Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/05/11. The contractual start date was in December 2014. The final report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in August 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Rodgers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Case study is commonly understood to be a method of research that engages in the close, detailed examination of a single example or phenomenon, and is an approach commonly used to understand activity and behaviour within a real-life context. When conducted well, organisational case studies can provide insights into organisational changes in health care that are not easily achieved through other study designs. They can be used to identify facilitators and barriers to the delivery of services and to help understand the influence of context, and high-quality organisational case studies have been used to examine ways of working in acute care,1 primary care,2 mental health services,3 residential care4 and across the NHS more broadly. 5–7

Yin8 describes a case study to be the preferred research method when (1) the main research questions are ‘how?’ or ‘why?’; (2) a researcher has little or no control over behavioural events; and (3) the focus of the study is a contemporary (as opposed to historical) phenomenon. However, there is no set methodology for a case study and the term is often used loosely, but typically combines qualitative and quantitative data collection with a strong observational component. Case study research can be conducted from both relativist and positivist perspectives, and can be used to generate new theories, validate existing theories or address both of these matters. 9 An individual case can be studied alone to understand something about the case itself and its contexts, or compared with other cases for illustrative, explanatory or evaluative purposes. 10

The case study has been proposed as an appropriate method for describing, explaining, predicting or controlling processes associated with phenomena at the individual, group or organisational level. 11 The majority of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme-funded case studies are specifically concerned with description or explanation at the organisational level.

In the past, many proposals for organisational case studies submitted to the HSDR programme have been poorly articulated and methodologically weak and were therefore unlikely to deliver robust research findings. Specific areas of concern raised by the HSDR programme included:

-

Absence of clear research questions that the case study method is intended to answer.

-

Vagueness about sampling frame/strategy. Proposals where it is not clear how organisations or sites were selected or what was the basis for sampling.

-

Insufficient theoretical basis. Many studies lack an organising theoretical framework; this can affect all stages, from sampling of sites through to analysis and how findings can add to the body of knowledge.

-

Lack of clarity about the unit of analysis. Some weaker proposals will not identify the unit of interest, whereas good case studies may include data streams around the individual, team, organisation and wider system, and will be explicit about the overall study design and interest.

-

Lack of any clear plans for analysis. Some proposals make no attempt to look actively for data that challenge emerging theories, findings or knowledge of systematic comparative case analyses. Many such studies are purely descriptive, without any explanatory power.

-

Lack of clarity about how data from a range of sources will be integrated.

-

Proposals increasingly claim to use realist evaluation methods for case study work, but make no attempt to establish a programme theory, identify candidate mechanisms or describe other features of realist evaluation.

Consequently, the HSDR programme expressed an interest in identifying the characteristics of good-quality case study research, and in devising quality and publication standards, with particular application to the NHS. More specifically, they described the need for a rapid evidence review alongside a Delphi or expert consensus-building exercise to identify elements of good practice and standards for reporting and publication.

Although some authors have proposed practical methodological guidelines for case study research methods,8,9 these have not been universally adopted. The broad diversity of approaches used within organisational case studies – and the contrasting paradigms that underpin these approaches – mean that any attempt to develop ‘definitive’ methodological guidance in this area is likely to be both highly contentious and resource-intensive. However, the ability of research funders, peer reviewers and other research users to establish methodological quality is at least partly contingent on the clarity of explanation of the methods proposed or utilised. Indeed, several of the concerns raised by the HSDR programme above specifically refer to vagueness or lack of clarity around the reporting of proposed research methods.

Reporting standards already exist for a range of study designs, including randomised trials,12 observational studies,13 systematic reviews,14 clinical case reports,15 qualitative research,16 realist syntheses,17 meta-narrative reviews,18 diagnostic/prognostic studies,19 quality improvement studies20 and economic evaluations. 21 However, to date, no such standards have been reported for organisational case studies.

By encouraging authors to consider how their methods are presented, the availability of an appropriate set of reporting standards for organisational case studies also has the potential to improve research conduct in general. A suitable first step towards better conduct of organisational case studies would be to establish agreement about what needs to be reported among the diverse group of researchers who undertake this kind of research. Should further guidance be needed about appropriate methods, the reporting standards can be used as a foundation on which to build.

The aim of this project has been to identify the characteristics of good-quality organisational case study research and devise reporting standards, with particular application to the NHS. Although a range of opinions and experiences has been sought, the project has not been concerned with case studies outside the remit of the work funded by the HSDR programme. Therefore, it is not intended the reporting standards should be applied to case studies of individuals or to those conducted in other research fields.

In the first instance, we would anticipate that these standards should be used to improve the standard of submissions to the HSDR programme. There may be further potential for dissemination of the standards to the wider world of organisational case study researchers.

Chapter 2 Methods

Research aim

The aim of the project was to develop reporting standards for organisational case study research, with particular application to the UK National Health Service.

Scope

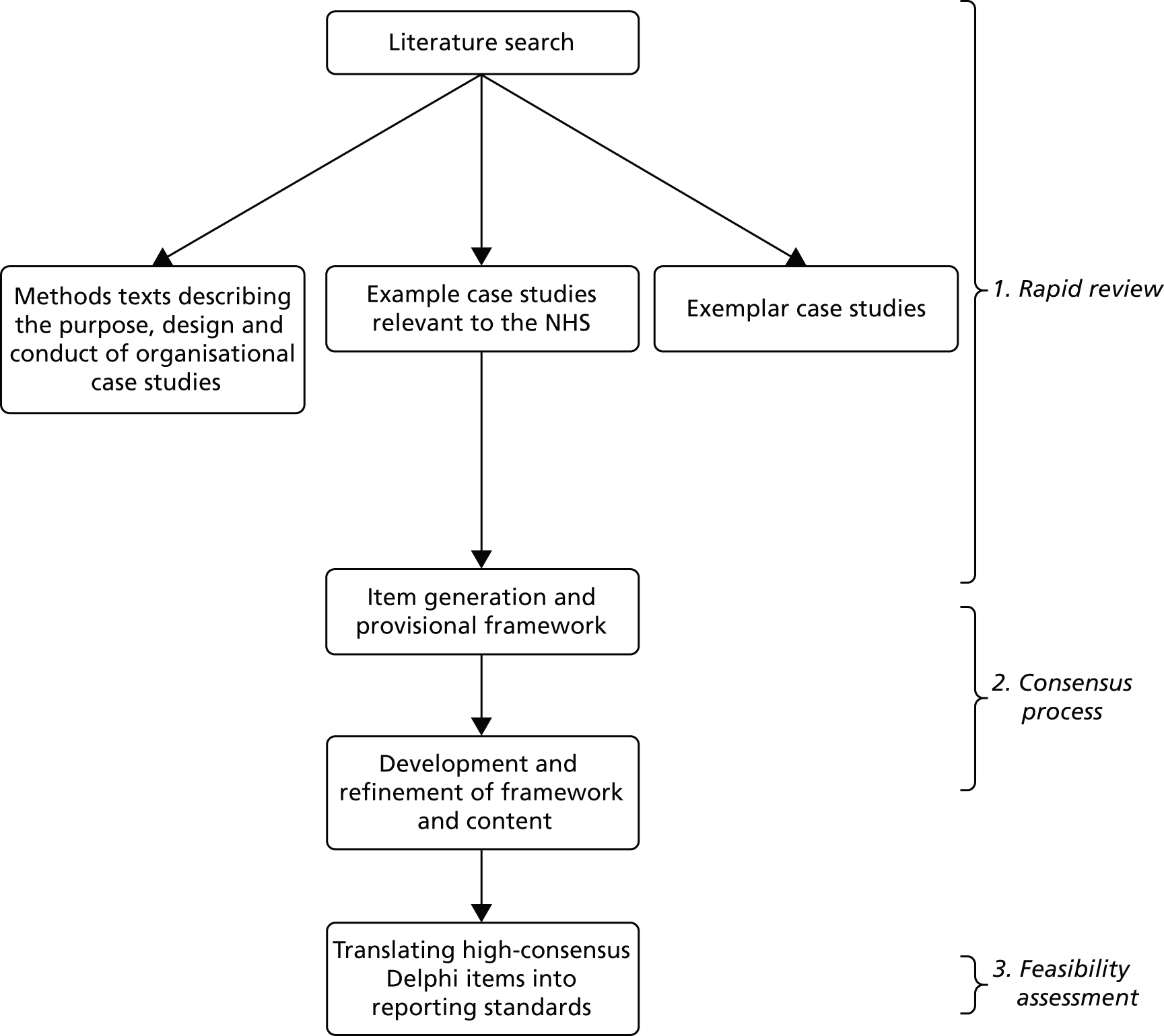

We developed the reporting standards in three stages, as shown in Figure 1:

-

a rapid review of the existing literature to identify content for the standards

-

a Delphi consensus process to develop and refine the final set of standards

-

application of the high-consensus Delphi items to two samples of organisational case studies to assess their feasibility as reporting standards.

FIGURE 1.

Outline of the research process.

Rapid review

A rapid review was used to generate items to populate a provisional framework for organisational case studies. Systematic review methodology was used to identify articles and extract and synthesise data. Because of the rapid nature of the review, the process was less exhaustive and contained less detail than would have been achievable from a full systematic review.

Literature searching

The aim of the search strategy was to identify material about organisational case study methods. It was anticipated that the literature on this topic would be found in textbooks, book chapters, journal articles and research methods guidance; therefore, the search strategy consisted of searches of library catalogues, key author searches, focused searching of health and social science databases and some targeted website searching.

Library catalogue searches

The following library catalogues specialising in health management literature were searched to locate books on case study methods:

-

Health Services Management Centre ONLINE (via the University of Birmingham; www.birmingham.ac.uk/facilities/hsmc-library/library-resources/index.aspx)

-

Health Management Online (via NHS Scotland; www.shelcat.org/nhml)

-

The King’s Fund Library Database (http://kingsfund.koha-ptfs.eu/).

Key author searches

Five authors, detailed in Box 1, featured prominently in the initial literature searches: David Byrne, Bent Flyvbjerg, Roger Gomm, Charles Ragin and Robert K Yin. Searches were carried out via Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) on each author to locate any lists of their publications. Publication lists were found for each author on either their institution website or, where this was not available, through searches of Google Books and Google Scholar.

-

Byrne D. Complex realist and configurational approaches to cases: a radical synthesis. In Byrne D, Ragin C, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Case-based Methods. London: SAGE Publications; 2009. pp. 101–13. 22

-

Byrne D. Introduction: case-based methods: why we need them; what they are; how to do them. In Byrne D, Ragin C, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Case-based Methods. London: SAGE Publications; 2009. pp. 1–10. 23

-

Byrne DS. Complexity, configuration and cases. Theor Cult Soc 2005;22:95–111. 24

-

Flyvbjerg B, Landman T, Schram S. Important next steps in phronetic social science. In Flyvbjerg B, Landman T, Schram S, editors. Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. pp. 285–97. 25

-

Flyvbjerg B, Landman T, Schram S. Real Social Science: Applied Phronesis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2012. 26

-

Flyvbjerg B. Case study. In Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2011. pp. 301–16. 27

-

Gomm R. Key Concepts in Social Research Methods. London: Palgrave Macmillan; 2009. 28

-

Gomm R, Davies C. Using Evidence in Health and Social Care. London: SAGE Publications; 2000. 29

-

Gomm R, Hammersley M, Foster P. Case Study Method – Key Issues, Key Texts. London: SAGE Publications; 2000. 30

-

Ragin CC. Reflections on casing and case-oriented research. In Byrne D, Ragin CC, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Case-based Methods. London: SAGE Publications; 2009. pp. 522–34. 31

-

Ragin CC, Schneider G. Case-oriented theory building and theory testing. In Williams M, Vogt P, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Methodological Innovations. London: SAGE Publications; 2010. pp. 150–6632

-

Ragin CC, Schneider G. Comparative political analysis: six case-oriented strategies. In Amenta E, Nash K, Scott A, editors. The New Blackwell Companion to Political Sociology. Chichester: Blackwell; 2012. pp. 78–91. 33

-

Yin RK. Applications of Case Study Research. 3rd edn. London: SAGE Publications; 2012. 34

-

Yin RK. Case study methods. In Cooper H, editor. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 141–55. 35

-

Yin RK. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2014. 8

Database searches

Initial database test searches revealed difficulties in locating case study methodology literature efficiently without retrieving large numbers of irrelevant results. Therefore, as this was a rapid review, a highly focused search strategy was developed on MEDLINE (via Ovid) to identify papers about organisational case study methods. Focusing of subject headings, use of subheadings and searching in the title-only field were utilised in the strategy.

Searches were restricted to English-language papers. A more limited range of databases than usual for a full systematic review was searched. In particular, no specific databases of conference proceedings, theses or foreign-language studies were searched.

Relevant databases covering literature from health, health management and social science were searched: MEDLINE & MEDLINE In-Process, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Health Management Information Consortium, PsycINFO and the Social Science Citation Index. The MEDLINE strategy was adapted for use in each database.

Website searches

The following websites were searched to identify any guidance documents on case study methods:

-

ESRC National Centre for Research Methods (www.ncrm.ac.uk/)

-

ESRC Research Methods Programme (www.ccsr.ac.uk/methods/)

-

The Social Research Association (http://the-sra.org.uk/)

-

Methods@Manchester (www.methods.manchester.ac.uk/).

Citation searching

Citation searching on case study methods texts from key authors had been planned in the protocol. However, test citation searches identified large numbers of results; therefore, given the rapid nature of the review, citation searching was not feasible within the timescale.

Records were managed within an EndNote library (version X6; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). After deduplication 3465 records in total were identified.

Further details of the full search strategies and results can be found in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We sought to identify three sources of information:

-

methodological texts that reported on the methods used in conducting organisational case study research

-

real-world ‘example’ case studies identified from the searches

-

methodologically sound ‘exemplar’ case studies identified by the NIHR HSDR programme.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in the following sections.

Methodological texts

Texts were included if they:

-

described the conduct of organisational case studies, where organisational means relating to an organised body of people with a particular purpose, such as a business, government department or charity group

-

contained practical advice on conducting case study research.

Texts were excluded if they were:

-

concerned with case studies of individuals (e.g. describing a single patient)

-

concerned with qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods in general, rather than case studies in particular

-

primarily conceptual or theoretical discussions without practical guidance.

Methodological texts were not restricted by topic area. Thus relevant methodological texts from outside health/social services literature, such as business and education, were eligible for inclusion.

We focused on practical rather than conceptual texts to identify potential items for reporting standards, but were mindful that organisational case studies can have different underlying epistemological assumptions (e.g. positivist vs. relativist), and that some paradigms lend themselves more easily to practical advice than others.

Example case studies

These were included if they:

-

reported an organisational case study (as defined above)

-

were undertaken in a UK NHS or social services settings.

The purpose of including the example case studies was to identify any additional items for the Delphi consensus process (see Delphi consensus process) that had not already been identified from the methods literature. We therefore prioritised those organisational case studies with particular relevance to a UK NHS and social services settings.

Exemplar case studies

The funders of this review provided examples of what they considered to be methodologically strong case study research projects funded by the NIHR HSDR programme. These were also examined to identify further items to inform the Delphi consensus process.

Selection of relevant evidence

Methodological texts

An initial examination of the EndNote library identified a very large number of irrelevant records referring to research methods more broadly, therefore we ran a search for ‘case stud*’ in the title or abstract in order to restrict the results to relevant methodological texts. Two reviewers (MR/ST) then independently screened titles and abstracts, with disagreements resolved through discussion. Full-text copies were obtained for potentially relevant records and again screened independently by the same two reviewers. Disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third reviewer (AE).

EPPI-Reviewer version 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, UK) text-mining software was used by one reviewer (ST) to screen the remaining titles and abstracts to establish whether or not any relevant texts could have been missed by our restricted search. The text-mining process ‘learned’ what were relevant texts as the reviewer progressed through screening and brought these to the top of the list, enabling faster retrieval of full texts for assessment and potential incorporation into the review. All titles and abstracts were screened, with a decreasing number of texts being selected as the process continued. Full-text copies were obtained for potentially relevant records and screened for inclusion by one reviewer (ST). A second reviewer (MR or AE) examined excluded records. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

Example case studies

To identify example case studies we further restricted the results gathered from the EndNote library by searching for the terms ‘organisational’ or ‘organizational’ in either the title or abstract within the ‘case stud*’ subset of results.

One reviewer (ST) screened the titles and abstracts, obtained full-text copies of potentially relevant records and selected these for inclusion. The selection was checked by a second reviewer (MR) and disagreements were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer (AE).

Exemplar case studies

Twelve case study projects were identified as exemplar case studies by the HSDR programme staff who commissioned the review. For each project, we downloaded the relevant commissioning brief and, where available, the protocol, final report and journal articles from the HSDR website.

Data extraction

Data extraction forms were created to capture the key methodological components described in individual studies. The forms provided a standard framework while accommodating different approaches; the authors’ own wording was used wherever possible.

The methodological texts were extracted first, beginning with the two most commonly cited case study methods texts. 8,36 The remaining methodological texts were then extracted in reverse chronological order. For the subsequent data extraction, we tried to restrict extraction to additional non-duplicate items; truly identical items identified from two or more sources (i.e. duplicates) were only extracted once, though if two or more items were considered to be similar (but non-identical), these were retained.

Data from the example and exemplar case studies were then extracted in a similar way. For included case studies, we focused on identifying the reporting methods, rather than critically appraising the underlying methodology; we aimed to develop a generic reporting structure that could be applied to a range of different types of organisational case study.

Data extraction was conducted by one reviewer (MR or ST) and checked by a second (MR, ST or AE). Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Synthesis

To generate items for the Delphi consensus process, the individual data extraction forms from the methodological texts were combined into one overall document. A comprehensive and iterative process of refinement was then undertaken, combining and grouping similar components and further removing duplicates. A similar process was undertaken to add in any additional components from the individual example and exemplar case studies.

An initial framework was created by broadly grouping items by research stage, as follows:

-

planning and study design

-

data collection

-

data analysis

-

reporting.

This provisional framework expanded and evolved as the items were extracted, synthesised and revised.

Delphi consensus process

The content of the framework was refined and developed through a modified Delphi consensus process. The Delphi technique is a structured and iterative method for collecting anonymous individual opinions from a panel with relevant expertise in the topic where consensus is required. 37 The basic principle is for the panel to receive successive questionnaires, each one containing the anonymous responses to the previous round, and for them to modify their responses until consensus is reached.

The Delphi consensus process was employed in order to obtain consensus from experts on the minimum set of reporting criteria that could form the basis of standards for the reporting of future organisational case studies.

Design

The reporting standards were developed over two rounds:

-

In the first round, participants were presented with all the unique items identified from the rapid review. They were asked to rate each item as being ‘essential’, ‘desirable’ or ‘not necessary’ for the reporting of organisational case studies. Participants were also asked whether or not the provisional framework in which items were presented was appropriate, and were given the opportunity to adapt this alongside the content.

-

In the second round, participants received a restructured list of items incorporating the results of the first round. Within each section, participants were first presented with high-consensus items (i.e. those receiving > 70% ‘essential’ responses in round 1), and given the opportunity to state whether such items should be reported by all organisational case studies, specific types of organisational case study or do not need to be reported. The remaining non-consensus items were ranked according to their positive/negative ratio of ratings from round 1. This ratio was calculated for each item by dividing the sum of ‘essential’ and ‘desirable’ counts by ‘not necessary’ counts. Consequently, a ratio value of 1 would indicate an even balance of positive and negative ratings. Participants were provided with each item and its corresponding ratio and again asked whether the item should be reported for all, some or no organisational case studies.

In both rounds, the high-consensus threshold was set at 70% agreement among respondents for each item. This threshold was chosen as it reflects a greater than 2 : 1 ratio of agreement to dissent, representing much stronger consensus than would a simple majority agreement threshold of 50% or greater.

Each round was open for 3 weeks, with a reminder sent to non-responders at the end of the first week.

Participants

Experts and parties interested in the conduct of organisational case study research (methodologists, research funders, journal editors, interested policymakers and practitioners) were invited to participate. Individuals were identified through the rapid review, personal contacts, and by contacting the following organisations: Health Services Research Network; the Social Research Association; the UK Evaluation Society; and the National Centre for Research Methods.

All contacts were assured confidentiality, with the aim of encouraging participation and openness, and all were invited to each round of the survey, including previous-round non-responders (unless they chose the option to withdraw from further contact).

In order to assess representation of different stakeholder groups and identify any important differences in their responses, professional characteristics were requested in each questionnaire. These included designation, topic area of interest, research method of interest and proportion of work relating to methodology.

Instrumentation

Questionnaires were administered electronically using on-line survey software Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) and all questionnaires were piloted before distribution.

Analysis

All responses were collected in Qualtrics for initial tabulation and analysis. Subsequent analyses and outputs were produced in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, 2010, Redmond, WA, USA). Where a respondent did not reply to a question, this value was recorded as missing. There was no imputation of missing values.

Ethical approval

Ethics approval for the consensus process was obtained from the University of York Health Sciences Research Governance Committee. Invitees were promised anonymity and submission of completed questionnaires was taken as implied consent.

Translating high-consensus Delphi items into reporting standards for organisational case studies

During the process of gathering the data from the real-world example case studies and the exemplar organisational case studies provided by HSDR, we became interested in how these might match up to the reporting standards. Although this step had not been part of the original protocol, we decided to add an additional step in the development process. One reviewer (ST) applied the list of high-consensus items, as far as was possible in retrospect, to all identified example and exemplar case study publications. These were subjective decisions made by one reviewer and are not intended to be a criticism of the quality of reporting in these publications. Rather our aims were (1) to determine the relevance of these items to the reporting of real-world organisational case studies and (2) to better understand how the results of the Delphi consultation might best be implemented as reporting standards. The results of this application are discussed in Translating high-consensus Delphi items into reporting standards for organisational case studies.

Chapter 3 Results

Rapid review

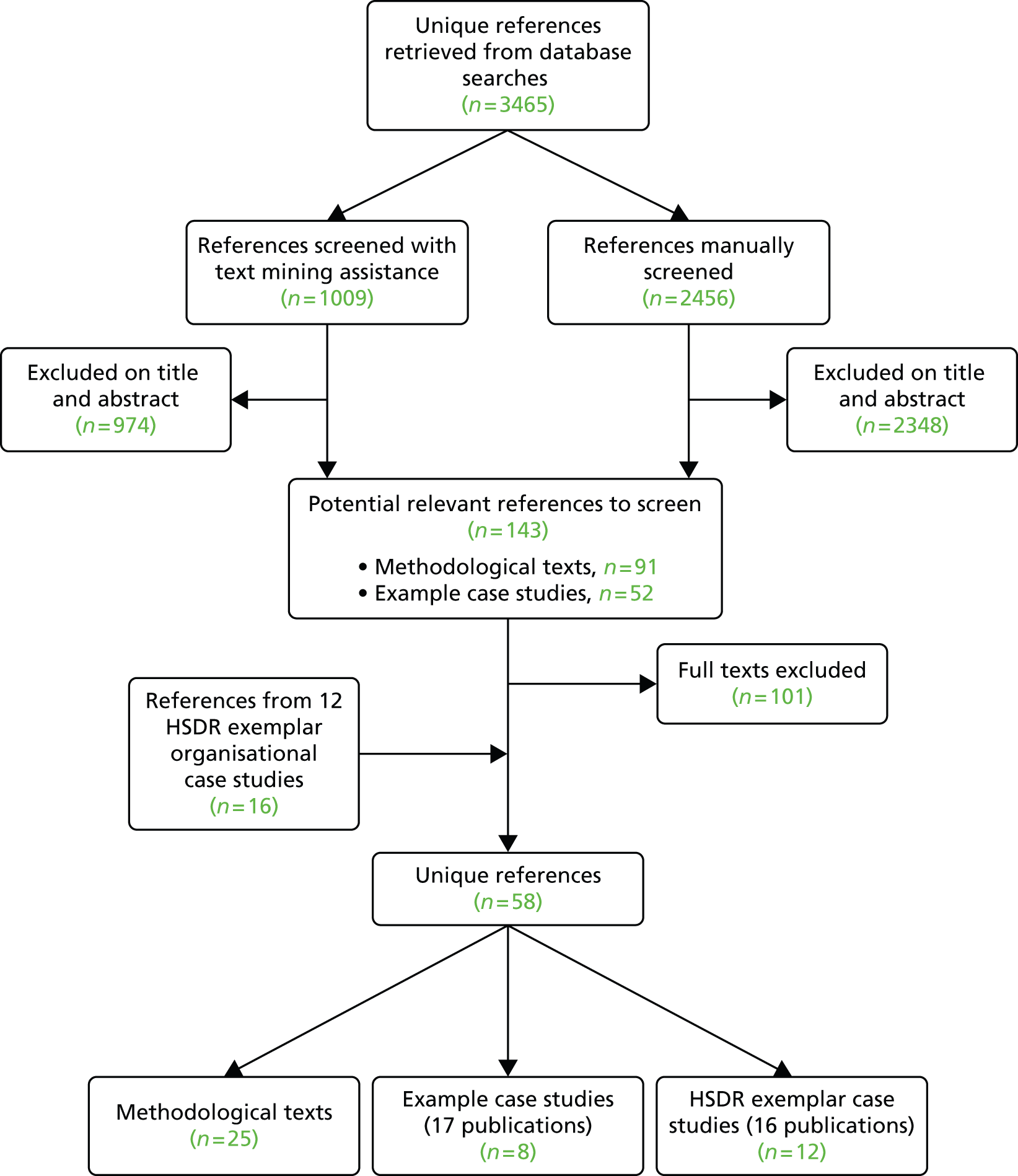

The searches identified 3465 potentially relevant references. After deduplication there were 2456 references, which were manually screened, with 2348 excluded based on title and abstract. Of the 1009 references screened with the assistance of text mining, 974 were excluded. Thirty-five records were identified from the screening of titles and abstracts during text mining, but no additional texts were included after reading of full texts. Following screening of full texts we included: 25 methodological texts,8–10,34–36,38–56 eight example case studies (17 publications)57–73 and 12 exemplar case studies (16 publications) provided by the HSDR programme. 1–7,74–82 The study by Raine et al. 77,78 was described in publications as ‘a prospective observational study’, but contained many elements of a case study and was identified as an exemplar of organisational case study research. See Figure 2 for details.

FIGURE 2.

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)14 flow chart.

Rapid review: methodological texts

Twenty-five methodological texts were included in the rapid review. 8–10,34–36,38–56 Dates of publication covered 20 years, ranging from 1994 to 2014. One text47 was received too late to include in the Delphi consensus process, but it included no new items to add to the final list.

A number of key authors in the field of case study methodology had been identified in the early stages of our review (see Chapter 2, Rapid review, Literature searching, Key author searches). Other key authors were also identified. A complete list of these authors and their publications is provided in Table 1. After reading the texts, we selected those that gave practical advice on conducting research.

| Author (year) | Title and publication details |

|---|---|

| Crowe et al. (2011)38 | The case study approach. BMC Med Res Methodol 2011;11:100 |

| Darke et al. (1998)39 | Successfully completing case study research: combining rigour, relevance and pragmatism. Inf Syst J 1998;8:273–89 |

| Fitzgerald and Dopson (2009)40 | Comparative case study designs: their utility and development in organizational research. In Buchanan DA, Brynam A, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Research Methods. London: SAGE Publications; 2009. pp. 465–83 |

| Gagnon (2010)9 | The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook. Québec City, QC: Presses de l’Université du Québec; 2010 |

| Gibbert and Ruigrok (2010)41 | The ‘what’ and ‘how’ of case study rigor: three strategies based on published work. Organ Res Methods 2010;13:710–37 |

| Gibbert et al. (2008)42 | What passes as a rigorous case study? Strategic Manage J 2008;29:1465–74 |

| Gilgun (1994)43 | A case for case-studies in social-work research. Soc Work 1994;39:371–80 |

| Gillham (2000)44 | Case Study Research Methods (Continuum Research Methods). London: Bloomsbury Academic; 2000 |

| Greene and David (1984)45 | A research design for generalising from multiple case studies. Eval Program Plann 1984;7:73–85 |

| Hays (2004)46 | Case study research. In deMarrais K, Lapan SD, editors. Foundations for Research: Methods of Inquiry in Education and the Social Sciences. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2004. pp. 217–34 |

| Hutchinson (1990)47 | The case study approach. In Moody LE, editor. Advancing Nursing Science through Research (Vol. 2). Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications; 1990. pp. 177–213 |

| Huws and Dahlmann (2007)48 | Quality Standards for Case Studies in the European Foundation. Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions; 2007 |

| Kaarbo and Beasley (1999)49 | A practical guide to the comparative case study method in political psychology. Polit Psychol 1999;20:369–91 |

| Meyer (2001)50 | A case in case study methodology. Field Methods 2001;13:329–52 |

| Moore et al. (2012)51 | Case study research. In Laplan SD, Quartaroli MT, Riemer FJ, editors. Qualitative Research: An Introduction to Methods and Designs. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2012. pp. 243–70 |

| Stake (2005)36 | Qualitative case studies. In Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 3rd edn. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2005. pp. 443–66 |

| Stake (1995)10 | The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1995 |

| Stake (1994)52 | Case studies. In Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1994. pp. 236–47 |

| Thomas (2011)53 | How to do your Case Study: A Guide for Students and Researchers. London: SAGE Publications; 2011 |

| Yin (2014)8 | Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2014 |

| Yin (2012)34 | Applications of Case Study Research. 3rd edn. London: SAGE Publications; 2012 |

| Yin (2012)35 | Case study methods. In Cooper H, editor. APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology, Vol 2: Research Designs: Quantitative, Qualitative, Neuropsychological, and Biological. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012. pp. 141–55 |

| Yin (2006)56 | Case study methods. In Green GL, Camilli G, Elmore PB, editors. Handbook of Complementary Methods in Education Research. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2006. pp. 111–122 |

| Yin (1999)55 | Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Serv Res 1999;34:1209–24 |

| Yin (1998)54 | The abridged version of case study research. Design and method. In Bickman L, Rog DJ, editors. Handbook of Applied Social Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1998. pp. 229–59 |

The most commonly cited publications were by the authors Yin8,34,35,54–56 and Stake. 36 Therefore, the items for the Delphi consensus process were initially drawn from six publications by Yin8,34,35,54–56 and three by Stake. 10,36,52 The remaining texts were read in reverse chronological order to identify any additional items, with a decreasing number of new items found as we progressed back in time. See Appendix 2 for the complete list of items together with authors.

The language and paradigmatic assumptions related to each extracted item are likely to reflect the position of the original academic author. For example, the application of concepts such as validity and reliability to case studies derives directly from the publications of Yin. 8,34,35,54–56

Across all the included texts authors gave various definitions of case study research, made different paradigmatic assumptions, and recommended different methods. Rather than taking a particular position, we aimed to capture all these variations for inclusion in the first phase of the Delphi consensus process.

Rapid review: example case studies

Eight example case studies (with 17 associated publications) were included. 57–73 All the studies were conducted in England, with most relating to the NHS and one evaluating prison mental health in-reach services. 73 Dates of publication ranged from 2004 to 2011. The methods, as reported by the authors, covered a variety of approaches (see Table 2 for details).

| Author (year) | Type | Summary of case study | Where conducted | Author-reported case study methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attree et al. (2008)57,58 | J | The study explored patient safety in an English pre-registration degree nursing curriculum, based on the Nursing and Midwifery Council 2002 curriculum guidelines | NHS health-care trusts, north of England | Multiple organisational case studies |

| aField et al. (2005)59,65,68,69 | R, J | Phase 2: five in-depth organisational case studies were conducted with adult hospice bereavement support services in England | NHS hospices, England | In-depth multiple organisational case studies |

| Hutchinson and Purcell (2010)61 | J | Drawing on case study research in seven NHS trusts, the study considers the role and management of ward managers and paramedic supervisors, focussing on their human resource management responsibilities | NHS, south of England | A multiple case approach |

| Kyratsis et al. (2010)62,63 | R, J | To understand the impact of differing organisational capacity and contextual circumstances on technology selection, as well as the subsequent procurement and implementation of the technologies in 12 English NHS trusts | NHS trusts, England | A qualitative, multisite, comparative case study |

| National Nursing Research Unit (2009)64 | R, J | Phase 2: issues of local implementation of ‘The Productive Ward’ programme in five NHS acute trusts | NHS acute hospitals, England | A mix of qualitative research methods |

| The Offender Health Research Network (2009)70,73 | R, J | Evaluating prison mental health in-reach services using case study sites across the North West, North East and Yorkshire, South West, South East and London regions | Prison and young offender institutions, England | Qualitative analysis and a multiple case study approach |

| aPayne et al. (2007)65 | J | Case study research methods in end-of-life care: reflections on three studies | NHS hospices, England; NHS hospitals, England; NHS UK | Reflections on methods used in three case studies, including Payne et al.a |

| aPayne et al. (2004)60,65–67 | R, J | Phase 3: six in-depth organisational case studies of community hospitals in the South East and South West of England to identify how palliative care for elderly people is delivered in practice from the perspectives of service users and service providers | NHS community hospitals, England | In-depth multiple organisational case studies |

| aRolls and Payne (2004)65,72 | J | A multiple case study design: the context and processes of childhood bereavement services, the experiences of families who use them and the complexity of the contextual conditions that surround UK childhood bereavement services | NHS UK | In-depth multiple organisational case study approach as part of a larger qualitative study |

Some of the case studies were parts of wider projects that included other methods of evaluation. In such cases we focused only on the methods used for the organisational case studies.

The level of reporting of organisational case study methods within individual publications varied. After assessing all the publications for each included organisational case study, no new items were found to add to the Delphi consensus process.

Exemplar case studies

Twelve case studies (16 publications) funded by the NIHR HSDR programme were identified by the funder as being methodologically strong. 1–7,74–82 The methods, as reported by the authors, covered a variety of approaches (see Table 3 for details).

| Chief investigator | Type | Project ID, title and link to HSDR project page | Where conducted | Author-reported case study methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Checkland K2 | R | 08/1808/240: management practice in Primary Care Organisations: the roles and behaviours of middle managers and GPs www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/081808240 |

Primary care trusts England | Qualitative case study methods |

| Closs J1 | P | 11/2000/05: the detection and management of pain in patients with dementia in acute care settings: development of a decision tool www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/11200005 |

NHS England | Multiple case studies with embedded units of analysis |

| Drennan VM74 | R | 09/1801/1066: investigating the contribution of physician assistants to primary care in England: a mixed-methods study www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/0918011066 |

NHS England | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) |

| Gillard S3 | R | 10/1008/15: new ways of working in mental health services: a qualitative, comparative case study assessing and informing the emergence of new peer worker roles in mental health services in England www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/10100815 |

NHS England | Comparative case study design |

| Goodman C4 | P | 11/1021/02: optimal NHS service delivery to care homes: a realist evaluation of the features and mechanisms that support effective working for the continuing care of older people in residential settings www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/11102102 |

NHS England | Realist evaluation |

| Martin GP5–7 | R, J | 09/1001/40: the medium-term sustainability of organisational change in the National Health Service: a comparative case study of clinically led organisational innovations www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/09100140 |

NHS England | Qualitative comparative case study |

| McCourt C75 | R | 10/1008/35: an ethnographic organisational study of alongside midwifery units: a follow-on study from the Birthplace in England programme www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/10100835 |

NHS England | Ethnographic study |

| McDonald R76 | P | 08/1809/250: evaluation of the advancing quality pay for performance programme in the NHS North West www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/081809250 |

NHS England | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) |

| Raine R77,78 | R, J | 09/2001/04: improving the effectiveness of multidisciplinary team meetings for patients with chronic diseases: A prospective cohort study www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/09200104 |

NHS England | Mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) |

| Randell R79 | P | 12/5005/04: a realist process evaluation of robotic surgery: integration into routine practice and impacts on communication, collaboration and decision making www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/12500504 |

NHS Trusts, England | Realist evaluation |

| Rycroft-Malone J80 | P | 12/64/187: accessibility and implementation in UK services of an effective depression relapse prevention programme: Mindfulness based cognitive therapy www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/1264187 |

NHS UK | In-depth case studies using exploratory and interpretive methods |

| Waring J81,82 | R, J | 10/1007/01: knowledge sharing across the boundaries between care processes, services and organisations: the contributions to safe hospital discharge and reduced emergency readmission www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/10100701 |

NHS England | Ethnographic study |

The list of exemplar case studies contains a number of completed and ongoing projects. Publications included protocols, final reports and journal articles. Most case studies were conducted in England, with one being conducted in all four countries of the UK. 80 All were conducted in the NHS.

After a thorough reading of the publications relating to case studies, no new items were identified to add to the Delphi consensus process.

Chapter 4 Delphi consensus process

Items identified from the literature

After deduplication, a total of 103 unique items were identified for inclusion in the Delphi consensus process. See Appendix 2 for the full list of items. During the extraction process, the classification of items evolved and expanded from four to the six following categories:

-

describing the design

-

background, context and theory

-

describing the data collection

-

describing the data analysis

-

interpreting the results

-

sharing the results and conclusions.

These categories were used to structure the questionnaire, though respondents were given the opportunity to suggest additions or changes to this classification (see Appendix 3).

Round 1 results

Response rate and participants

Of 36 experts invited to take part in the Delphi consensus process, 19 (53%) responded to the first round invitation. All respondents completed the entire questionnaire.

Following the distribution of questionnaires, the funder of this project was contacted by a learned society for social science researchers, which expressed concerns about perceived assumptions underlying the project. The three main concerns raised were (1) the difficulty in mandating standards of conduct for the wide variety of case study approaches, (2) the existence of a quality control system already operating through peer review of the HSDR programme-funded project reports and (3) the risk of moving towards excessive standardisation. Four of the experts invited to participate in the Delphi consensus process co-signed the letter, three of whom also went on to complete both rounds of the survey. The comments from these authors, as well as the concerns raised in the letter, were used to inform and refine the structure of the second round questionnaire, and are discussed further in Round 2 results.

The characteristics of respondents to both rounds of the process are given in Table 4, and their research interests are described in Box 2. The majority of respondents in round 1 were researchers (80%), with substantial experience of authoring or otherwise contributing to organisational case study research (see Table 4). Two respondents classified themselves as research methodologists, two others classified themselves as having an editorial or related publishing role, and one respondent was a research funder. Several respondents expressed research interests related to health and/or social care, and others an interest in different approaches to organisational case study research (e.g. ethnography, qualitative case studies, comparative and theory-related cases).

| Characteristic | Number of respondents | |

|---|---|---|

| Round 1 | Round 2 | |

| Professional role | ||

| Researcher | 15 | 1 |

| Research methodologist | 2 | 1 |

| Journal editor/board member/publishing | 1 | 1 |

| Other (‘researcher and journal editor’) | 1 | 1 |

| How many organisational case studies have you authored? | ||

| 0 | 2 | 1 |

| 1–5 | 6 | 5 |

| 6–10 | 5 | 2 |

| > 10 | 6 | 7 |

| How many organisational case studies have you been involved with other than as an author? (e.g. peer review, commissioning, advisory role) | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–5 | 6 | 3 |

| 6–10 | 3 | 3 |

| > 10 | 10 | 8 |

| What proportion of your work relates to research methodology? | ||

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1–40% | 13 | 10 |

| 41–60% | 4 | 2 |

| > 60% | 2 | 3 |

-

Health and social care.

-

Evaluation of health IT.

-

Qualitative case studies.

-

Development of different models of service delivery and interface between primary and secondary care.

-

Organisation of care in hospital wards.

-

Use of information technology in health-care settings.

-

Comparative cases; theory-related cases.

-

Evidence implementation; quality improvement

-

Public services broadly – health, children’s services, urban regeneration, disability services.

-

Health care.

-

Change; implementation of evidence; maternity care; user and professional experiences; ethnography.

-

Health services.

-

Ethnography.

-

Health-care organisation.

-

Research funder judging quality of organisational case study research. Also editor for NIHR Journals Library reviewing quality.

-

Research into health policy.

-

Hospitals.

-

Quality improvement and change management.

-

Organisational change.

-

Realist evaluation, qualitative methods.

-

Acute hospital settings.

-

Relationships between organisational structures and policy outcomes.

Rating of items

Respondents were asked to rate absolutely necessary items for reporting case studies as ‘essential’, to rate useful but non-essential items as ‘desirable’ and rate any unnecessary, unclear, redundant, or meaningless items as ‘not necessary’. None of the 103 items was definitively excluded by consensus (i.e. the proportion of ‘not necessary’ ratings was below 70% for every item).

Table 5 shows the 10 items that met the predefined minimum 70% ‘essential’ consensus level. The level of consensus for these items ranged from 74% to 95%, with the highest consensus for ‘describe how the data were collected’ and ‘describe the sources of evidence used’. None of the items classified under the headings of ‘background, context and theory’ or ‘sharing the results and conclusions’ met the 70% ‘essential’ consensus threshold.

| Item | Rating, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Essential | Desirable | Not necessary | |

| Describing the design | |||

| Define the research as a case study | 14 (73.7) | 5 (26.3) | 0 |

| State the broad aims of the study | 16 (84.2) | 3 (15.8) | 0 |

| State the research question(s)/hypotheses | 15 (78.9) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (5.3) |

| Data collection | |||

| Describe how data were collected | 18 (94.7) | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| Describe the sources of evidence used, for example documentation; archival records; interviews; direct observations; participant-observation; physical artefacts | 18 (94.7) | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| Describe any ethical considerations and obtainment of relevant/approvals, access and permissions | 15 (78.9) | 4 (21.1) | 0 |

| Data analysis | |||

| Describe the analysis methods | 17 (89.5) | 2 (10.5) | 0 |

| Interpretation | |||

| Describe any inherent shortcomings in the design and analysis and how these might have influenced the findings | 15 (78.9) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (5.3) |

| Consider the appropriateness of methods used for the question and subject matter and why it was that qualitative methods were appropriate | 15 (78.9) | 4 (21.1) | 0 |

| Discuss the data analysis (was it conducted in a systematic way and was it successful in incorporating all observations and dealing with variation?) | 14 (73.7) | 4 (21.1) | 1 |

Among items failing to meet the 70% ‘essential’ threshold, values ranged from 0% to 68%. In order to better inform respondents and to facilitate the rating process in round 2, these 93 non-consensus items were ranked according to their positive/negative ratio of ratings from round 1. This ratio was calculated for each item by dividing the sum of ‘essential’ and ‘desirable’ counts by ‘not necessary’ counts. Consequently, a ratio of 1 would indicate an even balance of positive and negative ratings. Where ‘not necessary’ counts were 0, a value of 0.5 was used to allow the calculation. Ratio values for the non-consensus subsequently items ranged from 0.58 to 38.

Round 1 comments

A number of themes emerged from the comments given by respondents to round 1 (see Appendix 5 for all comments).

Several comments raised concerns about the phrasing of items. These fell into two categories: the inability to label items because they were unclear, inappropriate or poorly worded; and the impression that some items were overly focused on quantitative research and/or were informed by a rigid and predominantly positivist paradigm.

Several other comments explicitly noted that the appropriateness of certain items would be context specific, and so a single rating could not be universally applied across different approaches.

Other comments objected to the very notion of producing standards for the kind of contextualised and creative interpretative processes that are often employed in qualitative research.

None of the respondents suggested any changes to the six item categories.

Round 2 results

Development of the questionnaire

The responses from the first round were used to refine and develop both the introductory information and the restructuring of the items in the next questionnaire, which was distributed in the second round of the Delphi consensus process.

Introduction to round 2

The round 2 questionnaire was prefaced with an introduction that directly addressed the main concerns raised by respondents to the first round.

First, it was clarified that while the funders originally proposed ‘a common quality and reporting standard for organisational case study research’, the research team had anticipated that generic standards for the conduct of organisational case studies would not be possible, and so chose from the start to focus on quality of reporting rather than scientific quality more broadly (i.e. to identify any aspects of case study reporting that could facilitate the reading and judgement processes used by peer reviewers and other audiences). However, in light of the letter received by the society of social science researchers and associated comments from round 1, respondents to round 2 were given the opportunity to explicitly state whether they considered such reporting standards to be feasible or desirable.

It was also clarified that the items presented in the Delphi consensus process were not created by the research team but were derived from the published academic literature, using the authors’ own wording wherever possible. Thus, the language used and the paradigmatic assumptions related to each item likely reflect the position of the original academic author. For example, the contentious application of terms such as ‘validity’ and ‘reliability’ to case study research came directly from the published work of Yin. 8,34,35,54–56

The introduction to the exercise also emphasised the research team’s impartiality regarding the final content of the reporting standards, along with the respondents’ prerogative to exclude any items that they considered inappropriate, confusing, poorly worded or meaningless.

Item presentation

Items were again grouped into six categories: (1) describing the design; (2) background, context and theory; (3) describing the data collection; (4) describing the data analysis; (5) interpreting the results; and (6) sharing the results and conclusions.

Within each section, respondents were first asked to agree or disagree with the inclusion of the high-consensus items from round 1 (> 70% ‘essential’) in generic reporting standards. They were then asked to either upgrade or discard the remaining lower-consensus items, which were presented in decreasing order of the positive-/negative-rating ratio. For all items, respondents had the opportunity to distinguish between items that should be reported for organisational case studies in general, those that should be reported for a particular approach and those that did not need to be reported.

Response rate and participants

Fifteen respondents completed the entire round 2 questionnaire; 14 of these respondents (93%) had taken part in the first round and one respondent only contributed to the second round.

Although a slightly greater proportion of respondents thought the establishment of standards for reporting organisational case studies was desirable than did not, several were uncertain (see Table 6 for response rates and all related comments). Others suggested that the usefulness of any standards would depend upon how they were applied (e.g. as ‘a reference point for aspiration’ vs. a means of enforcing inappropriate standardisation) and where they are applied (e.g. health service research vs. sociology; impact on post-structuralist approaches).

| Question | No opinion | Yes | No | Do not know | Other | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did you take part in round 1 of this Delphi exercise? | 93.3% | 6.7% | ||||

| Do you think that a publication standard for reporting organisational case studies is desirable? | 0% | 40% | 26.7% | 13.3% | 20% | It depends on the audience or community. Advanced ethnographic case studies targeted at anthropology, cultural studies, sociology or policy studies are arguably distinct from Health Services Research or trial research communities. Also, how do post-structuralist or even narrative case accounts fit with the idea of standards? Standards might constrain creativity and imagination!All depends how it is used. It is one thing to have a standard that acts as a reference point or aspiration; it is another if this is used inappropriately to enforce standards that are not universally suitable for all research that might be subjected to itYes but . . . recognise heterogeneity of case study research |

| Do you think that a meaningful publication standard for reporting organisational case studies is possible? | 6.7% | 33.3% | 26.7% | 26.7% | 6.7% | For some types of studies and not others, I suspect |

Respondents were similarly divided about whether or not meaningful reporting standards would be feasible for organisational case studies. Again, the issue of standards being possible for some studies but not others was mentioned.

As might be expected, given the very high proportion of overlap between rounds, respondents had a similar level of case study experience and range of research interests as in round 1 (see Table 4).

Appendix 6 contains all the free-text comments provided in round 2.

Rating of items

Items considered relevant to all organisational case studies

Thirteen items were rated as ‘should be reported for all organisational case studies’ by at least 70% of respondents. These included all 10 high-consensus items from the first round, plus three further items: ‘identify the specific case(s) and justify the selection’, ‘ensure that the assertions are sound, neither over- nor under-interpreting the data’ and ‘state any caveats about the study’ (Table 7).

| Item | Number of respondents (percentage of total) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Should be reported for all | Should be reported for specific types | Does not need to be reported | |

| Describing the design | |||

| Define the research as a case study | 13 (86.7) | 0 | 2 (13.3) |

| State the broad aims of the study | 15 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| State the research question(s)/hypotheses | 13 (86.7) | 2 (13.3)a,b | 0 |

| Identify the specific case(s) and justify the selection [e.g. key case (good example, classic or exemplary case); outlier case (showing something interesting because it is different from the norm); local knowledge case (example chosen on the basis of personal experience or local availability)] | 11 (73.3) | 1 (6.7) | 3 (20) |

| Describing the data collection | |||

| Describe how data were collected | 15 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Describe the sources of evidence used (e.g. documentation; archival records; interviews; direct observations; participant observation; physical artefacts) | 15 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Describe any ethical considerations and obtainment of relevant approvals, access and permissions | 13 (86.7) | 1 (6.7)c | 1 (6.7) |

| Describing the data analysis | |||

| Describe the analysis methods | 15 (100) | 0 | 0 |

| Interpreting the results | |||

| Describe any inherent shortcomings in the design and analysis and how these might have influenced the findings | 13 (86.7) | 0 | 2 (13.3) |

| Consider the appropriateness of methods used for the question and subject matter and why it was that qualitative methods were appropriate | 13 (86.7) | 0 | 2 (13.3) |

| Discuss the data analysis (was it conducted in a systematic way and was it successful in incorporating all observations and dealing with variation) | 13 (86.7) | 0 | 2 (13.3) |

| Ensure that the assertions are sound, neither over- nor under-interpreting the data | 11 (73.3) | 0 | 4 (26.7) |

| State any caveats about the study | 11 (73.3) | 0 | 4 (26.7) |

In round 2, the degree of consensus ranged from 73% to 100%, with four items (‘state the broad aims of the study’, ‘describe how the data were collected’, ‘describe the sources of evidence used’, and ‘describe the analysis methods’) achieving 100% consensus. For all 13 items, the degree of consensus was greater than in round 1.

As in round 1, none of the items classified under the headings of ‘background, context and theory’ or ‘sharing the results and conclusions’ met the 70% consensus threshold.

Items considered unnecessary

In the second round, 36 items (35%) were classified as ‘does not need to be reported’ by at least 70% of respondents (see Appendix 7). The degree of consensus ranged from 73% to 93%. This emphasises the much higher level of consensus among respondents relative to that seen in the first round.

Items considered relevant to specific types of case study

Seventy-two items (70%) were considered by at least one respondent to be appropriate in certain contexts but not others. Methodological approaches identified by respondents included ‘quantitative’, ‘qualitative’, ‘positivist’, ‘realist evaluation’, ‘explanatory case studies’ and ‘participatory/action research’. Other types of case study identified included ‘NHS based’, ‘policy-sponsored research’ and ‘charity-funded evaluations’. Respondents very rarely expanded on these labels.

However, there was no consensus that any item should be considered relevant to a particular type of case study (where method-specific items were identified, agreement ranged from 0% to 33%).

Items with no overall consensus

Fifty-two items failed to meet the 70% consensus threshold for either inclusion or rejection (see Appendix 8).

Combining counts of ‘should be reported for all organisational case studies’ with counts of ‘should be reported for the following type of organisational case study . . .’ would result in just three additional items achieving a 70% ‘overall positive’ consensus [‘state whether an inductive or deductive approach to the analysis has been taken’, ‘discuss the sampling (or case selection) and explanation of sampling strategy’ and ‘describe the data collection tool(s) (e.g. questionnaire or observational protocol, including a description of any piloting or field testing of the tool)’ (Table 8)].

| Item | Should be reported for all | Should be reported for specific types | Does not need to be reported | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State whether an inductive (e.g. grounded) or deductive (hypothesis testing/theoretical framework) approach to the analysis has been taken | 66.7% | 6.7% | 26.7% | It should be obvious |

| Discuss the sampling (or case selection) and explanation of sampling strategy | 66.7% | 6.7%a | 26.7% | Studies of heterogeneous populations of organisationsa |

| Describe the data collection tool(s) (e.g. questionnaire or observational protocol, including a description of any piloting or field testing of the tool) | 60% | 13.3%b,c | 26.7% | ’One that you want to publish in a positivist journalbWhen new or idiosyncratic data collection methods were usedc |

Chapter 5 Translating high-consensus Delphi items into reporting standards for organisational case studies

As an additional step in the development process, we applied the list of high-consensus items to all example and exemplar case study publications identified earlier in the review process, in order to (1) determine the relevance of these items to the reporting of real-world organisational case studies and (2) better understand how the results of the Delphi consensus process consultation might best be implemented as reporting standards. As stated in Chapter 2, Translating high-consensus Delphi items into reporting standards for organisational case studies, these were subjective assessments applied in retrospect by one reviewer and were used as practical examples to help with the development of the reporting standards and are not intended to be taken as a critical appraisal of the publications.

Example case studies

The high-consensus reporting items were applied to all 17 publications of the eight example organisational case studies (Table 9).

| Category | High-consensus items (see key) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Data collection | DA | Interpreting the results | ||||||||||||

| Case study | First author (publication type) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 1 | Attree57 | (J) | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | P | P | N | P | Y | Y |

| Cooke58 | (J) | Y | Y | N | P | Y | Y | Y | P | N | N | P | Y | N | |

| 2 | Field59 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | P | Y | N |

| Reid69 | (J) | Y | Y | N | P | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | P | Y | N | |

| Reid68 | (J) | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | P | Y | N | |

| 3 | Hutchinson61 | (J) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | N | N | P | Y | N |

| 4 | Kyratsis62 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | P | Y | Y |

| Kyratsis63 | (J) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| 5 | National Nursing Research Unit64 | (R) | N | Y | P | Y | Y | Y | N/A | P | P | N | U | U | N |

| Robert71 | (J) | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| 6 | Offender Health Research Network73 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Ricketts70 | (J) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| 7 | Payne65 (methods paper) | (J) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Payne67 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| Payne66 | (J) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | |

| Hawker60 | (J) | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | P | N | P | Y | P | |

| 8 | Rolls72 | (J) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | P | Y | N | Y | U | U | N |

Five of the eight case studies published reports. 59,62,64,67,73 One report from the National Nursing Research Unit appeared to be aimed at end users and contained little methodological detail. 64 All the case studies had at least one journal publication. One journal article65 provided some methodological detail for three of the included case studies and their publications. 59,60,66–69,72

Two linked publications exploring patient safety in the English pre-registration degree nursing curriculum met some of the criteria for describing the design,57,58 though one did not state the research questions/hypotheses (item 3)58 and neither fully identified the specific cases and justified selection (item 4). Both fully described data collection (items 5–7), but only partially described the analysis methods (item 8). Both poorly reported items related to interpreting the results (items 9–13).

A similar pattern of reporting was found in four linked publications evaluating adult hospice bereavement support services, which included a report,59 two journal articles68,69 and a stand-alone paper which reflected on the methods employed in this and other case studies. 65 The journal articles make reference to the full report, but the number of items reported was similar across all the publications. However, the journal articles do not state the research questions/hypotheses (item 3) and either did not report or only partially reported how the specific cases were identified and the selection was justified. Across these publications, there was generally poor reporting on the items relating to interpreting the results (items 9–13). The overarching methodological paper by Payne et al. was published after the three case studies were published and so was not referenced in the report or journal articles. 65

A case study to examine managing ward managers for roles in human resource management generated only one publication;61 this satisfied all the items for describing the design (items 1–4), collecting data (items 5–7) and describing the analysis (item 8). However, items for interpreting the results were poorly reported (items 9–13).

A study to understand the impact of differing organisational capacity and contextual circumstances on technology selection, procurement and implementation included a report62 and a journal article. 63 The items on describing the design (items 1–4) were all reported. Two questions related to describing the data collection were reported (items 5 and 6), but the item relating to ethical considerations (item 7) was not reported for either publication. The journal article63 reported all items for interpreting the analysis, but the report did not. 62

A study looking at issues of local implementation of ‘The Productive Ward’ programme included a report and a journal article. 64,71 The report appeared to be aimed at end users. Three items were reported or partially reported for design (items 2 to 4), two for data collection (items 5 and 6), one partially reported for data analysis (item 6), and one partially reported for interpretation of results (item 9). 64 The journal article reported more of the high-consensus Delphi items. Two items were reported in design (items 2–4), two in data collection (items 5 and 6), one in data analysis (item 9) and three for interpreting the results (items 11–13). 71

One report73 of a case study evaluating prison mental health in-reach services reported all high-consensus Delphi items. The associated journal article70 reported 12 of the 13 criteria, but did not report research questions/hypotheses (item 3).

A case study used to identify how palliative care for elderly people is delivered was published as a report67 and two journal articles,60,66 as well as being linked to the methods paper mentioned earlier. 65 The report reported all high-consensus Delphi items. 67 Items describing the design (items 1–4) were well covered in one article,66 but the other article60 reported neither the broad aims of the study (item 2) nor the research questions/hypotheses (item 3). Reporting of the data analysis and interpreting the results was generally well covered in one article66 but less so in the other publication. 60 Both the report and journal articles were published before the Payne et al. methodological paper65 and therefore did not explicitly reference it.

A case study examining the context and processes of childhood bereavement services72 was also linked to the above-mentioned methods paper. 65 This journal article did not state the research questions or hypotheses (item 3) and only partially reported on ethical considerations (item 7). Items relating to interpreting the data were also poorly reported. The journal article was published before the Payne et al. methodological paper65 and therefore did not explicitly reference it.

In summary, two publications reported less than 50% of the items,58,64 eight reported between 50% and 70% of items,57,60–62,68,69,71,72 four reported over 70% of items,59,63,70,66 and three reported all the high-consensus items. 65,67,73 Across all publications, the items describing the design (items 1–4), data collection (items 5–7) and the analysis (item 8) were largely reported. There was variation in reporting on interpretation of results and several studies either did not report or only partially reported their methods.

There was no clear pattern in the number of items being reported between journal articles and reports. This was a relatively small sample of publications aimed at different audiences, so it would not be appropriate to draw conclusions on levels of reporting within different types of publications.

These publications covered a range of case study methodology and were aimed at different audiences (e.g. end users); therefore, the lack of reporting should not be taken to mean a lack of quality in the methods used, nor as implied criticism of the original authors.

Exemplar case studies

Of the 12 exemplars, only seven had published reports. 2,3,7,74,75,77,81 Of these, two had a single additional journal article and one had two related journal articles. 5,6,78,81 The 13 high-consensus Delphi items of reporting standards were applied to each of the 11 publications (Table 10).

| Category | High-consensus items (see key) | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Data collection | DA | Interpreting the results | ||||||||||||

| Case Study | First author (publication type) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

| 1 | Checkland2 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 2 | Drennan74 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 3 | Gillard3 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 4 | Martin7 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | P | P | Y | Y | N |

| Martin6 | (J) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | |

| 5 | Currie5 | (J) | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | P | P | Y | Y | P |

| 6 | McCourt75 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| 7 | Raine77 | (R) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Raine78 | (J) | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

| 8 | Waring82 | (R) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Waring81 | (J) | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |

Six out of 11 of the publications reported all 13 of the high-consensus Delphi items. 2,3,74,75,81,82

Three publications for one case study did not fully meet all the items. 5–7 One report, which included data on follow-up to previous case study sites, did not explicitly state that the authors had ethical approvals, access or permissions (item 7). 7 The authors appeared to partially describe shortcomings in the design and analysis and how these might have influenced the findings (item 9). They only partially considered the appropriateness of methods used (item 10) and did not state any caveats about the study (item 13).

The two journal articles associated with the report also did not meet all the items. 5,6 One article, which was partly linked with the main HSDR programme-funded project detailed in the report, did not state the research question/hypotheses (item 3), nor did it describe any shortcomings in the design (item 9), consider the appropriateness of methods used (item 10) or state any caveats about the study (item 13). 6 The other article, published prior to the report, also did not state the research question/hypotheses (item 3). 5 There was no reporting of ethical considerations (item 7). There was only partial reporting of any inherent shortcomings in the design and analysis and how these might influence findings (item 9), consideration of the appropriateness of methods used (item 10) and caveats about the study (item 13).

A report77 and a linked journal article78 reported 12 out of 13 of items, but did not define the research as a case study (item 1). The authors of this study stated it was a prospective observational study but, because it contained many elements of an organisational case study, it was recommended by the HSDR programme for this project.

In summary, one exemplar publication5 reported 61% of the reporting standards, two6,7 reported 69% and six2,3,74,75,81,82 reported all of the reporting standards. The journal articles largely reported the same criteria as the corresponding reports. As with the example case studies above, these publications covered a range of case study methodology and were aimed at different audiences; therefore, the lack of reporting should not be taken as an indication of a lack of quality in the methods used in the studies themselves, nor as implied criticism of the original authors.

As a whole, the exemplar case studies (which had been considered methodologically strong by the HSDR programme team) more consistently reported the high-consensus Delphi items than did the example case studies drawn from the review searches. Of 11 exemplar publications, six (55%) reported all 13 items, compared with just 3 out of 17 (18%) of the example organisational case study publications.

Generic consensus-based reporting standards for organisational case studies

The exemplar organisational case studies identified by the HSDR programme as being of high quality were far more consistent with the high-consensus Delphi items than were a group of example case studies identified purely on the basis of topic relevance. If the latter group of studies are representative of the wider field of organisational case study research, then there is clearly scope to use the identified items to improve the improve the consistency and rigour of reporting in this area.

Though the high-quality case studies used different methodological approaches, they were consistent with one another on the high-consensus Delphi reporting items. This suggests that, although these items can detect consistency and rigour of reporting, they are also sufficiently generic to be applied to a variety of organisational case study methods.

The fact that journal articles sometimes satisfied more items than longer reports for the same case study suggests that the length of a publication is not necessarily related to how clearly the research methods are reported. This may be a deliberate choice. For example, authors may choose to exclude certain items from a report aimed at practitioners or policy-makers, yet include those same items in an academic journal article aimed at other researchers.

Similarly, there may be legitimate methodological reasons for a particular item not being reported. For example, a researcher conducting a purely exploratory case study might not consider it appropriate to state an initial research question or hypothesis (item 3 on the reporting standards); in this case it would be perfectly legitimate to briefly outline the justification for not doing so in the report.

However, it is not always obvious whether the absence of certain information is deliberate or an oversight; any reporting standards for organisational case studies should be aware of this distinction. Therefore, unlike reporting standards such as PRISMA, which mandate the inclusion of every item in a report,14 the reporting standards proposed in Table 11 require the author to refer to a place where the reporting item was reported or where justification for the absence of the item can be found. This approach intends to balance the research freedoms of the knowledgeable researcher with the information needs of the end user.

| Reporting item | Page number on which item was reported | Page number of justification for not reporting |

|---|---|---|

| Describing the design | ||

| 1. Define the research as a case study | ||

| 2. State the broad aims of the study | ||

| 3. State the research question(s)/hypotheses | ||

| 4. Identify the specific case(s) and justify the selection | ||

| Describing the data collection | ||

| 5. Describe how data were collected | ||

| 6. Describe the sources of evidence used | ||

| 7. Describe any ethical considerations and obtainment of relevant approvals, access and permissions | ||

| Describing the data analysis | ||

| 8. Describe the analysis methods | ||

| Interpreting the results | ||

| 9. Describe any inherent shortcomings in the design and analysis and how these might have influenced the findings | ||