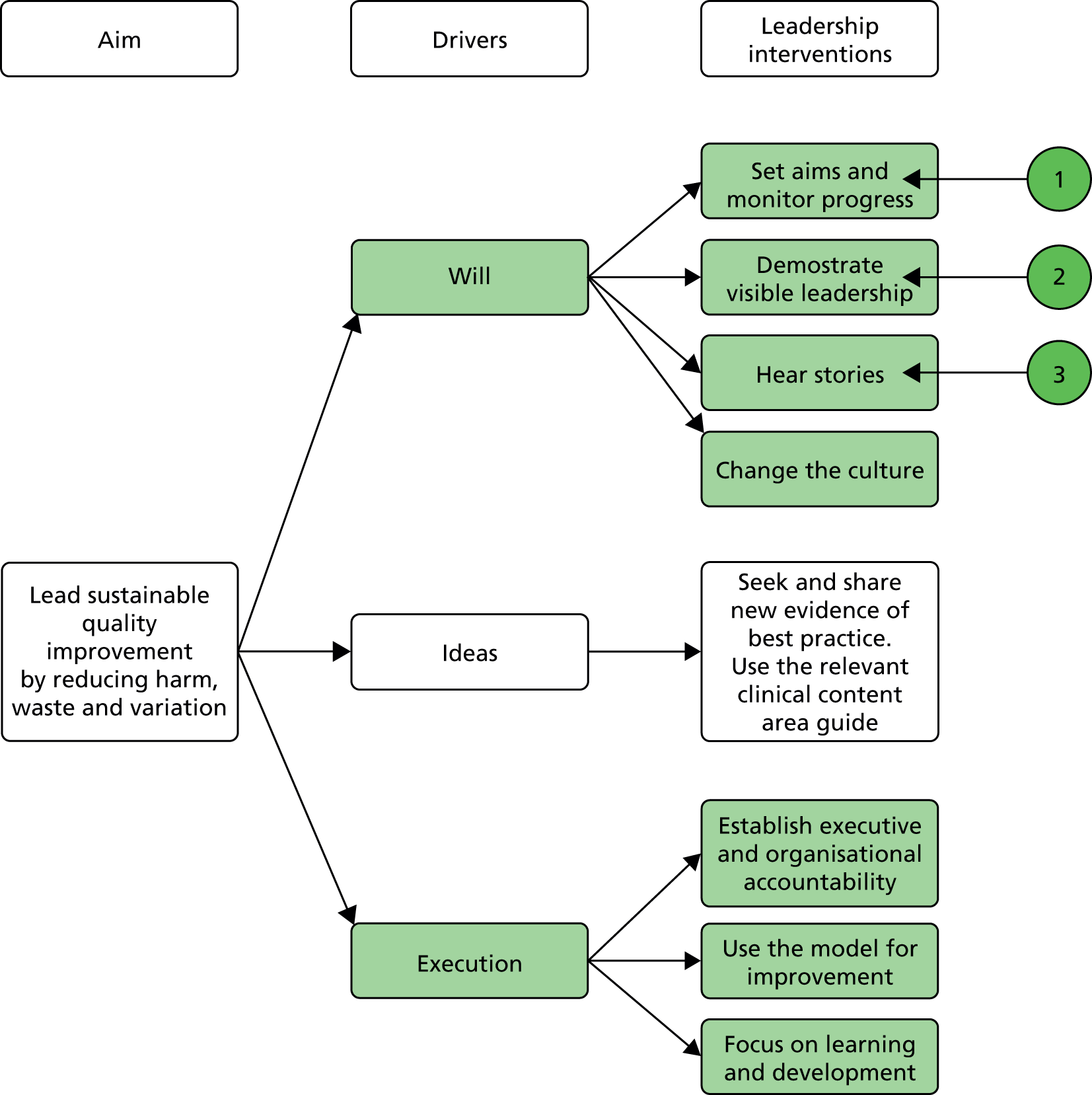

In April 2008, the Welsh 1000 Lives+ campaign was launched by a collaborative involving the Welsh Assembly Government’s Clinical Governance Support and Development Unit, the Wales Centre for Health, the National Leadership and Innovation Agency for Healthcare, the National Public Health Service and the National Patient Safety Agency. It had two distinct goals: (1) to reduce by 1000 the number of deaths caused by suboptimal care and (2) to reduce by 50,000 the number of adverse incidents. All health-care organisations in NHS Wales volunteered to participate in the programme. In 2010, the campaign was superseded by the 1000 Lives+ national programme. This continued the ethos of high-quality person-centred care and offered a broader range of patient safety interventions, and aligned resources, for NHS Wales’ health boards to implement. This ambitious and complex intervention built on the momentum of its predecessor and now forms a core component of the Welsh Government’s delivery framework for the NHS in Wales. As illustrated in Figure 1, 1000 Lives+ comprises a complex array of 11 core programme improvement areas.

FIGURE 1.

1000 Lives+ national patient safety programme areas.

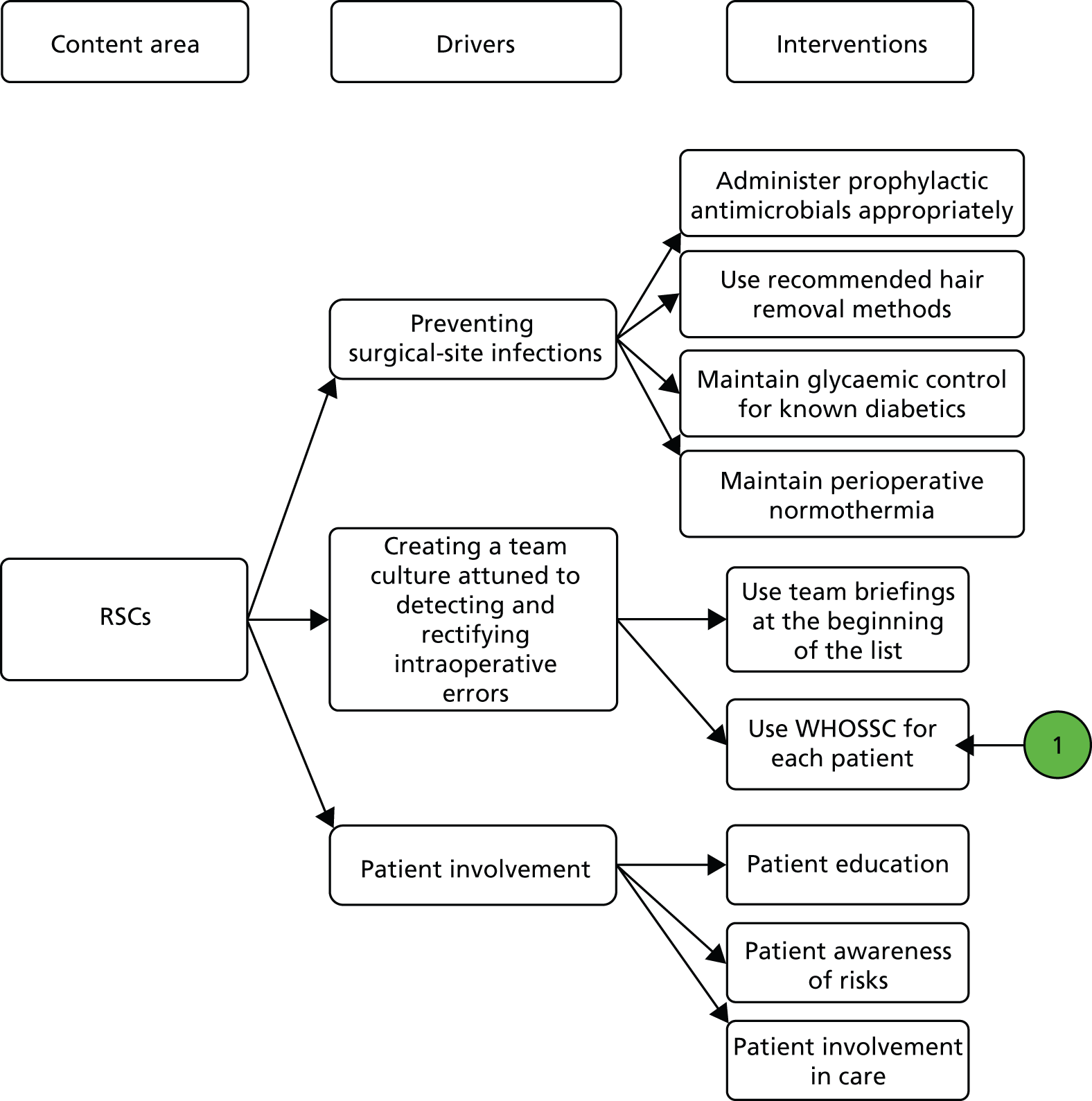

In this study, our attention is concentrated on three focal interventions: (1) ILQI, (2) RSC and (3) RHAI.

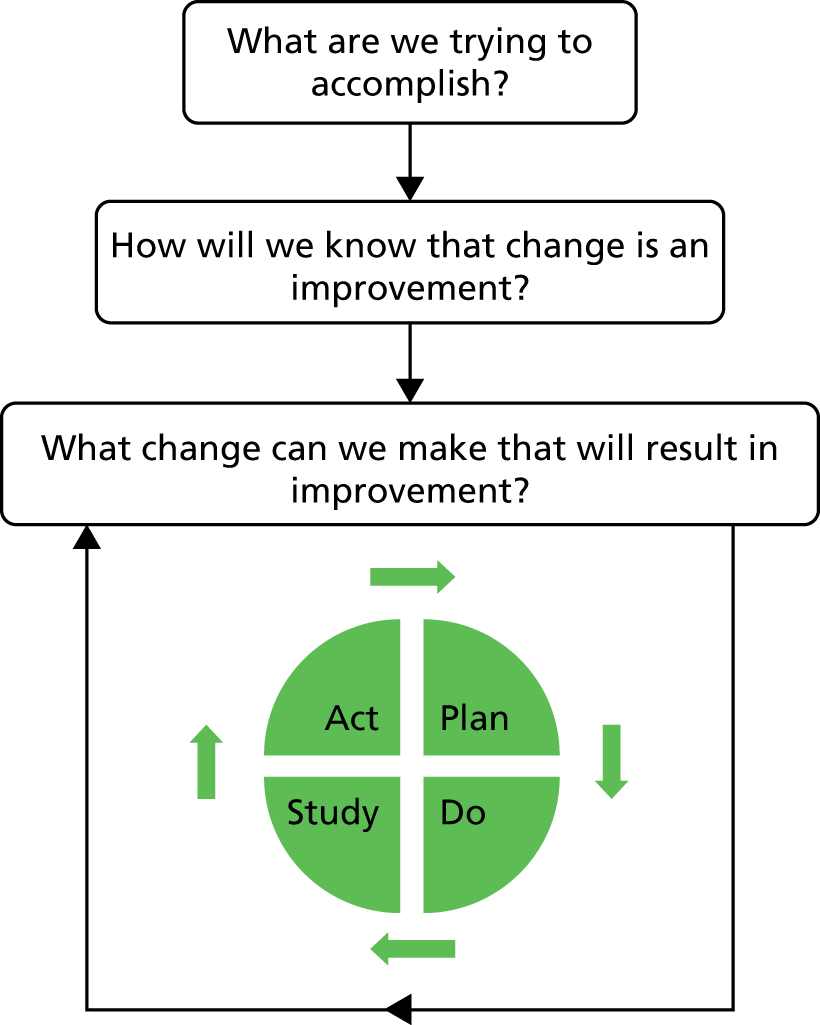

The 1000 Lives+ programme and its predecessor are adaptations of the IHI’s 100,000 Lives campaign. 162,177 Both are informed by the Model for Improvement (MI), developed by Langley et al. ,178 depicted in Figure 2. This model179,180 first directs attention to three questions: what are we trying to accomplish?; how will we know that a change is an improvement?; and what changes can we make that will result in improvement? It then prescribes the implementation of solutions through a Model for Improvement, Plan-Do-Study-Act (MI-PDSA) cycle.

FIGURE 2.

Model for improvement.

Centred on Deming’s system of profound knowledge,178 the MI-PDSA approach is an acknowledged cornerstone of the science of improvement,44,181 and is informed by a diverse array of theoretical perspectives.

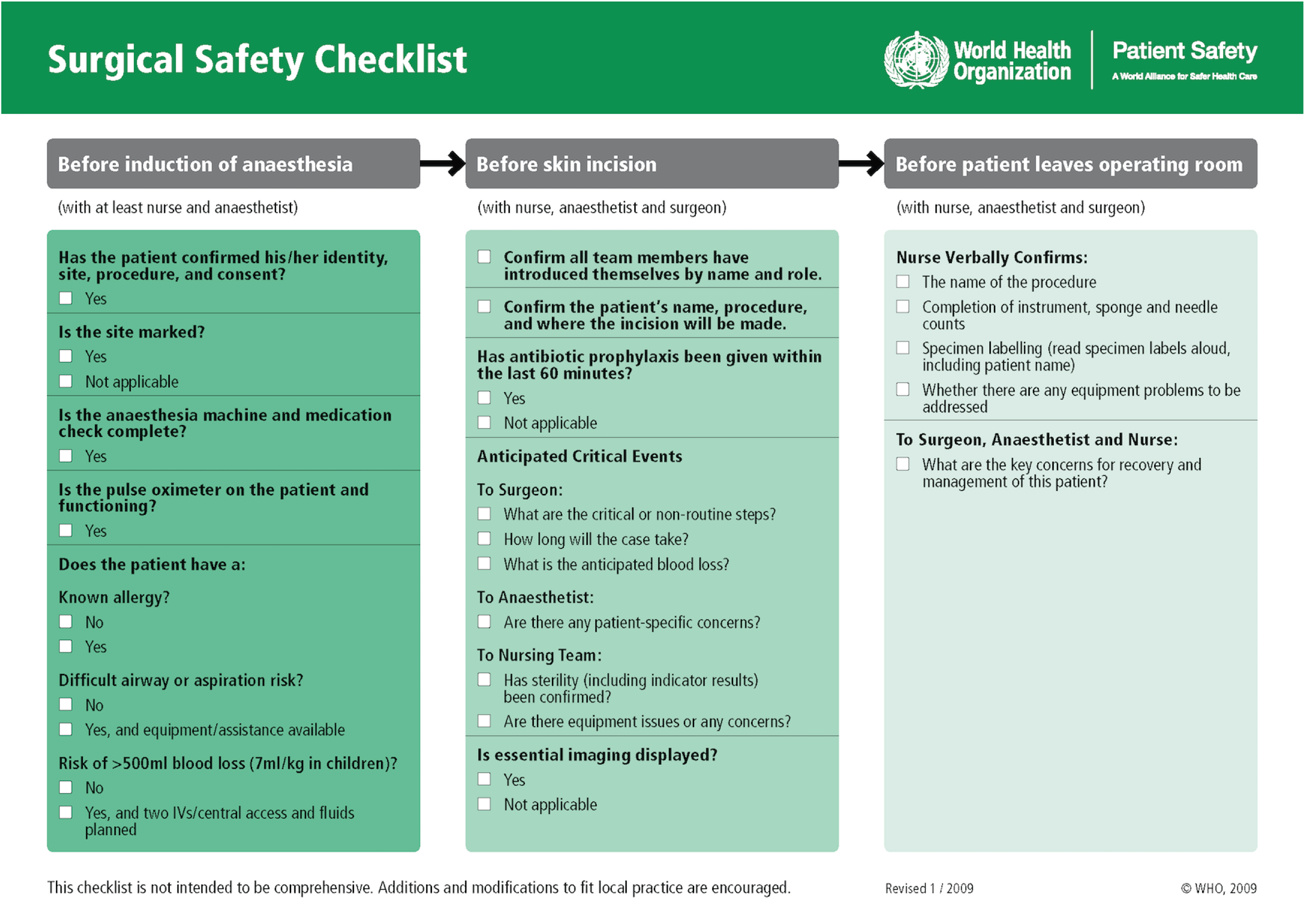

The MI-PDSA cycle has been promoted by the IHI as the means to foster the transformation of patient safety. 172 The strength and success of this promotion is reflected in the way that the MI-PDSA approach has been applied across a range of contexts, and to a variety of issues. Many of these themes are of direct relevance to this study, including (i) the role of local champions in leading change;182–184 (ii) the education of health-care professionals in evidence-based practice change;185–188 (iii) the implementation of the World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist (WHOSSC);169,189–191 (iv) the development and implementation of anti-infective prescribing policies,192–194 including those for correct hand hygiene;195 and (v) the large-scale transformation of health-care services through a heightened emphasis on patient safety. 5,196

Design, implementation and evaluation

The 1000 Lives+ national programme incorporated a range of IHI-inspired patient safety interventions that have been utilised worldwide. 5 These include (i) the use of checklists; (ii) care bundles (checklists and associated directive guidelines) for high-risk drugs197 and invasive practices;192,198,199 (iii) multicomponent interventions, such as those advocated for the prevention and management of pressure ulcers, falls and hospital-acquired infections;200–203 and (iv) various other forms of intervention, including staff training,118,204–206 adverse event simulation,207,208 computer-assisted care management,62,209 national and/or local alert systems and trigger tools. 28,53,210,211

Hospital patient safety: a realist analysis

Context matters

Despite having a basic improvement approach in common, the differences in scale and scope of the patient safety programmes impact on both the complexity of their implementation and the evaluation of their outcomes5,168,212–215 and the reported outcomes of these interventions are marked by considerable variation. However, although public inquiries and research evidence now concur that patient safety is, in part, a matter of context,168 there has been very limited systematic and independent analysis of the relationship between organisational factors which shape the local context of health care and the outcomes of patient safety interventions. 124,216–223

Prior to this study, relationships between the recently advocated ‘four high-priority’ features of organisational context:5,223 (1) external factors such as regulatory requirements; (2) organisational structural characteristics; (3) leadership, team work and patient safety culture; and (4) management priorities – and the outcomes of safety programmes were both undertheorised and poorly understood in empirical terms. 224 As a result, the context of patient safety remained amorphous225 and ill defined. 226 In contrast, this study is designed to address the conceptual and empirical knowledge gaps involving the context of patient safety.

Aim and objectives

This study employs insights from institutional theory227 within a realist analysis framework228–235 to examine the impact of context on the implementation of the 1000 Lives+ national programme across the Welsh NHS. We present and explain our conceptual framework in Chapter 2.

Our approach arises from an appreciation that the influence of organisational features on hospital patient safety programmes cannot be readily understood from traditional evaluation methods. 236,274 Building on findings from previous studies of the design237 implementation,21,220,238,239 and outcomes146,240 of patient safety improvement programmes, we examine the implementation of three focal interventions in a multisite comparative-intensive case study of hospitals in NHS Wales. We seek to reveal the complex interplay of context and concerns,234,235 captured through the organisational factors and competing institutional logics – belief systems – which guide acceptance of, or resistance to, the local adoption and adaptation of patient safety programmes. 3,240

This realist analysis of patient safety aims to ascertain which contextual factors matter, and how, why and for whom they matter, in the hope that processes and outcomes of future improvement programmes may be improved. Hence the unit of analysis in this study is the process of local implementation of the 1000 Lives+ programme, centred on the three focal interventions (rather than an evaluation of the 1000 Lives+ programme per se). The study has five main objectives:

-

to identify and analyse the organisational factors (e.g. structure, culture and managerial priorities) pertinent to the health outcomes of hospital patient safety interventions

-

to identify and analyse the contextual mechanisms (logics or belief systems) that interact with organisational factors to generate the health outcomes of hospital patient safety interventions

-

to develop and test hypotheses concerning relationships between organisational factors, mechanisms and the health outcomes of hospital patient safety interventions

-

to produce a theoretically grounded and evidence-based model of which organisational factors matter, how they matter and why they matter

-

to establish and disseminate lessons for a broad range of stakeholders concerned with patient safety policy and management.

The achievement of these objectives should allow us to suggest how a particular configuration of organisational factors may influence the mechanisms that lead to more or less successful health outcomes of the three focal safety interventions considered. It is hoped that these findings will inform policy-makers, managers and practitioners, locally, nationally and internationally; will empower stakeholders to develop improvement interventions that are more likely to work in their local contingent circumstances; and may serve as a diagnostic tool to be used as a precursor to the design of more differentiated and context-sensitive interventions in future.

Report structure

The remainder of this report is presented in eight further chapters. Recognising the complexity of the subject matter and the novelty of our conceptual framework, we have produced an innovative set of explanatory schematics to accompany each chapter, in addition to our use of standard data tables and figures. Below, we outline the structure of this report and the way in which we combine text, explanatory schematics and other forms of data presentation to ensure the clarity of our reporting.

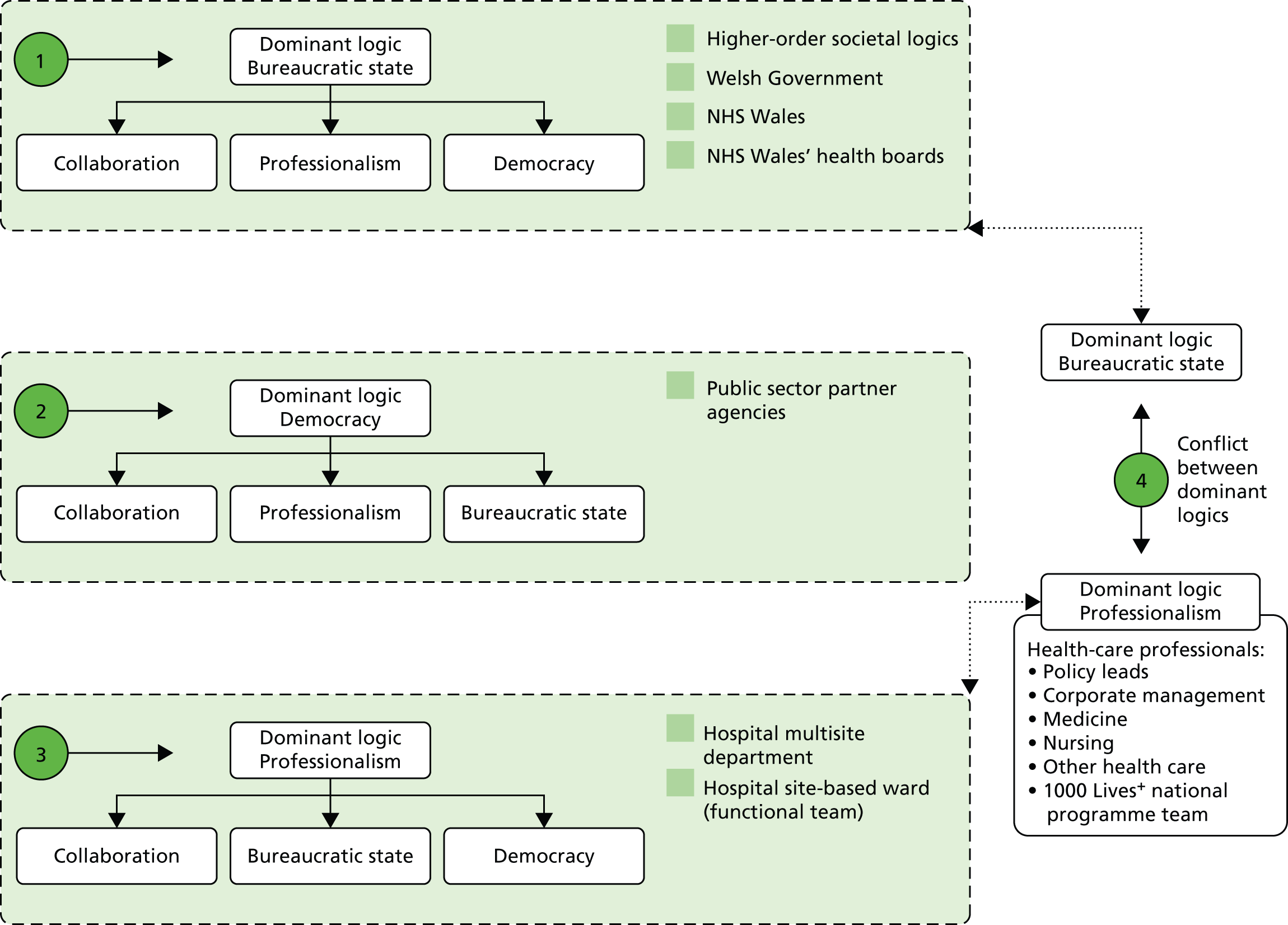

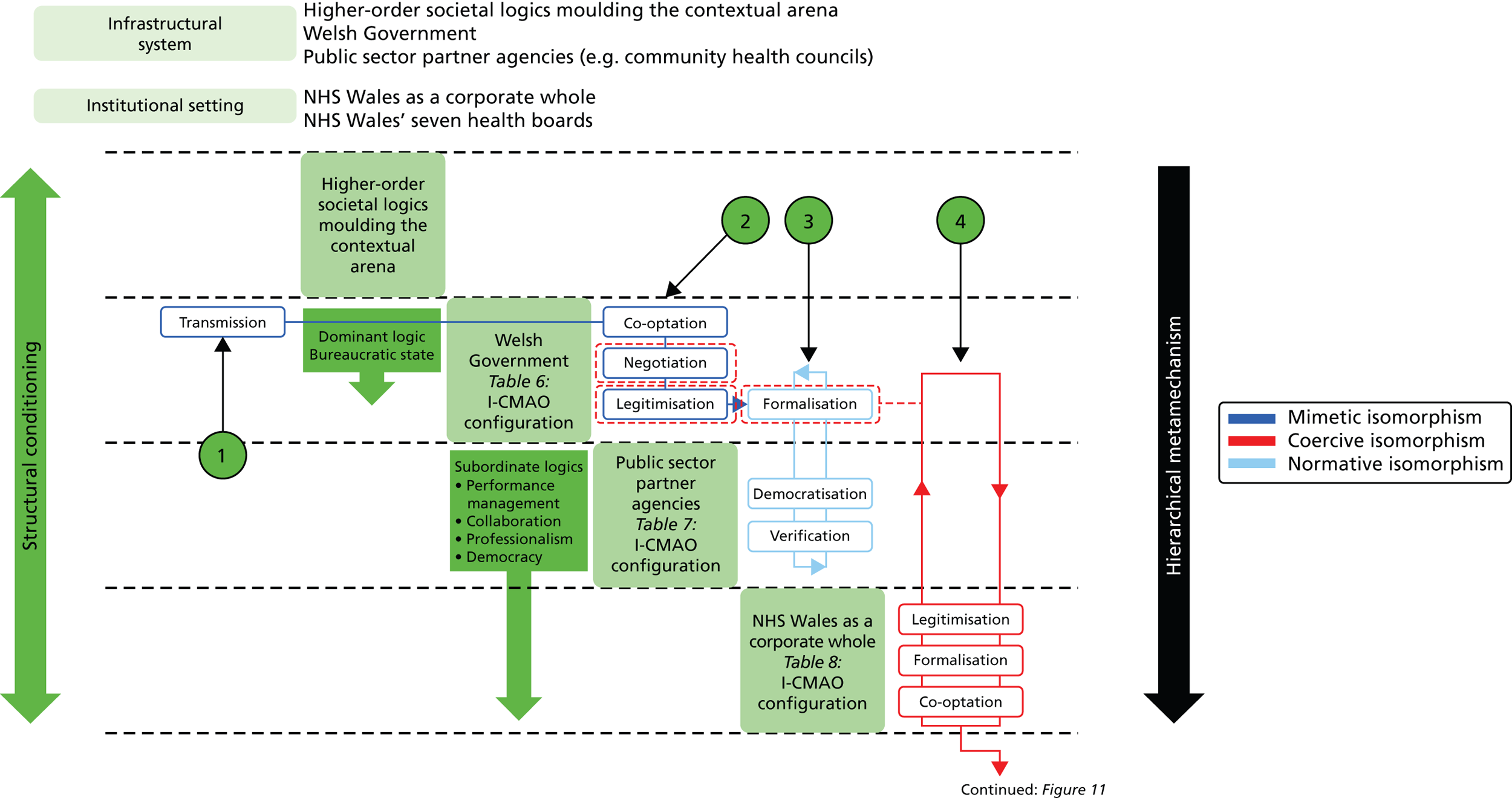

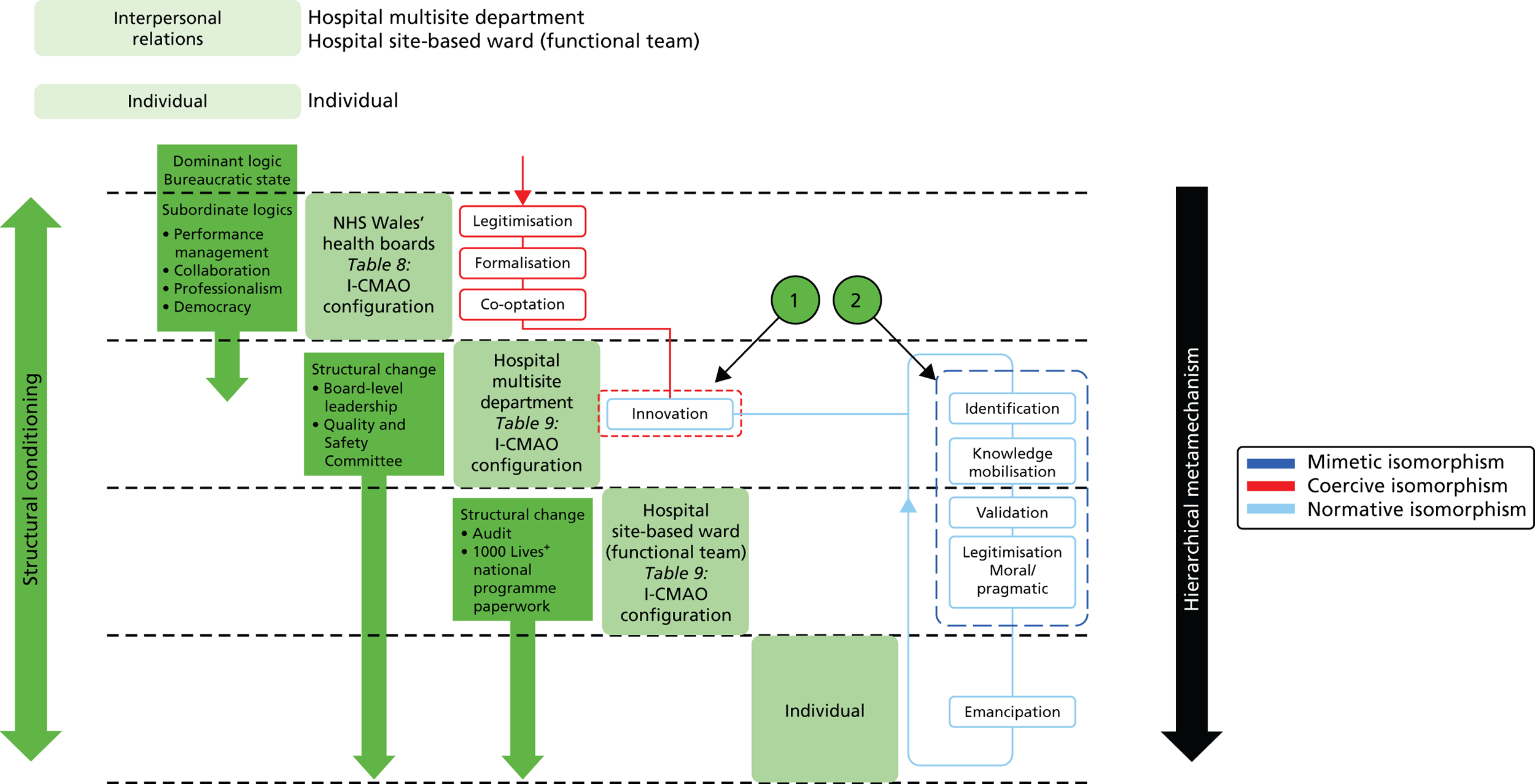

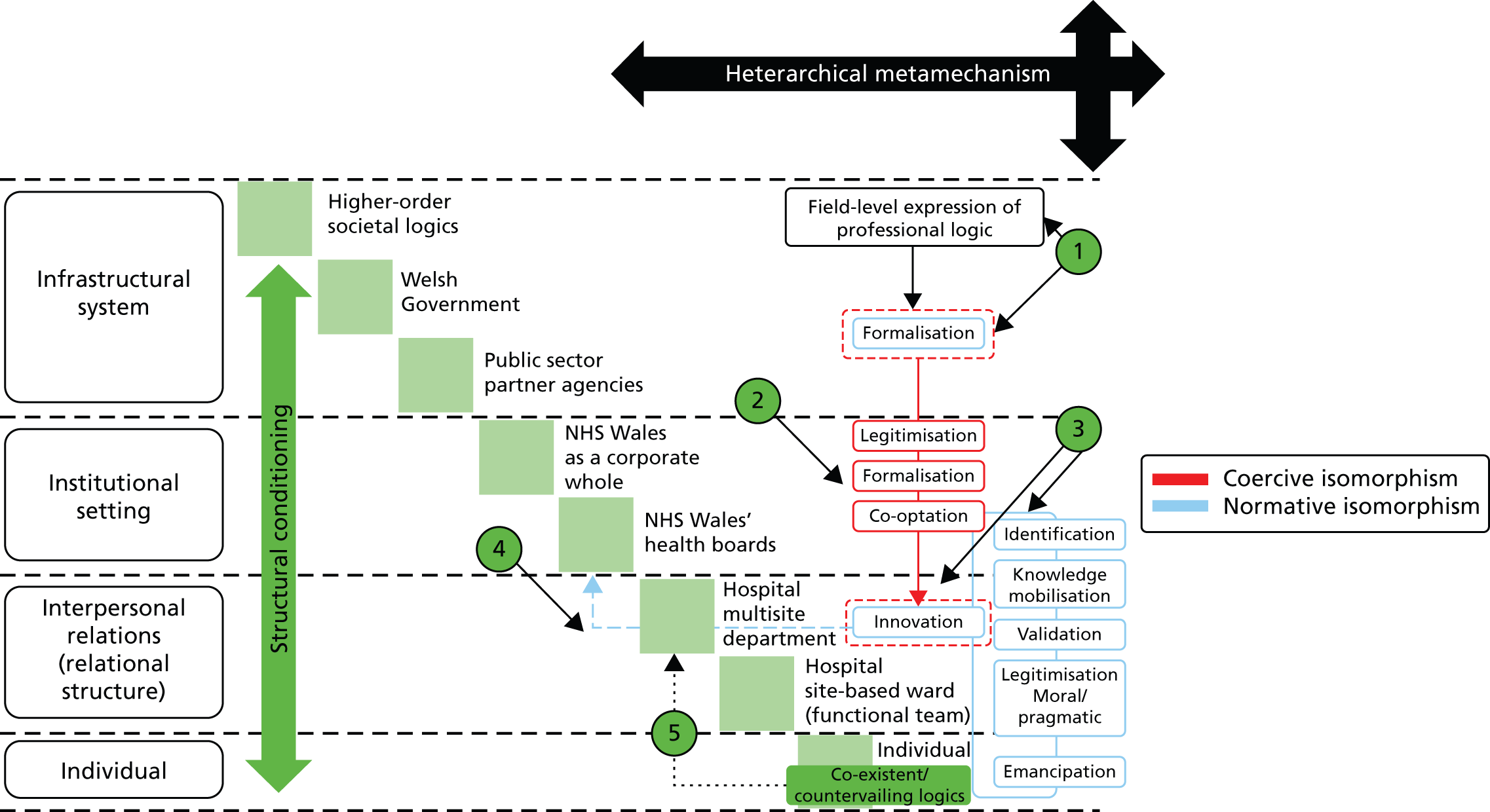

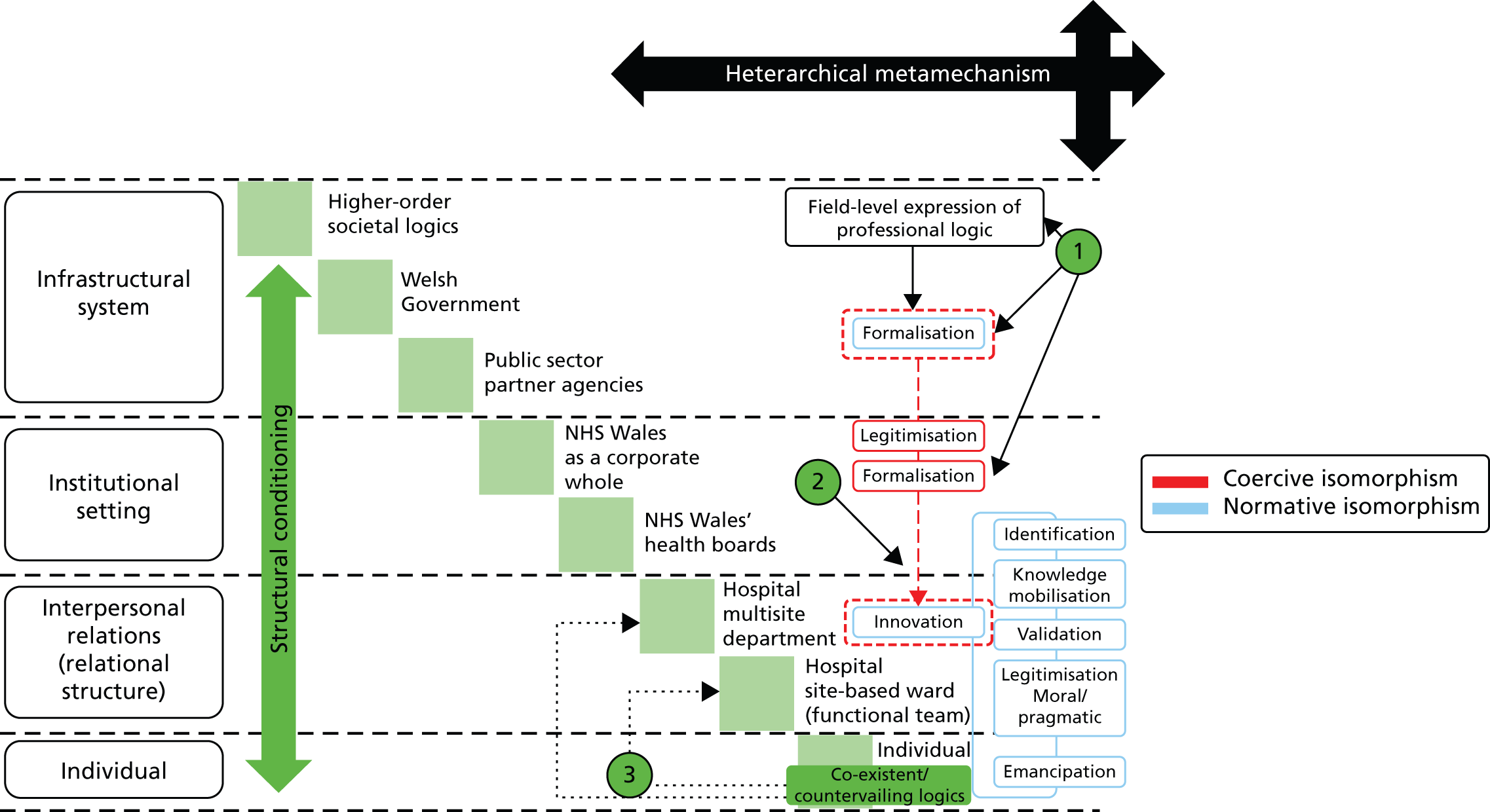

Chapter 2 presents the conceptual framework developed in this study – realist analysis – and defines our elaboration of established approaches to realist inquiry, centred on Archerian critical realism and augmented by sociological institutionalism and neo-institutional theory (see Figures 3–6).

Chapter 3 presents the research design – comparative case study – and multimethod approach to data collection and analysis (including our alignment to realist analysis) (see Figure 7 and Tables 2–5).

Chapters 4 and 5 present our analysis of the implementation and institutionalisation of the 1000 Lives+ programme in NHS Wales. Together, they form the foundation for our realist analysis of the three focal interventions selected from the programme. Chapter 4 presents our analysis of the bureaucratisation of 1000 Lives+ programme across NHS Wales, defining our preliminary understanding of the local implementation of the 1000 Lives+ programme (see Figures 8–11 and Tables 6–9). Chapter 5 explores interpersonal and individual engagement with 1000 Lives+ to offer an account of the normalisation of the programme at the level of the functional team within each health board (see Figures 12–15 and Table 10).

Chapters 6–8 present our realist analysis of the three focal interventions – ILQI, RSC and RHAI – and our understanding of the complex and dynamic relationships between organisational factors, generative mechanisms and the outcomes of hospital patient safety interventions: Chapter 6, Improving Leadership for Quality Improvement (see Figures 16 and 17, and Tables 11–21); Chapter 7, Reducing Surgical Complications (see Figures 18–20 and Tables 22–27); and Chapter 8, Reducing Health-care Associated Infection (see Figures 21 and 22, and Tables 28–33).

Chapter 9 presents the discussion and conclusion of our study, wherein we debate which contextual factors appear to impact on the implementation of patient safety improvement programmes, promoting or retarding their local success. In addition, we discuss the generalisability of our findings, the limitations of our study and potential for future work in this important area.

Intended audience

Throughout this report we have been concerned to ensure that our findings are accessible to the public, professionals, researchers and policy-makers wishing to (a) better understand existing improvement programmes and (b) design more effective ones in the future. We hope that our innovative use of neat description and summary graphics will assist in this objective, and the summaries presented in Chapters 1 and 9 are written for this extended audience in particular. In addition, we hope that much of the detailed narrative in the report will be of relevance to social scientists and others with an academic interest in the realist analysis of complex organisational phenomena.

Chapter 2 Conceptual framework

Overview

This chapter presents the realist analysis framework that was developed and then used in this study. It is presented in three main parts.

We begin by introducing the foundational realist philosophy of social science together with the approach to realist inquiry that underpins our framework. We then define the manner through which intervention, context, mechanism and outcome have traditionally been conceptualised and identify four challenges that have emerged.

The second section of this chapter, guided by Pawson’s241 belief that methods gain their spurs by thoughtful adaptation rather than mindless replication, introduces the conceptual resources from sociological institutionalism and Archerian critical realism that we have employed to address the challenges of applying realist inquiry.

In the final section, we draw from those resources and set out our innovative approach to the interplay of intervention, context and mechanisms in realist analysis. Briefly, our elaborations to realist inquiry are as follows. First, we include intervention as a separate analytical category in our realist analysis so that we may understand precisely ‘what’ is working, for whom, how and in what circumstances. Second, we forward a view of situated context as being stratified, conditioned, relational and temporally dynamic. Next, we distinguish the conceptual elements of mechanism from its ensuing outcomes and demonstrate the fundamental role of beliefs and values, institutional logics, on the propensity to act. Finally, in our realist analysis framework, outcome is not perceived as a simple, single aspect of change, such as a defined health outcome. Rather, we consider patterns of structural, political and ideational elaboration and maintenance.

Foundations of realist inquiry

Realist inquiry has emerged at the forefront of theory-informed policy evaluation methodology in health services and in other areas of social scientific enquiry. 228,241–243 Orthodox strategies for marshalling evidence in health-care research, epitomised by the Campbell and Cochrane Collaborations’ systematic reviews, seek to produce answers to the question ‘what works?’. In contrast, realist inquiry seeks to better bridge the gap between research, policy and practice244–246 by addressing the question ‘what works for whom, why and in what circumstances?’. 242,247 Within realist scholarship, two main approaches have gained prominence. Realist evaluation is the mode of inquiry for primary research, in which new data are collected from original sources. Its companion, realist review or synthesis, is the secondary research equivalent and involves analysis and interpretation of existing data. Both realist modes place emphasis on explanation of the interplay of contextual circumstances and mechanisms that foster the success or failure of an intervention. The principal aim is to refine understanding of how and why the intervention operates through the development of a more nuanced explication of what is termed programme theory, that is, the implicit or explicit hypotheses about anticipated outcomes on which a series of interventions (such as 1000 Lives+) are based. 247

Realist inquiry is rooted in the realist tradition in the philosophy of science. At base, realism steers a path between empiricist/positivist and constructivist accounts of scientific explanation243 and is regarded as the principal post-positivistic perspective. 242

The scholarship of Pawson and other realists is underpinned by a generative theory of causation. Hence the aim of realist research, such as ours, is not to identify variables that associate with one another as advocated by positivism. Instead, the research goal is to surface and explain how the association itself came about. 248 In this mode of inquiry, analysis is directed towards the identification and explanation of the underlying generative mechanisms which shape structure, agency, social relations and ensuing practices that are reproduced and/or transformed. 249,250 The realist approach to reviewing the evidence from complex interventions such as patient safety improvement programmes, therefore, assumes that deterministic theories cannot always explain or predict outcomes in every context. 251

The aim of realist inquiry is to further inform our understanding of the nuanced interplay between context, mechanism and outcome for particular interventions. 252–254 Its hallmark is, therefore, a quest to progress from a presumptive definition through to an evidence-informed refinement of a causal explanation. 247,255,256 Crucially, the conclusions of realist studies are recognised to be both provisional and fallible. 257

Realist inquiry

In realist inquiry, testable propositions of how an intervention is perceived to work are depicted through context–mechanism–outcome configurations (hereafter, CMO configurations). 228 In essence, a CMO configuration is a hypothesis that the programme outcome (O) emerges because of the action of some underlying mechanisms (M), which come into operation only in particular contexts (C). 256 Each CMO configuration, therefore, explicates and progressively refines the scope of the original programme theory. 258–260 In this manner, a virtuous circle is completed, fostering deeper understanding of the opportunities and challenges presented by an intervention, to inform future policy and practice.

Realist inquiry has gained increasing acceptance in health-care research, in part owing to its suitability for examining the implementation of complex interventions in heterogeneous, multiprofessional social systems. 261–266 However, a number of challenges have emerged concerning the operationalisation of each component of the CMO configuration. These challenges are discussed in the following four sections.

Intervention

Following Pawson, we recognise that while interventions designed to foster individual, organisational or system change (e.g. patient safety improvement programmes) are complex and diverse,260,267,268 they often depict consistent features. However, each intervention is dependent on collaborative human agency (motivated action) to achieve their effects. Consequently, the implementation chain of an intervention will be shaped by inconsistencies, as individuals and collectives, each differently enabled or constrained by the social system, engage with, adopt and adapt or ultimately reject the resources and reasoning provided by the programme. 251 The operationalisation of an intervention is, therefore, contextually dependent, influenced by the social system into which it is introduced and apt to mutate in situ. 251,269

There have been a number of realist approaches to analysing interventions in health-care organisations. For instance, an early application of realist inquiry into intervention in health care was research undertaken by Greenhalgh et al. into a major reorganisation of four inner-London health-care organisations176,261,270 They present an inclusive analysis of the interwoven components of an intervention, together with a postulated theory for each facet. 176,261,270,271 Similarly holistic approaches are illustrated in Byng et al. ’s evaluation of a complex health services intervention targeted towards people with long-term mental illness,264,272 Manzano-Santaella’s realist evaluation of financial incentives in English hospital discharge policy,273 and other causal explanations of interventions targeted at various stakeholder groups, including (i) patients;274–276 (ii) specific groups of health-care and aligned workers,277–284 and (iii) the standardisation of evidence-based practice through protocol-based care. 285–287

Alongside realist approaches that have been applied to consider ‘whole interventions’, more selective analyses of the discrete components of an intervention are depicted in studies such as Leone’s evaluation of an illicit drug deterrence programme. 288 This sanctions-based intervention is considered only with regard to the effects of its mandatory interview component. Similar approaches are demonstrated in other realist studies of health-care settings, such as (i) Blaise and Kegels’ evaluation of the development of the quality management movement in health-care systems in Europe and Africa;263 (ii) Ogrinc and Batalden’s evaluation of teaching about improvement of care in a clinical setting;289 and (iii) Pittam et al. ’s evaluation of employment advice provided to help people with mental health problems gain work. 290

Thus, it may be argued that previous applications of realist inquiry in health care have applied the concept of intervention inconsistently. Moreover, in our view, intervention is regularly underspecified and is too often conflated with context. As will be described later (see Intervention: a distinct analytical category), in this study we have tried to address these problems by treating intervention as a separate analytical category.

Context

In realist inquiry, four concentric layers of context are typically defined: (1) the broader infrastructural system, the outermost layer; (2) the institutional setting, encompassing the cultural aspects of a given contextual domain; (3) the interpersonal relationships which constitute the relational structure within which actors are embedded; and (4) the individual capacities of the key actors. 242 However, with rare exceptions (e.g. the work of Greenhalgh et al. 270 and of Byng et al. 264), realist studies in health care have, typically, been limited to a domain-specific notion of context. For example, focus may be directed towards the broader infrastructural system and associated aspects of the institutional setting as illustrated in Evans and Killoran’s realist evaluation of tackling health inequalities through partnership working291 or Pommier et al. ’s analysis of health promotion activities within the French education system. 292

Alternatively, realist inquiries have focused on discrete organisational sites293 as in Oroviogoicoechea et al. ’s evaluation of the impact of a computerised hospital information system on nurses’ clinical practice,294,295 Pittam et al. ’s evaluation of employment advice for those with mental health issues,290,296 and Tolson et al. ’s study of managed clinical networks in the care of individuals with cancer-related pain. 297

More recently, other aspects of context have been considered within realist studies in health care. These typically encompass the notion of organisational culture and influences emerging from wider interorganisational alignment. 3,298–300 Key contextual features include leadership, both by corporate management and by clinical health-care professionals,81,181,301 and governance systems, including performance monitoring, evaluation and feedback, which is increasingly patient informed. 28,146,302

Overall, as noted by Shekelle et al,223 many previous applications of realist inquiry have failed to agree on what elements of context are most influential and how context should be conceptualised. 27,303,304 We have tried to avoid this problem by using a multilevel approach to this issue (see Context: structural conditioning).

Mechanism

As originally described by Pawson, the mechanisms of a programme describe what it is about programmes and interventions that bring about any effects and are the processes by which subjects interpret and act on the intervention stratagem. 228,241,242 Thus, it is not programmes that work per se. Rather, it is the underlying reasons or resources that they offer subjects that generate change. 305 In this view, mechanisms explain causal relations by describing the powers, propensity or particular ways of acting inherent to a system and are linked to, but not synonymous with, the underlying programme theory. 306,307

Further insight into the nature of mechanisms is contributed by the work of Hedström and Ylikoski,308 who contend that a mechanism is a causal process that produces an effect or phenomenon. In addition, they posit that a mechanism has structure and operates in hierarchical sequence. This conceptualisation parallels that of Fleetwood,306 who sees mechanisms as consisting of a cluster of causal factors or components comprising social structures, practices, relations, rules and resources, with each cluster possessing the powers, capacities and potentials to do certain things. It is also important to appreciate that mechanisms produce contextually modulated effects according to their spatiotemporal relations with other objects, and have their own causal powers and liabilities, which may trigger, block or modify their action. 309,310

In realist inquiries, mechanisms are typically presented as part of a CMO configuration. 311,312 Indeed, some studies extend this explanatory analysis to expose the specific roles of different components of the intervention. This is exemplified in Mazzocato et al. ’s study,313 where candidate mechanisms, attributed to the operationalisation of service improvement methods, are used to define multiple CMO configurations. However, in studies where CMO configurations are not developed, merely disconnected mechanisms or outcomes, as opposed to a causal explanation, may be reported, as in Harris et al. ’s314 realist review of journal clubs and Gunawardena’s315 review of the effectiveness of geriatric day hospitals.

It is acknowledged in realist inquiry that one CMO configuration may be embedded in another or configured in a series (in which the outcome of one CMO becomes the context for the next in the chain of implementation steps). 307 This aspect of realist inquiry remains underdeveloped, as it demands a highly complex formulation of CMO configurations. 316–318

In addition, although it is acknowledged that mechanisms encompass the reasoning of its participants, this aspect of realist inquiry is also little explored,256 with few studies reporting participants’ thoughts about why they chose to change, or indeed adhere to, their established practice (for two exceptions, see Dieleman et al. 319 and Jackson et al. 320). The relative neglect of this aspect of mechanism may not be surprising as, as noted in Vassilev et al. ’s realist review of the role of social networks in the management of chronic illness,321 unpacking and conceptualising reasoning is fraught with difficulty as justifications for choices can operate within different, and often contradictory, stances.

Outcome

In realist inquiry, an outcome cannot be perceived as a simple, single aspect of change. The multifaceted nature of an intervention, particularly when implemented within different organisations, each shaped by their own contextual constraints and enablements, leads to different patterns of social transformation. 243,269

Many applications of realist inquiry in health care attempt to present the health outcomes of interventions. However, as noted by Floyd et al. ,322 the specification and measurement of outcomes poses challenges. For example, health outcomes may be obscured, merged with context and mechanism and depicted as factors,323 or simply framed in terms of the intervention’s effectiveness. 324 Outcomes supported by CMO configurations, and thus setting out a clear explanatory argument, such as Tilley’s325 realist evaluation of a British crime reduction programme, do something to tackle this problem. However, few studies explicitly address more subtle and aligned outcomes arising from the intervention.

To summarise, the above section has suggested that, despite the contributions made by realist inquiries in health care, four issues have consistently challenged researchers who have sought to apply existing models: (1) the tendency to conflate intervention with context; (2) the limited conceptualisation of context and mechanism, thereby inhibiting rigorous analysis of their boundaries; (3) the preoccupation with health outcomes, as opposed to wider organisational and systemic gains or losses; and (4) the limited capacity to frame the dynamic, temporal, interplay of intervention, context, mechanisms and outcomes. We now move on to explain how we sought to address these issues through an elaborated model of realist analysis.

Addressing the challenges of realist inquiry

In our realist analysis framework, we employ resources from sociological institutionalism and Archerian critical realism to help better specify context and mechanism and hence to address the challenges outlined above. In the next two sections we introduce the key concepts that inform the revised CMO model we present in Realist analysis: an elaborated intervention–context–mechanism–agency–outcome model.

Sociological institutionalism

Within organisation studies, there has been a ‘growing disenchantment’ with analytical perspectives that emphasise the influence of managerial rationality within organisational life. 326 Rejecting the tenets of strategic management and classical economic theory, sociological institutionalists examine the significance of institutions, the ‘regulative, normative and cognitive [see Glossary] structures that provide stability and meaning to social behaviour’. 327

Some of the main contributions to understanding institutional change and inertia in health care have emerged from analyses conducted at the level of organisational fields, defined as communities of organisations that ‘partake of a common meaning system and whose participants interact more frequently and fatefully with one another than with actors outside of the field’. 328 In a seminal example, DiMaggio and Powell329 suggest that within organisational fields, three forces – mimetic (copying those perceived to be successful), coercive (e.g. regulation) and normative (e.g. stemming from professional norms) – combine to produce powerful templates of what constitutes legitimate organisational structure and action, and we use these terms in our analyses of the data from our study.

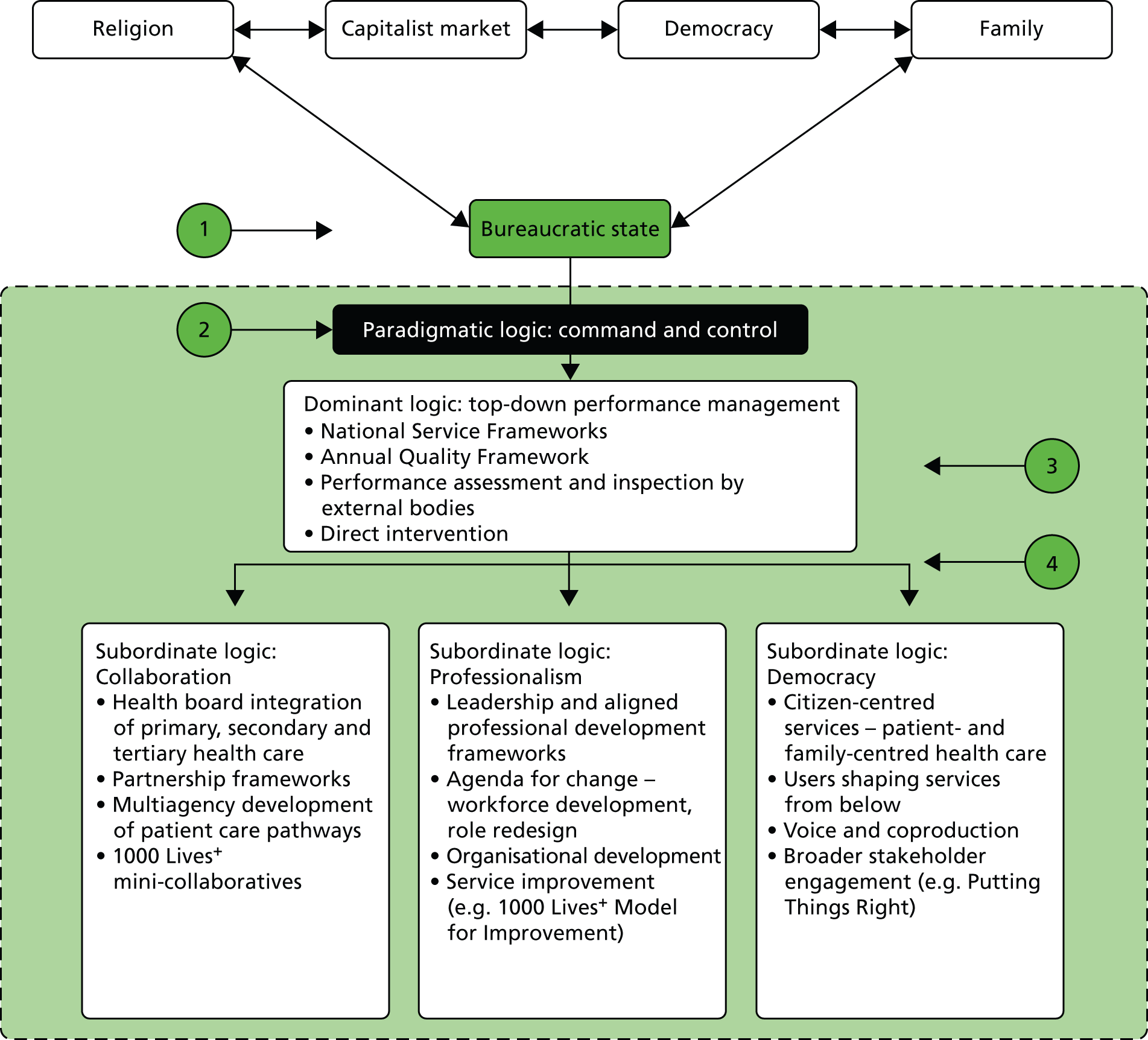

In common with critical realism, sociological institutionalism depicts a world of virtual depth,330 stratified and organised through different levels of institutional structures, along with their logics, or commonly held sets of beliefs and values. There are higher, or macro-level, structures; these include societal systems such as the bureaucratic state, capitalist markets, democracy and religion. Then come meso-level structures characterised as organisation sectors or fields; these are composed of those organisations that are involved in a particular issue or policy community. The concept incorporates field-level structures, participating organisations and the people working within and between these organisations. For instance, the field of health-care organisations comprises distinctive actors, diverse institutional logics and distinct governance structures. Finally, there is the micro-level of the individual organisation, together with further intraorganisational levels or groups.

Typically, the multiplicity of logics in a given domain is represented as some combinations of (i) higher-order societal logics,331 (ii) field-level logics332 and (iii) institutional or ‘cultural’ logics. 333 At the societal level, heterogeneous higher-order logics sculpt the social world, conveying the core organising principles of different sectors. 331 Institutional logics orchestrate lower-level institutional strata and ensuing practices. They shape organisational interests, individual preferences, define actors’ expectations about each other’s behaviour and organise their enduring relations with each other. 330,334

Previous studies of UK health-care fields have concentrated on the role of, and dynamics among, three logics: professionalism, bureaucracy and market. Professional logic was dominant for much of the twentieth century and gave workers with specialised knowledge (e.g. doctors) cultural and material privileges, including the power to organise and control their own work and that of others. 335,336 The primary justification for these arrangements was that service delivery is optimised when it is under the control of experts acting with the altruism they are assumed to develop during prolonged training and socialisation. During the latter part of the twentieth century, successive governments promoted combinations of two alternative logics in health care: (1) bureaucratic logic, which holds that service delivery is improved under the administrative control of work using techniques of performance management, and (2) market logic, which holds that improved service delivery arises from conditions of competition among providers and choice among clients.

In our framework, multiple layers of logics constitute and provide the inherent structure to context. However, organisational actors (or agents) may go along with or actively resist these social prescriptions,337 thus inhibiting or supporting change. The process of institutional change is, therefore, both enabled and constrained by (i) the array of institutions, which compose and condition the substructure of the health-care field, and (ii) agential theorisation, reflexivity and ensuing modes of institutional work. 338–340 Accordingly, even though institutions provide meaning to social life, such conditioning is non-deterministic. 229,341

Realist social theory

To further elaborate realist inquiry, we turn to Margaret Archer’s seminal work on critical realism. 229–235 As in Herepath’s study,342 our approach employs Archer’s conceptual approach to structure,229 culture230 and agency,231 together with her later work on reflexivity. 232–235 Our reasons for incorporating Archer’s realist social theory are threefold.

First, Archer’s ontological stance holds structure (context) and agency (mechanism) as separate entities. Consequently, Archer offers help to researchers who struggle over this distinction when analysing the complex interplay of context and mechanism during the development of CMO configurations.

Second, an Archerian approach resonates with sociological institutionalism. 343,344 Hence by harnessing institutional theory within an Archerian approach, institutions are given their due recognition and temporal role as both symbolic constructions and a set of material practices which guide actors’ behaviours. 345 This helps to reveal the multiple logics which shape adherence to, or disregard for, the components of an improvement programme and its underlying ethos.

Third, an Archerian approach offers a robust methodological framework composed of three phases,229 which parallel the context, mechanism and outcome components of a CMO configuration. Therefore, methodologically, the researcher is guided by an aligned approach that helps to distinguish the boundaries between context and mechanism and to reveal possible causal links between them.

Realist analysis: an elaborated intervention–context–mechanism–agency–outcome model

This section explains how our model of realist analysis draws from the resources outlined above to address the challenges of realist inquiry.

Intervention: a distinct analytical category

Our first elaboration to realist inquiry is to include intervention as a separate analytical category in our realist analysis model. This stems from our recognition that although realist studies have adopted similar Pawsonian conceptions of intervention, the absence of intervention as an analytical component has encouraged its underspecification and conflation within context. 286

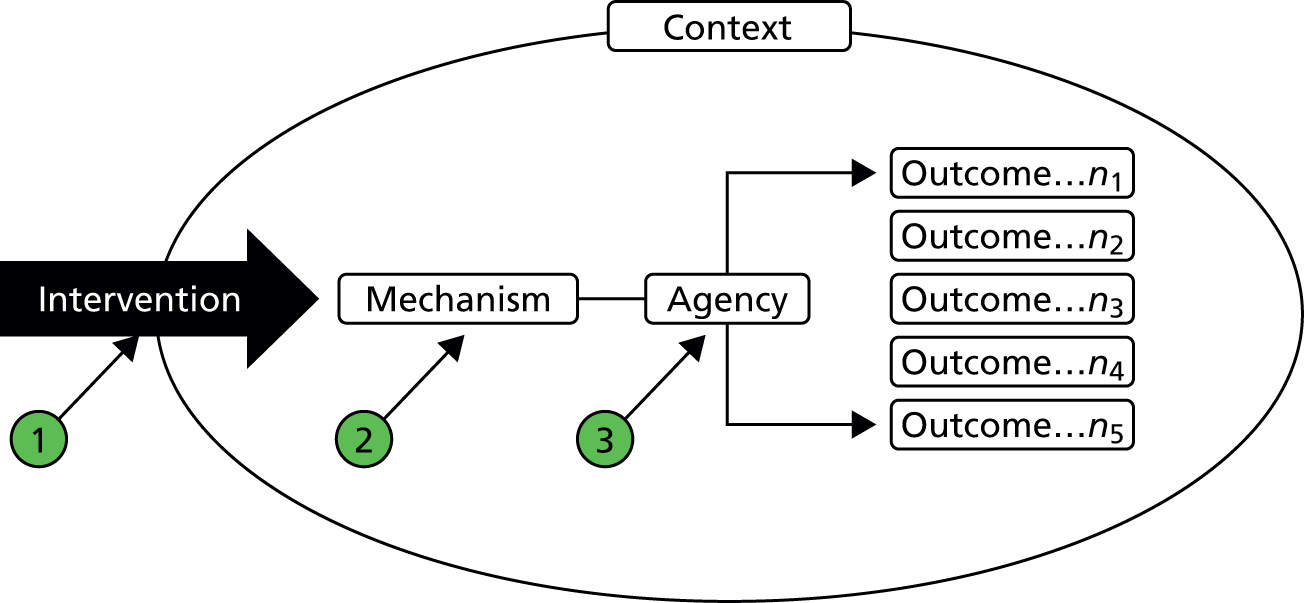

We therefore consider that there is an imperative within realist inquiry to (i) explicitly define the intervention ‘I’ and (ii) add this to Pawson’s original CMO formula to produce intervention–context–mechanism–agency–outcome (I-CMAO) configurations. This allows us to understand precisely ‘what’ is working in a situated context, for whom, how and in what broader circumstances. This refinement is depicted in Figures 3 and 4, and this method of representation forms the basis of all the translational schematics for the realist analysis presented in Chapters 6–8.

FIGURE 3.

Basic I-CMAO schematic.

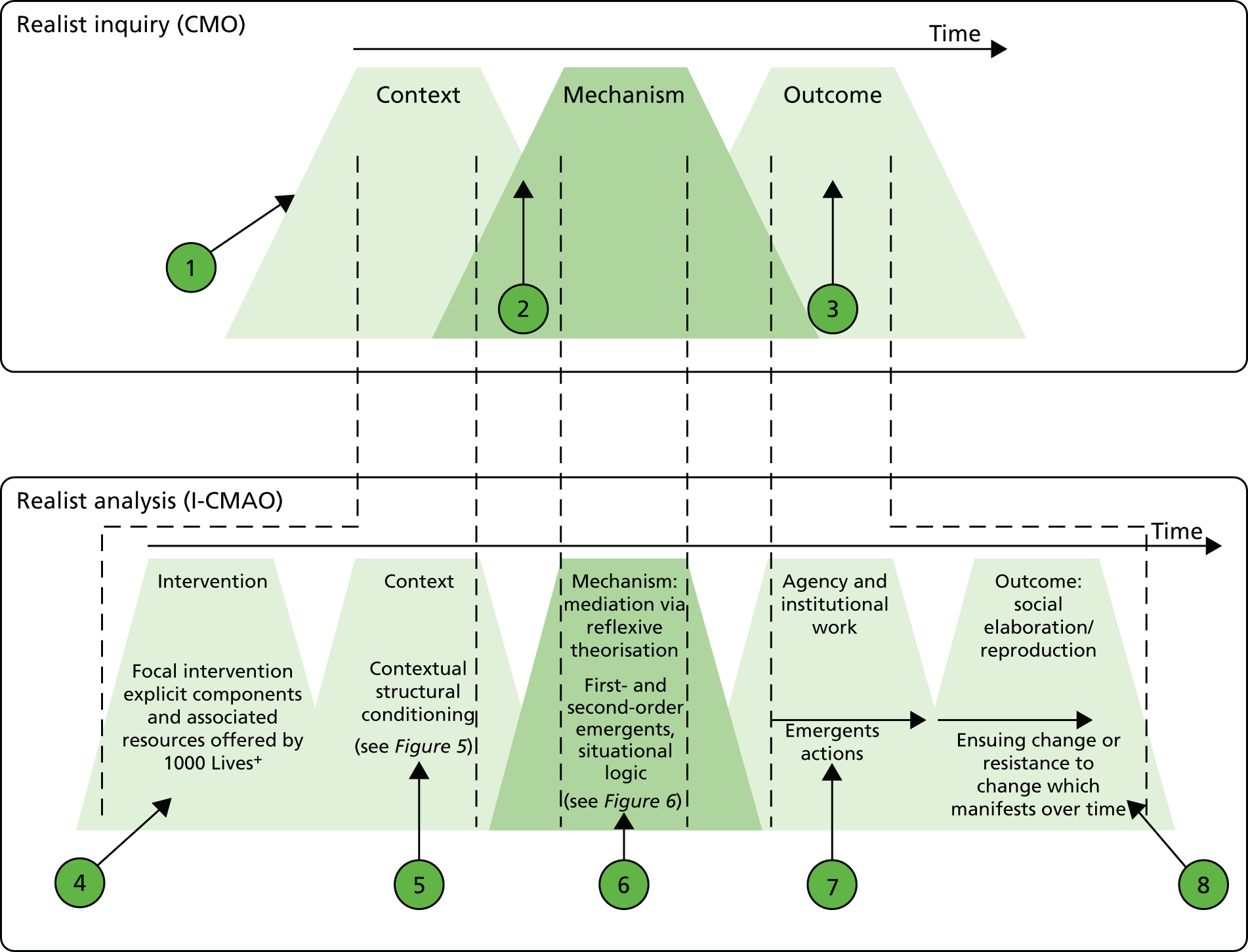

FIGURE 4.

Translation from a CMO configuration to an I-CMAO configuration.

In the upper graphic of Figure 4 we depict a schematic representation of a CMO configuration. As asserted in Realist inquiry, a CMO configuration is a hypothesis that the programme outcome (O) emerges because of the action of some underlying mechanisms (M), which only come into operation in particular contexts (C).

Point 1 highlights the absence of intervention as a separate aspect of the analysis.

Point 2 highlights the difficulty that may arise in distinguishing context from mechanism in realist inquiry due, in part, to the lack of clarity and consistency with which context is conceptualised and operated.

Point 3 draws attention to outcome in realist inquiry. An outcome cannot be perceived as a simple, single aspect of change; however, few studies explicitly address more subtle and aligned outcomes, which arise consequential to the intervention, impacting social elaboration or reproduction.

To address these issues, in the lower graphic of Figure 4, we depict a schematic representation of our I-CMAO configuration and set out our four elaborations.

First, as indicated by point 4, we include intervention as a separate analytical category embedded with the context under consideration.

Second, at point 5 we forward a view of context as stratified, conditioned, relational and temporally dynamic, as expanded in Figure 5. In doing so, we seek to define the ‘situated context’, through the dominant structural and cultural emergent properties in play, their attendant mechanisms and, thus, the impact on lower contextual strata.

Third, at point 6 we apportion mediation and reflexive theorisation to mechanism. In this manner, we distinguish the conceptual elements of mechanism from its ensuing outcome (this is expanded in Figure 6).

Point 7 highlights our goal of examining the ensuing process of institutional change, as opposed to that which ultimately manifests as an outcome, thereby recognising that such change unfolds through time, may be contested and may be at different stages of maturation in different situational contexts.

Finally, as depicted in point 8, outcome is not perceived as a simple, single aspect of change. Rather, we seek to reveal structural and ideational differentiation.

Context: structural conditioning

As noted earlier, both realist inquiry and sociological institutionalism not only stress the importance of context228 but also warn that to enable meaningful explanatory analysis, context cannot be reduced to the spatial, geographical or institutional location into which a social programme is introduced and that a more nuanced understanding of the multiple layers that compose a given context must be established. 236,244,257

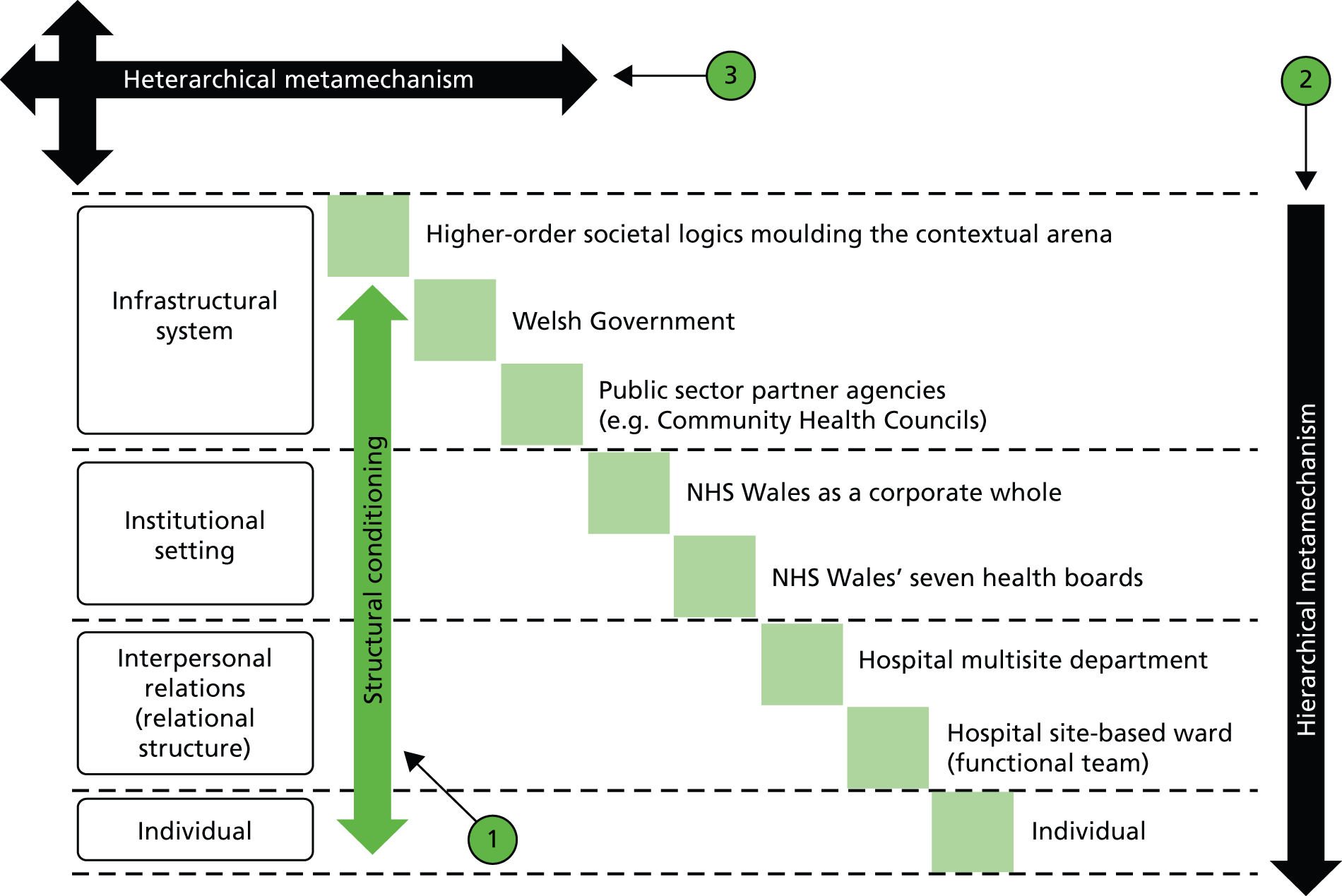

Guided by the approach to realist inquiry adopted by Pawson,228 we address the need to develop a more subtle analysis of context by specifying four main levels of contextual hierarchy (infrastructural system, institutional setting, interpersonal relations and individual) with all but the individual level divided into substrata (see Figure 5).

At the highest hierarchical level, we see the infrastructural system of the Welsh health-care state as comprising three strata: (1) the higher-order societal logics which mould this contextual arena; (2) the Welsh Government, as a devolved substate nation, and (3) the public sector partner agencies with regulatory oversight of health-care quality and patient safety, which operate in close liaison with, but distinct from, the Welsh Government and NHS Wales. The second highest hierarchical level of context, the institutional setting, is conceptualised through two strata: (4) NHS Wales, as a corporate whole, and (5) its seven constituent health boards as distinct multisite organisations. The third level, interpersonal relationships, which constitute the relational structure within which actors are embedded, is captured across two further strata: (6) a hospital site-based ward or multisite department and (7) the functional team (the group of people who carry out the tasks involved in running a ward or department). Our final stratum (8) describes the capacities of the individual actors.

However, a stratified model of context provides only the basic architecture of our argument, as it lacks the means to consider context as ‘situated’, meaning dynamic, conditioned, relational and temporally fluid. In essence, we see the dynamism of context as contoured by emergent structural, cultural and agential powers across time. Our recourse to Archerian critical realism, together with the work of Herepath,342 therefore offers a more complex yet nuanced means to develop I-CMAO configurations.

An underlying premise of realist theory and research is that context affects or mediates ensuing agential actions346 and hence the structural constraints and enablements of context are mediated to the agent as first-order emergents. First-order emergents encompass agents’ placement within their broader social context and roles, their vested interests, the opportunity costs associated with different courses of action and, thus, their perceived interpretive freedom. Such first-order emergents impact differently on each agent, enabling or frustrating the attainment of their desired goals depending on their social bargaining power, both as individuals and as members of groups. Consequently, our analysis of how context impinges on agents is stratified across three levels: social position, how their roles relate to others and the cultural logics of the institutional domain within which they are situated. In this way we expose the contextual constraints and enablements imposed on the agent.

The second stage by which the constraints and enablements of context are mediated addresses how agents, conditioned by their contexts, think about and influence the formulation of their desired projects, both individually and collectively. 232 These influences give rise to potential second-order emergents (i.e ‘the results of the results’ of the first-order emergent properties346), which in their turn affect the ways in which an intervention is implemented.

Accordingly, in our realist analysis, we separate context from its mediation (or the effects of the context on the intervention). As depicted in Figure 5, we first specify the explicit stratum concerned, so that hierarchical and heterarchical influences may be more readily appreciated within a situated context. Second, we identify dominant structural and cultural emergent properties within that context to define the structural conditioning in play. Third, we apportion its mediation to mechanism, as expanded in Mechanism: sociocultural interaction.

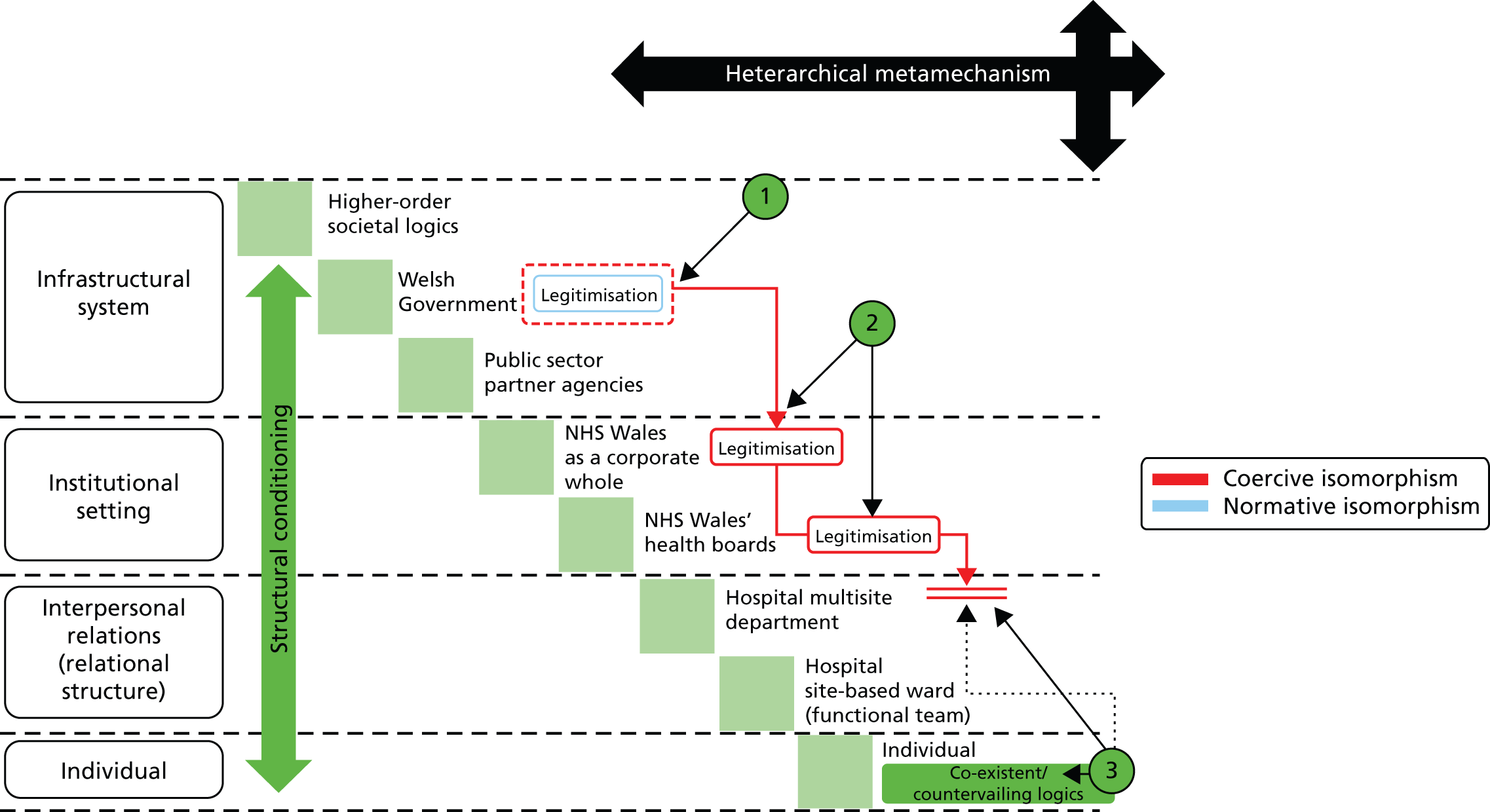

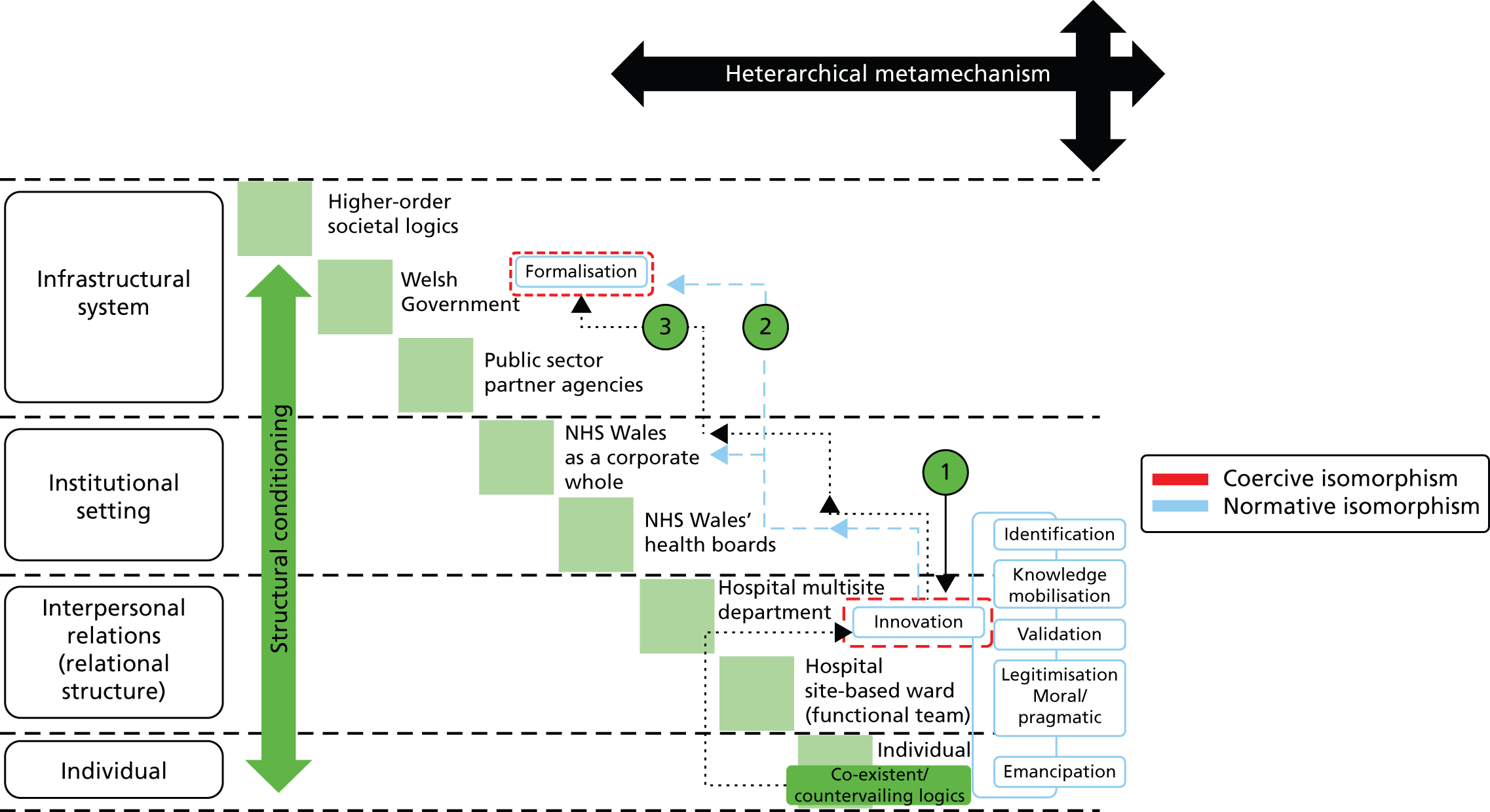

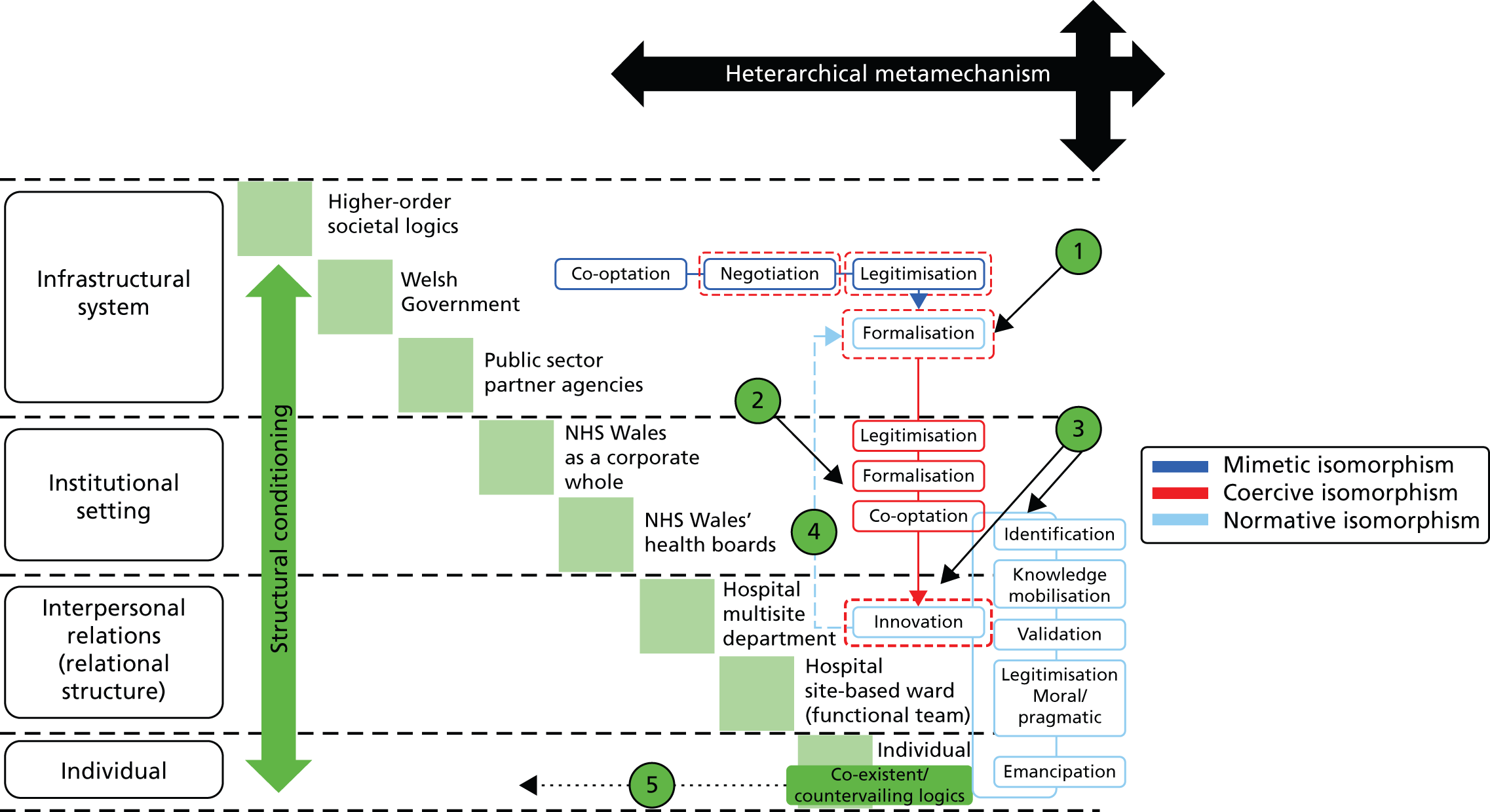

FIGURE 5.

Contextual strata: structural conditioning, hierarchical and heterarchical metamechanisms.

In Figure 5, we illustrate our view of context as stratified, conditioned, relational and temporally dynamic through the ‘steps’ of the contextual strata. This shows how the outcome of one I-CMAO becomes the context for the next in the chain of implementation steps.

In point 1, we depict the collective weight of structural conditioning impacting across contextual strata. This notion, as expanded in Context: structural conditioning, is an underlying premise of realist inquiry and Archerian realist social theory.

In addition, we highlight the notion of a ‘meta mechanism’ that functions as a ‘carrier’ for the 1000 Lives+ national programme across NHS Wales. Point 2, therefore, depicts a hierarchical meta mechanism emergent from the bureaucratisation of the programme across the policy/practice gap in NHS Wales.

Furthermore, point 3 depicts a heterarchical metamechanism inherent to normalisation of the programme at the level of the functional team across linked strata.

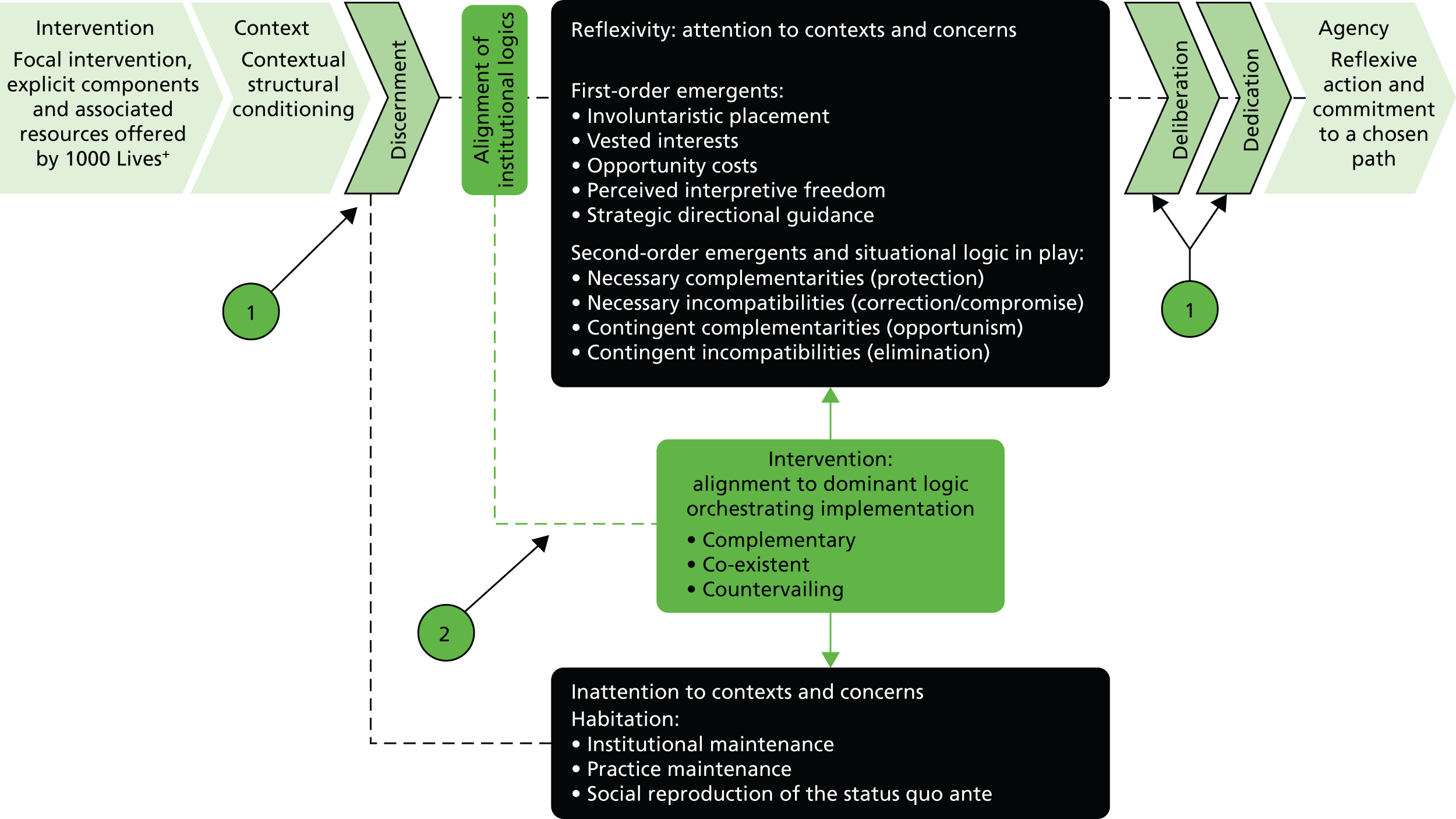

Mechanism: sociocultural interaction

In her later work, Archer has refined her conceptualisation of the mediation of contextual influences, which, she contends, is undertaken via two mechanisms: habituation, guiding routine action, and reflexivity, guiding those actions which demand a more creative response. 338 Critically, Archer asserts that such reflexive theorisation occurs through three stages: (1) discernment, the preliminary review stage of an issue of concern, where reflective retrospective and prospective thought informs practical action; (2) deliberation, involving the ranking of such concerns against others; and (3) dedication, entailing their prioritisation and alignment to foster a fallible yet correctable commitment to a chosen path. Reflexive theorisation thus represents the explicit interplay of social context and personal concerns that lies at the heart of Pawson’s notion of mechanism.

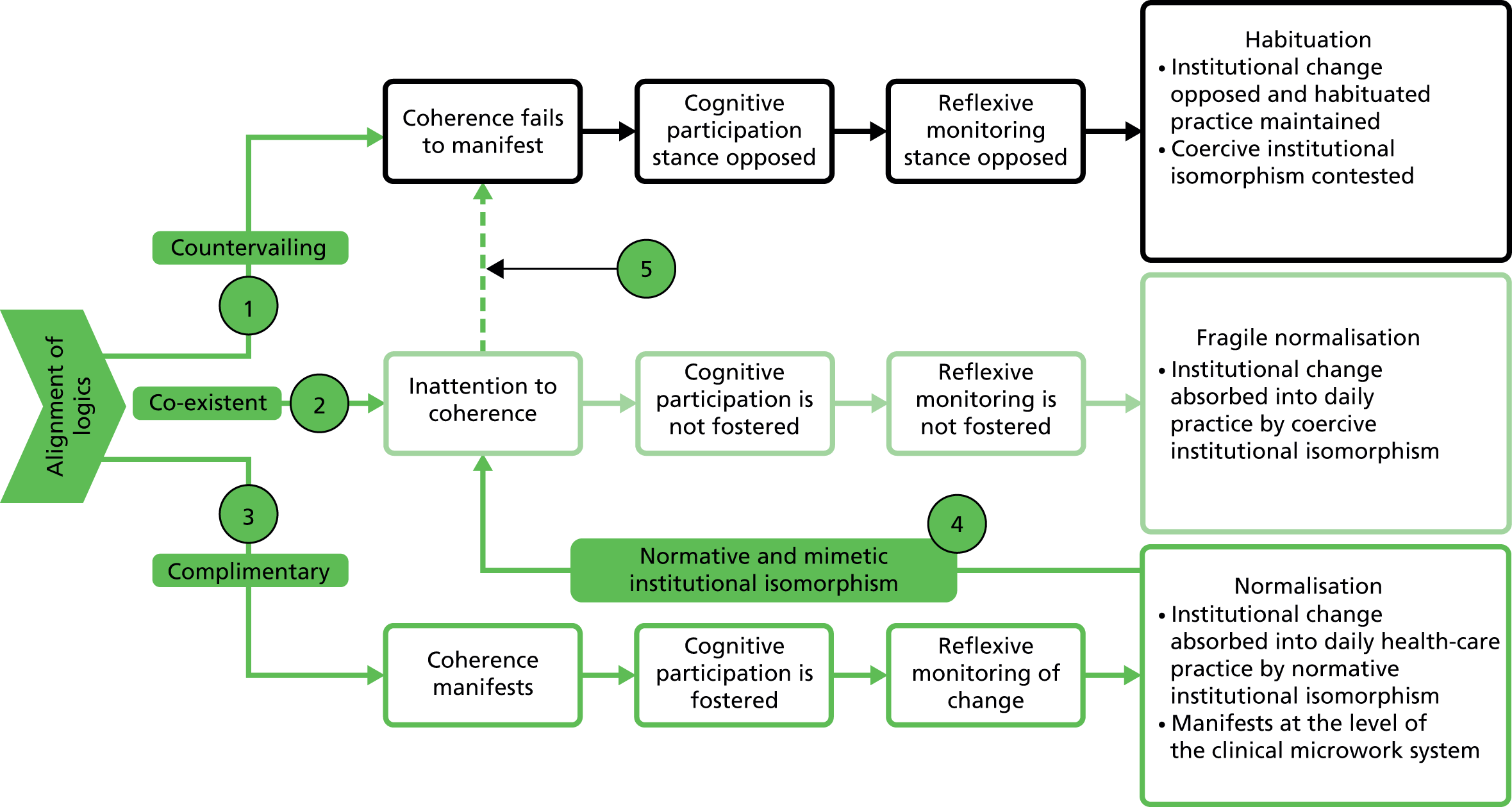

Following this approach, in our realist analysis we allocate contextual mediation to mechanism, and to this we add reflexive theorisation. Furthermore, as depicted in Figure 6, we distinguish the conceptual elements of mechanism from its ensuing outcome, illuminating the fundamental role of beliefs and values – institutional logics – on the propensity to act, and revealing the contested nature of institutional change and practice evolution.

FIGURE 6.

Mechanism: mediation via reflexive theorisation vs. habituation.

Figure 6 shows a preliminary outline of the key components of a mechanism. As noted in Figure 3, we apportion mediation and reflexive theorisation to mechanism. We thus distinguish the conceptual elements of mechanism from its ensuing outcome: the agential emergent properties, expressed through the unfolding strategic negotiation of change, and the mode of institutional work enacted, to deliver sustainable outcomes, be they elaborative or reproductive.

In point 1, we depict Archer’s refinement of her notion of contextual conditioning via the mediation of structure by agency. This, Archer contends, is undertaken via two mechanisms: habituation, guiding routine action, and reflexivity, guiding those actions that demand a more creative response. This manifests through three stages: discernment, the preliminary review stage of an issue of concern, where reflective retrospective and prospective thought informs practical action; deliberation, the ranking of such concerns against others; and dedication, their prioritisation and alignment to foster a ‘fallible yet corrigible’ commitment to a chosen path. Such reflexive agency thus represents the explicit interplay of social context and personal concerns.

In point 2 we assert that this three-stage process is modulated by the alignment of institutional logics. Complementarity, co-existence or contradistinction via a countervailing stance thus impact first- and second-order emergents to shape the individual’s situation logic and the ensuing stance that emerges from their deliberation and dedication to a chosen path.

In this study of the 1000 Lives+ programme, we examine the demarcation between context and mechanism, focusing on mediation, reflexive theorisation, ensuing agency via negotiation and the mode of institutional work enacted during two fundamental institutional processes: bureaucratisation and normalisation. These, we contend, operate as sociocultural and organisational meta mechanisms, the underpinning carriers347 of the processes of health-care change desired by 1000 Lives+. In essence, it is through successful embedding within these fundamental meta-mechanisms that the patient safety programme becomes institutionalised.

Bureaucratisation

Given that the logic of the bureaucratic state is predominantly that of command and control, we envisaged bureaucratisation as a vertical, top-down meta mechanism. In this manner, the Welsh Government has enacted state-centric control over NHS Wales. This is exemplified by the gradual bureaucratisation of the 1000 Lives+ national patient safety programme; specifically, the shift from optional engagement to mandatory engagement as defined in the Welsh Government’s tier 1 performance targets for NHS Wales. Such bureaucratisation now composes and conditions the substructure of the health-care field, creating a context of politicised force majeure. We therefore examine the consequences of adherence to the 1000 Lives+ programme and describe the mechanisms which foster institutional coupling to, and decoupling from, patient safety governance processes. 85,348,349

Drawing on the work of Greenwood et al. ,227 as well as terminology used by Lewin and Schein,350,351 we frame such institutional change through six stages – disconfirmation, deinstitutionalisation, preinstitutionalisation, theorisation, diffusion and reinstitutionalisation – and use these to develop our understanding of the local implementation of the 1000 Lives+ programme, as set out in Chapter 4.

Normalisation

We envisaged normalisation as a heterarchical metamechanism operating (i) horizontally across discrete functional teams, such as policy, health-care management or health-care clinical professionals; and (ii) hierarchically, bottom-up and top-down, across conceptual strata. Hence, to provide deeper insight into the implementation of the 1000 Lives+ programme, we use normalisation process theory, as developed by May et al. ,352–355 to refine our understanding of how agency embedded this patient safety improvement programme in a local context. The concept of normalisation acknowledges that those involved in the process of institutional change have to undertake institutional work – and thus theorise in a reflexive manner338,356– to reconfigure ensuing practices to meet local conditions. 357

This mid-range theory presented four possible generative mechanisms – coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring – which are viewed to be central to the embedding and integration of institutionally refined practices. As May and Finch353 point out, such mechanisms are subject to the power play of social actors. Therefore, by focusing on normalisation, our examination of the implementation of the 1000 Lives+ national programme was sensitised to the dynamic interplay of multiple logics.

Agency and ensuing outcomes: structural and cultural elaboration or reproduction

In our realist analysis framework, outcome is not perceived as a simple, single aspect of change such as a defined health outcome. Instead, it is recognised that the multifaceted nature of an intervention, particularly when implemented within different organisations, each shaped by their own contextual constraints and enablements, gives rise to discordant mechanisms which trigger different patterns of social transformation. 243,269 Moreover, such outcome patterns are contingent on all the tiny process and positioning issues that occur on the way to the goal. 244

Our framework is, therefore, concerned with the explication of these unfolding actions over time. Specifically, we seek to examine the means through which the health-care practice change advocated by the 1000 Lives+ programme, and the three focal interventions we consider in depth, are negotiated by the functional teams positioned within the contextual strata depicted in Figure 5. We thus seek to illuminate how health-care practice evolves (or not) over time, by considering the third-order emergents impacting within the contextual arena.

Third-order emergents arise from the effects of first- and second-order influences on the outcomes of the intervention. 229 This concept, therefore, captures structural and ideational differentiation, together with the regrouping inherent to the power play of a diverse array of agents.

Summary

We argue in this chapter that, as an established methodological complement to the critical realism of which Pawson is a key advocate, and as an innovative lens for realist inquiry, an Archerian approach provides both an explanatory framework for examining the interplay between structure (context) and agency (mechanism) and a viable means for developing and refining emergent I-CMAO configurations.

In seeking to demarcate context from mechanism and intervention, our stratified model of context depicts strata as hierarchical and interconnected. This purposely deviates from the notion of context bifurcated into external and internal domains,216,358 and echoes the broader realist literature in terms of a sociology divided into levels. 359,360 Moreover, by revealing the mechanisms that operate within and between these conceptual strata,316–318 as each action-level or arena is, simultaneously, a framework for action and a product of action,330 we carry forward these generative threads into our realist analysis to define the web of mechanisms operating within the focal context.

Chapter 3 Research design

Overview

This chapter sets out our research design and approach to data collection and analysis. First, acknowledging recent changes to research ethics and access permissions in NHS Wales, we provide a step-by-step account of our actions in the start-up stage to the study. Second, our comparative case study research design is presented, explaining our approach to realist analysis, case site selection and sampling strategy, and to data collection, coding and analysis. Finally, we reflect on the challenges encountered during our research across NHS Wales and discuss their impact on our realist analysis of hospital patient safety.

Research ethics and access permissions in NHS Wales

In February 2011, following notification of the award from the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme, an Integrated Research Application System project data set was developed prior to the formal start of the study in October 2011. Over the next 4 months, working in collaboration with the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research (NISCHR) Patient Safety and Healthcare Quality Registered Research Group, hosted by the School of Medicine, Cardiff University, and in close liaison with the Director General, Health and Social Services and NHS Wales Chief Executive, the ‘in principle’ engagement of all NHS Wales’ seven local health boards [Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board; Aneurin Bevan University Health Board; Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board; Cardiff and Vale University Health Board; Cwm Taf University Health Board; Hywel Dda University Health Board; and Powys (Teaching) Health Board] was secured. In each health board, study contacts with delegated strategic oversight for patient safety were recruited at medical director or associate medical director level.

Having gained NHS Wales’ ‘in principle’ engagement, sponsorship of the study was secured from Cardiff University and the required documents were submitted to the Main Research Ethics Committee (MREC) for Wales. MREC approval was granted in August 2011 and site-specific NHS research and development forms were submitted to the newly established NISCHR Permissions Co-ordinating Unit. Following this, full ethical and research governance permissions were obtained from Cardiff Business School, Cardiff University, and research passports were obtained for Herepath and Kitchener. Research validation and global governance approval was obtained in September 2011. The research and development committees of the seven health boards granted site-specific research permission and researcher access by December 2011, and Herepath and Kitchener received either honorary research contracts or letters of access.

Anonymisation

All seven health boards in NHS Wales participated in the study. Summary data describing each organisation are presented in Appendix 1. To ensure anonymity from this stage of the report onwards, participant health boards are identified via a randomly assigned code letter from A to G. Numeric subscripts are then used to identify a constituent major hospital (X1), a constituent district general hospital (X2) or a constituent small local community hospital (X3).

Comparative case study approach

The study set out to examine which contextual factors matter and how they matter, and to explain why they matter in the hope that this may lead to improvement in the design, processes and outcomes of patient safety programmes. A comparative case study research design is appropriate for research of this nature361 and was therefore adopted and aligned to realist analysis as discussed below.

Comparative case studies in realist informed research are shaped by five methodological principles: (1) explication of structure and context; (2) explication of events; (3) abduction and retroduction362–364 (see Ontological andepistemological alignment to realist analysis, below); (4) empirical corroboration (ensuring that proposed mechanisms have causal power and better explanatory power than alternatives365); and (5) triangulation and multimethods (using multiple approaches to support causal analysis based on a variety of data types and sources, analytical methods, investigators and theories365). Each of these features are employed throughout Chapters 4–8.

Ontological and epistemological alignment to realist analysis

The basic premise, or ontology, of critical realist informed research is that the world may be viewed as stratified into three domains in which are apparent structures, mechanisms, powers and relations; events and actions; and experiences and perceptions. 362,363 Research in this tradition focuses on the identification and explanation of the underlying generative mechanisms that shape structure, agency and the social relations that are reproduced and/or transformed. 252

The nature of the approach taken by realist research does impose limitations on what may be revealed through a comparative case study research design. However, it is a viable means for discerning structures and mechanisms, conveyed through our understanding of the social world and, thus, subject to revision as our collective knowledge is refined. 363,365 Nevertheless, one cannot connect powers or causal mechanisms to events and perceptions easily or securely by simple inspection. 366 This is because, once set in motion, they continue to have an influence even if other countervailing powers and mechanisms prevent this influence manifesting itself. The act of drawing conclusions from a comparative case study is, therefore, a complex matter. It is informed by epistemology (what we think is known), the nature of the comparisons made between cases and the mode of inference employed.

Comparative case study research designs using a critical realist approach must, therefore, seek to define constraining and enabling social structures, encompassing organisations, groups and individuals, together with the rules, practices, technological artefacts, discourse and culture which they manifest. 365 In addition, social actors’ interpretations of such structures, and their beliefs, values and theories, require detailed consideration. The comparisons made between cases draw on abductive and retroductive modes of inference as opposed to inductive and deductive. 363,364 Abduction involves the production of an elementary account of a basic process or mechanism. 363 Retroduction builds on this analytical stage to reconstruct the basic conditions for such phenomena to be what they are, so fostering knowledge of the conditions, structures and mechanisms in play. 362,363 Abstraction forms the basis of both abduction and retroduction. As empirically demonstrated by Herepath,342 abstraction draws out the various components within the situated context so that the researcher may gain new insight into the way they combine and interact.

Case site selection and sampling strategy

Case site selection was based on a two-stage sampling strategy. In phase 1, four clear and readily operable criteria – corporate parent, complexity, function and geographical coverage – were employed to define the purposive sample of case-site hospitals within each health board (see Appendix 1), and three within-case comparators were selected from each health board: (1) a major hospital, (2) a district general hospital and (3) a small community hospital. This approach ensured theoretical variation in I-CMAO configurations by optimising the scope for description, interpretation and explanatory analysis, while reducing chance associations. 367–369 In contrast, in phase 2, the focus of the study was narrowed to four local health boards, and centred on deeper examination of the most promising I-CMAO configurations for the three focal interventions examined from the 1000 Lives+ programme.

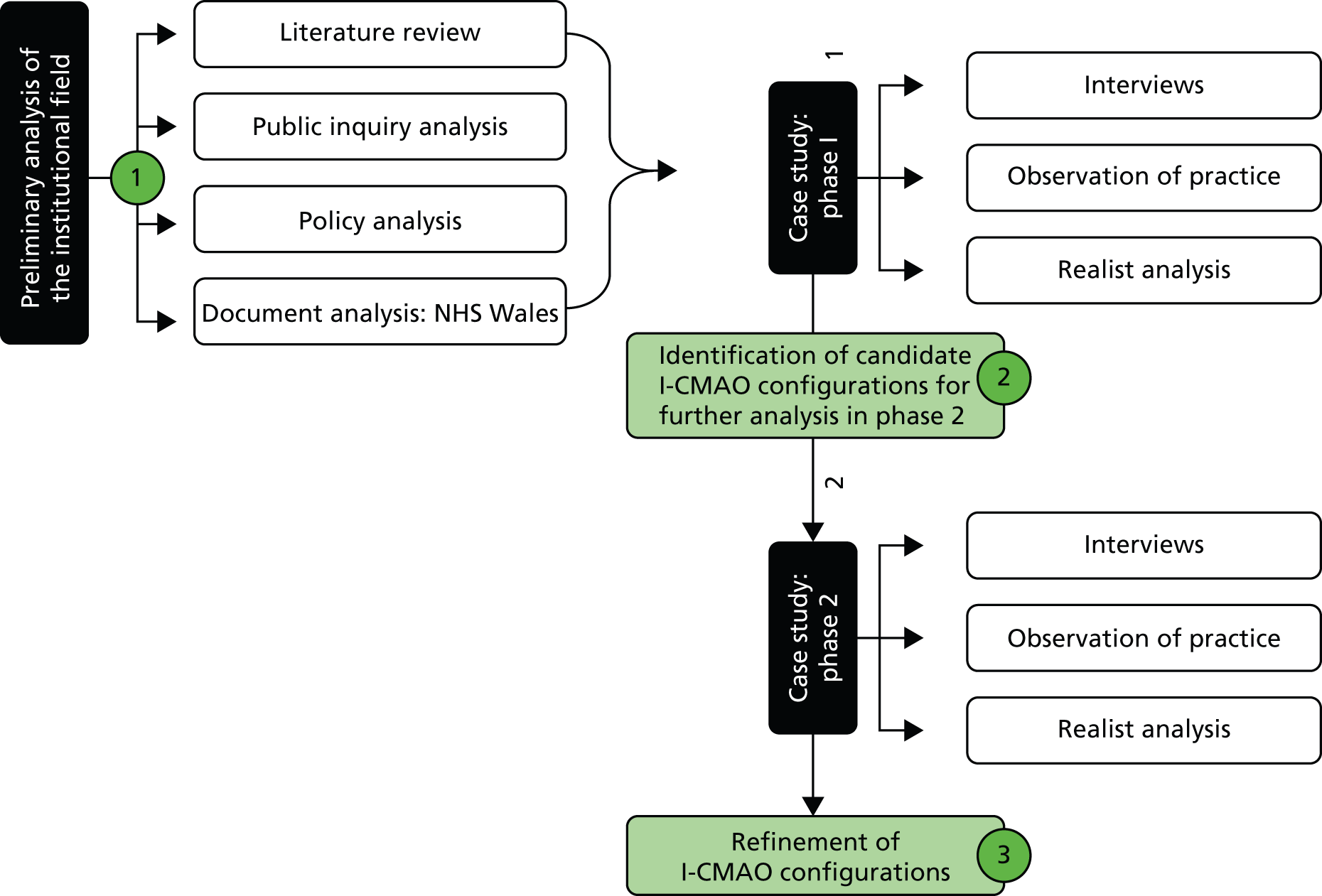

Data collection, coding and analysis

In adopting an overarching approach that combined realist inquiry with regard to the explication of I-CMAO configurations, this study sought to examine the contextual conditioning which predated the launch of the 1000 Lives+ programme, together with the mechanisms which emerged from the social interaction of different groups of health-care workers engaged in its implementation, and the subsequent outcome on the embedded practices of day-to-day health-care practice. As illustrated by the schedule of data methods and sources illustrated in Figure 7, and expanded in the following four sections, a wide range of data collection methods were used. 256

FIGURE 7.

Schedule of data methods and sources.

In Figure 7 we set out a schematic of data methods and sources, expanded below.

As set out in point 1, a series of data searches were undertaken. These included one that centred on public inquiries (see Table 5) as a means of gaining rapid awareness of significant systemic health-care delivery and patient safety failures. The literature review, policy and document analysis was maintained throughout the duration of the study. Points 2 and 3 depict the preliminary identification of candidate I-CMAO configurations and their progressive refinement throughout the study.

Welsh health-care policy context data

To build a coherent explanatory analysis of the context and events that led to the development and implementation of the 1000 Lives+ programme, our research commenced with an analysis of UK and devolved Welsh health-care policy spanning the period from 1997 to 2013. As indicated in Table 2, the UK coalition government’s White and Green Papers, together with other key legislative proposals, were accessed and downloaded from the Department of Health’s website. Those of the former UK New Labour government were sourced via the National Archives. Relevant Welsh Government documents, together with those from the National Assembly for Wales, were accessed from site-specific policy archives. In addition, Welsh health circulars and ministerial letters spanning the period 1997–2012 were accessed via the Health of Wales Information Service (HOWIS) intranet. A repository in excess of 1700 documents was established and archived in an electronic database to facilitate the exploration of the structural conditioning of the Welsh health-care system.

| UK government policy |

|---|

|

| Welsh Government policy |

|

Three analytical frameworks informed the coding of these data: (1) Friedland and Alford’s depiction of higher-order societal logics;331 (2) Barber’s three paradigms of public sector reform;370 and (3) Hood’s doctrinal components of new public management. 371,372 Collectively, these focused our approach to contextual conditioning and set out the requisite ‘vocabulary’373 through which the infrastructural system – specifically, the organisational and professional governance processes structuring health-care quality and patient safety – could be abstracted from the policy archive. As illustrated in Chapter 4, this centred on the interplay of the higher-order societal logic of the bureaucratic state with the field-level logics of the market, professionalism and democracy in health policy.