Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1809/1072. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The final report began editorial review in July 2014 and was accepted for publication in January 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Steven Ariss was lead evaluator for one of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) at the time of the evaluation. Richard Baker was the director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) CLAHRC for Leicestershire, Northamptonshire and Rutland between 2008 and 2013. Ian Graham was a member of the advisory panel for one of the CLAHRCs at the time of the evaluation. Gill Harvey was employed by one of the CLAHRCs at the time of the evaluation. Jo Rycroft-Malone is a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Board (commissioned research). Since completing this research she has been appointed as the editor-in-chief of the HSDR programme. Sophie Staniszewska is an associate member of the HSDR Board (researcher led). Carl Thompson was the CLAHRC Translating Research into Practice in Leeds and Bradford theme lead for the NIHR CLAHRC for Leeds, York and Bradford (2009–13).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Rycroft-Malone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Policy context: the birth of Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

The establishment of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) in England was the culmination of a number of policy initiatives over several years to bridge the ‘knowing to doing’ gap,1 the gap between the acceptance of research and its adoption and routine use in practice. The time taken to incorporate research into routine practice can be ‘unacceptably long’ (p. 20). 1 Given this, there is now a widespread recognition of the need for an increase in resources to accomplish the translation and implementation of research to have an impact on patient outcomes. 2 As a consequence, governments in Europe, Canada, Australia and the USA have been making significant investments in translational research initiatives as a vehicle to bridge the metaphorical gap between bench and bedside.

Historically, the worlds of academia and practice have tended to be divided and disconnected; therefore, investments in translational initiatives have been focused on the potential of collaboration and in collaborative entities. When the users and producers of research are brought closer together, in theory, they can work collaboratively to find solutions to practical and relevant problems. Arguably, Canada led the way in such initiatives, with an early example being the Quebec Social Research Council’s grant programme that was set up in 1992 to encourage collaboration between decision-makers, researchers and practitioners. Since then, the USA has established the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative of the US Veterans Administration,3 the Netherlands has set up the Dutch Academic Collaborative Centres for Public Health4 and latterly in Australia Advanced Health Research Centres have been created. 5,6 The UK has followed this pattern with investment in a number of different entities designed to encourage collaboration, for example Academic Health Science Centres (AHSCs), Academic Health Science Networks, Biomedical Research Centres and Units, and, more recently, the CLAHRCs.

The landscape that led to the investment in and establishment of the variety of different collaborative entities in the UK was born from a number of policies. Shortly after the launch of a 5-year Research and Development Strategy for NHS England,7 which aimed to create a health system that supported leading-edge research based on patient need, the Cooksey Report8 drew attention to the undervaluing of applied health research (i.e. research that directly addresses questions and issues of practical importance) and highlighted two gaps in the translation of health research. Of relevance to this study, Cooksey highlighted the gap between the identification and evaluation of new effective interventions that are appropriate for everyday use, and their actual implementation in practice in the NHS [second gap in translation (T2)]. The report also focuses on the structures and cultures in the NHS that militated against the development and impact of applied health research, including a lack of strategy and cultural, institutional and financial barriers.

In 2007, the High Level Group on Clinical Effectiveness was tasked by the Chief Medical Officer to develop an action plan to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of clinical care in England. 9,10 Its work led to a number of recommendations, including that there should be:

-

a more programmatic approach to the development and establishment of teams and investment in implementation

-

a gradual increase in investment through the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR’s) budget for this area

-

a long-term commitment to develop climates conducive to conducting implementation research and the activity of using research findings in practice

-

consideration of the establishment of a number of centres of excellence in implementation research. 10

These recommendations are directly relevant and related to the establishment of nine CLAHRCs in 2008. These entities were established to be collaborative partnerships between health-care organisations and higher education institutions (HEIs). Overall, the initiative received £100M funding by the NIHR for 5 years, with a similar amount of matched funding from participating partners. The CLAHRCs were funded to deliver on three interlinked functions:

-

conducting high-quality applied health research to generate knowledge to improve patient health and care

-

implementing findings from research in clinical practice for patient benefit

-

increasing the capacity of NHS organisations and the public, private and third sector organisations to engage with and apply research. 11

These functions were expanded on in the call for external evaluations of the initiative, in which the aims of the CLAHRC were described as follows (NIHR NCCSDO CLA258):

To secure a step change in the way that applied health research is done and applied health research evidence is implemented locally;

To increase capacity to conduct and implement applied health research through collaborative partnerships between universities and NHS organisations;

To link those who conduct applied health research with all those who use it in practice across the health community covered by the Collaboration;

To test and evaluate new initiatives to encourage implementation of applied health research findings into practice;

To create and embed approaches to conducting and implementing research that are specifically designed to take account of the way that health care is increasingly delivered across sectors and across a wide geographical area;

To focus on the needs of patients, and particularly on research targeted at chronic disease and public health interventions; and

To improve patient outcomes across the geographic area covered by the Collaboration.

There was no prescribed or single model for CLAHRCs; the expectation was that each would evolve to best reflect and serve local needs by being outward facing and community focused, which included active involvement of patients and the public and other relevant stakeholders. The CLAHRCs were designed to be pilots and a collaborative experiment in closing T2.

Framing the challenge: conceptual territory

The conceptualisation of the issue about what is known from evidence and what is practised is frequently framed as a metaphorical ‘know–do’ gap. Consequently, the way in which this gap is traversed, closed or bridged has been the challenge that has been taxing an ever-growing and interested community of researchers, practitioners and policy-makers. Many terms are used to describe the activity undertaken to solve the problem, including ‘diffusion’, ‘dissemination’, ‘implementation’, ‘knowledge transfer’, ‘knowledge mobilisation’, ‘linkage and exchange’ and ‘research into practice’. 12 On closer scrutiny, the terms are used to describe a multitude of overlapping concepts and practices, but also reflect the different perceptions and underpinning assumptions about the processes involved in knowledge and its action. Historically, the ‘know–do’ gap has been defined as a practice/service problem rather than a knowledge creation one, the conceptualisation of evidence has been relatively narrow and there has been a lack of attention to the situation of evidence use. 13

Over time there has been a shift (in the literature at least) from seeing knowledge and its mobilisation as an event to conceptualising it as a process. This has been in parallel to a greater recognition that such processes are not linear but that knowledge use is mediated by context, is complex and multifactorial and, therefore, is often unpredictable. Different conceptualisations reflect this shift in thinking, with, for example, the Pipeline Model14 representing action as following specific stages or phases and a linear trajectory, in contrast to others’ representations reflecting more complexity and a focus on action being situated within context. 15–20

Different terms also reflect underlying epistemologies and therefore assumptions. For example, ‘research into practice’ and ‘knowledge transfer’ tend to be used to reflect a more linear unidirectional conceptualisation of knowledge use, whereas the term ‘knowledge translation’ (KT), which has become particularly popular in Canada, embodies more complexity, for example:

Knowledge translation (KT) is defined as a dynamic and iterative process that includes synthesis, dissemination, exchange and ethically sound application of knowledge to improve the health of Canadians, provide more effective health services and products and strengthen the health care system. This process takes place within a complex system of interactions between researchers and knowledge users which may vary in intensity, complexity and level of engagement depending on the nature of the research and the findings as well as the needs of the particular knowledge user. 21

Similarly, the increasingly used terms (particularly in the UK and the USA) ‘knowledge mobilisation’ and ‘implementation’ (of research and practice) reflect multidirectional pathways for knowledge discovery, exchange and uptake, including the factors that might influence these processes. Therefore, within this report we use both terms (‘implementation’ and ‘knowledge mobilisation’) to refer to processes that concern being attentive to and acting on evidence, making changes to practice/service delivery that could be informed by propositional and non-propositional sources of knowledge, and taking account of action occurring within contexts that are complicated and complex, including with a variety of stakeholders. These conceptualisations are built on further as part of the development of the study’s evaluation framework reported in Chapter 3. The critical question about whether or not collaboration provides a condition for action was a central concern of this research study.

Reconceptualising the challenge

The conceptualisation of the challenge of using evidence in practice resulting from a gap between research and practice is perpetuated by the ‘two communities’ model of knowledge creation in which the producers and users of research occupy separate worlds. 22 It has been argued that, although there has been a huge investment in developing an infrastructure to fund and deliver high-quality health-related research in the UK, this has been achieved, in part, by splitting research production from the delivery of health-care services. 23 The impact of this has been an exacerbation of the boundary between research and practice, and a call for a change of paradigm.

Best and Holmes24 conceptualise three generations of thinking about how Knowledge to Action (K2A) has been conceived: linear models, relationship models and systems models.

The language incorporated within a linear model of framing the issue (e.g. ‘research uptake’, ‘research into practice’, ‘knowledge transfer’) suggests a one-way process, whereby researchers produce new knowledge, which is disseminated to end-users and then incorporated into policy and practice. Knowledge is seen as a product that is generalisable across contexts and its use is dependent upon effective packaging. 25 The exchange is seen as one-way, from research producer to research user, so effective dissemination is critical. The linear model is therefore the embodiment of the ‘two communities’ approach to knowledge creation and use.

Relationship models incorporate the linear model principles for dissemination and diffusion, and then focus on the interactions among people using the knowledge. The emphasis is on the sharing of knowledge, the development of partnerships and the fostering of networks of stakeholders with common interests (e.g. Graham et al. 17). Within this framing, knowledge is perceived to be derived from multiple sources, including research, theory, policy and practice, and its use is perceived to be dependent upon effective relationships and processes. Therefore, collaboration and shared learning are key features of knowledge creation and use through coproduction or engaged scholarship. 26

A systems model enhances linear and relationship conceptualisations by recognising that knowledge mobilisation processes are themselves organised and structured through structures and agents, that is systems. A systems thinking approach assumes that there is an interconnectedness and interdependency between components within a system and, therefore, knowledge mobilisation would be seen as only one aspect of a wider process of how organisations change and develop. Understanding knowledge mobilisation then needs to be understood in relation to how the system as a whole is operating.

As Best and Holmes’s24 conceptualisation highlights, there has been a growing emphasis over time on practice-based, collaborative and organisational approaches to knowledge and its use. They offer a contrast to an evidence-orientated understanding of knowledge use, which is predicated on an assumption that evidence is a product needing to be pushed out to its users over the academic–practice boundary. 27 Pushing out evidence in the form of, for example, guidelines has had some, but relatively limited, success (given the substantial investment in the development of such packages of evidence) in improving health outcomes. Therefore, reconceptualising the challenge by bringing together the creators and users of knowledge to cocreate solutions to real-world problems is appealing. In the context of this type of collaboration, in theory, the practice–academic boundary would be blurred, evidence would be created within communities of practice, it would be of relevance to that community and, therefore, the gap between practice and research would potentially be narrowed. 22 These sorts of partnerships are prevalent in industry, but less so in health care, particularly publicly funded health services.

Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care in a conceptual context

Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care were predicated on an assumption that providing a resource and the architecture to enable the research and practice community to work more closely together would facilitate the generation of more applied health research and accelerate its use in practice. Accordingly, the concept of CLAHRCs fits with interactional and relationship conceptualisations of knowledge mobilisation. We assume that that was the theory underpinning the creating and funding of CLAHRCs, which is tested in this study through a realist lens. Realist inquiry facilitates the building of context-rich, theory-led explanations of what is it about a programme that makes it work. The starting point for a realist inquiry is testing the ‘theory’ that was in the heads of the programme developers, namely that bringing HEIs and health-care organisations closer together accelerates knowledge mobilisation. We investigate this theory through some specific objectives:

-

to identify and track the implementation mechanisms and processes used by CLAHRCs and evaluate intended and unintended consequences (impacts) over time

-

to determine what influences whether or not and how research is used through CLAHRCs, paying particular attention to contextual factors

-

to investigate the role played by boundary objects in the success or failure of research implementation through CLAHRCs

-

to determine if and how CLAHRCs develop and sustain interactions and communities of practice

-

to identify indicators that could be used for further evaluations of the sustainability of CLAHRC-like approaches.

The report of this realist inquiry is structured as follows:

Chapter 1 sets the emergence of CLAHRCs within a policy context and in a conceptual territory.

Chapter 2 reports a rapid realist review that was conducted to identify and describe the existing evidence base underpinning the theory of whether or not and how bringing research producers and users together within a collaborative arrangement might accelerate knowledge mobilisation.

Chapter 3 describes the methodology and methods used in the study, including the conceptual platform developed and used to frame the evaluation.

Chapter 4 presents findings from each case framed around the conceptual platform used for the study.

Chapter 5 presents a cross-case and cross-framework narrative, which starts to build an explanation for what works, for whom, how and why knowledge mobilisation operated with CLAHRCs over time.

Chapter 6 presents a realist framed explanatory account of the findings through a set of context, mechanism and outcome configurations.

Chapter 7 outlines the key mechanisms and a programme theory, which provides an explanation for collective action in collaboration around implementation and is related to the wider literature. Finally in this chapter we draw some conclusions and implications about an area in which there is still much research and learning to be done.

Chapter 2 Collaboration between researchers and practitioners: how and why is it more likely to enable implementation? A rapid realist review

Introduction

As outlined in Chapter 1, closing the gap between research and practice has been a persistent and vexing challenge. It is widely acknowledged that, to date, relatively little attention has been paid to T2;28,29 however, CLAHRCs are one type of approach to closing this gap. As an example of a partnership model to knowledge mobilisation, the CLAHRC initiative has focused on translating high-quality research to meet the needs of patient groups through increasing capacity and capability by collaboration between academia and practice. 28 This approach embodies the view of KT as an ‘iterative, reciprocal exchange that takes place between researchers and research users’. 30

Although the benefits of collaboration provide a potentially attractive solution to the challenges of evidence use, the pathway from developing collaborative partnerships to the implementation of research or evidence in practice is far from straightforward, and yet to be established. In reality, ‘doing’ collaboration does not necessarily lead to the achievement of set goals, or to clarity about what outcomes may be achievable. 31 Moreover, the outcomes that are supposedly linked to collaboration are often described in abstract terms, for example related to the learning that occurs as a result of the collaboration,32 or to the development of new skills across partnerships. 33 However, whether or not and how collaboration promotes the implementation of knowledge by end-users is unclear. As this was the ‘theory’ in the heads of those who established and funded CLAHRCs, we undertook a rapid realist review to identify whether or not this theory is supported by evidence and, if so, why and how collaboration might prompt implementation. The review also provided some initial co-ordinates for the development of the study’s conceptual framework (described in Chapter 3).

Question

Why and how does organisational collaboration between researchers and practitioners enable implementation?

Rationale for realist review

Collaboration in health care is situated within complex social environments and described as a ‘nested phenomenon’. 34 Therefore, a realist approach seemed appropriate in that it focuses attention on seeking to understand what works, for whom, why, under which circumstances and how. 35 Realist review is a theory-driven method of synthesising knowledge, which is grounded in the realist philosophy of science. 36 It involves ‘an iterative process aimed at uncovering the theories that inform decisions and actions’. 37 For pragmatic reasons, we undertook a rapid realist review whereby the realist approach to knowledge synthesis is employed in resource-limited circumstances. 38 Rapid realist reviews use the principles of realist synthesis, within a restricted set of literature,25,35 with the aim of seeking out mechanisms that are specifically related to programme outcomes. 38 In addition, in contrast to a conventional realist review, the focus is not on the development of theory per se, so output may not (necessarily) include context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations.

To safeguard against compromising the thinking behind the realist philosophy, the review used the principles of the traditional realist review and engaged with the evaluation research group, who became the ‘expert group’ and ensured that the parameters of the review question were observed throughout. 38 The question for the review was drawn from discussions with the research team (February 2012 and August 2013) and based on programme theory being developed by Rycroft-Malone et al. 39 Where subject content areas are sparse, reference groups and expert panels are drawn upon to describe ‘current best thinking’. 38

Background search

An initial background search of the literature was undertaken to understand how collaboration is represented, and to seek out examples of collaboration between organisations or researchers and practitioners. The search sought evidence about collaborations within health care and behavioural sciences (Table 1), as well as in the wider public services literature, for example education, environmental sustainability and youth programmes (see Appendix 1).

| Health care and behavioural sciences | Other types of literature |

|---|---|

|

|

Defining collaboration

The background search showed how collaboration is defined within and across disciplines, and how it is perceived as an integral component for the transformation of services. Collaboration is becoming recognised as a clearly defined area of scholarly research40 but is a contested territory. 40,41 It has been suggested that collaboration is a process ‘through which parties who see different aspects of a problem can constructively explore their differences and search for solutions that go beyond their own limited vision of what is possible’ (p. 5)42 that is rarely clearly defined. 43 In contrast, interorganisational collaboration has been defined as an entity: ‘a co-operative relationship among organisations that relies on neither market nor hierarchical mechanisms of control’. 44 Alternatively, collaboration has been perceived as a contingency: ‘a process that can emerge as organisations interact with one another to create new organisational and social structures’. 40 In non-profit organisations, collaboration is seen as the relationship required for application and sustainability of research in practice. 44 From the communities of practice literature, interprofessional collaboration relies on interaction between different actors and systems, and factors that determine success can relate to interpersonal factors or organisational structures. 45,46

The authors of conceptualisations, including frameworks and models, describe collaboration as a process or continuum42,47 involving dimensions of governance, administration, organisational autonomy, mutuality and norms. 40 For others, collaboration is considered to be a cyclical process involving negotiation, commitment and implementation. 48 Academic–practitioner (or cross-profession) collaborations are defined according to related professions and organisations,43 and estimations of their success are defined by considering the extent to which goals are met, as well as the perceived benefits for individuals and teams. 43

Academic and professional collaborations are discussed in terms of increasing research productivity and quality,49 improving learning32 and enhancing the development of new skills across partnerships. 33 Organisational collaboration is described as reaching outcomes or goals. 34 The literature reviewed in the background search describes outcomes or impacts of collaboration as, for example, the dissemination and implementation of guidelines;50 improving aspects of services and affecting health outcomes or public health;51–53 promoting successful change; and closing the gap between potential and actual performance. 51,54,55 Other authors refer to increasing the number of agencies working together and promoting users’ better engagement with intervention programmes;56 having an impact on macro-level outcomes related to enhancing innovation; and expediting the translation of science for patient-focused benefits. 57,58

In summary, the background search provided some understanding of how collaboration is defined in the literature, which led to the next step of the review, a purposive systematic search of the literature about whether or not collaboration provides the conditions for implementation.

Searching process

Consistent with realist principles, the search was progressive and iterative, and was receptive to different types of evidence, including ‘grey’ literature. 36,59 The main databases searched were limited to the health and behavioural sciences and included Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, The Cochrane Library, PubMed, MEDLINE and JSTOR. A ‘snowball’ process was used to check and retrieve references cited in accessed articles if they were deemed to be relevant to the review. Links to relevant articles were also suggested by members of the research team. Initial search terms which referred to collaboration between researchers and practitioners were sought from the background search of the literature (see Appendix 2). It became evident as the review progressed that the wide range of potential search terms could lead to unmanageable amounts of retrieved literature; therefore, a decision was made to reduce the terms and focus the search on evidence that related to features to show if and how collaboration might enable implementation. The main search terms included ‘collaboration’, ‘coalition’, ‘co-operation’, ‘partnership’, ‘community partnership’, ‘inter-institutional relations’ and ‘joint working’. An additional search was conducted using more specific terms noted in the literature, for example ‘trans-disciplinary collaboration’ and ‘academic industry partnership’. The search was limited to documents written in English and published between 1994 and 2014, to capture the most relevant and recent evidence from the past 20 years. Methodological ‘filters’ were intentionally not used, to avoid missing any papers that could be relevant to the review. 36 The search was not confined to research studies, and included other evidence, for example case studies, column papers and reports.

Selection and appraisal of documents

Decisions about inclusion and exclusion of data from documents were based on judgements of relevance, as opposed to the overall quality of the document. The systematic search yielded an initial 6669 hits. Titles were screened for relevance, reducing the search to 87 papers. Papers were not saved if they related to implementing partnerships, developing and co-ordinating services, and service issues, or where reference to implementation was not apparent. Papers were not saved if they related to non-health-related disciplines, such as education. Screening of the abstracts reduced the papers to 18, which were then retrieved in full text. Further scrutiny of full text for relevance reduced the chosen papers to one, which was added to other relevant papers retrieved by chance, additional search and reference lists (nine).

The 10 papers retained were then subjected to a more rigorous review using the data extraction form designed for the review, as detailed below. The sequence of selection and appraisal is reported in Appendix 3.

The characteristics of the selected papers and their approach to describing implementation and knowledge mobilisation are reported in Table 2.

| Authors (year), title | Country | Paper type | Theme/main aims | Approach to describing implementation/knowledge mobilisation | Main findings/recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blevins et al. (2010),60 Collaborative research between clinicians and researchers: a multiple case study of implementation | USA | Original research report: evaluation study using mixed methods. Quantitative data consisted of survey and archival material, with qualitative data sourced from focus groups | Describes community-based participatory research in health, and reports an evaluation to establish the degree of collaboration across four funded projects in the Veterans Health Administration in the USA | Community-based participatory approaches conceptualised as acting on evidence-based interventions. Processes that have relevance (for the community), and sustainability or continuation of the intervention | Collaboration noted to contribute to better relationships and the production of research. Resources and support do not necessarily lead to sustainability of interventions. Collaboration not necessarily precursor to sustainability of interventions. Significance of clinicians’ prior research experience to the quality of the project |

| Kegler et al. (1998),61 Factors that contribute to effective community health promotion coalitions: a study of 10 Project ASSIST coalitions in North Carolina | USA | Original research report: survey conducted over 12-month period of 5-year intervention phase relating to local community health promotion coalitions | Paper relates to 7-year national project to reduce the numbers of smokers in US states (ASSIST). Aim of paper to seek factors that contribute to effective health promotion coalitions | Changes in health outcomes, community actions and community changes are perceived as ideal measures of coalition effectiveness. Processes of putting in place planned activities which are noted as measures of coalition effectiveness | Coalitions with higher levels of dedicated staff, with complex structures, and recognised as having better communication and cohesion than others are more likely to result in higher levels of implementation |

| Lasker et al. (2001),62 Partnership synergy: a practical framework for studying and strengthening the collaborative advantage | USA | Literature review and presentation of partnership synergy framework in health care | Partnership synergy postulated to influence partnership effectiveness and thus improve health and health-care issues. Determinants of partnership synergy identified in framework: resources, partner characteristics, relationships, external environment | Processes which lead to achievement of health and health system goals. Changes to programmes, policy and practice which affect health services | Partnership synergy conceptualised through framework which can be utilised to address policy issues relating to collaboration |

| Lesser and Oscos-Sanchez (2007),63 Community–academic research partnerships with vulnerable populations | USA and Canada | Review chapter | Reviews the state of community–academic research partnerships across the USA and Canada related to community health nursing | Processes which generate positive health outcomes and build capacity. Processes which result in communities and researchers becoming more empowered and knowledgeable. Impact influenced by how interventions appear specific to target population and culturally sensitive | Main findings relate to the importance of relationships to partnership success, allowing time to develop fruitful relationships, and how collaborations affect the conduct of research and improve processes |

| Olson et al. (2011),50 Factors contributing to successful inter-organisational collaboration: the case of CS2day | USA | Original research report. Online survey administered to 23 participants from nine organisations involved in CS2day health promotion collaboration to address tobacco smoking. Survey used adapted version of Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory | Describes an interorganisational collaboration in continuing medical education (CS2day). Factors considered to contribute to success discussed | Actual and intended practice changes. Creation of best practices. More effective care | Findings highlight factors thought to contribute to collaboration success including choice of topic, environmental factors, structures and processes, shared vision, communication, having measurable targets and creating value |

| Ovretveit et al. (2002),51 Quality collaboratives: lessons from research | Sweden | Systematic evaluation report | Presents guidelines to support quality improvement collaboratives in health care to achieve their goals. Authors suggest that the guidelines can be useful for organising collaboratives and future research into collaboratives | How knowledge and innovation are spread. Processes which improve quality of services. Closing gaps between actual and potential performance. Successful change | Accentuates promise of new quality improvement methodology using a structured framework to make improvements through collaboratives. Collaboratives can be learning organisations which are motivating, and provide tools to help support quality problems. Findings accentuate importance of culture and leadership to collaborative success |

| Purcal et al. (2011),56 Does partnership funding improve coordination and collaboration among early childhood services? Experiences from the Communities for Children programme | Australia | Original research report. Mixed-methods study: service co-ordination study using qualitative and quantitative methods. Survey administered to 41 project sites, repeated once, elicited 744 responses. In-depth interviews (n = 222) | Evaluation of human service delivery partnerships operating under national Communities for Children programme in Australia. Authors allude to current lack of evidence to show partnership outcomes from national programmes. Collaboration perceived as mechanism of partnership working | Improvements in services and service experience. Improvements in health of service users. Cost-effective and holistic services for clients. Improvements in service efficiency | Partnership outcomes identified from project sites. Increase in collaboration for project agencies. Better working relationships noted. Highlighted significance of pre-existing networks. Negative impact related to time and investment required to establish partnership |

| Shortell et al. (2002),52 Evaluating partnerships for community health improvement: tracking the footprints | USA | Original research report. Midstream process evaluation of 25 community partnerships using qualitative and quantitative data | Focus of paper on community health partnerships and factors which can influence how they achieve objectives. Research questions focused on extent of partnership progression towards meeting objectives, and the factors considered to account for progress | Extent to which partnerships can positively influence outcomes. Improvements in quality outcomes. Improvements in community health | Six main characteristics identified in successful model partnerships which made most progress in implementation: managing size and diversity, three-component leadership, focus, how conflict managed, recognising life cycles, and partnership ability to ‘patch’ |

| Stokols et al. (2008),64 The ecology of team science: understanding contextual influences on transdisciplinary collaboration | USA | Report on empirical literature from team performance and collaboration | Main focus of paper on transdisciplinary team science | Translation of scientific knowledge into interventions and policies to improve public health (especially intermediate and long-term collaboration) | Typology of influences on transdisciplinary collaboration drawing on factors considered to enhance or hamper effective collaboration. Factors include leadership, establishing trust and respect, and collaboration readiness |

| Roussos and Fawcett (2000),65 A review of collaborative partnerships as a strategy for improving community health | USA | Literature review of published studies of collaborative partnerships in community health. Thirty-four studies included in review; most used experimental or quasi-experimental design | Lack of empirical data to show effectiveness of collaborative partnerships for community health improvement, and assumptions underlying collaborative working | Processes which relate to changes in population-level health outcomes. Improvements attributed to collaboration activities. Can be influenced by environment/behaviours | Review emerged with set of modifiable factors that can support partnerships to create the conditions required for improving health outcomes |

Data extraction

The review questions were used to determine the relevance of documents, or sections within the documents, to the review. Consistent with realist approaches, a bespoke data extraction form was developed to guide the review of the selected documents and for extracting or mining relevant information. The bespoke data extraction form incorporated areas of relevance to the review purpose. The data extraction form was developed around a number of different theory areas: the nature of collaboration, characteristics of research users and producers, and issues related to implementation (see Appendix 4). This form was used to extract information on each piece of evidence. Using the data extraction form ensured that the focus remained on eliciting any information to illuminate the review question66 and identify evidence which linked collaboration with implementation and knowledge mobilisation. The development of the form was guided by existing templates for realist reviews,67,68 and based on questions developed by the research team. 39

Analysis and synthesis processes

We used the test of relevance and rigour as the criteria for the selection of documents. 36 Relevance refers to how the data contribute to programme theory development: why, how and in which circumstances collaboration between researchers and practitioners enables implementation. Rigour refers to the reviewer’s judgement of the credibility of the data. 36 The analysis and synthesis of the data extracted from the search process were focused on answering the review question through an inductive and deliberative process.

Findings

The synthesis of evidence from the selected papers shows how collaboration has the potential to impact on implementation and knowledge mobilisation in different ways. The findings are reported based on how the evidence informed the questions used in the data extraction process, reflecting key features which emerged across the papers. The findings from the review are summarised in Table 3 to show what emerged under each of the data extraction areas.

| Nature/design/capacity/capability | Organisational factors | Roles/relationships/interplay |

|---|---|---|

| Infrastructure Size Complexity Communication Resources Setting measurable goals Time Planning Subject/topic |

Support Proximity |

Power sharing Shared vision Trust Reciprocal learning Leadership Membership History |

How the design of a collaboration can facilitate implementation

Collaboration infrastructures can promote a balance between partners, thus reducing pressures on them. 50 Technical assistance and the availability of resources within collaborations are key strengths for project completions. 60 The strategies employed by collaborations to communicate across partners are important, for example face-to-face meetings, regular teleconferences, use of e-mail and digital file sharing, uniform marketing templates and logos, and standard reporting forms. 50,64 In particular, Olson et al. 50 refer to the significance of early face-to-face meetings to foster transition from groups of individuals to functioning partnerships.

Setting measurable and achievable outcomes is proposed to contribute to collaboration success, facilitating monitoring and evaluation, and therefore enabling teams to learn from each other. 50,51 This leads to better co-ordination and success towards achieving deadlines. Additionally, where grant makers require reporting of evidence of intermediate outcomes, this has the potential to promote success in the longer term. 51,52,65 These findings are linked to what Shortell et al. 52 describe as ‘recognising life cycles’, suggesting that, where members are familiar with the stages of development of the collaborating partnerships, they are more able to address issues and seek solutions.

A collaboration is perceived as a ‘temporary learning organisation’ when it is allowed time to learn and consider how to sustain improvements. 51 Where time is protected to develop high-quality action plans which are commensurate with local needs, are clear, have measurable objectives and identify persons responsible for task completion, this facilitates implementation, either because taking action is facilitated, or because the ability to mobilise resources is greater. 61 Careful action planning is associated with increased rates of change; good-quality action plans are associated with synergistic partnerships that have potential for success,62 and better sustainability of events and adoption of interventions by other organisations not within the collaboration. 61,65

Olson et al. 50 suggest that the choice of topic is a significant factor for success of the collaboration. In their collaboration, tobacco smoking was a clinically focused topic of importance, with recognised evidence-based interventions but with identified gaps between desired and actual practice. 50 Olson et al. 50 found that the success of the collaboration is promoted where personal and emotional connections to the subject area are made by those involved and thereby provide the motivation to make changes and take action. Collaborations involving initiatives which are linked in such a way that they appear to be related to each other are more successful, according to Shortell et al. ,52 who suggest that this relates to the synergy between initiatives, allowing partnerships to achieve their intended objectives.

A link was postulated between coalition size and effectiveness, including implementation of activities. 61 Complexity was interpreted on the basis of the number of task forces and committee structures that are associated with the coalition. 61

Linking the structure/function of the collaborating organisation with implementation

Features that contributed to collaboration success also focused on the organisations responsible for hosting. The review suggests that how collaborations structure themselves and the nature of the policies and procedures that they have in place are important factors to support the collaboration without placing unnecessary pressure on resources. 50 Shortell et al. 52 found that most successful partnerships operate within organisations which provide stability and legitimacy across time, but maintain a low profile, allowing the partnership to flourish.

For Olson et al. ,50 factors around proximity contributed to the success of collaborations. These included the physical proximity of collaborating organisations, so that existing relationships between people in the organisations promote better communication and co-ordination. Another factor theorised to contribute to collaboration success through communication networks is the physical proximity of partnerships involved in the collaboration. 50

The role of individuals or teams, the nature of relationships, and the interplay between individuals and groups within collaborations

Sharing power can enable participation across all collaboration partners,50,63 and egalitarian collaboration is more likely to result in implementation of evidence-based practice because of the shift of power towards the clinician. 60 Through clarifying shared vision, prioritising goals, and setting strategies and outcomes, opinions become less divided, resulting in the formation of a broad guidance framework across collaborating partners. 50 Sharing power through collaboration suggests that partners (community and researchers) become more knowledgeable and empowered, according to Lesser and Oscos-Sanchez. 63 Shortell et al. 52 found that the ways in which successful partnerships are able to ‘nip problems in the bud’ are related to how conflict is forestalled through the development of trusting relationships.

Trust is essential to success in collaborative research, and can be reached more smoothly where there is previous experience of working with different organisations. 54,64 If collaborators are allowed time to develop mutual respect and trust, this leads to the development of meaningful relationships, a crucial factor for success according to Lesser and Oscos-Sanchez. 63 This links to the findings of Olson et al.,50 who theorised that starting the collaborative process with an underlying assumption of partners’ specific abilities and strengths promotes the creation of value, and collaborative benefits are distributed fairly and widely, through a productive process of developing resources and mutual learning. Additionally, a collaboration can improve the conduct of research through a reciprocal approach to partners’ engagement with refining research questions, developing theoretical frameworks, recruitment, and data interpretation and sharing. 63

Leadership is the most often reported factor for creating change,65 and elements relating to leadership are important factors for partnership success. In particular, having one consistent executive leader in a dedicated role and the ability to delegate leadership to people most closely involved with partnership projects, described as subsidiary leadership, appear to be important. 52 Furthermore, choosing and using leadership skills at different stages of the collaboration is important. For example, the leadership skills of facilitation and listening may be more effective at the start of the collaboration, whereas negotiation and advocacy skills may be required in the later stages to bring about changes which are true to the collaboration’s mission. 65

Opinion leaders who operate within or outside the collaboration can support the collaboration and contribute to its success. 50 In collaborations between researchers and clinicians, formal mentoring roles provide the encouragement required to complete projects, as long as mentors have the skills, not only in the conduct of research, but also in implementation and community engagement, so that they can facilitate both the programme and its sustainability. 60

Members who display certain traits (e.g. expertise, availability and certain social skills) within collaborations are more likely to contribute to success, especially where synergy is observed across individuals’ skills, resources and perspectives. 62 Successful partnerships are more likely to have members who clearly display readiness to collaborate, and are more able to manage conflict in ways that forestall problems. 52,64

Olson et al. 50 found that a relationship history between collaborators fostered better communication and co-ordination, and contributed to the collaboration’s success. Collaborations which draw on pre-existing networks, previous knowledge and experiences, and build on prior positive experiences and working relationships from earlier collaborations, are also more likely to succeed and contribute to strengthening future collaborations, especially where individuals are experienced in sharing risks, resources and responsibilities in seeking common goals. 56,64,65

Synthesis

Evidence about exactly how collaboration might affect implementation and knowledge mobilisation is sparse. Producing evidence to show the effect of collaborations on implementation can be a lengthy process, which takes much longer than the lifespan of the collaboration or partnership. Therefore, outcomes are difficult both to track and to evaluate. 52,56,65 We found little evidence to link collaboration directly to knowledge mobilisation. However, there are some implicit ideas and, in programme theory terms, some contingencies that might explain collaboration and implementation (Figure 1). These areas are presented below and by drawing on a wider body of literature where appropriate. This wider evidence base was scrutinised because it describes features of more or less successful collaboration; unfortunately, however, the evidence within it falls short of making the explicit link to how these have an impact on knowledge mobilisation.

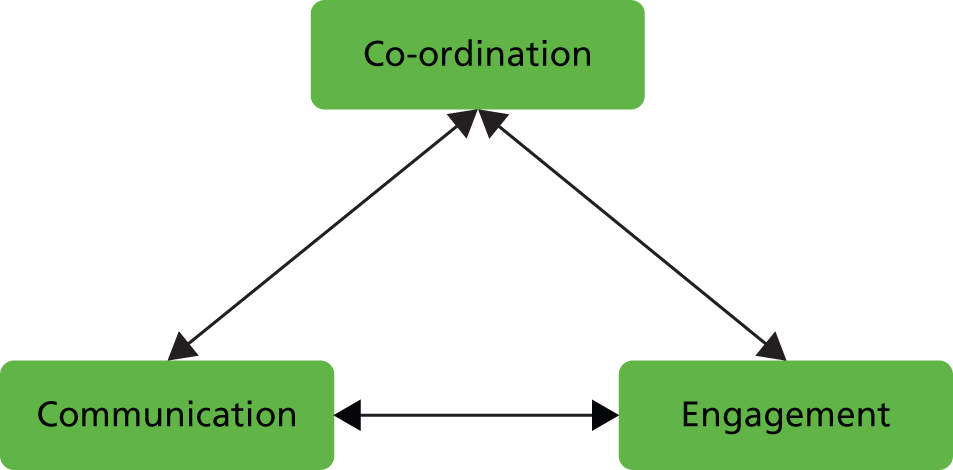

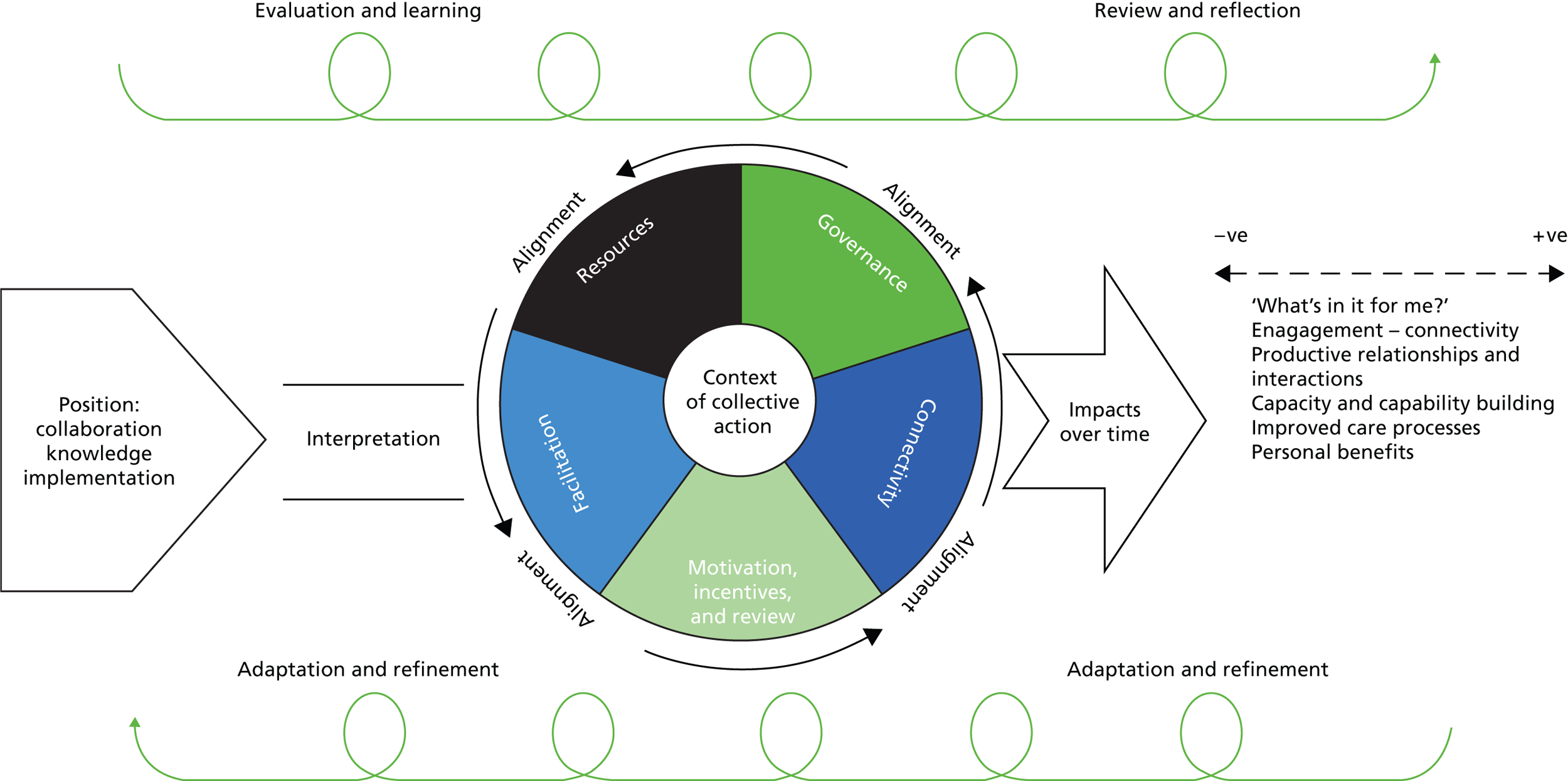

FIGURE 1.

Theory areas: successful collaboration.

Co-ordination

Collaborations that pay attention to structures, infrastructures, processes and management50 are those that have the potential to facilitate the success of designated centres to work together, to design, implement and evaluate health-related interventions and programmes. 69 These features provide the potential conditions for co-ordinating activity, resources and people. Leadership has a key role to play in the co-ordination of the collaboration.

We found an association with infrastructure and size, and the potential of the collaboration to result in successful implementation. Collaborations are perceived to be moveable structures, which means that members and tasks shift from time to time,70 but evidence points to the importance of some common features about infrastructure. The wider literature supports the importance of governance frameworks, thus ensuring that effective processes are in place for decision-making, administration, management, regular communication, conflict resolution and addressing competition for priorities. 50,55 While small networks can be self-governed, there is some evidence to support the idea that larger collaborations are more effective where the lead organisation is the administrative host, or where collaborative partners represent the widest possible range of potential participants. 52,70

The wider literature supports the importance of setting clear parameters using contracts; defining clear roles and responsibilities; having active management and organisational understanding; ensuring the formation of steering groups to escalate issues and keep projects on track; and setting measurable and achievable targets for the progress of the collaboration. 50,51,58 Success is further promoted where there are clear, explicit statements about property rights. 70 Further, improving accountability through aligning academic and clinical institutions can be strengthened by ensuring common frameworks are in place to evaluate performance across the collaboration. 71

The ways in which outcomes are set and evaluated can have an impact on the success of the collaboration. Where evaluation is focused on intermediate (as opposed to final or long-term) outcomes, this can promote the function of the collaboration through focusing on intermediate success or failure, while at the same time enabling the celebration of small or large accomplishments; it helps the collaboration to redirect attention if required and identify potential barriers to success. 55,65 Furthermore, wider literature about collaboration points to operational planning and setting strategic initiatives as activities associated with successful collaborations. 65,72 Rigorous planning leads to more significant activities which link to programme outcomes. 73 Additionally, coalitions with action strategies that use task forces and action teams are reported to be more likely to impact on interorganisational partnership. 70

Collaboration partners require clear lines of accountability about the control of resources, and resources need to be directed towards network-level and organisational-level goals. Resources important to collaborative success include finance, space, equipment and goods. The wider literature also supports building on collaborative partners’ strengths and resources to promote the exchange of resources and enhance resource links between partners. 57,70,74

There is agreement in the literature that individuals in visible, senior, leadership positions contribute to the success of collaborative efforts in implementation and improvement. 51,53,75 Committed and active leaders encourage collaboration and commitment to projects; communicate the vision and mission of the collaboration to key stakeholders; support the engagement of other leaders to implement change; and possess skills that are facilitating and empowering, for example networking, diplomacy, listening, perseverance, dedication and adaptability. 32,52,55,65,69,70 They thus provide a co-ordinating function. The core characteristics of desirable leadership for collaborations include the ability to embrace the expertise of partners; the ability to demonstrate effective communication, facilitation, negotiation and networking skills; and previous experience in similar partnership work. 55,65,74

Evidence suggests that leaders who are reflective practitioners and who engage in formal collaboration evaluations70 are more likely to contribute to success in implementation, especially if facilitative characteristics such as being supportive, democratic and committed are identified. 64 The wider literature supports the view that leaders (or subsidiary leaders) who give direction and listen to others are likely to succeed. 52,65,76 It is reported that leaders with empowering styles are more likely to bring about successful implementation and achievement of collaboration outcomes,64 as are leaders orientated to action who demonstrate relationship-building skills. 77

Engagement

There is evidence to support the notion that relationships between partners are the foundational element of collaborative research. 78 The engagement and involvement of members and stakeholders in the collaboration is prompted through the quality of partner relationships, and a sense of trust, resonance and shared vision/mission in the collaboration. Continued efforts to build and rebuild trust and relationships are integral to success, but this is conditional upon both structured and unstructured interactions between partners. Setting the co-ordinates for the collaboration through defining a clear purpose seems to be important. Involving all partners, clear common aims should evolve as the collaboration grows, which involves setting a direction, taking action and building trust. 70,78 Conversely, where there is lack of clarity in the overall vision for the collaboration, this can have a negative impact on the success of the collaboration. 55 Furthermore, shared vision can be hindered by poor communication. 72

Trust in collaborations appears to be a key factor, perceived as a cyclical process which is built over time, and is often more strongly established on previous experiences and/or reputation than through formal agreements and contracts. 32,63,65,69,70,79 Given this, pre-formation has been shown to be important in creating strong foundations for the collaboration and linkage at the early stages. 16,73 Where examples are used to show how collaboration partners employ an element of pre-formative work (e.g. collecting data or analysing the system before commencing the collaboration), this appears to contribute to a better understanding of the issues. 54 Newly formed collaborations which work on the assumption that teams are not already formed and functioning, and provide time for team forming, are more likely to be successful. 51

Where there is equity among partners and commitment to ongoing self-reflection and self-critique, this could avoid power imbalances, and thereby enhance the collaboration’s chances of success. 63 Collaboration success is contingent on structures that allow shared power, whereby decision-making is by consensus; successful collaborations are built on trust, they can leverage support for the cause through agreement across partnerships so that they are fair and balanced, and they distribute work fairly among their members. 50,55 ‘Shared memory’ describes how consistent membership across collaborations can develop mutual respect and willingness to work together, and can promote learning from mistakes. 51,53,80

Within the communities of practice literature, successful collaborations are usually large, incorporating a full range of potential stakeholders who are engaged throughout the whole process of planning, implementation and evaluation of programmes. 57,70 Conversely, inadequate staffing for collaborative projects can have a negative effect on the chances of successful implementation. 55

The subject or topic area around which the collaboration is focused also seems to be important for its success. For example, quality- and community-based collaboratives appear to have more impact if subject areas are practice based and specific. 51,72 ‘Good’ subjects which are regarded as important and specific, with strong evidence of effective interventions and reflecting clear national research priorities, are linked with the success of the collaboration. 50,51,54,65 Wilson et al. 54 found that collaborations focused on broader topics are more likely to result in better implementation of innovations. However, Ovretveit et al. 51 question the effectiveness of collaborations which are associated with broad topic areas.

Communication

The success or failure of collaborative teams has been reported to be contingent on how partners communicate and consult with each other. 81 The evidence in this review indicates that communication between collaborators is a significant factor for collaboration success, supported by internal and external communication channels and multiple communication strategies. Physical proximity of team members and the level of technical communication strategies employed within the collaboration are also important for communication. 64 Furthermore, communication has the potential to facilitate sharing and therefore potentially to enable learning.

Findings from a study of interorganisational learning in health care showed that it is the learning activities, facilitated by the knowledge-sharing infrastructure provided within the collaboration to engage with learning, which ultimately lead to improvement, rather than the collaboration itself. 82 In community health and school health, evidence was found that indicates that the use of advisory boards and learning in teams can foster communication between partners and allow them to learn from each other. 52,74 Nembhard82 found that the likelihood of a collaboration’s being effective is increased where partners participate and use the infrastructure and the knowledge-sharing features within the collaboration. Tools and materials developed together in partnership can also foster opportunities for mutual learning, contributing to interorganisational collaboration success. 51 Furthermore, support for the collaboration in the form of technology platforms or technical assistance including training and support, described as virtual readiness, can enhance core competencies throughout the collaboration’s lifespan. 55,60,65,83

Structural links, agreements for working together, and the presence of specific and essential roles and resource mobilisation to support and nurture the collaboration are also important. 55,57,61,70 Committees and work groups which lead to a lack of cohesion and communication across partnerships are perceived to be a threat to the success of collaborations. 55 In contrast, promoting opinion leaders with high levels of technical competence, champions and stakeholders within and outside the collaboration can work effectively to secure change, and dispersed leadership prevents problems associated with sole leadership, such as manipulation. 54,64,65

Summary

This project begins with the theory in the heads of the creators and funders of CLAHRCs: that collaboration between organisations should have the potential to foster the application of research. However, the evidence to support this theory is largely absent. In this review we have attempted to find and summarise some of the emerging contingencies evident in the existing literature about collaboration related to knowledge mobilisation. This was challenging, as few studies make this explicit link. However, it appears that collaborations that offer opportunities to co-ordinate purpose, activities and people, that provide members and stakeholders with chances and resources to engage, that foster mutual trust, and that provide the ways and means for communication and interaction might be those that offer more conducive conditions. It is unclear, however, if and how these collaborative conditions and features have an impact on knowledge mobilisation itself.

Chapter 3 Design and methods

Design

This study was a longitudinal realist evaluation using multiple qualitative case studies. Overall, our purpose in this study was to develop explanatory theory about implementing research through CLAHRCs and answer the question ‘what works, for whom, why and in what circumstances?’ We did this by focusing on the following aims and objectives.

Aims

-

To inform the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme about the impact of CLAHRCs in relation to one of their key functions: implementing the findings from research in clinical practice.

-

To make a significant contribution to the national and international evidence base concerning research use and impact, and mechanisms for successful partnerships between universities and health-care providers for facilitating research use.

-

To work in partnership so that the evaluation includes stakeholder perspectives and formative input into participating CLAHRCs.

-

To further develop theory-driven approaches to implementation research and evaluation.

Objectives

-

To identify and track the implementation mechanisms and processes used by CLAHRCs and evaluate intended and unintended consequences (impacts) over time.

-

To determine what influences whether or not and how research is used through CLAHRCs, paying particular attention to contextual factors.

-

To investigate the role played by boundary objects in the success or failure of research implementation through CLAHRCs.

-

To determine if and how CLAHRCs develop and sustain interactions and communities of practice.

-

To identify indicators that could be used for further evaluations of the sustainability of CLAHRC-like approaches.

Theoretical framework

The initial theoretical framework underpinning the study was a combination of two frameworks that focus on knowledge use in practice: Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS)15,84 and K2A. 16

Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services was conceived and developed as a means of understanding the complexities involved in the successful implementation of evidence into practice. As a framework that has been developing and refined over time through concept analysis and empirical validation and testing, it can serve as both a practical and a conceptual heuristic to guide and evaluate implementation. PARIHS maps out the elements that need attention before, during and after implementation efforts. Within PARIHS, successful implementation is represented as a function of the nature and type of evidence, the qualities of the context in which the evidence is being used and the process of facilitation. Each of these elements contains subelements:

-

evidence – research, clinical experience, patient experience and information from the local context

-

context – culture, leadership and evaluation

-

facilitation – the presence or absence of appropriate facilitation, including approaches ranging from task orientated to holistic.

These elements and subelements interact in different ways in different contexts to provide more or less conducive conditions for successful implementation.

The K2A framework was developed from a review of 31 planned action theories. The framework assumes a systems perspective and privileges social interaction and adaption of research evidence, taking local context and culture into account. The framework is a cycle of problem identification, local adaptation and assessment of barriers, implementation, monitoring and sustained use. Embedded within the cycle is attention to the knowledge creation process, knowledge synthesis and tools, and tailoring to local context. The authors state that adherence to each phase of the framework is not sufficient in itself for the successful application of knowledge; a key assumption underlying the framework is the importance of appropriate relationships between researchers and end-users, and between implementers and adopters.

These frameworks complement one another (e.g. they both consider the importance of context in implementation and that implementation is multifaceted), with PARIHS providing a conceptual map of the factors that have been demonstrated to lead to more successful implementation and K2A providing an action- or process-orientated representation of KT processes.

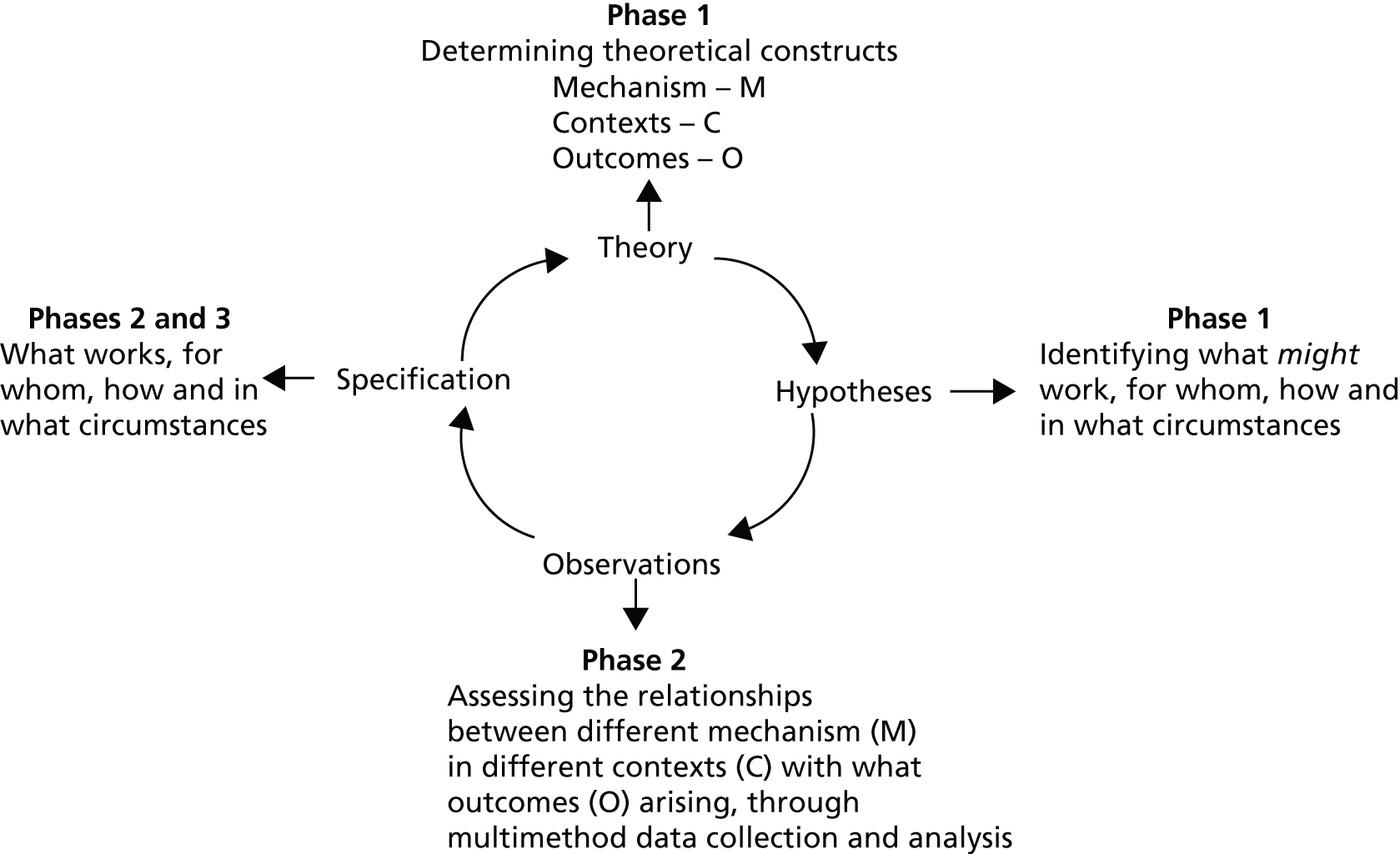

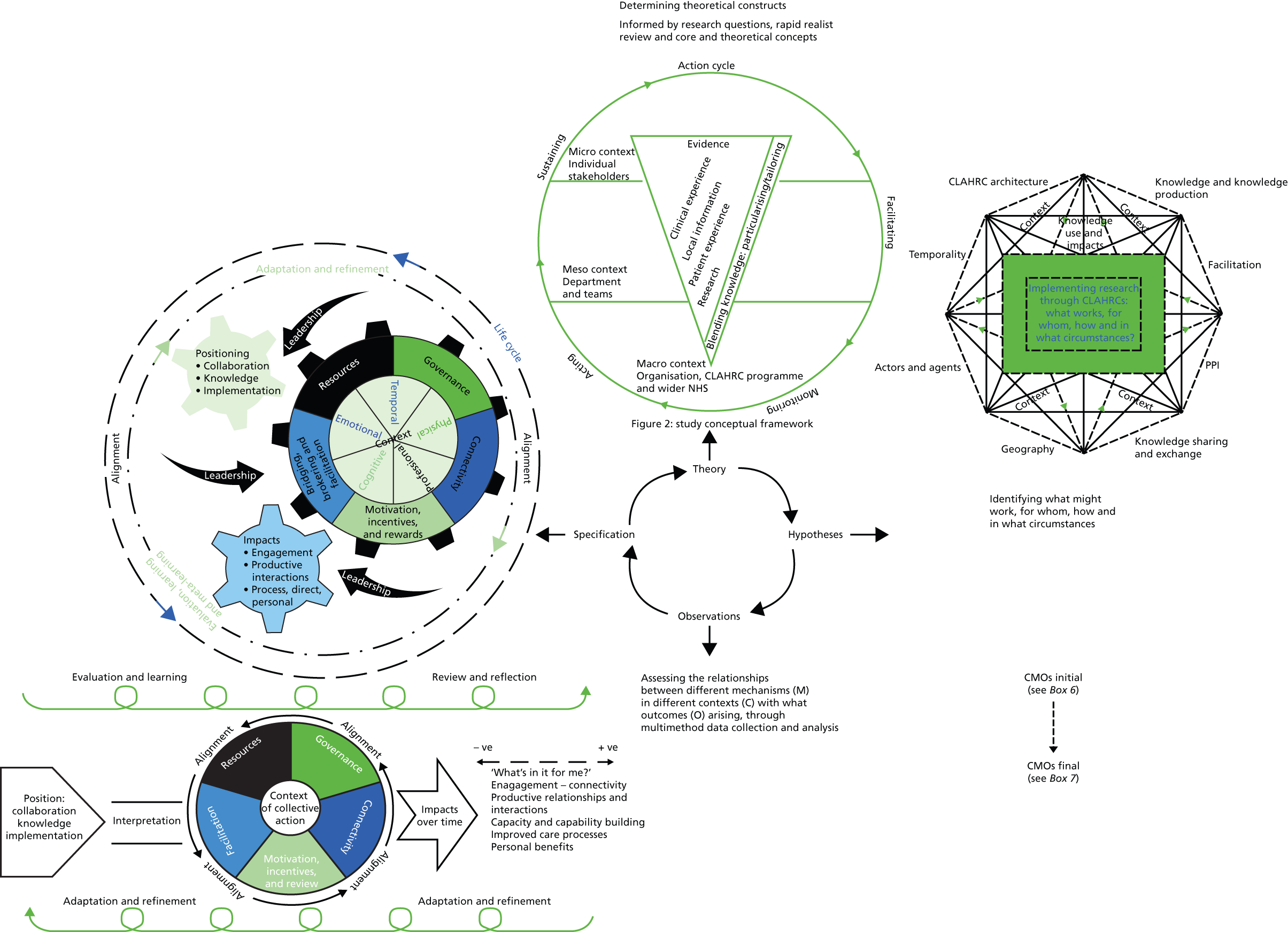

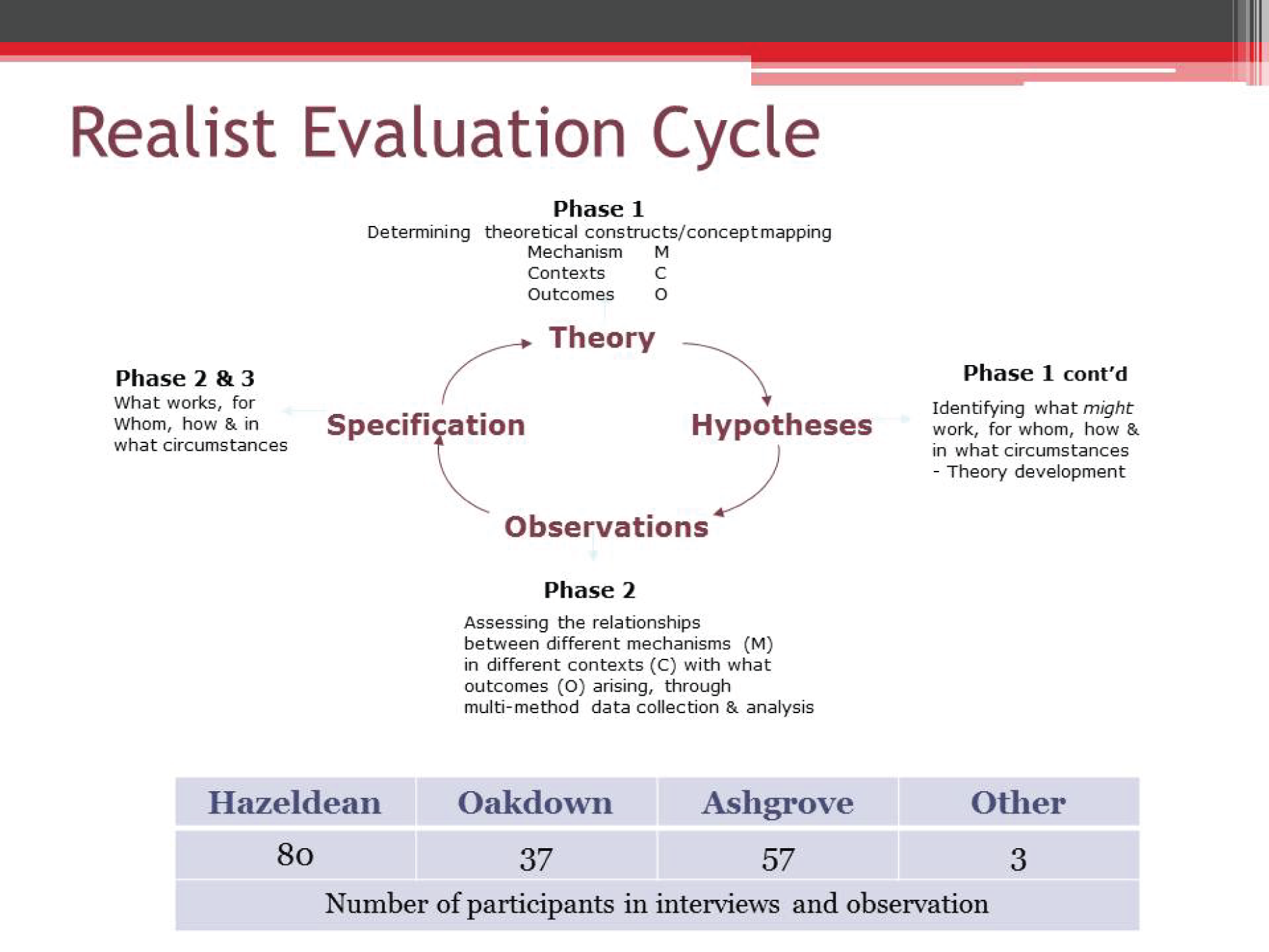

This framework provided an initial focus for the theory-building stage (phase 1) of the realist evaluation cycle (Figure 2). In practice this meant that, in the concept-mining phase of the development of the evaluation framework, concepts within the PARIHS and K2A frameworks were surfaced and combined with concepts from other sources of information and a subsequent mapping exercise was undertaken (see Development of conceptual framework and programme theories). Accordingly, PARIHS and K2A served as a starting point for the study, but through the theory-building process they became embedded in the evaluation framework and not visible in their original form.

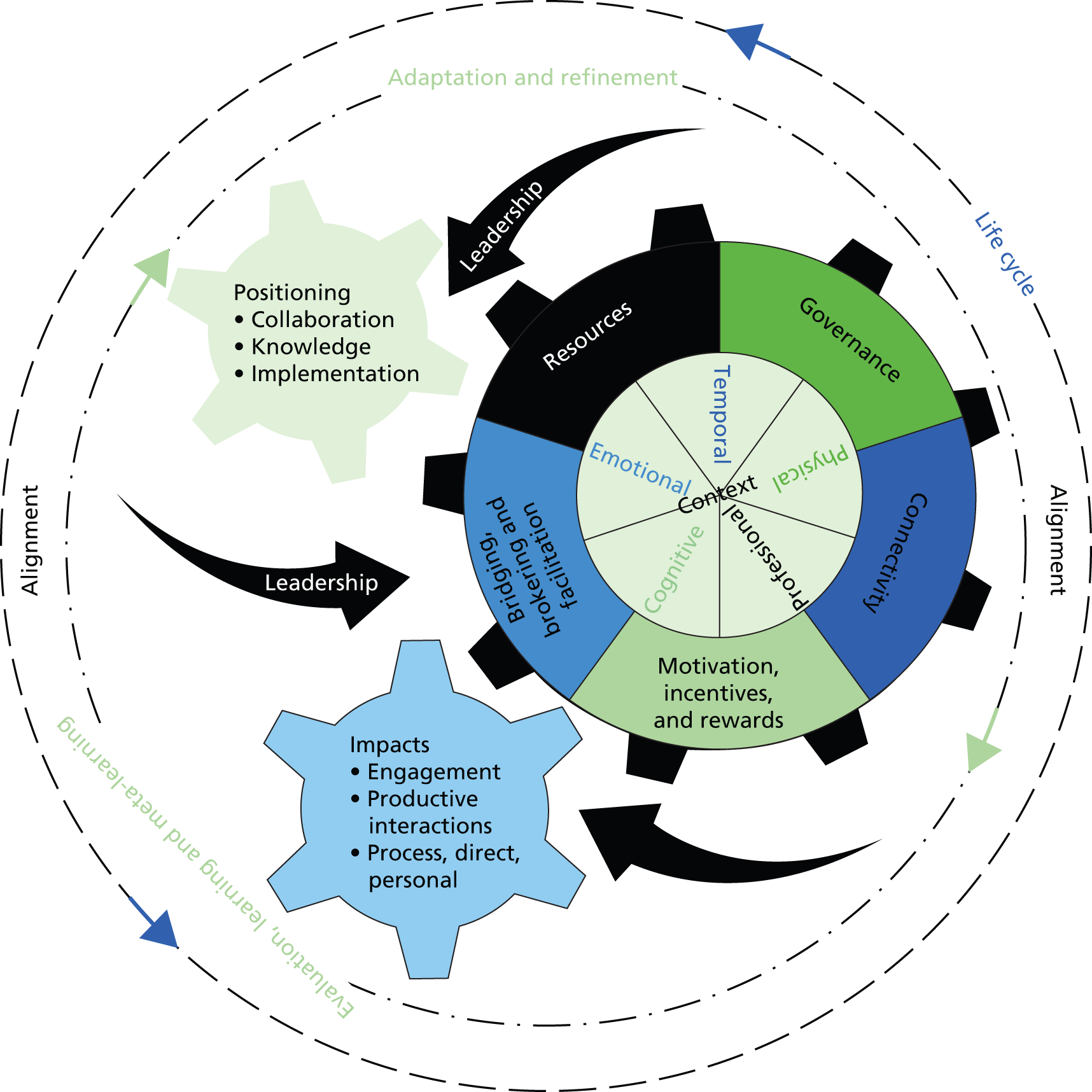

FIGURE 2.

Study’s initial theoretical framework.

Realist evaluation

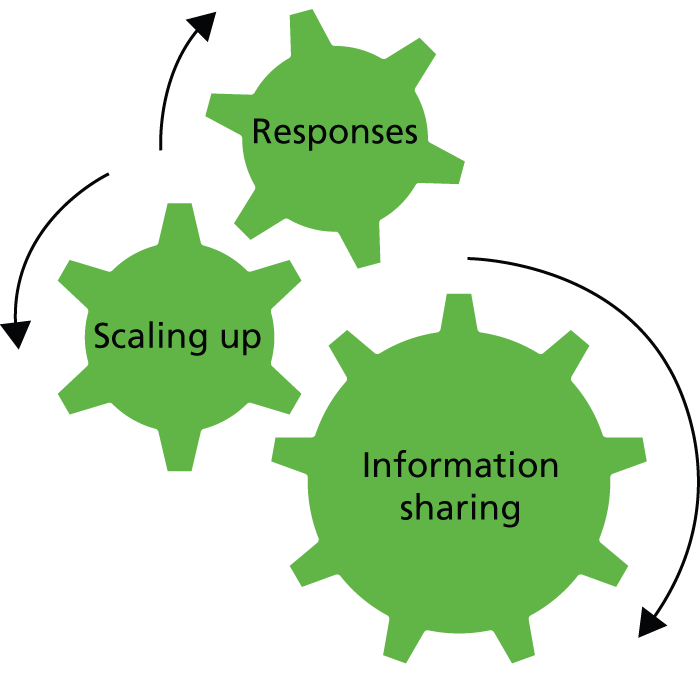

A fundamental assumption of realist evaluation is that ‘programmes are complex interventions introduced into complex social systems’ (p. 33). 85 Programmes are composed of theories, involve the actions of people, are rarely linear, and comprise a series of steps or processes that interact, are prone to modification and exist in open and dynamic systems that change as the result of learning. Realist evaluation is therefore an appropriate approach to exploring knowledge mobilisation within CLAHRCs, which, by their nature, are social systems, involve the actions of groups of people and have the potential to change over time. Observing CLAHRCs over time makes realist evaluation particularly appropriate because it is a cyclical and iterative approach.

Within realism, theories are framed as hypotheses about how mechanisms act in context to produce outcomes. We followed the realist approach promoted specifically by Pawson and Tilley. 86 Thus, programmes (in this study, CLAHRCs’ approaches to implementation) are interrogated to identify what it is about them (mechanisms) and the contextual conditions (context) that triggers these mechanisms to produce particular outcomes – commonly expressed as CMO (C + M → O) configurations. It is the CMOs that are the study hypotheses, which are refined and tested over time.

Contexts

The conditions that are necessary for a programme to trigger a mechanism to activate specific outcomes87 are critical for understanding how it works ‘for whom in what conditions’ (p. 72). 86 Context may be defined as space or place but can also be described as the ‘settings within which programmes are placed or factors outside the control of programme designers – people’s motivations, organisational context or structures’. 88 As such, context is not the backdrop to a site/study/case, as some have intimated,89 but is the condition that fires or triggers certain mechanisms.

Mechanisms

There is a paucity of literature relating to clarity of meaning of mechanisms; however, from the realist evaluator’s perspective, the underlying mechanisms that give rise to an event or outcome are the main focus of study. 90 Pawson and Tilley86 use the analogy of a clock to illustrate the meaning of a mechanism: it is only by examining the inside of the clock that it is possible to understand how it works, not by examining the clock face itself. Likewise with mechanisms, in realist evaluation the programme activity and processes are the mechanisms, which may be more or less hidden from view. Westhorp et al. 91 describe a mechanism in terms of how a programme changes people’s decision-making: what people do in response to the resources (of any kind) that a programme provides.

The other important aspect of mechanisms is that they lead to outcomes, but only when triggered by a particular context, or condition. 91,92 In realist evaluation the question is, therefore, not ‘does it work?’ but ‘how does it work and which mechanisms in which contexts give rise to particular outcomes?’.

Outcomes

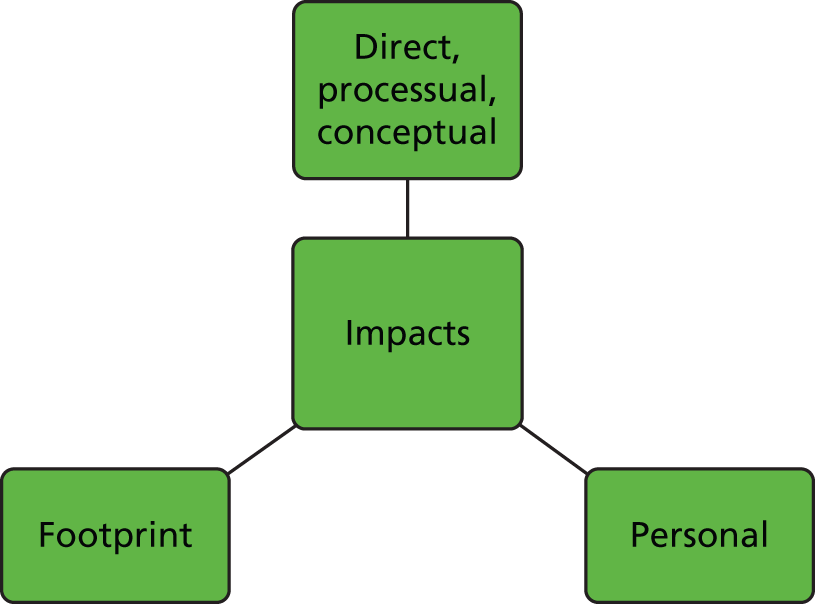

In realist evaluation, outcomes ‘reflect, or represent, the responses to different mechanisms in particular contexts’ (p. 77). 93 Outcomes may include the learning from programmes or can be related to impact (e.g. a change in behaviour) or processes (whether or not an intervention worked). 94 In this study we captured a range of different types of impact CLAHRCs’ implementation activity might have, from those that are more direct to those that are more conceptual and processual.

Case studies

Case study was selected in order to undertake an in-depth exploration within three CLAHRCs. As Yin95 states, a case study is an empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between the phenomenon and the context are not clearly evident.

In this study, implementation was the phenomenon that we wanted to study in the real-life context of the CLAHRC. Case studies are appropriate where one does not need to (or wish to) control events, and when one is interested in answering ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions.

Realist evaluation and case studies are an appropriate ‘fit’ in that both aim to be explanatory in nature,86,95 are about understanding a phenomenon in context, and enable an approach that collects multiple sources of data. 96 For this study a ‘case’ is the implementation team/theme/programme within a CLAHRC.

Tracer issues

Tracer issues were chosen as a way to provide a common focus across CLAHRCs, which were heterogeneous, complicated and multifaceted entities. At the time of proposal writing (before the CLAHRCs had set their agendas and approaches), we had expected that these tracer issues might be clinical issues, for example diabetes or stroke; however, as the CLAHRCs began to establish themselves it was evident that there was huge variability and a lack of cross-cutting themes that could provide a common thread. Therefore, in collaboration with CLAHRC study collaborators it was decided to select tracer issues that reflected processes. These were viewed as a watermark in CLAHRC activities: something that could be seen when specifically looked for in projects and initiatives, but which was not in the foreground or the main point of their attention.

The tracer issues were discussed with the CLAHRCs at a stakeholder meeting (in January 2011) where members of all nine CLAHRCs were present, and a consensus was reached. This was then finalised through follow-up telephone calls with the CLAHRCs participating in this study, and included:

-

Change agency: the focus of this was on the people in change agent/boundary-spanning/facilitation roles (each CLAHRC had given these different job titles). Roles were a useful focus in the first instance, but the processes of change agency became an increasing focus in terms of facilitating implementation and the impact arising from this. It was what these people did that became the focus of the tracer issue.

-

Collaboration and partnership: one of the issues that came over strongly from stakeholders was the difficulty in identifying and separating the research and implementation functions of the CLAHRCs. As a tracer issue it provided scope to look into a variety of formal and informal collaborations and the processes of collaborating at different levels within the CLAHRCs. Again, it enabled the individual CLAHRCs to select the projects and initiatives that they felt would be able to focus on collaboration and partnership.

-

Sustainability, adaptability and spread: this tracer issue arose from the concern of the CLAHRCs that change and knowledge use needed to be sustainable beyond the end of individual projects, in a turbulent context and shared across the individual CLAHRCs and beyond where appropriate.

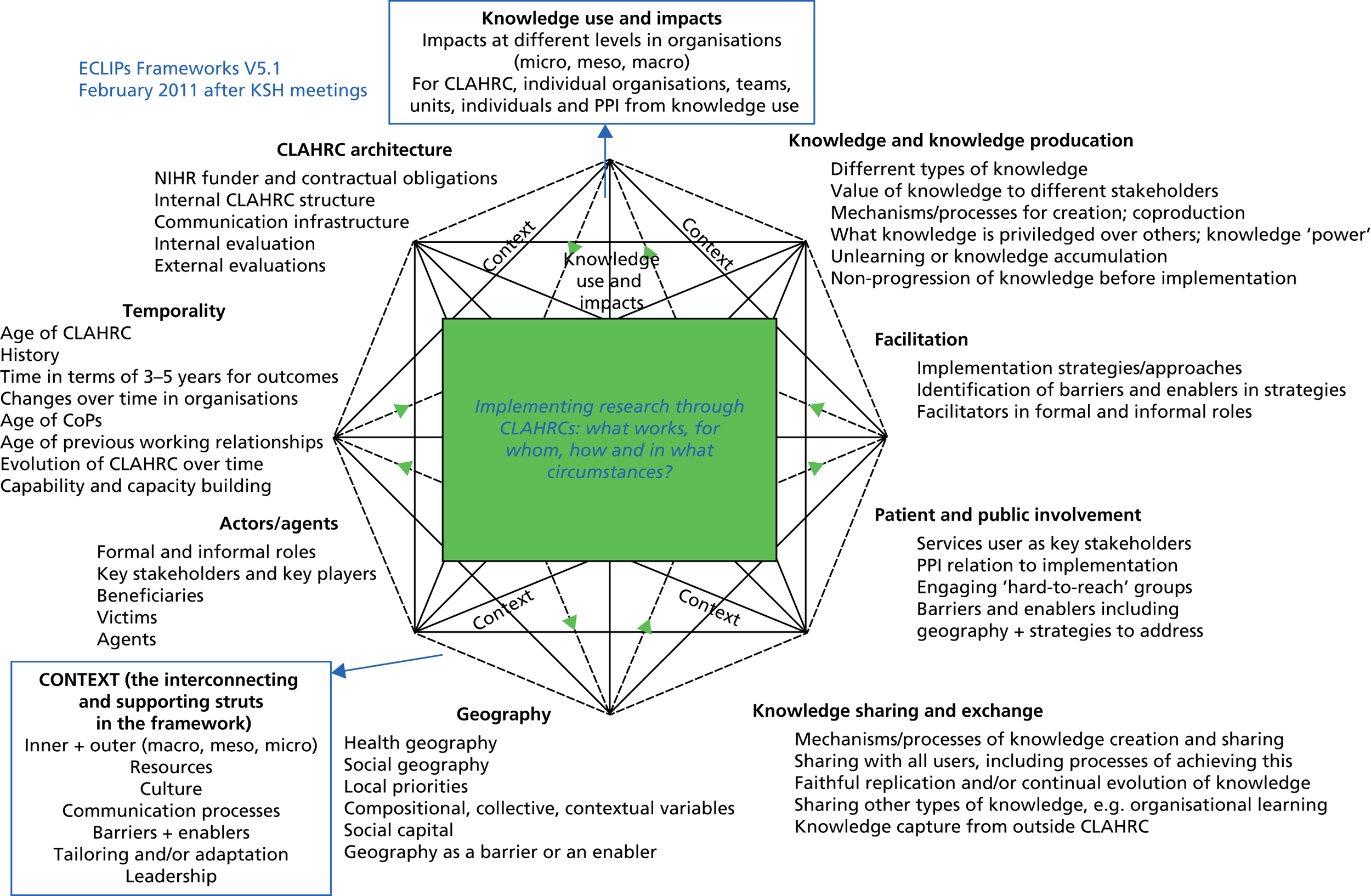

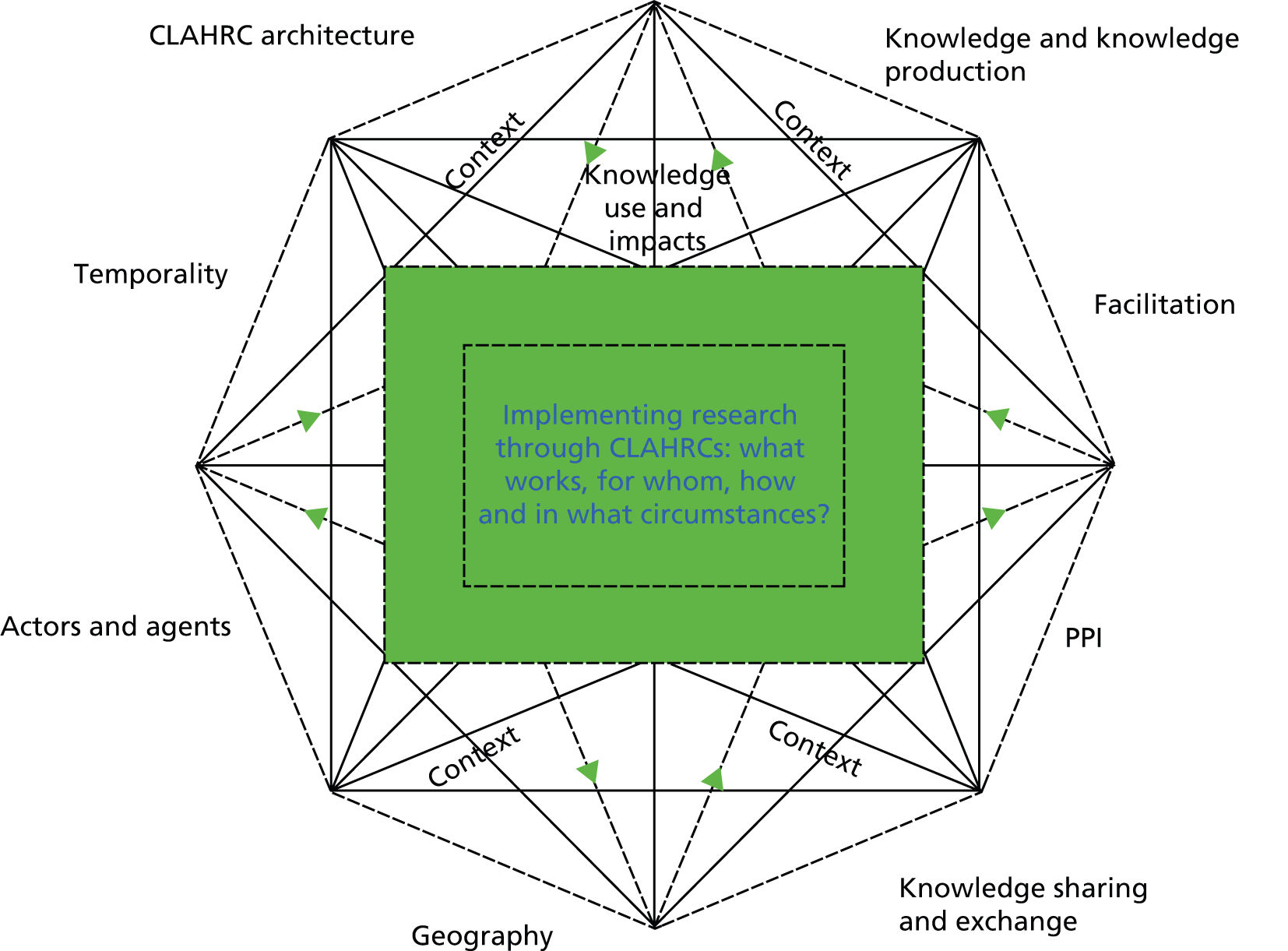

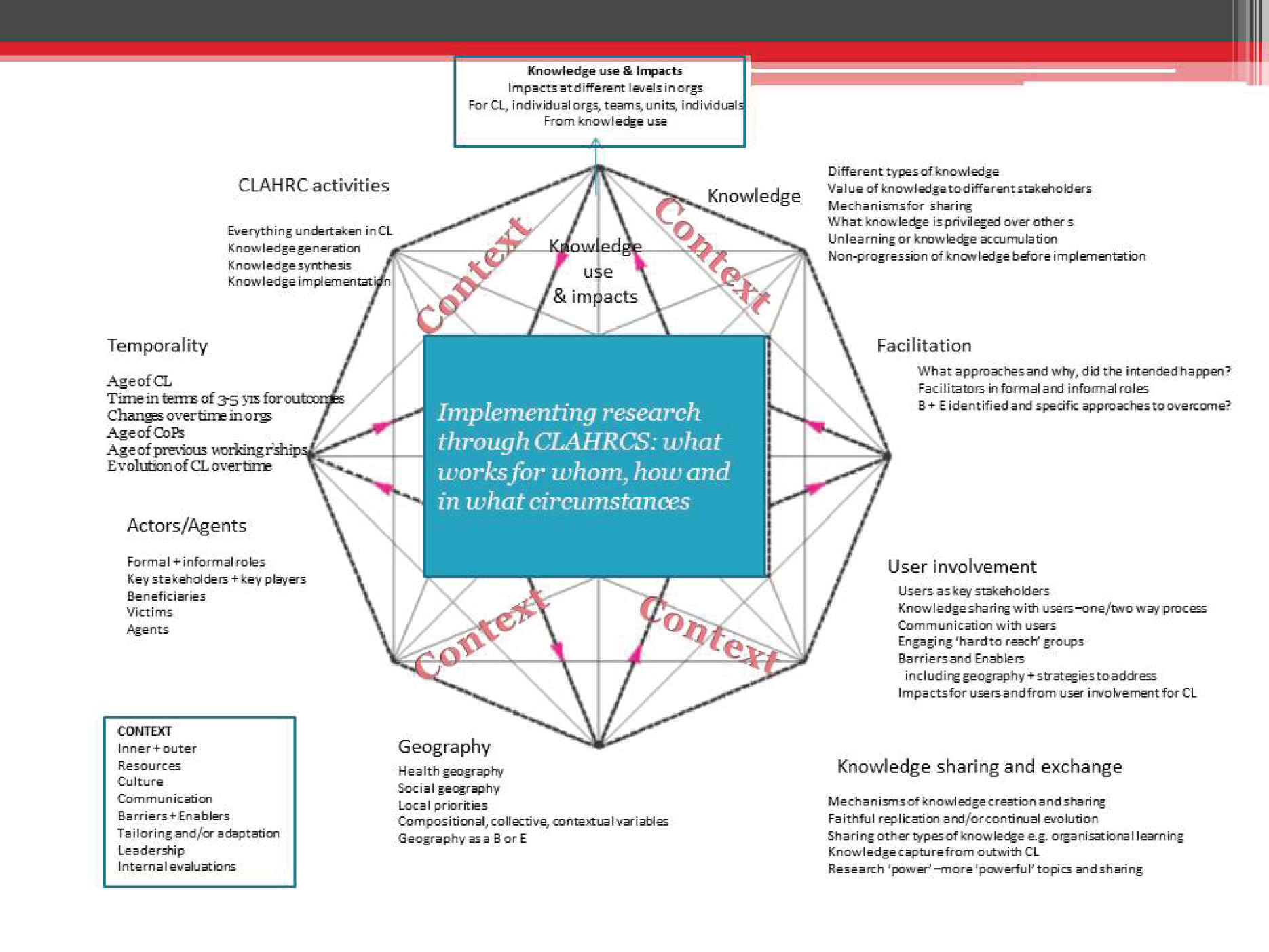

These issues mapped well onto the study’s evaluation framework (see Figure 4) and so were embedded in the questions asked at each round of data collection and in data analysis processes.

Sites

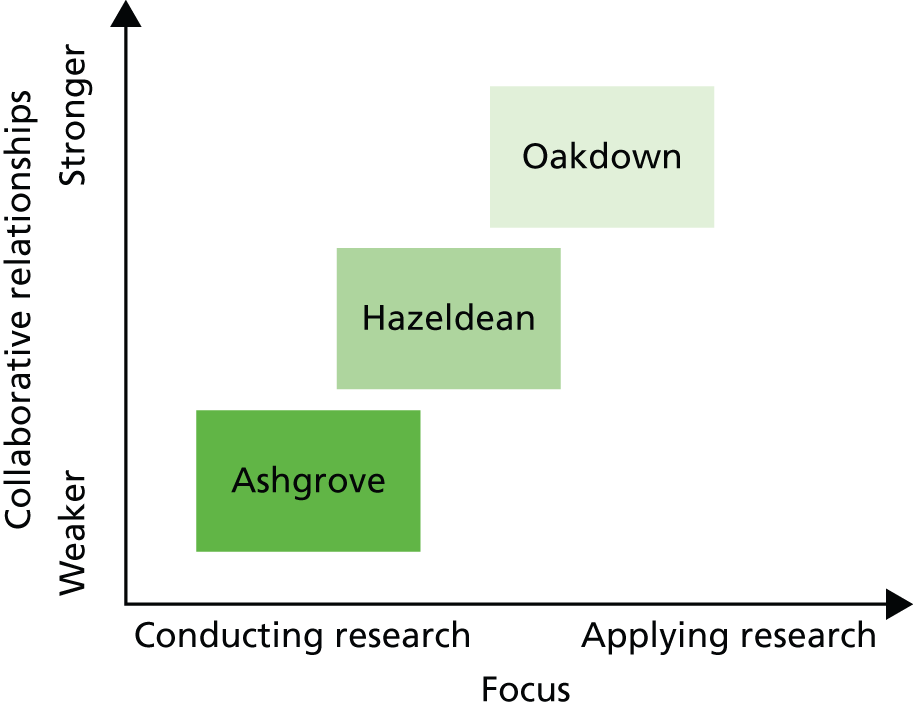

Given the collaborative nature of the CLAHRCs’ mission and realist evaluation’s emphasis on stakeholder engagement, we worked closely with those involved in CLAHRCs to develop the proposal and subsequently deliver the project. This included involving CLAHRC participants as coapplicants. We studied three CLAHRCs in depth (Ashgrove, Hazeldean and Oakdown) while providing opportunities for engagement with the wider CLAHRC community during stakeholder meetings and through an interpretive forum.

Patient and public involvement

As it was a stakeholder-driven project, patient and public involvement (PPI) was an important aspect of the study. Furthermore, we had been asked by the funder to ensure an explicit focus on PPI within implementation, as the other external evaluation projects were not funded to focus on this. Questions about how PPI happens within implementation are important and under-researched, and therefore warranted targeted attention in this project.

We also established a PPI group to help inform this aspect of the research and the work more generally. The group comprised five members: four from our case study CLAHRCs and one person from a non-CLAHRC area. Participants were nominated by the CLAHRCs themselves and as a group had experience of involvement as patients, as a lay member on a CLAHRC board and through participation in INVOLVE. An inaugural face-to-face meeting of the group was held on 12 December 2011. As part of agreeing ways of working, the preference was to engage with individual members of the group at points where their input would be most useful. Subsequently, they participated in the project by reading and commenting on, for example, draft reports, and through physical presence at research team meetings.

Data collection

The realist evaluation cycle represents the research process in three phases as hypothesis generation, refining and testing, and programme theory specification (over several rounds of data collection), as shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Realist evaluation cycle.

Development of conceptual framework and programme theories

This relates to phase 1 (see Figure 3).

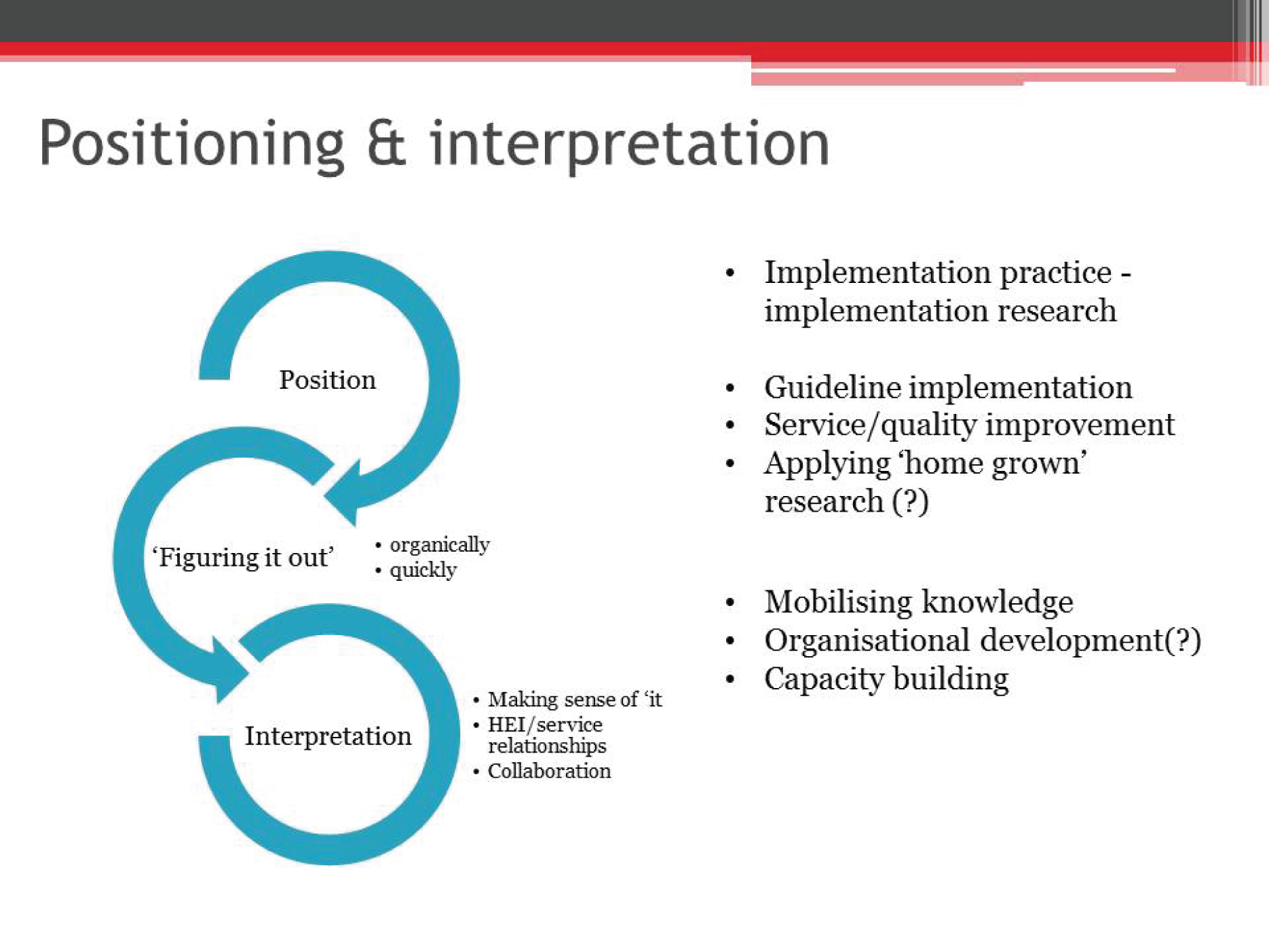

Realist evaluation is theory driven86 and theory guides us to know where to look and what to look for. It provides explanations and so directs us to vital explanatory components, their inter-relationships and the things that bring about those inter-relationships. 85 Interventions, for example CLAHRCs, begin as theories whereby there is always an expectation, hypothesis or ‘programme theory’ that if certain resources (social, cognitive, material) are made available this will lead to a change in action or behaviour. 97 As stated in Chapter 1, the establishment of CLAHRCs was a result of a theory in the creators’ and funders’ heads that collaboration would foster the conduct of applied research and the use of research in practice by providing an infrastructure, resources and a regional focus for building capability and capacity for implementation. There is no prescribed approach to the development of programme theories, or rules for working with implicit and explicit theory. Therefore, in this study a four-stage approach was used that was informed by Pawson and Tilley86 and Pawson85 to inductively identify the programme theories and a conceptual framework, while ensuring a focus on study objectives.

Development of the conceptual framework

The conceptual framework was developed through the following steps:

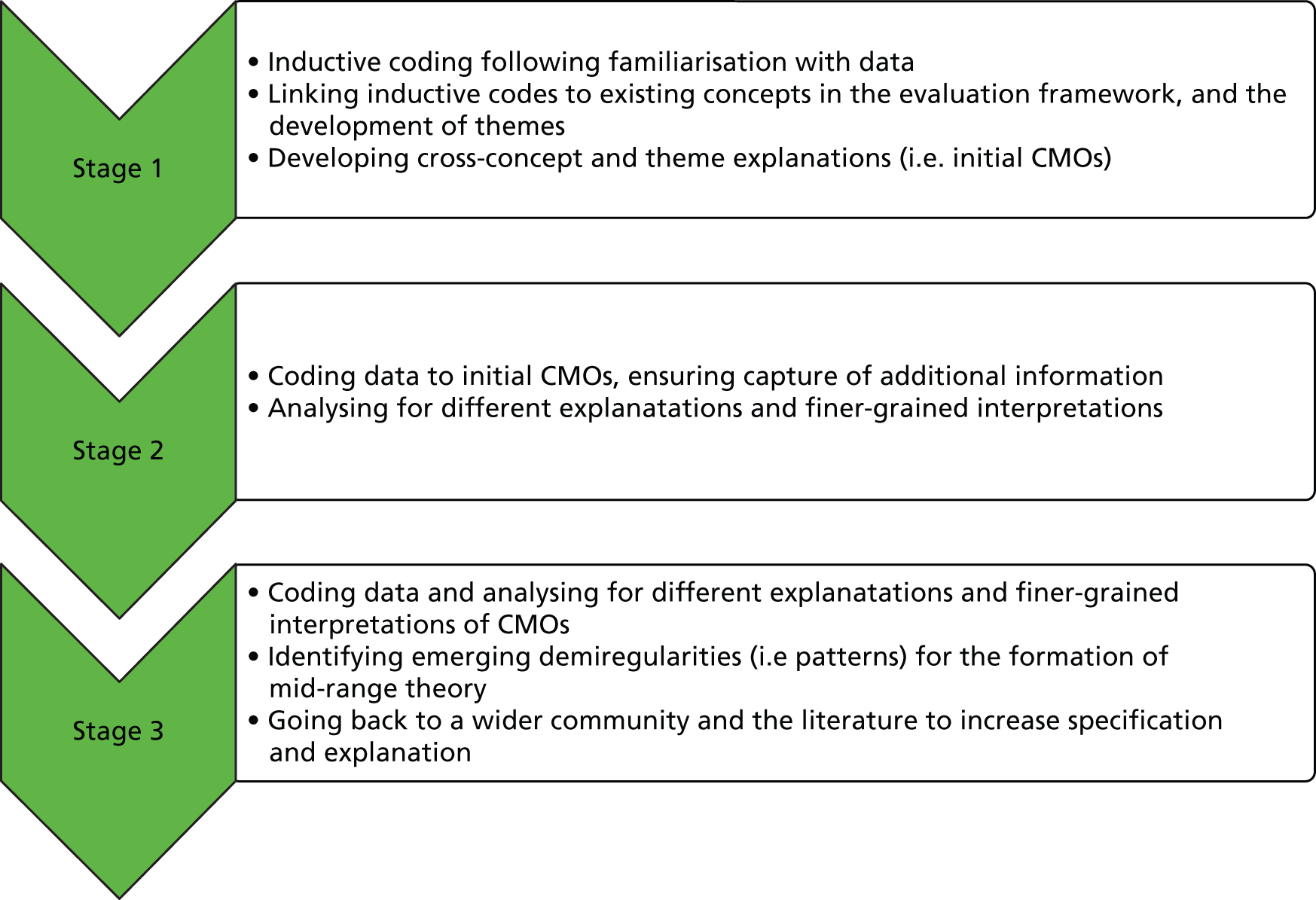

-