Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme as project number 13/05/12. The contractual start date was in October 2014. The final report began editorial review in April 2015 and was accepted for publication in June 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Turner et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

This rapid evidence synthesis has been written in response to a request by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme to examine the evidence around the delivery of urgent care services. The purpose of the evidence synthesis is to assess the nature and quality of the existing evidence base, and identify gaps that require further primary research or evidence synthesis.

Demand for urgent care (including emergency care) has increased year on year over the last 40 years. This has been reflected in growth in emergency department (ED) attendances, calls to the 999 ambulance service and contacts with other urgent care services, including primary care and telephone-based services. 1 The reasons for this are only partly understood, but comprise a complex mix of changing demographic, health and social factors. Over the last 15 years there have been a number of reviews of urgent care, policy recommendations for service changes and service-level innovations, all of which were aimed at improving access to and delivery of urgent care. Figure 1 provides a summary of some of the key developments that have been widely adopted within the NHS and related policy initiatives. The timeline shows when developments were first introduced; however, these developments have not remained static but have grown and changed over ensuing years.

FIGURE 1.

Selected key developments and policy initiatives for the delivery of emergency and urgent care.

Despite these initiatives, the emergency and urgent care system has come under increasing strain and media attention,1 most commonly reported as failings in meeting government targets. Nationally, EDs have not met the target of treating and discharging or admitting 95% of attending patients within 4 hours for any year quarter from October 2012 to March 2015 (URL: www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ae-waiting-times-and-activity/weekly-ae-sitreps-2014-15/). Similarly, there has been a reduction in the ability of ambulance services to meet the national target of responding to 75% of life-threatening (Red 1) calls within 8 minutes. Performance nationally reduced from 76.2% in March 2014 to 73.4% in March 2015 (URL: www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/ambulance-quality-indicators/), while at the same time the number of ambulance handover delays at EDs increased from 86,003 in November 2013–March 2014 to 139,970 for the same period in 2014/15 (URL: www.england.nhs.uk/statistics/statistical-work-areas/winter-daily-sitreps/winter-daily-sitrep-2013-14-data-2/).

In 2012/13, the intense public scrutiny culminated in a Health Select Committee inquiry,2 and this scrutiny has continued. The pressure of increasing demand has more recently been exacerbated by acute shortages of associated health-care professionals, particularly in emergency medicine,3 primary care4 and ambulance services. 5

It is increasingly recognised that provision of urgent care is a complex system of interrelated services and that this whole-system approach will be key to improvement and development in the future. In response to the clear pressure within the emergency and urgent care system, in 2012 NHS England embarked on a major review of urgent care services and in 2013 set out its strategy for development of a system that is more responsive to patients’ needs, improves outcomes and delivers clinically excellent and safe care. 6 The challenge now is to find ways to put this blueprint into practice.

Knowledge about the current evidence base on models for provision of safe and effective urgent care can support this process. The purpose of this rapid review is to examine what evidence there is on how efficient, effective and safe urgent and emergency care services can be delivered within the NHS in England, the quality of that evidence and the gaps in evidence which may need to be addressed.

Hypotheses tested in the review (research questions)

The NHS England review6 has set the agenda for urgent care, with recommendations on how the urgent care system and the services within it need to change. We have used the key themes identified in this review as the framework for this rapid evidence review to provide both focus and context for evidence appraisal and the identification of evidence gaps, which will be of direct relevance to future developments. The five key themes identified in the NHS England review are:

-

providing better support for people to self-care

-

helping people with urgent care needs to get the right advice in the right place, at the first contact

-

providing highly responsive urgent care services outside hospital so that people no longer choose to queue in accident and emergency (A&E) departments

-

ensuring that those people with more serious or life-threatening emergency care needs receive treatment in centres with the right facilities and expertise to maximise chances of survival and a good recovery

-

connecting all urgent and emergency care services, so the overall system becomes more than the sum of its parts.

The first theme, focused on providing better support for people to self-care, encompasses the much broader areas of health care related to reducing the need for urgent care. This theme warrants a separate review, as it involves complex issues such as management of long-term conditions, health promotion and injury prevention. As it targets an alternative health-care vision outside of urgent care; the potential scope was considered too broad and diffuse to be included within the constraints of this review. We have therefore excluded this theme and concentrated on the other four themes directly related to delivery of urgent care.

Within each of these four key themes the NHS England review sets out more specific proposals for service change and delivery, and these will form the focus of the primary scope for individual elements of this review. We have also added an additional underpinning theme, which was not identified as a separate issue by the NHS England review. In order to develop services that are responsive to the needs of the population using them, it is essential to understand the characteristics and drivers that underpin demand for services and the choices people make about how they use those services. Without this it is difficult to ensure alignment between service development and patient need. We have therefore included within our review a brief overview of a fifth theme focused on patterns and characteristics of the demand for urgent care (including change over time), and the factors that influence decisions about when and how to access urgent care.

Although these key themes provide focus, each one still potentially includes a range of issues. To keep the review process manageable within the time and resources available we have therefore restricted the research questions for some themes to a particular service area highlighted as of particular importance in the NHS England review.

Research questions

The research questions examine the evidence relating to the following:

-

To what extent does evidence on existing and proposed approaches to the delivery of urgent care support the development of four key themes in the NHS England review of urgent care?

-

Helping people to get the right advice in the right place, first time. This theme could potentially cover a range of services in terms of what care is eventually accessed. However, the process of providing advice and directing people to the right service when they first try to access care is firmly grounded in the NHS England review as the NHS 111 telephone service. This service is seen as the gateway to directing requests for emergency care to the right service. We have therefore focused on telephone-based access services in this review.

-

Providing highly responsive urgent care services outside hospital. This theme also potentially includes a range of community-based services; however, it was beyond the scope of this review to search and synthesise all of the potential literature about community-based urgent care. The 2013 NHS England review and related action plan make a clear statement that the ambulance service is considered a key provider in achieving this objective. We have therefore focused on the evidence for developing the ambulance service to manage more people in the community setting in this review.

-

Ensuring that people with serious or life-threatening emergency care needs receive treatment in appropriately staffed and resourced facilities. This theme is concerned with the provision of ED care, including both major regional facilities and local EDs. There is already a substantial evidence base about the impact of providing regionalised services (e.g. for stroke, heart attack), so there is no value in repeating this here. Furthermore, service pressure is greatest in general EDs (and major regional facilities also function as ‘local’ EDs). We have therefore focused this review on the evidence about different models and processes for delivering ED care to keep the review relevant to current NHS challenges.

-

Connecting urgent and emergency care services. The NHS England review sets out a clear view that the way to achieve this objective is through the development of urgent care networks to develop and manage local urgent care systems. We have focused this element of the review specifically on evidence about models of urgent care networks.

-

-

What evidence is there on characteristics of demand for urgent care, and why and how people access urgent care, that may help future service planning?

We have conducted and reported a rapid review for each of these five themes. For each review we have considered two additional questions:

-

What is the quality of that evidence?

-

What are the main/significant evidence gaps?

Chapter 2 Review methods

Overview of rapid review methods

This was a rapid framework-based evidence synthesis which needed to be completed within the relatively short time frame of 6 months to produce a review that met the HSDR programme’s needs. We have used rapid review methods to ensure the efficient identification and synthesis of the most relevant evidence. The multiple dimensions covered by the review questions posed a considerable challenge to the rapid review process. This challenge was further complicated by the fact that emergency and urgent care does not involve discrete populations or conditions, but encompasses whole populations and a heterogeneous mix of conditions and acuity, and care is delivered by a range of services. As a consequence there was a potentially huge pool of related literature.

Given the large scope and time and resource constraints we have not taken a standard approach to this review. Our aim was to provide a broad overview of the existing evidence base for each theme and any associated limitations. We have therefore applied the following criteria to structure the review process:

-

We have concentrated on identifying and synthesising the key evidence using a focused, policy-relevant framework to keep the task relevant and manageable. Framework-based synthesis has been identified as an efficient method for synthesising evidence to inform policy within relatively tight time constraints. 7

-

The review did not attempt to identify all relevant evidence or to search exhaustively for all evidence that meets the inclusion criteria; instead we have used a structured searching approach to identify the key evidence.

-

The data extraction and quality assessment have focused on the most critical information for evidence synthesis rather than aiming to exhaustively extract and critique all the available information in individual papers.

-

We have not appraised the evidence in terms of how future services should be provided, nor made recommendations about service configuration.

Framework

As the focus of this review is on models of care, that is service and system delivery, we have not searched for, or considered, evidence related to specific clinical interventions for specific conditions. We have also only included primarily evaluative research of actual interventions (although the definition of intervention can be broad and encompass changes to organisation, changing professional roles, new services, etc.) in order to provide an overview of what may or may not work in practice. For this reason we have purposely excluded the more theoretical literature, for example relating to organisational behaviour, professional development and clinical competence, work psychology, patient decision-making and behaviour. Where additional review in these related areas is of value, these have been highlighted in the individual review chapters as specific areas for further in-depth review and analysis.

For each of the four themes related to the NHS England review we have considered three main areas:

-

evidence on efficiency and clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of service delivery for any identified operating models, including individual service and whole-system perspectives

-

evidence on associated workforce issues where this is primary research evaluating the effectiveness of changing or developing new professional roles in the delivery of urgent care and workforce planning

-

evidence on any related patient experience outcomes.

Urgent care provision in England is a rapidly changing environment. The NHS England review has prompted a range of work programmes8 and professional bodies, for example the Royal College of Emergency Medicine,9 to regularly publish recommendations about delivery of services. Where relevant, we have used key policy documents published before October 2014 specifically related to the implementation of the NHS England reform of urgent care to develop the review framework.

The additional fifth theme on understanding demand and use of services has focused on primary research that:

-

reports analysis of not only level of demand but also the characteristics of that demand (e.g. age profiles, condition profiles, whole-system demand for different types of service)

-

reports patient-derived explanatory research concerned with decisions to access urgent care.

This framework has provided a clear structure with which to guide the review while retaining the flexibility that has allowed the development of each individual theme in terms of defining the scope of the search strategies, defining inclusion and exclusion criteria to specify what types of studies will be included in each theme and evidence synthesis.

Search methods

A variety of search methods were undertaken in order to identify relevant evidence for each of the review questions and themes in a timely fashion. We have used a number of different search strategies for this review while using a general structure of combining relevant terms, such as:

-

Population

-

Users of the range of services within the emergency and urgent care system (ambulance services, ED, other urgent care facilities, telephone access services, primary care-based urgent care services).

-

-

Outcomes

-

Processes – ED attendances, emergency admissions, ambulance calls, dispatches or transports, demand, appropriateness of level of care, adverse events.

-

Patient outcomes – patient experience and satisfaction, decision-making, cost consequences and cost-effectiveness.

-

Searches were conducted in two stages:

-

Stage 1 – general search on MEDLINE.

-

Stage 2 – targeted database searches around telephone triage, ambulance, demand, organisation of EDs and networks. To increase efficiency, where appropriate, we have utilised existing search strategies from related research we have conducted within the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) or from existing related systematic reviews.

Database search strategies

General search

An initial broad-scoping search was conducted on MEDLINE. This broad search aimed to find studies that evaluated the impact of changes in organisation, policy, structure and systems on urgent care. Descriptive studies without an evaluative component were not considered relevant. Key issues for consideration were access to services, appropriate management of patients, service delivery, models of delivery and clinically appropriate management of patients. The general search strategy used a combination of free text and medical subject headings (MeSH), as well as appropriate subheadings. A detailed description of the search strategy is provided in Appendix 1. The search retrieved a large number of results and refinements were made to the search to reduce this number. One key modification was the removal of the term ‘ambulatory care’, as this term retrieved a large volume of results related to outpatient rather than urgent care. The final search retrieved 9488 results. After careful discussion it was decided that, because of time constraints, a sample of 20% would be considered for inclusion for this search and further targeted searches conducted relevant to each of the five themes. From the 20% sample of the general search, potential inclusions relevant to the five themes were identified using keywords and any additional references identified from this search, and not identified in the targeted search, were added to the list of potential inclusions for that theme.

Targeted searches

For the targeted searches the following databases were searched: MEDLINE (via Ovid SP), EMBASE (via Ovid), The Cochrane Library (via Wiley Online Library), Web of Science (via the Web of Knowledge) and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; via EBSCOhost). Searches were limited to publication date from 1 January 1995 to current, in order to keep results relevant to current services, and publications were to be written in English. All searches were completed between October 2014 and January 2015. A detailed description of each of the targeted search strategies is provided in Appendix 1.

Targeted searches were conducted on the following areas: telephone triage, ambulance services, reorganisation of EDs, developing and building urgent care networks, and demand for emergency and urgent care services.

Telephone triage

Within ScHARR extensive previous work had already been completed on telephone triage and we were able to rerun an existing search strategy for this review with expansion of the dates from 1 January 1995 to 11 November 2014. After deduplication, there were 1127 unique references.

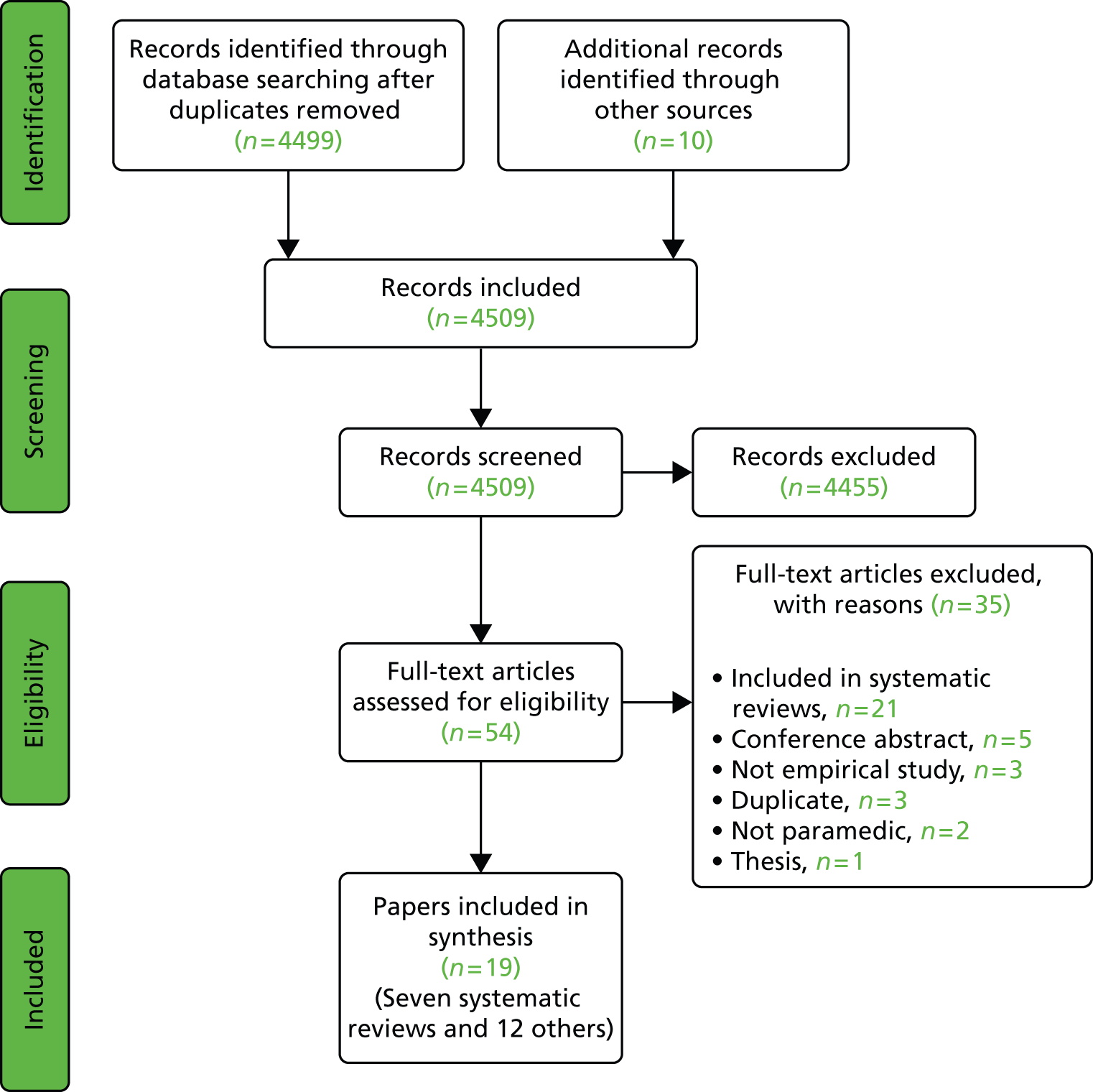

Ambulance services

The search on ambulance services focused on finding literature concerned with the impact of ambulance services treating people at home where appropriate and triaging them to more appropriate community or primary care services. Additionally, research was sought on developing the skills of ambulance personnel to enable them to perform extended roles. After deduplication, there were 4499 unique references.

Organisation of emergency departments

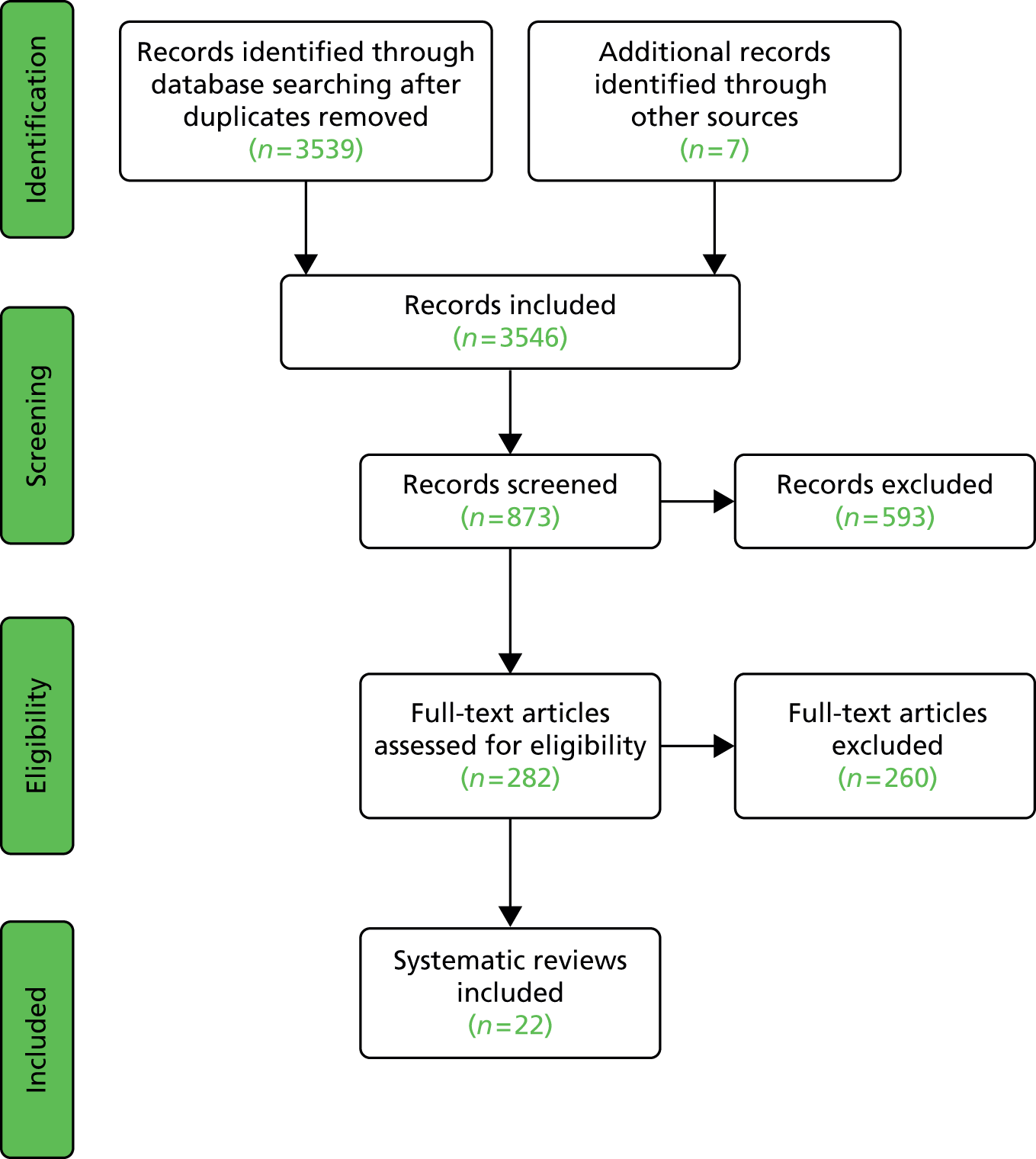

Targeted searches were also conducted on reorganisation of EDs. Targeted searches were conducted to find evaluative literature on service delivery following reorganisation of processes within the ED. After deduplication, there were 3539 unique references.

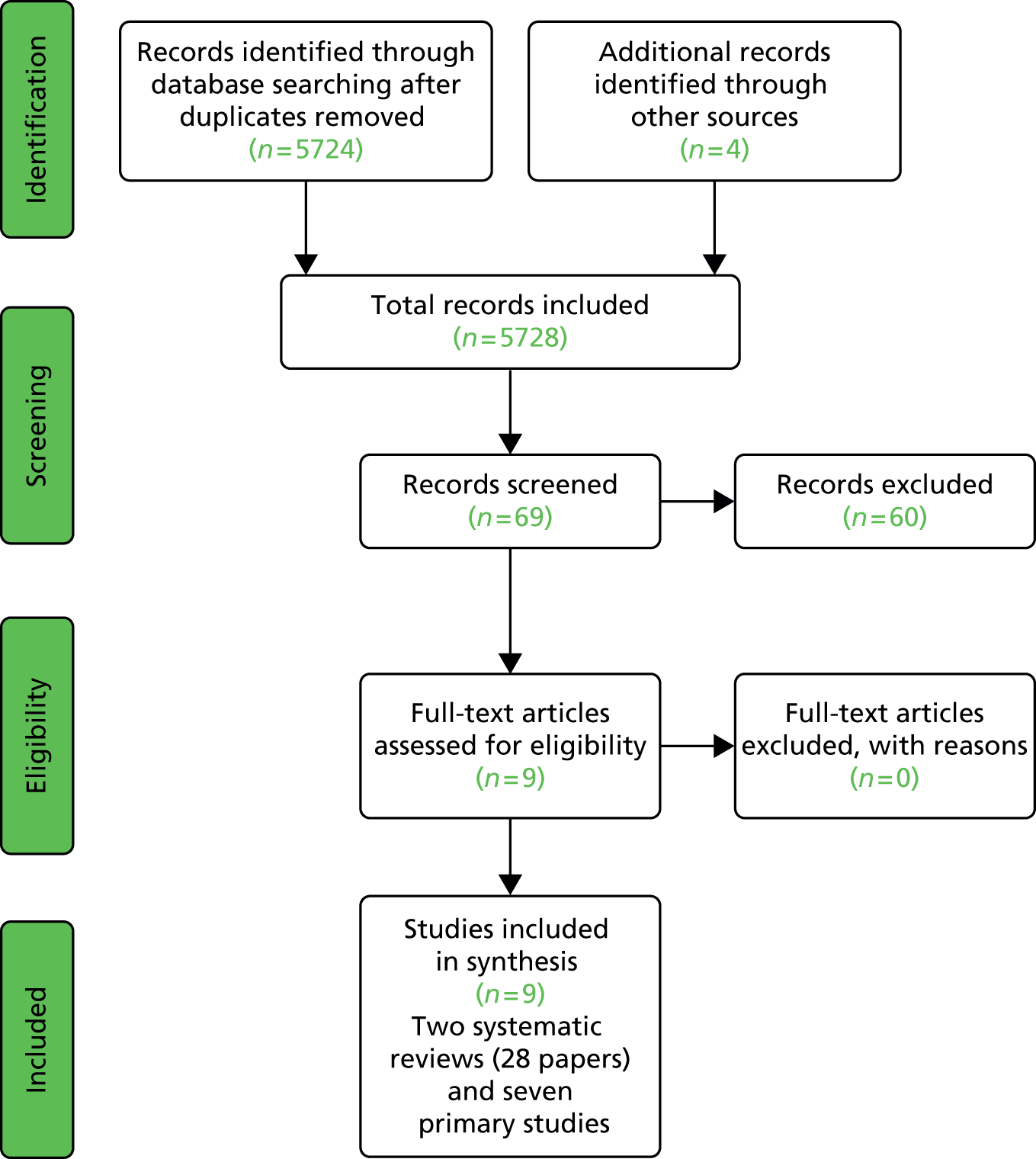

A recent report by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine9 recommended that all EDs should have a co-located primary care service. We identified an existing, relevant rapid evidence review conducted by the University of Warwick10 and updated the search strategy described in that review. After deduplication, there were 5724 unique references for this search.

Networks

Another targeted search focused on the development and use of networks within emergency and urgent care. After deduplication, there were 1301 unique references.

Demand for emergency and urgent care

The searches around demand for emergency and urgent care were based on searches previously completed for a project ScHARR conducted for the NHS Confederation, in 2013, and were expanded to encompass the full range of dates and databases. The search aimed to retrieve empirical research on urgent care demand, research on rising demand in the ageing population and empirical research on patient-derived reasons for accessing different emergency or urgent care services. After deduplication there were 1371 unique references.

The search results were downloaded into EndNote X7.2.1 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA).

Given the scope of each search and the limited time available, we were not able to conduct extensive supplementary searching, for example citation searching. However, in addition to the database searches we also identified key evidence through:

-

scrutinising reference lists of included relevant systematic reviews

-

utilising our own extensive archives of related research, including a number of related evidence reviews

-

the evidence review that NHS England produced as part of its consultation

-

consultation with internal ScHARR topic experts and some external topic experts.

Review process

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We have included both quantitative and qualitative empirical evidence in the review where relevant to one of the five themes. Both UK and international evidence have been included to ensure that alternative models of urgent care delivery designed to address the same objectives set out in the NHS England review (e.g. reducing ED attendances) are considered. We have only included published peer-reviewed evidence in order to ensure that we have synthesised evidence that has already undergone methodological and expert scrutiny. Emergency and urgent care changes rapidly in terms of demand, clinical care and service delivery, so we have limited the evidence included in the years from 1995 to 2014 to ensure that the evidence assessed has context and relevance to current policy and practice. Evidence for specific clinical interventions and conditions has been excluded as it is likely to be substantial for a large number of conditions; our focus is on whole services rather than narrow, condition-specific populations. However, we have included evidence for defined but broad (in terms of condition) populations, for example children or the frail elderly. To summarise, we have used a core set of inclusion and exclusion criteria for all five themes to ensure consistency in the review approach.

Inclusion criteria

-

Empirical data (all study designs).

-

Emergency/urgent care.

-

Report relevant outcomes.

-

Written in English.

-

Published between 1995 and 2014.

Exclusion criteria

-

Descriptive studies with no assessment of outcome.

-

Opinion pieces and editorials.

-

Non-English-language papers.

-

Conference abstracts.

Additional theme-specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were then applied to the core criteria. Theme-specific criteria are described in each review chapter.

Data extraction

Data extraction of included papers was undertaken for each theme. However, because of the number of themes and scope of each one, we could not complete detailed and exhaustive data extraction for all relevant inclusions. To make this task manageable, ensure consistency across the themes and enable comparisons to be made between themes we employed two strategies:

-

For each theme we used any existing, relevant systematic reviews identified from the searches as the starting point for decisions about which individual identified papers meeting the inclusion criteria we would extract data from. We did not extract data from individual papers already included in relevant systematic reviews, instead we extracted the data from the systematic reviews in to summary tables. Any additional papers not included in the systematic reviews had data extracted in to summary tables.

-

All data extraction was carried out directly in to summary tables rather than detailed data extraction forms, which would subsequently require summarising. Included research was highly heterogeneous, therefore we used a simple, broad template to summarise the key characteristics and findings from each included systematic review or individual paper. For each paper we summarised the study design used, population and setting, main purpose and objectives, including outcomes measured, and key findings and conclusions.

Quality assessment

Rather than using a standard checklist approach, we have focused on an assessment of the overall quality and relevance of the evidence included within each theme in the review. Relevance has been assessed based on various factors, including the number of relevant studies, particularly systematic reviews; study types and design; the country and health system in which the research was conducted; and whether the research is single centre or multicentre. Quality has been assessed based on study types, the strength of the evidence identified by related systematic reviews and other key factors. For each theme we have provided a narrative commentary on quality and relevance that will allow readers of the rapid evidence synthesis to make an assessment of the rigour and relevance of evidence included in the review.

We have effectively conducted five separate rapid reviews, one for each of the five themes set out in the research questions. We have therefore presented each review separately, describing any methods specific to that review, results, an appraisal and summary of the existing evidence and any evidence gaps identified which are likely to be critical to further development of the main urgent care delivery objectives related to a theme. This includes where additional, more detailed, topic-specific evidence reviews could be of value or where more primary research is needed, for example on a larger scale to provide definitive evidence of effectiveness.

The five reviews are presented in Chapters 3–7.

A summary of all the reviews, together with an appraisal of common evidence across themes to provide a more comprehensive overview that describes, compares and contrasts different approaches to the delivery of urgent care and a headline summary of key findings, is presented in Chapter 8. This review has been designed to identify evidence gaps and help inform future NIHR HSDR programme research priorities. As such, the analysis has been undertaken using a research-commissioning rather than service-commissioning perspective.

Chapter 3 Trends and characteristics in demand for emergency and urgent care

Introduction

The main focus of this rapid review is assessment of the evidence relevant to the NHS England review of urgent and emergency care. However, to provide context we have presented a short overview of the current state of knowledge of the characteristics and drivers that underpin demand for services. This may be of use in terms of future planning, the ability to develop services that are responsive to the needs of the population using them and ensuring alignment between service development and patient need, and so is of relevance to the later review about urgent care networks.

Increases in demand for ED care are well documented. In England, demand for ED care doubled from an estimated 6.8 million first attendances at type 1 (24-hour, consultant-led service) EDs to 13.6 million over the 40 years from 1966/7 to 2006/7 – equivalent to an increase from 138 to 267 first attendances per 1000 people per year. Since 2006/07 attendances at type 1 EDs have further increased to 14.3 million in 2012/13 and at the same time there has been a rapid increase in the use of minor urgent care services [type 3 – not 24 hours, may be run by nurses or general practitioners (GPs), limited facilities such as radiography], with attendances increasing by 46% from 4.7 million in 2006/7 to 6.9 million in 2012/13. 11 Similarly, demand for 999 ambulance services has also steadily increased from around 4 million calls per year in 1994/5 to 9 million in 2012/13 (an increase of 160%), with utilisation rising from 78 to 171 calls per 1000 people per year over the same time period. 1 People with health problems also access urgent care via NHS 111 and primary care, but NHS 111 is a relatively new service and there is a lack of national data on urgent care contacts with primary care, so it is difficult to assess whole-system demand for emergency and urgent care in England.

More detailed analysis of UK trends in demand is available in reports from the NHS Confederation1 and Nuffield Trust. 12 In this report we have examined the empirical evidence that may help explain why demand is changing.

Methods

The main inclusion and exclusion criteria, search strategies and review process have been described in Chapter 2. We have conducted previous reviews in this area and are aware of the relative scarcity of related evidence. In addition, this topic area is not concerned with interventions or service delivery and hence the effects on processes or patient outcomes. We have therefore included literature reviews that were not systematic reviews but which have described a structured search strategy. Search dates were from 1995 to 2014. For this review, specific additional inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to studies investigating the following:

Inclusion criteria

-

Trends in demand for emergency and urgent care over time.

-

Analysis of characteristics of demand.

-

Empirical, patient-based studies examining reasons why people access emergency and urgent care and how they choose which service to access.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies of demand that describe volumes of activity only at single points in time.

Review process

Studies were identified from updated and expanded database searching using a search strategy from one of our own previous reviews in this area1 and a review of the evidence on callers to the 999 service with primary care problems from an NIHR doctoral research fellowship currently awaiting publication in the NIHR Journals Library (Dr M Booker, University of Bristol, 2015, personal communication). As the aim of this part of the review was to describe an overview of current evidence to provide context for the more detailed rapid reviews on service delivery, we limited the studies included in three ways:

-

We previously conducted a scoping review of potential reasons for increases in ambulance demand and, as this is already in the public domain and available for reference, we have not considered papers included in this review. 13

-

We did not conduct a double 10% random sift of the results of the database searches. These were sifted by one reviewer (JT) and supplemented by potential inclusions identified in the 20% random sample from the general search, also sifted by the same reviewer.

-

Data extraction of individual papers meeting the inclusion criteria was only conducted for papers not included in relevant review papers identified in the searches.

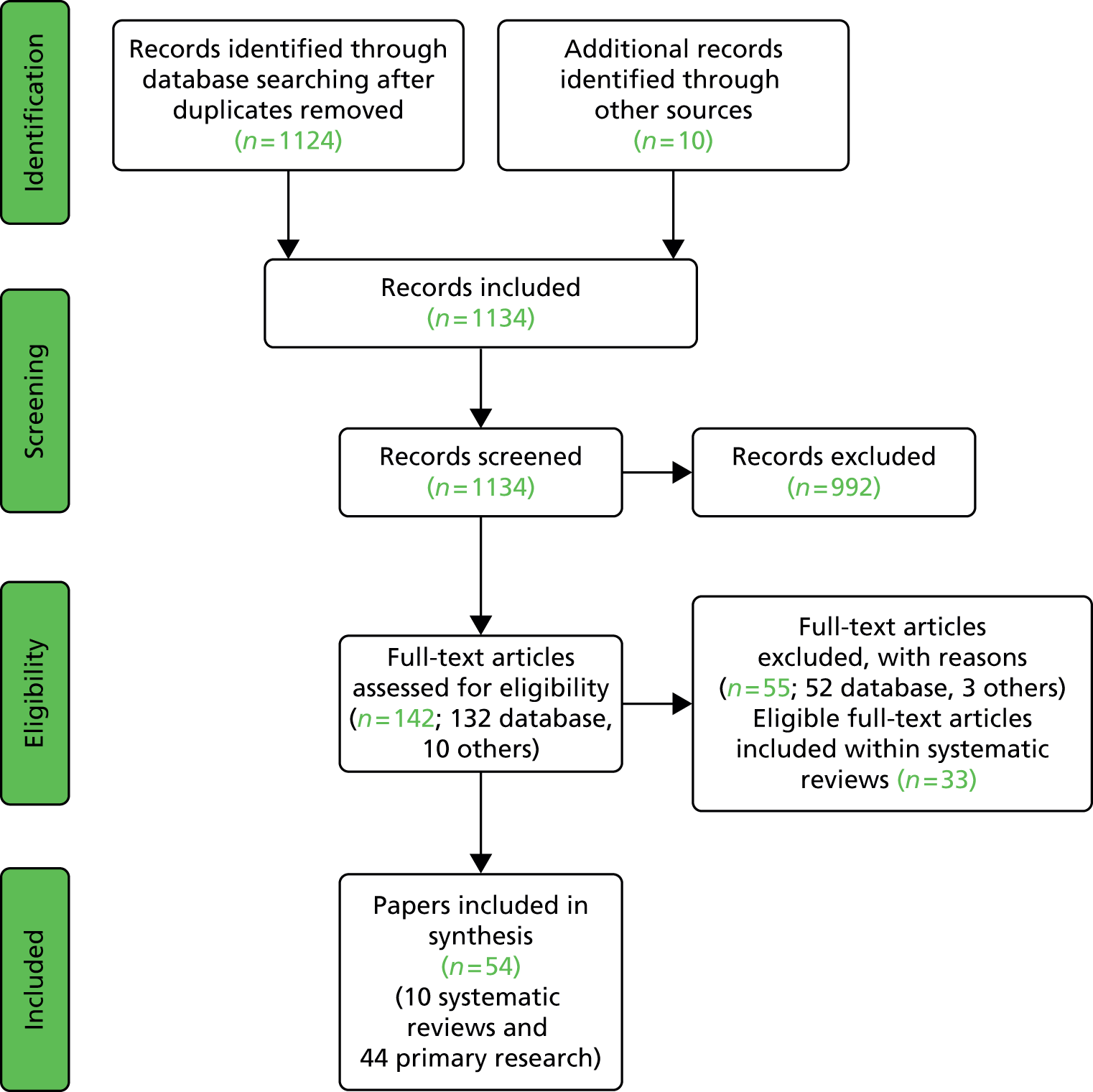

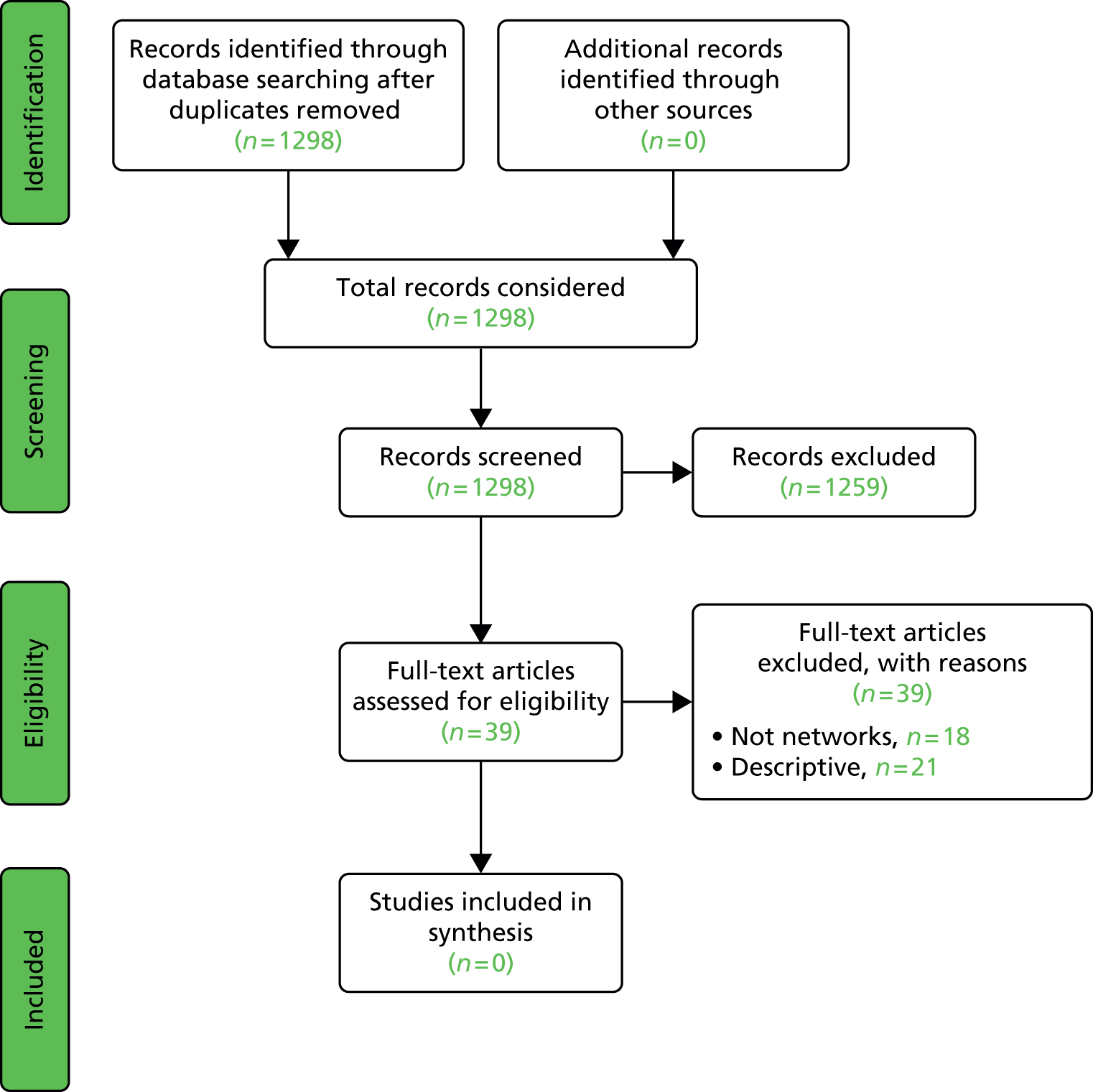

The results of the review sifting process are given in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram for emergency and urgent care demand searches.

Results

We identified four relevant systematic or rapid reviews, and an additional 39 primary studies not included in the systematic reviews. Of these 39, eight related to demand and 31 were patient-based studies exploring reasons and choice in terms of accessing urgent care. The characteristics and findings of the included reviews and primary studies are summarised in Tables 1–3.

| Author, year | Study design | Population and setting | Purpose | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lowthian, 201114 | Systematic review of published and unpublished reports generated between January 1995 and January 2010 | Attendances at ED in developed countries | To synthesise the evidence describing trends and drivers associated with increased ED attendances | A total of 56 peer-reviewed papers and additional (numbers not reported) related articles and reports included. Findings on trends and drivers were categorised under primary headings of ageing, which partly (but not wholly) explain growth in demand; loneliness and lack of social support; mainstreaming of psychiatric care and frequent attenders; organisation of services, access to primary care and co-payments; health promotion and health awareness; convenience and appropriateness of use; and risk aversion. Concluded factors associated with rising demand for ED services dependent on complex inter-related factors, including demographics, socioeconomic factors and community expectations |

| He, 201115 | Review article utilising multiple database searches and journal searching (Australian-based titles). Articles published between 1990 and 2011 | Attendances at ED, any setting. Paediatric attendances excluded | To identify factors affecting demand for ED care and describe the inter-relationships between these factors | A total of 100 papers and reports included. Utilised a conceptual framework to map the relationships between factors. Factors categorised as those describing patient health needs (chronic disease, acute illness, injury, drug/alcohol dependence); those predisposing patients to seek help (perceptions of severity, ability to self-manage, convenience, expected quality, population growth and ageing, seasonal influences); and policy factors (health insurance/payment, hospital number and size, availability of other services, geography – urban/rural). Review identified and mapped multiple inter-related factors affecting demand but no evidence on relative contribution of each factor |

| Lowthian, 201116 | Review article utilising Ovid MEDLINE and PubMed database searches supplemented by web-based Google and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) searches and article reference list searches. Searches conducted for years 1996–2009 | Emergency ambulance calls in developed countries | To review the literature on trends in utilisation of emergency ambulances and identify the major potential drivers perceived to be contributing to increases in utilisation | A total of 45 papers and reports included. Descriptions of growth in the UK, USA, Canada, New Zealand and Australia that were in excess of population growth. Some association with ageing, with reported higher utilisation in > 65 years and incrementally increasing with age, and likely to be associated with increasing chronic illness and declining cognitive function. One Australian study showed age-related factor only accounted for 25% of increased demand. Other potential factors include decreased social support and increasing numbers living alone, insurance coverage, accessibility of primary care and increased patient expectations and health awareness. Most ambulance-based literature described ambulance activity and volumes with little examination of possible associations between rise in utilisation and patient, community or health-system factors |

| Gruneir, 201117 | Systematic review and narrative synthesis of published articles up to 2008 (start date not specified) Identified from electronic databases and searching reference lists | Older adults using ED, any setting. ‘Older’ not defined | Review of literature on trends, appropriateness and consequences of ED use by older adults. Looked at nursing home residents as a subpopulation | A total of 55 articles included. Consistent findings on greater and disproportionate use of EDs by older people, regardless of country or health-care system. Attendances spike at > 75 years and > 85 years. Reason for visits predominantly medical and injury from falls. Also associations with self-care problems, decreased functioning and lack of social support. Older adults have higher acuity of illness than younger ones, spend longer in EDs and have more diagnostic tests and more admissions. These increase with age, suggesting that visits are appropriate. Needs are complex; there is a lack of research on individual-level risk factors and a lack of population-based studies to support this research |

| Author, year, country | Study design | Population/setting | Purpose | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leonard, 2014,18 Australia | Retrospective analysis of routine data | All ED presentations in Greater Sydney from January 2001 to December 2011 | To describe trends in population-based rates of ED presentation in the elderly. Measured age-specific rates for groups < 65 years, 65–79 years and ≥ 80 years | 11 million presentations included. 1.8% annual increase per 1000 population. Compared with the < 65 years group, adjusted incidence ratio was 1.6 times higher for the 65–79 years group (95% CI 1.4 to 1.8; p < 0.001) and 3.6 times higher for the ≥ 80 years group (95% CI 2.8 to 4.7; p < 0.001). For patients aged ≥ 80 years there were 40 patients per 1000 population more admissions compared with those aged < 65 years (β = 40, 95% CI 29 to 52; p < 0.001). The rate of increase in ED presentations in the group aged ≥ 80 years is disproportionate to population changes and higher admission rates |

| Pines, 2013,19 USA | Retrospective analysis of National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey | Patients 65 years or older attending EDs and recorded in survey, 2001–9 | To describe trends in use of ED by older adults, reasons for visits, resource use and care quality | Over an 8-year period, ED visits increased from 15.9 to 19.8 million (24% increase). Reasons for visits unchanged (main reasons chest pain, dyspnoea and abdominal pain). Resource use of investigations increased dramatically. The proportion seen in the ED, discharged and later admitted increased from 2% to 4.2%. If no changes to primary care, acute hospital facilities will need to plan for greater demand |

| FitzGerald, 2012,20 Australia | Time-trend analysis of ED presentations and population-utilisation rates over the 10-year period from 2000/1 to 2009/10 | Attendances at all public hospital EDs in all eight states and territories in Australia | To describe trends in ED use and population utilisation rates nationally and for individual states. Measured ED attendances ED utilisation rate per 1000 population |

Total growth in ED demand was 37% over the 10 years, with average growth of 3.6% per annum. Growth varied by state (range 14–73%). Some of this may be owing to reporting changes Trends varied, with a linear pattern in five areas, non-linear in two and no change in one. ED utilisation rates also varied between areas, from 38% lower in 2001 than in 2010 within one area to unchanged in three areas. Fluctuations in presentations during the 10 years Changes in ED presentations may be owing to population growth, but utilisation growth was greater than population growth. May be urban vs. rural differences, which cannot be detected from current data. Ageing population may have an effect, but this pattern was not consistent between areas |

| Lowthian, 2012,21 Australia | Retrospective analysis of routine public hospital data | All ED presentations in Metropolitan Melbourne from 1999/2000 to 2008/9 | To measure 10-year trends in volume and age-specific rates of ED presentations, population utilisation and ED LOS | Average annual 36% rise in rate of presentation after adjusting for population changes (95% CI 3.5 to 3.8). Almost 40% patients in ED for ≥ 4 hours in 2008/9 increasing for the acutely unwell. Patients aged ≥ 85 years were 3.9 times more likely to present than those aged 35–59 years (95% CI 3.8 to 4.0) and volume of older people doubled over a decade, more likely to arrive by ambulance more acutely unwell, 75% have ED stay ≥ 4 hours and 61% require admission vs. 35–59 years group. Presentation rates beyond those expected from demographic changes. Current models of emergency and community care do not meet needs for acute illness. The 4-hour targets were probably unachievable without whole-system redesign |

| Lowthian, 2011,22 Australia | Retrospective population-based analysis of routine ambulance data | All ambulance transports in Ambulance Victoria from 1994/5 to 2000/8 | To measure growth in ambulance use and the impact of population growth and ageing. Measured ambulance transportations and population utilisation rates for different age groups. Modelled future demand | Crude annual transports increased from 32 to 58 per 1000 people and by 75% (95% CI 62 to 89) over the 14 years. Represents average annual growth rate of 4.8% (95% CI 4.3% to 5.3%) beyond that explained by demographic changes. Patients aged ≥ 85 years were transported eight times more frequently than those aged 45–69 years. Forecast models suggest that the number of transports will increase by 46–69% from 2007/7 to 2014/15. Emergency ambulance use has risen dramatically beyond that expected by demographic changes. Increases were across all age groups, but more for older patients and likely to continue to increase |

| Chu, 2009,23 Australia | Retrospective ecological study of ED attendances from 2002 to 6 compared for two age groups: 14–65 years of age and > 65 years | All attenders at a major adult inner-city ED | To describe trends in ED use. Number of attendances Number in each category of the ATS Number of admissions Total ED time Access block (proportion of patients requiring admission, with total ED time ≥ 8 hours |

ED attendances increased by 7.7% over the 5 years. ED attendances in the age group > 65 years fell by 3.3%, whereas in the < 65 years group ED attendances increased by 9%. In both groups, ATS 5 (least serious) fell (–48.9%, > 65 years; –35.8%, < 65 years), ATS 1 and 2 decreased in the > 65 years group (–15.3%), but increased in the < 65 years group (16.1%), and ATS 3 and 4 increased in both groups. Percentage admitted fell in both groups, but higher rate in > 65 years group. Median ED time was higher in > 65 years group for admitted and discharged patients and increased overall for all patients. Access block increased from 7.7% to 33.3% over the 5 years Fall in attendances by the > 65 years group was unexpected. This reduction may be explained by population profile and change to aged care service. Increased demand by older people may not be uniform and local trends and population mix need to be considered for planning |

| Moll van Charante, 2007,24 the Netherlands | Prospective cross-sectional population study at two 4-month periods in 1997/8 and 2002/3 | All patient contacts with one GP co-operative and three EDs for a population of 62,000 | To assess OOH demand for GP and emergency care and referral patterns to ED by GP co-operatives and ambulance services | GPs managed 88% of OOH contacts and 12% of ED visits (275/1000 inhabitants vs. 38/1000 per year). A total of 43% of ED attendances were self-referrals, comprising 5% of all OOH contacts. ED self-referrals were predominantly young men with injuries. Patients taken to ED by ambulance or referred by GP were older and more likely to be admitted to hospital (p > 0.01). Most OOH urgent care needs were managed by GPs. GPs and ambulance services appropriately select patients who need ED care |

| Margolis, 2002,25 the United Arab Emirates | Retrospective cross-sectional survey of attendances abstracted from ED registers | Patients aged 65 years or older who visited ED in one hospital, 1989–9 | To describe change in ED use by the elderly in a major hospital ED | Visits increased from 321 to 1347 over 10 years. The mean age of patients aged 72.9 years did not change, but elderly attendances increased (3% to 5%; p < 0.001). The mean number of visits per person per year rose from 1.8 to 3.3 (p < 0.001). Acuity did not change, non-urgent attendances increased from 14% to 39% (p < 0.001), with a corresponding increase of dispositions to primary care |

| Author, year, country | Study design | Population/setting | Purpose | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amiel, 2014,26 UK | Survey using self-completed patient questionnaires | Patients presenting to open-access urgent care centre attached to ED providing urgent care and normal GP services without appointment | To explore why patients with minor illness choose to attend an urban urgent care centre for their health-care needs | A total of 649 participants with a median age of 29 years. 72% were registered with a GP; more women (59%) attended than men. The majority of participants rated themselves as healthy (81%). Access to care (58%) and expectation of receiving prescription medication (69%) were main reasons for attending ED. GP dissatisfaction influenced 10% of participants decision to attend an urgent care centre. 68% did not contact their GP in the previous 24 hours before attending. Young adults mostly registered with a GP used urgent care centres because of convenience and ease of access rather than satisfaction levels with their GP |

| Booker, 2014,27 UK | Qualitative study using semistructured interviews and thematic analysis | Ambulance: patients and carers who had called an ambulance for a primary care-appropriate problem. Selected by research clinician in ambulance (n = 16) | To explore and understand patient and carer decision-making around calling an ambulance for primary care-appropriate health problems | The primary theme was patient and carer anxiety in urgent care decision-making, and four subthemes were: (1) perceptions of ambulance-based urgent care; (2) contrasting perceptions of community-based urgent care; (3) influence of previous urgent care experiences in decision-making; and (4) interpersonal factors in lay assessment, management of medical risk and subsequent decision-making Many calls are based on misconceptions about the types of treatment other urgent care avenues can provide |

| Lobachova, 2014,28 USA | Quantitative. Cross-sectional survey via questionnaire of patients and simultaneous web-based survey of PCPs | Patients presenting to all areas of ED (n = 1062). Survey of PCPs who were also responsible for care of patients who presented at ED (n = 275) | To measure the distribution and frequency of the stated reasons why patients choose the ED for care and why PCPs think their patients utilise the ED | The most common reason for which patients came to the ED was belief that their problem was serious (61%), followed by being referred (35%). In addition, 48% came at the advice of a provider, family member or friend. By self-report, 354 (33%) patients attempted to reach their primary care physicians and 306 (86%) of them were successful. PCP survey showed that PCPs believed the most common reasons patients attended ED was that the patient chose to go on their own (80%) and patients felt that they were too sick to be seen in the PCP’s office (80%) |

| Shaw, 2013,29 USA | Qualitative research through study using semistructured interviews conducted at discharge | Locally residing patients attending ED who were subsequently triaged to a ‘non-urgent area’ for treatment (n = 30) | To explore patients reasons for visit to ED, knowledge of other non-urgent options, patient satisfaction | A total of 7 out of 30 patients had no knowledge of alternative primary care options. A total of 23 out of 30 patients attended for the following six reasons: (1) instructed by a medical professional; (2) facing access barriers to their regular source of care; (3) perceiving racial issues with a primary care option; (4) defining their health-care need as an emergency that required ED services; (5) facing transportation barriers to other primary care options; and (6) factoring in costs to use other primary care options vs. the ED |

| Schumacher, 2013,30 USA | Observational, cross-sectional study design | Emergency department: adults ≥ 18 years of age presenting to an ED at an academic medical centre in an urban community | To examine the relationship between health literacy, access to primary care and reasons for ED use among adults presenting for emergency care | After adjusting for sociodemographic and health status, those with limited health literacy reported fewer doctor’s office visits (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.4 to 1.0), greater ED use (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.4) and had more potentially preventable hospital admissions (OR 1.7, 95% CI 1.0 to 2.7) than those with adequate health literacy. After further controlling for insurance and employment status, fewer doctor’s office visits remained significantly associated with patient health |

| Toloo, 2013,31 Australia | Quantitative, cross sectional survey by questionnaire while patients were waiting for or under treatment | Patients presenting at ED via ambulance or self-transport (n = 911; 223 by ambulance, 619 by own/public transport and 69 by police/other/not answered) | To describe patient views of perceived illness severity, attitudes towards ambulance, and reasons for using ambulance | Likelihood of using an ambulance increased by 26% for every unit increase in perceived seriousness. Patients who had not used an ambulance in the 6 months prior to the survey were 66% less likely to arrive by ambulance. Patients who had presented via ambulance stated that they considered the urgency (87%) or severity (84%) of their conditions as reasons for calling the ambulance. Other reasons included requiring special care (76%), getting higher priority at the ED (34%), not having a car (34%) and financial concerns (17%) |

| Agarwal, 2012,32 UK | Qualitative interviews with researcher | Purposeful sample of patients and their carers attending the ED and urgent care centre at a university hospital (n = 23) | To explore the reasons for attendance at the ED by patients who could have been managed in an alternative service and the rate of acute admissions to one acute hospital | Four main themes emerged from the interviews that are pertinent to patients’ decisions to attend the ED: (1) anxiety about their health and the reassurance arising from familiarity with knowledge of the emergency service; (2) issues surrounding access to general practice; (3) perceptions of the efficacy of the service; and (4) lack of alternative approaches to care. These factors are important predictors of ED attendance rates |

| Becker, 2012,33 South Africa | Qualitative questionnaire conducted by ED staff | Patients presenting to ED who were subsequently triaged as ‘green’ by the South African Triage Score (n = 277) | To determine the patient-specific reasons for accessing the hospital ED with primary health care problems | Of the cases, 88.2% were self-referred and 30.2% had complaints persisting for more than 1 month. Only 4.7% of self-referred green cases were appropriate for the ED. The three most common reasons for attending the ED were that the clinic medicine was not helping (27.5%), a perception that the treatment at the hospital is superior (23.7%) and that there was no primary health service after hours (22%). Strict referral guidelines are needed and better methods of channelling primary health-care patients to the appropriate level of care are needed |

| Fieldston, 2012,34 USA | Focus groups with 25 guardians and 42 health professionals participated | Emergency department: non-urgent, paediatric. Guardians of children, primary care practitioners and paediatric emergency medicine physicians | To determine and to describe guardians’ and health professionals opinions on reasons for non-urgent paediatric ED visits | Guardians focused on perceived illness severity of their child and the needs for diagnostic and other interventions, alongside accessibility and availability at times of day that worked for them Professionals focused on systems issues, concerning availability of appointments, as well as parents’ lack of knowledge of medical conditions and knowledge of when ED use is appropriate |

| Gomide, 2012,35 Brazil | Qualitative interviews | New patients presenting to the ED who were aged 18 years or over (n = 23) | To identify reasons why users turn to emergency care services in situations that are not characterised as urgent or emergencies | A total of 23 users were interviewed; 13 were female and the mean age was 40 years. Reasons why patients choose emergency care: difficult to get immediate care at other services; limited opening hours for primary care services and most patients work during primary care opening hours; and patients feel that EDs have greater amount of diagnostics |

| Marco, 2012,36 USA | Prospective study. Structured interview questions | Adult patients attending ED in an urban university hospital (n = 292) | To identify factors that influence patients’ decisions to seek care in ED and assess their access to primary care | Most participants had a PCP 73% (n = 4214) and a minority had called their PCP about their current problem. Most participants came to the ED because of convenience/location or preference for this institution. Participants came to the ED, rather than their regular doctor, because they had no PCP, an emergency condition or communication challenges. Convenience, location, institutional preference and access to other physicians were the most common factors influencing patients’ decisions to attend the ED |

| Müller, 2012,37 Switzerland | Self-administered, paper-based questionnaire | Walk-in patients presenting to the ED during the hours in which GPs were also open (n = 200) | To investigate why walk-in patients use a university ED during GP office hours | Most walk-in patients (82%) were registered with a GP. 39% of patients visited the ED because they had reported greater confidence in the hospital ED. Most patients stated that they preferred the hospital to their GP in any kind of emergency and the majority defined an emergency as either a condition requiring rapid attention or a life-threatening situation (53%) |

| Penson, 2012,38 UK | Patient questionnaire and subsequent notes review | Emergency department: patients aged 14 years and over presenting to the ED of an urban hospital (n = 285) | To estimate the potential of alternative providers of care for minor health problems to reduce demands on EDs | The notes review confirmed that more than two-thirds of the presenting conditions could have been managed in settings other than ED. Attendees’ reasons on the questionnaire indicated a strong belief that the only provider able to deal with their concerns at that time was the ED. For some users, ED was not the first contact with a health-care provider for the same health problem. Few believed that they would be seen quicker in the ED or that the ED was more convenient. The most frequent reason for presenting to the ED was ‘being advised to attend by someone else’. The ‘adviser’ was often a health professional (doctor or nurse or NHS Direct) rather than ‘friends or family’ |

| Wilkin, 2012,39 USA | Qualitative interviews in community forum groups moderated by researcher | Adults (aged ≥ 18 years) within a defined geographical area and previous 911 users (n = 52) | What factors influence residents’ decisions to use emergency vs. primary care? | Participants had a wide variety of health-care experiences The findings revealed unique barriers to primary care related to both medical literacy and class disparities. Residents were not always able to evaluate which health symptoms necessitated emergency care Barriers such as transportation, scheduling, ability to afford health-care costs, and patients’ attitudes towards available primary health-care options might prevent people from changing their health-care-seeking behaviours |

| Nelson, 2011,40 Scotland, UK | Qualitative telephone interviews using structured questionnaires | Emergency department: patients attending ED with ‘standard, non-urgent’ conditions (n = 27) | To understand patients’ perceptions of the urgency of their condition and how this influences their decision to attend EDs | A total of 85% of patients attended with injury and pain as main reason for attending. A total of 37% of patients felt they needed radiography (15% referred by GP, 7% advised by GP receptionist and 4% unable to obtain GP appointment). A total of 52% of patients attended because of health-care professionals and friends/family advising them to attend ED A total of 48% said condition was urgent, 52% said non-urgent. No patients rated their own condition as very urgent. A total of 37% of patients had made contact with a primary health-care provider before attending and 67% said they would attend again if problem was urgent (22% because it is open 24/7 and no appointment needed) |

| McGuigan, 2010,41 UK | Semistructured telephone interviews of a purposeful sample of patients | Self-referring patients aged over 16 years who presented to ED triaged as non-urgent (n = 196) | To discover factors influencing patients’ reasons for attending the ED for non-urgent treatment | Most patients in sample thought that their conditions required urgent attention The largest proportion of patients presented with soft tissue injuries or haematomas Females attended because of other people’s advice more than males. Family and friends rather than health-care professionals were most common source of advice |

| Oetjen, 2010,42 USA | Qualitative survey questionnaire | Emergency department: insured patients presenting to four ED departments within a single state (n = 438) | To understand why insured patients use EDs rather than more appropriate medical alternatives available to reduce the strain they are placing on this critical portal of entry | Patients can be grouped into proactive, reactive and reluctant ED users, the majority of patients being reactive Most patients (83%) had a PCP. There was no correlation between ED use and whether or not patients had a PCP. A total of 39% of patients did not contact a PCP before attending ED A variety of factors were identified as to why patients may choose to attend ED and choose a particular ED including: PCP being busy, PCP referral, OOH referral, patient perception of condition being serious, ED more convenient, friend’s recommendation, quality, location and staff |

| Adamson, 2009,43 UK | Mixed-method study (cross-sectional questionnaire survey and semistructured interviews) | Patients selected randomly from a single GP list (n = 911 survey; n = 22 interviews) | To quantify the prevalence of opinion on whether or not people use health services unnecessarily within primary care and A&E in order to examine the impact of these views on help-seeking behaviour | Survey data suggest that most people believe individuals use either GP or A&E services inappropriately (66%). Strong views relating to inappropriate health care use were not associated with reported seeking of immediate care. Responders tend to consider other people as time wasters, but not themselves. Individuals’ generally describe clear rationales for help seeking, even for seemingly trivial symptoms, and anxiety level was strongly predictive of health-seeking behaviour The findings suggest that people do not take the decision to consult health services lightly and rationalise why their behaviour is not time wasting |

| Scott, 2009,44 USA | Cross-sectional questionnaire survey of patients seeking care at an urgent care clinic within a large acute care safety net urban hospital | Urgent care clinic: patients presenting to an urgent care clinic (n = 1006) | To determine the motivation behind, and characteristics of, adult patients who choose to access health care in an urgent care clinic | A total of 54% of patients reported choosing the UCC because of not having to make an appointment, 51% because it was convenient, 44% because of same-day test results, 43% because of ability to get same-day medications and 15% because co-payment was not mandatory. A total of 68% of patients did not have a regular physician and 57% lacked a regular source of care. This study suggests that patients choose the urgent care setting based largely on convenience and more timely care |

| Benger, 2008,45 UK | Qualitative, semistructured questionnaire | Adult patients admitted to inner-city hospital after either ED or GP attendance (n = 200) | To determine the route by which patients with acute illness are admitted to hospital, the reasons and outcomes for the actions taken and the extent to which these may contribute to increased ED attendances and hospital admissions | Direct attendance at the ED was more common when help was sought by bystanders or persons known only slightly to the patient. Most patients who attended the ED directly did so as a result of the perceived severity or urgency of their condition and there was incomplete awareness of the OOH GP service. The majority of older patients who are admitted to hospital with an acute illness seek professional help from primary care in the first instance, whereas younger people contacted OOH or other services. OOH patients tended to attend ED more often than primary care patients |

| Jacob, 2008,46 USA | Survey. Convenience sample of ED patients | Emergency department: paediatric and adult patients presenting to the ED (n = 311) | To define the characteristics of ED patients who used ambulance transport compared with non-ambulance users and to determine reasons for ambulance use | Users (n = 71, 22.8%) were older than non-users, and were sicker according to self-rated illness severity, higher nurse triage score and higher admission rate. Patient decision regarding ambulance use was associated with both having someone who called an ambulance for them and self-estimation of illness severity (or lack thereof). Physicians agreed with transport method in 68% of users and 92% of non-users |

| Redstone, 2008,47 USA | A 31-item, cross-sectional, self-administered, anonymous survey | Patients over the age of 18 years with a primary care physician presenting to the ED who were subsequently triaged as non-urgent (n = 240) | To investigate why patients with minor problems and a PCP present to the ED. Results compared those attending in WDD and NWDD | There were high levels of self-perceived urgency for treatment; a strong majority felt they could not wait 1–2 days for treatment. More WDD patients felt their case was too difficult for the PCP to handle as opposed to NWDD patients. Around 24% of patients in both groups felt they needed to be admitted to hospital A total of 70% of WDD patients were willing to contact their PCP, despite 45% feeling their condition was too complex for their PCP; 45% did not contact PCP at all A total of 60% of patients across both groups felt the ED was more convenient than their PCP |

| Hodgins, 2007,48 Canada | Descriptive correlational study | Emergency department: low-urgency patients (n = 1612) | To what extent can patients’ responses to less urgent health problems be predicted using Andersen’s criteria (predisposing, enabling, need determinants) and do these characteristics differ based on the place (geographic location) in which health care is sought? | Differences were observed in the percentage of participants presenting at urban and rural EDs by type of health problem The two items with the highest mean scores reflected participants’ perceptions of need (severity of symptoms and concern problem will get worse), while the next two items dealt with characteristics of the context within which health care was sought (no other option and availability of family physician). The next three highest rankings were, convenience of service, needed service only available at ED and advice from family or friends |

| Norredam, 2007,49 Denmark | Quantitative, questionnaire survey of walk-in patients and care providers at four Copenhagen EDs | General ED (n = 4); migrant and national citizen usage of ED (n = 3426). Response rate 54% | To investigate the extent to which immigrants and patients of Danish origin have different motivations for seeking emergency room treatment, and differences in the relevance of their claims | Groups of foreign origin are more likely to consider contacting primary care providers before attending ED. A higher number of immigrants were unable to access primary care and immigrant ED attendance was often caused by not being able to access primary care. In contrast, more national patients claimed that the ED was more relevant for their needs. Patients from non-western or middle eastern origin were significantly more likely to attend ED because they did not live locally and could not access their normal primary care giver. Care providers reported that 21% of all ED attendances were not relevant to ED, a significantly higher proportion of non-western or middle eastern patients had irrelevant ED visits and irrelevant ED attendance was significantly related to not being able to access primary care |

| Campbell, 2006,50 Scotland, UK | Four focus groups and 51 in-depth interviews with 78 participants | Patients aged between 45 and 64 years in eight urban and rural general practices in north-east and south-west Scotland | To explore if, and how, patients’ consulting intentions take account of their perceptions of health-service provision | Anticipated waiting times for appointments affected consulting intentions, especially when the severity of symptoms was uncertain. Strategies were used to deal with this. In cities, these included booking early just in case, being assertive, demanding visits, or calling out of hours but in rural areas, participants used relationships with primary care staff, and believed that being perceived as undemanding was advantageous. OOH decisions to consult were influenced by opinions regarding OOH services. Some preferred to attend nearby EDs or call 999. In rural areas, participants tended to delay until their own doctor was available or might contact them even when not on call |

| Worth, 2006,51 Scotland, UK | Qualitative, community-based study using 36 in-depth interviews and eight focus groups with patients and/or their carers and 50 telephone interviews with patient’s GP and other key professionals | Urban, semi-urban and rural communities in three areas of Scotland. Patients with advanced cancer who had recently used OOH services | To explore the experiences and perceptions of OOH care of patients with advanced cancer, and with their informal and professional carers | Patients and carers had difficulty deciding whether or not to call OOH services because of anxiety about the legitimacy of need, reluctance to bother the doctor, and perceptions of triage as blocking access to care and OOH care as impersonal. Positive experiences related to effective planning, particularly transfer of information, and empathetic responses from staff. Professionals expressed concern about delivering good palliative care within the constraints of a generic acute service, and problems accessing other health- and social-care services |

| Palmer, 2005,52 UK | Semistructured telephone interviews of patients to discuss recent ED contact | Emergency department; patients presenting to ED triaged to 4 or 5 on the Manchester Triage Score (n = 321) | To investigate why and how patients decide to attend A&E departments, and to assess their satisfaction with the experience, in a predominantly rural west Wales population | Of the study sample, 78% attended with injury or illnesses of recent origin, and 50% with actual or presumed musculoskeletal injury, 73% of which were sustained within 10 miles of home. Travel to hospital was by private transport for 86%, average distance 7.4 miles. Most (90%) were registered with a local GP, but 32% felt A&E was the obvious choice, and a further 44% considered their GP inaccessible to their needs. Patient satisfaction was generally high. Among the 87 patients (27%) who reported a less satisfactory experience, 48 (55%) of these complained of dismissive attitudes of doctors |

| Foster, 2001,53 UK | Focus group methodology, with qualitative data analysis undertaken using a grounded theory (framework) approach | People aged between 65 and 81 years, from community groups based in south-east London (n = 30) | To explore older people’s experiences and perceptions of different models of general practice OOH services | Two related themes were identified: (1) attitudes to health and health-care professionals with reference to the use of health services prior to the establishment of the NHS, a stoical attitude towards health and not wanting to make excessive demands of health services; and (2) the experience of OOH care and perceived barriers to its use, including the use of the telephone and travelling at night. Participants preferred contact with a familiar doctor and were distrustful of telephone advice, particularly from nurses. Older people appear reluctant to make use of OOH services and are critical of the trend away from OOH care being delivered by a familiar GP |

| Coleman, 2001,54 UK | Questionnaire and review of notes | Adults presenting to ED triaged to the two lowest priority streams (n = 267) | To estimate the potential of general practice, minor injury units, walk-in centres and NHS Direct to reduce non-urgent demands on A&E departments taking into account the patient’s reasons for attending A&E | Using objective criteria, 55% of patients with non-urgent health problems who attend EDs should be treated in either general practice, a minor injury unit, a walk-in centre or by self-care after advice from NHS Direct. Nearly 25% of non-urgent patients who self-referred had previously accessed other health services for the same problem. Most patients attended, as they believed they required radiography. There are disparities between the professional view and the patient’s perceptions of the seriousness of the health problem, and expectations of care |

| Hoult, 1998,55 UK | Qualitative interviews with patients | OOH: patients calling OOH services within 2 days of a GP consultation (n = 20) | To determine the proportion of patients who call OOH within 2 days of a GP consultation and to explore the reasons for the OOH call | A total of 15% of patients who made OOH contact had had a GP appointment within the previous 2 days. Two out of three of the calls were related to the initial problem, but with no evidence of patient dissatisfaction. Less than one-quarter of calls were for ongoing medical conditions, and one-quarter were about medication prescribed at the first consultation. One-third of patients had mental health problems. Many patients were high users of other services, including A&E and private medicine. Some patients called with specific queries or to develop better understanding of illness |

| Shipman, 1997,56 UK | Quantitative data collection on demographics and nature of complaints. Telephone surveys with 82 people who attended ED | Patients presenting to OOH services in a large capital city. Data from GP (OOH) and ED (n = 2564) | To examine differential use of OOH general practice and ED use and to describe differences in service users | There are differences in age-related demand and presenting complaints for each service. Children constitute a great proportion of all OOHs contact and more families with children under 10 years presented to GP services More digestive, respiratory, viral/non-specific complaints presented to GP, whereas musculoskeletal problems accounted for the largest category of ED presenting problems. Usage relating to perceived and actual ability of services appeared interchangeable between sites. A collaborative method approach is required to respond to and influence demand |

Summary of findings

This review has been conducted to provide a brief overview and context for the subsequent more detailed reviews. We have therefore only identified key themes that have emerged from the available evidence.

Trends and characteristics of demand for emergency and urgent care

We identified four review articles and eight primary studies that explored trends in demand and associated characteristics. One review17 and two primary studies19,25 only considered older populations. Two studies16,22 investigated emergency ambulance utilisation, seven focused on ED attendances and one24 on ED and GP out-of-hours (OOH) attendances. The key common themes that emerged were:

-

The trend of increasing, year-on-year demand for emergency and urgent care is consistent across developed countries. Population utilisation rates are also increasing and this appears to be greater for ambulance services than EDs.

-

Population and demographic changes explain some, but not all, of the increases in demand. Elderly people do utilise emergency and urgent care more frequently, particularly those aged > 80 years and are more acutely unwell, but this group accounts for only about 25% of increased demand. The impact of ageing populations may also vary by locality and the relative health and socioeconomic status of the resident elderly population.

-

Demand is likely to be influenced by a range of other characteristics and factors, including health needs (chronic conditions, acute illness, drug and alcohol dependency), socioeconomic factors (isolation and loneliness, lack of social support, deprivation), patient factors (decision-making behaviours, awareness, expectations, convenience) and policy (insurance coverage, numbers of hospitals, access to primary care, geographical differences in provision), but there has been little research examining the association between the rise in demand and these factors.

-

There have been few attempts to identify and map the different influences on demand and the relative influences of each factor to create a comprehensive profile of the different health-care needs of populations accessing emergency and urgent care to inform health-service planning.

-

There is a lack of population-based studies, identification of independent risk factors associated with accessing urgent care and whole-system (rather than individual service) demand studies. This is particularly constrained by a lack of information about urgent care within the primary care setting and modelling studies that can forecast likely future changes in demand.

Patient-based studies examining reasons for accessing emergency and urgent care

We identified 38 relevant studies from the database searches, seven of which were included in the four systematic reviews and so are not included in the summary table. Of the 31 studies we have examined in more detail, 16 were qualitative interview or focus group studies,27,29,32–36,39–42,50–53,55 12 were surveys26,28,31,37,38,44–47,49,54,56 and three used mixed designs. 30,43,48 The majority (23/31) were conducted in the ED, predominantly involving patients who presented with urgent rather than emergency conditions; two considered ambulance patients and six were in other settings, such as GP surgeries and urgent care centres. A number of frequent and common themes emerged from these studies, which concern reasons why patients used emergency or urgent care and their choice of where to access care:

-

Access to and confidence in primary care were prominent concerns. Factors identified included lack of awareness of options (particularly OOH services), dissatisfaction with GPs, limited opening hours, anticipated waiting times for appointments, previous experience using OOH services and perceived barriers. The elderly, in particular, did not like or trust telephone-based OOH services. In many studies, a high proportion of patients attending the ED were registered with GPs but still chose to access the ED instead.

-

Perceived urgency, anxiety and the value of reassurance from emergency-based services.

-

Being advised to attend the ED by family, friends or health-care professionals.

-

A belief that their condition needed the resources offered by a hospital, including hospital doctors (rather than GPs), diagnostics (particularly radiography), and treatment.

-

In some health systems, costs and transport options affected decision-making.

-

Convenience, in terms of location, not having to make an appointment and opening hours, was a factor. Older people were more likely to contact a GP first, but younger patients contacted urgent care centres, ED or OOH services, as they found this more convenient.

Conclusions

Despite serious concerns about rising demand for emergency and urgent care and the impact this has on health services, there is remarkably little empirical evidence that can fully explain why this trend in behaviour has occurred. The evidence included here has highlighted a range of factors that may influence demand, but much of the research has focused on either individual services or populations, such as the elderly. Most of the evidence presented here has come from Australia and there were no UK-based studies. However, there is scope to replicate some of the Australian studies using UK data.